Reusing the Architetcure of Oppression to Resist, Reclaim, Rebuild

Masters in Architecture Graduation Project

Rytis Budavičius

mentor

Jo Barnett

committee members

Kamiel Klaasse

Mark Minkjan

external examiners

Burton Hamfelt

Sofia Koutsenko by

Reusing the Architetcure of Oppression to Resist, Reclaim, Rebuild

Rytis Budavičius

mentor

Jo Barnett

committee members

Kamiel Klaasse

Mark Minkjan

external examiners

Burton Hamfelt

Sofia Koutsenko by

Preface

Colonialism & Postcolonialism in Lithuania

Visual Essay

Introduction

Language of Nature

The Rise of Suburbia

Neglecting the Past & then Future

Reconstructivism

Manifesto

Local Specifics

Klaipėda

Neighbourhood

People of Naujakiemis

Memories in the Trees

Chosen Location

1-464-Li

The 1-464 in Numbers

Analysis

Elements Library

Deconstruction

Sectional Deconstruction

Replica for Temporary Housing

Crafting Elements

Urban Hamlet

Connection to the ground

Response to the Environment

Typology

Ground Appropriation

The New Vernacular

Material Library

Adapted Elements Library

The Expression of Assembly

Two-storey Housing Cluster

Three-storey Housing Cluster

Afterword

Reconstructivism - the Further Journey

In Search of Expression

The landscape and urban environment in Lithuania is deeply imprinted with the physical intervention of the Soviet regime. Something that was forced upon and built as a part of occupation has now become a visual statement in Lithuania. These dominant, Sovietera buildings, while still retaining their basic functions, stand as a symbol of oppression, forced standardisation, erasure of cultural identity and foreign power control. This essay examines why Soviet architecture should be considered as a physical monument and part of the colonial system placed in Lithuania and why treating Lithuanian culture as postcolonial may help it to reclaim and develop its cultural identity.

The traditional understanding of colonisation is often that of Anglo-Franco or Western civilisations colonising other lands to settle or salvage resources. However, this westcentric terminology or understanding of colonisation should be criticised if we want to identify and broaden the concept of oppression in modern or past times. This slightly twisted and traditional view on colonisation stems from the western culture that before the twentieth century tolerated or accepted colonisation if the land was “peopled by uncivilized tribes which are not politically organized under any government possessing the marks of sovereignty” (Stockton, 1914, p. 73). The modern simplified definition of colonialism, at least by that of Ellis Cashmore, is “From the Latin colonia for cultivate (especially new land), this refers to the practices, theories and attitudes involved in establishing and maintaining an empire this being a relationship in which one state controls the effective political sovereignty of another polity, typically of a distant territory.”. At the end of the more elaborate definition of colonialism Ellis Cashmore hints that Soviet regime in occupied territories can be linked to colonialism stating that “The great imperial power of modern times was Russia: Soviet area of control, whether through direct or indirect means, spread under communism to encompass countries […]. Soviet systems did not, of course, operate slavery, but evidence suggests that their regimes were extremely repressive”.

Epp Annus, an Estonian literary scholar, writes in her essay The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics (2012) with an expression that allows Lithuanians define their own history of oppression as colonialism without falling into predominant westernfocused definitions:

“David Moore [American scholar] wrote in 2001: ‘to privilege the Anglo-Franco cases as the colonizing standard and to call the Russo-Soviet experiences deviations, as I have done so far, is wrongly to perpetuate the already superannuated centrality of the Western or Anglo-Franco world. It is time, I think, to break with the tradition’ (2001, p.123). A Baltic scholar should not worry about whether his or her research object fits into a certain established category, but instead generate interpretive models that would enable one to interpret Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian experience in connection with wider social and cultural processes. For the Soviet period this would include opening up Soviet experience as a local phenomenon towards wider processes of dominations and resistances, occupations and colonization in the world.”

