“ Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

President Victoria Riskin

CEO Raymond Pearce

Executive Editor Jamie Kageleiry

Head of Audience Kirsten Carroll

Editor Brittany Bowker, britt.bowker@bluedotliving.com

Senior Writer Leslie Garrett

Associate Editor Julia Cooper

Copyeditor Laura Roosevelt

Chief Financial Officer David Smith

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Designer/Production Manager Whitney Multari

Design and Production Vesna M. Nepomuceno

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Special Projects Alison Mead

Web Producer Grace Hughes

Ad Sales Josh Katz, adsales@bluedotliving.com

Social Media Emily Lamoureux

Contributors this Issue Nancy Aronie, Randi Baird, Brooke Bartletta, Bluerock Designs, Elizabeth Cecil, Arletta Charter, Jeremy Driesen, Kate Feiffer, Maria Thibodeau

•

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Please write us if you’d like to stock Bluedot Living at your business. Editor@bluedotliving.com

Sign up for the Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter, along with any of our others: the BuyBetter Marketplace, our national ‘Hub” newsletter, and Bluedot Living Kitchenr: bit.ly/MV-NEWSLETTER

Subscribe! Get Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard and our annual Bluedot GreenGuide mailed to your address. It’s $29.95 a year for all four issues plus the Green Guide, and as a bonus, we’ll email you a collection of Bluedot Kitchen recipes. marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com/magazine-subscriptions/ Read stories from this magazine and more at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Find Bluedot Living on Threads, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube @bluedotliving

If you saw someone slowly pedaling a bike through Oak Bluffs and Edgartown on one of the busiest days of summer — the day before the Fourth — no you didn’t. I was sweaty, running late, and definitely not wearing the right shoes (see page 38). It was a classic Vineyard summer day: hot, humid, and not a cloud in sight. I came over on the Hy-Line from the Cape (did you know you now have to reserve parking ahead of time? Try the RTA lot next door), and rented a bike at the first shop I spotted off the boat. Thirty bucks for a traditional ride, or fifty for an e-bike. The guy at the shop tried to upsell me; I resisted. Aren’t regular bikes better for the environment? I found out later that while traditional bikes have a lower manufacturing footprint, e-bikes can actually be more sustainable in the long run, especially if they replace car trips. Their emissions are minimal, especially when charged with renewable energy, and they make longer trips more

doable. Good to know for next time. I stuck with my analog wheels and pedaled down Beach Road, past the new recycled racks along Senge (see page 11), and into the Triangle, where traffic was at a standstill. Range Rovers, G-Wagons, even the VTA bus that had passed me 10 minutes earlier — all crawling. I cruised right by. And it really is the best way to see the Island. Every salty breeze and glimpse of glimmering water reminded

me why it’s so easy to fall in love with this place. It’s almost involuntary — the urge to say something out loud to no one about how stunning it is. By the time I coasted into town, legs burning, I was ready for something cold, something fresh, and something grown right here. (I went to Rosewater.) And that’s what this issue is all about — what’s grown, caught, cooked, and shared across the Island. Whether it’s a seafood shack in Menemsha or a nonprofit farm giving everything they grow away, food brings us together. And after a long bike ride, it tastes even better.

One of our own, Whitney Multari, who usually works her magic as our designer and production manager, did it all for this issue: she grew tomatoes, made a soup from them, wrote the story, took the photos, and designed the layout (see page 20). We’re grateful. And hungry. We hope you enjoy this issue, and as always, thank you for reading.

– Britt Bowker

Britt Bowker

Cheese a Better Climate Choice Than Meat?

Nancy Aronie just needed a little push to eat a more plant-based diet.

In the Bluedot Kitchen: Ann Berwick

By Laura D. Roosevelt

An environmentalist cooks with the climate in mind and family at heart.

Britt Bowker

Created by the Martha’s Vineyard Fishermen’s Preservation Trust, the book is a love letter to the Island’s fishing culture.

conversation with Shelley Edmundson and John Keene of the MV Fishermen’s Preservation Trust and MV Seafood Collaborative.

At Cape Cod Retractable Inc. we offer fast, responsive and detail oriented service. Our staff is knowledgeable, trusting and insured.

Explore diverse awning solutions for your home or business with Cape Cod Retractable, Inc. Choose from Residential and Commercial Retractable Awnings, Fixed Frame Awnings, and Specialized Awnings for Pergolas.

Elevate your space with Phantom Retractable Screens, Motorized Screens, Solar Screens, and Clear Vinyl Shades.

Safegaurd your property with our strom/hurricane protection options.

508-539-3307 |

By Nantucket Conservation Foundation

By Britt Bowker Boston, Massachusetts

Drive into East Boston from downtown — through the Callahan Tunnel and into a dense neighborhood of narrow streets and tightly packed homes — and you might miss it at first. Tucked underneath billboards and in between row houses is a sleek, glass-walled greenhouse filled with seedlings and tropical plants. It’s a warm, green refuge, even on the coldest New England days, and more than that, it’s a space for gathering, learning, and community connection. It’s also the region’s first greenhouse powered by geothermal energy.

This is one of several hubs run by Eastie Farm, a nonprofit rooted in this immigrant-rich neighborhood since 2015. It all started when a group of East Boston neighbors noticed an empty, overgrown lot and proposed transforming it into a community farm so that it wouldn’t be turned into another development. From the beginning, Eastie Farm has follow a simple ethic: care for the land, and for the people who live on it.

“A space for larger solutions while we tend for the needs of today,” is how Kannan Thiruvengadam, Eastie Farm’s executive director and one of its founding members, describes the mission.

Read more about Eastie Farm and the geothermal technology that powers its greenhouse at bit.ly/EastieFarm.

By Christopher Lysik Catskill, New York

Hidden deep in the woods of Catskill, New York, some 15 miles from Kaaterskill Falls, one of the tallest waterfalls in the eastern United States, lies a quaint little village. Like any good town, it contains a library, a chapel, some houses. There are quirkier attractions, too, helping lend some uniqueness to the place: The Archive of Lost Thought stands not far from a building known as the “Fun Palace,” to name but two. Finished after a long hard day of work? Why not take a load off at the local sauna, or meet up with some friends at the Whiskey Still!

It is, for the most part, a completely normal, totally run-ofthe-mill town…

Except it is built entirely from trash.

The project, known as b-home, is the brainchild of Matt Bua, an artist and “intuitive builder,” who has been toiling away at the land for nearly 20 years, alongside a ragtag band of fellow creatives.

It’s far from the first time that an artist has attempted to go off the grid and create work more sustainably. But at two decades of age, and containing nearly five dozen complex structures, b-home is certainly one of the most expansive of these projects.

Read more about Matt Bua’s b-home project at bit.ly/b-home-project.

By Allison Braden Savannah, Georgia

In a quiet creek off the Savannah River, tupelo trees arch over still black water. I guide a group of kayakers into what locals call the tupelo cathedral. Overhead, bright leaves catch the sun like stained glass. The trees will bloom for only about a week — just enough time for bees to gorge on their sweet nectar and make one of the world’s most sought-after honeys.

Tupelos, whose name comes from a Muskogee phrase for “swamp tree,” tower up to 50 feet out of the muddy creek bed, and alligators lurk in their roots. They grow densely enough to yield honey in just a few spots in south Georgia and northeast Florida, where, every spring, beekeepers launch their hives into the swamps. Bees will buzz between hundreds of blossoms a day to collect nectar, which will eventually become the gold goop that will sustain their hives through the winter. They’ll have plenty to spare for us — a healthy hive can make as much as 70 pounds more than it needs.

Read more about Georgia’s tupelo honey at bit.ly/tupelo-kayaking.

Have you noticed the new bike racks along State Beach? They’re made from recycled plastics, and part of a sustainability effort led by Friends of Sengekontacket in partnership with Chick Stapleton and her team at Island Spirit Kayak.

“It was a thrilling project to undertake,” Chick told us recently.

The old steel racks didn’t hold up well in the salty beach environment. They corroded quickly, breaking down into shards that scattered on the sand. For years, Island Spirit Kayak has worked with Friends of Sengekontacket to place and remove the racks each season, and to patch them up when possible.

“Each year, we have had to repair them using rust reformer and rustoleum paint, which are both harsh materials and part of a challenging process, especially when the repairs were unsuccessful,” Chick says.

