Behind the curtain: Sock ‘n’ Buskin P. 7

The fine print of Canadian campus media: Changes, costs and courage P. 9

Unified rugby builds camraderie P. 11

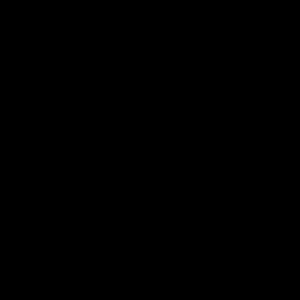

Cover by L Manuel Baechlin

Behind the curtain: Sock ‘n’ Buskin P. 7

The fine print of Canadian campus media: Changes, costs and courage P. 9

Unified rugby builds camraderie P. 11

Cover by L Manuel BaechlinEditor-in-chief: Isabel Harder • editor.charlatan@gmail.com

There’s something magical about newsrooms: the hustle and bustle and the unique energy each team member brings.

A lot of that work often goes unnoticed, including the hours of work that go into telling every story to package it into one tiny neat gift-wrapped newspaper-shaped box.

Behind the scenes at the Charlatan, we fill most of our free time with jokes about peaches and the campus groundhogs (chonkers) we all know and love. I’ll save those antics for April Fool’s. For now, let’s focus on the tireless efforts of newswriters and newsmakers to keep the world informed.

Thank you to our volunteers and editors for working around the clock to deliver unique and invaluable content to the Carleton University community and beyond. Thank you to the sources and media repre sentatives who put up with their constant pestering. The average reader doesn’t get to see the hours of work you put into telling these stories, so this one’s for you.

Here’s our peek behind the scenes—at campus life, at research, at art curation and at student newspa pers. Because there’s always so much more going on behind the scenes than the public sees. Volume 52, Issue 1

sure I take care of [my coworkers],” Adbullahi said. “I don’t want to just be their supervisor or their boss. I am their friend first and we work together as a team.”

Never without a smile on her face, Adbullahi has built a community with her co-workers, and even with Carleton students.

“I have interacted with students in the Carleton Athletics building, especially at the front desk. I tell them ‘good morning’ every day. I ask them if they’re studying for any exams and I encourage them,” she said.

Adbullahi’s caring nature and love of helping others comes from her past experience as a nurse.

When Kadra Adbullahi’s friend referred her to a custodial job at Carleton University four years ago, she was a little nervous. It would be her first job in a new country. She moved to Canada from Djibouti in 2016. Nevertheless, Adbullahi took the job and soon excelled.

In February 2019, Adbullahi became a clean-up supervisor for Carleton Athletics, leading a team of ten custodians with kindness and mutual respect. She credits “the great, very nice people” she works with at Carleton for making her feel at home in Canada.

“It is difficult when you are in a new country. But here in Canada, you have the feeling you are back home. No one looks at you like you are different, and you feel free,” she said.

Darren Bourque is a manager at C&W Services, the facility management company that manages Carleton’s custodial staff. He said Adbullahi demonstrated the

qualities the company looks for in its employees.

“She’s very professional. She’s a leader amongst her coworkers and is always smiling with a friendly word for everyone,” Bourque said.

Adbullahi’s work shift starts at 7 a.m. and ends at 4 p.m., but she gets up at 4 a.m. to get a head start. During that time, she prepares the sign-in papers for her employees and checks her email for work order notices.

Carleton’s custodial staff cleans up more than 293,299 square meters of building space on campus. Cleaning tasks include sweeping and mopping floors, emptying waste containers and washing walls, according to the facilities management and planning webpage.

Adbullahi supervises Raven’s Nest, the Ice House, the H.H.J. Nesbitt Biology Buulding and Robertson Hall. As part of her job, she ensures the custodians under her supervision carry out their tasks properly and assists them when needed.

“I’m always smiling and I make

She studied nursing in Djibouti, following in the footsteps of her grandmother, also a nurse. When Adbullahi moved to Canada, she had to create a new life for herself and her family.

“I came as an immigrant with my two youngest kids who were 15 and 17 years old. I left some of my family back home, like my husband and my oldest son,” she said. “I had the choice to [go back to Djibouti] and study or to sponsor my husband and son to come to Canada.”

Adbullahi chose to sponsor her family.

“I started the process to bring them here and I started to work to provide for us,” she said.

In 2020, she finally reunited with her husband and oldest son. After a long day of work, Adbullahi heads home to spend quality time with her family.

“When I look at my kids, I’m looking for them to have a different experience and a different future so that they can get more out of life than what we get back home,” she said. “They brought me here. They’re the reason I’m here.”

“Building trust with a therapist is kind of hard—it does take time,” Lipson said.

Now, Lipson accesses therapy through Empower Me, a service o ered by Studentcare, the Carleton University Students’ Association’s (CUSA) health and dental plan provider.

Empower Me is available to all undergraduate students at Carleton, including those who opt out of CUSA insurance coverage. It o ers virtual therapy and maintains a crisis line, where students can access a counsellor immediately.

Lipson, who is Chinese, said she had initially hoped to see a therapist from an Asian background so she could address cultural concerns, but Empower Me was unable to provide that.

“It’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t grown up in a similar environment,” she said.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, contact the Ottawa Distress Center Crisis Line: 613-238-3311.

Danielle Pybus, a third-year English student at Carleton University, contacted Health and Counselling Services last year. at step alone was di cult for Pybus, who had to phone the o ce to set up an appointment.

“For someone with anxiety, like myself, that’s not the most approachable way to ask for help.”

She said the barrier could be removed by o ering an online booking system for students. When she was matched with a counsellor, Pybus waited three weeks before her appointment, a wait she considers too long.

“A lot can happen within that time frame,” she said.

Pybus is not alone. Long wait times and having to switch counsellors are among the di culties Carleton students face when accessing mental health services.

Louise Shearman, director of student wellness at Carleton, didn’t provide an average wait time for counselling, but said in a statement midterm and exam seasons are

busier.

Shearman said students with urgent needs can access same-day appointments. at includes students with suicidal thoughts, victims of sexual violence and students experiencing the death of a loved one, among other concerns.

A er the wait, Pybus began attending regular sessions, which she said were helpful. But when she missed a session, she was hit with a $60 ne. e Health and Counselling Services website says students can be charged nes of up to $100 if they miss a session.

