Baking on the Land of the Ancestors

Baking on the Land of the Ancestors

www.rickconverypaintinginc.com rickconvery@gmail.com

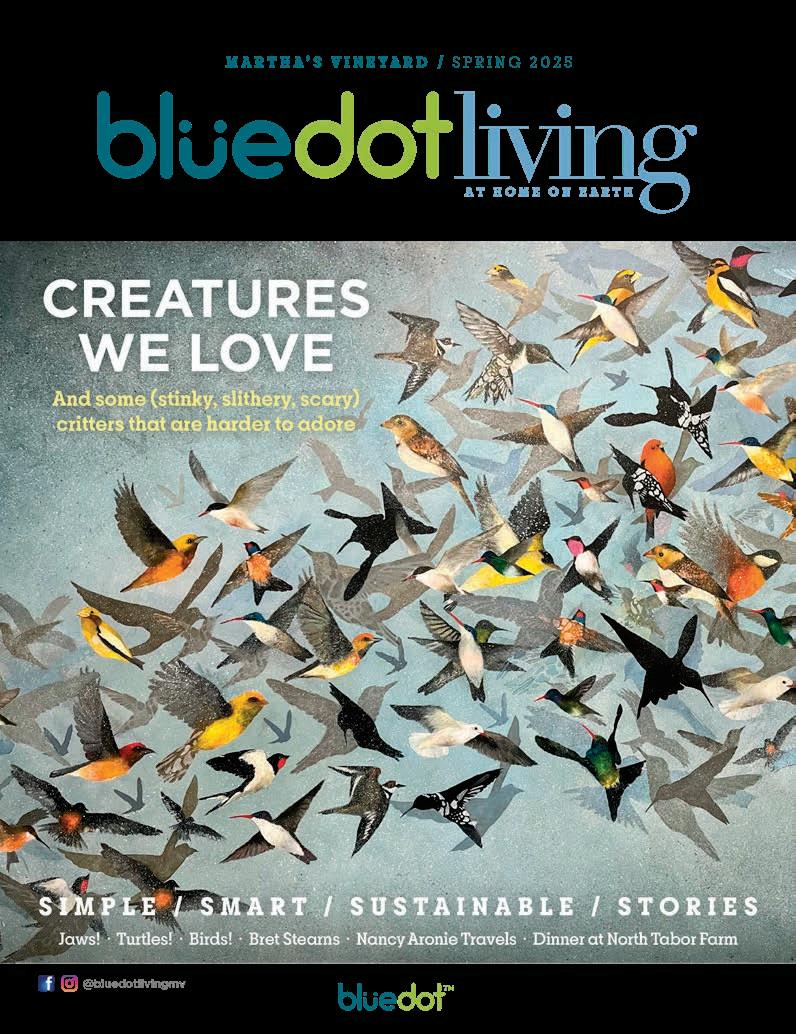

“ Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

President Victoria Riskin

CEO Raymond Pearce

Executive Editor Jamie Kageleiry

Head of Audience Kirsten Carroll

Editor Brittany Bowker, britt.bowker@bluedotliving.com

Senior Writer Leslie Garrett

Associate Editors Lucas Thors, Julia Cooper

Copyeditor Laura Roosevelt

Chief Financial Officer David Smith

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Designer/Production Manager Whitney Multari

Design and Production Vesna M. Nepomuceno

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Digital Assets Manager Alison Mead

Web Producer Grace Hughes

Ad Sales Josh Katz, adsales@bluedotliving.com

Social Media Emily Lamoureux

Contributors this Issue Nancy Aronie, Randi Baird, Jeremy Driesen, Kate Feiffer, Sheny Leon, Victoria Riskin, Alison Shaw

•

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Please write us if you’d like to stock Bluedot Living at your business. Editor@bluedotliving.com

Sign up for the Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter, along with any of our others: the BuyBetter Marketplace, our national ‘Hub” newsletter, and Bluedot Living Kitchenr: bit.ly/MV-NEWSLETTER

Subscribe! Get Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard and our annual Bluedot GreenGuide mailed to your address. It’s $29.95 a year for all four issues plus the Green Guide, and as a bonus, we’ll email you a collection of Bluedot Kitchen recipes. marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com/magazine-subscriptions/

Read stories from this magazine and more at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Find Bluedot Living on Threads, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube @bluedotliving

As we put this issue together, we noticed a theme: It’s full of remarkable Island women taking action for the planet. I had the pleasure of speaking with Maggie Craig, who’s using biochar — a carbon-rich soil amendment made from salvaged wood waste — to address climate and waste issues all at once. Our founder, Vicki Riskin, contributes two pieces to this issue, including a conversation with Claudia Macedo, who splits her time between the Island and Brazil’s Mata Atlântica, where she works to restore native tree populations in the rainforest. Vicki also visits Monina von Opel up-island, who, like many on the Vineyard, worries about the loss of Island Grown Initiative’s composting program. In her own yard, Monina has built a

in balance with nature. “We need to maintain the ancient knowledge, to try to work and live with reciprocity,” Juli says. And Sakiko Isomichi, through a Vineyard Vision Fellowship, continues to

research how native planting is gaining ground on the Island, shifting the paradigm away from sterile green lawns.

Reynolds, who heads the Martha’s Vineyard Tick Program and is on a mission to keep Island yards tick-free without harming the environment. Lucas Thors attends a mending workshop hosted by the Agricultural Society and writes about reviving a favorite old shirt – and keeping it out of the landfill. And essayist Nancy Aronie continues riffing on her husband’s climate devotion.

These are stories of people who saw a problem, rolled up their sleeves, and got to work — using the tools at hand and drawing strength from their communities. We hope these stories spark ideas, conversations, or even a project or two of your own. This issue also happens to be put together by an all-female editorial and design team — which feels fitting, and

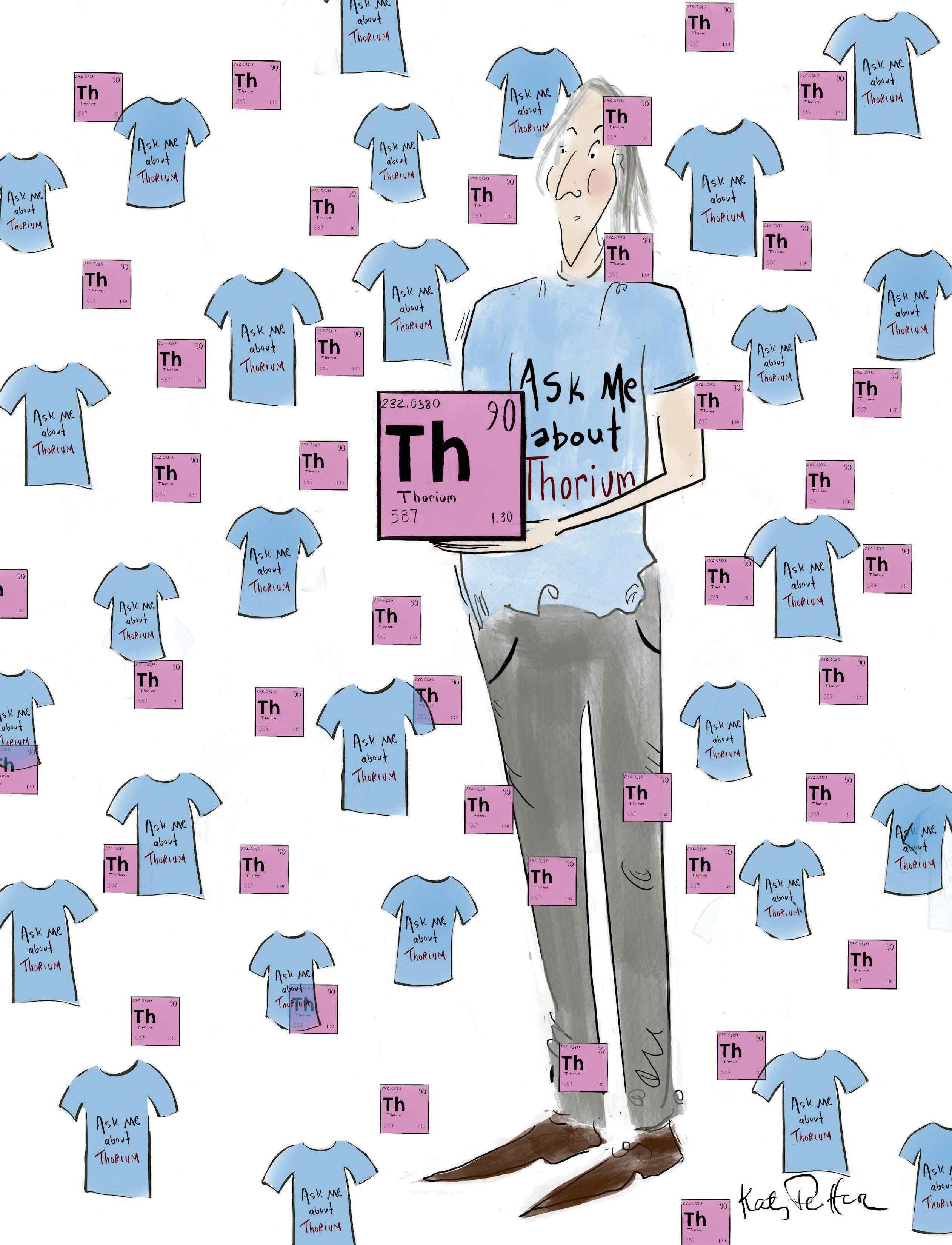

Nancy Aronie’s husband wears his Ask Me About Thorium T- shirts everywhere. They’re the catalyst for conversations he always wants to have.