With a lifespan of just two years, the steel racks weren’t

a long-term replacement. The new, more durable racks were purchased from Park Warehouse and fully funded by Friends of Sengekontacket. This year, teams from both organizations installed six of them, and they’re already planning to add more next year.

expands its reach with a new space — and joins a regional food system assessment to plan for the future.

By Britt Bowker

The Island Food Pantry, run by Island Grown Initiative (IGI), has a new home across the street from Tony’s Market in Oak Bluffs. Opened in November 2024, the space includes a walk-in freezer, warehouse storage, and a streamlined new system — all of which allow IGI to serve more food to more Islanders.

Clients now place pre-orders online and sign up for 15-minute pickup windows. “We pivoted from in-person shopping to online preorders for everyone other than seniors,” says IGI co-executive director Noli Taylor. “That means people can still have the choice of what they want and need from the pantry, which is really important to us, but it’s just become a much more efficient system.” Seniors continue to shop in person on Fridays, which Noli says provides a valuable social connection.

“They are so dedicated,” Noli says. “It’s just another example of food being this connector in the community.”

Future plans for the new pantry include renovations upstairs to create office space and make more room for food storage. “We want better shelving for vertical storage, especially for dried goods in case of ferry interruptions,” Noli says. Solar is another next step: IGI worked with Resonant Energy and Vineyard Power to develop plans to put a solar array on the roof and will be raising funds to install the array in the coming year.

Behind the scenes, volunteers pack and distribute orders in what Noli describes as a “well-oiled machine.” “Our pantry staff, Vinnie [Padalino] and Emily [Pinheiro de Souza], make it so fun,” she says. “On Saturdays they have a disco ball that they hang from the ceiling and they turn on the music really loud — because it’s busy. It’s a lot.”

Clients pull up, check in, and volunteers package and load their pre-ordered groceries into their cars. In the previous location at the PA Club, there used to be a 35–40 minute wait time. “Now people are waiting five to seven minutes,” Noli says. “For families under stress or working multiple jobs, it’s so important to make this as dignified and efficient as possible. And it feels like we’re really able to do that now.”

The pantry now runs six days a week, with pickups on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays, senior shopping on Fridays, and delivery and restocking midweek. The pantry serves an average of 1,000 Islanders each week.

Much of the food comes from IGI’s farm, which grows more than 100,000 pounds of produce annually — most of which goes to food access programs and primarily to the pantry. Local farms also contribute, including regular donations from Slough Farm and bread from The Grey Barn in the off-season. IGI also receives 7,000 pounds of food weekly from the Greater Boston Food Bank (GBFB), a key partner in the effort.

More than 300 volunteers support IGI’s pantry operations.

The GBFB’s most recent food insecurity report showed a continued rise in need, including on the Island. Thirty-seven percent of people in Massachusetts are considered food insecure. “The Food Bank team visited us a few months ago,” Noli says. “They were really impressed by how we’re addressing food insecurity holistically, through the pantry and prepared meals, climate-resilience farming, and our Island Grown Schools program. It’s this comprehensive community approach, and they felt there was nothing else like it.”

Looking ahead, IGI is also participating in a regional community food assessment, the first to include the Cape and Islands as part of Southeastern Massachusetts. The effort is led by the Marion Institute and uses a tool called CARAT — the Community and Agriculture Resilience Audit Tool — to evaluate everything from food access and farming to equity and climate resilience.

“It helps you see where you are and where the gaps are in your food system,” Noli says. The work supports long-term goals under the Martha’s Vineyard Climate Action Plan, which includes sourcing 50% of the Island’s food from the northeastern U.S. by 2040. “It’s an ambitious goal,” she says. “We’re going to need to work with partners in our region to really make our food system more robust. This assessment gives us an opportunity to do that.”

Learn more about IGI at igimv.org. To learn about volunteering opportunities, visit igimv.org/volunteer.

Keep our shores sparkling with free Beach Befriender cleanup kits, available at every Island library. Each kit includes a reusable bag, one or two pairs of gloves, a sticker for trash disposal, and an info card with easy instructions. When you’re done, drop off your collected trash for free at any Island transfer station.

August 23, 8–10 am

Join the post-fireworks clean-up! Teams will tackle Inkwell Beach, Little Bridge, or Jetty Beach before regrouping at Little Bridge for a trash tally.

September 20: 8–10 am

Edgartown and Chappy clean-up. Beaches TBD.

(508 )62 7- 292 8 | M V@ oh-DEE R .co m oh-DEE R. co m

•SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

•KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOES ON CONTACT.

•AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

Since launching on Earth Day in 2023, the Beach Befriender program has helped “BeFriend” dozens of local beaches. Hundreds of pounds of marine debris have been collected, documented, and properly disposed of. Big thanks to the Vineyard Conservation Society for leading this vital effort. Learn more about the program at bit.ly/BeachBefrienders.

ohDEER offers two all-natural pest control solutions for seasonal or year-round protection. Our deer control solution is an egg-based spray with garlic, white peppers, mint oil, and water that directly targets the plants deer love to feed on. Our tick and mosquito spray is a blend of powerful essential oils, including cedarwood oil, lemongrass oil, castor oil, and water. Our team provides customized, thorough coverage for your property, ensuring long-lasting protection.

Islanders Laney and Maddie Henson share their eco-conscious adventures from around the globe.

By Julia Cooper Photos by The Baggage Girls

Maddie and Laney Henson are two sisters on a mission to demystify the world of eco-tourism and encourage young people to follow their passions. They’re based on MV; their @baggagegirls accounts have amassed nearly 11,000 followers on Instagram and 23,000 followers on TikTok, so it’s clear that they’re not alone in their love of all things sustainable travel. (You can also find them at baggagegirls.com)

When I first came across the Baggage Girls social media pages, I must admit, I was skeptical. Having grown up on the Vineyard, I have a lot of opinions about the Island’s complex

relationship with tourism, especially when it comes to protecting the Island’s natural spaces. I thought, “Who are these welltraveled outsiders purporting to have the inside scoop when it comes to planning an eco-conscious trip to Martha’s Vineyard? Surely they’re exploiting the cultural cachet of my beloved hometown for clicks and views.” I was a shark hunting for “Oaks Bluff” blood in the water.

Within moments of meeting Laney and Maddie, my anxieties faded away. They are smart, thoughtful, and intentional in every aspect of the work they do. In addition to producing content for and building the Baggage Girls brand on social media, they also take local businesses on as marketing clients. Their goal is to help connect travelers to ethical, sustainable experiences on Martha’s Vineyard and beyond. Maddie also coowns Top Shell oyster farm in Edgartown’s Katama Bay.

“My sustainability journey started early on, when I was 16 or 17,” Maddie, the older of the two sisters at 26 and the first to move out to the Vineyard, told me. “The more I learned about climate change, it quickly felt very doom and gloom. I was very discouraged and stressed out for years. I didn’t have a lot of hope and was really hesitant to talk about it.”

After graduating high school, Maddie moved to the Bahamas for four months to work in marine conservation. She spent her time scuba diving, learning about marine species, and

working with marine biologists surveying reefs and reporting on endangered species. “We grew up in Chicago, so this was my first time living on the ocean and doing the things that I’m passionate about,” she said. “It absolutely changed my life.”

In the summer of 2017, Maddie came to the Vineyard and started working for Island Spirit Kayak while volunteering with Friends of Sengekontacket and the Lagoon Pond Association. “I learned that even working on a small scale, these Island organizations are having a tangible impact,” Maddie said. “That led me into oyster farming, which was my first attempt to make a real impact on a community I love and do something to promote sustainability on the Island.” Maddie moved to the Vineyard full-time in 2021 after completing a degree in marketing online while traveling, traversing the U.S. and visiting at least 15 different countries.

Laney, who’s 25, joined Maddie on the Island in the summer of 2020 when her corporate publishing internship went remote. “I fell in love with the natural beauty of the Island,” Laney said. “I started arranging my life around how I could keep coming back to the Vineyard.” In her senior year of college, Laney

wrote her honors thesis about eco-tourism and sustainable development on Martha’s Vineyard. After graduating college in 2022, Laney moved to the Island and started working on the blog that would become Baggage Girls.

“As we began building our business, our dad was dealing with [glioblastoma, a terminal brain cancer], and passed away. That was a huge catalyst for both of us, our desires to travel, try new things, and be less afraid of taking risks,” Laney said. “Our dad was our biggest supporter and he absolutely loved Martha’s Vineyard. He really inspired so much of what we do and was a big piece in building this brand.”