Pybus said the experience le her feeling discouraged.

“Maybe I couldn’t make it out of bed to go to counselling and then I’m stuck with these fees,” she said. “It stopped me from reaching back out to reschedule the appointment.”

Jordan Lipson, a second-year computer science student, accessed Health and Counselling Services’ residence counselling last year. Lipson waited two weeks before her rst appointment, but said the process was easy.

However, when she le residence a er her rst year, she was no longer eligible for the service and lost access to her counsellor.

Shearman said Health and Counselling Services can match students with counsellors from BIPOC or LGBTQ+ communities.

“Goodness of t is one of the most important aspects of counselling and we understand that some students may feel more comfortable with a counsellor who identi es or has lived experience with a particular community,” she wrote.

Studentcare didn’t respond to the Charlatan’s request for comment.

rough Empower Me, Lipson is entitled to six sessions with a therapist. With her nal session approaching, Lipson said she’s worried about losing access to a second counsellor.

CUSA vice-president (student issues) Faris Riazudden said Empower Me can extend sessions in some circumstances.

With Empower Me geared toward short-term mental health care, CUSA and Studentcare are piloting a new program, called Conversation, for longer-term support. Unlike Empower Me, this new program o ers an unlimited number of sessions.

For Pybus, despite the challenges, she said she still feels lucky to access mental health services.

“I’m just grateful to have them at all,” she said. q

National Editor: Evert Lindquist • national.charlatan@gmail.com

Amid growing costs of living, Karuna Dsouza at the University of Western Ontario is among a wave of teaching as sistants (TAs) pushing their university administrations to pay students higher wages.

Dsouza, who’s also president of PSAC 610’s Teaching Assistants’ and Postdoc toral Associates’ Union at Western and a doctoral student of media studies, said she and other TAs are paid only $13,000 per year.

Western pays TAs nearly double what those at Dalhousie University re ceive, though TA positions at Western are reserved for graduate students, and anyone at Dalhousie can TA. Dalhousie TAs started a strike on Oct. 19 over their lack of wage increase since the last col lective agreement ended in 2019, putting a pause on these vital student resources.

They aren’t alone in their cause.

Aparna Mohan, Dalhousie Student Union (DSU) president and fourth-year industrial engineering student, said TAs are instrumental in reinforcing learning.

“In the post-secondary context where we do tend to have large numbers of stu dents in classes and smaller numbers of professors, teaching assistants really help fill the gap and bring down the ratio of instructor to student,” she said.

Dalhousie professors and administra tors have received 10 to 13 per cent pay raises in the past two years, but TAs have continued to make only $24 per hour

“We’re living paycheque to paycheque and scrimping on resources because ultimately … we’re still getting below minimum wage,” she said.

since September 2019, Mohan added.

“The pay they’re getting right now isn’t matching inflation, it’s not match ing the cost of living and it’s not matching the actual hours,” Sydney Keyamo, DSU vice-president (academic and external) and fourth-year psychology and health sciences student, said.

Chris Hattie, acting assistant vicepresident of human resources at Dalhousie, said the goal is to increase TA wages so they’re more competitive with those at other U15 schools.

“Having TAs is a critical part of who we are as a university,” Hattie said, add ing wages have usually increased by 1.5 or 2 per cent in the past.

During the pandemic, living and housing costs have increased across Canada, partly due to inflation, and have stimulated concerns from students who are simply trying to get by.

“Western may have a higher wage rate [than Dalhousie], but we are capped at how many hours we can work a week,” Dsouza said. “Our income or stipend from the university is not adequate. The fight is actually on whether we are able to survive.”

Keyamo said students want to see uni versities “return to championing their

academic mission.”

“The decisions and the kinds of ac tivities that universities have engaged in [in] recent years especially have been making them resemble businesses more and more,” she added.

Dsouza said she hopes students will bring awareness to this issue and try to

ensure TAs are compensated for their time and work.

“Students need to organize them selves into unions,” she said. “Unions need to be quite clear about what their members want and connect with each other and be clear about what is required to live.” q

When Lindsey Keene stepped foot onto Carleton University’s Sock ‘n’ Buskin’ stage for the rst time this fall as Count Dracula, she continued her tradition of playing gender-bent roles.

Keene is a third-year public a airs and policy management student at Carleton and lead in Dracula, the rst production of the year for Carleton’s student-run theatre troupe. She said the decision to gender-bend characters was one of many choices con sidered while producing the play.

“I’ve seen a lot of theatre that is so bound to tradition that people close their eyes to innovating and trying new things,” Keene said. “It also represents innovation to me and turning the art into something modern and more inclusive.”

e decision to experiment with Dracula’s gender was made by second-year English student and rst-time Sock ‘n’ Buskin direc tor Naomi Badour*.

Badour earned the directorial title a er her rst experience behind the scenes of a production as assistant stage manager of e Importance of Being Earnest in April 2021.

As director this fall, Badour took the lead on lighting, costume and set design choices.

“It’s about what the movement will look like on the stage,” Badour said. “You have to spread the set pieces out to make sure that people get to use the whole set. If you want it to focus on one side of the stage, you make it intentional.”

Badour added she drew inspiration from the set and costume designs from other theatrical iterations of Dracula and other stage productions set in the late 19th century, such as Frankenstein

“In terms of costume, you kind of lead by the character,” she said. “You really have to sit down and think of what choices the character might make for themselves, but then also you have to think of it in terms of the colour sym bolism and how it will look onstage.”

Badour also guided actors during rehears

als to accurately portray their characters according to her creative vision, she said.

“ ere are times at rehearsal where I will be watching a scene, it’ll be like the very rst rehearsal where we’re doing this scene … and I’m just sitting watching it, giggling and kick ing my feet,” Badour said.

Working alongside Badour, the stage manager and assistant manager also ensured all elements of the production came together behind the scenes.

Stage manager Madison Edwards said she was responsible for tasks such as scheduling rehearsals and keeping track of props.

“It’s pretty di cult to deal with 15 people’s schedules, especially when they clash a lot,” Edwards said. “We now do a thing where we videotape a scene and at the end, we upload it to Google Drive … if [an actor] can’t make it, they can just watch it there.”

