New offers for Booklaunch Club members

If you live in the UK, you’re already able to buy any book free of postage via our bookshop—and usually at better prices than better-known online retailers. (Yes, you know who.)

We also offer FREE unlimited access to our archive, where everything we have ever published is searchable.

If you’re hungry to hear a book being read, we offer scrolling podcasts. And if you want to get published, we can talk you through the process and get you in print.

But if you join the Booklaunch Club, we will welcome you with a FREE copy of any book you choose by one of our publishing partners: EnvelopeBooks, PostcardBooks and Broadsheet Books.

Also, when our partners bring out a new book, you’ll be able to get it at half price.

Wait! There’s more! As a member of the club, you’ll get each quarterly issue of Booklaunch delivered to your door.

And before the print magazine reaches the wider world, you’ll get a digital version of it emailed to your computer or mobile phone. Maybe you’re already a member. Then why not enrol a friend? We want this happy family of Booklaunchers to grow. So go online and sign up now!

ON OUR INSIDE PAGES

Page 1 Ukraine: editorial

Page 3 Mark L. Clifford on Hong Kong and China’s abuse of power

Page 4 Our Reader’s Guide to Ukraine and Russia

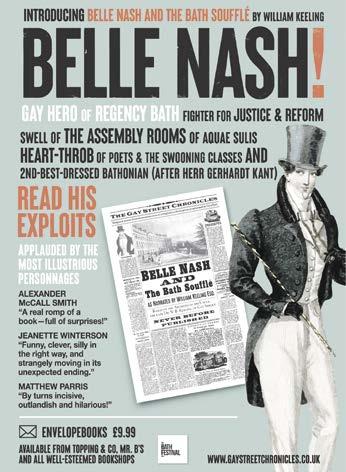

Page 9 The Gay Street Chronicle: Introducing Belle Nash, gay hero of Regency Bath

Page 13 Our Reader’s Guide to Ukraine-related fiction

Page 14 Stuart Sim defends dissent against its suppression

Page 15 George Tomaziu recalls Fascist and Communist imprisonment

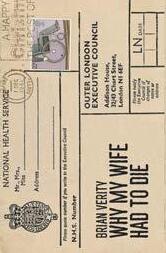

Page 16 Brian Verity’s wife inherited the Huntington’s gene

Page 17 Marguerite Poland’s awardwinning novel blasts South Africa’s Victorian churchmen

Page 18 Our sponsorship opportunity: Bart O’Fehfon’s Lingualia

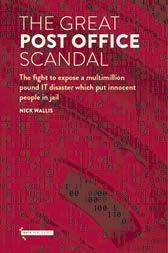

Page 20 Nick Wallis (of BBC podcast fame) on the Post Office’s Horizon IT scandal

EnvelopeBooks is looking for patrons to sponsor books and advise on new titles. If you’re interested in joining our co-publishing scheme, email: editor@booklaunch.london.

Ukraine. What next?

On 24 February Russia launched a barbaric war against Ukrainian civilians with the intention of not only acquiring an impoverished independent state with massive agricultural resources but of building a buffer-zone against countries that posed Russia no threat and, very possibly, trying to sucker those same countries into a larger war to justify its initial militarism.

One looks at all this in horror and wonders how it could happen, then thinks back to the history books and discovers that the real anomaly is not that Ukraine is now being fought over but that for much of the past 80 years, it hasn’t been.

Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, famously described by the then UK Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain as “a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

In Dark Continent, Mark Mazower’s much applauded history of Europe in the 20th century, Ukraine is referred to as one of Germany’s east-European trophies but the country does not reapper in Mazower’s narrative after 1942. To work out when the country meant anything to us, we have to go back to the Crimean war of 1853–56, during which time it was exactly the non-country that Putin says it is.

Putin’s already erratic behaviour and that non-military responses were preferable. That was not treachery or appeasement either; it was fear. Either way, it has left Ukraine having to fight its own war.

The response to opposition

To argue that NATO should be doing more requires us to welcome Russian military firepower being turned on us and the kind of all-out engagement that only Putin has a vested interest in (and perhaps North Korea too).

Our unawareness of Ukraine, until now, is the same unawareness that Donald Trump made a public virtue of in 2017 when he defended his unwillingness to involve America in Ukraine’s troubles on the grounds that Washington did not know what was going on in Ukraine and therefore could not evaluate it.

We cannot afford that because we know—just as Putin knows—that however damaging such a war would be to Russia, it would be more damaging to us, because we have considerably more to lose by it. Such a war would give Putin what he sees as his best shot at overturning a global status quo that in his view has kept Russia under the Western heel for more than a century.

booklaunch.london

booklaunch.london

@booklaunch_ldn

@booklaunch_ldn

For a Westerner, summing up Ukrainian history is almost impossible. There is no meta-story. Ukraine has been the endless victim of invasions, conquests, treaties and reconquests, sometimes not even as an end goal, more as the incidental booty of other ambitions. Ukrainians may insist that their country was an autonomous nation long before Russia was (and Russians may insists, contrariwise, on Ukraine’s having always been Russian) but for much of the last thousand years Ukraine has been snared in the expansionist struggles of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Kingdom of Poland, the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian Empire and the USSR. Shameless as Putin’s war is, it is only the latest land grab in a millennium of land grabs.

Booklaunch Literary Challenge

Readership 50,500 UK copies plus website users

Booklaunch

No.4 “Relay Race” Set by Maggie Bawden

A favourite game in our family involves making up name chains where the last surname becomes the next first name, thus Upton Sinclair Lewis Carroll Nye Bevan … or Leslie Stephen King Charles Kingsley Amis. I challenge you to produce the longest string, using famous names—

Although the largest state in Europe and the world’s breadbasket, Ukraine is also poor and easily overlooked. Unless we knew it for some other reason, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine can only remind us of

Building US policy on the back of ignorance—especially if it was feigned ignorance—rightly infuriated the Ukrainian volunteers who run the Euromaidan Press, and who accused Trump of treachery and appeasement. That was not quite right; Trump was not appeasing, merely revealing his cavalier disregard for the complex. Trump saw Putin as a warlord with every right to do in his own backyard what warlords have always done, which is why on 22 February of this year he described Putin’s invasion as “genius” and “wonderful”, the mark of “a guy who’s very savvy”.

That’s one approach to Ukraine. Another is the one agreed by members of NATO: that military involvement would only inflame

War would turn the world upside down, erasing Western advantage in what Michael Gove might recognise as a levelling-down exercise. We’d all be starting at ground zero but with Russia finally freed from the liberal reforms that the West wants as the precursor to a new entente. A war with the West would bolster Putin’s position as an autocrat and isolationist. It would give him considerably more freedom of action to do what he wants and, presumably, an even larger imperial land mass to do it on.

In terms of cold, hard realpolitik, Putin is doing nothing more than taking the long view. As an avid reader of history, he sees the West’s dealings with Russia as a continuation of the same hostility that led Britain

and France to side with an ailing Turkey in the mid-nineteenth century, and then to destroy the dockyard at Sebastopol, the largest city in Crimea, in order to subdue Russian naval power in the Black Sea and cut off Russia southern maritime gateway. Western outrage at Putin’s psychopathic violence is therefore written off by Kremlin propagandists as nothing more than what Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has described a “Russophobic frenzy”. As far as Russia is concerned, it counts for nothing.

That Russia’s woes and its belligerence are the product of the West’s ill-treatment of it is argued by Angus Roxburgh, a former BBC Moscow correspondent and a onetime adviser to the Kremlin. His book, The Strongman: Vladimir Putin and the Struggle for Russia (2013), seeks to explain how Putin went from reformer to tyrant. Drawing on dozens of exclusive interviews in Russia, from a time when he was advising Putin on press relations, Roxburgh not only repeats arguments put to him by his contacts but endorses them, claiming that the West threw away chances to bring Russia in from the cold by failing to understand its fears and aspirations following the collapse of Communism.

In this depiction of Russia as victim rather than perpetrator, Roxburgh blames Putin’s transformation on America, NATO and the EU:

Ever since [Putin] came to power, his biggest complaint to the West is that the post-Cold-War settlement never involved Russia. Russia wasn’t even consulted on what would happen. So America, basically, agreed to the accession of Eastern European countries into NATO and Russia had to put up with it but felt that it was cast as the villain in Europe—long before Putin

came to power—under Boris Yeltsin. Russian politicians were saying to Western leaders, “Look, we are democrats now. We have overthrown Communism, just as the people of Eastern Europe have. Why are you still treating us as if we are the enemy? It was the Soviet Union that was the enemy, it was the Communist power that was the enemy, and we are no longer that kind of state.” But effectively they were ignored and sidelined, and that became a festering sore for Putin. … Previous agreements—Yalta, after the war; the Helsinki Accords in 1975—the Soviet Union was involved in and so it could live with whatever came out of that, but the Pax Americana, which came into being after the Cold War, simply did not involve Russia. … Let’s face it, NATO has never really wanted to admit Ukraine and yet it pretended that it did, and that engendered even more anger in Putin. It possibly wasn’t a very sensible thing to do.

