Amsterdam School of Arts Academy of Architecture

graduation project developed under the supervision of Machiel Spaan (mentor), Anna Zań, and Bart Visser

© 2025 Tara Tayyebi Fard

Foreword

I’m fascinated by the stories that historical buildings tell; how they embody common memories and present a wealth of knowledge about society, history and architecture.

Following this interest, I started my graduation project with a search for historical buildings in Amsterdam. In that process, I stumbled upon three identical bathhouses with a characteristic round shape built in the 1920s by architect Westerman. None of the three are functioning as a bath house anymore; one is transformed to a theatre, one is a drum studio, and the third one that stood on Wittenburg has been demolished.

On the spot now stands a lamp post, closely connected to a bridge that was built at the same time as the bath house.

I looked further as I was intrigued to find out why the third bath house was demolished.

I studied the three identical bath houses and the neighbourhoods around each one; why they were built, when they were built, what other buildings they were surrounded with, what was happening in the country around the same time, what kind of people lived in those areas, what was the living and working arrangement for them, how the bath houses brought people closer, how this changed through time, what the streets looked like, what the key events were in the lifespan of the bath houses, how these events were narrated by the newspaper at the time, how the bath houses were affected by technology, how they fell into decay, how two of them got a new lease of life, and ultimately, why one was demolished.

To answer these questions, I collected various layers of information such as found floor plans, archival photos and documents, descriptions from books and old newspapers, and reached out to people who had experienced the bath houses.

I built my own archive with all my findings on a Miro board. This archive is the foundation for my stories and narrative, and ultimately, the narrative makes the archive assessable.

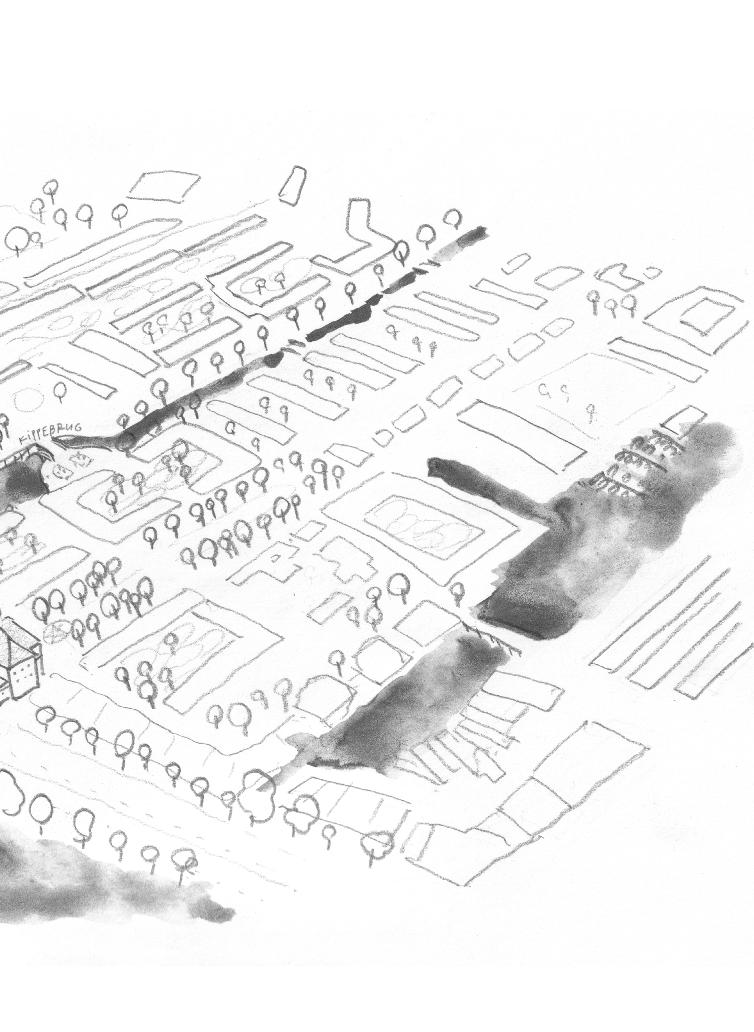

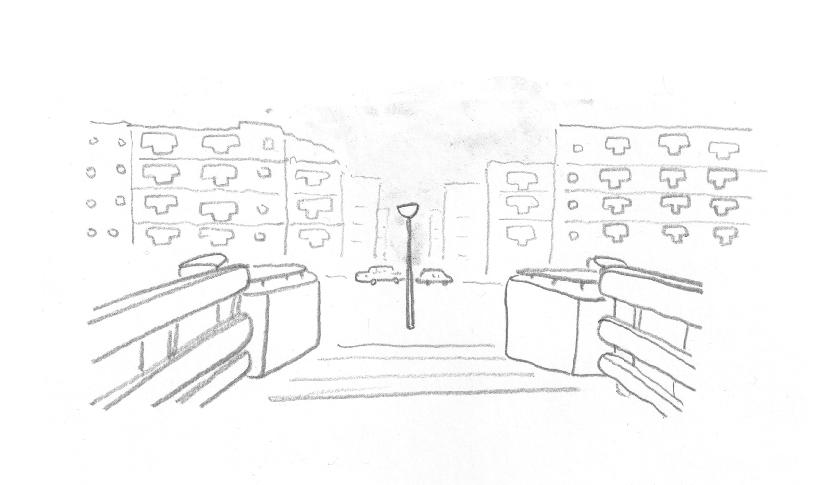

Throughout the process, I continuously made hand drawings. Every site visit, every conversation, every deep dive into the archive and every moment of reflection was accompanied by sketches.

