Until Covid-19, wealth in Europe was outflanking US growth rates

The pandemic has devastated economic performance and exacerbated sovereign debt. And while the superwealthy have already shrugged off their losses, most leading economists see wealth inequality growing, according to Oxfam at the end of January.

‘Rigged economies are funnelling wealth to a rich elite who are riding out the pandemic in luxury’, said Oxfam International’s Executive Director, Gabriela Bucher, and that’s ‘a policy choice’. ‘Governments must take the opportunity to build more equal, more inclusive economies.’

On the other hand, advanced countries with the highest GDP may have been knocked off their perches by Covid-19 and their higher levels of borrowing, resulting in a degree of levelling between the nations.

Five years ago, IMF data showed a very different picture. Household net wealth was high and growing in most advanced economies, with wealth-income ratios in France, Germany and the UK returning to the high levels last seen in the 19th century, and doing so faster than in the USA. See page 8.

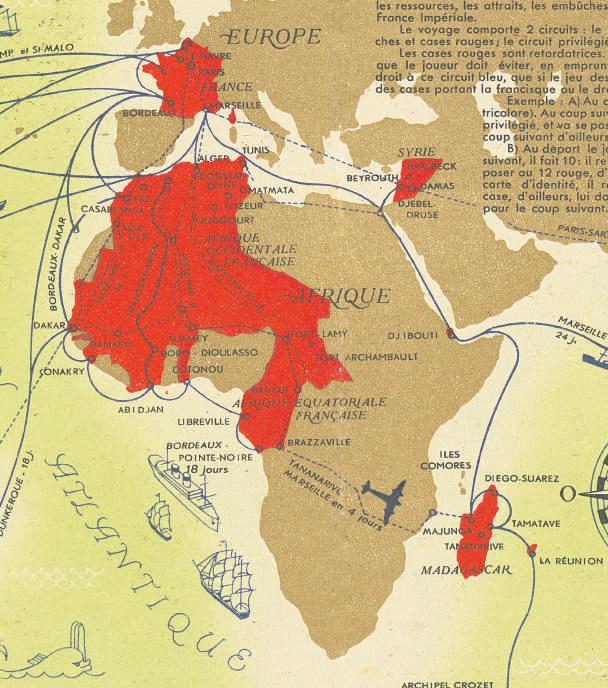

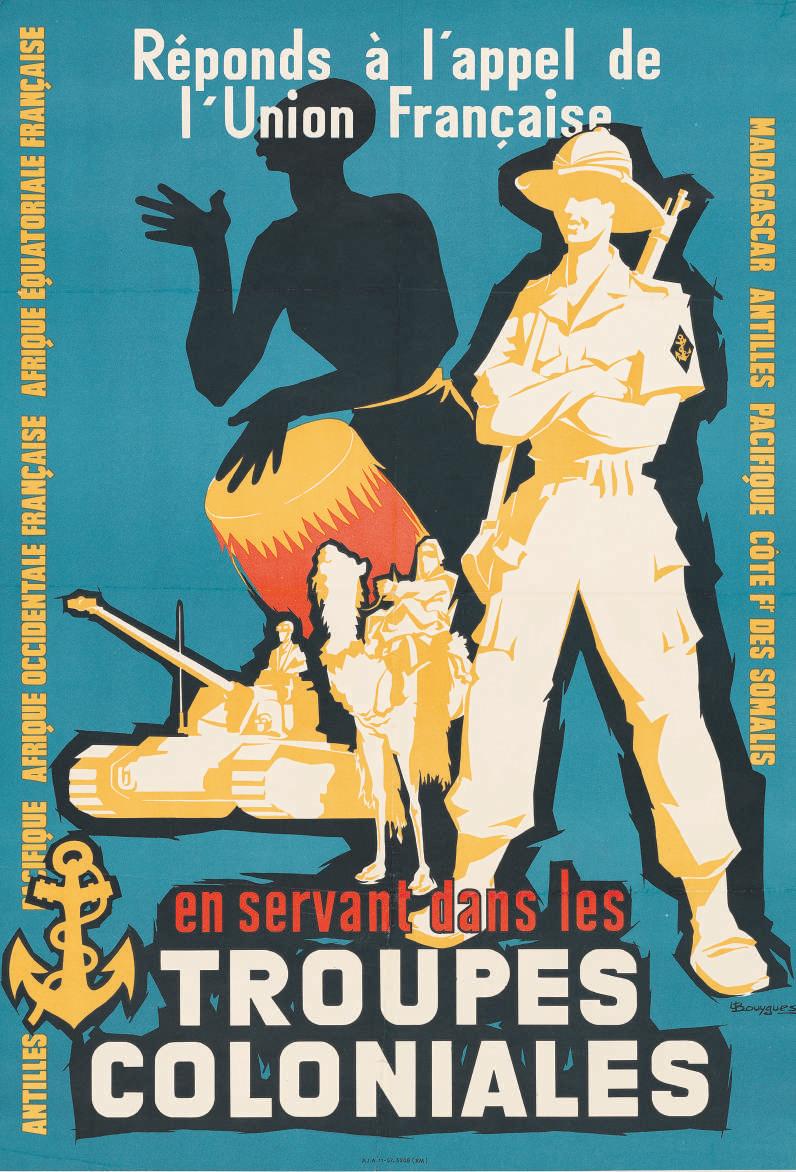

Much of France’s empire was closer to hand than Britain’s—a short ride down the Atlantic coast, past Spain to West Africa. France celebrated the fact in its International Colonial Exhibition of 1931, which gave visitors a ‘tour of the world in a day’. A new book from the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles illustrates some of the visual artefacts used by the French to represent and define their peoples. See page 6-7

How to promote social democracy to young voters

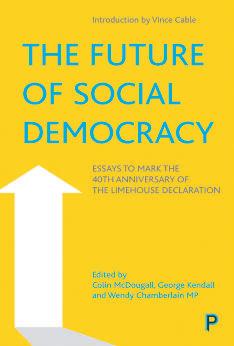

January 2021 marked the 40th anniversary of the Limehouse Declaration and the launch of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Through the 1980s, according to the authors of a new book on the future of social democracy, the SDP offered the most coherent ideas to challenge Thatcherism. Social democratic ideas were central to the ethos of the Liberal Democrats, the party formed from a merger of the SDP and the Liberals in 1988-89.

But they also, arguably, became the intellectual bedrock to Blairism and New Labour, leaving LibDem members with the problem of how to regain control of what they see as their own political heritage.

In 2015, the Social Democrat Group was formed to grapple with this problem and a new book of essays has now appeared, with contributions from, among others, Vince Cable, Chris Huhne and Roger Liddle, the latter of whom was more associated with the Labour Party, as Special Adviser on European matters to Tony Blair, before becoming Principal Adviser to the President of the European Commission.

The book is a defence of social democracy and an attempt to show how its ideas can be deployed to combat growing poverty, the aftermath of Britain’s exit from the European Union and the rise of populism, which it sees as an increasing threat. See page 4

Inside the tureen lay an envelope marked ‘Sherlock Holmes, Esq.’. He flicked it to me. It contained a single sheet of Trafalgar blue note paper upon which were written the words: ‘Dear Holmes, Your compulsive urge to interfere in my life presents a tendency of the most diabolical kind. Given our mutual interest in cascades, I suggest we meet at the Old Roar Waterfall above Hastings, conveniently near your bee-farm in Sussex. Shall we say around two o’clock on the afternoon of the first Monday of the coming month?’ See page 18

Parliamentarian or royalist? The mystery of a Civil War rebel

John Poyer is hard to understand. Although he was governor of ‘Penbroke’ [sic] and a force to be reckoned with in the politics of mid-17th-century Wales, he made enemies at a time when many were jockeying for position, trying to anticipate whether King Charles I would survive the Cromwellian revolt or be brought down by it.

Poyer, possibly more principled, called it wrong, prompting Lloyd Bowen, Reader in Early Modern History at Cardiff University, to want to know more.

Author of a more general study of Welsh politics leading up to the Civil Wars, Bowen specialises in the controversies surrounding Charles’s religious and financial innovations in Wales and has offered fresh insights into issues of Welsh allegiance.

Of his earlier book, The Politics of the Principality: Wales c. 1603-1642, The Parliamentary History Yearbook Trust said it gave ‘a convincing explanation for Welsh royalism in the 1640’s’—one that the Welsh History Review felt could not be ignored. See page 5

ON OUR INSIDE PAGES

Page 2 The editor speaks

Page 3 Bad language, Lingualia and survey

Page 4 The future of social democracy

Page 5 John Poyer’s political Civil War flip

Page 6 France’s Art Deco depiction of empire

Page 8 How fiscal policy can help the poor

Page 9 A new Britannica encyclopedia for children

Page 14 The bugler boy in the Napoleonic Wars

Page 15 From Bedales to the Royal Flying Corps

Page 16 Mobile phones as an economic tool

Page 17 The literature of military intelligence

Page 18 A Sherlock Holmes mystery

Page 19 Conan Doyle and literary appraisal

l Bernard Cornwell, who penned the Foreword to Stephen Petty’s historical tale about a bugler in the 95th Rifles, is bringing back his Richard Sharpe character in a new novel this autumn. See page 14.