It was difficult for Laney and Maddie to travel and build their business while wanting to spend time with family at home. “Working on [Baggage Girls] has given us so much hope and excitement. It’s a reminder that life is so beautiful, even when it’s hard,” Laney said. “We are always prioritizing talking about sustainable travel, but I also want to encourage people to go after what they love and are interested in.”

With Maddie’s photography, Laney’s writing, and their combined marketing experience and passion for sustainable travel, they turned Baggage Girls into the thriving brand it is today. “It’s not necessarily about pushing people to buy more, or to do this and that. But, as people go through the world, wherever they might find themselves, we can encourage them to be a bit more conscious about who they support and how they do it,” Laney says. “Sharing our stories just makes it easier for people who otherwise feel like they don’t even know where to start.”

Heading to the Edgartown light.

While Laney and Maddie both emphasize the importance of “leave no trace” travel and other small habits like always carrying a reusable water bottle, with Baggage Girls they encourage their followers to be especially conscious of the economic side of sustainable travel. “As travelers, the best thing we can do is support the small, local businesses in the places we travel to,” Laney said. “That’s how we keep money in the local economy and ultimately benefit the actual destinations themselves.”

Recently, Baggage Girls launched their first digital product, the Martha’s Vineyard Travel Guide. This e-book encourages visitors to the Island to experience Martha’s Vineyard through the lens of local businesses, nature, and community. In addition to restaurant recommendations, tips for getting around, and favorite outdoor activities, the Martha’s Vineyard Travel Guide includes small discounts for local businesses. “Our goal with [this travel guide] comes from recognizing that Martha’s Vineyard is a very largescale tourist destination, and it has been for many, many years,” Laney explains. “We wanted to do something that shared local businesses and local artists so that [visitors] can more easily find and support them.”

In addition to highlighting small businesses on the Vineyard, the Baggage Girls brand brings their followers with them on eco-adventures around the world. For example, they recently returned from a trip to the Galapagos and were amazed by how the country of Ecuador has implemented a unique tourism infrastructure that protects their endangered habitats while also educating visitors on the environment they’re seeing and the local cultural customs. “I feel like a lot of what we do is take something that people might think is very ‘nature-y’ and make it more mainstream,” Maddie said. “It’s all about making sustainability more approachable — it can be so overwhelming. To us it’s all about recognizing that people are going to travel anyway, so how can we make small, approachable changes that add up to making a real impact.” 43A Main Street, Vineyard Haven

CANAAN FAIR TRADE OLIVE OIL

Globally Certified: 2004 Fair Trade, 2007 Organic, 2024 Regenerative Agriculture

ORGANIC OLIVE OILS & FAIR TRADE TREASURES from Palestine, Guatemala, Haiti & beyond

ORGANIC OLIVE from Palestine, CANAAN 2004 Fair Trade, 2007

43A Main olivebranchfairtrade.org

Dear Dot: Is Cheese a Better Climate Choice Than Meat?

Dear Dot,

I know that meat consumption is bad for the environment. I’ve cut way back on meat but am not quite a vegetarian. Instead, I’m eating a lot of cheese. But a friend told me that’s just as bad as meat? Is it? (Please say “no.” Vegan cheese is … ugh!)

– Kayla

The short answer:

While cheese is up there with beef and lamb for its considerable carbon emissions, you can reduce the climate impact by supporting smaller, sustainably-minded local cheesemakers/farmers and, mostly, by using up every bit of the cheese you purchase (even keeping your parmesan rinds to be used in soups!).

Dear Kayla,

At the age of 22, Dot spent a semester at a tiny school in Villefranche, a small village perched atop a cliff in the south of France, with spectacular views of the Mediterranean. I was broke but who cared. I was in France. Each week, I would scrounge together what few francs I could and buy a baguette, some creamy Camembert, and a bottle of Beaujoulais nouveau. I might have been living a cliché but it felt like the height of luxury.

And so it is with le coeur lourde that I share the climate impact of cheese, which is … mauvais

How mauvais? Our World in Data, that ever-reliable information source that passes not judgement but speaks only in numbers, reports that meat tops the lists of both short-lived (methane) and long-lived (carbon) gas emissions. But also, sadly for non-vegan vegetarians and poor 20-somethings studying abroad, emissions from cheese are similar to those of beef and lamb, routinely ranking above most meats. However you slice it, the climate cost of cows (and cow products) is shockingly high.

That’s because dairy cows emit large quantities of methane, which, as Grist reports, has a climate impact 25 times higher than carbon. But cow manure also releases methane and nitrous oxide, and cows eat a lot of grain, including corn, which has a high climate impact. Might buying locally produced cheese put a smile on Mother Earth’s face? Possibly. Dot already crunched some numbers in response to a reader curious whether food miles or food waste was the bigger climate villain — and concluded that the decomposition of food in a landfill is worse than transportation. Surprisingly, transport isn’t so bad, unless the food was flown in. With “air-flown” food, which Our World in Data notes is rarely labelled as such, you can make a fair guess if the food in question has a very short shelf life and came from a far-flung locale.

But the real benefits of eating local come from how smaller farmers often conduct their operations — sustainably, organically, and humanely. As Grist reports, “Sustainable dairy operations lead to reduced use of chemical fertilizers and

pesticides, less water pollution, healthier soil, and more habitat for birds and other critters. Dairy farms can also help keep land developers at bay, preserving open space.” Cheese takes a lot of milk to produce — 10 pounds of milk, on average, go into producing a pound of hard cheese, reports Kari Hamerschlag, senior analyst at Environmental Working Group — but how and where that cow is raised does make a difference. On many (not all, of course) small farms, animals, rather than being raised in industrial feed lots, are pastured, eating better and living more happily. Climate change is important, of course, but it’s not the only value to consider.

What about cheese coming from sheep or goats? The difference is negligible. Grist reports that goats are slightly less bad than cows for climate impact, while sheep emit more methane compared to milk produced. So where does that leave those of

us still salivating for a tangy chunk of aged cheddar? Or a funky Gorgonzola?

Grist cites Environmental Working Group’s recommendation to lean toward lower-fat cheeses, noting that when some of the fat is removed from the cheese and redeployed in, say, butter, the climate impact is dispersed as well.

Slate magazine ranked cheese by its climate cost (though its story is somewhat aged), concluding that the most Earth-friendly options are feta, chevre, brie, and Camembert. Softer cheeses typically use less milk and a less extensive aging and cooking process.

Or we might consider vegan cheeses, which rely on nuts, tofu, and other plant-based ingredients instead of dairy. (Though, I confess, I share your review of “ugh.”) While the BBC reports that “The environmental cost of vegan cheese is not clear, nuts and soya milk or tofu, common vegan cheese ingredients, have a lower carbon footprint than dairy cheese.”

Whatever cheese you choose, Dot beseeches you to finish it. With 40% of the food produced rotting in landfills in the United States, food waste remains the most sinister of climate culprits so, please, store properly and find creative ways to use up leftovers.

– Cheesily, Dot

Please send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com

Want to see more Dear Dots? Find lots here: bit.ly/Dear-Dot-Hub

tomatoes and tradition on Martha’s Vineyard.

I’m Italian, so you could say tomato sauce runs in my blood. Ever since I was little, my Italian grandfather has had multiple gardens overflowing with tomatoes, grown from seed and pruned to perfection. Every summer, we picked ripe tomatoes, cucumbers, basil, figs, zucchini, beans; you name it, he planted it. You might even say I was a bit of a spoiled tomato myself, eating ripe vegetables straight from the garden. Summer dinners were filled with just-picked veggies. We didn’t know any different, it was simply how we ate. Then, come fall, we’d jar all the tomatoes and savor those bright summer flavors all winter long. We poured them over pasta and meatballs, added them to soups, served

them with chicken cutlets and spicy Italian sausage — however my grandmother felt like cooking that day.

(Funny fact: when we were little, we gave our grandmothers very accurate nicknames: My Italian grandmother was always cooking her amazing Italian food so naturally, we called her Grandma Meatball. My mom’s mother was a hairdresser who let us play in her salon chair, so she earned the nickname Grandma Haircut.)

In 2009, I moved to Martha’s Vineyard to work in restaurants for the summer, my first time living away from home. That summer,

You might even say I was a bit of a spoiled tomato myself, eating ripe vegetables straight from the garden.