As we live in a world where an endless amount of information is constantly thrown at us and we only sit back and scroll, the act of drawing felt like a rebellion. Drawing by hand takes time, is imperfect, allows for a more bodily experience of observations, and anchors a person in time and place.

Drawing helped me see and hear more attentively, stay present and remember what I experienced. It helped me not only understand and overlay my findings, but also see more details and reinterpret them as I was researching. By the end, I had an extensive archive stored digitally on Miro board and numerous sketchbooks filled with notes, drawings and printed materials.

I was inspired by architects like Piranesi and Carlijn Kingma who translate complicated concepts into layered drawings that convey information more effectively.

I also drew inspiration from other formats of storytelling; like creative writing, film making, picture books and graphic novels.

While drawing, I made connections between different bits of my findings that transformed individual pieces of information into a collection of short stories. Short stories in which different historical, social and architectural layers come together and give insight into the richness of a history.

Next came the questions about the extension of my timeline into the future possibilities for the demolished bath house. I entered conversation with locals, architects and designers; resulting in a series of visual stories about future scenarios, mapping a multitude of truths about what the future could hold.

Compiling my collection of stories about the past, present and future together, I experimented with different ways of making timelines and storyboards; overlaying the pieces together to make new connections between different parts of the narrative and get a better grip on the subject.

Although uncommon, these storyboards are helpful tools for architects to understand the complexity of a site and its transformation in time.

I concluded my research with building a framework for a bigger narrative that could host all the individual short stories. A narrative that is not only carrying data, but also emotions. A story about how we deal with the past and care about things that are lost. A personal story that helps us remember how much we miss that bath house that we had forgotten it ever existed.

Through this story, and as I share a glimpse of the rich history that is lost, I’m hoping to remind the inhabitants of the Eastern Islands of their neighbourhood’s identity, how it has changed through time, and how they have the power to change it again.

I hope to give the inhabitants a base of information that brings them closer to their neighbourhood, and creates a meaningful collective relationship.

And lastly, I hope this story acts as a starting point to look at our built environment in a new light, and that it triggers curiosity to ask more questions, enter conversations and rediscover what exists in the city but we have forgotten about.

Forget Me Not

a story about the invisible layers of the city

Sorry to bother you, but I haven’t spoken to anyone in a long time and I’m just tired of looking at this view.

You know, it wasn’t always this bad.

I used to face a round building with a cool hat.

She came around when I was only one year old.

I still remember the opening day; how the streets were decorated, how the people were extra fancy, and how I was covered in an ugly party dress.

I never got tired of looking at her; wondering where her eyes were, what her other side looked like, and if she had hair under her hat.

On the opening day, I met many people. Some of them never returned, but a lot of them did stick around.

For years I watched them frantically cross the water from one side to the other, and return time after time.

Were they lost?

Or could they just not decide where they wanted to go? Where were they so excited to go to anyway?

A hundred years later and I still wonder.

I mean I wish I could go visit other places too.

But being bound to this spot, I enjoy the company of people who stay for a little longer; whether it is to have a stinky snack,

to collect autumn leaves,

or even to have an unnecessary chat. Especially to have an unnecessary chat!

What was I talking about?

Oh right, the round building!

Every morning for forty something years, I watched a person open the doors to the round building.

Sometimes I could get a peek inside.

Other times I listened closely to the mysterious sound of rain coming out of the building, and the visitors’ conversations.

Some people visited the round building in groups; often going in with fuller bags than when they returned.

But whether individually or in groups, they always left the building smelling fresh.

As much as I loved watching the round building, I didn’t want to stare at her for too long.

Lest it get awkward between us.

And that often led me to look at my second favourite view; the two giant buildings a bit further away.

Especially the sharp one.

It’s a shame it’s gone now.

But I still hear about the passage behind it.

People say it’s beautiful, and somehow it does the same thing as the sharp or the round building used to do; bringing everyone together. I wish I could do the same thing myself.

The sharp building had a particular charm.

Both when it was standing,

and when it got demolished.

I have overheard so many stories about that place, and I still occasionally do.

It’s hard for me to blame the boy though. I like collectibles too.

Maybe a bit too much.

But if it were up to me, and if I had the space, I would have collected every person, every building, every boat, every hat, and every story dearly; keeping them all safe from being erased.

I wish I could go back in time and save the round building.

Because I’m sure she wouldn’t have stayed empty if she was here today.

And frankly, the same is true for a lot of other buildings too.

Maybe they just needed to get taken care of.

The same way I was taken care of not so long ago.

Would it really have been too much trouble to keep the old buildings?

