LAUNCH BOOK LAUNCH

Treaty

I go across London to meet you. It’s more than a year now

Since we parted. Where I pause on the railway bridge

There is a peculiar quiet, only one child shouting

From the back of a house, and a cold sun shining.

After a week of migraines, you are better you say, Doped and smiling, smelling of soap and tiredness.

The new sun is a rose rooted in Valium.

You tell me about your boyfriends, how silly they are.

I try to explain how it is now with my writing

But I do not speak of your pictures face to the wall. You draw your hair out in front of the fire

To dry it, already it glitters with silver.

You ask if it’s dry, I feel it, it’s like Hay in a summer wind, and when we go out together Past twenty-four sphinxes lining one side of the hill, Walking into the wind, we both feel weak, we are like ghosts Returning to a meal that went cold an age ago.

We eat wisely, we do not quarrel, for this is Ghost food we are eating, sunshine and smiles— Our smiles mixing together in sharp winter weather.

As you turn to leave me, stepping off from the pavement

Perhaps I’ll remember this day above all our others

As something withdrawn from time, like one card from the pack, This peculiar quiet, only one child shouting

From the back of a house, and a cold sun shining.

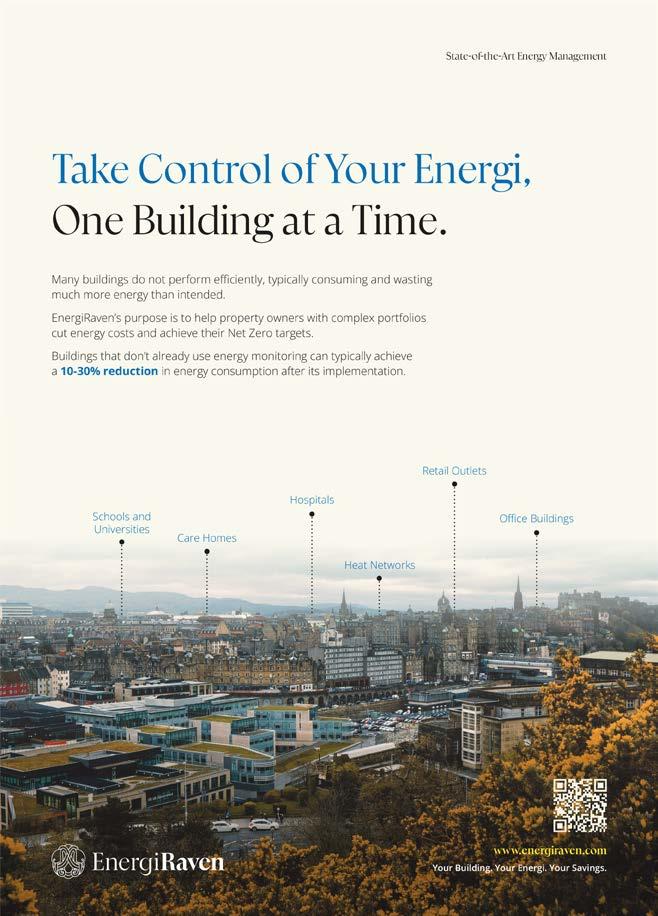

Simultaneously with these events in the UK, Germany’s leading bookshop chain, Weltbilt, declared insolvency for the second time in ten years, causing mayhem for book suppliers and putting vast num-

bers of publishing projects (including our own) on hold.

No doubt the five biggest publishers will have been able to ride out these

storms; smaller publishers, however, have been rocked by uncertainty, leading to an increased reluctance to advertise in smaller magazines such

as ours. It leaves us all having to tighten our belts and reappraise, and what we’re hoping is that the horror won’t prove as devastating as it seems to be

John Welch

JOHN WELCH COLLECTED

while it’s being lived through. We are, after all, an inventive lot. In the last couple of years, along with our regular offering of book extracts, Lingualia word puzzles, quizzes and challenging editorials, we have introduced author-led features which invite writers to explain why their book needed writing and in what way they have added to the existing canon.

We also set up the Architectural Book Awards scheme, to reward clarity of writing in a field that often seems to abhor it. (Yes, we should do the same for books in other fields too. Patience, patience.) Meanwhile, on the internet, we have given our website a facelift, with all our content being archived by two platforms that capture the look and feel of our print editions.

In a world where major publishers are part of an institutional culture that treats books as mere ‘products’ and readers as a ‘market’ to be exploited, we have dedicated ourselves instead to respecting the integrity of what we offer and those we offer it to.

And so we find ourselves weighing up our performance, and using this edition to try out fresh ideas, including one that takes us back to the classic days of Blackwood’s Magazine, with more substantial features than we have run hitherto. (For this reason, rather than putting other publishers’ titles in the firing line, we’ve focused on our own.)

Our new design moves away from print magazine conventions and embraces a podcast-inspired model. We emphasize a continuous, linear flow without interruptions, removing headings to encourage focus on the text itself. This change also allows for more detailed introductions.

Does it work for you? Do you like this new format with its fewer, longer excerpts? We value your feedback. Let us know if this change is as positive as we believe it to be.

And so to our new edition.

Just two months ago, the American Irish Historical Society, located opposite the Metropolitan Museum of Art on New York’s Fifth Avenue, staged an encounter between the Dublin-based activist, writer and media producer, Don Mullan, and the NYC-based international correspondent David Tereshchuk. Both men had survived the killings

of Bloody Sunday and together they reflected on their shared experience of how that still-not-fully explained massacre by British troops was treated by Britain at the time and how it should be regarded today.

On 30 January, 1972, soldiers in Derry, or Londonderry, opened fire on peaceful civil-rights protesters, killing thirteen and wounding a fourteenth who died some time later.

Tereshchuk, in his twenties, was covering the event as a reporter for ITV; Mullan, a fifteen-year-old schoolboy, was on the streets by chance.

The event began in what was widely agreed to be a “carnival atmosphere”; it ended with both being caught in a hail of bullets.

Years later, Mullan wrote a book in which he exposed the deeply flawed public inquiry headed by Lord Chief

Justice John Widgery that unjustly cleared the soldiers of wrongdoing and put the blame on the victims. Tereshchuk’s account of the same proceedings appears in his new book, A Question of Paternity, a dramatic extract from which ran in Issue 20 of Booklaunch during the summer.

Tereshchuk’s memory of covering Bloody Sunday and of his many other tours of duty as a TV journalist, including in Soviet Poland, Bangladesh and Mozambique, is an essential resource for any media student wanting to understand how broadcasting decisions are made on the fly, but it is intertwined with a more personal story: his lifelong quest to discover who his father was—a quest that his mother doggedly refused to discuss, that ran foul of the Catholic Church, that led to various genealogical wildgoose chases and that contributed to an existential crisis and a decades-long struggle with alcoholism.

PHOTO: DON MULLAN (LEFT) WITH ENVELOPEBOOKS AUTHOR DAVID TERESHCHUK

She would never talk about it. For decades my mother avoided the matter of how I came into being. She also remained unclear about most everything in our earliest life together. She expressed only the vaguest recollections overall. And I too ended up scarcely able to picture my own growing up, always peering back at it through some sort of hazy scrim.

But a disturbing story—utterly unvoiced at the start, never spoken of when I was a child, and then uttered only a very long time into my adulthood—was that I owed my existence to my mother’s being impregnated by a priest who raped her.

In my fifties my mother eventually told me that as a fifteen-year-old high school girl, she accompanied a friend to a Roman Catholic church service. Our family wasn’t Catholic. Very few families were, in our large village or small country town in the Scottish Borderland—and there was no Catholic church. We were nominally Anglican, though with only perfunctory observance. Our family might have sometimes attended the parish church, but I have no memory of it if we did. I do have a fuzzy sense of what might have been Sunday School, led a by a sweet young woman; I remember a tall man—of some awe to us kids,

but pleasant in manner—once coming in to address the children briefly, wearing a business suit and also what I’d very much later learn to call a clerical collar.

By contrast with us, my mother’s school-friend came from an observant Catholic family, Italian immigrants who ran the local ice-cream parlour. It was a place I’d come to love visiting as a child, with its soft, swirly ice cream, round marble-topped tables at chin-height and sugary drinks on tap with tongue-enticing Mediterranean names like Sarsaparilla. Behind the counter were several members of the Italian family, all buoyant and voluble with each other—so utterly different from our generally very quiet home. The Scottish word dour comes to mind.

