Embracing identity: Understanding Womanhood Through Artistic Expression

Introduction

In this reflection I aim to explore the intersection of my experiences with womanhood and art and how they have helped to shape my creative journey, particularly in my most recent projects. In this reflection I define womanhood as both the state of being a woman and a cultural experience, and I define art as an umbrella term which includes literature, fine art, and architecture.

Beginning with my earlier experiences with womanhood and how I began my understanding through literature I will show how I started critiquing my experiences through fine art. Ultimately, I will explore how I embraced the ideals which resonated with me and how I incorporate them into my work.

This piece delves into the process of internalising and contextualising themes across different periods of my life and illustrates how my understanding of womanhood parallels my artistic expression. I aim for this reflection to prompt readers to reflect on their own experiences and how they influence their work. While I focus on womanhood this can easily be replaced with another cultural experience such as manhood, grief, or socioeconomic status.

Part 1 – Literature and Subjection

I was born into the post feminism era where women had ‘achieved equality’, this is what I grew up believing. It wasn’t until I had started my secondary education that I found myself subjected to critiques that were not applied to my male peers. This is when I had started to suspect we had in fact not achieved equality, at least not as I knew it. While I did not yet have the capability or education to understand what objectification theory was, I did not connect my experience to it until later. I had quickly learnt of society’s expectation of women, an object of desire, more of a decorative ornament than a person. (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997.)

During this time my love for literature grew and it offered me an escape from the expectations I had started to mould myself into. However, it was not the perfect safe heaven as it too, critiqued me and the work I enjoyed.

As I delved deeper, I encountered a poem which epitomised the social expectations I was being taught. ‘My last duchess’ by Robert Browning (Appendix) shows the story of a woman stripped of her consent. She is literally turned into a piece art to be stared at and controlled by the same man who had her killed.

The essence of this poem is one which I saw reflected in literature. How the theme of women’s consent and agency are rarely considered in esteemed literature, instead they often contain graphic scenes of sexual assault or rape (Game of Thrones, 1996. or For Whom the Bell Tolls, 1940.) Many highly regarded books often lack a woman with agency and seldom pass the Bechdel or the ‘sexy lamp test’ (Yehl, 2013.) (The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, 2005.)

Opposing this are stories from what is usually deemed women’s literature. For example, the genre of romance, which typically centres consenting women, however it has a history of being seen as frivolous entertainment before being considered literature. This affected how I understood womanhood and my own agency. I became desensitised to violence against women because even

these moments of a women’s life were a spectacle, for the entertainment of others. Women’s pain was a means to an end, a tool to show how dark and serous a writer could be.

It was through literature that I started to contextualise and recognise injustices against women, and I began to voice my concerns but only on matters which seemed beyond individual control. This allowed the issue to seem further away, less likely to affect me but also afforded me the protection of maintaining a desired demeanour. At the time it seemed as though worse than being an object, was being the object, no one wanted to gaze upon.

Part 2 – Fine Art and Exploration

During my time of transitioning from consuming art to creating it, I was dealt the unfortunate opportunity of the pandemic. As my other studies began to take the backseat, I found myself homing in on my fine art course with the time to explore it both academically and personally. My focus turned to narratives particularly those that affected the stories of women. I started centring women in my work and began to discover patterns in fine art alongside my own. It was then when I realised myself to be both a creator and a subject.

