NEWS: Behind The Mic: A Closer Look Into UChicago’s Podcast Network

PAGE 4

APRIL 4, 2024

NEWS: Behind The Mic: A Closer Look Into UChicago’s Podcast Network

PAGE 4

APRIL 4, 2024

Members of Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 73, the union representing skilled facilities workers on campus, ratified a new contract with the University on March 12.

The agreement came after protracted negotiations that lasted four months after the union’s previous contract expired. SEIU leaders had raised concerns about persistent staffing challenges and uncompetitive wages. Last month, members of the union delivered a petition to University President Paul Alivisatos expressing willingness to strike if their conditions were not met.

“We had a strong majority ratify this contract with our members,” Joe Pruim, SEIU Local 73 UChicago unit president, told the Maroon. “I don’t think we have had a great relationship between the union and the University in previous years, but I believe that we’re really starting to put [together] a strong foundation to build on with the University.”

According to the union, the contract offers members 13.25 percent wage increases over four years, the “highest increase of other unions so far on campus.”

Representatives for the University did not respond to a question seeking to confirm that number. Other provisions in the new contract offered prescription safety glasses for workers and a paid holiday on Juneteenth.

The union also secured an option for workers to forgo their 30-minute unpaid lunches and instead work for uninterrupted eight-hour shifts. Building refrigeration engineer Tom Wright, the union steward for the Booth School of Business and a member of Local 73’s bargaining committee, told the Maroon that the possibility of an uninterrupted eight-hour workday was a top ask among members.

“That extra 30 minutes at the end of your day is a lot when you have to face traffic, and there are members that have childcare issues, that they’re unable to [pick] up their kids sooner,” Wright said. “It’s two and a half hours a week. Trying to put some quality of life back to the members was important to us.”

The contract did not assuage all of the union’s long-term concerns about staffing and retention. Funding for worker training, a sticking point in negotiations, did

not make it into the contract, though the parties agreed to create a committee to explore the issue.

“It’s going to be a work in progress, but at least we have the dialogue with them to build on something in the coming future,” Wright said. The contract also does not offer workers long-term disability insurance, another union demand.

“It’s the best contract I’ve seen since I’ve been here, and I’ve been here 18 years,” Wright said. “You know, with every negotiation, there’s always concessions, there’s give and take. You just have to build for the future and look towards the future and realize that we may not be where we want to be right now, but we’re going in the right direction.”

Other University employees, including collegiate assistant professors and nontenure-track faculty, also fall under the Local 73 umbrella but bargain separately from Facilities Services workers. The new contract would apply retroactively from November 1, 2023, when the previous one expired.

“The University is pleased to reach an agreement with SEIU Local 73 on the terms of a new four-year contract for approximately 150 employees in Facili-

ties Services,” the University wrote in a statement to the Maroon. “Each labor contract at the University is negotiated separately in good faith, with many terms and conditions of employment subject to discussion in addition to pay rates and increases. We are deeply grateful for the contributions of Facilities Services employees to the work of the University.”

Pruim and Wright cited members’ unity through the negotiations as a major factor in reaching the agreement. “We [distributed] flyers in the main quad, and [Graduate Students United] showed up to support us on that as well, and a lot of members took part in that just to get the word out and show our solidarity and our unity,” Wright said. “I think we brought that strength to the table, and I really believe that management took notice of that. I think that they were more receptive to the fact that we are a unified group, and we are willing to fight for what we feel we deserve. Things like that really helped turn the tide in negotiations.”

“A lot of members don’t think that coming out and supporting the solidarity makes a huge impact,” Pruim said. “But a lot of little voices together makes one huge voice.”

Faculty Forward (FF), the union representing non-tenure-track faculty at the University of Chicago, commenced its third round of contract negotiations with the Uni-

10 GREY: What’s the Incentive? Sellout Culture at UChicago

6 ARTS: All Tomorrow’s Parties

THIRD WEEK VOL. 136, ISSUE 13 VIEWPOINTS: A Double Whiplash

According to FF data, members con-

versity in early March. Since unionizing nine years ago, FF brokered two collective bargaining agreements in 2018 and 2021, establishing better wages and clearer promotion policies for non-tenure-track faculty. While fluctuating each quarter, FF represents about 450 part- and full-time instructional professors. Last October, Writing Faculty United, the union of Writing Specialists at the University, were granted the right to join FF. The addition of writing instructors and specialists expanded FF’s membership by 10 percent, pushing membership to more than 500 people.

13 SPORTS: A Sit-Down With Trailblazing UChicago Alum Kim Ng

“We are sort of the workhorses of the classroom.”

tribute significantly to undergraduate education at the University, teaching more than half of all college courses. Within some divisions, such as the Humanities Collegiate Division, that figure is as high as 75 percent.

“We are sort of the workhorses of the classroom,” FF Secretary Tristan Schweiger said.

For this new round of contract negotiations, FF identified increased compensation for non-tenured faculty as their foremost priority. In the past decade, a 41 percent increase in undergraduate tuition and a 32 percent increase in undergraduate enrollment has led to a substantial rise in the University’s revenue; despite this growth, salary for non-tenure-track faculty has lagged. According to data provided by FF, the gross increase in tuition revenue has outpaced the rise in aggregate academic salaries by 30 percent. Erica Warren, a member of FF’s Bargaining Committee, explained how this stagnation requires non-tenure-track faculty to “do more with less.”

Such stagnations in faculty compensation occur simultaneously with notable allocations to University executives. “In 2021, the University reported the salaries for the top 25 executives as totaling more than $32.5 million. In comparison, approximately 450 faculty members of FF, excluding writing instructors, made about $21 million in salary,” Warren said.

According to FF, this disparity in wages has adversely impacted the livelihoods of non-tenure-track faculty. Although prices for consumer goods have risen 18 percent since January 2021, FF has received wage

increases amounting to less than half of that.

FF Executive Committee member Jason Grunebaum said that the University’s reluctance to provide fair wages to non-tenuretrack faculty conflicts with the significant impact that they have on the education of undergraduate students.

“We would like to help nudge the University to get back to recognizing that its core mission is teaching and research and compensating those who are in the classroom with the students every day appropriately,” Grunebaum said.

In light of the University’s current budgetary constraints, staff hiring freezes, the closing of research institutes, and other cost-cutting measures have all been implemented. Even so, Schweiger refutes using the University’s financial uncertainty as a pretext for reducing faculty compensation.

“We absolutely reject efforts to make up [the budget deficit] by taking money from the people who do the work of teaching at this university,” Schweiger said. “We need to actually make a living wage.”

In a statement to the Maroon, the University said that the 2021 collective bargaining agreement included a 7.5 percent wage increase over three years for instructional professors and a 35 percent wage increase for part-time instructors at the Crown School.

The negotiations will also focus on improving visa arrangements for the union’s 88 foreign faculty members. Tenure-track faculty usually receive a H-1B visa, which imposes the fewest number of restrictions and offers a path to green card sponsorship.

According to Schweiger, the high cost of H-1B sponsorship means foreign non-tenure-track faculty are often given temporary visitor visas (J-1 visa) instead. These visas leave faculty members more “vulnerable” and often require the visa holder to return to their home country after a certain number of years. In some instances, non-tenure-track faculty have been asked to leave the country on a 24 hour notice, according to Schweiger.

Moreover, following the merging with Writing Faculty United, FF is demanding appropriate compensation for the University’s Writing Specialists. Schweiger said many writing instructors are working fullor close to full-time but are not eligible for any benefits.

Through their negotiations, FF seeks to redefine the University’s perception of nontenure-track faculty.

“Management has always been very insistent that there is a hard line between teaching faculty / non-tenure-track faculty and research faculty, and we have always fundamentally rejected that,” Schweiger said. “For one thing it undermines solidarity among workers, but also we feel that we are entitled to participate in the conversations among faculty and the benefits granted to faculty.”

Grunebaum said FF’s efforts in previous negotiations have contributed positively to the lives of faculty.

“I’ve really had the pleasure of seeing, over the years, just what a huge difference it’s made to the lives of my colleagues,” Grunebaum said. “There’s less and less part-time faculty having to run around to five different

campuses in the Chicago area just to make ends meet. I’m not saying that doesn’t still happen, because it does. But there’s less of that.”

Moreover, FF believes that the benefits of increasing faculty compensation trickle down to students’ educational experience.

“I think it all ultimately means better conditions for students. You want a professor who is engaged, supportive, and responsive to your questions and needs, and the worker who is doing that needs to be making a living wage and needs to not be worried about how they’re going to make ends meet so that they can devote that to the classroom…. It’s really an investment in the future,” Schweiger said.

The timeline for negotiations depends on progress made during each meeting. Nevertheless, members of FF expressed optimism for a productive dialogue.

“We hope that the University will be open and receptive to a conversation with us,” Grunebaum said. “We are 100 percent committed to these proposals, we’ve got a really fired up bargaining unit, and we expect a lot of participation.”