As assistant stage manager, Madonna Ga rang handled the sound and lighting of the show. She also followed the director’s creative vision and ensured the production adhered to copyright law.

Another behind the scenes member fea

tured in every Sock ‘n’ Buskin production is Gourd Boy, a statue of a boy holding a vase of water.

“We call it Gourd Boy because it looks like he’s holding a gourd,” Badour said.

Before every production, the cast hides the statue in unexpected places onstage. Its location is kept secret for audiences to catch as “a little easter egg” while watching the play, she said.

While every show o ers unique backstage dynamics, Keene said she has always experi enced rituals of encouragement with other cast members.

“Whether it’s in some sort of circle to decompress in the warm-up for the show, whether it’s getting ready with people in the dressing room beforehand … there’s just so many small things that seem to happen time a er time that I value just as much as that time in front of an audience,” Keene said.

Sock ‘n’ Buskin is now preparing for its upcoming shows, Elephant’s Graveyard in January 2023 and Clue in March 2023. q

*Naomi Badour has contributed to the Charlatan.

Preparations for a Sock ‘n’ Buskin show go beyond rehearsal.artist to create an exhibit that examined the gaps in representation of queer and Asian cultures.

“ ey told me that I’m the rst Asian Canadian to engage with this collection within its 100 years of existence,” he said. “I knew that was something for me to dig deeper into—[the] inclusion and exclusion rooted in Canadian settler colonialism.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the curatorial process for the exhibit was done virtually. Kwan said a scaled-down model of the gallery and consultation with curators who were familiar with the gallery helped determine the spacing and narrative of the exhibit.

“[ e virtual process] really highlighted the importance of collaboration and con versation,” Ho added.

e Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG) is a vi brant space full of works by Canadian artists. Behind the manicured walls and strategically placed lighting, there is a team of people working to ensure the impact of every exhibit is fully felt by viewers.

One member of this team is exhibition and interpretation co-ordinator Meghan Ho. She recently co-curated Landscape, Loss, and Legacy alongside artist Don Kwan and other members of the OAG curatorial sta . e exhibit opened in February and will be on display until January 2023.

Exhibits at the OAG are thoughtfully pos itioned to maximize the viewing experience.

e planning process for each exhibit begins three to four years in advance, starting with the research and consultation stages.

“It’s a lot of conversations to exchange ideas, and then deciding what narrative or thesis the exhibition will be centered around,” Ho said.

In addition to the narrative, the curator ial team also considers the physical space

available for each exhibit. Every detail of an exhibit’s layout is planned, including how long certain artworks can be on display. Since art made of paper is susceptible to light damage, another part of the planning process involves selecting a second batch of pieces to swap out to preserve the art.

Jennifer Gilliland, the OAG collections and building project manager, said the gal lery takes steps to protect items on display using UV- ltered Plexiglas and frames, dis play cases and signage.

e OAG works closely with artists dur ing the curatorial process to decide on a layout and narrative.

Kwan said he was approached by the OAG to design and co-curate an exhibit that engaged with the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art, a collection of works by in uential Canadian artists such as the Group of Seven and A.Y. Jackson. e Ontario Heritage Trust granted conservatorship of the collection to the OAG in 1992.

He said he wanted to honour the Fire stone Collection while drawing from his experiences as a queer Chinese-Canadian

e OAG tech team is responsible for the physical setup of exhibits, including the transportation and installation of art pieces. Kwan said he was not present for the major ity of the construction process.

For a display titled, “ is land is my land, this land is your land,” displaying six Mus koka chairs connected at the arms, Kwan said he gave the OAG tech team a sketch of his vision and spoke with them over Zoom to discuss the construction of the exhibit. However, he didn’t see the piece in person until two weeks before the exhibit opened.

Kwan said he appreciated the opportun ity to help bring the exhibit to life from its beginning stages alongside the OAG cura torial and tech teams.

“ e generosity and openness for them to involve me in every step of the process was really bene cial for my art and curator ial practice,” he said.

“They told me that I’m the rst Asian Can adian to engage with this collection within its 100 years of existence.

