Contents Contents

As I write, the lead stories are the UK’s mortality rate from covid-19; our response to the killing of George Floyd; and the controversy over J.K. Rowling’s comments on gender assignment. In each case, what troubles me is the binarism that each issue imposes on us.

At risk of walking into a minefield, I’d say that the third topic—is gender biological or self-determined?—is the least intractable, because it seems predicated on labelling. Labels are always being contested so I’d want to ask a lexicographer, or linguist David Crystal, how both sides could walk away from the most contentious terms and agree on a new terminology—though that would be like suggesting that Israelis and Palestinians resolve the problem of who owns Jerusalem by handing the Holy City to some international authority; easy to say if you don’t have skin in the game.

Behind the issue of labelling is the complaint by feminists that their long battle against the patriarchy is trashed if men can reassign themselves and then enjoy the fruits of feminist effort. That leaves us with a binary dispute between two victim groups, with the more recent painting the more established as an alternative patriarchy. That’s what a new lexicography would have to grapple with. (And that’s what I’m calling the least intractable?)

For many of us, the global protest at endemic racism is a clearer case of more obvious victims standing up to more obvious oppressors, though this simple polarity is challenged by the backlash of almost inarticulate whites (in the UK; very much less inarticulate in the USA) who feel that Black Lives Matter threatens their own self-definition.

These are another pair of victim groups, though few will rush to see them as co-equals on a par with trans and feminist groups—and that’s also part of the challenge. More problematic, if you accept the Black Lives challenge, is that it’s hard for non-BAME actors to have a view that counts. The test case here is Hitler and the Jews. It doesn’t matter that a Nazi might invoke the Versailles Treaty and hyperinflation to explain the popularity of Hitler. In this contest, the Jews win every argument—rightly. Equally, it doesn’t matter how whites might defend their privilege; slavery was eradicated in the UK by Wilberforce but whites are still living off the proceeds—and Blacks aren’t.

Men are similarly disempowered by feminism. There is no counter-argument to the attack on the patriarchy, unless one falls back on the hateful Roger Scruton. Males oppress: it’s the condition feminist critique traps them in and no argument will release them. (And that’s not to say they are thereby excused. But binarism can only place them in one box.)

The third challenge is the confluence of domestic politics and covid-19. One could say that the many who have suffered from the mismanagement of the pandemic have only themselves to blame for electing the charlatans who promised to square the circles of Brexit: most electors trusted cardsharps to run the country and this is the upshot.

That’s little consolation for the rest of us, especially if Boris Johnson’s affability is used to exonerate his having steered the 21st most populous country in the world into having the second highest death toll, until knocked into third place by Brazil. The slaughter resembles the Battle of the Somme and its Earl Haigs should be put on trial.

True, UK leaders haven’t said that the coronavirus was fake news dreamt up by leftists to damage the economy and steal the next election but their behaviour is no less a crime against humanity. Where it was always safer to assume a worse case scenario and take preemptive measures, ministers have stubbornly done the opposite, as well as lying about data and tests, and acting—in a re-run of the Brexit debate—as if stating an aspiration meant achieving it.

Which writers help us understand this? The two most obvious are relative newcomers to our shores: Ayn Rand, whose books glorified selfishness and blamed incompetence on collectivist caution; and Friedrich Nietzsche, her intellectual mentor. Dominic Cummings has learnt from both of them the contempt of the ruler for the ruled; but so have we. Convinced of our lack of agency, we either pull down statues or attack the police. Meanwhile the Earl Haigs drive to Durham. Binarism wins.

Stephen Games / Publisher and editor

Jonathan Lawley

Historical assessment of the Andaman islands and its endangered tribespeople

See Issue 7

AN

Brian Verity

True story of a man who discovers that his wife has Huntington’s disease and helps her to kill herself

See Issue 2

HAPPY NAPPY

Stephen Games

Delightful A.A. Milne-style rhymes for parents to enjoy with their babies

See Issue 5

GREEK GOLD

IN

Karen Strang

The 1870s Scottish poems of Arthur Rimbaud translated into broad Scots

See Issue 2

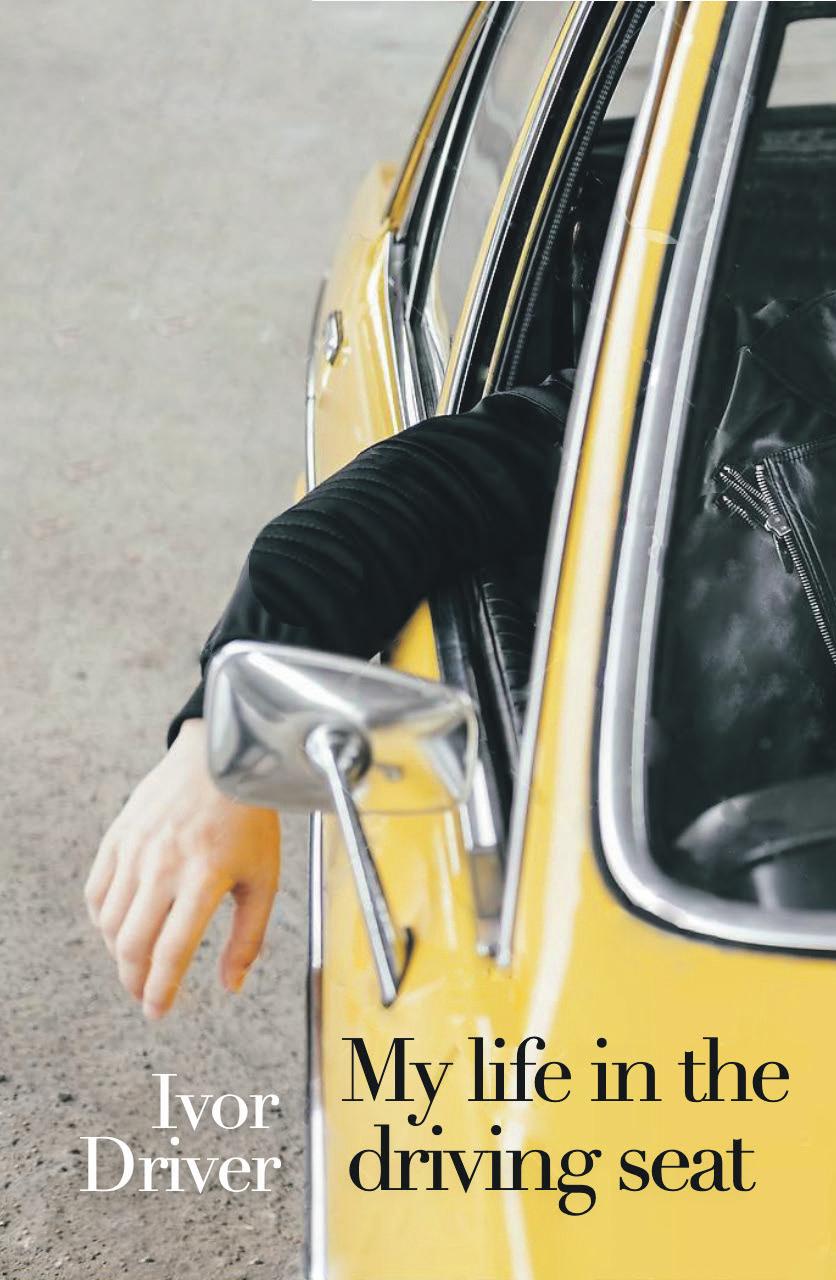

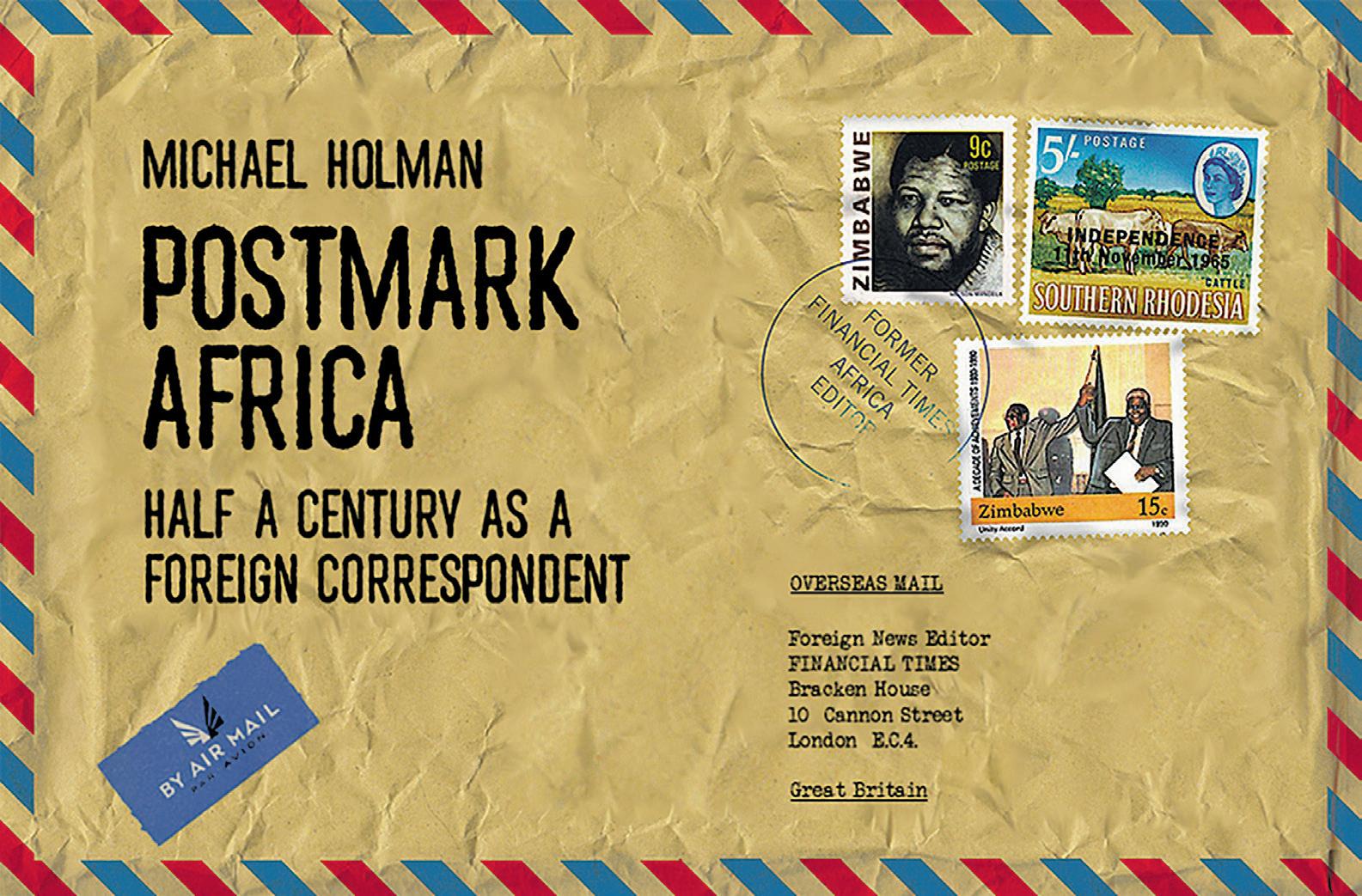

Michael Holman

Fifty years of reporting on post-colonial Africa, by the former Africa editor of the Financial Times

See Issue 7

SUPPOSE

Anita Mason

Political ghost story about a museum curator forced to question his certainties

See Issue 5

Susan Barrett

English woman searches rural Greece for the truth of her father’s wartime death

See Issue 4

EMPIRE’S LOVING

Jay Prosser

A chest of memories reveals unexpected links between Iraqi Jews, Singapore Chinese and the British