My mother said she’d been curious to discover just how her friend’s mysterious faith was celebrated on Sundays. She also found the location the Catholics chose for what they called their ‘Mass’ to be intriguing. Not an actual church, like our familiar Anglican house of worship, an imposing village landmark on a nearby hill, but instead the obscurity of an ordinary room above the office of a local family doctor, another of the area’s few Catholics.

A visiting priest would come to conduct the mass, assigned from the sizable city some ten miles away, which

had several Catholic parishes.

This particular January Sunday when my mother went along with her friend, the presiding priest, Father Francis (as full a name as she could give me) evidently ‘took a liking’ to her. I’m not at all sure in what sense she meant that phrase. She said he offered to walk her home after the service, she accepted, and part-way there he raped her.

This account of my conception, learned so late into my life, naturally sur prised—no, thoroughly staggered—me. I had no reason to doubt her account and I didn’t cross-question her about it. Listening quietly and intently, I was anxious not to stop her unaccustomed, vehement flow—and I thought I’d get other chances later to go back over it with her. She was never to give any such chances. And then sixteen years later she died at the age of eighty-five. Since that one day of revelations I’ve searched in many places for ways to corroborate or check them out. But in essence I continued to have for the story of my conception only my mother’s own story to go by.

For the longest time I never told anyone else about my secretive beginnings, nor for that matter did I ever acknowledge to myself what it might have meant to me. The man who ‘fathered’ me—in one sense only—disappeared around the time of my birth, accord-

ing to my mother. He was—again, in my mother’s account—moved away by his Church superiors to avoid scandal. She said she told no one what had been done to her except for her mother—and that her mother felt it was a shameful event for the family. Silence evidently fell upon us all.

She was sent away to give birth—120 miles to the south, to her elder, married sister’s home in England’s industrial belt. The shame of her pregnancy had, she told me, brought two strong pressures onto her, which she fully resisted with her fifteen-year-old’s determination. One: to have me aborted (a crime at that time, of course, to follow the crime of my creation). Two: to have me adopted as soon as I was born. But once born, I was allowed into my grandmother’s house. Only, though, under terms and conditions. One was that my mother give up her schooling and get a job. She had been on track to go to college and would have been the first in our family to do so. My ever-determined and practical grandmother felt that one more mouth to feed—mine—was too much of a strain on the family budget.

Another condition was the thin veil of a cover-story invented for my sudden appearance. It seems ludicrous looking back, but according to my mother they tried passing me off as just another child in my grandmoth-

er’s large brood—already nine children, most of whom had grown up and moved away. The ruse took little or no account of the fact that my grandfather had died eight years before, and my grandmother was already entering her fifties.

I saw little of my mother in daylight during my early years. From the age of sixteen, she became our household’s only bread-winner. Early each day she left by bus to work as a clerk in one of the city’s booksellers. The household was firmly headed by my grandmother, whom along with everyone else in the home I called Mam, the Scottish version of Mom or Mum. I called my mother by her first name, Hilda— and she seemed to be my big sister. There were two uncles there, too, affable boys some years younger than my mother, who were playmates for me—big brothers to all intents and purposes.

As I got older, there must have come a time by when I’d learnt that my mother was indeed my mother—but I can’t remember any epiphany. A gradual realisation is much more likely. And I probably deduced it for myself; I don’t recall ever being out-loud told anything.

Like many children of unknown parentage, I would fantasise about my origins. Maybe a passing multi-millionaire, or maybe even a royal personage, had tarried long enough in our village to create me, in some fairy-tale relationship with my mother. But I’d always expel such notions abruptly, dismissive of what I saw as childish silliness. ‘That’s stupid,’ I’d say—and, in the phrasing of later generations, I would move on.

For a good slice of my life or, in truth, an undeniably bad slice, I was an active alcoholic. It’s a curious phrase, active alcoholic, invented by specialists in addiction recovery who want to distinguish between people who have the disease of alcoholism—and drink anyway—and those who manage to stop drinking. The oddity of ‘active’ as a word, plus some sense of the disaster lying in wait for me if I were ever to drink again, is captured memorably in a trenchant cartoon I keep pinned above my desk, taken from an otherwise rather dry healthcare journal. It shows a woman screaming at her male partner, who is splayed out unconscious on a sofa with empty bottles piled around and on top of him. ‘You call this being ACTIVE?’ she yells.

I suppose my long active phase began when I was in my early teens, when it might have passed for harmless recreation and rarely involved anything stronger than beer. Actually, that’s not true: I was in heaven whenever I managed to score some hard liquor at the age of fourteen. Alcohol-use deepened in my college years, dressed with a liberal sprinkling of marijuana

as well, and I still regarded it all as utterly innocuous—except, that is, when I crawled back at dawn into my dorm room, after a ‘traditional’ all-night May Day bout of drinking champagne, whisky and brandy—and helplessly vomited again and again for two hours or more, moaning continually, ‘I will never drink again.’ This was the first of countless times I would bewail my state with that same forlorn vow.

And did I keep my promise? Never, of course. And just as unstoppably, the cycle of drinking and being violently sick would repeat and repeat.

It’s a progressive illness, we are constantly reminded. And in young adulthood I entered a profession, journalism, where I had plenty of cover for it as it progressed. Heavy drinking was something of a rite of passage among colleagues rather than a cause for concern. But the degree to which it was steadily taking me over had to be hidden, and called for determined measures. It’s impossible now to say how many mornings, having awakened or come to with a clanging hangover somewhere far from home, I had to sneak in (I hoped unobtrusively) as the day’s first customer for the barbershop at Harrods’s flagship London store. I’d get a shampoo and a shave, before buying a change of shirt and heading into the TV studios where I worked. Trying to look nonchalant to the front-desk receptionist and security guards, I’d make straight for the dressing room where I kept a change of suit and other clothing. I always bought the extra shirt because I could never remember how many I had left stacked in the dressing-room drawer just for this purpose.

Despite the front I presented as a serious-minded interviewer on camera, there steadily mounted a wretched off-screen toll of bar-room brawls (the pretexts for which I have no memory of), drunk-driving offences (several times making me abjectly beg a favour and, once, hand over a cash bribe to local district reporters not to cover my appearance in court), and car-wrecks that involved massive damage to my own and to others’ vehicles. My physical frame was somehow preserved from serious injury but a pallid and eventually florid bloating of both face and body indicated the decay going on inside me. One internist, dramatically if perhaps imprecisely, declared my liver to be ‘beyond repair’. So did I stop? I didn’t. I couldn’t. The disease’s grip on me was tenacious and relentless.

My work—always the most important element in my life, I thought— was where the pressure on me to get a grip mounted most persuasively. Brian, one of a few friends I retained from college and who happened to work in the same business, which meant I might listen to him, once spoke a lot more forthrightly to me than I expected or wanted. Sometime in the mid-1980s he and I chanced to

EnvelopeBooks | ISBN 9781915-023155 | £18.95 | $25.00

meet the day after a TV broadcast I had made—a half-hour report devoted to mental health services, of all things— and he commented: ‘Wasn’t so bad. You didn’t slur your words too much on-air.’

It was one of those excruciating but eventually irrefutable critiques that my peers came to voice, a lot, about my drinking. It got to the point where the TV company’s chief executive had to call me into his office to deliver a damning indictment: ‘David, you are paid the highest fees of anyone in this building, second only to me, and we are not getting our money’s worth.’

The dull but inescapable fact about an alcoholic’s life is that it can be extraordinarily tedious to live and even more tedious, I believe, to narrate to others. Throughout my twenties and thirties I had daily arguments with myself—often more frequent than daily, sometimes minute-by-minute— over whether I could safely pick up a desperately craved glass or bottle, followed by my inevitable defeat and capitulation. And nightly, or ever-earlier

in the day, I would end up disappearing into unconsciousness or oblivion. That latter term is a euphemistic misnomer. It suggests I’m forgetting something—but it’s never forgotten; the overwhelming compulsion to drink immediately returns, with flatteningly repetitive regularity. There was above all the constant drumbeat of lies to myself that I could still handle the substance that was killing me, despite the growing evidence to the contrary.

