'Sincerity and earnestness': D.G. Rossetti's early exhibitions 1849?53

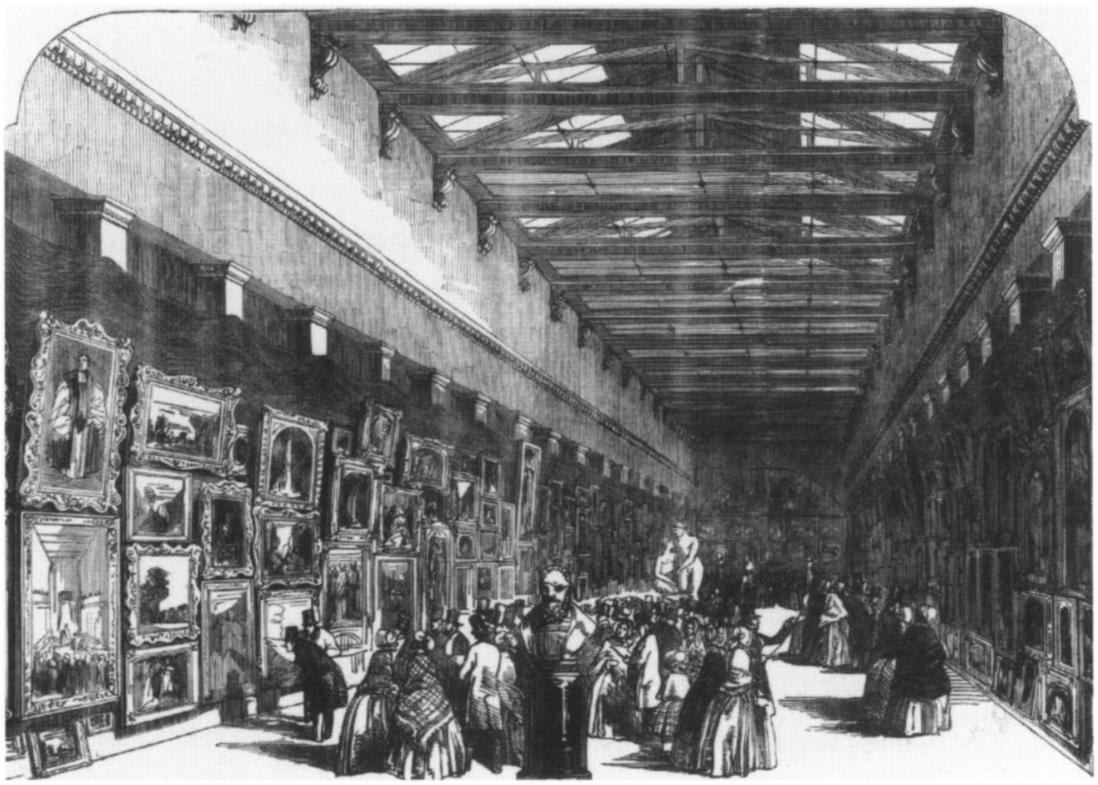

by COLIN CRUISE, Staffordshire University

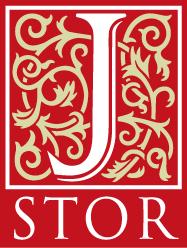

much recent scholarship on Dante Gabriel Rossetti has concerned itself with the interpretation of the symbol ism and imagery of his paintings. This article examines the exhibitions in which Rossetti chose to show his work at the start of his career, in an attempt to illuminate some of his professional aspirations. For example, both The girlhood ofMary Virgin (Fig.i) and EcceAncilla Domini! (Fig. 2), his first exhibited works, were shown at exhibitions organised by the Free Exhibition Society. Although to a great extent unorthodox both in style and theme, aspects of these paint ings were not without precedence in the works of Ford Madox Brown and, earlier, the German Nazarenes, already well known in England.l In showing them at an exhibition set up to liberate artists from submitting to theRoyal Acad emy, advocating 'absolute freedom' to the artist and afford ing free access for the public, Rossetti allied the stylistic unorthodoxy of his work to a new ideal in exhibiting. The Free Exhibition Society was 'characterised by ultra radical principles, in opposition to the close-borough politics of the Royal Academy'.2 In effect, Rossetti's paintings were a protest against the continued control of British art by the Academy.

Rossetti showed his work at four exhibitions in London between 1848 and 1853 before temporarily abandoning exhibiting for private sales. The exhibitions were: the Free Exhibition, opened inMarch 1849; the first National Insti tution Exhibition at the newly opened Portland Gallery, in April 1850; a benefit exhibition for the North London School of Drawing andWater-colour, sometimes referred to as the 'Christmas Exhibition', which opened at the Portland Gallery in late December 1851; and theWinter Exhibition of Sketches and Drawings, open to the public between December 1852 and January 1853. It is worth examining the context for the setting up of these exhibitions and to question some of the myths and inaccuracies which have grown up around them. One need only draw attention to the 1852Winter Exhibition of Sketches and Drawings to highlight some of the problems for contemporary scholars.

My thanks to Jan Marsh, Angela Thirlwell and Elizabeth Prettejohn for helpful suggestions, discussions and material and toDonato Esposito at the British Muse um, Patsy Williams at St Deiniol's Library, Simon Fenwick at the Royal Water colour Society, EvaWhite at the National Art Library, London, Lesley Marshall at Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre, Christine Hopper at Bradford Art Gallery andMuseum, Sabrina Shim at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Sophie Martin at theRoyal Academy of Arts, Albert Bowyer andRuth Brown at Stafford shire University and Susan Brady at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, for all their help and guidance. Some of the research for this essay was undertaken during a period of leave supported by Staffordshire University. Much of the research into periodical reviews was done during a residential fellowship at theYale Center for British Art. My thanks to both institutions for their support.

1 For a discussion of the relationship of English Pre-Raphaelitism to German painting, seeW. Vaughan: German Romanticism and English Art, New Haven and London 1979.

4 JANUARY 2OO4 CXLVI THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE

The show has constantly been assigned to thewrong exhibit ing venue and there has been a dispute about the number of works by Rossetti thatwere on display, amatter not helped by the artist himself who complained to Ford Madox Brown that his works had been rejected by the organisers. To other correspondents, on realising that his works had been accepted and hung, Rossetti described only two exhibits rather than three, a confusion still obscure in origin and which has been perpetrated inmuch critical literature.3

While scholars have assigned this exhibition to the gal leries of the 'Old' Water-colour Society, the actual venue was its rival, the 'New' Water-colour Society.4 The change of venue was clearly of significance for his contemporaries because William Michael Rossetti began his review with that information, noting the change from the 'Old'Water colour Society Galleries to 'the room atNo 121 Pall Mall, opposite the Colonnade, where the Amateur collection was seen in the summer'.5 And a writer in the Manchester Guardian concluded his review: 'Itmay be useful to add that the pictures are exhibited this year, not at the gallery of the Old water-colour Society, as in former years, but atNo 121, Pall Mall.'6 In the most comprehensive survey of periodical reviews of the Pre-Raphaelites since Fredeman's 'bibliocrit ical study', Thomas J. Tobin overlooks both theWinter Exhibition of 1852 and the North London School benefit.7 Such an oversight is regrettable when considering the stylis tic change thatRossetti's work underwent from religious to poetic subjects and the beginnings of his experimentation with watercolour. A correction of the venue allows us to check exhibition reviews previously overlooked and, as a consequence, verify the number of works Rossetti exhib ited and their reception.