See Issue 2

A HARD PLACE

Patrick Kelly

Gritty Romeo-and-Juliet novel about love across Northern Ireland’s sectarian divide

See Issue 5

TASTE WARS

Robert Best

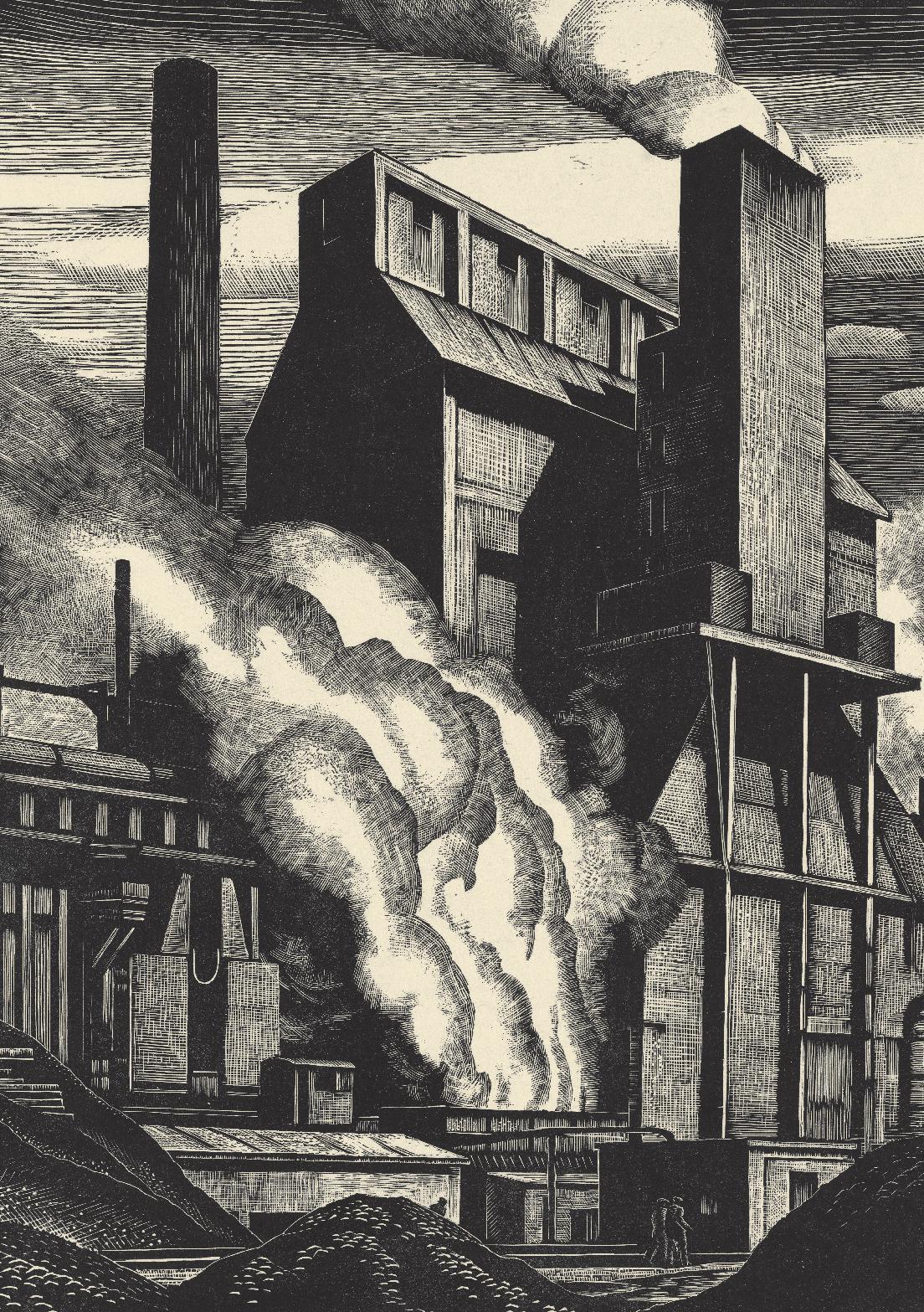

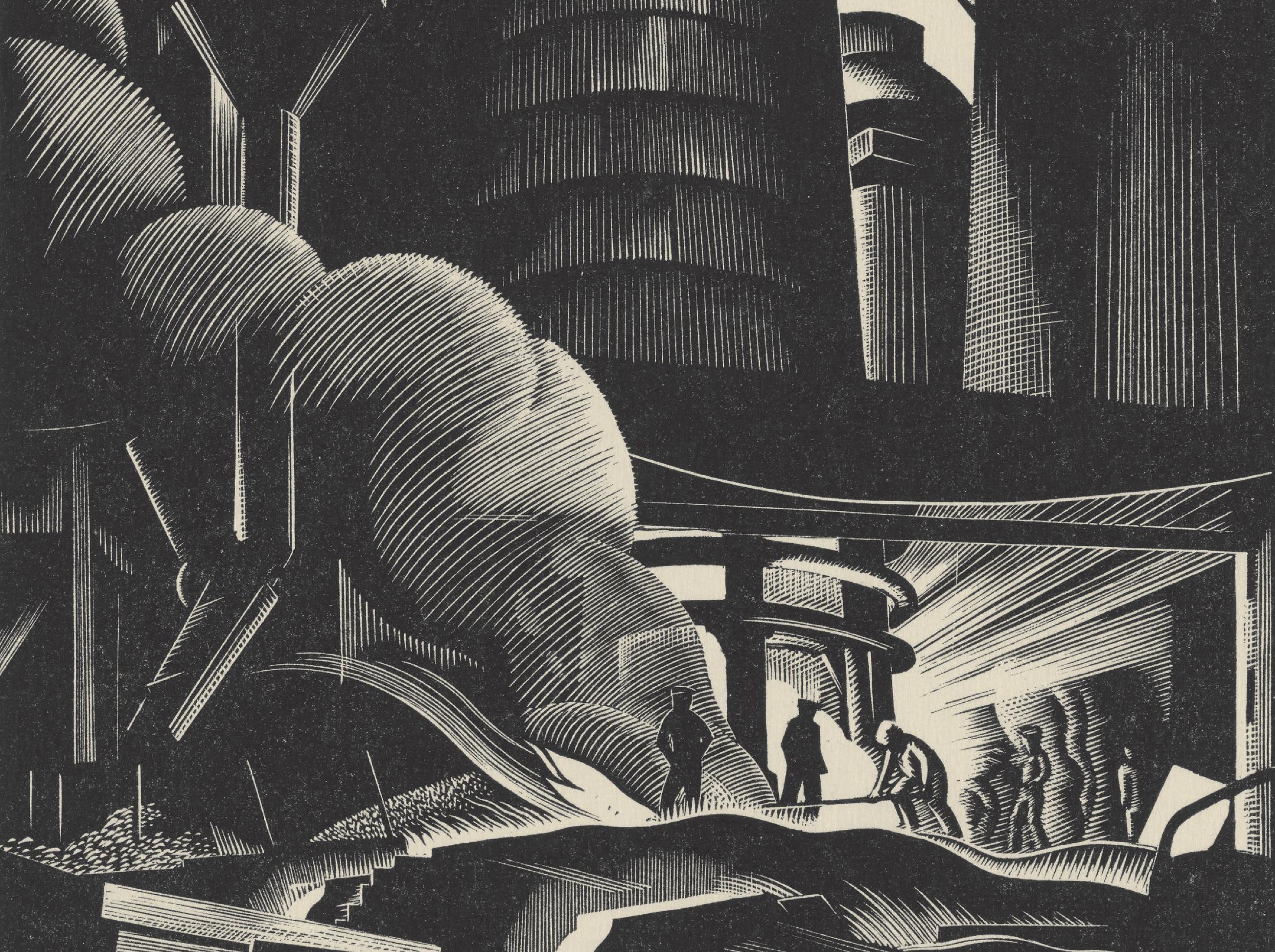

Ringside view of the English design profession in the first half of the 20th century

See Issue 1

GOOD MORNING

EARTHLINGS

Peter Archer

Comic existential sci-fi novel in the style of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy See Issue 2

CALIENTE

Chris Hilton

A torrid love affair with a Havana street girl leads to adventure in rural Cuba

See Issue 3

THE MOTHER OF BEAUTY

Kirby Porter

Memories of a past love in Northern Ireland bring up issues of identity that are difficult to confront

See Issue 2

SANS GILL

Kate Ashton

Sympathetic memoir of the political, religious and cultural milieu that the artist Eric Gill presided over See Issue 2

Booklaunch showcases published, self-published and unpublished books. All our previous books can be accessed for free online by clicking Archive in the header of our website: www.booklaunch.london. On other pages you’ll find audio of our authors reading, as well as featured pieces by guest writers. Listen also to audios with rolling text on our YouTube channel.

Since Booklaunch began 21 months ago, we have showcased 15 self-published books alongside over 200 more by mainstream publishers. We like to give independent authors a share of the limelight they cannot get in other publications. If you have self-published and want to promote your book, email a pdf of the full text to Maggie Bawden at book@booklaunch.london

In the classic story archetype, a hero is pulled unwittingly into some form of conflict and has to face off against a dangerous enemy. They could be fighting corruption at city hall, or battling a faceless, heartless insurance company. They could be called upon to protect the inhabitants of a small Western town against a marauding posse or to apply their forensic psychology skills in the hunt for a serial killer.

This structure is almost precisely the story of Donald Trump’s candidacy for president. It mixes together welldefined antagonists and protagonists; a challenging quest with an unlikely outcome; and page after page of memorable dialogue and storytelling.

We often think of storytelling in terms of making things up, of invention and fiction. Can this help explain why politicians—particularly those today—are seen as fabulists, lying their way to power, then continuing to lie with impunity throughout their spells in office? How are the parameters that define what counts as truthfulness and what counts as lying drawn in this context?

In an article on the trend in popular culture for a particular type of psychological drama, the journalist Zoe Williams suggested that ‘what we call post-truth politics would actually be better classed as gaslighting’. Gaslighting is a psychological condition named after a play written by the early-twentieth-century British writer Patrick Hamilton. Hamilton had something of a fascination for narcissistic sociopaths in his work. In Gas Light, the central character Jack Manningham mentally tortures his young wife Bella by manipulating her into believing that she’s losing her mind.

Over the last two decades, the term ‘gaslighting’ has started being applied to politics, and to many political commentators this is precisely the state of affairs that’s afflicting America, due to repeated exposure to Donald Trump’s persistent assault on truth.

The journalist Amanda Carpenter sees gaslighting as pivotal to Trump’s political success, and at the very heart of the post-truth phenomenon. She breaks down the Trump gaslighting technique into a five-stage process. First, he asserts something which has little or no basis in reality but is highly controversial and thus bound to attract attention—an early example was his advocacy of the idea that Barack Obama hadn’t been born in the United States (and thus wasn’t a ‘true’ American). He then spreads the rumour by citing vague or imaginary sources, while at the same time ensuring that he doesn’t explicitly commit to it himself—(‘Many people are saying …’; ‘A very reliable source has informed me ...’). He follows this by ramping up media interest by promising to reveal more about his knowledge of the issue at some indeterminate time in the future, then uses the furore he’s provoked as an opportunity to attack any of his opponents who try to criticize his pursuit of the issue. Finally, he’ll declare victory in the dispute, regardless of how the facts on the ground have played out—so, for instance, claiming that it was actually Hillary Clinton who’d raised questions about Obama’s place of birth, and that he, Trump, had been the one to resolve the issue by suggesting Obama should simply produce his birth certificate.

