BY AISLINN SARNACKI

Though many paddlers stow their gear at the end of summer, fall is a wonderful time to get out on the water. Maine’s ruthless blackflies and mosquitoes are dying down, and the waterways are no longer crowded with summer folk. Plus, after months of sunshine and heat, the water retains enough warmth, especially in early fall, for swimming.

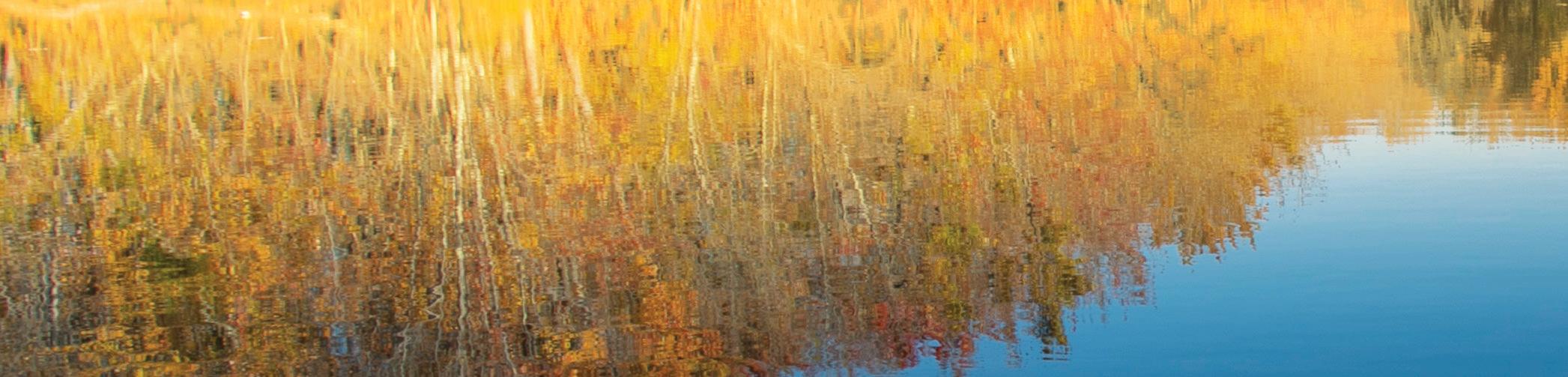

What’s most amazing about fall paddling, however, is the perspective it offers for viewing Maine’s incredible fall foliage. While gliding down a stream or along the edge of a lake, you’re treated to an unobstructed view of the trees that line the shore. In swampy areas, bright red maples will steal the show. In drier spots, oaks, sugar maples, and poplars pop with color.

If the water is calm, you’ll enjoy twice the fall foliage as shoreline trees reflect in the water below. It’s truly a magical experience.

But where to go? I like to start planning by looking at the Delorme Maine Atlas and Gazetteer. It’s like a treasure map for paddling spots.

The conversation always starts the same: “That looks interesting.” Finger pressed to a page, I wait for my paddling buddy to peer over my shoulder and agree.

After all, “interesting” could mean just about anything. A meandering stream that looks good for wildlife watching, a lake full of islands to explore, a remote pond with no houses along its shores — the atlas contains it all.

In this book of invaluable maps, the symbol of a boat launch is the simple shape of a motorboat seen from a bird’s eye view — a square stern arcing on the sides to a pointed bow. I simply search for that symbol in an area of the state that I’d like to paddle.

If the boat symbol is solid, the boat launch is trailerable, meaning you can drive a boat on a trailer straight into the water. If the symbol is hollow, it’s a handcarry site, suitable for launching small boats like canoes, kayaks, and stand-up paddleboards.

Lucky for me — and everyone else who loves paddling — Maine is filled with options, with roughly 2,500 lakes and ponds, 3,500 miles of coastline, and 32,000 miles of rivers and streams.

The Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands alone provides public boat launches at almost 400 locations throughout the state. In addition, many towns and outdoororiented organizations offer launch sites as well.

