25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, October 30, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, October 31, 2025, at 1:30

Saturday, November 1, 2025, at 7:30

J. STRAUSS, JR.

HINDEMITH

Overture to The Gypsy Baron

Symphony, Mathis der Maler

The Angelic Concert

The Entombment

The Temptation of Saint Anthony

INTERMISSION

DVOŘÁK

Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95 (From the New World)

Adagio—Allegro molto

Largo Molto vivace

Allegro con fuoco

These performances are made possible by the Juli Plant Grainger Fund for Artistic Excellence. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

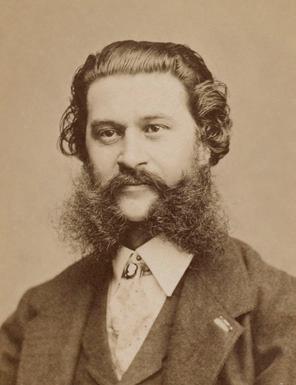

JOHANN STRAUSS, JR.

Born October 25, 1825; Vienna, Austria

Died June 3, 1899; Vienna, Austria

Even Brahms and Wagner, the two competitive, heavyweight composers of the era, shared a great fondness for the music by Johann Strauss, Jr. It’s difficult today to imagine music that is so popular with average people and connoisseurs, liberals and conservatives, young and old alike, and to realize that, in the nineteenth century, this music was serious business, if not serious music.

Johann Strauss, Sr., a gifted composer who started the family dynasty, tried to dissuade his three sons from the music industry, but he lost on all three counts. According to Johann Strauss, Jr., he and his brothers learned everything they knew from their father. “We boys paid close attention to every note,” he later said, recalling how they would try to recreate his style when they played the piano at social gatherings.

We familiarized ourselves with his style and then played what we had heard straight off, exactly in his spirited manner. He was our ideal. We often received invitations to visit families . . . and would play from memory, and to great applause, our father’s compositions.

Before Johann, Sr., died in 1849, at the age of forty-four, he saw his oldest son, Johann, Jr., surpass him in fame and fortune. Johann Strauss, Jr., wasn’t a particularly happy man—he married three times in an age when such behavior was exceptional, and he was regularly given to dark moods—but the music he wrote projects an aura of an almost hypnotic cheer and frivolity. At the height of his popularity, the younger Strauss employed several orchestras (all bearing his name) and dashed from one ballroom to another to put in a nightly appearance with each. Eventually Johann Strauss, Jr., would be acclaimed as the Waltz

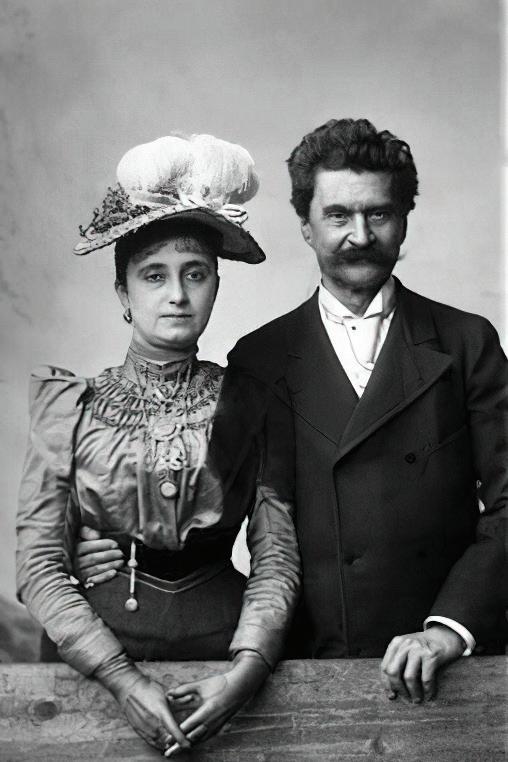

this page, from top : Johann Strauss, Jr., portrait by Fritz Luckhardt (1833–1894), 1899. Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris | Adele (1856–1930) and Johann Strauss, Jr., at Bad Ischl, Austria, ca. 1895, as photographed by Rudolf Krziwanek (1843–1905). Austrian National Library, Vienna | opposite page: Johann Strauss, Jr., and His Band at the Court Ball. Print after a painting by Theo Zasche (1862–1922), 1888

