The Intimate Outsider

Spatial Justice for the Live-In Helpers

PORTFOLIO

Chan Ka Hei, Brian ARCH 8084 Design 14

Roberto Requeto Belette Semester 2, 2024-25

00 Acknowledgement

This thesis has been rigorously questioned and critiqued by many around me, each offering invaluable subjective perspectives that allowed me to see my own project anew. Immersed in the work for so long, I had grown numb to its underlying logic and character. Special thanks to my friends Edward, Owen and Adrian, and my colleagues—Prudence, Jing, and Jessie—for fueling my project with their constant feedback and insights. In my eyes, they helped refine many flaws I might otherwise have overlooked.

Most importantly, thank you Roberto, for adapting to the nature of this project. Your bold suggestions often softened the proposal’s overly rational edges, making it both engaging and feasible. I find each of our discussions to be exceptionally uplifting and I will miss it. Under your guidance, I can proudly present this work as a true reflection of my deepest thoughts, uncompromised.

And thank you, Chang, for raising the question of “morality” long before I began this project. It served as a constant reminder of the agenda’s core, grounding every decision I made. Ultimately, it became a central point of discussion in the final review—who knows how things would have unfolded had I never considered it?

Last but not least, thank you to Peter, Yan, and my parents, for supporting every decision throughout my academic journey. I am deeply grateful for your time, resources, and unwavering belief in me.

Myself on the leftmost, at the occupation permit inspection, checking if the dimension of the roof is of the exact specified number one by one, photo taken on 25/3/2022

01 Position Statement

I spent two years working in a local architecture firm after graduating from my bachelor’s degree in 2021. During my term, I was fortunate enough to be involved in several key projects as they transitioned from construction to completion. Watching these buildings come to life— slowly emerging from drawings into physical form—I began to feel very uncomfortable of a troubling disconnect. The buildings stood as physical manifestations of compromise, their character diluted to the barest minimum, dictated primarily by whether they were profitable or not. It was constrained by an almost absolute framework, shaped not by design ideals, but by the expectations of clients, investors, regulators, and public sentiment. Many of the principles we had learned in school—about human well-being, spatial dignity, and the social responsibility of architecture—were reduced to little more than marketing rhetoric, deployed selectively to sell a vision rather than to shape a lived reality.

This tension is not new, nor is it unique to Hong Kong. In a capitalist market, architecture has always been a negotiation between idealism anda pragmatism. I understand that. And yet, I couldn’t shake the feeling that if our profession continues down this path—if design is reduced to mere compliance with standards and the fulfillment of pre-packaged expectations— something fundamental will be lost. Not just in the quality of our built environment, but in the role of the architect as a thinker, an advocate, and an agent of meaningful change.

This thesis, then, is an attempt to navigate that tension. As what may be my final academic project, I want it to strike a balance between the realities of professional practice and the provocative potential of architecture. I am not proposing a utopian revolt against market forces; that would be naive. Instead, I am looking for a way to work within the system while still pushing against its limitations.

Capsule sleeping pod located at Moscow, as a example of foreign counterpart: it resembles very similar style and concept of helper's accomodation in Hong Kong (Image courtesy: HostelsClub. com)

02 Agenda (I)

This thesis begins with domestic helpers - people who are not exactly "us," yet exist in unsettling proximity to our daily lives. They occupy a unique position in Hong Kong's social fabric: visible enough that we know their struggles, yet distant enough that we've grown numb to them. I've interacted with helpers working for my relatives, yet never truly connected with them as individuals. More often, I encounter them through news reports about employer disputes - stories so common they barely register anymore. These conflicts frequently stem from space-related tensions, from forced intimacy in cramped quarters to battles over basic privacy.

Hong Kongers have developed a dangerous immunity to spatial stress. When entire families live in cage homes or subdivided units, how can we expect people to recognize the suffering embedded in a 2.5m² maid's room? This numbness presents my core challenge: making the invisible visible. Throughout this thesis, I'm employing provocative dollhouse modelsdeliberately toy-like representations that invite viewers to engage physically and emotionally. My drawings prioritize figurative clarity over technical abstraction, allowing non-architects to immediately grasp the spatial realities at play.

Some might ask: Why focus on helpers when locals suffer worse space deprivation? The choice is intentional. By starting at one who are close yet distinct - we gain critical distance. Their living standards differ enough from ours that we can assess conditions more objectively. When we see a foreign domestic worker's quarters as unacceptable, it prompts us to reconsider what we tolerate elsewhere. Moreover, if we can improve housing at its most extreme compression (the helper's room), then scaling those solutions upward for locals becomes possible.

This project isn't about grand gestures, but about recalibrating our perception of basic dignity. Helpers' living conditions represent architecture's quiet complicity in inequality - and by making that complicity visible through deliberate representation, we might begin to change it. My goal isn't to solve all of Hong Kong's housing crises, but to create a wedge - a small opening where people might finally see what's been in front of them all along.

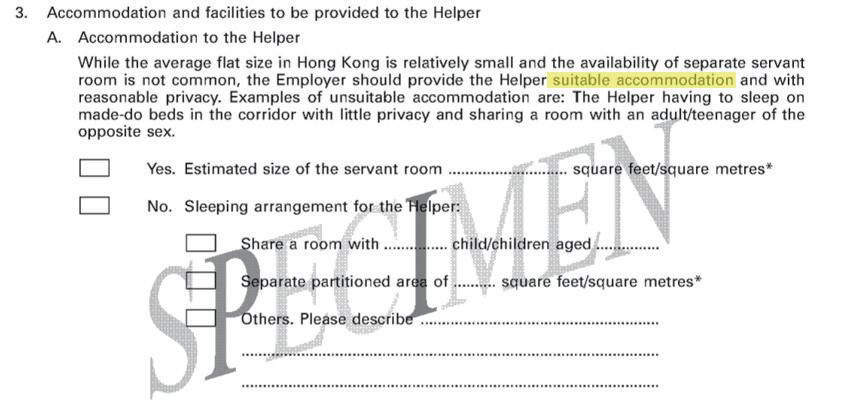

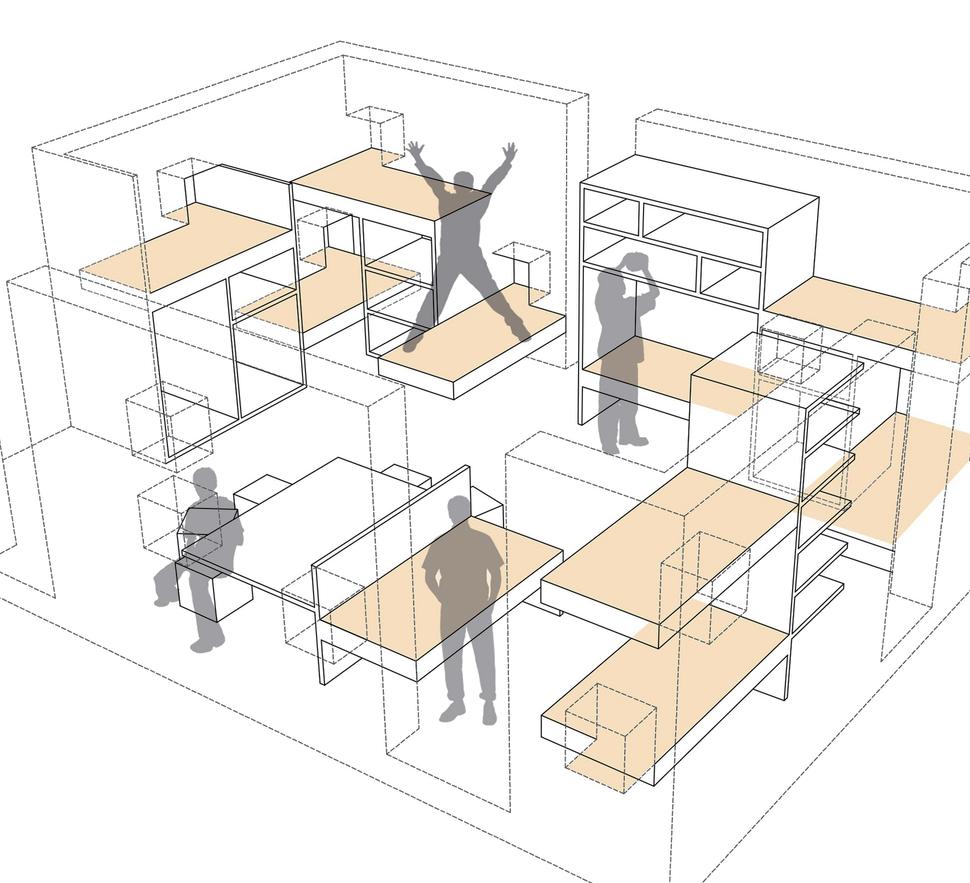

School Dormitory for 100 Students by ASA studio, discussed some potential spatial arrangement under a compact envelope, which still stinulate the creativity of the students, their positive feelings and their industriousness during all their daily activities. (Image courtesy: ASA Studio)

02 Agenda (II)

Then, to cope with the agenda, I should find an appropriate scale of work that could exercise my idea that covers the helpers while still seems radical and not extravagant. This would then constitute as the spine of my position towards this agenda.

Would it be sensible to propose a tower for the helpers? Or maybe smaller blocks of lowrise that are scattered around the city? Could we draw from the typology of social facilities— those peripheral yet essential infrastructures that support the city? What would be the implied circulations of work that seems to be another problem arises? How about the connection to the host families? Would they rather turn to local housekeepers if in that case helpers are no longer all around?

As it is often practiced, we tends to reduce complex social agendas to the formula of four walls and a roof—as if fulfilling this basic mandate absolves us of further responsibility. But in this case, leaping straight to a tower proposal feels misguided. Beyond its grand gesture, it risks misallocating scarce resources—land, roads, air rights—for a transient population whose stays are often limited to two years. It might seem relatively workable if all these take place in the western world where building tends to stretch horizontally rather than tapering and point straight up to the sky. Afterall, I refuse to let this proposal remain a mere inspirational gesture. Considered how Hong Kong market usually pitch and advertise a project, I struggle to see how this agenda could sensibly inhabit an independent building—be it low-, mid-, or high-rise. The constraints are too deeply woven into the city’s economic and spatial logic.

The famous "Domestic Transformer” by Gary Chang, which allows exceptional amount of occasions to take place within a 344 square foot apartment via reconfigurable partitions. (Image courtesy: Gary Chang)

02 Agenda (III)

Thinking from another extreme, could all these be made possible to situate itself within a domesticated piece that is of room size? What if making it as a domesticated furniture system? Would it be possible to draw inspiration from those applications on micro-apartment and storage units? How about make-shift spaces? Or transformable, deployable shelters that could work for another program whenever possible?

I have spent a few months last year looking at movable partitions, modular shelving systems and hundreds more revolutionary pieces on compact living. From the bottom of my heart, they inspire every inch of me, and I once feel extremely promising to have my project at a furniture scale, that my design would eventually be a very pragmatic, articulated piece that respond to every need of the helpers.

