LAST TO LIBERATION

LAW JOURNAL VOLUME II

LAW JOURNAL VOLUME II

LAW JOURNAL VOLUME II

LAW JOURNAL VOLUME II

The Black Pre-Law Association is committed to the education of the legal system and how it impacts the Black community. We created the first ever undergraduate Black law journal at UCLA to inform not only the Black Bruin community, but the larger UCLA community. We cover a wide range of topics regarding laws, policies, legislations, and our government. Our law journal serves as a motion to increase awareness on pressing issues and injustices within the Black community and what we can do going forward. There are no Black policy or government organizations as of June 16th, 2023 at UCLA. As a pre-law organization, the current President Allanah Smith has made a contribution and commitment to expanding the pillars of BPLA and the BPLA Law Journal to discuss politics, policy, and government.

This law journal will serve as a part of her commitment to make BPLA holistic in policy, government, and politics in addition to the law. We need a law journal that will cover the vast inequities that occur within our community and this is only part of the mission to make legal education accessible and a priority for our community. The Black Pre-Law Association is dedicated to uplifting and advancing our members in the area of professional, career, and personal development as well as community service. The Black Pre-Law Association Law Journal acts as a separate entity that is under the regular Black Pre-Law Association, but will serve on the journalism and media side. Our members and executive board that serve on our Law Journal team will have the opportunity to enhance and develop their writing, critical thinking, data analysis, and research skills.

The Black Pre-Law Association will advance its law journal members and executive board to have career and professional development in the areas of law, journalism, and media. We are committed to connecting with other media organizations at UCLA to prepare our members with the correct training and mentorship needed to discuss law, politics, and our government. It is our duty to make not only Black UCLA students accessible to this information, but other college campuses and the larger Black communities in which our universities neighbor.

The Black Pre-Law Journal was founded as a branch of the Black Pre-law Association last year, 2022, by BPLA members who were dedicated to the service of political and legal education. BPLA’s Vice President at the time, Allanah Smith, connected with me to reinvigorate the club with a new addition -- a law journal. As our second year comes to an end, we are immensely proud of the work our writers, editors, and dedicated editorial board have put forth to bring this program to life. Throughout the past two years as Editorin-Chief of the law journal, I have been inspired by the passionate writers, soon-to-be lawyers, that take their personal time to write about the issues and histories of our community, and look forward to the day all of our dreams come true as a collective. This issue is small, sucinct, and special. It is the final issue the founding members will produce, but it also signifies a moment of tangible growth for BPLA and its members. This issue explores the histories and currencies of protest over time, and examines the ways collective and individual determination can impact our communities in deep ways. I would like to offer this journal, and all other law journals that the Black Pre-Law Association will produce, as our own contribution to the histories that have shaped us. While we live on, so does the impact of the work of our ancestors, parents, and leaders. We hope this law journal will be a testament to the passion and growth of our people through the path of liberation. We may be last, but we are not stuck. We will simply wash the mud off of our feet, wade in the relfecting pool as we look into our soul’s mirror, and try again.

Leilani Fu’Qua BPLA Editor-in-Chief, 2022-2023Congratulations to all of the Black Pre-Law Baccalaureate Graduates of 2023!

BLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION STATEMENT OF PURPOSE

| Allanah Smith | BPLA President

ABOUT THIS ISSUE: A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

| Leilani Fu’Qua | Law Journal Editor-in-Chief

THE OTHER COLOR LINE: THE SILENT PROTEST OF

CLAUDETTE COLVIN

| Faith Ndegwa | Staff Writer

WHAT DOBBS V. JACKSON MEANS FOR BLACK WOMEN

| Brianna Lambey | Staff Writer

HOW GEORGE FLOYD CHANGED THE WORLD

| Ure Egu | Staff Writer

REVOLUTIONARY POLITICAL EDUCATION

| Leilani Fu’Qua | Law Journal Editor-in-Chief

Claudette Colvin became the first Black individual to refuse to give their seat up to a white person, sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott movement. This article will examine Colvin’s significant contribution to the Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s of contemporary America. It will review her peaceful protest, wrongful indictment, and eventual exoneration almost 70 years after her arrest. An analysis of both her protest and lack of recognition, especially in comparison to other activists like Rosa Parks, will provide context for more significant social issues in both Black and white communities. Lastly, this article will dissect her contribution to the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycotts and the overall desegregation of the United States.

