EnvelopeBooks title wins first prize

Just a year after bringing out its first book, Booklaunch’s publishing partner, EnvelopeBooks, has a prizewinner on its hands. Marguerite Poland’s powerful novel A Sin of Omission has been chosen by judges in South Africa as their 2021 Sunday Times CNA “Book of the Year”, the country’s most prestigious literary award.

A Sin of Omission is the fifth novel by Poland, a highly acclaimed novelist and linguist, fluent in both Xhosa and Zulu. Her book was published in South Africa by Penguin Random House in 2019 and will be published in the UK and Ireland by EnvelopeBooks in May. In 2020 it was shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction.

Set in the 1870s, A Sin of Omission tells the story of a young black Anglican priest torn between his loyalties to his people and to the Church.

Poland’s win coincides with fellow South African Damon Galgut’s winning of the Booker Prize for The Promise, after his being shortlisted twice before, in 2003 and 2010.

To sponsor this book and get your name in its list of patrons, email book@booklaunch.london.

Volunteers wanted for BL website makeover

Now in its fourth year, the Booklaunch website is being redesigned, to improve its utility and reach.

The design team is looking for 100 volunteers to take part in focus groups. We need feedback on what works and what doesn’t and what could work better.

Please email Jenny Chalcott at subs@booklaunch.london. Participants will be warmly rewarded with a literary gift.

Florentine enthusiast pens masterpiece

Florence is Western culture’s bridge between the medieval and the modern. In Richard Lloyd’s new magnificent book, the story of that journey is ably illustrated with photographs and explanations. Shown here: Orcagna’s tabernacle in Orsanmichele, Florence’s “most spectacular and ornate piece of Gothic art”. It was designed to house Bernardo Daddi’s Madonna delle Grazie, a formulaic image of the Virgin and Child that evolved, Lloyd tells us, from images of Isis, the Egyptian goddess of the Earth (holding her son Horus) to whom an earlier, Roman building on the site was probably dedicated. The year after Daddi completed his painting, the Black Death struck and many of those who survived credited their good fortune to the intervention of the Madonna. May be worth making a quick pilgrimage to it now. See also page 7.

ON OUR INSIDE PAGES

LINGUISTICS

Page 3 Lingualia Quiz, solution and wordplay

Page 4 Simon Prentis challenges Chomsky

Coming soon—Belle Nash

A new literary hero is about to burst forth: Belle Nash of Bath—dandy, city councillor and confirmed bachelor.

Surrounded by a bevy of female friends, and a couple of adoring men, Bellerophon Nash—grandson of Bath’s celebrated master of ceremonies Beau Nash—is about to investigate his first mystery: the failure of a soufflé to rise.

Trivial? At first sight, yes. But when Belle and his accomplices stake out two ne’er-do-wells, the corrupt state of Bath officialdom is laid bare—as is his new young assistant, though under different circumstances.

Belle Nash and the Bath Soufflé is due out in March and will be the first in a five-part series, The Gay Street Chronicles. It has been welcomed by Alexander McCall Smith (“a real romp of a book!”), Peter Tatchell (“a rollicking tale of intrigue and romance!”) and Matthew Parris (“incisive, outlandish and brilliant!”).

To sponsor this book and get your name in its list of patrons, email book@booklaunch.london.

EnvelopeBooks is looking for patrons to sponsor books and advise on new titles. If you’re interested in joining our co-publishing scheme, email: editor@booklaunch.london.

Readership 50,500 UK copies plus website users

Page 5 Lyle Campbell’s life in language research

Page 6 Bullying in Belfast and adolescent love

Page 7 How the Renaissance flourished in Florence

Page 8 Veterinary history around the world

MEMOIRS OF AN ENGINEER

Page 9 Harry Lott left a vivid account of his social and professional life in Canada, Iraq and Kenya as well as during the First World War

Page 13 The unequal fight for British Modernism

Page 14 Pros and cons of the informal economy

CULTURAL IDENTITIES

Page 15 Why was liberalism deaf to the black voice?

Page 16 The ascendancy of a Welsh Marcher family

Page 17 The White Rhodesian case for recognition

Page 18 Elemental science in an Edinburgh novel

Page 19 Po Cheng’s journey to medieval China

A digest of important new books in their own words. For readers who want to know more about more. Subscribe today. Issue 13 | Early Spring 2022 | £2.50 where sold We welcome enquiries from publishers and authors www.booklaunch.london

Booklaunch

Booklaunch Booklaunch Booklaunch Literary Challenge No.4 “Relay Race” booklaunch.london @booklaunch_ldn

booklaunch.london @booklaunch_ldn

Why not take out a New Year subscription to this national/international poetry journal to keep up with poetry that is a vital, inspirational force of life. A celebration of known and new voices, interview with multi-award winning David

Subscribe at: www.agendapoetry.co.uk

Subscription queries to: admin@agendapoetry.co.uk Tel: 01825 831994

Inland Subscription rates: Private £28; Concessions (students/OAPs) £22 ; Libraries and Institutions £35

WANT TO BE A PUBLISHED AUTHOR? TRUST BOOKLAUNCH

We’ll give you step-by-step feedback on your book

We’ll work with you to improve your manuscript

We’ll help you choose a great book title

We’ll design you a powerful book cover

We’ll help you choose the best publishing platform

We’ll format and upload your book

We’ll help you price your book

We’ll set up a print-on-demand service for readers

We’ll help you design a publicity campaign and we’ll reserve you a page in Booklaunch

Important note: We’re very selective. We won’t take on your project unless we’re really impressed by what you’ve written and think it has potential.

Contact us in confidence: book@booklaunch.london

FERNSBY HALL TAPESTRIES

Tapestry kits produced by Diana Fernsby from the original paintings of Catriona Hall. Kits from £55 Tel: 01279 777795

Kits@fernsbyhall.com

www.fernsbyhall.com

TAX CONSULTANTS

We are an established firm based in the City, specialising in handling the taxation and accountancy affairs of freelance journalists. We have clients throughout the UK.

We can help and advise on the new changes under Making Tax Digital including helping to set up the MTD compatible software and bookkeeping.

Our services include accounts preparation, tax reporting, business start-ups and advice on possible incorporation, payroll services, management accounts, bookkeeping and more.

For further details, contact us on T 020 7606 9787 E info@southwell-tyrrell.co.uk

SOUTHWELL, TYRRELL & CO

ADVERTISING | NICK PAGE | 07789 178802 | PAGE@PAGEMEDIA.CO.UK

SUBSCRIBE to this famous national/international poetry journal

Founded by William Cookson and Ezra Pound 1959, now edited by Patricia McCarthy (since January 2003)

Tread softly… Irish Poets in the uk Vol 54 Nos 3–4 Vol 54 Nos 3–4 Price £12 €14 $17 Tread softly… Irish Poets in the UK include: POEMS AMONGST OTHERS: MichaelLongley BernardO’BrienO’Donoghue CaitríonaO’Reilly Peter McDonald Belinda Cooke William Bedford ColetteBryce CathyGalvin Kevin GeraldCrossley-Holland Dawe John HaydenMcAuliffe Murphy LeontiaFlynn Seán Vona Groarke Maurice Riordan INTERVIEWS WITH Cooke Peter McDonald REVIEWS/ESSAYS BY: A.DavidMoody HilaryDavies John JeremyGreening Hooker PatrickLodge JohnMilneO’Donoghue Ben GerardKeatinge Smyth CHOSEN BROADSHEET POET: Tristram Fane Saunders CHOSEN REVIEWER:BROADSHEET Elizabeth Ridout FRONT COVER: painting bySarahLongley Weatherings Vol 54 Nos 3–4 Vol 54 Nos 3–4 Price £12 €14 $17 Weatherings include: POEMS BY, AMONGST OTHERS: Michael Longley Bernard O’Donoghue Sean O’Brien Caitríona O’Reilly Peter McDonald Belinda Cooke William Bedford Colette Bryce Cathy Galvin Kevin Crossley-Holland Gerald Dawe John McAuliffe Hayden Murphy Leontia Flynn Street Vona Groarke Maurice Riordan INTERVIEWS WITH David Cooke and Peter McDonald REVIEWS/ESSAYS BY: A. David Moody Hilary Davies John Greening Jeremy Hooker Patrick Lodge John O’Donoghue W Milne Ben Keatinge Gerard Smyth CHOSEN BROADSHEET POET: Tristram Fane Saunders CHOSEN REVIEWER:BROADSHEET Elizabeth Ridout FRONT COVER: painting by Sarah Longley Single copies available

Harsent, reviews, essays.