By Leslie Garrett

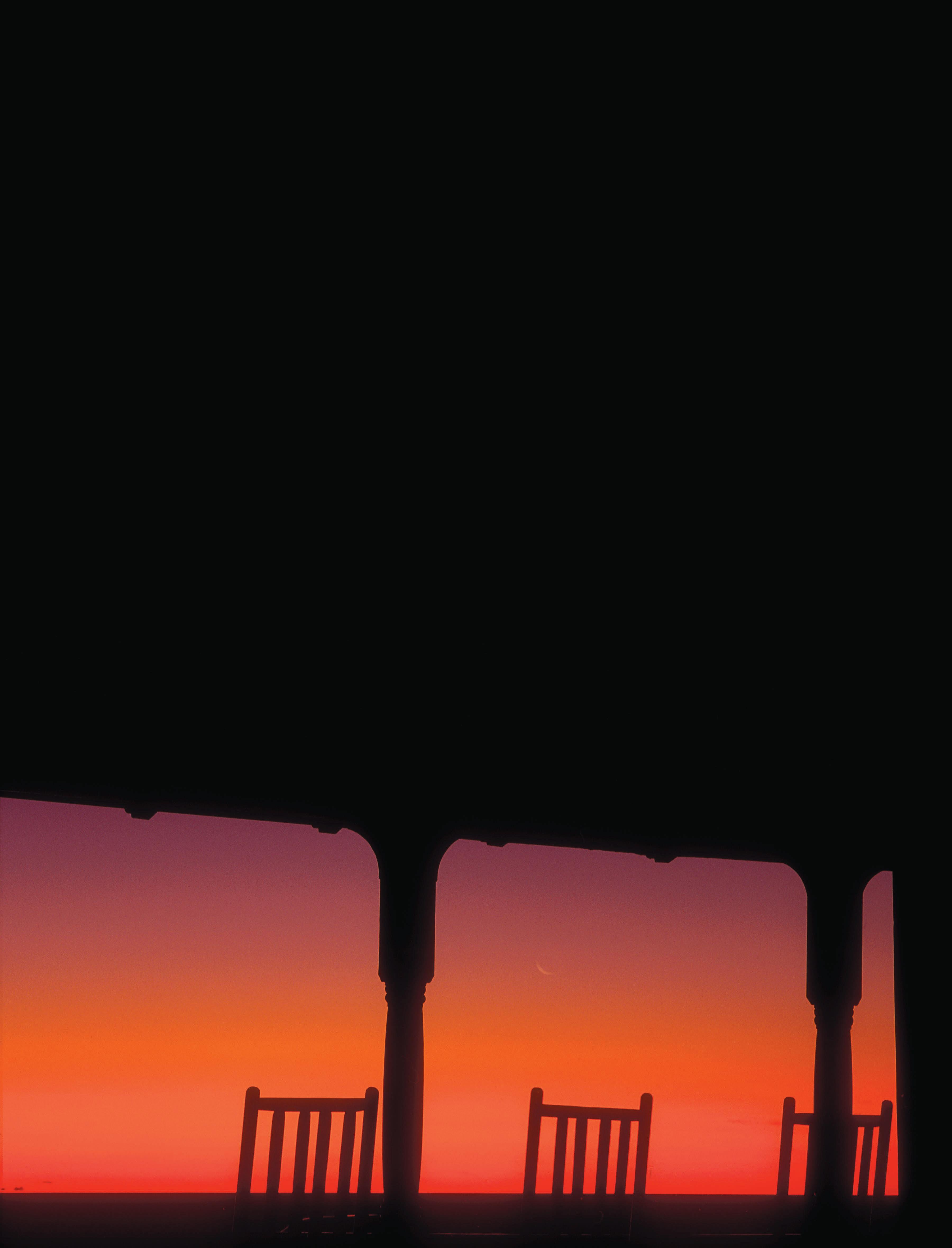

Porches and patios offer both the comfort of home and access to the outdoors. Make sure yours doesn’t offend Mother Nature: Choose planet-friendly furniture. Plus a porch cocktail recipe!

Laura D. Roosevelt

At Cape Cod Retractable Inc. we offer fast, responsive and detail oriented service. Our staff is knowledgeable, trusting and insured.

Explore diverse awning solutions for your home or business with Cape Cod Retractable, Inc. Choose from Residential and Commercial Retractable Awnings, Fixed Frame Awnings, and Specialized Awnings for Pergolas.

Elevate your space with Phantom Retractable Screens, Motorized Screens, Solar Screens, and Clear Vinyl Shades.

Safegaurd your property with our strom/hurricane protection options.

508-539-3307 | screensNshutters.com 9 Jonathan

By Mass Audubon

Bicknell’s Hawthorn is a rare tree found only on Nantucket. It is an endemic plant, a local in the truest sense of the word, so much so that it doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world. Let that sink in: This species cannot be found growing wild anywhere else on the planet. With fewer than 100 trees surviving on the planet, each and every one is vitally important and extremely vulnerable. The largest population of Bicknell’s Hawthorn resides on Mass Audubon’s lands, and staff are prioritizing their protection. By identifying, tagging, monitoring, and fencing each tree, the team will protect small and large specimens and nurture them against all floral and faunal foes.

Read more about how the Bicknell’s Hawthorn is fighting for a future at bit.ly/Bicknells-Hawthorn.

By Britt Bowker

On Nantucket, construction is constant. Turn down nearly any road and you’re bound to see something being built, renovated, or torn down. These projects generate a staggering amount of waste. Since 2022, at least 17,000 tons of construction and demolition debris are shipped off the island to landfills each year, usually in Maine or Ohio. That’s according to a study by Remain Nantucket and the Nantucket Preservation Trust (NPT), conducted with Boston-based consulting firm EBP. Remain, the NPT, and other local leaders are working together to raise awareness and promote practical solutions for reuse — from encouraging deconstruction to envisioning an island architectural salvage yard. Goals are to create a more centralized system and circular economy that reduces emissions, cuts down on costly waste transport, and helps ease the housing crisis by supporting more affordable housing.

Read more about construction waste reduction efforts on Nantucket at bit.ly/ACK-Salvage.

By Will Kinsella

I washed ashore (again) on Nantucket during Covid, like many people in our community, and returned to the former farm where my parents, brother, and I first lived as we made the transition from summer folk to year rounders in 1983. By the time I returned, most of the planet had awakened to our impending climate crisis. Collaborative efforts like Keeping History Above Water, Envision Resilience, and the Coastal Resilience Plan were helping Nantucket adapt to the most profound dangers of climate change to the island, namely sea level rise and increased storm intensity. Meanwhile, island organizations were promoting localized mitigation strategies that each and every one of us could employ to reduce our carbon footprints and avoid the worst for future generations. For every doom and gloom climate disaster scenario in the worldwide press, island organizations were providing information about preventative actions, adaptation, and lifestyle changes that every individual could embrace. Climate change demands actions on multiple fronts, and for me those included transforming our impoverished lawn into a grassland meadow. This simple change to the way our land was managed could provide enormous opportunities to capture carbon, rather than release it,

provide valuable wildlife ecosystems, eliminate the need for pesticides and fertilizers, and improve water quality. The economic savings can well be imagined by anyone with a lawn of their own, and I find the aesthetic beauty of tall grasses and their euphoric rustle to be magnificent.

Read more about Will Kinsella’s meadow lawn transformation at bit.ly/Grass-Not-Greener.

Bluedot publishes four print magazines, plus our annual Green Guide and a biweekly newsletter.

Ask about ad opportunities on the Vineyard and in our magazines, websites, and newsletters across the country (including Nantucket and Boston).

Contact adsales@bluedotliving.com to reserve a space in our publications!

By Teresa Bergen Point Reyes, California

On a farm in Point Reyes, in northern California, cows are fueling their own dairy with their manure. About half of the power at the Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Company comes from a methane biodigester, which turns liquid manure into clean fuel.

In the last couple of years, methane biodigesters have become big business among large farms in California’s Central Valley. While these larger operations have their critics, the Point Reyes farm installed its digester from a sustainability perspective.

Diana Giacomini Hagan, co-owner and CFO for the cheese company, talked to Bluedot Living about the purpose and challenges of installing a biodigester. “There’s a lot of greenhouse gas emissions that come off of manure,” she said. “So having a system where you can convert those is a win-win. You’re creating another energy source, and you’re also reducing your carbon footprint while reducing electricity costs.”

Read more about how farms are implementing methane biodigesters at bit.ly/Clean-Cow-Energy.

By Alec Ross Saratoga Springs, New York

When you stroll along a city sidewalk, you might notice a narrow strip of grass between the sidewalk and the curb. It’s usually there simply because it’s easy for the city to install and more attractive than bare dirt. But ecologically, aesthetically, and functionally, this strip is a waste of space (unless your dog needs to poop).

In the 1990s, horticulturist and gardening writer Lauren Springer Odgen dubbed these neglected, garbagecollecting, trampled-on areas “hellstrips,” and suggested that they could offer opportunities to beautify streetscapes and provide food and habitat for urban wildlife.

Since then, people across America have been transforming hellstrips into beautiful mini gardens that complement their front yards and make sidewalks a visual delight. In Saratoga Springs, New York, a small environmental nonprofit called Sustainable Saratoga recently launched Hellstrip Heroes, a program that encourages residents to take advantage of hellstrips to grow native plants, pollinator gardens, and small trees.

At Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, we believe a healthy Island begins with a healthy environment.

That’s why we eliminated the use of bottled water and installed bottle-less water coolers throughout the hospital. These coolers filter water to remove contaminants and improve taste — without the waste of single-use plastic.

By removing disposable cups, we also encourage staff to bring their own reusable bottles, like Yetis and Stanleys. And with digital counters that show the number of plastic bottles saved, these stations offer a tangible reminder that every refill makes a difference.

It’s a simple change — but one with a lasting impact.

Read more about the folks transforming hellstrips into pollinator havens at bit.ly/Hellstrip-Heroes.

www.mvhospital.org

By Annie Sherman Alicante, Spain

As sustainability infiltrates professional sports, one event is taking the lead. The Ocean Race — a triennial, 60,000-km sailing race — circumnavigates the world from Alicante, Spain, through the Southern Ocean, to Genoa, Italy. The race incorporates ecological practices and education into every facet of its operations.

These efforts occur both on and off the water, thanks to a sweeping sustainability action plan that prioritizes ocean and climate health, resource and carbon reduction, and environmental impact. Each 60-foot IMOCA class boat collects data from seawater and climate measurements as they race. At the race’s host cities, people can visit the race villages to learn about a range of environmental initiatives.

“Sailors are seeing the decline first hand,” says Lucy Hunt, The Ocean Race’s Senior Advisor for Summits and Learning. “They’re seeing more plastic or experiencing extreme weather events or seeing less animals. Our overarching goal is to try and accelerate the protection and restoration of ocean health.”

