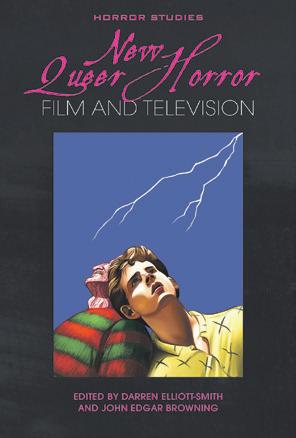

Self-published books showcased in Booklaunch

Other than giving us a chance to stay home and read— and I had just been re-reading Camus’s La Peste when news of covid-19 first broke: there’s irony for you— doesn’t there have to be a silver lining to this nightmare? I don’t mean that in the way some Downing Street adviser might: that the pandemic will cull the elderly and save the Treasury billions. I mean: surely everything now has to change.

Anyone contemplating plague has to be forgiven for getting a bit existential. Get this wrong and we could go extinct (a worry Jonathan Lawley addresses in a different context on page 14). We find ourselves asking: what does the coronavirus mean and what does it want from us? Are we its prey—or might it have an interest in our survival? (How else could it breed without us? There’s a consoling thought.) Or is it too stupid not to wipe us out?

Those of a religious bent—and that includes environmentalists—might see it as, if not divine punishment for humanity’s evils, then at least an instrument for frightening us and purging us of our worst excesses (though I did see a Facebook post about a rabbi who said it was sent to punish those who thought that things were sent to punish us. Ho ho.) More precisely, it might be seen as a scourging that forces us to confront our most damaging behaviours.

Thus, if you believe in the Gaia theory—and I don’t— you might say that covid-19 was our planet’s rebalancing mechanism. We couldn’t do it; nature had to do it for us. A more acusatory interpretation is that this is payback time for our arrogant abuse of a world we should have cared more for nature’s refusal to put up with us any longer.

Since Booklaunch began 18 months ago, we have showcased 15 self-published books along with over 200 more by established publishers. We like to give independent authors a share of the limelight they cannot get in other publications. If you have self-published and want to showcase your book, email Maggie Bawden at book@booklaunch.london

From that point of view, for all the horrors that will befall us, we can expect to see an upside. Here’s one: the shutdown in air travel and driving has brought about the first fall in air pollution since the 2008-09 financial crisis—something that seemed unachievable as recently as the Cop-25 climate conference in Spain in November. Global supply chains are on hold. Petrol is a redundant asset. We’re eating local produce. We’re making do.

Faced with the first real shock to have hit our unwary world since 1939, it feels as if we’ve come together in a way unimaginable during the fight for Brexit and prior. Faute de mieux, we are engaging with each other online (would that we all had shares in Zoom) as our children discover virtual classrooms and we join community groups or share online drinks as the sun sets over the yardarm. That’s good, however inconvenient. Those who once drove home from the pub no longer threaten our safety. Road accidents are a thing of the past; so are the chaos and emissions of twice-daily school runs.

Such changes must become permanent. Already, unbelievably, in exchange for lost freedoms, union bosses and hardline right-wingers have congratulated a “moderate” Conservative chancellor on his 80% bail-out for workers, raising the tantalising prospect, when this is all over, of a basic wage, a crucial element in any progress towards a just society. (The authors of Entrusted talked about this in our last issue.)

But is there really a new unity? I don’t think so. I think there’s a new schism, and one of biblical proportions; for while some of us are mortified by the existential question of how to afflict our souls so humanity survives, we’re bothered that others simply feel cheated out of partying that they’re not agonising except about how to bulk-buy toilet paper. And then there are criminals, petty and organised. And Russia, always up for mischief. And you thought Brexit was divisive …

Me, I’m a mortifier. (OK, and a finger-pointer.) I think we need violent shocks every so often to make us take stock of ourselves, and if we’ve gone wrong it’s because there haven’t been any recently. Call me Jeremiah but the worst news would be if we gained nothing from this purge, if our narcissistic self-indulgences once again became everyday life.

What, then, would be a good outcome? The death of capitalism? The end of stock-market profiteering? The banning of caramel frappuccino with extra cream? What do you think? Send me your thoughts.

Stephen Games Publisher and editorOver the last two hundred years, several clichés about Kant’s ‘philosophy of peace’ have developed. The first has to do with the historical assessment of this philosophy. Typical statements claim that ‘Kant was ahead of his time’ or simply ‘a child of his age’. Arms merchants talk of the ‘boomerang effect’ if a country sells high-powered military hardware that is later used against it. Intellectual and cultural historians face a similar problem; they may argue that an author is a child of their age only to find, decades later, the same argument turned against them.

German interpreters of the late-19th- and early20th-century are a case in point. They usually criticized Kant’s cosmopolitan, pacifist and republican thinking and offered two explanations: either that Kant was determined by Enlightenment prejudices and could not liberate himself from them (even if he had wanted to), or that he was simply too old and senile.

Things have by now changed. Kant’s early interpreters are seen as narrow-minded nationalists and monarchists, who endorsed German or Prussian militarism and reproduced the prejudices of their time. Kant, on the other hand, has turned into the far-sighted, independent-minded progressive thinker who anticipated a new cosmopolitan right.

These shifts indicate that we should be very careful with our own judgements about the historical place of Kant’s theory of international right and its philosophical merits. Kant was definitely embedded in and influenced by the Enlightenment and its debates but was not necessarily a child of his own age. What I find surprising is that it took us almost 200 years to work out that Kant offers a philosophical international relations theory of considerable importance.

Debunking the author of Perpetual Peace as a senile and naïve proponent of an outdated Age of Enlightenment is no longer tenable.

According to another cliché, Kant was ‘in favour of human rights, democracy, and world peace’. This is not downright wrong, but it has to be qualified. Kant had serious reservations about direct democracy (which he considered despotic), and he was partly influenced by the republican tradition (via Rousseau). Finally, Kant was a peace advocate or representative of legal pacifism, not a pacifist. He endorsed the rights of states to defend themselves, and to unite and fight against an ‘unjust enemy’.

According to another common perception, Kant was an early liberal. This is true, but again the statement has to be qualified. Kant was an early liberal, but also listened to his conservative critics. He believed that it is the duty of any philosopher to find out where one’s opponent is right and not where s/he is wrong. Thus, Kant was apparently led to believe that there was some truth in his opponents’ criticism.

Kant’s position is apologist and utopian at the same time. To put it more precisely, Kant argues on a level beyond and prior to the apologist–utopian dichotomy. He could be interpreted as being apologist; he could also be accused of being utopian. The truth is that Kant’s evolutionary theory mediates between both extremes. It is idealist but not necessarily utopian. It is embedded but not necessarily apologist.

The conflict between Kant and his conservative critics was part of the politicization of German philosophy in the 1790s and the crisis of the Enlightenment, which was challenged by romanticism and conservatism. The crisis of the Enlightenment was in turn a crisis of the authority of reason. For instance, many authors believed that French radicals such as Robespierre and Saint-Just embodied the rationalism of the Enlightenment. For them, pure reason had led to the terror and the guillotine. Many German radicals and conservatives thought that Kant’s philosophy provided the foundations of radical Jacobin theory.

The debate between Kant, Rehberg and Gentz in the pages of the Berlinische Monatsschrift revolved around four controversial issues. The first was the old dispute between rationalism and empiricism in ethics. In fact, Rehberg did not simply side with empiricism; he argued in favour of a compromise, supporting reason and historical traditions, custom and convention at the same time. Along with Kant, Rehberg believed that in real life we have to resort to standards of utility to determine our specific duties and to mediate between theory and practice.

My own approach to Kant entails the following features. First, I do believe that a historical approach is indispensable. Yet a historical approach should not be confused with a historicist approach, which assumes that there are no universal cognitive or moral standards. We should be careful with our own judgements. Texts are

usually complex and intricate combinations of ‘old’ and ‘new’, of the historically contingent and the universal.

Second, Kant is not the philosopher who has his head in the clouds but the philosopher trying to bridge the gulf between the ideal and the real. In this respect, he is often a victim of clichés and prejudices. Political scientist Friedrich Kratochwil, for example, claims that ahistorical, abstract Kantian moralism is dangerous, especially in international relations. Kant rejects universal principles, the categorical imperative and idealist ethics in favour of Humean moral sentiments.

I feel that Kratochwil’s interpretation reproduces standard clichés about Kant’s philosophy. Most arguments are directed against authors who (seem to) rely on Kant, whereas Kant himself is almost completely left out. Only one passage explicitly refers to a problem of international relations. Kratochwil quotes US Supreme Court judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, who has argued that the categorical imperative has to be rejected because it requires that soldiers be seen as ends in themselves, not as means, and that sending them into battle would violate this principle. Holmes judged it morally acceptable (‘I felt no pangs of remorse’) to send soldiers into battle and possible death, choosing to abandon the theory (Kantian moral philosophy) in favour of practice. This is not only interesting reasoning; it also fits perfectly into my overall theme of mediating between theory and practice.

If my argument is correct, then Holmes’s (and Kratochwil’s) syllogism is faulty. Kant would have argued that we must distinguish between right and ethics. He assigns the question of whether the government has a right to send its subjects into war to legal philosophy. One may argue that a state is entitled to defend itself and apply ‘all necessary means’, including the use of force, to do so. Kant is happy with the provision that the citizens give their ‘free consent’ to military action. Thus Kant does not seem to believe that soldiers are always and inevitably used by their governments as mere means if they go to war. Yet somehow, many of us expect Kant to think this way.

At this point, some tend to argue that Kant should have written along these lines, that the ‘true’ Kantian outcome has to be like that; or they arrive with Kratochwil at the conclusion that Kant’s theory is ‘overly moralistic’.

I have serious doubts about both conclusions. This book attempts to demonstrate that Kant is less ahistorical, abstract, moralistic, idealist or ‘liberal’ in the contemporary sense than usually assumed (which does not turn him into a communitarian, a classical republican or a conservative like Gentz or Rehberg).

