APRIL 30, 2025

SIXTH WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 14

APRIL 30, 2025

SIXTH WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 14

By NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Deputy News Editor and KALYNA VICKERS | Senior News Reporter

In its fourth invite-only budget town hall, held April 21, the University presented a mixed picture of its financial situation, reemphasizing the progress it has made toward eliminating its substantial budget deficit in the past year while expressing concern over continued uncertainty tied to recent federal policy changes.

University Provost Katherine Baicker and Enterprise Chief Financial Officer Ivan Samstein presented the University’s updated financial outlook, reiterating that the operating deficit had narrowed from $288 million in fiscal year (FY) 2024 to $221 million for the current fiscal year. Still, Baicker and Samstein highlighted major challenges, including the termination of nearly 40 federal research grants and lower-than-expected tuition revenue, which currently sits

$7 million below budget projections.

University President Paul Alivisatos opened the event by noting that recent changes in federal policy under the Trump administration could alter the University’s financial trajectory.

“This is a different kind of moment than previous budget town halls, so we will need to bring a different kind of spirit to the enormous challenges at hand,” Alivisatos said. “The present situation absolutely reflects a dramatically altered landscape from where we were in December.”

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, his administration has introduced a series of executive actions targeting federal research funding, discussed expanding taxes on endowments and philanthropic gifts, and signaled in-

terest in revisiting the tax-exempt status of universities.

Alivisatos emphasized the University’s commitment to its foundational values, including academic freedom and open debate. He noted that, although ongoing financial and policy volatility could constrain leadership’s ability to share detailed plans, the University is “ready to defend our values.”

The subsequent presentation shared a mixed picture of how key budget categories are tracking against expectations. According to presentation materials, the University’s projected net tuition revenue for FY2025 is $689 million—approximately $7 million below initial budget expectations.

Baicker described the deviation as “generally in range,” noting that core revenue sources are performing close to expectations despite broader economic headwinds.

The University is currently seeing higher-than-expected costs in staff salaries and

benefits (projected at about $7 million more than budgeted) and in supplies, services, and other expenses (projected at about $20 million more than budgeted).

Enrollment remained stable over the past year, with the incoming Ph.D. cohort mirroring that of past years and enrollment in master’s programs meeting the budget projection, according to Baicker. The University also launched four new non-degree programs, which could generate new revenue from tuition-paying learners outside of traditional degree pathways.

Looking ahead, Baicker noted that spending moderation would continue to be necessary as the University seeks to close its deficit by 2028. While the University’s long-term plan focuses primarily on growing revenue, Baicker said that spending moderation is necessary in the short term because “spending moderation can happen

CONTINUED ON PG. 2

By ELENA EISENSTADT | Deputy Editor-in-Chief and NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Deputy News Editor

Internal emails and documents obtained by the Maroon through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, along with new interviews and anonymous accounts, have revealed additional details about how the University administration, disciplinary committees, police, and local politicians responded to protest activity during and after the encampment.

These new sources reveal the tensions the University faced as it turned to the

NEWS: Booth School of Business Receives $100 Million Donation to Executive MBA Program

Chicago Police Department (CPD) and the courts for support outside of its own disciplinary policies in quelling what it deemed disruptive conduct.

One year ago this week, UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP) launched its “Popular University for Gaza” protest encampment on the main quad, erecting tents and artwork across a gradually expanding footprint. After nine days on the quad, the encampment was dismantled by

VIEWPOINTS: A Call to Institutional Honor and Moral Obligation

the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) in the early hours of May 7, 2024.

UCUP did not respond to requests for comment by time of publication.

According to a person with knowledge of the matter, University of Chicago Chief of Police Kyle Bowman did not make the final decision about whether to raid the encampment; the University, with the advice of UCPD, made that determination.

President Paul Alivisatos wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed on May 7 that, although he did not take “immediate action

VIEWPOINTS: UChicago Must Protect Its Community

against the encampment… when I concluded that the essential goals that animated those demands were incompatible with deep principles of the university, I decided to end the encampment with intervention.”

Just after midnight, encampment organizers wrote in their Telegram channel, “We have received credible information that police WILL be carrying out a raid against the UChicago encampment in the coming hours.” Hours before the raid, Illinois State Senator Robert Peters and two city hall reporters wrote on X that a police

CONTINUED ON PG. 6

ARTS: Maroon Musings

“It’s really important to share this information as it evolves... [T]he answers to a lot of these questions are going to be different next week from what they are right now.”

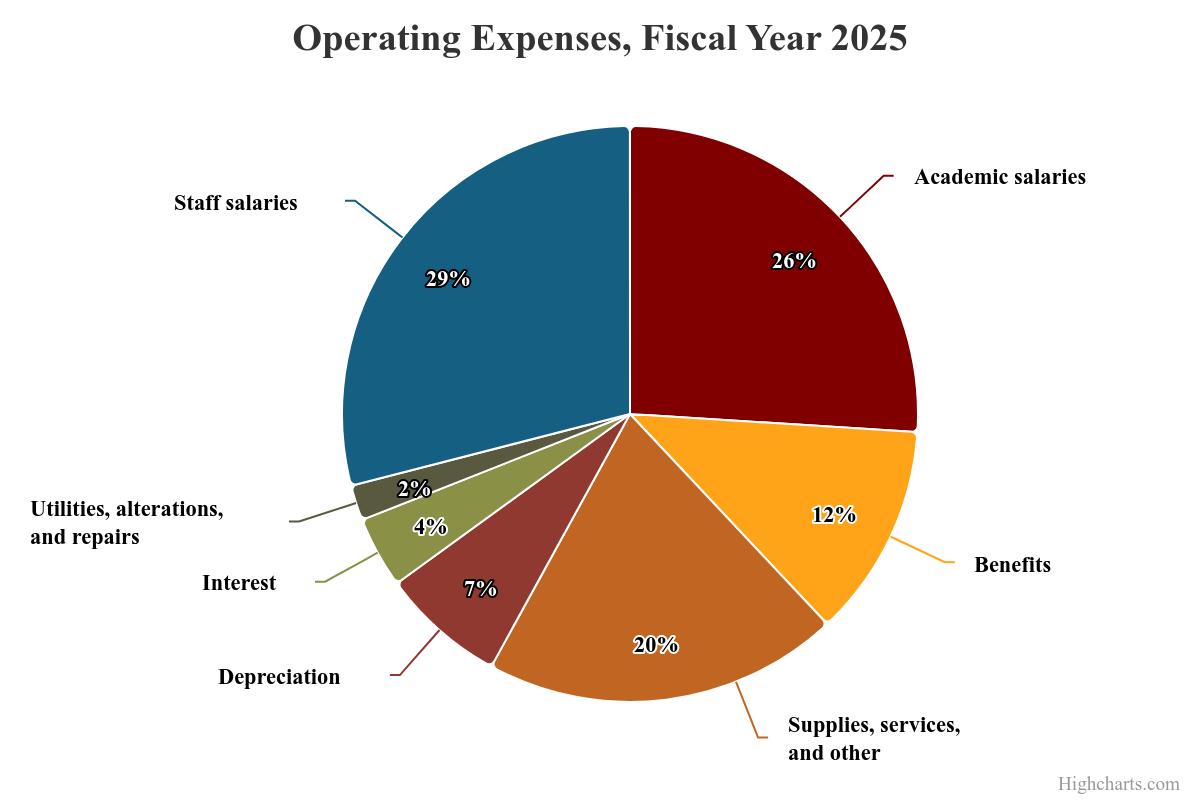

A figure breaking down the University’s operating revenue for FY2025. karen yi . A figure breaking down the University’s operating expenses for FY2025. karen yi .

more quickly than the revenue levers.”

