COLUMBIA

Ray Beck helped orchestrate the city’s growth for almost 50 years. PG 40

Calcium deposits in the walls of coronary arteries can put you at a greater risk for heart disease, heart attack and stroke.

To make an appointment for a calcium screening, call Boone Health at 573-815-8150. The non-invasive screening takes approximately 15 minutes and can be completed at Boone Hospital or at our Nifong Radiology clinic.

Secure your legacy

Are you prepared to protect your legacy and minimize your taxes?

Over the next 25 years, $124 trillion in financial assets is expected to transfer to the next generation. At Commerce Trust, we work to ensure your assets are strategically allocated to minimize tax liabilities while protecting what you pass on to your next generation and to your philanthropic beneficiaries.

From understanding taxable gifts to leveraging tax exemptions, your private wealth management team will work collaboratively with your estate attorney and tax advisor to craft an estate plan tailored to your goals.

Our holistic, team-based approach to servicing clients means your team of estate and tax planning, investment management, and trust administration professionals will work together to guide you toward achieving your personal and family goals while safeguarding your legacy.

Planning your legacy in the way you envision is at the heart of the Commerce Trust approach. Contact Lyle Johnson, your dedicated Market Executive for Commerce Trust, at (573) 886-5324 or lyle.johnson@commercebank.com to secure your legacy.

PRINT IS NOT DEAD!

PUBLISHING

David Nivens, Publisher david@comocompanies.com

Chris Harrison, Associate Publisher chris@comocompanies.com

EDITORIAL

Jodie Jackson Jr, Editor jodie@comocompanies.com

Kelsey Winkeljohn, Associate Editor kelsey@comocompanies.com

Karen Pasley, Contributing Copyeditor

DESIGN

Jordan Watts, Senior Designer jordan@comocompanies.com

MARKETING

Charles Bruce, Director of Client Relations charles@comocompanies.com

Kerrie Bloss, Account Executive kerrie@comocompanies.com

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Tyler Beck, Boone County Historical Society, Lana Eklund, Nina Furstenau, Jodie Jackson Jr, Anthony Jinson, Hoss Koetting, e State Historical Society of Missouri, John Trotter, Kelsey Winkeljohn

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Sunitha Bosecker, Beth Bramstedt, Barbara Bu aloe, Chris Campbell, Caroline Dohack, Hoss Koetting, Jodie Jackson Jr, Madeleine Leroux, Marcus Wilkins, Kelsey Winkeljohn

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Magazines are $5 an issue. Subscription rate is $54 for 12 issues for one year or $89 for 24 issues for two years. Subscribe at comomag.com or by phone. COMO Magazine is published monthly by e COMO Companies.

OUR MISSION STATEMENT

COMO Magazine and comomag.com strive to inspire, educate, and entertain the citizens of Columbia with quality, relevant content that re ects Columbia’s business environment, lifestyle, and community spirit.

Copyright e COMO Companies, 2025

All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of any editorial or graphic content without the express written permission of the publisher is prohibited.

FEEDBACK Have a story idea, feedback, or a general inquiry? Email our editor at Jodie@comocompanies.com.

CONTACT

e COMO Companies | 404 Portland, Columbia, MO 65201 573-577-1965 | comomag.com | comobusinesstimes.com

The COMO Mojo: The Stories We Carry

Memorial Day Weekend, 2025

I’ve just spent a few (or many) minutes soaking up the sun’s rays with my feet in a still-ice-cold pool. I’m at my grandmother’s old home. A place where, as a kid, I spent summer days darting around the pool, trying to somehow outrun the burning concrete and outswim the sting of chlorine.

e house remains in the family, though it’s been renovated and now serves as a rental property. e pool slide is gone. e once-wild (yet beautiful) landscaping has been trimmed and tamed.

But this weekend, the house is ours again, reserved for visiting relatives here for the second Hernandez family reunion. While most of my immediate family lives in the Kansas City area, we now have relatives scattered across the country, from Michigan to Texas to, more recently, Florida.

As I step back inside, voices boom from the family room. Stories y — the good, the bad, the absurd — from the days when nuns would smack misbehaving kids, to the time great-grandpa accidentally drank buttermilk on anksgiving.

Afternoon turns to evening, and the house hums with loud (because that’s the Hernandez way), lighthearted chatter. Great-Uncle Victor and his wife, Barbara, sit beside Great-Aunt Bea, all three beaming next to their brother — my nearly 86-year-old grandfather, Richard — happy to be together again.

My second cousin, Patrick, is in the kitchen, cooking beef tongue in a savory tomato sauce. My other second cousin, Renee, boils pasta for those of us who are less adventurous. Later, she scrolls through photos from her son Brandon’s wedding, pausing at the ones that make her laugh or tear up.

When I sneak upstairs for a quiet moment, I notice the photos that once lined the staircase are gone. No familiar faces

on the walls or end tables. A wave of emotion hits.

But then I spot my grandmother’s artwork, still hanging proudly. Little touches from her home country remain, scattered throughout the house. And there’s something undeniably special about everyone coalescing here, on this weekend — generations gathered in one place. People who rarely see each other falling into that familiar rhythm of catching up on the present while drifting into stories of the past.

e word “legacy” often carries a connotation of grandeur, as if it only belongs to those who’ve left an indelible, far-reaching mark on the world. And while that can be true, I think legacy lives with us regular folks, too, in the recipes passed down, family jokes that never die, the way someone folds a napkin or tells a story just so. It lives in the gatherings and in the small, sacred traditions that are passed down from one generation to the next. Beef tongue might even become one … unless Renee has anything to say about it.

Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to storytelling; it’s one way to make sure the little things aren’t lost. Legacy doesn’t have to be monumental. It just has to mean something to the people who carry it forward.

KELSEY WINKELJOHN ASSOCIATE EDITOR kelsey@comocompanies.com

ON THE COVER

Ray Beck served forty-six years as Columbia’s public works director and then city manager. His legacy is chronicled in an upcoming book.

Photo by Tyler Beck

The 2025 Hernandez family reunion in Kansas City, MO.

COMO’S ADVISORY BOARD

We take pride in representing our community well, and we couldn’t do what we do without our COMO Magazine advisory board. Thank You!

Beth Bramstedt

Church Life Pastor, Christian Fellowship Church

Heather Brown

Strategic Partnership Officer, Harry S Truman VA Hospital

Emily Dunlap Burnham

Principal Investigator and Owner, Missouri Investigative Group

Tootie Burns

Artist and Treasurer, North Village Art District

Chris Horn

Principal Treaty

Reinsurance Underwriter, American Family Insurance

Kris Husted

Investigative Editor, NPR Midwest Newsroom

Laura Schemel

Director of Marketing and Communications, MU Health Care

Art Smith

Author & Musician, Almost Retired

Megan Steen

Chief Operating Officer, Central Region, Burrell Behavioral Health

Nathan Todd

Business Services Officer, First State Community Bank

Casey Twidwell

Community Engagement Manager, Heart of Missouri CASA

Wende Wagner

Development Manager, DeafLEAD

Have a story idea, feedback, or a general inquiry? Email Jodie@comocompanies.com.

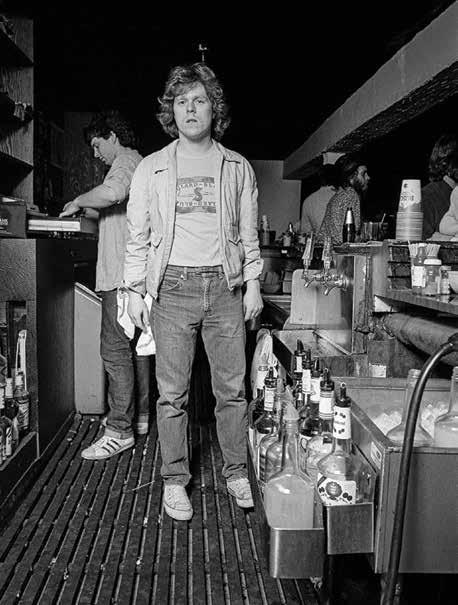

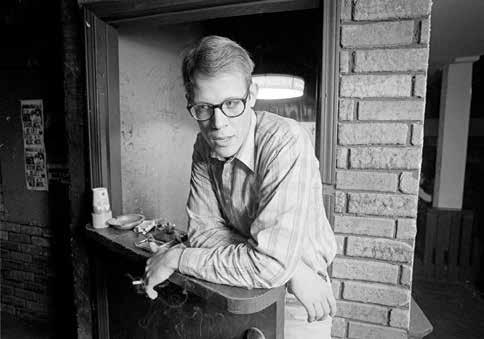

Richard King and Chris Nadler tending bar.

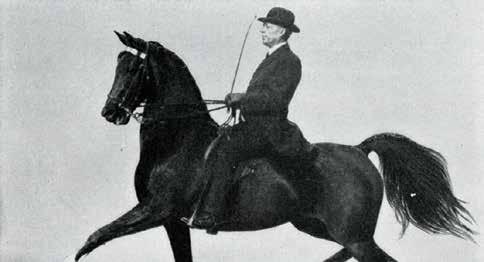

The Horse Whisperer

Tom Bass was Boone County’s ‘Michael Jordan’ of equestrians.

