Shades of Black Identity: Navigating Intersectional Spaces

he Black Pre-Law Association is committed to the education of the legal system and how it impacts the Black community. We created the first ever undergraduate Black law journal at UCLA to inform not only the Black Bruin community, but the larger UCLA community. We cover a wide range of topics regarding laws, policies, legislations, and our government. Our law journal serves as a m otion to increase awareness on pressing issues and injustices within the Black community and what we can do going forward. As a pre-law organization, the current Presidents Kennedy McIntyre and Jayda Jackson have made a contribution and commitment to expanding th e pillars of BPLA and the BPLA Law Journal to discuss politics, policy, and government.

This law journal will serve as a part of their commitment to ma ke BPLA holistic in policy, government, and politics in addition to the law. We need a law journal that will cover the vast inequities that occur within our community and this is only part of the mission to make legal education accessible and a priority for our community. The Black Pre-Law Association is dedicated to uplifting and advancing our members in the area of professional, career, and personal development as well as community service. The Black Pre-Law Association Law Journal acts as a separate entity that is under the regular Black PreLaw Association, but will serve on the journalism and media side. Our members and executive board that serve on our Law Journal team will have the opportunity to enhance and develop their writing, crit ical thinking, data analysis, and research skills.

The Black Pre-Law Association will advance its law journal members and executive board to have career and professional development in the areas of law, journalism, and media. We are committed to connecting with other media organizations at UCLA to prepare our members with the correct training and mentorship needed to discuss law, politics, and our government. It is our duty to make not only Black UCLA students accessible to this information, but other college campuses and the larger Black communities in which our universities neighbor.

n my inaugural year as Editor-in-Chief of the Black Pre-Law Journal, I set out to delve into a topic that resonated deeply with not ju st myself, but also with our team of writers, editors, and executive membe rs. Coined by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989, the term intersectionality transc ends mere discussions of race and gender. It permeates various facets of our lives, from healthcare and the legal system to our work environ ments and beyond. Understanding intersectionality is paramount in navigat ing the intricate dynamics of social movements and grappling with the c omplex challenges confronted by marginalized communities. Given our pre-law journal’s identity as a Black organization, I recognized that exploring intersectionality would offer a rich learning experience for our writers and editors. It is a pervasive force in our lives, shaping our dail y experiences in profound ways. As Black college students, we confront its manifestations daily on our campus—whether in the classroom or simply walking its paths. Discrimination and targeting are all too familiar, often occurring so routinely that they risk being overlooked. Thus, I am particularly gratified to dive deeper into this crucial topic. This year, I have been immensely proud of our writers and editors for all of their exceptional w ork. Working alongside a talented and diverse team of Black students, we hav e crafted and refined unique pieces for Volume III. As you peruse these pages, I hope each contribution offers you insight into the complexity of Black identity and life. Serving as this year’s Editor-in-Chief has been a privilege and I am thrilled to finally share the fruits of our labor with all of you.

Ure Egu

BPLA Editor-in-Chief, 2023-2024

Congratulations to all of the Black Graduates of 2024!

Black Pre-Law Association Statement of Purpose

Kennedy McIntyre & Jayda Jackson | BPLA Co-Presidents

A Letter From the Editor

Ure Egu | Editor-in-Chief

The Complexion of Crime

Faith Ndegwa | Staff Writer

Jeannine Briggs | Staff Editor

The Policing of Black Hairstyles in Professional Settings

Yadeal Asfaw & Dorothea Amadin | Staff Writers

Dorothea Amadin & Alana Akiwumi | Staff Editors

A Legal and Political Perspective on Modern-Day Institutional Racism

Anthony Yahya | Staff Writer

Jenna Besh | Staff Editor

Caste and Justice

A’shiyah Dobbs | Staff Writer

Jehlani Lewis | Staff Editor

Medical and Mental Care In Carceral Facilities

Zaia Hammond | Staff Writer

Combatting Period Poverty

Victoria Williams | Staff Writer

James McCann | Staff Editor

The Impact of Housing Policies on African Americans

Anthony Lewis | Staff Writer

Abigail Pastel | Staff Editor

Ure Egu | Editor-in-Chief

Political Science & African American Studies Major

Camille Whittaker | Secretary

Political Science Major & Labor Studies

Minor

Abstract

This journal examines the pervasive issue of colorism and featurism and its implications against the Black community within the criminal justice system. Research increasingly indicates that gradational differences in skin tone, along with features deemed “more” Afrocentric, are key factors in the internal stratification of life opportunities and future prospects for African Americans. These forms of discrimination contribute to the disproportionate targeting, arrests, and punishment of individuals with darker skin tones and certain features. Drawing upon previous Black Liberation and Abolition movements, this research explores the historical roots and societal influences that perpetuate different types of anti-blackness within historically oppressive institutions like the justice system. It delves into the intricacies of these biases, examining how they shape law enforcement practices, judicial decision-making, and sentencing outcomes. Furthermore, this piece highlights the psychological and social consequences of colorism and featurism, including internalized racism, low self-esteem, and limited opportunities for upward mobility. It concludes by underscoring and describing the urgent need for community engagement, educational reform, and changes in policy and educational initiatives to address these deeply ingrained biases and inequity within the justice system. This journal highlights the stark reality that, in America’s justice system, Blackness itself can be unjustly deemed a crime, necessitating immediate transformative action.

Introduction

Colorism is a form of discrimination that specifically targets and marginalizes people with darker skin tones, while featurism describes the preference or

favoritism towards features that align closer with Eurocentric beauty standards (Hunter & Taylor). Prejudices like colorism and featurism perpetuate divisions within the Black community and impact the treatment and experiences of Black people within the criminal justice system, influencing the severity of charges, sentencing, and even the likelihood of being stopped by law enforcement (Barideaux). These biases create an uneven playing field where justice is not color blind, but is influenced by immutable characteristics. True justice for the Black community will remain elusive in every system until the systemic issues of colorism and featurism are adequately addressed.

During the enslavement of Africans in America and the subsequent Black liberation and abolition movement of the 1990s, colorism and featurism were pervasive elements that further complicated the struggle for equality. Enslaved Black individuals with lighter skin tones, often the result of forced relations between a white master and a Black enslaved person, were sometimes afforded privileges, such as working indoors which increased their chances of learning practical skills like reading and writing, which inadvertently implanted a hierarchy based on color and features within the Black communities on plantations (Keith). This bias persisted into the 20th century, influencing the social dynamics of the Black liberation movement. Leaders with lighter skin or features closer to white beauty standards were perceived as more palatable to the broader public, receiving more attention and resources, while darker-skinned activists faced an additional layer of prejudice, complicating the fight for justice and equality (Monk). Even prominent Black activists such as W.E.B. Du Bois, who’s lighter skin may have influenced his initial denial of colorism and its impact, were not immune to anti-Black prejudices, underscoring a pervasive ignorance about the intersectionality within the fight for Black liberation (Kendi). Ignoring the prejudices of intersectionality within broader issues of race not only hinders progress towards resolution and liberation, but unfairly

shifts the blame onto darker-skinned individuals and those with Afrocentric features for their own discrimination. The intersection of colorism and feature with racial oppression highlighted the multifaceted nature of discrimination that activists had to address within society and even within their own ranks.

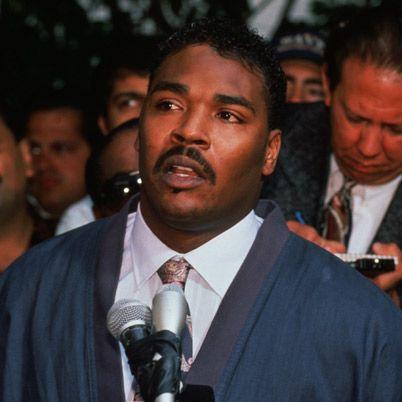

The legacy of colorism and featurism within the Black community is deeply intertwined with the history of the American criminal justice system. Originating from enslavement, slave patrols, or groups designated to catch Black people who tried to escape slavery, were precursors to modern policing; these patrols were influenced by prejudice, disproportionately targeting those with darker skin and more African features (Spruill). Policing bias persisted into the 20th century, exemplified by high-profile incidents such as the beating of Rodney King in 1991, which stands as one of the most widely publicized cases of police brutality and served as a wake-up call to many regarding the horrifying realities Black people have long endured (Jacobs). The inhumane treatment of Rodney King and similar atrocities have led to a deep-seated distrust among the Black community towards law enforcement, often manifesting as fear and hesitation to seek police assistance even in situations that would typically involve policing (Brunson). The lack of trust is evident in the daily lives of the Black community, as many individuals live in fear of law enforcement, with a prevailing worry that interactions with police could escalate due to preconceived notions and racial profiling, often rooted in colorism and featurism.

