Happy Nappy poems for you and your baby Page 2

How Greek drama framed 9/11 and later tragedies Page 4

Saving the Canadian salmon from eco-oblivion Page 5

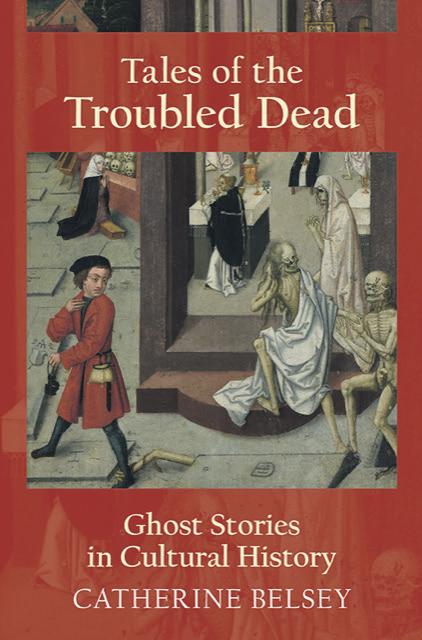

The ghosts that haunt literature Page 6

Can North Korea be rescued—from our errors and its own? Page 8

Inventing new foods and rediscovering old ones Page 9

Paul Murphy and the Good Friday Agreement Page 10

China and the future of investment Page 11

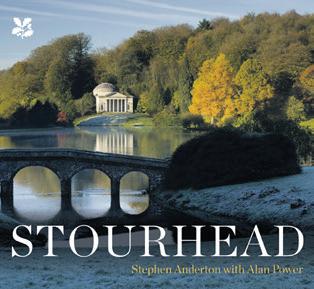

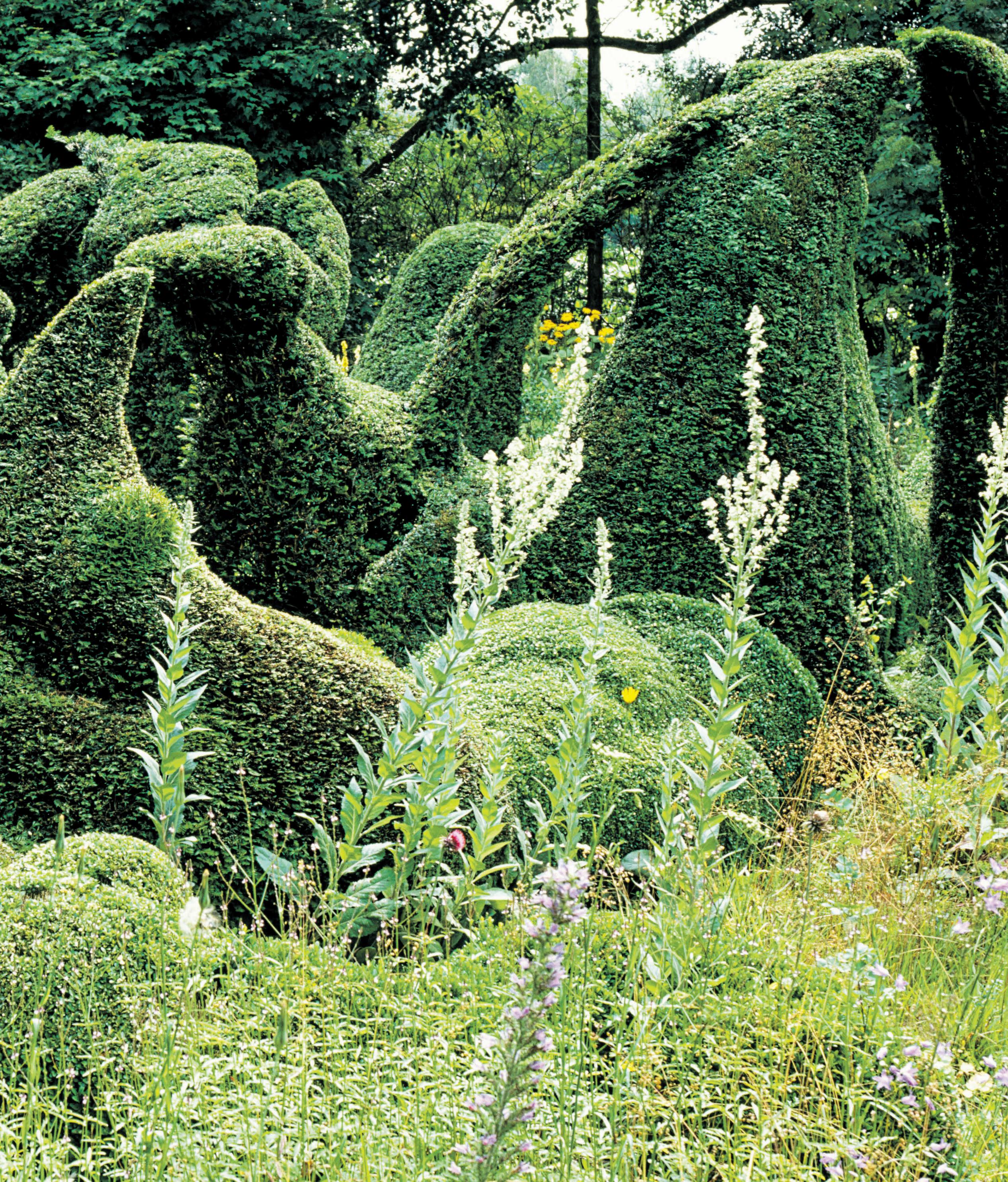

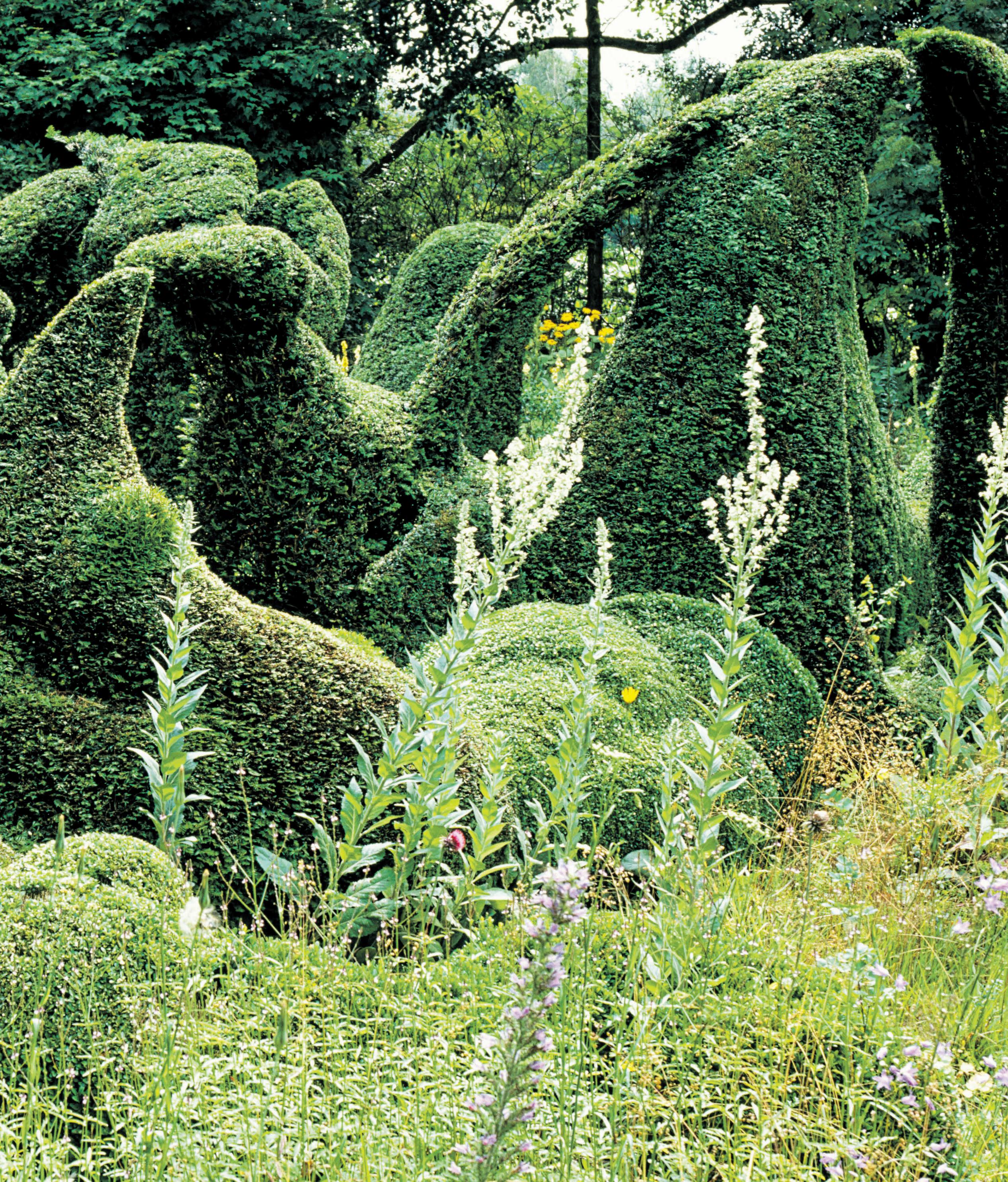

Penelope Hobhouse’s history of gardens Page 12

Why some people need an adrenaline rush Page 14

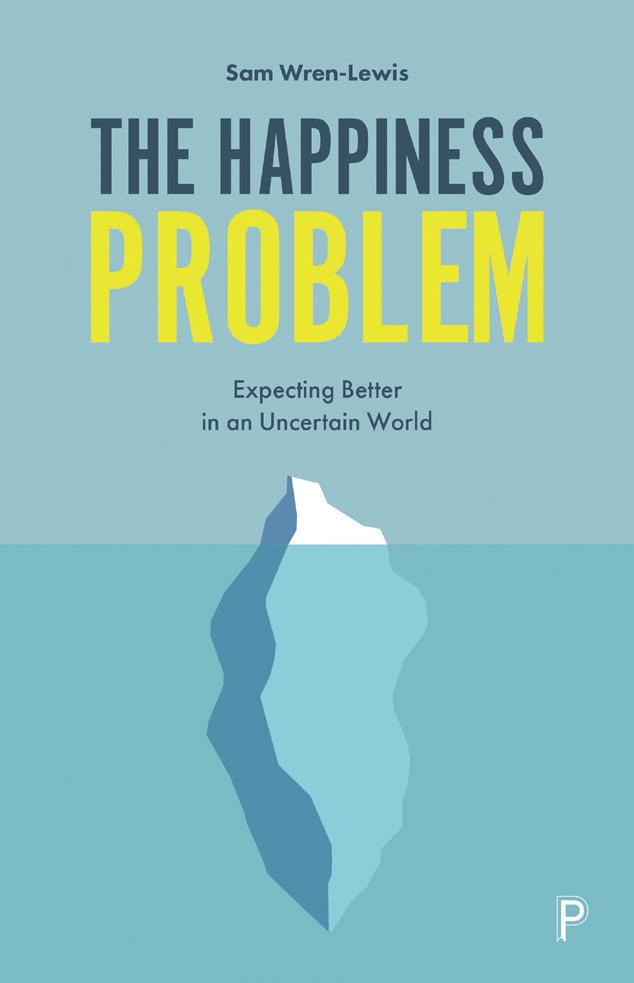

What are the basics of happiness? Page 15

Neil MacGregor on Poland’s view of Brexit Page 16

Keith Carter’s novel of mining, exploitation and human frailty Page 17

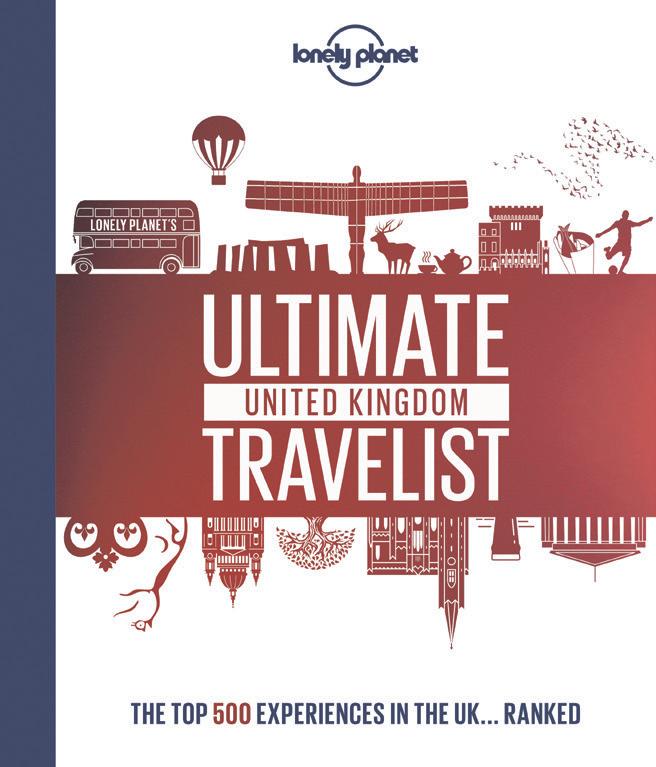

Lonely Planet’s Ultimate UK Travelist Page 18

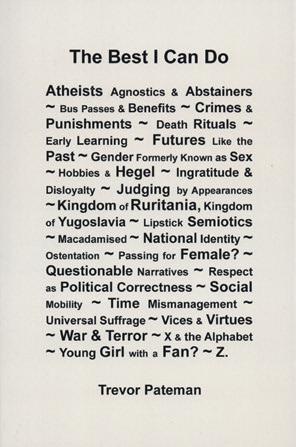

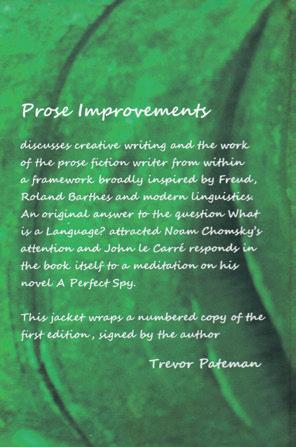

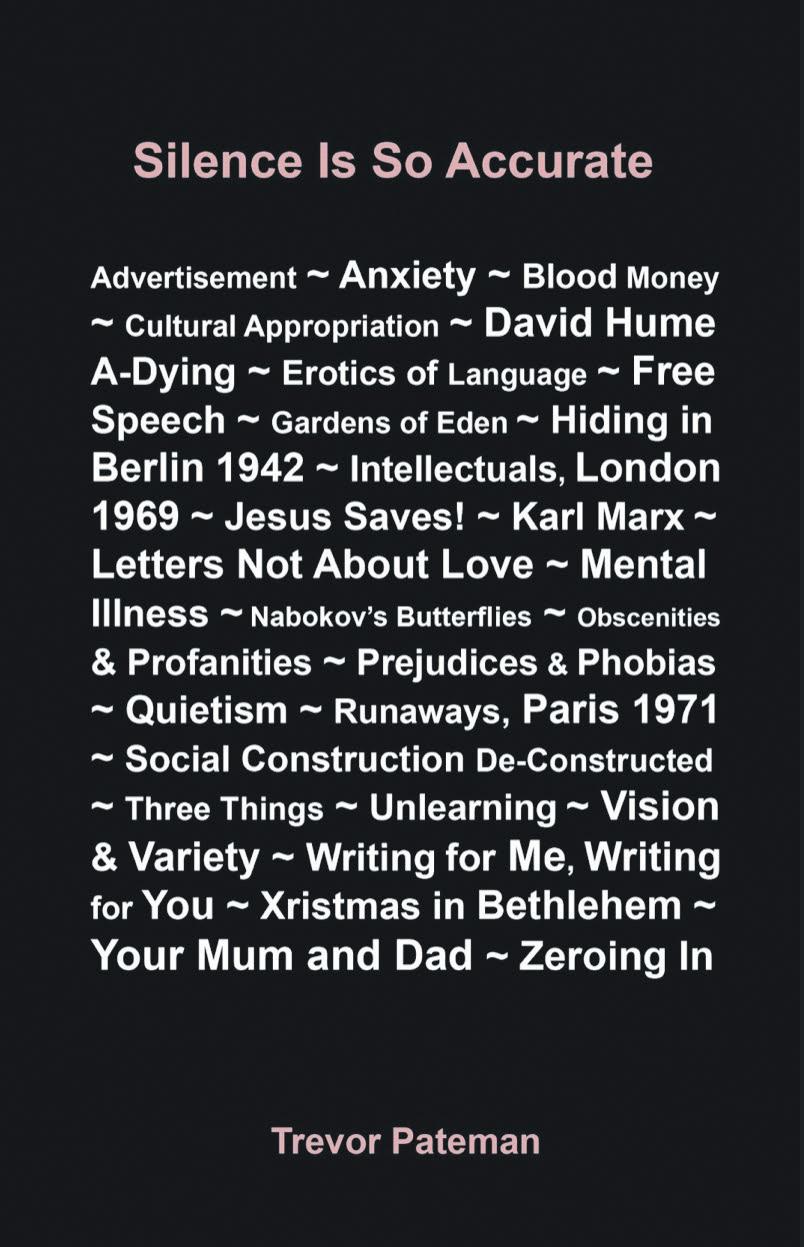

Trevor Pateman on the prudishness of publishers Page 20

Clive James and his poetic brain Page 21

Patrick Kelly: Love and The Troubles Page 22

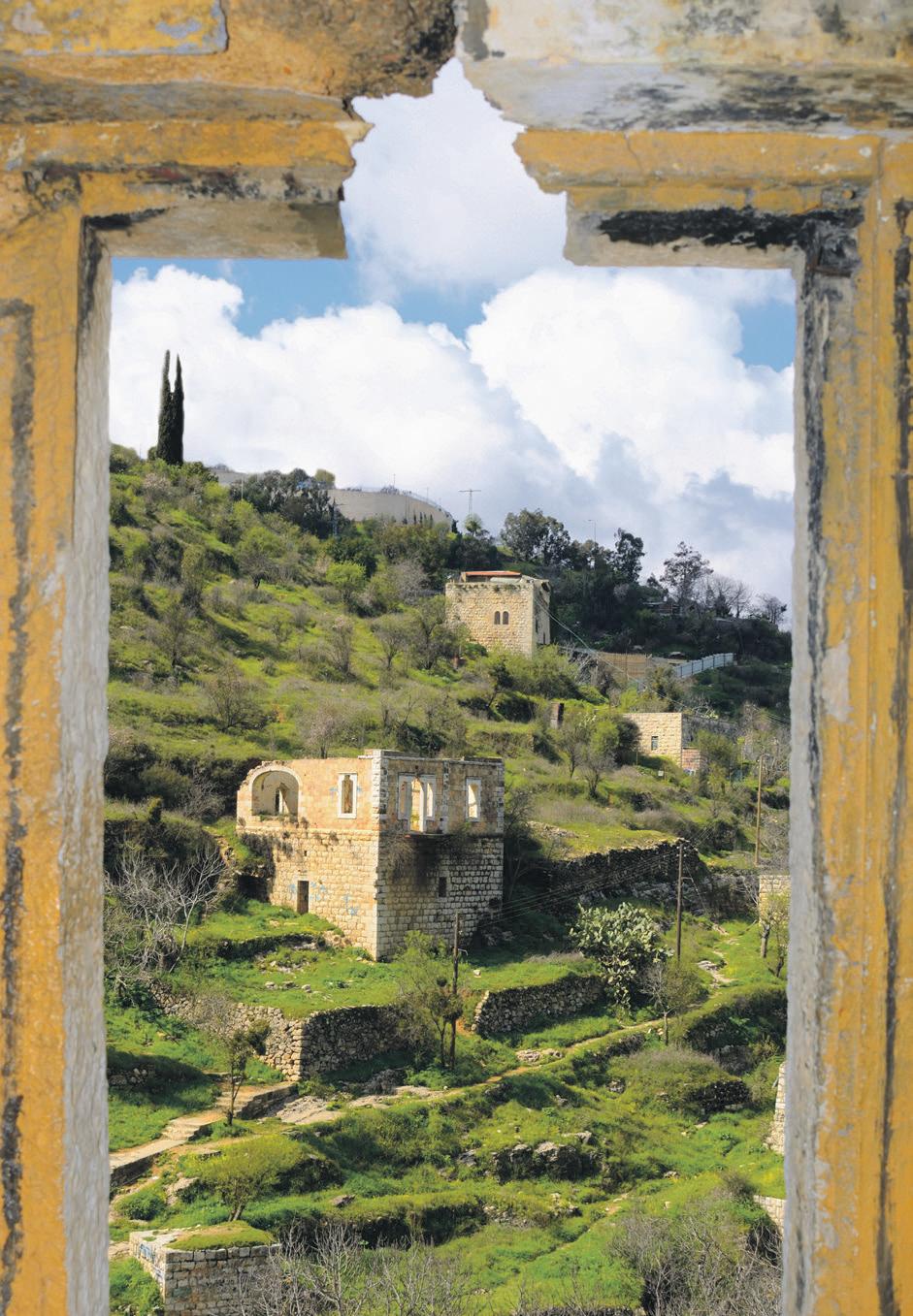

Anita Mason on the unravelling of certainty Page 23

Tianjin (Tientsin) Library, China (2017), by Dutch architects MVRDV.

Photo by Alex Fradkin

Tianjin (Tientsin) Library, China (2017), by Dutch architects MVRDV.

Photo by Alex Fradkin

Subscribe at www.booklaunch.london/subscribe To distribute Booklaunch at your book club or literary festival subs@booklaunch.london To showcase a new book or manuscript book@booklaunch.london To contact us editor@booklaunch.london Issue 5 First Anniversary Edition £3.75 Listen to our authors reading www.booklaunch.london/audio-page Booklaunch Circulation

This issue is free to UK book festivals, libraries, book clubs, publishers, agents and the media UK publishing’s biggest showcase of new titles. Our choice of extracts from the latest books and manuscripts

