Strengthening European Sovereignty

Towards Open Strategic Autonomy

▪

In view of the growing geopolitical and economic risks, the objective of the German government and the European Commission to strengthen the sovereignty and resilience of Europe is more pressing than ever. This includes both economic and security policy issues and will require EU member states to work together much closer than before.

▪

Enterprises and economic policy need to adjust to the massively changed situation. The EU and its enterprises cannot depend on the goodwill of autocratic political leaders. It is not only Russia’s war in Ukraine that has brought our strategic dependencies to light. In addition to the measures planned in energy and defence, enterprises and policymakers must take precautionary measures in other critical fields too Most importantly, policymakers from various disciplines must work together in this respect

▪

Regulatory policy should focus on four main objectives: stabilising supply chains, securing and expanding technological capacities, safeguarding industrial skills to preserve own agency including national security, and asserting international competitiveness, e.g. with fair and effective trade regulations.

▪

At the same time, specific projects must be swiftly initiated. Among other things, Europe must:

Expand production and development capacity in the field of semiconductors

Coordinate the expansion of a sustainable energy infrastructure

Diversify the supply sources and further processing of critical raw materials through import, domestic production, recycling and substitution

Create reliable structures in cloud and edge computing in the EU

Strengthen the European standardisation process, primarily by prioritising critical projects such as technologies for transport, energy, and artificial intelligence.

POLICY PAPER | EUROPEAN POLICY | RESILIENCE

29 October 2022

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 2 Content 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Strategic aspects 4 1.2 Basic points 5 2. Microelectronics..............................................................................................................................7 2.1 Initial situation 7 2.2 Necessary measures and open issues 8 3. Data, Cloud & Edge.......................................................................................................................10 3.1 Initial situation 11 3.2 Necessary measures and open issues ......................................................................................... 11 4. Raw materials policy.....................................................................................................................12 4.1 Initial situation 12 4.2 Necessary measures and open issues ......................................................................................... 15 5. Energy supply................................................................................................................................16 5.1 Initial situation 17 5.2 Necessary measures and open issues ......................................................................................... 19 6. Space policy ..................................................................................................................................20 6.1 Initial situation 21 6.2 Necessary measures and open issues 22 7. Security and defence....................................................................................................................23 7.1 Initial situation 23 7.2 Necessary measures and open issues 24 8. Chemicals policy 26 8.1 Initial situation................................................................................................................................ 26 8.2 Necessary measures and open issues 26 9. Standardisation 27 9.1 Initial situation................................................................................................................................ 27 9.2 Necessary measures and open issues 28 10. Public procurement and third countries 30 10.1 Initial situation.............................................................................................................................. 30 10.2 Necessary measures and open issues 31 11. Third country subsidies and internal market monitoring 31 11.1 Initial situation.............................................................................................................................. 32 11.2 Necessary measures and open issues 32 Imprint 34

1. Introduction

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has increased the urgency of the issue of European sovereignty in European policy. European sovereignty itself has featured in the political discourse for some time. As far back as 26 September 2017, the French president Emmanuel Macron presented his ideas for the further development of the European Union at Sorbonne University in Paris.1 His call for a ‘sovereign Europe’ initiated a far reaching debate. Meanwhile terms such as ‘open strategic autonomy’, ‘European resilience’, or occasionally ‘strategic interdependence’ may be heard instead.

The European Council’s Strategic Agenda 2019 2024 sets out the objectives of European sovereignty as follows: ensuring stability, setting standards and promoting the values of the European Union.2 Resilience also forms one of the pillars of the European Commission’s reconstruction policy to overcome the economic impact of the Covid pandemic 3 The European Commission has already presented methodically high grade analyses on strategic dependencies as part of the EU Industrial Strategy 4 The key areas requiring action are also well analysed in the Strategic Foresight Report 2021.5 In Germany, the SPD, the Greens and the FDP all supported the EU’s sovereignty mission in its coalition agreement, aiming to “increase the strategic sovereignty of Europe”. It also expressly mentions “the systemic rivalry” between democracies and autocracies.

There is broad debate within and between the member states about what exactly these terms mean 6 This debate has increased momentum since the beginning of the war and now has a sharper focus on security policy. The informal meeting of European heads of state or government on 10 and 11 March 2022 centred on “bolstering defence capabilities, reducing energy dependencies and building a robust economic base”. The European Parliament has also addressed the role of the EU in an evolving geopolitical environment, including a detailed study by its research service on the course of the debate so far.7

These discussions also need to cover the industrial political dimension. Which dependencies are especially critical? Who has what control over industrial production processes? And where does industry itself require protection against harmful interference?

The outbreak of the war has greatly increased the difficulty of taking strategic decisions, particularly in key issues. Recent events have prompted an in depth re evaluation not only of how best to establish our defence capabilities and safeguard our energy supply but also of investments in the health industry. Despite the current uncertainties, European sovereignty has become a top priority which must be addressed in parallel to the day-to-day priorities. This policy paper forms part of this endeavour.

1 Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (2017). Initiative for Europe from President Macron. A sovereign, united and democratic Europe. 26 September.

2 European Commission (2019). EU Strategic Agenda for 2019 2024. 21 June.

3 European Commission. Recovery and Resilience Facility

4 European Commission (2021). Commission staff working document | SWD Strategic dependencies and capacities. 5 May. Brussels.

5 European Commission (2021).Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council | Strategic Foresight Report. 8 September. Brussels.

6 Politico (2020). Europe wants ‘strategic autonomy’ it just has to decide what that means. 15 October.

7 European Parliament (2020). On the path to ‘strategic autonomy’: The EU in an evolving geopolitical environment. September.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 3

1.1 Strategic aspects

The European Union continues to pursue the objectives of free global trade in fair international competition, high global environmental and social standards, and the freedom of investment. Given that the current environment makes any progress in strengthening the multilateral order very difficult to achieve, and the increasing strategic rivalry with nondemocratic countries over the last few years, the traditional measures of national and international regulatory policy must be bolstered by suitable economic and security policy measures to achieve a good balance between social welfare and security objectives. Over the last few years, Germany and the EU have accordingly taken a tougher stance in their economic relations with China8 , in their overall relations with autocracies9 and, of course, now especially in their relations with the Russian Federation since the turning point on 24 February 2022.

It is therefore only logical that German and European economic policy also needs to be adjusted to the changed security situation. For some time now, it is no longer presumed that more countries and regions will want to commit to a rule based global economic system in the foreseeable future. The likely result is, instead, a co existence of competing economic models in the world. This prospect triggers serious concerns that competition for market access to third states will intensify alongside trends to wall off domestic markets.

A strong global position is imperative if the EU is to reach its goals, as much in security policy as in the protection of the environment. The principle of open markets ends when political interference, particularly on the part of authoritarian governments, aims to make Europe politically or economically dependent. More caution needs to be taken of state owned companies from non market economies, in particular. As soon as market participants make their decisions based on criteria other than the economic, a level playing field becomes untenable.

Over the last few years and, more recently, with increased momentum and urgency, the heads of state or government in the European Union have responded by formulating objectives and calling for measures by the EU and its member states to strengthen European sovereignty. Decisions have already been made to this end in many fields of policy, including foreign economic policy. In other fields, extensive analyses have been presented to enable individual member states and European institutions to take further action swiftly. The French presidency of the Council of the European Union presidency also aimed to initiate further decisions in the first six months of the year. Russia’s war in Ukraine has added additional stark challenges to the agenda, particularly in energy and raw material policy.

The European Commission has prepared a large number of dossiers. We welcome the declared intention of the European Commission to strengthen the position of the EU in the global economic setting and to confront systemic competitors with a European strategy This will first and foremost require close coordination between all areas of European economic policy. A successful strategy towards open strategic autonomy requires three things. First, a diversification of import and export partners in critical segments to enable swift diversion to other markets in general. We must learn the right lessons from the recent approaches of the German government in the field of energy policy, for example. General foreign economic policy must, from now on, include considerations of alternative markets as fallback options from the beginning. Second, EU trade policy can no longer be based on

8 BDI (2019). Policy Paper China. Partner and Systemic Competitor How Do We Deal with China's State Controlled Economy? 10 January. Berlin.

