HB 5101 An Act

Establishing a Tax Credit for Educational Access and Opportunity Scholarships is before the Finance, Revenue and Bonding Committee. It would not allow public oversight of private k-12 schools that have the benefit of a public tax credit. CABE opposes this bill and urges its members to lobby legislators against it.

Annually, CABE has voted to approve this resolution — “in order to insure that public funds are used for public education and to improve public education, CABE urges all citizens and particularly all school board members to oppose tax credits for expenditures for tuition or living expenses at private elementary and secondary schools”.

mendations in concussion management and treatment.

The role of women in our society has expanded throughout the years and we recognize that we must acknowledge the value of female voices, perspectives, and skills. We need to ensure that our educational system is a place where all our students feel safe, have what they need to thrive, see themselves represented in staff, classrooms, administrative offices, and leave our students well-prepared to have productive lives.

At March’s monthly State Board of Education meeting, board members approved the 2024-25 Concussion and Head Injury Annual Review for Coaches. The trainings are reviewed annually.

The 2022-23 Concussion and Head Injury Annual Review for Coaches was updated and reviewed by the Youth Concussion Advisory Group to ensure that the information represents current science and recom-

The Board voted to require the Fairfield Board of Education to submit an amendment to its Racial Balance Plan within 120 days and no later than July 3, 2024.

There were three charter renewals approved – Capital Preparatory Harbor School, Bridgeport, Great Oaks Charter School, Bridgeport and Common Ground Charter School, New Haven

A New Educator Preparation Program, Alternate Route to Certification Program in Mathematics, Middle School, 4-8, at Capital Region Education Council (CREC) was approved.

Finally, the members approved a Director of the Office of Internal Audit.

In the late 70s and 80s, the term “glass ceiling” became popular in our culture. It describes the obstacles that women face as they seek to expand their career options. A combination of studies indicates that these obstacles limit women’s access to top-level jobs in both corporate and non-profit sectors. Additionally, women of color referred to the same phenomenon as the “concrete ceiling” because in many cases, they were prohibited from “seeing” that which they did not have access and finding the ceiling unbreakable.

During last month’s Women’s History Month, I focused on my role as a member of the executive committee of my educational schoolboard and how I could be more supportive of the challenges that our female head of school faced as the person sitting in the top seat of our school community.

As it is budget season, April is a very busy month for local municipalities and state government.

Budget season encompasses considering all the priorities and laws that must be funded with a balance of resources and the ability to finance. As Boards of Education, we have similar focused responsibilities. We must approve the Board’s proposed budget with any modifications voted upon. Then, we must submit this budget to our local tax authorities for consideration. Many factors are considered, including town priorities and state funding. Tax authorities and citizens, via referendum, can cut the budget but can’t tell the Superintendent how to allocate the funds. The balance of authority and power highlights the beautiful art of politics when well executed. Our role is very essential. Student and parent voices are essential to advocating and aligning your town’s priorities.

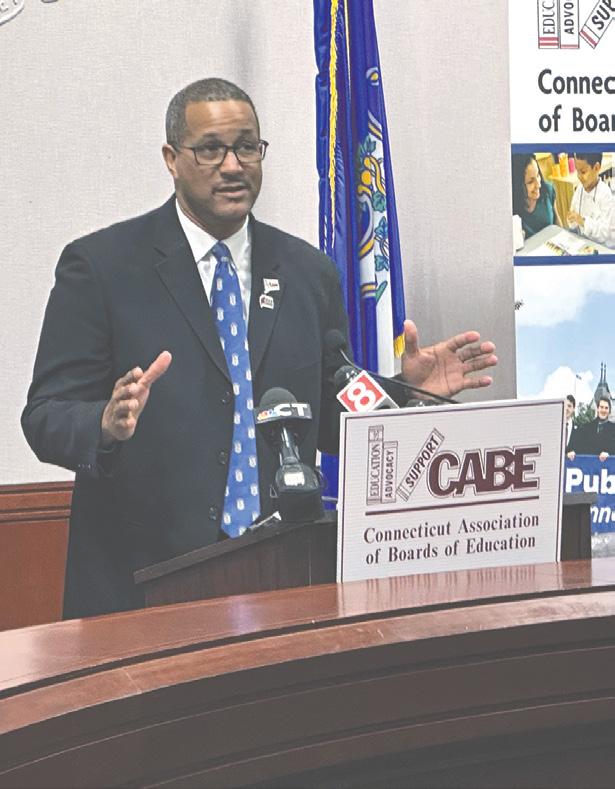

CABE hosted CABE Day on the Hill in March, which was inspiring for all involved. Students, board of education members, and school administrators from across the state filled the room. We began with a session at the Bushnell that allowed networking and hearing from CABE’s government relations staff about legislative priorities for the short legislative session. We also heard from the Education Committee’s chairs and ranking members and had the opportunity to ask questions. The morning’s highlight was receiving remarks and encouragement from our Lieutenant Governor, The Honorable Susan Bysiewicz. She thanked board of education members for remarkable volunteer service. She encouraged us to engage the legislative (CGA) and executive (SDE) branches of state government as we execute our duties on the local level.

Following the informative session at the Bushnell, we marched from

the Bushnell to the Legislative Office Building, loudly proclaiming, “KEEP THE PROMISE!” CABE held a press conference focusing on student voice while taking questions from the press. The talking points were:

• Funding.

• Student social and emotional needs support.

• Educator recruitment and retention.

• School board appreciation month.

The remainder of the day was filled with tours, meetings with legislators, and visiting various committee meetings scheduled for the day.

I wish to recognize the students who shared their voices with us at Day on the Hill – Ariana Mohamed (New Britain) and Ben Aviad (Amity Region 5). Ariana was one of several students featured at our 2023 Summer Leadership Conference in Westbrook, and both Ariana and Ben spoke during the Friday luncheon at the 2023 Annual CABE/CAPSS Convention in Mystic and during the CABE Day on the Hill press conference as leading student voices. Publicly, I thank them for their willingness to share perspectives and to address and learn about the issues that impact their education.

CABE encourages all boards of education to incorporate student voice on their board in a non-voting capacity. Students are the reason we are board of education members. Like students, we should advocate for parents’ voices and education during meetings and committees. All feedback is valued. Education about policy, curriculum, and finance is critical to help all stakeholders understand how they may participate in our districts.

All information is considered as the budget is crafted, deliberated, and debated for final adoption before being passed to the taxing authority for their consideration. Each town is different. In some districts, the taxing authority is the final stop.

In others, the taxing authority is required to submit to the public for referendum.