BY CHRIS CAMPBELL, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, THE BOONE COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Tom Bass was one of the most extraordinary talents to ever come out of Boone County, Missouri. And yet, unless one is familiar with equestrian feats of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in America, or a fan of American Saddlebred horses, most mid-Missourians have never heard of Bass.

Tom Bass was born on January 5, 1859, in a slave cabin on the 5,000-acre Eli Bass Plantation in southern Boone County near Ashland. His mother, Cornelia Gray, was a slave, and his father was a 22-yearold white man, William Hayden Bass, the son of the plantation owner, Eli Bass. Tom was born just four months after his father married Boone County society belle, Irene Hickman Bass.

When Tom was no more than 2 or 3 years of age, it was said that, to the horror of farmhands, he was playing in the bull pen — the bulls unbothered by the toddler’s presence. By the time Tom was 4, he was riding horses so large it was said he could have walked under their bellies without his head being touched. At the age of 9, Tom had taught the family mule to canter backward — a skill

Before Jackie Robinson ever donned a Dodger uniform — there was Tom Bass.

Before Rosa Parks ever demanded a seat in the front of the bus — there was Tom Bass.

Before Martin Luther King ever had a dream — there was Tom Bass — the Black horse whisperer.

Born a slave, the friend of Presidents, the most famous Black American horseman this country has ever known, today his story is consigned to oblivion. Yet, once his name was a household word synonymous with equestrian feats of unparalleled beauty and achievement.

But he didn’t start out famous. He started out in chains.

– WRITTEN BY CUCHULLAINE O’REILLY

unheard of for mules. e young boy was already developing a natural and special talent that would bring him fame and fortune as an adult.

In the spring of 1878, 19-year-old Tom left the Bass plantation for Mexico, Missouri, to take a job as a hotel bellhop. It was in Mexico that Tom would eventually open his own training stable.

As the years passed, Tom earned a reputation as a fair and honest man whose training methods produced remarkable results with horses — attracting wealthy and prominent individuals from across the country to his stable. eodore Roosevelt journeyed to Mexico to ask Bass to provide him a well-trained mount for the New York bridle paths. Queen Victoria invited him to London in 1897.

Despite the prejudice he often encountered at horse shows, Tom would earn tremendous personal and professional respect from statesmen and leaders all over the world — unheard of for an American Black man in that era. President William McKinley came to his home, as did William Jennings Bryan. On one of his visits to the Bass home, “Bu alo Bill”

Cody brought along a young Oklahoma cowboy named Will Rogers.

In 1892, Tom moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where he opened the Tom Bass Stables at the corner of 39th and Main streets. In that same year, when the Kansas City Fire Department needed a way to raise funds, Tom suggested a horse show. e horse show eventually became the American Royal — one of the biggest horse shows in the United States and one of the three jewels of the Saddlebred Triple Crown. Unsurprisingly, Tom Bass was the rst African American to exhibit a horse at the American Royal.

In 1893, Tom showed horses at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and won the championship on his Saddlebred mare, Miss Rex. Tom later moved back to Mexico and continued training horses. In 1917, it was estimated that over 1 million people had seen him perform with his horses. He was credited with making Mexico, Missouri, the “Saddle Horse Capital of the World.”

Besides the legendary Rex McDonald and other Saddlebreds, Tom trained the notable high school horse Belle

Beach, who could bow, curtsy, and dance. He invented a curb bit that became known as the “Bass bit.” It was designed to give the rider control without causing pain to the horse.

Interestingly, Tom never patented the invention. e Bass bit is still in use around the world. For his contributions to the state of Missouri, Tom was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians in 1999, becoming the twentieth person so honored. Tom is also featured in the American Saddlebred Museum in Mexico, Missouri, and the American Royal Museum in Kansas City.

Bass died of a heart attack on November 20, 1934, at the age of 75. His friends believed that grief from the recent death of Belle Beach, one of his best horses, contributed to his death. Bass is buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Mexico, Missouri. His tombstone reads, “One of the World’s Greatest Saddle Horse Trainers and Riders.” Upon Bass’s death, the legendary humorist, Will Rogers, devoted an entire newspaper column to him, saying in part:

“Tom Bass ... aged 75, died today. Don’t mean much to you, does it? You have all seen society folk perform on a beautiful three- or ve-gaited horse and said, ‘My, what skill and patience they must have had to train that animal.’ Well, all they did was ride him. All Tom Bass did was train him. He trained thousands of horses that others were applauded on. A remarkable man, a remarkable character.”

It is an understatement to say Tom Bass’ America was a vastly di erent country than the United States we know today. But there are some apt comparisons that help to illustrate the importance and fame of the horseman from Boone County, Missouri. One-hundred years before 20,000 fans would ll college and professional basketball arenas, or 70,000 fans would ll football stadiums, tens of thousands of spectators attended horse shows in towns across the country.

Tom Bass’ name was in the sports pages for decades and long before we

had heard of Jackie Robinson. Could it be fairly said that Bass was to the American Saddlebred what Michael Jordan is to basketball? I believe the answer is “Yes.” Could it be said that Bass’ training methods and accomplishments in that eld could be compared to the coaching of legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden? I believe the answer is “Yes.”

Tom Bass was not only honest and authentic, he was a man of integrity, an educator, a trainer, and a friend to thousands — he was a superstar.

For more information on this local legend, purchase the book Whisper on the Wind, e story of Tom Bass — Cele-

brated Black Horseman, by Bill Downey. e book is available on Amazon but can also be purchased locally in the museum gift shop at the Boone County History & Culture Center in Columbia.

(Primary and secondary source material for this article comes from Whisper on the Wind, The Story of Tom Bass — Celebrated Black Horseman, Bill Downey, The Boone County Historical Society, The State Historical Society of Missouri, CuChullaine O’Reilly of the Long Riders Guild, Will Rogers’ syndicated writings, public records, The Audrain County Historical Society, The Kansas City Star, and The Mexico Ledger.)

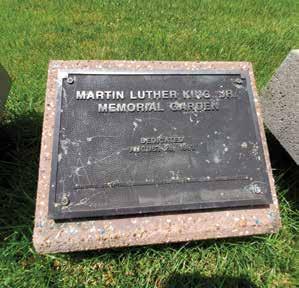

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial at Battle Gardens

A COLORFUL AND AROMATIC DISPLAY OF FLOWERING PLANTS, most of which are native Missouri ora, o ers a natural ebb and ow of life and energy. A visually captivating semicircular labyrinth, surrounded by a ve-step granite amphitheater with eight triangular upright columns, frames the structure and highlights the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

It’s the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial at Battle Gardens at 800 W. Stadium Boulevard, a legacy public art project that is part of Columbia’s expansive system of parks and trails. e memorial area was dedicated on August 28, 1993 — the 30th anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. e site is also a trailhead for the MKT Trail that runs from Columbia’s downtown to the Hindman Junction rest shelter on the Katy Trail.

BUT DID YOU KNOW ...

Many of Columbia’s parks are located on land reclaimed from use as sewage lagoons, one example of how city planners instituted a sort of recycling on a grand scale even before the city’s solid waste division began a residential trash recycling program. e MLK Memorial is, in some ways, the pinnacle of that reclamation process. e large, paved parking area there was once a sewage sludge drying bed.

AND NOW ...

According to the city’s website, “ e memorial is a place for community and cultural events to occur in a completely accessible site. e Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial at Battle Gardens is truly an environment designed to bring people together, whether for quiet meditation or active participation.”

e sculpture artist, Barbara Grygutis of Tucson, Arizona, was chosen in a national competition from among twenty- ve submitted models. A ve-member regional jury and a three-member national jury selected her proposal. e proposals were also posted at the Columbia Art League, eliciting some 500 comments and votes that were submitted to the juries for consideration.

e gardens can be reserved for outdoor weddings. ere is also a reservable picnic shelter, a reservable MKT Trailside building, and seasonal restrooms. e 4.5-acre park is open daily from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. e trailhead has exercise stations, seasonal water fountains, and an emergency telephone kiosk.

STORY AND PHOTOS BY JODIE JACKSON JR

The Song That Still Echoes

BY KELSEY WINKELJOHN

PHOTOS BY JOHN TROTTER

PROVIDED BY KEVIN

WALSH

“ at / wasted breath of neon light a frail / tattoo or come-on in pools / of rain. at street, at rain / No. Our street. Our rain.”

— “AFTER THE BLUE NOTE CLOSES”

BY LARRY LEVIS

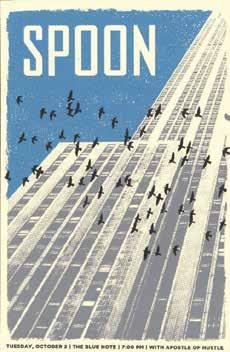

PUDDLES OF RAIN SIT STAGNANT AND QUIET outside a building at 912 Business Loop 70 East. at is, until an amp ips on and the stomp of a hundred eager feet charges toward the entrance. e year is 1980. ere are no algorithms. No endless scroll of events or social media invites. Just word of mouth and the heartbeat of a growing Columbia — a city centered around music and, like the rest of the world, on the cusp of MTV’s cultural tidal wave.

