Reginald Little

The ConTextos Authors Circle was developed in collaboration with young people at-risk of, victims of, or perpetrators of violence in El Salvador. In 2017 this innovative program expanded into Chicago to create tangible, high quality opportunities that nourish the minds, expand the voices and share the personal truths of individuals who have long been underserved and underestimated. Through the process of drafting, revising and publishing memoirs, participants develop self-reflection, critical thinking, camaraderie and positive self-projection to author new life narratives.

Since January 2017 ConTextos has partnered with Cook County Sheriff's Office to implement Authors Circle in Cook County Department of Corrections as part of a vision for reform that recognizes the value of mental health, rehabilitation and reflection. These powerful memoirs complicate the narratives of violence and peace building, and help author a hopeful future for human beings behind walls, their families and our collective communities.

While each author’s text is solely the work of the Author, the image used to create this book’s illustrations have been sourced by various print publications. Authors curate these images and then, using only their hands, manipulate the images through tearing, folding, layering and careful positioning. By applying these collage techniques, Authors transform their written memoirs into illustrated books.

This project is being supported, in whole or in part, by federal award number ALN 21.027 awarded to Cook County by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

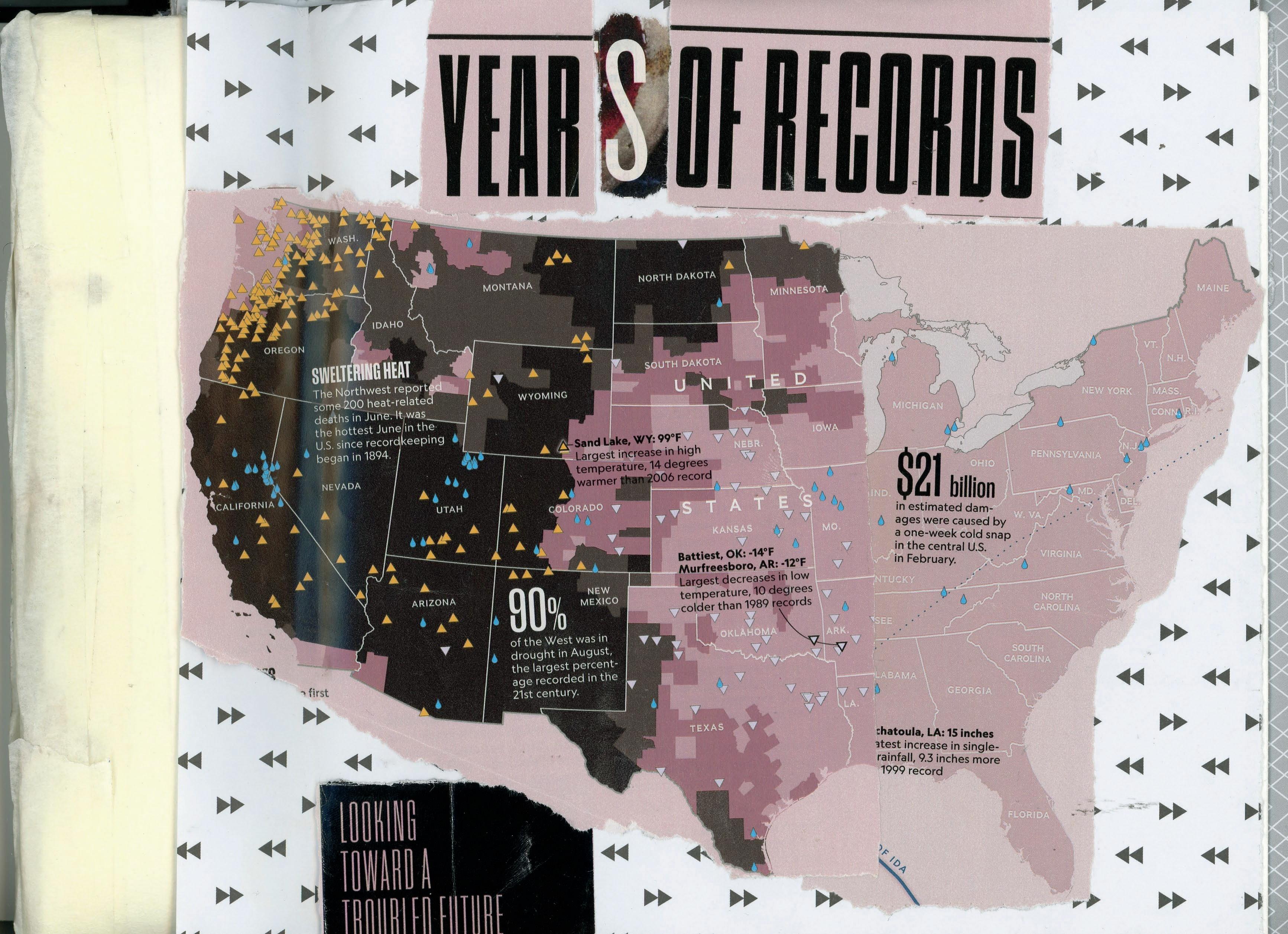

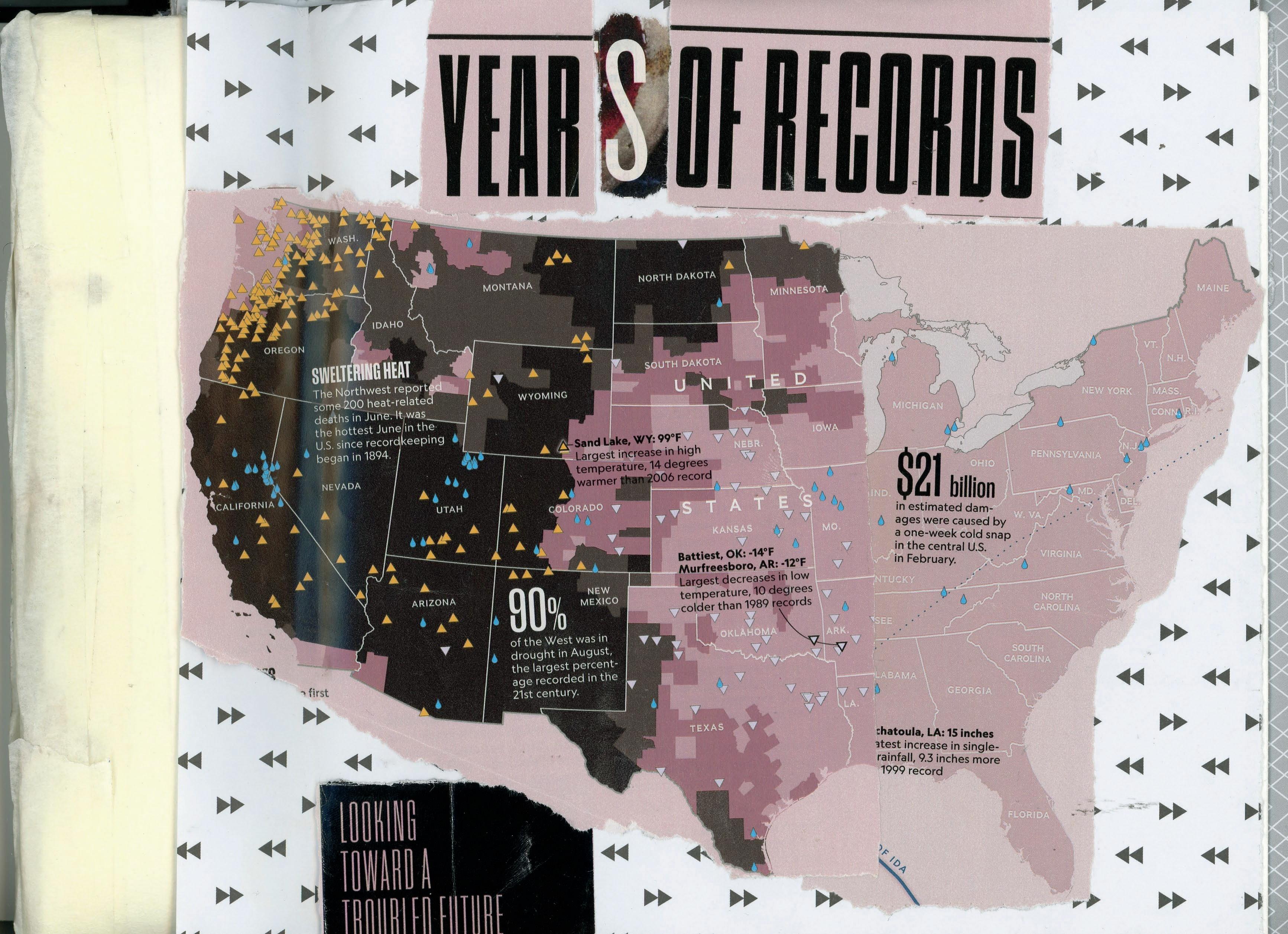

Reginald Little Years of Records

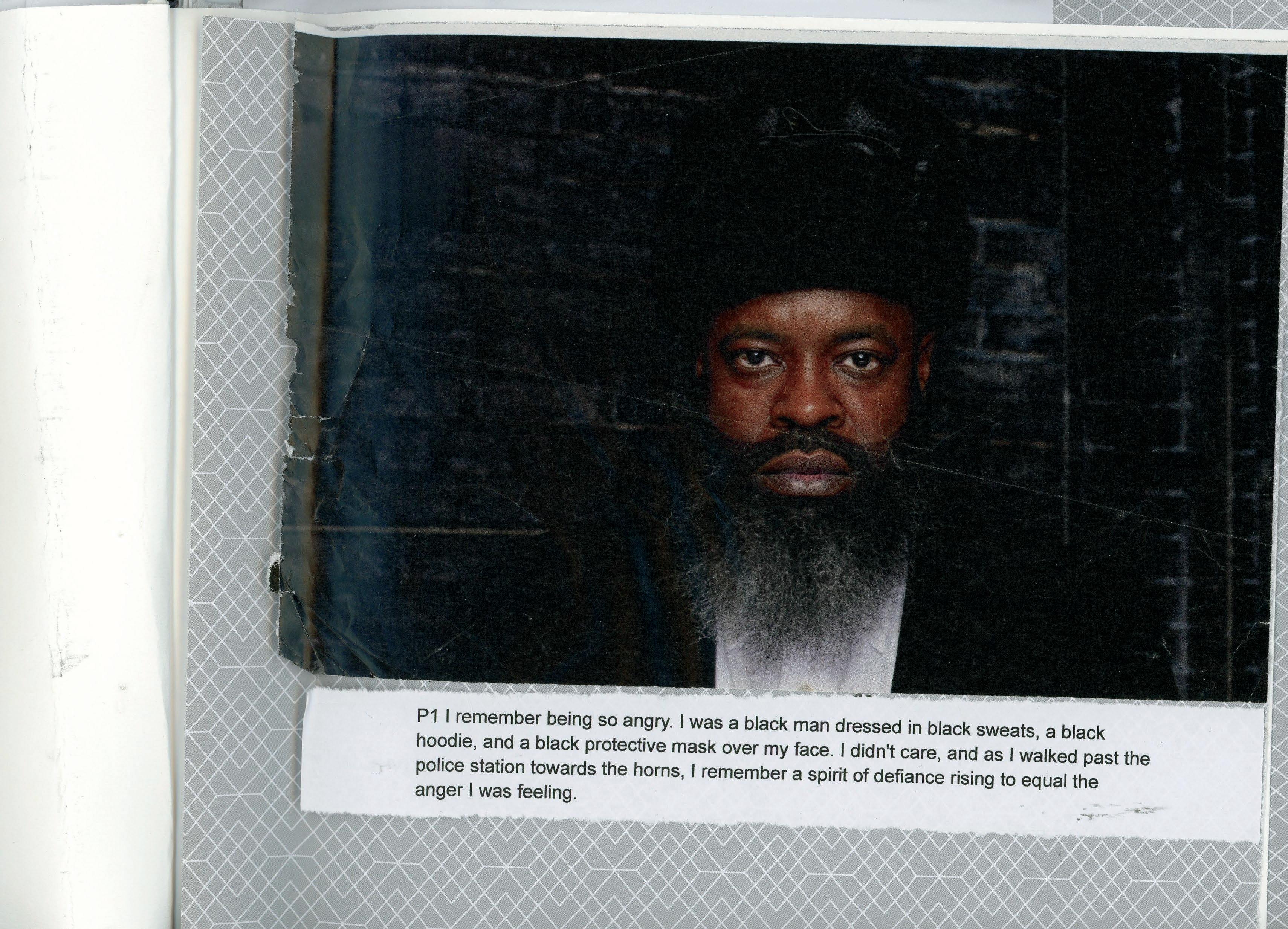

I remember being so angry. I was a black man dressed in black sweats, a black hoodie, and a black protective mask over my face. I didn't care, and as I walked past the police station towards the horns, I remember a spirit of defiance rising to equal the anger I was feeling.

I got around the anger I was feeling. I got around the corner to where the horns should have been. Instead of finding hundreds of similarly angry citizens calling out for justice, and drivers honking their horns in defiant agreement.

I found absolutely nothing. I was confused. I walked back to my little house, disappointed, and found myself on the couch staring at the fireplace once again. And then came the same damn horns coming from the same place. This time, I immediately got up and walked in the direction of the sound.

It took me to the gate at the back of the police station. I looked at the camera, and for the first time, I thought that I might look suspicious.The sound was coming from the opposite side of the building. I took the same walk, following the horns, and once again I found nothing. My walk back was slower this time.

