TWO SISTERS, TWO GREEN HOMES

Plus Recipes WAMPANOAG

MARTHA’S VINEYARD / FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

/ SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

SIMPLE

Local Hero: High School Senior Annabelle Brothers · Great Local Holiday Gift Ideas TM SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES marthasvineyard. .com FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

OF FISH IN THE (VINEYARD) SEA

PLENTY

ENVIRONMENTAL WISDOM

WITH CURRIER in

Truck

CRUISING

Melinda Loberg's Rivian

ARCHITECTURE. ENGINEERING. BUILDING. INTERIORS. SOLAR. SOUTHMOUNTAIN.COM Sanct·u·ary

RED VALLEY ROAD, CHILMARK

Offering 3.6 acres of open, rolling land with classic Chilmark stonewalls and beach plum bushes, this charming four-bedroom home with a pool, sits on a ridge and offers views that reach as far as Noman’s, the Atlantic, Nashaquitsa, the Elizabeth Islands and Menemsha. The property includes a garage for vehicle and boat storage. Squibnocket Beach is around the corner and private access onto Zack’s Cliffs beach in Aquinnah is included as part of Blacksmith Valley Association as well as deeded access to Quitsa Pond and a small dock where kayaks and a sunfish can be stored. Buyers can enjoy the house as it is or make plans to expand, renovate or rebuild in this exceptional location. Boating, swimming, fishing, and bird watching are right outside your door. Exclusively offered for $6,100,000.

504 State Road, West Tisbury MA 02575 Beetlebung Corner, Chilmark MA 02535 www.tealaneassociates.com

An Independent Firm Specializing in Choice Properties for 50 Years

508.645.2628 Chilmark

508.696.9999 West Tisbury

ENJOY MORE TIME OUTSIDE!

MARTHA’S VINEYA RD

Look

Publisher and Co-Founder Victoria Riskin

Editors Leslie Garrett, Jamie Kageleiry editor@bluedotliving.com

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Associate Editor/Reporter Lily Olsen

Social Media/Digital Projects Julia Cooper

Contributing Editors Mollie Doyle, Catherine Walthers

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Design/Production Sophie Petkus

Proofreader Irene Ziebarth

Ad Sales Jenna Lambert adsales@mvtimes.com

Anne Kelley anne@bluedotliving.com

Digital Media Consultant Ray Pearce

Contributors, this issue Randi Baird, Geoff Currier, Mollie Doyle, Jeremy Driesen, Kate Feiffer, Sheny Leon, Gwyn McAllister, Sam Moore, Kyra Steck, Lisa Vanderhoop, Catherine Walthers

DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com

oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

Bluedot, Inc. Co-Founders Walt and Nora McGraw

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc. Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine, published quarterly, is distributed by The Martha’s Vineyard Times. Find it free at The MVTimes, newsstands, select retail locations, inns, and hotels.

Visit the digital version of this magazine at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

See our new national website at bluedotliving.com

Sign up for our newsletters here: bluedotliving.com/newsletter Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @bluedotliving

Subscribe: Please inquire at admin@bluedotliving.com

2 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

BDL • OUR TEAM

• • • • • • ®

“

again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

3 marthasvineyard. .com

Dear Bluedot Living Readers,

In the weeks before we went to press, young activists had thrown tomato soup on Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers (followed by a similar act involving mashed potatoes against a work by Monet). Social media lit up with takes ranging from accolades to outrage. Regardless of what side you’re on, let’s take particular note of the age of these activists — just a year or two removed from their teens.

For many years at my children’s elementary school, I facilitated an eco-committee. Students led our group, choosing projects to tackle based on problems they identified — too much lunch garbage, for instance. When I felt defeated at the lack of progress world leaders were making on climate issues, these kids never failed to get me back on my feet to help them fight for the world they deserved. After all, this was their future. They had a lot more to lose than I.

On page 64 of this issue, you’ll meet our Local Hero Annabelle Brothers — who’s part of our newly launched Bluedot Institute. From the first conception of Bluedot, founder Vicki Riskin knew that she wanted young people to be part of the work we’re doing. The Institute, a non-profit, has partnered with schools around the country, including Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, where Annabelle is a student. Annabelle’s enthusiasm for the environmental projects she and her classmates are tackling underscores the Institute’s work to bring students and their teachers from across the country and around the world together to share solutions, learn from each other, cheer each other on, and report back to Bluedot readers.

Also in this issue, Kyra Steck, a former intern with Bluedot Living, shares how Indigenous people have been urging us to pay attention — to their traditional ecological knowledge but also to their current voices. “In order to really get people’s total and true buy-in, there needs to be an effort to ensure Native people will survive it as well,” Jonathan Perry, a tribal council member for the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, told Kyra.

There are many ways that people who are historically dismissed — young people, Indigenous people — ask others to stand in solidarity with them, to help foster change. However we judge the soup-throwing activists’ approach, they are demanding that we pay attention. We owe them nothing less.

BLUEDOT UPDATE

Come on in to Bluedot Kitchen, a weekly newsletter that will serve up delicious, healthy, planet-friendly recipes, along with tips on savvy shopping, storing, and food prep. Sign up now, and look for it this winter. Sign up for any of our newsletters here: Bluedotliving.com/newsletter

We also want to welcome another new member of the Bluedot family. Bluedot Brooklyn will share local news about green goings-on plus eco-conscious businesses, advice, recipes, and all you’ve come to expect from Bluedot Living. The website and a biweekly newsletter launch in early December; find it at brooklyn.bluedotliving.com

Watch us on YouTube! We've got a growing library of cooking videos and "how-to's" from Mr. Fix-it, who will help you get more life out of your stuff.

And finally, The Bluedot Institute will host dispatches from our cub reporters at high schools all over the country by year’s end at bluedotinstitute.org.

Thanks for tuning in!

–Leslie Garrett (and Jamie Kageleiry)

4 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023 EDITORS' LETTER 4

Annabelle Brothers and Cleo Carney (below) are members of our new Bluedot Institute.

The Hub, a Bluedot Living newsletter gathers good news, good food, and good tips on living every day more sustainably Delivered straight to your inbox bi-weekly.

Simple, Smart, Sustainable Stories — from all over.

ADVICE

Questions and answers for everyday eco-friendly living.

DISPATCHES

On-the-ground reporting highlighting a universe of ideas and changemakers.

MARKETPLACE

Strive to buy less, but when you do buy — buy better.

FOOD

Clean-cooking recipes and sustainable tips and tricks for buying and storing food.

SIGN UP HERE

Sign up for The Hub newsletter for a chance to be our next big winner!

bluedotliving.com/newsletter

DISCOVER

Meet Bruce Nevin of Edgartown, dining with his family at Atria. Bruce won our last $200 drawing.

CONTENTS Upfront

4 Editors' Letter

8 What.On.Earth. The sound (and stats) of silence.

9 Good News from MV and All Over

10 Buy Local at The Seven Sisters: Nearly every item selected by Ty Sinnett in her Vineyard Haven store has a story.

12 Buy Better: Gorgeous gifts from the Vineyard

16 In a Word: Psychogeology

16 Field Notes: Give Better — Nonprofits that make our Island (and our planet) better.

Features

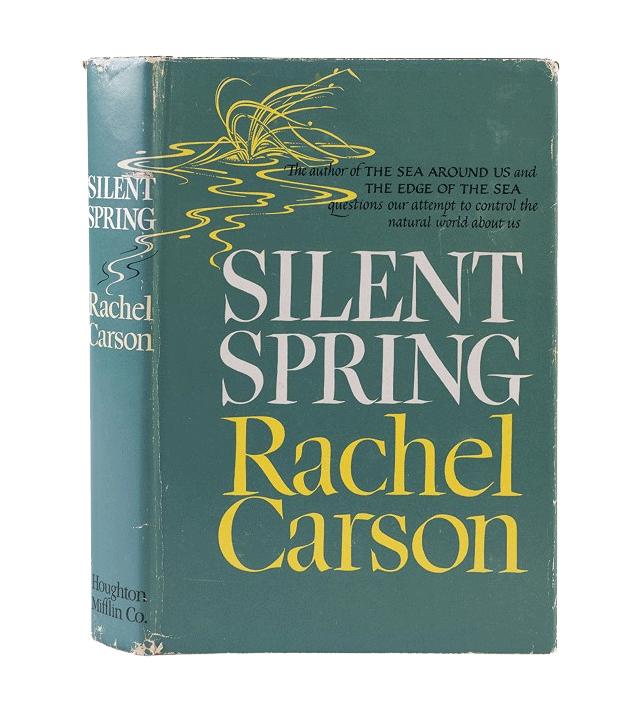

26 Rachel Carson in Woods Hole

By Kelsey Perrett

Before Silent Spring, the author was enchanted by the sea of Vineyard Sound.

28 How to Live on Mother Earth

By Kyra Steck

Generations of Wampanoag wisdom can help us care for our land (if we are ready to listen).

34 What’s So Bad About Private Jets?

By Sam Moore

Sure, they only account for about 5% of aviation emissions. But that’s more than some small countries.

