SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

SO DOGGONE HARD TO SLEEP SUSTAINABLY Room for Change to the Rescue

IT'S ELECTRIC! Cruising with Currier on the VTA

WE ARE ALL WHALERS A Scientist Tries to Make Right by Right Whales

WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES? Do Skunks Count?

MARTHA’S VINEYARD / WINTER – EARLY SPRING 2022

TM

The Whole Leek · Local Hero: Jonah Maidoff · Good Gardens

EXPERIENCE NOISE-FREE, CARBON-NEUTRAL, LAWN-CARE PERFECTION. EVERY DAY. Greener’s turnkey solution elevates your landscaper’s service with: Join today by visiting us at www.gogreener.us/get-started • Daily golf-course quality care • Dedicated lawn-care monitoring • Health and progress photo diaries • Customized case management

WEST TISBURY COMPOUND WITH EQUESTRIAN BARN

This oak post and beam home shares three acres with a guest cottage, three car garage and a three-stall barn. Main - high efficiency hydronic heat, central air, three ensuite bedrooms (one on the first floor), chef’s kitchen with walk-in pantry, mudroom/laundry room, half bath for visitors and a farmer’s porch. Guest - fully insulated, heated, and air conditioned with full bath and laundry. Barn – post and beam with concrete foundation and a loft. The stalls were configured to be easily removed for future possibilities. Property has multi-zoned irrigation and features stone walls, picket fencing, gardens, and paddocks. Exclusively offered at $3,200,000

An Independent Firm Specializing in Choice Properties for 50 Years 504 State Road, West Tisbury MA 02575 Beetlebung Corner, Chilmark MA 02535 www.tealaneassociates.com

508.645.2628 Chilmark

508.696.9999 West Tisbury

ENJOY MORE TIME OUTSIDE!

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love … on a mote of dust suspended on a sunbeam.” –Carl Sagan

Publisher Victoria Riskin

Editors Leslie Garrett Jamie Kageleiry editor@bluedotliving.com

Digital Projects Kelsey Perrett Manager

Associate Editor Lily Irelend Olsen /reporter

Contributing Editors Mollie Doyle Catherine Walthers

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Design/Production Sophie Petkus

Proofreader Irene Ziebarth

Ad Sales Jenna Lambert adsales@mvtimes.com

Bluedot, Inc. President: Victoria Riskin

DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com

oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

CALL US! 508.627.2928

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

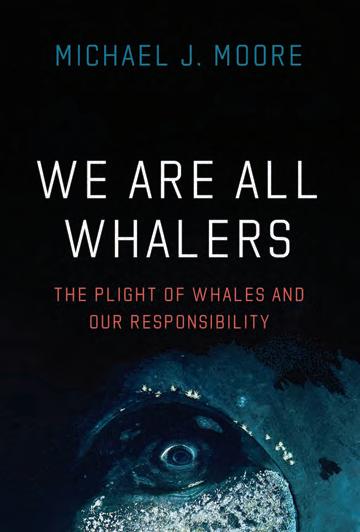

Vice Presidents: Walter and Nora McGraw

Cover Photo Jeremy Driesen

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc.

Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and distributed by The Martha’s Vineyard Times. You can find it at The MVTimes office, at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge.

You can see the digital version of this magazine at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Sign up for our biweekly newsletter here: bit.ly/Bluedot-newsletter

Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @bluedotliving

Subscribe: Please inquire at mvtsubscriptions@mvtimes.com

2 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

BDL • OUR TEAM

3 marthasvineyard. .com OUR TEAM • BDL Native plant specialists and environmentally focused organic garden practices. Garden Angels Design • Installation • Maintenance (508) 645-9306 www.vineyardgardenangels.com of martha’s vineyard • nmdgreen.com • INFO@nmdgreen.com Water Treatment • Maintenance Programs INSTALlATION & SERVICE Geo Thermal • Solar Hot Water • Heat Pumps Energy Management • Design & Consultation MARTHA’S VINEYARD SIGN UP ONLINE AT marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Dear Bluedot Living Readers,

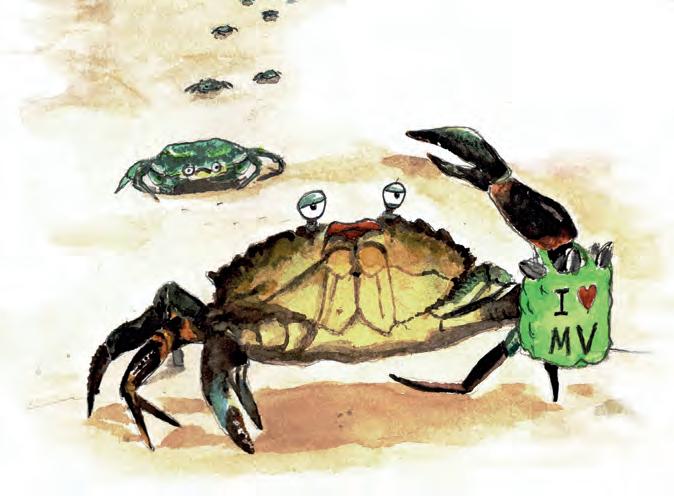

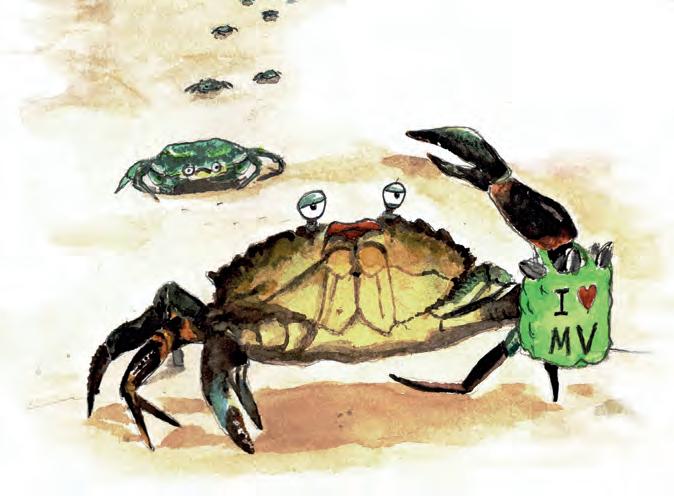

e were at work on a story about invasive species on the Vineyard when we heard rumor of a bounty on the heads of green crabs. We reached out to Emma Green-Beach, executive director and shellfish biologist with the MV Shellfish Group. Yep, she said, confirming the rumor. What’s more, she said, she’ll try to get us some crabs so we can cook ‘em up and test out a delicious way of dealing with these interlopers.

This type of partnership is how Bluedot sees our relationship to you, our readers. We love to introduce you to the fascinating people at work on the Island — protecting and preserving what we have, mitigating the climate changes we’re already seeing, and preparing all of us for shifts to come. And we are thrilled to have you along with us into our second year of Bluedot Living.

What we hear back from many of you is this question: “What can we do?” We share your passion to take action, which is why we’ve added a new feature to our stories, outlining clear and often easy steps you can take right now in your home, your yard, your community. Look for “What you can do.”

Bluedot is also thrilled to be participating in this year’s Climate Week, May 8 - 14, presented by the MV Commission

and offering workshops, seminars, and activities for all ages to engage in meaningful climate action. From an EV vehicle display to Bluedot Living’s own roundtables addressing local issues, you’ll find something that inspires you to get involved. Stay tuned: We’ll be updating the info on our website and in our newsletters. Not getting the bi-weekly Sunday Bluedot newsletter? Sign up here: bit.ly/Bluedot-newsletter. And please note, our website is here: martha's vineyard. bluedot living.com. Onward!