Connecticut’s school boards have

an obligation to all our students, and we count on the Governor and General Assembly to keep the promise of education funding. CABE asks to commit state funding to enable districts to support the continued need for counselors, mental health staff, and other support as federal COVID relief funds end. CABE asks that as they evaluate the bills before them with two critical questions: “How will this legislation promote student achievement?” and “What is the fiscal and administrative impact on local communities?” It’s fair to ask local boards of education to assess locally with the same lens when discussing subtractions, supplements, and additions to the local budget. What are the priorities of the local town for the school system? It’s the job of the Board of Education to seek that information and advocate. Every year, April and May reflect the time and effort invested during the entire budget process.

Our respective superintendents, our sole employees we supervise as a collective board, depend on us. We are tasked with delivering on the promise of Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a free and appropriate education for all of Connecticut’s children. We fulfill that promise with several partners—including school superintendents, public school faculty, administrators and staff, Gov. Ned Lamont, and the members of the Connecticut General Assembly who write the laws and the budgets that help drive and fund public education. The budget shall be properly funded to execute law (state and federal), implement policies, and deliver curriculum with all the required resources. We are the chief local and state ambassadors for the school districts. Our charge is very clear, and we stand together to provide high-quality education for all children in the State of Connecticut.

about strengthening public education

local school board/

success for each child.

| NSBA Director, Simsbury

Ethel Grant | Member at Large, Naugatuck

AREA DIRECTORS

Marion Manzo | Area 1 Co-Director, Region 15

Thomas van Stone | Area 1 Co-Director, Waterbury

Douglas Foyle | Area 2 Co-Director, Glastonbury

Tyron Harris | Area 2 Co-Director, East Hartford

Philip Rigueur | Area 2 Co-Director, Hartford

Karen Colt | Area 3 Co-Director, Vernon

Sara Kelley | Area 3 Co-Director, Stafford

Jay Livernois | Area 4 Co-Director, Woodstock Academy

Chris Stewart | Area 4 Co-Director, Putnam

Ailla Wasstrom-Evans | Area 4 Co-Director, Brooklyn

Chris Gilson | Area 5 Co-Director, Newtown

Tina Malhotra | Area 5 Co-Director, Ridgefield

Lee Goldstein | Area 6 Co-Director, Westport

Jill McCammon | Area 6 Co-Director, Darien

John Hatfield | Area 7 Co-Director, Seymour

Edward Strumello | Area 7 Co-Director, Seymour

Lindsay Dahlheimer | Area 8 Co-Director, Region 13

Seth Klaskin | Area 8 Co-Director, Madison

Kim Walker | Area 8 Co-Director, Westbrook

Carol Burgess | Area 9 Director, Montville ASSOCIATES

Julia Dennis | Associate, Berlin

Ethel Grant | Associate, Naugatuck

Robert Mitchell | Associate, Montville COMMITTEE CHAIRS

Lee Goldstein | Chair, Federal Relations, Westport

Laurel Steinhauser | Chair, Resolutions, Portland

Lindsay Dahlheimer | Chair, State Relations, Region 13 CITY REPRESENTATIVES

Christina Baptiste-Perez | City Representative, Bridgeport

A. J. Johnson | City Representative, Hartford

Yesenia Rivera | City Representative, New Haven

Gabriella Koc | City Representative, Stamford

LaToya Ireland | City Representative, Waterbury

VALEDICTORIAN

Connecticut Business Systems –A Xerox Company

Finalsite

SALUTATORIAN

Berchem Moses PC

Pullman & Comley

Shipman & Goodwin

HONOR ROLL

JCJ Architecture

Kainen, Escalera & McHale, P.C.

Newman/DLR Group

Solect Energy

SCHOLAR

Brown & Brown

Chinni & Associates, LLC

Coordinated Transportation Solutions Dattco, Inc.

ESS Franklin Covey

GWWO Architects

The Lexington Group Perkins Eastman

The S/L/A/M Collaborative

Zangari Cohn Cuthbertson Duhl & Grello, P.C.

American School for the Deaf Area Cooperative Educational Services (ACES)

Booker T. Washington Academy

Cambridge International Capitol Region Education Council (CREC)

Connecticut Alliance of YMCAs Connecticut Arts Administrators Association

Connecticut Association for Adult and Continuing Education (CAACE)

Connecticut Association of School Business Officials (CASBO)

Connecticut School Buildings and Grounds Association (CSBGA)

Connecticut Technical High Schools Cooperative Educational Services (C.E.S.)

EASTCONN EdAdvance

Explorations Charter School

Great Oaks Charter School

Integrated Day Charter School ISAAC

LEARN

New England Science & Sailing Foundation

Odyssey Community School, Inc.

The Bridge Academy

I am excited that CABE’s longstanding commitment to professional development and support for boards of education will be enhanced with several new initiatives supported by a contract with the State Department of Education. CABE’s expertise in providing professional development to board of education members is recognized by the Department, and CABE was asked to support the requirement that newly elected board of education members engage in professional development effective July 1, 2023.

We have designed a series of initiatives that include webinars and in-person sessions focused on board member roles and responsibilities. CABE’s in-person workshops, including those for individual boards of education, will continue to provide the critical interaction to strengthen understanding and collaboration among board members in individual districts.

By making webinars available on demand, our volunteer school board members will have the opportunity to receive the professional development opportunities they need as their schedules permit. Some topics will include school budgets, finance and the use of educational data provided on EdSight.

The ability to understand the budgeting process is an important responsibility for board members. The vast amount of data available on the state’s interactive EdSight portal is a resource as boards of education analyze not only fiscal data, but staff ratios, educator diversity and student needs.

CABE is expanding upon our monthly check-ins to support board of education chairpersons. A new initiative provides mentors to those board of education chairpersons who desire that support. The mentors are all former board of education chairpersons who can relate to the

challenges of that role and supplement the legal, policy and governance guidance provided by CABE’s experienced staff.

CABE will also provide an updated board member handbook, which is a reference tool for any board of education member. The topics include statutory authority, roles and responsibilities, establishing vision, board superintendent relations, board operations and community leadership.

We are excited to expand upon

CABE’s long-standing commitment to professional development. We know that board members who understand their roles and responsibilities are in the best position to support student achievement. Our goal is to insure that all 1,400 volunteer school board members in Connecticut have the skills and support they need to be effective.

The Nutmeg Board of Education makes many mistakes. The latest imbroglio created by the board will be reported here each issue, followed by an explanation of what the board should have done. Though not intended as legal advice, these situations may help board members avoid common problems.

As with school districts throughout Connecticut, the Nutmeg Board of Education has been struggling to adopt a budget because certain federal grants are ending this year. As the Board members have considered options, they have told Mr. Superintendent that the district must operate more efficiently to save money.

