SIMPLE

ARE GMO'S ALL BAD? (Dare we say no?)

HOW SWEET IT IS Brent Brown and family keep the honey bizzzz local

CRUISING WITH CURRIER

Catching up with Jed Katch in his Nissan Leaf

WOODWELL IN WOODS HOLE Masters of Carbon at the Climate Research Center

MARTHA’S VINEYARD / EARLY SUMMER 2022

/ SMART

SUSTAINABLE

/

/ STORIES

Sublime

·

· Planting for Pollinators · Buy Less/Buy Better TM

MVM's

Shiitakes

Local Hero: Julie Pringle

Farley Built, inc. www.farleybuilt.com 508 645-7800

WATERFRONT WITH PRIVATE BEACH AND POOL

One of the largest properties for sale in Aquinnah, this charming house offers privacy and magnificent views of the Vineyard Sound and the Elizabeth Islands. The well-built family home is a classic Colonial Saltbox from the front and all-glass in the back, offering endless views of the water. There are four existing bedrooms with the potential for another. Walk outside to a wrap-around water view deck and outside shower. Step down to the heated pool and spa and follow the path to the private beach. An easy walk to the Lighthouse and Philbin beach. The property is just a short drive to Menemsha Pond for sailing, fishing, kayaking, and swimming. A unique opportunity to purchase this 8-acre property that can provide many options with potential for a second home. Exclusively offered for $4,995,000.

An Independent Firm Specializing in Choice Properties for 50 Years 504 State Road, West Tisbury MA 02575 Beetlebung Corner, Chilmark MA 02535 www.tealaneassociates.com

508.645.2628 Chilmark

508.696.9999 West Tisbury

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com

oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

CALL US!

508.627.2928

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

Publisher and Co-founder Victoria Riskin

Editors Leslie Garrett, Jamie Kageleiry editor@bluedotliving.com

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Associate Editor/Reporter Lily Olsen

Digital Production Intern Julia Cooper

Contributing Editors Mollie Doyle, Catherine Walthers

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Design/Production Sophie Petkus

Proofreader Irene Ziebarth

Ad Sales Jenna Lambert adsales@mvtimes.com

Anne Kelley anne@bluedotliving.com

Corporate/Non-Profit Relations Meghan Burke meghan@bluedotliving.com

Digital Media Consultants Eric Hellweg, Ray Pearce

Contributors, this issue Randi Baird, Geoff Currier, Mollie Doyle, Jeremy Driesen, Sheny Leon, Angela Luckey, Gwyn McAllister, Sam Moore, Catherine Walthers

Bluedot, Inc. Co-Founders Walt and Nora McGraw

Cover Photo Sheny Leon

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc. Copyright © 2021. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine, published quarterly, is distributed by The Martha’s Vineyard Times. Find it free at The MVTimes, newsstands, select retail locations, inns, and hotels.

Visit the digital version of this magazine at marthasvineyard. bluedotliving.com

See our new national website at bluedotliving.com

Sign up for our biweekly newsletter here: bit.ly/Bluedot-newsletter

Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @bluedotliving

Subscribe: Please inquire at mvtsubscriptions@mvtimes.com

2 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

BDL • OUR TEAM

• • • • • •

DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

MORE

ENJOY

TIME OUTSIDE! “

3 marthasvineyard. .com BDL green contractors of martha’s vineyard 508.696.3120 • nmdgreen.com • INFO@nmdgreen.com Plumbing • Heating • Air Conditioning Water Treatment • Maintenance Programs INSTALlATION & SERVICE GREeN SERVICE Geo Thermal • Solar Hot Water • Heat Pumps Energy Management • Design & Consultation Digital Control Systems TM Bluedotliving.com Visit our new national website where we feature changemakers, stories, and solutions from all over the country. SIGN UP FOR THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD EMAIL NEWSLETTER marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Afew weeks ago, co-editor Jamie Kageleiry and I moderated a panel about climate journalism at the New England Newspaper and Press Association (NENPA) awards convention.

Alongside us were David Abel, climate reporter at the Boston Globe; Frank Mungeam, Chief Innovation Officer for the Local Media Association; and Sadie Babits, president of the Society of Environmental Journalists. When we opened up to questions, a young journalist asked how we remain determined and hopeful in the face of so much frightening data, dangerously ignorant policy, and, well, bad news.

We at Bluedot live with this question everyday. We know that more than 70% of Americans are “very” or “somewhat” worried about climate change, according to data from Yale University. We know that most Americans don’t think the media is covering climate enough. People want more information. And they want specific information, focused on solutions.

You’ll find solutions in these pages: in Gwyn McAllister’s story about a family determined to boost bees while creating something delicious; in Sam Moore’s profile of the scientists at Woodwell Climate Research Institute, quietly doing important work.

Meet the two fellows growing wildly delicious mushrooms on logs at Martha’s Vineyard Mycological. Meet Jessica Mason, who launched MV Island Eats to transform disposable take-out containers; and Julie Pringle, a champion of the Island’s great ponds.

When you have a minute, check out our new national website at bluedotliving.com, where we feature changemakers from all over the country — locals making a difference as they do here (our MV site is marthasvineyard.bluedotliving. com). You can sign up for newsletters for each site.

One thing that’s certain during these uncertain times is that action creates hope. We’re grateful for all of you who use this information to take action in your own lives, and for the advertisers and non-profits who support our work.

And finally, an apology to Skip Finley. In our Late Winter 2022 What.On.Earth. column, we stated that the number of Black whaling captains on the Vineyard was five. In fact, Finley had written, there were five “men of color,” including an Indigenous man who was lost at sea before he was able to captain the ship he was expected to; and “a mulatto, the last living captain with Native American ancestry.” Further, we cited The Atlantic Black Box Project as the source for some of our data, but it was first published in the Vineyard Gazette by Finley. Bluedot regrets the error.

4 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022 EDITORS' LETTER

(508) 627-2454 | GeesePartners.com | mv@geesepartners.com Commercial, Residential & Event Goose Control on Martha’s Vineyard Take Back Your Turf Safe & Eco-Friendly Goose Control Free Estimates We are a local, year-round island business

Readers,

–Leslie Garrett (and Jamie Kageleiry)

Dear Bluedot Living

5 marthasvineyard. .com

CONTENTS

4 Editors' Letter

8 What.On.Earth This one’s for the birds

9 In a Word: ‘Soft Fascination’

10 Buy Better: Rooey Knots, Helayne Cohen bowls, and Original Cyn jewelry

11 Local: Reimagining take-out containers

12 Good News from All Over

Features

16 Ginny Bee Honey Keeps It Local

By Gwyn McAllister

This family operation is generating quite the buzz.

20 Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs): What’s So Bad About Them, Anyway?

By

Leslie Garrett

Do the benefits outweigh the potential dangers?

25 Accounting for Carbon

By

Sam Moore

How Woods Hole’s Woodwell Climate Research Center became a hub for climate research and policy.

ONLINE

at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Field Note: The Felix Neck Crew catches us up

Field Note: IGI plants for the birds

Departments

14 Dear Dot Our eco-advice columnist responds: Is there an eco-friendly way to keep my yard tick-free?

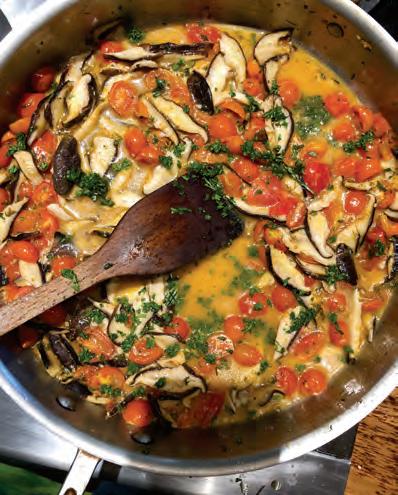

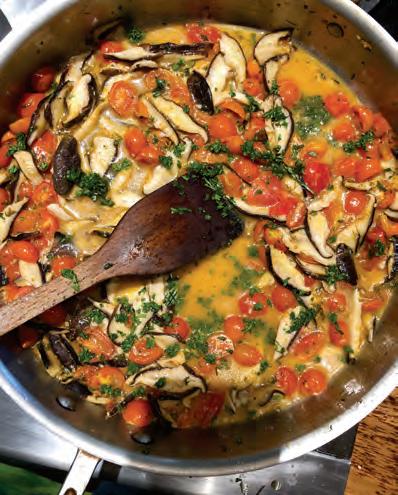

30 Good Food: Turning Wood Into Food

By Catherine Walthers

Martha’s Vineyard Mycological cultivates worldclass mushrooms. Plus recipes to use them!