“We spend most of our money—as we should—on our people,” Baicker said, highlighting that 29 percent of spending is allocated to staff salaries and an additional 12 percent towards benefits. However, non-personnel expenses (SSO, supplies, travel, equipment) are coming under review as part of a broader contingency planning effort.

Most of Baicker and Samstein’s presentation was devoted to discussing federal grant terminations, which had “some limited effect in this fiscal year, but [are forecasted to have] a more substantial effect for next year and the year going forward,” according to Baicker.

As of this month, nearly 40 federal research grants have been terminated with an expected aggregate impact of $10–15 million this fiscal year. That impact could grow to as much as $40 million during FY2026, Baicker said.

“We get new terminations weekly, so we expect that number to keep ticking up,” Baicker said. ”So that’s one of the areas where we really want to partner with the faculty and deans and the [research] teams to figure out how we help support researchers who are in the position of having their grant terminated.”

In addition to grant terminations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced plans in February to slash negotiated rates for coverage of indirect research costs—expenses like administrative func-

tions, building maintenance, utilities, and equipment—from 64 percent to 15 percent. According to Samstein, a cut of that size represents a potential annual loss of nearly $100 million for the University.

While a universal cut to the indirect cost rate is currently subject to a permanent injunction, the University is scheduled to enter its next routine renegotiation with the federal government for rates taking effect in July 2026.

The University’s annual federal grant portfolio sits at approximately $550 million, half of which comes from the NIH, according to presentation materials. “We are fortunate in that we have a pretty diverse revenue base,” Baicker said. “There are peer institutions where this grant number is a much more concentrated percentage of their numbers of their revenue base.”

The University’s FY2026 budget— which Baicker and Samstein added is typically finalized by this point in the year—also remains in flux as a result of the evolving federal situation. “We are having to be a little more flexible and take as much time as we can to be able to have as much information as we can before inking a plan for the coming year,” Baicker said.

Other potential threats to the University’s long-term financial goals include the possibility of the loss of its tax-exempt status or an increase in taxation on its endowment. After Harvard University stated that it would not comply with federal efforts to undermine its independence, Trump wrote on Truth Social, “Perhaps Harvard should

lose its Tax Exempt Status and be Taxed as a Political Entity.”

Samstein stressed that the loss of UChicago’s tax-exempt status is “lower on the spectrum” of his concerns. The endowment tax is placed on net investment income, which would not correspond to significant weight in the short term. However, he noted that each 1 percent increase in the endowment tax rate correlates to an approximate $10 million loss in revenue for the University.

Any increase in the endowment tax rate would more likely come from a congressionally approved bill, rather than an executive action, Samstein said. One proposal, introduced by Representative Troy Nehls (R-Texas) in January, would raise the endowment tax rate from its current 1.4 percent to 21 percent.

The endowment also faces pressure from stock market volatility in the wake of Trump’s tariff plans, but, as Samstein joked, “the good news is the stock market can’t drop at 5 percent a day, every day, forever.”

Baicker and Samstein also addressed uncertainties around Medicaid and federal healthcare policy, with potential implications for the University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMed).

“Our hospital here in Hyde Park is the largest Medicaid provider in the Midwest, of any single-site hospital,” Samstein said. “We are quite concerned about what might happen and what transpires in Medicaid.”

One particular area of concern is the

federal 340B Drug Pricing Program, which provides discounted pharmaceuticals to hospitals serving a large Medicaid population. Changes to the program—along with broader cuts or restructuring of Medicaid— could significantly alter UCMed operations. Although no concrete proposals have been introduced, Baicker warned that such reforms would likely appear in a future federal budget reconciliation bill and are “something we’ll need to monitor.”

Going forward, Baicker said the University hopes to broaden its funding base by pursuing partnerships with foundations, nonprofits, and industry, which is part of a larger effort to identify external support that can help research institutions reconfigure their portfolios as traditional federal grants are withdrawn.

The University also plans to expand global and hybrid education platforms to support international students, whose visa eligibility and status in the U.S. remain uncertain due to shifting immigration policy; three weeks ago, seven UChicago affiliates had their visas revoked by the U.S. Department of State without explanation.

“This has to be an iterative, collaborative endeavor, and we’re in the middle of it, and we’re going to be in the middle of it for a long time, so we will commit to coming back regularly with more information,” Baicker said. “But it’s really important to share this information as it evolves, because the answers to a lot of these questions are going to be different next week from what they are right now.”

By NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Deputy News Editor

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, his administration has enacted a deportation program targeting undocumented immigrants and legal residents alike. Hundreds of international students at schools including UChicago have had their visas revoked, often without explanation.

In some cases, the administration has labeled participation in pro-Palestine activism a threat to national security, allowing federal law enforcement to apprehend and detain even those with legal status who have not been accused of a crime.

To understand the rapidly shifting immigration landscape, the Maroon sat down with Nicole Hallett, a University of Chicago Law School clinical law professor and the director of the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, which provides legal representation and advice to noncitizens.

Hallett discussed the Trump administration’s mass deportation program, the rights of noncitizens, and how the administration’s efforts may cause conflict with the Supreme Court.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Chicago Maroon: What work does your clinic do under normal circumstances, and how has that changed under the second Trump administration?

Nicole Hallett: There’s lots of immigration work to do under any administration, including the Trump administration; my clinic represents immigrants in a variety of proceedings before the government. Sometimes we represent people whom the government is trying to deport. Other times, we’re representing people who are applying for humanitarian benefits with the government—for example, asylum or relief for victims of human trafficking or domestic violence. But we essentially will represent anyone—any noncitizen—in any matter related to their immigration status in the United States.

CM: How has that work changed or

increased since the beginning of the second Trump administration?

NH: I don’t think [our work] has changed. In some ways it hasn’t changed. It hasn’t changed in that the government continues to arrest people [and] continues to detain people.

I would say that the kinds of people who are being caught up in immigration enforcement have changed under Trump. So, it used to be, for instance, that maybe I would talk to a student who had an immigration issue once every year or two. Now I have students in my office every day asking questions because their visa has been revoked or because they’re worried that it’s going to be [revoked].

Under normal circumstances, the people who are really at risk of deportation are people who’ve been convicted of serious crimes and people who are undocumented. Now, it seems like the [Trump] administration is going after everyone, and so the kinds of people that end up in my office are a much broader group.

CM: What rights and protections do noncitizens in the United States have?

And then, more specifically, what rights do students and faculty members at this University who are in the United States on visas or [who] have lawful permanent residency have?

NH: All noncitizens have the right to due process if they’re inside the United States, and so the government cannot simply deport someone without allowing them to fight their case, usually in immigration court. That can take weeks, it can take months, [or] it can sometimes take years.

However, even though all noncitizens have the right to due process, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re going to have very many good ways to fight their deportation. Specifically for people on non-immigrant visas—so that’s people who are on student visas, as well as people on temporary work visas, which includes many people who are in faculty roles—those people can have their visa[s]

revoked, and the statute gives the government very broad authority to do that.

CM: Which statute gives the government that right?

NH: The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) is the statute that controls basically everything related to immigration—both who we admit to the country and who’s allowed to remain and under what conditions. And the government in this area and the area of immigration has always had very, very broad authority.

Courts have traditionally given the government very wide discretion in terms of who is allowed to enter the United States and who is allowed to remain and under what conditions. Traditionally, this was because immigration was seen as an outgrowth of the executive branch’s authority over foreign affairs and Congress’s control over naturalization [as specified] in the Consti-

tution. So, there has been, historically, very little judicial review over the laws that Congress passes and then that the executive [branch] uses to either prevent people from entering [or deport] people. Right now, [the Trump administration seems] to be revoking visas for very specific reasons that might not be permitted. They seem to be revoking people’s visas based on their speech or their protest activity. We really haven’t seen that much in the last few decades in the United States, and I think the courts are going to have to consider whether the government has the right to do that, but the statute does give them broad authority to cancel visas, and so people should just be aware of that. Even though they can contest their deportation and immigration court, the government has broad authority in this area.