Throughout his life a number of accounts of Rossetti's exhibiting practices ? or lack of them ? grew up, but most of them are inaccurate. Thus, following his death in April 1882, when he was commemorated in obituaries and mem oirs aswell as, in the following year, retrospectives at the Royal Academy and the Burlington Arts Club, critics noted

2 Literary Gazette, no. 1735 (20th April 1850), p.281; this notice reviews the histo ry of the 'Free' from its inception to the upcoming third exhibition of 1850. 3 Rossetti wrote to Brown on 4th December 1852: 'What do you think? My sketches are kicked out at that precious place in Pall Mall. I am, of course, more than ever resolved to paint my picture of the pigs. Alas! my dear Brown, we are but too transcendent spirits ? far, far in advance of the age. Do not let us bring up this subject to-morrow ifHannay or any one else is present, as it is of no use trumpeting one's grievances'; W.E. Fredeman, ed.: Correspondence ofDante Gabriel Rossetti, Cambridge 2002, I, 52:22, pp.210-11. A letter from Rossetti to Thomas Woolner (ibid., 8th January 1853, 53:1, p.224) informs him that he has 'two Dan tesque sketches' on view at theWinter Exhibition in Pall Mall, but a third paint ing isnot referred to at all. In an editorial note toRossetti's letters Fredeman repeats the misapprehension of the venue as the 'Old'Water-colour Society although he notes that there were three, not two, works on show (ibid., 52:15, p.206, note 1). V. Surtees, in The Paintings and Drawings ofDante Gabriel Rossetti (1828?1882): A

i.

[848-49.

how remarkable itwas to see any of Rossetti's works on public display at all. The reviewer for Blackwood's Magazine wrote that a 'sensitiveness to attack, which even in the expe rience of poetic temperaments seems to have been excessive, transformed a genial painter into a hermit; and the seclusion he sought for himself environed his works', adding that the artist was 'ofthat order of mind which is known to shrink from the rough ordeal of public exhibitions: never but once, when some association was formed in Liverpool congenial to the Pre-Raphaelite Brethren, have we encountered

Catalogue Raisonn?, Oxford 1971, clairns in her exhibition history of all three works that they were shown at the 'Old'Water-colour Society, 121 PallMall, rather than at the galleries of the 'New' Society (theOWS was in fact at 6 PallMall). J.Marsh, inDante Gabriel Rossetti: Painter and Poet, London 1999, p. 540, note 21, discusses both the venue and the possibility that the 'missing' third painting 'must have been To capernimbly' rather than Rossovestita. A letter from Rossetti to G.P. Boyce indi cates that he wished to borrow To caper nimbly from him to exhibit at theWinter Exhibition (Fredeman, op. cit., 52:15, pp.205-06).

4 The 'Old' Water-colour Society had been approached by Lewis Pocock on behalf of the 'Society of Amateurs of the Fine Arts' for the purpose of holding a Winter exhibition at the OWS Gallery. He paid a fee of ?100 on each occasion. Ihave been unable to trace the arrangement made for the 1852 exhibition at the 'New' Water-colour Society. My thanks to Simon Fenwick, archivist of theRoyal Water-colour Society, for helping me confirm this point.

5W.M. Rossetti, in Spectator (18th December 1852), p. 1211.

his pictures in public galleries'.8 F.G. Stephens, erstwhile Pre-Raphaelite Brother and, by the 1870s, an established art critic, made amore extreme and unsubstantiated claim in his entry on Rossetti in the Encyclopaedia Britannica: 'After these pictures were finished [i.e. The girlhood ofMary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini!], the outside world saw no more of Rossetti as a painter until it had prepared itself to seemod ern artfrom a higher plane than before.'9 At other times the artist's absence from public exhibition was seen as a kind of arrogance: he 'never condescended to exhibit at all'.10 In

6 Manchester Guardian (29th December 1852), p.875.

7 See W.E. Fredeman: Pre-Raphaelitism: A Bibliocritical Study, Cambridge MA 1965; and TJ. Tobin: Pre-Raphaelitism in theNineteenth Century Press: A Bibliogra phy, Victoria BC 2002.

8 'Contemporary Art - Poetic and Positive: Rossetti and Tadema - Linnell and Lawson', Blackwood's Magazine (March 1883), p.392. Even privately, however, Rossetti might be seen as shy of showing his work. For instance, George Price Boyce recorded a visit to the apartment shared by the Rossetti brothers, 14 Chatham Place, Blackfriars Bridge, in December 1852 when he saw several works by other artists in the studio but only one work (a sketch) by Rossetti him self; see V. Surtees, ed.: The Diaries ofGeorge Price Boyce, Norwich 1980, pp.8-9.

9 Encyclopaedia Britannica, nth ed., Cambridge 1910-n, XXIII.

10 'English art, as illustrated by the Pictures of the Past Year', London Quarterly Review 37 (January 1872), p.392.

terms of a larger history of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, however, Rossetti's decision to exhibit at the Free Exhibi tion rather than the Academy in 1849, and again in 1850, is often dismissed as the product of one of two contrasting characteristics: ambition or cowardice. Some observers see the decision as a type of opportunism, others as panic at his failure to achieve the correct standard for the Royal Acad emy. Either way the decision has been read as a betrayal of the aims of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood at the very start of its existence.11