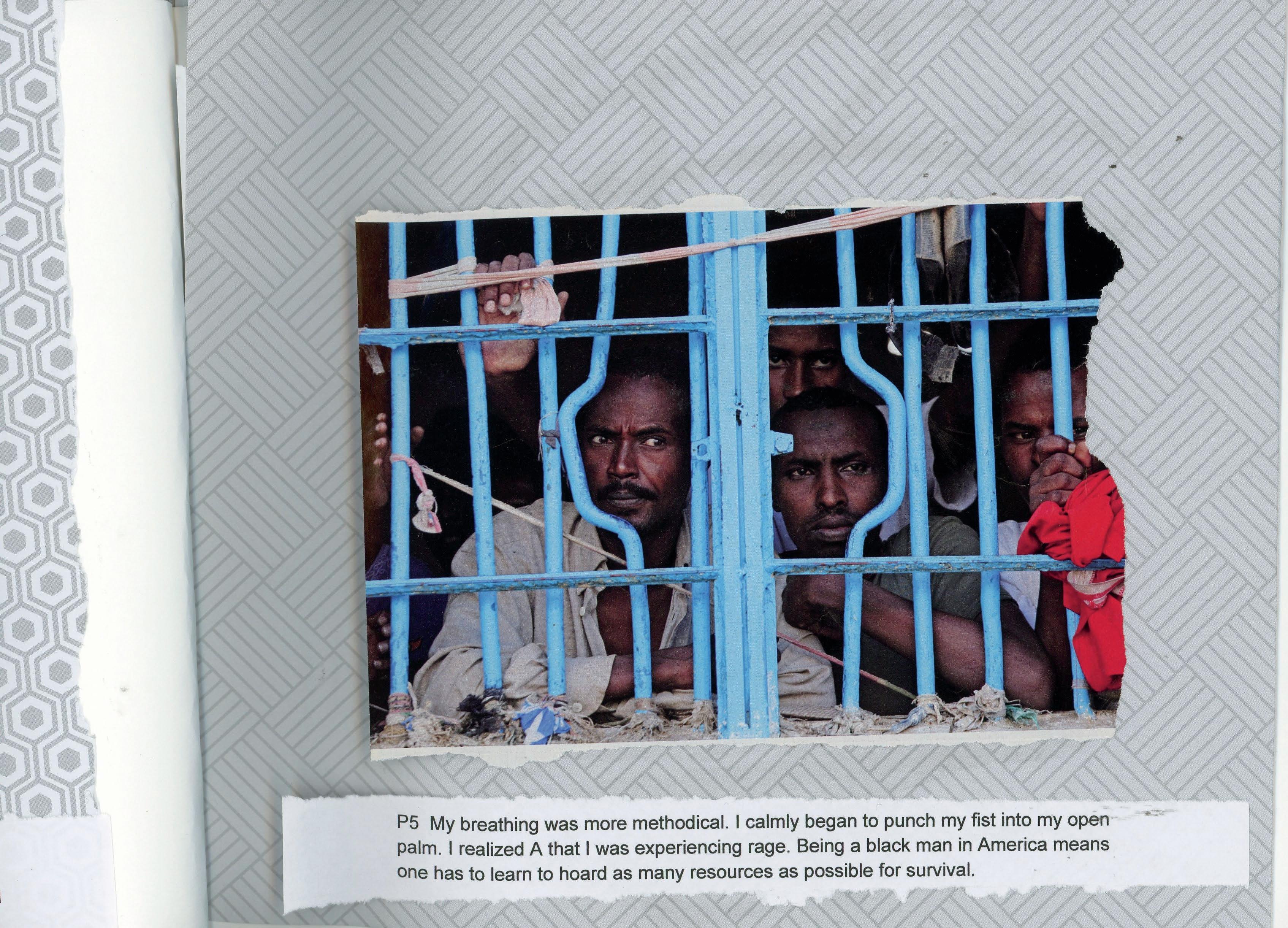

My breathing was more methodical. I calmly began to punch my fist into my open palm. I realized A that I was experiencing rage. Being a black man in America means one has to learn to hoard as many resources as possible for survival.

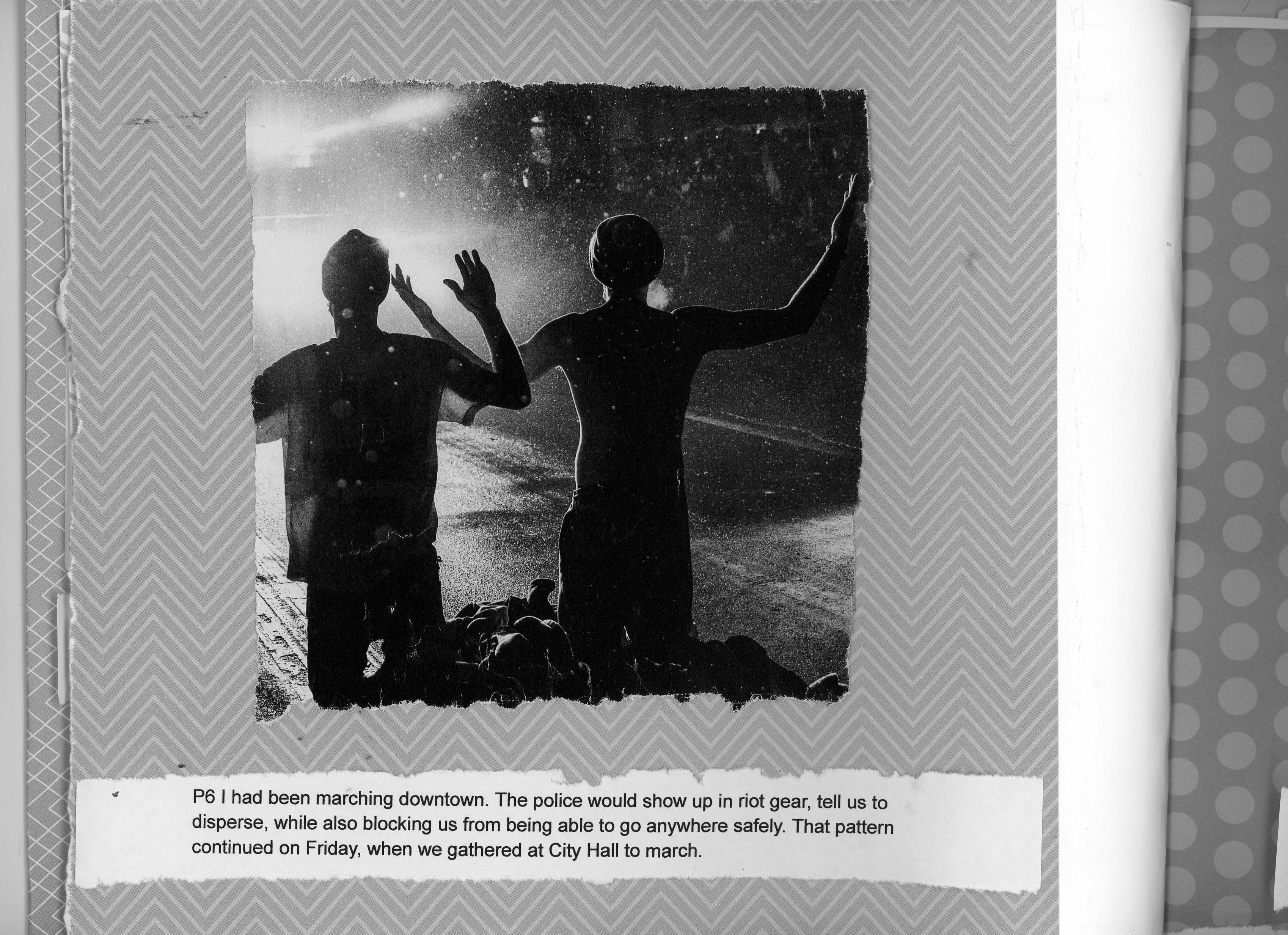

I had been marching downtown. The police would show up in riot gear, tell us to disperse, while also blocking us from being able to go anywhere safely. That pattern continued on Friday, when we gathered at City Hall to march.

