Situating access and breaking boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a provocation

bushra.hashim + dr. brian r. sinclair

Master of Environmental Design Candidate [2021], MArch [2020], BA in Urban Studies [2018]

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

PhD DrHC FRAIC AIA [Intl]

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

1

table of contents

2

CONTEXT

GAPS

ABSTRACT

RESEARCH

RESEARCH QUESTIONS CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK EXPECTED CONTRIBUTIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Situating Access and Breaking Boundaries : Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation [working title]:

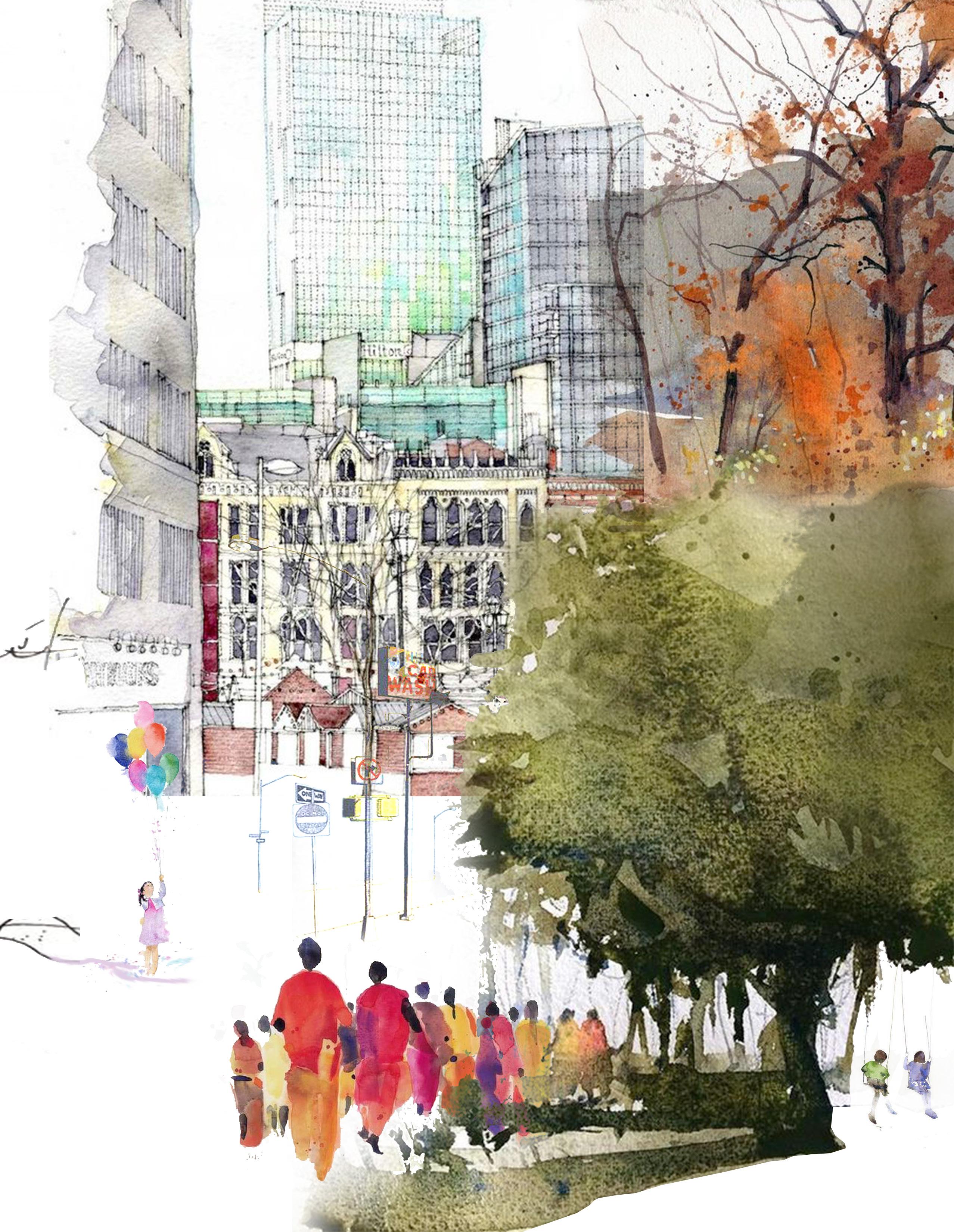

Contemporary society, including architecture, urbanism, and city planning, stands at a vital juncture. Calls for heightened equity amidst growing diversity offer an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider design thinking. A part of this equation pertains to the ways that users address and operate within the built environment past mobility, to include people with intellectual disabilities (ID).

