TBLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE

he Black Pre-Law Association is committed to the education of the legal system and how it impacts the Black community. We created the fi rst ever undergraduate Black law journal at UCLA to inform not only the Black Bruin community, but the larger UCLA community. We cover a wide range of topics regarding laws, policies, legislations, and our government. Our law journal serves as a m otion to increase awareness on pressing issues and injustices within the Black community and what we can do going forward. As a pre-law organization, the current Presidents Kennedy McIntyre and Cierra Anguiano have made a contribution and commitment to expanding t he pillars of BPLA and the BPLA Law Journal to discuss politics, policy, and government.

This law journal will serve as a part of their commitment to ma ke BPLA holistic in policy, government, and politics in addition to the law. We need a law journal that will cover the vast inequities that occur within our community and this is only part of the mission to make legal education accessible and a priority for our community. The Black Pre-Law Association is dedicated to uplifting and advancing our members in the area of professional, career, and personal development as well as community service. The Black Pre-Law Association Law Journal acts as a separate entity that is under the regular Black PreLaw Association, but will serve on the journalism and media side. Our members and executive board that serve on our Law Journal team will have the opportunity to enhance and develop their writing, crit ical thinking, data analysis, and research skills.

The Black Pre-Law Association will advance its law journal members and executive board to have career and professional development in the areas of law, journalism, and media. We are committed to connecting with other media organizations at UCLA to prepare our members with the correct training and mentorship needed to discuss law, politics, and our government. It is our duty to make not only Black UCLA students accessible to this information, but other college campuses and the larger Black communities in which our universities neighbor.

AABOUT THIS ISSUE:

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

s I refl ect on the events that have shook our country this year, I am overwhelmed with a deep sense of sadness and urgency. At times, the weight of it all has felt almost unbearable—so heavy it bor dered on hopelessness. As a Black student in higher education, it has often felt as though the odds are stacked against us. That is why this year’s theme, Black Joy, holds such profound meaning—not just for me, but for every member of this volume. At a time when our administration attempts to erase the legacies of Black leaders, our generation is rising to resist, to speak, and to preserve. From the radical roots of the Black Pan ther Party to the strategic brilliance of Stacey Abrams, the fi ght for freedom has not only endured—it has evolved. And through that evolution, we have thrived. Our stories matter. They are powerful. They are necessary. It has been an honor to work alongside a team of passionate individuals commit ted to this fi ght—not only for Black liberation as a whole, but specifi cally for ensuring that Black Bruins have a voice, and that this voice is channeled into real change on our campus. I hope this volume moves you. I hope that as you read each piece, you are reminded of the value of our st ruggle and the beauty that still rises from it—despite what the media or society may want us to believe. Serving as Editor-in-Chief of this volume has been one of my greatest joys. This publication is one I will carry with me always. I am endlessly grateful to have worked with such a brilliant, d edicated, and talented team. Every piece in this volume carries our heart s, our thoughtfulness, and our deep appreciation for Black life—and Black Joy. Ure Egu

BPLA Editor-in-Chief, 2023-2025

Congratulations to all of the Black Graduates of 2025!

Black Pre-Law Association Statement of Purpose

Kennedy McIntyre & Cierra Anguiano | BPLA Co-Presidents

CONTENTS STAFF

A Letter From the Editor

Ure Egu | Editor-in-Chief

From the Bay to LA: The Legacy of the Black Panther Party

Faith Ndegwa | Staff Writer

Dorothea Amadin | Staff Editor

Anna James | Graphic Design

Derrick Bell: Critical Race Theory & Fight for Racial Equity

Anthony Lewis | Staff Writer

Jenna Besh | Staff Editor

Ekene Duru | Graphic Design

Law and Love, Lock and Key: The Evolution of Black Wedlock in the Law

Jeannine Briggs | Staff Writer

Alana Akiwumi | Staff Editor & Graphic Design

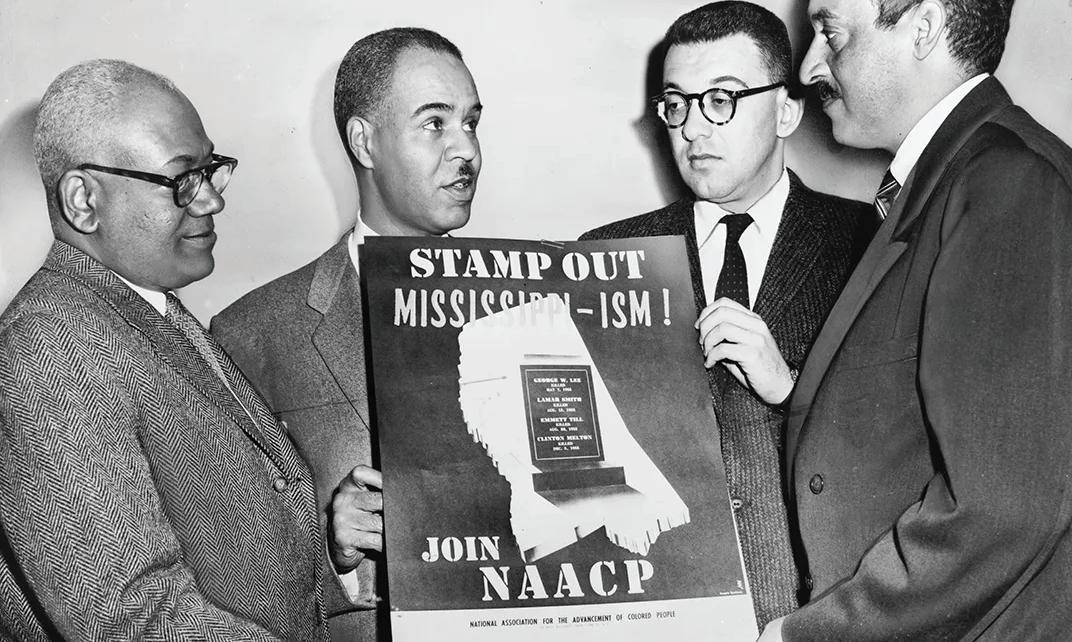

The Color of Justice in a Segregated Courtroom

Yadeal Asfaw | Staff Writer

Ure Egu | Staff Editor & Graphic Design

Constance Baker Motley & Her Unspoken Impact

Nadine Black | Staff Writer

Chiasokam Vincent | Staff Editor

Ure Egu | Graphic Design

Rest in Peace, Rest in Power Deborah Batts

Helio Luti | Staff Writer

Faith Ndegwa | Staff Editor

Alana Akiwumi | Graphic Design

Stacey Abrams: A Catalyst for Change

Jehlani Lewis | Staff Writer

Abigail Pastel | Staff Editor

Shelby Solomon | Graphic Design

Ure Egu | Editor-in-Chief

Political Science & African American Studies Major

Faith Ndegwa | Secretary

Public Affairs Major & African American Studies & Education Studies Minor

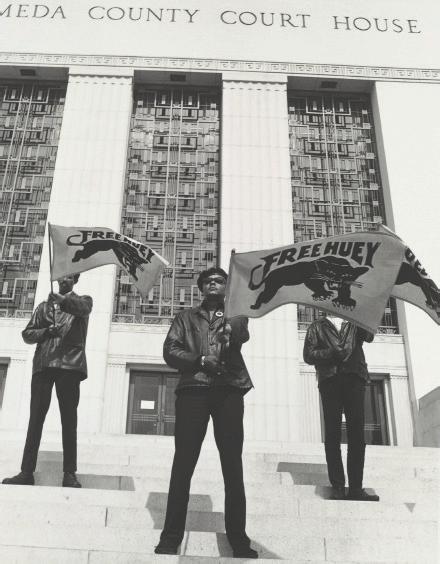

From the Bay to LA: The Black Panther Party’s California Chapters and Their Legacy of Empowerment