To establish an even stronger argument of existence of colonialism in Baltic states, a more elaborate and sobering David Moore’s comparison of well-accepted definition of colonialism in sub-Saharan African countries to the situation in Baltic region portrays the statement in clearer light:

“To suggest a richer understanding of what I mean by post-Soviet postcoloniality, I will describe an area whose postcoloniality is clear- sub-Saharan Africa. A historically rich and important set of cultures, of great diversity and sometimes little unity, subSaharan Africa before the arrival of Europeans has a long history of independence, though at times internal strife there is great. Then, an external colonization or imperial control begins at the borders and extends into the centre. Indigenous governments are replaced with puppet control or outright rule. African education is revamped to privilege the colonizer’s language, and histories and curricula are rewritten from the imperium’s perspective. Autochthonous religious traditions are suppressed in the colonial zone, idols are destroyed, and alternative religions and nonreligious ideologies are promoted. The colonized areas of Africa become economic fiefs. Little or no “natural” trade is allowed between the colonies and economies external to the colonizer’s network. Economic production is undertaken on a command basis and is geared to the dominant power’s interests rather than to local needs. Local currencies, if they exist, are only convertible to the metropolitan specie. Agriculture becomes mass monoculture, and environmental degradation follows. In the human realm, African dissident voices are heard most clearly only in exile, though accession to exile is difficult. Oppositional energies are therefore channelled through forms including mimicry, satire, parody, and jokes. But a characteristic feature of society is cultural stagnation”

Selected citation from Moore’s essay above combined with specific visual and written representations of Soviet regime in Lithuania establishes that even though what may have intentionally started as occupation, later evolved into a colonial rule of an oppressed developed European civilisation.

Colonial rule continued and after the expulsion of local communities and regional cultures, the standardisation to the oppressor’s identity started. I-464 building series was one of the tools of Soviet colonial power to write over the regional identity, forcing new urban developments to follow homogenised Soviet identity. Utilitarian buildings that had to stimulate the efficient function of the annexed region and create living spaces for settlers and oppressed people is now a physical heritage of the Soviet colonial rule in Lithuania.

It is crucial, however, to acknowledge and identify these buildings as colonial architecture. By clearly defining the history and what legacy (physical or cultural) it may have left in the region, Lithuania can take a different approach by reclaiming and intervening with these structures to pave the way for new post-colonial Lithuanian architecture. By accepting that these structures were a mere tool to control the colony and erase the local identity, Lithuania can demonstrate that they have the control of the inherited tool and can use it to create their own cultural autonomy. Symbols of oppression can be turned into monuments of resilience and self-determination.

“To suggest a richer understanding of what I mean by post-Soviet postcoloniality, I will describe an area whose postcoloniality is clear- sub-Saharan Africa. A historically rich and important set of cultures, of great diversity and sometimes little unity, sub-Saharan Africa before the arrival of Europeans has a long history of independence, though at times internal strife there is great. Then, an external colonization or imperial control begins at the borders and extends into the center. Indigenous governments are replaced with puppet control or outright rule (1). African education is revamped to privilege the colonizer’s language (2), and histories and curricula are rewritten (3) from the imperium’s perspective. Autochthonous religious traditions are suppressed (4) in the colonial zone, idols are destroyed (5), and alternative religions and nonreligious ideologies are promoted (6). The colonized areas of Africa become economic fiefs. Little or no “natural” trade is allowed between the colonies and economies external to the colonizer’s network (7). Economic production is undertaken on a command basis and is geared to the dominant power’s interests rather than to local needs (8). Local currencies, if they exist, are only convertible to the metropolitan specie (9). Agriculture becomes mass monoculture (10), and environmental degradation follows. In the human realm, African dissident voices are heard most clearly only in exile (11), though accession to exile is difficult. Oppositional energies are therefore channelled through forms including mimicry, satire, parody, and jokes. But a characteristic feature of society is cultural stagnation (12)”

“Is the Post- in Postcolonial the Post- in Post-Soviet? Towards a Global Postcolonial Critique” (2001) David Chioni Moore

Indigenous governments are replaced with puppet control or outright rule

Education is revamped to privilege the colonizer’s language

Students in the school “Red Room” - a glorification place of Communism - early steps to burocratic Russification and propaganda.

Histories and curricula are rewritten

Religious traditions are suppressed

Idols are destroyed

Nonreligious ideologies are promoted

Little or no “natural” trade is allowed

Economic production is geared to the dominant power’s interests

Scheme for USSR built environment policy governmental herarchy.

Local currencies are only convertible to the metropolitan specie

Lithuanian currency “litas” seized to exist.