Angus Roxburgh’s idea that NATO toyed with Ukraine to provoke Russia is sharply contested by Bettina Renz, Professor of International Security at the University of Nottingham and author of Russia’s Military Revival (2017):

Ukraine has been involved with NATO in the Partnership for Peace programme since the 1990s but it [really came to the fore] after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, where public opinion … in Ukraine really swung in favour of NATO membership. NATO has been offering Ukraine a comprehensive assistance programme for military reforms … focused on democratic reforms and the need for longer-term anti-corruption reforms … but from the Ukrainian point of view, the opinion was “We don’t have the

luxury of time right now, in the face of Russian aggression.”

Angus Robertson, also a former BBC journalist (covering Central Europe) and now a member of the Scottish Parliament, argues that the belief that Russia has been kept out of the post-Soviet reality is a political falsehood. Russia, he points out, is a major player in the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Europe’s biggest security organisation. (Russia has also retained all the positions formerly occupied by the USSR, not least its permanent membership of the UN Security Council, without its having to reapply, as it arguably should have done once the USSR was disbanded.)

Robertson adds that

Russia believes … that something was lost with the end of the Soviet Union, something was lost even with the end of Tsarist Russia, and all of the places that were formerly part of that empire, from Finland through the Baltic states, even including Poland, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia—all of these places should be part of the “sphere of influence” of Russia, and that’s code for “Doing whatever the Kremlin says they should.” …

I believe people should be able to make decisions for themselves and not have the Big Guy on the block—and in this case a Big Bully on the block—tell you what you should and shouldn’t do. Ukraine has not been threatening Russia; it is Russia that has invaded Ukraine, for no good reason.

We can argue the history of geopolitics till the cows come home; those are the basic facts and, unfortunately, Russia has seen fit over the last 30 years to invade a whole series of its neighbours. … They invaded Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, they occupied part of Moldova and Transnistria, they flattened Grozny and Chechnya. … We’re dealing with somebody who believes that everybody close to Russia should jump and they’re prepared to send in the tanks to make it happen if people don’t agree. It’s not acceptable.

National character

Even though current circumstances appear novel, it is tempting to see Russia’s behaviour as reflecting a mindset hardwired into the landscape and culture and history of the region. According to Keir Giles, a senior consulting fellow at Chatham House, although the Western liberal mind wishes it were not the case, “throughout the centuries, Russia’s leaders and population have displayed patterns of thought and action and habit that are both internally consistent and consistently alien to those of the West.” Giles believes that the distinctive relationship between the ruler, the state and its subjects has affected how Russia has interacted with its neighbours and the rest of the world. Each new confrontation with Russia causes surprise and disarray in the West, but this is usually not the result of any change of policy in Moscow.

Consistent Russian state behaviours and demands can be traced not just to Soviet times but back to czarist foreign and domestic policy, and further to the structure and rules of Russian society. In this respect, what surprises some Western observers so much about Moscow’s current behaviour is simply Russia reverting to type.

In Giles’s view, we have to recognise long-standing Russian typologies. Some of these have been spelled out by Maria Alexandrovna Lipman, a Russian jour-

How to read Ukraine

This is not the happiest edition of Book–launch. With Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine and the violent projection of his nasty, cruel, vain, narcissistic, self-pitying, psychopathic personality on a population of innocents, we found ourselves clutching for books to help us get up to speed with Ukraine’s history and current dilemma.

Our suggestions are far from definitive. We have not taken into account the many readings that may exist beyond the UK market. We don’t include any Chinese texts, or books from parts of the world that have sided with Russia in recent years. Nor have we noted the mass of literature that originates from the academic Left, which tends to sympathise with Putin as the victim of NATO, the EU and the American imperialist-militarist-industrialist- consumerist-capitalist complex—with one exception: the book we refer to briefly on Page 4.

We also offer no writings on Russia and Ukraine that may have emerged from the religious right, whether it be American evangelicals or the Orthodox church, both of which applaud Putin in his campaign against the “moral crimes” of abortion, homosexuality and secularism. Nor do the thoughts of Donald Trump put in an appearance.

Our guide is, however, hemmed in by titles that deal with other examples of autocratic, undemocratic regimes. On the facing page, Mark L. Clifford sounds alarm bells about China’s treatment of Kong Kong; on page 15 we carry George Tomaziu’s memoir of being incarcerated and brutalised for 13 years by Romania’s Communists, after having been incarcerated and brutalised by Romania’s Fascists during the war; and on page 14 Stuart Sim sounds a warning about the suppression of dissent here at home.

Nick Wallis’s The Great Post Office Scandal, on the back cover, could be said to document another sort of autocracy— that of the PO mandarins, who knowingly allowed innocent postmasters to suffer— while Marguerite Poland’s award-winning novel set in South Africa in the 19th century documents the indifference and condescension of the Church towards its black African pastors.

And then there is the late Brian Verity’s angry indictment of the ill-treatment of his wife, after she was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, by her doctor, the area health authority, her nursing colleagues, her local vicar, the media, the health minister, several support agencies, her own family and the author himself.

It is with relief, therefore, that we point our readers to four pages of silliness at the centre of this issue, all based around the extraordinary persona of the newly discovered Bellerophon “Belle” Nash. Belle, whom we are led to believe was the grandson of Beau Nash of Bath, lived an unapologetically gay life in Regency Bath of the 1820s and 30s, and fought against all forms of injustice. In future instalments of his books we will see him taking up the cause of plantation slaves in the West Indies. In the first book in William Keeling’s new series (The Gay Street Chronicles), Belle sets out to explore why a soufflé fails to rise and ends up challenging the cosy status quo of Bath’s legal establishment, a topic that Oliver Bullough warns us about, in respect of London and Russia, in “The Problem of Money” on page 8. Doh—and I was going to end this on a high.

Dr Stephen Phineas Games Editor and PublisherWhen the People’s Republic of China resumed sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997, it solemnly promised to uphold for fifty years the freedoms that had developed during the British colonial era. Halfway to that milestone, China has instead embarked on a campaign to systematically dismantle the territory’s foundational freedoms: of the press, of speech, and of assembly, all underpinned by the rule of law. The party has done this with the help of the Hong Kong government (not democratically elected) and its business elite, who are too shortsighted, too concerned with immediate monetary or

and torture are common. The territory’s police responded from the first days with needless violence, setting off an escalating but completely avoidable cycle of confrontation with protesters. There was no attempt to hold the police accountable, let alone to apologize for evident excesses. At the end of a year in which thousands of rounds of tear gas and rubber bullets were fired, one in which protesters invaded and vandalized the Legislative Council, burned subway stations, fired catapult and slingshot projectiles at police, and literally ripped up the city streets, a resounding majority voted for the demonstrators’ pro-democracy agenda.

book. The National Security Law explicitly states that its provisions are global; what China is determined to do in Hong Kong it intends to do next in Taiwan (which it regards as a breakaway province) and, to a lesser degree, in other Asian neighbors like South Korea and Japan, and then around the world, from Africa to Australia. The United States and Europe are not immune; in fact, U.S. citizens have already been targeted. Universities have warned their students that what they say or write in class could be used against them in China, and the State Department has recently urged citizens to reconsider travel to Hong Kong

takeover of eastern Europe in the late 1940s and the destruction of Shanghai following the 1949 Communist Revolution in China have we seen anything like the devastation Beijing is wreaking in Hong Kong. The free world ignores the tactics on display there at its peril.

This book makes an argument for freedom. The people who lived in late twentieth-century Hong Kong—most of whom were Chinese—developed the territory into one of the most freewheeling and prosperous places in the world. At its best, this process saw Hong Kongers and their colonial rulers combine the best of British

Welcome to Hong Kong: the canary in the cage of Chinese expansionism

EDITOR’S NOTE

Does British colonial status have an upside? For 150 years Hong Kong’s residents enjoyed freedoms that did not exist in mainland China. Today, under China, basic freedoms have disappeared and activists have been jailed en masse. Between 1992 and 2021 Mark L. Clifford got to know student protestors, billionaire businessmen and senior government officials. He argues that as China emerges as a superpower, all regions falling under its control will suffer in the same way. A powerful articulation of one of the most important geopolitical standoffs of our time.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Dexter Roberts: A must-read account of the ongoing destruction of Hong Kong and why it matters to the world.