38 Two Sisters Build Green

By

Mollie Doyle

One tackled a historic remodel while the other built new. But both prioritized sustainable materials and energy-efficiency.

50 Food: All the Fish in the Sea

By Catherine Walthers

The ocean’s bounty has limits, and some once-plentiful species are in decline. But there are lots of local fish available seasonally and year-round that Island fishermen are keen to put on our plates. Plus recipes!

Department

Departments

18 Dear Dot Our eco-advice columnist responds: Avoiding the creep of plastic-packed everything, and what’s a celebration without balloons?

22 Cruising with Currier

Our intrepid reporter takes a ride down “the dragon’s back” with an old friend in a brand-new Rivian

58 Room for Change: Rugs

By Mollie Doyle

A well-chosen area rug can elevate your whole room. Mollie Doyle guides us through the most sustainable solutions.

63 The 'Keep This' Handbook

Your eco-guide to composting, recycling, volunteering, activism, and more.

64 Local Heroes: We nominate Annabelle Brothers — an eco-wise teen intent on changing the world.

More

at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com and Bluedotliving.com

How to Get Rid of (Almost) Anything

The Bluedot Buy Better Marketplace

A Field Note from Felix Neck

Lots More ‘Dear Dots’

6 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Find Us! Sign up for our biweekly Martha's Vineyard Bluedot newsletter: bit.ly/Bluedot-newsletter

online

More

online

PHOTO THIS PAGE: THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Cover photo; Denny Jason, Jr., in Menemsha, by Sheny Leon

BDL 7 marthasvineyard. .com www.mvbuyeragents.com 508-627-5177 Email: buymv@mvbuyeragents.com 13 Coffins Field Road Edgartown, MA 02539-1661 “And, when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.” — Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist green contractors of martha’s vineyard 508.696.3120 • nmdgreen.com • INFO@nmdgreen.com Plumbing • Heating • Air Conditioning Water Treatment • Maintenance Programs INSTALlATION & SERVICE GREeN SERVICE Geo Thermal • Solar Hot Water • Heat Pumps Energy Management • Design & Consultation Digital Control Systems

What. On. Earth.

Silent Treatment

“In the last light of a long day, I sit on a chair on my porch and watch the sky drain colors down and out and I realize I want to hear my voice and only mine. Not the voice of my voice within a cacophony of old pains. Just mine, now.”

–Jenny Slate, from the book Little Weirds

1. Where noise ranked by the European Environmental Agency on list of environmental exposure most harmful to public health: 2nd

2. Estimated number of new cases of heart disease each year in Europe attributed to chronic noise exposure: 48,000

3. Increased decibels in median nighttime noise pollution levels (commonly includes industrial activity, traffic, and airports) in neighborhoods with at least 75 percent Black residents versus neighborhoods with no Black residents: 4

4. Year underwater sonar was introduced: 1950

5. Total number of mass strandings of beaked whales between 1874 and 1950: 10

6. Total number of mass strandings of beaked whales between 1950 and 2004: 126

7. Percentage of continental U.S. in which one could find “quiet” in 1900: 75%

8. Percentage of continental U.S. in which one could find "quiet" in 2010: 2%

9. Decibel level at which continued exposure to noise will cause hearing loss: 70

10. Decibel level of rainfall: 50

11. Decibel level of leaf blower: 110

12. Decibel level of fireworks at 3 feet: 162

13. Reduction in seismic noise during the pandemic year of 2020, the longest and most prominent global anthropogenic seismic noise reduction on record: ~50

8 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

1 and 2. Harvard Magazine; 3, Berkeley News; 4, 5 and 6. Newsweek; 7 and 8. BBC; 9, 10, 11, and 12.

13.

Noiseawareness.org;

Science.

PHOTO BY BOB AVAKIAN; see his work year-round at the Granary Gallery, and at bobavakianphotography.com

The Sky's the Limit for Black Skimmers

Black skimmers have increased in number and show signs of a more established population on the Vineyard in the future after a rocky start, BiodiversityWorks reports. The birds began nesting on-Island in 2010 at Norton Point beach in Edgartown, but no chicks survived to maturity that year. In 2011, when the persistent species tried their luck again, a hunting raptor forced them to abandon their nests. Finally, in 2012, four pairs of skimmers fledged chicks. At first, the skimmer population on Martha’s Vineyard grew slowly each year. But from 2018 to 2022, growth skyrocketed from 12 pairs to 22.

A Plus for Piping Plover Population

Martha’s Vineyard’s black skimmers aren’t the only winged creatures that enjoyed a productive year in Massachusetts. The piping plover, a species categorized as threatened and protected by state and federal law, has continued its decade of growth, with almost a thousand pairs nesting on the Massachusetts coastline this year, according to findings from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife.

The state’s piping plover populations have long been threatened by human activity, predators such as seagulls, and storms.

Ocean Breeze Bedding

But, a number of conservation efforts across the Massachusetts coastline have helped those numbers steadily grow. These projects involve monitoring nests and sectioning off plover habitats on the beach to protect them from humans and animals stepping on them.

Restoring Wampanoag Land

Wampanoag volunteers are restoring Massachusetts lands. As reported by The Associated Press and MassLive, a project called The Wampanoag Common Lands aims at restoring 32-acres of what used to be a Catholic summer camp along Muddy Pond in Kingston. The Native Land Conservancy received the donated land this year. The group hopes to restore the land with indigenous plants and animals, hold cultural ceremonies, and provide education for new generations about Wampanoag traditions.

The project location is historically significant — five miles from where the Mayflower touched ground and sparked English and later American colonization of native lands. Restoration projects such as this are especially important given the effects of climate change, which are threatening many tribes’ health and ways of life.

UPFRONT • GOOD NEWS 9 marthasvineyard. .com

good news

FROM ALL OVER

The Island’s source for organic mattresses, pillows, and bed linens. Ergovea is our organic and natural latex mattress brand, providing the purest night’s sleep; Ergovea’s pillows are paradise. Sleep and Beyond provides toppers, sheets, pillows, comforters and more of your bedding needs. 322 State Road, VH · 508-696-9600 oceanbreezemvbedding.net Get the purest night’s sleep Come see our collection of organic sheets

THE SEVEN SISTERS:

Ty Sinnett’s new store has a big mission.

By Mollie Doyle Photos Sheny Leon

When Ty Sinnett greets me with her dog, Leo (a rescue from Bali), at her new store, The Seven Sisters in Vineyard Haven, it feels more like we are walking into her home than a shop. Maybe it’s the abundance of beautiful pillows fashioned out of hand loomed wedding fabric from Bali. Maybe it’s the draped Lineage Botanica blankets, crafted with gorgeous heavy linen vintage textiles backed with organic cotton. Maybe it’s the ease of the store’s apothecary, which has shelves full of wonderfully designed, enticing beauty potions. But as I begin to talk with Ty, we figure it out: She has personal relationships and a story to go with nearly everything in her store.

Ty met jeweler Loan Faven of Naula Studio while she was living in Bali. She tells me that Loan is from New Caledonia, the French colony off the coast of Australia, and uses her ancestral history as inspiration for her pieces. There’s Jeanette

Farrier, who works with a women’s co-op in India to source vintage cotton saris for her luminous layered blankets. And then there are the rugs made with wool from Bulgarian Karakachan sheep. “The Soviets tried to exterminate the breed as part of their nationalization effort,” Ty explains. “There are only 400 left. About 30 shepherds keep them alive. They are treated like royalty. These rugs are made by hand. They are extraordinary.” Her dog Leo clearly agrees as he curls up on one.

“Some people might ask, ‘Why do you carry Le Jacquard Francais in with all of this other stuff?’ Well, my mother carried it. They use vegetable dyes and, while one set of napkins might cost more, I also know they will last for 30 years.”

Ty’s mother is Emily Bramhall, who owned Bramhall and Dunn, Vineyard Haven’s Main Street mainstay for homegoods for 30 years. Ty grew up on the Island, working in her mother’s shop. Her father Steven Sinett was one of the early members of the South Mountain team. Ty attended Bard and then the

LOCAL • UPFRONT 10 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

JOY ON VINEYARD

HAVEN’S MAIN STREET

Your Renewable Energy Solution Solar, plus smart, safe and long-lasting battery technology. Power your home with clean energy around the clock with solar and batteries. www.fullers.energy 508.696.3006 info@fullersenergy.com BLUEVIEW GUTTERS Seamless Aluminum, Copper, Fiberglass, Wood Installation, Repairs, Seasonal & Yearly Cleaning Joseph Cogliano 774-563-0938 FREE ESTIMATES CALL

School of Fashion Design in Boston. As she tells it, she has always been interested in design, but the definition has expanded. “My mission is to inspire people to have a more intimate, enjoyable relationship with things through curiosity, storytelling, and sensory delight.” She laughs, noting that she knows her mission is big. “But I want people to come in here and feel joy,” she says. “I don’t buy into this idea of the sacrificial narrative. That to support the Earth or be a good person, you must always be giving and/or depriving yourself. This is a sustainable commerce model. This means we want to nourish the lives of our clients, our supply chain, and the planet. And there’s no pressure to buy. Just come in here and, if something really connects, feels right, then get it. And you will have it, along with its particular story, for a really long time.”