Claudette Colvin’s Protest

On March 2, 1955, fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin was taking the Montgomery public bus home from school when she was ordered to give up her seat to a young white passenger. Having learned of activists like Harriet Tubman and Soujner Truth throughout Negro History Month the weeks prior, she refused to move, stating that history had her “glued to her seat” (CBS Mornings). Her continued defiance against the bus driver’s and eventually policemen’s orders resulted in her arrest – Colvin yelling, “It’s my constitutional right!” throughout her entire removal from the bus (Adler). Although Colvin refused her seat nearly nine months before Rosa Parks did in December of 1955, her revolutionary protest was overshadowed by Parks.

Colvin was later charged with two counts of violating Alabama’s city segregation ordinance and one felony count of assaulting a police officer. Despite her probation ending when she turned eighteen, Colvin was told that she would be on probation indefinitely (NowThis News). Though her arrest in 1955 was the only time Colvin faced criminal charges in her lifetime, she lived with a criminal record for over 60 years, even after the abolishment of racial segregation. At her current age of 83 years old, she has spent most of her life as a convicted juvenile delinquent. Colvin’s legal

team eventually filed a request in Montgomery County Court to have her record expunged in October of 2021. When Judge Calvin Williams, one of the few African American judges of Montgomery, read her appeal, he acknowledged that he was a byproduct of Colvin’s efforts and erased her 66-year criminal record (CBS Mornings).

Colorism, or the discrimination against individuals of darker skin tones, is an issue amongst African Americans that is slowly disunifying the diaspora. In America, colorism within the Black community can be traced all the way back to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. During this time, enslaved individuals with lighter skin were often treated better than those with darker skin tones - mainly because most lighter-skin people were usually the result of slave rape between a Black enslaved woman and a white enslaver. Since lighter-skinned people worked within the white master’s home, they were more likely to be taught basic skills, like reading and writing, that field workers never had the opportunity to learn (Uzogara). As the Black community advanced towards abolition, lighterskinned and mixed-race people made up the majority of the freed Black population, while dark skin people predominantly remained enslaved (Desergent). The intersectional issues of the Black community heavily impeded the overall efficiency and success of the Civil Rights movement. Although it was meant to improve the living conditions of Black people in America, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), held many biases that continued the cycle of oppression within the Black community - one of the most notable being colorism. The NAACP was established in 1909, thirty years before Colvin was born, as a response to the ongoing violence against Black Americans. When Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist and entrepreneur, first arrived in the U.S., he aimed to raise funds for the ongoing struggle in his home country and went to the NAACP for assistance. After arriving at their office, he stated that he was unable to tell if it was “a white office or that of the NAACP” because the staff primarily consisted of white and light skin people, pushing him to create the Universal Negro Improvement Association, or the UNIA (Kendi). The UNIA and NAACP worked together on various initiatives to alleviate the struggles of the Black

community, but often conflicted on the resolution of issues like colorism (McDonald).

Throughout the civil rights era, darker-skinned activists were not as respected or taken as seriously as their lighter-skinned counterparts (Desargent). Colvin was a dark skin woman - ultimately granting her lower status in both Black and white communities. Additionally, after getting pregnant later that same year, she was given the wild child reputation. The NAACP advocated for Rosa Parks to be the face of the Montgomery Bus Boycott movement because her fair skin, older age, and “clean” reputation would be taken more seriously than Colvin (Huguley). Colorism played a significant role in Parks’s recognition as a primary contributor to desegregation, while Colvin faced chastisement.