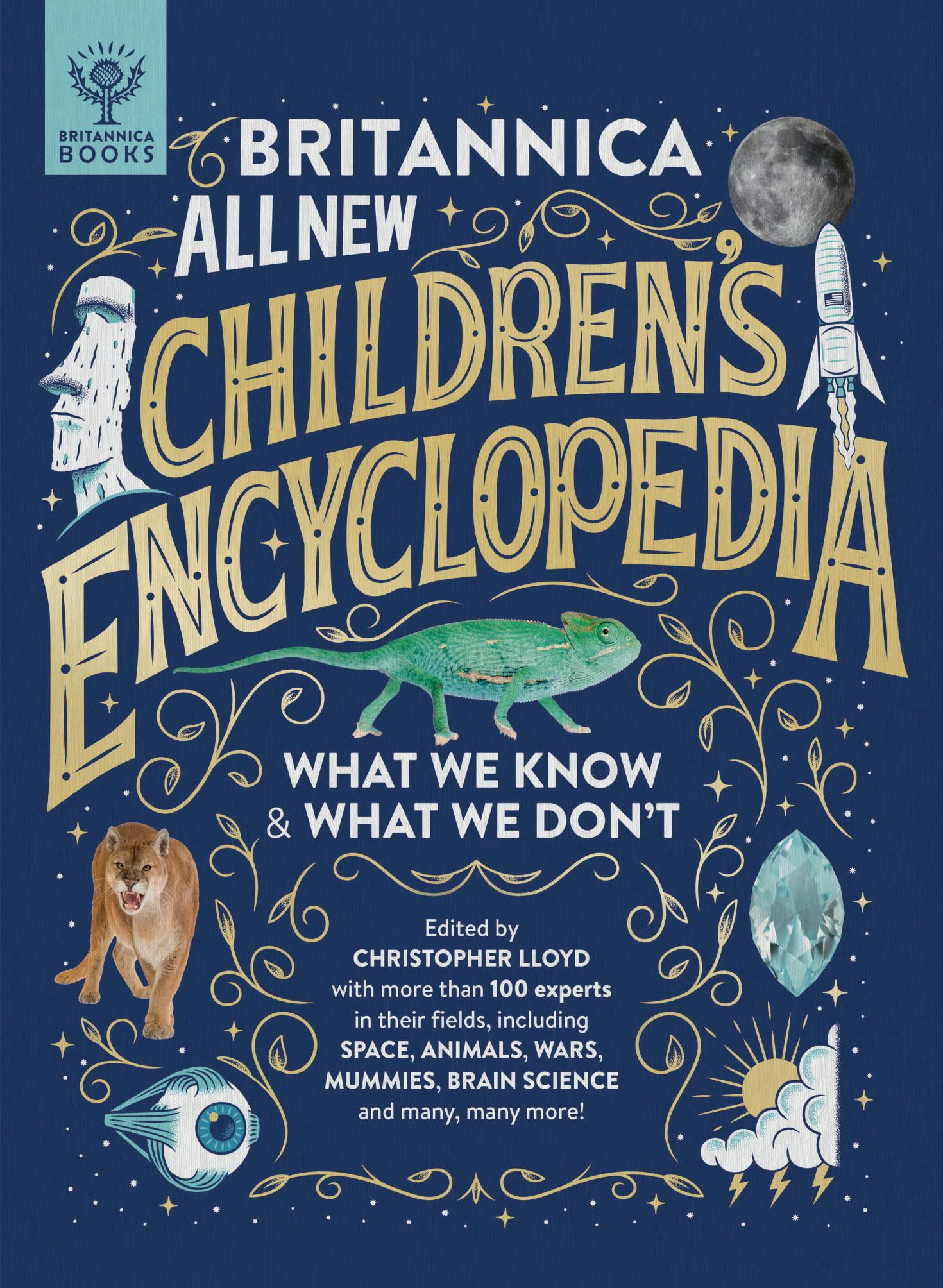

l What on Earth Publishing’s new children’s encyclopedia marks the first return to print for American partner Britannica since 2012. See pages 9–13. l Professor Simon Ball, writing about Britain’s spy masters, is our latest Leeds U. academic. See page 17

Editorial: Us and Them Stephen Games

Booklaunch 12 Wellfield Avenue, London N10

Distribution Upwards of 50,000 print copies

Website www.booklaunch.london

Publisher/editor Dr Stephen Games editor@booklaunch.london

Design director Jamie Trounce jamie@jamietrounce.co.uk

Assistant editor Maggie Bawden book@booklaunch.london

Advertising Nick Page page@pagemedia.co.uk

Tel: 01428 685319 Mobile: 07789 178802

Printer Mortons Media Group Ltd

Subscriptions Jenny Chalcott subs@booklaunch.london

UK £16.95/Overseas £24.95

With the cacophony of opinion on social media and the pointlessness of much of the popular press, a new publishing phenomenon is emerging—one that Booklaunch is proud to be part of—for readers who want to be taken seriously rather than treated like gossip partners or consumerist dopes.

Some of the most prominent of these new platforms— they’re all online—are The Conversation, Tortoise and The Browser, all of which offer a relatively compact amount of serious, thoughtful, insightful material rather than vast quantities of trivia.

The Conversation, launched in Australia in 2011 but London-based, now publishes in ten regional editions and four languages (English, French, Spanish and Indonesian) and invites topical essays from suitably qualified researchers and lecturers (slogan: ‘academic rigour, journalistic flair’). Each edition is sponsored by a regional consortium of universities and research bodies, and its content can be freely quoted from.

Tortoise, started by a former Times editor and BBC head of news in 2017, makes a virtue of longer, well developed articles rather than breaking news, and sees itself as a cross between TED talks and the Economist, though the New Yorker seems a more obvious precedent.

The Browser culls material from other sources

rather than originating its own, to end up wth five or six daily articles recommended by its two editors, plus a daily podcast and video. It was launched by an ex-staffer at the FT in 2008 and was inspired by The Weekly Dish, started by Andrew Sullivan in 2000 and now often quoted as grossing $500,000 a year.

These platforms all operate by emailing subscribers daily or weekly with a menu of fresh stories that take one either to their own website or, in the case of The Browser, to a story’s source. All invite subscriptions or donations but offer lower-level services for non-payers. Their shared ethos is to identify stories that matter, to get to the big picture, and to care about the consequences.

There’s a notion of openness that links them too. In the words of Tortoise, the sites are independent of political and commercial agendas, free of ads and protective of members’ data. All imply equality and communality between editors, writers and readers.

Booklaunch shares these aspirations but, uniquely, bases its content on books, not on other magazines, nor—in the case of another site called Medium—on a self-electing cohort of independent writers. Unlike other book magazines, it’s the author’s words that we focus on, not the reactions of third parties. That’s why we run extracts rather than reviews: so readers have the benefit

of the real thing rather than responses of untested value.

That’s a worthy aim, and one in which we were recently wished good luck by the Big Issue’s Lord Bird, a man we admire. It’s also why, in addition to appearing online, we choose to come out in print, and in a very large print run. We, and all these new titles, represent little salons distilling intelligence.

What bothers us is the uniformity implicit in the community of interest that Booklaunch and its peers aspire to cultivate. Each publication was started by white Englishmen of similar ages and similar cultural and educational backgrounds (three of us educated at Oxbridge). We have all worked at the highest levels of mainstream journalism and become frustrated with it. And we have all taken advantage of deunionisation to set up enterprises of our own to challenge the giants.

Fine. But where does this leave that much larger demographic whom we carelessly dismiss as less editorially discriminating? ‘They’, arguably, have far greater need of better writing than the cultured few, and aren’t getting it. It’s all very well catering for the catered-for; the great challenge is to undermine the commercialised trash and amateur sensationalism that defraud the unwary because, as we’ve seen in America only too recently, these feed a profundity of ignorance that threatens us all. Agreed?

Bad language Bart O’Fehfon

Tell us the truth

The Booklaunch survey 2

If you missed the survey we emailed recently about your bookreading habits, the deadline has now passed, but we’re keen to get more feedback. Having told us about your enthusiasms, please tell us now what gets your goat.

1. What books that publishers and reviewers have most talked up in the last year have you been most disappointed by?

2. The Tin Ear prize: nominate a celebrated author who seems incapable of good writing. Give us some examples and shame the publisher.

3. Book people seem to love lists (The Sunday Times Top-Ten Lockdown Poetry Anthologies; Indie Bookshops’ Covid-19 Slowest-Selling Travel Guides). Write a list of the five things you most dislike about book lists.

Define the c-word for me

Covid-19 is short for “coronavirus disease 2019”. So …

It’s not an acronym like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome).

It’s not an initialism like PPE (personal protective equipment) or WFH (working from home).

It’s not quite a blend / portmanteau word like ‘infodemic’ (‘information epidemic’—the gush of news, including fake news).

So what is it?

One idea is to call it a syllabism. But that doesn’t really work. For a start, the term already exists, referring for instance to the use of a syllabic rather than alphabetic writing system.

The alternative form syllablism is no improvement. It’s less mellifluous, and anyway it too already exists (though not yet widely enough to appear in dictionaries), referring for instance to a poet’s preoccupation with syllable-counts.

More importantly, the constituent elements of Covid19 are not all syllables, so syllabism or syllablism would be misleading.

A better term would be fragmentism

Any other ideas? And can you think of any other abbreviated words that originate in an equally patchy way?

Where do they get it from?

Given that the expanded form of Covid-19 already contains the word virus, it seems slightly odd to speak of the ‘Covid-19 virus’. Yet Google (around the end of January 2021) was giving more than two billion hits for the phrase.

In other words, the awkward phrase seems to have gone viral, ho ho.

The terminologists should have foreseen the problem and pre-empted it by naming the disease Cod-19 instead. Or perhaps not.

In fairness, the phrase Covid-19 virus is not really tautologous in the way that HIV virus is. (Other ‘hidden tautologies’ include PIN number, LCD display, and ATM machine.)

When did you say?

Some interesting datings, from the OED and elsewhere, and via a recent OED communiqué:

Covid-19, unsurprisingly, is first attested in 2019.

Coronavirus in 1968 (in the journal Nature).

AIDS in 1982 and SARS in 2003.

