CABALÍAN AHORA · POR SIEMPRE · Y PARA SIEMPRE A PUBLICATION ABOUT OUR BELOVED HOMETOWN . ⁂ . . MagellaninCabalían? Earthquakes,eruptions Alanguageofourown 14 10 ¡Ho , b kî! Aj p s lí s d kún lin , K mo bót n d kún hu , ¡Mob lik k s d kún likî! 6 © USS KIDD © RPBUSHCRAFT

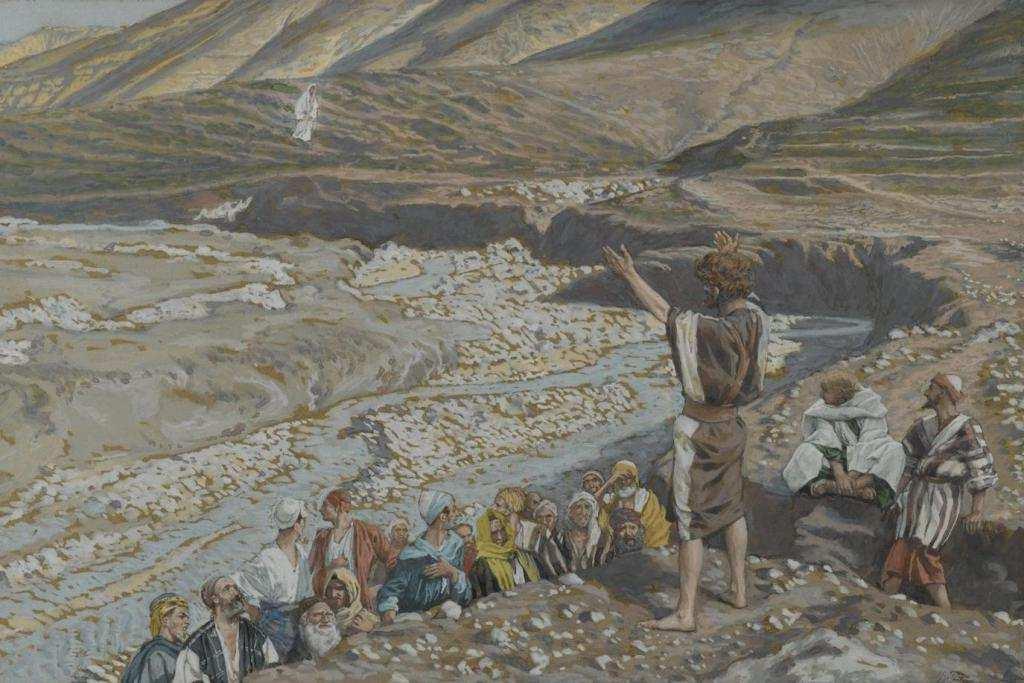

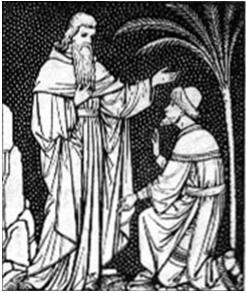

IN NATIVITATE S. IOANNIS BAPTISTÆ

Antiphona

Luc. C , DE, DF

P , qui natus e nobis, plus quam prophéta e : hic e enim, de quo Salvátor ait: Inter natos mulíerum non surréxit maior Ioánne Baptí a. v I e puer magnus coram Dómino. r Nam et manus eius cum ipso e . Orémus.

DIE 24 IUNII Oratio

D, qui præséntem diem honorábilem nobis in beáti Ioánnis nativitáte fecí i : da pópulis tuis 2irituálium grátiam gaudiórum ; et ómnium fidélium mentes dírige in viam salútis ætérnæ. Per Dóminum no rum Iesum Chri um Fílium tuum : qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus San8i, Deus : per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum. Amen.

Sa walâ pa ug sumidlak Ang adlaw sa katarun ̃an, Daan nang natawo si San Juan, N ̃a napunô sa kasidlak.

artwork: : ; < = < > ?@< >A> Et misit Dominus manum suam, et tetigit os meum. Ierem. , . Attendite, popule de longe : Dñs ab utero vocavit me. Is. "# ", $.

; I . Not all the time, of course. Ju during summer. Rizal famously averred that the Philippines suffers cuatro meses de lodo, cuatro meses de polvo, y cuatro meses de todo. We endure four months each of mud, du , and everything! So, when the sun personally visits us everyday for one trime er to desiccate Cabalían’s loamy terroir, we hallucinate about fro ier climes and chillier times. Humidity takes our imagination to unusual places. If we are not careful, we can end up wishing it snowed in the country. But the thought of what could happen to the kalamunggay and the bonbonaw in a whiteout recalls us to our sweltering reality.

Cry allised dihydrogen oxide is, therefore, out of the que ion. We’ll have to make do with what we have: HDO in liquid ate. As it turns out, water figures prominently in our culture and hi ory. Our ance ors raised settlements close to bodies of water: Cabalían retches along the coa line of a bay, crisscrossed by multiple rivers, blessed with a lake oppering a volcano. Our written and 2oken hi ory arts with an encounter with explorers sailing our sea and berthing in our inlet. So, when it’s time for lads to have their schmucks supercised, Cabalían kicks off her ismagol, and proceeds to waddle in her ony beaches, or plunge into her weired rivers.