Read more about The Ocean Race’s sustainability initiatives at bit.ly/Sailing-for-Science.

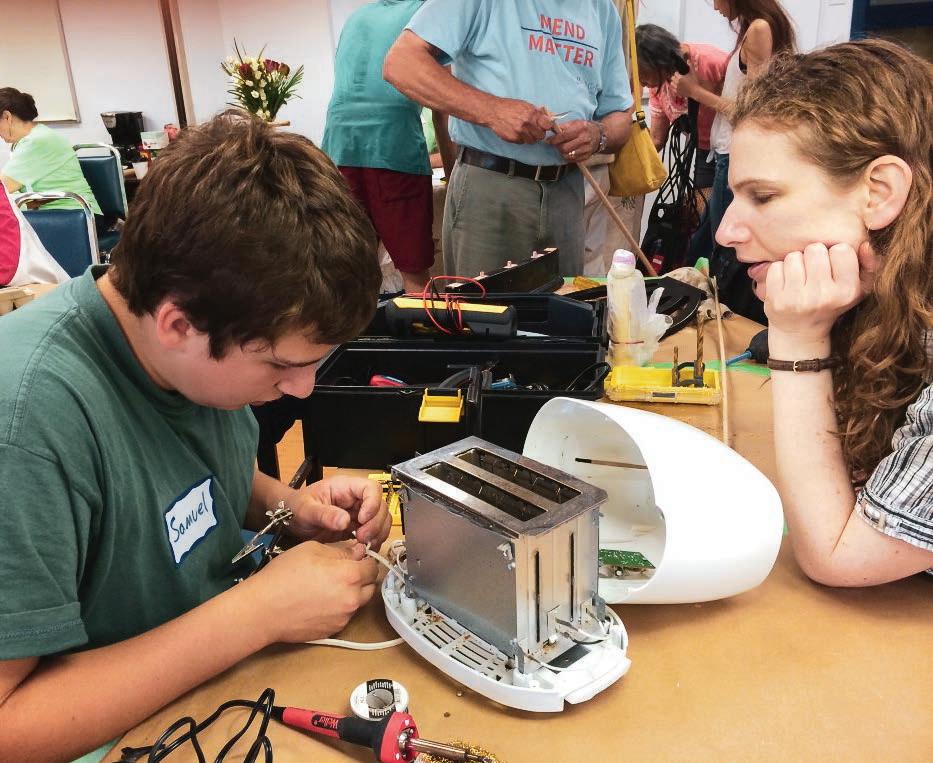

By Kym Wolfe London, Ontario

The community gathers at Reimagine Co in London, Ontario for their monthly Repair Café. Some are carrying small items — an electric can opener, a piece of clothing, a curling iron. One has a sewing machine, another a tool box. The event brings together volunteer fixers and people who would like to learn how to repair and reuse items rather than throw them out. It’s a scenario that plays out in more than 2,200 Repair Cafés around the world, a global movement that gives household items a new lease on life if they only require a simple fix. According to repaircafe.org, many people throw things out simply because they do not know how to repair something that’s broken. We may not have access to the correct tools, let alone know how to use them. Repair Café volunteers bring tools with them, and there are people to guide them through the repair process. By the end of an evening, some things will have been fixed, people will have learned something, and everyone will have had an opportunity to meet other members of the community.

We offer recommendations to benefit the island's pollinators, plants, and wildlife that match your interests and budget.

Your yard, your joy, their home. Join the Natural Neighbors Network!

Contact Rich Couse to sign up rcouse@biodiversityworksmv.org

By Andrea McHugh Chatham, Massachusetts

A first-of-its-kind study released in July of 2023 shows that Cape Cod is one of the largest hotspots for seasonal white shark gatherings in the world. Maddie Poirier is Community Educator at the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy (AWSC), in Chatham, and she’s noticed that the media’s portrayal of the people working to study and preserve shark populations is inaccurately skewed toward males.

“I think the media kind of portrays the wrong idea of the actual truth behind shark science,” she says, “because you don't see a lot of those female scientists on TV the same way that you might with some of the more popular male scientists.”

The AWSC’s Gills Club has been working since 2014 to change that perception by inspiring girls to become the next generation of shark and ocean advocates, and today, the club is stronger than ever. The club allows girls to connect with and be inspired by female scientists around the globe — and by each other.

Read more about the shark girls of AWSC’s Gills Club at bit.ly/Shark-Girls.

By Lucas Thors

When I was a freshman in college, I bought a light brown corduroy shirt that I wore nonstop until graduating — it was my favorite shirt. When I got out of school and went through my closet, I ended up stuffing that old shirt into a black trash bag during my hasty exfil from my college apartment.

Fast forward 10 years to when I saw a poster for a visible mending workshop the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society was hosting, and I dug that black trash bag out of storage and found my favorite shirt. It was pretty beat up, there were a few missing buttons, and the elbows were particularly threadbare (it had endured more than a few skateboard wipeouts). The advertisement for the Ag Society workshop read “Are your Carhartt jackets looking a little worse for the wear? Are your sweaters full of holes? Bring all your old and worn-down clothes to the Ag Hall and we’ll learn to mend them together!”

I was excited to get my shirt back in action. Based on the advertisement, I figured I would have multiple options to choose from in regards to the elbows on the shirt, and although I had sewed buttons in home economics class in elementary school, I definitely needed a refresher. When I arrived at the Ag Hall, my friend Lucy, who works for the Ag Society and put together the workshop, greeted me with a pair of light blue shorts that they were planning on patching up with some pretty floral fabrics and some doilies to line the pockets. I said hi to Dalila Bennett of Fire Cat Farm, who hosted the class, and they led me over to a big basket of fabrics of various colors and kinds. There were some solid contenders in the basket: a mix of paisleys and geometric patterns that I really dug. But the pattern that won me over was a mint green and pale-yellow mix of ferns and bright bluebells that would stand out perfectly over my light brown shirt. After bringing the two squares of fabric (already perfectly cut, which did factor into my final choice) back to the craft table, I placed them on the

elbows of my shirt and lined them up to make sure they were in the center of the sleeve. Dalila suggested that I use what they called a “baste stitch” to temporarily hold the fabric in place before doing my final stitch. After stitching a sloppy square of white thread into the center of the patch, I was ready to move on to the permanent stitch.

As the group was chatting and sewing away, Dalila told me they were always a crafty kid, and got into embroidery and needle felting through their mother, who passed down her

Vineyard Power, in partnership with the six towns of Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Light Compact, is proud to bring energy-saving solutions to our community!

For Homeowners:

•No-cost home energy assessments

• Insulation & heat pump incentives

• 0% financing for energy-efficient upgrades

• Increased incentives for income-eligible and moderate-income customers

• Rebates for heat pump water heaters, induction stoves, lawn equipment, and more!

longtime passion for all things needlework and textile arts. A few years ago, Dalila started making custom clothes using upcycled materials. “I would see a cool dress or a pair of pants, and I just had this thought ‘I could probably make this for myself,’” Dalila said. On top of running Fire Cat Farm alongside Casey Mazar-Kelley, Dalila has started a custom clothing brand, Slowhoneyy.

I worked my way through stitching both patches onto the elbows of my favorite shirt, and was surprised at how simple the process was. I did not prove myself to be a naturally gifted sewer, but completing this project inspired me. It made me think back to my days of home economics class, replacing buttons and using a sewing machine to make a rather lopsided pair of pajamas with multicolored racecars doing loop-de-loops across the legs (my parents would say the pants made me run faster). I think I’ll go buy a sewing kit and try my luck stitching some buttons onto my revitalized shirt, and will maybe even plan on crafting another pair of pajamas (sans racecars).

Whether you are looking to neaten up some of your worn out clothes or just want to add some spice to an outfit, mending keeps things out of the garbage and in your wardrobe rotation. Instead of throwing away your ripped jeans or tattered sweater, look for more mending workshops on the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society event page: marthasvineyardagriculturalsociety.org/upcoming-events.

For Businesses & Non-Profits:

• No-cost business energy assessments

• Up to 100% incentives for energy efficiency upgrades

• Eligible measures: HVAC, lighting, thermostats, refrigeration, weatherization, and more!

What if the future isn’t all doom and gloom? What if we actually get it right?

Pick up a free copy of What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures, by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson at the West Tisbury Library, and join the Climate Book Club for a conversation on Sunday, June 29 at 4 pm on the library porch. Everyone’s welcome. (If you want to start reading and you’re not on the Island, you can order the book on Amazon: bit.ly/Ayana-Book.)

Ayana is a marine biologist, climate policy expert, and all-around force for good. Her latest book mixes essays, interviews, art, and

big-picture thinking to help us imagine a future shaped by climate solutions — not just problems. It’s hopeful, grounded in justice, and was named a Smithsonian Best Book of the Year for a reason.

Want more from Ayana? We recommend her newsletter: ayanaelizabeth.substack.com.

The Climate Book Club is hosted by Nicola Blake and Sue Hruby. The group meets regularly to discuss different books about the environment, most recently reading Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer. For questions or to sign up, email wt_mail@clamsnet.org.

We love bringing you stories about Islanders addressing climate change.

Generous contributions from readers such as you help us do this.

Make a one-time, monthly, or annual contribution here.

OUR MEMBERS RECEIVE:

Our Bluedot Living Kitchen digital magazine Access to Bluedot Savings

Our gratitude for being part of the Bluedot Family

(508 )62 7- 292 8 | M V@ oh-DEE R .co m oh-DEE R. co m

•SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

•KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOES ON CONTACT.

•AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers two all-natural pest control solutions for seasonal or year-round protection. Our deer control solution is an egg-based spray with garlic, white peppers, mint oil, and water that directly targets the plants deer love to feed on. Our tick and mosquito spray is a blend of powerful essential oils, including cedarwood oil, lemongrass oil, castor oil, and water. Our team provides customized, thorough coverage for your property, ensuring long-lasting protection.

Dear Dot: Is Climate Change Causing More Allergies? Do Pollinators Benefit?

