“Every criticism hides a confession”

“When your education limits your imagination, it's called indoctrination.”

Nikola Tesla

“The wise learn more from the foolish than the foolish learn from the wise.”

Proverb

They say that to truly learn something, you have to be able to explain it. And yes! You have to digest things before you can excrete them!

In the process of digestion, whether physical or mental, we break down the components of what we have ingested in order to assimilate it, and in doing so, we incorporate it into our being, mastering it in our patent uniqueness, with which it will inevitably undergo its own transformations, special and imbued with our personality, when it comes out.

As much as mathematics is one in its conclusions, the paths to reach them are so different and differ from each other in such a way that they are unthinkable between different cultures and people. By this I mean that it seems impossible, and perhaps not even desirable, to try to find a single method of transmitting things. Thanks to this difference, there are teachers who make you love mathematics and there are those who make you hate it for life.

Every teacher, however, must strive to avoid transmitting their personal biases in the context of their classes. Knowing mathematics does not mean that students have to receive it wrapped up in the teacher's morals, ideology, or any other personal quirks; teachers must learn to refrain from indoctrinating their students, who already have enough to do trying to separate the teacher's personal patina from the subject matter, without having to put up with their psychological or personal deficiencies on top of that.

Teachers who believe that learning comes through suffering should apply hair shirts to their own flesh! Those who consider it the student's duty to sacrifice themselves should immolate themselves on their own altars! Those who demand obeisance and submission should genuflect over themselves and see if they can kiss their own asses! Those who sit at the right hand of God in their watchtower should eat their schizophrenic constellation with their bread!

A student, like a child, is not a sewer in which to deposit our waste, compensate for our deficiencies, or spread our flaws. All this “enducance” (education, as the ancients said) is really about them being able, thanks to our experience, to manage to be better than us. The whole idea of verbal and then written communication has been, since man has been man, that the accumulation of information would improve us as a species, as a group, and that memory would not be lost; that the efforts of so many lives and their experiences would thus be the platform for their successors to go beyond what their ancestors did. Anyone who betrays this principle and nullifies the value of this sacred task is therefore committing a crime against humanity!

Giving them the foundations to go further is not anchoring them in an idyllic and dreamy past where everything was better, but rather giving them the conditions and tools to learn to think for themselves and surpass their parents and grandparents. Without the necessary renewal, things rise, decline, and inevitably end.

One of the most difficult tasks for a gardener is pruning; knowing how to cut away the undesirable, the excess, so that the tree can express its nature in the best possible conditions. Poorly done pruning can even kill a fertile tree. That is why the dosage and accuracy in the application of this action must be exquisite and carefully considered by a teacher, otherwise he himself may end up surrounded by a barren forest, in a functional desert and in the greatest of solitudes.

Prescribing pruning is perhaps the most important task of a teacher. They must know how to choose the right moment and use it only when we are sure that this medicine is necessary. There is always time to prune, but once the pruning is done, there is no turning back. Watering, on the other hand, is always necessary, but if you overwater, you will flood the tree and it will die, bogged down in excess. Giving at the right moment, accompanying each person's cycles and transitions, is an art that few know how to practice and requires the teacher to know how to distance themselves from themselves.

The idea of teaching is not focused on knowledge itself, but on the person who will carry it, use it, and then, eventually, pass it on. It is not a question of adapting the person to the knowledge, but the knowledge to the person. Making clones, passing a camel through the eye of a needle, is pretentious, harmful (to both teacher and student) and, what is worse, pedagogically useless, but very effective in creating morons. In the words of bullfighter Rafael Guerra: “What cannot be cannot be, and moreover, it is impossible.”

“Prescribing cuts is perhaps the most important task of a teacher. They must know how to choose the right moment and use it only when we are sure that this medicine is necessary. There is always time to make a cut, but once the cut is made, there is no turning back.”

“Prescribing cuts is perhaps the most important task of a teacher. They must know how to choose the right moment and use it only when we are sure that this medicine is necessary. There is always time to make a cut, but once the cut is made, there is no turning back.”

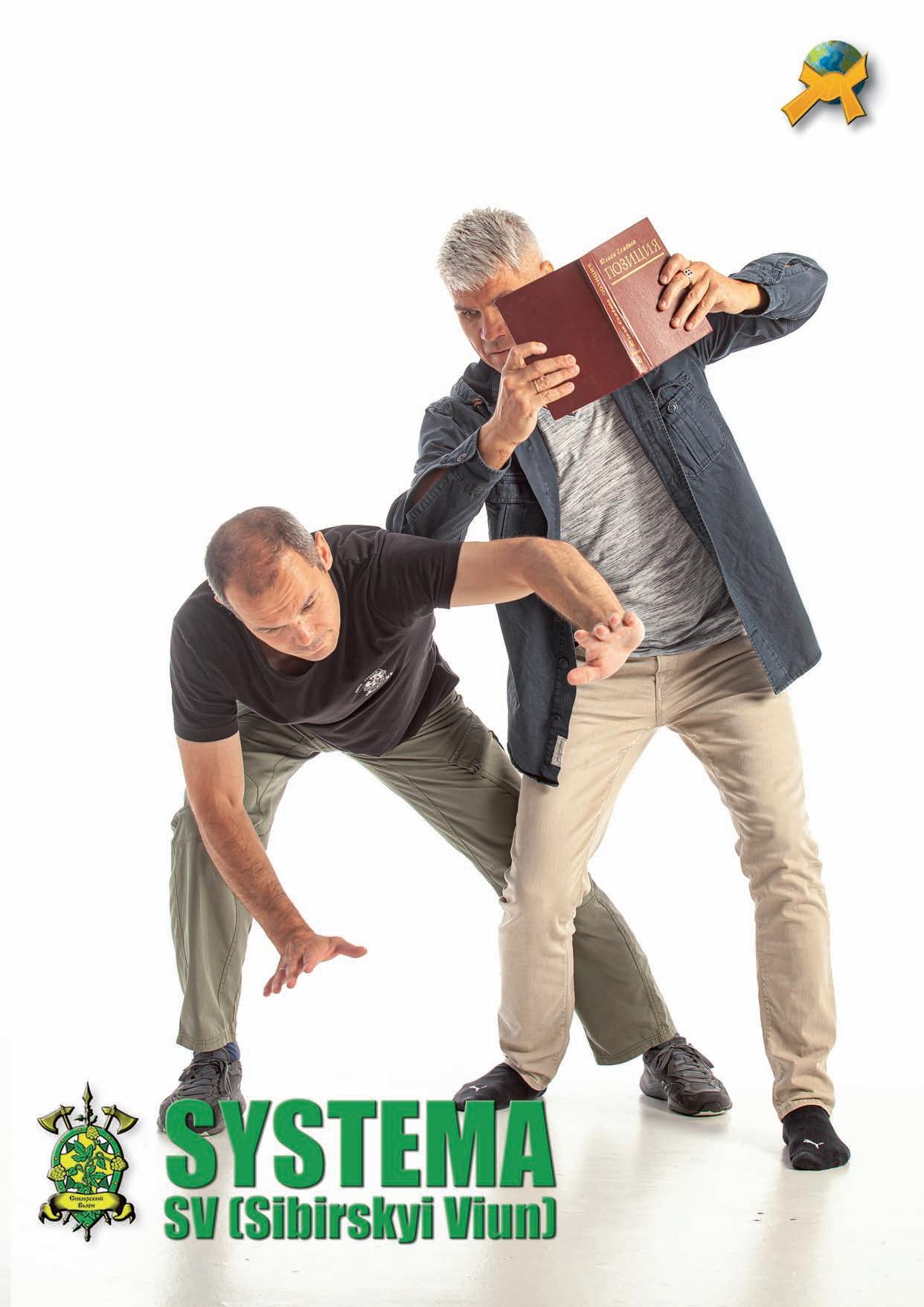

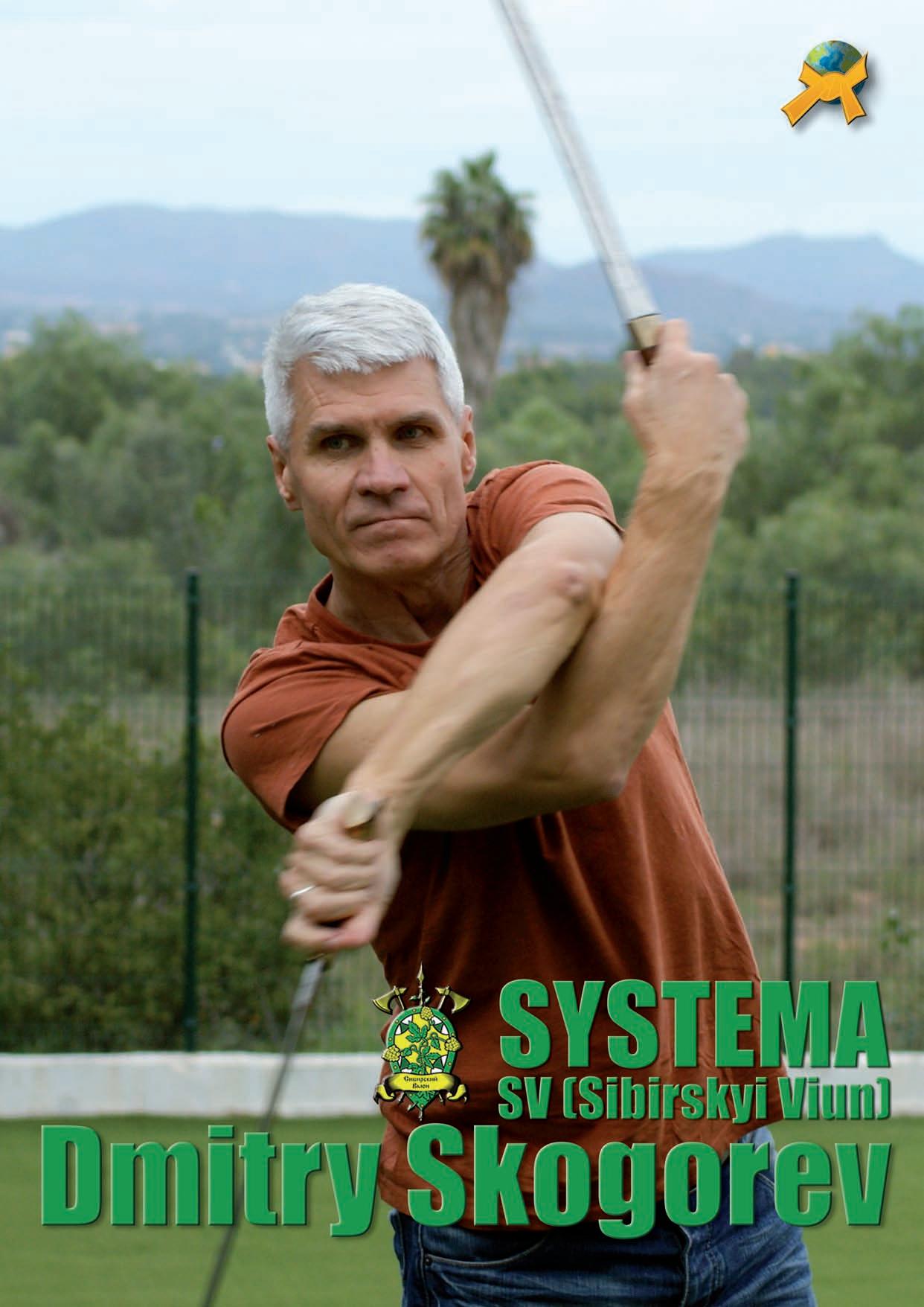

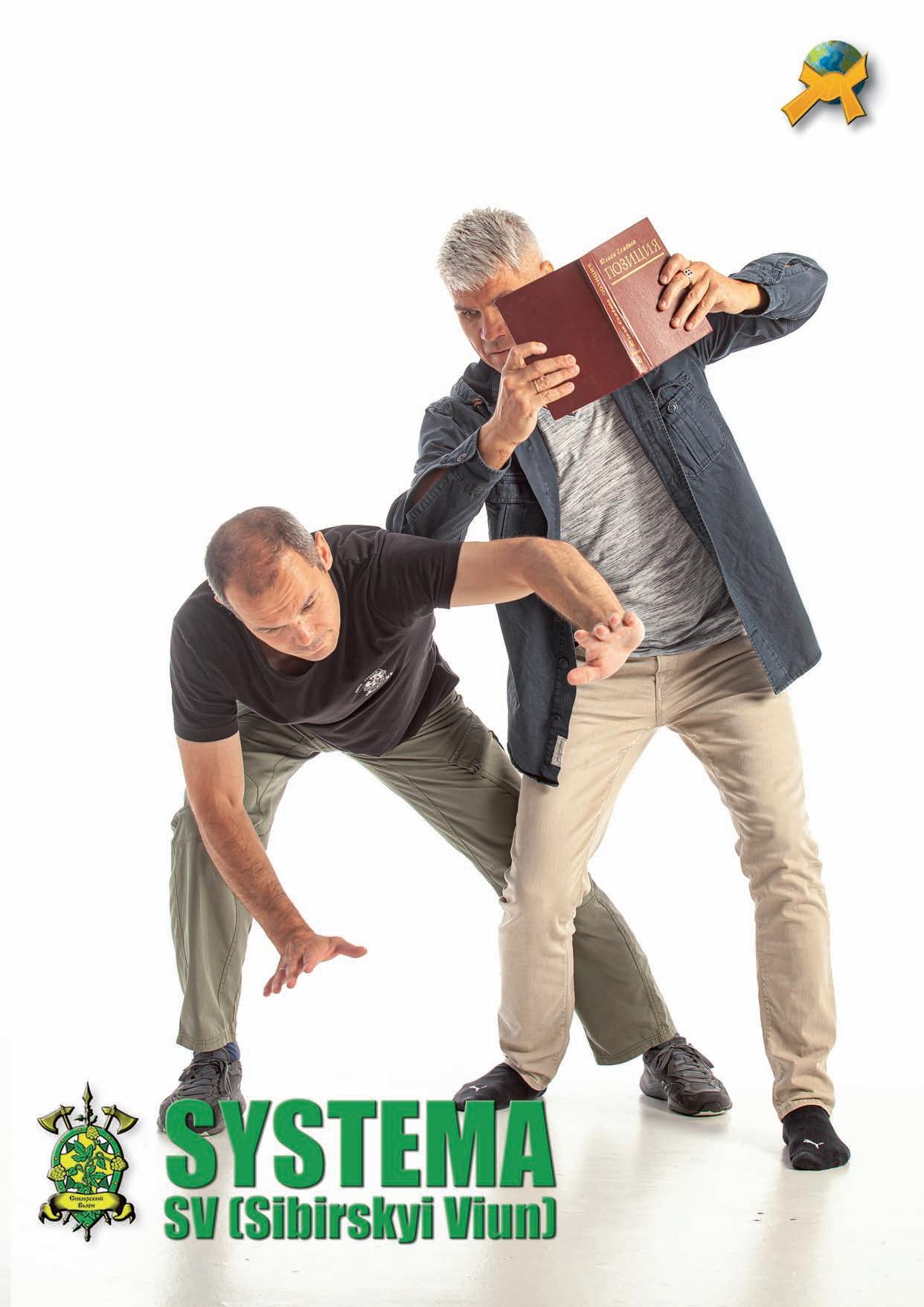

Dmitry Skogorev

Director of the Russian combat school “Siberian Eel” since 1988. President of the International Center for Russian Martial Arts (World Center for Russian Martial Arts) since 2005. Higher education, professor of Fine Arts (NSPU) and coach-teacher of Physical Education and Sports (SIPPPiSR).