“I honestly just want to have a normal room as possible”

A very casual response from one of the few helpers that I got connection with, breaks my fantasy that a creative, totally functional furniture piece might be nothing close to what they want. No matter how the piece in the end showcases its capabilities in spatial efficiency, human ergonomics and operability, helpers feel indifferent since it would be unfamiliar in the end. It would unavoidably seem like a specialized wheelchair that reminds them that themselves are of “special condition”. Not to mention if the piece fails to exhibit itself as a permanent setting but rather strive to be as adaptable as much as it could, the living space would doom to seem temporary like a camping site.

The sense of short-term, makeshift has to be carefully controlled as it would pose a great effect on how the helpers perceive the space, which in the end they have to spend 2 years in it unlike a traveller. Whether or not it is of the scale of a furniture, it ought to create resemblance to helpers of what they naturally understand and adapt to it. At that point, I set up the site of my thesis to be lied within the same building with the host family, permanent as possible.

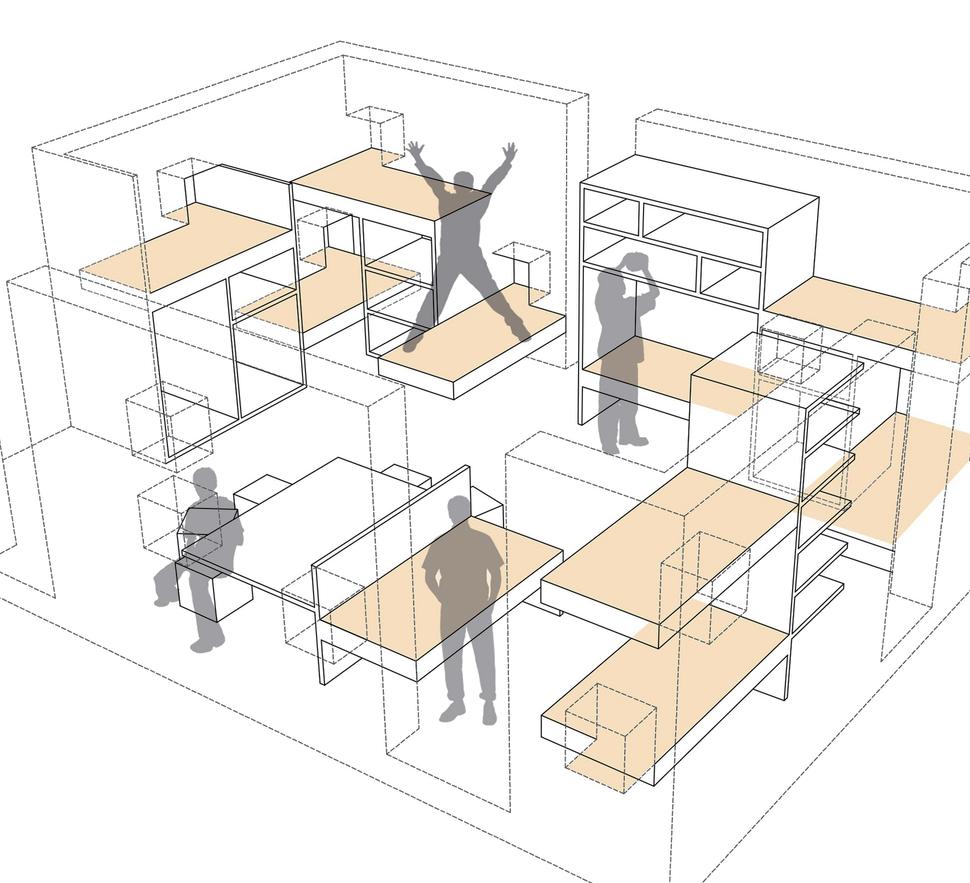

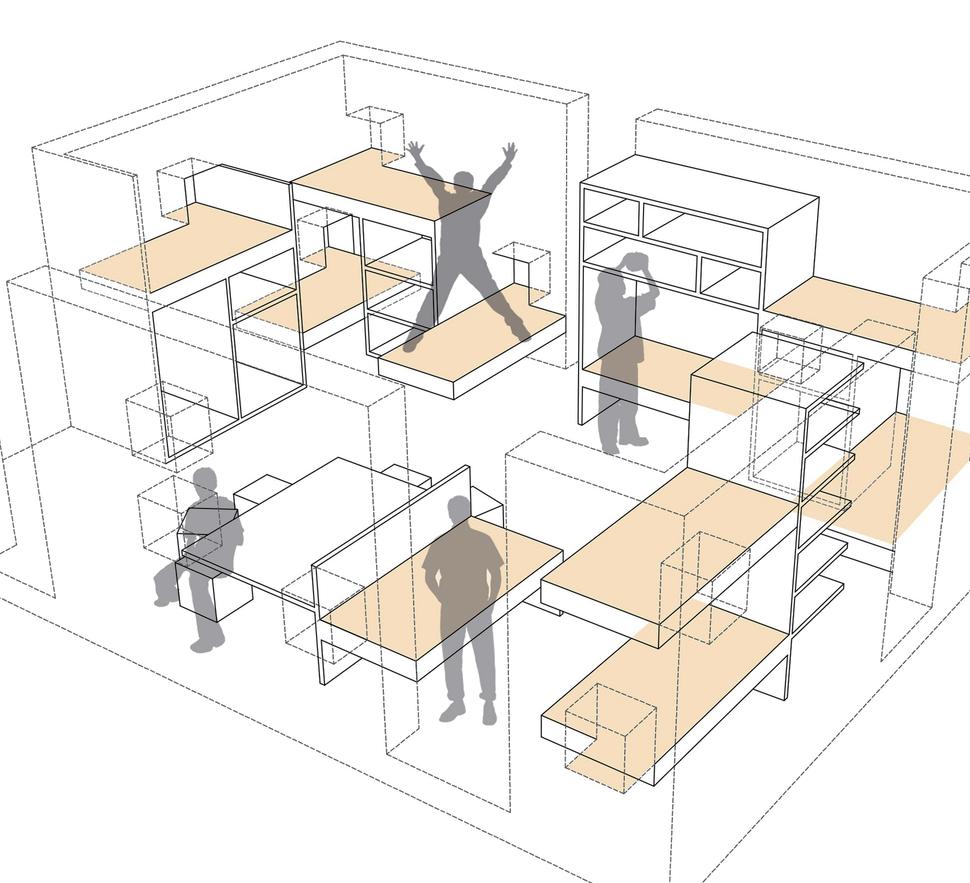

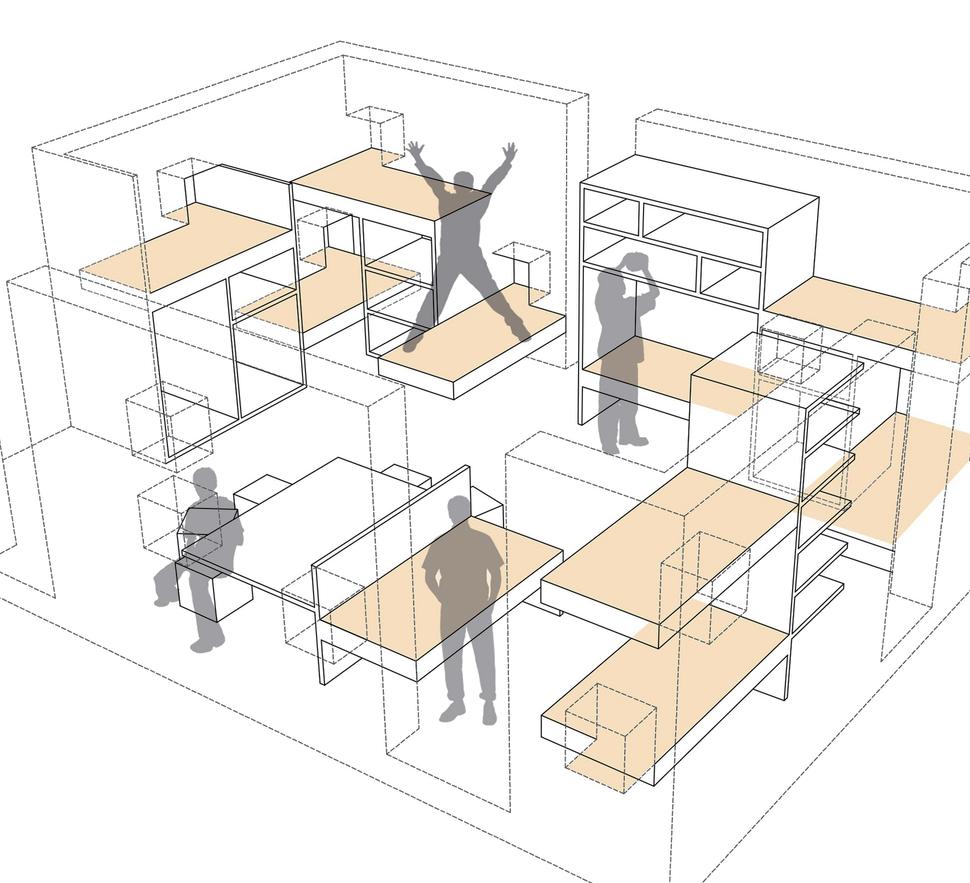

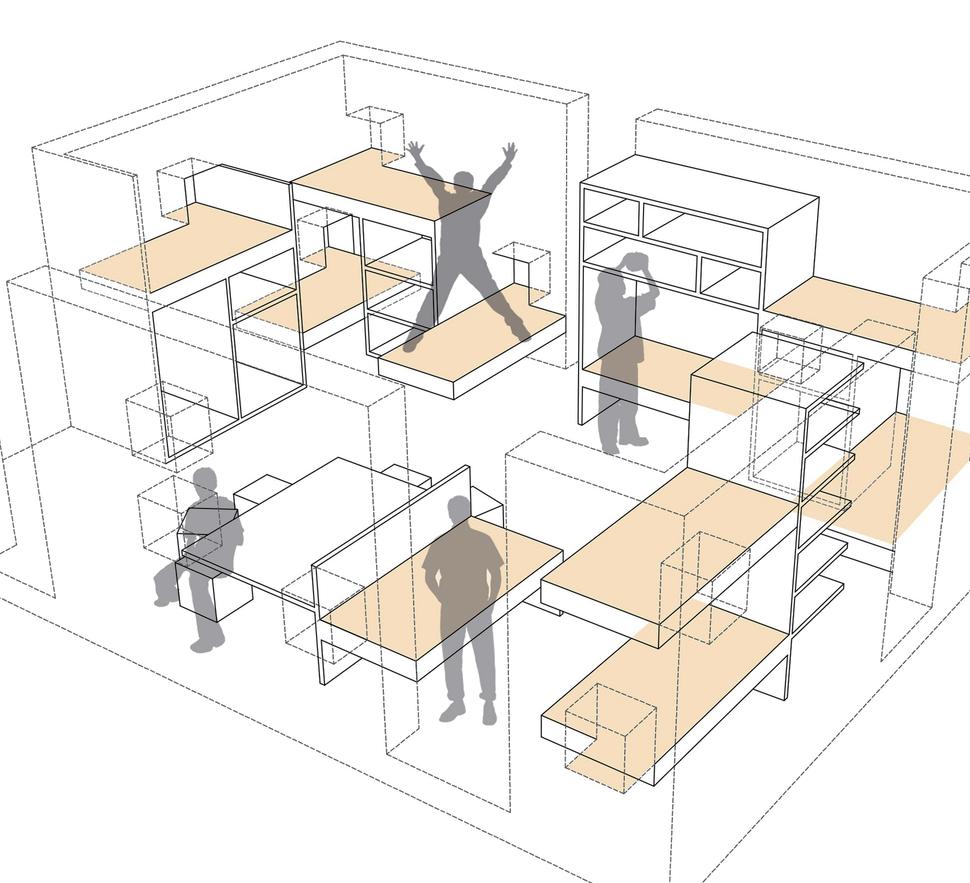

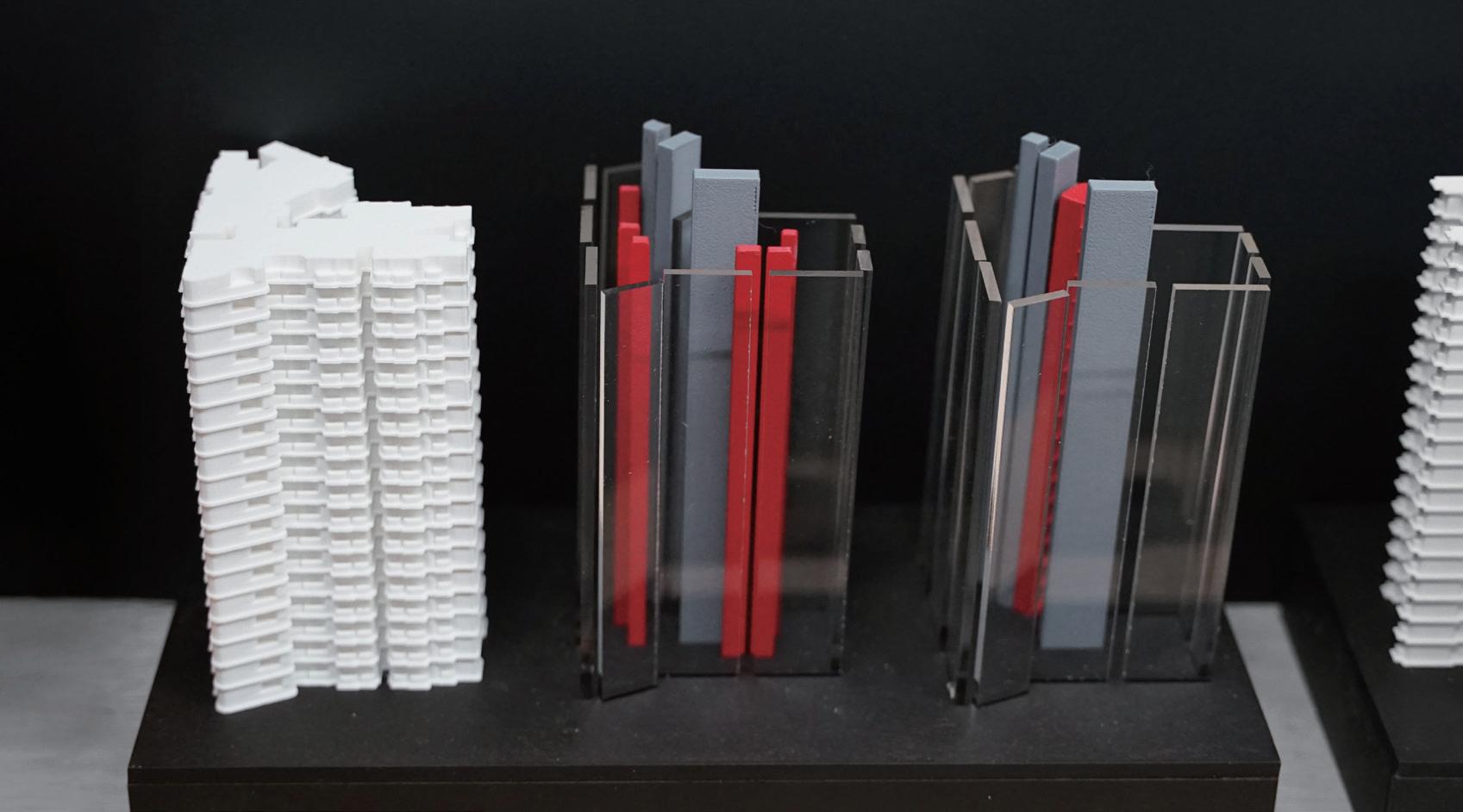

Study models on the application to several selected cases to testify whether the scheme would require specific condition to work well.

03 Site and context

Specifically, the physical ground for the thesis to take place was the LOHAS Park, which is an extremely expansive housing complex involving 13 phases, 50 towers (and counting) predominantly known to be home to mostly middle-income families. The design of the towers very often pioneered certain aspect of housing design, including but not limited to the clubhouse, balconies, refuge floor, etc. It appears this way due to the characteristic of middleincome families that they are usually wealthy enough to discuss what is better yet not enough to afford the best. The pioneer effort often lies on how to make the most out of what is available and what is the best bargain. Subsequently, most of the worst cases that we could reach regarding the helper’s room, are here at the LOHAS park.

