Geographies of inequity, Restoration of the Bananeras

Andrea Camila Camacho Gomez Student number: 217922

Master’s Thesis

Landscape architecture Land Landscape Heritage

Supervised by Marialessandra Secchi - Marco Voltini

Academic Year 2022-2024

CONTENT

0. About

0.0 Abstract

0.1 Introduction

1. Unveiling the flow: Overview of the Bananera’s plain

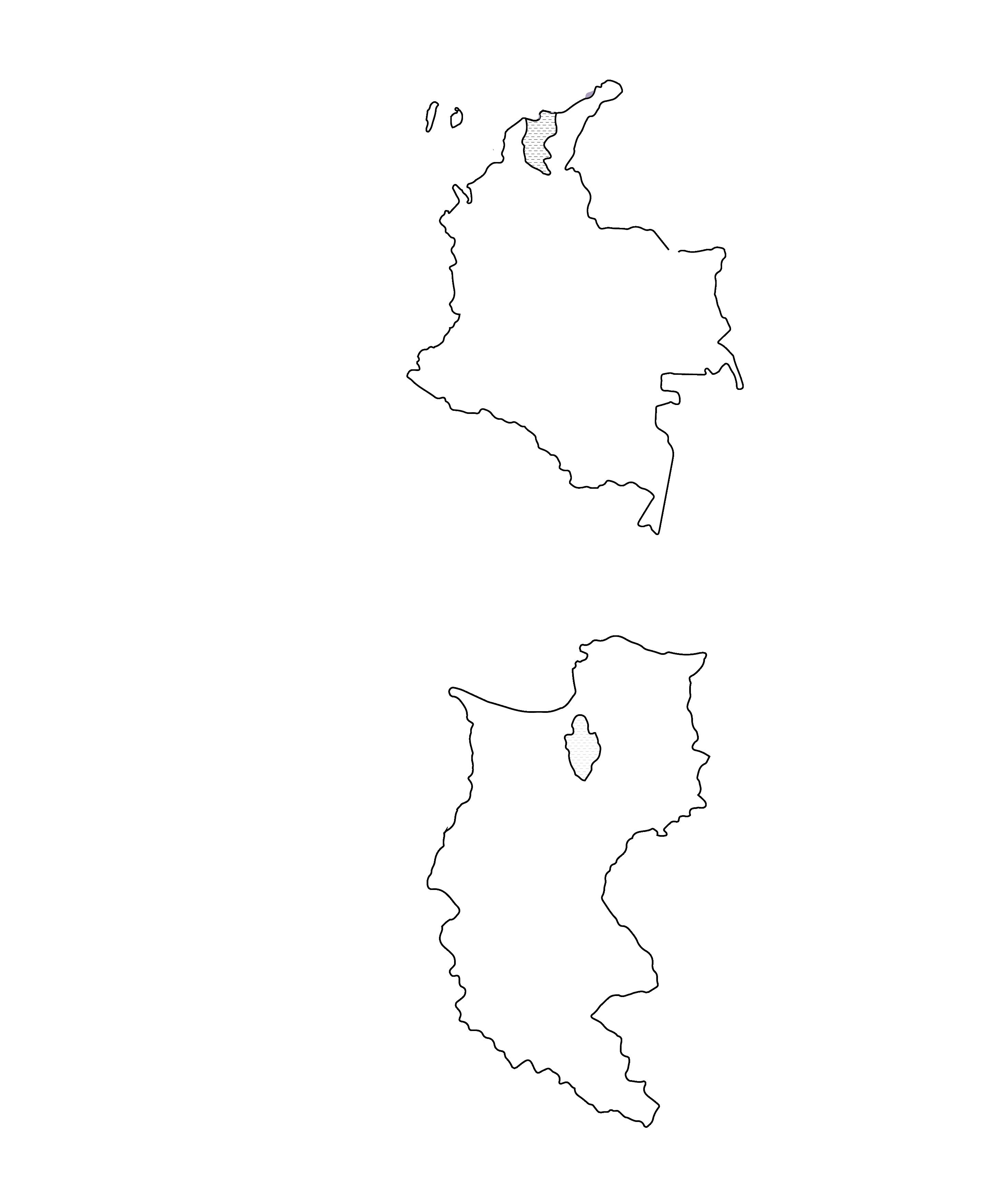

1.0 Location

1.1 Geographical Morphology

1.2 Geography

1.3 Altitude

1.4 Landuse

1.5 Agriculture

1.6 Geology & soil

1.7 Vegetation

1.8 History

1.9 Culture

2. Streams of Progress: Objectives and Method

2.0 Understanding the problematic

2.1 Oppotunities

2.2 Goals

2.3 Methodology

3. Strategy for water accesability and public space

3.0 Specific location

3.1 Analysis

3.2 Concept

3.3 Strategy for water accesabiliity and public space

3.4 Water arteries: Lines, Areas and Objects

3.5 Pilot project: Sevilla-Macondo

3.6 Insights

Ecosystem hotspot

Keywords:

Water

Ecological corridor

Inequity

Geography

Extractive Landscape

Social Gap

Alluvial/Flood plain

Soft infrastructure

Stratified infrastructure

Natural-based solutions

Water Monopoly

Indentity

Historical memory

Biodiversity hotspot

Energy

Geographies of inequity, Restoration of the Bananeras

0. Introduction

Colombia, renowned for its biodiversity and recently named the most beautiful country in Latin America by Forbes, presents a contrasting reality for those living in its rural areas. These regions, though rich in natural beauty, bear the scars of historical violence and neglect. The Zona Bananera municipality in Magdalena, Colombia’s second-largest banana-producing region, exemplifies this paradox. Despite its economic contributions, it suffers from poverty, decaying infrastructure, and social issues. Geographically significant for its proximity to the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, a biodiversity hotspot, Zona Bananera also holds historical and cultural importance, marked by the 1928 banana massacre, a tragic event that still resonates in Colombian collective memory.

