CABALÍAN

BRIEF PROFILE

5 TH CLASS

MUNICIPALITY

Countr= Region Province Municipalit=

Philippin s East rn Visa as South rn L t San Juan

BARANGAYS

A · B s k

Bobón A

Bobón B

D no

G rrido

Mino hò Os o 1on ·o

S n Jos

S n 2oqu4

S n Vic4nt4

S nt Cru S nt Filom4n

S nto iño

Somoj8

Su9

Timb;

0 BARANGAY precontact village before 1521 based on Spanish chronicles

0 ENCOMIENDA 25 JANUARY 1571 F

FOUNDATION DATES colonial land trust

demographic, assignment of taxpayers

6 SEPTEMBER 1571 F geographic, assignment of boundaries

0 PUEBLO independent town before 1853 F based on surviving tax records

0 PARROQUIA 15 SEPTEMBER 1860 F independent parish civil authorisation, via viceregal assent

13 JANUARY 1861 F canonical erection, via diocesan decree

NAME CHANGE

F 17 JUNE 1961 F

Republic Act 3088

CABALÍAN 1 4

(C b lí n) S n Ju n

© GEOPORTAL PHILIPPINES

W@ Magallanes’ fleet sailed by Cabalían, the ma of one of his ships broke. Oe natives, seeing what happened, shouted, “¡Gikabalian!¡Gikabalian!” Oe Spaniards, thinking it the name of the place, recorded Cabalían.

VERSION A

S UALL-MEDIATED

;@ rong winds of a subasko, which blew as the fleet crossed the bay, broke the ma .

VERSION B

FIRETREE-MEDIATED

;@ long branches of the dapdap, which grew abundantly along the bay, broke the ma .

B: the Spaniards arrived, Cabalían harboured numerous fore s and thickets of bulí. Consequently, natives living in the area called the place kabulihán. Much later, this toponym degenerated into Cabalían.

VERSION A

ENDEMIC SHIFT

;@ native inhabitants themselves, by dint of natural lingui ic development, changed the name.

VERSION B

ECDEMIC SHIFT

;@ Spaniards who colonised the area, ignorant of the language of the natives, changed the name.

THEORY 3

COASTAL DISCONTINUITY

P-? ; ?; natives who regularly travelled along the bay noticed that there is a place where it naturally curved back, giving the impression that it is fra8ured, or nabalì. Hence, these native sailors called the place Cabalían.

THEORY 4

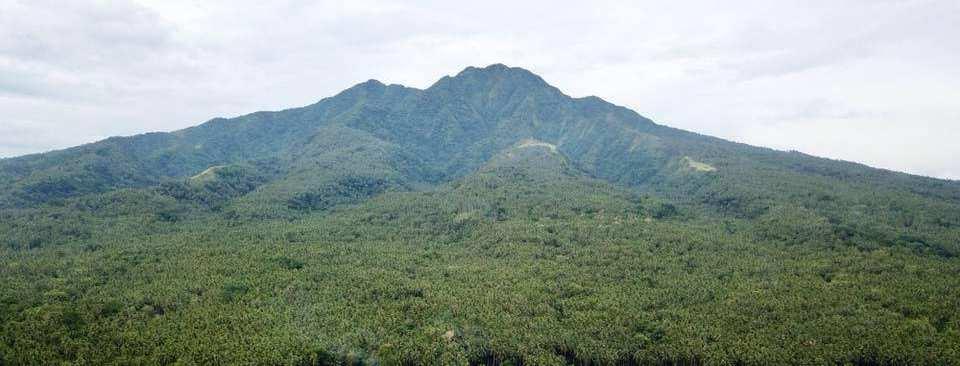

VOLCANIC ERUPTION

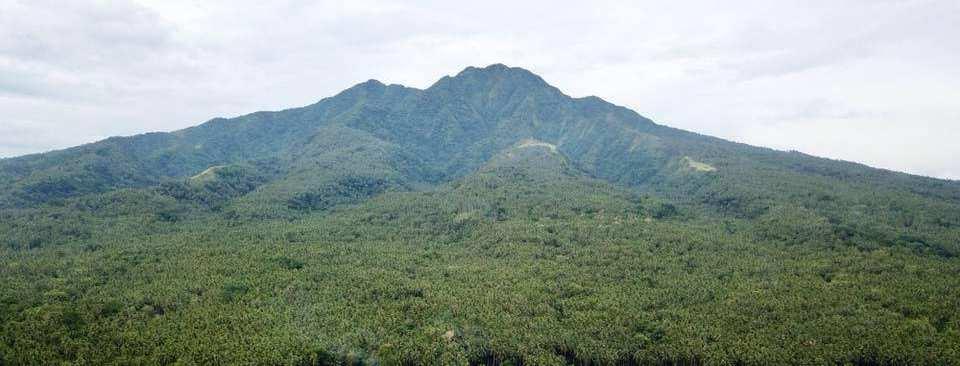

L[ before the place was inhabited, its resident volcano erupted so cataclysmically that its peak imploded. Settlers who knew about this called the volcano broken, or nabalì. Ois later became the placename Cabalían.

A. D. 2022 5

1 2 3 4

BROKEN MAST THEORY 1 TOPONYMIC ORIGIN © GP PH © CATS / FB © WIKI COMMONS © FNV

PALM PLANTATION THEORY 2

CHURCH inscriptions

;@ I’ ;@ . We’ve ju ignored them for as long as we can remember. In fa8, we’ve lived with the reality that they are merely relics of a di ant pa that no longer makes sense to us. Whenever we pass through the great doors of the church (whenever the sacri ánmayor forgets to open the side portals a little aQer the repiquegeneral begins for any Sunday Mass), our peripheral vision surveys them for a fra8ion of one breath. Oen we trudge on, nary a thought leQ on those ony letters. But what do they mean? Who are the personalities namedropped in them? When and why were they inscribed?

