JOURNAL 2022-2023 Published by Bentham Brooks Institute

RESEARCH

The Bentham Brooks Institute (BBI) is a student-led think tank based at University College London. Its mission is to inspire talented students to pursue careers in academia, think tanks, and the public sector. Through a yearly research program, the BBI brings students together to produce high quality, peer-reviewed research papers providing concrete policy recommendations and pragmatic solutions to some of the world’s most pressing issues.

The BBI proposes a yearly research agenda to encourage students to delve into an area about which they are passionate. The research agenda for the academic year 2022-2023 consisted of the following areas:

• Green Growth and Sustainability

• Global Health and Safety

• Social Justice and Equality

• Technological Risk and Governace

• Conflict and State-building

• Democratic Deficit and Authoritarianism

The Bentham Brooks Institute Committee would like to thank all the advisors and peerreviewers, without whom this publication would have never been possible. The time they set aside to guide and support researcher along the way has been invaluable.

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023

Green Growth and Sustainability: Improving Sustainability Frameworks: A comparative analysis of the views of stakeholders on the EFRAG’s European Sustainability Reporting Standards………..………..........................................................................................................3

Social Justice and Equality: The Integration of Ukrainian Migrants: A Study of the UK and Poland?.....................................................................................................................................40

Technological Risk and Governance: Critical Assessment of the EU Data Governance Act: To what extent does the EU Data Governance Act effectively enable NGOs in achieving open data sharing for social benefit? ................................................................................................64

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023

State-building: Measuring the Effects of Intrastate Conflict on State Stability in Africa

Deficit and Authoritarianism: A Tale of Two Americas:

January

to January 8th, a Report on Anti-Democracy Insurrections ...92

Conflict and

…………………………………… ...79 Democratic

From

6th

Improving Sustainability Frameworks: A comparative analysis of the views of stakeholders on the EFRAG’s European Sustainability Reporting Standards

Juliette Helfi1, Krishna Chetlapalli, Yan Hong, Maria Patouna, Vyacheslav Stupak, Marleen Walther.

Published April 2024

Abstract

Transparency and scope of corporate disclosures are essential to fostering the reliability of sustainability frameworks. Yet, academic research and empirical reviews alike point to shortcomings in the global climate information architecture. In this context, the draft European Sustainable Reporting Framework aimed at designing a stringent framework for non-financial reporting. We argue that the different stakeholders will generally agree with the European Union’s purpose of implementing a sustainable framework. Yet, we view the letters as a lobbying and communication exercise to improve and undermine the European Sustainability Reporting Standards. Analysing 203 letters from the public consultation organised by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) following the release of the draft European Sustainability Regulation Standards (ESRS), we find that the detailed feedback from the stakeholders’ letters reflects a large consensus. Stakeholders are predominantly concerned about the necessary harmonisation and consistency, the scope of disclosure requirements and the quality of standards. However, our analysis shows there is less concord on topics where groups focus more narrowly on their self-interest. Particularly, financial and non-financial actors focused on the organisation and financial burden the project would imply and underlined the perceived excess in granularity while NGOs are most concerned with standards, disclosure requirements and sustainability reporting.

Keywords: sustainability, EFRAG, reporting, climate architecture, financial actors, NGOs

Introduction

In June 2020, the EU mandated the EFRAG with the aim to improve the comprehensiveness and auditability of sustainability reporting. The EFRAG is a private organisation affiliated with the European Commission aimed at serving European public interests in the field of sustainability reporting. The EFRAG elaborated a game-changing set of non-financialreporting standards:the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). The purpose of publicly available sustainability reporting is to provide relevant, faithful, comparable and reliable information. The EU commission made it clear this regulatory effort would involve stakeholders.

Regulatory policy making is a ground on which different stakeholders, ranging from business associations to NGOs, engage in the process of rulemaking directed by a standardsetter. The depth of engagement of different stakeholders

impacts how rules will be designed, and hence which group will have their interest better taken into account. In an era where consensus-building processes have been institutionalised to the point of becoming crucial in regulatory policy-making, the EU has debated with the stakeholders concerned by this piece of legislation at different stages of the project. The ensuing public consultation resulted in stakeholders issuing position papers expressing their views on the project.

Our study aims at analysing the comments of different stakeholders in the public consultation initiated by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) on the new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) to uncover the balancing of feedback processes between stakeholders with diverse interests and policy-makers at the European level.

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Green Growth and Sustainable Development Programme

Institute Publishing

1 © 2024 Bentham Brooks

Analysing 203 letters sent by fourteen different stakeholders ranging from audit, NGOs, financial, and nonfinancial corporations, institutions to businesses, to the EFRAG in response to the first draft of the ESRS, we used an abductive qualitative approach. That is, we collected the data to “explore a phenomenon, identify themes and explain patterns'' (Saunders et al , 2019). Starting from the qualitative analysis, we computed a cross-sector table, using the number ofreferences tospecific themes inthe lettersso as tochallenge the results thatwe found foreach sectorindividually and bring a renewed comparative perspective on the findings.

Yet, considering the challenges, this study calls for further research to investigate the EFRAG’s response to the stakeholders and the final version of the ESRS. Limitations in the scope ofthe studyare due totimeand resourceavailability. In this paper, we find that the detailed feedback from the stakeholders’ letters reflects a large consensus. Stakeholders are predominantly concerned about the necessary harmonisation and consistency, the scope of disclosure requirements and the quality of standards. However, our analysis shows there is less concord on topics where groups focus more narrowly on their self-interest. Particularly, financial and non-financial actors focused on the organisation and financial burden the project would imply and underline the perceived excess in granularity while NGOs are most concerned with standards, disclosure requirements and sustainability reporting.

Following our findings, we advocate for more consultative sessions between the EU and the different stakeholders during the reporting phase so that reporting can be improved continually to adjust to the needs and conditions of stakeholders. In this sense, adjustability will be introduced from a perspective of the ever-evolving construction of the standards, not to bypass the regulation requirements.

By examining the consultative process on non-financial sustainability standards, this study lays out a case for other consultative initiatives in policy-making. Combining the European Union’s top-down approach with stakeholders’ bottom-up recommendations, this study sheds light on lobbying logic and calls for cautious incorporation of stakeholders' demands in line with the European Union’s regulation goals. This paper makes an original contribution as it offers a highly detailed analysis of a large panel of stakeholders’ feedback on the European Sustainability Reporting Standards. The letters’ analysis offers a new perspective on stakeholders’ reactions to the implementation of a coercive regulation. The lack of convergence and defensive positionsadopted on a diverse range oftopics shows that feedback letters are a lobbying and communications exercise to influence policy-making.

The paperisstructured asfollows. Section Ibrieflypresents background information on sustainable finance concepts paramount to understanding the evolution of sustainable and

responsible governance features globally and outlines the EU’s track record in terms of sustainable financial and nonfinancialreporting. Section IIcritically exposes thestateofthe literature on sustainability reporting and identifies potential gaps to be addressed. Section III specifies the methodology that we used to read, classify and analyse the stakeholders’ letters. In sections IV and V, we provide a detailed sector and cross-sector analysis shedding light on distinct as well as comparative elements addressed by the stakeholders.Section VI 4 outlines policy recommendations, incorporating some of the demands raised by the stakeholders while ensuring thatthe regulation will not be significantly watered-down.

1. Context

Priortodelving intothe literature review, understandingthe context related to sustainable finance is paramount as it would provide the foundation for the ensuing concepts. This section defines and provides a brief history regarding the various conceptions associated with sustainable finance such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Socially Responsible Investing (SRI), and Environmental, Social, and Governance factors (ESG). The section then focuses on the European Union’s sustainable finance design, reporting the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group’s involvement in the process, describing taxonomy and disclosure, and focusing on the 2014/95/EU directive and the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

Corporate Social Responsibility, Socially Responsible Investing, and Environmental, Social, and Governance factors all share origins with deep-rooted historic and moral influences which guided both corporate and individual behaviour towards business practices and business transactions (Townsend, 2020; Agudelo et al., 2019). However, it was in the 20th century when CSR, SRI, and ESG began to evolve into the broadly defined and heterogenous concepts understood today with CSR mainly relating to corporate behaviour and its impact on society, and SRI and ESG factors emphasising investor behaviour towards the consideration of social, ethical, and environmental good (Sandberg et al., 2009).

Until the 1950s CSR mainly consisted of philanthropic behaviour from corporations and the “protecting and retaining (of) employees”. (Agudelo et al., 2019), and it was not until the 2000s that there was a broadly accepted consensus on the interpretation of CSR as being mainly focused on ethical corporate behaviourand corporate behaviourpromoting social good. Between the 1950s and the 2000s many events amended the idea ofCorporate SocialResponsibility, aswellasSocially Responsible Investing, from mainly being related to philanthropy and the protection of employees to corporations’

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

attested responsibility towards ethical practices and their impact on society, attributable to the rise of protest culture of the 1950s and 1960s, regulatory committees affecting corporate behaviour in the 1970s, international collaboration spreading awareness on corporate failures in the 1980s, and globalisation and greater international cooperation in the 1990s (Agudelo et al., 2019). The European Union was principal in setting up a standard consensus on the definition of CSR and played an important role in expanding the scope of CSR. In the 2000s, the European Commission adopted that CSR entailed “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society and outlined what an enterprise should do to meet that responsibility” (European Commission, 2011), setting up a global understanding of CSR and actively applying the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The evolution of SRI can be seen in parallel with the evolution of CSR, with most of the episodes affecting the idea of CSR also affecting SRI. (Townsend, 2020) While SRI is terminologically, definitionally, strategically, and practically heterogeneous between cultural groups and different actors, the broad consensus holds that SRI is “the integration of certain non-financial concerns, such as ethical, social or environmental, into the investment process” (Sandberg et al., 2009). Investors participate in socially responsible investing by screening and engaging with corporations and investments that not only bring a greater financial return, but ones that also result in social good for example through the promotion and protection of human rights, the environment, and diversity.

Heterogeneity in SRI can be seen through the various strategies that investors engage with such as negative screening, divesting, positive investments, community investing, and shareholder activism (Sandberg et al., 2009; Cundill et al., 2017; Corporate Finance Institute, 2023). Historically SRI was associated with negative screening and divesting, as many investors abstained from investing in stocks that were perceived to be against the social good examples of which include the tobacco industry, the gambling industry, and the military (Townsend, 2020). While negative screening and divesting are still strategies used by socially responsible investors, the integration of ESG factors for the investment process is also heavily developed, making it a very common investmentstrategyforsocially responsible investors in recent times.

Environmental, Social, and Governance factors were broadly integrated into SRI following an initiative in 2006 by the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment along with the UN EnvironmentProgramme Finance Initiative and UN Global Compact. The initiative defined responsible investment as “the integration of environmental, social, and governance criteria into mainstream investment decision-

making and ownership practices” (Principles for Responsible Investing, n.d.; Sandberg et al., 2009), establishing a “definitional consensus” on responsible investing (Sandberg et al., 2009). ESG, while not only focusing on disclosure, makes iteasy forinvestors toinvestinsocially and sustainably responsible corporations guiding corporations to disclose standards relating toEnvironmental (Climate Change, Natural Resources, Pollution and Waste, Environmental opportunities), Social (Human Capital, Product Liability, Stakeholder Opposition, Social), and Governance (Corporate Governance, Corporate Behavior) criteria (Principles for Responsible Investing, n.d.).

The European Union’s history in establishing sustainable financialand non-financialreporting inline with CSR and SRI measures goes back to the 1990s when the European Union was seeking to create a transparent financial reporting market “to gain access to capital markets outside of Europe'' (Maystadt, 2017). To arrive at this, the European Commission and the European Parliament decided to adopt the IASB’s (International Accounting Standards Board) International Financing Reporting Standards in 2002 and mandated EUlisted companies to base financial statements on the IFRS from 2005 onwards. To check to see if the IASB standards were reliable and compatible with European Standards, the European Commission was given the task of adopting or rejecting standards on the advice of EFRAG (the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group). EFRAG provided technical advice to the European Commission and since then has been a technical advisor to the European Commission on accounting matters such as the ESRS and CSRD of late (Fenwick, 2023). The global financial crisis however led to transformation within EFRAG and sustainable financial reporting as criticsargued thatthereporting contributed topart of the financial crisis, leading to the EFRAG developing into a new board representative of the main stakeholders and responsible for the decision making of the body (Maystadt, 2017).

Non-financial reporting within the European Union since 2018 has been regulated by the EU Directive 2014/95/EU, the Non-financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), providing a framework for non-financial disclosure. The NFRD took the place of accounting directive 2013/34/EU, after amending it, and extended the scope of disclosure regulation (Green Finance Platform, 2021). For companies falling within the scope of the directive, the directive provides a framework for publishing information in the categories of “environmental matters, social and employee aspects, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery issues, and diversity on board of directors” (Directive 2014/95/EU), overall outlining ESG requirements. NFRD is also supplemented by Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation requiring companies to include statements on how their activities are “associated with

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

environmentally sustainable economic activities” (Green Finance Platform, 2021). Under the NFRD all large EU-listed companies, accounting for around 11700 organisations, are required to include non-financial statements based on guidelines provided by the directive (Fenwick, 2023; Green Finance Platform, 2021).