In its statement, the University said it was looking forward to continuing negotiations.

“The University is negotiating in good faith with Faculty Forward,” the statement said. “We are grateful for the contributions of the approximately 450 instructional professors represented by the union and look forward to working constructively on a contract renewal that will benefit employees and serve students. We are hopeful for a timely resolution to the negotiations.”

Truman Pierson, A.B. ‘23, always knew he wanted to be an entrepreneur.

“I think a lot of the time for people who are interested in entrepreneurship, it is somewhat inborn,” Pierson said in an interview with the maroon. “I get that question a lot—‘what would you do if you weren’t working on this?’ I’d probably be

working on a different company, trying to start something else.”

Since graduating early last fall, Pierson has devoted himself to being CEO of Theta Neurotech, a startup he cofounded with two students from Vanderbilt University. The company aims to develop a wearable earpiece using electroencephalography

(EEG) technology that alerts epilepsy patients 30 to 60 minutes before they have a seizure.

“Electroencephalography is a type of brain imaging technology utilized in clinics typically,” Pierson said. “What the EEG is doing is it’s monitoring the electrical discharges of the wearer’s brain. When your neurons are talking to each other and communicating with each other, they’re

often communicating with electrical signals. Essentially what an EEG does is it picks up on that electrical signal emitted by neurons, and based off of that signal you can make determinations about the patient, how their brain is functioning.”

After producing a prototype earpiece, the company hopes to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval

CONTINUED ON PG. 3

“We knew that we could take this technology that we’d been working on... and apply it to this specific use case and help a lot of people.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 2

within the next 18 to 24 months after two clinical trials: one at UChicago Medicine to determine whether the devices predict seizures as intended, and another larger, longer-term study to test their everyday use. Once the trials are complete, the company would focus on preparing for distribution. Pierson said Theta Neurotech’s product is especially important for the approximately 30 percent of epilepsy patients with uncontrolled seizures.

“Our goal is... to provide [patients] with an early warning sign for the seizures, one, so they’re not getting injured, [and] two, so they can also take seizure rescue medication to prevent the seizure before it actually occurs,” he said.

Pierson credits his cofounders with providing expertise that was critical in the development of Theta Neurotech’s product. “Myself, my background is in

computer science; I knew I could handle the load of the software side and the deep learning side,” he said. “My other cofounder, Ali [Hussain], his background is in neuroscience, in lab EEG research, so he had a lot of background understanding of the technology to start with. And our third cofounder, Chris [Fitz], is a chemical engineering student and has a deep understanding of the materials science required for developing the hardware.”

Epilepsy wasn’t always the focus of Theta Neurotech, which Pierson, Hussain, and Fitz founded in June 2022. Originally, Pierson said, they hoped to create a “Fitbit for your brain.”

“I felt that was going to be an area of demand in the future on the consumer side,” he said. “But as we got a feel for the state of the research, we found a much more clear problem/solution in the epilepsy space. We knew that we could take

this technology that we’d been working on and getting an understanding of and apply it to this specific use case and help a lot of people.”

That process helped focus Pierson’s personal priorities at UChicago.

“My junior year was hectic—I studied abroad. I was also still playing baseball at the time. I still had to focus on class. It wasn’t clear yet that the company would find the right direction,” he said. “But my junior year summer, we found this much clearer need and something that we knew we could accomplish. So after that, I realized it was time to quit baseball, it was time to graduate early, try to get out of school as quickly as possible.”

Pierson has high hopes for Theta Neurotech beyond epilepsy.

“We’ve also started developing an algorithm that can automatically detect Alzheimer’s from EEG signals,” he said.

“It’s important technology because [diagnosing] Alzheimer’s is expensive, it takes multiple tests, some of them are invasive, and then [they] are often not accurate. So our goal is to be able to provide a low-cost mechanism for automatically detecting Alzheimer’s and then, given early detection, be able to actually treat Alzheimer’s and prevent the buildup of amyloid to ensure that it does not develop further.”

In the long term, Pierson said, Theta Neurotech could move toward products aimed at a wider consumer base.

“Doing brain-computer interfacing, where people in general can interact with their phone or their computer just based off of their thought, whether it be thought to text or thought to image or thought to video, that’s the ultimate goal,” he said. “But epilepsy and Alzheimer’s are two primary focuses.”

Eva McCord & Kayla Rubenstein, Co-Editors-in-Chief

Anushree Vashist, Managing Editor

Zachary Leiter, Deputy Managing Editor

Allison Ho, Chief Production Officer

Kaelyn Hindshaw & Nathan Ohana, Co-Chief Financial Officers

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Rachel Wan, editor

Eric Fang, editor

Peter Maheras, editor

GREY CITY

Rachel Liu, editor

Elena Eisenstadt, editor

Eli Wizevich, editor

Evgenia Anastasakos, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Cherie Fernandes, co-head editor

ARTS

Noah Glasgow, head editor

SPORTS

Shrivas Raghavan, editor

Josh Grossman, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, lead developer

PODCASTS

Jake Zucker, co-head editor

Gregory Caesar, co-head editor

CROSSWORDS

Henry Josephson, head editor

Pravan Chakravarthy, head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO

Emma-Victoria Banos, co-head editor

Eric Fang, co-head editor

DESIGN

Elena Jochum, design editor

Haebin Jung, design editor

COPY

Caitlin Lozada, copy chief

Tejas Narayan, copy chief

Coco Liu, copy chief

Maelyn McKay, copy chief

SOCIAL MEDIA

Phoebe He, manager

NEWSLETTER

Katherine Weaver, editor

BUSINESS

Jack Flintoft, co-director of operations

Crystal Li, co-director of operations

Arjun Mazumdar, director of marketing

Ananya Sahai, director of sales and strategy

Editors-in-Chief: editor@chicagomaroon.com

For advertising inquiries, please contact ads@chicagomaroon.com

Circulation: 2,500

The UChicago Podcast Network (UCPN) features over eight shows that span a diverse range of disciplines—from politics and economics to astrophysics and human rights—highlighting scholarly discourse at the University of Chicago. the Maroon spoke with Big Brains host and Vice President of Communications Paul Rand, Not Another Politics Podcast cohost and Sydney Stein Professor in American Politics William Howell, and UCPN Assistant Director Matthew Hodapp about their experiences hosting and producing podcasts for the network.

“A rising tide lifts all boats,” Hodapp said, “so, we thought, why don’t we just put everything under a singular banner, under a similar mission of trying to be competitive in the larger ecosystem.”

Thus came to be UChicago’s very own Podcast Network, now the largest academic podcast network in the country, with nearly two million downloads over the last year.

Bringing over a decade of experience in podcast production, Hodapp has been with the University since 2019. He has been assistant director of the network since 2022. “There’s this thing in podcasting I call the pocket principle. When people are deciding to listen to a podcast, they’ll give it about 30 seconds be-

fore maybe clicking on something else,” he said. According to Hodapp, if you can convince your audience to put their phone in their pocket while doing the dishes or walking the dog, it’s unlikely they’ll take it back out. It is from this, he says, that arises a unique opportunity to put forward an exciting educational product.

When asked what makes UCPN unique, Rand promptly answered: rigor. “I think the students that thrive here are those that come for a true passion of learning, and it becomes a lifelong way of operating in the world. So, I think the podcasts are just part of fitting into that way of being in the world,” Rand said.

“We hold attention here that is born of two competing aspirations. One that has defined the University of Chicago, which is a commitment to understanding the value and integrity of evidence and ideas, in its own right,” Howell said. “There’s another ambition, especially here at the Harris School, which is to speak to people outside of our tribe and engage in something larger.”

According to recent studies by Forbes, podcasts have gained immense popularity across all audiences with its accessibility and diverse content offerings. Yet, their popularity coincides with a rising tide of misinformation across the media

ecosystem.

“We are [named] Not Another Politics Podcast because we aren’t just leaning back and slinging opinions about the latest headlines. We’re trying to model all that scholarship has to offer and what it means to productively and critically engage it. We don’t treat it as gospel; we don’t bow before it,” Howell said.

In this way, rigorous academia serves as a safe harbor among all the “bluster, chaos and posturing” that informs so much of political discourse today.

“I think one of the issues in media today is that we want to be as frictionless as possible. And, of course, reality, especially scientific reality, is not frictionless. If you don’t challenge and try to engage with some of the harder stuff, you’re maybe doing a disservice to your audience. We put a lot of effort into not falling into that trap,” Hodapp said.

Yet, beyond its endeavors to illuminate the latest findings in academia, the UCPN has also played a fundamental role in allowing the world to keep a firm finger on the pulse of the University’s own advancements. “It wasn’t that long ago that there used to be a belief at the University of Chicago that if people needed to know about us, they would find us,” Rand said.