Author of several books on hand-to-hand combat. Manual for hand-to-hand combat instructors at the Siberian Eel school, a book (educational and methodological) for operational combat units of the tax police (Novosibirsk, 1997), other titles include Interaction with Force, Russian Hand-to-Hand Combat, etc.

Author of numerous videos and seminars on hand-tohand combat and psychophysics, and writer of numerous magazine articles.

Official instructor of the special forces unit (Physical Protection Service) of the Russian Federal Tax Police Service for the Novosibirsk region between 1995 and 2001. He is also an artist, dedicated musician, and composer.

“A remarkable man, an honest teacher; someone in whom depth, far from conflicting with effectiveness, unites them with natural elegance.”

Alfredo Tucci

My martial arts career began in 1980, when I was 14 years old. My interest in it began a little earlier. As a child, I was neither healthy nor strong. In the winters, I got sick quite often and did not play sports.

We spent our time outdoors, running around the neighborhood, playing on construction sites. We jumped and climbed in dangerous places. We even climbed onto the cars of passing trains. They often stopped and then moved on. We chose the right moment and climbed onto the car, and then jumped off at a certain speed. Apparently, we were lucky that everything ended well. But there were other cases...

Sometimes, like all children, we fought with each other. I often fought with my classmate at his house. He was already into wrestling at the time, so I had no chance of beating him. This went on for a long time. I didn't know how to defeat him and thought that I simply wasn't strong enough.

Once, my father brought me a book called “Sambo.” It was a book for teenagers. It had clear illustrations and brief explanations. I liked it very much. The book belonged to someone else and had to be returned. Since I drew, I redrew some of the images and added the necessary explanations. Of course, I didn't understand everything completely, but some elements were clear to me even without training. That was my first contact with martial arts.

My first fight was at the age of 6. My father taught me how to throw a straight punch. He simply told me that when someone threatens you, you have to punch your opponent straight in the nose. When a boy suggested we “play boxing,” I agreed without thinking twice. I broke his nose... My parents were told about it and punished me. That was in kindergarten.

Did my first contact with martial arts pay off? Yes, it was really useful. I didn't even expect it to help me in any way, let alone lead me to a new understanding.

Spring came and we all started spending more time outside in the yard. The green grass had grown and the afternoons were getting warm, so my classmate and I decided to fight as usual.

After a brief struggle, I managed to grab him and squeeze his neck, pressing him against the ground. He didn't expect such a move because he was used to regular wrestling and didn't know that such a hold existed.

Technique and knowledge won out. He tried to break free for a long time and didn't want to give up. The whole process lasted between 30 and 40 minutes, but in the end, he gave up and got very angry. I never fought with him again.

I gained confidence in myself and became interested in studying this type of wrestling or unarmed self-defense, called “SAMBO.”

Yes, it was a choice. At that time, karate already existed, and I liked it too. I tried to stretch my joints, and I almost achieved full flexibility! I lifted my legs very high. It was interesting to strike with my hands, but wrestling at that time was more natural.

In the fall, as usual, new groups were being organized. My classmates and I went to the Dynamo sports complex. There was a sambo section there. We were unlucky; all the groups were already full, and they simply did not accept us. However, we were persistent, attended all the training sessions, and watched from the outside how the training was going. A month later, the coach accepted us into the vacant spots. The coach's name was S. Altukhov, he was a sambo sports master and an ambulance doctor. That's how our training began.

The training was exhausting. Lots of physical training. Throwing techniques and constant sparring in wrestling. All of this was difficult for me, an unathletic and sickly teenager, so after a short time, I was ready to give it all up. However, at a certain point, my body accepted that pace and pressure.

It was a very exciting time, and with it came new like-minded friends.

I didn't set any special athletic goals. I developed an interest in getting to know myself and others. It was at that moment that I met a guy during training who had already trained in karate and could share information about it.

Karate was an interesting and unknown world to me, along with Japanese culture. It amazed me and gave me the feeling of touching some secret. Evgeny Titkov explained it very well and taught us some punching and kicking techniques. Stances, blocks. All of this was intertwined with its own philosophy and history. A new world was opening up to us. I started keeping a new notebook with drawings and theoretical calculations about karate. That was my textbook. Sensei Nakayama's books were also republished. They had good photographs of all the basic karate techniques, and the movements were analyzed step by step and were in English.

In the spring, Evgeny became our leader, and the six of us became his students. We started training in the basement of one of the houses near where we lived. We studied everything meticulously, step by step. He was strict. We studied all the Japanese names for punches, stances, and blocks. We even learned to write in the Japanese alphabet. Our goal was to learn and teach our bodies as much as possible. To strike with great speed and precision. To overcome ourselves, to overcome difficulties and hardships. We were driven by the motivation of knowledge and a strong discipline that could overcome anything.

In the fall, our coach announced that there would be a karate competition. We were excited. We felt ready for the tests and knew we had already learned something. The competition we wanted to enter was one of the best in the city. At that time, karate was just beginning to develop; before that, it had been banned in the USSR. Therefore, for us, it was something new and incomprehensible. This opened up new horizons of knowledge for us.

The competition was very fierce: out of about 300 people, only 20 were accepted. The tests were varied: strength, reaction, flexibility, etc. We passed the tests easily and were simply radiant and ready to train day and night. Our training did not end with the main classes. We continued to train and hone our skills in any free time, and at that time we had a lot of it.

I studied the theory diligently and practiced striking techniques. The head coach was S. Danilov, a professor at the Institute of Electrical Engineering, where the main classes were held. He himself had good karate technique and tried to expand our knowledge of martial arts; we also learned Aikido from him. This art also sparked my interest.

I remember how we tried the first techniques of absorbing force and returning it. Many things were unclear... but this opened the way for me to search and, above all, to understand that knowledge has no limits.

Were there any factors that hindered your martial arts studies?

Yes, there were. When I was in high school (1985), karate was in danger of being banned again. Our fears were not in vain. Karate was banned for the second time in the country. But we continued to train independently.

In the fall of 1986 to 1988, I was drafted into the Soviet army. There I continued to train, and with it came a mixture of hand-to-hand combat and a new direction in the movement of knowledge.

Who were the leaders among the famous martial arts personalities for you at that time? Who did you admire?

Of course, there were some icons that I admired, but at that time there were few. Everyone knew Bruce Lee and admired his technique and his life. There were also television programs that showed the founder of aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, in documentaries. Of course, the founder of judo, Kano Jigoro. Karate masters G. Funakoshi and M. Nakayama. This is what we knew about Japanese martial arts.

From the domestic scene, I. Lebedev, V. Spiridonov, V. Oshchepkov, N. Oznobishin, V. Volkov, A. Kharlampiev, A. Ushakov. All these people made an invaluable contribution to the development and popularization of martial arts, in particular “Sambo.” And they also shared real knowledge. We studied from their books, and even then I decided on my path. I also wanted to contribute my grain of sand to this enormous work, or rather, to devote my life to it.

Which of your coaches had the greatest influence on your career in martial arts?

I wouldn't single out anyone in particular. All the people I have met and know have had and continue to have their influence in their own way, and they always hit the mark. It's like a mosaic of their experiences woven into my personal field of knowledge. My view of the world of martial arts consists of many directions, and at that time they were all different from each other. They solved different problems.

After my military service, we started getting together with friends who were interested in hand-to-hand combat and trained out of pure interest. We had no sporting goals. At that time, the concept of the universality of movements and the similarity of these movements in all martial arts emerged. It was a revolution of consciousness.

Later, we learned about A. Kadochnikov, who works as a continuation of the development of the national water martial art. There were only a few notes in newspapers and magazines, and the first booklet about the seminar was published, which was taught by A. Retyunskikh, one of his students.

This was the first subject that continued beyond my studies of “SAMBO.” Then there was a meeting and a seminar with G. Bazlov, who was a historian and was engaged in ethnographic work. He confirmed to us the correctness of the martial art approach. He explained to us that all nations have a martial art based on their culture. Since 1988, we have determined that we exist and are developing in this direction. We began to research and delve deeper into this idea. In fact, there are people who can convey this experience in a different way than Japanese techniques. For us, it is more understandable and simpler.

It's hard for me to call them teachers, but apparently that's the case. I have already said that I am immensely grateful to all the people with even the slightest experience and to all my first coaches who laid the foundation. Later, I met people like Prince B. Golitsyn. A man with enormous combat experience and great knowledge. A. Kadochnikov was not my teacher either, but I saw him twice, and we had good conversations. He shared some technical issues with me.

With A. Lavrov, in general, we developed an excellent relationship and even conducted two seminars together. We remain friends. I also communicated with M. Ryabko; I remember how he showed me his strike and literally controlled the process with my hand. The experience was positive.

First of all, the school emerged completely naturally. Various experiences accumulated. Students appeared. Teaching methods were developed. This is the process of systematizing and studying the cultural tradition of the Russian army. All this, in general, bore fruit. In the 90s, the situation in Russia was already difficult; the USSR no longer existed. Life was incomprehensible and unrestrained. Banditry and anarchy. People were trying to survive. Therefore, sports were not needed, but rather a system of survival. A system of life, and that included many aspects. We began to study the fundamentals of bioenergetics, psychology, and biomechanics.

Later, I wrote the book “Interaction with Force.” The second book was “Russian Hand-to-Hand Combat.” In these books, I tried to reflect the main aspects of Russian martial arts. Of course, the experience of my mentors, few in number, was very useful to me. For me, they were, most likely, a confirmation that what had already been done and where we were going was in the right direction.

Subsequently, we created a teaching method that no other similar school had. A 4- and 6-year training program was developed. A program for training instructors and their certification. In general, as it should be for the development of a school and a type of martial art.

At the moment, we do not have a large number of schools around the world. But the schools that operate in other countries are of high quality. Mexico, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, Sweden. The school lives thanks to the students and mentors; as a leader, I am only a conduit for this knowledge, nothing more.

In fact, all teachers are real, as they all have a wealth of experience in their knowledge. They have all come a long way and have also met a number of teachers. This experience is multiplied and passed on. This is the tradition when we do not worship ashes, but pass on the fire of life, made up of experience, knowledge, and interaction.

Martial arts are a reflection of our life. Only here can we simulate situations and live them, understanding the correctness of our actions. We are constantly in contact with the force that affects us, and we ourselves use it. It is very important to understand this and work with it. Not all types of martial arts are like this, therefore it is necessary to separate the tasks of sport and competition from the tasks of survival and self-improvement.

In martial arts, it is important to take into account the psychological aspect. The aspect of a person's reaction to a specific action, since the opponent acts according to the reaction, and these reactions can be tracked or triggered and then used. A person always reacts not to the action itself, but to a change in rhythm, and rhythm is our attitude towards life. For some, life is a whirlwind, and for others, the crunch of snow. One person sees nothing around them... another notices the little things. This is our life. Where are you now, where have you come from, and where are you going? Can we give unequivocal answers to these questions? I don't think so. Martial arts and, very often, communication in the world of martial arts give us many guidelines for working with the mind.

The important thing is not to hear the truth, but to approach it yourself. With your own awareness and understanding. That is true knowledge. I can say that growing up close to a teacher and becoming a teacher is easy, although it takes effort and work, but becoming a recognized teacher without a mentor is very difficult because you have to bring everything together into a single, harmonious, and logical system that is also understandable to others.

Have you had many assistants?

Of course, I won't deny it. First of all, during the 36 years that the school has existed, my wife Natalia Skogoreva has been involved in this business. She always supports and helps organize certain aspects of the school's work. She is also in charge of filming videos. She has filmed a large number of seminars. Of course, she also takes care of all the administrative work. The school could not function without this work either.

Now our daughter Alena helps us and works with us actively. She also takes care of administrative work and works with social media. All our instructors contribute to the development of the school. In the 1990s, the A. Karelin Foundation and Aleksandr Karelin himself helped us organize classes. (Three-time Olympic winner (1988, 1992, 1996; in the 130 kg category), nine-time world champion (19891991, 1993-1995, 1997-1999), 12time European champion (1987-1991, 1993-1996, 1998-2000)). We attend training sessions with his coach V. Kuznetsov.

All our representatives in different countries also contribute to the development of the school, and in a considerable way. Mexico. Alfonso Castellanos became our representative in 2008, and in 2012 we held the first seminar there and trained many instructors. Alfonso is a master of aikido, taekwondo, and other disciplines. For him, I am a martial arts teacher, and he is, to a certain extent, a teacher for me. It is a mutual position.

