Black History month

doing promoting such caricatures? And what damage did they do to British racial attitudes?

The question is worth asking—especially in Black History Month—because of Rupert’s status as a muchloved national icon (in which DreamWorks Animation now has a majority interest). Published in the Daily Express since 1920, Rupert and his adventures have been enjoyed by millions of children, if not in the daily paper then in the annuals that appeared every Christmas. So popular has he been that this September, the Royal Mail issued a commemorative set of eight Rupert stamps, celebrating his centenary, with different stamps appearing in Guernsey and five partly coloured 50p coins minted in the Isle of Man.

News about the stamps was syndicated in local papers, and carried in the Times and Daily Telegraph; naturally, the Express covered the story twice. But the Guardian, Independent and BBC ignored it—not just, presumably, out of a wish not to endorse the Express but because Rupert’s historic association with ‘coon’ imagery now makes him toxic.

Rupert was first illustrated by Mary Tourel but was taken over by Alfred Bestall in 1935 as her eyesight failed, and Koko and the ‘coons’ were an invention of his, albeit one that played on the pre-existing stereotype of ‘golliwogs’ and minstrel shows.

are bears; his friends have their origins in other species and geographies, with various dogs, a pig, two foxes, a Wise Old Goat, and various Chinese characters: a human (Tiger Lily), a Pekingese (Pong-Ping) and a dragon (Ming).

The stories are certainly founded on a Pax-Britannia mythology—innocent domestic hero goes round the world helping out—but his involvement is minimal and life continues as before when he returns home. Rupert is neither colonist nor capitalist. The places he visits—far away, below the ocean or up in the mountains—are idyllic and remain so.

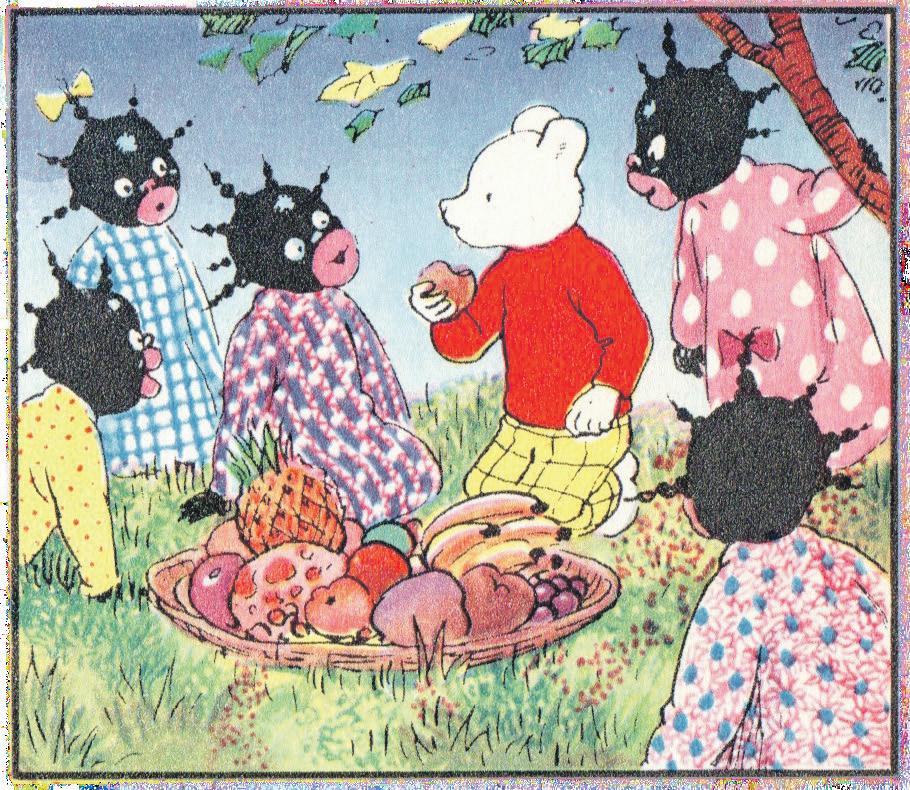

While a question mark hangs over the depictions of the ‘coons’, Bestall’s intentions are as far from the Stürmer’s as could possibly be. Rupert’s message is one of racial communality. Koko and his friends have the sweetest nature. They are morally responsible, self-organising, hospitable, socially concerned and in tune with their environment—all role model behaviours—and Rupert embraces them. Walking along the beach with Koko, the two hold hands. Rupert takes Koko home for tea, gives him his bed for the night and sleeps beside him on the floor. The next day Mrs Bear makes a picnic breakfast for the two of them and Rupert follows where Koko leads, eventually across the sea to rescue a white castaway, stranded alone on a deserted island.

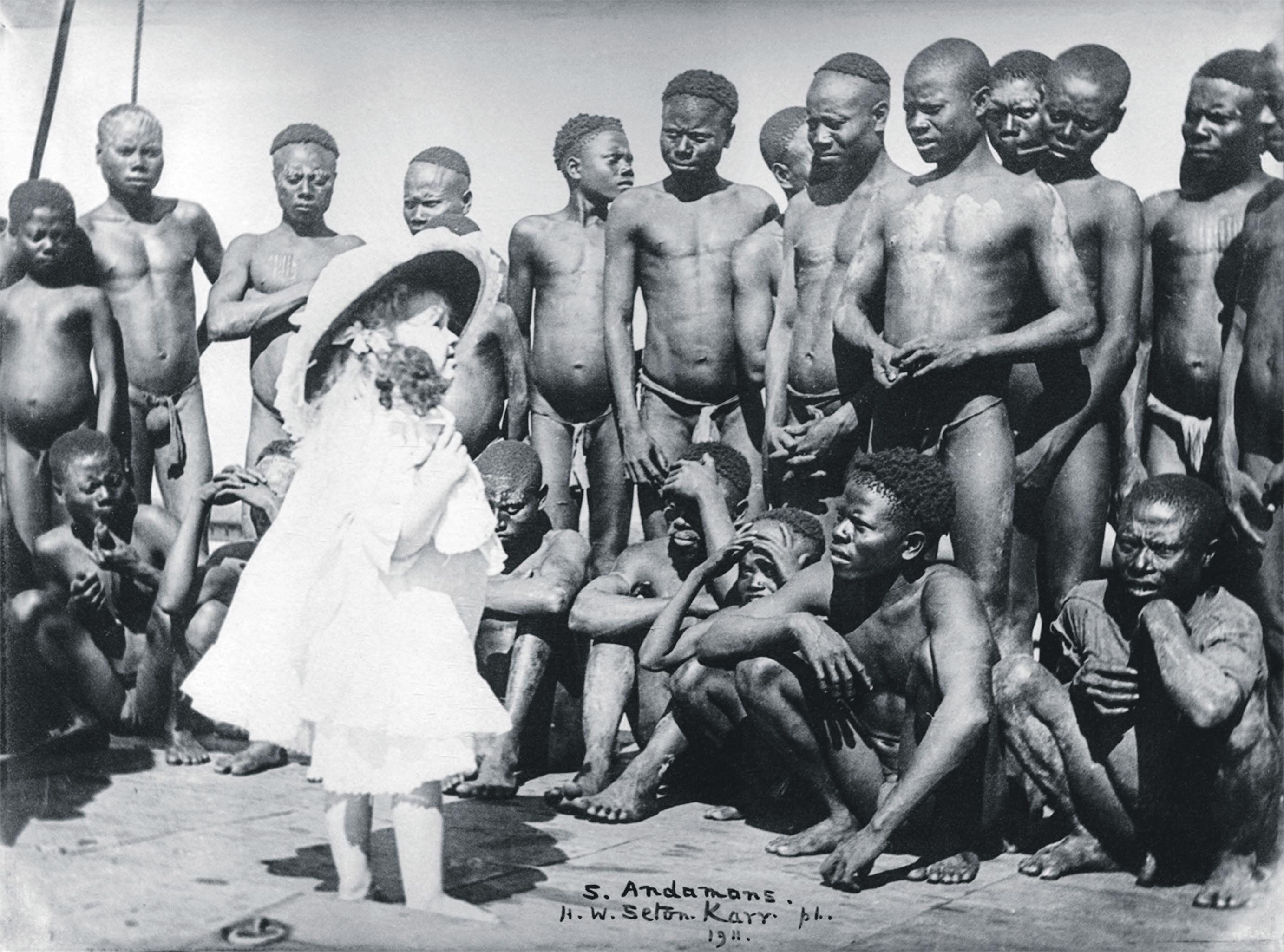

Look at this picture. It should cause any reasonable person a grimace of pain and embarrassment. It is one of several outrageous images that Beaverbrook Newspapers, the owner of the Rupert Bear franchise, thought fit for publication in its 1954 Rupert Bear Annual. Here, in a story called ‘Rupert and the Castaway’, Rupert rediscovers Koko, a character he had first met in 1945. Koko is a male but curiously ungendered child who lives across the sea on Coon Islands with other ‘coon friends’. Like Koko, ‘coons’ have black heads with white reflective highlights, ping-pong ball eyes, doughnut lips and ‘spiky hair’. They are described as ‘little darkies’, and ‘squeak’ ‘excitedly’ ‘in a queer langage Rupert cannot understand’. Another story depicts Koko as illiterate and only able to scribble. What on earth did Rupert’s creators think they were