I remember feeling a baton hit me, and we all began to run. We saw a parking lot over there, too. Two minutes after that, I saw police officers aim at protestors. I see one aim in my direction, ready to shoot his rubber-bullet gun. I turned left to try to escape, and as I turned, I felt the impact on my face.

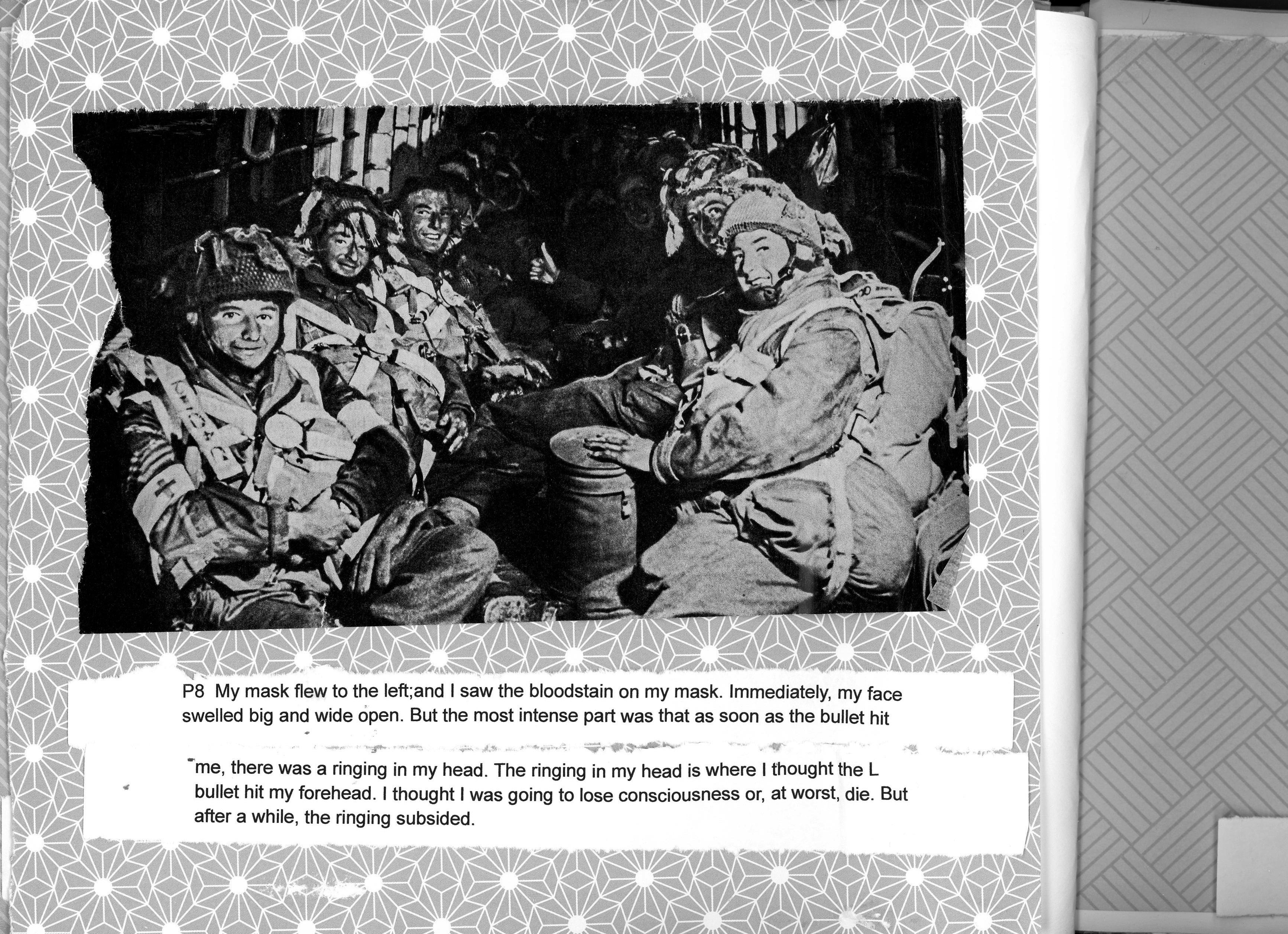

My mask flew to the left;and I saw the bloodstain on my mask. Immediately, my face swelled big and wide open. But the most intense part was that as soon as the bullet hit me, there was a ringing in my head. The ringing in my head is where I thought the L bullet hit my forehead. I thought I was going to lose consciousness or, at worst, die. But after a while, the ringing subsided.

My friend started carrying me out. Then I completely fell on the ground. A medical professional who was protesting ran up, and the bullet had literally broken my face. She began to disinfect it and wrapped the wound with gauze.

We tried to hail an ambulance, but no one stopped. This woman I had just met, whose name I can't remember, drove me to the hospital. I remember them telling me I was the first protester admitted that day.

In the ER, I found out that my entire zygoma area, the bone under my eye, was fractured. I had two broken bones in my face. I had a head injury and a facial laceration where my head was busted open that required twenty-seven stitches. I was there until midnight. Then I went home. I found out later, from an ophthalmologist, that the bullet hit me an inch from my forehead and my eye.