The proposed project for Zona Bananera aims to address the region’s critical challenges, including water accessibility, lack of recreational spaces, and poor connectivity. It seeks to enhance public spaces, improve infrastructure, promote sustainable tourism, and honor the region’s cultural heritage. By focusing on these aspects, the project aspires to foster social integration, improve quality of life, and contribute to the area’s reconstruction, all while respecting the natural environment and indigenous knowledge systems. Abstract

Colombia is the fourth most biodiverse country in the world1 , recently named the most beautiful country in Latin America by Forbes2 , and it’s worldwide known as a tropical paradise. However, for the people that inhabit the most natural areas of the country, the “paradise” is stripped of its utopian character. Colombian landscapes had been subjected to the severity of war. Crumbled, collapsed by violence. The identity of these landscapes belongs strongly to the territory and the events that occurred on it. Perhaps a person alien to the history of this country would not know, that the precariousness and oblivion of the little towns on these areas are just abandoned buildings and urban areas, left by the rural exoduses of the modern world, as if we were all going to the city for an urban phenomenon… This is not the case; these towns have been living in decay and abandonment for decades now. Degrading homes, without a glimpse of stability or comfort, scattered dusted areas wrongly names as “parks” and wrecking infrastructure are the normal in these populations’ urban contexts.

The project area is in the North area of Colombia, in the Caribbean Region Magdalena, specifically in the municipality of Zona bananera —that translates to banana plantation zone—, the second biggest banana and plantain production area in the country3. Even though is in one of the rural areas that produce one of the highest incomes for its services to the country, it suffers from severe poverty and decay.