Now, according to University Communications, there has been an observed trend of prospective students tuning into

UCPN shows, providing Rand with a direct lens into how scholars are “defining their fields while confronting some of the world’s most pressing research questions.”

“The benefits of doing this then have multiple layers, and it’s some of the most popular content we put out because people get to really experience life at the University. It’s almost like listening into a college lecture,” said Rand.

In discussing some of the challenges and criticism facing institutions of higher education, Rand said that conversations have become increasingly politicized in a way that is unproductive. “When you think about the value and the impact of higher education, helping people not only to learn but hopefully how to open up their minds to new ideas, to doing research that is truly changing the world during a time when we are facing some of the biggest challenges as a society.” Rand said he finds that answers to many of our challenges can be found within universities like UChicago.

“There’s a much bigger calling at stake: it’s very easy to criticize something that you don’t know anything about. It’s a lot harder to hate on something that you have a deeper understanding of. That is a big thrust of what we’re trying to do with the UCPN,” Rand said.

Provost Katherine Baicker, Vice Provost of Diversity and Inclusion Waldo E. Johnson, and Assistant Provost for Institutional Analysis William Greenland held a virtual town hall on Monday to discuss the results of the 2023 Campus Climate Survey.

Baicker opened with a brief summary of the results from the survey. The survey opened to students, academics, and staff in May 2023. The survey had response rates from those groups of 21 percent, 41 percent, and 42 percent, respective -

ly. Overall, 30 percent of the University community responded to the survey.

When addressing the response rate, Baicker said, “Of course, any survey is just a snapshot in time. I’m going to talk with you about the response rate, which was not bad for a survey conducted via this mode but leaves lots of opportunity for people with different views not to be represented. So, you always want to take that with a grain of salt.”

Overall, respondents reported a slight improvement from the 2016 Climate

Survey in racism, homophobia, socioeconomic status, and other dimensions. However, members of marginalized groups reported higher levels of intolerance on campus compared to the rest of the community.

Baicker emphasized that since these results were collected in May, they do not reflect any changes in campus climate due to the conflict in Gaza. “I mentioned this before, but I will say again, this was conducted in May, which is before a lot of things happened on campus and in the world in October and beyond,” Baicker said, specifically after discussing

the results about tolerance of religious identity.

The bulk of the virtual town hall was focused on answering questions from attendees. When asked how the University’s data compares to peer institutions, Johnson said, “Our response rates and findings are very similar to other universities.”

In 2018, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) conducted an Academic Climate Survey with a 39 percent response rate from students, a 49 percent response rate from staff, and a 69

“Johnson... hopes engagements and activities... such as more town halls and focus groups with students will help increase response rates for future surveys.”

This visual shows response rates to different universities’ Campus Climate surveys, broken down into rates for students, academics, and staff. nikhil patel

CONTINUED FROM PG. 4

percent response rate from faculty. All three of these response rates are greater than UChicago’s rates in their respective sections.

In 2021, Stanford University conducted a Campus Climate Survey with a 29 to 31 percent response rate from students, postdocs, and clinician educators, a 44 percent response rate from staff, and a 38 percent response rate from faculty. Thus, while UChicago’s response rates from staff and faculty are comparable to Stanford’s, UChicago’s student response rate still lags.

Brown University’s 2023 Climate, Diversity, and Inclusion Survey had response rates of 15 percent for undergraduate students, 62 percent for staff, and 33 percent for faculty. With the exception of the staff response rate, which is much higher, the faculty and student response rates are lower than UChicago’s.

Johnson said that he hopes engagements and activities after this webinar, such as more town halls and focus groups with students, will help increase response rates for future surveys, as well as gather more information related to the initial findings of the 2023 Climate Survey.

In the survey, respondents were asked to identify their academic or administrative unit. When asked whether more specific climate data will be provided to the heads of these units, Johnson said, “We will have to take care to make sure that no identities are compromised…. We are interested and willing to extend as much as possible to help units by providing this information, and so we’ll have a period of time immediately following this webinar to begin with providing the opportunity for people to indicate that this is something that an academic or an administrator unit would like to do.”

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) has announced that the Pediatric Cancer Data Commons (PCDC) at the University of Chicago is one of five winners of the 2023 OSTP Year of Open Science Recognition Challenge.

According to the White House, the challenge aimed to recognize science projects that demonstrated dedication to solving current global issues while promoting “open science,” which the OSTP defines as the “principle and practice of making research products and processes available to all, while respecting diverse cultures, maintaining security and privacy, and fostering collaborations, reproducibility and equity.” To be considered eligible, project submissions were required to secure funding from federal grants or utilize

federally-supported resources.

Funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), the PCDC established the largest “international sharing platform” of pediatric cancer data in the world with the goal of alleviating inaccessibility to cancer research findings and improving cancer diagnosis and treatment.

The data initiative began when PCDC principal investigator and pediatric oncologist Samuel Volchenboum and pediatric oncologist Susan Cohn collaborated with data expert Brian Furner to create a neuroblastoma data commons in 2016. Also leading the project was Doug Hawkins, chair of the Children’s Oncology Group and pediatric oncologist at the Seattle Children’s Hospital, alongside E. Anders Kolb, pediatric oncologist and CEO of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

The success of this initial project led the PCDC team to create data commons for other conditions, such as diabetes and epilepsy, and has inspired other researchers to build similar data-sharing platforms. The PCDC has also created GEARBOx, a data portal where physicians can match their patients to potential clinical trials. GEARBOx is currently only available for patients with acute myeloid leukemia but will be developed to include other cancer varieties. The PCDC team hopes that its data platforms can provide personalized support and “follow patients across their lifetime.”

Further, the PCDC cancer data collections are free to use and can be accessed through their online data portal.

“We focus on rare diseases and the need to aggregate and harmonize data from all over the world to fuel research and help improve the lives of patients,” Volchenboum commented to the OSTP.

“Being designated by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy as a Champion of Open Science is an incredibly meaningful recognition of our worldwide efforts to lower barriers to research of rare disease.”

According to the OSTP, PCDC’s endeavors have helped advance the goals of the Biden administration’s Cancer Moonshot, a plan to prevent millions of cancer-caused deaths in the United States over the coming decades.

“We can expand what’s possible with open, equitable, and collaborative science,” OSTP Assistant Director for Public Access and Research Policy Maryam Zaringhalam commented to the OSTP. “As we highlight these champions of open science, OSTP hopes to inspire others to share their stories about how science and technology can open opportunities for every person.”

the perceived delegitimization of “bizcon.”By ANIKA KRISHNASWAMY | Grey City Reporter

After first-year Nicole Tian committed to the University of Chicago, she opened the Class of 2027 Instagram page, eager to learn more about her new peers before the school year began. As she scrolled through her classmates’ profiles, however, she noticed nearly every post featured some variation of the same three words: “prospective economics major.” Words that she would only become more familiar with when she arrived on campus.

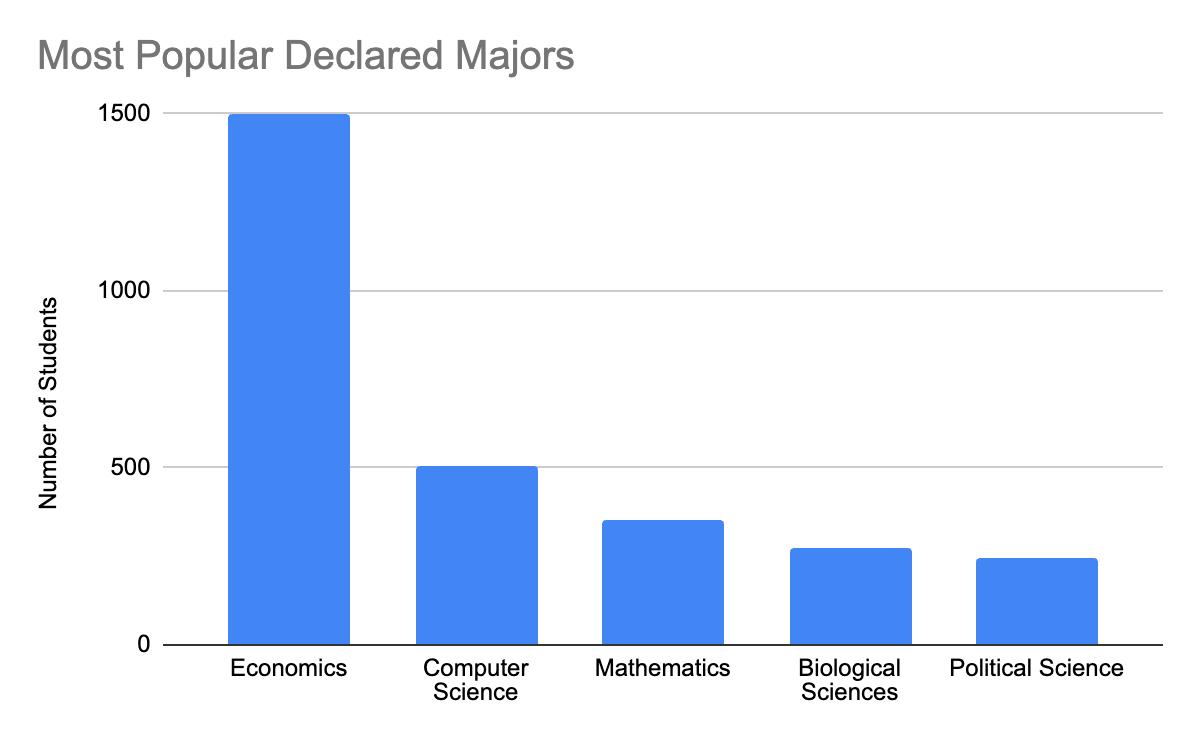

Having entered the College as an aspiring business economics student, Tian was far from alone in her initial choice of degree. As of Winter 2024, 1,498 UChicago students have declared intent to major in Economics.