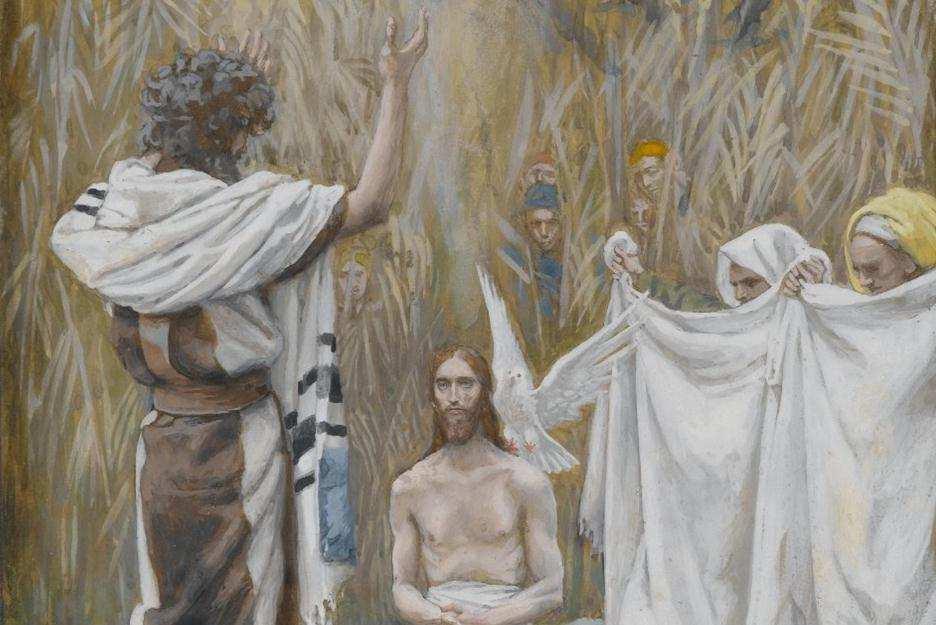

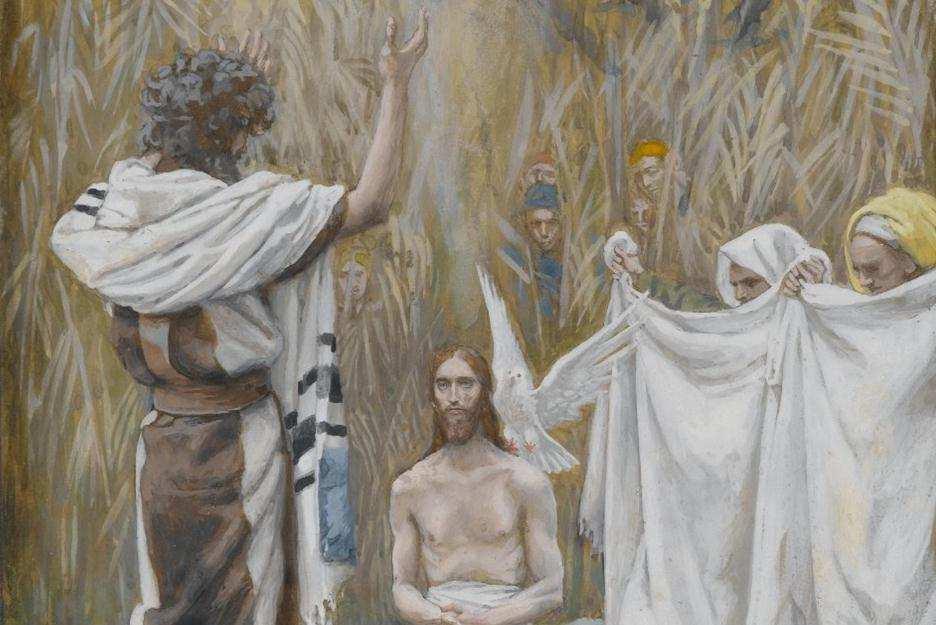

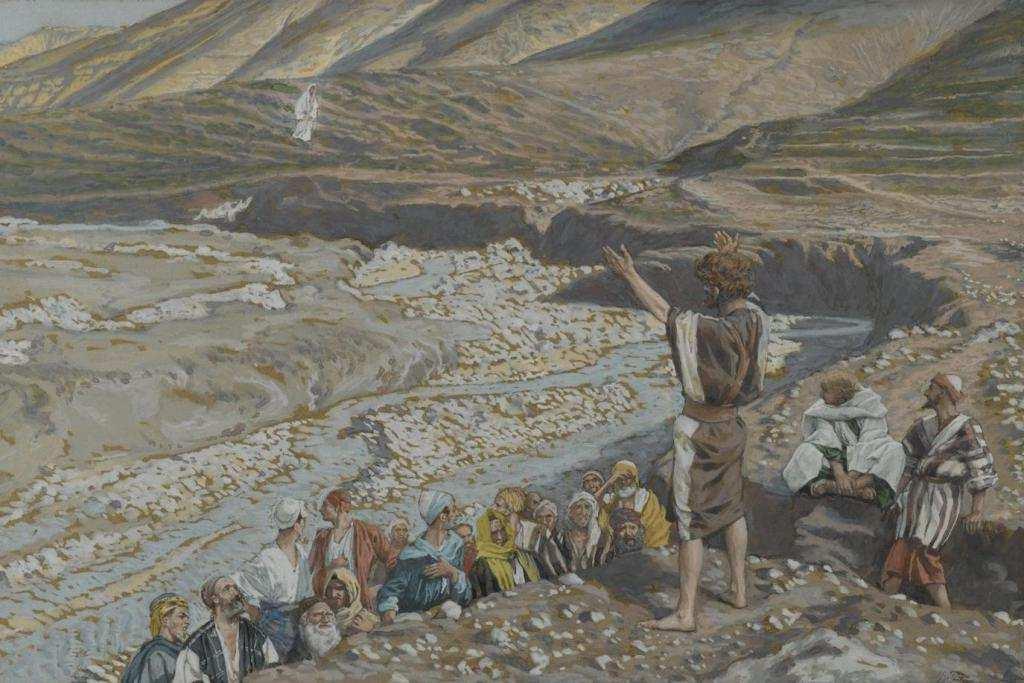

Mo of all, our patron and titular is ὁ Βαπτιστής, who baptised with water (Lk. , ^_). His intercession for us is very powerful, he even sends us a drizzle whenever we process his likeness through our reets. Lately, revellers have picked up the habit of dousing passersby with water during his birthday. (Assessed through its popularity, it needs no further endorsement to carry on.) One way or another, water, with its limitless manife ations, leads us back to Cabalían.

For que'ions, comments, sugge'ions, and submissions, please reach us through the following: cabalianonko.wordpress.com

tagibtiban@gmail.com/cabalianonko.bsml@cabalianon_ko

⁂ . . . DRAUGHTING

A. D. 2023 3

CABALÍAN

NOTES

G, Cri o, Ginoo, Jesús, Jesús, Dios Amahán sa laneit, Dios Anák Manunubos sa kalibotan, Dios E2íritu Santo, Santa Trinidad, Dios nea usá, San Juan Bauti a, San Juan, nea gipadalá ka sa Dios, ug gisaad sa ángel kang Zacarías, San Juan, nea gipanamkon ka tuneod sa pag·ampò labí pa sa kinaiyahan, San Juan, nea kahibudnean kang nahimugsò sa sabakán sa harianong katigulang ug giineóng apuli,

malooy Ka. malooy Ka. malooy Ka. dungga kamí. patalinghugi kamí. kaloy·i kamí. kaloy·i kamí. kaloy·i kamí. kaloy·i kamí. ipan aliya mo kamí. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya.

CABALÍAN 1 4

LETANÍA NI SAN JUAN BAUTISTA

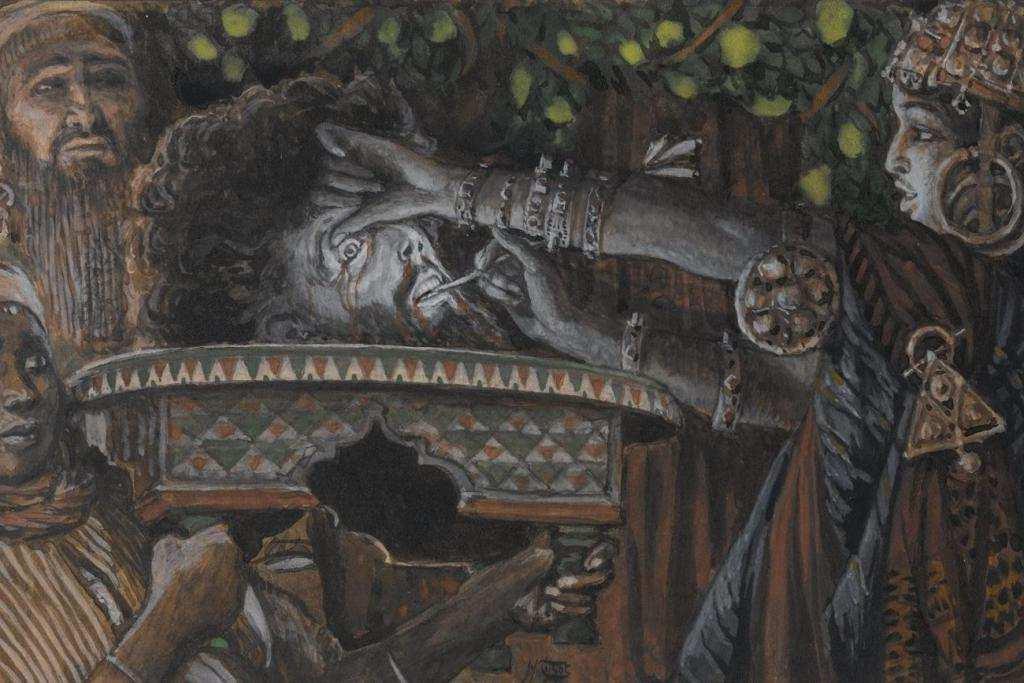

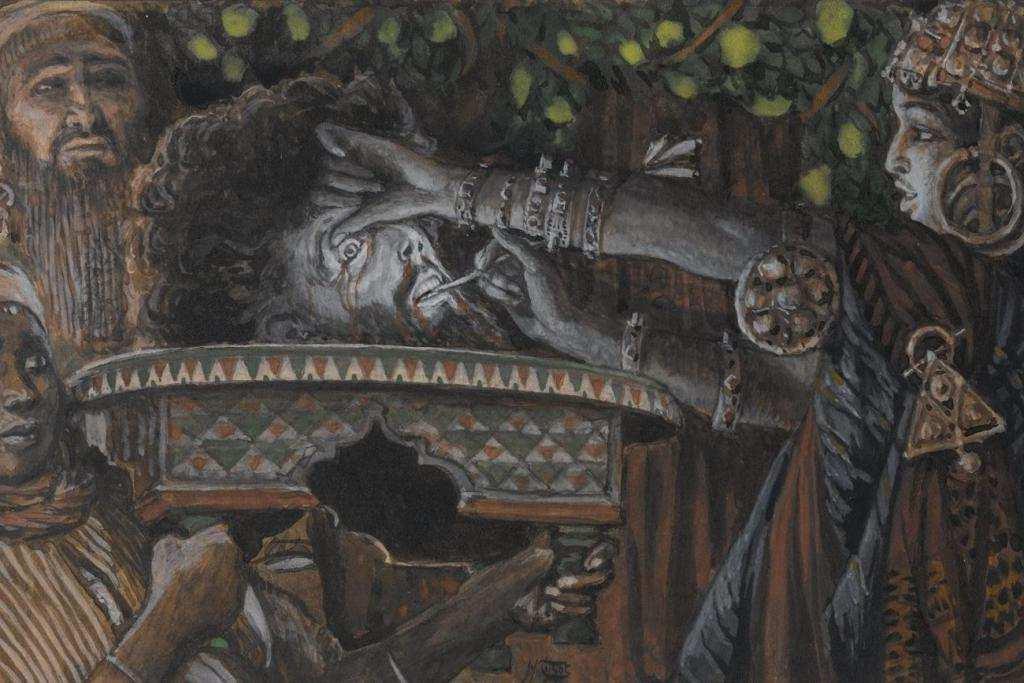

Artwork depicting the novena meditations of Saint J ohn’s life ©

BROOKLYN MUSEUM.

LETANÍA NI SAN JUAN BAUTISTA

San Juan, nea gibalaan ka ni Jesucri o sa sulód sa tagoangkan ni Isabel, sa walâ pa Siyá matawo, San Juan, nea gihupóng ka sa E2íritu Santo sa sulód sa tiyán sa imong inahán, San Juan, nea gigasahan ka ni Gabriel ug sa amáng mong amahán niining maóng nealan, San Juan, nea nahimo kang katinealahan ug timaan sa kalipay, San Juan, nea madasigon ka uyamut nea molupyò sa kamineawan sukád sa pagkapuyá, San Juan, nea inamuma ka dihâ sa pamatasan sa meá ángel ug dilì sa meá tawo, San Juan, nea sinukbotan ka sa panit sa camello ug sa kanding, San Juan, nea gitawág ka ni Cri o nea labáw sa tanáng meá inanák sa meá babaye, San Juan, nea dakû kang profeta ug labáw pa sa profeta sa atubanean sa Ginoo, San Juan, nea halangdon ka uyamut ug mapaubsanon uyamut sa neatanán, San Juan, nea walâ kay salâ uyamut ug malig·on uyamut sa pagpenitencia sa neatanán, San Juan, nea profeta kang gituga sa Ginoo neadto sa meá Gentil, San Juan, nea nagauná ka sa agianan sa Mesías dihâ sa e2íritu ug virtud ni Elías, San Juan, nea nagasangyaw ka sa bunyag sa makaluwas nea paghinulsol, San Juan, nea tineog ka nea nagasinggit: andama ninyo ang dalan sa Ginoo, San Juan, nea ginatudlo mo ang Cordero sa Dios nea nagawagtang sa salâ, San Juan, nea nagasaksi ka sa matuod ug dilì binuhat nea kahayag, San Juan, nea giilá kang matuod nea kahayag gumikan sa imong kaanggid, San Juan, nea iwag ka nea masanagon uyamut nea nagadilaáb ug nagadan·ag, San Juan, nea nagabunyag ka ni Cri o sa Jordán, San Juan, nea bulahan ka uyamut nea tigpugás sa bag·ong balaod ug sa putling tambag, San Juan, nea nagasagda ka ni Herodes mahituneód kang Herodías nea asawa sa iyang igsoon,

ipan aliya mo kamí. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya.

ipan aliya. ipan aliya. ipan aliya. namong m á makasasalà, O maaghop uyamut n a Jesús. luwasá kamí, O Jesús. luwasá. luwasá. luwasá. luwasá. nagapan amuyò kamí Kanimo, O Jesús. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. nagapan amuyò. pasayloa kamí, Ginoo. pamatia kamí, Ginoo. kaloy·i kamí, Ginoo.