Richard King and Phil Costello have just opened e Blue Note, a venue that will soon shape the sound of mid-Missouri. Music pulses through every corner of the community, from the stage to Streetside Records, where conversations begin with, “Have you heard this one yet?”

e story of this iconic venue starts just a few years prior. King and longtime friend Kevin Walsh (who would later become the rst employee of e Blue Note) bonded over a mutual love of music — Springsteen among their favorites — and a shared habit of seeking out live shows.

“Kevin came here [Columbia] to go to graduate school, and I was on my way to California,” King said. “I was staying on the couch for a few weeks and decided to stick around for a while.” at was October 1975. In the years that followed, King cycled through various jobs, including a brief stint managing e Heidelberg. Along the way, he met Costello and helped him land a bartending gig.

Like King and Walsh, Costello had an a nity for good music and attended shows with King at venues such as e Brief Encounter, where Costello would later work as a bartender, and Gladstone Manufacturing Company.

Eventually, Costello became roommates with King and Walsh, and the parties they hosted in their east campus house were not only legendary, but also served as a proving ground for what would become one of Columbia’s most beloved music venues.

“Music had always been a big part of the household,” said Walsh, “and the parties were ongoing, so it was just a matter of moving it and making it o cial.”

A SUMMER OF SOUND AND SWEAT

In 1980, Costello was privy to the news that Ron Roth, the owner of e Brief Encounter bar, and his mother, Gladys, wanted to sell the building, following Roth’s marital issues. With the owners wanting to sell quickly and at a low price, it felt like the kind of chance that doesn’t come around twice.

On August 1, under a blistering 108-degree sun, they hauled their gear into the building, which had no air conditioning and was, thereafter, a ectionately nicknamed “ e Dump.” But it had incredible acoustics.

“We were very lucky,” says King, regarding the acquisition and its timing. MTV was founded exactly one year after e Blue Note’s purchase, and according to King, it was the year they “started to believe.”

Initially, though, it was more a labor of love than an informed business plan. King and Costello operated solely on passion and a sense of “cool,” rather than a long-term vision — and certainly not

LEFT, TOP TO BOTTOM

Kevin Walsh and Richard King circa 1983, at the old Blue Note location.

Kevin Walsh and Alex Chilton, American musician and lead singer of the Box Tops and Big Star, in the old Blue Note’s office/dressing room.

Kevin Walsh and waitress Amy Manarelli at the downstairs bar in the old Blue Note. Richard is in the background.

with the expectation that it would take o the way it did.

“We didn’t have any money,” said King. “In fact, Kevin and everybody who worked for us worked for tips. We borrowed money from our girlfriends and our families to get it up and going.”

e crew, which consisted of the trio and volunteering friends, did everything, from bartending to curating lineups to cleaning and promoting. It took a few years for King and Costello to be able to begin writing checks to themselves.

With limited funds for radio promotions, King and Costello would crisscross the city daily carrying knapsacks full of carefully crafted yers to promote their upcoming shows, which featured emerging artists of the time, such as the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

“ e only logical thing that we had was that we could print out posters for three cents a copy and smack them all around town and campus,” said King.

While this method got the word out, some people were less than thrilled that the posters consumed all the advertising real estate in town. King received numerous letters of complaint from the University of Missouri and local building managers about the proliferation of posters.

“One particular instance — I was in Booches with Phil, and a local attorney started giving him a hard time about us putting posters up on telephone poles, and on windows and doors,” said King.

“No question, he was right, but the attorney was pretty rude to us. We were like, ‘Hey, this is all we really have, you know?’

Two days later, we see him again and he goes, ‘I’m going to the city council and asking them to put up kiosks downtown,’ and that made our lives a little easier having a spot to put our posters.”

Public radio stations KOPN and KCOU also played a role in the early success of e Blue Note, assisting with promotions during a time when only performers with guaranteed commercial appeal were receiving airtime. Additionally, the crossover with Streetside Records — where Walsh and other Blue Note employees also worked — helped amplify word of mouth and further rooted the venue in Columbia’s music culture.

ABOVE Spoon Poster Creator/Copyright: Ben Chlapek BELOW Girls Poster Creator/Copyright: Garrett Karol

Digitized by The State Historical Society of Missouri

Once MTV had taken o , underground bands began receiving more coverage, and thus, more people ocked to e Blue Note, eager to see fresh faces and sets.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS BACKSTAGE

One of the key di erentiating factors that e Blue Note presented — and what attracted tour managers — was its value for the bands that would perform.

“ ey [bands] would just come through town, and some of them were near destitute,” said Walsh. “I remember Phil had to buy R.E.M. a spare tire they couldn’t a ord. And that kind of thing establishes long-term relationships with bands. ey really remember shit like that.”

Additionally, according to Walsh, instead of o ering a standard deli plate backstage, King would send bands to local spots, such as Glenn’s Cafe (owned by his friend Stephen Cupp), where they’d be well taken care of.

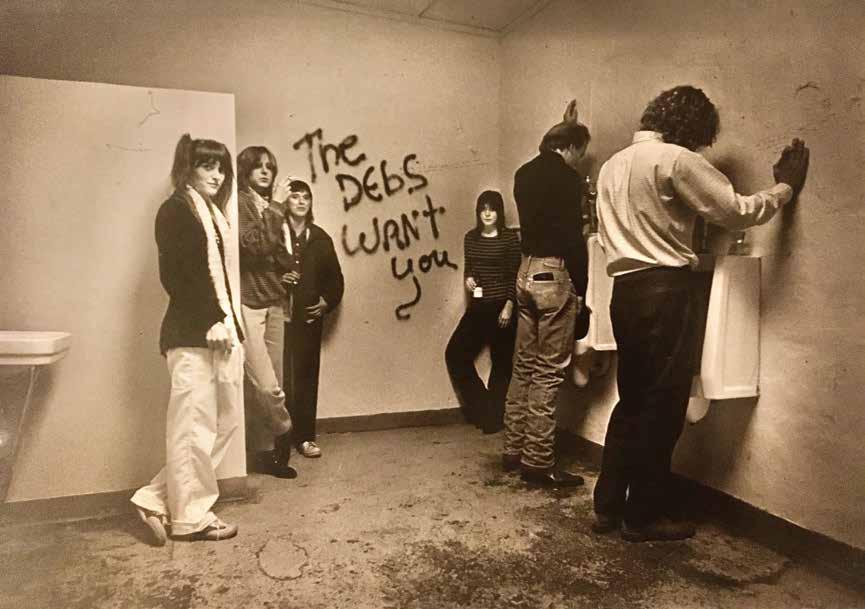

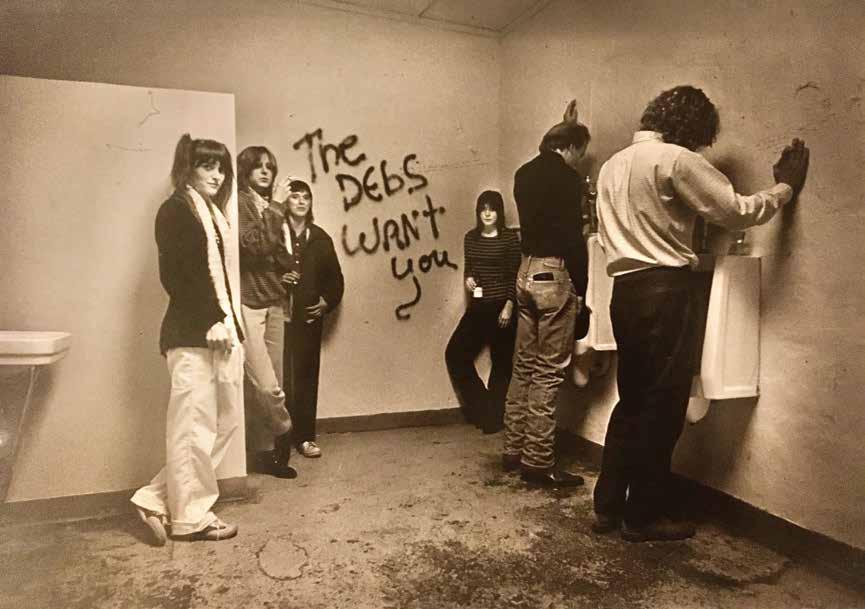

“It was very much a family a air,” said Walsh. “All bands — not the national acts,

but any other bands — would play both nights on the weekends, usually. And a lot of the bands would stay at the house. You would wake up, and e Debs would be there with their sound guy, and the reggae guys would be cooking oxtail soup and doing their laundry.”

is established camaraderie and profound connections between the Blue Note crew and bands, while ensuring a future of big-time, compelling performers, even ones who had outgrown the venue, such as e Pixies.

King also cites a diversity of performers, from country and rock to reggae and hiphop, as being one of the key selling points for the venue.

By 1990, Costello had been absent from e Blue Note for a few years, having left for a job with I.R.S. Records (and later moving to Capitol Records and Warner Brothers). King was ready to take e Blue Note to the next level. at year, he moved e Blue Note from Business Loop to its present-day location on 9th Street.

ABOVE Kevin Walsh and Phil Costello with the all-female band, The Debs in the old Blue Note's men's restroom.

RIGHT MIDDLE Phil Costello and Richard King take out the trash.