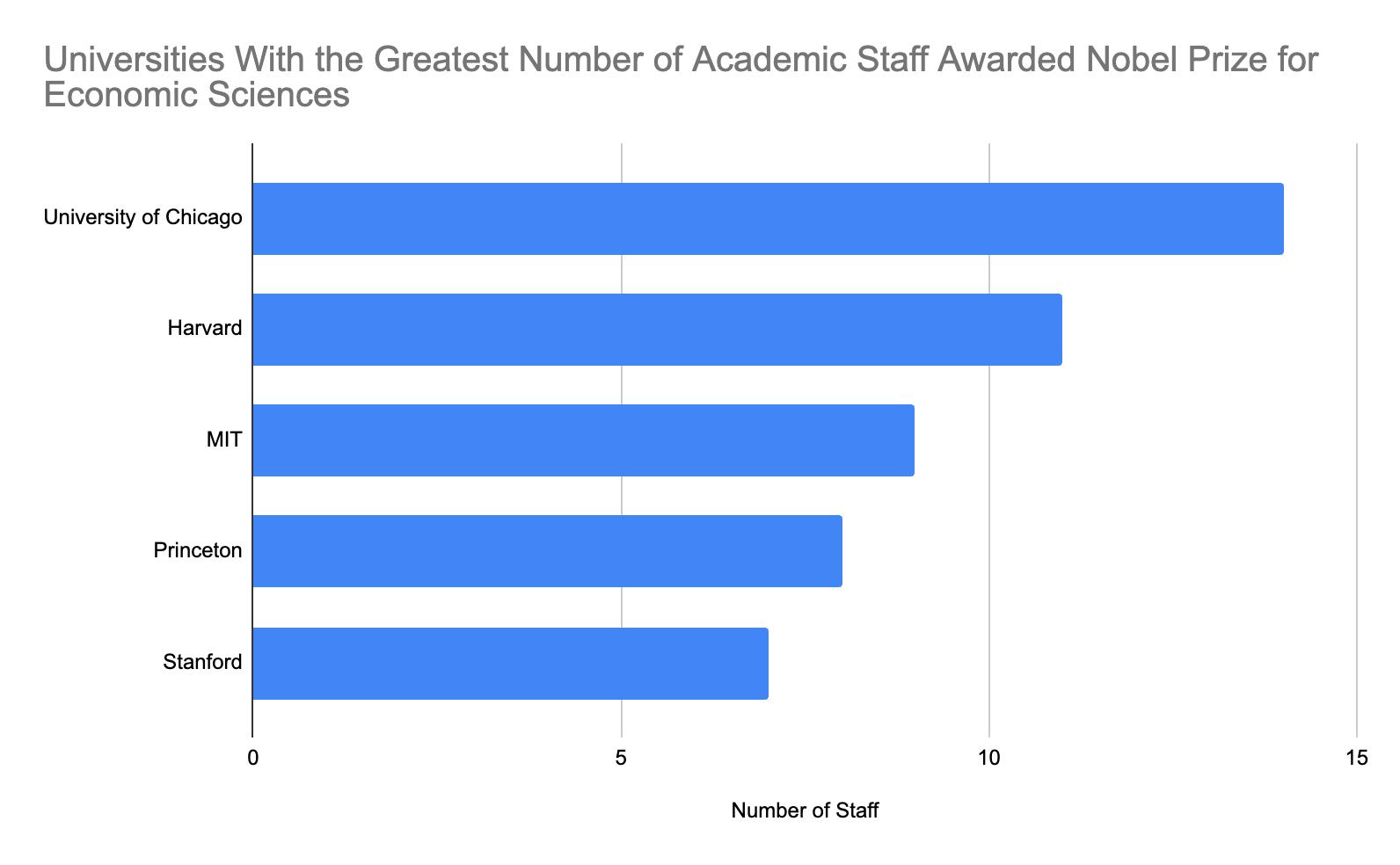

Professor Allen Sanderson attests to UChicago’s reputation for Economics. “We have produced a large number of Nobel Prize winners and have had some of the best minds in economics for the last 200 years, from Milton Friedman to Gary Becker,” Sanderson said, referencing the fact that 35 percent of Nobel Laureates in Economic Sciences have been affiliated with UChicago.

Sanderson added that the economics department’s relationships with other bodies on campus, like the law school and the business school, have added to UChicago’s status as an “economics school,” such that there are several “centers” for economic study. In Tian’s view, it’s precisely this reputation that has created so many prospective economics majors.

“Everybody knows that UChicago’s economics program is really strong,” Tian said. “So a lot of people, I think, if they don’t know what they’re going to major in, they’ll just say econ. They don’t say undecided,

they just say econ.”

Also a business economics major, third year M.R., who asked to remain anonymous to avoid backlash from classmates and clubmates, has observed the distinctive allure of UChicago’s economics program. To appeal to the university’s reputation for quirkiness, M.R. explained that some students will even deliberately indicate interest in “less popular” majors, attempting to improve their chances of admission and bypass the large pool of economics-interested applicants, only to switch to economics upon acceptance.

“[Many of the] students I know applied to UChicago because of the economics program,” M.R. said. “Of course, when we first apply no one has really decided on a major, but there are also people who got in for different majors. I’ve known people who applied for history [or] English literature, [but] it’s an application strategy to get around the group of applicants who are applying to econ directly.”

This “application strategy,” though perhaps useful at other institutions that admit by major, may not have a significant impact at UChicago, where students, aside from prospective Molecular Engineering majors, are admitted to the College as a whole. Yet many students, perhaps influenced by social platforms and peer advice, still believe in its effectiveness.

Regardless, M. R. has found that after acceptance, she and many of her peers switched to economics for the promise of a high-paying job after graduation, not because they actually enjoy it. At UChicago, economics is split into three tracks: standard economics, business economics spe-

As of Winter 2024, the most common major declared by students is irrefutably economics, with 1,498 students. Computer science is a very distant second with 508 students—barely a third of its size. anika krishnaswamy

As of 2023, UChicago has had the most faculty be awarded the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences of any other university. Currently, there are seven Economics Sciences Nobel Laureates among UChicago staff. anika krishnaswamy.

“Selling out is students choosing their career based off of how much money they’re going to be making out of that career.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 6

cialization, and data science specialization. Of the three, business economics, which is M. R.’s chosen specialization, is viewed as the most overtly industry-focused, with its official description even declaring it best for students interested in “careers in the private sector, the non-profit sector, and the public sector” rather than academia.

Tian added that job prospects are also one of the main reasons why students covet membership in hyper-competitive finance and consulting clubs, herself being a member of Paragon Global Investments—an RSO with multiple rounds of interviews and a detailed written application.

“I think students mainly join these clubs for connections,” Tian said. “A lot of these clubs, on their websites, have a list of where their alumni have gone on to work— big firms like Blackstone, BCG, McKinsey— and to have those kinds of connections and also be able to learn is a big thing.”

Likewise, M. R., who has been a member of one of these clubs since her first year, explained that, in her experience, they are often “overhyped.” She finds that these clubs try too hard to replicate the “highly competitive” cultures of traditional finance jobs—both social and professional—which has caused her stress in the past.

“[In my second year,] there were firstyears who came to me for advice about how to get into [one of those clubs],” M. R. said. “It’s really like a frat or sorority—just kind of a social symbol. Also, people would be really chasing after these so-called networking opportunities, but you can learn

those technical skills by yourself. I can buy a modeling class on Wall Street Prep and learn everything. I mean, of course, working in a team and on a real pitch is very valuable, but I think the membership of these clubs is really overvalued [to the extent that] it is seen as the gateway into finance.”

Many of these preprofessional clubs also have large budgets—for example, the Blue Chips manage a $150,000 equity profile—which gives them hands-on access to investing scenarios that most students wouldn’t otherwise have the financial means to engage with independently. This, M. R. says, is where the real “value” of these clubs shines, and why, despite not always enjoying their competitive culture, she remains a member.