– Leslie Garrett and Jamie Kageleiry

4 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022 EDITORS' LETTER 4

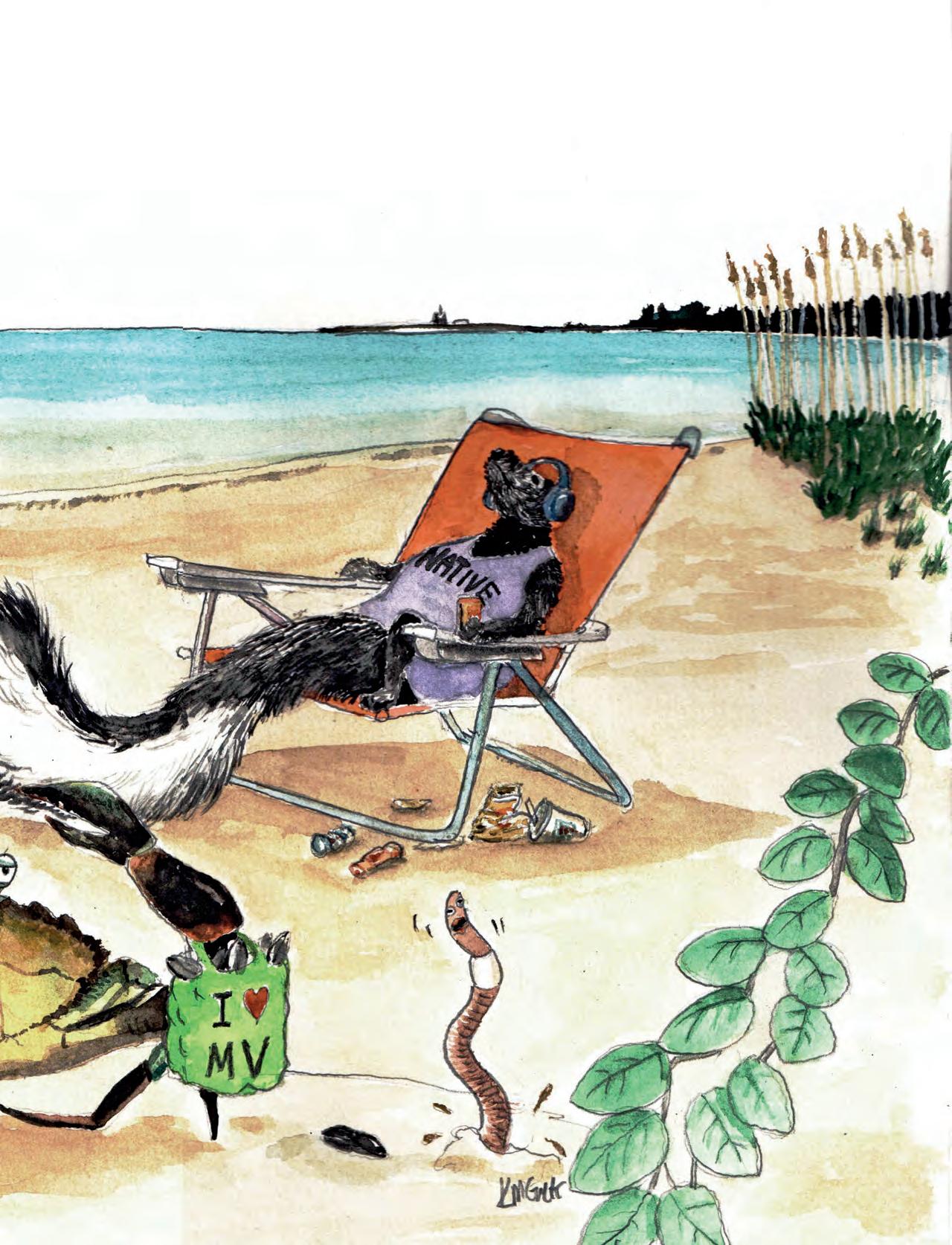

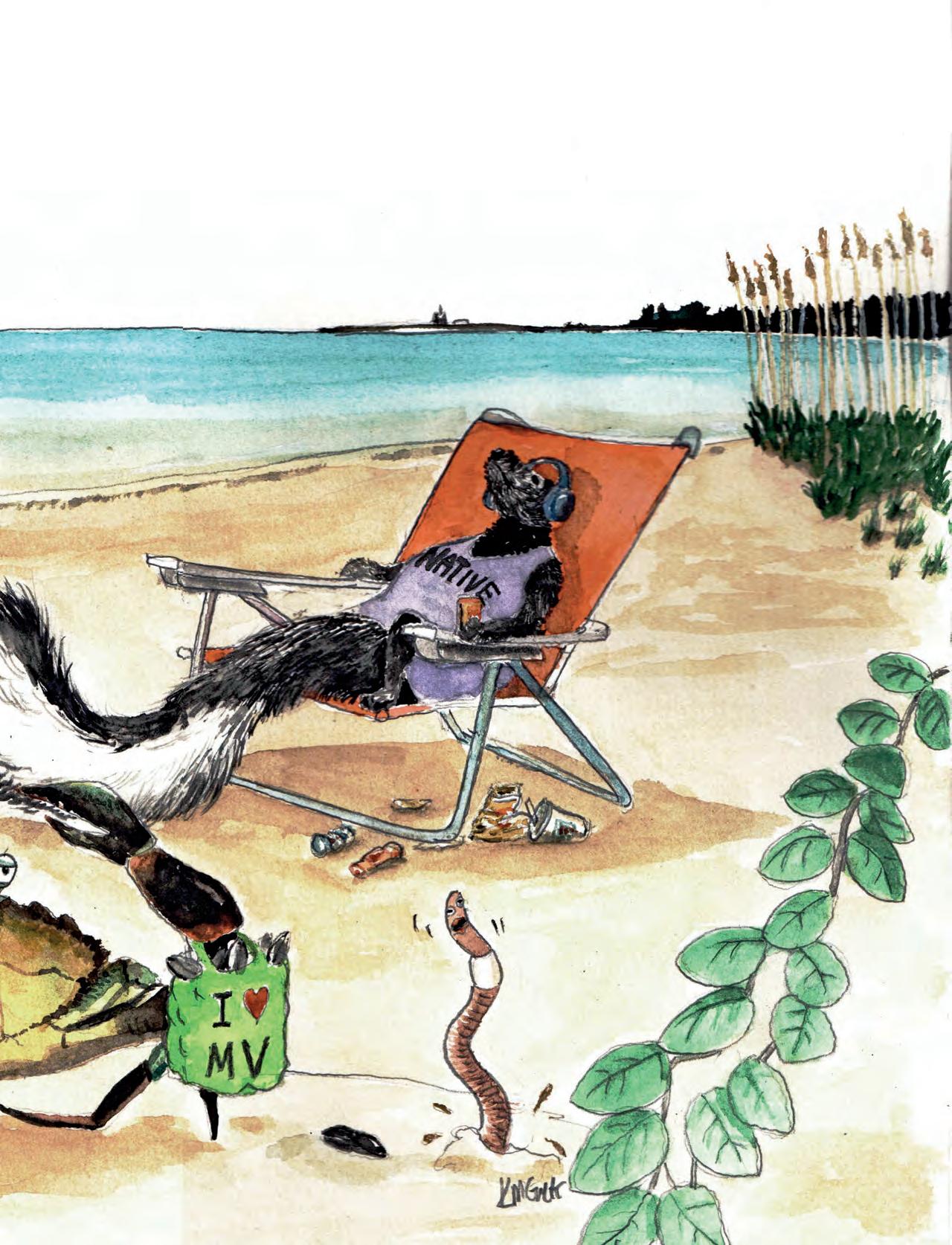

W(508) 627-2454 | GeesePartners.com | mv@geesepartners.com Commercial, Residential & Event Goose Control on Martha’s Vineyard Take Back Your Turf Safe & Eco-Friendly Goose Control Free Estimates We are a local, year-round island business ILLUSTRATION: KEVIN MCGRATH

5 marthasvineyard. .com

Features

14 Climate Action? By Sam Moore

Bluedot Living talks with the team behind the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Climate Action Plan. (It’s a pretty big deal.)

Features

16 Invasive Species: What's So bad About Them, Anyway?

By Leslie Garrett

They take over native ecosystems and offer little in the way of food or habitat. But some invasive species are here to stay and can even be useful. Is it time to make peace with invasives? And a little known fact about skunks.

24 In Exchange: An Island Barter Keeps Things Local

By Lily Walter

On Chappy, a balancing of the scales, a sharing of means, a neighborly act of camaraderie.

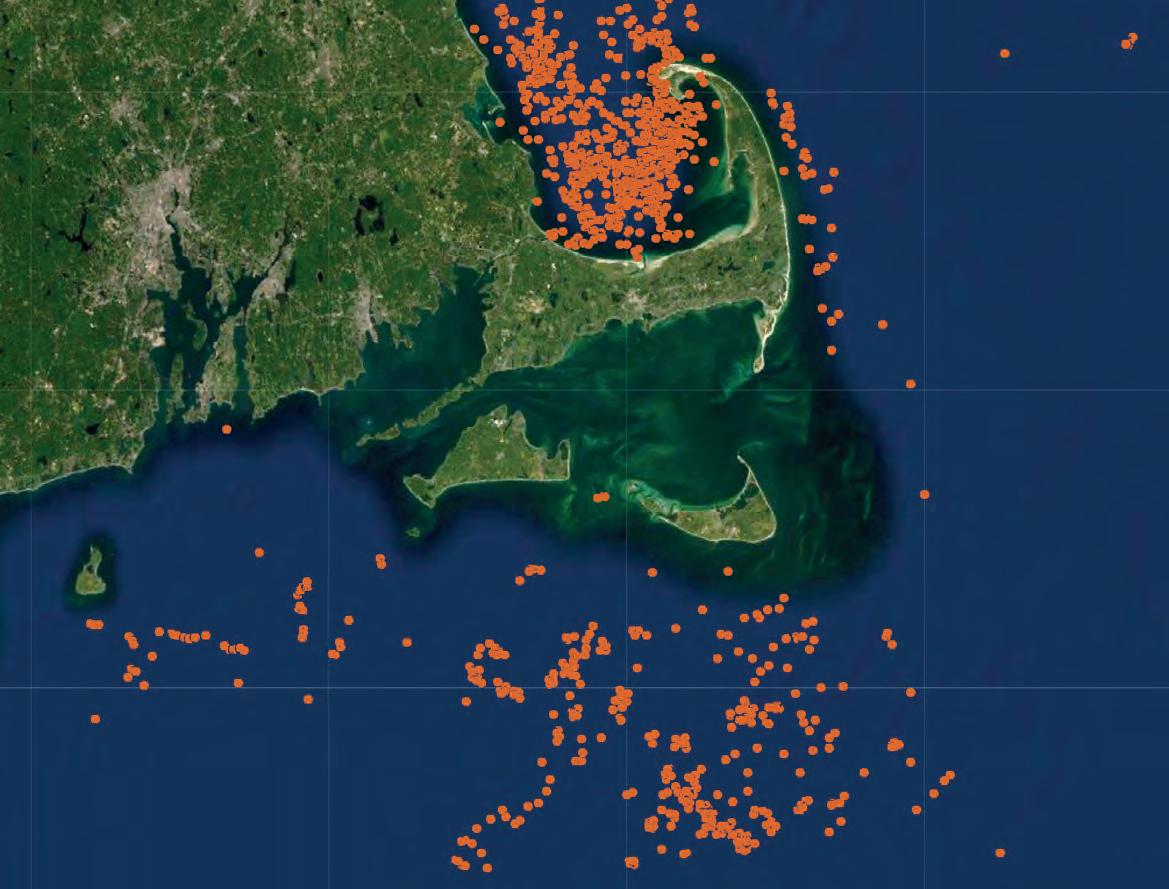

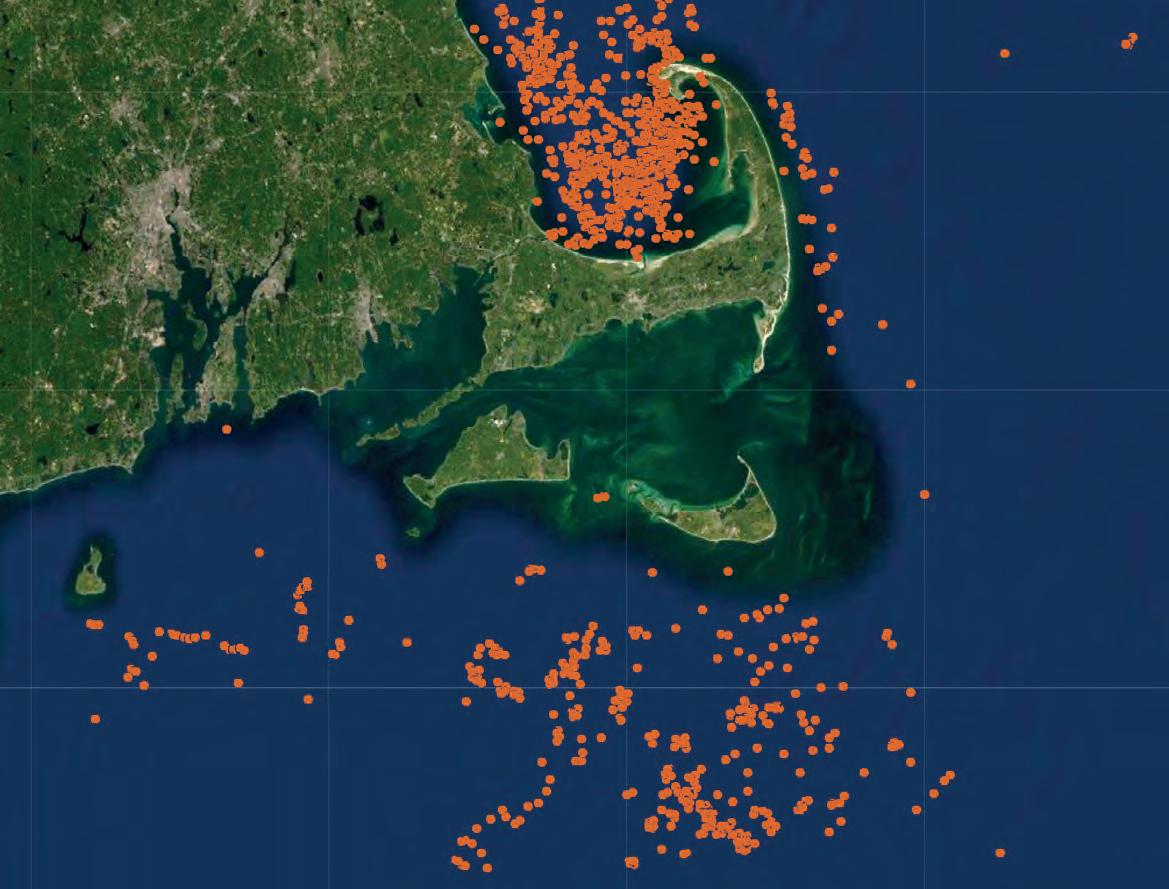

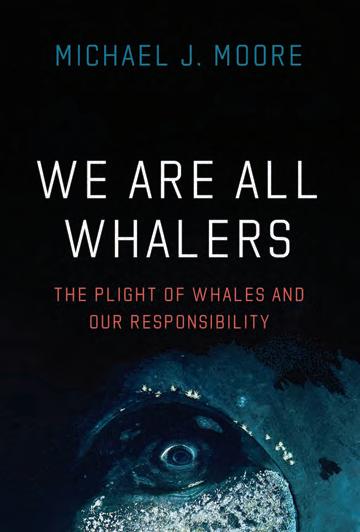

34 Whales in the Balance By Sam Moore

A veteran of marine mammal conservation in Woods Hole has a new book with a startling message: To save an entire species, we need more hands on deck.

40 Making a Garden for Changing Climes By Abigail Higgins

Create a low-effort, eco-aware, and gorgeous Vineyard garden.

Departments

12 Dear Dot Dot’s thoughts on finding a great solar installer, flushable litter vs your septic system, and whether it’s worth it to cool down your water heater when out of town.

22 Cruising with Currier

Ride along on a Vineyard Transit Authority’s electric bus.

30 Room for Change: By Mollie Doyle

Make your eco bed. And then lie in it.

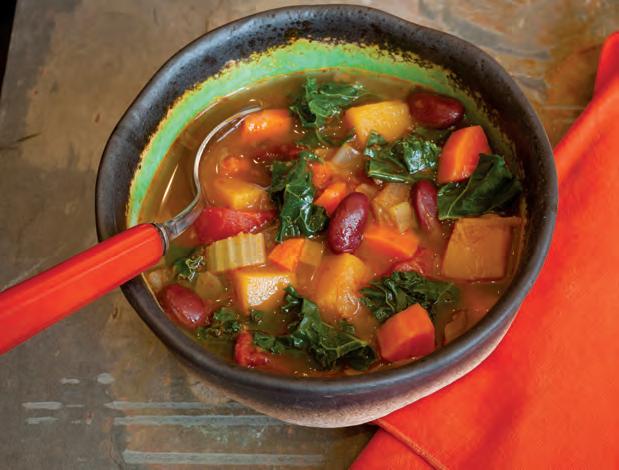

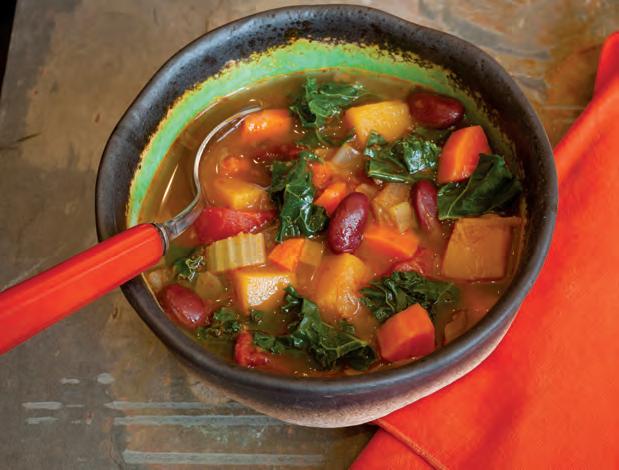

33 Right at Home — Leeks

'I can't believe I ate the whole thing.'

44 The 'Keep This' Handbook

Where to find Island composting/recycling/ volunteering.