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) is a directive within the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) that seeks to expand the scope of nonfinancial reporting. It would amend the NFRD as the following non-financial reporting directive. CSRD, an initiative of the European Green Deal which aims to make the European Union carbon neutral by 2050, directly addresses the UN Sustainable Development Goals and focuses on environmental,social,and governance factors.CSRDexpands the scope of the NFRD by covering more corporations under the directive and requires them to provide non-financial reports. With this reporting directive, the number of corporations required to disclose non-financial reports would almost quadruple to about 50,000 EU businesses compared to those required to disclose under the NFRD, as not only large corporations but also small and medium enterprises would be required to disclose non-financial information (Fenwick, 2023). CSRD also mandates disclosure regarding value chains and mandates disclosure through double materiality.

In April of 2022, EFRAG issued an initial draft of ESRS allowing for a public consultation of the standards to which EFRAG received 298 “unique position papers” from different sectors. Based on the consultation, EFRAG updated some of the standards (Fenwick, 2023). In December of 2022, ESRS and CSRD were approved, with the standards applying to some companies by 2024 at the earliest (Fenwick, 2023).

2. Literature review

2.1 The Shift Towards Sustainability Disclosure Frameworks

In recent months, the landscape of sustainability reporting and ESG disclosure has experienced a noticeable shift away from the “alphabet soup” of various voluntary disclosure frameworks provided by private ratings agencies such as Refinitiv and MSCI (Haddon, et al., 2022) and towards the creation of a new group of frameworks that aim to give companies, investors and consumers, a more reliable, standardised, and comprehensive setofdisclosures (Securities

and ExchangeCommission,2022). Prominently, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), which is a private organisation affiliated with the European Commission aimed at serving European public interests in the field of sustainability reporting, has released a draft of their EU Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). The ESRS is a mandatory disclosure framework for sustainability reporting using a double materiality approach that, along with other initiatives such as the EU taxonomy and SFRD, aims to combat the ongoing climate crisis.

Hence, in this literature review, we will aim to evaluate the effectiveness and limitations of the ESRS, particularly with regards to its usage of mandatory disclosure and double materiality. In doing so, we seek to illustrate the gap in existing literature on sustainability reporting concerning the perspectives of key stakeholders (firms, NGOs and standard setters etc.) on the introduction and implementation of new, mandatory disclosure frameworks that are centred around novelconcepts like double materiality. Ourstudy is conducted with the goal of filling this gap and providing much-needed insight on how the recent changes in the landscape of sustainability reporting will affect stakeholders.

We will also conduct a comparative study of the ESRS and two other notable disclosure frameworks, the United States’ Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) framework and the independently developed framework under the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). All three aimtobegin phase-inimplementation by 2023 (Haddon, et al., 2022) but differ greatly in their scope, jurisdictional authority and prescriptiveness.This section ofthe literature review aims to illustrate the lack of harmonisation that already exists between the three main disclosure frameworks even before their widespread implementation, making our study on the impact of said lack of harmonisation at an international level on stakeholdersinthe EU,even moresalientinits contribution to existing literature regarding sustainability reporting.

2.2 Voluntary and mandatory disclosures

The introduction of sustainability disclosure frameworks in important regions such as the EU and the US marks a general trend in the world of sustainability reporting from voluntary disclosure towards mandatory disclosure. Out of the three frameworks mentioned above, the ESRS and SEC are both mandatory disclosure frameworks while the ISSB remains as a voluntary disclosure framework due to its lack of jurisdictional authority (Haddon, et al., 2022). Mandatory disclosure is seen as an improvement by academics and regulatory bodies over voluntary disclosures due to two main reasons: (1) it reduces the likelihood of greenwashing and (2)

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

it allows regulators to ensure a more stringent methodology is used in sustainability reporting.

First, greenwashing is defined as “the act of misleading consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental benefits of a product or service”anda greenwashingfirmis therefore engaginginboth “poor environmental performance and positive communication about its environmental performance “ (Delmas & Burbano, 2011) simultaneously. According to empirical studies conducted on over 1500 companies from 12 countries, the probability that a company would engage in greenwashing is much lower in countries where mandatory disclosure frameworks exist (Mateo-Marquez, et al., 2022) and can force companies to be more transparent and honest aboutsustainabilityperformance as comparedtocountriesthat rely on voluntary disclosure frameworks.

Secondly, research carried out by the OECD have found that popular, private ESG ratings agencies such as Refinitiv and MSCI, which are often used by companies to voluntarily disclose ESG data, make use of problematic methodologies in their calculation of environmental (E) scores (OECD, 2022). These methodologies ascribe a disproportionately heavier weightage to the quality of a company’s corporate policies, targets and objectives and a disproportionately lower weightage to more tangible metrics like greenhouse gas emissions data. The study concludes that, if left to voluntarily disclose sustainability related information, most companies willend up with inflated Escores thatdo not accuratelyreflect their actual sustainability efforts.

Hence, the adoption of mandatory disclosure frameworks, while placing a heavier burden on the shoulders of firms to disclose a greater and more refined amount of information, helps to create a more stringent and stable regulatory environment that is more aligned with the goals of sustainabilityreporting and ESGdisclosure thatourregulatory institutions set out to achieve in the first place.

2.3 Double materiality

Next, a distinct feature of the ESRS is its adoption of the double materiality concept. Materiality originates from the discipline of accounting, where the exclusion of an item from a financial report was considered material if said item’s importance was such that its inclusion would then reasonably be expected to lead to a change in the judgement of a person who is reading the report (Messier, et al., 2005). Materiality has since been adopted for usage in sustainability reporting, where it is used to determine whether certain sustainability related issues are material and should therefore be included in disclosures (Jorgenson, et al., 2022).

While definitions and standards for materiality vary depending on the entity that defines it, two broad definitions of materiality have been widely accepted and used by many existing disclosure frameworks and other regulatory bodies: (1) financial materiality and (2) impact materiality. The former takes a so-called “outside-in” perspective on sustainability issues, and is concerned with how external factors like social and environmental issues can affect a company’s internal operations and enterprise value (Abhayawansa, 2022). Financial materiality therefore aligns more with the interests of investors. The latter looks at sustainability reporting from the “inside-out” perspective. Impact materiality focuses on how a company’s operations can affect the external environment in terms of social and environmental impacts and as such, is more aligned with the interests of stakeholders such as civil society and consumers.

What sets the ESRS apart from other existing or planned disclosure frameworks, is the fact that, it holds companies accountable forreporting underboth types ofmaterialitylisted above, rather than just one. The ISSB’s disclosure framework for example, uses a single materiality approach of only requiring financially material information to be disclosed. Whereas the ESRS defines double materiality as the union of impact and financial materiality, meaning that a sustainability matter is seen as material if it falls under the definition of impact materiality, financial materiality, or both (EFRAG, 2022). In theory, this approach would allow the ESRS to overcome the challenge of an overly myopic view on sustainability reporting that is characteristic of single materialityapproaches.Thisis illustrated by thecriticismsthat have been voiced against the ISSB’s usage of single materiality. Academics have been quick to point out that a narrow definition of materiality, such as financial materiality in the case of the ISSB, would exclude the critical inside-out perspective thatmanystakeholdersvalue.Thisleadstoserious sustainability-related issues like negative externalities, to be overlooked, which could then engender trends of shorttermism among companies (Adams & Mueller, 2022). The ESRS’s double materiality on the other hand, would feasibly avoid this problem because the inclusion of both prevailing definitions of materiality would require firms to engage with the perspectives ofmultiple stakeholders and notjustinvestors alone. This approach would more accurately account for the existing relationships between firms, their stakeholders and wider society in the context of sustainability (Adams, et al., 2021).

With that being said, double materiality is not without its shortcomings as well. Notably, many have called for frameworks like ESRS to give a greater degree of consideration for the dynamic nature of materiality in

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

sustainability matters (Marchi, 2021). One way in which double materiality might overlook the dynamic nature of sustainability matters is in the fact that sustainability matters can often change and intensify overdiffering time horizons. In the short-term, unpredictable events such as the global COVID-19 pandemic can cause issues to rapidly become material in the short term. Meanwhile, other sustainability matters may be considered unimportant in the present day but will intensify to become material in the long-term. An example of this would be negative externalities, which are costs or benefits borne by third parties. The implications of externalities on stakeholders might only be observable and thus, reportable if they trigger certain reactions from affected stakeholder groups in the long term (Cooper & Michelon, 2021), and as such, double materiality will have to expand its time horizon to include such matters.

Furthermore, there is also the problem of rebound and boomerang effects, which are implications of a company’s inside-out impact that the company itself ends up being exposed to as an outside-in impact. An example is provided by EFRAG: for a company inagriculture, the consequences of depleting land and biodiversity of a field could directly affect the yield of the crops and hence, the financial margin” (EFRAG, 2022). Hence, critics have pointed out that double materiality would presenta false dichotomy between financial and impact materiality that overlooks these rebound and boomerang effects (Abhayawansa, 2022) which might in turn, lead to confusion for companies over whether issues are considered material or not and from whose perspective an issue might be seen as material (Jorgenson, et al., 2022).

As it stands, despite some limitations, the ESRS’s double materiality approach remains one of the more comprehensive definitions of materiality currently being used. In the next section, we evaluate whether differences in materiality definitions and other aspects might lead to divergences between the ESRSand other proposed disclosure frameworks.

2 4 Comparative study between ESRS, SEC and ISSB

While all three disclosure frameworks mentioned thus far are still undergoing changes before implementation, it is already evident from the information released to the public thus far that any attempts at harmonisation between the three frameworks will be, at best, superficial. Based on what we have observed from our literature review, we can identify six key dimensions with which the three disclosure frameworks diverge significantly: (1) jurisdictional authority, (2) acceptance of alternative reporting, (3) target audience, (4) materiality, (5) scope and (6) prescriptiveness. We shall cover

each in detail to illustrate why harmonisation at an international level at this juncture is already a significant challenge.

Jurisdictional Authority As mentioned earlier, the ESRS and SEC frameworks are mandatory disclosure frameworks for large companies and all SEC registrants within the jurisdiction of the EU and US respectively (Haddon, et al., 2022) while the ISSB remains voluntary. This implies that companies with operations in both the US and EU will be required to follow the disclosure frameworks of both the ESRS and SEC, which may generate confusion.

Acceptance of Alternative Reporting. Simply put, it is yet unclear if each regulatory body will recognize the legitimacy of complying with a disclosure framework other than their own within their respective jurisdictional boundaries. For now, the 13 SEC does not allow firms under their jurisdiction to comply with alternative disclosure frameworks while the ESRS does, but only if the alternative framework is able to meet certain standards which are also still unconfirmed (Haddon, et al., 2022).

Target Audience Although, sustainability reporting should be targeting the interests of society as a whole in theory, in practice, the fact that the ISSB’s parent organisation, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the SEC are both organisations created with investors as their first priority (Giner & Luque-Vilchez, 2022) could lead to differences in objectives and motivations behind each framework.

Materiality.

As mentioned extensively already, the ESRS is adopting double materiality as its approach while the ISSB and SEC use single materiality. While we have already established the merits of a double materiality approach, the inconsistency between the definitions of materiality between each framework could lead to issues such as a loss of competitiveness among firms complying with the ESRS. Since the ESRS is much more demanding, events such as the case of human rights violations in China’s Xinjiang cotton industry, where Western companies like Nike that expressed their disapproval of the situation were hit with intense boycotting fromthe Chinese market,would disproportionately affect companies complying with ESRS as compared to companies that comply with other frameworks (Giner & Luque-Vilchez, 2022). As mentioned by Giner & LuqueVilchez, if companies voluntarily disclosed their disapproval of such events, this would bring about competitive disadvantages but also positive reputational effects. However, ifEU companies areforced intodisclosing disapprovalofsuch events due to mandatory disclosure frameworks, then they may suffer a competitive disadvantage as compared to their

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

competitors that lie outside of the ESRS’ jurisdiction. These non-EU competitors are under no obligation to disclose disapproval and can continue to conduct business and operations within the Chinese market as per normal. Moreover, the positive reputational effects that EU firms would have accrued for disclosing their disapproval of the human rights violations in Xinjiang would largely be negated if they are perceived to have disclosed their disapproval involuntarily. With that being said, such deleterious effects on competitiveness are likely to be less significant for large multinational corporations which also happen to be the companies that are more likely to be active in international markets in the first place. Hence, there remains a possibility that the competitive disadvantages arising from divergent definitions of materiality might only pose a significant threat to a small proportion of medium sized firms that engage heavily with foreign markets.

Scope

As of now, only the ESRS framework includes environmental, social and governmental disclosures, whereas the SEC and ISSB have only included environmental and climate-related disclosures within their scope. Although, both the SEC and ISSB have also indicated plans to expand their scope to eventually encompass the entirety of ESG in the future (Haddon, et al., 2022).

Prescriptiveness While all three frameworks generally took inspiration from the same set of disclosure recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the level of prescriptiveness used by each differs greatly. For example, the ESRS and ISSB both require all firms complying with their framework to include scenario analysis within their disclosures as a tool to help them formulate better forward-looking policies while the SEC remains laxer on its usage (Haddon, et al., 2022). The ESRS also includes numerous additional disclosures such as an integration of disclosures with the EU Taxonomy regulation, that the SEC and ISSB lack. This gives the ESRS a much more granular and detailed list of disclosures for firms to comply with compared to the other two frameworks.