Dear Dot,

I’ve never struggled with allergies as much as I am this year! I read somewhere that tree pollen has become more “allergenic" because of longer warm seasons caused by climate change. Is that really the case? Is more pollen all bad? Or is this good news for our pollinator friends?

– Julia

The short answer: While climate change is extending allergy season (close to three weeks in some regions), it’s unclear whether that increased pollen is leading to increased pollination and, if so, what plants might be benefiting. While research is being undertaken to deliver answers, what we do know right now is that allergies are on the rise.

Dear Julia,

Achoo! Dot is on week three of a congested nose and sneezing and a growing conviction that this isn’t just a stubborn spring cold. So let’s first consider this part of your question: Is climate change causing tree pollen to be more “allergenic”?

In 2020, in a report titled “Exactly what do we know about tree pollen allergenicity,” the Lancet answered, essentially, ‘surprisingly little,’ arguing that more information about the impact of specific tree species is needed to determine if cities’ planting programs as a way to combat climate issues are actually a net positive or a net negative.

It is widely accepted that a warming climate is producing more pollen.

As Climate Central, an independent nonprofit group of scientists and communicators, reports in Seasonal Allergies: Pollen and Mold, “North American pollen seasons became longer (by 20 days on average) and more intense (21% increase in concentrations) from 1990 to 2018. Human-caused warming accounted for about half of the shift

toward earlier pollen seasons and about 8% of the increase in spring pollen concentrations during this period.” But they argue it isn’t just pollen wreaking havoc with our respiratory systems. Warmer winters mean that mold that’s surviving through our cold seasons can trigger spore allergies.

Climate change is definitely intensifying allergen production.

“Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can stimulate plant growth, which directly impacts pollen production and supports mold growth,” the report tells us. And, lending credence to your suggestion that pollen is becoming more allergenic, the report notes that “A number of laboratorybased studies show that increased atmospheric CO2 could boost pollen and spore production — and in some cases, how allergenic they are [emphasis Dot’s] — in certain species, including grasses, ragweed, oak trees, and common allergenic fungi such as Alternaria alternata and Aspergillus fumigatus.”

Julia, your stuffed up schnoz is right in line with this research.

And you’re not imagining that this year seems particularly bad. Accu Weather’s Allergy Forecast for the US in 2025 predicted this in early April.

Itchy eyes and a runny nose might be the least of it. Medical professionals are increasingly alert to something called “thunderstorm asthma,” which is a storm that sucks millions of pollen particles into clouds then splinters them ever smaller before raining them down for us to inhale. An “unprecedented” and “catastrophic” thunderstorm asthma event in Melbourne, Australia in 2016 led to an eight-fold increase in emergency room visits for breathing problems. And it’s not just people with pre-existing asthma who were affected.

But while all this pollen might not be great for us, personally, does it benefit our planet? Our pollinators?

Dot took your query to Matt Pelikan, a lifelong naturalist who lives on Martha’s Vineyard and is the Atlas of

Life Director for the Island’s nonprofit Biodiversity Works. Pelikan is unaware of any studies on whether excess pollen from our extended springs is valuable ecologically. “Most of the pollen that causes allergies comes from plants that are wind-pollinated vs. ones that hire insects to help,” he told Dot. Airborne pollen is a very inefficient way to transmit it from one plant to another, he explained. Consequently, he said, “releasing more pollen is generally a good thing since it would increase the chances of pollen grains hitting their targets.” He does issue a caveat. Are all woody plant species producing more pollen? “If it's mostly invasive exotics like autumn olive that are producing more, the increased production may be making the invasive plant situation worse.”

This increased pollen is also only a boon if it means that it’s easier for pollinators to transmit the pollen from one plant to another. “Many spring-flying bees

get most of their pollen from the flowers on woody plants — willows, maples, cherry, etc.,” Pelikan said. “Once the pollen has been released into the air, there is no way for bees to collect it.” But if flowers are boasting increased pollen production, “this might be a benefit for bees collecting that pollen before it is released.”

So let’s recap, Julia. We know that this is, indeed, a worse-than-usual allergy season. We also know that a warming planet means that this increased pollen due to longer, warmer springs is our new normal. What we don’t know for certain is whether that increased pollen is actually leading to greater pollination and therefore new growth (as opposed to just taking up residence in our airways) or whether it’s making it easier for our pollinators to do their jobs.

While researchers root for answers, lets you and I keep the tissues handy and avoid thunderstorms.

– Sneezily, Dot

Sakiko Isomichi, here at the Cooke House gardens in Edgartown, is trying to understand what makes people (and landscapers) desire vast green lawns.

By Lucas Thors

For decades, green lawns have been the default in American landscaping — neat, uniform, and for many, a symbol of success. But on Martha’s Vineyard, a movement is gaining momentum, pushing homeowners, landscapers, and local officials to question that standard and embrace a more sustainable, biodiverse alternative.

Native plants support biodiversity, require less water, and eliminate the need for chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Yet lawns remain ingrained in Vineyard culture and aesthetics. Conservation advocacy group BiodiversityWorks and Vineyard Vision Fellow Sakiko Isomichi, a landscape architect at Harvard University, are working to understand why — and what it would take to change that.

As part of her fellowship, Isomichi spent 2024 hosting focus groups with homeowners, landscapers, and designers to better understand the cultural and practical barriers to reducing lawn space. Many homeowners, she found, still view the lawn as a marker of status — a mindset deeply rooted in postwar suburban ideals.

“It’s a major process to move people away from that way of thinking,” Isomichi says.

Isomichi also spoke with nine landscape design firms and six landscaping companies, many of whom cited similar challenges. Some clients are open to change, but others just want to stick with what they know. Even when there’s interest, native plant meadows can take three to five years to establish — a timeline many clients find daunting.

For landscapers, economics is another hurdle. Lawn maintenance is predictable and profitable. Native plantings introduce more specialized care, and a risk to their profit margin.

“Trying to do anything different is a risky action for businesses, and it’s even more difficult when you consider that the summer season is when you make most of your income; the margin of error is very small,” Isomichi says.

In response to these findings, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, BiodiversityWorks, Polly Hill Arboretum, and the Vineyard Conservation Society launched the Plant Local campaign — a guide to nature-based landscaping aimed at helping Islanders make informed choices about what to plant.

Native plant availability remains a barrier. SBS and Mahoney’s once sold a “Vineyard Mix” seed blend, but it was discontinued during COVID. Native species now account for less than 10 percent of plant stock at local nurseries, though that number is slowly growing. Polly Hill Arboretum has a good resource guide: pollyhillarboretum.org/plants.

Complicating matters further, definitions of “native” vary. Nurseries tend to use a broad regional definition, while local conservationists focus on species truly endemic to the Island.

“How do we define what a ‘native plant’ is that will benefit the local ecosystem best? Just choosing plants that are purely native to the Island is very restrictive,” Isomichi says.

The Natural Neighbors program

Isomichi’s research is part of the Natural Neighbors Program, a partnership between BiodiversityWorks and the Village and Wilderness Project. The program helps property owners create stewardship plans tailored to their land, emphasizing native plantings, invasive species removal, and wildlife habitat restoration.

Program director Rich Couse conducted about 80 property visits in 2024. His goal is to connect individual yards to the Island’s larger ecological web.

“If you take this invasive honeysuckle bush out, you can put a native bush there. Not only is this good for the environment in your immediate area and on the Island, but native plants and yards with more biodiversity are usually a lot less costly to maintain,” he says.

Still, Couse emphasizes that change takes time. “Sometimes it takes a year just to get the native plantings and plant them, and then they need to grow and establish themselves,” he says. “Then it might take two or three years for us to go back and see what changes have occurred in those ecosystems.”

BiodiversityWorks founder Luanne Johnson urges Islanders to slow down and tune in to their surroundings. “Just go out and be quiet. Look around. Are there birds flying around and chirping?

Are there pollinators landing in your flowerbed or in your yard?”

To Johnson, the lawn is more than an aesthetic issue — it’s symbolic of how disconnected we’ve become from the natural world. “This dominating aesthetic of the sterile green lawn with blue hydrangeas and a white picket fence — we want to change that paradigm.”

She also notes that replacing lawns with native meadows saves water, cuts costs, and eliminates the need for chemicals. “Seems like a huge win-win.”

Continues on page 44

PLANTING WITH PURPOSE in collaboration with BiodiversityWorks we are NURTURING

Native plant specialists and environmentally focused organic garden practices

By Nancy Aronie Illustration by Kate Feiffer

Last summer, my husband and I and a couple of friends went to the Hebrew Center to hear David WallaceWells, a New York Times columnist and author of the book The Uninhabitable Earth; Life After Warming

My husband, Joel, as some of you may know, walks around wearing a T-shirt that reads, ask me about thorium. He has about 30 of these (so don't worry it’s not always the same shirt), and he has given away as many. Thorium, he will tell you, even if you don't ask, is an element (90 on the periodic table). Joel has been researching the subject in depth, reading article after article after article and watching YouTube after YouTube after YouTube, and he will tell you, even if you don't ask, that small, safe thorium molten salt reactors are the answer to the energy crisis. He likes it for nuclear energy — it’s more plentiful than uranium, safer, and doesn’t require a water source for cooling.

And I will tell you, even if you don’t ask, that the energy crisis has been a sort of a midlife crisis for Joel, although admittedly, when I first met him in 1965, he was already outraged at people for not cherishing the planet properly.

So naturally, he was interested in going to this Life After Warming talk. Before we left, he Googled David Wallace-Wells and was reassured to read that his top three imperatives, when asked what can we do, were the same ones Joel has been espousing for 10 years: 1) don't fly; 2) drive an electric car (my husband thinks plug-in hybrids are fine, too); and 3) don’t eat red meat.

we’ve reached a climate emergency tipping point.

I sat there hoping that someone would challenge Mr. Wallace-Wells, the way Joel would have if he were not so set on not challenging anyone or showing off or sounding like an expert.

We were sad that Wallace-Wells never mentioned the three imperatives, even though people asked him for suggestions of what we, as regular citizens, could do now. Maybe he knew his audience — intelligent, curious people who can afford to travel and organic ribeyes — and knew it was hopeless to ask them not to fly or to stop eating cows or to trade in their gas-guzzling cars for hybrid plug-ins.

