2002.

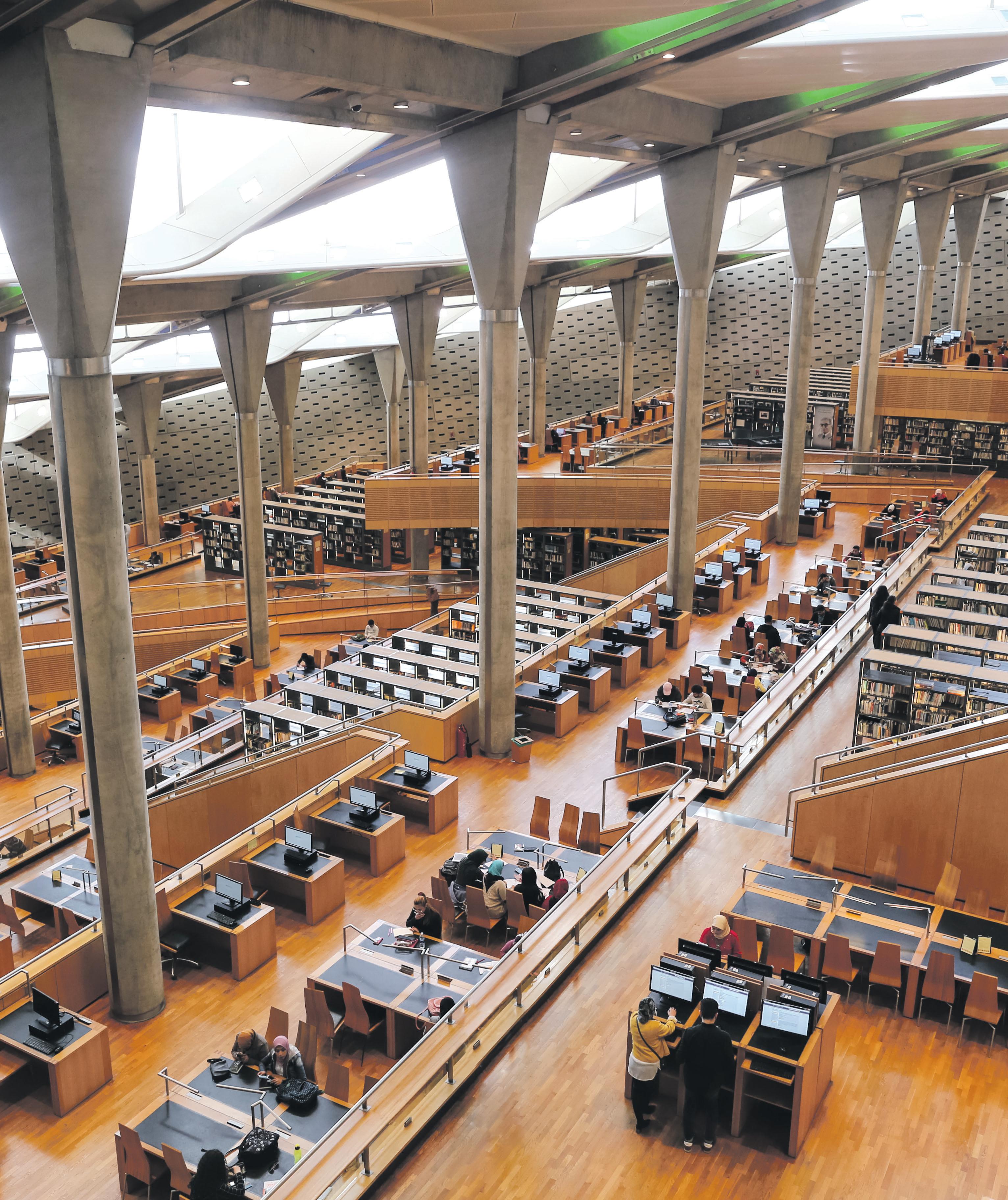

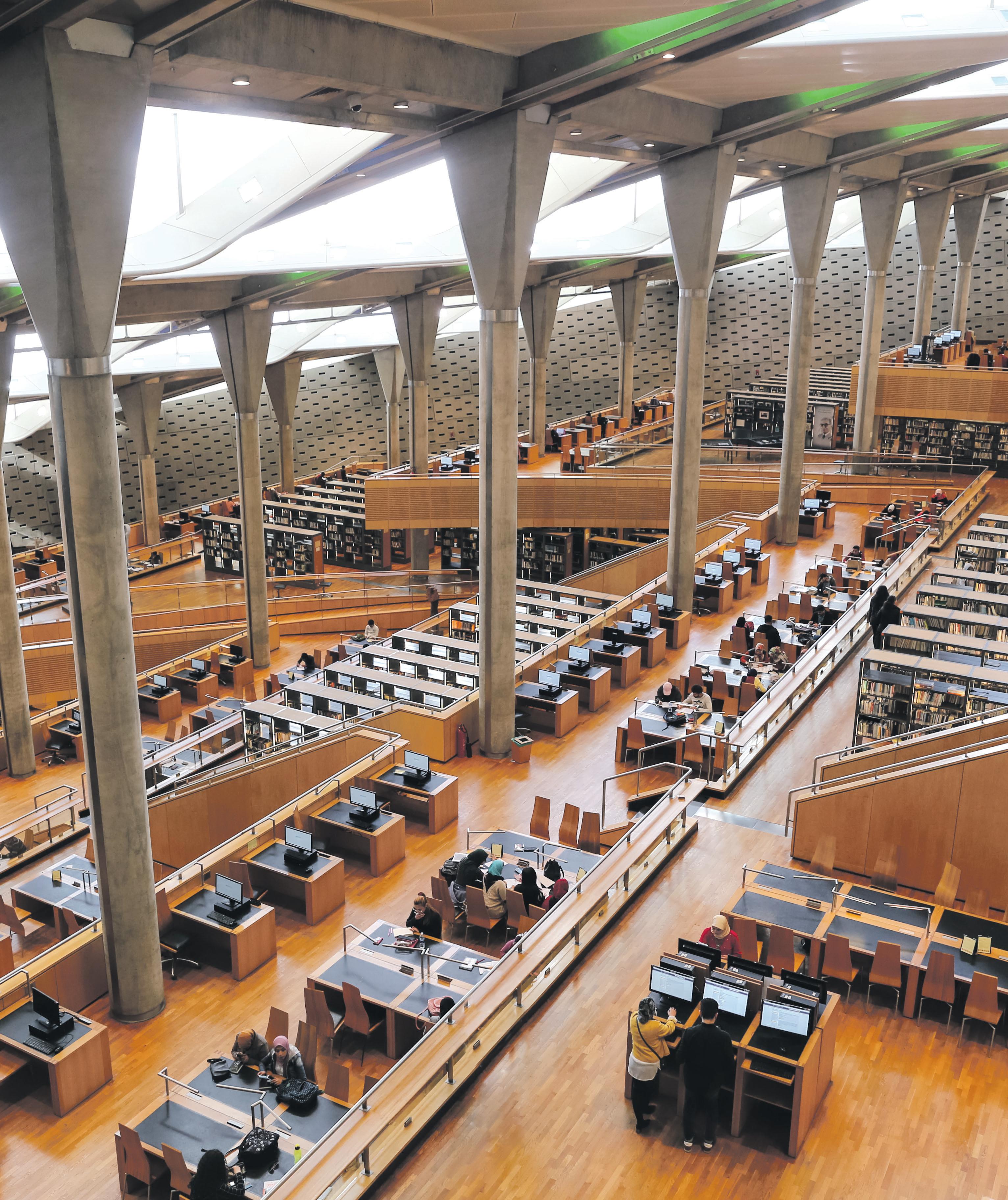

The Library of Alexandria in Egypt, designed by Norwegian architectural practice Snøhetta. Opened in October

Kalinbacak /

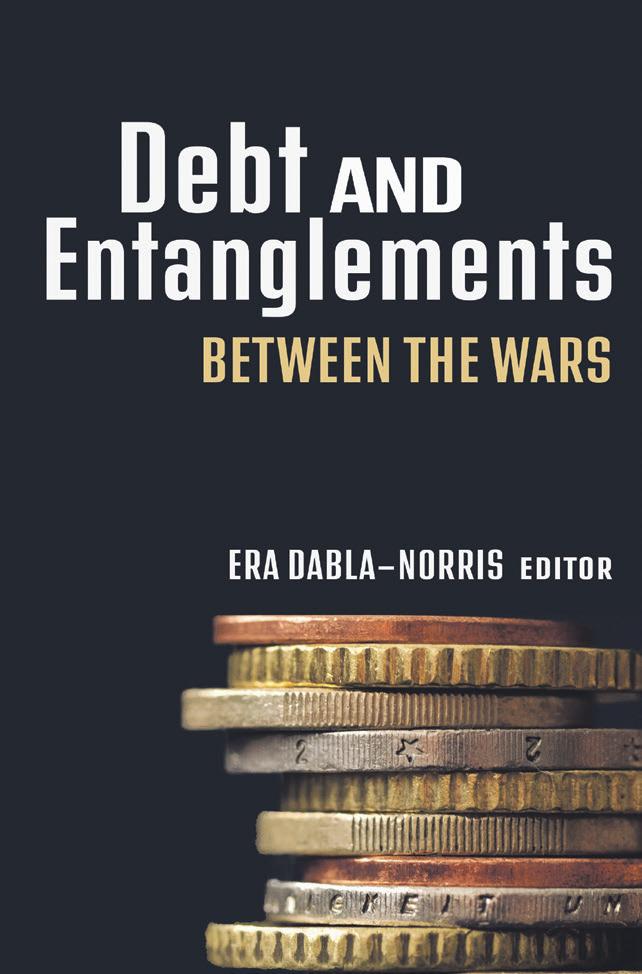

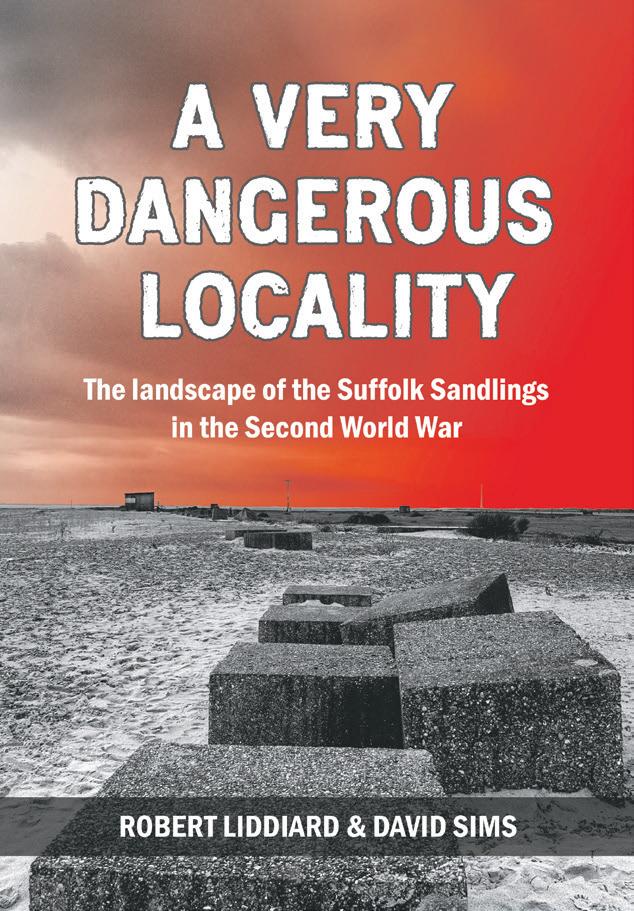

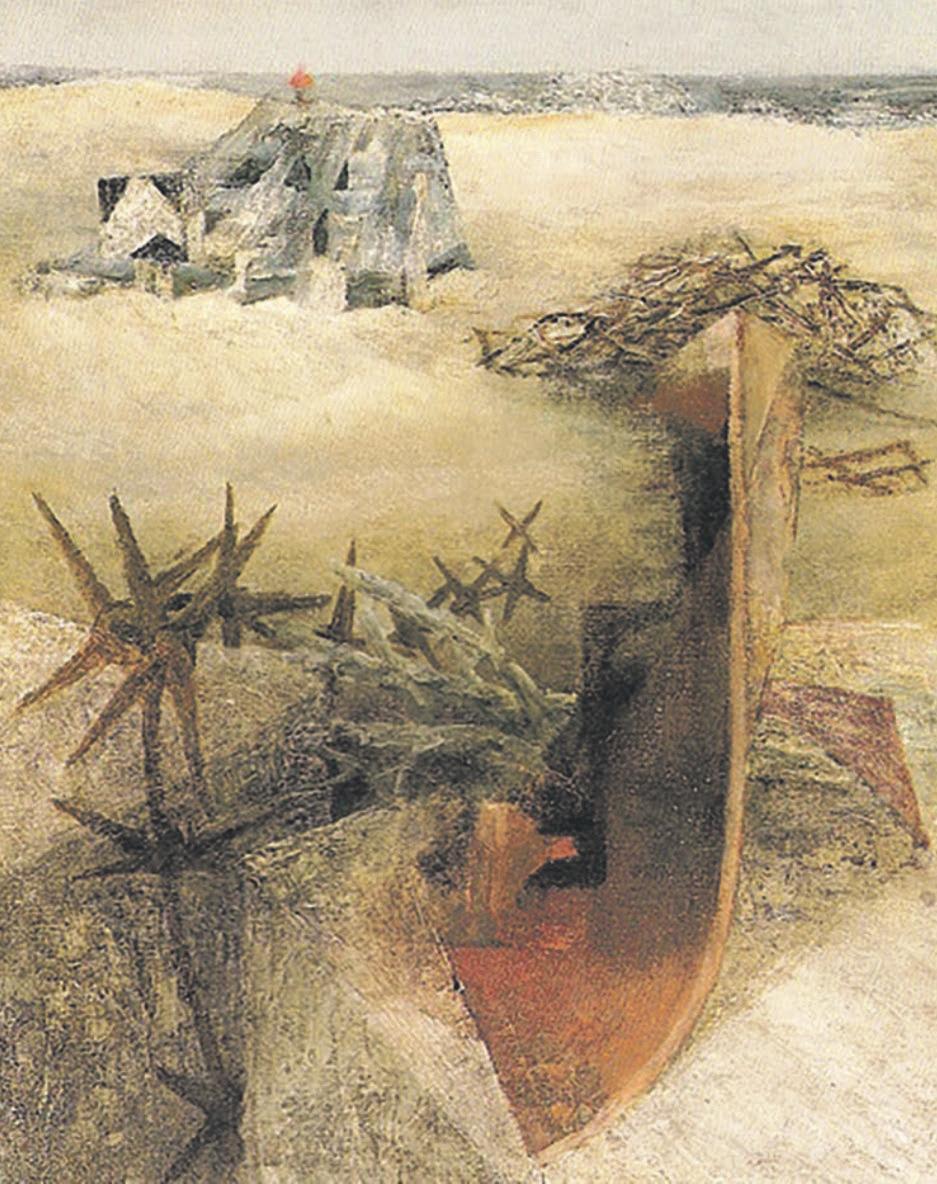

Booklaunch 82,000 distribution last issue Call us to stock Booklaunch at literary festivals, libraries and book clubs. Email book@booklaunch .london UK publishing’s biggest showcase of new titles. Our choice of extracts from the latest books and manuscripts For browsing without a bookshop Issue 6 Winter 2020 £3.75 www.booklaunch.london/audio-page Listen to our authors reading Former drugs czar David Nutt on drug policy Page 2 Protecting Saudi oil during Operation Desert Storm Page 4 A life in merchant shipping by Simon Quail Page 5 How Lady Betjeman hitched a ride to India Page 6 Sherlock Holmes’s search for Einstein’s lost daughter Page 7 Mary O’Hara pleads for an end to shaming the poor Page 8 Poles who found out they were Jews Page 9 The literature of Scottish devolution Page 10 The impact of war on the face of East Anglia Page 12 Ways to understand anthropogenic climate change Page 14 Literary art for sale through Booklaunch Page 15 How debt affected politics in the 1920s and 30s Page 16 The case for corporate stewardship in business Page 18 Should doctors prescribe love drugs and anti-love drugs? Page 19

