Does Hamas’s internationalism maximise Palestinian leverage?

‘As Brazil’s foreign minister during the 2003 to 2010 government of President Lula da Silva,’ writes Celso Amorim in Daud Abdullah’s new book, ‘Brazil was deeply involved in the struggle for a fair and peaceful solution to the conflict in the Middle East.

‘One of our last decisions in the field of foreign policy was the recognition of Palestine as an independent and sovereign state, which unchained a series of similar moves in Latin America and beyond.

‘During that period, our representative to Ramallah visited Gaza and had discussions with Hamas authorities. I was therefore very encouraged by Dr Abdullah’s words that through the intensification of diplomatic

How to make money in an Iranian kleptocracy: buy, sell or monopolise

efforts and global alliances, “Hamas can play a pivotal role in the restoration of Palestinian rights.”’

‘Discussion of Hamas in the mainstream media and academia has centred largely on its Islamic origins and character,’ adds Ramzy Baroud, Editor of the Palestine Chronicle, ‘somewhat reducing the movement to a confining, stifling discussion on “terrorism” and “suicide bombings”.

‘Abdullah’s book dismantles and reconstructs the old discourses to delve into Hamas’s internal dynamics, continual diplomacy and attempts to break away from its Israel-led isolation. A truly riveting and revealing account.’ See page 5.

Raymond Williams Centenary Year

Raymond Williams (below, top left) made his name in the field of cultural studies, alongside Richard Hoggart, E.P. Thompson and Stuart Hall in the years after the Second World War. His key works were Culture and Society (1958) and The Long Revolution (1961) and these continue to be read. In recent years, Daniel G. Williams has explored a different side to his namesake: his growing commitment to Wales as a focus of academic study and a preferable form of national identity in the face of English hegemony. Extracts from DW’s preface and RW’s writings appear on page 10. Key also to the emergence of Welsh identity politics was James ‘Jim’ Griffiths (below, bottom left), the UK’s first Secretary of State for Wales, whose biography, by D. Ben Rees, is featured on page 8. And on page 9, we carry an extract from Ralph A. Griffiths’s book which shows how a Scottish-American philanthropist primed modern Welsh political advocacy by underwriting an unprecedented programme of Welsh library building. Seen here: Bridgend Carnegie Library, 1907 (photo Colin Burdett | Shutterstock).

The move from carbon to hydrogen may save the planet but undermine the economic stability of states that have built their wealth on oil. That’s why some oil producers are ploughing billions into new technologies that will help them retain their market lead.

Others are concentrating instead on monopolising a shrinking market. It’s cheaper.

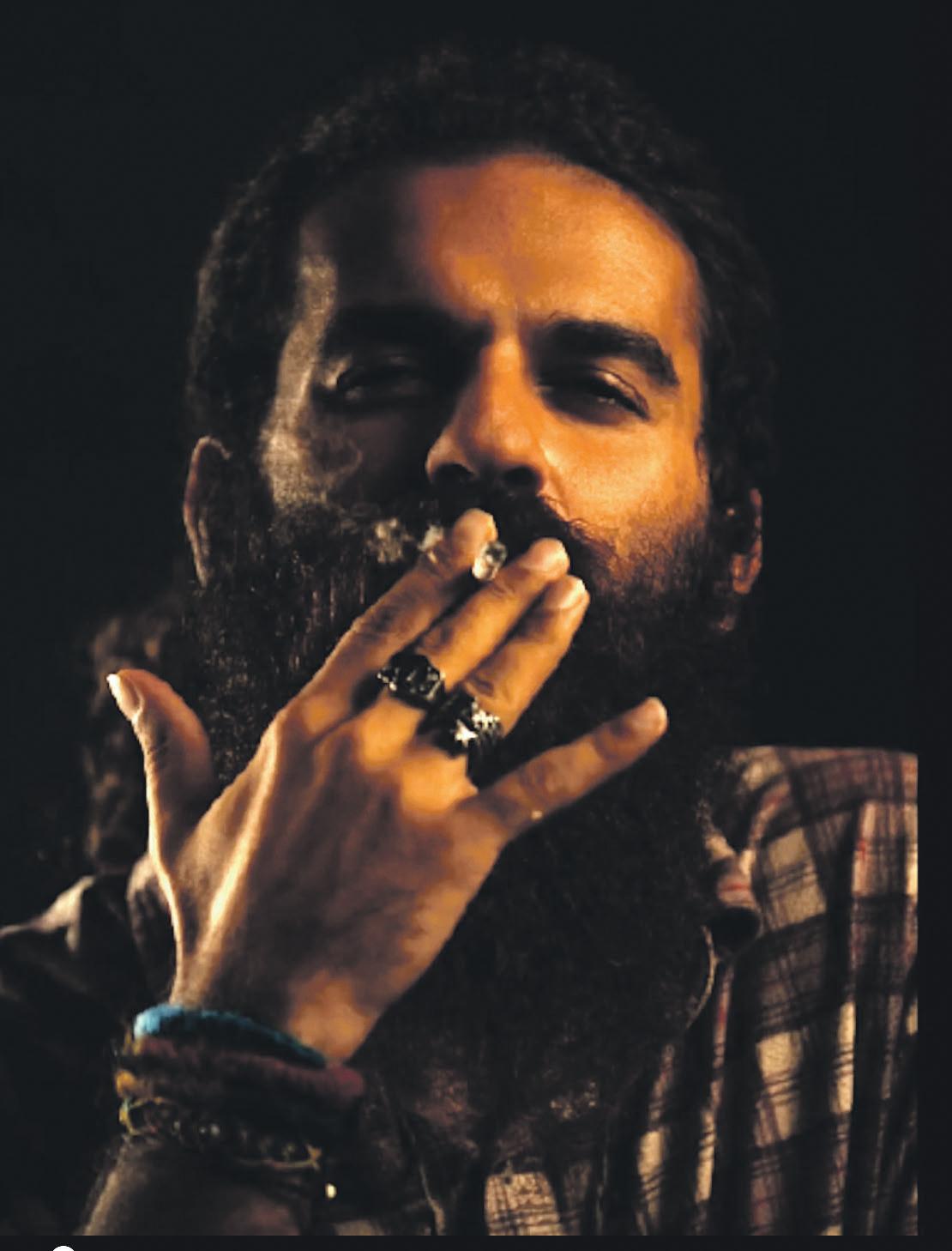

It’s also dirtier, in many ways. According to Martin Venning, whose new thriller is set in Iran, alongside the beauty of the country’s landscapes and the diversity of its peoples, Iranian kleptocracy promotes the basest forms of capitalism.

In The Primary Objective, everyone is on the take, from the selling of temporary marriage licences to the extorting of bribes. And when a covert team of investigators gets parachuted in to check out what might be a remote biohazard production site, it turns out that some of the players have wildly conflicting goals. See page 18.

ON OUR INSIDE PAGES

Page 2 The Tin Ear Prize and Bookshop.org

Page 3 Bad language, Lingualia quiz

Page 4 The collapse of the UK legal system

Page 5 Hamas as an international player

Page 6 The Renaissance’s fun machines

BOOKS ABOUT WALES

Page 8 Jim—star of the Attlee government

Page 9 Andrew Carnegie’s library legacy

Page 10 The Raymond Williams centenary

Page 11 Scottish poetry, Australian philosophy

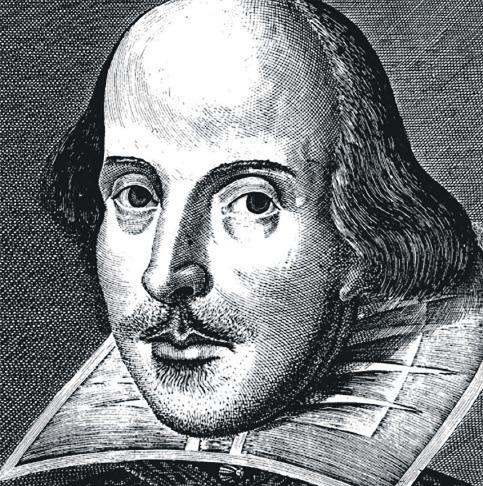

Page 12 Shakespeare’s neighbours in London

Page 14 Valentine Ackland: lesbian trailblazer

Page 15 Henry VIII as patron of the visual arts

Page 16 How Nazis got away with their crimes

Page 17 Helping the taxman outwit the Amazons

Page 18 Might Gulf oil instability end like this?

Page 19 When secret lives are wicked lives

Page 20 How to get your book published

Booklaunch A digest of important new books in their own words. Subscribe today to enjoy our online archives and other benefits Issue 11 | Spring 2021 | £2.50 where sold We welcome enquiries from publishers and authors www.booklaunch.london

Editorial: Bleakly Rammed Stephen Games

Booklaunch 12 Wellfield Avenue, London N10

Distribution Upwards of 50,000 print copies

Website www.booklaunch.london

Publisher/editor Dr Stephen Games

editor@booklaunch.london

Design director Jamie Trounce jamie@jamietrounce.co.uk

Assistant editor Maggie Bawden

book@booklaunch.london

Advertising Nick Page page@pagemedia.co.uk

Tel: 01428 685319 Mobile: 07789 178802

Printer Mortons Media Group Ltd

Subscriptions Jenny Chalcott subs@booklaunch.london

UK £10.00/Overseas £20.00 via our website

Tell us the truth #2

Your replies to our slightly whimsical questions in Issue 10 about books and bookshops and publishing were very welcome. We now know more about your largely warm relations with your high-street bookseller and your largely negative feelings about Amazon.

Here, quickly, are a couple of answers to our teasers. We told you that over half all fiction sales in 2018 were crime novels and that one book had accounted for more than 30% of the rest. We asked if you could identify that book and whether you were completely fine with it.

The answer was Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine. The clue was in the question.

We also asked who should have won the 2019 Booker Prize—Margaret Evaristo or Bernadine Atwood—and I shouldn’t be having to tell you that we switched the surnames and that both won, although the rules say that the prize should only go to one person. Come on, wake up at the back.

Can you trump this?

