THE FOREST GARDEN

Cultural Centre for Traditional Crafts and Knowledge

Vilnius, Lithuania

Tradition is not a static ‘thing’ to be inherited, preserved or possessed, as true tradition has to be reinvented and re-created by each new generation.

Cultural Centre for Traditional Crafts and Knowledge

Vilnius, Lithuania

Tradition is not a static ‘thing’ to be inherited, preserved or possessed, as true tradition has to be reinvented and re-created by each new generation.

Cultural Centre for Traditional Crafts and Knowledge in Vilnius, Lithuania

University:

Programe:

Project:

Date:

Student:

Committee: Amsterdam University of the Arts Academy of Architecture Msc in Architecture

The Forest Garden

27.08.2024

Dovile Seduikyte

Jo Barnett (mentor)

Machiel Spaan

Rogier van den Brink

Lithuanians have a long history of a close, even spiritual, relationship with the forest. Growing up, nature played a big part in my life. My (grand)parents taught me to recognise mushrooms, and berries, build fires, braid flower crowns, and extract birch sap. It’s some of the traditional skills passed down and not taught in schools. However, a lot of traditional knowledge, crafts and skills are almost forgotten.

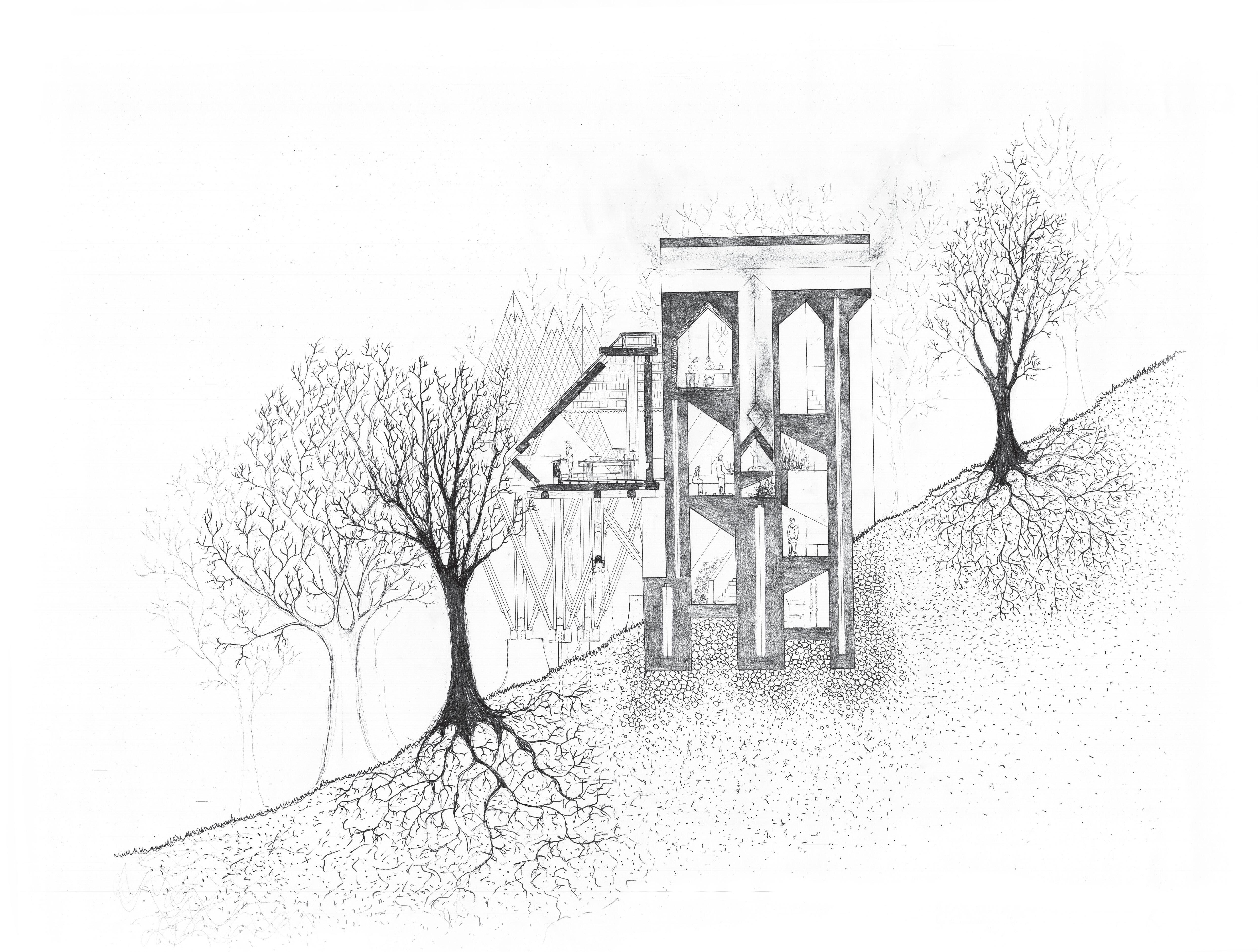

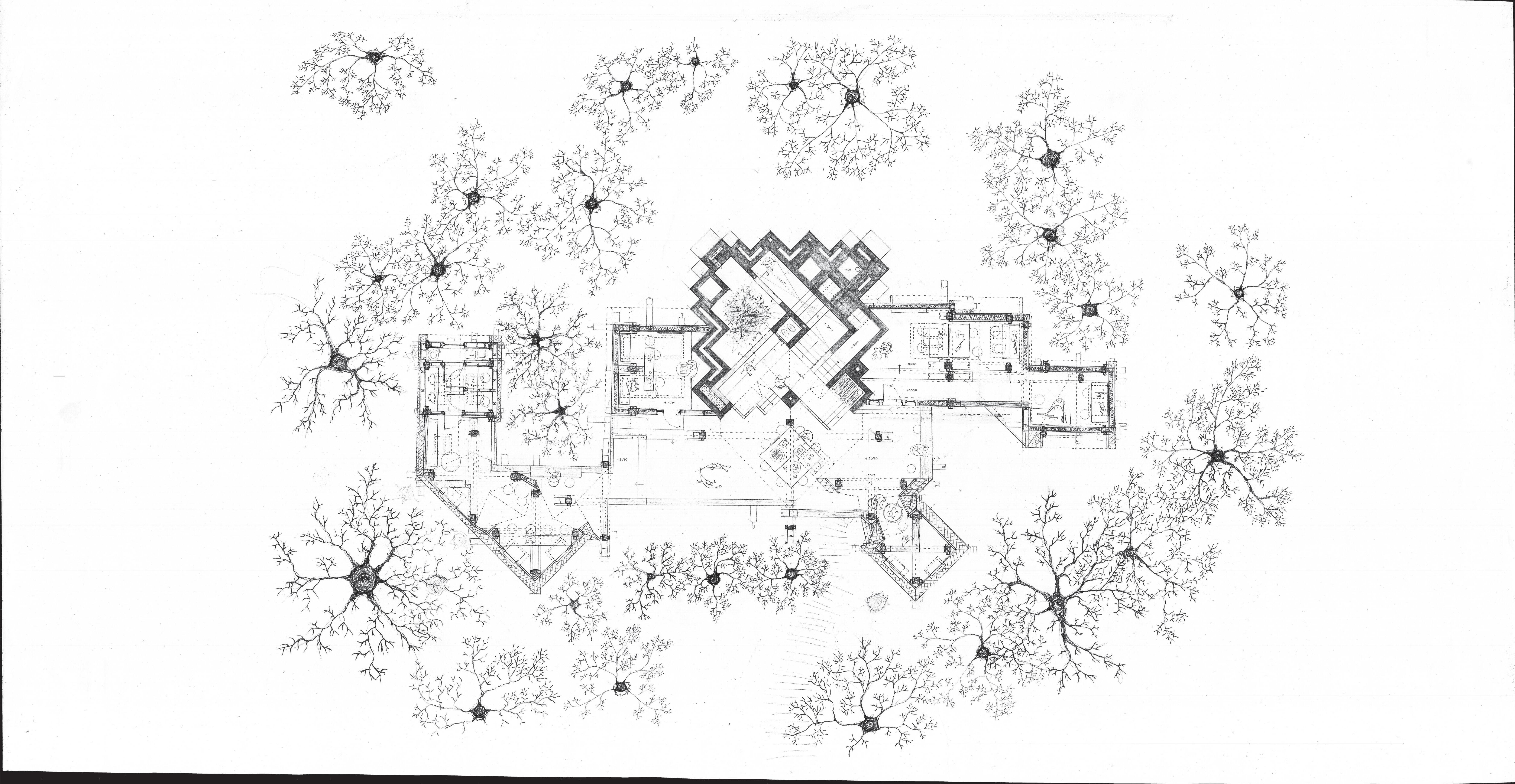

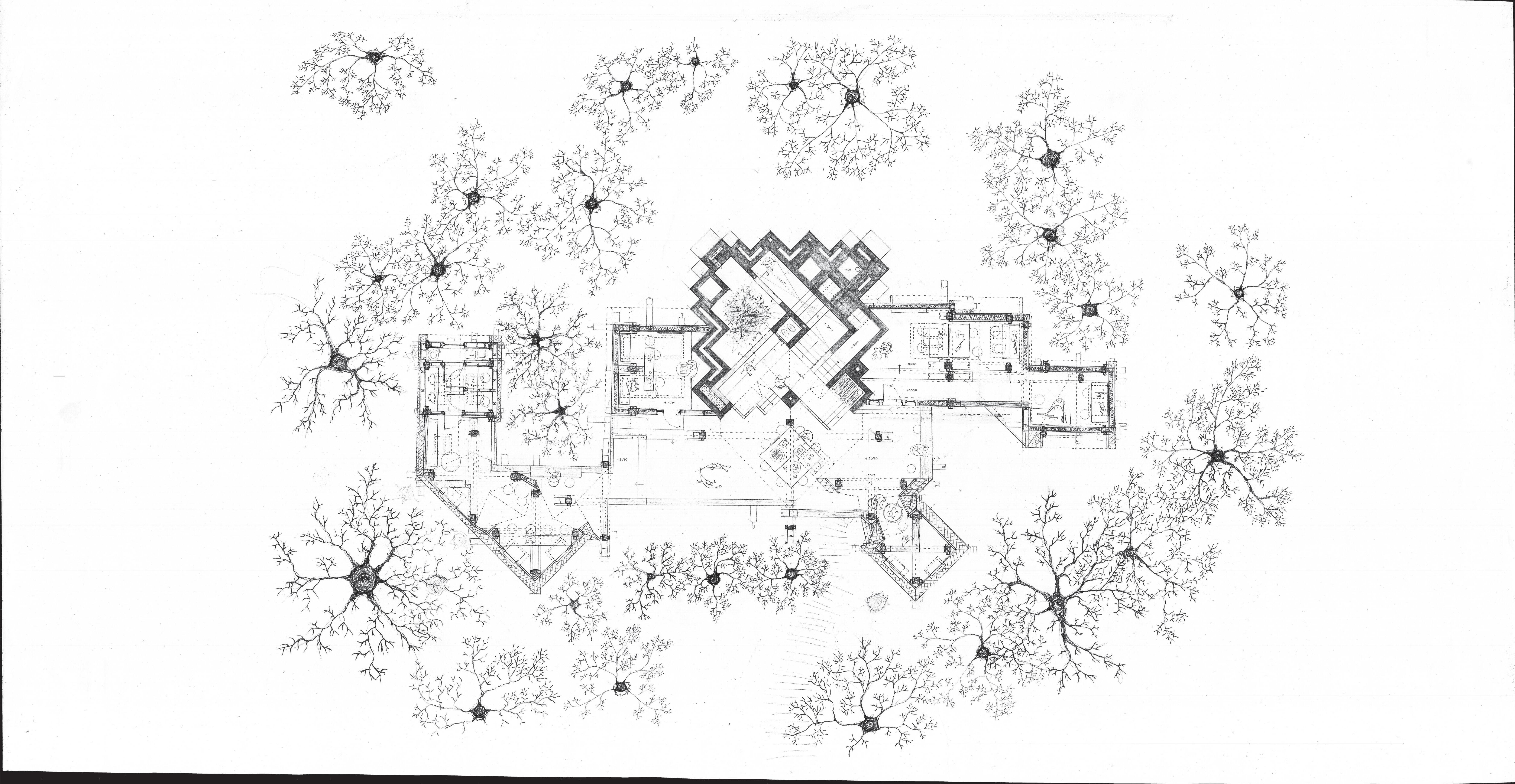

Therefore, using the building process as a learning opportunity for locals and other interested parties, we created a Cultural Centre surrounded by nature in my hometown Vilnius. Here school children, curious adults and foreign visitors can learn from the experts of ethnographic culture about the secrets of the forest, vernacular craftsmanship or traditional celebrations.

The building draws inspiration from Lithuania’s vernacular architecture, values and craftsmanship. Our ethnographic architecture mostly includes stacked wooden log houses, built and designed by craftsmen, developed since the Baltic tribes settled in modern-day Lithuania until the beginning of the 20th century. Further development has been halted by complicated political circumstances and a lack of wealth.

Comparable circumstances were faced by Wang Shu, when he created culture-sensitive Chinese modern architecture inspired by traditional art. Therefore, I followed his process and found inspiration in Lithuanian Straw-Gardens. Not only are they ancient structures of fundamental geometric shapes, but their simplicity allows for a plethora of symbolic and religious interpretations, such as a balance between the spiritual and the material. Traditionally, straw gardens are hung above baby cradles or dining tables to achieve harmony and fill homes with good energy.

While ‘growing’ my own Straw-Garden, I learned that it also encompasses Baltic values, such as connection with nature, patience, resourcefulness and sustainability. I wanted the Culture Centre to embody these values, hence the project adapts itself in a forest, is composed mostly of materials we could find nearby and grows, as well as diminishes, with time.

We harvested materials from 4 sources and constructed temporary pavilions on the journey to the site to act as material storage, as well as bringing interest to the area.