The color line refers to the social and systemic barriers that segregate people of color from white people. Ibram X Kendi, a Jamaican American professor and Black activist, states that colorism is a byproduct of the color line, prompting a new division: the other color line. The other color line refers to the intraracial hierarchy of complexion within the Black community; this hierarchy enforces the idea that lighterskinned Black people are superior to Black people with darker skin complexions. Like racism to white Americans, colorism is a concept often unfathomable and sometimes completely discounted by many lighter-skinned Black people, including renowned Pan-Africanist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois (Kendi). By denying the existence of colorism, individuals like Du Bois inadvertently blame darker skinned Black people for their own inequalities and disproportionate treatment. Colorism is further perpetuated when it is not acknowledged, which, as seen through Colvin’s story, substantially affects the lives of individuals with darker complexions.

Claudette

Bus Boycott

Following the abolition of slavery in 1865, racial segregation in the United States began. Local and federal governments established laws suppressing the Black vote and mandating racial segregation in public areas. The Supreme Court decision in Plessy v Ferguson further solidified this legal segregation of races, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities for different races were constitutional (Gold). The Montgomery Bus Boycott was the first successful protest against the laws enforcing racial segregation.

Despite Claudette Colvin’s initial efforts, the boycott did not begin until after the arrest of Rosa Parks. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led the Black community in a nonviolent protest against the city’s segregation by refusing to ride the Montgomery public transportation system (Stanford, Montgomery).

In his book From Jim Crow to Civil Rights, Harvard Law Professor Micheal Klarman writes that “rather than making minimalist concessions, Montgomery officials became intransigent, arresting boycott organizers on fabricated charges, joining the citizens’ council, and failing to suppress violence against boycott leaders” (Klarman 59). The protest lasted for over a year, ending after the Supreme Court ruled against racial segregation on public transportation in the trial of Browder v Gayle.

In 1956, the case of Aurelia S. Browder v. William A Gayle challenged the Montgomery City ordinances that mandated racial segregation on public buses. Four Black women arrested for refusing to give up their seats to white passengers on Montgomery city buses, including Colvin, served as plaintiffs throughout the case (Stanford, Browder v. Gayle). The arguments presented by plaintiffs’ lawyer, Fred Gray, argued that segregation violated their constitutional rights. He also noted that the “separate but equal” doctrine established by the Supreme Court in Plessy v Ferguson was inherently flawed and that segregation could never truly be equal, while the city countered by stating they were simply executing the laws as written. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that enforced segregation on public transportation violates the Constitution, specifically the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment. Although overlooked at the time, Colvin’s arrest and subsequent legal case served as the precursor to the more widely-known Montgomery Bus Boycott, helping to galvanize support for the Civil Rights Movement (Gold). The ruling in Browder v Gayle paved the way for further legal challenges to segregation and discrimination in other areas of American life.

Rosa Parks is a direct example of the privileges afforded by having a lighter complexion, not only in opportunities and social status, but in recognition as well. While today, school districts and streets have been named after Parks to pay homage to her efforts, individuals like Colvin are rarely mentioned in discussions of racial equality.

The legacy of many civil rights activists has been obscured or diminished by societal biases and prejudices, preventing their contributions from being fully recognized and appreciated. Despite their tireless efforts to promote equality and justice, many of these activists have been relegated to the margins of history, while others’ achievements were commemorated. The erasure of Claudette Colvin’s contributions to the civil rights movement highlights the ways in which colorism and other forms of systemic oppression shape our teachings and obscure the full scope of our history, underscoring the need for ongoing efforts to challenge these biases and ensure that all voices are heard and valued. To dismantle these prejudices, we must commit to sustained action and advocacy, including promoting diversity and inclusivity, creating equitable policies and practices, and cultivating critical consciousness and allyship among individuals and communities alike.

“The other color line refers to the intraracial hierarchy of complexion within the Black community; this hierarchy enforces the idea that lighter-skinned Black people are superior to Black people with darker skin complexions.

By denying the existence of colorism, individuals like Du Bois inadvertently blame darker skinned Black people for their own inequalities and disproportionate treatment.”