In LOHAS Park, helper’s rooms are ubiquitous, though they are rarely labeled as such. Officially designated as “storerooms” or “utility rooms,” they circumvent regulations meant to govern habitable spaces. Hiring a helper is often non-negotiable for their lifestyle as a dual-income family, yet they often lack the means (or willingness) to allocate proper living space. Most helper’s rooms here are criminally narrow—typically 1.25m wide, sometimes as little as 0.8m— barely accommodating a single bed. Developers are trying to neglect the fact that this room, of very high chance, would eventually house people rather than placing household miscellaneous, as Hong Kong locals rarely have the habit to store stuff within a “storeroom”. Not to mention the fact that the dimension of the room often subtly implies that it could fit a bed. The value of having a niche to store vacuum cleaners, foods and unwanted puff toys, would of course be much smaller than a room that could house a helper who take care of your families. Thus, storeroom was never advertised as a storeroom, but mostly likely “build-in maid room”.

Macroscopically, this thesis operates within Hong Kong’s ruthless capitalist housing market, attempting to carve out a solution that is both principled and pragmatically adaptable. The context is rife with constraints—some systemic, others self-imposed—but the project’s ambition is to navigate them without compromising its core critique. Only by engaging with these realities can the proposal hope to transcend theoretical exercise and achieve tangible grounding.

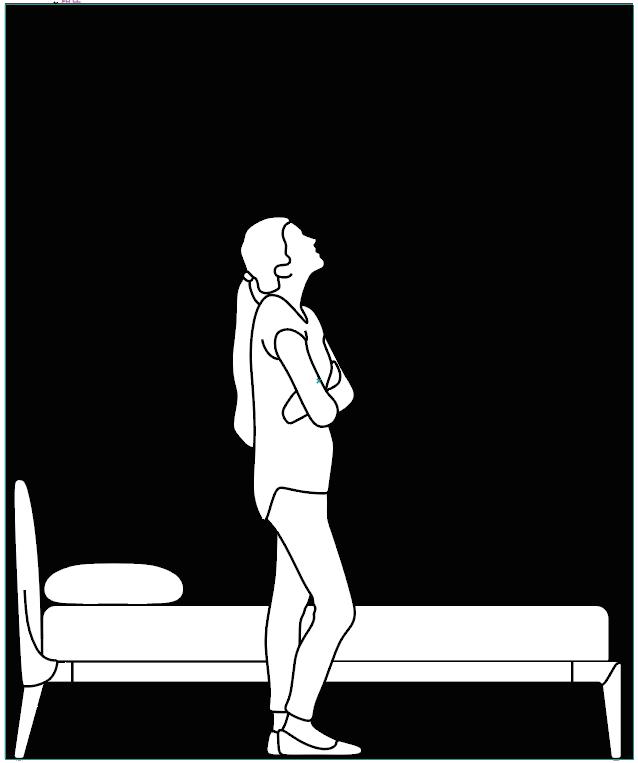

Standard Employment Contract

(For an employee recruited from outside Hong Kong under the Enhanced Supplementary Labor Scheme)

Standard Employment Contract

(For a Domestic Helper Recruited from Outside Hong Kong)

Differential treatment as indicated between the specification of:

Standard Employment Contract for Enhanced Supplementary Labour Scheme (ESLS) (Top);

Standard Employment Contract and Terms of Employment for Helpers (Bottom)