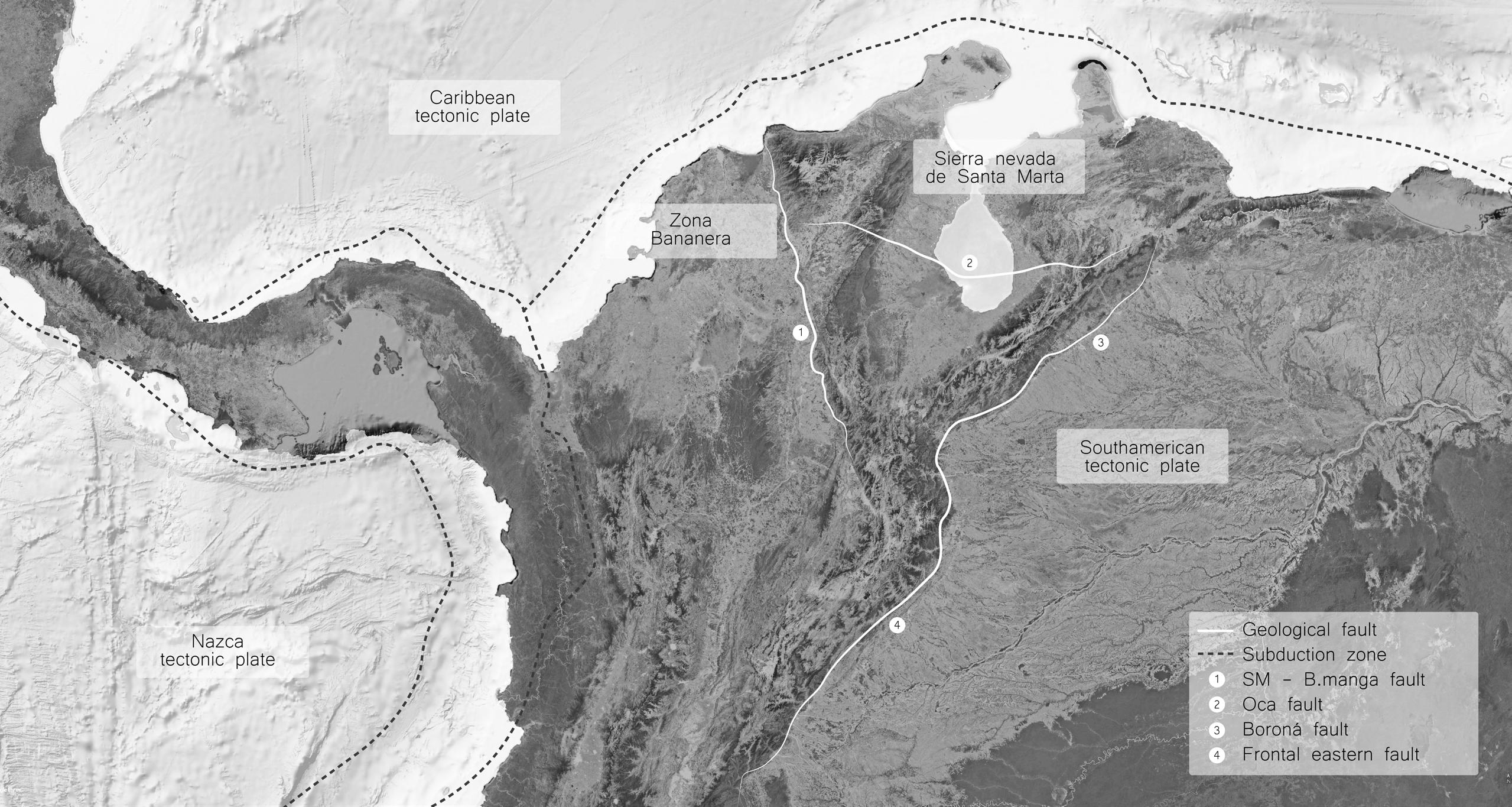

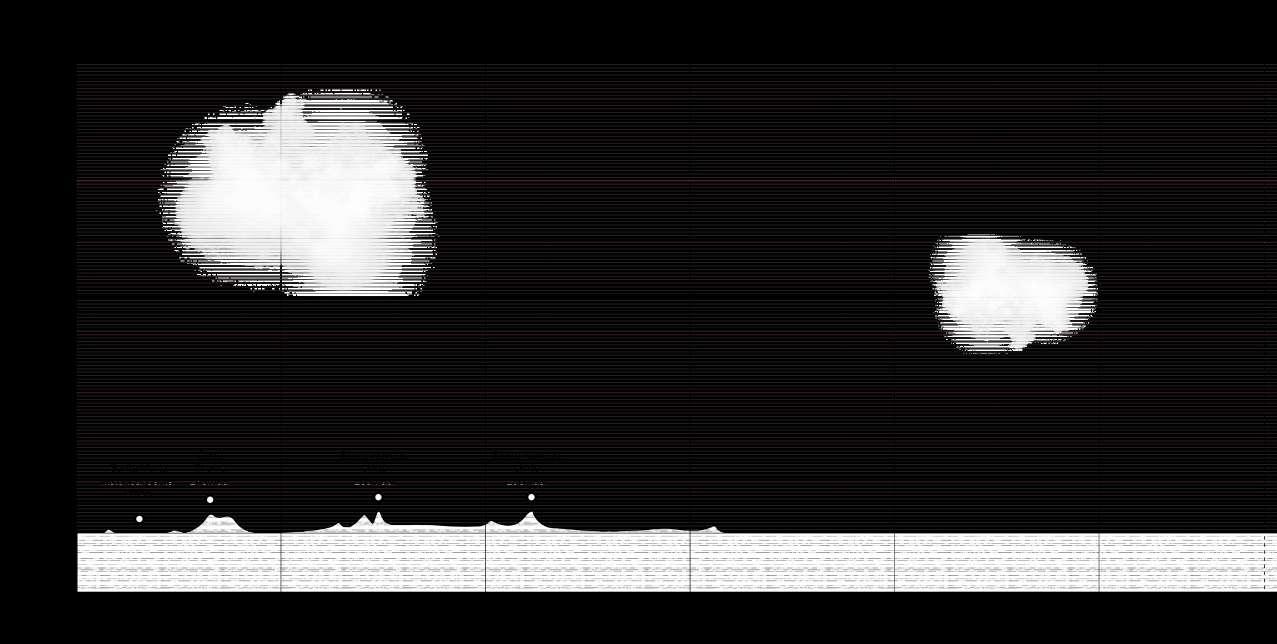

In a geographical context, this site and its relevance is because it sits on the plain area right next to the perimeter line of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, a glacier mountain range of Colombia that constitutes by itself an isolated system of the Andes Mountain range. The invisible line that separates the soft plain from the massive mountain that goes up to 5.775 meters above sea level4 is a geographical fault, the Santa Marta - Bucaramanga fault. The orography of the site makes it a biodiversity hotspot that allows a wide variety of agroecosystems, climate conditions and human activities around it.

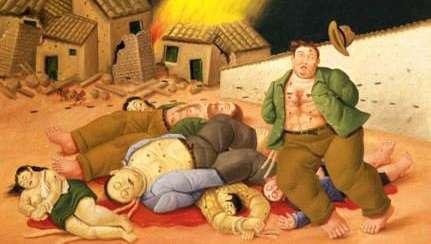

The Zona Bananera municipality is not only an interesting site for its outstanding natural conditions but also for the historical and cultural significance of the country. In 1870, the majority of the inhabitants of the United States had not heard of a banana, much less had the opportunity to eat one. However, by 1930 the United fruit company became rich by importing Banana, there were a lot of songs and jokes about bananas, which reflected the reality of the domination of the US in several Latin American countries. Historically, the development of banana production in the area was related to the construction of railway networks; both activities took place inland, south of Santa Marta, where banana cultivation was introduced once the railway network between Santa Marta and Ciénaga, in 1887. The railway was extended until Riofrío in 1892, to Seville in 1894 and until Aracataca and Fundación in 1906. The total distance from Santa Marta was ninety-four kilometers. United Fruit Company added eighty kilometers of rail from the rail line mainly to the plantations5 Not more than thirty-five kilometers away from the Zona Bananera municipality, on December 5 and 6 of 1928, the Colombian army murdered thousands of women, men, and children in Ciénaga,

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Magdalena, in the name of the United fruit company, an event that became known as La masacre de las bananeras —the massacre of the banana plantations—. The workers of the United Fruit Company went on strike in 1910, 1918 and 1924, but in 1928 a new strike would be shocking because of its organization and size. The strike advocated for the demands of day laborers and company employees and included sectors such as merchants. The 1928 list of petitions was signed by delegates from 15 unions (of workers, settlers, braceros, and peasants) and was signed by “thousands of workers”6.

After weeks of striking for better working conditions, the president of the conservative government Miguel Abadía Méndez gave the order to the military to shot directly at the protesters to protect the interests of the multinational United Fruit Company. Letter from the United States Embassy in Bogotá to the Secretary of State in Washington, dated January 16, 1929, reports that “the total number of strikers killed by Colombian soldiers exceeded one thousand.” There’s no exact recollection of how many people were killed but it is estimated that between a thousand and three thousand people were massacred.