Photograph:

Evren

Shutterstock

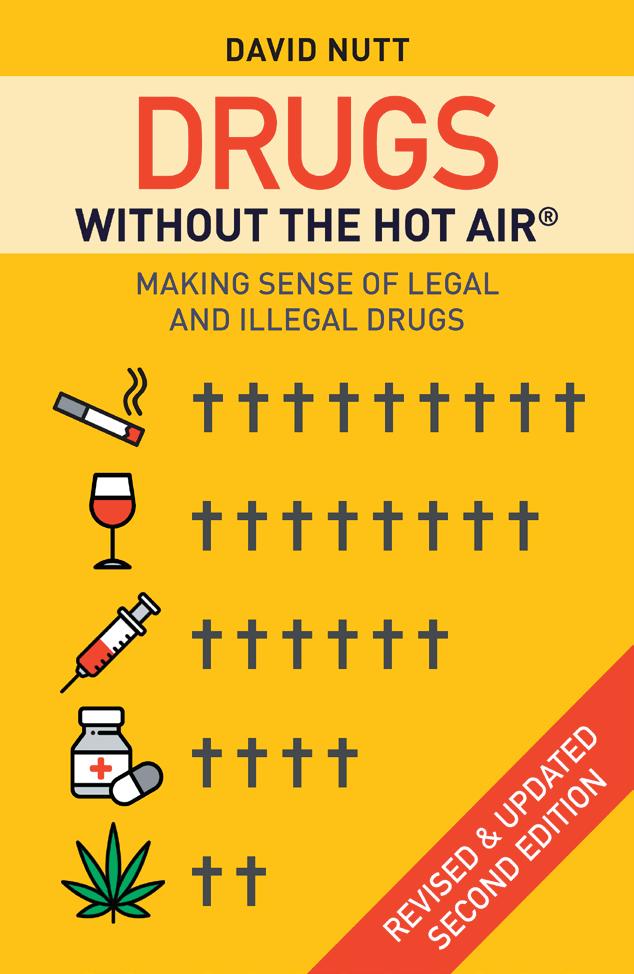

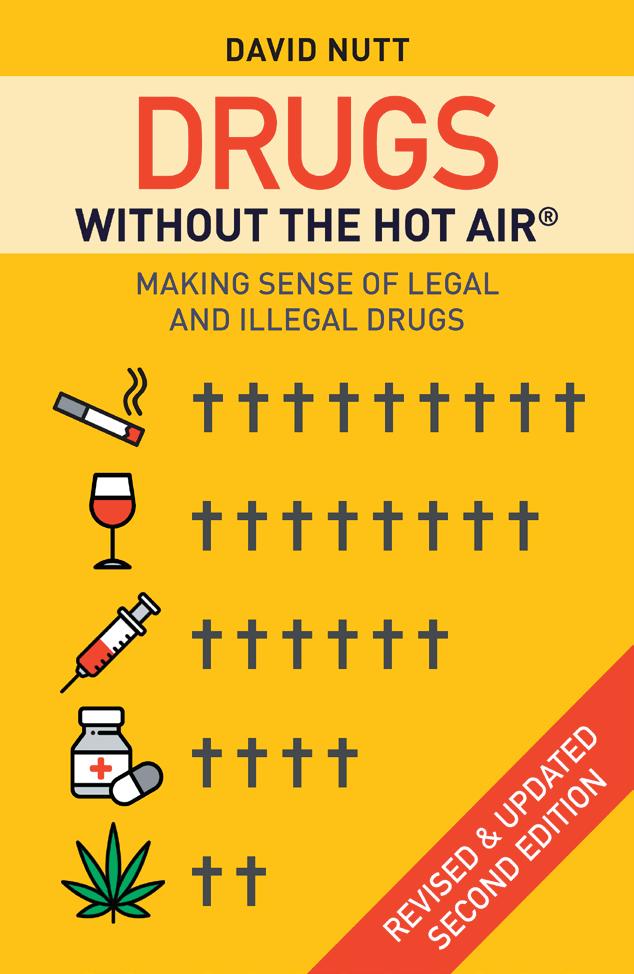

Many will remember me as ‘the government scientist who got sacked’. In many ways my departure from the UK government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) was my reason for writing this book, so it makes sense to start the story there. I was earlier head of the clinical research ward at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism NIH Bethesda, Maryland, where I acquired the deep knowledge of the harms of alcohol that eventually got me sacked.

In October 2009, a lecture I’d given a few months before was released as a pamphlet on the internet. This got picked up by the media and I was interviewed on BBC Radio 4. This generated more interest and several more interviews. A few days later I received an email from the then Home Secretary Alan Johnson asking me to resign from my position as chair of the ACMD. When I refused he released a statement saying that I had been sacked.

The lecture that sparked off this chain of events had covered a number of topics, but all the media wanted to talk about were my views on cannabis. Cannabis was downgraded to Class C in 2004, but in January 2009 it was re-upgraded to Class B, indicating increased harmfulness; the change was made against the recommendation of the ACMD. The Home Secretary at the time justified ignoring the recommendations of our report because, the ‘decision takes into account issues such as public perception and the needs and consequences for policing priorities. ... Where there is ... doubt about the potential harm that will be caused, we must err on the side of caution and protect the public.’ In the lecture, I discussed whether this was a rational approach, and particularly whether putting a drug in a higher legal Class in order to ‘err on the side of caution’ would actually protect the public and reduce harm. And why did she not act on a drug where there was proof of harms—alcohol?

I’d entitled my lecture Estimating Drug Harms: A Risky Business? because I knew from experience that talking about the harm done by drugs in relative terms was considered politically sensitive. This had been made very clear to me when a scientific editorial I’d written, comparing the harms of ecstasy with those of horse riding, provoked questions in Parliament and an unhappy personal call from the Home Secretary.

There had been a similar reaction to another paper, which tried to rank 20 drugs in order of harmfulness, taking into account nine different sorts of harm, including physical, psychological and social factors. What was remarkable about this paper was our finding that alcohol was the fourth most harmful drug in the UK, below heroin and crack cocaine but above tobacco, cannabis and psychedelics. Since alcohol was legal this challenged the logic underpinning the drug regulations which were supposed to be based on harms.

Politicians didn’t like the idea of some drugs being openly acknowledged as ‘less harmful’ than others (or even worse, less harmful than legal drugs such as alcohol), because it might be seen as encouraging more people to use them, or make the politicians seem less ‘tough’ in the eyes of the tabloid newspapers. This is despite the fact that the purpose of having different Classes of drugs built into the Misuse of Drugs Act—or the US controlled drug regulations—is to communicate to the public a degree of relative harm. Class B drugs should be less harmful than Class As, and Class C drugs less harmful than Class Bs. Incidentally, many drugs that have medical uses are both covered by the Misuse of Drugs Act, and regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Medicines Act. In the US the situation is similar but the classification system uses Schedules rather than Classes and has more of them.

Which brings us back to cannabis—the only drug in the history of the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 ever to be downgraded, following recommendations made by the Runciman report in 2000. After the downgrading of cannabis, however, the media, along with some politicians and medical professionals, became concerned that stronger forms of the drug (known as ‘skunk’) were causing serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia.

There was certainly a legitimate question as to whether new breeds of cannabis were more harmful than the sort that had been considered by Runciman and the ACMD in the past. As the government’s advisory council, this is exactly the sort of issue that our research was supposed to address, and we undertook a

very thorough study—one of the most comprehensive ever. Our conclusion was that, although there probably was a causal link between smoking cannabis and some cases of schizophrenia, this link was weak and didn’t justify moving the drug up to the next Class. Yes, there was a risk of developing a serious mental illness after using the drug, but it was smaller than the risks posed by other Class Bs such as amphetamines, which can also cause psychosis. This was the message that we wanted to send to the public by keeping cannabis in Class C.

Certainly, nobody was calling cannabis safe. However, as my 2007 Lancet report had shown, across a range of different sorts of harm, cannabis was by no means as damaging as many other drugs, particularly alcohol. This was a point I made in my lecture, and which got picked up in the radio interview: ‘surely you can’t be saying alcohol is more harmful than cannabis?’ I replied yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying, it’s in the Lancet, on the front page of the Independent and the Guardian—so it was hardly a secret. But this question was repeated in the other interviews that week—everybody wanted the quote that alcohol was more harmful than cannabis. It was an entirely defensible thing to say, as it was based on my own scientific work, and backed up by a similar study from Holland which agreed that alcohol deserved to be ranked among the most harmful of drugs. In these interviews I also observed that the government had asked the ACMD to determine which Class cannabis belonged in, but then hadn’t followed our advice.

In a letter to the Guardian a few days after he sacked me, Alan Johnson explained that I ‘was asked to go because he cannot be both a government adviser and a campaigner against government policy.’ I responded that I didn’t understand what he meant when he said I had crossed the line from science to policy, and that I did not know where this line was. The ACMD was supposed to advise on policy, and indeed it was set up by the Misuse of Drugs Act because the legal Class of a drug is supposed to inform the public about relative harm, and those who designed the act recognized this was best determined by a group of independent experts. By acting against our recommendations, the government had themselves blurred the line between science and policy.

The subtitle of this book refers to making sense about drugs and the harm done by drugs whether legal or illegal. This has always been my primary concern as a psychiatrist, and what I always hoped the advisory body (the ACMD) and the UN were working towards. The upgrading of cannabis to Class B was the third time we had been ignored. (The other two were when magic mushrooms were made Class A without consulting us, and when the government refused to downgrade ecstasy to Class B despite our recommendation. These are all discussed in more detail in later chapters.) The longer the government persisted in creating policies that conflicted with the scientific evidence, the more harm those policies would do, not least because they undermined our ability to give a consistent public-health message, especially around the dangers of alcohol. The more hysterical and exaggerated any government was about the harms of cannabis, the less credibility they would have in the eyes of the teenagers binge drinking themselves into comas every day. If we’re going to minimize harm, we have to have a way of measuring it, and a policy framework that can respond to this evidence. Comparing the dangers of cannabis and alcohol was considered a ‘political’ act that overstepped my remit as a scientist and physician.

I am not the only scientist to have suffered the displeasure of governments. The UK Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Sir Liam Donaldson warned of the rapidly growing medical costs of alcohol use and recommended a policy of increasing the price of the cheapest drinks. His report was dismissed by the government, leading to his leaving the post early. The past-president of the Royal College of Physicians of the UK Sir Ian Gilmore was also ridiculed by the press and government when he shared his view that the current drug laws were not working, and that the personal use of drugs should be decriminalized as in Portugal.

The day after I was sacked, I received an email from Toby Jackson, a man with a keen interest in science, who was rather wealthy. He offered to fund an alternative independent expert committee that could carry out drugs research free from political interference. Together, we founded the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs (since renamed DrugScience), and most of the scientific experts who resigned from the ACMD over my sacking joined the new group. (A few members have also worked with … continued in the book

Drugs without the Hot Air David Nutt

Former Government drugs czar David Nutt believes the debate on drugs remains hamstrung by prejudice, excusing alcohol while avoiding transparency on other substances. In Drugs without the Hot Air, he argues that the scientific objectivity that ought to guide policy and allow free choice continues to be ignored or devalued in the face of urgent questions about the nature of addiction, the dangers of vaping, the use of psychedelics to treat depression, and the extent and causes of the opioid crisis

David Nutt was at one time the UK Government’s chief drugs advisor. He is now Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, chair of DrugScience and President of the European Brain Council. He is also the inventor of “alcosynth”, a substance that mimics the pleasant effects of alcohol without causing a hangover

HEALTH & MEDICINE / POPULAR SCIENCE | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 3 This extract is taken from Chapter 1: Why Had to Write this Book

Making Sense of Legal and Illegal Drugs; Revised & Updated Second Edition Series: Without the hot air, UIT Cambridge, Cambridge, 400pp, Hardback, 9780857844941, 153mm x 233mm, 16 January 2020, RRP £18.99

Subscribe to Booklaunch www.booklaunch.london/subscribe From the same publisher

£2.28

price £16.71 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Save

Our

Arabian Night Patrol Ian Thewlis

Saudi arabia

12 January 1991

26 Jumada 1411, 21.00

Nine o’clock and only three more nights before the war starts. Rob Watson urges Cilla, his black Labrador, into the back of the patrol car, settles her on an old yellow carpet, and drives out of Acacia Court for his first night back on patrol. Swinging right past Banyan and Cactus Courts, he turns onto Perimeter Road and cruises beside the high chain-link fence of the airbase, headlights searching for breaks in the wire. Even at this time, the oil camp’s streets and courtyards are deserted, people huddled in their homes waiting for the next news bulletin, the first Scud alerts to start wailing out. But soon he’s feeling comfortable inside the patrol car, with the company’s Easy Listening music muttering over the radio and Cilla stretched out on the back seat, shifting occasionally to raise her head, look around, and settle back again.

Next year marks the thirtieth anniversary of Operation Desert Storm when a US led coalition of Western and Arab forces attacked Iraqi troops occupying Kuwait. Arabian Night Patrol is an international thriller about a desert oil camp in Saudi Arabia during the First Gulf War at the start of the War on Terror. The novel deals with issues that still haunt the Middle East and its relations with the West today

As he left the house, CNN were reporting that James Baker, the US Secretary of State, was visiting the airbase, checking the preparations for war. Now, beyond the perimeter fence, the base lies waiting, brooding through this wintry night, and gathering itself to attack. On this side, the oil camp’s courtyards are silent, oblivious to what Rob knows is the frenzied activity over there: trucks shuttling aviation fuel and supplies along the roads, the candy men loading planes and helicopter gunships with munitions, pilots being briefed for their reconnaissance flights over Iraq and occupied Kuwait. Yet despite the sharp silhouettes of hardened shelters, the pinpricks of light in the gloom marking the giant Galaxy transports, that feverish activity is difficult to imagine here, cruising slowly along by the perimeter fence.

He drives down towards the Utilities Department, its illuminated Pepsi vending machine standing guard outside the office building. Further along, the still waters of the sewage treatment ponds glisten under yellow sodium lights. The emerald grass around these ponds was recently mown and he remembers reading in the company newspaper about a crazy golf competition there, an event designed to publicize the company’s new sanitation system.

Next stop, the camp garage. Old cars and trucks are parked haphazardly outside, abandoned when their owners fled after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and threatened Saudi. Rob pulls into the space between a white Ford Transit and a Toyota pick-up with black garbage bags dumped in the back. Facing the padlocked gate, his headlights beam through the wire mesh onto the garage forecourt, the vehicles parked for repair and the inspection ramp curving up into the night sky. He gets out, scanning the area with his flashlight, checking for suspicious movements beyond the beam of his headlights. The smell of gasoline that always hangs over the camp is usually strongest here, but the chill wind from the sea is dispersing it, threatening more rain and discomfort for the troops camped up north near the Kuwaiti border. It’s the coldest and wettest Saudi winter he can remember, and he zips up his Security windbreaker and pulls the baseball cap firmly down on his head.

No lights show in the garage workshops where the remaining Filipino mechanics devote evenings and weekends to their private business, repairing Westerners’ cars and four-wheel drives. Behind the garage he can see the junk yard’s piles of rusting parts, with two large metal containers parked up against the fence. ‘It’s a weak point,’ warned Rick, the big American security boss, when he drove Rob around before Christmas. ‘Better stay alert.’

But tonight there are no suspicious movements. He reverses back onto the road, driving down towards the grove of palm trees screening the agricultural research station. He cruises into the car park, headlights washing over the dimly lit plant nursery and greenhouses, where tomatoes and cucumbers grow in plastic tubes without soil, sustained only by running water enriched with plant food. The tops of the palm trees are swaying in the breeze. The car is warm and comfortable inside, and he winds down the driver’s window. Already he’s feeling tired, needing this blast of cold air.

Past the agricultural station, the road turns sharp right, heading towards the lights of the bachelor housing block. But he drives straight on, following the chainlink fence. With a bump, he leaves the tarmac and pulls onto an unlit dirt track used by garbage trucks going to the landfill site. He drives more cautiously, headlights scanning the rough track and manoeuvring between

potholes. Before the invasion, this wasteland with its mounds of rubble was a testing ground for teenagers racing BMXs and dirt bikes. After the invasion, most kids were evacuated with their mothers, back to homes around the world. He wonders how many will return. And will Fiona, his wife, ever come back?