It was the blunt professional truths voiced by co-workers that finally got my attention, in a way that all the other serious warning signs never did. I cannot say why. Maybe it was just time. I needed medical help to put the drink down, and extended in-patient treatment. But I still relapsed, many times over. I couldn’t stop drinking decisively but it became clear to me that my days of ‘activity’ were numbered, and mercifully they eventually were.

The disease took twenty-seven years to run its course. continued in the book

How far would you go to live in freedom––the freedom to think, write and speak as you please?

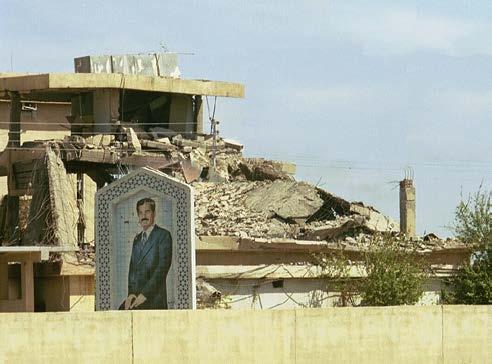

We in the West think too little about that question; the Iraqi editor, poet and teacher Ahmad Shawkat, worried about it every day. For each moment of his adult life he sought freedom and when he finally found it, in the wake of the US overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, he was killed.

Shawkat was a Kurd, born and raised in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul in 1951. Like the brightest of the post-colonial generation in the Arab world, he trained in science and was expected to help build his new nation. He became a lecturer in anatomy at Mosul University’s medical school but was also a poet and political thinker. As Iraq sank into dictatorship, his political activities led to his imprisonment and torture,

not once but on four occasions. He went into internal exile in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdish safe area created after the First Gulf War.

By chance, the night that Gulf War II was about to start, Shawkat met National Public Radio’s reporter Michael Goldfarb, who hired him to be his translator and fixer. In the intense circumstances of war, the two men became close friends.

With Saddam removed from power, Shawkat returned to Mosul and embraced the possibilities of freedom. He founded a weekly journal of politics and culture which he called Billatijah, meaning ‘no direction’, because no one told him what to write. He provided trenchant analysis of the political situation in the city and the country. And he openly criticised his countrymen for failing to embrace the gift of democracy, with all its liberties and responsibilities.

He managed to get eleven issues of his magazine out. Then he was shot in the back. His murderer is still unknown.

Goldfarb, who had already made a radio documentary about Shawkat, immediately wrote a book about him, now extolled by other leading investigative journalists including Carl Bernstein who, with his Washington Post colleague Bob Woodward, had famously revealed the details of the Watergate break-in, earning a Pulitzer Prize for their paper in 1973.

Goldfarb’s book, The Martyrdom of Ahmad Shawkat, is a mix of memoir, journalism and deeply researched history. It tells the story of the war to overthrow Saddam as it happened in the North, shows how Shawkat’s life was bound up with Iraqi politics, and outlines his daughter’s search for justice in the chaos that the Bush administration’s invasion unleashed.

The war started bang on schedule. From the moment it was first mooted in leaks to The New York Times in July 2002 you could have predicted it would start around the end of February or middle of March 2003. After all, there was the precedent of the first Gulf War in 1990–91.

As happened then, there would have to be diplomatic shadow plays at the United Nations to cover the time necessary to ship troops to the region. Emissaries from the international community’s organizations and self-appointed peacemakers from Britain’s left would go to meet Saddam Hussein and treat with him. Then, when all the troops were in place, there would be a collective inhalation of breath and silence on earth for about the space of forty-eight hours. And in that time the final, predictable actions would occur. The United States would order Saddam Hussein to get out of Iraq. The dictator would refuse. And the Kurds would take to the mountains.

Despite the establishment of a Kurdish safe area in northern Iraq after their failed uprising at the end of the 1991 Gulf War, very few Kurds felt that they would be protected from Saddam once this conflict began in earnest. As the deadline for the dictator to leave the country approached and the final countdown to war began, the Kurds of the northern city of Erbil loaded up their cars and headed for the mountains. Situated on the plain of the Fertile Crescent, with a division of the Iraqi Army deployed only a twenty-five-minute drive away, Erbil, with its population of more than half a million, was the most exposed large city in Kurdistan. With the expertise learned over decades of dodging Saddam and the Kurds’ own occasional bouts of infighting, the cars and ancient flatbed trucks were packed with necessary household possessions, the kids finding places to sit where they could. Then the vehicles headed up towards the mountains, suspensions strained to breaking point, undercarriages scraping along the bottoms of the switchback mountain roads.

The night before the war started, Ahmad Shawkat (photo, above) was seated in the Erbil Tower Hotel at the foot of the city’s Citadel. Most of his neighbours had fled, but Ahmad stayed in town. Like most Erbilians who could string three sentences of English together—and he could do much better than that—Ahmad was hoping to work as a translator for one of the dozens of Western reporters who had come to the Kurdish safe area of northern Iraq to cover the war. He had had a bit of work during the few months leading up to the start of the conflict but nothing proved steady. Reporters come. In the middle of the

night they get a phone call from their editors. Reporters go. Now it was getting late to hook up with someone. Anxiety shrouded him. At home he had a wife and six children, but he was providing nothing for them, and as war approached he saw his opportunity for work slipping away. He had spent most of the day moping about the house until Roaa, his oldest daughter still living at home, urged him to go to the Erbil Tower one more time. He dragged himself from the house and went to the hotel and counted out more of his life passing away. Sitting quietly. Waiting. Smoking. Watching but not really paying attention to a Fox News broadcast playing on an ancient large-screen TV in the lobby.

Asteady rain was falling in Erbil the day before the war started. Rain on the plain meant snow in the mountains. At the Iranian border, spring blizzards blew through the mountain passes, dropping weighty, wet snow on the trickle of late-arriving journalists heading down to Erbil through Iran. The border crossing at Hajj Umran is in a mountain pass almost a mile above sea level. As the road slid down from the pass, the snow turned to rain, and I could see the steady stream of heavily laden cars heading to the mountain villages or just pulling off to the side of the road, their occupants setting up camp in the mud. Men were putting up plastic sheeting for shelter, desperately grabbing at loose corners as sheets flapped in the wind. Women and girls in soggy burnt-orange and crimson dresses were down by fast-running streams drawing water for their families. Occasionally they

looked up into the car headlights rolling by, dark hollows around their eyes and pinpoints of white in their pupils. Their faces registered in my brain with the surreal clarity imparted by sleep deprivation. To get to Kurdistan before the war started I had been traveling for a day-and-a-half without sleep. That was on top of the adrenaline-laced, sleep-deprived last few days I had spent in London getting myself ready, sweating out my Iranian visa—by then the only way into Iraq was to cross over at the Iranian border—packing, checking and double-checking my recording equipment and, finally, taking delivery of my body armour, which arrived just a few hours before I was due to depart on Monday, March 17. It was a good bet the war would start on Thursday. And once it started, the Iranians might also close their border with Iraq.

Tuesday night I flew hundreds of miles farther east than I needed to, to Tehran. Then, in the morning, I doubled back by air northwest to Orumiyeh, up in the Iranian mountains, then traveled by taxi due south to the border with Iraq. In Tehran, I had been kept waiting through the small hours of the morning while the local authorities fingerprinted me, a retaliatory indignity for the mass arrest of hundreds of Iranian men in Los Angeles the previous summer. Then, at the border, I was kept waiting in my car while a blizzard rolled in and one of Iran’s local tyrants decided whether to acknowledge Tehran’s authority over him. A fax from the government’s Ministry of Islamic Guidance and Culture, giving me permission to go into Iraq, was on the desk in front of him. After a few freezing hours, it became clear what

was going on. A hundred-dollar bill opened the gates to Iraq for me. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) had handled my travel arrangements. Over the years the KDP, one of two main political groupings in the Kurdish north of Iraq, had put together a very effective media machine, facilitating journalist access to their hemmed-in, semi-autonomous entity. On the Iraq side of the border, cars were provided to get us to Erbil. I piled my gear into a Mercedes and headed down the mountain. As the car flashed past the Kurdish girls, their raven hair washed out from under their head scarves by the steady rain, the tension inside me began to ease. I’d made it. I was in. I didn’t even have to worry about finding a hotel. The KDP had booked me into a place with the magical name Dim Dim. “You will like it. It’s a five-star hotel,” their moustached representative at the border had told me. A five-star hotel sounded good, if unlikely. But at least I knew for certain I had a bed waiting. The war could begin now. All I needed to do was find a translator, though I figured that could wait until the next day. Now I needed rest. By the time our little convoy of late arrivals got to Erbil, it was already evening. The Dim Dim was not quite as advertised, but by local standards it was quite grand. On my previous visit to Kurdistan, in the summer of 1996, the hotel I’d stayed in was so foul, I’d ended up sleeping on the roof under the stars. But the Dim Dim was reasonably well maintained. Its rooms were a decent size, and the bathrooms had sit-down toilets and a plentiful, if slow-arriving, supply of hot water.