Firstly, we deconstructed three old log houses, within 1.5km of the site, and used their elements in various parts of the Cultural Centre. Inspired by the beautiful display of deconstructed Lithuanian traditional dwellings by artist A. Serapinas, I wanted to display the unique joinery and, in a way, preserve these pieces of history that would otherwise rot away or be used as firewood. The old timber logs are the primary material used for the construction of the platform and its roof. We also reused all the other elements of the log houses, such as windows, rafters and finishes throughout the project. The materials of the first two houses were used up entirely. From the third house, we harvest the windows and doors, as the spaces under the roof must be well-lit by daylight.

The timber obtained from thinning a part of the forest has been used to make extra beams, shingles and joinery between elements. The trees I chose to cut down also shaped the layout, as the stumps turned into foundations for the timber platform.

We harvested clay from the site to produce bricks to build the structural core of the building, which houses the fire, the focus of most Baltic rituals. The reed surrounding the pond on the way to the site was periodically harvested for the roofs of the pavillions and for the insulation of the Cultural Centre.

The result is a Forest Garden, where people can learn traditional crafts, skills and knowledge in an inspiring environment. The reused materials remind of our heritage and values, the openness of the structure creates spaces with a strong connection with nature and the Straw-Garden inspired geometry demonstrates that the vernacular has a place in the modern day.

INTRODUCTION

POGRAMME

INSPIRATION

LOCATION

MATERIAL

BUILDING

GROWING

Personal Motivation

Desire for Preservation

Lithuanian Vernacular Architecture

History of Oppression

Lithuania’s Architecture Today

Having grown up in Lithuania and leaving at 16 years of age allowed me to take a look at my country from farther away. It is a country of very patriotic people, who deserve their heritage and traditions to be reflected in modern architecture. Lithuanian vernacular craftsmanship has so far remained in the past, as complicated historical circumstances prevented its transition into the modern day. However, over the years I’ve seen an interest igniting to learn and preserve our ethnographic traditions.

Most of the traditions stem from the old Baltic religion, as Lithuania was the last country in Europe to convert to Christianity. Baltic religion personifies nature as gods or nature being the medium to connect with gods. Therefore, Lithuanians have a long history of a close, even spiritual, relationship with the forest and its protection.

Growing up, nature played a big part in my life. My (grand) parents taught me to recognise mushrooms, and berries, build fires, extract birch sap, and braid flower crowns. It’s some of the traditional skills passed down and not taught in schools. However, a lot of traditional knowledge, crafts and skills are almost forgotten. Therefore, I wanted to design an inspirational space where anyone interested could learn from experts of ethnographic culture.

