ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

Sunday, November 2, 2025, at 2:00

Epiphany Center for the Arts

CSO Chamber Music Series

GUADAGNINI STRING QUARTET

David Taylor Violin

Cornelius Chiu Violin

Wei-Ting Kuo Viola

Richard Hirschl Cello

CHERUBINI String Quartet No. 1 in E-flat Major

Adagio—Allegro agitato

Larghetto sans lenteur

Scherzo: Allegretto moderato

Finale: Allegro assai

INTERMISSION

BEETHOVEN String Quartet No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 18

Allegro ma non tanto

Scherzo: Andante scherzoso quasi allegretto

Menuetto: Allegretto

Allegro

Please join a postconcert Q&A session with CSO musicians.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

This concert is presented in partnership with Epiphany Center for the Arts.

COMMENTS

by Richard E. Rodda

LUIGI CHERUBINI

Born September 14, 1760; Florence, Italy

Died March 15, 1842; Paris, France

String Quartet No. 1 in E-flat Major

COMPOSED 1814

Beethoven wrote to Cherubini, “I value your works more highly than all other compositions for the stage.” Schubert maintained that Medea was his favorite opera, and Brahms called it “the highest peak of dramatic music.” The wealthy Berlin banker Abraham Mendelssohn, who could have consulted any musician in Europe, presented his brilliant son Felix to him for his evaluation and guidance. He ruled over the Paris Conservatory for twenty years, and Napoleon made him his music director. Luigi Cherubini, composer, conductor, teacher, administrator, theorist, and music publisher, was among the most highly regarded musicians of the early nineteenth century. Today, though he wrote thirty-nine operas, an entire repertory of sacred music, cantatas and ceremonial pieces, chamber works, keyboard compositions, marches, dances, pedagogical treatises and orchestral scores, Cherubini is largely remembered for just a handful of opera overtures, a

rare revival of Medea, two requiems, a single symphony, and some disparaging remarks that Hector Berlioz made about him in his memoirs.

Luigi Cherubini was born into a musical family in Florence in 1760, got his first instruction in the art from his father and several local teachers, and began composing as a teenager, including a cantata in honor of Duke Leopold of Tuscany, a work so promising that when Cherubini turned eighteen, the duke subsidized his study in Bologna and Milan with Giuseppe Sarti. The success of Cherubini’s first opera

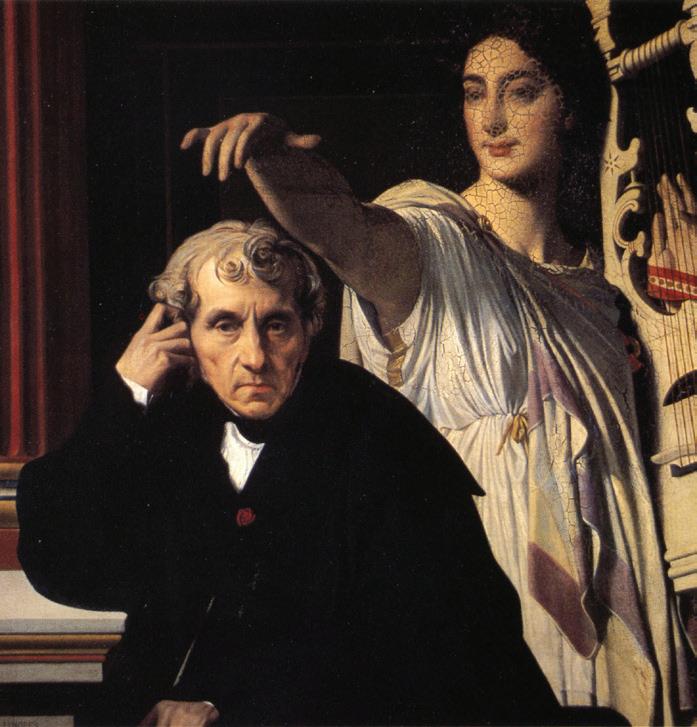

from top: Luigi Cherubini, lithograph by Julien-Léopold Boilly (1796–1874), 1820 | Luigi Cherubini and the Muse of Lyric Poetry, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), 1842. Louvre Museum; Paris, France

(Il Quinto Fabio, 1779) encouraged him to write eight more stage works during the next five years. He was appointed house composer at King’s Theatre in London in 1784, but during a visit to Paris the following summer to hear a performance of his music at the celebrated Concerts Spirituels, he was introduced to the French queen, Marie Antoinette (sister of Cherubini’s old patron Duke Leopold in Florence). Further successes in Paris followed, leading to his permanent move to that city in 1786.