48 Local Heroes: We Nominate

Jonah Maidoff

continued

Upfront

CONTENTS

4 Editors' Letter 8 Contributors

Good News from All Over + The Grist Report

In Memoriam Remembering

Note:

sets

In

7 What.On.Earth A Whale of a Tale 10

11

Kent Healy 29 Field

Housing Bank

sustainable standards 29

a Word: Aquamation

45 Field Note: Red Cedars in Winter

6

PHOTO BY SHENY LEON

CONTRIBUTORS

Here’s a few of our contributors; several shared their sustainable travel dreams and eco-resolutions.

Jeremy Driesen (pages 30, 48) is a Vineyard-based photographer who has worked for Vogue, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, The MV Times, and more. “I live my eco-friendly destination every day, weather permitting, with a 13-mile bike loop that features a dip in the Inkwell near the end!”

Abigail Higgins (page 40) is a landscape designer and writer: “My travel daydream is to get to Painted House Beach three times with my family, friends, and especially my grandson from Virginia.”

Photographer Sheny Leon (page 24), originally from Mexico, has made

and stop and do WOOFing (Worldwide Opportunities at Organic Farms) along the way. I also would love to do something like this with my five-year-old daughter (maybe not the biking part as much but definitely the woofing part).”

Illustrator Kevin McGrath is a librarian at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School and artist who drew the, ahem, charming Vineyard invasives on page 16. Find his work at mvzoo.com and on Instagram @mvzoo

Photographer and writer Sam Moore (page 34), often works in conservation. “I daydream about rowing and sailing a piece of the Maine Island

Sophie Petkus, Bluedot’s new designer, told us she’s “really trying to limit my food waste this year. Unfortunately, that means more and smaller trips to the grocery store but it’s definitely worth it.”

Susan Safford shot our beautiful garden story on page 40. She is the former production manager at the MVTimes, and lives in West Tisbury.

Lily Walter, (page 24) owns Slip Away Farm on Chappaquiddick. “My sustainable travel daydream is to visit some AMC huts in northern Maine. I would go in the winter

CONTRIBUTORS 7 marthasvineyard. .com

www.mvbuyeragents.com 508-627-5177 Email: buymv@mvbuyeragents.com 13 Coffins Field Road Edgartown, MA 02539-1661 “And, when you want

you to achieve it.”

something, all the universe conspires in helping

— Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist

What.On.Earth.

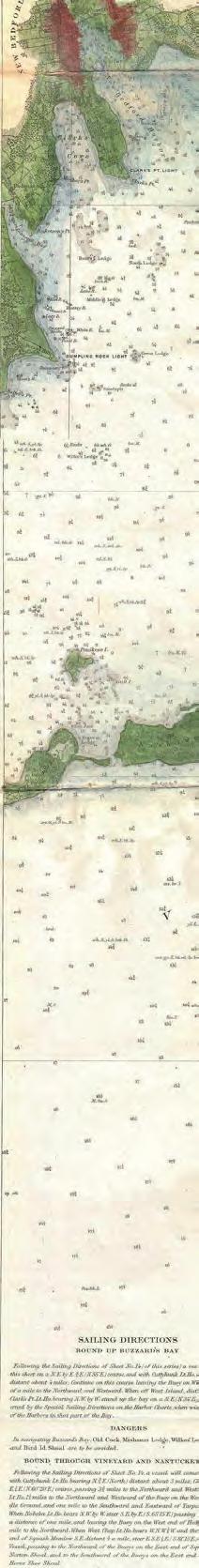

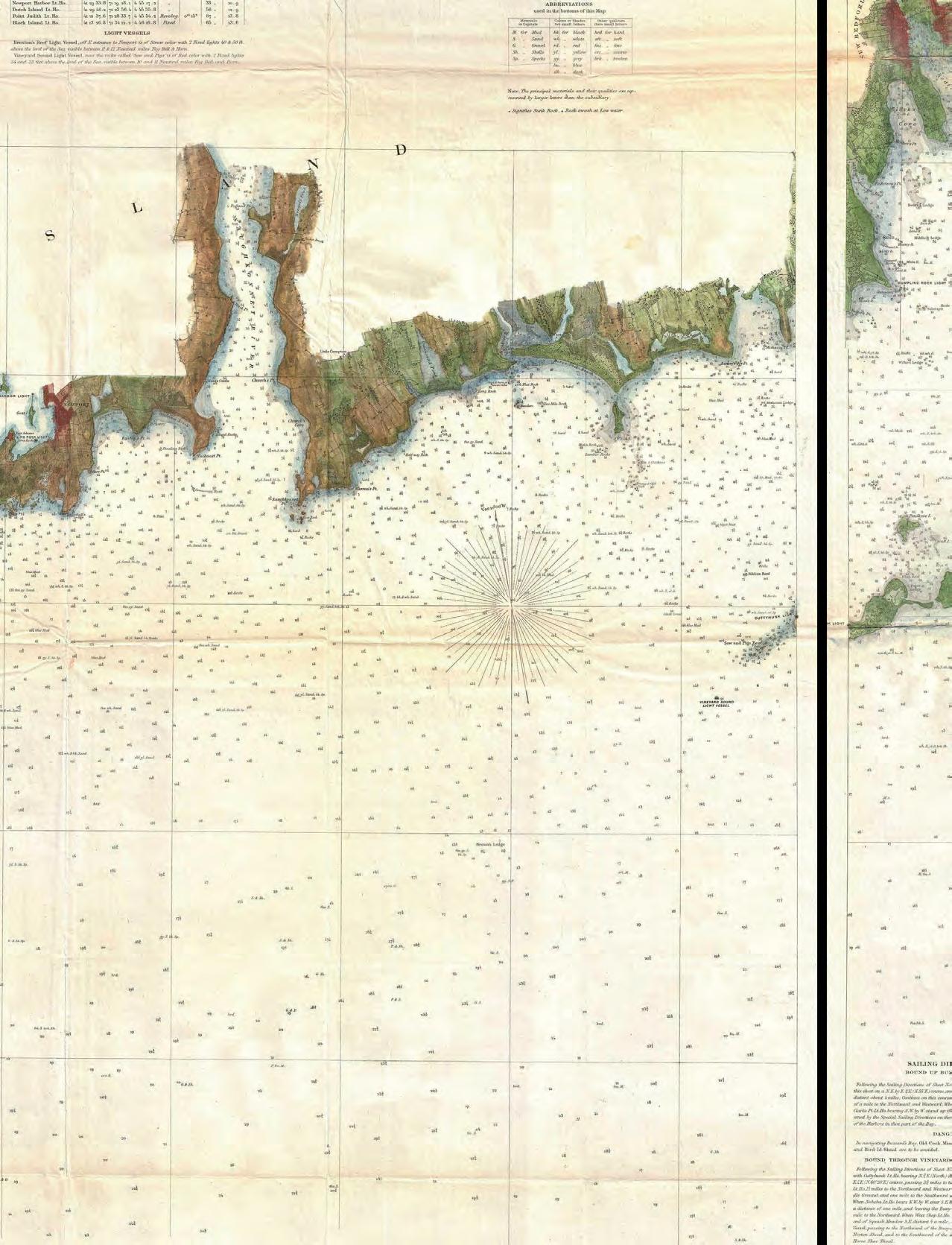

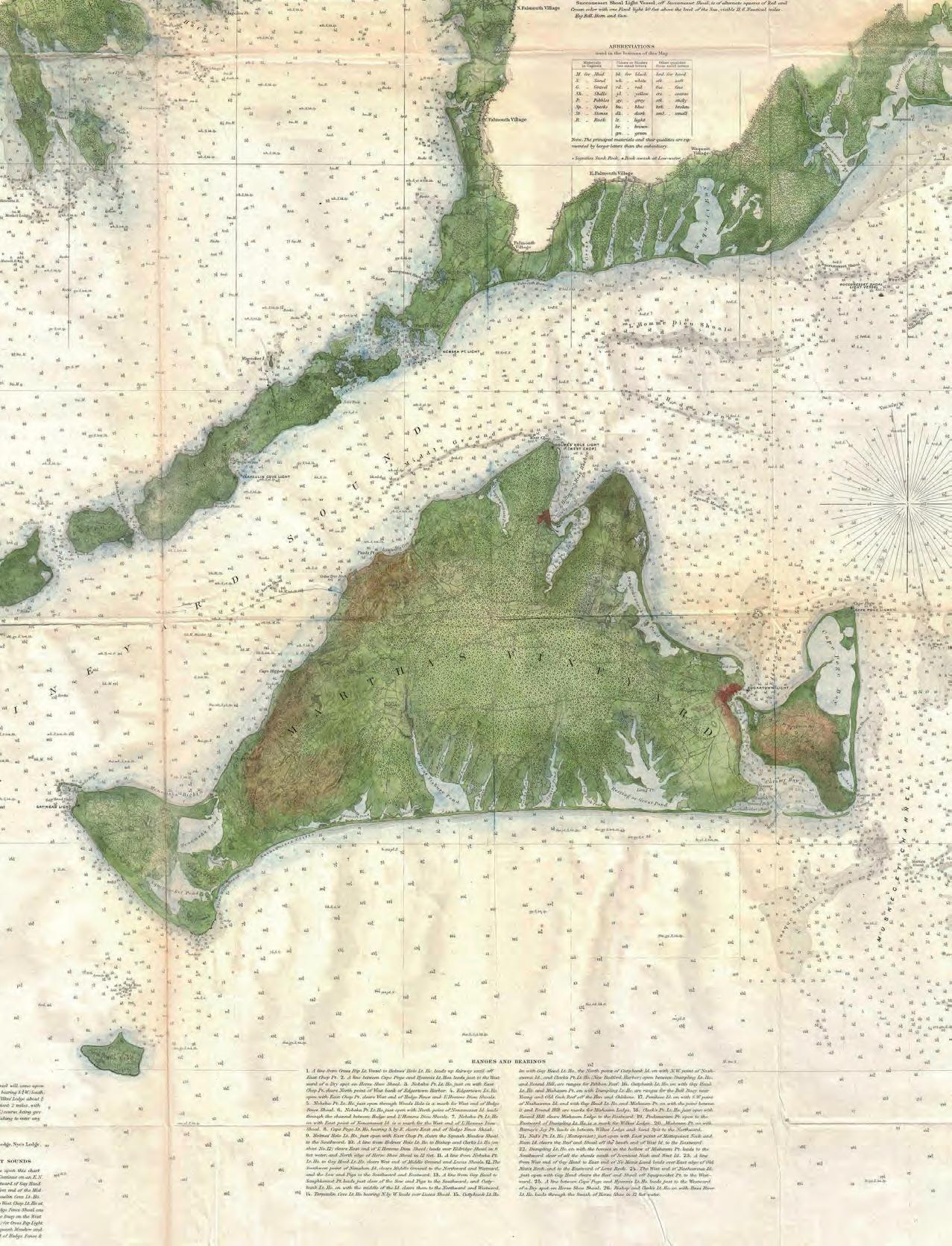

Melville,

1. Amount of carbon sequestered by protecting just eight whale species: 8.7 megatons

2. Number of wind turbines that would need to operate for one year to reduce carbon by the same amount: 6,000

3. Amount of CO2 absorbed by the average great whale over its 60-year life: 33,000 kg

4. Amount of CO2 absorbed by one tree in a year 22 kg.

5. Amount of the world’s CO2 absorbed by phytoplankton, which find ideal growing conditions in the iron and nitrogen of whales’ waste: ~40%

6. Number of Amazon rainforests required to absorb 40% of the world’s CO2: 4

7. Number of species a single whale carcass supports with food and habitat during final stages of decay: 200

8. Year the earliest recorded whaling ship left Martha’s Vineyard: 1738

9. Value of whale products brought back by Vineyard-based ships from 1818 to 1872: $134.6 million

10. Number of Black whaling captains on ships from the Vineyard: 5

11. Current value of carbon sequestered by a single great whale according to the International Monetary Fund: $2 million

12. Number of existing North American right whales: 366

13. Number of mother-calf pairs of right whales in 2021: 18

14. Average number of mother-calf pairs annually from 2010 to 2020: 23

15. Number of species out of the 13 Great whale species considered vulnerable or endangered: 6

16. Multiple increase of CO2 the ocean helps regulate compared to the atmosphere: 50

Sources: 1-2, Washington Post; 3-4, Our Planet; 5-7, BBC; 8-10, The Atlantic Black Box Project; 11, International Monetary Fund; 12-15, World Wildlife Fund; 16, International Atomic Energy Agency.

“There is no folly of the beast of the earth which is not infinitely outdone by the madness of man.”