And of course, every time he cycles through this formula, he provokes the press into promoting his distorted view of the world. So even if we don’t believe the endless catalogue of nonsensical assertions, they still dominate the news agenda.

Once gaslighting became a popular way of criticizing the propagandist techniques of those in power, it also became available for use by all parts of the political spectrum. Thus, at a rally in 2018, the NRA’s executive vice-president Wayne LaPierre could claim that the opponents of gun control, including the survivors and relatives of tragedies like the Sandy Hook shooting, are themselves ‘gaslighting tragedy. They exploit victims to advance their ultimate agenda: kill the NRA and napalm the second amendment.’ The point has been reached, in other words, where one group is gaslighting another about the use of gaslighting in society.

Gaslighting as a form of psychological manipulation is a very real form of abuse and resembles three other terms that started out referring to practices which actually exist in the world: ‘false flag’ operations in which one side in a conflict commits an atrocity while pretending it was perpetrated by the enemy; ‘political astroturfing’ where paid actors are brought in to look like grassroots support; and the ‘deep state’ in which secretive, behind-the-scenes forces work against elected officials.

Each of them has, over the last few years, been co-opted to describe paranoid fantasies or politically-motivated distortions of the world, and from this have been used as way of corrupting or confusing political discourse. The pro-

cess in each case is the same as what happened with ‘fake news’, all of which feeds into a single overarching narrative which mixes scepticism and suspicion about politics with an obsession with the processes of storytelling themselves.

In October 2018, Donald Trump held a press conference in the Oval Office with one of his most vocal supporters, the rapper Kanye West. Most of it was dominated by a monologue from Kanye, in which he speculated that if he ever decided to run for president himself it wouldn’t be until 2024, as he wouldn’t want to unsettle Trump’s second term ambitions.

Among West’s philosophical musings, one assertion that came across as perhaps a little more lucid than some of the others was the justification of his support for the president. As he astutely remarked, ‘Trump is on his hero’s journey right now.’ The reference here is to an idea put forward by the mythologist Joseph Campbell. The ‘hero’s journey’ is an archetypal story pattern which can be traced from ancient myths to modern dramas. For the study of story structure, it’s a seminal idea.

A story, at its most basic, is a recounting of the actions taken by a person (or other anthropomorphized character) as they try to achieve a goal of some sort. The drama is their struggle to attain this goal and the changes that take place as part of this struggle. Crucially, a good story will also have some sort of meaning. It’s not just about what happened, but about how we feel about what happened.

If you wanted to illustrate Trump’s self-styled story in two sentences you could do worse than the assertion he made to an audience at the NRA conference in May 2018. ‘Your Second Amendment rights are under siege’, he warned. ‘But they will never, ever be under siege as long as I am your president.’

The two assertions seemingly contradict each other— Second Amendment rights are currently under siege / they’re not under siege while I’m president (which I am at the moment)—but also illustrate the simple, single story at the core of Trump’s appeal that is structured around the ‘Overcoming the monster’ archetype. Seen within the context of his narrative of the political outsider doing battle against an elitist political class, the two sentences somehow manage a perverse coherence.

But there’s more texture to his narrative than just this. The story I’ll use as an example is the one enacted in his 2016 election campaign, the story he fashioned for himself, not one that others tried to tell about him—although the way it was told relied in great part on his interactions with the media and how they reported on these interactions. This particular version of his story begins with him deciding to run for office and ends with the result of the election itself.

The protagonist in Trump’s story is, of course, Trump. He pulled from the shelf a standard archetype (a caricature, even) for his political character: that of political outsider. This allowed him to present himself as a notable exception in the initial crowded field of contenders. As the writer Mark Pack notes, choosing this character offered practical advantages for campaigning. It’s easier ‘to sound principled and consistent if you’ve not actually done anything’ and have no track record in politics, whereas it’s ‘quite hard to be principled and consistent with all the countervailing pressures that are on you’ when you’re in office.

In setting himself up like this, Trump’s character was able to exemplify the theme of the narrative itself. The same dynamic is at work for most populist leaders: they frame themselves as the antithesis of career politicians, so they can position themselves as the individualistic hero, not beholden to anyone else, and thus free to represent the will of the people. In Trump’s case, his combative style of speaking, and his lack of concern with the traditional etiquette of elected officials, all spoke to his character, which in turn represented his narrative.

In a political story, the protagonist is always working on behalf of a community that’s under threat and in need of a champion. The threatened community in Trump’s story is a mixture of blue-collar workers whose standard of living has deteriorated or who’ve lost their jobs. The next step is to create a concrete target against which to fight. It’s here that Trump excels most as a storyteller. His tactic of picking fights and never apologizing for the ad hominem attacks he makes gives him an endless list of opponents. Ultimately, however, it’s not specific individuals he’s in conflict with. The personalities are interchangeable. Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton, for example, represented exactly the same values in the structure of narrative he was telling, despite being on different sides of the

The author teaches language theory at the Open University

Philip Seargeant

Bloomsbury Academic (London), Hardback, 272 pages, 138 x 216, June 2020, 9781350107380

Publisher’s price £21.99

Save £2.64

Booklaunch price £19.35 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

Athena Aktipis

Athena Aktipis

Princeton University Press (Woodstock), Hardback, 256 pages, 19 b/w illus., 156 x 235, April 2020, 9780691163840

Life has struggled with cancer since the dawn of multicellularity about two billion years ago. When we think of life on Earth, we typically think of multicellular organisms like animals and plants that are made up of more than one cell. The cells in a multicellular organism essentially divide the labour of making a living, cooperating, and coordinating to do all the functions that are needed in the body.

On the other hand, unicellular life forms—like bacteria, yeasts and protists—are made of a single cell that does all of the jobs of keeping that cell alive. Unicellular life dominated our planet for billions of years before multicellular life gained an evolutionary foothold. The world was cancer-free during these two billion years when unicellular life reigned. But when multicellular life entered the scene, it ushered in a new player: cancer.

Cancer is a part of us, and it has been since our very beginnings as multicellular organisms. Remnants of cancers have been found in the skeletons of ancient humans, from Egyptian mummies to Central and South American hunter-gatherers. Cancer has been found in 1.7-million-year-old bones of our early human ancestors in ‘the cradle of humankind’ in South Africa. Fossil evidence of cancer goes back further still; it is found in bones tens and even hundreds of millions of years old, from mammals, fish, and birds. Cancer goes back as far as the days when dinosaurs dominated life on our planet, and back even further than that, to a time when life was microscopically small. Cancer began before most of life as we know it even existed.

In order to manage cancer effectively, we must understand the evolutionary and ecological dynamics that underlie it. But we must also change our way of thinking about cancer, from viewing it as a temporary and tractable challenge to seeing it as a part of who we are as multicellular beings. Before multicellular life evolved, cancer did not exist because there were no bodies for cancer cells to proliferate inside of and ultimately invade. But once multicellular life emerged, cancer was able to emerge as well. Our very existence as multicellular organisms—as paragons of multicellular cooperation—is inextricably tied to our susceptibility to cancer.

faces that evoke modern art. Crested cacti are highly prized by professional botanists and backyard cactus lovers alike due to their beautiful and unusual mutated forms.

When I first saw a crested cactus on a visit to Arizona years ago, I was fascinated by the beauty and geometry of the plant. When I returned to my hotel room, I spent several hours looking at photographs of these natural biological formations and reading about them. I learned that the disrupted growth patterns of the mutated crested cacti sometimes result from damage during storms, sometimes from bacteria or viruses, and sometimes from genetic mutations during development.

I also learned that mutations that disrupt plant growth patterns are not unique to cacti—they happen across many plant species, from dandelions to pine trees. The technical term for these disrupted growth formations in plants is fasciation Fasciated plants are often more delicate than their nonfasciated cousins, and sometimes they do not flower normally, making it harder for them to reproduce and propagate themselves— however, fasciated plants are often cared for and propagated by gardeners and botanists. With proper care, crested cacti and other fasciated plants can live for decades with these cancer-like formations.

Learning about crested cacti marked the beginning of my fascination with cancer across forms of life. Why, I wondered, was cancer so pervasive across all forms of multicellular life? Cancer is uniquely a problem of multicellularity because multicellular life is made of many cells—cells that usually cooperate and regulate their behaviour to make us functional organisms. Unicellular life forms don’t get cancer because they are made of just one cell. This means that, for unicellular life, cell proliferation is the same as reproduction. But for multicellular life, too much cell proliferation can disrupt the normal development and structure of the multicellular organism.

Publisher’s price £22.00

Save £3.50

Booklaunch price £18.50 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

We can look to the natural world to recognize what cancer is and how it evolves. One of the most beautiful examples is the crested cactus. Sometimes the cells in the growing tip of a cactus will mutate as a result of damage or infection. These mutations can disrupt the normal controls on cell proliferation during the growth of the plant. This often leads to striking formations: desert saguaros that look like they are wearing crowns, potted cacti that look like brains, garden cacti with knobby geometrical sur-

You might feel like a unitary being, but in reality you are made of trillions of cells that are cooperating and coordinating their behaviour every millisecond to make you a functional human being. The number of cells inside our bodies is mind-boggling—more than four thousand times the number of humans on Earth. We are 30 trillion cooperating, evolving, consuming, computing, gene-expressing, protein-producing cells. How can 30 trillion cells make a being that seems so much like one single entity with one set of goals? How can I be made of so many cells yet feel so unitary?

One answer to these questions comes from evolutionary biology: we have been shaped by nearly one billion years of evolution on multicellular bodies to have cells that act in a way that enhances the survival and reproduction of the cooperative cellular society as a whole—the multicellular body. Our cells constrain their proliferation, divide labour, regulate their resource use, and even commit cell suicide for the benefit of the organism. The scope of cooperation inside us is beyond anything humans have ever accomplished—the cells inside us behave like a success story of a utopia, sharing resources, taking care of the shared environment and regulating their behaviour for the good of the body.

But sometimes this cellular cooperation breaks down. And when it does, this can set off an evolutionary and ecological process in the body that culminates in the ultimate form of cellular cheating: cancer. Cancer is what happens when cells stop cooperating and coordinating for the benefit of the multicellular body and start over-using resources, trashing the shared environment of the body, and replicating out of control. Inside the body, these cheating cells can have an evolutionary advantage over normal cells, despite the fact that they can damage the health and survival prospects of the body of which they are a part.

Although we feel like unitary individuals, fundamentally we are not. Because we are made of a vast population of cells, evolution naturally occurs within

‘Cancer cells are like bad roommates. They don’t do their share, don’t clean

and then invite

friends to stay over’

our bodies. Cells in the body can evolve just as organisms in the natural world evolve. And as we age, the population of cells that composes us continues to evolve, often in directions that put us at risk for cancer.

Cells are of course a part of who we are, yet they are also very much their own entities. Cells express genes, they process information, they behave—moving, consuming resources, and building extracellular structures like tissue architecture. In addition, they are a population inside our body that is evolving in a complex ecological environment. We need both of these perspectives—cells as a part of us and cells as their own unique evolving entities inside of us—to understand what cancer is and why we are vulnerable to it.

From the perspective of our bodies, cancer is a threat to our survival and well-being. From the perspective of the cell, cancer cells are only doing what every other living thing on this planet does: evolving in response to the ecological conditions they are in, sometimes in ways that are detrimental to the system of which they are a part. This leads to a seemingly paradoxical evolutionary scenario: Evolution favours bodies that are good at suppressing cancer, but evolution also favours cells inside the body that have the characteristics of cancer cells, such as rapid proliferation and high metabolism.