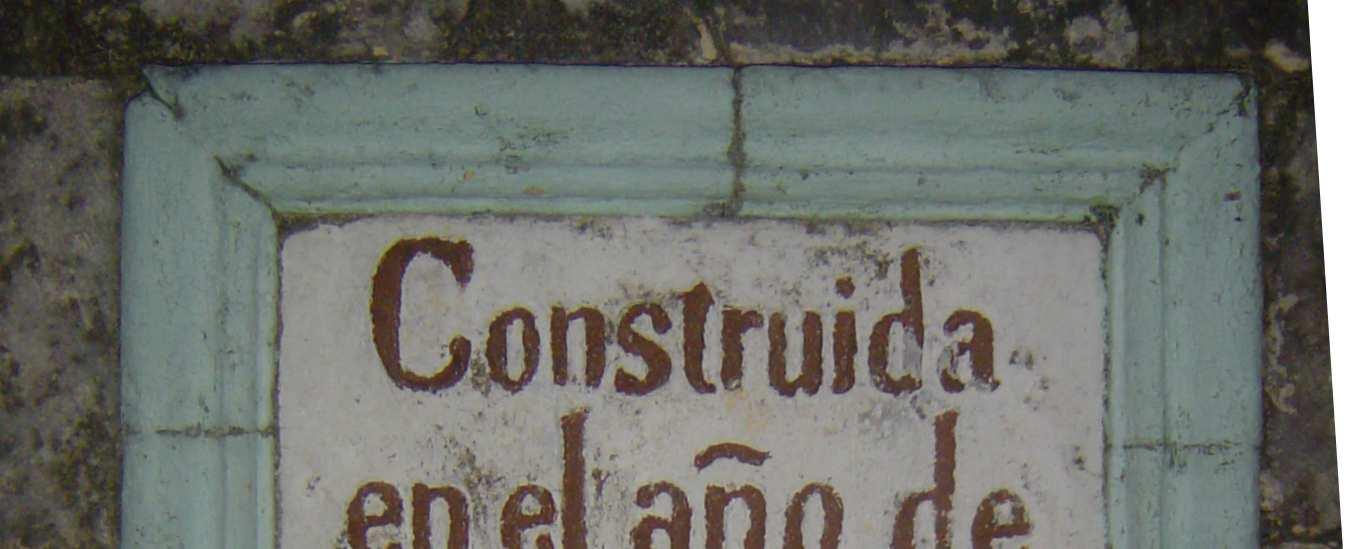

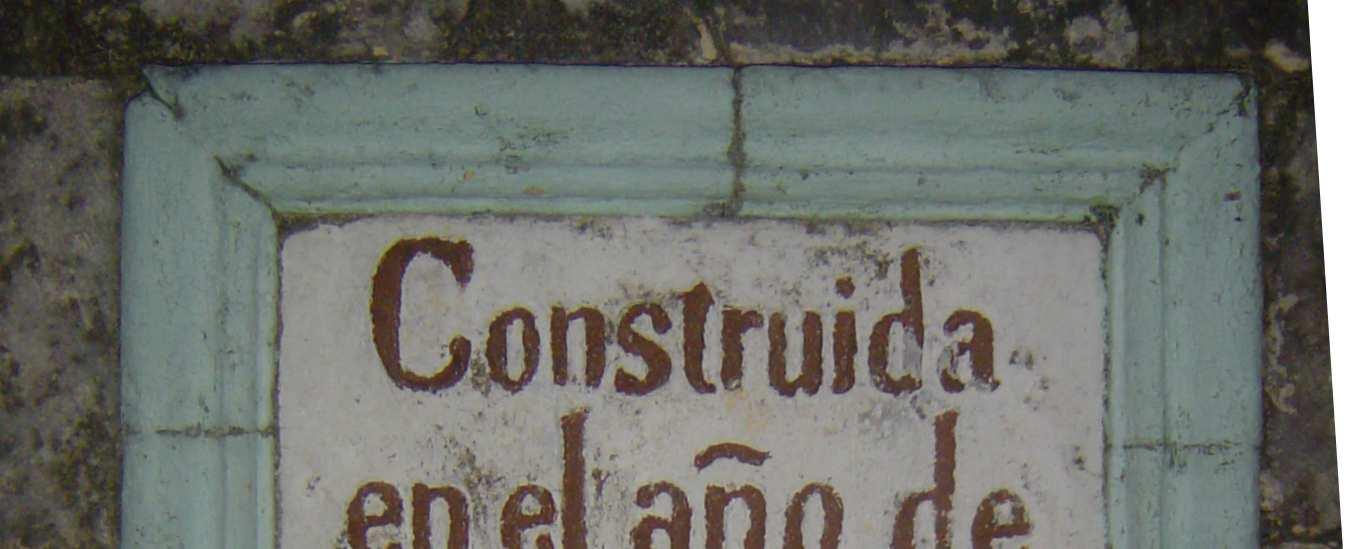

Oe façade of the old one church of Cabalían has four pila ers in its fir orey, dividing it into three bays. In colonial archite8ure, a orey is called a cuerpo, while a bay is called a calle. But let us abandon this fir . Our concern is the two central pila ers of the façade. Oe plinths of these pila ers contain a framed 2ace with an epigraph embossed upon each of them. Oese epigraphs commit to eternal memory the names of the parish prie and of the diocesan bishop when the church was finished.