Herman

Moby-Dick or, the Whale

8

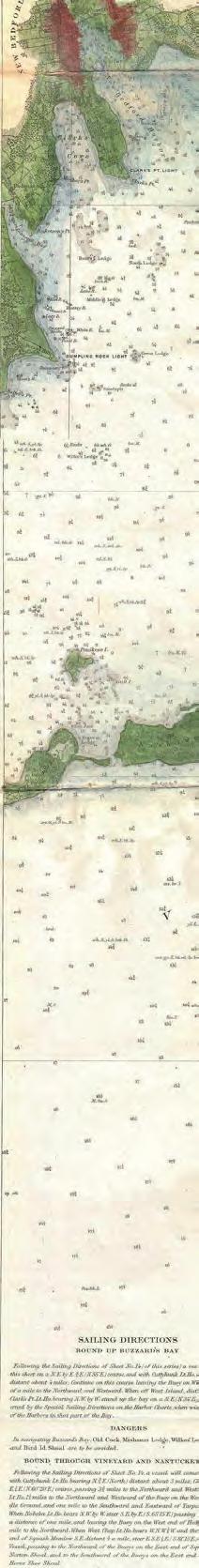

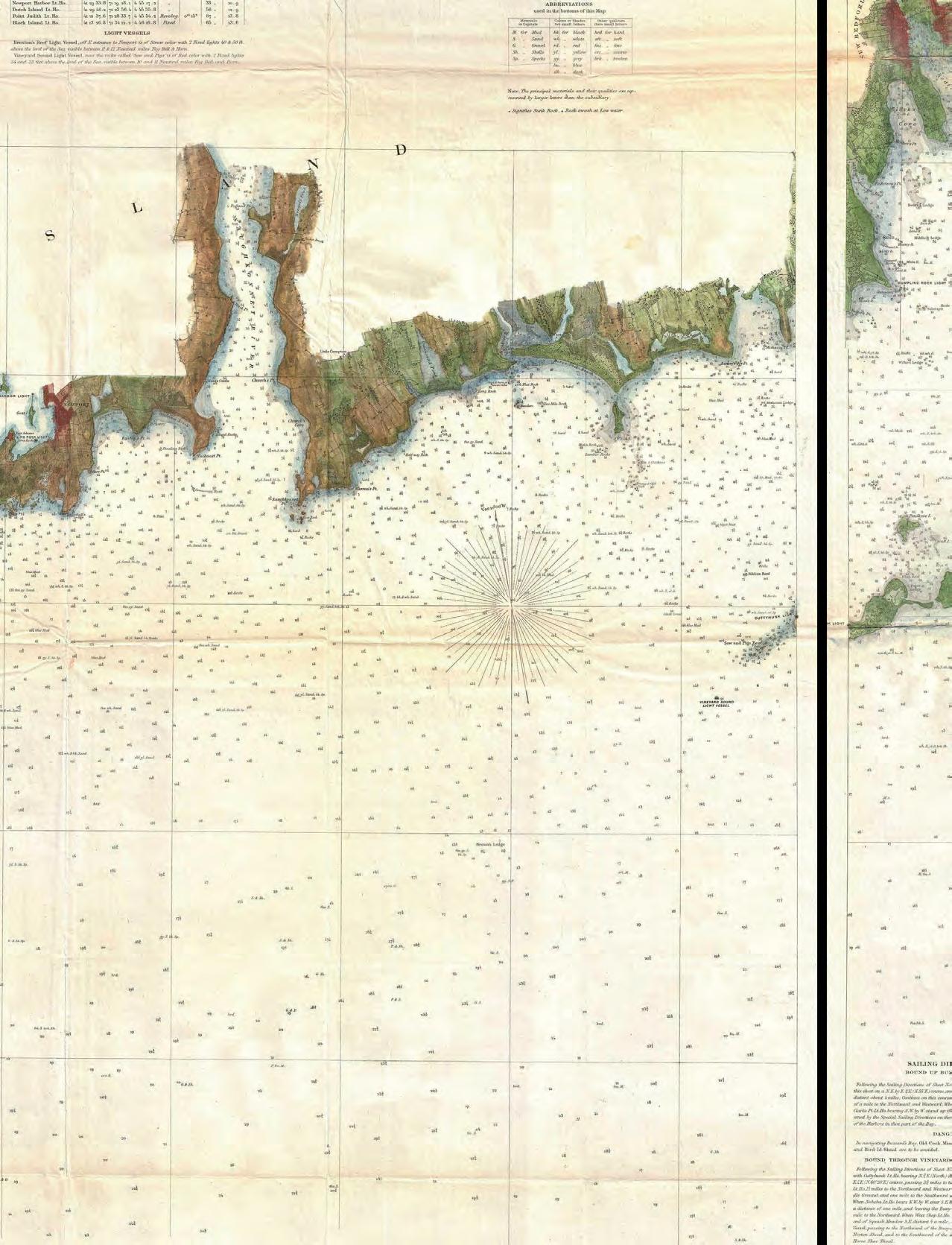

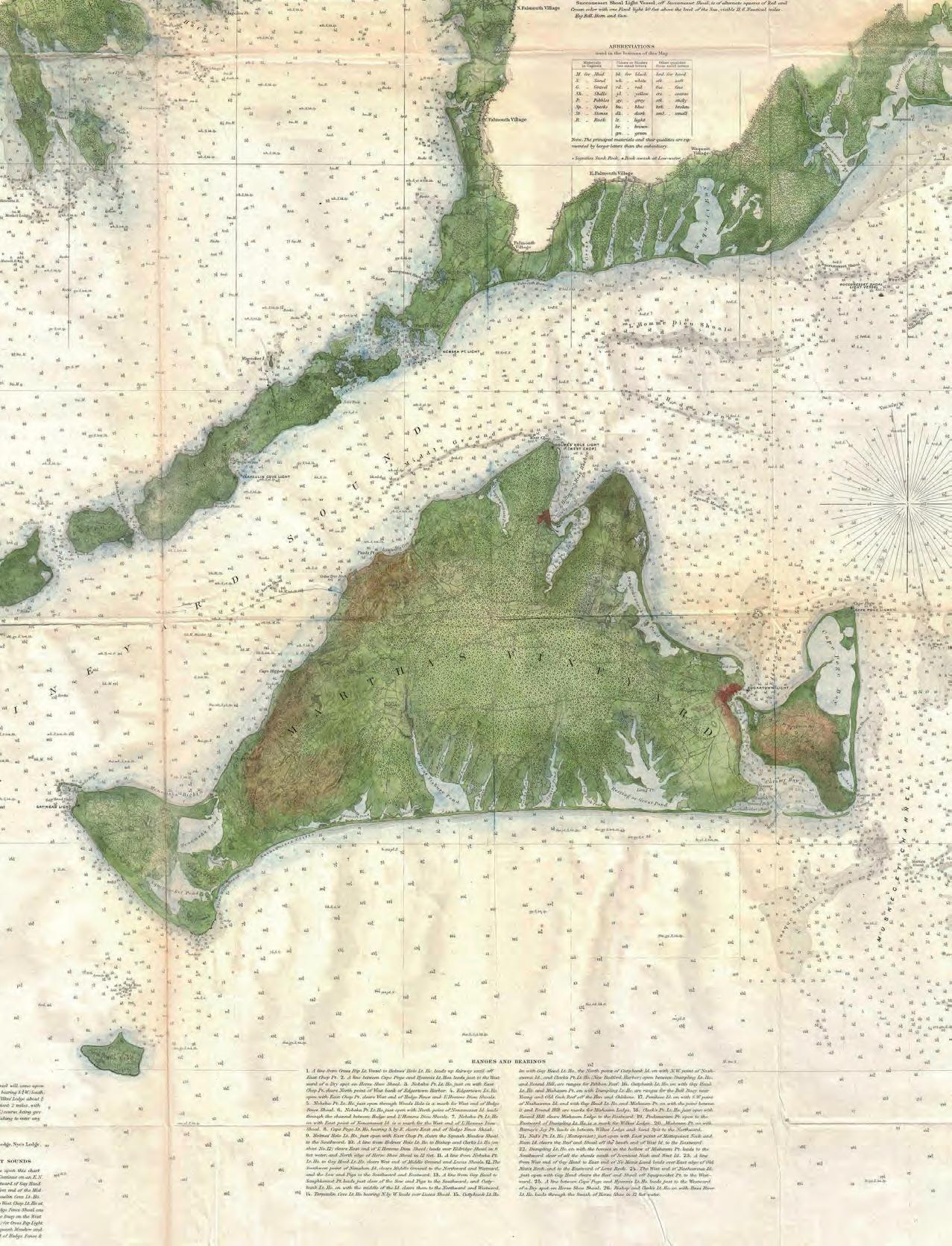

IMAGES FROM THE 19TH CENTURY WHALING LOGS OF THE ALEXANDER BARCLAY AND THE CHARLES W. MORGAN SHIPS, COURTESY OF THE M.V. MUSEUM.

TOGETHER WE’RE TACKLING CLIMATE CHANGE

Over the past 35 years, The Nature Conservancy has helped protect more than 1,500 acres on Martha’s Vineyard. We’re restoring unique habitats like rare sandplain grasslands for the survival of animals and plants. Learn more at: nature.org/MarthasVineyard

9 marthasvineyard. .com

good news

FROM ALL OVER

Search and Conserve

Google’s Year in Search proves what we at Bluedot Living already knew: Environmental awareness is growing. In 2021, searches for “how to conserve” reached an all-time high around the world.

Other climate change-related searches grew in popularity last year as well. Global searches about the impact of climate change and sustainability also reached all-time highs. In September, searches for second hand shops surpassed pre-pandemic levels in the U.S.

A Half Century of Clean Air

It’s been almost 50 years since Congress passed the Clean Air Act to enforce fuel emissions standards for vehicles — and it looks like the impact has been life-saving. A recent study indicates that the regulations have likely saved thousands of lives. Researchers estimate that between 2008 and 2017 alone, deaths caused by emissions-related illnesses decreased by nearly a third.

Cleaning up Bali’s Waterways

The rivers in Bali, Indonesia, central to burial rites and the placement of the island’s most sacred temples, have been overrun with garbage for years. As reported by Hakai Magazine, a new organization, Sungai Watch, is hoping to restore the pristine beauty to Bali’s waterways.

Gary Bencheghib, founder of Sungai Watch, got his start by collecting trash

from the river himself and selling it to a recycler. But when Bencheghib began sourcing sponsorships from organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund, he was able to expand the project. For an annual pledge as low as $210, donors can have a section of river named after them.

Sungai Watch removes trash from the rivers through a system of 110 barriers that trap the waste. Then, employees remove and sort the trash, diverting some to be recycled or composted, collecting data on types of plastic and the manufacturing brand, and working with governments and corporations to enforce better waste management. Since its start in October 2020, Sungai Watch has collected more than 800,000 pounds of plastic. Its next goal is to install 1,000 barriers throughout Indonesia and begin expanding its cleanup internationally.

Getting closer to the clean energy of nuclear fusion

According to the BBC, “European scientists say they have made a major breakthrough in their quest to develop practical nuclear fusion — the energy process that powers the stars.

Experiments at the UK-based JET laboratory produced 59 megajoules of energy over five seconds (11 megawatts of power), beating its own previous record by more than double in 1997.

The excitement around this, which produced roughly enough energy to boil water in about 60 kettles, is that

With more than 80% of ocean plastic coming from rivers, Sungai Watch installs simple floating barriers in rivers to stop plastic at the source.

it validates current research and shows incredible promise. “We’ve demonstrated that we can create a mini star inside of our machine and hold it there for five seconds and get high performance, which really takes us into a new realm,” the BBC quotes Dr Joe Milnes, the head of operations at the reactor lab as saying. Fusion differs from fission in that the process forces atoms together rather than splitting them, which is how existing nuclear fission reactors work. Though we’re still two decades or more from the commercialization of nuclear fusion, this breakthrough offers great potential for powering our planet with clean energy in the second half of this century.

EV Research Offers the Long Road

The transition to electric vehicles is underway, but one major hurdle is the range of these cars has long been eclipsed by that of fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Now, scientists have discovered a biologically-inspired membrane that has the potential to quintuple the range of electric vehicle batteries.

According to the Independent, the discovery was made by a research team at the University of Michigan that used recycled Kevlar, the material found in bulletproof vests, to create a network of nanofibers that resembles those in cell membranes. The researchers used this finding to fix a major issue with lithium-sulfur batteries, a next-generation battery being eyed as an alternative to lithium ion batteries in electric cars and a number of other technologies.

As a handful of countries at COP26 this fall committed to sell all-electric vehicles by 2040, it’s innovations like this that make such a sweeping transition more feasible.