Don Kwan Artist

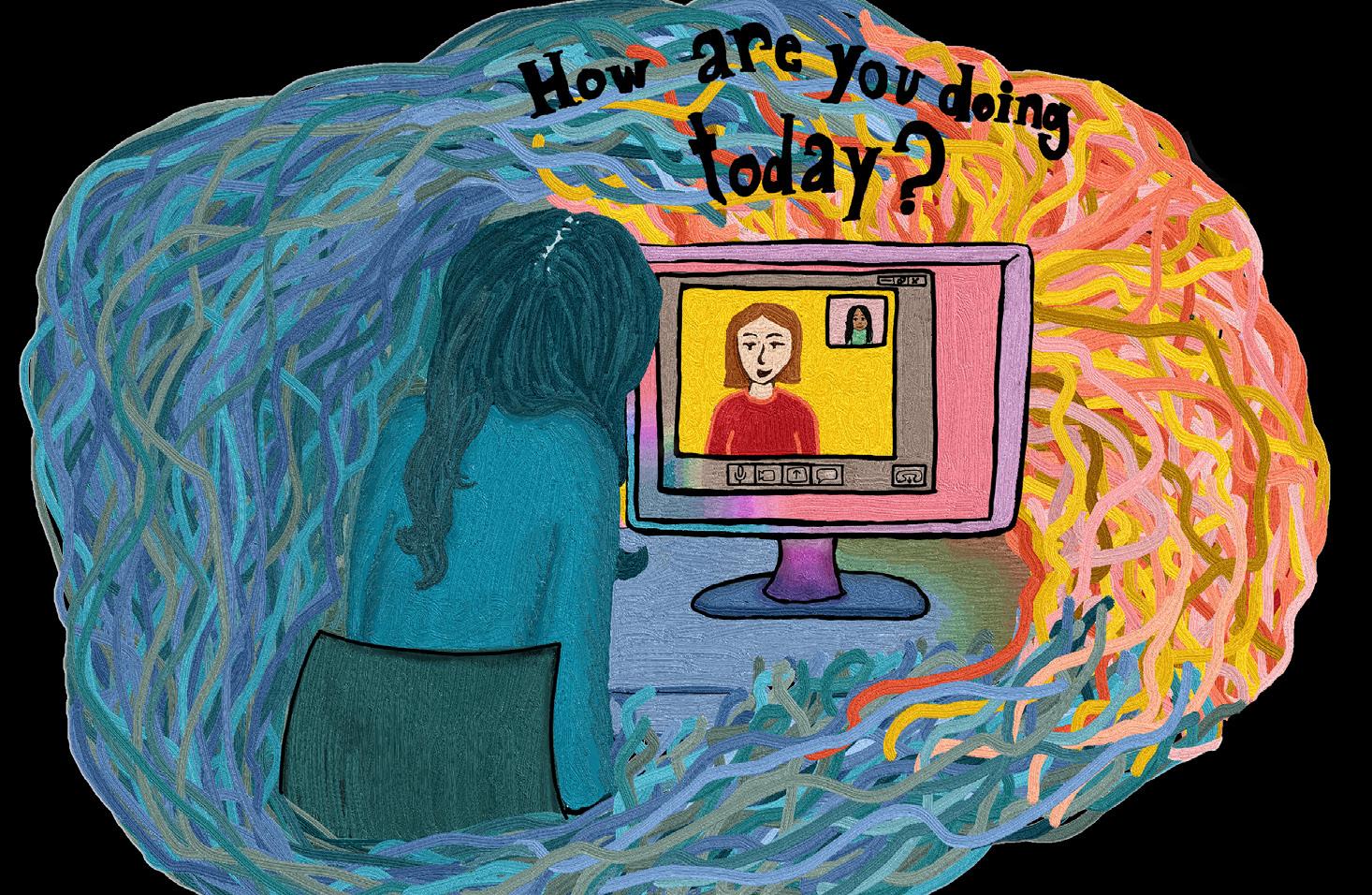

their passion for student journalism. Across Canada, journalists for student newspapers echo the sentiment that student journalism is as important now as ever.

Williams was a volunteer reporter and opinions editor at the Gateway before stepping into her current role as editor-in-chief. She has witnessed some of the student paper’s most tu multuous times since the 1970s.

Previously, the Gateway was funded through the collection of a $3.54 Dedicated Fee Unit (DFU) from full-time students’ fall and winter term payments. Every ve years, this DFU is renewed through a student vote.

In 2021, University of Alberta students voted to discontinue the Gateway’s fee. Since then, the Gateway has continued publishing under uncertain circumstances.

Since the 1970s, student journalists at the Gateway—the University of Alberta’s 112-yearold campus newspaper—have been ghting perpetual battles.

e Gateway is one of the oldest university newspapers in Western Canada. From its con ception in 1909 until achieving independence from the university’s student union in 2002, the editor-in-chief of the Gateway was chosen through a sta vote and typically respected by the union, which held the power to appoint the editor-in-chief.

But in 1972, a controversial decision was made by the student union to appoint a dif ferent editor-in-chief than the Gateway sta had elected. is decision quickly came to be known by sta at the time as “a threat to a free press on campus,” current editor-in-chief Emi ly Williams said.

In an act of protest, the Gateway sta published a scathing spread denouncing the decision while it was still in the works. Two pages displayed an image of a tombstone and the words: “In Memoriam of the Gateway.

Born September, 1909, sti ed February 14, 1972.”

e Gateway’s sta collectively resigned and founded their own newspaper, the Poundmaker. Former sta also requested the Gateway be expelled from the Canadian Uni versity Press (CUP)—a nonpro t cooperative and newswire service—where it held status as a founding member.

It took three years of hiring new sta and deliberate foregrounding of independent jour nalism for the Gateway to publish as a member of the CUP once again.

However, the Gateway’s challenges did not cease in the 1970s. In the coming decades it would face a loss of funding, a changing media landscape and disinterest from its student body. is ght to keep independent student media a oat is one that reverberates across the country. e absence of students on cam pus during the COVID-19 pandemic and the steep rise in university fees have forced many campus newspapers to adapt on the y in the name of survival.

roughout it all, many of those who work in campus media have been unwavering in

“We’re essentially working o of our sav ings while trying our best to nd alternative revenue,” Williams said.

Moving forward without funds, the Gate way has come to exist exclusively in an online format. e only exception to this came when students returned to campus in fall 2022, a er being asked to stay home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To increase readership, the paper’s sta decided to print a one-time, special edition paper welcoming students back to campus and re-introducing them to the Gateway. It was printed on nostalgic and budget-friendly newsprint instead of its previous magazinestyle.

A er selling ads for its special edition, the Gateway almost broke even. Following the success of this issue, the Gateway sta are now considering publishing another print edition in Winter 2023.

In the coming years, sta are hoping to run another DFU vote and restart their collection of a fee from students. Until then, the Gateway will do what it can to continue reporting in its community.

While some student papers, including the Gateway, have su ered a loss of funding, there

are also those that provide an example of what can be fostered when campus newspapers receive adequate funding. e University of British Columbia’s (UBC) student-run news paper, e Ubyssey, is one of those examples.

“We are extremely lucky to have a much bigger budget than a lot of other [student] newspapers in this country,” coordinating editor Charlotte Alden said.

According to Alden, the Ubyssey employs more than 25 sta each school year. is is a stark contrast to the Gateway’s six paid sta members and various volunteer contributors who provide the bulk of the Gateway’s content.

“Our sta is less than half what it was [be fore losing funding],” Williams said. “It’s tough.”

At the Ubyssey, Alden said their bigger budget gives them a sense of creative freedom and alleviates looming stress that other campus papers may deal with.

“We are not immediately worried about being defunded and that’s just a really big priv ilege to have as a student paper,” she said. e importance of post-pandemic print

A Canadian Media Fund study found the daily average for time spent reading online press last year among anglophone Canadians was 46 minutes. Meanwhile, the daily aver age time spent reading physical print press was only 31 minutes. Among francophone Canadians, the study found a similar, nearly 15 minute di erence between reading online versus printed press.

In this year’s Newspapers 24/7 study, News Media Canada reported 95 per cent of news readers choose to read on digital platforms while only 46 per cent continue to read print editions.

At the Ubyssey, Alden said the pandemic is the wrench that got stuck in their publishing plan. Before COVID-19 sent students home, the newspaper had been publishing a weekly print edition. A er returning to campus, it only picked up printing every two weeks.