Booklaunch 12 Wellfield Avenue, London N10 2EA

Distribution Upwards of 50,000 print copies

Website www.booklaunch.london

Publisher/editor Dr Stephen Games editor@booklaunch.london

Design director Jamie Trounce jamie@jamietrounce.co.uk

Assistant editor Maggie Bawden book@booklaunch.london

Advertising Manager Chi-Chi Chimbawa ads@booklaunch.london

Advertising Rep Nick Page page@pagemedia.co.uk

Tel: 01428 685319 Mobile: 07789 178802

Printer Mortons Media Group Ltd

Subscriptions Jenny Chalcott subs@booklaunch.london

UK £10.00/Overseas £21.00 via our website

I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said ... Bart O’Fehfon

While out walking with me, a neighbour described a passing bird as predacious. I should have known better than to query his use of the word, given that he’s a prof of biology, but it sounded dicey to me, and I duly asked him if it really was a technical term or if he was just using it as a conversacious alternative to predatory.

He assured me it was legit. I remained sceptical, and suggested that it was just a ‘potential’ word, mimicking rapacious, tenacious, mendacious, capacious etc. When we got home, I checked. Sure enough, predacious has its own headword even in my COED, not to mention my NODE (three times the size).

‘Potential’ words abound. (The linguist David Crystal claims that they outnumber real words.) Here are two that come to mind instantly: pecunious and disinform. A working definition might be ‘words that have not yet entered regular usage but that look plausible, thanks to being constructed from existing word-elements and/or through existing word-formation processes’.

Lingualia Quiz 5

We’re offering a prize for the most conscientious response: a copy of Richard Lloyd’s book on Renaissance Florence (see—once again—page 7). Good luck.

The following places have something in common with the following people. Can you identify the people and the common factor?

• Lake Tahoe, the Gobi Desert, the River Humber, East Timor, South Australia, and the Gulf of Bothnia

• a paedophile narrator, a notorious assassin, and an Asian pianist; and also, slightly more awkwardly, an Asian-American cellist, a Euro-American actress, a UN bigshot, a comic boating novelist, a modernist war novelist, and a Victorian/Edwardian painter.

Clue A. Here are a few borderline cases:

• the Faroe Islands, the Mississippi River, the Rock of Gibraltar, Lake Baikal, South Vietnam

• an Italian scientist, an imagist American poet, a miserable French protagonist, and a comic hero and his foils

Clue B. They also all have something in common with the following creatures:

• the red fox, black rat, common magpie, African leopard, and European toad and eel

SOLUTION TO QUIZ 4

We asked what the following four sequences had in common and whether you could add a further item at the end of each sequence:

• oblige, average, heather, metacarpal, identifiable, internationally

• Puck, Shylock, Fortinbras, Bassanio

• Grey, Baldwin, Macmillan

• Guinea, Germany, Singapore, Madagascar

The answer is that each item, as spelled, can be broken down into a number of separate English words consecutively (for example, for-tin-bras and in-tern-at-I-on-ally) with the maximum number of sub-words increasing by one in each item. Relevant follow-on items for each sequence in turn might be:

industrialisation / Robin Goodfellow / Campbell-Bannerman / North Macedonia

Sad to say, no one got it right this time so—no prizes.

So not all neologisms begin as potential words: contrast googling and instagramming. Prior to 1998, googling was not a potential word, since Google wasn’t an existing word or morpheme/word-element; by contrast, instagramming was a potential word, since the word-elements instant and -gram and -ing existed, as did the word-formation techniques of clipping, blending, compounding and function-shift.

One way to collect potential words is to find the gaps in ‘asymmetry charts’. See the highlighted items in this chart, for example:

predacious rapacious capacious preparacious trepidacious predatory rapatory capatory preparatory trepidatory predation rapation capation preparation trepidation predacity rapacity capacity prepacity trepidacity predacitate rapacitate capacitate prepacitate trepidacitate predator rapator capator preparator trepidator predare rapare capare prepare trepidare predarative raparative caparative preparative trepidarative

Having established that predacious is in fact a real word, I then assumed that it had graduated only recently from the ranks of potential words—in the way that restitute and weaponise have, for instance (neither of which appears in my NODE, dated 1998—the same year as Google was founded). But it turns out that predacious dates back to at least 1713.

For the record, it was indeed predated by predatory (that was an unconscious pun, by the way, when I wrote it), but not by much. Predatory dates back to 1589, according to the OED, though initially referring only to human pillagers. For referring to beasts of prey, its first recorded use was in 1626. And predator, surprisingly, emerged long after both adjectives—it’s first attested in 1922. Until then, it remained a potential word. Similarly with the related verb predate, first used as recently as 1974, according to the OED II (though again absent from my NODE).

Here are some other asymmetry charts:

intrepid trepid intrepidity trepidity intrepidation trepidation

arrive contrive deprive arrival contrival deprival arrivance contrivance deprivance arrivation contrivation deprivation

Here are a few more examples of potential words, in addition to the above-mentioned pecunious and disinform (which might be actual words, but don’t appear in my NODE):

ablute cathart impatriate intonate necrose surveille vexate blanketage conversal interdisciplinarity (and precarity and magicality) overdog

preferral (and referment)

bigly elsewhen reflexly thenabouts alacrous (and celerous) attitudinous combobulated fundamentary (and rudimental) precautious (and paucious) wistless (and doleless, fretless etc, and aimful, gormful, etc.)

Several other items on my list let me down by featuring happily in NODE:

disinvent exfiltrate potentiate altercate (though labelled archaic) unintelligence adultly somewhen (labelled informal) standardly burglarious (labelled archaic) consternated couth (labelled humorous) imitable kempt pervious scathed utile zeroth

(Not that NODE is failsafe. It obligingly omits two other words on my list, woke (adj.) and adolesce, but it turns out that they were attested as far back as the 1940s and the 1850s respectively.)

A potential word seldom fills a lexical gap, which is why potential words are seldom actualised into neologisms. (In the list three paragraphs above, only the underlined items would really fill lexical gaps.) Obversely, most neologisms were once potential words (though not all, as noted previously). Some recent examples, all absent from NODE, in addition to the above-mentioned restitute and weaponise:

boostered clickbait facepalm instrumentalise learnings metrosexual nonbinary repurposed side-hustle staycation stealthing transphobia

NODE, does however, have detectorist euthanize and chat room

What does it take for a potential word to graduate into an actual word? The blessing of a dictionary, perhaps. And what prompts a dictionary to allow that upgrade? Who knows? The OED’s policy used to be something like ‘ten occurrences in reputable publications’, yet the OED does contain some nonce words, such as Mammonolatry (coined by Coleridge).

Consider a few recent quotations containing words that look well-formed and plausible but that once again don’t feature in NODE.

‘The whole cause of their inimity was that they were describing the same phenomenon in different words …

(Sam Leith, in The Spectator online)

‘I’m very perseverant, and never give up.’

(Nick Mocuta, quoted in the Daily Star)

‘Elon Musk … has become embroiled in an “absurd” dispute over his company’s use of a flatulating unicorn image.’

(Mark Molloy, in the Daily Telegraph)

‘Here are some tentative answers that I’ve managed to find online or to research elsewise.’

(Lingualia 14)

Nasa instrument systems engineer Begoña Vila adds: ‘…

We know when we first focus on a star in space, … the 18 individual mirror segments won’t be aligned. But then we’ll adjust the mirrors to bring all the spots together to make a single star that’s not aberrated and good for normal operations.’

(BBC news website)

And a couple of quotations from earlier in the 20th century:

‘… and in these following pages, written only for certain eyes to delectate … I pay my tribute to the cause of so many tender hours of bittersweet reading.’

(‘Woodbine Meadowlark’, in The Pooh Perplex by Frederick C. Crewes)

‘Funes the Memorious’

(translation of the title of a J.L. Borges story).

LINGUALIA | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | PAGE 3

‘When

Head of Medusa (c. 1597) in the Uffizi by Caravaggio. The Medusa’s head was worn by statues of the Medici on their breastplates. See page 7.