9 BDI (2021). Discussion paper. Responsible Coexistence with Autocracies in Foreign Economic Policy Making | Discussion Paper on Shaping Global Economic Relations for Systemically Challenging Counterparties. 16 July. Berlin.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 4

potential benefits in terms of value added alone. The general approach must also include and foster diversification and (operational) risk management. Third, in areas in which diversification by itself proves not to be sufficient, critical competencies need to be specifically established and fostered. Furthermore, an ongoing procedure needs to be put in place at the political level to identify and address emerging strategic risks.

In the opinion of German industry, economic dependencies need to be identified and initial proposals for solutions developed. This statement is only the beginning of this process. It centres mainly on how to establish a more robust economic base (see Versailles declaration of 10 and 11 March 2022) and addresses in detail microelectronics, data, cloud and edge computing, raw materials policy, energy policy, space policy, issues of arms policy, chemical policy, standardisation, and public procurement

Given the current high momentum in foreign policy, further dossiers in the context of sovereignty will have to be discussed at a later date. Above all, this would include steps to strengthen our defence capabilities and reduce our energy dependency. Special attention also needs to be paid to the production of battery cells on account of its complex role in the value chains across many industries. Many steps have already been taken in the field of trade policy tools.

In all these issues, European institutions need to consult with industry on a much broader basis in order to coordinate resilient strategies, design suitable economic policy packages and, depending on the dossier, encourage consistent action on the part of enterprises, industries, and possibly also economic policymakers at German and European level.

European companies also need to hold a broad debate on the various aspects involved in reducing politically sensitive economic dependencies. The changed security situation means that corporate procurement decisions can no longer be based solely on business management indicators. Increased political risks and supply chain security must be given more consideration within corporate strategic planning. Another aspect that needs to be discussed is the medium term approach for dealing with global shortages or bottlenecks in critical raw materials and inputs.

1.2 Basic points

The management of strategic dependencies must be based on an analysis of the status quo with a definition of objectives and measures to meet these objectives in every field. This cannot be a one off stocktake. The critical dependencies of Europe are dynamic and in constant flux with the emergence of new products and production processes. We therefore need an ongoing process of analysis between the Directorates General of the European Commission and the private sector

The mission here is not to completely eliminate strategic dependencies but to reduce them at reasonable cost, to manage emerging risks, and to make the structure of value chains more robust by establishing a more differentiated business landscape according to region, industry and company size, and to contain any arising negative external effects

In the present situation, German industry believes the following topics should be the focus of analysis:

▪ Europe has substantial raw material dependencies not only in energy raw materials but also in critical metals and minerals. Europe’s dependency on many mineral raw materials from China, for example, already outweighs its dependency on Russia for oil and gas. However, in the case of mineral commodities there are no national (strategic) reserves as there are for oil and gas. Global demand until 2050 compared to the year 2010 is forecast to rise by

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 5

215 percent for aluminium, 140 percent for copper and nickel, 86 percent for iron, 81 percent for zinc and 46 percent for lead, which means that shortages of these minerals are going to become more severe. As a buyer on the international raw material markets, Europe competes with other global economic powers. Conventional market mechanisms have become less significant in mineral raw materials at the global level over the past few years. It is of crucial importance that Europe diversifies along the different pillars of securing raw materials. Excessive raw material dependencies on individual countries will be a luxury we cannot afford Diversification needs to be strengthened through a holistic and strategic European three pillar raw materials policy, consisting of: non discriminatory access to raw materials from abroad (pillar 1); stronger domestic supply, production, and processing of raw materials (pillar 2); the recycling of raw materials (pillar 3). No individual pillar will be able to secure the supply of raw materials for Europe alone

▪ The EU needs to take a coordinated approach on energy supply. Impending disruptions to the energy supply in one member state will put supply chains at risk of breaking down. While national resilience strategies are to be welcomed, they should not be implemented at the expense of other EU member states. Europe, and particularly Germany, will remain an energy importer in the long term. The future energy infrastructure therefore needs to be based not only on swiftly achieving decarbonisation but also, and essentially, on a strategically planned diversification of suppliers in order to ensure both supply security and keep energy affordable

▪ There are similar dependencies in certain chemicals. Policymakers and industry must clearly identify which chemicals are difficult to substitute (by using different production methods, for example). Ideally, imports could be procured at short notice from other regions of the world. In individual cases, onshoring will need to be considered. Small and medium sized companies, in particular, cannot structure their sourcing purely based on the criteria of cost. As the political risks increase, supply sources must increasingly be selected according to supply reliability. This trade off is a management decision which is taken on the basis of the relevant market information, also that of the public sector

▪ Europe is still the biggest global player in matters of standardisation. It is important that Europe strengthens this role. Standardisation processes need to be accelerated in areas that are of particular relevance. A broad debate is needed within Europe to identify which areas these are, including emerging technologies in the fields of transport, energy (hydrogen in particular), artificial intelligence, microelectronics, cybersecurity, battery technologies and the circular economy In future, standards will not be based on technical criteria alone. Standards can only be established successfully if they are based on market relevance and practicality, and if the parties involved are included in the process of defining these standards, thereby legitimising them. Standards developed along these basic principles are applied by the businesses involved on a voluntary basis and can therefore unfold their full benefits in practice

▪

Setting standards for our own market will not be sufficient. Whether Europe remains capable of exporting in the long term will also depend on preserving access to global sales markets in third countries Standards must therefore form a central element of EU trade strategies and agreements. In negotiations on market access between the EU and third countries, European and international standards need to form a standard part of public tenders. This applies particularly to the implementation of the Global Gateway.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 6

▪

In the technologies in which Europe aims to have leadership in future, we need to start defending and expanding on our lead now. Europe must learn from the past and ensure that competencies in resilience related industries do not fully migrate to other regions. Enterprises and policymakers must together agree on the focal points of open strategic autonomy which are then fostered through investment in relevant research and development projects.

▪

Semiconductor production is currently very much in the public eye and so it should be. Market access to semiconductors is absolutely decisive and many of the current megatrends in the economy depend on chips for their implementation. Solutions based on artificial intelligence, autonomous driving, smart grids, and machine learning will increase demand for semiconductors in the long term. Given this context, a worldwide market share for the EU of 20 percent in this field, as targeted by the European Commission, is the right way to go. It is also good that the EU is planning on strengthen its own capacities in this field and make supply chains (possibly with onshoring) more robust. One important point is not featured enough in the current debate it is unclear whether the EU intends to make inroads in the semiconductor market in the high tech segment which has development potential and high margins. The volume of this market is small. Looking at the current production disruptions, however, what is primarily needed is high quantities of chips. Strategic investment decisions and state aid schemes need to be structured along the precise political priorities: supply chain security first and then the further development of technological capabilities

▪ Europe needs joint, transnational projects, particularly investment in artificial intelligence, microelectronics, and chips. The first flagship projects in this area have been very successful (including the Important Projects of Common European Interest, ICPEIs). However, the toolbox for these projects is very limited. For example, member states finance IPCEIs with national funds. This tool cannot be applied in some cases as critical investment does not always qualify as an innovation, which is, however, a prerequisite for funding. Furthermore, smaller and financially weaker member states should not be allowed to fall behind. Their competitiveness is also decisive for German industry which invests in almost all European countries. In the long run, the use and distribution of funds should be organised at European level. As this is very unlikely to happen in the current political situation, member states need to be in a position to pool their money in order to be able to set up individual projects on the required scale. It will be a challenge to swiftly set in place a legal framework for the internal market for forward looking investment by member states. There are bound to be substantial conflicts of interests here with requirements related to competition policy

2. Microelectronics

2.1 Initial situation

A severe global shortage of semiconductors is currently resulting in a loss of vast amounts of revenue as well as hampering a swift upturn of the world economy as it recovers from the pandemic. The chip shortage has cost alone the German automotive industry 50 billion US dollars in revenues. This is equivalent to around 1.5 percent of German GDP.10 Several developments on both the supply and

10 AlixPartners (2021) Shortages related to semiconductors to cost the auto industry $210 billion in revenues this year, says new AlixPartners forecast. Report. 23 September. New York.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 7

demand side of the global semiconductor market are responsible for this shortage. While the main factor is certainly the enormous increase in demand for entertainment electronics triggered by millions of people working and studying from home during the pandemic, the war in Ukraine has further strained the situation with bottlenecks in raw materials and sanctions rightfully imposed by the EU against Russia.11,12 Given that it takes a lot of time and money to expand semiconductor manufacturing capacities, we can expect these shortages to continue in the foreseeable future.

