AHORA · POR SIEMPRE · Y PARA SIEMPRE

A PUBLICATION ABOUT OUR BELOVED HOMETOWN .

CabalíansawLegazpi What,then,isours? Joyousstrainsofprayer

Antiphona P , qui natus e nobis, plus quam prophéta e : hic e enim, de quo Salvátor ait: Inter natos mulíerum non surréxit maior Ioánne Baptí a. v I e puer magnus coram Dómino. r Nam et manus eius cum ipso e . Orémus.

DOratio Luc. C , DE, DF

, qui præséntem diem honorábilem nobis in beáti Ioánnis nativitáte fecí i : da pópulis tuis 2irituálium grátiam gaudiórum ; et ómnium fidélium mentes dírige in viam salútis ætérnæ. Per Dóminum no rum Iesum Chri um Fílium tuum : qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus San8i, Deus : per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum. Amen.

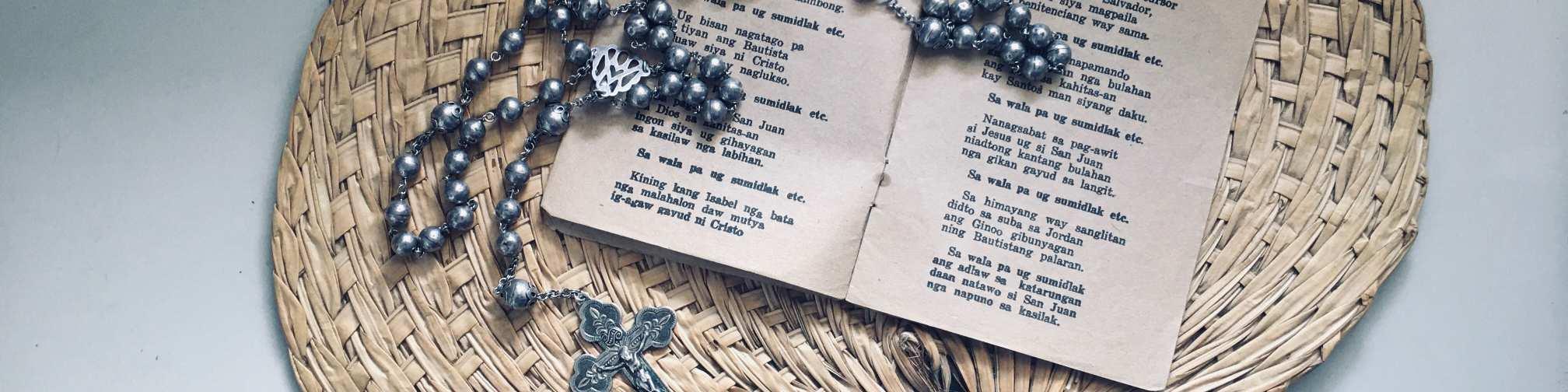

Sa walâ pa ug sumidlak Ang adlaw sa katarun ̃an, Daan nang natawo si San Juan, N ̃a napunô sa kasidlak.

; > ; = ; ? . Once a series of a8ions builds a routine that achieves a goal, it becomes a ritual. Ius, an a8ivity as simple as walking, when performed along a chosen pathway to untether the mind from trifling thoughts, becomes a ritual. Crossing over the fumid fire built near the cemetery arch is, without doubt, a ritual. Whether this ceremony discourages clingy 2irits wishing to accompany us home, or exterminates harmful germs thriving athwart in any necropolis, is a matter we’ll defer for now to career anthropologi s.

As creatures of habit, humans develop and employ behaviours that are repetitive and symbolic, in order to orche rate and comprehend an experience. Ie rituals our forebears developed and employed transcend generational boundaries, and become ours in the process of inheritance and retrofitting. We observe our ance ral rite of welcome in the recorded protoencounter between natives and rangers. Forcedtotrade,didweinheritahabitofju lettingotherstakewhatrightfullyareours? is a que ion worth asking but ultimately not answered.

While rituali ic jives with ceremonious,routinary concurs more with monotonous. Iis la word’s etymon, the ancient Greek μονότονος, brings us to the realm of notes and tones. Ritual and music interse8 in religious praxes, which are not easy to document. Ie terrain and terroir that tin8ure our temperament can be photographed. So can the edifice and equipment that elocute our ingenuity. Ie impalpable and disincarnate, however, go where the wind of whimsy di2erses them. And yet, they are no less important. For, like our language, Cabalianon rituals and ceremonies reinforce our personalities. Above all, they empower our identities.

For que(ions, comments, sugge(ions, and submissions, please reach us through the following: cabalianonko.wordpress.com

tagibtiban@gmail.com/cabalianonko.bsml@cabalianon_ko

Texto tradicional

Sawalâpaugsumidlak AngAdlawsaKatarun an, DaannangnatawosiSanJuan, N anapunôsakasidlak.

Kadtong Adlaw nUa Diosnon

Nanaug sa kabukiran, Ug didto Iyang himpalgan Kiníng santos nUa maambong.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Ug bisan nagatagò pa Sa tiyán ang Bauti a, Giduaw siyá ni Cri o, Ug sa kalipay naglukso.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Sa pag·ilá ni San Juan Sa Dios sa kahitas·an, InUón siyá ug gihayagan Sa kasilaw nUa labihán.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Kiníng kang Isabel nga batà, NUa malahalon daw mutyà, Ig·agaw gayúd ni Cri o, Niadtong natawong Verbo.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Si San Juan nUa Precursor Sa Diosnon nUa Salvador, Sa Belén siyá magpailá Sa penitenciang way sama.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Napatultol, napamandò Kang San Juan nUa bulahan Ang Dios sa kahitas·an, Kay santos man siyáng dakû.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Nanagsabát sa pag·awit

Si Jesús ug si San Juan Niadtong kantang bulahan NUa gikan gayúd sa lanUit.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

Sa himayang way sanglitan, Didto sa subâ sa Jordán, Ang Ginoo gibunyagan Ning Bauti ang palaran.

Sawalâpaugsumidlak,&c.