RIGHT BOTTOM King and Costello in front of the old Blue Note (From the Blue Note & Rose Blog)

“ ings were going really well,” said King. “ at’s when I was o ered the theatre downtown … e scariest thing I’ve ever done is move the club from the Business Loop to downtown. But it was also the best move I could make for myself and the club.” e move proved successful. Late-night shows carried on, with legendary acts like Johnny Cash, Cheap Trick, and Weezer gracing the stage. e new location also enabled the further integration of downtown culture and the safe accommodation of roughly 400 more attendees. In 1998, it became the rst building and the rst commercial structure to be named to the city’s list of Notable Properties.

LEFT

The late Forrest Rose, for whom Rose Music Hall was named after. Rose was a musician, doorman, and well-known journalist for the Columbia Tribune

KEEPING THE MUSIC GOING

e expansion didn’t stop there, though. In 1999, King bought Mojo’s, another venue in the downtown area, just one street over from the new Blue Note location.

Although King sold both e Blue Note and Mojo’s to Matt Gerding and Scott Leslie in 2014 after 34 years at the helm, the venues remain cornerstones of Columbia’s music legacy.

On January 1, 2015, Mojo’s was renamed Rose Music Hall in honor of the late Forrest Rose, a beloved bassist, local columnist, and friend to many in the scene, including King. e name honors not only Rose’s memory, but also the community spirit that shaped the venues from the beginning.

Upgrades followed, including the 2017 addition of Rose Park, an outdoor stage and gathering space that marked the venue’s next chapter and an investment in the future of Columbia’s music scene.

“ is stage is the culmination of the work of a lot of visionary people planning the next chapter of e Blue Note and Rose Music Hall,” said Tanner Lee of the Atlanta-based Tanner Lee Band in a Columbia Missourian article that year.

King, meanwhile, began his next chapter at Cooper’s Landing in 2019, channeling his passion for music into a new space by the Missouri River. ese days, he focuses less on nationally touring acts and more on giving everyday musicians a stage, still believing in the magic that happens when you hand someone a mic and a crowd.

e venues may have changed addresses, hands, and names, but the mission remains the same: Give the music a place to live, and it will echo far beyond the walls. e stomp of feet toward the stage, the hum of a crowd, the rst notes cutting through the stillness — they all carry the same charge they did back in 1980.

LOVE YOUR HEART Cardiac Screening

Catch potential cardiovascular issues before they become a problem with our Love Your Heart Cardiac Screening. Screenings cost $120 and include a full lipid panel, A1C lab analysis and a cardiac calcium score. Get a complete image of your heart health along with recommendations and next steps. No insurance required.

Consider a cardiac screening if you:

Have high blood pressure or cholesterol (even if medically managed)

Have a family history of heart disease

Have Type 2 diabetes

Are a smoker or have ever smoked

Appointments are available in Columbia and Jefferson City. Schedule at your convenience — no referral necessary.

Learn more at muhealth.org/heart-love-screening

Give 5

Matching retirees with nonprofit volunteer opportunities.

As a retired college professor, Frances (Dee) Montgomery, Ph.D., was ready and eager to “Give 5.” She just needed to find the right opportunity.

With that, Dee discovered, The Heart of Missouri United Way’s (HMUW) Give 5 initiative, which is a free, innovative, civic volunteer matchmaking program that matches retirees, those about to retire, and those over 55 who live in Boone County with nonprofit volunteer opportunities.

Montgomery, a Curator’s Distinguished Teaching Professor Emerita, has used her service skills of effectively serving on committees and fundraising to help HMUW as both a graduate of a Give 5 cohort and now one of the program’s most ardent supporters. Her academic teaching and writing skills have also helped pay dividends for the volunteer generation initiative.

“My most direct impact for Give 5 has been supporting the program itself,” she said, “helping with recruiting efforts, short presentations, and providing assistance to the leaders of each of the cohorts.”

Each Give 5 class meets one day a week for five weeks, visiting more than 15 nonprofits. The next cohort begins August 14, with orientation from 8:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., then 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. August 21 through September 11. Classes take place at Williams Keepers, 2005 W. Broadway.

A graduation event is scheduled at 11:30 a.m. on September 18 at Boone Electric Coop, 1413 Range Line.

Montgomery echoed the Give 5 program’s directive to “have fun, make new friends, and learn about volunteer opportunities that match your talents, passions, and personality.”

She also calls herself an “informed super fan” of the HMUW.

“My biggest impact with Heart of Missouri United Way has been more indirect,” Montgomery said. “From the first month of moving to Columbia in July 2022 and

learning about the needs of the Columbia community, I discovered there are many nonprofit organizations, that the HMUW directly or indirectly supports, trying to help those in need.”

Her connection was quick and visible.

“I was able to channel this enthusiasm — with some fundraising skills — to help an organization that has been a consistent contributor to the HMUW increase their donations significantly for the past two campaigns,” Montgomery explained.

With a virtual army of skilled Baby Boomers already retired and another wave of boomers retiring over the next decade, Boone County and Columbia is ideally positioned to be a community that offers effective volunteer matchmaking opportunities for retirees and seniors to thrive.

Program days last between five and seven hours, with lunch and snacks included.

Each day, participants will board a bus to visit various nonprofit locations. At least one guide is with the class at all times and coordinates and guides each program day. Each class session is interactive, fun, and social. Each host organization is responsible for planning an interesting, interactive, and informative presentation to the Give 5 class.

After the last program session, our hope is that each participant has chosen a non-profit and will volunteer at least 5 hours a month with that non-profit. A beautiful thing often happens, and many of our Give 5 graduates/friends volunteer many more than 5 hours a month! At the ceremony, graduates are publicly celebrated and valued, and a representative from the non-profit they have chosen is often present to welcome them to their organization.

We’re very fortunate…Our Give 5 friends are so giving and are such a vital part of our community. They are also amazing ambassadors for the Give 5 program and making a difference through their volunteerism.

For more details and to register, visit uwheartmo.org/volunteer/give-5

ABOVE: September 2024: Dee and her husband Bob, with 2024 HMUW campaign co-chair, Lauren Brengarth.

RIGHT: August 2022: Dee, her husband Bob, & daughter Missy (HMUW Board Member) at her Give 5, Cohort 1 Graduation.

In His Hands

Is the world going to be all right?

BY BETH BRAMSTEDT

One of my favorite weekly activities is doing Pilates. For me, it’s 45 minutes, three days a week, of peaceful refreshment. While I’m in class with six to seven other people, the exercises are known, the pace steady, and the rhythm comforting. e room is quiet except for the hum of the easy-listening music playing in the background and the occasional instructions from the teacher.

It’s been a pleasure to get to know the men and women in my classes, and they are quick to let me know when they’ve read my latest article.

Recently, one of these ladies stopped me in the parking lot after class, and with a concerned look on her face, she asked, “Is the world going to be all right?”

IS THE WORLD GOING TO BE ALL RIGHT?

She mentioned a series of current events, concern for her grandkids, and her sad-

ness with all the hate in the world right now. And she wondered, as a spiritual person, did I think the world was going to be okay?

e words to an old African American spiritual came to mind. You might remember it:

He’s got the whole world in his hands.

He’s got the whole world in his hands. He’s got the whole world in his hands. He’s got the whole world in his hands.

e verses continue with “He’s got the little, tiny baby in his hands …, He’s got you and me, brother, in his hands …, He’s got everybody here in his hands …”

So I shared with her this simple truth: Yes, the world is going to be all right. God cares about us and the world he created more than we ever could, and he’s holding the whole thing in his hands. He’s got us.

I gured that if this was the question on her heart, she probably wasn’t the only one.

I’ve shared Hebrews 12:28 before. It says, “ erefore, since we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, let us show gratitude, by which we may o er to God an acceptable worship with reverence and awe.” is verse brings me peace and strength when the world seems chaotic and out of control, so I want to restate it in my own words:

“Do you see what we’ve got? An unshakeable kingdom! And do you see how thankful we must be? Not only thankful, but brimming with worship, deeply reverent before God.”

Author and spiritual director James Bryan Smith puts it this way; “You are the one in whom Christ delights and dwells. You live in the strong and unshakeable Kingdom of God. His Kingdom is not in trouble, and neither are you.”

For those who are followers of Jesus Christ, the Bible gives us unbelievably good news. When we have responded to God’s initiative to have a relationship with us, it is no longer us who live, but Christ who lives in us (Galatians 2:20). In other words, it’s no longer me, but Jesus in me. He is here holding us and protecting us from all that is shaking around us. e world is not in trouble, and neither are we.

I hope this truth quiets your mind, strengthens your heart, and acts as a balm to your soul. You can live with the certainty that he’s got the whole world in his hands.

Beth Bramstedt is the Church Life Pastor at Christian Fellowship.

What We Leave Behind

BY BARBARA BUFFALOE

When I rst moved to Columbia in the late ’90s to attend the University of Missouri, I didn’t know this place would become home. I certainly didn’t expect to raise a family here or to one day serve as mayor. But I fell in love with this city — its green spaces and bike trails, its creative energy, and, most of all, its people.

Now, having spent years working in and with our local government — from my time as Columbia’s rst sustainability manager to my current role as mayor — I’ve come to think di erently about what legacy really means.