San Juan, nea gitambog ka sa bilanggoán alang sa kamatuoran ug kaputlì, San Juan, nea gipunggotan ka ug ulo isip pahalipay sa mahilas nea sumasayáw, Magmapuaneoron Ka, Sa tanáng kadautan, ug sa tanáng kasal·anan, Sa tanáng naghineapíng kalineáw sa ilimnon ug kalan·on, Sa tanáng kahumok sa meá sapót, Sa tanáng kailibgon sa meá paneagpas, Sa tanáng kabuta sa hunàhunà ug kagahì sa kasingkasing, Tuneód sa dilì mabatbat mong Maneuneuna, Arón dumtan namò ang meá panglumáy niining kalibotan, Arón magapalabón kamí sa pagpalandong ug sa pagpasakop sa kasingkasing, Arón magasaksi kamí sa kahayag dihâ sa pulong ug sa buhat, Arón magapabilin kamíng putlì sa kalág ug sa lawas, Arón mahimò kamíng hingpit nea mapaubsanon ug mahinulsolon, Arón sa kinabuhì magapuyô kamíng mabinantayon, matarong, ug maalampoon, Arón takús mong itugot kanamò nea mamatáy sa kamatayon sa meá matarong, Cordero sa Dios, nea nagawagtang sa salâ sa kalibotan, Cordero sa Dios, nea nagawagtang sa salâ sa kalibotan, Cordero sa Dios, nea nagawagtang sa salâ sa kalibotan, v Ig·ampò mo kamí, San Juan Bauti a, Precursor ni Cri o.

r Arón mahimò kamíng takús sa meá saad Niya.

Mag·ampò kitá.

OD , nea gihimò Mo kiníng adlawa sa pagkatawo ni San Juan Bauti a nea takús namong pagapasidunggan: itugot sa Imong meá lungsod ang gracia sa meá kalipay nea e2irituhanon; ug mandoi ang meá kasingkasing sa meá cri ianos neatanán sa matuod nea dalan sa kahimayaan. Tuneód ni Jesucri o nea among Ginoo.

r Amén.

A. D. 2023 5

Pag·ampò

MAGELLAN IN CABALÌAN?

< ’ se8ion on toponymic origins li ed the broken ma0 as the fir possible source of Cabalían’s name. In the fir version of this theory, the rong winds of a squall are thought to have been re2onsible for breaking a ma in one of the vessels of the fir European fleet ever to sail around the world. It is, therefore, fitting that we open this second issue with an analysis of a ory that has anchored itself in the bedrock of our folk memory.

But fir things, fir . As we will be tackling some legendary weather anomaly here, we will hereaxer refer to Magellan in Portuguese, Fernão de Magalhães, because, well, why not? If our readership thinks they can endure our meanderings, then they’re very much welcome to accompany us as we wa e our time examining this town lore of ours, trafficked from one generation to another, and embroidered in many places with details innocuous enough to enjoy mode disregard, discrete enough to disinvite massive su2icion, and sentimental enough to nurse our amour propre. Not that many details, yes, but ju enough to render separating imagination from reality at this point a significantly

taxing task.

What could possibly make this enterprise taxing? Well, top in our li of ob acles is the absence of any surviving notarial a8 from this expedition, 2ecifically the segment where the fleet sojourned over the waters of our archipelago. te renowned armada de Maluco reached our isles with three ships (kudos to Magalhães for such rare feat!), and each of these ships had a notary among its crew: León de E2eleta in the Trinidad; Antônio da Co a, originally notary of the Santiago, which capsized in a squall in the Santa Cruz River on DD May ^vDw, also in the Trinidad; Sancho de Heredia in the Concepción; and Martín Méndez in the Vi,oria.

CABALÍAN 1 6

Separating fact from fiction

Plenty of escribanos, right? Yet not one of their penned writs survive. As they perished, so did their papers. E2eleta and Heredia died in the po -Ma8án banquet ambush orche rated in Cebú on ^ May ^vD^. Méndez did complete the circumnavigation, but was apprehended by the Portuguese at Cabo Verde, only to be released later and return to Spain on ^v O8ober ^vDD. Co a attempted the return voyage on board the Trinidad, but was seque ered by the Portuguese in Maluku. te la notary, Gerónimo Guerra, found himself back in Spain earlier than Méndez, on _ May ^vD^, together with the mutinied crew of the San Antonio.

Where the notaries failed, others ood to the occasion and proved their mettle. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian nobleman from Vicenza who arrived in the imperial court in Barcelona in the company of the papal nuncio Francesco Chiericati, accepted as a supernumerary in the Trinidad upon recommendation of Charles V himself, kept a journal of his a8ivities. Pigafetta, who had composed this personal diary and travel guide hybrid in Venetian 2rinkled with Spanish and Italian, fir di ributed handwritten copies to his patrons, many of which are

now lo . Andrea da Mo o published a critical edition of this journal based on an original version in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Next, Francisco Albo (Φρα~ίσκος Ἄλβος or Κάλβος in Greek), a native of the island of Chios (Χίος in Greek) who had settled in Seville as a certified pilot, enrolled as a sailor in the Trinidad, kept a logbook detailing in almo bare nautical terms the progress of the expedition. At present, the logbook, which has been assessed to be more accurate in terms of cartographical positioning that Pigafetta’s diary, is safeguarded in the Archivo General de Indias.

La ly, Ginés de Mafra, an Andalusian sailor from Jerez de la Frontera in Cádiz, one of the four survivors from the Trinidad, wrote his recolle8ions of the Magalhães expedition only when he was back (and temporarily randed pending ship repairs) in the Philippines as part of the Villalobos expedition. His manuscript changed hands multiple times before reaching Spain axer transcription by another editor, lay forgotten in the Archivo General de Indias for almo four centuries, and was finally published shortly axer its fortuitous discovery in ^àDw.

A. D. 2023 7

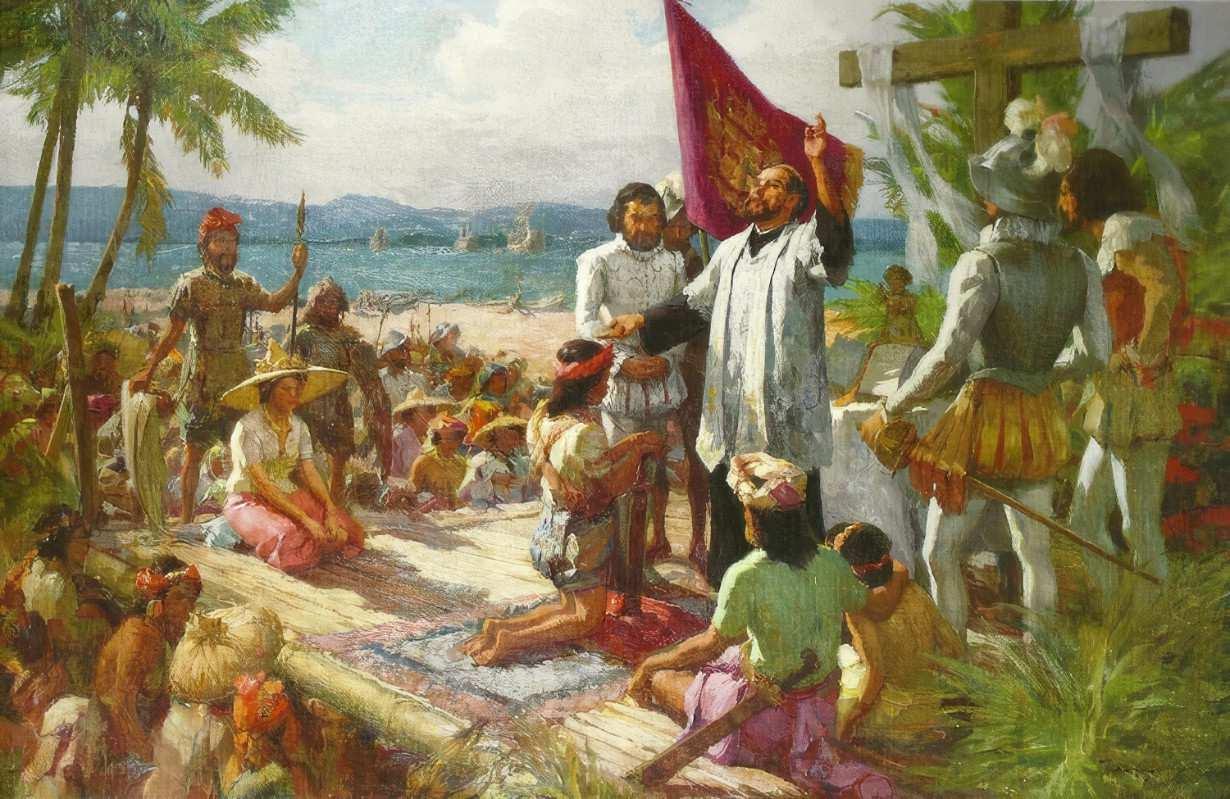

Chilean painter Guillermo Muñoz Vera reimagines in this majestic piece the moment the three remaining vessels— the Victoria, the Trinidad, and the Concepción—of the armada de Maluco crossed the Strait of Magellan.

© FUNDACIÓN ARTE Y AUTORES CONTEMPORÁNEOS

MAGELLAN IN CABALÍAN?

Of these three, only Pigafetta noted events that we can scrutinise for any Cabalianon involvement. And he delivers the following passage to our hungering eyes:

On Holy Monday, the twenty-fifth of March, feast day of our Lady[’s Annunciation], […] we sailed between west and southwest, amid four islands, namely, Cenalo, Hiunanghan, Ibusson, and Abarien.

Hmn, do these four islands sound familiar? Of course, they sound familiar! Cenalo is Silago, Hiunanghan is Hinunan an, Ibusson is Gibusong, and Abarien is Cabalían. But wait! Silago, Hinunanean, and Cabalían are not islands. Worry not. te term island applied to all four places implies that the fleet assumed to be islands those land formations separated from each other by a body of water, without verifying whether said water was salt or fresh. Influenced by a gamut of fa8ors, the explorers incorre8ly concluded that the great waterways separating these present municipalities were sea channels. tis inference was by no means irregular. Precedent to this misclassification of rivers as raits is Magalhães’ hunch that the Río de la Plata was a shortcut conne8ing the Atlantic to the Pacific, ultimately disproved axer the entire armada probed the watery passage and discovered that it lo its salinity further ahead.