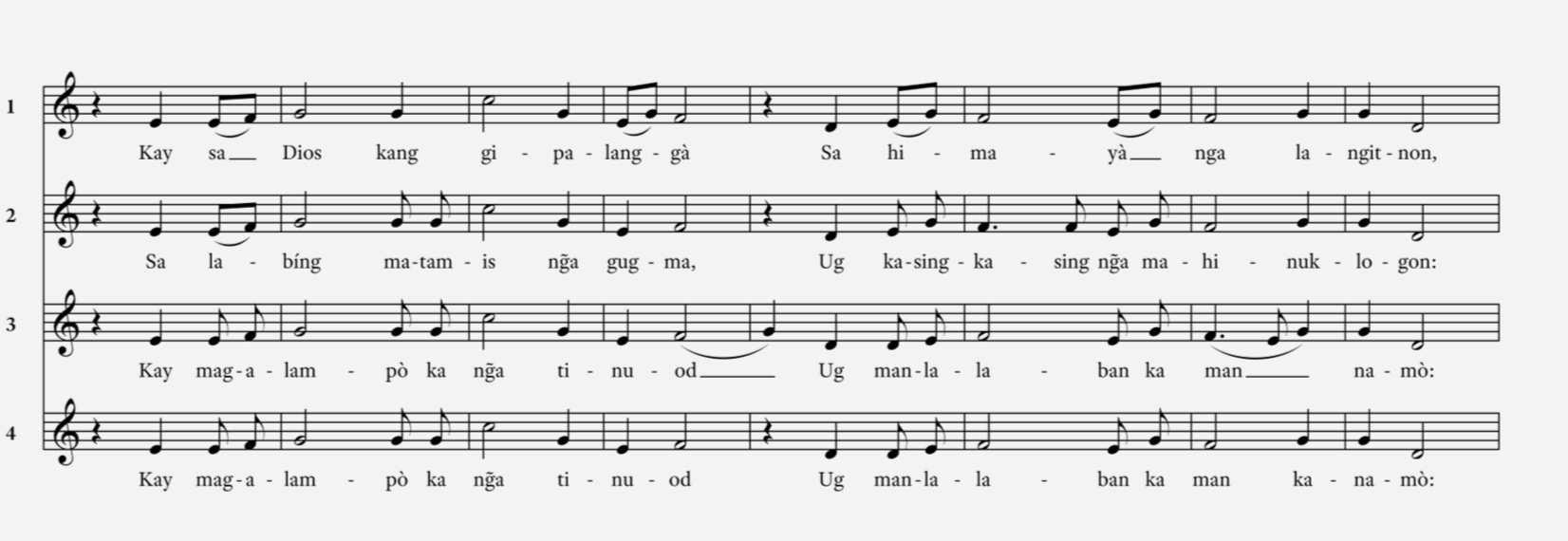

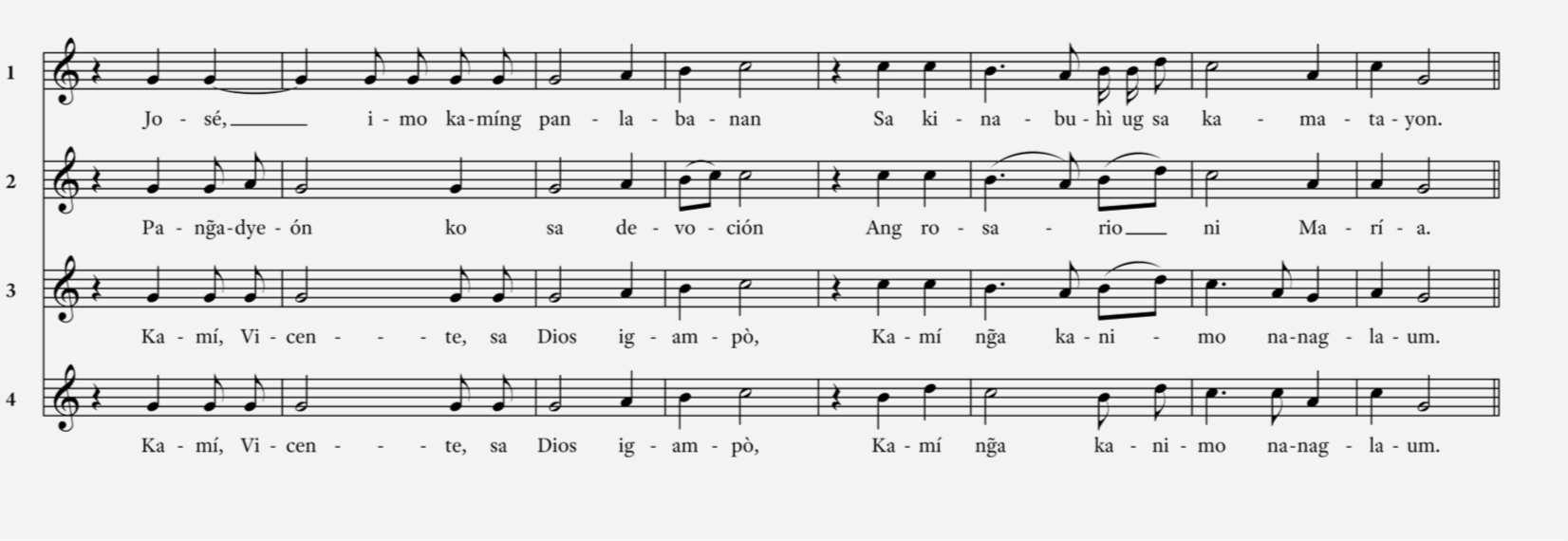

Tonada tradicional de Cabalían arreglopor D. S ;?@ > A< < _` _

a a a on daw mutyà

For gozos, text is body, tune is soul. Li ening to our elders sing the gozos of Saint John the Bapti in church, year in, year out, in the tonada notated in the preceding sheets, we might have already concluded that it induces sleep. Make no mi ake, though. >e tune’s soporific tendency does articulate its dulical intention. It’s not easy to pinpoint in a tonada that is metronomically bradycardic, but sensus fidelium did work its art in this regard. As the melodic line repeats every half-quatrain, that is, every two verses we get the sense that we are singing the gozos to a newborn child. So, of course, we sound like we are lulling Saint John the Bapti to sleep!

On the other hand, the text’s dida ic potential re s mightily on its exegetical composition. Without sounding like a crash course in hermeneutics, the gozos of Saint John the Bapti teach us about his life of holiness and righteousness, and how the figures of the Old Te ament attained fulfilment in the New. Nevertheless, we mu admit that it takes some level of convincing to agree that the nanoscale epopee, which gozos inevitably and invariably end up being, does re on a solid groundwork in Holy Writ.

For arters, the copla that is repeated in full a)er each e rofa, courtesy of the ru ure of the gozos, which is in the second form (see p. +, for a fuller treatment on gozos), ates a simple hi orical and scriptural fa : John, who is filled with light (Jn. /, 01), was born six months before Jesus, Who is the Sun of Ju ice (Mal. 2/, 34). For when Zacharias was chosen by lot to mini er at the altar of the Lord (Lk. 2, 7–9), the angel Gabriel appeared to him and announced John’s conception in Elisabeth’s womb (Lk. 2, ++–+0). Six months later (Lk. 2, 3< and 0<), the angel Gabriel appeared to Mary and announced the Messias’ conception in her womb (Lk. 2, 37–0+).

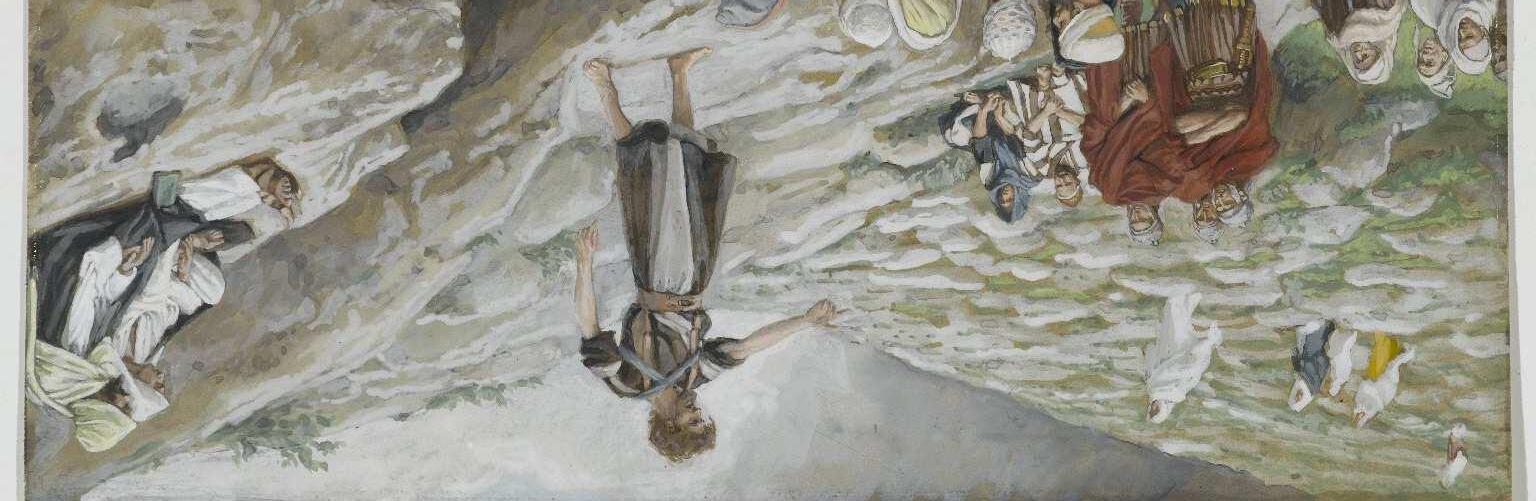

>e fir and eighth e rofas bookend the gozos in John’s role as the Bapti by anchoring their theme in the baptism of Jesus, which we regard as the onset of His mini ry. >e fir estrofa emphasises the second recorded encounter between Jesus and John, the prelude to His baptism. Jesus, Whose face would later gleam as the sun in Mount >abor (Mt. ?/22, 3), went from the hills of Nazareth in Galilee (Mk. 2, 9) down to the valley of the Jordan (Mt. 222, +0), where John was baptising (Jn. 2, 37). And John, whose countenance bore no semblance to a reed shaken by the wind (Mt. ?2, B; Lk. /22, 3,), saw Jesus approaching (Jn. 2, 39) from up the slopes.

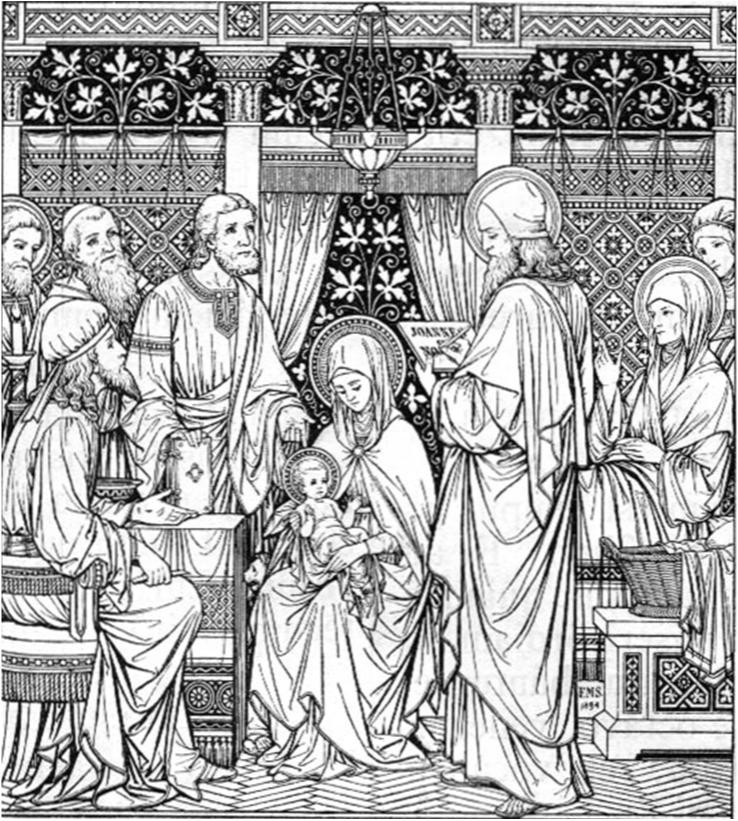

The angel Gabriel announced John’s birth to Zacharias Lk. – ). John would be a great prophet, the Forerunner of the Lord.

At the start of Jesus’ public ministry, John baptised the Lord in the Jordan (Jn. –&). The heavens opened, the Holy Ghost descended, and the Father’s voice echoed.

>e second e rofa at once pivots back to the fir recorded encounter between Jesus and John, as unborn children. Jesus, whil yet hidden in Mary’s womb, visited John, whil equally yet hidden in Elisabeth’s womb. Upon acknowledging Jesus’ presence through Mary’s greeting, John leapt in the womb to Elisabeth’s utter delight (Lk. 2, ,+–,1). John leapt because, as promised by the angel Gabriel to Zacharias (Lk. 2, +1), he was, at that very moment, endued with the Holy Gho in Elisabeth’s womb (Lk. 2, ,+). And this operation is a te ament to the divinity of Jesus: the Holy Gho proceeds from the Father and the Son.