In Greek mythology, the Pleiades were the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas. Because he had the unenviable task of holding up the sky for eternity, he was unable to protect his daughters from

LOCAL

being raped by Orion or turned into stars by Zeus. In the myth, six were turned into stars, while one marries a mortal and that is why we cannot see her in the sky. Ty chose to name her store after these seven sisters because similar stories have been told by Aboriginal, African, Asian, Indonesian, and Native American cultures. What about the Pleiades makes people — across space, time, and culture — look up at the sky and see this same story? We don’t know. But what we do know after spending time in The Seven Sisters store is how aptly it’s named, because no matter where the goods are from, there is a universal theme to Ty’s offerings: Like the myth, they can be traced to a source and tell a story. On thesevensisters.co, Ty sums up her store’s philosophy, “We believe that when consumers have a more connected, intimate relationship with the products we consume and the people who make them, we all feel better.”

Seven Sisters will be open through December, then back in the spring.

11 marthasvineyard. .com

Buy Better Find your gifts locally

MADE ON

MARTHA'S VINEYARD

By Gwyn McAllister Photos Courtesy of the Artists

With a keen eye for color, Wolf pairs the beads in coordinating shades that mimic the blues and greens of the ocean, or in rainbow combinations that spotlight the uniqueness of each colorful bead. Many of the necklace styles feature multiple strands of beads in which the flattened mini tiles hang gracefully and show off the beauty of each individual bead.

The Stefanie Wolf studio offers numerous lines of the jeweler’s creations, along with other artisan-made products, including ceramics, bags, candles, clothing, and more.

Stefanie Wolf Designs, 37 Circuit Ave., Oak Bluffs.

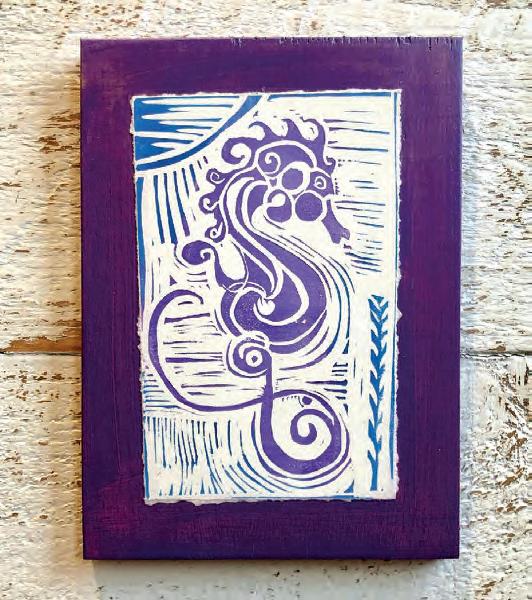

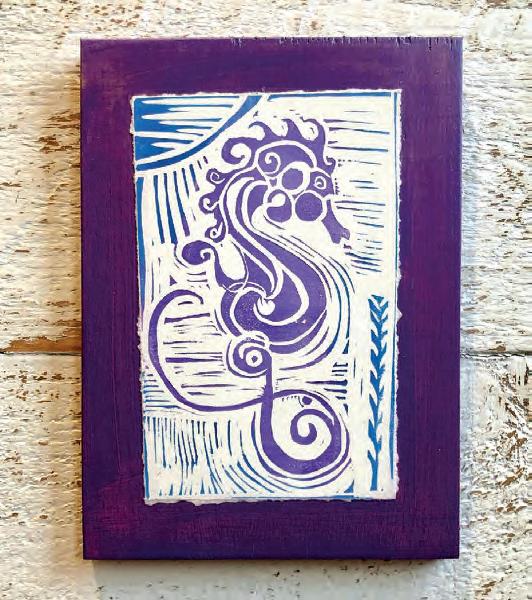

Althea Designs

Artist Althea Freeman-Miller, born and raised on the Island, creates designs on linoleum blocks which she then transfers to prints mounted on wood, tee shirts, tote bags, coffee mugs, and cards. The expertly carved intricate designs are lively, often whimsical representations of animals and fruit, as well as tools and ordinary household items like a colander or a flashlight. Some designs are more elaborate and multicolored, such as a western-themed scene with horse and rider, or a trio of fish leaping in the waves.

Stefanie Wolf

If you have a jewelry lover on your gift giving list (and who doesn’t?) you should really check out the Stefanie Wolf studio and boutique on Circuit Ave. in Oak Bluffs. Wolf has been creating unique beaded necklaces, earrings, and bracelets on the Island for almost 20 years and is continually adding items to her inventory.

Stefanie’s most popular line, Trilogy, features tiny, richly colored glass tiles made in the Czech Republic. Each bead is a work of art. The rounded rectangular tiles have hand-painted edges — similar to the look of stained-glass panes — that inspired their name “Picasso windows.”

BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD • UPFRONT 12 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

More recent designs include a series of dancers and an anatomical heart that beautifully shows off the intricacy of that organ.

Given the nature of the process, each print is unique and the designs come in a variety of colors. Freeman-Miller also creates colorful, hand-painted, laser-print engraved wood cutouts and layered carved paintings. She also offers custom-designed linoleum block prints.

Althea Designs is located at 34 Beach Road, Vineyard Haven. Open by chance or by appointment. (802) 777-5137.

influence,” she says. However, her early years growing up on the Island were what really instilled a reverence for nature in the first place. “I’ve always loved just walking around the Island,” she says. “My dad knows pretty much every plant here. He would teach me about everything.”

Available at The Trust Shop, 9 Main Street, Vineyard Haven and Kenworthy, 38 Winter Street, Edgartown.

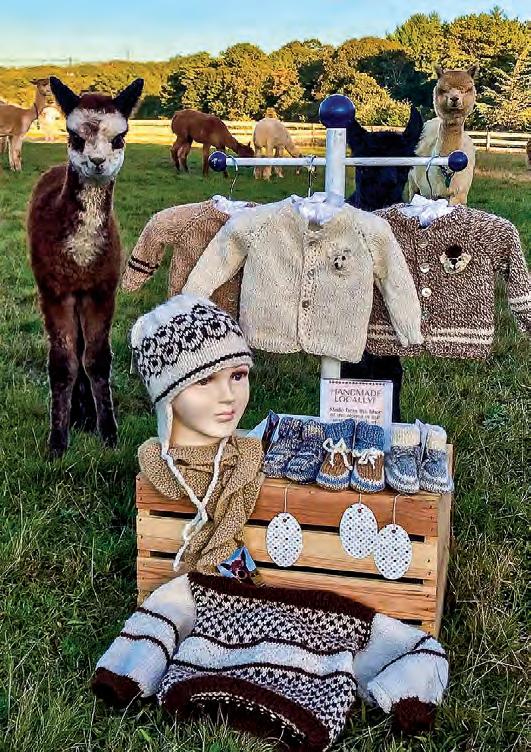

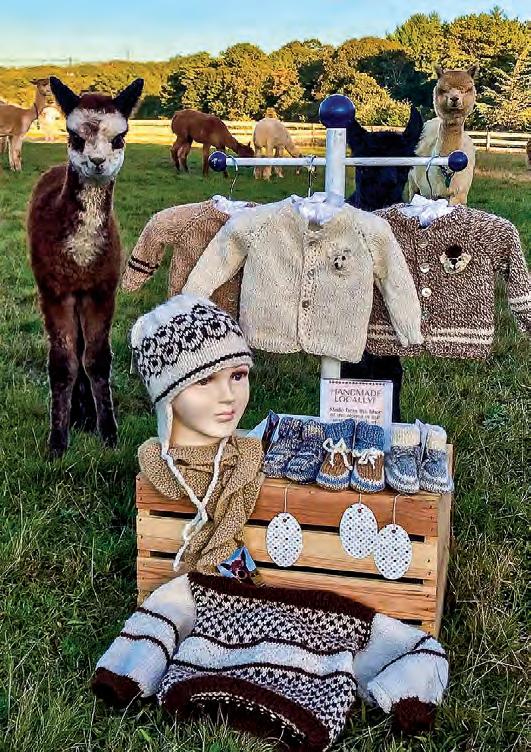

Island Alpaca

You may have seen Barbara Ronchetti’s herd roaming the fields at Island Alpaca off the Vineyard Haven-Edgartown Road. The animals — 35 or so — brave the winter weather owing to the unique properties of their coats. If you want to keep warm and cozy this winter, take advantage of that extra warm fleece yourself — without having to curl up with an alpaca.

The farm’s gift shop offers all types of items made from alpaca fiber, including a number of garments made by local knitters. You can find hats, scarves, gloves, mittens, baby jackets, and booties made from the fiber of the farm’s softest residents — baby alpacas.