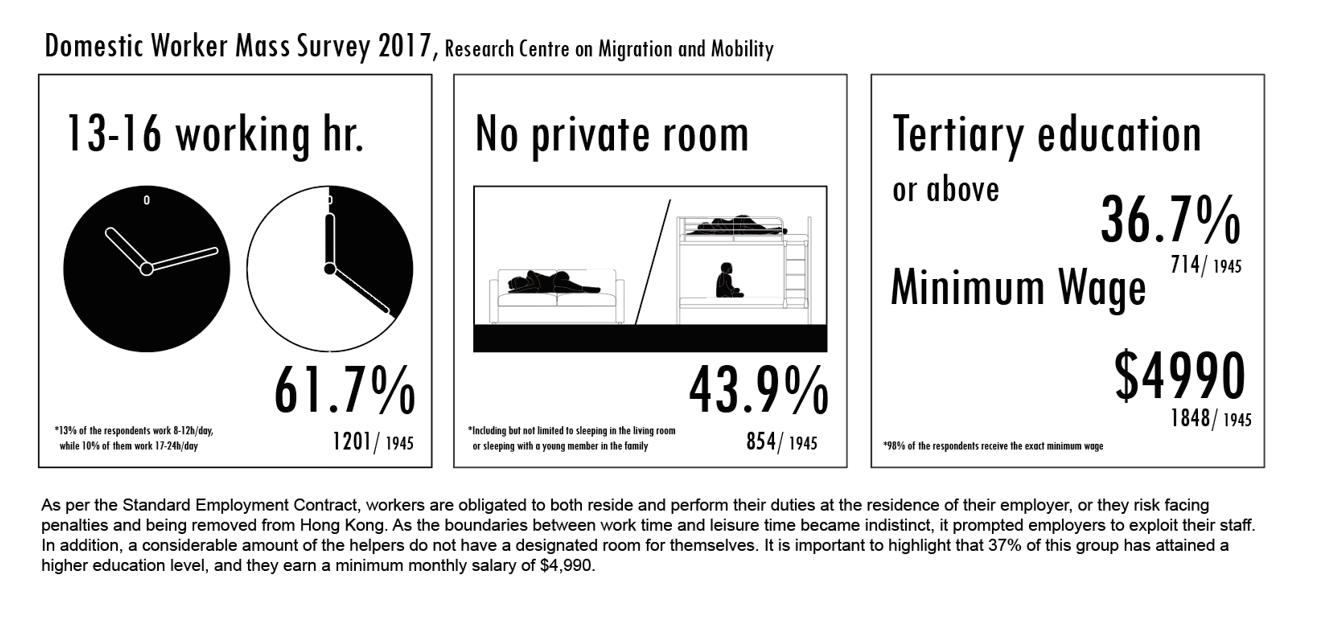

04 Urgency

This thesis emerges at this point of time as we have much higher reliance on foreign labour in Hong Kong. During the recent 10 years, it appears that there is more imported labour at different fields via several pioneering schemes. And because they were set up more recently as compared to domestic helper’s, the employment condition appears to be more mature and well-defined - such that there is obvious preferential treatment. Taking imported workers from mainland China as an example: their employment contracts specify precise spatial requirements - minimum area allocations, mandated amenities, and quality standards for their accommodations. These provisions stand in stark contrast to the deliberately vague "suitable accommodation" clause found in domestic helpers' contracts. This ambiguity is clearly intentional, and to some degree pragmatically necessary - the government cannot realistically guarantee living standards for such a vast population. While the labor department screens extreme cases (like makeshift toilet dwellings), most situations occupy a gray area not dissimilar to locals inhabiting subdivided flats - spaces hovering at the edge of reasonable acceptability.

Projections indicate Hong Kong's domestic helper population will swell to 600,000 by 2047. As the city's spatial pressures intensify, we can anticipate further compression of helpers' living areas to reclaim space for locals. But this raises a disturbing question: how much smaller can these rooms realistically become when many already barely accommodate a single bed

This timeline presents both urgency and opportunity. We have approximately twenty yearsuntil 2047 - to establish transitional housing standards that evolve from the current ad-hoc arrangements to properly regulated living conditions addressing fundamental human needs. The window for intervention is closing as spatial pressures mount, making proactive measures increasingly difficult to implement.

Groups of Indonesian domestic workers came together on a Sunday at the Mong Kong footbridge to have a good time, singing, snacking, and chatting. (Image courtesy: SCMP)

Domestic helper is, in fact, not somebody that is commonly accepted and understood in modern time, especially where we are now in a period that is rather distant from previous wars and people have already developed much higher standard of moral for one another. They are byproducts of globalization that generated from the income gap between relatively wealthy and underprivileged regions and has become deeply rooted in Hong Kong from colonial period. The 380,000 helpers currently working here constitute about 10% of our total workforce, forming an invisible pillar supporting Hong Kong's economy. Their contribution extends far beyond household chores; they enable countless professionals (predominantly women) to remain in the workforce by providing childcare and eldercare solutions. One might argue this system constitutes a form of modern slavery - less visibly brutal but equally controlling through restrictive policies. Yet outright rejection of domestic help would ignore historical context and practical realities, substituting pragmatic engagement with only unrealistic idealism.

I positioned myself first as a local, who understood the place as it is and it was; then, as an architectural designer, who committed to professionally entertain the need of people in the form of architectures. I acknowledge domestic helper as a historically rooted labor system while seeking to elevate its standards within existing constraints. While I may critique certain current practices, this proposal consciously avoids political manifestos, focusing instead on tangible spatial improvements that respect both helpers' dignity and local realities.

The target audience of the project aims to cover as much as possible from the professional practitioner to commoners, as the influence of the proposal would only expand when it propagates to change local’s perceptions. The helper's room has become Hong Kong's collective blind spot, its inhumanity rendered invisible through familiarity. Intellectual exchange with professionals is surely important but different practitioners might have different but equally brilliant ideas on how to better provides to the helpers. The foundation of the thesis lies on whether it could communicate sufficient to offer a different eyepiece to the locals, which forever would be the top priority of any town planners.

Figurative drawings and models as the main spine of communication tools in the discussion of compact spaces.

06 Methods and Structure (Phase I)

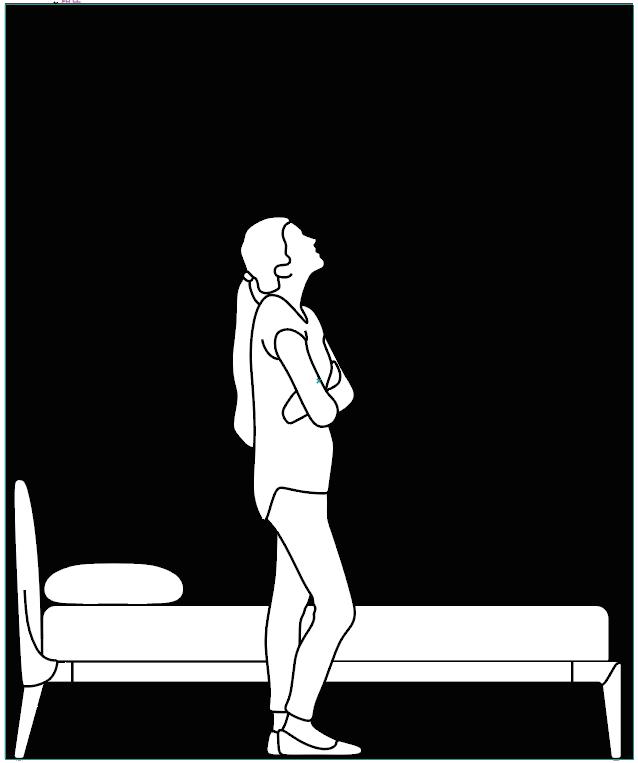

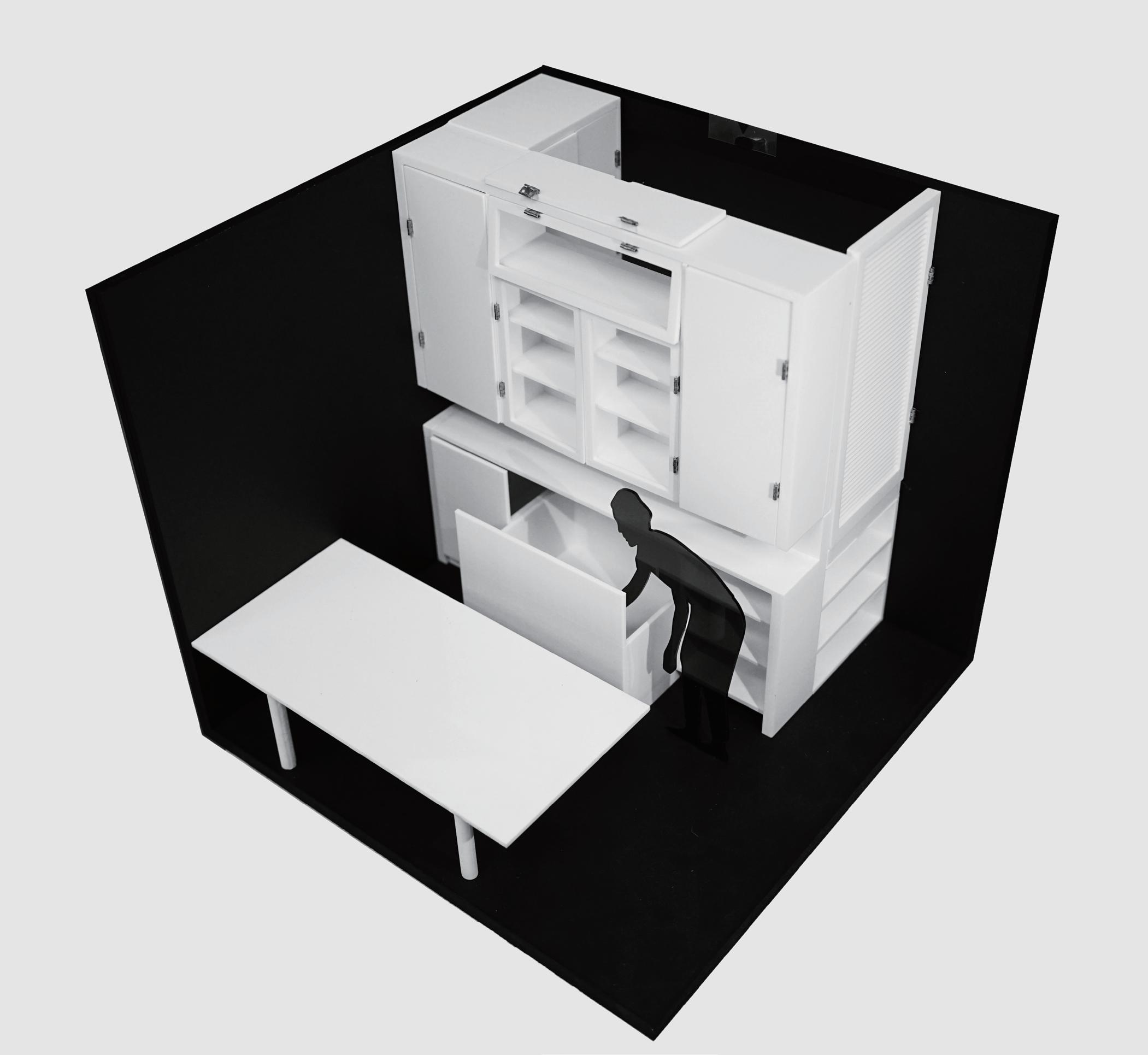

The key method being employed in this thesis aims to communicate “one’s feeling to a space” to its fullest, by a figurative approach that create accurate correlation of scale as possible.

In most cases within my studies and design outcome, I tried to present them with a dominant number of figures that not as mere scale references but as active participants that reveal how bodies negotiate tight spaces. This challenges conventional architectural representation where human presence is often reduced to abstract silhouettes or omitted entirely in favor of clean geometries. Architects typically operate at the macro scale, prioritizing crowd movements and circulation flows over individual bodily experience, as major means of testifying the spatial quality. It is, however, extremely important when the discussion of space started to shrink and reach to a point where the intimacy of the architectural enclosure to individuals almost attain only bare minimal. Of which, it is observable that Hong Kong would be the one of the few cities that first reach this end of the shrinking. Public and private housing, as an example, started to become ridiculously small and often being put onto the table of discussion by press. Where I believe, at this point, we should navigate our discussion slightly off the mainstream of how ones usually derive an architecture from a broad picture of the users - it should rather be more a zoom-in, less flexible and more assumed picture of the users.