Perry Link: A masterly study of Hong Kong as the front line in the worldwide quest for human freedom.

Jeffrey E. Garten: A riveting and passionate account of China’s attack on Hong Kong.

status advantages, or too willfully naïve to understand what is at stake.

In 2019, the people of Hong Kong mounted the most sustained challenge to China’s rule since Mao Zedong founded the People’s Republic in 1949. Hong Kongers had long been pressing Beijing to make good on its promises in the city’s mini-constitution for universal suffrage. This wasn’t anything radical, simply the right to elect the mayor (known locally as the chief executive) and the city council (the Legislative Council, a largely toothless body that didn’t even have the authority to initiate spending bills). Notwithstanding its repeated pre-handover promises, Beijing couldn’t stomach the idea of sharing power with anyone who wasn’t a ‘patriot’ who ‘loves the country’. Only those politicians who support the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are eligible for office now, thus disqualifying the overwhelming majority of Hong Kongers who support democracy. Simply put, Beijing’s refusal to let Hong Kongers elect their mayor and city council set the stage for conflict. Hong Kong’s fight to preserve its freedoms against threats from mainland China is an ongoing test of a democratic society’s ability to withstand authoritarian China’s pressure. The results to date have been discouraging for anyone who believes in democracy.

The summer of 2019 began with peaceful demonstrations, as some two million people filled the city’s streets to oppose a law that would have allowed extradition to mainland China, where Hong Kong’s legal protections do not apply and where arbitrary arrests

TODAY HONG KONG, TOMORROW THE WORLD

WHAT CHINA’S CRACKDOWN REVEALS ABOUT ITS PLANS TO END FREEDOM EVERYWHERE MARK L. CLIFFORD

The History Press Hardback, 304 pages February 2022 9780750999465

RRP £20.00

China’s Communist Party, angered at its inability to bring Hong Kong to heel and convinced that Western plots to overthrow China lay at the roots of the protests, responded by ushering in an ominous new phase with the July 1, 2020, imposition of a draconian National Security Law and subsequent arrests of dozens of leaders of the democracy movement. Thus began a period of ‘reeducation’ redolent of Mao Zedong’s bloody Cultural Revolution, ten years of madness from 1966 to 1976 that saw friends and families on the mainland turn against one another as the revolution devoured its own. In the first year of the National Security Law’s introduction in Hong Kong, more than one hundred people, including journalists and political leaders, were arrested under the law’s vague and sweeping provisions. Many were denied bail, implicitly deemed guilty by handpicked judges even though it would be a year or more until their trials. Neighbor spied on neighbor, reporting in to a special national security hotline, and kindergarten children goosestepped in fulsome displays of patriotism. Books were stripped from library shelves, movies censored, and the Apple Daily newspaper forcibly shuttered. Even the act of laying flowers at the site of a pro-democracy suicide victim was deemed criminal.

What is happening in Hong Kong provides a blueprint for the sorts of tactics that China is increasingly wielding against democratic societies around the globe—its strategy of crushing dissent and silencing independent voices is central to its international play-

‘due to arbitrary enforcement of local laws’. The challenge posed by China has grown since the 2008 global financial crisis. The United States and other open societies relied in large part on China’s massive stimulus program to reflate the global economy and, in turn, they muted their longstanding concerns about civil liberties and human rights violations in the People’s Republic. For China, the financial crisis revealed the Western financial system, which it had long tried to emulate, as corrupt and showed governments unable to mount coherent reforms. More recently, the erratic response to COVID-19 in liberal democracies has further strengthened China in its belief that illiberal authoritarianism, buttressed by its techno-surveillance state, represents a viable alternative not just for China but for other countries as well.

China’s use of a combination of aggressive legal and security policies, above-ground allies and underground organisations is not just a threat to Hong Kong (where, remarkably, the Chinese Communist Party remains an underground organisation). This tiny former British colony is a testing ground for attempts to limit the freedoms of open societies. The Communist destruction of the territory’s liberties marks the only time in contemporary history when a totalitarian government has destroyed a free society— has shuttered a free press and ended free speech and freedom of assembly, and curtailed the right to be presumed innocent, the right to a jury trial, and the right to hold private property without the government arbitrarily seizing it. Not since the Soviet

institutions (rule of law, and freedom of press, religion, and assembly) with a lighttouch government to develop a strong sense of civic freedom—but without democracy, without a chance to choose their leaders at the ballot box. Notwithstanding a belated attempt by Chris Patten, the last colonial governor, to introduce more representative democracy; despite the repeated and clear support for democracy by Hong Kong voters for the three decades since Legislative Council elections began; and contrary to the repeated promises of the incoming Chinese rulers, Hong Kong has been denied democracy. This democratic denial had strong support in both the Chinese and expatriate business communities who were eager to see taxes and wages remain low. For its part, the United States was too preoccupied with Hong Kong’s role as a Cold War ally to press for more democracy. Despite ongoing official efforts to tamp down politics, Hong Kongers took advantage of Britain’s drawn-out colonial rule—its departure from Hong Kong in 1997 took place almost half a century after it left most other colonies—to develop a unique culture of freedom. That freedom is now being extinguished by a China that permits only the control of oneparty rule. This book is about how freedom was nurtured, how it blossomed and how it now struggles to survive in an increasingly hostile environment.

The Summer of Democracy

June 4, 2019—the thirtieth anniversary of the killings near Tiananmen Square, when Chinese

Our price £13.99 inc. free UK postage www.booklaunch.shop continued in the book

A Reader’s Guide to Ukraine and Russia

In an attempt to understand Russia’s war on Ukraine and the obstacles that stand in the way of peace, Booklaunch has compiled a Reader’s Guide with a range of mostly contemporary, mostly non-fiction titles. We categorised what we found under the titles “The Character of Ukraine”, “European Background”, “Under the Soviets”, “Under the Nazis”, “The Problem of Russia”, “The Problem of Putin” and “The Problem of Money”. With the exception of one title at the foot of this page (bottom right), we have not included examples of the contrarian double-think favoured by the Kremlin, prevalent though it is on university campuses. We thank three leading academics who also kindly recommended books for our list: Robert Brinkley (RB), British Ambassador to Ukraine 2002–06 and a senator of the Ukrainian Catholic University; Ľubica Polláková (LP), Assistant Director, Russia and Eurasia Programme, Chatham House; and Uilleam Blacker (UB), Associate Professor in the Comparative Culture of Russia and Eastern Europe, UCL.

The character of Ukraine

UKRAINE

BIRTH OF A MODERN NATION

SERHY YEKELCHYK

OUP, 2007

take on the interpretations developed by pre-Soviet patriotic historians. They were also influenced by the concepts and methods of the Soviet historical profession. Ukrainian nationalists and Soviet ideologues both believed in ethnic groups that possess clearly defined features and share a common destiny. Grounding a nationality in an ancient past granted it legitimacy, and defining the exact moment of its emergence as a separate ethnic group justified present-day political boundaries.

Present-day historians of continued in the book

READERS’ COMMENTS

Andrew Wilson: This is a wonderful book, ideal for students and non-specialists alike. It takes the story up to the Orange Revolution in 2004, and provides an excellent primer for further study in either Ukrainian history or contemporary politics and society.

When Ukraine became independent in 1991, the new state began developing a historical pedigree that would anchor modern political realities in a venerable past. This was not a task unique to Ukrainian historians. Italian and German historians faced a similar problem in the 19th century. The temptation to write history backwards was also typical of new national histories elsewhere.

In any case, Ukrainian scholars were not writing history from scratch. They could

Ronald Grigor Suny: Serhy Yekelchyk has written a modern history of modern Ukraine that questions nationalist mythologies and patriotic claims to an uncontested past and shows how making a nation requires the hard work of scholars and poets, soldiers and statesmen, and even Soviet bureaucrats. This is simply the best history of this new nation that we have!

Recommended by UB

UKRAINE A NATION ON THE BORDERLINE KARL SCHLÖGEL Reaktion Books, 2018

In recent years, Ukraine has been forced to confront the political conundrum posed by Russia’s invasion of its eastern regions and by its ongoing information war. To his exploration of this problem, Karl Schloegel, Professor Emeritus of the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder), adds detailed explorations of Ukraine’s major cities: Lviv, Odessa, Czernowitz, Kyiv, Kharkov, Donetsk, Dnepropetrovsk and Yalta, cities whose often troubled and war-torn histories are as varied as the nationalities and cultures that make them what they are today—survivors with very particular identities and aspirations, never more united than they are today.

THE GATES OF EUROPE A HISTORY OF UKRAINE SERHII PLOKHY Penguin, 2016

one week after the Ukrainian referendum and President George H.W. Bush declared the final victory of the West in the prolonged and exhausting Cold War.