CONTINUED ON PG. 4

Tiffany Li, editor-in-chief

Elena Eisenstadt, deputy editor-in-chief

Evgenia Anastasakos, managing editor

Haebin Jung, chief production officer

Crystal Li & Chichi Wang, co-chief financial officers

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Sabrina Chang, head editor

Gabriel Kraemer, editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, editor

Peter Maheras, editor

GREY CITY

Rachel Liu, editor

Celeste Alcalay, editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Camille Cypher, co-head editor

ARTS

Miki Mukawa, co-head editor

Nolan Shaffer, co-head editor

SPORTS Josh Grossman, editor

Shrivas Raghavan, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, lead developer

Austin Steinhart, lead developer

PODCASTS

William Kimani, head editor

CROSSWORDS

Henry Josephson, co-head editor

Pravan Chakravarthy, co-head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon head editor

DESIGN

Eliot Aguera y Arcas, editor

COPY

Coco Liu, chief

Maelyn McKay, chief

Natalie Earl, chief

Abagail Poag, chief

Ananya Sahai, chief

Mazie Witter, chief

Megan Ha, chief

SOCIAL MEDIA

Max Fang, manager

Jayda Hobson, manager

NEWSLETTER

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon, editor

BUSINESS

Adam Zaidi, co-director of marketing Arav Saksena, co-director of marketing Maria Lua, co-director of operations

Patrick Xia, co-director of operations

Executive Slate: editor@chicagomaroon.com

For advertising inquiries, please contact ads@chicagomaroon.com

Circulation: 2,500

“They want noncitizens to be afraid to speak out, to protest, and to do anything that will get them in the crosshairs of the administration.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 3

CM: Recently, the Supreme Court has taken a little bit more of an active role in some of the higher profile cases. The New York Times reported that the president of El Salvador said he would not return an individual who was deported from the United States that the Supreme Court ordered the U.S. government to return. What is that setting up? Is there recourse beyond that, and what is ultimately going to happen in that case?

NH: The Supreme Court did order the [U.S.] government to facilitate his return, and I think the Supreme Court was hoping that the administration would make a good faith effort to do so.

It seems very clear at this point that they have no intention of making any effort at all, and so this issue will almost certainly go back to the Supreme Court, and it’s being set up to be a conflict between the judiciary and the executive [branches] and potentially the first time in this administration that we’ve seen them directly flout a court order.

That remains to be seen, and it also remains to be seen how far the Supreme Court is willing to go to try to get the administration to comply, or whether they will back down in the face of the intransigence that they’re seeing from the administration. Now, I don’t have a crystal ball, so I don’t know how the Supreme Court is going to rule. But I think that this is really being set up as a test case for the administration in terms of how much they have to listen to [the] courts and how much they can assert their own prerogatives in the area of immigration.

CM: What would the Supreme Court asserting itself in the realm of immigration look like? What recourse do they have to essentially force the executive branch to take an action that [the courts have] ordered?

NH: In the previous order, the Supreme Court was very deferential, and it allowed the executive to determine the steps that it needed to take in order to bring Mr. Garcia back to the United States. The government has refused to take any steps, and so I think that the

Supreme Court could order the administration to take more specific steps.

If the [Trump] administration then were not to comply with the order to take specific steps, the district court could hold government officials in contempt. That could include fines, it could include jail time, and we haven’t really seen a court go that far yet. They haven’t been required to.

But I think it’s also equally as likely that the Supreme Court will throw up its hands and say, “Well, we asked them to do what they could. They’ve told us they could do nothing, and so therefore they’ve complied with the order.”

I don’t know how it’s going to come out, but I think if the Supreme Court gives the government that power, they are going to use it broadly. They’re not just going to use it against [noncitizens]. We heard [on April 14] from President Trump in the Oval Office [that] he intends to send U.S. citizens to this mega prison in El Salvador. And so I think this would be the first of many situations in which the administration believes that it is above the law and acts accordingly.

CM: Some of the higher profile deportation efforts, specifically of people like [Columbia University graduate and pro-Palestine activist] Mahmoud Khalil, have been justified under a provision of the INA. Can you explain that provision and how it’s being used specifically to target the political speech of noncitizens?

NH: It’s a provision in the INA that allows the secretary of state to declare that a person’s presence in the United States is a risk to the foreign policy interests of the United States, and then, if the secretary of state makes that determination, it renders that person deportable.

The statute gives the secretary of state broad discretion to make those determinations. This statute was originally enacted during the Red Scare of the 1950s, [and] it has essentially not been used since then. It remains to be seen whether the federal courts—where this will eventually get litigated—are going to allow the administration to invoke it, when really what we’re talking about

is protected speech. But the text of the statute itself is very broad and is intended to be used exactly the way that the administration is using it, although not necessarily in this particular context.

CM: How does the federal government’s current program of revoking student visas differ from the way that it has revoked visas in the past?

NH: The government could always revoke visas. Oftentimes that would occur when someone was convicted of a serious crime or there were other national security concerns that arose. That authority was usually not used to handle minor infractions.

What the government is doing right now, my understanding is that they’re comparing a list of students and faculty who are on temporary visas with law enforcement databases, and if there’s any hit at all, those visas are revoked almost automatically. That can mean something as minor as a traffic ticket [or] being arrested and then immediately released and no charges being filed. You know, very, very minor things.

You might wonder, why is the administration doing this? I think there’s a couple of reasons. The first is that I think the administration is trying to form a culture of fear on U.S. campuses and universities. They want noncitizens to be afraid to speak out, to protest, and to do anything that will get them in the crosshairs of the administration. And so I think they’re really succeeding at that. I talk to people every day that are terrified that their visa is going to get revoked. I think that is an explicit goal of the policy.

The other reason I think the administration is doing this is that they have promised that they would deport a million people in the first year of Trump’s second term, and they are not nearly on track for that. It turns out that it is very difficult to deport people; particularly if you’re talking about undocumented immigrants, it’s very difficult to locate them. They usually are living in the shadows, and so [the administration looks at] these students [whom] they have… addresses [for]. They know where they

live, and they know that [these students are] much less likely to contest their deportation and more likely to simply go home if their visa is revoked.

[The students are] sort of acting like low-hanging fruit. [The Trump administration] can get their numbers up, and they can make it seem like they’re being very tough, even though the number of [deported] “serious criminals” or undocumented immigrants remains fairly steady from previous administrations.

CM: For people who have their visas revoked—who are informed either by the State Department or by the organization that is sponsoring them—what recourse do they have? Can they contest that decision or do they just have to leave the country?

NH: They can contest the decision. There [are] a couple ways that they can do that. They can file a request for reinstatement with the government. That’s sort of an administrative procedure. They can also go to court and file a lawsuit in federal court and allege that revocation of their visa is arbitrary and capricious and that the government simply cannot do it for the reasons that they’re giving.

And then, of course, there’s always a third option, which is to remain here and sort of remain in the shadows so that hopefully [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] (ICE) doesn’t find you and detain you and deport you. And then I think some people are choosing to self-deport. So there’s really four options. There’s two different ways to challenge it legally. There’s the option of sort of laying low and hoping that ICE doesn’t find you. And then there’s the option of leaving. I know students that are in all four of those categories.

CM: For people who choose to fight the decision, either through the administrative method that you mentioned or by filing a lawsuit, how successful are those efforts typically?

NH: Well, what’s happening right now is very unprecedented, so it’s hard for me to say whether they will be successful or not. In the past, requesting

“But certainly there could be more that the University could do to support these students beyond giving them some basic advice.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 4

reinstatement is sometimes successful. It’s unlikely, I think, that this administration is going to reinstate many people, because they have obviously decided that this is their policy, and I don’t think they’re going to back down if individuals request reinstatement.