In summary, the differences listed above seem to be consistent with the “contested arena” concept proposed by Afolabi, Ram and Rimmel, in which they liken the field of sustainability reporting to be a contested arena with complex interactions between the major stakeholders such as companies, politicalinstitutions and rule enforcers (regulatory bodies like EFRAG and SEC) (Afolabi, et al., 2022). The lack of harmonisation between frameworks is explained as a result of each actor purposefully attempting to maintain their own influence and relevance in determining the rules and authority within the sustainability reporting arena, and that the diversity

of interests and beliefs of each of the major actors within the arena will ultimately act as the main obstacle for achieving harmonisation. The way forward appears to be through the facilitation of knowledge-exchange and cooperation between the regulatory bodies of the three frameworks in an effort to establish a “global sustainability reporting baseline” (Giner & Luque-Vilchez, 2022) that can allow for “comparability and consistency of application across jurisdictions''.

2.5 Con2clusion of literature review

To conclude, our literature review has produced two key findings. Firstly, the introduction of a novel approach towards sustainability reporting using double materiality represents a concerted effort from the ESRS to cover the wide range of stakeholders involved in sustainability reporting. Though this is a more holistic approach compared to the ISSB or SEC, a double materiality approach is still expected to be vulnerable to dynamic changes in global events and rebound and boomerang effects. As such, ourstudy aims toinvestigate how the various EU stakeholders are reacting to the introduction of double materiality and other aspects of the ESRS. Secondly, we find thatthe ESRS, ISSB and SEC are fundamentally, very different frameworks and that harmonisation between the three on an internationallevelis unlikelytobe very significant at their respective stages of implementation and so our study will also focus in on how this lack of harmonisation might implicate EU stakeholders and how we might mitigate said implications.

3. Methodology

The focus of this study is to analyse the comments and responses of different stakeholders in the public consultation initiative by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) on the new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)tosee whatimprovements can be made to the framework. This research is valuable as it helps identify areas where improvements can be made to the ESRS framework, which could lead to more effective and comprehensive sustainability reporting. First, we expect that the stakeholders will push for the harmonisation of the ESRS

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

and its convergence with otherpieces of regulation such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Second, we expect to find that double materiality and rebuttable presumption are divisive depending on the sector. Third, we believe thatdisclosures ofScope 3 emissions are controversial due to the difficulty in measuring them and unequal conditions. Fourth, in some sectors, we expect to find that due to limited resources, SMEs will struggle to comply with the disclosure requirements on the value chain and this could constitute a competitive disadvantage. Lastly, we positthatthe transition and phase-in approach will be a point of disagreement between the different stakeholders as little time has been included in the ESRS to adjust to the numerous disclosure requirements.