Pigafetta, therefore, offers evidence that the Magalhães expedition sighted Cabalían on Dv March ^vD^. But what about the orm that broke the ma ? Since Albo’s Derrotero and Mafra’s Libro decided to forego describing the 2ecifics of this transit, we then consult the fir account of the voyage ever published, von Sevenborgen’s De Moluccis Insulis, bylined with the author’s Latin name Maximilianus Transylvanus.

Axer the Vi,oria arrived back at Sanlúcar de Barrameda on _ September ^vDD, the surviving crew, headed by Juan Seba ián de Elcano, Francisco Albo, and Hernando de Bu amante, presented themselves before the imperial court at Valladolid. Here, in the course of their ay, they recounted the voyage to the Dutch humani Maximiliaen von Sevenborgen, who served as secretary to Charles V, and

claimed affinity through his wife as nephew-inlaw to one of the expedition’s financiers, Cristóbal de Haro, who was brother to Diego de Haro, and uncle to Diego’s daughter Francisca. Sevenborgen produced his Latin tra8 as a letter to Cardinal Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg, archbishop of Salzburg. A copy of this letter reaching printers resulted in its fir publication in ^vDä.

Sevenborgen reports the following events axer Homonhón:

Having restocked water in Acacan, they set sail towards Selani. Here an adverse tempest caught them, such that they could not bring seacrafts to land in the island, and they were instead driven to another island Massana.

tis time, the placenames sound alien. But because scholars have already perused the text before us, the identity of the places does not eddy for long in the realm of the esoteric. Acacan, which comes across as a corrupt Latinisation of Aguada, is Homonhón. Selani is usually identified as Panaón; whereas Massana, usually identified as Limasawà, is the geographical location of the fir Mass in Philippine territory attended by natives.

We’ll segue for a bit and explain why there is a qualification above. te fleet was already in Homonhón on ^ã March, which was Passion Sunday in ^vD^, traditionally called domingo de Lázaro, a holdover from the Mozarabic liturgy which patently evokes in its propers the raising of Lazarus, formerly reading at Mass Jn. = , ^–và. (te Roman liturgy reads a different pericope, Jn. C , E_–và.) Motivated by this, Magalhães baptised Samar and Leyte as the archipiélago de San Lázaro. te following Sunday was already Palm Sunday, what we call domingo de ramos. It would be prepo erous to think that P. Pedro de Valderrama did not offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass on these two Sundays, as well as on the intervening Lenten ferias.

Now, we go back to our regular programming. Two days into Holy Week, the fleet lex Homonhón, and reached the next port three days later, at the beginning of the Sacred Triduum. Notice what the text tells us about what happened when the fleet tried to approach Se-

CABALÍAN 1 8

lani. It confides that “an adverse tempe0 caught [the fleet]”. In other words, whil Magalhães attempted transit from Homonhón to Selani, sailing over the waters bordered by Silago, Hinunanean, Gibusong, and Cabalían, a squall or brief orm drove him in ead to Massana.

In Spanish nautical parlance, such tempe or squall at sea, typically a rain shower accompanied by heavy wind, or a sudden dark cloud in the horizon, is called a chubasco. Itself descended from chuvasco via a Portuguese or Galician pathway, Spanish chubasco sired the Visayan subasko.

Two points arise from these fa8oids: fir , Magalhães did indeed pass near Cabalían; and, second, there was a subasko during the sailby. Yet the million-dollar que ion remains for us:

Did a subasko dema one of Magalhães’ three ships? te answer is a qualified negative, in the sense that, while it is not outside the realm of possibility that a squall with sufficient wind force can dema a ship, the chronicles do not mention such accident. Neither Pigafetta nor von Sevenborgen implies that this happened. terefore, we cannot say that hi ory supports the legend that Cabalían was named axer a broken ma . And, as for the conta8 between Cabalianon natives and Spaniards, the records do not atte that this tran2ired during Magalhães’ expedition. However, Legazpi’s fleet did indeed intera8 with our ance ors, a hi orical jun8ure that deserves a separate treatment, so we will op now, and calendar this topic to the next issue in DwDE.

REFERENCES

G ë M : , ed. A ; B>íAì A I D >î Aî > , Libro que trata del descubrimiento y principio del e0recho que se llama de Magallanes (Madrid ^àDw).

F ? ? A>ï , ed. M ;ñ F í A NC ; , Derrotero del viaje de Magallanes desde el cabo de San Agu0ín en el Brasil, ha0a el regreso a E>aña de la nao Vi,oria (Madrid ^Fäã).

A ; P î : ;; , ed. A M ; , Relazione sul primo viaggio intorno al globo (Rome ^FàE).

M = < > C S C ï î , De Moluccis Insulis (Cologne ^vDä).

Missale Mozarabicum (Toledo ^vww).

Orationale Visigothicum (Tarragona c. ãäE).

Sacramentarium Toletanum (Toledoc. àww). Manuale Hi>alense (Seville ^EàE).

⁂

A. D. 2023 9

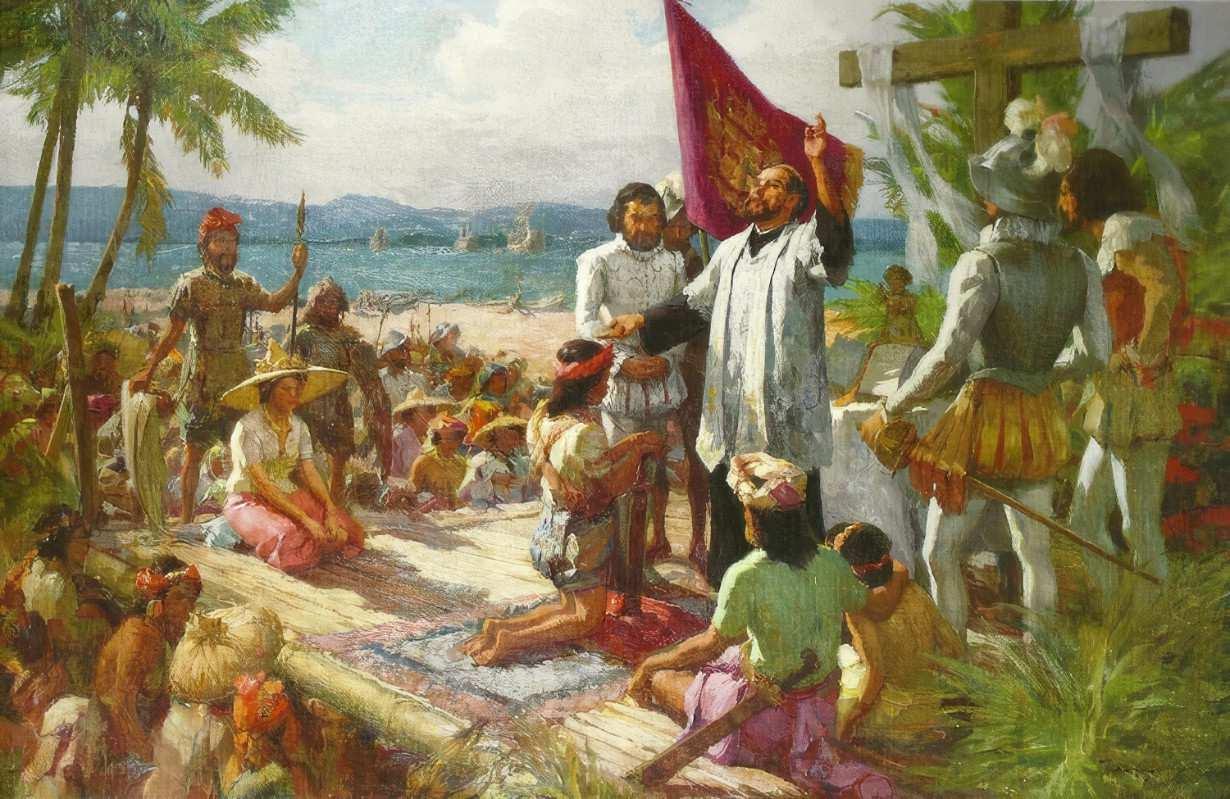

Fernando Amorsolo portrays in this scene the baptism of Humabon, the ruler of Cebú, whilst his chief consort, Humamay, sitting on the gospel side of the temporary altar, watches the proceedings. At this point, P. Pedro de Valderrama is infusing baptismal water on the baptisand’s head, according to the use of Seville.