Law Enforcement Practices, Judicial DecisionMaking, and Sentencing Outcomes

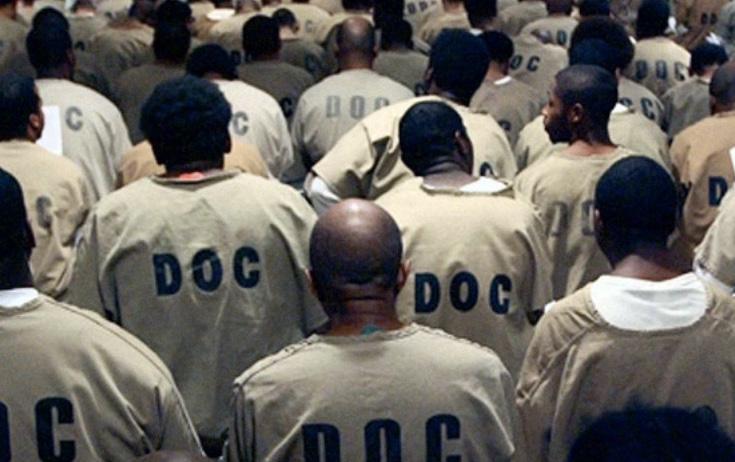

The influence of anti-blackness within law enforcement is a critical concern as individuals with darker skin and more prominently Afrocentric features are often disproportionately targeted and subjected to worse treatment. Profiling can result in an excessive use of force, as seen in cases like Rodney King or, more recently, the global protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd. When darker-skinned individuals are more frequently stopped, this increases their likelihood of subsequent arrests and convictions, irrespective

“Profiling can result in an excessive use of force, as seen in cases like Rodney King or, more recently, the global protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd.”

The bias in policing practices contributes to a cycle of criminalization that disproportionately impacts communities of color, perpetuating stereotypes and exacerbating social and economic inequalities. ”

Faith Ndegwa Douglas Burrows/Liaison/Getty Imagesof actual criminal activity (Smart). The bias in policing practices contributes to a cycle of criminalization that disproportionately impacts communities of color, perpetuating stereotypes and exacerbating social and economic inequalities. Additionally, encounters with law enforcement are not benign – they can, and often, escalate, leading to tragic outcomes which, in turn, continue to build a sense of distrust between Black communities and the police forces that are meant to serve them.

In the realm of judicial proceedings, the impact of colorism is similarly troubling.Research indicates that darker-skinned individuals are more likely to receive harsher sentences than their lighter-skinned counterparts for comparable offenses (Smart). This bias reflects deeply rooted preconceived notions that associate darker skin and certain physical features with aggression and guilt, often leading to a presumption of criminality and other harsher sentencing outcomes. Such biases undermine the foundational tenet of equality before the law and highlight the urgent need for reforms to address these long-standing prejudices.

Individual and institutional discrimination against the Black community goes beyond physical dangers and the lack of opportunities.

David R. Williams, a professor of African American studies and Sociology at Harvard, aimed to study how unjust police killings affect the mental health of Black Americans. Williams analyzed police shootings over three years and compared them with data from the CDC about mental health, discovering a link between fatal police shootings of unarmed Black Americans and the declining mental health of Black individuals within that state. Additionally, he found that the shooting of a Black person, armed or unarmed, had no major effects on the mental states of white people within that state (Pazzanese). Studies like the one Williams conducted demonstrate that discrimination against the Black community not only poses a threat to the community’s safety but seriously impacts their mental wellbeing.

To combat the deep social and systemic issues of colorism and featurism within the criminal justice system, a multifaceted approach is necessary, encompassing policy reform, active community engagement, and educational initiatives. Policy reform should aim to target the systemic biases that exist at every level, such as the mandatory minimum sentencing laws that disproportionately affect Black individuals (Fischman). Legislation like The First Step Act, a bipartisan criminal justice bill signed into law in 2018, began to address such disparities by reducing mandatory minimums for nonviolent drug offenses (BOP). Community engagement is also pivotal; programs like the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) initiative work to bridge the gap between law enforcement and the communities they serve, aiming to dismantle prejudices and foster mutual trust (COPS). Lastly, education reform can play a transformative role by incorporating anti-racist and culturally competent curricula that challenge colorism and featurism, preparing future generations to recognize and resist these biases. By instilling a more comprehensive understanding of the historical and social contexts that shape perceptions of various complexions and features, educational institutions can cultivate a more just society.

When examining the intersectionality of race, colorism and featurism within the criminal justice system, it is evident that these biases have significant implications on members of the Black community in America. The historical context and social influences contribute to the disproportionate targeting, arrests, and harsher punishments faced by individuals with darker skin tones and more Afrocentric features. To address these systematic disparities, it is crucial to engage communities and implement educational reforms. By promoting cultural competence and positive representation, we can challenge stereotypes and reshape perceptions both within and outside the Black community. These efforts, coupled with policy reforms, have the potential to create a more equitable and just criminal justice system that recognizes and values the diversity of individuals, regardless of their skin color or physical features.

Your Hair, It’s

If you were to take out your phones and begin a search on the internet for “professional hairstyles,” only photos of white men and women with straight hair would show up. The inverse is true too; if you were to google “unprofessional hairstyles,” the images that show up are Black men and women, rocking their braids, afros, or dreads. In 2016, an MBA student by the name of Rosalia discovered this, when she googled “unprofessional hairstyles” for work (The Guardian). Her tweet about this went viral, reaching not only thousands of people but resulting in the diversification of the hairstyle images that pop up today – including braids. After getting called out, Google images changed their algorithm but this issue may have just revealed a wider social landscape.

In the hit show, Scandal, the main character Olivia Pope is portrayed to be a well put together African American lawyer that wears her hair perfectly coiffed and straight throughout the entire series. That is of course, until Olivia starts to face challenges and hardships in her life, that her character begins to wear her natural afro-styled hair— as if to reflect the fact that Olivia had become “undone.” It was whenever her character went through crises or even got kidnapped, that we began to see her curly hair. Somehow, it still seems that these perceptions of Black hair or Black people as a whole go beyond the scope of Google search engines or the media.

In 2010, child psychologist and University of Chicago professor Margaret Beale Spencer, a researcher in child development, conducted a study that tested 133 children from different socioeconomic and racial backgrounds on how they saw different skin tones (CNN News). When presented six different dolls varying in skin color, the children consistently associated negative traits to the darkest dolls presented. Most notably, when asked to “point to the ugly child,” around 60% of the children, including African American children, pointed to the darkest doll (CNN News). From the Google search engine, to how the media portrays Black women, to even the way children perceive a doll’s skin color; the question of how these all connect emerges.

More importantly, what factors aid in the perception that Black aesthetics are unprofessional, and how does the legal system influence this, if at all? The court system has slowly begun to unveil the racist and biased social landscape hidden in our realities. To African Americans however, this issue is nothing new or novel– minorities have suffered hair discrimination for decades. In 2019, the Creating a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair, (C.R.O.W.N) Research Study surveyed 1000 black women and 1000 white women from the ages ranging from 25 to 64 about workplace discrimination against natural hair. The study showed that African American women face the highest cases of hair discrimination and thus are most likely to get sent home from their workplace (Dove, The CROWN Research Study). This same study showed that an overwhelming 80 percent of African American women feel the need to change their hairstyles in order to fit in. The legal system unfortunately only worsens thesecases and statistics as it underscores a more systemic issue.

Most notably, in 2010, a flightattendant by the name of Rene Rogers was forced by American Airlines to stop wearing her cornrows hairstyle as it did not fit the work’s standards (Henson). Fueled with both rage and confusion, she filed a lawsuit against American Airlines, when she was threatened to lose her job unless she began wearing her hair in a bun. In court, Rogers argued that her inability to wear her cornrows hairstyle was discriminatory specifically for Black employees, like herself. Rogers also highlighted the cultural and historical significance of Cornrows in Black history. Shockingly, or perhaps not, the court immediately dismissed Rogers’ case, as they explained that the cornrows hairstyle was an “easily changeable characteristic” in accordance with Title 6; a grooming policy (Henson). The court did however acknowledge this particular hairstyle to be associated socioculturally to African Americans but ruled against Rogers. So, what was the court’s suggestion, you may ask? Well, Rogers was told that she can simply change back and forth between her cornrows

and her natural hair style between work hours. Dismissing the long hours it takes to achieve such protective hairstyles (over 8 hours of labor), how expensive these hairstyles can be but also how simply unfair it would be for Rogers to spend her valuable time and money while her peers simply did not have to do anything.