What was then hidden prior to their reHe ive nativities, is later professed in the open. Here, the third e rofa summarises John’s te imony of Jesus’ divinity. For John, whom Zacharias prophesied as the prophet of God the Mo High (Lk. 2, B<), acknowledged the divinity of Jesus (Jn. 2, +–+,). John was not the light, but he gave te imony of the True Light (Jn. 2, <–9), Who is Jesus Himself (Jn. /222, +3). Jesus, in turn, declared John’s te imony as true (Jn. /, 03–00), and recognised John as a burning and shining light (Jn. /, 01). According to the prophecy, John therefore walked before the face of Jesus (Lk. 2, B<), and His word was a lamp to his feet, and a light to the path (Ps. I?/222, +41) that he was preparing for Him (Mal. 222, +; Is. ?J, 0). Indeed, John received light from God, and so he enlightened those who lay in darkness (Lk. 2, B9).

A)er this affirmation of the Hiritual bond between John and Jesus, the fourth e rofa re ates their biological bond: Jesus and John are cousins through their mothers. Mary gave birth to Jesus (Lk. 22, B). Elisabeth gave birth to John (Lk. 2, 1B). Mary and Elisabeth were cousins (Lk. 2, 0<). Jesus, born of Mary, is the Word made flesh (Jn. 2, +,). John, born of Elisabeth, is a precious gem, because his conception li)ed the reproach of his parents’ barrenness (Lk. 2, 3,–31); because his birth a onished the people in their realisation that the hand of God is upon him (Lk. 2, <0–<B); because his future beheading at Herod’s command (Mt. ?2/, +4) is precious in the sight of God (Ps. I?/, +1).

Familial relationship thus reinforced, the fi)h and sixth e rofas expound mini erial relationship. John is the Precursor, the Forerunner (Lk. 2, B<). Jesus is the Saviour, the Redeemer (Lk. 22, ++). From a very tender age, John lived a life of au erity to fulfil his mission, growing up in the desert (Lk. 2, 74) near Bethlehem in Judea, neither eating bread nor drinking wine (Lk. /22, 00). He wore camel’s hair with a leathern belt, and ate locu s and wild honey (Mt. 222, ,; Mk. 2, <), preaching penitence in the wilderness (Mt. 222, +–3) for the remission of sins (Lk. 222, 0). John the Forerunner prepared the ways of the Lord

(Mal. 222, +; Is. ?J, 0), and converted the hearts of the people to Chri (Mal. 2/, <; Lk. 2, +B).

Jesus the Redeemer is God the Mo High (Ps. J??/22, 01), Who chose for Himself a prophet (Lk. 2, B<). In this divine mission, John ood great before the Lord (Lk. 2, +1), he who was born a great prophet with no equal (Lk. /22, 37).

>e penultimate e rofa frames the conversation between Jesus and John before His baptism (Mt. 222, +0–+1) again Zacharias’ prophecy when his voice at la returned (Lk. 2, <7–B9). Where Zacharias prophesied that Jesus “delivered [us] from the hand of our enemies,” that “we may serve Him without fear, in holiness and ju ice before Him, all our days,” John complained to Jesus: “I ought to be baptised by >ee, and come >ou to me?” Where Zacharias prophesied that John “[shall] go before the face of the Lord to prepare His ways: to give knowledge of salvation to his people, unto the remission of their sins,” Jesus assured John: “Suffer it to be so now. For so it becometh us to fulfil all ju ice.” Holy Church calls this prophecy (Lk. 2, <B) the canticle of Zacharias, and sings it at lauds. By its incipit,

this canticle is rightly blessed, because it begins with the word benedi us in Latin, that is εὐλογητὸς in Greek. Likewise, this canticle is from heaven, because it marks the in ant Zacharias received the gi) of prophecy from God, when he recovered his lo voice upon obeying God’s command in confirming by writ that the child’s name is John.

>e la e rofa guides us back to the very beginning of the Lord’s mini ry. John, who is called the Bapti (Mt. 222, +; Mk. /2, +,; Lk. /22, +7), baptised Jesus in the Jordan (Mt. 222, +0 & +<; Mk. 2, 9; Lk. 222, 3+ & 2/, +; Jn. 2, 0+). Glory unmatched, unequalled, unparalleled, verily, is the baptism of Chri because of what immediately happened a)er (Mt. 222, +<–+B; Mk. 2, +4–++; Lk. 222, 3+–33; Jn. 2, 03–0,): the heavens opened; God the Holy Gho appeared as a dove and descended on Jesus; God the Father acknowledged Jesus as His Son. When for the la time the copla returns as the tornada, we go back to the simple of truths: >e Bapti was born before the Lord.

Once again: For gozos, text is body, tune is soul. It is an axiom we are resolved to live by. It reminds us of the Precursor’s greatness.

Putting things in perspective

2W XYZ [\IXW] 2[[Y\, we calendared the topic of Legazpi’s Cabalían visit to this year. Since we intend to deliver on that promise, we fir quip that, while Magallanes’ flimsily hi orical sailpa in our waters enjoys transmission from one generation to another, Legazpi’s solidly hi orical opover, never mind the similarly incontrovertible andoff between natives and explorers, does not rouse the same level of intergeneration traffic in narrational beque .

Before anything else, we mu ensure that we are in possession of as many fa s as would be humanly possible, le we fail to situate the events we are about to examine in an informed context, and interpret the nuances they so generously offer. So, let’s close our eyes, and imagine for a moment that we have been journeying for months in a range place where it is impossible to get meat, at a range time when eating meat is about to be forbidden. If it’s difficult to inhabit this situation, imagine in ead that you went trekking with friends in the jungle. More than halfway through the trek, you all lo your smartphones. Sure, some of you did bring keypad phones, but you le) them at the ho el. It’s

1 6

too late now to return, and, once you reach the campsite, you would need to inform your loved ones that you will be entering the la leg of the trek within a no-signal zone. By chance, another group reaches the campsite, so you tell them about your predicament. Some details get lo in translation, but they agree to lend you their phones at sunset. A)er the sun sets, however, with neither word nor warning, they refuse to let you use their phones. Any attempt at coaxing them ju elicits their blank ares. So when everyone has fallen asleep, you decide to eal one of their phones, so you can at once inform your family about your situation, and continue the trek the following morning.

MALAHALON DAW MUTYÀAgustí Querol i Subirats honours in this monument the memories of Miguel López de Legazpi and Fray Andrés de Urdaneta, O. E. S. A., whose expedition to the so-called Islas del Poniente definitively established Spanish dominion over the Philippine Islands that lasted 566 years. Legazpi and Urdaneta were in Cabalianon waters in March 7898.

Ie parallels do not match well, but, more or less, Miguel López de Legazpi faced quite a similar problem when he reached the archipelago on kl February kmnm. Ie expedition landed in Samar. On km February, the chief ensign, Andrés de Ibarra took possession of the island, and Legazpi ratified the a8 on Do February.

Aberwards, the fleet sailed south, crossing the channel to Leyte. On Dl February, Legazpi took possession of San Pedro Bay. By then, he had already sent Martín de Goiti to reconnoitre the island’s coa al settlements. Goiti, unaccustomed to the geography, sailed for days without seeing anything, until aber February. Between k and l March, Goiti finally reached a large bay “on which was situated a large settlement comprising many families,” where “the people had many swine and poultry, with an abundance of rice and potatoes.” Martín de Goiti had come in sight of Cabalían.

Goiti returned to the fleet, relaying happy news upon his arrival on E March. Ie fleet set sail immediately, and on the abernoon of the Monday of Quinquagesima, m March, the fleet anchored in front of the bay of Cabalían, which the Spaniards later chri ened Malitik Bay.

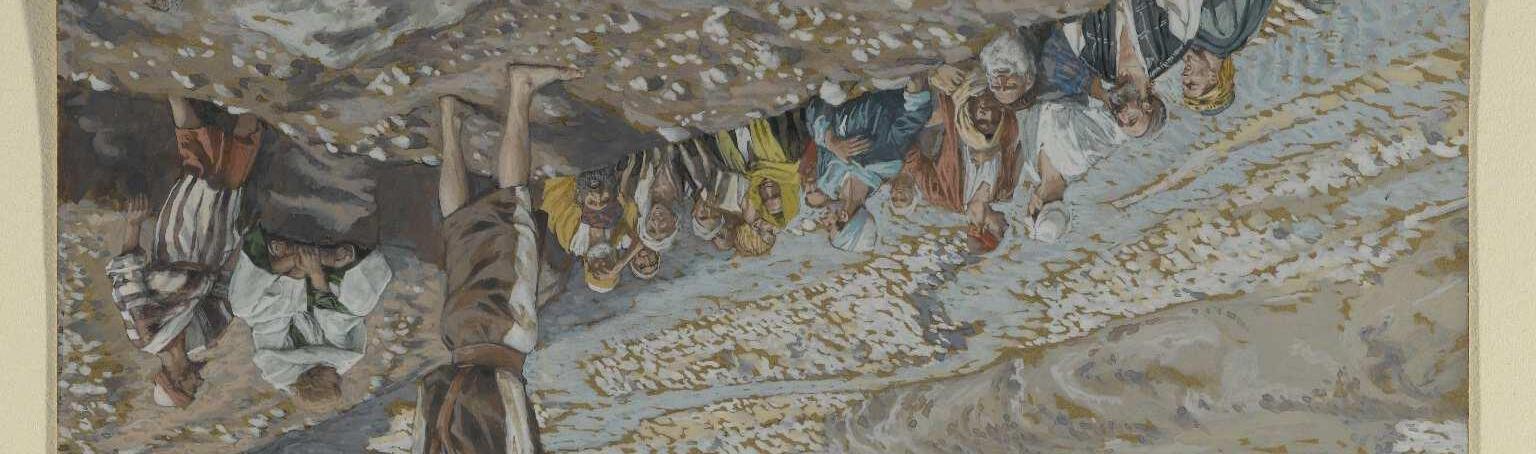

What followed evokes the screenplay of a melodramatic period series. Cabalianon natives welcomed the Spaniards with blood compa8, promising to bring food the following day, only to renege. Ho ages were taken. Goods, looted. People wanted to eat before the long puasa for cuaresma. Iat Shrove Tuesday, the Spaniards seque ered thirty to forty crates of tubers, and forty to fiby heads of swine, big and small, with which they observed meatfare. Ie next day, h March, Ash Wednesday being a day of precept, given the obligatory fa ing and ab inence, the crew also refrained from servile work. Ie following Iursday, F March, second day of Lent, Legazpi sent one of Kamutuhan’s co-detainees ashore to pay the native owners (of the tubers and swine) in kind, with beads, pearls, velvet caps, blades, shears, among others. Ie following pages contain the transcription and translation of the record of these events.