In terms of the federal courts, the first cases have been filed, and there have been a few orders issued by courts that enjoin the government from detaining and deporting students who’ve had their visas revoked. But those cases are at a very early stage, and so it’s really too early to say how they will come out and whether those students will be successful.

CM: Can you explain the difference between the typical federal court system that I think many people are familiar with and the immigration court system, and how those two different bodies respond to the executive [branch]?

NH: Most of what happens in immigration law happens at the agency level. So, there are several immigration agencies. There’s ICE, which is Immigration and Customs Enforcement, there’s CBP, which is [Customs and] Border Patrol. And then there is USCIS [U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services], which is the agency where you apply for affirmative benefits with the immigration system.

Those are part of the executive branch, and those agencies make de -

cisions all the time that affect people. They grant visas, they deny visas, they put people into removal proceedings. They deport people. All of those things happen at the agency level.

However, because we live in a constitutional system, there has to have been some review of those decisions by the judiciary. So, in most cases, individuals who are subject to an adverse agency action can then go to federal court to challenge that. Now it is true that in some cases, the immigration agency sort of looks like a court, so there are things called immigration courts that exist within an agency of the government. Although they’re called courts, they’re actually just agency proceedings, and, in those cases, individuals still have the right to appeal to what’s called an Article Three court, which is the independent judiciary that’s set up by the Constitution.

CM: Recently, seven UChicago affiliates, including three current students, had their visas revoked by the State Department for reasons that [the department] would not specifically explain. What can the University, as the organization that is sponsoring those students, do to offer support, and what should it be doing in those cases?

NH: I think primarily the University needs to support those students in making decisions about their future and also giving them options for fighting the visa revocation. At many universi-

ties, there are programs where students can access outside legal counsel that can help them fight their cases. Sometimes those resources are actually in-house; there are lawyers within the university that are helping students apply for visa reinstatement or filing lawsuits.

To my knowledge, the University of Chicago has not done that yet and is simply providing advice on an individual basis to the students that are affected. But certainly there could be more that the University could do to support these students beyond giving them some basic advice.

CM: What would you recommend, in your capacity as a director of an immigrants’ rights clinic, that the University do?

NH: I think it’s important that every student who’s had a visa revoked has access to legal counsel. And as you probably know, it’s very expensive to hire a lawyer in this country, and many students are not in a position to pay very much money to a private lawyer to take their case, and there just simply are not enough nonprofits out there to represent people pro bono.

I would like to see the University make resources available to those students, so that even if the University is not going to bat for them directly, it’s providing them the resources so that they can contest the visa revocation, and I would think that the University would think that that was in [its] best interest.

These are students who were admitted to the University, who are currently in degree programs, who are currently paying tuition, and it seems like it would be in [the] University’s interest to make sure that they could finish their degrees. And so I am anxiously waiting to hear what steps the University is going to take in order to support these students.

CM: Where should people go if they’re interested in learning more about the rights that they have and what recourse they have if they are contacted by the State Department or if deportation processes are initiated against them?

NH: There are many organizations that are providing information online, so I think the first thing that a student should do is to try to do a little bit of online research to find out what is happening [and] what their options are, and then, like we said, it’s going to be really hard for a student to do anything about it unless they’re in touch with a lawyer. There are lots of immigration lawyers, for instance, in the Chicago area, where you can do at least a free consultation. My clinic has been providing brief advice to students who are in this situation as well, although we don’t have the capacity to take on everyone’s individual cases. Primarily, I think they need to be seeking out information and then trying to identify legal resources that they can use to get some advice before they make a decision about how to proceed.

By OLIVER BUNTIN | Deputy News Editor and ISAIAH GLICK | Senior News Reporter

The University Student Government (USG) elections committee announced the results of this year’s student government elections on Friday, April 25. On the executive slate, the Phoenix Party defeated the newly formed Happyness Party. Elijah Jenkins was reelected as USG president and Alex Fuentes was elected USG vice president.

For the rest of the cabinet, which leads USG’s projects and initiatives, Annie Yang was elected vice president of campus life, Andrea Pita Mendez was elected vice president of advocacy, Malaina Culberson was elected vice president of student affairs, and Tim Lu was elected trustee and faculty governance liaison.

On the College Council, the main decision-making body and voice of the Student Association, Grace Beatty, Aidan Keesler, Esther Ma, Destiney Samare, and Joseph Ayalew were elected for the Class of 2028. Eric Wang, Demetrius Daniel, Kevin Guo, Nefeli Abutahoun, and Kyle Obermeyer were elected to represent the Class of 2027. Finally, Johnny Fan, Ben Fica, Logan Toe, Sebastian Davis, and Logan Hansler will represent the Class of 2026.

According to Nevin Hall, the chair of USG’s Elections & Rules Committee, this year’s elections saw 892 ballots cast, representing around 12 percent of UChicago’s undergraduate population. Hall said voter participation had declined by about 500 students compared to last year’s elections.

Hall also noted that one of the College Council elections was decided by only two votes, and 21 candidates only received a single vote.

“UCPD was concerned that, if protesters knew in advance about the raid, they would lose a tactical advantage and potentially face a more dangerous situation.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

raid was likely to occur in the early hours of May 7.

According to persons with knowledge of the matter, UCPD had postponed the raid until later that night because encampment participants had learned about the original time of the planned raid, allegedly through the Chicago Office of the Mayor.

UCPD was concerned that, if protesters knew in advance about the raid, they would lose a tactical advantage and potentially face a more dangerous situation, according to a person with knowledge of the situation.

Neither the Mayor’s Office nor CPD responded to requests for comment by time of publication.

The University declined to comment about why UCPD had postponed the raid time and what were the security concerns that led to this decision.

Just after 4 a.m. on May 7, UCPD officers drove police cars onto the quad and informed those at the encampment that “the University of Chicago [did] not permit their

assembly in this area,” and that they were “hereby notified that [they were] committing criminal trespass by remaining on… private property without permission.”

According to a person with knowledge of the matter, UCPD had planned for arrests during the raid in the event that encampment participants refused to leave.

The University declined to comment about this plan by time of publication.

Internal emails obtained by the Maroon through a FOIA request show that Bowman asked CPD as early as May 3 about what support they would be able to provide in the event of escalation, including for prisoner transportation. The emails also indicated that the raid was initially planned for May 4.

At 5:14 p.m. on May 6, 11 hours before the raid would begin, Bowman emailed CPD Director of Community Policing Glen Brooks asking for assistance.

“As we discussed, are [sic] goal is to gain voluntary compliance in getting individuals to leave,” Bowman wrote. “The Univer-

sity has communicated that the activity is not permitted and after asking individuals to disband and clear the area has directed us to address the trespassing issue.”

Bowman continued: “If [CPD is] unable to provide direct assistance to the encampment area, we would ask that you increase patrol in the arear [sic] off campus that we would normally call out [sic] extended patrol area.”

The request was sent shortly after a meeting between the University, CPD, and City of Chicago leadership. Bowman, CPD Chief of Staff and former General Counsel Dana O’Malley, Deputy Mayor of Community Safety Garien Gatewood, and UChicago Associate Vice President for Safety & Security Eric Heath were all in attendance.

At 9:46 p.m., Brooks declined Bowman’s request for direct support, citing “the constraints of the UCPD’s operational tempo.”

“[W]e are unable to meet the public safety requirements necessary to provide resources beyond our operational patrol

units. Please note that, as always, our district patrol resources are available for emergencies and officer safety incidents,” Brooks wrote.

A person with knowledge of the matter noted collaboration between CPD and UCPD has sometimes generated tension due to disagreements about their respective responsibilities.