That was a sort of blessing. I could've been blinded or had a deadly head injury. I come from a spiritual background, and there is this constant thought and reflection, in which I ask God to use me. What would you have me do? As always part of my deeper reflection, there's trauma with this that becomes harder.

There's the dizziness, coughing up blood, things that make you scared to go to sleep, thinking you may not wake up. Then come the dreams and nightmares. I woke up in the middle of the night with the sensation of that ringing in my head, when I thought I was going to die. Besides the trauma, it's the idea of knowing that I feel changed.

In the story of that one afternoon in Chicago, I experienced feeling loneliness, depression, frustration with systemic oppression, anxiety about expressing anger in a Black body, and helplessness. One of the first times I remember experiencing any kind of victimization centered on my Blackness was during my freshman year at college. It was common to spend the entire night working in the gym.

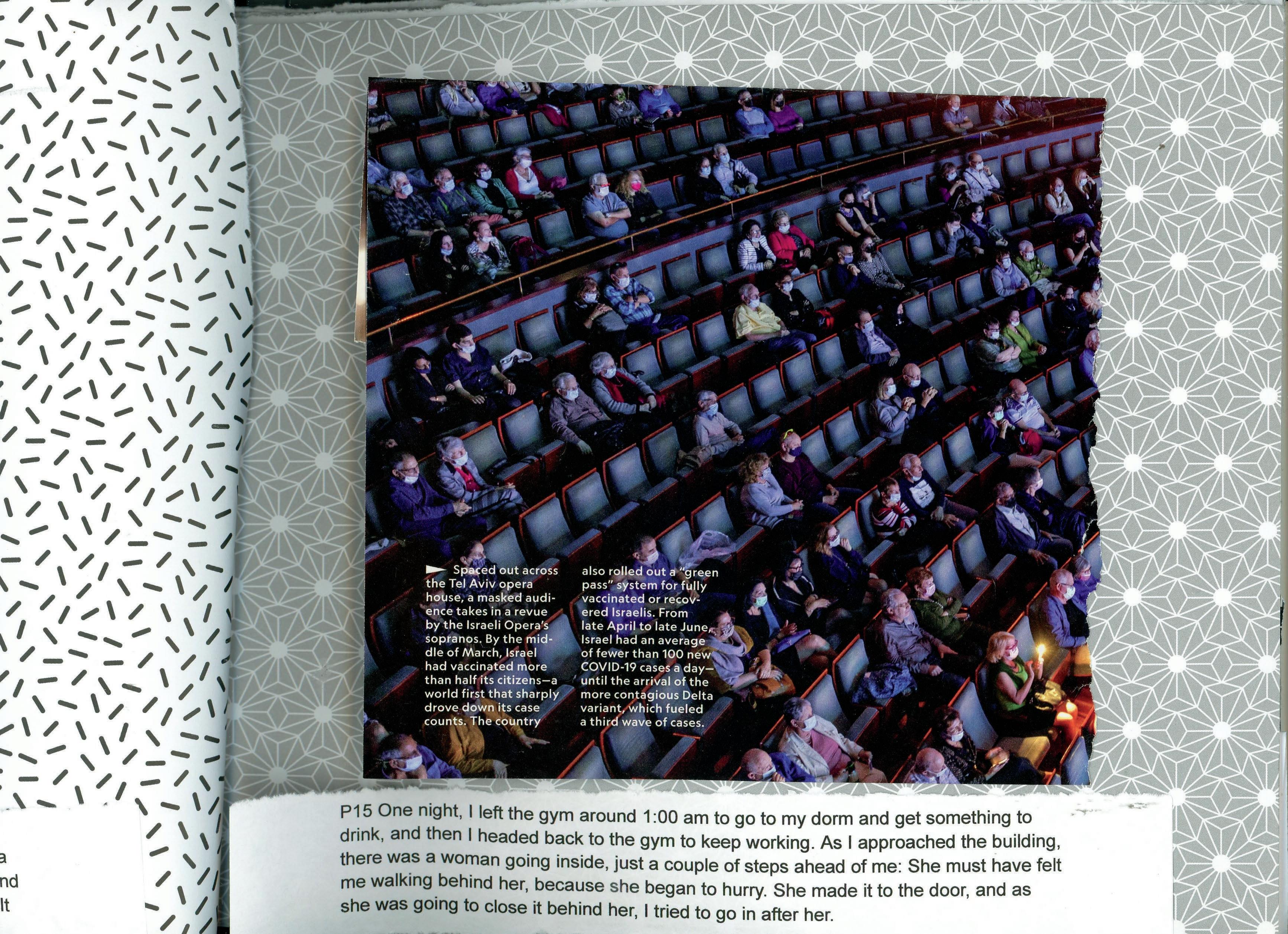

One night, I left the gym around 1:00 am to go to my dorm and get something to drink, and then I headed back to the gym to keep working. As I approached the building, there was a woman going inside, just a couple of steps ahead of me: She must have felt me walking behind her, because she began to hurry. She made it to the door, and as she was going to close it behind her, I tried to go in after her.