Me picking mushrooms as a child and now

Over the last few years, I noticed a growing appreciation of our heritage among Lithuanians. Maybe it’s because the trend to ‘Westernise’ is wearing off, maybe people are looking for their unique identity in this increasingly globalised world, or we simply start to see value in something as it starts to become sparse.

ARTICLE READS:

Another Wooden House in Žvėrynas (Vilnius) is Being Demolished - it is no Longer a Secret What Will be Built in its Place

On Saturday, wonderful spring weather prevailed in Vilnius, which encouraged residents to go out for a walk around the city. However, spring walks did not brighten the mood for everyone. For some, it was the opposite when they saw that a wooden house was being demolished in Žvėrynas.

Vilnius residents express their anger on social media, as such a beautiful and unique house is being demolished.

Article from newsportal lrytas.lt

The first buildings in current day Lithuania were rectangular structures with decks or large rocks as a foundation and interlocking horizontal logs stacked on top. The reed roof had two or four slopes with a bark/clay chimney in the middle to let the smoke out. This is where early Lithuanian tribe families lived, stored their grain and other things.

Lithuanian architecture is very much based on the geographical conditions. The abundance of forests led to almost everything being made from wood. Log construction, especially horizontal log construction, requires a lot of material. However, this was not a problem in the area. The main objective was to create a shelter from the harsh weather conditions and horizontal log construction provides the best thermal insulation for the technologies of that time.

The mass and the proportions of the house are already pleasing to the eye. However, the effect is enhanced by a careful use of decorations. Usually, they are focused on the entrance, extensions, windows and doors. According to P.Galaunėėėėėe, Lithuanians do not like flat monolithic mases. Even the structural columns have various cutouts, which makes them elegant and light. The planks placed over the logs are often arranged in a pattern to break up the surface, this is also quite common in door designs. The various cutout patterns in the wood also get rid of monolithic surfaces by creating a play of light and shadow. Most of these patterns come from the pagan times, they are very symmetrical, geometric, sometimes referencing nature and animals.

“

Visit with Expert Rasa Bertasiute

Lithuanian traditional architecture is very pragmatic.

”

Rumsiskes Open-Air Museum is a place where ethnographic buildings from all regions of Lithuania were taken apart and brought to showcase for educational value. I have visited the museum a few times as a child, however, this time I looked at the exhibits with the eye of an architect.

Here I also got the oportunity to talk to an expert of Lithuanian etnographic architecture Rasa Bertasiute. She stressed that, in essence, our traditional architecture is very pragmatic. Even decoration has four purposes: aesthetic, religious, functional, and informational.

What is fascinating is that these wooden buildings can stand for hundreds of years. The structures have no paint, coatings, or charring to protect them. Most of the time, only a mixture of cow dung and clay separates the wooden logs from the ground. Typically, pine or spruce was used for the construction, with only the bottom one or two logs being a more resistant oak.

This is the testament to the high quality of timber back in the day. Not only was the wood more dense, as it was grown in an old forest, but long processes such as girdling and sinking the wood to the bottom of a lake, were used to further improve the strength and resistance of the material.

The development of Lithuanian statehood and cultural tradition was interrupted by a complicated history. The peak of Lithuania as a power was in the 14th century, when it stretched all the way from the Baltic to the Black Seas. However, due to the threat of the Russian Empire, Poland and Lithuania decided to form a Commonwealth. Durig this time, a lot of influence, especially in the cities, came from Poland and beyond.

Due to a complicated political situation, the Commonwealth fell apart and was divided up between 3 countries. Most of the Lithuanian territory fell to the Russian Empire. Durig this time Lithuanians faced major oppression, as even the Lithuanian language was outlawed.

In the 20th century, Lithuania was occupied by either Russia or Germany most of the time. After regaining their independence in 1991, Lithuanian architects decided to look at the Western and Scandinavian countries for inspiration, as there was a drive to disassociate as much from Russia as possible. Lithuanians wanted their cities to be an image of a free, liberal and modern society. However, in this chase for new identity, Lithuanian roots were largely forgotten. Only more recently, I have noticed more people taking interest in our crafts, traditions and ethnographic architecture. As well as their decay or even destruction.

Lithuania’s expansion in 13th - 14th century

Partition of the Commonwealth 1795

Russian occupation 1944 - 1990

Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569 - 1795

German occupation 1942

Lithuania’s position today 2024

There were a few attempts to bring back a sense of national identity. However, they only scratch the surface of what could be a much deeper interpretation of Lithuanian tradition. That’s why I’m driven to continue this exploration.

Vilnius is known for its Baroque in particular, which is from Italy. As well as the famous Gothic brick church. Then Soviet Brutalist architecture from the 20th century, which is a reminder of oppression for many. And since gaining independence, Lithuanian architects looked at the West and North Europe for inspiration, in a push to be perceived as a modern western country and dissociate from the idea of backwards, communist Eastern Europe.

Current Culture Centre

Vernacular Crafts

Vernacular Knowledge

Baltic Celebrations

There already is an Ethnic Culture Centre in Vilnius. It’s 3 main objectives are: teaching ethnic culture, Lithuanian celebrations and Publications.

It currently shares an Art Deco villa from 1938 in the city centre with a museum for writers. It’s a lovely building, however, it has nothing to do with ethnographic tradition and it is too small for the program of the center. It hosts occasional classes, workshops or conferences, but they often also need to find alternative spaces.

As there is a growing interest in ethnic culture, I thought it would be great to have a building for the Culture Centre that embraces tradition in material and in spirit. A building that lets you connect with nature, rediscover tradition and its possibilities. The old building in the city centre remains, the function of the Forest Garden is to host various workshops (particularly allowing wood craftsmanship), classes and lectures (especially to do with foraging and forest knowledge), as well as traditional events and celebrations.

Foraging Forest Knowledge

There was a very big oak tree. They say that whoever cuts it will die. That oak has grown quite old - everyone was afraid to cut it. Then two such men appeared, got drunk, and said:

- We’ll go, cut him down - and die ourselves!

They cut down this oak tree. One died quickly, not even a year had passed, and the other had his hands cut off.

They say he was cursed!

Revenge of the stork

There was such a mischievous child who tore up the stork’s nest and threw his children out. Once the child saw a stork flying in with a speck in its beak. He placed it on the roof of the barn, where his nest once was. The barn caught fire. Then more huts from that barn. Then almost half of the village burned down.

Mushrooms - flowers of the earth

Mushrooms - flowers of the earth

Mushrooms are the flowers of the earth. As most of the plants bloom, the earth also blooms when in the summer it rains, and the sun shines, mushrooms grow - that is, they say, the blooms of the earth.

Mushrooms are the flowers of the earth. As most of the plants bloom, the earth also blooms when in the summer it rains, and the sun shines, mushrooms grow - that is, they say, the blooms of the earth.

The anger of Perkūnas and the devil

Wind with no pants

The anger of Perkūnas and the devil

Why is the mole blind?

Why is the mole blind?

One day, Mr. god ordered all the animals to go lay roads. All the animals gathered and worked all day. Only one mole did not come. Then Mr. God went to the mole and asked:

One day, Mr. god ordered all the animals to go lay roads. All the animals gathered and worked all day. Only one mole did not come. Then Mr. God went to the mole and asked:

- So why didn’t you come to work, mole? - It’s because I can’t see well and I couldn’t read the order, - the mole lied, although his vision was no worse than other animals.

- So why didn’t you come to work, mole?

- It’s because I can’t see well and I couldn’t read the order, - the mole lied, although his vision was no worse than other animals.

Mr. god got angry and said:

- You are lying, so from this day on you will not see.

Mr. god got angry and said:

- You are lying, so from this day on you will not see.

Since then, the mole has been burrowing underground and can no longer see anything.

Since then, the mole has been burrowing underground and can no longer see anything.

Perkūnas (god of thunder, storms, sky) had many stones in a pile and the devil stole one of them. He put it in the foundations of his house as he as missing one. When Perkūnas found out he got angry and now tries to hit him with lightning wherever he sees the devil.

A girl went outside to rake hay and saw the wind basking in the sun with no pants on. The frightened wind asked the girl not to tell anyone about it.

Perkūnas (god of thunder, storms, sky) had many stones in a pile and the devil stole one of them. He put it in the foundations of his house as he as missing one. When Perkūnas found out he got angry and now tries to hit him with lightning wherever he sees the devil.