The University declined to comment on the typical nature of coordination between CPD and UCPD or how the encampment impacted that working relationship by time of publication.

A final briefing was scheduled to take place at 2 a.m., two hours before the raid, according to the emails between Bowman and Brooks.

Ultimately, 12 Cook County Sheriff’s Officers stepped in to coordinate traffic and provide crowd control during the raid, according to documents obtained by the Maroon through FOIA. No CPD officers were present on campus during the raid or its aftermath.

By CELESTE ALCALAY | Senior News Reporter

The University announced on Tuesday that Russian-born private equity investor Konstantin Sokolov (M.B.A. ’05) donated $100 million to support the Executive MBA Program at the Booth School of Business. The donation represents more than 10 percent of Sokolov’s net worth and is among the largest ever made to Booth, according to the Chicago Tribune

“This gift will help the school further adapt and refine its offerings to meet the evolving global business landscape,” Madhav Rajan, dean of Booth and George Pratt Shultz Professor of Accounting, said in a University press release.

Booth’s Executive MBA Program, a 21-month program taught across Booth campuses in Chicago, Hong Kong, and London, is designed for professionals who

want to pursue a business degree while remaining in the workforce. The program will be renamed to the Sokolov Executive MBA Program in Sokolov’s honor.

According to the release, the donation will ensure the continued availability of scholarship and operating funds and allow for the program to build its alumni network. A new clinical professorship, a role filled by a practitioner with experience in their field, will also be established for a scholar who teaches Executive MBA students.

The donation comes less than a year after Booth received $60 million from two alumni to support the Master in Finance program. Due to increased uncertainty around federal funding, institutions are increasingly relying on private donors—

including alumni who want to give back to their alma maters—for support. Booth’s official website reports that 39 percent of its revenue comes from alumni giving.

In a recent Chicago Tribune profile, Sokolov said he still looks up his classmates when he is in Chicago and credits the Booth program for launching his career. This month, he is celebrating the 20th anniversary of his graduation.

“The lessons I learned, the experiences I gained, and the friendships I forged at Booth remain the foundation of my career and my life,” Sokolov said in the University press release.

Determined to pursue a career in telecommunications, Sokolov moved from St. Petersburg, Russia, to the United States in 1997 at the age of 21, according to the Tribune. He then enrolled at Booth in 2003. He is also the founder of IJS Investments,

a Chicago-based private equity firm. Sokolov previously donated $1.5 million to Booth, which funded improvements to the student lounge at the Gleacher Center, Booth’s downtown Chicago campus.

By EVGENIA ANASTASAKOS | Managing Editor and JULIAN MORENO | Senior News Reporter

The U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) announced in an April 11 press release that the state of Illinois and several educational institutions, including UChicago, had suspended participation in a state-run scholarship program for minority students pursuing graduate degrees. In a statement to the Maroon, the University said it has not participated in the program since 2023.

In the release, the DoJ said an unspecified scholarship program had “unconstitutionally discriminated on the basis of race in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment,” citing the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellow of Harvard College.

Multiple Chicago-area institutions, including the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and Loyola University of Chicago, “informed the Justice Department that they had ended their participa-

tion in the program” after being notified of the DoJ’s findings, the press release stated.

The DoJ did not respond to a request for comment.

A UChicago spokesperson confirmed to the Maroon that the program in question was the Diversifying Higher Education Faculty in Illinois program (DFI).

“In 2023, the University informed the program’s administrators that it would no longer be accepting new fellows,” the spokesperson wrote in the statement to the Maroon.

The DoJ’s actions to end the DFI initiative are part of a wave of anti-DEI actions directed at higher education by the Trump administration.

In February, the Department of Education distributed a letter to colleges and universities instructing them to end DEI programs and policies or risk losing federal funding. Last month, the University of

Chicago became one of 45 schools under investigation by the department for violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits race-based discrimination in programs receiving federal financial assistance.

DFI was established in 2004 to diversify tenure-track faculty at Illinois institutions of higher education. The program offers up to four years of need-based financial aid for minority students pursuing graduate degrees, with the condition that fellows must agree to accept a teaching or staff position at an Illinois institution of higher education or an education-related position in a state agency after they receive their degree.

Before the program began, African-American faculty made up 5 percent and Latino faculty 2 percent of all faculty at Illinois institutions of higher education, according to a 2003 report from the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE), which oversaw the DFI program.

“For underrepresented students, in

particular, a diverse faculty creates a more welcome campus climate and provides increased opportunities for students to find mentors who can also serve as role models,” the report said.

The IBHE did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2022, ABC7 reported that the percentage of non-white faculty still lagged behind the percentage of non-white students at multiple Chicago-area universities, including Northwestern University, the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), and Loyola University of Chicago. For instance, while roughly 57 percent of UIC’s students were non-white, people of color accounted for only 33 percent of faculty. The University of Chicago declined to share faculty demographics with ABC7.

From 2021 to 2023, a total of ten DFI graduate fellows in fields including political science, social work, anthropology, Middle Eastern studies, and cinema and media studies studied at the University of Chicago, according to the IBHE website.

By JULIAN MORENO | Senior News Reporter

On June 24, 2025, New Yorkers will vote in an open primary for their mayor, with nine Democrats challenging embattled incumbent Eric Adams. Brad Lander (A.B. ’91), the current comptroller of New York City, has been a vocal critic of Adams since 2021 and is among the more progressive Democratic primary candidates.

Lander spoke with the Maroon about his studies at the University and his New York City mayoral campaign.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Chicago Maroon: Were you involved in any political activism during your studies at the University of Chicago?

Brad Lander: A lot of my career, both

in affordable housing and community development and in politics, got its start at the University of Chicago. I was very active in community development and affordable housing work on the South Side. I helped create a student group called “Partners in Community Development” that worked with the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, Centers for New Horizons, and The Woodlawn Organization, trying to help fix up public housing [because] at the time those neighborhoods had seen tons of abandonments. That’s really what launched me into a career in affordable housing and community development, which is then what took me into the city government.

I was also active with a Chicago organization called the Jewish Council in Urban

Affairs (JCUA), and a lot of the folks involved in JCUA had been part of the [former Chicago Mayor] Harold Washington administration. He died when I was a firstyear in the College, [but] there had been a lot of energy behind his campaign and the coalition he built, and I was really inspired by that.

Unfortunately, his death demobilized that movement, and the funniest thing is that I actually worked on a local Board of [Aldermen] race for a guy who I’m pretty sure was an alum of the College, or at least in the University somewhere, and was representing Hyde Park. His name is Larry Bloom, and we all thought he was squeaky clean—one of the reformers fighting the boss, [former Chicago Mayor Richard] Daley, and fighting the machine—except that then a few years later, it turned out [Bloom] was corrupt, and he went to prison.

CM: I noticed you majored in Fundamentals at UChicago. What was your question?

“I’m working hard to run a campaign that shows people we’ll really deliver on what matters to them.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 7

BL: My question was, “What is a person?” with the relevance of that question for politics. Like, how do we think about what a person deserves in the sense of human rights and dignity, and what is a person capable of in terms of contributing to democratic decision-making and the polity?

I’ll see if I can remember my books. They were Plato’s Crito, Antigone—Greek was [a] language which I could read then but cannot now—[Tocqueville’s] Democracy in America, Rousseau’s Second Discourse, Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, and Louis Dumont’s Homo Hierarchicus.

CM: As comptroller, you challenged Mayor Adams’s attempt to reduce funding for city public schools. What are the main threats to K-12 and higher education today, and how do you plan to address them?

BL: Unfortunately, Donald Trump and the MAGA, federal government is the biggest threat to New York City’s budget in general, including our public schools. The ways that they’re defunding the Department of Education risks student loan funding [and] risks direct funding to [the City University of New York] and New York City public schools. [New York City public schools] have about a $30 billion budget, of which about $2 billion is federal funding, so it’s not the majority, but $2 billion is a lot of money.