The global semiconductor market is forecast to generate sales of over 600 billion US dollars in 2022.13 The range of application of semiconductors is very broad so the industry is closely connected to the rest of the global economy. The most common application is in global data and communications, estimated to have accounted for around two thirds of total semiconductor sales in 2021. In the EU, only around one third of total semiconductor sales are to the data and communications industry The largest buyers of semiconductors in the EU are the automotive industry and industrial electronics, which together make up 63 percent of all EU wide purchases.14 The European automotive industry has been amongst the hardest hit by the chip shortage so the need for action is greater there, particularly given the many employees working in this industry.

Rising geopolitical tensions, particularly between the United States and China, are also exacerbating the competition in technological policy in which the production of semiconductors is a central issue Furthermore, the supply chains of semiconductors are very complex. No individual country or region is currently autonomous in the production of semiconductors. Seventy five percent of global semiconductor production capacities are currently located in South East Asia. Taiwan is dominant in the production of chips under 10 nm and accounts for almost one half of global supplies in this segment. The biggest producer in the 10 18 nm segment is South Korea, whilst China has a major share in larger sizes (>18 nm).15 Despite their formidable production capacities, countries such as Taiwan, South Korea and China do not dominate the semiconductor market. The United States, for example, is dominant in the decisive area of chip design and accounts for over 14 percent of global production capacities on account of the local establishment of global chip producers which it is consistently expanding.

By comparison, nine percent of chips are designed in the EU and eight percent are produced in the EU. Europe, and Germany in particular, is strong in the area of sensors, actuators and power electronics, which will be crucial in the transition to green energy and mobility. Other European strengths are chemical precursors, mechanical and plant engineering, and communication technologies. In this context, setting up a closed value chain in a single region would require investments of around one billion euros. In addition, prices for microelectronics would likely increase by around 35 to 65 percent, according to a Boston Consulting Group study16. A completely closed value chain is not necessary in every region to ensure technological sovereignty. Mutual dependence paired with alternative resilience approaches would be sufficient. Smooth running global value

11 German Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) (2022). Annex VII of Regulation (EU) No. 833/2014 (in the version amended by Council Regulation (EU) 2022/328) concerning restrictive measures in view of Russia's actions destabilising the situation in Ukraine. 1st Council Regulation. 25 February. Brussels

12 European Union (2022). Official Journal of the European Union, L 111 8 April. Brussels.

13 Semiconductor Industry Association (2021): Global Semiconductor Sales Increase 24% Year to Year in October; Annual Sales Projected to Increase 26% in 2021, Exceed $600 Billion in 2022. Report. 3 December. Washington.

14ZVEI The Electrical and Electronics Industry (2021) Discussion Paper. Semiconductor Strategy for Germany and Europe October. Frankfurt am Main.

15ZVEI. The Electrical and Electronics Industry (2021). Future Strategy and Market Development | Semiconductor Industry | Germany and Europe.

16 Boston Consulting Group and SIA (2021). Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain in an Uncertain Era April.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 8

networks are a basic precondition for maintaining the high pace of innovation and affordable semiconductor products.

The severe global shortage in semiconductors is likely to persist in the foreseeable future and will affect the EU especially in the automotive industry and industrial electronics. The following measures are recommendations to combat the supply bottlenecks and to attain technological sovereignty in the complex semiconductor value chain.

2.2 Necessary measures and open issues

Germany and Europe must ensure that their industries and public authorities have a high capacity to act independently in conflict and crisis situations. Alongside a broad research base, this includes the ability to procure critical microelectronic components, also in times of crisis, either from domestic production or through supply chains that cannot be manipulated, politically or otherwise. Achieving this kind of resilience will require close cooperation along semiconductor value chains, Furthermore, a balanced and diversified access for all industries to production capacities and raw materials is paramount

Germany is in a good position with its strong research base and a closely intertwined network of technical universities, research institutes and enterprises. Economic policy must now make targeted use of this strength. Specifically, this means expanding existing production capacities and developing and building more competencies, especially in chip design. Current competencies in the design of hardware, embedded software and automated solutions need to be extended along a broad base starting with universities. The competencies in semiconductor solutions for key national sectors such as automotive, mechanical engineering, electronics, energy, security, and communications need to be further improved through the generation of product specific IP for the European semiconductor value chain based, among other things, on the open source approach RISC V.

Furthermore, current strengths based on the highly developed European competency in system integration need to be consolidated. It is wrong to think that ‘leading edge’ only applies to semiconductors under five nm. Important power semiconductors that are much larger than five nm and sensor cells up to 350nm are also ‘leading edge’ in their categories. At the same time, chips based on structural sizes below five nm are leading edge in the areas of AI / ML, 5G / 6G and HPC. Chip design, creation of intellectual property, and chip production must all be expanded based on a correctly understood concept of ‘leading edge’. In addition, the development of intellectual property must also be fostered in the areas of 5G / 6G, edge computing / edge AI, electromobility, cybersecurity, AI, aerospace and defence to tackle weaknesses and make full use of existing potential.

Semiconductors and microelectronics must not be treated as a separate field in research and development, but as a central dimension of technological sovereignty, and therefore, an integral dimension of a national and European industrial strategy. Core competencies in the field of semiconductors are imperative not only for the industrial future of Europe but also to meet the ambitious sustainability targets of the EU. The European Green Deal can only be implemented successfully with a targeted development of energy efficient semiconductor technologies, above all, in the industrial, automotive and energy sectors. Power electronics, as a key technology, is just as significant to the transition as efficient processors. In this context, it is important to include the entire value chain as well as the main inputs, such as polysilicon and silicon carbide based semiconductors. In addition to reaching the objectives of the EU Green Deal, powerful hardware to protect European infrastructure from cyberattacks is also crucial.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 9

EU Chips Act

According to the mission presented by the European Commission, the European semiconductor production should represent at least 20 percent of global production by 2030. The current European semiconductor strategy is based on two initiatives towards this target. The Alliance on Processors and Semiconductor Technologies is an umbrella organisation in which political decision makers, research organisations and industry leaders work together to develop a roadmap for the European semiconductor ecosystem The European Chips Act published by the European Commission on 8 February 2022 is designed to create a modern European chip ecosystem including production. With a volume of 43 billion euros, the EU Chips Act has the potential to strengthen Europe as a global actor in the production of chips and fuel the ecological and digital transformation of Europe as a business location The EU Chips Act covers three dimensions: (i) strengthening semiconductor research and development (with eleven billion euros in Chips for Europe), (ii) promoting first of a kind factories for semiconductors in Europe, (iii) monitoring and measures for a crisis mode such as export restrictions, obligations to provide information and order obligations.

Especially in view of the intensifying global competition, German industry regards the prospect of public sector support for the development of a European semiconductor ecosystem, particularly for European first of a kind facilities, as a very positive step towards the aim of achieving supply chain resilience. We welcome the requested transparency along chip supply chains. At the same time, German industry is concerned about the crisis mode measures (allocation or monopolisation of the purchase of chips and the discretionary power of the EU in the definition of ‘crisis’) in terms of regulatory and competition law. The EU Chips Act should focus more on strengthening international alliances with likeminded partners based on mutual dependencies, also through trade agreements.

Many other countries alongside the European Union are now also striving to increase their semiconductor production capacities, above all the United States and China. Increasing semiconductor production capacities is very important given the rising demand across all industries. We therefore very much welcome the Important Project of Common European Interest Microelectronics and Communication Technologies (IPCEI ME/CT), for which proposals are currently being evaluated, as well as the proposal of the European Commission for an EU Chips Act to provide a strategic framework. The European Commission and EU Member states should nonetheless work towards global value chains instead of protectionism, and global cooperation instead of a global subsidy race. As companies are experiencing a severe shortage of semiconductors on a global level, policy and initiatives on semiconductors of the different regions and countries across the world should be coordinated to ensure that the global supply of semiconductors can meet the global demand in future

The semiconductor ecosystem spans the globe. Initiatives such as the Transatlantic Trade and Technology Council (TTC) should therefore be used to a greater extent to strengthen the core competencies of Europe and North America and bring about closer cooperation at the same time. Closer transatlantic cooperation is an important prerequisite to strengthen the competitiveness of the semiconductor industry in both regions. International standardisation roadmaps and technical standards should be advanced to improve collaboration. It is also important to ensure a level playing field in terms of market access and competition Specifically, this entails a mutual dismantlement of barriers to investment, avoiding new trade restrictions and coordinating measures to control exports A further relevant point is the development of joint strategies to secure the semiconductor supply chain and a common understanding of ‘leading edge’ semiconductors to ensure that public investment (grants and tax incentives) is channelled to meet the current and future needs of all industrial sectors. In this context, BDI’s Transatlantic Business Initiative (TBI) welcomes the European Commission’s

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 10

latest amendment to the temporary framework for state aid to support national semiconductor projects under the Reconstruction Fund.