We’re evidently more touchy, rather than touchy-feely, than our readers. In the last edition we invited you to

nominate a celebrated author who seems incapable of good writing. What we had in mind was bestseller-writers whose prose is dire and ought to be held to account. One correspondent thought we were wanting you to humiliate amateurs who were just doing their best. Not at all: amateurs deserve every encouragement, and we try to give it.

To illustrate what we had in mind, here are our candidates for the Booklaunch 2021 Tin Ear Prize (like the Booker, we’re honouring two recipients this year). First, Donald Trump. Trump sells big—as he would put it— and all major publishers want a slice of his action. His first book, The Art of the Deal, is said to have sold over a million copies and has just been reissued by Random House (i.e. Penguin).

For a book written by a hired hand—journalist Tony Schwartz, who now says it should be reclassified as fiction—Penguin Random House is benefitting financially from promoting the myth that Trump can think and write coherently, and that what appears under his name is authentic and plausible.

In fact it’s a double myth because the Tin Ear that we’re recognising actually belongs to Schwartz, whose fabrication of Trump’s big-shot language—‘I don’t do it for the money. I’ve got enough, much more than I’ll ever need’— reveals a deafness to truth.

By any standards it’s an outrage, as are Trump’s numerous other titles: Think Big, Great Again, Think Like a Champion, Think Like a Billionaire, and Midas Touch. If you were a publisher, wouldn’t you feel sullied by having these in your stable? And yet, here is Penguin, currently puffing The Art of the Deal on its website as ‘an unprecedented education in the practice of deal-making … the most streetwise business book there is—and the ultimate read for anyone interested in making money and achieving success.’

Shameless. (Rather wonderfully, though, Amazon lists the hardcover of Trump’s Crippled America as having a reading age of 3–5.)

The bookies’ choice

Closer to home is the late Dick Francis—admittedly not a new discovery—but I challenge anyone to read the first chapter of Shattered (a favourite of HRH the Prince of Wales) and not curl up in pain at its many solecisms.

Francis isn’t venal in the way Trump is—his books aren’t doing double time selling as well as telling—but they are no less false, with Francis at his clumsiest and

2EA

PAGE 2 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | EDITORIAL

Some gifts are easily forgotten. Yours will last for generations. For people who love church buildings Registered charity number 1119845 St Michael’s church, Cornhill, London © David Iliff CHURCHES ARE AT THE HEART of communities throughout the UK and have been helping local people keep safe during the coronavirus lockdown. The National Churches Trust is dedicated to the repair and support of the UK’s churches, chapels and meeting houses. Leaving a gift in your Will helps us to keep these precious buildings alive for future generations. To find out how you can help keep the UK’s churches alive, please call Claire Walker on 020 7222 0605 , email legacy@nationalchurchestrust.org visit nationalchurchestrust.org/legac y or send the coupon below to the National Churches Trust, 7 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QB (please affix a stamp). If you would like to receive information about the work we do, and how you could leave a gift in your Will please complete the form below. Forename Surname Address Postcode If you would prefer to receive information by email, please provide your email address instead: Please see our privacy policy at www.nationalchurchestrust.org/privacy as to how we hold your data securely and privately. You will not be added to our mailing list and we will only use your details to send you this speci c information. ✁ BL 05-21 continued on page 3, column 1

most pretentious when he thinks he’s being at his most suave (‘the air in his spacious car swirled richly full of smoke [richly full of smoke!] from his favourite cigar, the Montecristo No 2, his substitute for eating’; ‘Priam Jones [Priam!] from arrogance [from!] had just wrecked his own car in a stupid rash of flat tyres [stupid rash!]’).

Unfair to attack him? Just doing his best? If Francis’s yarns about UK racetracks and the Jockey Club make him seem homelier than Trump think again: his 42 novels, selling more than 60 million copies in 35 languages, put Trump in the shade. He’s definitely out there, promoting a vulgarity about language that embraces a crudeness of thought and conscience.

Here, for example: ‘I’d lost my licence for a year through scorching at ninety-five miles an hour round the Oxford ring road (fourth ticket for speeding)’—a souped-up explanation for why the speaker isn’t driving his own car that is both preening (I’m another James Bond) but also condescending about public safety.

Not convinced? How about ‘The sight of the girthwrapped [girth-wrapped!] piece of professional equipment, like my newly dead mother’s Hasselblad camera, [!] bleakly rammed into one’s consciousness the gritty message that their owners would never come back.’ Oh, that’s the gritty message that your newly dead mother’s Hasseblad camera bleakly rammed into your consciousness, is it?

Normally, you’d want a kindly editor to take your writer in hand and help them out. Here, you get the idea that the publisher is complicit. Either an editor has turned a sow’s ear into something only slightly less than a sow’s ear, or they’ve tiptoed round the great man and let him write whatever he likes. Result: popular appeal and the chinging of cash registers. You can’t argue with that. Well, you can and should.

Cui bono? His publisher—oh, it’s Penguin again.

Saviour of the human race?

Maybe our criticisms are too robust. We learn from you that many bookbuyers feel that books are a frail commodity and need protecting, not questioning, especially after the year we’ve just lived through. Bookshops feel the same about themselves; they’re an asset to any community but operate on slender margins and struggle to survive.

It’s on this presupposition that Bookshop.org has come to prominence in the UK. Bookshop.org is a US-based online bookselling platform, which means—as far as bookbuyers are concerned—that it does exactly what homegrown firms like Blackwell does, and Waterstones, and Foyles, and Wordery, and Books Etc, and numerous others—not to mention the egregious but non-homegrown Amazon.

Bookshop.org has a very special USP, though. Its pitch is that bookselling is, in its own words, a ‘fragile ecosystem’ and that it’s here to help. If you can’t get to your local bookseller, you can buy instead from its website, and your bookseller (if it has affiliated to the Bookshop.org network) will get 30% of the sale. If you don’t nominate a beneficiary bookseller, 10% of the sale price will go into a pool, shared equally among all the affiliate shops every half year.

It’s not only booksellers who can benefit. Book websites, literary organizations and individuals can earn 10% of any sale they direct to Bookshop.org, with a matching 10% going into the profit-sharing pool for bookstores.

Rather than promoting itself, therefore, Bookshop. org promotes its mission. ‘Support local bookshops,’ it chimes on its homepage; ‘shop online with bookshop.org.’ And at the top of every webpage it posts a running total of what it has put into the pot for local booksellers since launching late last year. The more time goes by, the more impressive the figure gets. As I write, it’s at just over £1.3 million.

It all looks good and booksellers all over the country have told us they are in favour of it. The bottom line is, it makes money for them. To quote one shop, ‘It’s 30% pure profit, zero overhead. I’ll take that any day!’

With their doors closed by the pandemic since Spring 2020, booksellers have actually been positive about the app since it arrived, rallying to the cause as maidens to a white knight. Of the 950 or so independent booksellers in the UK, almost half are now affiliates. Normally investigative newspapers have fawned over it, and continue to do so. Even Booklaunch affiliated briefly to find out what all

continued on back page

It’s pronounced Fooks Bart O’Fehfon

For our eyes only

The semi-successful (i.e. failed) Israeli lunar probe two years ago was known as Beresheet. The name corresponds to the opening word of Genesis and is meant to be pronounced with three syllables, stressed on the final syllable. The standard transliteration of the final vowel would be i rather than ee, but for once Israeli PR made a sensible decision. (The really sensible decision would have been to choose an entirely different name in the first place. Mind you, they might then have chosen Apocalypse, so perhaps it’s just as well.)

Not all PR or marketing departments make sensible decisions. Brand names are common victims of booby traps: the French breakfast cereal Crapsy Fruit and fizzy drink Pschitt; the Portuguese tinned tuna rejoicing in the name of Atum Bom Petisco, and the Swedish chocolate bar Plopp. Sadly, I can find no evidence for Zit Zitronensaft, Mukk yoghurt, and various other EU products widely referenced on the Web.

Was the Rolls-Royce Silver Mist rebranded for the German market, I wonder? And the Toyota MR2 in France? Certainly the Chevrolet Nova retained its name in the Latin American market (no va in Spanish means ‘it doesn’t go’), but it still, pace Ben Trovato, sold well there. (Ben also claims that the Vauxhall Nova was renamed Opel Corsa when sold in Spain: in fact, the Spaniards built the Opel Corsa themselves and it bore that name from the start.)

The market did compel a name change, however, in the case of Vick vapour rub. In German, the word Vick would be pronounced just like the word Fick!, which is the German form of the f-word. So in Vienna or Munich, the product keeps its English pronunciation but adopts the spelling Wick—which in turn wouldn’t work very well in English-speaking markets.

What about IKEA?—how do you pronounce it? The ‘correct’ Swedish pronunciation sounds like eekáya, with the stress on the middle syllable. In the UK and US, people tend to keep the stress on the middle syllable but adjust the vowels of the first two syllables, so the word sounds like eye-kéy-a. No harm done, but the company was taking a risk. Supposing the Anglophone public had favoured a first-syllable stress. The store would then be widely referred to as ‘ickier’. (What do you mean ‘But it is!’?)

The problem obviously extends well beyond the commercial domain. Speakers of one language can flinch when hearing innocuous personal names, place names, or even everyday words from another language. Anglophones make a reasonable effort to imitate the German pronunciation of Hegel, for instance, but shy away from doing the same with Kant. Conversely, they will strive for an accurate pronunciation of the towns Condom in France and Wankum in Germany. The Germans really should

Lingualia Quiz 3

Can you make sense of the following string of letters?

It will help if you relocate three words. Having done so, send us a word string of your own, together with the answer to ours. Book prizes to the first clever solvers.

RESULTS OF QUIZ 2

What do the following have in common? Dick Carter | Gus Painter | M.A. Carpenter | Charlie Weaver | Max Marsh (aka Max Fracture) | Johnnie Brook | Al Hill |

have given more thought to their vocabulary, before establishing nouns such as Faktor ‘factor’, Vater ‘father’, Bescheid ‘info’, and Fahrt ‘journey’. Sniggering schoolboys are particularly partial to Vakanz ‘vacancy’—double value there. Cf. the Dutch vakantie ‘holiday’. Dutch also, unavoidably, makes very frequent use of kant ‘side or edge’ and vak ‘profession, academic subject etc’.

