Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need.

Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success. Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

CAMPBELL COMMENTARY

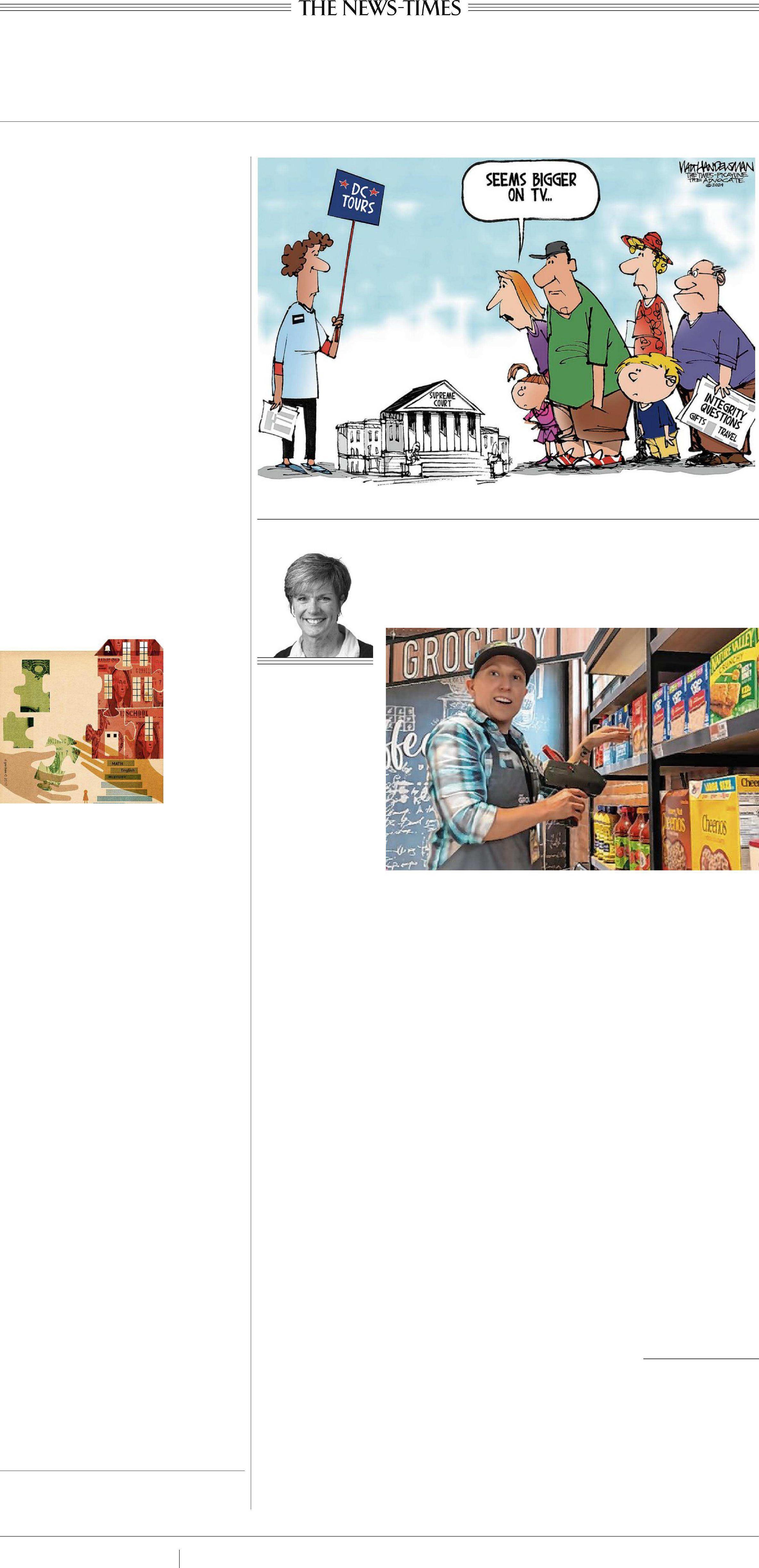

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores.

So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery store where pricesareset by income

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad.

Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel.

“Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need.

Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success. Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

SUSAN CAMPBELL COMMENTARY

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores. So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery store where pricesareset by income

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad.

Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel.

“Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need. Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget. Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success. Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores.

So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery

store where pricesareset by income

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad. Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel.

“Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need. Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success. Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

SUSAN CAMPBELL COMMENTARY

On a recent afternoon, Nicole(Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers. She Ubers to this Hartfordjob from Middletownand her cashier/associate shifts among the shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery On Broad Streetareoften the best partofher week.

Thisisnot a regularjob because thisisnot a regular grocery store Customers’billsarebasedon theirincome The storeis atraining ground,and the latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’sFrog Hollow neighborhood,a former manufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the median household income $17,333— isa quarterofthe state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities,another nonprofit in the neighborhood.

If ever there wasa neighborhoodin need ofa new approach tofood, it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, where residents’ access to affordable, healthy foodis restricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp, there’s plenty of food available but not nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverished neighborhoodandcount the fast-foodoutlets. Or walk into a bodega andseeif you canfind a fresh apple. You’re morelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content,says MayraRivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Thoseare all over the shelves of neighborhood stores.

So the store has price tags that arecolor-coded for sodiumcontent. Part of the store’s purposeisto educate the public about eating healthy, and the planisto have nutritionistsinthe store to explain how toprepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery

store where pricesare set by income

ple have signed up tobe members. Storeofficials are planning for far more, as word getsout.

Fundedinpart by the MelvilleCharitable Trust, and partneringwith Connecticut Foodshare (with somepandemic funds, and a $250,000 federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grandopening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheirbill, dependingonindividual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow diners topay what they want for theirmeals, this grocery store may be the first of its kind.

Years ago, when he was overseeing the community foodpantry at Manchester’s MACC, Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreamingof different ways toprovide fresh food for peoplelivingon the financial edge.

Forge City’s motto is “Foodisthe tool we useto empower,” and that’s through job trainingand otherprogramsaround the capitalcity Starting with the 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhoodbuildingknown as the Lyceum, the organization expanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogram that morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

And thisis key— peopleare not asked to bringinreams of paperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated card that identifies them asmembers.

The simplicity of the processis onpurpose.

“Why create a system for the 2% ofpeople who will take advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people will take advantage of it, anyway Why not have asystem that offerspeople somedignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but this may the perfect time Though the cost of groceries has fallenlately, pricesare still nowhere near what they werebefore the pandemic In 2022, the USDA said the cost of groceries rose 11.4% —thebiggest increase since theinflation of ’79. And thenprices rose again by5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlier this month, officials at Stop& Shop,with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announced they will soon close “underperforming stores. Will that include a nearby Stop& Shop on New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

Unlike a big store such as Costco Dubow’s idea included noannual membership fee, and healthy food specific totheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanic neighborhood, that means somethinglike Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square foot operation that requires massive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailers to make deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such as the store on Broad.

Back on theladder, Mankusisexplaining pricingand how surprised new customersare whentheylearnthe model.

“Thisjob makes me wake up in themorning,” Mankus said.

Rivera said that though Hartford may bethe only place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing details have been meticulously recorded, said Dubow, and they’reanxious to share Imagine:A Grocery On Broad or Main or River Street, scattered throughout the state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need.

Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success.

Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

SUSAN CAMPBELL COMMENTARY

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores.

So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery store where pricesareset by income

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad. Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel.

“Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need. Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success. Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

Agrocery store where pricesareset by income

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores. So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad.

Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel.

“Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

FORUM

Schoolfunding challenges demandsome commonsense

ByPatrice McCarthy“Theseare thetimes that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wroteinDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallying hisreaderstothe causeoffreedom, his wordsresonatetoday, as Connecticutcitiesandtowns of every size wrestle with budget shortages as publicschool systems finalize financial plans forthe fiscal year beginning July 1.

The challengesofbudgetbalancingare faced at all levelsof government, but they are felt most intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators, teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationare collaborating to deliver on Connecticut’s constitutional mandate to provide a freeand appropriateeducation for all of Connecticut’s childrenon someof thetightest budgets.