R > A? < > H ; , Colección de documentosinéditosdeUltramar, ser. D, vols. D (Madrid kFFn) & l (Madrid kFFh).

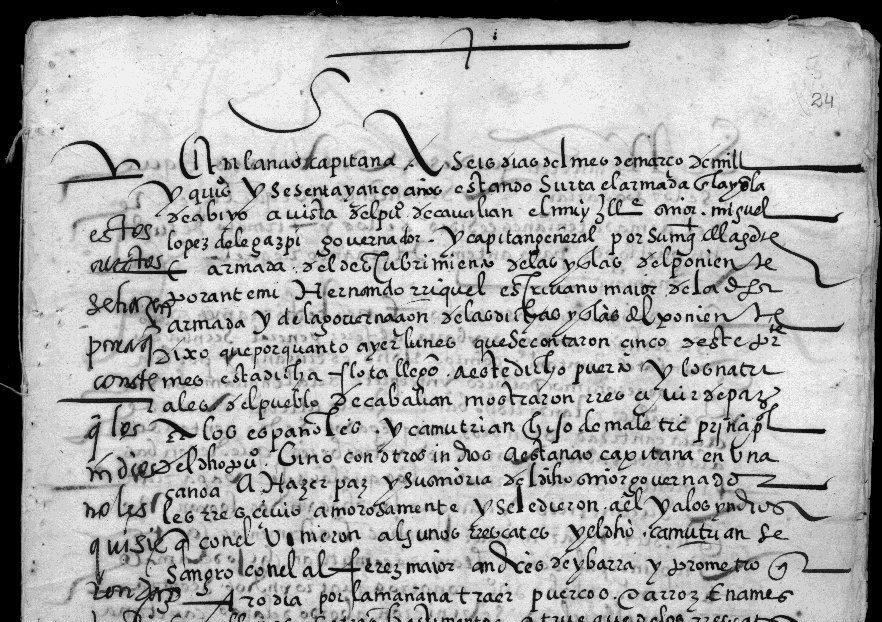

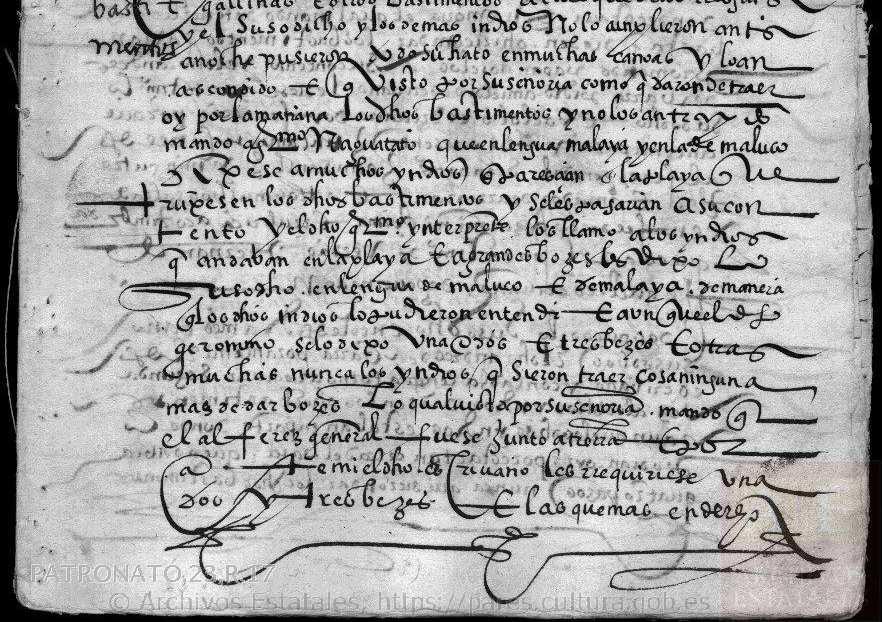

AGI, Pat. Dl, R kh.

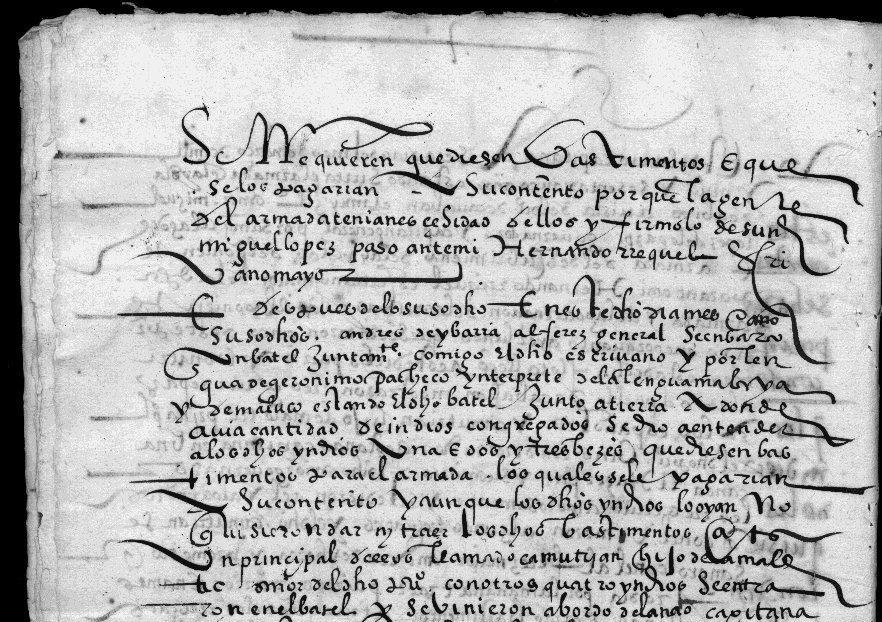

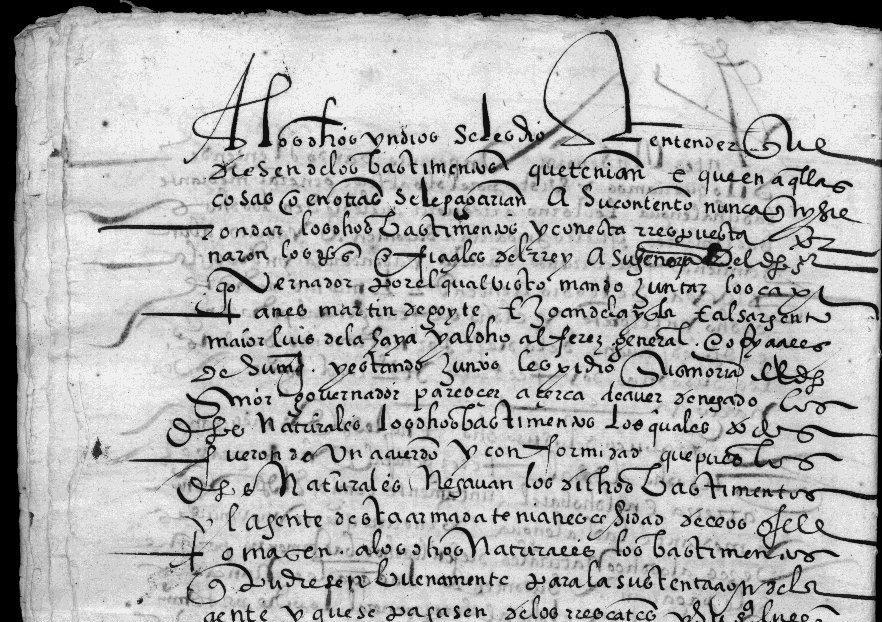

This archival copy of the notarial acts of Legazpi’s stopover in Cabalían is kept in the Archivo General de Indias. Catalogued in Patronato <5, it describes events during the ‘sanctioned’ looting on Shrove Tuesday, 9 March 7898.