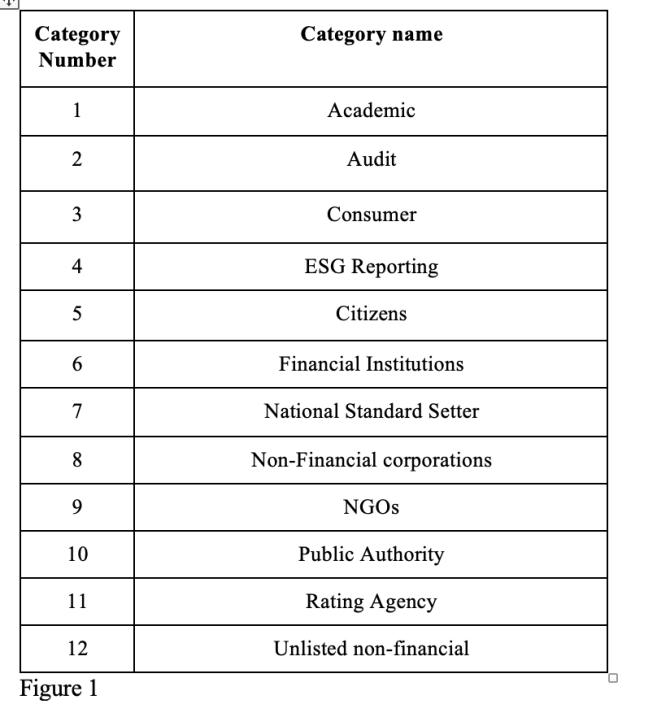

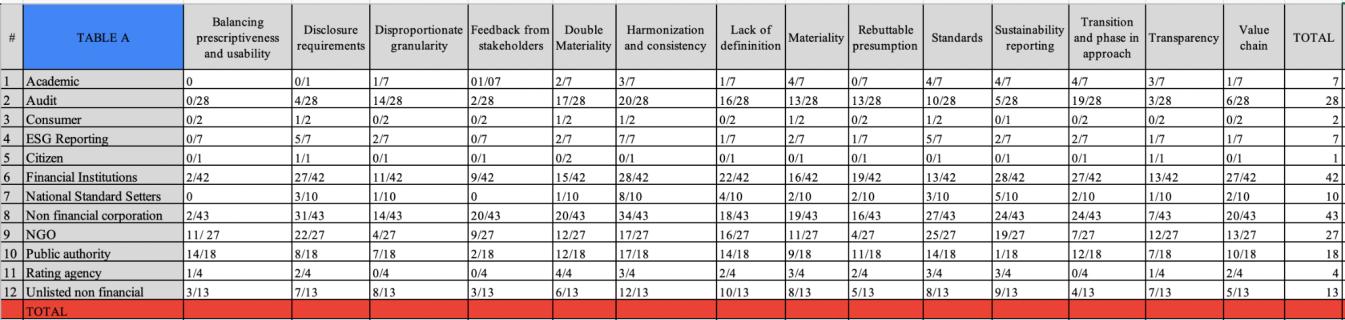

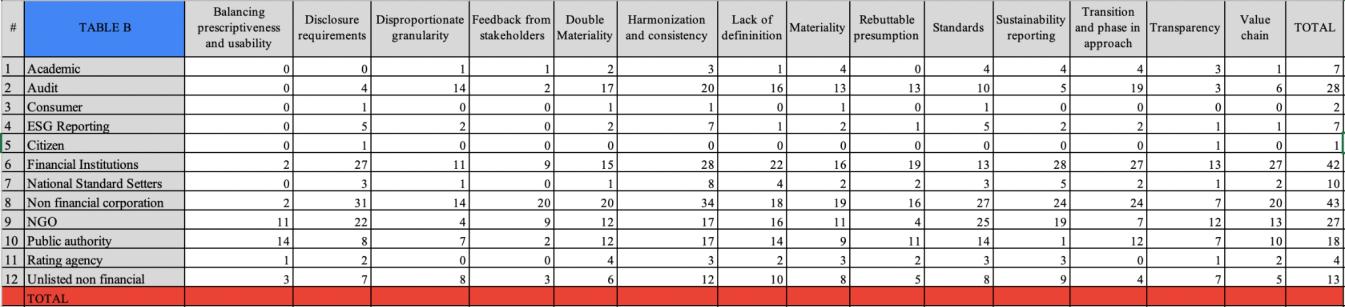

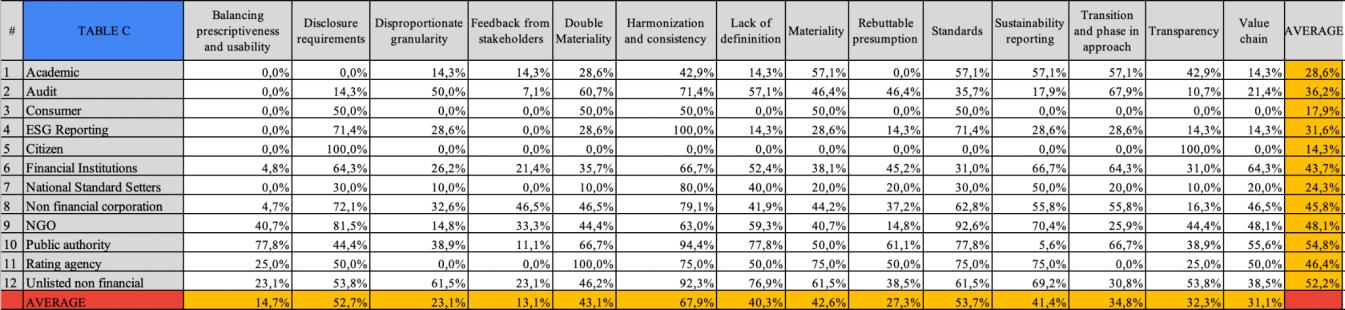

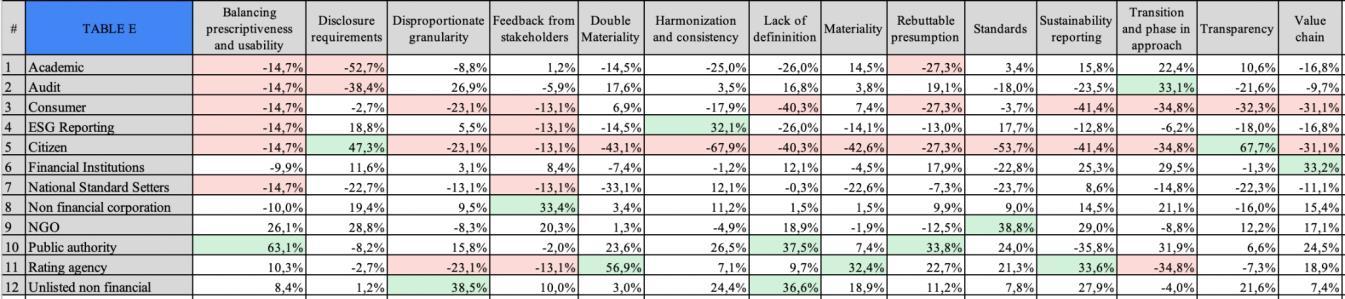

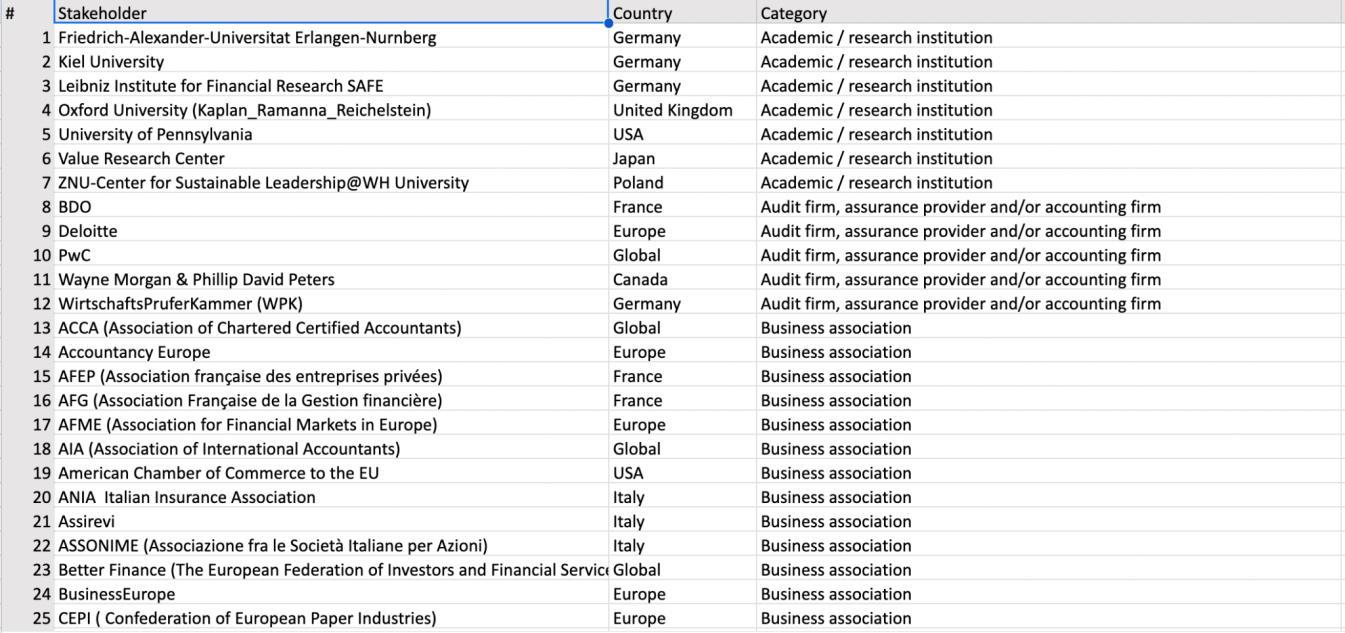

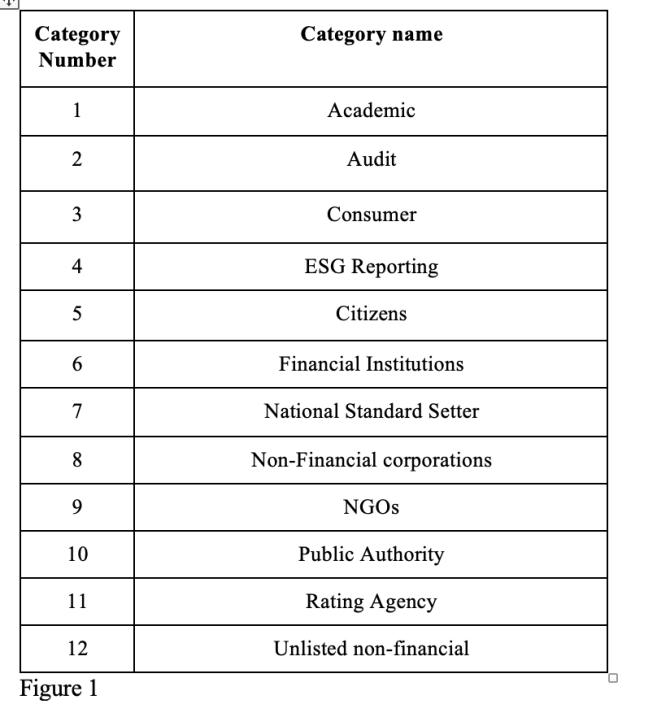

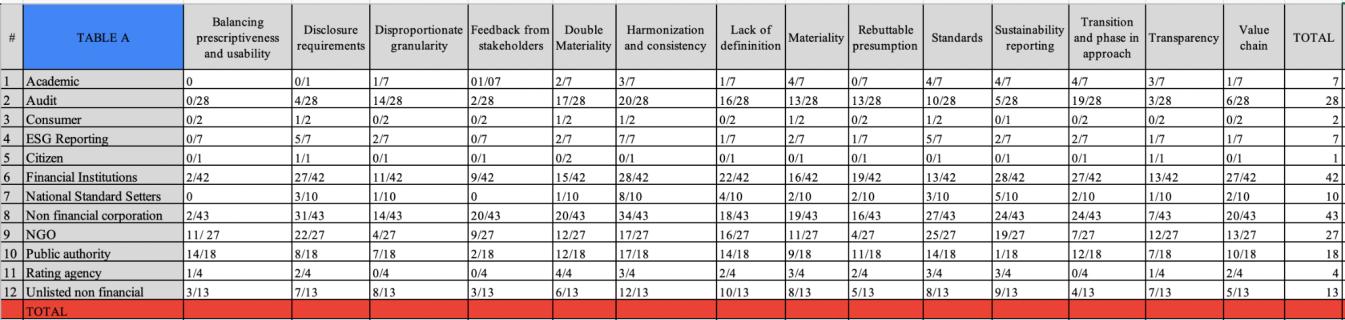

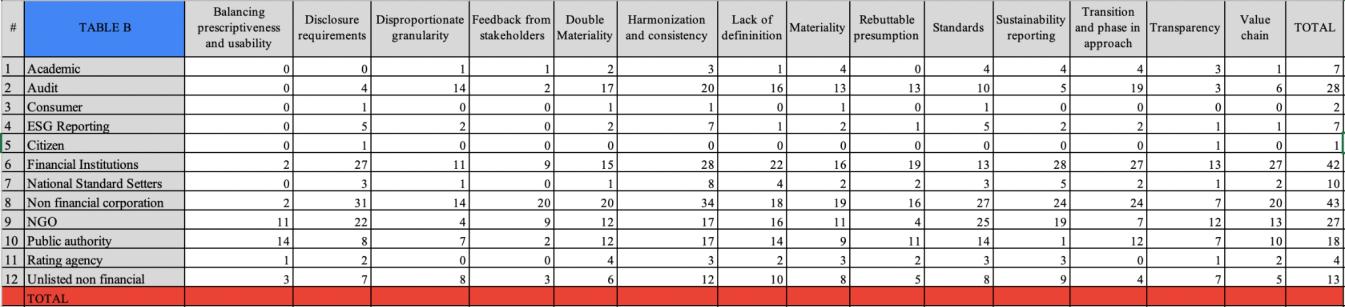

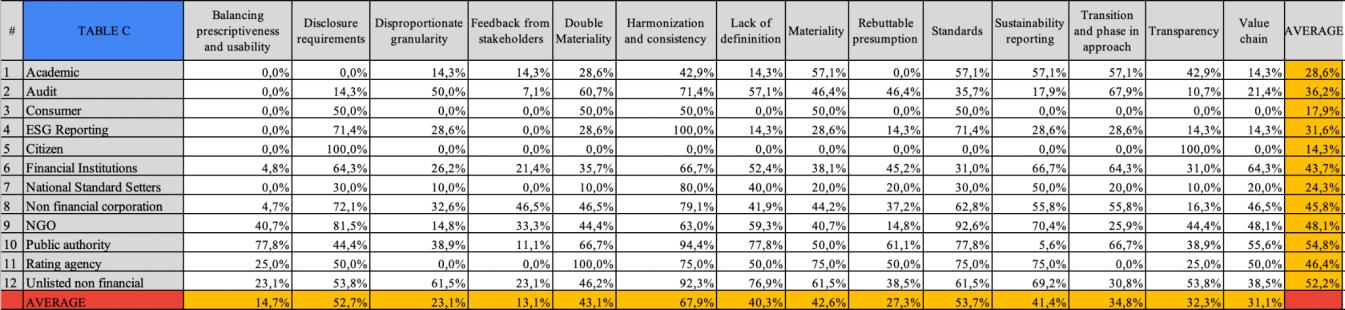

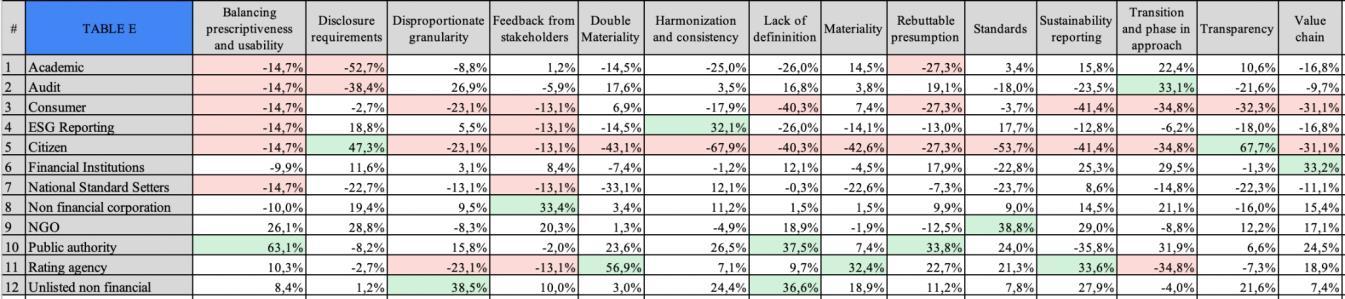

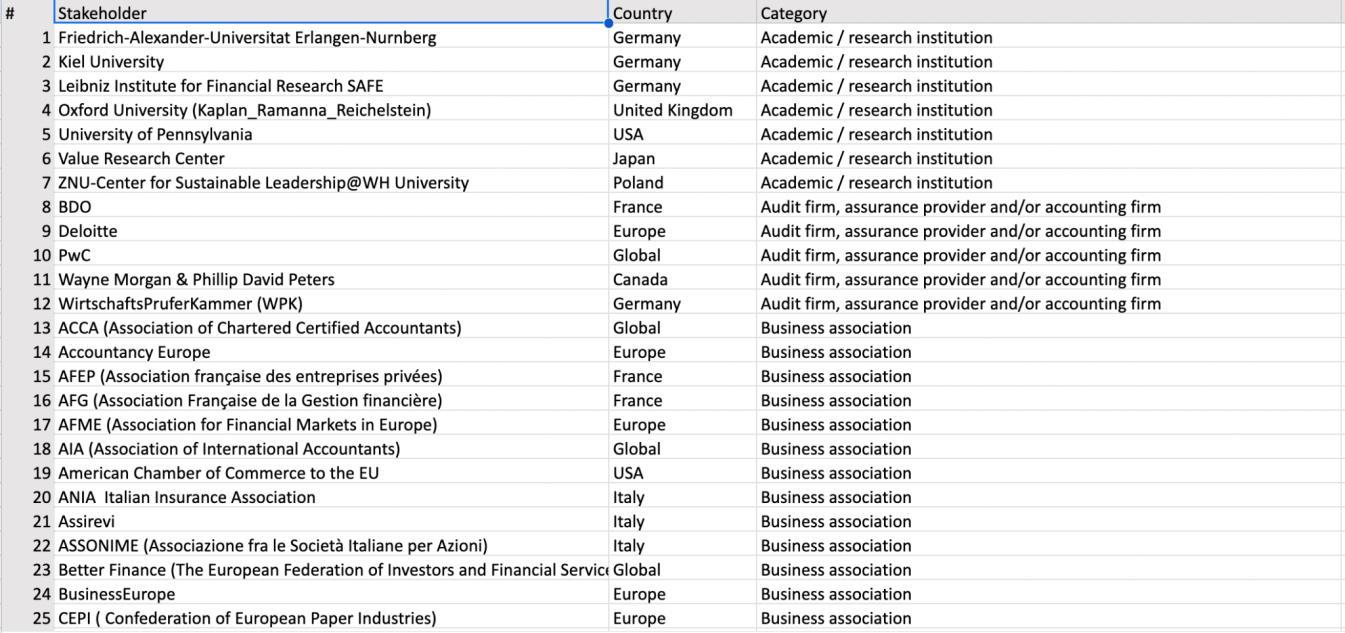

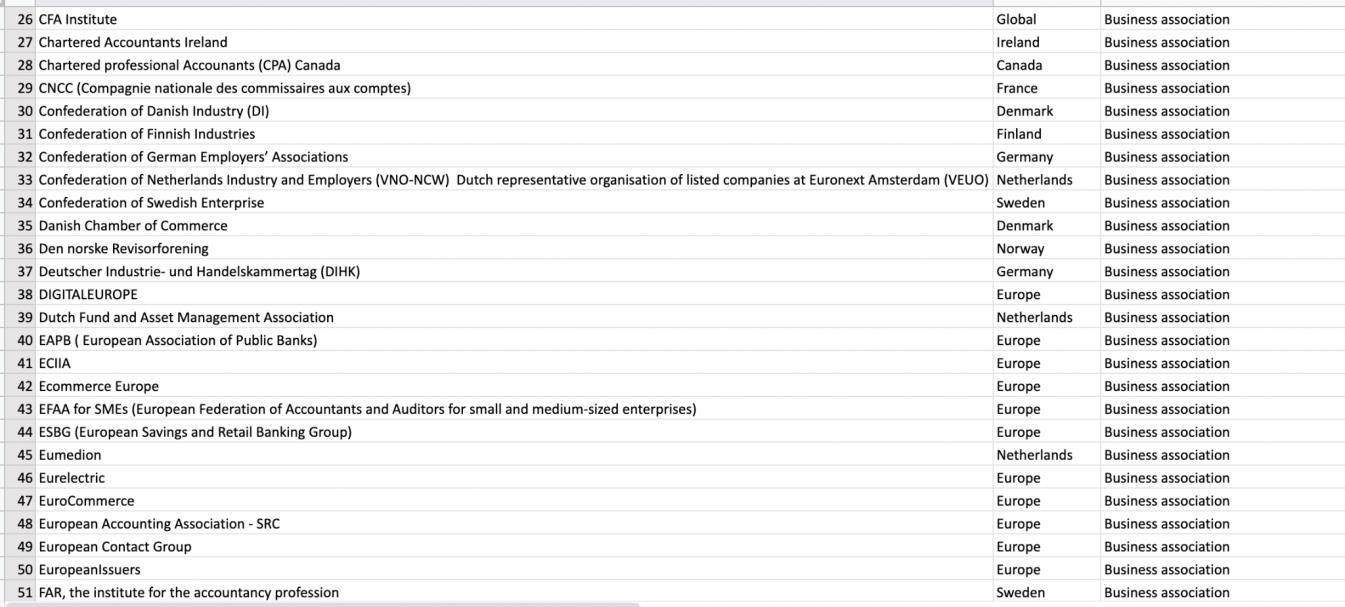

The letters were accessed and selected through the EFRAG website which were openly published for public review. 202 out of 243 letters were used. 41 letters were not analysed because they were not written in English or could not be categorised in one of the 12 stakeholder groups. By extension, we only focused on the letters relevant to our initial research questions which focused on concerns of stakeholders. The letters were divided into 12 categories (seen in Table 1). The categories of stakeholders were set by our research team after a thorough review of all letters and relying on the EFRAG categorization.