At the simplest level, language is just an agreement that certain noises mean certain things, and other animals do this too. Some monkeys have different alarm calls to distinguish between predators like snakes and eagles, and use them to warn others in their group to take the appropriate evasive action. We humans are by no means unique in using unrelated signs and noises as a way of conveying meaning to others.

But it’s what we’ve done with these noises that matters. It’s a small thing in itself, but it’s the crucial difference between human language and animal communication. What we’ve done is to isolate some of the noises and use them as units of sound that we combine to make words. What that means is that, unlike other species, we don’t just make a different single noise for each thing—a unique analog representation of objects with sounds. You’d soon run out of noises that way. What we do instead is to put small numbers of noises together in a digital sequence, using them in combination. That makes new sounds easier to create and remember.

The International Phonetic Alphabet uses over 150 symbols to represent all the known sounds used by humans in their languages—but no language uses them

SPEECH! HOW LANGUAGE MADE US HUMAN Hogsaloft Softback, 303 pages May 2021

9781916893542

RRP £12.19

of Brazil; it may have only eight consonants and three vowels but its speakers have little difficulty in expressing themselves. That’s because even with the simplest of combinations, at least 8 x 3 = 24 different syllables can be made using this tiny range of vowels and consonants. That means that with two-syllable words there are 24 x 24 = 576 possible combinations, and by adding one more syllable the language can have as many as 24 x 24 x 24 = 13,824 different words. So with three syllables made by combining as few as eleven sounds, the number of potential words available is already close to the number of words the average adult is familiar with—in any language.

With that in mind, we can begin to see how language could have evolved through a process of gradually reducing the number of analog calls in use, and using them in digital clusters instead—and there is increasing evidence that other species have begun the process of combining sounds in this way. That doesn’t mean they’re about to burst into speech, however. All such processes are extremely gradual. The archaeological record shows that early humans started using simple stone tools as long as two million years ago, but another million years passed before any significant change was

Leading

possible ways to arrange them in a sentence. They are SVO (the order we use in English), SOV, OSV, OVS, VSO and VOS, all of which exist in human languages, although the last three are quite rare. And though it may seem common sense to native speakers of English that the order of a sentence should be subject-verb-object, nearly half the languages we know about use the order SOV, with the verb coming at the end of the sentence. This means man dog eat is the most common way of expressing a good result for the human. But it doesn’t matter which arrangement is used, as long as it’s consistent. SVO works perfectly well for English, despite being a minority choice.

The development of grammar probably occurred quite slowly. Like the switch from analog to digital in the creation of words, grammar is unlikely to have burst fully-fledged onto the scene. But there is likely to have been a quite natural progress from using words literally, to using them to show the relationships between things. We don’t need to go back very far in time to find examples in the historical record. Consider the expression ‘going to’. We know that even as recently as Shakespeare’s time ‘going to’ meant what it literally says, that you were physically going somewhere to do something.

https://geni.us/ SPEECH

READERS’ COMMENTS

Steven Pinker: I think you’re right … .

Desmond Morris: Crisp and clear—I agree with your hypothesis.

James Lovelock: I couldn’t stop reading it … this book should be widely read!

Yoko Ono: Bravo! A compelling read.

Jee Mandayo: Sapiens fans will love this.

all, or even most of them. All a language requires is that you have a range of them that can be used in combination. This is the raw material of speech. We all do it, even if the sounds we make when speaking French can be very different to those of German, Swahili, or Chinese. It’s the same trick in every case. A small number of sounds are combined to make a large number of words. In linguistics, each of these distinct and different sounds is called a phoneme. You can think of them as vowel and consonant sounds, a closed set of noises that is the signature of that language.

For language to work it doesn’t matter what the sounds are, only that there is a limited number of them and that they are used consistently and exclusively: the big secret of human language is its ability to generate a huge number of different words from a small number of sounds. Of course, language is not just about words: without grammar to organise them, it’s difficult to make yourself understood with any precision. But words are still the indispensable first step, for without them there can be no grammar. So it should be no surprise that our animal cousins show so little sign of being able to use grammar: they don’t have the words to make it necessary.

With spoken language, the basic unit is the syllable, which in its simplest form is a combination of a consonant and a vowel—like la, di and da. English has a relatively large number of phonemes (around 44, depending on the dialect) and some of the oldest known languages, such as the Khoisan group of so-called ‘click’ languages, use as many as 24 vowels and 117 consonants. But even languages with very few phonemes can manage just fine: as a crude rule of thumb, the number of syllables available is the number of vowels multiplied by the number of consonants.

Take the Pirahã language spoken in the rain-forests

EDITOR’S NOTE

Language distinguishes us from animals; how did it develop? Noam Chomsky credited it to a “Language Acquisition Device” but that’s a little woolly, suggests linguist Simon Prentis. Although we can now locate specific areas in the brain that handle speech and have found a gene that may be involved with language production, that still doesn’t explain how language started. It couldn’t have sprung into existence fully-formed; there had to be a process. Our task, now, is to work out what that process might be. How could speech have begun to emerge from animal communication? The key, says Prentis, is digitisation.

made to the sophistication of these tools. Things take time to develop.

But understanding the essential simplicity of the trick that lets us create and use large numbers of words can help us unmask the mystery of language. Once the idea of putting noises together in this way has taken hold, it’s just a question of slowly agreeing which combinations of sound refer to the things we are interested in. The key thing is that it doesn’t matter what the sounds are. There’s no reason why the molecule H2O, the essential building block of life, should be called water rather than eau, acqua, νερό, पानी or 水. It’s essentially an accidental and random process, limited only by the range of noises we can make with our mouths.

Grammar school

Once the idea of using words has taken root, the next logical step is to find a way to use combinations of words to express more complicated ideas. All languages do that. But once you start to do it, you soon need to have an agreement about word order. To give a simple example, if we already have the three words man eat dog, the meaning of the sentence will depend on what we’ve decided about the order of words. If we’ve decided that the person doing something should be mentioned before the thing that’s having something done to it, then man eat dog tells us that the man is the one getting a meal. But if we’ve decided that the rule in our language is that the thing should come first, then the same sentence, man eat dog, means that the dog is the one getting the meal. Speakers of English may consider that strange, but languages do exist that naturally use that order.

The key parts of any sentence in any language are the ‘subject’, ‘verb’ and ‘object’, and there are only six

But during the 18th century the meaning began to change to mean simply the intention to do something, a more neutral marker of the future—a process that linguists call ‘semantic bleaching’.

The evolution of grammar is also reflected in the types and frequency of the words we use when we speak. Linguists make a distinction between so-called ‘content’ words—nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs like dog, eat, dirty and slowly, which tag physical objects and qualities in the real world—and ‘function’ words which map the connection between them, like in, on, under and through. What’s interesting is that content words make up the vast majority of our vocabulary: as many as twothirds of all the words we know are nouns, around 20 percent are verbs, with adjectives and adverbs together accounting for most of the rest. Despite that, between one half to two-thirds of all the words we use when we speak are function words, a fact that is less surprising when you realise they are the glue holding the structure of a sentence together.

If the first step to human language was the creation of words through the digitisation of analog sounds, we would expect the earliest stages of human speech to have been as clumsy as we can feel when we start to learn a foreign language—trying to make ourselves understood with just a handful of nouns, verbs and gestures. This is largely the way children learn their first language too—using first one word at a time, then two, and only later learning how to use function words. It is tempting to see a parallel here with the way an embryo mirrors the evolutionary history of the animal it will become. And there is another, clearer hint that this may be so.