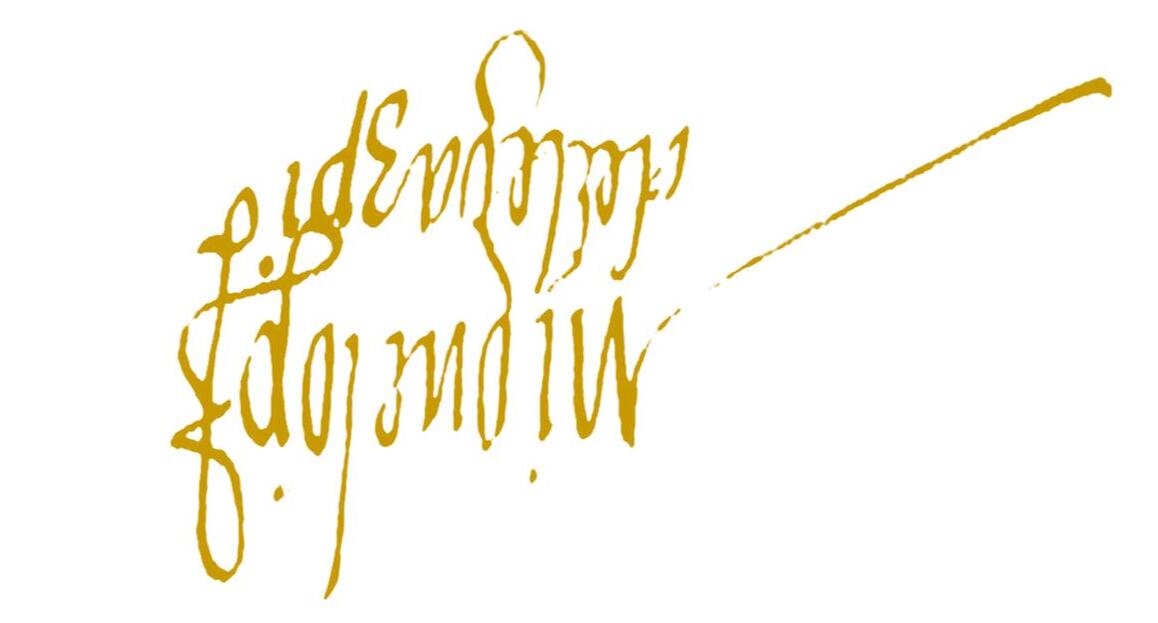

En la nao capitana, a seis días del mes de marzo de mil y quinientos y sesenta y cinco años, estando surta el armada en la isla de Abuyo, a vista del pueblo de Cabalían, el Muy Ilustre Señor Miguel López de Legazpi, Gobernador y Capitán General por Su Majestad de la gente y armada del descubrimiento de las Islas del Poniente, por ante mí, Fernando Riquel, escribano mayor de la dicha armada y de la gobernación de las dichas Islas del Poniente, dijo, que, por cuanto ayer lunes, que se contaron cinco de este presente mes, esta dicha flota llegó a este dicho puerto, y los naturales del pueblo de Cabalían mostraron recibir de paz a los españoles, y Camutujan, hijo de Malétic, principal del dicho pueblo, vino con otros indios a esta nao capitana en una canoa a hacer paz, y Su Señoría del dicho señor gobernador les recibió amorosamente, y se le dieron a él y a los indios que con él vinieron algunos rescates, y el dicho Camutujan se sangró con el alférez mayor, Andrés de Ibarra, y prometió que otro día por la mañana traería puercos y arroz y ñames y gallinas y otros bastimentos a trueque de los rescates, y el susodicho y los demás indios no lo cumplieron, antes anoche pusieron todo su hato en muchas canoas y lo han escondido; y que, visto por Su Señoría como quedaron de traer hoy por la mañana los dichos bastimentos, y no los han traído, mandó a Jerónimo Naguatato que, en lengua malaya y en la de Maluco, dijese a muchos indios que andaban en la playa, y a grandes voces les dijo lo susodicho en la lengua de Maluco y de Malaya, de manera que los dichos indios lo pudieron entender, y aunque el dicho Jerónimo se lo dijo una y dos y tres veces y otras muchas, nunca los indios quisieron traer cosa ninguna más de dar voces. Lo cual visto por Su Señoría, mandó que el alférez general fuese junto a tierra, y por ante mí el dicho escribano les requiriese una y dos y tres veces y las que más en derecho se requieren que diesen los bastimentos y que los pagarían a su contento, porque la gente del armada tenía necesidad de ellos. Y firmólo de su nombre, Miguel López. Pasó ante mí, Fernando Riquel, escribano mayor.

Y después de lo susodicho, en este dicho día, mes y año susodichos, Andrés de Ibarra, alférez general, se embarcó en un batel juntamente conmigo el dicho escribano, y por lengua de Jerónimo Pacheco, intérprete de la lengua malaya y de Maluco, estando el dicho batel junto a tierra, adonde había cantidad de indios congregados, se dio a entender a los dichos indios una y dos y tres veces que se diesen

A Spanish transcription of these pages (ff. <@r/v and <8r/v), one that preserves the orthography and resolves all the scribal abbreviations, appears in the second

In the flagship, on the sixth day of the month of March of the year one thousand and five hundred and sixty and five, while the fleet was anchored in the island of Abuyog, within sight of the settlement of Cabalían, the Very Illustrious Lord Miguel López de Legazpi, Governor and Captain General, on His Majesty’s behalf, of the folk and fleet of the discovery of the Islands of the West, in my presence, Fernando Riquel, chief notary of the said fleet and of the governance of the said Islands of the West, stated that, inasmuch as this said fleet reached this said port yesterday Monday, which was counted the fifth day of this present month, and the natives of the settlement of Cabalían appeared to receive the Spaniards in peace, and Kamutuhan, son of Malitik, chieftain of the said settlement, approached this flagship in a canoe with other natives to make peace, and His Lordship, the said Lord Governor, affectionately received them, and some gifts were bestowed upon Kamutuhan and upon the natives who came with him, and the said Kamutuhan made blood compact with the chief ensign, Andrés de Ibarra, and promised that, on the morning of the following day, he would bring pigs and rice and yams and chickens and other provisions in exchange of the gifts, and the aforesaid and the other natives did not fulfil it, rather they loaded all their belongings in many canoes last night and stowed them away; and that, having seen that they have yet to deliver by morning today the said provisions, and that they have not delivered these, His Lordship ordered Jerónimo the Interpreter to speak in the Malay tongue and in the Maluku tongue to as many natives as roamed the shore, and in a loud voice he spoke of the aforesaid to them in the Malay tongue and in the Maluku tongue, in a such a way that the said natives were able to understand it, and even though the said Jerónimo spoke of this one and two and three and many more times, never did the natives want to deliver anything other than to yell. Having seen this, His Lordship ordered the chief ensign to go near the shore, and to ask the natives in my presence, the said notary, one or two or three or more times as would lawfully be needed, to supply the provisions, and for which they would be compensated to their contentment, because the folk of the fleet were in need of them. And he signed it in his name, Miguel López. It transpired in my presence, Fernando Riquel, chief notary.

And after the aforesaid, on this said day, month and year aforesaid, Andrés de Ibarra, chief ensign, boarded a rowboat together with me, the said notary, and by means of the tongue of Jerónimo Pacheco, interpreter of the Malay tongue and of the Maluku tongue, while the said rowboat remained near

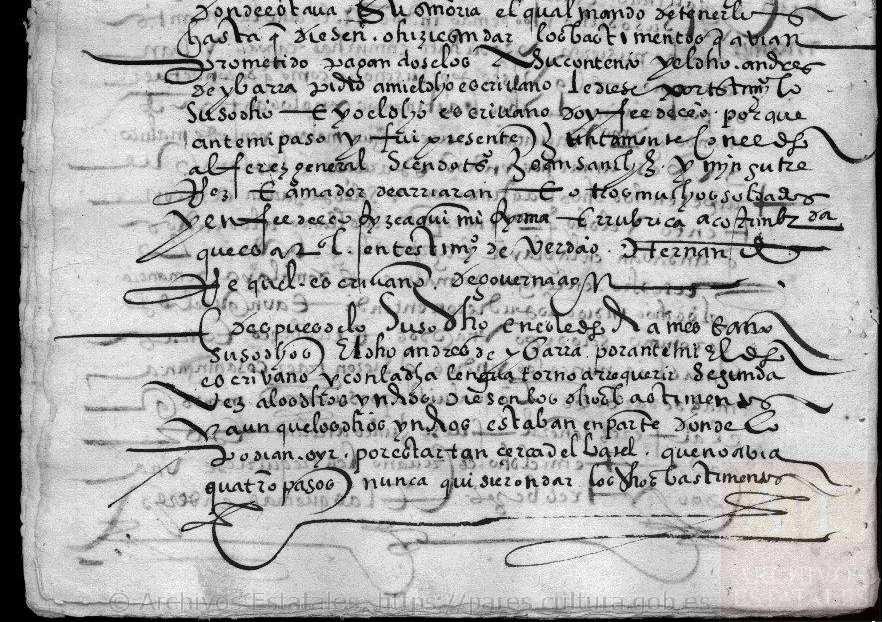

series of the Colección de documentos inéditos de Ultramar.bastimentos para el armada, los cuales se les pagarían a su contento, y aunque los dichos indios lo habían no quisieron dar ni traer los dichos bastimentos, antes un principal de ellos, llamado Camutujan, hijo de Malétic, señor del dicho pueblo, con otros cuatro indios se entraron en el batel y se vinieron a bordo de la nao capitana, donde estaba Su Señoría, el cual mandó detenerlos hasta que diesen o hiciesen dar los bastimentos que habían prometido, pagándoselos a su contento. Y el dicho Andrés de Ibarra pidió a mí el dicho escribano le diese testimonio lo susodicho. Y yo el dicho escribano doy fe de ello porque ante mí pasó y fui presente juntamente con el dicho alférez general, siendo testigos Juan Sánchez y Martín Gutiérrez y Amador de Arriarán y otros muchos soldados. Y en fe de ello, hice aquí mi firma y rúbrica acostumbrada, que es a tal, en testimonio de verdad, Fernando Riquel, escribano de gobernación.