© AYALA MUSEUM

ARTH UAKES

RUPTIONS

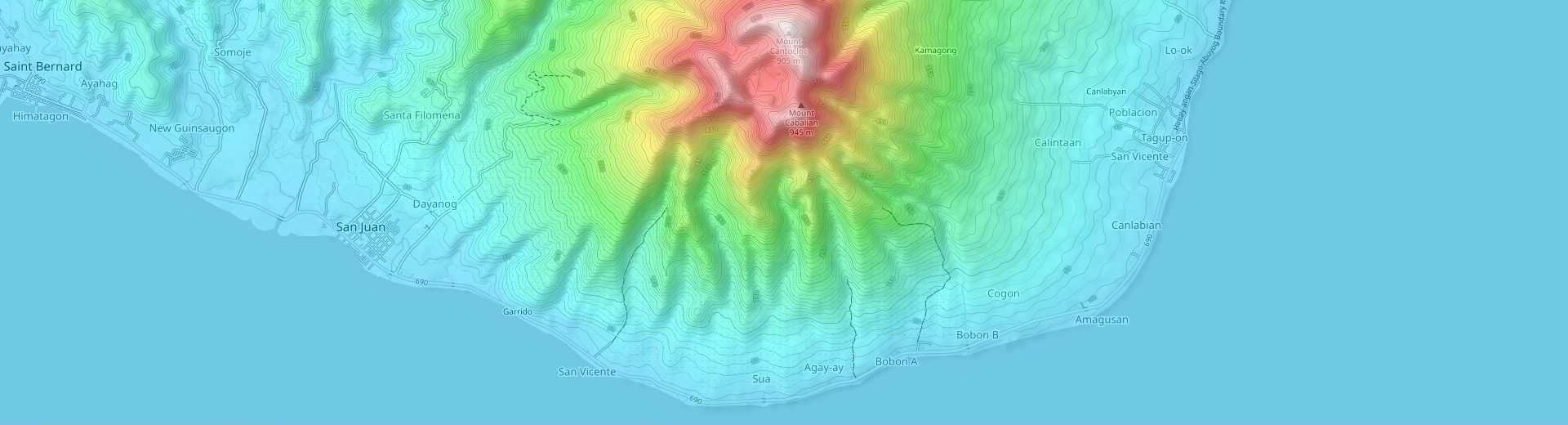

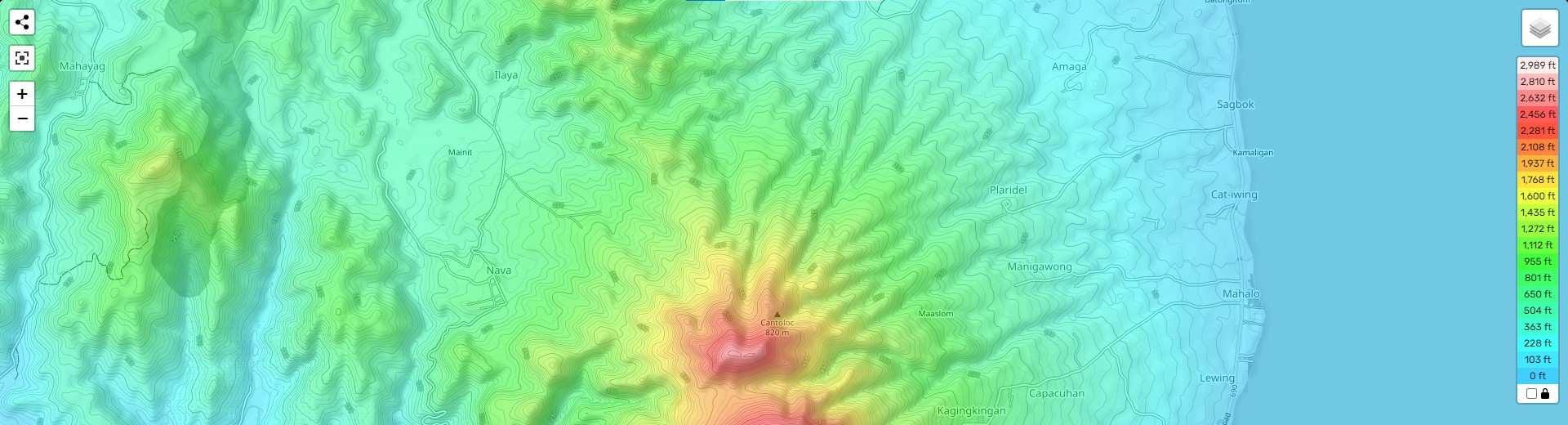

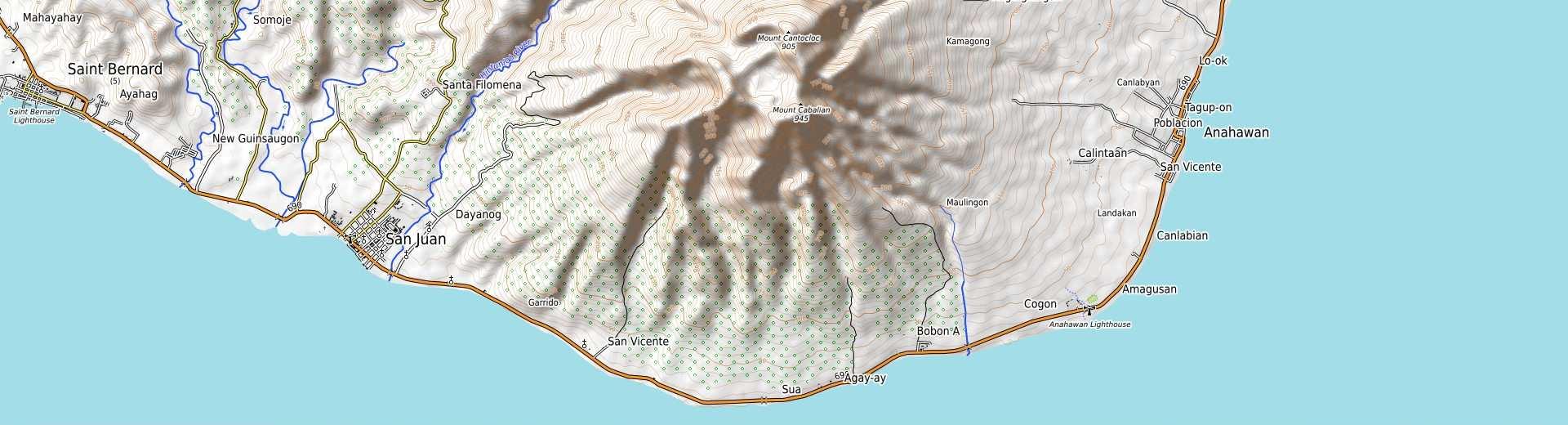

;@ ò ? : ? î : : sits the tiny archipelago that we call home, the Philippine Islands. In their mid runs the complex te8onic boundary of the Eurasian Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate, bounded to the we by the Manila Trench, and to the ea by the Philippine Trench. Close to the Philippine Trench lies the island of Leyte, traversed by the Leyte Central Fault. Around ^w kilometres southea of the fault’s terminus, a àEv-metre volcano rises like a teatless boob from an F.v-kilometre base.

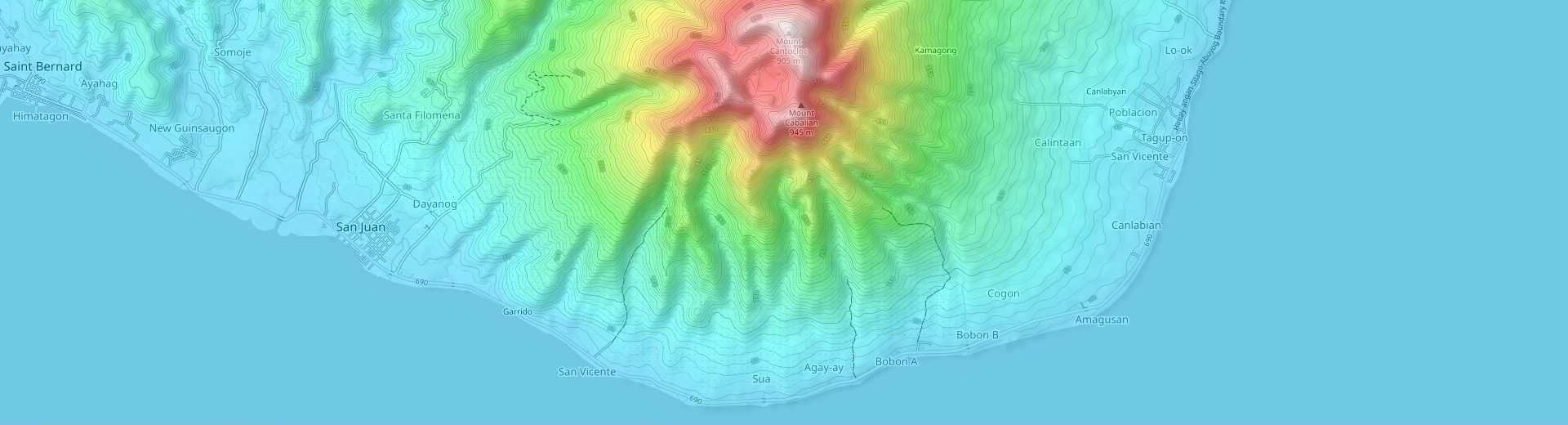

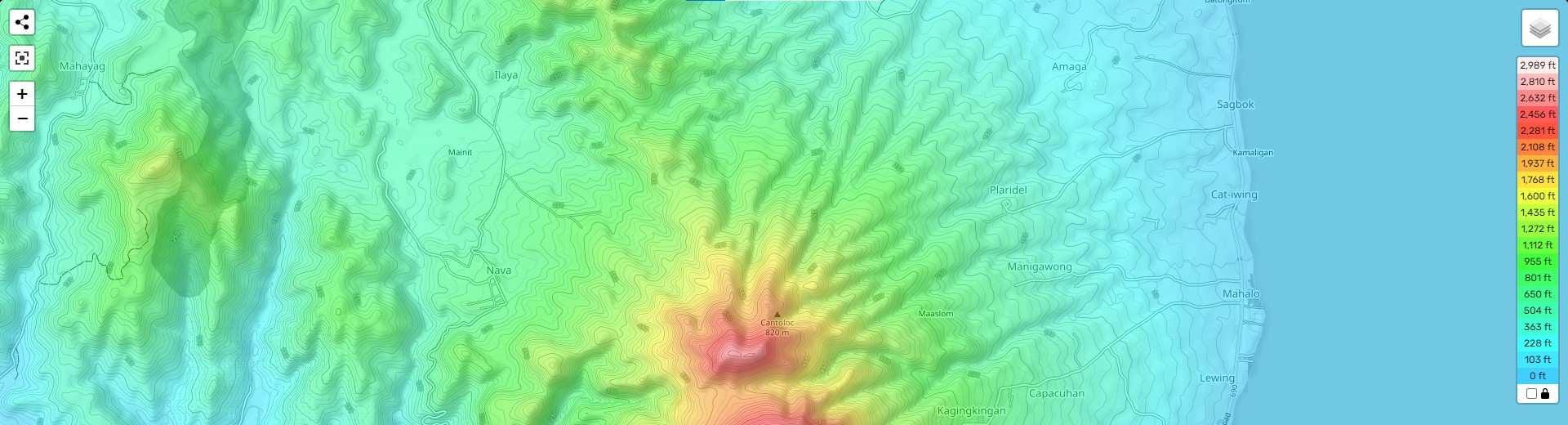

Cartographers plotted this unnippled bosom as Mount Cabalían, but we have always called it Kantayoktok. An a8ive ratovolcano, whose deep green slopes gli en blue from afar, it harbours a lake vww metres wide in its crater, and ãää metres above sea level. Cabalianons refer to this lake simply as danaw (because this is the Philippine word for pool or lake), in the same way our compatriots living near Hitunlob River refer to it simply as subâ or tubig.