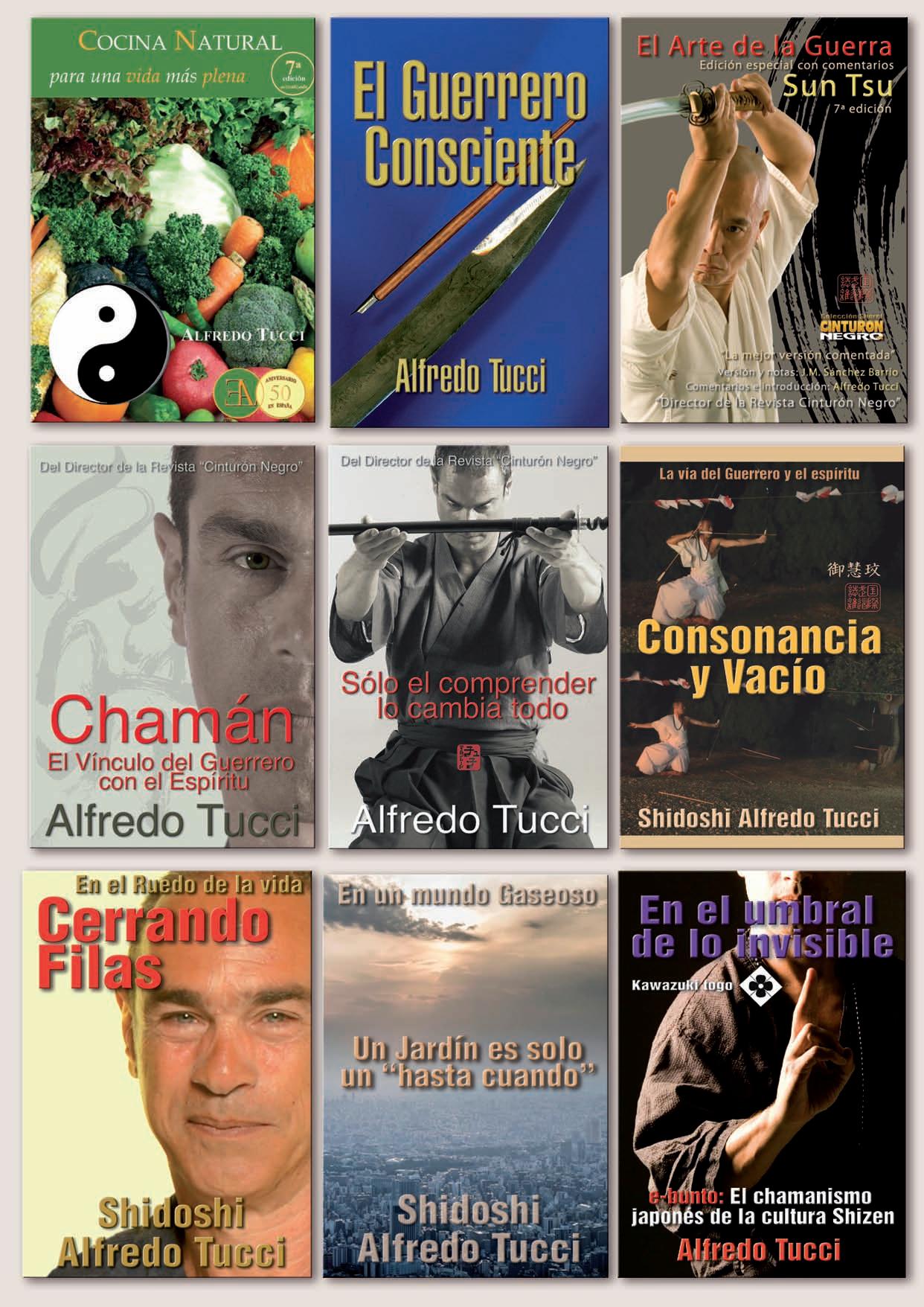

Spain. Ramón Mane, a profound and meaningful person, above all else. He has the right attitude towards martial arts and perceives them as understanding truth and interaction. An excellent instructor in constant search and development. I want to say about Alfredo Tucci, with whom we have been friends since 2011, that at first our communication was purely on the level of publishing his magazine. But in 2018, when we first met in Valencia, A. Tucci revealed himself to me as a master of the Japanese martial arts tradition. As an artist and sculptor. As a philosopher and author of books on martial arts. It is always interesting and informative to communicate with him. I can also consider him my teacher in a certain respect.

All people, and especially those with a lot of experience, are a great help in overcoming your path, and if this path is interesting to someone else, that's great. That's how schools are born. Ours is no exception.

How is the school developing today?

Life flows, yes, some changes occur, and that's good. Now our school has a wide range of students. The youngest are between 3 and 5 years old. Regular classes and seminars, including various competitive events for children and teenagers. For adults: the Way of Life!

(N. Skogoreva)

You are the teacher, you are the warrior How difficult it is! To teach and tell with care, it is also difficult to give direction to the soul, without breaking the feelings of others. Your experience accumulates over the years.

And what happens is like a river, a river of inspiration, on the banks of time.

A book open throughout the centuries and transmitted in a moment, or perhaps through a poem... Short verses... that is what is important.

To have time to unfold everything, in an instant.

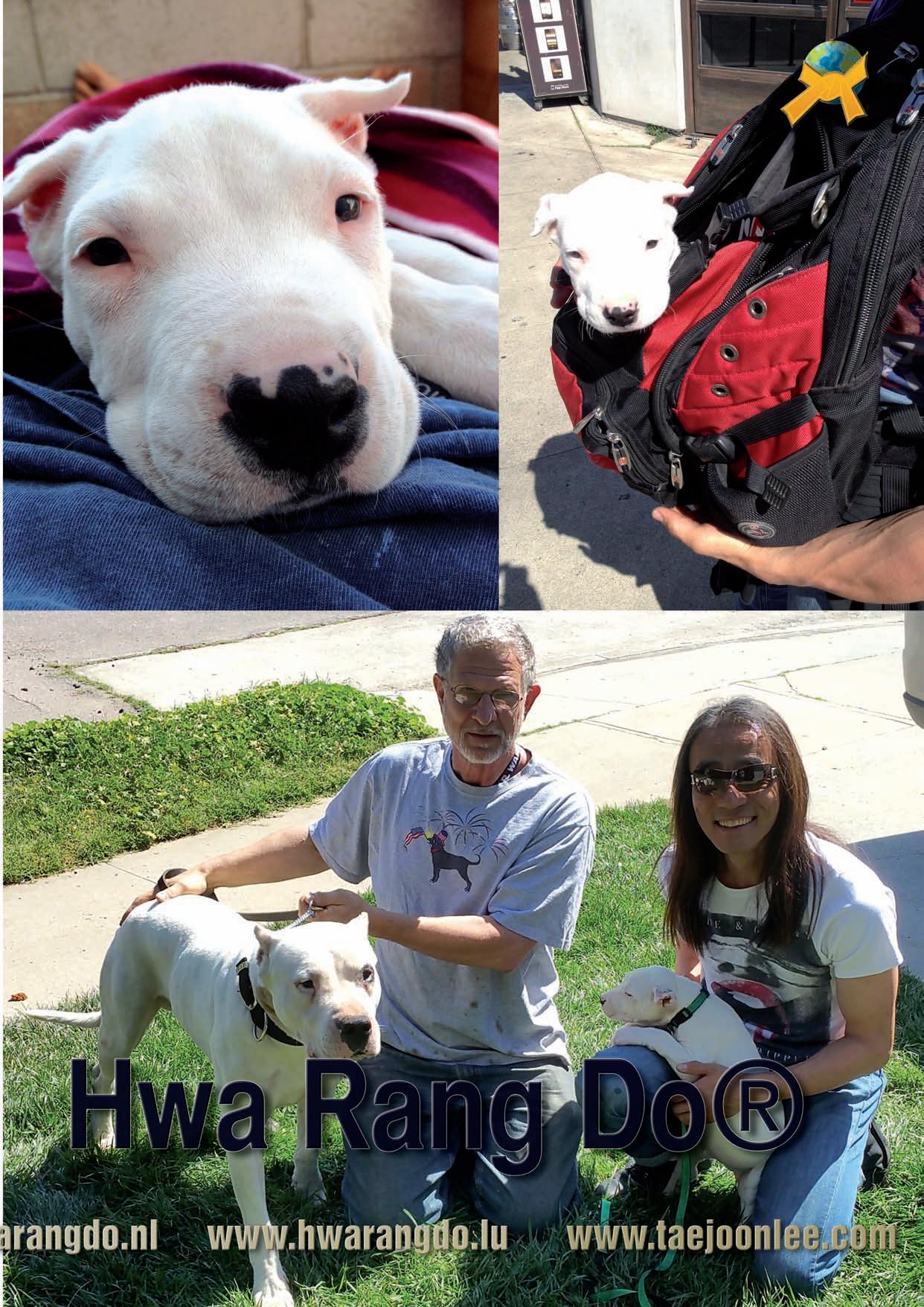

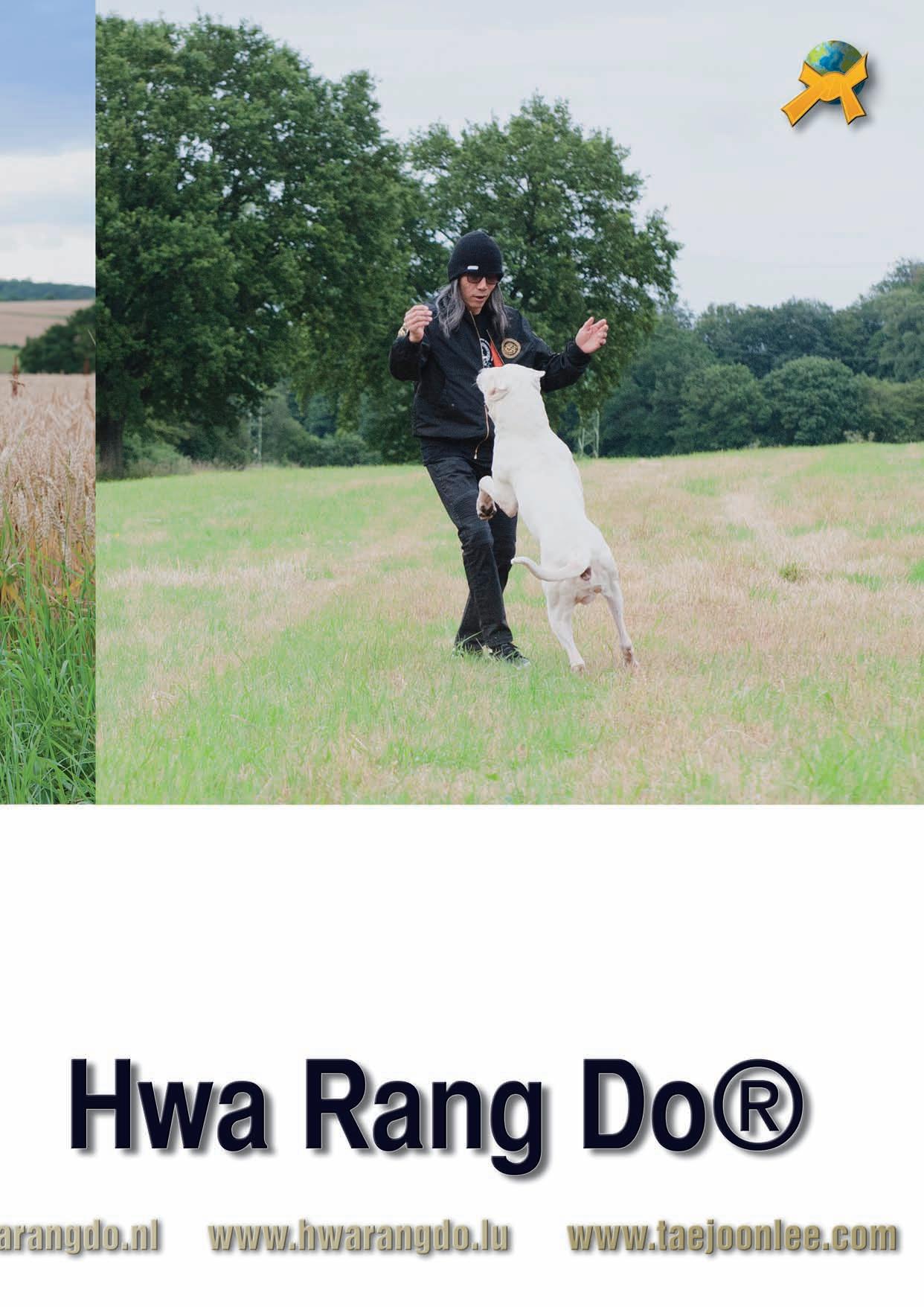

Man's best friend... there's little more I can say after reading Master Taejoon Lee's story of pure and true love with his friend Kilbo.

There's always a dog in our lives, but only if we're capable of deserving it... they open the doors of the warrior's heart like no one else, because beyond sentimentality, there is a relationship that transcends life and its many circumstances. There's always a dog behind that opening of the heart's doors... for me, it was my dog Eleuteria; for my brother Taejoon, it was Kilbo. Anyone who hasn't been there, in the loss, in the celebration of a life, in the brotherhood of unconditional love, can't understand it, never will...

It took me many years after Eleuteria left to open my heart again, and a little girl, Almendrita, who also passed away, managed to do so...

I've learned that everything is temporary, but that unconditional love is eternal and can manifest itself through all beings, because love transcends everything, but it is personalized in a unique way, and therein lies its mystery, its power, its greatness.

I am with my brother in his pain, but above all, I am with him in the greatness of what he has discovered. Dogs make us great, because in their eyes we are, their teachers, their mentors… In exchange for what we have left over, they give us everything… Who can compete with that?

Whoever is capable of loving a dog like Taejoon demonstrates his spiritual greatness, because nothing that is not already inside can come out. Bravo, brother! The pain will pass very, very slowly, but love will always prevail and remain. Blessed experience! Blessed love! It always returns, despite so much pain in loss… We learn to die by their example… We learn to live by their example… Who can give more?