Likewise, though M. R. doesn’t always draw enjoyment from her economics coursework, her main intention with both her major and extracurriculars is to maximize her chances at obtaining a lucrative career in finance after graduation.

“[The business economics major] is meant to gear you up for finance jobs and [though] I did enjoy a lot of the classes, I definitely enjoyed my core classes more than the econ classes in general,” M. R. said. “[Still,] I’m just trying to get into investment banking.”

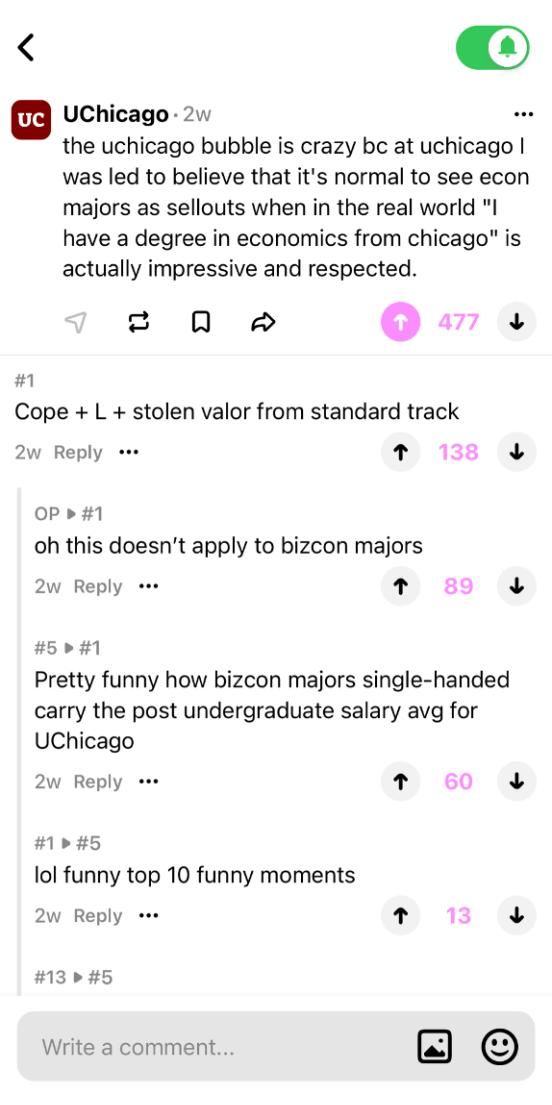

According to alumna Jessica Zhong (A.B. ’23), however, this mindset isn’t always viewed favorably by the rest of the student body, with many referring to students like Tian and M. R. as “sellouts.”

“Sell[ing] out is students choosing their career based off of how much money

they’re going to be making out of that career, rather than a love or passion for the subject,” Zhong said. “I think, at UChicago in particular, it’s a controversial subject because we emphasize intellectualism and academics so much more than other institutions, so any student who chooses a more money-focused career stands out.”

Zhong added that this disdain for prioritizing money over passion is exacerbated by the fact that many UChicago students tend to be “privileged” enough to study more “esoteric, academic” subjects without considering salary, making those who choose to “sellout” stand out by contrast. However, she also notes that the business economics major is composed of students from all financial backgrounds, many of whom have parents already involved in the finance industry.

“There’s a level of affluence and privilege [at UChicago] that’s not reflected in the real world, where college is mostly seen as a pathway to a higher standard of living or a higher salary and that’s seen as respectable,” Zhong said. “In the real world, where the average salary is much lower, nobody can blame you for trying to improve your livelihood [by selling out].”

For Sanderson, too, this practicality-focused mindset is completely understandable. “[Rather than] ‘sell out,’ I would define it as: ‘economics [is] a really interesting field where I can get a job after I pay $70,000 for four years [and be able to] pay off my loans,’” Sanderson said. “People are just responding to that sentence: ‘What’s the incentive?’”

The comments shown in this screenshot, taken from the popular anonymous social platform Sidechat, are not unusual in their denouncement of “bizcon”—i.e., business economics— majors. Many students view business economics as “easier” than standard track due to its less stringent math requirements, leading to its perception as the inferior version of the major. anika krishnaswamy

Tools like ChatGPT are a type of forbidden fruit, tempting even those who wouldn’t normally fudge their assignments.By JOSIE BARBORIAK | Grey City Reporter

“In the hallowed halls of the University of Chicago, where intellectual prowess reigns supreme, an unexpected compan-

ion has emerged in the pursuit of academic excellence: ChatGPT. As students navigate the labyrinth of scholarly pursuits, this

digital oracle has proven to be more than a mere tool; it’s a confidant, a sounding board, and an indispensable ally in the quest for eloquence,” ChatGPT wrote.

I thought that if I was going to write

an article about ChatGPT at UChicago, I should go straight to the source. ChatGPT suggested that I begin this article with the paragraph above—stylistically over-

CONTINUED FROM PG. 7

wrought and unnecessarily wordy.

For many at UChicago and other universities, this style has become practically ubiquitous. Since November 30, 2022, students have used the large language model known as ChatGPT to write discussion posts on The Odyssey and score dating-app matches, and it’s become a frequent companion in our classrooms.

UChicago is distinctive for its Core, which preaches that students should respect and commit themselves to multiple forms of learning. The school prides itself on encouraging all students to critically engage with qualitative and quantitative work, no matter what subject a particular student is inclined toward for their major.

These ideals don’t always hold up in practice. Many students face the temptation to cop out of some facet of the Core, and ChatGPT can provide an easy way to do so. A math major taking honors STEM classes and IBL Calculus along with the Humanities sequence might not want to use more time on assigned readings. An art history major immersed in reading-and writing-based classes might see Core Biology as a mere chore. Tools like ChatGPT are a type of forbidden fruit, tempting even those who wouldn’t normally fudge their assignments.

ChatGPT is a large language model (LLM). It uses natural language processing to mathematically map out connections in language that humans understand instinctively. It’s called a large language model due to the enormous dataset of forums, articles, and books upon which it is trained. The newest iteration, GPT-4, uses the entirety of the internet as it appeared in September of 2021, which is rumored to have around 1 trillion parameters, or learned variables.

Other AI assistants are showing up everywhere; from Handshake’s Coco to X’s Grok. New digital tools like ChatGPT are part of a quest for optimization and to eliminate drudgery from our daily lives, perhaps at the expense of some humanity. If an AI can drive your car, check your resume, or mediate a breakup with your situationship, what can’t it do?

Though ChatGPT can appear to be an

independent actor, having conversations and answering questions, it’s more like your phone’s predictive text feature set to a massive scale—it considers each word in a sentence as a statistical likelihood to try to determine which word should come next. And, like the Internet upon which it’s based, ChatGPT has a fuzzy relationship with truth. Science fiction writer Ted Chiang wrote in the New Yorker that ChatGPT is a “blurry picture of the Internet.” Just as a JPEG compresses an image file, ChatGPT condenses the infinite information on the Internet into grammatically correct sentences. But that doesn’t mean that it’s always correct.

This compression is the reason ChatGPT is often unable to pull genuine quotes from specific sources. In an endof-year discussion on LLMs, students in my Self, Culture, and Society class shared secondhand anecdotes of essays written completely with ChatGPT. Some students realized only after the deadline that not a single quote the LLM included in the essay existed. The professor, Eléonore Rimbault, who led the discussion, revealed that the department had indeed seen some bogus quotes in the past two quarters, and that ChatGPT usage was more obvious than students may think.

For a user accessing ChatGPT, the clean design and free-floating blocks of text appear to come from nowhere. The chatbot doesn’t cite the sources from which it draws, which has raised the question of the ownership of ideas. Not only is a coalition of authors filing a class-action lawsuit, claiming that it’s a copyright violation to train on preexisting works of fiction and nonfiction, the New York Times is also suing for lifting near-verbatim chunks from its news articles.

When AI usage appears ubiquitous, students begin to see it as an alternative to falling behind on classwork. In the Core especially, students confront subjects unfamiliar to them, adding strain to an academic environment that is already challenging. Students may want to bypass the confusion that occurs when learning new content, which involves understanding dense texts, concepts, or diagrams and requires a significant time commitment.

During class discussions in my Media Aesthetics class, a friend told me that his whole side of the room was just “a bunch of screens of ChatGPT.” Another friend completely avoided the task of reading The Odyssey, using ChatGPT to write discussion posts for her Human Being and Citizen class.

I spoke to a second-year student who used ChatGPT extensively in his first year, who asked to remain anonymous for future employment reasons. He was assigned Dante’s Inferno for his Humanities class, Human Being and Citizen. “I found it very interesting, but extensively dense,” he said. To answer discussion posts, he’d have to sit with the text for an hour or two and “think really hard.” When ChatGPT became available, he started to use it as a time-saver to guide the questions he would ask in discussion posts and essays.