3. Data, Cloud & Edge

3.1 Initial situation

The availability of trustworthy data infrastructure is an imperative building block towards encouraging the responsible use of data, lifting innovation potential and maintaining the digital sovereignty of the state, citizens and enterprises. Trustworthy cloud infrastructures are particularly important because many innovative business models and services (in e government, for example) are based on the features and scalability enabled by cloud based solutions. Reliable and secure cloud solutions that comply with data protection regulations are absolutely essential in these times of inexorable digitalisation. Given that the cloud market is still strongly dominated by providers from the United States,17 strengthening European cloud competencies is certainly a priority.

Edge computing solutions, where data is processed de centrally at the edge of a network, i.e., on the level of the individual components (e.g., terminals, sensors, microcontrollers), are also becoming more significant. The advantages of this kind of network architecture are, among other things, minimal latency so data can be analysed and processed in practically real time These properties also make edge computing solutions very important in the industrial environment. This relevance will also increase significantly across industries in the coming years, as it is estimated that 80 per cent of data will be processed locally in the future. 18 European companies are particularly strong in edge technologies so that the initial situation is very favourable for securing a leading role in edge computing for the long term. In this context, it is again extremely important that Europe establishes sovereign European data ecosystems, both to close current gaps in capabilities (in the area of cloud computing) and to further consolidate current strengths (in the area of edge computing).

In order to make full use of the potential of sovereign European data ecosystems, Europe does not just need stronger technological foundations and key competencies but also legally secure and practical framework conditions for the transfer and processing of data within transnational value added networks. This is of paramount importance, particularly for the globally highly integrated German industry. The Schrems II judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) of 16 July 2020 (Case C 311/18 Schrems II / Privacy Shield) has shaken the legal foundation for international data transfer and continues to have a huge impact on the globally networked German industry. The legal uncertainties in international data transfer are curbing digital innovations in industry, such as the (further) development of data driven business models and cross border data use and cooperation, which are so very important in the conservation and reconstruction of the bruised economy. Not only the larger corporations have been affected, the Schrems II judgment has also had consequences for small and medium sized enterprises that store data in clouds, use the software of US providers, are active on social networks or use the online conference systems of international providers. The basic agreement between the EU and the United States of 25 March 2022 on the creation of a ‘Trans Atlantic Data Privacy Framework’ is therefore a step in the right direction to establish a new legal foundation

17 Statista (2022). Market shares of companies with highest global revenues in could computing in 2nd quarter 2022. 2 August.

18 German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) (2021). IPCEI on Next Generation Cloud Infrastructure and Services | Europa gemeinsam auf dem Weg zur Cloudinfrastruktur der Zukunft 25 May.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 11

for the transfer of personal data in the United States but is not yet a final solution. A new legal foundation for data transfer is not expected before the end of 2022 in any case

3.2 Necessary measures and open issues

In view scale of international competition, national solutions for individual countries within the EU is not a promising long term approach. We need to follow a consistent, pan European approach. In the field of cloud computing, Europe should not be aiming to follow the example of current US and Chinese models and establish a European hyperscaler. It should rather encourage the creation of trustworthy data infrastructures that are based on European values, accessible to all market participants, and meet defined technical and regulatory criteria. Important measures to strengthen European sovereignty in the area of cloud and edge computing which are expressly supported by the BDI include the European cloud integration outlined in the European Data Strategy, ongoing projects such as Gaia X, and the project advanced at European level by the federal government, the EU level Important Project of Common European Interest to set up the next generation of cloud infrastructures and services in Europe (IPCEI CIS) which specifically also includes edge technologies.

Appropriate solutions for the legally secure transfer of data at the international level will only be found on a political level through adequacy decisions. First and foremost, the Trans Atlantic Data Privacy Framework for data transfer between the EU and the United States needs to be developed swiftly to replace the invalidated EU US data protection agreement Privacy Shield The European Commission should also reinforce its efforts with other third countries. Alongside the adoption of adequacy decisions for specific third countries, the EU should also rework the EU standard contractual clauses to make them more user friendly and simplify an international data transfer that is compliant with data protection regulations and thus encourage the further digital and analogue development of the globalised economy

4. Raw materials policy

4.1 Initial situation

Raw materials are key to achieve the Green Deal

Raw materials are right at the beginning of the value chain of all innovative technologies and applications. Without raw materials there can be no digitalisation or Industry 4.0, no energy transition or e mobility, no green deal or compliance with the Paris climate targets. European industry depends upon a secure and sustainable supply of raw materials. The growing importance of emerging technologies for a decarbonised, digital economy and information society has triggered increasing demand for raw materials, above all mineral resources such as metals or industrial minerals. Each emerging technology, for example those used in wind turbines and electric cars, increases the range of raw materials needed. Key strategic industries such as the security and defence sector are also dependent on critical raw materials. Demand will continue to increase in the next few years. However, free and fair access to raw materials is often obstructed through state measures that distort trade. Compounding the secure access to raw materials further is the high concentration of supply in one or a few countries as well as the current rise in geopolitical tensions.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 12