Y después de lo susodicho, en el dicho día, mes y año susodichos, el dicho Andrés de Ibarra, por ante mí el dicho escribano y con la dicha lengua, tornó a requerir segunda vez a los dichos indios diesen los dichos bastimentos, y aunque los dichos indios estaban en parte donde lo podían oír, por estar tan cerca del batel que no había cuatro pasos, nunca quisieron dar los dichos bastimentos, antes enseñaron un perrillo, dando a entender si lo queríamos. Y visto por el dicho alférez general, mediante la dicha lengua, les tornó a requerir que le diesen los dichos bastimentos, que se les pagarían a su contento. Y a mayor abundamiento fue corriendo la costa, y adonde había indios en la playa, se les dio a entender lo mismo, mediante el dicho intérprete. Y el dicho alférez general pidió a mí el dicho escribano se lo diese por testimonio, siendo testigos los susodichos. Doy fe de ello, Fernando Riquel, escribano de gobernación.

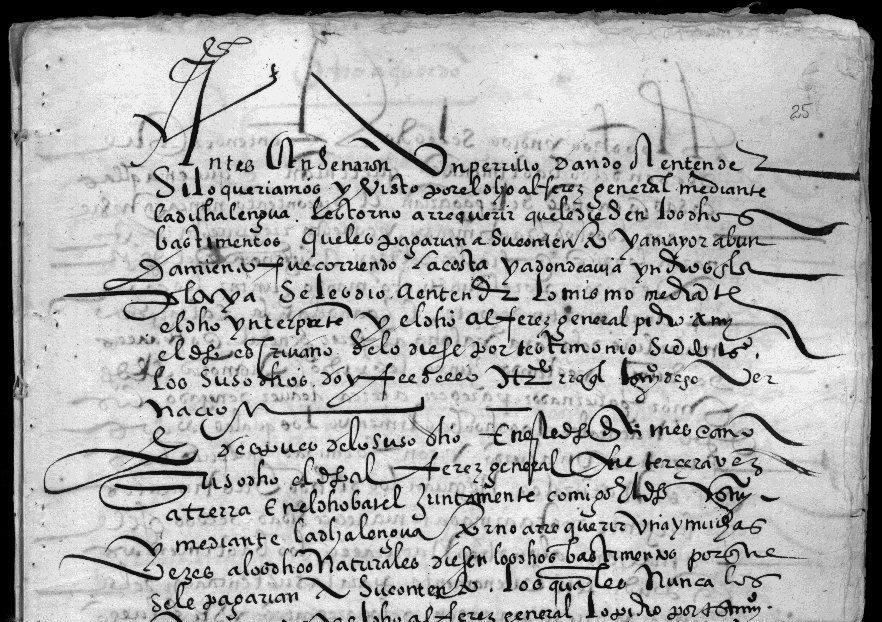

Y después de lo susodicho, en el dicho día, mes y año susodichos, el dicho alférez general fue tercera vez a tierra en el dicho batel juntamente conmigo, el dicho escribano, y mediante la dicha lengua tornó a requerir una y muchas veces a los dichos naturales diesen los dichos bastimentos, porque se les pagarían a su contento, los cuales nunca los quisieron a dar. Y el dicho alférez general lo pidió por testimonio, testigos los dichos. Fernando Riquel, escribano de gobernación.

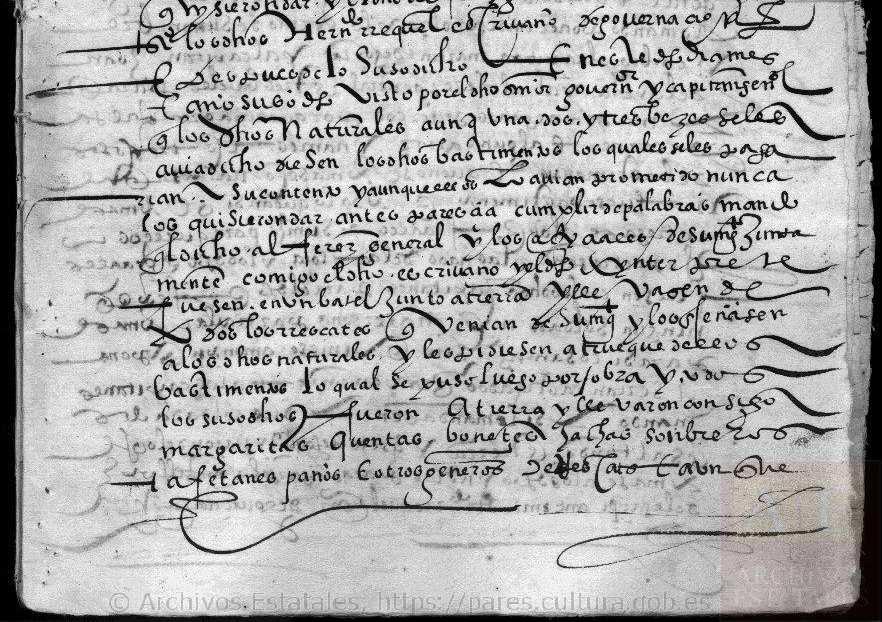

Y después de lo susodicho, en el dicho día, mes y año susodichos, visto por el dicho señor gobernador y capitán general que los indios naturales, aunque una, dos y tres veces se les había dicho diesen los bastimentos, los cuales se les pagarían a su contento, y aunque ellos lo habían prometido nunca los quisieron dar, antes parecía cumplir de palabras, mandó que el dicho alférez general y los oficiales de Su Majestad juntamente conmigo el dicho escribano y el dicho intérprete fuesen en un batel junto a tierra y llevasen de todos los rescates que venían de Su Majestad, y los enseñasen a los dichos naturales, y les pidiesen a trueque de ellos bastimentos, lo cual se puso luego por obra. Y todos los susodichos fueron a tierra y llevaron consigo margaritas, cuentas, bonetes, hachas, sombreros, tafetanes, paños y otros géneros de rescate, y aunque a los dichos indios se les dio a entender que diesen de los bastimentos que tenían y que en aquellas cosas o en otras se les pagarían a su contento, nunca quisieron dar los dichos bastimentos, y con esta respuesta tornaron los dichos oficiales del rey a Su Señoría del dicho señor gobernador, por el cual visto, mandó juntar a los capitanes Martín de Goiti y Juan de la Isla, y al sargento mayor Luis de la Haya, y al dicho alférez general y oficiales de Su Majestad. Y estando juntos, les pidió Su Señoría del dicho señor gobernador parecer acerca de haber denegado los dichos naturales los dichos bastimentos, los cuales todos fueron de un acuerdo y conformidad, que pues los dichos naturales negaban los dichos bastimentos, y la gente de esta armada tenía necesidad de ellos, que se les tomasen a los dichos naturales los bastimentos, que pudiesen buenamente para la sustentación de la gente, y que se pagasen de los rescates. Y Su Señoría luego lo mandó poner así por obra, y lo firmó de su nombre, y envió al capitán Martín de Goiti, y al capitán Juan de la Isla, y al alférez general en tres bateles para que tomasen algunos puercos porque había gran falta de carne, y algún arroz y ñames y otras cosas de bastimentos, y que no se tomase otra cosa que no fuese bastimento, y todo lo que así se tomase entregasen a los oficiales de Su Majestad, para que ellos lo repartiesen en las naos de la flota, y los dichos oficiales fuesen con los dichos capitanes para el dicho efecto, y que ningún soldado ni otra persona particular tomase para sí cosa ninguna, sin que viniese a montón, so pena que serían castigados gravemente. Y a los capitanes mandó así lo mandasen a sus soldados en saltando en tierra, y que se tuviese cuenta y razón de los que se tomase a los dichos indios para pagárselo. Miguel López de Legazpi, ante mí, Fernando Riquel, escribano de gobernación.

(Here ends the Spanish transcription. The paragraphs are spaced to match the English translation.)

the shore, where a crowd of natives had gathered, made the said natives understand one and two and three times that the provisions for the fleet be delivered, for which they would be compensated to their contentment, and even though the said natives had these, they wanted neither to give nor bring these said provisions, rather, one of their chiefs, called Kamutuhan, son of Malitik, chieftain of the said settlement, came with four other natives into the rowboat and aboard the flagship, where His Lordship was present, who ordered them detained until they delivered, or caused to be delivered, the provisions that they had promised, with them being compensated for these to their contentment. And the said Andrés de Ibarra asked me, the said notary, to render the aforesaid as testimony to him. And I, the said notary, bear testimony to this, because this transpired in my presence, and I was present together with the said chief ensign, witnesses being Juan Sánchez and Martín Gutiérrez and Amador de Arriarán and many other soldiers. And in witness whereof, I hereunto affix my signature and customary flourish, which is thus, in testimony of the truth, Fernando Riquel, notary of governance.

And after the aforesaid, on this said day, month and year aforesaid, the said Andrés de Ibarra, in my presence and with the aforesaid tongue, came for a second time to ask the said natives to deliver the said provisions, and, even though the said natives were present in a place where they could hear him, being so close to the rowboat that there were no more than four strides in between, never did they wish to deliver the said provisions, rather they showed a puppy, making us understand whether we liked it. Having seen this, the said chief ensign, by means of the same tongue, came for a third time to ask them to deliver the said provisions to him, for which they would be compensated to their contentment. And, furthermore, he went rowing along the coast, and wherever natives were present on the shore, he made them understand the same, by means of the said interpreter. And the said chief ensign asked me, the said notary, to render this as testimony to him, witnesses being the aforesaid. I bear witness to this, Fernando Riquel, notary of governance

And after the aforesaid, on this said day, month and year aforesaid, the said chief ensign went for a third time to shore in the same rowboat together with me, the said notary, and, by means of the said tongue, he again asked one and many times the said natives to deliver the said provisions, because they would be compensated for these to their contentment, but never did they wish to deliver these. And the said chief ensign asked this for testimony, witnesses being the aforesaid. Fernando Riquel, notary of governance.