Ronchetti explains the advantages of alpaca fiber over wool (the fleece of sheep or goats): “Because alpaca fiber is hollow cored, it acts as an effective insulator and is known to be 30 per-

Tea Lane Apothecary

Tea Lane Apothecary — a line of herbal skincare, teas, and remedies — is about as local as you can get. Emma Tobin, who grew up on the Vineyard and went on to study botany and herbalism, uses many Vineyard-grown plants to create her all natural products.

Tea Lane Apothecary products include aids for everyday needs like sleep, focus, immunity, stress, anxiety, tick/bug repellent, hair and skin care, and more. All of the herb-infused oils, salves, tinctures, syrups, and glycerites are produced on Island using foraged native plants and herbs grown in Tobin’s garden whenever possible.

“Many of the herbs used in homeopathic medicine grow just about everywhere,” says Tobin, who calls her foraging expeditions “wildcrafting.” “ It’s really amazing how abundant they are and how people think of them as weeds.”

Tobin’s family owns and operates Tea Lane Nursery and Farms. She studied plant sciences at UMass Amherst and The California School of Herbal Studies — a natural for someone whose early life was immersed in nature and plants. As well as working as farmer, gardener, and landscaper, she also worked at her cousin’s organic farm in Vermont, which inspired her to dig deeper into the plant world. “That was probably my biggest

UPFRONT • BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD 13 marthasvineyard. .com

cent warmer than most breeds of sheep. It helps keep you warm in winter and cool in summer. It also naturally wicks and draws moisture away from the body and allows it to evaporate quickly, so you stay dry and comfortable.”

Alpaca fiber is durable, stain resistant, and hypoallergenic, making it a good choice for those sensitive to wool. The Island Alpaca herd includes animals in a variety of colors so the knitted products can be found in various shades of cream, gray, beige, and brown. Along with locally made items, the gift shop features many products made from alpaca fiber from around the world. And if you’re really adventurous, inquire about purchasing a member of the herd for yourself.

Island

Alpaca, 1 Head of the Pond Road, Vineyard Haven

Miles from Mainland

Show your love for the Vineyard with a handmade wood item from the Miles from Mainland line. Designs include ornaments with a cutout of the Vineyard, tissue boxes, trinket boxes, and pencil boxes similarly decorated.

Carnegie Blair Designs

The team of Linda Carnegie and Nancy Blair Vietor have been designing and selling items for kitchen, dining, bath, and elsewhere for almost a decade. Vietor, an artist and decorative painter and Blair, an interior designer, combined their talents in 2013, starting out with a series of placemats in colorful, often Vineyard-inspired themes. The business took off from there.

The line includes cork-backed placemats, wooden whitewashed trays, glass cutting boards, absorbent tile coasters, and a few other items (including whimsical dog and cat food mats).

Designs include floral motifs and ocean-themed images like lobsters, crabs, starfish, shells, and fish, a compass rose, and an image of the ferry “The Islander” surrounded by scenes of lighthouses from around the Island.

Ornamental designs include ones based on oriental carpets, sisal rugs, and Delft tiles. A unique design called “Jazzy Coral” features a colorful array of seaweed and coral

branches, while one of the Delft tile designs incorporates scenes from around the Island (the Ocean Park bandstand, an oyster fisherman) alternating with traditional Dutch images in classic blue and white.

All of the products are made in the U.S. Carnegie did a great deal of research to find manufacturers in this country. The two partners are continually expanding the line to include new designs and products.

“The painter in me likes to experiment,” Carnegie says. “The designer in me is always seeking new ideas for attractive yet functional products.”

Available at Beach House, 30 Main Street, Vineyard Haven and Past & Presents, 37 Main Street, Edgartown.

BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD • UPFRONT 14 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Available at Rainy Day, 66 Main Street, Vineyard Haven.

Leather Treasures

Marie Meyer-Barton handcrafts leather goods from her original designs in her home workshop on Martha’s Vineyard. She uses buttery soft, locally sourced deerskin and other fine leather to create baby moccasins, purses, pouches, dopp kits, backpacks, wallets, belts, and leather jewelry. Meyer-Barton’s designs come in many colors and some of the items incorporate intricate designs imprinted in color on the leather. Others incorporate Native American-made wampum beads and buttons.

Available at Night Heron Gallery, 58 Main Street, Vineyard Haven, and Martha's Vineyard Made, 29 Main Street, Vineyard Haven.

UPFRONT • BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD 15 marthasvineyard. .com

Native plant specialists and environmentally focused organic garden practices. Design • Installation • Maintenance (508) 645-9306 www.vineyardgardenangels.com Garden Angels Bring beauty to your property

Icannot offer you a dictionary definition of psychogeology because the word is not in the dictionary. What I can do is tell you that the author who coined the term, Kim Stanley Robinson, wanted a word to define how we are shaped by the places where we live or have spent time. Psycho, as a prefix, refers to relating to the mind or the soul. Geology, broadly, means the substance of the earth.

in a word

Psychogeology

experience was so transformative for Powers that he found himself still thinking about it a year later.

“If you’re still preoccupied with a place and how you felt in that place after such a long period of time after only a fourday exposure,” Powers said, “that’s got to tell you something.”

Robinson chose to use the term “geology” and refers specifically to mountains. The Sierra mountains (the focus of his most recent book, The High Sierra, a Love Story) make him feel differently than Swiss mountains, he says, inviting us, too, to notice how different places make us feel.

“I think the mountains are a space where you are taken outside of your ordinary urban mind and are thinking a

little deeper — or, no, that might not be the right way to put it,” he said during an interview on The Ezra Klein Show. “Things are coming together in your head in a different way.”

Richard Powers, author of Bewilderment and The Overstory, described his first foray into the Smoky Mountains to Ezra Klein in a separate interview. The

Watch dolphins at play on Malibu Beach

There is a particularity to psychogeology, according to Kim Stanley Robinson: “I talk about psychogeology as the trying to understand why, for instance, the Sierras feel so different than the Swiss Alps or the trans-Antarctics or the Himalayas.” It is the character of these places, he posits to Klein, that coalesce into a particular feeling. … You can try to explain it, but it’s more of a gestalt. And that’s psychogeology.”

–Leslie Garrett

–Leslie Garrett

IN A WORD 16 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Psycho [sahy-koh ] geology [jee-ol-uh-jee]

Closest-in private waterfront home just 6 miles from Santa Monica. 3 bedrooms and 3 bathrooms, top of the line amenities, Japanese garden, 1 - 3 month min. Call Realtor Steve Drust at 310.733.7487. Visit beautyandthebeachmalibu.com to see more of what this pristine property has to offer. And get out of the cold!

villa

Romantic beachfront vacation

Email us at adsales@mvtimes.com to inquire about sponsored business posts Reliable information and advice on #ClimateChange and #Sustainability Let's start here, at home on earth. Scan below to become a follower

"THE WALK HOME" BY JACK YUEN

Featuring brands: Rareform, Rothy’s, Reformation, Cariuma, Cotopaxi, Ecozoi, Eileen Fisher, Hydros, Dropps, Amour Vert, VEJA, TenTree, Terra Thread, Teeccino, Toad & Co., and Who Gives a Crap (among others)

Featuring brands: Rareform, Rothy’s, Reformation, Cariuma, Cotopaxi, Ecozoi, Eileen Fisher, Hydros, Dropps, Amour Vert, VEJA, TenTree, Terra Thread, Teeccino, Toad & Co., and Who Gives a Crap (among others)

IN A WORD marthasvineyard. .com bluedotliving.com/marketplace Br wse the collection Buy less, but when you do — buy better. Shop Bluedot’s ‘Buy Better’ Marketplace

Want an Eco-Friendly Holiday? bluedotliving.com/marketplace Browse the collection Buy less, but when you do — buy better. Shop Bluedot’s ‘Buy Better’ Marketplace

Want an Eco-Friendly Holiday?

Dot tackles your thorniest questions from her perch on a porch: Is it a party without balloons? And how can I eliminate plastic?

Dear Dot,

How can I celebrate an event without balloons?

–Cathy, Chilmark, Mass.

dot DEAR

traffic accidents, and injuring two prize-winning horses who were spooked by the arrival of balloons in their pasture. (The litigious farmer won a $100,000 settlement from the city.) Ultimately, the powers-that-be at the Guinness Book of World Records refused to recognize the event due to the fallout. The moral of the story? What goes up must come down.

Dear Cathy,

One day in third grade, my teacher Mrs. Wright showed us a movie in which a young child encounters a balloon that seems to have a mind of its own. Perhaps, Cathy, you saw it too? It was French, silent, and called Le Ballon Rouge. Wikipedia tells me it was an Oscar-winning short created in 1956 that became beloved by educators, which explains why I was at my desk in 1974 watching it while Mrs. Wright, her candy floss hair piled high on her head, nodded off at the back of the classroom. While my classmates giggled at the balloon’s antics, I sat mute and terrified. To this day, I remain staunchly anti-balloon, even of balloons without free will.