The lobby of the Dim Dim was covered in marble and it was full of men.

The lobby of the Dim Dim was always full of men: translators, drivers, bodyguards. In Kurdistan men are rarely at home. Home is a foreign, feminine country from which men flee each morning, return to briefly in the midday for a meal and a nap, and then run away from again. They return only when there is no longer an excuse to stay away. There would be plenty of translators to choose from in the morning.

In the morning I worked my way around the lobby and quickly figured out there was no one suitable. Most of the people in Erbil who spoke English reasonably well had already been hired. But I needed more than reasonably good translation anyway. My assignment for the public radio program Inside Out was to follow the war through an Iraqi’s eyes. I had come up with the fanciful idea of finding someone who had suffered under Saddam’s regime, documenting their liberation, then turning their experience into an hour-long program ready to air on radio within a month. All I needed to do was find a willing subject. That would be my translator’s first task. He or she would have to know Erbil very well to help me find this person. Then we could proceed to the linguistic skill department. What I needed from my translator, aside from grammatically proficient English, was detailed accuracy. For a short daily news report, summary translations are okay. So long as the translator accurately and quickly renders the basic facts—what happened, when, how many people were killed, how many people fled you have the information to fill up three minutes of airtime. But when a reporter tries to take people deep inside someone else’s war-torn world, to keep listeners attentive the journalist has to offer clear details of what’s being said.

For example, I interviewed a Muslim peasant woman in eastern Bosnia who was returning to her homestead five years after the conflict there ended. The last time she was in that place Serbs butchered her husband in front of her. The old woman was telling me the most intimate, heartrending details of her tragedy. A translator’s natural tendency is to mediate and retell the story in the third person: “She says the Serbs destroyed her life.” What I needed to hear was the direct, first-person story “The Serbs came and destroyed my life”—otherwise the tape would not be usable.

Then a broadcaster needs the details. Conversation flows more freely when a reporter picks up on the detail of what’s being said. The interviewee recognises that the journalist really cares about what he or she is saying, and is inclined to open up even more. But to get all the details the translator needs to have an impeccable sense of timing. The translator has to know

when and how to stop someone in midflow to translate what has been said already and not cause the interviewee to lose his or her train of thought.

I also look for someone who won’t edit comments that he or she thinks reflects unfavourably on their country. In the Arab world this is a particular problem. Arabic speech is characterised by magnificent, allusive rhetoric. Expressions of criticism, anger, or hatred are never simple and direct, and they flow in torrents. If someone is angry about an American policy, the way in which that is expressed can sound offensive if translated literally, so a translator will tend to smooth the anti-Americanism out.

Then there is anti-Semitism. People in Arab countries often speak to strangers about Jews in the same way many Whites spoke to strangers about Blacks in pre-civil rights Mississippi. There is an implicit assumption that you, too, know they are an inferior, barely human group who really shouldn’t be sharing space on the planet with you. Most potential translators in the Arab world are aware of the sensitivities of American reporters to such blatant anti-Semitism, and many will try to tone it down. But that takes a reporter further from the truth of what an interviewee actually believes. Usually, at some point in my reporting trips to the Middle East, the subject of the Zionist entity—many Muslims will not say the name Israel, since that would imply that the state has a right to exist—comes up, and I will have to tell my translator to translate fully what is being said. I have to assure the translator that, as a Jew, hearing people express their anti-Semitism in an unguarded way is very use-

ful. Bigotry is a subset of the category stupidity. It helps me gauge someone’s intelligence.

I hear a lot of this hatred. Most of the ordinary people I talk to in the streets do not recognise me as a Jew. My looks don’t conform to their stereotype. I don’t have a beard nor do I wear a yarmulke. My name, which would cue most Americans or Europeans to the fact that I am Jewish, doesn’t register that way either. The Arabic custom in naming is simply to give a child a single name. Then add on the name of the father, possibly grandfather, and perhaps an indication of tribe or village. So when I introduce myself as Michael Goldfarb, people in the Arab street hear my name as Michael. I am called, politely, Mr. Michael instead of Mr. Goldfarb. Michael has a generic European sound to it. My translator in Jordan explained that most people in the Arab street think a Jewish name sounds like David Ben-Gurion or Binyamin Netanyahu or Ariel Sharon Israeli names.

I have still more requirements of a translator. I need someone at ease with all strata of his society. This is not always possible because in many places the person who speaks English to the standard I require comes from the well-educated upper classes and may not have a natural ability to talk to peasants or the working classes, the people who usually suffer most when the world is in upheaval.

Beyond linguistic accuracy I need a good companion. We’re going to be together in a car for hours every day for weeks at a time traveling to wherever the news is. You need to be able to joke, talk about your families, and discuss politics without getting into ar-

guments. I also need to be certain that the translator has a good work ethic. The harsh necessity of deadline overrides everything, even having lunch. Finally, a translator needs courage, because in a conflict reporters have to get as close as possible to the fighting. We are required to see as much of it as we can ourselves, to talk to combatants and civilians on the front line, to be the firsthand source of information. If your translator isn’t willing to go to the closest vantage point, you won’t get the story.

It is almost impossible to find someone who meets all these criteria. It’s very hard to meet someone who fits most of them. It is often a matter of luck whether a reporter scores a good one. When you are stuck with a bad one, the results can be painfully hilarious. During the war in Afghanistan to overthrow the Taliban, I was in Iran. My translator turned out to be an alcoholic, a neat trick in a country where booze is banned. It took me a while to figure out that he was a drunk. His breath certainly smelled of alcohol. And I noticed that sometimes people we interviewed in the street pulled back from him. He also hit on women we interviewed. I chalked it all up to rudeness and an embarrassing lack of social grace, until one morning, in the holy city of Mashhad, I walked into his hotel room and found him chugging back industrial-strength vodka from a can. It was 10 a.m. “To take the edge off,” he explained when I confronted him about it.

In Egypt I worked with a son of the military upper classes. He had competed for his country in international martial arts competitions. One day, crawling through Cairo traffic en route

to interview the head of the Muslim Brotherhood, a bicyclist who was from the lower orders of society bumped his car. My translator leaped out and launched a karate assault on him. By the time the police arrived and the fracas had ended, we were an hour late for the interview.

But when a reporter finds a good translator, it is a beautiful thing. You can feel the metaphorical walls separating reporter from interviewee being broken down. A good translator bridges two separate realities in the most extreme of circumstances. Sometimes you can actually see an interviewee’s pupils widen in surprise that a foreigner seems to understand their culture, their particular circumstances. Sometimes a little black humor of mine, accurately translated, brings out a smile. From that smile, you are invited to probe deeper. The only way these moments can happen is because your translator is giving you a quick, accurate translation and sending back your English with equal speed, and has established rapport and trust with the interviewee.

The young men filling the lobby of the Dim Dim were doing what young men throughout the Muslim Middle East do: sitting, talking, smoking, and drinking tea. I worked my away around the few still available for hire. They spoke English with varying degrees of precision. None met my minimum standard. I visited a couple of other hotels around the city, but the situation was the same.

Now I was getting a little nervous. I still hadn’t found anyone suitable, and it seemed likely the war would begin sometime in the night. As evening brought the conflict even closer, I decided to visit the BBC office at the Erbil Tower Hotel to see if they had the name of someone I might hire. The Erbil Tower had been turned into a fortress with a perimeter of roadblocks circling it. A couple of burly Kurds with Kalashnikovs manned checkpoints. On one of the upper floors the windows were filled with sandbags. An observer would have thought that an important Kurdish politician was headquartered there. But it was just Fox News’s team taking no chances should Saddam single it out for attack. The paramilitary presence kept people away. The lobby of the place was nowhere near as full as at the Dim Dim. The half-dozen or so well-fed men who were hanging around watching Fox on a large-screen TV looked like bodyguards rather than degree holders in English literature. At the front desk I asked for the BBC office, and a few minutes later a young Kurdish woman came downstairs. I introduced myself and explained I was looking for a translator. She pointed to a small, quiet, middle-aged man I hadn’t seen in this lobby full of bruisers. “He is a very good man.” From the way she said good I couldn’t tell if she meant “good for the job” or the deeper sense of good as in

a morally correct person, reliable in a pinch. “He is the father of my friend,” she added, which made me think it was probably the latter.