Third, I assume that this book paints an unconventional picture of Kant’s philosophy of international right. He is not only the philosopher of grandiose, sweeping statements about justice and peace. We do find these statements in his writings but the picture I present in this book is different: it is the ‘pedantic’ Kant of numerous definitions, qualifications and caveats. This might be disappointing for some readers. Yet I think that this is one reason why Kant’s theory is indispensable for our times. It combines two elements: the idealistic and normative, focusing on principles and the goal; as well as reflections on how to attain this goal and put these principles into practice.

In the 1790s, the fate of the Enlightenment (Aufklärung) was at stake, and the end of the century saw its demise. Yet the 20th century has seen the rebirth of some Enlightenment ideas. Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls, two prominent authors of political philosophy in the second half of the century, both stand for a critical reassessment of Enlightenment ideas and both draw on Kant in particular. In his course of lectures on international relations at the London School of Economics, Martin Wight claimed ‘that there is very little, if anything, new in political theory [and] that the great moral debates of the past are … our debates’.

Kant is a case in point. His moral, political and international theory is food for our thought. He offers basic principles, and we cannot do without them. We also cannot avoid going beyond him because many of our contemporary problems are not covered by Kant. We do not find anything about private international law, economic integration, or the impact of the internet on the freedom of speech in his writings. Yet the general moral and legal principles of Kant’s philosophy give us a firm starting point in evaluating these issues. Last but not least Kant helps us to avoid mistakes. He offers a reliable framework, although we must fill it. The idea of justice lies at the heart of the Pax Kantiana; we still have to spell it out.

POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY NOW

KANT AND THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL RIGHT

Georg Cavallar

University of Wales (Cardiff), Softback, 9781786835529, 288 pages, 138 mm x 216 mm, 1 April 2020

Publisher’s price £39.99

Save £2.23

Booklaunch price £37.76 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

FROM

WRITING WALES IN ENGLISH

AND FLIGHT ESSAYS ON RON BERRY

George Burdett, Sarah Morse (eds) RRP £24.99 Save £0.45 Our price £24.54

£0.45

Our price £24.54 Find

Simon Spiegel, Andrea Reiter, Marcy Goldberg (eds) RRP £75.33

SPIES, SPIN AND THE FOURTH ESTATE BRITISH INTELLIGENCE AND THE MEDIA

Paul Lashmar

Paul Lashmar

Edinburgh University Press (Edinburgh), Softback, 9781474443081, 256 pages, 138 mm x 216 mm, 30 April 2020

A powerful motivation for writing this book was my anger and despair that the UK’s official oversight and accountability system had failed to be inquisitive, robust and critical. I could only identify a handful of occasions in a quarter of a century when oversight bodies or officials had been in any way critical of the intelligence agencies, and then only when the case was irrefutable.

However, my critique was partially confounded when, in little over a week in June 2018, a series of reports by oversight bodies appeared that were notable for their unprecedented criticism, including two reports released by the parliamentary oversight body, the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC), whose past record had been supine.

These new reports contained disturbing details about Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) involvement in the CIA’s rendition and torture policy after 9/11. This involvement had been deliberately concealed for over a decade. In December 2005 the then Labour Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, the minister responsible for the SIS and GCHQ, issued a categorical denial of SIS involvement in rendition and torture when he told the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee:

Unless we all start to believe in conspiracy theories and that the officials are lying, that I am lying, that behind this there is some kind of secret state, which is in league with some dark forces in the United States … there simply is no truth in the claims that the United Kingdom has been involved in rendition.

pendent court set up by the government to investigate unlawful intrusion by public bodies, concluded that the Foreign Office has, on several occasions, given GCHQ carte blanche to extract data from telecoms and internet companies. The judgment noted: ‘In cases in which … the foreign secretary made a general direction which applied to all communications through the networks operated by the [communications service provider], there had been an unlawful delegation of the power.’ To my pleasant surprise two oversight mechanisms were seen to act as guardians rather than ostriches.

Jack Straw has never explained his 2005 denial that British intelligence was involved in rendition and torture. Perhaps he did not know, but in that case he has a responsibility to say so in public. In response to the 2013 publication of the Snowden documents, prime minster David Cameron said that GCHQ operated within the law and was ‘properly governed intelligence’. It is now clear that that was false and that GCHQ was often operating outside the law or, at its most benign, covering its legal exposure with a threadbare patchwork of antiquated laws never drafted for the modern age.

‘It was all a bloody lie’

Publisher’s price £14.99 Save £1.80

Booklaunch price £13.19 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

Straw was setting out the line for government and the intelligence agencies to parrot for a decade. Significantly, some 13 years later, the ‘cheerleaders’ at the ISC had evolved into ‘guardians’ and it seemed that Jack Straw had misled the media and public. The ISC’s full oversight of MI6’s involvement in rendition and torture was constrained because it lacked the key powers to investigate further. It noted that the then Prime Minister Theresa May had intervened to exempt SIS officers from public accountability and the rule of law. The ISC was unable to require the senior SIS officers who had overseen cooperation with the US rendition programme and the junior SIS officers who took part in these events to give evidence.

The ISC’s four-year inquiry found that the UK had planned, agreed or financed some 31 rendition operations. Moreover, there were 15 occasions when British intelligence officers consented to or witnessed torture, and 232 occasions on which the intelligence agencies supplied questions put during interrogation to detainees who they knew or suspected were being mistreated.

MI5 had helped to finance a rendition operation in June 2003. In October 2004, the then foreign secretary, Jack Straw, authorised the payment of a large share of the cost of rendering two people from one country to another. The underlying proposition was that national security trumped the rule of law.

INTELLIGENCE, SURVEILLANCE

SECRET

THE ARAB WORLD AND WESTERN INTELLIGENCE ANALYSING THE MIDDLE EAST, 1956-1981

Dina Rezk

RRP £24.99

Save £4.57 Our price £20.42

That the ISC had found some guts, if not teeth, may be down to Dominic Grieve, the maverick Conservative politician and a very different ISC chair from his predecessor, Sir Malcolm Rifkind. That accountability appears so dependent on the character of the chair is a concern. The 2018 reports reflected a robust and critical tone but were still constrained by the committee’s inability to subpoena officials. The Committee forcefully made the point that it needed greater powers to undertake its work effectively.

The ISC reports were timely and came just a month after the then prime minister Theresa May issued a public apology to Abdel Hakim Belhaj, who was kidnapped in 2004 with the assistance of the SIS. He was rendered to one of Muammar Gaddafi’s prisons, along with his pregnant wife Fatima Boudchar, and tortured. These reports are important landmarks for accountability, but a year later one of the first actions of Boris Johnson on taking office as prime minister, was to block the next stage of the inquiry, a decision The Guardian (2019) labelled ‘immoral’.

INTELLIGENCE, SURVEILLANCE AND SECRET WARFARE THE TWILIGHT OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE BRITISH INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERSUBVERSION IN THE MIDDLE EAST, 1948-63

Chikara Hashimoto

RRP £24.99

Save £5.59 Our price £19.40

SPYING ON THE WORLD THE DECLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS OF THE JOINT INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE, 1936-2013 Richard J Aldrich, Rory Cormac, Michael S Goodman (eds)

RRP £29.99

Save £6.00

Our price £23.99

Two days before the ISC reported, an important independent tribunal judgment was delivered, officially confirming that the British government broke the law by allowing spy agencies to amass data on UK citizens without proper oversight from the Foreign Office. GCHQ had been given greatly increased powers to obtain and analyse citizens’ data after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 on the condition that it agreed to strict oversight from the foreign secretary.

The Investigatory Powers Tribunal (ITP), an inde-

The release of the scathing ISC reports in 2018 sparked one of the most powerful condemnations of the deceitful nature of the British intelligence community I have seen in recent years. It came from the Observer’s Peter Beaumont, who had been dealing with official intelligence contacts over many years. He noted that the denials are what readers get to see—the carefully formulated statements written in government press offices, often after a period of to-and-fro with the journalist.

What readers don’t get to see is another kind of to-andfro: the direct appeal to editors and reporters, the insistence that our secret services ‘don’t do this kind of thing’, are bound by rules, by UK, EU and international law, are ‘Crown Servants’, and in any case are bound by a sense of decency.

Except, as it is now quite clear, it was all a bloody lie. The answers given to journalists at the Observer over the years, as well as colleagues at the Guardian and at other news organisations, as they investigated these allegations, were rotten with untruth and evasion.

More likely, the exasperated Beaumont fumed, it was worse than that: it was nothing short of a long-running cover-up that persisted for a decade and a half, to sustain the impression that torture is something that only happens in other countries.

In recent years, the agencies have given assurances that they are concerned with human rights. However, we have no way to check. We have little idea whether MI5 or (in a different mode) the SIS continue to take advantage of innocent participants, as the Special Demonstration Squad did, and we cannot know until the archives become available.

One evolving and major concern about the intelligence world post-9/11 is the outsourcing of intelligence operations. The direction of travel by the Five Eyes network (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States) means surveillance capability is subject to gradual integration with the private sector, which is at least partly motivated by profit. The power of algorithm-based technology and artificial intelligence, where public and private sectors become indistinguishable, has the potential for mass behavioural modification. This presents a terrifying prospect.

The closed nature of the intelligence services makes it difficult for the media to exercise a coherent critique. We do not know what the value systems are of those who populate the intelligence services or how their value systems guide them. The UK intelligence community has successfully resisted any kind of external ethnographic study, as far as I am aware. I only know of two such studies and both were in the United States. In the unlikely event that psychometric tests of recruits were ever published, they might help us understand what intelligence staff think their job is and who they think they protect.

Intelligence historian Christopher Andrew points out that the ‘under-theorisation’ of intelligence studies is not simply a problem for academic research:

It also degrades much public discussion of the role of intelligence. Since September 11, 2001, the media

Find out more about this book on our website

‘Unless I am lying, the UK is not involved in rendition.’ Really, Mr Straw?

Shortly after the Brexit referendum result was declared early on Friday 24 June 2016, David Cameron emerged from the front door of 10 Downing Street to make two important announcements.