I didn’t have the space or time to grow a garden of my own. I moved to the Island full-time in 2014 and the dream of gardening stayed with me. It wasn’t until 2020 that I finally had an apartment with some outdoor space. I started small, with basil, oregano, and rosemary. Nothing wildly successful, but I always managed to keep the basil hanging on.

While working for Bluedot Living, I got creative and sustainable by repurposing an old filing cabinet into a raised garden bed. I flipped it on its side, filled the bottom with leaves and wood for drainage, then topped it off with (a lot of) dirt. That’s where I planted my very first tomato plants!

Unfortunately, my rookie mistake was placing the planter in a sunny spot in early spring, but once the trees filled in, it didn’t get enough light. Not enough sun meant not enough tomatoes and the planter was far too heavy to move. Still, I wasn’t discouraged.

This year, my garden lives in four galvanized metal buckets. (I passed my repurposed filing cabinet planter along to a friend whose home gets better sun.) I planted two tomato starters from a friend at Hamilton's Homestead in West Tisbury, two cherry tomatoes from the Martha’s Vineyard High School plant sale, and one bright Sun Gold from the tomato pruning workshop I took with Lydia Fischer this spring. Nearby, a couple of pots are filled with a fragrant mix of basil, parsley, oregano, and rosemary — plus four pepper plants and some cheerful nasturtiums for a burst of color.

Since taking Lydia’s workshop, I’ve been approaching my tomato plants with a new level of care and intention. Each morning, I head out to check on them, clipping a few leaves here, pinching off a sucker there. I’ve learned to look at each plant as a living structure, something to gently guide rather than just let grow wild. It’s not about cutting everything back, it’s about shaping the plant so it grows strong and healthy, with plenty of airflow and room for fruit to thrive.

Instead of letting my tomatoes sprawl, I’ve been training them to grow upward using wooden stakes for support. I keep the base of each plant tidy, removing leaves that droop too low or look a little tired. It’s subtle work — sometimes just a small snip or shift — but it really makes a difference. The plants are thriving, full of life, and already showing off clusters of little green tomatoes. Some cherry tomatoes are even starting to turn red and ready for eating!

As an added bonus, after every pruning session, my hands smell like tomato plants, easily my favorite scent. It always brings me right back to childhood summers in my grandfather’s garden.

Growing a garden on the Vineyard feels like planting new roots while honoring the old ones, and there’s something really meaningful in that.

Someday, I hope to have a garden as big and bountiful as my grandfather’s. I may not be harvesting enough to jar my own tomatoes just yet, but I’ve still found ways to carry on the family tradition.

Over the past few Septembers, I’ve collected tomato “seconds” from farms across the Island: Ghost Island Farm, North Tabor Farm, and other local stands. These slightly bruised or overripe tomatoes are perfect for canning and usually sold by the pound. With around 10 pounds, I can fill about four jars, just enough to bring a little taste of summer into the colder months. I usually toss in some basil and spicy peppers to deepen the flavor. It might only be a few jars, but to me, it means everything. It’s a way to carry on a family tradition and start something of my own. Growing a garden on the Vineyard feels like planting new roots while honoring the old ones, and there’s something really meaningful in that.

This spring, I took the Tomato Pruning Workshop with Lydia Fischer of The Garden Farm, hosted by Lucy Grinnan at the Agricultural Hall. We each received a Sun Gold Cherry Tomato plant from The Garden Farm to work on during the class and take home afterward.

Lydia guided us through the anatomy of the tomato plant, using this helpful diagram to break it all down. They shared some really useful pruning tips.

Here are a few key takeaways:

• Keep the bottom third of the plant clear (except fruit clusters)

• Remove any leaves touching the ground to avoid disease

• Avoid pruning before heavy rain (plants are more vulnerable then)

• Don’t over-prune: leaves are important for absorbing sunlight

• Pruning helps redirect energy to make stronger fruit and a healthier plant

• Create airflow by removing dense foliage

• Use a trellis to keep plants upright and supported

• Tame unruly growth so plants don’t take over the garden

• Pinch small suckers with your fingers

• Use clippers for larger suckers to avoid damage

• Train each plant to have two main stems, each with:

- Their own true leaves

- Their own suckers

- Their own fruit sets

• Avoid cutting the growth point: this is where new fruit comes from

• Think of it like “bonsai-ing” your tomato plant: focus its energy on growing intentionally

TOMATO VARIETIES: WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE?

Determinant Varieties

• Reach a set height

• Set all their fruit at once

• Require minimal pruning

• Great for sauce-making

Indeterminate Varieties

• Keep growing throughout the season

• Produce fruit continuously

• Better suited for cherry tomatoes like Sun Gold

TOMATO ANATOMY

Some plant anatomy we learned from class:

• Cotyledons: The first two baby leaves; they fall off naturally or can be plucked

• True Leaves: The plant’s mature leaves

• Growth Point: The top of the plant, don’t cut this! It’s where new fruit is produced

• Suckers: Little shoots that grow in the “V” between a leaf and the main stem; you can even propagate them

• White hairs on the stem: These are potential roots, plant your tomatoes deep so these root hairs can grow!

• Super Sucker: A sucker that grows from beneath the soil (great for propagation). These often appear when the plant is planted deeply.

COMPOST TIP: When pruning, avoid tossing tomato leaves into your regular compost pile. Discarded leaves can carry disease and compromise the health of your compost.

Located in West Tisbury at Flat Point Farm. You can find Lydia and The Garden Farm produce this summer at:

• Edgartown Village Market – Tuesdays, 10 am - 2 pm (Last market is August 26th)

• West Tisbury Farmers Market – Saturdays, 9 am –12 pm, (Last Saturday Market is October 25th)

Check for updates from The Garden Farm on instagram @thegardenfarmmv or on the website, thegardenfarmmv.com.

You can find upcoming classes and workshops hosted by the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society, from gardening and composting to beekeeping and cooking, at marthasvineyardagriculturalsociety.org/upcoming-events.

For more information about classes and programs at the Ag Hall on follow them instagram @mvagriculturalsociety.

Read more about how to protect your tomatoes at bit.ly/protectyourtomatoes.

Bluedot publishes four print magazines, plus our annual Green Guide and a biweekly newsletter.

Ask about ad opportunities on the Vineyard and in our magazines, websites, and newsletters across the country (including Nantucket and Boston).

Contact adsales@bluedotliving.com to reserve a space in our publications!

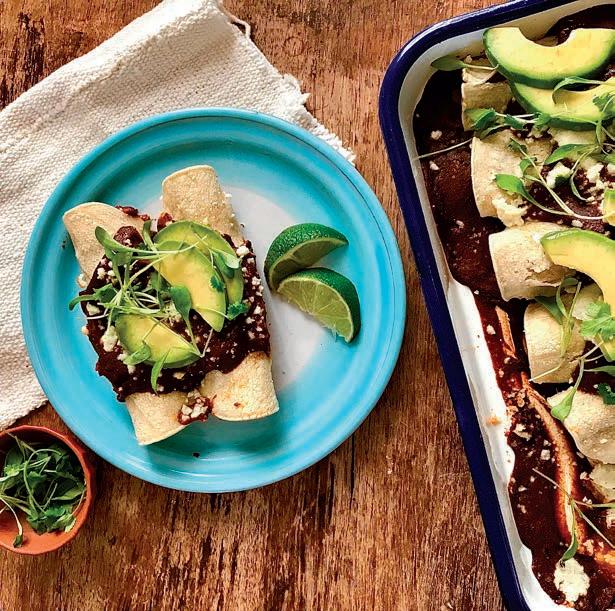

This soup earned the name "Daddy Soup" because my dad rarely cooked — but when he did, this was his signature dish. Bursting with the bright, fresh flavors of summer, it’s made with ripe garden tomatoes, fragrant basil, and salty, melty cheese. A comforting family favorite, it’s perfect for warm summer nights or for chilly winter days when you’re craving a little taste of sunshine. It tastes like summer in every spoonful. Serves 4

1 Tbsp of olive oil

3 garlic cloves, chopped

1/2 small white onion, chopped

5 large fresh tomatoes, diced (or 1 28-oz. can of diced tomatoes)

Handful of fresh basil, chopped

Salt and pepper to taste

5 cups water

1 cup pastina pasta (or any small pasta shape)

GARNISH: a drizzle of virgin olive oil, fresh Pecorino Romano cheese or Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, and fresh basil leaves

1. Sauté garlic and onion until fragrant in olive oil.

2. Add tomatoes and basil to garlic and onions and mix. Add Salt and pepper tomato mixture. Cook down for 2-3 minutes. (Leave some of the basil aside for garnish.)