The 30s was a time when offensive imagery flourished, the most obvious being the depiction of Jews in Der Stürmer, which thrived in Nazi Germany. As far as one can tell, however, Bestall had no similar intent. He was born in Burma in 1891 to a Methodist minister father and artist mother, returning to England in 1897, attending art school in the 1910s and then drawing for the illustrated weeklies. His god-daughter described him in 2003 as ‘a saintly man whose faith supported him throughout his 93 years’. Pictures in his 1924 travel notebooks of Arabs in Cairo and Jews in Jerusalem are sensitive and respectful.

Bestall’s depiction of Rupert’s world from 1935 seems equally benign. While all the characters and settings are formulaic in appearance and behaviour, the point of them seems to be to reflect the world’s diversity. Though set in the chocolate-box village of Nutwood, they promote an early idealisation of harmonious multi-culturalism in which none of the heroes is Anglo. Rupert and his parents

This is a world of equals and were it not for the imagery, it would be an object lesson in racial harmony. Our fear, however, is that the awkward images may be made to do double duty as a rallying point for racists protesting their virtue outwardly while privately—even provocatively—relishing the hurt they cause.

Cartoons are always clumsy. Rupert was not intended for a black readership when he first came out and while it is clear from the context that he was meant to inspire children, in this case the moral message has been hijacked by the visual. I would rather give the victory to the moral message, but then I’m not injured by the depiction of Koko and his friends; others are. If Rupert, set in an idyllic England, leaves flag-waving supremacists feeling good about themselves while black Britons feel hurt, the injured party must have the final say. In this edition of Booklaunch, especially, with four white writers discussing white attitudes to black history, that caveat is vital. I welcome your feedback.

Stephen Games / Publisher and editorIn medieval society, the ass was an unremarkable but indispensable beast; it carried packs, contributed to farm life and pulled heavy loads. The ass helped the poor and the rich carry out their daily commitments; it accompanied armies on their campaigns, took produce to and from markets, enabled merchants to make deliveries, and carried people to and from their destinations. Yet despite its hard-working reputation, the ass was also associated with laziness— slow-to-react and sluggish.

In medieval society then, the ass was a paradox. It was at once a mundane, everyday beast but also, in medieval texts, the epitome of obstinacy and folly. Fable asses had a reputation for being stupid, and the bestiary ass was stubborn and slow.

Asses were associated with notions of the sacred and the virtuous. Sainte Foy of Conques, a fourth-century child martyr, performed the miracle of resurrection, reviving a dead ass, and in the Old Testament, Balaam’s ass delivered God’s word through the act of speaking. In the New Testament, Christ’s decision to ride an ass into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday meant that the lowly beast became associated with the Christian virtues of patience and humility.

Asses also had a reputation for sexual deviancy. According to some medieval writers, asses who mated with horses to produce mules practised unnatural copulation. One fictitious ass was compelled to have sex with a woman. In a 14th-century Spanish text, ‘The Book of Good Love’ (Libro de buen amor, c.1300), Juan Ruiz, a Spanish archpriest, offered lessons through a series of short stories on God’s good love and worldly, foolish love that made humans sinful. As a didactic example, he reworked the fable ‘The Ass and the Lapdog’, exploiting the ass’s sexual nature, resulting in a sexualised reading of the fable that was more fabliau-like—i.e. obscene— than fable. In Ruiz’s rendition, the dog and the ass shared a mistress rather than a master, and the attention that the dog lavished on its mistress was highly sexualised. The dog licked and kissed with its tongue and mouth, and wagged its tail euphemistically before standing on its hind legs to exhibit its masculinity. When the ass mimicked the dog’s actions, it entered the mistress’s personal space by invading her dais before it covered the mistress frontally and placed its forelegs on her shoulders. This action revealed the ass’s sexual prowess, as its phallus was exposed and the whole manoeuvre was described in terms more suited to a sexually frenzied stallion (commo garañón loco el nesçio tal venía—‘like a mad stud the fool came on’). The ass also brayed (rebuznando), recalling the sexually frustrated wild asses who brayed to relieve their sexual tensions. As in the original fable, the ass was then severely beaten with phallic-shaped clubs for its transgression.

In the medieval world, the ass’s reputation—sacred or profane, derided or acclaimed—was codified in fact, fiction and image. However unusual its binary nature may seem to the modern-day reader, paradoxical rhetoric was a common feature in medieval beast genres, and the fact that the ass had contesting reputations offers multiple avenues for analysis. Even the various names ascribed to the ass are eclectic and contradictory. Often the ass would be instantly recognisable as much by its diminutive or pet name as by its Latin name. It is not until the eighteenth century when Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, introduced his binomial nomenclature that the ass was identified by its scientific name—Equus africanus asinus.

Asinus, assellus or onager, Brunellus (sometimes Burnellus) or Carcophas, donkey or ass? These are just some of the medieval and modern names that have been ascribed to the humble beast of burden. Like the ass’s reputation they too can be contradictory, with descriptive, ironic and even modest nomenclatures.

In the Middle Ages, learned authors used a variety of Latin names to identify the ass: asinus (‘ass’) and assellus (‘little ass’). Isidore of Seville’s etymological assessment associated asinus with the Latin verb sedere (‘to sit’) to reinforce the ass’s subjugated nature.

The wild ass, onager, had a descriptive title whose name was derived from the Greek on, meaning ‘ass’, and agrios for ‘wild’. It did not inhabit medieval Europe, but it was known by medieval authors and featured in animal compendiums. The onager shared its name with an ancient and early medieval form of catapult. Just as the beastly onager was reputed to use its back legs to kick stones at its hunters, the operative of the onager weapon violently hurled rocks at its enemy, invoking the image of the proverbial ‘kick like a mule’.

Literary asses, such as Brunellus and Carcophas, also had descriptive names. The 12th-century Canterbury monk Nigel Wireker, in his satirical Speculum Stultorum, named his ass Brunellus. Wireker derived the ass’s name from the Latin brunus (‘brown’), meaning ‘little brown’ and whilst this, no doubt, reflected the ass’s colouring, it also suggested a dull, unintelligent quality—Wireker’s Brunellus to a tee.

Another ‘brown’ literary ass was Burnell, who appeared in the Chester Cycle plays. Rather than implying a dull animal, Burnell was likely an ironic name. In this play, Burnell was the antithesis of its Old Testament owner, Balaam: the metaphorically blind and thus unintelligent prophet, who rode the all-seeing, intelligent ass. There is also conjecture that donkey, the modern anglophone word for ass, is a similar colour derivative, stemming from the adjective dun, to denote the ass’s dull greyish-brown colouring.

Even today the ass is known by various names. Although English speakers more readily recognise the ass by its anglicised name—donkey—the medieval world knew the ass by its Latin name—asinus. In the romance languages of France, Italy, Spain and Portugal, lexically the Latin tradition has persisted through l’âne (l’asne—OF), asino and asno respectively. In the anglophone world however, ass (beast of burden) is also understood as arse (bottom) depending on the mode of pronunciation. And it was late 18th-century English, with its varying pronunciations of a long or short ‘a’, that led to the introduction of the replacement word ‘donkey’ to spare any embarrassment to speaker, reader or listener.

This then, is a book about donkeys in the medieval world. It is not about arses, bottoms, rears, derrières or behinds, although it will consider the donkey’s sensual and sexual appetite, as understood by medieval society.

Before the ass arrived in medieval Europe, it already had a long association with humankind, and its early history is worth outlining momentarily here as it underpins medieval understandings of this beast. From a natural world perspective, archaeological evidence reveals that humans domesticated the ass around 6,000 years ago in the Middle East, an area often referred to as the Fertile Crescent.