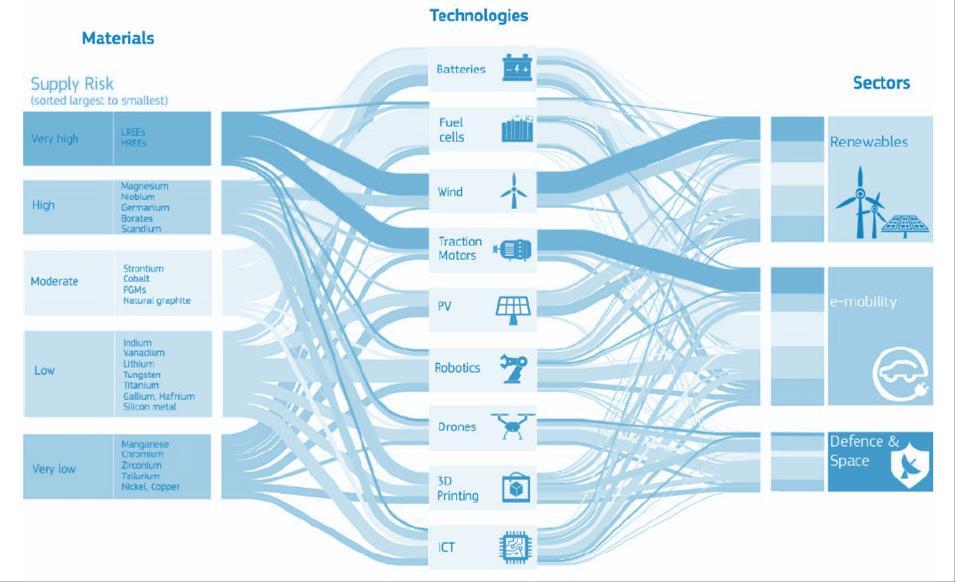

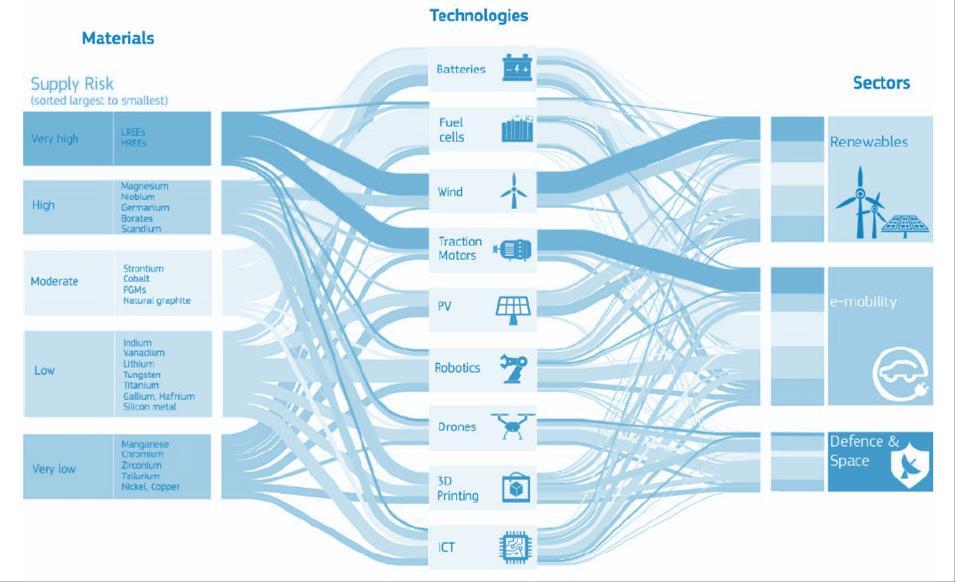

Availability risk of raw materials, by technology and sector

Source: European Commission

Criticality of metals in emerging technologies

Although Europe is rich in resources, it is significantly dependent on imports in the case of many critical metals. The extraction and processing of the raw materials required for emerging technologies is often concentrated in a few countries such as China (rare earths), the Democratic Republic of Congo (cobalt), Chile (lithium) and South Africa (platinum group metals).

The European Commission’s list of critical raw materials currently contains 30 raw materials (as of 2020), expanding from 14 in 2010. New additions to the list include raw materials such as lithium and cobalt that are needed for the generation of energy. The European Commission measures the criticality of a raw material by its importance for industrial end use in the EU, its substitutability, its recyclability, potential supply risks through a high proportion of global production concentrated in a single country, the extent of dependency of the EU on imports, trade restrictions and the political governance of a country (including environmental and human rights aspects).

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 13

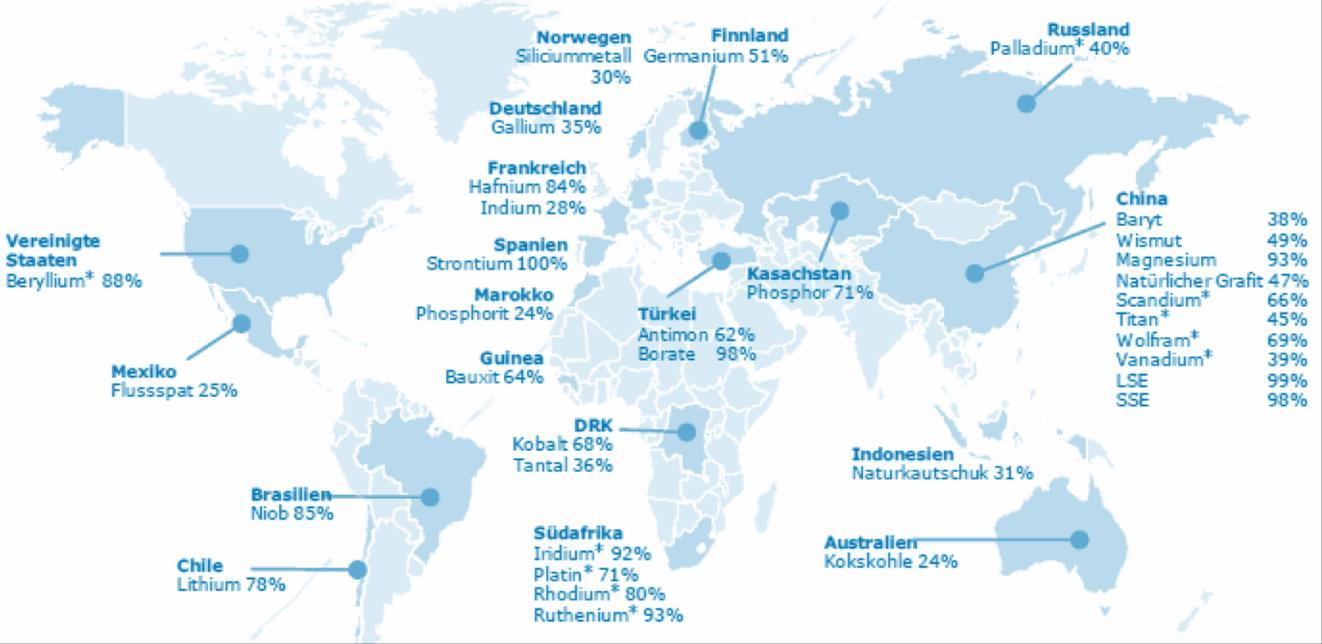

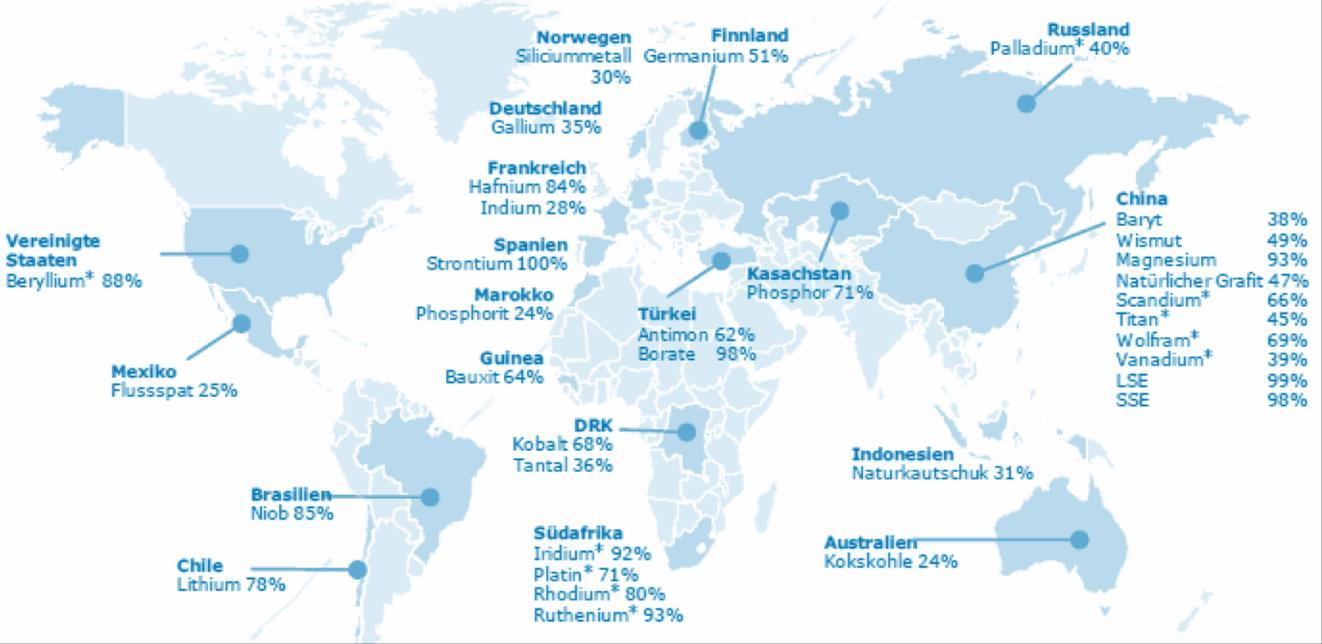

Main supplier countries of raw materials to the EU (proportion of global production)

Norway Silicon Metal 30%

United States

Turkey Antimony 62% Borates 98%Mexico Fluorite 25%

Brazil Niobium 85%

Source: European Commission

Germany Gallium 35% France Spain Strontium 100% Morocco Phosphorite 24% D Guinea Bauxite 64% DRC Cobalt 68% Tantalum 36%

South Africa Iridium* 92% Platinum* 71% Rhodium* 80% Ruthenium* 93%

Growing demand and rising prices for raw materials

Finland Australia Coking Coal 24%

Kazakhstan Phosphorus 71%

Indonesia Natural Rubber 31%

Russia China Barite 38% Bismuth 49% Magnesium 93% Natural Graphite 47% Scandium* 66% Titanium* 45% Wolfram* 69% Vanadium* 39% LSE 99% SSE 98%