Virus in 1599, though in the sense of ‘venom’; in the

Lingualia Quiz 2

What do the following have in common?

Dick Carter Gus Painter

M.A. Carpenter

Charlie Weaver

Max Marsh (aka Max Fracture)

Johnnie Brook

Al Hill

Claud Greenberg

Fred Cream

Len Amber

Clue: others in the same category include J.P. Branch and Dick Bouquet (aka Dick Battle aka Dick Ostrich). Another clue: the first item—Dick Carter—is slightly misleading. Book prizes for first three winners.

sense of ‘microscopic pathogen’ it was first used in 1881, the year after Pasteur first used it in French. The adjective viral dates back only to 1948, and its extended sense (relating to the rapid spread of info) only to 1989. And the phrase to go viral was first used in 2000, it seems.

Epidemic as an adjective is first attested in 1603, and as a noun in 1799 (or 1757, though used in a figurative way rather than of an actual disease).

Pandemic as an adjective appears first in 1666 (the time of the Great Plague), and as a noun in 1853.

Infodemic dates from 2003 (in relation to SARS).

PPE (in the relevant sense) in 1977. And personal protective equipment way back in 1934.

WFH as a noun in 1995. And as a verb (really?) in 2001. (Not to be confused with WTF, first recorded in print in 1985.)

Social distancing in 1957, though with reference to a snooty attitude rather than to fear of disease.

Quarantine as a noun (in the relevant sense) in 1669, in Pepys’s diary. (An earlier use, dating back to 1609, relates to a widow’s right to continued occupancy of her mansion house.) As a verb, in 1804.

Self-quarantined in 1878.

Self-isolation and self-isolating in 1834 and 1841 respectively (though they tended in the 19th century to be used with reference to countries and their political and economic isolationism).

Care to split an infinitive?

In 1964, TSE (=Eliot) was challenged in the Daily Telegraph by Bertrand Russell over the split infinitive. Russell quoted Lycidas—‘To tend the homely slighted Shepherds trade / And strictly meditate the thankles [sic] muse’—to show that the last line here, unellipted, would read ‘And to strictly meditate …’. A subsequent correspondent, however, wrote to say that the line could equally well read: ‘And strictly to meditate the thankles muse…’ and that Milton had not necessarily stooped. The sequence of letters ended with a Bellocian poem:

Mary, having shot in dozens Sisters, Aunts and Second Cousins, Told the judge with eager zest, ‘I hope to soon bump off the rest.’ Reaching for his black cap, he Cried out, ‘Ye Gods, what infamy! The liquidations I’d forgive But not that split infinitive.’

Results of Lingualia Quiz 1

What do the following have in common? (Booklaunch 7)

average weekly wage / arts and crafts / mass media / motor neurone disease / Martha’s Vineyard / Washington Times / Train à Grande Vitesse

Answer: The clues all share official acronyms with Shakespeare plays. AWW (All’s Well that Ends Well); A&C (Antony and Cleopatra); MM (Measure for Measure); MND (A Midsummer Night’s Dream); MV (The Merchant of Venice); WT (The Winter’s Tale); TGV (The Two Gentlemen of Verona). The Shakespeare acronyms used here are those from The New Oxford Shakespeare. The standard American English source, the MLA Handbook, has some variations, including Ant. for Antony and Cleopatra, and Wiv. for (The Merry Wives of Windsor) No winners, I’m afraid. So Live, Love, Laugh!

4. Do photographs of authors in book reviews influence your buying decisions? Do the pretty and the handsome write better than the lived-in and crumbly, in your experience?

5. Why do you think publishers use photographs in their publicity packs?

6. Did you buy Richard Osman’s book because you’ve seen him on ‘Pointless’? (Go on, admit it.)

7. Which of the following has done most good for the bookselling business: Amazon? Oxfam? bookshop.org? Waterstones? Friendly local bookshops?

8. Do you mostly buy books from online retailers or do you prefer to order through your friendly local bookshop and wait two weeks?

9. Have you ever sussed out a book in your friendly local bookshop and then bought it online? (Be honest.)

10. How friendly is your friendly local bookshop, actually? Out of ten.

11. Can you guess why?

12. Would you choose to forego your discount on a book just to spite Amazon?

13. If a book were only available on Amazon, would you refuse to buy it?

14. Do you think household-name publishers treat authors well? (Really? You really think that? Oh boy.)

15. OK, then: which of these publishing groups is the cuddliest and least rapacious? Penguin Random House? Hachette? Harper Collins? Macmillan? Bloomsbury? OUP? Explain your answer. (Do you work for any of them?)

16. Informal social-media book influencers are now the Trojan horse of big publishing (and smaller publishing too). Knowing that, would you encourage your child to marry a book influencer or disown them if they did?

17. Kindles and ebooks are definitely the way to go, aren’t they?

18. In 2018 over half of all fiction sales were crime thrillers. One book accounted for 30% of the rest. Can you name it, and are you completely fine with that?

19. Who should the 2019 Booker Prize have gone to: Margaret Evaristo or Bernadine Atwood?

20. Is anything fair, when you come to think of it?

Email us your answers and your permission to quote you, or otherwise: book@booklaunch.london. Prizes if we chuckle.

The unexpected Conservative majority in December 2019 was a painful defeat for both Labour and the Liberal Democrats and was compounded by the fact that many of those on lower incomes, whose lives we seek to improve, switched to the Conservatives. This is a serious political failure and we need to consider why it happened.

On 9 September 2016, Hilary Clinton said: ‘you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. … They’re racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic.’ It was a catastrophic gaffe that was used repeatedly by the Trump campaign. Not only did it energise Trump’s base, but some who were still undecided thought her insult might be directed at them. She quickly apologised, but the damage was done, perhaps because her words were perceived to reflect the underlying attitude of many liberal members of the Democrats. Social democrats and liberals in the UK should consider whether we have made similar mistakes.

Engaging with these voters will sometimes require us to make compromises. Such compromises are not a betrayal of our values. Those who voted tactically for Hillary Clinton to keep out Trump in 2016, whether from the Left or the Right, were compromising, but they

THE FUTURE OF SOCIAL DEMOCRACY ESSAYS TO MARK THE 40TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LIMEHOUSE DECLARATION

Policy Press

Softback, 144pp 15 January 2021 9781447361268

RRP £12.99

Our price £10.33

were also acting out of deep principle. We want voters to give us tactical support in the UK, but we will be unable to do so if we reject the idea of seeking common ground with them.

Vince Cable

Political parties that could be described as social democratic have been in decline for some years, particularly in the countries where they have historically been strongest: Britain, Germany and in Scandinavia. Others outside the Western world, as in India and Brazil, have largely disappeared. Almost everywhere, competing voices—nationalism, ethnically based populism and authoritarian ‘strong men’—have drowned out the appeal of social democracy and captured much of the electoral base of social democratic parties. That base was in any event contracting because of the decline in manufacturing and unionised employment, and the greater priority for younger voters of new issues like the environment. The main appeal of social democrats— that they offer the best of capitalism and socialism—was increasingly seen to be not credible.

The Covid-19 pandemic could hasten the decline of social democracy but could also help it stage a revival. Certainly, the challenges now being thrown up are those to which social democrats have produced answers in the past: mass unemployment; the re-emergence of large-scale mass poverty in the poorest countries; protectionism and lack of international cooperation; and growing dependence on the state to coordinate, plan and be the health provider, employer and safety net of last resort. Social democrats, in government and out, were key to the post-war consensus that was instrumental in tackling these problems, which have now resurfaced in a new way.

READERS’ COMMENTS

This extract taken from the Forward, Introduction and Chapter 1.

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running.

However, there are competing political models and ideas. Nationalism and populism are powerful forces in some countries (the US, Russia, China, Brazil, Mexico and India). Then there are what can be called the ‘welfare technocracies’ of East Asia. There are pockets, which may grow, of aggressive and radical individualism. And, in contrast, there are strongly communitarian movements at local level: sometimes inclusive; sometimes exclusive. The issue for social democrats is whether they can offer a mixture of competence and compassion that can transcend the competition in a democratic context.

Who are the social democrats?

The social democratic tribe is a lot bigger than represented by the parties that are descended from the socialist tradition like the UK Labour Party, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Germany, and other assorted social democrat parties around Europe and in Australia. There are some social democratic parties that call themselves ‘socialist’, as in Spain, or ‘labour’, as in Norway, or ‘democrat’, as in Italy. We should not include some that call themselves ‘social democrat’ but are rebadged ‘communists’. We should include the US

Despite the efforts of Anthony Crosland and others to achieve a similar clarification in the UK, ambiguity remained, leading initially to the SDP breakaway. Moreover, despite the efforts of Neil Kinnock, John Smith and Tony Blair to cement the social democratic character of the Labour Party, they succeeded only temporarily, leading to the bizarre spectacle of their party being captured by revolutionary socialists. Brexit has also created new geographical and ideological wounds. In the meantime, the Liberal Democrats became the voice of many social democrats, as well as liberals, but is marginalised by the electoral system.

This eclectic mix of parties and political traditions makes it difficult to locate the common denominator. There is a common thread in the Rawlsian tradition of thought, which emphasises individual freedoms alongside a shared sense of fairness and that has at its heart a ‘social contract’. The current crisis is also forcing social democrats to come up with new or reworked policy ideas to tackle new problems or old problems in a new guise.

What is to be done?

Among the most significant challenges for social democrats are mass unemployment, poverty, the problems

Democrats, who never went through a socialist phase. There are also ‘social liberals’ who emerged from classical liberal parties but are now largely indistinguishable from social democrats, like the Canadian Liberals (though they have competition from the New Democrats), and others like the Dutch 66, the Swedish Liberals and Macron’s En Marche where there are big areas of overlap. The Liberal Democrats in the UK are such a hybrid, and the identification often has more to do with a country’s voting system and its history of political schism than meaningful working definitions of social democracy.