The scale of cellular cooperation in our bodies is astonishing. But even more stunning is how resilient our bodies can be when faced with cellular cheating—how we can survive and thrive despite the threat of cancer. Multicellular bodies have evolved many different cancer suppression mechanisms over billions of years. Like the crested cacti, which can coexist with their cancer-like growths for decades, perhaps we also can live with cancer.

Before I learned about cancer’s evolutionary nature, I thought of cancer as nothing more than a rather uninteresting disease. My work focused on deep and fundamental questions about the evolution of life: Why are so many organisms social? What makes cooperation stable despite the possibility of exploitation from so-called cheaters? I had always been drawn to theoretical questions, so I shied away from any topic that seemed to require the memorization of an endless catalogue of facts with no framework to hold them together. Cancer seemed to be one of those topics—no theoretical grounding, just an endless number of studies on mechanism after mechanism with no underlying principles to discover. It was certainly worthy of study because of its importance to human health, but I had no interest in studying it myself.

Then I moved to the University of Arizona to work as a post-doctoral researcher, and I began working with John Pepper, a pioneer in cancer evolution, a new field at the time. I realized that cancer was a cellular example of exactly what I was already studying: it follows the same rules that all evolutionary and ecological systems follow. Placing cancer in an evolutionary framework provided a starting point for understanding its complexity.

The great evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky—one of the pioneers of evolutionary thinking in the 20th century—once said, ‘Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.’ If Dobzhansky were around today, he might very well say, ‘Nothing in cancer biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.’

Evolutionary theory explains how cancer can exist on two different levels. First, it shows how evolution among the cells in our body—often called somatic evolution— leads to cancer. The cells in our body vary in terms of how evolutionarily fit they are inside our bodies; some cells replicate faster and survive longer than others. The cells that proliferate more and survive longer subsequently make up a larger portion of the next generation and eventually come

to dominate the population. This is evolution by natural selection, the same process that has shaped the evolution of organisms in the natural world.

In addition, evolutionary theory helps explain why cancer has persisted over the course of life on Earth. Organisms have evolved over millions of years to suppress cancer—to keep somatic evolution under control—so that we can live long and evolutionarily successful lives. These cancer suppression systems are the reason that multi-cellular life is even possible—without them, multicellularity would never have been able to overcome the challenges of cellular cheating from within. But these cancer suppression systems are not perfect. Evolutionarily speaking, keeping would-be cancer cells 100 percent under control is not possible.

The reasons we can’t completely suppress cancer are varied and each is fascinating in its own right. Sometimes, lower cancer risk is associated with lower fertility, creating an evolutionary bind for organisms evolving to suppress cancer. In addition, organisms can’t suppress cancer completely because there is a mismatch between past and current environments: modern humans are exposed to mutagens like cigarette smoke and lifestyle factors such as low physical activity, which lead to greater susceptibility to cancer. An even more bizarre reason why we can’t suppress cancer is that there is a battle over our growth happening between genes we inherit from our mothers and genes we inherit from our fathers. Some of the genes we inherited from our fathers are epigenetically set to

promote growth and cell proliferation, contributing to an increased risk of cancer.

In cancer biology, the environment around a tumour is called the tumour microenvironment. This is essentially the ecosystem of the tumour, in many ways like an ecosystem in the natural world. The ecosystem of the tumour provides necessary resources that allow the cells in the tumour to survive and thrive, but it can also threaten the survival of cells when resources run out, waste products build up and the immune system starts preying on cancer cells. Cancer cells can alter their environment as they consume resources such as glucose; for instance, they can reduce the supply of resources for neighbouring cells and leave behind waste products like acid. Those changes, however, can trash the ecology of the cancer cells, making it difficult for them to survive and thrive. The destruction of the microenvironment can create selection pressures for those cells to move. Cells that can move and are able to relocate to a new and better environment in the body will survive and leave more cellular progeny, spurring the evolution of invasive and metastatic cells. Ecology is central to the ways in which cancer emerges and progresses. Just as we can’t understand how and why organisms evolve without knowing about their environments, we can’t understand how and why cancer evolves without knowing the ecological dynamics in and around a cancerous tumour.

The common metaphor for cancer is war—patients ‘fight’, ‘battle’, ‘win’ or ‘lose’. The war metaphor for cancer is powerful and compelling. It can help to rally support for cancer research and bring people together around a common goal, but it can also be misleading. We can’t completely eradicate something that is fundamentally a part of us. This aggressive approach to the disease seems like a good idea if we view cancer as an enemy to eradicate. But unless we see cancer for what it is—a population of diverse cells evolving in response to every treatment we throw at it—we run the risk of

ALIEN OCEANS

THE SEARCH FOR LIFE IN THE DEPTHS OF SPACE

Kevin Hand Princeton University Press (Woodstock), Hardback, 304 pages, 15 colour + 22 b/w illus., 156 x 235, May 2020, 9780691179513

If we have learned anything from life on Earth, it is that where you find liquid water, you generally find life. Water is essential to all life as we know it. Every living cell is a tiny bag of water in which the complex operations of life take place. Thus, as we search for life elsewhere in the solar system, we are primarily searching for places where liquid water can be found today or where it might have existed in the past.

At least six moons of the outer solar system likely harbour liquid water oceans beneath their icy crusts. These are oceans that exist today, and in several cases we have good reason to predict that they have been in existence for much of the history of the solar system. Three of these ocean worlds—Europa, Ganymede and Callisto—orbit Jupiter. They are three of the four large moons first discovered in 1610 by Galileo. The fourth moon, Io, is the most volcanically active body in the solar system and does not have water. At least two more ocean worlds, Titan and Enceladus, orbit Saturn. Neptune’s curious moon Triton, with an orbit opposite to the direction it rotates, also shows hints of an ocean below.

These are only the worlds for which we’ve been able to collect considerable data and evidence. Many more worlds could well harbour oceans. Pluto may hide a liquid mixture of water, ammonia and methane, creating a bizarrely cold ocean of truly alien chemistry. The odd assembly of moons around Uranus—such as Ariel and Miranda—might also have subsurface oceans.

Finally, throughout the history of the solar system, ocean worlds may have come and gone. Early in our solar system’s history, oceans might have been commonplace, be they on the surface of worlds like Venus, Earth, and Mars, or deep beneath icy crusts of worlds in the asteroid belt and beyond. Today, however, it is the outer solar system that harbours the most liquid water.

This distinction—between liquid water in the past and liquid water in the present—is important. If we really want to understand what makes any alien organism tick, then we need to find life that is alive today and that requires the presence and persistence of liquid water.

The molecules of life (e.g. DNA and RNA) don’t last long in the rock record; they break down within thousands to millions of years, which, geologically speaking, is a short amount of time. Bones and other mineral structures of life can stick around much longer and form fossils. Fossils are great, but they only tell you so much about the organisms from which they formed.

This is important because I really want to understand how life works. What is the biochemistry that drives life on another world? On Earth, everything runs on DNA, RNA, ATP and proteins. I want to know if there could be another way. Can life work with some other fundamental biochemistry? Is it easy or hard for life to begin? Does the biochemistry of the origin of life converge toward DNA and RNA? Or were there contingencies that made these the best molecules for life on Earth but perhaps not on other worlds? If we were to find extant life in an ocean world, we could begin to truly answer these questions.

In the 20th century, with the advent of the space age, our human and robotic explorers to the Moon, Venus, Mars, Mercury and a host of asteroids have revealed that the principles of geology work beyond Earth. Rocks, minerals, mountains, and volcanoes populate our solar system and beyond.

But when it comes to biology, we have yet to make that leap. Does biology work beyond Earth? Does the phenomenon we know and love and call life work beyond Earth? It is the phenomenon that defines us and yet we do not know whether it is a universal phenomenon. Is biology an incredibly rare phenomenon or does life arise wherever the conditions are right? Do we live in a biological universe?

We don’t yet know. But for the first time in the history of humanity, we can do this great experiment. We have the tools and technology to explore and see whether life has taken hold within the distant oceans of our solar system.

To answer these questions, we need to explore places where life could be alive today and where the ingredients for life have had enough time to catalyze a second, independent origin of life.

This aspect of a second, independent origin is key. Take Mars. Even if we were to find signs of life on Mars, there are limits to what we’d be able to conclude about that life form and about life more generally. Mars and Earth are simply too close and too friendly, trading rocks since early childhood. When the solar system and planets were rela-

tively young, large asteroids and comets bombarded Earth and Mars with regularity, scooping out craters and spraying ejecta into space. Some of this debris would have escaped Earth’s gravity and may have ended up on a trajectory that eventually impacted Mars (or vice versa).

We know that life was abundant on Earth during many of these impact events and thus it is not unreasonable to expect that some of the ejecta were vehicles for microbial hitchhikers—some few of which could (with a small probability) have survived the trip through space and the impact on Mars. Even if just a few microbes per rock survived, there were enough impacts and enough ejecta that the total number of Earth microbes delivered to Mars has been calculated to be in the range of tens of billions of cells over the history of the solar system. If one of those Earth rocks came careening through the Martian atmosphere about 3 billion years ago, it could have dropped into an ocean or lake on Mars, and any surviving microbes on board might have found themselves a nice new home on the red planet.

This possibility, however remote, would make it difficult to be completely confident that any life we discovered on Mars arose separately and independently—in other words, that it was really Martian. Life on Mars could be from Earth, and vice versa.

The ocean worlds of the outer solar system do not suffer these pitfalls. First, by focusing on worlds with liquid water oceans, we are focusing on worlds that could harbour extant life; and thus we could study their biochemistry in detail. Second, the ‘seeding problem’ is almost negligible. Very few rocks ejected from the Earth could make it all the way to Jupiter and Saturn. In a computer simulation done by the planetary scientist Brett Gladman at the University of British Columbia, six million ‘rocks’ were ejected from the Earth and sent on random, gravitationally determined trajectories around the Sun. Of those six million, only about a half dozen crashed into the surface of Europa. Slightly more made it onto the surface of Titan.

The rocks that did impact Europa did so at a speed that would cause them to vaporize on impact; none would be big enough to break a hole through Europa’s ice shell. Therefore, any material that managed to survive the impact would be left on Europa’s surface, exposed to harsh radiation. Thus, even if we discovered DNA-based life there, we could reasonably conclude that those organisms represented a second, independent origin of life.

I should clarify that when it comes to looking for a separate, second origin of life and biochemistries that could be different from ours, I am not referring to what I call ‘weird life’—that is, life that does not use water as its primary solvent and carbon as its primary building block. We examine this topic in more detail when we explore Titan’s surface, but for now, when I refer to ‘alternative biochemistries’, I am still referring to water- and carbon-based life. What is ‘alternative’ here is the prospect of finding different molecules that run the show, that is, an alternative to DNA.

In our efforts to see if biology works beyond Earth, we start with what we know works. Water- and carbon-based life works on Earth and thus we look for similar environments beyond Earth.

Our own alien ocean

You may have seen old maps where sea monsters, giant squid and dragons dot the vast expanse of seas yet to be explored. One globe from 1510 bears the phrase that has become synonymous with unknown dangers and risks: Hic sunt dracones; ‘Here be dragons.’

The ocean has long been the source of myths and legends. It was—and continues to be—home to aliens of a closer kind. How did we come to explore our own ocean and its many secrets?

The Challenger expedition, departing England December 1872 and returning home four years later, was the first to survey the biology of the deep ocean. The expedition’s Royal Navy ship, the HMS Challenger, carried its crew around the world’s oceans, covering a distance equivalent to a third of the way to our Moon. It was, and remains to this day, one of the most important and pioneering scientific expeditions to set sail.