After undertaking a comprehensive review of district practices, Mr. Superintendent discovered that the district employs a number of para-educators in the elementary schools to accompany students to lunch and special classes, relieving teachers of the responsibility to do so. At the meeting of the Nutmeg Board of Education last week, Mr. Superintendent reported that the district could cut two paraeducator positions at each of the district’s elementary schools and simply ask teachers to resume their traditional responsibility for supervising their students on the way to lunch and to special classes. Given the turnover the district is experiencing with paraeducators, Mr. Superintendent elaborated, no layoffs will result when the Board eliminates these positions. The Board members were pleased to take this modest step to reduce its budget request, and the Board voted to cut the positions as recommended by Mr. Superintendent.

The next day, however, the President of the Nutmeg Union of Teachers (NUTS) sent Mr. Superintendent an email with the caption, “Not So Fast.” In her email, the NUTS President informed Mr. Superintendent that teachers would not be resuming such duties because in 1998 NUTS settled a grievance by way of a memorandum of understanding (MOA) between the Board and NUTS that specified that paraprofessionals would accompany students to lunch and special classes, freeing teachers to do “more important things.”

Mr. Superintendent informed Ms.

Board Chairperson of this development, and the Board held an emergency meeting in executive session to discuss next steps. Veteran Board member Bob Bombast was clear – no worn-out MOA from the last century should prevent the Board from taking the steps necessary to operate more efficiently. Board member Mal Content was more conciliatory, and he suggested that the Board negotiate with NUTS to change the terms of the MOA to permit the elimination of the paraprofessional positions in question. After discussion, a majority of the Board voted to rescind its prior action to eliminate the paraprofessional positions and to ask NUTS to negotiate over changes in the MOA.

Mr. Superintendent and the Board were shocked by the response of NUTS. Instead of accepting the invitation to negotiate changes to the MOA, the Union staff representative informed Mr. Superintendent that NUTS declined to negotiate and that the Board would have to wait for the next round of contract negotiations to negotiate over the terms of the MOA.

Mr. Superintendent called another emergency meeting to inform the Board of this development, and now even Mal was antagonized. “If NUTS won’t even sit down to negotiate a change,” Bob Bombast said, “we need to do what we need to do. I renew my motion to eliminate the para positions.” With that, the Board unanimously approved the motion.

Does NUTS have a valid claim against the Board here?

If and when teachers are assigned to accompany their students to lunch and special classes, NUTS will have a valid claim because the grievance settlement remains in effect.

The Teacher Negotiation Act contemplates that there will be situations in which boards of education must negotiate with the teachers’ union during a contract term. If a board of education wants to change working conditions (for example, by terminating a past practice of permitting teachers to leave early the day before a holiday), the board of education must first negotiate with the teachers’ union over that proposed change. If the change relates to a permissive subject of negotiations, such as a change in the length or scheduling of the student school day, the board of education

must only negotiate over the impact of the change on the teachers. However, if the proposed change is prohibited by current contract language, the board of education may not demand negotiations, and it is stuck with the contract language until a successor contract is negotiated.

When midterm negotiations are permitted, the procedures set out in Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10-153f(e) apply. The parties are required to notify the Commissioner of Education within five days of commencing negotiations, and the Commissioner puts the parties on a negotiation timeline similar to (but shorter than) the regular teacher contract negotiation timeline. In midterm negotiations, the parties have twenty-five days to negotiate, followed by a mediation period of twenty-five days. If the parties have not reached an agreement by the fiftieth day after negotiations commenced, by statute the Commissioner imposes the same binding arbitration procedures that apply to successor contract negotiations.

A board of education that wants to change working conditions must notify the teachers union (or other affected union), and the union is obligated to request negotiations. The State Board of Labor Relations has ruled that a failure by a union to request negotiations in such situations can result in a waiver of the right to negotiate, permitting the board of education to proceed with the change unilaterally,

All that said, it appears that NUTS is correct here, and that the Board is stuck with that MOA for the contract term. As noted above, boards of education cannot demand negotiations to change contract provisions during the term of a collective bargaining agreement. The State Board of Labor Relations has also ruled that a grievance settlement that does not specify a duration is binding for the duration of the collective bargaining agreement. If the board wants to change the terms of the settlement, it must raise the issue in negotiations for a suc-

See SEE YOU IN COURT page 6

Below are the highlights of activities that the CABE staff has undertaken on your behalf over the last month. We did this:

By providing opportunities for members to learn how to better govern their districts:

z Presented Roles and Responsibilities workshop for the Andover and Franklin Boards of Education.

z Responded to 40 requests for policy information from 30 districts, providing sample materials on policy topics. Further, districts continue to access CABE’s online Core Policy Reference Manual and/or online manuals posted by CABE for policy samples. The topics of greatest interest were those pertaining to increasing educator diversity, ages of attendance and play-based learning.

z Provided support to board members and central office administrators regarding policy matters.

By promoting public education:

z Staffed CABE ad hoc Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee meeting.

By providing services to meet member needs:

z Responded to a variety of legal inquiries from members.

z Participated in phone support for several board chairs, Board members

and superintendents.

z Revised policies, as part of the Custom Update Policy Service, for East Hampton, Marlborough, New Fairfield, and New Hartford

z Prepared materials, as part of the Custom Policy Service, for Region 14 and Stratford

z Preparing an audit of the policy manual for the New Britain Public Schools.

z Preparing a targeted series audit for the Newtown Public Schools.

z Currently assisting East Haddam, Montville, and Region 1 Boards of Education with their superintendent search.

z Facilitated virtual meeting of superintendents’ administrative professionals.

z Facilitated monthly Board Chair Check-In.

By ensuring members receive the most up-to-date communications:

z Emailed one issue of “Policy Highlights” which provided CT Leader and Educator Evaluation and Support Plans 2024 and Kindergarten Age Guidance for Families.

By helping school boards to increase student achievement:

z Facilitated a board retreat on goal

setting for the Plainville Board of Education.

By helping districts operate efficiently and conserve resources:

z Posted policies online, as part of the C.O.P.S. Program for Avon, Derby, Griswold, Monroe, Region 16, Ridgefield, Somers and the CABE CORE Manual.

By representing Connecticut school boards on the state or national level:

z Participated in NSBA State Association Counsel calls.

z Attended State Board of Education Policy and Legislative Committee meeting.

z Attended State Board of Education meeting.

z Prepared testimony for various public hearings.

z Attended CABE Area 2 legislative breakfast.

z Attended CABE Area 2 Forum on Disengaged Youth

z Facilitated Board Chair Check-In.

z Participated in WhatWillOurChildrenLose

(continued from page 4)

cessor agreement, and the settlement agreement will be binding until it is changed through negotiations for a new contract. City of New Haven, Dec. No. 3060 (St. Bd. Lab. Rel. 1992).