“We’re trying to shi our papers to being more of a collectible,” Alden said.

In order to increase the appeal of print edi tions, Alden said the Ubyssey tries to market online content as separate from printed stor ies. is way the appeal of their print stories remains special and exclusive.

e exclusivity of printed editions is some thing Grace Anne Paizen, managing editor of the Manitoban, leaned into for the cover of the

paper’s October issue. e front page featured a large Frankenstein’s monster to match the month’s Halloween theme and the sheer num ber of articles it boasted.

“ e joke is we have Frankenstein’s mon ster as the front cover. So of course, it had to be monstrous, it had to be a big beefy boy,” Paizen said.

To produce this monstrous edition, Paizen had to stay in the o ce until 3 a.m. on produc tion night. As one of the few student papers still doing weekly print editions, it’s not uncom mon for Paizen’s Monday nights to go this way.

While getting home at a reasonable time on Mondays may be appealing to the Manitoban’s sta , Paizen said students made it clear that they missed the paper’s print editions during their pandemic publishing break.

“Some students thought we were going away over the pandemic because suddenly they couldn’t get the physical paper. So that was really nice to know, people are actually picking up the physical copies,” Paizen said.

At Trent University’s independent student newspaper, Arthur, print issues may have de creased from weekly to monthly this year, but distribution rates are still high.

“When we do distribution, we have about 20 or 30 businesses downtown that we take our papers to and they always accept them,” editorin-chief Bethan Bates said.

Without papers on newsstands over the past year, Williams said the Gateway also strug gled to engage with its student audience.

“We were nding that without a physical presence on campus, a lot of students just don’t know who we are,” she said. “Just having papers in the stands is a powerful thing.”

While Williams works to nd a way to ful ll print quota without losing money, Bates said Arthur’s nest egg of funds has grown during the pandemic thanks to its printing break. Now, Arthur is bringing back a reduced quota of print editions and continue to save money that otherwise would have been used up by weekly prints.

Student journalism: An essential

According to the Local News Research Project, 50 community newspapers across Canada closed or temporarily closed due to COVID-19. Recently, Postmedia Network Inc. announced it would be ending Monday print for nine of its urban daily newspapers. Two of these dailies included B.C.-based papers the

Vancouver Sun and the Province

Closures like these are the reason people in metro Vancouver are paying more attention to the Ubyssey, Alden said.

is theme is seen among other studentrun papers in Canada, such as the Gateway. Williams said in many small towns, campus media is the only news outlet. She described many student papers as “lone soldiers” and the last to cover local content.

“We see our role as being there when the mainstream media outlets can’t be,” Williams said.

At Trent University in Peterborough, Bates said the paper is o en used as an essential source of community knowledge.

“Campus media is this place that, for a lot of people, it’s their rst real introduction to the big wide world,” Bates added.

As the community newspapers of small towns dwindle, campus media is playing double-duty keeping both students and locals informed. But the vantage point of student-led media can be undeniably unique, especially when taking an introspective look at academic institutions.

“We are the students.,” Paizen said. “We know what’s going on.”

Editors at the Ubyssey agree.

“We are the only newspaper that spends a lot of time reporting on the biggest university in this province,” Alden said. “I think we do a public service here in paying that much atten tion.”

For Sie Douglas-Fish, design director of the University of Victoria’s independent news paper, the Martlet, campus news can also be a place that many students nd their voice or trust in the media.

“A lot of Gen Z are really passionate about social change and they don’t know how to go about having faith in media,” Douglas-Fish said. “[At the Martlet] we take ourselves very seriously.”

Student journalism represents a similar space for many campus papers across Canada. Alden said she entered her undergraduate de gree knowing she wanted to be a journalist.

“I would not have known what to do with that ambition if I had not been a part of the stu dent paper,” Alden said. “It’s really great that we are allowed to foster the kind of newsroom that we want to see … I can’t explain how much it’s meant to me.”