Written by Faith Ndegwa

Edited by Dorothea Amadin

Background

Young political activists Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, disappointed by the Civil Rights Movement’s inability to change systemic issues faced by Black Californians’, organized disenfranchised African Americans into the Black Panther Party in Oakland in 1966 (Smithsonian, 2020). Inspired by Malcolm X and anti-colonial movements, the Panthers focused on self-defense and armed resistance, in contrast to the Civil Rights Movement’s emphasis on nonviolent methods while addressing systemic issues and viewing racial oppression as part of a broader system of class exploitation. They chose their name and symbol of the Black Panther rom the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), a political party formed by Black activists in Alabama, as a symbol of power and resilience (CSU Dominguez Hills, n.d.). Newton and Seale created the Ten-Point Program shortly after, outlining demands for freedom, economic justice, and protection from systemic oppression.

Despite California’s reputation as a progressive state, Black communities faced deep racial inequities. Segregationist practices like redlining and financial discrimination in cities like Oakland restricted Black homeownership and the growth of Black-owned businesses by limiting access to capital, ultimately depriving communities of opportunities to build generational wealth. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Police Department’s racialized policing and violent treatment of Black residents further heightened tensions (Reid, 2009 & Bandes, 2000). Frustrated by the lack of tangible change from racial legislative victories in the South, which had little impact on Black communities in the North and West, many Black Californians, especially youth, shifted from nonviolent protest to armed self-defense and direct community action. To address these inequalities, the Black Panther Party established chapters across California, from urban centers like the Bay Area, Sacramento, and Los Angeles to rural regions, with urban chapters receiving more historical attention because their larger Black populations, heavy policing, and media presence made their struggles more documented.

Political Ideologies and Community Engagement

The Black Panther Party’s core ideologies of socialism, self-defense, and global solidarity were strategically used to advance Black liberation and challenge systemic oppression. For one, the Panthers were built on the belief that Black communities had the right to bear arms for self-defense, which Panthers saw as necessary for protection against state violence and police brutality. Inspired by Malcolm X’s advocacy for self-defense, the Panthers armed themselves to patrol law enforcement, using California’s open-carry laws to police the police (Smithsonian, 2020). As governor of California, Ronald Reagan, a conservative white man, responded to Black radicalism with aggressive measures, including public denouncement, increased policing, and support for the Mulford Act, which banned the open carry of firearms in public

was a political statement rejecting stereotypes of Black passivity. Unlike East Coast BPP chapters, whose more sharp,formal, and uniformed look was influenced by the Nation of Islam and academic influences, Panthers in California incorporated West Coast Black radicalism into their fashion, fusing the state’s counterculture and activism with a more laidback yet still militant style (Talor, 2022). The BPP’s aesthetic and political imagery have impacted countless artists and media, from Beyoncé’s 2016 Super Bowl halftime show, where she and her dancers paid homage to the Panthers’ iconic style during Formation, to West Coast legend Tupac Shakur, whose emphasis on Black empowerment in his music was shaped by his mother, Afeni Shakur, a former Black Panther herself (Elgot, 2017 & Kaur, 2023). Their presence has also been depicted in film, such as Forrest Gump, where a scene set at a Panther gathering in Washington, D.C., briefly portrays their activism but filters it through a Hollywood lens emphasizing militancy over their broader community efforts (Zemeckis, 1944). The cultural legacy of the Black Panther Party still persists today, as their unapologetic imagery of Black pride continues to inspire movements for racial justice and empowerment.

Conclusion

The legacy of the Black Panther Party, primarily through its California chapters, will always continue to be a powerful force in the ongoing fight for racial justice. The Panthers’ commitment to self-defense, socialist policies, and global solidarity addressed immediate needs within Black communities while laying the groundwork for future activism. Their powerful resistance to structural injustice and lasting impact on culture, politics, and social spaces continue inspiring modern-day movements for Black liberation. As their influence persists today, the Black Panther Party’s unique combination of radical activism, community service, and pride remains central to global Black resistance. The Panther’s legacy strives to remind us that the pursuit of justice is not limited to one period but is an ongoing journey of empowerment and change.

Derrick Bell: The Godfather of Critical Race Theory & The Fight for Racial Equity

Written by Anthony Lewis

Edited by Jenna Besh

The Development of Critical Race Theory (CRT)

Following the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., many Harvard law students advocated for the hiring of a Black professor. Subsequently, Bell accepted a position at Harvard Law School, becoming the university’s first Black law professor. (Salem Press, 2016). By 1971, Bell was tenured. During this time, Bell’s most influential work began to take shape, including his book Race, Racism, and American Law (1973), which became a foundational text for CRT. In this book, Bell asserted that American law is fundamentally racist and has been used to maintain racial hierarchy. He declared that legal institutions are not neutral, but are systems created to serve the dominant racial group while marginalizing Black Americans. Additionally, Bell's “Interest Convergence Theory” through his article, Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma contributed to the development of CRT. Bell theorized that significant civil rights advancements for Black Americans occur primarily when they align with the interests of white Americans (Bell, 1980). He argues that the Supreme Court’s Decision in Brown v. Board of Education was more about improving America’s international image during the Cold War than about achieving racial equality. Both pieces became foundational to CRT because it provided a lens for understanding why legal victories are often temporary, how law and policy are shaped by power, and why racial progress follows a cyclical pattern of advancement and reversal.

Bell’s

Predictions for our Current Time

Bell’s critique of the legal system as conditional and often reversible is more relevant than ever. Today, just as Bell predicted, efforts to address systematic racism are facing increasing resistance. The simple fact that CRT is being distorted and banned across the U.S. underscores the very patterns Bell identified–where racial progress is tolerated only to the extent that it does not change existing power structures. Just recently, the Department of Education announced that the federal government cut $600 million in funding for schools and nonprofits that trained teachers on topics such as CRT, DEI, and any anti-racism efforts (U.S Dept of Education, 2025).

Furthermore, on January 22, 2025, the White House released a fact sheet detailing why the administration terminated DEI. It reads, “Trump signed a historic Executive Order that protects the civil rights of all Americans and expands individual opportunity by terminating radical DEI preferencing in

federal contracts and directing federal agencies to relentlessly combat private sector discrimination” (The White House, 2025). Additionally, these government initiatives have led to companies ending DEI initiatives, most notably Google, Meta, Amazon, and Target (Adamczeksi, 2025). Dismantling CRT and DEI strips marginalized groups of opportunities for upward social mobility, and prevents society from addressing systemic flaws that sustain inequality. These actions reflect a broader shift toward reinforcing existing power structures rather than dismantling them, demonstrating precisely the cyclical nature of racial progress and retrenchment that Bell warned against.