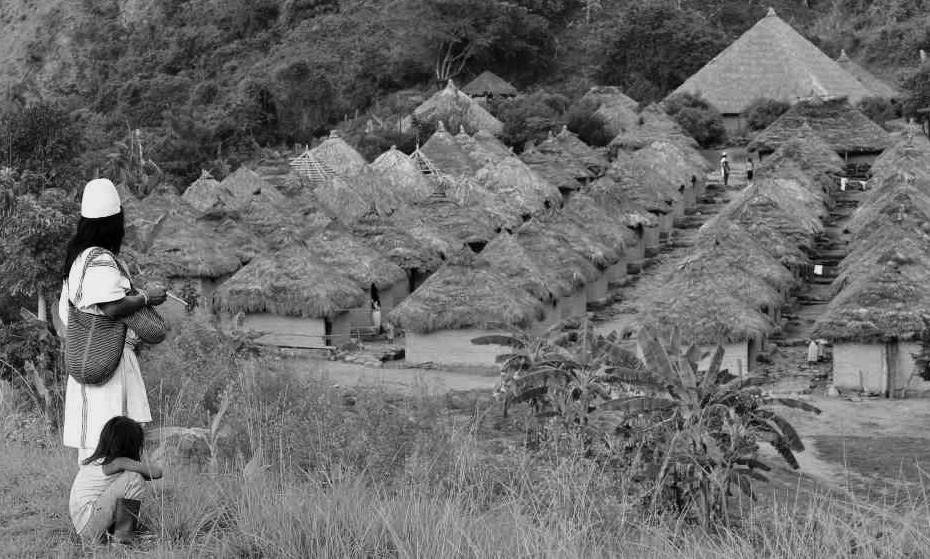

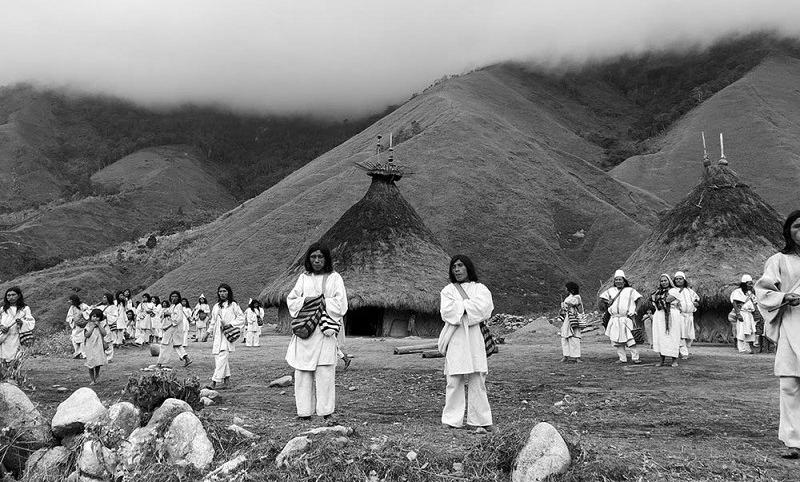

This horrifying act it’s part of the history of the country and of the collective memory of its people, so much that even Gabriel García Márquez, —born in Aracataca just nine kilometers from the last town in the Zona bananera municipality— makes reference to it in Cien años de soledad —A hundred years of Solitude— and nowadays, it’s still one of the harrowing event that mark our history. Culturally, the area of the municipality has also a major significance, since it’s home of some of the indigenous people from the tribes of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Four different but related indigenous tribes live on its slopes: the Arhuacos (or Ikas), the Wiwas, the Kogis and the Kankuamos. Together, they number more than 30,000 people. For the indigenous people, the Sierra Nevada is the heart of the world. It is surrounded by an invisible “black line” that covers the sacred places of its ancestors and demarcates its territory. The ancestral knowledge system defines the sacred missions related to the harmony of the four tribes with the physical and spiritual universe. This knowledge is part of the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO since 20227

Colombian identity was strongly emancipated from the architectural identity that the conquest brought, we have taken it upon ourselves to build a world from our territory, to build houses and buildings made of jungle, mountains, of the Atlantic and the Pacific themselves, in the midst of the overwhelming vestiges of the Spanish house and the civil war. Even though Colombia complied with a peace agreement eight years ago, we continue to live in the remains of the violence that ruled the country for so many decades and that disadvantages the most “unfortunate” if we can blame it to something as random as fortune. What we are left with is to think about reconstruction, amendment and identity. Somehow, as Landscape architects, we are called to trace reconciliation from what is within reach, decent housing, community life, public space and an enormous effort to not only provide spaces for memory in the city, but in promoting the appropriation of people to the territory.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras 0. Introduction

1 IndiaTIMESOFINDIA.COM/, T. of. (2024, April 14). Top 10 biodiverse countries in the world; India on the list. Times of India Travel. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/destinations/top-10-biodiverse-countries-in-the-world-india-on-the-list/articleshow/109244253. cms

2 Forbes is a global media company, focusing on business, investing, technology, entrepreneurship, leadership, and lifestyle. Forbes Magazine. (n.d.). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/

3 Direction of agricultural and forestry chains, & Ministry, A., Cadena de Banano (2020). Republica de Colombia.

4 Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. (2020, July 21). Parque Nacional Natural Sierra nevada de santa marta. https://old. parquesnacionales.gov.co/portal/es/ecoturismo/parques/region-caribe/parque-nacional-natural-sierra-nevada-de-santa-marta-2/

5 Brungardt, M. P. (n.d.). La United Fruit Company en Colombia (chapter).

6 La Masacre de las Bananeras. Informe Final - Comisión de la Verdad. (n.d.). https://www.comisiondelaverdad.co/la-masacre-de-las-bananeras

7 UNESCO - Sistema de conocimiento ancestral de los cuatro pueblos indígenas, Arhuaco, Kankuamo, Kogui y Wiwa de la sierra nevada de santa marta. Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. (n.d.). https://ich.unesco.org/es/RL/sistema-de-conocimiento-ancestral-de-los-cuatro-pueblos-indigenas-arhuaco-kankuamo-kogui-y-wiwa-de-la-sierra-nevada-de-santa-marta-01886?RL=01886

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

The big strike broke out. The crops were left half-grown, the fruit was spent on the vines and the trains of one hundred and twenty cars stopped on the branch lines. Idle workers overflowed the towns. Turks Street reverberated on a Saturday of many days, and in the billiard room of Jacob’s Hotel, twenty-four-hour shifts had to be established. José Arcadio Segundo was there, the day it was announced that the army had been in charge of restoring public order. Although he was not a man of omens, the news was for him like an announcement of death, which he had expected since the distant morning when Colonel Gerineldo Márquez allowed him to see an execution. (…)

Martial law empowered the army to assume the role of arbiter of the dispute, but no attempt at conciliation was made. As soon as they were displayed in Macondo, the soldiers put aside their rifles, cut and shipped the bananas, and mobilized the trains. The workers, who until then had been content to wait, took to the mountains with no weapons other than their work machetes, and began to sabotage the sabotage. They burned farms and police stations, destroyed the rails to prevent the transit of trains that were beginning to make their way with machine gun fire, and cut the telegraph and telephone wires. The ditches were stained with blood. (…)

Once the decree was read, amid a deafening screech of protest, a captain replaced the lieutenant on the roof of the station, and with the gramophone horn he signaled that he wanted to speak. The crowd fell silent again.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” said the captain with a low, slow, a little tired voice, “you have five minutes to leave.”

The screeching and redoubled shouts drowned out the clarion call that announced the beginning of the deadline. Nobody moved.

“Five minutes have passed,” the captain said in the same tone. One more minute and a fire will start.

José Arcadio Segundo, sweating ice, took the child off his shoulders and handed him to the woman. “These bastards can shoot,” she muttered. José Arcadio Segundo did not have time to speak, because he instantly recognized the hoarse voice of Colonel Gavilán echoing the woman’s words with a shout. Intoxicated by the tension, by the wonderful depth of silence and, furthermore, convinced that nothing would move that crowd stunned by the fascination of death, José Arcadio Segundo raised himself above the heads in front of him, and for the first time In his life he raised his voice.

-Bastards! —he shouted—. We give you the remaining minute.

At the end of his scream something happened that did not frighten him, but rather a kind of hallucination. The captain gave the order to fire and fourteen machine gun nests responded immediately. But it all seemed like a farce. It was as if the machine guns had been loaded with pyrotechnic tricks, because you could hear their longing clicking, and you could see their incandescent spit, but not the slightest reaction, not a voice, not even a sigh, could be perceived among the compact crowd that she seemed petrified by instant invulnerability. Suddenly, on one side of the station, a death cry tore through the enchantment: “Aaaay, my mother.” A seismic force, a volcanic breath, a roar of cataclysm, exploded in the center of the crowd with enormous expansive power. José Arcadio Segundo barely had time to pick up the child, while the mother and the other were absorbed by the crowd in panic. Many years later, the boy still had to tell, even though the neighbors continued to believe him to be a crazy old man, that José Arcadio Segundo lifted him above his head, and let himself be dragged, almost in the air, as if floating in terror. from the crowd, towards an adjacent street. The boy’s privileged position allowed him to see that at that moment the runaway mass was beginning to reach the corner and the line of machine guns opened fire. Several voices shouted at the same time:

-Get on the ground! Get on the ground!