* Share of global production

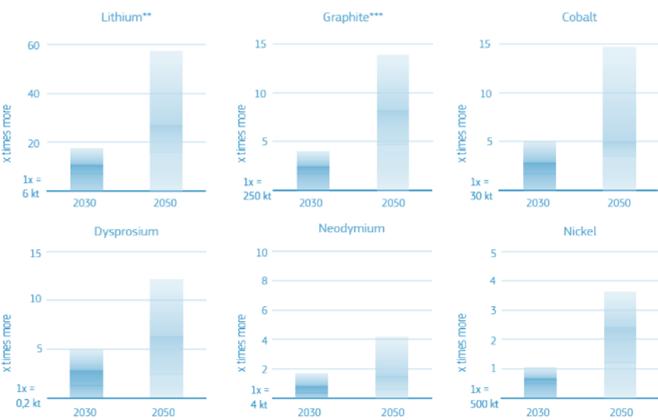

The demand for raw materials is growing across the world. In view of the increasing use of electric vehicles, mobile electric devices and stationary decentralised energy storage, the European Commission forecasts demand for lithium ion batteries alone to increase by more than 30 percent every year for the next ten years

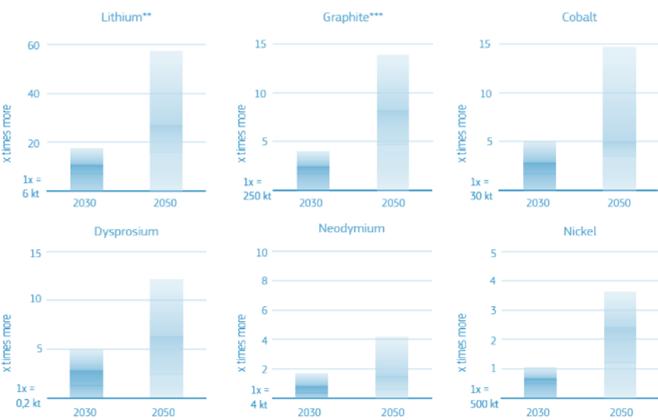

Growing demand for raw materials

Source: European Commission

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 14

* of refined supply (Stage II) instead of ore supply (Stage I) *** increase in demand of all graphite in relation to natural graphite Medium Demand Scenario High Demand Scenario

Low Demand Scenario

with limited supply will increase

to 500 percent until 2030, for lithium up to 180

percent

a buyer, Europe is in

to a study by the

for cobalt could well increase by

for nickel around 160 percent, and for copper

other global economic powers.

4.2 Necessary measures and open issues

to identify the reasons why these

the geographical concentration

have developed in order to counter them: Alongside the globally increasing demand for

reserves,

and processing

the increase of state intervention and

other factors include consolidation processes in the European mining sector, the lack of a global level playing

investment in new exploration

in the mining industry include the long and high risk timelines of projects, possible changes in demand and disruption caused by innovations, of the lock in to deposits, high entry barriers and pricing monopolies. Finally, there is a lack

social awareness

the

of raw materials.

member

the

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 15 The high demand coupled

prices. According

German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) 19, the prices

up

percent,

around 70

As

competition with

We need

strategic dependencies

raw materials and

of

extraction

facilities,

field,

low

projects. Additional challenges

of

and acceptance for

domestic extraction

The three-pillar strategy for a sustainable supply of raw materials In order to reduce its strategic dependencies, the EU and its

states need to pursue all three pillars of a sustainable supply of raw materials: first, strengthening domestic extraction of raw materials; second, securing fair access to raw materials from abroad; third, expanding recycling and

circular economy 19 DIW (2022). DIW Weekly Report No. 4/2022. Data based on International Energy Agency sources, Schwerhoff and Stuermer (2020), US Geological Survey, IMF. 6 14 35 106 37 217 16 8 44 38 13

Kupfer Nickel

Kobalt Lithium 2020 2030 2040 Sources: DIW/Boer, International Energy Agency, Schwerhoff und Stuermer, US Geological Survey, IMF * in thousand US dollars per tonne Copper Cobalt Price trends in a net zero emissions scenario* 70 percent. As a buyer, Europe is in competition with other global economic powers.

EU Action Plan and European Raw Materials Alliance: In autumn 2020, the EU adopted an action plan on raw materials to reduce vulnerabilities in its supply of raw materials. Part of this plan was the founding of the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA) in September 2020. The ERMA is developing an investment pipeline for a European value chain for rare earths and permanent magnets for electric cars. Regarding rare earths, identified European projects should cover up to 20 percent of the European demand for raw materials until 2030. There are deposits of most of the required critical raw materials within the EU Lithium, for example, can be extracted in Germany, the Czech Republic and Serbia.

Germany

Deutschland

Tschechien

Czech Serbia Spain Portugal Austria Finland

Serbien Spanien Portugal

Österreich Finnland

of 2021, in tonnes

Source: Handelsbaltt

A high level working group on magnesium, a key raw material for many industries including the automotive industry, has been tasked with developing ideas to ensure that 15 percent of global production takes place in Europe by 2030. The challenge here is not the storage and extraction of the primary raw material so much as the long term competitiveness of the European metal production in general, particularly given the rising energy prices. Planning and approval processes on the national and regional level need to be accelerated and simplified. Two projects of common European Interest (IPCEI) in the area of batteries are already working on initiatives for sustainable mining, refining and recycling. The BDI would welcome a separate IPCEI on raw materials, structured according to the IPCEI criteria

Investment / financing: Investment and financing also plays a role in these efforts. The EU and the member states have various funds at their disposal that can be used for raw materials projects such as the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), NextGenerationEU, the venture capital fund InnoEnergy, and the EIB and EBRD programmes The ERMA also plans to set up its own fund dedicated to investment in critical raw materials, and the European Battery Alliance has also

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 16

2,700,000 1,300,000 1,200,000 300,000 270,000 50,000 50,000

*as

European lithium reserves *

announced an investment fund with a volume of 400 million euros for sustainable battery materials. This could be used for participations in mines outside of Europe. In the opinion of German industry, it would be important to link up the various financing activities and structure the fund by market principles. In the discussed EU taxonomy system, mining must not be categorised as not sustainable as this would encumber access to investment for exploration and mining projects. The adopted EU principles for sustainable raw materials illustrate the understanding of the member states of sustainable raw materials extraction (from exploration to post closure) and processing operations Criteria used should take account of the significant contribution of environmentally friendly mining, processing and recycling activities to meeting the EU Green Deal targets.

Strategic raw materials partnerships: Lastly, the EU is working on strategic raw materials partnerships. These have so far been concluded with Canada and Ukraine. Others are planned for Serbia, interested countries in Africa and the EU’s neighbourhood. The decisive step is to secure access to different markets in third countries. The EU should very swiftly forge sustainable raw materials alliances with African partners, give political support to private sector operations and use development cooperation instruments to support local government authorities and enterprises and financing tools such as guarantees to support European companies. Diversification in relevant third markets should be fostered through the dismantling of trade policy barriers. European raw materials interests should also be reflected in EU trade policy and (energy and industrial) foreign policy, especially with likeminded partners such as the United States, Japan and others

At the political level, enterprises can be supported in particular with diversification, raw materials monitoring to identify critical raw materials, and storage (e.g., through tax incentives), and by setting market based incentives to increase resource efficiency and expand the circular economy

5. Energy supply

5.1 Initial situation

Changing times for Europe’s energy security

Energy has become a geopolitical and security issue at the European level. Since the Russian attack on Ukraine, Europe´s energy security has been severely tested and past misconceptions about the geopolitical and ideological motivation of Russia brought to light. In the last few years, not less but more energy has been imported from Russia and too few alternatives established. This has led to a considerable dependence on Russia, particularly for the supply of gas Market interdependencies and the so called ‘peace dividend’ were long considered sufficient mechanisms to ensure Europe´s supply security (‘Handel durch Wandel’). While historically the EU has used its trade relations and diplomacy as a successful foreign policy tool and continues to do so, a geopolitical shift towards more realpolitik is inevitable and will require a change of perspective in its energy policy

Russia’s market share in Europe’s energy supply over recent years is an expression of the asymmetry developed between the two partners. In 2021, Russian supplies accounted for 39 percent of total European gas imports, 29 percent of oil imports and over half of its coal imports. Other countries supplying Europe with gas include Norway (21 percent), Algeria (eight percent) and Qatar (five percent). Due to a higher flexibility in the international oil market, European countries can purchase oil from distant regions such as the United States (nine percent), Norway (eight percent), Saudi Arabia (seven percent), the United Kingdom (seven percent), Kazakhstan and Nigeria (six