"The simple fact that CRT is being distorted and banned across the U.S. underscores the very patterns Bell identified–where racial progress is tolerated only to the extent that it does not change existing power structures."

- Anthony Lewis

Conclusion

As Black individuals and other marginalized groups have made significant progress in recent decades, their advancements have instilled fear in white individuals who see this progress as a threat to their dominance. Since our interests no longer align with theirs, they are responding by rolling back initiatives, suppressing discussions of systemic racism, and attempting to maintain the status quo. Recently, many Black individuals are fearful that our contributions to society will be erased, fearful that we will no longer be given a fair chance at success, fearful that future generations will have fewer rights than we did. However, this paper is not meant to instill fear in any reader. It is a call to action—we can fight back to ensure history does not continue to repeat itself. Sustained progress takes hard work–it is not easy. As former Vice President Kamala Harris states, “Sometimes the fight takes a while—that doesn’t mean we won’t win.”

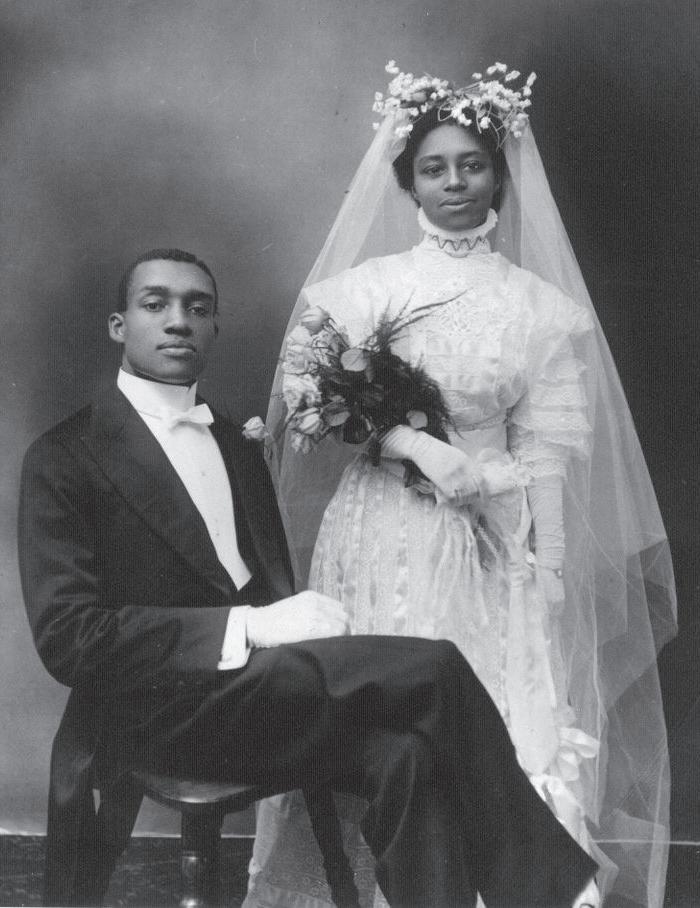

Law and Love, Lock and Key: The Innovative Ways By Which Black People Have Overcome the Continued Denial of Wedlock Recognized

and Protected by Law

Written by Jeannine Briggs

Edited by Alana Akiwumi

Introduction

To be recognized by the law is not merely a matter of legal standing—it is an affirmation of one’s humanity. But what happens when the law itself becomes a tool of oppression and exclusion? How does one both defy legal injustice and preserve dignity, identity, and joy? For much of U.S. history, the evolving illegality of Black wedlock has been a perpetual barrier, fundamentally altering how African Americans were legally permitted to build families and establish unions and communities. Black people have demonstrated various innovative methods to circumvent unjust and biased marriage laws in the practice of joy and love. Today, we can look to these strategies as inspiration for succeeding movements for civil liberties.

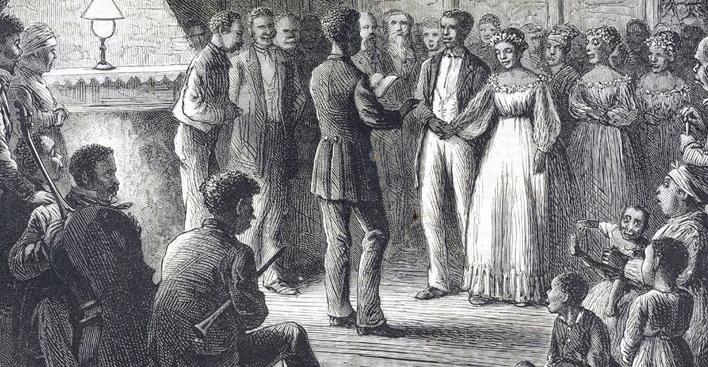

Black Marriage Under Enslavement

From the moment enslaved Africans were condemned to sustain the agricultural industry that built the United States, they existed as property. Their humanity was erased in service of others' economic gain. As chattel, enslaved Africans were not legally recognized beneficiaries of the rights and protected institutions that white citizens were awarded, like parental authority over one's children or the entering into a formally recognized contract. The United States's famous pursuit of life and liberty, and especially the pursuit of happiness, saw an abrupt halt at the reach of Black people.

In 1857, Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) reinforced this legal doctrine of exclusion. Dred Scott was a legally enslaved Black man who sought his freedom through legal action. After hearing the case, the Supreme Court held that Black individuals, whether enslaved or free, had no standing as citizens under the U.S. Constitution. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared that people of African descent were not and could never be considered citizens of the United States. This ruling enforced the stature of Black people as property even when they were free, living outside areas that sanctioned slavery. This decision not only ruled against the legal claims of Dred Scott, who lived in a free area, but also set a dangerous precedent for future legal contention over the civil rights of Black people in the nation. By implication, as Dred Scott v. Sandford stood as the law of the land, Black marriages were not legally recognized and Black people could not dispute this because they held no rights to legal action.

In consequence, enslaved and free Black people found ways independent of their legal provisions to establish familial unity and marital commitment. Historian of African American Studies, Tera W. Hunter, explains in Bound in Wedlock that some enslaved Africans bargained with slave owners for exceptions that would keep partners together and children near their parents. However, agreements like this were rare and unreliable. Thus, enslaved Africans more commonly turned to extralegal cultural practices to solidify and celebrate their unions. Because Black women were often forced into “breeding” in

procreation with other enslaved men, Black people sometimes honored secret marriages or “sweetheart” marriages that symbolized companionship but not sexual exclusivity. Another way Black people established partnerships under enslavement was the tradition of “jumping the broom” – an act that symbolized the creation of a committed union despite the absence of legal or sometimes even religious recognition. Enslaved Africans in the United States adapted this ceremonial practice, drawing on African cultural precedents and pagan traditions, and reinterpreting them within the constraints of bondage. The act of leaping over a broom symbolized the couple's commitment to one another. However, its informality reflected the harsh reality that this union was not meant to last until death, but rather until one or both individuals were sold or transferred to a new "owner" as property.