As theorganization representing thelargest group of elected officials in the state— the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education the Connecticut Associationof Boards of Educationcan confirm that while many soulsare beingtried, there are still signsofhope and promise.

In therecently closed2024session of theConnecticut General Assembly, lawmakers from both parties and Gov. Ned Lamont followed through onthepromise theymade to Connecticut’s publicschools in their twoyearbudget passedin2023. By maintaining theircommitment topublic schoolsthrough an accelerated phase-inofthe EducationCost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protected the state’s primary fundinggrant for localeducation. Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plans mid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswill be abletoreceive theECSfundingthey had been planning on.

DonnaGrethen/TNS/2016TNS

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedtheuniform and streamlined way to fund schools of choice such asmagnetschools, agriculturalscienceandtechnology centers Open Choice and charterschools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linked to theECSfoundationand student need.

Lawmakersalsomodernized educator certification programs to enhancethe qualityanddiversity of the educator workforce, whileremovingbarriers tocertificationthat preventedcandidates fromenteringthe teaching profession.

The legislaturealso trimmedback some of themandatesthat drive up thecost burden onpublicschool districts. Annual professional development requirements wereeasedto every five years,maintaininghigh standardsandallowingprofessional development time to focus on local student needs. Recognizingthat many schoolsare facedwith a lack of qualifiedprofessionals to inspect buildingheating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was extendedto2030, maintainingsafety standardsandlessening budgetconstraints.

As thankfulas we are forthese accomplishments, we cannotignoretheunfinished work that facesall publicschool districts. Teacher, paraeducatorand other staff positionsare being eliminatedbecausecombinedlocal, state andfederal resourcesare inadequate to meet the needsofall students In some municipalitieseducation budget increaseshave beenminimal, despiterisingcosts.

Specialeducationcosts continuetorise The Special EducationExcess Cost Reimbursement Grant helps alleviate these costs,but it iscapped,creatingholesin the fundingsafetynetfordistricts. Withoutfull reimbursement, districts of every sizeareforcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget. Beyond these systemicpressures, this yearmarks the end of the COVID dollars that many school districts received tocover thecosts of additional staff and servicesneededto addresstheincreasedneedsthat the pandemic brought onpublic schools. To be sure, thisfunding was temporary, butmany ofthe measures that were put inplaceto addressdisconnected students andlearninglossare stillvital to student success.

Thisisnot thefirst time Connecticut’s publicschool systemshave faced daunting challenges, and it won’t be thelast Through it all,and despitethetrying times that bring Thomas Painetomind,the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doing their best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver on the promise of educationwith our state andlocal partners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive directorand General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of BoardsofEducation.

SUSAN CAMPBELL COMMENTARY

On a recent afternoon, Nicole (Nic) Mankus was on a ladder stocking shelves withaneye out for new customers She Uberstothis Hartfordjob from Middletownandher cashier/associate shifts amongthe shiny produce and ready-to-eat meals at The Grocery OnBroad Streetare oftenthe best part of her week.

Thisisnot a regular job becausethisis not a regulargrocery store Customers’ billsare basedon theirincome The storeis atrainingground,andthe latest innovation from nonprofit Forge City Works in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood,a formermanufacturing powerhouse wheretoday, the medianhousehold income $17,333 isa quarter of the state median householdincome of $65,521, accordingtothe Partnership for Strong Communities, another nonprofit intheneighborhood.

If everthere wasa neighborhood inneed ofa new approach tofood it’s Frog Hollow, which is considered a food swamp. That differs from a food desert, whereresidents’ accesstoaffordable, healthy foodisrestricted, or doesn’t exist. In a food swamp,there’s plentyof food available butnot nearly enough of it is healthy. Drive through any impoverishedneighborhood and count the fast-foodoutlets.Or walk into a bodega and see if you canfind a fresh apple. You’remorelike tofind somethinglike Hot Pockets with a high sodium content, says Mayra Rivera, The Grocery’s general manager. Those areall overthe shelves ofneighborhood stores.