The world next saw Ukraine on television screens in November 2004, when festive orange-clad crowds filled the squares and streets of Kyiv demanding fair elections, and got their way.

Events in Ukraine took an unexpected and tragic turn in early 2014, when a confrontation between protesters and government forces violently disrupted the festive, almost street-party atmosphere of the earlier protests. In full view of television cameras, riot police and government snipers opened fire, wounding and killing dozens of pro-European demonstrators.

The images shocked the world. continued in the book

READERS’ COMMENTS

Robert Brinkley: Born in Soviet Ukraine, Plokhy is now Professor of Ukrainian History at Harvard. This is a wonderfully readable and accessible book, which wears lightly Plokhy’s profound learning and understanding.

Ukrainians probably have as much right to brag about their role in changing the world as Scots and other nationalities have. In December 1991, as Ukrainian citizens went to the polls en masse to vote for their independence, they also consigned the mighty Soviet Union to the dustbin of history. The events in Ukraine then had major international repercussions and did indeed change the course of history: the Soviet Union was dissolved

Simon Sebag Montefiore: Complex and nuanced, refreshingly revisionist and lucid, this is a compelling and outstanding short history of the blood-soaked land that has so often been the battlefield and breadbasket of Europe.

Recommended by RB, UB, LP

WESTERN MAINSTREAM MEDIA AND THE UKRAINE CRISIS A STUDY IN CONFLICT PROPAGANDA OLIVER BOYD-BARRETT Routledge, 2018

This study by an apologist for Russia, argues that Western media went out of their way to demonise Vladimir Putin after Russia’s annexation of parts of Ukraine in 2014, and complains of the overthrow of the “democratically elected Yanukovych government” by US-backed NGOs and rightist militias. He also “counters Western media concentration” over who shot down Malaysian Airways flight MH17. The author is not a known Ukrainian expert and quotes no standard Ukrainian language sources.

THE UKRAINIANS UNEXPECTED NATION

ANDREW WILSON

Yale University Press, 2015

present Ukraine—as the product of various imaginations, both Ukrainian and other. Alongside the more obvious narrative of political and social change, I have therefore included representations of Ukraine in literature and the arts and, in the chapter on geopolitics, cartographers’ images.

I have also tried to deconstruct, in the sense of debunk, myths about Ukraine and its past—both Ukrainian nationalists’ flights of fancy and Russian and other rival nationalists’ attempt to belittle or deny Ukraine. This should not be taken as an attempt to undermine the Ukrainian idea, just to build it on more secure foundations.

The Ukrainians may now be becoming a nation before our very eyes, but this does not mean that they were always Ukrainians or that they were always destined to become such. Often the inhabitants of what is now Ukraine would have been better described as rebellious peasants, members of a particular faith, left-wing activists or whatever. Often they thought in terms of a local identity; often they saw themselves as part of other communities, some still existing, some long disappeared. The process whereby they became Ukrainians could’ve unfolded in different ways. continued in the book

UKRAINE CRISIS WHAT IT MEANS FOR THE WEST ANDREW WILSON Yale University Press, 2014

within central Europe, aided by US diplomatic inattention in the area, and how Putin’s conservative values project is widely misunderstood in he West.

The book examines Yanukovych’s corrupt “coup d’etat” of 2010 and provides the most intimate day-by-day account we have of the protests in Kiev from November 2013 to February 2014 (at which Wilson was present). It explores the military coup in Crimea, the role of Russia and long-term tensions with the Muslim Crimean Tatars. It covers the election of 25 May 2014 and the prospects for the then new president Petro Poroshenko. And it analyses other states under pressure from Russia—Georgia, Moldova, Belarus. “Russia will clearly not stop at Ukraine.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nationalists tend to see their nation as eternal, as an historical entity since the earliest times. Their history is written as the story of the nation’s trials and triumphs. In reality nations are formed by circumstance and chance. Ukrainians like to talk about the “national idea”. Precisely so. Concepts such as nations really belong to the realm of political and cultural imaginations.

The approach of this book is therefore deconstructivist. Nations are cultural constructs and this is how I have tried to

BORDERLAND

A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ANNA REID

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2015 revised edition

READER’S COMMENT

Robert Brinkley: A lively, detailed and well informed account by the UK’s leading academic expert on Ukraine. Wilson is Professor of Ukrainian Studies at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London. Recommended by RB

sionately pro-European, harks back to Ukrainians’ long struggle against foreign rule and has a small but nasty far-right fringe. The second, which powered the Maidan and dominates the current government, is about values rather than ethnicity. Being “Ukrainian”, for the hordes of patriotic young people manning a starburst of new charities and campaign groups in the capital, is not about what your surname is or what language you speak. It is about making a moral choice, about wanting a decent country and being a decent person.

They are proud that the Ukrainian journalist who initiated the Maidan is Afghan by background, and that the first two demonstrators shot dead by police were ethnically Belarusian and Georgian. continued in the book

READERS’ COMMENTS

Robert Brinkley: An excellent introduction to over 1,000 years of conflict and culture by a British writer and journalist who has lived in Kyiv and knows Ukraine well.

The Ukraine issue has rapidly escalated into a major geopolitical crisis, the most severe test of the relationship between Russia and the West since the Cold War. And it is far from resolved. Andrew Wilson’s 2014 account situates the crisis within Russia’s covert ambition since 2004 to expand its influence within the former Soviet periphery and over countries that have since joined the EU and NATO, such as the Baltic States. He shows how Russia has spent billions developing its soft power

UKRAINE

THE STORY OF A DEAD SOLDIER TOLD BY HIS SISTER OLESYA KHROMEYCHUK ibidem, 2021

Andrew Wilson has published widely on the politics of Eastern Europe, including Ukraine’s Orange Revolution and Virtual Politics: Faking Democracy in the Post-Soviet World, both of which were joint winners of the Alexander Nove Prize, 2007. His publications at the European Council on Foreign Relations (www.ecfr.eu) include The Limits of Enlargement-Lite: European and Russian Power in the Troubled Neighbourhood and Meeting Medvedev: The Politics of the Putin Succession

personal memoir and essay, Khromeychuk attempts to help her readers understand the private experience of what until January 2022 was an almost forgotten war in the heart of Europe and the private experience of war as such. This book will resonate with anyone battling with grief and the shock of the sudden loss of a loved one.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Anna Reid: Moving, intelligent, and brilliantly written, this is a sister’s reckoning with a lost brother, an émigré’s with the country of her childhood, and a scholar’s with her own suddenly acutely personal subject matter. A wonderful combination of emotional and intellectual honesty; very sad and direct but also rigorous and nuanced. It even manages to be funny.

Ukraine is now solidly and indisputably a real country. Two generations can no longer remember or even conceive of rule from Moscow. For them there is nothing comic or surprising about the idea of a Ukrainian parliament, Foreign Ministry or Supreme Court—the institutions may be loathed but their existence is taken for granted.

Two strands of national identity have come into being. The first, though pas-

Daily Telegraph: A mixture of travelogue, history, political analysis and anecdote makes this a highly digestible introduction to the tragic plight of a country whose very name means “Borderland”. “The West … had difficulty taking Ukraine seriously,” Reid writes. Her first book is a praiseworthy attempt to correct this injustice.

Recommended by RB, LP

A poignant recollection of losing her brother Volodya in combat in the Donbas in 2017 by the Director of the Ukrainian Institute London. The story is of one death among many in the war in eastern Ukraine, and its author takes the point of view of a civilian and a woman, perspectives that tend to be neglected in war narratives, focusing on the stories that play out far away from the war zone. Through a combination of

Rory Finnin: There has always been too much silence around the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine — Europe’s forgotten war. Olesya Khromeychuk refuses to bend to this silence. In vivid, intimate prose and with unflinching honesty, she introduces us to the brother she lost in the war and found in her grief. Wise and unforgettable. Recommended by RB, UB

European background

BLOODLANDS

EUROPE BETWEEN HITLER AND STALIN

TIMOTHY SNYDER

Vintage Books, 2010

Under the Soviets

Socialism and Stalinism (1933–38), the joint German-Soviet occupation of Poland (1939–41) and then the German-Soviet war (1941–45), mass violence of a sort never before seen in history was visited upon this region. The victims were chiefly Jews, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, Russians and Balts, the peoples native to these lands.