Dissident voices are heard most clearly only in exile

about the occupation.

Agriculture becomes mass monoculture

Mass urbanisation and farming industrialisation was forced upon.

Since 1945 old books were kept in one of the baroque churches. The curch with archive were hidden from the public eye. Household, not culture and history, were made a priority.

This project proposes an architectural approach that reclaims Lithuania’s built environment by transforming its oppressive Soviet past into the foundation for a new vernacular future. Through dismantling, reassembly, and the integration of bioregional materials and social rituals, it explores how a new, unique, and locally attuned architectural language can emerge. A Soviet-era housing block becomes the material and spatial basis for an urban hamlet composed of low-rise housing clusters.

Since the restoration of its independence, Lithuania caught up and jumped one of the last capitalism trains. Individualism and neoliberalism in post-oppression country have reduced a common vision and search for identity to individualistic expression. There is a general notion that by rebuilding long-lost historical landmarks (or reviving classical styles) Lithuanian architectural or national identity can be restored. Whereas buildings of Soviet times are being demolished ignoring its value for local communities, are refurbished in the cheapest and least considerable fashion, or finally are replaced by agenda of single individuals or commercial companies. This culture for rapid, unthoughtful renovations of historical buildings and the continuous erasure and demolition of last-fifty years buildings is leading to one of the messiest history cover ups and architectural timeline manipulations. Currently there is a greater will to prioritise ego-goals, without a thought for the scarcity of resources, without a greater common vision of what is the modern Lithuanian architectural vision, approach and identity, without a notion of how does today’s built environment in Lithuania represent itself for the world and future generations.

The decay of ‘Vaidila’ cinema. Instead of renovation and implementation of a new function, the developers decided to demolish the entire structure and build a new, “random” looking building.

Soviet-era cinema in the city centre of Klaipėda have accidentally (?) collapsed during the renovation to make space for the new shopping centre. The same volume have been preserved due to municipal requirements, unfortunatelly with low quality materials and questionable layout of internal functions

Again another Soviet-era cultural buildings have been dismissed. Unfortunatelly, this time it was fully functioning independent cinema with events for the local community. The inhabiting collective have been moved out, and a new gallery of modern art have been erected, under the famous Lithuanian artist Stasys. After scandalous and unecessary one art sphere replacement by another, the artist himself stated that knowing the cultural cost of this development he wished his named to be removed from the project.

Independent Lithuania very quickly caught up with the global trends of consumption, carbon fuelled and the construction for economic advantage rather than durability. Car-centric culture is dominant and dictates the nature of urban developments. An overall detachment from pre-Soviet occupation values of living in tune with nature, use of regional resources and valuing the craftsmanship has led to the rise of ‘American’ suburban living.

Entry gate to one of the suburbian areas in the middle of the fields. (right: images of the neighbourhood)

Lithuanian language and old traditions are very much intertwined with the rhythms of nature. Lithuania was the last European state to be christianised. Pre-christian Lithuanian polytheism was influenced by and utterly focused on nature and its elements. Some of pagan-rooted traditions and beliefs gradually were adapted and shaped to suit the European customs. Perhaps the late conversion to man-focused religion and preservation of old Baltic language have shaped modern Lithuanian mentality and subconscious connection to nature.

This connection to natural roots may be heard in Lithuanian conversations or literature, however it is rarely expressed in other, more visual and sensual forms - such as built environment. The relation to nature should be saturated in Lithuanian home and the fulfilment of it should be explored.

While exploring the local market, I stumbled upon two gentlemen having a deep conversation at the nearby cafe.

Perhaps I can finally see the Cuckoo this year. It is my dream to see it while it’s singing... in May... then I think I would be ready to die.

Surely not...

Well yes maybe not dying after that. But still... they say you can never see Cuckoo bird in its nest. Imagine seeing her singing, in her nest, in May. That would be something no?

You know I’ve heard that they have a lot of nests down by the port [most souther part of the city], perhaps you can see one there... Oh by the way since we are on about birds. Yesterday they said it is not going to rain, but I saw this morning swallows flying so low, and the heavy air right now. Do you think it is to rain?

I hope not, I want to sit in the sun for a bit longer.