My drawings document this through orthographic tracings of my own movements, capturing imagined activities in proposed spaces. These layered gestures form motion studies akin to circulation diagrams, but for individual bodies rather than crowds. Admittedly, real users will deviate from these projections - no one lives according to an architect's diagrams. Yet in spaces measuring barely two square meters, successful design requires making assumptions. Where conventional architecture embraces flexibility, these micro-environments demand precise calibration to anticipated needs. The figurative approach thus serves dual purposes: as design methodology (testing spatial adequacy through embodied representation) and as communication tool (making spatial injustices viscerally apparent to viewers).

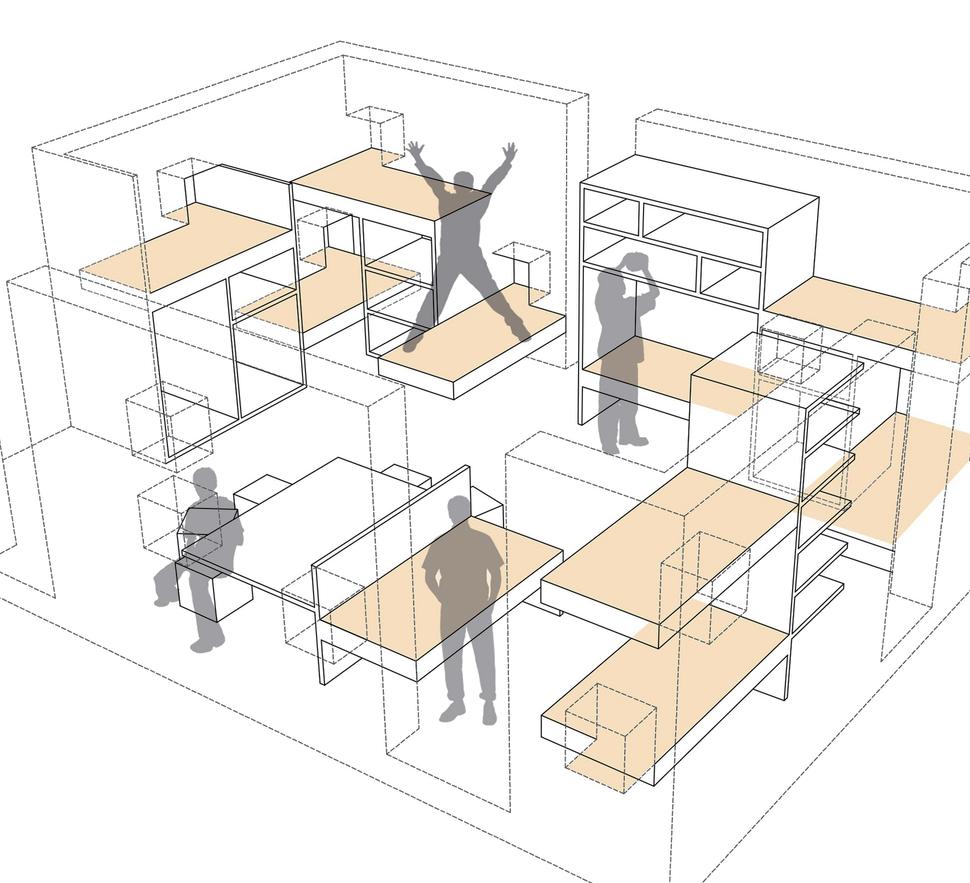

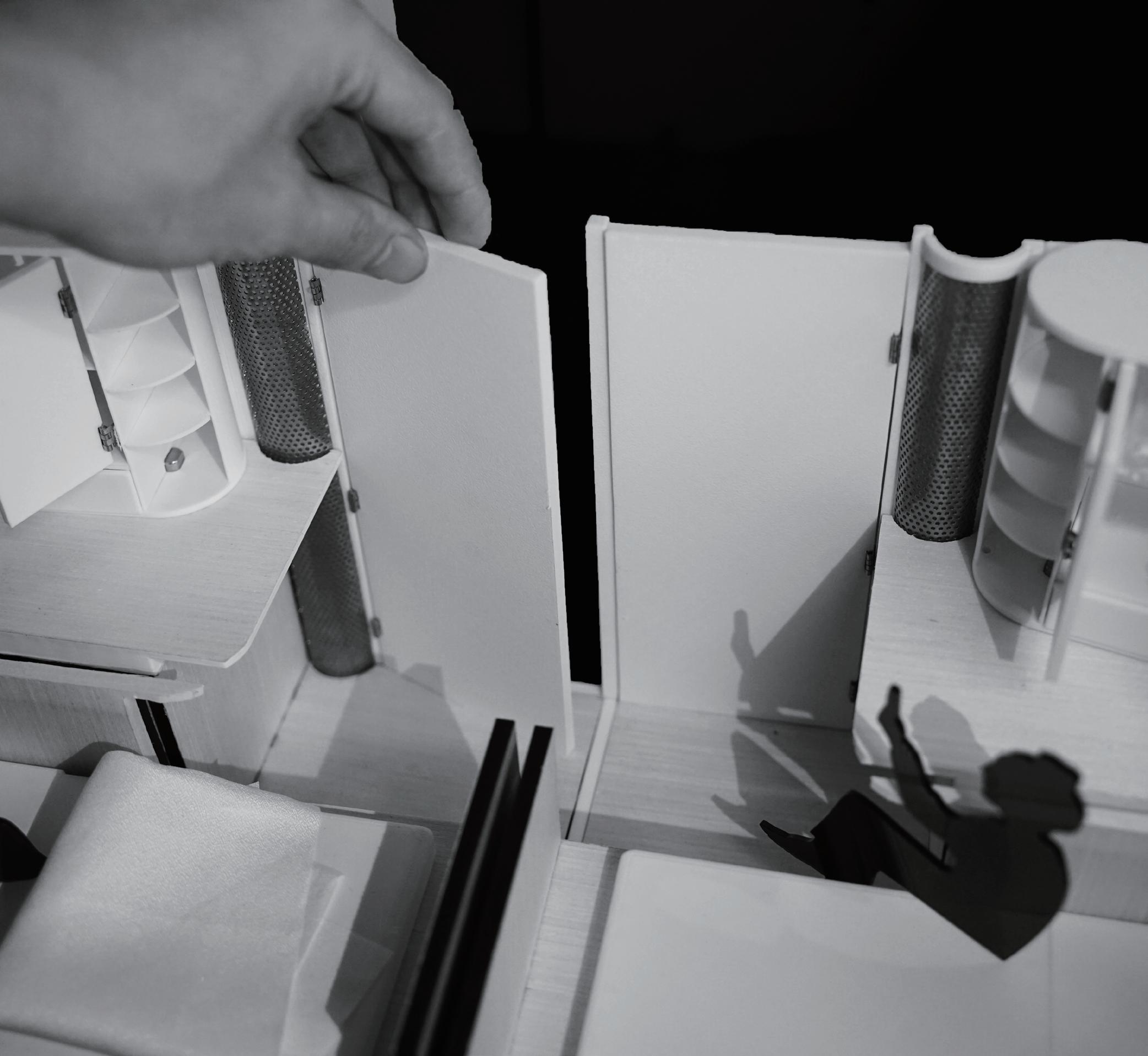

Models are made to be inspected with high operable details, via different angles, inviting viewer to tangibly confront with the cases put forward.

06 Methods and Structure (Phase II)

This commitment to tangible experience extends to physical models, which I conceive as interactive artifacts bridging professional and public understanding. Operable elements - doors that open, drawers that slide - aren't mere gimmicks but deliberate strategies to engage non-architects. They create moments of surprise when viewers discover what these miniature spaces contain, breaking through the apathy surrounding helper accommodation debates. Observation confirms their effectiveness: people instinctively interact with these movable components, their curiosity overcoming initial disinterest. While this interactivity risks misrepresenting my actual design intentions. While the models suggest transformability, the proposed spaces themselves reject makeshift solutions. There's a critical distinction between using operable models to demonstrate spatial conditions versus designing spaces that constantly require user adaptation. The dollhouse becomes both diagnostic tool and provocation, asking viewers to physically confront spaces we've learned to ignore.

My resistance to transformable architecture stems from profound psychological considerations. Each folding bed or convertible surface, no matter how ingeniously designed, reinforces the helper's status as temporary occupant rather than rightful resident. The more a space declares its versatility, the more it whispers "you don't belong here permanently." This temporal anxiety compounds when applied to shared domestic zones - a wall that folds by day and unfolds at night might optimize square footage, but it turns basic living into a daily negotiation of territorial claims. My design therefore limits mechanical complexity, favoring spatial configurations that remain stable over time. The operable model components thus serve an ironic purpose: by letting viewers physically manipulate miniature spaces, they experience why real living spaces shouldn't require such constant manipulation.

Government approved dormitory for domestic helper at Singapore, with disposable sheets, to be thrown away between the stays of each worker. It represents one possible reality of formalized accomodation for doestic helper in a densed city. (Image courtesy: weekbly.com)

07 Significance

The significance of my thesis lies on its provocative role to arouse discussion on something that is numb to be acknowledged again. As an outcome, my thesis compiles a set of studies that is essential to look through when one’s attempting to propose something for domestic helpers. They reveal genuine, yet unexpected feelings from domestic helpers, on what was provided to them. There is also a sufficient amount of case studies of what is currently being set up already, either as permanent unit planning, or furniture pieces. They have never been compiled in such way that we could understand them as a general picture.

As for the design outcome, which I personally regarded as a by-product of the thorough studies, points to a very legible and sensible way of how we could do better for the domestic helpers. Even though collective accommodation is not something revolutionary, the proposal clearly layout a way of how to place it relative to the host family; how do we access the accommodation is of sufficient standard; what should we include and exclude as additional services to the helpers. They together represent a guideline of how to easily pioneer the scheme as a new type of housing in Hong Kong, which recognize the importance of the role of helpers.

Final review, discussion session with, from left to right, Professor Zhu Tao, Professor Elspeth

Lee, Dr. Chen Chen and Mr. Mudhura Prematilleke.

08 Review transcription

Midterm review:

The post discussion of midterm review lies on my stance of “WHAT” to be proposed as a better option for the domestic helpers. Some critics were already imagining my proposal to be purely a domesticated furniture piece, while some others imagine it in the scale of a housing project. It seems that I fail to project a vision to their expectation, in the mid run of the project. Me, at the time, would like to leave it open and wait until my research prompt me an opportunity to react. The discussion was however a good external force that informs me of the expected outcome, which is seen as highly correlated with my heavy focus on research. Meaning that a failed attempt to propose something new, also implies a failure of the research effort. It quickly prompted me to try out some of my thought and test of its feasibility.

Final Review:

The feedback from final review is quite positive. They do recognize the urgency of the agenda that I have presented, as something that should be handled with immediate care. Some of them have personal experience that touched on the agenda and found my proposal connected with some of their internal thought. The discussion lies outside of the design details, but more on the broader sense of how we should position ourselves as professionals under this agenda that crosses on moral. Afterall, should we still promote the employment of the domestic helpers using our power to imagine future city. I, personally, went through this question multiple times in my mind during this term, and I do not see there would be chance where the domestic helper in Hong Kong would suddenly be let go of. That is why I expect, there would still be a long way run till there is another picture depart from what is currently possible. I wish to at least allow the helpers to live up to their own right, before the society decide to set up a better standard. The review discussion ends quite open-ended.