Faith Ndegwa

On June 24 2022 in a six to three vote the Supreme Court ruled in the Dobbs v. Jackson case that abortion was not a right granted in the U.S. constitution. This landmark case overturned Roe v. Wade which granted all women the right to abortion based on privacy clauses in the fourteenth amendment of the constitution. During the time of the Dobbs decision there were no Black women serving on the Supreme Court, Black women had no representation on an issue that will impact Black women the most. The fallacy that many people fall victim to in the abortion debate is that it is a matter of pro choice or pro life. Reducing this big of an issue into two categories misrepresents the experience of Black women in America. For Black women in America pregnancy is significantly more dangerous than any other race in America.

In order to fully grasp the effect of the Dobbs decision on Black women people must first understand the effect of Roe v. Wade.. The decision in Roe v. Wade determined that it was a woman's constitutional right to have an abortion based on the due process clause in the fourteenth amendment that is concerned with protecting individuals privacy from their state’s government. This decision gave all women in the country, no matter the state they resided in, the right to have an abortion in their first trimester of pregnancy without regulation from the state. Under Roe v. Wade states had the right to impose reasonable abortion regulations, and if the pregnancy progressed to the third trimester and became viable states had the right to ban abortions in this stage of the pregnancy. During the era of Roe v. Wade Black women accounted for forty percent of all abortions recorded.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson denied that the amendments in the constitution gave women the right to an abortion explicitly or implicitly. The decision didn’t ban all abortions in the United States, but instead left the regulations of abortions up to the individual states. While states like California and New York quickly implemented policies to protect women’s right to an abortion many states, particularly southern states, jumped at the chance to ban abortions except in select cases where the mothers life may be in danger. A map of the United States depicting the states with the most and least restrictive abortion regulations, shows that almost all the southern states have the most restrictive abortion policies . This is especially concerning for Black women as more than fifty percent of the Black population in the United States is concentrated in southern states. This statistic coupled with Black women accounting for the highest percentage of recorded abortions is just one way the Dobbs decision will disproportionately affect Black women.