Unknown to many, there is another volcano next to Kantayoktok, and this is what maps label as Mount Cantoloc. (One volcano is more than enough. A sy em of two volcanoes? Nah,

CABALÍAN

that’s grand overkill!) Many would notice that this name su2iciously resembles Kantayoktok, as though someone poshified Kantayoktok into Kantoktok, then corrupted it into Kantoklok, and finally reduced it to Kantolók, rendering it in colonial orthography as Cantoloc. And this observation is probably right, attributable to miscommunication between visiting geologi s and local busybodies. Fortunately, this ratovolcano is ina8ive, so, apart from the 2ark of intere the lingui ic barrier that misrecorded its name rikes up in us (all too common in Philippine narratives of protoencounters), we shall ignore this geological formation for now.

1 10

Life in the foothills of a ticking timebomb

tat way, we return to our a8ive andesitic volcano, which visits our dreams with 2inetingling visions of cata rophe. We cannot escape them. We are, axer all, geographically predi2osed, e2ecially because south from the shores of Cabalían lie the segmented submarine portions of the Philippine Fault crossing Surigao Strait with a number of di in8 rands. And faults and earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are all interrelated. When a fault slips, it can trigger an earthquake. When a fault slips near a volcano, it can trigger an eruption. In less raightforward terms, when the earth shivers, something is bo to blow a fuse.

But has this volcano blown a fuse already? It’s qu tempting que ion we’re not ready to answer. But sci foils our hesitation. Kantayoktok’s la known erupt based on the radiocarbon data of the pyrocla ic-flow deposit in Cabalían, occurred between ^ãàw and ^Fvw ^FDw ± äw years. By any chance, did somebody docume this eruption? tis seems to be case. te Augu inian Fray Agu ín María de Ca ro described the seismic a8 ities in Leyte, during his ation in Jaro and later lang. His Order had sent him and other friars to tak the missions vacated axer the Crown expelled the Jesuits. Fray de Ca ro reports:

1743

1744

1749

In the year and , great earthquakes took place that destroyed many settlements, and a mountain crumbled more than a hundred fathoms deep. In the year , the volcano exploded through six vents of fire; for fifteen days, the su was not seen at daytime; and the aftershocks lasted an entire year, to which thereafter ensued epidemics, spells of lightning, and extremely annoyingrainsof ash.

It’s possible that Fray de Ca ro was reporting abo the eruption of Mount Mahagnao or Mount Cancajanag,

A. D. 2023 11

(above) Panoramic view of the danaw, that is, the lake, at the summit crater of Mount Cabalían. (below) Topographic images of the volcanic system formed by Mount Cabalían and Mount Cantoloc. The bigger at-elevation area is the active cone of Mount Cabalían; whereas the smaller at-elevation area is the inactive cone of Mount Cantoloc. Both are andesitic-type stratovolcanoes. Mount Cabalían is Kantayoktok to us.

© TOPOGRAPHIC-MAP © TOPOGRAPHIC-MAP

© ADONIS DOMINO LLOREN / LAGATÁW

Aplaca, Señor, tu ira, tu justicia y tu rigor, dulce Jesús de mi vida, misericordia, Señor.

Orémus.

D:ë , quǽsumus, Dómine, beáta María semper Vírgine intercedénte, i am ab omni adversitáte famíliam : et toto corde tibi pro rátam, ab hó ium propítius tuére cleménter insídiis.

O< ñò ; sempitérne Deus, ædificátor et cu os Ierúsalem civitátis supérnæ ; cu ódi die no8úque locum i um, cum habitatóribus eius : ut sit in eo domicílium incolumitátis et pacis.

O< ñò ; sempitérne Deus, qui ré2icis terram, et facis eam trémere : parce metuéntibus, propitiáre supplícibus; ut, cuius iram, terræ fundaménta concutiéntem, expávimus, cleméntiam, contritiónes eius sanántem, iúgiter sentiámus.

D, no rum refúgium in labóribus, virtus in infirmitátibus, adiutórium in tribulatiónibus, solámen in flétibus : parce pópulo tuo, ut dignis flagellatiónibus caigátus, in tua miseratióne re2íret.

D, cui semper plácuit humílium et mansuetórum deprecátio : exáudi nos miséricors deprecántes, et de tua misericórdia præsuméntes. Per Dñm.

San8e Polycárpe, San8e Æmýgdi,

ora pro nobis. ora pro nobis.

Please mellow, Lord, Thy anger, Thy justice, and Thy strictness, Sweet Jesus, my life’s Master, Shew mercy, Lord, forgiveness.

Let us pray.

D: , we beseech tee, O Lord, through the intercession of blessed Mary ever Virgin, this family from all adversity: and, from the snares of foes, propitiously in ty mercy, prote8 us pro rate before tee with all our heart.

A>< î@;I and everla ing God, builder and guardian of the heavenly city of Jerusalem: prote8 day and night this place, with its inhabitants; that there be in it a dwelling place of safety and peace.

A>< î@;I and everla ing God, Who looke upon the earth, and make it tremble: forgive those who dread, soothe those who beg; that we, who fear ty wrath shaking the foundations of the earth, may always feel ty mercy healing the deru8ions of the earth.

OG , our refuge in labour, rength in weakness, aid in tribulation, solace in tears: forgive ty people, that, being cha ised with appropriate scourges, they may be revived in ty mercy.

OG , Who art pleased in the prayer of the humble and the meek: mercifully and graciously hear us pleading, who tru in ty mercy. trough.

Saint Polycarp, Saint Emygdius,

pray for us. pray for us.

TO RESTRAIN EARTHQUAKES PRAYERS

r Amen. r Amen. 12

© GALLERIA D’ARTE MODERNA

both closer than Kantayoktok is to his mission. However, while Cancajanag has no reported eruption in the Holocene period, ^Fàv is the la reported eruption of Mahagnao. terefore, considering the proximity of the earlie e imated year ^ãàw to an a8ual record of an eruption in the year ^ãEà, there is great probability that the cata rophic eruption related by Fray de Ca ro was from Kantayoktok, an account which corroborates our oral tradition that the volcano’s summit sank during an eruption, allowing a lake to eventually form in the crater.

Kantayoktok has not exploded since, but the possibility of an imminent eruption ever looms over the town. Dread grips the populace whenever the pro2e8 rears its head, like what happened from ^ã to Dv May ^àwã, when Cabalían experienced a series of earthquakes. te ordeal began at wD:w_ ò< on ^ã May, followed by another at ^D:Ev ò< on ^à May. Fortunately, both quakes regi ered only at intensity . But a particularly rong one, clocking at intensity C , occurred on Dw May ^àwã, at wä:Eà ò<, originating in the southea ern extremity of the Philippines, rocked Leyte, Cebú, and northea ern Mindanao. At wE:wä ò<, a less intense earthquake followed. Even though the epicentre was located at äw kilometres northea of Maasin, and the mesoseismal region was confined in the Libagon-Liloan peninsula, Cabalianons believed that Kantayoktok was irring from its slumber, menacing them with tremors by way of announcing di ressing and terrifying days ahead.

On the day of the ronge quake, Dw May ^àwã, the municipal judge D. Ramón Escaño wrote a letter to the Weather Bureau, ating:

Some of the stronger quakes have triggered landslides in the mountains

EARTHQUAKES, ERUPTIONS

17th

close to the town. Since the , on which the first quake was felt, fifty very perceptible quakes have already been tallied, at intervals of some hours, and sometimesof minutesonly.

In another letter dated Dv May ^àwã, when another earthquake, this time at intensity , shook Cabalían at ^^:Ew ò<, D. Ramón Escaño reported that axershock frequency had escalated, and their number had increased to sixty.

Conducive for anxiety, right? te fa8 that the quakes happened right smack in the middle of Whitsuntide, with Penteco Sunday on ^à May, possibly contributed to the panic. Even if P. Carrillo reminded his flock that earthquakes can be manife ations of the power of the Holy Gho , as when the bands of Paul and Silas in prison were broken (A,. =C , D_), the town’s alertness had probably already autoswitched to apocalypse mode. Everyone moved about like damselfish beached at midsea. Likewise writing from Cabalían on Dv May ^àwã, D. Isidro Arcega, observer assigned to the Weather Bureau ation in Maasin, enumerated the problems produced by the consecutive earthquakes and interruptive axershocks. Frequent tremors hampered daily chores in Cabalianon households, many of which, e2ecially those made of nipa, collapsed with their po s.

We cannot evade this disorder and disquiet. While foreca ing volcanic eruptions is ill imperfe8, the process is becoming more reliable. tere will be warning signs, and crucial to our safety is noticing them, and li ening to the advice of qualified volcano observatory aff. It bears repeating that ignoring foreca s can expose an entire community to risk. We mu pray with ardour, we mu think with insight, and we mu a8 with caution.

REFERENCES

B I M : ; , D C > L> < , M A -

> , Geometry and segmentation of the Philippine Fault in Surigao Strait (ä March DwDD): Frontiers in Earth Sciences

^w (March DwDD) ^–^ã. Accessed DF May DwDä doi: ^w. ääFà/feart.DwDD.ãààFwä

G> ï > V >? < P î <, Cabalían: S< ;@I ; ; ; , ed. E ù V Aû , Volcanoes of the World (v. v.w.E; ^ã April DwDä). Accessed DF May DwDä doi: ^w.vEãà/si.GVP.VOTWv-DwDD.v.w.

Cancajanag, in op. cit.

Mahagnao, in op. cit.

⁂

Aî ;ñ M ñ C ; I A< , O. E. S. A., ed. M > M Pë A, O. S. A., Osario venerable (Madrid ^àvE).