While some might argue that balloons are the very symbol of celebration, I am not swayed. So I am grateful for the chance to address this scourge and offer up some jolly alternatives.

If you’re a beachcomber like me or, perhaps someone who hikes along a river or stream, you’ve likely come across evidence of past frivolity in the form of deflated balloons, their ribbons filthy and tangled. What you’re not seeing unless you, too, have come across the Balloons Blow website, are the many balloon bits found in the stomach of, say, a Hawksbill sea turtle or a Bighorn sheep, each of whom mistook balloons for food.

We find another cautionary tale in the Great Cleveland Balloon Release Disaster of 1986. Cleveland wanted to get into the Guiness Book of World Records (and not for being the city most likely to set its river on fire). The record the city had its eyes on was largest balloon release in the world, with roughly 1.5 million balloons slated for the heavens. I mean … what could go wrong, right? At the balloons’ release, the crowd went wild. But shortly after the release, a storm rolled in off the Great Lakes, changing air pressure. Instead of floating away into the arms of God, the balloons fell on Cleveland, closing the airport, causing

But, while balloons might now be spherus non grata in Cleveland, the lesson hasn’t caught on in the rest of the world, despite laws that prohibit balloons in many cities, states, and countries. Incidentally, the balloon lobby (Big Balloon, so to speak) is fighting these laws.

The folks at Balloons Blow — and a hearty Dear Dot shoutout to whomever named that organization! — tell us that beach litter surveys show a tripling in balloon pollution, an increase not the least bit surprising to any of us who pick up litter along the shore and head home laden with latex. The Balloons Blow site is a virtual natural history museum of marine and land animals who’ve met gruesome deaths by swallowing plastic, getting caught in ribbon, or other forms of murder by balloons. And don’t be fooled by promises of latex’s biodegradability. These deflated or burst balloons can wreak havoc for years.

And let’s also consider the helium that is often used to keep these orbs aloft. Helium isn’t just the stuff that allows us to crack up the crowd by singing in a falsetto at wedding receptions. It’s a finite resource that is used in any number of scientific and medical applications, and the world is running out, according to a physics professor and Nobel Prize Winner from Cornell.

But never let it be said that Dot is a total party pooper, a balloon-hating blowhard, a killer of helium-filled frivolity. I like to celebrate! I can be festive!

Balloons Blow’s pinned Facebook post offers up a few alternatives to balloons, including blowing bubbles, colored lights, chalk writing/drawing, stepping stones. You can also use flowers or plants, or decorate with birdhouses. The great party planner that is Google suggests streamers, paper flowers, pinwheels, kites, and windsocks.

Alternatives to balloon releases include Flying Wish Paper, or sending flower petals down a stream, or passing out seedballs (and not the kind you’ll find at Burning Man). Of

18 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Illustration Elissa Turnbull

course, always check that you’re not introducing an invasive species into an ecosystem.

With a little imagination and a refusal to cave to convention, Cathy, the sky’s the limit.

Celebratorily, Dot

Celebratorily, Dot

Dear Dot,

Has anyone noticed the slow creep of plastic packaged produce in the vegetable and produce aisles in our grocery stores? Many items pre-sliced (mushrooms, spiralized squashes, and so on) or pre-cooked (beets, lentils, etc). For sure a convenience, but at what cost? Others just bagged and boxed. Even organic salads boxed in plastic! Whatever happened to being able to just put the produce of your choice in the quantity of your choice in a string bag? A recent visit to Whole Foods, where most produce is still available unpackaged, suggests to me that we could do better.

–Lowely Finnerty, Martha’s Vineyard

Dear Lowely,

I have indeed noticed, and I share your dismay. But, as you know, I am a take-action kinda gal and I encourage both of us, now that we’ve grumbled and lamented, to join forces to create the change we want, or at least slow down the plastic proliferation that threatens to invade every part of our lives. There are a few things we can do:

✔ We can use our wallets to purchase products that aren’t overpackaged.

✔ We can use our voices to tell store managers exactly what we want to see and why (and let them know when they’re getting it right).

✔ We can encourage our politicians to push legislation that bans single-use plastics for packaging, such as the recent Canadian ban on single-use plastics, which includes clamshell packaging, like the kind in which our berries and our salads are often sold. Unsure how to effectively communicate with your reps? The University of California has put together a helpful guide: bit. ly/Berkeley-reps. Regarding plastics, California is out in front with legislation that demands a 25% drop in single-use plastic by 2032 and that at least 30% of plastic items sold or bought in California are recyclable by 2028. It’s a start, I suppose, but every state needs to be doing better.

✔ We can support organizations that are dealing with the existing plastic fallout (literally — researchers have found microplastics in our drinking water, the air we breathe, even in the placentas of unborn babies). Just look at the work and impact of organizations such as Surfrider Foundation with chapters around the U.S. that keep the focus local, and The Story of Stuff Project, two of my faves! I promise you’ll be inspired.

Unpackagedly, Dot

DEAR DOT 19 marthasvineyard. .com

Please send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com PROUD SPONSOR OF 1-800-797-6699 CapeLightCompact.org With high energy prices, efficiency upgrades can help you save! Renters and owners can shedule a no-cost home or business energy assesment. We can help you: Create an energy action plan Access incentives for energy efficiency upgrades ENERGY EFFICIENCY ADDS UP

Cruising with Currier

Our writer’s childhood friend drives him out to the Crick House.

When I heard that my friend Melinda Loberg was getting a new Rivian R1T electric truck I knew just whom I’d be taking on my next Cruising with Currier ride. And I knew just where we’d be going for the trip.

Rivian is an American-made electric vehicle automaker based in Irvine, California, that has a line of sports utility vehicles. But we’d be driving in one of the Rivian R1T pickup trucks, which helped Rivian earn a place on Time Magazine’s list of 100 most influential companies of the year in 2022.

Melinda is known on the Island as a former Tisbury selectperson and has been active in a number of environmental causes. She was part of the effort to bring nitrogen-reducing septic technol-

ogy to the Island; she was involved with various stormwater initiatives through the Tisbury Waterways Inc., chaired the Tisbury Climate Committee, and was a member of the Island Grown Initiative and Vineyard Vision Fellowship Organics Committee that helped bring composting to the Island.

Melinda and I grew up in the same town outside of Boston, but her roots on the Island run deep. Her grandfather, Raymond Cleveland Fuller, was born and raised on William St. in Vineyard Haven and ran a small grocery store in town.

From the 1950s on, I spent many a summer at “the Crick House,” the name the Fullers gave to the cottage out at the end of Herring Creek Road, out by the breakwaters leading into Lake Tashmoo. There had always been a few fishing camps out there but the hurricane of 1938 reshaped the landscape. Up until then, Lake Tashmoo had been a freshwater pond, and Herring Creek Road ran

all the way to Menemsha, and was used for delivering mail and milk. After the hurricane, the Army Corps of Engineers put in the jetties and opened up Tashmoo to the ocean.

Melinda’s grandfather bought three small slices of land out at the end of Herring Creek Road to pass along to his family and had a little prefab cottage brought over by barge. And it was here that Melinda’s family, often joined by us Curriers, would spend idyllic times on the beach in a tiny cottage with no utilities, out at the end of a three-mile dirt road that was so rough it was like taking a ride on the back of a dragon. I knew this was the place to take Melinda’s new Rivian for a test drive.

The Rivian R1T bills itself as being the ultimate adventure car, taking camping and off-road exploration to the next level. As Melinda said, “This car really puts the emphasis on camping and offroad adventuring.”

20 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Story by Geoff Currier Photos by Sheny Leon

FEATURING MELINDA LOBERG’S RIVIAN R1T

With our photographer, Sheny Leon, in the back seat, me riding shotgun, and Melinda at the wheel, we set off for “the Crick House.” The first thing Melinda did was put the car in the off-road setting and we could literally feel the car lift up — it rises 13 inches — giving it extra clearance.

My memories were of my head being smashed against the ceiling in previous rides along Herring Creek Road. “This doesn’t seem as rough as it used to be,” I said, turning to Melinda.

She explained that the town and the Land Bank had been working to smooth out the road, but added, “It’s the car. The reason the ride is smoother is the car!”

The Rivian isn’t the Lobergs’ first experience with an electric vehicle. They previously leased a Tesla S and totally bought into the EV mentality, but when the lease was up, Melinda said, “You know, I was thinking that I’m not really a car person, and my husband liked the idea of having a truck so when we saw the Rivian electric pickup we thought that this could be the car for us.

“There are no dealerships,” Melinda

said, “so we negotiated the purchase online and we were assigned what Rivian called ‘a handler’.” Melinda said she thought, “my God, am I joining a cult?” As it turned out, the whole process was handled about as smoothly and expeditiously as possible. In fact, someone at the Registry of Motor Vehicles went out of their way to compliment Rivian on how well they had handled their customer service process.

“We placed the order around last Thanksgiving,” Melinda said, “and they told us we could expect delivery around the first of 2022. However, it took until around June before we started getting calls

from the manufacturer and we took final delivery in August.”