The Fight for Interracial Marriage

The emancipation of enslaved Black people did not mark the end of the Black struggle to secure legally recognized marriages. Although enslaved individuals had been liberated and marriage rights within their race were acknowledged, they were still denied the right to marry someone of a different race. Many are familiar with the landmark Supreme Court decision, Loving v. Virginia (1967), which nationally nullified state laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The Court ruled, without dissent, that laws banning interracial marriage violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. It is important to recognize, however, that several legal cases challenged interracial marriage bans before Loving v. Virginia, dating back to the 19th century.

One of the earliest cases was Pace v. Alabama (1883), in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Alabama’s anti-interracial marriage laws. Tony Pace and Mary J. Cox were both convicted under Alabama’s law for criminal interracial cohabitation because Pace was Black and Cox was white. Alabama’s state law at the time affirmed that “If any white person and any negro… intermarry or live in adultery or fornication with each other, each of them must, on conviction, be imprisoned in the penitentiary or sentenced to hard labor for the county…" The Court ruled that since the state's law applied equally to both races, it did not violate the national Equal Protection Clause. This decision upheld the constitutionality of state laws that enforced segregation in matrimony for decades and reinforced the state-sanctioned racial segregation of marriage.

During the nearly 90 years of state-sanctioned racial discrimination in marriage between Pace v. Alabama and Loving v. Virginia, interracial couples devised ways to avoid the legal prohibitions on their unions. Some would move, abandon their homes, and flee to states that allowed for interracial marriage. Others attempted to hide their partnerships. Most interestingly, some Black people “passed”, or physically appeared in public life, as white to legally marry white partners. It is important to note that the social and legal opposition to interracial marriage were not separate forces but mutually reinforcing. Legal restrictions depended on societal enforcement, while social disapproval was legitimized by law.

Another way Black people established partnerships under enslavement was the tradition of “jumping the broom” – an act that symbolized the creation of a committed union despite the absence of legal or sometimes even religious recognition.

- Jeannine Briggs

Conclusion: A Conversation for Today

How do legal structures stand in the way of Black unions today? One strong example is the effects that disproportional mass incarceration of Black men and women has on building and sustaining Black partnerships. Some scholarship argues that a “Black-White marriage gap”, that is, the clear divergence in marriages between white women and Black women in the U.S., can be attributed to the mass incarceration and mass unemployment of “marriageable” Black men. Issues of unemployment and over-policing, which contribute to mass incarceration, can be traced back to the era of slavery and its aftermath. Even more, it is clear that the denial of legally protected unions for people at that time created a legacy of broken community networks and unattained generational wealth that has permanently altered the “Black family”.

When Black joy and love are incessantly disturbed and complicated by the law, we must ask ourselves to challenge it, not solely through the legal system. We can ensure the law stands for justice while leaving space for communities to define their own experiences. Ultimately, we can conclude that the law has been restricting and yet created the conditions for Black joy in holding the key to wedlock, forcing Black people to craft their own means of liberation. Today, we must ask: in what ways does the law control the lock and keep the key? Most importantly, how might we forge a new key through innovation and resistance?

The Color of Justice in a Segregated Courtroom

Written by Yadeal Asfaw

Edited by Ure Egu

Introduction

It was the perfect tabloid sensation— a Negro chauffeur had raped Connecticut socialite Eleanor Strubing four times, on a cold and rainy night in New York City. According to Mrs. Strubing’s narrative, he had forced her to write a ransom note for $5,000 and then thrown her off a 14-foot bridge. Needless to say, tabloids took this story and propagated racial stereotypes, claiming a ‘colored servant’ had struck again. The problem with this story, however? None of it ever happened.

The accused was a 31 year old, Joseph Spell, who had a completely different recollection of the events that occurred that night—so different that it reached the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a legal organization for Black lawyers, to bring on a clever and prideful lawyer from Baltimore that would change his life in more ways than one.

Biases Biases Biases and you Guessed it, More Biases

This talented lawyer from Baltimore, Thurgood Marshall, has no idea what he is in for. The judge presiding over this case is Judge Foster, a close family friend of the lead prosecutor who is representing Mrs. Strubing. In the preliminary hearing, Judge Foster kindly asks the prosecutor, Mr. Willis, “Oh, Mr. Willis, how’s your father doing? I haven’t spoken to him in a while” (Marshal 2017). Biased, it is certain that Judge Foster had already made up his mind about the case.

Judge Foster looks over the defense, composed of two Black men, Marshall and Joseph. However, to his surprise, they were all sitting next to a Jewish lawyer named Samuel Friedman. To everyone’s surprise, Friedman is in fact a civil and insurance lawyer, who had absolutely no experience in criminal defense work, with zero interest in helping the case. Friedman was meant to simply sit with the defense and provide the help of optics. That is the only reason he is there—to help legitimize the defense as Friedman is an upstanding white man.

Within seconds of this preliminary hearing, Judge Foster begins to interrogate Marshall, ultimately ruling out the need for out-of-state counsel and therefore Marshall’s involvement in this case as lead attorney. But Judge Foster then says something that would set the tone for the rest of this case.

“However, the court wants to maintain the appearance of fairness as well. Therefore, the court will allow Mr. Marshall to enter his written appearance, but he may not speak at any point during these hearings. He may sit at the counsel table, but he may not speak, argue, or examine witnesses, and if he does, both of you will remain in contempt of court” (Marshall 2017).With that, Friedman, the insurance lawyer who has never even set foot in a criminal courtroom, has the life of Joseph Spell in his hands. Ironically, Thurgood Marshall, one the highest regarded criminal defense attorneys in the U.S, has been subjected to silence. All because of his race.

A Strong Need to Win this Case: NAACP Funding Issue

In order to understand the high stakes in this trial, it is important to take into account that funding is at stake during the time of this trial. Marshall, alongside the NAACP, had a plan to take on cases that “would prove the best vehicles to advance certain legal principles and then hope to find plaintiffs who could assert appropriate claims” (Crew 2019). In other words, winning and arguing in this case would bring about racial biases that have been embedded in the justice system for decades. A loss from this case, therefore, would not only have legal setbacks but also cause funding issues as

the NAACP faced the threat of bankruptcy as a result of lawsuits and criticisms about its relevance from proponents of the Black Power Movement (Crew 2019). In the 1980s, the Reagan administration tried not only to reduce the budget of the Equal Opportunity Commission but also to reduce the number of civil rights attorneys in the Justice Department, forcing the NAACP to find new ways of maintaining its mission to help African Americans (Library of Congress 2009). With all of these issues in mind, it was all the more important for the accused, Joseph Spell, to be innocent. It was to everyone’s shock that he was not.

Joseph Spell Was Not So Innocent After All

Up until this point, Joseph had stuck with the story that he was simply the chauffeur of Mrs. Strubing the night of the assault—but they both left out a very important piece of the puzzle. They did engage in sexual intercourse that night. And it was completely consensual. Yet why did Joseph lie to his very own lawyer if he was completely innocent?

To elaborate, Joseph had been the chauffeur of the Strubings for many years now, long enough to see how abusive Mr. Strubing had been to his wife. The evening of the incident, Joseph went to their home to ask for his check. He found Mrs. Strubing alone in her room, sobbing uncontrollably due to the constant fighting and abuse from her marriage. In his attempt to calm her down, Mrs. Strubing acted out of emotion, kissing Joseph, and it consequently led to consensual sexual intercourse.