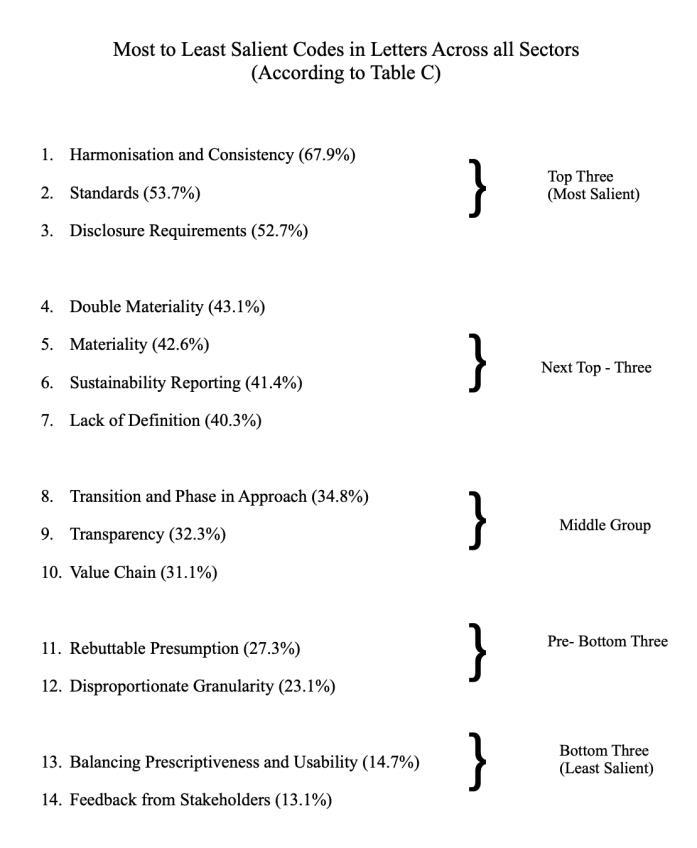

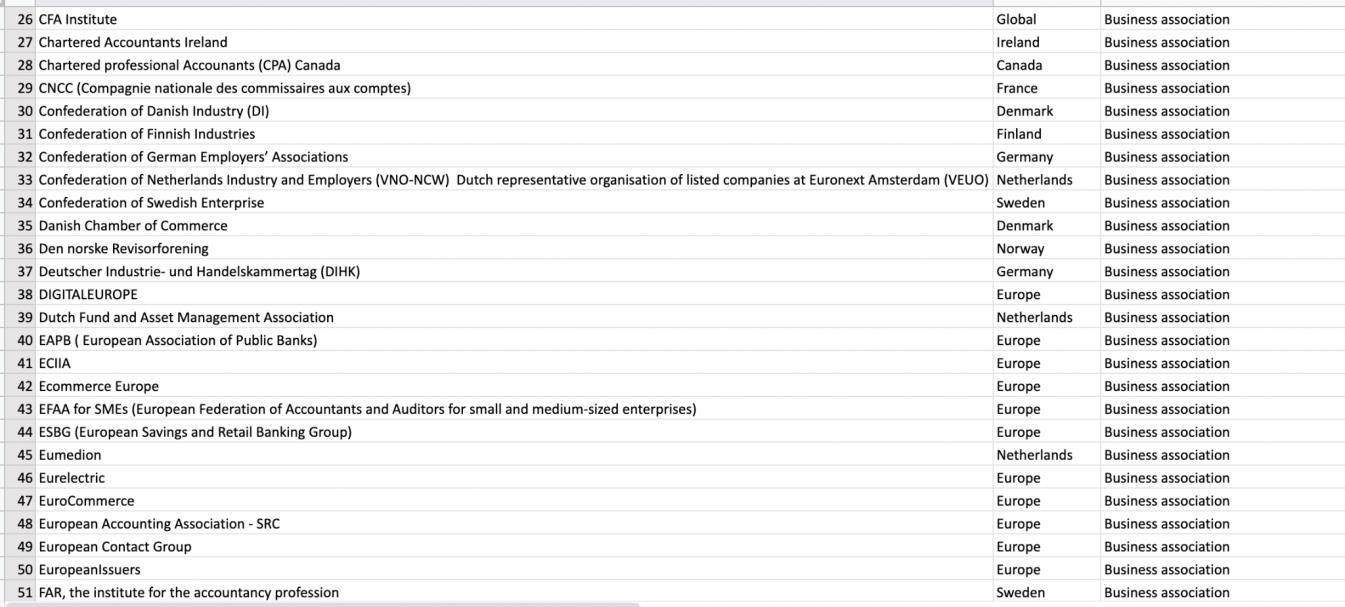

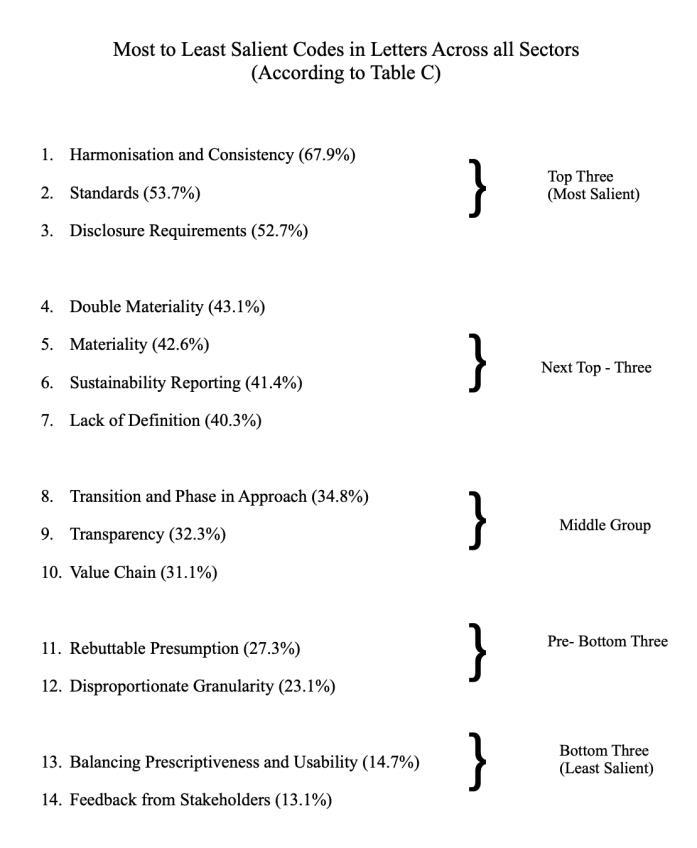

evocative attribute” to the text (Saldana, 2013, p. 31). To create a code hierarchy, a number between one and three (the “weight”) was attributed to each code to denote its importance (3 being the most important and 1 the least important). The weighting system was used to maximise the methodological use of NVivo. The weighting of themes was decided based upon the salience of themes in the literature review and the first reading of the sample of letters before starting to code. This hierarchy helped us organise the codes efficiently. After this, sub-groups were created under each code to organise the information. Figure 1.1 and 1.2 demonstrate the 14 codes, their sub-groups, and their weight.

Table 1: List of categories

The research team focused on 14 key themes in the letters (as seen in Figure 1.1 and 1.2). These themes were inputted intoa qualitative text-analysissoftware, NVivo,underspecific “codes.” A code in qualitative analysis is a short phrase that assigns a “summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Bentham

Figure 1.1: NVivo Codebook part 1

One of the challenges was that readers could interpret the terminology of “codes” differently which would alter our results. To solve this, the research team outlined a clear terminology to minimise subjectivity during analysis. For example, “materiality” was defined as the effects of climate change on finance and corporate activities. “Double materiality” added a layer to the “material” conception by including the impacts of finance and corporate activities on climate change (Täger, 2021). Along the same lines, “rebuttable presumption” was defined as a way to circumvent disclosure obligations by classifying disclosures as not material for the undertaking. By outlining an agreed-upon terminology, the research team was able to locate the appropriate themes more efficiently. Along the same lines, the members paid attention to the equivalence of words. For example, terms such as “convergence” and “harmonisation” could be used interchangeably in some letters and differently in others. To overcome this obstacle, each letter was read critically, and themes were extracted from specific keywords in NVivo.

To analyse the themes in the letters, qualitative and abductive methods were used. The qualitative method was implemented to quantify non-numerical data extracted from written text. The qualitative data set provided an opportunity for in-depth analysis where relationships between sectors and the “codes” emerged and produced well-grounded and contextualised explanations. During this research, the process of data collection and analysis was interrelated. For example, the letters were critically assessed during the collection phase and then again during the final analysis. This way, the quantitative method allowed us to understand the stakeholder’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviour toward the EFRAG much better. Furthermore, this helped shape the direction of data collection during the abductive approach. An abductive approach involves the collection of data to identify themes and explain patterns in the letters (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019, p. 796). This approach was chosen (instead of inductive or deductive) as it allowed us to explore the relationships between concepts and measure themes quantitatively. Consequently, we were able to move back and forthbetween theory todata (as indeduction) ordata totheory (as in induction) while we were identifying themes (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019, p. 155). In other words, the abductive approach combined both deductive and inductive methods to enable effective data collection.

NVivo was used to organise the themes and find patterns in the letters. We chose to use NVivo because this software facilitates common qualitative techniques for organising, analysing, andsharing data collected. Forthis research,NVivo was used to group the various “codes” and compare the occurrence of themes to determine the relevant concerns of

stakeholders. Firstly, the research team created a “codebook” outlining the 14 major themes and sub-groups. This allowed us to gather material from the letters and observe the emergence of patterns. Secondly, the research team uploaded all letters from a specific category they were assigned into an NVivo file. The letters from each industry were grouped into different files. Thirdly, the letters were treated by selecting and coding the themes outlined in the codebook. In other words, the first coding cycle is analysis (taking the letters apart). The second cycle of coding is synthesis as the team assembled codes to find meanings (Saldaña & Omasta, 2018). During the treatment of the letters, the members looked for concerns regarding questions such as:

• Whatmainmessage does the authorofthe letterwant to convey?

• Is the information in the letter factually accurate?

• What recommendations and solutions do the authors propose?

To access the extensive list of questions, please refer to our research protocol in Appendix 3

To extract relevant themes, the research team implemented specific filters in NVivo to find relevant information from keywords. Additionally, the length of coded paragraphs in comparison to the whole letter was considered to see the relevance of certain topics. Finally, the excerpts that the members coded were annotated to rely on the notes when writing the finalanalysis. As aresult,the research teamarrived at finding the relevance of themes by computing word matrixes for each sector and comparing the emergence of themes.

The research teamchose this approach foranalysisand data collection because it allowed us to comprehensively analyse each letter and ensure thatrelevant themes were identified. By extension, acombination ofqualitative andabductive methods provided the best means for our research team to detect the most salient concerns of stakeholders and address the relevant aspects of our research question. We also reviewed previous research studies and consulted experts about our methods which showed that a combined approach of individual text analysis and computational data collection is mostappropriate when working with a large amount of text. Furthermore, a strength of our research is that we followed established methods and protocols for analysing and collecting data through NVivo and ensured its reliability and validity. The teamkeptdetailed records ofthe methods used andsteps taken to ensure that the results could be replicated and verified by other researchers. A possible limitation is that despite coding the letters there is an element of subjective human interpretation which could alter how themes were classified.

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Another possible limitation is that the EFRAG already released new policy recommendations during this research. Despite this, our analysis demonstrates alternative changes and alterations that could be made. As a result, our research provided detailed and comprehensive answers about how the sustainability framework could be improved.

4. Sector Analysis

4.1 Audit

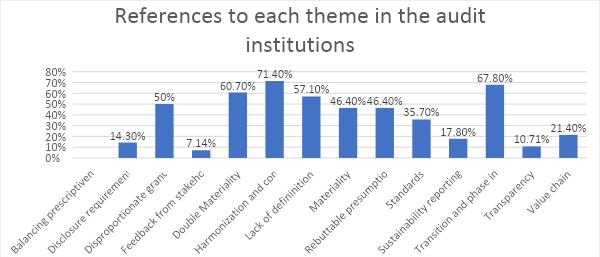

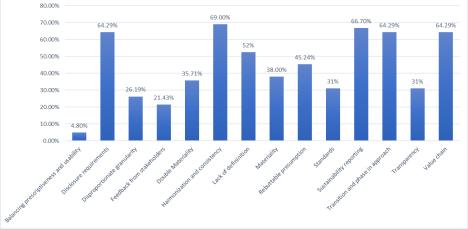

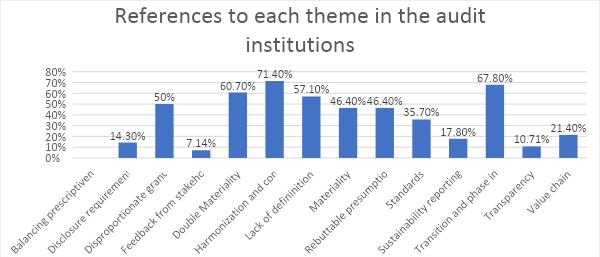

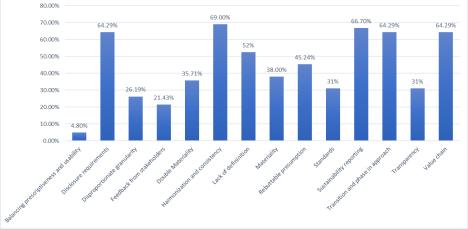

Institutions fromthe auditsectorare mostly concerned with issues related to harmonization and consistency, the concept of ‘double materiality’, the transition period and phase-in approach and disproportionate granularity.

We have coded 31 direct references to recommendations for the harmonisation of sustainability standards. 71.42% of the Audit institutions’ letters refer to “harmonisation and consistency”. Audit institutions urge EFRAG to work towards an accepted global baseline on sustainability reporting standards. More specifically, ACCA, Accountancy Europe, ASSIREVI and the Association of International Accountants encourage enhanced coordination and collaboration between EFRAGand the ISSB, supporting theidea ofa globalbaseline. However, as the CFA Institute highlights, the challenge “is thatmultiple jurisdictions are working on the same disclosures at the same time. Each is using similar ingredients but using a different recipe which will result in a different outcome in standards and different disclosures for investors…while the idea of a global baseline is a worthy goal, the reality is that the three mostsignificantbodies are developing differentversions simultaneously and even basic disclosures that should be part of a baseline are simply different” (CFA, 2022). Although the organisation welcomes the pursuit of a global baseline, it underlines that there “needs to be consensus on what a global baseline really means…it needs to be a shared pursuit and objective” (ibid).