The first was that he would be resigning as prime minister. The other was that the government would not immediately be notifying the European Council, under article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, of its intention to withdraw from the EU.

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union says that a member state can withdraw from the EU ‘in accordance with its own constitutional requirements’. But what were they? The UK’s constitution is ‘uncodified’ – largely unwritten – and there was nothing in the referendum legislation to say what should happen next.

In a newspaper article published a few hours after the result was declared, I suggested that giving effect to Brexit would require parliamentary approval. … That proved to be correct – although I did not go so far as to say that it would be unlawful for the government to trigger article 50 without first obtaining an Act of parliament. The credit for that argument must go to three constitutional lawyers: Nick Barber, Tom Hickman and Jeff King. In a blog published the following Monday, they argued that ministers could not use their prerogative powers to overturn a statute. … ‘Before an article 50 declaration can be issued,’ they wrote, ‘parliament must enact a statute empowering … the prime minister to issue notice under article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon.’

That was an important proposition that needed to be tested in the courts. Mishcon de Reya was one of several law firms that took up the challenge. Its lawyers signed up a public-spirited investment manager named Gina Miller and argued on her behalf that triggering Brexit would require primary legislation. On 3 November 2016 the High Court agreed.

Judgment in the Miller case was delivered by Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, Sir Terence Etherton and Lord Justice Sales. ‘The sole question in this case,’ said the three senior judges, ‘is whether, as a matter of the constitutional law of the United Kingdom, the Crown – acting through the executive government of the day – is entitled to use its prerogative powers to give notice under article 50 for the United Kingdom to cease to be a member of the European Union.’

The judges’ answer was unflinching. Without specific authority from parliament, they ruled, ‘the Crown cannot through the exercise of its prerogative powers alter the domestic law of the United Kingdom and modify rights acquired in domestic law under the European Communities Act 1972 … We hold that the Secretary of State does not have power under the Crown’s prerogative to give notice … for the United Kingdom to withdraw from the European Union.’ …

If ministers could not use their inherent powers to trigger Brexit, ministers would have to ask parliament to pass legislation. But some of those who had voted to leave the EU … didn’t want MPs to have anything to do with the article 50 notification. If parliament had to give its approval, Brexit might never be triggered. On this argument, the judges could be seen as trying to obstruct the referendum result.

What

Viewed from a constitutional perspective, the High Court judgment was entirely supportive of democracy. In what amounted to a choice between government and parliament, the lord chief justice, the master of the rolls and a lord justice of appeal had come down on the side of the legislature.

Unfortunately, the High Court missed a trick by making no effort to ‘sell’ its judgment to the people. It would only have needed another sentence – perhaps in a press summary – explaining that a simple Act of parliament would permit the government to do as it wished.

Spelling this out would have helped to shape broadcast news coverage on the day of the ruling. But it might not have had much effect on the Brexit-supporting newspapers. Coverage the following day played to readers’ prejudices.

The Sun carried a picture of Gina Miller under the headline ‘Who do EU think you are?’ The Daily Express, in a front-page comment headlined ‘We must get out of the EU’, said that Britain was now facing ‘a crisis as grave as anything since the dark days when Churchill vowed we would fight them on the beaches’. It asserted, without a hint of irony or self-doubt, that 3 November 2016 ‘was the day democracy died’.

The Daily Telegraph, which used to be regarded as

a serious newspaper, printed official photographs of the three judges in monochrome – with a blue tint to make them look more sinister. Its headline read: ‘The judges versus the people’.

But the Daily Mail could be relied on to top that. Its front-page story carried the by-line of James Slack, who later joined Downing Street as Theresa May’s spokesman. But it was written by Paul Dacre, the then editor. This is how it began:

MPs last night tore into an unelected panel of ‘out of touch’ judges for ruling that embittered Remain supporters in parliament should be allowed to frustrate the verdict of the British public. …

Above the story were slightly out-of-date photographs of the three judges, two of them in the full-bottomed wigs that are worn only on ceremonial occasions. The sub-heading was ‘Fury over “out of touch” judges who defied 17.4m Brexit voters and could trigger constitutional crisis’. And the headline, dominating the page, was ‘ENEMIES OF THE PEOPLE’.

As Thomas’s successor noted nearly two years later, that was ‘a phrase used by tyrants throughout history to justify the persecution and death of those who do not toe the line’. Looking back, a former foreign editor of The Times said it was ‘one of the most chilling headlines ever to appear in a British newspaper’. But it was only a headline.

My first reaction was to dismiss the Mail’s headline as something that would soon be forgotten: ‘today’s news –tomorrow’s fish-and-chip paper’, as we used to say. The lord chief justice and his two colleagues were far less relaxed and looked to the government for support.

In decades gone by, the lord chancellor would have spoken on their behalf. But that great office of state was then occupied by Liz Truss MP, who was something of a political lightweight. Nothing was heard from her for a couple of days, presumably because she was waiting for instructions from Downing Street and nobody in the prime minister’s office grasped the dangers of delay. Eventually, Truss expressed the view that judicial independence was ‘the foundation on which our rule of law is built’. When pressed, she said it was not for her to condemn the newspapers.

A little too late

Indeed, it was not. But what Truss was being asked to do was to defend the independence of the judiciary, in line with the oath she had taken on her appointment. As the judges saw it, that meant explaining that they had been traduced in the media. Truss’s response was condemned by Lord Judge, the former lord chief justice, as ‘a little too late and ... quite a lot too little’.

A couple of years later, Lord Neuberger said that Truss had completely missed the point. She had been free to criticise the press and she should have done so. But Neuberger, who by then had retired as president of the Supreme Court, was in forgiving mood.

‘In fairness to her, she was a very recent appointment. She had had no experience of the rule of law and of the judiciary,’ he said. ‘It was unfortunate, and she should have got it right, but I think there were ... mitigating circumstances.’

What Truss could fairly have pointed out was that, under the new constitutional settlement reached more than a decade earlier, she was no longer head of the judiciary. That role had been transferred from the lord chancellor to the lord chief justice. ‘The whole point of the 2005 reforms,’ said Professor Graham Gee in 2019, ‘was to standardise the role of lord chancellor –so that lord chancellors would take not an independent line but a governmental line on matters relating to the judicial system.’ Truss could have argued that Thomas should have been defending himself and his colleagues, self-serving though that would inevitably have appeared.

But there is no way round the fact that it is the duty of the lord chancellor to uphold and defend judicial independence. Lord Dyson, who before his retirement was the most mild-mannered of judges, was still incandescent when he wrote, in a memoir published two years later, that Truss’s 11 months in office had been ‘disastrous’:

Not the least of her shortcomings was her failure to discharge the statutory duty to protect the independence of the judges when [they] were pilloried by some of

ENEMIES

HOW JUDGES SHAPE SOCIETY

Joshua Rozenberg

Bristol University Press (Bristol), 176 pages, Softback, 9781529204506, 148 mm x 216 mm, 21 April 2020

Publisher’s price £14.99

Save £1.80

Booklaunch price £13.19 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

WOMEN, WORK, AND ECONOMIC GROWTH LEVELING THE PLAYING FIELD

Kalpana Kochhar, Sonali Jain-Chandra, Monique Newiak (eds) International Monetary Fund (Washington), Softback, 9781513516103, Illustrated, 180 pages, 155 mm x 229 mm, 2017

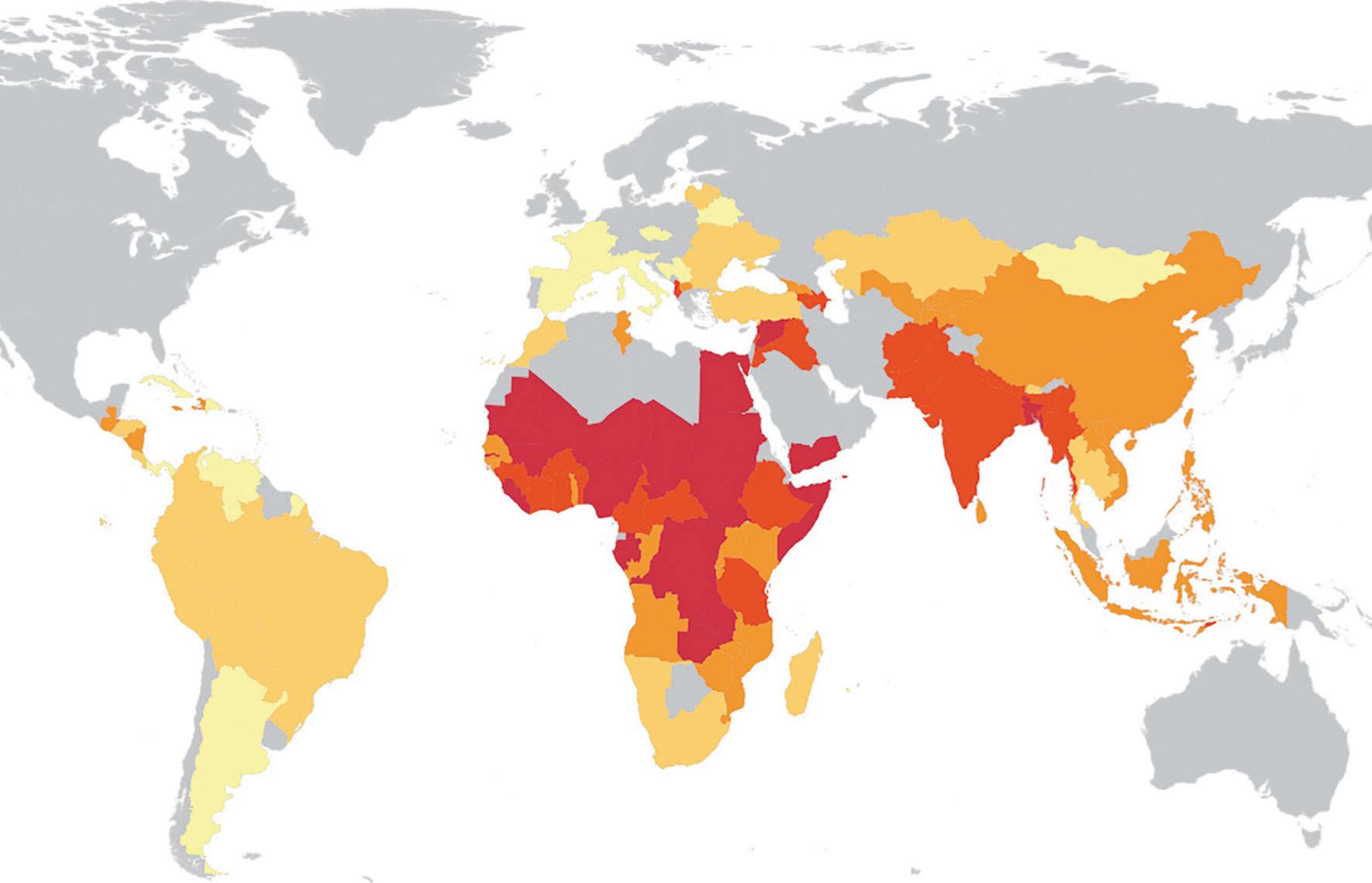

Gender-Based Restrictions across Countries, 2014. Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI). www.genderindex.org. Note: Numbers in the map indicate SIGI ranking (1 = very low degree of discrimination in the lightest colour, 5 = very high degree of discrimination in darkest colour). Numbers inside countries denote countries’ rank among all assessed countries (1 = best).