Once domesticated, the ass’s usefulness as a pack animal facilitated extended trade routes and offered migration possibilities, leading to the geographical spread of people, ideas, goods and the ass itself across and beyond north Africa and the Middle East. The ancient Greeks brought the ass to the Balkans and the northern shores of the Mediterranean, and the Romans introduced the ass into the rest of continental Europe and the British Isles.

The ass of the ancient world held a religious and elite significance that predates Christianity, yet informs medieval understandings of the ass. In the Hellenic, Judaic, Roman and other religious traditions, the ass often symbolised sacredness. It also claimed a lofty position in the realm of high priests, kings and gods. In ancient Egypt, asses were ritually immured in royal tomb complexes, carefully oriented eastwards, possibly in response to a sun god and sunrise. The 18th-century BC king of Mari, Zimri-Lim, was exhorted to ride an ass as a sign of his kingship. In Damascus white asses were specially bred for use by the elite class, and Greek and Roman gods rode on the backs of asses. Ancient religious customs conveyed an association between animal, human and deity that influenced medieval religious perspectives of the ass.

Ancient philosophers and naturalists wrote about the ass in their attempts to explain the natural world, scholars produced practical guides on animal husbandry, and other authors anthropomorphised the ass for entertainment. Aristotle’s Historia Animalium (‘The History of Animals’, 4th century BC) took a zoological approach to explain the whys and wherefores of animals and their behaviours; Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis (‘Natural History’, c. AD 79) had an encyclopaedic approach, offering a universal sketch of the ass; Varro’s 1st-century BC Rerum rusticarum libri tres (‘Three Books on Agriculture’) demonstrated the Roman scholar’s close knowledge of farming and mule production; and although it was Phaedrus’s fables that survived into the medieval period, they were usually credited to Aesop, the ancient Greek slave. Combined, these ancient sources underpinned medieval knowledge of the ass.

This book considers medieval receptions of the ass and its relation to humans from social

INTRODUCING THE MEDIEVAL ASS

Kathryn L. Smithies

Medieval Animals, University of Wales Press (Cardiff), Softback, 128 pages, 7 b/w illustrations, 129 x 198, September 2020, 9781786836229

Publisher’s price £11.99

Save £0.83

Booklaunch price £11.16 inc. free UK delivery from our website

The ass was the medieval world’s white van, and one that also carried metaphorical burdens.

Léon Werth (1878–1955) was a brilliant French essayist, writing against militarism, French colonialism, Nazism and the Vichy regime. During the First World War Werth served in the French army, then used the character of an invalided soldier — Clavel — to voice his anti-war position, characterising the war’s hospitals and convalescent homes as ships of fools. His writing is modernist, with diary observations transformed into impressionistic collages of conversation, polemic and interior monologue

PRIVATE CLAVEL PATIENT IN WAR

Léon Werth (transl. Michael Copp)

Grosvenor House (Tolworth, Surrey), Hardback, 276 pages, 135 x 210, April 2020, 9781839750564

From his bed, Clavel catches a glimpse of the tops of some plane trees, with their leaves glinting in the atmosphere of a Paris September sun, flickering like sequins.

His ear rubbed against the pillow. Was that noise a mouse?

The movement of his left arm was, in the darkness, briefly reflected against the bar of his brass bed: a dark shape, moving quickly in a straight line and then suddenly disappearing. Was that a big rat?

But he soon gets used to things. He recognises the hospital noises and the vague murmur that comes through the open window and the ‘whoo … whoo …’ puffing noises of the inner circle trains and the sudden ‘whoo … whoo …’ of trains farther away.

It was all very simple. He was smoking his pipe in the trench. A sudden impact on his arm, then a sort of numbness and the blood running down his greatcoat. It could have been four o’clock in the afternoon. He was carried to the dugout. He stayed there stretched out until the evening. But already he didn’t feel he was part of things anymore. He thought: I won’t do the next relief. After the rudimentary dressing applied by the stretcher bearer, he tried hard to stay still although it was painful. He didn’t want to cause a disturbance. That’s how he wanted to show things to the doctor. And the comrades around him, the comrades he was going to leave, already seem to him to be far away. They were staying in the game. He was leaving it.

He also thought: Will I have to lose my arm? Will I stay disabled? But he was hardly troubled by these thoughts, and they disappeared without any effort on his part. He waited for the stretcher bearers who were to carry him by night to the first-aid post.

And it was even simpler than that. From the first aid post he went to the division ambulance and then to the transit station. He was lifted onto the hospital train. He was aware of nothing but his fever. A label was attached to his greatcoat. On the hospital docket the doctor had written: Multiple fracture of the central part of the left humerus by a shell splinter.

And on the train, emboldened by his wound, he enjoyed the luxury of indulging in familiar exchanges with a young doctor who spoke to the soldiers in a remote and disgusted manner.

Now Clavel is lying in a bed in this bedroom in a palace which has been transformed into a military hospital. There are two beds in the bedroom, but for the time being, the other one is empty. His good fortune has brought him to Paris, and in a top-class hospital, of the sort visited by important personages, who then have their photographs in magazines.

Publisher’s price £16.99

Save £1.27

Booklaunch price £15.72 inc. free UK delivery from our website

Clavel had not slept in a bed for over a year, had not undressed to go to sleep for over a year. When he found himself, for the first time, in front of the brass bed, his astonishment was that of a beggar transported into a palace. But this astonishment was short lived. As soon as he had been washed and deloused, he was stretched out in the bed. Clavel felt nothing but a pleasant torpor. The war had disappeared; like waking up from a nightmare. His body forgot the earth of the trench, the planks of the camp, where he had slept for a year. With this bed, he re-discovered the habit of bed. It was, quite simply, a feeling of well-being, and not a mirage anymore. A newspaper lay open on the white sheet. Clavel luxuriates in a lie-in. He does not pick up the newspaper. He does not feel like picking it up. And he realises that a great change has come about in him: When I was back there, he says to himself, I opened every newspaper I came across, even one eight days old, with a furious impatience. I searched their lines for the vaguest promise of peace. I was in the war, like an unjustly locked up prisoner. But at this moment, I accept … I accept that the war will not end this very day.

A cleaner was sweeping the bedroom. She leans for a moment on her broom and looks out of the window at the street lined with small private houses. She points at the houses.

‘That’s the house of M. Rodier, an engineer; that one belongs to M. Lagrange, he’s ever so rich; that’s M. Dalou’s house, I don’t know what he does … that’s M. Manset’s house, he died in the war …”

‘Died in the war … .’ That’s a sort of profession, thinks Clavel.

cated a heroic and hearty life, a clear contrast with the monotonous life that she, as a middle-class woman, led before the war.

They are also silent through weariness, through a vague consent to the conventions of the period and through that feeling of cowardice and timidity which, in peace time as in war time, causes ‘lower-class’ men to tell lies when faced with a scholarship holder or someone learned. The soldier is condemned to tell lies. If, in peace time, sick soldiers were cared for by the wives and cousins of their colonels, would they tell the truth about the barracks? And would they want to, how would they struggle, with their pathetic little comments, against the idea of propriety, of hierarchy and necessity that the colonels’ women and cousins have about the barracks? Now, the war is a large barracks, more dangerous, that’s all.

The period in hospital, the length of planned convalescence, depends on the doctor’s assessment. A word from the nurse often influences his decision. ‘He is so sweet … he is so tired … he’s lost all use of his arm.’ Also, the soldier learns very quickly, through instinctive cunning, a conventional courtesy, like the one that a man of the world possesses. Clavel understood all that more clearly by certain words of his nurse. She complained that the soldiers did not distinguish properly between the voluntary care of society women and the paid care of professional nurses. She naïvely expressed the idea that the soldiers had got accustomed to hospital routine.

‘They are much nicer now. But at first, there were some who didn’t even say thank you … If you as much as reproached them gently, they would answer: “We fought on your behalf, you can at least look after us …” At first, but no longer; you should hear what they said about the officers … .” ’

And Clavel thought: ‘You can’t imagine a period less heroic than this. The men face death, when they can do nothing else. But their only worry is their individual safety. And the best ones only differ from the rest because they also want their friends to avoid death. It’s not among the soldiers that you should look for the ardour to “serve”. If they think about the need for soldiers to make war, each individual man would seek to escape. But, without being forced to do so, some women serve the country and the church.’ And he remembered certain Red Cross ladies made known to him by wounded comrades he had met while on leave. They denounced to the authorities any soldiers who uttered words of anger or despondency. And they used the most cunning schemes with the doctors to shorten the hospital stay for soldiers who resolutely refused to go to Mass. But there were very few of these soldiers. For the Mass wisely confused obedience to the Red Cross ladies with obedience to the military leaders.