Aî ;ñ M ñ C ; I A< , O. E. S. A., Relación sucinta, clara y verídica de la toma de Manila por la escuadra inglesa, ch. ^w in M > M Pë A, O. S. A., Páginas misioneras de antaño: Missionalia Hi>anica à (^àvD) ^Dä–^äà.

M î > S M ü, S. J., Seismological Bulletin (May ^àwã): W ;@ B , ed. J ë M ñ A>î ë S >> @†, S. J., Monthly Bulletin (^àwã) DDE–DD_.

A. D. 2023 13

A language of our own

Appreciating our mother tongue

;@ ; ù : ? ï >ñ prides itself for its rather unique tongue. Cabalianon is the language of our home, our childhood, our cosmos even. It shrouds in my ique our disarming idiosyncrasies, allowing us to appreciate ordinary moments of amusement whenever people from neighbouring towns fail to under and what we are talking about (bunáy is a cudgel, not an egg), or second-guess their own eps before approaching us (for fear of being snapped or shouted at). Dome ic squabbles, reet mêlées, axernoon chinwag, bingo sessions, and other social covenants are never as dele8able to the ear as they are supposed to be if they are not condu8ed in Cabalianon. tere is that glorious feeling of contentment and security—euphoria, if one prefers it called thus—at once poignant and edifying, whenever we hear the phonetic barrage and morphophonemic caprice of Cabalianon 2eech.

CABALIANON

OUR OWN LANGUAGE

officia y

Kinabalián

| ki·na·ba·li·án | /ki.na.ba.liʔ'an/

also called Bisayâ Kinabalianón

ISO639 cbw

GLOTTOLOG kina125

SPEAKERS 14,900 in 2020

Every Cabalianon is capable of speaking Cabalianon. But not everyone chooses to do so. At present, only a diminishing number speak Cabalianon habitually and consistently on a daily basis. The vast majority deliberately code switches to Southern Kanâ to communicate, even in barangays considered as enclaves of deeper and more archaic registers of Cabalianon.

CABALÍAN 1 14

(C b lí n) S n Ju n ©

/

© GEOPORTAL PHILIPPINES

PANSITKANTON

REDDIT

But the lingua Danca remains to be Southern Kanâ (not Cebuano or Boholano, as some believe), as it is the tongue 2oken throughout Southern Leyte, except, hi orically, in Cabalían. Southern Kanâ, however, is classified as a diale8 of Cebuano, which is our liturgical language, the language of our prayers and devotions. Cebuano only came in Cabalían in the later part of the ^àth century when a considerable number of migrants from Cebú settled in some areas of Cabalían.

On Dv Augu Dwwà, a formal reque was made to change elements in the ISO EFG Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part F: Alpha-F code for comprehensive coverage of languages, addressing the need to create a new language code element for the language of Cabalían. It was denominated as Kinabalián. te only gaffe made in the reque was the fa8 that Cabalianon was classified under the Warayan family tree. te reque was finally granted on ^w January Dw^w. tereaxer, Cabalianon became an internationally and officially recognised language.

CABALIANON

OUR LINGUISTIC PATRIMONY

: >û from neighbouring towns oxen rib us about our intriguing phonetics, which replaces intervocalic ⟨y⟩ with ⟨j⟩, as well as intervocalic ⟨l⟩ with ⟨y⟩, and resi s elision of this latter feature, even to the point of re oring it where it has already disappeared. Time and again, the phrase ang kayajo nokayatkat sa boyongbong would reappear to summarise what makes Cabalianon different. But we also have kalooy sa Dijós (in ead of the monosyllabic Dios) in our occasional archaisms, together with tableja, and huyagbong, and kinahangyan colouring our vocabulary smörgåsbord.

We all know that Waráy is as close to Cabalianon as Pluto is intimate to the sun. Surigaonon, on the other hand, is almo similar to Cabalianon. te profusion of j’s and y’s in our daily 2eech is a telltale sign of our lingui ic relationship with the islands to the ea of our bay. While it is true that the settlements dotting the northern coa of Leyte and even those lining the southern beaches of Samar knew Cabalían at the time of the Spanish conta8, language diffusion across mountains could only have succeeded had resettlement of native and a8ual 2eakers occurred. Otherwise, lingui ic affinity would remain at the level of loanwords. te conta8 between Cabalían and the northern townships of Mindanao, principally Surigao and Butuan, is atte ed throughout our local hi ory. te fir in ance we have of an ethnolingui ic description of the people of Cabalían is by P. Francisco Ignacio Alcina, superior for a very long time of the Jesuit missions in Leyte and Samar. In the second part of his monumental work about the natives and islands of the Visayas, P. Alcina devoted the fol-

A. D. 2023 15 C b li non do c t hous> fir> m n om n s no l t>r idô kurín b l k l o l l ki b b > h mb l subón k rón irô irín b? k jo l ki b j> in ̃ón k rón unj@ irô irín b l k l o l l ki b b > in ̃ón k rón un @ so pus@ b h pó l l ki b b > s bi n ón m m @ idò idín b k jo l ki b b j> l ón kum n n j· n idò idín b k jo l ki b b j> l ón kum n n j· n m udín b l k l o l l ki b b > sirín nC ni n m ikós h rón k l o l l ki b b i t r m n ̃on n ts n

En lish T lo C bu no S.K n Hili

non C.Bikol W r Suri onon

Images from left to right © PEXELS by contributors (1) MATHEUS BERTELLI, (2) TAHIR OSMAN, (3) NIKOLAEVA NASTIA, (4) ARMINE M’SIOURI, (5) HAROLD VILLAPANA, (8) ANTONIO GARCÍA PRATS, and (9) OLIA DANILEVICH. Image (6) of a Mansaká woman © JACOB MAENTZ / JACOBIMAGES. Image (7) of a Catholic bishop speaking to a diaconand © FSSP WIGRATZBAD.

A LANGUAGE OF OUR OWN

lowing sele8 words to describe the cu oms of the people living in Cabalían, mo importantly their chara8er and 2eech:

Th> p>opl> of th> co st of C blí n r> no l>ss d untl>ss, onc> som>h t mor> r>ssiD> th n th> Bohol nos, for b>in d>sc>nd nts of th> Cr ns, ho bord>r th>m; nd this d , I do not kno if th>r> r> mor> C rns inh bitin th> to n of C b lí n th n th> Vis ns ho r> its n tiD>s, nd th> r> s m l m t>d in th>ir int>rm rri >s s th> pp> r mor> C r n th n L> t> n in th>ir l nu > (>D>n thou h it is Vis n, it is D>r much mor> complic t>d nd l>ss r>fin>d th n th> l n u > of th> oth>r to ns of th> co st).

P. Alcina wrote throughout his missionary years in the Visayas, but his manuscript was only compiled axerwards, for the purposes of publication. It, however, did not materialise. Nevertheless, as early as ^__F, the language of Cabalían was already unconscionable to the untrained ear, having been affe8ed by the Caragan presence in the town. te Caragans were the ancient inhabitants of Surigao and Butuan, as well as some parts of Davao. te hi oric appellative of this people survives in the name of present-day Region XIII.

te Caragan presence in Cabalían was not only circum antial. Many settled in Cabalían because they intermarried with its people, presumably Visayans of Waráy extra8ion, and vice versa, as P. Alcina’s observation atte s. Owing to this wide2read phenomenon, apparently,

the resident Visayan language (again, presumably heavily based on Waráy), was smothered or, at lea influenced, by the Caragan tongue, that a new language was born from it. Whether Cabalianon was a produ8 of di2lacement or of replacement, the entire conje8ure remains hypothetical. (Axer all, we’re only holiday lingui s, lingui s who hold no degree, but only pure fascination for languages.) By ^__F, however, the language 2oken in Cabalían had already sufficiently diverged from the template language of Leyte, enough for P. Alcina to describe it as “more complicated and less refined” than the language of the re of the island.

Conta8 with the northern settlements of Mindanao did not end with the intermarriages mentioned by P. Alcina in ^__F. Axer the Jesuit expulsion in ^ã_F, Augu inian friars took over the missions in Samar and Leyte. Axer his visit to all the mission ations in the islands, Fray Agu ín María de Ca ro wrote about the places he had visited. His work provides us with proof that the natives of Cabalían and Sogod, and even faraway Maasin, travelled to Surigao to obtain gold, purposefully to decorate their churches. tey canoed to Surigao, even with the threat of a Moro attack at sea. te bonds shared between our language and the inherent languages of Surigao, Butuan, and Agusan would have been galvanised by this continued conta8.

tere is some gleeful mischief in remarking “¡Aw, bajàbajà bajâ!” or labelling someone as bayasón sin alipudhan, and having only a few outside Cabalían under and what the intejection and the idiom mean.

REFERENCES

F ? ? Iî ? A>? , S. J., ed. V ?; Y ò , Hi0oria sobrenatural de las Islas Bisayas (Madrid ^ààF).

Aî ;ñ M ñ C ; I A< , O. E. S. A., ed. M > M Pë A, O. S. A., Osario venerable (Madrid ^àvE).

¡Aw, bajàbajà bajâ!

;@ < ¶ ;I : ? , Cabalianon bajâ fun8ions like the Cebuano diáy (including bayâ to some extent) and the Tagalog palá, which is to express a realisation different from the expe8ation, or articulate an inference contrary to the assumption. In Au ronesian languages, repetition is employed to manipulate the meaning of the original unit. In Cabalianon, it mo ly diminishes the magnitude of a noun, or augments the frequency of a verb. Hence, bajàbajà encodes mild extraordinariness in some a8ion or event. Stringing these words together forms an interje8ion that communicates surprise at an outcome whose fulfilment was not expe8ed.

We deep-dive into some of the oft-used Cabalianon idioms in the next sheet.

⁂

16

bayasón sinalipudhan

sandy in the cowlick in a state of habitual or situational incapacity to comprehend basic directions and simple instructions

Anay pa. Gisugò ta káw sa ubós sin isdà. ¿N ̃aman bahóg sa manók man nín imo dayá? ¿Unhon ko man ní? ¿Puston nakò ní sin dahón sa kakáw, un·unán? ¿O tuktukón rakán ní natò arón tibway? Kabayasón bâ gajúd in dimo sinalipudhan.