An elementary school teacher asked what he should tell his young students about climate change, because he didn't want to scare the kids with the actual, crucial, factual information. I can’t remember exactly what David Wallace-Wells said, but I think he was sympathetic to the guy, and they agreed that it was a tough situation.

Later (when no one could hear him) my husband said, “he doesn’t want to scare them? Of course scare them!!! It’s their effing future! Greta got scared. EFFING scare them! Please!”

In the (hybrid) car on our way to the Hebrew Center, our friends asked Joel if he was planning on asking a question. “Maybe,” he said, but I knew there was no way he would raise his hand and — on a mic in front of an audience — ask a question or show off anything he knows. He’s a classic introvert.

The place was packed, and Wallace-Wells was articulate and fully informed on his topic. He talked about the fires, the droughts, the floods, the permafrost, the methane, the melting ice caps, and of course the storms. My husband, like many others, knows all about these things, and certainly knows that

Meanwhile, a year later, Joel is still wearing his ask me about thorium T-shirts and suffering from watching his favorite planet go up in flames. And he still stops and explains thorium when an individual actually does what the shirt requests. And I still roll my eyes because I’ve heard it all before. But, inwardly, I'm very proud that he’s passionate about the survival of our Mother Earth.

It occurs to me, as I write this, that wearing that T-shirt is Joel’s way of offering to share what he has learned, without having to initiate the conversation or sound like a pompous blowhard by going on about it unasked. I know he wouldn't approach anyone on the street or at a dinner party and say, “What do you all think of thorium?” The ask me about thorium T-shirt is the catalyst for the conversation he always wants to have. Always, and any time.

Maybe he’ll reach his own tipping point and become one of the guys onstage at the speaker series this year.

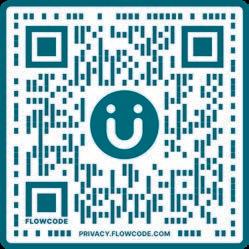

Porches and patios offer both the comfort of home and access to the outdoors. Make sure yours doesn't offend Mother Nature: Choose planet-friendly furniture.

By Leslie Garrett

When my husband and I first purchased the 180-year-old cottage on Main Street in Vineyard Haven, our first priority was to shore up a crumbling foundation and a sagging roof. But a close second was to extend

the porch to three sides. The house, in our minds, was just a useful structure for supporting a porch.

But when an Island engineer concluded that the only thing holding the house up was the horsehair plaster walls (and those, too, were beginning

to crumble), we tore down our little cottage and began construction of a new home. But one part of our original plan that didn’t change even slightly was the wraparound porch. That was non-negotiable.

If you stroll past our home, that’s

where you’ll find me, no matter the weather. Furnished mostly with a mix of old wicker and wood, thanks to Chicken Alley, Act Two, some contributions scavenged from neighbors, and a friend of a friend connected with Habitat for Humanity who had access to a barn filled with donated furniture ours for the taking, our porch is where our Vineyard life happens. Its proximity to Main Street allows us to chat with anyone heading into or returning from town. Where people might not knock on your door without calling first, neighbors don’t think twice about dropping by and pulling up a chair on the porch. We eat there, we birdwatch there, we read there, we gossip there, we even snooze there.

None of this is surprising to architect Charlie Hailey, author of Porch: Meditations on the Edge of Nature (on Amazon and on Bookshop bit.ly/PorchMeditations). Hailey is a porch evangelist and beautifully articulates just why we love our porch so much.

A porch, he explains, straddles indoors and out, private and public, sheltered and exposed. Consequently, even though its popularity thrived in an era before air conditioning, it remains uniquely suited for this moment in time, as we confront challenging questions around privacy, around community, around climate. As Hailey put it, “sitting on a porch calms me down, but it also makes me anxious, because here, on the house’s edge, nature tells how everything is changing.”

Attitudes toward porches are changing too, according to Hailey, who cites construction industry data reporting an increase from 42 to 65 percent in homes built with a porch between 1992 and 2016. Millennials — known for their love of outdoor recreation — are evidently particularly enamored of porches, with 78% of them considering it either desirable or necessary. “This porch renaissance hints at our openness to the outdoors,” Hailey wrote. “It points toward nature.”

Hailey himself has a front row seat for nature, often in a blue plastic Adirondack chair delivered to his doorstep by Hurricane Helene. (“Probably Polywood,” he tells me, “which from what I understand floats quite well.”)

Even without hurricanes and tropical storms to deliver furniture your way (and let’s be grateful for that!), you can find great, previously loved porch furnishings at sites like Facebook Marketplace, eBay, your local Habitat for Humanity Restore, Goodwill, Offerup, or higher end vintage furniture sites like Chairish or your local consignment stores, and the thrift stores on the Vineyard.

If you’re buying secondhand, there are considerations, given that outdoor furniture often takes a beating. If the furniture is metal, look for rust spots. If you’re purchasing online, ask for photos from all angles. Rust isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker, but make sure it hasn’t caused any structural damage, and prepare to employ some elbow grease and a metal brush to get your items in good shape.

Wicker is a classic and often worth the money. But outdoor wicker doesn’t always age well. Look for signs of broken strands (wicker can be repaired — but the sooner, the better) or rotting. Hailey has

had better luck with rattan, which is well suited for his hot, wet climate. “We flood, but rattan dries really quickly,” he said. Also, “it’s relatively light and it sort of ventilates itself.”

If you’re purchasing new, look for furniture that’s sustainably made. If you’re going with wood, look for the third-party verified Forest Stewardship Council certification, which means it’s from wood sourced in an environmentally-friendly, socially responsible, and economically viable manner. Marketplace editor Elizabeth Weinstein recommends furniture with a warranty to provide both peace of mind and some indication that the furniture is built to last.

If you’re open to plastic, there are increasingly sustainable options, including the pioneer of recycled plastic, Polywood, which has been around since 1990. Polywood uses HDPE plastic (primarily milk and detergent jugs) destined for landfill or the ocean, turns it into pellets, and then turns the pellets into furniture. “They were the originators,” says Megan Pierson, EVP of Polywood. “They found that it was more durable. It can basically be engineered to withstand sun, salt, rain

without cracking, rotting, fading, and is virtually maintenance free.” According to Charlie Hailey, Polywood furniture can withstand hurricanes too. “He’s right,” laughs Pierson, who notes that they hear “so many cool customer stories.” And Elizabeth will be delighted that Polywood comes with a 20-year warranty (though Pierson says, “we call it forever furniture.”) Given that it lasts a very long time (or forever), it’s nice to know that Polywood offers a number of different styles of furniture.

Other companies are getting into the recycled plastic furniture marketplace, including Trex (check out what Dear Dot had to say about Trex’s composite decking material: bit. ly/Dot-deck). Patio Productions did a comparison of the top recycled plastic lumber brands, including Trex, and reported that “Trex uses a proprietary blend of recycled wood fibers and recycled plastic film, allowing their

products to closely mimic the look and feel of natural wood. They’ve also incorporated using Polywood’s HDPE lumber.” The reviewers took a look at Berlin Gardens, which also uses a composite of recycled plastic and wood fibers and incorporates Amish handcrafting techniques that, Patio Productions says, allows for great attention to detail and sets the resulting furniture apart. Seaside Casual, another recycled plastic patio furniture manufacturer, similarly relies on composite materials. The site declares Polywood a winner in the sustainability contest, noting its vertically-integrated manufacturing and zero-waste process, something Pierson also emphasized, adding that “what really sets us apart is true transparency.”

There are others, including Loll Designs and Neighbor, which offer a variety of style options and materials. However you furnish your porch or

patio, Charlie Hailey has some parting thoughts about the value of such a place. He recently participated in an architecture conference in Venice at which he incorporated a porch into the overall theme of “architecture of generosity.” Porches, he says, are a hybrid of public and private, something, he says, that’s really important right now as we consider the value of community.

“I think a lot about how we can connect to nature and how we can learn from what we see and from all the amazing things around us,” he says on the phone from his porch in Florida. “And with climate change, with the changes around us, porches allow for a kind of increased sensitivity to all those things, right?”

But perhaps most importantly, Hailey says, “I think also that porches are just a really good place to sit and read and relax and daydream.”

Whatever porch furniture you’ve chosen — second-hand or new — let’s talk about how to ensure that it looks good for a long time. Keep wood, plastic, metal, wicker, or rattan furniture clean with a few simple steps:

• Vacuum (using the brush attachment) twice a year — when you take it out and before you put it away. Periodically clean it using a mild soap and water mixture and soft-bristle scrub brush. Avoid abrasive, chlorinated cleansers.

• Bluedot’s Marketplace editor Elizabeth notes that Sunbrella fabric for cushions and pillows really does hold up over time, though she recommends bringing cushions indoors during inclement weather. If you’ve been playing (and losing) the “is-it-goingto-rain/should-I-bring-in-the-cushions?” game, get yourself a furniture cover.

• If your cushions are mildew stained, mix hot water and oxygen bleach (never chlorine bleach, which will discolor) and scrub with a soft-bristle brush, then pat dry.

Webster’s Dictionary defines “cooperation” as: “operating together to one end; joint operation; concurrent effort or labor.’’ This accurately describes VINEYARD HOME IMPROVEMENTS’ culture and approach to every project. Our staff recognize the importance of partnership, and the ability to work as a team, as well as the necessity of being fair and flexible.

• Experienced in all phases of residential and commercial building construction.

• Skilled Craftsmen

• Design & Value Engineering

• Team Approach

In 1882, tuberculosis killed one in seven people infected in the United States and Europe. And without a cure for the highly infectious disease, those afflicted were often prescribed what essentially amounted to fresh air and a cottage porch. Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, a resident of New York City whose brother died from TB, retreated with his own case of the illness to the natural beauty of the Saranac Lake region in upstate New York, an area he was familiar with from his youth, where he expected that he, too, would die. When, instead, he began to recover, he established a treatment center in 1884 for other TB sufferers, dubbed the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium.