And the problem exists not just between languages but within a single language. A standard pronunciation in one region might cause cringes in another. According to urban legend, when the Antarctic explorer Sir Vivian Fuchs was being honoured in Leeds, the Lord Mayor opened proceedings by repeatedly referring to ‘Sir Vivian Fucks’. Eventually his embarrassed guest leaned across and whispered, ‘Your honour, it’s pronounced Fooks”, and the mayor whispered back, “I know that, but there are ladies present.”

(In Richard Dawkins’ version of the story, recounted in a letter to The Guardian, the mayor’s reply was ‘Aye lad, I know, but I couldn’t say that in pooblic, could I?’)

Word records: Round #2

Booklaunch Issue 7 discussed the question of which English word is misspelt most often. Here are two further questions about English orthography. Let me know your answers. Here are mine:

1. Which is the richest homograph? i.e. which spelling corresponds to the greatest number of (etymologically) different words?

Tricky. The Web is no help. Short of checking every page of a dictionary, you have to guess and check. My biggest desk dictionary, the New Oxford Dictionary of English (NODE) offers four separate headwords for chase, and four for band. But in the lead (so far) are mole and bay, with five each—for bay, for example, the senses relate to a harbour, a tree, a recess, a colour, and a howl.

2. Which English word has most senses?

The longest entry in the printed OED is apparently for set. But for actual number of definitions, set now comes second to run (according to a recent report)—a mere 430 vs 635. Next in line are go, take and stand, all in the 300s, and then get, turn, put, fall and strike, all in the 200s.

Claud Greenberg | Fred Cream | Len Amber Clue: others in the same category include J.P. Branch and Dick Bouquet (aka Dick Battle aka Dick Ostrich). Another clue: the first item—Dick Carter—is slightly misleading.

Answer: They are all composers: Richard Wagner | Gustav Mahler | Marc Antoine Charpentier | Carl Maria von Weber | Max Bruch | Johann Sebastian Bach | Alban Berg | Claudio Monteverdi | Bedrich Smetana | Leonard Bernstein | Jean-Philippe Rameau | Richard Strauss.

Note: Wagner isn’t standard German; presumably the name originates in its adoption by/ascription to wagoners, but the current term for a carter or driver is Fuhrmann or Fahrer or Führer

LINGUALIA | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | PAGE 3

Together Wells toreador ear lyre port age André con vie wit, as sure heritage ration swell André ally war rants re side.

from page 2

continued

JUSTICE IN A TIME OF AUSTERITY STORIES FROM A SYSTEM IN CRISIS Bristol

University Press

Hardback, 232 pages 22 June 2021

9781529213126

RRP £19.99

Our price £17.59 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

It’s Monday morning on level five of the 16-storey, glass-fronted Manchester Civil Justice Centre. District Judge Hassall has 19 cases on a busy housing list in court seven. First up is an application by a landlord concerning a tenant with mental health problems. The judge accepts that the man is a danger to himself and others as well as a disturbing presence on the estate.

Two solicitors are on today’s duty scheme, which is run by the housing charity Shelter. They cover two lists: one in the morning for antisocial behaviour; and rent arrears possession cases in the afternoon. Tenants can be evicted on account of their antisocial behaviour for breach of a court order or injunction.

Next up is a case concerning the occupants of a one-bedroom flat in a block of 16. The court hears of ‘overwhelming evidence of the supply, sale and production’ of crack-cocaine as evidenced by ‘a constant smell of ammonia’ and the frequent sighting of ‘people wearing respirators’. Neighbouring tenants complain of addicts blocking the stairwell using ‘heroin with foil and needles’. Four residents have received death threats.

Some 19 cases are listed but only four tenants turn up for the morning session. At one point, Judge Hassall

READERS’ COMMENTS

Baroness Shami Chakrabarti: If you are a tribune of the people who has ever poured scorn on ‘activist lawyers’, I dare you to read this. It may just tempt you to reconsider.

Michael Mansfield QC: Successive governments have been keen to suppress the impoverished. ... This book gives a stark measure of a society without due process.

expresses concern about his own potential to ‘over-react’ when a hearing concerns a tenant who is neither present nor represented in court. How can he properly test the evidence without the risk of adding to ‘a chain of fallacies’?, he asks.

The morning’s duty solicitor, Ben Taylor assists on three cases. “It’s a poor turnout,” he says, “but most of the cases were gas injunctions and tenants tend not to come.” Landlords have to provide an annual gas safety certificate and they are allowed access to properties on 24 hours’ notice to ensure that properties are compliant and safe for their occupants and neighbours. Issues often arise when tenants refuse access, and an injunction can be granted to allow entry. ‘If they don’t provide access once an injunction order is given as made by the court they could end up in prison for contempt for two years plus a £5,000 fine,’ Taylor says.

The Ministry of Justice only funds possession proceedings. However, the court expects the duty scheme to deal with all cases. Taylor does do this on an unpaid basis. ‘We might pick up paid work through the scheme but we also want the courts to have a smooth-running system,’ he says. ‘The courts don’t care if it’s possession because of rent arrears or whatever. They just hope that there is a duty solicitor there to help.’

Two connected themes are the increasingly ragged state of disrepair of our courts (the shabby Stratford Hearing Centre is a typical example of a neglected court) and the government’s court closure programme.

Over the last decade, the government has embarked on a massive programme of court sell-offs. Almost half of all courts in England and Wales were closed between 2010 and 2018: 162 out of 323 magistrates’ courts and 90 county courts. Underutilised, neglected courts sit on

You’re a rough sleeper and you’re due to appear in court. What are your chances of gaining equal access to the law?

Jon Robins and Daniel Newman

prime real estate. In answer to a parliamentary question in March 2018, it was revealed that the sale of 126 court premises in England and Wales since 2010 had raised £34 million – ‘each going for little more than the average house price’, as the Guardian put it.

Manchester Civil Justice Centre is a rare thing: not only a new addition to our court estate but an architectural triumph. The £160 million building was commissioned by the New Labour government and opened for business in 2007. It is the first major court complex built in Britain since the Royal Courts of Justice in 1882 and was listed by Design magazine in its top ten buildings of the first decade of the 21st century. The magazine breathlessly described it as ‘a spectacle of justice—a place where justice can be seen to be done’, and one that tapped ‘into the commercial and moral heart of Manchester’. Locals call it ‘the filing cabinet’ on account of its cantilevered floors.

The reality is that people living in the outskirts of Manchester, previously well served by local county courts, struggle to make the journey into town; hence the poor turnout. Just ahead of our visit to Manchester, the government had confirmed a further cull of 86 courts across the country, including 10 in the capital.

EDITOR’S NOTE

it dropped to £58.’

In 2015 the fact-checking charity Full Fact looked at the myth of ‘fat cat’ legal aid lawyers’ fees following an inflammatory remark in Parliament by the then justice minister, Lord Faulks. ‘The question that arises out of social welfare law is whether it is always necessary for everybody who has quite real problems to have a lawyer at £200-odd an hour, or whether there are better and more effective ways of giving advice,’ Faulks had said.

‘There are lawyers, and there are lawyers,’ began Full Fact. Some were very talented and their skills earn them hundreds of pounds per hour; others were equally talented but did not work in sectors that commanded ‘the big bucks’. ‘Squarely into this latter camp fall social welfare solicitors paid by the government to help people who can’t afford a lawyer,’ said the group.

The fact checkers explained that when social welfare lawyers were not paid on a fixed fee, they tended to be paid £50–£70 an hour. For a relatively simple housing case a fixed fee is about £160.

If the case is more complicated, more than a day’s work, an hourly rate might kick in. The rate for legal help and advice is just under £50 per hour for some social welfare cases, just over for others.

Some academic books are theoretical and remote. Not this one. In researching their subject, the authors immersed themselves in the day-to-day workings of the justice system as experienced by people on the edge. Over 12 months they visited a foodbank in London, a community centre in a former mining town, a homeless shelter in Birmingham and a destitution service for asylum seekers on the South coast as well as courts and advice agencies up and down the country. What they discovered was a catastrophic inability to access justice and an equally catastrophic failure to deliver. The result is a passionate critique.

Ben Taylor calls the civil justice centre the ‘last dedicated property investment before the property crash’. ‘All the courts that have been closing are being shoehorned into this building, our Palais de Justice. A huge white elephant which for a long time was half empty,’ he says. Courts in Tameside, Altrincham, Oldham and Bolton have been shut down and relocated to the justice centre’s 47 courts.

There is a bitter irony that the then Department of Constitutional Affairs (now Ministry of Justice), which commissioned Manchester’s extravagant ‘spectacle of justice’, also introduced massive reorganisation of the local legal aid sector, effectively dismantling the delicate network of local legal advice provision.

The advice sector has withered in the intervening years. ‘There has been a desertification of the North West. I’m not sure that’s a word but that’s what I’d call it,’ says Taylor, who has specialised in housing law since 1992. ‘Over the last few years key players have pulled out. LASPO [The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012] was the last nail in the coffin.’

LASPO removed most housing from the legal aid scheme, with some exceptions. “Homelessness, disrepair where there’s risk to health, and possession proceedings are still in scope,’ says Taylor. Helen Jackson, a solicitor with Shelter, says Shelter ‘props up’ a massively limited legal aid scheme through income from its charitable donations.

Fat-cat lawyers

‘Do you know how much a legal aid lawyer gets paid an hour?’ Ben Taylor asks me. They used to get paid £66 an hour, but he points out that now the rate is £58. ‘It’s an absolute disgrace,’ he says. ‘The £66 rate was decided in 1997. It was that rate for 18 years, then LASPO came and

The Law Society has described the rates of pay as ‘catastrophically’ low and as having led to law firms leaving publicly funded work in droves. The solicitors’ group pointed out that fees paid for civil legal aid provision had not increased since 1994, equating to a 49% real-terms reduction. On top of this, fees were cut by a further 10% in 2011. As a result, the solicitors’ group argued, more than half of local authorities in England and Wales had no publicly funded legal advice for housing.