Hours later, lying next to Joseph, realization sunk in for Mrs. Strubing for how it would look to the outside world if she was pregnant with a Black child and ordered Joseph to drive her somewhere, anywhere as long as it was far away from here.

Moments into this drive, Joseph gets pulled over by the police as he “looked suspicious driving a luxury vehicle on this side of town” as the police officer would later claim in court. Mrs. Strubing was lying flat in the backseat, so she was not seen by the officer. This becomes an important piece of information later.

After showing his license, Joseph was let go, and their drive continued until Mrs. Strubing yelled at Joseph to stop when they got to a bridge. Mrs. Strubing then attempts to jump off the bridge as she could not bear to live with herself and the state of her life after what she had done. Even with Joseph’s attempts to calm her down, she jumps off the bridge, and Joseph speeds off in shock.

Joseph couldn’t tell anyone this story because the truth made him look even more suspicious. This is the fate many Black men share even in the 21st century.

The Beginning of the End

Marshall and Mr. Freedman, however, knew exactly how to win this case. They decided to bring in the officer who pulled the two over the night of the incident. When they got pulled over, it is crucial to understand that Mrs. Strubing had claimed that Joseph had ripped her clothes apart and made a make-shift gag to wrap around her head as well as her arms and legs, making her unable to move and beg for help from the officer.

What Mrs. Strubing had forgotten to leave out was that her vocal cords were working perfectly fine. Even if she was in shock and gagged, Mr. Freedman argued that she could have easily screamed for help when they got pulled over, and to prove it, Mr. Freedman in court put a gag in his mouth and yelled at the top of his lungs, leaving the courtroom in utter shock.

This was the beginning of the end. After 14 hours of deliberation, strategic Jury vetting by the defense, and Marshall silently helping Mr. Freedman on the sidelines, Joseph Spell was proven not guilty.

“In

recognizing the humanity of our fellow beings, we pay ourselves the highest tribute”

– Thurgood Marshall

Why Black Joy Tastes so Good

At the center of this story, beyond the legal, emotional, and racial battles, sits the striving for true Black Joy. The striving for Black Joy, as shown in the Spell case, is not simple. It makes you lie to keep your innocence, gets you subjected to silence in your own courtroom, makes you seek white allies to keep legitimacy in your mission, and that is why it tastes so good to actually experience Black Joy.

Hidden underneath the national attention this fine Black Figure has acquired for himself is the silent struggle and the self-deprecating world out there that tried to hinder his wins. Monumental Black figures, both the kind that make local or international impact, endure a level of scrutiny and mental brutality that make it all the harder to make a difference, let alone found the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in 1940. You see, Black Joy is finding the light in dark spaces, it is experiencing joy in the name of repelling Black racism and oppression. Black Joy is a distribution of culture because it has systematically been engraved in us to slave, to devastate, and to hide behind our white aof their wins, because although paradoxical, their contribution to the very society that deems their Joy to be undeserved, needs it. A man who stood for this all was named Thurgood Marshall. It is all thanks to him that we may continue to pay ourselves the highest tribute in recognizing humanity.

Constance Baker Motley and Her Unspoken Impact

Written by Nadine Black

Edited by Chiasokam Vincent

Introduction

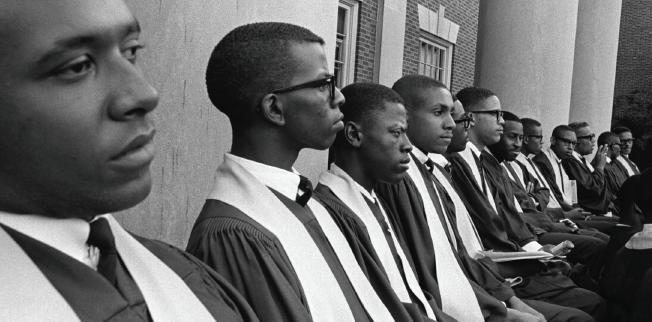

Constance Baker Motley, the first Black Woman to serve as a federal judge, proved herself to be a force within the legal field. She successfully argued and assisted with numerous Supreme Court cases, most notably Brown v. Board of Education. This case overturned the separate but equal doctrine that was established by Plessy v. Ferguson, ruling that it violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, ruling that segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Every person within the NAACP Legal Defense Fund was vital in contributing to the landmark decision that set a precedent for the future of racial segregation within the United States. Ofte, when people think of Brown v. Board of Education, they think of only the plaintiff, Oliver Brown, Thurgood Marshall, and Chief Justice Earl Warren. However, few acknowledge Constance Baker Motley's critical role in the case. In Brown v. Board, Motley drafted the original complaint, a crucial step in initiating the lawsuit. Although the complaint laid the fo undation for the plaintiff’s case, Motley’s contributions remain largely unrecognized. Her involvement is rarely acknowledged in classrooms, lecture halls, documentaries, and other forms of historical retellings. In addition to drafting the complaint, she assisted in developing the legal argument alongside Thurgood Marshall. This article focuses on examining Motley’s contributions to Brown v. Board and the broader implications to her exclusion from historical narratives.

Motley’s nearly concealed involvement in Brown v. Board is jarring considering her role within the case. Her involvement and knowledge was directly influenced in the court’s ruling, yet her contributions remain largely unrecognized. Motley being excluded from most scholarship on Brown v. Board of Education highlights a larger issue: the persistent marginalization of Black women in the legal field. Oftentimes in literature about legal cases, Black women are excluded, especially in cases from the 20th century. Black women in the legal field are a topic that is scarcely covered due to a history of racism and discrimination that continues to manifest itself through a lack of diversity within the legal space. The legal field does not accurately reflect the population that it represents, with almost 70% of California attorneys being white, while 60% of the California population is made up of people of color as of 2019 (Almarante, 2019). When Motley was just breaking into the legal field in the 40s and 50s, this gap regarding representation was more vast. Despite there being some advances over the decades, it is still hard for Black women to get into the field due to being marginalized both by their race and gender. There is a large disparity amongst women of color attorneys and their white counterparts, with women of color making up 16% of California attorneys while white women make up 26%. Representation matters. The parallel between Motley’s struggle to break into the legal field and the substance of Brown v. Board is a prime example of how her exclusion is a deeper concern within American society. Black struggle seeps into every aspect of life, whether it be achieving an equal education to one’s white

peers or entering the legal field to assist in expanding black rights. The inclusion of successful Black women within the legal field.

Brown v. Board was an integral case in a slew of civil rights cases that have been attempting to dismantle civil injustice. Motley utilized the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause in the complaint to push for the desegregation of public schools. It was argued that the segregation and white and Black children in public schools “solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregations denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment – even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors of white and Negro schools may be equal” (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)). Legal loopholes had allowed for segregated schools to be legal until this case was decided. Motley, alongside the NAACP Legal Defense Fund successfully challenged this discriminatory policy to allow for Black students to receive the same education as their white counterparts. Despite legal victories, social barriers continue to hinder Black students’ full integration into schools.