Regarding ‘double materiality’, 60.71% of the Audit institutions’ letters refer to this concept: 5 out of audit firms are strongly supportive of the ‘double materiality’ approach. The IMA is the only respondent who is coded as being “against” the idea; they argue that “the term needs to be reconciled with conventional concepts and financial market regulations” and therefore encourage the “standard setters to use the term ‘impact accounting’ rather than the confusing terminology ‘double materiality’” and note that “this suggested rephrasing would not change types of information that an entity gathers for disclosure, but it would identify the specified user for reported information”. Numerous audit institutions strongly suggest that EFRAG defines and clarifies

the ‘double materiality’ terminology and that it provides more application guidance and illustrative examples to help the implementation. Characteristically, the institutions unanimously call for “more guidance and clarity” to “support practical implementation” as well as “illustrations on double materiality” (Accountancy Europe, 2022; ASSIREVI, 2022; CNCC, 2022; PANA, 2022; PwC, 2022).

Regarding audit institutions’ views on issues related to the value chain, 21.42% of the letters refer to this issue. In their references, the institutions call for “further explanations, illustrations and guidance as it relates to the value chain requirements and its boundaries” (ESRS, 2022). Indeed, “this should include clarity on how indirect relationships with all third parties along the whole value chain should be treated” and “more guidance on the calculation and reporting of metrics in respect of different elements of the value chain is needed” (PwC, 2022). The Institute of Public Auditors in Germany (IDW, 2022) suggest that EFRAG considers “a phasing-in approach in the context of value chain information i.e., thatindividualstandards allow more time before requiring reporting of information that will have to be obtained from within the reporting entity’s value chain”. SRA (2022) argues that “that value chain information should be at a less detailed level. This lowers the reporting burden that may inadvertently be placed on suppliers that fall outside the proposed scope of the CSRD.”

Indeed, audit institutions are also concerned with the transitionperiod:67.85% oftheir letters refer tothe ‘transition period and the phase-inapproach’. Theyexpress concerns that “the feedback received in such a compressed comment period may not be sufficient to ensure that standards are of good quality and capable of implementation (ACCA, 2022). The Charted Accountants of Ireland (2022) characteristically state that “the time allowed of approximately three months is insufficient for EFRAG to receive an adequate response from all relevant stakeholders… we would recommend a longer phasing-in period as well as a prioritisation of matters to be reported on in the earlier years”. The Institute of Public Auditors in Germany (IDW, 2022) agrees, and urges “consideration of a phasing-in approach whereby corporate sustainability reporting would initially focus on key disclosures, with further granular disclosure requirements gradually introduced over time”. The Association of International Accountants (2022) feels that “EFRAG has tried to do too much, too soon”. Overall, audit institutions fear that the deadlines and the pressures on the organisation are taking precedence over substance, quality and realism.

Another recurrent comment amongst audit institutions’ letters is that standard requirements are too granular: 50% of the letters discuss this issue. When considering the level of

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

detail and quantity of information to specify in the standards, the European Contact Group characteristically suggests that EFRAG retains “only those disclosures that are the most urgent requirements of the EU legal framework”. This is because “too wide-ranging and granular requirements… run the risk of turning the reporting process into an extensive compliance exercise while obscuring the sustainability information to the detriment of users (FAR, 2022). Numerous institutions are worried that the granularity and complexity of disclosures “are likely to lead to information overload and reduce its quality”; it “mayimpair effective reporting and lead toa compliance exercise” (ASSIREVI;NorwegianInstitute of Public Accountants).

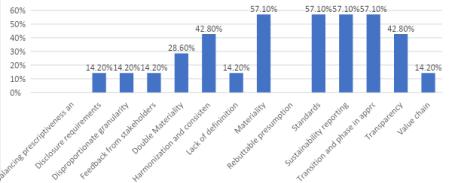

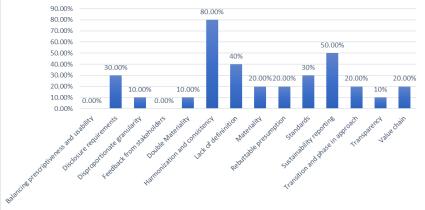

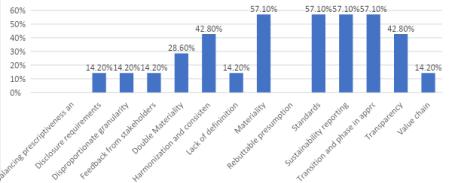

4.2 Academic

Institutions from the academic sector are mostly concerned withissues relatedtoclimate standards,the conceptof‘double materiality’, sustainability reporting and harmonisation and consistency. 57.14% of the academic sector’s letters refer to ‘standards’. Regarding climate standards, Oxford University (2022:2) is particularly concerned with greenhouse gas emissions. It highlights that EFRAG allowing the use of industry-average data “rather than specific and traceable data fundamentally undermines the integrity of Scope 3 measurements” and rather, “the only acceptable assurance for a GHG emissions report be a ‘present fairly opinion,’ which would deny assurance to Scope 3 reports based substantively on 5 industry-average data. Such true-and-fair audit opinions would enable entities’ GHG reports to have the same reliabilityas theirfinancialstatements,and, like these, provide a sound basis for investment decisions and accountability for corporate performance”. Also, the Value Research Centre (2022:8) underlines that “EFRAG fails to cover specific goals within the Biodiversity theme aimed at (N5-B) Humane, Compassionate Treatment of All Animals, and (N5-C) Zero Palm Oil Use”. To reduce the risk of greenwashing, the use of specific standards should be limited.

28.57% of the letters in the academic sector are in favour of the ‘double materiality’ concept. Characteristically, the Friedrich-Alexander University (2022:3) holds that “the concept of double materiality leads to a truly sustainable transformation of companies and prevents the short-term greenwashing efforts”. However, it also argues for the “building block approach in that on the one hand financial materialityis applied forthe IFRSS and on the otherhand, the inside-out perspective is part of the reporting for the ESRS according to the concept of double materiality (ibid). The Value Research Centre’s (2022:6) response is coded as ‘against’, because they argue that “while EFRAG’s reports emphasise a double materiality focus, the disclosure approach that they have currently published unfortunately enables further value washing within the impacts that they require companies to report”.

57.14% of the academic sector’s letters discuss issues related to ‘sustainability reporting’. The Friedrich-Alexander University (2022:1) highlights that “onlylarge capital marketoriented companies that have already disclosed corresponding sustainability reports in the past will probably be able to cope with the increasing challenges of sustainability reporting…softened reporting requirements could cushion the burdens at the beginning in order to gradually introduce the companies to the new, considerably extended reporting requirements”. The Leibniz Institute (2022:1) argues that “the definition of relevant ESG metrics is crucial – it should be science-based and clearly separate from the political process of formulating and issuing regulatory rules”.

Harmonisation and comparability were mentioned in 42.85% of the academic sector’s letters.The institutions argue that to create a holistic sustainability reporting framework, standards ought to be harmonised despite diverging understandings of materiality

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022 et al

Figure 2: References to each theme in the audit institutions

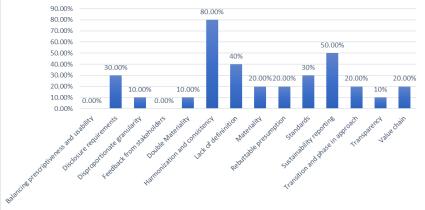

Figure 3: References to each theme in academic institutions

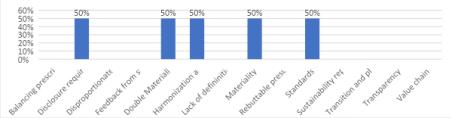

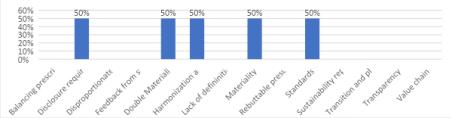

Figure 4: References to each theme in the consumer institutions

4.3 Consumer

Looking at the consumers' responses towards the EFRAG draft, their comments focus on standards, harmonisation and consistencyas wellas the concept of‘double materiality’. The DSW’s strongly recommends consolidating all governancerelated standards and is concerned with the phrasing ofArticle 29b because it could constitute a “huge step backwards in the quality of governance reporting” by implying the deletion of some standards (2022:1). Also, Consumers Internationalurges “the CSRD tomake clearreferences tothe ISSB tosupport the creation of the global baseline for capital markets, and to GRI to maintain consistency with double materiality” (2022:1). The organisation is in favour of “enhanced compatibility to make every endeavourtoestablish ISSB as the globalbaseline for sustainability-related financial disclosures” (ibid).

4.4 ESG reporting

Institutions from the ESG Reporting sector are mostly concerned with issues related to harmonisation and consistency, standards and disclosure requirements.

All the letters from this sector’s institutions refer to ‘harmonisation and consistency’. The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) and the Investor Relations Society call for greater consistency; the latter is concerned that “EFRAG’s current proposed draft ESRSs are not fully interoperable with the ISSB standards” (2022:2) and therefore “ideally, the EU will adopt the ISSB’s standards or will closely align their disclosure requirements with the ISSB standards as explained by their building blocks approach” (PRI 2022), VCMI “recommends advocating for alignment of the ISSB standardswith the ESRS, andcallsupon EFRAGand the European Commission to continue cooperation with the ISSB, inorderto reach a globalconsensus and avoid divergent standards” (2022:5).

71.42% of this sector’s institutions refer to ‘standards’. Specifically, regarding GHG emissions standards, the VCMI “recommends strengthening the disclosure requirements regarding carbon credits to increase market transparency and allow users of the reported information to properly assess the nature and quality of those carbon credits, and therefore their level of credibility” (2022:6).

28.57% of the letters discuss issues related to ‘materiality’. When it comes to financial materiality, “GRI strongly recommends aligning this definition with the approach of the ISSB, which focuses on ‘enterprise value’, rather than on general ‘value creation’ and ‘capitals’. This alignment will also help drive the consistent application of financial materiality globally” (2022:2)

71.42% of the ESG Reporting sector’s letters discuss ‘disclosure requirements’. Characteristically, GRI “disagrees that all mandatory disclosure requirements established by the ESRS shall be presumed to be material and recommends reviewingthis approach”(ibid).PRIis infavourof“additional guidance and disclosure requirements on: (i) considering interlinkages between risks, opportunities and impacts arising from all sources, such as management decisions; and (ii) aggregating risks, opportunities and impacts to measure total financial consequences and impacts on people, planet and the environment (cf. Question 10). This would help to ensure that information on various sustainability issues is not reported in silos” (2022:6).

4.5 Financial institutions

The qualitative data analysis of the letters from financial institutions demonstrates that the theme of harmonisation (found in 69% of the letters) and sustainable reporting (found in 66.7% of the letters) are the main concerns of European companies. For example, financial institutions stress the importance of aligning the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) with frameworks such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, Global Reporting Initiative, and SEC. Additionally, disclosure requirements, transition periods, and value chains are highlighted by the companies and connected to the theme of “harmonisation”.

This concern is natural as the institutions want to ensure a consistent reporting landscape for investors and stakeholders globally. Frameworks that demand different requirements create a risk of market fragmentation and additional costs for European companies that are already struggling from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing war (Garrault, 2022). Furthermore, institutions argue that a collaborative approach between regulations will create an efficient model to support current national and international policies that could help companies achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement.

Financial institutions also highlight that the current sustainable reporting requirements will create challenges for policymakers, industries, and investors as they require to disclose copious amounts of information (found in 66.7% of the letters). Consequently, this will lead to immense administrative challenges and additional costs for the companies. Additionally, several companies stress that EFRAG's disclosure requirements should not lead to the publication of information that is confidential according to national labour, business law, or other relevant national frameworks. In otherwords, they worry thatthe EFRAGis not compatible with European confidentiality laws. As a result,

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

some companies emphasise that the ESRS should adopt "leaner" disclosure requirements to protect sensitive information.

The broad disclosure requirements propelled some companies to advocate for extending the "phase in" period as this will give more time for institutions to provide relevant sustainability information and prevent administrative burdens (found in 64.3% of the letters). Along the same lines, some institutions questioned how they should cover value chains mentioned in the EFRAG. For example, some propose to focus on direct supplies and direct customers while others suggest adopting a phased approach to value chain reporting.

This analysis shows the interlocking nature of many concerns raised. The lack of harmonisation leads to issues of reporting which calls into question disclosure requirements, transition periods, and value chains. Therefore, holistic changes to the ESRS will be more effective at resolving the concerns of financial institutions. For example, according to many institutions, the main priority is to align the ESRS with other environmental frameworks currently implemented to ensure institutions agree on the disclosure requirements, the transition periods, and concerns regarding value chains.

4.6 Standards organisations

The main themes highlighted in the letters from standards organisations are harmonisation (80%) and sustainable reporting (50%). The main issue expressed is the various terminologies used in different frameworks that make reporting more complicated for organisations. By using agreed-upon terminology, standards organisations can avoid misunderstandings and “duplications” of information. For example, three letters mention that the conception of “materiality” displayedby the EFRAG diverges from the ones expressed by frameworks such as the IFRS, ISSB, GRI, and SEC. Additionally, the vagueness of the “reporting boundaries” in section 2.3 and its relation to the value chain is questioned and needs clarification.

28

A uniformity of language between standards will mitigate topics subject to interpretation and ensure consistent reporting requirements. Consequently, by converging towards a single set of definitions and standards, organisations can have a clear structure for sustainable reporting which would accelerate the reporting process. Furthermore, consistency between frameworks would prevent unnecessary losses of costs in the collection of data and measurement ofemissions for standards organisations. Therefore, clarifying definitions highlighted by standards organisations should be a priority for the EFRAG.