These people were all victims of murderous policy rather than the casualties of war. Not a single one of them was a soldier on active duty. Most were women, children and the aged; none were bearing weapons; many had been stripped of their possessions, including their clothes. continued in the book

READER’S COMMENT

RED FAMINE STALIN’S WAR ON UKRAINE ANNE APPLEBAUM

Allen Lane, 2017

not begin with the famine and did not end with it. Arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals and leaders continued through the 1930s. For more than half a century after that, successive Soviet leaders continued to push back harshly against Ukrainian nationalism in whatever form it took, whether as postwar insurgency or as dissent in the 1980s. During those years Sovietisation often took the form of Russification: the Ukrainian language was demoted, Ukrainian history was not taught.

In the middle of Europe in the middle of the 20th century, the Nazi and Soviet regimes murdered some 14 million people. The place where all the victims died, the “bloodlands”, extends from central Poland to western Russia, through Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic states.

During the consolidation of National

Tony Judt: The stunning contribution of Tim Snyder’s book is to present a synthetic account by an East European historian in which the focus is on the geographic zone where the lethal policies of Hitler and Stalin interacted, overlapped, and mutually escalated one another. As Snyder vividly demonstrates, their combined impact on the people living in the “bloodlands” was quite simply the greatest man-made demographic catastrophe and human tragedy in European history.

Recommended by RB, UB, LP

Under the Nazis

BLACK EARTH

THE HOLOCAUST AS HISTORY AND WARNING

TIMOTHY SNYDER

Vintage (2016)

caust was a unique event. But as Timothy Snyder shows, we have missed basic lessons of the history of the Holocaust, and some of our beliefs are frighteningly close to the ecological panic that Hitler expressed in the 1920s. “He argues that the world is still susceptible to the inhuman impulses that brought about the Final Solution,” writes Jeffrey Goldberg. As ideological and environmental challenges to the world order mount, our societies might be more vulnerable than we would like to think.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Anne Applebaum: In this unusual and innovative book, Timothy Snyder takes a fresh look at the intellectual origins of the Holocaust, placing Hitler’s genocide firmly in the politics and diplomacy of 1930s Europe. Black Earth is required reading for anyone who cares about this difficult period of history.

What actually happened in Ukraine between the years 1917 and 1934? In particular, what happened in the Autumn, Winter and Spring of 1932–33? What chain of events and what mentality led to the famine? Who was responsible? How does this terrible episode fit into the broader history of Ukraine and of the Ukrainian national movement?

Just as importantly: what happened afterwards? The Sovietisation of Ukraine did

EAST WEST STREET

PHILIPPE SANDS

Orion Publishing (2017)

Above all, the history of the famine of 1932–33 was not taught. Instead, between 1933 and 1991 the USSR simply refused to acknowledge that any famine had ever taken place. The Soviet state destroyed local archives, made sure that death records did not allude to starvation, even altered publicly available census data in order to conceal what had happened.

But in 1991 Stalin’s worst fear came to

READERS’ COMMENTS

Dominic Sandbrook: Meticulously researched, blisteringly written.

Simon Sebag Montefiore: Magisterial and heartbreaking.

Nick Rennison: Compelling in its detail and in its empathy.

Timothy Snyder: Her account will surely become the standard treatment of one of history’s great political atrocities.

Recommended by RB, LP, UB

their own families, in and around Lviv. It is through these two remarkable men—Hersch Lauterpacht and Rafael Lemkin—that the words ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘genocide’ became part of the judgement at Nuremberg and our lexicon of hate. A powerful meditation on the way memory, crime and guilt leave scars across generations.

A law professor at University College London, Philippe Sands QC has written widely about international law and participated in the 1992 Climate Change Convention and legal cases concerning the Belmarsh and Guantánamo detainees. He is currently pressing for a new internationally

READERS’ COMMENTS

Lisa Appignanesi: Even when charting the complexities of law, Sands’s writing has the intrigue, verve and material density of a first-rate thriller.

Snyder’s Bloodlands (2010; see above) was an acclaimed exploration of what happened in Eastern Europe between 1933 and 1945, when Nazi and Soviet policy brought death to some 14 million people. Black Earth explores the ideas and politics that enabled the worst of these policies, the extermination of the Jews.

It comforts us to believe that the Holo-

Ian Kershaw: Timothy Snyder’s bold new approach to the Holocaust links Hitler’s racial worldview to the destruction of states and the quest for land and food. Black Earth uses the recent past’s terrible inhumanity to underline an urgent need to rethink our own future.

Recommended by LP

Everything that happens is inevitable and yet comes as a surprise. An invitation to deliver a lecture in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv leads international human rights lawyer Philippe Sands to unearth the origins of international law and fill in the terrible gaps in his own family’s history. Sands reveals the extraordinary story of two Nuremberg prosecutors who discovered the responsibility of the former Nazi governor they are prosecuting for the murder of

Daniel Finkelstein: A magnif–icent book. A work of great brilliance. There is narrative sweep and intellectual grip. Everything that happens is inevit–able and yet comes as a surprise. I was moved to anger and to pity. In places I gasped, in places I wept. I wanted to reach the end. I couldn’t wait to reach the end. And then when I got there I didn’t want to be at the end.

Recommended by LP

In Occupied Ukraine

IN ISOLATION DISPATCHES FROM OCCUPIED DONBAS STANISLAV ASEYEV

Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2022

The problem of Russia

suffer in Russia’s hybrid war on its territory. Arrested and unlawfully imprisoned by separatist militia forces for “extremism” and “spying”, Aseyev was held captive and subjected to intermittent torture for over two and a half years. In 2021, In Isolation was awarded the prestigious Taras Shevchenko National Prize.

MOSCOW RULES WHAT DRIVES RUSSIA TO CONFRONT THE WEST KEIR GILES

Brookings Institution (2018)

READER’S COMMENT

In this collection of reports, Stanislav Aseyev attempts to understand the reasons behind the success of Russian propaganda among the residents of the industrial region of Donbas. For the first time, an inside account shows the toll on real human lives and civic freedoms that citizens continue to

Julian Evans: A rare and unsettling insider’s account of conditions in the “Donetsk People’s Republic”. … Aseyev examines unrelentingly, piercingly and scathingly why Ukrainians in the east of the country supported, and continue to support, the separatists and mercenaries and their Kremlin sponsors — in effect, how Putin’s misinformation campaign successfully revived the Soviet mindset in the Donbas.

Recommended by UB

The problem of Putin

PUTIN’S PEOPLE HOW THE KGB TOOK BACK RUSSIA AND THEN TOOK ON THE WEST CATHERINE BELTON

William Collins (2020)

people conducted their relentless takeover of private companies and the economy, siphoned billions, blurred the lines between organised crime and political powers, shut down opponents, and then used their riches to extend influence in the West.

Of particular interest is how Putin took advantage of London lawyers’ willingness to take huge fees to do his business for him and tie up his rivals in red tape.

In a story that ranges from Russia to England and Switzerland to Trump’s America, Putin’s People is a gripping and terrifying account of how hopes for the new Russia went astray, with stark consequences for its inhabitants and, increasingly, the world.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Peter Frankopan: This riveting, immaculately researched book is arguably the best single volume written about Putin, the people around him and perhaps even about contemporary Russia itself in the past three decades.

Chris Patten: An extraordinarily important book.

Oliver Bullough: Meticulously researched and superbly written; terrifying in its scope and utterly convincing in its argument … The Putin book that we’ve been waiting for.

Recommended by LP

In Moscow Rules, Keir Giles argues that Western leaders have for too long expected Russia to see the world as they do. But the world looks very different from Moscow. Seen through Western eyes, Russia appears unpredictable and irrational. Yet Russian leaders from the czars to Vladimir Putin have followed a consistent internal logic

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT PUTIN HOW THE WEST GETS HIM WRONG MARK GALEOTTI

Ebury Press (2019)

when dealing with their own country and the world outside.

Giles, a senior expert on Russia at Chatham House, suggests that accepting that Russia will never think and act as a Western nation is essential for managing the challenge from Moscow. He argues that recognising how Moscow’s leaders understand the world around them—not just Putin but his predecessors and eventual successors— will help their Western counterparts find a way of living with Russia without lurching from crisis to crisis.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Stephen J. Blank: Elegantly written, with vital insights on virtually every page, this book far surpasses most of the current literature on Russian domestic and foreign policy. Giles illuminates Putin’s world in all of its dimensions in a way that few other authors have done.

Sir Roderic Lyne: Keir Giles has explained with clarity, concision and deep knowledge why Russia cannot be understood by Western criteria alone. His book is a much-needed antidote to simplistic judgements. It should be required reading for all who deal with Western policy towards Russia.

Recommended by LP

the man behind the myth, addressing the key misperceptions of Putin and explaining how we can decipher his motivations and next moves. From Putin’s early life in the KGB and his real relationship with the USA to his vision for the future of Russia—and the world—Galeotti draws on new Russian sources and explosive unpublished accounts to give unparalleled insight into the man at the heart of global politics.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Foreign Affairs: Easily the shrewdest and most insightful analysis yet of Putin’s policymaking.