50,000+

Happy Nappy Phineas Foster

When you were a Bump in my Tummy

When you were a bump in my tummy I didn’t know what you would be. A boy or a girl or a moon-child, A copy of daddy or me.

And now you’re asleep in your cot, my sweet baby I still don’t know what you will be. A tinker, a tailor, a soldier—or A marvelling creature like me.

Hunger

You are the hungriest boy I know The hungriest boy alive. You started your meal at ten to four And now it’s half past five.

What have you done?

What have you done? What have you done? What have you done in your pot?

Poems in which parents address their young children directly are some of the most tender writings we have. They may not aspire to literature in the sense of expressing new ideas in creative language, but that is not their purpose: their purpose is to communicate and reinforce the bond of love. In Happy Nappy, the writer, evidently inspired by A.A. Milne, has mapped some of the most familiar interactions between mother and father and baby, though at an earlier stage of childhood development than Milne’s When We Were Very Young

Phineas Foster is an older father and is often taken to be his own child’s grandfather, particularly when waiting at the school gates at the end of the day. The upside, however, is that he anticipates offering his child a generational haven when she starts rebelling against her parents as a teenager

What have I done? What have I done?

I’ve done a lot lot lot!

Tired Eyes

It’s very late, it’s very dark, I’m tired of counting sheep. I wish that I could shut my eyes I need my beauty sleep.

But every time I get to bed I hear your sorry sob. Oh baby, let me get some rest Or I may lose my job.

Stars in the Sky

Let us look out of the window How many Stars can we see? The Big Bear, the Small Bear, The Pole Star, Andromeda, Baby And Me.

Let us look out of the window How many stars can we see? Joan Crawford, Gene Kelly, Madonna, Jack Nicholson, Baby And Me.