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 17

percent each).20 Yet there are major differences in the degree of dependence among individual EU member states Germany, with its significant industrial sector, is the largest off taker of Russian gas and is therefore exposed to higher economic and geopolitical risks than France, for example. Thus, it should be in the mutual interest of all member states to act in a coordinated and united manner

Growing energy demand and lasting high prices

The military instrumentalization of energy supplies is not the only reason why Europe needs to increase its energy security. Since the second half of 2021, energy prices have risen dramatically both in the EU and globally Already before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, high prices were a major challenge for the European industry. Multiple concordant factors are responsible for the soaring prices, including a higher gas consumption in Asia following the Covid 19 pandemic (with a particularly steep increase LNG demand), a cold winter in 2020/21, compounded by geopolitical tensions with Russia and the associated oil and coal embargos. High forward prices for the next few years indicate that the energy crisis is not going away any time soon. The European industry and energy intensive companies are particularly hard hit as production costs have increased by almost 50 percent in some sectors.21 Furthermore, the dire energy price outlook is not only a problem for German industry but jeopardizes entire European and global supply chains. The disruption of production in one industry can have a negative effect all the way to a production standstill in upstream and downstream industries. This cascade effect could be triggered, for instance, by a production crisis in the chemical industry, whose products are needed in 90 percent of all production processes across the industrial sector 22 Robust supply chains are particularly important for the renewable energy transition.22 Access to critical raw materials is a decisive factor for the successful expansion of a sustainable energy supply and must be reflected in European trade policy and raw materials strategies.

System change on the energy market

The EU and Germany are currently facing a triple challenge: the geopolitical crisis with Russia which led to the energy crisis, the Covid 19 pandemic and the growing global climate emergency 23 In these times of crisis, a smoothly functioning and resilient energy sector is vital to ensure the day to day activities of critical infrastructures and help delivering a rapid economic recovery. However, the market liberalization and the integration of renewable energies has made this task increasingly complex. The decarbonization of the economy through the use of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar requires a fundamental transformation of the entire energy system. The impending electrification of entire sectors, such as transportation, will increase the exposure to shocks and complexity of the European energy system 24 Hence it is of paramount importance to rapidly advance the digitalisation and decentralisation of the energy system and establish a stable, cross border electricity grid in Europe. The transition away from natural gas towards renewable energies requires the expansion of a high voltage grid in Germany and Europe able to cope with high demand during the winter season and

20 Eurostat (2020). From where do we import energy? Brussels.

21 Eurostat (2021). Energy statistics an overview. Brussels.

22 Ntv.de (2022). Chemical association criticises putting private households first | Debate on gas distribution. 11 July. Cologne.

23 Heffron, R. J., Körner, M. F., Schöpf, M., Wagner, J., & Weibelzahl, M. (2021). The role of flexibility in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic and beyond: Contributing to a sustainable and resilient energy future in Europe Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 140, 110743.

24 Nolting L. (2021). Die Versorgungssicherheit mit Elektrizität im Kontext von Liberalisierung und Energiewende (Supply Security with Electricity in the Context of Liberalisation and the Transition to Renewable Energy), Institute for Future Energy Consumer Needs and Behavior, RWTH Aachen University.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 18

peak load periods.25 Finally, it is to be noted that segments depending on gas for heating, such as parts of industry, cannot readily switch to electricity

price development from July 2020 to June 2022

Source: Macrobond

5.2 Necessary measures and open issues

Setting priorities and achieving a coordinated EU energy policy

Coordinated action priorities must be defined at EU level to counter the worsening energy crisis On 18 May 2022, the European Commission presented its REPowerEU Initiative to mitigate the high energy prices in the short term and pave the way to guarantee energy security during the winter. In the long term, the EU aims to terminate its dependency on Russian energy imports. To finance the package, the EU has allocated 210 billion euros to first accelerate the development of renewable energy, second diversify energy imports and third incite energy savings

Plans to overcome the emergency include mitigating consumer prices and supporting the hardest hit companies. Possible tools to implement these steps are price regulations and transfer mechanisms to protect consumers and industry, provisional taxation of windfall profits, and the use of higher revenues from emission trading to alleviate energy costs Yet, additional measures need to be taken to guard against possible gas shortages this winter. The EU has identified enormous gas saving potentials in the industrial sector of more than 35 billion m3 , especially in the sectors of non metallic minerals, cement, glass and ceramics, chemicals production and refineries

Substituting coal, oil and gas in industrial processes can contribute to jointly reducing Europe’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels and initiate the transition to cleaner energy sources. In the short

German Energy Agency (dena) (2022). Final Report dena Grid Study III. January. Berlin.

European Commission. (2022). REPowerEU: Joint European Action for more affordable, secure and sustainable energy for Europe. Brussels.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 19

26

25

26

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

European gas

term, however, the ability of German industry to substitute its use of gas is limited and this winter, the best alternative to switch away from gas is light heating oil Companies need longer lead times to convert to climate friendly energy sources such as electricity, hydrogen, or biomass 27 Until all our energy is supplied by renewables, energy mixes must be composed of an intelligent combination of various sources.

The question therefore remains which supplier countries should be considered for the supply of primary energy sources such as oil and gas 28 Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is an important alternative to Russian gas as it can be purchased from faraway regions in the world and does not rely upon inflexible infrastructure such as pipelines. Thus, the import infrastructures for LNG (including LNG terminals, e.g.) needs to be expanded in the EU and particularly in Germany. Furthermore, these infrastructures could possibly be used to feed in imported hydrogen

The opportunities of the energy transition for an improved energy security

Accelerating the development of renewable energy under the framework of the REPowerEU package and the Green New Deal will reduce both emissions and the one sided energy import dependency of EU member states Thus, the climate crisis can be a chance to reposition Europe´s energy supply. As renewable energies can be produced almost anywhere in the world, they harbour huge potential for diversification. However, the energy transition will not suffice to render EU member states self sufficient and will remain relying on energy imports from third countries, particularly imports of green molecules such as green hydrogen. These facts justify the need for the EU to develop short and long term diversification plans. In order to minimise the vulnerability of European energy systems to the geopolitical influence of autocratic regimes, it is crucial to consider both economic and political risks when selecting new international energy partners. A fundamental principle here should consist in ensuring that no single country becomes the sole supplier for energy, intermediate products or raw materials, as is the case today with China´s solar cell supremacy 29 Additionally, political and social questions such as the protection of human rights and the environment must be included in decision making processes. In general, stronger precautionary measures and safeguards shall be established to protect the EU against major future economic, technical and political crises.

To substitute today´s consumed Russian gas in the long run, hydrogen and biomethane are considered as the top candidates as they are set to play a major role in industry, especially in the so called "hard to abate" sectors, where direct electrification will be technically or economically hardly feasible. Powerfuels, derivates of low carbon hydrogen, offer promising opportunities for the transformation of energy systems in the heavy and chemical industries 30 Hydrogen can also be used to store energy and to couple various energy sectors. To ramp up the hydrogen market however, the EU’s electrolyser capacity and cross border hydrogen infrastructures need to be expanded quickly. On a regulatory level, sound international standards and flexible green electricity procurement mechanisms must be implemented Furthermore, the technology openness must be preserved to let low carbon and renewable hydrogen develop jointly. Internationally, diverse energy import

27 BDI Gas Survey (2022). Climate and Energy Policy Department (unpublished survey). June. Berlin.

28 Lang, J., & Hohaus, P. (2017). Europäische Energiesicherheit Politische Rahmenbedingungen | Industrielle Energiestrategie (European Energy Security Political Framework Conditions | Industrial Energy Strategy) (pp. 19 34). Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

29 Manuel, A., Singh, P., & Paine, T. (2019). Compete, Contest and Collaborate: How to Win the Technology Race with China. The Technology and Public Policy Project. Freeman Spogli Institute for International Relations at Stanford University. Stanford. California.