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Figure 5: References to each theme in the ESG reporting institutions

Figure 6: References to themes in financial institutions

Figure 7: References to themes in National Standard Setter Organisations

4.7 Non financial institutions

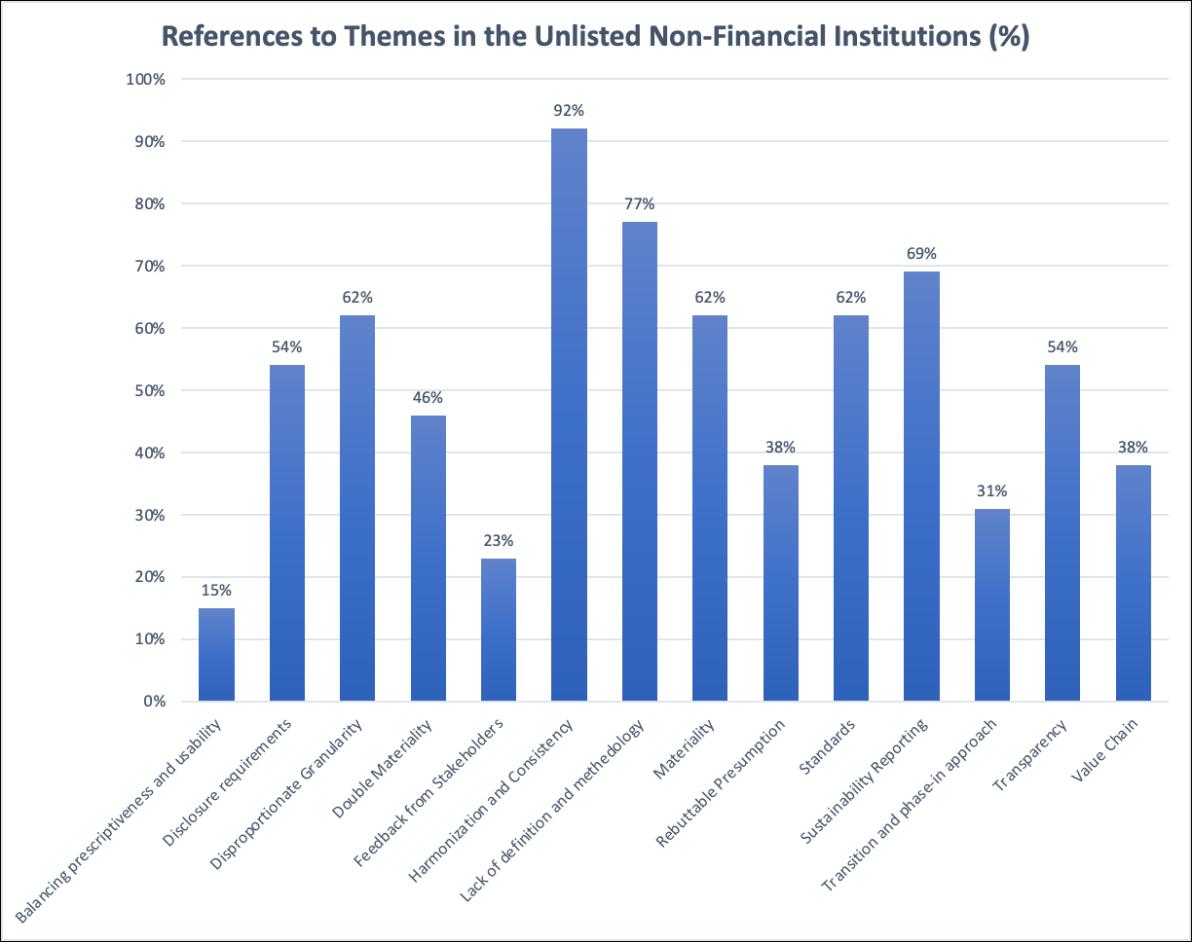

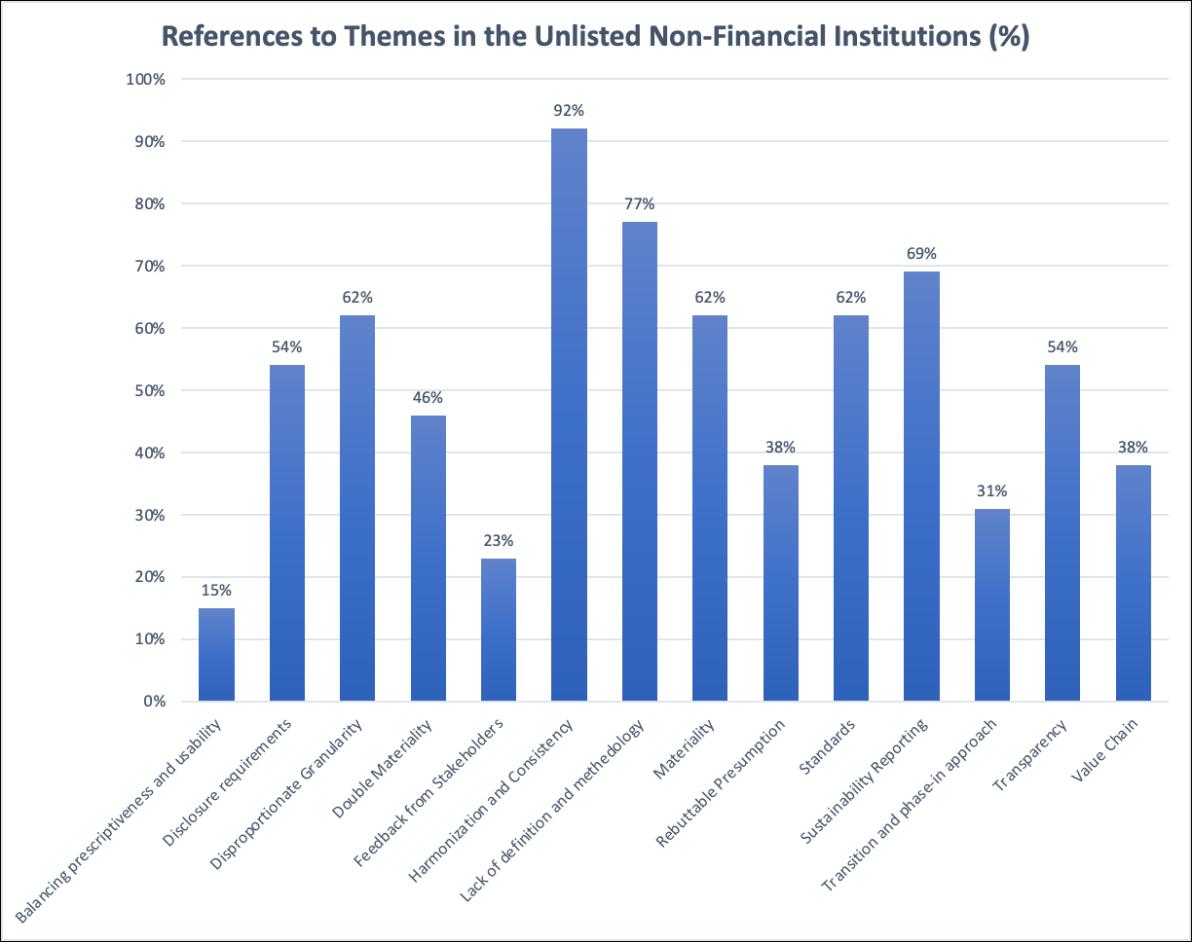

Non-financial institutions “produce goods and services for the market and do not, as a primary activity, deal in financial assets and liabilities” (UK Office for National Statistics). 43 letters fit into that category. As shown in the following graph, the main areas that non-financial corporations addressed were disclosure requirements (72%), harmonisation and consistency (79%) and standards (63%).

More precisely, a recurring theme within harmonisation and consistency was the need to align with other international initiatives such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to avoid the unnecessary duplication of sustainability reporting. The interoperability with other EU legislations has also been pointed out as a challenge to the ESRS applicability. Noncompliance with the requirements of the CSRD is highlighted as problematic. Specifically, within the ESRS Governance package, diversity policy raises questions as it is not covered by European Law.

As far as disclosure requirements are concerned, many corporations underline the difficulty of complying with the high level of granularity required in the ESRS. As mentioned by BMW, “ESRS contain no less than 137 disclosures requirements with many “sub disclosures''. Data may not be available or not reliable for some of the disclosure requirements. In the Scope 3 emission case (indirectemissions that occur in a company’s value chain), only approximations can be made for now, corporations call for a delay of 6-12 months in gauging Scope 3 emissions as they represent an incremental change towards more sustainability. Relying on the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) Standard or the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol) might be a realistic solution. The call for a broad disclosure requirement on greenhouse gas emissions should however be rejected since it would significantly reduce the ambition of disclosure on GHG which is currently one of the biggest problems linked to ESG implementation in the economy. In addition, a majority of corporations criticise the disclosure of sensitive information that might harm their competitiveness. For example, the American Chamber of Commerce deplores that “details of raw material cost, and on payment practices' could significantly harm the reporting company's ability to compete. Yet, this fear should be nuanced as the EFRAG ‘s DraftESRSis supported by substantive research on the impact companies might suffer from after the introduction of the ESRS. It is however true that medium-sized companies will be particularly affected by these disclosures due to their limited resources.

Standards are often criticised as being too complex and making the exercise of sustainability reporting arduous. Suggestions of a “core and comprehensive approach” to streamline the reporting exercise and make ESRS enforceable have been made. Concerns about the ability to report on Resource use and circular economy due to the current lack of data are understandable. However, this should serve as an excuse to downplay the ESRS ambitious standard. Instead, progressive implementation on E5 should be considered More specifically, “biodiversity” (19%), “climate standards” (22,5%) and “own workforce” (19%) are the most addressed standards in the letters.

More generally, non-financial corporations have asked for an extended and gradual phase-in approach (56%) as well as increased specificity of definitions since some terms could lead to different interpretations (42%) (e.g. own workforce, value chain, fair remunerations, double materiality, financial impact).

Ultimately, the debate around rebuttable presumption and double materiality is divisive since non-financial corporations in majority agree with the relevance of introducing double materiality in their reporting while the rebuttable presumption has been discarded due to its impracticability.

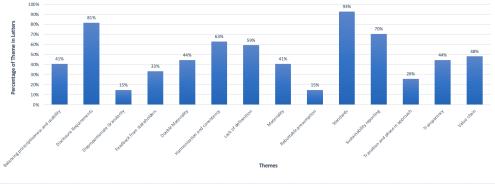

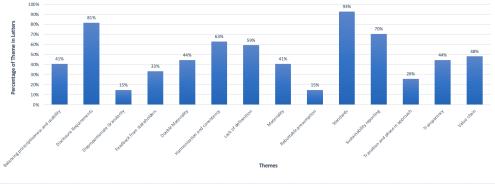

4.8 Non governmental organisations

The qualitative data analysis of letters from NGOs reveals that the key issues of this sector are connected to Standards, Harmonisation and Consistency. Most of the NGO’s advocate for environmental concerns, vulnerable populations (such as indigenous and people with disabilities), as well as pro-bono consulting organisations on environmental finance. The major source of worry in standards was the sub-code 'affected communities,' specifically its disclosure requirements. Individuals' effect inside the value chain and understanding of diversity across sectors and geo-locations appeared to be lacking for this industry. These issues seeped into harmonisation recommendations, notably on comparability and convergence. In their comments on EFRAG, European NGOs frequently recommend that affected communities be represented in cross-cutting standards to increase clarity and convergence. As a result,many companies emphasise the need of aligning the EFRAG framework with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

NGOs commend EFRAG for adding concerns about affected communities, notably the consequences on indigenous people. The three most vocal companies were Climate Company, Club EMAS, and DIHR. DIHR was the biggest advocate specifically for improving standards related to affected communities. Notable as well is Shift 22 who was in the top three of NGOs’ coding about standards. Standards

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

are addressed 92.6% in the letters submitted by NGOs, with 72% referring explicitly to affected communities (Graph1). Thisemphasisisunderstandablegiven thatthese organisations frequently represent the interests of minority communities (Schnellbach, 2012). However, the methodology was said to lack due diligence on an individual's influence on the value chain. For example, in ESRS S3-affected communities, cultural rights are stated alongside economic and social rights but do not include cultural diversity. This is emphasised since local concerns and culture will have varying effects inside each community. Capitals Corporate states: “A wider set of stakeholders are identified by businesses when conducting sustainability assessments beyond contractual groups. These should include, but are not limited to, local and affected communities, workers in the value chain and citizens.” As a result, several companies have pushed EFRAG to focus on sector-specific criteria that include performance-related disclosures about value chain employees and affected communities.

This industry critiqued the ambiguous definitions and methods that make comparison and convergence difficult. Particularly when it comes to the Standards and the lack of a unified data approach. For example, 63% mentioned ‘Harmonisation and Consistency’ and ‘Lack of Definitions and Methodology’ in 59% of letters. Including precise definitions in the ESRS standards will assist uniform data creation, allowing firms' achievements and development to be compared:“We recommend that the ESRS clarify how information should be gathered and when these approximation processes should be used ensuring thatadequate incentivesare given to collect data'' (DIHR). Improving definitions and methodology will in turn improve comparison and convergence. This is especially true for the impacted community standards, since many elements overlap with all three E, S, and G standards. As a result, many businesses advocate aligning the framework with the four-part International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) framework. The purpose of ISSB and ESRS is the same: to assist organisations in communicating their sustainability performance to stakeholders. Although their methodologies and degrees of governance differ, their aims and structure are similar enough to match frameworks.