IMF books are not available commercially, except direct from the IMF website: www.imf.org/en

When men and women are subject to different laws, women typically face institutions that are stacked against them. Can these differences explain the gap between male and female labour force participation, specifically whether such legal differences in treatment have an impact on female labour force participation rates over and above such determinants as demographic characteristics, educational gaps, and family policies?

Our empirical analysis is enabled through use of the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law (WBL) database, which focuses on how laws and regulations differentiate between men and women and, in turn, alter incentives to join the labour force. The WBL database is based on existing laws (de jure) and does not take into account how laws are put into practice (de facto). As a result, in the absence of comprehensive data on the practical application of laws across countries, this chapter relates existing legal restrictions to gender gaps in participation.

The WBL database provides detailed information on legal and regulatory barriers to women’s economic participation and entrepreneurial activity in 173 countries. It also focuses on seven indicators of gender-related differences in the legal and institutional framework:

• Accessing institutions—Women’s legal ability to interact with public authorities (for example, the acquisition of national identity cards)

• Using property—A woman’s legal rights to own, control, and inherit property

• Getting a job—Restrictions on women’s work (for example, restrictions on night shifts for women)

• Providing incentives to work—Tax considerations (such as tax credits and deductions available to women relative to men)

• Building credit—Access to finance

• Going to court—Access to small claims court and the weight provided to a woman’s testimony

• Protecting women from violence—The strength of laws to prevent violence against women

Some countries have numerous legal restrictions, with 30 countries having in place 10 or more restrictions on women’s participation. Only 18 economies were found to have no legal differences in the treatment of economic rights for men and women. In contrast, the WBL data suggest that almost 90 percent of the economies have at least one restriction on economic activity by women.

The nature of the restrictions varies across countries. In 18 countries, husbands can prevent their wives from working, and laws or regulations in 100 countries restrict non-pregnant and non-nursing women from pursuing the same economic activities as men. Other restrictions impede women’s property rights and thereby their access to finance.

Specifically, the World Bank and International

Finance Corporation (IFC) (2015) shows that in countries with property rights more favorable to women, there is greater financial inclusion of women (10 percentage points more bank accounts owned by women). Gender-based differences in property rights also make it more difficult for women to deploy immovable property as collateral in order access credit.

There has been a steady easing of legal restrictions against women and thereby a gradual leveling of the playing field in most countries. For two WBL indicators—accessing institutions and using property—the data set provides detailed information for 100 economies spanning the period from 1960 to 2010. The data show that more than half the restrictions in accessing institutions and using property in place in 1960 had been removed by 2010. In particular, 280 changes took place in the gender-based legal framework, mostly in the areas of introducing a nondiscrimination clause based on gender, female property rights, and the legal ability of married woman to get a job and pursue a profession. The restriction on married women working (for example, needing their husbands’ permission) was removed in 23 countries (for example, by Turkey in 2001 and in South Africa and Guatemala in 1998). Restrictions on married women opening a bank account were relaxed in 20 countries, including by Mozambique in 2004 and Lesotho in 2006.

The progress has continued in the recent years, with several countries passing or changing their laws in favour of more gender inequality since May 2013. For instance, Egypt’s new constitution features ‘sex’ as a new category in its non-discrimination clause. In Belarus, the number of professions in which work by women is prohibited was reduced from 252 to 182. In Nicaragua and Togo, men and women now have equal rights to be the head of household. In Kenya, a new law on matrimonial property gives both spouses equal rights to administer joint property. But despite this progress, there are still many gender-related restrictions in place, particularly in the Middle East and north Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and south Asia.

The continued prevalence of gender bias in jurisdictions is confirmed by rankings from related databases as well. One of these is the ‘Social Institutions and Gender Index’ (SIGI) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is highly correlated with a number of subcomponents of the WBL, including equal inheritance rights and the rights of women to get a job or pursue a profession. Similarly, country rankings in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index are highly correlated with those in the WBL and SIGI databases.

The data suggest a strong relationship between

Find

In November 2017 the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, representing 700,000 female farmworkers and women in farmworker families across the US, wrote a letter of solidarity to the Hollywood women at the centre of #MeToo. ‘We do not work under bright stage lights or on the big screen,’ the letter said. ‘We work in the shadows of society in isolated fields and packinghouses that are out of sight and out of mind.’ Nevertheless, it continued, ‘we believe and stand with you.’ The question left unasked, taken up in discussions in the days that followed, was: ‘will you believe and stand with us?’

This question inspired the Time’s Up initiative, a legal defence fund to help women in all industries fight sexual harassment. The first meeting was held at the home of actor Jessica Chastain; other white actors involved included Reese Witherspoon, Natalie Portman, Nicole Kidman, Amber Tamblyn, Jennifer Aniston and Margot Robbie. But women of colour were also at the forefront from the start. The founders of Time’s Up included National Women’s Law Center president Fatima Goss Graves, producer Shonda Rhimes, actors Rashida Jones, America Ferrara, Eva Longoria, Lena Waithe and Kerry Washington, and director Ava DuVernay. In 2018 Time’s Up awarded $750,000 in grants to 18 organisations across the US supporting low-wage workers.

The profile of women of colour in such a mainstream initiative made Time’s Up a departure from the norm. Nevertheless, it was criticised for being an ‘exclusive club’ and concentrating too much on white celebrities. It was also accused of using activists of colour as window dressing: for instance, at the 2018 Golden Globes, when eight white Hollywood stars each took an activist as their ‘plus ones’. Time’s Up occupies a complex position in a feminist mainstream dominated by white and privileged women. Even when women of colour are in leadership roles, the pull of whiteness is strong.

This is the trouble with mainstream feminism, encapsulated in the title of my book Me, Not You. The #MeToo movement, started as a programme of work by Black feminist and civil rights activist Tarana Burke in 2006, went viral as a hashtag 11 years later after a tweet by white actor Alyssa Milano. And mainstream movements such as #MeToo have often built on and co-opted the work of women of colour while refusing to learn from them or centre their concerns. Far too often the message is not ‘Me, Too’ but ‘Me, Not You’. And this is not just a lack of solidarity. Privileged white women also sacrifice more marginalised people to achieve our aims, or even define them as enemies when they get in our way.

#MeToo is a movement about sexual violence, most of which is perpetrated by cisgender men. This book is also about violence—especially the violence we can do in the name of fighting sexual violence. When I say ‘we’, I mainly mean white women and white feminists. This book is addressed to my fellow white feminists; although it is dedicated to Black feminists, they will not need to read it. For feminists of colour, the arguments I make here will probably be nothing new (and I hope this book will help ease the burden of constantly having to explain whiteness to white women).

I am ambivalent about writing about whiteness: I am concerned, as some readers might also be, that in critiquing whiteness from within, I am trying to absolve myself of my own. I am worried that I am trying to be one of the ‘good white people’ who perform what feminist scholar Sara Ahmed calls a ‘whiteness that is anxious about itself’.

And deep down, that might be the case. Whiteness is wily: white supremacy is so embedded in our psyches that we end up doing it even while we claim (and believe) it is what we oppose. You are entitled—even invited—to make up your own minds about my motivations. But regardless of why you think I have written it, I hope you find something in this book of value. And if not, I am happy to be told I am wrong: knowledge is always partial, and we learn through dialogue with one another.

My analysis of mainstream feminism comes from 15 years of research on, and activism around, sexual violence. I am a white academic in this field, with all the privileges that entails. But my experience of it has been ambivalent and complex. I experience class anxiety in academia. My politics tend to differ from those of many other scholars and activists in my area, as well as (in other ways) those of my family of origin. I am what Sara Ahmed would call a ‘wilful child’: I do not fit in. I am also a queer woman with non-paradigm experiences of sexual trauma.

To understand all these things, I have repeatedly

turned to the words and actions of Black feminists and other feminists of colour, trans women and sex workers (and women who fit two or more of these categories). Their ideas are what Ahmed would call my feminist bricks; it has been my privilege to spread some mortar between them.

This is a book about mainstream feminism. And by this I mean mostly Anglo-American public feminism. This includes media feminism (and some forms of social media feminism) or what media scholar Sarah Banet-Weiser has called ‘popular feminism’: the feminist ideas and politics that circulate on mainstream platforms. It also includes institutional feminism, corporate feminism and policy feminism: the feminism that tends to dominate in universities, government bodies, private companies and international NGOs. This is not a cohesive and unified movement, but it has clear directions and effects. In other texts, it has been called ‘neoliberal feminism’, ‘lean-in’ feminism and ‘feminism for the 1%’. This is because it wants power within the existing system, rather than an end to the status quo.