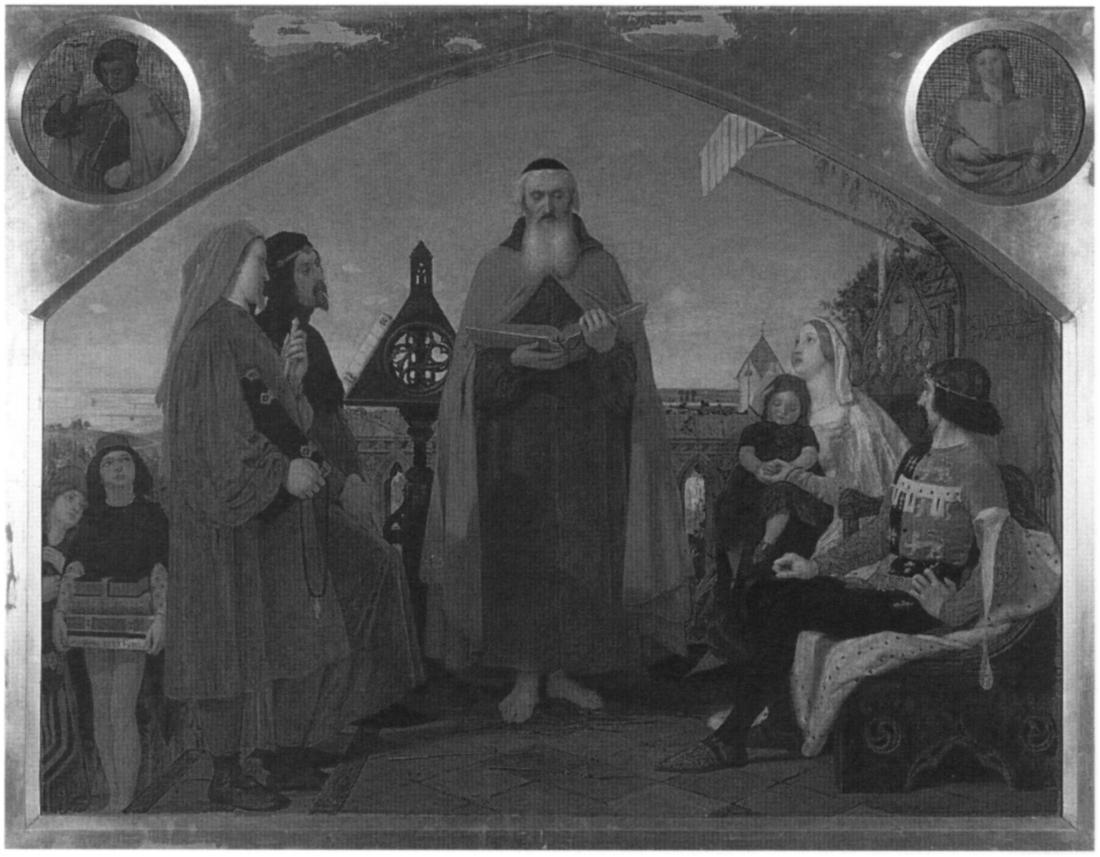

The first two exhibitions inwhich Rossetti showed were organised by the recently formed Free Exhibition Society and the third one was held in its new premises, the Portland Gallery. Several changes of name aswell as constant reloca tions in the first years of the Society's existence have obscured what we might otherwise identify as Rossetti's consistent commitment to a new and experimental venture, a real alternative to the Royal Academy. Between 1846 and 1852, the Society is variously referred to in the press as the 'British Artists' Own Exhibiting Society', the 'Free Exhibi tion', the 'Free Exhibition ofModern Art' or 'The Nation al Institution for the Exhibition of Modern Art' etc. Its venue changed from the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly for the first exhibition, to 'the Chinese Exhibition Gallery' or the 'Hyde Park Gallery' (sometimes even more confusingly referred to as 'Hyde Park Corner') for the second, before the opening of the Portland Gallery at 316 Regent Street in April 1850, where the third and subsequent exhibitions were held. The Portland was built specially to house the Society's exhibitions and became synonymous with its activities.

The Free Exhibition was a force representing the interests of artists rather than amovement based around a style or aesthetic preference. It quickly went from a genuine 'alter native' status to acceptance and orthodoxy, and Rossetti's involvement was peripheral and brief. Its inception inApril 1846 was not greeted with enthusiasm by the Art-Union which had several objections to the foundation of such a society:

from the manner in which 'The British Artists' Own Exhibition' is brought forward, we cannot augur favourably of its success; since such a scheme can never secure the confidence of artists of certain position, with whose productions it is so much the ambition of the rising talent of the profession to see their own exhibited. Our present impression is, therefore, against this scheme ? notwithstanding our earnest wish for some means by which artists may obtain a permanent exhibition room. In the present instance, we are not content with the locality, nor with the aspect of the proposed gallery, nor by the mode by which it receives light; neither have we sufficient confidence in the 'committee of reference', nor in the parties towhom must be intrusted the delicate task of'hanging'; we think the rule which prevents a picture from remaining in the rooms longer than three months fatal to its utility; we consider ten per cent., independent of 'fees', too large a demand upon sales effected; and, especially, we think a shilling too much for admission; if not altogether a free exhibition, it should be nearly so; and that 6d. is too much for the 'catalogue'.12

The Literary Gazette, on the other hand, approved, finding the Society and its exhibition a 'step in the right direction for artists and the arts':

The private view took place on Thursday [14th May] at the Egyptian Hall, and a collection of above 200 workssculpture, paintings, drawings, and engravingswere got together within a very short time tomeet the occasion. It will strike every visitor, that many of these productions, though exhibited before, will be seen here for the first time; ashigh and low places, octagon-rooms, and mixture with architecture, or other incongruities, have prevented their having a previous chance of vision and appreciation. For these and for novelties, the production of themetrop olis and more particularly ofmeritorious provincial artists, this plan offers a perpetual mart, susceptible of, and calling for, continual change. It cannot, therefore, be regarded but with a favourable eye by the public.13

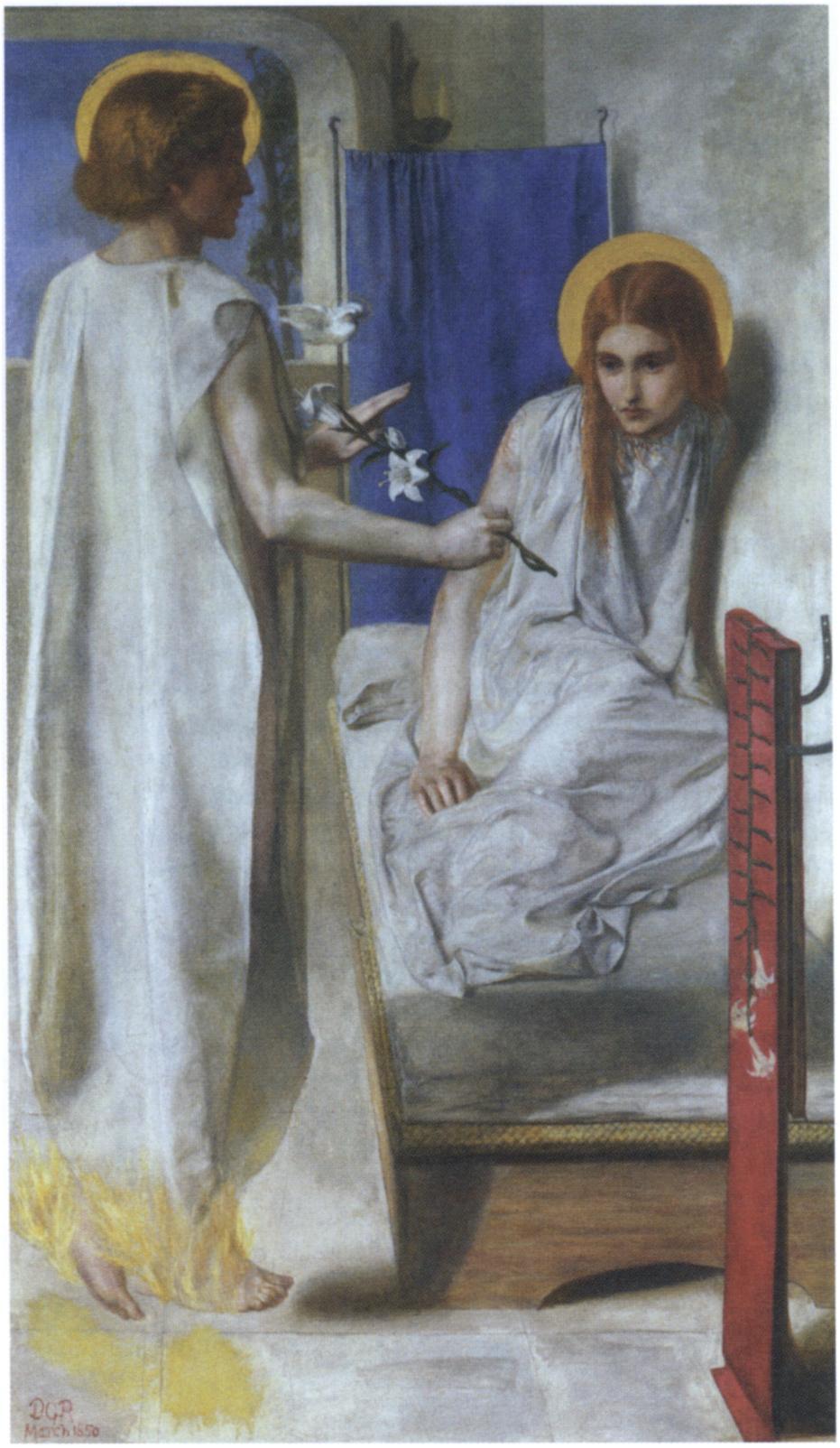

Ford Madox Brown showed Wycliffe reading his translation of theNew Testament (Fig.3) at the 1848 Free Exhibition

11See S.Weintraub: Four Rossettis: A Victorian Biography, London 1978, pp.36-37, inwhich Rossetti is seen as choosing the Free Exhibition because he was 'worried about possible reaction to [hisworks'] crudities'.