Then he had tender memories of an old primary school teacher whom he considered to be ridiculous in peace time. She would keep on saying: ‘Atheists, of whom I am one …’, and she would suddenly insult Napoleon in the middle of the most banal conversation: ‘Napoleon, that rogue, that murderer …’. The picture of the little old woman, gaunt and kindly, had entered his mind. And, for a moment, she was the incarnation of the spirit of peace.

The second bed in the bedroom was now occupied by an Engineers corporal, in hospital for having been gassed. A small young man, well-behaved and right-thinking, and who spoke while sucking his words. He had just got engaged and was thinking about objects to decorate his drawing room with:

‘When I get out, I’ll go to the antique shops. Should I buy Moustiers1, Delft or Chinese?”

He had the smooth talk of a stupid man-about-town.

‘Do you like photography? I’ve learned to do the Rembrandt portrait … .’

When he was able to go out, he came back one evening with an old tattered canvas by Jouy2, and asked Clavel:

‘It’s not poor taste, is it? … You’re a bit of a connoisseur, perhaps? …’

RRP £18.99 Save £1.71 Our price £17.28

2009

RRP £28.00

The cleaning woman ceased her chatter because the nurse, Mme. Monnerot, was coming in. She was the wife of an architect. She derived obvious pleasure in calling the wounded men ‘my dear man …’. For her, that indi-

And faced with this idiot, Clavel has a weird desire to weep, to throw his arms around him, and to ask for his forgiveness, as if he, Clavel, was responsible for his foolishness. Or is there a means of dealing with the foolishness, in the way a surgeon would tackle an abscess or dress a wound? Perhaps it would be better to look away, as one would with a cripple, to look as if you hadn’t noticed anything … But this corporal insists on talking. He thrusts his tumour into

continued in the book

What is wine, and what are its effects? What has made men from the first recorded time distinguish between wines as they have done with no other food or drink? Why does wine have a history that involves drama and politics, religions and wars? And why, to the dismay of young men on first dates, do there have to be so many different kinds? Only history can explain.

Wine has certain properties that mattered much more to our ancestors than to ourselves. For 2,000 years of medical and surgical history it was the universal and unique antiseptic. Wounds were bathed with it; water made safe to drink.

Medically, wine was indispensable until the later years of the 19th century. In the words of the Jewish Talmud: ‘Wherever wine is lacking, drugs become necessary.’ A sixth century BC Indian medical text describes wine as the ‘invigorator of mind and body, antidote to sleeplessness, sorrow and fatigue ... producer of hunger, happiness and digestion’. Enlightened medical opinion today uses very similar terms about its specific clinical virtues, particularly in relation to heart disease. Even Muslim physicians risked the wrath of Allah rather than do without their one sure help in treatment.

But wine had other virtues. The natural fermentation of the grape not only produces a drink that is about one10th to one-8th alcohol, but its other constituents, acids and tannins in particular, make it brisk and refreshing, with a satisfying ‘cut’ as it enters your mouth and a lingering clean flavour that invites you to drink again. In the volume of its flavour, and the natural size of a swallow (half the size of a swallow of ale), it makes the perfect drink with food, adding its own seasoning, cutting the richness of fat, making meat seem more tender and washing down dry pulses and unleavened bread without distending the belly.

Because it lives so happily with food, and at the same time lowers inhibitions, it was recognized from earliest times as the sociable drink, able to turn a meal into a feast without stupefying (although stupefy it often did).

But even stupefied feasters were ready for more the next day. Wine is the most repeatable of mild narcotics without ill effects—at least in the short or medium term. Modern medicine knows that wine helps the assimilation of nutrients (proteins especially) in our food. Moderate wine drinkers found themselves better nourished, more confident and consequently often more capable than their fellows. It is no wonder that in many early societies the ruling classes decided that only they were worthy of such benefits and kept wine to themselves.

The catalogue of wine’s virtues, and value to developing civilization, does not end there. Bulky though it is in transit, and often perishable, it made the almost-perfect commodity for trade. It had immediate attraction (as soon as they felt its effects) for strangers who did not know it. The Greeks were able to trade wine for precious metals, the Romans for slaves, with a success that has a sinister echo in the activities of modern drug pushers—except that there is nothing remotely sinister about wine.

In this sense it is true to say that wine advanced the progress of civilization. It facilitated the contacts between distant cultures, providing the motive and means of trade, and bringing strangers together in high spirits and with open minds. Of course, it also carried the risk of abuse. Alcohol can be devastating to health. Yet if it had been widely and consistently abused it would not have been tolerated. Wine, unlike spirits, has long been considered the drink of moderation.

Even at its most primitive (perhaps especially at its most primitive) wine is subject to enormous variations— most of them, to start with, unlooked for. Climate is the first determining factor; then weather. The competence of the winemaker comes next; then the selection of the grape. Underlying these variables is the composition of the soil (cold and damp, or warm and dry) and its situation—flat or hilly, sunny or shaded. Almost as important as any of these is the expectation of the market: what the drinker demands is ultimately what the producer will produce.

As soon as wine became an object of trade, these variables will have started to affect its price. Consensus arrives surprisingly quickly. The wine the market judges better makes more profit. If the merchant and the maker work together and do the sensible thing, they reinvest the profit in making their wine more clearly better—and more distinctive.

It is easy to see this process happening in the modern marketplace. It is the standard formula by which repu-

tations for quality are built. The key word is selection: of grape varieties, yes, but also of a ‘clone’, a race of vines propagated from cuttings of the best plants in the vineyard. Then restraint in production: manuring with a light hand, pruning each plant carefully to produce only a moderate number of bunches, whose juice will have far more flavour than the fruit of an overladen vine. In the ancient world such practices probably first developed in the sheltered economy of royal or priestly vineyards. It would have been the king’s butler who commended a particular plant and told the vine dressers to propagate from it. But the principle has not changed. Selection of the best for each set of circumstances has given us, starting with one wild plant, the several thousand varieties of grapes which are, or have been, grown in the course of history. And each grape variety has given the possibility of a distinctive kind of wine.

Taking this panoramic view, the discovery that must have done most to advance wine in the esteem of the rulers of the earth was the fact that it could improve with keeping—and not just improve, but at best turn into a substance with ethereal dimensions seeming to approach the sublime. Beaujolais Nouveau is all very well (and most ancient wine was something between this and vinegar). But once you have tasted an old vintage burgundy you know the difference between tinsel and gold. To be able to store wine, the best wine, until maturity performed this alchemy was the privilege of pharaohs.

It was wonderful enough that grape juice should develop an apparent soul of its own. That it should be capable, in the right circumstances, of transmuting its vigorous spirit into something of immeasurably greater worth made it a god-like gift for kings. If wine has a prestige unique among drinks, unique, indeed, among natural products, it stems from this fact and the connoisseurship it engenders.

Archaeologists accept accumulations of grape pips as evidence (of the likelihood at least) of winemaking. Excavations in Turkey (at Catal Hüyük, perhaps the first of all cities), at Damascus in Syria, Byblos in the Lebanon and in Jordan have produced grape pips from the Stone Age known as Neolithic B, about 8,000 BC. But the oldest pips of cultivated vines so far discovered and carbon dated—at least to the satisfaction of their finders—were found in Soviet (as it then was) Georgia, and belong to the period 7,000–5,000 BC.

You can tell more from a pip than just how old it is. Certain characteristics of shape belong unmistakably to cultivated grapes, and the Soviet archaeologists are satisfied that they have evidence of the transition from wild vines to cultivated ones some time in the late Stone Age, about 5000bc. If they are right, they have found the earliest traces of viticulture, the skill of selecting and nurturing vines to improve the quality and quantity of their fruit.

The wine-grape vine is a member of a family of vigorous climbing woody plants with relations all over the northern hemisphere; about 40 of them close enough to be placed in the same botanical genus of Vitis

Its specific name, vinifera, means wine-bearing. Cousins include Vitis rupestris (rock-loving), Vitis riparia (from river banks) and Vitis aestivalis (summer fruiting), but none of them has the same ability to accumulate sugar in its grapes up to about one-third of their volume (making them among the sweetest of fruit), nor elements of fresh-tasting acidity to make their juice a clean and lively drink. The combination of these qualities belongs alone to Vitis vinifera, whose natural territory (since the Ice Ages, when it was drastically reduced) is a band of the temperate latitudes spreading westwards from the Persian shores of the Caspian Sea as far as western Europe.