Motley’s invisibility within the talks about this case highlights the issue surrounding disparities regarding Black women in the legal field. Being in a male-dominated field, Motley’s contributions are often overlooked in favor of her male counterparts or other publicized male figures from the Civil Rights Movement era. More discussions surrounding Motley must occur, as her potential influence on Black girls across the country could lead to a drastic increase in the number of Black attorneys, as they would have an idol to look towards. According to the State Bar of California, the number of licensed Black attorneys in California was just 5% in 2023. Although this number has increased from 3%, this number is still shockingly low.

Some argue that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in the legal field undermine merit-based selection. Despite arguments against diversity, Black representation within the legal field is cited as an important aspect of the field by the State Bar of California. They state, “The State Bar advances diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the legal profession by focusing on key areas of influence, specifically the pipeline into the legal profession, retention and career advancement, and judicial diversity. The State Bar adopted as its diversity definition the reporting categories in Government Code section 12011.5(n): race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, and veteran status.” DEI within the legal field focuses on the systemic racism that keeps Black individuals from progressing into the field, with access to the legal world being blocked due to a lack of mentors, representation, and access to education. When figures like Motley are recognized in legal history, they inspire more Black individuals to pursue careers in law, with the help of programs that allow for access to be more fair access. Representation in the legal field is vital for improving access to legal help within not only the Black communities, but also other minority communities. Black attorneys bring lived experiences that can help dismantle systemic discrimination and make the law more equitable for all communities. The inclusion of Black attorneys allows for a more fulfilling representation in interpreting laws, with them bringing their perspective. Their lived experiences help challenge systemic injustices and create a

Rest in Peace, Rest in Power: The Enduring Impact of Judge Deborah Batts

Written by Helio Luti

Edited by Faith Ndegwa

A Reflection on Her Life

Recently, the world lost the soul of Deborah Batts on February 3rd, 2020. Deborah Batts was more than a federal judge, but also a professor and an advocate who presided over the U.S Southern District of New York (The HistoryMakers, 2025). Batts is a strong example of the power of intersectional identities, wit, and a mission toward justice. This article stands as a way to honor that history.

“Debbie greeted me as a kindred spirit,” quoted from Professor Kainen at Fordham Law, a close colleague of Deborah Batts. This woman was known as a mother, a lesbian, and a friend. Her open nature resonated with every person she met. Working with people was important for her. When asked what she would have pursued outside of law, she said “loved to be a doctor” for it was a people-oriented profession (Kainen and Shlahet, 2020). Her demeanor allowed her to be a mentor for others. She was known for her sharp mind and kindness when communicating with other judges. Deborah Batts helped to cultivate deep ties in a tense judicial world.

Beyond being a federal judge, Batts was an academic within the legal field. Deborah Batts received her Juris Doctorate from Harvard Law. She then became Fordham Law’s first African American professor, holding the position of tenured associate of law in 1980 (ACS, 2020). These details are the first aspect of her trailblazing legacy. Contextually, the 1980s were a time that had very low amounts of representation within law academia. During this period, only “four percent of faculty were identified as non-white”. Within this 4 percent of people of

“Batts is a strong example of the power of intersectional identities, wit, and a mission toward justice.”

- Helio Luti

color in academic positions, she was a Black woman who defied these statistics. Her role as a professor paved the way for law professor diverse representation today. According to the 2024 American Law School Faculty Study, faculty representation has changed dramatically for “Black professors and other professors of color represent a combined 42 percent of tenure-track faculty” (Kuehn, 2022). People such as Deborah Batts opened the door for diverse faculty, which is essential for law students to feel as though they are represented within their schooling. Deborah Batts brought the perspective of a Black woman's experience within practicing law to an academic space.

Her journey within law did not stop at academia, but her courage pushed her to move and pursue a career as a federal judge. Moving forward, Deborah Batts left her impact within the judicial system, and loudly continued being who she knew she was meant to be. In 1994, Deborah Batts became the first openly gay federal judge to take office. At this time, being queer had not been legalized or codified into law. The relationship between the queer community and the judicial system was difficult due to the lack of representation within the federal judiciary of queer voices leading to “many LGBTQ+ Americans distrustful and wary of the federal judiciary” (Article III Judges, 2024). However, Judge Batts helped change that narrative. In the last 20 years since her appointment, there has only been one other Black openly queer lesbian as a federal judge (The Advocate, 2020). To get to her position, Deborah Batts had to fight for her beliefs, and often, people did not support her because of her “life.” Upon her first appointment toward

this position, President Bush declined her appointment because Batts “did not align with federal judge values” (The Advocate, 2020). Homophobia has been an active issue within the legal field, but despite this, Deborah Batts still prevailed in becoming a federal judge within the Clinton presidency – a true testament to her will.

Furthermore, Deborah Batts represented a low percentage of Black women in high judicial positions. The judicial appointments in the year 1994 were primarily filled by white men. While Clinton’s appointments had a total of 106 women, Black women were 4 percent of that demographic, with only fifteen African American women appointed. Deborah Batts was a part of the 4 percent of Black women who were appointed to be federal judges during her year. This experience contributed to her work towards diversifying the pool of young lawyers. Deborah Batts played a key role in the development and implementation of the RISE program, which focused on “increasing diversity among lawyers appointed for indigent defenders”(ACS, 2020). As a Black woman, she not only worked to expand the legal field, but also to ensure people from her community were given the retribution they deserved.

One of the greatest examples of her impact was her ruling within the Central Park Five case, often nicknamed the Exonerated Five. To give detail, the Central Park Five case was one of the greatest examples of wrongfully convicted young Black men within the judicial system. Five young Black and Brown boys were wrongfully imprisoned for the rape and assault of a white woman. It was later revealed that the evidence used to incriminate them involved the use of coercion for false testimonies. Young Black and Brown boys were the victims of corruption within the New York City Police Department. The Central Park Five men sued the city for wrongful prison sentences that ranged from seven to thirteen years (Allie, 2014). Deborah Batts dismissed New York City’s motion for the case to be dismissed. Without Batt’s decision, these men would have lost the opportunity to be repaid with $40 million dollars. Her decision led to Black men getting fair compensation for lost time.

Conclusion

To end with, Batt’s legacy lies in how she used her identities to inform how to create an equitable legal system. As queer person, she understood how the queer community felt ostracized from the federal judiciaries. As a Black woman, she advocated for creating diverse backgrounds among young lawyers through the RISE program. Her judicial decisions changed the lives of many people, the Exonerated Five being amongst that group. She became the first Black professor within a white-dominated university. As one tells the story of Deborah Batts, her immense accomplishments can be seen. Multiple aspects of the legal industry were shaped through her actions. Batt’s life offers a key source of hope for administering change.

Rest in Power, Deborah Batts.

Stacey Abrams: A Catalyst for Change

Written by Jehlani Lewis

Edited by Abigail Pastel

Early Years of Advocacy

Stacey Abrams, a well-known champion for justice, civil rights, and voter equality, has single-handedly influenced the legal and political landscapes of Georgia. Well-known for her commitment to justice, Abrams has accomplished a plethora of significant milestones, such as being the first Black woman and the first female to occupy high-ranking political positions in Georgia. Abrams has been dedicated to civil concerns since she was young, beginning her voter registration advocacy as a freshman at Spelman College. (Voting Rights in America with Stacey Abrams: Transcript | JFK Library). After graduating from Yale Law School, she made impressive progress through the legal industry, rising to the position of Deputy City Attorney in Atlanta at the ripe age of 29. She first showed her extraordinary leadership abilities while serving as House Minority Leader in the Georgia House of Representatives. Her perseverance and passion led her to be the first woman to lead in the Georgia General Assembly, and the first Black American to lead in the House of Representatives.