Alfredo Tucci

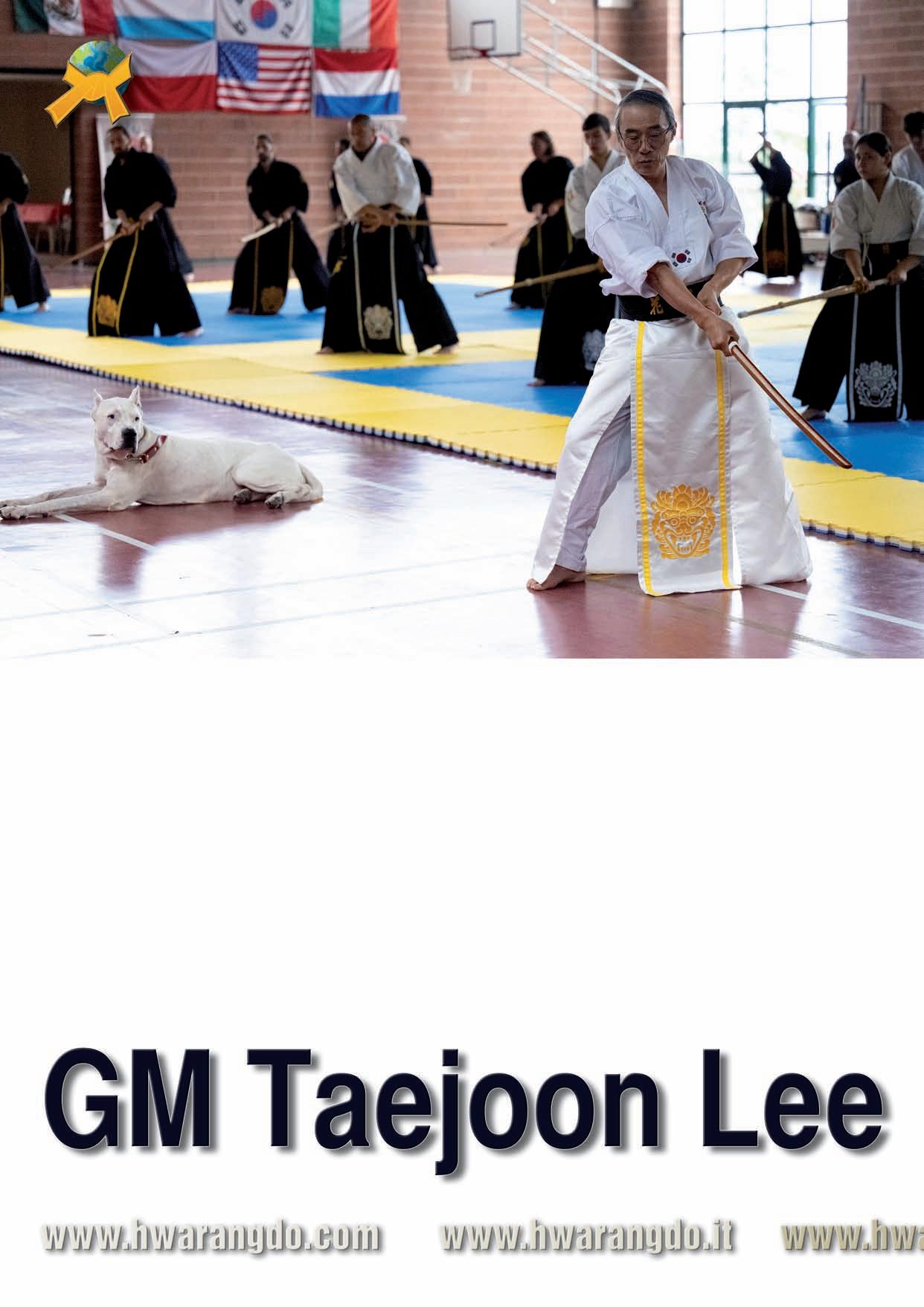

By Grandmaster Taejoon Lee

by Claire Davey, Lisbeth Ganer

The earliest stylized form of poetry in Korean history developed during the Silla Kingdom (57 BCE – 935 CE) was known as Hyangga (향가 , 鄕歌 ), which literally means “native songs” or “songs of our land.” Hyangga was a distinctly Korean poetic form, composed using the hyangchal writing system — an adaptation of Chinese characters to represent Korean sounds and grammar. Flourishing between the 6th and 10th centuries, these poems gained its significance and popularity by the Hwarang Knights (화랑 , 花郞 ), the elite youth order of Silla renowned for their dedication to both martial training and moral cultivation.

Hyangga poetry was deeply expressive, serving as a medium for religious devotion, philosophical reflection, and aesthetic appreciation of nature. It also embodied the ethical ideals of the Hwarang — loyalty, patriotism, duty, honor, and an unwavering warrior spirit — blending Confucian virtue, Buddhist faith, and native Korean sensibility into a uniquely spiritual art form.

Among the surviving examples, one of the most remarkable is “The Ode to Knight Kilbo” (길보가 / 吉寶 歌). This poem is particularly noteworthy because it was unusual for a Hyangga to be devoted to a specific individual. Composed by the Buddhist monk Wolmyongsa in memory of his fallen brother, a Hwarang warrior named Kilbo, the poem stands out for its emotional depth and profound synthesis of grief, spiritual longing, and moral admiration. Through this work, the poet immortalized not only his brother’s valor but also the enduring ideals of the Hwarang and the spiritual essence of Silla culture.

“The Ode to Knight Kilbo”

The moon that pushes her way Through the thickets of clouds, Is she not pursuing

The white clouds?

Knight Kilbo once stood by the water, Reflecting his face in the blue. Henceforth I shall seek and gather In pebbles the depth of his mind. Knight, you are the towering pine, That scorns frost, ignores snow.

In 2015, I endured one of the most traumatic and devastating chapters of my life. By my mid-forties, I had already devoted every breath, every heartbeat, to Hwa Rang Do®. I was born into it — it was not simply my path, it was my inheritance, my destiny. As the first-born son of my father, the Founder, the responsibilities placed upon me were enormous. I carried the burden of expectation — to continue his legacy, to lead, to teach, to preserve something far greater than myself.

I trained relentlessly. I traveled the world teaching, spreading the way of the Hwarang. I cultivated thousands of students, molded leaders, and built schools that became my life’s work. And yet, despite all I accomplished, I felt empty. I should have been fulfilled, but inside I was hollow — quietly suffering, lost in a storm I couldn’t name.

I grew up fast — too fast. Childhood was something I never really knew. By thirteen, I was already teaching. At sixteen, I earned the title of Master. I had to fight for every ounce of respect, constantly proving myself worthy of my father’s legendary shadow — a man larger than life, whose shoes no one could fill. I sacrificed sleep, food, and youth itself for the pursuit of perfection. My goal was always more — to train harder, move faster, rise higher, achieve the impossible. And so I did… but greatness always demands a price.

While I achieved much for Hwa Rang Do, my personal life was in ruins. In my mid-forties, I was still alone — drifting through unstable relationships, never truly grounded. Since my teenage years, I had dreamt of marriage, of a big family, of love. But in reality, I placed Hwa Rang Do first. Always. It was equal to my father, my blood, my purpose — and everything else came second.

Then, in a moment of inner weakness and outward stability, she appeared. A woman who would change everything. What began as hope — a promise of love and healing — became a storm. It was that kind of mad, passionate love that feels like destiny, yet carries destruction hidden in its beauty. I was vulnerable, and I gave everything. For the first time in my life, I placed love above duty, above Hwa Rang Do, above my family — above all.

Blinded by desire, I surrendered everything I had built. I gave away my school — twenty years of blood, sweat, and tears — to a student who lost it all in one year. I cut ties with friends, distanced myself from my family, and still, she was never satisfied. After five long years of a chaotic, soul-draining relationship, it all collapsed — just after she accepted my proposal of marriage, even marriage was not enough. When it ended, I fell apart. The love I had worshipped became my idol, and its destruction brought me to my knees — not before her, but before God.

It was as if God had given me everything, I thought I ever wanted in a woman — beauty, intelligence, wealth, passion — only to reveal the painful truth behind the old saying: “Be careful what you wish for.” For the first time, I truly understood the commandment: “There shall be no idols before Me.”

What I had been searching for all my life — that sense of wholeness, of completion — was never something another person could give. The void within me could not be filled by human love, by success, or by any treasure of this world. It could only be filled by the love of God.

And yet, the only way I could come to that realization was to lose everything — to be given all that I desired, to exhaust every ounce of my will, every effort, every dream — until there was nothing left of me but the truth.

I had to be broken. And broken completely.

All my life, I wastaught to be a warrior — to never surrender, to never yield, to fight through all pain and all obstacles. But this was a battle I could not win. This was the one fight where victory required surrender. And only God could bring me to that place — for I would never have bowed to any man.

It was through that surrender that I finally saw the Truth.

And in His mercy, God sent me an angel — a guardian to walk beside me, to guide me through the darkness, to cleanse and purify my heart, and to prepare me for rebirth — not as a warrior of the world, but as a child of Christ.

The pain was unbearable. I saw no light, no reason to live. I withdrew from everyone — my family, my friends, my students. I hid from the world like a hermit monk in a cave, drowning in grief and silence. I tried everything to numb the pain, but nothing worked. My heart was shattered, my mind restless, my spirit broken.

In desperation, I turned inward. I began to meditate — five minutes became thirty, thirty became hours. In stillness, I found moments of calm, but the emptiness remained. I learned to quiet my mind, to walk the middle path — neither joy nor sorrow, neither elation nor despair. I thought I had healed, but deep inside, I was still void.

Then one day, by chance — or perhaps by divine will — I turned on the television and found The Dog Whisperer with Cesar Millan. I was amazed by his ability to transform broken, aggressive dogs through nothing more than energy — calm, assertive energy. I realized that’s what I needed: a living mirror to reflect my inner state, a companion who could feel the truth beneath my stillness.

So, I began researching breeds, watching videos from A to Z, until I found the Dogo Argentino — a majestic, allwhite mastiff bred in Argentina to hunt wild boar and puma. Strong, fearless, loyal — and yet gentle with those it loved. I fell in love at first sight.

I found a breeder in Southern California who had just welcomed a litter. While waiting for my puppy, something miraculous happened. God broke me open completely — and I surrendered. I accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior. My faith journey, I will share another time, but what

I can say now is this: that puppy was no accident. He was sent to me — a guardian angel in the form of a dog.

When I finally held him in my arms, I knew his name instantly: Kilbo, after the Hwarang Knight from the ancient Hyangga, “The Ode to Knight Kilbo.” It was my tribute to the noble warrior who embodied loyalty, courage, and sacrifice. And true to his name, Kilbo became all of those things for me — my protector, my teacher, my best friend.

Kilbo healed me. He taught me patience, humility, unconditional love. Through him, I learned the language of presence, of trust, of grace. He walked with me through every step of my healing, through my rebirth in faith.

Ten years later, he died in my arms.

It has been a few months since his passing, and my heart still aches. But now, through the tears, I see what he came to teach me. Kilbo’s life was a divine gift — a reflection of everything I needed to learn: devotion, compassion, surrender, and the strength to love without fear.

I write these words in his memory. This is my tribute to my beloved Kilbo, my guardian angel — the companion who saved my life and showed me what it truly means to live.

“The moon that pushes her way Through the thickets of clouds, Is she not pursuing The white clouds?”

In the ancient Hyangga, the moon symbolizes Wolmyongsa, the elder brother — the poet — searching for the soul of his departed brother, Knight Kilbo, represented by the white clouds. The moon’s struggle through the thickets of clouds speaks of persistence in grief and love — the kind of love that will not rest until reunion is found beyond the veil of life and death.

The clouds are that veil — the barrier between worlds — and the moon, radiant and restless, is the soul that refuses to give up the pursuit. It is the eternal yearning of the living to touch, once more, the spirit of the departed. The moonlight becomes enlightenment breaking through illusion, truth piercing sorrow.

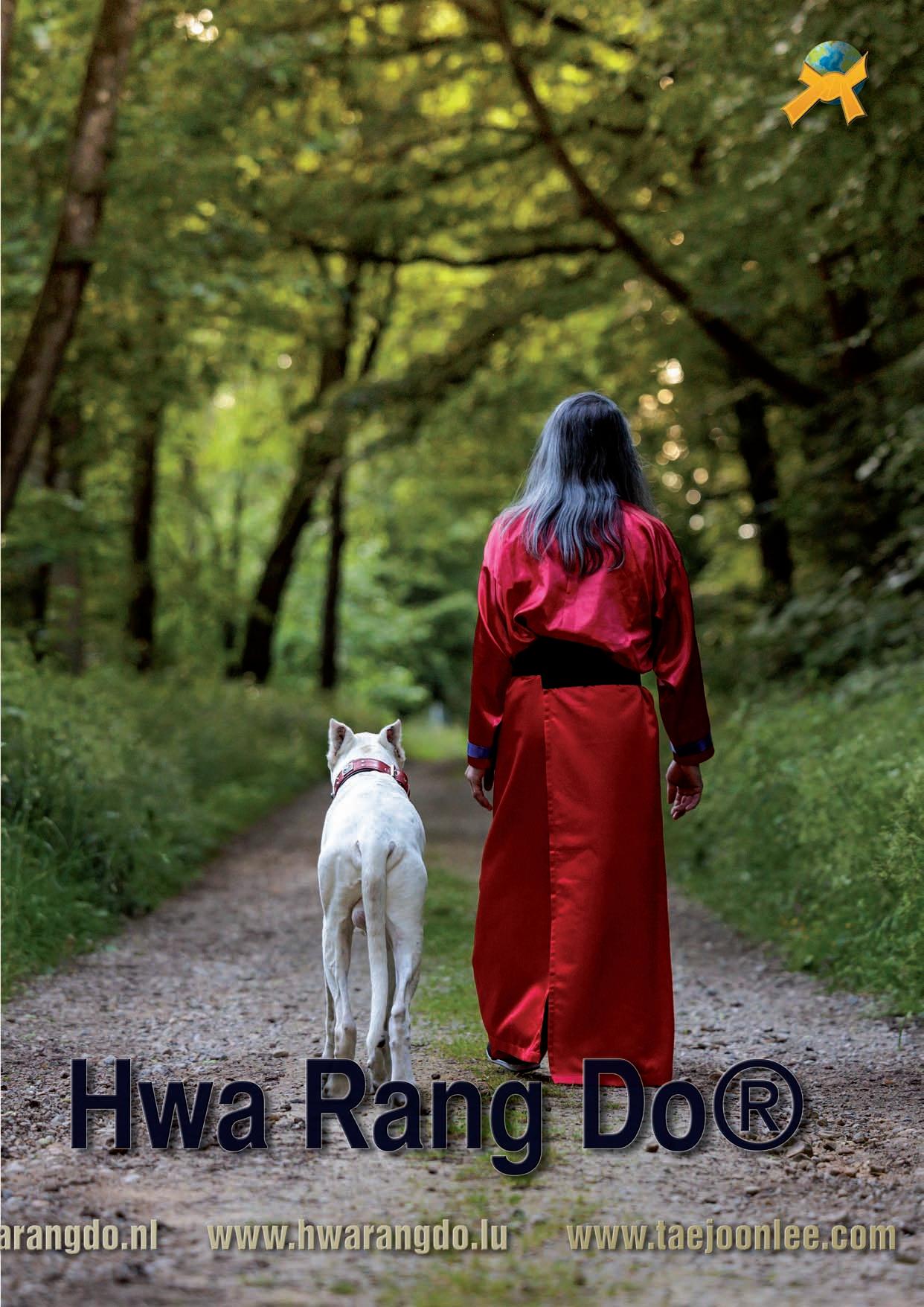

I, too, mourn and seek my Kilbo. His memory is etched into every fiber of my being — into the folds of my soul and the rhythm of my days. We shared everything: the material and the spiritual, the seen and unseen. There was no corner of my life untouched by his presence.