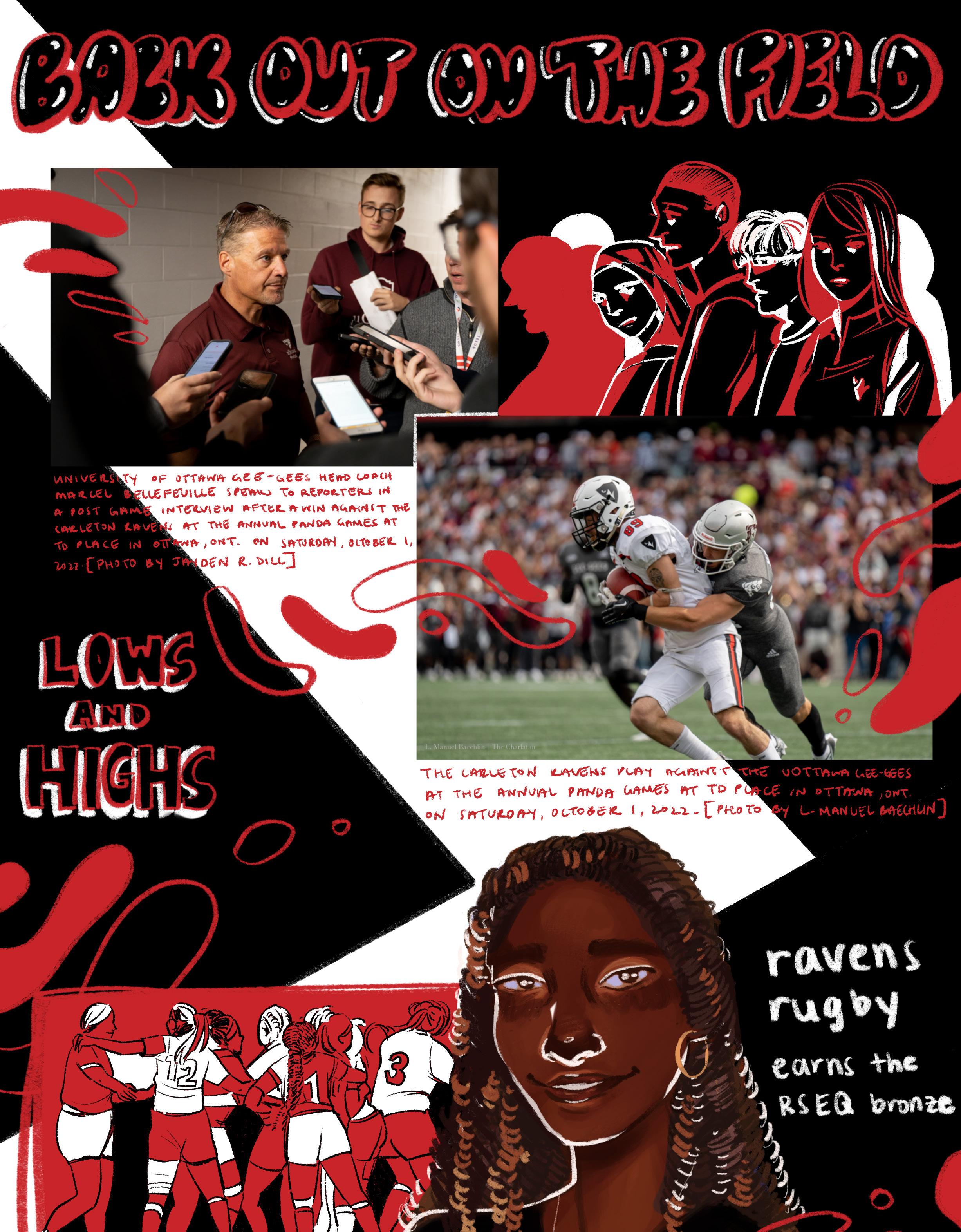

It was 2016 when LeeAnn Na piorkowski rst saw a tweet about several professional women rugby play ers running a workshop for athletes with disabilities. As an inclusion teacher in the Ottawa Catholic School Board (OCSB) and the Carleton Ravens men’s rugby head coach, Napiorkowski’s two worlds married each other.

In awe of what she had seen, Napi orkowski contacted Canada Rugby and asked to create a similar program. Six years later, Napiorkowski’s vision has become the Uni ed Rugby Jamboree, an annual event that invites athletes with and without disabilities to learn and compete in an inclusive touch rugby en vironment.

“I talked to other inclusion teach ers [within OCSB] and tried to provide a sporting experience that our players [don’t o en] get,” Napiorkowski said. “We wanted to provide sporting op portunities for athletes who o en get overlooked in classes, [so] we put this

opportunity together.”

Napiorkowski said there are commun ity organizations that o er opportunities for athletes with disabilities, but the high school system lacks the same option. One of those organizations is the Canadian Jax Rugby Football Club, the rst uni ed rugby club in Canada where Napiorkow ski is also the president.

“Our mentality is see the ability,” Na piorkowski said. “Instead of seeing things our players can’t do, we like to celebrate all the things they can do.”

A er COVID-19 halted the event for two years, the jamboree returned on Oct. 5 at Ravens eld with roughly 100 par ticipants from eight schools across the OCSB.

Napiorkowski said turnout was lower than usual and cited labour shortages in the school board as a reason to keep this years jamboree a bit more “low key.”

Before the event paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the jamboree had 185 participants in 2019 a er averaging around 85 participants in prior years.

To help this event run, inclusion teachers like Napiorkowski are needed to assist some of the participants. Jess Faria, a special assignment assistant at St. Matthew Catholic High School, works one-on-one with students who need sup port.

She attended the event to assist a student at St. Matthews and said it’s re warding for students to participate in new environments.

“It’s very important for the them to feel included with the [community],” Faria said. “It’s a di erent environment for the kids … they have to go over a hur dle of doing di erent things and come out of their comfort zone.”

Faria has attended the jamboree be fore. In 2019, the student she assisted went home with a “full smile.”

“ ey go home feeling extra happy,” Faria said.

Napiorkowski said she can see par ticipants’ con dence increase when they play sports, speci cally rugby.

“Everybody, when they’re proud of

Alexandra Je rey and Max Roman Nantel at the Uni ed Rugby Jamboree.what they do, walks di erently,” Napi orkowski said. “Your shoulders come back, your head comes up … we see kids who come through our program make eye contact, shake hands and high ve people.”

e jamboree is hosted by the Carle ton Ravens men’s and women’s teams and the Canadian Jax, who also o er summer and winter programs. While these programs support uni ed sport, the event operates on a “shoe string budget,” according to Napiorkowski. She said nding resources is one of the biggest challenges of running the event. Co-ordinating and “trying to do more with less” leaves the organizers reliant on donations and volunteers.

Alexandra Je rey is a consistent sup porter of Canadian Jax events. Her son, Max Roman Nantel, a Grade 11/12 ECL student at Notre Dame High School, has attended the jamboree twice before. Nantel is an athlete with autism. Je rey said Nantel had not participated in large group events when he rst got to high school, but the jamboree and playing rugby interested him.

Nantel said he enjoyed the jamboree in previous years and that he’s glad its re turned since its COVID-19 hiatus. When asked about his favourite part of the day, Nantel responded, “ at’s simple, tack ling.”

e Canadian Jax events have helped Nantel with his disability, according to Je rey.

“He was more open,” Je rey said. “He learned a lot about working with other people and about himself and building his own con dence … Realizing and understanding his own disability was not an easy thing. It took time learning to ac cept his own di erences.”

Je rey added meeting other people with disabilities at events like this was an eye-opener for Nantel. She said at tending the jamboree taught him to be patient and accepting of others’ di eren ces as well as individuals with disabilities.

“ is particular event, the people who work here—it brings out that openness in kids,” Je rey said.

Je rey credited a group of girls from St. Peter Catholic High School, where Na piorkowski works, as some of the people who made the jamboree enjoyable. Farjoe

Cobby, Faith Dimbongi, Franckie Cobby, Ma-Eva Versailles, Rafaella Decastro and Danika Timothee play on their school’s rugby team and volunteered to help out with the jamboree.

“Everyone was involved no matter who they are or what capabilities they have,” Versailles said. “Everyone has a chance to play this sport and it’s nice to see the atmosphere of everyone smiling.”