Mainstream feminism, exemplified by campaigns such as #MeToo, tends to set the agenda for parliamentary politics, institutional reform and corporate equality work. It tends to be highly visible internationally because Western media forms are dominant across the globe. But this mainstream movement is by no means the whole of feminist politics. I am aware that defining ‘feminism’ as white and privileged risks (re)constituting it as such and I do not want to erase the fundamental contributions of feminists of colour. A founding assumption of this book is that the mainstream Anglo-American movement is often taken to represent feminism, when in fact it does not.

White and privileged women dominate mainstream feminism. These demographics shape the movement’s politics but are perhaps partially hidden by monikers such as ‘neoliberal feminism’, ‘popular feminism’ and the rest. In contrast, this book centres race, giving an additional reading of the movement at a time when white supremacy is being violently reasserted.

There is already increasing discussion of ‘white feminism’, used to denote a feminism that ignores the ideas and struggles of women of colour. This book is based on the concept of political whiteness, which describes a set of values, orientations and behaviours that go deeper than that. These include narcissism, alertness to threat and an accompanying will to power. And perhaps most crucially, they characterise mainstream feminism and other politics dominated by privileged white people. They link movements such as #MeToo with the backlashes against them. And they link more reactionary forms of white feminism with the far right.

Political whiteness tends to be visibly enacted by privileged white people (but can cross class boundaries) and can also be enacted by people of colour because it describes a relationship to white supremacist systems rather than an identity per se. It is produced by the interaction between supremacy and victimhood: the latter includes the genuine victimisation at the centre of #MeToo and similar movements, and the imagined victimhood of misogynist, racist and other reactionary politics. I am not denying that mainstream feminism is rooted in real experiences of oppression and trauma. I am not saying that these experiences do not deserve to be taken seriously. But I am asking: how are these experiences politicised, and what do they do?

My analysis of mainstream feminism is grounded in the principle of intersectionality. Developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw and other Black feminist scholars, this refers to the complex relationships that make up our social world—relationships between categories such as race, class and gender, and between the associated oppressions of racism, classism and sexism. These are produced by intersecting systems: heteropatriarchy, racial capitalism and colonialism.

Patriarchy refers to the domination of women by men. This pre-dates capitalism (at least in the West), but capitalism embedded it by separating production and reproduction and making women responsible for the latter. Capitalism relies on social reproduction—creation of and care for human life—but doesn’t want to foot the bill. Historically, white bourgeois home-makers were confined, unpaid, to the private sphere. Working women have been (and are) over-represented in the low-status and low-paid caring professions which also

Publisher’s price £12.99

Save £1.56

Booklaunch price £11.43

inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

White feminists may be playing into the hands of the resurgent

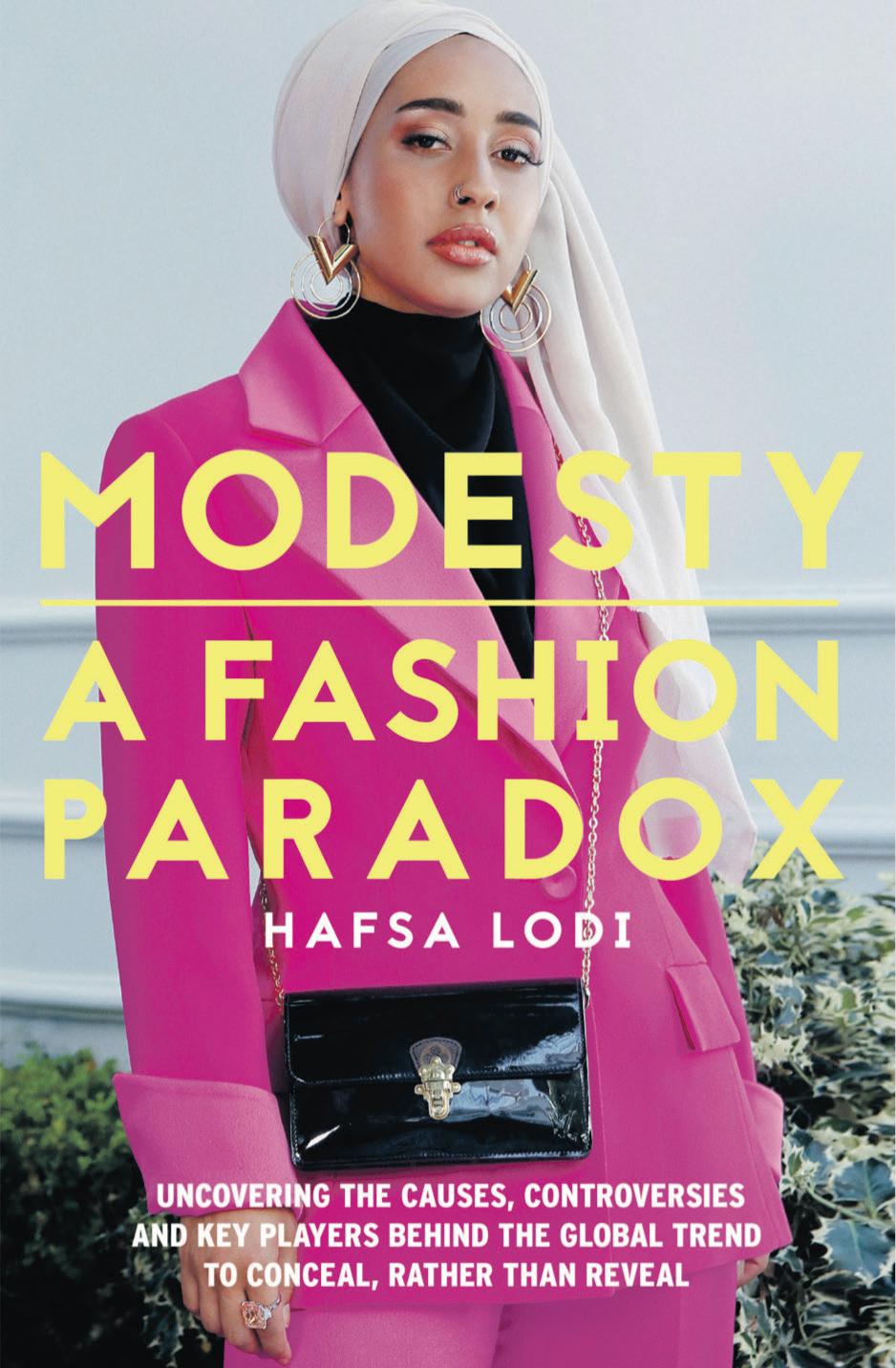

As a fashion enthusiast who doesn’t wear a hijab but has always tried to dress modestly from the neck down, I’ve waited for mainstream acceptance of modest fashion for over two decades. I … never anticipated seeing a whole Wikipedia page dedicated to modest fashion, or a news story in the Guardian titled ‘The end of cleavage: how sexy clothes lost their allure.’ Nor did I ever imagine I would type in vogue.com and be greeted by an image of two Caucasian models in black jumpers and trench coats, with their faces bordered by tight-fitting black headscarves, topped off with black hats.

It’s clear that modest fashion is being embraced by millions of women who have no religious affiliations, as well as Christians, Orthodox Jews and Muslims. Not to mention the style movement that’s gaining traction with men, who are eschewing sagging pants and muscle vests for more polished looks, in the name of modesty.

So I can’t help but ask—what is driving this trend, and why is it happening now?

While modesty is relevant to consumers of all … faiths and backgrounds, it’s retailers’ preconceived notions of Muslim and Middle Eastern wealth that is the reason for modest wear skyrocketing into the mainstream over the past few years. Author Shelina Janmohamed, who uses the phrase ‘Generation M’ to refer to the growing group of young Muslim millennials and entrepreneurs who share the characteristics of faith and modernity, points out that while Muslims may welcome the industry’s increased focus on modest wear, it’s not a black-andwhite embracement of diversity. ‘While reaching out to Muslim consumers might leave their audience with a warm fuzzy feeling, there are financial incentives too,’ Shelina claims.

In 2015, Muslim consumers worldwide spent around US $243 billion on clothing, with around US $44 billion, or 18 percent, on modest fashion purchases by Muslim women, according to the ‘State of the Global Islamic Economy Report’ from Reuters and DinarStandard.

The report estimates that by 2021, Muslim consumer spending worldwide will reach US $368 billion—a 51 percent increase from 2015. Muslims are expected to account for 30 percent of the global population by 2030, with more than 50 percent of that population aged under twenty-five. Their spending power, attributed mainly to Middle Eastern millennials, is what the global fashion industry is now scrambling to attract.

In an article about the modest fashion industry for Bustle, journalist S.I. Rosenbaum writes, ‘Financially, its biggest engine is the global Muslim market, particularly in wealthy but devout Gulf nations with money to spend and religious standards to keep up.’ And so, still reeling from recurring global recessions, more brands are turning their eyes to Middle Eastern wealth.

These population projections and financial motives are no secret—it’s widely recognized across the globe that international fashion labels’ increasingly covered-up runway presentations are not paying homage to Middle Eastern cultures, but rather to their deep pockets. ‘It would of course be naive to ignore the fact that modest clothing is another way to market towards consumers from Muslim-majority countries with young populations and many, many petrol dollars,’ states Kashmira Gander in the Independent.

Professor Reina Lewis, British art historian and cultural studies lecturer at the London College of Fashion, has extensively studied the contemporary evolution of modest dress. She found that, before modesty began trending, early Islamic-based lifestyle magazines struggled to convince the press offices of fashion houses to loan them products for their fashion shoots, as they didn’t view the predominantly Muslim readerships as target audiences for their fashions. Some stylists and editors had to resort to deceptive devices, like hiding the fact that their publications were in any way aligned with Muslims, to get their hands on these coveted clothes. Now, the tables have turned.

It’s impossible to ignore the undeniable financial potential unlocked by businesses that take special steps to cater to Muslim consumers. As I reach my 30s, after gaining a master’s in Islamic Law from the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and working for a decade as a fashion journalist in the Middle East, I’m often finding it difficult to reconcile my two worlds.