2020 Presidential Election

Abrams finally gained recognition that she deserved after her impact on the 2020 presidential election. As the 2020 election approached, the stakes were higher than ever. The country was under intense political turmoil. Two candidates who represented polar opposite sides of the political landscape were at war. Former Vice President Joe Biden and Republican incumbent Donald Trump were neck-and-neck in a time plagued by many pivotal events in modern American history. The country was still grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, and Americans were questioning how each candidate’s public health policies would address their biggest concern. In addition to this, there was significant civil unrest in the country following the brutal and publicized murder of George Floyd by a police officer, triggering a nationwide discussion regarding racial inequality, ongoing structural discrepancies, and holding law enforcement accountable. Americans were finally coming together to call for social change, which could only be done under proper leadership and through efficacious policy reforms. High-risk issues needed solutions, and the American people recognized this, leading to the highest voter turnout in the US in over a century, with 159 million Americans participating in the democratic process. (2020 Presidential Election Voting & Registration Tables Now Available).

She directly assisted hundreds of thousands of individuals with registering to vote, creating new opportunities to participate in the electoral process for Black, Latino, and younger voters. By providing informational resources, she ensured that Georgian voters knew various methods of voting such as mail-in ballots, pre-election voting, and in-person elections. Through these endeavors, Abrams was able to change Georgia from being a swing state, which is one where two parties have very close levels of support, to a fully blue state for the first time in three decades. This was accomplished by continually spreading the message of the importance of being present for elections, as every vote matters. She has emphasized that “the antidote for voter suppression is voter turnout”.(MSNCB interview). Abrams' strongest weapon against voter suppression is her voice. She would host public outreaches in order to inform new voters on their

rights, ensuring that they were well equipped to participate in the voting process. She made sure that people know the significance of their vote, while simultaneously making sure that it was possible for them to even do it. Voting stations in communities of color were riddled with broken voting machines, and through litigation, she was able to get the state to allocate funds for a massive haul of new machines. (Voting Rights in America with Stacey Abrams: Transcript | JFK Library). Her influence went beyond just the presidential election, she also shaped the results for Georgia’s Senate runoffs in 2021, which is what guaranteed Democratic control of the United States Senate. Abrams was able to recognize the importance of voter participation in influencing politics and effectively make a change in her community through grassroots organizing.

This high-stakes election would have had very different results if it weren’t for the tireless efforts of Stacey Abrams. Although she couldn’t reach every individual affected by the election, he influence was seen all across Georgia. She fought hard against voter suppression that has plagued the South since the Reconstruction era. To advocate for voter equality, she founded Fair Fight Action, which effectively increased access to ballots in marginalized neighborhoods where availability is limited. Abrams did this through grassroots organizing, providing education to voters, and spreading awareness about voter misinformation.

Local Initiatives

Abrams has helped to dismantle oppressive laws that have been designed throughout history to restrict people of color’s access to voting polls. Her work in Georgia is especially significant because, as a southern state with a long history of racism, it is notorious for trying to silence black voices in politics. Despite provisions in the 14th and 15th Amendments, as well as legislation like the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guarantees equal protection, Georgia has repeatedly employed legal tactics to try and skew the black vote. For example, just four years ago, Georgia imposed a new law called the Election Integrity Act in response to the fraudulent accusations of the 2020 election. This act required an ID for absentee ballots, which are ballots placed from home, as well as limited the number of ballot drop boxes, and even made it a crime to pass out food and water to voting lines. (Georgia Republicans speed sweeping elections bill restricting voting access into law | CNN Politics) Although Georgia republicans claimed that the law was created to ensure secure and fair elections, its primary consequence would inconvenience disenfranchised groups that may struggle to meet such requirements.Such restrictions could have significant implications on elections in the future, both locally and nationally. When the law was passed, Abrams was already hard at work combating previously instated voter limitations. Fair Fight Action is centered around exposing and battling anti-voter policies. The organization had already had an active case open against the Georgia Secretary of State in court for similar legislation. The case, Fair Fight Action, Inc v. Reffensperger, argued that the law specifically targets black voters, as they are more likely to use remote voting methods, while less likely to have the identification that the law recquires( Federal judge upholds Georgia election law in challenge brought by Abrams)In addition to this, the 2021 provision that banned the distribution of food and water was blatantly discriminatory, as the average wait time at ballot spots are longer in communities of color than predominantly white communities (Waiting to Vote | Brennan Center for Justice). Unfortunately, the court determined that the evidence provided by Fair Fight Action was insufficient to demonstrate the weight that the new burdens

had on voters. This decision was made despite indications that the new ID system put nearly 50,000 voter registrations on hold right before midterm elections in 2018 (Federal judge upholds Georgia election law in challenge brought by Abrams). Even though the courts upheld Georgia’s election laws, it became the longest-running voting rights lawsuit, remaining unsettled for four years - a testament to Abrams' dedication to the cause. Despite the loss, the case’s widespread reception brought attention to the issue of the state’s suppressive election tactics. It gave voter rights activists exposure and a stronger voice to be heard. Abrams did not let the disappointing court decision discourage her, as she inspired over 3,000 Georgians to start using their platforms to advocate for voters through this case alone. Through such efforts, Stacey Abrams has continued to fulfill her vows to be the main obstacle in the course of legislation that seems intent on “reviving Georgia’s dark past of racist voting laws”. (CNN interview). Conclusion

There is is no denying Stacey Abrams' influence on Georgia's political scene. In addition to revolutionizing the state's electoral process, her commitment to justice, civil rights, and voter equality has created a strong standard for grassroots movements across the country. She strengthened underrepresented groups and made their voices heard in one of the most important elections in American history. For the first time in decades, Georgia became a Democratic state because of her leadership, determination, and calculated actions. Abrams has reshaped what it means to be a leader, an advocate, and a force for change in the US, thus, her impact goes far beyond a single election. Despite the victory in 2020, the current state of the United States shows that there is still significant work to be done in creating equity for all. She claims that “now, more than ever, Americans must demand federal action to protect voting rights”(Voting Rights in America with Stacey Abrams: Transcript | JFK Library). Stacey Abrams cannot combat inequality everywhere, but by starting with the polls, she has made a significant impact on nationwide disparities.