Continuing our trip out Herring Creek Road, we stopped at the Crick House to take some pictures. This gave Melinda a chance to take us through some of the features of the car, which, given that she’d only taken delivery of it a couple of weeks earlier, she was still just learning about.

As Melinda said, Rivian was really going for the camping market and the company was doing everything it could to take you into the niche of roughing it in style. Starting with a kitchenette.

We stood outside the car and Melinda pointed to an 11-cubic-foot, so-called “gear tunnel” located just behind the rear

FEATURE • CRUISING WITH CURRIER 21 marthasvineyard. .com

The Rivian R1T can go from zero to 60 in 3.3 seconds. Readers are advised not to try this on the Island's dirt roads.

Geoff Currier and Melinda Loberg grew up as childhood friends.

As Melinda said, Rivian was really going for the camping market and the company was doing everything it could to take you into the niche of roughing it in style. Starting with a kitchenette.

seats where you could see from one side of the truck to the other and where a kitchenette could be accommodated. The Lobergs hadn’t purchased the kitchenette feature, but their son who does a lot of camping did purchase it for his car.

According to an online manual, the kitchenette, when installed, would contain a grill, a collapsible sink with a spray faucet, and a four-gallon water tank. Mini-kitchen drawers would contain everything from titanium cutlery to a water kettle.

Beyond the kitchen, the thing that really caught my eye, as someone who enjoys occasionally going off-road, was that the R1T comes with an onboard compressor. Press a button and you can take pressure out of the tires to enable the car to drive on the sand, and when it’s time to head home, the compressor can refill the tires to their prescribed levels, which eliminates the need to find a gas station. Another attractive feature is a roomy tent that can sleep three and sets up off of the flatbed.

Admittedly, you pay a price for the Rivian R1T, depending on which package you choose. The vehicle starts in the high $60,000s range. But consider the performance.

While Melinda has only had the car for a few weeks, she’s still working out the actual numbers. But according to the

manufacturer it has a highway range of 220 miles, goes from 0 to 60 in 3.3 seconds, can climb a 45-degree incline and gets an impressive 35 MPGe for mileage. “MPGe” is the more useful metric for comparing energy consumption of electric vehicles. The Lobergs charge the Rivian

overnight with a level two 220-volt charger they had installed in their house. And then there are those headlights. Rivian calls them “stadium lights,” and what makes them unique is that they’re vertical. They’re arguably the most distinctive headlights in the automotive industry today. Which depending on the eye of the beholder are either ugly or the second coming of E.T. I happen to think they look pretty cool.

Editors’ note: As we sent this issue to the printer, Rivian announced a recall for the RiT truck to address steering issues.

The Facts

2022 Rivian R1T

electric vehicle pickup truck

From $73,000 (less rebates)

Highway range: 317 miles

Battery charge time: 13h at 220V

Battery: 135 kWh lithium-ion

Bed length: 54"

Cargo volume: 11.9 ft³

All wheel drive

Towing capacity: 11,000 lbs

Where to charge an electric car on Martha’s Vineyard: bit.ly/MV-E-Cars

22 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Currier and Loberg spent summers hanging out at the Crick House when they were kids.

Below, the "gear tunnel," which alllows for the optional kitchenette.

It was here that Melinda’s family, often joined by us Curriers, would spend idyllic times on the beach in a tiny cottage with no utilities and out at the end of a three-mile dirt road that was so rough it was like taking a ride on the back of a dragon.

GIVE Better

Conservation-minded nonprofits share their progress and wish lists.

As you consider your year-end giving, please remember these Island organizations..

To : Bluedot Living

From: MVAtlas of Life

Subject: Subject: 3,100 MV species!

A community-based project to document the Vineyard’s biodiversity, the Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life (MVAL) launched a brand new website this past summer at mval.biodiversityworksmv.org. The site includes links for reporting wildlife sightings, listings of wildlife-related resources and events, and most importantly, a collection of checklists and brief essays presenting what is known about various groups of species on the Vineyard. The website will grow over time as more information becomes available, with the goal of being a one-stop resource for anyone interested in studying, appreciating, or conserving the unique biodiversity of Martha’s Vineyard.

Much of the momentum and information for the MVAL comes from its associated project in iNaturalist, a community science platform found at iNaturalist. org. The project, essentially a compilation of observations contributed to iNaturalist by users on Martha’s Vineyard, has grown rapidly in 2022 and currently contains about 21,500 records documenting more than 3,100 Island species. The iNaturalist platform, which operates worldwide, provides identification assistance to users and includes built-in tools for data analysis.

Begun in February 2021, the MVAL is a joint project of BiodiversityWorks and the Betsy and Jesse Fink Family Foundation (BJFFF.org). You can support the MVAL effort by visiting its new web-

site, by using iNaturalist, or by making a donation at biodiversityworksmv.org/ support-us.

To: Blue Dot Living

From: Great Pond Foundation

Subject: A productive season of ecosystem monitoring on Island Ponds

The Great Pond Foundation (GPF) had an action-packed field season on the ponds and in the lab conducting collaborative research to preserve the ecologically fragile coastal ponds of Martha’s Vine-

yard. From May through October, 2022, Scientific Program Director Julie Pringle and Watershed Outreach Manager David Bouck led water quality and cyanobacteria monitoring programs across ten ponds, an increase from five bodies of water in 2021. The water quality data is used to assess ecosystem health and inform local management. The cyanobacteria collection is part of the MV CYANO program, a partnership among Island Boards of Health and GPF scientists to monitor cyanobacteria locally.

Additionally, the field work and laboratory research included summer interns, seasonal staff, and visiting scientists. To showcase the flora and fauna of Island

23

.com

marthasvineyard.

· · ·

Great Pond Foundation crew members Owen Porterfield, Emma Rosser, and Katelyn Hatem deploy a drop camera to monitor seagrass abundance in Edgartown Great Pond.

ponds, the GPF team also conducted four beach seine events — a hands-on approach to develop young scientists interested in Island coastal ecology! After a season filled with science, education, and collaboration, GPF staff look forward to analyzing the 2022 data to promote conservation of coastal ecosystems.

2022 Scientific Fun Facts:

• 945 cyanobacteria samples collected (and counting!)

• 67 days in the field, often visiting multiple ponds in one day

• 50 regularly monitored sampling locations

• Greater than 2,000 unique data points collected (and counting!)

• 26 water quality parameters monitored

You can donate here: greatpondfoundation.org/make-a-gift/

As Polly Hill Arboretum heads into its 25th year as a public garden, we celebrate our community connections and our international reputation as a plant science organization. But to carry out our mission in the future, we are clearly dependent upon our ability to hire and retain high-quality staff.

They conduct our education programs, maintain our grounds, propagate seeds, and protect our collection.

Will the buildings be environmentally friendly?

Yes, the Arboretum is in the Mill Brook watershed and we have taken that into consideration by planning an enhanced denitrification septic system. The houses will have solar panels and are placed to minimize both tree cutting and clearing and their impact on the woodland and wildlife. The homes will be heated/cooled using electric heat pumps and there will be an electric car charging station.

To : Blue Dot Living

From: The MV F ishermen’s Preservation Trust

Subject: MV Fishermen’s Preservation Trust

Sustainable Project Recap

Throughout the summer and fall of 2022, we have been working with the University of New Hampshire on the development of an alternative bait for the whelk/conch fishery, which currently relies on the use of horseshoe crabs. That is far from ideal, as horseshoe crabs play important ecological roles. They are bioturbators as they forage for food, their eggs are a vital food source for migratory shorebirds, and their blood is essential in the biomedical industry.

The overall goal of our project is to find an effective, alternative bait that utilizes less or no horseshoe crabs, is lower in cost, lower in environmental impact, and utilizes sustainable ingredients such as waste products and invasive species. Using the “Whelk TV,” an underwater camera system mounted over a typical conch pot designed to capture more than 24 hours of day and night footage, we can assess how effective the alternative baits are at attracting whelks. So far, we have tested baits that rely on invasive green crabs, surf

To : Blue Dot Living

From: Polly Hill Arboretum

Subject: Sustainable staff housing

The Arboretum has embarked on a staff housing initiative using sustainable building design, including solar, and a denitrification system. Here is a link to the project (bit.ly/polly-hill) and some current photos.

Landscape plants are being grown by Polly Hill, utilizing wild-collected seeds native to Martha’s Vineyard.

The final cost will be about $1.4 million; Polly Hill aims to raise $700,000 of that, and $400,000 has already been raised. The project should be complete by the end of summer, 2023.

To donate: bit.ly/polly-hill-housing

24 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

·

· ·

· · ·

Polly Hill's staff housing project.

An MVFPT whelk project.

clam bellies, and other waste from the clam processing industry. The numbers have not been crunched yet, but we are planning to continue to modify the recipe and are hopeful it will eventually eliminate or lessen the use of horseshoe crabs as bait.

Here’s how to donate: mvfishermenspreservationtrust.org/donate.

To: Blue Dot Living

From: V ineyard

Conser vation Society

Subject: Take Back the Tap!