36 Room for Change: The Kitchen

By Mollie Doyle

You don't need all that gear! Create a clutter-free, planet-friendly kitchen.

22 Cruising with Currier

44 Garden: Making Room for the Birds and the Bees

By Angela Luckey

Plant your yard to roll out the welcome mat for pollinators and wildlife.

46 The 'Keep This' Handbook

Your eco-guide to composting, recycling, volunteering, activism, and more.

47 Field Note: SMF'S Adam Moore plants chestnut trees

48 Local Heroes: We nominate Great Pond protector Julie

Pringle

6 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

Ride along in a Nissan Leaf EV with Island activist Jed Katch.

Upfront

PHOTO BY SHENY LEON

BDL 7 marthasvineyard. .com www.mvbuyeragents.com 508-627-5177 Email: buymv@mvbuyeragents.com 13 Coffins Field Road Edgartown, MA 02539-1661 “And, when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.” — Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist OPEN FOR DINNER TUESDAY ~ SUNDAYS FROM 5-10 CLOSED MONDAYS ATRIAMV.COM · 508-627-5850

What. On.Earth.

This one’s for the birds…

1. Percent of the world’s bird species that are songbirds: ~50

2. Percent of songbird species in which the females sing: 66

The slow overture of rain, each drop breaking without breaking into the next, describes the unrelenting, syncopated mind. Not unlike the hummingbirds imagining their wings to be their heart, and swallows believing the horizon to be a line they lift and drop.

3. Percent decrease in volume of Sparrows’ song during the early pandemic when noise pollution was down: 35

4. Number of acorns that Acorn woodpeckers store individually in holes in trees, fence posts, utility poles, and buildings: up to 50,000

5. Percent of North American bird species that feed insects to their young: 96

6. Number of species of butterflies/moths supported in North America by native oaks: ~550

7. Number of caterpillars a clutch of Carolina Chickadee chicks eat in the 16 days between hatching and fledging: 9,000

8. Number of songs Sparrows sing: ~10

9. Number of songs Brown Thrashers sing: ~2,000

10. Distance north that seven North American Warbler species have shifted in past quarter century: 65 miles

11. Distance south that 35 North American Warblers have shifted: 0 Miles

12. Number of bird species that have gone extinct in past five centuries: 150

13. Number of bird species protected from extinction by stabilizing carbon emissions and holding warming to 1.5 degrees C: 150

14. Percent increase in sightings of Wood Thrushes, Eastern Towhees, Veeries, and Scarlet Tanagers (all species of conservation concern) in yards with native plantings as compared with yards landscaped with typical alien ornamentals: 800

1/2: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology; 3: Eos; 4: Allaboutbirds.org; 5/6/7: Audubon; 8/9: The New York Times; 10/11: Nature Canada; 12: Our World in Data; 13: Audubon; 14. Allaboutbirds.org.

8 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

–Excerpt from ‘Mind’ from The Dream of The Unified Field by Martha’s Vineyard poet Jorie Graham

PHOTO SAM MOORE

in a word Soft Fascination

When Spencer Kelly was in grade five, his teacher became exasperated by what she called his “daydreaming.” While the other kids had turned to the appropriate page in their textbooks, Kelly would be staring out the window. When his classmates were turning in their assignments, Kelly was still sketching in the margins. Helicopters, which were a fascination of his. Sharks.

His parents joked they could send him to his room to retrieve his shoes, only to discover him, 45 minutes later, still shoeless but having constructed a Lego Blackhawk. Unlike those around him, Kelly saw no problem with his daydreaming.

Neither, increasingly, do some researchers who have coined different terms for it. Attention Restoration

Theory, for instance, uses the term “soft fascination,” and holds that, according to New York Times columnist Lisa Damour, “soft fascination relieves stress by helping us close those mental browser tabs; unhurried reflection lets us sift through mental clutter, quiet internal noise, and come up with fresh, useful solutions.” Soft fascination is the opposite of our productivity-obsessed culture. It isn’t about achievement at all.

Not surprisingly, we often experience soft fascination in nature, where stress is relieved, our ability to focus is restored, and little that our society values is accomplished.

Johann Hari, author of Stolen Focus, discovered soft fascination, which he called mind wandering, when, exhausted from what he described as fattening himself up

on information “like some sort of foie gras goose,” he began walking in nature. “I came back from these long walks feeling so alive and mentally fertile,” he told podcaster Ezra Klein. “And I started building in loads of space for mind-wandering. I started to see connections between things I hadn’t thought about before, I started processing things in my past, I started creating visions for the future.”

It is likely only a matter of time until our culture commodifies soft fascination, giving us goals and strategies to achieve it. But the joke’s on them. All it takes is an aimless walk in the woods or, if that’s impossible, the willingness to do nothing more than stare out a window and let your mind do the wandering.

–Leslie Garrett

IN A WORD 9 marthasvineyard. .com

The Island’s source for organic mattresses, pillows, and bed linens. Ergovea is our organic and natural latex mattress brand, providing the purest night’s sleep; Ergovea’s pillows are paradise. Sleep and Beyond provides toppers, sheets, pillows, comforters and more of your bedding needs. 322 State Road, VH · 508-696-9600 oceanbreezemvbedding.net Get the purest night’s

Come see our collection of organic sheets

Ocean Breeze Bedding

sleep

/sôft/ /,fasə'nāSH(ə)n/

Buy Less, but Buy Better

By Gwyn McAllister Photos Courtesy of the Artists

By Gwyn McAllister Photos Courtesy of the Artists

Rooey Knots

Even prior to the rise in work-from-home culture, men had pretty much eschewed neckties for a more casual look. According to fashion forecasters, ties are on their way out, which is just fine with the majority of men, who are happy to release themselves from the windpipe restricting accessory. This is also good news for Gareth Brown of Rooey Knots whose cottage industry is based on repurposing discarded silk neckties, which she picks up at second-hand stores, to create colorful women's headwear.

Each Rooey Knots' creation incorporates two or more ties, either twisted into a half-and-half design, knotted into a fun flapper style band with a front bow, or woven together into a multi-patterned

headband. Brown also constructs more elaborate designs like a flower crown with a ring of roses made entirely from sculpted ties. The neckties provide wonderful patterns and colors that the designer mixes and matches to complement each other. The unique beauty of each is enhanced by the pairings.

More recently, Brown has started making little crossbody bags with stripes of patterned tie material, backed with reclaimed denim or leather, and embellished with a leather fringe. She also twists necktie material into bracelets and necklaces. Generally Brown limits her designs to silk ties, but if she finds a particularly eye-catching pattern in a man-made fabric, she will incorporate it into one of the small bags.

Rooey Knots served as the launching pad for Brown's fashion line, which currently includes dresses, blouses, dusters, and jumpsuits, all made from remnant fabrics — another way that the designer focuses on using surplus or other materials destined for the landfill in her various lines.

Continued on page 41

BUY LESS/BUY BETTER • UPFRONT 10 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022 Masterson Tree Care STEPHEN MASTERSON 774-563-0528 | Mastersontreecare.com * Seasonal Clean ups * * Tree removals * * Tree and Shrub pruning * * Fruit tree pruning* * Transplanting * * Vista pruning * 20+ yrs experience Degree in Horticulture / I.S.A. Arborist Certified in natural area land management Your Renewable Energy Solution Solar, plus smart, safe and long-lasting battery technology. Power your home with clean energy around the clock with solar and batteries. www.fullers.energy 508.696.3006 info@fullersenergy.com

JESSICA MASON TACKLES TAKE-OUT TRASH

A new pilot program urges you to take away, don't throw away.

By Gwyn McAllister Photos Courtesy Island Eats

You may not realize this but, even with all of the current recycling initiatives in place, most plastic is still never recycled. According to Jessica Mason, founder of the pilot program Island Eats MV, a whopping 91% ends up in landfills, including plastics that are produced to be recyclable, and even those that conscientious consumers throw in recycling cans and bins.