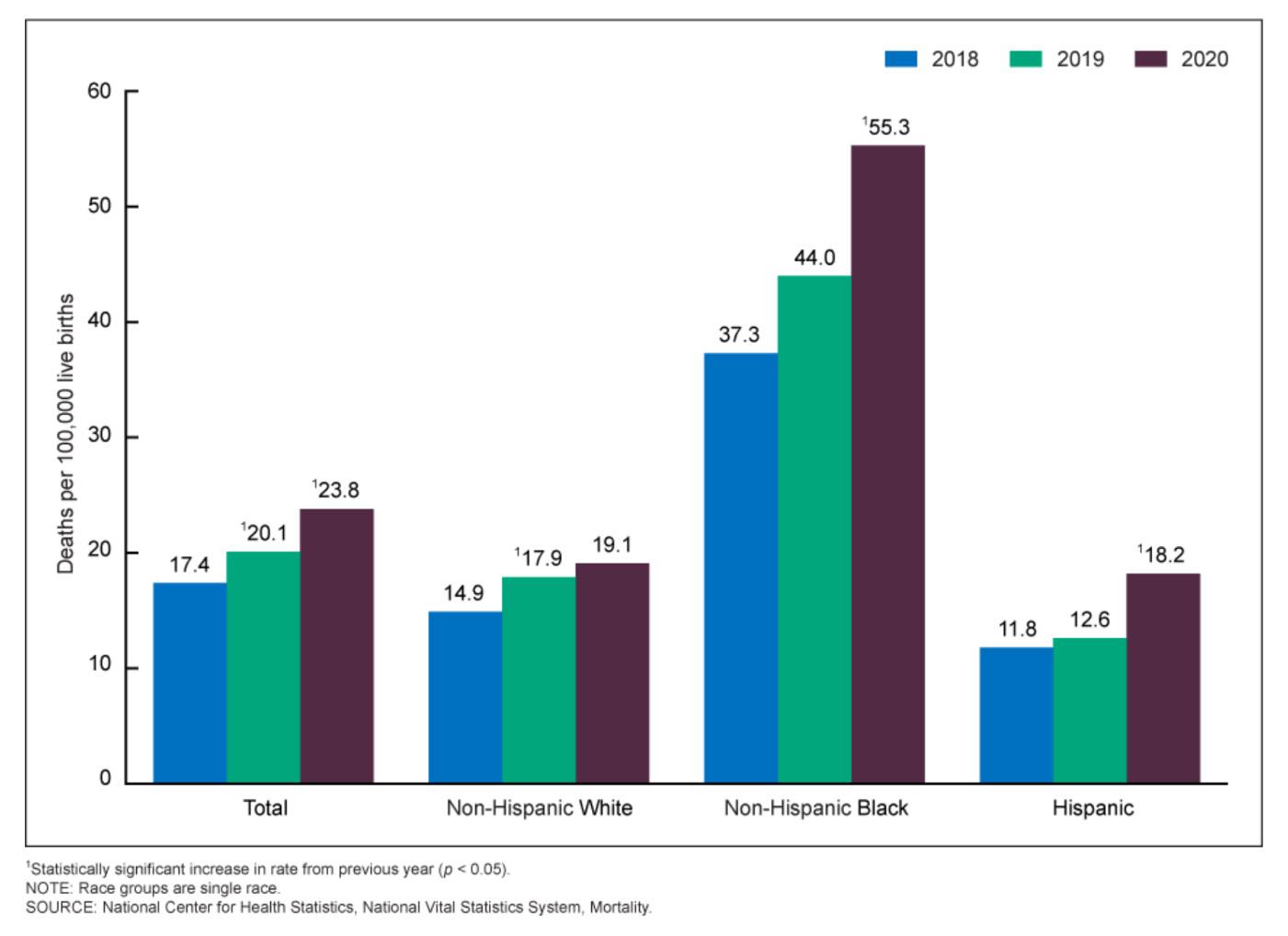

In many of the states with the bans on all abortions, exceptions to the ban have only been allowed for abortions to be performed when the pregnancy is endangering the life of the mother. However it is difficult for medical officials to determine exactly when this point is. In states with these types of restrictive bans, women “are facing harmful, potentially deadly delays,” as they are forced to wait for their life to be endangered enough to have an abortion. This is especially concerning for Black women who have historically and consistently had the highest rate of complications during pregnancy. A chart depicting “the percentage of births with mothers admitted to intensive care unit during delivery,” shows that the statistic for Black women has been significantly above the national average and consistently double that of White women. In 2016 the percentage of Black mothers admitted to intensive care unit during delivery was about 25% while the percentage for White women was almost half that at 13%. Similarly in 2020 the percentage of Black mothers admitted to intensive care unit during delivery had slightly decreased to about 24% which is still double the percentage of White women which decreased to about 12%. The United States Government Accountability Office also reported that Black women have the highest maternal death rate in America, and it is over double the death rate of White women. The maternal death rate of Black women in 2021 was 68.9 per every one 100,000 live births which actually increased from 2019 when the maternal death rate for Black women was 44. This statistic is significantly higher than the maternal death rate of White women which in 2021 was 26.1 which had also increased since 2019 when the maternal death rate was 17.9. The disparity in the death rates is largely an issue that has been ignored which is shown by the fact that the maternal death rate for Black women keeps getting unreasonably higher. Black women in America have historically had and will continue to have the highest maternal death rate of any race, yet the Dobbs decision will subject more Black women to following through with unsafe pregnancies.

Given that Black women are already at an increased risk of having a life threatening complication while giving birth it’s clear that Black women will be disproportionately affected by doctors having to wait to perform a life saving abortion. The statistics of the maternal death rates of Black women and the percentage of Black mothers admitted to intensive care unit during delivery coupled with the southern states extensive bans on abortions shows how Black women will be disproportionately put in situations where their life is endangered. With southern states’ strict abortion laws doctors will have to choose between performing a life saving procedure, or face prosecution for performing an abortion. Decisions like these will cause more delays to necessary abortion procedures that will result in further complications or even death. With the maternal death rate of Black women being the highest rate in the country, Black women cannot afford to wait for a court to grant them an abortion if something goes wrong during labor. Given all the statistics it’s fair to assume the maternal death rate for Black women