For more good news go to marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

10 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

UPFRONT • GOOD NEWS

SUNGAI WATCH

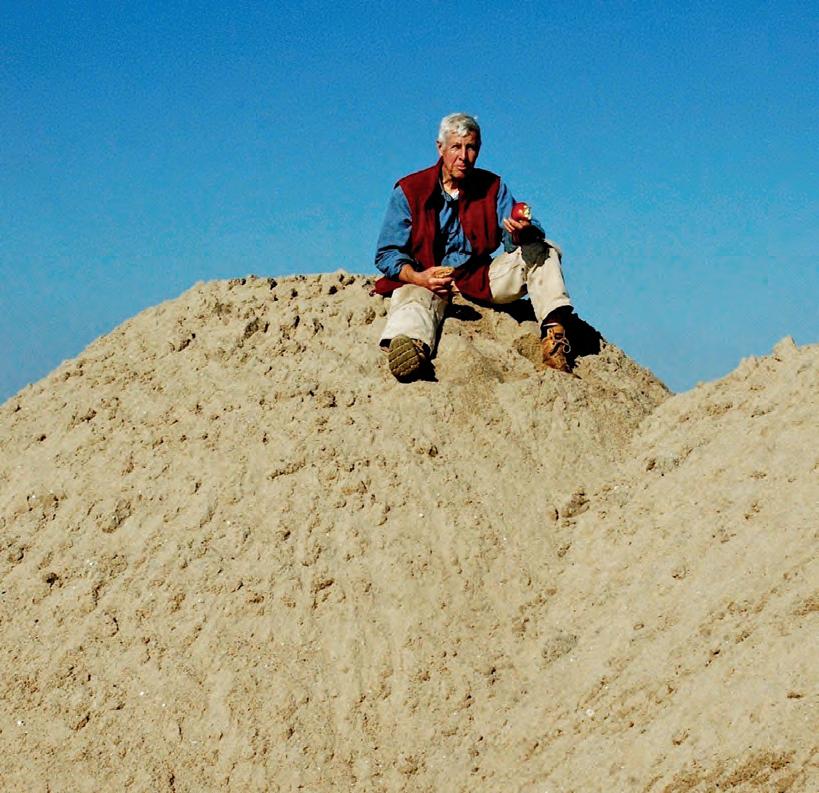

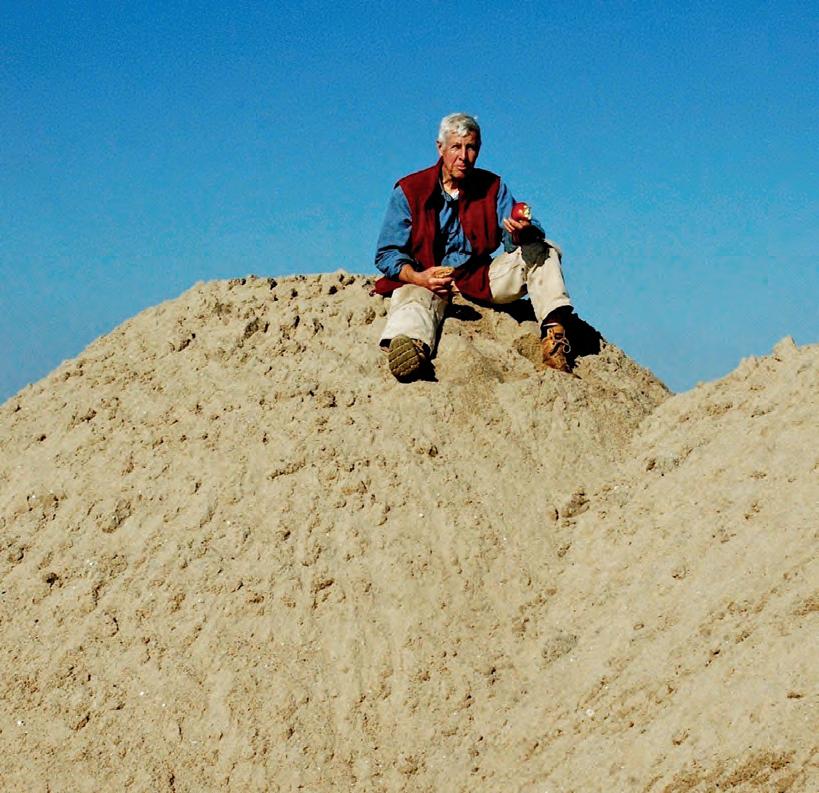

REMEMBERING Kent Healy

At a recent meeting for the Great Ponds Foundation, GPF’s watershed outreach manager Dave Bouck spoke about Kent Healy, who died at age 89 in October.

“Kent dedicated much of his life to the stewardship of our Island water resources, as a civil engineer, as the town sewer monitor, and later, as a selectman for the Town of West Tisbury. His careful attention to detail and meticulous collection and recording of environmental data throughout many of the ponds and watersheds of the Vineyard helped to form the baseline for much of the knowledge and understanding that we possess today.”

Kent, who had a Ph.D from MIT and taught at the University of Connecticut, was one of the founding members of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Before returning to the Island with his family in 1983, the Healys spent summers in a home near Quansoo that was powered by windmills and solar panels, long before most people were doing such things.

Several Islanders wrote to us at Bluedot about working with Kent.

“Kent was helping me lay out a guest house in the Chilmark woods,” architect John Becker wrote, “after a surprise April Fools Day blizzard had dumped over a foot of wet snow. The going was tough and soon Kent (15 years my senior) noticed I was lagging behind. He tossed me a roll of duct tape and told me to pull my pants over and outside of my boots, and to tape the pants tight around the ankle. The trick cut the ‘snow friction’ beautifully and soon I was almost keeping up with this wiry expert. I remember a heady sense of pride of my newly acquired woodsman skill. Nowadays I look back on it and wonder: Who else but Kent could produce a roll of duct tape in the middle of nowhere?

“[Kent] was often amused with most peoples’ use of ‘science’ to support an agenda that may have been energized more by personal motive than by openmindedness. His wry smile would break, he’d quicken to the occasion with questions, possibly contradictory

observations — always to broaden the horizon of any issue at hand. He loved the measuring and collecting of data as much as the drawing of conclusions. Applied science was nothing without openminded observation.”

Prudy Burt of West Tisbury wrote of her long working relationship with Kent: “Kent was passionate about data and facts, and adamant that anyone making any claims about water quality must have copious and comprehensive data to back up that claim. He kept a small notebook and pen in his front shirt pocket at all times. If someone stopped him at the post office to ask about when Tisbury Great Pond (TGP) was going to be opened, and claiming that the pond ‘was as high as I’ve ever seen it,’ Kent would pull out his notebook, flip to the pertinent page and say ‘No, that would have been on this date’ and then proceed with a history of high pond conditions over the last 70 years.

“For well over 40 years, Kent went out every week and monitored TGP water levels and salinity levels. He and I would often run into each other in the woods along Mill Brook. We liked to lean on the fence at the Mill Pond dam along West Tisbury/Edgartown Road and chat about things, usually what his grandchildren were up to, or how much we enjoyed pie, knowing that people driving by were sure that we were up to no good — when we were really just enjoying a fine day outside in the sun.

“Before Kent died, he was really thrilled to make arrangements with the Great Pond Foundation to collate and digitize all of his data — notebooks, maps etc. This work is now underway.

“Short story long, Kent showed up like no-one I’ve ever known, and quietly did his work every day for his whole life.”

–Jamie Kageleiry

V ideo recordings of all of the Island Pond Community Workshop sessions, including the final one with a tribute to Kent Healy by Great Ponds documentarian Ollie Becker, can now be found on the GPF’s website: greatpondfoundation.org/ipcw/

IN MEMORIAM • KENT HEALY 11 marthasvineyard. .com

Kent Healy sits and watches the annual Tisbury Great Pond opening.

JOHN BECKER

dot DEAR

Dear Dot: Desperately seeking solar, “flushable” cat litter? and more. Dot tackles your thorniest questions from a cozy chair by the fire.

Dear Dot,

I would like to put solar panels on my home. Can you recommend reputable solar companies servicing the Island?

—Lisa Maxfield, Oak Bluffs

there are few industries where that is as clear as green energy. Right now offers a golden opportunity to install solar panels on your roof (or in your yard).

Sean Buckley with Harvest Sun Solar installations in Vineyard Haven (and, full disclosure, the company Mr. Dot and I have hired to install solar panels on our roof) says it’s no longer necessary to have a southfacing roof (he’s not convinced it ever was) and that just about everybody is a fit for solar, with the occasional exception of those with lots of trees who refuse to trim back any of them. (I can get behind trimming…)

There are also loads of incentives (check them out here at dsireusa.org), according to both Buckley and Rob Meyers, who co-owns South Mountain, another solar installer.

Dear Rona,

I too am possessor of both a septic system and a number of cats (two of my felines insist that I do not possess them but am merely granted the privilege of attending to their needs. The third is asleep on my clean laundry). So I was curious to hear the answer to your question. And hear it I did. You perhaps did too. For it was loud. And resounding. When asked for his thoughts about whether or not to flush biodegradable “flushable” cat litter, the voice of environmental consultant and registered sanitarian Doug Cooper rang out from Edgartown and it said thus: “NOOOO!”

When pressed to explain, Cooper put it this way: “Even if biodegradable, it is introducing solids that unnecessarily burden the tank. It can settle in low spots in the plumbing system, can coalesce with paper products to create clogs…” Or, more concisely, “NOOOO!”

So what can you do?

Dear Lisa,

Fifteen years ago, Mr. Dot and I were forced to rebuild our roof when it became clear — thanks to water plip plopping onto our bedroom floor — that our roof was leaky. Trying to see the bright side, we decided it offered the perfect opportunity to install solar panels. But — again this was 15 years ago — more than four solar installers told us that there was no point: Our house didn’t have a south-facing roof, and we had too many trees. (As if there is such a thing as too many trees! I scoffed.)

Lucky for us, times have changed and

To find a solar installer, talk to those who have solar panels. I’ve spotted plenty in Oak Bluffs. And take a look at EnergySage, which not only provides info, it allows local installers to quote on your particular installation. Cape Light Compact is also super helpful and includes a link to Energy Sage: capelightcompact.org/solar.

This is the golden age of solar, Lisa. Welcome to it.

Shiningly, Dot Dear

Dot,

My biodegradable cat litter says it's flushable. We have a septic tank, which makes me hesitant to flush. What should I do?

–Rona, West Tisbury

Clay litter is nasty from start (mining) to finish (landfill) and both the dust and the litter itself is dangerous for pets who can breathe it in or ingest it when they clean their paws, creating clumps in their digestive tracts. So stick with the eco stuff. The greenest way to dispose of biodegradable cat litter is composting, with some caveats: Separate out urine or feces and dispose of them in the trash, then take what’s left, put it in your compost heap, but use that only in gardens that have nonedible plants. According to the EPA, pet waste is considered a pollutant that we do not want getting into our waterways. Cat feces can carry the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, something any formerly or currently pregnant cat companion (nobody “owns” a cat, my cats insist) can attest. Even many municipal water treatment plants can’t effectively treat that. Purringly, Dot

Dear Dot,

What should I do with the temperature on my water heater when I leave for a week’s vacation?

–Wayne, West Tisbury

12 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

Illustration Elissa Turnbull

Dear Wayne,

Your question raises something of a tempest in a water heater. On the one hand, heating water for our homes uses roughly 1/5 of the energy consumption of the average U.S. household. So we might as well take the opportunity, if we’re away from our homes for more than a long weekend, to reduce that consumption (and the subsequent bill) when it’s as simple as turning the temperature on our water heater down to 120°F or “vacation” mode if your model has it. Even my math-challenged brain knows that makes cents.

You can also insulate an older tank and the pipes that carry the hot water to our faucets, which will further reduce energy consumption and cost.

But, and it’s a big but, as our climate crisis deepens, it is becoming abundantly clear that we must have a system-wide shift in where we source our energy, including how we heat our water. All of us. As a society. Which means consistently pushing those who make decisions to phase out polluting fossil fuels and move us toward cleaner, greener energy.

When the time comes, switch to a hot water heat pump. Cape Light Compact will even help you find ways to afford it. Or talk to your plumber about whether a tankless water heater would work for you. Or maybe, like Lisa who asked Dot about finding a solar installer, it’s time to power your entire household

I hope you don’t feel like you’re in hot water for just asking a reasonable question, Wayne. It is mid-winter and I am grumpy. And I worry deeply that, in our uber-responsible desire to take every possible teensy tiny step to make the world better, we miss the systemic ways in which certain non-green choices are forced upon us. Let us do our small parts but also let us continue to push hard for change.

Grumpily, Dot

Dot has lots more to say (bit.ly/ DEAR-DOT) about the usefulness of expiration dates on food, the veracity of the claim that Martha’s Vineyard runs on 100% renewable energy, whether to trust eco-certifications, if you should toss your batteries for rechargeables, and the methane emissions of conventional vs grass-fed cattle.

Please send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com

DEAR DOT 13 marthasvineyard. .com

Considering a CapeLightCompact.org | 1-800-797-6699 Check out available rebates and see if you qualify for 0% financing up to $25,000. A heat pump can offer: Efficient heating and cooling Year-round comfort Positive environmental impact Convenient whole home or modular installation *Financing available for residential installations only HEAT PUMP?

THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD Climate Action Plan

A Q&A with the team behind the MVC’s response to climate change.

By Sam Moore

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Could you briefly introduce yourselves?

Liz Durkee: I’m the Climate Change Planner at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. When the Coastal Planner retired a couple of years ago, the position was changed to Climate Change Planner. Before that, I was the conservation agent for the town of Oak Bluffs for 26 years.

Meghan Gombos: I am an independent consultant. I’ve been working in marine resource management and climate change adaptation for 20-plus years, mostly in the Pacific Islands and the Caribbean. I was on the climate resilience committee with Liz and Cheryl and others, so I became part of the facilitation team through that process.

Cheryl Doble: My background is in landscape architecture and planning. I worked for a number of years directing the Center for Community Design Research at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. I am also on the Tisbury Planning Board. Like Liz and Meghan, I was also on those early committees that started up the Climate Task Force and the Climate Resilience group.