The “fresh air” prescription gave birth to the rise of sleeping porches or rooftop bedrooms, including one in the White House. Today’s White House Solarium “dates to the early twentieth century, when President William Howard Taft added a rough-built sleeping porch to the roof of the White House so his family would have a cool place to pass Washington’s steamy summer nights,” the White House Historical Association tells us. Charlie Hailey, author of Porch: Meditations on the Edge of Nature (on Amazon and on Bookshop bit.ly/PorchMeditations), described it as “a screened porch built on top of the White House so that they could crawl out of the attic windows of the White House and sleep outdoors.”

With our most recent pandemic, porches found a prescriptive purpose again — as a place to gather safely outdoors, and host concerts or performances.

Martha’s Vineyard is blessed with a robust circular economy. As one Islander put it, “you give something away and end up buying it back at a yard sale a decade later.” Here are some of the best spots to score porch furniture:

Our art director, Whitney Multari, and Jules Gulliksen scored this porch set via MV Stuff For Sale.

CHICKEN ALLEY: chickenalley.org

ACT TWO: acttwosecondhandstore.org

DUMPTIQUE AT THE WEST TISBURY DUMP: westtisbury-ma.gov/west-tisburytransfer-station-landfill-local-drop

HABITAT FOR HUMANITY: habitatmv. org/restore.html

MV BARGAIN BIN: mvtimes.com/classifieds/

MV STUFF FOR SALE: bit.ly/mvStuff

VINEYARD GAZETTE’S GOODIES AND GIVEAWAYS: bit.ly/Gazette-Goodies

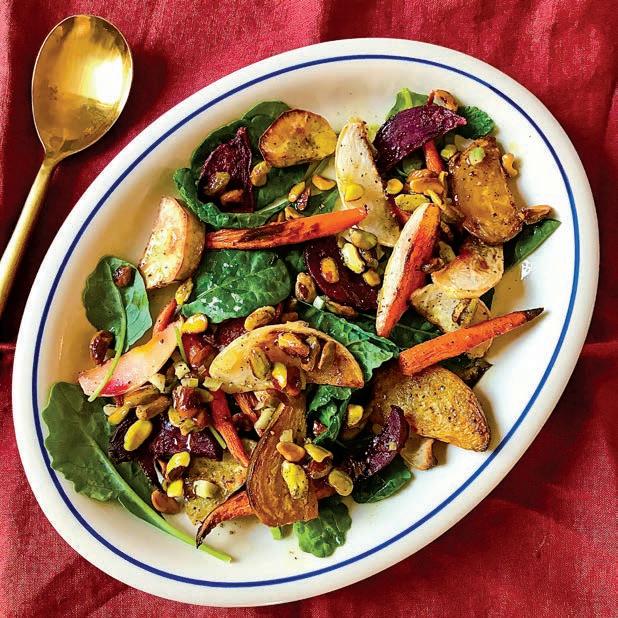

Recipe and photo by Leslie Garrett

My secret to sustainable summer drinks is my Soda Stream. (Find them on Amazon: bluedotliving.com/ SodaStreamRoomforChange.) These bubble-creating CO2 machines reduce the need to buy soda and seltzer in cans or plastic. Plus, they add a quick and easy “spritz” to any drink. Try this one with a splash of limoncello and a sprig of organic mint from your garden.

Seltzer water

Limoncello

Fresh mint

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Pour a glass of seltzer water over ice and add a splash of Limoncello. Garnish with fresh mint. You can also add a bit of torn or muddled mint to the drink for a stronger bite. Enjoy your plasticfree drink in your favorite place to lounge on a hot summer day.

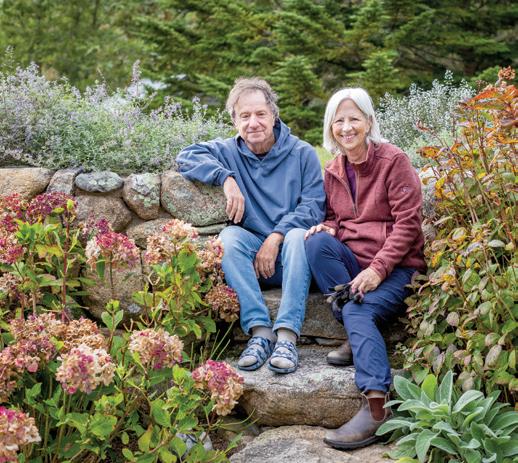

By Vicki Riskin Photos by Alison Shaw

Last fall Claudia Macedo stood before a group at the Vineyard Haven Library to tell the story of her ambitious rainforest restoration project in Brazil. She began with an apology for being an inexperienced public speaker. Then, like most people passionate about what they do, she came alive, stood tall, and gestured with her hands as she walked us through her slides. The audience was transfixed. The hour flew by. At the end she introduced her husband, Lew French, the storied stonemason artist on the Island, and asked him to fill in some details. The

audience hung around after, eager to learn even more about the couple’s life and work in Brazil’s Mata Atlântica.

The Mata Atlântica rainforest hugs Brazil’s coastline and once stretched from the northern to the southern tip of the country, hosting a vast and rich ecosystem teeming with life. Today, less than 12% of the original rainforest remains, 8% of which is contiguous. Most of the land has been cleared for agriculture or logging by locals seeking merely to survive, leaving behind a fragmented and endangered landscape.

It was kismet, or maybe destiny,

that Lew and Claudia met on Martha’s Vineyard, and a shared interest in the Mata Atlântica evolved. Now they live much of the year in this remote part of the world.

As a boy, Lew spent summers with his grandparents at their cabin on a lake in northern Minnesota, where he felt at home in nature and working with his hands. In the mid-1980s, his friend David Flanders encouraged him to come to the Vineyard, where, in time, his artistic stonework garnered national attention. His unique relationship to stone is beautifully

described in Barbarella and David Fokos’ documentary about Lew: The Power of Stone. Across the Island and beyond it, outside and inside homes, Lew’s creations have been commissioned as signature focal points, evolved from his meditative vision. “Stone is just waiting for you to reveal it,” he often says.

Claudia was born to a well-to-do family and grew up in the northeast of Brazil in the big city of Salvador, once the capital of Brazil and a hub for slave trade. Claudia, too, experienced a deep sense of happiness during summers in the countryside at her extended family’s farms. She came to the United States for her education in 1991 and moved to the Vineyard in 2006. She worked at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital as a physical therapist. That’s when she met Lew. They married in 2007.

Nearly three decades ago, before the two got together, Lew had searched for a place to connect more deeply with

the Earth and find a slower pace of life. Through a friend, he found the Mata Atlântica, where, in stages as he could afford it, he bought 2,000 acres of a 1940s farm near a town called Bananal

“The minute I got there, I fell in love and felt more at home, more myself than anywhere. I felt grounded.”

– Claudia Macedo

in the state of São Paulo. In his book Sticks and Stone: The Designs of Lew French, (with photographer Alison Shaw; available locally and on Amazon: bit.ly/ Sticks-Stones-Book ), he describes the

natural beauty of the place.

“There is water everywhere — in hundreds of waterfalls and springfed rivers, trickling down every leaf and flower petal from dew in the early morning and by way of incredible tropical storms that arrive without warning on the sunniest of days.”

When they planned Claudia’s first visit, Lew feared his bride would be alarmed and find the place unwelcoming. She had grown up in comfort. The mud hut where they would stay before he could build them a house was filled with scorpions, bats, rats, and spiders — some deadly — and had no electricity. At night it was so dark they couldn’t see each other once the candles were out. And they would have to rely on the old wood-burning adobe stove to cook.

Claudia says, “The minute I got there, I fell in love and felt more at home, more myself than anywhere. I felt grounded.”

Claudia and Lew's house, which sits on 2,000 acres, is open to the outdoors.

When I asked them how long it took to build the house, Lew laughed and said “Ten years later and we’re still not done.”

When I asked them how long it took to build the house, Lew laughed and said “Ten years later and we’re still not done.”

He built most of the house himself, sometimes with a few workers, and the photos taken by Alison Shaw for Lew’s book show a beautiful home that is open to the outdoors, yet anchored inside by stone walls and wood beams. And they even have electricity! The challenges were constant though. He writes that

they often “had to fix long stretches of washed-out roads by hand in order to get material suppliers to drive their trucks up our mountain. The process was repeated every time there was a downpour.”

Over time Claudia felt more and more at home and connected to the forest around them. When she came down the hill to town, the vast deforested areas and the heat were disquieting to her. She talked to an

She recruited locals, including school kids, and even some colleagues from the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital came down to help. She began with 2,000 native species and planted 13,000 trees, and headed back in December to plant 40,000 more.

old-timer who recalled how, as a kid, he needed ropes to cross a nearby rushing river now diminished to a sad trickle of water. She wondered if there was anything she could do to help reverse the damage.

She took time to look, listen, and understand. Lew points out that she had the benefit of knowing how things work in the U.S. and what might be possible, and she also knew how to win the trust of the local people.

She says, “It takes time because people can’t imagine someone helping them without wanting something back. They aren’t used to collaboration or having any power. People are very poor and beaten down. Without resources, they barely sustain themselves and often go hungry. Some live deep in the forest and are forgotten…maybe unknown. To eat, they forage and are ashamed of their situation.”

For inspiration, Claudia visited a woman running a well-known restoration program in Caatinga, another Brazilian region suffering from severe desertification.

Claudia told me, “I drove nine hours with nothing on the roads, and if I broke down, I wouldn’t be found. When I got there, I had never seen such poverty, kids with distended bellies, no shoes, some naked, and they had tears when they saw me, thinking I might help them.”

The area, called Raso da Catarina, located in the state of Bahia, is home to a number of endangered rare blue (or Hyacinth) macaws and is the driest region in Brazil. The restoration project aimed to create buffer zones in a large park and plant native species to provide nourishment to local people and their animals — cows, goats, pigs. Several communities live in the buffer zone, including indigenous tribes (Quilombos, who are descendants of escaped enslaved Africans), fishermen, and several settlements of mostly women living with their children and elderly relatives while their partners work in big cities (and often don’t return).

To help, Claudia procured 150,000 donated native trees, including fruit trees, but she needed to raise funds to transport them and build nurseries, as well as to hire personnel to carry out the reforestation.