- I will make you rich for this, he says.

- How will you make me rich? - asked the girl.

- Well, when you get married, when it’s needed, I will bring you rain, and when it’s not needed, I will blow it away.

Perkūnas sometimes finds the devil siting on a stone, in a tree or swimming in the water. The devil tries to crouch on a taller rock or in a taller tree so he could see Perkūnas better. Therefore, people should not stand under a tall tree when the presence of the god of storms can be felt.

Perkūnas sometimes finds the devil siting on a stone, in a tree or swimming in the water. The devil tries to crouch on a taller rock or in a taller tree so he could see Perkūnas better. Therefore, people should not stand under a tall tree when the presence of the god of storms can be felt.

The girl got married, and everything was going well until she told no one about the incident. But once, lying with her husband in the barn, she started telling him how she found the wind without pants, and how he asked her not to talk... In the blink of an eye, a tornado swept away the roof and destroyed the barn.

Laumės and a baby

Laumės and a baby

A woman went out to rake hay. She did it for a long time, rushing before rain and because of the rushing she forgot her baby in the meadow. She runs back and sees dirty rags folded and her child in a cradle swaddled in silks. Laumės (a dual gods with a strong sense of justice) are swaying and chirping:

A woman went out to rake hay. She did it for a long time, rushing before rain and because of the rushing she forgot her baby in the meadow. She runs back and sees dirty rags folded and her child in a cradle swaddled in silks. Laumės (a dual gods with a strong sense of justice) are swaying and chirping:

Hushaby baby forgotten, Left behind on accident.

Hushaby baby forgotten, Left behind on accident.

The neighbour of the woman found out and she went out to reek hay. She’s reeking, rushing, the clouds are coming. When she walks away she leaves her baby on purpose. Some time later she comes back and sees that Laumės twisted her baby’s neck and with his body on a bench they’re chirping:

The neighbour of the woman found out and she went out to reek hay. She’s reeking, rushing, the clouds are coming. When she walks away she leaves her baby on purpose. Some time later she comes back and sees that Laumės twisted her baby’s neck and with his body on a bench they’re chirping:

Hushaby baby not forgotten, Left behind on purpose.

Hushaby baby not forgotten, Left behind on purpose.

References

Visits Interviews

Just 5 km from the site, there is an outdoor kindergarten and primary school surrounded by nature. I participated in two classes with the children. I talked with them and their teachers to find out the struggles they were facing and what was important to consider when designing for outdoor education.

The obvious struggle is bad weather. They do have indoor classrooms inside of shipping containers. The cold Lithunian weather most of the year makes it difficult to write outside, as the hands freeze quickly. There is also no shelter from rain or wind outside. Loose papers would threaten to fly away at the slightest gust of wind.

The teachers pointed out the importance of having a variety of spaces for the pupils to work. The children unitedly demanded places to take naps.

My thoughts on traditional architecture in a modern context were sparked when I came across the Ningbo Museum in China several years ago and was intrigued to research it further. I found that, in a way, China and Lithuania have some overlapping in terms of traditional architecture in modern context, such as not having traditional architects but rather craftsmen, and struggle to find its place in modern day.

Wang Shu looked at traditional art, an old mountain painting by Li Tang, as the concept for the museum. He also used reclaimed materials from demolished traditional dwellings and revived an old traditional building technique called wa-pan. He created experiences and feelings of nostalgia instead of just considering materialistic aspects.

I wanted to attempt to do something for Lithuania, what Wang Shu did for China and he gave me a blueprint for it. I went looking for inspiration in traditional arts. I realised that there is an extremely old craft in North-Eastern Europe, so old we don’t know the details when or where it exactly originated. In Lithuania, they are called Straw Gardens. Traditionally, they are hung above baby cradles or dining tables to achieve harmony and fill homes with good energy as they spin.

By paskuivaivorykste.lt

They’re ancient structures of fundamental geometric shapes, but their simplicity allows for a plethora of symbolic and religious interpretations, such as balance between the spiritual and the material. While ‘growing’ my own straw garden, I learnt that it also encompasses Baltic values, such as connection with nature, patience, resourcefulness and sustainability. I wanted my interpretation of Lithuanian modern architecture to reflect these values, hence the project adapts itself in a forest, is composed mostly of materials I can find nearby and can grow or diminish with time.

During my research, I was intrigued by a vernacular architecture example where a dwelling has a chimneykitchen in the middle of the house. I also visited such a house in the Rumsiskes museum, and I really loved the atmosphere the most out of all the vernacular examples there.

“ It is all about the beauty of craftsmanship. ”

Lithuanian artist A. Serapinas brought up the issue of these traditional log houses being destroyed or neglected, and not being protected as heritage. He is’saving’ them by transforming into something new. In his case, deconstructed art pieces that display the unique joinery, otherwise mostly hidden.

The owners don’t really care about these buildings. Just want to get rid of them. They don’t know much about them. It was forgotten when they were built a hundred or more years ago.

The large logs are still very strong after many years. The logs and roof trusses will be in good condition as long as there are no holes in the roof. They could definitely be reused for structural functions. The first thing to do is to clean away any mould and take the logs apart to dry them.

“Wood

Strive to Save Japanese Wood Craftsmanship

“ You can keep the building, we’ll keep the culture. ”

In Japan, moving a building costs a lot of money, and there is no need for it. So we thought, If somebody is interested and has the financial means to move a building, why not Europe?

Many of the old handmade materials used in traditional houses are of superior quality to modern cheap ones. Relocating a house probably costs about the same as building a new one in Japan, but for the same money, the quality is so much higher. Also, when these houses were everywhere, it wasn’t anything special. But now that the number of traditional buildings is in such a rapid decline, people are finding value in it.

Relocating a building, we send the older generation, who have the knowledge, and the younger, so the knowledge gets passed on. The same knowledge is needed in taking a house apart as in putting it together. As long as the skill is there and we can keep fixing and relocating old buildings, we keep the ability to build new ones. But next to the skill, it is also a way of thinking and approach to architecture, and I think that’s the most important and hardest part to save because it’s something that lives in the mind.

Traditional buildings are very strong. They do shake, but they don’t fall during earthquakes. However, there is no way to put the calculations of a traditional building on a computer. Every structural beam is naturally bent and has individual characteristics. So, there is a struggle to comply with the regulations.

- Interview with Hajime Wilds (Craftsman)

Building in very bad condition - use timber for furniture

The house is situated amidst a forest on the small island of Miyake in the Pacific Ocean. It was planned in the 1970s by students of the New Left and members of the Peace Movement as a communal residential building and place of retreat. Financial constraints meant that the inhabitants had to build the house themselves. Shin Takasuga’s decision to use old, wooden railway sleepers resulted in a five-year construction time. But it was not the use of sleepers that was novel, rather the universal utilization of one single type of construction element for the whole structure – walls, floors, columns, roof structure, the builtin furniture too.

-Hidden Architecture

The reused materials lead the design process and resulted in a building full of character and atmosphere.