“When you start to dive into the depths of it [recycling], it’s an incredibly complex system,” says Mason. “When we put something in the recycling bin, we think we’ve done our job. It’s not that easy. Recycling isn’t the panacea that we thought it might be.”

LOCAL

of a reusable 75%-recycled stainless-steel container system, Mason aims to help cut back on plastic and other forms of landfill bound waste.

“Think of it as all our favorite takeout without the heart-wrenching waste,” says Mason.

token back when you return the bowl to any of the participating businesses.” Island Eats will collect the bowls from the businesses and wash them at Kitchen Porch’s commercial kitchen facility before returning them to the restaurants.

For the pilot program, five local businesses have signed up — MV Salads, Bobby B’s, Black Sheep, Pawnee House, and the Katama General Store.

Although many Island restaurants are now opting for plastic alternatives, Mason notes that even those are not a foolproof solution. In a press release, she writes, “ Those so-called 'biodegradable’ and 'plant-based’ containers? Most are really a combination of plant-produced starch and … plastic. And even ‘compostable’ containers are just regular trash piling up in landfill unless we can ensure they actually make it to a commercial facility.” Apparently, even under the best of circumstances, much recyclable material actually ends up as regular trash.

To address this problem, Mason launched the initiative Island Eats MV, a closed-loop reusable takeout container system. The program, started in May with a trial run through September, will provide a workable solution to the problem of the landfill-bound waste created by restaurant to-go containers. By providing consumers with the option

She explains how the model works. “You purchase a wooden token, which entitles you to use one reusable container at a time. When the restaurant gives you the [stainless-steel] bowl for your takeout you give them your token. You get the

Mason notes that a number of other Island businesses were interested in jumping on board but she had determined that the trial program needed to be capped at five. Mason, a Chilmark resident and executive director of a national nonprofit that helps launch cooperative businesses, hopes that one day Island Eats will become self-reliant. “The goal is for it to be a restaurantowned cooperative. The businesses would share the governance and profit with the community.”

Mason notes that similar reusable takeout container programs have proven successful in US cities and places in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. She had anticipated that the system would work well here and, so far, the program has been met with enthusiasm by both consumers and business owners. She has had to put some local restaurants and consumers on a waiting list for the future, when, hopefully a more full-scale program will follow the pilot.

“I think we have a community here that is largely conscious of how we are impacted by the climate and environmental issues,” says Mason. “We live so closely to the land. We feel it more strongly than other folks do. The landfill is a really important issue on the Island.”

LOCAL • REUSABLE CONTAINER PROGRAM 11 marthasvineyard. .com

FROM ALL OVER

By Lily Ireland Olsen

Green Living Gives Back

A lot of hesitance around adopting more environmentally friendly habits comes from a fear that the sacrifices mean settling for an unsatisfactory lifestyle. A swath of recent research, however, indicates that greener lifestyles are linked to higher levels of happiness. Taking actions that benefit others and align with one’s values lead to psychological benefits.

One study in particular found that a positive correlation between environmentally beneficial lifestyles and happiness exists whether or not someone lives in a rich or poor country. The study evaluated 7,000 people across seven countries.

Many green habits provide benefits other than merely psychological ones. Low-carbon diets tend to be healthier, for example, and riding your bike instead of driving allows you to get more exercise. So, if you’re looking to make the switch to greener habits but are worried about leading a more mundane or complicated life, fear not. If anything, you’ll likely be healthier and happier.

Massachusetts Moves Forward on Climate Policy

A new bill offers sweeping upgrades to Massachusetts’ green practices. In early April several senators introduced the bill called the Act Driving Climate Policy Forward, according to WBUR. The bill would bring change to a number of sectors.

In transportation, the bill would decrease the cost of electric vehicles and provide funding for better charging infrastructure. It would also ban the sale of internal combustion engines by 2035 and mandate an all-electric bus fleet by 2028. In energy, the bill would offer a $100 million investment fund for the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center and provide flexibility on project costs for offshore wind development. The bill also aims to change solar regulations by allowing homeowners to place solar panels in more than one place on their properties and allow farmers to put solar panels where they raise livestock or grow food. Lastly, when it comes to building codes, this bill promises to bring in environmental groups and the public to plan for the future

GOOD NEWS • UP FRONT 12 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022 raw honey + beeswax candles + propolis throat spray + clean moisturizers full-service, professionally managed beehives for your property pollination services · swarm removal · honeybee art 17 Proprietor’s Way VH, by appointment only 508 693 6288 | @islandbeecompanymv generating buzz since 1999 BLUEVIEW GUTTERS Seamless Aluminum, Copper, Fiberglass, Wood Installation, Repairs, Seasonal & Yearly Cleaning Joseph Cogliano 774-563-0938 FREE ESTIMATES CALL

good news

of natural gas in the state, diminishing the power that utility companies have long had over the process. These and many other policy changes could broadly improve environmental practices in the state if the bill is passed.

Boston is Shining a Light on Clean Energy

Boston’s centuries-old street lamps may soon be revamped as part of the city’s efforts to limit its environmental footprint, The Boston Globe reports. The 2,800 colonial street lamps, which line streets from the Back Bay to Charlestown, are currently gas-powered and stay lit 24/7. These lamps contribute 5,000 metric tons of greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere each year. In March, however, city officials began replacing the lights with energy-efficient LEDs, which simulate flames. If implemented on a broader scale, this switch could preserve the ambience of historic Boston while also cutting down on greenhouse gas emissions.

The Grist Report: Hope for Wind Energy

A lease for offshore wind development went for a record-breaking bid in February, reports Grist, signaling that investors and developers see potential in offshore wind. When the Biden administration leased almost half a million acres of the Atlantic Ocean for offshore wind development, fourteen companies drove up the bid to a closing price of $4.37 billion. The largest tract went to Bight Wind Withholdings for $1.1 billion.

This per-acre lease price is nine times what companies paid in the last U.S. offshore wind auction. This comes as state and federal policy support for the industry has grown. This latest sale may be a building block toward Biden’s goal of developing enough offshore wind power to supply 10 million homes with energy by 2030.

New York City Oysters Guard Against Storms

New York City restaurant-goers can now protect the city from storms by feasting on oysters. Thanks to the Billion Oyster Project, restaurants can donate oyster shells for use in building breakwaters, reports The Guardian.

The organization is building nearly a half-mile of partially submerged breakwaters covered in oyster shell reefs. These reefs are aimed at minimizing erosion and flooding. They will also provide habitat for sea creatures.

Oysters are a particularly useful tool for green infrastructure, as the bivalves are resilient to ocean currents and crashing waves when they’re attached to rocks. They also act as water filters, with each oyster able to filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, removing pollutants and improving water quality.

The project is mutually beneficial too — oyster populations are revived as these creatures protect human populations.

Stay

· Water Quality

· Pond Biodiversity

· Pond Opening Info

· Eelgrass Ecosystems

· Blue Carbon & Climate Change

visiting greatpondfoundation.org

Cyanobacteria, a.k.a. blue-green algae, are a group of microorganisms found in all Vineyard waters. When cyanobacteria bloom, they can produce cyanotoxins, which when concentrated, can cause adverse health effects in humans, pets, or livestock who wade in or ingest blooming waters.

See current conditions by visiting greatpondfoundation.org/mvcyano

UP FRONT • GOOD NEWS 13

.com

marthasvineyard.

The choices we make as an Island community over the next few years will shape the fate of our waters for generations.

Please join the Great Pond FoundationTM in our efforts to restore the ecological health of our coastal ponds through scientifically informed management, public education, and community collaboration.

informed and engaged by

MV CYANOTM is a collaborative initiative among Island Boards of Health and Great Pond Foundation to monitor cyanobacteria on Martha’s Vineyard.

TM

TM REPORT

dot DEAR

nymphs are the size of poppy seeds, and like to nestle into our bodies’ warm humid crevices (armpits or groin, for example), Johnson recommends that we feel for them when we shower. If there’s a tiny bump that wasn’t there yesterday, it’s likely a tick nymph.

on that later) but they will seek out certain plants. Rhododendron is a popular tick hangout, as are the invasive plants, Russian olive and bittersweet, giving us yet another reason to banish those from our yards.