Before Kilbo, I often woke without purpose. There were days I questioned why I should rise at all. But once he came into my life, there was never a question. No matter how weary I felt, I knew — Kilbo needed me. I had to get up, take him out, care for him. Rain, snow, or sun, we walked together. And in those walks, the world came alive again. Through him, God taught me to see the quiet beauty in all things — the perfection in every moment of His creation. Kilbo gave my mornings meaning and my days rhythm. He was my anchor in faith, my barometer of peace, my mirror of the soul.

When I lived in Los Angeles — during what I call my “cave years” — I reconnected with an old childhood passion: skateboarding. I began designing and building my own boards, and soon Kilbo and I were gliding through the streets together — him in his harness, me holding on for dear life. We explored the Westside, racing under the moonlit alleys and through the bright streets of J-town. Those nights were pure freedom — a man, his dog, and the open road beneath the stars. And it was through Kilbo that I was able to reclaim, if only for fleeting moments, the childhood I had lost — to feel again the wonder, joy, and innocence I had long thought gone.

When I later moved across the ocean to Luxembourg, Kilbo came with me. He could not fly with me on commercial airlines as he was too large and had to be flown in a cargo plane. I’ll never forget the heartbreak of crating him for his long flight. I flew ahead, and he followed, alone in the dark for twenty-eight long hours — transferred from plane to plane, left waiting in vast, empty hangars. When I finally found him, he was quiet and trembling, covered in his own fear and exhaustion. At first, he didn’t even recognize me. But once I took him outside, cleaned him, and let him feel the grass beneath his feet, something changed. He looked at me, his eyes lit up, and he began to leap and bark with joy. That moment erased all my worry, all my guilt. In his forgiveness, I felt grace.

When I arrived in Luxembourg, I had only two suitcases and Kilbo. No family, no friends, no distractions. Just a few students — and him. And in that isolation, God was sanctifying me.

Holiness means to be set apart, and that’s exactly what He did. Through solitude and companionship, through devotion and duty, God purified my heart. Kilbo was my guide through that sacred loneliness — my teacher in patience, loyalty, and unconditional love.

He was always by my side. We went everywhere together — shopping, cafes, restaurants, long road trips, even snowboarding in the Austrian Alps. My students knew: when they invited me, they were inviting Kilbo too. His presence was non-negotiable, and his loyalty was absolute.

But separation always broke him. Whenever I had to leave him in boarding, no matter how comfortable the place, he suffered. He’d lose weight, develop hives, grow restless — as though part of him had gone missing. And truthfully, it had — because I was gone.

Once, I left him in the care of my parents in their spacious home. He had everything: a garden, a pool, love, and constant attention. Yet, soon after I left, he broke out in hives again. My mother, in her late seventies, carried that enormous dog to the vet over and over, determined to care for him. The doctors were astonished at how gentle and obedient he was, even under stress. However, the veterinarian had no idea what the cause was, and no remedy could cure him. And then, like a miracle, just days before I returned, he healed. When I asked my mother why she hadn’t told me, she smiled softly and said, “I didn’t want to worry you.” And, Kilbo must have sensed that I was coming home, and also not wanting me to worry, he made himself well again.

When I came home, Kilbo was overjoyed — jumping, crying, his tail wagging furiously. In his embrace, I felt a kind of love that no human being had ever given me — pure, forgiving, steadfast.

We shared the same bed, the same room, the same life. Everything I owned, I would have given to keep him here just a little longer.

Now, he’s gone — my white, majestic angel — and I mourn him with the same eternal yearning that Wolmyongsa felt for his brother. Like the moon, I will forever pursue him through the thickets of clouds — in dreams, in spirit, and one day, in Heaven.

Until that day, I live in faith that Kilbo rests in the merciful hands of God. And when my time comes, I will seek him again — as the moon chases the clouds — never ceasing, never tiring, until we are reunited in the eternal light.

“Knight Kilbo once stood by the water, Reflecting his face in the blue.”

This image recalls a moment of stillness — the poet beholding Kilbo gazing into tranquil water, his reflection merging with the sky. It is a vision of purity and introspection, a soul mirrored in creation. In the symbolism of the Hyangga, water is not only a mirror of the self, but also a threshold — the quiet boundary between life and death, between the seen and the unseen.

“The blue” evokes peace and transience — the way reflections shimmer and fade at the lightest ripple. It speaks of life’s impermanence, the fragility of memory, and the yearning to preserve what time must eventually take away. So too did I watch my own Kilbo gaze into the stillness — his eyes calm, curious, pure. And in that gaze, I saw myself. It is a mystery how a human and a dog can commune so deeply without uttering a single word, yet understand everything that must be known. Through no language but love, everything is communicated — the intention, the emotion, the truth.

At times, I wondered what Kilbo was thinking as he looked into my eyes, but deep within, I already knew. His thoughts were simple and whole — untainted by doubt, unspoiled by deceit. In his eyes lived joy, trust, and a purity of devotion that words could never express. When he stared into me, I felt seen — not for what I did, but for who I was. When I was sad, angry, or lost, he became my silent pillar. At times he comforted me with quiet presence, other times with relentless licks of compassion. He knew when to stay close, and when to give me space, yet never withdrew his watchful love.

A dog’s nature is to protect and to serve. Within the pack, the strongest must lead — not through dominance, but through the strength that gives peace. If the leader falters, the pack cannot rest. The dog tests this truth again and again, seeking assurance that it is safe to surrender. Only when he knows his master’s strength can he finally lay down in peace.

Kilbo was at peace, because he knew I would protect him with my life — just as I trusted he would do the same for me. Through this, I came to understand something profound: true freedom and peace is found in surrender.

The Bible’s most frequent command is, “Do not be afraid.” When we surrender to the Lord — to His strength, His will — we find rest for our souls. Kilbo, in his surrender and trust, taught me what it means to trust my own Master, my Lord. As he rested in me, so I learned to rest in Christ.

Though powerful and noble, a dog is utterly dependent — like a child who never outgrows infancy. He cannot survive without care, protection, and love. Through the years of nurturing Kilbo — feeding him, walking him, bathing him, cleaning after him — I came to understand what it means to serve and to love unconditionally. Sometimes I wondered if he was not the master after all, and I the servant. He gave nothing material in return, yet through his very being he gave everything that matters: joy, companionship, and purpose.

Despite doing nothing to “earn” love, he was loved beyond measure — and that, I realized, is how God loves us. We do nothing to deserve His grace, yet He lavishes it upon us freely. As Scripture says in 1 John 4:19:

“We love because He first loved us.”

Kilbo’s love never wavered. Whether I was kind or harsh, near or far, his devotion never faltered. He never held my failures against me, never doubted who I was. Even as a powerful Dogo Argentino — bred for strength and courage — he was gentle to every creature. Though made to hunt, he never harmed. He barked only to protect, never to harm. He lived not to dominate, but to love.

In Kilbo, I witnessed the living parable of divine love. Through his faithfulness, I glimpsed how we ought to love God — with total trust, without pride or condition. He loved perfectly, and in doing so, revealed my own imperfections.

Kilbo taught me what it means to love with the heart of Christ — patient, steadfast, forgiving. Through him, I learned how to serve with humility, to lead with strength, and to rest in grace.

He was more than my companion. He was a reflection — a mirror in the water of my own soul. And though his reflection has faded from this world, its image remains etched in eternity, in “the blue,” where memory and spirit intertwine.

When I think of the line, “Knight Kilbo once stood by the water, reflecting his face in the blue,”

I see him still — calm, noble, eternal — standing at the edge between worlds, his spirit clear as water, his heart one with Heaven.

And when I look into the water now, I see not only his reflection, but my own — united by love, by faith, by the divine bond that neither death nor time can break.

“Henceforth I shall seek and gather In pebbles the depths of his mind.”

The poet kneels beside the stream, sifting through small stones — each one a fragment of memory, a trace of the beloved’s soul.

In the act of gathering pebbles, he is not searching for possession, but for communion. Each pebble holds a whisper of what once was, smoothened by time, shaped by the current, yet enduring.

So it is with grief — it does not vanish; it transforms. The sharp edges of loss, over time, are worn smooth by remembrance and love.

When I think of Kilbo, I too find myself gathering pebbles — fragments of moments that still glisten in memory: the sound of his paws against the earth, the weight of his head resting on my lap, the rhythm of his breath beside me through countless nights.

Each moment is small, yet sacred — each one a stone in the riverbed of my soul.

I have learned that grief, when purified by love, becomes devotion.

And devotion, when offered to God, becomes peace.

Like the poet of old, I search the depths of the water not to find what is lost, but to understand what remains — the reflection of his spirit, the echo of divine design that speaks through all living things. For Kilbo’s mind, though wordless, was deep beyond measure.

In his silence was wisdom; in his gaze, truth.

As I walk now along rivers and trails, I see pebbles glinting beneath the current, and I remember:

each one is a prayer, a testament to a love that once took form and now has returned to the eternal.

In the Gospel, Christ says, “If they keep silent, the stones will cry out.” (Luke 19:40)

So too, the stones I gather cry out — not in sorrow, but in praise.

They remind me that nothing loved is ever truly lost. Every act of love, every moment of devotion, is written into the fabric of creation, as eternal as the river that shapes the stones.

Kilbo’s mind — pure, loyal, free of deceit — reflected the divine nature more faithfully than most men’s hearts. In seeking the depths of his mind, I was truly seeking the mind of God — the quiet perfection of love expressed through His creatures.

And so, I keep gathering pebbles.

Every memory, every lesson, every glimpse of grace becomes one.

I lay them at the feet of my Lord, and through them, I see again the reflection of my dearest companion — the Knight who walked beside me, who taught me faith without words, and love without condition.

“Knight, you are the towering pine,

That scorns frost, ignores snow.”

The pine — ancient sentinel of the East — stands evergreen through the fiercest winters. It bends, but never breaks. It is a symbol of loyalty, courage, and endurance, unshaken through the tempests of life. In these final lines of The Ode to Knight Kilbo, the poet does not grieve what has been lost, but sanctifies what endures — the spirit of a warrior who transcends decay, who stands tall against the cold.

For me, those words do not belong to a distant age of knights and kingdoms. They belong to my Kilbo — my companion, my guardian, my angel in the shape of a dog. He was, in every sense, a towering pine.

I remember the summer his ordeal began when he was just about five years of age. One morning, I noticed a small patch of raw skin on his flank — nothing serious, I thought. Yet within days, the wound spread. His thick white coat, once immaculate and proud, began to fall away in clumps. His skin cracked and bled as though burned by acid. The sight filled me with horror. I rushed him to the veterinarian, who dismissed it as a “hot spot.” She gave me ointments, antibiotics — but nothing worked.

Soon, the infection devoured his back, his tail, his sides. The smell of rot hung heavy in the air. Still, Kilbo endured in silence. He never cried out. He only looked at me — eyes deep, patient, trusting — as though to say, “I know you will help me.”

Desperation drove me to a specialist. The tests revealed nothing conclusive. “Bathe him daily with this medicated shampoo,” she said. “That’s all we can do.”

“For how long?” I asked.

She replied, “For the rest of his life.”

And so, I did. I had no other choice — an immigrant in a foreign land, unable to speak the language, unwilling to impose any burden on others.

Every day, in that cramped apartment bathroom, I lifted his 50+ kilogram body into a small tub. The walls dripped with steam and water; the tiles echoed with our struggle. He stood there, motionless, letting me scrub every wound. The stinging solution burned his skin raw, but he never resisted — until one day, he whimpered. Just once. A soft, heartbreaking sound that shattered me. I looked into his eyes and saw what I had not wanted to see — pain. Pure, unbearable pain.

That night I fell to my knees and prayed. I begged God for mercy. For guidance. For hope.

Then I remembered a student once speaking of an unorthodox veterinarian in Germany — a holistic healer. I had nothing left to lose.

The journey was long — hours on the road, through summer rain with my loyal student accompanying me. Kilbo lay in the back seat, resting in silence, his breath deep and steady. I spoke to him softly as we drove, promising him that I would not give up.

The doctor’s clinic was secluded in a remote farmland, quiet, filled with a strange peace. He examined Kilbo not with machines alone, but with touch — hands firm, eyes closed — feeling the energy of his body. He performed light therapy, spoke of energy and balance, and prescribed a regimen of natural supplements.

I asked him what was wrong.

“It’s good the toxins are coming out,” he said. “If they stayed inside, they would destroy him. This is not illness — this is purging. The cause is the same that poisons humans: processed food. You must change everything — what he eats, what he breathes, what he is surrounded by. Then he will heal.”

He promised recovery in two months. I wanted to believe him — but faith in man is never without its doubt. Still skeptical but out of options, I followed his instructions exactly, day after day.

And then the miracle happened.

Slowly, Kilbo’s skin began to heal. The wounds closed, the redness faded, and fine white fur — soft as snow — began to grow again. Within two months, he stood restored. Strong. Radiant. Alive. I wept in gratitude, thanking God for granting me this grace.

From that day on, I fed him only what was pure and natural, only what this holistic vet recommended. He thrived. His spirit seemed even brighter than before, his eyes full of life and wisdom. I often thought of the pine — green even in the dead of winter — and knew he embodied it.

Years passed, and time, as it always does, began to claim its due. On a routine checkup last year, the vet found a small growth near his stomach. “He’s too old for a biopsy or surgery,” he said gently. “There’s nothing we can do.”

He was nine then — his body was thinning, yet he was strong and resilient, just a little more relaxed and calmer. His joy never faded. He still greeted me with boundless excitement, his tail wagging, his eyes glimmering with devotion.

In the final months, his strength waned. He lost weight, his steps slowed, but he never complained. Even as his body weakened, his heart remained resolute — loyal to the end.

Then came the last week. His health declined rapidly. Diarrhea, exhaustion, labored breathing. I cooked him boiled chicken and rice, feeding him by hand. He still ate, still wagged his tail, still looked at me with love that transcended pain.

On Saturday morning, before I had to teach, I took Kilbo to the vet once more. The ultrasound showed that the tumor had grown immensely. There was also internal bleeding which made him look bloated.