The situation confronting the Nutmeg Board of Education here underscores the importance of being careful with grievance settlements and other memoranda of understanding (MOAs). During any successor contract negotiations, it is advisable for the parties to inventory all outstanding MOAs and negotiate over whether MOAs should terminate or carry over. It is also advisable to agree that either party has the right to negotiate midterm over the terms of any other MOAs that surface during the term of the successor contract.

Finally, we note that the Nutmeg Board of Education held two

Coalition meeting.

z Chaired Education Mandates Working Group meeting.

z Participated in CT Educator Certification Council meeting.

z Participated in RESC Alliance Legislative Forum

z Attended Discovering Amistad Ship Committee and Board of Directors meetings.

z Attended a meeting of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology.

z Participated meeting to plan NESPRA Annual Conference.

z Participated in NESPRA Executive Committee meeting.

Shannon Hamilton joined the CABE staff on February 26. Shannon lives in Cromwell with her husband and three children. She enjoys golfing and crafting. Shannon has several years of administrative experience and is eager to apply her attention to detail, organizational skills and work ethic to her work in the Policy Department. She looks forward to working with everyone involved with CABE. Welcome Shannon!

“emergency” meetings to discuss these matters. Under the Freedom of Information Act, “emergency” meetings are simply special meetings that are not posted at least twenty-four hours in advance because of a pressing emergency. In such cases, the FOIA provides that the public agency must include a description of the emergency in the minutes of the meeting and file a record of what occurred at the meeting within seventy-two hours. However, as annoying as the situation was here, it was not an emergency that justified the Board’s foregoing the twenty-four-hour posting requirement in the FOIA for special meetings.

Attorney Thomas B. Mooney is a partner in the Hartford law firm of Shipman & Goodwin who works frequently with boards of education. Mooney is a regular contributor to the CABE Journal. Shipman & Goodwin is a CABE Business Affiliate.

Assistant Research Professor, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Connecticut

Sandra M. Chafouleas, Ph.D.

Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor, NEAG Endowed Professor of Educational Psychology, Co-Director, Collaboratory on School and Child Health, University of Connecticut

Emily Wicks

Manager of Operations and Collections, Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, University of Connecticut

Nearly seven out of 10 school administrators have reported increases in the number of students seeking mental health supports since the COVID-10 pandemic; however, less than 15 percent indicated capacity to effectively provide services to meet this need.

Now that the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding is ending, simple and cost-effective solutions are needed to promote emotional well-being for all students and staff.

As one solution, our team at the University of Connecticut created Feel Your Best Self (FYBS), a free toolkit centered around 12 emotion-focused coping strategies. Skills to navigate emotions in everyday situations are an important piece to overall emotional

well-being. These life skills help us to feel our best at any life stage.

To identify the 12 FYBS strategies, our team first mapped existing evidence in emotion regulation to identify strategies that could be easily taught in simple steps. We then organized the strategies into three categories. Calm Your Self strategies include skills that can help kids settle their bodies or refocus their attention.

Catch Your Feelings strategies help kids build self-awareness about their emotions, which can help them to refocus their attention or shift their thoughts away from unhelpful stimuli. Finally, Connect with Others strategies focus on building supportive social relationships that promote choosing, offering, or seeking connection. We packaged these strategies into an online toolkit that can be flexibly and quickly integrated into existing classroom routines. The main options in the FYBS toolkit include: an introductory video and Feelings Forecast, 12 strategy videos, strategy cards, reflection sheets, facilitator materials, and supplemental

materials for puppet-making.

We have heard from users that FYBS fills a need within social emotional learning (SEL) curricula given explicit focus on building skills related to emotion. Emotion skills such as knowledge and expression of emotions, emotional regulation, empathy, and perspective-taking are critical for responding to everyday situations. At school, these situations might include having to complete group work with unfamiliar peers or struggling to grasp a new concept in math. In fact, research has shown that students who have stronger emotion regulation skills have been shown to demonstrate positive academic outcomes across elementary and secondary grades.

FYBS is designed to be universally accessible, with extension to address targeted and individualized goals. In our ongoing research to iteratively develop and evaluate FYBS, we have partnered with schools and districts across the state. Recently, we asked two of our collaborating school administrators to share their

perspectives on using FYBS. Overall, both shared a need for easy-to-use, effective SEL. They shared that FYBS integrated seamlessly with other curricula without substantial resources or disruptions to ongoing work — which their teachers appreciated. Finally, they both observed students using FYBS strategies throughout the day. Here are more detailed responses from our conversations.

What drew you to use FYBS?

Mr. Eben Jones, former principal at Natchaug Elementary School (Windham, CT), currently of American Nicaraguan School (Managua, Nicaragua): We are an urban school where many students have experienced trauma, and we are also the school with most need based on socioeconomic data, English language data. Additionally, when I first arrived at the school there was a laser focus on achievement but no SEL program in place. FYBS supported the other SEL work that we had put in place.

It’s fair, if not obvious, to say that a tension often exists between boards of education and laws that mandate their specific actions.

For a point of clarification, not all laws, court decisions, or executive orders require boards of education to adopt a policy. For example, the recently passed General Statute §10212k, which requires by September 2024, boards of education to provide free menstrual products, does not require a board policy. However, districts are required to carry out this law as they would any law, court decision, or executive order.

Boards may choose to adopt such a policy to ensure all staff and public members are aware of the board’s legal obligation and its commitment to adhering to the statute. The “School Climate and Restorative Practices” legislation, on the other hand, requires boards to adopt a policy, as the General Assembly included in its legislation a variation of this critical phrase used when mandating policy adoption: “Each local and regional board of education, beginning with the (________) school year, to adopt a (_______) policy to be implemented by (_______).” Where the new menstrual products statute requires mandated action, the school climate and restorative practices statutes specifically require boards to adopt and enact policies along with their prescriptive requirements.

With the heavy burden on boards responding to a wide array of policy and legal mandates ranging from implementing a new school climate policy to the heavy lift of requiring boards to effectively implement a newly designed Educator/Leader Evaluation and Support system, it’s easy to see why there’s such a visceral reaction to what may seem like practical ways to help support schools’ efforts to improve teaching and learning and build accepting learning communities. Boards of education and superintendents understand that adopting policies is one thing; effectively implementing them is another. While there may be significant justification and support for adopting these policies, they require significant resources, minimally including extensive profes-

sional development and time for established committees to meet and plan.

While laws and policies may be well-intentioned, simply adding them to the books will not transform a complex and dynamic system and yield the intended impact. Instead, attention needs to be directed to roll out. Important questions include, “How do we share this new policy with our school community?” “What work needs to be done and cultural shifts made to ensure our school community embraces the required shift in practice?”

ty,” simply adding dispensers in the required bathrooms will likely result in confusion and perhaps vandalism. School administrators and staff will need to consider effective ways of rolling out this new initiative with students. Effective student rollout also requires attention to developing staff understanding and acceptance, both of which require a need for building a culture of acceptance.