ALL IMAGES:

Front/Back Cover & Contents: Photographed and edited by Tristian Kinney

The Black Panther Party & Its Legacy by Faith Ndegwa

-AFRICAN & BLACK HISTORY (@AfricanArchives), Twitter (Oct. 15, 2022, 9:30 AM), https://x.com/ AfricanArchives/status/1581321591757344768

-I was at the birth of the local Black Panther Party. There’s still so much work to be done. https://www. sandiegouniontribune.com/2024/02/02/i-was-at-the-birth-of-the-local-black-panther-party-theresstill-so-much-work-to-be-done/ (last visited Apr 26, 2025)

-Black panther demonstration in front of the Alameda County Court House, Oakland, California, during Huey Newton’s trial, July 30, 1968, from the vanguard: A photographic essay on the black panthers SFMOMA, https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/2014.70/ (last visited Apr 26, 2025)

Derrick Bell: CRT & The Fight for Racial Equity by Anthony Lewis: - Photograph of Derrick Bell speaking at Harvard Law School protest, 1990, The Harvard Crimson, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2021/11/4/derrick-bell-memory/ (last visited May 5, 2025). The Harvard Crimson

-Photograph of Derrick Bell in 2007, BlackPast.org, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/bell-derrick-albert-jr-1930-2011/ (last visited May 5, 2025). BlackPast.org

Law and Love, Lock and Key: Evolution of Black Wedlock by Jeannine Briggs

- Born to John and Elizabeth Van Der Zee who worked for President Ulysses S. Grant, Van Der Zee made his first photographs as a boy in Lenox, Mass. By 1906 he Source: Harlem World Magazine

The Color of Justice in a Segregated Courtroom by Yadeal Asfaw Rest in Peace, Rest in Power: Deborah Batts by Helio Luti

-Deborah Batts, First Openly Gay Federal Judge, Remembered for Trailblazing Career, The Harvard Crimson (June 28, 2022), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2022/6/28/deborah-batts-federal-judge/.

-Fordham Law Mourns Death of First African American Faculty Member Hon. Deborah Batts, Fordham Law News (Feb. 3, 2020), https://news.law.fordham.edu/blog/2020/02/03/fordham-law-mournsdeath-of-first-african-american-faculty-member-hon-deborah-batts/. -Bill Hutchinson, First Openly Gay Federal Judge, Deborah Batts, Dies at 72, ABC News (Feb. 3, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/US/openly-gay-federal-judge-dead-72/story?id=68727176.

Constance Baker Motley and Her Unspoken Impact by Nadine Black -Photograph of Constance Baker Motley with colleagues at a 1992 judicial event, United States Courts, https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2020/02/20/constance-baker-motley-judiciarys-unsung-rights-hero (last visited May 5, 2025).

United States Courts

-Portrait of Constance Baker Motley (1921–2005), oil on canvas by Samuel Adoquei, Columbia University Libraries, https://library.columbia.edu/libraries/avery/art-properties/acquisition-highlights-2010-2019.html (last visited May 5, 2025).

Stacey Abrams: A Catalyst for Change by Jehlani Lewis -Image of Stacey Abrams, Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/4996249577704695/ (last visited May 2, 2025).

-Image of Stacey Abrams, Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/4611615784268297216/ (last

The Black Panther Party & Its Legacy by Faith Ndegwa

“Black Power: Selections from the Gerth Archives at CSU Dominguez Hills: The Black Panther Party and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.” n.d. Black Power: Selections from the Gerth Archives at CSU Dominguez Hills. https://scalar.usc.edu/works/black-power-selections-from-the-gerth-archives-at-csu-domi nguez-hills/the-black-panther-party-and-the-student-nonviolent-coordinating-committee. Bandes, S. (2000). Tracing the Pattern of No Pattern: Stories of Police Brutality. Loy. LAL Rev., 34, 665.

Elgot, Jessica. 2017. “Beyoncé Unleashes Black Panthers Homage at Super Bowl 50.” The Guardian. The Guardian. November 29, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/feb/08/beyonce-black-panthers-homage-blacklives-matter-super-bowl-50.

Felicich, N. C. (2017). Eating your greens: community gardens and gentrification in Oakland. Kaur, Anumita. 2023. “How Black Panthers’ Ideals Shaped 2Pac — and His Groundbreaking Music.” Washington Post, August 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/08/11/2pac-hip-hop-black-panthers/. McFadden, Chuck. 2017. “Armed Black Panthers in the Capitol, 50 Years On.” Capitol Weekly. April 26, 2017. https://capitolweekly.net/black-panthers-armed-capitol/. Reid, C., & Laderman, E. (2009). The untold costs of subprime lending: Examining the links among higher-priced lending, foreclosures and race in California. San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Senescall, Marie. 2022. “Global Center for Climate Justice.” Www.climatejusticecenter.org. March 22, 2022.

https://www.climatejusticecenter.org/newsletter/feeding-our-young-how-the-black-panthe rs-brought-school-breakfast-to-america.

Smithsonian “The Black Panther Party: Challenging Police and Promoting Social Change.” 2020. National Museum of African American History and Culture. August 23, 2020. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/black-panther-party-challenging-police-and-promoti ng-social-change?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Taylor, Nateya. 2022. “More than a Fashion Statement.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. September 16, 2022. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/black-panther-party-uniform. Verso Books. 2020. “Black Panthers’ United Front against Fascism Conference.” Verso. June 3, 2020.

SOURCES

Derrick Bell: CRT & The Fight for Racial Equity by Anthony Lewis Bell, D. A. (1980). Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93(3), 518-533. https://doi.org/1340546

Bell, Derrick, 1930-2011. (2004). Silent covenants: Brown v. Board of Education and the unfulfilled hopes for racial reform. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press,

Coates, T. (2021, September 20). The man behind Critical Race Theory. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/20/the-man-behind-critical-race-theory Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Thomas, K. (Eds.). (1995). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New Press.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York University Press.

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5441df7ee4b02f59465d2869/t/5d8e9fdec6720c0557cf55fa/ 1569628126531/DELGADO++Critical+Race+Theory.pdf

Harpalani, V. (2017, November 10). “It just means telling the truth”: Professor Derrick Bell’s Critical Race Theory. University of Pittsburgh Center for Civil Rights and Racial Justice. https://www.civilrights.pitt.edu/it-just-means-telling-truth-professor-derrick-bells-critical-raceth eory

Los Angeles Times. (2025, January 29). Trump's orders target Critical Race Theory and antisemitism on college campuses. Los Angeles Times.

https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2025-01-29/trumps-orders-target-critical-race-theory-and -antisemitism-on-college-campuses

Perez Jr., J., & Wilkes, M. (2025, January 29). Trump issues orders on K-12 ‘indoctrination,’ school choice, and campus protests. Politico.

https://www.politico.com/news/2025/01/29/trump-k12-indoctrination-school-choice-campusprot ests-education-00201235

Salem Press. (2016). Derrick Bell. In [Title of the book]. Salem Press. https://online.salempress.com/articleDetails.do?bookId=832&articleName=INVH_001

The Advocate. (2025). Why companies are abandoning DEI initiatives. The Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/news/companies-abandoning-dei#rebelltitem14

The White House. (2025). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump protects civil rights and merit-based opportunity by ending illegal DEI. The White House. Law and Love, Lock and Key: Evolution of Black Wedlock by Jeannine Briggs Act of Dec. 19, 1865, No. 4736, 1865 S.C. Acts 291 (Black Code).

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857).

Elizabeth Caucutt, Nezih Guner & Christopher Rauh, Is Marriage for White People?

Incarceration, Unemployment, and the Racial Marriage Divide, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13275 (2018).

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883).

State v. Samuel, 19 N.C. 177 (1836).

Tera W. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century (Harvard Univ. Press 2017).

U.S. CONST. amend. XIV, § 1.