"THE RIGHT TO JOY"

A BILL OF RIGHTS FOR USERS OF ARCHITECTURE by teaM ARCHITRAVE

Architecture shall provide every person who inhabits a building:

The right to physical, emitional and spiritual Well-being

The right to public open space

The right to private open space

The right to interact with nature

The right to fresh air

The right to feel the breeze and/ or warmth

The right to natural light

The right to experience sunrise and sunset

The right to control the relationship between inside and outside

The right to privacy

The right to personalize

The right to dignity

The right to cope with disabilities

The right to age with dignity

The right to an environment that will age gracefully

The right to building with what you have

The right to affordability

The right to grow

The right to hope

The right to joy

The previous archives my internal debate before and during the thesis,

The following would reveal my reseach and design attempts stage by stage...

From left to right, top to bottom:

1. A bunk bed that is hovered above the dining area and integrate with the lighting trough.

2. A living room cabinet, that partitioned off a 3-foot sleeping space, storage slides right beneath the bed.

3. A TV console cabinet, that is covering a upper bunk, with a 2 feet wide walk-in closet

4. A display cabinet, that dedicated the lowest compartment as a 3 feet wide sleeping zone with obviously suffocating enclosure.

(Image courtesy: HKET)

09 Case study

Hong Kong's compact living conditions have given rise to specialized furniture systems that serve dual daytime and nighttime functions. Among these, the helper cabinet represents a particular architectural response to spatial constraints. These units typically maintain the appearance of conventional household furniture - most commonly television consoles, shoe storage units, or display cases - while concealing a sleeping space.

I dissected several of these units, mapping their ergonomic failures—the contorted entry sequence, the suffocating enclosure. Some reveal ingenuity: ventilation slits disguised as decor, hidden compartments for valuables. While this duality still fascinates me—how can something so thoughtfully detailed still feel so degrading? My drawings amplify these invisible violences. By rendering the cabinets at human scale with traced bodily movements, I expose what polite design obscures: a bed narrower than shoulders, a "room" that disappears each morning. The more perfectly the cabinet performs as furniture, the more brutally it fails as a habitat.

The findings contribute to ongoing discussions about alternative housing models in highdensity urban environments, particularly regarding temporary occupant accommodations. The study documents both the technical innovations of these systems and the compromises necessitated by their dual-purpose nature.

From left to right, top to bottom:

1. A storage unit that is used to partition a full-height, 90cm-wide niche as sleeping zone, with 30cm openings serving as exchange of conditioned air.

2. A living room cabinet, that first embeded with 2 chairs and a dining table (bottom left), a huge drawer for micellaneous (bottom right), and covers a 90cm-wide sleeping zone at behind.

3. A TV console cabinet, that is covering a upper bunk, with a shortened access panel leads into the compartment.

4. A shoes cabinet, that elongates upward with matching style and covers a upper bunk, with access ladder on the side.

(Image courtesy: HoHome Design Limited)

From left to right, top to bottom:

1. A subdivided area, which is partitioned by several shelve units, contains a bunk bed for helper and one of the host member.

2. A extensive shoes cabinet that is keeping space for a upper bunk inside the kitchen.

3. A tailored bunk bed designed as a "playroom" for kid at the bottom and a upper bunk at the top.

4. A subdivided room for helper in a 188 square feet public housing unit.

(Image courtesy: HKET)

COMPOSITE FURNITURE PIECE AS SLEEPING POD FOR DOMESTIC HELPERS

CASE STUDY A / 1:10

SLEEPING

ITEMS FOR HOST

VENT

Display Cabinet?

Case A, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model, showcasing a cabinet with a lower sleeping area measuring three feet and an upper section intended for displaying various items. Air passages are incorporated into the cabinet's framework and are hidden amoung the decorative repetitive relief.

The decorative elements maintain aesthetic continuity with typical living room furnishings while providing necessary airflow to the sleeping area. It is however more disturbing as the upper display section literally prioritizes decorative objects above the human occupant, materially expressing their lower social valuation. It also reinforces their status as someone whose presence should be hidden, reducing them to an object that gets stored away by daylight.

COMPOSITE FURNITURE PIECE AS SLEEPING POD FOR DOMESTIC HELPERS

CASE STUDY B / 1:10

CABINET

DRAWERS

ELEVATION

SCALE 1:10

MECHANICAL VENT

SHELF MISCELLANEOUS

CLOSET (REAR-OPEN)

CABINET (SIDE-OPEN)

TELEVISION

WALK-IN CLOSET

FOR HOST

TV Cabinet?

Case B, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model, showcasing a cabinet functioning as a TV holder and a second-level sleeping area measuring 2.5 feet in width. Additionally, there is a hidden walk-in closet intended for the helper, along with some space for various household items and decorative pieces.

This dual-purpose furniture system combines entertainment storage with compact sleeping quarters in a vertical arrangement. The base functions as a television cabinet with integrated wardrobe featuring classy lighting and adequate dressing space. However notably, the entry, ladder, bed with missing corner, walkin closet with 60cm wide maneuvering space, all implies negligence, if not indifference, in the design. The creativity remains like a dressing to the suffocating enclosure.

COMPOSITE

FURNITURE

CASE STUDY C / 1:10

PIECE

AS SLEEPING POD FOR DOMESTIC HELPERS

CLOTHES / PERSONAL VALUABLES

Shoes Cabinet?

Case C, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model, showcasing a cabinet that cleverly integrates a three-foot-wide sleep space by partitioning a shoe organizer located beside the dining room table. It features two exceptionally deep compartments that can hold luggage, additional seating for visitors, and appliances used during specific seasons. The compartment situated at the top serves as a vent.

This innovative yet problematic furniture solution attempts to maximize functionality in minimal space by combining a sleeping area with storage compartments. The design incorporates a raised sleeping platform measuring 0.9 meters wide and 1.9 meters long, accessible via integrated storage drawers that double as steps. The unit’s reliance on convertible storage elements—drawers as stairs, cabinets as ventilation shafts—communicates that the occupant’s living space is secondary to the household’s storage needs.

Side reference - Elderly nursing home

Side reference A, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model, showcasing a typical Hong Kong governement approved elderly nursing home, with large area of curtain for better surveilance during daytime. Partitions are modulized to allow for quick modification/ adaptation to elderly with special needs. Partitions are also shortened to ensure sufficient air flow.

The parallels between Hong Kong's substandard domestic helper accommodations and overcrowded elderly care facilities reveal systemic patterns of spatial deprivation. Both scenarios demonstrate how vulnerable populations are subjected to compressed living conditions that prioritize space efficiency over human dignity. These spatial constraints reflect deeper societal attitudes that tacitly accept diminished living standards for care-dependent groups. The common justification of "limited space availability" in both contexts masks a troubling willingness to compromise fundamental needs of marginalized communities.

Side reference - Capsule hotel

Side reference B, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model, showcasing a famous capsule hotel sleeping pods module located in Japan. It features generous capsule interior at 2150mm (D)* 1050mm (W)* 1020mm (H), which is a rare provision amoung other counterparts.

While Japanese capsule hotels exemplify efficient temporary accommodation for travelers, Hong Kong's domestic helper furniture represents a disturbing permanent adaptation of this concept. Capsule hotels operate on short-stay logic - their compact pods serve travelers for nights, not years. The helper cabinets, however, force long-term occupation of similarly confined spaces without the hotel's compensatory amenities (communal baths, lounges). This crucial difference highlights how spatial solutions designed for transient use become oppressive when applied to residential contexts.

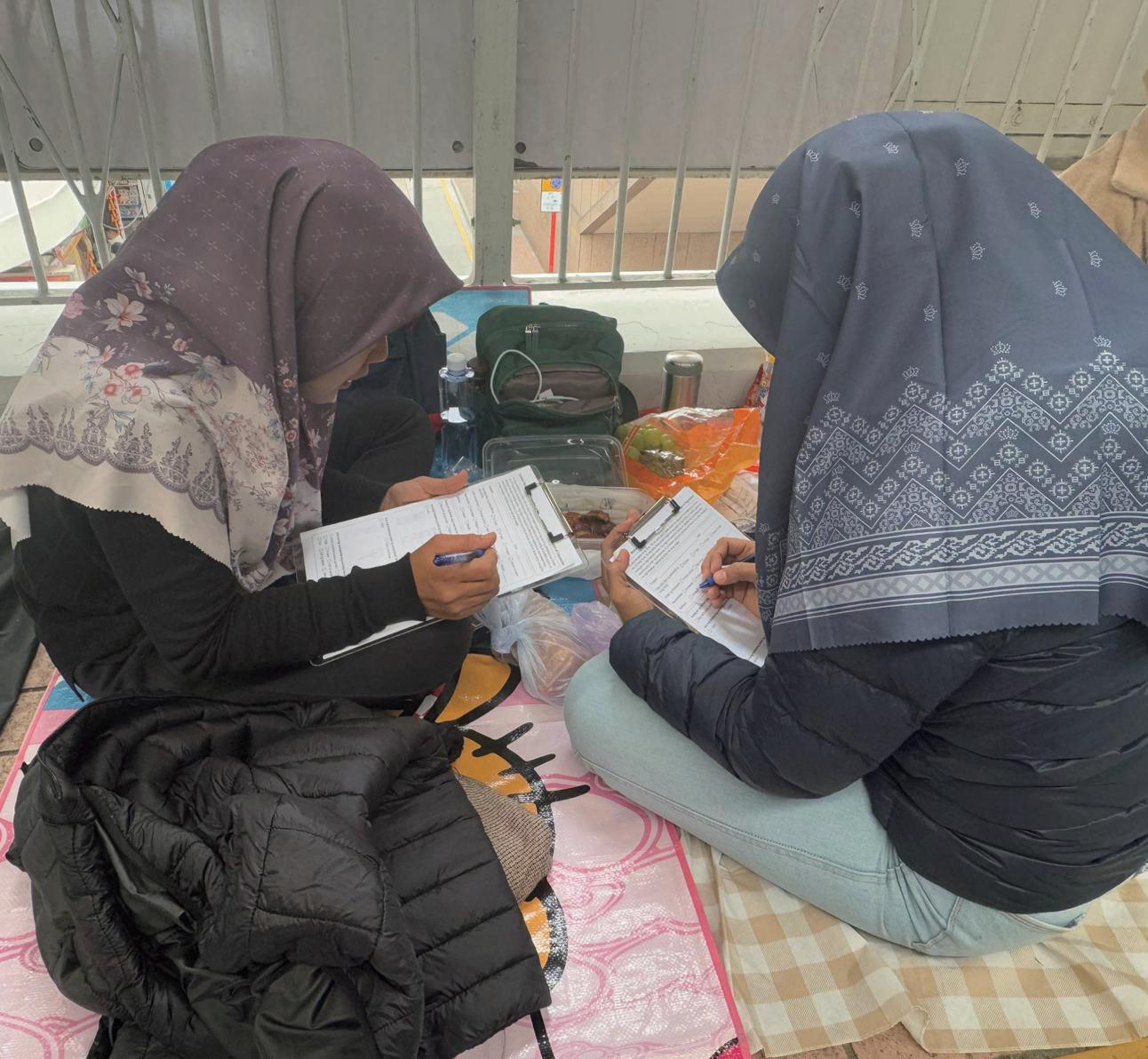

Field survey with two Indonesian domestic helpers at the Mong Kok Pedestrian footbridge, on 2/2/2025. Many others refused to be on camera.