The literature review has surveyed:

[1] how intellectual disabilities have been conceptualized historically

[2] the naturalization of difference and the ableist worldview

[3] the importance of innovating architectural solutions

Ultimately, the goallis to support and enhance the user’s agency, the performance of the environment, and the optimization of experience.

The design of our everyday spaces and places need to ensure all users are more abled, not less disabled.

lit.rev : context

intellectual disabilities

shoehorning

experiential equity

holistic responsivity

neuroarchitecture

agile architecture

cybernetics

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 3

nomenclature: “idiots/cy” “insane” “mentally deranged” “mental retardation” “mental deficiency” “intellectual disability”

classifications: AAMR > AAIDD EHA > IDEA ADA > ADAA ADASAD APA

first manuscript [nomenclature]

American Association on Mental Retardation

American Psychiatric Association

Education of All Handicapped Children Act

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act +

Americans with Disabilities Act

American Association on Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

1846 : Traitement Moral, Hygiène, et Education des Idiots [Edouard Seguin)

ADA Amendments Act

ADA Standards of Accessible Design

Rosa’s Law [nomenclature]

Physiological Method : vision, hearing, taste, smell, touch

1876: founding father of American Association of Mental Retardation

2017 : “mental retardation” > intellectual / developmental diability

[1] : history

1838 - 2017 + ongoing 1838

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 4

1892 APA 1975 EHA 1990 IDEA ADA 2007 AAIDD 2008 ADAA 2010 ADASAD 2017

1876 AAMR

Today, intellectual disability is a “disability characterised by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour that affect many everyday social and practical skills.”

It may also be referred to as a developmental disability, which includes autism spectrum disorders (ASD), epilepsy, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, fetal alcohol syndrome (FASD), and other disorders that occur from birth to 18 years of age.

Adaptive behaviour refer to basic skills needed for everyday life; including but not limited to “communication, self care, home living, social skills, leisure, health and safety, wayfinding, functional academics, and employment.”

defined : intellectual disability

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 5

“FIXED SPACES, NOT FLUID ONES, IN A PREDICTABLE AND PERMANENT RELATIONSHIP TO ONE ANOTHER...”

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

[Butterworth, 2000]

[Gray, Gould, and Bickenback, 2003]

[Tuckett, Merchant and Jones, 2004]

[Salmi, Ginther, and Guerin, 2004]

[Salmi, 2007]

[Castell, 2012]

[Gillen, 2015]

[McConkey et al., 2019] etc.

The collective of these studies were in mutual agreement on the relative exclusion of people with Intellectual Disabilities than those with Physical Disabilities

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 7 intellectual.ableism : built

1838 1876 1892 1975 1990 ADA 2007 2008 30 YEARS ADAA 2010 ADASAD 2017 2020 ADA Amendments Act ADA Standards of Accessible Design TODAY Americans with Disabilities Act

PHYSICAL

[ [

the lack of a coherent set of guidelines or body of research

[Tuckett, Merchant and Jones, 2004]

[Castell, 2012]

RATIONALES

lack of the ADA’s consideration of neuroarchitecture + impact of the built environment on the central nervous system perception of the ADA as costly and inhibiting creativity

[Gray, Gould, and Bickenback, 2003]

[Gillen, 2015]

DESIGNSOLUTIONS

design solutions limited to wayfinding

[Salmi, Ginther, and Guerin, 2004]

[Salmi, 2007]

[Castell, 2012]

i.a : limitations

devaluing the importance of social inclusion within accommodation

[Butterworth, 2000]

[McConkey et al., 2019]

Today’s static environments, in tandem with marginalization through existing political and social structures, continue to reinforce the physical and psychosocial isolation associated with intellectual disabilities.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 8

[ [

lack of participation in the built environment

[Gray, Gould, and Bickenback, 2003]

[Van de Putten and Vlaskamp, 2017]

[Raczka, Theodore, and Williams, 2020]

CONSEQUENCES

deterioration of mental health

[Halpem, 1995]

[Butterworth, 2020]

STATISTICS CANADA

those who are institutionalized or unable to self-report remain uncounted

[Morris et al., 2018]

quality of life (QOL), or an “individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live.”