Legacy isn’t a title or a name on a building. It’s about what you leave behind in the everyday lives of others. It’s the systems you help build, the people you lift up, and the choices you make today that shape tomorrow.

If I’m fortunate enough to leave a legacy, I hope it’s that I helped make Columbia more connected — both physically and socially. I want future generations to be able to walk or roll safely to school or work, to live in homes they can a ord in neighborhoods where they feel they belong, and to access reliable transit that connects them to opportunity.

But I also want them to feel connected to something deeper: a sense of belonging in a city that listens, learns, and leads with empathy.

As a planner, I think in systems. at perspective has shaped how I approach policy: not as quick xes, but as part of a long-term design for a more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient Columbia. at’s why we are currently updating our codes and about to start the process to update our comprehensive plan. We’re doing this so future housing re ects the

needs of real families, not just ideal blueprints. It’s why I continue to advocate for investments in public transportation that expand access while reducing our carbon footprint. And it’s why we’re developing more robust data tools to guide our decisions — because transparency and accountability are cornerstones of good government.

Some of this work is quiet and technical. You may not see it in a ribbon cutting or headline, but it matters. Because legacy lives in the details. In the ordinances that make a city more welcoming. In the budgets that prioritize the public good. In the meetings where a young voice is not just heard, but heeded.

At the same time, legacy is personal. I hope people remember that I showed up, whether it was at a neighborhood meeting, a trail opening, or a classroom visit. I want them to recognize that I led with heart, that I listened, and that I didn’t

just ask people to trust the process — I invited them to shape it.

Maybe most importantly, I hope someone sees me and thinks, maybe I could do that too. If I can help open doors for the next generation of leaders — especially young people, especially women and girls — then that may be the most meaningful impact of all.

We don’t always get to see the fruits of the seeds we plant. But we plant them anyway — with intention, with hope, and with trust in the community we serve.

at’s the kind of legacy I want to leave: one rooted in care, shaped by collaboration, and designed to last.

Barbara Bu aloe is currently serving her second term in o ce as the mayor of Columbia.

Theresa plays a critical role in the success of the Consumer Banking Department, having responsibility for all things operational. She is a go-to person when her fellow coworkers have questions or need advice on something. She is always positive and professional. Theresa’s dedication and reliability make her truly Legendary!

573-874-8100 • centralbank.net/boonebank

Marinara Sauce with Stewed Tomatoes

BY HOSS KOETTING

You say “tomato,” I say “tomahto,” but in reality, what di erence does it make? It’s delicious either way. e important point is that those wonderful, locally grown red globes are in abundance at our local farmers markets.

Whom do we have to thank for this juicy fruit? (Yes, botanically it is a fruit, as are eggplants, squash, and several other species. “Vegetable” is merely a culinary term, so one would be correct to refer to a tomato as either.) Apparently, the natives of Central and South America were the rst to cultivate the tomato, and it is indigenous to those areas, as is its cousin, the potato. One of the few positive results of the Spanish conquest of the New World was the exportation of these plants to Europe and the rest of the world. Initially viewed with skepticism, due to their membership in the nightshade family, they were eventually embraced worldwide and are now internationally popular.

In 2022, 186 million tons of tomatoes were produced worldwide, with China producing the most — three times the output of the second-place country, India. Turkey, the U.S., and Egypt rounded out the top ve producers. But why do the locally grown tomatoes taste so much better than those “store bought”? First and foremost, they are picked when ripe; generally the same day as you buy them. Commercial tomatoes are often picked green, then ripened using natural ethylene gas to start the process. Of course, you could use them as a substitute for a baseball, if necessary.

e second reason locals are better is that the varieties grown are picked out more for taste than shipping ability, and the growers know that their reputation rides on the product. As in most other endeavors, the farmers take pride in what they o er and strive to o er maximum quality.

So, it’s at this time of year that I make an effort to use the fruits of the season as much as possible. I’ll make everything from fresh salsa cruda to marinara sauce and fresh tomato chili, which is well worth the e ort. But there are only so many that can be consumed in the relatively short window of time that we have to enjoy the local crop.

ere is, however, a way to maximize your enjoyment. Every time you want to make a batch of a recipe, make four times (or two times) as much, and freeze the extra in mealsized containers. at way, you can enjoy the avor of summer year ‘round. Or, make a large batch of stewed tomatoes, and freeze them by the quart, then retrieve what you need from the freezer through the winter.

Either way, your palate will thank you for the e ort!

STEWED TOMATOES INGREDIENTS

• 2 lbs. fresh locally grown tomatoes

• 1 c. nely diced yellow onion

• 2 tbsp. minced fresh garlic

• Olive oil

STEWED TOMATOES DIRECTIONS

1. Place tomatoes in boiling water for about a minute until the skin splits and can be easily removed.

2. Remove the seeds. Chop the tomatoes or pulse them in a food processor.

3. Sauté the onions until lightly caramelized, add the garlic and tomatoes, bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for about 1-2 hours.

e stewed tomatoes can now be frozen, canned, or used in your sauce of preference.

MARINARA SAUCE INGREDIENTS

• 3 tbsp. Hoss’s Italian seasoning

• 1 tsp. red pepper akes

• 1 tbsp. sugar

• Stewed tomatoes

MARINARA SAUCE DIRECTIONS

Jim “Hoss” Koetting is a retired restaurateur/chef who enjoys gardening, good food, good bourbon, and good friends.

1. To make marinara sauce, add the Italian seasoning, pepper akes, and sugar to the stewed tomatoes.

2. Simmer for another hour and serve.

FORGED by Food

Columbia's dining scene connects past, present, and people.

BY CAROLINE DOHACK

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI

What does it mean to crave COMO? If one were to curate a tasting menu, it could go in any number of directions.

ose who came here for college might include — depending on one’s vintage — campus-adjacent stalwarts like Shakespeare’s Pizza, e Heidelberg, Flat Branch, Addison’s, Room 38, and Harpo’s.

ose with a yen for global avors might list Bangkok Gardens, Jina Yoo’s, Osaka Japanese Restaurant, Beet Box, e Syrian Kitchen, Jamaican Jerk Hut, Mahi’s Ethiopian Kitchen, Las Margaritas, and CoMo Arepas.

Want comfort food? ere’s Big Daddy’s BBQ and Flavor & Comfort. Feeling fancy? ere’s CC’s City Broiler, Grand Cru, and Chris McD’s.

And for those who seek the sweet, there’s Sparky’s Homemade Ice Cream, Buck’s Ice Cream, Mugs-Up Drive In, U Knead Sweets, e Chocolate Factory, Uprise Bakery, and — I couldn’t not mention it — Tropical Liqueurs.

A Legacy of Flavor

While local restaurant goers enjoy nding new tastes to savor, much of the appeal of Columbia’s dining scene rests on what might be called “legacy foods.” Countless Columbians have happily downed a slice from Shakespeare’s or a plate of Addison’s nachos, to name just two favorites. en there are the restaurant stalwarts: Booches, opened in 1884; Ernie’s, opened in 1934; Glenn’s Cafe, which opened at its original location in 1939; Mugs-Up Drive In, opened in 1956; and G&D Steakhouse, opened in 1970.

Oh, and let’s have a moment of silence for some of the restaurants that are no longer here: Jack’s Gourmet, Coley’s American Bistro, 44 Stone, Co ee Zone, Interstate Pancake Howse, e 63 Diner, Kostaki’s Pizza, Ninth Street Deli, Harold’s Donuts, and International Cafe. I might need to see a cardiologist to examine the sandwich-sized hole that was left in my heart when Sub Shop closed.

Without doubt, a Sub Shop Italian would qualify for the honor, but what makes a food a legacy food? Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, the author of such titles as Biting through the Skin: An Indian Kitchen in America’s Heartland and Green Chili and Other Imposters, says she reached out to a few friends for their feedback on Columbia’s culinary icons. Furstenau, whose work often weaves memoir with musings on menus, meals, and the makings thereof, reports that their responses ran more toward nostalgia than nourishment.

“ ey started immediately jumping in with di erent restaurants that have been here and the di erent occasions they’ve gone to them,” Furstenau says. “Mostly, they were describing the environment and the people they were with. When you go to restaurants in Columbia, they each have a personality. You're seeking that almost as much as you are the food. And when you're there with your friends, you perpetuate that personality yourself. Because you're there, you’re part of it.”

Creating Community Community was on Leigh Lockhart’s mind when she opened Main Squeeze back in 1996.

“I was obsessed with those old shows where there was a general store: Little House on the Prairie, e Waltons, Andy Gri th. ere was always a place where everybody could see each other, and that’s what I wanted,” Lockhart says. “I think food is the great uni er. It brings people together.”

With a bit of money saved up from her Murry’s bartending gig, Lockhart found herself situated behind the bar in a little alcove at Lakota Co ee Company.

“I gave Lakota owner Skip DuCharme 10 percent of my sales, which was a great way to pay rent. I couldn’t predict the money or how it was going to go,” Lockhart says.

But the juice biz was boomin’.

“By the time I moved out, I was paying all of his rent with my 10 percent. He even came to me — because he’s a very fair and good guy — and he said, ‘It appears you’re probably paying me more than is fair,’” Lockhart says.