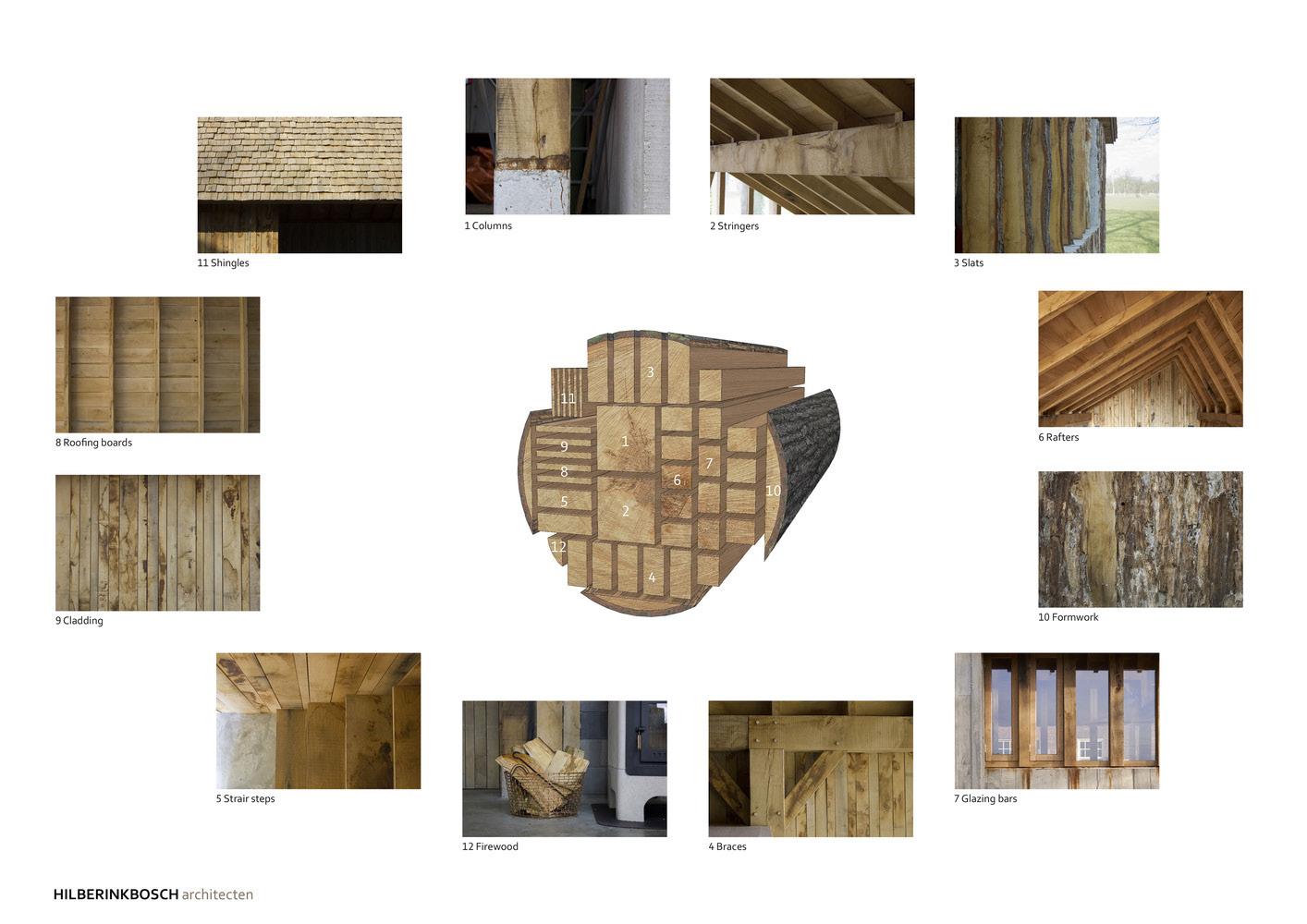

Traditionally, most farmhouses in the Meierij of ’s Hertogenbosch, a were built from locally available materials and largely followed the structural pattern of the farmhouses themselves.

We were told that seven of the century-old oak trees in our yard were in bad shape. They had to be cut down. Instead of following the usual path and selling the trees to the paper industry, we decided to reinstate an ancient tradition.

A mobile sawmill was brought to the yard and used to cut the fresh tree trunks into structural timber for the frames and roof as well as planks for the façades.

- HilberinkBosch architects

50 students from 5 international schools deconstructed the last remains of a 100-year-old barn

Taking the Expo theme of sustainability seriously, we constructed the pavilion out of 144 km of lumber with a cross-section of 20 x 10 cm, totalling 2,800 cubic meters of larch and Douglas pine from Swiss forests, assembled without glue, bolts or nails, only braced with steel cables, and with each beam being pressed down on the one below. After the closure of the Expo, the building was dismantled and the beams sold as seasoned timber.

- Peter Zumthor

Timber paths in natural areas

Vilnius Regulations

Routing

Site Ritual Observations

Location: Vilnius, Lithuania

Walking through Lithuanian cities today, visitors and locals alike sense they are in Europe. They see a tapestry of different architectural styles and historical times. The capital Vilnius is well known for baroque architecture from its Grand Dutchy of Lithuania times (17th-18th century). Many brutalist Soviet buildings remain unchanged, reminding of the recent past. Most recently built areas could be somewhere in Western Europe or Scandinavia. They don’t give an impression of a uniquely Baltic environment.

Growing up in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, I sense a lack of national identity in the architecture of my hometown. Lithuanian people have a difficult history and are extremely patriotic. Therefore, they deserve to see their culture and traditions reflected in the modern context.

relationship

Nature and forests play an important role in Lithuanian tradition. The Baltic religion views old forests almost as a church and trees as mediums between humans and gods. Back in the day, Lithuanian forests were very abundant and provided for our ancestors. To this day, picking mushrooms and wild berries is a common pastime.

Therefore, I wanted to design a building that has a close relationship with the forest. I looked for a suitable site in an area I am familiar with. The chosen site is a 20 minute walk away from where I grew up and a 30 minute walk to the city centre through an area of recent development. Site: Markuciai

- Site - Park - Forest - Nature Reserve - Green Area - Built Area - Buildings - Water - Roads - Train Tracks - Regional Park Boundaries

Lithuania used to be completely covered in forest, which led to its people developing a very close practical and spiritual connection with the woods. Even today, one-third of Lithuania has forests growing and the Lithuanian people have a strong drive to preserve the remaining woodlands.

For this reason, very strict laws exist, limiting and controlling construction on forest land. Especially in the forests of capital Vilnius in the beautiful Pavilniu regional park. There, construction is legally impossible and heavily controlled, even in non-tree covered areas.

However, my project aims to embrace the traditional Lithuanian values and immerse the visitors in the forest environment. It will be an example of how sensitive architecture can complement the existing ecosystem and cause minimal damage to the area. It will be a sustainable project that will take time through different phases. The final phase of the Cultural Centre construction could be 10 years later. The regulations could change by that time, especially if the public and officials feel positive about seeing a new approach to traditional architecture in the forest.

From protected territories regulations document:

14.1.9. it is prohibited to build buildings and develop engineering infrastructure, convert forest land into other uses, as well as exploit minerals;

- Site

- Bus Stop / Parking

- Permanent Pavilion

- Temporary Pavilion

- Fastest Route

- Alternative Routes

- Markuččciai Manor

- Power Lines

72,7m

The site is conveniently located close to the city and transport, while being in a beautiful forest. The fact that it’s a regional park, means that even if the city keeps expanding, this area will always remain relatively green.

There is a bus stop and a parking lot about a 12 min walk from the site. It’s a beautiful journey though as you walk through the Markuciai park. You can take multiple paths, climb up through the hill overlooking the pond, or walk around with minimal change in altitude.

This park is also important to the project, because numerous interventions took place here during the construction of the Forest Garden, temporary pavilions in particular.

Many large oaks Dwellings in the distance

The area is hilly, and following traditional knowledge, I decided to build halfway up a slope. The bottom of the hill would be too damp, and the top would be too windy. I made sure to build at the point where the ground becomes dry to minimize the number of stairs people would have to climb up.

As a start to the project, I hosted a workshop with some children where we buried some objects on the site and placed a foundatuon stone over it in traditional spirits.

To mark the place, we constructed a small structure out of the fallen branches nearby and spent some time there to observe the qualities of the site, collect objects and study plants.

Houses

HARVEST

MAP

MAP

- Site + harvesting timber and clay

- Site + harvesting timber and clay

- Harvesting old houses

- Harvesting old houses

- Harvesting reed

- Harvesting reed

- Road transport

- Road transport

- Foot transport

- Foot transport

- Train station

- Train station

Extending the log

Roof beam connections

Research was organised with some students to document the old wooden buildings in the neighbourhood. This allowed us to choose 3 abandoned or rundown buildings that could be used as material banks.

This one was by far in the worst condition, hence we started with it. We took the building apart, which allowed the student to learn about traditional construction. They also made a material log, which I used when designing the Forest Garden.

S-30 x2

S-29 x2

S-28 x2

S-27 x2

S-26 x2

S-25 x2

S-24 x2

S-23 x2

Log House : Sroves st. 6

Exterior Door

This house has been repaired in patches in the past and the residents were pushed away by new developments. Therefore, we chose it to preserve as elements in the Forest Garden.

Just as before, I held some workshops with students to deconstruct the house and log its materials.

We also took apart another house, which was not a log house, but also in a deteriorating condition.

The reason for this is because we needed more windows for the Forest Garden to have plenty of daylight, while providing shelter.

As I had an idea of the layout I could start harvesting the selected trees. During my design process I favoured chopping down the older trees.