COMPOSED 1885

FIRST PERFORMANCE

October 24, 1885; Vienna, Austria

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion, harp, strings

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

June 30, 1940, Ravinia Festival. Eugene Ormandy conducting December 31, 1951, Orchestra Hall. George Schick conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 16, 1968, Ravinia Festival. Willi Boskovsky conducting

December 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, and 23, 2022, Orchestra Hall. Alastair Willis conducting

King, although he wrote nearly as many polkas as waltzes and could have earned his reputation on the basis of his sixteen operettas alone.

It was Strauss’s first wife, Henriette, a soprano, who convinced him to try his hand at writing operettas. Indigo and the Forty Thieves was his first, premiered in Vienna in 1871, the year before Strauss made a highly successful tour of the United States, and he soon spun out a steady stream of hits, including the one that has achieved the most lasting fame, Die Fledermaus, three years later. It was his third wife, Adele, who introduced Strauss to the novel Saffi by the

Hungarian writer Mór Jokai, suggesting that its mix of Viennese gayety and gypsy exoticism would be ideal territory for musical treatment. The Gypsy Baron, as it was titled, is often regarded as Strauss’s first attempt to turn away from the frivolity of operetta and draw closer to the more serious nature of the opera. It was a great international success following its Vienna premiere in October 1885 and is still performed with some frequency today. The brilliant overture, flavored with abundant exotic touches and featuring a big waltz tune, is stamped throughout with the unmistakable Strauss genius.

PAUL HINDEMITH

Born November 16, 1895; Hanau, near Frankfurt, Germany

Died December 28, 1963; Frankfurt, Germany

Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933. Paul Hindemith was not Jewish, but his wife, Gertrude, was half Jewish by birth—it was she who later prompted Hermann Göring to make his often-quoted remark, “I’ll decide who’s Jewish”—and so the composer was particularly watchful of the new government’s policies. Later that year, he abandoned work on an operatic love story and turned his attention to the tale of the German painter Mathias Grünewald, who was torn between a self-centered commitment to his art and a life of political activism.

Mathis der Maler (Mathis the Painter) became Hindemith’s personal testament, conceived during the most challenging and difficult period in his life. It is his magnum opus. For nearly three years, he worked on little else, and every day he grappled with the relationship between music and politics and pondered the artist’s responsibility when the world around him is torn apart by violence and hatred. Regularly, if privately, he weighed the value of his own work—at a time when art, to many, seemed a horribly selfish, if not completely irrelevant, pastime.

In the end, both Grünewald and Hindemith come down on the side of art, although the painter’s dilemma, during the Peasants’ Revolt that followed the Reformation, was neither as complicated nor as treacherous as that of a well-intentioned composer working in Hitler’s Germany. Hindemith’s choices were not always easy ones, and his decisions did not satisfy everyone. For several years he remained in Germany, watching, one by one, his Jewish colleagues Arnold Schoenberg, Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, and Artur Schnabel—as well as his own chamber music partners, Emanuel Feuermann and Szymon Goldberg—leave the country. Hindemith’s brother-in-law spent a year in a concentration camp.

Although Hindemith remained isolated from world events while he was writing Mathis der Maler, by the time it was completed in 1935, the opera put him in the middle of controversy. A broadcast of Mathis der Maler was canceled when word leaked out that Hindemith had once spoken disparagingly of Hitler. Wilhelm Furtwängler was advised not to stage the work

COMPOSED

November 1933–March 1934 (symphony)

FIRST PERFORMANCE March 12, 1934 (symphony)

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, glockenspiel, snare drum, cymbals, triangle, bass drum, strings

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

April 2 and 3, 1936, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting July 1, 1944, Ravinia Festival. Pierre Monteux conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