She took me over. He got up and with exaggerated courtesy shook my hand and made a little bow, as if we were meeting at an academic conference. He introduced himself: “Ahmad Shawkat.” I told him my name, and we sat down. There was a little awkward silence. A bit of sizing-up began. He was a slight fellow, thinning hair going gray, and did not have a mustache, which in this part of the world was most unusual. His voice when answering simple questions about his translating experience was very quiet—not halting, but not confident either. My initial impression was this just would not work. Ahmad seemed a bit shy; more important, he was too old. At first glance he looked to be in his late fifties, maybe even sixty. Age mattered to me. If we came under fire and needed to run or were among a crowd of people that turned into a mob, I didn’t want to worry that my translator was physically incapable of running away with me or, worse yet, was going to have a heart attack when the pressure was on. The other thing about hiring an older person is what any director of human resources will say: people get set in their ways and are very difficult to train when they get past a certain age. Then there was a corollary of the Groucho Marx axiom about not joining clubs that will admit you: This guy was willing to work with me, but if he was any good, why was he still available?

In the Middle East, good manners require that two men discussing business go through a period of small talk before getting down to the matter at hand. I was in a hurry, however, and went straight to the formalities: Had he worked for Western journalists? How well did he know the country? The local political leadership? Did he speak Arabic as well as Kurdish? He gave brief, satisfactory answers. Then he volunteered the fact that he wasn’t actually from Erbil. He was from Mosul, over in Saddam regime territory. I asked if he was Kurdish. “Of course,” he replied. “Mosul is a very mixed city.” I asked him how old he was. There was a pause while he calculated what the boundaries of plausibility were. I know because, being past fifty myself, I’ve taken that pause when asked the same question. “Forty-five,” was his answer. A wholly implausible figure. Before I could say anything, Ahmad changed the subject.

“Do you know William Faulkner?”

“Well, not personally. But of course I know his writing.”

“I love Faulkner. The Compson family. I love The Sound and the Fury. I have read it many times. I love it, how he writes from inside the mind of the boy who is mentally ill.”

I nodded. “Benjy. One of my favourite sentences in the English language

is ‘Firelight was still the same bright shape of sleep.’”

“Yes. He is a very Arab writer.”

“I’m not so sure about that.”

“No, really. We like him very much.”

Then he added, “I like the sentence ‘They endured.’”

Now, this was not a conversation I expected to be having on the eve of war in Iraq. But I hadn’t discussed or thought about Faulkner in a long time and I went along for the ride. We spent a few minutes trading Faulkner trivia: two middle-aged men competing like the smartest kids in the class about who knew more about a favorite author. Then he said, “I can see you are well cultured.” It was an unusual phrase, one that required a bit of consideration; it seemed that meant I had met his requirements. He asked, “You understand that you cannot write about Iraq without knowing about the people and the history also?” I nodded. “I know these things very well. I will work with you and tell you about

them. But you must agree that we stay together until the war is over.”

It was an extraordinary demand. Still, it’s not every day you meet someone in a war zone who speaks English as idiosyncratically as Faulkner wrote it. Ahmad seemed unlikely to meet my first linguistic criterion for a translator: simple clarity. But on the other hand, he would certainly meet my last: on a tedious three-hour drive through the mountains we probably wouldn’t lack for conversation. So I found myself agreeing to his demand that we stick together, and decided to hire him. Business finished, I said I was going back to the Dim Dim. I was tired and wanted to rest. But Ahmad decided for us that my education would begin immediately. He dragged me up the steep slope leading to Erbil’s Citadel. By going up the hill we were going back to the beginning of civilization.

“They say this is the oldest continuously inhabited settlement on the face of the Earth,” Ahmad explained. “Since 5000 B.C., maybe 6000 B.C.,

people gathered in this place. The Assyrian empire, the first empire on earth, was founded not far from here. But even before that there was a settlement here.” Each millennium had added layers to the Citadel. The walls now towered nearly 105 feet above the town. At the top of the slope, near the gate into the Citadel, a bonfire was burning. It was the start of Narooz, a festival that goes back to the founding of the Zoroastrian religion sometime in the first millenium before Christ and, like the origins of the Citadel itself; probably beyond that in time. Fire is critical to worship among the Zoroastrians. Natural fire, not the kind made by striking flints to get a spark, is a unique feature of this part of the world. Not far from Erbil, fire comes up out of the ground, great pools of it.

Ahmad began a little lecture. “Oil seeps out of the ground in this area. Sometimes it catches fire. There are many fire-worshipping cults. There is a place near Kirkuk called Baba Gurgur. … In ancient times women went there who could not have children. They bathed in the oil and became pregnant.”

Fire and oil, oil and fire: the foundation of the world of men. As it is now, was then, and evermore shall be. Normally, on the eve of Narooz, Erbil would have been full of people dancing around bonfires, but on this night, with war soon to begin, only a small group of fellows was hanging around this solitary fire at the entrance to the Citadel. A crew from Syrian television drove up, and the Kurds began a desultory performance of a traditional dance for the camera. I recorded a bit

Wof the singing. We watched for a while longer and then walked through the darkened complex.

Despite its grand name and the pride with which Erbilians speak about it, the Citadel is a wreck. Layer upon layer of human civilisation has risen for eight thousand years to a topographical high point, but inside the walls development seems to have stopped a couple of millennia past. The interior was a mud-hut peasant village, the houses crumbling away, its higgledy-piggledy pathways unpaved. A single lightbulb illuminated a front room somewhere off to our left. It was the only sign of human life in the little village inside the wall. The residents had fled to the mountains, but their animals—dogs, cats, sheep, and chickens—wandered underfoot as we walked carefully through the darkness, talking about this and that.

Although the language Ahmad and I used was formal, there was an odd familiarity in our conversation. A couple of bookish men talking a bit about authors and local history, the subjects intellectuals all over the world use to feel out new acquaintances. But both of us were so advanced into middle age that we didn’t express any surprise at having this conversation while wandering through an empty city on the eve of a war. It was a simple pleasure not worth remarking on.

We moved from small talk to getting-to-know-you talk. We spoke of children. He asked me if I had any. “No.” It’s a painful subject for me, so I quickly shifted the question back to him. Ahmad was typically fecund in this area: he had eight; six children

hen white writers portray historically oppressed groups, they risk perpetuating stereotypes and other harmful misrepresentations. It is legitimate to worry about this. Cultural appropriation can trivialise and there is always the risk of treating the marginalised as ‘exotic’.

One cannot, however, require writers to avoid racially sensitive topics, any more than one can tell theatre directors who they can cast: that way lies apartheid. Whatever else it is, writing is also an expression of freedom, and so one looks for examples of where cross-racial writing has been carried out responsibly, with nuance and accuracy, to ensure that marginalised voices are heard and respected on their own terms.

Marguerite Poland is a celebrat-

were living with him in a house not far from the Citadel in an “old quarter, very intellectual”. He had two married daughters still in Mosul.

“Why did you leave Mosul?” I asked. “Politics?”

“Yes. Things I wrote. I have been arrested many times.”

“Tortured?”

“Of course. When I released, I came here.”

As we wandered through the ancient walls we later learned that American jets were striking “a target of opportunity” in Baghdad. This attempt to take out Saddam on March 19, 2003, would fail, and from that moment on a full-scale invasion was inevitable. We walked down a steep flight of stairs on the other side of the Citadel across from the shuttered-up bazaar. The empty city had lost its background din; a Kalashnikov fired for fun several miles away could be heard as clearly as if it had been fired around the corner. The thunking of an old taxi’s engine caught our ears long before we saw it. We hailed the cab and jumped in. Erbil’s main streets are laid out in circles around the Citadel. We swung around the great mound, and just by a dilapidated office building Ahmad had the cab stop.

He pointed at the building. “Can you remember this place ?” “Yes.”