3. Add water, drizzle of olive oil and bring to a boil.

4. Add pastina and cook until pasta is finished. (Don’t add too pasta much or you will get more of a pastina porridge rather than a soup. If this happens, add more water.)

5. Bring soup to a simmer.

6. Once ready, serve in bowls. Garnish with a drizzle of virgin olive oil, freshly grated cheese, and basil leaves.

NOTES: if you use enough cheese, the cheese will melt and stick to the bottom of the bowl and the spoon, creating a cheesy flavored spoon with each bite!

Recipe by The Multari Family Photo courtesy of Whitney Multari

10 lbs ripe tomatoes (Roma or plum tomatoes work best)

A bunch of fresh basil

3–4 spicy peppers (optional, for a little kick)

Water (enough to fully submerge your jars in pot)

KITCHEN TOOLS

Large stockpot

Sharp paring knife

Colander

Large mixing bowl

Gloves (optional, for handling tomatoes and peppers)

3–4 wide-mouth 32-oz. Mason jars

3–4 wide-mouth lids and screw bands

Spoon

Clean dish towel

TOMATO SECONDS

1. Prep Your Jars: Sterilize the jars by running them through the dishwasher or boiling them in water for 10 minutes.

2. Prep the Tomatoes: Use a sharp paring knife to carefully remove the skins from each tomato wearing gloves. Cut the peeled tomatoes and place them in a colander over a large bowl. Use your hands or a spoon to squeeze out excess juice and seeds. Save the tomato “guts” (flesh and pulp) and discard the skins.

3. Bring Water to a Boil: While you’re working, fill your stockpot with enough water to fully submerge the jars and bring it to a boil.

4. Fill the Jars: Using your hands or a spoon, pack the tomato flesh into the sterilized jars, leaving about 1 inch of space at the top. Add a few basil leaves and one spicy pepper (if using) to each jar. Press

Canning tomatoes has always been a cherished tradition in my family. We’d gather in the kitchen to savor the last of the season’s tomatoes and preserve them for the colder months ahead. My Italian grandmother taught us with no fancy equipment, just a few basics and a lot of love. This method may be simple, but it’s full of flavor and nostalgia. Feel free to put your own twist on it! It’s a great way to capture summer in a jar.

Makes 3–4 jars of tomatoes

down gently to release any air pockets and excess liquid, but don’t over pack.

5. Seal the Jars: Wipe the rims of the jars with a clean towel to ensure a good seal. Place the lids on top, then screw the bands on until fingertip-tight (not too tight).

6. Process the Jars: Carefully lower the jars into the boiling water using tongs and a towel. Boil for 35–45 minutes, making sure the jars stay fully submerged.

7. Cool and Store: Remove jars from the pot and place them on a towel-lined surface. Let them sit undisturbed for 12–24 hours. Once cooled, tighten the bands if needed and check that the lids are sealed (they should not flex when pressed). Store in a cool, dark place for up to a year. Enjoy summer tomatoes all year long!

Check your local farm stands for "seconds." These slightly overripe or bruised tomatoes are farm-fresh, budget-friendly, and perfect for canning.

By Whitney Multari

Founded in 2024 by husband-and-wife team Vesna and Regis Nepomuceno, Reunion is a mobile wood-fired pizza kitchen rooted in a shared passion for food, hospitality, and community. What began as a longtime dream has grown into a family-run business dedicated to bringing people together through simple, high-quality ingredients and the warmth of a wood-fired oven.

You can find Reunion serving at public events, including regular stints at Nomans; they’re also available for private catering. The three lines in their logo represent Vesna, Regis, and their 3-year-old daughter — representing the family at the heart of the business. Reunion is a celebration of connection, community, and craft.

Vesna and Regis met while working in the restaurant scene on the Vineyard, where food quickly became the foundation of their relationship. Hosting backyard dinners, feeding friends, and celebrating through food was always part of their rhythm. During the pandemic, like so many of us, they felt the ache of separation and the name “Reunion” was born. Their dream was to create something that would bring people back together, around a table. “There’s no reunion without food, so pizza it was!” says Vesna, who also works at Bluedot as a graphic designer. When she is not making pizzas, she is building our newsletters.

Their wood-fired oven was custom-built in Florida back in 2010 and has had a few Island lives before finding its way into Vesna and Regis’s hands in 2024. Regis inherited it from Lou Pasciello, fellow pizza enthusiast and Islander, and now fires it up with reverence and excitement. It takes three to five hours to reach its perfect temperature of 850 degrees — but once it’s ready, each pizza cooks in just about two minutes, emerging with that perfect Neapolitan-style, charred crust and bubbling goodness.

Handmade dough? Check. House-made sauce? Check. Local ingredients? As much as possible, sourced from Island Grown Initiative and Ghost Island Farm, of which they are CSA members.

Reunion typically offers four to five pizza options at public events, including:

• Cheese and pepperoni, perfect for the little ones

• Five cheese with hot honey

• “Funtastic Fungi” (a local favorite)

• Classic Margherita

Plus, custom creations for private events — from brunch pies with shakshuka or scrambled eggs, to sweet treats like strawberry-banana-Nutella with whipped cream.

For Vesna and Regis, sustainability is a way of life. Regis, who grew up in a coffee-growing region of Brazil, brings a

Neapolitan-style pizzas cooked to perfection.

“There’s no Reunion without food, so pizza it was.”

— owner Vesna Nepomuceno

strong respect for sourcing and land stewardship. Vesna, a nature and science lover, adds thoughtful practices to every aspect of the business.

Reunion’s commitment to sustainability is reflected in the small, intentional choices they make every day. They use kiln-dried wood from local vendors to fire their oven, where nothing goes to waste. Oven ash is repurposed as natural fertilizer in their home garden to deter slugs, while biochar is added to their compost, helping eliminate odor and improve soil texture. At events, they prioritize compostable cutlery, napkins, and plates whenever possible. The newest addition to their setup is a beautifully crafted mobile cart, built locally by Rosewood Carpentry & Joinery, which allows them to

bring their wood-fired experience to private events with both elevated design and function.

WHERE TO FIND REUNION THIS SUMMER:

• Wednesdays and Thursdays 5 – 9 pm at Nomans: Perfect for grabbing a pizza and staying awhile or picking one up to take to the beach.

• The Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair in August (where Reunion had its very first pop-up in summer 2024!)

• Pop-ups at the PA Club, Katama General Store, Tivoli Day, and Vineyard Haven’s First Friday, schedule permitting. Whether they’re catering a backyard wedding, serving up slices at Nomans, or chasing their daughter through the grass between pizzas, Vesna and Regis are building something special, one reunion, one pie at a time.

For more information about Reunion and where they'll be popups, check out their instagram @reunionmv.

Where the dough is handmade, the veggies are homegrown, and the vibes are pure Chilmark.

On a warm Monday evening at the edge of Chilmark, you’ll find a slice of paradise and it comes wood-fired, topped with farm-fresh veggies, and served with a side of slow living.

Welcome to North Tabor Farm’s Pizza Night, where pizza isn’t just dinner, it’s a community event rooted in seasonality, sustainability, and good food. Owners Rebecca Miller and Matthew Dix have created something really special here: a farmforward pizza night that lets you taste what the land is offering right now.

I follow the signs to the back field, behind the greenhouses; a custom-built wood-fired oven glows quietly next to a few picnic tables strung with bistro lights. The vibe is very Vineyard — very Chilmark. A couple sips wine as the sun filters through the trees. A family entertains their child with a just-picked carrot from the garden. The centerpiece on the picnic tables? A basil plant in a repurposed tomato can. Kyle Bullerjahn, the chef of North Tabor Farm, makes pizzas right in front of you in a wood-fired

oven; nearly everything, from the herbs and arugula to the squash, onions, and fennel, has been grown steps away. Even the dough is handmade by their daughter Ruby, and the pork comes from their own Island-raised pigs. The cheese is outsourced, but every bite still feels like a taste of home.

Orders are staggered to keep pickup smooth and parking easy. While I wait, I wander through the farmstand, admire the adorable piglets, and snack on just-pulled carrots that Rebecca has passed around. The wood-fired oven, a three-chamber beauty designed by Andy Magdanz of Martha’s Vineyard Glassworks and built with the help of Kyle Bullerjahn, can cook up to five pizzas at once. It even has a cooler chamber for roasting veggies or meats, making the most of every bit of firewood.