This is nothing new, according to researcher Renee Henson, where there are grooming policies that enable the court to tell Black men and women to adhere to white standards as their hair is an easily changeable characteristic. Not snowing that changing our hair is changing our identity, and our ability to express the freedom just recently granted to African Americans (Henson). Researcher Henson shows that our inability to have racially inclusive policies and laws shows how the court system directly contributes and worsens the perception that Black hair is in fact unprofessional. This systemically legal issue scopes beyond workplaces, showing up in schools as well. There have been countless instances where students have been sent home or withdrawn from their school due to their hairstyles. In 2018, a 16-year-old Black high school wrestler in New Jersey was given an ultimatum at the beginning of his wrestling meet: - he could cut off his locs or forfeit his match (CNN News). The referee publically and haphazardly cut off his locs before the meet. Schools are able to further restrict black students’ hairstyles through stringent and discriminatory dress code policies. Again, there are countless cases in which Black individuals all around the US endure constant scrutiny and consequences for simply existing.

So much so that the C.R.O.W.N Coalition became enacted in certain states. This organization is an alliance of organizations (including Dove, Color of Change, Western Center on Law and Poverty, and the National Urban League), dedicated to the advancement of antidiscriminationlegislation. CROWN, standing for Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair, prohibits discrimination based on hair style and hair texture. But with any enactment comes refusals. Certain states have chosen against enacting the CROWN Act, most notably a 2017 case against

the Catastrophe Management Solutions, ruling against the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The court held that refusing to hire someone because of their dreadlocks is legal (EEOC v. Catastrophe Mgmt.). There are, however, three states where it is illegal, California becoming one of the first states to pass the Crown Act to ensure protection against natural hair discrimination.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the policing of Black hair and traditionally Black hairstyles is not a new phenomenon, it is ingrained in virtually every aspect of American society. From critical depictions of Black women’s features in film and TV, to the negative way we socialize children and young adults in schools to feel about Blackness, to the limiting regulation of Black women’s hairstyles in their places of work. It is abundantly clear that although traditionally Black hairstyles are not explicitly prohibited through legislation, there are still powerful socially constructed barriers against Black hair and blackness in the United States. Fortunately, “The C.R.O.W.N. Act,” a meaningful California law is continuing to gain traction. Hopefully, states nationwide will pass similar legislation to fight these discriminatory practices.

This article examines the legal and political intersections of modern-day institutional racism within the United States. It argues that, despite progress made through civil rights legislation, racist oppression remains deeply embedded in American laws and policies. This analysis aims to highlight the implications of such contemporary manifestations with blatant systemic racism. These political and judicial factors include mass incarceration, voter suppression, and discriminatory policing practices. These are all rooted in a long history of legal and political disenfranchisement of African American citizens. This article further emphasizes the need for comprehensive legal and political reforms which dismantle such unjust systems and work towards a truer form of racial equity and justice within our greater society

While blatant legal discrimination against African American is now prohibited, institutional racism continues to impact our community in today’s society. These current manifestations of systemic oppression are more subtle, yet continue to cause substantial harm to the greater community. From instances of marginalization, racial profiling, and police brutality, African American citizens often still face immense barriers to true equity. These injustices are perpetuated through legal statutes, laws, policies, and political structures within American society. Thus, these socio-political inhibitors often serve to fuel a sense of exclusion among the community. It also

purports discriminatory narratives that African Americans exhibit more “threatening behavior” due to an inflated carceral rate.

The U.S. criminal justice system has become a powerful tool for the legal and political oppression of African Americans post-slavery. Statistically, African Americans only make up about 13.4% of the U.S. population but are impacted on 22% of overall fatal police shootings. Furthermore, the War on Drugs initiative in the 1970s and other ‘‘tough on crime’’ policies brought about in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in an unprecedented expansion of incarceration. This increased carceral rate disproportionately targeted African Americans as they made up 11.1% of the country but substantially made up about 46.7% of the population within state correctional facilities. Currently, as of 2021, African Americans are arrested at a rate 3.4 times that of their White peers and this trend of carceral displacement seems to only be increasing in recent years. Several policing system practices such as the “stop-and-frisk” have only led to increasing arrests amongst the community but have also purported narratives of institutional racism. The idea behind such a practice is that an officer can perceive you to be suspicious and then frisk you on the spot to check. Although in theory this might sound proactive, such a procedure often serves as a greater tool for discrimination against African Americans who are frisked at an abnormally high rate when compared to other groups and at times wrongfully arrested. Such policing activity serves to increase incarceration but is also implemented in conjunction with mandatory minimum sentencing laws. These laws would serve to impact African Americans and increase the cycle of incarceration with no regard to the individual circumstances occurring in the context of a person’s life or their lived experiences.

The New Jim Crow: Discrimination in Current Convictions

In particular, these discriminatory policing practices and cruel sentencing laws have seen a large host of implications in modern society. Most notably, the overbearing conviction-rates have created a racialized system of social-control that legal scholar Michelle Alexander has termed ‘‘The New Jim Crow’’. This concept is extremely important when understanding the political and legal reforms that are necessary to rectify such systems of control. It’s noted that an aexcessively large percentage of African Americans

are trapped within the carceral system and thus denied their freedoms. However, the exploitation within this system expands further than a limitation of one’s personal freedom. Instead, incarcerated individuals have also been found to participate in forced-labor inside of these prisons. This modern-day slavery is permissible under a constitutional loophole which allows for large corporations and industries to profit off the labor of incarcerated individuals.

Institutional racism also operates through laws and policies designed to suppress the political participation and power of African American voting groups. Currently, there are felon disenfranchisement laws that prohibit this population from voting. This understanding, coupled with the disproportionately high incarceration rate, means that over six million Americans will be unable to vote, including 1 in 13 Black adults. Other voter suppression tactics, such as strict voter ID requirements and the removal of voter polls have also been utilized to disenfranchise African Americans. Several polling locations within minority neighborhoods have also been closed down. This primarily serves as a political tool to perpetuate voter suppression and institutional racism. These political efforts disproportionately impact African Americans’ ability to vote. However, other political tools serve to inhibit the political influence of the African American community such as gerrymandering and redistricting.

Gerrymandering is categorized as influencing district boundaries that are utilized to determine representation in the electoral system. Such instances of biased redistricting serve to advantage or disadvantage a particular voting group. These tactics are imposed through “cracking” which splits up groups of voters with similar characteristics and inhibits their ability to elect their preferred candidates in any district. Another practice in this context is “packing” which serves to cram certain groups of voters into as few districts as possible, which unfairly impowers such groups to elect their preferred candidates which unfairly impowers such groups to elect their preferred candidates. These political strategies help to further embed institutional racism into politics as communities of African Americans have been historically “cracked”, especially in the context of Southern states. Thus, these political barriers hinder the ability of this group to vote and shape the policies and leadership that directly influence their daily lives.

Beyond this, these impactful legal and political systems must strive to become a greater instrument for dismantling racism, rather than upholding it. This will require a fundamental rethinking of legal doctrines and constitutional principles to improve racial equity and challenge the legacy of marginalization in the American justice system. Instances of such reforms are already brewing as a recent constitutional amendment is aiming to combat carceral slavery and forced labor by enacting a crucial change. ACA 8 aims to amend the constitution in order to, “prohibit slavery in any form, including forced labor compelled by the use or threat of physical or legal coercion”. However, at the time of this article, this amendment has yet to be enacted. This demonstrates the blatant need for proactive anti-racist legislation and policies to remedy these past injustices which have historically marginalized African Americans. Political leaders and institutions must also commit to anti-racism with concrete steps in mind to empower the African American community given the context of several forms of institutional racism. Thus, increasing diversity and representation in politics, governing bodies, and the judicial system would serve as an example of crucial reform that is necessary to reshape policymaking and restore equity.16 Political organization and mobilization must continue in the face of adversity amongst the African American community to better push for accountability and equitable reforms.

As previous protests have powerfully demonstrated, the legal and political struggle for racial justice is truly far from over. Institutional racism remains a defining feature of American society that is upheld by political systems and their structure. This demands for immediate reform in such systems which uphold modern day marginalization. As we confront this difficult reality, we must also recognize our collective power to influence these policies and truly forge a more equitable future for all. This path forward is by no doubt extraneous, however the cost of inaction is far greater. Our laws and policies must become tools for liberation, rather than factors in oppression.

Conclusion: Combating Institutional Racism Through Impactful Reform

In conclusion, the deep-rooted institutional racism that persists in the United States today is a direct result of a long history of discriminatory laws, policies, and political structures that have systematically disadvantaged African Americans. From the mass incarceration crisis fueled by the War on Drugs and “tough on crime” policies to the suppression of Black political power through felon disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, and voter suppression tactics. These legal and political systems have long since been used as tools of racial oppression. Dismantling these unjust systematic practices that are deeply rooted in several institutions will require a multi-faceted approach which addresses the intersectional impacts of institutional racism. For instance, criminal justice reform must prioritize ending discriminatory policing practices, reforming sentencing laws, and investing in rehabilitation/support services. This would aim to protect and expand upon essential voting rights to better ensure that African Americans have the ability to elect representatives which they align with to better advocate for their rights and freedoms. Thus, broader anti-racism measures such as police and legal reforms are entirely necessary to address the systemic inequities faced by African Americans.