“This is my street,” he said, pointing down a narrow, darkened road. “If anything happens you can come to my house and you will be safe.” It was a polite thing to say, but if Saddam decided to launch a chemical or biological attack on Erbil, there really wasn’t

ed white South African author admired for her deep understanding of her country’s cultural history. Born in 1950, she has a background in anthropology and literature, frequently engaging with the complexities of race relations and the deep scars left by colonialism. In her fiction and non-fiction, she has contributed extensively to the preservation and understanding of African oral traditions, languages and folklore. She also has a particular interest in Church history, with which she has family connections.

Poland’s novel A Sin of Omission is set in the 1870s in South Africa and is based on real historical events. The protagonist, Stephen Mzamane, is a fictional reworking of Stephen Mtutuko Mnyakama, a young Xhosa man sent to England to train as an

much we would be able to do about it. As Ahmad was getting out of the car, I realised I didn’t have his phone number. I grabbed his arm and asked him for it. He took out his business card and handed it to me. There were three email addresses. I looked at him quizzically. “These first two email addresses belong to my daughter. This one is mine,” he explained.

“Al-Fatih 51,” I read out loud.

“Al-Fatih means ‘the leader,’” he said. “It was my name in underground movement.”

Interesting, I thought to myself, then I asked him where his phone number was.

He confessed he didn’t have one. He wrote down a number and explained it was not his own phone. It was the number of his neighbor, and if I needed him for anything, anything at all, I was to call there and his neighbor would find him. If I had known that he didn’t have a phone, I might not have hired him, but now it was too late. Besides, I had enjoyed our conversation. I already liked the guy.

He got out and the cab took me on to the Dim Dim. I kept thinking about something he said as we walked through the Citadel.

“When the U.S. gets rid of this bloody Saddam, I am going back to Mosul.”

Mosul was just sixty miles away. There were two rivers, one ridge and a single division of the Iraqi Army between Ahmad and home. It didn’t seem like an impossible dream. I thought it might be worth following him home.

continued in the book

Anglican priest but betrayed by the Church on his return.

Poland wrote A Sin of Omission to shed light on how black converts to Christianity were dislocated from their African identities while being exposed to the hypocrisy of a Church that failed to live by the values it presumed to teach. The resulting novel examines the tragedy of a good man held back because of his race and alienated from his own people by the Christian beliefs he had internalised.

The book has been enthusiastically received, winning South Africa’s Sunday Times CNA Literary Awards Book of the Year Prize, getting shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and being longlisted for the Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize for evocative travel writing.

Usually, when he rode from homestead to homestead evangelising, Stephen sang hymns. He did not sing today. He wondered if he would ever raise his voice in song again or preach with conviction. He simply gazed across the arc of the horse’s neck as the hills seemed to dip and stumble to its gait.

If belief was fragile and his hymns could give no comfort, he knew—he trusted absolutely—that Albert would be waiting for him. Albert with his long thin legs, his jaunty beard, his beaming little spectacles, his shortcropped sandy hair. At the Missionary College in Canterbury, even when he had chivvied Stephen, he had never been impatient, only rolled his eyes and laughed at Stephen’s dawdling. ‘Come on, old chap! You have no sense of time at all!’

And Stephen would shrug goodnaturedly. What was the use of rushing?

‘The teashop closes at five. The bell will go before we’re done and we’ll be late.’ Ah yes, the bell!

But time was not the only constraint in visiting the teashop. Stephen did not have the money and he could not always allow Albert to pay.

‘Bother the Bishop!’ Albert would say if Stephen shook his head at every invitation. ‘After all, you’re not earning fees to teach me your language and I’m

hungry! So we’ll have two Welsh cakes and bring a penny bun back with us. That’s only fair. Come along.’

No, Albert would not let him down.

Even with his cheerful innocence about the world, he had a sense of duty and a touching loyalty on which Stephen had always depended. How many times Albert had saved him from awkward moments in the drawing rooms of Canterbury, or shown him unobtrusively the way to hold his knife, to greet a lady, to ignore a slight. If he could not share in the gravity of Stephen’s burden now, Stephen could count on his kindliness and tact. Stephen knew he would help him in any way he could—with food, a bed, a horse.

And prayers.

When Albert prayed, he would always close his eyes quite tightly, raise his chin and chat confidingly with God—so different from the Warden of the Missionary College, Dr Bailey, or Mfundisi Basil Rutherford, intoning through their noses, alert to the sonorous sound of their own voices. So different from Stephen’s own silent, apprehensive reverence. Albert did not have the gravity of a man in Holy Orders. He was more like a child kneeling at his bedside, looking up into his father’s face before the candle was blown out and loving hands tucked him in between the sheets.

Once they had prayed, Stephen

knew Albert would suggest a pot of tea and then divert him with memories of Canterbury—japes at the tutors; jokes in the dining hall; waylaying the Superintendent of Students or old Blunsom, the porter, with outrageous requests—and laugh at how the Warden had chided them both for irreverent behaviour.

They had been friends almost since the day that Stephen had walked through the door of the Missionary College, standing, simply overwhelmed, his eyes scanning in bewilderment the towering arches and Gothic windows.

To begin with he was led about in

a haze of staring confusion—unprepared, unrehearsed and silent—until he was taken to the workshop and given a lathe by the carpentry master, who began by speaking to him in a pidgin English and explaining the tool as if it were an artefact from another world and he an idiot.

But here Stephen was on familiar ground: Mr Simeon Gawe’s coaching at the Native College had been expert and swift. ‘Thank you, sir,’ Stephen had said quietly to the master. ‘On what would you like me to work?’

A little nettled, the carpenter had given him a length of wood. ‘Round this off and let me see how you do.’

Expected to fail, Stephen had failed. He had no vice to hold the wood and, under scrutiny, he had allowed the lathe to slip and clatter to the floor, damaging the handle. Everyone in the carpentry shop had stopped their work and looked up.

It would have been better to have been chastised, to have been cuffed as Mr Gawe would have done with a few well-aimed but not ill-natured curses, calling him ‘Sidenge’, a useless fellow, rather than this polite and supercilious silence.

Except for Albert.

‘Ah!’ He hurried over—a young man with inordinately thin, long legs—ears flushed red as if the condescension had been directed at him instead of Stephen. ‘Sorry, old chap,’ he said un-

der his breath as he picked the lathe up off the floor. He examined it. ‘I know this lathe,’ he said more loudly. ‘It’s got a tricky handle. I believe I split it long before today. Bad luck.’

‘Newnham,’ the carpentry teacher said, ‘get back to your work.’

‘Got a replacement?’ said the young man airily, looking directly at the master.

‘No.’

‘I can share mine then,’ he said and grinned ingenuously. He took Stephen by the arm, leading him away to his workbench. ‘He always does that to new students,’ he said, winking at Stephen. ‘It’s an old trick to put them in their place, especially if they’re foreign.’ He meant ‘native’. He had often heard the master call them ‘uncouth little animals’. But he was far too tactful to say it.

After that, Stephen—hanging back but eager—had looked for Albert Newnham, an anchor in his bewilderment. Albert had even been good enough—making a detour though pretending not to—to show him the more secluded lavatories behind the chapel. ‘I find fellows bother one,’ he laughed, ‘when one doesn’t want to be bothered!’ And the reddening about his ears was more earnest than embarrassed. ‘If you ever need a dose of castor oil, tell me rather than Mrs Blunsom, who will advertise your complaint all over College. She’s used to me now and doesn’t make remarks any more.’

It was Albert, too, who coached him for the College Vow—the solemn committal to vocation which every student made on enrolling. ‘As it’s a vow,’ Albert had said more seriously than usual, ‘and vows can’t be broken, you must be absolutely sure you want to make it. If you’re in doubt you must tell the Warden now.’

‘I want to make it,’ said Stephen.

‘They say that only half the fellows end up keeping it.’

‘I will keep it.’

Nor could Stephen doubt that the vow could be anything but binding after the Archbishop of Canterbury himself had given the sermon on Founders’ Day, setting forth the urgent need of providing ministrations in the colonies and the consequences of a Failure of Faith.

‘How lamentable the extent to which darkness, ignorance, heathenism and idolatry prevail among those who have been ignorant of the covenant of grace. But,’ and he had paused and gazed around at the assembled students, ‘if there are degrees of wretchedness, surely it is they who have once tasted of the heavenly gift but who have forgotten the covenant of baptism and retained the name without the character of a Christian, it is they who are undoubtedly the most wretched of all.’