Here’s what was on the menu the night I visited (subject to change with the season, of course):

• Salad Pizza: Fresh arugula, shaved fennel, lemon, Parmesan Reggiano, fresh mozzarella, and pesto

• Pork & Calabrian Chili Pizza: Hot Italian sausage, ricotta, turnip greens, spring onion, Calabrian chili oil, and red sauce

• Summer Squash Pizza: Farm squash, fresh mozzarella, herby pesto, and a sprinkle of Parm

• Margarita Pizza: A classic with fresh mozzarella, farm basil, red sauce, and farm-made basil oil

I ordered the Salad Pizza and the Pork & Calabrian Chili Pizza — each bite better than the last. I loved the squeeze of fresh lemon on the Salad Pizza; it gave the whole thing a bright, summery zing. The heat from the Calabrian chilis on the pork pizza was perfectly balanced by the creamy ricotta — spicy, rich, and just right. I brought my pizza home, but next time I’m staying to enjoy the farm. Bring a bottle of wine, catch the sunset, and let the slower pace give your week a fresh start.

Pizzas are pre-order only, and orders open the Wednesday before and close at 3 p.m. on Monday (or earlier if they sell out, which they usually do). People can pick up their pies Monday night during their allotted time, or stay at the farm to eat.

Order Here: north-tabor-farm.square.site

To ask any questions, email: northtaborfarmmv@gmail.com

Head to Juli Vanderhoop’s popular pizza nights every Wednesday and Thursday from 5 to 8 pm; or Fridays from noon to 4 pm. Orange Peel is native owned and based on the Wampanoag lands of Aquinnah, incorporating food traditions from around the world. Check out the website (orangepeelbakery.net) for more information, and Instagram (@orangepeelbakery) for updates.

The folks at Stoney Hill Pizza operate a mobile wood-fired pizza oven that uses local produce to make beautiful pies right in your backyard. Owned by Nina Levin, the business sources ingredients from local farmers and purveyors, and is accepting limited bookings for the 2025 season. If you’d like to have Stoney Hill cook pizza at your next event, fill out the form at stoneyhillpizza.com/eventinquiryform. For more information, visit stoneyhillpizza.com.

Webster’s Dictionary defines “cooperation” as: “operating together to one end; joint operation; concurrent effort or labor.’’ This accurately describes VINEYARD HOME IMPROVEMENTS’ culture and approach to every project. Our staff recognize the importance of partnership, and the ability to work as a team, as well as the necessity of being fair and flexible.

• Experienced in all phases of residential and commercial building construction.

• Skilled Craftsmen

• Design & Value Engineering

• Team Approach

Links to ingredients and green products to make shopping easier

You’ll find simple, planet-friendly recipes, inspiring stories, and smart tips to reduce food waste and shop sustainably. With our digital magazine, you’ll get: Visit bluedotliving.com/kitchenmag50 to subscribe today! An interactive experience on any device with one-click access (no login!)

Enhanced audio feature to listen to articles and step-by-step instructions A bonus 32-page Recipe Collection plus access to previous issues!

In the early days of mobile poultry processing, this unit was used at the Good Farm to rinse the chickens and loosen their feathers.

You can’t have a robust farm economy on an island without a way to slaughter animals locally. Thanks to some forward-thinking Vineyarders, the Mobile Poultry Processing Unit delivers a humane answer.

By Leslie Garrett

Any of us who travel on highways are accustomed to seeing trucks, loaded with pigs or chickens or sometimes cows, on their way to slaughter. The pigs are often pressed up against the metal walls, their plump pink bodies bulging out through the air holes. Chickens are beak to cheek, feathers flying. Cows are, well, cows. It doesn’t look pleasant for any of the animals involved, and one day in the early aughts, I decided I couldn’t stomach it anymore. Literally.

talk to about this. (By the way, if that name sounds familiar, it’s because as Ali Berlow, she was the longtime editor of Edible Vineyard.) She doesn’t accuse me of hypocrisy. Or anthropomorphism. Or privilege. Instead, she talks easily and earnestly about things like humane slaughter, because it matters to her, too. It matters so much, in fact, that she spearheaded a coalition dedicated to delivering that option to chicken farmers and homesteaders on the Vineyard.

But it wasn’t just the chickens that concerned Alice. She also cared about the farmers raising those chickens. She

Island farmers and homesteaders who’ve raised the birds care about this. It matters to them that the birds not suffer.

My vegetarianism lasted about four years, during which I became slightly anemic. And hungry. Blame my lackadaisical approach, sure, but I wanted meat — meat, however, without the cruelty. I wanted meat that came from animals who had lived a good life, however short.

Alice Berlow is that rare person I can

wanted to help the farm community that wished to put those chickens onto the plates of Islanders, which, of course, means she also cared about the eaters. She wanted to provide a service that would ensure that chickens were handled locally, safely, humanely, and profitably.

And so, around 2010, while Alice was at Island Grown Initiative (IGI), which

Early days at IGI: Alice Berlow, with Michael Pollan.

she helped found, she set out to make this happen.

At the time, she says, there was an existing “underground” meat processing system already at work. “I'm going to call it underground,” she says. “You know, meat processing, animal processing outside of the system has always happened.” Alice’s philosophy — and that of IGI — was to work within the system, with appropriate regulations.

Because “that's where real, systemic change can happen,” she says, and also where the greatest economic potential and growth is available to farmers. But as Alice and her collaborators, including local farmers Richard Andre and Matthew Dix, among others, explored the regulatory landscape, the issue of humane slaughter kept rearing its head. “One of the things that we consistently heard [about] was access to humane slaughter,” Alice recalls, something she said Islanders had wanted for a long time. “We weren't the only group to try to solve that problem or barrier.” But as regulations related to slaughterhouses and access to slaughter had changed with the growing consolidation of the meat industry, Alice says access to humane slaughter became more and more prohibitive to small family farmers, especially on an island, where transport is always a challenge.

But Alice and the others learned that, while Massachusetts had clear rules around the slaughter of four-legged animals — it had to be conducted in a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)-approved slaughter house — the federal laws contained an exception for poultry. And they further

learned that, while some states filled in that gap with state laws prohibiting the slaughter of poultry except in USDA slaughter houses, Massachusetts wasn’t one of them. In other words, there was a hole in Massachusetts law, perhaps big enough to drive a mobile chicken processing trailer through.

But while all this was happening in the late aughts — and it’s possible now to take for granted the robust farm community and poultry processing production of the Vineyard — there was also a cultural shift underway.

“There was a movement going around,” Richard Andre explains, referring to the revitalization of small farms — a pushback against the previous many decades of industrialized agriculture, which had brought us to an era of widespread factory farming and slaughter houses that, while they might have met the letter of the law in terms of human health and safety, didn’t account for the health or wellbeing of the animals themselves.

“The industrialization of our meat system also meant that there was an industrialization and scaling up of slaughterhouses,” Alice adds, “which basically made it very difficult, if not impossible, for small family farmers to get a spot.” What’s more, while Alice says she understands those who are uncomfortable talking about slaughter — “it’s not everybody’s cup of tea” — she believes in a system that ensures that the process is as calm, respectful, and conscientious as possible.

The patron saint of this growing small farm movement was a Virginian named Joel Salatin, who was urging small farmers to take back control of their food. (He wrote a book called Everything I Do is Illegal: War Stories from the Local Food Front, which you can find on Amazon: bit.ly/Salatin-Book.) Alice reached out to this self-described “preacher-farmer,” invited him to the Vineyard, and shared with him the community’s dream of processing chickens locally. “He was a bit of a rebel,” Richard says, “He said, ‘Just do it. Raise the chickens. Make them stop you. This is about your rights.’”

His words landed on fertile ground.

Although Massachusetts allowed for the slaughter of poultry outside of USDA-approved facilities, the state Department of Public Health was saying nope. Inspired by Salatin, Alice, Richard, and the others heard that nope as maybe. Let’s try. As Richard points out, “Technically, we were allowed to do this.”

So Alice and Richard returned to the folks at the state Department of Public Health and Department of Agriculture and said something along the lines of

allow a mobile poultry processing unit, henceforth known as the MPPU. The pilot program would operate on the Vineyard and in another Massachusetts community that had been pushing for a similar program — Belchertown in the state’s Pioneer Valley. “So that,” Richard says, “was a huge breakthrough.”