Furthermore, according to our second hypothesis, "we should discover that double materiality and rebuttable presumption are two of the most addressed concerns and are controversial depending on the industry." In accordance with this view, the concepts, particularly rebuttable presumption, were not widely used inside the NGO sector. Double materiality was referenced in 48% of letters, whereas rebuttable presumption was cited 14.8%. (Figure 10). The overall response to double materiality was encouraging, with

46% of corporations in favour and 15% opposed. Companies, on the other hand, suggested a better definition of double materialityand aframework forhow itshould beincorporated. CDP Europe states, “a double-materiality approach in sustainability reporting is the right way to go,” yet suggests, “with reference to the impact on people and planet, the definitions should be fully aligned with the GRI Standards.’ Similarly comments for clearer definitions and structure to improve harmonisation were made concerning rebuttable presumptions.

Thus, the NGO sector is preoccupied with standards, harmonisation, and consistency, which are largelythe resultof a lack ofdefinition and defined frameworks. As a result,many letters advocate for harmonising the ESRS framework with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

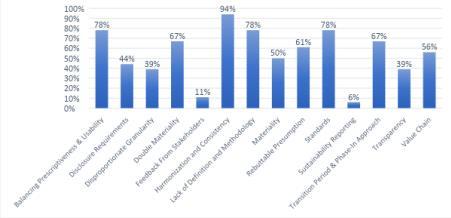

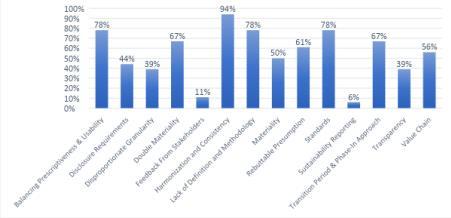

4.9 Public authority

Qualitative analysis of the public associations (PA) sector indicates thatPAs are primarily concernedaboutthe following three key aspects of the ESRS, as reflected by the high density of their corresponding coding references in Figure 11: (1) Harmonization both externally with other disclosure frameworks and internally with other EU laws, mentioned in 94% of letters with 79 total references, (2) a lack of clarity with definitions, methodologies and language used, mentioned in 78% of letters with 32 total references and (3) Scope 3 emissions standards, which overlap with concerns regarding transition periods of small-medium enterprises (SME), mentioned in 78% and 67% of letters respectively, with 27 references for climate standards and 21 references for a transition period and phase-in approach. In addition, (4) the PA sector broadly supports double materiality with 67% of public associations adopting a for/nuanced stance, but broadly rejects the inclusion of rebuttable presumption with 56% of public associations adopting an against/nuanced stance.

It is no surprise that PAs would see the harmonisation of ESRS with other disclosure frameworks, with the IFRS being the most mentioned, as a top priority. A lack of harmonisation between ESRS and other frameworks would essentially constitute “non-tariff trade barriers” between the EU and the rest of the world. The relatively stricter and more prescriptive regulatory environment that would be created by the ESRS in EU might also lead to the rise of regulatory arbitrage by firms with less ofan exposure tothe EU marketand a corresponding decrease in the competitiveness of firms that are fully reliant on the EU market (Alamillos & de Mariz, 2022). Moreover, some PAs, like the Securities and Markets Stakeholder Group of ESMA, have called for EFRAG to improve its interoperability with the already crowded and complex arena of regulation in the EU, suggesting that the current version of

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

Figure 8: References to the most important themes in the non financial institutions (%)

Figure 9: References to themes in the non financial institutions (%)

Figure 10: References to themes in non-governmental organisations (%)

Bentham Brooks Institute Policy Journal 2022-2023 Helfi et al

the ESRS will lead to an overload of unnecessary reporting information from companies when coupled with additional regulatory requirements from the CSRD, taxonomy and SFRD.

Next, PAs were also concerned with the lack of clarity observed in the ESRS. Common points for clarification included the relationship between cross-cutting standards and sector-specific standards, and definitions of key terminologies such as “value creation” and “time horizon”. Additionally, many PAs also commented on the heavy usage of terminologies and abbreviations that would unnecessarily obfuscate the process of disclosure for many companies.

Third, PAs also showed a much more pronounced concern forreporting standards relating toscope3 emissionscompared to any other standard within the ESRS. On one hand, PAs generally commend EFRAG for the ambitiousness of their climate standards in trying to lower scope 3 emissions, which represent a staggering 75% of all greenhouse gas emissions fromcompanies on average (Lloyd, et al., 2022). On the other, PAs are extremelyconcerned with the lack of guidance shown by EFRAG towards helping SMEs in the value chain to conduct credible reporting. In fact, SMEs are often disproportionately burdened by the costs of ESG reporting as compared to larger firms (Gjergji, et al., 2021), so PAs would naturally be invested in balancing the extensiveness of scope 3 emissions reporting against costs incurred for SMEs in the EU.

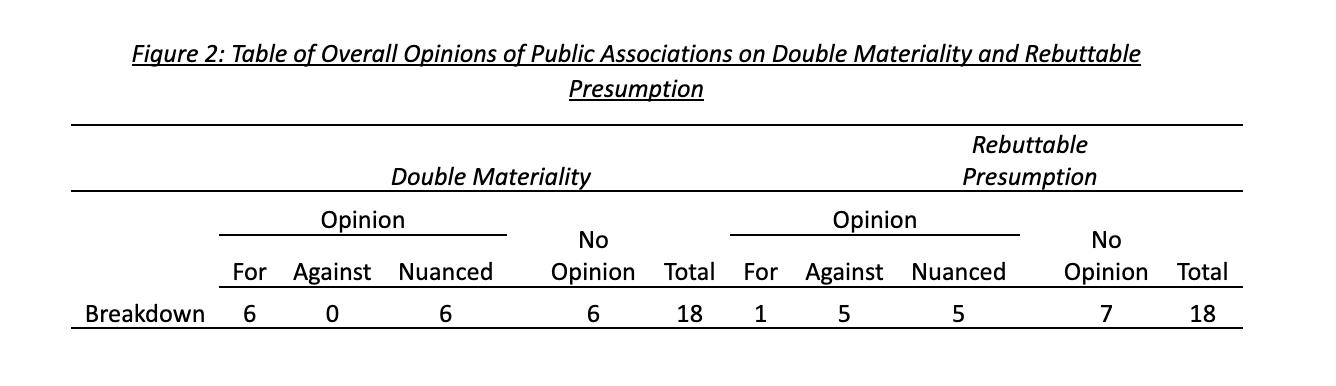

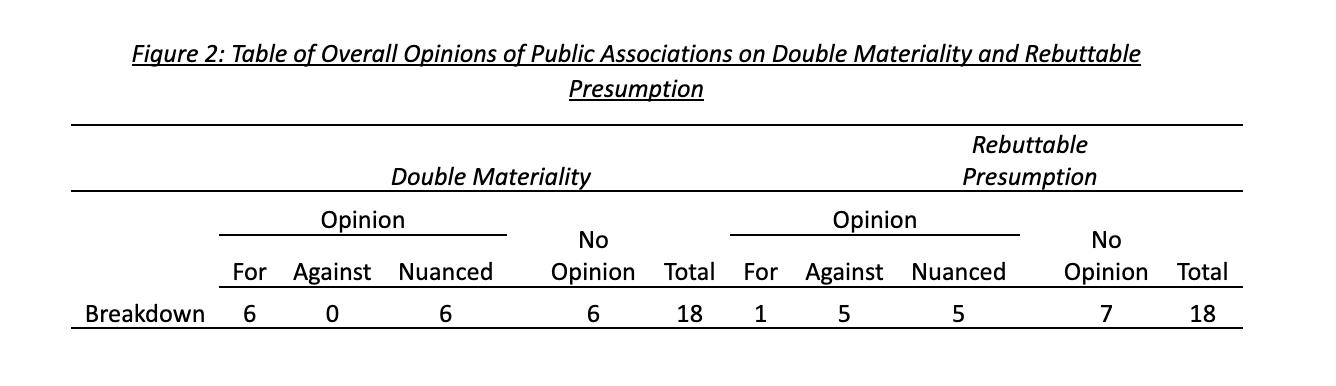

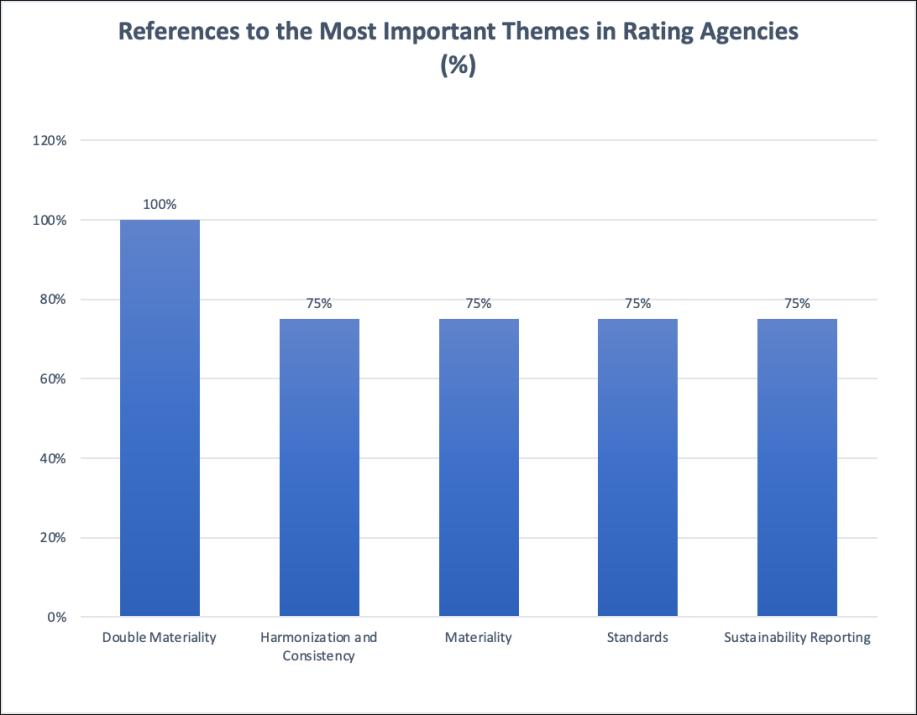

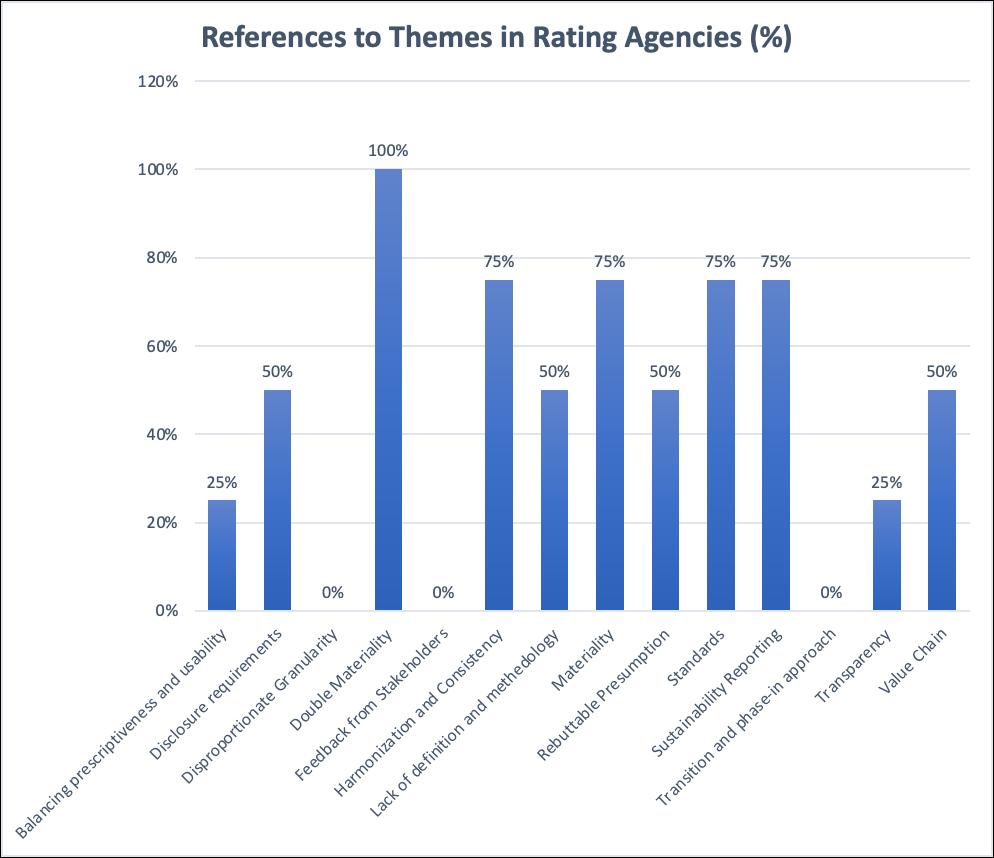

Lastly, there is the overall stance of PAs on the contentious decision of the EFRAG to structure the ESRS around the concepts of double materiality and rebuttable presumption.