And after the aforesaid, on this said day, month and year aforesaid, having seen that the native inhabitants never wanted to deliver the provisions, even though they had been asked one, two and three times to deliver these, for which they would be compensated to their contentment, and even though they had promised so, as it seemed that they fulfilled their word in the past, His Lordship ordered the said chief ensign and the officers of His Majesty together with me, the said notary, and the said interpreter, to go near the shore in a rowboat, and to bring all of the gifts that had come from His Majesty, and to show these to the said natives, and to offer them these in exchange of those provisions, which was thereafter carried out in deed. And all of the aforesaid went to shore, and brought with them pearls, beads, caps, hatchets, hats, silks, drapes and other kinds of gifts, and even though the said natives were made to understand that they ought to give from the provisions that they had, and that they would be compensated for these and other things to their contentment, never did they wish to deliver the said provisions. And, with this response, the said officials of the King returned to His Lordship, the said Lord Governor, who, having seen this, ordered the captains Martín de Goiti and Juan de la Isla, the sergeant major Luis de la Haya, and the said chief ensign, and the officials of His Majesty, to gather together. Being gathered together, His Lordship, the said Lord Governor, asked them to think about how the said natives withheld the said provisions, all of whom were of one accord and concurrence, that, because the said natives withheld the said provisions, and the folk of this fleet were in need of those, the provisions that could amply provide sustenance to the folk ought to be taken from the said natives, and that they ought to be compensated with the gifts. And His Lordship thereafter ordered that this be thusly carried out in deed, and he signed it with his name, and sent the captain Martín de Goiti, and the captain Juan de la Isla, and the chief ensign, in three rowboats, so they could take some pigs, because there was great want for meat, and some rice and yams and other kinds of provisions, and so nothing that is not provision be taken, and so they could hand over all those that had thusly been taken to the officials of His Majesty, that they might apportion these amongst the ships of the fleet, and so the said officials could accompany the said captain to the said effect, and so no soldier nor any other private person could take anything for himself without it coming in heaps, under pain of being gravely punished. And he ordered the captains to thusly order their soldiers when going to shore, and to take account of and pay attention to the things that would be taken from the natives, in order for them to be compensated for these. Miguel López de Legazpi, in my presence, Fernando Riquel, notary of governance.

Discomforting questions to ponder

s ; _ ; t ; ; . As individual persons, and as a people in general. Much has been said of the inju ice surrounding social aid and relief goods. Communal wisdom oben whi2ers the phrase duóy sa luwág to euphemise civic bias. Ie closer one sits next to the wielder of power, the quicker one absorbs the attendant benefits. If one is penniless, one needs to suck up to get the be bits. If one is moneyed, or at lea gainfully employed, even if a supertyphoon ju levelled down one’s home, one doesn’t deserve assi ance at all. Calamity is an equaliser, and helping those who were once advantaged, in a dog-eat-dog society, amounts to obscenity.

Needless to say, at lea once in our checkered lives, we’ve been at the receiving end of some form of alienation of something. Mo of the time, the experience is personal, but, in the rare cases that it’s not, it affe8s the entire community. Our recorded hi ory begins ju with that. Legazpi and his crew came, all worn and weary, hankering for meat before the long fa of Lent, and took away yams and pigs. He paid the natives who owned the crop and pork, of course, but neither jewels nor fabrics diminish the fa8 that the barter was as forced as faeces passing through a haemorrhoidal re8um.

Closer to our time is the political manoeuvre that witnessed the popular canonisation of a provincial governor, when Cabalían was rent asunder and ended up in two portions, one disproportionately bigger than the other. Our luminaries saw it for what it was, a gerrymandering. A cold, clever, calculated machination that never ceases to trouble the people its deathless hands have touched. A fission that continues to sire problems (not that an analysis of causation has been done) that only beset us. At lea , the Spaniards did mu er the gumption to arrange for the turnover of some compensation for the goods they had taken.

Still more recently, unsolicited cada ral interpretation has dabbled in this art. Subje8 in que ion is the lake pooling up in the sealed mouth of the volcano that trumpets our town’s name in official maps. Concern is seldom not a fun8ion of proximity, e2ecially in an archipelago whose people 2eak languages that encode deixis in calibrated nuances of contiguity. Yes, we can afford nonchalance when a world power squats in our territorial waters, but we refuse to re rain or conquer our indignation when an agency awards a body of water in our mountain to another circumscription.

Are natural wonders really in short supply these days, wre ing limnic formations is now an acceptable method of acquisition? We pose this que ion only in the moral sense because we are aware that laws can be tinkered to ve liceity in something that is otherwise que ionable and obje8ionable. It happened before. It can happen again. Who knows, if we put up no fight now, they might ju get more creative in their design. Perhaps, in the next decade or so, some careless vagrant would claim, “Hey, wait a minute. Iat old church belongs to us!” Never mind if its foundations have been sunk deep smack in the middle of Cabalían.

⁂

© JOSEPH PASALO / FACEBOOK

© JOSEPH PASALO / FACEBOOK

Mapping our charodulic heritage

;@ >< : s ;;x > _ < ;; , ora et labora ranks high up in the pecking order. Pray and work, aye, is the paramount Benedi8ine counsel. However, probably because the monks arrived very late in the archipelago, or because the Filipino tongue had not yet worked out the intricacies of Latin phonetics at that time, our inherited and time-honoured paraliturgical praxis in ead operates under the principle of ora et devora. Pray and eat, indeed, is what it means. For whenever we gather in our chapels to ask our heavenly advocates to intercede for us, we always find food at the end to warm our pious tummies. Aber all, in every devotee slumbers a gourmand.

We’ve always called these aberprayer minifea s painit, even when the food choices now clearly gravitate towards the cold. Gone are the days when the mangadjeay and the mananabat sipped coffee boiled from roa ed corn, or received a wad of tabakò and tigoy with a tilád of mamâ. Iced juice and iced candy are present aples, oben paired with ta y bread slaked in mayonnaise or budbud broken into many segments. In chicer and posher in ances, the upmarket carte du jour typically matches doypacked liquids or tetrapaked fluids, with clingwrapped savoury turnovers or cellophaned baked confe8ions. Ie mo opulent so far recorded is one whole inasál for everyone.

While the ga ronomical variety that gives painit a chara8er of its own will scare today’s dietitians, it did ele8rify (and perhaps continues to ele8rify) generations and generations of children. No matter how convoluted the intercessions were, we dawdled close to the chapel so as not to miss painit. No matter how cantankerous the purveyors were, we ill queued ju to get nibbles. Mayhem, it was. A few ate more than one helping; many ate air and nothing.

So it’s not a onishing that we acquired an important life skill from this experience. Painit trained us how to line up for relief goods, and face the inevitable disappointments! Fir come did not usually mean fir served, but it helped. Alot. So we learned to wait for a sign. It is here that the gozos obtain paramount importance. If comets are harbingers of war, gozos are heralds of banquets. Ie moment we heard the gozos, we rushed to the chapel like germs to a morsel.

And so we face the age-old que ion. What are gozos exa8ly? In the bare terms, gozos are pieces of devotional poetry. Iey are devotional because they transmit faith, and they express devotion. Iey are poetry because their idiom is elevated, and their form is ru8ured. Ius, a copla and several e rofas form the backbone. A andard copla has four lines; the la two are the e ribillo. Meanwhile, a andard e rofa has six lines; the la two are the letrilla. If the e rofas have six lines, the e ribillo is repeated aber the letrilla of each e rofa, and the entire copla is said in full at the very end as the tornada. If the e rofas have only four lines, the entire copla is repeated aber each e rofa.

VERNACULAR ORIGINALSPANISH

SANTO NIÑO

Estribillo

Letrilla

Batobalanì sa gugma, Sa daang tawo palanggà, KanamòmalooyKauntà N aKanimonan ilabà.

Ang sa Sugbong pagkadunggò

Sa mUá Katsilang tawo, Dinhi himpalgan Ikáw Sa usá nilang soldado, Kay kaniya nagpakità Gikan lamang sa Imong gugma. Kanamòmalooy,&c.

Imán dulce de mi amor, Dulce dueño enamorado, Socorred,Niñoagraciado, Alqueimploratufervor.

Al saquear e a ciudad, En una caja os hallaron, Y en Vos, ¡oh Niño!, encontraron El arca de la piedad, Y pues lo sois con verdad En toda pena y dolor. Socorred,&c.

SAN JOSÉ

Estribillo

Letrilla

Kay sa Dios kang gipalangga, Sa himayang lan2itnon: José,imokamíngpanlabanan Sakinabuhìugsakamatayon.

@ | _ } } ;:

Sa nanamkon na si María, Dilì mo ang mi erio hibaw·an, Gituyò nUa minUawon NUa mobulág ka kaniya: Kasakit nUa dakúng tuod, Makalilisang ug hatas·on. José, imo,&c.

Pagday’gon sa makalibo Ang labíng santos nUa kahoy, Kay sa Cruz dihâ gihimò Ni Jesús ang Iyang kalooy.

Estribillo

Pues de Dios llegas a verte

En el cielo gran privado: Sed,José,nue*roabogado Enlavidayenlamuerte.