Though at the age of 14, I believed ‘Modest is Hottest’ to be a catchy, clever and relevant slogan that summed

up my world view, the social media obsession that many fellow millennials are afflicted with has led me to question the way in which the modest style revolution has used digital means to communicate its message to consumers worldwide. In Islam, modesty is encouraged to promote a certain veil of privacy between men and women. But where’s the privacy in sharing selfies— albeit conservatively dressed ones—on Instagram to billions of strangers? If women are using apps like Instagram to show off their skin-covering outfits, are they still embodying the Islamic ideal of modesty?

Plus, there’s a whole other dispute brought up by this style revolution. While hordes of fashion bloggers on social media may celebrate it, there are many women for whom the term ‘modest fashion’ feels like an insult.

Julie Burchill slammed the concept of modest fashion in an article for the Daily Mail. ‘What I don’t like at all is when modesty is used as a shaming stick which women use to beat other women,’ she writes. ‘When applied to clothing, the word implies, by default, that any other form of dressing is immodest, that is, tarty, exhibitionist and “wrong”.’

The argument is not a solely Western one. Many women of Asian and Middle Eastern heritages, for whom modesty may have been strictly enforced in their own upbringings, are staunchly against using the word ‘modest’ to promote a certain way of dressing. Gita Sahgal, a prominent Indian writer on feminism, fundamentalism and women’s rights, claims, ‘Whether they know it or not, the global fashion business is marching in step with Islamists when they create lines of “modest” clothing—as opposed to a range of choices for women and girls.’

‘Islamists promote hijab for political reasons, the fashion industry complies to make money. It is a nasty alliance,’ claims Iranian activist Maryam Namazie, who says that ‘modesty culture’ teaches girls from a young age that if they fail to dress modestly, they will become vulnerable to violence from predatory men, who are unable to resist sexual urges. ‘Women have been fighting modesty rules for as long as the rules have existed, but what is worrying is the return to the mainstream of modesty rules, albeit packaged in a lovely silk-chiffon … Whether via acid attacks or Dolce & Gabbana adverts, the message is clear: a good woman is a modest one.’

Some women argue that the modest styles currently in vogue appear overtly elitist, and are only suited to certain body types and budgets. ‘Only those blessed with the privileges money and slim looks bring, these women seemed to suggest, could get away with wearing a dress that evokes virginal drabness at best and cult-style patriarchal oppression at worst,’ writes Naomi Fry in a New York Times Style Magazine feature titled ‘Modest Dressing, as a Virtue’. She points out that popular television show The Handmaid’s Tale, based on the novel by Margaret Atwood, uses modest clothing—namely longsleeved, ankle-length dresses and cloaks, in addition to head coverings for handmaids and servants—to connote obedience and submission.

While it may be true that in some Middle Eastern and Asian communities, conservative dress is enforced upon women—be it by their governments or patriarchal families—many women in the West are adamant that dressing modestly, whether that includes a headscarf or not, can be liberating. Personal interpretations of modesty vary among different women, but the resounding message at the crux of the movement is one and the same: choosing to cover up is a matter of personal choice.

Women who opt for more layers and fabrics over the comparatively bare offerings in stores are making the profound decision to take ownership of their bodies, rather than succumb to Western societal pressures that deem a woman’s body—or her hair—to be her ultimate beauty, which she should use to attract men.

And the modest silhouettes that are now infiltrating storefronts are providing these women with an abundance of stylish options—their covered up outfits need not be dull, ill-fitting or uninspiring. Instead, they can exude character and confidence, with the layers, colors, patterns and accessories combining to create an armor that’s fashioned from motives far more meaningful than frivolous trends.

Soon after the September 11 terrorist attacks, New York’s Democratic congresswoman Carolyn Maloney donned attire that is worn by a minority of Muslim women, influenced by the countries where they live and the cultural dress norms handed down from

Hafsa Lodi

Neem Tree Press (London), Softback, 9781911107262, 258 pages, 25 col. photos, 156 mm x 234 mm, 19 March 2020

Publisher’s price £20.00 Save £5.01

Booklaunch price £14.99 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

FROM

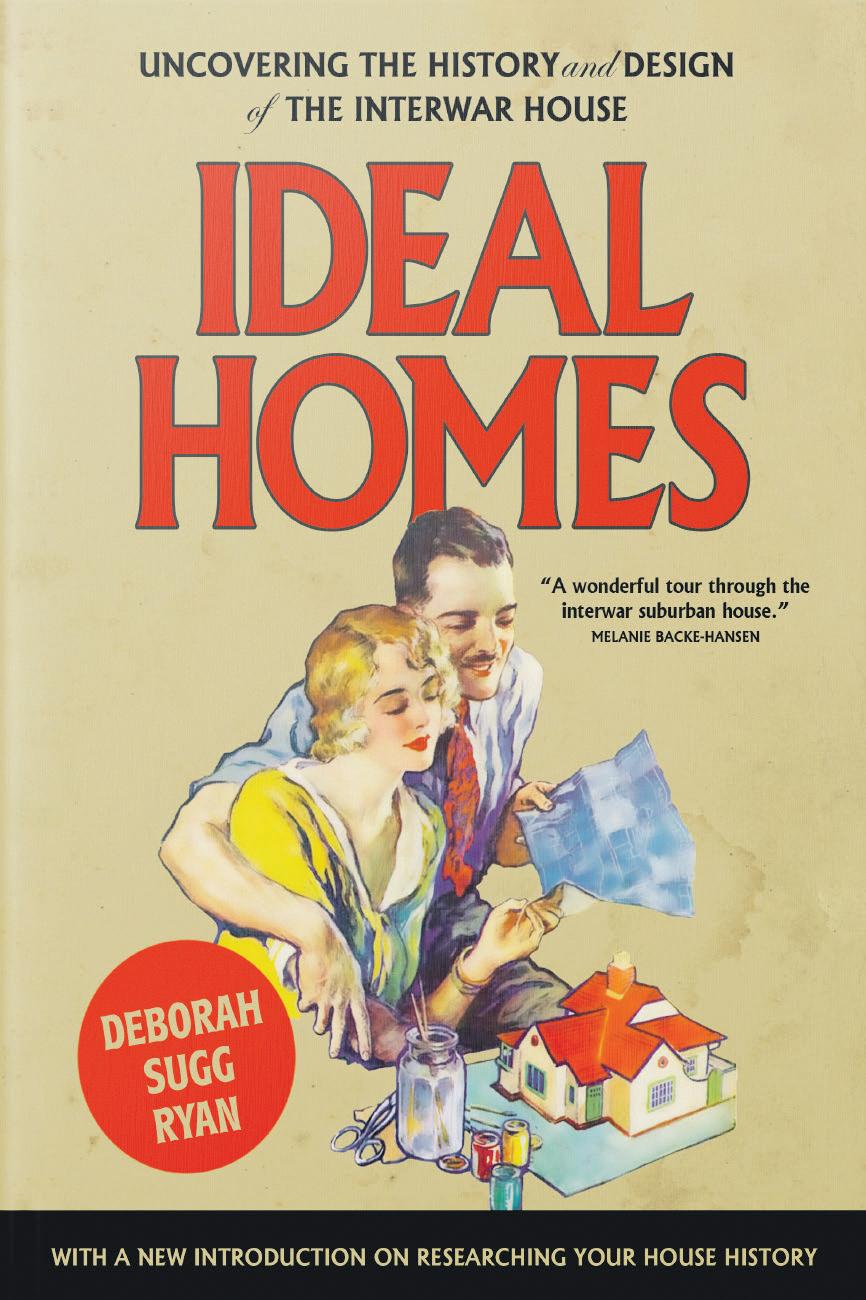

The interwar semi has tended to be regarded as an object lesson in ‘bad design’, all the better to demonstrate the virtues of modern mass production exemplified by bent plywood and tubular steel furniture. In this book I challenge the dominance of Modernist aesthetics and values on writing on design, architecture and consumption by exploring popular conceptions of the ‘modern’ that accommodated past and present, nostalgia and modernity within their social and historical contexts.

I stress suburbanites’ own agency as consumers, especially where they resisted and contested official notions of ‘good’ taste and design. And I question the way ‘period’ rooms in museums [are] nearly always seen through the lens of the invented retrospective term ‘Art Deco’. As Mark Turner, the former curator of Middlesex University’s Silver Studio Collection, said,

In all the years I have spent looking at untouched interwar houses, I have never once seen an interior that was the riot of Art Deco Moderne which museums and television would have us believe was typical. Very few suburban residents could buy all their furniture new and immediately. Pieces were acquired as money allowed, and Modernism was thought to be more appropriate for easily replaceable wallpaper and mats.

What we now call Art Deco was referred to at the time by terms such as ‘Jazz Modern’, ‘Modernistic’ or ‘Moderne’ and I have adopted the term ‘Modernistic’. … This book will contribute to recent literature by art and design historians on ‘other’ modernisms. For example, Christopher Reed argues that what he terms the ‘amusing style’ was a specific form of modernity formulated by the Bloomsbury set in their homes. Michael Saler suggests that the Arts and Crafts movement inspired ‘Medieval Modernism’ in the design of the London Underground. Paul Greenhalgh describes an ‘English compromise’ as a response to Modernism. Alan Powers identifies a ‘modern George VI style’.

Publisher’s

Booklaunch

To

However, these studies are few and far between, and design historians have lagged behind literary critics such as Nicola Humble, Alison Light, Melissa Sullivan and Sophie Blanch, who have exhaustively studied multiple Modernisms, particularly focusing on what they term ‘middlebrow’ writers, outside the canon of literary Modernism.

The meaning of objects is not just formed by designers but also throughout their lives by users. This is especially useful for understanding objects for which there is no known designer or readily identifiable style. Design historians and art historians have been influenced by social anthropologists who investigate how objects embody sets of social relations and acquire values and symbolism through use, and help form personal identities.

The interwar house

How did the domestic design of the interwar suburban home in England both dictate and express the identities and sense of belonging of homeowners to wider communities and networks, including their hopes, desires and aspirations?