IGI received a licence to operate the unit. The trailer would travel from farm to farm and enable poultry farmers to process their chickens and — this part is key, of course, says Richard — sell them to the public.

Then, Alice says, “we invited all the boards of health to a demonstration at the Grange. And we set up tents and stuff, and we had the mobile processing unit ready.” She had donuts and coffee for everyone, and though she can’t recall which farmers came, some did, with their birds. “God bless them, they came,” she says, acknowledging again that witnessing slaughter isn’t everyone’s idea of a good time. But transparency was important. And, of course, she says, everybody was committed to the same main goal, which was a safe process. But also a local process that was both

The chicken dies quickly, he says, and, therefore “more humanely.” He corrects himself. “I hate that word when it comes to killing. It’s killing. It’s not humane, but it’s more conscientious.”

“Listen, we understand you’re saying no, but we’re telling you we’re going to do this. … How do we get [you] to yes?” Richard admits it wasn’t perhaps that polite. “There was an element of anarchy,” he confesses. A bit of “we’re going to do this regardless; try to stop us.”

There was, he says, “a lot of arm wrestling and cajoling,” but eventually the coalition got the boards of health (both state and local) and the Department of Agriculture to agree to a pilot program where they would

economically viable for the farmers and free from the stress of transport on both the animals and the farmers.

“And then we were off and running,” Richard says.

Well, maybe not quite. There were some hiccups, Alice says. For instance, part of the slaughter process is dunking the just-killed birds into cold water. And that water, which would then contain biological bits and pieces of the bird, needs to be disposed of away from any ponds or streams that could be

contaminated by the process. “But we still had water going into the ground,” Alice says. She was concerned about it. Regulators were concerned about it.

So she took her quandary to Josh Scott, a landscaper in Chilmark who was also raising birds. Josh had an idea. He suggested using wood chips to filter out the waste from the water; afterward, they could compost the wood chips. “The perfect solution,” Alice says. That process became part of the standard protocol for any farm using the unit.

But they also needed someone to perform the slaughter, as well as train other farmers to do it. Enter newcomer to the Island, Taz Armstrong. “I had just moved to the Island, and I was very poor,” Taz says. “There was a need, and I was desperate for work, so …”

Turns out that Taz was uniquely suited to the job. “Not necessarily the killing aspect,” he says, “but being able to assist in providing this service to the community felt very important.”

The procedure is pretty straightforward, he tells me, noting that he’s gesticulating “wildly” while speaking with me over the phone. He describes the process in detail — carotid arteries, 140°F scalders, rubber-finger pluckers, the whole operation. The chicken dies quickly, he says, and, therefore “more humanely.” He corrects himself. “I hate that word when it comes to killing. It’s killing. It’s not

humane, but it’s more conscientious.”

Taz reiterates what both Alice and Richard have said: that Island farmers and homesteaders who’ve raised the birds care about this. It matters to them that the birds not suffer.

“As long as everything goes properly,” Taz says, and he makes it a point to ensure that it does, “it’s a very quick process.” Specifically? “About 15 to 30 seconds,” he says.

So there was Taz, a newcomer, traveling the Island performing a task that many didn’t want to perform but nonetheless

wanted performed safely, within regulations, and without animal suffering.

“We went to farms all over the Island,” Taz says. “We also went to a lot of backyard growers. People who just want to raise 20 birds for their families every year can use the unit as well. It was just a really great way to introduce myself to the Island, and also be introduced to the Island.”

It’s hard to overstate the MPPU’s impact on the Island’s poultry farmers.

“There was so much room for this market, for whole fresh organic chickens,” Richard says. Each bird was selling for $30, which, says Richard, seemed like a lot until people tasted it. There was such demand from consumers, he says, that it was “like storming an open door.” Within two years, the Island was raising, processing, and selling 9,000 birds, about 2,000 of which came from Richard’s own Cleveland Farm.

Just after COVID, IGI passed off oversight of the MPPU to the Ag Society, noting that it more closely fit into the Ag Society’s mission of supporting farmers. And with that change, the folks there realized that the way the system was operating needed correction. Rather than having someone like Taz processing the birds, regulations required each farm to be licensed to operate it themselves. Taz’s role shifted to trainer, and the Ag Society

Folks gather at the Agricultural Hall for poultry processing. A steel set of cones allows for clean and efficient draining following the incision.

began getting individual farms licensed.

Today, half a dozen farms are certified, with more in the pipeline. Homesteaders raising their chickens for their own families don’t require a license.

“It really makes it a viable business option,” says Anna Swanson, Operations Manager with the Ag Society. “It's enabled economic viability for raising poultry in a regenerative way on the Island.” She notes the regenerative benefits of pasture-raised poultry, which help cycle nutrients and improve soil. The MPPU also eliminates the carbon emissions of travel off-Island. “We're one of maybe two [communities] in the whole state that have this, and I think we're very lucky to be able to provide [this service] to the farming community,” Anna says. “It’s pretty unique.”

And it keeps the local food system closed-loop. “Our food is the food that is grown and raised on farms then can

Processed, packaged, and ready to go.

be processed and bought and eaten onIsland,” Anna says. “Chickens play an important role in a regenerative system –their poop creates fertilizer.”

Something interesting happens when you talk to anyone involved in this undertaking, regardless of when they joined the effort: each person insists

that you must speak with others, listing names and insisting that this and that person was instrumental in the longtime and current success of the MPPU. It harkens back to something that Richard Andre said when describing the cultural backdrop of the local food movement and Joel Salatin’s visit to the Island. Following Salatin’s prodding of farmers to just get on with it, someone wondered aloud whether raising and processing more birds might saturate the market. The Island, after all, has a small yearround population — farmers might feel competitive toward each other. But that’s not what happened at all. Instead, there was collaboration, there was mutual support. And the success of each fed into the success of the overall community. Alice sums it up, speaking specifically of the unit, but her words also apply to the community: “It took many people, voices, and,” she says, “much effort.”

Promising an “any-length saga” of Nantucket’s efforts to launch its own Mobile Poultry Processing Unit that we’d be interested in, Posie Constable, Managing Director of Sustainable Nantucket, brings us up to speed — quickly. (One gets the sense she doesn’t move slowly.)

Nantucket found itself grappling with a similar dilemma to that on the Vineyard: How do we create food security on the island? How can we support a somewhat isolated farm community? Or, as Posie puts it, “How do we grow more food on the island and make that food more readily and widely available, and what are the things that we don't have enough of?” Answering herself, she says, “We don't have enough of anything.”

While her group put into motion plans and supplies to help homesteaders and small farmers

grow more food, one food group that remained undersupplied, she says, was protein. Supplying chicken coops helped solve part of the problem. But when it came to getting those chickens onto menus and plates, Nantucket needed what the Vineyard had — a local unit that would slaughter the birds. She and others visited the Vineyard to meet with the folks involved with the MPPU and to witness the process. And then, with a group of four keen students from the Worcester Polytechnic Institute who take on an island project each year, the Nantucket crew drafted a plan to get the town and the health department on board. The Community Foundation for Nantucket secured a Community Development Block Grant to buy the equipment.

But then Posie hit a roadblock — farmers didn’t want the unit on their property. Plus, there

are distance requirements from wells and wetlands. The state health department suggested a neutral site, “a place where we could just set up our equipment and have everybody bring their birds, not all at the same time, but schedule slots wherein they could bring their birds to slaughter as a service, not for profit,” Posie explains. While multiple public and private sites were considered, Sustainable Nantucket hopes to use its farm composting field as the initial venue for slaughter training by Taz Armstrong, to be overseen by the Town's Board of Health and the state Department of Public Health. The group is seeking additional farm sites as interest in raising meat birds grows.

Posie is undaunted by the challenges and predicts that the unit will be operational this summer. After all, she says, “Hope springs eternal.”

How this nonprofit farm blends agriculture, art, and community — focusing on impact, not income.

By Britt Bowker

Flip-flops and farm pastures don’t usually go hand in hand. But at Slough Farm, they sort of do.

Neat garden beds with clearly marked paths leave little question about where you can and can’t step. Lettuce heads, peas, and trellised tomatoes grow in orderly rows. Even the half-mile trudge out to the herd of cows and flock of sheep — or the “flerd” as executive director Julie Scott calls it — is surprisingly manageable. I made it just fine in my faded pink Olukais, save for a few unavoidable brushes with dung along the way. I’m not saying this is the best footwear for farm visits. I’m just saying that at Slough Farm, it’s doable.