12 'The British Artists' Own Exhibition', Art-Union (May 1846), pp.139?40. Although originally opposed to the 'Free', the Art-Union eventually gave its approval and even formed an alliance with it.

13 'Association for the Free exhibition of Modern Art', Literary Gazette, no. 1585 (16thMay 1847), pp. 370-71.

**Letter from D.G. Rossetti to F. Madox Brown (March 1848), in Fredeman, op. cit. (note 3), 48:3, pp.58-59

15 Information from Rossetti's letter to his aunt, Charlotte Lydia Polidori (April 1848), in ibid., 48:4, p.60.

which opened less than amonth after his historic first meet ing with Rossetti (Fig.4). The consequences of Rossetti's letter to Brown of March 1848 are too well known to be rehearsed here but the context is important for Rossetti's future exhibitions.14 There is a distinct possibility that his decision to exhibit at the 'Free' was due to Brown's influ ence. Brown had exhibited in several other venues and Rossetti had found his address in an exhibition catalogue.15 He already had some degree of fame, the Builder describing him as 'of cartoon celebrity' when he showed at the Free Exhibition in 1848 and finding him entitled 'to a higher place in the list of British artists' in 1849.16 Yet Brown had clearly made a choice to exhibit at the 'Free' rather than the Academy and showed works at both the 1848 and 1849 exhibitions which are now seen as central to his early career aswell as significant to themedieval revival inBritish paint ing. Rossetti sawWycliffe reading his translation of theNew Tes tament in Brown's studio before itwas publicly exhibited, and the furious intensity of Brown's working method and thework's destination must have impressed itself upon him. Given Rossetti's early appreciation of Brown's works and the developing intimacy between the two artists, it is scarce ly surprising that the first work Rossetti sent to the 'Free' owes something of its style to Brown's painting practices of the 1840s. Certainly Rossetti appears torn between Brown's medievalising tendencies in historical painting and themore innovative Pre-Raphaelite subject painting, apoint made by Holman Hunt in his memoirs in apassage on Rossetti's early career.17 A comparison of the critical responses to their exhibits in the Free Exhibition helps us see how similar Brown's and Rossetti's works struck contemporary review ers. The Builder found the 'finish' of their individual contri butions of 1849 noteworthy, Brown's being a 'perfect marvel' and Rossetti's 'finished with extraordinary minute ness and displaying a high tone of mind', adding that Ros setti's was 'one of the most noticeable pictures in the gallery'.18 Sometimes even further similarities were detect ed. InApril 1848, for example, the Art-Union noted Brown's Wycliffe reading his translation of theNew Testament when it was shown at the Hyde Park Gallery:

This is a beautiful and valuable production, brought forward in themanner of fresco, with amarked feeling for the style of the early Florentine school.... The compo sition is semicircular, the spaces being enriched with gilding. This is, perhaps, themost entirely successful pro duction we have ever seen in this manner of Art. The aspirations of the old schools are inimitably rivalled and, we confidently say, surpassed in qualities atwhich they only aimed. A higher praise on awork of Art we cannot bestow.19

16Notices in the Builder 6, no.272 (22nd April 1848), p.246; and ibid. 7, no.321 (31stMarch 1849), p. 145. In the 1848 Free Exhibition catalogue the work was listed as no.216 - 'The First Translation of the Bible into English' - and is accom panied by the text which serves as a subtitle: 'Wicliff reading his translation of the New Testament to his protector, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, in [the] presence of Chaucer and Go wer, his retainers.' Itwas priced at?210. 17W. Holman Hunt: Pre-Raphaelitism and thePre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2 vols.,

The following year the Art Journal reviewed Rossetti's The girlhood ofMary Virgin at the Free Exhibition with strikingly similar references, adding some art-historical flourishes to validate the more obvious judgment: 'This picture is the most successful as a pure imitation of early Florentine art thatwe have seen in this country. The artist has worked in austere cultivation of all the virtues of the ancient fathers with all the severities of the Giotteschi, we find neces sarily the advances made by Pietro [sic] della Francesca and Paolo Uccello, without those ofMasolino da Panicale.'20 Rossetti's debut made an immediate impression upon reviewers who, almost unanimously, praised his work's references to early Italian painting. The Literary Gazette drew special attention to Rossetti in its first short notice of the exhibition, stressing the combination of religious iconography with technique and style: 'We must not forget to direct attention to a very uncommon work, in emulation of the old missal style, highly finished, indeed, though in oil; it is stippled all over, and the hairs, every one of them, touched with gilding . . ..'2IThe Athenaeum elaborated this stylistic analysis, finding an interesting theological dimension in both the style and subject of The girlhood ofMary Virgin:

The personification of the Virgin is an achievement worthy of an older hand. Its spiritualized attributes and the great sensibility with which it iswrought inspire the expectation that Mr. Rossetti will continue to pursue the lofty career which he has here so successfully begun. The sincerity and earnestness of the picture remind us forcibly of the feeling with which the early Florentine monastic painters wrought; and the form and face of the Virgin recall the words employed by Savonarola, in one

London 1905, esp. pp. 120-23.

18Builder j, no.321 (31stMarch 1849), p.145. Brown showed Cordelia at the bedside ofLear (T?te, London) at this exhibition. '9Art-Union (April 1848), p. 144.

20 'The Hyde Park Gallery', Artfoumal (May 1849), p. 147.

21 'Fine Arts: The Free Exhibition ofModern Art', Literary Gazette, no. 1680 (31st March 1849), p.239.

of his powerful sermons ? 'Horpensa quanta bellezza havea laVergina, che avea tanta sanctit? che risplendeva in quellafac cia; della quale dice S. Tommaso, che nessuno che la vedessi mai laguardo per concupiscentia, tanta era la sanctit? che rilustrava in lei.'Mr. Rossetti has perhaps unknowingly entered into the feelings of the renowned Dominican who in his day wrought asmuch reform in art as inmorals. The coinci dence is of high value to the picture.22

The point here seems to be a denominational one with a particular contemporary application: that while Rossetti somewhat resembles aCatholic painter of the fourteenth or fifteenth century his vision of the Virgin is, fortunately, a reformed onereformed, as itwere, before the Reforma tion. The critic, by implication, finds in the work a deeply religious feeling which is distinct from the corruption of Catholic Mariolatry, as a kind of delayed response to the austerity of Savonarola.

Hunt's account ofRossetti's showing at the 'Free' in 1849 implies that Rossetti was motivated by panic rather than treachery. It shows Rossetti abandoning Pre-Raphaelitism at the earliest opportunity and at the most crucial moment and serves to demonstrate Hunt's 'true' leadership of Pre Raphaelitism. According to this narrative, Rossetti's haste to exhibit work displaying the initials 'P.R.B.' exposed the group to ridicule and hostility, an interpretation which does not account for some of the dismissal of Pre-Raphaelite work before the 1850 Free Exhibition. It is unlikely, how ever, thatRossetti's decision to show at the Free Exhibition was made at the lastminute, if only because the Free Exhi bition system demanded that wall space be booked several months before the exhibition opened. The press of the time commented adversely upon the need to buy wall space early; the Art-Union, for example, noted the system for the alloca tion of wall space for the 1849 exhibition several months before its opening: 'The spaces are, it appears, to be allotted soon after the first of November, by which day all applica tions are to be sent in; we trust and believe that the com mittee will exercise sound judgment and strict justice in the decisions they are called upon to make.'23 For Rossetti to have decided to show his work just before the opening of the exhibition, for whatever motive, he would have had to depend upon a space either becoming free or having

22 'FineArts: Free Exhibition ofModern Art', Athenaeum, no. 1119 (7thApril 1849), p.362. The reference to Savonarola is a quotation from his Sermon (no.28) on Ezekiel; see L. Villari, ed.: Life and Times ofGirolamo Savonarola, New York 1888, p.498, where this famous passage isparaphrased inEnglish: 'we read concerning the Virgin, that her great beauty struck allwho looked on her with amazement, but that shewas so encircled by a halo of sanctity, as to excite impure desire in no man, all, on the contrary, holding her in reverence.' The Athenaeum review must have been themost gratifying any young painter could have desired.