“For the discussion posts that looked harder, I needed a catalyst,” he said. ChatGPT gave him a starting point. He would ask it to help structure an argument in response to the prompt or suggest evidence from the text to support a point. Over time, he got better at creating prompts for the LLM, which he says translated over to asking better questions during in-class discussions. In a way, rather than as a crutch, the LLM functioned like a pair of training wheels.

The same student stressed the importance of fact-checking everything the LLM outputs. GPT-4’s generation speed is slower and more in-depth, but it still makes a lot of mistakes. This fall quarter, he was using it for neuroscience classes. Though AI helps him understand complex diagrams and organize his thoughts for discussion posts and essays, he’s trying to limit his dependence on it.

“I’m trying not to use it at all this week,” he said. “For having high-level thoughts, I feel like my soul has to be attached to that,” he continued. “ChatGPT is an easy cop-out, and there’s a part to learning and critical analysis that I’ve missed. It detaches me from what I write about.”

Discussion posts and speaking in class are worth much less than exams, large projects, and essays in most grading breakdowns at UChicago. A student might think

this makes them less essential components of a course. Amidst optimization-related rhetoric and suggestions to “work smarter, not harder” at UChicago, students may want to leapfrog past a state of confusion to get them done.

But studies show that confusion is good for the deeper kind of learning that allows one to apply knowledge to new situations. Being forced to sit with a new concept longer encourages reflection and deliberation, allowing one to make sense of contradictions and gain a fuller understanding. So, even minor ChatGPT use could be hurting students.

Later on in our conversation, the same student came to a conclusion I found surprising based on his prior behavior. “I know this is hypocritical, given how much I’ve used it, but I wholeheartedly think it should be banned,” he said. “I really regret using it so heavily in my first year. And if you go to the A-level [of the Regenstein Library] now, you’ll see so many screens with ChatGPT!”

The University does not have an official stance on ChatGPT. Instead, it is explicit only about intellectual property, forbidding outright plagiarism. “Individual instructors have the discretion to set expectations regarding the use of artificial intelligence, including whether the use of artificial intelligence is pedagogically appropriate,” said a University spokesperson. They’re allowed to determine to what extent using AI to clarify dense topics is helpful or harmful to overall learning, which could vary across disciplines.

“Our basic goal here is that students learn,” said Navneet Bhasin, a biology instructor whose stance on ChatGPT is that the LLMs are no replacement for the true work of learning. “[Students] have to take in the material, research it, and call it their own, and then be able to integrate it into their Core education and an informed society.”

Now, the biology department must consider the potential use of LLMs when evaluating students’ work. Instructors have changed assignments to focus more on writing during class, without the use of the internet. Bhasin has altered the

creative muscles that are fundamental to

CONTINUED FROM PG. 8

weighting of points for lab reports, prioritizing results over introductions and discussion sections, the basic summaries for which ChatGPT is most suited.

“Students are not just a conduit for answers,” she told me. “They have to learn how to relate to the material.” To her, this is the true work of learning, and it’s the purpose of the Core Biology curriculum. Bhasin said that directly copying from ChatGPT is no different from plagiarism, and it makes students lose the opportunity to apply the writing and expression skills that are a big piece of Core Bio.

The Biological Sciences Division requires that students cite their sources if ChatGPT is used as a supplemental tool in any assignment. “Policing is something we as educators don’t like to do,” Bhasin said. She pointed out that, in many ways, these issues will regulate themselves. An LLM’s products are often “misinterpretations of reality,” which must be verified. “If students use an LLM and need to fact-check it, our goal has been fulfilled. They have learnt it.”

“Eventually, I see [ChatGPT] being integrated, like phones and computers, or considering an LLM like a part of your study group,” she said. For now, “there’s too much at stake in the real world” from trying to bypass learning.

Bhasin told me she isn’t currently seeing a lot of student work that looks like an LLM wrote it. But from my conversations with students, I wondered if that was really the case. I could see how a student who understands the material and knows what buzzwords to hit could use ChatGPT to put the sentences together, avoiding doing the work itself. Perhaps direct plagiarism isn’t the only way to be intellectually dishonest.

Indeed, as students and professors have continued to discuss the use of ChatGPT, some have tried to incorporate it formally as a learning tool. After all, maybe there’s utility in having access to the sum total of human knowledge found online, providing some automated version of a popular consensus. To that end, I spoke to Felix Farb, a second-year in the College, about his experience encountering ChatGPT in the Power, Identity, Resistance sequence

this past autumn quarter.

As a supplement to reading about Rousseau’s concept of the body politic, the instructor assigned the students to make a body politic of their own and to create a law together. Near the end of the class period, a student suggested asking ChatGPT to complete the task. The class decided this was a valid idea on the basis that Rousseau concludes in The Social Contract that “Gods would be needed to give laws to men.” Rousseau’s legislature is all-knowing of human nature but divorced from it, a being with “superior intelligence” who “has no connection to our nature and yet understood it completely”—that sounds a whole lot like ChatGPT. Another student with a subscription to GPT-4 pulled out a computer and prompted it to design the law.

The students wondered if artificial intelligence could function like this supreme, law-giving being. After 80 minutes of student discussion, the LLM had reached similar conclusions as the class. But the text was “far more formulated,” Farb said. “It was doing more, faster.” They watched as the law unfurled on the screen.

Many share this awe at ChatGPT’s power. Farb described in detail one note-taking method he has witnessed at the University, which has involved his classmates asking GPT to provide them with questions to pose during class discussions. “I don’t look down on that at all,” he said. “It’s someone using a tool to help them understand a dense topic in a simple manner…If it’s better than us, is it wrong to use it for some insight?”

Farb’s holistic feelings on LLMs are more mixed. He admitted to trying on occasion to use the tool to improve specific sentences but said that he doesn’t “bounce ideas” off ChatGPT like some of his friends do. He drew a distinction between GPT3.5, an earlier version, and GPT-4. To him, GPT-3.5 looked like “a 16-year-old trying to write an essay”—it was stylistically lacking in a way that didn’t tempt him to use it. Not a resounding endorsement. Additionally, “It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking you understand something,” he said, and it’s a trap he wants to avoid. It is possible that ChatGPT atrophies in its frequent users the logical and

creative muscles that are fundamental to generating new thought.

ChatGPT’s inadequacies can also be pedagogically helpful. Farb brought up a problem set for Real Analysis, a math class, in which the instructor assigned students to ask ChatGPT to do a specific proof, then try to fix where it went wrong. The LLM’s solutions, Farb told me, were unimpressive.

“ChatGPT isn’t even in its infant stages for math,” he said. Similarly to its predictive text capabilities, it can produce proofs that look real at a cursory glance to non-experts. But, like a house built on a shoddy foundation, the logic isn’t valid, and the proofs fall apart upon examination by a mathematician.

Andre Uhl, a theorist at the Institute for the Formation of Knowledge, is hopeful about the possibilities of ChatGPT. Uhl’s background is in visual arts and film, but he’s recently been doing policy work in AI ethics. He studies technologies and the frameworks of knowledge around them as they relate to humanity’s search for collective meaning.

“There’s a prevalent anxiety, and the shortcut is to ban [ChatGPT] and take a step back,” he said. I thought of the student I’d interviewed whose learning had been so impacted that he believed a ban was for the best. Uhl’s perspective is different. He thinks universities will ultimately need to adapt classroom and research practices to embrace new tools like LLMs and delineate spaces that encourage or preclude their use.

A year is a short time, Uhl said, and ChatGPT is still a new tool that people are testing out, one that’s “not that different from the internet or a library.” He pointed out that it is substantially helpful in cases like proofreading articles for academics who’d learned English as a second language. Uhl’s first language is German, and ChatGPT had helped his English-language writing conform stylistically to the academic space.

“We need to create spaces where it is safe to experiment and collaborate across generations to create new forms of expertise,” Uhl said. Uhl himself is in the process of developing a comprehensive AI litera-

cy curriculum with tailored modules for students across various fields of study and professionalization.

People in my generation, Gen Z, are often referred to as “digital natives;” we’ve grown up navigating digital environments as much as physical ones and relate to each other through our participation in a diverse set of online communities. It makes sense that we’d be the most comfortable doing homework hand-in-hand with an AI. However, Uhl also spoke to the importance of understanding ChatGPT’s limits, and where we should be cautious about using it.

Uhl stressed that ChatGPT is a tool, not an actor or entity, and it should be treated as such. “Even calling it artificial ‘intelligence’ may not serve the right purpose,” he said. I thought about how the tool’s name has become a verb; students say, “I’ll just ChatGPT that” in reference to low-level Core writing assignments. You could compare this with the common “I’ll Google that” or “I’ll Wikipedia that.” “Verbifying” these human-created machines seems to give them a life of their own, imbuing them with a new level of certainty, and eventually, a new level of power.