While progress has been made since the civil rights era, the persistence of institutional racism in the 21st century is a stark reminder of how much work remains to be done. The legal and political reforms outlined in this article are not an easy fix but rather an essential building block to forming a more just and equitable society. It will require sustained activism, political drive, and a deep commitment to anti-racism in order to dismantle the structures of oppression in the modern day. We must aspire to become a nation where everyone can truly experience opportunities and justice under legal and political practices. Only by confronting the uncomfortable truths about our past and present, and taking bold action to rectify centuries of injustice, can we hope to live up to the promise of America’s founding ideals- to create a future in which all people, regardless of race, are equal.

In her book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Isabel Wilkerson defines the Caste system as a type of social hierarchy that is based on characteristics such as race or religion with a dominant Caste that has control of a subordinate Caste. Wilkerson argues that throughout American history, the subordinate caste in the United States has been African Americans with the dominant Caste being white Americans. Wilkerson traces the start of the Caste system back to when slaves were first brought to America in 1619, when religion was first used to distinguish who was higher in society’s social hierarchy. This originally put Native Americans and Africans at the lowest. However, as African Americans began converting to Christianity, there were challenges to keep this religious-based hierarchy with the white Americans as the dominant Caste. This led to the transition to social hierarchy being based on race, thus putting African Americans firmly at the bottom of the social hierarchy. This social hierarchy was further worsened by the extreme power dynamics that arose from slavery. Slavery in America was distinct in it was such an extreme form of domination which is argued by Orlando Patterson in Slavery and Social Death. Patterson finds that while all human relationships allow for inequality or domination, what matters is the range of which it is from. In the case of slavery in America it was one of “the most extreme forms of the relation of domination as it is approaching the limits of total power in the viewpoint of the master, and total powerlessness from the viewpoint of the slave” (Patterson, 2018, p.1). While colonists had tried to enslave Native Americans, it was difficult to do on their land. As Wilkerson says “This left Africans firmly at the bottom, and, by the late 1600s, Africans were not merely slaves; they were hostages subjected to unspeakable tortures that their captors documented without remorse” (Wilkerson,2020, p.42). By understanding the roots of the Caste system and the power dynamics created within it, it becomes evident how they’ve played a role in the continuation and new form that it takes in the modern-day Caste system.

Caste

Wilkerson argues that Black Americans have been the scapegoats in society originating from the legacy of slavery, and this percieved reputation can be seen within the modern legal system. Wilkerson defines a scapegoat as someone “cast out to suffer for the sins of others” (Wilkerson,2020, p.190), This is why Wilkerson describes the modern Caste system as an invisible infrastructure or invisible guide of how people

auto-evaluate the people around them writing, “Each of us is in a container of some kind. The label signals to the world what is presumed to be inside and what is to be done with it” (Wilkerson,2020, p.59). In the context of the US legal system, the subordinate Caste Black Americans act as scapegoats as it is a necessary part that “help unify the favored castes to be seen as free of blemish...” (Wilkerson,2020, p.191). Elizabeth Jones further elaborates on Black Americans being built-in scapegoats within the modern criminal justice system in The Profitability of Racism: Discriminatory Design in the Carceral State. Jones argues that the era of mass incarceration and mass criminalization which involves “disproportionate arrests, sentencing, detention, incidences of police brutality, and traffic stops for black people in America” (Jones,2019, p.62), is not a random occurrence, but rather, deliberate and embedded within the legal framework, stemming from the legacy of slavery. This further adds to Wilkerson’s argument that the Caste system has taken a new form in the judicial system so that it can continue to be embedded into everyday life to the point of normalization. By examining the historical roots and systemic biases inherent in the criminal justice system, Jones and Wilkerson shed light on the enduring legacy of racial discrimination and inequality, highlighting the urgent need for systemic reform and social justice initiatives.

The role of the Caste system within the modern legal system is made more complex by intersectionality. Intersectionality recognizes that people can be subjected to more than one type of oppression at the same time, including racism, sexism, classism, etc. African Americans, especially women, experience intersecting forms of racial and genderbased discrimination in the US. This intersectionality amplifies the challenges they encounter within the legal system, as they navigate not only racial biases but also gender biases. Moreover, intersectionality highlights how other factors, such as socioeconomic status and education level, intersect with race and gender to compound the systemic injustices faced by marginalized communities. Thus, understanding intersectionality is crucial in addressing the complex interplay between the legal system and the caste structure, as it reveals the multifaceted nature of oppression and discrimination experienced by African Americans and other marginalized groups. Notably, Black women bear a disproportionate burden within this system, facing harsher sentencing

and increased likelihood of victimization by law enforcement compared to their white counterparts. According to the NAACP, the imprisonment rate for African American women is twice that of white women. Statistics from the Vera Institute of Justice reveal alarming disparities, with one in 18 Black women born in 2001 likely to be incarcerated in her lifetime, compared to one in 111 white women. Additionally, despite comprising only 13 percent of the female U.S. population, Black women account for 44 percent of incarcerated women. The evident legal discrimination that Black women experience in the American legal system through the intersectionality of gender and race discrimination highlights the long-lasting impact of the caste system in America. This issue is further demonstrated in the case of Davis v. County of Los Angeles (1979). This case involved a lawsuit by a group of African American and Latina female probation officers against the Los Angeles County Probation Department, alleging gender and race discrimination in promotions and assignments compared to white women. This case displays the caste system’s continued impact on American culture as well as how African-American women frequently find themselves at the crossroads of gender and racial discrimination. Even though there have been legal advancements toward equality, Davis v. County of Los Angeles is a reminder of the ongoing injustices African American women experience in the legal system and society emphasizing the critical need for ongoing efforts to address and eliminate systemic barriers to opportunity and justice.

Due to both political and social progress in America, some may believe that our country has entered a time where the Caste system no longer exists, and that we have entered an era of race no longer matters causing a growth in discussion revolving around post-racialism theory. In Post-Racialism and the End of Strict Scrutiny by David Scheaub, he defines the idea of post-racial America as “one where race is no longer a fault line for social strife or perhaps, a morally significant trait whatsoever” (Schraub,2017, p.599). The argument that Schaub makes is that regardless of whether one is speaking in terms of having already accomplished living in a post-racial society or if one is speaking in terms of aspirations, they are diminishing the significance of the role race plays in America. Arguments in support of post-racialism overlook the persisting realities of racial inequality, illustrated

in cases such as PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA VS. DAYSTAR PETERSON (2023) which demonstrate the intersectional effects of race and gender in law regardless of individuals’ socioeconomic backgrounds and professions. This case revolves around allegations of assault involving rapper Tory Lanez (Daystar Peterson) and hip-hop artist Megan Thee Stallion. The incident reportedly occurred in July 2020, with Megan alleging that Lanez shot her in the foot after an argument. Lanez faced charges related to the incident, including assault with a semiautomatic firearm and carrying a loaded, unregistered firearm in a vehicle. Due to the high-profile artist, this court case attracted a lot of media attention and started conversations about accountability in the entertainment industry and violence against women. The defense’s potential attempts to challenge Megan Thee Stallion’s credibility based on stereotypes or biases related to her identity as a Black woman further highlight the enduring influence of the Caste system and its intersectionality with gender discrimination. This is further seen in topics regarding domestic abuse and assumptions of guilt and innocence about Black women. Cases like PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA VS. DAYSTAR PETERSON demonstrate why arguments in support of America being a post-racial society fail to acknowledge the ongoing systemic injustices perpetuated by these forces, highlighting the crucial need for continued examination and knowledge to address racial inequality.

Conclusion

The book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson sheds light on the Caste system in America, particularly centered on race, with white individuals comprising the dominant caste and Black Americans forming the subordinate caste. In knowing the historical origins and power dynamics inherent in the caste system, a deeper understanding emerges of its profound impact on the legal system and the role intersectionality plays in the modern legal system. Using this framework one can examine how Black women’s experience systems of oppression overlap to create distinct experiences. Acknowledging the the role intersectionality plays in the legal system highlights the long-lasting impact of the caste system in America and demonstrates how America has not achieved being a post-racial society meaning there is a need to combat ongoing systemic injustices perpetuated by these forces. Wilkerson’s quest to understand the historical results of the subordinate Caste being used as a scapegoat in the American caste system highlights the need to further investigate and gain knowledge on the beginnings and development of social hierarchy and power dynamics.