‘You don’t do this job for the money,’ says Taylor. ‘You do it because you have won the lottery or because money isn’t important. I love this job. I can’t imagine doing anything else. Would I advise anyone to come into this area of law who is interested in being a lawyer? No way. There is no future in legal aid.’

A brutal process

We spoke to a housing judge who works on the South East circuit, on condition of anonymity. How did they manage the frenetic pace of such crowded lists? ‘You develop techniques,’ the judge told us. ‘The number of issues you need to be able to check on a possession case is huge and you have to take a realistic view. You cannot check everything.’

In the judge’s experience, ‘about one third of people don’t turn up; about one third are represented by the duty solicitor; and about a third have had to deal with the landlord, housing association or local authority beforehand.’

How did they feel, presiding over a court where the stakes were so high and yet so few tenants even turned up? ‘In some way making an order that a mother and her three children leave the property is easier than a young single man because the woman and three kids are going to be rehoused by the

PAGE 4 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | LAW AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

continued in the book

Several defining historical events have shaped Hamas’s foreign policy and international relations. These include Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and 1991, Israel’s expulsion of hundreds of Hamas members to Lebanon in 1992, the PLO’s signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 and Hamas’s election success in 2006. Spanning all of these, US-led attempts to isolate and crush Hamas have failed to sway the organisation from the objectives to which it has been committed since it was founded in 1987. Hamas has survived not only military aggression but also concerted and sustained economic strangulation.

External challenges

Of course, mere survival is not enough. If Hamas is to realise its objectives, the movement will have to overcome a number of external and structural obstacles as well as breathe new life into its foreign relations. Externally, the US-initiated and widely imposed classification of Hamas as a terrorist organisation has drastically curtailed the movement’s ability to establish friendly relations with most western countries. Equally, Israel has played a key role in deterring governments, institutions and individuals from engaging with Hamas.

Undoubtedly, Hamas can and should do far more to cultivate relations with countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Instruments that work in the Middle East or Africa might not be suitable for Latin America and the organisation must, therefore, establish new mechanisms to overcome any legal and security obstacles it encounters. Accordingly, it is in Hamas’s best interests to train and develop a competent diplomatic corps to meet the challenges and demands of coming decades.

Perhaps one of the most contentious issues that has impeded Hamas’s ability to function internationally has been its determination to resist Israeli occupation and pursue national liberation by all means necessary, including armed struggle. Although the right to armed struggle is upheld in UN Resolutions 2955 and 3034 of December 1972, the stronger trend in contemporary international relations is for disputes to be resolved peacefully. On several occasions, Hamas leaders have offered to suspend hostilities with Israel unilaterally in return for Israel’s complete withdrawal from the territory occupied in 1967. As early as February 1994, Musa Abu Marzouq referred to this in the Jordanian newspaper As Sabeel. Ten years later, both Shaykh Ahmad

refugee

Daud Abdullah

Apart from calling for Hamas’s unilateral disarmament and renunciation of violence, Israel and its allies have insisted that the movement recognise Israel as well as all agreements signed between Israel and the PLO. Hamas has refused to meet these demands and remains blockaded in Gaza, driven underground in the occupied West Bank and demonised in most western countries.

At another level, Hamas’s ability to engage on the global stage has been severely undermined by the PLO and its dominant faction, Fatah. Instead of accepting Hamas as an equal partner in the national movement, Fatah has dealt with Hamas, at best, as a rival, and, at worst, as a threat. A striking example of this occurred when Yasser Arafat, and later Mahmoud Abbas, lobbied the South African government to cancel visits by Hamas leaders.

Despite the campaigns of its adversaries and detractors, Hamas has managed to develop cordial working relations with a number of countries. Malaysia, Qatar, Iran, Turkey, South Africa and Russia are all prominent examples. In Europe, non-EU member states such as Switzerland and Norway have engaged with Hamas at various levels. Of the UN’s 193 member states, 137 (71 per cent) have recognised the State of Palestine.

Accordingly, in December 2017, 128 states approved a UN resolution calling on the USA to withdraw its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Similarly, in December 2018, the Trump administration failed to secure sufficient votes to pass a UN resolution condemning Hamas. However, the results of the 2018 vote must also be seen as a wake-up call—87 countries voted in favour of the resolution, 57 opposed it, 33 abstained and 23 others absented themselves. If Hamas does not win more friends in the UN’s General Assembly soon, that resolution might well become a fait accompli.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Yasin and Abdul Aziz al-Rantisi repeated the offer. Both were assassinated by the Israelis within months of doing so.

Internal weaknesses

Internally, Hamas must address certain structural weaknesses to improve the conduct of its international relations. Over the years, the movement has allowed several institutions to work in the international arena on its behalf. Although this route was chosen out of necessity, it has given rise to discordant understandings, incoherence, a duplication of efforts and a waste of resources.

In addition, while the movement has a well-established tradition of ‘democratic governance’ and leadership rotation, the first generation of leaders will soon have to make way for the next. In 2012, Khaled Meshaal acknowledged this when he announced that he would be stepping down from the leadership to make way for ‘new blood’. Having forged strong bilateral relations with a number of countries, the movement must ensure that the next generation of leaders has the necessary academic qualifications, experience, communication and social skills to function effectively on the global stage.

Undoubtedly, much of Hamas’s international credibility and recognition rests on its domestic strength. Its 2006 election victory marked a watershed in the movement’s international relations—it was after this that countries such as Russia, South Africa and Malaysia engaged with the Hamas-led elected government. However, subsequent confrontations (and the rift with Fatah, which came to a head in 2007) have since deterred foreign interlocutors and impeded Hamas’s ability to expand its international relations. Ultimately, the greatest losses from the rift have accrued neither

Palestinians in the occupied territories live in two separate entities—Gaza and the West Bank— each governed by rival administrations: Hamas and Fatah. In this book, Daud Abdullah explores the ascendancy of Hamas, locally and globally, looking in particular at its foreign relations policies and its success or otherwise in helping Palestinians achieve their national ambitions. The author is the director of Middle East Monitor (MEMO) and a former senior researcher at the Palestinian Return Centre (London). He has lectured in History at the University of Maiduguri (Nigeria) and in Islamic Studies at Birkbeck College, University of London.

to Hamas nor Fatah but to the Palestinian national project. The need for Palestinian national reconciliation and unity cannot be overemphasised.

Meshaal acknowledged this in November 2017, at a conference organised by the Gaza Centre for Studies and Strategies, stating that ‘the Palestinian cause is experiencing an unprecedented decline at all levels.’ He also stressed the need to ‘unify Palestinian ranks and Palestinian national institutions’.

Facing the future

Throughout its history, Hamas’s central leadership has depended on friendly neighbouring or regional countries for sanctuary. This, in itself, has challenged the movement’s independence and decision making. The movement’s experience in Syria was instructive in this regard. While there was no evidence that the Syrian government ever meddled in Hamas’s internal affairs, when the crisis erupted in 2011, Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, expected Hamas to support him. The difficult choice facing Hamas was whether to adhere to its founding principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries, or to support a regime that had provided the movement with all manner of assis-

ENGAGING THE WORLD

THE MAKING OF HAMAS’S FOREIGN POLICY

Afro-Middle East Centre (AMEC)

Softback, 272 pages January 2021

9780994704825

RRP

https://www. memopublishers. com

tance for a decade. As soon as Hamas had chosen the former, it was only a matter of time before its relationship with Assad’s regime collapsed.

Just as Hamas has aspired to ground its foreign relations on the principle of non-interference, the organisation is strongly committed to a policy of non-alignment with rival regional blocs. It is important to understand that these policies derived from lessons Hamas learned from observing the PLO in the 1970s and 1980s. However, by 2011, Hamas’s relationship with Syria, Iran and Hizbullah had evolved into the so-called Axis of Resistance. Palestine’s liberation was the goal that brought them together and the alliance seemed to show that Hamas’s early idealist approach to foreign relations had given way to a decidedly realist one. Nevertheless, it can be argued that it was precisely because of its idealism that Hamas had to abandon its base in Syria in 2012.

Ideally, Hamas still favours this policy of non-alignment with any bloc, but realities on the ground suggest that the Palestinians will have to forge alliances if they are to realise their national aspirations. Whether the movement succeeds in weaving strands of both idealism and realism into its international relations will be a subject of ongoing debate. However, what can be said now is that its general approach is by no means one-dimensional. It is, as senior Hamas official Imad al- Alami pointed out, prepared to employ every means to secure maximum benefit for the liberation of Palestine and the restoration of its people’s rights in ways that are consistent with Islamic law.

From its inception, Hamas has regarded the Arab and Islamic lands as their ‘strategic depth’; certainly, the formulation of its foreign policies was based on this perception. However, the situation in the Arab lands in 2020 is quite different to what it

continued in the book

READERS’ COMMENTS

Ilan Pappé: Challenges successfully the common misrepresentation of Hamas in the West. A must-read.

Nur Masalha: The most comprehensive account of Hamas’s international relations to date. Meticulously documents the achievements and shortcomings of a dynamic non-state actor.

MIDDLE-EAST POLITICS | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | PAGE 5

£24.00 inc. free UK postage

From its

camp and Muslim Brotherhood origins, Hamas is now the Palestinians’ main advocate. For better or worse?