10 User survey

As an important pre-requisite of this project, Hong Kong domestic helpers are not allowed to live outside of the host family. They must declare to live with their employer and at the same time the employer must declare a part of their home for them to live in. While the definition of the accommodation requirement is very ambiguous and almost imply that there would be abuse of service. This pre-condition is very important to the discussion of what would be a better solution.

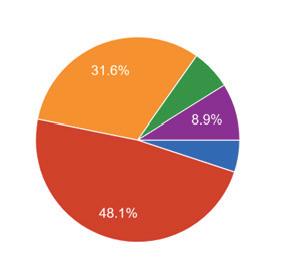

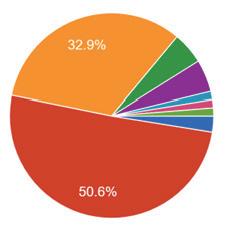

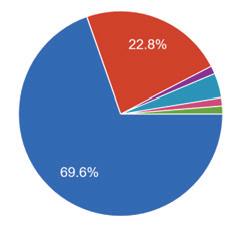

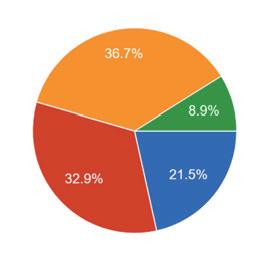

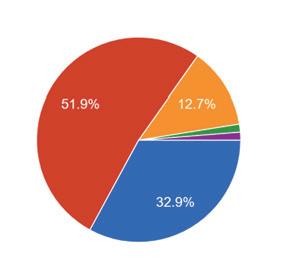

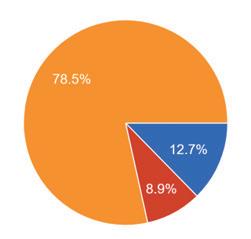

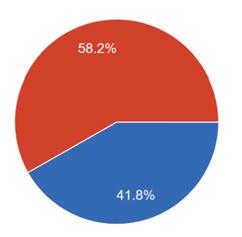

I spent the first two months’ time to consolidate research that could support my decision making. The first thing I did is a survey with the helpers to get a sense of what they were given. I got 79 responses, there are a few key takeaways:

17/79 of them sleeps on a bed that is 60cm, 26/79 of them sleeps on a bed that is 75cm. noted that a standard single bed is 90cm wide, a 75cm bed is considered as a small single bed, and a 60cm bed would need to be specially customized.

Next, 31/79 of them sleeps in a room without a window. 41/79 of them are not provided with an aircon.

Lastly, 26 of them are not allowed to eat on the same table, 14 of them are not allowed to share the fridge, 8 of them are not allowed to use the washing machine.

The above pretty much constitutes my understanding to their standard of living. Despite being small which is quite predictable, it is also poorly ventilated, and common utilities are often not being shared to them due to various reasons.

My Own Survey, 2-14 Feb 2025

Around 1/4 of the helpers live in a room without a window.

Around 1/5 of the helpers were not allowed to eat on the same table, noted they are usually not the group who were provided with table and chair.

10 User survey

UNEXPECTED COURSE OF THE SURVEY:

1. Usually, hygiene is not a concern because they are the one responsible for cleaning, but the rating on hygiene usually reveals how they feel towards the household.

2. Some helpers seem to have very humble wish while some might still feel unsatisfied even when they were provided with a room. Rating might not correlate with the quality of space, but only capable to reflect their feeling, to a certain extent.

3. Living away or not is also independent from how they think of their own space, might be more possibly related to their preferred way of living, whether they feel like living alone, together with peers or living with the employers (host).

4. Indonesian workers, because of the language they speak (usually Cantonese and Indonesian only), very often falls into the more unsatisfied or mistreated side of this pole. Very likely because they are often employed by grassroot.

5. However, this survey fails to sufficiently intake the opinion of the Indonesian, because they often decline the survey or refuse to talk. It might be because of the language barrier is more difficult to come across, when they have low proficiency to speak Cantonese while I am also incapable of speaking Indonesian. And the sense of unfamiliar and suspicion came very strong.

6. It is difficult to erase the power hierarchy in the survey because I unavoidably represent Hong Kong people who they would perceive in correlation to their host. They might refuse to disclose any inner thought because they see it as a form of complaining. This was slightly alleviated after I ask for help from some domestic workers (from my family) to spread it.

10 User survey

STAGE FINDING OF THE SURVEY

1. Majority of the helpers were provided with their own room, disregard of the size of the room. Otherwise, helpers often share a room with a host member, which is usually a kid or elderly.

2. A vast majority of the helper shares the toilet and shower with the host.

3. Around half of the helpers sleep on a bed that is 60-75 wide, noted that 90cm is the size of a standard single bed.

4. Around 1/4 of the helpers lives in a room that is around 1.5m wide, which is a common provision of a “storeroom” in Hong Kong, that could be coming with or without a window.

5. Around 1/2 of the helpers lives in a room that is around 2m wide, which is a common provision of a standard bedroom.

6. Around 1/5 of the helpers lives in a room that is around 2.5m wide, which is a common provision of large bedroom, if not the master bedroom. It is noted that a few respondents from this group shares a bedroom with a host member. The room does not entirely belong to them.

7. Very unlikely but occasionally, there are respondents sleeping at other parts of the house, such as the couch/ foldable bed at the living room, or the stock room under the staircase. Noted that this is not a legal provision to helpers.

8. Around 1/4 of the helpers live in a room without a window.

9. Around 1/5 of the helpers were provided with table and chair.

10. Around 1/5 of the helpers were not allowed to eat on the same table, noted they are usually not the group who were provided with table and chair.

11. Around 4/5 of the respondents are fine to live together with the host family, this includes people who rates extremely low regarding their provided space or being disallowed to share some common utensils at the house.

12. Opinion on the size of the room is varied, mostly were neutral.

13. Opinion on the privacy of the room is varied, mostly were satisfied.

14. Opinion on the ventilation and hygiene of the room is inclined to be on the good side, especially for hygiene.

15. Around 1/3 of the helpers know someone living in the mentioned furniture piece, while around 2/3 of the helpers do not prefer to live in such condition unless left with no choice.

Some families do not allow their domestic helper to use shared household equipment. For example, the washing machine. Which of the following household utilities you are given access to? (You can tick multiple)

Washing machine (Are you allowed to use the washing machine for your own clothes?)

Refrigerator (Are you allowed to share the refrigerator for your own food?)

Dining table (Are you allowed to eat on the same table?)

Eating utilities (Are you allowed to use the same batch of spoon, chopsticks and fork?)

Kitchenware (Are you allowed to use the same cooking pan, pot and knifes?)

Are there any specific amenities or items you feel lacking in your private space?

Would you choose to live outside from your host family, if money was not a concern?

Yes I prefer to live away Maybe, if the living location & size are ok. No.

Please rate the room provided to you, in terms of the following aspects (10 for highest)

12345678910

Size (Big?)

Privacy

Ventilation (Fresh air?)

Hygiene (Clean?)

The following picture shows a type of furniture build for the domestic workers. It has basic storage, sleeping zone, electrical sockets... Do you know any domestic helper living in such arrangement?

Yes No

Do you prefer to live in such arrangement?

Yes, I feel fine with it

Maybe, it depends. No, I don’t prefer it unless I have no choice.

Bed is Here Bed is Here

is Here

is Here

10 User survey

WHO DECIDED THIS WAS ACCEPTABLE?

Helpers arrive mentally prepared to accept substandard living quarters - windowless cells, shared spaces, rooms barely fit for storage. Host families, in turn, instinctively allocate the absolute minimum space possible. This mutual expectation of "just enough" reveals a disturbing social contract, where both parties have internalized deprivation as normal. What began as compromise has hardened into unquestioned standard.

WHO DETERMINED THIS WAS ADEQUATE?

Consider the 60cm "bed" - narrower than a standard mattress, barely wider than human shoulders. When basic furnishings defy anatomical reality, we must ask: shouldn't objective bodily dimensions set the baseline for humane accommodation? Hong Kong may have normalized cramped living, but physical suffering shouldn't be disguised as spatial efficiency. Some discomforts demand intervention, not acceptance.

WHO CLAIMED THIS CONSTITUTES PRIVACY?

The shared room arrangement presents a particular fiction - both helper and host may declare the situation "acceptable," but consent given within unequal power dynamics deserves scrutiny. Without concrete standards, we risk mistaking resignation for agreement. True privacy either exists or it doesn't; its absence can't be waived away by mutual desperation.

Survey Summary

Where are you from?

79 responses

What is your age?

79 responses

Survey Summary

How long have you stayed in Hong Kong?

79 responses

What is your level of education?

79 responses

Survey Summary

What is your religion?

79 responses

What kind of sleeping area are you provided with?

79 responses

Survey Summary

What is the approximate size of your bed?

79 responses

What is the approximate size of your room? (Please specify if none of the options are close enough)

79 responses

Survey Summary

Whaich of the followings are available in the room assigned to you?

(You can tick multiple)

79 responses

Which of the following common household utilities you are given access to? (You can tick multiple)

79 responses

Survey Summary

Would you choose to live outside from your host family, if money is not a concern?

79 responses

The following picture shows a type of furniture build for the domestic workers. It has basic storage, sleeping zone, electrical sockets.

Do you know any domestic helper living in such arrangement?

79 responses

Survey Summary

Please rate the room provided to you now, in terms of the size. (Is it big enough?)

79 responses

Please rate the room provided to you now, in terms of the privacy.

79 responses

Survey Summary

Please rate the room provided to you now, in terms of the hygiene.

79 responses

Please rate the room provided to you now, in terms of the ventilation. 79 responses

An image from a promotional campaign for home renovation services displays a tailored bunk bed that fits seamlessly into a "storeroom" at LOHAS Park phase III Hemera. (Image courtesy: 牛牛傢俱 )

11 Plan study

This study examines 47 apartment plans from the past 15 years featuring designated helper accommodations, representing approximately 15-20% of such developments in Hong Kong during this period. The sample reveals consistent spatial patterns through orthographic plans highlighting helper areas relative to overall unit layouts.