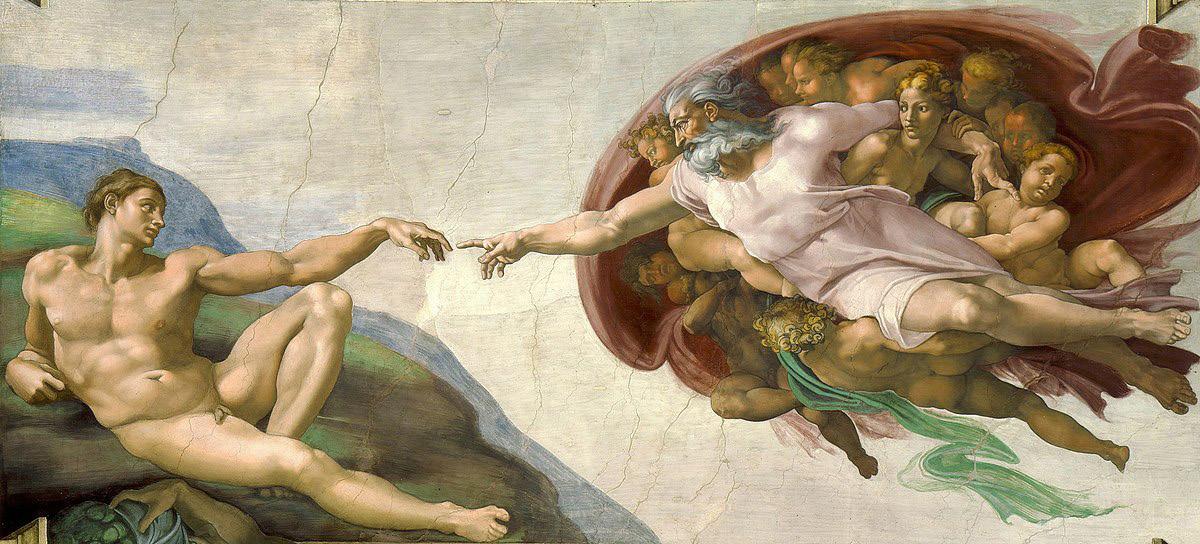

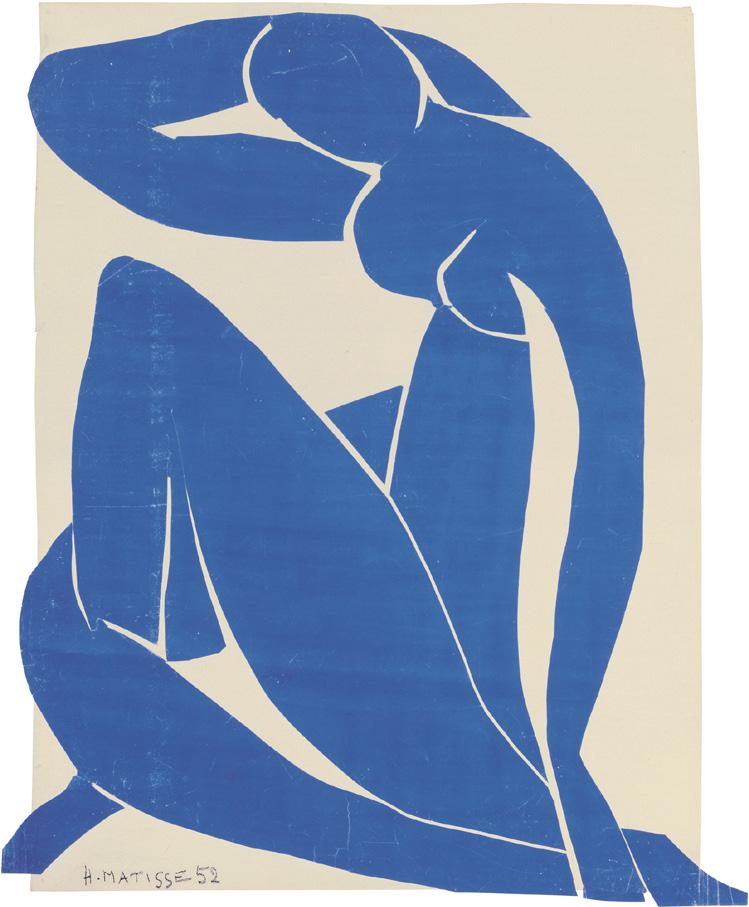

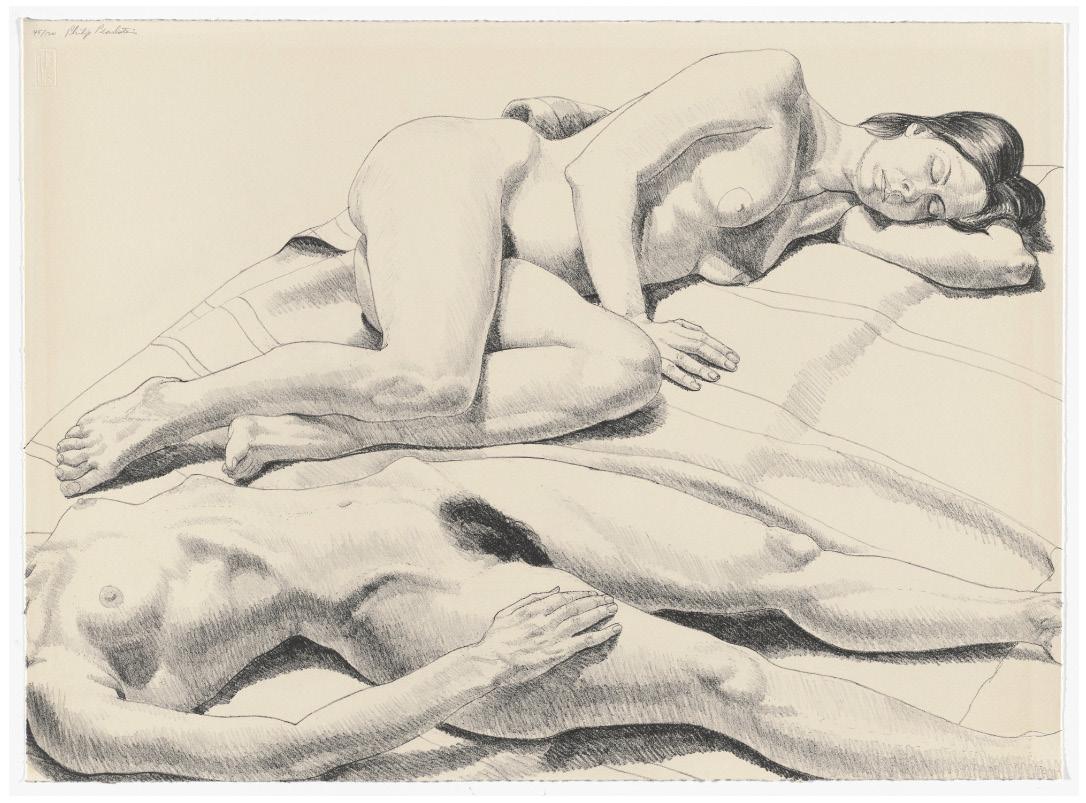

The most prevalent pattern was the portrayal of women as decoration which is best understood through the comparison of men in art, particularly in reference to nude art. Male nudes are

Embracing identity: Understanding Womanhood Through Artistic Expression

typically in a biblical or mythological context, a moment of importance to be remembered. (shown in fig.1 & 2) Whereas nudes which depict women’s bodies often do so to depict the figure (shown fig. 3 & 4). A keynote to apply to both depictions are the creators, all of which are men. This typically leaves female nudes as decorative ornaments of someone else’s depiction.

I used art to explore and critique the womanhood I felt I was faced with, something that was not quite my own, as though everything I did was to be a performance for someone else. Part of this exploration was through various media including embroidery (For example figure 5); an art form which unlike many others, has historically been female dominated. It led me to String Art (Shown in fig. 6) and gave me a chance to connect with femininity that was not focused on the body but the feeling.

Part 3 - Architecture and Acceptance

By critiquing and understanding the role womanhood played in my life I was able to make it my own. As I transitioned my art form to architecture, I began to lean into my femininity. I learnt to mould my own version of womanhood as I expanded my knowledge of art, finding other women who had taken control of the narratives that surrounded them (Louisa May Alcott, Barbara Hepworth, Jeanne Gang.) Instead of scrutinizing all that I felt womanhood pushed onto me, I began to take all that it could offer me and weaved it into my creative process, feeding it intentionally into my work.

Women’s art is often categorised under ‘feminist’. It acts to separate their work much like with female literature. I often found that this occurs even when the artists themselves have not made their political views clear. I feel fortunate that this has not been the case for myself in the past few years studying architecture. I believe this to be in part due to the liberal leaning arts environment of the university where most of the cohort is female. My work seems to have been judged on its

Embracing identity: Understanding Womanhood Through Artistic Expression merits rather than by my identity. This separation between creator and creations has allowed me the freedom to play with femininity on my own terms where I am now able to incorporate it in my work.