August 8, 1974, Ravinia Festival. Lawrence Foster conducting

October 4 and 5, 2018, Orchestra Hall. Riccardo Muti conducting February 15, 2020, Frances Pew Hayes Hall, Artis-Naples, Naples, Florida. Riccardo Muti conducting

this page : Paul Hindemith, portrait, 1931. Photo by Ullstein Bild DTL via Getty Images

opposite page: Detail from The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a panel from The Isenheim Altarpiece, painted by Mathias Grünewald (ca. 1470–1528), 1512–16

next spread: A stylized stage design by Helmut Jürgens (1902–1963) from a production of the opera Mathis der Maler, performed in Munich in 1948

because, he was told, Hitler had, years before, walked out of a performance of Hindemith’s News of the Day, incensed by the sight of a soprano singing from her bathtub. (She was extolling the joys of an apartment with hot running water.) Ultimately, Furtwängler rose to Hindemith’s defense with an essay that ran on the front page of local newspapers, and Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, made a speech denouncing the composer. Hindemith was no longer on the sidelines. In 1938 he was included—along with Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Irving Berlin, and Louis Armstrong—in the now-famous traveling show of “Degenerate Music.” That September the Hindemiths left Germany for a new home in Switzerland. (They moved to the United States in 1940 and became American citizens in 1946.)

The idea for an opera about Mathias Grünewald had been suggested to Hindemith by his publisher, Willy Strecker, in 1932. At first Hindemith was more interested in Strecker’s other suggestion—an opera about Gutenberg. But he quickly came to realize that the Grünewald story was not only timely, but of enormous personal significance. Eventually, he grew to understand that Grünewald’s story, in a sense, was his story. By the time the opera was done, Hindemith admitted that Grünewald’s experiences had “shattered his very soul.”

Mathias Grünewald was born in the third quarter of the fifteenth century and died, like his more famous German contemporary Albrecht Dürer, in 1528. Grünewald sympathized with the German peasants in the bloody uprisings that began in 1524, and, as a result, he lost the patronage of the cardinal-archbishop of Mainz. Ultimately, however, Grünewald realized the futility of his political actions and came to understand that only by returning to painting could he truly better mankind.

Grünewald’s masterpiece—his magnum opus—is the many-paneled altarpiece he painted around 1515 for a monastery and hospital in Isenheim, near Colmar. This great monument, one of the most powerful and expressive works in the history of art, is, in effect, the scenic

Shortly after Hindemith began work on the opera, Furtwängler asked him to write a new piece for the Berlin Philharmonic. Preoccupied as he was with Mathis der Maler, he decided to write a symphony on the same subject, taking its musical material from the pages of sketches that already cluttered his desk. The symphony was completed more than a year before the opera.

Each of the three movements represents one of the panels from Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece. The Angelic Concert, the opera’s overture, begins solemnly, with three resounding, organlike chords, followed by the trombones intoning an old German song, “Es sungen drei Engel ein’ süssen Gesang” (Three angels sang a sweet song). (The song is played three times, each time a third higher.) From there the movement takes wing, in sequences of radiant and soaring music.

The Entombment is a gentle—but ultimately fearless—meditation on death. It moves slowly toward a somber climax, with a resoundingly peaceful ending. Hindemith originally planned to use this music at the end of his symphony, as the last of four movements. For a while, when he did not know how to go on, he even considered leaving it a two-movement work. But then he seized on the idea of ending not with death, but with another of Grünewald’s panels, The Temptation of Saint Anthony. This turned out to be the symphony’s longest and most complex movement, written on deadline in just four weeks. The music is anguished and driven, then

tormented and seemingly defeated, until the winds begin to play the Gregorian Lauda Sion salvatorem (Zion, praise the Savior). The brass offer a glorious halo of alleluias at the very end. This is the proud music of hard-won triumph. As Hindemith wrote of Grünewald,

Caught in the powerful machinery of church and state, he had the strength to resist these forces, and in his painting he could report clearly enough how profoundly he was shaken by the wild tumult of his time, with all its suffering, its sicknesses, and its wars.

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

Born September 8, 1841; Nelahozeves, Bohemia (now Czech Republic)

Died May 1, 1904; Prague, Bohemia

Let’s start with Mrs. Jeannette Thurber, the wife of a New York millionaire wholesale grocer and a self-appointed cultural maven, who abandoned her English-language opera company (after putting a serious dent in her husband’s fortune) to foster an American school of composition.