Introduction

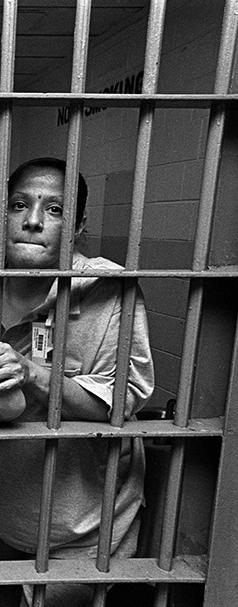

Science and medicine are tools that have historically been used to uphold racism and structures of inequality. The claimed objectivity of science persists today in the sustainability of scientific racism and the dehumanization of black bodies in America, all of which are reflected in the current day’s carceral system. The medical negligence that occurs in the United States’s current day carceral system demonstrates a dire health crisis that is attributing to the deaths of inmates each year. The lack of medical attention for inmates with mental illness and substance abuse disorders, the absence of federalized standards governing reproductive health for incarcerated people, and the role that the U.S. Medical Examiner and Coroner System plays in upholding the unaccountability of law enforcement involved in in-custody deaths can specifically be demonstrated in the Los Angeles County jail system. Thus, all contributing to the devaluation of incarcerated individuals’ lives and the health of black bodies altogether. Notorious for poor management, and altogether terrible jail conditions, the Los Angeles County jail system is an absolute spectacle for the health crisis that exists for humans behind bars in the United States. Despite legal codes and Supreme Court rulings that protect incarcerated individuals’ rights to medical care under the Eighth Amendment, medical negligence kills hundreds of inmates nationwide every year. In the 1976 Supreme Court case Estelle v. Gamble, it was ruled that “failure to provide adequate medical care to incarcerated people as a result of deliberate indifference to serious medical needs” violates the Eighth Amendment, and

Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Imagestherefore is considered cruel and unusual punishment (Pazzanese). However, inmates are often denied the Amendment. Moreover, they are disproportionately men and women of color. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, although Black Americans constitute only 13% percent of the general U.S population, 2.3 million Black Americans made up the 6.8 million correctional population in 2014, thus constituting 34% of the correctional population (U.S. Census Bureau). Thus, African Americans are incarcerated at a rate far more than the rate of whites, thus increasing their subjectivity to medical negligence in jails. The Los Angeles County Jail system is the largest in the United States, leading the nation in in-custody deaths (Shapiro and Keel). Between 2009-2018, 260 deaths were reported to the Department of Justice (DOJ) and 34% of those deaths were Black inmates (Shapiro and Keel).

The lack of mental health treatment and attention to drug addiction attributes to the increased rates of suicide and drug-related deaths in carceral facilities. Forty percent of the jail population has serious mental illness, and of those, 61% are likely candidates for diversion (Dugdale and Garrova). Meaning they are appropriate to be redirected from the criminal justice system and into mental health and substance abuse systems. In a LAist interview with LA Jail Medical Staff, one worker said that “medical care in the [Men’s Central County Jail] was “terrible” and believed that the health care system is “critically short-staffed” (Garrova and Dugdale). The severity of this issue prompted the U.S DOJ to cite L.A County in 2000 for the mistreatment and abuse of incarcerated people. Fifteen years later, the county entered a settlement that is still in effect with the DOJ, which requires increased training for jail staff, and providing inmates with mental illness more time outside the cell along with many other reforms (Garrova and Dugdale). Despite these efforts, the necessary precautions not taken for individuals who are candidates of diversion leads to questioning how many individuals are housed in jails and prisons that should not be placed in these institutions in the first place, and rather in forensic or psychiatric facilities. Furthermore, this brings into question what type of rehabilitation is truly being provided to incarcerated individuals, especially those with mental illnesses. The overturning of Roe v. Wade has caused drastic effects for women across the country, even more importantly

for incarcerated women. Presumptive to the overturn, reproductive rights– abortion access and contraceptive use– did not fall under federal standards for jail systems to begin with. Every year, approximately 58,000 pregnant women enter jails and prisons, leading to forced in jail births, and consequently miscarriages due to the lack of prenatal care in jail facilities (McCann). A study of 22 state prison systems revealed that “27% of states did not offer contraception at all” (McCann). However six other prison systems only allowed for tubal ligation, a form of permanent sterilization, but no other forms of contraception (McCann). Furthermore, Black women are 9% of the women in the United States, and yet they make up 33% of all women locked in LA County’s Jail system (Walker). A report published by the ACLU of California listed that pregnant women reported to them of “inadequate and infrequent prenatal care, illegal shackling, insufficient and unhealthy diet, and lack of access to the comfort accommodations they needed while incarcerated” (Goodman et al.).

The surveillance and brutality of black bodies that still occurs today is resonant with the violation of reproductive rights, and a lack of access to prenatal care for incarcerated women. Rejecting incarcerated individuals’ rights to menstrual and reproductive care is punitive, and essentially punishment within punishment.

Science has been used as a weapon that devalues the health of Black bodies. As a vessel of this weaponization, autopsy reports demonstrate the power that science holds in naturalizing deaths. These reports determine whether police officials involved in deaths are held accountable or not, and in turn are insulated from criticism due to their position in the scientific world as objective. UCLA’s own, Dr. Terence Keel’s BioCritical Studies Lab currently carries out research on autopsy reports produced by the U.S Forensic. In collaboration with Dr. Nicola Sharpiro’s

Carceral Ecologies Lab, Dr. Keel’s lab produced a 2018 report revealing that “young Black and Latinx not dying merely from ‘natural causes,’ but from the actions of jail deputies andcarceral staff” (Shapiro and Keel).The report also revealed that from 2009 to 2018, 260 deaths in Los Angeles County were reported (Shapiro and Keel). Only 58 of these 260 cases were accessible for analysis, however 26 died from “natural” causes, and of those 26 cases, 64% were Black (Shapiro and Keel). Natural deaths made up 73% of all Black deaths, and Black deaths are nearly twice as likely to be designated as “natural” compared to Latinx, White, and Asian death (Shapiro and Keel). Rather than taking into account how pre-existing health conditions and environmental factors can contribute to a person’s death, reports produced by forensic personnel focus on justifying why these deaths are inevitable and to be expected. For instance, in cases where it is evident that foul play occurred, the medical coroner will often report the cause of death as undetermined, allowing them to minimize the connection between foul play and death. By assessing and collecting data from these autopsy reports, an analysis of the interactions between the medical examiner/coroner system and law enforcement has revealed how science and medicine are at play during instances of death in custody, and how this in turn reduces accountability for law enforcement.

Conclusion

The limited access to adequate healthcare that individuals in jail systems experience disproportionately affects Black inmates, and furthermore reflects how structures of inequality exist in the intersections of health and medicine, law and governmental institutions, and science altogether. Despite efforts to increase rehabilitation and proper reproductive care in the Los Angeles jail system, a dire health crisis still exists. When people are incarcerated, the state is responsible for their healthcare, wellbeing, and rehabilitation. Yet, rather than adhering to these responsibilities, prisons are more concerned about holding poor people accountable and maintaining a violent and vacuous cycle of recidivism. As a greater population, we must continue to give voice to those in jail who cannot advocate for themselves. We must continue to recognize the humanity in people– the incarcerated and the condemned. There is power in restorative justice, and once the U.S prison system can recognize what that truly means, we can make substantial efforts in humanizing those behind bars.

Women typically spend thousands of dollars over the course of their lifetime on feminine hygiene products that are imperative for their health. Still, some Black women are silently struggling with the ability to afford these necessities on a monthly basis. While period poverty is often excluded from conversations and research regarding reproductive justice due to the stigmatization surrounding menstrual cycles, certain menstruating individuals in the United States experience further marginalization due to the current inaccessibility of menstrual products. Menstrual equity, which argues for low-cost access to menstrual products, is a basic human right not available to all. Most often, this current inequity impacts low-income Black women and women of color, who are disproportionately unable to afford these feminine hygiene products that they cannot live without. As a result, menstruation is increasingly burdensome for these women, as it imposes an additional financial strain. Feminine hygiene products such as tampons, pads, menstrual cups and discs, and sanitary tissues are fundamental necessities, but these products are often difficult to afford for those facing financial insecurity. Women in this position experience the phenomenon of period poverty, where they are forced to sacrifice in order to afford these basic necessities, such as some being forced to choose between purchasing food or feminine hygiene products. As traditional menstrual products are financially unattainable, some Black women report substituting household items which can potentially lead to health complications. This review will advocate for legislative measures that address the systemic inequity of period poverty in the United States and explore the legal basis for providing free menstrual products in federally owned public spaces in order to work towards eliminating the inequities that menstruating individuals endure.