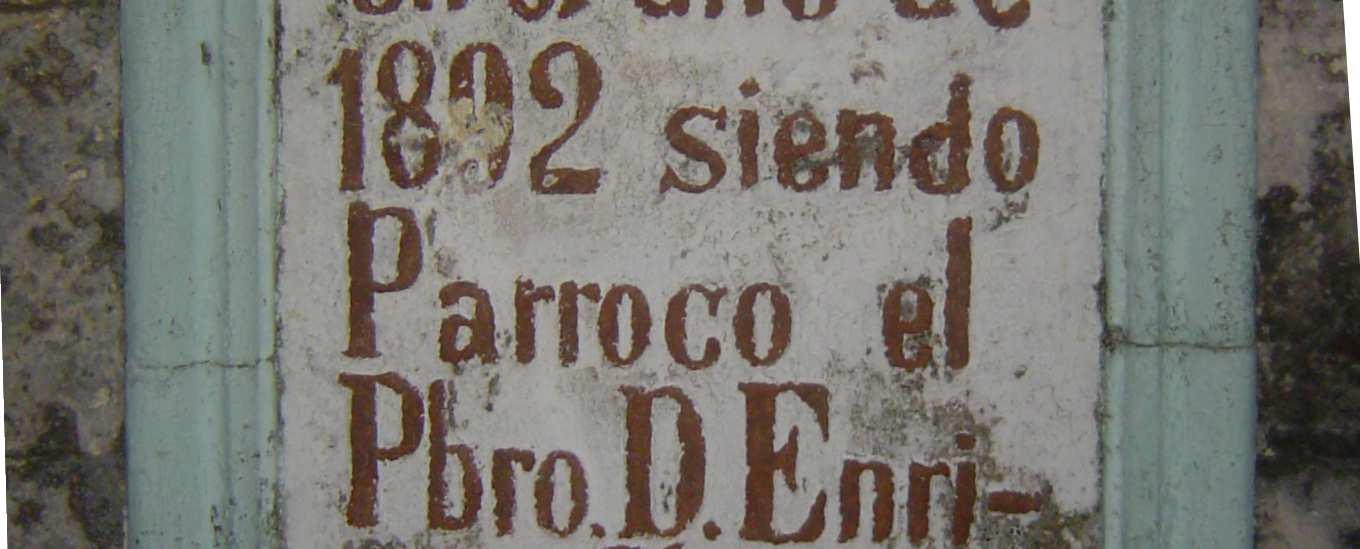

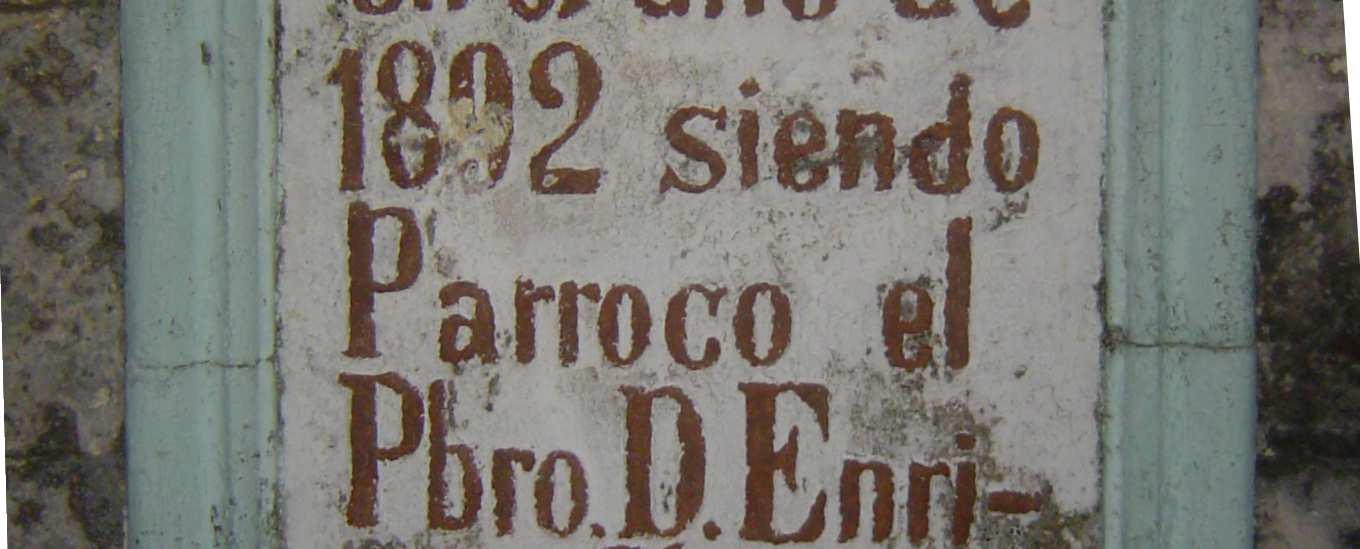

Oe right inscription contains the name of the parish prie : D.EnriqueCarrillo.

It also gives a year: ' . Ois is not the year the church was founded, or con ru8ion arted. Oe parish was canonically founded on \] January \F_\, five months aQer the decree separating the parish from Malitbog was issued by the governor general in Manila. Ois could also not be the year con ru8ion arted, because towns were normally founded or separated during the Spanish era if they already had churches. Oe relevant books available to us point at \F`D as the year the church was finished. From \F`a to \F`D, the parish of Cabalían was classified as de ascenso, which means

CABALÍAN 1 6

Behind the twin text adorning the façade of our church

that its population had reached the number set by law for the parish and the town to be considered of significant importance. Oe prie in a parish for promotion receives an increase in his endowment, as ipulated by law. D. Enrique Carrillo in the same period was classified as párrocointerino, meaning interim or temporary parish prie . Ois probably had something to do with D. Lucas Soto, the prie re2onsible for enlarging the church. Oe ate of his health might have prompted the bishop to assign a temporary parish prie , or his death might have caused a vacancy which could not be filled in immediately. AQer \F`D, D. Enrique Carrillo assumed incumbency of the parish of Cabalían.

P. Carrillo was born in Órmoc, and udied in the Seminario Conciliar de San Carlos in Cebú, receiving Holy Orders on \] Augu \FC_. He admini ered the va parish of Cabalían, with its multiple chapelries and satellite missions, for more than a decade, aided from time to time by coadjutors. He would be succeeded by D. Pelagio Avilés, a compaisano ordained on \ November \F`F. D. Enrique Carrillo was parish prie of Biliran before he was assigned to Cabalían.

INSCRIPTION

RIGHT PILASTER

Construida en el año de 1892 siendo Párroco el Pbro. D. Enrique Carrillo.

Con ruida en el año de \F`D siendo Párroco el [Presbítero] [Don] Enrique Carrillo.

Con ru8ed in the year \F`D, when the Parish Prie was the Presbyter Father Enrique Carrillo.

In this tenor, we call out another intereing note from the inscription: the fa8 that it calls D. Enrique Carrillo a presbítero, abbreviated in Spanish as pbro. Ois means that he was a secular prie , not belonging to any of the e ablished regular orders in the archipelago. Ois also means that he was either a me izo or a fullblood indio.

La ly, the inscription confirms the 2elling of his surname: Carrillo. With two r’s. Oe reet to the right of the church, the one with the old municipal di2ensary, is labelled Padre Carillo Street, with only one r. Perhaps, it is time to corre8 this blunder. AQer all, we do not need to check an encyclopaedia to confirm the corre8 2elling.