She turned around and pulled on the door and wouldn't let me in. She said,-"Stop, you don't belong here". I said "What are you talking about? I'm going to the gym. I'm going to the same place as you " . And she said, "Please stop. You don't belong here". As we stood on either side of the door, still slightly open, I went to pull out my I.D to say, "Look, I'm a student too". She* said, "I'm going to call the police and tell them that you ' re trying to rape me " . I pulled the door open and she began running and screaming at the top of her lungs. "Help! Help! He's trying to rape me"! It's 1:00 am and I'm trying to get her to be quiet, but she's still screaming, so I just stopped and let her walk. I knew there was no rationalizing with this person.

Two minutes later, I walked into the gym and sat down. I saw her across the room, but she wouldn't make eye contact. The campus police came in because she called them. They asked her to step out to talk, and then they called me out to ask what happened. They apologized and left. What more could they do? I went back to my workout area, and I remember being so angry that I cried. It was frustrating. I deserved to be there. Period. That was my reminder that even if I did everything right, played the game by the book, some things in life would be unavoidable.

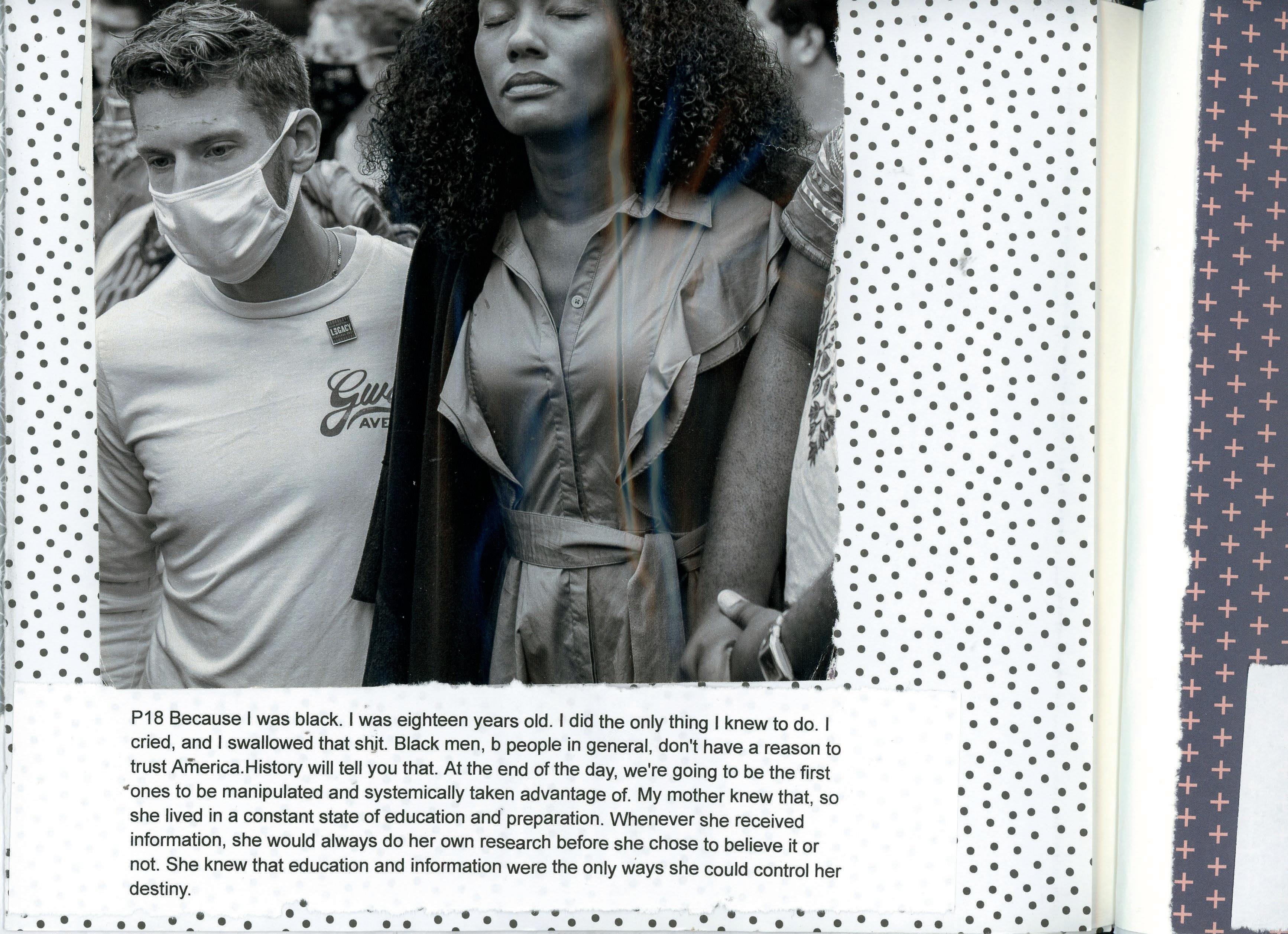

Because I was black. I was eighteen years old. I did the only thing I knew to do. I cried, and I swallowed that shit. Black men, b people in general, don't have a reason to trust America.History will tell you that. At the end of the day, we ' re going to be the first ones to be manipulated and systemically taken advantage of. My mother knew that, so she lived in a constant state of education and preparation. Whenever she received information, she would always do her own research before she chose to believe it or not. She knew that education and information were the only ways she could control her destiny.

My mother is Mary, and I grew up with the same view of therapy that a lot of other black Christians from the south. I held the belief that prayer was the answer to everything. It wasn't until 2017 that I finally motivated myself to go. I found a black therapist, a woman, and within three minutes, I'm telling her everything. I'm comfortable because she can relate, and I trust her. She's black. We speak the same language.