When space became available for a stand-alone storefront, Lockhart jumped at the opportunity to expand to a cafe concept. ere she served plant-based fare until 2023 when, feeling burned out on running a restaurant, she pivoted to a retail format selling eco-friendly household goods and cleaning supplies.

Last year she sold the business to Amanda Rainey and John Gilbreth, a wifeand-husband duo who also own Pizza

Tree and Goldie’s Bagels. Main Squeeze reopened as a cafe in March 2025.

“When I sold the restaurant, there were only three conditions: I wanted a fair price for the business, I wanted them to commit to keeping it vegetarian, and I wanted them to sell my ice cream,” Lockhart says.

Lockhart’s still in the game with her vegan venture, a small-batch non-dairy ice cream brand called Oso Cremoso, which is available by the pint at Main Squeeze and Clovers Natural Market.

Something Old, Something New

Although Main Squeeze is the newest eatery in the couple’s family of restaurants, Rainey says the restaurant has always been meaningful to their family. e Ruby — Lockhart’s vegetarian version of the classic Reuben — was the rst meal Gilbreth ate when he moved to Columbia. Rainey enjoyed eating there as a college student. When lunch was somehow overlooked on Rainey and Gilbreth’s wedding day, Rainey’s cousin made a Main Squeeze run. is personal history was a major motivator in the couple’s decision to purchase the restaurant.

“So many people who live here came for college or at that age,” Rainey says. “We kind of have a nostalgia for that simpler time in our lives. Looking back, you had less responsibilities and less worries and way more time because you were only going to class 12 hours a week. Maybe you worked at a local restaurant and had a little cash.”

So when they heard Lockhart was looking for new owners, the couple decided the time was right to revive an old favorite. ey met with her several times in the months before they opened to learn the ropes behind some familiar favorites, and they hired back a handful of long-time employees.

But Rainey and Gilbreth are putting their own stamp on the place, too. ere are several new menu items, and the interior has changed signi cantly. Gone are the tables made from recycled doors. Abstract paintings in minimalist frames line the walls. e menagerie of toy animals that once stood in for order-number placards now enjoy their retirement on a shelf behind the counter.

Lockhart says she tries not to make a habit of going into Main Squeeze too often — she’s good with passing the baton — but she just so happened to be making an ice cream delivery on the morning I met with Rainey in the cafe. e two exchanged some gossip, and on her way out the door, Lockhart expressed her appreciation for the direction Rainey and Gilbreth are taking things. Having been an early devotee of the farm-totable ethos, she is happy to see Rainey and Gilbreth nurturing relationships with producers like ree Creeks Farm + Forest, Linnenbringer Farms, Hemme Brothers, and Fiddle & Stone Bread Co.,

Leigh Lockheart pictured in Main Squeeze, back in 2023.

Photo by Anthony Jinson.

and she was delighted that the day’s Buddha Bowl special would be made entirely with local ingredients.

“You are doing things I wish I could have done,” she told Rainey.

A Connection to Local Producers

Main Squeeze is not, of course, the only restaurant to put locally produced foods front and center. Barred Owl Butcher & Table, Flyover, Sycamore Restaurant, Pasta La Fata, Broadway Brewery, Belly Market & Rotisserie, and Ozark Mountain Biscuit & Bar are part of a non-exhaustive list of popular places known for elevating the homegrown.

Broadway Diner owner Dave Johnson says he’s been buying pork products from Patchwork Family Farms since it was known as Tiger Packing.

“It’s a wonderful product, and more importantly their mission is fantastic, and they do great work,” Johnson says.

Patchwork, a project of the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, is a marketing operation that buys hogs from independent family farmers and sells directly to consumers as well as grocery stores and restaurants under the Patchwork label. Patchwork doesn’t do lard, though, so Johnson gets that from Sullivan Farms, owned by Brittany and Bill Sullivan. Sometimes he gets eggs from Liz Graznak’s Happy Hollow Farms. Johnson especially loves baking pies, and he always looks forward to using peaches from Peach Tree Farm.

Few will dispute that a tomato grown in local soil and harvested at peak ripe-

ness is exponentially better than a tomato purchased from a wholesaler, and Johnson is proud to support the local economy in this way. He cherishes the relationships he’s built with these suppliers.

“ at’s what I’m always trying to do: Build community,” Johnson says.

Acknowledging the Past, Enriching the Present

e diner itself has represented a means of community building since 1989, when Johnson’s father, Ed Johnson, purchased the business — then known as Fran’s Diner — some forty years after it opened its doors as e Minute Inn.

ere were some things the Johnson family kept, including a borderline architectural creation known as e Stretch, made with hash browns, scrambled eggs, chili, cheddar, diced green peppers, and onions. e Stretch remains a go-to menu item for many a diner enthusiast.

“If I had a nickel for every ten I sold, it would be amazing,” Johnson says.

But there are other aspects of the diner’s history that aren’t quite so savory. Johnson says it’s important to acknowledge the role it once placed in enforcing the painful practice of racial segregation.

“I meet people nearly every week who were young enough then to have not been allowed to eat inside and have memories of being served out of our side window,” Johnson says.

In 1960, e Minute Inn was the site of Columbia’s rst organized sit-in. While there’s no erasing that past, Johnson

has found ways for the diner to make a more positive impact. During the rst weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, Johnson began o ering free take-out meals to children and families who might be experiencing food insecurity.

“We were all so terri ed at the beginning. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know what tomorrow or the next couple weeks would bring,” Johnson says. “I knew I had an inventory that would go bad and be wasted, but I could work and get some good out to people.”

Over the next year and a half, he distributed more than 10,000 hot meals.

“ e community really stepped up. People started dropping by with cash or sending money,” Johnson says.

And so he kept at it.

“I’ve always felt that feeding people is more than feeding them food,” Johnson says. “It’s lifting them up, it’s welcoming them, it’s including them, and it’s being enriched by them.”

I was intrigued by that last point. inking back to my conversation with Furstenau, who described a give-andtake between people and the places they eat, I asked Johnson for an example of how he’s been enriched by the people he’s met. He didn’t hesitate in his response.

“ e very best example is my wife. I met her through an employee, her son,” Johnson says. “He thought we would be the best of friends. She was widowed when Cooper was very young. We met, and a month and half later we were married. It’s been just the best 15 years I could ever have imagined.”

(Re)Discover COMO

One recent recurring theme is that some of Columbia’s most recognizable businesses have earned a spot in the community’s heart because they have been around quite a while. at's certainly true for local stalwarts like e Candy Factory and Murry's, and the same principle can apply to the storied small town of Rocheport.

The Candy Factory

For more than 50 years, e Candy Factory has been creating and perfecting delicious gourmet candy recipes in the heart of downtown Columbia. e Candy Factory's unmatched quality can only be achieved by making candy the old-fashioned way — by hand — in small batches and by using only the very best ingredients. Guests are welcome to step into e Candy Factory's seasonal immersive showroom and indulge in all their senses, then take a trip to e Viewing Room to watch skilled artisans make confections by hand.

e Candy Factory was founded in 1974 by Georgia Lundgren, who began selling her homemade candies from a small shop on Walnut Street. In 1986, the business was sold to Sam and Donna Atkinson, who continued its legacy of creating gourmet chocolates and confections. e Atkinsons’ children and grandchildren have also been involved in the business, making it a multigenerational family enterprise.

e Candy Factory is known for its handcrafted chocolates, including trufes, to ees, and chocolate-covered strawberries, and a variety of gift items and seasonal treats.

Murry’s

Part of Columbia’s dining and music scene since 1985, Murry’s has a history rooted in the city’s bar scene and a passion for good food and jazz. Murry’s was initially established by Mick Jabbour, owner of Booches, who named it after a snooker-playing customer. Former Booches employees Bill Sheals and Gary Moore took over the

space, initially running the business with friends as customers. Eventually, Murry’s became known for its inviting atmosphere, eclectic menu, and commitment to live jazz music, working with local musicians and the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series.

Murry’s was conceived as a straightforward, adult-oriented establishment with a focus on good food, good jazz, and a relaxed atmosphere. e restaurant recently celebrated its 40th anniversary and has been making some rare menu changes. (So hurry on in — no reservations required or accepted — to nd out what all the buzz it about.)

Murry’s uses many locally sourced products for the restaurant and the bar that complement daily lunch and dinner specials, and the restaurant’s mantra remains: Keep it simple, and make it good.

Rocheport, Missouri

Rocheport has literally stood the test of time, keeping the same calm, peaceful presence and small-town charm since its founding in 1825. It’s easy to feel like you’ve stepped back in time and get lost in the moment when appreciating the

gorgeous surroundings of the Katy Trail, sipping savory wines, or enjoying the amazing artwork and live music that embody what Rocheport is all about.

Whether it’s for a leisurely weekend escape or a quick day trip, Rocheport has a lot to o er. Park the car because you won’t need it to start exploring the wonderful restaurants and unique shops. Discover the pleasure of charming inns, each unique and o ering a wonderful variety of breakfast cuisine, gorgeous views, and amenities galore.