Gegužė (May) is named after Cuculus canorus bird - Gegutė. The bird is said to bring the spring, usually can be heard around the first week of May. The connection to nature is deeply embeded in Lithuanian language, beliefs, and traditions.

Later, the duo enjoyed the last rays of sun before it, indeed, started to rain...

Lithuanian architecture, which might have evolved independently and naturally, has been significantly shaped by the forces of imperial dominance. To understand and redefine Lithuania’s architectural identity, it is essential to acknowledge the historical imprints left by Soviet colonisation. This project employs the term “post-colonial architecture” to refer to Soviet-built architecture in Lithuania, using it as a critical lens to examine and reclaim spaces constructed during periods of oppression—encompassing both the Soviet era and earlier phases of foreign control in the region.

Reconstructivism explores how Lithuanian architecture can continue to evolve autonomously, embracing its regional and cultural specificity. However, this evolution must engage with the past—a past that has already been “scripted” by external regimes. The project seeks to demonstrate how Lithuania can begin to rewrite its architectural narrative, transforming the remnants of its colonial history into a story of resilience and renewal.

By situating Soviet-era buildings within this framework of evolution, Reconstructivism proposes to repurpose what was once a tool of dominance into a symbol of empowerment. This approach allows Lithuania to reclaim its inherited architectural heritage while forging a path toward a built environment that authentically reflects its cultural identity and resilience. Through this lens, the Reconstructivism project offers a method for critically engaging with past structures while shaping a future rooted in collective experience—unlocking the untapped potential of existing circumstances.

A Manifesto for Reclaiming Architecture in Lithuania and Designing for Further Evolution

Place is not just a background; it is an active

The new type of architecture that seeks to rewrite the evolution of cultural identity must engage with its surroundings, not as an aesthetic exercise, but as a continuation of local history, culture, and regional material use.

The built environment carries the weight of past narratives and may be a standing relics of a collective trauma, but it can also act as a site of renewal and healing.

Acknowledging the history does not mean tolerating it - it can be a means of reclaiming the narrative of place and directing it to our advantage.

Lithuania must write its own architectural language

Global architectural and cultural trends flatten local identity. Place must now act as a force of resistance - insisting on an architecture that emerges from its surrounding context rather than imported ideas.

The scars of occupation are not erased by demolition but by adaptation and repurposing. Reclaiming Soviet structures allows for a confrontation with history, transforming trauma into empowerment to seek new opportunities. Spaces in postoppression sites should be transformed to foster social experimentation.

Spaces designed through oppression do not have to remain symbols of external dominance. They can be reinterpreted, dismantled, reintegrated to serve the people today. Similarly, newly designed communal spaces should yield for appropriation by locals, rather than impose idealogical way of living.

Rather than longing for past eras or rejecting unwanted already-built structures outright, Lithuania must engage with its diverse architectural inheritance dynamically - using it as a foundation for a forward-looking, adaptable way of living together that is unique for this region.

Buildings are not static relics, nor are they disposable assets. They are evolving layers of materials and collective memory. Demolition is replaced by careful deconstruction.

Soviet-era concrete in the shape of brutalist housing blocks is not an obsolete burden for the free nation, but a resource for resistance. Through cutting, reshaping, and repurposing, a new, unique and locally attuned architectural language emerges.

Not only are regional materials and practices promoted, but the city itself is seen as a resource. The cycle brought by the global consumerist culture - demolition and new construction as an economic tool - is rejected in favour of reclaiming local practices and reassembling the built environment.

Transformation must unfold seamlessly, allowing communities to transition from old structures to new ones without displacement. This includes the continuity of already established habits and relationships. It is crucial to keep the existing community intact to allow them to flourish.

An architectural approach that grounds design in the ecological, environmental, material and cultural realities of a region, while acknowledging the historical and political forces that have shaped it. Pragmatic and forward-oriented, it challenges extractive global systems by rooting design practices in local climates and promoting the use of regionally available materials.

The future of unique Lithuanian architecture lies not in erasing the past or replacing it with lost nostalgia and alien practices, but in absorption, transformation and redefinition. Soviet scars become material for constructing progressive regional architecture, reviving local crafts as a source of innovation. The use of available materials and construction methods shapes architectural expression.