With the heavy burden on boards responding to a wide array of policy and legal mandates… it’s easy to see why there’s such a visceral reaction to what may seem like practical ways to help support schools’s efforts to improve teaching and learning and build accepting learning communities.

As we prepare for Spring, perhaps the best analogy comes from the yearly ritual of planting seeds. One may desire to plant seeds that will result in healthy and colorful salads through summer. However, without the correct soil conditions and care, it’s likely one will end up disappointed and purchasing salad fixings at the local supermarket.

So is the case with policies and statutes designed to shift practice. Connecticut General Statute §10-212k requires that on and after September 1, 2024, each local and regional board of education will be required to provide free menstrual products in women’s restrooms, all-gender restrooms and at least one men’s restroom, which restrooms are accessible to students in grades three to twelve. While this new requirement is well-intentioned as it increases accessibility and responds to concerns related to “period pover-

Similar district-wide culture and climate initiatives must be considered as boards adopt a mandated “restorative practices response policy.” For the school year beginning July 1, 2025, each board of education must adopt such a policy, which will need to be implemented by school employees for incidents of “challenging behavior” or student conflict that is nonviolent and does not constitute a crime. In addition, §10 in Public Act 23-167 stipulates that this policy does not involve SROs or other law enforcement officials unless the behavior or conflict becomes violent or criminal.

The CABE policy department is in the process of updating its policy and will be available for boards as they will now be required to adopt a policy that supports restorative practices. Many schools across the country have adopted such practices in an effort to improve school climate and student outcomes while reducing exclusionary discipline, as these practices are

designed to proactively build community, improve relationships, and help students amend harm when conflict occurs.

Once again, however, adopting a policy, even after rigorous deliberation, is easy compared to the work required of superintendents. They will be required to embrace the challenging task of working with principals to revamp current discipline policies in their schools. Principals will be challenged with working with staff to change their attitudes, beliefs, and practices related to discipline. Making these cultural shifts will require time and resources, both finite and in heavy demand.

Despite their best intentions, these laws and policies add to the number of plates districts are required to spin. Perhaps one thing upon which we can all agree is the need to examine the existing mandates and determine which may be obsolete or duplicative. One outcome of the 2023 legislative session was requiring CABE to convene an 11-member Education Mandate Working Group to recommend repealing or amending obsolete or duplicative educational mandates to the legislature.

This Working Group, chaired by CABE’s Executive Director, Patrice McCarthy, includes representatives from CAPSS, CASBO, PTA, AFT, and CEA and is tasked with identifying mandates that are overly burdensome or limit or restrict providing student instruction or service. Please reach out to any of these organizations with representatives in this Group with suggestions you’d like them to consider. We can be hopeful that with fewer unnecessary mandates, there will be more time to ensure well-intended initiatives have the space to become accepted practice in our schools.

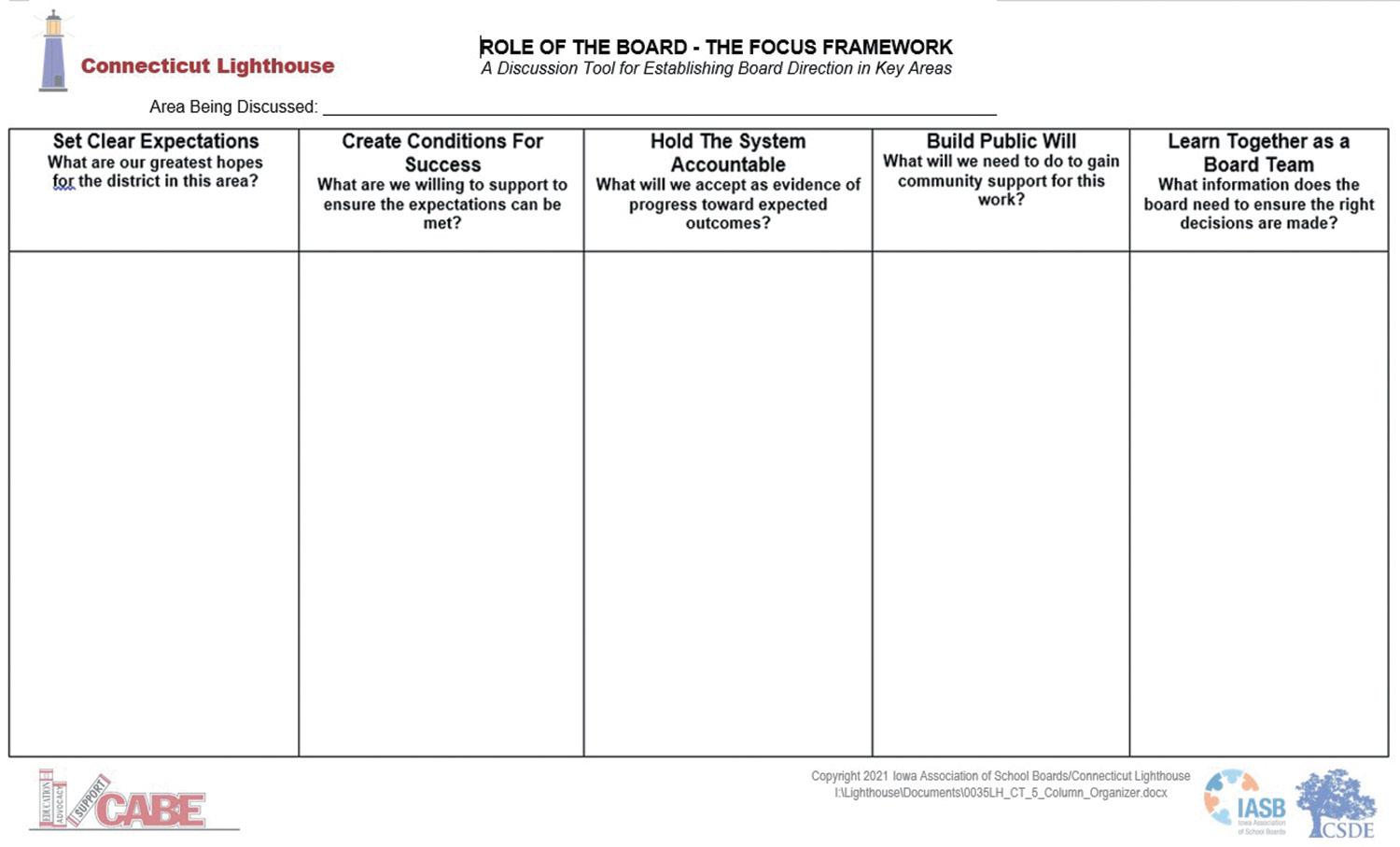

One of the most important studies of boards of education and their potential impact on student learning was the Lighthouse Study done by the Iowa Association of School Boards. This research project studied how boards functioned in high achieving districts and how they compared to boards in low achieving districts.