Period poverty “refers to the state in which people who menstruate find themselves without the financial resources to access suitable menstrual products” (Bobel et al., 2020). Black women who face financial insecurity struggle to secure the resources necessary to manage menstruation in a way that meets societal expectations. For some, the only way to get a pad or tampon is by asking other women that they know. Other women choose to substitute these products with toilet paper or towels, though this practice commonly leads to the spread of illness and bloodborne pathogens if the blood is not contained. To great detriment, outdated patriarchal standards push communities of women to believe that menstruation is gross or disgusting. This creates internalized sensations of shame and guilt when individuals are unable to access menstrual products, which creates internalized sensations of shame and guilt when individuals are unable to access menstrual products. These feelings of shame are amplified in Black communities, where a history of institutional racism in the medical industry makes it more difficult to seek help when struggling with menstruation related issues. When individuals experience this inequality, they are vilified for being unable to control their bodily functions, while subsequently not being provided access to the supplies they need to adequately function while on their menstrual cycle. As a result, Black women can suffer from heightened symptoms of irritability, stress, anxiety and depression on a monthly basis. The societal stigma around menstruation makes it more difficult for women existing on the margins to seek and receive adequate care if they are unable to afford traditional products. Therefore, it is crucial that these products are more accessible; this can be achieved through providing menstrual products in all federally owned public buildings. By doing so, this will decrease the financial burden that comes with purchasing these products and women who are unable to purchase these products can access them without worrying about feelings of embarrassment.

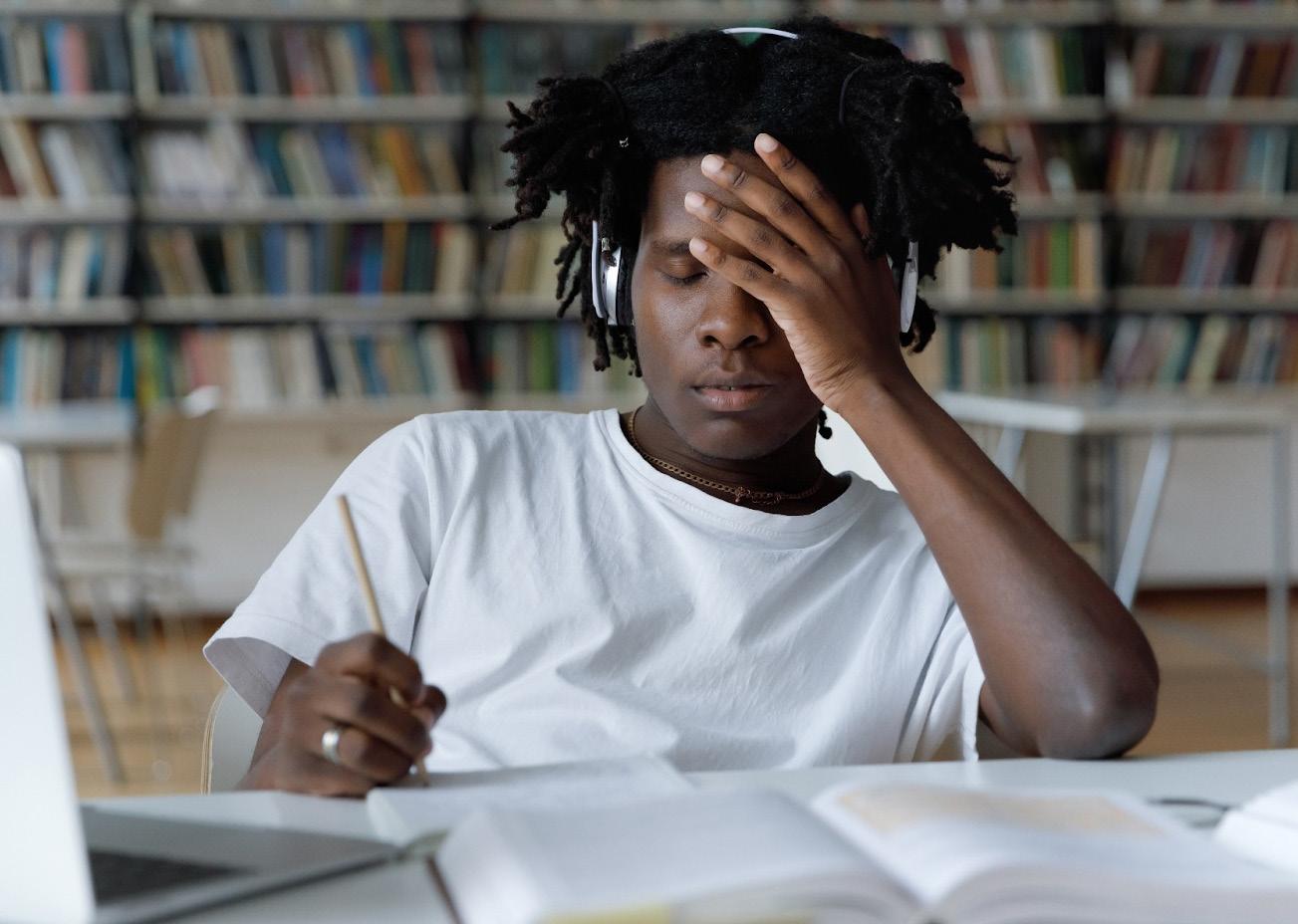

This issue directly hinders equitable access to education for experiences of Black women in college across the country. In a recent study among college students, researchers found that 19% of Black women — about one in five individuals — reported experiencing period poverty in the recent year. In addition, 7.6% of Black female undergraduates claimed that they experienced period poverty on a monthly basis (Cardoso et al., 2021). Without being able to purchase menstrual products, women may use rags, toilet paper, or other objects that can absorb blood, which can increase the risk of reproductive and urogenital infections as well as mental health issues (Lancet Regional Health– Americas, 2022). These alarming statistics signify that a portion of Black women aspiring towards higher education are not getting their needs met because of these barriers to an equitable education.

Black women’s first experiences with their menstrual cycles are often introduced through interpersonal relationships with other women in the community. In interviews done for a 2020 study, Black women that identified as low-income referred to their periods as “evil,” “smelly,” or “fishy” when asked to give a description of their menstrual cycles, and most declared that this was taught by other female family members (Martinez, 2020). These negative sentiments surrounding periods is a common experience shared amongst Black girls learning their bodies for the first time, which originate from the dehumanization of Black women and their femininity during slavery. As these negative perceptions of menstrual cycles continue to persist throughout communities of Black women, it will perpetuate the cycle of shame and embarrassment which will make many women less likely to seek help for accessing menstrual hygiene products. When women are unable to afford these products and they refrain from seeking help, they may resort to substituting other items. This can contribute to the disproportionate amount of health complications that Black women already face as they navigate through society.

Federal policy should be implemented that requires access to menstrual products for no cost in all public buildings. This type of legislation was recently introduced in the House of Representatives in May 2023 (H.R. 3646), which proposed that tampons and sanitary napkins should be available for free in restrooms in federal buildings that are open to the public, on campuses of institutions of higher education, and businesses with at least 100 employees. So far, this bill has been ignored. California is the first and only state to pass a law requiring public colleges to provide free menstrual products to students (Luna, 2023). The government making these products available across the country in federally funded buildings will increase accessibility and eliminate feelings of shame that individuals may experience for having to seek help from a healthcare provider. This shows that there is precedent for change through legislation, and this change must be pursued. Passing this initiative on a federal level will allow women across the country to live without fear of their reproductive needs not being met.

Conclusion

By prioritizing access to free menstrual products, the financial burden on women facing financial insecurity can be alleviated and hopefully a society that denormalizes the shame surrounding periods. Too many communities of Black women are facing lack of access to products that are basic necessities, and advocating for passing this legislation can lead to alleviating this burden from Black women across the United States.

Abstract

Slavery was abolished, the Civil Rights Amendments gave us “equal rights,” and segregation based on race was made illegal. Therefore, many people believe that the United States is a post-racial society. However, that is not the case; racism is rampant, and segregation is still prominent. This is shown through the existence of pervasive systems of racial inequality, including housing discrimination, educational disparities, and disparities in employment opportunities. The introduction of various legislation acts aimed to address challenges within housing infrastructure, including the clearance of slums, urban revitalization efforts, and notably, the provision of resources for lowincome housing, which seem advantageous for Black communities began during the mid-20th century. In theory, this legislation was revolutionary, perpetuating the narrative that the American government now cared about Black Americans’ well-being and expressing this through affordable housing. However, the truth is that these “homes” strategically partitioned poor Black people from educational opportunities, medical care facilities, job opportunities, and upward social movement. By the 1980s and 1990s, these neighborhoods had become synonymous with crime, disorder, and the existence of violence, all of which were blamed on residents. Moreover, the presence of high levels of law enforcement in these neighborhoods often led to overrepresented levels of black individuals within the criminal justice system. Today, many communities are still segregated because of the housing plans, and this ongoing segregation perpetuates disparities in education, economic opportunities, and overall quality of life for African American residents–highlighting the enduring legacy of racialized space in the United States.