Headlights pierce the gloom and a US army Humvee, with a searchlight and machine gun mounted on top, bounds along the track on the other side of the fence. Spotting the white patrol car, the base guards flash their lights, acknowledging their common purpose. They’re heading towards the Patriot battery hidden among the small limestone jebels, rocky perches overlooking the airbase, waiting to shoot down missiles attacking the base. The Pentagon has spent billions of dollars on missile defence systems but will this Patriot work? At first the Americans and British said that Saddam’s Scuds couldn’t even fly this far, but now they say they’ll shoot them down.

Rob parks and lets Cilla jump out to roam around while he walks up a small jebel where he can smoke a cigarette and perhaps spot James Baker’s plane on the tarmac. Five years since he stopped smoking, but for this time and place he’s awarded himself the luxury of just one Marlboro cigarette each night.

Lighting up, he savours the deliciously illicit taste, this moment saved for tranquillity, and looks across the base. The shapes of hardened shelters and barracks stretch into the distance, and the low moaning vibration of generators carries on the wind. It feels like he’s living next door to a friendly giant who’s kindly offered to take care of him. Or a mass murderer, whose surreptitious movements disturb him during the night, but who he sees him in the morning, waves cheerfully on his way to work.

No sign of James Baker’s plane. Perhaps he’s already left. Rob wonders what he should think about tonight to while away the hours on patrol. Football? He and Chris, his student son, went to Anfield on New Year’s Day to see the Reds beat Leeds. So, are Liverpool going to win the League this year?

Or maybe he should think about his family. Back in Southport, on his last night at home, his parents and some friends phoned asking if he was still going back to Saudi. It was obvious there was going to be war and maybe thousands killed. Not sure whether he sounded brave or just foolish, Rob told them he was returning and gave his usual reasons—that he wouldn’t be dictated to by Saddam Hussein, that people at work depended on him, and that he had to go back for Cilla, the family dog. Nobody seemed convinced.

After dinner he had sat drinking coffee with Fiona and Chris round the kitchen table. ‘So why are you really going back, Dad?’ asked his son, more confident after his first term at university. ‘Is it the money?’

Fiona didn’t join in the questioning. He was conscious of her strained expression, her determination to let him make his own decision, no matter how ill she felt. But how ill was she? He’d been reluctant to inquire too deeply as she might flare up at him. She’d seen the doctor about headaches and depression and returned with some pills. Hopefully, they’d work.

In just a few months he’d complete ten years and qualify for full severance benefits. ‘I’m coming back after ten,’ he’d promised Fiona, as he nuzzled into her hair at Manchester airport. ‘Only a few months to go.’

Now he crushes his cigarette into the sand, strolls down the bluff to the patrol car and opens the back door to let Cilla jump in. On the radio, Phil Collins is singing about something in the air tonight, as Rob checks in with the Big House.

‘Assalamu alikum. Welcome back to Paradise, my friend.’ Abdul Karim—Al to his Western colleagues— greets him through the crackling, his Texan accent a legacy of detective training in Dallas. ‘How’s the family? You have good Christmas?’

‘Good. So how’s your family, Al?’

‘Zain. I take to Riyadh for safety. Only strong men stay for this war, sideeki.’

Al’s usual good humour sounds constrained. Is Rick, his American boss, listening in?

‘You see Mr Baker?’ Al asks. ‘He’s visiting the guys at the Base.’

‘No, he’s probably left. Nothing to report here. All’s quiet.’

‘Alhamdullilah. Good to know you’re back, my friend. But be careful out there.’ Al concludes with the familiar warning from the roll-call sergeant in Hill Street Blues

INTERNATIONAL THRILLER | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 4

This extract is taken from the start of Chapter 1: Another Night in Paradise

… continued in the book

Silverwood Books Ltd, Bristol, 274pp, Softback, 9781781328194, 148mm x 210mm, April 2019, RRP £8.99

Subscribe to Booklaunch www.booklaunch.london/subscribe From the same publisher

Ian Thewlis taught at colleges and universities in the UK, Libya and Nigeria before joining the Middle East oil industry. He has written books on business but now devotes his time to writing fiction. Arabian Night Patrol, the first novel in a planned trilogy tracing the birth and development of the War on Terror, draws on his experience of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, the start of Al Qaeda and the subsequent invasion of Iraq

Our price £9.99 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Fifty years ago I boarded the first of 37 merchant ships and went to sea. I experienced a way of life no longer available to the modern mariner.

In August 2019 the world’s largest container ship the MSC Gülsün arrived in Europe from China. She can load an astonishing 23,756 standard container boxes. At 1,300 feet long, MSC Gülsün—247,900 dwt—is three times the length of my first ship, MV Deido and carries 26 times more cargo. Built 58 years before, Deido was 450 feet long 9,400 dwt and needed a crew of 50 to man her engine room, maintain and work her 22 derricks and five hatches, and keep navigation and cargo watches. In 1965 Elder Dempster’s entire fleet of 49 merchantmen reached its peak total of 293,853 gross tons. That fleet required approximately 2,000 officers and crew. Despite her size, MSC Gülsün needs a crew of just 26.

This scaling up of vessel size and scaling down of crew numbers is a dramatic illustration of the vast changes experienced in the world of marine transport.

And of the life at sea—and long days in port—experienced in my day? All gone. In 50 years.

We may need fewer crew and ships but we still import by sea 95 percent of the goods that Britain needs every day. That is eight tonnes for each person in the UK. It would surely be good for the balance of payments deficit if the Red Ensign flag were flown on more British-owned vessels.

Data from the Department of Transport shows that the number of British-flagged ships fell by more than a third between 2009 and 2014, but 2019 figures from the UK Chamber of Shipping show that since 2015 fleet tonnage has picked up 12 percent to a total of 16.7 million GT and is now the world’s 14th biggest in terms of tonnage. Of 537 UK flagged vessels, 277 were registered to UK companies.

International shipping is a growing industry. If Britain played its part in not only providing officers and men but in financing UK shipping companies, as we used to 50 years ago, then this island nation could begin to reclaim its proper place sailing the world’s oceans, navigating us more securely through stormy economic seas.

The numbing cold of riveted steel decks plates has leached into my boots. My ears still echo with the clang of chipping hammer on rusty hulls. The smell of Brasso immediately invokes polished portholes.

I have witnessed myriad sunrises and sunsets over steel grey horizons and smoky headland, and stood lookout under a canopy of glittering stars. From bridge or bow I have had a grandstand view of dancing dolphin pods, shocks of flying fish and stuka-diving gannets. Snug in a hammock rigged on the monkey island I have been lulled to sleep by a gentle swell. Like a wild horse in bucking seas, the kick of the deck has sent me sprawling. I have been covered with choking cargo dust, and been threatened by rope, wire and heavy block. I survived. But three ships and many of their crew did not. They sank into the deeps, lost forever.

To me ships are not a prosaic construction of steel and machinery. Every time I read that a ship has been broken up, it hurts. It hurts because these ships were my home, the home where I ate, rested, worked, played, sometimes drank too much, sometimes enjoyed parties on board. Slept. Woke up to another day as my ship sailed inexorably onward, laying a silvered wake across a carpet of deepest blue.

We crew lived together for months on end, shared good times and bad times, in rough weather and glorious. Went ashore together. Came back to our ship. Glad to be back after a good run ashore. But sometimes sad to be stuck on board and wishing to be home.

The older the ship, the greater the character. The Glenorchy, built in 1941, had 27 years of history rammed into her deck caulking when I joined her and countless thousands of marine encounters under her keel. Ships built in the 1980s had less charm, built to be efficient steel boxes but still carrying the freight of mariners’ lives, their hopes and fears, their dreams and sodden realities.

‘Scrapped at Kaohsiung’ may be an acknowledgement of a commercial reality but it was a heartless epitaph, a kick in the teeth to the sentiment we mariners felt about her, our ship. It wasn’t about economic turnover for the sailor. Her loss was a loss of memory, a loss of shared experience, of a voyage safely completed. ‘Finished with Engines’ was only meant to be for now, this port, not for ever. I felt that most strongly when leaving that old rust

bucket, Rogate. I was the last man aboard. The last to feel her as a living vessel before she became a steel hulk and was razor bladed.

These ships also made a ship owner a minimal profit. When that thin margin vanished, the sentence was to suffer the ultimate indignity of being scrapped, taken to the knacker’s yard in Europe, India or Taiwan.

Some ships arouse feelings of unreasonable dislike, usually due to a master careless of his crew, or poor maintenance. Ships have to be cared for, by captain to cabin boy, from bridge to keel, from cable locker to propeller. Or they turn nasty on you.

In seeking to discover meaning in my own life I have discovered that ships have a life of their own, worthy of celebration. And commemoration. These ships and men have vanished from the seas. I tell my tale so that the vessels and those who lived on board will not be erased from our national memory.

To climb up a gangway is to commit yourself to the ship, trusting her (for a ship is always feminine) to complete the voyage safely, to survive the unknown encounters ahead, be it storms or hidden rocks.

To climb a gangway is to seek life beyond.

To step down the gangway onto solid land is to give up an unspoken expression of thanks for the voyage safely completed, the biblical chaos of the waters survived.

A ship’s gangway is the link between the hidden worlds of life at sea, over the horizon, and the more known world of life ashore. A gangway invokes a complex metaphor of the link between the solidity of the land and the mysterious, often dangerous, instability of the seas and oceans that circle our planet.

The call of the sea was in my blood. I discovered several years ago that my great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather were both master mariners. Thus it was, even though I lived in a Cotswold hamlet one hundred miles from the nearest sea, that sea salt flowed in my veins. After the gangway had been hauled in and the ropes let go, and we set sail away from the safe, solid shore, I wanted to discover what lay beyond the distant flat horizon.

Every time I joined my ship, every time I went ashore, from Archangel to Yokohama, the gangway was the link between these two contrasting worlds.

I have learned that once a sailor vanishes over the horizon, he is forgotten by the landlubbers who remain ashore. The mariner is no longer held in close affection by the community memory because so few British men and women go to sea. There are no longer, as in my day, the numerous family connections to those who follow the call to go a-roving, very few left behind who talk about absent fathers and brothers away for up to two years at a time, leaving behind ‘grass widows’ to bring up families all alone. There is no residual understanding among landlubbers, and the seafarer’s life is a lost world.

The wake of life stretches away behind us, silvered by a rising moon of memories, its ghostly illumination casting a pale light on recalled events. This memoir is an evocation of my past. You may have similar memories of a time when the British Merchant Navy was at its peak, when 3,000 British ships under the Red Ensign—the Red Duster—plied the oceans of the world, manned by British officers and sailors, under conditions that have never been bettered.

For centuries the ships of the British Merchant Navy carried the lifeblood of Britain, their bulging holds crammed with goods to satisfy every perceived need and luxury, to sate the population’s appetite.

Not now. These arteries have had a transfusion of foreign bodies. Ships have grown huge and fat. They are rarely sustained by British blood. Their stories belong to other shores.

My story is of seafaring five decades ago, of men like me who filled the fridges of families with groceries, manufactories with raw materials, foundries with base ores, who then sailed away to live their lives over a distant horizon.

So climb up the gangway and glimpse a world long gone, a world which shaped and sustained a nation.

Tottering along the narrow slippery deck of the submarine I headed towards the access hatch and scrambled down the ladder. Inside the narrow steel tube all was strange: smells of hot oil, steel and stale air. I peered into the periscope eyepiece. The images of ships in the Solent appeared to be upside down.

After a whirlwind tour we left that claustrophobic, windowless world.

‘Do hurry up! And take care!’ gasped my mother confusingly,

Gangway: A Life at Sea Simon Quail

Life at sea has shrunk as ships have grown fat. In Gangway Simon Quail looks back at the challenges faced by cadet, navigator and chief officer in the last age of the general cargo motor ship, but before the age of the supership. More than a personal memoir, Gangway offers a reminder of a world long gone, of the camaraderie among large crews at work aboard, and of adventures ashore during days in port

Captain Simon Quail went to sea as a deck apprentice in 1966 when the British Merchant Navy was at its height. Employed by 11 very different shipping companies, he sailed the oceans of the world for 20 years, serving on three dozen ships as a deck officer on general cargo ships, passenger ships, chemical tankers and bulk carriers. Now retired, he is a Liveryman of the Honourable Company of Master Mariners

MEMOIR / SHIPPING | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 5

This extract is taken from the Introduction and Prologue

… continued in the book

Racing Rabbit Press, Rudgwick, 288pp, Softback, 9780244751692, 145mm x 201mm, Illustrated, September 2019, RRP £9.99

From the same publisher

Subscribe to Booklaunch www.booklaunch.london/subscribe Our price £9.99 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Summoned by the Hon. Mrs John Betjeman Christopher Maycock

‘I’m coming with you, Dickoi darling!’ crowed the Hon. Mrs Penelope Betjeman. She had just heard that medic Dick Squires had organised a mixed party of four young people—he and I, Elizabeth Simson, a talented artist friend of Dick’s sister, and Dick’s American girlfriend, Isobel—to travel overland to India in September 1963. For five years Dick had been dreaming about this trip. Now his fantasy was coming true.

Penelope had been on the point of flying to India to rediscover the Kulu Valley, retracing on ponies the steps she had taken in 1931 with her mother Lady Chetwode, wife of the Commander-in-Chief in India, Lord Chetwode, so an overland journey with us was preferable to taking a plane, and considerably cheaper. In the days before budget airlines British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was expensive and served only major cities, making the overland route the most practical way to explore Middle-Eastern countries.

Penelope had some time earlier told the Tatler magazine, in an article entitled ‘Summoned by Temple Bells’, that there was ‘nothing at all surprising’ in setting out on an 8,000-mile journey to India. ‘Having looked after my husband and children badly for 30 years I need a break, don’t you think? … Everybody nowadays wants to do things like crossing a continent by Mini, but if you do it, you need to choose carefully. You must have people who can deal with an appendix in the desert and take out an engine by the light of a candle.’

The Orient fascinated us, especially Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan and the Indian sub-continent, but our experiences were considerably enhanced by Penelope’s presence as the elder mentor, who insisted on visiting historical sites and regaling us with stimulating ideas. Indeed, the journey opened our eyes to the remarkable interdependence of the architecture and religions of the regions visited—unwelcome though this perception may be to some believers.

Young Englishmen often travelled abroad before settling down to a career; the Grand Tour was as much a rite of passage in the 18th-century as the deb’s coming-out ball in the 19th. But what was it like to travel overland to India in the early 1960s, just ahead of the hippie trail? And what was it like to travel with John Betjeman’s 53-yearold wife—daughter of the former Head of the Indian Army and a specialist in ancient culture? Christopher Maycock kept a diary

Christopher Maycock is ex-senior partner and GP trainer in a Mid-Devon medical practice. He was educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge and St Thomas’ Hospital London, and gained a Certificate of Theology (Distinction) at the University of Exeter. He is an Honorary Fellow of the Woodard Schools Corporation and has lectured in The Hague, at South-West Medical Centres, The King’s Fund, The Wordsworth Trust and Chawton House Library. He enjoys astronomy and country sports, is married to Rachel and has twin children, James and Charlotte

Dick and I met at the Betjemans’ house in Wantage, Berkshire, now in Oxfordshire. The future Poet Laureate sat comfortingly and benignly in his study—not surprisingly, perhaps, as Penelope’s absence would give him free rein with his long-standing amour, Lady Elizabeth Cavendish. But it was also the beginning of a new lease-of-life and freedom for Penelope, who had been much saddened by the rift with John.

The Betjemans’ interests were as different as chalk and cheese. John was intrigued by Victorian architecture; and as he said to Edward James, ‘Isn’t abroad awful?’ Penelope was a mine of information on many religions and an intrepid, exotic traveller. Both were enthusiastic Christians, but in significantly different ways: John a High Anglican with a fear of death and prone to guilt; Penelope a convert to Roman Catholicism, full of optimism and bouncy high spirits—not an easy match yet remaining fond of each other to the end. We thought it was remarkably game of Penelope at 53 to be joining our trip.

In Istanbul we met Mrs. Warr, the Consul-General’s wife. One of the benefits of having Penelope on board was that news of our journey preceded us. She was the draw, with the tedious snag for hosts that we were part of her retinue. Mrs Warr, welcomed us at the splendid building set in a small, very English garden, originally the British Embassy, the second largest in the world and designed in part by Sir Charles Barry, renowned for his Reform Club in Pall Mall.

The following night Penelope and Elizabeth, craving the meagre joys that Istanbul could offer, stayed in a hotel, while the rest of us drove out to a deserted quarry for a meal of beef stew, sweet peppers and potatoes, which Dick was overjoyed to be cooking himself.

Mrs Warr had invited the whole party to lunch the next day, so we dressed up. It seems amazing in retrospect that we had brought dark suits, ties and clean shirts, which we donned in the clayey ground of the quarry, Dick scrubbing himself down naked like a buffalo and Isabel making up in the VW’s wing mirror. Penelope and Elizabeth had endured the night in their ghastly hotel where rats could be heard running around the attic. The Warrs’ lunch at the Consulate was magnificent, served by an impeccably correct Turkish waiter: mussels in batter followed by fried chicken accompanied by chestnuts and exotic vegetables washed down with

red wine. A fluffy pudding concluded the feast—all most welcome after wet nights and camp life.

Forty years later Al-Qa’eda terrorists suicide-bombed the Consulate, killing the Consul-General and a number of Turks.

Passing through the old quarter of Ankara, we collected Elizabeth and Penelope from the Museum. Off again! At sunset, we reached the town of Nevshehir, approached through a deep gorge and built on the side of a steep hill topped by a fortress. In spite of Kemel Ataturk’s reforms, many women here were still in purdah. Originally Nevshehir had been the town of Nazianzus, seat of bishop and theologian Saint Gregory Nazienzen, one of the great fourth-century Cappadocian Christian Fathers.

Camping well out of sight of the town in a stubble field, the pattern of our camp routine became finally established. I erected the tent while Dick and the girls unpacked. Penelope was chief chef with Dick assisting, though allowed to be in charge once a week. The girls peeled the spuds and cut up onions while I wrote the diary. After the meal, I assisted with the washing-up if the diary was finished. On that chilly night, Penelope eased the party to sleep with readings from Plato’s Life of Socrates

Rising early the next morning, Penelope climbed a nearby hill with Dick to photograph the sunrise. The views from the fortress of Nevshehir were superb. The occasional tourist, arriving in an expensive American taxi and wearing smart Western clothes, seemed incongruous among the local people, who travelled on foot and by donkey, many of the women veiled in yashmaks. A middle-aged woman with a weather-beaten face brought her daughter to me. It seemed that she wanted to sell her—there was no other way to interpret her gesticulations. The girl was sweet and shy, and wore a headdress edged with shining metal beads. I managed to turn the offer down, I hope without implying that the goods were in any way unacceptable.

A young man, followed by 30 inquisitive townsmen, led us to a backyard on the edge of town. It was crowded with chickens, cows and a few braying donkeys. Penelope selected two chickens. But aware, as she saw it, of the Islamic method of killing them by slitting their throats and allowing them to bleed to death, she was determined to slaughter them in the ‘humane’ English way by wringing their necks. There were murmurings of disquiet in the crowd, who couldn’t believe the birds were dead, when Penelope started to pluck them as their limbs twitched reflexly. It was an unforgettable image, to see Penelope bent down in the middle of a now aggressive crowd, her tweed-skirted backside haloed by flying chicken feathers. It said much for the tolerance of the Turks that we escaped unscathed, despite breaking one of their major Koranic religious taboos against eating the flesh of a strangled animal.

During the afternoon at Pasargadae, Cyrus the Great’s Persian capital, Penelope enquired if she might have a ride on a horse, which David Stronach the archaeologist then arranged. A scraggy-looking nag, with a tall, thin and even scraggier owner arrived at 5.00 pm, an hour late. He was obviously expecting to lead it and Penelope gently round the field by the reins. But no one had told him that Penelope was used to hunting with the Old Berks. He was astonished when she marched out of the hut in riding breeches, smart brown riding-jacket, shirt and cloth-tie. The horse and Penelope hit it off immediately, breaking loose together and cantering across the plain. It turned out that the man was not the owner, which partly explained his anxiety. As he saw a small cloud of dust disappearing into the distance, he must have imagined that a female horse-thief was stealing his stallion. Horrified, all he could gasp was, ‘Asp chahar kilometer, asp panj kilometer’ ‘Horse four kilometres, horse five kilometres’. He nearly had a fit when I countered with, ‘Asp davazdah kilometer’—‘Horse twelve kilometres’. Penelope returned from her exhilarating ride an hour later, still firmly mounted on the horse.

Just before Ghazni in Afghanistan, we stopped for Penelope’s most welcome porridge, boiled eggs and coffee. It was 20 November. The Afghan winter had arrived. Penelope announced that Dick and I must shave off our beards. She refused to cross the frontier of what had once been British India with bearded Englishmen. She herself donned riding breeches, smart shirt and tie, powdering

TRAVEL HISTORY & HUMOUR | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 6

This extract is taken from passages throughout the book

… continued in the book

Overland to India in 1963 on the Cusp of the Hippie Trail Bookcase, Carlisle, 341pp, Softback, 9781912181148, 150mm x 212 mm, .128 b/w illustrations, October 2018, RRP £16.00

Subscribe to Booklaunch

From the same author

www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

Our price £16.00 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm and grew up in Munich, bustling, wealthy towns in the Swabian region of southern Germany. At the age of five he was shown how a compass needle always swings to magnetic North. From that moment he determined to become a great physicist, more famous than Isaac Newton.

At 23 Einstein sired an illegitimate daughter with Mileva Marić, a fellow physics student at the Zurich Polytechnikum, who later became his first wife. No one to date has solved the mystery of the infant’s fate. Mileva and Albert referred to her by the Swabian diminutive ‘Lieserl’ Little Liese. Her life was fleeting. At around 21 months of age she disappeared from the face of the Earth. The real Lieserl may never have come to the eyes of the outside world but for an unexpected find, 83 years after her disappearance. In California, Einstein’s first son, Hans Albert Einstein, investigated an old shoebox tucked away on the top shelf of a wardrobe. It contained several dozen yellowed letters in German type, exchanges between Albert and Mileva. Italian, Swiss, German and Austro-Hungarian postmarks reflected their peripatetic life. Letters dated between early 1901 and 1903 mention Lieserl. After September 1903 her name never appears again, anywhere.

Lieserl remains a subject of mystery and speculation. Researchers regularly trek to Serbia to conduct investigations. They comb through registries, synagogues, church and monastery archives throughout the Vojvodina region, the place of her birth and short life, but to no avail. In The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter Holmes exclaims, ‘the most ruthless effort has been made by public officials, priests, monks, friends, family and relatives by marriage, to seek out and destroy every document with Lieserl’s name on it. The question is why?’

As the American scientist Frederic Golden put it in Time magazine, ‘Lieserl’s fate shadows the Einstein legend like some unsolved equation.’

Three hapless ‘must have’ theories hold sway. Lieserl must have died in an outbreak of scarlet fever in NoviSad in the late summer of 1903. She must have been adopted by family friends in Belgrade. She must have been placed in a home for children with special needs.

In The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter, Holmes and Watson are led to a dramatic Fourth Theory.

PRELIMINARIES BY DR. JOHN H. WATSON, LONDON

The events I relate in The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter took place well into the reign of King Edward the VII, the year in which the Simplon Tunnel was driven through the Alps and when Charles Perrine discovered Jupiter’s seventh satellite, Elara. In faraway South Africa, Thomas Evan Powell brought the Cullinan, the world’s largest rough diamond, to the surface. In England there was talk of a new automobile association employing cycle scouts to help unwary motorists avoid police speed traps.

Sherlock Holmes held Albert Einstein’s future in his hands.

In the spring of that year, my comrade Sherlock Holmes undertook an investigation into what at first appeared to be a very humdrum matter concerning a recent graduate of the Physics Department of a Swiss Polytechnikum. It turned out not to be so humdrum a matter after all. The young man’s name was Albert Einstein. He was soon to become the world’s most revered scientist, gaining fame and respect the equal of, or greater than, presidents and prime ministers.

1: I AM OFFERED A COMMISSION

CHAPTER

Early in 1905 the Strand Magazine’s publisher, Sir George Newnes, approached me with an offer: would I accept the kingly sum of six hundred guineas in return for securing a photograph of Sherlock Holmes at the now-infamous Reichenbach Falls in the Bernese Oberland? Sir George wanted an engraving or half-tone illustration from the plate to grace the Strand’s Christmas cover. The Falls were the site of the death of the arch-criminal Professor Moriarty at the great detective’s hands fourteen years earlier, on 4 May 1891. Six hundred guineas was the equal of three years of my Army half-pay pension, hard-earned in the arid Pãriyãtra Parvata and a pestilential stint at the Rawal Pindi Base hospital, both of which I deemed myself lucky to have survived.

‘A front-cover picture of Sherlock Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls will increase the run by at least a quarter of a million,’ Sir George opined gleefully.

He was right. A cover reprising Holmes’s miraculous escape from a watery grave at Moriarty’s hands would generate a welcome boost to sales.

Until his reappearance some three years later, it was believed that my great comrade had died in the struggle with Moriarty. During this Great Hiatus the obscure mountain stream and waterfall soon became a place of pilgrimage. The nearby Englischer Hof guest-book was filled with guests’ comments, keen to pay their respects. Visitors included the New York Police Department alongside a delegation from the French Sûreté led by Monsieur Dubuque, and James McParland of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Troupes of young London City men and members of the burgeoning Sherlock Holmes societies travelled to the Falls in charabanc loads, wearing bands of black crêpe around their bowlers. Gaggles of women dressed in long grey travelling cloaks clustered at the cliff edge, staring silently down. Some cast a facsimile of Holmes’s fore-and-aft cap (on sale at the local hotels) into the roiling waters below. The suicide watch at the cliff edge, normally posted for forlorn young lovers, now looked out for lone figures of distraught men and women ready to throw themselves into the chasm after the man they called ‘the Master’.

The Strand would pay all costs for a journey retracing our original route. Holmes and I would tread once more in the footsteps of Goethe, Tolstoy and Nietzsche along the charming Rhone Valley. Sir George wanted the photograph to show Holmes standing on the lip of the chasm, down which Moriarty tumbled (or rather, had been tumbled) to his end. The photograph was to capture the atmosphere of Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon at the Saint-Bernard Pass as Bonaparte himself put it, ‘Calme sur un cheval fougueux’. In the picture, my comrade-in-arms should stare down on the torrent, behind him crags piled one on the other. My publisher had looked at me quizzically. Did I think Holmes could be persuaded to strike a chord on his violin, staring down over the precipice as though viewing Moriarty’s body cannonading from rock to jutting rock?

I replied that it was a ludicrous idea. The spray from the rushing torrent would badly upset a Stradivarius.

My publisher’s wish for an exclusive front-cover to boost sales was understandable. The publishing business was becoming highly-competitive. The daily journey to work for large numbers of the population had triggered a demand for reading material from newspapers such as the Daily Mail and magazines with short articles and stories. Titles like the Harmsworth Magazine or Pearson’s Magazine offered articles of scientific and historical interest, cartoons and celebrity gossip. The Strand looked over its shoulder at the rapid growth of a particularly vulgar halfpenny dreadful, the Penny Blood Union Jack magazine, popular with young men. The Union Jack’s circulation had been lifted by the adventures of the upstart detective Sexton Blake, the poor man’s Sherlock Holmes, and his scent hound Pedro. Another rival was Hornung’s disgraceful invention, A. J. Raffles, the ‘gentleman thief’, whose criminal exploits promoted the sales of Cassell’s Magazine

In the early stages of the Great Hiatus I was approached only once for assistance by Lestrade, the ferret-like Scotland Yard inspector. On this occasion, through my medical knowledge, I was instrumental in solving a crime dubbed by the Evening Standard, ‘The Case of The Ghost of Grosvenor Square’, a sobriquet picked up and parodied by Punch

After Holmes’s assumed death, I had welcomed an invitation from his brother Mycroft to return to Baker Street, to put my former comrade’s papers and possessions in order. Tears had sprung to my eyes when I looked at a lifetime’s souvenirs the Yupik wolf mask sent from a shaman in Nunivak in 1890, a huge barbed-headed spear, a carving of the demi-god Maui, Lombardini’s Antonio Stradivari e la celebre Scuola Cremonese, the tennis rackets and cricket gear Holmes last employed in his short time at university.

I relocated the most precious of these household gods and books from the sitting room to his bedroom, which became for me as great a shrine as the bedroom of the late admired Prince Albert in Queen Victoria’s eyes. I left three physical reminders of my friend’s stillpalpable presence centre-stage on the deal-top breakfast table. The violin, with its well-flamed maple fine belly grain and orangey brown varnish glowed where it lay in the morning sun. At its side the bow, like the bayonet of a fallen soldier. And his pipe-rack.

Upon Holmes’s miraculous reappearance, Mrs. Hudson and I had

Sherlock Holmes and The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter Tim Symonds

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories represented the rationalisation of mystery, satisfying the late Victorian belief that scientific method, acute observation and the application of rigorous logic could dispel the darkness of the unenlightened mind. Since 2012 Tim Symonds has been constructing new adventures for Holmes, set against unusual circumstances occurring in the early years of the 20th century. The novel featured here has been likened to Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor

Save £2.00

Our price £6.99 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

From the same author

LITERARY DETECTIVE FICTION | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 7

This extract is taken from the start of the book

… continued in the book

Sherlock Holmes editions MX Publishing, London, 195pp, Softback, 9781780925721, 140mm x 220mm, January 2014, RRP £8.99

Tim Symonds was born in London and grew up in Somerset, Dorset and Guernsey. He travelled widely, farmed in the Highlands of Kenya and lived along the Zambezi River in Central Africa, before emigrating to the USA. He studied at Göttingen, Germany, and at UCLA, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in Political Science. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. His other Sherlock Holmes novels can be found on his website http://tim-symonds.co.uk

The Shame Game Mary O’Hara

When I was ten I entered the regional disco dancing championships. I’d never been to that side of town with its big houses and manicured gardens. It was like another world. The convention centre was vast. Multicoloured lights suspended from the ceiling swept around the huge room where the competition was to be held. The wooden floor shone in a way I didn’t think wood could. Groups of girls began piling in, giggling and sparkling in the most incredible outfits I had ever laid eyes on. A posse of mothers followed the girls, all carrying little pink or powder-blue coloured cases.They checked for creases, applied blusher, fixed bows and clips in their daughters’ hair.

I approached the long table at the front of the room, my hair still wet from the rain, where I handed over my 50p entrance fee and a middle-aged man gave me a white, square piece of paper with the number 11 on it. He asked if I was OK in a way that made me think the man thought I was in the wrong place. It would be fine, he assured me, before patting my shoulder and turning to talk to a woman nearby who then glanced over and shook her head slowly.

A bouncy older woman in a sequinned jumpsuit at the front of the room made announcements over a microphone. Girls, clucking loudly and preening, raced to the floor and took up spaces. One by one they edged me towards the back. Mothers stared at me from the side lines. Not in a bad way, but with a look I would soon come to understand was a combination of pity and disdain. My presence seemed to make them uncomfortable. I was out of place.

What does it mean to be poor? For too long, poverty has been explained away as the product of personal ineptitude and bad life decisions. Such accusations hurt people who are financially vulnerable, robbing them of rights and opportunity. Drawing on two years of research, Mary O’Hara asks how a misrepresentation that perpetuates inequality and injustice can be overturned and turns for answers to the experts in the subject—those who suffer it

Mary O’Hara is an award-winning social affairs writer and author of Austerity Bites: A Journey to the Sharp End of Cuts in the UK, voted one of the Guardian’s best books of 2014 by Owen Jones. She was educated at St Louise’s Comprehensive in Belfast and Magdalene College, Cambridge, where she read social and political science. In 2010 she was an Alistair Cooke Fulbright Scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, researching into press coverage of mental illness and suicide

My eyes filled with water but I willed the tears back. I pinned the number card to my chest and pushed out my chin as I waited for the opening beats of the music. One, two, three, four.

BEING POOR: A SHORT PROLOGUE

The incident at the dance competition is the first memory I can recall of when I felt the sting of other people’s pity and when I think I realised, on a visceral level, that being from a poor background came with a stigma attached to it. Being poor or ‘on welfare’ was a source of shame.

Over the years there would be many other incidents that sharpened my understanding of the intersection of poverty, pity and shame. Like realising our first home, the one I lived in until we were re-housed when I was seven into new, public housing, was nothing short of a slum. Our first house had just two tiny bedrooms for eight people, and was perpetually damp. Rats were so commonplace they may as well have been members of the family. (A shovel was kept handy in the living room for when one appeared.) There was no bathroom, indoor toilet or central heating and the kitchen was a makeshift scullery with a plastic corrugated roof. Having a fridge or washing machine was unimaginable. My mum kept it immaculately clean and looking as nice as possible, but there’s only so much make-up you can put on a pig.

As I got a bit older and my dad became unemployed there was the realisation that claiming the ‘dole’ (unemployment benefits), as my father had to do for long periods of time, was a source of humiliation, even within a community where many people were in the same situation. And there was the knowledge that relying on state assistance to get by was not something that everyone had to face and was seen by some people as a sign of parental failure. There was the awareness too that while the food in our cupboards mostly met our daily needs (we had to borrow from neighbours when things got really tight) and that even though we had occasional treats (often paid for by going into debt with loan sharks), this was not how everyone lived.

West Belfast, which was also one of the main flashpoints during Northern Ireland’s sectarian conflict in the 1970s and 1980s, was among the most deprived areas in the whole of Western Europe—but even if I had known this, I doubt it would have made my younger self feel any better about how much we had to struggle or how much shame there was at not being able to afford what others could.

I’d seen enough TV to know that there were people who were well off or rich. I knew my teachers were better off. I’d just never really been anywhere near a wealthier part of town and interacted with people who lived there. I’d never met anybody from that background in any intimate way. Like most poorer families—and

this is true today in Britain and America—we lived our lives in the poorer parts of town. We didn’t have middle-class friends. But when I first began to understand that we were looked down upon or pitied by many more financially fortunate people, the undercurrent of shame stayed with me for a long time.

Anyone who has grown up poor will have similar stories to tell: those small or large experiences or encounters that force you to register that your family is not just lacking in material things (as hard as that may be) but that as a kid you are set apart from other children. Maybe it’s your first day at a new school when you look around and realise that the kids whose parents have jobs, or better-paid ones than yours do, have pocket money or better clothes. Maybe a teacher tells you that the best you can hope for in life is a minimum-wage job at a fast-food chain and not to set your sights too high. Perhaps it’s watching a parent struggle to make sure there’s enough food on the table or warmth in the room when you have a new friend round whose family don’t seem to have the same financial hardships.

Or maybe you don’t ever ask friends to come to your house because there’s nothing in the cupboard to offer them. It could be that you overheard a conversation where someone commented on how scruffy you and your siblings look or criticised your parents for failing to take ‘proper’ care of you. If you’re female, you may have experienced the humiliation and discomfort during adolescence of not being able to afford sanitary products and having to improvise while spending the day fretting that it might not work.

If you didn’t grow up in poverty, these sorts of indignities most likely will not have affected you, and you will be unaware of the enduring impact they can have on a young person. You might never have thought much about the reasons people end up trapped by poverty or the dearth of opportunities that keep them there. If you have never lived on the breadline, it’s probably difficult to grasp that for many people, no matter how hard they work at their minimum-wage precarious jobs, they just never have enough to make the rent, eat nutritious food every day, or buy a much-needed new pair of shoes for their kids. You might not have thought about what it feels like to have no choice but to swallow your pride and go to a food bank to stock up on essentials because you don’t qualify for state assistance. Yet, every single day, people all over the US and the UK live with the gross injustice that is being poor and with the humiliation of being blamed for circumstances beyond their control.

It doesn’t have to be this way. It really doesn’t.

As someone who directly benefited from the structural redistribution in the UK that followed the Second World War including the founding of the Welfare State, affordable council housing, the National Health Service and free school meals, I know that where there is a will, we can provide a springboard to better things for the poorest among us. A fairer, more equitable society where we don’t blame and shame the poor is not beyond the reach of wealthy nations like Britain and America. It’s an honourable, gettable goal.

For a long time in the US and the UK, two of the wealthiest yet most unequal nations on earth, the primary story told about poverty has been that it is the fault of the individual and is the result of personal flaws or ‘bad life decisions’ rather than policy choices or economic inequality. If only people worked harder, if only they ‘pulled themselves up by their bootstraps’ or got ‘on their bikes’ as the one-time Tory Secretary for Education Norman Tebbit once declared, they too could find a job.

This book is about a ‘shame game’ that is being played out against millions of the poorest people in Britain and America. It tells the story of how a pervasive toxic narrative that shames and blames the poor has secured a stranglehold on our collective understanding of poverty. Drawing on interviews with people who have first-hand experience of poverty in both countries this book documents how a powerful story propagated by powerful people plays a pivotal role in sustaining and justifying high levels of poverty and inequality by repeatedly misrepresenting, and stigmatising, people who are poor. And this book looks at how we can alter the way we talk about and understand poverty in order to shift perceptions and to work towards building a consensus on how to tackle poverty and improve people’s lives.

So, stand up, stand proud and don’t play their game any more. Read this book to educate yourself. Read this book to hear from the people who are being shamed, whose

POVERTY / SOCIAL JUSTICE | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 8

This edited extract is taken from pages 17–20 and 1–2 … continued in the book

Overturning the Toxic Poverty Narrative Policy Press, Bristol, 232pp, Softback, 9781447349266, 138mm x 216mm, 27 February 2020, RRP £12.99

Subscribe to Booklaunch www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

the same publisher

From

Save £1.56 Our price £11.43 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Polish Jewry was once the beating heart of European Jewry. With a population of 3.3 million on the eve of the Second World War, Poland’s Jews were renowned for their varied and multi-layered religious, cultural and political life. These Polonised Jews played a major role in fashioning the country’s modern commercial, intellectual and creative industries. Indeed Polish history is difficult to grasp without acknowledging the Jewish contribution.

By the end of the war three million Polish Jews had perished in the Holocaust. For the survivors, their former world disappeared beneath a landscape of apocalyptic devastation. Ongoing and often murderous anti-semitic incidents, combined with an increasingly repressive Communist regime, convinced many survivors that their future lay outside Poland. Waves of post-war emigration throughout the 1940s and 1950s to Israel and western countries significantly reduced the Jewish population.

In 1968, the Communist government unleashed an anti-semitic campaign which stripped most of those who were left of their jobs and prominent positions, forcing many thousands (often Communist Party members) into exile.

By the 1970s Poland appeared, to the outside world, a country empty of Jews. Polish behaviour gave the impression the country was relentlessly anti-semitic. Jews in the Diaspora concluded that Jewish life in Poland would never recover; their main interest was therefore confined to the history of the Holocaust and the Nazi death camps.

I was one of them. On the road to north-eastern Poland, to my mother’s shtetl, I couldn’t escape the realisation that the region had once been thickly populated with bustling shtetls, but began to sense that Poland was not as empty of Jews as I had thought. Over the course of my visit I heard many anecdotes about growing numbers of Poles discovering and exploring their Jewish ancestry. Soon the idea gripped me that this story needed to be told, in the words of the individuals themselves.

From the outset it was clear my book would be designed for a general audience. The specialised field of Polish-Jewish studies was flourishing and I had no intention of competing. Instead I wanted the profiles to be

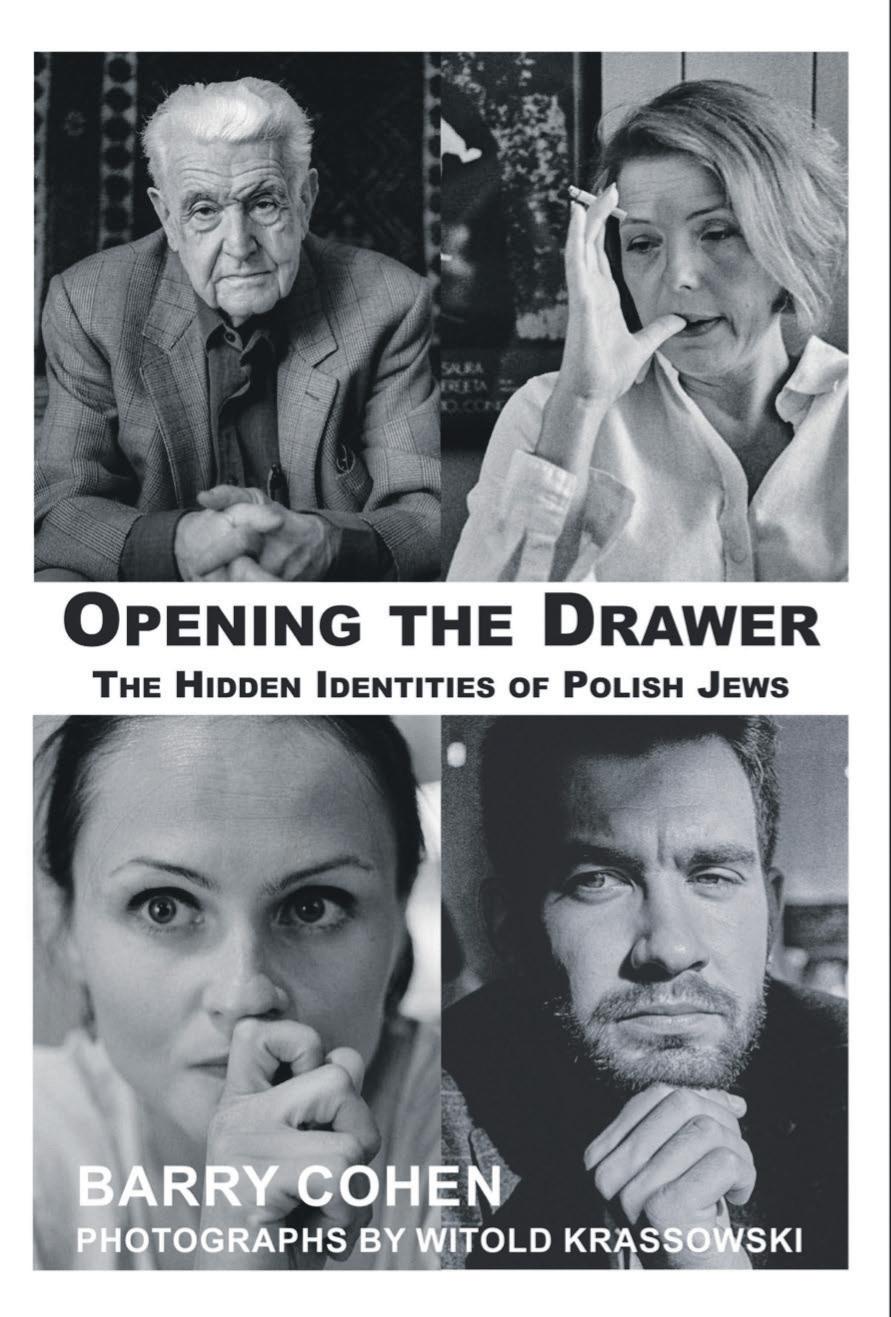

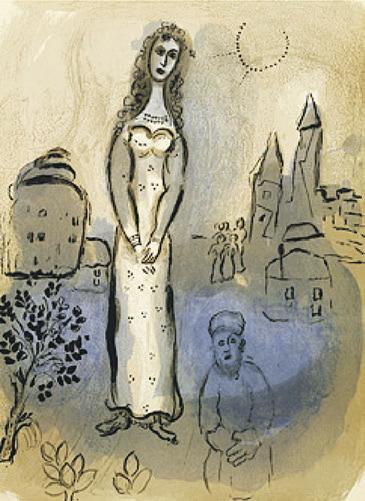

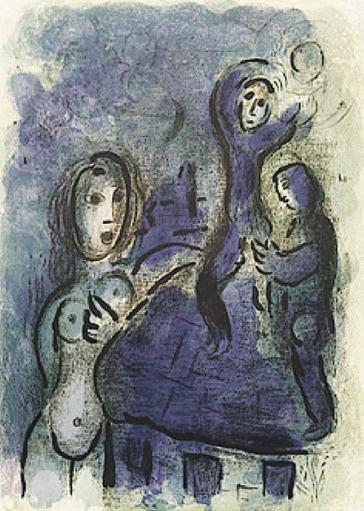

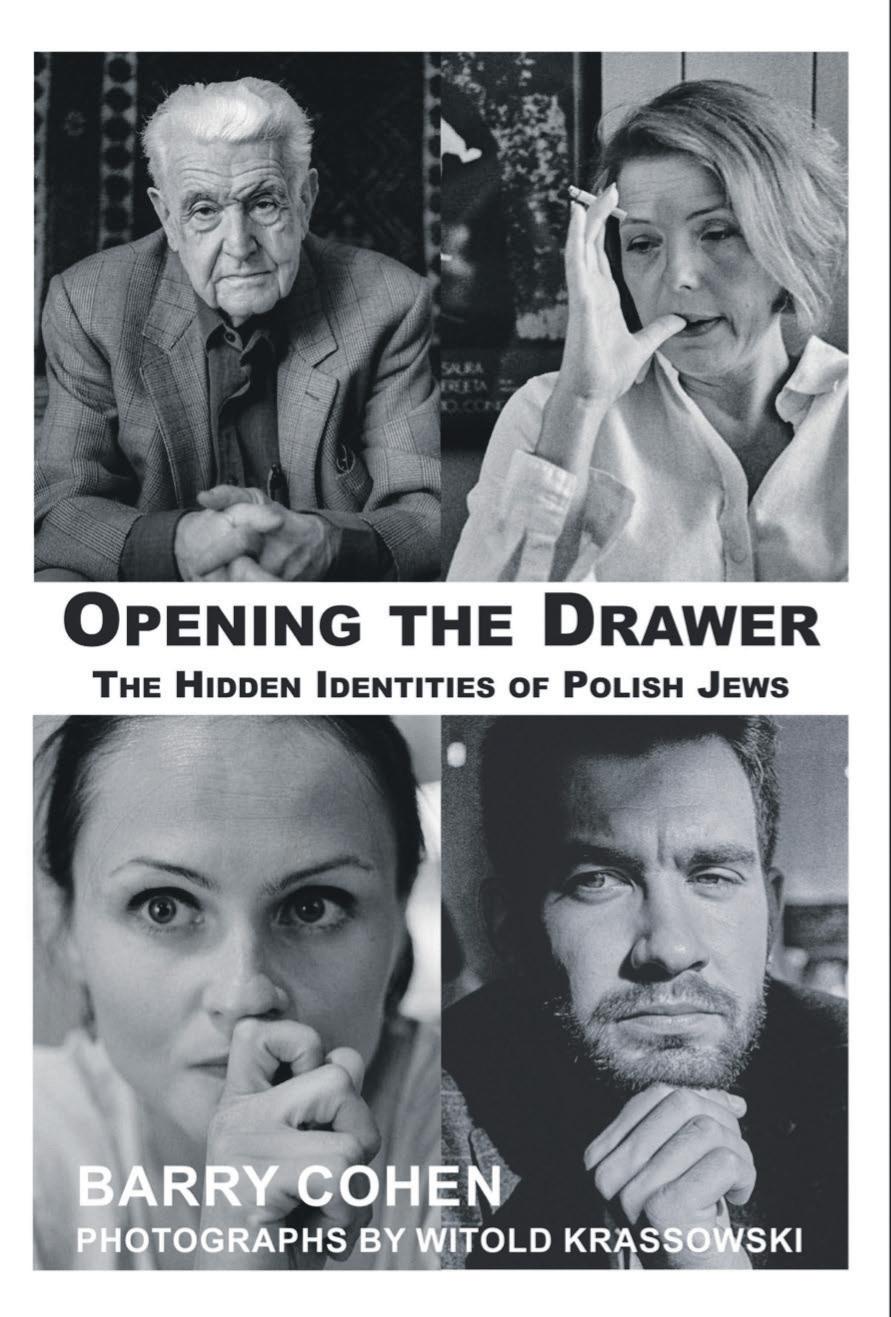

Opening the Drawer: The Hidden Identities of Polish Jews Barry Cohen

photographs by Witold Krassowski

photographs by Witold Krassowski

accessible: to involve members of three generations who were prepared to recount their experiences, the impact of the discovery on their relationships and lives.

Each generation grew up in a specific period of Polish history. Holocaust survivors usually emerged from the war as orphans, lacking the structure and psychological support of a family. The creation of the Association of Children of the Holocaust in 1993 proved seminal. Many members of the association were traumatised by the wartime experience of being separated from their parents, and hidden by Catholic families or religious institutions.

The organisation provided a crucial sense of belonging and, in many ways, served as a therapeutic forum. At the same time, some members continue to maintain their Catholicism as a key component of their identity, leading the Polish writer, Konstanty Gebert, to wryly observe: ‘The Association of Children of the Holocaust is unique. It’s the only Jewish organisation in which most members are Catholics.’

A good deal of the credit for the revival of Jewish life can be attributed to members of the second generation. Many are the offspring of Communist Party or leftist parents deeply committed, in the post-war period, to building a socialist society. They were also militantly internationalist, which tended to exclude any form of Jewish consciousness. This was reinforced by pressure within the Communist regime for Jewish party members to polonise their names and outward identities. ‘My father decided to pass as a Pole because it would be easier to persuade people about the merits of Communism if he promoted the ideology as a Pole and not as a Jew’, recalls Jarosław Górnicki.

Many second-generation Jews also experienced a traumatic period during the anti-semitic campaign of 1968. As the purge spread, individuals were suddenly informed of their Jewish origins for the first time in their lives. This resulted in the loss of jobs, government positions and university places, even leading up to the revocation of citizenship and, ultimately, exile. Those who managed to remain in Poland felt compelled to adopt an underground identity.

After the horrors of the Holocaust and the oppression of the Communist regime, the third generation can be regarded as comparatively fortunate. Emerging into a civil society that is also a member of the European Union, this

Three generations of Poles either buried their Jewish origins or only discovered them by chance. Drawing on interviews with Holocaust survivors, the post-war second generation and the post-Communist third generation, Barry Cohen’s research unlocks memorable accounts of how long-hidden family histories and secrets came to light. They include sometimes emotional stories of ordinary people, including a Catholic priest and a former Jewhating football hooligan, who grew up thinking of themselves very differently from how they have come to regard themselves now

Barry Cohen is a Canadian writer and journalist based in London who has worked as an editor for many publications, including as foreign editor of the New Statesman. He has also contributed to many other British, US and European magazines and newspapers, mostly focusing on foreign affairs and international business and financial issues. He has won several financial journalism awards and holds degrees in political science and international relations from universities in Canada, Britain and Italy

POST-HOLOCAUST STUDIES | ISSUE 6 | PAGE 9

This edited extract is taken from the Introduction

… continued in the book

Vallentine Mitchell, London and Portland OR, 323pp, Softback, 9781910383810, 155mm x 235mm, 53 b/w portraits, 2018, RRP: £17.50

Subscribe to Booklaunch www.booklaunch.london/subscribe Save £1.51 Our price £15.99 inc. free UK delivery To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