While the study pointed out a rich assortment of findings, there were two critical areas that were clearly different in how boards functioned.

In high achieving districts there was a strong belief system supporting student learning, as well as a set of conditions that supported those beliefs.

Furthermore, the research identified five critical roles that high functioning boards focused their attention on. These attributes were consistent in high achieving districts. Furthermore, a comparison of other research on effective school boards (or any other high functioning leadership organization, for that matter) show very similar

characteristics in each. The Center for Pubic Education’s eight characteristics of Effective School Boards, The National School Boards Association’s Key Work of School Boards and 4 Pillars of Effective School Board Leadership and FranklinCovey’s Great Boards program all identify common characteristics of good leadership that aligns with the Lighthouse research.

1. Set Clear Expectations.

Effective leaders start with a clear, shared vision. A clearly defined set of goals is the first step towards improving student learning.

2. Create conditions for Success.

The board’s decisions all revolve around creating conditions for success. Are your action items focused on providing the necessary resources to ensure progress on your goals? A very important role of the board is prioritizing what resources you have to most effectively support teaching and learning.

3. Hold the system accountable to the expectations.

This is one area that many boards do not spend enough time on. The focus of the boards’ work should be on how effective programs and activities of the district are in meeting the expectation highlighted in the district’s vision. Board meetings should always include items related to achievement and progress on goals.

4. Build Public Will.

In order to be successful in your work, your community must be behind you. Community outreach is critical to gaining the support you’ll need to be successful. Decisions that will have the most impact on improving student learning often have negative perceptions that need to be dispelled if you are going to get your constituents to support you.

5. Learn together as a Board Team.

Quality professional development

is the tool that will most clearly impact improvements in teaching and learning, and effective boards recognize that this starts with themselves. Boards who learn together, and spend time together sharing thoughts and expectations have a better grasp on what needs to be done, and how they can best support improvements in student performance.

From this work, the IASB, working with several other state school boards associations, developed a professional development program to help boards reach that level of leadership. CABE was fortunate to have been part of that experience. The project developed numerous tools to help boards do their work more effectively; one of which was a 5-column organizer, based upon the 5 Roles of the Board. In each case, the team developed a question for each attribute of the 5 Roles. This Focus Framework is replicated below.

These questions are:

1. Set Clear Expectations.

What are our greatest hopes

See

(continued from page 8)

Mr. James Dineen, principal at Tolland Intermediate School (Tolland, CT): Our school was in need of a program that would enable teachers to provide students with social emotional supports/strategies. We wanted a program that could provide students with useful, developmentally appropriate SEL strategies that made sense to them and were easy to apply. Such a program would need to be adopted immediately, without lengthy formal training and provide a flexible implementation timeline. FYBS met all of our criteria.

What changes among staff and students have you noticed during or following FYBS use?

Eben Jones: I noticed students employing the FYBS strategies and being able to verbalize how they could use those strategies to resolve conflict. I also noticed staff members embracing the new learning, and that having an understanding of this could support the academic work in their classrooms.

Jim Dineen: The use of coping strategies to manage anxiety and stress

has become increasingly necessary among our students. As a result of... FYBS, pockets of students began incorporating strategies to help them manage their emotions more effectively. Developmentally appropriate coping strategies such as breathing exercises and meditation to physical activity and journaling were introduced to our students. By practicing coping strategies in the classroom setting, students were able to build resilience and learn to manage their emotions in a healthy way.

What advice do you have for other administrators who may be considering FYBS?

Jim Dineen: The program’s ease of implementation is due to its user-friendly interface and intuitive design. Teachers and staff can quickly and easily navigate the program without needing extensive training or technical expertise. Additionally, the program comes with pre-built lessons and resources, so there is no need for time-consuming lesson planning.

Principal Jones: My advice would be to implement FYBS...[it] gives students specific strategies that support their well-being and social skills. Additionally... FYBS gives students

an opportunity to be creative as they build and get to know their [sock puppets – created as one component of the program] – great cross-curricular opportunities through art and SEL.

For more information and additional ideas for using FYBS, visit www.feelyourbestself.org or @FeelYourBestSelf.

(continued from page 11)

for the district in this area?

What is the goal and what will it look like in our district?

2. Create Conditions for Success.

What are we willing to support to ensure the expectations can be met?

The board’s decisions all revolve around creating conditions for success.

3. Hold the system accountable to the expectations.

What will we accept as evidence of progress toward expected outcomes?

The board’s meetings should include time to review the results of various initiatives. In my mind this is the most important question that should be asked when any proposal comes before the board.

4. Build Public Will.

What will we need to do to gain community support for this work?

This is probably where the board can be most effective in moving a community forward. If there is strong community involvement in the board’s decision-making processes there will be greater likelihood of success.

5. Learn Together as a Board Team.

What information does the board need to ensure the right decisions are made?

Boards govern a learning organization, so it stands to reason that a board that spends time learning, as

well, will be better suited to move the district forward.

Using this template, boards can better focus their attention on fulfilling their initiatives. I’ve seen some interesting problems solved with the use of this tool. We recommend a board spend time with this tool going over your district goals to better align the

board’s work with the district vision.

While CABE no longer provides the full Lighthouse experience, we often facilitate board workshops using what we’ve learned from our involvement in this program for over 15 years to help them better govern their district. For more information, contact Nick Caruso, ncaruso@cabe.org

Board members are likely wellaware of the impending new cutoff date for the age of kindergarten enrollment in the state. In February, Connecticut’s State Department of Education (CSDE) and Office of Early Childhood jointly released guidance to families on the topic.

While this guidance has the intended audience of parents and guardians, it follows previous CSDE guidance released last October that contains more technical information for district officials who must implement the change. Both sets of guidance are three pages in length and worth a read for education leaders.

As a refresher, the law regarding the new cutoff date was contained in two 2023 public acts, which is important to know because two aspects of the kindergarten starting age were modified last year: first, students must now be age five by September 1 (shifted from January 1), and second, a new process by which districts could enroll students younger than five. The former was enacted by Public Act 23-208 and the latter by Public Act 23-159 and both are effective as of July 1, 2024.

Understanding the second modification is just as important as the first. Previously, a student under five could be admitted by a vote of the board of education at a meeting. Now that

decision is up to the “principal and an appropriate certified staff member of the school.” Importantly, and as both sets of guidance note, if a parent makes a request in writing for early enrollment, the district must consider the early enrollment.