Klaipėda

As a starting point I chose my hometown - a port city by the Baltic sea. What once was the regional centre and home for Lithuanian and German community, city established by Teutonic Order, became a sandbox for the Soviet Urbanisation scheme and settler colonialism fulfilment.

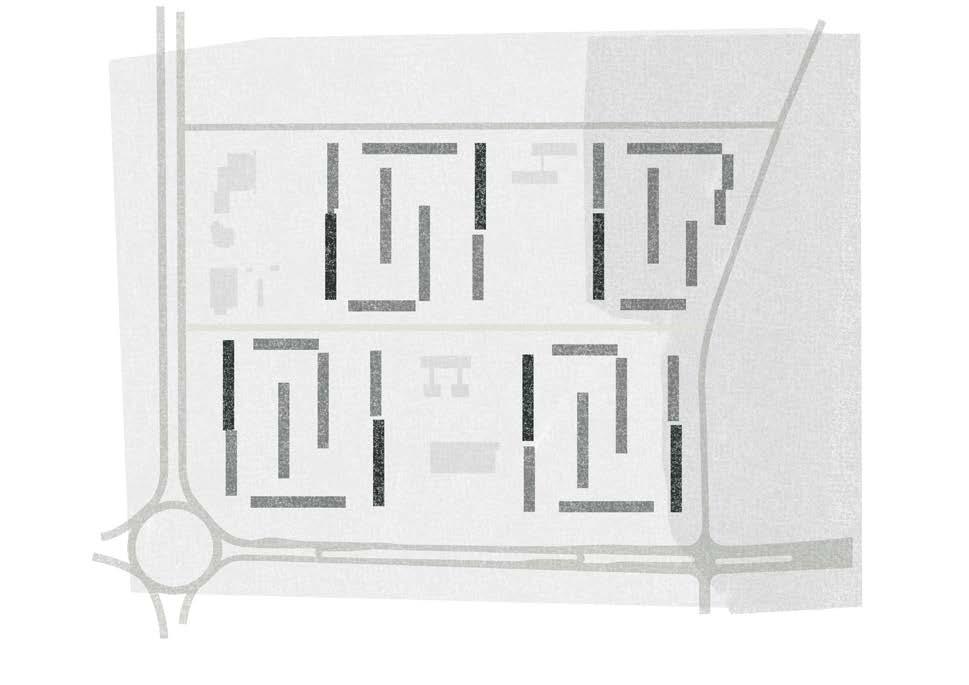

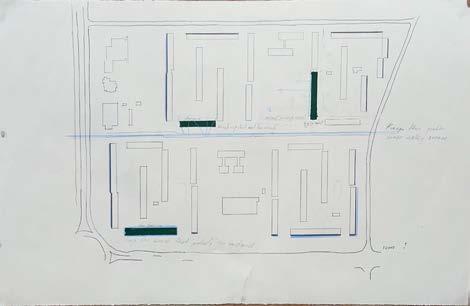

Neighbourhood - Naujakiemis

The neighbourhood, situated in the southern part of the city is named “Naujakiemis” (eng. the new yeard) is an open courtyrads formation of Sovier-era prefabricated concrete housing blocks.

It was built in 1970s during a massindustrialisation and transformation of the seaside city. A neighbourhood where people from Lithuanian rural areas, shared homes, and farther Soviet countries were moved to inhabit and contribute to the port’s economy. My grandparents were one of the first inhabitants, my mother grew up there, and for the first several years of my childhood I lived there too.