Unfortunately, keeping Lone Star ticks at bay isn’t so simple. Johnson calls them the “cheetahs” of the tick world because they move so fast. “For years, we’ve been telling people they don’t need to worry [about ticks] on their lawns,” says Johnson, but Lone Star ticks react to carbon dioxide. So if you’re breathing or sweating on your lawn, he says, “they will come after you, across the lawn from the woods, and seek you out and bite you.” Yes, that’s right: Lone Star ticks will seek you out and hunt you down like micro-assassins. If you have a major tick problem, or if Lone Stars have moved into your territory, there are a few options available to you to reduce their numbers.

Dear Dot: Is there something I can put on my lawn that doesn’t harm wildlife, including my pets or grandchildren, but that deters ticks?

—Rose, Vineyard Haven

Dear Rose,

I know I’m supposed to love all bugs because they play a part in the ecosystem and blah blah blah but c’mon … Ticks? Ugh.

While most of us go out of our way to avoid ticks, Island biologist Dick Johnson seeks them out. Johnson is the tick guy on the Island, spending his days hunting these tiny terrorists to better understand where they are and what they’re doing. The Lone Star nymphs (such a glorious name for such a nasty creature) are already out by early April. The deer tick nymphs emerge a bit later — mid to late May, says Johnson — and are dangerous because they’re so tiny at that stage. Be vigilant. If you, your kids and grandkids, or pets have been outside, follow up with a tick-check. Because the deer tick

A tick “bite” is something of a misnomer, says Johnson. What ticks actually do sounds like something from a horror movie. With their barbed “hands,” ticks essentially breaststroke into your skin, then jam in a mouth part called a hypostome — Johnson says it acts like a straw. Except that this straw also has hooks akin to a miniscule chainsaw. Compounds in the ticks’ saliva make our blood pool beneath the skin and the tick begins to sip, a delicate feast that can last three to ten days. “If [ticks] were the size of a cow, they’d be really scary,” Johnson tells me, ensuring that I will begin to have nightmares of cow-sized ticks.

What can we do to prevent these blood-thirsty, chainsaw-wielding noncow-sized-but-still-horrible ticks?

The first step is in your yard, Johnson says. If you’re in a tick-prone area, get rid of leaf litter and pine needles that offers the damp shady conditions that ticks love. I’m reminded, however, that eco-gardening experts urge us to leave that stuff for precisely the reason that it’s ideal habitat for so many of the other insects we love.

At minimum, if your yard abuts a wooded area, create a three-foot wide strip of gravel or large wood chips to act as a barrier to ticks. This can also serve as a visual reminder to you that beyond is tick territory.

Ticks aren’t typically on lawns (more

Keep your grass short, no taller than 3 to 3 ½ inches.

Encourage birds in your yard. Ground-feeders like sparrows, that pick about in leaf litter, feast on ticks.

Johnson is leery about the impact of larger birds, such as turkeys and quail, which he says some people are employing to tackle ticks: “That's making me very nervous because Lone Star ticks in particular feed on birds so they may be eating some of the ticks but at the same time, you're feeding a whole bunch of ticks.” A dead turkey that Johnson recently examined had five Lone Star ticks attached to it.

“Most ticks die from not getting a meat blood meal,” he explains. “Between the different stages as they hatch, they have to get a blood meal to become a nymph, which I call the teenagers. Teenagers have to get a meal before they become an adult so they have to feed twice and most ticks don't make it — they either get eaten or just don't ever get the blood meal they need to live. When you put out a quail or something like that, you may just be keeping more ticks alive. So the question is how many ticks does the quail eat versus how many ticks feed on it and increase the population?”

For really difficult tick problems, Johnson says, you might want to pull out the big gun, a chemical called permethrin.

14 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

Illustration Elissa Turnbull

Dot tackles your thorniest questions from a perch on her porch

“It’s actually a type of plant, a relative of the chrysanthemum,” he said, though in North American it’s been reconfigured as a synthetic pesticide. Johnson says it’s considered safe for children and dogs (permethrin is highly toxic to cats), though Consumer Reports noted that permethrin is an endocrine disruptor so use should be careful and judicious and a last resort. Another problem is that permethrin is indiscriminate — killing our beloved pollinators as effectively as it does the dastardly ticks.

Still, it’s hard to argue with its effectiveness. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Medical Entomology determined that clothing treated with permethrin was 58% more effective at protecting the wearer than non-treated clothing. You can purchase permethrintreated clothing from manufacturers (including L.L.Bean) or purchase a permethrin spray and apply it to your clothes, being careful to follow instructions.

If you do find a tick has chosen you as its next blood meal, remove it by using tweezers

as close to the skin as possible and pulling straight up. It takes 24 to 48 hours for a deer tick to begin transmitting Lyme disease so sooner is better than later to check your body for ticks. If you are bitten, get doxycycline as a prophylactic, Johnson says. “There's a good study in The New England Journal of Medicine that showed an 85% reduction in incidence of Lyme disease with people who were treated within the first couple of days with a dose of doxycycline,” he says.

Of course, it isn’t just Lyme disease that’s of concern. Though less prevalent, ticks can also carry babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Lone Stars can carry tularemia and anaplasmosis, two illnesses that can lead to death.

Johnson is optimistic that a new vaccine against Lyme disease (already available to our dogs) will be available in three to five years.

In the meantime, let’s review our options: a gravel or mulch barrier, removal of plants where ticks like to congregate, encouraging ground-feeding birds

such as sparrows and discouraging larger birds like turkeys and quail, and donning permethrin-treated clothing when spending time in tick territory.

But let’s not overlook some simple steps: When you’re gardening or hiking, wear long pants, socks, and a long-sleeved shirt at minimum. Do a daily tick check of yourself and others for ticks, including their favorite bodily hideouts. Johnson himself is well covered in permethrin-treated clothing that he sends to Insect Shield, a company that will treat your clothes and return them to you (clothes remain treated through roughly 60 launderings) and even though he’s logged many hours in tick habitat intentionally handling thousands of ticks, “we don’t get bitten,” he says.

May we all be so lucky. Avoidantly, Dot

Please send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com

DEAR DOT 15 marthasvineyard. .com

Read more at bit.ly/DEAR-DOT

Cut Down Emissions and SAVE! $30 chainsaw rebate $75 lawnmower rebate $30 string trimmer rebate $30 leafblower rebate NEW REBATES FROM CAPE LIGHT COMPACT ON BATTERY-POWERED LAWN EQUIPMENT: CapeLightCompact.org 1-800-797-6699

This family operation is getting quite the buzz.

SWEET DREAMS • FEATURE 16 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

Story By Gwyn McAllister Photos by Sheny Leon

Ginny Bee Honey Keeps it Local SWEET DREAMS:

Brent and Lisa Brown with (from left) Harrison, Maybeline, and Eleanor.

Brent Brown has found the perfect way to realize his dreams of farming the land. Rather than raising crops or animals, Brown tends much smaller livestock — honeybees.

“I’ve always dreamt of having a big farm and growing all kinds of vegetables,” says Brown, who eventually had to accept the reality that the price of real estate on Martha’s Vineyard made that dream prohibitive. Instead, he decided to farm bees. “It’s a happy medium,” he says. “You don’t have to have a lot of property or even have your own property at all. They fly wherever they need to go.”

Currently Brown operates a small apiary on the grounds of the Norton Farm on the Vineyard Haven/Edgartown Road. There he has set up a number of hives from which he extracts honey to sell at the farm’s produce and baked goods store.

Ginny Bee honey is all natural, unlike commercial honey which can contain glucose and fructose, among other additives and, best of all, it’s all the product of Island flowers. Brown notes that aside from giving you some immunity to local types of pollen, buying Vineyard honey helps sustain our local environment.

“Eating local honey is supporting your local beekeeper and also helping support the local bee population, which is in decline worldwide because of habitat loss,” says Brown. “You’re supporting the honeybees being out there and cross pollinating and producing our food. Bees do a wonderful job of pollinating our crops.” It’s said that one of every three bites of food is brought to you by honeybees.