Mrs. Thurber contacted Antonín Dvořák in June 1891 with her proposal. She wanted the famous Czech composer to move to America; become the director of the National Conservatory of Music, where he would teach composition and instrumentation (for an annual salary of $15,000); serve as a figurehead for her new cause; and, in his spare time, write a number of new works, including an opera based on Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. Oddly, Dvořák agreed.

As soon as the SS Saale completed the Atlantic crossing the composer had dreaded, Dvořák found himself an instant celebrity; he, in turn, became a keen observer of American life. When he wasn’t teaching—or conducting the conservatory choir and orchestra—Dvořák explored New York City. By day, he walked in Central Park to talk to the pigeons and dropped by Lower East Side cafes, where other central Europeans liked to hang out. At night he visited assorted watering holes. (One night he drank the distinguished critic James Huneker under the table.) He loved to check out the ocean liners along the wharves and clock the trains as their locomotives roared into the city’s stations. And, with Mrs. Thurber on his arm, he even attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

But how much of America’s musical tradition he absorbed is another question altogether. The question, in fact, was raised with the first major work Dvořák wrote in America, his Ninth Symphony, which came to be known as From the New World.

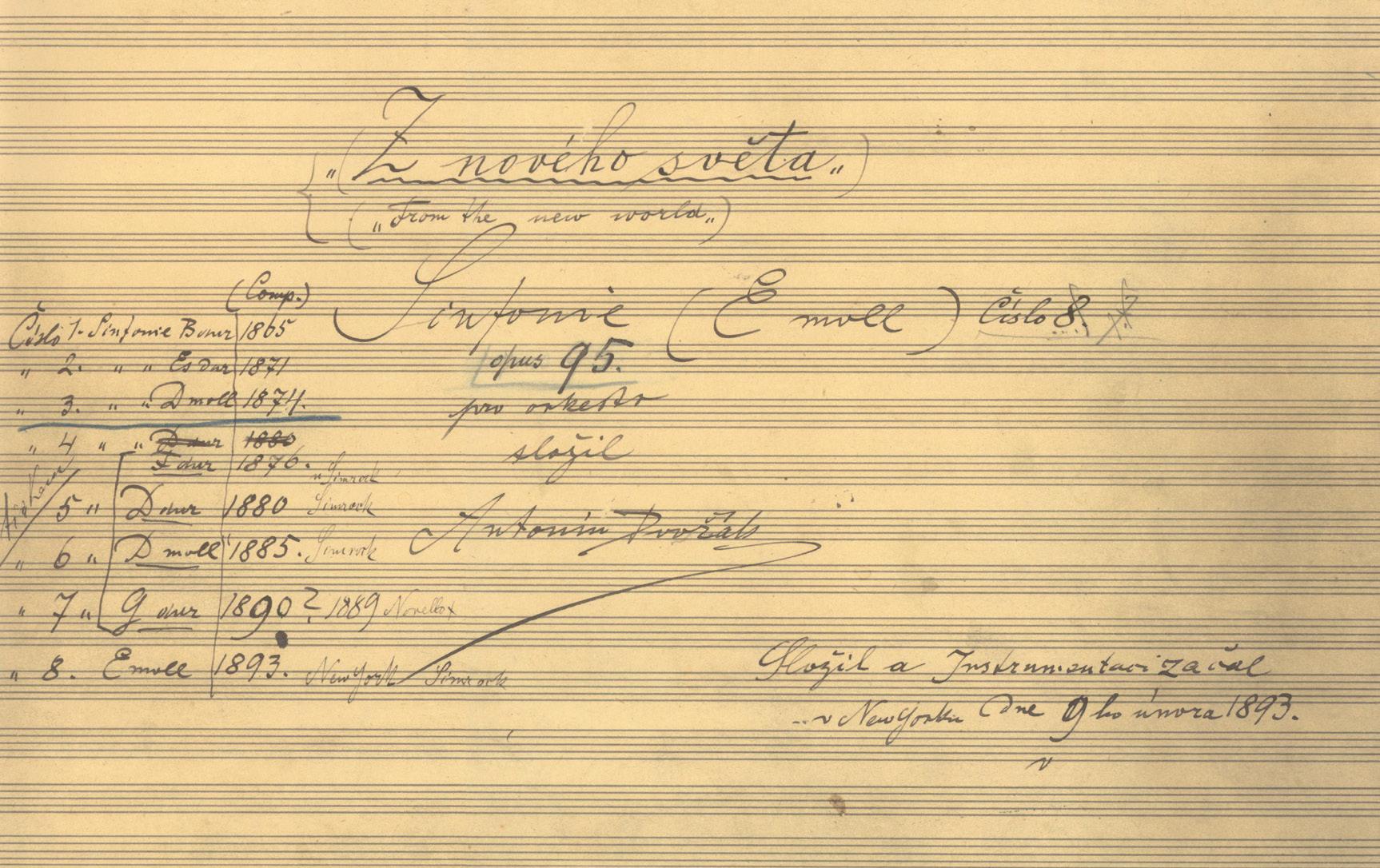

Dvořák began sketching his E minor symphony only three months after he arrived at the dock in Hoboken. (He was always meticulous about dating his manuscripts, both at the beginning and at the end of a piece, and the pages of the symphony tell us that he worked from January 10 until May 24, 1893.) And while he was writing his Ninth Symphony, he remarked, “The influence of America can be felt by anyone who has a ‘nose.’”