Chief scientist of the expedition, Charles Wyville Thomson, was given permission from the Royal Navy to overhaul the ship, removing much of the weaponry on board and replacing it with instruments and labs. One instrument was little more than a fancy spool of line with a weight on the end. Simple as it was, this instrument

The period 1925–7 was undoubtedly key in the development of quantum physics, a period that saw the birth of a consistent and logical theoretical framework coupled with a philosophical basis. It is no surprise that many contributors such as Max Born, Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli and Erwin Schrödinger were awarded Nobel prizes for their work. This was the peak of a revolution that spanned the first quarter of the 20th century.

In retrospect, it is natural to view the period as a successful finale that secured the status of quantum physics. At the time, however, there was much uncertainty and mistrust. Niels Bohr received a mixed reaction to a lecture he gave in Como in 1927, principally because of the gap it opened between his vision and classical physics. Nevertheless, it became clear that the new physics constituted an extremely productive way to understand the structure of matter.

The emphasis in the postrevolution period therefore became the development, extension and refinement of the new theoretical tools that subsequently led to a host of successes in the field of atomic and molecular physics and, particularly with the development of accelerators, in the field of particle physics.

In many areas, of course, classical physics continued to provide a perfectly suitable base for establishing and developing a research programme. But for many young physicists, the excitement and strangeness of quantum physics, and the inherent challenges it offered, were a great attraction. In this context, it is noteworthy that Evan James Williams’s early years coincided with this revolutionary period. He was born between the emerg ence of Planck’s ‘quantum’ and Einstein’s claim that the light quantum (the photon) is real, and by the time he went to Swansea Technical College in 1919 to study physics, the ‘old’ quantum theory had come of age. Given that Williams’s studies at Swansea would have concentrated on classical physics, however, it is questionable whether he would have been fully aware during his time at the college that the inadequacies of the old quantum theory were becoming increasingly apparent, leading to a sense of crisis.

In leaving Swansea for Manchester in 1924, Williams moved from a department that was still in its infancy to one at the forefront of developments. Ernest Rutherford’s leadership at Manchester’s Department of Physics had ensured that its research was among the best in Britain, and by the time Williams arrived there, after Rutherford had left to take over the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, it was being led by the 29yearold William Lawrence Bragg who, with his father, had won a Nobel Prize in 1915 for his work on Xrays, crystals, diffraction and wave theory.

Williams’s supervisor for his doctorate was John Mitchell Nuttall but Williams chose not to join the department’s main research focus—the analysis of crystal structures—but to study the scattering of Xrays, focusing on elementary particles that emerged as a result of collisions between Xrays and the atoms of various gases. In order to track the particles, he used a cloud chamber, a vessel filled with these gases, through which he directed the Xrays. The basic notion was that a collision between a sufficiently energised charged particle and an atom can ionise the atom by releasing one of its electrons, leaving the rest of the atom—the ion—positively charged. Therefore, as a particle speeds through the gas in the chamber colliding with a stream of atoms in its path, ions are formed along that path.

To observe the path, the gas in the chamber is saturated with water vapour. By lowering the pressure of the gas suddenly (thereby also lowering the temperature), water droplets condense on the ions and leave a visible trace akin to morning dew on the strands of a spider’s web. Cameras can then record the tracks. The process won a Nobel Prize in 1927 for C.T.R. Wilson, who had developed it, and the cloud chamber went on to become the mainstay of the experiments conducted by Williams.

One result, already well known, was that the electrons released when Xrays collide with gas atoms fall into two classes. The first, known as photoelectrons, are associated with Xray absorption, a process that corresponds to the photoelectric effect discovered by Philipp Lenard. The second, known as recoil electrons, are the product of the scattering of an Xray quantum and the release of an electron as a result of the collision. The energy of the electrons in the first class—the photoelectrons—is significantly greater than that in the second class, so that their tracks in the cloud chamber are much longer. The two classes can therefore be distinguished by how they appear on the photographs of the tracks.

Williams conducted experiments to measure the tracks of both classes of electrons. As a result, he was able to confirm the accuracy of the American Arthur Compton’s theoretical predictions, based on the quantum picture, that an Xray behaved like a particle when scattered. He was also able to show that the number of scattered Xray photons corresponded to the number of electrons released, thus providing further confirmation of the validity of the quantum picture.

Williams later made measurements comparing the momentum of an absorbed Xray with the momentum of the released photoelectron. This time, the experimental results did not agree with those predicted on the basis of the ‘old’ quantum theory, thus raising new questions.

It is significant that after leaving Manchester Williams demonstrated that Arnold Sommerfeld’s theoretical analysis based on quantum physics established a relationship between the momentum of the Xray and that of the photoelectron which did agree with the experimental results.

Williams’s work was already highlighting his originality and ability as an experimenter, and his publications also showed his confidence in applying theory relevant to his experiments. Much of his output not only included details of the experiments and their results, but also an analysis of the relevant theory and calculations that allowed him to compare experimental results with those predicted by theory.

Additionally, Williams was able to complete and submit his doctoral thesis in November 1926 (not 1927, as recorded by many, including Blackett in his memorial tribute), just over two years after he had started in Manchester, and many months before the end of his scholarship term.

Having been awarded his doctorate, Williams turned his thoughts to the next step in his career. It was no surprise that the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge was high on his list but he would need to apply for a scholarship in order to secure financial support. His attention was drawn to an endowment by Viscount Rhondda to Gonville and Caius College. The scholarship gave preference to students from Wales seeking to study Mathematics and the sciences, and Williams applied for and won it but since he had also gained an 1851 Royal Exhibition senior scholarship, based on a fund established following the exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 to promote research in science and engineering, his Rhondda Scholarship was awarded without any associated funding.

Williams was formally admitted to Gonville and Caius, but a fire at the college in early 1929 meant that he lost all his books and other belongings—for which the college authorities duly reimbursed him with a grant equal to the value of the Rhondda Scholarship for two terms. He also secured a position in the Cavendish.

His senior scholarship began in July 1927 and he spent the first three months in Manchester completing work on the momentum of photoelectrons (as referred to above). This was published in 1928 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, with Nuttall and another student as coauthors. Williams had succeeded, at the ripe young age of 25, in appearing in one of the most prestigious British scientific journals, with his name printed first in the list of authors.

At the start of October 1927, Williams moved to Cambridge to work on his second doctorate, this time under Rutherford’s supervision. He worked in a small research room on the first floor of the Cavendish, where one of his neighbours was a specialist in nuclear physics, Norman Feather. Other neighbours were Fernand Terroux, a Canadian who had also been awarded an 1851 Royal Exhibition scholarship and who later became Professor of Physics at McGill University in Canada, and a third Royal Exhibition scholar, Ernest Walton who, with his colleague John Cockcroft achieved world fame by being the first scientists to split the atom.

Those starting their research at the Cavendish received training for their practical work in blowing glass and constructing equipment. Even researchers who had already served an apprenticeship elsewhere were expected to attend some sessions and Williams was no exception. Another custom was the closing of the laboratory at six every evening. No exceptions were permitted. Rutherford argued that evenings should be used to think, to read and to write. Williams was frustrated by it though some years later, he told John Wheeler, who later worked with Bohr on the mechanism of nuclear fission, that this prohibition had been the reason why he turned to theoretical work during his time at the Cavendish. At Cambridge, the theoretical

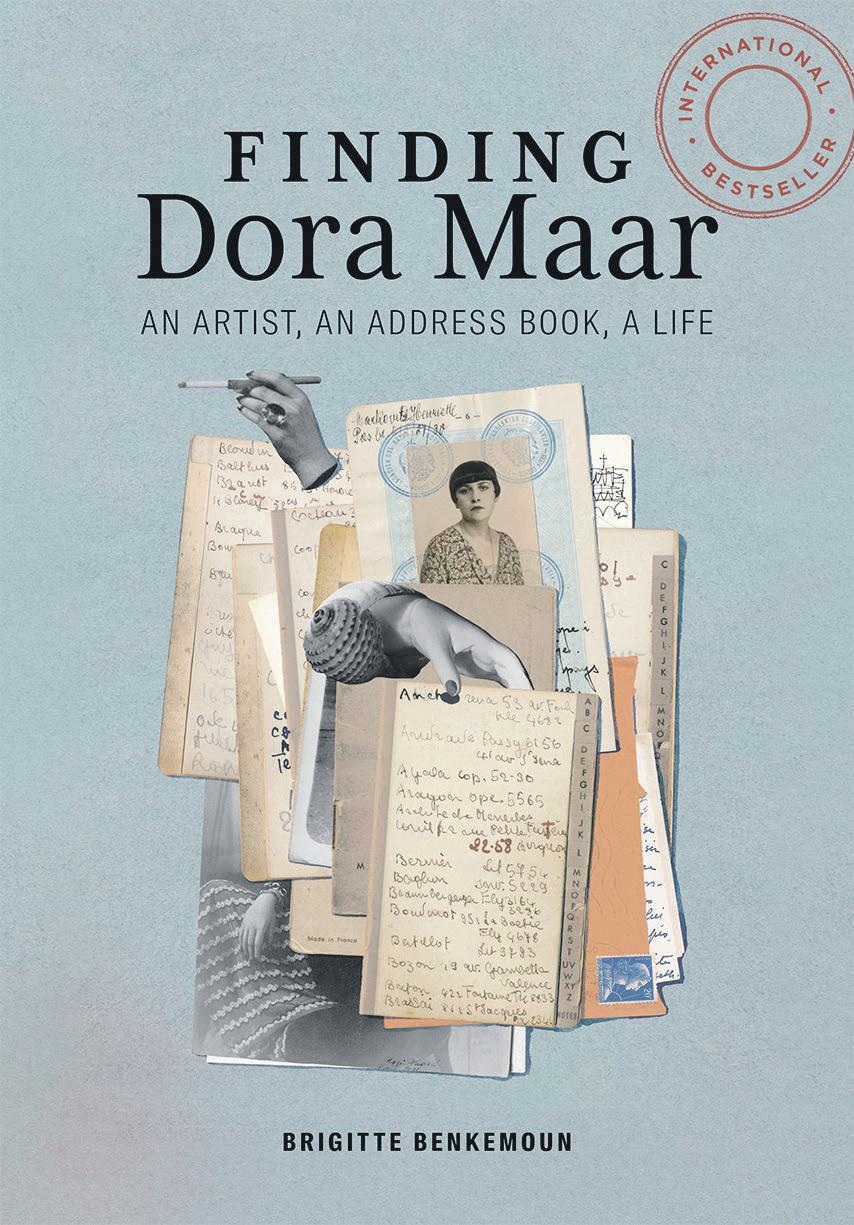

Brigitte

Getty Publications, Los Angeles, Softback, 216 pages, 146 x 210, 30 June 2020, 9781606066591

It arrived in the mail, carefully packed in bubble wrap. Same trademark, same size, same smooth leather, but redder, softer, with a well-used sheen.

He’ll like this, I thought, maybe even better.

He had just lost a small Hermès diary, newer than this one, but somehow ageless from constantly sliding in and out of pockets. As always when he loses something, which happens regularly, I had to help him look. But this time the diary could not be found. After several days, T.D. resigned himself to buying a replacement.

‘Sadly, that kind of leather isn’t made anymore,’ a salesclerk answered, vaguely apologetic, politely definitive. But T.D. never gives up. His lucky find showed up on eBay under ‘small vintage leather goods.’ Seventy euros. And a few days later it arrived.

Obsessive behavior is a con tagious disease; in his absence I wanted to verify that the found object really was an exact replica of the lost one. I inspected it from every angle. Then I opened it.