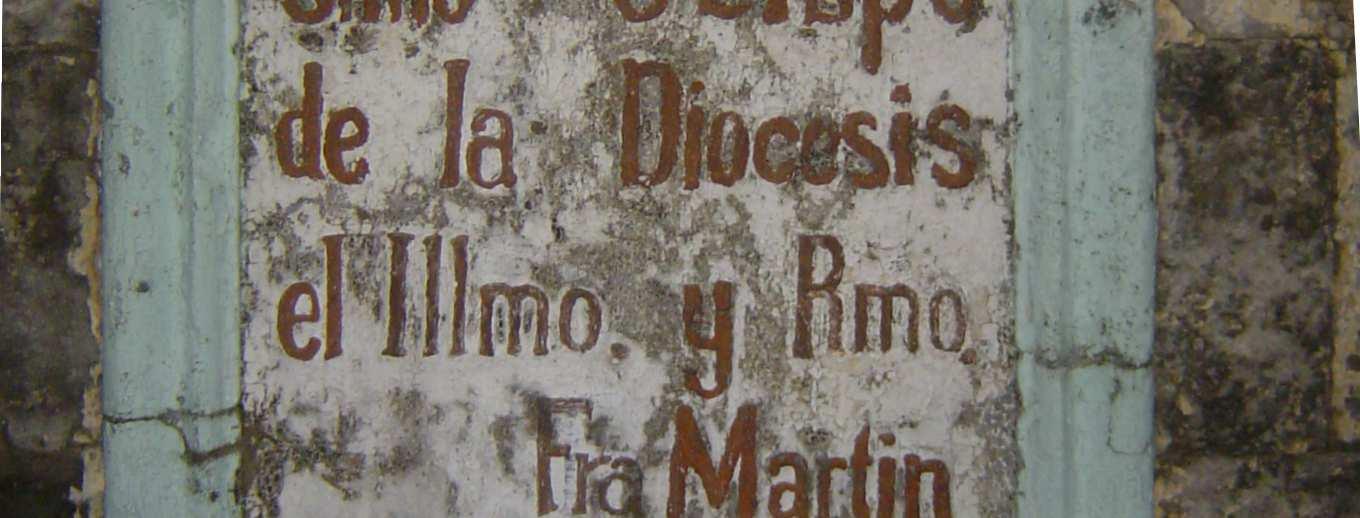

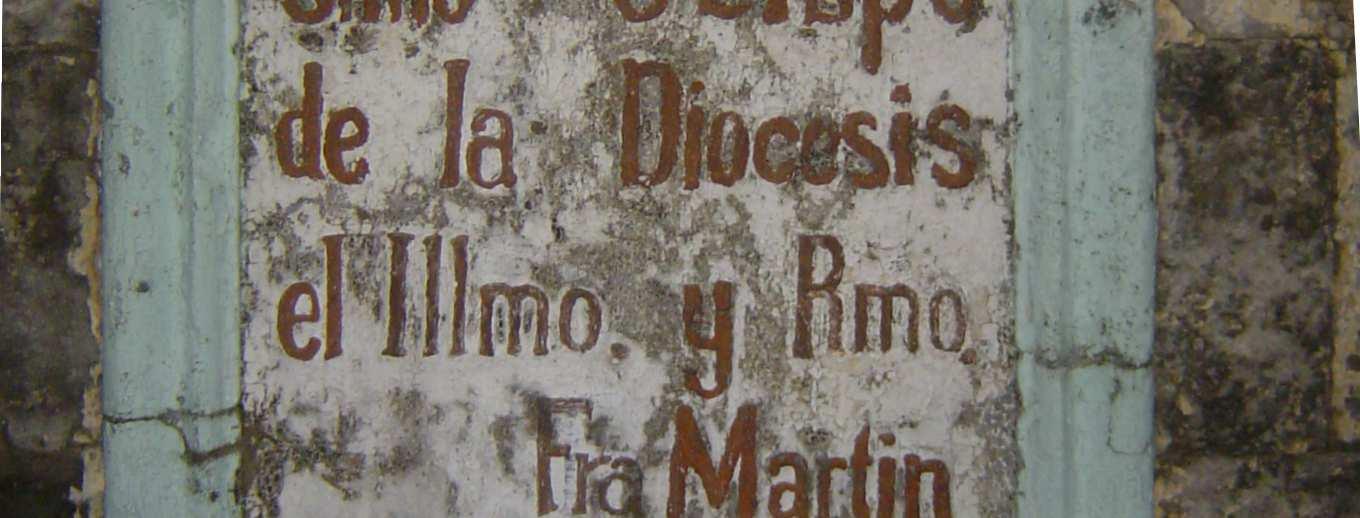

; ;@ =;: Oe leQ inscription contains the name of the local ordinary: Sr.D.Fr.MartínGarcíayAlcocer.

Oe inscription is now botched. Re orers forgot the two honorifics (Sr. and D. are missing), 2elled out Fray (without the y, to boot; should be Fr. only) and García (should be G.a only) completely. Nevertheless, the name is ill inta8. Fray Martín García y Alcocer was born on \D November \FED in Albalate de Zo-

A. D. 2022 7

Text of the right inscription as of 2009, with its transcription and translation.

rita in Spain. A Franciscan friar of the Alcantarine branch, he was ele8ed bishop of Cebú on C June \FF_, and was consecrated on D_ September \FF_. When Fray Bernardino Nozaleda y Villa, O. P., whom we remember as the beleaguered archbishop of Manila, resigned on E February \`aD, Fray Martín became apo olic admini rator of the metropolitan see. Oe dire*orium of Manila for \`a] bears his name.

Nobody really remembers Fray Martín in Cabalían now, but we owe to him one of the surviving traditions of the town. Oe novena that we sing every dawn before each misa de aguinaldo, in honour of the Virgin of Bethlehem, received its license from Fray Martín on \a Augu \F`E.

Now, we mu recall that Fray Martín ruled the see of Cebú at the time of the greate upheavals in Philippine hi ory, what with the revolution in Luzón that cascaded into the Visayas, and the arrival of the Yankees and their benevolent assimilation. Oe troubled revolution saw him successfully convincing Gen. Arcadio Maxílom y Molero, head of the revolution in Cebú, to enter the city without bloodshed, aQer having sent two of his prie s, D. Emiliano Mercado and D. Ismael Parás, on D_

S[ r < Obi2o de la Diócesis el [Ilu rísimo] y [Reverendísimo] [Señor] [Don] [Fray] Martín [García] y Alcocer.

W@ > ;@ < ; p ;@I

Bishop of the Diocese was the Mo Illu rious and Mo Reverend Lord Friar Martín García y Alcocer.

December \F`F, to confer and discuss with the revolutionaries in their headquarters in the convent of Pardo. Stacked upon these complications was the birth of a nativi church that sought to expel all Spanish ecclesia s from every tiny chapel and every great see back to the arms of Spain.

p ? >I 2eculate when and why these immortal words were embossed in one. An old undated photograph of the façade of the church shows the plinth of the right pila er empty. Of course, we can be wrong because the lighting might have prevented the letters from regi ering, but suppose we accept this conje8ure, we are now leQ wondering why the inscriptions were later added.

One possible explanation is the schism that occurred in Cabalían between \`\_ and \`\C. By this time, Cabalían was already under the jurisdi8ion of the bishop of Calbayog, D. Pablo Singzon de la Anunciación (a me izode sangley). On \a April \`\a, Pope Saint Pius X issued the bull Novas erigere diœceses, e ablishing the see of Calbayog in a territory taken from the see of Cebú. By then, D. Juan Bauti a Gorordo y Perfe8o (a me izo) governed the

Siendo dignísimo Obispo de la Diócesis elIllmo.yRmo.

Sr.D.Fr.Martín

G.ª y Alcocer.

INSCRIPTION LEFT PILASTER

CABALÍAN 1 8

Text of the left inscription, botched as of 2009, with its correct transcription and translation.

see of Cebú. Oe parishes of the southern portion of Leyte were at this time organised into one vicariate, with D. Leoncio Faelnar, parish prie of Malitbog, as the vicar forane. D. Adriano Alagón, an indio born in Baclayón, Bohol, who udied in the Seminario Conciliar de San Carlos in Cebú, and who was ordained on \C November \`aE, hitherto coadjutor of Maasin, had ju taken possession of the parish of Cabalían in \`\s, succeeding D. Pelagio Avilés who had been transferred to Banday (now Tomás Oppus). Anecdotally, P. Alagón is said to have grown uncouth and self-important by \`\_, di2laying his glaring lack of urbanity during the fie a of Bobón. It was, so to say, the proverbial raw that broke the camel’s back. Oe principalía, thereaQer, decided to conta8 the dissident prie of Hinunanuan to e ablish the indigeni church in Cabalían, finally formalising all paperwork by \`\C.

By this time, it was no longer possible for the group to occupy the old one church. Ten years earlier, in \`a_, then apo olic admini rator of Nueva Cáceres, D. Jorge Barlín Imperial, who would later become the fir Filipino bishop, won the case again D. Vicente Ra-

mírez, former parish prie of Lagonoy, Camarines Sur, who refused to vacate the church aQer joining the movement birthed by Isabelo de los Reyes and later san8ioned by Gregorio Aglipay. Carving the names of the prie and bishop when the parish was finally promoted, ood as a commentary to this vi8ory over the agents of division, and underlined the continuity of the Faith in Cabalían.

We know that D. Enrique Carrillo never joined the mentioned movement aimed at indigenising the Church in the Philippines. In fa8, when the bishop of Calbayog convoked the Fir Diocesan Synod of Calbayog in \`\\, D. Enrique Carrillo attended in his capacity as parish prie of Cabalían, serving as one of the three procurators of the clergy during the synod (the other two were the parish prie s of Villaba and of Basey), and sitting as a member of the Commission of Fees (ComisióndeArancel) that recalibrated the tariff for ole fees. Inscribing the façade with the names of the parish prie and of the diocesan bishop when the church was finished is truly a te ament—nay, a monument—to the faith of Cabalían, her en-

during fidelity to the Roman Pontiff. ⁂

A. D. 2022 9

Fray Martín García y Alcocer, O. F. M. Alc., the last Spanish bishop of Cebú, resigned his see on 17 July 1903, and was appointed titular archbishop of Bostra on 30 July 1904.

This undated photograph of a processional carroza stationed in front the main portals of the church shows the right inscription-bearing pilaster apparently empty with no embossed letters.