While he takes his beekeeping very seriously, Brown notes that he’s able to work full time as project coordinator for Rosbeck Builders while pursuing his hobby after hours and on weekends. Aside from frequent hive inspections, the bulk of the work takes place in the spring and early summer months, when he can sustainably collect the honey.

“I only harvest honey from the bees in May, June and July,” says Brown. “What they make in the summer is

FEATURE • SWEET DREAMS 17 marthasvineyard. .com

Brent is able to pursue the beekeeping after work and on spring and early summer weekends.

excess. When the flowers are out again in the fall, I leave that honey in the hive for the bees to eat during the winter months. I’m very cautious not to take too much honey.”

Brown notes that not all honey producers are as scrupulous as he is. “There are plenty of beekeepers out there who will take every ounce of honey that the bees make and replace it with a sugar water solution. There’s a lot more to honey than sugar.”

Brown prioritizes maintaining large, healthy thriving colonies that will yield as much honey as possible, while keeping the Island’s bee population up. He notes that his hives house from 40,000 to 60,000 bees in the summer, with the population decreasing to around 10,000 in the winter (much like the Vineyard’s seasonal human population differential, but not as drastic).

Along with the Norton Farm hives (which number from 10 to 20 depending on the season), Brown also keeps bees on other properties around the Island but he doesn’t harvest the honey from these smaller hives, which need whatever they can produce.

It doesn’t take much in the way of equipment to harvest and process honey. Brown explains the extraction process: “I take home the wooden frames that the bees create the honeycomb on and I use a knife to cut off the wax. I put the frame in a spinner that uses centrifugal force to pull the honey from the frame. I filter it once and then bottle it. What you eat is straight honey, no additives.”

Born and raised in Colorado, Brown had never considered beekeeping as a hobby until after he moved to the Vineyard in 2016. “Seven years ago I decided

to take the plunge. I purchased the equipment and the hives and watched a lot of YouTube videos.” Trial and error played a big part in Brown’s education. “Experience is a good teacher,” he says. “I learned from my mistakes.”

Brown credits his move to the Island as inspiration for his apiary aspirations. “I fell in love with nature and the beautiful landscaping and uncultivated areas all around us. I work in the office all day long. Beekeeping is a nice break for me. It gets me out in nature.”

Another incentive for Brown was finding a venture that he could share with his three children. “I really created it for my kids,” he says, “to help them learn

SWEET DREAMS • FEATURE 18 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

“Eating local honey is supporting your local beekeeper and also helping support the local bee population, which is in decline worldwide because of habitat loss,” Brent Brown says.

The Browns’ bees number close to 60,000 in summer. Brent credits his move to the Island for his apiary aspirations. You can buy the honey at the Norton Farm.

about business and nature. Any profit we’re trying to save for college.”

The Brown kids – ages six, nine, and eleven – all help out with the bottling and preparation of the all-natural beeswax lip balm, which is also available at the Norton farm stand. Brown’s wife, Lisa, does the photography, among other things. “Everyone in the family has a little part in this,” says Brown.

He also makes it a part of his mission to educate others. During the summer months, Brown hosts tours of the Norton Farm apiary where he talks about the lifecycle of bees and their important role in the environment. Guests then don bee suits for a hive inspection. He will open up a hive so that visitors can see the inner workings and even hold a frame full of thousands of bees if they choose to. The tour concludes with a taste test comparison between Ginny Bee and commercially produced honey.

“In doing something they’ve never

done before, people can better understand the process and maybe overcome some of the apprehension they have about honeybees,” says Brown. “Being in the apiary and finding out that the bee’s primary goal is to collect nectar and pollen goes a long way towards

WHAT YOU CAN DO

As for encouraging others to take up beekeeping, Brown notes that it’s not something that one can experiment with and then give up on when the novelty has worn off. “It’s not like buying a bicycle and then putting it away when you’re over it,” he says. “You have a responsibility to a colony of living creatures.” Instead, he has a suggestion for those who want to do their part in sustaining the Island bee population. “People can plant a variety of different types of flowers that bees are attracted to,” he says. (See our Attracting the

understanding the importance of bees in our ecological system.”

Gwyn McAllister writes frequently about local eco-friendly products for Bluedot Living. She is also a regular contributor to Edible Vineyard.

Birds and Bees story on page 44.)

“You should be aware of planting flowers that have blooms throughout the year. That way the bees will have something to constantly forage from. In the spring and summer the bees have plenty to choose from but, come September, it’s critical for them to build up their honey supply for the winter.”

If you really have your heart set on starting your own apiary, Brown has some practical advice. “It can be a great hobby as long as you do all your research first. But don’t do it for the cheap honey. It will be the most expensive pound of honey you’ve ever purchased.”

FEATURE • SWEET DREAMS

19 marthasvineyard. .com

A woman harvests rice in Bangladesh. Genetically modified Golden Rice has considerable health benefits and may soon be on people's plates there.

GENETIC MODIFICATION • FEATURE 20 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

SHUTTERSTOCK

GENETIC MODIFICATION?

Story by Leslie Garrett

WHAT’S SO BAD ABOUT W

hen we cross the border from Canada en route to the Vineyard, my husband and I typically stop to refuel in upstate New York where we always buy a bag of Chex Mix. Chex is an American thing for us, hard to find in Canada. My doctor thinks my inability to get Chex regularly is a good thing, noting my rising cholesterol.

At his urging, I’m more carefully reading food labels, which is why I recently noticed this on the Chex bag: “Contains Bioengineered [BE] Ingredients.”

Or, put another way, “You are eating genetically modified food.” Ask anyone about genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, or bioengineered ingredients (all terms for the same process) and you will typically hear strongly held opinions. As a supporter of local organic farms, where I buy my family’s weekly meat and produce, and as an environmental journalist, I myself have held a few strong opinions. While I hesitated to believe genetically modified food to be “Frankenfood,” an evocative and catchy term coined by GMO opponents, I didn’t want GMOs in my food, or more to the point, my children’s.

I settled on being a strong proponent of labeling, the so-called Right to Know: We all deserve the right to avoid GMOs, if we chose.nto ponds and rivers and lakes and oceans.

FEATURE • GENETIC MODIFICATION 21 marthasvineyard. .com

From “Frankenfood” to eradicating disease, GMOs have been regarded as both peril and promise. But one thing’s for sure: They’re here to stay.

Isettled on being a strong proponent of labeling, the so-called Right to Know: We all deserve the right to avoid GMOs, if we chose. There were — are! — a lot of us. Enough that the Obama administration passed a law — mandatory as of January 1, 2022 — that food manufacturers, importers, and others that label food for retail sale must designate products that contain bioengineered ingredients as such.

Hence, the label on my bag of Chex Mix.

But a funny thing happened between my “Right to Know” stage and gleefully scarfing Chex Mix clearly labeled as containing BE ingredients. I stopped fearing GMOs.

Because, obliviously or not, I’d been consuming them in some form or another since roughly the mid-90s. Indeed, most of us had.

And while there’s no denying that GMOs have problems, safety doesn’t seem to be one of them.

Executive Director of Project Drawdown Dr. Jonathan Foley put it this way in an article he wrote for his GlobalEcoGuy site: “My concern about GMOs is that they are being used very poorly right now, and without larger social and environmental consequences in mind.” He notes that even “the more enlightened proponents” of genetic modification are being cavalier about long-term impacts.

To-may-to, to-mah-to Food that is genetically modified has either itself been altered through a process called recombinant DNT (or gene splicing) to create a desirable trait — or it contains ingredients whose genetic makeup has undergone that process. Genetically engineered foods differ from non-GE foods in that they contain one or more new genes and usually make a new protein.

Let’s look at the one that started it all: the Flavr Savr tomato (the greater assault might be on literacy!). The Flavr Savr was modified to stay firm after harvest and was the first genetically altered food product to be approved by the FDA. It

was put on the market in 1994. Unfortunately, according to a 2016 story in Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News, Flavr Savr didn’t live up to its hype — hype that consumers at the time largely embraced or, at least, accepted. Calgene, the California-based company that launched the Flavr Savr, was spending more than it was making, even with the tomatoes priced higher than the conventional ones. When agri-tech giant Monsanto bought Calgene, it retired the Flavr Savr. But, of course, Monsanto had plenty more genetically engineered products up its sleeves, including Posilac —bovine somatotropin (bST), a growth hormone that increases output of milk from dairy cows; and Roundup Ready versions of corn, cotton, canola, and soybeans, primarily used in animal feed, high-fructose corn syrup, and corn ethanol. Both changed the game. Roundup Ready crops were impervious to Roundup, the glyphosate-based weed killer, so farmers could liberally spray their crops. But glyphosate was known, even then, to be harmful to human health, notes the Sierra Club, citing “decades of research [that] connected the weed killer to cancer.”