The Times: In fewer than 150 pithy pages, Galeotti sketches a bleak but convincing picture of the man in the Kremlin and the political system that he dominates.

Despite the millions of words written on Putin’s Russia, the West still fails to truly understand one of the world’s most powerful politicians, whose influence spans the globe and whose networks of power reach into the very heart of our daily lives. In this essential primer, Professor Mark Galeotti uncovers

The Guardian: Mark Galeotti, in We Need to Talk About Putin, has distilled a great deal of research and thought into a slim and engaging volume that reads like a primer for anyone poised to enter a negotiation with the Russian president. The Scotsman: Dynamic, authoritative and often witty.

The Problem of Money

THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY UNDER PUTIN EDITED BY TORBJÖRN BECKER, SUSANNE OXENSTIERNA

Routledge (2019)

A comprehensive view of the state of the Russian economy, edited by the Director of the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE) at the Stockholm School of Economics and the Deputy Research Director at the Swedish Defence Research Institute (FOI). It considers the extent of Russia’s integration in the world economy and the prospects for economic reform.

MONEYLAND

WHY THIEVES AND CROOKS NOW RULE THE WORLD AND HOW TO TAKE IT BACK OLIVER BULLOUGH

Profile Books / Main edition (2019)

READER’S COMMENT

Tom Tugendhat: Corruption undermines democracy, weakens institutions and erodes trust, it destroys lives and impoverishes millions. Moneyland starts from that truth and tells London’s part of that story.

PUTINOMICS

HOW THE KREMLIN DAMAGES THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY

ALBRECHT ROTHACHER

Springer (2021)

This book sheds new light on the political economy of Russia under Putin’s rule. The author, a former EU diplomat, presents a historical review of Russian economic activity and its 60 years of state-Communist mismanagement, followed by oligarchic privatization. The book offers profound insights into the mechanics of the way the country is managed, the arbitrariness of Russian law, and the often corrupt administration that systematically discourages entrepreneurship and the emergence of an independent middle class.

TAX CONSULTANTS

We are an established firm based in the City, specialising in handling the taxation and accountancy affairs of freelance journalists. We have clients throughout the UK. Our services include accounts preparation, tax reporting, business start-ups and advice on possible incorporation, payroll services, management accounts, bookkeeping and more.

For further details, contact us on T 020 7606 9787 E info@southwell-tyrrell.co.uk

SOUTHWELL, TYRRELL & CO

Waterproof washable elegant raincoats for men and women beautifully made in our Oxfordshire workshop

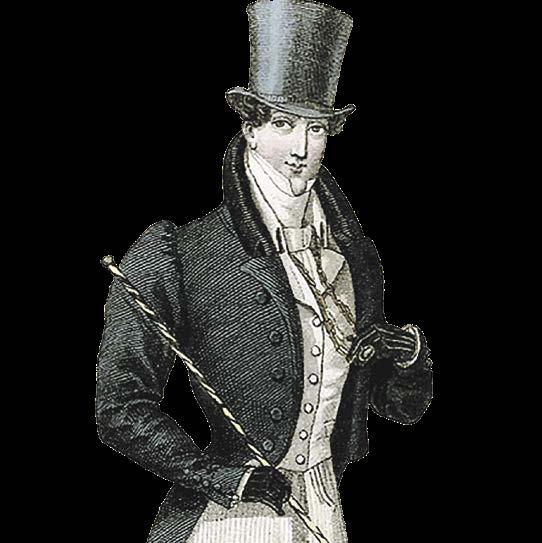

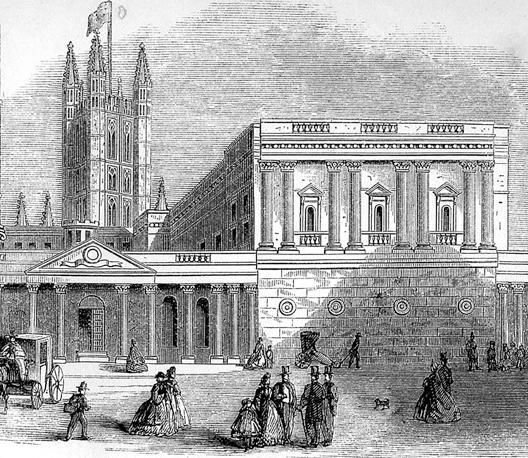

Being a true accounting of certain uncommon events occurring lately to divers persons in and around the City of Bath

HISTORIC ARCHIVE FOUND IN GAY ST.

Neighbours are astonished.

An old trunk, discovered in Gay Street, Bath, has been found to contain a treasure trove of relics from the early 1800s.

The trunk had belonged to a Dr. William Keeling, resident of Gay Street, who died in 2016.

The material secreted in the trunk includes letters, diaries and other 19th-century documents, as well as an incomplete manuscript, written by Dr. Keeling.

The manuscript brings together details of a former Bathonian, Bellerophon “Belle” Nash, whose life is fully documented in the letters and diaries but whose memory had been erased from history, for reasons that remain unclear.

According to Dr. Keeling, Belle Nash was a grandson of Bath’s celebrated master of ceremonies, Beau Nash. During the 1820s–30s, he had been a trailblazer in Bath, using his position as a much-loved city councillor to expose corruption and oppose bigotry.

EX-FT WRITER’S WORK.

The discovery of the trunk and its contents was made by Keeling’s nephew, William “Bill” Keeling, a former foreign correspondent on the Financial Times and also a Bath resident.

Having been gifted the trunk and other materials in his uncle’s will, Mr. Keeling has worked tirelessly on completing his uncle’s writings. His first volume of discoveries, Belle Nash and the Bath Soufflé, has just been published by EnvelopeBooks.

Mr. Keeling’s research has established that Belle Nash was at the centre of a small coterie of lady friends, including Gaia Champion, widow of the former solicitor Hercules Champion, whose impact on Bath’s legal infrastructure has also inexplicably been written out of the records.

Together with his female allies, Belle was able to reveal in 1831 the existence of networks of fraud pervading Bath’s legal system as well as human rights abuses by notable figures in society who visited Bath during “The Season”.

Mr. Keeling has, in addition, established that Belle was an enthusiastic bachelor, introducing to Gay Street a series of gay lovers who, in deference to the law of the time, were disguised as “cousins” and other family members.

Belle Nash and the Bath Soufflé will be the first in a five-volume series that looks at Belle Nash’s role in highlighting the attitudes of his time, often at consdiderable personal cost. The first book lays bare a condition of moral turpitude that other Regency Bathonians somehow overlooked.

Belle Nash and the Bath Soufflé is available to citizens of Bath, and to others further afield, at £9.99 from all good booksellers.

INTRODUCING BELLE NASH: REGENCY BATH’S GAY HERO Fighter for justice and reform.

Councillor belle nash is a controversial figure in Bath, courting as much love and adoration from his female friends in the Assembly Rooms as suspicion and contempt from more bigoted male members of the City Corporation.

He is, of course, a vocal critic of Guildhall corruption, and one whose bachelor habits have a tendency to polarise opinion and confuse the causes for which he fights with his own belief in personal liberty.

The redoubtable Mrs. Crust—pre-eminent pie-maker of Bath—is an unequivocal supporter.

“He is the hardest-working councillor in

HEART-THROB OF POLITE SOCIETY.

the city,” Mrs. Crust told our intelligencer, “taking on legal matters that have been allowed to fester for generations.”

Magistrate Obadiah Wood profoundly disagrees. “Mr. Nash is an interfering radical, with the temerity to challenge Bath’s happy status quo.

“As for his personal life, he is an abom-

ination. “Like all bachelors, he should be strung up, and he will be if I get to meet him on the bench.”

In recent months, Belle Nash has been seen in the company of his Prussian cousin, a Herr Gerhardt Kant, lately arrived on these shores from Königsberg.

Herr Kant has astonished Bath residents with the size of his powdered wig and the quantities of scented powder with which he dresses it.

We hope to keep our readers apprised of the doings of all the above, and the company they keep, in the pages of The Gay Street Chronicle

PRINCESS VICTORIA TO OPEN NEW PARK.

MILLINERS REPORT STRONG SALES IN ANTICIPATION.

Bath city corporation has announced that Princess Victoria is to open Bath’s new public park.

The building of a park has been an ambition of the Corporation for many years. From what we hear, it will soon be planted with exotic species.

It may attract them too. The Corporation has put the task of organising the park’s opening ceremony into the hands of Councillor Belle Nash, who is well known for cultivating exotic varieties.

BEAUTIFUL FOREIGNERS OBSERVED IN BATH.