[WHO, 1998]

lack of reflection and replication of meaningful social relations

[Curtis and Rees Jones, 1998]

[McConkey et al., 2019]

[Sheerin, 2020]

These social structures are reflected in the built environment, resulting in their lack of participation in the built environment.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 9

[ [

T I O N

WORLDHEALTHORGANIZA

i.a : effects

Systemically conditioned by a network of ideas, processes and practices throughout one’s life, a “particular kind of self and body – the corporeal standard – is projected as the perfect species – typically and therefore essential and fully human…people and society, [for example], expect a person of being able of walking, deciding what they want to do, and managing daily life on their own – whoever does not possess the expected skill to do so is perceived as different. Disability is then cast as a diminished state of being human” (Campbell 2009, p.5).

[2] : naturalization of difference

10

disablism: ableism:

the naturalization of individuals differentiating between people with disabilities and people without.

disabled individuals are marginalized or excluded from society through oppressive socially, politically, and economically produced practices because of these differences.

The ableist worldview assumes that disability always equals suffering.

“the canon of skills for being acknowledged as fully human is subject to change, and despite this, people tend to categorize persons who do not have the skills to complete everyday occupation in a way considered normative in a particular setting in the category of dis/ ability” (Wolbring 2012).

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 11

consequence of

difference : ableism + disablism

Filling the Gap =

Holistic Responsivity is a term coined to convey the notion that designers shoulder serious responsibility for creating built environments that are responsive across the wide-ranging abilities of users.

Design Equity

Sensory Integration

Responsive Environments

Digital Tools

Current Pandemic Marginalization

[3]

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 12

: Holistic Responsivity

1. How can current environments be more responsive to the individual needs of people with intellectual disabilities?

2. How can architecture influence automatic behaviours to allow people with intellectual disabilities to partake in the built environment in a more experientially equitable way?

3. How can architects design buildings and public spaces that promote the dignity, inclusion, and participation of people with intellectual disabilities?

4. How can architects begin to build a knowledge base around the environmental needs of people with intellectual disabilities?

5. How can design processes be informed to bridge the gap between Holistic Responsivity and its NAAC [neuroarchitecture, agile architecture, cybernetics] research approach, and current arguably exclusionary architectural practices?

framing : research questions

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 13

1. How can current environments be more responsive to the individual needs of people with intellectual disabilities?

1) HOLISTIC RESPONSIVITY

3. How can architecture influence automatic behaviours to allow people with intellectual disabilities to partake in the built environment in a more experientially equitable way?

2) NEUROARCHITECTURE

4. How can architects design buildings and public spaces that promote the dignity, inclusion, and participation of people with intellectual disabilities?

3) AGILE ARCHITECTURE

4. How can architects begin to build a knowledge base around the environmental needs of people with intellectual disabilities?

4) CYBERNETICS

5. How can design processes be informed to bridge the gap between Holistic Responsivity and its NAAC [neuroarchitecture, agile architecture, cybernetics] research approach, and current arguably exclusionary architectural practices?

5) SYSTEMS THINKING

framing : concepts

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 14

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

CYBERNETICS + SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018]

[Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019] [Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

APPLICATIONINARCHITECTURE

THEORY [EDUCATION + DESIGN]

[N] = Neuroarchitecture

[AA] = Agile Architecture

[C] = Cybernetics

PRACTICE

[APPLICATION + PERFORMANCE]

[Hall & Imrie, 1999] conceptualizing : NAAC Framework

15

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

CYBERNETICS + SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018]

[Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019] [Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

APPLICATIONINARCHITECTURE

THEORY [EDUCATION + DESIGN]

PRACTICE

[APPLICATION + PERFORMANCE]

[Hall & Imrie, 1999]

With design theory tending to concentrate on the technocratic and technological, reducing questions of access and form to the functional aspects of the subject, few and ineffective design solutions have been considered for people with intellectual disabilities.

16

NAAC

application :

Framework

[ [

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018] [Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019] [Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

CYBERNETICS +

SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

According to neuroscience, the ability to process information consciously is less than 1% of unconscious processing; thus environmental information, such as image, sound, and design, is unconsciously retained by the brain in a way to that alters behaviour subconsciously (Andréa de Paiva, 2018).

Architecture can be used to increase adaptive behaviour and provide more experientially equitable spaces.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 17

a space that “invokes environmental manipulation to effect internal change in the [user], decreasing maladaptive behaviour, reducing stress, and producing more adaptive behaviour.”