Trump is shredding things in every direction, but he certainly has made clear his intent to come for cities like Chicago and New York that have sanctuary city policies and stand up for immigrant families. As mayor, we’re not going to let ICE into our schools or our hospitals or our shelters.

I am proposing a set of policies. We have a report coming out Wednesday [April 16] looking at the impact on the New York City budget of the tariffs, which unfortunately have a very real chance of leading to at least a mild and possibly a more serious recession, which would hit the city’s revenues.

Luckily, we had a pretty good year this year, so I’m proposing a big increase to our reserves from this year’s budget so that we’ll have a reserve next year both against cuts that Trump might make and against revenue shortfalls that could come from a

tariff-induced recession.

CM: How can cities such as New York defend the rights of workers, immigrants, and vulnerable populations despite the current presidential administration’s aggressive policies towards those groups?

BL: Let me give an example of each. Most American workers are what’s called “at will employees”.… If you’re an employer, you don’t have to give a reason, you could just fire someone. You’re not allowed to fire them for bad reasons—you can’t fire them because of their race—but you can just fire them without cause. It’s not like that in most of the world. In most of the world, even if you’re not in a union, you have what are called “just cause” or “good cause” employment protections. There’s got to be a reason to fire you.

We did that in New York City for fast food workers. I’m proposing that we pass that law for all New York City workers [so] that there has to be a reason to fire you. When you organize a union, if the boss fires you for organizing a union, that’s illegal, and your recourse is to go file an unfair labor practice with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), but that’s going to be useless during the Trump administration. If New York City passes this just cause employment law to end at-will employment here, then we can protect workers when they organize a union and get them their jobs back, even if Trump’s NLRB is toothless.

For reproductive rights and gender-affirming care, right now, New York City Health and Hospitals (H+H), the city-run health authority with 11 public hospitals and a lot of clinics, provides abortions and gender-affirming care. H+H has about a $4 billion budget; about $1 billion of that comes from the federal government. The abortions and gender-affirming care are less than $100 million, and I’m worried that at some point they’re gonna say, “Well if you do that, we’re going to stop giving you the billion dollars.” So my plan is to create an independent authority funded by city, state, and private dollars that will do the abortions and contraception and gender-affirming care, and then we can protect the billion we get from the federal government because H+H won’t be doing those things;

they will be done by the independent authority.

So there’s some creative strategies, and then there’s just standing up to bullies and for our sanctuary city laws. If somebody has been convicted of a serious violent offense, then the city by law cooperates with ICE, but otherwise ICE is not welcome in our schools or jails or public hospitals or shelters, and I will enforce that law and work together with other cities so that we have strategies for going into court together and standing up together.

CM: Have you adjusted your political strategy in light of New York’s shift to the right this past presidential election? How can New York Democrats win over these voters?

BL: I’ve said on the campaign trail a bunch of times that I think progressives, myself included, were slow to reckon with the rising sense of disorder coming out of the pandemic and that it’s important to address that.

I’ve made the number one issue in my campaign ending street homelessness for people with serious mental illness in New York City. We don’t have to be a city where a couple thousand of our mentally ill neighbors sleep on the subway platforms and the stoops of our buildings, a danger to themselves, obviously in a condition that no one wants to live, and sometimes a danger to others.

There have been several very high-profile incidents: people getting pushed onto the subway tracks, one woman getting set on fire. We can end that and use this policy called “Housing First” that cities like Houston and Denver and Salt Lake City are using very effectively. They get people off the street and into housing with services, and then we’ll have a safer city and a more humane one. When I talk to voters about that, regardless of who they voted for for president or how they think about themselves ideologically, everybody I talk to wants to live in a city with fewer mentally ill people sleeping on the streets and subways.

I’m working hard to run a campaign that shows people we’ll really deliver on what matters to them: the sky-high cost of living, housing and childcare, [and] feeling safe in their neighborhoods. I think part of

the reason why some New Yorkers shifted to voting for Trump is [they’re] just fed up with [a] government that [they don’t] feel like is actually fighting hard for them and delivering for them. I have a track record of making government work for people, actually preserving and creating affordable housing, really making neighborhoods safer, helping workers have better jobs, desegregating our public schools, and helping them run better, and that’s what I’m running on.

CM: What is the best way for progressive candidates like yourself and others to defeat Andrew Cuomo and other establishment candidates in general?

BL: You get out there and talk to everyone, which is what’s great about New York City. It’s just like this incredibly diverse city. It’s fun to be in every corner of it, talking to people. Cuomo’s got a long history not just as an establishment candidate but as an abusive and corrupt person, you know, with this long [history of] sexual harassment—we thought it was 13 women, but then the former mayor of Syracuse last week added her name to the list of someone whom he abused and forcibly kissed.

During the pandemic, he sent thousands of seniors to their deaths in nursing homes and then lied about it and was shown by Congress to have personally edited a Department of Health report to lie about and undercount the number of COVID deaths. There’s a new audit out; during the pandemic, he overruled the [state] health department that historically bought all the health equipment and centralized the purchasing under his own office, spent half a billion dollars purchasing 250,000 pieces of medical equipment, and literally only three of them ever made it out to help New Yorkers. The other [249,997] pieces are still rotting in warehouses. It’s a time of a lot of distraction because Trump has people pretty distracted, but I think when people really look at Andrew Cuomo’s terrible record and abusive personality, New Yorkers will realize he is not what we want for mayor.

CM: What do you think were the major lessons from the pandemic in New York about how we can respond adequately to CONTINUED ON PG. 9

“I’m focusing on

homelessness and expanding childcare—practical things that matter in people’s lives.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 8

future public health crises?

BL: This is such a hard question because I think what we need is an effective public health infrastructure that people trust, and one thing the pandemic did was weaken trust in that infrastructure. I would point people to—here I’ll be very “UChicagoan”—David Wallace-Wells, [who] has had some really good articles recently, kind of at the five-year anniversary, on pandemic lessons.

There is a great book by Rebecca Solnit called A Paradise Built in Hell about the ways in which disasters can bring out solidarity in people. We saw that here after Superstorm Sandy. When you get walloped by a disaster and the neighbors really show up for each other, you get a kind of communal feeling that you want to protect your neighbor and help them even if they’re very different from you ideologically or politically

or demographically. Unfortunately, the pandemic is not the only reason we have polarized politics and an attention deficit and a big lack of trust, but it has really contributed to that.

I think what we have to do—this kind of comes back to the campaign I’m running— is have bold and ambitious ideas for things that will really deliver for people. That’s why I’m focusing on housing and public safety and ending street homelessness and

expanding childcare—practical things that matter in people’s lives—and then [I’m] actually going to deliver [on] them and govern the city more effectively with some small steps.

Rebuilding trust by having government deliver on things that matter to people, I think, is what we’re charged to do, both coming out of the pandemic and given the real crisis of democracy that Trump reveals and is exacerbating.

By ALEX AKHUNDOV | News Reporter

Community members from Hyde Park and surrounding neighborhoods gathered on April 19 for a cleanup of Jackson Park and a renovation of the landscaping surrounding Hyde Park Academy High School.

The service event was held in anticipation of Earth Day and was organized by the Obama Foundation in collaboration with several other organizations, including the Emerald South Economic Development Collaborative, the Chicago Parks Foundation, and the Jackson Park Conservancy. Attendees gathered in front of Hyde Park Academy against the backdrop of the Obama Presidential Center site, scheduled to open mid-2026.

“Every year we like to pull together volunteers from all across Chicago for special projects around Earth Day,” said Joshua Harris, vice president of public engagement for the Obama Foundation.