© PRIVATE COLLECTION © SALÍN SA GUBAT / FLICKR

Which John?

Finding the roots of our devotion to Saint John the Baptist

;@ ? v > ’ June schedule is pretty much set in one: jornadas on the \sth; anteví2eras on the DDnd; ví2eras on the D]rd; kahuyogan on the DEth; and liwas on the Dsth. It’s a yearly cycle that time so honours, a sort of circadian rhythm that orders the town’s tempo. On one hand, it’s a cadence wed to the tranquilising lilt of Sawalâpaugsumidlak, the patronal gozos whose brevity is thought-provoking. On the other, it’s a pulse exulting to the beat of makeshiQ drums (all sharp and harsh to the point of hellraising cacophony) that guide us devotees as we perform the votive dance in the narthex of the church, receiving aQerwards the foot eps of our patron on our head, arms, shoulders, or whichever parts the mangadjeay on duty decides to hallow.

CABALÍAN 1 10

In this 1482 fresco in the Sistine Chapel, Pietro Perugino depicts Saint John baptising our Lord in the Jordan.

© WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

How did we end up with the Precursor of the Lord as our patron? Apart from the Blessed Virgin and the Lord, whose birthdays we re2e8ively commemorate on F September and Ds December, Saint John is the only other saint whose earthly birthday we celebrate. Previously, Chri ians of old even kept Ds September as Saint John’s conception, in clear parallel with our Lady’s conception on F December, and our Lord’s on Ds March. Was this choice happenance? Or was it rooted on something more?

We know that, mo probably aQer iterated petitions, on \s September \F_a, the governor general of the Philippines, D. Juan Herrera Dávila, finally authorised the bishop of Cebú to e ablish the parish of Cabalían. Under the patronatoreal, any alteration to the ecclesia ical landscape had to be approved by the king of Spain, where it is called a real aprobación; or his representative in the Philippine Islands, the governor general, in which case it is called a superioraprobación. Ous, only aQer this authorisation was Fray Romualdo Jimeno Balle eros, O. P. able to canonically ere8 the parish of Cabalían under the patronage of Saint John the Bapti , on \] January \F_\.

Ois date is quite significant in that it is the o8ave of the Epiphany. Every _ January, Holy Mother Church commemorates a triple manife ation of Chri : fir , when the Magi adored Him; second, when the voice of the Father was heard at His baptism; and third, when at Cana He changed water to wine. Oe go2el pericopes are di ributed this way: adoration of the Magi on the fea of the Epiphany; baptism of Chri on the o8ave of the Epiphany; miracle at Cana on the second Sunday aQer Epiphany. Ous, Fray Romualdo in ituted the parish of Cabalían on a day that would later be designated as the fea of the Lord’s Baptism, when He descended into the Jordan and was manife ed in Israel by the baptism of penance, and Saint John saw the Holy Gho come down upon the Lord, giving te imony that He is truly the Son of God.

Ois, however, proves no causality. It can mean any of two things: that Saint John is our patron because we were e ablished on the fea of the Lord’s Baptism; or that we were e ablished on the fea of the Lord’s Baptism because Saint John is our patron.

Town lore, on the other hand, hints at a hi orical basis for our devotion to Saint John the Bapti , the Precursor of the Lord, in the person of D. Giovanni Domenico Aresu, a Jesuit missionary who was martyred in Cabalían, known in Spanish as D. Juan Domingo Aresu. Of his a8ivity in the Philippines, we have primary sources: D. Francisco Roa, Jesuit provincial from \_E] to \_E_; D. Diego de Oña, who wrote a detailed account of the Philippine missions around \__s; and D. Francisco Ignacio Alcina, the fir to write about the natural history of the Visayas.

P. Aresu was born in Tertenia in Sardinia on _ February \_as. He entered the Society of Jesus on E O8ober \_DD. AQer many petitions to go to the Far Ea as a missionary, he finally received permission to go to the Philippines in the company of E] Jesuits headed by D. Diego de Bobadilla. Oey reached Cavite on C July \_E], and then Manila three days later on foot. Shortly, thereaQer, P. Aresu travelled with four companions to Carigara, upon which Cabalían depended. From here, he would later go to his mission: the reduced village of Cabalían. Here, his greate labours began, and it was not without failures, which in ead of dampening his 2irit, only eeled his resolve.

A former katalonan, a prie ess communicating with elements, preternatural beings, and the devil himself, had apparently converted. We say apparently because her conversion, ultimately, was shortlived, and might have been motivated by reasons other than genuine faith. She soon returned to her animism and sorcery, her heathen pra8ices. When a grave disease smothered her, she showed signs of embracing the True Faith. Dear P. Aresu admonished her, many times, gravely, paternally, persi ently, to publicly acknowledge her error and renounce her former perversion, but the woman delayed it every time, until such point where, her lesions having healed, she refused to carry it out altogether. She later died without the consolation of the sacraments, a renegade and contumacious pagan.

But P. Aresu’s greate enemy was vice. In Cabalían, as was throughout Leyte at this time, it was drunkenness, corroborated by the observations made by P. Alcina, once assigned to Cabalían and by this time superior of Carigara.

A. D. 2022 11

WHICH JOHN

And who could be the wor person to harbour this predile8ion for intoxication but the village teacher, who, whenever P. Aresu was away mini ering to other communities within the territory, was also charged with the duty of catechising the children. He was a pathological imbiber, an irredeemable slave to toddy, the very embodiment of inebriation.

P. Aresu had tried and tried to persuade him to abandon this vice, but, as though alcohol had replaced the very blood that coursed through his veins, he was beyond reproof. He would not be parted from his wine. P. Aresu, aQer contemplating and deliberating on the matter, made the difficult decision of removing the man from all his charges. How could he, a prie of God, riving to become a paragon of virtue on earth, preach again and obliterate vice, when he himself would countenance association with men freely and uninhibitedly given to vice? Ju ice had to be satisfied.

To a mind addled by alcohol, however, it was inju ice. Oe man felt P. Aresu slighted him. Oe more he drank to drown his miseries, the more his bitterness consumed him. Revenge was the only freedom. Oe indignity to which his person was consigned had to be paid with blood. Oere was no other redemption for him. He recruited two other drunks, and together they made their designs to rid the earth of P. Aresu, who, aQer all, was ju a foreigner who had come to disrupt their gleeful intercourse with wine and eliminate their very own cu oms eeped in alcohol.

P. Aresu was in the habit of going to a large cross planted in the vicinity of the village. Ois is mo certainly the cross planted by the fir missionaries aQer they had chopped down and de royed the umalagad in the village. Oe umalagad, recorded in Spanish and Latin texts as omalagar, were shrines made of large beams of wood planted by the natives in the fields for the 2irits to sit on, from where they believed the elementals condu8ed and governed the affairs of mankind. Praying on this site, we can 2eculate, was to P. Aresu an a8 of pilgrimage to obtain from God the grace to extirpate heathenism. AQer all, the Chri ian cross now anding in the place of the heathen umalagad ood as a te ament to the triumph of the light of Chri over the darkness of animism.