Writing also began as an analog system, with pictures representing words. And just as we

PAGE 4 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | LINGUISTICS/SOCIOLOGY

linguists still accept Chomsky’s 1960s idea that genetic mutation led to language learning. Simon Prentis has another theory

continued in the book

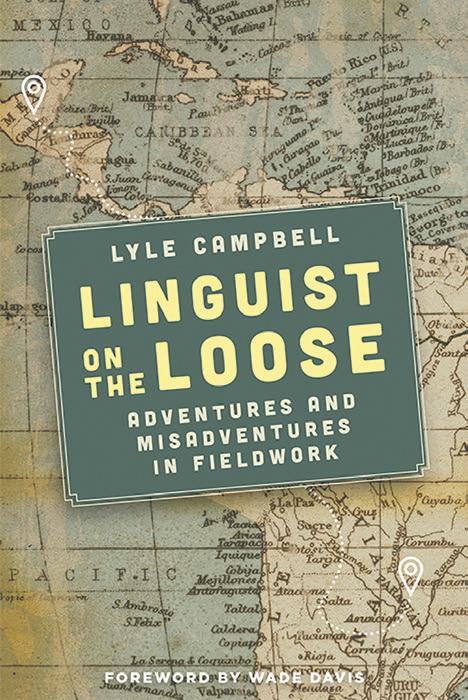

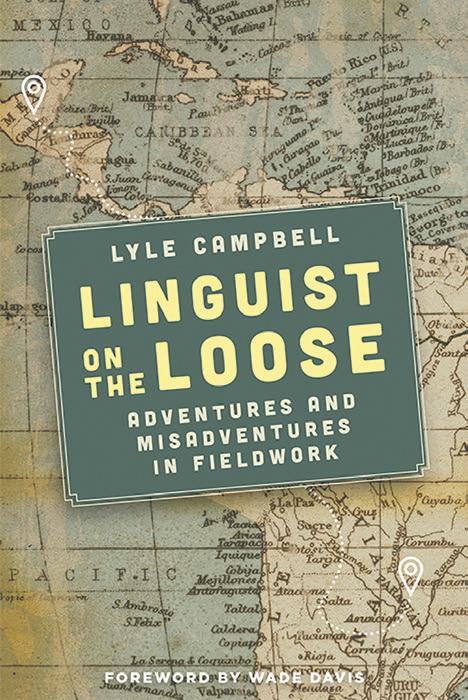

Linguists usually focus on results; here, Lyle Campbell recalls a lifetime of datagathering and discovers that he’s a

Languages are becoming dormant at an ever faster rate, and with so many in threat of imminent loss, linguists feel that undescribed or poorly described languages should be documented urgently. Documentation also needs to be carried out for communities who want data so they can attempt to learn their languages, teach them, revitalize them and reverse the trend towards language loss. Collaborating with communities whose languages are under threat to provide adequate documentation is one of the greatest services linguists can render.

It is difficult to overstate the seriousness and severity of the endangerment crisis. The full status of language endangerment in the world is made particularly clear in the Catalogue of Endangered Languages. It reports endangered languages on all continents except Antarctica and in nearly all countries of the world with very few exceptions.

The Catalogue of Endangered Languages lists 3,113 currently endangered languages. This is 45 percent of the 6,851 living languages in the world as listed by Ethnologue in 2018—a shocking proportion of the overall linguistic diversity of the planet. Of these, 815 languages are severely or critically endangered—that’s 26 percent of all the endangered languages—and 437 languages are critically endangered.

The consequences of language endangerment can be seen from the perspective of whole language families. There are, or were, about 398 independent language families known in the world, including language isolates (language families with only one member). Of these, 91 have lost all their mother-tongue speakers, i.e. no language belonging to any of these families has any remaining native speaker (Campbell 2018). This means that 23 percent—nearly a quarter—of the linguistic diversity of the world, calculated in terms of language families, has been lost.

Moreover, two-thirds of these 91 language families have lost their last mother-tongue speaker in only the last 60 years. This confirms reports of the dramatically accelerated rate of language loss in recent times. Many other languages and language families are on the brink of total dormancy and so the numbers representing the world’s linguistic diversity will soon dramatically worsen.

Though not really comparable, the loss of a specific language can be likened to the loss of a species, say the Siberian tiger or the right whale. but the loss of whole families of languages is similar in magnitude to the loss of whole branches of the animal kingdom, say to the loss of all feline animals or all cetaceans. Just imagine what the distress of biologists would be, attempting to understand the animal kingdom with major branches missing. Yet what confronts us is the staggering loss of essentially a quarter of the linguistic diversity of the world, already gone forever.

A mystery variety of Quechua

Early in my academic life, when I was a graduate student just about to go off to do my dissertation research, I was invited to participate in a survey of Quechua dialects

READERS’ COMMENTS

Prof. Judith Maxwell, Tulane University: A rollicking account of the dos and don’ts of fieldwork, Linguist on the Loose does for linguistics what Indiana Jones does for archaeology with the advantage that Linguist is all true: an impassioned plea for language documentation, a call to adventure … and hard work.

in Peru and Bolivia. As we did our survey, we kept being told of a strange and different dialect in Apolo, Bolivia. We resisted going there because the only ways in were either a trek of many days on foot over the Andes or a bush plane. However, we were told so often of this unusual dialect that ultimately we decided to check it out.

Apolo is on the jungle side of the Andes, at about 7,000 feet (2,000 meters) elevation. At that time, guerrilla activity had been announced in the area and this required us to obtain a salvoconducto, an official document from the government in La Paz, a permission to enter the dangerous area. The bubonic plague was also announced in the area.

The flight was, unsurprisingly, delayed. When we showed up at the scheduled departure time, pieces of wing and the plane’s tail were scattered around on the ground with the pilot and his assistant filing down bits here and there so that flaps would move without sticking. Eventually the plane was reassembled with all its pieces. Before take-off, the plane was sprayed with DDT—for the bubonic plague. We, naturally enough, knew nothing about bubonic plague nor about what DDT might be able to do to keep a plane from catching it; only later did I figure out that the DDT was for killing fleas and stop them coming back over the mountains with the plane to infect other areas.

The smallish cargo hold of the plane was filled with beef carcasses to be flown out to Apolo and due to the combination of DDT and beef carcasses, the plane stank; fortunately once airborne, the smell was no longer so noticeable. The plane itself had only four seats for passengers—we were five passengers.

The section behind the seats had been loaded with iron elbows for construction, tied down with ropes. Being a gentleman, I ended up seated on the iron elbows, grasping onto the ropes that tied the iron elbows down.

The international airport in La Paz, our starting point, is the highest in the world, at an altitude of 13,325 feet (4,062 meters). The flight to Apolo had to cross the Andes, over 21,000 feet (6,000 meters) high, flying through mountain passes of around 17,000 feet (5,500 meters) altitude, unpressurized and with no oxygen.

Upon arrival over Apolo, the plane’s landing gear would not come down and as darkness was coming on, the pilot flew the plane up quite high, let it fall nosefirst, for what seemed a great distance, and then sharply pulled the plane out of its nosedive as we got close to the ground. This was done some three times before the wheels finally came down and we landed.

We were met at the airstrip by the comandante in charge of the outpost there. He was drunk. He alternated between aggressively demanding our salvoconducto document in Spanish and demanding ‘the contraband’ in Portuguese, contraband activity in the area being something we were unaware of until it was demanded of us. After a seemingly long time of aggressive harangue, we finally convinced him that we would appear in person in the morning and bring our salvoconducto to the official headquarters. The next morning a junior officer officially registered us and our documents;

Professor Sarah G. Thomason, University of Michigan: This remarkable book, part fieldwork advice and part fieldwork autobiography, is written by one of the most experienced field linguists in the world. Practical advice on such topics as what to take to the field and how to avoid exotic diseases and political violence is punctuated by sometimes hairraising personal anecdotes—monkey attacks, an

LINGUIST ON THE LOOSE ADVENTURES AND MISADVENTURES IN FIELDWORK

Edinburgh University Press

Softback, 296 pages 31 March 2022

9781474494151

RRP £14.99

Our price £13.19 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

the comandante was apparently sleeping it off.

It turns out that the guerrillas were nowhere near this area; reportedly they were much further east and south of there, nor was there any sign of bubonic plague.

The dialect of Quechua in Apolo, though interesting, was not as unusual as we’d been told. It appeared to be the result of immigrants from further north, in Peru, whose dialect sounded unusual to those speaking Bolivian varieties of Quechua.

Apolo was a very pleasant place—sunny, warm, not hot, not so high as to cause altitude sickness, with lots of orange trees and beautiful waterfalls. We had planned on being there just a couple of days but had to wait until they could get a plane without landing gear problems.

This one was even smaller but again with only four seats for passengers, one of whom was a Quechua woman with a stereotypic large round basket on her lap with chickens’ heads sticking up through the netting covering it, gawking around nervously. This time, however, the mountains were completely socked in with clouds and the pilot flew by his wristwatch, making slight turns every few minutes to adjust the direction of flight. I still had shocking images in my mind of nearly scraping mountains on either side of the plane on the flight out to Apolo when the visibility had been good. This return flight through the clouds evoked varied emotional reactions of the most negative and unpleasant sorts.

I have flown on other bush planes elsewhere, including one in Chiapas, Mexico, that had pieces of it strewn about, with filing and hammering on plane parts going on before take-off. However, these were few, and I always avoided them unless there was no other choice.