The trees included birch and alder. Therefore, I assigned different uses for them while considering their properties. I used birch for construction, as it is stronger and more durable. Whereas, alder is better suited for more intricate woodworking.

- Harvested Alders

- Trunks Used as Foundations

Workshops were held to harvest clay, purify it, shape it into bricks and then fire them in a primitive construction brick oven. (Source: Youtube - Primitive Technology) The brick structure was built while the bricks were being made.

We found that the typical temperature used to fire bricks works well for this material. However, as baking it in a primitive way makes it harder to control the temperature, there are some colour variations.

Firing the bricks

The reed surrounding the pond on the way to the site, was periodically harvested for the roofs of the pavillions and for the insulation of the Cultural Centre. As temporary pavilions were dismantled, the reed from their roofs was stored to be reused in the Forest Garden.

Timeline

Shelter Pavilion (temp.)

Fishermen’s Pavilion (temp.)

Woodchopping Pavilion

Exhibition Pavilion (temp.)

As the project uses many materials harvested over time that need to be documented or processed, it was vital to consider where to store them while they await construction. Constructing temporary pavilions on the route to the site not only acted as functional storage but also ignited knowledge and interest in the area years before the Forest Garden was complete.

- Site - Permanent Pavilion - Temporary Pavilion - Alternative Routes - Fastest Route

As the first log house was deconstructed, we used its parts to construct a temporary shelter and storage next to the site. It was inspired by the deconstructed pieces of A. Serapinas and acted as an intriguing art piece, bringing more interest to that area of the forest as well as providing shelter for outdoor workshops when the weather turns bad.

After chopping down the selected trees on the site, the wood had to be dried and stored somewhere. Therefore, I organised a workshop with some architecture students to design and build a pavilion for the fishermen seen around the park pond.

The idea for this was based on the Swiss Sound Pavillion. This way the timber created value while drying and getting stressed. Furthermore, it brought more interest to the park

After digging out all that clay at the bottom of the hill, we had quite a large mud pit. Therefore, it was a good idea to build a passage over it, on the natural path to the Culture Centre. Therefore, this is where we decided to build a woodchopping pavilion.

The pavilion came in useful when constructing the timber part of the culture centre and processing the wood from the forest before dragging it up the hill to use as firewood. The woodchopping pavilion was designed and built by architecture students using a combination of leftover elements not planned to be used in the construction of the wooden platform, some new timber from the fishermen’s’ pavilion and reed from the pond for the roof.

Exhibition Pavilion (temp.)

Similarly to the Shelter Pavilion. As we deconstructed the other two houses, the elements were used to construct a pavilion, as the materials awaited to be used. This time it was an exhibition pavilion, which was used to showcase the work that has already been done to the public, as well as present future ideas and hold talks on traditional architecture.

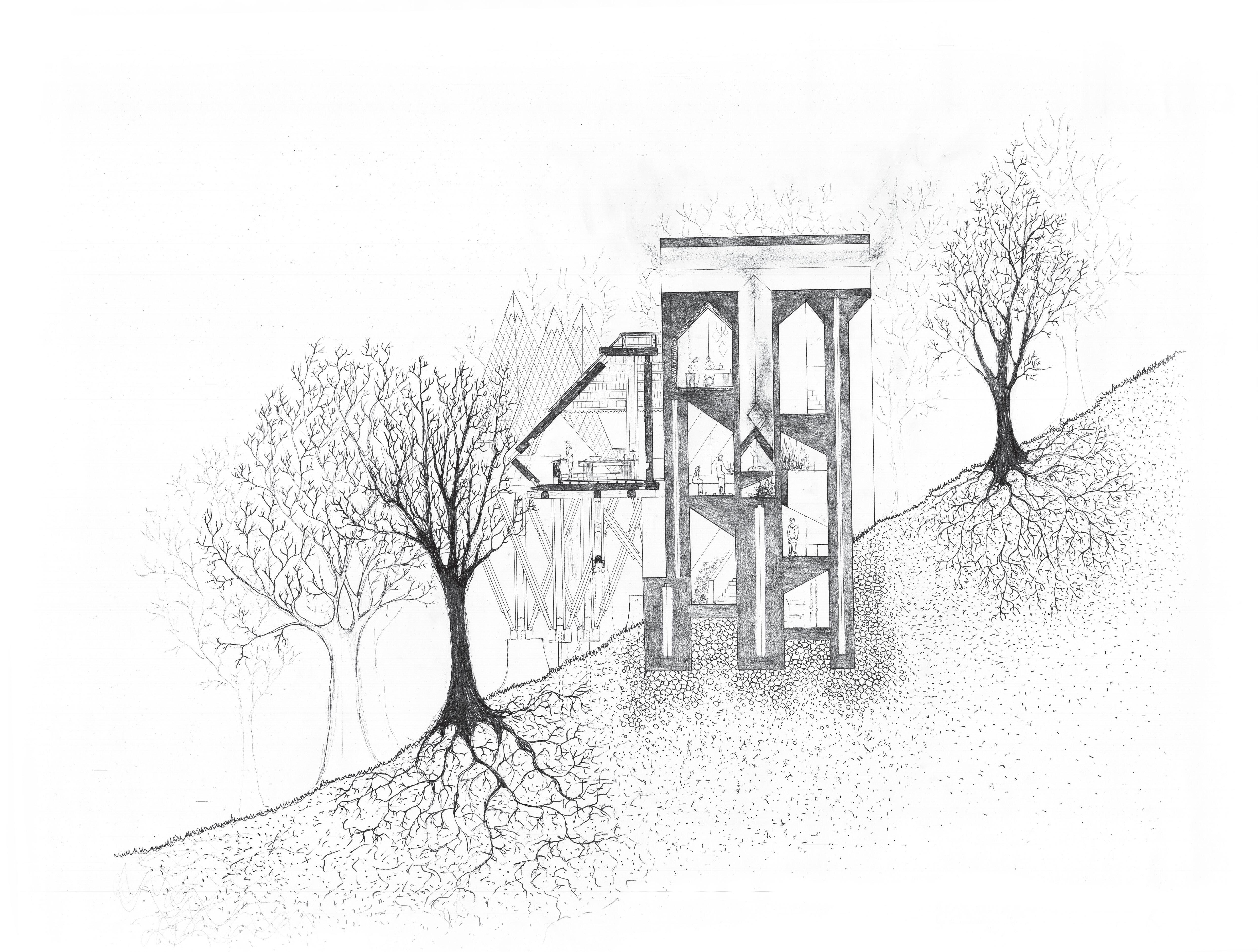

The Brick Heart is the first and crucial part of the project, as it allows for a big fire in a forest in a safe manner and provides stability for the structure that goes around it in later stages.

The clay was obtained and made into bricks on site, using it as a learning opportunity.

All the windows and doors from the first harvested log house were incorporated as their original function or made into furniture. As well, as a timber facade turning into flooring for the top floor.

The brick itself is a Russian brick, which I decided to use as it is good at heat storage and fit in well into a Flemish bond unit that I developed. I made the unit that size because it allowed the most efficiency in my floorplan. I used the Flemish bond because it has a pattern and is strong and some of the most famous castles in Lithuania use this bond. Also, I designed the quarter brick to be shorter, creating more dimension in the walls.

Brick Layout in Plan View

Ground Floor Plan

Acts as storage for wet wood, as well as cold storage, as it’s partially underground

The rotated rectangle plan came from me interpreting the geometry of straw gardens. It allowed to make my building very solid and strong at the bottom, reducing the thickness of the walls at the top.

This setting inwards of the walls as they go up also created ‘shelves’ for other structures to attach. Visually, it created a more varied facade. This is very important, as traditionally, Lithuanians disliked having monolithic surfaces. If they had a large wall, they would put the timber planks in a pattern, for example, to break it up.

The first floor has the most important element, which is the fire. All brick construction makes it possible for the fire to shine brightly in the middle of a forest.

It is smartly designed to burn well, with a lot of oxygen coming in, the smoke being efficiently directed towards the chimney and maximising the use of the heat. This fire also heats the oven, fish smoker, as well as the spaces around. The space above in particular, which functions as a space for people to warm up, especially in winter, due to the open nature of the Cultural Centre.