23Holman Hunt, op. at. (note 17), pp. 176-77; 'The Free Exhibition', Art-Union (November 1848), p.342. The reviewer also commended the new system of book ing wall space as advantageous to artists 'who, not being members of the Royal Academy or of the Society of British Artists, have but small chance of obtaining reward alike of fame or of money for their labours during awhole year'.

24Hunt was aware of the dating of Rossetti's decision to show at the 'Free' only after the first edition of his memoirs had been published. William Michael Rosset ti wrote to him to point out his error and he amended the text of the second edi tion by appending a note. However, the guarded language and the use of the term 'purchased exhibition' indicate a residual hostility and speak of Hunt's reluctance to change his opinion of Rossetti's motives: 'William Rossetti tellsme thatGabriel

remained unsold, or, possibly, having to sub-let it from a friend or other contact. As Rossetti's entry in both the earlier and later printings of the catalogue is the same, his decision must have been made in time for his details, includ ing the supporting sonnet, to be printed in full and itwould seem that the 'Free' had been his chosen destination for The girlhood ofMary Virgin for some months.24

Rossetti had two presences, of sorts, at the next manifes tation of the Free Exhibition, 'The National Institution for the Exhibition of Modern Art'. His portrait appeared as the figure of Feste inWalter Howell DeverelTs Twelfth Night (Forbes Collection, sold Christie's, London, 19th February 2003, lot 36), and his own Ecce Ancilla Domini! was hung as no.225.2* The exhibition was tantalisingly previewed not

bought awall space at this gallery, feeling doubtful whether he would get his pic ture into the Academy, but he mentioned nothing about this to us nor did Iknow of the purchased exhibition until his brother had read the first edition of this book'; W. Holman Hunt: Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, rev. ed., London 1913, II, p.300. See alsoW.E. Fredeman, ed.: The PRB Journal, Oxford 1975, note 21:22, p.233. The picture was hung as no.368 and is described in the catalogue as '"The Girlhood of Mary Virgin" by G.D. Rossetti', the price being ?80. The catalogue entry is the entire sonnet beginning 'This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect .'which differs in several ways from the revised version printed in W.M. Rossetti, ed.: Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, London 1890, I, p.343. In the catalogue the sonnet reads: 'This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect/ God's virgin. Gone is a great while, and she/ Dwelt thus inNazareth of Galilee;/ Her kin she cherished with devout respect./ A profound simpleness of intellect/ Was hers, and supreme patience. From the knee/ Faithful and hopeful; wise in charity;/ Strong in grave peace; in duty circumspect./ Thus held she through her girlhood; as itwere/ An angel-watered lily, that near God/ Grows, and is quiet. Till one dawn, at home,/ She woke in her white bed, and had no fear/ At all, ? yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed;/ Because the fulness of the time was come.'

25The title was shown with double quotation marks but no exclamation mark

once but twice by the Literary Gazette who promised 'agreat treat' and suggested that 'it is likely to create some sensation as it contains some very superior examples of living art'.26 In an address to the public from the Portland Gallery, dated 13thApril 1850 in the opening pages of the exhibition cat alogue, the organisers commended the Society's new-found importance aswell as the catholicity of its exhibits, admon ishing that such liberality was the key to its future success.27

When discussing Rossetti's Ecce Ancilla Domini!, the reviewer of the Art Journal returned to the theme of medieval pastiche:

This is a small picture, the subject of which is the saluta tion of Mary by the Angel Gabriel. It is painted in the manner of the Florentine school, before the advent of Masaccio, every portion being stippled with the utmost nicety. The Angel, to whom is given a straight hanging white drapery, stands with his back to the spectator, and offers to the Virgin awhite Uly ? the latter also wearing white. The background iswhite; indeed, so generally white is the picture, that it is only here and there broken by coloura treatment allusive to the purity of the Virgin. The work is perfectly successful in its imitation of the school which it follows.28

The short review in the Builder was more mixed:

In a performance full of affectation, Mr Rosetti [sic] has shown himself a poet-artist, somuch real genius (misdi rected, though itbe) pervades this, that one wonders how the author can subserviently submit his abilities to so confined a sphere. Surely light, shadow, and colour, with the marvellous mysteries of their respective influences are matters worthy the attention of a painter. Nevertheless, this is a striking work for intensity of expression and the cleverly arranged and carefully drawn white draperies.29

Having promised much for the exhibition as awhole, the Literary Gazette review must have been a disappointment to Rossetti. The notice began: 'If one class be Pre-RaphaeVa term the Gazette had used to describe Deverell's work - 'this isPre-Pre, or ancient Byzantine. There is a purity and beau ty about it, however, and a fancifulness which may assort well with a fanciful religion. As for art, unless retrograding be advancing, we are inclined to believe that unless the turn

thus: "Ecce Ancilla Domini". The price was ?so; see exh. cat. The Exhibition of the National Institution: Portland Gallery, London (Portland Gallery) 1850.

26 Literary Gazette, no. 1734 (13th April 1850), p.264; and ibid., no. 1735 (20th April 1850), p.281.

27The address gives some details of the development of the Society and its inten tions, once more stressing the dissatisfaction of the Society's founding artists with the established possibilities of exhibiting in London. The free admission was soon abandoned as 'onerous' and by 1850 the galleries charged but were opened 'at the end of the season for a fortnight, free of charge, for the benefit of theworking class es'; see Art Journal (May 1850), pp.138?40.

28 Ibid., p. 140.

29 'The Portland Gallery, Regent Street', Builder 8, no.376 (20th April 1850), p. 184 (reviewer's emphasis).

30 'The National Institution', Literary Gazette, no.1737 (4thMay 1850), p.312. Sur prisingly, perhaps, the reviewer had earlier described Deverell's Twelfth Night as 'clever' and belonging 'to a somewhat novel phase in our fine arts,which has been designated the Pre-Raphaelite School. It represents a concert of the quaintest kind, in the quaintest of old costume, but exceedingly good in picture. It is full of humour and humourous expression, capitally grouped and composed, and kalei

given to the fashion of the day is checked, we shall be in danger of going back to immaturity and early effort, instead of availing ourselves of the past as lessons for the future. This style might embellish books, but never adorn a picture gallery.'3?

It is interesting to note thatRossetti abandoned the Free Exhibition at the point when itwas becoming an established venue for exhibiting paintings in the permanent, purpose built Portland Gallery. One recurring interpretation of this decision, based directly on Hunt's memoirs, was that Ros setti was profoundly disturbed by the reception of his work. John Gere, for example, claimed that Ecce Ancilla Domini! 'aroused a critical attack at its exhibition at the Portland Gallery and thereafter Rossetti refused to exhibit again in London'.31 We can observe two things here, however: first, that the reviews of Rossetti's work were by no means universally bad and cannot be blamed for the artist's reluc tance to present his work to the public; secondly, he did, indeed, show at the Portland Gallery again that year, displaying Ecce Ancilla Domini! once more for a London audience, in an exhibition that has been almost entirely overlooked in the literature on the Pre-Raphaelites.