Such early enrollment is to be considered via an “assessment . . . to ensure that admitting such child is developmentally appropriate.” And while the public acts require that the principal and other certified staff member conduct the assessment, CSDE’s October guidance to districts notes that districts should consider allowing parents/guardians to offer information during the assessment, either formally or informally. The guidance also suggests that districts seek insights from a child’s preschool teacher or early care provider.

That same guidance instructs that districts have discretion in what the assessment may consist of including whether it is a stand-alone tool or a holistic approach. The CSDE suggests that the Connecticut Early Learning and Development Standards (ELDS) can be of assistance but notes that the CSDE will not identify a specific assessment tool to be used. However, it does offer several considerations for an assessment process:

• any assessment tool should yield results that are valid and reliable

• a holistic approach should address a variety of developmental domains (e.g., cognitive, social-emotional, physical development and health, etc.)

• an assessment should be culturally and linguistically appropriate (e.g, questions should avoid using language or context that is familiar to only one culture),

• a schedule of dates for receiving requests for assessment that is specific but varied

• regarding different dates for assessments, districts should be attentive to fairness in the scheduling as those conducted too early may not provide a fair assessment of a student’s developmental level

• assessments should be meaningful, administered universally across all schools in a district, and efficacious

The October guidance for districts also contains additional considerations regarding children with disabilities, whose parents and guardians are eligible to request early entry as well.

The guidance encourages districts to employ communications strategies to support family engagement, including sharing information about a school’s kindergarten program so

parents/guardians and schools can engage in meaningful discussion about a child’s developmental ability. The communication should be in multiple languages and various formats.

The guidance also suggests that sharing information regarding alternatives to kindergarten for those with children who miss the cutoff date may help strengthen a district’s relationship with families. And districts are encouraged to partner with early care and education providers and other community organizations to communicate the new requirement.

Finally, the CSDE acknowledges that enrollment predictions for 202425 may be lessened or unpredictable, and suggests flexible staffing models. Of course this is not novel to district and school leaders, but the guidance does mention specific suggestions, including use of the Emergency Generalist application, use of the Durational Shortage Area Permit (particularly for staff with the 113 endorsement), and a reminder that teachers with a 165 endorsement can teach special education preschool.

The guidance documents referenced in this article can be found on state websites and are entitled New Entry Age for Kindergarten: Considerations for School Districts and New Kindergarten Age Guidance for Families

There are 1,400 members of Connecticut’s local and regional public boards of education, making us the largest group of elected officials in the state. We are tasked with delivering on the promise of Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a free and appropriate education for all of Connecticut’s children, and we fulfill that promise with several partners— including school superintendents, public school faculty, administrators and staff, Gov. Ned Lamont and the members of the Connecticut General Assembly who write the laws and the budgets that help drive and fund public education.

With March designated Board of Education Appreciation Month, there is no better time to shine the light on the important role board members play and the challenges and opportunities that we see for Connecticut public education in 2024.

I serve on the Windsor Board of Education and chair the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education Board of Directors. CABE represents 90 percent of Connecticut’s public boards of education and works with school board members to support their work in local districts and we advocate on their behalf at the State

Capitol. This Wednesday is our annual “CABE Day on the Hill,” a day when board members from the four corners of the state come to the State Capitol to meet face-to-face with state lawmakers on the important matters facing all of us.

Our top message: Keep your promises. Given the number of new initiatives and reforms put in place by the federal, state and local governments, this is a time where we need to maintain our commitment to our public schools. Lawmakers and Gov. Lamont demonstrated their commitment to funding public education by the accelerated phase-in of the Education Cost Sharing, or ECS, formula, which is the state’s primary funding grant for local education. CABE commends them for this—as well as the elements of their two-year budget that created a more uniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such as magnet schools, agricultural science and technology centers, Open Choice, and charter schools based on a per-student state subsidy linked to the ECS foundation and student need.

You see, the economic challenges faced at all levels of government are felt most intensely at the local level, where we are in the middle of the budget development and adoption season. Changing plans mid-stream only makes our challenges more difficult, and we are urging legislators and the

governor to stick with their plan. Board of education members also continue to advocate for full funding for the Special Education Excess Cost Reimbursement Grant, which is currently capped. This cap creates a hardship on local districts, which is why we are urging legislators to remove the cap to restore the safety net available to districts for these extraordinary — and rising — educational costs. Loss of these funds impacts the district’s full budget as mandated programs for students with special needs can force a district to remove funding for programs outside of the special education designation.

We are also urging the legislature to:

• Help us continue to reengage students with poor attendance through the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program — as poor attendance in the early grades is linked to a lack of success in reading, a critical skill for learning.

• Allow flexibility in the implementation of the reading program mandate to recognize successful programs.

• Invest in programs that promote the training, hiring and retention of educators of diverse backgrounds and increase opportunities for districts/RESC “grow your own” programs.

• Commit state funding to enable districts to support the continued need for counselors, mental health staff and other supports as federal COVID relief funds come to an end. My own board in Windsor, for example, is working to keep some of the positions that were funded through federal COVID relief such as social-emotional learning specialists, a social worker and a math interventionist.

Connecticut’s school boards have an obligation to all our students, and we count on the governor and General Assembly to keep the promise of education funding. We ask that as they evaluate the bills before them with two critical questions: “How will this legislation promote student achievement?” and “What is the fiscal and administrative impact on local communities?”

With this lens, we can help ensure the strength of the partnership we have delivering the promise of public education to our state. And with this letter, I ask that you join me in thanking the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s boards of education.

Leonard Lockhart is a member of the Windsor Board of Education and President of the CABE Board of Directors.

Over the years, CABE’s policy department has provided districts with, among other services, two frequently requested products: The Policy Audit and the Customized Policy Service. Both are fee-based services for member districts. The audit provides boards with an analysis of existing policies and a narrative report on the strengths and weaknesses of their policy manual, along with a chart identifying incomplete and out-of-date policies

with suggestions and recommendations for future policy work.

The Customized Policy Service provides a review and analysis of existing policies for relevance and compliance and provides updated specific policy language while providing sample CABE model policies where necessary. The Customized Policy Service, as it provides updates to policies for the entire manual, can be overwhelming to districts that may have a concern with one or two sections of their manuals or may wish to update only mandated policies and ensure

all such policies are adopted.

CABE’s Targeted Customized Policy Service is designed to reduce paperwork, ensure compliance, and assist boards concerned with specific areas of their policy man-

uals – mandated policies, a specific series, or an area of anticipated concern. For more information regarding this or any CABE policy service, please feel free to contact Jody Goeler at jgoeler@cabe.org

“Some people want it to happen, some wish it would happen, others make it happen.”

– Michael Jordan

By learning about her journey and the barriers that stood in her way, as well as the difficulties of entering a space that is traditionally occupied by mostly men, I found answers and gained new insight as to how I could be more supportive during the school year and make the task of evaluating her work a more authentic and helpful experience.