The wild vine, like many plants (willows, poplars and most hollies are examples), carries either male or female flowers; only very rarely both on one plant. Given the presence of a male nearby to provide the pollen, the female plants can be expected to fruit. Males, roughly equal in number, will always be barren. The tiny minority of hermaphrodites (those which have both male and female flowers) will bear some grapes, but about half as many as the females.

The first people to have cultivated the vine would naturally have selected female plants as the fruitful ones and destroyed the barren males. Without the males, though, the females would have become barren too. The only plants that would fruit alone or together are the hermaphrodites. Trial and error, therefore, would in time lead to hermaphrodites alone

Save £5.00

Booklaunch price £25.00

To buy this book and those below, visit www.academieduvinlibrary.com using the code BLAUNCH9

The corresponding eBooks are available from Amazon

Hugh Johnson’s classic biography of wine has been revised.

William Morgan is my great-great-great-grandfather. Born in 1750, he was a Dissenter and a reformist. He mixed with the radical thinkers of the day, amongst them Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, John Howard, Thomas Paine, John Horne Tooke and Francis Burdett. Through his membership of reformist societies and through his own publications, William campaigned for electoral reform and government accountability. In doing so he took colossal risks and narrowly missed being sent to the Tower of London.

William spent 56 years at the Equitable Life Assurance Company, where he learnt how to understand and manage financial risk. In 1789, for his work on the mathematics of life assurance, he was awarded the Copley Medal, the Royal Society’s most prestigious decoration. Subsequent generations have hailed him as ‘the father of the actuarial profession’—recognition of his having established many of the rules and standards on which the science is based.

In the course of his tenure as Actuary, the Equitable became one of the most successful insurance companies of its time. Its success continued under William’s son, Arthur Morgan, and by the 20th century the Equitable was the dependable insurance company of choice for many professional people. Its problems in the 1990s and its demise in 2000 were a shock to the financial world. Had it stuck to William’s rules of prudent management, the crash could have been avoided. He would have been devastated by its ignominious end.

William gets a mention, and due praise, in works on the history of actuarial thought. He has a cameo role in the autobiographies of his great grandson, Arthur Waugh, and his great-great-grandson Evelyn Waugh. He gets a significant part in the numerous biographies of his uncle, Richard Price, most recently Liberty’s Apostle, by Paul Frame. He also appears in Travels in Revolutionary France, the edited letters of his brother, George, from Paris in1789.

William was born club footed. Today a club foot can be corrected either with surgery or with a series of plaster casts, each moving the foot very slightly until the bones lie in a normal position. We do not know how William’s foot was treated but subsequent events show that his disability was visible and was to have a profound effect on his life and his career.

William’s parents could not protect him from taunts and teasing but they could—and did—give him a secure and loving family circle. When he was only 19, he composed some verses in imitation of the Odes of Horace, Book 4, which celebrated the ‘peace of mind’ that a return to one’s birthplace can give, and which was addressed to his younger brother, George. In fact William had good reason to envy George who, clever and good looking, was allowed the freedom to choose his studies and went up to Jesus College Oxford to study Classics; William with his deformed leg and a rather plain face had his career decided for him by his father. He was to become a doctor, even though he had ‘a greater inclination for academical learning than for the study of pharmacy’.

Had his father charged higher fees for his own medical services, there might have been enough money to pay for a decent medical training; instead, William suffered considerable financial hardship in his apprenticeship. He was just 19 when in 1769 he said goodbye to his family and set off for London and the home of his mother’s brother, Richard Price.

At Newington Green, William was happy in the midst of what he described as the ‘unbounded love’ of ‘heavenly minded friends’. Richard Price and his neighbour Thomas Rogers had a weekly supping club where discussion and debate were as important as the meal. As a guest, William would have been exposed to a heady mix of radical political and intellectual thinking. In his Memoirs of the Life of Richard Price (1815) he records differences in metaphysical thought between Richard Price and Joseph Priestley. Elsewhere in the Memoirs he writes about another disagreement, that between Price and David Hume.

Price was willing to give his nephew financial support but William did not want to take advantage of him. Instead, he set about apprenticing himself to an apothecary, a Mr Smith of Limehouse Docks. It was a dodgy appointment and one that William quickly regretted. For a start, Smith was only a self-styled apothecary. His name is not included in the records of the period at the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries, membership of which, by then, was on a professional basis. It is unsurprising that he practised in Limehouse Docks,

an insalubrious area where the patients were poor dock labourers. William was expected to work long hours and, at the end of the day, to sleep under the counter.

‘He treated me no better than a dog,’ William recorded in his diary. He stuck it for three months until his ‘Welsh temper could stand it no longer’ and he laid Smith in the gutter. He had, however, timed his flash of rage very conveniently and made advance preparations. On the following day, 11 October 1769, he was apprenticed to a new master, Joseph Bradney, in Cannon Street.

By this time William seems to have been ready to accept financial help from his uncle to meet the annual fee of £16, and the further expense six months later when, in May 1770, he entered St Thomas’s hospital as one of the pupils and dressers. Dressing pupils paid as much as £50 for the privilege of changing bandages and attending to wounds. They were also allowed to perform minor operations, such as the commonly prescribed bleeding, and to give general assistance to the surgeon in his work.

Little more than a year after he started at St Thomas’s, William received the news of his sister Betsey’s death, aged 26. Only a few months later his brother Jack, aged just 14, became ill with a fever which quickly proved fatal. Dr Morgan was himself in poor health by this time and died in the summer of 1772.

William had not completed his medical training but knew he must return to Bridgend and take over his father’s practice. His father’s patients viewed him with suspicion. Not only was he young and inexperienced, he was a cripple. His club foot was regarded as a weakness. How could anyone trust a doctor who could not heal his own malady? Besides, there was by now a rival doctor in the town. Jenkin Williams, six feet tall and quite the dandy in his gold-laced hat, inspired confidence in his patients. To make matters worse, he had fallen for William’s sister Kitty and in 1773 they were married. In the same year William relinquished the practice and returned to London where his only course of action was to seek out Richard Price and ask his advice.

Price had a wide circle of influential friends and had been a fellow of the Royal Society since 1765. He had published a number of papers on financial matters and was a regular consultant to the recently formed life assurance company, the Equitable Society, and this was to give William the opportunity for a new career. In the autumn of 1773, shortly after William’s return to London, John Edwards, who held the key post of Actuary at the Equitable, died. A replacement was urgently needed. The exchange between William and his uncle has become part of actuarial folklore. ‘Billy,’ Price said to his nephew, ‘do you know anything of mathematics?’ ‘No, Uncle,’ the young man replied, ‘but I can learn.’

William set about learning the very difficult mathematics of life assurance calculations. In April 1774, he was appointed Assistant Actuary at the Equitable on a salary of £100 per annum. His hard work paid off. When, less than a year later, the post of the replacement Actuary fell vacant, William was unanimously elected by the directors.

It is inconceivable today that anyone so young and inexperienced could be appointed to such a post. A 21st-century actuary climbs the career ladder by means of study, training and examinations. William had invaluable guidance from Price but in many respects had to make it up as he went along. During his time the Society became one of the wealthiest corporations in the world.

One benefit of William’s medical training was his expertise in judging the fitness of those wanting to take out life assurance policies—a signed declaration of their state of health being a key part of the process. Applicants had to come in person to the Society’s office after 11 o’clock on a Tuesday, where they met the Actuary and in his presence filled in the relevant forms, giving name, address, occupation and age. Sometimes the assurance was to be on the life of another person, in which case more details were required, not least to make sure that the policy was not merely a respectable front to gambling.

In the early days of life assurance there was nothing to stop you effectively taking a bet on whether someone might die before a certain date, then collecting your winnings if the insured person lived beyond that date. In 1774, the Life Assurance Act put a stop to such ‘gaming or wagering’ by requiring that the insurer had to have a ‘legitimate interest’ in the person whose life was being insured.

The list of those on whose lives policies were granted includes members of the aristocracy, parliamentarians and members of the clergy. These one might expect—also a host of literary names:

expectancy to

How we interact with digital devices matters. Digital technologies are accelerating and fragmenting our everyday lives, and the data our devices gather are used to profile and target us. So we should step back, even if just a little, to try and seize some self-control. We are not against computing and the digital age but there needs to be more balance. We call this ‘slow computing’: the need to be more careful in how we lead a digital life and how we allow our digital society and economy to operate.