Flip to any topographical map in the Delorme Maine atlas and you’ll find boat launches — aside from page 60, on which an extremely remote northwest part of

the state borders Canada and there’s extremely limited road access. (Yes, I flipped through the entire atlas to check.)

Once you’ve found a boat launch that looks “interesting,” do a little research. The Lake Stewards of Maine website is a great resource for learning more about lakes and ponds, including the area they cover and their depth. Google provides helpful satellite views of bodies of water, but keep in mind that water levels change throughout the year and features, such as beaver dams, can pop up overnight.

But I like leaving a little bit of mystery. It adds to the sense of adventure and exploration.

That being said, I make sure to prepare with the necessary safety gear and navigational tools, plus ensure my boat is suitable for the water conditions (for example a sea kayak for tidal waters or a paddleboard for a small pond).

In addition, I always travel to a new-tome boat launch with a plan B, and sometimes a plan C. That way, if I turn up and am confronted with whitecaps or a washed out road, I can easily pivot to another equally exciting adventure without any heartbreak.

One woman’s 20-year mission to hike the Appalachian Trail

The day we had been looking forward to for 20 years was finally here — the day we would summit Katahdin. Our adventure section-hiking the Appalachian Trail was drawing to a close. Anticipation mixed with sadness filled my heart.

For the past 20 years, my husband Paul and I knew exactly what we would be doing on our vacations — section-hiking the Appalachian Trail, a week in the spring and a week in the fall. It was a journey that started at Springer Mountain in Georgia in 2005 and carried us over countless mountains through 14 states — 39 section-hikes in all.

When my husband and I were newly married almost 50 years ago, he learned that I like to hike and told me there was a trail called the A.T. that went all the way from Georgia to Maine. I honestly thought he was joking. I was a girl who grew up in New York City and was very familiar with highways, noise, and crowds of people, but knew little about solitude and wilderness. But solitude and wilderness were calling me, and after learning that there was such a trail, I promised myself that one day I would indeed hike from Georgia to Maine.

That dream of mine was put on hold for a few years due to raising three children, but it was never far from mind. Finally, at the age of 51, I said to myself, “It’s now or never.”

My daughter was more than willing to join me on my first section-hike. We flew to Atlanta, Georgia, and hiked the first 66 miles of the 2,197-mile journey. She turned 21 on that hike, the first of many memories to come.

My daughter returned to the Trail with me a couple more times after that, but it was my husband Paul who became my steadfast hiking companion over 36 hikes. I don’t think he’ll

ever comprehend how much it meant to me to have him by my side. I remember one of the hikes in western Maine when he was ahead of me on the Trail and met another hiker. They struck up a conversation and I heard Paul say, “The A.T. is my wife’s dream, but now it is my dream as well.” He didn’t know I heard him say that, and it touched me to the core.

We discovered that each section-hike was a miniadventure unto itself: different roads to get to the Trail, different towns to experience, different terrain to hike across — from rolling farmland to rugged peaks.Each hike blended to form a rich and colorful tapestry.

Here are just a few of the highlights:

• A starry night atop Siler Bald in North Carolina

• Hiking through the Smoky Mountains in a drought, carrying 5 quarts of water each to make it through

• Max Patch, a panoramic grassy bald that was later decimated by over-zealous campers during the pandemic, but was later restored to its wild state

• Crossing the Hudson River on Bear Mountain Bridge

• Losing the Trail the day after a tornado obliterated it in New York

• Post-holing through snow on Moosilauke

Lakes of the Clouds Hut in the Presidential Range

• Gale-force wind and rain traversing Franconia Ridge

• Stayingat the Huts in the Presidential Range in New Hampshire

• Bypassing the Carrabassett River ford by hiking down Sugarloaf ski slope

• Crossing the Kennebec River in a canoe

• Impassable streams and rivers in the 100 Mile Wilderness

• Spectacular sunset while tenting by ourselves on the shores of Nahmakanta Lake

• Hiking 14 sections with our dear, sweet border collie Denali

• Time spent with family at Kidney Pond in Baxter

Now, there was only one day and one hike left — the summiting of Katahdin.This hike was different than all the others. Our three children were joining us.Erin (40), Adam (38), and Jason (36) wanted to experience the culmination of this amazing journey. We were so happy and proud to have them beside us as we reached the final summit.