Monsanto became the face of GMOs, an easy enemy to those of us suspicious, not only of the technology, but who controlled it and how.

Fear of something new has always been an easy sell. “The easiest message to convey to people is that, well, we’re tinkering around with things that we don’t fully understand so how can we possibly know all of the consequences,” says Jon McPhetres, an assistant professor of psychology at the U.K.’s Durham University who studies why

GENETIC MODIFICATION • FEATURE 22 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

The focus at Island Grown Initiative has been less about GMO resistance, says Noli Taylor. “It starts with the seed … and represents the values of the work we do in the community, which is about equity, access, regenerative systems, community care, care for the people, care for the land … all of that can be embodied in the seed system.”

Before she moved to Martha's Vineyard, Noli Taylor made her home in Hawaii, which is where she first saw the community impact of GMOs up close.

JEREMY DRIESEN

we sometimes reject science. It’s a message that resonated. And while McPhetres does think there are potential problems with GMOs, he told me, “The one that people are scared about is the biological one, which I think is probably misguided.”

Safe is not the same as harmless

Before she moved to Martha’s Vineyard, Noli Taylor made her home in Hawaii, which is where she first saw the community impact of GMOs up close. The Hawaiian government had given considerable farmland to agricultural companies in an attempt to save the papaya industry, which was collapsing due to the papaya ringspot virus. But though many credit the “rainbow papaya,” a genetically modified papaya created by a Cornell scientist, with saving the key crop, there’s no arguing with how quickly the GM version eclipsed the conventional one, leaving even those who wanted organic (non-GMO) papayas with no choice, due to spread.

What’s more, says Taylor, Senior Director, Programs, at Island Grown Initiative, there was considerable division between those who blamed the pesticides being sprayed on the rainbow papayas for making people sick and those who saw the GM version as saving their industry.

To Taylor, it offered an argument for the type of farming that she and IGI espouse. “Our focus has been less about GMO resistance and more on creating these pathways for different approaches to how we grow seeds, how we connect with the community around foods.” For Taylor, “It starts with the seed … and represents the values of the work we do in the community, which is about equity, access, regenerative systems, community care, care for the people, care for the land…all of that can be embodied in the seed system.”

Golden opportunity?

Much of the pushback against GMOs has fallen along the same lines as Noli Taylor’s desire to see food and the control of it remain in the hands of people, not corporations.

This, at least in part, led to the backlash against so-called Golden Rice, a rice that was genetically modified to have beta-carotene in the edible part of the rice. Millions of people primarily in Asia, including an estimated 250 million preschool children, who rely on rice as a staple food suffer from

Vitamin A deficiency, which can lead to blindness and premature death.

The pushback to Golden Rice was swift and severe. Promises from the company that produced it that it would always be given to qualifying farmers free of charge were challenged. Opponents argued that it was better to encourage and strengthen local farming communities. Some maintained that a public health initiative aimed at providing nutritional supplements was preferable to promoting a GM crop. But proponents pointed to a technological advance created for humanitarian use and available free of charge to those who needed it (and who could save their seeds) and that it could improve the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

A combination of things, including the considerable regulations required, sidelined Golden Rice’s promise though it seems poised to be on people’s plates in the Philippines and Bangladesh sometime soon. It will be too soon for those opposed and not soon enough for those — including more than 150 Nobel Laureates who in 2016 signed an open letter to the UN, governments of the world, and Greenpeace — urging a more balanced approach to Golden Rice.

Can education open minds?

The story of Golden Rice underscores important considerations around GMOs, including that there must continue to be robust vigilance and testing before crops are put on the market. Currently, governments around the world implement strict protocols, including laboratory and field testing spanning many years, according to a release

from the Cornell Alliance for Science, adding “The resulting plants and foods are far more tested than their conventional counterparts.”

Which begs another question. Are the two approaches fundamentally incompatible? Or is there a way to incorporate GMOs while strengthening organic farming communities and ensuring that they don’t lose control of their products?

Jon McPhetres believes education can play a key role in shifting people’s understanding of GMOs. “There’s a lot of good evidence for simply teaching people basic scientific facts,” he says. “It’s not about completely reversing people’s opinion … but I think we can shift people to being slightly more positive, or at least less negative towards [GMOs].” He has noticed a similar shift in people’s opinions around nuclear energy, vaccines, and, yes, GMOs when people’s level of knowledge is increased. He admits that the rise of anti-vax sentiment is disheartening. He would like to see scientists do a better job of communicating with the public. “Science is really about change and changing your mind and changing your mind a lot, whereas people think that science is about finding the answer quickly and then never changing your mind from that.” We should change our minds, he says, when we learn something new.

McPhetres himself is fascinated by gene editing though he says he can “understand why people might be scared of it.” The answer, he insists, is talking about it, talking about safety, and realistic outcomes.

23 marthasvineyard. .com

The genetically modified rainbow papaya divided a community.

SHUTTERSTOCK

Genes creep in on tiny mice feet

Realistic outcomes are hard to hold onto when proposals seem like a combination of wishful thinking and science fiction. Take the Vineyard and Nantucket mice, for instance.

Kevin Esvelt, a biologist, associate professor, and one of the founders of the Mice Against Ticks project at MIT as well as an MIT PhD candidate and the project’s research director, Joanna Buchtal (who lives part-time in Menemsha), were tired of worrying about their children contracting Lyme disease. Ticks are a huge problem on the Cape and Islands, and so the project was created to harness the promise of CRISPR technology to alter the genetic code of the mice that ticks frequently use as their first host.

CRISPR, while often referred to in the same breath as genetic engineering, differs in that, while genetic engineering involves the introduction of foreign genetic material from a different organism (transgenic) or from the same organism (cisgenic), CRISPR involves changing or altering original base pair arrangements within the genome of an organism — there are no introductions.

Subject to CRISPR technology, these white-footed mice would create antibodies to kill the bacteria that carries Lyme disease, an immunity that would be passed down through generations. With fewer mice able to transmit Lyme to the ticks, fewer ticks will transmit Lyme to people, or so the thinking goes.

“We won’t be impacting the population with Mice Against Ticks,” explains Sam Telford, a professor of infectious diseases and global health at Tufts University who has dedicated his career to eradicating tickspread diseases. “We’ll simply be making that population less likely to have [Lyme] infection.”

“It’s not a new idea per se,” explains Telford. “After all, genetically modified mosquitoes are being deployed to try and reduce the risk of certain viral infections transmitted by mosquitoes, and there’s a big push to use genetically modified mosquitoes to combat malaria in Africa. It’s really the wave of the future.”

But if people are uncomfortable with scientists tinkering with tomatoes, one can imagine the hesitation with bioengineering hundreds of thousands of mice and then releasing them into the wild.

Or … wait.

Despite legitimate questions about potential problems of the ‘how would we ever put the genie back in the bottle,’ type, a variety of bioengineered Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have already been released in the Florida Keys in hopes of eradicating the diseases — Zika, dengue, chikungunya, and yellow fever — that this type of mosquito carries.

And the Mice Against Ticks project, though not a slam dunk, is being greeted by many on Nantucket with open-mindedness, according to a recent Boston Globe story, not least because ticks themselves have become an overwhelming concern. Similarly, Martha’s Vineyard has been the site of info sessions over the past few years about this initiative.

Telford calls the Mice Against Ticks project simply “another tool”, alongside habitat modification, insecticides, and reducing the number of deer, another favorite host of ticks.

And he, along with Esvelt and Buchtal, are clear-eyed about what they are asking people to approve. They insist that even after the considerable vetting required by local, state, and federal regulators, the project won’t go ahead without the support of both the Island communities — Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard — where the experiment will be undertaken.

So what’s the real issue?