Many the attendees echoed the joy they felt and the smiles they saw. Former Canadian rugby all-star Al Charron said he attends the event as a supporter be cause he loves the smiles on kids’ faces and the growing interest in rugby in Can ada.

e girls said they had recently started to play rugby and getting to share this learning experience with others showed a sense of community.

at sense of community is what Napiorkowski aimed to build. She said parents have told her several ways their kids have been overlooked on school teams: ey aren’t celebrated for scoring tries, are absent from the yearbook, never get to wear a jersey—all things that they get to do at the jamboree.

“Uni ed or mixed ability sport is such an important thing that I don’t think get’s enough airtime in Canada,” Napiro koski said. “ ere’s so much opportunity to create empathy, to create understand ing, to create a climate where everyone belongs. I think now more than ever the world needs a spot where everyone be longs.” q

When asked how the Ravens Racing team selects its coveted driver position, Jake ibault, a third-year aerospace engineering student and Ravens Racing member, was all jokes.

“We just pick the kid who has no fear of losing his life,” ibault said.

While Formula-style car racing surely isn’t for the faint of heart, the truth is that it requires much more than a fearless driver to compose a functional racing team.

For Ravens Racing, it takes more than 100 proud team members working in sync.

Carleton University’s racing team com petes in the Formula Society of Automotive Engineers (Formula SAE), the largest engin eering design competition in the world. e team manufactures and races open-wheeled Formula-style race cars.

Formula SAE’s major annual event is FSAE Michigan, which happens every May at the Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, MI.

More than 100 teams from universities in North America, South America, and Europe compete in various racing events.. is year will be Carleton’s 26th year competing in Formula SAE.

What most spectators don’t see is the year-long, behind-the-scenes e ort that goes into the design and build of a Formula SAE car.

“It’s actually a new car every year,” ibault said. “By rules, every time a chas sis races at a competition you are required to build a new one.”

As far as building the car, this particular year is one of turnover and growth within the team.

“We’re trying to get back to our funda mentals,” ibault said. “ is is a relatively young team, all things considered. A lot of our experienced members all graduated at the same time, leaving us with a fast car, but not a lot of knowledge transfer on how to keep it fast.”

us, the focus this year is on building the car from scratch, without reusing any parts. According to ibault, even if the team is only remaking old designs from previous years, it is still valuable for members to learn the fundamentals of racing.

ose fundamentals will matter come May, when the car will be scrutinized ac cording to the Formula SAE rulebook before it reaches the track.

“ ere are more than 700 individual rules for compliance and the car has to meet each one,” Michael Silveira, team co-lead and fourth-year electrical engineering student, said. “A team of judges will go through and inspect the car back to front, one rule at a time, and make sure everything is to stan dard. It’s like a four-hour process.”

It wouldn’t matter if the team knew how to put a racecar together if they didn’t have nancial backing. As it turns out, they require plenty of it. Teams are evaluated o -track on the nancing and design of their cars, in addition to their performance during the race.

“In terms of materials, you’re graded on a cost event, where basically the less money you theoretically spend on your car as if it’s a product, the higher points you score,”

ibault said.

e parts they build the car from have xed prices assigned by Formula SAE, total ling approximately $16,000.

“ at $16,000 is $16,000 in FSAE cur rency, where a nut costs exactly y cents,” Silveira said. “Everything is scaled because they have teams using Euros, Swiss francs, Canadian dollars, American dollars, Pesos, and whatever else, so they standardize every thing to their own currency.”

e team is grateful to have such a large supporting cast of sponsors to make their ra cing possible.

Even with the enormous wave of support behind it, Ravens Racing is always seeking out more volunteers.

“We really stress that anyone can come out,” ibault said. “We’re always looking for people outside engineering with di erent perspectives.”

Silveira said the best way to get involved is to visit the team’s website, ravensracing.com, and join the team’s Discord.

Building a race car is no easy task, but a well-oiled machine of volunteers makes it possible.

“It’s a lot of moving parts all working in parallel to each other,” Silveira said. q

Ravens Racing practices in parking lot 6 at Carleton University.

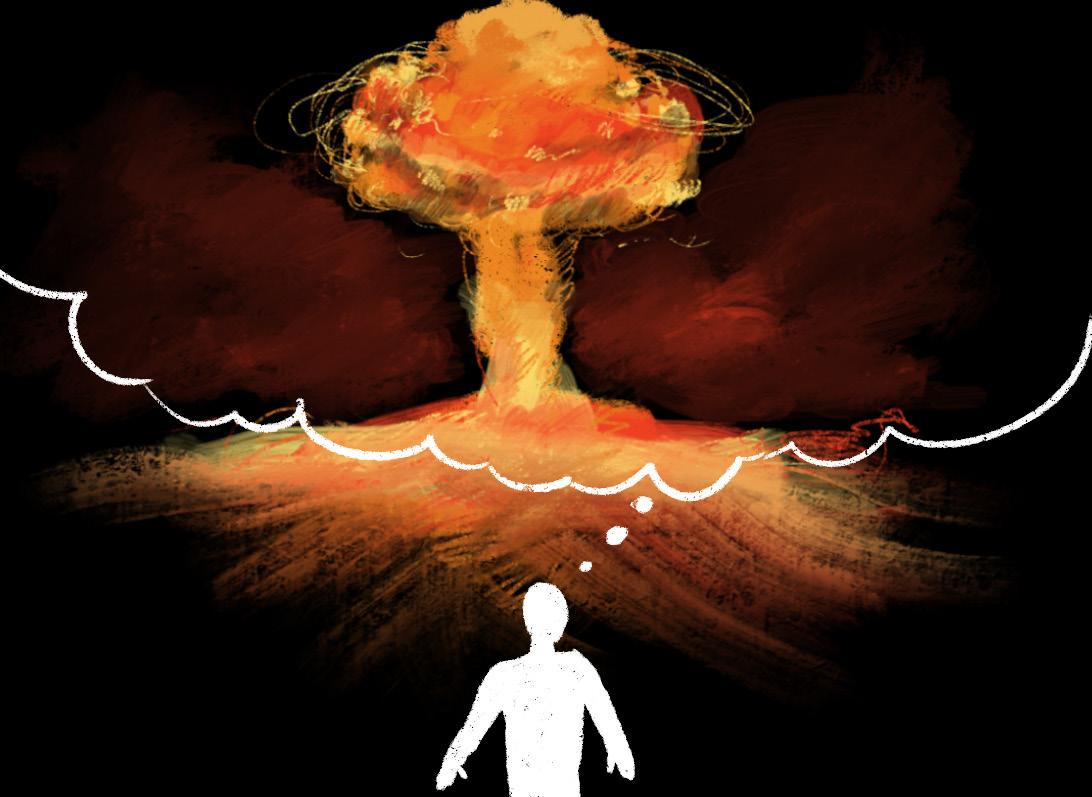

With the consistent escalation of con ict in Russia’s war in Ukraine, fear of nuclear weapons has risen. Not only do nations have to focus on preparing their resources to manage a hypothetical crisis, but they have to alert and prepare citizens for emer gencies.