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[Ayres, 1979]

Conceptualized through Sensory Integration (SI) theories and therapies, the success of the Snoezelen Room as a therapeutic tool during treatment is thus contingent in its adaptive sensory environment, which is built to modify incoming sensory stimuli rather than inhibit it.

neuroarch : snoezelen

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 18

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018] [Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

CYBERNETICS + SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019] [Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

Imam&Sinclair,2012;Sinclair,2019:

“…ameasurewhichismoreindependent,responsiveandholistic; a measure that integrates aspects of durability, flexibility and sustainability; a measure that unifies the scattered facets of contemporary sustainable designs; a measure that introduces alllayersofphysical,social,environmentalandfinancialfactors in the form of continuously evolving and dynamic framework; a measure better interlacing design phases to construction, operation,occupancy,disassemblyandreuse.”

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 19

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018] [Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

CYBERNETICS + SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019] [Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

TheoryofConversations(Pask,1969):

“...explores how humans and machines learn. It seeks to create responsive spaces wherein the environment is no longer the subconscious controller of its inhabitants, but rather one that is consciouslycontrolledbythem.”

TheCyberneticTheoryofArchitecture(Dubberly&Pagaro,2015):

“...architecture can no longer be static, but needs to implement design that inherently embodies rules of evolution, through self-governed feedback loops, in order to ensure healthy and responsibleoutcomes.

20

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

NEUROARCHITECTURE

[Shapiro et al., 1997]

[(Andréa de Paiva, 2018]

[Gillen, 2015]

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

AGILE ARCHITECTURE

[Sinclair, 2019]

[Imam & Sinclair, 2012]

APPLICATIONINARCHITECTURE

THEORY [EDUCATION + DESIGN]

PRACTICE

[APPLICATION + PERFORMANCE]

[Hall & Imrie, 1999]

CYBERNETICS + SYSTEMS THINKING

[Dubberly & Pagaro, 2015] [Pask, 1969]

Holistic Responsivity, informs a logic for perceiving architecture as an interdisciplinary system, engages computational thinking through the lens of development, communication and control, and subsequently proposes the revolution of current design processes to integrate those which may predict future behavioural and environmental evolutions immediately informed by such a system.

Transdisciplinarity, collaboration, and performance have become key themes that need to inform the broader system of environmental design within which this research nests.

21

[ [

: holistic responsivity

Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

defining

Situating

NEUROARCHITECTURE

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

HOLISTIC RESPONSIVITY

RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE

APPLICATION IN ARCHITECTURE

AGILE ARCHITECTURE PRACTICE

CYBERNETICS EDUCATION

EXPERIENTIAL EQUITY

BEHAVIOUR CONSCIOUS

RESPONSIVE/FLUID

DIGNITY AUTONOMY/AGENCY

SENSORY INTEGRATION FEEDBACK LOOPS

WELL-BEING

INCLUSION

PARTICIPATION

SYSTEMS THINKING

APPLICATION PERFORMANCE COLLABORATION THEORY DESIGN

SOCIAL COGNITIVE

PHYSICAL

TECHNOLOGICAL AFFECTIVE

Bridge the current gap in environmental design research and practice relative to accessibility of people with intellective disabilities. Acknowledge that design processes and subsequent performances need to be addressed in broader ways to cover crucial cognition encounters and experiences.

goals : expected contribution

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 23

A provocation towards design thinking that adds the necessary lens of Holistic Responsivity to the status quo of built environments, making them more inclusive and participatory for people with intellectual disabilities.

Through the exploration and application of neuroarchitecture, agile architecture, and cybernetics [NAAC], both knowledge and practice could be better positioned for a next generation of design that is more responsive, resilient, and responsible. The goal is to support and enhance the user’s well-being, agency, and dignity, informed by systems thinking and circular causal relationships.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 24

E: bushra.hashim2@ucalgary.ca W: linkedin.com/in/bushrahashim/

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

E: brian.sinclair@ucalgary.ca W: ucalgary.academia.edu/DrBrianRSinclair

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

: bushra.hashim + dr. brian r. sinclair

Situating Access and Breaking Boundaries : Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