Because making new ones wasn’t easy either.

And for me, as a resident with no legs or wheels,

I’m destined to watch what’s in front of me day after day.

And it’s boring.

Am I the only one who is disappointed?

Am I missing something?

Did people think this was a good idea?

Why didn’t anyone stop this? Why?

Hmm...

I wonder what will change next.

Will I be looking at the same view in a hundred years?

Will I even be here then?

What if in a hundred years all the buildings look the same?

What would I even call each building?

What if we have nothing to talk about anyway?

Or maybe I would be long gone by then...

But what if I’m not?

What if I’ll be standing here, looking around without

remembering anything or feeling connected to anyone?

But I am still here now.

I remember everything, and I care about this place and its people.

What if I’m not the only one feeling this way?

What will I be looking at in a hundred years then?

Could it be the round building?

Yeah, dream on.

“If we walk down a street and all we see is grey terraces that are devoid of any meaning, we might start to think that we’re living in a bit of a rat trap. And you do that for long enough and you’re going to think “I’m living in a rat trap. I’m a rat, aren’t I?”

It’s going to soak in. Because to some degree we are the places that we live in.

Whereas if you’re walking down a street and you know its history; if you know all the rich circumstances that have led up to that place, it’s like walking down a street from the Arabian Nights. It will be like walking down a fantastic avenue of glory and mythology. And you will think after a while “Hey I’m living in a mythological landscape! Maybe I am a mythological being.”

It works both ways.

Find out about places and make them burn with meaning and significance again, and you will find that the people living there will burn with meaning and significance.”

- Alan Moore -

Afterword

Architecture is not limited to buildings, and buildings are not merely a compilation of materials, functions and numbers. We are humans with memories, interests, emotions and friends, and architecture is the built environment in which we live.

Reducing buildings to materials, affects the humans experiencing it. If the buildings we build, have no connection to our memories, then it’s only a matter of time until we forget who we are. And once we forget who we are, we lose meanings, and the problem would be far greater than architecture.

As modern architects, we are expected to continually design more buildings. But there must be a point where we pause and wonder why we need new buildings. Which problem are we trying to solve and is making a new building the right answer to that problem?

The issue is that as the pace of work is rapidly increasing, there is often no time for pausing and reflecting. We can barely keep up with day-to-day tasks and maybe that’s part of the problem.

But what if we spend all our lives working diligently towards a dystopian future without realising where we are heading to?

There are so many buildings already standing in our cities. Each one embodies thoughts, memories and traditions of a certain time and place, and together they form clusters of spaces with a unique relationship.

By rushing to design new buildings, we recurrently miss the chance to learn and explore these relationships, let alone engage with them. While taking the time to learn about the existing buildings could entirely change the way we design. As we would then be designing for a place we know and care about, rather than a footprint with a certain number of square meters.

We, as humans, are social beings with needs beyond food and shelter. From ancient times, we have been communicating our thoughts and emotions through stories. Stories that take us on a journey to think and feel, and help us put ourselves in other people’s shoes and understand the world around us better.

But as we pile up mindless work on our desks throughout the day and scroll our way to sleep, we are slowly forgetting to tell stories.

Storytelling is a powerful tool that can also be used in architecture and design.

In my project, I used narrative to convey information in a personal and emotional way to show the multitude of truths about the same history. By turning research and data into a story, we have a better chance to connect, empathise and remember the information. Here, narrative also acts as a design tool to preserve the demolished bath house and shift its meaning to the bigger social and historical issues that follow us into the future.

Ultimately, we are living at a time with serious environmental issues. In the past few decades, we have been trying to implement sustainability into architecture; shifting from building with concrete to wood, adding solar panels and green rooftops. But at the end of the day, these new green buildings still require a great deal of demolition and construction. And perhaps the most sustainable solution is to be more mindful of what new buildings we truly need to build, and otherwise invest in renovations instead.

There are currently different groups and organisations led by architects such as ACAN and House Europe who are taking action to demonstrate how existing buildings can be renovated and transformed into affordable living spaces that preserve memories. They explain why demolitions waste homes, energy, and history, and how we need to rethink our value system through activism and direct democracy.

As we acknowledge that architects, through their work and design, influence human behaviour, we need to imagine a form of architecture that exists without building. One that shapes experiences, relationships, and environments without the need for physical structures.

My project is proof that narration, through design elements like storytelling, can shift a place’s meaning and therefore act as an architectural intervention.

It is a continuation of an architectural profession with a long history. It touches upon the same values as Juhani Pallasmaa speaks about in his book The Eyes of the Skin, highlighting the value of sensory and bodily experience of architecture.

This design methodology is especially relevant now that we are facing outrageous iconoclasm of the fast-paced digital world and artificial intelligence is taking over. It is a plea to look at the design brief in a new way and explore what we already have before conquering new landscapes.

At the end of the day, I want to work hard, using all my skills to make the world just a little bit better. And as an architect, if I can do that more effectively through storytelling and bringing awareness to the existing spaces that carry meaning and richness in our cities, instead of making new buildings, then I would gladly do that every day.

The goal should be to make a positive change, not to produce more.