COMMENTS

by Richard E. Rodda

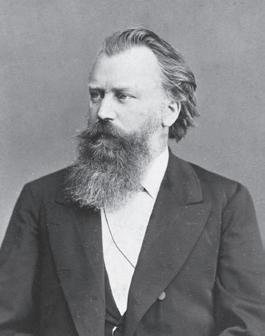

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born May 7, 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died April 3, 1897; Vienna, Austria

Four Piano Pieces, Op. 119

COMPOSED

1892–93

Brahms was a gifted pianist who toured and concertized extensively in northern Europe early in his career. He made his recital debut in Vienna in 1862 and returned there regularly until settling permanently in that city in 1869. By then, his reputation as a composer was well established, and he was devoting more time to creative work than to practicing piano. He continued to play, however, performing his own chamber music and solo pieces both in public and in private, and even serving as soloist in the premiere of his daunting Second Concerto on November 9, 1881, in Budapest. His last public appearance as a pianist was in Vienna on January 11, 1895, just two years before he died, in a performance of his clarinet sonatas with Richard Mühlfeld.

Brahms’s pianism was noted less for its flashy virtuosity than for its rich emotional expression, fluency, individuality, nearly orchestral sonority, and remarkable immediacy, and his compositions for the instrument are marked

by the same introspection, seriousness of purpose, and deep musicality that characterized his playing. His keyboard output, though considerable, falls into three distinct periods: an early burst of large-scale works mostly in classical forms, dating from 1851 to 1853; a flurry of imposing compositions in variations form from 1854 to 1863 on themes by Schumann, Haydn, Handel, and Paganini; and a late blossoming of thirty succinct capriccios, intermezzos, ballades, and rhapsodies from 1878–79 and 1892–93. To these must be added the dance-inspired compositions of the late 1860s: the waltzes (op. 39) and Hungarian Dances. Brahms’s late works, most notably those from 1892 and 1893, share the autumnal quality that marks much of the music of his ripest maturity. “It is wonderful how he combines passion and tenderness in the smallest of spaces,” said Clara Schumann. To which William Murdoch added,

Brahms had begun his life as a pianist, and his first writing was only for the pianoforte. It was natural that at the end of his life he should return to playing this friend of his youth and writing for

this page: Johannes Brahms, cabinet card photograph by Fritz Luckhardt (1843–1894), ca. 1885 | opposite page: Carl Czerny, lithograph portrait by Josef Kriehuber (1800–1876), 1828

it. This picture should be kept in mind when thinking of these last sets. They contain some of the loveliest music ever written for the pianoforte. They are so personal, so introspective, so intimate that one feels that Brahms was exposing his very self. They are the mirror of his soul.

The Intermezzo in B minor, op. 119, no. 1, among the last piano music Brahms wrote, mirrors not only his own thoughtful time of life but also the sorrow he experienced following the recent deaths of his sister, Elise, and his friend and faithful correspondent Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.

The agitated outer portions of the Intermezzo in E minor, op. 119, no. 2, are perfectly balanced by the gentle waltz at the center, not just in mood

CARL CZERNY

Born February 20, 1791; Vienna, Austria

Died July 15, 1857; Vienna, Austria

and style but also through the use of the same theme in different guises for both sections.

The Intermezzo in C major, the shortest and happiest movement of the op. 119 set, is both an expressive contrast within the group of four pieces and a modest rebuke to criticisms that Brahms could not write cheerful music in his later years.

The Rhapsody in E-flat major, op. 119, no. 4, is built from a noble strain in marchlike rhythms and a passage in anxious triplet figurations in a darker key that surround a flowing, subtly decorated melody at the center. The work’s closing section comprises a return of the triplet rhythms and a playful, staccato version of the noble opening strain, and then its reprise in its original form before the rhapsody closes with a powerful coda in a stern minor key.

Variations on a Theme by Rode, Op. 33

COMPOSED 1820

Though his legacy is commonly reduced to just the finger-strengthening but spirit-dulling exercises that have been the bane (and boon) of generations of piano students,

Carl Czerny was one of Vienna’s most respected musicians during the early nineteenth century. Czerny was the son of a piano teacher, a strict disciplinarian who forbade his son to play with other children lest it interrupt the boy’s musical studies. Carl was playing the piano at three, noting down some little pieces at seven, debuting publicly (in Mozart’s Concerto no. 24 in

COMMENTS

C minor, K. 491) at nine, and exhibiting a phenomenal musical memory at ten, when he played Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata for the composer himself and was eagerly accepted as his student. Czerny worked closely with Beethoven for the next three years, not only perfecting his own keyboard technique but also imbibing his teacher’s style of performance (concerning which he left valuable reports), studying each new piano composition as it came along (he was the first to play the Emperor Concerto in Vienna), and becoming his friend. Beethoven mapped out a tour for his pupil in 1804, but political unrest forced the venture’s cancellation, apparently much to the relief of Czerny, who claimed that he lacked “the brilliant, calculated charlatanry necessary for touring virtuosos.”