So the storehas price tags that arecolor-coded for sodium content. Part of the store’s purpose isto educatethepublic about eatinghealthy, and the planis tohave nutritionistsinthe storeto explain how to prepare a healthy meal.

So far, nearly 250 peo-

Agrocery store where pricesareset by income

ple have signed up to be members Store officials are planningfor far more, as word gets out.

Fundedin part by the Melville Charitable Trust, and partnering with Connecticut Foodshare (with some pandemicfunds, anda $250,000federal grant through U.S. Rep. John Larson, who was at the store’s grand opening), The Grocery offers shoppers a 3% 25% or 50% discount offtheir bill, depending on individual or householdincome.

Though restaurants have popped up that allow dinersto pay what they want for theirmeals, thisgrocery storemay be the first of its kind.

Years ago, whenhe was overseeingthecommunity food pantry at Manchester’s MACC,Ben Dubow, now executive directorof Fire by Forge, another programof Forge City, begandreaming of different ways toprovide fresh foodfor peopleliving on the financialedge.

Forge City’s mottois “Foodis thetool we use to empower,” andthat’s through job trainingand other programs around the capital city Starting withthe 2003 purchase of astately brick neighborhood building known as the Lyceum, the organizationexpanded to housing community gardens, a farmer’s market,an afterschoolprogramthat morphedintoa youthkitchen classroom, and most recently —a grocery store.

Unlike a big store such

as Costco Dubow’s idea includedno annualmembership fee, andhealthy foodspecifictotheneighborhood. In a heavily Hispanicneighborhood, that means something like Goya productsandingredients for sofrito.

And thisis key— people are not asked to bringinreams ofpaperto prove theirincome People fill out a one-page form,andareissueda laminated cardthat identifiesthemasmembers.

The simplicityofthe processison purpose.

“Why create a system for the2%of people who willtake advantage of it?” Dubow said. “A few people willtake advantage of it, anyway Why nothave asystemthat offers people some dignity?”

Not only is Frog Hollow the perfectplace for this, but thismay the perfect time Though the cost of grocerieshas fallenlately, pricesare stillnowhere near what they werebeforethepandemic In 2022, the USDA saidthe cost ofgroceries rose 11.4% —the biggest increase sincetheinflation of’79. And then prices rose again by 5% the following year says the USDA.

In addition, earlierthis month, officials at Stop& Shop, with storesin roughly 75 Connecticut towns,announcedthey will soon close“underperforming stores. Willthat include a nearby Stop& Shopon New Park frequented by Frog Hollow residents? That’s anybody’s guess.

The current business model of such grocery behemoths, said Dubow, is a 30,000-60,000-square footoperationthat requiresmassive room for parkingand roads big enough toallow tractortrailerstomake deliveries. Urban settings don’t have that kindof space, so residents rely on smaller stores such asbodegas or operations such asthe storeonBroad.

Back on theladder, Mankusis explaining pricingandhow surprisednew customersare whenthey learnthemodel. “Thisjob makesme wake up inthemorning,” Mankussaid.

Rivera saidthat though Hartfordmay be theonly place with such an enterprise thebusiness model canbereplicated. Planningand organizing detailshave beenmeticulously recorded,said Dubow, and they’re anxiousto share Imagine:A Grocery OnBroad or Main or River Street, scatteredthroughoutthe state. Interested? Dubow can be reached at ben@forgecityworks.org

Susan Campbell is the author of “Frog Hollow:Stories from an American Neighborhood,” “TempestTossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker” and “Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl.” She is Distinguished Lecturer at the University of New Haven, where she teaches journalism.

COMMENTARY

Schoolfunding challenges demand common sense

By Patrice McCarthy“Thesearethetimesthat try men’s souls,” Thomas Painewrote inDecember 1776 And whilethe Revolutionary War author was rallyinghisreadersto the causeoffreedom,his wordsresonate today, asConnecticutcitiesand towns of every sizewrestle withbudget shortages aspublicschool systems finalizefinancialplans for the fiscal year beginning July 1. The challengesofbudgetbalancing are faced at alllevelsof government, but they are feltmost intensely at the locallevel. Thisis where superintendents, administrators,teachers, staff and Boardsof Educationarecollaborating to deliver onConnecticut’s constitutionalmandatetoprovidea freeand appropriateeducationforallof Connecticut’s childrenonsomeof the tightest budgets.