This challenge has been hugely complicated by the coronavirus pandemic. Apart from its impact on our domestic and working lives, it has propelled new social and technological arrangements that amplify surveillance and data extraction. Led by governments and companies, these technologies have been rolled out for five primary purposes:

1. Quarantine enforcement/movement permission (knowing people are where they should be, either enforcing home isolation for those infected or close contacts, or enabling approved movement for those not infected)

2. Contact tracing (knowing whose path people have crossed)

3. Pattern and flow modelling (knowing the distribution of the disease and its spread and how many people passed through places)

4. Social distancing and movement monitoring (knowing if people are adhering to recommended safe distances and to circulation restrictions)

5. Symptom tracking (knowing whether the population are experiencing any symptoms of the disease).

Numerous digital technologies are employed to perform these tasks, including smartphone apps, facial recognition and thermal cameras, biometric wearables, smart helmets, drones and predictive analytics.

For example, citizens in some parts of China have been required to install an app on their phone and then scan QR codes when accessing public spaces (e.g., shopping malls, office buildings, communal residences, metro systems) to verify their infection status and permission to enter. The Polish government introduced a home quarantine app that requires people in isolation to take a geo-located selfie of themselves within 20 minutes of receiving an SMS or risk a visit from the police. Israel repurposed its advanced digital monitoring tools normally used for counterterrorism to track the movement of phones of all coronavirus carriers in the 14 days prior to testing positive in order to trace close contacts.

As of mid-April, 28 countries had produced contact tracing apps that use Bluetooth to detect and store the details of nearby phones and contacts them if someone who had been near them tested positive, and another 11 were planning to launch imminently. Other states have utilised technologies designed to measure biometric information. For example, hand-held thermal cameras have been used in a number of countries, some mounted on drones, to screen movement in public space.

Technology companies have offered, or have actively undertaken, to repurpose their platforms and utilise the data they hold about people as a means to help tackle the virus. Most notably, Apple and Google, who provide operating systems for iOS and Android smartphones, are developing solutions to aid contact tracing. In Germany, Deutsche Telekom are providing aggregated, anonymized information to the government on people’s movements; likewise Telecom Italia, Vodafone and WindTre are doing the same in Italy.

Unacast, a location-based data broker, is using GPS data harvested from apps installed on smartphones to determine if social distancing is taking place, with several other companies offering similar locational and movement analysis. Experian, a large global data broker and credit scoring company, has announced it will be combing through its 300 million consumer profiles to identify those likely to be most impacted by the pandemic and offering the information to ‘essential organizations’, including health care providers, federal agencies and NGOs. Some of the most problematic aspects of surveillance capitalism have been repurposed by the state, further legitimating and cementing their practices.

Beyond society-wide surveillance to combat the pandemic, some companies have rushed to implement their own versions of these technological solutions, for example scanning the temperature of workers or deploying their own contact tracing systems. These are likely to become more common as restrictions are lifted, and their use might become a mandatory condition of entering workplaces.

In addition, many have adopted remote work sur-

veillance systems so they can monitor the activity and productivity of their employees working at home, including recording keystrokes, how many emails are sent and their contents, and what employees are printing, or seeking constant status updates or that work is always undertaken while a video call is live. These companies argue that they are trying to ensure that their workers are not taking unfair advantage of flexible work arrangements, or are not leaking confidential information. They take no account of workers trying to cope with changes in their workplace environment which may not be conducive to work due to increased care duties, living in a shared space, or having poor or no broadband, or their having to learn new systems and procedures at short notice, or not necessarily having the technical competence to perform any IT services needed to set up and maintain home-based work.

Some citizens will no doubt embrace surveillance technologies in the hope they will help to limit the spread of the virus and thereby save lives. Others will accept that companies should be able to know if their employees are performing the work they are paid to do.

An underlying problem, however, stems from the track record of digital technology providers and governments in handling, protecting and extracting value from data. It seems logical to expect that data on movements, contacts or health will have value beyond the current public health crisis and they will be repurposed in some way that is not necessarily beneficial to citizens. There are legitimate concerns as to whether public health and workplace surveillance systems will be turned off after the crisis or whether they will become a normal part of a new surveillance regime, as was the case with systems adopted after 9/11. Without embracing data sovereignty, privacy, civil liberties, workers’ rights, citizenship and democracy are under renewed threat.

In this regard it is significant that civil liberties organizations have set out ethical principles designed to protect privacy and rights, while acknowledging the potential utility of digital tools to tackle the virus. The key argument is that we should strive to ensure both civil liberties and public health, rather than simply trading the former for the latter. For example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, American Civil Liberties Union, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the European Data Protection Board have demanded that:

• data collection and use must be based on science and need;

• the tech must be transparent in aims, intent, and workings;

• the tech and wider initiative must have an expiration date;

• a privacy-by-design approach with anonymization, strong encryption and access controls should be utilized;

• tools should be opt-in with consent sought, with very clear explanations of the benefits of opting in, operation and lifespan;

• the specification and user requirements, a data protection/ privacy impact assessment, and the source code for state-sanctioned coronavirus surveillance should be published;

• data cannot be shared beyond the initiative or repurposed or monetized;

• no effort should be made to re-identify anonymous data;

• the tech and wider initiative must have proper oversight of use, be accountable for actions, have a firm legislative basis, and possess due process to challenge misuse.

In other words, the tools must only be used when deemed necessary by public health experts for the purpose of containing and delaying the spread of the virus and their use should be discontinued once the crisis is over. We would add that we must also be vigilant to any potential control creep; that is, the risk that apps designed to limit movement based on health status will continue to be used and their criteria extended.

The temporal and organizational aspects of tackling the coronavirus pandemic raise other questions about the ethics of digital care. How do we ensure wellbeing and protect our civil rights while responding rapidly to an emerging crisis? How can we find a balance between the interests of public health and the economy and our own self-care? We don’t have ready answers to these questions; formulating individual and collective interventions for slow computing within such a context is not straightforward. We are all now dealing with radically different circumstances.

But an obvious conclusion to draw about the crisis response hitherto is that employers and employees need to define and deliver an ethics of digital care. For sure, some managers will have pursued admirable practices: facilitating flexibility and accommodating workers with respect to workload, hours, continued in the book

The pace of population growth seems terrifying. In 1820 there were a billion people on Earth. A century later, there were more than 2 billion. After a brief hiatus resulting from the Great Depression and World War II, the rate of growth gathered breathtaking speed: 3 billion by 1960, 4 billion by 1975, 5 billion by 1987, 6 billion by 2000, and 7 billion by 2010. ‘Population control or race to oblivion?’ was a tagline on the cover of Stanford University professors Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s highly influential book The Population Bomb, published in 1968.

The reality is that by 2030 we will be facing a baby drought

Over the next few decades, the world’s population will grow less than half as swiftly as it did between 1960 and 1990. In some countries, the population will actually decrease in size. For instance, since the early 1970s, American women have on average had fewer than two babies each over their reproductive lifetime—a rate insufficient to ensure generational replacement. The same is also true in many other places around the world. People in countries as diverse as Brazil, Canada, Sweden, China, and Japan are starting to wonder who will take care of the elderly and pay their pensions.

As birth rates decline in East Asia, Europe and the Americas, combined with a slower decline in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, the global balance of power shifts. Consider: For every baby born nowadays in developed countries, more than nine are being born in the emerging markets and the developing world. Or, for every baby born in the United States, 4.4 are being born in China, 6.5 in India, and 10.2 in Africa. Moreover, improvements in nutrition and disease prevention in the poorest parts of the world have made it possible for an increasing number of babies to reach adulthood and become parents themselves. Half a century ago one in four children under the age of fourteen in African countries such as Kenya and Ghana died, whereas today it’s fewer than one in ten.

To assess the worldwide impact of these demographic shifts, focus your attention on 2030. By that year, South Asia (including India) will consolidate its position as the number-one region in terms of population size. Africa will become the second-largest region, while East Asia (including China) will be relegated to third place. Europe, which in 1950 was the second largest, will fall to sixth place, behind Southeast Asia (which includes Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, among other countries) and Latin America.