With the fear of such a wretchedness ringing in their ears, the vow was

taken, student by student, before the Warden and the assembled clergy, before the benefactors of the College in their grandeur and their eminence, crowded into the College Chapel.

Stephen, awaiting his turn, had gazed along the pews in search of Albert, seated among the students who had been inducted the year before. Albert winked, nodded encouragingly, made a small gesture of support and Stephen had stood, slight and graven-faced under the weight of music, the smell of incense, of pomade and lavender and musty kneelers, enraptured by the vision of the clergy in their robes, the Bishop’s mitre, the gleaming cross.

Struck by the magnificence of God.

At last he had stood before the Warden: ‘Is it your deliberate intention to devote yourself, with all the powers of mind and body which God in His goodness has given you, to His service in the ministry in the Church of England in the distant dependencies of the British Empire or in the Foreign Mission Field?’

‘It is my solemn intention,’ Stephen replied—as Albert had coached him. It was not long after, alert to aptitude and sympathies, that their tutor suggested that Albert should go to British Kaffraria instead of India. Stephen had agreed—delightedly—to teach Albert the rudiments of Xhosa. In exchange, Albert would coach him in Latin and Greek, a prerequisite after ordination as a deacon to the elevation of the priesthood. ‘Maybe, one day we’ll both be bishops, Stephen!’ Albert had exclaimed. They had laughed together at the absurdity of Stephen in a mitre or Albert as a prelate.

Until that time Stephen’s mother tongue had almost been lost to him. After the age of twelve, when he had been sent to the Native College in Grahamstown, speaking it had been forbidden during school hours. As students came from many different regions, English was an easier choice than Xhosa, Sotho, Zulu or Tswana, even in the dormitories at night. Here, at the Missionary College in Canterbury, any African language was completely unknown.

Stephen had not spoken a word of Xhosa since leaving the Cape—not until he was asked to teach Albert conversation. In tutoring, the words and their alliteration returned to him like a refrain and the first few tentative phrases that grew between them made an intimacy, a shared purpose that held promise for their work together in Kaffraria.

The Warden, too, had assured his students that if an African—or Indian or Melanesian or Chinese or any foreign student—taught a designated English classmate his native tongue, they could well be posted together. Experience had taught him that such mutual support would help the English clergyman understand his foreign flock and would obviate—for the ‘na-

tive’—the risk of what he called ‘backsliding into heathen ways’: a bolster against the ‘barbarous influences’ that could be exerted on a young missionary returning alone to his own people. With an English missionary at his side, the Warden had declared, each would hold steady to his purpose. That the Englishman, and not the native, might have wavered in resolve was not conceded.

Yet the Warden knew all too well the chief cause of ‘backsliding’. He had a sheaf of reports from colonial bishops in India, China, Kaffraria, the Cape: the isolated missionary without a wife, lured to immorality or worse. Or, more likely, the demanding, selfish English spouse wrecking the vocation of a worthy man!

The Church was littered with such cases.

At Nodyoba, Stephen had no wife, either to support him or exert a baleful influence on his vocation. The mission community was surrounded by heathen homesteads. The young men had gone away to work at the diamond fields or in distant towns, the girls— traditional and illiterate—tilled the fields. Most of the converts at his mission were displaced: the elderly, the widowed, the destitute, the feeble, the very young. There were few with even a rudimentary education.

In England he had been too young, too preoccupied, too astonished by his situation to think of anything else. He had neither thought of women in his enthusiasm for his calling nor doubted the incalculable distance between him and the pale girls that he encountered in Canterbury. Then, one day, he had been walking down the high street on his way back to College from his lessons at the hospital. He was brought up short.

Stopped. Gazed.

There, in the window of Mr Baldwin’s Photographic Studio, there among the small and modest rows of prints of comely matrons, bewhiskered gentlemen, solemn children; there, among the crinolines, the lace tippets, the furled parasols—a black face.

It was a woman.

So unexpected, so utterly arresting.

Underneath the picture was a caption:‘Kaffir Woman’.

He had stood, the small gusts of autumn wind sliding round the corner and catching the brim of his hat, the cold fingering his neck within the stiff, starched collar. All the other portraits were marked with a name, a rank, a place. But she—she was Kaffir Woman. A generic for all women from southern Africa: a species, a type.

As was he: Kaffir Man

To be wondered over.

The woman in the portrait was turned to the left, her face untouched by consciousness of the lens, detached

from this sombre city with its towers and turrets, its cold damp wind, its ivied walls.

Stephen put his hand on the knob of the door of the shop and pushed gently. A bell tinkled as he entered. The man behind the counter looked at him keenly—a collector’s fervour—as if already lining up a shot. ‘Can I help you?’

At a loss to know what to say, to admit the irrational impulse of barging in, Stephen stammered, ‘What is the cost of taking my picture?’ He did not know why he had said it when he had scant money in his pocket. Was it some vague wish to be placed beside her in the window? A complementary specimen?

The portrait was far more than he could afford and he owed Albert tea—a dozen teas—but he counted out his coins, promising to pay the balance on collection, and pulled his collar straight. The photographer hesitated, clearly weighing up the chance of an interesting picture against Stephen’s commitment to pay.

‘Right,’ he said. ‘Come this way.’

Stephen was ushered into a studio. He was shown a mirror and adjusted his necktie. What luck that he had borrowed one of Albert’s hats for the visit to town, his own shabby as a workman’s. He rubbed the dome with his handkerchief, smoothing the nap, and patted his hair. It was styled as Mzamo’s had always been, with a parting down the centre. He had waited, watching, as the man prepared the glass, painted on collodion and then, adjusting his instruments, indicated that Stephen should take up a position with one hand on the back of an ornamental chair placed before a draped curtain. Stephen had stood—quite agonisingly frozen—in a posture of feigned repose, one leg flexed across his ankle, cane and hat on the seat of the chair.

He stood very upright, his hand at his hip.

He set his gaze beyond the man behind the camera, staring into infinity as she had done, a counterpoint to her angled stance.

Set side by side, their glances would cross.

Kaffir Man

When the picture had been taken he said, ‘Who is the lady in the portrait in the window?’

‘There are many portraits of ladies in the window.’

‘The black woman.’

‘Ah! She was a member of a choir that came to London some time ago. I went up to take their likenesses. They performed energetic heathen dances. Most exotic!’

‘She is not dressed like a heathen.’

‘No. They were engaged to show their savagery but I believe they were members of a Nonconformist church choir. They even sang before the Queen. A great fuss was made of them and—the lady herself told me—they were entertained most royally in a number of grand houses. She even sported a string of pearls a member of the nobility had given her. I took her picture when she was not performing.’

Stephen smiled. Should he have come dressed in skins and feathers?

He left the shop and stooped to look again at the print of that serene and haunting face.

It was a week later that he had returned to collect his photograph. As he entered the shop he noticed that the display in the window had changed. She was no longer there.

The photographer brought out the portrait of Stephen and handed it to him with some pride. It was a fine likeness. There he stood, keen and upright in his overcoat and shining boots.

‘Thank you,’ Stephen said. ‘My mother will be pleased with this.’ He scanned it again and slipped it into an envelope. Then he said, rather awkwardly, not looking at the man, ‘What has happened to the picture of the native lady whose portrait was in your window?’

‘I have changed my display and most of the prints have been claimed. I do not expect that lady to come for hers. She has returned to the Cape. It was a trifle for my own interest.’

‘Is there a copy?’

The man appraised Stephen with the hint of a leer.

‘Five shillings for the original.’

Twice what he’d paid for his own picture. ‘I will come tomorrow.’

‘Mind where you get the money.’ Stung, Stephen had left the shop.

Coming from the Chief Inspector of Education, the report in the Cape Colony’s newspaper on the Church’s policy of educating Africans in England was a rap over the Metropolitan’s knuckles from a distinguished government official. And, by association, from the politicians.

‘The spade, hammer, plane and saw should take the place of playing chess with Lady Bountiful … ,’ it had run. No more students to England to indulge themselves in seeking the patronage of country parishes, no more young black Englishmen. The climate had

defeated them: two had died and four had been repatriated before they had graduated for fear that they too might contract consumption. On their return to the Colony there had been a further death, and only one had proved himself suitable for Holy Orders. The others had acquired a worldliness and independence over which the Dean in Grahamstown crowed to his Bishop, ‘What did I tell you, my Lord!’