Those in the first lines had already done it, swept away by the bursts of shrapnel. The survivors, instead of throwing themselves to the ground, tried to return to the square, and panic then gave a dragon’s tail, and sent them in a compact wave against the other compact wave that was moving in the opposite direction, fired by the other. dragon’s tail from the opposite street, where the machine guns were also firing relentlessly.

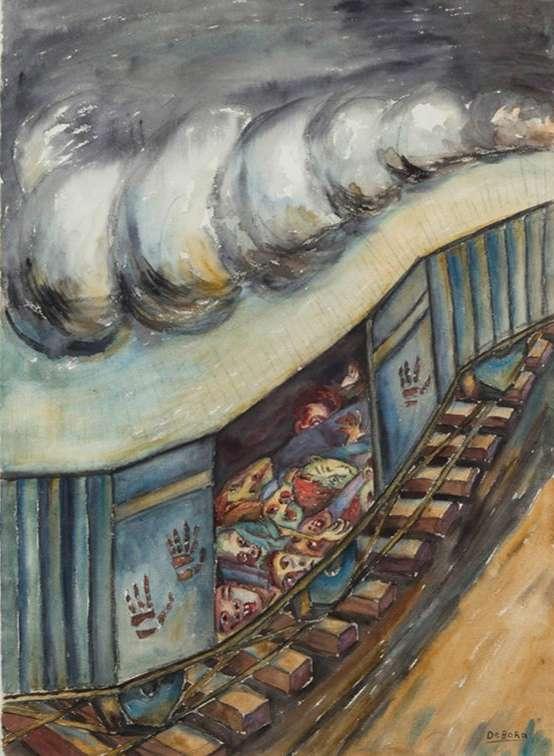

They were cornered, spinning in a gigantic whirlwind that little by little was reduced to its epicenter because its edges were being systematically cut round, like peeling an onion, by the insatiable and methodical scissors of the shrapnel. The boy saw a woman kneeling, with her arms crossed, in a clean space, mysteriously closed to the stampede. José Arcadio Segundo put him there, at the moment of collapsing with his face bathed in blood, before the colossal troop devastated the empty space, with the kneeling woman, with the light of the high drought sky, and with the fucking world. where Úrsula Iguarán had sold so many candy animals. When José Arcadio Segundo woke up he was face up in the darkness. He realized that he was on an endless, silent train, and that his hair was matted with dried blood and his bones ached. He felt unbearable sleep. Prepared to sleep for many hours, safe from terror and horror, he settled on the side that hurt the least, and only then discovered that he was lying on top of the dead. There was no free space in the carriage, except for the central corridor. Several hours must have passed after the massacre, because the corpses had the same temperature as plaster in autumn, and the same consistency of petrified foam, and those who had put them in the wagon had time to arrange them in the order and direction in which they were placed. that the banana bunches were transported. Trying to escape from the nightmare, José Arcadio Segundo crawled from one car to another, in the direction in which the train was advancing, and in the lightning that exploded between the wooden slats as it passed through the sleeping towns, he saw the dead men, the dead women, the dead children, who were going to be thrown into the sea like the rejected banana. He only recognized a woman who was selling soft drinks in the square and Colonel Gavilán, who still had the belt with the Morelian silver buckle rolled up in his hand with which he tried to force his way through the panic. When he reached the first car he jumped in the darkness, and lay in the ditch until the train had passed. It was the longest he had ever seen, with almost two hundred freight cars, and a locomotive at each end and a third in the center. It carried no lights, not even the red and green position lamps, and it glided at a stealthy, nocturnal speed. On top of the cars you could see the dark shapes of soldiers with machine guns in place.

After midnight a torrential downpour fell. José Arcadio Segundo did not know where he had jumped, but he knew that walking in the opposite direction to that of the train he would reach Macondo. After more than three hours of walking, soaked to the skin, with a terrible headache, he saw the first houses in the light of dawn. Attracted by the smell of coffee, he entered a kitchen where a woman with a child in her arms was leaning over the stove. “Good morning,” he said exhausted. I am José Arcadio Segundo Buendía.

He pronounced the full name, letter by letter, to convince himself that he was alive. He did well, because the woman had thought it was an apparition when she saw the emaciated, shadowy figure at the door, with his head and clothes dirty with blood, and touched by the solemnity of death. I knew him. I brought him a blanket to cover him while he dried his clothes on the stove, I heated water for him to wash the wound, which was just a tear in the skin, and he gave him a clean diaper to bandage his head. Then he served him a cup of coffee, without sugar, as he had been told the Buendías drank it, and opened the clothes near the fire. José Arcadio Segundo did not speak until he finished drinking his coffee.

-“There must have been about three thousand,” he murmured.

-What?

“The dead,” he clarified. It must have been all that were at the station.

The woman measured him with a look of pity, -Here there haven’t been any deads —she said—. Since the times of your uncle, the colonel, nothing has happened in Macondo.

“Surely it was a dream,” —the officers insisted—.

-In Macondo nothing has happened, nor is it happening, nor will even happen.

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Geographies of inequity, Restoration of the Bananeras

1. Unveiling the flow: Overview of the Bananera’s plain

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the

Zona Bananera, located in Magdalena, Colombia, is the nation’s second-largest banana production and export region. This area holds immense natural, historical, and cultural significance. Its fertile lands contribute substantially to the economy, while its rich history, tied to Colombia’s banana industry and labor movements, shapes a unique cultural identity rooted in resilience and agricultural heritage.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Sierra:

Set of mountains whose summits have a broken or sawn appearance (similarity with a saw), and which are part of another larger set like a mountain range. More longer than tall.

Alluvial Plain:

Similar to Wavy plain slope; in the alluvial plain tho, material is deposited whenever rains. Its physiographic position is inferior to the valleys.

Flood Plain:

Lands where water accumulates in times of heavy rains because they are areas with little —2% — or no slope.