> ` < :

Al ver encinta a María, Tanto mi erio ignorado, Confuso e abas pensando

En dejar su compañía: E e fue dolor muy fuerte, Muy terrible y dilatado. Sed,José,&c.

SANTA CRUZ

Alabado sea mil veces El santísimo madero De la Cruz, en que murió Jesús el remedio nue ro.

Copla

Estrofa

Man5amuyòkamíKanimo, NianangCruzn5anamatyanMo.

Kaynatawokaarónmagharì, Kaayohannamòn atanán: Kamíngmakasasalàtaban i, VirgensaBelénn aInahán.

¡Oh Inahán sa Dios ug Reina!, Pinilì ka sa mUá bulak, TunUód kanimo maluwás ang kalag Sa daghang mUá makasasalà.

Kaynatawoka,&c.

Puesnaci*eparareinar, Paratodosnue*roBien: Amparadlospecadores, VirgenMadredeBelén.

¡Oh Reina, Madre de Dios!, Fui e escogida en las flores, Por Vos se salvan las almas De los muchos pecadores.

Puesnaci e,&c.

Estrofa

Estribillo

Copla

Estrofa

Estribillo

Estrofa

Copla

Copla

JOYOUS STRAINS OF PRAYER

Iis con ru8ion predi2oses the gozos to music. Ie e rofas a8 as verses, and the copla a8s as the refrain or chorus. Iis type of musical poetry traces its root back to the klth century, surviving under related names in the Iberian peninsula. Catalans call them goigs. Valencians, gojos. Ca ilians, of course, gozos. Down the Pyrenees and across the Pillars of Hercules, gozos echoed in honour of our Lady, our Lord, or the saints, in processions and devotions, as thanksgiving for blessings, or as plea for favour. Ie name therefore befits, for what are gozos, but expressionsofgladness. Spanish gozo comes from Latin gaudium, which means interiorjoy. So gozos the musical poetry are, literally, overturesofrejoicingandexuberance. And, if you’re a kid sat with your grandmother in a pangadjê somewhere in Cabalían, trying to divine what snacks await the mananabat, the singing of the gozos signals something worthy of exultation. Painit is close at hand!

But before gozos could announce the temporal proximity of the painit, they fir needed to cross oceans. And cross they did! Fleets ferried the gozos from Iberia to America, and into the Islands. Friars taught them to the natives, and our forebears embosomed the gozos. In so doing, they melded the peninsular and the insular, repurposing epic chanting for the preservation of the faith. Under the aegis of Chri ianity, the feats and trials of heroes surrendered to the virtues and miracles of the saints.

Recognising how this poetry in song forms a piece of the mosaic that is our intangible patrimony, we worked towards colle8ing all surviving Catholic gozos in Cabalían, together with the jaculatorias, the plegarias, the trisagios, and the letanías. In terms of form, our gozos can be grouped in three: fir , the andard form, with all the shebang (copla + e ribillo,e rofa + letrilla); second, the alternative form, with neither e ribillo in the copla, nor letrilla in the e rofas; la , the truncated form, with only an e ribillo aber the e rofas. In the preceding page, Santo Niño’s and San José’s gozos are in the fir form; the gozos of Our Lady of Bethlehem are in the second form; and Santa Cruz’s gozos are in the third form. All other gozos are in the fir form, except those of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, and of our patron, Saint John the Bapti (see p. E), which are both in the second form.

CABALÍAN 1

Ie copla normally begins the gozos, then closes it as the tornada or vuelta. Iis is true in the andard and alternative forms. In the truncated form, however, the fir e rofa opens the gozos. Yet this rule adju s to how the novena prints the text. Case in point is the gozos of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, ru8ured in the second form, yet open with the fir e rofa rather than the copla. Bottomline is that, whereas joy arises when the body processes certain known hormones, there are many triggers that prompt their release. Which is an elaborate way of saying that, while gozos are quantifiable and qualifiable, they remain impermanent.

Ieir tonadas, at lea , so to say. So to preserve these tones from the ill effe8s of time, we colle8ed recordings, and sent copies for safekeeping in the Philippine Women’s University. However, the task is far from complete, as we ill have no recording of the gozos from Somojê, Sun·ok, and Basák, which were only recited at the time colle8ion was progressing. Nevertheless, we can report that our inventory regi ers at lea eleven unique tonadas, of which five are shared in multiple geographies: Agay· ay with Osao; San José with Loóg, Timbà, and Bobón; Dayanog with the parish patronal novena; Pong·oy with Anislag; and the enclave of Inakapa with Minoyhò. Variations attend these shared tonadas. Anislag, for example, sings the e rofas an o8ave lower than Pong·oy does. On top of repeating the e rofa (to account for the extra verse), Osao resolves the e ribillo with a cadence different from what Agay·ay sings. Minoyhò and Inakapa diverge in the la verse as well as in the fir two verses of the copla.

But why catalogue these religious rains? Surely, we’ve outgrown the urge to run to our chapels, whenever haloed crones inchoate the gozos over the megaphone, ju to munch on that free nosh aber the Ave,Maríapurísima,sin pecado concebida. Can’t we ju leave it to the passage of time to either hallow these ditties in our memory, or consign them to oblivion? All things considered, we ill cannot arre obsolescence. Why bother then? Familiarity breeds contempt, true, raritybringsadmiration. Under this two-pronged principle operates the hotte vogue to pass over the native and gander at the foreign, to reje8 the onerous and embrace the comfortable.

Boxed above are sections where a notable difference appears in the four gozos. These boxes highlight those areas where the hypothetical original tonada received—for a lack of better term—embellishments. While the boxes tell us that melodies do undergo evolution attendant to the change of their associated demographic, they do not tell us which one is older or better or closer to the protomelody. Elaboration, simplification, and alteration, such as the ones seen above, are amongst the plethora of evolutionary tendencies observable in orally-transmitted melodies.

Disdain for the habitual leads some people to disregard the time-honoured tonadas of our gozos in favour of newfangled beats from other places. Pursuit of ease incites others to forego singing altogether! When human beings mediate to obliterate, alarm bells sound. Any effort in favour of preservation goes a very long way. Hence, we catalogue our own gozos.

Gozos are musical tokens of our humanity, poetic echoes of our in in8 to form a society. Iey remind us that, before we were humans epoxied to a little screen in our hand, we were humans intera8ing with others in community. Depositing gozos offers future generations an opportunity to access them, look back and say, “Ah, this is how our forefathers prayed!”

⁂

S ? > , Singing the gozos (DE June Dokn): Dei præsidiosuffultus. Accessed km September DoDl https://dei praesidiosuffultus.wordpress.com/Dokn/on/DE/singing-the -gozos/ R > A? < E ` Å > , gozo:Diccionariodela lenguae?añola (Madrid DokE; updated online version Dl.h November DoDl). Accessed Ç May DoDE https://dle.rae.es/ gozo

G ` E ? ?> `É C ; > , goigs: Gran enciclopèdiadelamúsica (Barcelona kÇÇÇ–Dool). Accessed DF March DoDE https://www.enciclopedia.cat/gran-enciclope dia-de-la-musica/goigs

J ; B > G ?@, Los goigs en Cataluña: Revi adefolklore (Fk kÇFh) Fk–Fn. Accessed F January DoDE https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/mÇFmk/ bmcFkÇEl

A. D. 2024 17

San José 1 Bobón 2 Loóg 3 Timbà 4v. | hu·yág | /hu'jag/

. u n kuluk did n k ihu n s s . : to condu a shouting match from outside another’s house

Th0 mistr0ss is asham0d, b0caus0 th0 2if0 shout dath rfromoutsid h rhous .

@ ` , no other experience allows us to hear the phonetic barrage and morphophonemic caprice of Cabalianon 2eech, a language famed for its belligerent intonation, than witnessing a fight between two women, where one woman ends up cornered inside her house while the other recounts in an amplified voice her colourful misdeeds from outside. Cabalianon women forged the time-honoured principles governing the art of huyág centuries before Sun Tzu could think about composing the thirteen chapters that eventually made up Eeartofwar. Black Agnes prevailed whil under siege because her foes were English men. Hi ory would have gone in a different traje8ory had she faced a battalion of Cabalianon women. Iey would blockade the ca le, and initiate a word war in a swirling cloud of ta8ical hi rionics and theatrical balli ics that would put today’s Juilliard and We Point out of business. Hellhathnofurylikeawomanscorned, claims the adage. We say, hellhathnofurylikeaCabalianonwomanscorned. When someone wrongs her brood, or flirts with her 2ouse, she would march with the might of her fearsome ance resses to defend her injured honour, and confront the malefa8ress in her own turf, and there proceeds to dress her down for all the onlookers to see and hear. Bladed weapons wound the visible flesh, aye, but bladed words wound the invisible soul. Iough huyág permits no bloodbath, the de ru8ion it causes can obtimes be total.

T;@ , we Filipinos are a mother-loving people. We love our mothers to a fault. Our fir encounter with human love was in the womb that carried us for nine months, and in the paps that suckled us for the fir years of our lives. And that love, that adoration, extends to the home that sheltered our fir memories, to the land that browned our unshod feet, and to the air that infle8ed our disarming 2eech.

Ie motherland, our hometown, penetrates our very being, moulds our very psyche, and colours our very chara8er. Hiding this conne8ion behind pretences and affe8ations amounts to moral treason. So, in a chorus that embraces both the pitch perfe8 and the tone deaf, each of us here ca s our individual declaration: Cabalianonko. I am a Cabalianon.

C b lí n, tú pu5blo mu pulcro, Tierna madre de prole vivaz, D0sd0 cuna 9 hasta s0pulcro, Te loemos ceñida de paz.

Ideoamnostouqeouoairwnthnamartiantoukosmou