To understand not just its high art but the mind of the Renaissance, it is necessary to understand its contrivance of humour Philip Steadman

EDITOR’S NOTE

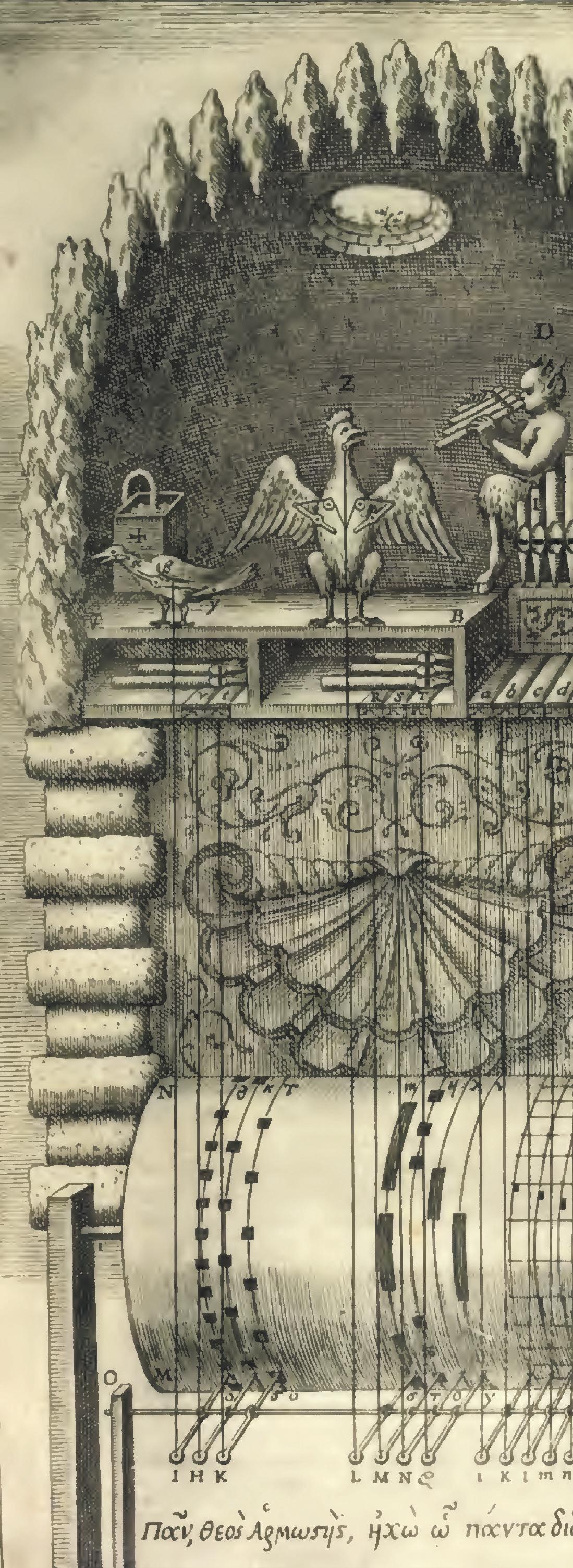

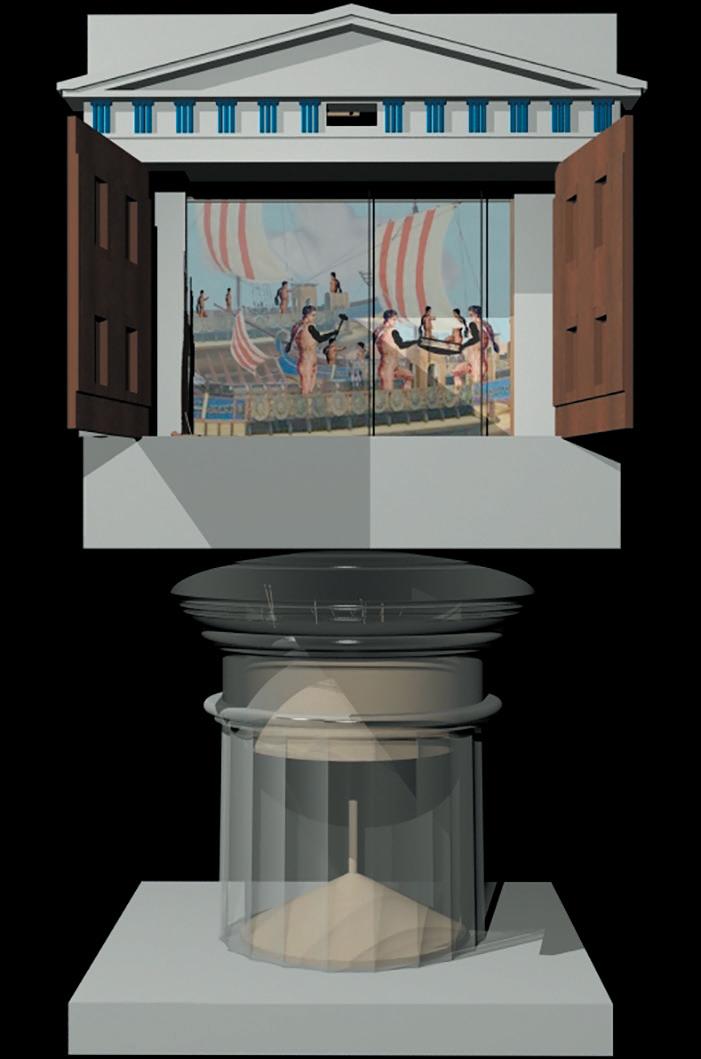

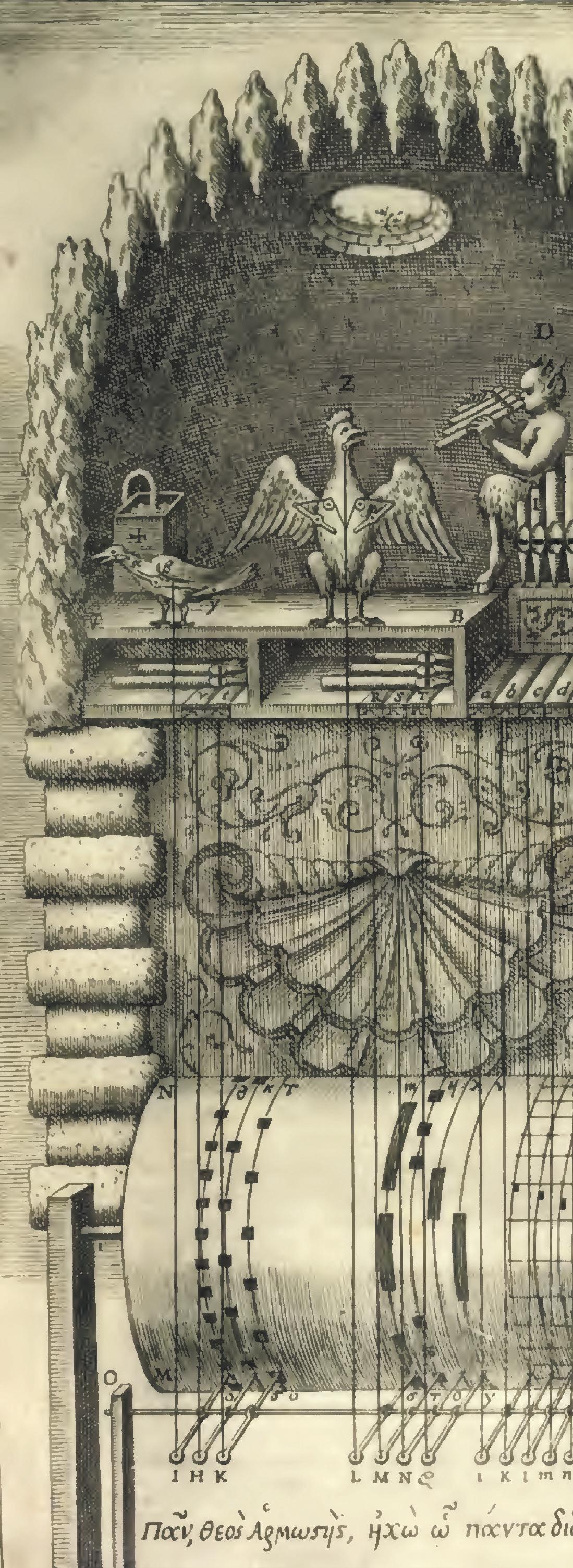

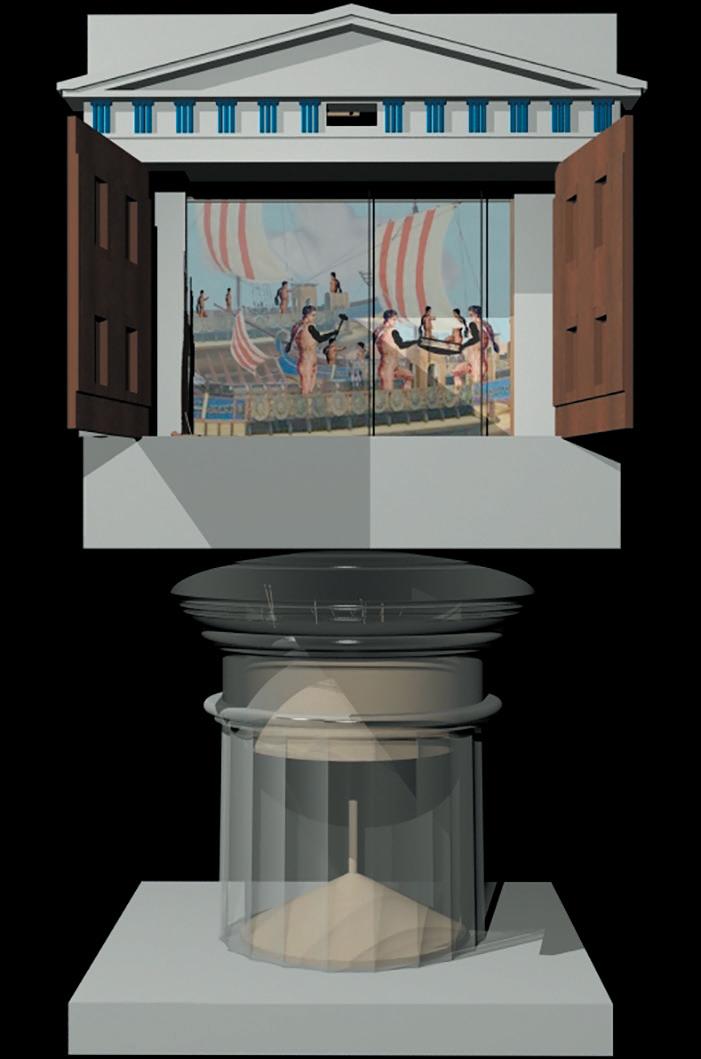

Renaissance Fun is both an examination of how Renaissance entertainments were made to work and a scholarly essay about the impact on Renaissance designers first of Vitruvius and, as his influenced waned, Hero of Alexandria. Vitruvius, who advised the Roman army on every aspect of building and engineering in the 1st century BC, is the better known; Hero, a century later, much less so but his writings on pneumatics and automata inspired 16th- and 17th-century entertainments as well as providing the model for the proscenium-arch theatre. Read how seas were created on stage and how mechanical birds imitated real birdsong.