I asked the doctor quietly, “How long?”

She hesitated, then said, “Maybe a month.” But I noticed her glance at my student and, in her native Luxembourgish, she whispered, “A week at most… perhaps not even through the weekend.”

I stood there in silence, my heart sinking. Then I asked what I should feed him and how often. The vet replied softly, “Give him whatever he wants — as much as he wants.”

I laughed faintly in front of her, pretending not to understand the weight of those words, but inside I was shattered. Those were the words of farewell — the permission for a final meal. The acknowledgment that death was near.

I couldn’t accept it. I couldn’t imagine life without him. The thought of his absence was unbearable. My mind filled with all the things I had yet to share with him — finishing the garden where he could run freely, off-leash and proud; our next snowboarding trip for the first time to the Italian Alps; the visit to Rome we had planned for next year, on their twenty-fifth anniversary. All those dreams dissolved into the cold certainty that our time together was ending.

But I had to keep going. I had classes to teach. I had to hold myself together, if only for a few more hours. I dropped Kilbo and my student off at her home, then drove to teach. I wept the entire way. Every turn of the road blurred behind tears.

During the lesson, I forced myself to focus — to stand, to speak, to teach — though my spirit was elsewhere. I was teaching with a breaking heart, the weight of loss pressing against every word.

On the drive back, I could no longer contain it. I broke down completely, sobbing as I drove through the amber streets at dusk. When I arrived, my student and Kilbo were waiting outside for me. As soon as I stepped out of the car, Kilbo ran toward me with what little strength he had left.

I fell to my knees and wrapped my arms around him, holding him close, tears flooding down my face. I cried out uncontrollably — all the pain, all the fear, all the helpless love pouring out of me.

And then, for the first and only time, Kilbo growled. A low, sharp growl — not of anger, but of command. He pulled back and looked at me, his eyes steady, unyielding.

In that instant, I understood. My weakness was hurting him. He was telling me to be strong. To stop grieving before his time had come. To not pity him, but to honor him — as the warrior he was.

Even in his final days, he was teaching me.

I wiped my tears, placed my hand gently on his head, and said softly, “Alright, my boy. I’m sorry.”

I stood up, straightened my back, and promised him — I would not cry in front of him again.

The next day, Sunday, I awoke early. The house was silent, but my heart was heavy with the weight of what I knew must come. Kilbo lay quietly by my bedside, his breathing shallow yet steady. When I looked into his eyes, I could see it — he knew. He always knew.

That morning, I prayed long and hard. I asked God for mercy, for strength, and for understanding — not for myself, but for Kilbo. I prayed that He would not let my beloved companion suffer, that He would take him gently when it was time, and that I might have the courage to let him go.

Later that day, I went to the market. I wanted to give Kilbo a feast — his final meal, though I could hardly bring myself to think of it that way. I bought the thickest, juiciest steak I could find, one I would have never given him before nor would I even buy for myself, seared it perfectly, and served it to him on a silver plate like a king’s banquet.

I sat down in front of him with the plate and his eyes lit up for the first time in days. His tail wagged faintly, and I fed him by hand piece by piece, and he ate with such joy, savoring each bite as though he knew it was his last gift from me. Watching him eat filled me with both peace and sorrow — peace that I could give him this final comfort, and sorrow knowing it meant the end was near.

Then I gave him the bone, and for a brief, fleeting moment, he was himself again — the proud, strong, playful Kilbo I had always known. His eyes brightened, his tail flicked faintly, and in that instant, I let myself believe. Somewhere deep in the quiet corners of my mind, a fragile hope whispered, Maybe he’s alright. Maybe he’s going to be alright.

But that illusion broke as quickly as it came. Moments after I took the bone away, he began to gag — a sharp, dry heave that tore through the silence — and then came the blood. Dark, heavy, final. The sight of it struck me like a blade to the chest. My heart sank as I realized the truth I had been fighting to deny: my warrior, my steadfast companion, was slipping away.

Afterwards, we sat together in the quiet of the evening. The house was dim, the air still. He rested his great head on my lap, and I stroked his fur slowly, feeling his warmth, memorizing the rhythm of his breath. Every moment felt sacred — as though time had stopped, and the world had fallen away, leaving only us.

By late night, his breathing grew shallow. He could hardly move, yet he kept looking at me, those same eyes filled with loyalty, strength, and love — the very same gaze that once met mine on every morning walk, on every mountain path, on every long road trip.

I whispered to him softly, “It’s alright, my boy. You’ve done enough. You can rest now.”

But Kilbo held on. He was waiting — waiting for me to let go. Waiting for permission to leave. It was as if his spirit refused to depart until he knew I could bear it.

Around two-thirty in the morning, I could no longer bear to watch him suffer. The room was heavy with silence — only his shallow breaths breaking the stillness. Then, without warning, he drew in one long, trembling gasp and rolled gently onto his back. In that instant, I knew. The moment had come.

Even then, Kilbo summoned the strength to rise on his own and walk to the car without my help. Even in his final moments, he carried himself with quiet dignity — proud, steadfast, and unyielding to the very end.

We drove through the quiet night as fast as we could toward the only 24-hour emergency clinic. Even there, Kilbo found the strength to climb out of the car on his own. Though he had never been to that place before, I sensed that he understood why we had come. With calm resolve, he walked ahead of me toward the front door — steady, silent, and sure — as if he were ready to face what awaited him.

At the clinic, the doctor confirmed what I already knew — there was nothing more to be done. I nodded silently. My body trembled, but I held him close, feeling his heartbeat against mine.

Even then, Kilbo was calm. His body was frail, but his spirit was unbroken. He looked up at me one last time, his eyes still shining with that same unwavering faith. Then, as the medicine began to flow, he relaxed. His eyes softened, and he rested his head against my arm.

In that final moment, he gave me one last gift — peace.

His breathing slowed. His eyes closed. And with a gentle

sigh, he went to sleep — not in fear, not in pain, but in perfect silence.

I sat there, holding him long after he was gone. The room was quiet, except for my sobs echoing softly against the walls. My student wept beside me.

Even in death, Kilbo looked strong — like the towering pine that scorns frost and ignores snow. The same spirit that had carried me through my darkest years was now free.

I whispered through tears, “You were my warrior, my teacher, my guardian, my friend. You were my Kilbo.”

And in that moment, I understood the final meaning of the poem:

“Knight, you are the towering pine, That scorns frost, ignores snow.”

He had endured every hardship, every storm, without complaint. He lived and died with dignity, with love, and with faith.

Kilbo was more than my dog. He was my angel, my reminder of God’s mercy and grace. Through his life, I learned how to love unconditionally, to serve selflessly, to endure without fear, and to surrender without shame.

He was the embodiment of the Hwarang spirit — loyal, courageous, pure of heart — and the reflection of divine love itself.

He lived more than ten years — ten years of loyalty, joy, and unconditional love. That summer, as though guided by divine will, he saw everyone who loved him one last time. My parents, my family, my students — all had gathered for our annual event. Kilbo greeted them with calm dignity, tail wagging weakly but proudly. He endured until he had fulfilled his duty, until his circle was complete.

Even a week before his death, when my student of over forty years came to visit me from Germany, Kilbo walked beside us — slow but determined — ignoring the frost and the snow within his own body.

He was the towering pine.

Through him, I learned the meaning of love untainted by condition, of faith unbroken by suffering, of strength that serves without pride. He taught me how to surrender — not in defeat, but in devotion. He showed me that love, at its purest, is service.

He was my guardian angel in flesh — sent by God to guide me, to teach me compassion, patience, and humility. And when his work was done, he returned home.

I thank God for lending him to me. For letting me walk beside such a noble soul. My heart is broken, but I know that the pine does not wither; it only sheds its needles to grow anew.

Now, as I walk alone, I still feel his presence beside me — in every breeze that brushes against my hand, in every moon that pushes her way through the thickets of clouds. And when my own winter comes, beyond this life, I shall seek and find him again — my white, majestic angel I know will be waiting for me — standing tall beneath the eternal pines of Heaven.

Rest well, my beloved Knight Kilbo. Until we meet again.

Hwarang Forever!

The Art of War is to Avoid — But Most Humans Are Not Into Art

It is hard to live in this country and so easy to die in it — a phrase echoed across many conflict zones. Is it possible to live by the concept of *Amor Fati* — “love of one’s fate” — embracing everything in life, good or bad, with acceptance?

Consider a story: soldiers entered a village and assaulted the women. One woman resisted, killed a soldier, and emerged with his head in her hands. Rather than celebrate her courage, the other women condemned her.

They feared their husbands would ask why they had not resisted. They murdered her. They killed honor so shame could live. This reflects today’s corruption, where honest voices are silenced to preserve a corrupt status quo.

The world prepares for war to hide its corruption. Defense budgets rise; the gun hanging on the wall is doomed to fire. As dialogue disappears, force replaces discourse. Nations divert funds from technology, development, and welfare to weapons. While many long to avoid conflict, the machinery of war grows.

The younger generation, raised far from war, grows up in a liberal, consumer-driven world. Yet powerful hands manipulate them with the same three triggers: hate, fear, and consumption. “The desert teaches us more about water than the ocean.”

When something is abundant, we take it for granted. Scarcity awakens attention, gratitude, and understanding.

Peace is undervalued until it is lost. Love feels strongest in its absence. Silence teaches more than noise.

But losing peace leaves us in a desert. Human behavior shows how easily people can be turned toward cruelty. Sixty-two years ago,

Dr. Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments revealed most participants were willing to inflict life-threatening shocks on others simply because an authority told them to. Inspired by Eichmann’s “just obeying orders” defense, Milgram showed that ordinary people, under pressure, will commit immoral acts. Two-thirds of participants went to the highest “shock” level despite screams and pleas.

This chilling result led to global reforms in research ethics. About a decade later, Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment found similar results. Ordinary students, assigned as “guards,” quickly displayed sadistic behavior toward “prisoners.” Both experiments show how thin the wall is between a normal person

and one capable of cruelty under authority or social pressure. They remind us of the importance of moral responsibility, democracy, and education.

Another story illustrates how fear divides: A teacher told her class they would play a game. Each child was secretly told they were either a “witch” or a “regular person.” The goal: form the largest group without a witch. Suspicion spread instantly. Groups formed, splintered, and excluded anyone uncertain. At the end, no one raised a hand as a witch — because there had been none.

The class erupted in frustration. The teacher asked: “Were there real witches in Salem, or did people just believe what they were told?”

The lesson: fear alone divides communities. Labels change — liberal, conservative, for this, against that — but the tactics remain. Make people afraid. Make them suspicious. Divide them. The danger is not the “witch” but the rumor, the suspicion, the planted lie. Refuse the whisper. Don’t play the game. The second we start hunting “witches,” we have already lost.

Returning from the United States, I realized something interesting: America and “the USA” are not always the same. The idea of America we grow up imagining— full of dreams, freedom, and energy—sometimes feels different from the daily life that people actually live there. Yet during my stay, I had the chance to live like an American myself, surrounded by friends, humor, and new experiences that reminded me how much life can change for all of us.

One phrase I often heard made me smile: “He’s a few French fries short of a Happy Meal.” It’s a funny, slightly teasing expression used to describe someone who might not be thinking clearly or who seems a little eccentric. It belongs to a family of similar idioms like:

- “A few cards short of a full deck.”

- “Not the sharpest tool in the shed.”

- “One sandwich short of a picnic.”

These lighthearted sayings show how Americans often use humor to deal with imperfection. The Happy

Meal image is particularly playful—if the fries are missing, it’s incomplete, just like someone who’s “a bit off.” This phrase, and many others like it, taught me how humor can connect people, even when they come from different backgrounds.