Before we get to the action plan, we should ask: how will climate change affect Martha’s Vineyard?

Durkee: Because we’re an Island, sea level rise, stronger storms, and all the coastal issues are extremely important for us to address. Climate change is going to impact every aspect of our lives: our land and water, our human health, our economy, our emergency preparedness. We need to become more energy resilient and decrease our greenhouse gas emissions. It’s all interrelated, and we need to look at the whole big picture if we’re going to address these issues in a smart way.

Gombos: In addition to increased storms and sea level rise, sea surface temperature increases and ocean acidification are going to have huge impacts to our marine environment. Our marine ecosystems, our fisheries, shell fisheries — things that are really important to the Island community in both livelihoods and quality of life. And also just the heat of increased temperatures. We have so many people who work outside, who recreate outside.

Durkee: Heat is going to affect our human health; it’s going to increase respiratory issues and vector-borne diseases, and mental health issues — like if we have a major hurricane and people are displaced. We’ll have increased rain, and drought. It goes both ways. So, it’s not like you can handle one thing first, and then handle another. There’s a relationship here that you have to understand. We have to look forward in a way that addresses that. We have to come to grips with how we help each other in a moment of real extreme challenge, and then how we’re going to respond afterwards, because it’s very difficult to come up with ideas in the middle of a disaster.

So, what is the Climate Action Plan?

Gombos: The Climate Action Plan is basically looking at all of these issues and looking forward to 2040, and maybe even further. What are the impacts going to be to the Island? And what do we want to do to build? What do we want to do now to build our social, ecological, and environmental resilience to those changes?

Durkee: This summer, we received funding from the Mass Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness Program, so this is actually phase two of the Climate Action Plan. Phase one was more foundational, doing background research and the adaptation reports that Meghan prepared.

What are the outcomes you are hoping for?

Gombos: We’re trying to achieve a plan that has a 2040 outlook, and then has more immediate and measurable actions that we want to take in the next ten years. So, between now and 2030, what are we going to do? We can’t do everything. What are the biggest things to tackle? Where will we get the most bang for our buck? We’ve put together six working groups around six thematic areas: food security, transportation and infrastructure, economic resilience, land use, natural resources and biodiversity, energy transformation, and public health and safety.

Durkee: Collaboration is a huge piece of this, and the pond associations and the shellfish group, the insurance companies, the nonprofits, conservation groups, food security, and public health groups are all going to play a role in the implementation. It’s going to be an Island-wide plan.

Doble: My hope from this process is that it builds our capacity to collaborate in new ways. I feel that we’re not starting dead in the water. We really have so much going on, which gives me hope that we can do so much more.

Gombos: Like Cheryl said, there’s so much good work that’s happening. It’s just getting folks to be able to pause and sit down and talk and share what’s happening and then say, ‘Hey, what if we could combine these efforts?’

Who else is involved?

Gombos: For each of the working groups, we have a liaison who’s a community leader in that space. They’ve got expertise, they’ve got the relationships, and we’ve asked them to help pull together a variety of people from around the community that can guide that component of the plan. We’ve asked the towns to provide a repre-

CLIMATE ACTION PLAN • Q&A 14 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

sentative to each working group. And then we have businesses, NGOs, and students we’ve asked to participate.

Doble: When this process began, the Commission went to each of the towns and asked them to form a Climate Committee to work with them on this project. The Wampanoag also have representation, and the Brazilian community as well.

Can you give a few examples of actions that might come out of the plan?

Durkee: The residents of Aquinnah got together and organized a Community Emergency Response Team [a disaster response initiative based on FEMA guidelines], and they had their emergency manager train residents in emergency response, first aid, and things like that. It’s an amazing program, and we really would like to see all the towns develop a CERT team. On a policy note, another example is that we're really hoping the planning boards and all the towns will update their floodplain bylaws to address flooding.

Gombos: Transportation and infrastructure. When we’re upgrading roads and culverts, let’s do it in a way that’s thinking about what the climate projections are, so we are not setting ourselves up to have to redo something.

If we’re talking about the next 20 years or so, what are the resources that the Island has, and what does it need?

Durkee: As we have said, there are a lot of organizations and individuals working on a lot of these issues now. On the other hand, it’s going to cost money to do all these things. We need to look at ways to come up with very large amounts of money. There are other things to think about. Does the commission need more climate change staff? Do the towns need to have a staff member who is focusing on climate issues for their towns? Are nonprofits going to need to add staff members if they’re going to be ramping up what they’re doing?

Doble: I’m not going to be around to see the end of this plan happen. It’s a long-term

process. One of the things I’m starting, as I’ve worked on projects here, is we begin by taking our first steps. And we make good investments now. And the second is that, this can be phased.

Gombos: I totally agree. Even though we have a twenty-year horizon for this plan, the meat is really in the next five to ten years. With the infrastructure bill, there are opportunities there. I think there is going to be more funding available as we go forward. The more we’re in a place to say, ‘This is what we want to do,’ the better off we are.

Durkee: We’ve developed a Climate Action Fund, through the Martha’s Vineyard Community Foundation, that people can donate funding to [marthasvineyardcf. org]. If we get a grant where the locals have to match the grant funds, this fund could help us to pay for that town’s portion of the grant.

Doble: That program is important because it makes us a little bit more nimble than when you have to go through town government and county meetings to get allocation for grant funding.

What is the difference between mitigation and adaptation on Martha’s Vineyard?

Durkee: It’s harder for people to grasp the adaptation. Mitigation, yeah, you could buy an electric car, put solar panels on your house. One of the things that we need to start dialogue on, in terms of adaptation, is managed retreat from the shore. It’s a reality. People don't really like change on this Island, and things are going to change. We’re working to change them in the best possible way we can, but there are going to be tough decisions to make in some areas.

What are some short- and long-term goals for some of these projects?

Gombos: There are certain issues like moving roads away from the shoreline, where it’s long term and it’s going to take a while to do that. But then there are other things that people can do in their

own backyard, like gardening or building habitat. Those are smaller actions where you see progress immediately while we’re working on the big clunkers that take a while to happen.

Durkee: Sometimes people don’t recognize that things are happening because they’re moving slow. Yeah, it doesn’t look like anything’s happening, but it is happening. I think that’s so important. Because it’s discouraging when you put time into a plan, and then you don’t see things happen. And with communities, with government, with the groups that we’re working with, this is all going to take time.

Where can people keep track of the planning process?

Gombos: The plan is going to launch on a live website (thevineyardway.org). We really took some time to look at the history of planning on the Island, and heard some trepidation about ‘another plan that will just sit on the shelf.’ The website allows people to go and see what’s happening and for us to be able to update it as we go. It allows us to track and show progress, which I think has been challenging for other plans.

What is the best way to get involved?

Durkee: Well, [people] can get involved in climate week, which is coming up May 8-14. Many organizations and people and businesses are going to be having events to get the community thinking about these things. That’s our big community outreach component. The Island Climate Action Network also has a lot of information on how people can get involved. We have monthly presentations on climate issues related to each of the thematic groups. Those are announced on the ICAN webpage.

Gombos: The students at the high school are putting together “Climate Cafes” each month, and they’re very inspiring. It’s nice to support them, because they’re really motivated. We’re excited to be coordinating with the students on this plan, because we think that their voices are critical.

To follow the Climate Action Plan, visit thevineyardway.org

Q&A • CLIMATE ACTION PLAN 15 marthasvineyard. .com

WHAT’S SO BAD ABOUT

WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES? • FEATURE 16 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

Story by Leslie Garrett

by Kevin McGrath

by Kevin McGrath

Inva ive Species?

17

Illustration

Who’s native? Who’s not? And are they all unwelcome?

BY LESLIE GARRETT

The Vineyard plays host to a number of species that aren’t, historically, from around here. Some of these interlopers behave themselves. But others wreak havoc, displacing valuable native species and transforming fragile ecosystems. Should we fight back?

If you haven’t yet spotted a brown marmorated stink bug on the Vineyard, just wait. MV Atlas of Life director Matt Pelikan has the distinction of being the first to document the interloper’s appearance on the Vineyard in 2018 on iNaturalist, the citizen science social network that shares observations about the natural world. Since then, he says, “they’ve settled in as pretty common around my house, and lots of other people are finding them, too, sometimes in pretty large numbers.”

But though brown marmorated

stink bugs are deemed an invasive species in Massachusetts (and plenty of other locales), they don’t seem to be anything more than a smelly nuisance on the Vineyard — and that’s only if you squash them.

Pelikan says the word invasive “is really pretty slippery and context dependent. And means different things to different people.”

Suzan Bellincampi, Islands Director, Mass Audubon (and director at Felix Neck Sanctuary), differentiates between native, non-native, non-native invasive, naturalized — “It’s a continuum,” she says, and just because a species is unwelcome, doesn’t mean it’s invasive. Stink bugs might be unwanted on the Vineyard but they aren’t, at least not yet, invasive here. Skunks, long the scourge of those of us who just want to walk our dogs at dusk without a standoff, are believed by most Islanders to have been imported here in the 1960s by a Vineyarder who shall remain

Plant this not that

Beach plum NOT

Switchgrass NOT silvergrass (Miscanthum)

Bee balm or swamp milkweed NOT purple loosestrife

Red or sugar maple NOT Norway maple

Winterberr y NOT autumn olive

nameless. Not so. They are, in fact, natives. “We have multiple sources from the fossil record and historical record to tell us that they were here,” says BiodiversityWorks’ Luanne Johnson (who studied skunks for her Ph.D).

The same holds for poison ivy. We all hate it but it was here millennia before we were.

What do we mean by “invasives”?

“Invasives are plants, animals, organisms that have a negative effect on the ecosystem,” Bellincampi says. “They disrupt beneficial processes, they spread diseases, they alter the ecology.”

Invasive is a relatively new descriptor. It was in 1999 that President Clinton issued Executive Order 13112 that read, “An invasive species is defined as a species that is 1) non-native (or alien) to the ecosystem under consideration and 2) whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.”

“Habitat destruction, invasive plants or animals are the leading cause of species extinction,” says Tim Boland, executive director of The Polly Hill Arboretum. “When you have a local extinction, a whole suite of codependent lifeforms — invertebrates, micro and macro organisms, etc. — are also correspondingly lost.” And that loss isn’t just ecological, Boland says. It’s aesthetic. The world becomes not only “less diverse and less biologically active, it’s less beautiful.” It’s also personal, he says. “The cascade effect will eventually catch up with the human species.”

As much as we like to think we have dominion over the natural world, we are, ultimately, just another species.

Again, it’s important to make the distinction between non-native species, which often coexist quite nicely with natives, and those that genuinely pose a threat, especially to the Vineyard’s rare ecosystems.

No habitat is immune to intruding species. They arrive in any number of ways. Some marine species arrive on

WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES? • FEATURE

Multiflora rose

18

Phragmites on the shores of Farm Pond in Oak Bluffs.

boat hulls or in ballast water. Seeds are carried here by wind or dropped here in bird feces. Contaminated soil is a huge problem, say, on the roots of that shrub an Islander brought to transplant from New Jersey, or in the bag of soil purchased from Lowe’s. We’ve brought some invasives here (albeit often unintentionally) because they’re beautiful and they grow well in this environment.

It’s Japanese knotweed that particularly worries Matt Pelikan, who notes that, for the most part, “there aren’t too many insects or animals that I’m terribly concerned about on the Vineyard.” But while a lot of species considered invasive in Massachusetts don’t do well on the Island — “they’re not able to handle the high acidity and drought conditions,” Pelikan says — knotweed is quite comfortable in our unique sandplain soils.

Oriental bittersweet torments Suzan Bellicampi. “I’m going to be 90 years old pulling bittersweet in my retirement,” she says. It’s among the plants strangling milkweed, which Monarch butterfly larvae need for survival. And it isn’t just

Use autumn olive berries in smoothies.

If you can't beat 'em, eat 'em!

Some invasive species are surprisingly tasty. Herewith, inspiration for putting our problems on our plates:

Garlic mustard : Use to make pesto or mixed with salad greens

Phragmites: Take the shoots right where they meet the roots, boil and toss with butter.

Green crabs: Use the meat any way you’d use any crab meat.

Japanese knotweed: Since this tastes something like rhubarb, use it in similar ways — in baking, soups, or stews. Or steam it and toss with garlic. Take the shoots when they’re 6 to 8 inches tall. Any taller and they’re tough.

Autumn olive: Use the berries in smoothies, mixed with yogurt, or make into jams and jellies

Kudzu: Parboil the leaves to soften the sometimes bristly hairs and then use in salads, or as wraps.

plants that concern Bellincampi. Green crabs, which likely arrived in tiny zoea form on the hull of someone’s boat or in ballast water, are quickly outcompeting native blue crabs in Vineyard ponds. Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota have been sounding the alarm about invasive jumping earthworms, differentiated from more common earthworms by a creamy white band toward its tip. But while worms are typically a sign of soil health, these jumping worms impact the nitrogen, fungi, and soil bacteria, leaving soil that’s been likened to “coffee grounds” and is far less supportive of native species. They’re now here — likely transported

in their tiny cocoon stage via soil, or mulch, perhaps even on the bottoms of people’s shoes — and there are reports of them in many Island gardens.