Opening ourselves to the promise of gene editing, however, doesn’t mean we should swallow the GM story whole. Much of what proponents want us to believe — that GMOs will help us feed the world, that they will always boost yield — has been credibly challenged, even by those who aren’t vehe-

mently opposed to GMOs in principle.

“The real problem is that large-scale industrial monocultures are simply a bad idea — for the food system, for the environment and for us long-term,” wrote Dr. Jonathan Foley. GMOs, he continued, are part and parcel of this type of farming, perpetuating the problems. His concern is that GMOs are primarily driven by profit, without larger social and environmental consequences in mind.

Noli Taylor agrees. “Food shouldn’t be in the hands of a few big companies,” she says. “It should be in the hands of the people and the community. We should have the right and the ability to feed ourselves and help make sure that our neighbors have enough to eat and that all begins with the seed,” she says.

Jon McPhetres is also notably leery about the role that big agriculture companies play. “People can patent these kinds of seeds and they can take away people’s livelihoods,” he says. “This is a really different kind of issue. I think that’s the real issue.”

Chex mate

Ultimately, genetic modification is a new technology that isn’t, inherently, good or bad. Like any technology, it can be employed to solve problems or, used irresponsibly or corruptly, it can create problems, or worsen them.

But GMOs have become part of our food system and that isn’t going to change. We can, indeed must, ensure that oversight remains robust and principled. And though I personally haven’t made complete peace with genetic modification, for now, I am happy, as I dip my hand into a bag of Chex mix, to eat it.

24 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

GENETIC MODIFICATION • FEATURE

SHUTTERSTOCK

Proponents of genetically modified Golden Rice tout its health benefits, specifically to combat Vitamin A deficiency. But opposition has been fierce.

Looking at the stately Woodwell Climate Research Center, which sits on a hill off the road leading to Woods Hole, you might not guess that the renowned institution began in one man’s basement. That man is George Woodwell, and since 1985, the center he founded has been deeply involved in climate research and policy at home and abroad. Today, it employs nearly

100 scientists and staff, whose work on everything from permafrost to wildfires is shaping our understanding of the world we live in — and what we’re doing to it.

The Center’s scientists have been lead or contributing authors at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) since the outset, and in recent years its leaders, including John Holdren and Philip B. Duffy, have been science advisors to the Obama and Biden administrations.

H ow did these scientists all wind up here, in this hamlet on Cape Cod, which also boasts the Marine Biological Laboratory, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, and the National Marine Fisheries Service? Perhaps because Woods Hole attracts migrating scientists like a duck decoy — many arrive for a stopover, and some get bagged. “It could be, some say, that this is the place to be for a scientist in summer,” the New York Times gushed in 1997.

25 marthasvineyard. .com

How a littleknown center in Woods Hole became a hub for climate research and policy.

C 6

ACCOUNTING FOR

Carbon 12.011

George Woodwell at his home in Woods Hole.

The Woodwell Climate Research Center on Woods Hole Road got its start in George's basement.

By Sam Moore

Photos by courtesy Woodwell Climate Research Center

SAM MOORE

It's a hotbed of scientific opinion, and George Woodwell’s take is: “The accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere presents a serious worldwide problem that threatens the stability of climates within the lifetimes of people now living,” and “the time to take steps to mitigate those problems is now.” It’s pretty conventional wisdom — but these words are from 1979. And for Woodwell, it was old news then.

and to the scientists who worked to understand relationships between Earth and life at the planetary scale.

George Woodwell graduated from Dartmouth College in 1950 and joined the Navy, sailing aboard an oceanographic survey vessel in the North Atlantic. His ship ran back and forth across the newly discovered Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and its crew watched with deep-sounding sonar as the undersea

recalled. “We got a spectacular set of data showing not only the DDT in the soils and the fact that DDT was everywhere, but also showing that DDT was accumulating in the living systems of the place.”

Though their findings were published in the rarefied pages of the journal Science, it was Woodwell’s participation in a ramshackle lawsuit brought by a small group of volunteers that stopped the spraying of DDT in Suffolk County.

In 1967, on the heels of their successful injunction against the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission, Woodwell, Wurster, and a handful of fellow Long Island “troublemakers” met in a conference room at Brookhaven, where they signed the founding documents of the Environmental Defense Fund. Their work, and the legal strategy the EDF pursued, led to a federal ban of the substance in 1972.

“From my standpoint, we should have just gone hammer and tongs to reduce the buildup of CO₂ in the atmosphere and cool the Earth,” Woodwell, now 93, told me when I visited him at home in April. “And we should be doing that now.”

Woodwell first began worrying about carbon dioxide when it was present in the atmosphere at around 320 parts per million. Today, that number is somewhere around 420 parts per million, and global temperatures have risen by almost 2 degrees Fahrenheit over the long-term average.

Our observations have improved, but the forecast has not, Woodwell says. The center he founded, and the work it continues to do, are at the heart of how climate science plays out in the public sphere.

Masters of Carbon

The origins of the Woodwell Climate Research Center can be traced to the early days of ecology,

mountain range rose up to meet them.

Off the boat, Woodwell got a doctorate in botany at Duke under groundbreaking ecologist Henry J. Oosting, one of the “old boys of the subversive science” as Woodwell once affectionately called them. After a few years at the University of Maine, he moved to the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, where his wide-ranging research laid the groundwork for his move to Woods Hole and all that followed.

Right away, Woodwell embroiled himself in red hot issues like pesticide exposure and nuclear radiation as he set out to understand their effects at an ecosystem scale. He’d begun studying DDT in Maine, collecting soil samples after aerial spraying. In the 1960s, he continued his investigations at Brookhaven, joined by Charles F. Wurster, a young chemist with a keen interest in ornithology.

“We spent a summer collecting birds and fish and mud from the bottom and sediments in the salt marsh,” Woodwell

“George was the most respected scientist in the room, and he was always the strongest advocate for maintaining our scientific integrity,” Wurster wrote in his memoir of that time.

But Brookhaven was an atomic energy laboratory, after all, so Woodwell also set up experiments to study the ecological effects of nuclear contamination. Winching a piece of Cesium-137 up and down from a safe distance away, he exposed a forest of pitch pine and oak to ionizing radiation, and observed as the effects rippled out from the source.

Detailed measurements from this “gamma forest” showed zones where all higher plants had been killed, and those where only sedges, then shrubs, then oaks, and furthest out, the sensitive pitch pines, were able to persist. Whether from war, accident, or energy, these were the new risks of the nuclear age. Woodwell wrote in 1962 that this forest and other models “provide at least an understanding of what is happening to the environment, if not the wisdom to control it.”

Woodwell remembers his stint at Brookhaven fondly for his freedom to design and conduct basic research along-

ACCOUNTING FOR CARBON • FEATURE 26 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

George Woodwell is a bridge between the origins of the modern American environmental movement and its future, from the now-textbook cases of nuclear radiation and DDT to the ongoing reckoning with climate change.

side supportive colleagues and administrators. “We had a wonderful Institute of Ecology, we could do anything, I could build anything, I could design anything,” he recalled. And so he designed all kinds of ways to measure the dynamics of the ecosystem around him, and also to measure carbon dioxide.

“We built all kinds of equipment for measuring the metabolism of a forest,” Woodwell said. Their new equipment took precise readings of photosynthesis and respiration from leaves, branches, stems, bark, and roots. “So that was very exciting, to be able to take what we called an ecosystem apart, and watch it through a whole day or a month or a year or longer.”

Woodwell said, “That was when the issue of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was first beginning to appear on the front pages of newspapers, and also appear in the scientific literature, as Dave Keeling at Scripps built up a record showing the year-by-year accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, a beautiful record which was his life's work.”

Richard A. Houghton, a scientist who spent his career working alongside Woodwell from their days at Brookhaven through retirement from the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told me, “George had the foresight to really think that climate was going to be an issue because we were putting a lot into the atmosphere.”

Most of the people doing global carbon math at the time were oceanographers and atmospheric scientists, Houghton said, “and they had no idea what land was doing.” As ecologists with a particular interest in botany and terrestrial systems, Woodwell and his colleagues at Brookhaven began trying to detail the carbon absorbed and released in the biosphere.