30 European Commission (2020). EU reference scenario 2020 | Energy, transport and GHG emissions Trends to 2050. Brussels.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 20

partnerships will play an important role for the EU as green hydrogen can be produced at much lower cost in other parts of the world With this in mind, we should avoid sealing off the European hydrogen market and instead push the negotiations for clear hydrogen standards and regulations at both the European and international level. Diversification of partnerships will avoid further unilateral dependencies and promote real market competition with a view to the rapid development of hydrogen

The transition to renewable energy offers the EU the opportunity not only to increase its energy security, but also to consolidate its leading position in the development of clean technologies and to conquer new markets through green technology exports. For the achievement of this goal, industry will play a central role in the development and production of the necessary components of clean technologies (e.g., electrolysers). To ensure that decarbonisation efforts do not lead to the de industrialisation of Europe, decision makers must not forget to include European industry when designing new policies. Additionally, in order to consolidate Europe's leadership in renewable technologies, there is an urgent need to promote renewable energy development projects as soon as possible as the time necessary for a new technology to reach the market is often more than ten years. Indeed, once a new technology has been discovered, various feasibility studies and pilot projects are needed and only then, actors will take the risk to apply it it to bigger projects. New funding instruments and stable regulatory framework conditions will be a crucial factor in keeping up with international technological competition. Among the existing policy instruments for the implementation of climate targets and technology promotion are Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfDs), lead markets for green commodities and quotas for climate neutral products Finally, to accelerate the uptake of these key technologies, infrastructure (e.g. a hydrogen distribution network) must be developed promptly.

6. Space policy

6.1 Initial situation

NewSpace, the commercialisation of the space sector, and its growing interconnection with the non space economy is gaining significance across the world. In the digital age, space holds the key to emerging technologies such as autonomous driving, Industry 4.0, the Internet of Things (IoT) and real time global connectivity anywhere in the world. NewSpace helps make our economy and society more sustainable, more digital and more innovative as well as strengthening competitiveness in many sectors.

NewSpace also makes an important contribution to the global protection of the environment and climate and increased sustainability on Earth. Satellites provide precise data and information on the atmosphere, the air and water quality, and the condition of soils and plants continuously and across territorial borders. This data helps us to better understand climate change and other environmental phenomena and to develop effective measures for the protection of the climate and the environment. With laser communication, cloud computing and artificial intelligence, individual applications can use this data and information more quickly and more effectively.

NewSpace can also contribute to meeting social and political sustainability goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations (UN). NewSpace can also contribute significantly to effective civil protection and proactive and reactive crisis management in the event of natural disasters such as floods and forest fires

NewSpace harbours immense potential for data based business models, integrated value chains and innovations far beyond the space sector. Already today, 76 percent of German NewSpace companies

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 21

service customers outside of the space industry and this percentage is rising. Enterprises from industries such as logistics and transport, agriculture, insurance, energy and raw materials use satellite based data and services for fleet management, precision agriculture, the identification and evaluation of damage caused by natural disasters, and monitoring infrastructure networks. Urban and land use planning and smart cities also benefit greatly from NewSpace.

As a growth and innovation driver across many industries, the space sector bolsters the competitiveness of Germany and Europe, creates high quality jobs and increases societal prosperity The interdisciplinary nature of the space sector gives it macroeconomic relevance which should be reflected in the structures of the German government, and its authorities and institutions

The broad range of the NewSpace ecosystem in Germany and Europe with its mix of start ups, small and medium sized enterprises, and established companies and system integrators is a big strength. At the same time, the distance between the space sector in Europe on the one hand and the United States and China on the other has increased substantially over the last few years. Non European technology corporations dominate the field, from rocket launches and the development of mega constellations in space to human space travel. Europe runs the risk of being left behind in this key emerging field. The current funding tools are mostly too inflexible, to strongly focussed on research, and largely still stem from the last millennium.

NewSpace is strategically important for building and maintaining the foreign and security policy scope to act and assess independently. The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has further underlined the value of satellite based data. Space systems have long become part of the critical infrastructure. An outage would have wide reaching consequences on the whole industrial sector

Cooperation in the space sector between Russia and the European Space Agency (ESA) has been discontinued in many areas, including cooperation in the field of Soyuz launchers and the use of the European space station in Kourou. This is significant because in the past year more Soyuz launchers (7) were launched under the European flag than original European rockets (3 Ariane, 3 Vega).

European rockets including the Vega contain components (particularly engines) produced in Ukraine and Russia. Furthermore, the launch of the new Ariane 6 has been postponed. Launches with Soyuz and Vega rockets have therefore been discontinued indefinitely and there is no replacement in sight. At the same time, there are fewer US transport capacities available as an alternative. Whether and to what extent the new Ariane rockets can compensate for this remains to be seen. The current Ariane 5 is an old model.

Countries that fail to invest now will soon lose their capacity to act independently and will have to pay twice the price later on. Our dependency on Soyuz launchers should serve as a warning to Germany and Europe

6.2 Necessary measures and open issues

An increasingly data based and networked industrial and information society depends on independent and smooth critical infrastructure and service availability at all times. Unrestricted access to space with own launchers is an essential prerequisite to ensuring the strategic sovereignty of Germany and Europe. Since the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, Europe is in danger of losing, at least temporarily, its access to space. The changing times in defence policy is also and especially a change in times for the European space sector. The consequences of this are dramatic.

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 22

Europe and the German government need to take immediate and urgent action. Germany needs to step up its efforts here particularly as it has the leading NewSpace ecosystem in Europe, the biggest economy with corresponding resources, and would suffer the most economic damage in the event of a breakdown of space infrastructure

Urgent action is needed in the form of a substantial and sustained upscaling of the national space programme needs, support for commercial micro launchers, and a provision of spaceports on mainland Europe. The private sector initiative for a European launchpad in the North Sea has never been more relevant than it is today. Authorisation for this launchpad should be given soon. Germany should swiftly increase the volume of its national programme for innovation and space to draw level with France. Paris and Berlin should act in concert for Europe

The European space sector also needs a system change along the lines of the US model in which the state is primarily a customer. Public institutions can benefit much more from innovative solutions and services through anchor contracts. Contracts are the most effective and best form of support in terms of regulatory policy

This will require the political will to align current structures and processes closer to the NewSpace dynamics. An international comparison shows that Germany and Europe do not make full use of the potential at state level.

Human space travel will become more important with the return of humans to the moon. Peking and Moscow are jointly planning a moon station. In contrast to the civilian Artemis programme of the United States, the Chinese project is military in nature.

We need a European entry into human space travel. Europe does have astronauts, but it does not have its own spacecraft. Alone the transport of European astronauts to the international space station ISS with SpaceX costs around 150 million dollars. There are ambitious companies and start ups in Europe that would be keen to develop spacecraft in a competitive environment. Without an entry into human space travel with its own spacecraft, Europe will become irrelevant in space in the long term.

7. Security and defence

7.1 Initial situation

The annexation of the Crimea in 2014 and the illegal war of aggression on Ukraine destroyed the fundamental pillars of Europe’s security architecture that were jointly established after 1990, namely the prohibition of violence between states, the respect of the sovereignty of other countries, the right to freely chose alliances and the principle of the rule of law. The assumption that close economic interdependence will prevent military conflict has also been proven wrong. The rule and rights based order on which Europe is founded now faces a country that practices the rule of the jungle.

The attack of Russia on Ukraine does not only underline the value of security and military deterrence, but also shows that there can be no security or peace in Europe without the United States. The political, economic and military support of the United States are of decisive importance for the enduring resistance of Ukraine. The strong support of the United States could, however, be reduced at any time, be it through political developments within the country or through a shift in strategic priorities. The European debate on strategic autonomy needs to move on to implementation more urgently than ever before. Efforts must be focussed on safeguarding EU security and providing credible deterrence in future conflicts, in an emergency also without the aid of our transatlantic partner

Strengthening European Sovereignty | Towards Open Strategic Autonomy 23

The aim of strategic autonomy does not translate either to a separation from transatlantic security or to an excessive military build up for the purposes of deterrence and defence. The aim is rather to secure Europe’s capacity to act and shape Europe independently into the future and the capacity to safeguard security within the European Union and define own foreign and security policy priorities and decisions, and to implement these in cooperation with third parties or, if necessary, alone. The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine shows that there is a substantial need to catch up on this front. Germany and the EU have been lulled into a false sense of security for too long and have entered into dependencies that are now severely restraining the EU’s ability to shape its own destiny and take action and is therefore diametrically opposed to strategic autonomy

7.2 Necessary measures and open issues