In November 1643 the diarist John Evelyn set out from England on a series of journeys around the Low Countries, France and Italy in an early version of the Grand Tour. He visited the classical ruins of Rome and southern Italy; and he saw many of the paintings, sculptures and works of architecture produced in the Renaissance of the visual arts of the previous two centuries.

But Evelyn also enjoyed a great variety of other entertainments and amusements, some serious and refined, others vulgar and trivial. In November 1644 he paid a visit to the Jesuit college in Rome, where the polymath Athanasius Kircher entertained him and his friends with ‘many singular courtesies’. For Evelyn’s party Kircher brought out, ‘with Dutch patience’, his ‘perpetual motions, Catoptrics, Magnetical experiments, Modells, and a thousand other crotchets & devises’. ‘Catoptrics’ was the study of mirrors and the reflection of light. Kircher devised several optical entertainments making use of mirrors and lenses, including camera obscuras and magic lanterns.

Evelyn visited many of the great Renaissance and Baroque gardens of Italy and France, and admired their walks, parterres, groves and statuary both ancient and modern. He was entranced by the ‘jettos’ of water that made patterns of spray in the air in the shapes of glasses, cups, crosses, crowns, and suns. Other fountains imitated the sound of thunder or produced artificial rainbows. In May 1645 he went to the gardens of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, where he enjoyed the scale model of the city of Rome with its stream representing the Tiber. He writes:

In another

a

artificial,

This was not the only water-powered organ that Evelyn saw. He mentions hearing ‘artificial music’ in several places on his travels.

One more type of entertainment about which Evelyn was greatly enthusiastic was the theatre. Arriving in Venice in June 1645, he went to the opera accompanied by ‘my Lord Bruce’ to see a performance of Hercules in Lydia. The music and singing were ‘excellent’, ‘with variety of Seeanes painted & contrived with no lesse art of Perspective, and Machines, for flying in the aire, & other wonderfull motions (2). So taken together it is doubtlesse one of the most magnificent & expensfull diversions the Wit of Men can invent.’ In Hercules the scenes were changed 13 times.

The common factor in all this variety of entertainments was that they depended on machines. The fountains relied on elaborate systems of water control: aqueducts, reservoirs, pipes and nozzles. Animal and human automata were worked by concealed hydraulic, pneumatic and mechanical apparatus. The machinery of the Renaissance theatre brought celestial personages down from the clouds (‘gods from machines’) and brought charac-

ters from the Underworld up from below. Scenery was rotated, slid, rolled and replaced using yet more mechanical devices. Sets were built and painted to create realistic illusions of depth using the new methods of perspective.

How did these machines work? How exactly were chariots filled with singers let down onto the stage? How were flaming dragons made to fly across the sky? (3) How were seas created on stage? (4) How did mechanical birds imitate real birdsong? How could pipe organs be driven and made to play themselves automatically by waterpower alone? (5)

The designers of Renaissance entertainments looked back to the work of their predecessors in the ancient world. They studied such archaeological evidence as remained: the fountains, theatres and ruined villas of Rome and the Empire. Above all they read those few texts on machines that survived from Rome, Greece and Alexandria. These were translated into Latin and Italian and were studied intently by Renaissance engineers in an attempt to recover and recreate some of that lost world of knowledge and expertise.

First among these ancient writers was Vitruvius, a Roman military engineer and architect who lived in the first century BC. His book On Architecture covers the design of theatres and the scenic decoration of the ancient drama. Vitruvius also devotes just a few sentences to painting in perspective, and its use in the design of stage scenery.

The impact of Vitruvius’s writings on Renaissance theatre design from the fifteenth century was very great, and reached a high point in Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza of 1585. After this, however, Vitruvius’s influence waned, with a move in theatrical taste away from classical drama towards modern comedies and musical entertainments that demanded a very different kind of theatre building, with much more elaborate scenic machinery.

Interest among designers turned to a second ancient writer: Hero of Alexandria, who lived in the first century AD and worked in Alexandria, where he probably taught and studied in that city’s far-famed Museum and Library. His best-known work is the Pneumatics, which despite the title is largely devoted to ingenious and entertaining devices, some of which operated automatically. These provided models for the automaton figures of humans and animals that populated the garden grottoes of late Renaissance gardens (6).

Hero wrote another book, much less well known, On Automata-Making. This describes the construction of two miniature theatres that put on elaborate performances without human intervention. One of these had a proscenium arch with doors that opened onto a series of scenes, in which figures of men and gods moved in front of mobile scenery (7). It is thus quite unlike the classical open-air theatre; but it does bear close similarities to both the form and the workings of the new Italian theatres of the late sixteenth century. Hero’s importance for Baroque theatrical machinery—which has previously been little appreciated—was crucial.

continued in the book

PAGE 6 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | ART HISTORY

5 6

garden

noble Aviarie, the birds

& singing, til the presence of an Owle appeares, on which the[y] suddainly chang their notes, to the admiration of the Spectators (1): Neere this is the Fountaine of Dragons belching large streames of water, with horrid noises: In another Grotto, called the Grotta di Natura, is an hydraulic Organ …

RENAISSANCE FUN THE MACHINES BEHIND THE SCENES

UCL Press

Softback, 418 pages

1 April 2021

9781787359161

RRP £30.00

Our price £26.40 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

READER’S COMMENT

Philip Tabor: Who wouldn’t have paid a scudo to see a cast of hundreds, some naked, all shrieking, while stagehands run about setting the scenery aflame? This generously illustrated book is to be relished for its hair-raising descriptions and thoroughness.

WHY ARE MOST BUILDINGS RECTANGULAR? AND OTHER ESSAYS ON GEOMETRY AND ARCHITECTURE

Routledge Softback, 270 pages August 2017

9781138226555

RRP £39.99

Our price £35.59 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

READERS’ COMMENTS

Adrian Forty: Erudition and subtle wit make this a most enjoyable book.

Kevin Lomas: A must-read … Steadman’s explanations display polymathic knowledge.

Meta Berghauser Pont: A clear ode to the work of Leslie Martin and Lionel March.

Matthew Allen: Approaches rigorously focused questions with a seemingly inexhaustible array of sources.

VERMEER’S CAMERA UNCOVERING THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MASTERPIECES OUP

Softback, 207 pages April 2002

9780192803023

RRP £14.99

Our price £10.71 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

READERS’ COMMENTS

David Hockney: This book is terrific.

Brian Sewell: Exegesis at its most intelligent. Quentin Williams: Diagrams demonstrating how Vermeer used the camera are the most cogent I’ve ever seen.

Frank Whitford: Take it from me: this book is really something.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Philip Steadman is Emeritus Professor of Urban and Built Form Studies at UCL.

ART HISTORY | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | PAGE 7

1 3 2 7 4

From my childhood in rural Cardiganshire (now known as Ceredigion), I was aware of two outstanding Welsh politicians—Aneurin Bevan and James Griffiths. Both played an important role in our lives as a result of their efforts to create the Welfare State but, of the two, James Griffiths was ‘one of us’ as he spoke Welsh and came from Betws, in neighbouring Carmarthenshire, whose community closely reflected my home village of Llanddewi Brefi.

Bevan was not a Welsh speaker and Tredegar, his home town, not only seemed far away to those of us who could not afford a motor car but its Welshness was different. Also, due to his proximity and understanding of my part of Wales, James Griffiths never missed an opportunity to visit Cardiganshire at election times and would fill the largest halls with his oratory and socialist fervour.

When I was a student in Aberystwyth I came to know him personally, and appreciated his support for our student magazine, Aneurin. I still remember the thrill of reading his memoir, Pages from Memory, but felt rather disappointed that his remarkable life—from a boy miner in the Amman Valley, to MP for Llanelli (from 1936 to 1970), to the Cabinet, as Minister for the Colonies, Min-

JIM

THE LIFE AND WORK OF THE RT. HON. JAMES GRIFFITHS

Modern Welsh Publications

Hardback, 354 pages 13 April 2021

9781999689858

RRP £20.00 Contact garthdriveben@ gmail.com

https://www. booklaunch.london

ister of Pensions, Chairman of the Labour Party, Deputy Leader of the Labour Party and first ever Minister for Welsh Affairs—deserved greater recognition.

The life and work of James Griffiths is a romantic saga. His father, William Griffiths, was a blacksmith and was steeped in the issues of the day. He hero-worshipped W.E. Gladstone and later Tom Ellis and David Lloyd George, and was a loyal member of the local Welsh independent chapel in Ammanford. Meanwhile, Griffiths’ mother, Margaret, cared for her four sons and three daughters, never forgetting the two infant children she lost. Due to the family’s financial circumstances, the seven surviving children were all working by the age of 13 and so never progressed to secondary school. As such, their only means of education was the local elementary school and the chapel.

When he started work as a young collier, Jeremiah became known as James, and was already known simply as ‘our Jim’ or ‘Jim yr Efail’ (Jim of the Smithy/ Forge) when he became President of the South Wales Miners’ Federation. At the beginning of his working life he experienced the 1904-5 Religious Revival and the new theology associated with Reverend R.J. Campbell, as well as the extraordinary impact of Keir Hardie as the prophet of Socialism. His conversion from Liberalism to Socialism had taken place by 1908, the year he lost his eldest brother Gwilym in a mining accident and nearly lost his talented, poetic brother David Rees, known by his eisteddfodic name, Amanwy.