Participants helped dig and prepare the gardens in front of Hyde Park Academy as music from the check-in table played through speakers. The attendees also worked together to plant and water several perennials that will decorate the exterior of the building.

Landscape architect Ernie Wong was recruited by Ghian Foreman, president and CEO of Emerald South Economic Development Collaborative, to design the new landscape for the perimeter and campus of Hyde Park Academy.

“Ghian calls me up and says, ‘Hey, we have this initiative to try to clean up Hyde Park High School.’ And me, I kind of got a little distraught because I’m a Kenwood Broncos alum, so I was like, ‘What? Why would I want to do that?’” Wong jokingly recalled.

Wong is the founding principal and president of Chicago-based landscape architecture and urban design firm Site Design Group, continuing a family legacy from his father, who was also an architect. His company has been involved in many landscaping projects all over the city as well as at the University of Chicago, such as the Arts Lawn and Campus South Walk. The firm is leading the local landscape architecture for the Obama Presidential Center.

“Everybody talks about a new landscape and what that does. What people never talk about is the amount of maintenance that requires,” Wong said. “Dealing with volunteers is really difficult, and especially [with] this many volunteers. So, [today] we really had to make sure that the planting design was simple enough but beautiful enough in order to really make an impact on the front of the school.”

At a second site within Jackson Park, another group of volunteers fanned out to pick up trash, starting from the soccer fields and continuing onto Wooded Island toward the Garden of the Phoenix. Others worked to mulch trees alongside the walk-

ing paths, carting around large mounds of soil.

Organizing staff manned a lunch table, providing light snacks and water for the attendees. The Obama Foundation also CONTINUED ON PG. 10

“Parks should be democratic institutions where people... from all races, from all generations, can come and be together.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 9

hosted 30-minute guided tours throughout the day, showing interested participants around the perimeter of the Presidential Center.

Louise McCurry, a member of the Hyde Park community for 56 years, said that the occasion marked a continuation of longstanding efforts by many residents such as herself towards the maintenance and care of Jackson Park. Now 75 years old and in a wheelchair, she continues to actively participate in such events.

“You don’t live forever. And so you celebrate when you can, when you’ve got cherry blossoms… when you’ve got trees that are alive,” McCurry said. “You keep them alive.”

of the Obama Center complex. The building is slated to feature a multipurpose gymnasium with an NBA-size basketball court, fitness equipment, and other sports amenities. It will serve as a hub for various leadership and community engagement opportunities for youth and adults alike.

“I think sustainability and obviously civic participation are two important aspects of the Obama Foundation and our mission. And so anytime that we can get people together in the community to also give back, the better,” Harris said. “This is a lovely event that I look forward to every single year.”

McCurry has worked with several local organizations throughout her time here, including by previously serving as the president of the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference (HPKCC), a community organization that hosts multigenerational activities and discusses major issues that affect the future of the neighborhood. She is also involved with Jackson Park Conservatory.

“The idea is to take Jackson Park, which is the most used park on the South Side, and make it safe for families and children, and for critters, and for dogs and cats,” McCurry said. “Parks should be democratic institutions where people… from all races, from all generations, can come and be together.”

Despite its recent efforts to promote local development, the Obama Center’s construction has not been without controversy. Community members and organizations have raised concerns, ranging from availability of affordable housing and residents potentially being forced out due to rising property taxes, to the detraction from public parkland space for the construction of the privately owned complex.

However, Harris thinks the arrival of the Center will have a positive impact on the community through spaces like Home Court, an athletics facility just across the street from Hyde Park Academy and part

Local resident Travis Williams, one of the many volunteers manning the wheelbarrows in Jackson Park, has been involved with the HPKCC for three years and recently became its president. Speaking to the role that he hopes the Obama Center can play within the community, Williams said that he hopes it can bring stability and a boost to small businesses by providing more traffic and visitors to the area.

“Some people are for it, some people aren’t. But I’m for it,” Williams said. “Whatever’s going to bring money into the community that we can use for other things, that’d be great.”

The large turnout and diversity of participating groups highlighted the potential for synergistic partnerships between the Center and community. McCurry particularly emphasized the importance of young people to sustain these efforts.

“We need young people,” McCurry said. “I’m 75. We will die off, and there’ll be nobody. So we want to get back to the young people.”

Harris hopes the Obama Foundation can continue to facilitate such engagement in collaboration with programs like My Brother’s Keepers Alliance and Girls Opportunity Alliance, both of which form other partnerships between the Foundation and Hyde Park Academy. These initiatives aim to connect local grassroots organizations with schools, educate young people about career opportunities, and help empower them to effect positive change on their community as well as the wider world.

Many of the older volunteers and staff mentioned a sense of wanting to give back to the community as a driving force for their participation.

“I grew up on 51st and Kimbark. I’m a native of the community, so it’s been nice to be able to come back and to contribute,” Wong said. “Given everything that’s going on in the world right now, this is a really fun event to get all the stupid shit that’s going on off of [people’s] minds and bring people together. I mean, you can’t go wrong with plants.

On the first anniversary of UChicago United for Palestine’s “Popular University for Gaza,” the Maroon revisits last spring’s protests and the University’s response.

By ELENA EISENSTADT | Deputy Editor-in-Chief and NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Deputy News Editor

This piece is the third of a three-part series on the history of protest and the disciplinary system at UChicago. It covers the 2024 pro-Palestine encampment and its aftermath. Other articles have covered 1967–1974 and 2010–2020.

One year ago this week, UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP) launched its “Popular University for Gaza” protest encampment on the main quad, erecting tents and artwork across a gradually expanding footprint. After nine days on the ground, the encampment was dismantled by the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) on May 7, 2024.

A banner reading “End the Siege on Gaza,” Ceasefire Now,” and “Free Palestine” hangs inside the encampment. nathaniel rodwell-simon

Throughout the 2023–24 school year, pro-Palestine student groups responded to the October 7 attacks and the escalating Israel–Hamas war with protests, rallies, and sit-ins at colleges and universities across the country. At UChicago,

UCUP called on the University to divest from Israel-aligned businesses and enact a program of reparations for Palestine and the South Side.

Throughout the academic year, many university presidents were brought in front of Congressional committees to justify their handling of the protests, and multiple university leaders, including Harvard University President Claudine Gay and University of Pennsylvania President Elizabeth Magill, were forced to resign.

UCUP protestors in April 2024. nathaniel rodwell-simon

Tensions simmered as the spring wore on, with demonstrations continuing intermittently until early April, when students at Columbia University established the first “Gaza Solidarity Encampment” and sparked a new wave of demonstrations following in their example.

The wave of protest encampments reached UChicago on April 29, when protesters gathered on the western end of the main quad near Swift Hall and established an encampment of their own. While UCUP’s plans had been leaked

the previous week, the University community was not entirely prepared for its launch that day. As the Hyde Park Herald reported, one UCPD officer said that they “weren’t expecting this until Wednesday.”

Encampment participants gather around the “Welcome Tent,” where organizers distributed information and supplies. nathaniel rodwell-simon

Within hours, University President Paul Alivisatos released the first of several messages to the University community “concerning the encampment.”

In the message, Alivisatos indicated his willingness to allow the encampment to remain as a testament to UChicago’s commitment to free expression but warned that “if necessary, we will act to preserve the essential functioning of the campus against the accumulated effects of these disruptions.”

In his statement, Alivisatos also included an extended digression concerning the military roots of the word “encampment,” earning him the brief addition of “etymologist” to his Wikipedia profile.

Notable local leaders, including Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr., Weather Underground co-founder Bill Ayers, and

25th Ward alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez visited the encampment to express their support, participating in rallies and hosting teach-ins on topics related to protest history and Palestine.