People-eaters

There were once four languages in the Xinkan language family; today there is no longer any native speaker of any of them. At that time three of the languages, though extremely endangered, were still spoken by a few elders of their communities. The fourth language, Yupiltepeque, no longer had any speakers, though a few elders could still remember a handful of words and phrases they had learned as children from old people in the community, long ago.

When working with Guazacapán Xinka of southeastern Guatemala, I encountered very trying difficulties in attempting to analyze the glottalized consonants. In frustration one day I gathered a group of eight of the most knowledgeable remaining speakers to ask them questions to try to solve the problem. In this meeting, don Alonso, the oldest and most respected of the group, announced to everyone present that apparently the gringos, meaning North Americans in this context, were not the people-eaters and that it must be the ingleses, the English. I hadn’t previously been aware of this suspicion.

The idea of foreigners as people-eaters, I learned later, seems to have come from hospitals and from the practice of using cadavers of Guatemalan Indians in medical training. Often the Indigenous people there would resist going to the hospital, continued in the book

attempted coral snake incursion into the author’s bed, clever thieves, and more.

About the Author

LINGUISTICS/SOCIOLOGY | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | PAGE 5

sociologist too

Lyle Campbell is Professor of Linguistics at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

April 1967

A new student sits next to me in class I must have been seventeen when I saw you for the first time. I was in a French class, sitting in my usual seat in the middle file at the back of the class, half slouched in a desk that would soon be too small for me, my tie slightly crooked in a manner that for some reason enraged even the most placid of teachers.

Simpson, our teacher, was late, an event that was not unusual and that we hardly took any notice of. I wouldn’t have cared if he hadn’t turned up at all. I intensified my slouch. The rest of the class talked in whispers, not wishing to attract the attention of the headmaster, whose office was nearby.

The door opened. Simpson at last.

‘This is Frances Creighton,’ he said. ‘New girl.’

He rambled on about a new pupil, trouble in her last school, needed time to adjust, someone to look after her in her first few weeks. I wasn’t really listening. I never did. How was I to know how important it would become?

He must have looked round the class for an empty desk and found the one beside me. Though now I’m not sure if he hadn’t planned to put you beside me from the beginning. He and I had never really got on. There was something about him that brought out the worst in me: I took to handing in all my work late and going home early on those days when I had French last period, but also always made sure that any work I did for him was perfect and it infuriated him that he could never fault me on it.

‘There is an empty desk over there,’ he said. ‘You could do worse, I suppose, though admittedly not much. And Roberts could do with someone fresh to liven him up.

The class laughed and, at the sound of my name, I looked up. And saw you, for the first time. Frances.

You were still standing beside him, half smiling in an effort to remain inconspicuous. I suppose you were nervous but you didn’t look it—not as nervous as I would have been in your situation. You were dressed in your own clothes: mustard corduroy trousers and a plain white blouse with a small gold cross at your throat. I remember thinking I had never seen anyone who looked so well. Your black hair was swept away from your face and did I imagine it or was that a trace of lipstick on your lips? Not being in uniform made you look older, more self-assured, someone apart and extraordinary. Simpson looked ridiculous beside you, even if he didn’t realise it.

‘This is Frances,’ he said again. ‘Say hello, Roberts.’

I managed to stammer something and the class laughed again, enjoying my discomfort. You allowed yourself a half smile as you turned towards me and the laughter in your eyes was enough to save me from utter disgrace. Simpson went on, pleased with his introduction. He was obviously having fun.

‘Roberts,’ he said to you, ‘is one of our enigmas. You will note that he needs a haircut. Some of my colleagues send him home from time to time to get it attended to but I never do. I have always worried that, like Samson,

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kirby Porter grew up in Belfast near the Harland and Wolff shipyard. He studied Russian at Queen’s University Belfast, took further degrees at the University of London and the University of Wales, and became a Head of Library Services in London. A once-active trade unionist, he gave talks on Russian and Irish poetry. He now lives in Scotland.

his strength resides in his hair and that, were it to be cut, he would be unable to remain upright at all, and I would be forced to teach him French as he lay helpless on the floor. He would not be my ideal as a companion for you but as there is a free desk beside him I am afraid you are lumbered with him. As are we all—as are we all. And, you never know, you might get on. Samson and Delilah, as it were.’

He directed you to your seat and there was further laughter. I was surprised there wasn’t applause.

You walked uncertainly towards me and as you sat down you smiled at me again. So much for my putting you at your ease, I thought; you were the one rescuing me. As the laughter died away I was grateful once again for the smile and the bond I imagined it had created between us.

Nine years earlier

My Pentecostal church holds a Bible class Brother Sammy clapped his hands.

‘Well, now,’ he said. ‘What about a quiz?’

‘Oh, yes please,’ a hundred voices shouted. Relief was now universal. Everyone liked quizzes.

Brother Sammy was good at his job. He didn’t speak at once.

He knew how to wait, how to allow the promise of prizes to work its magic.When he next spoke the hall throbbed with suppressed anticipation.

‘All right,’ he said.‘Here’s the question. What’s the difference between Brother Archie and Michael Roberts?’

I jumped at the sudden mention of my name. And at the strangeness of the question.

The rest of the children stirred uneasily. This wasn’t what they’d expected.

‘How many days did Jonah spend in the belly of the whale?’

‘How many times did Joshua blow his trumpet before the walls of Jericho came tumbling down?’

Those were the usual sort of question. This was something new: something terrible.

I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move. The back of my throat hurt and I had difficulty breathing. I knew something awful was going to happen.

Brother Sammy continued to smile. ‘Come on now,’ he said. ‘Isn’t it as plain as the nose on your face,’ he said.

‘Look.’ He held up a shilling between the thumb and forefinger of his right hand, moving it so that its shiny smoothness glinted in the light.

‘There’s the shilling that will go to the one who gets it right. What about you, Jackie? It’s not like you not to have a go. Come on, now. What’s the answer? What’s the difference between Brother Archie and Michael Roberts?’

He must have been desperate; a shilling was untold riches to the boys and girls sitting in front of him.

I looked up at Jackie, silently begging him not to say anything. He was my friend after all and I was sure that if he said nothing, then I’d be all right.

Jackie looked at me, and then back at the shilling, and hesitated for a moment longer.

‘Brother Archie’s older than Michael,’ he shouted. The floodgates had opened. All around me arms went up begging for attention. The bolder children just shouted out their answers.

‘Brother Archie’s got black hair.’

‘Brother Archie’s got brown eyes.’

‘Michael still wears short trousers.’

Brother Sammy let them go on with their wild guesses, timing his eventual intervention to perfection once again. With the children at fever pitch he held up his hands for silence.

‘I’m afraid I’m going to have to tell you,’ he said at last, smiling as sweetly as ever.

‘Brother Archie’s name is written in the Lamb’s Book of Life, put there by the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ so that, when he dies and the Day of Judgement is at hand, he will be allowed to pass unscathed through the Heavenly Gates to sit at the feet of God the Father. But Michael ...’

He paused here, perhaps trying to recapture his mood of righteous indignation.

‘But Michael,’ he shouted, ‘is a sinner. His name has been expunged from the Lamb’s Book of Life by his actions tonight and when he dies he will go straight to Hell, to burn in the fire for ever and ever and ever. There will be wailing and gnashing of teeth.’

The last words were thundered at the top of his voice while he struck the top of the table over and over again with the palm of his hand until the sweat poured down his face.

‘Stand up, Michael Roberts,’ he said in a voice which scared me even more because of its measured, reasonable tone.

I forced myself onto trembling feet. I think I must have been crying despite myself, because my throat was sore and dry.

I tried to turn away from Brother Sammy’s stern eye but everywhere I turned, another Brother pinned me down: Brother Archie, Brother Ivan, Brother Robert.

People who I’d liked and respected—and who I thought liked me.

At that moment, they all looked alike, smiling replicas of Brother Sammy, devoid of any individuality, any semblance of humanity.

‘Pride is the worst of all sins,’ they said, not to me now but to the other children, who sat, as before, at once terrified and relieved—terrified of the awful menace of the Brothers’ anger—relieved that it was being directed at someone other than themselves.

‘That is Michael’s sin,’ they continued, their voices still not above a whisper.