Happy Nappy

What do you do to your milk, my girl, That gives you such a very smelly nappy? It makes me mad But it can’t be bad

And it seems to keep you happy.

What do you do to your milk, my girl, Inside your big fat roly-poly tummy? It can’t be nice But you’ve done it twice. I must have a word with your mummy.

What do you do to your milk, my girl, That causes you to be so very smelly? It’s something odd Ordained by God Deep down inside your belly! Poo!

A Baby is a Lovesome Thing

A baby is a lovesome thing, God wotty.

Especially when seated on the potty. The problem, though, is really rather knotty: How do I get you back into your cotty?

Hungary Babies

Every year

In Hungary

Hungry babies are born. Raised on rye and oats and barley Maize and beet and corn.

Imre Noj (Which rhymes with stodge) Said ‘This is what we do. Open wide—now even wider— Here comes apple stew!’

Cruel Gruel

Baby, Baby, eat your gruel. Don’t you know it’s very cruel After all the care I’ve taken Not to eat your beans and bacon?

Baby, Baby, eat each bite. Don’t you know it’s cooked just right?

You’ll be grateful, wait and see. Do it, Baby, just for me.

Baby, Baby, you can trust Every crumb and every crust. Baby, don’t you know it’s rude Not to eat up all your food?

Baby, Baby, eat each scrap. Don’t drop crumbs into your lap. If you dribble down your bib You’ll go straight back to your crib!

Baby, baby, let’s be friends. I’d so like to make amends. If you eat up ONE more bite You can stay up LATE tonight!

I haven’t heard a Burp

I haven’t heard a burp all evening Although you had your milk an hour ago.

I’d like to hear a burp (A little tiny burp) So you can go to bed and I can go.

I haven’t heard a burp all evening Although you had a bottle and a half.

If I could hear a burp (A little tiny burp) Your father could go off and have a bath.

I haven’t heard a burp all evening

What do I have to do to make it come?

If I could hear a burp (A little tiny burp)

I’d kiss you on your tubby tubby tum.

The Man in the Moon

The man in the moon Is coming soon And what will he say to you?

The sleepy-time train Is late again. All passengers change at Crewe.

Burping on the Stock Exchange

Next year, when I’m one year older If you put me on your shoulder

I’ll say ‘Daddy, put me down. I’ve got deals to close in town.

‘Though I’ve only just been hired, Daddy, you will get me fired. Yes I know my tummy’s fullish But the trading floor is bullish.

‘And although I ate my food, Twelve-month nappies don’t look good.

This is not the time to wind me While I’m trying to read The Indie ‘Gilts have never been so low. Daddy, I will let you know When I need to burp again.

Til that time I’m buying yen.

‘Mummy put me into Shorts For a sum with lots of noughts. As you croon your baby songs I should make the move to Longs.

‘All the time you pat my back There’s a risk I’ll get the sack. Wall Street’s closed up half a tick. Whoops! I think I’ve just been sick.’

The Queen of England

The Queen of England said to me ‘Which of our subjects ought to be The next King of England?’ I said ‘Maybe The next King of England ought to be Baby.’

The Queen said ‘That’s a very good idea.

Here’s the throne of England And twenty pounds a year.’

The Duke of Edinburgh said to me ‘Which of our subjects ought to be The next Duke of Cornwall?’ I said ‘Maybe The next Duke of Cornwall ought to be Baby.’

The Duke said ‘That’s a very good idea.

Here’s the royal duchy And ten pounds a year.’

Princess Diana said to me ‘Which of our subjects ought to be My next kiss and cuddle?’ I said ‘Maybe Your next kiss and cuddle ought to be Baby.’

The Princess said ‘That’s a very good idea.

Here’s a kiss and cuddle To last for a year.’

Early in the Morning

It’s really very early in the morning. The milkman’s not yet loaded up his float.

The postman’s noisy feet Have yet to hit our street. The paperboy’s still putting on his coat.

The overnight D.J. is talking nonsense. John Humphrys hasn’t started getting tough.

But Baby, you’re awake, And what a noise you make!

I’m sure our neighbours must have had enough.

Photo credit: Sergiy Bykhunenko / Shutterstock … continued in the book Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

CHILDREN’S POETRY | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 2

Booklaunch literary competition

No.5 “It’s a first”

Set by Maggie Bawden

We’re all bothered by the decline of the book and the migration of the young to other media. But imagine that we did in fact live in an age when there were no books, and no one could remember seeing one. Your government charges you to write the world’s first book—or maybe it’s your own crazy idea. What would the first sentence of that first book be? First sentences, please, to us. Best entries get published; the best of the best get a prize.

Email your suggestions to comp@booklaunch.london, putting Comp5 in the subject line, and supplying your name and full postal address, with postcode, in case you’re one of the worthy winners.

Result: No.4 “Relay Race”

No beating about the bush this time. I asked you to make up a chain of names where one person’s surname stands as the next person’s first name (Upton Sinclair Lewis Carroll Nye Bevan … or, Leslie Stephen King Charles Kingsley …) or the end of one literary work kicks off the start of another (This Side of Paradise Lost Horizon …) and I offered a prize for the longest chain.

I’m not going to waste time on the also-rans (sorry, Also-Rans) because one entry stood head and shoulders above the rest—actually, head, shoulders, torso and thighs. Huge congratulations, then, and a fabulous Booklaunch T-shirt to Hazel Shaw from Trowbridge for the following tour de force. Admittedly Hazel cheats a couple of times, but even the gods may stoop to conquer; the rest of us can only bow our heads in admiration:

Cities of the Plain Tales from the Hills and the Sea Hawk in the Rain Forest of the Night and Day of the Dog So Small Back Room with a View from the Bridge of Lost Desire and Pursuit of the Whole of the Story Girl in Winter Words Without Music and Silence of History of the World and his Wife of Bath Comedy of Masks of Time of My Life at the Top Girls on the Run River of Stars in my Pocket Like Grains of Sand[s] of Time to Weep Before God[s] Little Acre of Land of Green Ginger Man who Loved Children[s] Hour Glass Lake Wobegon Days Without End of the Affair …

Readers’ letters

What else we do when we’re working

Lynn Pettinger’s survey of contemporary industrial conditions (What’s Wrong with Work?, Issue 4, page 8) is a welcome corrective to workplace sociology. Academics too often apply theoretical frameworks to obsolete conditions or fail to locate work in a theoretical framework, preferring anecdotal vignettes. Pettinger adeptly avoids both pitfalls, presenting instead a useful critique for the digital age. There remains, of course, the challenging question: for how much longer will there be any work for anyone to do? Politicians need to grasp this, and ask about the condition of the non-workplace, in the wealthy West as AI takes over, but also in the world’s most distressed regions.

Randeep Mathur, Northampton

Change—for better, for worse

Susan and Peter Barrett’s reminiscences of their time in Greece (The Garden of the Grandfather, Issue 4, page 7) reminded me of my own happy travels in the 60s. So many communities then lived without electricity, telephone lines or indoor plumbing. Change since then has been profound and sudden.

This has allowed the developing world to believe that hyper-modernity equals Westernisation, fuelling both hostility and emulation. Both add dangerously to political tensions and the carbon footprint. The fact is, technological advances are something we all have to grapple with or they will bring us all down.

Penny Hancock, Penrith

Were we ever nice?

Peta Tait’s history of travelling menageries (Fighting Nature, Issue 4, page 13) is timely in the year when they have finally been outlawed in the UK. I confess to have thrilled, as a child, at glimpses of lions and tigers as circus convoys drove through our town but always cringed at the crack of the ringmaster’s whip that brought elephants onto their hind legs. How odd that it took us so long to recognise circus behaviour, and our complicity in it, as abusive.

Glyn Blackstone, Wellingborough

Introducing our website: www.booklaunch.london

Booklaunch is a website, not just a magazine. Everything on our home page is clickable. Click Audio Page to listen to authors reading from their featured books. Click Issue 1, 2, 3 or 4 or Our Pages to read earlier editions. Click Shop Online to buy our books and any others. Click Publishers to find out how to showcase your new book. Click Festivals to stock Booklaunch at your literary festival. Click Subscribe to subscribe. Click everything!

First anniversary edition

Phineas Foster’s Happy Nappy poems on the facing page remind us that Booklaunch is still in its infancy, but how we have grown since we first appeared a year ago! We now distribute upwards of 50,000 copies around the UK and have showcased 90 books, with 16 unpublished manuscripts and another 62 small ads.

We have reached visitors at 24 literary festivals as well as countless book clubs, reading groups and libraries, not to mention our own subscribers. UK subscribers to the Spectator, New Statesman, Times Literary Supplement, London Review of Books and Church Times have all also received at least one free copy of our publication.

Because we believe in printed books, we are absolutely committed—in the face of all financial logic—to bringing out a print magazine, but our website has rapidly become an essential addition (see below left). Most importantly, you can now hear many of our authors reading from their books if you click the Audio Page option on our home page—and this feature will grow in the coming year. In addition, all the books we showcase can be bought at our online shop, with delivery carried out for us by Blackwell, the bookshop chain with outlets in many university towns. (From October, Blackwell will also be giving away free copies of Booklaunch in its Oxford stores.)

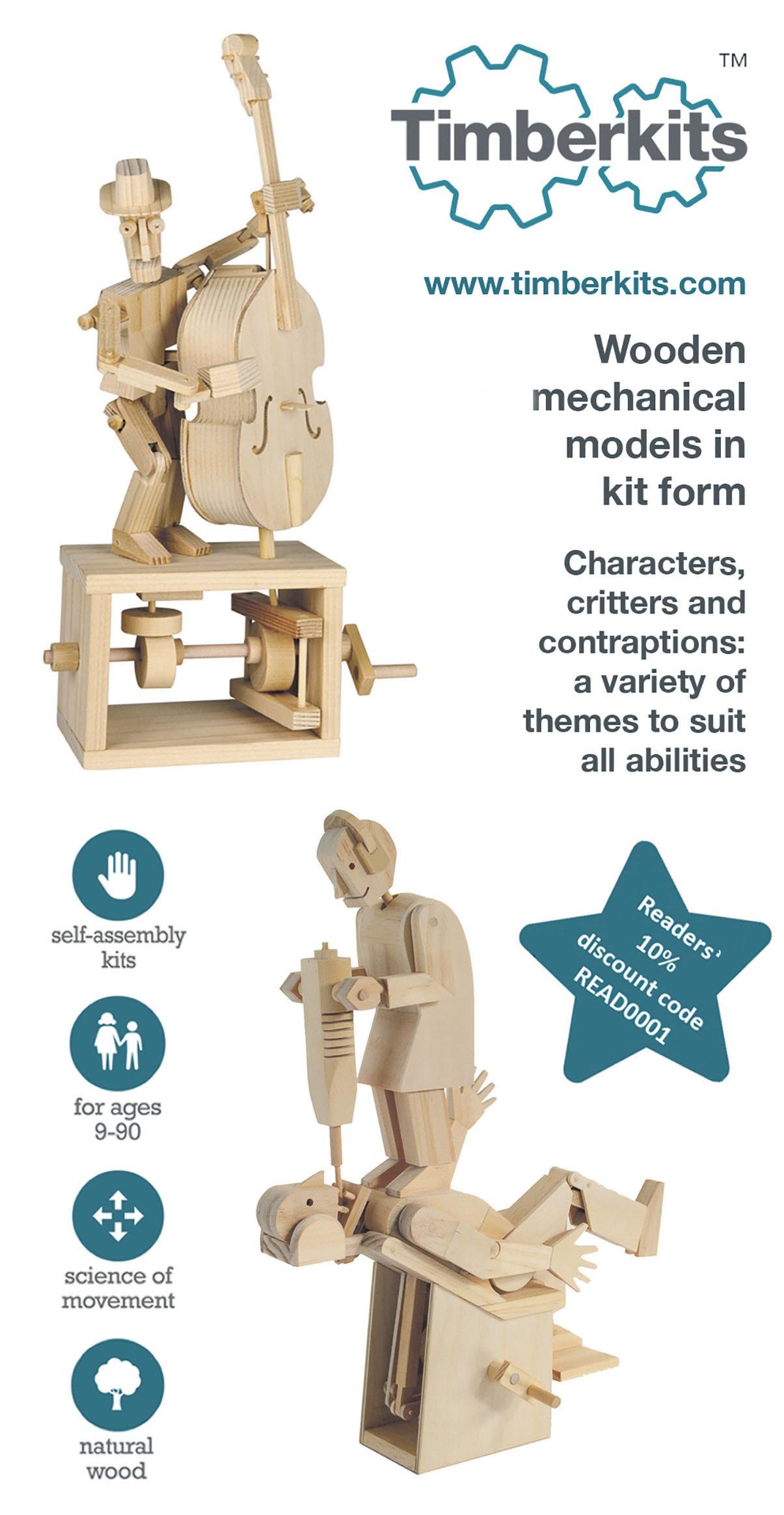

We have been able to halve our advertising rate, and during the summer we have run a half-price subscription offer of just £9.99. We have started offering publishers up to three thumbnails of other books on each page and have begun taking non-book-related ads on our back page (see this issue).