Thinking about how AI tools have appeared and been used as agents, I asked Uhl about AI-generated images, which often appear alongside art created by humans. In cases of intellectual and creative property, ethics become especially important, Uhl told me, and AI is a genuine threat; he pointed to the then-ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike. If human writers and actors protest poor working conditions, LLMs and digital likenesses could replace them, à la Black Mirror. I recognize this danger. On Instagram and TikTok, AI-generated “art” or “photography” have started to dominate suggested content. Within minutes, AI image creators like DALL-E can show you everything from “the cutest possible kitten” to “Succession characters in the style of Wes Anderson.”

“The point of the creative practice is to learn about the other person’s soul,” Uhl suggested. The presence of artificial intelligence that can throw together surface-level elements doesn’t take away from the value of learning how to write or make

Is this a

Or could it be the start of something greater?

CONTINUED FROM PG. 9

art. There are places, perhaps, where we don’t need to hear what a chatbot has to say. Uhl said, regarding AI art: “We could, but should we?”

This seems to be the central question of how we will approach artificial intelligence for learning and creating. ChatGPT is, after all, constantly getting better. Most of our interactions up until this point have been with GPT-3; GPT-4 is more sophisticated and harder for plagiarism tools to detect.

We’ll have to start drawing lines between what work can be done by the robots, and what work belongs to us. David Graeber

pointed out in his book Bullshit Jobs that automation could pave the way towards eliminating drudgery—writing formulaic emails, entering data into spreadsheets, or scheduling events and projects. How much more would this university be able to indulge the Life of the Mind if we let future iterations of these tools do the boring stuff? Or should we forgo AI completely, following the basic idea behind the Core— that all work and all learning, even if you don’t recognize it as such, has meaning?

After all, we may not be able to cleanly divide work which is drudgery and that which builds important organizational

skills. Constructing and reconstructing arguments, interpreting charts, and finding relevant text passages could all fall in a gray area, since student and ChatGPT alike can accomplish these tasks. Universal categorization of situations in which ChatGPT usage is helpful or detrimental to learning could be impossible, posing a genuine problem for the instructors who are tasked with setting clear rules around new technology.

Regardless of what course syllabi may say, one only needs to enter a study space to spot someone with ChatGPT open for a discussion post. Imagine a campus tour

group peering through the windows of Ex Libris cafe as a tour guide launches into a spiel about the Core Curriculum. UChicago students, the guide says, have a respect for all forms of learning, and the Core helps clarify their individual interests. The guide gestures towards the Reg, a place where collaborative learning is sure to occur. Inside, students sit in groups, laptop screens flickering with ChatGPT as they copy and paste essay prompts and type requests for explanations of complicated concepts. Is this a horror-inducing transformation? Or could it be the start of something greater?

Six months ago, Whiplash was my favorite movie. Whiplash was sweaty Miles Teller gripping at bloodstained drumsticks. It was J.K. Simmons looming over hi-hat cymbals and launching chairs. All the rushing and dragging and jazzy rhythms and dissonances thrummed against the TV screen, syncing my pulse to the four-four beat that Miles could never get quite right. But that’s where it all remained once the credits played, contained behind the TV screen, allowing me to walk away having deemed Whiplash my favorite movie and nothing more. Even Google concurs: when you type “Whiplash” into the search bar, “2014 Film” appears, and that’s it—there’s no desire to scroll down.

Five months ago, I scrolled down.

In September of 2023, after headbanging too hard at a concert, followed by a long-forgotten minor back-up collision into a gas station pole during my road trip to college, I developed whiplash. I remember sitting through the Aims of Education speech, gripping my neck with my hands, steadying my head as if it were a greasy bowling ball threatening to slip off and wondering if the tooth fairy would materialize right then and there. Whiplash was not supposed to be real. How could I be diagnosed with “2014 Film” on my first day of college?

Anger is the easiest emotion. It is tricky to gift yourself happiness and it is embarrassing to let yourself be sad, but anger wraps itself around it all like a spiky safety blanket. So I bundled up and got angry. Expressing the discomfort of whiplash is impossible to someone who has

never experienced it: imagine a piano with cables tied to its legs, and these cables end in carabiners, and these carabiners pinch your ears, your temples, your shoulders, your neck, and every strand of hair, letting the piano hang like a necklace. Sitting still was torture, and I’d nearly dunk my head into every plate of food or book I had in front of me. I was furious I had to navigate O-Week with such pain—the stakes seemed immeasurably high. O-Week was like hundreds of mini conferences clustered around campus, rumbling with elevator pitches on why you should be friends with this person and that person. Whiplash immediately exhausted me of the energy I had stored all summer for constructing a social life that, according to so many, was the one that made high-school friends seem like fillers when it

really stuck. Fortunately, I made one friend, who introduced me to another friend, and we all stuck together. I considered shrugging off my spiky safety blanket a little. As I skipped O-Week events to rest, they networked for me. They told people that I was worth it behind the whiplash, that the symptoms would soon pass and being friends with me was a “long run” ordeal, like visionary architects reporting on a dilapidated building with solid foundations they picked up down the road. I was appreciative of their support but devastated regardless. I was devastated by my lack of control, by the whiplash odds that were very much not in my favor, and, most of all, by the fact that this experience of college was falling so far short of my expectations.

There is so much build-up to attending university in the United States. I grew up in Amster-

dam and only moved to Brooklyn at the age of sixteen. University in the Netherlands, and more broadly in Europe, is more of an extension of your high-school experience rather than a ginormous, competitive cherry on top to your education that requires you to uproot your life and leave everything behind. Thus, after moving to America, I thought college would be like stripping the dead skin off the past and moving forward into adulthood and professionalism, a land of unwavering emotional maturity and appropriate decision-making, of thriving social lives and parties. Whiplash certainly targeted the latter, so I clung onto the former because I thought that, at least, regardless of pain, I could function as a grown-up in a grown-up setting. In hindsight, this was a faulty, naïve convic-

CONTINUED ON PG.

“Whiplash occurs when we do not brace, and I did not brace correctly for college.”

tion.

I have always been a capital-R Romantic. I like to look into the future through a warm-toned lens while gentle instrumental music hums in the background. I zoomed in on my future in America while in Amsterdam and conjured up this image of myself as a grungy, artsy NYC teenager reading poetry on the subway with an aura of cool aloofness. Who did I become, really? A girl that wore the same sweater, jeans, and Uggs combination every day that barely left her neighborhood. This past summer, I saw myself on the UChicago main quad lying on a picnic blanket with friends, discussing philos-

ophers whose names I’m not sure I can pronounce, listening to a friend strum a guitar and play a tune my parents would be proud of. Now, I’m a girl that wears the same sweater, jeans, Uggs, and piano Whiplash necklace every day. I do leave my dorm, however—Woodlawn is bleak.

This is my problem—the romanticization. I set an idea in stone and sulk when life won’t bend accordingly. Whiplash was not in the cards. But I have quickly learned that every aspect of college life is unforeseen. We, especially first-years, are kids cosplaying adults. We do not miraculously acquire every nugget of wisdom and maturity out there. I call my parents every day

on how to sign emails and how many Tide PODS® is too many Tide PODS®. If you shoved the average frat brother into a lineup of high-school-junior boys, told me to close my eyes, and asked them to share their take on hookup culture, I’d struggle to pick him out. People talk behind others’ backs and use the word “clout” unironically. And there hasn’t been a drastic shift in academics. I remember sitting in the Reg after my first physics lecture with nothing to do and thinking that something was seriously wrong, that I had missed the secret meeting where our professor told us how to spend our every waking moment preparing for the next class.

After my car accident, my doctor told me that when someone throws a punch at us, we brace for impact to minimize injury. Whiplash occurs when we do not brace, and I did not brace correctly for college. The reality of it all whipped my neck back so strongly, a double whiplash to compound my pain. Assessing the reality of college next to its romanticized depiction generates a different kind of pain, a cycle of grief that repeats with every frat party or midterm or snowstorm or silly concert and car punch.

I think growing up is breaking the cycle. Growing up is yanking college down from its pedestal and stringing it into the

wider narrative of your life. It’s letting the frame of your future be filled with time and accepting every ugly or wonky addition. It’s acknowledging that life is not romantic. Not at all. Life is a 2014 film but also a list of neck injury symptoms. Life runs and drags and will never, ever get that fourfour beat quite right. Right now, at this exact moment in my life, my whiplash means more blood runs down my drumsticks. But at least I’m playing. The music sounds good and at least I’m living.

Sofia Cavallone is a first-year in the College and Viewpoints CoHead Editor.

True equality can only prevail in America once we recognize the depravity of DEI and seek colorblind alternatives.By ANONYMOUS

Editor’s note: This piece is one part of a two-part critique on DEI efforts within academia, political spaces, and broader society.