That’s partly because everything here is especially well tended. Not just the vegetables and pastures, but the presentation. The main farmhouse feels more like a boutique retreat center than a barnyard hub, with its floorto-ceiling windows, cedar walls, vaulted ceilings, and four bedrooms and four baths. There’s a stunning kitchen, an open-concept living space, a long communal table, and a 1970s mahogany grand piano. People come here to cook, to weave, to garden, to learn. Some are artists. Some are kindergarteners (who might also be artists).

Funded by private donors and nestled within a landowners’ association in Katama, Slough Farm doesn’t operate for profit. Instead, it runs as a working educational farm and nonprofit — growing food not to sell, but to give away, and offering artist residencies, wellness programs, and cooking classes on the same campus where chickens are processed and compost piles cook.

The farm crew grows on about 1.25 acres using no-till, regenerative methods.

Slough Farm is a place of overlap. It’s part working farm, part arts center, part classroom. And while it’s not open to the general public, its impact ripples through the Island community — in donated produce and meat, workshops and garden collaborations, grants, and support for other farmers. “We’re not trying to grow bigger and bigger,” Julie says. “We’re just trying to get better and better at what we’re doing.”

That means rotating animals daily, both to improve soil health and to provide the “flerd” with “a new salad bar every day,” Julie says. It means cultivating dye gardens and native plants, and washing hundreds of eggs a week in a humming prep room downstairs (which “takes a lot of focus,” culinary director Charlie Granquist jokes). It’s a place where a five-year-old might be felting wool while a visiting chef prepares an elegant tasting menu.

That intentional blending of production and hospitality, grit and grace, is what makes Slough Farm so interesting.

Slough Farm spans several growing and pasture properties across Katama: the main campus and 25 acres at the townowned Katama Farm, also known as the FARM Institute, which Slough manages in partnership with the Trustees of Reservations. Altogether, the farm stewards about 80 acres, most of it devoted to pasture-based livestock. Everything Slough produces — meat, eggs, and vegetables — is donated through partnership with food equity organizations

The silo is the only structure that remains from the old farm.

There are four bedrooms for visiting artists and speakers; two upstairs and two downstairs.

including Island Grown Initiative (IGI), the Island Food Pantry, local senior centers, schools, and libraries.

In two gardens on its main campus, the farm cultivates about 1.25 acres of vegetables using no-till, regenerative methods. The garden crew — a small team of three — adds heavy compost once or twice a year and tailors granular and liquid amendments to the specific needs of the soil and plants. To prevent soil depletion, they rotate crops at least every three years.

“We also do a number of things to promote insect populations in and around the garden,” says garden manager Carla Walkis. “We use beneficial nematodes in the spring to target specific pests, and we participate in ‘No Mow May’ to help pollinators get established for the season.”

They don’t use any insecticides, even those certified organic. Instead, pollinator patches and insectary beds are intentionally integrated throughout the gardens to support biodiversity.

In terms of method, “I usually describe what we do as a market garden approach,” Carla says, “meaning, we are growing a full seasonal range of vegetables on a small portion of land.”

“We grow pretty much everything,” Julie adds. “Our soil is so sandy that the root crops really love it. Our onions, carrots, and garlic are so happy here.”

Last year, the farm harvested just under 14,000 pounds of food. About 8,000 pounds were donated, and the remaining 6,000 were used on site for cooking classes, dinners, and other programs. The main donation outlets include the West Tisbury Library “freedge,” the Island Food Pantry, the Edgartown Council on Aging, and the Boys and Girls Club. They also regularly donate to the MV Center for Living, Island Health Care, and the Martha’s Vineyard Ocean Academy.

“Over my time running the garden, we have narrowed our impact to focus on supporting prepared food [programs] for seniors and children, keeping highly trafficked ‘mini pantries’ stocked, and filling in gaps at the food pantry,” Carla says. That includes growing specialty crops — things that grow well in the Vineyard’s climate and resonate with the diverse communities served by the food pantry. One example is callaloo, a nutrient-rich amaranth green popular

in Caribbean cuisine, grown specifically for the pantry.

The garden crew also grows flowers — primarily donated to Hospice and Palliative Care of Martha’s Vineyard. In 2021, they launched a “Cut Flower Club” in late summer, where participants pick two bouquets: one to keep, and one to donate. Hospice volunteers deliver the arrangements throughout the community.

“It’s a really lovely thing,” Carla says, “to work hard at something you love and then get to turn around and give it all away.”

On the livestock side, Slough raises grass-fed beef and lamb, along with pasture-raised pigs and chickens. “It takes a lot of land to do that,” Julie says.

The farm raises heritage cattle breeds — four Belted Galloways and seven Randall Linebacks — along with 8 to 30 pigs per year, 350 laying hens, 500 meat chickens, 25 mama sheep, two rams, up to 60 lambs, and a small flock of turkeys.

“Our cows and sheep move together,” says farm manager Christian Walkis. “Then three days later, we follow with the laying hens — because that’s the time period that fly larva take to be born in manure. The chickens eat the larvae, which adds protein to their diet and keeps the fly pressure down. Which is

Julie Scott with one of the rare heritage breed cows.

great, because anytime an animal is spending trying to get flies off of its back, it’s not grazing, [and grazing] is what we want.”

So far this year, Slough Farm has donated 1,137 dozen eggs, 1,553 pounds of pork, 1,002 pounds of beef, 25 pounds of chicken, and 51 pounds of lamb. “The majority of our meat donations happen in the fall, as that is when the animals come back from the butcher, so this will go up substantially before year end,” Julie notes.

Slough has also built a workforce housing property in Edgartown to help house both their own staff and employees from other Island farms. (The Slough Farm team includes 14 year-round staff and two seasonal workers.) They use a classroom and office space, located in a horse barn on adjacent land owned by the Nature Conservancy, for staff and educational programming. During my visit, one of the stalls housed a brood of two-week-old chicks.

Across their facilities, Slough offers hands-on learning in gardening, cooking, woodworking, natural dyeing, and yoga and movement classes. Recent workshops included a bao bun cooking class using farm-grown ingredients, and a bark-weaving bracelet session for kids. Every Friday during the school year, students from the Martha’s Vineyard Charter School come for experiential learning. The farm has partnered with Island Grown Schools, Island Autism, and the Red House to offer more programming throughout the year.

Artist residencies are also a key part of the mission. Visiting creatives spend one to two weeks here throughout the year and share their work through food, music, painting, or storytelling — finding inspiration and new ways to connect community and place. Program director Emily Becker runs this side of the operation and also plans all the programming. Her favorite part? “Working with the wonderful array of rainbow personalities of people on this Island — and when I get to teach classes,” she tells me.

Much of what Slough Farm does happens behind the scenes. They offer grants to local nonprofits and farmers, including a special fund for various farm projects through the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society. Their Slough Support Fund, recently expanded to support off-Island organizations that benefit the Island, is part of that mission. They also collaborate with Martha’s Vineyard Community Services to offer a childcare stipend for families who earn too much to qualify for state subsidies — providing $5,000 per family per school year for care at licensed facilities. And since 2020, they’ve partnered with IGI to support the Prepared Meals Program, which distributes weekly meals to Island Councils on Aging, the Island Food Pantry, MV Family Center, homeless shelters, libraries, the Visiting Nurses

Association, Hospice, and individuals and families in need.

“We’ve always wanted to support other nonprofits,” Julie says, “and we always thought about donating our food. We’ve expanded with our education program, and as we’ve learned about needs, we’ve tried to meet them.”

The farm’s founding story starts with a mother and son who once rented a home bordering what’s now Slough Farm. When the homeowners approached them about purchasing the property, the family asked: “What’s going on with the farm next door?”

At the time, the property was a gentlemen’s farm, and part of it was once known as Heron Creek Farm. It had a history of agriculture but hadn’t been actively farmed in years. The family saw an opportunity to create something special and purchased the property as a newly incorporated nonprofit in 2016. They were introduced to the late Sam Feldman, a philanthropist and visionary, who recommended talking to Julie, who was then working at the FARM Institute. Known for her farming expertise, she was brought on as a consultant along with her husband, Laine Scott.

“They were interested and had passion, but didn’t know a whole lot about the Island or agriculture,” Julie says of the founders, who wish to remain anonymous. “They had some really wonderful ideas.” Together, they began to reimagine the property and rebuild. All the original buildings came down in 2016. The farm has been growing ever since.