Second Saturdays are also a treat. Family-friendly Second Saturday events for the remainder of the season are: August — e Dog Days of Summer; September — Art, Art, Art; October — Leaf on over to Rocheport; November — ankful in Rocheport; and December — Shop ‘Til Ya Drop in Rocheport.

(Re)Discover COMO is a monthly feature sponsored by the Columbia Convention and Visitors Bureau highlighting places, events, and historical connections that new residents and visitors can discover, and not-so-newcomers and longtime residents can ... rediscover.

by Lana Eklund

Photo

WHAT THE HOME PROS KNOW

TRENT JONES MANOR ROOFING & RESTORATION

MIKE MESSER SHELTER INSURANCE

AUSTIN M c BRIDE

ROST LANDSCAPING

WHY CHOOSE MANOR FOR YOUR WINDOWS AND DOORS

By Trent Jones

Let’s be honest—shopping for new windows and doors isn’t exactly the most thrilling home improvement project. But it *should* be exciting. After all, you’re not just picking out panes and panels—you’re upgrading the look, feel, and energy efficiency of your home. And if you’re going to invest in something that impacts your utility bills, security, and curb appeal, why not do it with a team that actually makes the process smooth, simple, and (dare we say?) enjoyable?

That’s where Manor comes in. For nearly 20 years, we’ve been helping MidMissouri homeowners bring in more light, more style, and more peace of mind—one door and window at a time. Real People. Real Expertise. Zero Gimmicks.

Our team knows windows and doors inside and out. Literally. Whether you’re replacing old, drafty windows that whistle every time the wind blows, or finally swapping out that front door from 1994 (you know the one), we’ve got the products and the pros to get it done right.

We guide you through every option— vinyl, fiberglass, wood, double-hung, casement, sliding, swinging—and help you pick what works best for your home and your budget. No jargon. No upsell Olympics. Just real advice from people who actually care.

Energy Efficiency That Actually Works!

Sure, new windows and doors look great—but they also do real work behind the scenes. We install ENERGY STAR® rated products that help keep the summer heat out, the winter chill at bay, and your energy bills from skyrocketing into outer space. It’s like giving your HVAC system a break (you’re welcome, little guy).

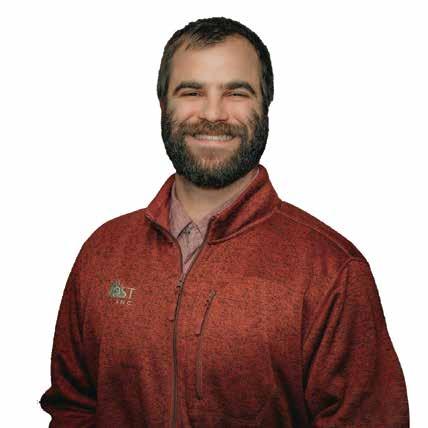

TRENT JONES

ACCOUNT MANAGER / COMMERCIAL REP

THE HOME PROS KNOW

Trent was born and raised in Paris, MO, and joined Manor in 2023. He is a graduate of the University of Central Missouri and Linn State Technical College. Trent enjoys playing golf, attending sporting events, playing basketball, and spending time with his family.

573.445.4770 | exploremanor.com

We Don’t Do Cheap. We Do Quality! You won’t find box store shortcuts here. We work with manufacturers we trust—brands that deliver durability, performance, and warranties that mean something. Because the last thing you want is a door that starts peeling, sticking, or creaking before your next oil change.

Style That Says “Wow” (Not “Why?”)!

From clean, modern lines to charming, classic details, our selection of styles, colors, glass options, and hardware lets you customize every inch. If your neighbor’s jealous when they walk by— well, we won’t say we told you so.

The Manor Way

We’ve built our reputation on being honest, dependable, and just the right amount of obsessive about doing

things right. Our process is smooth, our communication is clear, and our crews are respectful and skilled (and yes, they clean up after themselves).

More Than Just Windows and Doors!

At Manor, we’re not a one-trick pony. We do the whole exterior—roofing, siding, decks, gutters, windows, doors —so we know how everything works together. That means no guesswork, no fingerpointing, and no calling five contractors to solve one problem. Just one team, one solution, and one solid result.

Ready to Upgrade?

Give us a call and let’s bring some light (and personality) into your home—with windows and doors that work hard and look great doing it.

YOUR GUIDE TO LED LANDSCAPE LIGHTING SYSTEMS

By Austin McBride

Over the past several years, landscape lighting systems have improved in regards to technology, durability, and ease of installation. Low voltage, LED lighting systems have become the most desired option as they offer the same benefits of spot lighting your landscape and added security while adding the ability to customize your lighting setup.

LED Landscape Lighting Benefits

The obvious benefits of landscape lighting are accenting certain features of the landscape or shining light on your pathways and patios at night. This allows you to enjoy your outdoor spaces long after it gets dark.

One of the advantages that landscape lighting provides that is often overlooked is security. Adding lighting to areas of your landscape that are hard to cover with your house lights can add to the security of your home. Extending the lights further from the house can keep potential intruders away.

Additionally, there are multiple options that are available with LED landscape lighting systems that allow you to customize your setup the way you want it.

Types of LED Landscape Lighting Systems

• Standard On/Off: The on/off system is just as it sounds and is the most basic. The lights can be turned on or off by using a timer, photo eye or by manual operation.

• Zone Dimming: The zone dimming systems are a step up by allowing you to adjust the brightness of the lights. This type of system also allows you to

Austin is a Sales Manager for irrigation, lighting, fencing, and estate gates at Rost Landscaping. He is also a Professional Water Witcher. When he is not on the job he enjoys hunting, fishing, raising livestock, and be being a full time family chauffeur.

separate lights into different zones, giving you the ability to adjust the brightness or turn on and off only certain groups of lights.

• Zone Dimming Color:

The zone dimming color system has all of the features of the zone dimming but also gives the options to change the colors of the lights. This is a great feature around the holidays or to show your team spirit. Both types of zone dimming systems can also be controlled by your smartphone or tablet.

Installation

These LED fixtures have safeguards to prevent overheating which increases safety but also means you can expect bulbs to last 50,000 hours or more eliminating the need for continual bulb replacements.

and Maintenance

Low voltage systems allow us to install lights and wires in existing landscape without burying underground hubs and pipes that would normally disturb landscape plantings.

This also makes for an easier process of adjusting and moving lights as the landscape grows.

LED fixtures also use significantly less power than traditional halogen bulbs so energy costs are nearly 80% lower and there is less environmental impact.

The benefits of an outdoor lighting system along with the updated technology and features makes for a great addition to any landscape. If you are considering making changes to your outdoor spaces, landscape lighting should be a feature that is on your list.

LEAVE A LEGACY WITH LIFE INSURANCE

By Mike Messer MMesser@ShelterInsurance.com

What steps do you take to protect the ones you love? If we stop to consider our everyday choices, we usually go to great lengths to keep each other safe. We secure our homes to prevent intruders. We buy the highest safety rated vehicles and car seats and buckle up. We learn how to swim, wear a helmet and eat smart foods. We try to be responsible and teach our children about online and reallife predators.

Protecting our loved ones is clearly important, so it just makes sense to add “buy life insurance” to the list. Life insurance helps our loved ones financially after we’re gone, but it isn’t just about protection. Life insurance is also about leaving a legacy.

We’ve seen people use life insurance to help the next generation hold on to a farm that’s been in the family for decades. It’s also a way to help with living expenses, homes and higher education for family members. Some people extend their legacy to a church or charity that touched their hearts through life insurance—or provide a lasting gift to the college or university that changed their lives. Whatever your goal— we can help.

If you’re buying life insurance for the first time, then you probably have questions.

Who (or what) are you trying to help financially? What’s your reason?

• How much life insurance do you need and how much can you afford?

• Who would your beneficiaries be?

MIKE MESSER

WHAT THE HOME PROS KNOW

AIC, LUTCFSHELTER INSURANCE ® ®

With over two decades in the insurance industry, Mike Messer has served as a claims adjuster, supervisor, and underwriter, giving him a well-rounded understanding of how policies work when it matters most — before and after a loss. He prioritizes building relationships based on trust and personalized service, recognizing that every client’s needs are unique. Through annual policy reviews, he helps ensure clients stay informed, confident, and properly covered, providing them with peace of mind and financial security.

• You know about current financial needs, but what about future needs?

• What’s the difference between Term Life Insurance and Permanent Life Insurance?

• Why do kids need life insurance?

To get answers to these questions and talk about leaving a legacy, contact Shelter Insurance® agent Mike Messer. He can help answer your questions and help decide which plan may be right for you based on what kind of legacy you want to leave behind.

Simon Rose

KBXR, KFRU

Columbia’s favorite Brit packed more than his unmistakable Manchester accent when he crossed the pond in 1981. Simon Rose also brought a passion for the Beautiful Game and a love for his homeland’s punk, metal, and New Wave scenes.

“ e reason I got into music was largely because of the legendary DJs on BBC Radio 1 — John Peel and Tommy Vance,” says Rose, who counts e Clash, Motörhead, and Iron Maiden among his favorites. “I started listening more seriously and buying records. Now vinyl is back in, which is fantastic.”