The seller had removed the annual diary refill but a small index for telephone numbers remained, slipped into the inner pocket. Without thinking, I began to leaf through it. I must have been a bit distracted because it took me three pages before a name caught my eye: Cocteau! Yes, Cocteau: 36, rue Montpensier!

difficult to reach, on vacation, busy, obviously unmoved by the romance of the found address book: ‘I hardly know this pair of sellers, especially since they recently moved very far from this area. I think it’s likely that either their ties with the former owners of these diaries are nonexistent or that they don’t want to hear about this.’

Publisher’s price £18.99

Save £3.00

Booklaunch price £15.99 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

I remember a shiver running down my spine, then the breath taking discovery of Chagall: 22, place Dauphine! I flipped wildly through the pages: Giacometti, Lacan … Here was the whole lineup: Aragon, Breton, Brassaï, Braque, Balthus, Éluard, Fini, Leiris, Ponge, Poulence, Signac, Staël, Sarraute, Tzara—twenty pages on which the greatest postwar artists were listed in alphabetical order. Twenty pages I had to read over and over to believe. Twenty astounding pages, like a personal telephone directory for Surrealism and modern art. Twenty pages I gazed at in wonder. Twenty pages that I touched softly, hardly breathing, afraid they might self-destruct or fade like a dream. And at the very back, to date the treasure, a 1952 calendar, proving that it had been purchased in 1951. Never again would I scold T.D. for losing things.

Now, of course, I wanted to know who had written these names in brown ink. Who could have rubbed elbows with these twentieth-century geniuses? A genius, clearly!

The ad on eBay noted that the seller was an antique dealer located in a hamlet about thirty kilometers from Brive, in Cazillac, a charming Lot village in the green valleys of the Causse de Martel. Cazillac, with fewer than five hundred inhabitants, known (a little) for its Romanesque church, twelfth-century tower, wash houses, bread oven, and the Sauvat cross that symbolically marks the forty-fifth parallel, the halfway point between the equator and the North Pole. That’s where my address book came from! A forgotten place on earth, but exactly in the middle of our hemisphere.

I did find the name of a Surrealist artist who came from that area. But who would have known Charles Breuil? Not Breton, apparently, or Braque, or Balthus.

Edith Piaf was also a frequent visitor to the Causse de Martel. In the 1950s, ‘The Little Sparrow’ (la Môme) returned many times to a rest home a few kilometers from Cazillac. At sunset she went to pray at a small dilapidated church perched on the cliffs. She was even said to have paid for the restoration of its stained-glass windows, swearing the priest to secrecy during her lifetime. So was this Piaf? She had been friends with Cocteau, she knew Aragon during the Liberation, and Brassaï had taken her photograph.

But in a speedy response to my first message, the seller of the address book put a quick end to all speculation regarding Piaf and Cazillac: ‘Many years ago, I bought a lot that included two Hermès diaries during a wonderful auction in Sarlat, in the Perigord. I know nothing more about them, but I do know the person in charge of the auction house, and I can ask him if he has information on the sellers.’

A month later, she kept her promise: the seller was a woman from Bergerac who apparently delivered the diary herself, along with other items, to the auctioneer. Michèle S. also remembered the exact date of the auction: May 24, 2013, in Sarlat. She suggested that I contact the person in charge of the auction house to learn more. But he proved

Clearly he himself had no desire ‘to hear about this’. I did not let up on the manager of the Sarlat auction house. He would not bend. It was impossible to get from him the new address of the sellers, or even any information on what other items they might have delivered to him. He agreed only to forward a letter to them, to which they never replied. And he stopped answering my messages as well: ‘It’s a delicate matter that I cannot “legally” push further without incurring possible complaints.’ Legally speaking, I knew he was right. But intrigued by his remark, I returned to his last message and considered it more carefully. Why tell me that he hardly knew this couple? He knew them well enough to know that they had moved ‘recently’ and ‘very far from this area’. And he must have called them if he could state with so much certainty that ‘their ties with the former owners of these diaries are nonexistent’ and that ‘they don’t want to hear about this.’ Why such secrecy?

There had to be a reason why, one day in Bergerac, someone had come upon this red leather case and decided to sell it without thinking of emptying its contents. Who could have lived or died in Bergerac, and also known all the notables of Paris?

Wikipedia lists a certain number of ‘figures linked to the district’ who might have visited the geniuses in the address book in the 1950s:

— Desha Delteil, ‘classical American dancer famous for her acrobatic postures’

— Hélène Duc, actress

— Jean Bastia, director and screenwriter

— Jean-Marie Rivière, actor, theater and music hall director—Juliette Gréco

None of these profiles really corresponded to the address book entries. Not even Juliette Gréco: her 1951 address book would have included instead the names of Sartre, Vian, Kosma—this was not exactly her world.

But I would find out sooner or later. I would not give up. I would learn who had owned this address book.

Achille de Ménerbes / 22 rue Petite Fusterie, Avignon

Forget Bergerac! Forget the sellers and auctioneers! Since I had at my disposal exhibit A, I could subject this piece of evidence to a kind of interrogation: decode it line by line and page by page, make a list of the known friends of the unknown genius, search the others on the internet. I would end up solving the mystery.

A-B: The first entry is illegible because it is partly blotted out with black ink. The second might be ANDRADE, then AYALA. On the fourth line is the first familiar name: ARAGON! Followed by a few contacts that call up nothing for me: ACHILLE de MÉNERBES, BERNIER, BAGLUM … Then a few entries for whom he or she listed an address as well, perhaps because they were closer friends: BRETON, 44, rue Fontaine; BRASSAÏ, 81, rue Saint-Jacques; BALTHUS, château de Chassy, Blismes, Nièvre.

For the letter C, COCTEAU is the first entry: 36, rue de Montpensier, RIC 5572, or 28 in Milly. But are the first entries always the closest friends? And this poet was such a figure on the Paris social scene that everyone must have known his number. Followed by the painters COUTAUD, 26, rue des Plantes; CHAGALL, 22, place Dauphine …

Implicitly, the address book’s ownership was being revealed through these relationships. This was someone who kept company with the greatest poets of the time, many of them, though not exclusively, Surrealists: ÉLUARD, ARAGON, COCTEAU, PONGE, André du BOUCHET, Georges HUGNET, Pierre Jean JOUVE

Someone knew the address of every artist in Paris. But who?Benkemoun, (Jody Gladding, transl.)

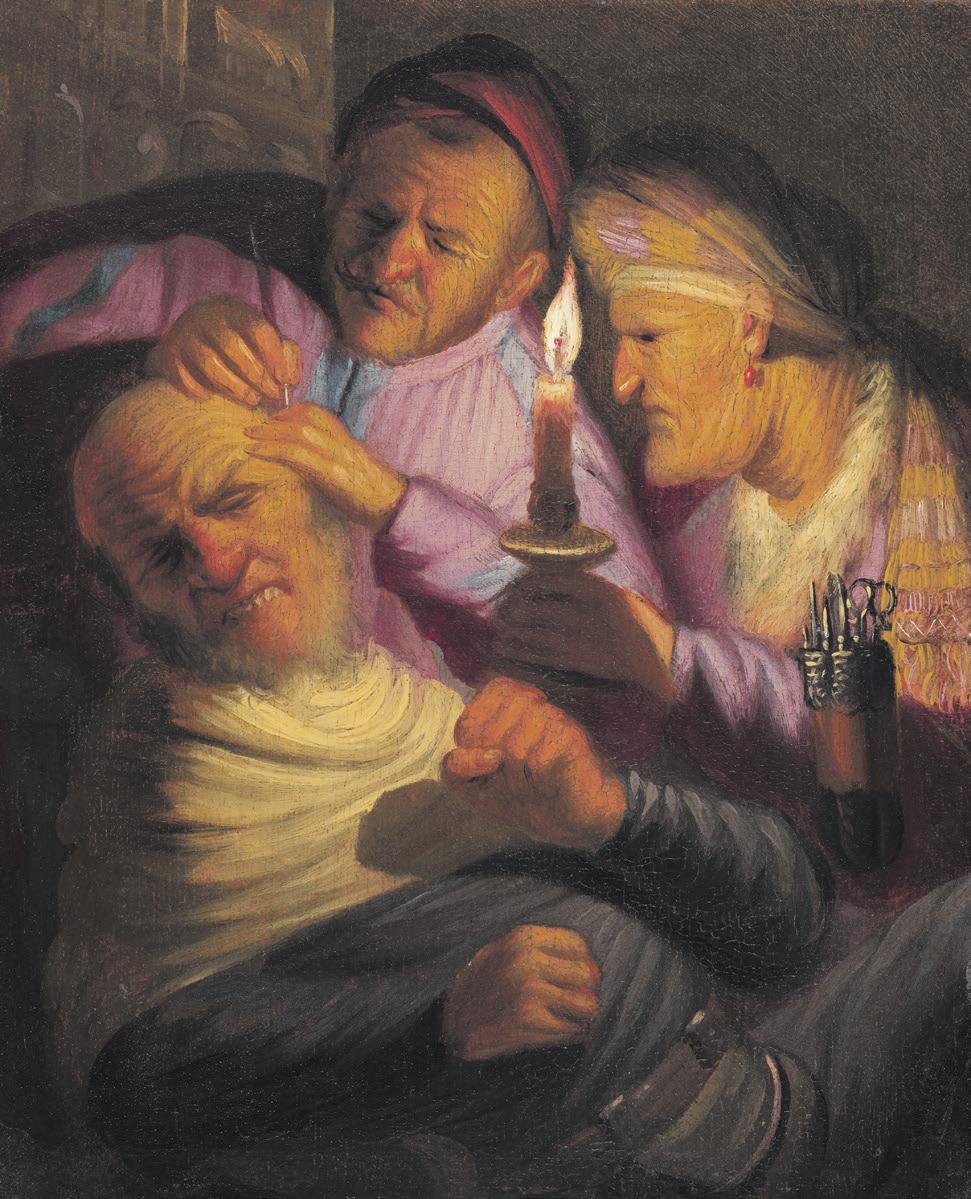

Unlike earlier shows that sought to establish attribution, a new exhibition that ran in Leiden (Rembrandt’s birthplace) at the end of 2019 and is planned to open in Oxford in August examines Rembrandt’s artistic development in the first ten years of his career. Early paintings and prints are shown alongside preparatory drawings, as well as prints made after the same paintings, either by Rembrandt or by his collaborators, in order to assess Rembrandt’s debt to his masters, contemporaries and pupils. The exhibition catalogue includes essays that allow the three curators to explore Rembrandt’s development and working methods thematically, in some cases juxtaposing works of art showing the same subject across different media. (Check the Ashmolean website for details of postlockdown re-opening)

YOUNG REMBRANDT

An

Publisher’s price £25.00

Save £4.70

Booklaunch price £20.30 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

IT’S A LONDON THING

HOW RARE GROOVE, ACID HOUSE AND JUNGLE REMAPPED THE CITY

Caspar Melville

Manchester University Press (Manchester), Softback, 288 pages, 13 b/w + 8 col illus., 138 x 216, November 2019, 9781526131256

By the end of the 1990s, London black music culture had moved beyond drum and bass. UK garage achieved hegemony over black clubbing for a few short years, subgenres like dubstep, wonky and bassline emerged and subsided, and a new rap-based genre— grime—emerged, developed by a younger generation in the same east London breeding grounds that produced jungle.

But jungle/drum and bass was not dead: it had just gone outer-national. As the internet facilitated the rapid globalisation of music cultures, drum and bass—the London contribution to black Atlantic bass culture—started influencing music production in America. Goldie recorded with KRS-One; hip hop legend Afrika Bambaataa added jungle into his DJ sets; and drum and bass producer Rupert Parke (Photek) moved to LA to make movie soundtracks.