My article this month is to share how the “glass ceiling” has affected the hiring process and lived experiences of women in the superintendency and what actions we can take to encourage more educators to consider the job as an opportunity to make a substantial difference in the lives of students and their families. Included are insights from those across the nation who sit in the superintendent’s seat on what support they need as they deal with the challenges of being in that space.

The good news is that Connecticut is doing better than many other states in hiring female superintendents. According to the current information from the Connecticut State Department of Education, 40.24 percent of our 169 public school districts are led by women either as active, interim, or permanent positions. According to

Education Week, nationwide, 28 percent of superintendents in the 20222023 school year were women.

https://www.edweek.org/leadership/ advice-from-8-women-superintendents-for-those-following-in-their-footsteps/2024/03

When I first began research on the “glass ceiling” in 2005, there was a paucity of information on public-school female superintendents and even less on female superintendents of color. As women began to secure this position, more research studies about the challenges that women who broke through the glass ceiling faced in an environment that was primarily male-dominated surfaced. Much of the research focused on the preparation and pathway to the superintendency. Once a critical mass of women secured the position, a new focus of exploring the lived experiences of female superintendents surfaced.

Basic barriers that women face as they seek superintendency are:

1. Hiring bias-make sure the job description doesn’t contain words or phrases that are associated with a certain gender. Bias awareness training is recommended for those on the search committee.

2. Leadership opportunity gaps for elementary school classroom teach-

ers who are mostly woman may put female candidates at a disadvantage.

3. Women stay in the classroom longer than men and tend to wait until they feel qualified in every area before seeking a superintendency. This may delay many women in the progression to the superintendent position.

4. Societal expectations of women, especially if they are the main family caregiver, are stricter than for men. Long hours and late meetings may interfere with family time and may present a conflict for women who might otherwise be interested in seeking the position.

What can school boards do to support superintendents?

1. Support the superintendent’s need to gather with those who can mentor them. They need to surround themselves with those who are encouraging and willing to be a thought partner.

2. Budget for professional development, membership to professional organizations, and journals. Even people at the top need to be life-long learners.

3. Support and value their strengths and passions. They must fulfill the needs of the district and have the opportunity to use their expertise to

work on what is important to them.

4. Understand and encourage them to take care of their work/life balance.

5. Understand and implement pay equity for women.

6. Create and implement policies that address and remedy the inequities of women.

Almost 50 years ago, in 1975, Dr. Edythe J. Gaines, a trailblazer in education, was hired by Hartford public schools to become a public-school superintendent, making her the first woman and the first African American to serve as a superintendent in a Connecticut School District. I leave you with a thought question. What advice would Dr. Gaines give us if she were still alive today?

References

https://web.archive.org/ web/20160204091046/http://www.cwhf.org/ www.cwhf.org/inductees/education-preservation/edythe-j-gaines/#.VrMVouzP3wN

https://www.edweek.org/leadership/ advice-from-8-women-superintendents-forthose-following-in-their-footsteps/2024/03 Important study to read:

https://www.edweek.org/leadership/a-new-study-details-gender-and-racial-disparities-in-the-superintendents-office/2023/12

Because of the nature of the work that the superintendent and board chair do together, they must develop a different relationship than “regular” board members and the superintendent. They need to work together to ensure the agenda meets the needs of the board, with the superintendent often relying on the chair for guidance in preparing information for the board. This relationship can sometimes be a source of contention, either between the chair and superintendent or between the board and the chair/ superintendent team.

Sometimes there is disagreement between the board chair and the superintendent about how they should communicate. The chair may expect the superintendent to respond immediately any time he or she gets a call from the chair. I’ve seen chairs drop in unannounced and expect the superintendent to drop everything they are doing to discuss whatever is on the chair’s mind. I’ve also heard from superintendents that some chairs are too disengaged and leave too much to the superintendent. There needs to be a happy medium. There are times when other board members feel the chair and superintendent are too close and are leaving them out of too many discussions.

There are numerous models of chair/superintendent relationships –many that work effectively. However, that dynamic is subject to change

whenever the board elects a new chair. In some cases, the board chooses a new chair because they are uncomfortable with the way the chair and superintendent have interacted in the past. Those boards will be looking for a new direction. Board members will sometimes question how agendas are built or how items are added to the agenda.

Communicating with the board/ superintendent

One question that comes up regularly is “Who talks to the superintendent?” When issues arise, is your board’s protocol to call the board chair or the superintendent directly? In some districts the chair acts as a filter and brings items to the superintendent when he or she feels it is appropriate. In other districts, the superintendent wants the contact with individual board members. Neither is better than the other, but there should be a consistent expectation on how things are done in your district.

When a new chair is elected I recommend the chair and superintendent sit down and agree to a set of protocols. These questions can serve as a framework for that meeting.

1. Do the chair and superintendent need to meet regularly? If so, when and where?

In some districts those meetings might include the executive committee (vice-chair and other officers).

2. What are the items that need to

Tuesday, April 2, 1-1:15 p.m.

High schools can help prepare young people not just for college or work, but to live a “good life” they define for themselves. That’s the conclusion from a new report from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) and the Center for Public Research and Leadership (CPRL) at Columbia University that examined how six New England high schools are defining student success after graduation. CABE and CAPSS will co-host a webinar about the report exclusively for our members. The webinar will feature a presentation by the report’s co-authors, Chelsea Waite (CRPE) and Maddy Sims (CPRL), followed by a panel discussion with representatives from Connecticut public school districts. Go to www.cabe.org/professional-development/upcoming-workshops/webinars to learn more and register.

be discussed in those meetings (agenda topics, calendar dates, issues the superintendent wants to run by the chair before bringing them to the full board, etc.)?

3. How should the chair and superintendent communicate in emergencies?

4. What information should be forwarded to the chair vs. the whole board?

Plan a board self-evaluation to discuss board/superintendent interaction

Likewise, the board should meet with the superintendent to make sure everyone is on the same page when it comes to communication with the board. These discussions should include:

• when and under what conditions the board members should call the superintendent directly,

• when the superintendent should contact board members or rely on the chair to let the board what is happening.

• the superintendent’s expectations when it comes to board members contacting other district staff, visiting schools and responding when a member of the public or staff member contacts them looking for assistance.

These are areas that, without some sort of protocols or procedures, have the potential to cause disruption and bad feelings. The board should look at their policies and bylaws around communications to ensure the board and superintendent are comfortable with them.

In general, problems arise when there are no clear set of expectations regarding communication among the superintendent, board chair and other board members. Having a conversation before an issue arises is much easier than trying to fix a problem while in the middle of it. If you would like assistance from CABE in facilitating such a discussion, please contact Nick Caruso at CABE at ncaruso@cabe.org or 860-571-7446.