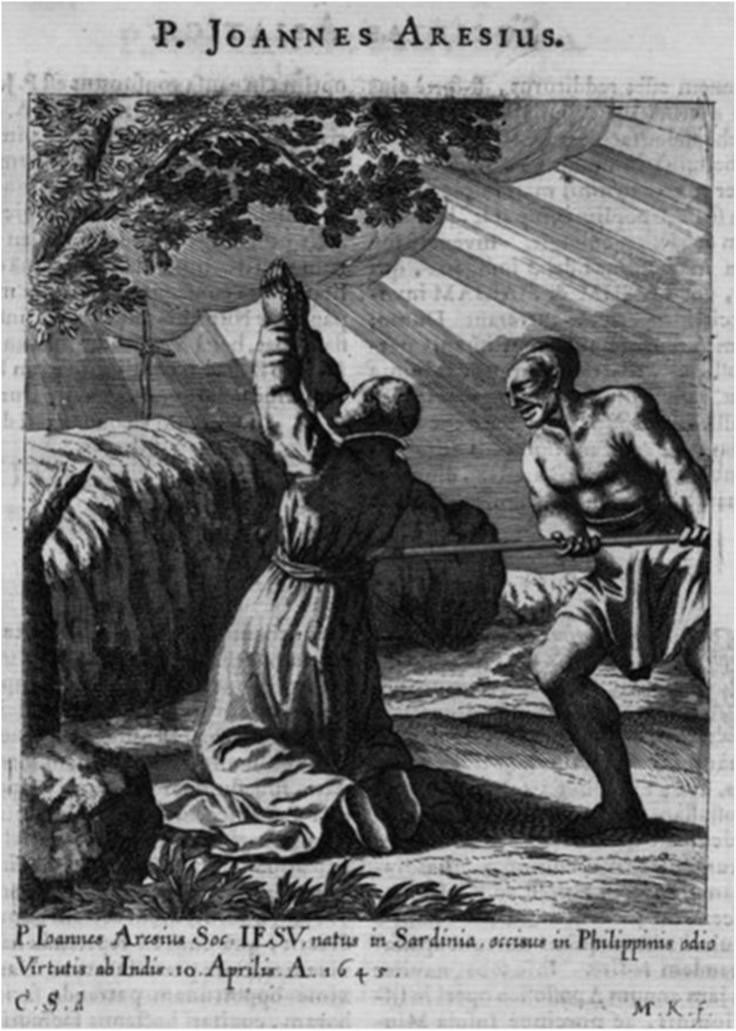

Towards sunset on \a April \_Es, P. Aresu came to the place as usual, and thither poured out himself in prayer. While the prie ood deep in meditation, the assassins arrived. Tiptoeing, the disgraced approached, and wielding a cryse, with one blow dealt a lethal wound to the prie , who, aQer two or three eps, collapsed headfir into the ground. Death was quick. Barely had he shouted the names of Jesus and Mary, he perished. Oe people discovered him drenched in his own blood. Oe accounts were much grislier. Oey pi8ured P. Aresu swimming in a pool of his own blood. It was Holy Monday.

Oe governor immediately launched an inve igation. Oe principal perpetrator was named Tuinga, who was a [fir cousin] of Buligan, chieQain of Cabalían at that time. Oe three were soon apprehended, and aQer a swiQ trial, were sentenced to death by rangulation (precursor to the later garrote). Oe governor ordered the bodies to be hung from a tree, and the harquebusiers that accompanied him fired a volley of shot at them, disfiguring them. He then 2oke to the people, and in ru8ed them how to treat their prie s with reverence. Overcome with awe and fear, the people vowed to abandon their vices, and to forever revere the martyred P. Aresu.

P. Aresu had the supreme honour of anticipating the Passion of the Lord, on the day when we hear in the propers of the Mass the Lord Himself calling out to His Father. Oe lesson of the day bears witness to P. Aresu’s martyrdom: “I have given my body to the rikers, and my cheeks to them that plucked them.” Of the device hatched again him by the disgraced, the little chapter of lauds 2eaks: “Let us put wood on his bread, and cut him off from the land of the living, and let his name be remembered no more.” But until the very end, the Name of the Lord was on P. Aresu’s lips, as though echoing the words of the introit: “Say to my soul: I am thy salvation.”

Oe Jesuits numbered P. Aresu “among the generous athletes killed for the faith,” who in many in ances honour him with the title of Venerable. In fa8, the parish of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Assemini, in the archdiocese of Cagliari, already li s P. Aresu among the saints and blesseds of Sardinia, calling him a

CABALÍAN 1 12

WHICH JOHN

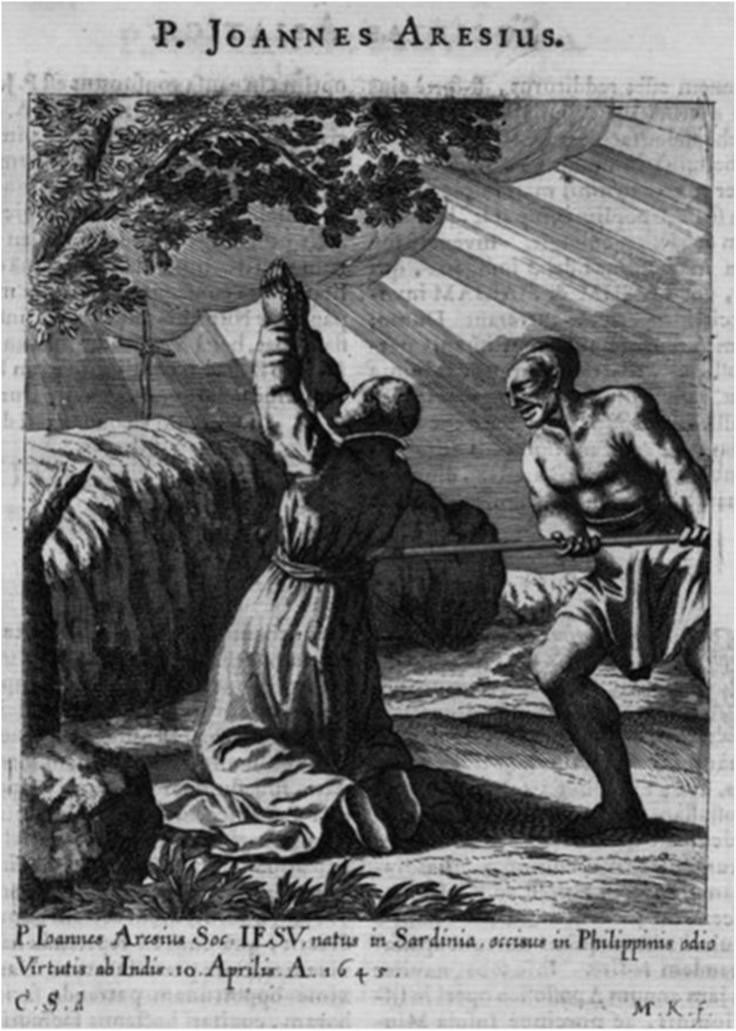

A 17th c. engraving showing the martyrdom of P. Aresu. Its basis is the secondary narrative by Tanner, which explains (1) why P. Aresu is kneeling, and not standing, and (2) why the instrument is a lance, and not a cryse.

P. IOANNES DOMINICUS ARESIUS

P. Ioannes Aresius Soc. IESV, natus in Sardinia, occisus in Philippinis odio Virtutis ab Indis, \a Aprilis A. \_Es.

Father Giovanni Aresu, of the Society of Jesus, born in Sardinia, killed in the Philippines in hatred of virtue by natives, on \a April \_Es.