It was also the year he took responsibility for a new branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in Ammanford. His ILP convictions brought him into the fellowship of a group of young men alienated from the Liberal Party and the chapels which staunchly supported Lloyd George and the Liberal tradition. A pacifist during

READER’S COMMENT

Huw Edwards (BBC): Ben Rees’s analysis of Griffiths’ rejection of the Liberal tradition and his embracing of Labour is fascinating. Griffiths was a loyal child of the chapel and his early political journey was difficult. Students of the Blair, Brown, Miliband and Corbyn projects will appreciate some striking parallels.

the First World War, James Griffiths made a name for himself as a left-wing firebrand, greatly admired by George Lansbury and others who visited the socialist citadel, Ty Gwyn (White House).

He went on to win a scholarship, through the Miners’ Union, to the Central Labour College in London, where he met like-minded miners such as Bevan, Ness Edwards, Bryn Roberts. His ambition was to be a leader in the trade union movement and achieved this through service, ability and charm as well as through the support … of his young bride, Winifred Rutley from Hampshire, with whom he would have four children. He worked as a political agent, then a miners’ agent, finally becoming Vice President and President of ‘the Fed’, the South Wales Miners’ Union (SWMU). In a by-election in 1936 he kept Labour’s firm grip on Llanelli and proudly served his constituency for the next 34 years, gaining wide respect as a defender of the working class.

Griffiths achieved much during his political career and it was a fitting tribute that, at the age of 74, he became the first Secretary of State for Wales, laying the foundations for the future growth of devolved government in Wales.

the 1870 Forster Act and, under Lewis, every child was forced to learn the English national anthem as quickly as possible.

In the last year of young Jeremiah’s schooling, however, a new teacher, Rhys Thomas, joined the staff. Unlike Lewis, who had not given music any significance in the life of the school, Thomas conducted the local brass band and soon formed a school choir, which Jeremiah joined and enjoyed. The new teacher also spoke Welsh whenever possible and his brother, the Reverend John Thomas of Soar Welsh Independent Chapel in Merthyr Tydfil, went on to be the formative influence on the Griffiths children.

The Ammanford chapel was an important influence on the young Jeremiah and his siblings, with morning and evening worship, the Sunday School in the afternoon and the twice weekly Band of Hope. The first Band of Hope of the week was held at five o’clock on Sunday afternoons and its members met to prepare for the different Christian festivals and especially for the many services held during the Christmas season. The Band of Hope … conveyed to the children the values of temperance, leaving Jeremiah a staunch teetotaller for the rest of his life.

D. Ben Rees

At the end of the Victorian era, the Amman Valley and Gwendraeth Valley saw an influx of newcomers who came to seek work in the anthracite coalfield and the developing tinplate industry. Many coal mines were opened in these valleys and were often given poetic Welsh names.

In the 30 years between 1870 and 1900, collieries rapidly opened in rural Carmarthenshire. Indeed, the small village of Cross Inn became an important population centre and was renamed Ammanford, or in Welsh, Rhydaman. As recorded in the 1891 census, Ammanford was a thoroughly Welsh-speaking town, as were all the villages surrounding it, and this remained the case for generations: the 1961 census noted that 79 percent of the population of Betws spoke Welsh. The colliery in Betws was opened in the 1890s and it was mainly responsible for the growth of the village, which stands across the river Amman.

It was in Betws that James Griffiths was born in 1890. His parents named him Jeremiah Griffiths, after the Old Testament prophet, with a secret wish that one day he would be a well-loved preacher in the pulpits of their Welsh Independent denomination, Yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg (the Welsh Independents), an exclusively Welsh-speaking denomination. The newly born baby was christened at Gellimanwydd chapel (known locally by its English name as the Christian Temple).

In his adult life, James Griffiths always paid homage to his upbringing in the Sunday School and the Band of Hope, and in particular, the influence of the local station master, John Evans, who presided at the meetings. Evans had an amazing ability to communicate with the children, and they in turn hero-worshipped him. His first sentence at the beginning of every Band of Hope meetings was always ‘Nawr, ’te, mhlant i’ (Now then, my children) and every Sunday afternoon and week-night meeting began with the well-known children’s hymn, Mae Iesu Grist yn derbyn plant bychain fel nyni (Jesus Christ accepts small children like us).

As well as warning about the evils of alcohol, he taught them to participate in debate and public speaking, and built up their confidence. When Evans died on 5 November 1918 at the early age of 46, Griffiths paid him a hearty tribute in the local weekly newspaper, praising his lost mentor for the ‘wonderful way he had with us’.

The problem of our age [he wrote] is the proper administration of wealth, that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship. There remains, then, only one mode of using great fortunes; but in this we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich and the poor.

The charisma and the influence of Evans remained with Griffiths into later life:

Young Jeremiah was educated in the local Board School in Betws and the Christian Temple Sunday School in Ammanford. The headmaster of the Board School, John Lewis, was a staunch Anglican, ran the school for 42 years from 1871 to 1912 and, despite being a Welsh speaker, was never heard speaking Welsh within the confines of the school. The Welsh language was effectively banished from all schools in Wales after continued in the book

Gone are the sermons we heard in those days, few of the exhortations remain, but the memory of John Evans and his Band of Hope remains as a sweet, ennobling influence in our lives.

At the end of every Band of Hope meeting, Evans would recite the verse:

EDITOR’S NOTE

James Griffiths was a remarkable combination of Britishness and Welshness. He was the originator of several UK political institutions in the second half of the 20th century. As Minister for National Insurance he created the modern state benefits system, and introduced the Family Allowances Act 1945, the National Insurance Act 1946 and the National Assistance and Industrial Injuries Act 1948. He also served as the first Secretary of State for Wales from 1964, having campaigned for such a post for 30 years. In Jim, Ben Rees explores his life from his childhood to his rise through colliery politics and his central role in the Labour Party.

PAGE 8 | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | WELSH POLITICS / BIOGRAPHY

Less remembered now than Aneurin Bevan, the MP James Griffiths was arguably the brightest star in the Attlee firmament

The richest man in the world emigrated to America in 1848 but built 35 libraries in Wales. Their impact was transformative Ralph A. Griffiths

EDITOR’S NOTE

Andrew Carnegie was the world’s wealthiest industrialist in the late 19th century and its most generous. He wrote about the importance of philanthropy and led by example, giving away 90 per cent of his own wealth—about $350 million—in his later life. Wales benefited massively. The library system that Carnegie’s bounty created helped to transform Welsh literacy, especially political literacy, at a time when public education was hugely in demand. The author discusses Carnegie’s achievement and legacy as well as looking at his buildings’ likely future.

Free public libraries are at the heart of civil society in the United Kingdom and stand as witness to its quality. During the 20th century they strove to bring knowledge, learning and leisure to the entire population, men, women and children, if more easily in towns and cities than in country districts—and they continue to do so.

At the beginning of the century the challenge was to establish free public libraries from coast to coast and to sustain them by engaging the public that they were intended to serve. At the century’s end, the challenge appears to have been to maintain the publicly funded countrywide library system which had emerged by mid-century to enrich‘the cultural fabric of communities’, despite the consequences of two world wars. This is as true of Wales as it is of the other countries of the United Kingdom.

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919), the Scots-American industrial entrepreneur and philanthropist, was a pivotal figure during early stages of this saga, in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and more broadly in the USA and elsewhere in the English-speaking world. His permanent legacy is represented by a considerable number of Carnegie Foundation Trusts which continue to support cultural, educational and other causes, and, in Wales, by library buildings which remain part of the country’s social, cultural, educational and architectural heritage.

Carnegie was a remarkably successful industrialist and steel-maker who became one of the world’s most notable entrepreneurs and philanthropists. He is judged to be ‘the world’s first modern philanthropist’ and, according to his fellow billionaire J. P. Morgan, during his lifetime the world’s richest man. In the winter of 2013–14 an exhibition held at the Scottish Parliament by the Carnegie Trust UK (in association with the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland) celebrated his international educational and cultural legacy. His native Scotland has been a handsome beneficiary of this legacy, but Carnegie did not neglect Wales, especially in the way he helped to create public libraries in communities where few or none had existed before.

Yet his Welsh legacy has been neglected, not least because the extent of his personal support for library provision in Wales has not been fully identified and recorded. A proposal in December 2013 that his and the Trust’s philanthropy in Wales should be celebrated with an exhibition at the National Assembly for Wales was not pursued.

However, the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales’s website, www.coflein.org.uk, has begun to record some of the thirty or so libraries which were created as a result of generous gifts by Carnegie himself, totalling thousands of pounds, in the decade before the First World War—and that is aside from the grants he offered and which, for a variety of reasons, were not taken up. The Carnegie libraries of Wales helped to boost the public library movement in Wales and were instrumental in transforming the lives of the communities they served, in all parts of Wales from Dolgellau to Barry, from Tai-bach to Wrexham.

Now that public libraries are facing financial difficulties and, in some cases, a less certain future, Carnegie’s support for towns and parishes which were keen to sponsor free libraries for the general public is an inspiring example of how private wealth can be set to the public good.

Some Carnegie libraries—such as the buildings at Abergavenny (opened in 1906), Bangor (1907) and Treharris (1909)—continue to function as libraries, engaging the public and inspiring pride in those who work in them. A few are neglected (including Aberystwyth’s library, opened in 1906), and yet others have been strikingly refurbished by their local authorities (as at Colwyn Bay (1905) and Cathays, Cardiff (1907)), or are now given over to other public community purposes (as in Brynmawr (1905) and Bridgend (1907)). Only a very small number have been either disposed of (such as the small library at Troedyrhiw) or demolished (as in Abercanaid (1903)).

Like church and chapel buildings in Wales, the Carnegie libraries were built close to the heart of their communities, acting as community centres and meeting places or else, more fundamentally, as freely available havens for quiet contemplation and self-improvement. Today, when the professional public librarian seems to be about to join the ranks of endangered species, the local librarian and their (usually volunteer) assistants who staff these libraries are the successors of those librarians who have placed their specialist knowledge at the disposal of young readers as well as adult men and women, the poor and the better-off and thereby changed lives, deploying what has been identified as their ‘capacity for empathy’.

andrew carnegie was not the first to sponsor free public libraries in Wales, the United Kingdom and the United States. In Great Britain and Ireland he was able to further his ambition within a context set by several Public Libraries Acts passed by parliament from 1850 onwards. These gave powers to a broadening range of local authorities in the second half of the 19th century to establish free libraries and museums. Despite some persistent opposition, boroughs, then towns and then parishes were empowered to levy a halfpenny and then a penny rate for this purpose, provided they secured a measure of democratic endorsement.