The Vineyard Conservation Society has been working to make fresh potable tap water more readily available on the Island by installing water bottle refill stations. These stations reduce the need for plastic water bottles. So far we have saved thousands of plastic water bottles from the waste stream here on the Island.

VCS Bottle Refill Station Background

Beginning in the fall of 2015, we began working with the MVRHS environmental club to install a refill station in the high school. From there we gained momentum and with the help of a generous donor looked to all the schools on the Island with the purpose of installing at least one unit in each school. After many meetings, letters to administration, and haggling with plumbers, we finally installed the last school unit at the end of 2017. Although it was a great accomplishment, it was more like the first of many stages in our TBT (Take Back the Tap) initiative! The second stage was to be all non-school public buildings, mainly those that serve children. We are still somewhat in phase 2, while also delving into stage 3 — mostly outdoor locations (parks, community centers, downtowns, etc.). We aim to create a network of refill stations on MV that will cover every town, public

building, transportation hub, and tourist destination! Currently there are over 25 working units all over the Island. More are going in each month!

MV Tap Map. A decal is available for businesses to display their support for this initiative.

Here’s where you can donate: bit.ly/vinCS-support

To: Blue Dot Living

From: BiodiversityWorks

Subject: BiodiversityWorks

is Digging into our Mission

PFMV

Plastic Free MV has successfully banned plastic water and soda bottles in all of the six Island towns. Enforcement has been an issue, and we feel the more public refill stations we can provide to the public, the easier it is to comply.

MV Tap Map

We have created a Google map with all of the working, in-process, and wishlist locations of the refill stations. The MV Tap Map is an interactive map that can be accessed at our website by scanning the QR code on our decals and PFMV water bottles, or on the TrailsMV app. See the MV Tap Map here: bit.ly/MV-TAP-MAP

Building the Refill Station Network

Collectively with the installation of refill stations, VCS is asking businesses to participate in the “Take Back the Tap” initiative. Participating in the initiative could look like a self-serve dispenser, staff trained to fill a customer’s reusable water bottle, or purchasing and installing a refill unit. Participating businesses will be highlighted on the Vineyard Conservation Society website and

Over the last year, BiodiversityWorks began to dig into our mission in new ways. With a federal grant, we are building and testing underground hibernation sites for bats because the dirt crawl spaces and cinder block foundations under houses where they typically hibernate are disappearing when older houses are sold and demolished. Attracting bats to these new safe, underground hibernation sites is the next step in our work. We are also creating underground hibernation sites for snakes in protected areas so that they do not have to cross roads to find winter shelter. Black racers, the Island’s largest snake, were common across the Vine-

Continued on page 61

GIVE BETTER • NONPROFITS WISHLISTS 25 marthasvineyard. .com

· · ·

· · ·

A VCS refill station.

A BiodiversityWorks hibernation site.

Rachel Carson In Woods Hole

It’s fitting that there are ospreys wheeling over the Rachel Carson statue in Woods Hole when I visit one hot afternoon in May. Sightings of these fish-eating raptors are commonplace around Vineyard Sound today, although populations were decimated in the 1950s and ’60s. The decimation can be attributed to DDT — a pesticide that rendered osprey eggs thin and crushable, until it was federally banned in 1972. And the ban on DDT? That can be attributed, in large part, to Rachel Carson.

Carson’s hit book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement in the U.S., and it made Carson, a former writer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a household name. Published in 1962, Silent Spring warned against the deleterious impacts of DDT on humans and the environment. Although Carson received criticism from the chemical industry and its allies, she bravely defended her research until she died from complications of cancer in 1964.

But before Carson’s public recognition and controversy, before the science advisory committees or Silent Spring’s serialization in the New Yorker; before the Atlantic articles or the uncannily profound Fish and Wildlife brochures … there was Woods Hole.

“I had my first prolonged contact with the sea in Woods Hole,” Carson wrote, a quote now engraved beside her statue. “I never tired of watching the tidal currents pouring through the hole — whirlpools and eddies and swiftly racing water.”

The 22-year-old Carson first arrived at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole in the summer of 1929, just a couple of months before she was slated to begin graduate work at Johns Hopkins University. Her requests to the MBL were meager: just the “usual laboratory facilities for dissection.” But what Carson found was an artistic and scientific muse, tucked between Buzzards Bay and Vineyard Sound.

26 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Story by Kelsey Perrett Photo by Sam Moore

A statue in Waterfront Park honors the esteemed nature writer's little-known connection to the Cape Cod coast.

“Woods Hole is really a delightful place to biologize,” Carson wrote in a letter to a friend. “I can see it would be very easy to acquire the habit of coming back every summer.” Carson did not return to Woods Hole every summer, but she did return often. She learned to swim here. She became the first woman to go to sea on a Bureau of Fisheries (now the National Marine Fisheries Service) research vessel. And the inspiration she siphoned from the sea was the impetus for some of her most impactful works. Chief among those was The Sea Around Us, a 1952 National Book Award winner, and the second book in Carson’s “sea” trilogy. The Sea Around Us catalogs a near-complete natural history of the ocean, poetically spanning the whole of geologic time in the course

“There is no doubt that the genesis of … The Sea Around Us belongs to this first summer in Woods Hole,” Carson’s biographer, Linda Lear, wrote. And so it was in Woods Hole that Carson’s publishers staged the publicity photo for The Sea Around Us — the very photo on which her statue is based.

In it, the author is posed with a pen and a notebook at Sam Cahoon’s Fish Market, not far from the Steamship Authority dock. Her eyes are turned seaward, and although there is a calm pensiveness about her gaze, it is likewise resolute, determined. Perhaps not the idealistic gaze of a young woman looking toward a future in marine biology, but of a woman who knew enough of the Earth’s history to have some reservations about the Earth’s future. A future when, on an unseasonably warm May day, the sun will render the bronze sculpture scalding hot — hot enough that the caretakers of Waterfront Park will erect a warning sign.

So when sculptor David Lewis cast Carson’s face, he changed the original image slightly, adding just a hint of a smile. Because after all, Carson was in Woods Hole, looking towards the sea she so loved. Because yes, it may be getting hot. The surf may creep closer to the statue’s skirts each year. But as long as there are Rachel Carsons, those who champion science and the environment against all odds … there may also be ospreys.

The coastal ponds of Martha’s Vineyard are globally rare and ecologically fragile treasures whose preservation and restoration are fundamental to the Island’s long-term sustainability. These living waters define both the spirit and the character of our community.

MISSION STATEMENT

PROFILE • RACHEL CARSON IN WOODS HOLE 27 marthasvineyard. .com

Stay informed by visiting GreatPondFoundation.org

To cultivate the resilience of our coastal pond ecosystems through science, collaboration, and education.

TM

HOW TO LIVE ON MOTHER EARTH

Editor's note: Island painter Doug Kent works in a primitive style that evokes early times. We thought his style was appropriate for a story celebrating ancient wisdom.

"FALL" DOUG KENT, COURTESY OF THE GRANARY GALLERY

TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE • FEATURE 28 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

One afternoon during the summer of 1984, seven-yearold Jonathan Perry and his family set out to explore the woods in Tiverton, Rhode Island, part of the traditional territory of the Wampanoag nation.

As they grew closer to the edge of a wetland, the soil beneath the deciduous trees became dark and spongy, and mosquitoes hung in the humid air. It was Jonathan’s father who made the discovery — an Indian cucumber, identifiable by its two-tiered umbrella of leaves and light-colored flowers on top. They dug one up from the soil and made a refreshing snack of it.

The moment struck Jonathan and stayed with him throughout his life. Traditional harvesting practices and subsistence living — both key elements of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) — confirmed for him that the world around him would provide for

him, strengthen him, and at times, heal him. Now a tribal council member for the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, Jonathan has been practicing TEK his entire life, accumulating an encyclopedia of Indigenous knowledge. He feels lucky to have grown up in a family that

I harvest the Indian cucumber in small quantities for my family,” he says, “I celebrate that gift of knowledge and that day, that moment.”

Traditional Ecological Knowledge is an integrated system of knowledge, practices, and beliefs, developed and passed down over millennia in Indigenous cultures. It encompasses patterns of fluctuation in climate, sustainable harvesting, adaptive resource management, and the use of disturbance regimes, such as fires or grazing, to manage land. Central to TEK is a philosophical respect for the environment and a sacred, non-exploitive relationship with the land.

Increasingly, TEK is being recognized as critical to our approach to climate change. “We were given provisional instructions — how to live on Mother Earth,” explains Bettina Washington, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head.

“We lived like that for twelve to fif-

FEATURE • TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE 29 marthasvineyard. .com

GENERATIONS OF WAMPANOAG WISDOM CAN HELP US CARE FOR OUR LAND (IF WE ARE READY TO LISTEN).