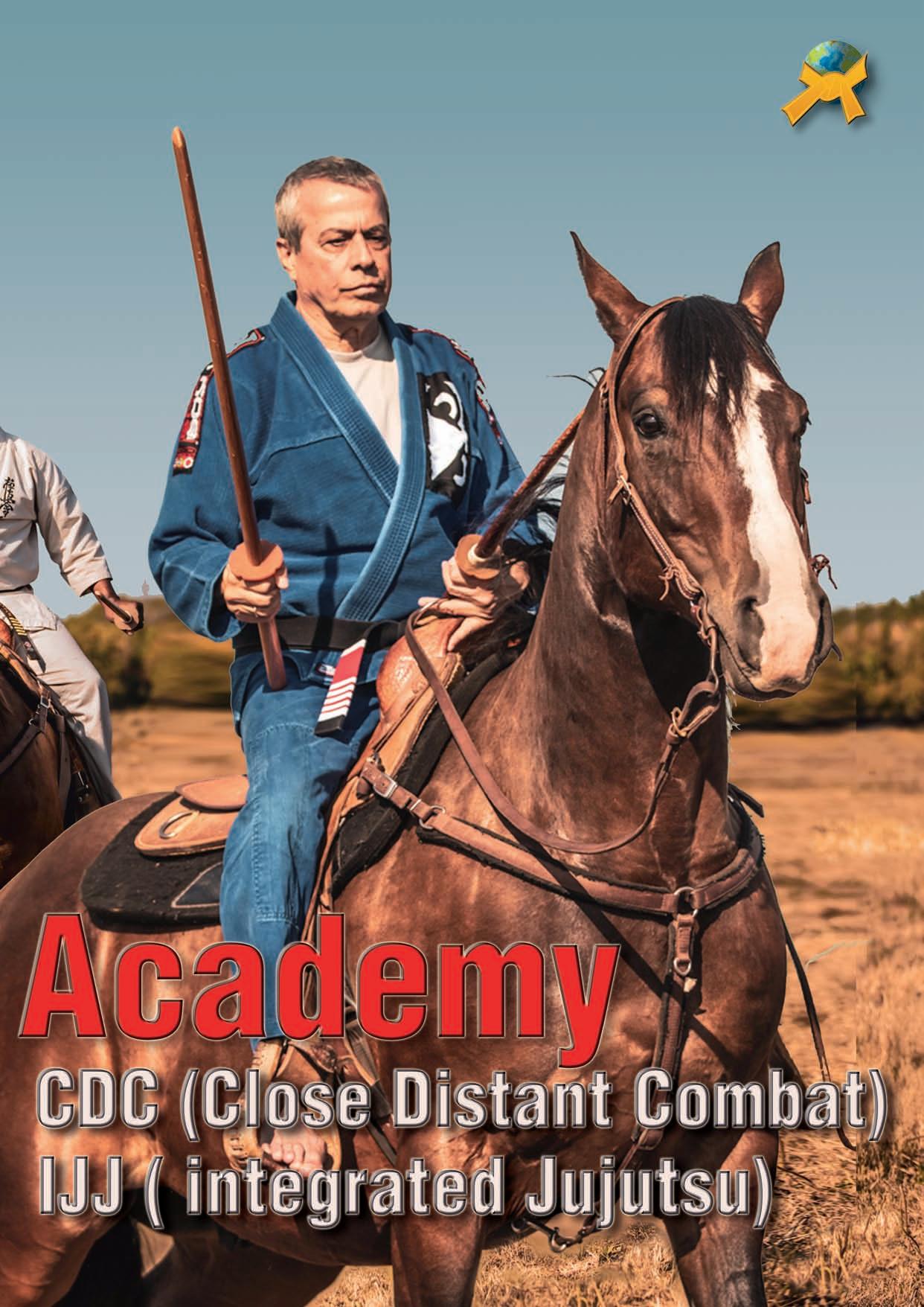

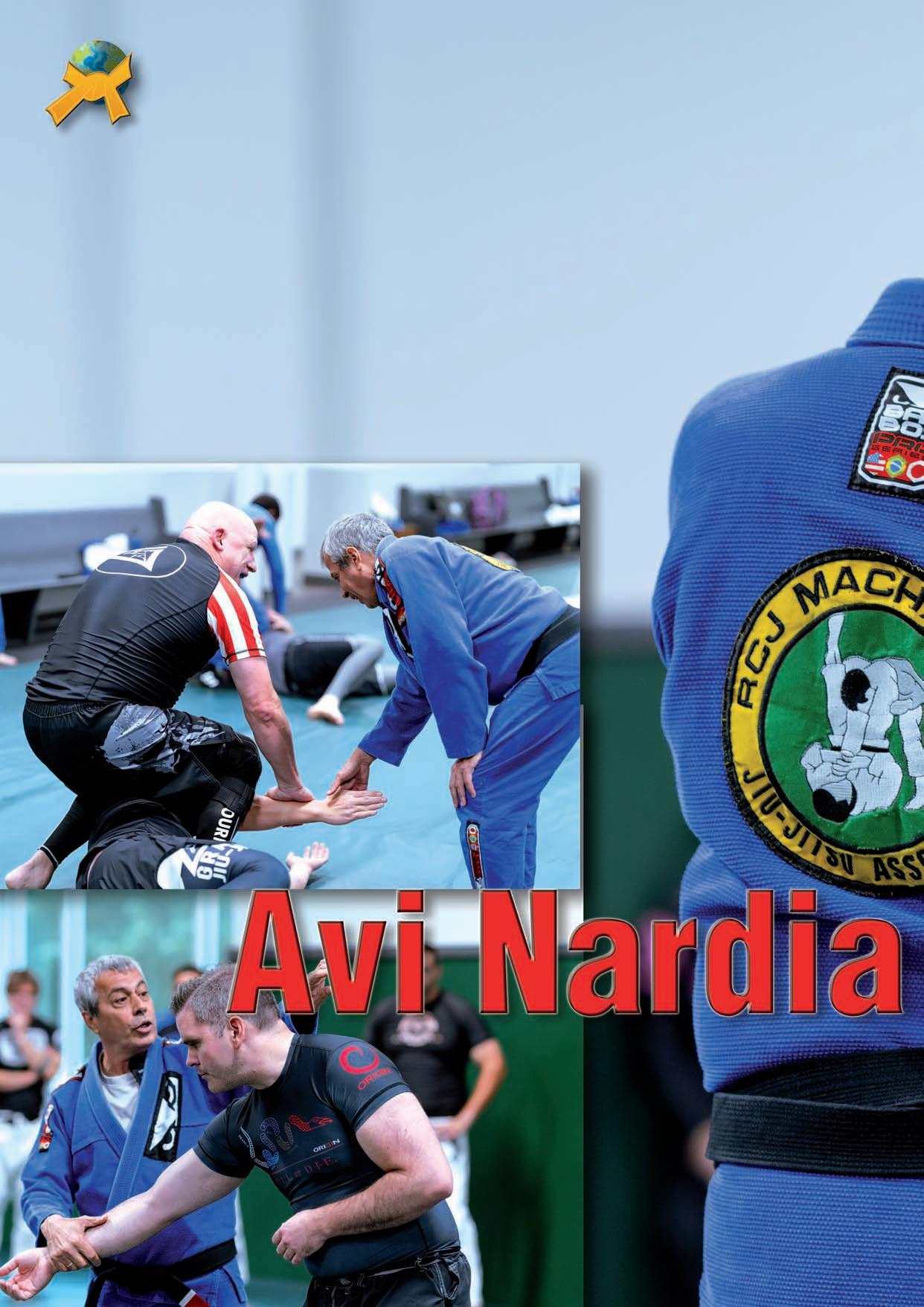

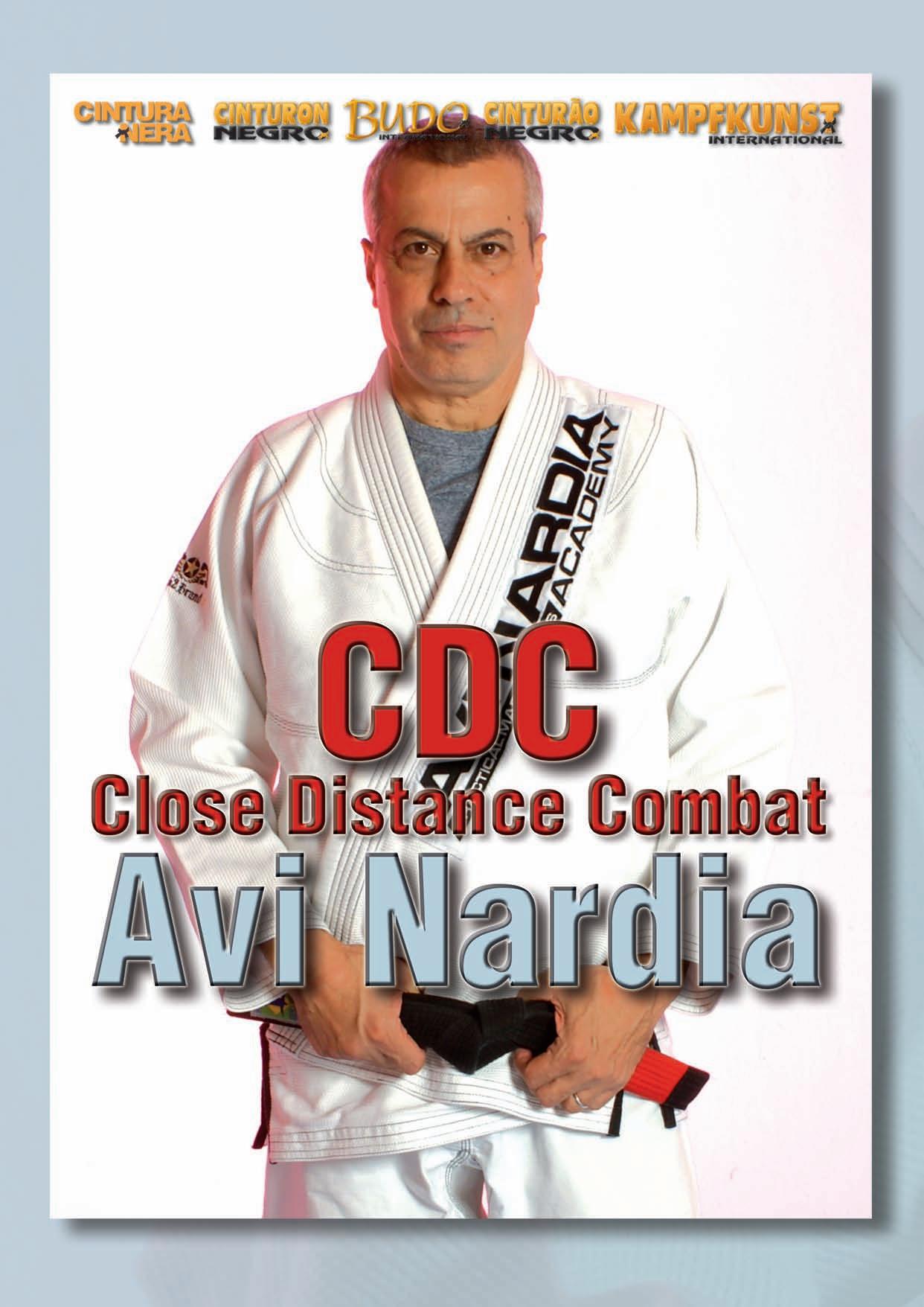

My trip this time combined both teaching and learning. It began with a Surveillance and CounterSurveillance Course, which brought together martial artists, security professionals, and students from many walks of life. Some participants were active in the security field, while others came from martial arts backgrounds, yet we all shared the same passion for discipline, awareness, and personal growth.

I was joined by old friends and students who supported me during the course. One former student, now an instructor at the Rochester Police Academy, contributed valuable insights about law, liability, and the legal boundaries surrounding surveillance. It was enlightening to discuss how to apply these skills effectively without crossing ethical or legal lines.

The course combined classroom instruction with practical exercises in real environments—on the streets, in markets, and inside malls. It was masterfully organized by Chris Cotter, a cybersecurity and physical security expert who has spent over 15 years refining his craft. Chris also trains under Professor John Machado

in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ), while maintaining a diverse background that includes Silat, Judo, and Krav Maga.

The next workshop took place in Lynchburg, Virginia, featuring guest instructors Shihan David Melker and his son Sensei Regev Melker. Shihan Melker, who is also a talented chef, treated us to an unforgettable Israeli lunch that brought everyone together around one table. The training sessions focused on the integration of knife and firearm defense, Jiu-Jitsu, and Krav Maga, blending technical precision with the spirit of cooperation.

One of the proudest moments for me was presenting a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt to Sensei Bruce Rubenberg on behalf of Professor John Machado, who joined us live via Zoom to give his blessings. Bruce is a respected martial artist and owner of a thriving dojo with a strong sense of community. His students treated one another like family, reflecting the best of martial arts culture: respect, humility, and mutual growth. Seeing the harmony among instructors—each with their own experience and teaching style—felt like listening to a symphony where every instrument added its own tone.

One of the highlights of the trip was leading another large Surveillance and CounterSurveillance course, this time for more than 40 students, including international participants from Greece who joined us via Zoom. It was an incredible experience to see such enthusiasm and curiosity about a topic that combines both mental and physical awareness.

Thanks to Chris Cotter’s expert coordination, the exercises ran smoothly, whether we were on foot or in vehicles. Watching students develop sharper observation skills and teamwork in realtime reminded me why teaching is so rewarding—it’s not just about techniques, but about awakening awareness.

Another meaningful stop was visiting Shoshin Dojo, led by Shihan Chris Shabaz and Kaicho Jose Rivera. We’re currently working together on a new article about Shoshin Dojo and my long-term collaboration with them. Meeting again with these teachers felt like reconnecting with family; years of friendship and mutual respect have built strong bonds among us.

The final workshop of my journey took place at the Gracie BJJ School in Victor, New York, under Professor John Ingalina. We shared the mats with Professor Paul Colon, blending Machado and Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, Krav Maga, and Integrated Jiu-Jitsu in an exchange that felt almost like jazz—each instructor took turns leading, improvising, and complementing the others.

It was a joyful reunion for me. Years ago, Professor Ingalina and I were neighbors, our dojos just 50 meters apart—he taught Karate while I taught BJJ. Both he and Paul Colon had started their Jiu-Jitsu journey with me, and seeing how far they’ve come as teachers and mentors filled me with pride. Their success is a reminder of what martial arts is truly about: sharing knowledge and watching it grow in others.

This trip was more than just a series of seminars; it was a reunion with old friends, an exchange of cultures, and a reminder of how martial arts can bridge distances. From New York to Virginia, from classrooms to street exercises, every moment carried lessons about humility, focus, and connection.

As I look forward to publishing new articles about Shoshin Dojo and Professor John Ingalina, I carry with me not only memories of great training but also the laughter, friendship, and inspiration that made this journey special. The USA may be full of contrasts, but one truth remains clear: wherever martial artists meet with open hearts, we are already home.