Booklaunch

International migration might partially mitigate these epochal changes by redistributing people from parts of the world with a surplus of babies toward others with a deficit. In fact, that has happened repeatedly throughout history, as when many Southern Europeans migrated to Northern Europe during the 1950s and 1960s. This time around, however, migration won’t offset the population trends. I say this because too many governments seem intent on building walls, whether the old-fashioned way (with brick and mortar), by leveraging technology such as lasers and chemical detectors to monitor border crossings, or both.

But even if the walls are never built or something renders them ineffective, my forecasts indicate that … migration may not have a big impact on these population trends. Given present levels of migration and population growth, sub-Saharan Africa—the fifty African countries that do not border the Mediterranean Sea—will become the second-most populous part of the globe by 2030. Let’s assume for a moment that migration doubles over the next twenty years. Twice as much migration will merely delay that reckoning until the year 2033. It won’t derail the main population trends leading to the end of the world as we know it, but merely postpone them by approximately three years.

In Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, there are millions of women today who give birth to five, ten, or even more babies over their lifetime. On average, however, the number of babies per woman is falling in the developing countries as time goes by, and for the same reasons it began to plummet in the developed world two generations ago. Women now enjoy more opportunities outside the household. To seize those opportunities, they remain in school and, in many cases, pursue higher education. This, in turn, means that they postpone childbearing. The change in women’s roles in the economy and in society more generally is the single most important factor behind the decline in fertility worldwide.

Women are increasingly determining what happens around the world. Consider the case of the United States, where women’s priorities have shifted rapidly. In the 1950s, American women married on average at the age of 20; men, on average, married at 22. Nowadays it’s 27 and 29, respectively. The average age of first-time mothers has also climbed, to 28. Much of this change has been driven by longer schooling. More women now graduate from high school, and more of them go on to get a college education. Back in the fifties about 7 percent of women between the ages of 25 and 29 had a college degree, half the rate of men. Nowadays, the proportion of women with a college degree is nearly 40 percent, while for men the figure is only 32 percent.

Our declining interest in sex

Philosophers, theologians, and scientists have wrestled for centuries with the question of how many human beings can be supported by Earth’s resources. In 1798, the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, a British economist and demographer, warned about what would later become known as the ‘Malthusian trap’, or our tendency to overbreed and deplete our sources of sustenance. During Malthus’s lifetime, the world’s population was below 1 billion (compared to today’s 7.5 billion). He thought that humans are their own worst enemies because of their unfettered sexual impulses. In his view, runaway population growth would result in famine and disease because the food supply could not keep pace with the population. Malthus and many of his contemporaries feared that the human species was at risk of extinction due to overbreeding. ‘The power of population,’ he wrote, ‘is so superior to the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race.’

With the benefit of hindsight, we can say today that Malthus underestimated the potential of invention and innovation, which has led to phenomenal improvements in agricultural yields. He also downplayed the immense possibilities for expanding the food supply through international trade thanks to faster and cheaper transoceanic transportation and missed how modern technology might reduce our appetite for sex.

The connection between the two is disarmingly simple. The greater the number of alternative forms of entertainment that become available to us, the less frequently we engage in sex. Modern society offers a panoply of entertainment options, from radio and TV to video games and social media. In some developed countries, including the United States, rates of sexual activity have been declining over the last few decades. A comprehensive study published in the Archives of Sexual Behaviour found that ‘those born in the 1930s (Silent generation) had sex the most often, whereas those born in the 1990s (Millennials and iGen) had sex the least often.’ The study concluded that ‘Americans are having sex less frequently due to an increasing number of individuals without a steady or marital partner and a decline in sexual frequency among those with partners.’

The new kids on the block: The African baby boom While populations are not replacing themselves in Europe, the Americas and East Asia, they are growing in sub-Saharan Africa, albeit much more slowly than in the past. Even so, its population is projected to grow from 1.3 billion today to 2 billion by 2038 and 3 billion by 2061. Some people predict that a big war or a devastating epidemic might derail Africa’s demographic momentum. … The global AIDS epidemic has so far resulted in 36 million deaths, of which two-thirds occurred in Africa, with South Africa, Nigeria, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda and Zimbabwe suffering the most. And yet … during the 1980s and 1990s, when the epidemic was at its most lethal, the population curve for Africa barely shifted. Thus, only a massive war or epidemic claiming hundreds of millions of lives would significantly alter the continent’s demographic growth relative to other parts of the world.

You might be thinking that Africa cannot possibly accommodate its projected population growth. Consider, however, how big Africa actually is. Cartographical representations of the continent in our school textbooks greatly underestimate its true size relative to the Northern Hemisphere. In fact Africa’s landmass is just about as big as that of China, India, Western and Eastern Europe, the United States and Japan combined.

To be sure, there are big, largely uninhabitable deserts in Africa. But that’s equally true of each of those

other countries on the map (except Japan). Even Europe has deserts—the famous movie Lawrence of Arabia was filmed not on the Arabian Peninsula but mostly in southern Spain. Even taking into consideration the vastness of the African deserts, the continent contains the most undeveloped yet fertile land for agricultural development on the planet. Given Africa’s size, overpopulation seems unlikely. The continent currently has 1.3 billion people; the other countries on this map have populations that exceed 3.5 billion. Today the density of the population per square mile is more than three times higher in Asia than in Africa, and four times in Europe.

Africa’s population growth creates some thorny problems. The continent is home to some of the world’s most intractable hotspots of religious and ethnic conflict. About half of Africa’s 54 sovereign states are beset by political chaos, anarchy and lawlessness. Much of the migration from rural areas to cities, and from those to international destinations, mostly in Europe, is due to conflict and violence, which endanger not only personal safety but also economic development.

Thus Africa is not risk free, but the potential returns to its own growing population are huge. Because of its increasingly large population, Africa can no longer be ignored. For better or worse, its fortunes will matter globally. If things go well, Africa will be a vibrant source of dynamism to the benefit of the entire world. If things take a turn for the worse, the negative consequences will be felt globally. Demography is not destiny, but it does shape people’s lives.

Feeding Africa’s population as huge opportunity

The future of Africa’s babies, most of them born in rural areas, hinges on the transformation of its agricultural sector. Despite its enormous landmass and abundant water, the continent is currently a net importer of food. And while extractive industries such as cocoa, mining and oil have been fundamental to national economies for the longest time, most African growth in the near future will result from the expansion of agriculture and of the associated manufacturing and services catering to the continent’s expanding population.

The agricultural challenge is dual: bringing into cultivation up to 500 million acres of land—about the area of Mexico—and vastly improving productivity. In order to realize this potential, many different kinds of organizations and companies are bringing new ideas and new practices to African agriculture. For instance, one ingenious way to turn the African population boom into an opportunity involves growing, harvesting and processing a prodigious plant called cassava. This root vegetable, which is native to South America, is remarkably resilient to drought, can be harvested at any time within a flexible 18-month window and requires manual labor to be planted, thus providing locals with a source of income. In sub-Saharan Africa at least 300 million people rely on it for their daily dietary needs. Additionally, cassava is naturally gluten free and has a lower sugar load than wheat, making it a healthy alternative to grains and a better carbohydrate source for diabetics. As the continent improves cassava yields, some portion of its production could also be turned into higher value–added products for export: it’s an ingredient in plywood; it’s used as a filler for many pharmaceuticals, including pills, tablets, and creams; and it can be turned into a biofuel.

The silicon savanna

Beyond the coming agricultural-industrial revolution, Africa has leapfrogged into the 21st century faster than anyone else in one area: mobile telecommunications technology. Mobile technology has proved to be especially helpful in the healthcare sector. In Kenya, for example, most of the rural population lives at least an hour away by bus from the closest doctor or medical facility. To solve the issue of access, many mobile services have been launched, from medical hotlines and early-diagnosis tools to education, medicine reminders, and follow-ups. Today, 90 percent of the population has a cellphone. Phone records in Kenya are actually more comprehensive than official censuses. Government agencies use cellphone data rather than payroll or school records to plan for healthcare policy and outreach.

Like many other countries—rich and poor alike— Kenya faces a shortage of qualified healthcare personnel, rising costs and skyrocketing demand. There are hundreds of e-health projects and programs benefiting an increasing number of rural residents. The model of using mobile telecommunications technology in

healthcare, as seen in Kenya, may offer a technological solution to healthcare access that is both efficient and inclusive, something that other nations can emulate— even a country like the United States, where healthcare has been a perennial political talking point and the costs of care seem to increase year after year.