‘To set himself above the God who made him, who made us all, in wonder and majesty. To substitute his own words for those of God, to act as the mouthpiece of Satan himself. And in his anxiety to do the devil’s bidding, to try and involve all of you in his wickedness; to trap you with his conceit—you, who had thought him your friend.continued in the book

EDITOR’S NOTE

Much of the fiction emerging from Northern Ireland in the last 50 years has centred on the Troubles. In this novel, set in the late 1960s, the protagonist is not yet conscious of the tribal tensions that will soon beset his native Belfast. His are interior troubles: teenage insecurity--but an insecurity with a dark back story that will hamper him and his personal development as he tries to navigate his place in an emergent youth culture indifferent to the deference of the past. A brilliant first work.

PAGE 6 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | NORTHERN IRELAND FICTION FRANCES CREIGHTON: FOUND AND LOST EnvelopeBooks

210 pages November 2021

£9.99 Special offer to Booklaunch readers £6.49 (Half Price) inc. free UK postage via our website

Softback,

9781838172077 RRP

When his girlfriend is killed, Michael Roberts finds himself reliving painful memories of childhood love and bullying Kirby Porter

https://www. booklaunch.london

The city that gave us the florin and the florentine also gave us the Fine Arts, product of trade, theology and tyranny. Richard Lloyd guides us around

EDITOR’S NOTE

In 1633 the Pope condemned Galileo for challenging Church teachings on astronomy, and he was exiled to Arcetri, in the hills south of Florence. It wasn’t until a century later, nearly 20 years after the Church had lifted its ban on his books, that his body was brought back to Florence and entombed in the church of Santa Croce. For the author, Galileo’s return marks the end of Florence’s history as the centre of artistic development. He begins his story with the Baptistery of the Cathedral, the oldest public building in the city and in many ways its symbol (pictured below). In between, he explains the evolution of Renaissance art and interprets the stories of Christian saints and Greek mythical characters on which so much post-medieval creativity then depended.

THE HEART OF THE RENAISSANCE THE STORIES OF THE ART OF FLORENCE Unicorn

Hardback, 576 pages

March 2021

9781913491185

RRP £35.00

Our price £24.99 inc. free UK postage https://www. booklaunch.london

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Lloyd’s love of the Italian Renaissance began at Winchester College, where he was a scholar. After a brief period at the British Institute in Florence, he studied PPE at Oxford University and then went into the City. Following his retirement he has returned to Florence as a guide and to research Christian and pre-Christian mythology.

ART HISTORY | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | PAGE 7

Veterinary and human medicine are separate endpoints of one discipline. Both evolved at about the same time, had a common root and shared advances, initially with veterinary adoption or adaptation of learning from its human partner. Later, this led to knowledge flowing from animal to human patient. (There have always been individuals such as Aristotle who recognised the value of comparative studies, though collaboration has been frequently interrupted by religious dogma.)

Graphic images from the Palaeolithic era show that animals have constantly played a significant role in human interpretation of their own lives. The use of these very early images, frequently beautifully executed with significant accuracy, can enable dating, and therefore establish a time frame that gives the basis for creating a record.

The first written evidence of veterinary ‘professionals’ and veterinary procedures has been dated to around 2000 BC. The first specifically veterinary books appeared in print in the late 1400s and early 1500s, the most important being derived from surviving Roman and Byzantine manuscripts.

Printing enabled and enhanced education, the enlarge-

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce Vivash Jones graduated from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) in 1951. Since retiring from his consultancy business in 2003 he has been studying the history of the veterinary profession and of veterinary medicine. He is published by 5mBooks.com, which specialises in agricultural books for farmers and smallholder.

ment of libraries and the establishment of universities. This aided the training of a specific group of individuals, who became known as veterinarians. The first school was established at Lyon, France, by Claude Bourgelat in 1761 and was the forerunner of the now global teaching of veterinary medicine and science.

The societal activities of humankind arose in three centres of civilisation. The first centre was Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Aegean (Greece), which became the dominant global culture for veterinary and human medicine, influenced by the Christian religion.

The other two centres were China and India. These old, sophisticated and highly developed civilisations not only created their own medical science but understood veterinary and human medicine as two parts of one discipline. Again, both were influenced by a spiritual dimension: Confucianism in China and Buddhism in India.

These cultural centres interacted with other neighbouring communities creating significant spheres of influence. Following the introduction of Islam in the 7th century AD, there was intense interest in all branches of science including veterinary medicine, which resulted in the preservation of much Byzantine and Greek knowledge, to which contributions were made in the Arabic language.

In all these centres there was a strong background belief in mythologies involving animals. Almost all beliefs involved animals in fables associated with their founder, and animals were given god-like roles. They were also involved in sacrifice, frequently with the use of body organs for divination.

Warfare provided the prime motive to develop, understand and expand what became the veterinary art. From about 4000 BC, it was realised that domesticated horses had a greater value when trained to be ridden or draw

Mutton —Alice.’ How do we relate to animals? Bruce

vehicles than to be used as meat. This in turn created a need to care for them, feed them well and train them and a class of professionals was created that took on these duties, including treating post-conflict injuries. While veterinary medicine advanced the cause of equine welfare, warfare in turn drove veterinary progress.

Dogs have a similar history. While their use in ancient war may be exaggerated, dogs played a significant role as messengers and still do in guarding. They are also significant in hunting for sport, which they appear to enjoy. This has resulted, over the centuries, in much wounding and injuries, and canine medicine and surgery again advanced to deal with these issues.

The utilisation of animal products is affected by religious belief. This is most obvious in the consumption of pig meat, which is eschewed by two major world religions. Another religion prohibits the eating of bovine meat and a fourth favours vegetarian practice and promotes animal welfare. The impact of religions on veterinary medicine is variable; the use of animals in ritual slaughter, for example, involves selection of healthy beasts, which may have influenced clinical observation skills. The remains of sacrificial beasts reveals that such animals were seldom diseased.

EDITOR’S NOTE

and Inspector-General of French Veterinary Schools. He was reputed to have amassed a private library of some 40,000 volumes. While not all of a veterinary nature, the library did include almost all known printed veterinary works up to 1838, as well as many rare and priceless manuscripts. When the collection was dispersed a significant part was acquired by the Alfort Veterinary School and is held in its library. Fortunately, the collection was catalogued by P. Leblanc and a copy is held in the British Library (BM, No.822, c1). Leblanc also wrote a summary of those items that related to veterinary medicine and animal husbandry. These totalled 5,812 works with 1,598 directly related to veterinary medicine (up to 1838). At that time by far the majority were by French authors. One category, Treatises on the Diseases of Different Animals, comprised 216 works, of which 115 were in French while just seven were in English. Huzard’s summary was published in English in 1848 (Leblanc, pp. 214–16).

In 1851 Count G.B. Ercolani, writing in Italian, published the first volume of his Historico-Analytical Researches on the Writers of Veterinary Science, with the second volume in 1854. J.C.F. Heusinger, a German national, living in Cassel, France, and writing in French, produced Researches in Comparative Pathology in 1853;

The ambition of this book is massive. Based on written records going back 4,000 years it pieces together how humans have interacted with animals and how their knowledge of animal disease, welfare and medicine has developed. The book can be read from front to back or topic by topic, says its author, and it covers “equines, bovines, ovines, caprines, porcines, canines, felines, avians and aquatics”, on every continent. Its range of enquiry goes from the early domestication of animals and their exploitation for food, fibre, traction and transport to their use as companions.

One area of veterinary research that lags behind its human counterpart is that of the archaeology of animal disease. Apart from the rare graves of pet dogs, diseased animals were either buried in unmarked graves or burned. However, some recent discoveries have helped to add to our knowledge and show many of the ailments and injuries from which humans also suffered in antiquity.

Veterinary education commenced in 1762 in France and by 1800 existed in every major European state including, belatedly, Britain in 1791. By the mid-1800s it was becoming established in the United States, Canada, India, Egypt and Mexico, and by 1900 had approached global coverage. With the establishment of veterinary schools, organised research, national disease eradication programmes and, in particular, a profession of specifically trained individuals was created.

The recording of the history of veterinary medicine has an interesting history in itself. From the beginning there have been individuals working to trace its roots. The earliest printed publications came from France, with the first identified author being P.J. Amoreux at Montpellier, who produced a listing of authors of veterinary related topics up to 1773, followed by C.F. Saboureux de la Bonneterie with A Translation of old Latin works relating to Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine (1773) and L. Vitet, Lyon, who wrote An Analysis of Authors who have written on the Veterinary Art since Vegetius (1783). Amoreux then elaborated on his earlier work with An Historical Precis of the Veterinary Art (1810). All these books were in French, with French authors being prominent as the first writers on veterinary history.