What is striking and disappointing is that social democracy has not travelled well outside the heartland of Western Europe, North America and Australasia. In Asia, Lee Kuan Yew’s People’s Action Party (PAP) in Singapore was modelled on the British Labour Party but came to despise the welfare state. On the bigger canvass of India, the Congress Party seemed to have similar values to European social democrats but succumbed to rampant corruption. The same can be said for the Brazilian Workers Party. There are recognisably social democratic parties in many places (Ghana, Jamaica, South Africa, Costa Rica, Japan, Taiwan and Korea) but national idiosyncrasies tend to outweigh what they have in common.

Those national variations stem from different histories. Some social democratic parties, as in Sweden, broke with their revolutionary socialist ancestry over a century ago and have maintained a consistently reformist and democratic personality ever since. In some cases, as in Germany, there was a moment when the party redefined itself as unambiguously social democratic— the Bad Godesberg conference in 1959—and it has remained aloof from parties of the far Left like Die Linke.

EDITOR’S NOTE

posed by big data companies and the weakening of multinational institutions caused by rising populism. Social democrats should remain committed to a Keynesian approach to economic matters, should learn from best practice in other countries and should adopt pragmatic, evidence-based policies.

The policies they should pursue include: a commitment to lifelong training and education; support for generous in-work benefits to low-earner families; making the case for taxing assets whose value has been inflated by recent monetary policies; a more effective authority to counter business takeovers that stifle competition or undermine the country’s science base; and rebuilding the UK’s relationships with our overseas partners to pursue policy objectives that cannot be achieved at a national level. However, social democrats will not return to power in Britain on the basis of policy ideas alone; they will have to overcome the tribal divisions of British political parties and the obstacles of the British ‘first-past-the-post’ voting system by means of tactical cooperation.

Wendy Chamberlain MPThe Liberal Democrats have been arguing for electoral reform for many years, largely focused on replacing the first-past-the-post voting system for Westminster. During that time, despite progress in delivering more proportional systems for both the Welsh Senedd and the Scottish Parliament, the party and others have failed to make a compelling case for change.

Since the alternative vote (AV) referendum during the Coalition period, two further referendums have taken place: on Scottish Independence in 2014 and on leaving the EU in 2016. Putting to one side the position that AV is not in itself a pro-

This book is rooted in the Liberal Democrat party’s problems in re-establishing a presence in British politics. Its title echoes that of another book with the same name that came out in Canada in 1999. Both contain essays. Those in the Canadian book were written by former social-democrat leaders from around the world musing on how to reaffirm social democracy in the face of neo-liberalism and the rise of the right; those in the British book are by British liberals offering more local solutions to vexed policy questions such as housing, free trade and environmentalism. The writing in this latter book is deeply felt; the next step is to sell the vision.

With politics going populist, what must the centre ground do to electrify the electorate? Wendy Chamberlain, George Kendall, Colin McDougall (eds)

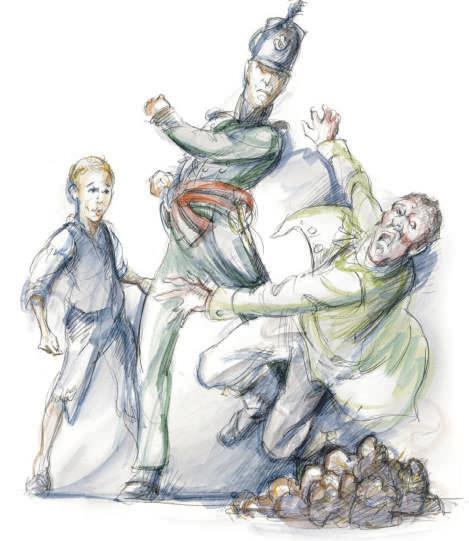

John Poyer was Wales’ greatest parliamentarian in Britain’s first Civil War. Then he flipped and went over the Royalists. Why? Lloyd Bowen

EDITOR’S NOTE

What did John Poyer represent: himself or a principle? His contemporaries seem to have written him off and to have written him out of the chronicles of his time. Lloyd Bowen has made it his mission to fill the gap. The questions that he raises can be asked of many political figures who have said of themselves that they did not change their position—it was everyone else that moved. As Bowen says, we should be more aware of the difficulties Poyer faced in trying to remain faithful to a parliament increasingly seeking to engineer his ruin, against a background of vicious national and provincial sectarianism.

Most books examining the British civil wars (c.1642–51) have an entry in their index: ‘Poyer, John’. It usually is only a single entry, however, denoting a brief mention of John Poyer’s role in an insurrection against parliamentary rule in 1648. Poyer rebelled against the parliament which had been victorious in the first civil war (1642–6) and his actions helped to initiate a series of uprisings and provincial revolts which, along with the invasion of the Scottish Covenanters in the summer of 1648, are collectively known as ‘The Second Civil War’.

But Poyer also had a fascinating history before April 1648 which can help us better understand his motivations and actions during that tumultuous spring and summer. He was essentially a nobody; born into an obscure family in a run-down town ‘in a nooke of a little county’, as one contemporary put it, on the western periphery of the British mainland.

Yet he became a leading light of the parliamentarian war effort in this part of the country in the early 1640s and held out as mayor in his bastion of Pembroke as the royalist tide swept up to the town’s walls.

Poyer was a charismatic and capable individual who managed to mobilise the local population in desperate times. His early declaration for parliament should have left him in an enviable position after the king’s defeat in 1646. Many parliamentarians were rewarded with offices and positions of local power as the new order needed trusted servants to implement its policies in the provinces.

This was not to be Poyer’s fate, however. Although he remained governor of Pembroke, he was crossed by local gentry enemies who initially supported King Charles I but later found their way into parliament’s camp. As one Poyer supporter put it at the time, ‘in our distresse [they] were our greatest enemies and successe onlie induced [them] to profess our frindshippe’.

Despite Poyer’s steadfast support of parliament, then, the aftermath of the civil war saw him effectively ‘frozen out’ of local government as his enemies rose to positions of authority through their friendships with powerful figures in parliament and its New Model Army. His marginalisation eventually led to outright resistance, and in early 1648 Poyer rebelled against parliament and the New Model Army, declared his support for the imprisoned Charles I, and even sought aid and assistance from the exiled Prince of Wales.

This royalist revolt spread quickly through south Wales but was ruthlessly suppressed, and parliament sent down Lieutenant General Oliver Cromwell to besiege Poyer and his recalcitrant royalists … After a long and attritional siege Poyer surrendered to parliament’s mercy in July 1648 and was put on trial in Whitehall shortly after King Charles I was beheaded. He and two others were found guilty and sentenced to death, but it was decided to show mercy and execute only one. A child drew lots on their behalf, Poyer lost and on 25 April 1649 he was executed by firing squad in Covent Garden.

The central problem with trying to write about Poyer

is that although he was a man who could inspire considerable loyalty and allegiance, even his staunchest admirers saw him as an irascible and splenetic individual who was difficult to like and admire. His enemies seem truly to have hated him and made sure they told the world how they felt. The result, which few historians have sufficiently recognised, is that we tend to look at him through his adversaries’ hostile gaze. Because he only left a handful of letters and petitions, all ‘official’ in nature, we invariably fall back on reports and pamphlets by others, all written with a very jaundiced eye.

The principal author of such accounts was Poyer’s bête noire, John Eliot of Amroth (Pembrokeshire), a skilled publicist and Poyer’s implacable antagonist. Eliot was adept at inserting his partial and prejudiced view of Poyer (often anonymously) into many forms of print, and historians have often treated such pieces uncritically.

The present volume is no apologia for John Poyer but does argue that we need a more critical and evaluative eye than has hitherto been the case. In fact, our modern view of Poyer often comes uncomfortably close to the perspective promulgated by John Eliot in the mid-seventeenth century. This volume acknowledges that while Poyer was a divisive and contentious figure we should none the less be more aware of the difficulties he faced in trying to remain faithful to a parliament which was increasingly seeking to engineer his ruin.

There is something unsavoury about a man who changes his allegiance and shifts his positions. However, it is one of this book’s arguments that Poyer was, in fact, a consistent politician who failed to adapt to the shifting politics of his times and ended up before a firing squad because of his inflexibility. Rather than seeing Poyer’s royalist declaration in 1648 as an aberrant shift from his earlier public politics, this volume argues that we need to take Poyer’s own words more seriously, that in 1648 he ‘still continue[d] to [his] … first principles’. Poyer considered that parliament had become a radical body which had fallen away from its original undertaking to seek moderate reformation and an accommodation with the king; it had departed from him rather than vice versa.

This volume, then, seeks to better understand and contextualise Poyer within his milieu and the local and national politics of his times. It argues that Poyer needs to be located within the bitter factional politics of civil war Pembrokeshire, and that we should pay greater attention to the connections these factions made with figures at Westminster. This study is the first to explore in any depth Poyer’s background, and it reveals that he was an intimate of the Meyrick family of Monkton, near Pembroke. This helps place him within the orbit of the influential Earl of Essex, leader of parliament’s army in 1642. His brother-in-law and fellow parliamentarian soldier Rowland Laugharne was also close to Essex, as was Poyer’s sometime ‘master’, the Pembroke MP, Sir Hugh Owen of Orielton.