Czerny instead devoted himself to teaching and became one of the day’s most renowned (and expensive) piano pedagogues; Liszt, Thalberg, Leschetizky, Heller, and Beethoven’s nephew Karl were among his students. Though his friends—Hummel, Mozart’s son Franz Xaver, the piano manufacturer Andreas Streicher, Beethoven, and his intimate circle—recognized in him a warm personality, Czerny chose to follow a reclusive life ruled by the stern work ethic instilled by his father: he renounced marriage, almost never socialized, rarely played in public, seldom attended concerts or opera, and remained in Vienna all his life except for one-time trips to London, Paris, Leipzig, and Italy. During the day, he taught up to twelve hours; at

night, surrounded by an ever-growing pride of cats, he composed, turning out symphonies, concertos, overtures, sonatas, chamber works, sacred music, variations, potpourris, dances, character pieces, arrangements (including all of Beethoven’s symphonies and Mozart’s Requiem), and an entire arsenal of pedagogical items that accumulated to several thousand separate numbers, as well as treatises on music theory and history and an autobiography. Czerny was forced to retire from teaching when his health declined during the 1840s, and he had become almost disabled by 1850. On June 13, 1857, a month before his death, he made out his last will, a testament to both his thoughtfulness and his life of solitude: except for amounts left to his housekeeper and for a memorial mass to be said on the anniversary of his death, he bequeathed all of his considerable estate to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, the Society for the Support of Needy Musicians, the Institute for the Deaf, and the Monks and Nuns of Charity.

The theme on which Czerny built his brilliant Variations, op. 33, was composed by the French virtuoso Pierre Rode (1774–1830), teacher at the Paris Conservatory, concertmaster at the opera, violinist to Napoleon and Czar Alexander I, and catalyst and first performer of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata in G major, op. 96. Rode originally wrote the theme for violin for his Variations, op. 10, but the Italian soprano Angelica Catalani worked it up in a vocal version and made it the show-stopper

on her recitals. Czerny’s subtitle for his Variations, op. 33—La Ricordanza (The Recollection)—may indicate that

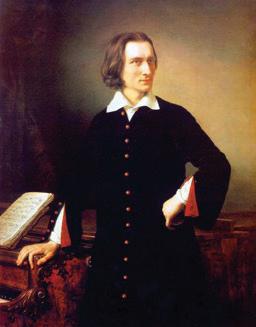

FRANZ LISZT

the piece commemorated Signora Catalani’s appearances in Vienna in 1820.

Born October 22, 1811; Doborján, Hungary (now Raiding, Austria)

Died July 31, 1886; Bayreuth, Germany

Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi sonata) from Années de pèlerinage, Deuxième année: Italie

COMPOSED 1839

After a series of dazzling concerts in Paris in the spring of 1837, Liszt and his longtime mistress, Countess Marie d’Agoult, spent the summer with George Sand at her villa in Nohant before visiting their daughter, Blandine, in Switzerland and then descending upon Milan in September. As the birth of their second child approached, they retreated to Lake Como, where Cosima (later the wife of Hans von Bülow before she was stolen away by Richard Wagner) was born on Christmas Eve. They remained in Italy for the next year-and-a-half, making extended visits for performances in Venice, Genoa, Milan, Florence, and Bologna before settling early in 1839 in Rome, where their third child, Daniel,

was born on May 9. Liszt’s guide to the artistic riches of the Eternal City was the famed painter Jean-AugusteDominique Ingres, then director of the French Academy at the Villa Medici; Liszt was particularly impressed with the works of Raphael and Michelangelo and the music of the Sistine Chapel. He took home as a souvenir of his Roman holiday the now-famous drawing that Ingres did of him and inscribed to Mme d’Agoult. Liszt’s Italian travels were the inspiration for the series of seven luminous piano pieces that he composed between 1837 and 1849 and gathered together as book 2 of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) for publication in 1858.

Liszt and Marie were avid readers of Dante Alighieri, the patriarch of Italian literature, and while in Rome in 1839, Liszt was moved by the “Inferno” in the poet’s Divine Comedy to compose his Après une lecture du Dante (After

this page: Franz Liszt, oil portrait by Miklós Barabás (1810–1898), 1847. Hungarian National Museum | next page: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano. Painting in oil by Josef Danhauser (1805–1845), 1840. Others depicted include George Sand, Nicolò Paganini, Marie d’Agoult, and Hector Berlioz. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

a Reading of Dante). The work was thoroughly revised ten years later and included in book 2 of the Années de pèlerinage. (The Divine Comedy inspired a full symphony from Liszt in 1855–56.)