Meanwhile, jungle DJs started to travel widely to cities across Europe, America and Australasia, where proto-drum and bass scenes emerged. Jumping Jack Frost claims to have DJed in all the major cities of the world and drum and bass clubs and festivals sprang up in Croatia, Sardinia (‘Sun and Bass’), the Netherlands, Japan, Singapore and Dubai. Jungle/drum and bass is, 25 years later, in rude economic health, providing viable careers for a wide range of London music producers and DJs, though its rebellious energy has been tamped down through its institutionalisation.

This has led some to mourn the decline in the UK of the last pre-digital ‘local’ music that was not reliant, as EDM and grime were, on YouTube or social media. For the music theorist Mark Fisher, jungle represented the last gasp of musical modernity’s ‘future shock’: ‘Play a jungle record from 1993 to someone in 1989,’ he wrote in 2013, ‘and it would have sounded so new that it would have challenged them to rethink what music was, or could be’, whereas ‘the 21st Century is oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion. It doesn’t feel like the future.’ Instead, we have been delivered into a world of endless recycling, defined by ‘retro-mania’—a world where the future has been cancelled.

For the cultural theorist Jeremy Gilbert, the problem is that jungle and drum and bass never delivered the political solidarities its sonic radicalism implied, serving instead to dissipate into political impotency. For Fisher, Gilbert and Reynolds, the idea of a drum and bass festival in the air-conditioned ex-pat enclaves of authoritarian Dubai or Singapore in 2018 would precisely symbolise the problem, their very definition of ‘post-future’ hell.

Publisher’s

Booklaunch price £14.68 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

If, as I have done in this book, you place jungle in the context of the racialised divisions of London, the emergence of reggae sound systems in the 1960s and 1970s, the warehouse parties of the 1980s, rave and hardcore in the 1990s and the musical subcultures of UK garage, dubstep and grime which followed, jungle can be read as the sonic articulation of a racially mixed city. It is not segregated by necessity, as is reggae, nor hidden away like the warehouse parties; it does not resolve multicultural heterogeneity through pharmacological utopianism, like rave. Instead it marks the moment when London finally puts something back into the circulating flows of black Atlantic culture from which it has taken so much.

In the late 1990s, at the highpoint of drum and bass, one could be optimistic about transcending old divisions of race and the role music might play in this process. The emergence of jungle seemed to offer a multi-cultural alternative to ethno- nationalism. But such optimism now seems less plausible, even naive. Mark Fisher was perhaps right that with the arrival of streaming services like Spotify the possibilities of music delivering ‘future shock’ have been cancelled. What has happened to London in the early twenty-first century seems to confirm this view.

As early as 2004, Stuart Hall had already noted the trends that were undermining the promise of racially diverse cities like London offering more equitable multicultural futures. London, he argued, was being ‘reshaped’ by forces that were separating it into enclaves of ‘ultra high net worth individuals’ for whom property was investment not dwelling, defensive zones of ‘white flight suburbs and estates’ and ‘run down inner urban areas’ of social deprivation. Against the backdrop of neoliberalism, Hall saw little reason to be optimistic about London’s future.

This has had consequences for the spaces where ‘everyday mixity’ can emerge. The warehouses and club spaces of Bankside, Paddington Basin and Kings Cross, where club multiculture was incubated, have been transformed into high-end residential, commercial and leisure zones, promising luxury living, innovation and, as the South China Morning Post put it in 2017, exceptional returns for Hong Kong investors.

In 2018 the London-based genre drill, a ‘dark and nihilistic’ adaption of Chicago rap made predominantly by black working-class youth from the housing estates of Brixton Hill, Tulse Hill and Kennington, became subject to a moral panic for its glorification of violent crime and drug dealing. In May 2018 YouTube removed thirty videos by London drill artists, at the urging of the Metropolitan Police, for their ‘incitement of gang violence’.

Before the moral panic around drill, London musicians had been making links between the rise of plutocratic money-laundered London and the rise of violence on the streets in ways politicians had failed to do. In ‘Hangman’, released in February 2018, the Streatham grime/hip hop artist Dave provided a sonic counterpoint, addressing knife crime and postcode wars—‘too many youts are dying and I’m sick of it’—over a heart-breaking piano riff and deep sub-bass. The recent jailing of his brother and the rise in stabbings—‘Snaps in a prison cell, bodies in a coffin’—led Dave to conclude that ‘London is cursed, this city’s got a problem’.

But there are rays of light. Though drill could be read as both a cry for help and a bitter warning of the consequences of urban racism, it is simultaneously building an audience far outside the confines of south London estates.

There is an analogy here with the story of grime, the London-born British rap genre which emerged from the estates of east London at the end of the 1990s, drawing on the reggae sound system, jungle and garage, but placing the MC—the rapper—at the centre. As journalist Dan Hancox shows in his definitive grime history, Inner City Pressure (2018), the genre’s restless inventiveness allowed it to build a global following and become an established pop genre, with Thornton Heath grime artist Stormzy in 2018 establishing a publishing imprint with Penguin, endowing scholarships for disadvantaged youth at Cambridge University and headlining at the Glastonbury Festival in 2019.

Grime and drill are, in many ways, distinct from the dance multicultures of rare groove, rave and jungle. They are not in a strict sense dance genres, but, as with reggae, garage and jungle, though most of grime’s producers are black, the grime audience, both in London and globally through the internet, is decidedly multi-cultural (there is even a passionate grime scene in Japan).

Alongside the rise of grime has come a renaissance of London jazz. Live performances by an array of new jazz acts have emerged in the city, offering a viable alternative to disc- based club culture. These are influenced by a range of American jazz styles from hard bop to spiritual jazz, by Nigerian Afrobeat and by the reintegration of jazz into American hip hop by LA artists like Flying Lotus, Thundercat, Kendrick Lamar and Kamasi Washington.

This new jazz scene has emerged in small venues like the Total Refreshment Centre in Stoke Newington (currently suspended), the free jazz jam Steam Down in a small bar in Deptford, and the Mau Mau Bar in Portobello Road and at established venues like the South Bank and the Roundhouse. This scene—which includes Ezra Collective, Sons of Kemet, Kokoroko, Binker and Moses and the Seed Ensemble—has been nurtured through a network of music schools, training programmes like the one run by the Tomorrow’s Warriors organisation and funding provided by the Arts Council and PRS foundation.

This jazz scene—unlike the white middle-class acid jazz scene of the early 1990s—is driven and supported by young black multicultural Londoners, with a far higher proportion of prominent young women—for instance tenor sax player Nubya Garcia, composer and bandleader Cassie Kinoshi, trumpeter Sheila Maurice-Grey and multi-instrumentalist and producer Emma-Jean Thackray.

Both jazz and new forms of rap like drill and Afroswing reflect the changing composition of multiculture in London. A shift in London’s black population since the 1980s (which saw a large influx of migrants from Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Congo and Somalia) has meant that black London is no longer majority Caribbean, and this has had an influence on the music being produced in the capital. Numerous jazz, grime and Afro-swing artists—Skepta, Dizzee Rascal, Lethal Bizzle, Donae’o, Sneakbo—hail from West African families, and the influence of the West African music they heard at home is placed in juxtaposition with the reggae, hip hop, rave and garage music of the city, producing distinctive new hybrids.

As I write these last lines, London, as viewed through its black music multicultures, seems to be looking in two directions at once. Drill is

In British society, Muslims have been prioritised as problematic: sexual predators, radical terrorists, social and spatial segregationists, not to mention chronic underachievers. There are a host of other markers through which Muslim identity is rehearsed as challenging, particularly through pre-existing narratives that seem to do little more than perpetuate notions of danger, difference and threat.

All of this may seem out of place in a book about cars. However, this is also a book about how we, as social beings, construct ourselves and others, at least in part, through our understandings of car culture, to pinpoint how identity is carried, presented and finessed by the car. And here, connections between the car and identity result in a need for us to make sense of what we encounter: an expensive car in a seemingly ‘deprived’ area may elicit the need for some form of logic to explain the car’s presence—the driver is a rich landlord, a visiting celebrity, a criminal. Once such imaginative but coherent impressions are unpicked, a more comprehensive, in-depth and grounded understanding of social situations is revealed.

This sociology includes not only the voices of research participants but also informal, acutely non-academic field notes, written over the span of the research. These are presented not as a means of somehow trying to demonstrate street credibility or some unresolved creative authorial ambition but to offer an unambiguous form of depth and insight that is not always present in sociological work. Being an insider researcher can result in the boundaries between the personal and the professional becoming porous; you are a researcher, but you are also one of those being researched. Acknowledging this too may have costs and implications, however:

It does bug me a little. I’m out there and talking to people about their cars and all that, trying to convince them that I am genuinely interested in them—and especially what they’ve got to say about cars. I might see someone, or a car, that looks interesting. Light goes on in my head and I’m now on—in recruiting mode. I’ll go up to them, offer a Salaam and then maybe say something to them about their car. It’s like I’m chatting them up, giving them compliments—this is probably how people who ‘groom’ operate. So now I’m a car groomer. Sometimes they even ask me what it’s like working at a university. Some of them even say ‘Ma sha Allah’ [God has willed it; an expression of appreciation/happiness], like they’re proud of me which I guess they might be—me being like them, but somehow breaking my way into a middle-class profession. I wish they didn’t claim me because now I’m a role model; now I’m a token. But you know what?

All that’s fine—it’s the price of doing business. Problem is, there always comes a point where I have to remind them that I am also researching and that I will be writing about this, possibly about what they’ve got to say. It does feel odd, forming these relationships in a natural and quite organic way, only for it all to be risked by a tape recorder. I know. I am being neurotic. If I was a social worker, I’d be calling myself reflective. (Field note, March 2016)

Most of this entry is probably based on a mild habit of being fixated about arguably minor aspects of research as process. However, within the extract, it’s clear that first, ethnography can become layered with complexity and impact on the researcher and participants. It may be that they see me, relatively speaking, as successful and that elicits a sense of ‘ethnic’, class or even local pride. Conversely, however, since minority ethnic academics are relatively rare, when they are present, regardless of their specialism, some can be seen as ‘responsible for race matters’. This is further reinforced because ethnography allows for the professional and the personal to merge comfortably, and at times, unnoticeably:

Seems I’m always on these days. Everything is data. Even when I’m at home, doing nothing ‘ethnographic’, along comes Top Gear and I start making notes about the cars that the presenters are fawning over: it’s always one or the other with that show—they start with ‘This is a piece of crap’ and then, usually Clarkson, growls something like ‘But it all makes sense when you press this button …’. And even when I’m on the road, on the way into work or back, usually rush hour, I see private plates, tinted glass, custom paint jobs, big exhausts, whatever. But also weirder stuff, things people do when in their cars: people picking their noses, or bouncing around in their seats while listening to music, putting on make up, arguing, laughing, daydreaming. People even cry in their cars. Sometimes, that little metal box seems like the

safest place on earth where you can do what you want, be who you want. How much of this stuff do I actually cover? I mean, where does this thing end? (Field note, September 2013)

Mediated and fictional cars are cultural reference points and become meaningful at the level of personal biography. I therefore make use of various reference points (film, television, popular music and childhood play) where the car is used to produce meaning and value, as well as in relation to advertising and commodity fetishism. I then explore how cars are used within hip-hop-oriented popular music and videos.