On the other side of this factional divide we can locate Poyer’s enemies, principal among them being the Lorts of Stackpole and their allies John Eliot and Griffith

9781786836540

RRP £14.99

Our price £14.36

READERS’ COMMENTS

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

White. The factional politics of civil war Pembrokeshire is a murky business which no previous study has satisfactorily explored or understood. For example, the role of John White, MP for Southwark, and Richard Swanley, the parliamentarian vice admiral, in assisting the Lorts and frustrating Poyer’s requests for promotion and payment of his arrears, is discussed here for the first time. Chapters 3 and 4 offer a sustained analysis of the ways in which such political connection and factional confrontation were important in shaping Poyer’s civil war experience.

A discussion of Poyer’s life during the 1640s, then, reveals something important about the conduct of provincial politics in the transformed circumstances of civil war. The capacity to make and sustain political connections at the centre was crucial in obtaining and maintaining parliament’s good graces. In this, Poyer’s enemies were more adept and agile than he and his associates were, and the appointment of John Eliot as Pembrokeshire’s ‘agent’ at Westminster in early 1645 is shown here to be crucial. Through an analysis of Poyer’s experiences, then, this volume offers more general insights into the conduct of political business in the aftermath of the war and the means by which local power was acquired and preserved.

In examining the operation of political connection across the 1640s, this book also offers a case study of the ways in which the fissures within the post-war parliamentary coalition were transmitted into the provinces. The rise of the New Model Army and of political Independency after 1646 offered a rich set of opportunities for the Lorts and their allies. Poyer, Laugharne and their associates, by contrast, looked to the more moderate Presbyterian political bloc to represent and defend their interests.

Thus it was that the factional differences within Pembrokeshire’s parliamentary politics assumed a more overt ideological form, although issues of power, money and authority were always present in these confrontations. This is not to say that ideological divisions were not present before, but rather that they were instrumentalised and weaponised, and adopted new forms when the immediate business of fighting the royalists was done.

In their political alignments, however, the Lorts had chosen a more potent set of allies than Poyer. TheEarl of Essex died in September 1646 and although Poyer and his associates still had some political successes, such as the election of his Presbyterian ally Arthur Owen to the Pembrokeshire constituency seat, the Presbyterians lost ground rapidly to their Independent opponents both centrally and locally as 1647 progressed.

Poyer’s presence among these Presbyterians places him as something of a political moderate, but the discussion here reveals that he was a religious conservative also. Somewhat unusually among precocious parliamentarians, Poyer was not a thoroughgoing puritan who had advanced ideas about Protestant reform. He was certainly anti-Catholic, and his first emergence into public view was as a bulwark against

We welcome either written responses or MP3 voice tracks. All contributions are moderated. Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running. continued

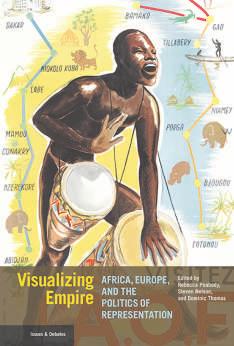

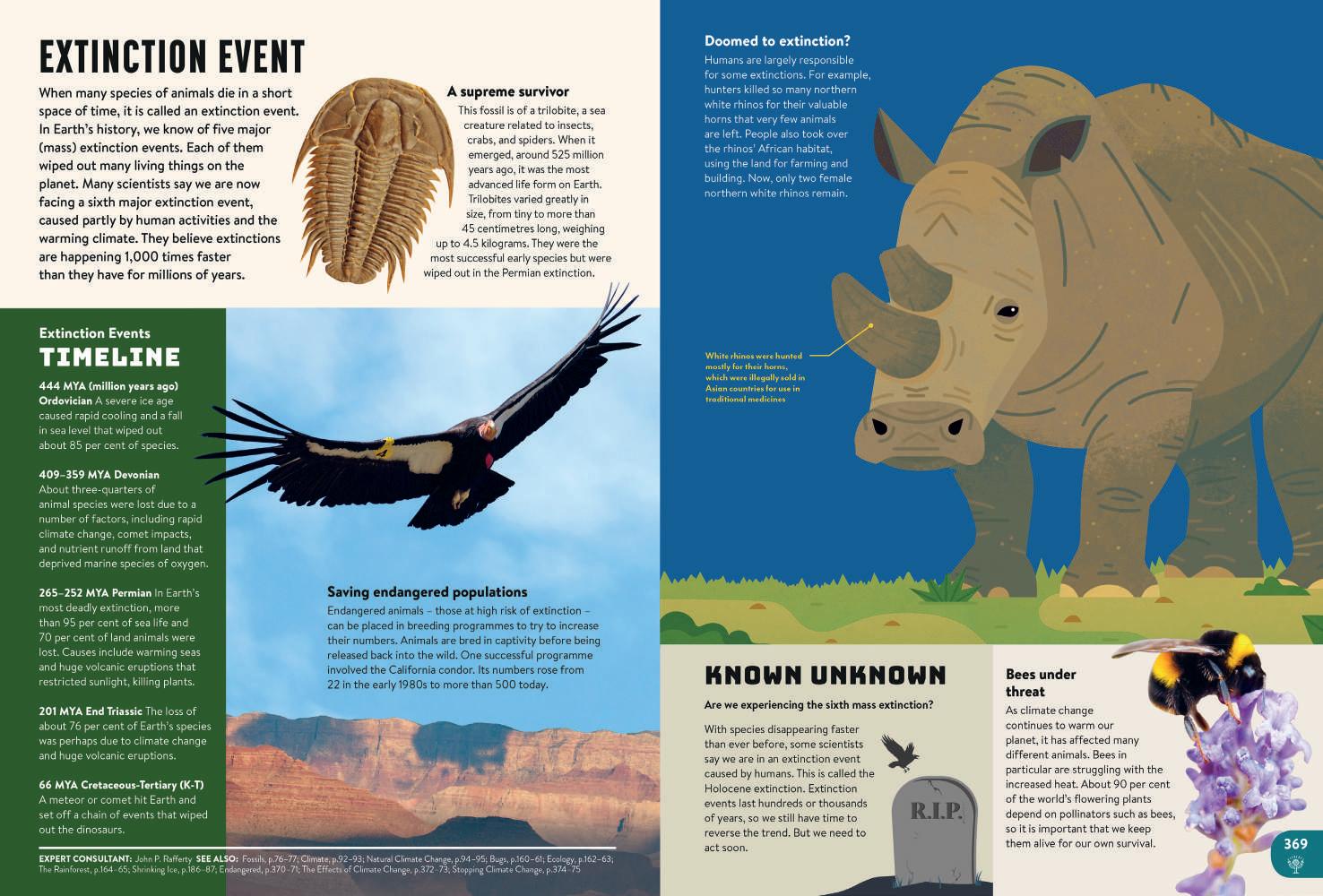

We don’t tolerate colonialism any more, but the art that defended it still appeals to us. That’s uncomfortable Peabody, Nelson, Thomas (eds)

EDITOR’S NOTE

Look at this big spread of Art Deco pictures. We like Art Deco: it was the most successful art movement of the 20th century—instantly popular around the world. But these images sum up France’s ‘golden age of colonialism’ and so we ought to deplore them. That dilemma lies at the heart of Visualizing Empire, a book based on potent materials acquired by the Getty Research Institute but whose siren temptations it has to argue with. This is not the first time custodianship and political critique have pointed in different directions, but it could become a test case.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when few Europeans had travelled overseas, anyone with a shilling or a franc could step into the cultures of other continents in their nation’s empire at the London Crystal Palace Exhibition (1851) or in Paris at the Exposition Universelle (1855), where exhibits and other materials glorified and promoted the benefits of their empires. In the decades that followed, as the French Empire rapidly expanded, world’s fairs increasingly focused on the colonies in order ‘to transform public indifference, and draw attention to both the necessity and the legitimacy of the colonial project.’ These exhibitions displayed economic and social concerns, products, and overseas infrastructure, as well as eugenics and racial violence in pavilions populated by flora, fauna, and, eventually, people. France’s colonial expansion and dissemination of propaganda were similar to those of Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Germany, and Great Britain.

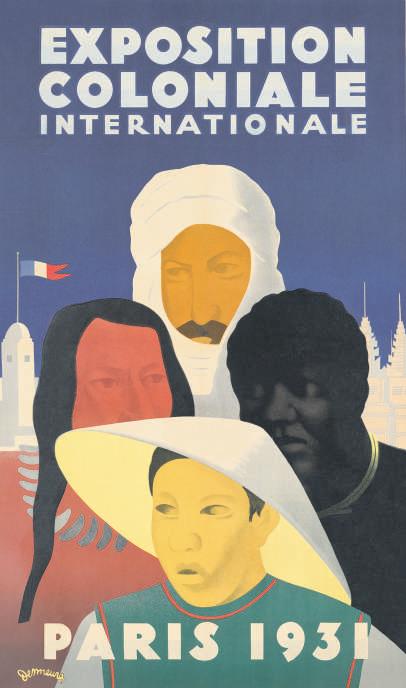

By the end of World War I, France had entered what French historian Jean Suret-Canale has called the ‘golden age of colonialism.’ Having fortified their colonial holdings in the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, the Indian Ocean, and Asia, the French could rightly claim to have expanded their dominion to the four corners of the earth. This point was celebrated in the summer of 1931, when 33 million people attended the Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale. In that world’s fair, imperialism was not a subtheme, but rather the explicit purpose; visitors could, as the government’s slogan advertised, have a ‘tour of the world in a day’, touching down on continents and oceans that represented the breadth of France Overseas.

As a result of the imperial ‘civilizing mission’, and in the span of less than a century, residents of the metropole and colonies experienced ‘the dissemination of thousands of pieces of audio/visual material’ and were ‘immersed in a veritable colonial bath. Each image participated in the elaboration of a social imaginary, through which the national community, appropriating a common patrimony, constructed itself.’