Access to the location

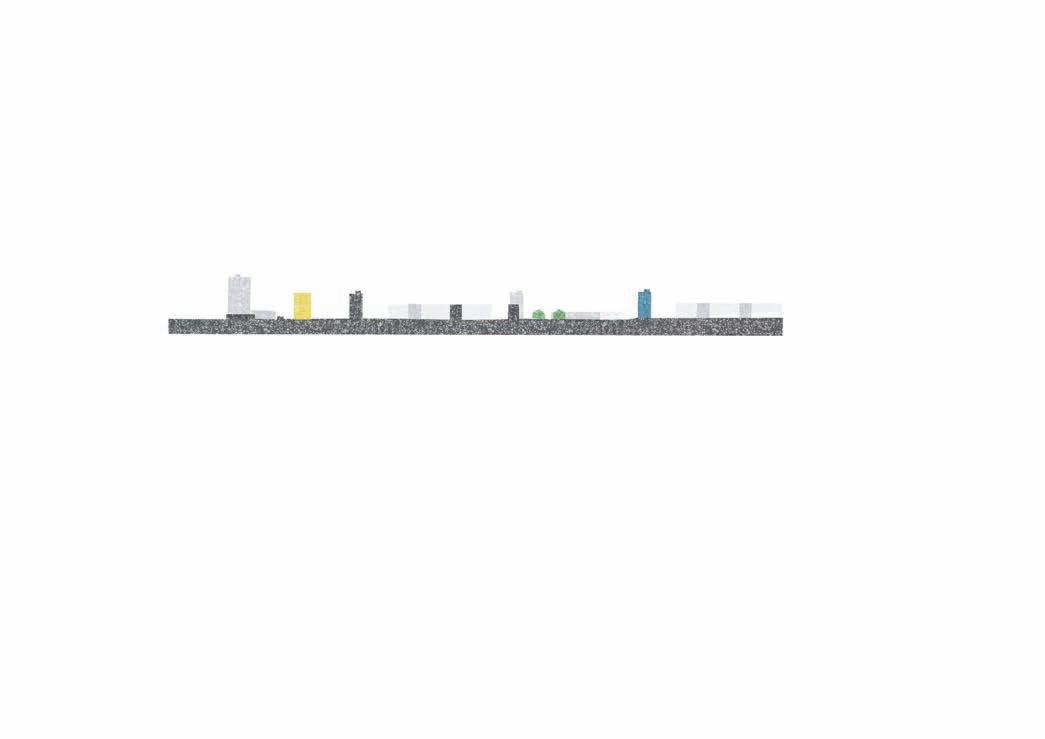

The neighbourhood consists of nine-storey and five-storey residential buildings. Whether intentionally or not, buildings respond to the environment of a coastal city: taller buildings positioned to face the sea region to the west protects from prominent winds; and urban buildings layout prioritises the eastern and western sunlights with an exception for buildings that face the pedestrian route - a connection to the grater grid system to city functions.

In and around the chosen neighbourhood there are trees that were planted by the first residents. Residents, most of whom moved from rural parts of Lithuania, were met by empty apartments and post-construction desert. They have collectively planted trees, practice that have connected them. Talking to remaining residents, there is a note of remembrance of their long-gone and once loved community members through those trees. Nature is the only remainder of gone people in the faceless Soviet urban development.

“They cut down the fir tree, the one that was planted by my neighbour Petras, may he rest in peace... He lived few storeys above. It feels a bit sad and hollow that they cut it down, even though they said it obscured the sunshine to our apartments. Well it did cast a darker shadow indeed. But it still is a bit of a shame that the tree is gone... I used to look at the fir while passing by, remembering Petras, well and the others eventually, the ones who also planted trees here around, and their family. And now it is gone, the tree; the memory is also fading...”

from the interview with Virginija, Naujakiemio 19

Naujakiemio 23 - was the first home of my grandparents, who were one of the first inhabitants to move in and plant trees

Greenery in and around the siteplanted by residents

The chosen location is situated in front of the nine-storey housing block. It is a low quality and entirely unsed vast green space - a green desert. While studying many other locations, this specific spot was chose for its unused space for potential.

Before the final location was chosen, in total three potential locations were considered.

1-464-Li

Analysis of chosen 1-464-Li building. This was the most widely spread housing series in the Soviet Union. This Housing series is one of the best examples of Soviet planning, eradication of individualism and self-determination through home to meet fiscal standards set in Moscow.

architects: B. Krūminis, V. Sargelis, A. Umbrasas

engineer: V. Zubrus

year: 1968-1976 (site development)

construction: prefabricated

two (bed)room*

1 unit** - bathroom & kitchen

1 unit - room 32m2

two (bed)room

1 unit - bathroom & kitchen

2 units - room 49m2

three (bed)room

1 unit - bathroom & kitchen

3 units - room 49m2

*room in 1-464 series is “multifunctional”: for living/sleeping/hosting etc.

**unit in 1-464 series is 18 m2 for either services or a living function

The 1-464-Li series building consists of over 4000 prefabricated concrete elements. These lements were recorded and analised, categorised for their function, dimensions, volume, finish.