In the 1930s, many urban cities had both white and Black working-class families. However, former President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced New Deal programs aimed at segregating integrated neighborhoods. This is evident from the Federal Housing Administration’s strict rules that benefited white working-class families (a component of New Deal programs), such as allowing them to move into single-family homes in white suburbs through government-backed home loans. The FHA also prohibited selling, reselling, or renting homes to any African American, which compounded black people into specific neighborhoods, leaving no economic opportunity,

“The stark reality is that low-income housing projects are one of the largest contributors to mass incarceration” Anthony Lewis

which exacerbated poverty. A contributing factor to poverty includes home evaluations. Today, in the U.S., Black neighborhoods are valued at $48,000 less than predominately white neighborhoods, combining for a total loss of approximately $156 billion in equity. To further segregate neighborhoods, Congress introduced the American Housing Act. Passing it in 1949, Congress aimed to have grants for slum clearance, easier loans for home buyers, and a goal of building 500,000 public housing units in four years. However, slum clearance later became known as ‘Negro removal.’ The Act’s provisions allowed for unprecedented government control, including forcefully removing specific individuals into designated areas. “Coincidentally,” the government was also building large high-rise public housing projects throughout the country. As a result, 80% of the people relocated were low-income African Americans, and the existence of new slums was created in condensed areas that later became known as “project ghettos.” Most of these ‘ghettos’ are in cities such as Detroit, Chicago, South Los Angeles, New York, and Atlanta, to name a few. Initially proposed to be 500,000 units, the 1949 Housing Act authorized the construction of 810,000 housing units. Which later spurred the creation of nearly 1.1 million housing units with approximately 2.2 million residents.

Further impoverishing Black communities, the U.S. government enacted the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1965, which approved the construction of interstate highways usually built through African American neighborhoods. The highways often destroyed homes and displaced Black people—but they enhanced the flow of white commuters in suburban neighborhoods, further exacerbating the wealth gap. While the Fair Housing Act was introduced in 1968 to offset racial biases in home ownership and mitigate housing disparities across the U.S., no enforcement measures were introduced until 1988, which caused the Act to largely fail at eliminating any discriminating practices. In 1994, 52% of all public housing units were comprised of African Americans. Today, African Americans still make up 48% of the public and subsided housing, although they make up 13% of the total U.S. population.

Carceral Environments

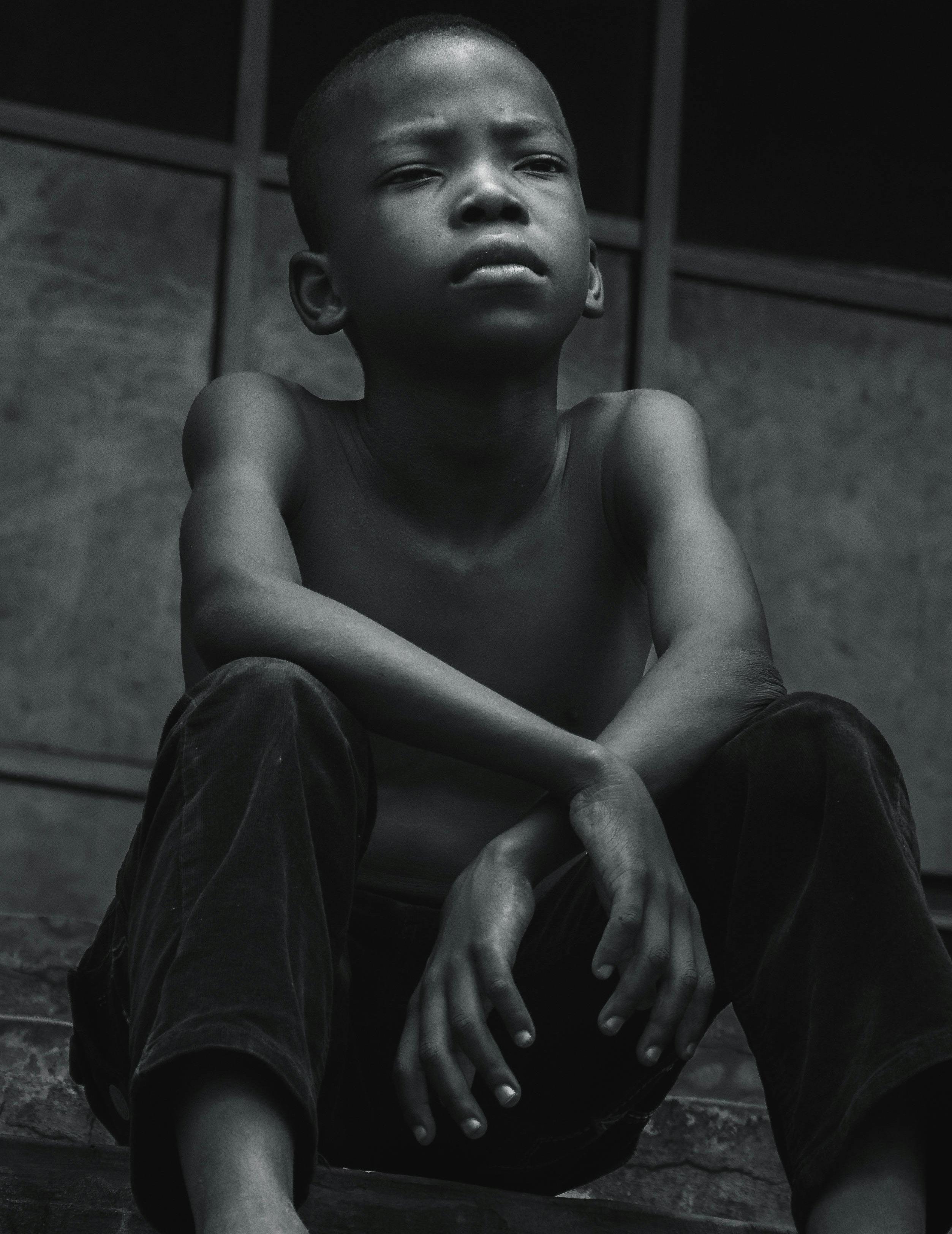

The Prison Policy initiative shows that 37% of people in jail or prison are Black, even though, Black people

only make up a minority of the U.S. population. Black people are also nearly twice as likely as Hispanics and six times as likely as white people to encounter prison during their lifespan. Sociologist Michelle Alexander states that there are more Black people in jail, prison, on probation, or parole than there were slaves 10 years before the Civil War began. The stark reality is that low-income housing projects are one of the largest contributors to mass incarceration. This is evidenced by the fact that in the U.S., low-income housing projects frequently implement controlled visitation policies, curfews, metal detectors, and apartment inspections—features commonly associated with prison environments. The existence of carceral geography functions where Black people typically reside prepares them for entering and exiting prison throughout their lives. Many might assume that these harsh public housing policies violate rights; however, through the Fourth Amendment, public housing residents have fewer rights than typical home residents, enabling “proactive policing.” Proactive policing practices aim to prevent crimes before they occur, leading to officers defining “high crime areas” through their testimonies and eliminating any credibility a resident wishes to establish. This often causes Black neighborhoods to be targeted as many law enforcement officers have negative biases that associate Black neighborhoods with crime. The constant overpolicing of public housing communities has created an environment of government-enabled poverty and has forced African Americans into inadequate living standards. Consequently, Black people feel like they have limited pathways due to constantly feeling like societal outcasts. Some examples include low-paying jobs, committing crimes, and entering and exiting prison.

A Geography of Little Opportunity

Research has shown that education is a key factor in the upward movement on the social ladder for people living in poverty to improve their financial circumstances. Affluent families vigorously focus on access to the best schools and colleges for their children, thereby perpetuating intergenerational wealth. Nonetheless, schools near low-income housing often lack resources, experienced teachers, and rigorous curricula compared to predominantly white schools. For instance, 67% of teachers in affluent schools are credentialed in Oakland Unified, while only 49% are in low-income schools. Districts with high concentrations of low-income housing receive $6,355 less per pupil in funding. Students in low-income housing often attend schools that have inadequate access to college networks and job opportunities, while suburban schools often provide a college-focused curriculum. In lowincome neighborhoods, schools often become another source of criminalization for students, as police interaction is frequent, especially for young Black males. In school districts where more than 80% of students are low-income, the arrest rate is seven times higher in comparison to schools where 20% of the students are low-income. At any given moment, those schools can collectively punish, stigmatize, monitor, and criminalize young people in an attempt to control them. Therefore, they are set up for a world in which they are constantly viewed as criminals. Although Black youth have the agency not to commit crimes, a system of punitive control and stigmatization robs them of their positive right to education. As a result, due to the limited access Black people have to resources that could break the cycle of poverty, some believe that committing crimes may be one of the few options to escape this cycle. Furthermore, the presence of racialized spaces exacerbates the psychological toll of navigating racially charged environments and can negatively impact the well-being and sense of belonging of individuals. Which perpetuates the cycle of poverty and further diminishes the well-being of African Americans, particularly within the context of low-income housing and segregated schools.