The night before, Paul, Adam, and I were tenting at Abol Campground. Adam had flown in from Washington State. Erin and Jason, along with their spouses and kids, were staying at a cabin on Kidney Pond. We told them we wanted to be hiking by 6 a.m. the next day. It would be a long day, and now in our 70s, Paul and I needed every hour of daylight to complete the hike.

On Saturday, August 31, 2024, Paul, Adam, and I awoke at 4:45 a.m. We ate a quick breakfast, then drove to Katahdin Stream Campground. Erin and Jason arrived there too, right on time. The sun was just rising above the mountain. We didn’t dally, but threw on our packs and started up the Hunt Trail, which is part of the A.T. The old brown sign showed 5.2 miles to Baxter Peak.

The Hunt Trail is one of the most challenging trails up Katahdin. Soon we were climbing up and over gigantic boulders, bending and twisting our bodies around them as we plodded upward. Clouds moved swiftly across the sky below and around us, giving us glimpses of rocks, woods, and ponds far below. On the upper reaches of the dinosaur’s spine of a rocky ridge, the wind roared. We pulled out our wind breakers. The wind tried to grab them from our hands. In the mist, we crested the false summit onto the Tableland, a relatively flat, rock-covered plateau that made me think what the moon must look like. Only one mile to go to the true summit. The five of us trudged on. Within half a mile of the top, Paul’s boot caught a rock and he went flying face first. He landed with his head just inches from a rock. He got back up onto his feet and kept going, bemoaning the fact that the mist had condensed on his glasses, making it difficult to see.

Suddenly the big cairn atop Baxter Peak loomed out of the fog. I grabbed Paul’s hand, and we raced toward it together. I heard clapping from bystanders. Our kids stepped aside to let us through. Our dream was fulfilled.

The Blue Hill Peninsula is often associated with boatbuilding, lobsters, and maritime history, but it would be a mistake to not consider its rich agricultural heritage as well. The landscape is dotted with small farms and gardeners who take pride in tending to the land and growing both food and community. Getting to know local food producers in this area is as fun as it is delicious, and there are a lot of different ways to connect.

There are dozens of farmers and producers in this area and one of the easiest ways to get a sense of what’s available is to browse the Brooklin Food Corps website. They keep a running list of producers in Brooklin, Blue Hill, Brooksville, Castine, Deer Isle, Orland, Penobscot, Sedgwick, and Stonington. Or, depending on where you’re heading, you’ll pass by a handful of farm stands along the way. Don’t be shy about stopping by. You’re likely to find something delicious, and if you have the good fortune to cross paths with someone there, they can recommend where to go next.

“We try really hard to be good neighbors and help each other out how we can,” said Lorelei Cimeno. Cimeno and her husband own Rainbow Farm in Orland, and when she’s not tending to their land and livestock, she manages the Blue Hill Farmers’ Market.

“Our goal is to increase food access in our community and there are so many good things happening here,” she said. “The peninsula has really deep farming roots and we’re lucky to continue that tradition.”

Happytown Farm’s Angelica Harwood feels much the same. A Colorado transplant, she is a careful steward of land in Orland that has been farmed for over 45 years. She is passionate about connecting customers with local foods and offers workshares for folks who trade their time and hard work for a box of veggies at the end of a shift.

“One of my favorite parts of being a farmer is being able to work, learn, and teach alongside the community members, while providing them with fresh, healthy, nutrient-dense food that has never touched a chemical,” Harwood said. “We need each other more than ever and I feel so grateful for a community that supports its farmers the way the people up here do.”