Après une lecture du Dante is largely constructed from two contrasting subjects, perhaps depicting heaven and hell. The first consists of transformations of two motifs: an ominous augmented fourth (a harmonically unsettling leap

known since the Middle Ages as the “devil’s interval”) and anxious chromatic octaves evoking the descent into the abyss; the contrasting second subject is serene, idyllic, and heavenly. Only a few moments of calm recalling the second subject slow the furious pace of this unforgivingly virtuosic evocation of Dante’s weird and horrible visions as it drives toward a dramatic and ferocious close.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

Born August 2, 1862; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, France

Died March 25, 1918; Paris, France

Suite bergamasque

COMPOSED

1890

During his early years, Debussy turned to the refined style of Couperin and Rameau for inspiration in his instrumental music, and several of his works from that time are modeled on the baroque dance suite, including the Suite bergamasque. The composition’s title derives from the generic term for the dances of the district of Bergamo, in northern Italy, which found many realizations in the instrumental music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The rustic inhabitants of Bergamo were said to have been the model for the character of Harlequin, the buffoon of the Italian commedia dell’arte, which became the most popular theatrical genre in France during the time of Couperin and Rameau. Several of Watteau’s bestknown paintings take the commedia dell’arte as their subject. The poet Paul Verlaine (1844–1896) evoked the bittersweet, pastel world of Watteau and the commedia dell’arte with his atmospheric, evanescent verses, which Debussy began setting as early as

1880. In 1882 he wrapped the words of Verlaine’s “Clair de lune” (Moonlight) with music and made another setting of it a decade later as the third song of his first series of Fêtes galantes:

Your soul is a rare landscape with charming maskers and mummers [masques et bergamasques], playing the lute and dancing, almost sad beneath their fantastic disguises.

With the calm moonlight, sad and lovely, that sets the birds in the trees to dreaming and the fountains to sobbing in ecstasy, the great fountains, svelte among the marbles.

Debussy best captured the nocturnal essence of Verlaine’s poem not in his two vocal settings, however, but in the famous (and musically unrelated) “Clair de lune” that serves as the third movement of his Suite bergamasque. The suite surrounds the gossamer strains of “Clair de lune” with three dance-inspired movements indebted to the spirit and forms of Couperin: a flowing prelude; a wistful menuet; and a piquant closing passepied.

above: Debussy, 1895, photographed by Paul Nadar (1856–1939)

IGOR STRAVINSKY

Born June 17, 1882; Oranienbaum, near Saint Petersburg, Russia

Died April 6, 1971; New York City

Three Movements from Petrushka

COMPOSED 1911

ARRANGED FOR PIANO

1921

Just as Stravinsky was finishing The Firebird in 1910, he had a vision of “sage elders, seated in a circle, watching a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring.” His idea blossomed into the plan for the epochal The Rite of Spring. Before he undertook the difficult labor of writing another ballet, however, he wanted, he said, to refresh himself “by composing an orchestral piece in which the piano would play the most important part—a sort of konzertstück” about a grotesque puppet suddenly endowed with life and human emotions. The project quickly outgrew the keyboard, and Stravinsky found himself immersed in another stage work: Petrushka. The score was to be one of the seminal compositions in twentieth-century music.

Early in 1921, the celebrated pianist Artur Rubinstein approached Stravinsky with a commission (for “the generous sum of 5,000 francs,” the composer

reported) to transcribe music from Petrushka for his recitals. Though the finished orchestral score of Petrushka contained several important solo passages for piano, Stravinsky had really paid little attention to the instrument during the first two decades of his career: some juvenilia, the Four Studies (1908), accompaniments for a handful of songs, a little 1917 piece on Spanish motifs for player piano (Study for Pianola), and the delightful Five Easy Pieces for Piano Duet, written in 1916–17 for his children, which were later arranged as the Suites for Small Orchestra. Stravinsky accepted Rubinstein’s commission in order “to provide piano virtuosi with a piece having sufficient scope to enable them to add to their modern repertory and display their technique.” From the complete ballet, Stravinsky selected three excerpts (Russian Dance from the end of scene 1, Petrushka’s Room, and Shrovetide Fair) and transcribed them for solo piano in Versailles and Anglet, near Biarritz, during the summer of 1921. Work on the Three Movements from Petrushka so kindled Stravinsky’s interest in the piano that he decided to use four of the instruments in the

above: Igor Stravinsky, portrait in oil, 1915, by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861–1942). Cité de la Musique, Paris, France

wondrously clangorous orchestration of Les noces in 1922, and then wrote the Concerto for Piano and Winds a year after that.