will only increase after the Dobbs decision, and the disparity between the maternal death rate of White women and Black women will only grow larger. The high maternal death rate and risk of complications for Black women shows they will be the most likely to need an abortion, but given the previous statistic that showed Black women account for the most recorded abortions, Black women will probably be the people denied the most abortions. The Dobbs decision is a slap in the face to Black women as it shows how the government has time to limit Black women’s access to reproductive care, but not time to help lower the maternal death rate for Black women. Even after overcoming the risk of pregnancy Black women are at a higher risk of suffering from “maternal mental health conditions” which about 40% of Black women experience after birth, but Black women are also “half as likely to receive treatment” for these conditions.

The right to an abortion is a right that grants women the ability for socioeconomic advancement as it

eliminates the possibility of an unwanted pregnancy postponing careers or schooling. From a socio economic standpoint the Dobbs decision further marginalizes Black women, as it will make it significantly harder for many Black women to pursue careers or schooling if they are ever faced with the financial strain of an unplanned pregnancy. Having an unplanned pregnancy can derail careers, schooling, and other life goals due to the huge commitment of raising a child, or even just the time spent pregnant with a child. The rate of unintended pregnancies is the highest among Black women which can be attributed to “disparities in access to quality contraceptive care and counseling” when even provided the contraceptive care. The United States is also one of the few developed countries that doesn’t require companies to have paid maternity leave. This can be a major stressor as women are forced to decide whether they should keep working in the later stages of their pregnancy or after the birth, or not receive income for an extended period of time. The Urban institute found about 80% of women think an unexpected pregnancy would negatively affect their lives. Given that Black women have a higher rate of unexpected pregnancies it follows that Black women will be the group most negatively affected by unplanned pregnancies. Being forced to follow through with an unplanned pregnancy has been described as “mentally debilitating” which is an understandable feeling considering the financial and mental demands of having a child, especially one a woman may not be prepared for. In a “turnaway study” conducted between 2008 and 2010 researchers studied pregnant women seeking abortions, and what happens to the ones able to get an abortion versus the ones who are denied an abortion. The result of the study concluded that “Turnaway-Birth group had much higher rates of receipt of public assistance,” and “income was also lower” for the group unable to receive an abortion.

The CEO of the the Black Women’s Health imperative

Linda Blount has predicted that “Black poverty rates [will] increase by up to 20%” with the recent bans on abortion .

With the recent passing of the Dobbs decision it is fair to expect maternal death rates, and poverty rates in the Black community to increase. Black women will be the group to suffer the most and the worst consequences from the restriction of reproductive care. For Black women the Dobbs decision isn’t about pro choice or pro life, as it impacts every aspect of a Black women’s health and financial stability.

Ten minutes. On May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for ten deadly minutes as Floyd cried out the words, “I can’t breathe!” as he was being suffocated in broad daylight. These words would soon echo through social media barriers as the video of this vicious murder surfaced on various platforms. The world fell silent as millions of people watched an innocent Black man be killed by one meant to protect them. The same energy within the media took to the streets. Millions participated in protests in their communities to advocate for this vicious act of police brutality and most importantly, bring justice to George Floyd. As a result, these protests shed a brutally honest light on the white supremacy that exists within the police system and called for cities to defund their police departments and increase funding for community services. This article will analyze the ways in which George Floyd’s death forced states to financially and legally reshape their police systems to provide more for the protection of life and community resources.

by Ure EguStarting at the end of May 2020, protests arose in over 141 cities across the United States including Los Angeles, Memphis, and Minneapolis where George Floyd was killed (New York Times). Those protestors took to the streets making the statement “Defund the Police” their main message to the justice system in the United States.

This same year, various cities across the United States acknowledged this call for change and took action to defund the police. As a result, cities were able to use this to give resources to underprivileged people in their cities. The Los Angeles City Council took its $89 million originally slated to pay for police services to now be used towards anti-gang initiatives, universal income programs, homeless services, education and jobs initiatives, and more community services (Smith, Zahniser).