“I called One-Tree Planted (she found them on the internet) and they asked how much we needed. How many trees? 150,000, we told them. How much

from One-Tree Planted. She recruited locals, including school kids, and even some colleagues from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital came down to help. She began with 2,000 native species and planted 13,000 trees. “There is a lot to do to prepare the land,” she said, “including [applying] a hydrogel to hold the moisture in the dry months. But once you dig a hole and plant a tree, it’s a

a specific nursery, but not enough to also purchase the materials for planting the saplings. By March, they had planted 5,000 trees, but they will need more financial help to plant and maintain the remaining 35,000. They want to employ local workers and train them so that afterward, they can work for other projects in the region as well.

One recent bump in the road on the

money? $150,000. And they said okay.” She could hardly believe how easy it was. Her success drew the attention of BBC Earth based on the recommendation of One-Tree Planted. She thought, “I guess I can do this!”

Back home again, Claudia joined neighbors to begin reforesting in their area, planting trees again with help

powerful thing.”

When I talked with Lew and Claudia last November, they told me they were heading back in December to plant 40,000 more trees. “It’s planting season,” they said, “and we have to get back.”

The area of their new reforestation project was affected by wildfires last year. They raised funds to truck saplings from

project has a silver lining. A supplier sent saplings that were much smaller than they’d expected, and they had to return them. “They would never have survived a week out of the greenhouse,” Claudia said. Trying a new tack, she partnered with the main water and sewage company in the state of Rio de Janeiro, which runs a program called “Replanting

Lives.” The program builds nurseries inside penitentiaries and provides inmates with job training and paid work raising native saplings to be used in reforesting degraded areas of importance for water production. “This company stepped in to provide us with the trees we needed to reforest our region. As a way to help their nursery program, we have engaged our community, as well as cities around us, to collect native tree seeds, and we are donating the seeds to the nurseries this company created inside nine penitentiaries.”

But Claudia’s vision for her area is even more expansive. In her view, as long as people are hungry, dispirited and poor, they won’t see the value of protecting the trees.

She has won the trust of teachers and brought environmental experts into classrooms to inspire the young. She takes young kids into the field to help plant trees and develop in them a pride about where they live. She works with families to show them how to plant their own vegetable gardens and sell their extras, if they have them: “When it works, people don’t go hungry.”

She’s become a familiar figure in town, where she gives away plants at the outdoor market — mostly Atlantic Rainforest species, meant for reforestation — and encourages people to donate back seedlings to create their own vegetable gardens. She hopes to set up a permanent place in town with plants for the locals, and the town mayor may be donating land for her project.

“As part of the plan to create community enthusiasm for planting in general,” she said, “I created a project through my nonprofit where hundreds of flower plants, orchard, and vegetable garden plants are donated as well. My husband and I spend three to four months planting cuttings of our own garden plants in order to plant them during giveaway events. And using financial donations from family and friends, we buy seedlings for vegetable gardens at farms nearby, and donate them as well.”

She works closely with the local Ecological Station and hopes to attract researchers and students from international universities around the world to come study and work on the restoration.

The town’s modest economy relies on women’s crochet work, but their designs are old-fashioned. Claudia has recruited a designer from Rio to teach them how to extract fibers from the jungle and crochet modern designs. They have a new style they suggested to the artisans — introducing forest themes into their pieces, and they’ll showcase their work in September during their first ecological festival. She envisions a market for their work overseas, perhaps even in Paris.

Margaret Mead’s familiar quote seems apt: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”

In the case of Lew and Claudia, their “world” is the Mata Atlântica, one of the planet’s many exquisite rainforest canopies vital to the earth’s survival.

Claudia has left her job at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital to work fulltime on the project and her nonprofit, IBIOS - Instituto Biosfera. “As much as I have enjoyed helping people with their health in a hospital setting, I feel that I can contribute further by helping rebuild the forest here in Brazil.”

Donate:

Claudia and Lew have created a page for their reforestation project with GlobalGiving, an international nonprofit that assists other nonprofits around the world by making it possible for donations to be tax deductible. “Soon we will be writing other projects for different agendas, such as building vegetable gardens for impoverished families. The main thing now is to find a grant for seed money, so we can hire office help in order to assist us looking for grants and writing projects. Here’s where to donate: bit.ly/Claudia-Lew-Trees

For more options, contact Claudia at claudiapessegal@gmail.com

Check out their Instagram: instagram.com/ibios_instituto_biosfera/reels/

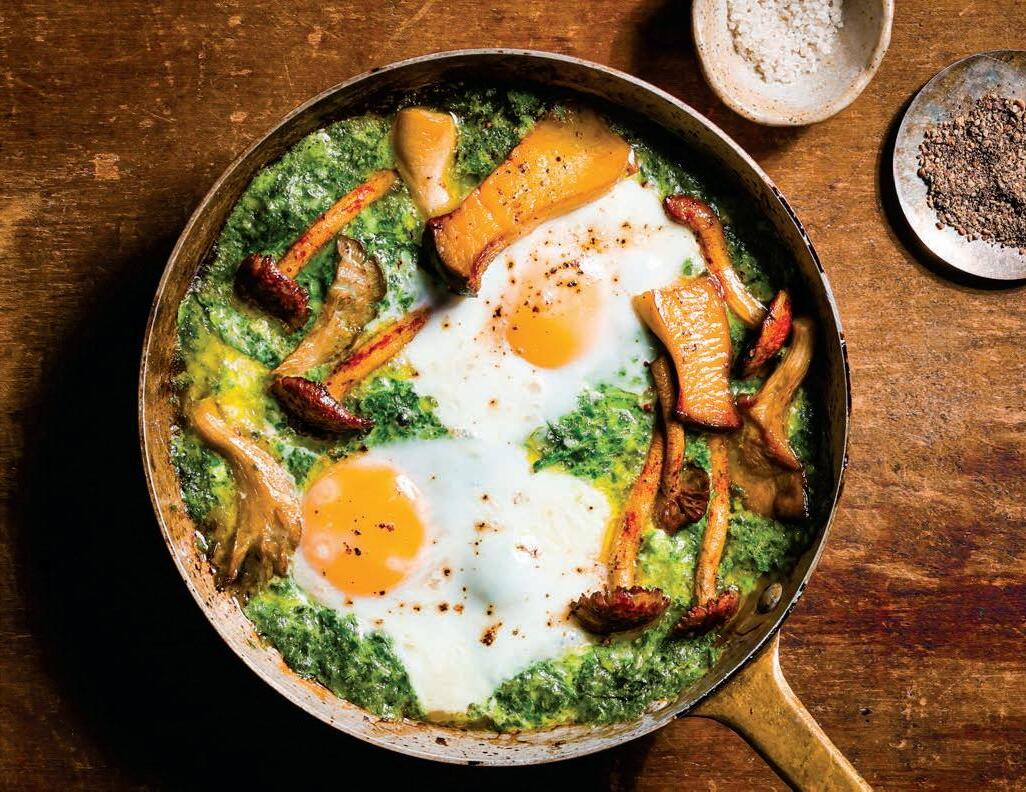

Biochar can help restore degraded soil and support healthy forest growth.

An orange blaze flickered through the air as smoke swept skyward from a six-paneled metal box — a flame cap kiln — holding a slow, steady burn of wood and brush. On this sunny Mother’s Day at Mermaid Farm, Maggie Craig, clad in a yellow fire jacket and face shield, stood close by, steadily feeding the flames. What would eventually emerge from the embers wasn’t ash, but something far more valuable: biochar.

“Biochar is a legacy of the Indigenous burning practices,” Maggie said after she lit the kiln — also known as the Umptopia 3.0, her third flame-cap kiln on the Island, built from sheet metal, roofing, and barn rails.

Maggie has been championing biochar on Martha’s Vineyard for several years.

By Britt Bowker

As a second-year Martha’s Vineyard

Vision Fellow, she’s leading a biochar project in partnership with Island farms, conservation groups, and waste management facilities. Her sponsoring organization is the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. She collects wood waste, builds kilns, and gathers data on biochar production. She also researches its uses in soil and water systems, and spreads the word through hands-on demonstrations at places like Mermaid Farm, Whippoorwill Farm, Allen Farm, Native Earth Teaching Farm, and John Keene Excavation.

So … what exactly is biochar?

Picture a block of charcoal — that’s essentially biochar. It’s created by burning wood waste or other organic material (biomass) in a low-oxygen environment through a process called pyrolysis. Maggie uses a flame cap kiln, which creates high

heat while limiting oxygen below the flame cap — a key condition for pyrolysis to occur. The result is a jet-black, carbonrich, porous material that can be used in gardens or on farms to improve soil health, store nutrients and water, increase plant growth, and sequester carbon. Biochar can also treat water. It’s a way to turn local organic waste into a powerful climate solution. The carbon-based molecules in wood are converted into stable forms that resist microbial decay, which means biochar can remain in the soil for thousands of years. Smaller pieces mean more surface area for absorption, so it is recommended to crush biochar to less than half an inch, though in soil and compost, some larger pieces are okay “because it will help keep things aerated,” Maggie says. Maggie sources wood waste used to make biochar from a wide network of

The

The result is a jetblack, carbon-rich, porous material that can be used to improve soil health, store nutrients and water, increase plant growth, and sequester carbon.

partners: South Mountain Company saves construction cutoffs, BiodiversityWorks dries out invasives like bittersweet collected during their community blitzes, and local landscapers and arborists contribute waste from their jobs. “When you start to do these processes, you cease to think of it as waste,” Maggie says

That shift in thinking is part of what drew her to this work. A longtime summer resident, Maggie returned to the Island in October 2020 after finishing a summer internship at Capital Press, an agricultural newspaper in Oregon. She had just earned a biology degree and hoped to pursue science writing.

“It was a very interesting time out west. Not just the pandemic — there was a social movement underway; there were massive wildfires,” Maggie says. While working on a story about turning conifers into biochar to restore oak habitat, she was struck by the material’s potential. And back on the Island, she kept seeing landscape crews with “truckloads of fodder perfect for a flame cap kiln,” Maggie says. “It seemed like it had so many solutions to environmental and potentially social issues … I moved here [in 2021] with the hopes of exploring it more.” She worked as a mobile mechanic while she looked for grant opportunities, and in 2023, she found one. “The Vision Fellowship has been an excellent match,” Maggie says.