As did other major composers during the early twentieth century (notably Bartók and Prokofiev), Stravinsky, in the Three Movements from Petrushka, utilized the piano’s percussive possibilities rather than its harmonic and lyrical attributes. He made the point that, though he applied the term “transcription” to these pieces, he intended this to be music specifically for the piano that

exploited the instrument’s inherent coloristic and contrapuntal qualities rather than having it serve merely as a substitute for the orchestra. He succeeded so well that, if anything, the piano version clarifies and distills rather than simply imitates the original score.

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association is grateful to the Niwa family for an estate gift establishing the Raymond and Eloise Niwa Endowment Fund, which supports violin and piano soloists.

PROFILES

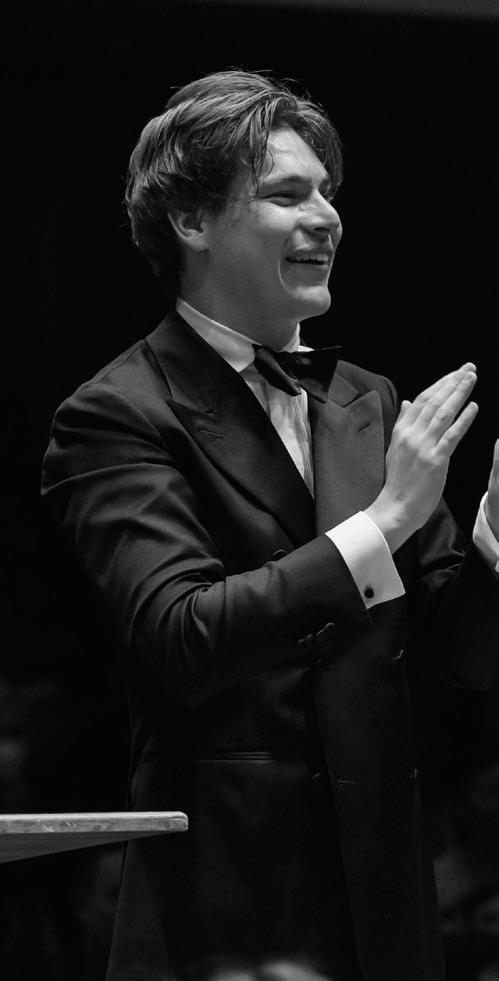

Behzod Abduraimov Piano

Behzod Abduraimov’s performances combine an immense depth of musicality with phenomenal technique and delicacy. He performs with many of the world’s leading orchestras and conductors, and his critically acclaimed recordings have set a new standard for the piano repertoire.

Abduraimov has a number of notable debuts in the 2025–26 season, including with the New York Philharmonic and National Symphony Orchestra, both with Gianandrea Noseda. Other concerto performances include the Houston and Pittsburgh symphony orchestras, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Frankfurt Opern- und Museumsorchester, and Hong Kong Philharmonic.

Recital highlights this season include his fourth solo recital at Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium and a return to the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, among other appearances in the United States and Europe. He has performed in many of the most important international recital series presented by Alte Oper Frankfurt, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, CAL Performances, La Società dei Concerti di Milano, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Seoul Arts Centre, Shanghai Concert Hall, and Toppan Hall. He regularly appears at the

leading international festivals, including Aspen, La Roque d’Anthéron, Lucerne, Ravello, Rheingau, and Verbier.

In September 2025 he opened the Tsanandali Festival with Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1 at the invitation of Gianandrea Noseda and also gave two chamber music concerts.

Abduraimov’s critically acclaimed recordings have won numerous international awards, including the Choc de Classica and Diapason Découverte. He records for Alpha Classics. Shadows of My Ancestors, released in January 2024, features works by Ravel, Prokofiev, and Uzbek composer Dilorom Saidaminova. It was recognized as a Gramophone Editor’s Choice, shortlisted for a Gramophone Award, and named one of Apple Music’s 10 Classical Albums You Must Hear This Month. His first recital album for Alpha Classics in 2021 includes Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. In 2020 two of his albums were nominated for the 2020 Opus Klassik Awards in multiple categories: Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and Piano Concerto no. 3.

Born in 1990 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Behzod Abduraimov began playing the piano at five as a pupil of Tamara Popovich at Uspensky State Central Lyceum in Tashkent. In 2009 he won first prize at the London International Piano Competition with Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto no. 3. He is artist-inresidence at the International Center for Music at Park University, where he studied with Stanislav Ioudenitch.

PHOTO BY EVGENY