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 16, 1893, New York City

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling english horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, strings

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 2 and 3, 1894, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 23, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Isaac van Grove conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 16, 2022, Ravinia Festival. Marin Alsop conducting

March 23, 25, and 26, 2023, Orchestra Hall. Thomas Wilkins conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1951. Rafael Kubelík conducting. Mercury

1957. Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1977. Carlo Maria Giulini conducting. Deutsche Grammophon

1981. James Levine conducting. RCA 1983. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

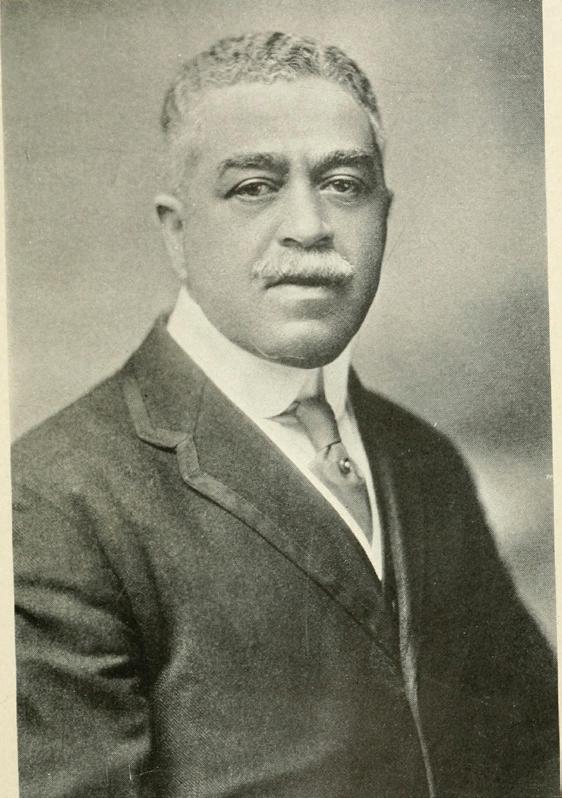

This is where the picture begins to blur. There’s no question that Dvořák was seriously interested in music of Indigenous Americans and African Americans. We know that he often invited Harry T. Burleigh, a gifted young Black singer, to perform spirituals for him. But during his first year in the New World, Dvořák made a number of comments that virtually guaranteed the acclamation of his new symphony as a genuine musical evocation of America and started lots of high-handed talk about the use of spirituals and Indian songs in a symphony. When, just before the first performance in December 1893, Dvořák added his title, From the New World, he continued the controversy.