Ribbon to be Cut.

Among the highlights of the opening of the new park will be a ribbon-cutting ceremony, in which a ribbon will be cut. The cutting will be carried out by Princess Victoria, who will wield the same pair of royal scissors as was used by her grandfather, King George III, for an earlier ribbon-cutting ceremony in the 18th century.

She will not be cutting the same ribbon, however. It will be a different ribbon, though equally ceremonious.

Music Hath Charms.

The boys’ choir of the Bath Abbey School has been booked to sing at the opening ceremony, and will be conducted by its music master, Mr Arthur Quigley.

Mr Quigley will, as always, be recognisable for wearing a tea cosy on his head, rather than more traditional headwear.

This is because, say wits in the choir, their conductor does not know how to conduct himself.

(According to The Chronicle’s Humour Editor, this is a play on words—“Does not know how to conduct, himself”, a quip so mirthful that we were obliged to take a pinch of snuff.)

A Word from our Chairman.

Asked by The Gay Street Chronicle to comment on Princess Victoria’s opening of the park, the Corporation’s 90-year-old chairman, Ernest Camshaft, said that he had lost his spectacles and therefore had nothing to say. He did however recall meeting King George III at some time in the past and looked forward to seeing the king’s scissors again.

PRUSSIAN EXOTIC SETS TONGUES WAGGING.

Canal-workers reserve judgement.

Keen-eyed residents of Bath will have noticed increasing numbers of foreign personnages in the city.

One such visitor is Herr Gerhardt Kant, handsome nephew of the famous Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Herr Kant is currently living in Gay Street with his cousin Councillor Nash, having travelled hither from Königsberg. He is an acknowledged expert on the breeding of European flora and fauna, and on the breeding of European royalty, he told me when we met at the Assembly Rooms a week ago.

“In bose cases, selection is needed to advance the species,” he said. “This is why the German prince, Prince Albert, has fine

and noble propotions while your Prinzessin Victoria ist ein midget.”

When I pointed out that Her Royal Highness is half-German, Herr Kant scoffed.

“‘Her Royal Highness,’ you say,” he told me; “I would razzer call her ‘Your Royal Lowness’.”

And with that, he rolled over on the floor and roared with impolite laughter, while more refined persons turned their backs and said nothing.

“I have ein Witz made and you stand around like a row of cabbages,” said Herr Kant, wiping his eyes. “Ze English are cripples.

“You all need mein course to take, on the

liberation of repression through regression. Two guineas per session and leave your clothes by ze door.”

Herr Kant was referring to his experiments into childhood regression, a type of therapy he believes is urgently needed by the English, who (he opines) exhibit the unhealthiest repressive tendencies in Europe.

Herr Kant is noted for his unfavourable views on everything English and his admiration for Prussia.

“The British monarchy, they are alle deutsch. and Friedrich the Great was ein großartiger gardener. I, however, am beautiful.”

“Funny, clever, silly in the right way, and strangely moving in its unexpected ending. I love the alt-Regency Bath that Keeling has built.”

THE EDITOR’S PAGE.

The most reliable INTELLIGENCER for all Bath in which truth is prised from feckless gossip.

mrs gaia champion is now officially out of mourning, following the unfortunate death of her husband a year ago from the plague of cholera.

To mark the occasion, Mrs Champion held a supper to celebrate not her own re-emergence into society but the birthday of her good and honourable friend, Bellerophon Nash, whose manly looks laugh off his thirty-five years.

In attendance were Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor, Mrs. Pomeroy of Lansdown Hill and Miss Phyllis Prim.

NO LAW FOR WOMEN.

We understand that Mrs. Champion is disappointed by the lack of positions for women in her late husband’s field the Law.

Before his sad demise, Mrs. Champion had worked closely with Mr. Hercules Champion to protect the Rights of Man— and Women—in Bath.

It is whispered, she feels she could carry forward his vocation, if only opportunity were forthcoming.

That, sadly, is an unlikely prospect in today’s Bath, even for those of us of a forward-thinking disposition.

Magistrate Obadiah Wood, by contrast, is satisfied with keeping the gentler sex at bay.

“A woman’s place is in the withdrawing room, playing—either a fortepiano or a hand of cards,” he says. “Give females access to the law and we would all be laced up in whalebones and crinolines. Divel take them!”

FELIX INFELIX.

Acat belonging to the Bishop of Bath & Wells became stuck in a croquet hoop Saturday afternoon last.

Among those present was Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor, who found His Eminence spread-eagled on the palace croquet lawn, trying to force his cat, Horace, from the hoop.

According to Lady Passmore, Bishop George Monstrance had ordered a break in play so the cat could attempt to chase a mouse.

We understand that the episcopal gardener had tied the mouse to the hoop with a piece of string, to make it easier for the cat, which is overweight. “Horace swallowed the mouse whole, and then got stuck.”

Efforts to release the feline included tempting him with his favourite tincture of milk and Armagnac, to no avail.

A croquet mallet eventually proved efficacious.

PUBLIC NOTICES.

Mrs H Bakes Exceedingly Hard Cakes

Enjoy Mrs Haytit’s rock cakes at Mrs Haytit’s Tearooms, Abbey Green. Baked fresh every month. Crumpet on the side.

Martin Babbage

Tooth Surgeon and Barber

Teeth-pulling and a shave for less than a penny. Lead fillings extra. Located next to Hickory Undertakers.

Joshua Simpkins & Co

Four all yur printin rechoirmentts expurt typsetters. Fyunereal notices a specialitity. Alfo lokated next to Hickorys.

Porter’s Best Value Flour

Why pay more for flour when you can get it cheap with Porter’s Finest? As recommended by Mr. Cullen of Oldfield, supplier of cattle feed. Recommended also by Shirley Haytit (tearoom proprietrix), who testifies that Porter’s Finest (manufacturer: Mr. Hezekiah Porter) is what makes her rock cakes so hard and manly.

Bath’s Bachelors

The Flora & Fauna Society will be holding its Annual General Meeting for Bath’s Bachelors in the shrubbery by the pond in Royal Victoria Park at midnight next month. Umbrellas advised

MAGISTRATE’S CIRCULAR.

Last week, Magistrate Obadiah Wood, hereby, ruled as guilty:

Master Thomas Perry, aged 12, stealing an apple (fallen)—six months turning the crank in prison.

Mr Franklin Jones, aged 26, for poaching a rabbit—three years in a Workhouse.

CUSHION MANIA HITS BATH. POLITE SOCIETY IS THRILLED.

Mr ernest camshaft, Chairman of the Bath City Corporation, has issued a statement deploring the demand for cushions. This followed a warning of a run on cushions issued by Stuckey’s Bank.

Messrs. Croft and Lloyd, soft-furnishings managers at the newly opened Jolly’s store on Milsom Street, confirmed the news.

Mr. Croft declared himself that, “We have seen unprecedented demand for cushions in recent weeks. Such home accessories are put into service not only on chairs, but also on beds. We do not put cushions on beds at Jolly’s and we see no reason for the practice.”

The managers report that they will have no new stock until Thursday hence.

Disappointedcustomers.

The demand for cushions has split public opinion. Mrs. Pomeroy of Lansdown Hill is among Jolly’s disappointed customers.

“I put a couple of cushions on my bed a month ago and they looked wonderful nice. Now I have thirty-two on the bed and none left on the chairs. I feel badly let down by Jolly’s.”

Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor, however, was more chary, describing Mrs. Pomeroy’s use of cushions as “not amus-

ing but typically selfish and quite possibly immoral”.

Lady Passmore reveals that she has told Mrs. Pomeroy that there should never be more than one cushion on a bed, and never for decorative purposes.

Miss Prim of Gay Street attests that cushions are conducive to happiness and that she has knitted and stuffed cushion covers for the Mineral Water Hospital for more than a year. Dr. Griffith, the Superintendent of the Hospital, confirmed that the hospital had been experiencing a surfeit of cushions, thanks to the enterprise of Miss Prim. “We appreciate Miss Prim’s kindly efforts,” Dr. Griffith noised to us, “but her cushions are not really suitable for hospital purposes. We are of a mind to offload them onto the abbey church.”

The suggestion was applauded by Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor, who noted that “the abbey pews are deplorable hard.”

The public craving for cushions is said to extend beyond Bath, to Chippenham, onward to London and even to the distant dominions of the English Empire. No cushions have been reported in Radstock, but recently returned mariners affirm that some have been seen as far away as the Caribbean.

Messrs Croft and Lloyd, aged 43 and 46, for failure to supply a cushion on request to the Office of Magistrate—six months in Pulteney Gaol.