Austin, Texas went from spending 40% of its $1.1 billion general fund on police to now allocating about 26% of this fund toward its law enforcement. The Austin police funds were reallocated to emergency medical services for Covid-19, community medics, mental health first responders, services for homeless people, food access, workforce development, and more. The city council has also used the money saved from the police budget to provide supportive housing for homeless residents (Levin).

The Salt Lake City Council reduced the budget for the Salt Lake City Police Department by $5.3 million which will set aside $2.8 million for the city commission on racial equity and policing and $2.5 million for community services including a social worker program (Johnson).

Thus, the call to defund the police after George Floyd’s death forced many local governments to reconsider their current police funding and redistribute it to parts of the community that would benefit from it. This redistribution provides more housing, necessities, and mental health resources for the community.

Just a month after his death, on June 26, 2020, Congress introduced the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2020. Officially passed in February 2021 with 219 to 213 Democratic to Republican voters, this act prohibits police systems from racial profiling, bans chokeholds, and no knock-warranties, according to (Congress.com). This act also takes away qualified immunity from police officers.

Since being passed, several states have utilized this act to better their police systems. Maryland, Virginia, and Washington are among the states that enacted laws banning chokeholds, limiting no-knock warrants, and increasing transparency around disciplinary records for law enforcement (Crampton). After the circumstances of Floyd’s death, it is exceptional to see how states are reframing laws to prevent similar situations from happening again.

Although the George Floyd Policing Act bill addresses racial inequality, it does not necessarily put an ultimate end to racism and the murder of Black life in America. The bill only exists on a federal level, therefore leaving independent control to each state to choose whether they would adopt such laws within their systems.

According to Joan E Greeve of TheGuardian.com, the George Floyd Policing Act is unlikely to be passed due to the current Republican control in the House and their inability to pass what is considered a Democratic bill. As time goes on and the bill is still not being passed, many Black Americans continue to face the same fate as George Floyd as they are not given the legislation and framework to protect themselves. Just three months into 2021, twenty-three Black Americans were killed by the police including those that were killed by the police for mental health reasons (Collins). In January 2023 alone, six unarmed Black people have been shot and killed by the police (Marks).

Conclusion

George Floyd’s death has challenged the current legal climate in the United States today by forcing society to open its eyes to what the system truly is; an outlet for white supremacy to thrive and for Black life to be brutalized. He has also fostered an opportunity for politicians to provide more to their communities while reevaluating the effectiveness of their police systems. Protestors, politicians, and police have used Floyd’s death as a reminder of what this country indeed presents; a place in need of fundamental legal and social change in order to support and protect the lives of the underrepresented and the underserved.

Igrew up in Southern California. The community that I lived in was racially diverse, but there was a very small concentration of Black people. In my neighborhood, there were four Black families that lived on our block, we all knew each other. In our schools, there were very few Black educators, so much so that during my matriculation from Kindergarten to senior year of high school, I didn’t meet a Black educator until seventh grade. I never had a Black teacher before starting college at UCLA at age 18. However, the importance of a holistic education was not lost on my father, who was at one point a lawyer and became a college professor – as a child, he was my source of political education and the voice of liberation. Still, because of his proximity to me, and my innate stubbornness to his directions, some of the history and movement-making fell on deaf ears and I continued in without the guidance of any other Black educators. In suburban communities, the loss of political education occurs as communities are dispersed and individualistic, schools do not reflect the diversity of their constituents, and cultural education becomes inferior to common-core curriculum. In large cities and predominantly-Black communities, the driving factor for political education is the proximity to the issue, as well as proximity to others facing the same issues. Regardless of location, Black students deserve access to their history, culture and the knowledge to be passed onto them. For Black students, acquiring an education, both traditional and political, is a greater struggle than their non-Black counterparts. A political education is defined as “teaching students to take risks, challenge those with power, honor critical traditions, and be reflexive about how authority is used in the classroom.” For Black Americans, the importance of political education coincides with breaking early cycles in traditional education systems that cause Black students to feel inferior or provide disrupting narratives through “Western” pedagogy. Changing those cycles through political education looks like questioning the political agenda and/or assertions made about their race through selected educational texts, challenging feelings of imposter syndrome, altering the axis of power from hierarchy between teachers and students to mutuality, or honoring their culture and beliefs in peaceful acts of self-expression. One major was we are combatting the issue of political education is by having more Black educators in our classrooms, which has proven to not only benefit Black students but all students in the class. The challenge presented from a lack of Black educators and lack of at-home political