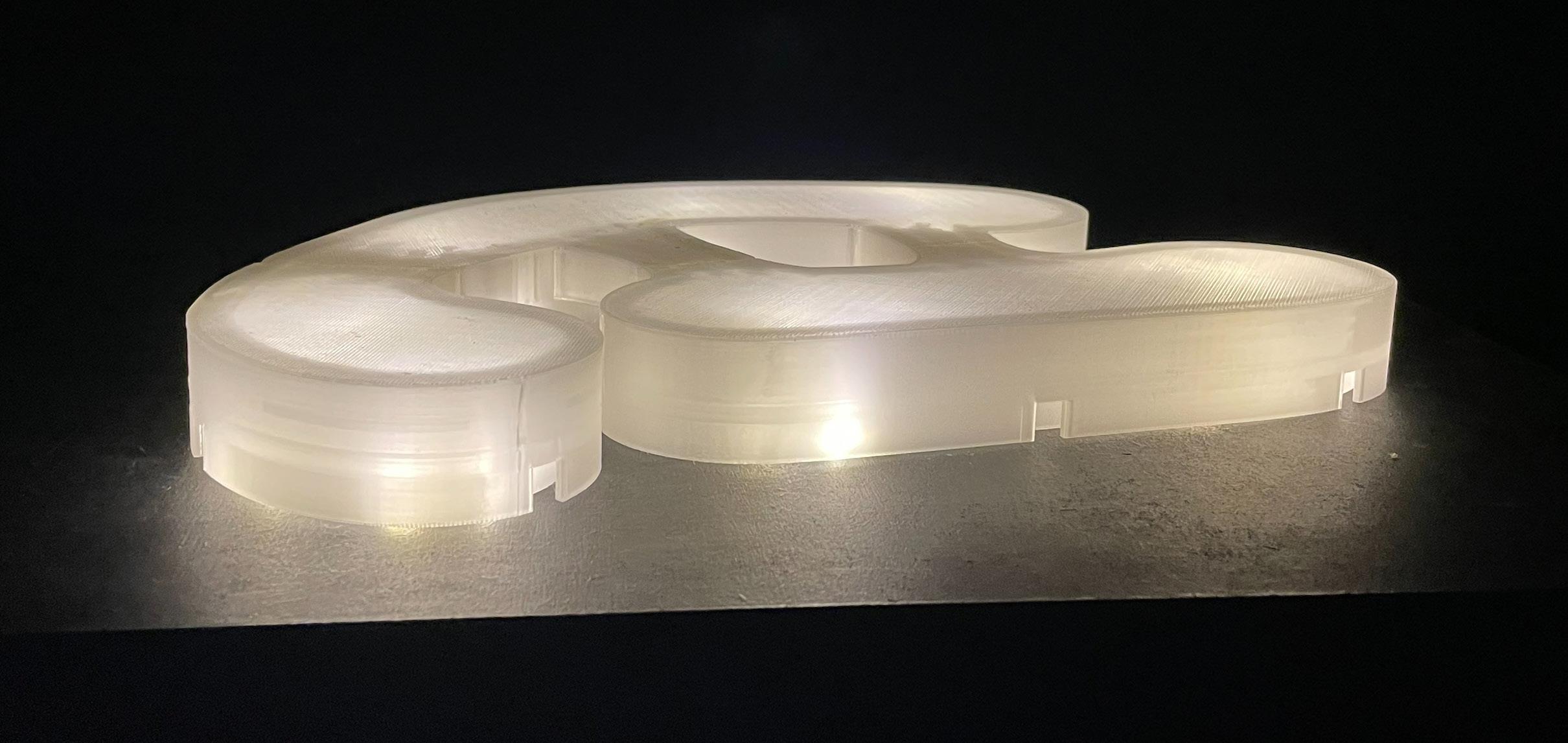

I have been inspired by many female artists, in my most recent project I have particularly focused on Barbara Hepworth. She has been a key point of refence while creating a school of sculpture and weaving my femininity into the project with her soft but powerful work. This project embodies my acceptance of womanhood, drawing from its essence to inform the overarching design. I wanted the project to not only house art but be art. I find it fitting that Hepworth was one of the first female artist I was introduced to and now I end this journey alongside her once more.

List of Figures

Figure 1: The Creation of Adam Di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, M. (1508 – 1512) The Creation of Adam [Fresco]. Sistine chapel, Vatican city.

Figure 2: The Statue of David Di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, M. (1501 - 1504) David [Marble sculpture]. Accademia Gallery, Florence.

Figure 3: Blue Nude II

Matisse, H. (1952) Blue Nude II [Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, on white paper, mounted on canvas]. MOMA, New York.

Figure 4: Two Reclining Nudes on Rug Pearlstein, P. (1972) Two Reclining Nudes on Rug [Lithograph]. MOMA, New York.

Figure 5: mother and child Maue, J. (2018) Mother and Child [hand embroidery on found linen]. available from https://www. joettamaue.com/ [Accessed 5 May 2024]

Figure 6: Untitled String Work Vriend, A. (2020) Untitled String Work [String around nails on wood]. In possession of: the author.

Figure 7: Clay Model Vriend, A. (2023) Clay Model [Clay]. In possession of: the author.

Figure 8: Current project Vriend, A. (2024) Architectural model [3D printed]. In possession of: the author.

Bibliography

Fredrickson, B. & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Vol. 21 No.2.

Yehl, J. (2013). Kelly Sue DeConnick talks Captain Marvel, Pretty Deadly, and the Sexy Lamp Test [online]. Available from: https://www.ign.com/articles/2013/06/20/kelly-sue-deconnick-talks-captain-marvelpretty-deadly-and-the-sexy-lamp-test [Accessed 15 May 2024].