Mr Tobias Bailey of no fixed abode, aged 18, for having no fixed abode—transportation to, and hard labour in, Australia

Miss Florence Whately, aged 17, Maid—a fine of ten shillings for claiming goods sold to her by Mr. Hezekiah Porter were not fit for consumption.

No defendants were found innocent because all were guilty, which should have been obvious without having to take up the court’s time.

Lost & Found Property.

Lost—Miss Phyllis Prim of Gay Street reports the loss of two balls of wool and a double-point knitting needle, from last Sunday’s 10 o’clock service at Bath Abbey.

Lost Mr Arthur Quigley, music master, has lost a set of spoons, but is pleased to report that he has found his Landolfi violin, which he had mistaken for a quill.

Found a pair of spectacles bearing the initials EC.

Correction: Dr Sturridge, who had previously informed The Chronicle that he had lost his marbles, now wishes it to be known that he has not lost his marbles. Dr Sturridge avers that his marbles, along with 223,612 other marbles, can be found approximately two miles north east of the city of Shangdu in Mongolia.

“By turns incisive, outlandish and hilarious! … there’s a brilliance in The Gay Street Chronciles, half-modern, half Dickensian.”

MATTHEW PARRIS

Mrs.Champion discards her blackcrêpe.

ALEXANDER MCCALL SMITH

LESS INTERESTING NEWS ABOUT THE ROYAL VISIT.

Mrs. Crust chortles.

Mrs. Crust, the proprietrix of Mrs. Crust’s Pie Shop on Abbey Green, hopes the forthcoming visit to Bath by Princess Victoria will provide a boost to trade.

“If Her Royal Highness would only honour me by dropping by, I’m sure that others will follow,” she told The Chronicle, when we paid a visit to her pie-lover’s emporium last week.

“Then I will call her my Pied Piper!” she added, chortling. We chortled too, but more politely, being of a higher social standing than the pie-maker.

Three ladies polled.

Apoll of three ladies indicates universal excitement at the visit of Princess Victoria to the city.

Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor will be wearing her wedding jewellery for the occasion. She tells our intelligencer that this will remind her of the devotion of her husband, Lord Admiral Passmore, who has

been living in Jaipur for twenty years and is not expected to return.

The attendance of Mrs. Pomeroy of Lansdown Hill on the great day is not in doubt.

“In case dear Mrs. Crust runs out of pies, I will be having several cakes baked to mark the day,” she assured The Gay Street Chronicle

“A Battenburg Cake, to celebrate the princess’s German antecedents. And a Genoise, to celebrate the princess’s Italian antecedents. Also, a Seed Cake, in case of any other ante-seed-ents.”

Bunting of no medical use.

NEWS FROM QUITE A LONG WAY AWAY.

Explorers return to Bath.

All society is relieved to learn that local explorers Dr. Erudite Whittlemarsh and his wife Mrs. Tulip Whittlemarsh have returned to Bath following their latest daylong expedition.

Dr. Whittlemarsh and his wife had availed themselves of the clement weather to walk up to Combe Hay and thence along the Cam Brook river. The walk is a long one.

“We found people living a further two hours distance in a village called Peasedown St. John,” Dr. Whittlemarsh confided to The Gay Street Chronicle. “We had heard rumours of this village but can now thoroughly confirm its existence.”

their rustic utterances and quaint ways.

“The people of Peasedown St. John bespeak one big happy family,” bespoke Dr. Whittlemarsh afterwards, “named Hobhouse. They like to keep it that way, apparently.”

On their travels to these distant regions, the explorers witnessed farmhands at work, harvesting apples, collecting eggs and besporting themselves in sundry barns and haycocks. In his diary of scientific jottings, he noted, “The farmers have chickens and ducks. Both lay eggs that can be boiled, fried and scrambled. The rustic people like to be laid and scrambled too.”

Miss

Phyllis Prim, Bath’s foremost knitter, will be knitting two hundred feet of bunting, which she has offered to re-work into a patchwork quilt for the Mineral Water Hospital after the event.

We understand that Dr. Griffith, the Superintendent of the Hospital, intends to turn the offer down. He says he is not aware of any medical value in bunting, except perhaps as a swab.

Mrs Whittlemarsh had taken with her

Asked about future expeditions, Dr. Whittlemarsh recalled that, whilst in

a steak-and-venison pie, bought from Mrs Crust’s Pie Shop, and had asked her maid Mary to share her slice with the local countryfolk whom they encountered en route

While the villagers of Peasedown St. John betook themselves of Mrs. Whittlemarsh’s provender, Dr. Whittlemarsh betook himself of the opportunity to make notes about

Peasedown St. John, the name of another nearby habitation was bevoiced, viz. R*dst*ck. Great-grandfather Hobhouse, however, warned of dangers facing gentlefolk approaching what he said was “a vile, sinful place”. Dr. and Mrs. Whittlemarsh have therefore foresworn forevisiting R*dst*ck but to bevisit beother betowns instead.

“A real romp of a book – full of surprises!”

“Bravo. A rollicking tale of corruption, intrigue and romance. A racy read!”

PETER TATCHELL

A Reader’s Guide to Ukraine and Russia

Remarking on her novel A Sin of Omission (p. 17), the author Marguerite Poland comments “Had biography been my métier, I would prefer to have honoured the subject of my book with a meticulous history. But I am a novelist, and so I wrote a novel instead.” Poland does herself a disservice: her novel reaches out to us in ways that a history could not, as do the novels and short stories that follow. We are grateful again to Ľubica Polláková (LP) and Uilleam Blacker (UB) for their recommendations.

THE ORPHANAGE SERHIY ZHADAN

Yale University Press, 2021

Recalling the brutal landscape of The Road and the wartime storytelling of A Farewell to Arms, The Orphanage excavates the human collateral damage wrought by the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine. When hostile soldiers invade a neighbouring city, Pasha, a thirty-five-year-old Ukrainian language teacher, sets out for the orphanage where his nephew Sasha lives, now in occupied territory. Venturing into combat zones, traversing shifting borders, and forging uneasy alliances along the way, Pasha realizes where his true loyalties lie in an increasingly desperate fight to rescue Sasha and bring him home.

Recommended by UB

ODESSA STORIES ISAAC BABEL

Pushkin Collection, 2016

Odessa was a uniquely Jewish city, and the stories of Isaac Babel—a Jewish man, writing in Russian, born in Odessa—uncover its tough underbelly. Gangsters, prostitutes, beggars, smugglers: no one escapes the pungent, sinewy force of Babel’s pen. From the tales of the magnetic cruelty of Benya Krik—infamous mob boss and one of the great anti-heroes of Russian literature—to the devastating semi-autobiographical account of a young Jewish boy caught up in a pogrom, this collection of stories is considered one of the masterpieces of 20th-century Russian literature.

Recommended by LP

GREY BEES ANDREI KURKOV

MacLehose Press, 2020

Little Starhorodivka, a village of three streets, lies in Ukraine’s Grey Zone, the no-man’s-land between loyalist and separatist forces. Thanks to the lukewarm war of violence and propaganda, only two residents remain: retired safety-inspector-turned-beekeeper Sergey Sergeyich and Pashka, a “frenemy” from his schooldays. Under the ever-present threat of bombardment, Sergeyich’s one remaining pleasure is his bees. As spring approaches, he knows he must take them far from the Grey Zone so they can collect their pollen in peace. This simple mission on their behalf introduces him to combatants and civilians on both sides. Wherever he goes, Sergeyich’s childlike simplicity and strong moral compass disarm everyone he meets. But could these qualities also spell disaster for him?

BABA DUNJA’S LAST LOVE ALINA BRONSKY

Europa Editions, 2016

Baba Dunja is a Chernobyl returnee. Together with a motley bunch of former neighbours, she sets off to create a new life for herself in the radioactive no-man’s land. In spite of the Geiger counter and irradiated forest fruits, the group finds everything it needs in its abandoned patch of Earth. Terminally ill Petrov passes the time reading love poems in his hammock; Marja takes up with 100-year-old Sidorow; Baba Dunja whiles away her days writing letters to her daughter. Rural bliss reigns, until one day a stranger turns up in the village, and the small settlement faces annihilation once again.

Recommended by LP

DEATH AND THE PENGUIN ANDREY KURKOV

Vintage, 2003

Viktor is an aspiring writer in Ukraine with only Misha, his pet penguin, for company. Although he would prefer to write short stories, he earns a living composing obituaries for a newspaper. He longs to see his work published, yet the subjects of his obituaries continue to cling to life. But when, finally, he opens the newspaper to see his work in print for the first time, his pride swiftly turns to terror. He and Misha have been drawn into a trap from which there appears to be no escape.

Recommended by LP

LIFE WENT ON ANYWAY OLEG SENTSOV Deep Vellum Publishing, 2019