With my therapist, I wanted to be able to talk about being black, I wanted to be able to use my vernacular.

I didn't want to have to explain what it felt like to have to explain what it felt like to have someone follow me around the store.

I just wanted to talk about the fact that it happened and have that person understand. Eventually, I left therapy with a better sense of self. Then I began telling everybody about it. Man, I started doing therapy, and it changed my life! It changed the way that I believed in myself, the way that I began to move through the world.

I had a completely new understanding of what therapy could be, and as I'd talk to my friends about it, they would say, "Yeah, I've been thinking about therapy too". There was this collective curiosity that I didn't even know was there.

Historic disenfranchisement kept those resources out of reach - to the point that many believed that our rejection of therapy was primarily cultural.

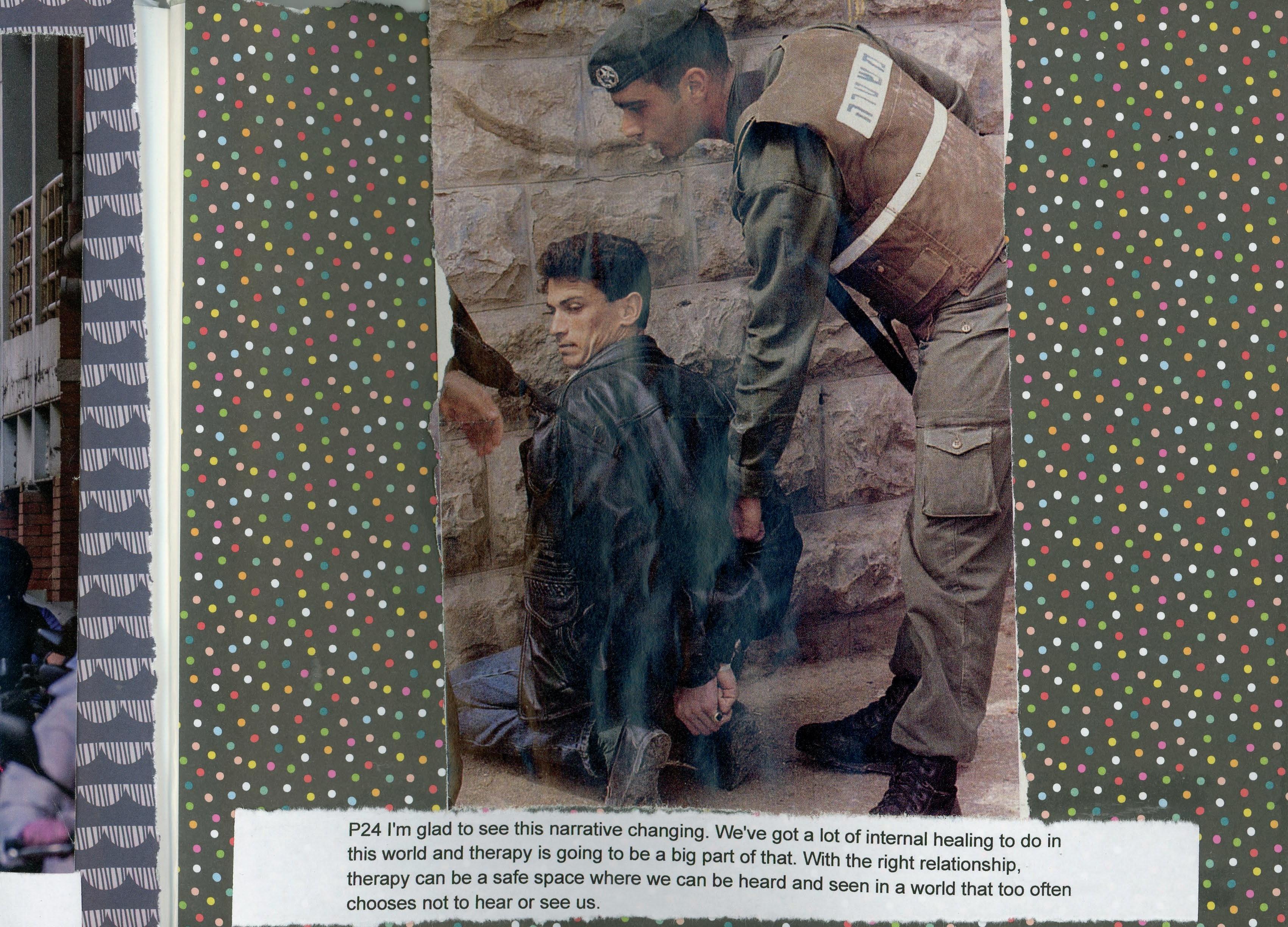

I'm glad to see this narrative changing. We've got a lot of internal healing to do in this world and therapy is going to be a big part of that. With the right relationship, therapy can be a safe space where we can be heard and seen in a world that too often chooses not to hear or see us.

Reggie Little

I Am From

I’m from Chicago

From the the first black mayor and president

I am real blackness

I am from the dirt on the ground

And roots from the tree

I’m from Mary and Wilbur

From Sunday morning church

And from love

I’m from you have no friends

And from a hard head makes a soft ass

I’m from God the father

I’m from the rack

From fried chicken, sweet corn and greens

From MJ. MLK. Malcolm X

I am from self love

Until the lion learns to write their own story, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter - African Proverb