Ecosystem hotspot :

Limit between land and water where we find a variety of rich ecosystems, that cohabit together in one specific area.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Wide shrubs

Wide shrubs

Dense shrubs

Dense shrubs

Gallery and repatian forest

Gallery and repatian forest

Crop mosaic

Crop mosaic

Mosaic crops and natural areas

Mosaic crops and natural areas

Mosaic crops, grass and natural areas

Mosaic crops, grass and natural areas

Mosaic grass and natural areas

Oil palm

Mosaic grass and natural areas

Oil palm

Forested grass

Forested grass

Undergrowth weeds grass

Clean grass

Undergrowth weeds grass

Clean grass

Plantain and banana

Plantain and banana

Secondary and transitioning vegetation

Secondary and transitioning vegetation

Swamp areas

Swamp areas

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

1. Unveiling the flow: Overview of the Bananera’s plain

BANANA AGROECOSYSTEM

RAINFED AGROECOSYSTEM

INTERVINED INDIFFERENTIATED

CIÉNAGA SWAMP

WATER STREAM

HIGHWAY

RAILWAY

1.5 Agriculture Fields of Growth: Agriculture and its Impact

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

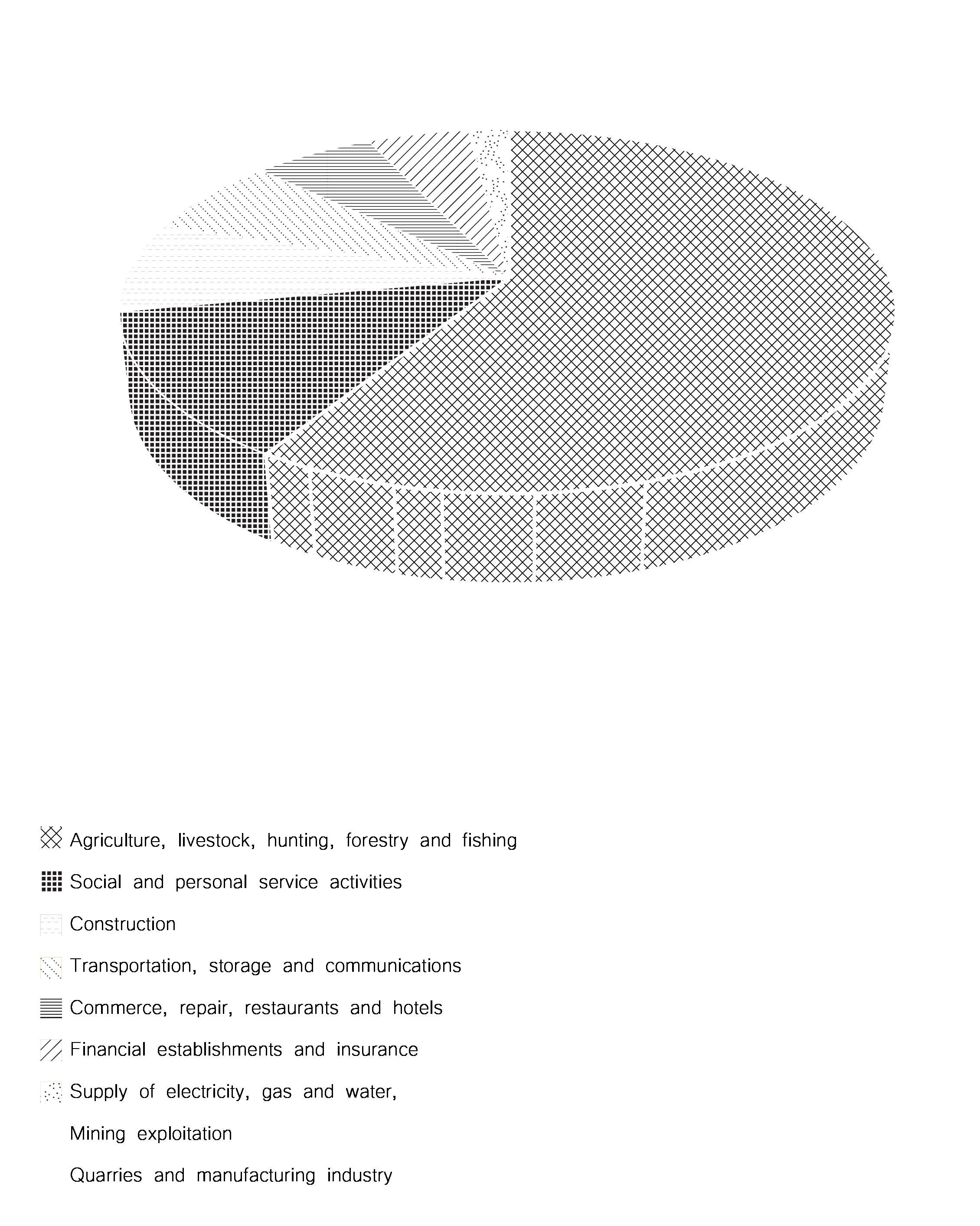

Important areas of corn, rice, beans, fruit trees, horticulture and cassava are planted. In addition, there is a very significant area planted with Bananas and African Palm. This clearly tells us that in the Banana Zone there is both agriculture and economics traditional and technical, which greatly facilitates the development of the municipality. Part of the corn production is used to make buns, another part in corn together with cassava it is sold in supermarkets and industries in Barranquilla and the rest is used for animal husbandry or for the next planting. The rice production is sold to lemon groves in the region, and palm oil and bananas are exported to the US and Europe. (PGT, 2012 – 2015)

The Caribia Research Center is a project with a variety of locations throughout the whole country. One of them is on the study area, that was one of the properties used between 1896 and 1964 by the North American company for the production and export of bananas. In 1964, for the crisis that characterized the world market, this company liquidated its activities in Magdalena Department. In 1966, the land passed into the hands of two companies — Bananeros Asociados S.A. and Consorcio Bananero S.A.— which, with the advice technique from the French Institute for Fruit Research —IFAC—, created the Center for Colombian Banana Research —CIBACO—. Two years later, faced with crisis in the sector, the banana leaders requested support from the Minister of Agriculture, who determined that the banana research should be of public character and developed by the Colombian Agricultural Institute —ICA— In 1971 it was given the name of Caribia, in honor of the indigenous Caribe family that inhabited the northern coastal region of the country. In 1993, when the ica was reformed and the research functions were transferred to the new Corpoica —today AGROSAVIA—, the property was handed over to the Corporation, under a long-term agreement for the purpose of scientific research: A) some oriented to the agronomic management of horticultural species and fruit crops from warm climates with competitive advantages for export from theThe Caribbean Region; B) others focused on staple foods for regional consumption such asplantain, cassava, corn and beans; and C) a last group of investigations on crops agro-industrial crops such as cocoa, oil palm and forestry species. (AGROSAVIA)

URBAN AREAS

PROTECTED ENVIRONMENT

CRYSTALLINE BASEMENT

EXPLORATION AREAS

MINING PERMIT

HIGHWAY

RAILWAY

A Size: small

Stage: Exploration Exp. date: 2013

Mineral: Talc(Magnesium silicate), Limestone (for construction), Pozzolana, Basalt, Granite, Sandstone, Quartzite, Gypsum, Anhydrite.