Authors have promoted their unpublished books on our “Looking for a Publisher” pages, and this is an area we want to develop further. We are particularly interested in working with freelance literary agents to bring authors to publication, and would welcome inquiries.

In short, we have made amazing progress in the 12 months that we have been in existence, and we hope to grow more. We like the idea of remaining a freesheet, though we have to charge for copies posted direct to your door. But there are ways round this. If you can bring us five other subscribers, we will reward you with a free year’s subscription—and if you undertake to deliver copies to your local book festival, reading group or library, you are welcome to snag one for yourself. We welcome hearing from you with feedback about Booklaunch, as well as your thoughts about any of the books we carry, for publication in our new Letters column. We also welcome your participation in our brilliant literary competitions—currently the only way of gaining one of our prized Booklaunch T-shirts!

To all our readers, authors and publishers: thank you for your interest in us thus far, and we look forward to your continued company as we enter our second year.

Stephen Games, Editor and

publisher

Booklaunch is a project of New Premises Ltd

12 Wellfield Avenue, London N10 2EA

Website www.booklaunch.london

Publisher/editor Dr Stephen Games editor@booklaunch.london

Design director Jamie Trounce jamie@jamietronce.co.uk

Assistant editor Samuel Warshaw book@booklaunch.london

Advertising manager Jenny Chalcott ads@booklaunch.london

Competitions editor Maggie Bawden comp@booklaunch.london

Distrubition Robin Clarke (West of England), Alex De Lusignan (East Anglia), Patti Cust (Derbyshire)

Printer Mortons Media Group Ltd, Horncastle, Lincolnshire LN9 6JR Subscriptions subs@booklaunch.london UK £19.99/Overseas £25.99

Welcome to Booklaunch Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe AUTUMN 2019 | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 3

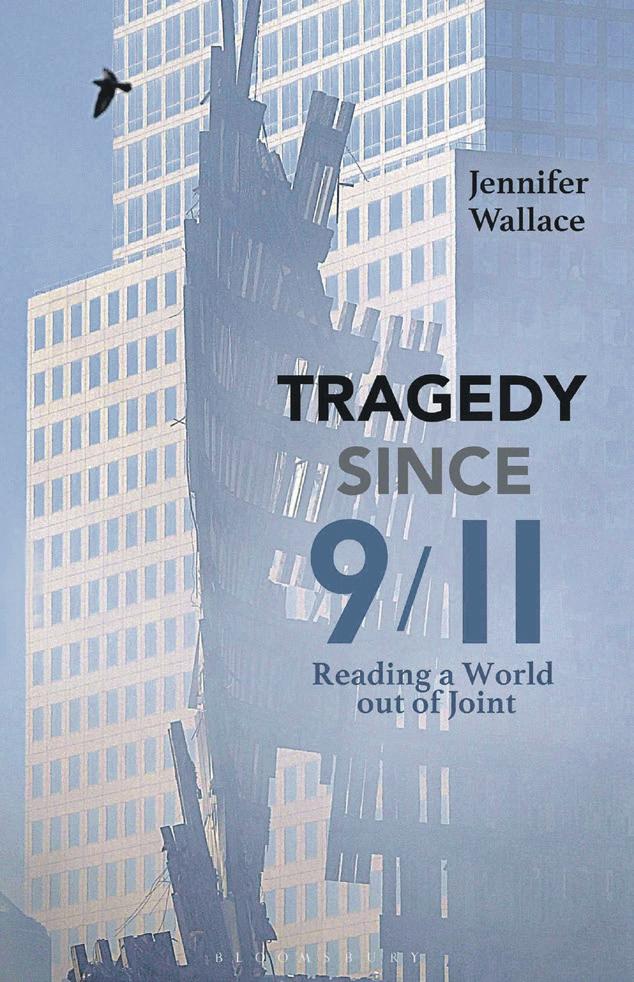

Tragedy Since 9/11

Jennifer Wallace

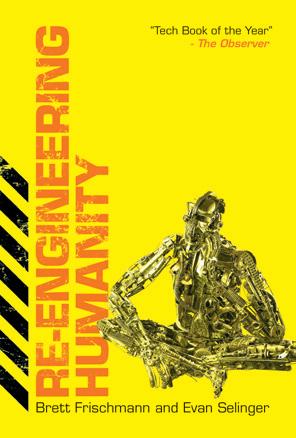

Reading a World out of Joint Bloomsbury (London), 240pp, Softback, 9781350035621, 138mm x 216mm, September 2019, RRP £18.99

How do we understand tragedy? How do we talk about it? In her wide–ranging study, Jennifer Wallace looks at how our reactions to the downing of the Twin Towers and to subsequent traumas correspond to the dramatic structures and language formulated by Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides in the ancient world and to Shakespeare, Ibsen, Beckett and others more recently

Jennifer Wallace studied Classics and English, and has been Senior Lecturer and Director of Studies in English at Peterhouse, Cambridge since 1995, as well as an affiliated lecturer in the Faculty of English. She has served on the jury of the annual London Hellenic Prize since 2010 and has organised four international conferences on the performance of Greek tragedy. She runs the Peterhouse Theory Group, writes extensively and lectures all over the world

To

On 11 September 2004, waking up to a hot, latesummer Saturday morning in New York City, I caught the subway down to Chambers Street for the annual commemoration of the 9/11 terrorist atrocity. The hallowed site of Ground Zero, where once the two great towers of the World Trade Center had soared, had by this date been completely cleared of the rubble of the past. The diggers had reached bedrock, the hard, grey granite on which Manhattan was founded. But in 2004, the massive new construction which now dominates downtown had not yet begun. Instead, Ground Zero was a huge pit, ringed by a high-wire mesh fence on which pilgrims and tourists had attached flowers, tributes and messages over the years.

When I arrived at the site that September morning, it was already thronging with people peering through the wire squares of the fence at the city dignitaries, the firefighters and the families of the victims gathered beneath the stars-and stripes in the pit below us. Mayor Bloomberg spoke over the loudspeaker. A minute’s silence was observed by the whole arena to mark the moment the first plane hit the North Tower at 8.46 am. Governor George Pataki quoted President Eisenhower: ‘There’s no tragedy in life like the death of a child.’ Rudolf Giuliani, the former mayor, read out a letter from Abraham Lincoln, comforting a mother whose sons had been killed in the civil war. Another minute of silence to mark the moment the second plane hit the other tower at 9.03 am. A lone trumpet struck up the Last Post. And then the voices of bereaved parents and grandparents began to read out the names of the dead in alphabetical order, the sound echoing against the empty shells of buildings behind us and the rock below—Gordon A. Aamoth, Jr. Edelmiro Abad. Marie Rose Abad.

Later that evening, I made my way down to the Hudson River for the alternative 9/11 ceremony. Gathering at a pier on the west side of the city, and looking across at the beam of light shooting into the sky where the World Trade Center once loomed, the informal group lit paper lanterns, in the traditional Japanese toro nagashi fashion, and set them on the water to float away down the river in the sunset and out to the open water, past the Statue of Liberty, past Staten Island. Different family members of those who had died in the September 11 attacks made speeches and offered prayers. ‘I want to remember all those who died on 9/11,’ said the brother of one woman who had died three years earlier. ‘But I also want to remember all those who have died since in the name of 9/11.’ This was 2004. The Taliban had been toppled and much of Afghanistan flattened. Saddam Hussein had been captured. Civil war was beginning, with hundreds of Iraqi civilians and police being killed by Sunni-led bombings. The first battle of Fallujah had erupted a few months earlier. And American abuse of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib had recently been exposed by the publication of a few photographs.

These two ceremonies to remember the dead were both versions of tragic ritual. Like tragic performances there were some principal ‘officiants’ reading the names, making the speeches, throwing the paper lanterns out into the Hudson—and of course there were the ‘heroes’ whom we were remembering and lamenting—but the rituals were participatory, designed to draw the mourners and the city together. The whole crowd held the minute’s silence with the city mayor or joined together in reflective memory by the water’s edge. Yet in other respects, these two ceremonies were in marked contrast. The first focused entirely on the American lives lost in New York City three years earlier. The second ceremony looked outward and was prepared to acknowledge that the events on September 11, 2001, had not ended neatly on that date. A parallel was being drawn between ‘us’ in New York and ‘them’ in Afghanistan or Iraq, those ‘who had died in the name of 9/11’. As the lanterns floated out in the Hudson, traditional boundaries were being questioned.

These two responses to the catastrophe three years earlier strikingly mirrored the stark choice facing the American people that Rowan Williams had articulated so presciently in the aftermath of the attack. He himself had been there on the morning of September 11, 2001. As American Airlines Flight 11 was crashing into the North Tower, the clergy of Trinity Church in Wall Street were sitting down just a few blocks away with invited guests to record a discussion about religious practice and belief.

They were ‘interrupted’, said Rowan Williams, the future Archbishop of Canterbury and head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, by terrorists driven by their own version of religious belief. Williams joined everyone else in the area stumbling out of the building in a thick dust of burning ash. There were shouts, sirens, the ‘indescribable long roar of the second tower collapsing’. What he remembered particularly, however, was his lack of feeling, or even as he put it living ‘in the presence of the void’.

Reflecting on the event a few weeks later, Rowan Williams attempted to do justice to this void, to write about its challenges, its potential and its temptations. There were, he said, two courses of action for the American people and indeed everyone around the world who were shocked and still grieving. One option was to use the initial passionate and understandable anger about the injury done to us and turn it into a violent response, continually fuelling the rage with recollections of the attack. In effect, this would mean seeking revenge, acting quickly for the sake of being seen to do something and bombing the enemy in return. The other option was to pause and reflect, to think about our own vulnerability and that of others, to learn a radical and risky compassion. ‘The trauma … is not just a nightmarish insult to us but a door into the suffering of countless other innocents’, wrote Williams. His pamphlet professed to offer ‘hope that risk and reconciliation are a new and living way to avoid the relentless spiral downward to more and worse aggression’.

The war of choice

Tragic narratives of revenge usually begin with a choice. To avenge or not to avenge? To seek to impose rightful punishment or to keep quiet and turn the other cheek? But revenge tragedies mostly operate as if in fact there is no choice, as if everything compels the protagonist to one course of action. At the beginning of the Trojan War, Agamemnon, leader of the Greek army, is presented with a terrible decision. The goddess Artemis is angry with him and is preventing the wind from blowing and thus the ships from sailing over to Troy. She can only be appeased by the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter, Iphigenia. When Agamemnon hears this injunction from the prophet, he realizes immediately the starkness of his choice. Either he can refuse the goddess’s demand and thus betray the army or he must kill his daughter and thus store up the seeds of violent hatred in the hearts of his family. In Aeschylus’s Oresteia, as recollected by the chorus, he weighs up the options:

The senior lord spoke, declaring ‘Fate will be heavy if I do not obey, heavy as well if I hew my child, my house’s own darling, polluting her father’s hands with slaughter streaming from a maiden at the altar: what is there without evil here?