I have spent a great deal of time poring over the surviving representations and actual material culture of the home in repositories such as Middlesex University’s Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Getty Images (which incorporates the Hulton Picture Library, which supplied publications such as Picture Post), newspapers (especially the Daily Mail) and the publications and records of the Daily Mail Ideal Home exhibitions. I have also scoured antique shops and fairs, auctions, car boot fairs, charity shops and eBay as well as exhibitions, advice manuals, trade literature, advertisements, magazines, novels, memoirs, photographs and films as well as actual examples of suburban architecture, interiors and material culture.

I have been influenced by novels and memoirs, both interwar and contemporary, in which stories of houses and home-making activities feature prominently. Several books present biographies of houses fused with personal memoir, notably Julie Myerson’s Home: The Story of Everyone Who Ever Lived in Our House (2005), Rosa Ainley’s 2 Ennerdale Drive: An Unauthorised Biography (2011) and Margaret Forster’s My Life in Houses (2014). Akiko Busch’s Geography of Home: Writings on Where We Live (1999) and Ben Highmore’s The Great Indoors: At Home in the Modern British House (2014) also deserve particular mention for their fusion of historical and sociological observations on the design and

use of the twentieth-century home with the authors’ own experiences.

Snapshots

One of the biggest challenges has been to try and capture the domestic design of the interwar home as it was inhabited and lived in. I looked hard for photographs of lived interiors in modest semi-detached homes that had not been tidied up for the camera. They have proved elusive. However, photographs of working-class rented homes from the interwar period, particularly slum dwellings, are more readily available. These continued a tradition of photography as a tool of social exploration that started with John Thomson in the 1870s and continued in the twentieth century with the post-First World War concern with slum clearance and the ethnography of Humphrey Spender’s Mass Observation photographs. A rich vein of interwar photographs reveal slum interiors located in older 19th- and 18th-century buildings.

One case in point is a photograph of a working-class home showing a family eating a meal in their kitchen/ living room. Washing is strung over the table and there is a traditional range. Yet on the wall there is startling Modernistic wallpaper. I found many other examples where the modernity of some of the interior decoration is in striking contrast with items from an older period.

Most often this takes the form of wallpaper in a riot of ‘Jazz Modern’ patterns, which could be purchased cheaply and was frequently papered over previous layers. Or sometimes it is a small item of ceramics, such as a vase depicting a camel, no doubt influenced by the Egyptomania craze that followed the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen. Modernistic elements sit alongside traditional Windsor chairs and the piece of lace that covers the mantelshelf over the range.

Photographs like this suggest a sense of ‘making do’ and point to a human need for colour, pattern and modernity. They also go some way to explaining why such wallpaper might have been seen in its time by designers and cultural critics as cheap, nasty and vulgar—in ‘bad taste’ and as an example of ‘bad design’.

Relatively few people decorated their homes, or went out and bought brand new furniture and furnishings, all in one go. Moreover, few subscribed to one particular style, and fewer still to the tenets of Modernist ‘good design’ advocated by the design reformers of the interwar years. New homeowners who had struggled to scrape together the deposit for their houses and strained to make the monthly repayments often had to manage with borrowed things. There was a thriving market in second-hand furniture, with some big furniture shops selling used furniture alongside brand new.

However, if they were given a choice and had the means, many opted for new furniture but in a reassuring traditional form. They did not value antique furniture for its patina, which for them was associated with dirt and making do. Moreover, it was common for people to hang on to their furniture for years, whether for sentimental or purely pragmatic reasons.

Consequently, when I have been lucky enough to stumble upon unstaged amateur photographs, which are nearly always undated, they are also nearly always impossible to place within a design history chronology of style, progress and fashion.

For many, the home they made in the interwar years stayed very much the same for subsequent years once it was ‘done’. The modernity or otherwise of the interwar years stalled because of the Second World War. Rationing and austerity compelled people to ‘make do and mend’, as a government campaign advised. After the war, exhibitions such as ‘Britain Can Make It’ (1946) and the Festival of Britain (1951) promised the modernity of the ‘Contemporary Style’. In the dream palace of the cinema, British audiences swooned over the new consumer world of goods depicted in American films. However, even if such luxuries as a fitted kitchen made of Formica were available, for the majority they remained firmly out of reach, prohibited by cost and lack of credit.

In his Homes Sweet Homes (1939), which satirised the interwar English obsession with homemaking, the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster commented on a noted tendency to produce multi-purpose objects:

It is significant that the Old English fondness for disguising everything as something else now attained the dimensions of a serious pathological affliction. Gramophones masquerade as cocktail cabinets; cocktail

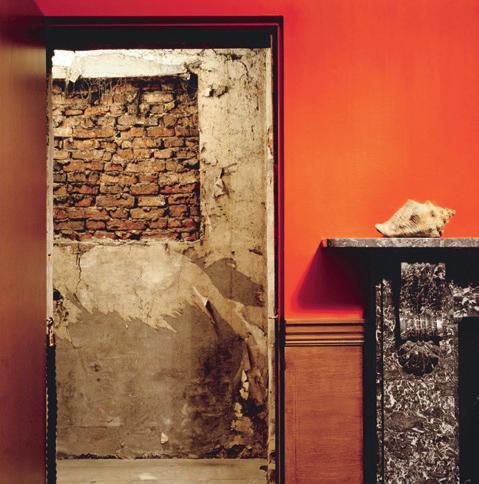

Age wasn’t always respected in old buildings; past layers tended to be stripped away. That changed in the 1870s, when the “anti-scrape” movement started to value the accretions of time. In his new book, Richard Griffiths gives examples of how his own architectural practice has adapted cathedrals, castles, stately homes, hotels and old industrial buildings to face the future without misrepresenting their past

Publisher’s price £30.00 Save £5.00

Booklaunch price £25.00 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

Richard GriffithsAt a dinner in Cape Town, just after South Africa’s first democratic government had taken office, someone said “I am starting to miss apartheid.” For a few moments the conversation ceased. Had the diners not been senior members of the ANC, the comment would have been intolerable. But everyone there had been in the front line of the battle against apartheid, in a rainbow alliance of whites and Blacks, politicians and church leaders, trade unionists and academics, students and activists. All were united by a common cause.

Then the silence was broken—by chuckles, and nods of understanding; the speaker was missing the clearer battle lines, the more obvious enemies, the friendships forged in hardship. Michael Holman was at that dinner. He has been writing about Africa all his life and his journalism over those years is now looking to be published

Michael Holman has spent his life working for the Financial Times, first as a correspondent, later as its Africa editor. He was brought up in a small town in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) by his Cornish father and white South-African mother. While a student he was restricted to his home town of Gwelo (now Gweru) after being named a danger to the the state by a Rhodesian MP. Released after a year, he took a post-graduate degree at Edinburgh University, thanks to the intervention of Malcolm Rifkind, then a young lecturer in Rhodesia. He has had Parkinson’s disease since 1986 and had a pioneering deep-brain electrode operation in 2006. He has written three novels, set in East Africa, and continues to write for the FT and other papers

1974. An obituary in the British South Africa police magazine Outpost begins:

The term ‘complete Rhodesian’ can be applied to several local personalities but never with as much justification as when we refer to the late Police Reservist Delville Vincent who was killed in action (against guerrillas) in Northern Mashonaland on April 3, 1973. Del was born in South Africa in 1929 …

And that is, and will be, Rhodesia in the 1970s. White immigrants dying, defending with the gun the country whites took by the gun.

Because we’re all Rhodesians and we’ll fight through thick and thin, We’ll keep our land a free land, stop the enemy coming in, We’ll keep them north of the Zambezi till that river’s running dry, And this mighty land will prosper ’cos Rhodesians never die.

We’ll preserve this little nation for our children’s children too, Once you’ve known Rhodesia no other land will do. We will stand in the sunshine with truth upon our side, If we have to go alone we’ll go alone with pride.

This charming ditty, ‘Rhodesians never die,’ is sung by an immigrant (he happens to be Prime Minister Ian Smith’s son-in-law). He is one of 60 per cent of the ‘white Rhodesians’ who were born outside Rhodesia.

I met another immigrant not very long ago. Hitching from Gwelo, in the heart of the Rhodesian Midlands, my friend and I were given a lift. The driver was a young, lean, deeply-tanned South African farmer, with a broad Afrikaans accent. He managed a pyrethrum estate on the eastern border. No, he didn’t miss his home. ‘You can talk to the munts (Blacks) here; you can’t in South Africa. Here I can say, “Bugger off, you shithouse.” I say that in South Africa and I get into trouble. You just can’t talk to the munts there anymore.’

One reason for his satisfactory labour relations no doubt lies in the fact that Black agricultural workers and domestic servants—no less than 55 per cent of all Blacks in employment—work under the Masters and Servants Act. This harsh and archaic piece of legislation (‘it is illegal in terms of the Act for any of his family, by desire of his master on any journey within southern Rhodesia … on which his master orders him to go …’) was enacted in 1901 and is based on legislation introduced into the Cape Province of South Africa in 1856. There is no provision in the act for trade unionism, collective bargaining, or other wage setting machinery. No wage minimum is established under the Act.

You can, however, get guidance on wages—as far as domestic servants are concerned—from the Information Booklet issued to new members of staff by the University of Rhodesia Women’s Club. It recommends $10–$12 a month plus rations (one dollar is about 75 pence) and ‘Hours of indoor servants are usually about twelve hours in duration’—two more than the minimum permitted by the Master and Servants Act.

The wages of Black farm workers average about $10–$15 a month plus rations. In real terms there has been a decline in their income over the past decade. There is a farm workers union, but there is also a catch: it does not receive recognition and is thus prevented from acting as a negotiating body. There is not the slightest chance that it will be recognised.

Addressing one farmers’ meeting, an official of the Rhodesia National Farmers Union warned: ‘Trade unions are ready and willing to exploit any grievance the worker may have. A recent example was the intervention of Mr Mpofu (the general secretary of the Plantation and Agriculture Workers Union) at a chicken farm near Salisbury. A pay dispute was built up by this individual to include grievances over housing and latrines and many other aspects the employees had not originally complained of.’ Both Mr Mpofu and the president of the union were restricted last year, joining about 60 of their colleagues from other unions.