In December 1850, Rossetti, along with Brown and Millais, contributed paintings to help raise funds for the North London School of Drawing and Modelling, 'estab lished about a year ago with the laudable object of aiding in the diffusion of art-education, thus partially acting as auxil iary to the Government School of Design', asWilliam Michael Rossetti recorded in his notice of the exhibition in the Spectator J2 The School's prospectus is dated February 1850 and shows that Brown was on the Committee along with Charles Lucy and Thomas Seddon; Cave Thomas was the 'Drawing & Modelling Master'. Thus, an informal group of artists from Brown's circle and from the formative years of the Free Exhibition Society had a presence in the School. The object of the School was the improvement of the taste of the 'English Artisan', its committee recognising the role of the Government School of Design but consider ing that the great distance of the Schools at Somerset House and Spitalfields from where theworkmen actually lived 'vir tually excludes [them] from the advantages to be derived from such Schools'. Camden Town was considered 'very favorable' for the purpose.33

doscopically coloured with famous effect.' The comments on Rossetti have to be seen in relation to this loose definition of Pre-Raphaelitism.

31 J. Gere, in V. Surtees, ed.: exh. cat. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Poet and Painter, London (Royal Academy of Arts) 1973, p.25. 32W.M. Rossetti, in the Spectator (4th January 1851), pp.19?20.

33 My thanks to Lesley Marshall atCamden Local Studies and Archives Centre for supplying me with the School's prospectus. The Illustrated London News (17th Jan uary 1852) carried an illustrated item on the School's activities. Prince Albert's 'fur ther subscription of?25' is recorded in an item in theArt Journal (December 1851), p.327. See T. Newman andR. Watkinson: FordMadox Brown, London 1991^.55, which records that Brown attended the first coirirnittee meeting of the school.

A. Grieve, in The Art ofDante Gabriel Rossetti: The Pre-Raphaelite Period 1848-30, Hingham 1973, p.20, observes that the exhibition was organised by Thomas Sed don 'to raisemoney for theNorth London School of Design', the first ofwhat were to be 'Suburban Artisan Schools' and something of an experiment. Cave Thomas was replaced as drawing master by Brown in 1852. Charles Lucy had previously established a drawing school for prospective artists (rather than artisans) inCamden Town; Tom Seddon was one of his students.

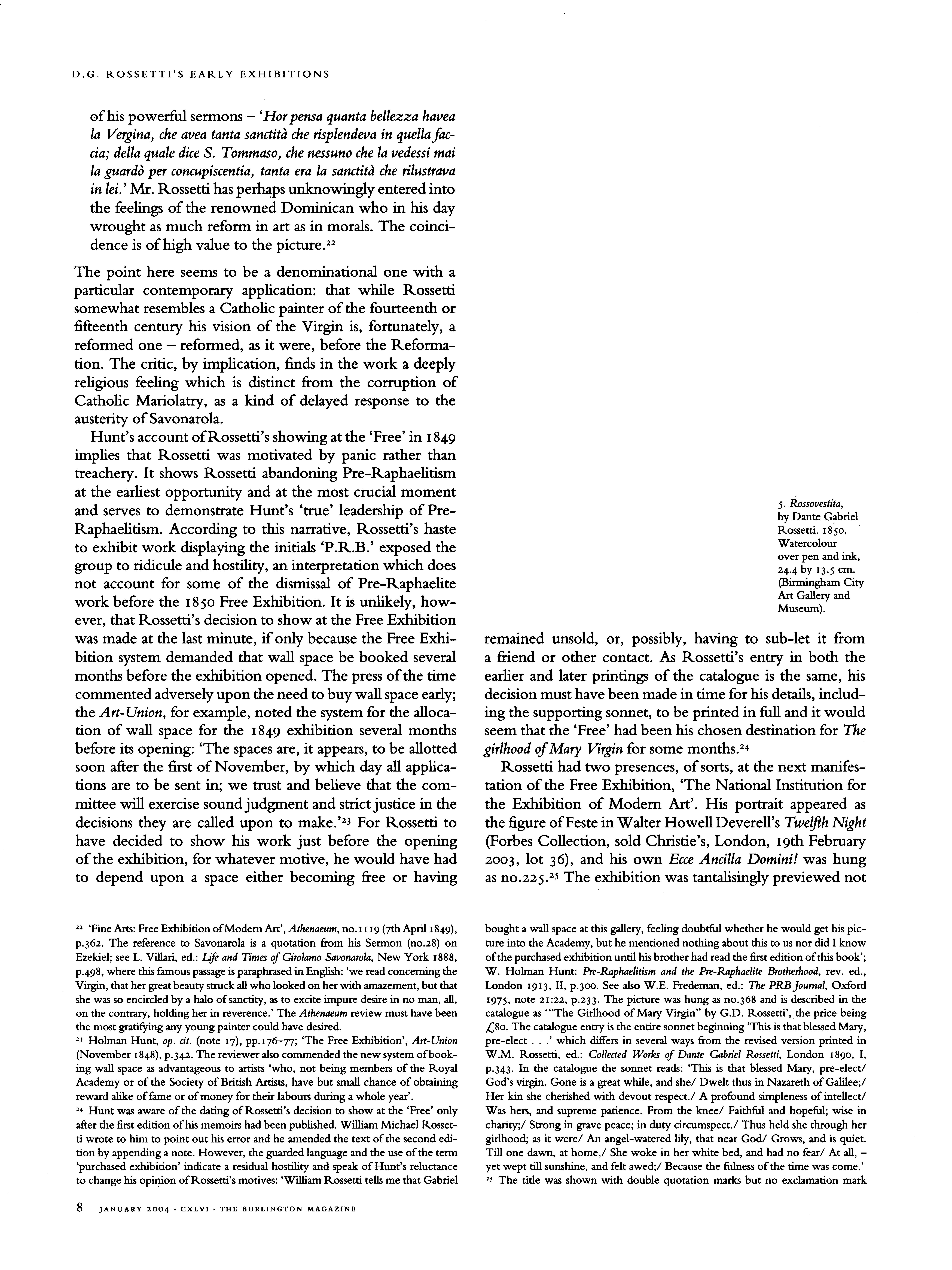

In amemoir of his brother Thomas who was themoving force in the founding of the School, James Seddon writes that, owing to the insufficiency of the funds from students to cover expenses, itwas decided 'to get up an exhibition of works of art, during the Christmas holidays at the close of the year 185o'.3* Unfortunately, Seddon's account is short on detail about the exhibition or the role played in it by Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite circle. One of the abiding mysteries isRossetti's choice of paintings: the retouched Annunciation scene and the watercolour picture of awoman inVenetian dress, now known asRossovestita (Fig. 5),which the artist had already presented to Brown.35

The conspicuously varied contents of the exhibition show Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelite Brothers and sym pathisers in contact with older artistswith whom they might have had some affinity and others with whom there could only have been the remnants of a youthful antipathy. Thus, hanging together, were William Mulready's drawings for Choosing thewedding gown and The painter's studio and some other works by him; Brown's Lear and Cordelia, first exhib ited at the 'Free' in 1849; Cave Thomas's Evening', three designs by Ruskin after works by Fra Ang?lico; three draw ings by Millais including a representation of the last scene of Romeo andJuliet, and works by Lucy, Anthony, Woolner, Clint, Pyne, Cattermole, W. Henry Hunt, Armitage, both Seddon brothers, and Etty, among others. Holman Hunt was not represented.36