B

Size: small

Stage: Explotation Exp. date: 2039

Mineral: Limestone (for construction), Pozzolana, Basalt, Granite, Sandstone, Quartzite, Gypsum, Anhydrite.

C

Size: small

Stage: Explotation Exp. date: 2039

Mineral: Clay, Feldspatic sands, Recebo, Industrial sands, Silicean sands, Gravel (for construction).

D

Size: medium

Stage: Explotation Exp. date: 2040

Mineral: Kaolin, Limestone (for construction), Pozzolana, Basalt, Granite, Sandstone, Quartzite, Gypsum, Anhydrite. E

Size: medium

Stage: Explotation Exp. date: 2043

Mineral: Uranium, Gold (both minerals and concentrates

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

The municipality is formed by strata or sedimentary mantles of the tertiary period (3-65 million years) of the Cenozoic Era. The soil consist mainly from successive strata made of:

Sandstones Clays

Oligocene —26 to 38 million years—

Miocene —12 to 26 million years—

Calcareous Sandstones

Marly Limestones

Coal Layers

Pliocene —3 to 12 million years ago—

Calcareous Limestones

The limit between the western slope of the Sierra Nevada and the plain of the Area is very marked. The rupture line of the terrain corresponds to the general north-south strike of the extensive Santa Marta fault, which separates the metamorphic rocks and igneous rocks of the Sierra of the tertiary layers —sedimentary— that make up the subsoil of the Zona bananera. The fault is covered by Ejection cones or Alluvial fans that cover both the basement rocks at the foot of the hills as the underlying strata of the tertiary area —sedimentary— of the plain The fans and terraces have interlocked in such a way that its morphology cannot be appreciated with the naked eye since they form a continuous plane inclined slightly to the West and Northwest. (PGT, 2012 – 2015)

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

HILLS — SOIL TYPE VII

ALLUVIAL PLAIN — TYPE I, II, III, IV

FLOOD PLAIN — TYPE V

CIÉNAGA SWAMP

WATER STREAM

HIGHWAY

RAILWAY

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

1. Unveiling the flow: Overview of the Bananera’s plain

1.6 Geology & soils

The soil is the product of the decomposition of the parent rock, caused by the action of elements such as water and heat, among others. In these are, we have seven different types of soils, of which:

ؔ Class I & II: are lands suitable for agriculture and intensive livestock.

ؔ Class III: Similar to I and II with less capability to grow plants.

ؔ Class IV: Have very severe limitations. The installation of crops is restricted; These require very careful tillage and cultural conservation practice.

ؔ Classes V, VI, VII, Not appropriate for clean or technical crops, but if appropriate for perennials and natural vegetation, and native forests.

(PGT, 2012 – 2015)

Geomorphology Land % Soil type

Hills 8.6 VII

Valleys 3.7 III

Wavy plain 11.9 VI

Alluvial plain 70 I, II, III, IV

Flood plain 5.8 V

1.7 Vegetation

Zone classification

According to Holdridge’s classification —life zone classification scheme—, the area is located in the vegetal formation.Very dry tropical forest (bms-T) that occurs in height from 0 to 500 meters above sea level. With temperatures above 24 degrees Celsius, the formation of this formation loses its foliage in the dry period only some species like the orange tree they preserve it. In this formation it is worth mentioning the presence of mangroves, which is a vegetation adapted to living in soils regularly flooded and brackish; They are located in areas close to the mouths of the rivers

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras 1.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Railway & Sevilla station

The Santa Marta Railroad was a cargo and passenger rail network in Colombia. This transport system supplied the municipalities of Fundación, Aracataca and Zona Bananera with Santa Marta’s harbour. It was liquidated in 1991 together with the National Railways of Colombia. The line is currently under concession to the company Ferrocarriles del Norte de Colombia (FENOCO), which was authorized to function as cargo transport.

The Santa Marta Railway Company was an english company that obtained legal status from the Government of Colombia on June 27, 1890 and continued with the construction of the Railroad and by 1906 they had built the line to the southern part of the Fundación River, and the creation of the settlement which today is the municipality of Fundación, the growth of the line was more concentrated in the branches that crossed the Zona Bananera, around the towns of Río Frío, Sevilla, Reten and others. By 1910, the main line connected Fundación with the Port of Santa Marta, it had 64.6 km of secondary lines. The banana transport arrived at the port without interruption every day of the year. More than 70% of the cargo came from fruit, 15% were passengers from the plantations and the rest of the percentage was other cargo.Nowdays, the station is still there being a landmark for history and heritage.

The railed infrastructure was restored and currently is part of the licenced project “The Atlantic Railway Network” that has two main lines – Santa Marta line and the Bogotá – Belencito and Bogotá – Lenguazaque branches, with an extension of 1,493 km, crossing the departments of Cesar, Magdalena, Santander, Boyacá, Antioquia, Cundinamarca and Caldas. The contract (Start date: Friday, 3rd of March 2000

Finish date: Saturday, 2nd March 2030)was signed by Fenoco -Ferrocarriles del norte de Colombia- in which 60% of the contractor contributors are nationals and 40% are from the USA. Once again, history repeats itself, and we have a strong presence of the North American country in the desicion making and investment of the territory.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is a unique pyramid-shaped mountain found at the northern end of the Andes in northern Colombia. Four different but related indigenous peoples live on its slopes: the Arhuacos (or Wintukuas), the Wiwas, the Kogis and the Kankuamos. Together, they number more than 30,000 people. The top of the mountain is located at about 5,000 meters of altitude. At its base, on the shores of the Caribbean, a dense tropical jungle lines the low plains. As the mountain gains height, the jungle transforms into open savannah and cloud forests.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Indigenous tribes

For the indigenous people, the Sierra Nevada is the heart of the world. It is surrounded by an invisible “black line” that covers the sacred places of its ancestors and demarcates its territory. In reality, the Black Line is, as if it were a building, the base or foundation of the Sierra, and it results naturally as the line through which the force of the Sierra Nevada is projected around it to your own balance. The Black Line exists by itself.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras 1. Unveiling

“The Black Line of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is the connection with the principles of origin of life. The mangroves, madre-viejas, river mouths, coastal hills, reefs, meadows and marine savannahs that are located along the Black Line constitute protective barriers against catastrophes, hurricanes, natural diseases and epidemics in the upper parts of the Sierra”

-Arhuaco People

Geographies of inequity, Restoration of the Bananeras

2. Streams of Progress: Objectives and Method

2.0 Understanding the problematic Introduction to problematic

To understand Zona Bananera’s main problematics we will refer to the PGT of the latest major government from 2020 — 2023. First, we must mention that 93,5% of the population of the municipality live in rural areas while only the 6,5% live on the urban centers. Of this population, most people are between 5-24 years old. In these kind of municipalities on the rural areas of Colombia, this shows an opportunity to take advantage of the economic activity since the group that conform the working market moves around from 15-24 years old. Not only does this represent a problem because people these ages in a normal context should be studying, but because it creates a vulnerability for the structural problems of the municipality such as unemployment, teenage pregnancy, poverty, among others.