In 1789 the count of Provence (later Louis XVIII) founded a company at the Théâtre Feydeau to present Italian comic operas in Paris and appointed Cherubini as the troupe’s music director. Lodoïska, premiered at the Feydeau in 1791, was Cherubini’s first great Parisian and international success, but the outbreak of revolution the following year shut down the company and drove Cherubini to Rouen and then to Le Havre. He returned to Paris in 1794, married a musician’s daughter, resumed composing, and got a job teaching at the newly founded music school of the Garde Nationale, reorganized two years later as the Paris Conservatory. He scored a triumph at the reopened Théâtre Feydeau in 1797 with Medea and Les deux journées in 1800.

In 1805 Cherubini was invited to direct some of his works at the Vienna Court Opera, and there he met Joseph Haydn (whom he presented with a medal on behalf of the conservatory) and Ludwig van Beethoven (Cherubini attended the premiere of Fidelio on

November 20, 1805) and was ordered by Napoleon, whose troops had overrun the city a week before the Fidelio premiere, to organize concerts at his newly occupied residences in Schönbrunn and Vienna. Napoleon requested that his music director return to Paris, but when Cherubini arrived there in 1806, he was disappointed to find that audiences by then were preferring lighter fare than he was comfortable dispensing. The unsettled state of his life and his career precipitated a descent into depression for the next two years, when he fled Paris, withdrew from composition, and busied himself studying botany and painting.

In 1809 Cherubini returned to the capital, where he composed ceremonial music for Napoleon and tried unsuccessfully to reestablish his reputation in the theater with several new operas. He turned increasingly to writing sacred music, including the masterful Requiem in C minor, composed in 1816 in memory of the executed King Louis XVI, and was named director of the royal chapel that same year. In 1822 he became head of the Paris Conservatory, restructuring its curriculum and organization (including admitting women in significant numbers) and acquiring a reputation as an effective, if authoritarian and conservative, teacher. Among the many prestigious honors Cherubini earned during his lifetime were Knight of the Legion of Honor, Member of the Academy of Fine Arts, and Commander of the Legion of Honor, the first musician to receive that title. Luigi Cherubini was given a state funeral and buried at Père

COMMENTS

Lachaise Cemetery, where his friend Frédéric Chopin was laid to rest in the adjacent grave seven years later.

During his disappointing later years, when he had given up the theater for teaching and his work at the royal chapel, Cherubini turned to writing sacred pieces and chamber music, including the six string quartets he composed between 1814 and 1837. Encouragement to compose such works came from two of his violinist faculty colleagues at the conservatory: Pierre Baillot, who established a pioneering chamber music series in 1814 to introduce the works of Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, and other Viennese masters to Paris; and Rudolphe Kreutzer, dedicatee of Beethoven’s best-known violin sonata.

Cherubini’s String Quartet no. 1 was composed in 1814 but not published until 1836, when it was reviewed favorably by Robert Schumann in his influential Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music) and became a staple of the nineteenth-century chamber music repertory.

The E-flat quartet’s sonata-form opening movement bears the influence of Beethoven in its scale, thematic development, and skillful interweaving of voices, but traces of Cherubini’s long experience in the dramatic genre of opera also appear in the score—sudden dynamic changes,

expectant pauses, harmonic shading for expressive effect. The first movement opens with a slow, cantabile introduction as preface to its main theme, which comprises a spirited, short-phrased motif and a long-note, stepwise rising phrase; the subsidiary subject is smoother and more graceful. These two thematic elements provide the material for the central development section, which culminates in an agitated imitative episode. A full recapitulation of the opening exposition rounds out the movement.