How Covid-19 impacts the trends discussed here Most people believe that a major crisis disrupts ongoing trends, as if there is a clear ‘before’ and ‘after’. The coronavirus pandemic is one such crisis, but contrary to conventional wisdom it will most likely intensify and accelerate—rather than derail—the trends analyzed here. Consider the declining fertility rate discussed in Chapter 1. There are three reasons why a pandemic will accelerate that trend. First, people usually postpone major decisions (like having a baby) when faced with uncertainty. Second, having a baby is a financial commitment, and the threat of a recession will force many to reconsider whether the timing is right. (We saw this during the Great Depression in the 1930s and in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.) Third, life-altering events like war, natural disasters, and pandemics disrupt our daily routines and priorities, and this includes our fertility decisions.

The divergence of generational experiences, discussed in Chapter 2, is another trend that will accelerate. As of this writing, the virus is considered lethal to people who are immuno-compromised, which includes many people over the age of 60 and people with pre-existing medical conditions. As we look to the future, with Europe and East Asia composed of an older age cohort and Africa and South Asia experiencing a baby boom, the share of the world’s population moving to the latter will only accelerate if the mortality rate internationally continues at the pace we are witnessing.

The crisis will also continue the existing trend toward inequality: the working poor and the homeless, in particular, are unlikely to have access to good healthcare, and their immune systems may already be compromised due to poor diets or insalubrious living conditions. While the virus won’t discriminate by income or healthcare coverage, people at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid are far more exposed to the consequences of infection.

There are also grave economic consequences to this crisis we must consider. For example, the pandemic comes at the worst time for many European coun-

tries, which are still recovering from the 2008 financial crisis. Italy and Spain, in particular, are among the most affected, and with their public sectors severely underfunded, they will be limited in what they can do. Europe’s middle class is already stagnant compared to the middle classes of emerging markets, as we saw in Chapter 3, and this trend will only intensify during the pandemic. For countries that are already politically unstable or economically vulnerable, like Iran, the crisis will be a severe test for leadership, as pressure will mount from all sides by an already anxious public.

As a society, we are generally prepared to cope with familiar natural disasters like earthquakes or hurricanes. There are guidelines to follow. And commercial buildings and residential housing are built to withstand such catastrophes. Are we equipped to do the same with pandemics? Generally, the world faces a global pandemic every 40 to 70 years: the Third Plague of 1855, the flu pandemic of 1918–1919, the AIDS pandemic beginning in the early 1980s, and now Covid-19 in 2020. Significant earthquakes occur in roughly the same intervals: for instance, in the San Francisco Bay area, the last two big earthquakes occurred in 1906 and 1989. The public and private sectors should have protocols in place to manage the moment when an epidemic becomes a pandemic. The existence of such protocols should ease public hysteria and concern. They would include, of course, a healthcare system that’s well staffed and equipped to handle a public health crisis and to scale its efforts accordingly.

Aside from policy decisions, personal responsibility solutions such as social distancing and lockdown to limit community spread are more important in densely populated areas like cities (which is where most people are headed in 2030 and beyond). These will intensify several trends under way: online shopping (Amazon, feeling the demand surge, went on a hiring spree and increased overtime pay for all warehouse employees), virtual communication (from remote work to maintaining social connections, nearly everyone has turned to telecommunication services like Zoom or WhatsApp to stay in touch), and digital entertainment (producers of movies, books, and music, for example, will be forced to find their customers online rather than in bricks-andmortar retail establishments).

The sharing economy, already a disruptive force, will further accelerate under the crisis; which industries suffer consequences (like

continued in the book

Gerd Schwartz, Manal Fouad, Torben Hansen and Genviève Verdier International Monetary Fund (Washington, DC), Softback, 340 pages, Illustrations, 152 x 229, August 2020, 9781513511818

Public infrastructure is a key driver of inclusive economic growth and development and the reduction of inequalities. Roads, bridges, railways, airports and electricity connect markets, facilitate production and trade, and create economic opportunities for work and education. Water and sanitation, schools and hospitals improve people’s lives, skills and health. Also, if done right, broad-based provision of public infrastructure can support income and gender equality, help address urgent health care needs (for example, during epidemics), reduce pollution and build resilience against climate change and natural disasters.

Yet, creating quality—that is, infrastructure that is well-planned, well-implemented, resilient and sustainable—has often been challenging. Almost all countries have infamous white elephants—major investment projects with negative social returns—that have never delivered on their initial promise. One does not have to search far to come across infrastructure projects that were poorly designed, had large costs overruns, experienced long delays in construction, and/or yielded poor social dividends. Examples of poor project appraisal, faulty project selection, rampant rent seeking and corruption, or lack of funding to complete ongoing projects abound, and not only in low-capacity countries. And even perfectly good public infrastructures may deteriorate quickly when maintenance is inadequate, which often reflects a lack of funding or political attention.

Losses and waste in public investment are often systemic. On average, more than one third of the resources spent on creating and maintaining public infrastructure are lost because of inefficiencies. These inefficiencies are closely linked to poor infrastructure governance defined as the institutions and frameworks for planning, allocating and implementing infrastructure investment spending. Estimates suggest that, on average, better infrastructure governance could make up more than half of the observed efficiency losses.

The need for stronger infrastructure governance for quality investment is widely recognized, and initiatives have been launched to provide guidance on good practice. Yet, although much has been written on what constitutes good infrastructure governance or public investment management, most countries still lack the institutions needed to produce good infrastructure outcomes. Countries frequently stumble over key institutional issues. For example, they may struggle to select projects with the highest social and economic returns and finance projects in a fiscally sustainable way, given limited resources, or struggle to ensure that funding is available as needed throughout project implementation. Budgeting for operations and maintenance costs, ensuring that procurement is transparent and rigorous, or harnessing private sector skills, innovation and funding without creating undue risks to public finances can also be challenging.

In the wake of The Great Lockdown and the Covid-19 pandemic, more infrastructure investment and strong infrastructure governance are likely to become even more important. First, with economic growth turning negative, public investment will have to be part of stimulating weak aggregate demand. For example, in the area of health, the pandemic has revealed a lack of preparedness of many health systems and an urgent need for upgrading health infrastructure that will have to be addressed. Second, countries will emerge from the pandemic with scarce fiscal space, elevated debt levels, large financing needs, and therefore a renewed need to make every dollar count, to ensure the efficiency of investment spending.

This book addresses how resources for public investment can be spent well. The overall message is simple: aspirations to end waste in public investment and create better quality infrastructure outcomes have to be met by specific actions on infrastructure governance to reap the full economic and social dividends from public investment.

Quality infrastructure plays a crucial role in fostering economic development.

• Public investment improves delivery of public services and the quality of life of citizens. Quality infrastructure affects our physical well being at the most basic level. An estimated 2.2 billion people worldwide do not have access to safe water. Their health and livelihoods are at risk from a variety of diseases and epidemics. (For example, the World Health Organization (2016) estimates that environmental factors, including the availability of sanitary water sources, account for 57 percent of those affected by diarrheal diseases.) Research has found that

interventions to improve water and sanitation infrastructure have been the most effective in reducing morbidity from these diseases (Freeman and others 2014; Wolf and others 2014; World Health Organization 2016).

• Public investment connects citizens to economic opportunities by supporting private sector activities. For example, quality transport infrastructure can reduce travel times and transportation costs significantly (BenYishay and Tunstall 2011), and contribute, among others, to better access to jobs and the facilitation of trade.

• Public investment is a catalyst for inclusive economic growth and development. Public investment can increase demand in the short term and productivity in the long term, sometimes even with limited increases in indebtedness, if spending is done efficiently (IMF 2014, 2015; Chapters 2 and 8 of this book).

Infrastructure spending needs are staggering almost everywhere. Low-income developing countries and many emerging market economies have looming infrastructure needs in most sectors. In September 2015, governments assembled at the United Nations agreed on a comprehensive development agenda with 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will require a large scale-up in infrastructure, particularly in water, sanitation and hygiene, energy, and transportation. The estimated total cumulative investment needs to meet the SDGs by 2030 are more than 36 percent of GDP in low-income developing countries and emerging markets.

Many advanced economies have aging infrastructures and see urgent spending needs for their upkeep and modernization. For example, in the United States, the American Society of Civil Engineers (2017) estimates cumulative spending needs of more than $10 trillion through 2040 to maintain, repair, or rebuild existing infrastructure. In Europe, in November 2014 the European Commission announced an Infrastructure Investment Plan to unlock more than €315 billion for investment spending. In the same year, the IMF (2014) called for an infrastructure spending push to help support both short-term demand shortfalls and longer-term development needs; the OECD (2019) did the same more recently.