The moment struck Jonathan and stayed with him throughout his life. Traditional harvesting practices and subsistence living — both key elements of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) — confirmed for him that the world around him would provide for him, strengthen him, and at times, heal him.

teen thousand years and, if we were not interrupted by European settlement, we’d still be living that way and the Earth would not be in the condition that it’s in right now,” says Linda Coombs, a tribal member and researcher for the Wampanoag Project at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums in Plymouth. “It worked, and

that’s why we kept doing it. We did not make the Earth conform … We observed the Earth and what it could do, and then our culture, our thinking, was formulated around that.”

According to a 2021 report from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Indigenous

peoples account for 5% of the world’s population, but manage a quarter of the Earth’s land surfaces. These lands hold 80% of the planet’s biodiversity, and 40% of all terrestrial protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes.

Growing up in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, Jonathan Perry absorbed ecological knowledge from many ancestral connections, including family members from the Vineyard, Westport, and New Bedford. His immediate family, including his older sisters, served as his first teachers.

In Dartmouth, his family found both traditional and contemporary ways to engage with and care for the landscape, including fishing, canoeing, camping, and beach cleanups. They took part in lectures and classes, such as animal observations and fish studies, at a local environmental studies center.

But Jonathan’s speciality was always in harvesting and subsistence living. “I learned at a very early stage in my life that you appreciate the very first things that you find, but you don’t touch them,” Jonathan says. “You go farther out, because you always want things to

30 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Bettina Washington at a tribal powwow in Aquinnah

"BERNICE" DOUG KENT, PHOTO BY GARY MIRANDO

PHOTO: LISA VANDERHOOP

come closer to your community and closer to your home. You always want the plants to be abundant and to spread.” He learned about edible and medicinal plants. There are hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of uses for a single plant depending on how and when it is gathered and processed, Jonathan says. Strawberries, or wutâhumunash, for instance, are called the “heart berry” because they look and bleed like a heart and work as a blood thinner. The leaves can be used for tea or cut for ceremonial tobacco. The berries themselves can be medicine — a detoxifier high in antioxidants.

Jonathan learned to assess soil quality by observing plant growth, considering the taste, distribution, size, and health of the plants to understand the density or acidity of the soil. He planted nut-bearing trees, anticipating that each year he could fill an entire bag with the harvest it produced.

He learned the traditional method of hunting sturgeon, venturing out in dugout canoes under the light of the full moon, luring the sturgeon to the surface of the water with torches, and harpooning their vulnerable lower stomachs. Because of the collapse of the sturgeon population, however, Jonathan has seen very few in his lifetime.

He learned how the moon corresponded with key harvest times. He followed lunar phases for planting, timing of crops, the arrival of certain fish, and migration patterns.

“For my ancestors, learning is a lifelong journey that stops only when your heart stops,” Jonathan says. “There is no knowing it all, and there is no getting to a point where you’re done. It just goes until you can’t do it anymore, and then the mantle is taken up by the people who hopefully you’ve taught your whole life, who are able to take it a little further.”

Jonathan’s son Tristan, named after family ancestors, is five years old. Like his father, he is growing up with a family dedicated to passing down elements of TEK. He already wanders through the woods, identifying species of plants and gathering wild edibles. He digs

for quahogs at low-tide. He taps maple trees, helping boil the sap down to syrup and sometimes even to granular sugar for baking and coffee.

“He thinks it’s totally normal,” Jonathan says. “It makes you acknowledge the abundances and makes you sensitive to drought and environmental concerns. It teaches you to have respect for the land around you and take care of it as opposed to thinking of it as something that’s convenient and can be exploited in whatever way you see fit.”

Bettina Washington: Watching traditions fade

When Bettina Washington was born on the Island in 1959, most Aquinnah Wampanoag had a daily routine that was what we’d now call subsistence living. She remembers an abundance of family gardens — her grandfather, great aunt, and uncle each tended to the earth, growing sunflowers, squashes, beans, and tomatoes. Meals came from the ground or the ocean. The Wampanoag community didn’t have a word for money, she says. The wealth was always in the food itself, and it came in its own time.

The timing of food provided opportunities for ceremony and celebration, she says, noting that it’s difficult for others to understand now the joy that the Wampanoag felt in the spring when the herring returned. After surviving the cold months eating stored smoked and dried fish, she says, they would rejoice in their newfound abundance. Her family focused on self-sufficiency, rarely venturing down-Island and learning to make do with what they had. Her older cousins told her of a time that her

FEATURE • TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE

31 marthasvineyard. .com

Jonathan Perry dressed for a powwow at the Gay Head cliffs.

PHOTO: LISA VANDERHOOP

“We observed the Earth and what it could do, and then our culture, our thinking, was formulated around that.” –Linda Coombs

grandmother would pick a chicken from the backyard to prepare for dinner.

But soon enough, neighbors within the community turned to the Island grocery stores, and practices such as slaughtering chickens dwindled.

“For the majority of the population, all that unsavory business has been taken care of. We’ve met the sterilized version,” she says. “But it’s all alive. We have to say thank you, we need to acknowledge their life.”

As long as people can pay for it, she says, food is always accessible, regardless of the Earth’s season.

“When you walk into the grocery store, you see all this food — it’s like it just

magically appears,” Bettina says.

“You can get strawberries anytime. But nothing tastes as sweet at those strawberries that you pick right from the ground. When you see the little white blossoms, you know that nothing tastes like that.”

Disruptions to TEK — climate change, colonization and urbanization

Climate Change

Generational TEK has been threatened by a multitude of factors over the past few centuries. The interrelated challenges of climate change, colonization, and separation from the land have taxed

Indigenous communities’ ability to practice traditions and pass down knowledge. The key to being able to do what my ancestors did frequently was having a healthy environment, says Jonathan.

He says the assumption that the devastation of Indigenous communities is because of sickness and guns is over-simplistic and unrealistic. Rather, he points to environmental degradation from invasive species imported by Europeans, overfishing, over-hunting, clear-cutting and deforestation, and the replacement of commercially valuable species that sustained communities. Each of these contributed to the destabilization of Indigenous cultures, he says.

Extractive practices diminished the availability of resources that were critical for TEK. Certain types of woods or plants, for example, are necessary to frame the cordage to form the eel trap, he explains, but during European contact, these sources were overharvested or cleared for animal grazing. “Then guess what? No more eel traps,” Jonathan says. “Nothing is what it was for our ancestors.”

Europeans also introduced a completely different way of looking at the environment, Jonathan says, “a different way of valuing the diversity of plant and animal species is one of the things that ended a lot of traditional practices and a lot of opportunities to maintain our communities.”

Colonization

Colonization and compulsory processes of assimilation also diminished TEK, explains Linda Coombs. “Civility,” enforced through Christianization, mandated relocation and dictated that Indigenous communities change their relationship with the land.

“We didn’t just one day lose everything,” says Linda. “That was a gradual process … We lost language, we lost culture, we lost land. One of the biggest factors in losing culture was losing our land, because it was our relationship with the entire landscape that really formed the parameters of how we acted. Our whole culture is based on that.”

32 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /FALL-WINTER 2022-2023

Camille Madison in Aquinnah.

PHOTO: JEREMY DRIESEN

Urbanization

Urbanization and development continues to impact the Wampanoag community, many of whom left their traditional lands because of resource scarcity, and relocated to Boston or other urban centers. “We’ve been removed in some ways from the stewardship that we once had with the land, and our responsibilities to it,” says Camille Madison, a member of the Wampanoag nation, who grew up in the Gallivan housing project in Mattapan. Separated from her land and community, she has spent her adult life reconnecting with Wampanoag culture.

Camille’s grandmother, Freda Belain, was raised in Aquinnah, where she became well acquainted with the landscape, knowing where to find the cranberry bogs and abundant food. When she was older, Freda spent the summer sea-scalloping. Yet, as the conditions of the Island changed and the scallops depleted, she and other members of the Wampanoag community could no longer rely on those methods to feed their families. Freda moved her family to Boston in the late 1960s, to a new high-rise apartment on Tremont St. where even gardening was not possible. Separated from the land, it became challenging for Freda and Jean Anne, Camille’s mother, to pass down TEK to Camille. “Without having the woodlands there, it’s hard to teach about the woodlands,” Camille says. “It’s hard for a child to even want to engage in learning about the woodlands if

[she’s] not there. There’s nothing relatable … I wasn’t raised in the place where I felt like that knowledge lived,” she says.

Every few months, however, Camille would travel with her grandmother and mother to Aquinnah to attend a social event, such as annual family day or cran-

could still hear the rustling of nature and the waves crashing on the cliffs. She had always wondered what it meant to truly be Wampanoag, and while on Island, she was determined to learn more about the land, the plants, and her ancestral culture.

As a high school sophomore, Camille attended the North American Indian Center of Boston. One moment was pivotal for her: An elder asked her to find a pinecone and observe its spirals. After examining the patterned edges, Camille finally saw the design.

“The elder came back to me and started talking about how everything moves in circles,” she says. “And I think that was my introduction to really understanding — maybe not ecological knowledge, but how math ties into nature and also to ourselves. That was my first thought of how nature could potentially mean something bigger or have a greater purpose than what you think it does.”