It’s difficult to determine the extent of the American influence on Dvořák, but it’s fairly easy to lay to rest a couple of myths regarding Dvořák’s use of the pentatonic scale and a highly attractive tune. The pentatonic scale (a five-note scale without half steps, best visualized as the black notes on the keyboard) colors many of Dvořák’s themes here and was thought to duplicate the sound of Indigenous American melodies, but it is also ubiquitous in folk music worldwide and popped up frequently in Dvořák’s music before he ever crossed the Atlantic. The big tune is the one many listeners know as “Goin’ Home,” the haunting english horn melody of the second movement, and it is still regularly mistaken for a spiritual. It may have been influenced by spirituals—we know that Dvořák ultimately picked the english horn because it reminded him of Burleigh’s voice—but the tune is Dvořák’s, and the words were later added by one of his students.

Dvořák, with the best of intentions, spoke in glowing terms about the spiritual—“tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn . . . ideal material for a national melodic style”—but he had used similar words earlier to describe Scottish and Irish folk songs during his visits to Britain. And, although he was evidently impressed by the Native American songs he first heard in Spillville, Iowa, during the summer of 1893 (after he had finished the Ninth Symphony, incidentally), he sometimes confused this music with that of Black Americans and said as much in an interview with the New York Herald.

Eventually, Dvořák modified his stance. In 1900 he wrote to a conductor who had programmed the New World Symphony: “Leave out the nonsense about my having made use of American melodies. I have only composed in the spirit of such American national melodies.” He later referred to all his works written in America as “genuine Bohemian music,” and said that the title of his Ninth Symphony was only meant to signify “impressions and greetings from the New World”—a musical postcard to the folks back home.

And so, it all comes down to the music. To many concertgoers, this symphony is so familiar and welcoming that it resists explanation. There are, however, a few highlights worth noting. The formal hallmarks of the piece are the use of a motto theme—that vigorous horn call that charges up and down the E minor triad— in all four movements, and the reappearance of earlier themes, like relatives at a family reunion,

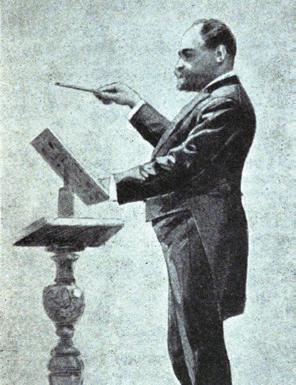

previous page: Antonín Dvořák conducting the Exposition Orchestra (the Chicago Orchestra expanded to 114 players) at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago on “Bohemian Day,” August 12, 1893. Illustration by Emanuel Václav Nádherný (1866–1945), Czech American painter, illustrator, and engraver | this page: Harry Thacker Burleigh (1866–1949), gifted composer, arranger, and baritone. Mishkin Studio, New York City, 1918 | opposite page: Title page of the autographed score of Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9 (From the New World), 1893

in the finale. Neither idea is the least bit novel, but both are beautifully handled.

The first movement begins in a melancholy mood, often interpreted as evidence of Dvořák’s homesickness, that is quickly shattered by the vaulting horn theme. Later, a gentle tune reminds many listeners of the spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” but there is no evidence that this is what Dvořák had in mind.

The first movement ends decisively in E minor, and the great Largo theme begins in the relatively inaccessible key of D-flat major. Dvořák takes the scenic route, via a beautiful progression of seven deep, broad chords that get us to D-flat quickly and without incident. (We now know that Dvořák originally sketched the famous Largo melody in C but transposed it to D-flat just so he could use this series of chords as a bridge.) Near the end, the motto theme barges in, unexpected and full of terror, but the english horn quickly reinstates calm, and the movement ends pianissimo, with the double basses alone.

The scherzo begins with a thunderclap; however, this isn’t storm music, but according

to the composer, music inspired by the feast and dance of Pau-Puk-Keewis in The Song of Hiawatha. It seems that Dvořák got no further than a few preliminary sketches for the Hiawatha opera Mrs. Thurber wanted and decided to put his ideas to good use here.

The finale boasts a bold brass theme and two other lovely pastoral melodies of its own, but Dvořák grants visitation rights to the principal themes of the previous three movements early in the development section, and he is thus able to build a thrilling climax by throwing them all together near the end. Even the stately chord progression from the Largo appears.