As with many Americans, my upbringing significantly influenced my political beliefs. Unlike many Americans, I became disillusioned with partisan politics early on. I blame my parents. As ardent progressives, they often tried to foist their political (read: woke) ideals on me. In high school, they implored me to join affinity groups. In 2020, they crafted signs in support of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters. When former President Donald Trump was elected, they were vocal about their disdain for him. Truly, I had every reason to turn out as partisan as they were. The only reason I did not was because I resented how their political loyalties revolved around race. This motivated me to challenge their views, form my own beliefs, and eventually identify with moderatism.

I felt indifferent towards my race as a child because I had little reason not to. Although my hometown is less than one percent Black, I always felt like an equal there. I was never marginalized or coddled (which often feels the same). Likewise, I was never compelled to vocally align myself with my identity. In fact, I railed against efforts to establish an ethnic club and hire a DEI officer in the wake of the 2020 riots because they threatened to undermine our town’s racial harmony. Drawing attention to my race would make me feel visible or special in some way, thereby segregating me and the few other

minorities from the broader community.

From elementary to high school, I repudiated DEI ideology on this basis—to the chagrin of my town’s bleeding-heart progressives. I did not accept that my worth is tied to victimhood. I felt, and still feel, that DEI wrongly teaches that success is a birthright, and furthermore, that DEI conditions one to cheat their way through life by imagining oppression and demanding pity. I speak from experience; I was indoctrinated with these ideals practically as soon as I left the womb. Demanding reparations. Celebrating pity parties such as Juneteenth. Leveraging my race when applying to jobs. These values and customs were taught to me at birth and typify the martyr complex I was expected to embrace. In essence, DEI taught me to advance in the world through fraud.

Gradually, I came to resent this. My immigrant grandparents instilled in me an appreciation for grit and merit. They came to this country destitute and toiled to give my father a better life. Despite enduring brazen and cruel prejudice, they succeeded. They did not do so by playing martyr. Indeed, they triumphed despite their oppression, not because of it. My mother’s grandparents, descendants of African slaves, did likewise. They brushed off the casual racism they endured every day to build the soapbox that many minorities now climb up on to wail about oppression. Likewise, I have always felt that identifying with victimhood would trivialize the victories they made for equality. In my eyes, DEI expresses a perversion of the civil rights movement. My grandpar-

ents yearned to equalize the pendulum of privilege, for all races to have equal rights and opportunities. In championing DEI, I would not be striving towards a country wherein people “[are] not judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” as Martin Luther King Jr. did, but the opposite: one wherein I wield power over overrepresented groups due to my race. In essence, I would not be advocating parity, but advantage—which is precisely what my grandparents fought against.

This is to say that I accepted early on that I alone am responsible for my circumstances in life. I have nothing to gain from victimhood but an aspiration to mediocrity, an expectation that success will be handed to me through quotas and pity, at the expense of my dignity and intellect and to the detriment of others. However, my experiences contradicted the narrative that Black people raised in lily-white enclaves feel isolated from or oppressed by their white peers. At some point, I understood that certain parents are wary of homogeneity; they fear that raising their children in predominantly white environments will engender racist sentiments in them. I had read of parents who decided to raise their children in neighboring towns for this reason. However, my own experiences taught me otherwise.

And yet, my parents constantly tried to foist this victimhood on me. Despite my feeling like an equal growing up, they believed that my race handicapped me. To their credit, their concerns were not unfounded. I learned what “n****r” meant when it was sprawled across a hallway in middle school. One year, students in

blackface ran around my school goading others into yelling the slur. In writing this, I am not attempting to elicit sympathy. The fact is that I never felt marginalized by such incidents. I suppose one could argue I was “handicapped” in that I was more vulnerable to racism than my white peers. However, my point is that I did not feel this way. I was never personally discriminated against, nor did I hear about other underrepresented minorities (URMs) being harassed due to their race. Likewise, when incidents of racism did occur, I was not offended or alienated; in fact, I found them so outlandish that they were amusing.

Indeed, my most haunting memories from childhood had nothing to do with the racism I witnessed, but with the virtue signaling and moral panic that these racist incidents provoked. Often, this manifested as assemblies, heated school board meetings, and loudspeaker lectures peddling DEI. The town’s DEI brigade would overcompensate for racism by making baseless generalizations about the community.

When racism occurred, it felt like there was no middle ground; one either supported DEI or they were considered racist. I realized then the ability of partisan panic to dictate people’s views. I resented this. I resented that the truth— that racism existed, but it was not endemic in our school district as was claimed—was suppressed. I resented that I was expected to feign victimhood and that people lent credence to partisan accusations out of fear.

As I grew older, my resentment of how partisanship perverted reality led me to identify with moderatism. I wanted to in-

terpret reality for myself, to form my own opinions about the world and my place in it rather than regurgitating those fed to me. Partisanship traps me; no matter which ideology I identify with, I am forced to reckon with inadequacy. To participate in partisan politics as a URM is to cede your dignity to a game of tug of war: at one extreme are people who like you to a fault, and at the other are those who like you very little. I tired of this game once I realized I do not have to externalize my worth.

Moderatism gives me the agency to break from this dichotomy, power to deduce things by assessing facts for myself rather than blindly siding with rigid partisan ideals. I want my own say. I have a voice and prerogative to reflect on policies that directly concern me. I am not interested in seeking refuge in one ideology and pretending it does not dehumanize me. This freedom from ideological constraints I have discovered is very useful. Because I am beholden to no ideology, I maintain broader perspectives on issues than many partisans do. I am not afraid of challenging DEI and being branded a “racist” or upsetting Republicans and being cast as “woke.” In that way, moderatism has instilled in me an altruistic purpose: to reflect on issues objectively and strive to reconcile them in a way that maximally benefits others. In pursuing this purpose, I have realized true equality can only prevail in America once we recognize the depravity of DEI and seek colorblind alternatives.

Gregory Ceasar is a third-year in the College and a Head Podcast Editor.

Every tornado starts with a butterfly flapping its wings somewhere, and every wild night starts with a quiet morning. That is why, when I learned that I was covering “Klubnacht Presents: LUVNACHT”—the Valentine’s Day–themed iteration of a legendary basement techno rave at 62nd and Kimbark—I knew I had to seek out the place’s denizens early in the day, and watch Klubnacht take form in utero. I found them eating bagels under the pipe-studded ceiling of Robust Coffee Lounge. They had just come from a rehearsal for their nascent, still unnamed, indie rock band.

“I think Klubnacht has historically been a place that really brings beautiful romantic relationships. After the last Klubnacht I ran home and did snow angels on the Midway. And I lost my hat,” said thirdyear Zach Ashby with a wistful smile, fiddling with a giant pair of sunglasses in his hands.

“I didn’t know it was happening until really recently,” bleary-eyed fourth-year Eli Wizevich admitted. “I went there only once to drop someone off, and while I was there I had to use the bathroom, and it kind of looked like [the building] was habitated but also really moldy, and the door didn’t have a lock or a latch on it...when I walked outside there was someone drinking vodka and milk, so I left.”

Wizevich brightened at this pleasing recollection. Meanwhile, Klubnacht organizer fourth-year Oscar Dorr offered a more philosophical description of the event.

“We want to provide the transcendent experience,” the curly-haired and bouncy Dorr rhapsodized. “We realized that most people don’t possess the social skills to gather in a big room and actually talk to each other, so we decided that if we played music loud enough, it’d encourage people to dance; they could have some semblance

of fun without ever having to actually meaningfully interact with another person. So, hence, from that, and with our glorious leader Will Tom embodying that principle more than anyone else, Klubnacht was born.”

Dorr had uttered the name whose monosyllabic components would be repeated by patrons of Klubnacht like the beat of a techno song: Will Tom.

“He learned to DJ, he bought nice DJ decks and all sorts of accoutrements. He bought lights; he bought a smoke machine,” Dorr elaborated.

The students withdrew into their breakfast sandwiches, but I had heard enough. It seemed that Klubnacht was a microcosm of life itself, bringing out the snowy angels as well as the vodka and milk-drinking demons in the human psyche, all under the direction of an elusive architect—third-year Will Tom—willing to stop at nothing in his quest for the perfect basement techno rave.

Winged Cupid

I was greeted at the entrance to Klubnacht by a black cat, perched on a small ledge beside the door. The door itself was hard to find, labeled only with a handwritten sign in grammatically incorrect German. The black cat gazed into my eyes. Whether it was daring me to enter, or asking to be let in, I couldn’t tell.

Inside, blue and yellow lights swept over the tarp-covered ceiling. Two bartenders served original cocktails—with names like AphroDJac and Sex on the Subwoofer—on a plastic folding table while a volunteer laid out free Narcan kits on a washing machine. A pile of coats grew by the door.

The dance floor opened up beyond this improvised lobby. It was only about 10:15 and fairly empty. But if the room was wanting in attendees, a DJ known only as “love doctor” provided more than enough