Bill Ayers speaks to encampment participants during a teach-in. nathaniel rodwell-simon

After three days of the encampment, the University offered the encampment’s organizers a one-hour meeting with Alivisatos and Provost Katherine Baicker in exchange for the removal of the encampment and cessation of further violations of University policy. In addition to a private meeting, the University offered an open forum with the president and provost to discuss “the many viewpoints related to the Israel–Hamas War and divestment.”

UCUP declined the proposal on the fourth day, refusing to dismantle the encampment unless the University committed to their demands.

A thunderstorm later in the day prompted University Facilities Services to take down the American flag from the main quad, in keeping with protocol, which protesters quickly replaced with a Palestinian flag. The day ended in a brief rally around the flagpole and a confronCONTINUED ON PG. 12

“We know that this is not about us; this is about Palestine.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 11

tation with UCPD officers trying to take the Palestinian flag back down. Security officers removed the Palestinian flag the next morning and cut the halyard, preventing any flags from being raised.

On the morning of May 3, the encampment’s fifth day, University community members received a second email from Alivisatos about the encampment.

“On Monday, I stated that we would only intervene if what might have been an exercise of free expression blocks the learning or expression of others or substantially disrupts the functioning or safety of the University,” Alivisatos wrote. “Without an agreement to end the encampment, we have reached that point.”

Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine, an organization composed of pro-Palestine faculty and staff members, decried the email in a statement to the Maroon. “The administration has not negotiated in good faith with our students, offering them absolutely nothing in hastily arranged meetings. In light of the brutal police repression of students, faculty and staff across the country, threatening to forcefully dismantle the encampment is a serious escalation.”

Around noon that day, the encampment hosted a rally with more than 200 participants; at the same time, opposing student group Maroons for Israel hosted a picnic on the other side of the quad. Shortly afterward, a group largely made up of fraternity members marched toward the encampment waving American flags.

Protesters and counterprotesters faced off across the center of the quad, with pro-Palestine protesters chanting, “UChicago you can’t hide, you invest in genocide,” and counterprotesters chanting, “U.S.A., U.S.A.” and playing patriotic songs.

At 1:06 p.m., the University sent out a cAlert asking community members to avoid the quad as the crowd grew to roughly 1,000 people. Twenty-five UCPD officers, some in riot gear, lined up between the two groups and prevented people from crossing to either side. Chicago Police Department (CPD) and Allied Security officers were also present on the scene.

you don’t have the freedom to vandalize, you don’t have the freedom to obstruct University walkways, and you don’t have the freedom to disrupt learning, spraying ‘Death to America’ on buildings, chanting ‘Death to America.’”

front of the building, where it remained for several hours.

A person with knowledge of the situation told the Maroon in an interview in 2025 that protesters brought barricading tools, medical equipment, locks, smoke bombs, tactical equipment, and food into the building.

Heidi Heitkamp, director of the IOP, was inside the building during the occupation and exchanged words with the protesters before UCPD escorted her out. In a April 2025 interview, Heitkamp told the Maroon, “It was not well thought out on their part in terms of how they were going to occupy this building.”

“Eventually I just said, ‘I’m not leaving.’ And they said, ‘Well, you know, you’re going to get hurt.’ And I said, ‘Who’s going to hurt me?’”

As the demonstration died down, Arthur Long, a fourth-year in the College who led the counterprotest, told the Maroon, “I’m all for freedom of speech. And I love that UChicago protects that… But

In a statement to the Maroon that afternoon, UCUP said they would “[remain] steadfast in holding the encampment but will not engage in escalation with police or Zionists.”

Following a rally around the alumni beer garden on May 17, a group of “autonomous” pro-Palestine protesters, many of whom were alums, marched from a second rally on the Midway Plaisance to the Institute of Politics (IOP) building near 57th Street and South Woodlawn Avenue.

UCPD removed protesters from the building after less than half an hour while CPD officers observed from the street. No arrests were made, and protesters remained on the property until around 9 p.m. when UCPD officers forced them out of the IOP’s backyard.

The group reconvened outside of Alivisatos’s house, where they rallied again, rehanging and beating the piñata-style effigy of Alivisatos on the front lawn.

Before the group split up, one organizer said, “We know that this is not about us; this is about Palestine.”

Protesters entered the building, barricading doors and spray-painting security cameras. Others gathered on the lawn outside, hanging banners and erecting tents. One demonstrator hoisted an effigy of Alivisatos onto a tree in

This piece was produced by the M aroon ’s Investigations team, whose members are Celeste Alcalay, Evgenia Anastasakos, Elena Eisenstadt, Gabriel Kraemer, Zachary Leiter, Tiffany Li, and Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon.

A trauma surgeon reflects on the pro-Palestine encampment, reimagining our University as a site of conscience, violence prevention, and resistance.

By TANYA ZAKRISON

As trauma surgeons at the University of Chicago Medical Center, we consistently confront a tripartite taxonomy of violence in our practice. First, massaging the heart of an eight-year-old in traumatic arrest from a gunshot wound is the obvious direct violence we witness, with firearm injury now the top cause of death of children and adolescents in the United States since 2020. Second, there is an emotional violence that we impart, as trauma surgeons, on desperate parents and family members that await—in our ironically named “quiet room”—updates on their child. The sounds that emanate from parents upon learning that their child is dead are carried deep within us forever. The third form of violence we encounter is structural violence: the harm caused by social systems and institutions that create or maintain inequity. Rooted in supremacist ideologies, racial hierarchies, and other forms of discrimination, this violence perpetuates historical patterns of domination and subordination through economic policies, healthcare access disparities, and political structures, stripping certain groups of their basic human needs, leading to increased high-risk survival behavior and direct physical violence. This multilayered cycle of devastation persists because institutions of influence—universities among them—too frequently

avert their gaze.

This cycle manifests with stark geographic specificity on Chicago’s South Side, where historical redlining practices have produced a cartography of disinvestment that corresponds with alarming precision to contemporary patterns of firearm violence—patterns disproportionately affecting African American and Latino communities. The same cyclical violence operates in Gaza; I witnessed it firsthand as a medical student conducting research in the Middle East in 2000. I remember the shame of a Palestinian host family kindly tolerating my survey questions as they were unable to offer me tea due to a 72-hour water shortage. No more than 100 feet away were Israeli children in a settlement swimming in their backyard pool. Today, my surgical colleagues in Gaza confront the three forms of violence in analogous scenarios: the treatment of Palestinian children presenting in traumatic arrest from gunshot wounds, the grim responsibility of conveying catastrophic news to any surviving family members, and the moral burden of bearing witness to genocide against a population systematically denied the basic necessities of life. In Gaza, similar to the U.S., preventable direct violence and its corrosive, destabilizing effects represent the predominant cause of pediatric mortality.

This structural-direct violence dialectic has catalyzed resistance movements at our own institution. South Side Black youth community activists

employed disruptions, demonstrations and direct action to demand the establishment of an adult trauma center at the University of Chicago Medical Center. These actions were met with institutionally sanctioned force via the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD). More recently, a coalition of students, staff, and faculty established the “UChicago Popular University for Gaza” encampment on April 29, 2024, articulating interconnected demands for the University: acknowledgment of the genocide in Gaza, severance of ties with Israeli companies and the Israel Institute, transparency regarding investments in weapons manufacturers, and commitment to reparative justice “from Palestine to the South Side.” This mobilization similarly encountered institutionally authorized police intervention, again from UCPD.

Violence prevention, whether direct, emotional, or structural, constitutes a fundamental dimension of our professional mandate as trauma surgeons within the larger rubric of injury prevention. Similarly, universities bear an institutional responsibility to contribute to societal betterment. Thus, this collective ethical obligation extends to confronting atrocities to which we may be contributing, whether through action or calculated inattention. The campus pro-Palestine encampment represented such a necessary ethical intervention. Indeed, silence in the face of such circumstances would have consti-