First Floor Perspective - fire, oven, wood storage, rainwater storage

The Warm Space is well insulated and heated. The insulation was covered with clay plaster and a lime wash to keep the top-level construction light. Whereas the walls of the chimney and fish smoker attached to it remain uninsulated, as they radiate heat. Therefore, you can see which walls are warm.

This phase of the project created a large shelter from rain, which is very common in Lithuania. With it, more outdoor classes started taking place. Traditional craftsmen would come in to teach how to carve small sculptures, make flower crowns, teach traditional knowledge about foraging and nature. Also, traditional celebrations, such as midsummer, were held here with a big fire, dancing and magic.

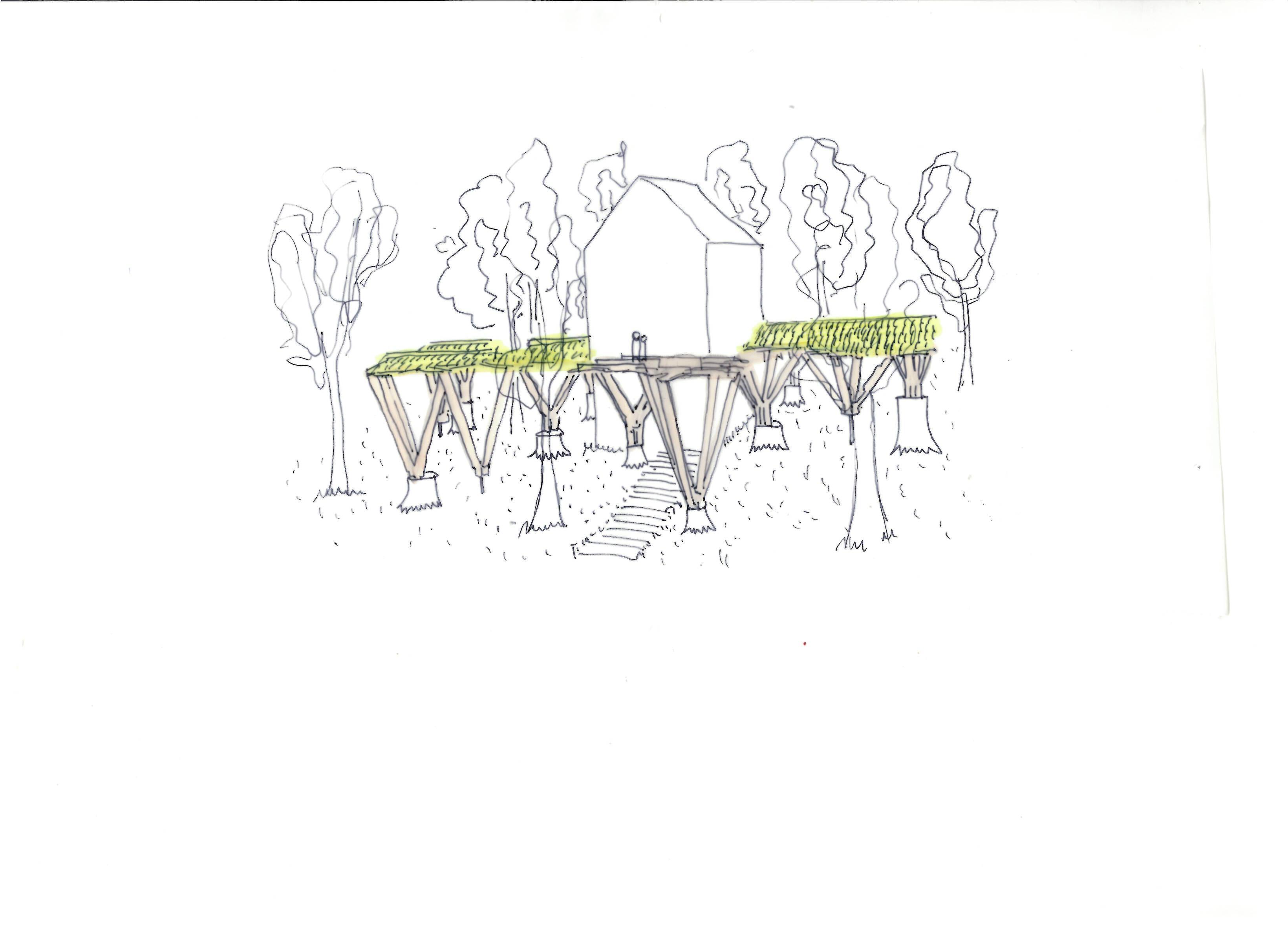

I came up with a module that would let me create a large level surface in the crowns of the trees. I used tree trunks as foundations (or screw in piles) for a reused log and rafter structure. The original joinery would act as decoration and have educational and nostalgic value.

As you enter the forest, you are first greated by the woodchopping pavilion, from which you are directed up the hill, going up the wooden stairs, fluidly laid out on the forest floor.

As you approach the trees turn into the platform structure and you can admire the details of the old logs as you walk under. Before you reach the brick core, the stairs start becoming more orderly and transition into the brick core.

You spiral up the stairs, where you’re immediately greeted by the intense heat of the fire on your right.

The current phase of the Forest Garden creates a variation of spaces on top of the Platform. The finished design completed the shapes of the Straw Garden. The geometric shapes bring order among the chaos of the forest, just as the Garden is intended to.

The Forest Garden

You journey up through the core to the first floor, from which a few wooden steps take you on top of the platform, to a covered area overlooking the tree crowns.

Here you will often encounter an outdoor class, cooking workshop, a feast or a celebration.

This area is the middle of the platform, which connects to all other spaces.

You have smaller outdoor working spaces on both sides of the event area. To either side of the core, you have the two indoor spaces: the workshop and the classroom.

First florr function diagram

In the workshop, you mostly have woodworking workshops held. Craftsmen from around the country are coming to teach from the topics of art to architecture and repair. As the activities here can be a bit physically demanding, the lower temperature is favourable.

The classroom is a warmer space as it shares a wall with the fir eplace. Whereas the workshop, even though insulated, has a lower temperature in winter than we are used to in modern days.

The classroom, on the other hand, hosts more mentally demanding activities; hence, the brick wall radiating heat is very comfortable in the colder months. Here experts come to give talks on forest knowledge, tell Baltic fairytales or explain traditional methods of preserving your foraged goods.

The Forest Garden

Some walls are insulated with reed and some areas use the massive, reused logs to separate the inside from the outside. This difference, therefore, is also visible on the outside, as well as inside.

In addition to these more formal indoor spaces, there are various smaller working areas on the platforms outside, providing a variation of spaces depending on where a visitor would like to complete their educational tasks. A warm classroom, large tables of the workshop, a corner for a small group, a spot overlooking a fire or (as depicted here) a more quiet working area where you can gaze over the trees.

At this point, the Forest Garden functions as desired and there are no future plans for the building. However, we don’t know what the future holds. Just as a Straw Garden, the Forest Garden might grow, diminish or change with time.

The beauty of the timber module that I created is that more log houses can be harvested and turned into extensions of the Forest Garden, if the future program demands it. Parts can be replaced and the plan can morph into something else...

On the other hand, if a Cultural Centre is not needed anymore, the timber structure can be taken apart to be used elsewhere. Only the Brick Heart remaining as a more permanent building. Maybe turning into a dwelling for my retirement...

Hands - on Process

Explorations

Wrong Turns

The material log from the deconstructed house led the design process. I tried to use as many secondhand materials as possible and minimise the need for new timbers. The entirety of the design for the Culture Centre was done by hand. Making 1:20 models of the materials I had and letting the shapes inspired by the Straw Gardens come intuitively.