education is equity. We see the issue of equity in our California school systems as Black students are gravely underperforming compared to their counterparts, especially since the covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the population’s exposure to health crisis, financial burden, and food insecurity. There are just over 300,000 Black students in Calfornia schools, and the statistical underperformance is a calling card for transformation in our school systems. According to “Black in School,” a panel of Black educators and policymakers dedicated to the improvement of Black student achievement, Black Californians:

67% of California Black children do not read or write at grade level.

86% of Black students are not at grade level in science.

31% of Black students have completed their A-G requirements, (necessary for admission to a California State college or university) as opposed to 49% of White students and 70% of Asian students.

77% of Black students graduate high school, in contrast to 88% of White students and 93% of Asian students.

The underperformance of our children is directly connected to the inequitable distribution of resources and funding in schools, and continues to impact students after their secondary education ends. We know that education directly affects the likelihood of being incarcerated in a lifetime, and if Black and Latino students are systemically and historically underserved, we will remain the largest populations in prison. Of the 58 counties in California, only six counties arrest their white residents at a higher rate than its Black residents. (3) That means 90% of California’s counties are overpolicing Black Americans, who consist of six percent of the state’s population. This cycle of disenfranchisement is why high school drop-outs are arrested at 3.5 the rate of graduates and only 20% of California inmates are considered “literate.” (4) Latinos constitute 44% of California inmates, and Black inmates are 28% as the two largest demographics in the prison system.

So what makes our political education revolutionary? An early education on Black Americans legal rights and how to use them. While learning from Black educators and incorporating culturally competent curriculum is uber important in the struggle, the focus on legal education for

Black Americans could alleviate a small threshold of the burden that the fear of incarceration bears on us. Black communities, parents, women’s groups and movement spaces have all advocated for legal education as a preventative measure, and in some cases impart it themselves upon their community; here, the fear of incarceration or death by police becomes an emotional labor expended by Black people – even when the threat of violence is not imminent, many of us have routinized and naturalized ways to protect ourselve into our daily modes of being. To take this further, we must mobilize on the praxis that this is not a labor of love, but fear, and to transform the small ways we protect ourselves into a knowledge base with access to resources and people who will fight with you. If we can make change with one less plea deal or one less invasive traffic stop, then we have made change. I am not saying that knowing our rights will end the violent persecution of Black people by police and the justice system, as we know that system was built to work against us and is doing so effectively. We mourn the loss of those lives daily. We know the systems of knowledge and power in this country are not constructed with Black faces in mind, yet use Black bodies to actualize their visions. What I argue is that we have been doing the work. The unintentional labor of care and passion for community is apart of the work. The ability to gain knowledge and pass it on, is apart of the work. Becoming the Black teacher you never had or the Black lawyer someone may have needed is apart of the work. A political and legal education (composed of legal rights and how to use them effectively) is one piece of the puzzle that has the ability to impact Black Americans, Indigenous peoples and Latinos on the scale of the individual. When one teaches, two learn.

PRESENTED BY THE BLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION IN COLLABORATION WITH NOMMO NEWSMAGAZINE, THE AFRIKAN PEOPLE’S MAGAZINE, AT UCLA 2023.

Designed and edited by Leilani Fu’Qua

PRESENTED BY THE BLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION IN COLLABORATION WITH NOMMO NEWSMAGAZINE, THE AFRIKAN PEOPLE’S MAGAZINE, AT UCLA 2023.

Designed and edited by Leilani Fu’Qua