A postscript. Jeannette Thurber died in Bronxville, New York, in 1946, more than four decades after Dvořák died back in his homeland. In her last years, Mrs. Thurber liked to take credit for suggesting to Dvořák the idea for the New World Symphony.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Riccardo Muti

Born in Naples, Italy, Riccardo Muti is one of the preeminent conductors of our day. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s distinguished tenth music director from 2010 until 2023, Muti became Music Director Emeritus for Life beginning with the 2023–24 season.

His leadership has been distinguished by the strength of his artistic partnership with the Orchestra; his dedication to performing great works of the past and present, including seventeen world premieres to date; the enthusiastic reception he and the CSO have received on national and international tours; and twelve recordings on the CSO Resound label, with four Grammy awards among them. In addition, Muti’s contributions to the cultural life of Chicago— with performances throughout its many neighborhoods and at Orchestra Hall—have made a lasting impact on the city.

In Naples, Riccardo Muti studied piano under Vincenzo Vitale at the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella, graduating with distinction. He subsequently received a diploma in composition and conducting from the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan under the guidance of Bruno Bettinelli and Antonino Votto.

He first came to the attention of critics and the public in 1967, when he won the Guido Cantelli Conducting Competition, by unanimous vote of the jury, in Milan. In 1968, he became principal conductor of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, a position he held until 1980. In 1971, Muti was invited by Herbert von Karajan to conduct at the Salzburg Festival, the first of many occasions, which led to a celebration of fifty years of artistic collaboration with the Austrian festival in 2020. During the 1970s, Muti was chief conductor of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra (1972–1982), succeeding Otto Klemperer. From 1980 to 1992, he inherited the

position of music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra from Eugene Ormandy. From 1986 to 2005, he was music director of Teatro alla Scala, and during that time, he directed major projects such as the three Mozart/Da Ponte operas and Wagner’s Ring cycle in addition to his exceptional contributions to the Verdi repertoire. His tenure as music director of Teatro alla Scala, the longest in its history, culminated in the triumphant reopening of the restored opera house on December 7, 2004, with Salieri’s Europa riconosciuta.

Over the course of his extraordinary career, Riccardo Muti has conducted the most important orchestras in the world: from the Berlin Philharmonic to the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and from the New York Philharmonic to the Orchestre National de France; as well as the Vienna Philharmonic, an orchestra to which he is linked by particularly close and important ties, and with which he has appeared at the Salzburg Festival since 1971 and is an honorary member. When Muti was invited to lead the Vienna Philharmonic’s 150th-anniversary concert, the orchestra presented him with the Golden Ring, a special sign of esteem and affection, awarded only to a few select conductors. In 2021, he conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in the New Year’s Concert for the sixth time; he will conduct the concert again in 2025. In May 2024, Muti led the Philharmonic in its 200th anniversary performance of the premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Muti has received numerous international honors over the course of his career. He is Cavaliere di Gran Croce of the Italian Republic and a recipient of the German Verdienstkreuz. He received the decoration of Officer of the Legion of Honor from French President Nicolas Sarkozy and in 2024 was bestowed the title of Commander of the Legion of Honor while on the CSO’s European Tour in Rome. He was made an honorary Knight Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II. The Salzburg Mozarteum awarded him its silver medal for his contribution to Mozart’s music, and in Vienna he was elected an honorary member

of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna Hofmusikkapelle, and Vienna State Opera. The State of Israel has honored him with the Wolf Prize in the arts. In July 2018, President Petro Poroshenko presented Muti with the State Award of Ukraine during the Roads of Friendship concert at the Ravenna Festival in Italy following earlier performances in Kyiv. In October 2018, Muti received the prestigious Praemium Imperiale for Music of the Japan Arts Association in Tokyo.

In September 2010, Riccardo Muti became music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and was named 2010 Musician of the Year by Musical America. In 2011, Muti was selected as the recipient of the coveted Birgit Nilsson Prize and received the Opera News Award in New York City and Spain’s prestigious Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts. That summer, he was named an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic and honorary director for life of the Rome Opera. In May 2012, he was awarded the highest papal honor: the Knight of the Grand Cross First Class of the Order of St. Gregory the Great by Pope Benedict XVI. In 2016, he was honored by the Japanese government with the Order of the

Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star. In August 2021, Muti received the Great Golden Decoration of Honor for Services to the Republic of Austria, the highest possible civilian honor from the Austrian government.