Contemporary society, including architecture, urbanism, and city planning, stands at a vital juncture. e. Calls for heightened equity amidst growing diversity offer an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider design thinking. A part of this equation pertains to the ways that users address and operate within the built environment past mobility, to include people with intellectual disabilities (ID). The way intellectual disabilities have been conceptualized understood historically and its manifestation of intellectual ableism within the built environment reveal the imminent need to foster a greater understanding understand of the environmental needs of this group’s needs. current design research and practice People with under-represent intellectual disabilities remain under-represented within current design research and practice, affirming the importance of innovating innovative architectural solutions as well as deploying design that encourages inclusion and participation. Holistic Responsivity a is thus a term coined to convey this notion that designers shoulder serious and imminent responsibility for creating built environments that are responsive across to the wide-ranging abilities of users. (Gray et al., 2003; Gillen, 2015; Butterworth, 2000). It is proposed as a provocation and expansion of the current status quo, in critique of current universal design’s current one-size-fits-all approach to accessibility. , often limited toonly addressing mobility. Informed by neuroarchitecture, agile architecture, and cybernetics [NAAC], Hholistic Rresponsivity provides a conceptual framework that both theory and practice can be appliedy to design processes. This knowledge research is consolidated through case studies, primary data collection via three survey methods, and actionbased research. Collected data is qualitatively analyzed through content, narrative, and discourse analysis to understand the experiences of people with cognitive disabilities and perceived barriers in the built environment from one side, and how disability is perceived within architectural practice and education from the other. Through logical argumentation, this methodology will allow for the consolidation ofconsolidates primary and secondary research towards experiential equity and well-, being through, via proposed proposing new design guidelines for a next generation of design that areis more responsive, resilient, and responsible.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 26

research : abstract

America, Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of. Education for all Handicapped Children Act of 1975, Pub. L. No. 773 (1975). https://www.govinfo.gov/ content/pkg/STATUTE-89/pdf/STATUTE-89-Pg773.pdf.

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 2nd Session (n.d.). https://www.ada. gov/1991ADAstandards_index.htm.

Andréa de Paiva. (2018). Neuroscience for Architecture: How Building Design Can Influence Behaviors and Performance. Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 12(2), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2018.02.007

Architecture, K. A. (2018). Entoto. http://www.kindrachuk-agrey.ca/#!/projects/entoto

Ayres, J. A. Sensory Integration and the Child. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1979.

Brue, Alan W., and Linda Wilmhurst. “History of Intellectual Disability.” In Essentials of Intellectual Disability Assessment and Identification, 1st ed., 15–29. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2016.

Butterworth, Ian. “The Relationship between the Built Environment and Wellbeing: A Literature Review.” Melbourne, 2000.

Campbell, Natalie. “The Intellectual Ableism of Leisure Research: Original Considerations towards Understanding Well-Being with and for People with Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 2019, 16. https://doi. org/10.1177/1744629519863990.

Castell, L. “Adapting Building Design to Access by Individuals with Intellectual Disability.” Construction Economics and Building 8, no. 1 (2012): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.5130/ ajceb.v8i1.2994.

Corby, D., & Sweeney, M. R. (2019). Researchers’ experiences and lessons learned from doing mixed-methods research with a population with intellectual disabilities: Insights from the SOPHIE study. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 23(2), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629517747834

Curtis, S., and Rees Jones. “Is There a Place for Geography in the Analysis of Health Inequality?” In The Sociology of Health Inequalities, edited by Mel Bartley, David Blane, and George Davey-Smit, 1st ed., 236. Wiley-Blackwell, 1998. Department of Education, Office of the Secretary. Rosa’s Law, 82 § (2017). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2017/07/11/2017-14343/rosas-law.

Dubberly, H., & Pagaro, P. (2015). How Cybernetics Connects Computing, Counterculture, and Design. October, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92910-9_15

Foundation, R. H. (2010). Rick Hansen Foundation. https://www.rickhansen.com/ Gillen, Victoria. “Access for All! Neuro-Architecture and Equal Enjoyment of Public Facilities.” Disability Studies Quarterly 35, no. 3 (September 2, 2015). https://doi. org/10.18061/dsq.v35i3.4941.

Gray, David B., Mary Gould, and Jerome E. Bickenback. “Environmental Barriers and Disability.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20, no. 1 (2003).

Hall, P., & Imrie, R. (1999). Architectural practices and disabling design in the built environment. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 26(3), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1068/b260409

Hall v. Thaler, 75201 Supreme Court of the United States (2010).

Halpem, D. Mental Health and the Built Environment: More than Bricks and Mortar?

London: Taylor & Francis, 1995.

Imam, Salah, and Brian R. Sinclair. “Dysfunctional Design + Construction : A

Cohesive Frame to Advance Agility in the 21 St Century,” 2018.

Kamstra, Aafke, Annette A.J. Van Der Putten, and Carla Vlaskamp. “Efforts to Increase Social Contact in Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities: Analysing Individual Support Plans in the Netherlands.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 21, no. 2 (2017): 158–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629516653037.