Venerable. Six years ago, we collaborated with D. Tonino Loddo of the Diocese of Lanusei in the hope of convincing the Diocese of Maasin to formally open the case for P. Aresu’s sainthood. We forwarded all relevant documents to the diocese in a letter dated DE June Da\_, but we have not received any re2onse yet. In a letter dated ]\ March Da\C, we asked the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints to see if there is an open case on P. Aresu. We received their negative re2onse in a letter dated D June Da\C. On the Secretary’s advice, we wrote to the Jesuit General Curia in Rome on _ O8ober Da\C, and the General Po ulator replied on \s November Da\C, informing us that “an official Inquiry on [P. Aresu’s] life and martyrdom was never in ru8ed,” carefully noting that their documents go back only to \``D. All these boil down to the fa8 that, whether or not a venerable in the canonical sense, no altar could ill be consecrated in P. Aresu’s honour. Loddo, therefore, calls him unmartiresenzaaltare.

In every sense of the phrase, P. Aresu indeed is amartyrwithoutanaltar.Still without an altar. Ois year is the ]CCth anniversary of his

martyrdom. Loddo observes that all contemporary accounts of P. Aresu’s death note unanimously that it was perpetrated in odium fidei or inodiumvirtutis. Should a canonical process for his canonisation be opened, provided all the criteria are satisfied, a decree of martyrdom inodiumfidei would be enough for his beatification. He was martyred in Cabalían less than \a years aQer the martyrdom of Saint Lorenzo Ruiz in Nagasaki, almo three years before the martyrdom of P. Francesco Palliola in Zamboanga del Norte, and almo ]a years before the martyrdom of Blessed Diego Luis de Sanvitores and Saint Pedro Calungsod in Tumhon.

Brethren in the faith, it was in our native soil where P. Aresu 2ilt his blood for the faith. For his defence of the Sacraments, and his fervent love for souls, he finally earned the corona martyrum which he had considered forfeited forever when his superiors sent him to the Philippines in ead of to the missions he desired. It had been whi2ered by our elders that Saint John the Bapti was chosen as the patron saint of Cabalían because he is the name-

sake of P. Juan Domingo Aresu. ⁂

REFERENCES

F > J R IS , Brevereseñadeloque fueydeloqueeslaDiócesisdeCebú (Manila\FF_)no.]\.

T L , Un martire senza altare: Il Padre Giovanni Domenico Aresu, gesuita terteniese (XVII sec.): StudiOglia rini \D(Da\s)]`–__.

T L , Giandomenico Aresu: Un martire missionario oglia rino del ‘@AA: LCOglia ra ]E (ottobre Da\s)D\.

M ;|} T , Societas Iesu usque ad sanguinis et vitæprofusionemmilitans (Prague\_Cs)pp.EDD–ED].

A. D. 2022 13

© KAREL ŠKRÉTA & MELCHIOR KÜSEL

BOATLOAD fannies of

A thirty-year-old joke in song and rhyme

< [ ~ ; : J ? , watching what looks like a variety show where boys and girls sing and dance, their innocence and adorability balancing out their otherwise intolerable lack of tone and timing, when suddenly one child breaks the monotony by singing about a boat, er$while boarded by shapeshi2ers, suddenly boarded by twats. By twat, please do not imagine na y women in red pumps others would rather call bitches. Imagine inead the anatomicalpart.

One would think that piety would push the crones, apople8ic with indignation and paroxysmal with rage, towards the brink of madness, but no, sir, they showed none of these. In true Filipino fashion, where we discover elders forever captive to the charm of a child, the pious crones laughed.

Some Cabalianons tell us this really happened in the town. Once. During one of the many events organised for the centennial celebration of the parish church in \``D, Cabalianon children showcased their talents in a show. No less than the parish prie , Fr. (now Msgr.) Félix Paloma (qué enpaz descanse), was in attendance. One boy went up the age, coy and i2uting (smartly dressed), and belted out the song we now know as Sakajánumpak-umpak.

Ois is the anecdote behind the nursery rhyme that we learned under the noses of our

ri8 aunts. Its creator borrowed the tune of the Filipino folksong Vamosaplantar arroz, a rain that is more widely known in its Tagalog version, Magtanímay‘dibirò. (Yes, yes, all the folksongs we learned in school were originally written in Spanish.) Its lyrics, playing upon the natural rhythm of Visayan 2eech, arts with a whimper and ends with a bang. Below we present said lyrics, and in the following page its transcription.

Aware that this is merely a silly children’s rhyme, we nevertheless launch an appraisal of its composition.

CABALÍAN 1 14

Sakaján umpak-umpak, Nanakáy purós wakwak; Pag·abót sa Biasong, Nanakáy purós bisóng.

Oe fir line positions the narrative in the sea. A sakaján in Cabalianon refers to the double outrigger canoe that fishermen employ for their trade, navigating the waters in search for a good 2ot to ca their nets. When cu ombuilt with a bigger hull fitted with benches for sitting and an awning for prote8ion again the sun, it is now normally called a ferryboat, but ill recognised as a sakaján.

Oe predicate umpak-umpak confirms the navigational nature of the song, being in itself an onomatopoeic rendition of the noise made by the conta8 of the outriggers (katig in Cabalianon) with the surface of the sea.

Oat the fir line alludes to this latter form of the sakaján as a mode of tran2ort becomes clearer in the second line. Oe verb sakáy is applied to a8ions involving riding or boarding a

A. D. 2022 15

© CABALÍAN NEW FACE / FACEBOOK

(above) Notated transcription of Sakaján umpak-umpak. (below) Almost non-existent waves lazily toss a gaggle of sakaján moored near what once was the BFAR along Cabalían Bay.

vehicle to get from one place to another. Oe phrase purós wakwak explains that all those boarding the sakaján are hags. In the Cabalianon cosmos, a wakwak is a human being capable of transforming into an animal at will (a shapeshiQer); endowed with collapsible wings that they can employ to cruise the night sky in search of their prey (a riga); and harbouring an insatiable dietary preference for human liver, children’s particularly (a lamia).

Oe second line a8ually posits a que ions that we mu silently answer. Why are the hags in a canoe and not flying? One possible answer is salt. Oe salty breeze of the sea incapacitates the hags, and therefore prevents them from flying. Once again, we are reminded of the redeeming and preserving qualities of sodium chloride. Another possible answer is the long di ance of the travel. Where might these rigae and lamiae be going? Are they afraid to meet the sunrise and thereby suffer what upid and ill-advised nightflyers get for their imprudence? As Icarus erred in flying close to the sun, so some had erred in flying towards the sunrise.

Oe third line provides us with the only topological marker in the song. Biasong is a common toponym in many Visayan islands. Oere are barangays called Biasong in Cebú and Bohol. In the area of Southern Leyte facing the Pacific Ocean, there are at lea two barangays called Biasong: one in Hinunangan; another in Hinundayan. Oere are, of course, other barangays in the province called Biasong but we only mention the two above because they are the ones near Cabalían.