So what is the optimal way for those working behind the scenes to prepare cit izens for a potential nuclear crisis?

e rst step is preventing world gures from normalizing the possibility of nuclear warfare because of how massive the threat really is. Following this, we must renew conversations of denuclearization as a way of reassuring frightened citizens.

e smallest nuclear weapons pose a potential for a serious crisis. Much media coverage of possible threats focuses on the idea that Russia could use tactical nuclear weapons. ese are much smaller than the apocalyptic warheads that instill fear in every nation, but the bombs that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki are on the weaker side of tactical weapon strength. Any nucle ar weapon, no matter the size, could cause mass devestation.

Nuclear threats were normalized in infamous exercises North American gov ernments implemented during the Cold War, referred to as ‘duck and cover’ drills. Students were taught to dive under their desks and cover their heads in the event of a potential nuclear attack. ankfully, that attack never came, but the drills instilled lasting fear in participants.

For many born a er the Cold War, this sounds like something out of a dystopian novel. ese drills were very real, and serve as an example of governments acting as if a catastrophic bombing was inevitable, rath er than preventable.

Atomic warfare is not new, and while it is important for the horrors of its potential to be known, we have seen with previous examples of threats that they have frequent ly fallen through.

1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis was the peak of the Cold War nuclear threat, with na tions worldwide scrambling to prepare for possible disaster. Recently, North Korea’s announcement that they own weapons of mass destruction brought about fears of a worst case scenario becoming reality.

Global fear is increasing. In a 2017 Can adian poll, 55 per cent of participants said they feared the possibility of nuclear ag gression a er an increase in North Korean threats, compared to only 36 per cent who said the same the previous year.

While making sure citizens stay in formed and aware of the severity of nuclear warheads is important, promoting fear is a side e ect of this that must be reduced. Anxiety is linked to worsening physical health and other mental health conditions. It is essential for the well-being of all na tions to try to ease the emotional burden on citizens.

Educating the public is important in a time of uncertainty, but what is even more important is prevention.

e process of denuclearization— getting rid of atomic bomb weapons globally—is one with many moving parts. It will not happen overnight, but it is not impossible.

However, there are issues with the idea of denuclearization. Russia’s current inva sion of Ukraine might not be taking place had Ukraine not agreed to give up their atomic weapons. At the time, they owned the world’s third largest collection. e pro cess of agreeing to rid the world of atomic bombs can lead to vulnerability, so it will be di cult. However, the mutually assured destruction that comes with actually using the bombs should motivate every nation to denuclearize.

Leaders should not normalize the threat of nuclear warfare to their already anxious citizens. Potential nuclear weapon usage is a concern, but widespread panic is not the solution. Governments should act behind the scenes and do everything they can at the negotiation table to make a hypothetical crisis as improbable as possible.

ferent because I couldn’t imagine myself doing the same mundane job day in and day out. Journalism helps me achieve the perfect amount of mental stimulation be cause it’s challenging while also being a creative outlet.

Journalists get to serve the community in such a unique way that it’s hard not to become addicted to the profession.

However, the news waits for no one. One thing that journalism school fails to prepare students for is the lack of worklife balance. Being a journalist means constantly battling deadlines, juggling multiple stories and giving up my free time to edit or report. Technology has made it even harder to stop working because the process has become instant. Journalists live in a world of constant quotas, meet ings and interviews.

FAITH GRECOI’m studying to become a journalist be cause I am passionate about storytelling.

In my three years of education and work experience, I’ve learned I love my fellow journalists, hunting down informa tion, chatting with sources and spending long hours tediously editing my work. De spite these perks, there is a price to pay for choosing this fabulous, fast-paced profes sion.

I remember the rst time I told my family I was planning to pursue journal ism. A er announcing it at the dinner table, my aunt made sure to tell me and the rest of the ensemble that journalism was dead. My aunt was the rst but, unfortu nately, not the last.

Of course, I eventually got used to tell ing non-journalists that while traditional newspapers might be going out of style, journalism is still alive in the digital era.

is was my rst encounter with some thing I would become too familiar with: the

stigma associated with being a journalist. Not only are journalists constantly re minded of their “dying” eld, but we also bear witness to the best and worst of what the world has to o er. Journalists are on the ground, reporting and seeking infor mation on natural disasters, government wrongdoings, criminal activity and more. Some don’t watch the news because it can cause anxiety, but many forget the experi ences of those behind the scenes reporting it.

According to a recent report published by the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma and Carleton Uni versity, one in 10 media workers surveyed has thought about suicide a er covering harrowing stories. However, the report also indicates high levels of job satisfaction, meaning journalists continue to love their jobs while climbing through emotional hurdles.

I’ve come to understand that there is no such thing as a boring day working as a journalist. I love that every story is dif

To add to this pressure, civilians ex pect journalists to be all-knowing. It’s stressful to have friends, family and others constantly turning to you for informa tion on anyone and anything and being disappointed when you turn out empty pockets. I’m not saying that journalists shouldn’t stay up to date on relevant world news—that’s a part of our job—but it’s un realistic for others to expect us to be aware of every story being reported.

However, if you’re like me, being in the know invokes a feeling of connectedness and deadlines provide an electric kind of motivation, making journalism the perfect career option. Yes, the world of journalism is competitive but that means your peers will motivate and push you to be the best version of yourself.

Becoming a journalist is no easy task, yet despite these untold truths and hard ships, there’s no better feeling than having a conversation with a passionate interview ee, nding the truth or helping someone tell their story.

Although I’ve had to learn how to navigate the harsh world of journalism, I wouldn’t give it up for the world. q