The essays in this volume focus on the role of visual culture in these processes of national self construction, using a collection of materials held in the Getty Research Institute (GRI) acquired from the Paris-based Association Connaissance de l’Histoire de l’Afrique Contemporaine (ACHAC) archives. Through a diverse and interdisciplinary range of essays, our goal has been to reveal the complex ways in which the French displayed, defined, and represented their empire. As one of the panels in a recent exhibition at the Deutsches Historisches Museum argued, ‘the world of colonial images in the German Empire shows that visual relationships are also power relationships. Photographs, consumer goods, and advertising all transmitted themes of colonial conquest and racist stereotypes.’

The Global Impact of the ACHAC Research Group

During a visit to Algeria, French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron stated in an interview broadcast on Echorouk TV on 14 February 2017 that ‘[c]olonization is

part of French history. It is a crime. It is a crime against humanity, a truly barbarous crime that is part of our history, and we need to confront this past by apologizing to the women and men against whom we committed these acts.’ He sparked a firestorm, unleashing a furor that underscored France’s incapacity to come to terms with its complex past, a past whose spectre, whose legacy continues to haunt the contemporary landscape. It is literally a past that, as French historian Henry Rousso famously claimed, does not pass. Furthermore, ‘[o]ver time, colonial culture has come to infiltrate the cultural, political, and social unconscious. Traces and vestiges are to be found everywhere.’ Perhaps not surprisingly, those European countries that gathered at the Berlin Conference in 1884–85 to negotiate territorial allocations find themselves today reckoning with that history, to varying degrees. Postcolonial populations living in Europe (many of whom are descendants of the formerly colonized) have, alongside activists, called for greater official recognition of some of the darker chapters of that history. In France, for example, these claims have also coincided with demands for a museum devoted to colonial history. To this end, the work of organizations such as ACHAC is of great interest in terms of raising public awareness of these matters, but also deeply politicized and often controversial.

The official poster for the Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale of 1931, held in the ACHAC collection, is an iconic image of interwar French colonialism. Designed by graphic and fine artist Victor Jean Desmeures, the poster reduces the people and architecture of the French colonial empire into schematic images that recapitulate the racist stereotypes that undergirded colonialism’s ‘civilizing mission’. The central group of four types represents nonwhite races (Arab, Native American, African, and Asian) by means of skin color, physiognomic features, and clothing. In the background, Angkor Wat’s spires and a North African tower evoke the exotic architecture of France Overseas. Like the architecture of the pavilions, these representations of the races had a long history within French culture. Immediately recognizable, the figures conveyed meanings to the French public that had accumulated over decades, culminating in the apogee of the Exposition Coloniale and its spectacle.

In the poster, we see what seems to be a minaret topped with a French flag. Or it might be French colonial building in the synthetic neo-North African style developed under Maréchal Hubert Lyautey’s leadership in Morocco. On the right, Angkor Wat’s towers are clearly identifiable, familiar after decades of depictions and reconstructions at previous expositions. The grouping forms a static composition of four racial types, an allegorical group that stands for both peoples and places. Reduced to a few characteristic features, the human figures are flattened into a non-place and nontime. The buildings are similarly iconic. The vivid colors and simple forms are arresting, particularly because they are monumentalized on the huge format of the poster (54 by 73 cm). The people depicted are almost

lifesize, but, due to their schematic representation, they produce difference rather than identification with the viewer, who is assumed to be white.

The Imperial Archive

The poster and other objects from the Exposition Coloniale belong to two archives: the ACHAC collection within the Getty Research Institute (GRI) archives and the so-called imperial archive. The imperial archive is not a physical one, but, rather, a concept that encompasses the long history of representations of the races, architecture, and geography of the colonies. Beginning from Michel Foucault’s work on genealogy and the archive, scholars of colonialism have extended his theories to the imperial archive. Foucault understood the archive as part of the systems that control enunciation and knowledge. It is neither the sum of the texts that a culture preserves nor those institutions that record and preserve them. For Foucault, the archive of a society, a culture, a civilization, or a whole period cannot be described exhaustively, particularly our own archive. ‘It emerges in fragments, regions, and levels, more fully, no doubt, and with greater sharpness, the greater the time that separates us from it.’ The analysis of the archive involves a privileged region that is close to us yet different, ‘it is the border of time that surrounds our presence … it is that which … delimits us.’

Postcolonial thinkers have extended Foucault’s concept of the archive to define the imperial archive, the epistemological systems through which colonizing powers exercised control over their distant empires. Ann Laura Stoler links the archive to colonial power: ‘What constitutes the archive, what form it takes and what systems of classification signal at a specific time, is the very substance of colonial politics.’ Thomas Richards characterizes the imperial archive as ‘a fantasy of knowledge collected and unified in the service of the state and Empire.’

For six months in 1931, the Exposition Coloniale Internationale in Paris welcomed the public to celebrate the accomplishments and the future of colonialism, featuring sections for the French colonies and the colonial empires of Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, and the United States. Advertised as ‘Le tour du monde en un jour’ (A tour of the world in one day), the Exposition Coloniale gave its visitors the experience of the world’s cultures and peoples without the inconvenience and danger of global travel. At the exposition, as in the poster, representative objects and peoples from the colonies were displayed and reconstituted into a new colonial realm, frozen in a timeless state, as if they were outside evolutionary change and the effects of modernization. The exposition promulgated a contradictory message of the colonies as the Orient—the site of degeneration, sensuality, and irrationality—and the colonies as a laboratory of Western rationality. It occupied a middle region where the norms, rules, and systems of French colonialism both emerged and collapsed.

The Exposition Coloniale made fictions from continued in the book

Getty Publications

Softback, 200 pages

12 January 2021

9781606066683

RRP £45.00

Our price: £36.43

CLICK

READERS’ COMMENTS

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

We welcome either written responses or MP3 voice tracks. All contributions are moderated. Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running.

In most advanced economies, household net wealth is high and growing. After a steady decline throughout much of the twentieth century due to the adverse shocks of the two world wars and the stock market crash of 1929, household wealth-income ratios have been rising rapidly since the early 1970s, with a swift acceleration during the new-economy boom of the 1990s. This increase has been particularly pronounced in Europe.

In the United States, wealth has increased at a slower pace, marked by two significant corrections during the financial crises of 2002 and 2008. Japan has followed a more idiosyncratic path, with stronger wealth accumulation during the 1980s, followed by a decline in the early 1990s after the bursting of the asset price bubble. In most countries, the global financial crisis severely affected the net wealth of households, but after a steep decline in 2008, most wealth ratios bounced back to their previous levels.

Today, households’ net wealth ranges between three and six times GDP in most advanced economies. These are high levels by historical standards. Based on long-term series constructed for four large advanced economies (France, Germany, the United Kingdom,

INEQUALITY AND FISCAL POLICY Clements, de Mooij, Gupta and Keen (eds) International Monetary Fund Softback, 442pp

September 2015

9781513567754

RRP £39.95

and the United States), Piketty and Zucman (2014) show that wealth-to-income ratios are returning to the high values observed in Europe in the nineteenth century.

Abstracting from country-specific developments, the sharp increase in wealth accumulation during the past 40 years was driven by a series of common factors. First, the growth slowdown following the 1973 oil shock raised the interest rate-growth differential, mechanically inflating the wealth-to-output ratio. Second, valuation effects also played a major role. Asset prices grew rapidly during the period: the new economy boosted financial asset values in the 1990s, whereas the 2000s saw a sharp acceleration in real asset prices, reflecting in some cases the formation of property market bubbles. Finally, in some countries, private savings have increased over time as a result of structural factors, including population aging; the financial deregulation of the 1980s, which increased households’ participation in financial markets; and the development of funded pension systems.

Global Trends

The availability of household balance sheet data is more limited for emerging markets and low-income countries.

Credit Suisse (2013), which collects and reports data at a global level, finds that household wealth has increased in all regions of the world since the early 2000s. Global household net wealth rose by about 110 percent between 2000 and 2013, while net wealth per adult rose by 80 percent. Household wealth declined significantly during the financial crisis in 2007–08, but recovered subsequently and exceeded its precrisis level from 2012 onward. This trend was observed in all regions of the world and in most countries, with the exception of some European countries.

READERS’ COMMENTS

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

We welcome either written responses or MP3 voice tracks. All contributions are moderated. Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running.

Today, wealth is unequally distributed across regions. Both North America and Europe account for about one-third of global wealth, while 20 percent is held in the Asia-Pacific region. The rest of the world (China, India, Latin America, and Africa) owns the remaining 16 percent of total household wealth despite hosting 60 percent of the adult population.

Wealth Composition

The composition of household portfolios varies widely across countries). In general, nonfinancial assets represent more than half of total wealth. Spain and New Zealand are among the advanced economies with the highest share of real assets (more than 70 percent of gross assets at the end of 2012). The United States is an outlier with financial assets representing about 70 percent of the total.

Many factors can explain the cross-country differences in wealth composition. In general, the share of financial assets is higher in countries with private pension systems, a large public housing sector (which discourages home ownership), a high level of financial development, and smaller households (large households tend to accumulate more real estate assets).

small fraction of total net wealth. In Denmark, this share is even negative, reflecting few incentives for the middle and lower classes to accumulate assets in a country with strong social security and public housing programs.

From the beginning of the twentieth century until the 1970s, wealth inequality declined dramatically in most countries for which long time series of wealth distribution are available. This trend has reversed in the past three decades, with wealth inequality rising in most advanced economies. For instance, between the mid1980s and early 2000s, the growth of wealth in Canada and Sweden was all concentrated in the two upper deciles of the wealth distribution. During the same period, the Gini coefficients of wealth distribution in Finland and Italy rose from about 0.55 to greater than 0.6.