Oe placename Biasong comes from the wild citrus biyasong native to Cebú and Bohol. Its scientific name is Citrusmicrantha, of which two varieties are accordingly recognised: the small-flowered papeda (C. micrantha var. micrantha); and the small-fruited papeda (C.micrantha var. microcarpa). Oe fir one is biyasong; the latter is samuyaw. If a certain plant grew abundantly in a certain hill, locals would conveniently chri en that hill and the entire area surrounding it aQer that plant. Oat is how barangays called Biasong got their appellation. But do not ask why hags would have ele8ed to go to Biasong. Maybe they had a coven there.

CABALÍAN 1 16

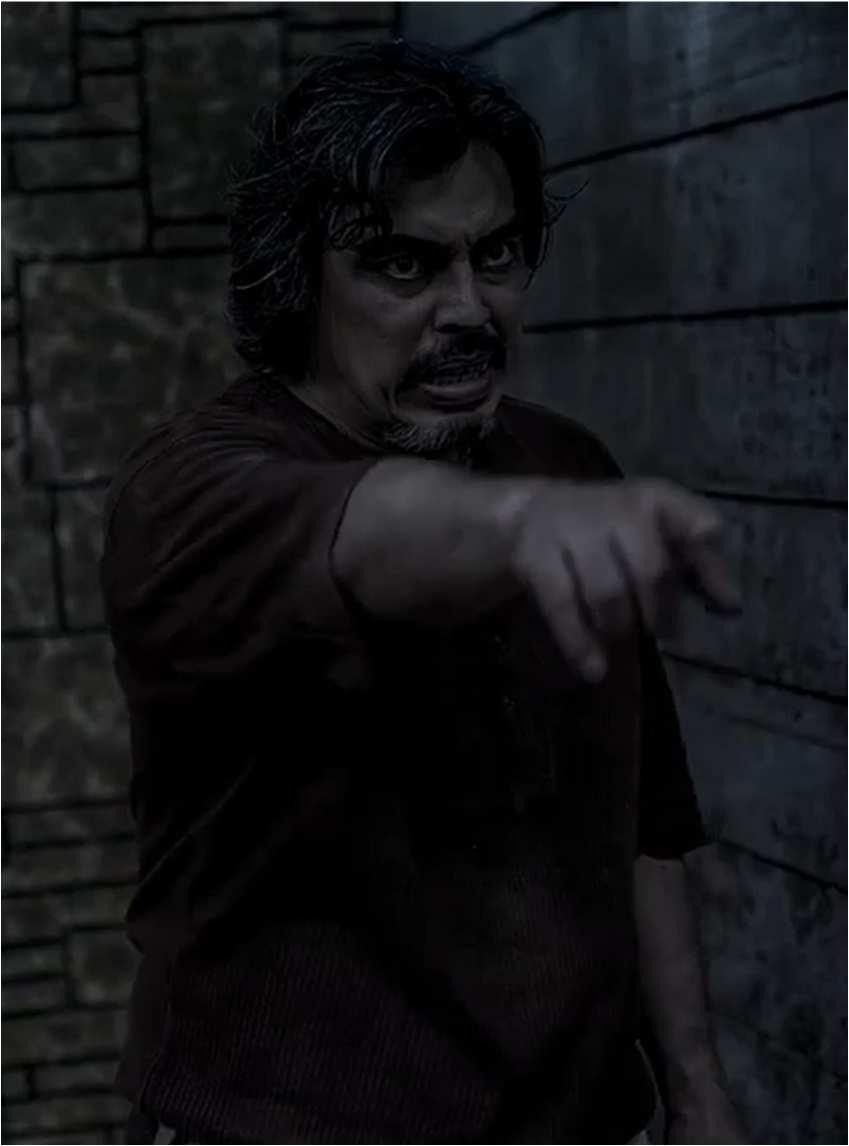

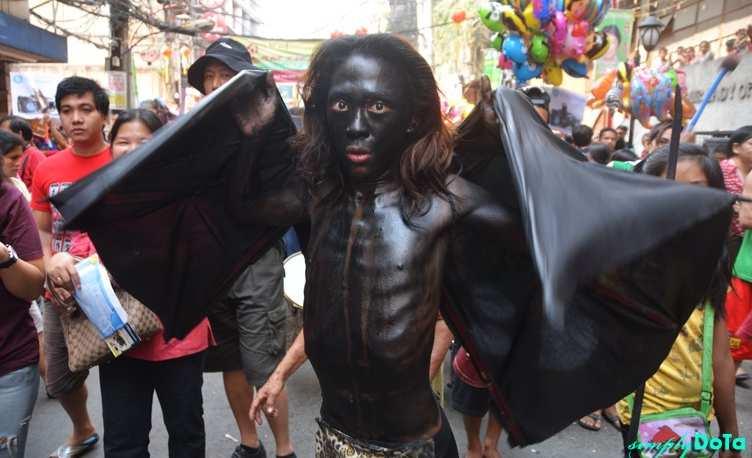

Common depictions of wakwak in Filipino popular culture: (left) An epicene youth pretends to be a wakwak in its winged allomorph in the Aswáng Festival in Capiz; (right) Mike Gayoso plays the role of aswáng Ringo, one of the many antagonists in the 2012 film Tiktík: The aswáng chronicles.

© GMA FILMS © SIMPLY DOTA / CHITCHAT & WHATEVER

Or perhaps a centennial conventicle. Oere might have been a subasko (squall; sudden and short orm) not mentioned in the song that drove the passel of hags to Biasong. We discover no indication in the song that docking in Biasong was part of the itinerary of the sakaján. Oe verb pag·abót simply tells us about the mere a8 of reaching the place. No causality whatsoever can be e ablished. (But, again, this is a silly children’s rhyme; if we fail to map its logic, it is not probably our fault.)

Oe final line is the proverbial twi in the song. Calling it twi ed would not be amiss. Oe person behind this simply removed the second syllable of biyasong and shiQed the accent to the la syllable, thereby generating bisóng. In many Visayan languages, this refers to the female genitalia. But like mo Visayan words, it encodes a certain 2ecificity. It is mo ly used to refer to the genitalia of female individuals between the ages C and \F. Before or aQer this range, there are other words that better capture its anatomical (im)maturity.

Let us not try to imagine the logi ic impossibility of cramming these womanly parts— independent of the re of their physiology—in the hull of a double outrigger canoe. (We are aware that synecdoche is probably employed here to comedic effe8s, that bisóng is used to refer to women as juridical beings. Suppose, however, we forgot we know figure of 2eech, then we continue with our train of thought on the literal meaning encoded by the word.) It would be something akin to IeVaginaMonologues, minus the mere soliloquy. Oere would be dialogue, and—if our creativity and blatant chauvinism should ever be tru ed—a good deal of gossip.

As soon as the boy, i2uting and nonchalant about what he was doing, enunciated this noun, every 2e8ator—man, woman, clever, silly, child, crone, lad, lass, droll, dour, mayor, prie —forgot everything about the wakwak. Whatever happened to these shapeshiQing rigasomic nightflyers, nobody cared. Oe bisóng

brought the house down. ⁂

A. D. 2022 17

© LAVANCHER / TIME © LABAO FARMS / FACEBOOK

(left) Small-flowered papedas (C. micrantha var. micrantha), biyasong, pile in a basket after harvest. (right) Half of Conceived in Brooklyn, clad in a vag suit, attempting some pose in the streets of New York.

WORD OF THE YEAR