Furthermore, they had roused up their fellow countrymen to continue lobbying for the release of the chiefs still incarcerated on Robben Island. Even in South Africa, too many who had been students at the Anglican native colleges in Cape Town and Grahamstown had had to be sent home ill or as ‘unsuitable’. Since then many had returned to their people and reverted to heathenism while others had quit the Colony rather than suffer the indignity of colonial scorn:

—Impertinent.

—Indulged.

—Absurd. Why, that fellow’s wife wears finer dresses than my daughter!

The experiment was an expensive failure. Unless Stephen Mzamane was the man to prove the critics wrong.

‘He won’t fail us,’ Henry Turvey said to the Bishop.

‘He’s such a deferential fellow, though,’ lamented the Bishop. ‘Pity about his brother. I had real hopes for his development.’

‘If you start a fire you cannot complain when it burns you,’ said Turvey drily.

‘He wasn’t your choice?’

‘Vocation makes a priest,’ said Turvey.

The Bishop sighed. ‘And all too rare amongst the best of us?’

‘All too rare.’

Stephen did not see the article but the Warden, Dr Bailey, was sent it by the Metropolitan in Cape Town. Bailey wrote a letter fierce with protest but it found no place in either the local or the colonial newspapers. By the time it reached the Cape the matter had been forgotten. Nor would his anger have been shared. The colonial argument had always been that the missionaries were wasting time and money in educating Africans in anything but trades. Book learning was a spur to sedition and discontent.

—It makes them crafty.

—It encourages them to aspire beyond their proper station.

—It gets in the way of land reform. It was a hopeless situation. What was the point, Warden Bailey wondered, in writing to the paper and informing its readers—against all expectation from the Colony—that Joshua Morosi had headed the class lists at the Missionary College, outperforming Englishmen with an English education? Had he not been chosen as the most able, pious, worthy student of his

year? Where was the disparity between him and the English students?

But Joshua had died of typhus while on a holiday in Shropshire and all hopes of a triumphant Christian heir to a paramount Chief, ordained into the Church and returning to lead his people, were dashed. All that was left was a marble gravestone in a country churchyard and a stained-glass window of St Philip converting a eunuch.

Joshua had been four years older than Stephen and inspired a reverence for his seniority, lineage and cultivation that ensured Stephen’s deep deference in his company. If, in speech and manner, Joshua had been an Englishman, his presence and bearing had been those of a chief. Stephen, the only fellow African that year, had held him in silent awe.

At the end of his first term, the Warden had called Stephen into his study and informed him that as no other invitation had been forthcoming for the Christmas holidays and as it was not desirable that he should stay alone in the Foreigners’ Wing, an arrangement had been made with Joshua Morosi: Joshua had been persuaded to allow Stephen to accompany him—as a sort of attendant—when he visited the home of a former fellow student.

They had travelled by train, puffing through the countryside, Joshua absorbed in a newspaper while Stephen pressed his face to the window as the fleeting fields and flocks passed by. Stephen had carried the luggage and

sat respectfully listening to the pronunciation of every word when Joshua had taken out his prayer book and read a passage aloud. There had been little further conversation although Stephen was aware of Joshua’s shrewd— and not unkindly—appraisal. He felt curiously protected.

They had stayed in a large rectory, the guests of Joshua’s former classmate’s parents. Joshua’s friend, Norbert Whitmarsh—sensitive to Stephen’s youth and shyness—attempted to include him by telling jokes which Stephen did not understand and which Joshua was too solemn to approve. At table he ate in silence except for answering, now and then, the nudging enquiries of the Rector or Mrs Whitmarsh.

‘Would you fancy another slice of beef, Mr Mana?’

‘No thank you, ma’am.’

‘Whereabouts in the Colony is your home?’ the Rector had said, laying down his knife and fork and wiping his mouth with his napkin.

It was not a question Stephen could answer with any certainty. ‘I am not sure, sir.’ He glanced anxiously at Joshua. Is that a foolish answer? Joshua held his gaze. ‘I was raised at a mission in Kaffraria, sir,’ Stephen said to the Rector. Joshua nodded imperceptibly.

‘But you have parents?’

‘Yes, sir.’

The Rector glanced at Joshua then. ‘I thought all the foreigners at the College were the sons of the nobility.’

Stephen looked in confusion from one to the other, not understanding.

There was a pause, then Joshua said, ‘I believe it is sometimes wiser to choose ability above rank. And, after all, each diocese must have its chance. In the event they might send those with particular attributes.’

‘Aah.’ The Rector leaned back in his chair and took up his wine glass, examining Stephen more closely. ‘I see.’

‘Do not make the young man feel conspicuous, my dear,’ said Mrs Whitmarsh. ‘Mr Mewroozi, another slice of beef?’

Whenever they took an afternoon walk—Joshua and Norbert Whitmarsh deep in discussion on theological matters—Stephen trailed a respectful pace behind. In fine weather they had wandered in country lanes, taken tea in village tea shops, bowed and raised their hats to passing ladies whose astonishment at seeing them was barely concealed. When it was wet they had played chess and it was from observing that that Stephen first learned the rules.

Then, immediately after New Year’s Day, Joshua had suddenly fallen ill. He had lain for a week in an attic room in a tangle of sheets. Norbert Whitmarsh kept a hovering distance and Stephen—wide-eyed with dismay—sat in vigil near the door. The village ladies, both curious and concerned, brought gifts and comforts, and Mrs Whitmarsh wrung her hands and wished the responsibility for the young chief

had not devolved on her. The doctor came and went.

On the tenth day, as evening fell, Joshua died. Stephen, faithful to his post, had heard him calling out. He had crept towards the bed, standing at the foot. Joshua had gazed at him with some abstracted recognition. Then he had begun to speak in his own tongue. Softly. Almost fiercely. Stephen did not know Sesotho but the cadences, the phrasing, struck a deep chord of remembrance and he answered in Xhosa, tentatively at first and then more firmly. The words went back and forth, words learned long before either took up a slate and chalk or was baptised.

Joshua spoke his own Sesotho name—Tsekelo—over and over, urgently evoking an older theology than the one they served. Then the names of the great ones of his people, calling them up, mustering a lineage. A clan. A place.

As evening came outside the latticed window and the beech trees picked up the stirring of the evening wind, Joshua fell silent. He set his face to the wall and said no more.

When they buried him, the whole village turned out. Stephen stood guardian near the coffin. The prayers were all familiar, the psalms chanted by the choirboys. But for Stephen, apart from the melody of the English hymn echoing in the nave of a country parish church, he sensed a counternote that reached back across the leagues of sea to where the mountains

of the Basotho kingdom reared against a southern sky, distant, still and blue. In time, a stone slab with Joshua’s name, his age, his date of death, was erected by the Rector through subscriptions from the village and the Missionary College. But the hopes of the Governor and the Bishop in the Cape of installing a black Englishman among his people—secure in his loyalty to the Colonial Administration— were laid waste. The heir to a paramount chief rested with the rural poor in a churchyard in England, excised from tribal memory.

Once there was a man, Tsekelo … Once there was a paramount’s son.

Joshua had gone and no students came from the Cape at the start of the year.

There would be no more playing chess with Lady Bountiful! No more Stephens to challenge the wealthy and indulgent parishioners from the community who contributed to their education.

For Stephen himself, chess had become his chief delight. He was coached in it by the Superintendent of Students. He had learned to play diffidently—in time, often trouncing his tutor, but always with a self-deprecation, making excuses gracefully for his opponent’s blunders. Once he was proficient, he had been taken about to the genteel houses in Canterbury, a showpiece who played with skill and ease.

He had sat in stuffy drawing rooms, tea and cakes pressed upon him, daughters kept well away from approaching too closely, sons sent out on errands, only the ladies and gentlemen—beyond any possible harm— his chosen fellow players. Warden Bailey was delighted at his success: a sure indication, despite the protests, that the College had not been unwise in admitting the sons of the African elite.

Joshua had been the brightest hope of all.

But he had died.

Not long after Stephen’s return to College for the start of the Spring term, Albert had called him from his books and said, ‘Do you know how to carve stone?’

‘I only know how to carve wood.’

‘Well, today it’s stone. The master asked me to engrave Joshua’s name on the wall of the memorial crypt. Can you help?’