It is not easy to trace early veterinary texts in manuscript form. A notable early collector was J.-B. Huzard (1755–1838), Professor at the Alfort Veterinary School

the title is misleading as the text is about historical literature and animal plagues. G.A. Piétremont wrote The Origins of the Domesticated Horse (1870) and Horses in Prehistoric and Historic Times (1883), both in French.

The interest in historical veterinary medicine then moved away from France with the Outline of the History of Veterinary Science for Veterinarians and Students (1885) by F. Echbaum, Berlin; History of Cattle Breeding and Medicine in Antiquity (1886) by Anton Baronski, Vienna, author also of The Training and Taming of Domestic Animals in Prehistoric Times (1896). A. Postolka, Vienna, contributed A History of Veterinary Medicine from its beginnings to the Present Times (1887). All these works were in German.

The first record of veterinary history in English in book form was made by Delabere Blaine as the opening chapter in his Outlines of the Veterinary Art (1802). He discussed both the ancient origins as well as the establishment of the London Veterinary College. The Encyclopaedia Britannica in the fourth edition (1806) included a good article on the subject (but under the Farriery title), said to have been written by Jeremiah Kirby. Later editions had revised texts by William Dick and George Fleming. The Short History of the Horse (1824) by Bracy Clarke includes a section that traces the origins of veterinary literature.

Sir Frederick Smith wrote excellent books enhanced by his practical knowledge of veterinary medicine and the profession, as well as many papers. The Early History of Veterinary Literature and its British Development (1919–1933) in four volumes, remains a valuable and unique resource; The Veterinary History of the War in South Africa (1919) gives a first-hand description of the Boer War (1899–1902) and its horrific wastage of animals; and The History of the Royal

PAGE 8 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | VETERINARY SCIENCE

continued in the book

THE HISTORY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE AND THE ANIMAL-HUMAN RELATIONSHIP 5m Publishing Hardback, 700 pages November 2021 9781789181180 RRP £85.00 Special offer to Booklaunch readers £59.50 (30% off) inc. free UK postage via our website

Vivash Jones Visit https:// www.5mbooks.com

‘Let me introduce you to that leg of mutton,’ said the Red Queen. ‘Alice—Mutton;

EDITOR’S NOTE

Harry Lott’s memoirs are a jaw-dropping reminder of what the British Empire really meant—its astonishing reach and the assumption of unimpeded access. There were obstacles; posted after the First World War from northern France, where he was helping to clean up the battlefields, to Iraq, Lott records that the Arab Revolt of 1920 “caused us a great deal of anxiety and expense” but also treats it with the same resignation that might have been accorded to an outbreak of dengue fever. Global access is matched in his accounts by social access. Sailing to Kenya in 1924 “I made several new friends including Lord and Lady Howard de Walden.”

In my young days there were five distinct classes of society in East Anglia, a district almost entirely devoted to agriculture.

• The landed gentry and the owners of large estates;

• Professional people including doctors, lawyers and the clergy;

• Yeoman farmers and smaller landowners;

• Tradespeople including shopkeepers, innkeepers, millers, blacksmiths, bakers, grocers, and owners of small businesses;

• The working class, mainly farm labourers (male) and servants (female).

My family and direct ancestors were all yeoman farmers or small landowners employing one or two servants and several labourers.

None of my ancestors were from the landed gentry, nor were they professionals. I was the first in the family to go to College and graduate with a degree in engineering —but even that was hardly considered ‘professional’ in those days.

The members of each class kept very much to themselves and rarely married out of their class. Almost all my ancestors married into similar yeoman farmers’ families. The term yeoman was used for those farmers who owned land, either freehold, leasehold or copyhold.

A yeoman would be one of the Principal Inhabitants of the town or village and might typically perform certain civic duties such as constable, churchwarden, local surveyor, or bailiff to the lord of the manor. My great-great-grandfather, John Lott No.2, was one of the Principal Inhabitants of East Bergholt where he was churchwarden and also local surveyor responsible for repair of the roads.

The gentry, often titled and with a family estate, generally employed a butler, one or more footmen, a lady’s maid, a valet and a housekeeper with a staff of female servants including a cook, housemaids and kitchen maids. Sir Richard Hughes, from whom John Lott No.2 bought a moiety in the Valley Farm, was a member of the East Bergholt gentry.

The wife of an English emigrant to Canada, in whose

VOL 1 / 1883-1907

englAND: A childhood in village and CITY

homestead I stayed some months when in Saskatchewan in 1911, told me that she had been an assistant cook in an English household where there were 30 indoors servants. She had married an assistant gardener on the estate and they had emigrated to Canada in 1883, the year that I was born.

Of the ‘professional’ class the clergy were generally graduates of either Oxford or Cambridge and were often younger sons of the gentry who, incidentally, often held ‘advowsons’, or the right to appoint a parish priest.

Relationships between Employer and Employee

One may deplore the class difference between employer and employee of those years, but I can personally affirm that the relations between them in my experience were cordial. The employer was far more considerate than many are today and the employees showed a great interest in and zest for work as well as a respect for their boss.

A domestic servant girl was probably more comfortable working for a considerate mistress than living at home in her parents’ cottage. It seemed quite natural to both parties that she should have all her meals alone in the kitchen where she had access to as much butter, bread, and cheese as she wanted. When she removed the main course from our midday lunch in the dining room, there was always a good helping of meat or poultry cut ready for her on the dish and she could also have what was left of the sweet course which was generally steamed or baked pudding or pie. However, I must, with sadness, tell two true stories. The first was told to me by my father of one of his farm-workers, a man whom I remember well and who had a family of young children. In those days there were

READERS’ COMMENTS

David Shannon: An invaluable window on a now obscure part of the common history of the British Empire and Mesopotamia.

Peter Topping: Fascinating to read of Balfour Beatty’s ability to bring together syndicates to finance the engineering of major projects in politically unstable areas.

no children’s allowances, free medical attention, or free transport to schools.

About five hours after starting work in the fields, the men stopped for elevenses to eat some bread and cheese and to drink (as a rule) cold tea. The small piece of cheese, held in the hand with bread, was called a ‘thumb-piece’. This man told my father that every week he kept his thumb-piece till Saturday, pretending to eat it each day, as he did not want his mates to know that he couldn’t afford more than a small piece of cheese once a week.

The other story was told to me by my aunt Alice who died in 1947, aged 96. It was about the annual festive family gathering in July, which they called the ‘Fair Party’, when my grandparents at Wenham Place entertained as many relatives as possible staying in the house, the remainder finding accommodation in The Priory and the Hill House, both occupied by near relatives. All of them came in their own horse-drawn transport, either a two-wheeled chaise, or trap or high dogcart with iron tyres. None, I think, brought their grooms, so that no accommodation for servants had to be provided.

One of the special sweet dishes always produced for the feast was a rich ‘syllabub’ with warm milk added straight from the cow into the bowl of wine and spices. The cowman, years later, told Aunt Alice that after he had milked the cow into the bowl, he had always wished he could have had a taste of the wonderfully scented dish.

I am afraid that sharing a little of it with him or the servants never occurred to anyone. Those were not good days for everyone.

The KiTchen Boy

When my father was farming at Woodgates the resident servant had the help of the ‘back’us’ (back-house) boy, as he was sometimes called. He was probably the son of one of the farm-workers and, after leaving the village school in his early teens, earned a few pence (later a shilling or so) a day until he was old enough to work on the farm. His hours of work were nearly as long as the

MEMOIR | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | PAGE 9

This is classic social history, a five-volume memoir recalling the impact that Canada, France, Iraq and Kenya had on a British engineer— Harry Lott—and he on them, from 1907 to 1933

men’s, from 6 am (or 7 am in the dark winter days) to 5.00 or 5.30 pm, with half an hour off for breakfast and an hour for lunch. On Saturday he probably left work at lunchtime and only did a few essential jobs on a Sunday morning.

His first job was to pump many pails of water and carry them to the ‘copper’, a circular brick-encased tank with a hemispherical bottom, in the back kitchen. He had to light the fire underneath the copper and keep it going with wood until the water was nearly boiling. A large round removable wooden lid prevented the steam from escaping. This provided the hot water for the house and, once a week, for the laundry.