The building will go through a carefully designed process of deconstruction. All four building sections will be demounted one after another, giving time to treat elemetns and rehouse residents of the latter section to a temporary housing on site.

Sectional deconstruction starts by dismantling first section of the 1-464-Li building. Inhabitants of that section are transferred to temporary housing, materials are transferred to crafting site to be treated, cleaned, cut, and stored.

Sectional deconstruction starts by dismantling first section of the 1-464-Li building. Inhabitants of that section are transferred to temporary housing, materials are transferred to crafting site to be treated, cleaned, cut, and stored.

When final section of the nine-storey building is dismantled and last residents are housed in temporary housing, the preparation of the basement structure starts. On top of old foundation an underground facilities are built and a base for last houses on a new “hill” is constructed.

When final section of the nine-storey building is dismantled and last residents are housed in temporary housing, the preparation of the basement structure starts. On top of old foundation an underground facilities are built and a base for last houses on a new “hill” is constructed.

When final - fourth - section of the nine-storey building is dismantled and last residents are housedin temporary housing, the preparation of the basement structure starts. On top of old foundation an underground facilities are built and a base for last houses on a new “hill” is constructed.

Last residents move from temporary housing to their new home. Excavated ground that was surrounding the old basement is used to smoothen the hill to the eastern side of the hill residencies. The temporary buildings is either kept for further developments in the neighbourhood, established as a new housing for other people, or dismantled and stored for its revival or reuse.

Last residents move from temporary housing to their new home. Excavated ground that was surrounding the old basement is used to smoothen the hill to the eastern side of the hill residencies. The temporary buildings is either kept for further developments in the neighbourhood, established as a new housing for other people, or dismantled and stored its revival or reuse.

Analysis of chosen 1-464-Li building. This was the most widely spread housing series in the Soviet Union. This Housing series is one of the best examples of Soviet planning, eradication of individualism and self-determination through home to meet fiscal standards set in Moscow.

9 storeys timber elements

36 apartments

page to be updated

page to be updated

Rural Lithuanian settlements that existed before the ocuupation often consisted of several houses sharing common ground ‘kiemas’

The current detatchment between neighbours and the nature (above)

144 apartments

typology

extra unit for each type

144 apartments

Urban Hamlet typology

apartments

152 apartments

5 clusters in Urban Hamlet

8 apartments in one cluster (two of each type)

x 10 x 10 x 10 x 10

47m2

small layout ground floor apartment designed with less-abled individuals in mind

68m2

small house for one/two individuals

74m2

medium size house for two individuals / two individuals + one small individual. With access to a small roof terrace

132m2

biggest house for biggest families of three/ four or a big group of friends

37m2

studio type layout designed with less-abled individuals in mind

14 clusters in Urban Hamlet

8 apartments in one cluster (two of each type)

55m2

smaller type house for one/two individuals

large house for a family of three/four or a group of friendly individuals living under one roof x 28 x 28 x 28

78m2

medium size house for two individuals / two individuals + one small individual

95m2

all directly connected to the ground

A proposal to create spaces for social and cultural experimentations within the community. Proposed areas for pavilions and common spaces. These spaces can be appropriated by community members through initiative and motivation, discussed during community gatherings. Speculative sketch ideas show possible outcomes and uses of these spaces.

inhabitants vote for which common spaces can be appropriated by who

forum

The project responds to decades of architectural and cultural erasure, and the threats posed by monotonous globalisation, by asserting Lithuania’s need to shape its identity through design. Soviet housing is not demolished but dismantled - treated as a quarry of raw material, memory, and resistance. The 1-464 building elements are reused, cut, and combined with materials native to Lithuania’s bioregion. In this intersection between rough concrete and regional biomaterials, trauma and craft, the foundations of a new vernacular are laid.

The project responds to decades of architectural and cultural erasure, and the threats posed by monotonous globalisation, by asserting Lithuania’s need to shape its identity through design. Soviet housing is not demolished but dismantled - treated as a quarry of raw material, memory, and resistance. The 1-464 building elements are reused, cut, and combined with materials native to Lithuania’s bioregion. In this intersection between rough concrete and regional biomaterials, trauma and craft, the foundations of a new vernacular are laid.