This was a major step beyond the earlier creation of privately endowed and subscription libraries.

Scepticism lingered in a number of quarters, and the ambition of some small towns and parishes to have their own libraries outran the ability of their populations to raise sufficient funds from the rates, hence the need for philanthropy to support the public library movement almost from its beginnings. The present-day dilemma for local authorities as the democratic and accountable bodies responsible for public libraries is not new. Whilst still in his 40s, Andrew Carnegie resolved to help.

Carnegie was a visionary, and rare among the wealthy entrepreneurs of his day—and for long after. His philanthropy was not directly linked to his own business interests or to his family, and his countless benefactions were made throughout much of his career, not simply

FREE AND PUBLIC ANDREW CARNEGIE AND THE LIBRARIES OF WALES University of Wales Press

Softback, 176 pages

15 Jun 2021

9781786837745

RRP £11.99

Our price £10.55 inc. free UK postage

https://www. booklaunch.london

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ralph Griffiths is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at Swansea University, Hon. Vice-President of the Royal Historical Society and a former Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales.

towards its end. His gift-giving, especially in the United States of America, gathered speed during the 1880s and 1890s when he was still an active businessman and entrepreneur. Moreover, he formulated a personal philosophy of philanthropy which he publicized in his writings. Among his prolific writings on industrial, economic and political issues are two essays written in 1889 on ‘Wealth’ and ‘Best Fields for Philanthropy’, which were first published in the North American Review His extraordinarily influential essay on ‘Wealth’ was reprinted many times and with the more elevated title, ‘Gospel of Wealth’.

He wrestled with questions of the social and economic purposes of wealth, how it should be deployed by those who possess it and the social equality that it could and should promote. For, like a number of fellow prominent businessmen, he had a fundamental belief in political and social equality allied to equality of opportunity.

The problem of our age [he wrote] is the proper administration of wealth, that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship. There remains, then, only one mode of using great fortunes; but in this we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich and the poor.

For Carnegie, charity was not an end in itself, but rather it should ‘help those who will help themselves … to assist, but rarely or never to do all’; neither should giving be ‘impulsive and injurious’. Drawing on his own life and experiences, his conclusion was, for him, inescapable: among ‘the best uses to which a millionaire can devote the surplus of which he should regard himself as only the trustee’ is a ‘free library … provided the community will accept and maintain it as a public institution’. As for the wealthy , his verdict is famous: ‘The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced’. In a later essay, in 1891, ‘The Advantages of Poverty’, Carnegie went so far as to declare that ‘There is really no true charity except that which will help others to help themselves, and place within the reach of the aspiring the means to climb’. His ideas and declared intentions were popularly admired, in Wales as elsewhere, especially in places which were in receipt of his benefactions. In the industrial port of Barry in south Wales, to which he granted the large sum of £8,000 for a new library in 1902, the Christmas eisteddfod held at the Welsh Congregational Chapel in dockland awarded the main prize for extravagant verses on ‘Carnegie’ that rose to biblical hyperbole:

An influence for good, a mighty power Is wealth in hands that know its real worth. Who hold their riches not as fortune’s dower, But held in trust for Him who rules the earth. Who seek not acclamation or reward, But simply follow the Divine command, And, as a faithful steward of the Lord’s, Dispense His bounty with a lavish hand; Which is the man whose name a household word Is now where’er the English tongue is heard. No sporting millionaire is he, who fain Would crown an empty head with wreath of bay,

WELSH HISTORY | BOOKLAUNCH ISSUE 11 | PAGE 9

continued in the book

WHO SPEAKS FOR WALES? NATION, CULTURE, IDENTITY

University of Wales Press

Softback, 432 pages

9781786837066

RRP £18.99

Our price £16.71

inc. free UK postage

https://www.

READERS’ COMMENTS

Cornel West: The last of the great European male revolutionary socialist intellectuals.

Michael Sheen: A truly landmark publication…. The new afterword shows how Raymond Williams’s thinking is as important and relevant today as it has ever been.

Preface | Daniel G. Williams

Who Speaks for Wales? first appeared in March 2003. It collected in one place the Welsh-related essays of Raymond Williams (1921–88) and was conceived and compiled in the years following the narrow vote for Welsh devolution in the referendum of 1997.

If a distinctive Welsh political culture was to develop, and if devolution was to be a ‘process’ rather than an ‘event’, a sense of common aspiration and interest would need to be forged between the socialist and minority nationalist threads of Welsh political radicalism as embodied institutionally in the Labour party and Plaid Cymru.

Raymond Williams’s thought and writings offered resources for forging a rapprochement between these traditions, and that is what I was attempting to foster in my emphasis in the introduction on the pluralism of Williams’s vision, on the questions asked as opposed to the answers offered, and on the ways in which Williams’s self-defined ‘Welsh-Europeanism’ could be seen as a manifestation of his call on socialists to engage in a project of exploring ‘new forms of “variable” societies in which different sizes of society’ could be ‘defined for different kinds of issue and decision’.

When the volume was launched, the Labour government of Tony Blair was two years into its second term in Westminster. Raymond Williams had warned in the 1980s that destroying public common interests in the name of private solutions would drive whatever was left of the ‘public’ sector into crisis, starved of investment. This is what the Thatcherite neoliberal agenda delivered, perpetuated by Blair’s Labour.

Wales registered an early resistance to this neoliberal programme in the first elections to the new National Assembly in 1999. While Blair openly admitted that he regarded the devolved institutions to be little more than ‘parish councils’, Wales at least now had a vehicle where its political voice could be heard.

In the first elections to the new Assembly, Labour won as expected, but Plaid Cymru surpassed expectations by gaining 30.5% of the vote (outperforming her Scottish sister party, the SNP). Labour learnt its lesson and soon deposed the Blairite Alun Michael, putting Rhodri Morgan in his place as First Minister. Morgan had political roots in the hopes and aspirations of the Labour movement and, as the son of T. J. Morgan, onetime Professor of Welsh at Swansea University, also had a foot in the traditions of Welsh language culture. Evoking the legacy of Aneurin Bevan, Morgan set out to create ‘clear red water’ between ‘classic’ Welsh Labour and Blairism.

Morgan understood that welfare systems have profound effects on the wider social framework. He knew that the principle of ‘social insurance’ was not only efficient but was also a way of underwriting an evolving sense of Welsh citizenship; that ‘universalist’ policies (free bus passes, free prescriptions, free school breakfasts) were essential to binding the richer sections of society into collective forms of welfare. Thus, while Blair was reconstructing the Labour Party along the lines of

Raymond Williams embraced Europeanism and Welsh nationalism. Brexit defeated both. Where does that leave him? Daniel G. Williams

EDITOR’S NOTE

First published in 2003, this collection was the first to bring together Raymond Williams’s musings on the meaning and significance of Welsh identity. At the time it seemed to provide a fresh basis for reviewing ideas of nationalism and socialism in Welsh thought. This new edition, with new material and a new afterword, appears at a very different time, following the apparent rejection of Williams’s Welsh-European vision by Welsh voters in the 2016 Brexit referendum and the great superstructure of analytical socialism that he subscribed to. Nonetheless, says its editor, Williams remains essential reading on questions of nationhood in Britain and beyond.

Bill Clinton’s neoliberal Democrats in the United States, Rhodri Morgan was establishing a new Welsh polity based on European social-democratic values.

This social-democratic vision informed the period of coalition with Plaid Cymru from 2007 to 2011. The affirmative ‘Yes’ vote (63.49%) for Wales to have law-making powers in the referendum of 2011 seemed to suggest that the ‘Welsh European’ project was very much on track.

Retrospectively, the low turn-out of 35.2% in that referendum should have been a cause for concern. The form of ‘Welsh welfarism’ failed to escape the straightjacket of British politics. Labour in Wales had to keep its devolution-sceptic wing happy, making sure that it never appeared ‘too nationalist’. Yet, the party’s electoral success depended on the impression that it was ‘standing up’ for Welsh interests.

The way to alleviate these tensions was to trumpet relatively minor state interventions as ‘standing up for Wales’. Welshness was made equivalent to welfarism, in a process that equated class with cultural identity. The project of common social advancement was largely abandoned by Labour for the administration, alleviation and ultimately—if unintentionally—preservation of relative poverty. This political stagnation led to the rise of the Right-wing populism that was an unfortunate feature of Welsh politics in the 2010s.

We celebrate Williams’s centenary under the dark shadow of the European Union membership referendum of 2016. While Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in Europe, Wales followed England in voting to leave. In the face of a virulent, intolerant Right, there was space to develop a federal vision in which English, Welsh and Scottish Europeans would rejuvenate the Left—a realisation of the rainbow coalition of green, minority nationalist and socialist forces that Raymond Williams imagined in his final years. The failure to do so will haunt progressive politics for a generation.

It remains to be seen whether the writings of Raymond Williams document a vision of a ‘Europe of the peoples and nations’ that was never to be realised, or whether they will become crucial, foundational, texts in the rejuvenation and future fulfilment of that Welsh-European vision. Williams noted that Welsh history testifies to a ‘quite extraordinary process of self-generation and regeneration, from what seemed impossible conditions’. This new Centenary Edition has been prepared with these words in mind.

The

Welsh Industrial Novel | Raymond Williams

The inaugural Gwyn Jones Lecture

April 1978

English middle-class novelists observed the industrial landscape under the crisis of Chartism. All shaped what they saw and showed with narratives of the reconciliation of conflict. That part of their ideology is easily recognized. But all to some extent, and Elizabeth Gaskell to a remarkable extent, succeeded in peopling this strange, fierce world; succeeded, that is, in the crucial transition from Dickens’s type of industrial

panorama to the industrial novel.