‘We have a very sympathetic Minister of Labour,’ the official continued, ‘and you can rest assured that an agricultural trade union will not get recognition’ (the speech from which I take these extracts was not published).

Seventeen of the 49 RF (Rhodesia Front) MPs are farmers; 10 of the 18 cabinet ministers are farmers.

One must assume that former British Prime Minister

Mr Harold Macmillan was not aware of the Masters and Servants Act—and several other acts for that matter— when he wrote (in the last volume of his memoirs) that before the Rhodesia Front came to power in 1962 Rhodesia enjoyed ‘a tradition of moderation and even of liberalism’. But he is not the only one who believes in this tradition. His successor, Sir Alec Douglas Home, does too, and so does the main white opposition in the country, the Rhodesia Party, who see themselves as the inheritors of that tradition. ‘Rhodesia’s long and proud history of racial tolerance, harmony and understanding,’ proclaims the RF manifesto, ‘is today yielding to petty and unnecessary racialism.’

After persistent questioning Allan Savory (leader of the RP) admitted to me that the RP does not see its way clear to pledging repeal of the Act should it ever get into power.

The truth of the belief in this tradition of ‘moderation’ is possibly not as important as the role it plays in British policy. Around the belief is built the theory that as pressure on white rule increases, so white Rhodesians, becoming aware of their folly and their predicament, will get together and sort things out.

Every one of the dozen or so by-elections since Mr Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence puts the theory to the test, and always it takes a battering when RF candidates are returned by substantial majorities, occasionally being threatened by extreme right-wing candidates. The two by-elections on February 28 this year were no exception.

The votes in the two constituencies were:

Sinoia-Umvukwes: RF 553, RP 249, Rhodesia National Party (extreme right wing) 199, Centre Party (moderate white) 27,

Raylton, Bulawayo: RF 783, RP 371, CP 31.

Yet the pressures on white rule were apparent in February not simply to those with inside information, but to all those who read the leading daily, the Rhodesia Herald. Three whites were killed in guerrilla attacks in the Centenary area, which is part of the Sinoia constituency (in the north east of Rhodesia) just ten days or so before voting took place.

Men over 25 with no military commitments at present are now liable to call-up periods of one month. Rhodesians look with concern at Mozambique as rail links with the coast come under attack by Frelimo (the Mozambique Liberation Front). Hardly a day goes by without anxious reference to a black birth rate of 3.6 per cent which annually exceeds the white population of 280,000 in Salisbury. Stringent petrol rationing began in February due more to a shortage of vital foreign exchange than any supply problem.

All this and much else is public knowledge. Yet in the ninth year of UDI there is little evidence that the Rhodesia Front is losing any substantial support. I visited Centenary the day after the shootings, but I heard no reappraisal of white rule, no questions about the cost of white rule. Instead there were demands from local farmers for harsher punishment of tribesmen and farm workers who aided ‘terrorists’. (Although just two weeks previously 110 tribesmen had been taken into custody at Bindura, for allegedly collaborating with guerrillas in the murder of several Africans in the Madziwa TTL. Their crops and huts were destroyed and their cattle impounded. The Rhodesia Herald, falling over itself in an effort to plug the government line, headlined the news: TERROR MURDERERS AIDED BY TRIBESMEN although they had no evidence other than the allegations in the government communique.) The farmers also wanted a dusk-to-dawn curfew in the area, and the right to shoot ‘anything that moved’ during the curfew period.

The cattle impounded on the above and other occasions [MEANING?] are generally sold. There have been cases where the cattle have been shot. One needs to know something of the importance of cattle to the people to appreciate the enormity of this. Cattle are not measured in terms of so many pence per pound of flesh. One black writer says: ‘A family without cattle in Shona society is like a house built on sand … Cattle are the enduring foundation of traditional Shona society.’ Their slaughter is part of the ritual at marriage and death. ‘They plough the fields and carry crops … pull carts.’ ‘In Shona society, one’s social status and wealth are determined by numbers of cattle. Thus to have many cattle is the summit of a Shona’s desire. Except in cases

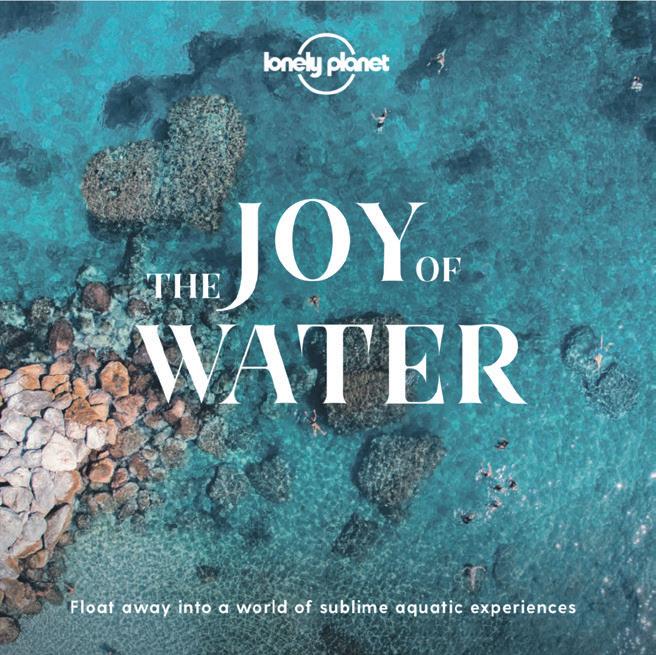

The Joy of Water offers personal stories of wild swimming and magical coves in more than 60 locations around the world. Use your time in lockdown to plan snorkelling trips in Mozambique’s coral reefs, soaks in Iceland’s geothermal pools and dives with nonstinging jellyfish in Palau

THE JOY OF WATER Lonely Planet (London) Hardback, 9781838690465, Illustrated, 272 pages, 200 mm x 200 mm, 10th April 2020

Publisher’s price £15.99

Save £1.92

Booklaunch price £14.07 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

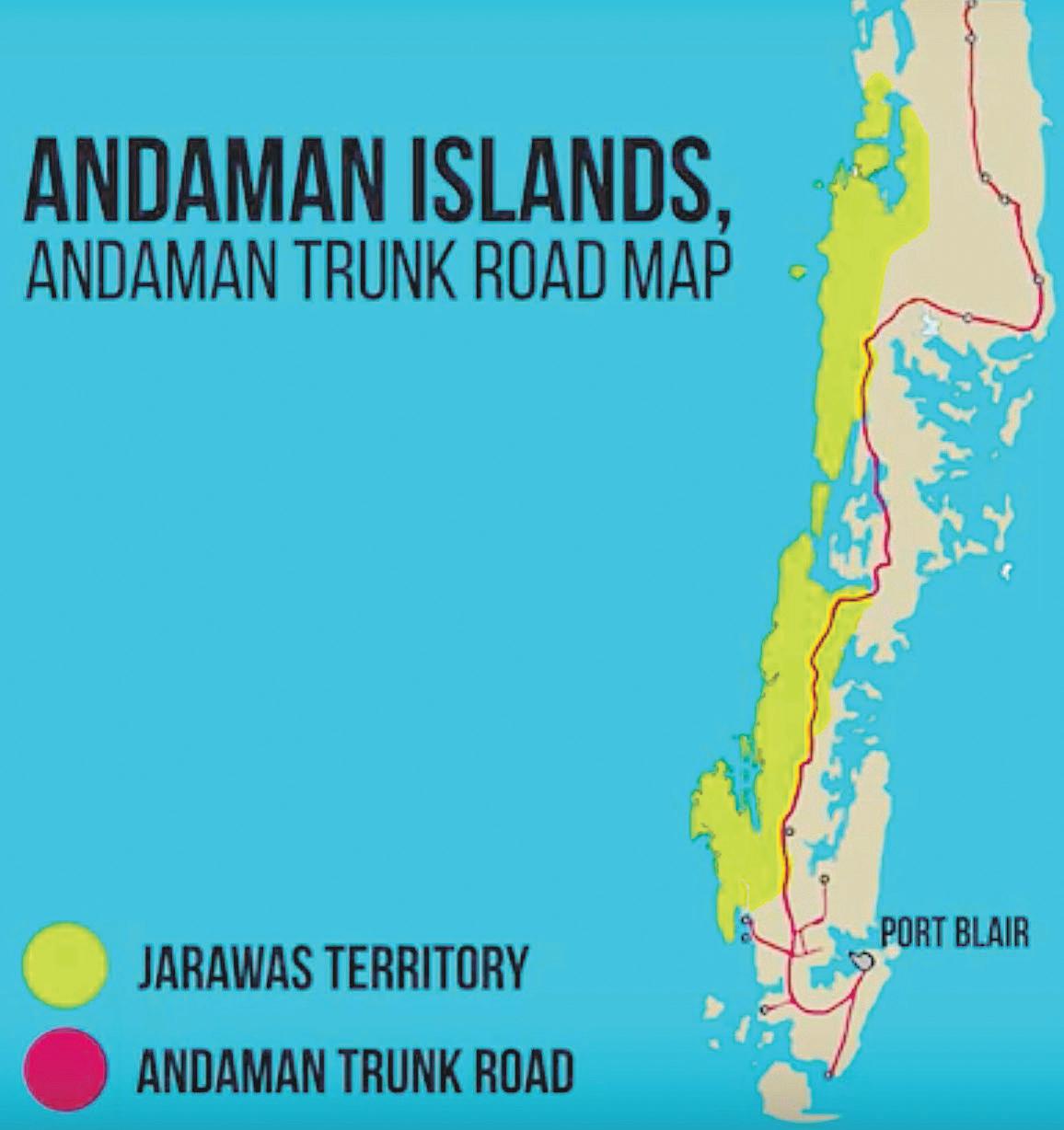

The Jarawa tribe, in India’s Andaman Islands off the coast of Burma, used to keep its distance from Western intruders. That is no longer possible. In his new book, Jonathan Lawley, whose family has roots in the area going back five generations, makes an impassioned plea to stop the Indian authorities treating the Jarawa like a human zoo