Filmic representations are important and were referenced frequently among participants. The following extract, while focused on a car that is probably less relevant to most personal histories, nevertheless holds some emotional detail that could apply to many of us:

The Batmobile in that first Batman film, the one with the Beetlejuice guy in it that was my first car crush if you like. I used to have dreams about that car. I must have been about ten when it came out. I watched that film, I don’t know, probably hundreds of times. It was a big deal back then but for me it was because of the car. I mean, it looked amazing, it looked like something else. (YK, 36, male, 23 July 2015)

This interview, conducted with a self-confessed car ‘fanatic’, was one of several in which childhood relationships with and understandings of cars featured as formative. YK illustrates how even fictional cars may help develop what become normative understandings of aesthetics, function and aspiration. This particular incarnation of the Batmobile was located in a dark, gothic and, albeit darkly and comically so, cinematic Gotham City. The Batmobile was spectacular, perhaps ‘magical’, and signified a range of meanings; loaded with gadgets, it was big, powerful and dark and looked ‘aggressive’, a matter that was probed further:

YK Some cars, they look really aggressive—don’t say they don’t, because they do. Audis, Fords, Vauxhalls, Jap cars—not even the sports version ones; a lot of cars, they look strong; just the way they’re designed. In the 1920s and 1930s, you had these great big sports cars—they weren’t aerodynamic, but they were ripped; like they had muscles, you know. But like modern cars, even ordinary cars, nowadays especially, they’ve become a bit more sharp in design, maybe because we want a car that looks strong.

YA So, and that’s what the Batmobile was about, then.

YK Well, I mean, if you’re Batman, then yeah. I mean, anything goes for that guy—he’s Bruce Wayne, bloody billionaire and all that.

YA Not everybody’s got money, though. Not everyone’s Bruce Wayne.

YK No one’s Bruce Wayne. You’re missing the point, Bro— when I watched that film, I knew it wasn’t real. When you’re a kid you think that you could make your car special like that and that’s what’d make you special. You could make it look how you wanted it to look.

YK talked about the toy cars of his childhood, most of which were designed to look powerful and exciting. As he grew older, he had more sophisticated toys, including remote-control stunt cars as well as one toy designed to withstand high-speed collisions.

LG It is ridiculous, if you think about it. Most people do this: they always change their cars because, because why? They don’t need to, do they? But they think buying a car, it’s an exciting thing to do and it’ll make them happy. Back when you were younger, I bet you didn’t change your car every three years.

YA Drove them until they died.

LG Because it was just a car, then. It’s more than a car, now. It’s you. But most people just fancy a change. It’s the done thing.

YA Sort of standard practice.

LG Standard practice now. And they don’t just go like-forlike. No, they’ll upgrade. It has to be something better as in comparison to what they’re driving now. Like start off with a standard A3, then jump to an S Line A3. Then S Line A3 to, I dunno, a Mercedes Benz, and then three years later, Mercedes to a newer Mercedes. It never ends, does it? (LG, 30, male, 17 February 2019)

Commodity fetishism, developed by Marx in Das Kapital

Publisher’s price £14.99

Save £1.80

Booklaunch price £13.19 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

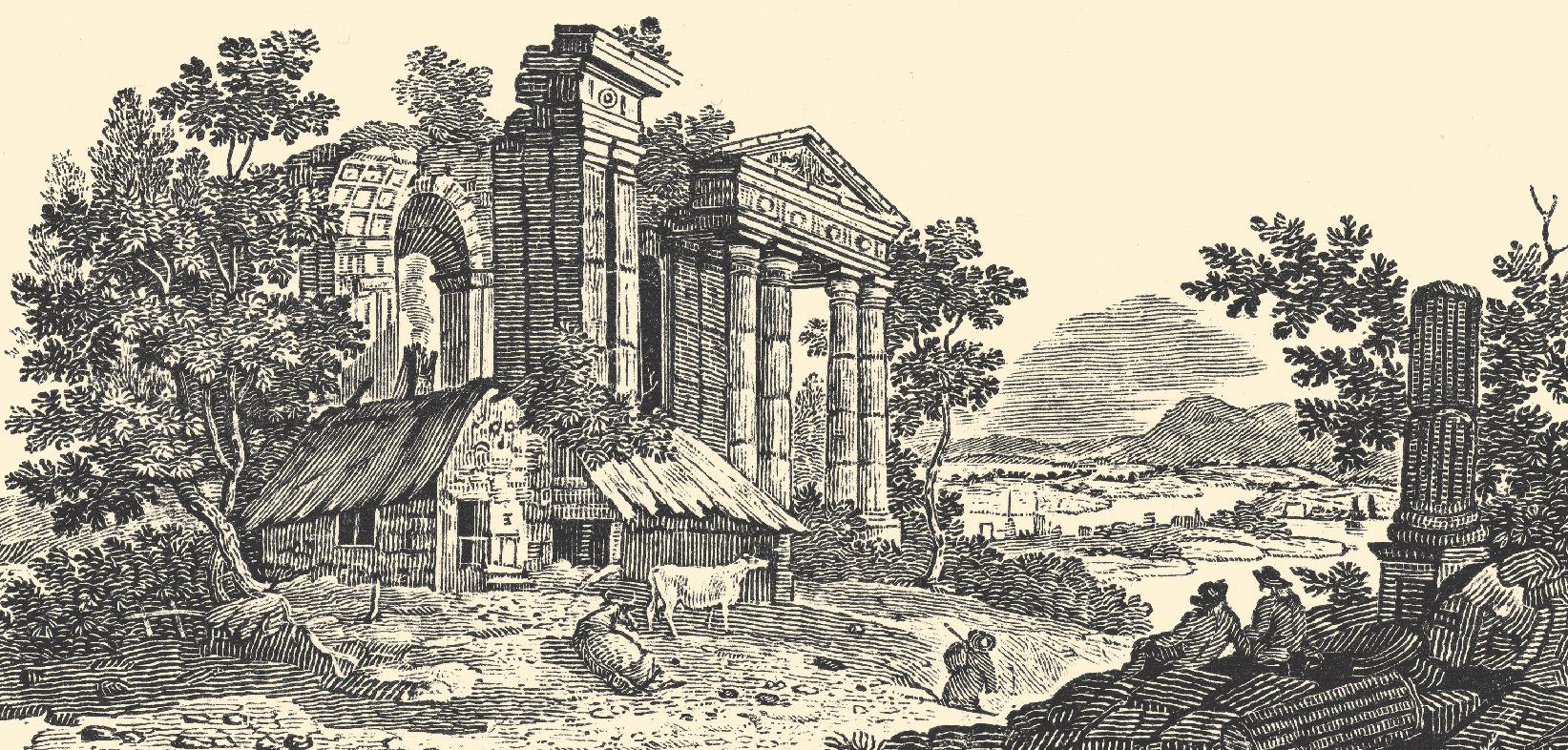

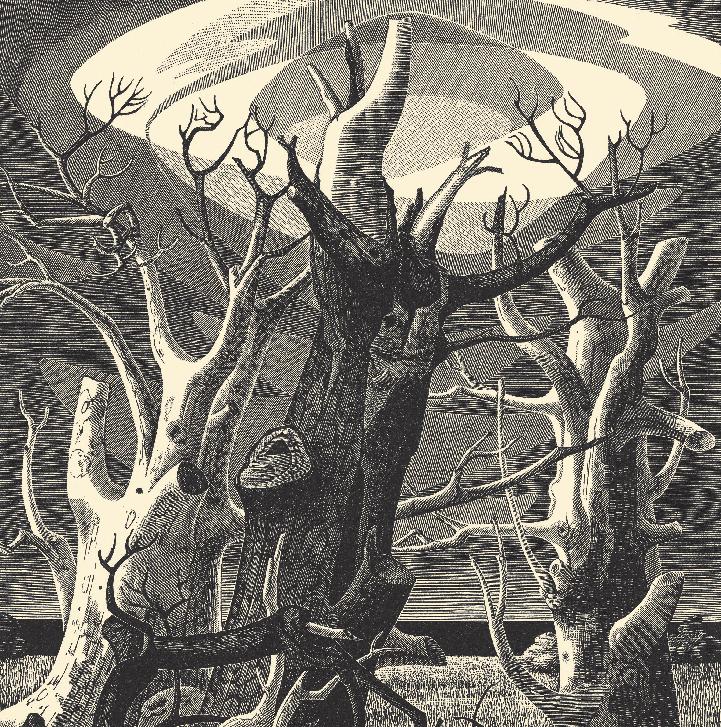

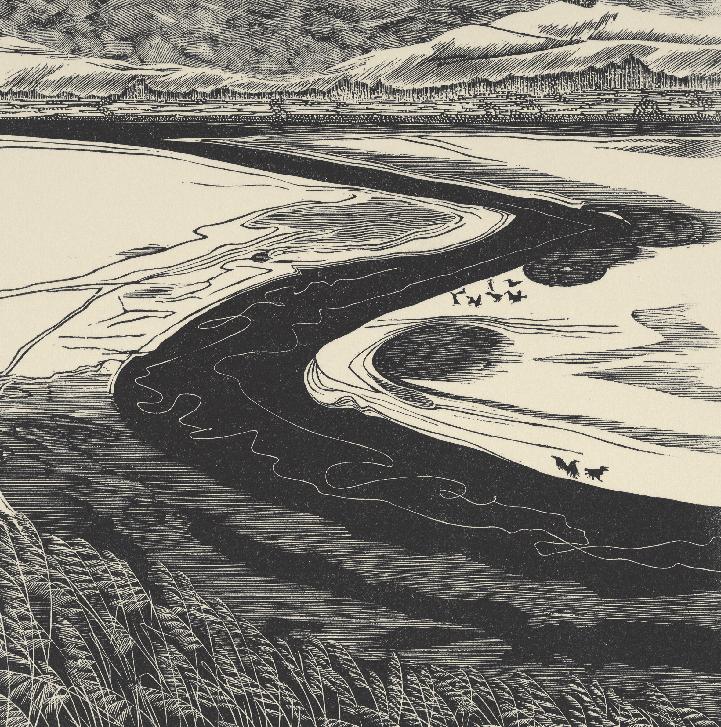

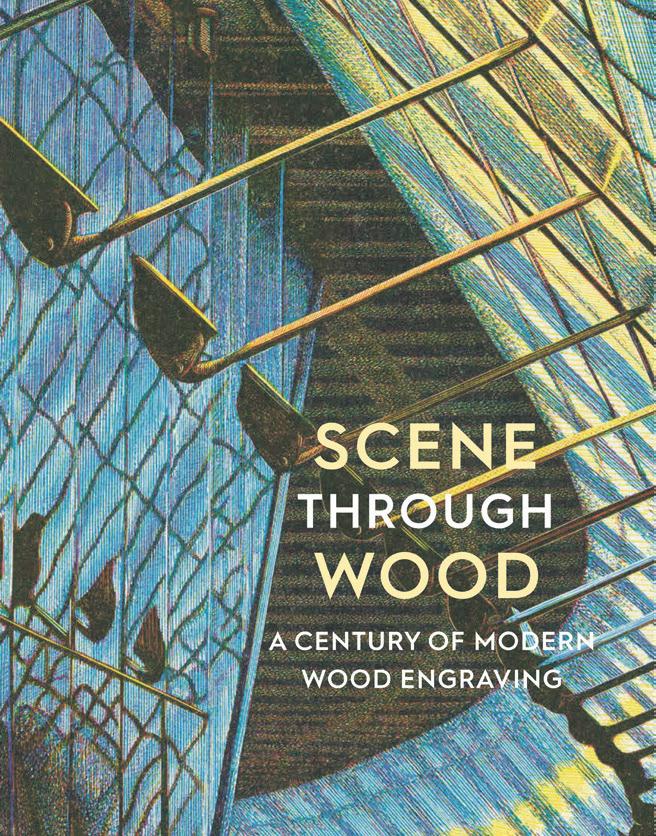

A century of