Without giving the North London School exhibition too great an importance either for Rossetti or for Pre Raphaelitism, it is clear that an involvement with design and craftsmanship at this stage was prescient of Rossetti's later concern with design reform and education during his asso ciation with William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Move ment. Although only marginally involved with the North London School in 1851, within four years Rossetti was actively involved with the practical instruction of artisans at theWorking Men's College inRed Lion Square.37 Further, while the re-exhibition of Ecce Ancilla Domini! is a surprise for several reasons, the inclusion of Rossovestita indicates a change of direction inRossetti's concerns ? away from the 'medievalised' religious subject to a more direct relation with both the poetic subject and the imaginative recon struction of the medieval past, as in the life of Dante and the incidents recorded in the Vita Nuova. This early collision of Rossetti's two modes in this exhibition, 'Christian' and 'Fleshly' or, perhaps, spiritual and sensual, is significant even if it appeared in an obscure exhibition. It is suggestive of the direction of Rossetti's future work both in imagery and in technique.

3* J. Seddon: Memoir and Letters of theLate Thomas Seddon, Artist, London 1858, pp.n-12.

35Surtees, op. cit. (note 3), in her provenance for Rossovestita (no.45.14), claims that itwas shown at theNational Institution, Portland Gallery, London, in 1850.

36 Information from the list of artists andworks which appeared inRossetti, op. cit. (note 32).My thanks toAngela Thirlwell for help in tracing this review.

37Rossetti taught at theWorking Men's College from 1855; seeMarsh, op. cit. (note 3), pp. 135-39.

38For Pocock's role asHonorary Secretary, seeA. King: 'George Godwin and the Art Union of London 1837-1911', Victorian Studies 8 (December 1964), pp. 101-30.

Almost a year passed before Rossetti exhibited in public again; when he did, it was at the Winter Exhibition of Sketches and Drawings of 1852. This was the third such exhibition in Pall Mall and can be seen as an extension of the principles of the Free Exhibition, even a further reform of them. Indeed, its organiser was the collector Lewis Pocock who had been instrumental in the formation of the London Art-Union and acted as itsHonorary Secretary.38 Rossetti had attended the two previous exhibitions and had reviewed

39 [D.G. Rossetti]: 'Exhibition of Modern British Art at the Old water-colour Gallery, 1850', quoted in Rossetti, op. cit. (note 24), II, pp.473-75. William Michael's notes to the above (pp.519-20) record the circumstances: 'The main incentive was that in 1850 Iwas the art-critic of the Critic, and, for some years from the autumn of the same year, of the Spectator: and my brother felt minded now and again to express some opinion of his own, which was inserted into an article of mine. InDecember 1850 he wrote for the Critic the preUminary remarks on an exhibition of sketches at the Old Water-colour Gallery.' In the Spectator (23rd November 1850), p.1122, William Michael Rossetti saw the exhibition as different from a dealer's exhibition ? 'amatter of business benefiting its agent,

D.G. ROSSETTI'S EARLY

them covertly for the press when his brother was unable to do so or when he felt that he had something important to say about a group of exhibits. Thus, we have the unusual, if largely unremarked, spectacle of Rossetti contributing part of the review of the Pall Mall exhibitions; in 1850 he reviewed the exhibition for the Critic and in 1851 for the Spectator. Rossetti's contribution to the review of the 1850 show particularly reflects his feelings about the freedom of admission to exhibitions while, at the same time, takes issue with both the nature of the current Associateships of the Royal Academy and the general quality of the show: 'The principal claim to support made by the promoters of this new Winter Exhibition rests on its being entirely free of expense to the artists exhibiting, even in the event of a sale; no charge being made for space, as at the Portland Gallery, nor any percentage levied on purchases, as at all other exhi bitions with the exception of the Royal Academy.'39 In the following year Rossetti was happier with the exhibition, finding it 'an experiment which promises to prove a suc cessful one'. He praised Brown's preparatory sketch for Chaucer at the court ofEdward III, here called 'Composition illustrative of English Poetry', which had been exhibited that summer at the RA, and found Cave Thomas's design 'among the loftiest embodiments which art has yet attempt ed from Scripture'.40

According to the catalogue for theWinter Exhibition of 1852, Rossetti showed three works: a 'Sketch for a Picture', now called Giotto painting the portrait of Dante (Fig.6), a 'Sketch for a Portrait, in Venetian Costume' (Rossovestita), and 'Beatrice, meeting Dante at aMarriage Feast, denies him her salutation. ? A Sketch for a Picture' (Fig.7, seen here in its replica of 1855; see Appendix 1below). It is intriguing to think of Rossetti showing these watercolours, now seen as so formative to his development as a painter, alongside works by John Martin and Abraham Solomon as well as Holman Hunt, whose sketch for his Academy picture, Valentine rescuing Proteus, was somewhat dismissed in a hith erto overlooked review in the Manchester Guardian. The same review noticed Rossetti's work with approval and compared it favourably with that of his Pre-Raphaelite brothers:

Mr DJ. Rossetti [sic] contributes two sketches of remark able power, both having references to Dante. In the one (7), the great poet is sitting for his portrait to Giotto; the other (196), represents him meeting Beatrice at her mar riage feast, when the fair lady refused to salute him. Both these works, though with a slight tendency to extrava gance of expression, have still a certain depth of earnest

through both artist and public' - such as the exhibition organised by Mr Grundy the winter before. He also noted that the exhibition affords the public, especially 'visiters [sic] and foreigners, who would scarcely know inwhat direction to look for a compendious sample of living art, a chance of viewing modern British art in London between July and February'.

40 Spectator (6th September 1851), pp.859-60.

41Manchester Guardian (29th December 1852), p.875. Some two years before, in a long review of the Germ (referred to as Art and Poetry: Being Thoughts Towards Nature), theManchester Guardian critic had fleetingly noted Rossetti's third exhibi tion presence: 'Some of the best papers are by two brothers named Rosetti [sic],

ness, well according with their subject. Mr Rossetti is a genuine prae-Raffaelite (the word is amisnomer applied toMillais and Hunt) ? he really imitates to a considerable extent the manner of some of the earlier Italian painters, and in away which we are not always able to approve.

The present works appear to us farmore promising than any others of his that we have previously seen, and we shall be curious to see the finished works arise from these sketches.41

William Michael Rossetti's review in the Spectator confirms that there were three, rather than two, Rossetti contribu tions to the exhibition from the start and that another work was not added later. His description of the works, which is quoted here in fiill (seeAppendix 2), echoes the artist's own account in a letter to Thomas Woolner.42

One can only conjecture why Rossetti did not take full advantage of the opportunity to exhibit and sell entirely new or previously unseen works at the exhibitions in 18 51 and 1852. Ecce Ancilla Domini!, albeit 'slightly retouched' and Rossovestita, already owned by Brown, might have been shown again for a variety of reasons, not least that the artist had no other works ready to consign. Yet again, the works may have been a glimpse for discerning collectors of what might be available for sale from the artist's studio. Certainly his work was beginning to find purchasers among a small circle of admirers, asJanMarsh has pointed out in discussing Rossetti's career at this stage.43