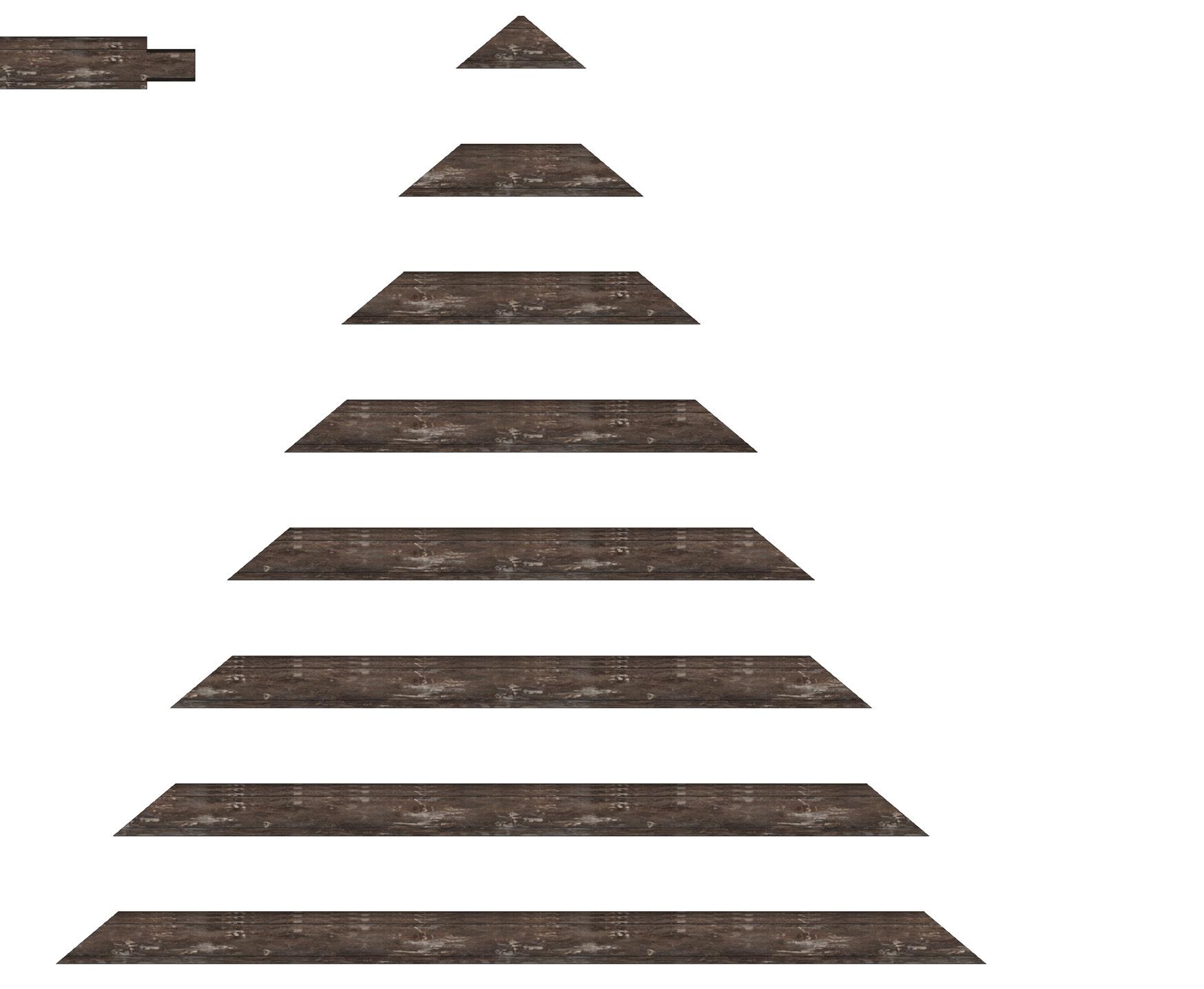

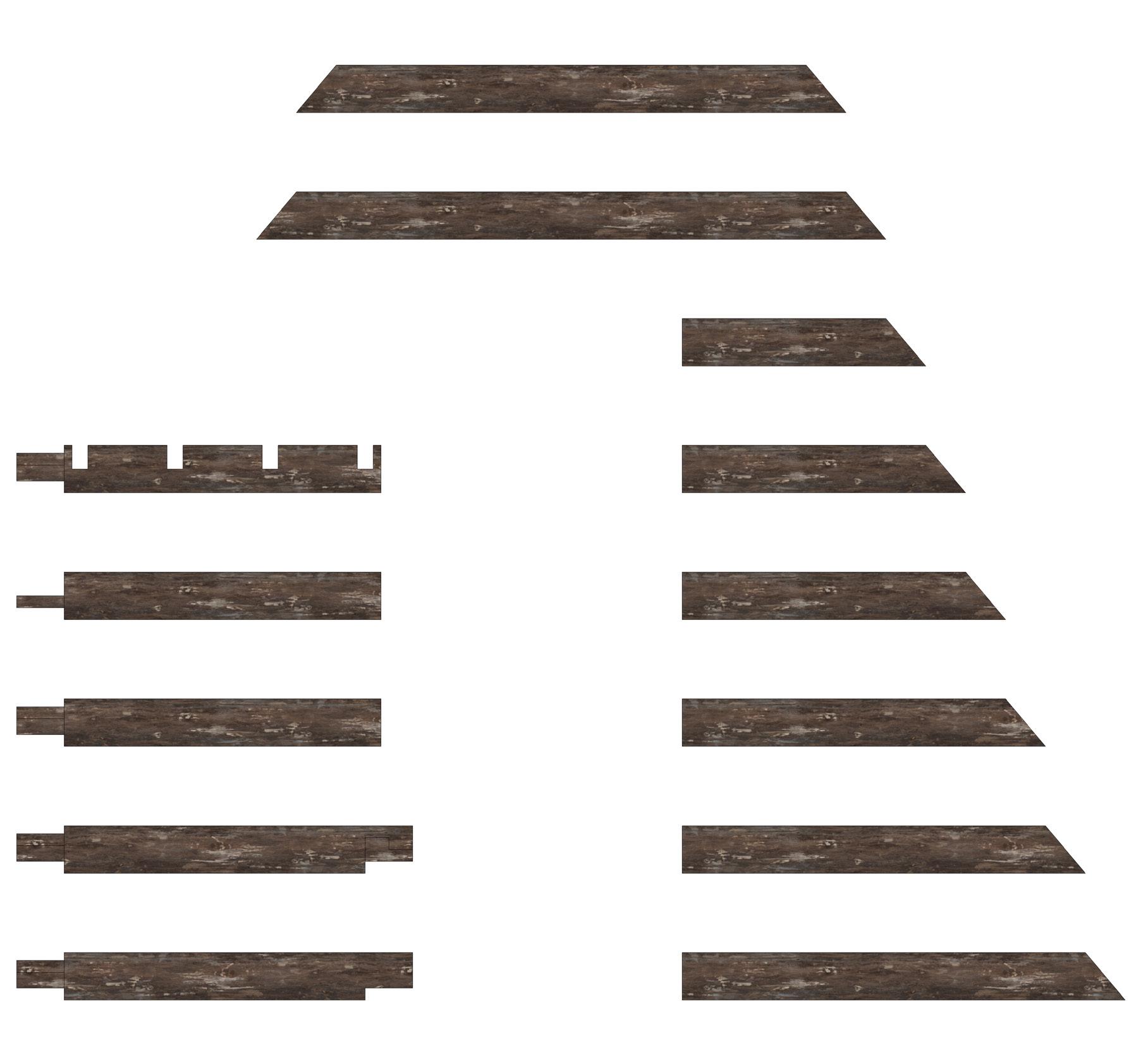

All the timber logs from the first deconstructed house in 1:20 scale

Functional timber storage first ideas

Connection with the trees and evolving with time

Dealing with the slope

Šešelgis, K. (1988). Savaimingai susiklostę kaimai. Vilnius: Mokslas

Šešelgis, K., Baršauskas, J., Čerbulėnas, K. and Kleinas, M. (1965). Lietuvių liaudies architektūra. Vilnius: Mintis

Baliulis, A., Drėma, V., Jankevičienė, A., Kitkauskas, N., Levandauskas, V., Miškinis, A., Puodžiukienė, D., Rupeikienė, M. and Žilinskas, A. (2014). Lietuvos architektūros istorija IV: 1918-1944. Vilnius: Savastis

Serapinas, A. (2022). Space Can. Zuoz: Galerie Tschudi

Sennett, R. (2009). The Craftsman. London: Penguin Books

Zwerger, K. (2015). Wood and Wood Joints: Building Traditions of Europe, Japan and China. 3rd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Juhani Pallasmaa, 2012, Newness, Tradition and Identity: Existential Content and Meaning in Architecture, Architectural Design, Volume 82, Issue 6

Baker, J. (2020). The Woodworker’s Pocketbook. 3rd ed. [Place of publication not specified]: Bad Axe Tool Works.

Wingender, J.P. (2016). Brick: An Exacting Material. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura.

Dovile Seduikyte

Graduation Project

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

August 2024