How can I desert the fleet and fail the alliance?

Why, this sacrifice to stop the wind, a maiden’s blood, is their most passionate desire; but Right (θέμις: themis) forbids it. So may all be well!’

In Robert Icke’s recent adaptation of the play, Agamemnon’s choice is put even more starkly, in terms that draw on the classic ethical dilemma commonly cited in philosophy: ‘What you’re being told is that the road is about to split, that an action is coming which you either perform—or you don’t. Make that judgement’, says the prophet Calchas.

Yet the choice is not portrayed as a neutral one. Fate has already tipped the scales. Agamemnon seems compelled to choose the course for war. He must opt for the male, public demand for vengeance rather than the female, private alternative of refusing the rush to the military campaign. In Aeschylus’s famous words, he ‘dons the yoke of necessity’ and from then on is committed to the war effort, filled with daring and the capacity for violation. In Euripides’ version of this scene, Agamemnon is influenced by the intense pressure of a scarcely controllable army, a huge crowd of men desperate to go to war and baying for blood. ‘We are slaves to the common people,’ he complains, and those common people are driven by a ‘mad desire’ (or ‘aphrodite’ in the original Greek) to sail to ‘the land of the barbarians and put an end to the rape of Greek wives’.

His efforts to change his mind and overturn the demand for Iphigenia to be brought for sacrifice are thwarted by Menelaus, Odysseus and the other Greek generals.

This

edited extract is taken from the start of Chapter 3: “The Dogs of War”

… continued in the book

to Booklaunch now! Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

the same publisher

£4.00

price £14.99 inc. free UK delivery

Subscribe

From

Save

Our

buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

LITERARY STUDIES | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 4

In 1990, word of a disturbing report spread like a virus through the conservation community. The first analysis of Pacific salmon populations had been conducted, and the results were beyond distressing. Salmon were disappearing—and they were disappearing fast. In just twenty years, the winter chinook of the Sacramento River fell from roughly 86,000 to 500. In thirty years, the fall chinook of the Snake River had dropped from 30,000 to 1,000. In forty years, Snake River sockeye had gone from 3,000 to one single fish.

Guido Rahr had known that the rivers in Oregon were changing; now he knew it was not only his home rivers that were being affected but the rivers up and down the western seaboard.

The state of Oregon dived headlong into the issue and immediately found itself grappling with all it had failed to understand about one of its most precious creatures. The state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife, responsible for managing Oregon’s salmon, had been blaming the diminished salmon population on what they believed was the obvious cause—not dams, logging or agriculture, but overfishing in the ocean and rivers. The agencies’s response was to build hatcheries, and artificially produce more fish to make up for the lost numbers, which did not end up being a solution at all.

Salmon needed three things to survive: access to their home rivers, clean and cold water, and a place to spawn. Oregon had compromised each of these requirements, starting with dams. These concrete walls spanned rivers, blocking salmon from swimming upstream and reaching their spawning grounds. In the Columbia Basin there were at least sixty dams, only some of which had fish ladders. Salmon, determined to the last, often died in the futile attempt to get past these barriers.

Trees presented the next threat. The majority of lumber companies in the Pacific Northwest practised clear-cutting, razing every tree from a designated acreage and leaving huge squares of denuded land. The removal of trees created a number of problems. Without their shade, the river was unprotected from the sun and heated up, starving fish of oxygen. The root systems also gave stability to riverbanks. Without the trees to hold the land in place, the regular winter rains brought these barren, unstable hillsides crashing down into the rivers, turning the water to mud and creating impassable blockages.

Farming and agriculture exacted a final price. Throughout the year, farmers used the water from salmon tributaries to irrigate their crops. Eventually, excessive diversions and withdrawals from nearby rivers dried up creeks and streams, while the agricultural herbicides and pesticides leaked into the water system, impacting the aquatic insects the young salmon fed on.

The combination of dams, logging, and agriculture had led to a slow and steady degradation of salmon habitat. Looking back at it all a decade later, it was no wonder that, after millions of years of successful migrations, salmon were finally unable to complete their life cycles. The result was that the most fragile salmon runs were starting to disappear. Populations of summer steelhead and spring chinook were the first to vanish. Others would follow.

When Oregon’s sockeye salmon were listed as endangered, the state would never be the same. Salmon were a symbol of the region. It was said that they had once swum so thick in the Columbia that one could almost walk across the water on their backs. That the fish were now disappearing was unimaginable.

The newly written Endangered Species Act had the effect of a bombshell. Suddenly salmon featured regularly on the front page of local newspapers and the industries, practices and systems influencing critical salmon habitat were scrutinized and assessed for their part in the mess. Lumber companies, farmers, dams, private home owners, the state—they were all culpable.

Guido listened to the hubbub. The system had failed salmon. It wasn’t out of lack of knowledge—the needs of salmon were understood—it was that no one had been looking down the road at the long-term consequences of current practices. What made it unconscionable was that this same scenario had already played out with Atlantic salmon—twice: once in Europe and again on the eastern seaboard.

Guido felt in his gut that he had a role to play in preventing the impending tragedy, but he was nowhere near the stage. He was a graduate of a mid-level university

where he had failed to achieve academic distinction. Up until now, good grades had simply not been important. But the ESA listing changed everything. The only way for Guido to gain credibility was with a higher degree. He had to go back to school. And in his mind, there was only one school worth trying for.

Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies had fostered visionary conservationists since the early 1900s. Its graduates now affected environmental policy at the highest level. Guido decided this was the school for him. There would, he knew, be challenges to getting in. For starters, he didn’t have the academic record he needed to be considered by an Ivy League school. On paper he looked like a derelict who was resistant, uninterested or possibly mentally deficient. Which meant that, if he was going to have a prayer at being accepted, he would have to break into the admissions process at Yale. He would have to sell himself directly.

It was the spring of 1990 when Guido jumped into his Volkswagen van and got on Interstate 95 heading north from DC, alternately listening to the radio and composing his presentation on the six-hour drive to New Haven, Connecticut. Guido had done his research; in his pocket was a list of four professors he needed to see. His strategy was simple: he was going to tell them who he was, what he had done with his life so far, and why he belonged at Yale. He began knocking on doors. By the end of the day he had presented his argument four times, and without exception the professors had listened. Guido’s understanding of biological systems was exceptional and his experience in the field highly unusual. He described the intricate ecosystems of the high desert, the cloud forest and the salmon rivers with passion and knowledge, speaking about these places as if they were his home.

Guido drove back to DC thrilled to his core. Back in his apartment, he typed a letter to Professor Stephen Kellert, the director of admissions, thanking him for his time and reiterating his profound impression that he and Yale were a perfect fit. A few weeks later, he heard back from Kellert. The committee had unanimously agreed that he was an ideal, if unconventional, candidate and encouraged him to apply.

The next step was less comfortable. Guido winced inwardly when he called to have a college reference sent from the University of Oregon; he knew the document was not a great testimony to academic commitment. It took a few more weeks for Yale to respond. Professor Kellert wrote the letter himself; it was brief and brutal. Guido’s reference was one of the worst they’d ever seen; they couldn’t let him in.

Guido read the words without taking them in. They were wrong. They had made a mistake. Critical ecosystems were at risk, ecosystems upon which they all depended. People needed to be educated.

He got back in his van and headed north again, preparing his rebuttal as he drove. College, while not a peak performance, was six years ago and every year in Guido’s life since spoke of his commitment to conservation; every year his understanding of ecosystems grew. He was a willing and able envoy for a vital environmental cause. Was Yale going to slam the door in his face because of a few mediocre grades?

When Kellert agreed to see him, Guido made a simple plea. ‘Please don’t judge me on the past.’ Kellert remained unswayed. Guido was simply too much of a risk. Guido had arrived at a reality he had eluded for a long time. To get what he wanted, he would have to play by someone else’s rules. He embarked on a plan B, seeking out members of the admissions committee and asking them what was required to make him the most competitive candidate the following year. He wanted to know the rules. The clearest answer came from Kellert. Guido needed to do a few things, none of which was easy. The first was to address his performance in college. He had to explain to Yale, and maybe to himself, how he came by such poor grades. Then he had to demonstrate his passion, discipline and mission in the real world. Lastly, he had to brush up on his math skills.

Guido listened to all of this in concentrated silence. ‘Okay,’ he said. If they wanted bold action, they would get it. Guido bought a ticket to South America and headed straight for the vast rain forest of Brazil. Here, in the heart of the Amazon, the Rainforest Alliance was actively saving the rain forest but had no program for the fish of the mighty Amazon. Guido knew that, just like the salmon of the Pacific Northwest, these fish faced threats. In fact, he informed the Alliance, the fish of the Amazon were as important as the rain forest itself. They were an integral part of

… continued in the book

Stronghold Tucker Malarkey

Heroes aren’t always recognisable at first. Guido Rahr grew up on the rivers of Oregon and only discovered his life’s mission when ecological disaster struck the bio-systems that everyone else took for granted. In Stronghold, Tucker Malarkey observes a determined individualist rising to the challenge and contending with a host of obstacles on America’s Pacific coast and across the Pacific in Russia’s eastern wilderness, in an attempt to ensure the survival of the salmon

Save £4.68

Our price £12.31 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Subscribe to Booklaunch now!

Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

From the same publisher

This edited extract is taken from the start

Chapter 5:

Ivory

of

“Scaling the

Tower”

One Man’s Quest to save the Wild Salmon—before it’s too late Short Books / Octopus (London), 362pp, Hardback, 9781780724010, 135mm x 216mm, colour photo section, September 2019, RRP £16.99

Tucker Malarkey is the author of bestselling novels An Obvious Enchantment and Resurrection. With a career that began at the Washington Post, her love of human culture and wilderness has taken her all over the world. She now lives with her son in Berkeley, California. She grew up fly fishing, studied Sovietology, and has travelled to Russia numerous times. Stronghold is her first major non-fiction work

NATURE / SCIENCE | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 5

Tales of the Troubled Dead Catherine Belsey

Strange news from Cornwall Ghosts don’t stay put. Seen by glimpses, they come and go unpredictably. And so, it seems, do their stories. The tale of Dorothy Dingley, due to evolve as time went on, first entered the written record in the seventeenth-century memoir of the Reverend John Ruddle.

On 20 June 1665 Parson Ruddle was unexpectedly drawn into a ghost story, when an elderly gentleman and his wife appealed to him for help with their son. The lad, once full of promise, was now in a serious decline. His parents suspected the boy of malingering. His reluctance to go to school might be the effect of laziness; perhaps he was in love; alternatively, it might be that he wanted an excuse to join his elder brother in London. But the youth himself maintained that he was haunted and they counted on the minister to talk him out of such fancies.

Left alone with the boy, the parson found him open and frank. For a year or so on his way to school, he claimed, a woman had passed him, sometimes more than once in the same field. At first, he had paid no attention, supposing her to be a local resident, but when he looked more closely, he recognised Dorothy Dingley, dead these eight years. He often spoke to her but she never replied. When he changed his route, she changed hers and met him in the lane.

To the boy’s relief, Rev. Ruddle agreed to walk with him the next morning. And there, in a field well away from human habitation, was the woman, just as the boy had described. The minister had meant to address the ghost but somehow could not bring himself to do so, nor to look back at the departing figure.

Ghost stories grew up in counterpoint to formal literature, sometimes operating in competition with it, sometimes in harmony. In Tales of the Troubled Dead, Catherine Belsey charts the evolution of the genre, monitoring specific stories to show not just how they have grown and been elaborated but how their role and reception have changed as they have been brought into the canon by writers from

Homer and Shakespeare to Susan Hill

Catherine Belsey is Professor Emeritus at Swansea University and Visiting Professor at the University of Derby. She has consistently supported innovations in the study of culture and writing, and challenged the blurring of literary criticism and nostalgia. She now lives in Cambridge and chairs a range of reading groups. She is a Fellow of both the English Association and the Learned Society of Wales

Puzzled, but thoroughly enlisted in the adventure, he returned to the field alone as soon as other matters permitted, and there she was again, only ten feet away. A third time, the boy and his parents came too. On this occasion, she seemed to move faster. Ruddle and the boy turned to follow her but she crossed the stile and then vanished. He now noticed that she appeared to glide rather than walk. And a spaniel that had joined the company barked and ran away. The terrified parents, who had attended Dingley’s funeral eight years before, had no wish to encounter the apparition a second time.