In the United States, the Gini coefficient for wealth, after rising steeply between 1983 and 1989 from 0.80 to 0.83, remained stable until 2007, and then increased sharply to 0.87 during the financial crisis. Wealth inequality has risen for a number of reasons. The stock market boom of the 1990s was particularly beneficial to rich households who own higher proportions of stocks, bonds, and other financial products than poor households do. Tax reforms, including lower marginal

Differences in risk tolerance, taxation, and valuation effects also influence the composition. For instance, the Swedish tax reform of 1991, which reduced capital income taxation with the introduction of a flat rate, had a lasting impact on the portfolio composition, increasing the share of financial assets.

In emerging market and low-income economies, household balance sheet data are generally not available. Based on survey data, it seems that the share of nonfinancial assets is even larger than in advanced economies. This share apparently exceeds 80 percent in some countries, such as India and Indonesia.

Wealth Distribution

Wealth is very concentrated within countries. Household wealth is much more unequally distributed than income. The Gini coefficient of wealth in a sample of 26 advanced and developing economies in the early 2000s was 0.68, compared with a Gini of 0.36 for disposable incomes. The main reason for this discrepancy is that high-income individuals have higher saving rates and thus accumulate wealth faster than do poorer households, and they generally hold riskier assets with higher yields.

However, there are important country differences. The share of wealth held by the top 10 percent ranges from slightly less than half in Chile, China, Italy, Japan, Spain, and the United Kingdom, to more than two-thirds in Indonesia, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. In Switzerland and the United States, where wealth is most unequally distributed, the top 1 percent alone holds more than one-third of total household wealth.

In most countries, the lowest 50 percent of households in the wealth distribution generally hold only a very

EDITOR’S NOTE

tax rates on top incomes and lower taxes on all forms of capital, also played a role in the widening of wealth disparities during the period.

Taxing wealth to reduce inequality

There are several quite different types of taxes on wealth. These taxes can be grouped into two broad categories: those that apply to wealth holdings—immovable property tax and net wealth tax (NWT)—and those that apply to wealth transfers, which is further divided into transaction taxes (levied when the asset is sold) and gift and inheritance taxes (levied when the asset is given). Their base is generally the gross value of assets but some taxes bear on net wealth (assets minus liabilities).

Taxes levied on wealth, especially on immovable property, can be used for redistributive purposes. These taxes, of various kinds, target the same underlying base as capital income taxes, namely assets. Because wealth is concentrated among the better off, even a small proportional tax on the capital stock can increase progressivity. Wealth taxes can thus be considered a potential source of progressive taxation.

[But] the redistributive properties of wealth taxes come at a cost. Capital taxes, if too high, can have high efficiency costs because of their distortionary effects on savings and investment. Moreover, taxing capital can be administratively difficult in light of its mobility, with the risk of creating ample evasion and avoidance opportunities. Another issue is that the mobility of capital allows firms to shift a large share of the burden of these taxes onto labour or consumers, thereby affecting the distributional consequences.

Revenues from Wealth Taxes

Although wealth taxes can, in themselves, con-

continued in the book

Governments influence economies by adjusting spending levels and tax rates: their strategy for doing so is what we call fiscal policy, and this goes hand in hand with monetary policy, which tells central banks how much money to issue. This book argues that fiscal policy is a government’s most powerful tool for addressing inequality and that with a good mix of policy instruments, countries can narrow the wealth-poverty gap and improve efficiency. This needs to be read not just by politicians but by all who hold their feet to the fire. Available in the UK from Eurospan: www.eurospanbookstore.com. Find other IMF titles at www.imf.org/pubs.

Tax policy may help the poor but have unwanted trade-offs. Theory and case studies offer guidance. Clements, de Mooij, Gupta, Keen (eds)

Hardback, 424pp

1 October 2020

9781912920471

RRP £25.00

Our price £19.99

Lloyd and J.E. Luebering

Britannica has been inspiring curiosity and the joy of learning since 1768. This book continues that tradition. It will take you on an amazing journey through all of history and across the Universe. You’ll have the opportunity to dive into a black hole (and emerge unscathed!) and take a tour of a medieval castle. You’ll also be given the power to peer into the future and learn about what might matter most to us here on Earth. Each time you turn a page, you’ll find something new to explore—and, maybe, you’ll even be a bit alarmed, like I was, when you run across the section on creepy crawlies.

But as surprising and fascinating as each page is, everything we are sharing with you is always subject to change. And that is something that we embrace: watch for sections that describe Known Unknowns. The scholars, researchers and other brilliant minds who have helped us create this book are the ones who, in their dayto-day lives, are shaping the boundaries of knowledge. They’re driven by their passion and their dedication to accuracy and, because of that, they’re helping all of us better understand the world. And that includes understanding what we don’t know yet.

We believe that facts matter, and we strive for accuracy through rigorous fact-checking of all the information we share on every page of this book.

Chapter 1: Universe

Buckle up for an incredible journey through our Universe. At this moment you are riding on an enormous ball of rock. That rock is soaring through space at thousands of miles an hour in a swirling galaxy of billions of giant balls of fire. That rock, of course, is our Earth. And the giant balls of fire are stars, including our own Sun. I hope that fact alone is enough to convince you that reality is so much more amazing than anything you can make up.

In this chapter, we begin with an unimaginably tiny speck of infinite energy from which the Universe exploded into existence 13.8 billion years ago and finish with a Known Unknown: how, when, or if the Universe will come to an end. Which is a reminder that for every answer we find, there are dozens more questions: is there intelligent life somewhere else in the Universe? Why is there more matter than antimatter? What would happen if an astronaut fell into a black hole? There’s lots to discover, even about the unknown.

The Big Bang

The Big Bang is the moment we think the Universe was born 13.8 billion years ago. It describes how a teeny-tiny dot suddenly expanded faster than the speed of light, creating the entire Universe. Belgian astronomer Georges

Lemaître, who first proposed the theory in 1931, called the dot the primeval atom. All matter in the Universe began in this tiny dot and eventually became everything you see around you today.

What happened in the Big Bang?

The Big Bang took place in a split second. Scientists think it was an expansion rather than an explosion. Everything started out incredibly hot, billions of degrees in temperature, but then cooled. When it cooled to thousands of degrees Celsius, atoms joined together and formed matter. This eventually clumped together to make stars, galaxies, solar systems and planets.

Evidence for the Big Bang

Our best proof for the Big Bang comes from something called the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), seen in our photo of the night sky. The picture shows heat left over from the Big Bang that spread thinly all over the Universe. The image was taken by scientists using NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP).

Pigeon interference

In 1965, American astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were using a radio telescope to study the Universe when they saw a

For 250 years, Encyclopaedia Britannica was the world’s foremost source of knowledge. Now there’s a children’s version Chris

LIGHTER THAN AIR

The first passengers on a hot-air balloon flight on 19 September 1783 were a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. They all survived. Humans took to the air in a balloon two months later. These early pioneering experiments kick-started the history of aviation. They led to the development of the motor-powered flying machine. Hot-air balloons also played a key part in establishing the ‘ideal gas law’, which describes how gas temperature, pressure, and volume affect each other.

The ideal gas law

Three gas laws combine to make the ideal gas law: Boyle’s, Charles’s, and Gay-Lussac’s. Boyle’s gas law states that if a gas expands, its pressure drops. Charles’s law states that as temperature rises, gases will expand proportionally – as long as the pressure stays the same. Gay-Lussac’s law states that if the volume stays the same, pressure will increase as the temperature increases.

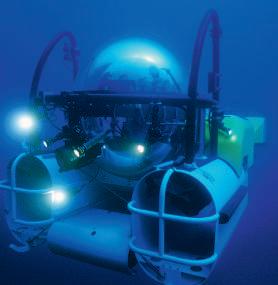

THE DEEP SEA

The ocean is the planet’s largest habitat, most of which is deep sea, yet scientists have explored only a fraction of the deep sea floor. In fact, we know more about the surface of the Moon than we do about the deepest ocean. The invention of new underwater vehicles called submersibles is changing all that, revealing many kinds of strange and fascinating creatures.

LAYERS OF THE SEA

Scientists divide the ocean into layers according to depth, pressure, and the amount of sunlight they receive. In the deepest zone, the pressure is so great it’s as if an elephant is standing on each square inch of the ocean floor.

Glow-in-the-dark

Many animals in the deep sea are bioluminescent – they light up in the dark. They can do this because of a chemical reaction in their bodies or in bacteria that they host. Female deep sea angler fish, which live in the twilight and midnight zones, have a bioluminescent bacteria-filled lure on the end of a long fin like a fishing rod. The light attracts prey towards its tooth-filled mouth.

The tripod fish is 30–40 centimetres long and stands on stilts formed by its pelvic and tail fins. It is then at the right height to catch passing prey swimming in the current.

Deep-sea exploration

Note from theexpert!

Snailfish

The snailfish is 15–30 centimetres long. In 2017, Japanese scientists filmed a snailfish 8,178 metres deep in the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench –the deepest place on Earth.

Underwater vehicles called submersibles are specially strengthened to resist high pressures at great depths. They enable scientists to observe deep-sea animals. Scientists sometimes bring creatures to the surface in cooled and pressurized tanks so that they can study them in the laboratory.

were during vacations to the Mediterranean Sea as a child. Fascinated by the diversity of animals in the sea, she went on to study zoology and marine biology.

“ Only when you go down to the bottom of the ocean in a submersible do you start to understand how huge this habitat is.”

RELIGIOUS BELIEF

What do people believe in? Statistics show that with 4.4 billion followers between them, Christianity and Islam are the world’s two largest religions. Each has many branches. For example, Catholicism is a branch of Christianity, and Sunni is a branch of Islam. Some religions are a mix of different beliefs and practices. There are also millions of people who have no religious beliefs.