In western Lithuanian, reed grows alongside the coastline of Curonian Lagoon. In the last century reed was planted to protect the erosion of the coast. Today, however, around 7 ha every year are being cut, as reed has become invasive and harmful for the balanced ecosystem of the lagoon.

Locality: southern area of the Curorian Lagoon

Application: roofing

Type: bio-based

Cement- the binding material for concrete, as well as mortar. Lithuania has limited resources of lime cement. The production and distribution of this local material is often overshadowed by imports from other countries. Many parts of upper layer of the ground in Lithuania contains large amounts of sand. Using local cement, together with locally sourced aggregate (crushed building waste i.e.) and sand - concrete can be made closer to the building site.

Locality: Naujoji Akmenė, North Lithuania

Application: concrete and lime mortar

Type: excavated virgin material

Traces of hemp fabrics and seeds dating back to 3500-3000 BCE are the oldest archaeological findings of cultivation in the Lithuanian region. It was widely used for textile, cuisine, as well as it was the main export. This ancient regional practice was banned during the Soviet regime. It took more than twenty years since the Independence for hemp to slowly return to Lithuanian farming and manufacturing.

Locality: suitable for all regions

Application: hard insulation

Type: bio-based

Lithuanian word “asla” cannot go unnoticed when reading older Lithuanian literature. The worddescribing rammed earth floor in houses of the old craft - often plays as a canvas for the everyday home action of the folk tales. Many farmers houses in noncoastal regions were built using adobe construction (hay mixed with clay. Due to harsh seaside conditions this type of construction was not widely practiced in the western region. Application of earth was rather limited for the floor construction. During the forced industrialisation and urbanisation the craft of building with earth, lime, clay has been pushed to the margins and forgotten.

Locality: south of the project site, other regions

Application: floor screed, plaster

Type: excavated virgin material

Timber in Lithuania has been long used in construction. This renewable material is on the rise again in the building industry. While the country still boasts luscious forests and timber still is one of the biggest exports, the conscious use and extraction of wood is essential to maintain the positive impact of the timber construction. Hence reusing urban materials should be prioritised in combination with virgin, sustainably harvested timber.

Locality: Southern and Eastern Lithuania

Application: superstructure, windows, doors, stairs

Type: bio-based

Lightweight gravel made from recycled glass offers thermal insulation, moisture resistance and high compressive strength, that can be used for foundation insulation. It is made by grinding (salvaged) glass into a powder, mixing it with a foaming agent (such as carbon, calcium carbonate, or biobased starch), and heating it to high temperatures, where gases create a porous structure. The material is then cooled and processed into granules or slabs.

Locality: 1-464-LI window glass

Application: hard insulation for foundation Type: reclaimed urban material

Metal cladding on the existing ninestorey building seems to be in a good, still functional condition. After the deconstruction, profile metal cladding can be straightened, cut and folded again to craft covering caps for the reed roof of the three-storey housing clusters. These metal caps would protect the top fibers of the reed roof from water. Reused metal can be also used to shape gutters situated at the top of the three-storey housing patio.

Locality: 1-464-LI metal cladding parts

Application: reed roof cover; water gutters

Type: reclaimed urban material

The project responds to decades of architectural and cultural erasure, and the threats posed by monotonous globalisation, by asserting Lithuania’s need to shape its identity through design. Soviet housing is not demolished but dismantled - treated as a quarry of raw material, memory, and resistance. The 1-464 building elements are reused, cut, and combined with materials native to Lithuania’s bioregion. In this intersection between rough concrete and regional biomaterials, trauma and craft, the foundations of a new vernacular are laid.

This project is a carefully crafted example of Reconstructivism - locally specific interpretation of the 1-464-Li series housing block, which was reconstructed to align with local needs, social and cultural traditions. It is an example of what once an oppressed culture might undergo to heal and reclaim its identity within the current constraints of global crisis. Hopefully this documented journey could be used as an initial tool to further raise critical questions about todays consumption-driven architecture, face-less practices, and what is the role of colonial relics in a journey to self-determination. This project is not intended as a universal prototype for further developments across other regions. But rather it is a roughly drafted story that would help to decrypt the architectural language of evolution.

BB1-5/7