Others on this Least Wanted list include (but are not limited to) Phragmites, invasive honeysuckle (there is a native honeysuckle), and garlic mustard.

Invasives: fight them, or surrender?

But agreeing that invasives are transforming landscapes isn’t the same as agreeing what to do about them.

Indeed, the term “invasive” itself has become loaded. A recent Vox story noted

19 marthasvineyard. .com FEATURE • WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES?

Ecologists and wildlife biologists tell us to expect to see more of what are called ‘rangeshifting’ or ‘climatetracking’ species as climate change makes certain locations more hospitable to some species and less hospitable to others.

that “‘invasive species’ is a concept so ingrained in American consciousness that it’s taken on a life of its own, coloring the way we judge the health of ecosystems and neatly dividing life on Earth into native and invasive.”

It’s a binary that invites a vocabulary of war: eradicate, battle, invade, destroy.

There’s a vast middle ground, say ecologists. And it’s growing because of climate change. Species from Miscanthus (silvergrass) to Lone Star ticks are moving from areas where they are well-established, if not technically native,

SPIRITED HON EYSUCKLE

of a landscape we’ve made attractive to them.” And this range-shifting is only going to increase, challenging scientists and the rest of us to consider how, in some cases if, we respond.

Might invasives serve a purpose?

It’s an unpopular opinion (one source says she gets “slammed” if she even mentions it) but it’s worth considering how these invasives might be useful to us.

Though Phragmites, for example, take

tells us, an acre of phragmites contains, on average, 100 lbs of nitrogen in its above-ground tissues, equivalent to the nitrogen contained in the edible part of about 130,000 harvested oysters, or an estimated urine-nitrogen output from 11 people in one year. “All around the world, [scientists] have studied these things,” she says. “They've studied the use of Phragmites to clean up wastewater from retention ponds. In Europe, they've been used traditionally like this for centuries. So none of this is a new concept, it’s just not something that is done or embraced around here.”

Continued from page 19

(Strain out the spiders)

Collect honeysuckle flowers and fill a mason jar (do not crush or pack in flowers)

Pour your favorite spirit over the flowers (vodka and gin work well)

Store in a cool place for a few weeks

Strain out pollen, plant bits, spiders, and other debris

Use in your favorite cocktail or make a simple syrup (feel free to infuse more flowers) to make it a liqueur or cordial Cheers! (Thanks, Suzan Bellincampi!)

into areas where the habitat might be welcoming but the human inhabitants less so.

Ecologists and wildlife biologists tell us to expect to see more of what are called “range-shifting” or “climate-tracking” species as climate change makes certain locations more hospitable to some species and less hospitable to others. Luanne Johnson calls them urban adaptors, generalists, synanthropic. “These aren’t invasive species, necessarily. They are simply taking advantage

over brackish water ecosystems (take a look at the shores of Farm Pond) and do not provide the food or habitat that native plants do, they also absorb more nitrogen than many native plants and help raise the salt marsh base to help protect against sea level rise.

Emma Green-Beach, a biologist with the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group (MVSG), has a thick folder full of peer-reviewed scientific studies that underscore how effective Phragmites are at nitrogen uptake. For instance, she

What has been done by the MVSG is what Green-Beach calls “harvesting” Phragmites. With a grant from the Environmental Protection Agency, the Group monitors Phragmites in small, isolated spots, then cuts them back mid-July or so before they flower. The timing is critical, she explains. If you cut them back too early, they might have time to grow back and flower. What the Group has noticed is that native species are starting to come back. So the Phragmites do the superior work of removing nitrogen but are kept somewhat in check. It’s “making lemonade from lemons,” says Green-Beach, who says that the Phragmites are far too established to be completely eradicated so we might as well turn their presence into a positive while minimizing the negative effects. The experiment hasn’t gone beyond a few small areas but the potential is there, if others can get on board.

In the Midwest, Tim Boland says, Phragmites are chopped to the ground right when they’re starting to flower to weaken them, thereby preventing them from seeding. The biomass gets used as a burning fuel.

Recently, says Green-Beach, they took some of the Phragmites and had them turned into biochar, which was then given to IGI to use in their fields to improve soil health. “So we continue to chip away at various aspects of this concept,” she says.

Green crabs are being similarly tapped as a resource in places along the east

20 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022 WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES? • FEATURE

WHAT YOU CAN DO

and west coasts of the U.S. and Canada where cooks are putting them on the menu. Researchers at McGill University in Quebec are attempting to create a biopolymer from green crab shells and a partnership between Parks Canada and Nova Scotia’s Dalhousie University aims to turn the crabs into liquid fertilizer. The goal isn’t to eradicate the invasive crabs — that horse is out of the barn, so to speak — but to keep the populations in check and allow native species to thrive and adapt.

a study he conducted to explore how different Indigenous communities were dealing with invasive species. He and his colleagues discovered that, even within communities, there were many different approaches but most centered around traditional knowledge to find solutions. “Indigenous communities seek to build relationships with [invasive species],” Reo said.

“Every plant is a gift from the Creator,” Vandal explains. “We are to respect them and give thanks for their presence.”

Duh … don’t plant invasives.

Remove invasives if they’re on your property but do so in a way that doesn’t cause further spreading. Persistently cutting them back will often do the trick. There are some species, such as Japanese knotweed, Phragmites, and Japanese stilt grass, that should be removed only by professionals.

Plant native species that support biodiversity, especially pollinator gardens, which attract all kinds of insects.

If you have a landscaper, ensure that they have an understanding of the problem of invasive species and a commitment to planting native or noninvasive species.

Don’t bring plants, soil, or mulch from off-Island.

Embrace messiness. Leave seed heads for birds, leave leaf debris for cocoons and larva.

Reduce lawn size and expand garden size.

Install bird houses, bat boxes, and owl boxes in close proximity to native plants.

Tap into Polly Hill Arboretum’s vast database of native or non-invasive options at bit.ly/PHA-invasives.

On the Vineyard, Emma GreenBeach has heard rumors of a bounty on green crabs. “All the shellfish departments trap green crabs because they are shellfish predators,” she says. “Some give/barter/trade them to conch fishermen for bait. They also make really good compost and a good broth at the least.”

A recent study by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health confirms that spotted knotweed shows promise treating Lyme disease in the 25% of sufferers who don’t respond to antibiotic treatment, something Liz Durkee, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s climate change planner, says she first heard from Rebecca Gilbert at Chilmark’s Native Earth Teaching Farm.

Carole Vandal, a Wampanoag tribal member, says Indigenous medicine knowledge, referred to as the “Midewiwin” use herbal medicines to cure illnesses. The Midewiwin is an Algonquin medicine society found historically among the Algonquian of the Upper Great Lakes (Anishinaabe), northern prairies, and eastern subArctic. Vandal says that it instructs us, “If you are ill, go outside and look at the plants in your backyard … often the cure for what ails you can be found right under your nose and feet.”

Indigenous people have long looked at the presence of non-native species as opportunities; we should consider how they might be useful, according to Nicholas Reo, an assistant professor of Native American and environmental studies at Dartmouth College. Reo spoke to a Canadian radio show, Unreserved, about

If an invasive species is spreading into food gardens and interfering with a person’s ability to feed themselves or their family, Vandal says, “we dig them up and move them to a more suitable place to reside, or sometimes they will be left to die. But the divide and conquer ethos is not our way.”

It’s an approach similarly articulated by Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, professor of environmental biology at Syracuse University, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Kimmerer told an interviewer for the Biohabitat site, “When [Indigenous people] look at new or ‘invasive’ species that come to us, instead of having a knee-jerk reaction of ‘those are bad and we want to do everything we can to eliminate them,’ we consider what are they bringing us.” View them as teachers, she urges, noting that “we have created the conditions where they’re going to flourish.”

While there’s little argument that we have, indeed, created the conditions for these species to flourish, the fact remains that valuable native species dwindle when certain new species gain a foothold, leaving us with a dilemma. How do we respond? While Tim Boland agrees with Kimmerer that these losses are driven by humans and that the plants themselves are not inherently evil, “they are evolutionarily programmed to survive and reproduce.” Particularly, he notes, they are opportunists which thrive in damaged or altered ecosystems.

And we all agree who’s to blame for that.

21 marthasvineyard. .com FEATURE • WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT INVASIVE SPECIES?

While methods to eradicate invasive plant species run the gamut from mechanical removal to applying herbicides — which need to be left to the pros — there are still important ways each of us can help.

Cruising with Currier

FEATURING ANDRE BONNELL AND HIS ELECTRIC VTA BUS.

On New Year’s Eve afternoon of 2021, I boarded the route #3 bus from the Steamship Authority in Vineyard Haven to ride out to the West Tisbury Town Hall with Andre Bonnell at the wheel. Bonnell has been with the Martha’s Vineyard Transit Authority (VTA) for 25 years and he has been tapped to be the unofficial goodwill ambassador for the VTA’s line of electric buses.

“I came to the Island for the weekend in June of 1970,” Bonnell tells me as we head toward West Tisbury, “and I’m still waiting for Monday to come around. So I guess you could say it’s been a very long weekend.” And there, in a nutshell, you have Andre Bonnell, an amiable guy with a gift for gab and more one liners than Shecky Greene.

“I’ve got a corner office with a beautiful view,” he said. “I get paid to travel and to drive the company’s $700,000 vehicle.”

Speaking at a ceremony last spring announcing the $4.5 million solar energy project (which includes seven solar canopies at the VTA headquarters in the

OAirport Business Park), Bonnell likened the conversion from diesel to electric as going from the “Fred Flintstone” era to the “George Jetson” era of transit.

“I love driving these electric buses,” Bonnell says, “because they’re a lot easier to handle. And our customers seem to love them as well. They’re quieter and they're loaded with USB ports so people can charge their cell phones or tablets.” Bonnell says that riders especially like them in the summer months because of the air conditioning. “With the old diesel models,” he said, “we used to have what we called 20/40 air conditioning … we'd open twenty windows and go 40 miles per hour.”

Bonnell says that the VTA has been running electric buses for two years now and that people seem to really notice the difference. “A lot of people from off-Island have never seen electric buses and they comment on how peppy the buses are, and how they like all the accessories. It makes me proud to show off our Island and demonstrate how we’re one step ahead.”

Bonnell goes on to explain the economies of having electric buses and how, compared to diesel buses, there’s relatively low maintenance. “The old diesel buses were not meant to run at low speeds,” Bonnell said. “They're meant to run long distances at higher speeds, so as a result, when they’re used on the Island with lots

22 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

Written by Geoff Currier Photos by Jeremy Driesen

Electric buses are more than four times as energy efficient as diesel buses, and will save 40,000 metric tons in carbon dioxide emissions over 12 years.

of stops and starts, they end up spending a lot of time in the shop.”

Bonnell explained that the VTA maintenance crew had to go back to school to learn how to deal with the new electric buses. In a way, they had to go from being mechanics to being electricians. In the end, there is less maintenance because there’s no internal combustion engine anymore. “It’s sort of a white glove thing,” Bonnell said. “They don’t have to get their hands so dirty any more.”

Angie Gompert, the VTA administrator, told me on the phone that the electric buses are more than four times as energy efficient as diesel buses and will save an estimated 336,000 gallons of diesel fuel, translating into a 40,668-metric ton reduction in carbon dioxide emissions over the 12-year service life of the buses. This is the equivalent of taking 8,500 passenger cars off the road for a year.

“At this point, 16 out of the 32 VTA buses are electric,” Gompert said, “and moving forward we won’t be replacing any diesel buses. Our goal is to go entirely electric, and the same applies to our fleet of vans and cars.”

Gompert explained that funding for the electric bus program came from several sources.

”We have received four years of low or no emission (LoNo) funding for transit buses from the Federal Transit Authority (FTA) as well as $2.3 million for the differential costs of converting diesel buses over to electric. We’ve also received about $3.8 million from the MassDOT Regional Transit Authority Capital Asset Program (RTACAP), and then there was the $3.9 million that came from Volkswagen.”

As you may recall, about six years ago Volkswagen was fined for lying about their emissions. A settlement distributed significant funding to each state. The VTA’s share from the state of Massachusetts was $3.9 million.

After about half-hour on the road, Andre and I arrived at the West Tisbury Town Hall and Bonnell’s shift was over. From there, he’d be taking one of the VTA’s electric cars, a Hyundai Kona, out to

the VTA headquarters to pick up his car.

Bonnell seemed to like the Kona nearly as much as his electric bus, with one added advantage — it’s a whole lot easier to park.

CRUISING WITH CURRIER • THE VTA 23 marthasvineyard. .com

Currier and Bonnell in West Tisbury.

Buses charge at the VTA headquarters.

Life on a sparse island can be full of abundance.