The Larghetto is a set of elaborately filigreed variations on a leisurely theme, with one variation aggressive and dramatic and another almost triumphal in mood, both products of Cherubini’s long experience as a theater composer. Robert Schumann, in his review of the quartet, thought the buoyant scherzo to be based on a “fanciful Spanish theme.” Cellist and music scholar Raymond Silvertrust wrote, “The movement’s central trio is a Mendelssohnian elves dance, however, since Cherubini composed it when Mendelssohn was but five, it would probably be more accurate to call Mendelssohn’s movements ‘Cherubinian.’” Schumann evaluated the closing Allegro assai, a fiery, virtuosic sonata-rondo form that substitutes a repeat of its opening theme for the traditional development section, as “a glittering diamond that was resplendent from every angle.”

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770; Bonn, Germany

Died March 26, 1827; Vienna, Austria

String Quartet No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 18 COMPOSED

The year of the completion of the six op. 18 quartets— 1800—was an important time in Beethoven’s development. He had achieved a success good enough to write to his old friend Franz Wegeler in Bonn,

My compositions bring me in a good deal, and may I say that I am offered more commissions than it is possible for me to carry out. Moreover, for every composition I can count on six or seven publishers and even more, if I want them. People no longer come to an arrangement with me. I state my price, and they pay.

At the time of this gratifying recognition of his talents, however, the first signs of his fateful deafness appeared, and he began the titanic struggle that became one of the gravitational poles of his life. Within two years, driven from the social contact on which he had

flourished by the fear of discovery of his malady, he penned the “Heiligenstadt Testament,” his cri de coeur against this wicked trick of the gods. The op. 18 string quartets, his first in the genre, stand on the brink of that great crisis in Beethoven’s life.

The Quartet no. 4 in C minor, op. 18, which shares its impassioned key with the Fifth Symphony, Third Piano Concerto, Pathétique Sonata, Coriolan Overture, and some half dozen of Beethoven’s other chamber compositions, opens with a darkly colored theme that rises from the lowest note of the violin to high in the instrument’s range. The subsidiary subject is a sunshine melody derived from the leaping motif that closed the main theme. Both the main and second themes are treated in the development section. The recapitulation recalls the earlier thematic material to balance and round out the movement. Rather than following the highly charged opening Allegro with a conventional slow movement, Beethoven provided a witty essay titled scherzo, which is realized as a miniature sonata form. The movement

above: Ludwig van Beethoven, engraving by Johann Joseph Neidl (1776–1832) after a portrait by Gandolph Ernst Stainhauser von Treuberg (1766–1805), 1801

begins with a jolly fugato, and the texture remains largely contrapuntal thereafter. The somber menuetto that follows is balanced by a delicate central trio of almost Schubertian grace. The quartet closes with a Haydnesque rondo based on a sparkling theme reminiscent of the exotic “Turkish” music

PROFILES

David Taylor Violin

David Taylor joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra as assistant concertmaster in 1979. Born in Canton, Ohio, he began studying the violin at age four with his father and continued at the Cleveland Institute of Music with Margaret Randall and Rafael Druian. He later studied with Ivan Galamian and Dorothy DeLay at the Juilliard School, where he received both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Taylor became a member of the Cleveland Orchestra in 1974 as a first violinist. With the Chicago Symphony, he has made numerous solo appearances, including performances with Sir Georg Solti. He has also served as acting concertmaster of the St. Louis Symphony and concertmaster of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra.

that was popular in Vienna at the end of the eighteenth century.

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

Taylor served as concertmaster of the Ars Viva Symphony Orchestra, which disbanded in 2015. As a lover of chamber music, he often appears in recital and solo performances in the Chicagoland area, at the Ravinia Festival, and on WFMT-FM. He frequently performs with the Pressenda Trio with fellow CSO cellist Gary Stucka and pianist Andrea Swan. Taylor is also a soloist with the region’s local orchestras. He teaches privately at the Moody Bible Institute of Chicago and at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts. A coach of orchestral violinists, he has students in orchestras across the United States and Japan.

David Taylor resides in downtown Chicago with his wife, violinist Michelle Wynton. He plays a J.B. Guadagnini violin, made in 1744.