In the end, the clergyman resolved that he must speak to the ghost. At five the next morning he crossed the stile into the field. He spoke authoritatively to the dead woman and gradually, reluctantly, she replied. They met again an hour after sunset and, in the light of their exchanges, the spectre vanished for good. The testimony, committed to writing by Mr Ruddle himself, concludes with an assertion of its veracity. ‘These things are true, and I know them to be so, with as much certainty as eyes and ears can give me.’

Ruddle dated his manuscript 4 September 1665, adding that, since he was young and new to the area, he thought it best to keep the story to himself. It appeared in print even so, but not until 1720, when ‘A Remarkable Passage of an Apparition’ was included, somewhat incongruously, in a pamphlet about a deaf fortune-teller, and then reprinted in a more substantial volume that same year, the second edition of The History of the Life and Adventures of Mr Duncan Campbell

What prompted publication over fifty years on? In the early eighteenth century, accredited ghost stories had become highly saleable. For half a century or more, the Anglican Church had felt itself threatened by materialist Enlightenment philosophies that allowed no special place for the supernatural. If there were no ghosts, or no possibility of suspending the laws of nature, the way was open to declare that there was no God. In defence of religion, a number of divines took to promoting the apparitions that a century earlier Protestantism had denied as delusions of the devil. Stories of attested encounters with spirits, always popular, became exceptionally marketable.

So, at the same time, did anything written by Daniel Defoe. For many years, it was believed that the Ruddle memoir was actually the work of Defoe, master impersonator of other fictional storytellers, including the prostitute Moll Flanders and the largely imaginary castaway Robinson Crusoe. Defoe was already known as the author of A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs Veal. Why not add, then, the record of an obscure Cornish clergyman’s encounter with the supernatural? But that attribution is no longer secure and John Ruddle’s authorship remains a distinct possibility.

The tale evolves Ghosts exist in their stories, and Dorothy Dingley’s did not end with publication in 1720. Instead, it was to survive as the theme of speculation and debate. Her tale would be variously defended as fact or enhanced as fiction, and would develop as time went on to accommodate new modes of storytelling. Dorothy’s spectre slipped from memoir to history, and from there to romance, short story and, eventually, folklore, shifting in line with these distinct genres.

The narrative also changed with the times, marking new ways of understanding what it was to be a ghost. In addition, it came to focus more specifically on what might trouble a woman in the grave. As her tale was taken up, explained, embellished and elaborated, the matter that drove Dorothy to walk, unspecified in Ruddle’s memoir, was gradually sexualised.

While her changing shapes demonstrate the power of ghost stories to seduce successive generations of writers and readers, they also throw into relief some of the difficulties we meet in engaging with the troubled dead. In 1817, nearly a century after its first appearance in print, the haunting made its way into local history. C. S. Gilbert reproduced the story in his Historical Survey of the County of Cornwall, adding that the boy’s father, unnamed by Ruddle (now Ruddell), was Mr Bligh of Botathen. Seven years later, Fortescue Hitchins and Samuel Drew summarised the story in their own History of Cornwall. They too named the Bligh family but this time the ghost was identified as Dorothy Durant.

These historians evidently found the story sufficiently credible to merit such supplementary information. Drew, who edited The History of Cornwall, adds a note of personal scepticism: ‘On this strange relation, the editor forbears to make any comment.’ But he did not delete the narrative from the historical record. Gilbert, on the other hand, was inclined to take the matter seriously, as, from a different perspective, was T. M. Jarvis, who in 1823 included the tale among his Accredited Ghost Stories, a work designed to support the religious case for the immortality of the soul.

If the story proved attractive to local historians and defenders of the supernatural, it was even more seductive to writers of fiction. What mattered in 1720 was that a dead woman genuinely walked and the supernatural was real. In the epoch of the novel, however, the pressing question was why she walked. What so troubled Dorothy Dingley that she could not sleep in her grave? In 1845 Anna Eliza Bray took Ruddell’s account from Gilbert’s history and included it in her romance, Trelawny of Trelawne. Mrs Bray was more alert than Hitchins and Drew to the nuances of the record. In Gilbert, as in the Ruddle memoir he repeated, the boy’s mother was a ‘gentlewoman’, the ghost a ‘woman’. Bray’s novel makes Dorothy a servant. Her guilty secret, revealed at last in the field to the minister, is that she once concealed documents proving that the haunted boy was in reality the true heir to a landed estate. Years later, the dead nursemaid walks the field to meet her former charge. Eventually, she tells Mr Ruddell where to look for the papers and justice is finally done.

This avowedly fictional explanation was not to be the last, however. In 1867 R. S. Hawker published what has since become a canonical Victorian chiller. ‘The Botathen Ghost’ first appeared in Charles Dickens’s journal All the Year Round. There Hawker claims to have had access to the original ‘diurnal’ of Parson Ruddall, as the vicar has now become. On the basis of this journal, Hawker resets the story in winter, the appropriate time for apparitions. He also reduces the interval between the funeral and the sighting to three years, within the likely reach of a schoolboy’s memory. The allusion to tradition, along with increased probability of detail, brings the tale into line with the conventions of nineteenth-century ghost stories.

Moreover, since ghosts are dedicated followers of fashion, the spectre now adjusts her appearance accordingly. The solid revenant that the lad initially mistook for a local woman has here taken on the wraithlike features of a properly Gothic ghost. Dorothy (now Dinglet) has a ‘pale and stony face’ with ‘strange and misty hair’. ‘She floated along the field’, the minister records in Hawker’s version, ‘like a sail upon a stream, and glided past the spot where we stood, pausingly. But so deep was the awe that overcame me’, he continues, ‘as I stood there in the light of day, face to face with a human soul separate from her bones and flesh, that my heart and purpose both failed me.’ Hawker’s ghost is a phantom, visible but not

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe From the same publisher Save £2.75 Our price £12.24 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here FOLKTALES AND THE SUPERNATURAL | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 6

Ghost Stories in Cultural History Edinburgh University Press, 288pp, Paperback, 9781474417372, 138mm x 216mm, 10 b/w illustrations, September 2019, RRP £14.99

to be mistaken for a living body, at once perceptible and insubstantial, of a different composition from her material surroundings.

A sexual secret

As this development implies, the supernatural has a history. Ghosts change their nature from one epoch to the next. And that differential history also redefines the nature of the trouble that wakens the dead. While any kind of unfinished business might keep male ghosts from resting in peace, by the nineteenth century what had come to trouble women most was their sexual past. Hawker’s fictional parson notes that, on recognising Dorothy Dinglet, the boy’s elderly father, Mr Bligh, shows signs of anxiety. When the clergyman finally persuades the ghost to speak, she confesses to ‘a certain sin’, although the minister does not name it. Since ‘Pen and ink would defile the thoughts she uttered’, those thoughts remain veiled. At evensong, the minister has a long talk with ‘that ancient transgressor’ Mr Bligh, who shows ‘great horror and remorse’. Satisfied with his penitence, the ghost is duly laid to rest.

Whose was the unspeakable sin? Mr Bligh’s, evidently. But was Dorothy his victim, or his willing partner? The story does not say. We are invited to construe that the sin was sexual—and our guess may be a good deal more lurid than anything that could be spelt out in a Victorian journal for family reading. In the story the facts remain elusive, shadowy and uncertain—like ghosts, perhaps. If sex has now become the female secret, it remains undefined, suggested in hints for imagination to work on.

Oddly enough, however, part of Hawker’s fiction resurfaced in the twentieth century as popular local legend and, in the process, Dingley’s story acquired a more specific sexual core. In 1940 Christina Hole incorporated ‘The Botathen Ghost’ into her English Folklore. This book, claiming the story as Cornish belief, actually reproduced word for word Hawker’s description of the apparition, complete with the stony face and misty hair. But it omitted the guilty secret. Thirty years later, when the renowned folklorist Katharine Briggs repeated Hole’s account in her four-volume Dictionary of British Folk-Tales, she tentatively adduced a different cause for the dead woman’s restlessness. Briggs stated in a footnote that, according to ‘Hunt’, Dorothy had had an affair with the elder brother of the boy she haunted.

But it turns out that Robert Hunt, author of Popular Romances of the West of England, published in 1865 and frequently reprinted, had made no such claim. On the contrary, he abridged, with acknowledgement, the account given by the historian, C. S. Gilbert, which matches the first printed version of 1720, and makes no reference whatever to a troubled past for Dorothy. What

could have prompted the scholarly Briggs to suppose he did? By this time, there were in circulation several versions of the earliest printed account. Was the affair between Dorothy and the elder brother a creative misreading of John Ruddle’s memoir? Romance, after all, came into that story, however obliquely. The worried parents thought love might be to blame for the boy’s decline. He also had an elder brother who had gone to London. Had these two pieces of information somehow been elided?

Indeed they had, but not, in the first instance, by local legend. Instead, they were brought together in ‘The Woman in the Way’, a short story by Oliver Onions and published in 1924 in a collection called Ghosts in Daylight. Here the tale is presented as fiction and the storytelling is as ingenious as the sexual politics are misogynist. ‘The Woman in the Way’ begins with John Ruddle’s memoir. It pays close attention to the particulars of the narrative, points to the gaps there and fills them with what it explicitly calls conjecture. It inventively coaxes the memoir to reveal that the boy’s mother ‘wears the breeches’ in the household. When her elder son shows signs of wanting to make his fortune in the big city, what would she do but find him a nice local girl to marry instead? But suppose he had already contracted a relationship of his own with Dorothy Dingley? And what if Dorothy, scorned by the family as not good enough for their son, chose in anger to lead him on? We cannot be sure, the story continues, whether the elder son left for London teased but rejected, or whether, on the contrary, he prevailed with the young woman and departed in triumph. Either way, Dorothy died but, after seven years, returned to set about a vengeful seduction of the younger boy in his turn. No wonder the parents were frightened when they recognised her in the field.

Truth

In the fiction of the roaring twenties, then, the ghost has become a vamp—and half a century later Dorothy’s sexual relationship with the elder brother has entered Briggs’s Dictionary as folklore. In the three hundred years since 1720, a tale that, in the first instance, may or may not have been invented passes into history and, from there, back into fiction, which then reappears as local legend. The story of Dorothy Dingley/Durant/ Dinglet is still told in the neighbourhood of Launceston and in some current versions she died in childbirth, after a sexual relationship with the boy’s brother, who abandoned her and disappeared in London.

Where, if anywhere, does the truth lie? Is there anything here that we can safely believe? Did Dorothy Dingley ever live? If so, did she walk after her death? Did John Ruddle/Ruddell/Ruddall lay her ghost to rest and record the encounter but not what she said? At the heart

of this evolving story is a spectral woman who cannot rest until she tells her secret. Her motive for walking might or might not be a troubled sexual past. But her existence, real or imagined, depends on a memoir, itself conceivably genuine, but possibly not. All we have is the version of it printed in 1720. The original manuscript of this memoir, dated 1665, remains as spectral, as uncertain, as the ghost herself.

What do we know for sure? It turns out that the Reverend John Ruddle existed—and the variations in the spelling of his name are not out of the ordinary. He was vicar of Launceston at the date of the haunting until his death in 1698. But did he write about the ghost, and was his record put into print in 1720? Dingley was a common name in the neighbourhood. The topographical accuracy, such as it is, remains remarkable: the author seems to have known the neighbourhood.

But it remains a puzzle that the Cornish manuscript should have come into the possession of a London publisher so long after the events in question and in defiance of the secrecy Ruddle had thought prudent. On the other hand, by 1720 John Ruddle had been safely dead for more than two decades, and the hauntings had taken place over thirty years before that. No one was likely to complain at the release of his secret; equally, no one was likely to be in a strong position to challenge the veracity of the published tale.