Passionate about teaching young musicians, Muti founded the Luigi Cherubini Youth Orchestra in 2004 and the Riccardo Muti Italian Opera Academy in 2015. The purpose of the Italian Opera Academy—which takes place in Italy, as well as in Japan since 2019 as part of a multi-year collaboration with the Tokyo Spring Festival—is to pass on Muti’s expertise to young musicians and to foster a better understanding of the complex journey to the realization of an opera. Through Le vie dell’Amicizia (The Roads of Friendship), a project of the Ravenna Festival in Italy, he has conducted in many of the world’s most troubled areas in order to bring attention to civic and social issues.

The label RMMUSIC is responsible for Riccardo Muti’s recordings.

riccardomuti.com riccardomutioperacademy.com riccardomutimusic.com

The CSO’s Music Director Emeritus for Life Riccardo Muti had an eventful summer and early fall that included his annual concerts at the Salzburg Festival, the latest edition of his Italian Opera Academy in Tokyo, and new honors bestowed upon him in his native Italy.

At this summer’s Salzburg Festival, Muti conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in performances of Schubert’s Tragic Symphony no. 4 and Bruckner’s Mass no. 3 in F minor. “Maestro Muti first conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in 1971,” wrote Jay Nordlinger in his review for The New Criterion. “In recent seasons, he has gone from strength to strength. I think of an Aida (the Verdi opera). Those Bruckner symphonies, that Beethoven mass. Two Tchaikovsky symphonies: 4 and 6. This Bruckner mass. The guy is on a roll,” he continued. Muti’s annual three concerts at the festival were, as Wilhelm Sinkovicz of Die Presse pointed out, “notoriously sold out.” He continued in his review, “Anyone who experiences Muti conducting Schubert also understands why this is so.”

The second half of the program featured Bruckner’s Mass in F minor, considered the Austrian composer’s most important and final mass setting.

Requiring the considerable forces of four soloists, a large choir, and a huge orchestra, the work marks an important crossroads in Bruckner’s career and is emblematic of the enigmatic and powerful symphonies to come after he relocated to Vienna in 1868. “After interpretations of the Seventh and Eighth, it seems fitting that Muti should also celebrate Bruckner’s greatest mass composition in Salzburg, with the serenity that this music demands,” wrote Florian Oberhummer in the Salzburger Nachrichten. “In this setting of the mass, the Vienna Philharmonic’s strong contrasts in dynamics and timbres were wonderfully realized . . . under the once again commanding Riccardo Muti,” wrote Helmut Christian Mayer of the Kurrier.

From September 2 to 15, Muti led the fifth iteration of the Italian Opera Academy in Tokyo, focusing on Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra. During the two-week academy, Muti trained five young conductors selected by audition, and the daily rehearsals were open to the public. On September 2 Muti held a master class for the conductors with full orchestra, chorus, and soloists, and on September 11 the conductors led a concert performance of the opera. Muti also conducted two concert performances of Simon Boccanegra as the grand finale of the Italian Opera Academy.

On September 25, in Santena, near Turin, the Camillo Cavour Foundation President Marco Boglione awarded Riccardo Muti the 2025 Cavour Prize for “masterfully embodying the Italian musical and artistic tradition.”

On October 7 Marco Massari, the mayor of Reggio Emilia, presented Muti with the Primo Tricolore, the city’s highest honor, “for [Muti’s] artistic merits, the social values he has conveyed, and the closeness he has demonstrated to [local] citizens.”

Learn more at cso.org/experience.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Discover the benefits of making a legacy gift to your Chicago Symphony Orchestra

“The symphony is a major part of my life, and I want to see it continue for generations so that others may enjoy the beauty of classical music and hear the best orchestra in the world.”

— Merle Jacob

Named in honor of the founding music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Theodore Thomas Society recognizes individuals who have included the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in their will, trust or beneficiary designation.

Contact Karen Bippus at 312-294-3150 or visit cso.org/PlannedGiving for more information.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation, Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

Olivia Jakyoung Huh Cello

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie

Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery