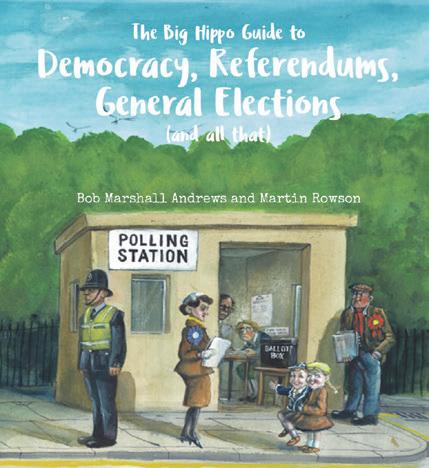

Not quite so illiterate: the 18th-century poor Page 9

What you need to build your own dragon Page 10

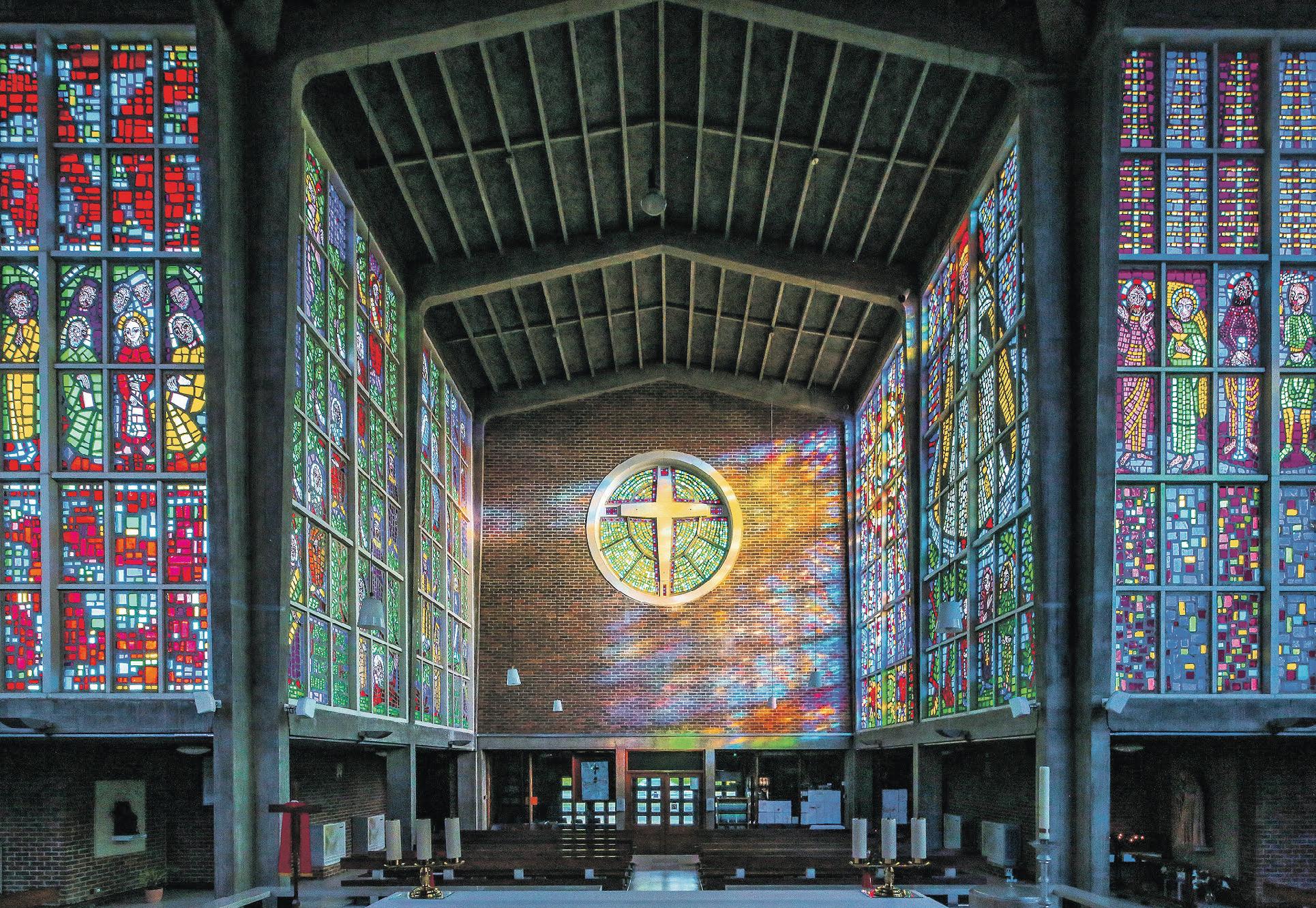

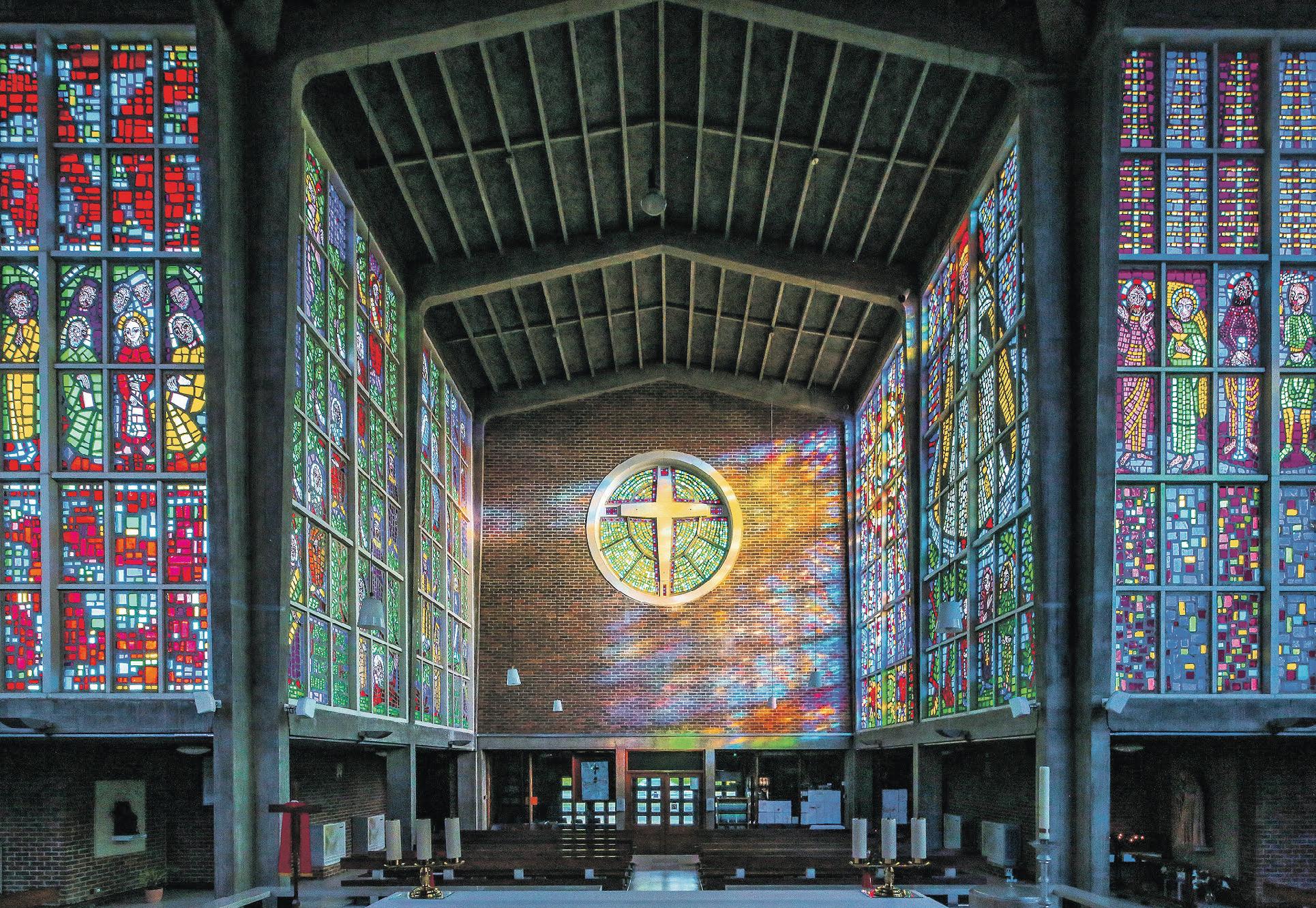

How modern churches vary in style Page 11

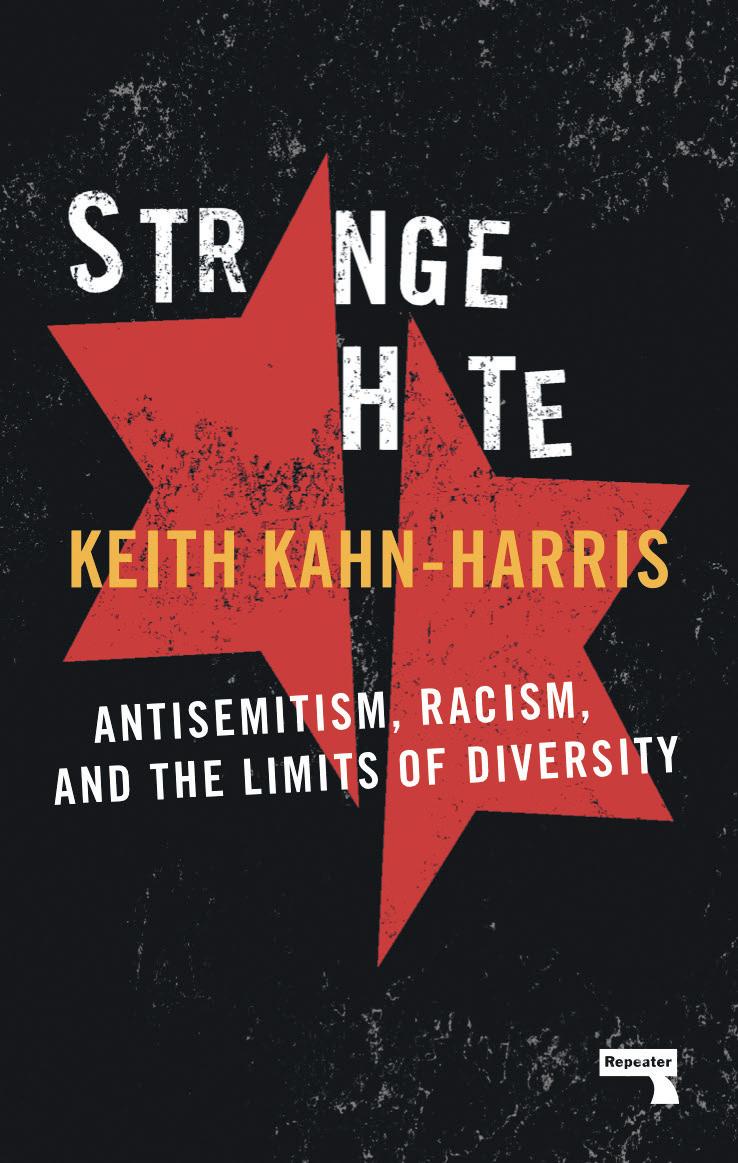

Liberalism’s anti-semitic blind spot Page 12

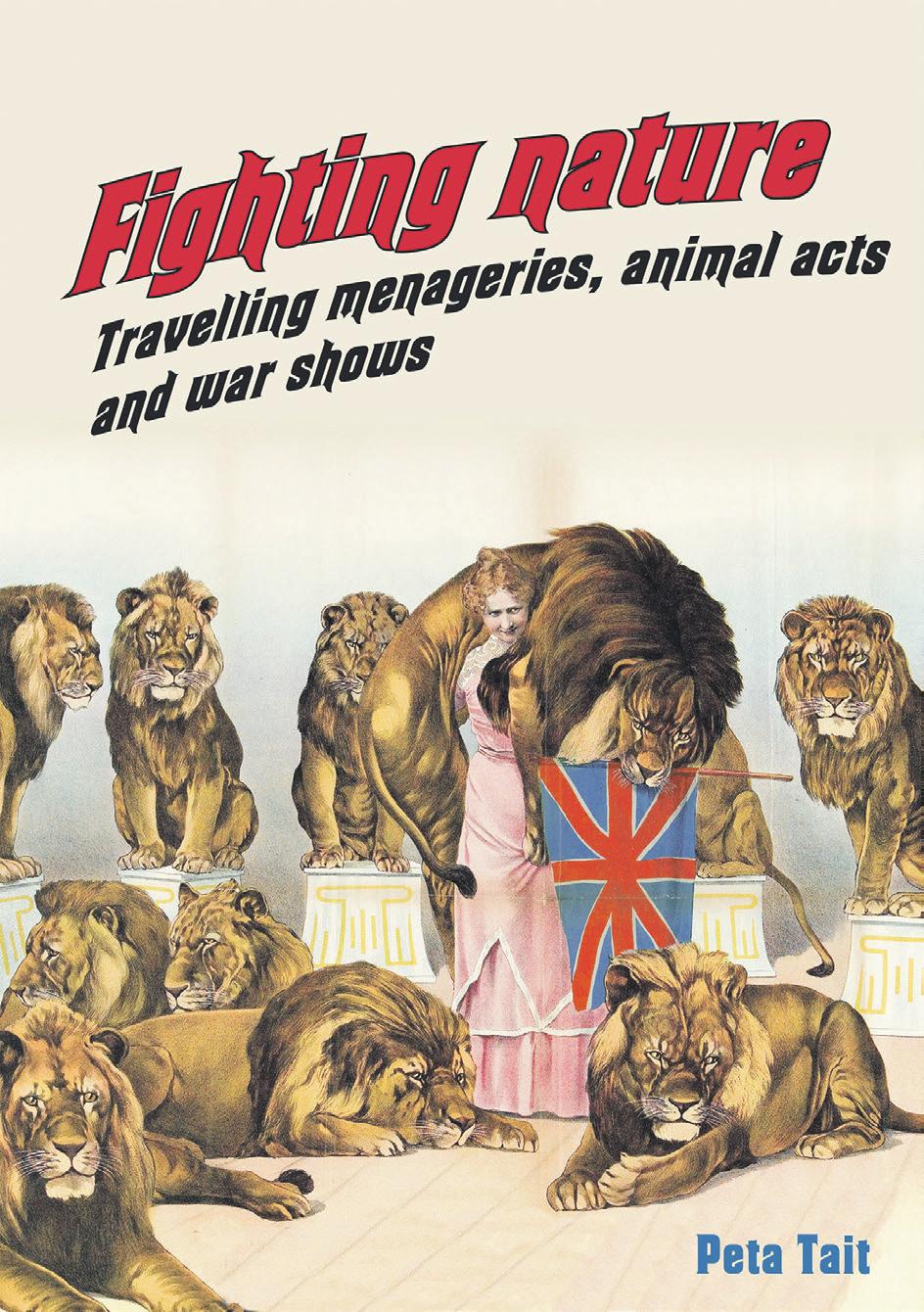

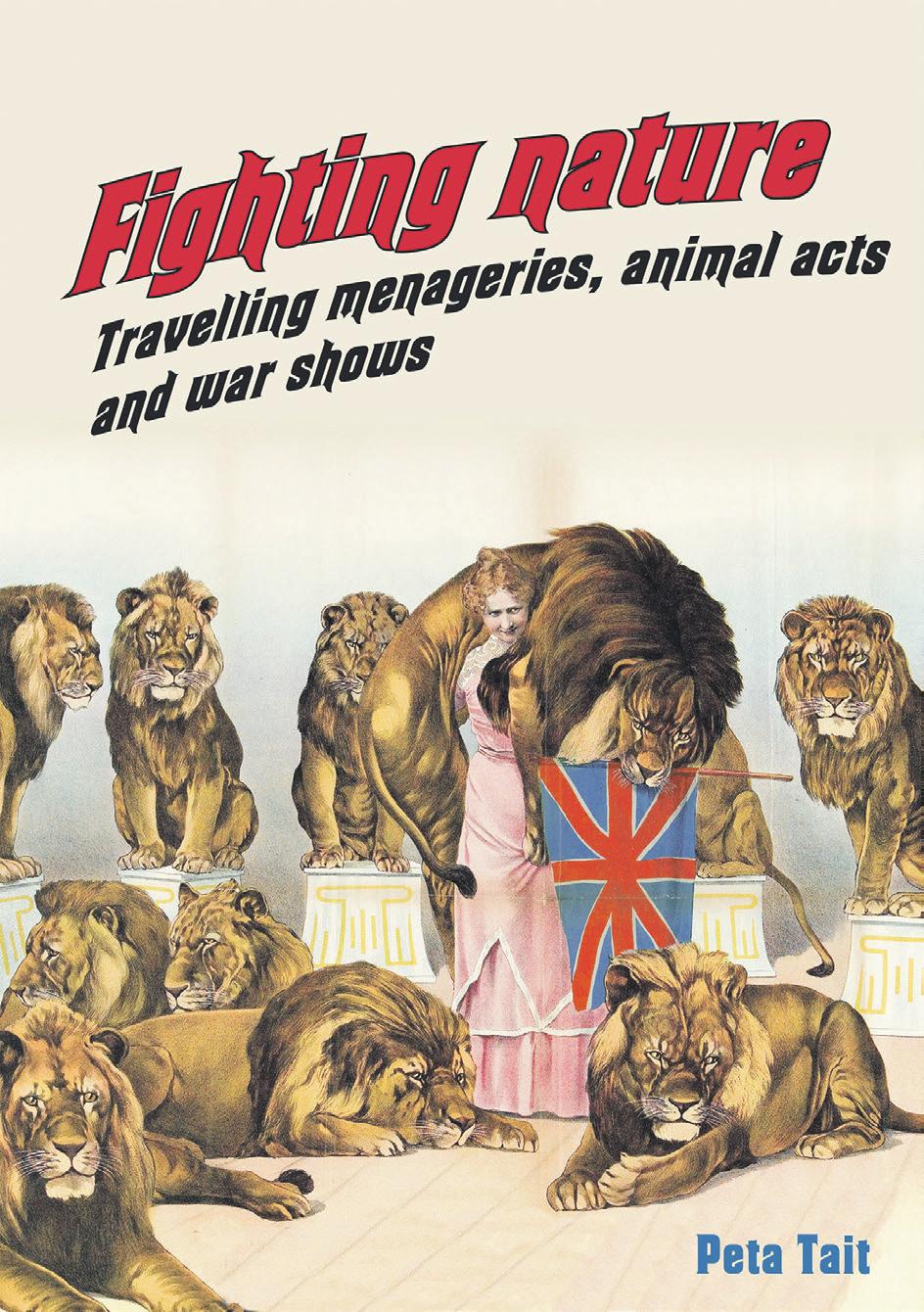

Why we abused animals for the fun of it Page 13

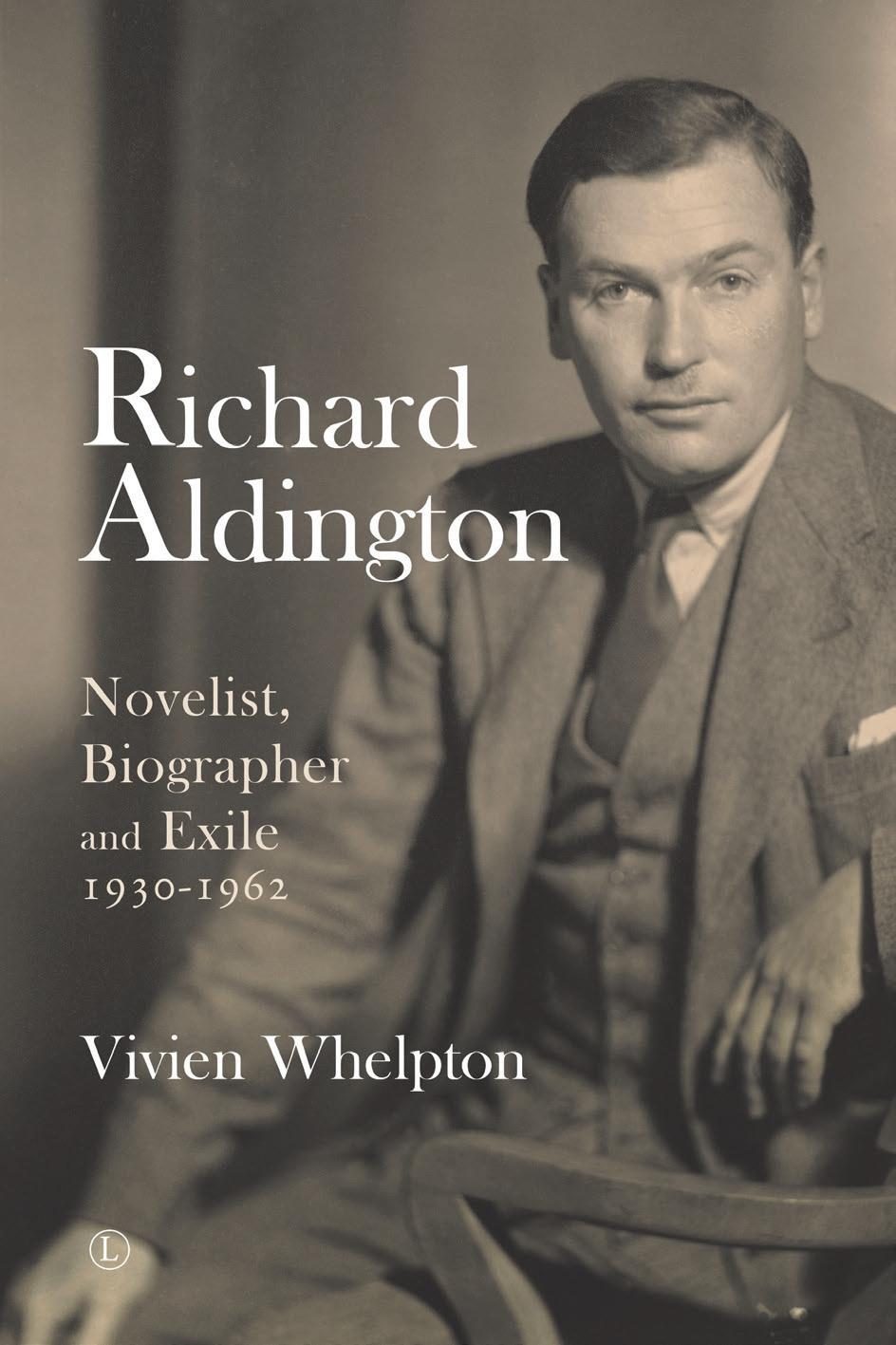

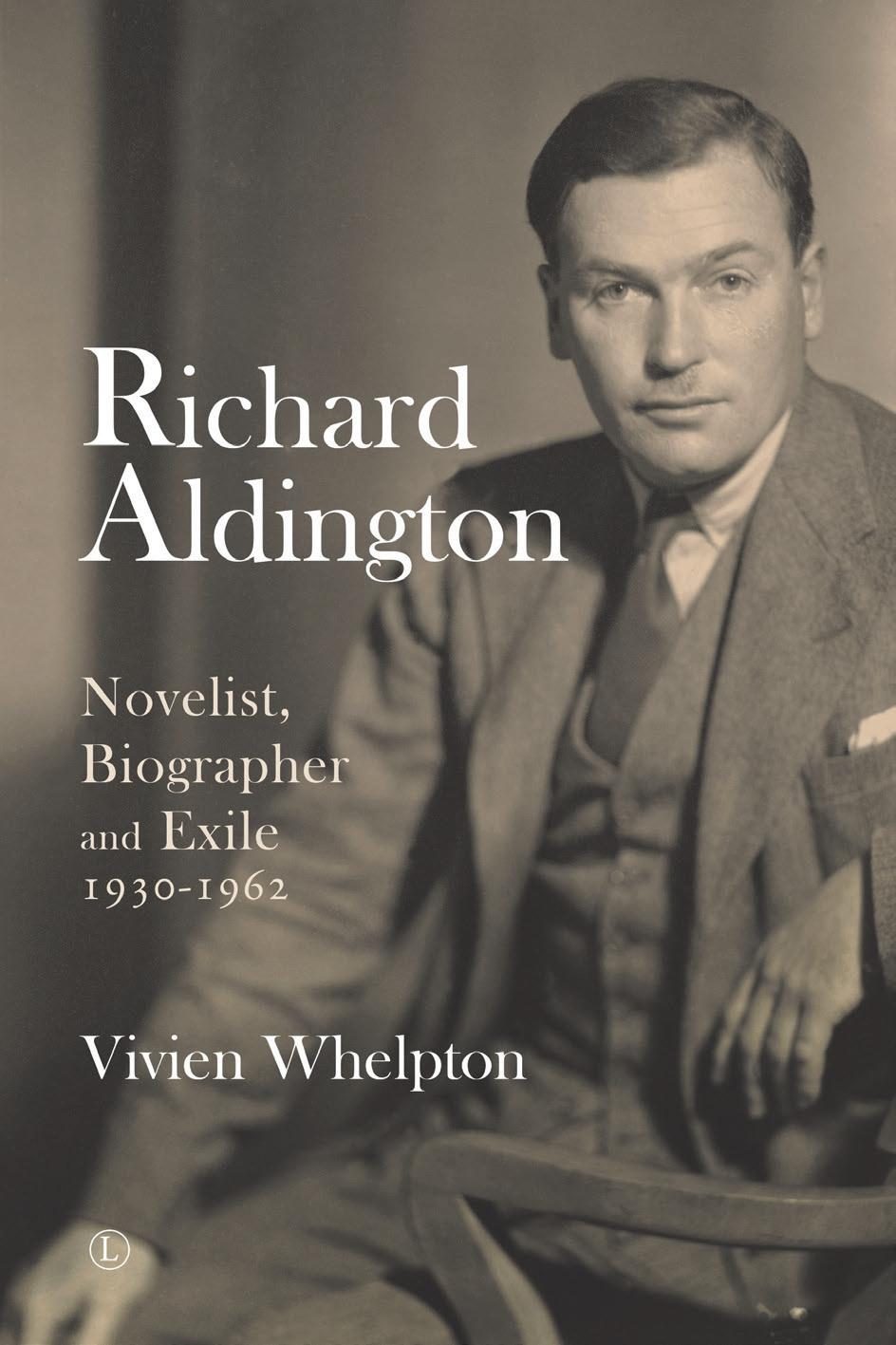

The bursting of T.E. Lawrence’s balloon Page 15

Looking for Daddy: a wartime op that went wrong Page 16

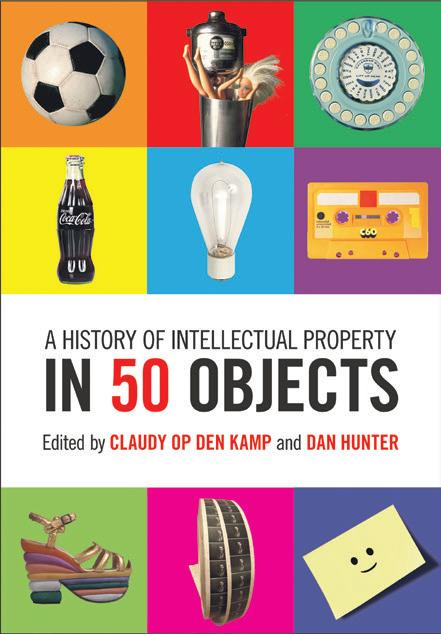

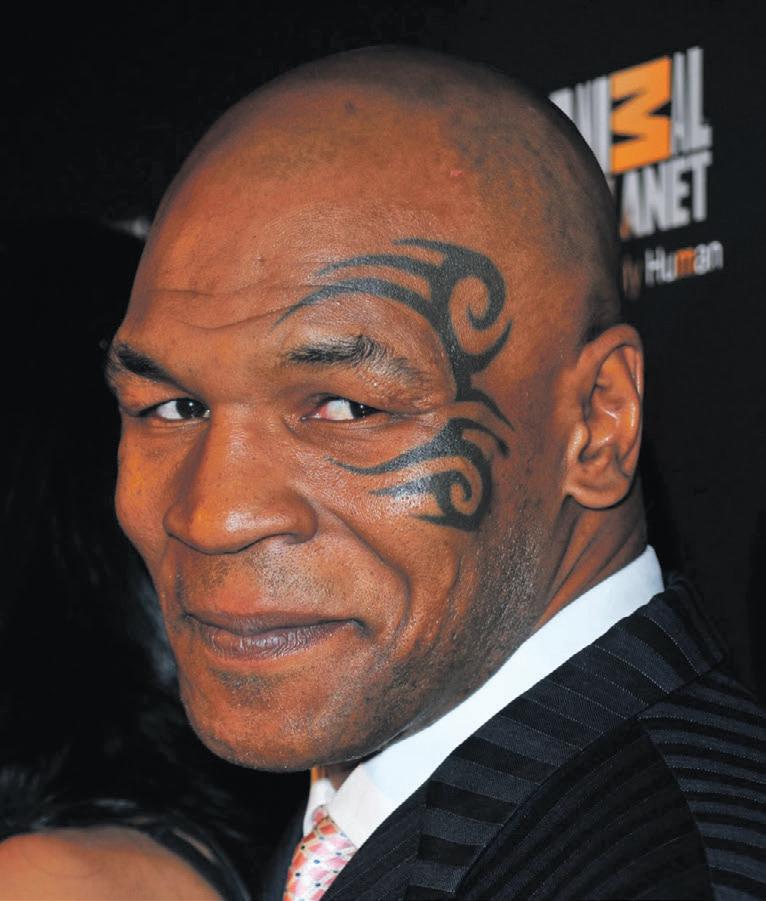

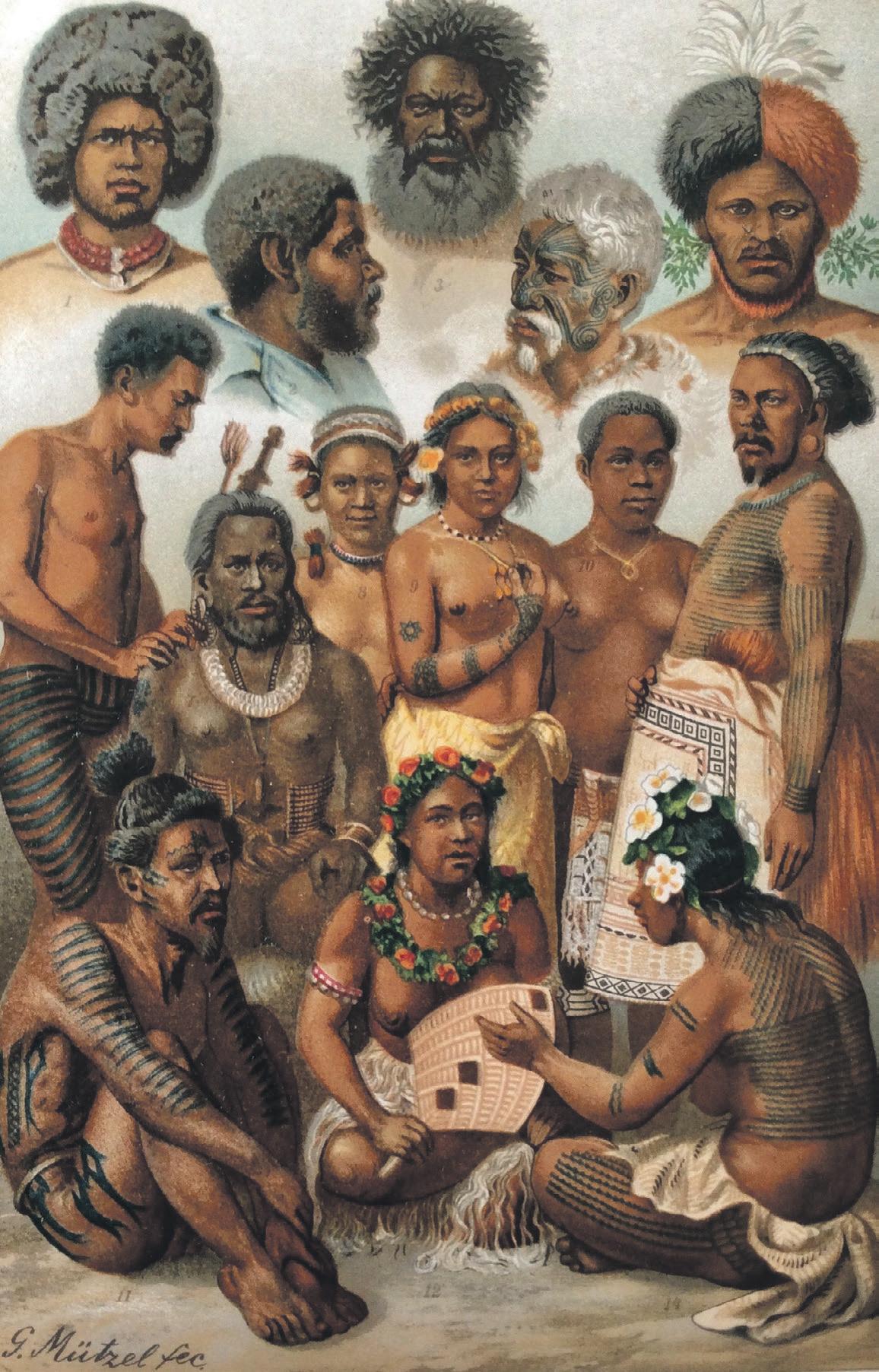

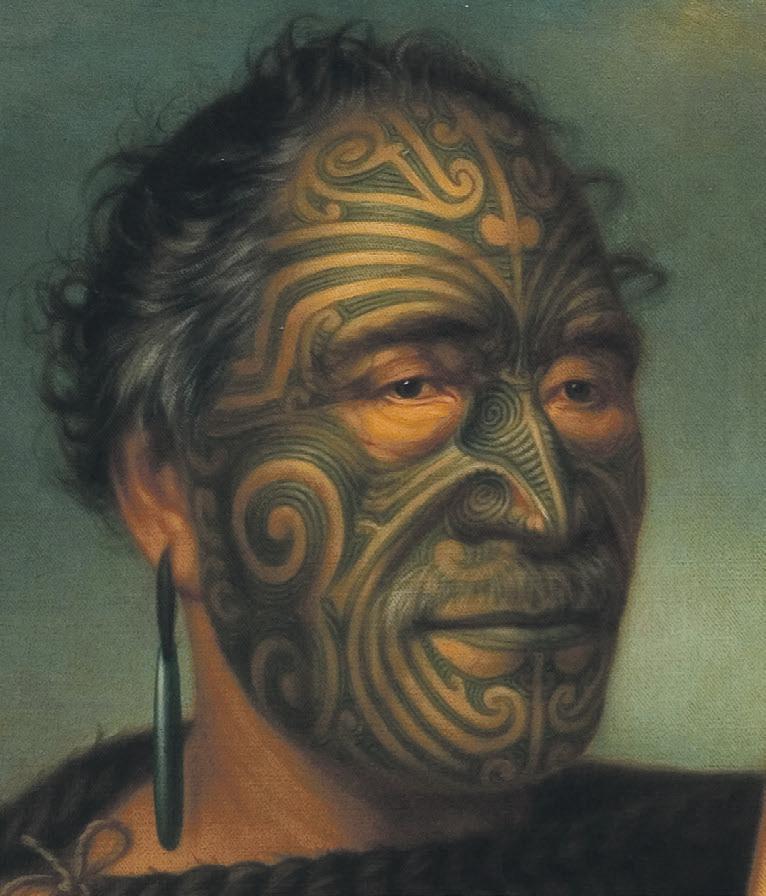

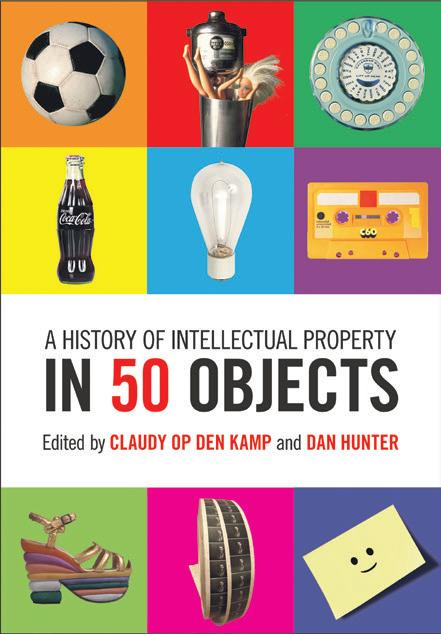

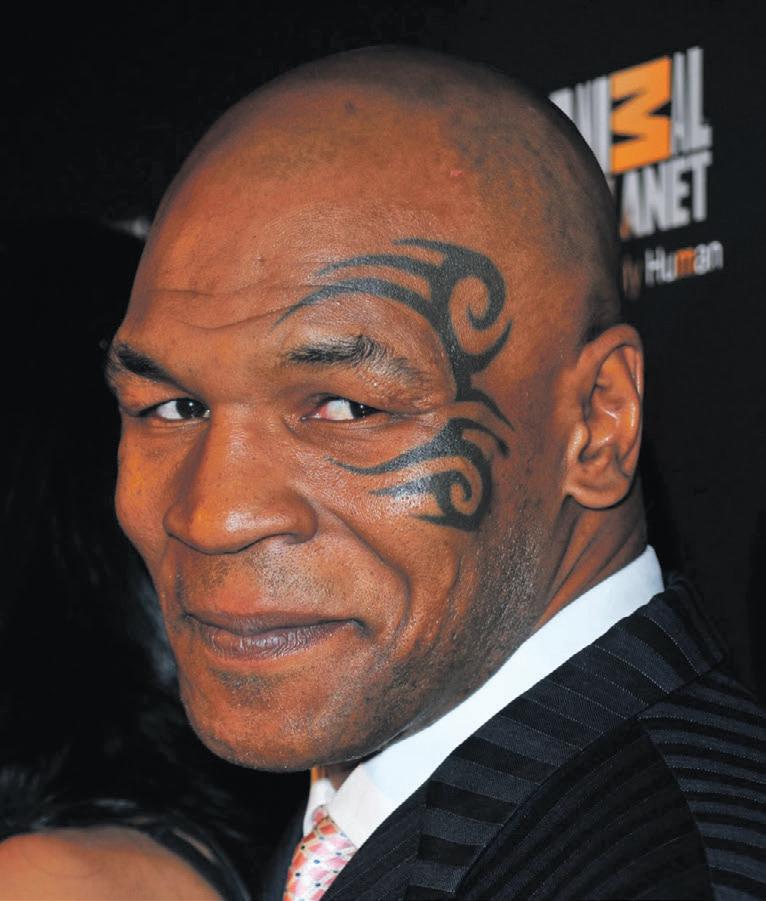

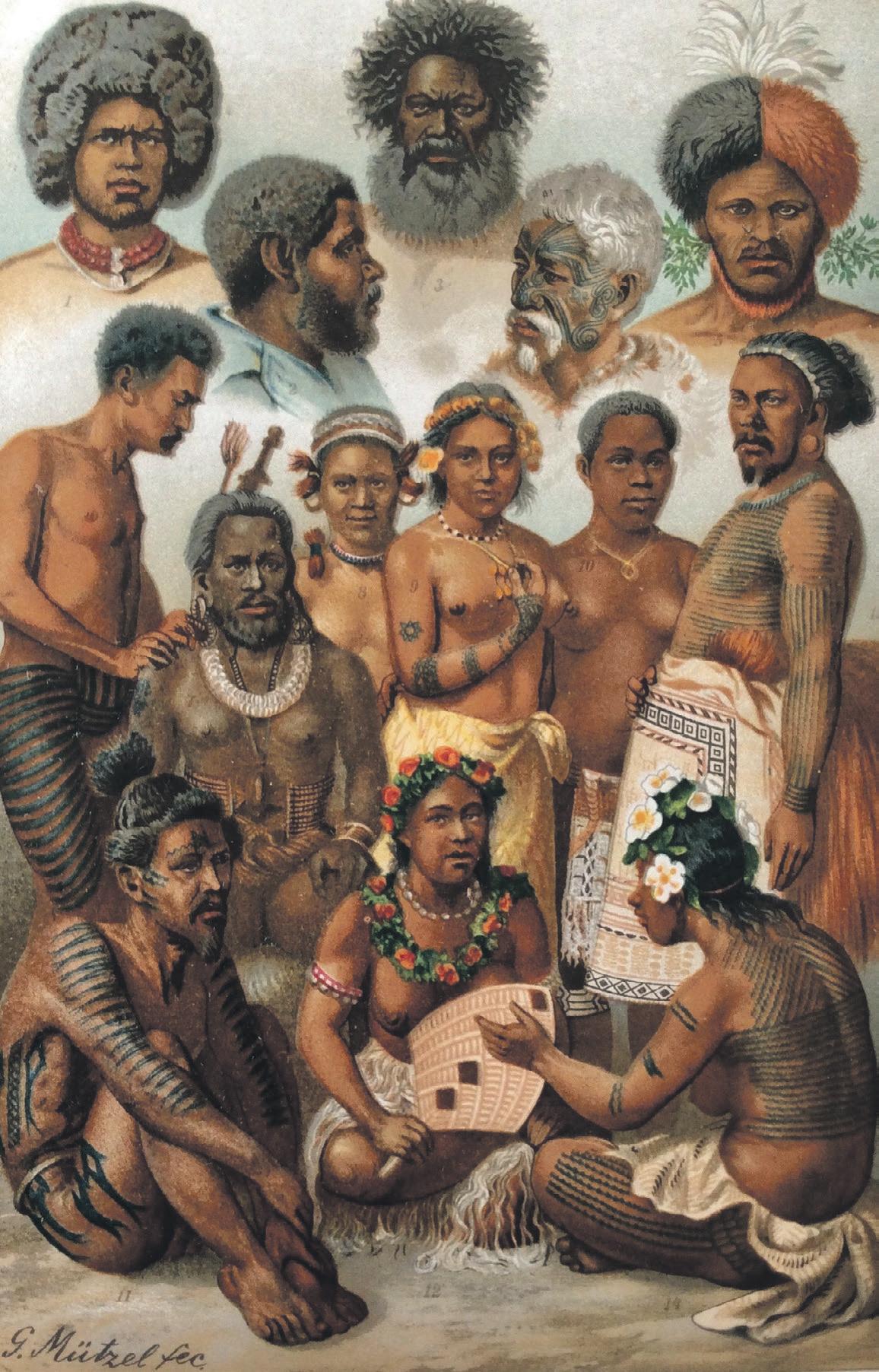

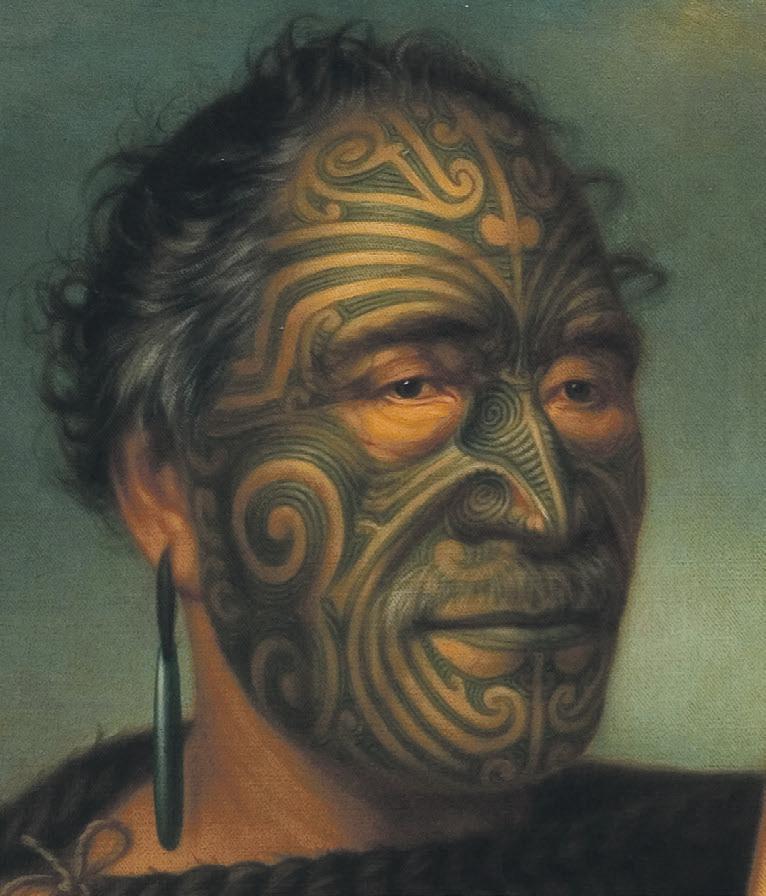

Did Mike Tyson’s tattoo break Maori copyright? Page 14

Vendetta: can a Sicilian emigrée ever escape? Page 17

Surviving psychosis and its delusions: Page 18

Finding serenity in La Serenissima Page 19

Booklaunch Competition and results Page 20

UK publishing’s biggest showcase of new titles. Our choice of extracts from the latest books and manuscripts Booklaunch Issue 4 Special summer literary festival edition Priceless Circulation 50,000+ This issue is free to UK book festivals, libraries, book clubs, publishers, agents and the media New Birmingham Library | Architect Mecanoo Structural Engineer Buro Happold Opened 2013 Photo James Merrick / Shutterstock To stock copies of Booklaunch for your book festival, reading group, library, school or shop subs@booklaunch.london To showcase your new book or manuscript book@booklaunch.london To help distribute Booklaunch editor@booklaunch.london To inquire about our writers rights@booklaunch.london To subscribe subs@booklaunch.london

Jesus to London gang members Page 2 The case for a New British capital

3 The letter X: what is it good for?

Can Brazil ever defeat its own corruption?

5 Naguib Mahfouz returns to pre-modern

Talking

Page

Page 4

Page

Cairo Page 6 Rural Greece in the years of the junta Page 7 New theories for surviving the workplace Page 8

The London Yoot Bible

A tool for linguists and urban clerics

Missionary publishers have always been inventive in using language to win converts. The London Yoot Bible is a first attempt not just to render the Bible into gang speak but to help those involved in youth work visualise gang culture better. While it cannot avoid the charge of patronising those whose language it aspires to represent, it nonetheless aims to offer a legitimate linguistic transcription of a dynamic, hypercontextual patois without any obvious written form

Potential Subscribers

To sponsor the development and publication of this book, please email: rights@booklaunch.london

King James Version Mark 14

12 And the first day of unleavened bread, when they killed the passover, his disciples said unto him, Where wilt thou that we go and prepare that thou mayest eat the passover?

13 And he sendeth forth two of his disciples, and saith unto them, Go ye into the city, and there shall meet you a man bearing a pitcher of water: follow him.

14 And wheresoever he shall go in, say ye to the goodman of the house, The Master saith, Where is the guestchamber, where I shall eat the passover with my disciples?

15 And he will shew you a large upper room furnished and prepared: there make ready for us.

16 And his disciples went forth, and came into the city, and found as he had said unto them: and they made ready the passover.

17 And in the evening he cometh with the twelve.

18 And as they sat and did eat, Jesus said, Verily I say unto you, One of you which eateth with me shall betray me.

19 And they began to be sorrowful, and to say unto him one by one, Is it I? and another said, Is it I?

20 And he answered and said unto them, It is one of the twelve, that dippeth with me in the dish.

21 The Son of man indeed goeth, as it is written of him: but woe to that man by whom the Son of man is betrayed! good were it for that man if he had never been born.

22 And as they did eat, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it, and gave to them, and said, Take, eat: this is my body.

23 And he took the cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them: and they all drank of it.

24 And he said unto them, This is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many.

25 Verily I say unto you, I will drink no more of the fruit of the vine, until that day that I drink it new in the kingdom of God.

26 And when they had sung an hymn, they went out into the mount of Olives.

Mark 15

1 And straightway in the morning the chief priests held a consultation with the elders and scribes and the whole council, and bound Jesus, and carried him away, and delivered him to Pilate.

2 And Pilate asked him, Art thou the King of the Jews? And he answering said unto them, Thou sayest it.

3 And the chief priests accused him of many things: but he answered nothing.

4 And Pilate asked him again, saying, Answerest thou nothing? behold how many things they witness against thee.

5 But Jesus yet answered nothing; so that Pilate marvelled.

6 Now at that feast he released unto them one prisoner, whomsoever they desired.

7 And there was one named Barabbas, which lay bound with them that had made insurrection with him, who had committed murder in the insurrection.

8 And the multitude crying aloud began to desire him to do as he had ever done unto them.

9 But Pilate answered them, saying, Will ye that I release unto you the King of the Jews?

10 For he knew that the chief priests had delivered him for envy.

11 But the chief priests moved the people, that he should rather release Barabbas unto them.

12 And Pilate answered and said again unto them, What will ye then that I shall do unto him whom ye call the King of the Jews?

13 And they cried out again, Crucify him.

14 Then Pilate said unto them, Why, what evil hath he done? And they cried out the more exceedingly, Crucify him.

15 And so Pilate, willing to content the people, released Barabbas unto them, and delivered Jesus, when he had scourged him, to be crucified.

16 And the soldiers led him away into the hall, called Praetorium; and they call together the whole band.

17 And they clothed him with purple, and platted a crown of thorns, and put it about his head,

18 And began to salute him, Hail, King of the Jews!

19 And they smote him on the head with a reed, and did spit upon him, and bowing their knees worshipped him.

London Yoot Version Mark 14

12 Pre Easter on an early ting. When man have shanked the Passover lamb, the gang say ‘which nizz you want us to cook in?’

13 So he send two of his bredren, and he go, ‘Dere’s a man, in the ends, wot carry pure water. Meet up wit him. Follow man.’

14 And when he get to the trap, tell the guy wot own it, ‘My top guy say: “Where is the romp room (with the bottles poppin’) where I am gonna get loose with my yutes?”’

15 and he gonna show you this pad upstairs (all Fendi and Balenci shining). Cook up your meal there— hear me now?”

16 So gang hit road. Trappin in the city, and it just like Jesus told them. So they cook up a mash wit the recipe.

17 And dat evening, Jesus, no wet guy who still hold down da crib, moved wit his boys.

18 And while they is all lacking, he announce, ‘This is for real, mans: one of you is a paigon—one of you’s a snake in the grass.’

19 They are well hurt and say in turn, ‘I’m no paigon. For real. I know I respect my Donny.’

20 And he respond, “What I’m sayin’ is, it’s like one of gang—like one of you who mashes up shows with me on the reg.’

21 Son of Man set out, as it is written in the Good Book (mad religious): now I’m saying’, check this out— don’t you dare disrespect man, or else you’ll get a bang to the teeth. I’ll run up on man with a skeng.

22 And as they ate, Jesus took the grubs, and blessed it (yes lawd), and snapped it. He gave it them, and said, ‘feel like a G, cos you holdin my body.’

23 And he take the cup, and when he had pre’d on a man, he gave it to them: and they all got yakked.

24 He spoke to them, like Samuel L, saying ‘This is the colour of too many wounds. This is the blood of my word, wot I shed for my goons.

25 No more henny, til I’m blessed up.

26 And when they had sung a tune, they hit up the local Mount of Olives.

Mark 15

1 Early morning the chiefs sketch out a plan wid the ancients and profs, decking Jesus, and droppin him to Pilate, a tough guy.

2 And Pilate ask him, ‘So you is Donny of the Heebs?’ And he tell them, ‘Wot you said.’

3 The feds said holla, but he don’t pipe up.

4 So Pilate ask him again, saying: ‘You snitch or else you dotty? The cops have receipt.’

5 But Jesus stay quiet; legendary focus like 300.

6 Now at that feast he said he’d let one out the box, so pick a certi bredren.

7 One yute called Barabbas had boxed up a yute, ran him up with a rusty.

8 And the peoples cried out to bless man. Offer him freedom from the neeks in cell.

9 But Pilate answer, ‘What if I prop the Donny of the Heebs?”

10 Cos he know dat chief priests had made man gush, real emotional talk.

11 But the chiefs pressed on, urging Barabbas to head back to the block.

12 So Pilate answer again, ‘What do the team want me to do wit dis old king?’

13 And they cried out, ‘Batter man.’

14 Then Pilate say, ‘Why, has he snitched or put disrespect on man’s name?’ And they bellowed louder, to ching man.

15 So Pilate, a bottle popper, released Barabbas from cell, and sent Jesus, having chastened man, to get run up.

16 And the troops led him into the hall; and they call together the whole crew, the new links intact.

17 And he was kinda drippin in purple, but wit a crown that stung,

18 And they saluted man, ‘Hail, leader of the T!’

19 And they banged him on the head with a rod, and spat at man, and bowed their knees, on some messed up ting.

20 And when they had disrespected Jesus, they tore off his garms, and hassled man even more.

21 And they told some G Simon, a Cyrenian, who was passing by, to come with the cross.

22 And they brought him to Golgotha, which is a shabby nizz. … continued in the book

2 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

TEXT / YOUTH LINGUISTICS

BIBLE

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special summer offer: 50% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

These extracts are taken from the New Testament, The Book of Mark, Chapter 14: 12–25 and Chapter 15: 1–22

Put aside other explanations for a moment and consider this: that it’s the dominance of London that explains the outburst of Brexitism in the rest of the country. However far reaching London’s grasp, outsiders see it as self-sufficient, self-satisfied, insular, not needing the provinces and not understanding them. London either outcompetes the regions or blindsides them.

It is the most dynamic city in Europe. It houses a sixth of the UK’s population—equivalent to the whole of Scotland and Wales—and has an economy that makes it the equivalent of a state within a state.

People used to speak of “England” interchangeably with “Britain”; today, they might as well say “London” because the UK can easily be mistaken for an outlier of the capital—the hinterland of a London empire. London’s commuter belt alone has a radius of 100 miles. It’s not unusual for a homeward commute to take over two hours.

This is over-centralisation and we have seen versions of it before. In 18th-century France, absentee aristocrats, grand and remote, clustered around Versailles and had their heads cut off. The patrician class in England, supposedly a model of rural decentralisation, lived on the land and survived.

Industrialisation in the 19th century consolidated the UK as a network of provincial centres. The siting of the capital in the south east corner of the country was uncontentious; it gave easiest access to Europe by sea, but the rest of the country had its own resources to exploit and made its own contribution to Britain’s global might. There were other complaints but few felt done down by London in the way they do now.

Today, with Britain’s captive imperial market long gone, and domestic cheap labour undercut by the Third World poverty that we are content to exploit, cities that thrived on industrialisation and colonialism no longer have any grand economic engine. Liverpool once had its docks, Stoke had its potteries, Sheffield had steel, Hull had fishing, Glasgow and Belfast had ship building. From London’s vantage point, it is not clear what any of them now offer—what the point of them is—and they know it and feel belittled by it.

This is versaillification and it offers ample scope for anger. Those who feel ignored and outdone also feel resentful and it is easy to orchestrate that resentment further, as Nigel Farrage knows only too well.

At the same time, London is insensitive to the way its own interests always come first. Whitehall continues to spend money on High Speed 2, for example, to rush rail passengers between London and the North, while people in the North still lack the basic rail infrastructure for efficient local travel. Too often, London’s gain is the rest of the country’s loss; at best, the rest of the country only wins if London wins more. How could there not be a backlash?

There is a flipside, however. The dynamism that outperforms the rest of the country is also self-injuring. London’s elite may be protected from its worst effects— especially property speculators who live abroad and do not suffer the conditions that their portfolios give rise to—but for everyone else, the quality of life is worsening. From out-of-reach house prices to suburban traffic jams to air pollution, the very appeal of London is clogging it up.

Oddly, however, every government consultant appointed to look at London’s problems calls for more growth, as if size was a test of the capital’s virility (and of the virility of the advisors, perhaps). So, we are told, Heathrow Airport needs to grow, London’s underground railway system needs to grow, London’s office accommodation needs to grow, its housing needs to grow, its density needs to grow, its height limits need to grow, and its utility infrastructure needs to grow too to keep pace with this growth.

According to the Strategic Plan for London, “the only prudent course is to plan for continued growth.”

In short, for London to keep going, it has to keep growing. Those of us who are not in the business of strategic planning will recognise this at once for what it is: a Ponzi scheme—a type of fraud in which new investment is constantly needed to sustain old investment.

It cannot go on. Both for the health of the country and of London, the UK needs to be rebalanced. But how?

Throwing money at the UK’s most depressed regions is an obvious answer, but not one that comes with an obvious strategy or a guaranteed return. Our seaside resorts are a case in point. Since the arrival of airlines and cheap foreign travel, their economies have collapsed, turning once prosperous towns into dormitories for the most needy, but no local authority has yet worked out how to turn them around. Whatever revival may fitfully have

occurred has depended on informal and unplanned gentrification—urban incomers turning Regency terraces into Colefax-and-Fowlered B&Bs while benefitting those at the bottom of the pile not at all.

It is possible, however, that we have been looking in the wrong direction. Rather than looking for ways of rescuing the country, or rescuing it from London, what we need is to rescue London from London. Rather than trying to speed up the regions, London needs to slow down while everyone else catches up.

The Government could do this by relocating one of London’s primary drivers—and there are only two candidates. One is the financial sector. A new banking city created in a region of severe deprivation would be transformative. It cannot happen, however, because banking would resist. If bankers had to leave London, they’d quickly gather in Frankfurt or Paris instead.

That leaves Government with only one other option: relocating itself. Other countries have done so. In the last 200 years, the USA, Finland, Greece, Canada, New Zealand, India, Turkey, Australia, Lithuania, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Tanzania, the Philippines, Nigeria, Germany and Burma have all moved their capitals. Their reasons were different in each case, but all did so to survive. The UK has to decide whether survival is something it wants to invest in; at present it appears that it doesn’t.

Relocating a new capital in a region needing urgent help would re-energise the economy. It would also help the UK to redefine itself at a time when the reasons for the union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are becoming less obvious. Britain needs to rethink its own rationale. A new capital should symbolise what the Union now stands for and restore the electorate’s faith in it.

Technically we can do it. Half the big architectural and planning firms in the UK seem to have been doing little else over the last 20 years than building new cities in the People’s Republic of China. Creating a new city would confirm our ability to think ourselves out of the dilemma that Brexit and Mr Farrage have articulated and exploited.

What stands in the way is our conservatism. However radical some of us might feel, we mostly dislike change and distrust those who campaign for it. When it come to innovation, the very purpose of Parliament is to restrain the utopian and revolutionary impulses of the populace: that’s why Brexit has taken so long, and it’s not necessarily a bad thing. In our road, rail and air networks, we also have an aged and complex infrastructure that now impose on us the shape that originally shaped them.

Finding a more equitable siting of the capital and ensuring that this re-siting brings equitable benefits to the entire country is the right solution because it would shake the country up at a time when it needs to be shaken up and in the most constructive way. What is difficult, ahead of any popular head of steam, is to predict what slam-dunk arguments might best win hearts and minds. Alongside all the benefits, moving our capital would also be disruptive and expensive, and would be met not just by knee-jerk protests but by articulate, well-researched opposition.

Among the most intransigent opponents would be our MPs, and not only in the south and south-west. For them, there is in London all that life can afford and while the dimmest will find it hard to fathom the arguments for a move, the brightest would mostly likely be cowed into submission by the fear of being deselected by recalcitrant constituents if they did not object as well.

But MPs haven’t exactly led the political agenda in the last three years: it has taken Mr Farrage’s protest parties—first UKIP, then the Brexit Party—to make all the running. With funding but no policies, he has twice shown that clever rhetoric, cleverly deployed, gets results. From nowhere, he now leads the biggest political group in the EU, created just six weeks before the election that brought it to power.

And this was not inevitable. Two thirds of us voted to remain part of the European Communty in 1975; the idea of attributing to the EU whatever woes we may have suffered since then had to be constructed. Setting aside the merits or otherwise of that construction, it has changed the UK’s political geography. From now on, for better or worse, single-issue campaigners will probably prefer to sideline Parliament and go it alone.

The case for building a new London will also, therefore, need to be constructed. The ammunition for it is there, along with the fertile ground of resentment and disadvantage. The question is, who could safely lead it? Any takers?

The Case for a New British Capital Stephen Games

Forty years after first writing about architecture for the Guardian, Booklaunch editor Stephen Games argues that the only way to quell Brexit unrest, revitalise the regions, remodel the Union for the 21st century, and save London from itself is to build a new British capital elsewhere in the country

Taken from New Premises Position Statement 10: The Case for a New British Capital

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special summer offer: 50% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

Booklaunch is a project of New Premises Ltd

12 Wellfield Avenue, London N10 2EA

Website bookshop https://www.booklaunch.london

Publisher/editor Dr Stephen Games editor@booklaunch.london

Design director Jamie Trounce jamie@jamietrounce.co.uk

Assistant editor Samuel Warshaw book@booklaunch.london

Advertising manager Jenny Chalcott ads@booklaunch.london

Competitions editor Maggie Bawden comp@booklaunch.london

Distribution Robin Clarke (West of England), Alex De Lusignan (East Anglia)

Printer Mortons Media Group Ltd, Horncastle, Lincolnshire LN9 6JR Subscriptions subs@booklaunch.london UK £15.99/Overseas £20.99

EDITORIAL OPINION 3 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

The Best I Can Do

Trevor Pateman

INTELLECTUAL IRREVERENCE

X & the Alphabet

The letter X does not pull its weight in the alphabet. There are only 26 letters in the English alphabet and they have their work cut out to represent a million words. How come X is still in a job when it manages to start off only one hundred or so words, most of which we don’t know anyway? And those hundred or so words could all be started off with a Z quite satisfactorily (zeroxes, zylophones, zenophobia). It’s as if the team is a player short.

Well, in its defence, you could say that it has found a second job working as an adjective rather than a letter, fronting up hyphenated words like X-ray and what would normally be hyphenated words like xbox. This is true but not exclusive to X: we have B-movies and G-forces. As a second line of defence, you could point out that at the end of words X does another grammatical job indicating that a word is singular rather than plural: box, cox, fox, pox are all singular, though they would sound the same if spelt bocks, cocks, focks, pocks, and those are at the same time versions which can cope with a plural, so fockses instead of foxes is at least as transparent. Cocks, docks, locks, socks—under the present regime, words ending in cks—are always plurals. The proof of this is demonstrated by the fact that we know that sox as an alternative plural of sock (as in Bobby sox) is just a gimmick.

But this idea that X is doing work for grammar is dubious; it makes it sound like X is moonlighting twice over, just because it has only a part-time job as a letter of the alphabet.

You may be inclined to persist in defence of X and I think that might be because somehow you just feel that a letter of the alphabet surely must be fit for purpose. If it wasn’t, it would have been eliminated long ago. Well, that’s a popular neo-Darwinian way of thinking which used to be summarised in the expression (or eckspression) The Survival of the Fittest. In turn, that doctrine connects to a smiley-faced version of the same idea, All is for the Best in the Best of All Possible Worlds—interfere at your peril.

Trevor Pateman studied PPE in the 1960s at Oxford, where he learnt to write two short essays every week, each based on a day or so in the library. Fifty years and an academic career later, he is still happy to try his hand at any topic, and his collection The Best I Can Do comprises 26 musings organised alphabetically, the subjects sometimes whimsical, sometimes more serious

Title: The Best I Can Do

Author: Trevor Pateman

Publisher: degree zero

Location: Brighton

Pages: 168

Format: Softback

ISBN: 9780993587900

Size: 129 mm x 199 mm

Date of publication: 2016

Recommended retail price: £8.95

Save £3.96

Our price £4.99 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

The All Is for the Best doctrine is clearly ludicrous and the idea that everything in the world is fully fitted to purpose and can’t be improved on—the fancy name for this idea is eufunctionalism—is falsified by such simple observations as this: the fact that all the cars on the road today are being driven around does not prove that they are all in equally good running order. Likewise, just because the letter X is there in the alphabet being taught every day in school does not mean that it is in as good shape as A or B. Frankly, it’s struggling.

made the switch. Everyone now alive is very happy that they did.

Another story is a bit different. Czechoslovakia’s government had already committed to switching from driving on the left to driving on the right when the country was occupied by Germany in 1939. As a result, the planned transition was accelerated by the simple fact that German military traffic entered the country on the right hand side of the road and stayed there. In some places every driver had switched within 24 hours and, in the country as a whole, the changeover triggered by force majeure was completed within a fortnight and with one fatality.

As another example of changing a co-ordination arrangement, it took the Russian Revolution to impose a more accurate calendar—in Bolshevik Russia, the changeover took place in 1918 with 31 January followed by 14 February. I have a card from a Danish traveller in Omsk writing home on the 14th February and noting that it’s for the first time the same date in both Russia and Denmark. In the early revolutionary period the Soviets also edited the Russian alphabet and spelling, sending in the military to confiscate from printers the type used to set the abolished hard sign. In both cases, change was seen both as a pre-requisite for entering the modern era and as the enforcement of rationality.

We stick with the creaking cultural technology of our old alphabet as with so much else. True, it’s preferable to bloodshed. And, true, that with the arrival of the Internet it would probably now take a world government to change it. But it takes its toll. In British primary schools, there is this thing called Phonics, the product of our best brains and industry, which launches all right on A and B but promptly gets sea-sick on curly C and kicking K (I think that’s called re-arranging the deckchairs) before drowning in X. For school children, it’s a voyage on the Titanic. The survivors are those who manage—probably with parental help—to climb overboard in time. (If you are a parent and want to explore how Phonics is working for your child, here’s a suggestion: When their next birthday comes round, ask them to write down for you the names of the friends they want to invite. Maybe you will have to help and sound out for them, but this time no cheating to turn a – n into Anna and so on down the list and fingers crossed that there is no one in class called Xavier).

Atheists, Agnostics & Abstainers

Trevor Pateman was a pupil of Roland Barthes and went on to teach at Sussex University, specialising in Chomskyan linguistics. He now lives in Brighton

At this point the story ought to shift to the task of explaining what you might call the Persistence of X. Written languages and the alphabets that enable them are surrounded by an ocean of spoken language, constantly moving and shifting. Spoken language is liable to unending and sometimes quite rapid changes, some of them very difficult to describe and explain. You can’t turn them away, any more than you can turn back the waves. Written languages and alphabets float on this ocean. They would not exist without it but their relation to it is changing, uncertain and sometimes disastrous. Spellings change a bit to reflect, after the event, what has happened to intonation or pronunciation—in English in the recent past Rumania and Roumania have given way to Romania. But alphabets barely change at all and then only over extended periods of time. Alphabets may end up having nothing to do with spoken language and, for some languages, that is quite true or partly true.

The alphabet we know connects better to spoken Italian than it does to spoken English, for instance, which may have something to do with the fact that it’s a Latin (Roman) alphabet and Italian is even now a Latin (Romance) language. English isn’t. It just happens to be represented through the alphabet of Britain’s former colonial masters.

Certainly, alphabets, like QWERTY keyboards, are structurally rigid in the sense that it is hard to interfere with one element without disrupting the whole. In addition, alphabets solve a co-ordination problem, ensuring we all behave the same way when there is no obvious right way. So it becomes one of those cases where we really need a government to order a change and ensure that we all follow its lead and, ideally, at the same time. That is, for example, usually the only way you can change from driving on the left to driving on the right. Sweden made the change as late as 1967 and it’s an interesting story: a referendum was held and an overwhelming majority rejected any change; the government bided its time and a few years later

Teetotallers (once called Total Abstainers) and vegetarians are people who renounce something which they may well find attractive—in the case of alcoholics, too attractive. Some vegetarians are repelled by the thought of eating dead animal flesh. Others aren’t: the novelist Jonathan Saffran Foer, for example, author of an extended defence of the vegetarian case, Eating Animals (2000). The smell of your barbecue wafting into his house triggers temptation not disgust. But for him the temptation is one to be resisted, on moral grounds.

I sometimes think of myself as abstaining from religion, both from practice and belief. Some religious things I find repulsive but not all of them. There seem to be attractive aspects to all religions, though I only have experience of one. But when you start to put things in the balance, for me the scales always tip one way.

Start with religious practices. I won’t attend an infant christening. I think it’s morally wrong—mildly abusive—to take your new born child and sign them straight up for something which ought to be a matter for considered choice. When I was baptised into the Church of England in 1947 my godparents (I remember their names but nothing more) were handed little cards to instruct them in their Duties and my parents got a copy which I inherited. It is headed Take this child and nurse it for Me [capital M in the original] and instructs Mr and Mrs Mardell:

1. To pray regularly for my Godchild.

2. To ask myself frequently: Does my Godchild know, or is he being taught, the promises which he made by me [that is to say, through the godparent] at his Baptism, namely:

(a) to renounce the devil and all his works, the vain pomp and glory of the world, with all covetous desires of the same, and the carnal desires of the flesh … ?

Yes, that and more is what I am supposed to have promised as a mewling babe in arms with these godparents I don’t know from Adam taking power of attorney because of my own inability to say the words ‘I promise’. … continued in the book

4 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special summer offer: 50% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

These extracts are taken from the essays “X & the Alphabet” and “Atheists, Agnostics & Abstainers”

Italy has suffered the worst economic performance and the highest rates of corruption of any developed economy. Evidence suggests that the strong reaction by the political system to the Mani Pulite (‘Clean Hands’) investigations may have contributed to this situation.

A sting operation based on a denunciation by the owner of a small cleaning company hired through a public tender led to the arrest of Mario Chiesa, the president of a public retirement centre, who had taken a cash bribe. Shortly after his arrest, the defendant agreed to a plea bargain in court and testified that he had received bribes from several other businesses, setting off a chain reaction that uncovered a widespread, long-standing system of corruption involving businesspeople, politicians, public officials, and members of the police and the judiciary. In addition to enriching government officials personally, the bribes funded the careers and campaigns of most politicians from practically all political parties.

At first, Bettino Craxi, president of the Council of Ministers at the time, commented that the arrest of Chiesa was insignificant, since he was only a ‘lone swindler’ who had besmirched the image of a clean party. Soon afterward, in the wake of an avalanche of indictments, Craxi himself denounced in Parliament a system of illicit political payments involving nearly all politicians and parties. No one in the chamber dared to contradict him, thus highlighting the amazement of everyone about the gravity and scope of the facts coming out every day. Very soon, 4,200 people had been incriminated, including four former presidents of the Council of Ministers, 12 ministers, and 130 deputies and senators. By the 1994 elections, five parties had disappeared, including the Christian Democrats, who had dominated politics since the postwar period.

At that point, the political system mounted its reaction against the investigations, with the political debut of Silvio Berlusconi, a successful building contractor, closely tied to Craxi. Berlusconi also controlled a media empire, with national TV networks, newspapers, and a soccer team. Regarding the accusations of corruption investigated by Mani Pulite, he told historian and journalist Indro Montanelli in 1993, ‘I am obliged to go into politics. Otherwise they’ll arrest me, and I’ll be broke.’ He ran for Parliament and won in 1994, becoming prime minister with the new party Forza Italia, whose slogan was ‘Away with old politics. We want different, new, clean politics!’ He headed a strong media attack against members of the operation, which had to face a true ‘sea of mud’, fed by a war of fake dossiers and accusations that the judges’ real objective was to eliminate all politicians. …

Meanwhile, another lethal attack was launched not only against Mani Pulite but against Italy’s very future, with a series of new laws, many of them unconstitutional and soon to be repealed, but which demonstrated that the political class and the government would do anything to put an end to the operation. Several crimes of corruption were legalized, and sentences were reduced for those that remained on the books, tying the judiciary’s hands regarding punishing these kinds of crimes.

With a demoralized judiciary, after a relentless campaign of defamation, and new laws to ensure impunity from crimes of corruption, Italy’s recent lackluster performance is not at all surprising. It combines the worst ranking in corruption perceptions and in the quality of other governance indicators with the lowest economic growth of any of its peers.

Two decades later, could Brazil follow in Italy’s footsteps? With the arrest in March 2014 of a money changer (doleiro) known in Curitiba for several past crimes, members of the police, federal prosecutors, and federal judge Sergio Moro could not imagine the scale of what they would uncover in the years to come, through what came to be known as Operation Lava Jato (‘Car Wash’). An SUV delivered as a ‘gift’ to a former supply director at Petrobras led to the disclosure of a gigantic corruption and money-laundering scheme involving Petrobras and its main suppliers and contractors, as well as several political parties loyal to the government. Investigations revealed that the scheme went beyond Petrobras to various government agencies, amounting to a serious situation of systemic corruption.

At Petrobras, overbilled construction work contracted out to and done by some of the country’s biggest civil engineering companies was organized in a cartel that lasted many years. Operated by doleiros, the bribes found their way into the overseas bank accounts of Petrobras directors and to the parties responsible for

naming the corporation’s upper echelon, to be used in election campaigns and for other purposes.

Participants include members of the highest ranks of the country’s political and business elite, several of them now—or recently—in prison. Former President Lula da Silva was sentenced to 12 years in prison by an appeals court and is awaiting the outcome of six other criminal cases now being heard in federal trial courts. Four former Petrobras directors have received prison sentences, two of them after making plea-bargain agreements. Dozens of executives in the builders’ cartel were found guilty of paying kickbacks. In its 2015 annual report, Petrobras recognized it had lost 6 billion reais (about US$1.8 billion) to corruption, and in 2018 it signed a US$3 billion settlement with shareholders in the United States. Three of Brazil’s largest building companies—Camargo Correa, Andrade Gutierrez, and Odebrecht—signed leniency agreements with federal prosecutors, committing themselves to abandon illicit practices and return billions of reais to the public treasury.

With the high level of corruption in Brazil, identified by any of the ratings used internationally, it is no surprise to see the country shaken by scandals from time to time, like ‘Collorgate’ in 1992, which led to the impeachment of President Fernando Collor; the ‘budget midgets’ in 1992; the SUDAM case in 2001; Operation Anaconda in 2003; Operation Sanguessuga in 2006; and the Mensalão in 2005 (see Power and Taylor 2011).

What makes Lava Jato different from the previous cases? Lava Jato has been successful for several reasons. Luck put the case in the hands of Judge Moro, who has had a solid career in court as well as expertise in money-laundering crimes. Conversant with the Mani Pulite case, he was one of the first to publish an article on it in Brazil, in 2004. Its coming in the wake of the Mensalão trial was an important advantage (Moro 2018). Despite the slow pace of that trial, it was the first time the Supreme Court had tried and imprisoned icons of the PT (the Workers’ Party) and some government officials for crimes of corruption, criminal conspiracy, and other charges. A 2016 Supreme Court decision allowing defendants to begin serving prison sentences after their conviction was upheld on a first appeal that helped suspects recognize that they could no longer count on endless appeals to stay out of prison, thus encouraging the plea-bargaining option to reduce their impending penalties. Growing international opposition to crimes of corruption and money laundering—in battles against financial schemes for terrorism, drug trafficking, and corruption—facilitated Brazil’s collaboration with countries where the proceeds of corrupt acts had been deposited. Modern ICT has also been used well in the operation, including the rapid publication of testimony and denunciations and live broadcasts of trials. Access to information, along with a free, high-quality press in Brazil, ensured strong public support for the operation, with noisy street and online demonstrations every time Lava Jato appeared to be threatened.

By confronting gigantic, deep-rooted interest groups, Lava Jato became a symbol of the fight against corruption, but it also gave rise to a horde of stakeholders interested in its ruin. Several bills in Congress tried to reduce the independence of judges, to legalize offthe-books campaign donations, to grant amnesty to politicians on the take, and so on. There is an ongoing (2018) attempt to overturn a Supreme Court ruling on the enforcement of a prison sentence after a defendant is convicted by the first appeals court, particularly with regard to the prosecution of former President Lula. Time will tell if Brazil will turn this sad page in its history or fall back under the yoke of powerful interest groups to the detriment of the majority of the population.

As it nears its conclusion and having dealt with the subject matter for which it was created, Lava Jato can be deemed to have been a successful operation, but it is still incomplete—only because of the naturally slow pace of Supreme Court deliberations on accusations against politicians who enjoy special forum privileges. Even so, one cannot expect Lava Jato to put an end to corruption in the country. The skill of the prosecution and the rapid punishment meted out for crimes of corruption, which Lava Jato pioneered, represented necessary, albeit insufficient, steps toward reducing corruption once and for all in Brazil. To reduce corruption meaningfully, it will be crucial to ensure the population’s ongoing engagement in the fight against corruption, breaking with old cultural habits, and the emergence of political leaders who embrace the anti-corruption agenda. Here, as in

Brazil: Boom, Bust and the Road to Recovery Antonio Spilimbergo and Krishnan Srinivasan

Brazil was an economic success story until the 1990s; then everything went wrong. Global and regional crises were partly the cause, but internal problems also contributed. Drawing on detailed work done by the IMF and by leading policymakers, academics and think tanks, this multi-faceted study shows that reforms have brought progress but that courage is still needed to tackle the many challenges that hold the country back

Title: Brazil: Boom, Bust and the Road to Recovery

Editors: Antonio Spilimbergo and Krishnan Srinivasan

Publisher: International Monetary Fund

Location: Washington

Pages: 382

Format: Softback

ISBN: 9781484339749

Size: 152 mm x 229 mm

Illustrations: Tables and Figures

Date of publication: February 2019

Recommended retail price: £25.50

Our price £25.50 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

5 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

… continued in the book BRAZILIAN ECONOMICS

This extract comes from the 20th of 21 essays: “Lava Jato, Mani Pulite, and the Role of Institutions” by Maria Cristina Rondelli Pinotti

Antonio Spilimbergo is the IMF’s Assistant Director in the Western Hemisphere Department and has been mission chief for Brazil, Italy, Slovenia, Russia and Turkey

Krishna Srinivasan is an Assistant Director in the European Department at the IMF and its Mission Chief for the United Kingdom

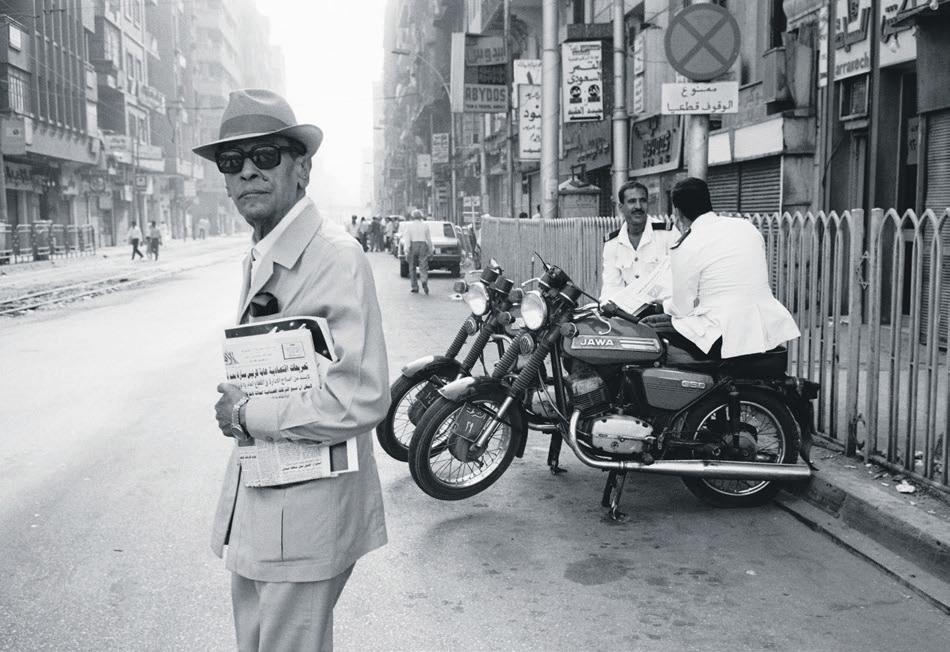

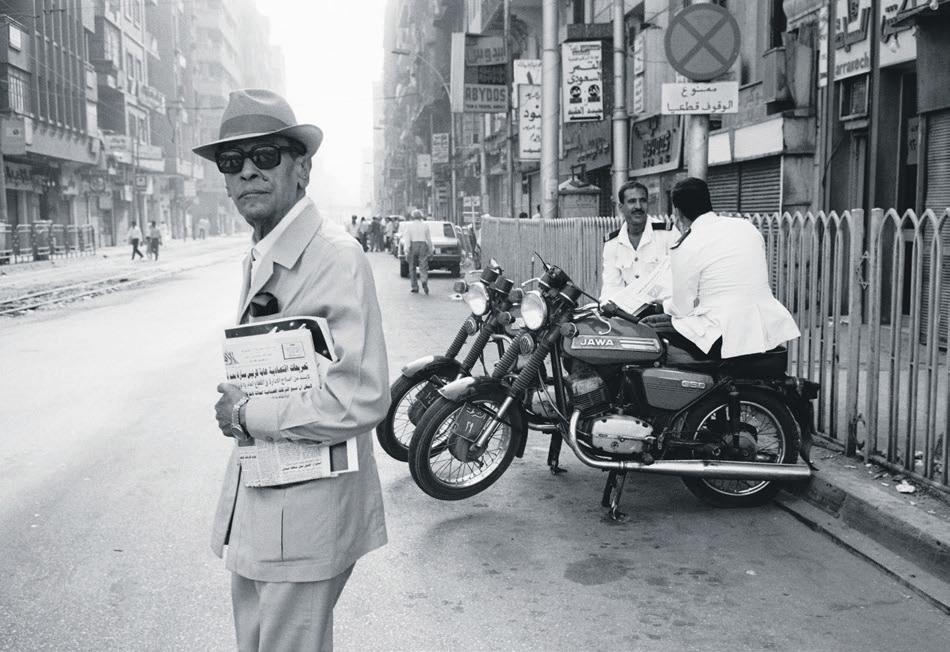

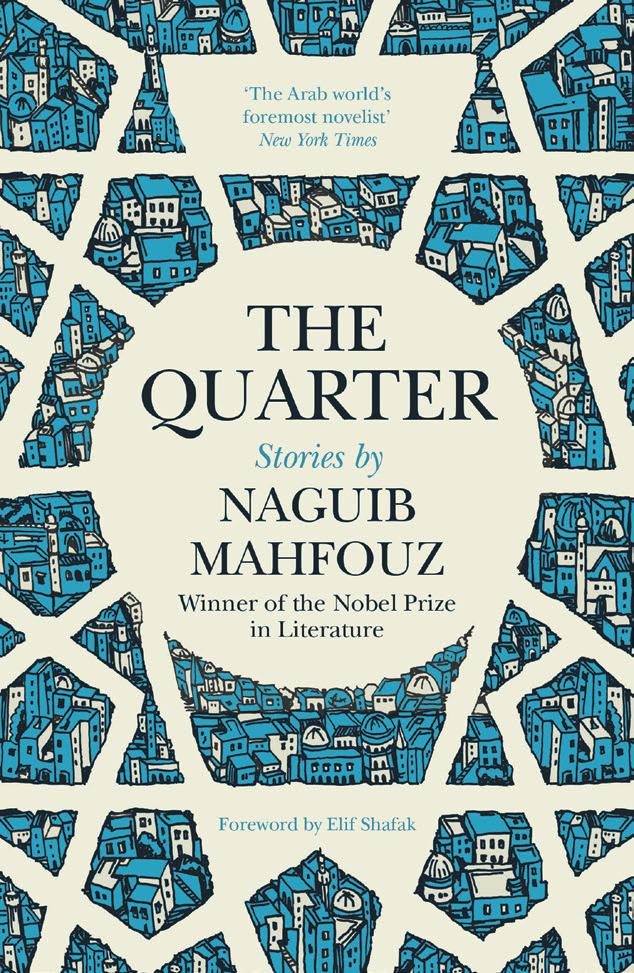

The Quarter

Naguib Mahfouz

ARABIC FICTION

Foreword by Elif Shafak

I first read the works of Naguib Mahfouz in Istanbul in Turkish. Back then, as a university student, I used to frequent a second-hand bookshop—a low-ceilinged, musty-smelling place with plank floors, just a stone’s throw from the Grand Bazaar.

The owner of the bookshop—a sour-tempered, middle-aged man with thick glasses and a haircut that had never been popular in any era—genuinely loved books and equally disliked human beings. At times he would randomly pick a customer and quiz him or her on their knowledge of literature, history, science or philosophy.

I had seen him scold people before, and though I had never witnessed it myself, urban legend held that he refused to sell books to customers who failed his tests. No doubt there were many other bookshops in the city where you didn’t have to inhale dust or risk bumping your head on the door frames, and where you could choose books without being grilled by the owner. Yet I kept returning to this place. Getting the bookseller’s seal of approval felt like a rite of passage, an unspoken challenge. Young and vain as I was, I secretly wanted him to question me on French, English or Russian novels in translation, which I believed were my ‘strong point’. But on this rainy day in late autumn, he looked at me and asked, ‘So, have you read Mahfouz?’

I froze. I had no idea who he was talking about. Slowly, I shook my head.

attacked by a mob of fundamentalists in the Anatolian town of Sivas, where he happened to be for a cultural festival. His hotel was set on fire and thirty-five people were killed—most of them were poets, writers, musicians and dancers. Once again in human history, fanatics targeted art and literature, words and notes, and destroyed innocent lives.

Mahfouz thankfully survived the attack in Cairo. Always a prolific writer, the physical damage and the constant pain he suffered afterwards considerably slowed him down. This, too, must have saddened him.

Throughout his entire literary journey, Naguib Mahfouz produced stories, novels, plays, scripts, experimenting with forms. One thing remained constant: his unwavering love for Cairo and its people. This city had made him who he was and in return, he re-created Cairo on the page. It is this existential challenge that strikes me most deeply perhaps. Mahfouz clearly yearned for freedom and autonomy, but he also had a remarkable loyalty towards and a longing for the motherland that denied him these basic rights.

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) was Egypt’s foremost writer, acclaimed for his urbanism and experimentalism. Over the course of five decades he wrote copiously and remains the only Arabic writer to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. In this newly discovered late collection of short stories, Mahfouz goes back to traditional storytelling, siting his characters in an unidentifiable pre-modern Cairo populated by demons and the smell of sweet halva. The stories are allusive and lepidopteran, alighting briefly, then moving on without leaving a trace

The bookseller said nothing, though his disappointment was visible. When I finished perusing and walked to the till, ready to pay for the books I had selected, he turned towards me with a frown. For a moment I feared he was going to kick me out of the shop. Instead, he grabbed a book from the shelf behind him and pushed it into my hands. Then he said, loud and clear: ‘Read him!’

The book that the grumpy bookseller in Istanbul sold me on that day was Midaq Alley. For a while, I postponed reading it. Then, about two months later, I started the book, not knowing what to expect. Inside, I found a rich world that was at once familiar and magical, well-founded and elusive. The stories of the people of the alley—families, street vendors, poets, matchmakers, barbers, beggars and others—were so deftly told that I felt as though I knew them, each as the individuals they are. Istanbul, too, was full of such streets and neighbourhoods unable to keep up with the bewildering changes surrounding them, and it remained both isolated and central, both inside the city and on its periphery. By delving into this world with a sharp mind and compassionate heart, Mahfouz had shown me the extraordinary within the ordinary, the invisible within the visible, and the many layers underneath the surface. His writing, just like Cairo itself, pulsed with life and a quiet strength.

Mahfouz’s Cairo was a fluid world. Nothing seemed permanently settled; nothing felt solid. As a nomad I was familiar with that feeling, and suddenly I found myself looking for more Mahfouz books to read.

Title: The Quarter

Author: Naguib Mahfouz

Series: Saqi Bookshelf

Publisher: Saqi

Location: London

Pages: 128

Format: Hardback

ISBN: 9780863563751

Size: 129 mm x 198 mm

Illustrations: 9 b/w scans of Mahfouz’s handwriting

Date of publication: 1 July 2019

Recommended retail price: £10.99

Save £1.32

Our price £9.67

inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

Naguib Mahfouz was brought up in a strict Muslim family in Egypt, becoming a writer and entering the Egyptian civil service after graduating in philosophy from Cairo University in 1934. In the 1950s he became Director of Censorship in the Bureau of Arts ad had a special interest in cinema. In the course of his 34 novels his focus moved from history to politics and the social challenges of modern urban life

And here was the odd part. Mahfouz was not well translated into other languages in the region for a long time. It was only after he received the Nobel Prize in Literature—the first author writing in Arabic to do so— that more of his oeuvre crossed national and ethnic borders. It troubled me back then, and still does, that in the Middle East we do not follow each other’s writers and poets as well as we should.

Over the years I continued reading Mahfouz, mostly in English. He was a political writer. He knew that novelists from turbulent lands did not have the luxury of being non-political. I also read his interviews with interest. In these interviews there were moments when I did not agree with his views, which at times could be nationalistic, but I always respected his storytelling.

Many of his books were banned in Arab countries, in the very language he breathed in. This must have hurt him deeply. Mahfouz knew first-hand how painful it is to carve out a personal space of artistic freedom in lands without democracy and without freedom of speech. Significantly, he was among the literary figures who supported Salman Rushdie’s right to write after a deadly fatwa was issued against the author. It is noteworthy that Mahfouz did this at a time and in a country where it wasn’t easy for him to do so—although he later also made negative comments about Rushdie’s novel, which he said he hadn’t read.

In 1994, Mahfouz was stabbed by an extremist, who accused him of being ‘an infidel’. The year before, in Turkey, Aziz Nesin, a prominent writer and satirist, who had announced his decision to publish The Satanic Verses in Turkish in defence of freedom of speech, was

I was excited when I learned the news that eighteen previously unknown stories by Naguib Mahfouz had been recently discovered among his old papers. Irrational as it may be, there is a part of me that thinks he must be very happy. I imagine him caressing this new book while smoking a slim cigarette, with a cup of strong Turkish coffee by his side. I imagine him with a smile on his face, not a tired one, but the hopeful smile of the young novelist he once was.

The Oven

The disaster had happened. Ayousha had run off with Zeinhum, the baker’s boy. When the news broke, fragments scattered all over the quarter. Down every alleyway, at least one good heart expressed disbelief.

‘God help us all! What a disaster for you, Amm Jumaa, you are a good man!’

The Amm Jumaa in question was Ayousha’s father. Head of the family, he was the father of five strapping lads. Ayousha, his only daughter, was now fated to knock him off his pedestal of decency and respect.

It was only after the scandal blew up that anyone had anything to say about her. She was said to be beautiful and charming. Umm Radi, who sold spice-paste, declared:

‘She’s beautiful; there’s no denying that. But she’s too bold. Glances from those flashing eyes of hers go straight into the heart of the person she’s talking to, so they forget what they’re talking about.’

Amm Jumaa and his sons were devastated and simply stared at the ground. At first, they were so angry that they took to spreading out across the quarter, searching and listening for information. But it was fruitless.

‘Mistakes can lead a person to commit crime,’ the Head of the Quarter eventually told Amm Jumaa. ‘He’s lost, whatever happens.’

Amm Jumaa kept a grip on himself on account of his sons.

‘Just tell yourselves your sister’s dead,’ he told them. ‘God will have mercy on her. Leave everything else to Him.’

Everyone put the story together as they saw fit, but it was predictable enough. The girl had met and fallen in love with the boy as he took the dough to the oven and brought home the bread. It would never be possible for the baker’s son to ask for the hand of the daughter of a rich cloth-merchant; the two lovers had decided to run away. Ayousha collected her own jewellery and as much of her mother’s as she could find, and they fled. The only conceivable conclusion to the story was that they would get married, wherever they were.

That was the end of the story of Ayousha and Zeinhum. It took a very long time for the wound in Amm Jumaa’s family to heal. They went back to their normal lives but suffered the usual downward spiral. The merchant went bankrupt and made plans to sell his house.

In the very depths of his misery, a messenger he did not recognise arrived with the money he needed.

‘This money has been sent by your daughter, Ayousha,’ the man said. ‘Divine will has decreed that it is her husband, Zeinhum, who brings it to you.’

The man’s son-in-law informed him that his wife had sold the jewellery she had taken and used it to open a bakery for him. After some hard times, they were now doing well.

‘Do you see?’ the Head of the Quarter told the mosque Imam. ‘The girl’s come back at just the right moment. You have no need to forgive her sin.’ … continued in the book

6 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

The foreword in this extract has been condensed

Subscribe to Booklaunch now! Special summer offer: 50% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

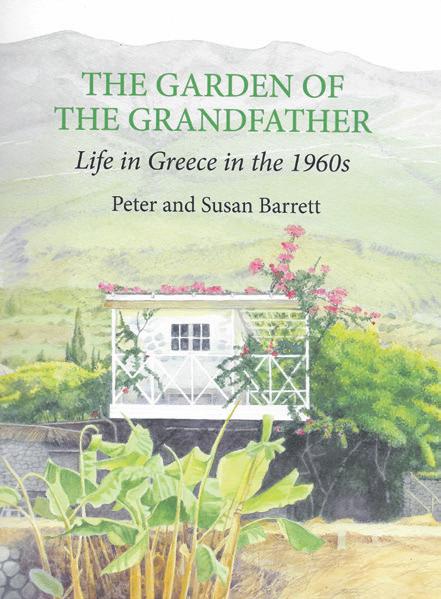

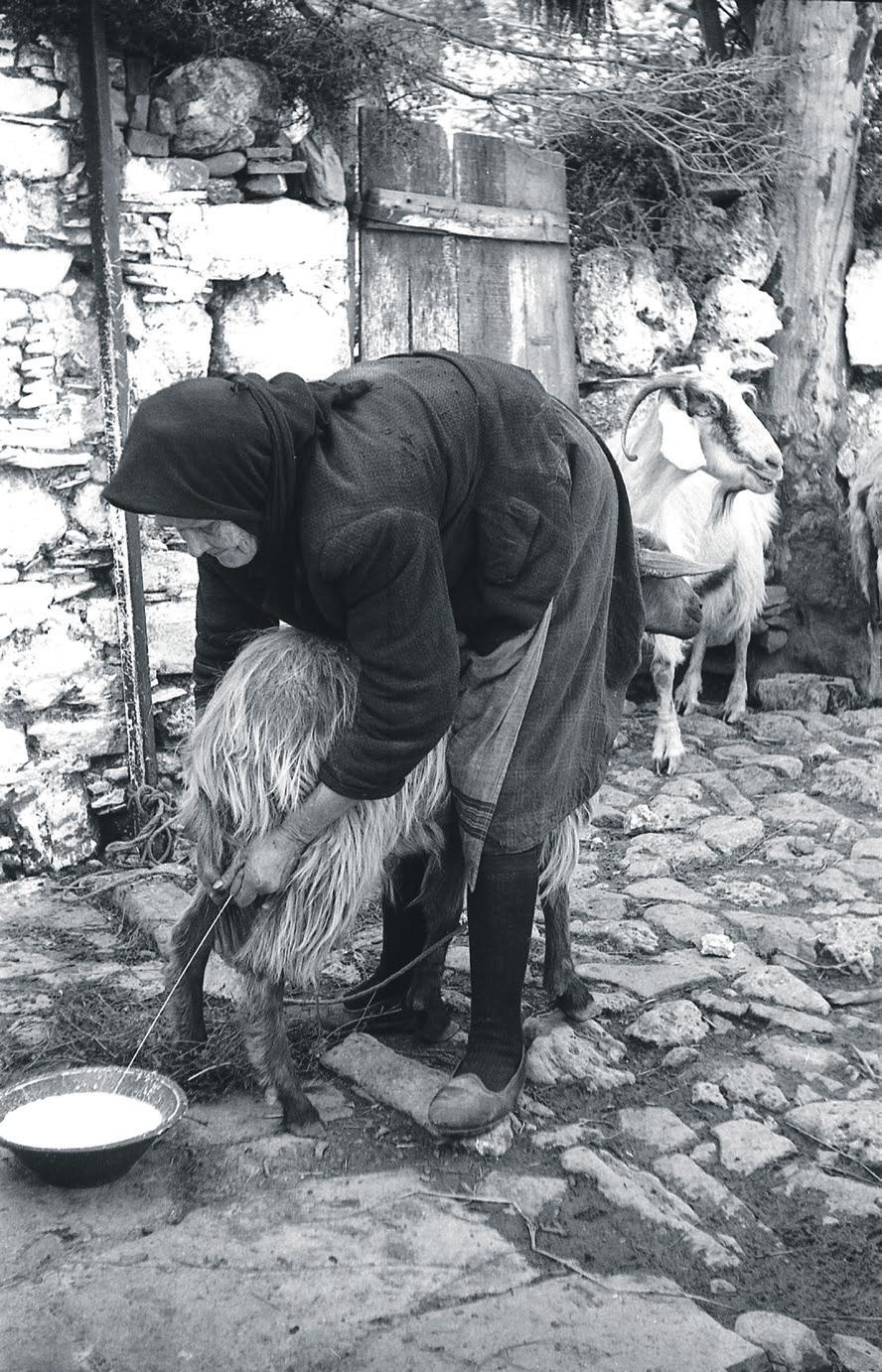

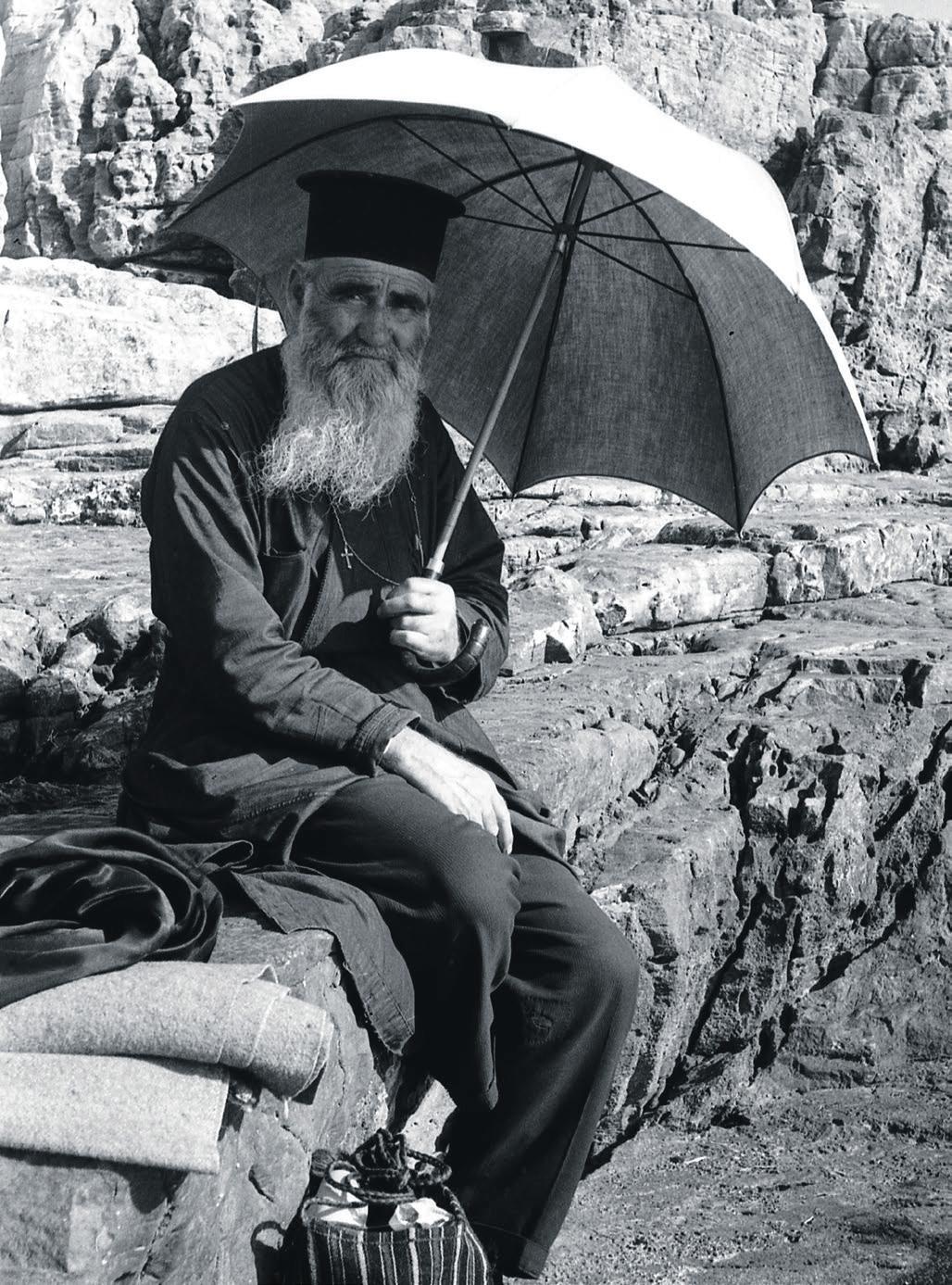

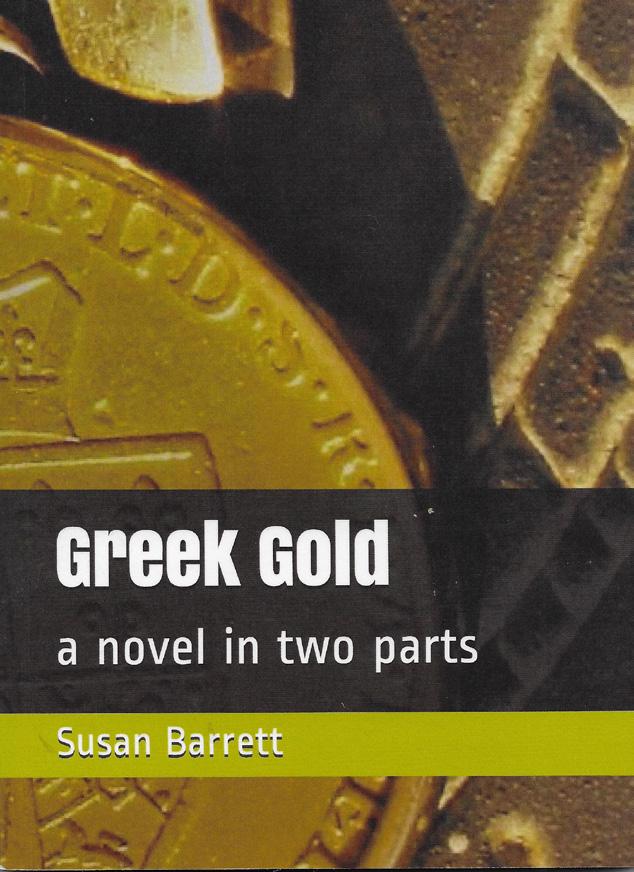

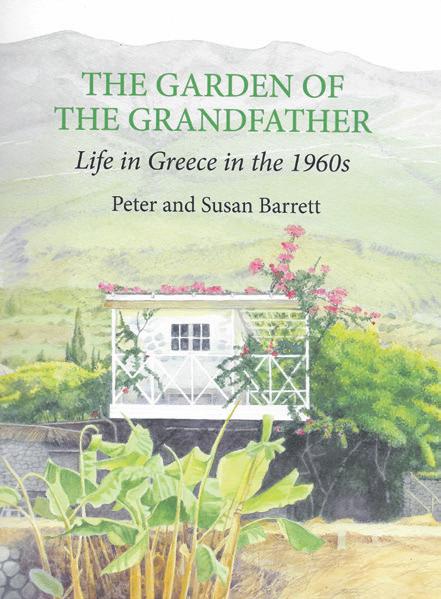

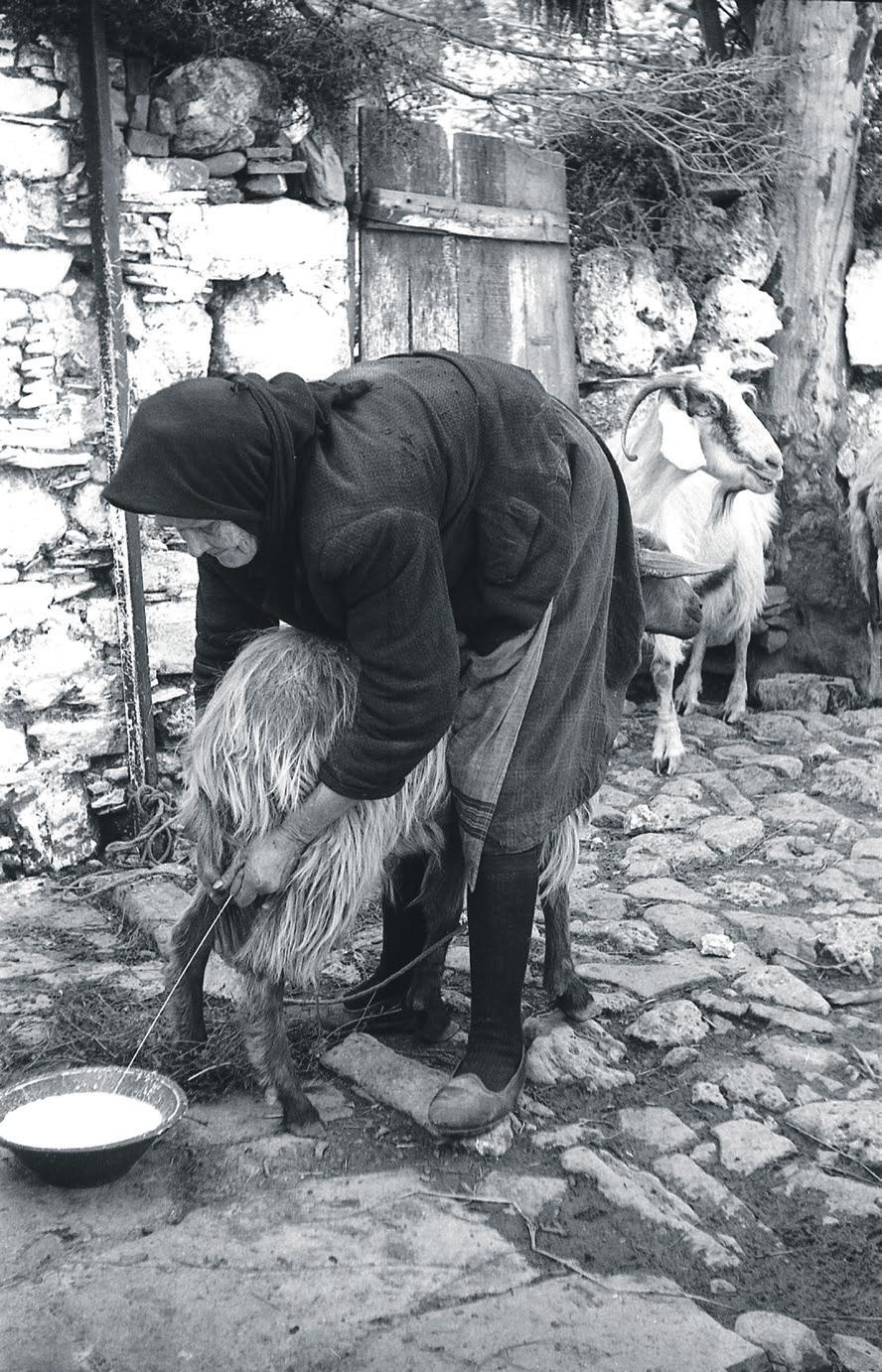

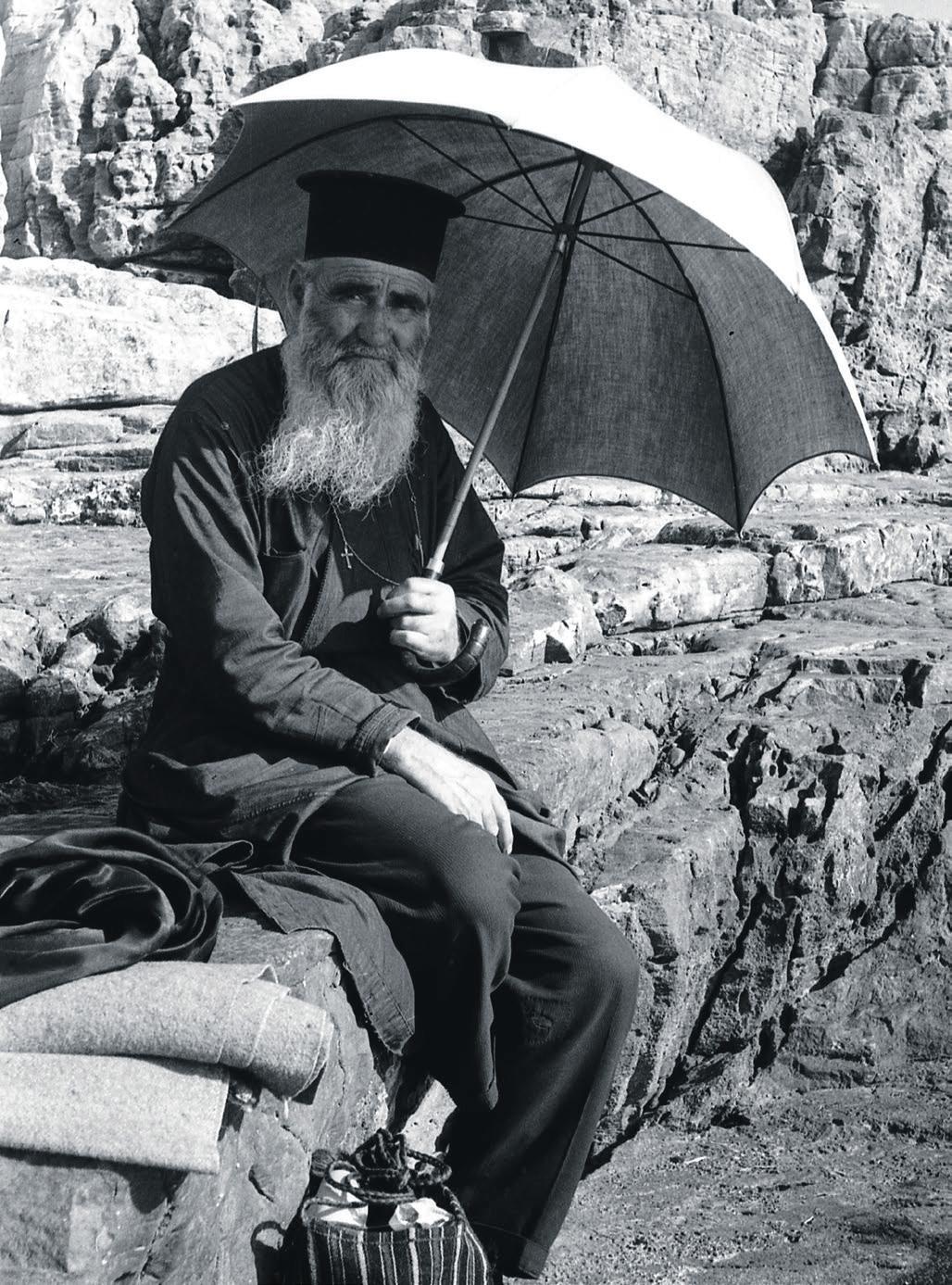

Peter Barrett was an English graphic designer who wanted to paint, Susan was a copywriter who wanted to write a novel. Two years after marrying in 1960, and with only enough holiday money to last three weeks, they drove through the Alps and Yugoslavia to try out a new life in Greece. The Garden of the Grandfather is their account, in words, drawings and photos, of what attracted them and other outsiders to Greece and how Greece changed in response

the Grandfather

The Garden of

Recommended

Our price £18.00 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

The Sixties had ended, but our decade in Greece was continuing as the island changed. Electricity had come to the villages. Prekas had installed a television set. The old men sat and stared at it, enchanted. Markos became fixated on Fleur, of The Forsyte Saga. The quay was enlarged enough for the vapóri to dock. Gone was the flurry of the little boats, the shouts and excitements of embarking and disembarking. Passengers simply walked off! More foreigners found their way to Amorgos. More people wanted to buy land. People on holiday indulged fantasies of alternative ways of life.

Simply by leading our own lives in the way we wanted, we attracted others. Sitting in pride of place in our amphitheatre of Ta Nera, we’d been nervous of development around us ever since we first bought the land. As we and Father Lorenz had managed to get permission to build outside the village, others could follow suit. The first to do so was Dionysia, originally from Chora, resident in Athens, married to a Cretan, Apostolos, who worked as a bus driver in Athens airport. Dionysia owned the parcel of land directly behind us. The building of a small single-storey house was the first challenge to our equanimity. Not only did we feel our space had been invaded, but we felt bad to feel this way; after all, we were the invaders in the first place.

The next challenge came from a rumour that a German architect had bought a large stretch of hillside on which he was going to build a holiday village. The hillside sloped down to the strip of shingle between the church and the rounded hill before the last shingle beach called Maltezi. On this knoll an American couple who’d been living in Athens had built a one-roomed house.

Another American who’d rented a little house the other side of the bay, a short walk from Katapola, was rumoured to be a CIA agent. Two Greeks in suits came to the house one day and asked a number of politely-phrased questions. This was in connection with a London-based plot to rescue a political prisoner held under house arrest on Amorgos. A former government minister, George Milonas, had been arrested in 1968. He’d been pointed out to us in excited, proud, conspiratorial whispers when he happened to pass by as we were having a coffee. He was free to roam the village between nine in the morning and six in the evening, then had to sign in at the police station and remain indoors for the night, with the police on watch outside. We only learnt about his dramatic escape after it happened. Milonas had rigged up the lights in his house to come on at a reasonable hour in the evening and to go off at his usual bedtime. The regularity of his habits, and the seeming impossibility of escape from the island, gave his guardians the confidence to retire to a nearby cafe as soon as Milonas was indoors. The next step was to look out for a couple of tourists who would walk through the village carrying a copy of a certain book. This was the signal that a rescue yacht would be offshore over the next three nights, waiting to pick him up from the beach of Agia Anna, the beach at the foot of the steep descent from Chora to the sea.

In July 1969, while the escape was carried out, we were, as usual, absorbed in our own life, unaffected by the junta except insofar as we experienced the damping-down of conversations in Prekas’s cafenion.

… continued in the book

7 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019

Peter Barrett

GREEK SOCIAL HISTORY / MEMOIR

Peter and Susan Barrett

The Garden of The Grandfather

Life in Greece in the 1960s

Peter and Susan Barrett

Pencross Books Location: Hemyock, Devon Pages: 128 Format: Softback

9781999648008

230 mm x 276 mm Photos 199 b/w; drawings 69 b/w

of publication: September 2018

Title:

Subtitle:

Authors:

Publisher:

ISBN:

Size:

Date

retail price: £18.00

1968-1972”

Susan Barrett This extract is taken from the

Chapter: “Family Life on Amorgos

What’s Wrong with Work?

Lynne Pettinger

The concepts scholars think with are both revealing and obfuscating. They legitimise some thoughts and delegitimise others. Critical discussions in the 19th century about the effects of industrialisation, and then again in the 20th century about the effects of scientific management and the development of production lines, are the heart of much insight into the study of work by sociologists. These critiques, developing from the problematic of how work is organised and the concepts that have been developed as a result of that framing, have generated deep understandings of the burdens and pains of (paid) work. But in avoiding the other questions, they provide only a partial understanding.

The most influential critical analysis emerged from Marx and Marxist ideas. These were developed through studying industrialised capitalism in 19thcentury Europe, especially Britain. The common story goes: industrial capitalism, marked by desire for profit, private ownership, a factory system, a complicated division of labour and the routinisation of work, relied on a massive growth in the numbers of wage labourers, as well as transport infrastructures, urbanisation, mechanisation of production processes and so on, as well as new economic ideas. The new workplaces of industrial capitalism were mills, factories and coalmines, and they relied on wage labour: on men, women and children who sold their labour power in return for pay. Working bodies were controlled through disciplining mechanisms like clocks, explicit rules enforced by managers, and the rush and power of the machines themselves, so significant to industrialisation.

Factory work

How does work affect us? As changes occur in how work is organised across the globe, Lynne Pettinger shows that the way in which workers are treated has wide implications beyond the lives of workers themselves. Recognising gender, race, class and global differences, What’s Wrong with Work looks at three kinds of increasingly important work: green work, IT work and the “gig” and considers the ways formal work is often dependent on informal work, especially domestic work and care work

Title: What’s Wrong with Work?

Author(s): Lynne Pettinger

Series: 21st Century Standpoints

(published in partnership with the British Sociological Association)

Publisher: Policy Press

Location: Bristol

Pages: 230

Format: Softback

ISBN: 9781447340089

Size: 216 mm x 138 mm

Date of publication: 24 April 2019

Recommended retail price: £12.99

Save £0.39

Our price £12.60 inc. free UK delivery

To buy this book, visit www.booklaunch.london/sales or point your smartphone here

The common story about factory work has a 20thcentury manifestation too. Scientific management emerging from the workplace observations of Frederick Taylor, combined with the rationalising desires of Lillian and Frank Gilbreth, respectively, a psychologist and a timeandmotion expert (famous as the inspiration for the original Cheaper by the Dozen) and with the insights of a host of other American experts, was welcomed by manufacturing companies. It seemed to promise a compliant workforce, a smooth production process, and a regulatory structure that enabled profit making, emblematised in the Fordist production line that emerged in the early 20th century. Here was a heightened, extended, measured and apparently efficient division of labour created by applying technorational theories to human ‘inputs’.