After breakfast he cleaned the boots of the family.

VOL 2 / 1907-14

CANADA: YOung land of opportunity

I was musical and enjoyed playing the piano, becoming organist of our church at the age of 15, a position I held until I went to study Engineering at the Central Technical College in London.

After three very frugal years at college, my first real job was with a consulting engineering firm which sent me on the Atlantic cable laying expedition in 1905. During that trip, whilst our ship was being repaired in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I fell in love with Canada. It was a young country with many opportunities for a young man and I decided to return.

So it was that on 5 July 1907, having obtained Father’s permission and two weeks before my 24th birthday, I boarded the SS Victorian at Liverpool docks, bound for a new life in Canada.

Canada was a popular destination for engineering graduates from the Central Technical College and there were a number of us in Montreal. With E.G. Sterndale Bennett (the future theatrical impresario), I helped to organise a dinner for Old Students at the impressive CPR railway hotel, Place Viger. Sterndale Bennett was also one of the prime movers of a group of us who began to meet in the evenings to discuss the idea of forming a contractors’ company for prospecting in the West.

In early January I met members of the Zingari Snowshoe Club for a tramp over Mount Royal, across the Park Slide lit up with arcs and thronged with tobogganers. Tobogganing on the Park Slide was so popular that there was a long waiting list for membership. The slide was a run of about half-a-mile long, straight down the slope of the mountain, well lighted with electric arc lights.

I was lucky to be friendly with a member and had a thrilling experience on my first evening. The flat toboggans, on lignum vitae or bone runners, were started at the top with a push off by one of the crew. There were four parallel grooves, so that four toboggans could go down in a race together. I believe that the best runs took about half a minute so that, allowing for the gradual slowing down to a halt at the

continued in the book

There were no shoes worn in the daytime in those days and farm boots were generally very dirty. He had to scrape off the mud with a blunt knife and then use Day & Martin’s Blacking, which had to be mixed with a little water before being applied with a brush. Then it took another few minutes’ brushing with another brush to get a shine on the boots.

He had to chop enough sticks, from hedge faggots, to light all the fires in the house. There were fires in all rooms, including the bedrooms, and they were started with wisps of straw. He then had to fill and keep filled all the coal scuttles and the big kitchen range.

The knives had to be cleaned on a board about 2ft

6ins long and 6ins wide, covered with a thin leather. To this a little knife powder was added and each knife was rubbed until it was shiny. Stainless steel knives were unknown.

He fed the fowls and brought in the eggs and, once a week, turned the handle of the churn to make butter. Sometimes this took only half an hour—sometimes three times as long. He was also useful for other odd jobs and running errands.

On baking day, once a week, he had to fetch enough faggots to heat the long brick oven, starting the fire about 9am and keeping it going until noon, when he cleared all the ashes with a broom of green twigs, leaving the floor of the oven ready continued in the book

VOL 3 / 1914-19

France: trenches and reinforcement

Not until 21 March 1918, when Ludendorff’s armies launched their mightiest assault of the War, were preparations made in our area for a plan to construct a complete system of defences behind the lines for use by our armies if forced to retreat. This part of the defence was 65 miles long. The assistant engineer-in-chief had under his orders about 40,000 men, who had been ‘thrown out of work’ when trench warfare changed to battles in the open. These men included tunnelling companies, forestry companies (which had been responsible for providing the timber for dugouts and props for mine tunnels), army troops companies and labour companies, some of them West Indian and some Chinese.

I had to do much of the detailed siting of the new

trenches and machine-gun positions. As soon as we had marked out each new scheme, it was my job to brief the officers commanding the units who had to do the actual digging and construction.

My first base was at Hauteville, from where I made daily visits to the divisions in the line. On one section of the line I found a Chinese labour company with only a few men doing any work. Having asked why, I learnt that the task, a heavy one of digging over 100 cubic feet, had been completed by these men in four hours—a very creditable performance—so I asked them to march away, for fear that a very senior inspecting officer would get a bad impression, seeing so many of the men idling, especially as imported Chinese labour was expensive.

No sooner had the Chinese gone than Field Marshall Haig appeared and I was introduced to him. After a walk around the works in the area, I was invited by him to share their picnic lunch, which his ADC had laid out under a hedge. Haig was the perfect host, getting up from the ground to offer me a second helping of chicken and salad which, with strawberries and cream followed by hot coffee, made a perfect meal. And so 21 June was a red-letter day for me.

Page 9, left: The Lott grandparents’ home at Great Wenham.

Page 9, right: A mowing team at Wenham Grange in 1880.

Above: The Park Slide, Montreal, c. 1908.

Below: A Ford run-about, used for inspecting the Light Railways in Northern France

PAGE 10 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 13 | MEMOIR

On 9 July 1918 I heard of my appointment as Controller of Foreways, 5th Army—a staff job. The Foreways were the Light Railways (LR) used to supply men and materials, water and rations to the trenches, heavy and field ammunition to the batteries at the front and to evacuate wounded personnel. I had three Army Tramway Companies under my orders and administration:

• No.3 Foreway Company RE, consisting of three Officers and 112 other ranks (ORs) with 67 ORs attached, had to maintain 12½ miles of track and eleven 20hp tractors in the Forest of Nieppe back to Divisional Dumps at Harstone and Thiennes and had to operate the system as far back as La Lacq Corps RE Dump.

• No.8 Foreway Company RE, consisting of six Officers and 150 ORs, had just completed 2½ miles of track on the Hinges and Plocy Farm lines and had instructions to survey and construct the Canal Line beside the La Basse Canal to connect with the Gonnehem Light Railway. It had two Tractors and 30 one-ton wagons.

• No.10 Foreway Company RE, which was operating and maintaining the Essars Line and carrying about 80 tons nightly to the 40th Division.

I went first to see the tracks at Hinges and the 12 miles

VOL 4 / 1919-24

Mesopotamia: Laying basic infrastructure

Soon after the Armistice in November 1918, I and several of my colleagues caught Spanish Flu; I spent three weeks in hospitals in Lille and Étaples before being sent to convalesce in the luxury of the Grand Hotel du Cap Martin, not far from Nice. When I returned to the battlefields in February 1919, I joined the staff of the Royal Engineers as senior construction engineer managing the clearance of the battle areas.

I remained in that role until September, when my engineering experience was required in Mesopotamia, where I was to look after the existing electricity generating, water supply and refrigeration facilities, and construct new ones to service British garrisons and the local population in an area 800 miles from east to west and 300 miles north to south around Baghdad.

Besides having a team of Army officers, all engineers, under my command and administration, I also had about 8,000 men, most of whom were civilians. The majority of these were locally recruited Arabs and Persians, with a few Baghdadi Jews.

For skilled craftsmen such as electricians, mechanics, and wiremen, also clerks and store-keepers, I had several companies of enrolled Indians from the Indian Army, including Hindus and Muslims, Sikhs, and Punjabis. The Indians were highly skilled and were indispensable in running the electric power stations, erecting power lines, wiring barracks and working as brick-makers, patternmakers, etc. Each company had its own British officers and NCO’s, and Sikhs predominated amongst the mechanics and electricians.

My first few days in Baghdad were taken up settling in, meeting my staff, and making familiarisation visits to the Hinaidi filtration plant, a flour mill, a meat freezing plant, our dairy farms, the workshops, a new jetty, and the site of a new pumping station.

An interesting sideline to my main duties in Mesopotamia was the completion of the 350 mile stretch of new road from Khanaquin, on the Mespot-Persian border, to Kasvin, not far from Tehran. The route had been selected extremely well by Russian engineers under General Denikin, and became the main route into Persia (Iran) from Iraq, crossing three mountain ranges over passes at elevations of 6,500ft to 7,700ft, all reached by a series of hair-pin bends. Our work involved widening and surfacing the track, and installing culverts and bridges where necessary; for this I had several detachments of Punjabis operating stone-crushers and road rollers along the route.

When I visited any of our works, I would raise Cain if I found any of the men, Indians or Arabs, slacking. A certain amount of surplus labour at times was inevitable, but the climate, personal inclination, and surroundings, as well as cheap labour and supervision, all tended towards slack performance of duties.

On my arrival in Basra I was able to catch up with Inglis, Morgan, and several others. We visited Shaiba to see the new cantonment and RAF buildings, the ice