A SHARING OF MEANS • FEATURE 24 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

In Exchange An Island Barter Keeps Things Local

One morning this past fall at Chappy Point, I stood in rubber boots and work overalls in the back of a borrowed dump trailer. I watched as Chappy Ferry co-owner, Peter Wells, behind the wheel of a skid steer, expertly plowed into an enormous pile of fresh seaweed, lifting out a bucketful of the heavy, wet strands. He then pivoted the agile machine, and delivered the load to my waiting

trailer where I kicked and tamped, spreading the seaweed evenly across the bed as he turned for another haul.

The day before, the Island was hit with a Nor'easter that left Chappaquiddick and other parts of Martha’s VIneyard without power for two days and deposited yards and yards of fresh seaweed across the Chappy Point parking lot. Now it all needed a new home.

I used this seaweed, rich in micronutrients, to form the foundation of

my vegetable and flower farm on Chappy. Over the next few months, landscaping companies, grateful to avoid additional ferry and dump fees, will add leaves, grass clippings, and pine needles to the growing pile.

In trade, come next fall, they will return with dump trucks and a front end loader, much larger than any of our own equipment, to help us move the finished material out to our production fields. The dump trucks are too large for our narrow, trail-like access road, so

FEATURE • A SHARING OF MEANS 25 marthasvineyard. .com

a new compost heap at Slip Away,

Story Lily Walter Photos Sheny Leon

On Chappy, a balancing of the scales, a sharing of means, a neighborly act of camaraderie.

The farmstand at Slip Away Farm on Chappaquiddick.

we will ask our neighbor for permission to cut across his property. In exchange, we will bring him a load or two of compost to feed his own garden.

Because of the two ferries that separate us from the mainland, we cannot affordably ship in compost from elsewhere, but must instead produce all that we use. This reduces our carbon footprint and keeps our fertility plan hyperlocal. But this critical process requires assistance from many in our community: Peter and his skid steer, my friend’s dump trailer and truck, the landscaper’s inputs and machinery, the

neighbor's permission for drive-in access.

Although no money has been exchanged, no capital lost or gained, many who help us will also benefit, either now or in the future.

We call this informal trade island barter. With limited resources, inflated service fees associated with living in a seasonal, tourist-driven economy, and a desire to keep things local, we rely on each other for equipment or skills, childcare, and food.

I am neither a hunter nor a fisherman. I know nothing of harvesting food from the woods or pulling catch from the sea.

A SHARING OF MEANS • FEATURE 26 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

How

do you measure the worth of a successful small farm or the lifetime care of a trusted carpenter?

Neighbors on Chappy rely on each other for equipment or skills, childcare, and food.

Walter will trade vegetables for proteins from a neighbor who hunts or fishes.

I know farmland: long rows of crops stretching out in front of me in a flat, open field. Because of my profession, vegetables dominate my dinner table, substituted with meat from other Island farms or occasionally the grocery store. But over the years, I have been fortunate to cultivate barter relationships with Chappy neighbors. My dinner table frequently features Island protein harvested by others.

Years ago, our then-mailman, an avid hunter and fisherman, occasionally delivered a big striped bass or a bluefish along with our daily mail. In the fall, he spends many hours up in a tree stand, hunting deer, first with a bow and then, as the season progresses, a shotgun. Some years, at Christmastime, we return home to find a bag of fresh venison hanging on our front door. In those winters, sausages, ground venison, and the coveted back strap make their way to our kitchen table.

Another acquaintance visits Chappy twice a year, once in the late spring and again in the fall. He spends his time on-Island fishing and clamming, absorbing all the Chappy shores have to offer. Once or twice on his visits here, he drops by the farm, pops open his tailgate and pulls out bluefish caught an hour or two earlier. For dinner on those nights,

we stuff a few lemons inside the fish and toss the whole fish on a hot grill. We serve it on a wooden cutting board, each pulling off chunks of the briny meat, avoiding the delicate bones.

In exchange, I offer these two individuals what I can, depending on the season. In spring, it may be salad greens, radishes, or pea shoots to go with the fresh catch. In summer, a few pounds of tomatoes, a pint or two of fairytale eggplant, or a handful of shishito

peppers to cook on the grill. Come late fall, a newly harvested deer might hang for several days in our walk-in cooler.

My favorite barters are around food. I love that I can have an entirely Chappy dinner, one in which I was responsible for only a few of the components. I imagine the hunter or fisherman sitting down to a similar meal, experiencing a similar joy. We are eating in a way that feels right. Resources were shared, dinners were made, people were fed,

FEATURE • A SHARING OF MEANS 27 marthasvineyard. .com

These friends and neighbors wanted to see us thrive. They wanted to encourage small-scale agriculture and enable us, a small group of young farmers, the chance to make a living here.

Slip Away crew: Collins Heavener, Madi Howard, Lily Walter, Sheny Leon, Lars Schuster, and Baxley the farm pup.

all from within a few square miles.

Frequently, Island barters revolve around skills or trades. We live in a place where finding an available tradesman, particularly during a building boom or in the summer months, can be challenging if not impossible. Plumbers, electricians, and carpenters are in high demand and, if secured, expensive. For many islanders, bartering helps level the playing field. There is the electrician who recently wired an infrared sauna in exchange for a lamb. The carpenter who renovated a kitchen to offset the purchase of a dream vacation condominium. And the plumber who exchanged his work for a cavalry sword used in World War I.

Sometimes, Island barter involves less tangible trades or an item may be given without any expectation of a near-term return. When I first began the farm, I often felt like we could not reciprocate for many of the gifts that came our way.

We had neighbors bringing perennial plants for our herb garden and lending a hand when we skinned our first hoophouse. Friends loaned us equipment, plowed our first fields, let

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Find existing groups for sharing, such as the MV Plant Trading Facebook page, where you can trade for shrubs, flowers, and houseplants.

Create a Facebook group — you can make it private, invitation-only among those you trust — and share lawn mowers and power tools, or childcare and errands. Chat with like-minded neighbors and establish something informal, though you’ll want to be sure to create some structure so that borrowed items don’t languish in someone’s garage, or there’s an agreed-upon approach if something breaks when in use. Be a good neighbor and always return items in good condition.

Do you participate in a neighborhood sharing economy? Tell us about it: editor@ bluedotliving.com or via Twitter and Instagram: @bluedotliving

us borrow dump trucks and flatbeds, sponsored our first bee hives, installed a new well, graded our driveway. We received a grant to purchase a new tractor, but before we did so, a neighbor offered us his big John Deere for free, allowing us to direct the funds towards other needed infrastructure purchases.

What I have come to learn with time is that none of these things were given with the expectation of a physical return; instead, the trade was the success of the farm. These friends and neighbors wanted to see us thrive. They wanted to encourage small-scale agriculture and enable us, a small group of young farmers, the chance to make a living here. They hoped to one day avoid a ferry line across to the other side and instead find dinner in our farmstand, perhaps greeting a neighbor while selecting their salad greens or bouquet.

I hope that those who gave to us in the early days now feel that their barter has been met, but it also feels good to have something more tangible to offer in trade: a truck or tractor, flowers or vegetables.

The beauty of barter is that there is no metric. A bluefish, in dollar value, may or may not be equivalent to a dozen eggs offered in trade. How do you measure the worth of a successful small farm or the lifetime care of a trusted carpenter? Is a freezer stocked with lamb comparable to a wired sauna? It may be impossible to assign a price to all that is offered in trade. Yet, if each recipient feels the worth of their half is met, suddenly both parties stand on equal footing. It is a balancing of the scales, a sharing of means, a neighborly act of camaraderie. One for the other, returning.

Lily Walter is the owner of Slip Away Farm on Chappaquiddick.

A SHARING OF MEANS • FEATURE 28 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /WINTER–EARLY SPRING 2022

Lily Walter at Slip Away.

FIELDNote

To: Bluedot Living

From: John Abrams

Subject: Housing Bank L egislation has Strong Environmental Standards

First, some background: I’m hopeful that all six Vineyard town meetings and ballot votes will send the proposed MV Housing Bank (MVHB) transfer fee bill to the state legislature this spring. The 2% fee on real estate sales above $1,000,000 will provide a long-term steady source of funding for attainable year-round housing. Modeled after the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank, this is a critical resource that our community has lacked for too long.

Our local legislation will contain innovative environmental restrictions that may have far-reaching implications. They could serve to raise building standards Islandwide. And with statewide enabling legislation currently pending — which would allow similar housing banks anywhere in the state — these standards can serve as a model for other towns, cities, and regions.

The Vineyard legislation provides that all funds spent by the Housing Bank (aside from administrative costs) must comply with the following requirements:

• No less than 75% of Island-wide annual funding commitments shall be allocated to projects on properties previously developed with existing buildings. This provision

may be the most important. The Housing Bank’s task is not to promote development; it’s to provide stable year-round housing for locals. Using existing housing — and especially converting current seasonal and short-term rentals to year round — is the best way for the Island, and the least expensive.

• No new construction shall use fossil fuels on site (except as needed during construction, renovation, repair, temporary use for maintenance, or vehicle use), and all new construction shall achieve a HERS (Home Energy Rating Service) rating of zero and, to the maximum extent possible, shall produce no new net nitrogen pollution. Nitrogen pollution is the greatest threat to our ponds and groundwater supplies. HERS ratings measure building performance and are becoming more common in building codes and a HERS rating of zero means the building(s) is capable of producing as much energy as it uses.. These requirements are not easy to achieve. That’s the point.

• All new construction on undeveloped properties of more than five acres shall preserve a minimum of 40% of the property and minimize tree removal. This promotes clustering, preserves open space, and protects the carbon embodied in trees.

• All projects shall minimize disturbances to the local ecology. Native landscapes and low-impact development practices are important.

• If a project receiving Housing Bank funds includes both income-restricted and market-rate units, the requirements listed here shall apply to the entire project. They should, in fact, apply to all Vineyard development. Someday they will. In addition to those requirements, there are three additional environmental priorities. These recognize that not all projects will be able to meet them, unlike the standards above. The MVHB will prioritize:

• Projects that are close to existing services (honor “Smart Growth” principles). Walkable neighborhoods close to services and public transportation.

• Projects that are not in priority habitat areas as defined by the Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Act. This speaks for itself.

• Projects that mitigate the effects of climate change, such as projects which do not use fossil fuels or have a master plan to delineate a path to fossil-fuel free operation and net-zero annual site energy consumption. This priority is for existing buildings (all new construction is subject to the absolute requirements above).

The MV Housing Bank Steering Committee is proud of this aspect of the legislation. Your participation is crucial to this legislative effort. Vote for the MV Housing Bank at your annual town meeting and at the ballot this spring. Please be certain to do that. Find out more at ccmvhb.org

John Abrams is CEO of South Mountain Company and a member of the Coalition to Create the MV Housing Bank Steering Committee.

in a word Aquamation

[Aa·kwuh·mey-shuhn]

On December 26, 2021, Desmond Tutu died, leaving a legacy of deep justice and faith.

So it’s perhaps no surprise that he chose to have his remains disposed of by a method that is particularly light on Mother Earth — aquamation.

Also known as alkaline hydrolysis or, colloquially as water cremation, aquamation involves placing the deceased’s body in a pressurized metal container that contains

about 95% water and 5% alkali, typically sodium or potassium hydroxide. The liquid is heated at high pressure to between 200 and 300 degrees Fahrenheit for up to four hours. What remains are bones, soft enough to be crushed to dust and delivered to the deceased’s family, if they like. The liquid is usually benign enough to be disposed of like any wastewater, including being used to water a garden. Unlike cremation, aquamation releases no greenhouse gases,

and doesn’t require a coffin or the toxic chemicals used to embalm bodies. Although the use of roughly 100 gallons of water per process is significant, it’s still better for the planet than embalming or cremation.

To date, aquamation is legal in 20 states. In Massachusetts, there is no specific legislation or regulations governing its use for people — though it is legal for pets, so Fluffy and Fido, at least, can go out with an earth-friendly splash.

FIELD NOTE

PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Room For Change:

The Bed

In my junior year, my dear and brilliant friend whom I’ll call Rose got kicked out of college. Due to the drug-related nature of her dismissal, Rose had to make a fast exit so she left me her bed — a two-month-old very expensive queen mattress and box spring — and a set of new sheets from Gracious Home, a high-end home store in New York City. I had always slept on futons or whatever was there with whatever sheets and blankets were available. My first night in Rose’s bed was a revelation. (And, before we go any further, let me pause and say, “Don’t worry about Rose.” She eventually graduated from an amazing school and has gone on to live a productive life.)

Since then, I’ve been obsessed with sheets and beds. I’ve tried dozens of kinds of sheets and sheet companies and many mattresses. My husband and I currently have the best bed I’ve ever slept in. The sheets are soft. I have an organic cotton waffle blanket that cools in the summer and traps heat in the winter. And an insanely expensive mattress manufactured with sustainably sourced natural fibers that has the perfect combination of softness and support. And most of all, the mattress has a 25-year guarantee, which allows me to sleep easily even with the crazy price.

So when the Bluedot team got together to discuss what Room for Change topic we could tackle next, we thought, “It’s winter, where do we find ourselves most?” Our answer: “Curled up in bed!” I thought, “Great. Given my 30+ years as an avid consumer, this will be easy. I can write this in my sleep.” It turns out my depth of knowledge of beds was, at best, shallow.