During the nineteenth century, various respectable people claimed that others, equally impeccable, had seen the original memoir. Evidence for the truth of the record, stoutly declared incontrovertible, was in practice thin, and no manuscript has been produced. In the event, when it comes to apparitions, it may be that the truth is not an option. Facts are elusive; too much is lost in the telling and retelling.

Fabrication, on the other hand, belongs to a distinct category. That the truth is out of reach or uncertain does not mean that there is no difference in principle between attested narratives and stories that are simply made up. It is too easy to assume that, if truth cannot be guaranteed, ‘it’s all fiction’, as they say. Even if the line between the two is not always hard and fast, there is a distinction between accredited stories and inventions. The difficulty, however, as Dorothy Dingley’s story demonstrates, is to tell one from the other.

While truth remains an object of desire, it does not necessarily lie waiting for us on the other side of writing or speech. The troubled dead walk in their stories, and perhaps only there. Those tales have a history and, as the consecutive revivals and rewritings of this one imply, a strong and continuing appeal to readers and listeners.

That history and that appeal are the main concerns of this book. … continued in the book

This

FOLKTALES AND THE SUPERNATURAL | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 7

extract is taken from the introductory Prelude: “The Changing Shapes of Dorothy Dingley”

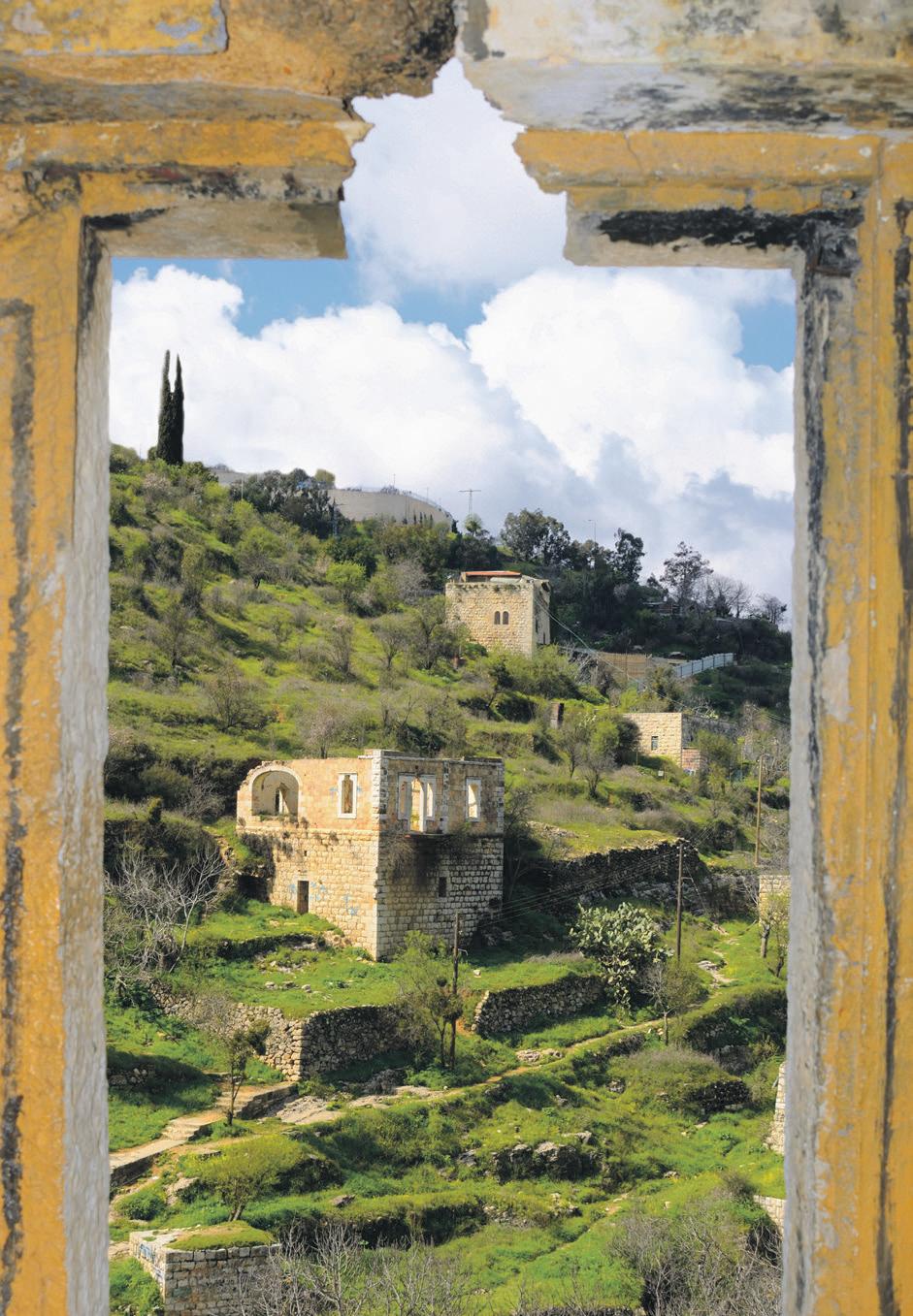

Photograph: Lario Tus / Shutterstock

Talking to North Korea Glyn Ford

It was during the 1966 World Cup in England (North Korea 1—Italy 0) that I first discovered the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). It was longer before they found me. When I was elected to the European Parliament (EP) in 1984, one of my first interventions in committee was to propose that a report be prepared on EU-North Korea trade relations. In that report, the Extemal Economic Relations (now International Trade) Committee concluded there were neither relations nor trade. The North was out of sight and out of mind. As with all EP reports, it concluded with a standard formula instructing that a copy of the report ‘be sent to the Commission, Council, Member States and Government of the DPRK’. Two years later, when I finally visited the DPRK embassy to UNESCO in Paris for the first time, I asked them for their response to the EP Report. They replied that they’d never seen it. Back in Brussels, I asked the EP’s administration what happened. The official response was, ‘We didn’t have an address.’

While acknowledging that it is both deeply flawed and repressive, former Labour MEP Glyn Ford challenges the idea of North Korea as a rogue state run by a mad leader. Instead, informed by unique access and nearly 50 visits, he argues that parts of its leadership are keen to modernise and end their global isolation, and that more creative dialogue is needed to avoid a disastrous North-East Asian war

Glyn Ford began his career as an academic before moving into politics. He was a Member of the European Parliament from 1984 to 2009, and sat on its Japan Delegation and the Korean Peninsula Delegation. Between 1989 and 1993 he was a member of Labour’s National Executive Committee and is currently a member of its National Policy Forum. Ten years ago he founded the Public Affairs and International Relations consultancy POLINT, and in 2015 he started the Brussels-based NGO Track2Asia

That was to change. By 2004 the EP had a standing delegation for the Korean peninsula. But it was not all for the better. Pyongyang has now spent a quarter of a century plastered across the world’s front pages, as it apparently threatens the world with its nuclear weapons and missiles, if no longer with its ideology. I initially decided to write North Korea on the Brink; Struggle for Survival (Pluto, 2008) because the only books I found either—largely—painted it entirely black or—rarely— totally white; ‘axis of evil’ or socialist utopia. It’s neither. The North is fifty shades of grey—some dark—rather than black or white, a product of its enemies as much as of its friends and itself. Ten years later, history has moved on. Everything has changed, and nothing. The last year has seen the Peninsula closer to war than peace. The book needed an update.

North Korea is a poor, beleaguered country run by an unpleasant regime that has served its people ill. However, the alternatives proffered by its enemies would only compound its pain.

I wanted two things with the first book: first, to provide an appreciation and understanding of North Korea’s history, politics and economics, taking into account that the North went from feudalism to colony to Communism with no democratic detour or interregnum; second, to advocate the application of ‘soft’ rather than ‘hard’ power. I argued for ‘critical engagement’—for ‘changing the regime’, not ‘regime change’— to provide ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’.

I still want to deliver on those two promises the second time around. But you can never step in the same river—or nuclear crisis—twice. Events and I have moved on apace. When I wrote North Korea on the Brink I had visited the country barely a dozen times; now I am approaching my fiftieth visit and for the last seven years have been involved in an extended political dialogue I established with the Vice-chairman of the International Department of the Party. In some facets I understand some things more and others less, but for both I have a more nuanced appreciation.

Introduction: The Pyongyang Paradox Pyongyang is trapped in a paradox. The very measures it has felt essential to ensure its long-term survival are precisely those that put it in short-term jeopardy. Kim Jong Un’s byungjin line—which gave equal weight to building the nuclear deterrent and developing the economy—was designed to provide the security, time and space to allow the economy to grow. The ultimate intention was to transform the country into an unattributed variant of Vietnam or China. Yet the nuclear strand of the policy threatens to precipitate a ‘preventive’ strike by Washington and its ‘coalition of the willing’, triggering a second Korean War—with devastating consequences.

Washington sees North Korea as an undeveloped Communist state in hock to Beijing, led by an irrational playboy with an odd haircut—and thus as a dangerous pariah that is unsusceptible to the normal political leverage of cause and effect. It would be more accurate, however, to see the DPRK—as it prefers to be known— as constrained in a situation where its choices are narrow. With a failed industrial economy rather than an emerging one, its ruling regime has legitimate reasons to distrust the outside world and is desperate to ensure its survival in the face of clear existential threats. From Pyongyang’s perspective, its actions are the inevitable

corollary of this struggle for survival. Here the political stratigraphy of North Korea is revealing: the base feudal layer overlaid by the deep lessons of brutal Japanese colonialism (Japan occupied Korea from 1910 to 1945), then the careless division imposed by the United States in the aftermath of World War II. All followed by initial victory in a civil war, converted into a surrogate clash of civilisations that ended in a half-century stalemate, before it was in danger of being buried under the rubble of a collapsing Soviet empire. North Korea’s recent behaviour is less a war cry than a cry for help.

There have been numerous attempts to explain North Korea, some less successful than others. Among the most risible is John Sweeney’s North Korea Undercover, which parleyed a standard week’s holiday into a heroic feat of daring and deserves marks for chutzpah, if nothing else. Victor Cha knows his stuff, without question; nevertheless, his The Impossible State reveals much about America’s outdated misperceptions of the North. Yet Pyongyang hardly welcomes contemporary cutting-edge analysis. James Pearson and Daniel Tudor’s North Korea Confidential, which illuminates the further shores of Pyongyang’s market reforms, sufficiently irritated the North that Seoul felt it necessary to place the authors under round-the-clock protection.

For sheer encyclopaedic knowledge of the road to war, Bruce Cumings’s two-volume The Origins of tbe Korean War is unsurpassed, but is matched page for page by Robert Scalapino and Lee Chongsik’s Communism in Korea, charting the regime’s first decade. For something to challenge the West’s more recent received wisdom, Andrei Lankov’s collection of books does exactly that. For those who like to cut fact with fiction, the pseudonymous James Church’s early ‘Inspector O’ stories serve.

I first visited North Korea in 1997, during its darkest days since the war, at the height of the famine. I have been back almost fifty times since then, under a variety of guises. I served on a series of ad-hoc delegations dispatched by the European Parliament consequent upon my visit in 1997 and in 2004 I successfully proposed the establishment of a standing delegation with the Korean Peninsula that still exists. Early on in my peregrinations it became clear where power lay in Pyongyang. Like in China, it was the Party, not the Ministries, that makes its mark.

Thus the majority of my visits have been under the auspices of the Workers’ Party of Korea’s (WPK) International Department.

In 2012 I was asked if I could set up a dialogue with politicians from the European Union. This I did, with Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s former chief of staff and founder of the mediation charity Inter Mediate. Since then we’ve had an ongoing series of track 1.5 meetings; our current host is a member of the Politburo’s Executive. In parallel, Pyongyang’s perspective on the South is delivered by the Korea Asia-Pacific Peace Committee (United Front Department). In the twelve months leading up to this book’s publication, I have been back to Pyongyang five times. This unique access has opened doors, from the White House to the Blue House, the Japanese cabinet office to the Chinese foreign ministry, the United Nations to the US Pacific Command, the EU’s External Action Service to the National Security Councils.