The municipality is made up of 14 districts and 56 rural counties. From these we will be studying the 7 districts that are connected to the historical railway and that represent a parallel line between the Sierra and the Swamp, in the center of the alluvial plain. —Sevilla, Riofrío, Guamachito, Varela, Orihueca, Guacamayal and Tucurinca—

Within the main problematics of the municipality, we find the lack of reliable education, health, dwelling, potable water, sports and recreation and culture and inclusion. On the strategy line for education of the PGT is mentioned that the principal obstacles are the lack of proper educational infrastructure, the inhabitants have reported that the state of the educational centers is precarious and there is very low prioritization and investment specially for labs and enhancement of public services and spaces for recreation and sports. Among these lines is specially mentioned the very low articulation of extracurricular content that allows the students to develop in other intelligences. This lack of an effective system generates in cascade several collateral effects, such as the fact that between two and three students of every hundred desert high school. In addition, the results show that only two of every ten students that present the ICFES (The State of the Quality of Higher Education exam, Saber Pro, is a standardized evaluation instrument for the external measurement of the quality of higher education that evaluates the competencies of students who are close to completing the different university professional programs)handle the areas of math and critical reading in an advanced way. Moreover, the teenage pregnancy is also a problem that’s directly related to the lack of education and understanding of sexual education, which also results in poverty and unemployment, not only for the fact that most teenage mothers end up deserting school but also the upbringing of another person in the already poor conditions of households in the municipality.

In relation to education, we find the problem of the low quality of sports infrastructure. Culture, sports and recreation are fundamental for human beings since they contribute massively to physical and mental health. Likewise, this problem leads to inappropriate use of free time and the increase of juvenile delinquency. Among the prioritized problems the government highlights the low quality of spaces for sports, the absence of support for the cultural sector and the low feeling of appropriation and identity within the tangible and intangible cultural goods that the municipality has. To mitigate the problem, the PGT proposes a strategy to promote recreation, physical activities and sports, with interventions to the open space, parks, and sports infrastructure.

Secondly, but equally important, the municipality has a major problem of health and water since only 26,1% of the whole population has access to potable water. Undoubtedly, this represents a big alert because a low quality of the water signifies also the development of disease.

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

2.0 Understanding the problematic

Introduction to problematic

Among the characteristics that generate progress and close the gaps of inequality and poverty there is the infrastructure of public services and basic sanitation. By 2020 it was found that the aqueduct coverage was low and there were several houses that nowadays still don’t have access to water, by this time, the municipality had a coverage of 20,80% while in the whole region is 42,40% and in Colombia 76,80%.

According to the PGT of the 2016 – 2019 the problems generated for the usage of water go back to the first half of the XX century, when irrigation became an imperative activity for the municipality and the construction of an irrigation system was needed because of the rainwater being collected only once a year and the low intensity of the water flow. However, this activity was monopolized almost immediately by the United Fruit Company.

The conflict of water has been constant even though is filled by a latticed net of rivers, creeks and the Cienega Grande of Santa Marta swamp, and being the biggest coastal lagoon complex of the country.

In relation to the coverage of irrigation water for agriculture, we found that of eighteen irrigation districts in the country, four are in the Magdalena region and three are in the Zona Bananera municipality —Tucurinca, Sevilla, Rio Frio—. They irrigate 21.076Has (8%); for crops such as, palm, banana, rice, critics, cassava, different fruits, cacao and grass. Although the Zona Bananera municipality counts with these three irrigation districts, currently, the water volume is insufficient to withhold the number of hectares for production. Consequently, it limits the expansion of existing or new crops that could represent new investments to strengthen the sector and would energize the economy of the territory generating employment and wealth. In relation to the water, there is also an issue of connectivity because of the state of road infrastructure, that specially during the “winter” (Since Colombia is a tropical country, it does not have seasons, the word winter is used to refer to the rain season, in opposite to the dry season.) —when it rains up to 900 to 1500mm/year— gets specially damaged since they’re mostly unpaved. It’s undeniable the importance of road connectivity not only for economic activity but also for the development and social integration, especially on these inland areas where most of the population is settled in the rural area. On this context, the secondary and tertiary road net plays a fundamental role since constitutes most of the transport infrastructure of the municipality. The main street of the municipality —parallel to the railway— is paved with visible deterioration. This and other paved streets in a bad state constitute 13,3% of the municipality while the other streets —86,7%— are unpaved. Most of the year, the conditions range from bad to dreadful. On summer —dry season— there are health problems from dust causes due to the circulation of vehicles both light and heavy, and in winter —rainy season— they’re impassable because of the mud. The bad state of the streets limits an efficient mobility; represent a larger chance of accidents, difficult the transport of urgency health patients that even compromises their life, and fosters insecurity —robbery and even kidnapping—. (PGT, 2020 – 2023)

All of the problems mentioned above are somehow related to each other but most importantly, all of them address the relation between human beings and their territory, in this relationship —landscape—, we can start thinking how molding the open space and the resources on it can contribute to the progress of the area and most important the well-being of its inhabitants.

2.0 Understanding the problematic

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

2.0 Understanding the problematic

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

Geographies of inequity: Resignification of the Bananeras

The Zona Bananera municipality in Magdalena, Colombia, is a complete opposite to Santa Marta city — Capital of Magdalena region — largely due to its geographical isolation and rural setting. Its economy relies heavily on agriculture, particularly banana plantations, which are vulnerable to market fluctuations, pests, and extreme weather conditions like floods. In contrast, Santa Marta benefits from its coastal location, fostering tourism, trade, and a more diversified economy. Santa Marta’s better access to infrastructure, such as roads and ports, boosts its economic opportunities, while Zona Bananera’s remote location and reliance on a single industry limit development.