Knox, P. L. (1987). The Social production of the Built Environment: Architects, Architecture and the Post-Modern City. Progress in Human Geography, 11(3), 354–377. https://doi. org/10.1177/030913258701100303

Maleki, M. R., & Bayzidi, Q. (2017). Application of Neuroscience on Architecture: The Emergence of New Trend of Neuroarchitecture. Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research, 2(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.24017/science.2017.3.62

McConkey, Roy, Brendan Bunting, Fiona Keogh, and Edurne Garcia Iriarte. “The Impact on Social Relationships of Moving from Congregated Settings to Personalized Accommodation.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 23, no. 2 (2019): 149–59. https://doi. org/10.1177/1744629517716546.

Minister, Office of the Deputy Prime. “Final Report for Signage and Wayfinding for People with Learning Difficulties: Building Research Technical Report,” n.d. http://www.communities. gov.uk/publication%0As/planningandbuilding/finalreport.

Morris, Stuart, Gail Fawcett, Laurent Brisebois, and Jeffrey Hughes. “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile of Canadians with Disabilities Aged 15 Years and over, 2017,” 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2018002-eng.htm.

Northway, Ruth. “To Include or Not to Include? That Is the Ethical Question.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 18, no. 3 (2014): 209–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629514543863.

Pask, G. (1969). The Architectural Relevance of Cybernetics. Architectural Design, 6(7), 494–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850100307

Raczka, Roman, Kate Theodore, and Janice Williams. “An Initial Validation of a New Quality of Life Measure for Adults with Intellectual Disability: The Mini-MANS-LD.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 24, no. 2 (2020): 177–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629518787895.

Ralabate, P. (2011). Universal Design for Learning: Meeting the Needs of All Students. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/ universal-design-learning-meeting-needs-all-students

Salmi, P., D. Ginther, and D. Guerin. “Critical Factors for Accessibility and Wayfinding for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities.” In Designing for the 21st Century III: An International Conference on Universal Design. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004.

Salmi, Patricia. “Identifying and Evaluating Critical Environmental Wayfinding Factors for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities.” University of Minnesota, 2007.

Sattler, J. M. Asessment of Children: Cognitive Applications. 2nd ed. San Diego: University of Californis, 2001.

Schalock, Robert L., Ivan Brown, Roy Brown, Robert A. Cummins, David Felce, Leena Matikka, Kenneth D. Keith, and Trevor Parmenter. “Conceptualization, Measurement, and Application of Quality of Life for Persons With Intellectual Disabilities: Report of an International Panel of Experts.” Mental Retardation 41, no. 1 (2002): 66. https://doi.org/10.1352/00476765(2003)041<0066:E>2.0.CO;2.

Shapiro, Michele, Shula Parush, Manfred Green, and Dana Roth. “The Efficacy of the ‘Snoezelen’ in the Management of Children with Mental Retardation Who Exhibit Maladaptive Behaviours.” The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities 43, no. 2 (1997): 140–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1179/bjdd.1997.014.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation

research : bibliography

Sheerenberger, R. C. A History of Mental Retardation. Baltimore: P.H. Brookes Publishing Company, 1983.

Sheerin, Fintan. “Our Shared Humanity.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 24, no. 3 (2020): 287–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629520949809.

Sinclair, Brian R. “Integration | Innovation | Inclusion: Values, Variables and the Design of Human Environments.” Cybernetics and Systems 46, no. 6–7 (2015): 554–79. https:// doi.org/10.1080/01969722.2015.1038481.

Sinclair, Brian R. “Shelving the Shoehorn : Architectural Resiliency , Responsivity + Responsibility in Spheres of Uncertainty,” 2019.

Tuckett, Polly, Ruth Marchant, and Mary Jones. “Cognitive Impairment, Access and the Built Environment.” England, 2004.

United States, Department of Justice. “2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design.” Title II. Washington, D.C., 2010.

Watchman, Karen, Matthew P. Janicki, Leslie Udell, Mary Hogan, Sam Quinn, and Anna Beránková. “Consensus Statement of the International Summit on Intellectual Disability and Dementia on Valuing the Perspectives of Persons with Intellectual Disability.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 23, no. 2 (2019): 266–80. https://doi. org/10.1177/1744629517751817.

World Health Organization. “Annotated Bibliography of the WHO Quality of Life Assessment Instrument – WHOQOL.” Geneva, 1998.

Situating Access + Breaking Boundaries: Holistic Responsivity as a Provocation 28