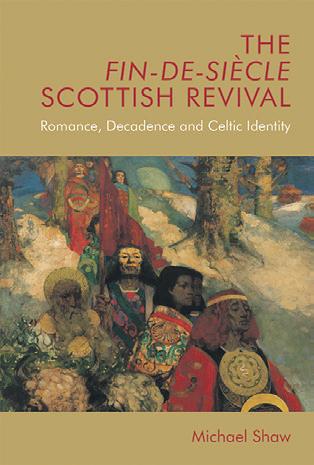

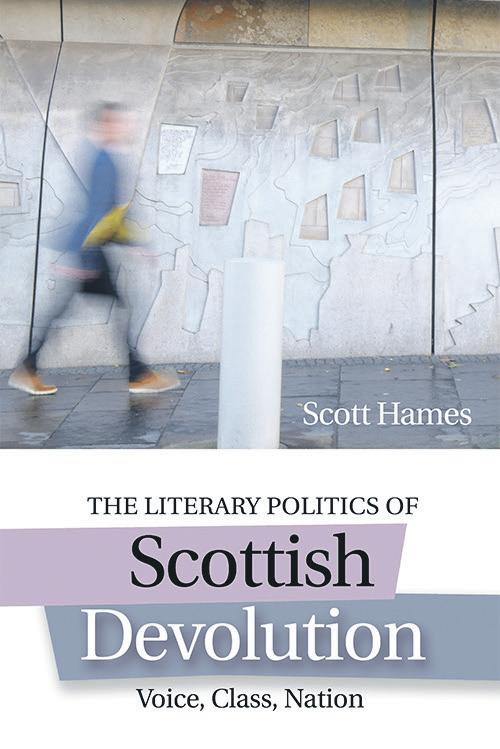

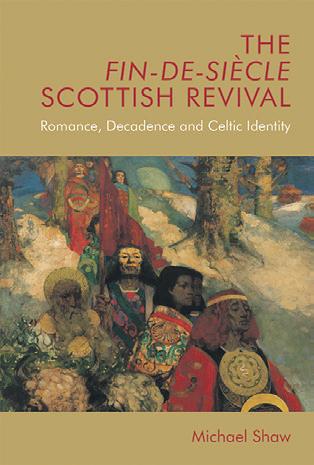

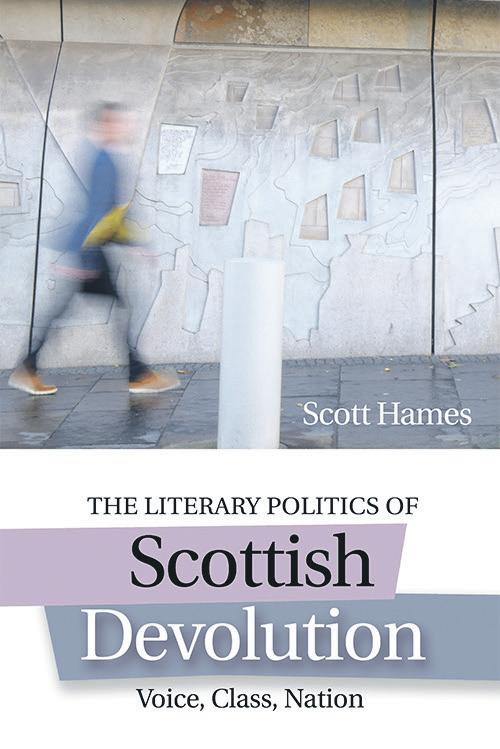

The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation Scott Hames

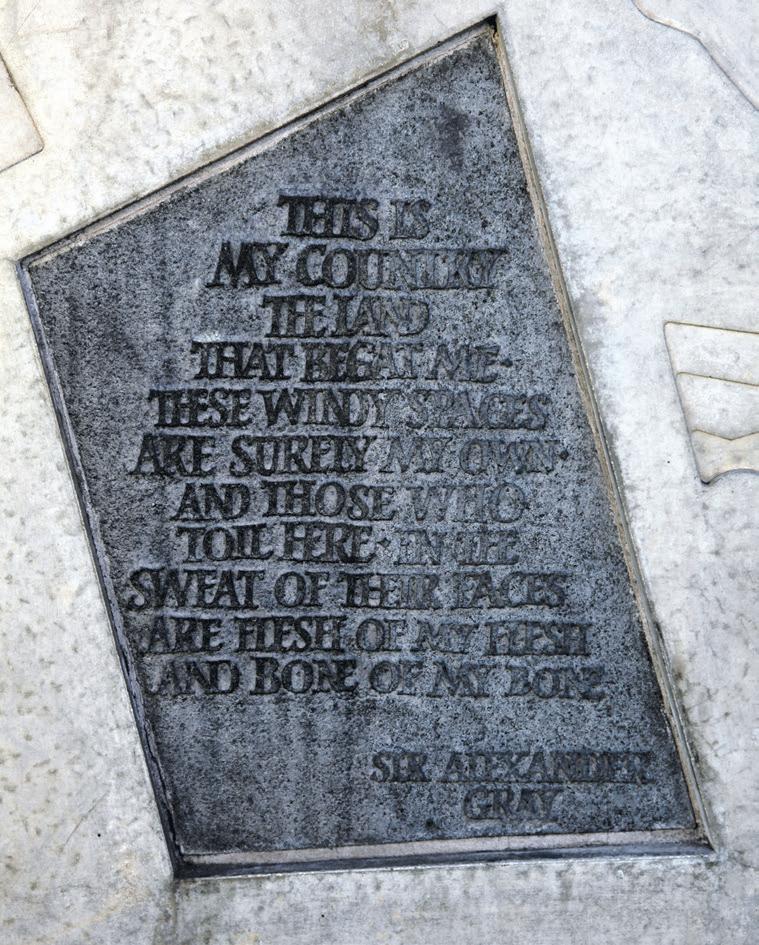

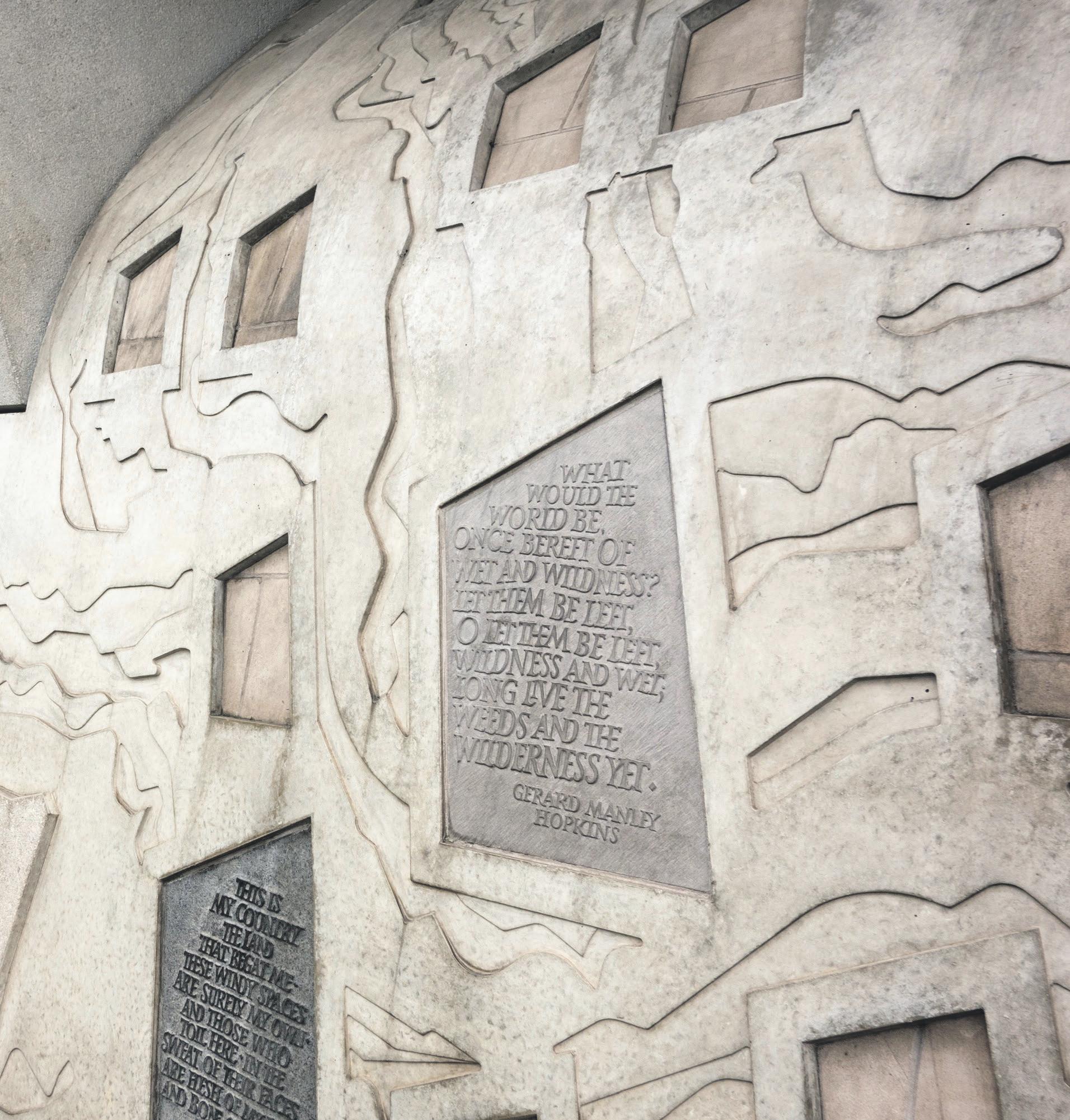

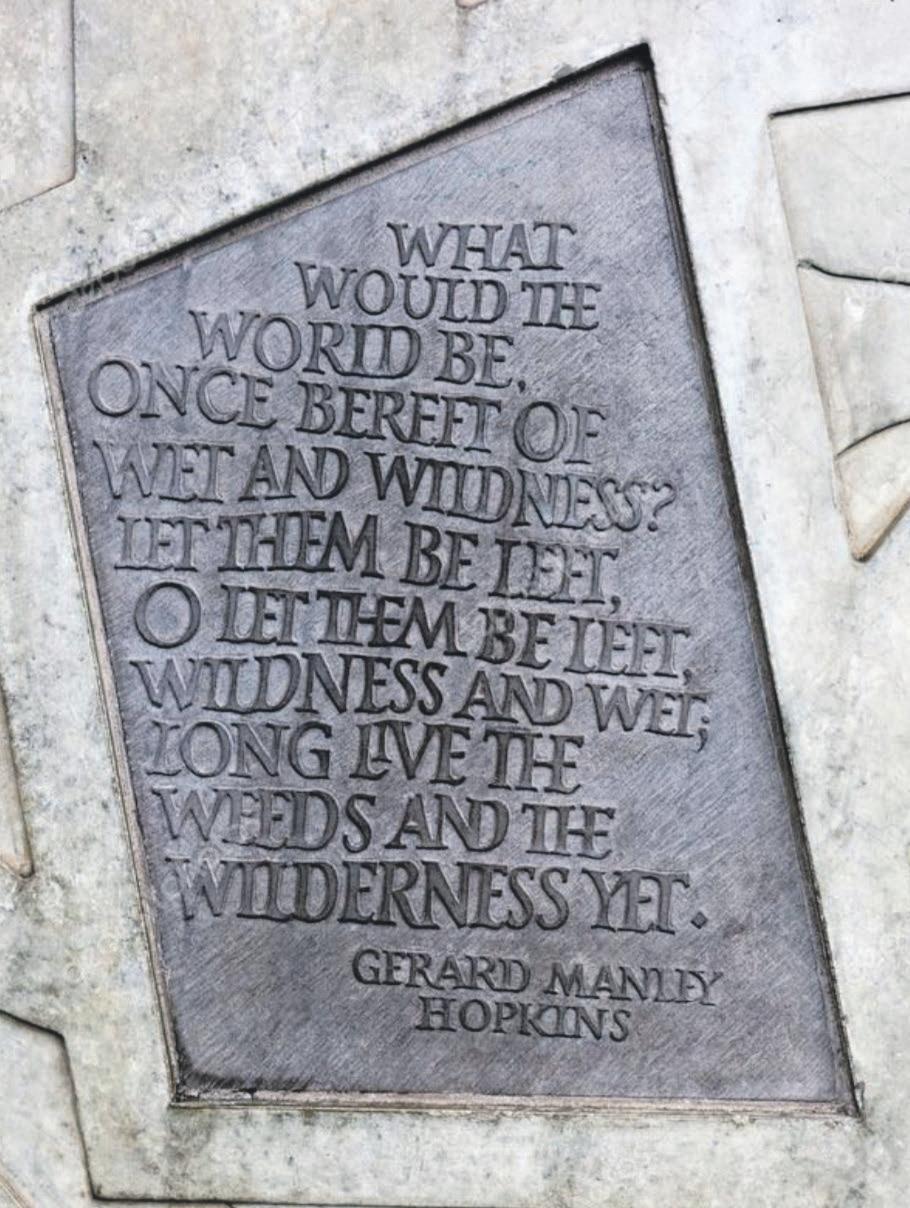

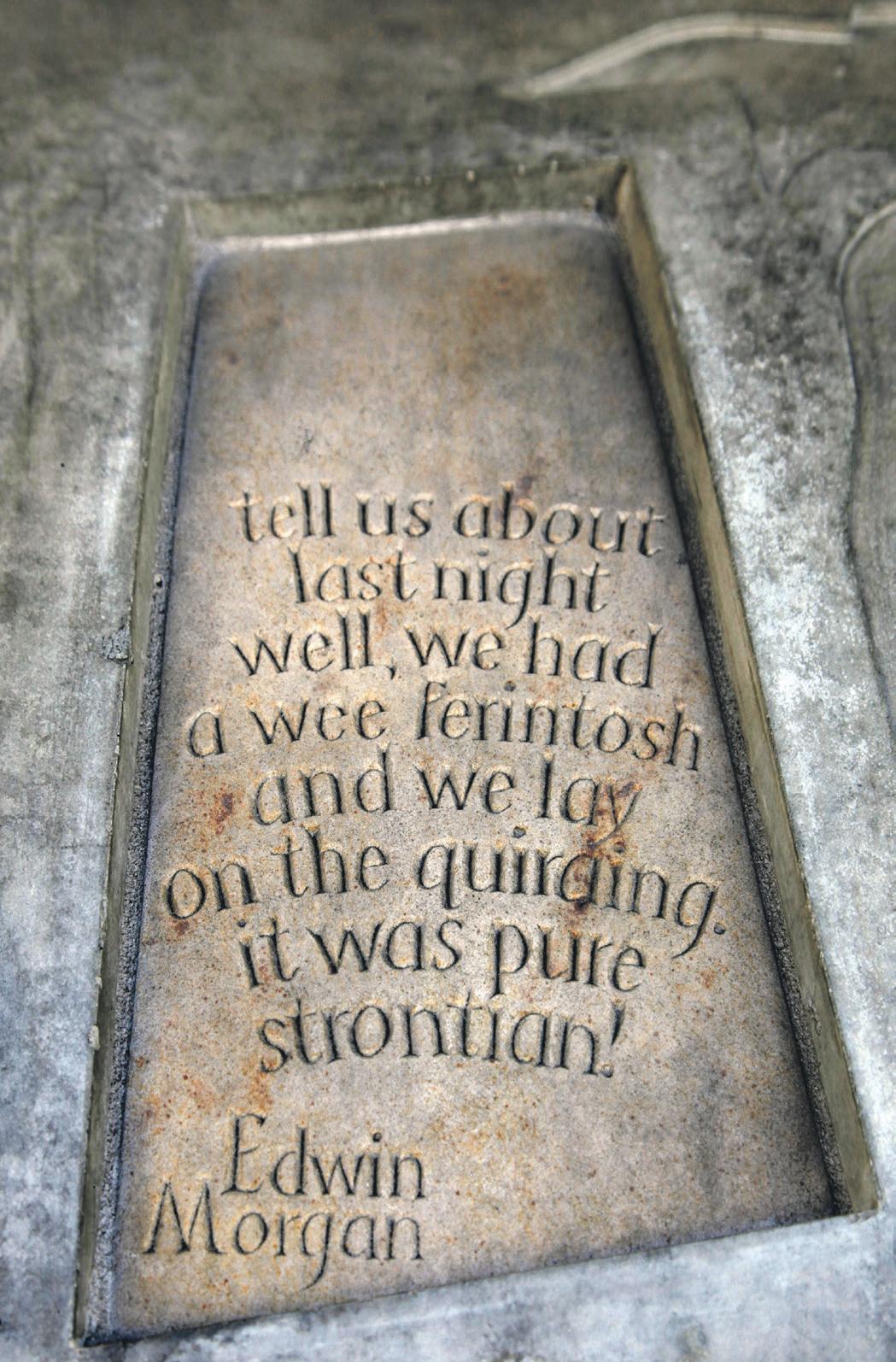

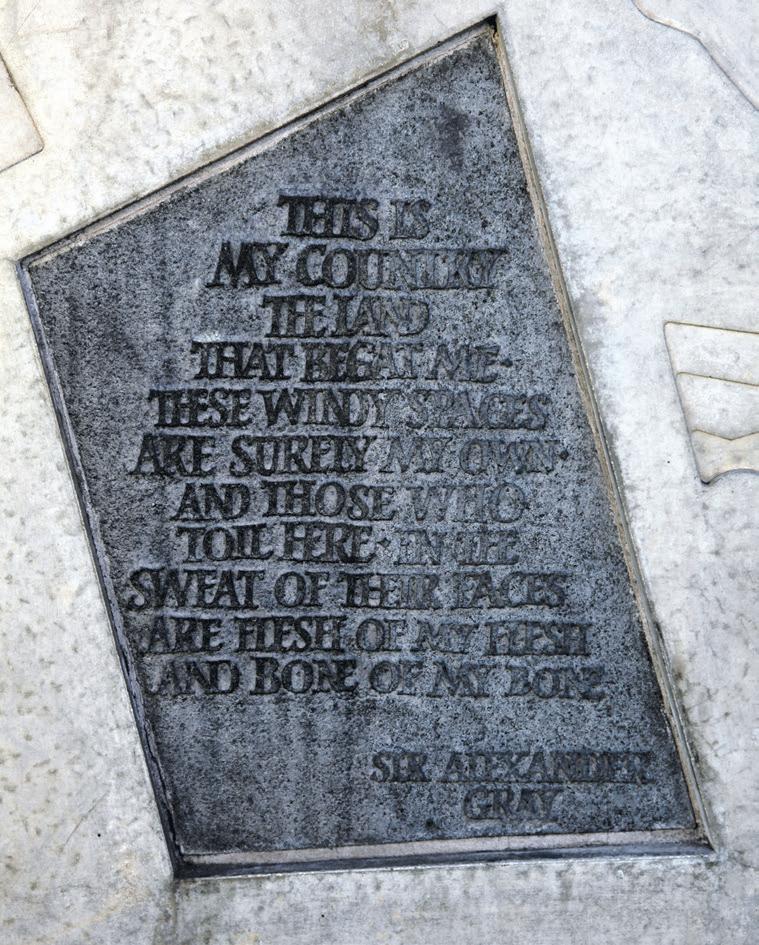

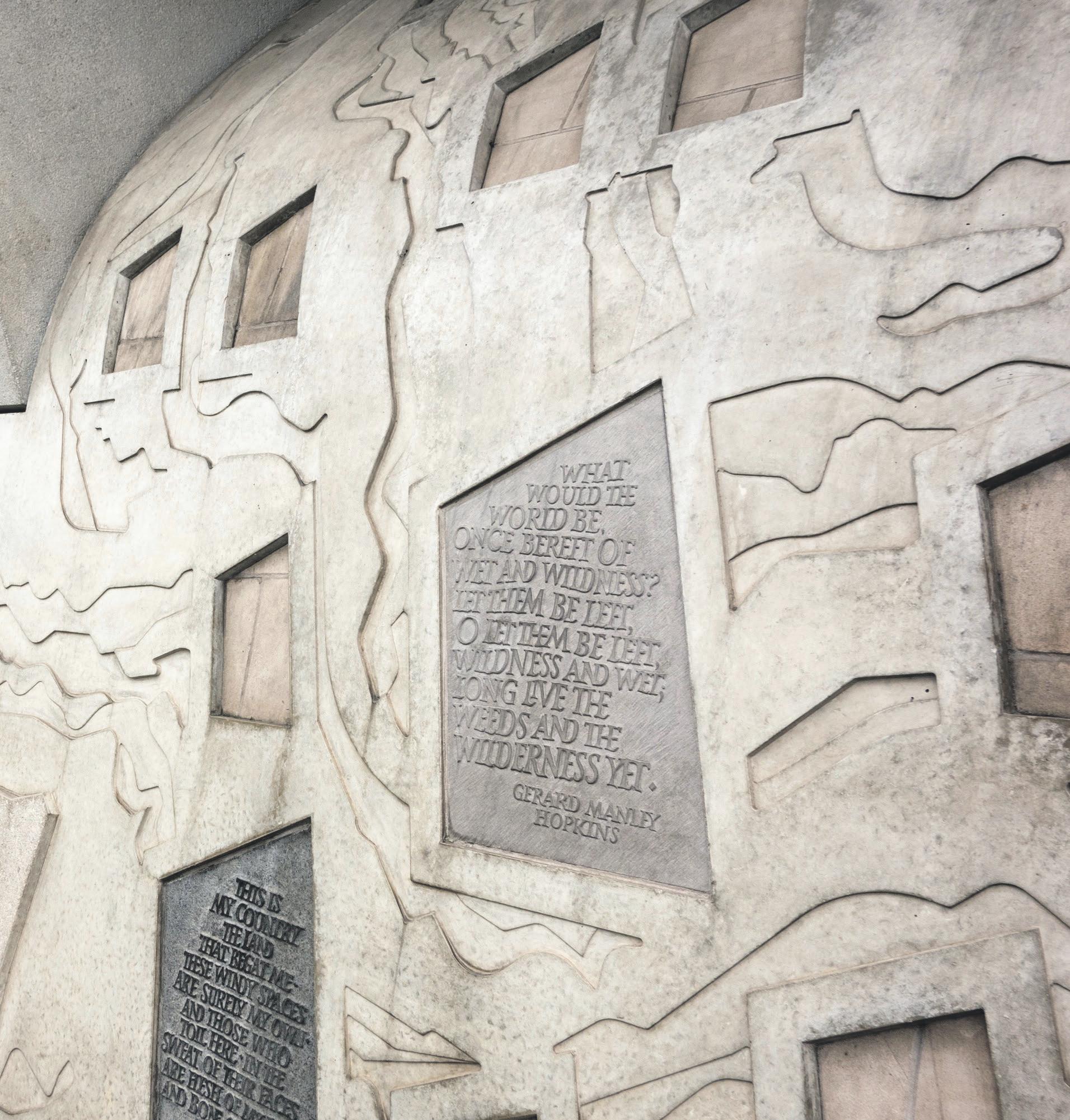

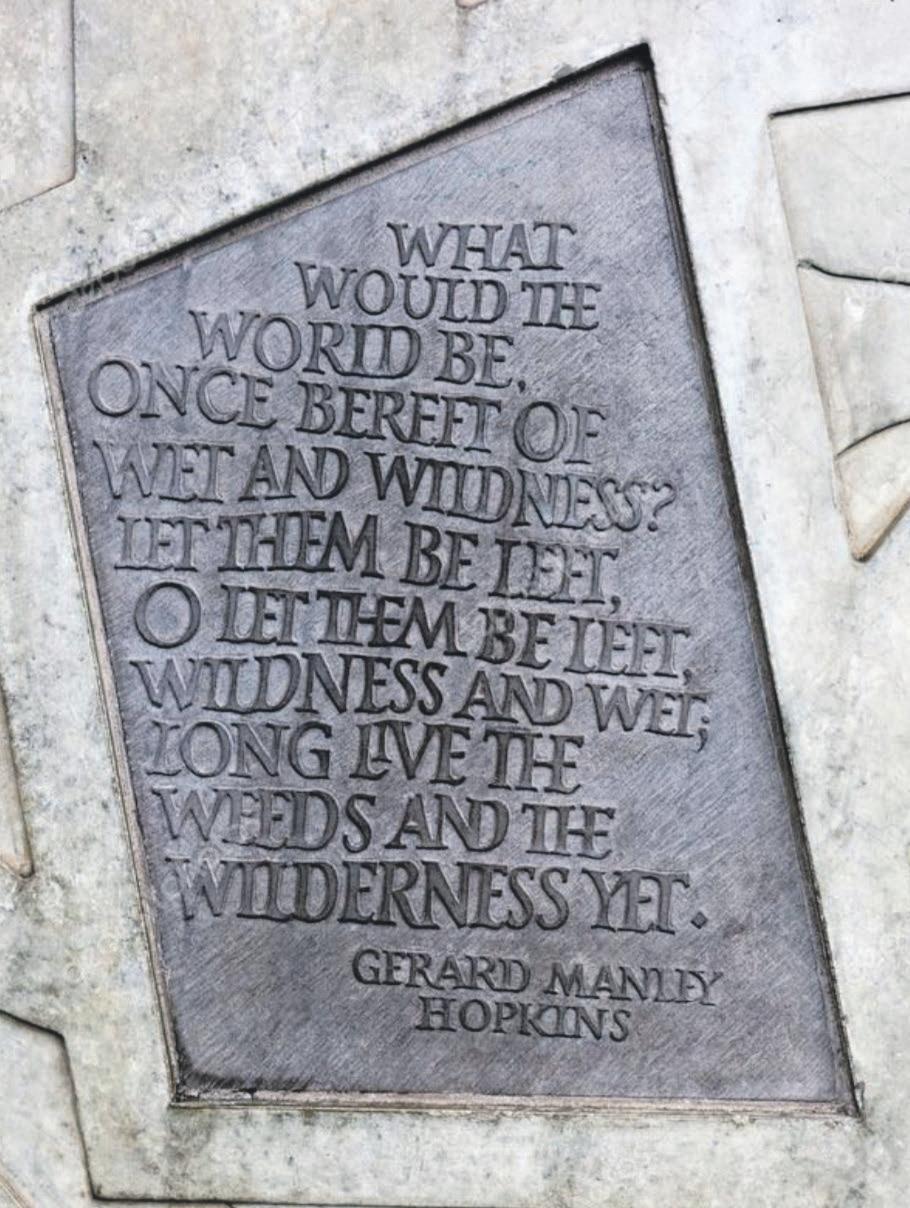

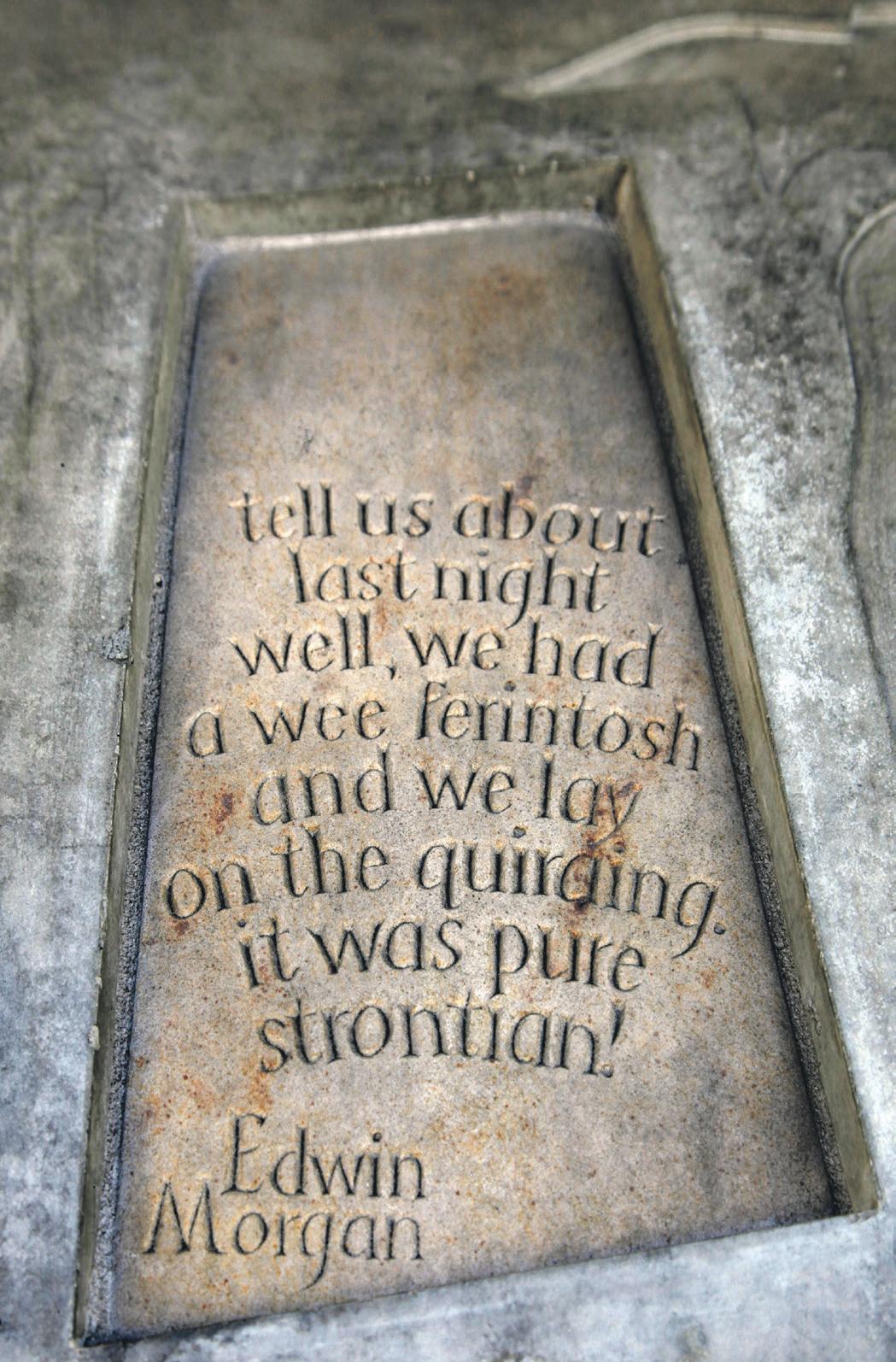

The Canongate Wall forms the northern edge of the Scottish Parliament building, at the very foot of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Embedded in the wall are 26 decorative panels of Scottish stone with inscriptions that gather a kind of pebbledash pantheon of modern Scottish literature, including Robert Burns (twice), Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Hugh MacDiarmid (thrice), Hamish Henderson, Norman MacCaig, Edwin Morgan and Alasdair Gray. The first version of Gray’s stone—bearing the unofficial credo of devolutionary nationalism, ‘work as if you were living in the early days of a better nation’— misspelled his first name, and had to be re-made. But the ‘vernacular’, hand-crafted particularities of the wall make errors of this kind seem forgivably natural.