Interest in local foods isn’t just some new fad here. In 1974, a group of dedicated farmers and foodies organized a buying club to make purchasing whole foods, fresh produce, and dairy products more affordable. While the intention wasn’t totally driven by an interest in eating locally, it helped energize the focus on foods grown on the peninsula; a few short years later the club incorporated as the Blue Hill CoOp. Since then, the co-op has been a hub of local activity and an access point for shoppers who may not otherwise recognize their neighbors as farmers and producers. You’ll notice markers throughout the store indicating where specifically each locally-sourced product is from, especially in the produce and meat and dairy aisles. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, don’t hesitate to ask. The staff are generous with their time and enthusiastic about helping customers connect with local vendors.

The best way to experiment with local foods is by browsing the offerings at an in-person market. There’s nothing better than being able to chat with the farmer who grew your food. More often than not, there’s at least one booth that has prepared foods on hand so you can munch on a homemade muffin or breakfast sandwich while you shop. The Blue Hill Peninsula boasts a handful of farmers markets throughout the week; you can stock up once or rotate through the different locations over the course of several days.

The Maine Federation of Farmers’ Markets maintains a list of markets that you can sort by location or by day, and each listing has its own page. It’s a super easy tool to help you find the best options near you and provides helpful information on what you’ll find at each. Visit mainefarmersmarkets.org.

UNTREATED OUT-OF-STATE FIREWOOD IS BANNED IN MAINE, AND EVEN IN-STATE FIREWOOD CAN SPREAD PESTS TO NEW AREAS.

Healthy forests improve air and water quality, provide wildlife habitat, scenic backdrops for recreation, and important rural jobs.

The movement of firewood speeds up the spread of destructive forest pests. For example, about three-quar ters of the early infestations of emerald ash borer in Michigan were directly tied to firewood transport. Some domestic spread of the invasive Asian longhorned beetle has also been traced to the movement of infested firewood

The next time you head out on an outdoor adventure, follow these firewood tips

• Leave firewood at home.

• Buy firewood from as close to your destination as possible Find sources at firewoodscout.org.

• If you’ve already transpor ted firewood, don’t leave it or bring it home – burn it! Tr y to burn it within 24 hours, and burn any small pieces of bark and debris that may have fallen from the wood

Help prevent the spread of insects and diseases that harm our forests by choosing heat-treated firewood or firewood from close to your destination. Find more tips at maine.gov/firewood.

Two great firewood choices:

• Local (from within 10 miles) or

• Certified heat-treated firewood (heat-treated to 160 degrees Fahrenheit for at least 75 minutes)

What exactly is local?

When it comes to untreated firewood, 50 miles is too far, 10 miles or less is best.