An examination of Rossetti's exhibitions raises questions of the artist's choice and judgment. The Free Exhibition was a radical, artist-focused, anti-institutional movement which allowed the artist to identify himself with an older yet unestablished practice which had some aspects in common with Pre-Raphaelite aspirations but had a larger political as well as pictorial end. In deciding to show at the Pall Mall Winter Exhibition in 1852 Rossetti allied himself with both alternative painting practices and alternative exhibiting spaces; moreover, it was genuinely 'free', a factor which had some significance for him. The consistent presence of Brown is a telling factor, too, in the younger artist's deci sions which sometimes seem at odds with those of his fellow Pre-Raphaelites. Rather than being seen as a betrayal of his 'Brothers' in the PFJ3, his exhibiting at the 'Free' might be viewed as a clear, even long-considered, decision. Itmight even make us question the motives of Hunt and Millais in adhering to the conservative centre of Victorian art, the Royal Academy. Nevertheless, Rossetti's attitude to exhibiting was complex, his opinion veering from not want ing to exhibit at all to having an ambitious ? and, at the time,

one of whom, Mr D.G. Rosetti, has a very curious but very striking picture [Ecce Ancilla Domini!] now exhibiting in the Portland Gallery. Mr Deverell, who has also avery clever picture in the same gallery, contributes some beautiful poetry.' A great deal of the rest of the review considers the merits of Rossetti's poem 'The Blessed Damozel'; Manchester Guardian (28th August 1850), p.623. The date of publication indicates a lapse of several months between writing and publication.

42D.G. Rossetti's letter toWoolner is quoted in note 3 above. The last sentence ofW.M. Rossetti's review refers to his earlier review of the North London Bene fit Exhibition, quoted in note 32 above.

43Marsh, op. cit. (note 3), p.96.

almost unprecedented ? one-man show. William Michael Rossetti's frank analysis of his brother's confusion in this matter helps explain Gabriel's state of mind on the subject. It appears in a letter toWilliam Bell Scott: whether from a desire, on intelligible personal grounds, to 'make the worse appear the better reason', or from sincere conviction so far as himself is concerned ? he now declares that the notion of exhibiting in galleries is altogether amistake, and that he won't, under any fore seeable circumstances, give into it.He talks of exhibiting in a kind of private way ? as at Colnaghi's, for instance. However thismay be - with his present commissions, and the prospect they open of others, his future seems now in his own hands, if he will only use it.44

Rossetti's public career as a painter was briefly resumed in the later 1850s with his central involvement in the Oxford Union Mural scheme in 1855, the Hogarth Club in 1857, and his interest in the expanding Liverpool Academy. These ventures show a willingness to gain some kind of public recognition although itwas always negotiated, even con trolled, by the artist himself. He paid dear for his exclusivi ty,mainly in terms of contemporary acclaim. For example, his work was not included in the Art Treasures exhibition at Manchester in 1857 where Millais and Hunt were discov ered by awider public and where WaUis's Death ofChatter tonmade such an impact. His reluctance to exhibit created a myth, not of exclusivity alone, but of secrecy and even immorality. Robert Buchanan's attack on the artist-poet in 1871, the infamous essay 'The Fleshly School of English Poetry', was made possible by the relative invisibility of Rossetti's paintings at public exhibitions.45 Buchanan could impute the nature of their content in relation to the sup posed themes of the poetry. Given that the language used to describe his works in the first four exhibitions suggested that they displayed, variously, 'ahigh tone of mind', 'sincerity and earnestness' and 'some high aim', we might conjecture that his reluctance to exhibit damaged rather than enhanced his reputation in the short term. Ultimately, however, the alternative myth of the reclusive artist who refused to show his work in public became a formative and persistent one and, in the process, the history of his earlier exhibiting choices has been misrepresented.

Appendix

i. Catalogue entries for Rossetti's three exhibits at theWinter Exhibition of Sketches and Drawings, London 1852.

7 'Sketch for a Picture' ? D.G. Rossetti.

'Credette Cimabue nella pintura/ tener lo campo: e ora ha Giotto ilgrido,/ si che lafama di colui e scura:/ cos?ha tolto Vuno alValtroGuido/ La gloria della lingua;/ eforse ? nato/ chi Vuno e Valtro caccer?del nido.' Dante, Purgatorio, canto xi

20 'Sketch for a Portrait, inVenetian Costume' - D.G. Rossetti.

196 'Beatrice, meeting Dante at aMarriage Feast, denies him her salutation. ? A Sketch for a Picture' ? D.G. Rossetti.

'Therefore I feigned to leanmy person unto a painting which ran round the walls of thatmansion; and fearing lest others should discern my confusion, I lifted my eyes, and looking on those ladies perceived among them the most gracious Beat rice; whereupon many of the Ladies, noticing the change thatwas come upon me, began tomarvel and towhisper, mocking me with my lady.' Dante, La Vita Nuova

2. Extract from William Michael Rossetti's review of the Winter Exhibi tion of Sketches and Drawings, Spectator (18th December 1852), p.1212.

In a 'Sketch for a Picture', Mr. D.G. Rossetti illustrates those lines from the Pur gatorio of Dante where he shows the vanity of earthly fame by the waning of Cimabue's renown in painting before Giotto's, and of Guido Guinicelli's in poet ry before Guido Cavalcanti's ? both, as his genius prophesies, to die out in the light of his own. An historical incident is chosen to embody this subject: Giotto paint ing that portrait of Dante - then in his early youth - which has within these few years been discovered in aChurch in Florence. The words 'Dante Aligherii Juven tus? Ars, Amor, Amicha' ? written underneath the sketch, indicate that it is further designed to symbolize the youth of Dante himself in its chief threefold relation. The combination of these several elements of the theme is effected in a composi tion which includes, together with Dante, his gracious lady Beatrice, his friends Giotto the painter and Cavalcanti the poet, and Cimabue. Seated on a platform, while Giotto paints, Dante, who holds, as in the portrait, a pomegranate, the sym bol of religious mystery, has just become aware of the presence of Beatrice, as she passes beneath in a church-procession; and his gaze changes from abstraction to earnest intentness. Behind his chair stands Cavalcanti, holding a volume which the line *Al cuorgentil ripara sempre amore' shows to be the poems of Guinicelli, whose place in the subject is thus represented in the picture. At the other side, old Cimabue has got up the scaffolding to see his successor's handiwork: he looks very sad,with his worn faded face and nervous hands. There is plenty of material here for an intellectual painter towork out to effect in a picture: the principal executive quality of the sketch is its grave and even melancholy intensity of expression. Cavalcanti's knees appear to us placed somewhat too low, and Dante's hands are drawn rather harshly. Mr Rossetti sends another sketch from the poet of the Divina Commedia: 'Beatrice, meeting Dante at amarriage-feast, denies him her salutation.' The space is crowded by the bridesmaids, who pass inward to themar riage-feast, the bride and bridegroom coming last;Dante, with Cavalcanti, stands confusedly at the head of the stairs as his offended lady goes by him without sign of recognition; and peasants are plucking baskets of grapes for the banquet. The anxious rebuked face of Dante is the one exception to the holyday gladness of the scene. A remarkable effect of colour ? not inharmonious, we conceive, if carried out with the matured resources of a picture ? isproduced by the green and azure dresses of the bridal ladies. Of Mr Rossetti's third contribution, 'A Sketch for a Portrait, inVenetian Costume' ? and in aVenetian style and tone of colour ? we spoke in noticing a former exhibition.

44Letter dated ioth March [1853], inR.W. Peattie, ed.: Selected Letters ofWilliam Michael Rossetti, University Park 1990, p.37.

45Buchanan's attack was published under the pseudonym 'Thomas Maitland' in the Contemporary Review (October 1871).