Rose played on Hickman High School’s inaugural boys soccer team before earning an English degree from MU in 1990. He took a part-time job at KFRU, working mostly graveyard shifts, and joined KBXR when it launched in 1993. e station’s focus on lesser-known bands and female artists was a perfect t for the audiophile with an encyclopedic knowledge of the music industry.

Today, Rose hosts e Morning Meeting With Simon Rose (9–11 a.m.) on KFRU and Afternoons With Simon Rose (2–7 p.m.), BXR’s agship alternative rock show.

And of course, listeners still hear his signature line throughout the day: “One oh two three — Bee Ex Ahh!”

Donna Battle Pierce

Syndicated columnist whose work as a writer and editor has appeared in the Columbia Daily Tribune, the Chicago Tribune, Ebony, NPR’s e Salt, and many more.

Donna Battle Pierce feels most at home among words, as evidenced by the 1,500+ books lling the living room she transformed into a personal library.

Her love of reading was sparked early by her parents, Columbia civil rights leaders and lifelong educators Eliot and Muriel Battle.

“My mother was on the library board, and every Saturday I’d search for the books I wanted,” says Pierce, who was among the rst Black students at Grant Elementary School after its desegregation in 1957. “My home library is my dream come true.”

She carried that passion to Stephens College, originally eyeing a career in fashion journalism before nding her niche writing about people and culture. Today, her work focuses on cultural traditions, Black history, and missing biographies.

Now based in Santa Monica, California, Pierce continues research for a book and screenplay about Freda DeKnight, the groundbreaking food editor, fashion writer, and cookbook author, best known as Ebony magazine’s rst food and fashion editor.

“I don’t identify as a food writer. I write about people, places, and family history,” Pierce says. “In the beginning, I found it was easier to use food as the entry point to important stories about my culture.”

Mahlon Aldridge

1915–86, KFRU

For nearly three decades, there was only one “Voice of the Tigers” for Missouri sports fans: Mahlon Aldridge. e late Aldridge was an unknown reporter for the Je erson City News Tribune and part-time basketball referee when fate changed his life in the late 1930s. After a broadcaster at KWOS called in sick, Aldridge was asked to ll in on play-by-play. He was a natural, soon becoming the station’s news director.

In 1942, Aldridge moved to KXOK in St. Louis, where he befriended baseball broadcasting legend Harry Caray.

“One day someone asked Dad to do a Cardinals game, but he couldn’t,” recalled his son, Jim Aldridge. “He

says, ‘I think Harry would do a ne job.’ e rest is pretty well history.”

In 1948, Aldridge partnered with Columbia Daily Tribune owner H.J. Waters Jr. to purchase KFRU. e station became a training ground for MU broadcast students and home to Aldridge’s smooth, enthusiastic delivery of Tigers games.

“Dad taught me integrity and the importance of community in small-market radio,” says Jim, who also worked at KFRU from 1968 to 1983. “He refused ads from St. Louis or Kansas City, choosing instead to support local businesses.”

Matt Fetterly

Historian, Boone County Historical Society

In Columbia, the term “townie” gets tossed around to distinguish locals from the transient student population. But for Matt Fetterly — whose greatgreat-great-great-great-grandfather, Absalom Hicks, helped select the site for Columbia — it carries deeper meaning.

Fetterly’s obsession with local history began on a whim, when he set out to collect every book ever written about Columbia, expecting to nd about 10. His collection now tops 180.

“As a Shakespeare’s Pizza truck driver, I noticed the natural and human variation across Missouri — the Rhineland, the glacial plains of northern farms, the Bootheel, Joplin mining country,” he says. “It always amazed me how few people know the origins of their town names.”

Fetterly has become a respected local historian, writing for CoMo Preservation Inc., contributing over 180 Wikipedia articles, and making 25,000+ site edits. Today, he researches for the Boone County History and Culture Center Society, curates artifacts, and leads tours of its historic villages.

“I’m always educating myself,” he says. “But not through formal schooling — I’ve just been a self-taught oddball in this eld.”

Bill Clark

Columbia Daily Tribune

From the in eld dirt on his umpiring jersey to the international skies, where he crisscrossed Europe and the Americas scouting baseball talent, Bill Clark has spent a lifetime observing the world. It’s a grand perspective re ected in his writing style and shared in his nostalgic narratives over the years, mostly in the Columbia Daily Tribune.

Born in 1932 in Clinton, Missouri, Clark served with the Army before using the GI Bill to earn a degree from MU. He and his beloved wife, Dolores — who died in May 2024 — raised ve children in Columbia while Clark built a multifaceted career as sportswriter, umpire, newspaper distributor, and Major League Baseball scout for teams including the Atlanta Braves, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Cincinnati Reds.

“I might be the youngest guy to ever graduate from professional umpire school,” Clark says. “I wanted to be a ballplayer, but the Cardinals cut me on day one of a three-day tryout. ey sent a message — but at least I got started in the right direction.”

Perhaps thanks to all that time spent in the sky, Clark became an avid birder, a passion he has pursued every Wednesday for 17 years. He’s logged more than 2,000 species and contributed to Missouri Audubon Society history books.

He also championed the sport of weightlifting, launching associations, founding a gym, and writing extensively on the topic.

“Of all the things I’ve written, my proudest was a column about my wife,” says Clark, his voice faltering. “It wasn’t hard to write — but it was hard to read.”

Rod Kelly 1950–2018, KFRU

From 1975 to 1989, the late Rod Kelly was the trademark voice of Mizzou men’s basketball — as well as Columbia

College and Hickman and Rock Bridge high schools — his vibrant personality resonating across Boone County and beyond. But it was a twist of fate — and knee — that launched his radio career.

Running late to Hickman basketball practice, Kelly leapt down a ight of stairs and tore ligaments. While Kelly was recovering in the hospital, former Columbia Public Schools Superintendent Jim Ritter introduced him to KFRU Sports Director Chris Lincoln, hoping the sidelined Kewpie could man the mic.

“Rod was such an extrovert I used to call him a friendly Cocker Spaniel,” says John Kelly, Rod’s older brother. “He worked the late shift and brought rock and R&B to KFRU. When we were kids, he’d announce pickup games on the neighborhood courts — and he was good at it!”

Kelly earned degrees from MU and Central Missouri State and spent 27 years in the CPS system as assistant principal, teacher, athletic director, and basketball coach.

“He loved his students — they gravitated to him,” John says. “He’d even get up in the middle of the night to help someone out.”

Paul Pepper

Host of Pepper and Friends on KOMU

As the eponymous ringmaster of Columbia’s beloved variety show, Paul Pepper experienced plenty of memorable moments during the live program’s 27-year run. Once, when a dance troupe’s collective kicks caused part of the set to collapse during a broadcast, Pepper and the crew rushed to hold up the plywood and stave o injury. e show must go on, of course.

en there was the time a visiting circus elephant succumbed to nature’s call just before a cooking segment, prompting Pepper and friends to grab shovels and frantically scoop.

“As we were nishing the segment, the elephant stuck his trunk in the food to grab a bite,” says Pepper,

laughing. “You have to have fun, and you have to be honest and authentic. People can spot a fake.”

Pepper joined KOMU fresh out of junior college in 1969 as a booth announcer and, later, weathercaster. Inspired by e Charlotte Peters Show in St. Louis, the friendly frontman hosted thousands of guests and rarely said no to local charities or worthwhile causes seeking airtime.

“I love how open and accepting the people of Columbia and Boone County have always been,” says Pepper. “On Pepper and Friends, what you saw was what it was. And when we made mistakes, we didn’t hide it.”

Darren Hellwege

KBIA

Like the many cables surrounding his microphone, Darren Hellwege has been plugged into the Columbia community for 38 years. His steady voice has anchored Morning Edition for more than three decades, and he serves as the PA announcer for Mizzou’s successful wrestling, softball, and gymnastics programs.

Hellwege has spent so many hours at MU’s NPR a liate, KBIA, that he witnessed the 1988 re that destroyed e Shack, the legendary campus hangout south of Jesse Hall where the station was once housed.

“We were doing a pledge drive and didn’t leave until 1 a.m. When we walked to our cars, we saw e Shack was on re,” Hellwege recalls. “Nobody had noticed yet. So we ran back into Jesse Hall, and my colleague called the re department while I called the news director.”

Like Rod Kelly, Hellwege’s radio career was brought about by injury — a broken arm that made writing-intensive college work di cult. He joined the campus station at the University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond, his hometown, where he met Mike Dunn, KBIA’s future general manager.

“It’s a cliché, but I always try to ‘think audience,’” Hellwege says. “What are listeners doing right now? How do I keep them from pushing the button to another station?”

Teresa Snow

News anchor and reporter, KMIZ, KRCG

As far back as fth grade, Teresa Snow remembers sitting at the kitchen table, watching Sam Donaldson and Jane Pauley deliver the news — and imagining herself on the other side of the screen. e life of an intrepid journalist, jet-setting across the country or reporting live from the White House, captured her ten-year-old imagination.

Snow turned those childhood dreams into reality over a twenty-six-year career as a reporter and anchor for KQTV (St. Joseph), KMIZ, and KRCG, before switching to lead strategic communications at MU Health Care. ese days she manages rental properties and farm life alongside her husband, Ben, and is running for a spot on the Boone Electric Cooperative Board of Directors.