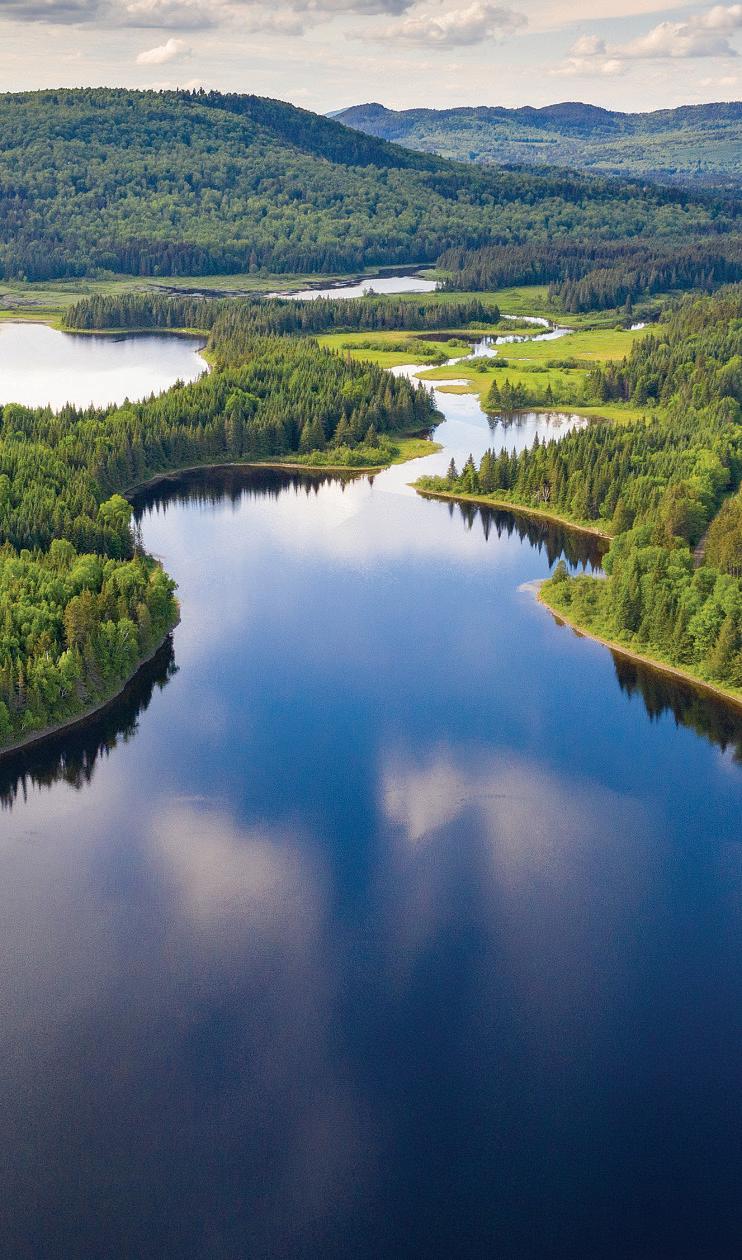

At the far western edge of Maine, in the heart of the Northern Appalachian forest, an expanse of landscape with shimmering waters seem to stretch on forever — past the horizon, over the rugged shoulders of the Appalachian Mountains, and beyond. A person could get lost here, if they weren’t careful. But what they might find, should they choose to explore, is extraordinary.

These are the Magalloway lands and waters. Seventy-eight thousand acres of critical fish and wildlife habitat and productive timberlands, a vital part of the largest intact mixed temperate forest in North America, and a puzzle piece that connects half a million acres of permanently conserved lands across the Appalachian Corridor. The Magalloway lands and waters are a rest-stop for dozens of species of migratory birds, including more than 20 different species of warblers, which makes it a great destination for birders. With 2,400 acres of mapped wetlands, the Magalloway lands and waters provide food and shelter for popular game species like waterfowl and Ruffed grouse. They are home to black bear, moose, white-tailed deer — and even the elusive Canada lynx.

Parmachenee Lake is one of only six lakes in Maine over 500 acres that does not currently provide secure public access. Conservation of the lands will guarantee 10.9 miles of shoreline on the lake is available for recreational uses compatible with habitat and wildlife conservation. Nearly 170 miles of rivers and streams crisscross the property, cold flowing headwaters that feed Parmachenee and Aziscohos Lakes and create one of Maine’s most resilient watersheds for cold water fisheries. According to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, the Magalloway watershed system supports habitat for all life stages of native brook trout and landlocked salmon. Parmachenee and Aziscohos Lakes also contain self-sustaining smelt populations — an important food source for salmon.

Currently, the Magalloway lands have no special protections against development, fragmentation, or the sale of kingdom lots.

The Magalloway Collaborative aims to change that.

Forest Society of Maine (FSM), Northeast Wilderness Trust (NEWT), Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust (RLHT), and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), collectively known as the Magalloway Collaborative, have partnered to conserve the Magalloway landscape. After years of discussion and negotiation, an agreement has been reached with the landowner to conserve Magalloway forever. The project is a careful balance, designed to protect and sustain traditional activities and livelihoods like guiding and forestry alongside natural features and sensitive habitats. It will help to ensure that western Maine remains a world-class destination for fishing, hunting, paddling, wildlife-watching, and other forms of outdoor recreation.

To complete the project, the Magalloway Collaborative must raise $62 million by spring 2026. Several early leadership commitments have been made toward that goal, but there is much more work to be done. To learn more about the Magalloway lands and how you can become a part of the effort to conserve this incredibly special part of Maine, please visit magalloway.org