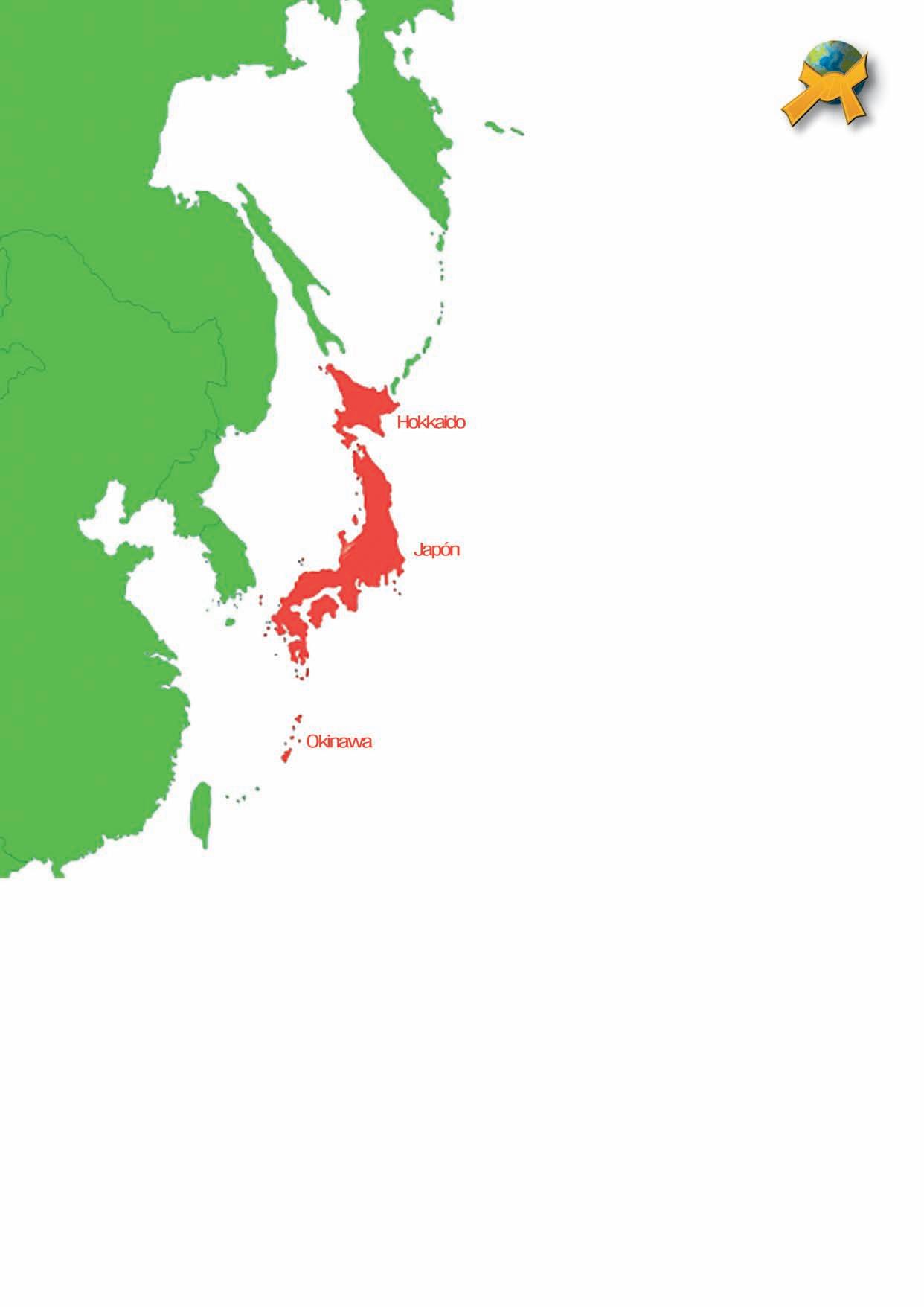

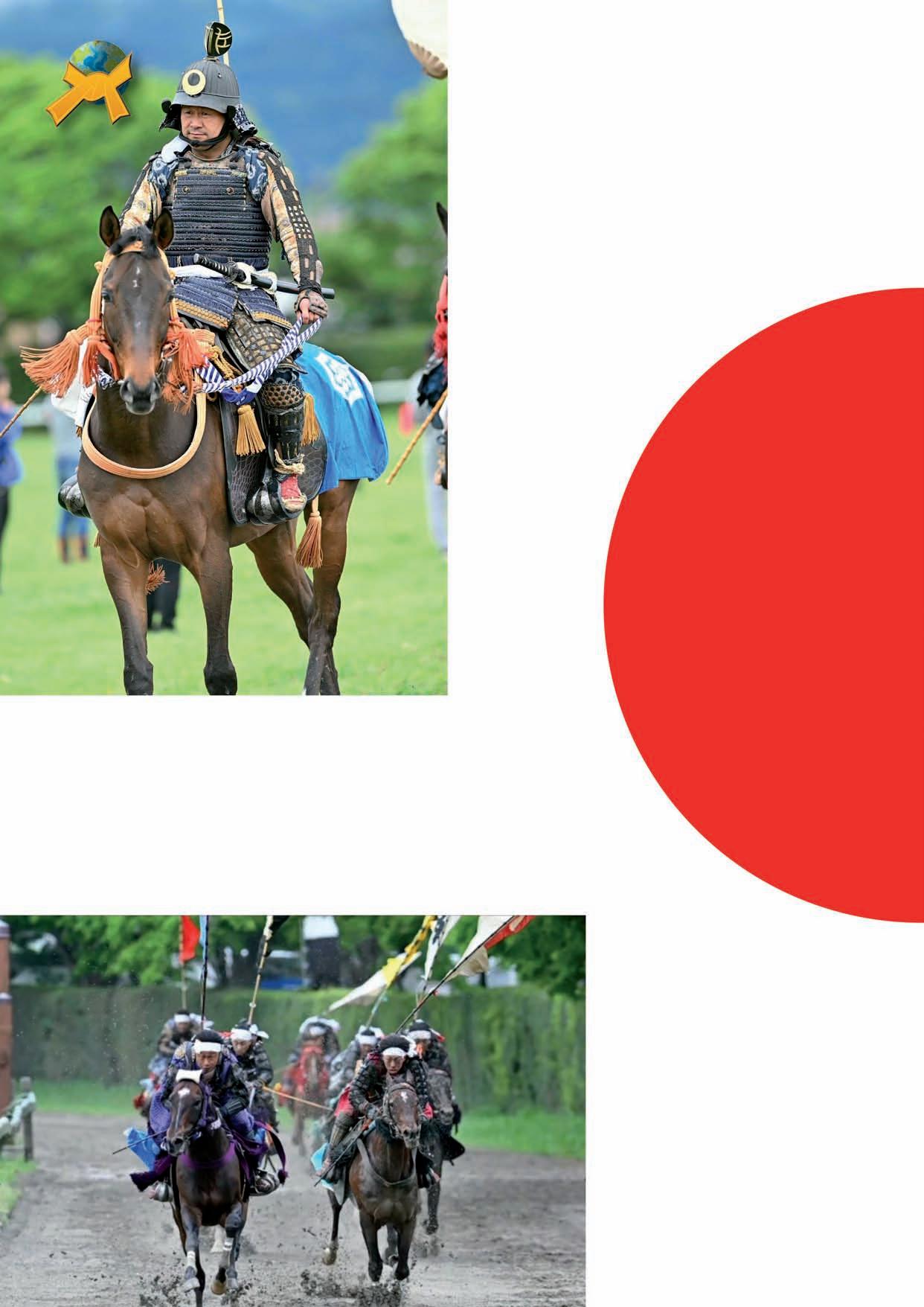

The extremes of Japan. Okinawa and karate, Hokkaido and the Hagumo, the foreign shadows of mysterious Japan.

Japan and its culture extend and define themselves between two worlds that are geographically and culturally located at opposite ends. On one side, in the north, is the island of Hokkaido, and on the other, in the far south, is the island of Okinawa.

Both extremes became part of Japan during its expansion. Every nation that has found its identity tends to become an empire, provided it has sufficient expansive forces. The central culture of Japan is based on the Yamato. This ethnic group currently accounts for most of the genetic makeup of the Japanese people. They arrived in different waves from Southeast Asia, bringing with them important achievements such as rice cultivation. The original tribes of Japan had very varied characteristics as a result of previous immigrations in prehistoric times and organized themselves into highly developed groups such as the Emishi. Under pressure from the Yamato, many of these tribes moved north, mixing with the native inhabitants of the area, most of whom had Caucasian genetic characteristics, such as long hair, thick beards, large size, etc. Tribes and cultures such as the Ainu and others had a genetic component linked to the Mongols and to tribes from the Russian and Siberian steppes.

Alfredo Tucci Alfredo Tucci

During the shogunate period, information about these cultures began to appear through Jesuits such as De Angelis, who visited northern Japan and spoke of tribes of hunter-gatherers, strong nomads with no attachment to property, free-spirited and who eventually traded with the Japanese, but remained beyond their control, as these areas were not then considered part of Japan.

In this context, cultures such as that of the Hagumo, known to the Japanese as the Shizen, “the natives,” emerged in the 12th century around four villages, Tayo, Yama, Kawa, and Yabu, with their own language and culture that have remained incredibly alive and secret to this day. The villages and their island were eventually conquered militarily, but the culture and its components remained intact despite mixing with the Japanese, becoming a silent but essential point of influence in the development of modern Japan. In particular, their knowledge of the invisible (e-bunto, called Ochikara by the Japanese) had an immense influence on Japanese culture and remains to this day a secret tradition passed down from master to student.

Their fierce and pragmatic combat arts, known as Uchiu Shizen, include techniques for fighting with stones in the hand against armored warriors, techniques for tying with ropes or breaking limbs and bones, which in Spain and Europe are only taught by Shidoshi Jordan Augusto in Valencia, <Shidoshijordan@gmail.com>, a living treasure of these traditions. In their subsequent mixing with the Japanese, they perfected their forms of combat to excellence, making this school (Kaze no Ryu, “the school of the wind”) one of the most powerful ancient schools of our day, including techniques of Ju jutsu, Aiki ju jutsu, Naginata Jutsu, Yari, Shuriken, etc.

The Yamato have never been known for their creativity; they are magnificent copiers and excellent, meticulous perfectors of techniques, capable of appropriating and making their own what belongs to others, as they have demonstrated with Western culture after being defeated in World War II. The Japanese economic miracle is proof of these abilities.

In Okinawa, the Andalusia of Japan, a group of northern islands with a warm climate, a culture very different from that of Japan was formed. Even today, its people are much more relaxed and enjoy extraordinary health, producing some of the longest-lived humans in the world.

Okinawa & Hokkaido: Okinawa & Hokkaido:

The loose verses of hidden Japan

The loose verses of hidden Japan

Shidoshi Jordan Augusto “Yamori Kawazuki” Heir to the martial and spiritual tradition (e-bunto) of Kawazuki in Hokkaido

Okinawan culture is shaped by its proximity to China, which has had a great influence on it. The Okinawans were robust farmers, hardened by their wild natural environment. For this reason, after the invasion of the Yamato and the fall of the Okinawan kingdom, the use of weapons was restricted by law, even limiting the use of kitchen knives! This fortunate event ultimately led to the birth of kobudo, training with farming tools such as the nunchaku, used to thresh wheat and separate the grain from the straw, or the eku, the oar, the bo, a simple stick, the Timbei, a shield made from a turtle shell, and of course the refinement of unarmed combat, which existed at that time under the name of To-te or To-de, and which is at the very origin of modern karate.

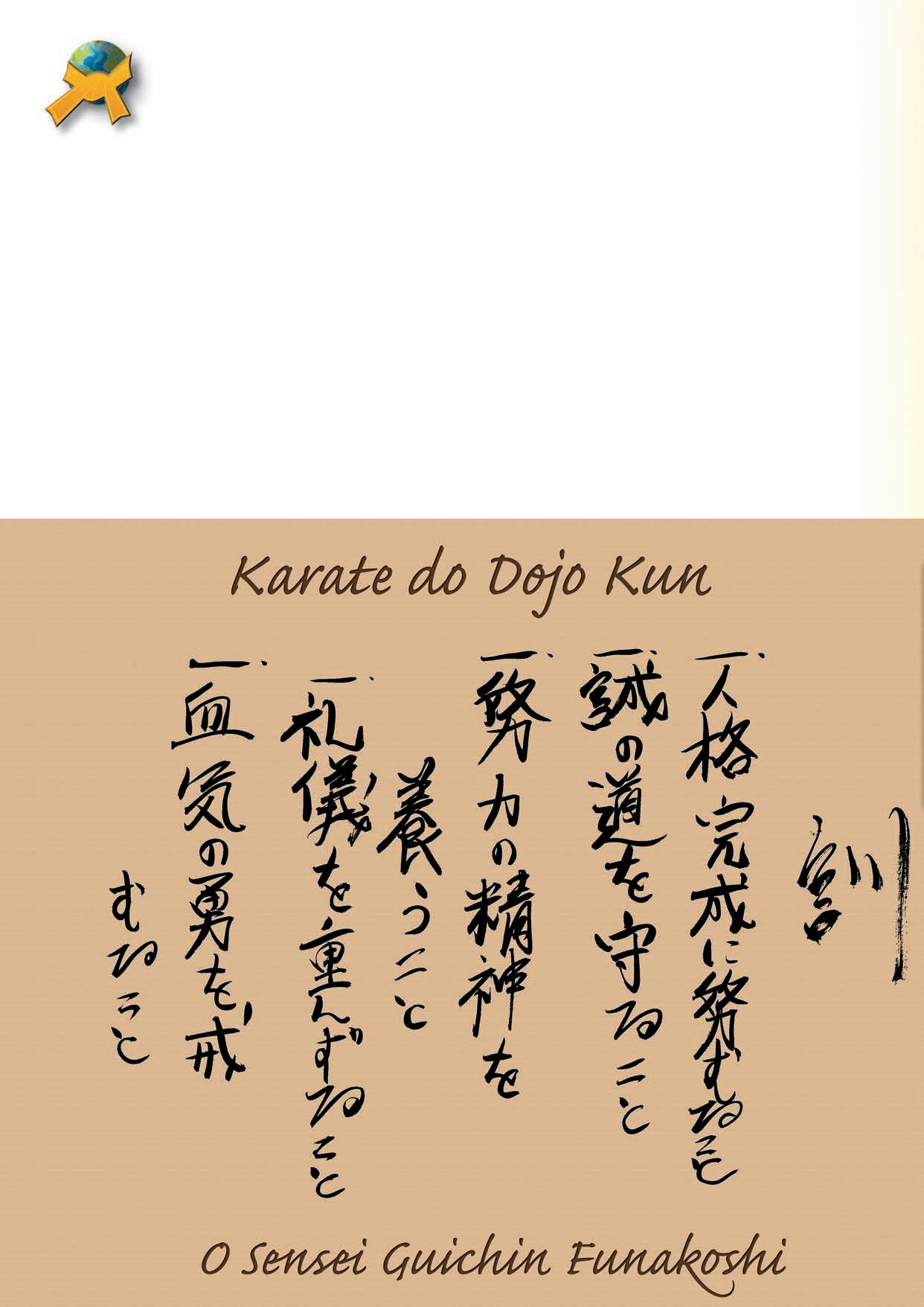

Gichin Funakoshi was the systematizer of this form of combat with punches and kicks that has now become popular all over the world, but to do so he had to “Japanize” the Okinawan tradition, even renaming his art with Japanese kanji, playing with an ambiguous meaning, which led him to call it Karate, understood as “empty hand” (the emptiness of the kanji is often interpreted as a spiritual position, although it primarily expresses the fact that there are no weapons).

The influence of karate is therefore very Chinese, and these foundations are evident in treatises such as the Bubishi, which teaches the vital points of the human body based on Chinese anatomical knowledge (energy meridians, etc.). Its oldest forms have similarities with animal forms from southern China, and many of its kata are inspired by animal movements, something typical of kung fu.

Its breathing exercises in styles such as Goju Ryu make this influence evident in forms such as Ten Sho, San Chin, and Suparimpei. Funakoshi, being a school teacher, that is, knowing how to write Japanese (in fact, he was known as “Shoto,” the name with which he signed his poems!

Hence the name Shoto-kan, -kan meaning house, i.e., the house of SHOTO!) he knew how to make that transition. Many of the masters of the time were illiterate, and while they may have been more competent in combat, they could not overcome the barrier of their limitations when dealing with the dominant culture of the time, Japanese culture.