No element of the design places democracy on a solemn neoclassical pedestal, or encourages hushed reverence for governing power; indeed, the human faults and frailties of parliamentarians are a running theme. In pride of place, the left-most stone quotes Mrs Howden from Scott’s Heart of Midlothian: ‘When we had a king, and a chancellor, and parliament-men o’ our ain, we could aye peeble them wi’ stanes when they werena gude bairns—But naebody’s nails can reach the length o’Lunnon.’ A firm reminder, in demotic Scots, that the parliament is accountable to the local voices and dissenting energies of its immediate lifeworld. Far from monumentalising their power, the wall reminds MSPs of the socially limited character of their role.

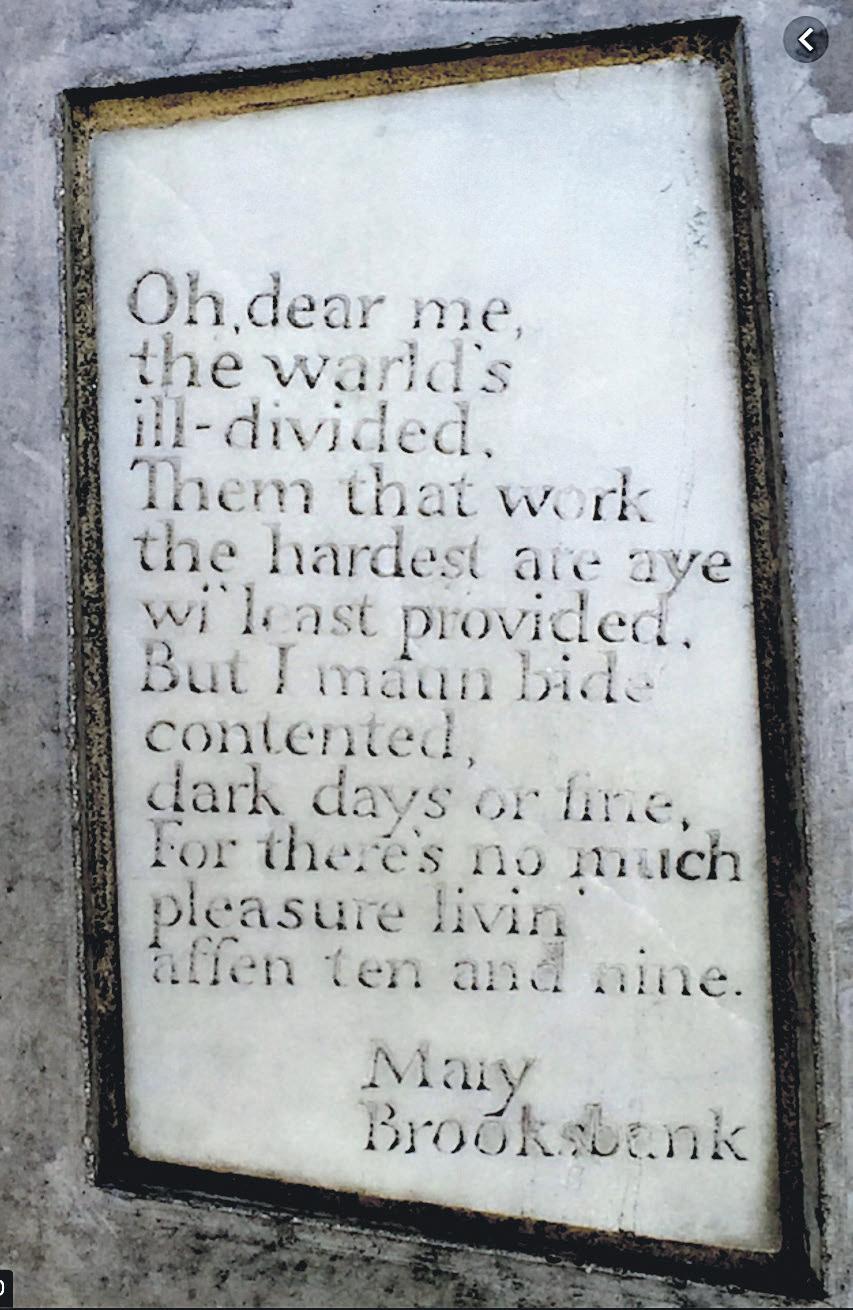

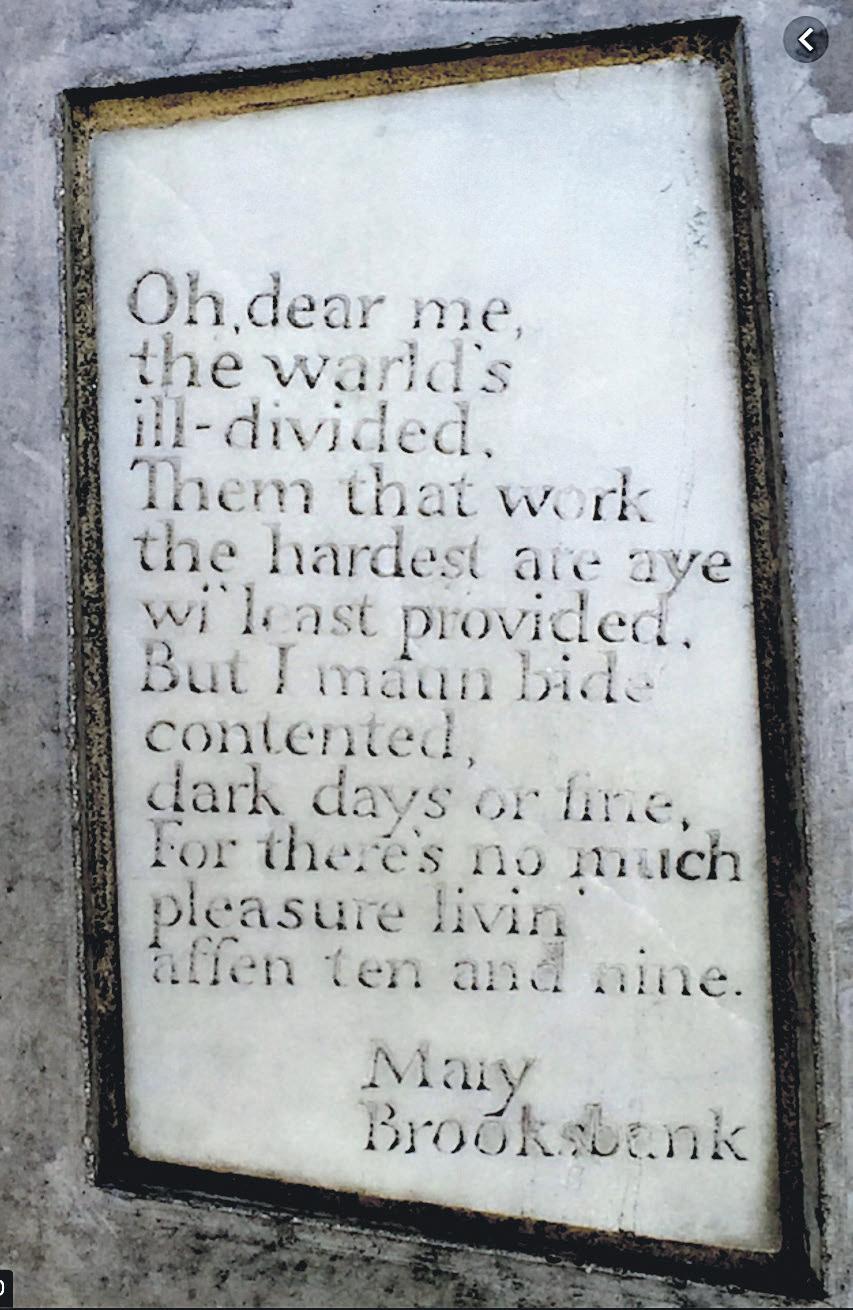

This patchwork of stone and script—including several Gaelic inscriptions, works by English authors, and religious texts—might be held to embody the ‘diversity of voices’ the building exists to represent, and yet it would be impossible to read the wall as democratically reflecting the nation. Of the 26 panels, 20 feature quotations by men. There are four authorless proverbs and songs, a psalm, and just one stone featuring the name of a woman, the songwriter and communist mill-worker Mary Brooksbank. All the named authors are white.

If we pursue this thought, and think critically about the imagery of national representation, the Canongate façade begins to take on a rather different countenance. Its oblique planes and irregular surfaces might even begin to suggest handholds and footholds: potential means of scaling the outer skin of Holyrood, perhaps to seek another point of entry, from an angle discouraged by the confident architecture. That thought is close to the impulse behind this book.

LITERATURE AND/AS POLITICS

A few weeks prior to the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, Colin Kidd argued that ‘Scottish literature is for the SNP not a frill, but a matter of central concern’:

For [First Minister Alex] Salmond, literature is a kind of QED: Anglo-Scottish differences in diction, lilt, sensitivity and worldview prove the grand truths of nationalism. He has argued, plausibly enough, that it is impossible to mistake the differences between a Scottish novel and an English novel. Novels, he believes, reveal fundamental differences in the values and ethos of Scots and English.

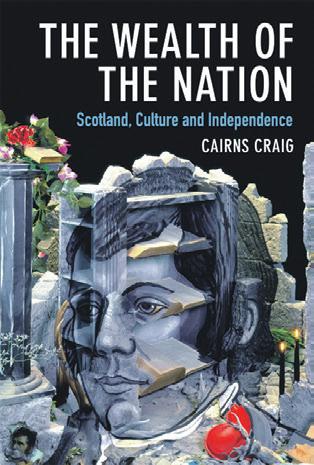

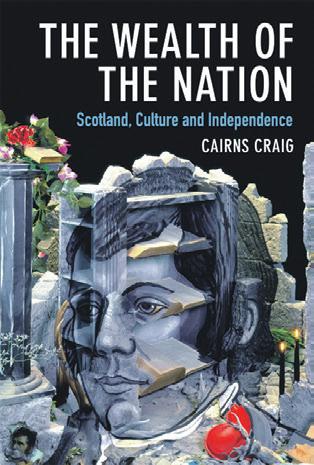

In the summer of 2014 one did hear such arguments, among many others. And yet few prominent Scottish writers who supported the campaign for independence would accept this firm equation between literary Scottishness and the demand for statehood, as though one predicated the other. The modern SNP is noted for its ‘acultural’ nationalism, placing far greater emphasis— particularly under Salmond’s leadership—on economic powers, and confining to Burns Night its appetite for literary inspiration. Indeed, Cairns Craig notes with regret ‘that there is probably no nationalist party in the world that has been less focused on mobilising culture as part of its political strategy than the SNP’, despite Scotland’s bounteous possession of ‘cultural wealth’ ripe for the purpose.

But the minimal presence of programmatic literary patriotism is only one part of the story. There really has been a complex and pervasive intermingling of Scottish literature and politics over the past few decades, with far-reaching consequences in both domains: for how we read (and over-read) the politics of Scottish writing, and for how we conceive the place of cultural and literary ‘identity’ within the project of Scottish nationalism. That is, broadly, what this book is about. In sketching its pur-

view, we must begin by amending Kidd’s history: it is precisely in the absence of an official literary nationalism that Scottish writers and artists have claimed—and been burdened with—special ‘representative’ clout.

This is particularly the case in the post-1979 period on which this study is mainly focused, but is also evident in earlier debates. Jack Brand’s 1978 study of the National Movement in Scotland found, in Christopher Harvie’s paraphrase, ‘that although literature may have mobilized members of the party elite—and was interesting for this reason—the intellectual trend in Scotland had really been away from nationalism towards socialism. Paradoxically, Brand argued, this aided SNP organization. Political mobilization did not conflict with an existing scale of literary values—or with literary nationalists throwing their weight around’.

This too was only half true: there were plenty of bellicose literary nationalists in the 1970s, many spoiling for a fight with Scotland’s ‘deracinated’ political class, but they kept a wary distance from the SNP. For some, this was indeed an expression of socialist distrust of ‘bourgeois nationalism’; for others, the SNP weren’t nationalist enough (or indeed nationalist at all). But such debates occurred at the fringe of Scottish politics. They only gained purchase in the political mainstream following the failed referendum on a Scottish Assembly held in March 1979. While the SNP vote crashed following the 40 per cent rule debacle, Harvie continues, ‘the 1980s saw a nationalist stance become general among the Scottish intelligentsia. […] The orthodoxy now is that the revival in painting, film and the novel, in poetry and drama—staged and televised—kept a “national movement” in being.’

This ‘orthodoxy’ has an extensive history of its own Harvie was writing in 1991, at the height of its influence and plausibility and is less a neutral historical description of how things transpired than a mobilising narrative constructed within the diffuse, campaign-like process and milieu it describes. As Jonathan Hearn observes, ‘members of the intelligentsia have an interest in treating Scotland as an object of concern, study and discussion’. The political utterances of literary figures such as William McIlvanney, James Kelman, Irvine Welsh and Alasdair Gray are thus located by Hearn within a broader ‘network of intellectuals, academics, artists, writers, journalists and media figures through whom the ideas of the [self-government] movement were constantly being articulated and re-articulated’ in the 1980s and 90s. The ‘committed’ (and preferably outspoken) Scottish writer was a key and prominent contributor to the pro-devolution social consensus which so strongly conditioned the critical reception of their art.

INTELLECTUALS AND CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS

This presents a certain dilemma, for literary critic and political historian alike. Few of the key scholars and commentators cited in this study have remained aloof from the events and investments at issue, but (once acknowledged) this does not diminish the interest of their reflections and analysis. On the contrary: post-war Scotland is an enormously rich and well-documented case of what Michael D. Kennedy and Ronald Grigor Suny call the ‘mutual articulation of national discourses and intellectuals’. As we shall see, a whole constellation of writers, journalists, artists and thinkers embraced their role ‘as constitutive of the nation itself’ during the period this book examines, with several overtly committing themselves to (re-)establishing ‘the very language and universe of meaning in which nations become possible’.

The majority of these figures remain active in Scottish cultural debate, so it is with a degree of unease that I take up a critical stance on their work of several decades—work which I respect, whose political motivation I largely share, and the fruits of which have undoubtedly benefitted me personally. Nonetheless, there must be a space for critique ‘within-and-against’ nationalist intellectualism, if any of its liberating and clarifying energies are to be realised within the scholarly fields it helped to consolidate.

Kennedy and Suny observe that ‘intellectuals face a double risk when enveloped by the nation. On one hand, as patriots, they lose their credentials as critical or independent. On the other hand, as critical intellectuals questioning the very “authenticity” of the nation, they are either ignored, marginalized, or cast out altogether’.