STOPPING CLIMATE CHANGE

EDITOR’S NOTE

We know climate change is harming our planet, and we also know human beings are causing much of it. But what can be done to stop it? In 2015, an international agreement was reached in Paris and later adopted by all nations. They said they would keep global temperatures within a safe limit by reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, but progress has been slow. Now many people are demanding that more urgent and more drastic action is taken to limit the damage to ecosystems, species, and our common future.

OTHER RELIGIONS

850 million, including:

1. Falun Gong (10 million): Combines meditation techniques and ritual exercises. Founded in China, 1992.

2. Cao Dai (8 million): Takes ideas from Daoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Roman Catholicism. Founded in Vietnam, 1926.

3. Baha’i faith (5–7 million): Belief that all people belong to one religion with one God. Founded in Iran, 1863.

4. Confucianism (5–6 million): An ancient religion that follows the teachings of the great Chinese thinker Confucius.

5. Jainism (4 million): Faith with belief in the eternal human soul. Has roots in India in the 6th century BCE

6. Shinto (3–4 million): Followers believe in ‘kami’ (spirits) and visit shrines. Founded in ancient Japan.

7. Wicca (1–3 million): Centres on witchcraft, with a focus on nature. Spread from England in the 1950s.

8 Rastafari (1 million): A religion and political movement that began in Jamaica in the 1930s.

9. Tenrikyo (1 million): Shinto-based religion whose followers believe in one god called Tenri-O-no-Mikoto. Started in Japan in the 1800s.

10. Zoroastrianism (1 million): Worship the supreme god Ahura Mazda. Began in Iran in the 6th century BCE

9

Climate protests

In 2019, millions of people around the world protested the way governments were handling climate change, including these Extinction Rebellion (XR) supporters in London, UK. XR is a worldwide protest group demanding that governments take immediate action to stop mass extinction of species by reducing greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2025.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Reaching a safe limit

Text-heavy books don’t work for children any more: kids are too easily tempted away by more visual alternatives. Britannica’s challenge, then, was how to deliver meticulous and authoritative information engagingly. Their answer is a stunningly designed 424-page compendium of over 1,000 powerful photos and explanatory illustrations, all with the visual punch of an Avengers movie, plus bite-size chunks of information, delivered in appealing formats including lists, quizzes, knowledge connectors and unusual facts. The story arc is refreshing, too: a timeline of the universe. See www.whatonearthbooks.com for more.

Scientists warn that global warming of 2°C would severely damage ecosystems, human health, livelihoods, food and water security, and infrastructure. A safer limit would be below 1.5°C. To keep to safe limits, governments, businesses, and individuals must take action.

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

We welcome either written responses or MP3 voice tracks. All contributions are moderated. Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running.

When the 95th Rifles was formed in 1800, buglers were given the special role of transmitting signals ordered by their officers. Each of the ten battalion companies was allocated two buglers and right from the beginning buglers were considered as belonging to a company. First and foremost, they were soldiers.

At a time when battles were noisy and confusing affairs, a bugle call could be heard above the din. A bugle call would carry some distance even though muskets crashed and cannon roared. Military bugles are capable of sounding five notes ranging from low C to high G, a span of one-and-a-half octaves. Each regiment of Rifles or Light Infantry had its own regimental call which would be recognised instantly by the officers and men.

The Regulations for Riflemen laid down the meanings and notations for bugle horn signals. There were signals for ‘March’, ‘Skirmish’, ‘Fire’, ‘Cease firing’, ‘Retreat’ and so on.

Buglers would need considerable skill to master their breathing and regulate their pitch. A bugler also needed to develop other skills, such as the ability to perform under pressure, self-discipline and quickness

OVER THE HILLS TO TALAVERA THE ADVENTURES OF BUGLER

GEORGE MILTON

Chosen Man Media

Softback, 90pp 16 November 2020

9781527272675

RRP £9.99 plus p&p

From: https:// chosenmanmedia. com

READERS’ COMMENTS

To comment on this book, email your thoughts to book@booklaunch.london

We welcome either written responses or MP3 voice tracks. All contributions are moderated. Our online Comment page will launch in the Spring. Subscribe now and we’ll send you an alert when it’s up and running.

of thought, for these were all crucial to survival in the chaos of the battlefield.

Buglers of the Rifles functioned in three ways: they could act individually, in pairs or sometimes as the complete Corps of the Bugles.

The Corps of the Bugles was under the command of the Bugle Major. He was a senior sergeant and reported directly to the Adjutant. Each bugler would pick a comrade from his company and the pair would become inseparable. The special status of a bugler was marked by exemption from mess duty and cooking.

The life of the Regiment was governed by bugle calls. At dawn, Reveille was sounded by two buglers. The Orderly Bugler sounded ‘Breakfast’ followed by the Drill Call. Buglers would operate on a rota basis.

After drill, the Orderly Bugler sounded the Buglers Call. Upon hearing this, all the Corps of Bugles assembled and then two buglers would sound a warning call to alert the Regiment that a parade was imminent.

When a parade was due to form up, two buglers would sound the Parade Call. The Corps of Bugles under the Bugle Major would parade together and not with their respective Rifle companies, alongside would be the Band of Music.

At the end of the Parade, the Orderly Bugler sounded ‘Orders’ after which the Bugle Major went to the Orderly Room to get the Orders of the Day from the Adjutant.

Next came the Dinner Call, sounded by two buglers. When it was time for the Sergeants’ dinner, the Orderly Bugler was used and, after the meal, the Orderly Bugler played the Drill Call.

When Drill was over, the Orderly Bugler sounded the Warning Call for evening parade. Next was the sound of a single bugle for ‘Buglers’. All the buglers then assembled to sound ‘Tattoo’ en masse. As dusk fell, the

Duty Buglers played ‘Lights Out’, signifying the end of the day.

Whether a Regiment had a band of music or not depended upon the wishes of the Colonel. It was entirely at his personal expense and generosity to pay and fit out the musicians. Early bands of music were small and largely recruited in Hanover or other minor German states so the first military bands were made up of professional musicians. Given their status as non-combatants, those bands who did serve overseas often found themselves acting as stretcher-bearers on the battlefield. A typical band would include two oboes, four clarinets, two bassoons, one trumpet, two horns and a serpent.

When George enlisted, his details were entered on to the Regimental Muster Roll. Next he was marched down to the Quartermaster’s stores to be issued with his uniform, kit and equipment. Never in his short life had George been given so much to look after and he felt an immense pride at having such responsibility.

The Quartermaster Sergeant handed George a green jacket, a waistcoat, a pair of trousers and a pair of shoes. George’s heart swelled when he finally received his green jacket. As he was a bugler, his jacket was slightly different from that worn by a rifleman as its shoulders

formed part of his clothing issue. The forage cap was made of black cloth with white edging and ‘95’ embroidered in white thread.

One item was detested by all of King George’s men: the black leather stock. It was a collar of stiff black leather designed to maintain the neck at the correct angle for good military posture and bearing. The men hated it, for it was rigid and its edges dug into the neck, causing sores and welts.

Many of the necessaries were designed for cleaning and tidying, such as a clothes brush, three shoe brushes, two combs, oil and emery paper. Necessaries were kept in a knapsack. When in barracks or the depot, everything had to be kept in a particular way. A rifleman had to fold his mattress and bedding neatly. A rifleman and his kit were inspected daily. If any item was found to be damaged or missing, the rifleman would have his pay docked by the value of the items damaged or lost.

If a rifleman lost his clothes brush, he was stopped 6 pence. If he damaged a shoe brush, he was stopped 5 pence. A misplaced shirt would see 5 shillings and 6 pence withheld which, considering that a day’s pay was 1 shilling, was no small amount. Soldiers quickly learned that the Army accounted for everything and few

What did the bugle mean to troops during the Napoleonic wars? An orphan joins a crack British regiment and finds out Stephen Petty

EDITOR’S NOTE

So much of what was commonplace in the past is now not just unfamiliar but beyond our comprehension. The use of children in war is one example. Fictional but plausible George Milton is only a boy when he joins the 95th Rifles in the early 1800s but boys younger than him served as powder-monkeys on Royal Navy ships and a five-year-old girl tore up lint and helped bandage the wounded at the battle of Waterloo. In this educational story, George becomes one of the most valued soldiers in his regiment, not as a rifleman but as a bugler. It’s a far cry from drone attacks. NB: Profits from the sale of this book will be donated to the Rifles’ Regimental Charities.

were adorned with wings of black cloth. He was also given a shako made of black felt and leather with a bugle horn cap badge, cords and tufts of green.

By far the largest amount and variety of kit and equipment were those items known in the Army as ‘necessaries’. It was impressed upon George that the Army would hold him personally liable should any item be lost or damaged. George’s necessaries included a turn screw, brush and worm to help keep the flintlock firing mechanism of a Baker Rifle in perfect working order. Three shirts, three pairs of socks and a forage cap

would ever get off scot free.

George was quick to learn. He did this by watching how the experienced riflemen went about their daily routine. He was also very fortunate that his chosen comrade, Rifleman Cooke, was a first-class soldier of fine character who set an excellent example and offered George guidance whenever it was needed.

At first, George was taught the basic elements of drill. Alongside the other new recruits, George spent two intense hours each day on the parade ground under the orders of the Drill Sergeant. George was to find out very quickly that Drill Sergeants knew everything and missed nothing. He had no wish whatsoever to be on the receiving end of a reprimand from the Drill Sergeant and he dreaded being sent to join the Awkward Squad, the shame of which would be impossible to live down.

Recruits who struggled to follow the barked commands were sent to drill with the Awkward Squad. A recruit was not permitted to wear full uniform or be instructed in Rifle Drill until he had perfected the drill movements. A recruit had twenty-two basic movements to memorise before progressing to Firearms Drill.