One thing I have learnt is that the North is steeped in history and precedent. For them, history matters. They imbibe from birth a national narrative that shapes their comprehension of the world and their adversaries. Unlike in the West, where ‘vision’ means thinking beyond the next electoral cycle, North Koreans think long-term. The past is the key to the present. Thus any attempt to understand the DPRK and its people needs the vision to at least glimpse reality through their eyes. I hope this book will help you do that.

First, let us begin by dispelling the fabulous. The five biggest myths about the DPRK are that:

1. It’s a Stalinist state run on the basis of Marxism-Leninism. No, it’s a theocracy with communist characteristics whose catechism is KimilsungismKimjongilism.

2. Beijing and Pyongyang are like ‘lips and teeth’. No, the regime deeply distrusts and resents China. For the last decade they have barely been on speaking terms; Pyongyang is prepared to fight if necessary.

3. Pyongyang wants early unification. No, the North’s leadership is all too well aware that with its GDP at barely more than 2 per cent of the South’s, early unification would only be assimilation by another name.

4. It’s a command economy. No, since the famine in the late 1990s it has

This extract is taken from the start of the Preface and Introduction

Ending the Nuclear Standoff Pluto Press (London), 240pp, Softback, 9780745337852, 125mm x 195mm, 34 b/w photographs, 2 tables, 1 map, October 2018, RRP £14.99 … continued in the book

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe From the same publisher

£3.24

price £11.75 inc. free UK delivery

buy this

or point your smartphone here

Save

Our

To

book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales

ASIA / POLITICS | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 8

Bioculture is an emerging technology for producing food products from cultures of the cells from plants, animals, fungi and microbes. It is the commercial realisation of the tissue cultures which have been used in agricultural, biological and medical research since the technique was discovered by Wilhelm Roux in 1885.

Among the eyecatching advances under way are cowless meat and milk products, chickenless eggs and meat, pigless bacon and fishless fish. These are not substitutes made from vegetable material like soy—they are indeed true meat cultivated by carefully feeding embryo stem cells with the right nutrients to turn them into muscle fibre. The only thing missing is the animal in the middle of the process—which goes direct from living embryo to meat product at a speed and with an efficiency no animal can match.

The technique was demonstrated by Professor Mark Post at Maastricht University when, in 2011 he produced the world’s first ‘test-tube sausage’ followed a couple of years later by the first hamburger. This breakthrough in food production has since been followed by biotech and food startups around the planet, in what some experts consider may become a technology boom to rival or exceed solar energy.

The UN Global Environment Facility explains why: ‘Analyses show that producing 1,000 kg of cultured meat requires approximately 99% less land, 82–96% less water, 78–96% less greenhouse gas emissions, and 7–45% less energy compared to conventionally produced European livestock. Research is [also] focusing on: creating meat substitutes from plant-based protein; engineering microbes to produce dairy products like milk; and making other products such as leather, fur, and wood.’

The first cultured hamburger, a research product, cost $325,000 to produce in Professor Post’s university laboratory. Two years later a company called Future Meat Technologies said it had the cost down to $325 a pound and was aiming for $2–3 a pound by the early 2020s.

Cultured meat is controversial. On the one hand it offers meat which is free from cruelty (to either animals or humans) and meets contemporary ethical standards with a much lower environmental footprint than conventional meat from animals. On the other hand, its critics claim it is ‘not real meat’ and that its climate credentials may not be as good as natural grazing of animals (which, if done sustainably, can lock up large amounts of carbon). However, since the cultures are raised in bioreactors, they are immune to the impacts of weather and climate that afflict livestock systems. On the dietary side, it is likely they can offer a meat alternative that is designer-profiled to the needs of consumers with particular health problems, at an affordable price.

Meat is far from the only new food product that can be produced from biocultures. There is also milk made from yeast cells, vegetarian ‘meat’ and eggs made from plant cells. With gene editing, it become possible for bio-factories to make new medical drugs, biofuels, bioplastics and green chemicals, even insulation, textiles and construction materials.

Carolyn Mattick of the American Association for the Advancement of Science assesses it as ‘a technology that presents opportunities to improve animal welfare, enhance human health, and decrease the environmental footprint of meat production. At the same time, it is not without challenges. In particular, because the technology largely replaces biological systems with chemical and mechanical ones, it has the potential to increase industrial energy consumption and, consequently, greenhouse gas emissions’.

The big question is: will consumers eat biocultured food? The answer, it appears, is that today’s consumers do not know what is in a sausage, a pie, a chicken nugget, a dim sum or a crab stick anyway—and will probably eat it provided the price is right and the food is tasty and safe. In support of this view is the fact that in the 1950s nobody on Earth wore synthetic fabrics made from petroleum— and today almost everybody does, suggesting that novel technologies can be universally embraced provided they meet consumer needs, wishes and budgets.

A major challenge facing this very new technology is how it will be received by the highly complex system of food law and regulation, institutions, commercial networks, healthcare policies, technical factors and social mores that influence the modern food supply. These have posed no real obstacle to the introduction of genet-

ically modified foods, and so may be expected not to do so for biocultured foods. However, the issue will be decided, in the end, by consumer preferences.

Another big question is: what effect will cultured meat have on the 60 billion animals which are slaughtered every year to feed humanity—and on the hundreds of millions of people who raise and process them? Since livestock now represents 65 per cent by weight of all the vertebrate land animals on Earth, clearly an alternative way to grow meat could potentially replace many of these—and so help to restore the ecosystems which humans have destroyed or damaged in trying to raise and feed so many livestock, allowing wild animal numbers to recover. However, it is likely that many consumers will still prefer their meat ‘natural’, in the same way that many people still choose to wear cotton, linen or wool over synthetic textiles. This means there will still be a large market for meat from livestock reared sustainably on eco-farms or grazed sustainably in the rangelands— and that animal meat, as an up-market product, will command a premium price.

Coupled with biocultures, potentially, is 3D printing of food from raw ingredients, or even from basic nutrient materials produced in biocultures. Food printers have a range of possible applications, from printing out hamburgers, pizza, donuts and snackfoods in fast food outlets and vending machines, to automated production of airline meals, to the sculpting of unique and beautiful designer desserts in elite restaurants. In the home they can be used to print out novel processed foods from raw, heathy ingredients, thus sidestepping the unhealthy chemical dyes, additives and preservatives and excess salt, sugar and fat of the industrial food chain. Dozens of different food printers are already on the market, and hundreds of tech startups and major corporate players are forecast to be distributing them by the 2020s.

Exploring an Unexplored Planet

Today the average consumer eats fewer than 200 different plants as food. Yet there are, according to Australian agronomist Dr Bruce French, no fewer than 29,500 edible plants on the Earth.

Dr French gained the first inkling to this stunning insight in the 1970s, when he was working in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, teaching the locals about modern farming methods. Instead the locals—who had been farming for around 12,000 years—taught him a thing or two about the richness, variety and nutritional value of a diet still substantially based upon a wild harvest and native crops. In 2005 Bruce gave a talk to his local Devonport Rotary Club about what he’d observed in PNG, and how he thought this hidden indigenous knowledge could help ease world hunger. In less than two years he had teamed up with Rotary International to compile a world catalogue of plants that are good to eat, drawing heavily on the rapidly eroding store of knowledge of native peoples still living on their land around the globe. This, plus an accompanying education program called Learn*Grow, has since been shared with over 35 partner countries.

The aim of the Food Plant Solutions project was to produce an online database of useful edible plants from all continents, how to grow and prepare them as food, for countries struggling with hunger and poverty—but, in the event, Dr French should probably also be cast in bronze by the World Chefs Association for identifying tens of thousands of novel ingredients their members, the best chefs on the planet, had never even heard of. Thanks to an observant eye and a flash of insight, Bruce French has reshaped the human culinary destiny, the future of food and of farming.

The take-home message from the life’s work of Bruce French is that modern humans, while dreaming of settling the Moon or Mars, have yet to explore the Earth. At least, in terms of what is good and healthy to eat. We have, for generations, ignored what is under our very noses—especially in the modern age, whose oppressively narrow food boundaries are defined for us by a handful of gigantic food and supermarket corporations.

In Australia, where the European (and, latterly, American and Asian) diet has reigned for 250 years, Dr French has identified no fewer than 6,100 edible native plants used by the continent’s Aboriginal peoples for food and medicine for tens of thousands of years. So far, only about five of these foods have found their way into even the regular Australian diet, let alone the world diet—the macadamia nut being the best-known example.

With the recycling of urban nutrients—especially micronutrients—this

Food or War Julian Cribb

What are the chances of our planet’s being able to feed growing numbers of us without the environmental impact of doing so wiping us out and, with us, the rest of the natural world?

Julian Cribb has been exceptionally concerned about the price we pay for food, existentially, for many years. In his latest book, he looks at historical challenges—including the horrors of war and famine—and explores modern opportunities

Julian Cribb writes about science, agriculture, mining, energy and the environment. He has been scientific editor for The Australian newspaper, director of national awareness for the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (an Australian federal government agency), and president of various professional bodies that report on agriculture and science. He has received numerous awards for his journalism

Save £1.20

Our price £8.79 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Subscribe to Booklaunch now!

Special autumn offer: 30% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

From the same publisher

EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE | ISSUE 5 | PAGE 9

This edited extract comes from Chapter 9: “The Future of Food”

… continued in the book

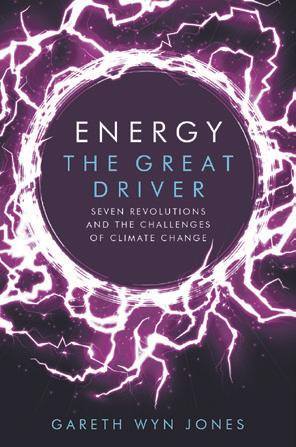

Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 350pp, Softback, 9781108712903, 139mm x 215mm, 42 b/w illustrations, October 2019, RRP £9.99

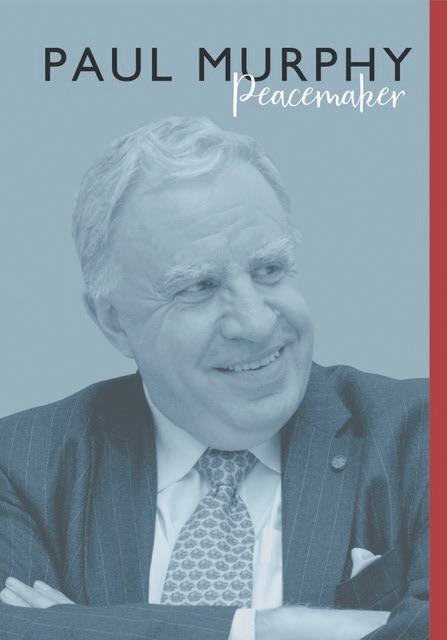

Peacemaker Paul Murphy

University of Wales Press (Cardiff), 208pp, Hardback, 9781786834720, 156mm x 234mm, 45 b/w pictures, September 2019, RRP £25.00

Paul Murphy joined the Labour Party more than 55 years ago, serving on his local council before succeeding Leo Abse as MP for his home constituency of Torfaen, Wales, in 1987. In this book, he describes how the socialist beliefs he grew up with helped shape his early political consciousness, and led eventually to his playing a leading role in negotiating the Good Friday Agreement as Northern Ireland Minister under Mo Mowlam

Paul Murphy, MP for Torfaen from 1987 to 2015, was Welsh Secretary in the UK Government from 1999 to 2002 under Tony Blair and again from 2008 to 2009 under Gordon Brown. He was also Northern Ireland Secretary in the Labour government between 2002 and 2005. He now sits in the House of Lords as Lord Murphy of Torfaen

To