Cornelius Chiu Violin

Cornelius Chiu joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1996. Born to Chinese parents in Ithaca, New York, he began violin lessons at age six. His older brother, Frederic, is a successful concert pianist and Yamaha recording artist with whom Chiu collaborates regularly.

Chiu is a Starling Foundation full-scholarship recipient, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees with high distinction, a performer’s certificate, and a coveted fellowship from the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

A winner in the Irving M. Klein International String Competition and the National Arts and Letters Competition, he has performed as a soloist with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Washington Chamber Orchestra, and at the Kennedy Center in Washington (D.C.). Recent solo performances include appearances with the Sinfonietta DuPage orchestra and the Drake University Symphony Orchestra.

An avid chamber musician, he frequently appears with his colleagues on the CSO Chamber Music series at Northwestern University, Wheaton College Conservatory of Music, and Roosevelt University. Chiu has performed at the Sarasota and Aspen music festivals, the Rencontres Musicales Festival, Ravinia Festival’s Steans Music

Institute for Young Artists, and with the Ensemble Villa Musica in France and Germany.

Cornelius Chiu currently teaches at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts and has maintained a private studio for more than thirty-five years. He and his wife, Inah, a pianist on the faculty of the Music Institute of Chicago, have performed together as the Corinah Duo on many Chicago concert series. Chiu is especially proud of his three musician children: Krystian (Indiana University/Rice University), Karisa (the Curtis Institute of Music, Cleveland Institute of Music, Juilliard, and substitute violinist at the CSO), and Cameron (Carnegie Mellon University).

Wei-Ting Kuo Viola

A native of Taiwan, Wei-Ting Kuo has been a member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since his 2014 appointment by Riccardo Muti. From 2011 to 2014, he served as assistant principal viola of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. Kuo began his viola studies at age nine and, upon completing his army service in Taiwan, came to the United States at age twenty-four. While a student, he was invited to perform as part of the Taos Music Festival, Ravinia Festival, and the Verbier Festival Academy. His competition experience includes selection as a 2008 finalist in the

Primrose International Viola Competition and two awards from the 2009 Tokyo International Viola Competition.

An active soloist and chamber musician, Kuo has performed throughout Asia with violist Nobuko Imai in both capacities. He has also worked with Frank Almond, Nai-Yuan Hu, Menahem Pressler, and the Arcas Quartet, in addition to a concerto performance in 2014 with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra.

Kuo earned a bachelor’s degree from the National Taiwan Normal University in Taipei, a master’s degree from the Mannes School of Music, and an artist diploma from the Colburn School, where he also minored in piano performance. Kuo has studied with Paul Coletti, Hsin-Yun Huang, and Yizhak Schotten. He joined DePaul University’s viola faculty in 2017.

Richard Hirschl Cello

Richard Hirschl joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s cello section in 1989. A native of Washington, Missouri, he began cello lessons with his father, an amateur cellist. His intermediate studies were with Savely Schuster, associate principal cellist of the St. Louis

Symphony. He was accepted into the class of Leonard Rose and Channing Robbins at the Juilliard School, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1987 and a master’s degree in 1988.

Before moving to Chicago, Hirschl was an associate teacher at Juilliard. He was the winner of the Juilliard Concerto Competition and Irving M. Klein International String Competition in 1988 and the St. Louis Symphony Scholarship Competition in 1980.

In addition to his New York debut with the Juilliard Orchestra, Hirschl has given concerto performances with the Peoria Symphony, Jupiter Symphony, St. Louis Philharmonic, Maracaibo Symphony (Venezuela), National Repertory Orchestra, St. Louis Chamber Orchestra, and Philharmonia Virtuosi of New York.

Hirschl has appeared in chamber music performances with celebrated pianists Daniel Barenboim, Sir András Schiff, and Ursula Oppens; cellists Lynn Harrell and Yo-Yo Ma; and violinist Vadim Repin. He is on the faculty of the Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University, where he also serves as head of the string department. Hirschl plays a Venetian cello made by Matteo Goffriller in 1710 and a cello made in Chicago by William Whedbee in 2014.

He and his wife, Laura, make their home in a downtown high-rise where they are the proud parents of Ava Clare and Vivian Rose Hirschl.