Putting sand in the head contradi8s hygiene, which people may interpret as an indicator of poor intelligence.

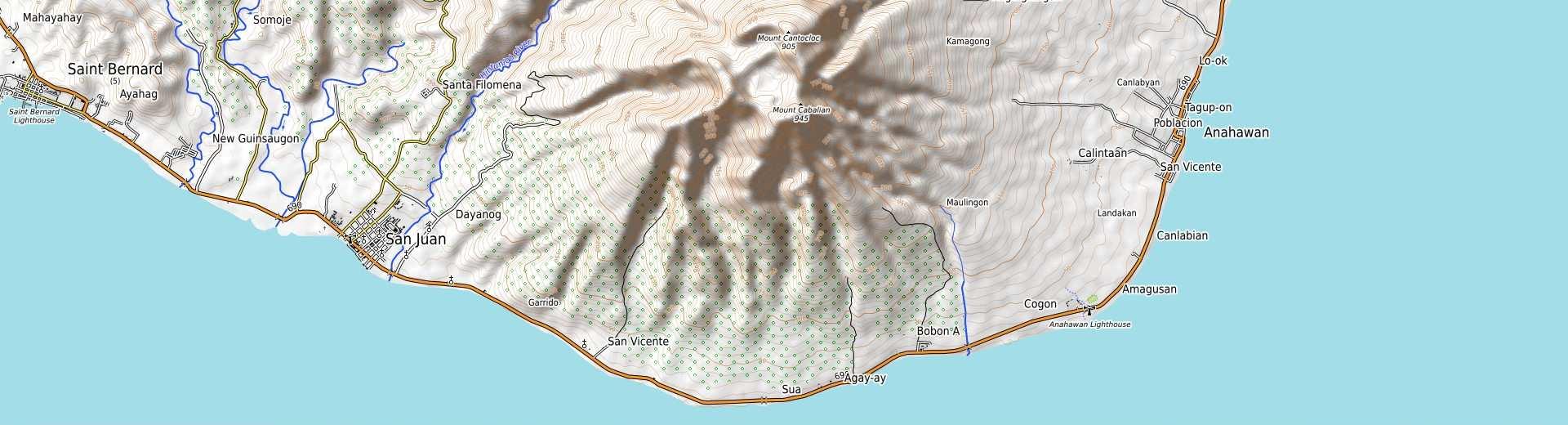

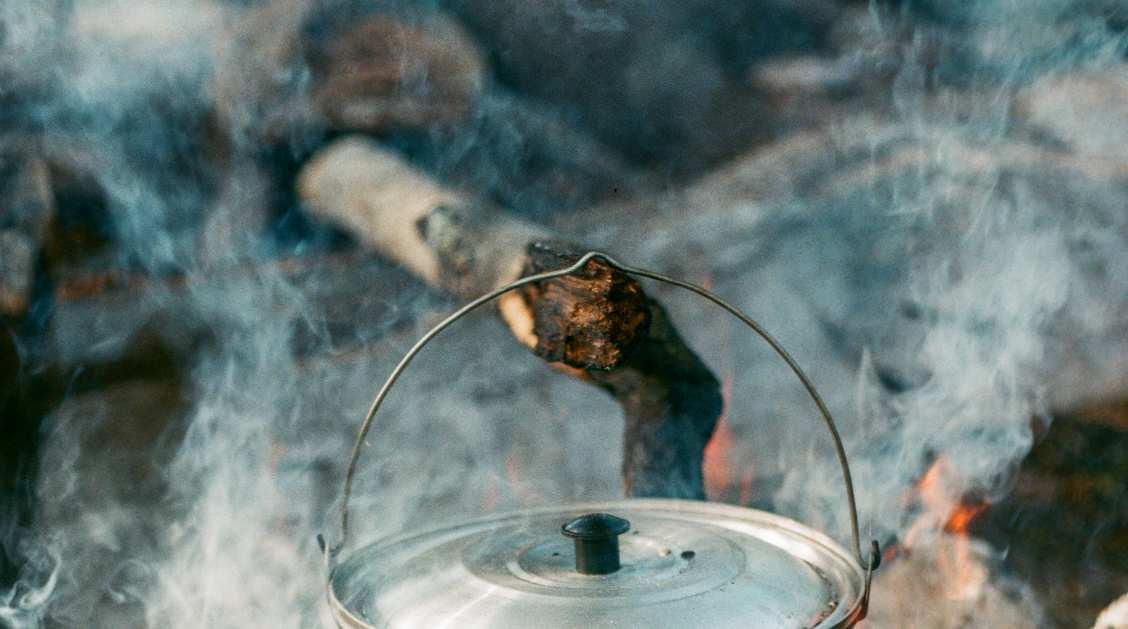

kasab·ongán sin caldero

suitable for hanging a cauldron

in a state of petulant annoyance or displeasure manifested by pursing the lips and pinching the corners of the mouth

Simpamundak dâ. Ajáw ko basoja n ̃a wayâ káw tugti sanán imo amâ mobaile ha, kay malaparo ta gajúd káw. Nagn ̃ayân ̃ayâ laman tón kahimô mo. Imusmos ko tón, tagám ka man gajúd igkagisì sanán simód mo n a kasab·on ̃ánsincaldero.

A bar should sufficiently protrude from a wall for it to accommodatethe circumference of a pot whensu2ended.

himungaan nga gikapus·an

eggbound hen

˜ ˜ in a state of conspicuous enervation caused by physical, mental, and/or psychological overexertion

Inín wayâ ta maanad sin hagò no, madugay tandogonon na ta. Pabitbitón ra sin galón kab·anán, manluspad na, bagán gilunosan. Amó ka ra man sin himun ̃aan n ̃agikapus·an. Gamáy n ̃a lihok, luja. ¿Uman, mahamyot káw kun sugoon káw?

If an egg uck in a hen’s ovidu8 (eggbinding) breaks, it can cause an infe8ion, and the chicken can die as a result.

payatá

nga nahubsansa piliw

damselfish beached at midsea

in a mental state of high arousal caused by anxiety, panic, and/or confusion

Aráng kasipát bataana uy. Tamagduslibán ang bra sa ija maestra n ̃a gisabyay sa kasilyas. Punó kay tanayumtum na. Nagsalimuáng tawon ang nanay, morá nan payatán ̃anahubsansapiliw, labí na kay talihagbong na jaón ija bigwis.

Fish canbe beached very far from theshoreline ifseawater retreats axer an earthquakewhen a tsunami forms.

aray dabóng

possessing an unripe fruit in a relationship, either unverified or substantiated, with someone significantly younger, not rarely a minor Jaón na sad si kuwán hô, aráng na sad kaisputing. Naglunó ang buhók, morán modiscurso. Nanahóndahón tón sijá kumán kay arà tón sijáydabóng. Motoo pa kamó sa dilì. Ija laman tuodtuoron tón ija idíng·iding sa ija pajág daplin sa sapâ.

Immature seasonal fruits require diligent and meticulous care to properly ripen with its complete ta e profile.

= literal meaning | = contextual meaning | = usage

Images from top to bottom © PEXELS by contributors (1) COTTONBRO STUDIO, (2) ALEXANDER NEROZYA, (3) ELLIE BURGIN, (4) KEVIN CHARPENTIER, and (5) SHILPA DEEKSHITH. 17

˜

˜

WORD OF THE YEAR

pilan ̃ag

: to cry loudly and unconsolably

< <ï that time years ago when people abroad arted receiving white envelopes in the mail containing nothing but black powder? It was the fir time we heard of anthrax, and learned that it is a biological weapon. te pro2e8 of mail-to-order disease terrified world leaders, who were busy mothering their countries and fathering their nations. No wonder some who lived through this scare now think it was ju a dry run for the pandemic. No matter. Back in our day, nanay and tatay had to contend with a different weapon, pilan ag. Different, but equally de ru8ive, more so in the smaller scale that it delivers its potency. Pi8ure this. Jornadas is fa approaching. Moros have mushroomed in the reets. Baubles and trinkets of every ripe, gizmos and gadgets of every shape charm windowshoppers. A lone brat wanders through, and demands a toy. Nanay refuses. But no is never the corre8 answer, so the imp ages a tantrum, complete with an era-defining pilan ag. It is one weapon in a Cabalianon misfit’s arsenal capable of compromising, if not altogether annihilating, his parents’ dignity.

Public pilan ag invites judgment from onlookers. And parents, who would otherwise swear their babe looked like God’s cherub, now scold the same as Satan’s 2awn. Crying communicates, but the impa8 depends on, er, performance. tere’s tuwáw and tuáw, there’s bakhò and kuligi, there’s hibì and bin ít, there’s kuyagò and uyâ. Only pilan ag takes the proverbial cake.

CABALÍAN 1 18

¡Simpupil n g dC k C t ip lít sitón t r kt r k!

v. | pi·la·ng̃ag | /pi'la.ŋag/

Stop cr,ing thQrQ, bQcausQ RQ can’t afford that toS car!

© DOUBLE_H / SHUTTERSTOCK

CABALIANON KO

AHORA POR SIEMPRE Y PARA SIEMPRE

T;@ , we Filipinos are a mother-loving people. We love our mothers to a fault. Our fir encounter with human love was in the womb that carried us for nine months, and in the paps that suckled us for the fir years of our lives. And that love, that adoration, extends to the home that sheltered our fir memories, to the land that browned our unshod feet, and to the air that infle8ed our disarming 2eech.

te motherland, our hometown, penetrates our very being, moulds our very psyche, and colours our very chara8er. Hiding this conne8ion behind pretences and affe8ations amounts to moral treason. So, in a chorus that embraces both the pitch perfe8 and the tone deaf, each of us here ca s our individual declaration: Cabalianonko. I am a Cabalianon.

photo: ¶ ?û > A /C <

C b lí n, tú pu>blo mu pulcro, Tierna madre de prole vivaz, DQsdQ cuna S hasta sQpulcro, Te loemos ceñida de paz.

; ? ï > ß ⁂ < C C ? ï

Ecce agnus Dei, ecce qui tollit peccatum mundi. Ioann. I, 29

Ideoamnostouqeouoairwnthnamartiantoukosmou