In the biography “There Are No Children Here,” examining the lives of two black boys, 10-year-old Lafayette Rivers states, “If I grow up, I’d like to be a bus driver.” Lafayette was a resident of the Henry Horner Homes in the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. The fact that Lafayette says “if” encapsulates the feelings of many Black individuals across the country. Due to living in a constantly racially charged environment, some Black individuals often feel the pressure of society that forces them to leave their childhood behind. Dealing with many factors that the majority population does not have to face, the goals of many Black people are low aspired. Although he aspires to be a bus driver, which is a noble career, Lafayette and many others believe that they are only worth low-paying jobs and that their contribution to society can be minimal, which contributes to the continuous cycle of poverty. Unfortunately, Lafayette’s sentiments are a reflection of the pervasive lack of opportunities experienced by residents in low-income housing throughout America.

Furthermore, the goal of this article is not to garner pity for Black individuals. It is to make the majority aware of the negative circumstances that Black individuals have been forced into for generations. To exit the cycle of poverty, the population must be aware of the circumstances so we can garner support to create advantageous policies and institutions.

A Comprehensive Look at Racialized Space in the United States and Its Ongoing Impact on African

“Legal Timeline - The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom | Exhibitions - Library of Congress,” October 10, 2014. https://www.loc. gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/legal-events-timeline.html.

“A History of Residential Segregation in the United States” 34, no. 4 March, 2019. National League of Cities. “Housing for BlackLed Households,” February 6, 2024. https:// www.nlc.org/article/2024/02/06/housing-forblack-led-households/.

“USHMC 95: Public Housing: Image Versus Facts.” Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.huduser.gov/periodicals/ushmc/ spring95/spring95.html.

5 Gorenflo, Neal. “Timeline of 100 Years of Racist Housing Policy That Created a Separate and Unequal America.”

Shareable, October 31, 2019. https://www. shareable.net/timeline-of-100-years-of-racisthousing-policy-that-created-a-separate-andunequal-ameri ca/.

“Public Housing History | National Low Income Housing Coalition,” April 8, 2024. Weisburd, David, Anthony A Braga, and Phillip Atiba Goff. “COMMITTEE ON PROACTIVE POLICING: EFFECTS ON CRIME, COMMUNITIES, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES,” 2018.

9“The Criminalization of Public Housing Residents.” Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-journal/blog/the-criminalization-of-public-housing-residents/.

8 FRONTLINE. “Michelle Alexander: ‘A System of Racial and Social Control.’” Accessed April 20, 2024.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/ michelle-alexander-a-system-of-racial-and-social-control/.

7Initiative, Prison Policy. “Race and Ethnicity.” Accessed April 20, 2024.

11 The Commonwealth Institute. “Unequal Opportunities: Fewer Resources, Worse Outcomes for Students in Schools with Concentrated Poverty.” Accessed April 20, 2024. https://thecommonwealthinstitute.org/research/unequal-opportunities-fewer-resources-worse-outcomes-for-studentsin-schools-with-concentrated-poverty/. “The Right to Remain a Student: How CA School Policies Fail to Protect and Serve | ACLU of Northern CA.”

Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.aclunc. org/publications/right-remain-student-how-caschool-policies-fail-protect-and-serve. Kotlowitz, Alex. 1992. There Are No Children Here : The Story of Two Boys Growing up in the Other America / Alex Kotlowitz. First Anchor books edition. New York: Anchor Books.

Combatting Period Poverty By Victoria Williams

Bobel, C., Winkler, I. T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K. A., Kissling, E. A., & Roberts, T.-A. (Eds.). (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-06147

Cardoso, L. F., Scolese, A. M., Hamidaddin, A., & Gupta, J. (2021). Period poverty and mental health implications among college-aged women in the United States. BMC

Women’s Health, 21(1), 14. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12905-020-01149-5

H.R.3646 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): Menstrual Equity For All Act of 2023. (2023, May 26). https://www.congress.gov/ bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3646

Luna, I. (2023, April 4). Did California keep its promise to provide menstrual products on college campuses? CalMatters. http://calmatters.org/education/higher-education/college-beat/2023/04/menstrual-equity -for-all-act-california/ Martinez, L. V. (2020). Racial Injustices: The

Menstrual Health Experiences of African American and Latina Women. https://digitalrepository.salemstate.edu/ bitstream/handle/20.500.13013/782/Revised_Fin al_Thesis_8_5.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Regional Health– Americas, T. L. (2022). Menstrual health: A neglected public health problem. Lancet Regional Health - Americas, 15, 100399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100399

Straighten Your Hair, It’s More Professional: The Policing of Black Hairstyles in Professional Settings By Yadeal Asfaw & Dorothea Amadin Amir Vera, Family of the black wrestler who was forced to cut his dreadlocks speaks out CNN (Dec. 26, 2018). www.cnn.com/2018/12/25/us/ wrestler-dreadlocks-new-jersey-comments/index.html

EEOC v. Catastrophe Management Solutions 852 F.3d 1018 (11th Cir. 2016)

Jill Billante & Chuck Hadad, Study: White and Black children biased toward lighter skin CNN (2010, May 14). www.cnn.com/2010/US/05/13/ doll.study/index.html

JOY Collective, C.R.O.W.N. Research Study, DOVE, (2019) static1.squarespace. com/static/5edc69fd622c36173f56651f/t/5edeaa2fe5ddef345e087361 /1591650865168/Dove_research_brochure2020_FINAL3. pdf

Leigh Alexander, Do Google’s ‘unprofessional hair’ results show it is racist? THE GUARDIAN (Apr. 8, 2016), www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/08/does-google-unprofessional-hair-results-p rove-algorithms-racistRenee Henson, Are my Cornrows Unprofessional?: Title VII’s Narrow Application of Grooming

Policies, and its Effect on Black Women’s Natural Hair in the Workplace, 1 BUS. ENTREPRENEURSHIP & TAX L. REV. 521 (2017). scholarship.law.missouri.edu/ betr/vol1/iss2/9

S.B.188, 2019 Regular Session. (CA 2019).

Legacy Of Slavery By A’shiyah Dobbs Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death. Harvard University Press, 1982. Wilkerson, Isabel. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. Thorndike Press Large Print, 2021.

Jones, Elizabeth. “Racism, fines and fees and the US Carceral State.” Race & Class, vol. 59, no. 3, 9 Oct. 2017, pp. 38–50, https://doi. Schraub, David. “Post-Racialism and the End of Strict Scrutiny.” Academia.Edu, 29 Mar. 2018, www.academia. edu/23753873/Post-Racialism_and_the_End_of_ Strict_Scrutiny. Los Angeles County Superior Court. People of the State of California vs. Daystar Peterson.

The Complexion Of Crime By Faith Ndegwa ABOUT THE COPS OFFICE | COPS OFFICE. (n.d.). Cops. usdoj.gov.

https://cops.usdoj.gov/aboutcops

Barideaux Jr, K., Crossby, A., & Crosby, D. (2021). Colorism and criminality: The effects of skin tone and crime type on judgements of guilt. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 16(2).

BOP: First Step Act Overview. (2018). Www.bop.gov. https://www.bop.gov/inmates/fsa/overview.jsp#:~:text=The%20First%20Step%20Act %20requires

Brunson, R. K. (2007). “Police don’t like black people”: African-American Young Men’s Accumulated Police Experiences. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(1), 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00423.x

Fischman, J. B., & Schanzenbach, M. M. (2012). Racial Disparities Under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines: The Role of Judicial Discretion and Mandatory Minimums.

Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 9(4), 729–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2012.01266.x

Hunter, M. (2007). The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00006.x

Jacobs, R. N. (1996). Civil Society and Crisis: Culture, Discourse, and the Rodney King Beating. American Journal of Sociology, 101(5), 1238–1272. https://doi.org/10.1086/230822

Keith, V. M., & Herring, C. (1991). Skin Tone and Stratification in the Black Community.

American Journal of Sociology, 97(3), 760–778. http://www. jstor.org/stable/2781783

Kendi, I. X. (2017, May 24). Colorism as Racism: Garvey, Du Bois and the Other Color Line. AAIHS. https://www.aaihs.org/colorism-as-racism-garvey-du-boisand-the-other-color-line/

Monk, E. P. (2021). The Unceasing Significance of Colorism: Skin Tone Stratification in the United States. Daedalus, 150(2), 76–90. https://doi. org/10.1162/daed_a_01847