The kiln Maggie uses was designed by her mentor, Ken Carloni, who’s based in southern Oregon. She first met him while reporting on that original story. The double-walled kiln at Mermaid Farm is the third she’s built on the Island. The first two — the Umptopia 2.0 and the Daisy Chain (a series of 55-gallon barrels riveted together in the shape of a daisy) were also based on Carloni’s designs. Maggie’s kilns are designed to be portable and modular.

“Ideally, the kiln is set up where the wood waste is generated,” Maggie says.

Her burns typically last about four hours, during which she steadily feeds the flames to maintain an even temperature. The wood at the bottom is pyrolized and falls into the oxygen-deprived zone beneath it, turning to char.

“Biochar is happening in a regular open burn pile, but within a flame cap kiln it’s controlling the airflow in a way that makes more biochar,” Maggie says. “It becomes really artful how you operate a flame cap kiln to make as much char as possible,” she adds, noting that her process must be manual — machine loading can smother the flame.

At Mermaid Farm, Maggie and a few volunteers layered the smaller bits of yard waste on the bottom of the kiln, then slowly added larger and thicker pieces of wood on top. A top layer of dry kindling was added for ignition, and the kiln was lit from the top, creating a flame cap that helped burn up smoke efficiently. As the initial pile burned down, Maggie added more material, and she included larger pieces as the kiln heated up. The larger boards were crisscrossed in order to allow a small amount of air to flow through the entire pile. Volunteers chucked hay and small kindling on top to keep it going.

After the burns, Maggie often hands out samples for people to experiment with at home. But before it can go into the garden, biochar must be “inoculated.”

“When you make biochar, or biologically activated char, it’s not biologically active yet if all those pores are still empty,” Maggie says of the material’s porous surface area. “They need to get charged up with nutrients to be able to offer that up to the plants in lieu of them sucking the nutrients away from the plants or locking them up in the soil.”

Biochar is highly absorbent and negatively charged, meaning it’ll attract positively charged nutrients. That’s good — once it’s charged — but if added raw, it can deprive plants of nutrients.

“It acts like a mirror to whatever is already there,” she says.

To avoid this, Maggie recommends mixing biochar with something nutrientrich, like compost. “The suggested portion is 10% by volume into compost,” she notes. (See box below for more details on recommended biochar-to-compost ratios.)

There are other options, too. “Urine is a really, really good one,” she says. “It has a lot of nitrogen. Honestly, this is a big win. If people are peeing into a bucket

full of char, letting it sit for a couple of weeks, you’ve got ready-to-go char for the garden — and that’s urine that doesn’t end up in the pond. It’s very easy DIY urine diversion.”

After it’s charged, “biochar in the soil is holding water, holding nutrients, and providing habitat for microbes that are very beneficial to the soil, and it kind of charges the soil,” Maggie says.

Master gardener Roxanne Kapitan started using biochar after meeting Maggie two years ago. Maggie gifted her a sizable bag, and Roxanne has since incorporated it into three areas of her gardens. She mixed it with rainwater and urine, let it sit for about a month, and diluted the mixture before applying it. (Rainwater contains a lot of ambient nitrogen, Roxanne notes.)

She’s seen real results. A beech tree that had shown signs of viral decline is now leafing out. Lilacs that never

bloomed produced profuse flowers. A native dogwood that hadn’t bloomed in years came alive again.

“I feel like everything I applied biochar liquid to — after the dilution process — and then scattered the remaining char at the base, it made a difference,” Roxanne says.

She’s now layering it into compost to see how it performs over time. “I think there’s merit in it,” she says. “People just need to be patient. Most gardeners want instant results from fertilizer, but that has such a large carbon footprint — from production to packaging. I just think biochar has huge potential.”

“It’s really for people on the cutting edge of gardening — beyond Miracle-Gro and granulated fertilizer,” she adds. “It requires dedication and some attention.”

Maggie also conducted a study with Island Grown Initiative to compare how well char charged by different resources

A beech tree that had shown signs of viral decline is now leafing out. Lilacs that never bloomed produced profuse flowers. A native dogwood that hadn’t bloomed in years came alive again.

could grow calendula. She tested urine, fish fertilizer, compost extract, and chicken manure. For the chicken manure, the char was used as bedding and incorporated into the feed of chicks at North Tabor Farm, with help from longtime farmer Matthew Dix. The results were promising. “The urine was very consistent — the calendula was robust through the whole season,” Maggie says. “And at the very end of the season the chicken manure kicked in.”

Eastham produces and sells biochar compost blends. He also fabricates retort kilns — midsize, stationary kilns that burn biomass.

Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation has produced some biochar using an air curtain burner — a box-like incinerator they obtained special permission to use during their southern pine beetle mitigation efforts. Much of the infested material was processed through this

“If people are peeing into a bucket full of char, letting it sit for a couple of weeks, you’ve got ready-to-go char for the garden — and that’s urine that doesn’t end up in the pond. It’s very easy DIY urine diversion.”

– Maggie Craig

For additional insight on the poultry side, Maggie consulted Jefferson Monroe, a pig and chicken farmer formerly of the GOOD Farm. He uses biochar regularly and swears by its benefits: It cuts down on smell and helps prevent disease. “He told me one time he ran out of biochar, the smell was so bad that he wouldn’t be a pig farmer if he didn’t have biochar,” Maggie says.

Biochar can also clean water. Maggie recently launched an experiment in Tashmoo Springs Pond, near the pumping station, to see how well biochar can remove excess nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff. “There are lobster pots full of char in laundry bags,” she says. “And I’m going to be sampling the water above and below the char pots over the next six months.” The pond has long battled algae issues, and the char could offer a natural filtration tool. “The char that’s in the pond is raw char,” Maggie says, “so it removes the [unwanted] nutrients from the water.”

For now, biochar isn’t commercially available on Martha’s Vineyard, though Maggie shares her own. Nearby, Bob Wells of New England Biochar in

system, and the resulting biochar is slated for distribution to the Town of Tisbury and Morning Glory Farm. Tisbury plans to use it to filter stormwater runoff from a storm drain at Owen Park before it enters the harbor. Morning Glory will mix it with compost and apply it on the farm.

“We also had a nice offer from SBS to bag it up and sell it at the store,” says Adam Moore, president of Sheriff’s Meadow. The organization won’t be able to produce more, however — the incinerator must be returned to its owner in New York. Sheriff’s Meadow had the finished product tested at a lab, Moore adds, and it came back 90 percent carbon. “We’re all learning from each other, and I think there’s a lot of potential for this,” he says.

Biochar’s origins trace back thousands of years. In the Amazon basin, Indigenous people created “Terra Preta” — dark, fertile soil enriched with charred biomass. Maggie also learned about the Umpqua tribe in Oregon, who used fire to maintain oak habitats. That sparked her curiosity about indigenous fire stewardship on the Island.

“I believe there’s a lot of evidence

that the Wampanoag used fire to steward the land as well,” she says. “Biochar is very clearly a legacy of indigenous burning practices.”

Even routine landscape burning deposits pulses of char into the soil. Maggie recalls a conversation with Wampanoag elder Kristina Hook. “She remembers gathering with her whole family every year to burn the garden,” Maggie says. “Her grandfather would go out to specific berry patches to burn them. We have this impression that it’s ancient history, but it’s still very present.”

Maggie plans all the burns herself, but gets plenty of volunteer help. A grant from the Ag Society’s Healthy Soils Fund has helped pay for extra hands at demonstrations. You may have seen her outside last year’s Climate Action Fair at the Ag Hall.

As awareness grows, so does interest. Maggie now does private burns at homes, like one in Edgartown where neighbors contributed yard brush. She turned it into biochar on-site. The homeowners plan to convert their front yard into a native plant meadow — and hope biochar will give it a healthy start.

Due to open burning regulations, these projects can only take place on private property between January and May, with permits and coordination from local fire departments. But with each new burn, Maggie’s network grows — along with curiosity about turning waste into soil-building, water-cleaning carbon gold. She plans to continue her work and expand on it by merging the kiln into forest management.

As she sees it, biochar isn’t just a soil amendment. It’s a tool for reconnection — with land, with waste streams, with ancestral knowledge, and with each other.

“I think we could all slow down, and the world benefits,” Maggie says.

Want to host your own neighborhood burn? Email craig@mvcommission.org.

Maggie’s biochar project also accepts donations via check, made out to the Martha’s Vineyard Commission attn. Biochar Fellowship. This will help compensate flame-cap kiln workers.

Lucas Thors contributed to this story.

The general recommendation is to add 10% biochar by volume to your compost pile. “But it’s more complicated,” Maggie says. Depending on the biochar, the materials available, and the end goal, the recommended range is anywhere from 3% to 25%.

Biochar will alter the C:N (carbon-tonitrogen) ratio of compost. This is the balance of browns and greens that make up an active compost. Without biochar, the C:N ratio is 30 to1. Biochar can alter it up to 100 to 1.

Carbon: Biochar is mostly carbon, but only 5 to 30% of that carbon will break down in the compost. The range is due to the pyrolysis temperature. Biochar made in high-temp pyrolysis is a more stable form of carbon — microbes live in it, but can’t eat it up.

Nitrogen: Biochar absorbs nitrogen, so you need more nitrogen to compensate for the nitrogen that gets locked up in the char. Adding biochar without compensating the nitrogen it locks up means that it will just take longer for the same ratio of ingredients to make soil.

Another factor to account for is moisture. Biochar holds water, so an enclosed system will need more watering to keep the pile active.

If you already have a composting system figured out, the easiest way to incorporate biochar is to add biochar to a high-nitrogen substance first (i.e. manure, fish fertilizer, urine), and then into your regular compost C:N regimen. This is recommended by The Biochar Handbook, by Kelpie Wilson, a good guide for all things biochar.

The following is an excerpt from Kelpie Wilson's The Biochar Handbook (Chelsea Green Publishing June 2024) and is printed with permission from the publisher.

When you have very high-nitrogen ingredients like food waste, urine, grass clippings, and fresh manure, add biochar as the waste is generated to preserve nitrogen that wants to volatilize. In my vegetable production system, I use bokashi [fermented food scraps] to pickle and preserve nutrients from my food waste in a precomposting process before I add it to the compost pile. Here is my recipe for handling food waste.