And not just in forests. They drew detailed diagrams of how carbon moves around in Long Island marshes, tracking the flow of organic matter among

the cascading relationships of life in the tidal world. It was carbon accounting, a set of equations they could extrapolate to a planetary scale: this much in, this much out.

processes of a living, breathing Earth — the cycles of photosynthesis and respiration that balance the global atmosphere, and the human activities that can tip the scales.

Woodwell has worked cheek to jowl with many others at the leading edge of ecology and its real world implications. He’s worked with people who re-classified the kingdoms of life, discovered acid rain, and established the world’s longest running study of atmospheric CO₂, and with those who founded, in addition to the EDF, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the World Resources Institute. In this way, George Woodwell is a bridge between the origins of the modern American environmental movement and its future, from the now-textbook cases of nuclear radiation and DDT to the ongoing reckoning with climate change.

Woodwell and his colleagues tasked themselves with an accounting of anthropogenic change at a planetary scale. Half a century later, their work has left us with an alarmingly detailed balance sheet.

“We were masters of carbon,” Woodwell said.

In 1972, Brookhaven hosted a hundred scientists for an appraisal of carbon in the biosphere. The proceedings of this conference, edited by Woodwell, began with a stark premise: “The change that man is making in the world carbon budget is among the most abrupt and fundamental changes that the biosphere has experienced in all of world history. The change is in the stuff of life itself and is by now common knowledge.”

Tasked with describing the consequences of this change, and armed with only an inkling of the processes at work, the scientists asked: “Why has the change not been more? Or less? Where does the carbon go? What does the future hold?”

Their efforts began to diagram the

A New Center for Ecology

Eventually, George Woodwell said, “I did think that it was time to move on and do something different.” He talked about leaving Brookhaven with his wife, Katharine, “whose famous response was, ‘yes, George, you can go wherever you'd like to go. As long as it’s within fifty feet of salt water.’”

They found that proximity in Woods Hole, where Woodwell was recruited to start the Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory, which opened its doors in 1975. Houghton followed him there, and with other staff members they sharpened their focus on carbon dioxide and global change.

In global carbon equations, the work of solving for difference continued. Houghton said, “We've just been lucky in a sense, because both oceans and land

FEATURE • ACCOUNTING FOR CARBON 27 marthasvineyard. .com

have so far responded by taking up a little more than half of the emissions every year. There’s no reason why that should go on forever.”

In the mid-1980s, Woodwell again moved on, this time to start the Woods Hole Research Center, the institution to which he would devote the rest of his career (it was renamed in his honor in 2020).

Woodwell’s daughter, Jane, said “He had a year’s sabbatical from the MBL and we set up his office in the basement just to raise money that first year.” Home for the summer, Jane helped to write letters.

“When a foundation said no, we wrote them back and told them, ‘you’re wrong, you need to say yes,’” Jane said. “And they would say yes.”

“That's almost literally true,” George said, laughing. “You can't take no from a foundation.”

ing into a carbon-neutral campus in 2003.

The new building’s net zero design was ahead of its time, although not as far ahead as its founder, who installed a homemade bank of solar panels at his house in the 1970s. The center is built with recycled materials and designed for maximum efficiency with thick insulation, triple-glazed windows, and lots of natural light.

For the energy it does use, a bank of solar panels and a wind turbine sit steps away from the front porch.

“The goal was to be, if not off the grid, then carbon neutral over the course of a year,” said Houghton. “So in the summer months, we’d make a lot. And in the winter months, we’d use some of that. That would have worked, except that we had our own computers running, and they consume.”

The computers weren’t just running

to adapt to and mitigate the changes that threaten their ways of life.

She’s a typical scientist in some ways. “When I go for a walk, I'm usually thinking about carbon,” she told me.

In other ways, though, she is an embodiment of the mission-oriented zeal that characterizes Woodwell. She said, “When I got out of college I was like: Do I want to do science? Or do I want to do something that can have an impact? One of the things I really love about Woodwell, and why I stayed, is because I can do both of these things.”

The Center and its founder have never been afraid to wade into the fray. On DDT, nuclear war, and then climate change — catastrophic human interventions in the finely-tuned workings of the biosphere — George Woodwell took what he knew straight to the people he thought should hear it.

Houghton told me, “We landed in Woods Hole talking about climate change. I remember standing in a meeting in Washington, DC, somewhere in those days and saying, ‘climate is going to be a big one.’ And the response from the agencies was, ‘Well, come on. We’re worried about acid rain, don't just give us a new problem.’ That was really it. ‘We're full. We’ve got problems. Don’t give us a new one.’”

When Jane returned to college, her mother, Katharine, reluctantly “came down into the basement and did my job. And way more. I mean, she and Dad did the Center together from there.”

Soon enough, Houghton left the MBL to join the Center. Others bolstered the ranks, like I. Foster Brown, an environmental geochemist who specializes in the Amazon basin and now coordinates the Center’s presence in Brazil.

They grew from a basement, to a church building, to a network of several more buildings until finally consolidat-

office programs — they were crunching through high resolution satellite imagery. “So we were using more energy to cool our computers than we were to heat our place in Massachusetts,” Houghton said.

Science in the Arena

Susan Natali, an Arctic ecologist who’s worked at Woodwell since 2012, is a project lead for “Permafrost Pathways,” an ambitious new effort to study the warming Arctic, factor its melting permafrost into climate models, and work with Indigenous communities

In the 1970s, as the country reeled from oil shocks, the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations scrambled to find oil alternatives and to conserve energy. At the same time, a growing concern about fossil fuel emissions drew Woodwell into an effort among scientists, government officials, environmentalists, and oil companies to reckon with greenhouse gasses and recommend solutions for dealing with them.

In 1979, at the request of James Gustave Speth at the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, Woodwell authored a report with leading climate scientists Charles Keeling, Roger Revelle, and Gordon Macdonald, called “The Carbon Dioxide Problem.” They described serious changes to come, and warned that “enlightened policies in the management of fossil fuels and forests can delay or avoid these changes, but the time for im-

ACCOUNTING FOR CARBON • FEATURE 28 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /EARLY SUMMER 2022

Woodwell map of carbon stored in global forests.

plementing the policies is fast passing.”

Alarmed, government officials asked for a follow up from the National Academy of Sciences. This ad-hoc investigation became the Charney report, which is now seen as a major milestone in climate science. It largely confirmed the earlier research, and predicted global warming of between 1.5 and 4.5 degrees celsius if CO₂ doubled — remarkably consistent with modern scenarios. Its warning: “A wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late.”

In the 1980s, Woodwell continued to work with policymakers on climate change, testifying before congress several times and contributing to influential reports.

Speaking before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in 1980, Woodwell acknowledged that scientists might disagree on the details of global warming, but that “such disagreements are an intrinsic part of the search for knowledge and their existence cannot be taken as a reason for ignoring, neglecting, or failing to act on the central issues.”

“The series of problems associated with the carbon dioxide problem will become major issues in the next century whether we address them at the moment or not,” Woodwell told the committee.

Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas, the committee’s chair, jokingly retorted, “but the primaries will be over by then.”

“This set of primaries may be,” Woodwell replied. Later in his testimony, he expressed his confidence that “these are problems that well-governed, wise nations are capable of addressing successfully.”

“When you find one, let me know,” Tsongas said.

In congressional hearings, where Woodwell often testified alongside other well-known climate scientists, such as NASA's James Hansen, his role was often to fill in the details of terrestrial ecology — the interactions of the living Earth with the chemical, atmospheric, and oceanic circumstances described by others.

He called attention to the delicate

balance between photosynthesis and respiration, and the limits of scientific knowledge about how climate change will affect these processes. He warned that we were flying blind when it came to landscape change, that “it is madness not to have data flowing in regularly, monitored on a year-by-year basis, telling us what is happening to forests around the world.”

nies like Exxon were funding climate research, including at Woodwell’s Center. By the late 1980s, efforts to alleviate other atmospheric pollutants were paying off, and it seemed like the greenhouse gas issue would be resolved the same way.

But Woodwell was right in the thick of things as what began as a team effort splintered into a contentious fracas.

Woodwell, like many prolific scientists, was sometimes crunched for time. At one hearing, Rhode Island Senator John Chafee sensed a rush and asked, “Dr. Woodwell, what is your problem?”

“An airplane at 12 o’clock,” Woodwell replied.

“You have got more than a problem,” Chafee said. “You have got a disaster.”