As theorganizationrepresenting the largest group ofelectedofficialsin the state— the 1,400 volunteermembersof Connecticut’s localandregionalpublic boards of education theConnecticut AssociationofBoardsof Education can confirmthat whilemany soulsare beingtried,thereare still signsof hope and promise.

In the recently closed2024sessionof the ConnecticutGeneral Assembly, lawmakersfrombothpartiesandGov. Ned Lamont followed through onthe promisetheymade toConnecticut’s public schoolsintheirtwo-yearbudget passedin2023. By maintainingtheir commitment topublicschoolsthrough an acceleratedphase-inof the Education Cost Sharing(ECS) Formula,they protectedthe state’s primary funding grant forlocaleducation Thankfully, they resistedthetemptationto change plansmid-stream,andlocalcommunitieswillbe abletoreceive the ECS fundingtheyhad been planningon.

We are very pleasedthat the governor andlegislatorsmaintainedthe uniformand streamlined way to fund schoolsof choice such asmagnet schools, agricultural scienceand technology centers,OpenChoiceand charter schools basing it on a per-student state subsidy linkedtothe ECS foundationand student need.

tor certificationprogramstoenhance the quality and diversityofthe educator workforce, while removingbarriers to certificationthat preventedcandidatesfrom entering the teachingprofession.

The legislature alsotrimmed back someofthemandates that drive up the cost burdenonpublic school districts. Annualprofessional development requirements were eased to every five years,maintaining high standardsand allowingprofessional development timeto focusonlocal student needs.

extendedto2030, maintaining safety standardsandlesseningbudget constraints.

As thankful as we are forthese ac-

SEND US YOURFEEDBACK

complishments, we cannotignorethe unfinished work that facesallpublic schooldistricts. Teacher, paraeducator and other staffpositionsarebeing eliminatedbecause combinedlocal, state and federal resourcesareinadequate to meet the needs of all students. In some municipalities educationbudgetincreases have been minimal, despite rising costs.

Special education costs continueto rise. The Special Education ExcessCost Reimbursement Grant helpsalleviate these costs,but it is capped, creating holesinthe funding safety net for districts. Without full reimbursement, districts of every sizeare forcedtomake difficult decisionstomaintain a balancedbudget.

Beyondthese systemicpressures,this year marks the end of theCOVID dollarsthat many schooldistricts received to cover the costs of additional staffand services neededto addresstheincreased needsthat thepandemicbrought on public schools. To be sure, this funding was temporary, but many ofthe measuresthat wereputinplaceto address disconnected studentsandlearningloss are still vitalto student success.

Thisisnotthe first timeConnecticut’s public school systems have faceddaunting challenges,and it won’t bethelast. Through it all,and despitethetrying timesthat bring Thomas Painetomind, the 1,400 volunteer members of Connecticut’s schoolboardsare doingtheir best to apply Paine’s common senseto deliver onthepromise of educationwith our state andlocalpartners.

Patrice McCarthy is the executive director and General Counsel of the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education.

What do youthink? We want to know. The Journal Inquireroffers a variety of opinions everydayinprint andonline,but we are missing some —including yours. You can respond to editorials, columns, letters to the editor,and cartoons ina variety of ways, including:

• Online at CTInsider.com/journalinquirer

• Onsocial mediaplatforms,including Facebook

Lawmakersalsomodernizededuca-

Recognizingthat many schoolsare faced with a lack of qualifiedprofessionalsto inspectbuilding heating, ventilatingandairconditioning systems,the deadlineforinspections was

• By email. Letters to the editor shouldbe sent to letters@journalinquirer.com. Include yourhometown and aphone

number for verification. Lettersshouldbe no longerthan300 words.Donotsend more than oneinany 21-dayperiod. All lettersaresubject to editing for grammar,spellingandclarity. Be civiland base your lettersand commentson facts.