Sociological insights into the effects and implications of Taylorist production for workers came in the 1960s. This is the time when the discipline of sociology expanded, and was even a bit cool. The ‘sociology of industrial societies’, a subdiscipline where discussions about work took place, studied manufacturing to explore issues of status and belonging for male workers such as the car workers in Luton studied by Goldthorpe et al. Alienation was a buzzword, developed by Marxist writers such as Herbert Marcuse to make sense not only of work, but of the rest of life, and most insightfully for studies of work by Robert Blauner in the compellingly titled Alienation and freedom. Alienation for Blauner is not an absolute objective state (as for Marx), but varies according to four factors: the degree of control over work, the sense of purpose of work, the degree of social integration with colleagues and the degree of involvement with work. Blauner’s typology was intended to make it easy to compare work of different kinds.

problems of factory work. It aimed to emancipate workers through action at the level of the firm/organisation. As in the case of labour process theories, it reflects the concerns of its times. It drew on social psychology to address two problems of the day. The first problem was the rather paternalistic concern about how people were recruited to support extremist political parties because they were alienated by their work. Memories of European fascism and contemporary fear of communism mattered. Also in the air of the 1960s, exploding in the spirit of 1968, was a new politics of human life, a politics of subjectivity and identity beyond social class. QWL programmes offered a kind of humane capitalism by working on designing jobs that might not be completely dreadful to do. Designing better jobs meant thinking about what made good work. The 1960s list (with brief explanation) included:

• compensation (pay and benefits);

• safe and healthy (avoids damage to bodies and minds);

• develops human capacity (skill development, involved in decisions);

• growth and security (employability, personal development);

• social integration (organisational climate);

• constitutionalism (employee rights and representation);

• total life (work–life balance);

• social relevance (social responsibility in organisation).

Two ‘good’ attributes to bring the list into line with 21stcentury ideas about what people want from life are individual proactivity, where a worker can show initiative in a supportive context, and flexible work that benefits the worker, rather than just the organisation. These ideas reflect the idea that ‘good’ work is not only a question of pay and skill, but also of secure work that feels meaningful, with good colleagues. Like Marilyn Strathern, though, I suspect bullet points ‘allow no growth … create no knowledge’ because they carry no meaning. Or rather, the meaning they carry is the same kind of meaning as a shopping list. There is no space for contradiction or compensation or complexity. What on earth do these attributes actually feel like in work? On the one hand, they’re impossible to disagree with, but on the other hand, that’s because it’s not clear what they involve, or how they can be achieved. It’s complete but it’s not coherent.

QWL faded away in part because alternative management strategies emerged. Kaizen movements that organise work to encourage worker commitment have similarities, but ‘lean production’ ideas showed little interest in the conditions under which employees worked (as ‘lean’ is translated as ‘cheap’); ‘human resource management’ went for quick fixes like statements about not tolerating bullying—far easier and cheaper than getting rid of bullies. QWL left some important insights. One is that how managers and technicians design jobs is important to how they are experienced. Another is that the firm is one point where action to improve work can be taken. …

Clearly, factory work captured the imagination of sociologists of work as they tried to make sense of the effects of how this work was organised on those who did it. It’s right to have concepts to understand factory work, which remains a significant global employer. In both Marxist and nonMarxist theories for thinking about what’s wrong with work, social class is key. That bothers me.

Dr Lynne Pettinger is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick and explores work in contemporary capitalism. She is currently working on how “green-collar” workers bring eco-ethics to market; the role of higher education in producing “employable” workers for global cultural industries; and the impact of the new regulations on care and work practices in the NHS

Subscribe to Booklaunch now!

Special summer offer: 50% off www.booklaunch.london/subscribe

Critical Marxist accounts of the production line take Braverman’s Labour and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century as the lodestar. This, and the factory ethnographies it inspired, were essential to a set of concepts for studying work known as labour process theory (LPT). This tradition has been effective in generating analyses with resonance for understanding the damages of work. It prioritises three problems with wage labour: that wage labour brings exploitation as the worker receives less than the value their work adds (they are alienated in Marx’s sense of that concept); that workers cede control of their bodies for the duration of work; and that managerial control over workers’ bodies is achieved by degrading work processes to make them require less skill. Workers are bored, their tacit knowledges unrecognised and unrewarded, their potential and autonomy denied.

The quality of working life

Quality of working life (QWL) research emerged in the US, UK and Scandinavia in the 1960s to understand the

Exclusions of gender and race ‘on the shopfloor’

Of the many, many ethnographic studies of factory work, I’ve picked one to show how easy it is for researchers to obscure important features of working lives. Donald Roy’s ‘Banana time’ has become a classic study for insights into play and boredom in factory work. It discusses the games that four machine operatives (George, Ike, Sammy and Donald himself) make up to help time pass as they do incredibly repetitive jobs. In reading Roy’s paper, it’s easy to miss that there’s another person in the room with them, referred to only twice—once as ‘a female employee who performed sundry scissors operations of a more intricate nature on raincoat parts … [in] a cell within a cell’ and a second time as Baby, one of two black women who held that job during Roy’s research. Roy’s gang warn any black male workers who come to pick up the work they’ve done to ‘Stay away from Baby! She’s Henry’s girl.’ Baby’s own thoughts on her gendered and racialised sexualisation are not recorded, nor does she … continued in the book

8 www.booklaunch.london Summer 2019 SOCIAL ISSUES AND PROCESSES / WORK AND LABOUR

This edited extract is taken from Chapter Two: “Work as Production”

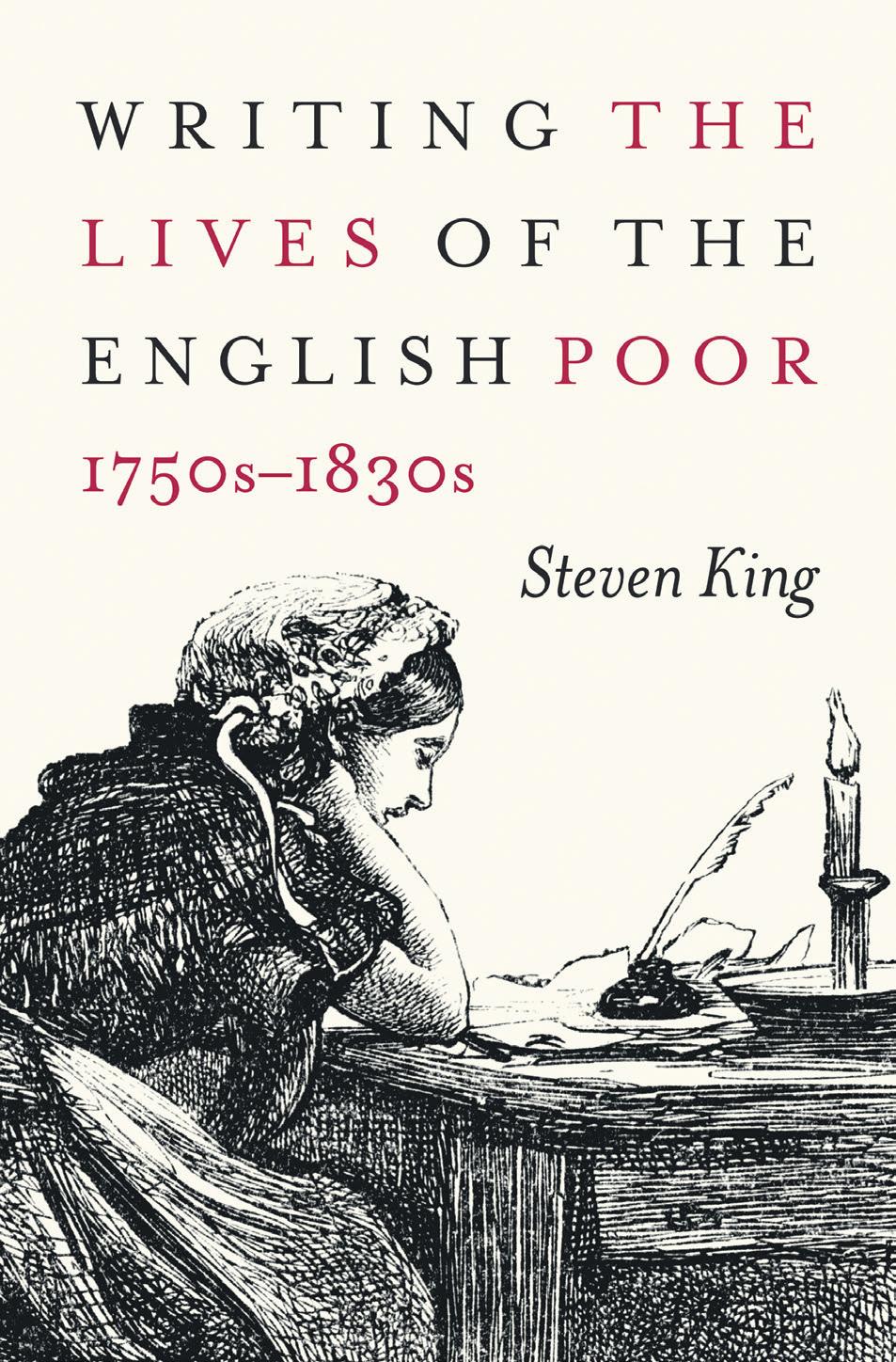

This book started with the discovery in the archives at Leeds of a set of pauper letters for the area around Calverley in West Yorkshire on 17 December 1989. My doctorate, then in its very early stages, involved undertaking a family reconstitution for Calverley-cum-Farsley and surrounding villages and subsequently linking it to other sources related to the everyday lives of ordinary people. Until that December, my efforts to understand the experiences of the poor and the place of the poor law in their demographic and socio-economic life-cycle had concentrated on the overseers’ accounts. I had taken this record of payments made to the poor on a daily and weekly basis as a firm record of who got what and thus of the place of the poor law in everyday life in that locality.

The letters of William Spacey turned this comfortable train of thinking on its head. He was not locally resident at the time he wrote, although he had been before and would be afterward. His letters were of the oral writing style that characterises Writing the Lives of the English Poor, with little punctuation, random capitalisation and the poorest of spelling, overlaid with a strong thread of local dialect. They were fascinating as material objects and for what they revealed about a seam of popular literacy that I had been led by the historiographical literature to believe did not exist.

But they were important too for other conceptual reasons. Over a series of letters, Spacey made claims on his settlement parish that included payment of arrears of rent, cash allowances and a demand that the parish supply a midwife for the birth of his eighth child. His letters were polite but firm, and they occasioned several replies from local overseers, both positive and negative. The essence of this process was that poor relief was negotiated, sometimes between the claimant and the overseer and sometimes through the intervention of someone writing on Spacey’s behalf. In this process, he did not get all that he requested, which clearly suggests that what was recorded in the overseers’ accounts represents the end of a process of relief, with the actual amount and form of relief given potentially bearing no relation at all to what was asked for.

Here, however, was a further puzzle because, although I knew that Spacey had gained relief given that his letters acknowledging such survived, there was no record of him in what were seemingly highly comprehensive overseers’ accounts. It took me many months to work out that all relief given to the poor of the town in which Spacey lived was bundled together and given as a lump sum to a local grocer who dispensed relief when business took him to that place. The payment was to him, not the thirteen or so claimants who lived in the same community as Spacey. Further research brought the discovery of sections of the Calverley vestry book, which showed very clearly that the same negotiation process was at the heart of the relief eventually recorded in the overseers’ accounts for the proximately resident settled poor. And a further chance discovery of a payment ledger for a grocer in Leeds who was tasked with paying allowances to those settled in Leeds but resident in the Calverley area added more complexity. None of the poor named in that ledger, although variously observable in the reconstitution, appeared in the overseer’s accounts for Calverley, such that a parallel system of poor relief for the nonsettled poor was actually in process.

The logic of these discoveries had important implications for my doctorate. Subsequently, my work on the Old Poor Law began to reveal many hundreds more collections of letters that mirrored or exceeded those identified for Essex by Thomas Sokoll. A careful consideration of vestry minutes (where letters of this sort were read out or otherwise recorded) and overseers’ accounts (where the costs of receiving and responding to letters were recorded) showed clearly that letters were sent in large numbers to every parish in England and Wales, and indeed in Scotland.

The fact that large collections of letters written by the poor, advocates, overseers and other officials survive in places such as Kirkby Lonsdale or Hulme, I understood, was simply an accident of preservation. All parish archives would once have looked, at least in terms of the volume of letters, like these. Some confirmation of that fact was had when I found that an overseer in the town of Thrapston in Northamptonshire had at some point disposed of individual letters but copied all of them into letter books, which then survived in the town’s archive precisely because they were books.

In this sense, and given the sometimes contemporaneous survival of vestry books for hundreds of parishes,

it became plausible and essential in my view to write about the ‘process’ of poor relief rather than simply about the outcomes that have underpinned almost all of the historiography of the Old Poor Law. A grant from the Wellcome Trust and two grants from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, along with the efforts of many paid and unpaid research assistants, volunteers and friends, generated a substantial set of letters by or about the poor, allowing me with confidence to reconstruct the tripartite epistolary world of the parish: claimant, advocate and official.

This book, then, is the product of research started in 1989 and shared with and by many others. At its heart is a dual proposition: for both the proximately resident poor and those who wrote from other places, garnering poor relief was a process, and at the heart of this process was the act of negotiation. Without an understanding of these two issues, I suggest, perspectives drawn from end-of-process overseers’ accounts give a very lopsided picture of the character, meaning and role of the Old Poor Law. To put it crudely, two entries of 5 shillings side by side in an overseer’s account do not mean, and were not meant to mean, the same thing. It matters for our understanding of both the meaning of relief and the role of the Old Poor Law what those two people had originally asked for, how and whether they had negotiated, and how parochial officials had received those acts of negotiation. Giving an allowance willingly to a blind woman of 102 years of age was different from giving an allowance of the same amount to a charlatan whom officials wished to heaven that they could get rid of.

Against this backdrop, Writing the Lives of the English Poor presents five central contentions. First, officials, claimants and advocates shared a common pot of language—a common linguistic register, as it were—with which they framed the negotiation process, whether the poor were inside or outside the parish. They spoke (and wrote) in a common currency. Second, claimants and officials understood and accepted that the stories told by and to them would have an element of fiction. In part, this aspect of the letters reflects the organic nature of the claims of individual poor people, but there was also a wider process at work in the sense that uncovering ‘truth’ was for officials likely to be a costly and time-consuming business. The poor marshalled their histories and sought narrative consistency rather than absolute truth. Officials punished narrative inconsistency rather than partial truth and acts of fiction. Third, officials expected, and were expected by the poor and their advocates, to engage actively in the process of negotiation and epistolary communication. A failure to reply to letters or to negotiate in good faith allowed claimants and their advocates to extend their case and solidify their position on the relief lists. Fourth, although officials, advocates and the poor shared a common pot of language, what mattered for the negotiation process was the way that this language was confected in rhetorical terms to press levers of deservingness. I reconstruct this rhetorical infrastructure—which might for instance include dignity, suffering, character and gender—and develop a new model for classifying and analysing pauper letters and other correspondence in the tripartite epistolary world of the parish. Finally, the poor and their advocates used their letters and personal vestry appearances to construct a distinctive ‘pauper self’. Most of those who wrote or appeared before the vestry had experienced long periods of their lives as independent economic actors. Many would go on to regain this status. Writers thus sought to construct themselves as ‘ordinary’ and their temporary dependence as ‘extraordinary’ and in some senses inevitable given the precarious nature of the lives of ordinary people.

Collectively, these arguments add up to a different sort of Old Poor Law from what we see in much of the historiographical literature, one with agency and negotiation at its core and one in which the power and rules of the state were essentially malleable at the local level. The complete and universal inability of parish officers to get the charlatan poor off relief lists and to keep them off, which is played out in deep colour across the letter collections, tells us something important about the essential character and role of the Old Poor Law. Two allowances of the same amount side by side in the overseers’ accounts really are not the same, and those end-of-process accounts really cannot locate the sentiment and meaning of poor relief, especially during the last few decades of the Old Poor Law during its so-called crisis phase. I construct, then, a more positive Old Poor Law

Writing the Lives of the English Poor, 1750s–1830s Steven King

In explaining how the English poor claimed parish funds either side of the 1800s, Steven King challenges long-held preconceptions about the language, power and social structure of ordinary people. Based on hitherto unresearched parish records, he reveals a more sophisticated interaction between advocates, officials, and the poor than was previously understood, and greater literacy in contesting and negotiating appeals for welfare

Title: Writing the Lives of the English Poor, 1750s–1830s

Author: Steven King Series: States, People and the History of Social Change

Publisher: McGill-Queen’s University Press

Location: London, Montreal, Chicago

Pages: 488

Format: Softback

ISBN: 9780773556492

Size: 152 mm x 229 mm

Illustrations: 8 b/w

Date of publication: February 2019

Recommended retail price: £27.99

Save £3.83