Key findings demonstrate three primary characteristics of these spaces:

Environmental Conditions:

Over 50% of rooms lack natural ventilation or daylight, circumventing building regulations through classification as "utility rooms" or "storerooms" despite their residential use.

Dimensional Standards:

1. 50% measure approximately 120cm in width

2. Smaller units range down to 80cm in width

3. Larger accommodations (150-200cm) appear exclusively in apartments exceeding 1500 sq.ft.

Spatial Allocation: Helper rooms typically occupy residual spaces with irregular geometries (triangular, trapezoidal) that challenge standard furniture placement, reflecting their low priority in unit planning. Most situate adjacent to or within kitchen areas, with approximately 30% containing compact ensuite bathrooms.

The study employs two complementary representation methods:

1. Scaled floor plans showing room-to-unit proportions

2. Orthographic projections with 165cm human figures demonstrating spatial relationships

These configurations establish a baseline understanding of current market standards for helper accommodations. The prevalence of sub-optimal conditions - particularly nonrectangular layouts and substandard dimensions - reflects systemic spatial inequities in residential design.

This empirical data serves as critical context for developing pragmatic improvements. Rather than proposing utopian solutions disconnected from market realities, the research identifies achievable intervention points within existing development frameworks. The findings will inform subsequent design proposals seeking incremental yet meaningful upgrades to helper accommodations while remaining feasible within Hong Kong's housing production system.

Larvotto, Flat A,

940

sq. ft.

Mayfair by the Sea, Flat A, 18/F, Block 3A 779 sq. ft.

Seasons Bay 2A, 1-9/F Flat C1, 477 sq. ft.

Wetland Seasons Park, Flat A3, 2/F, Tower 21, Phase 1 636 sq. ft.

Wetland

One Beacon Hill, Flat D, 2/F, Tower 6, 1093 sq. ft.

Pavilia Farm,

Wetland Seasons Park, Flat A3, 2/F, Tower 21, Phase 1 636 sq. ft.

Pavilia Farm, Flat C, 60/F, Tower 6B 866

Fleur Pavilia,

Lohas Park LP6, Flat B, 68/F, Tower 1, 1313 sq. ft.

The Pavilia Bay, Flat A,

The

The

Fleur Pavilia, Flat D, 7/F, Tower 1, 783 sq. ft.

Lohas Park

The Pavilia Bay, Flat A, 5/F, Tower 2, 1252

The Pavilia Bay, Flat A, 9/F, Tower 1, 1366 sq. ft.

The Southside South Land, Flat A, 23/F, Tower 1A, 1205

Fleur Pavilia, Flat D, 7/F, Tower 1, 783 sq. ft.

The Pavilia Bay, Flat A, 5/F, Tower 2, 1252 sq.

The Southside South Land,

A, 23/F, Tower 1A,

Phase 2 participatory study was conducted via f2f interview, aiming for qualitative responses of personal preference and feelings in response to detailed decision making. (interview snapshot on 8/5/2025)

Interview session conducted with Ali (left), took place at my home when she came over to visit my family. It turned out to be quite a relaxed and fluid conversation.

A little bit before I dived into the design that I have had in mind, I did an interview with a helper that is taking care of my grandma, to run through my perception of their need one last time:

Format: f2f with recording Duration: under 60 minutes

1. Physical Living Space

Objective: Understand the actual conditions of the helper’s room Questions:

• "Can you describe your room to me?"

o Probe: "Is it a converted storage space, or a dedicated room?"

• "Do you have a window? How do you cope with heat/humidity?"

o Probe: "Have you ever felt sick from poor ventilation?"

• "How much luggage did you bring when you first came to Hong Kong? (e.g., 1 large suitcase + 1 carry-on?)"

• "Do you keep seasonal items (e.g., winter clothes, extra blankets)? Where do you store them now?"

o Probe: "What’s your usual belonging and where do they store?"

2. Work-Life Balance

Objective: Assess how living conditions intersect with rest Questions:

• "What time do you start/finish work?"

o Probe: "Is the working hours considered too long for you?"

• "Has your employer ever woken you up after bedtime? What happened? "

o Probe: " Do family members disturb you during breaks?"

3. Employer Treatment & Household Dynamics

Objective: Uncover live-in power dynamics and unspoken rules. Questions:

• "Are there rules about when you can enter/leave your room? "

o Probe: "Can you stay in your room during short breaks?"

• "Are you allowed to use the living room and kitchen when not working?"

o Probe: "Do you eat meals separately from the family?"

• "Do family members knock before entering your space?"

o Probe: "Has anyone gone through your belongings without asking?"

4. Emotional Well-Being & Social Needs

Objective: Explore their social pattern Questions:

• "Where do you go on Sundays?

o Probe: " What do you enjoy doing for your day-off?"

• "Do you know other helpers in your building? Do you ever support each other?"

o Probe: " Are your closest friends here from your hometown, or did you meet them in Hong Kong?"

• "Is it hard to make friends in Hong Kong? What makes it difficult?"

• "Where do you spend your rest days? Do you feel pressured to stay out all day?"

o Probe: "Do you need your own space during rest days?"

From top to bottom: LOHAS Park phase 5 MALIBU tower 1; LOHAS Park phase 3A HEMERA tower 1; LOHAS Park phase 10 LP10 tower 1 (main application in this thesis)

13 Application

This proposal outlines a pragmatic approach to centralize domestic helper accomodation within existing residential towers, focusing on three key implementation criteria:

1. Spatial Requirements

• Minimum threshold of 4 original helper rooms (180-200 sq.ft. combined) to ensure meaningful shared amenity spaces when consolidated

• Optimal placement within building re-entrants (4-6m width) when external perimeter placement is unfeasible, maintaining adequate natural ventilation and daylight through properly scaled openings

2. Circulation Strategy

• Connection to service lift cores for vertical movement segregation

• Distributed amenity rooms (laundry, storage) at 3-floor intervals to promote stair usage, reducing lift dependency

• Priority given to towers with existing service lift lobbies that can be repurposed as dedicated helper access points

3. Environmental Performance

• External-facing units as preferred option for direct air and light exposure

• Re-entrant placement requiring minimum opening width matching room depth to prevent deep light wells

• Strategic positioning to avoid concave geometries that compromise air flow

The system demonstrates greatest efficiency in towers meeting these baseline conditions This phased implementation model targets achievable upgrades within current market constraints, using existing architectural features (re-entrants, service cores) to deliver measurable quality improvements without requiring structural modifications.

Still frames from videotaping myself performing certain imagined movement.

14 Movement envelope study

This research methodology examines the spatial implications of human movement through systematic recording and analysis of bodily gestures. The study began with first-person movement documentation, capturing a series of actions relevant to three primary domestic functions: sleeping, food preparation, and cultural/religious activities. These movements were video recorded, with key frames subsequently traced to establish volumetric envelopes representing minimum spatial requirements.

The analysis extends beyond basic movement paths to incorporate multiple ergonomic factors. Headroom clearances were mapped for both standing and seated postures. Particular attention was given to the body's ergonomic centers during different activities, determining optimal reach zones and pivot points. When examining group interactions, the study calculated interpersonal spacing thresholds - first establishing minimum separation distances to prevent physical contact, then expanding to determine comfortable ranges for unimpeded gesturing during conversation or collaborative tasks.

These movement envelopes serve as a verification system for spatial proposals, providing measurable criteria to evaluate design adequacy. The traced sequences create a threedimensional framework that identifies both functional requirements (minimum clearances) and qualitative considerations (comfortable movement ranges). By grounding spatial assessment in empirical movement data rather than standardized dimensions, the method accounts for the full range of bodily occupation in constrained environments. The resulting envelopes inform not only initial space planning but also ongoing design refinement, ensuring proposed environments accommodate actual use patterns rather than idealized assumptions.

GETTING TO A HIGHER SURFACE / LOWER SURFACE ELEVATION / 1:10

300-350(MAX)

COOKING IN GROUP ELEVATION / 1:10

EATING AT DIFFERENT SURFACES

ELEVATION / 1:10

PRAYING / CLEANSING ELEVATION / 1:10

GROUP GATHERING ELEVATION / 1:10

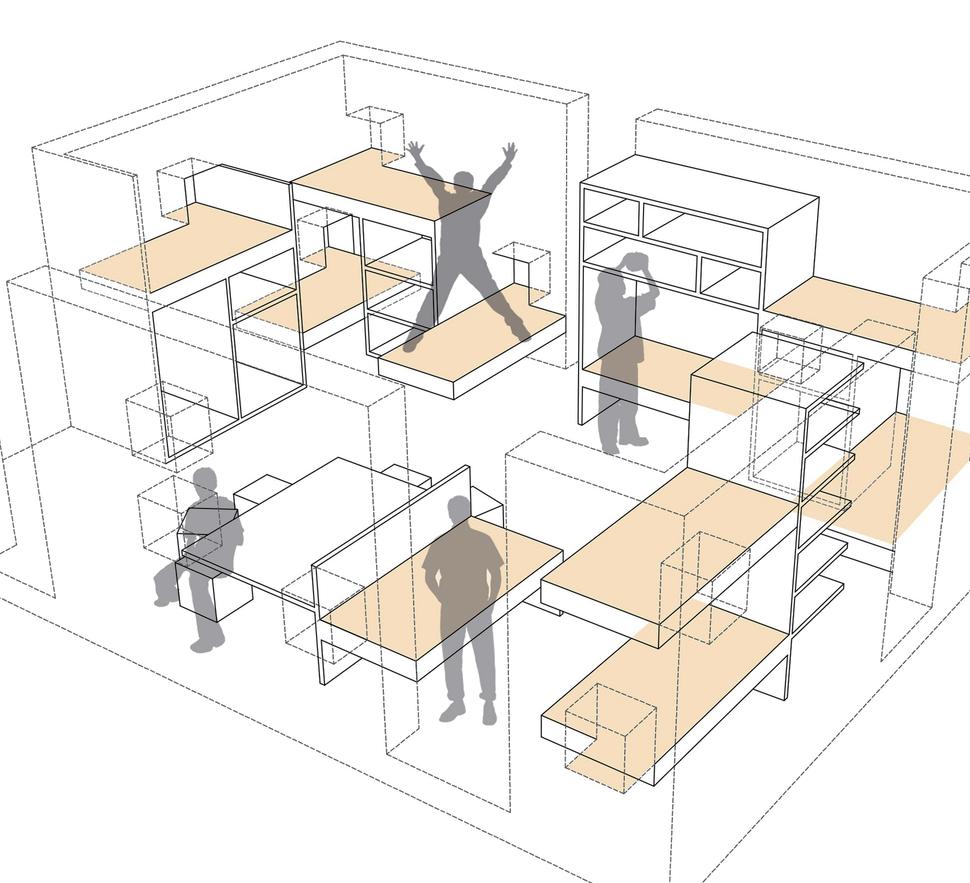

1:20 final model, showing the centralized helper's accomodation, adhering to the service liftcore, with close proximity to the host's units

15 Final design

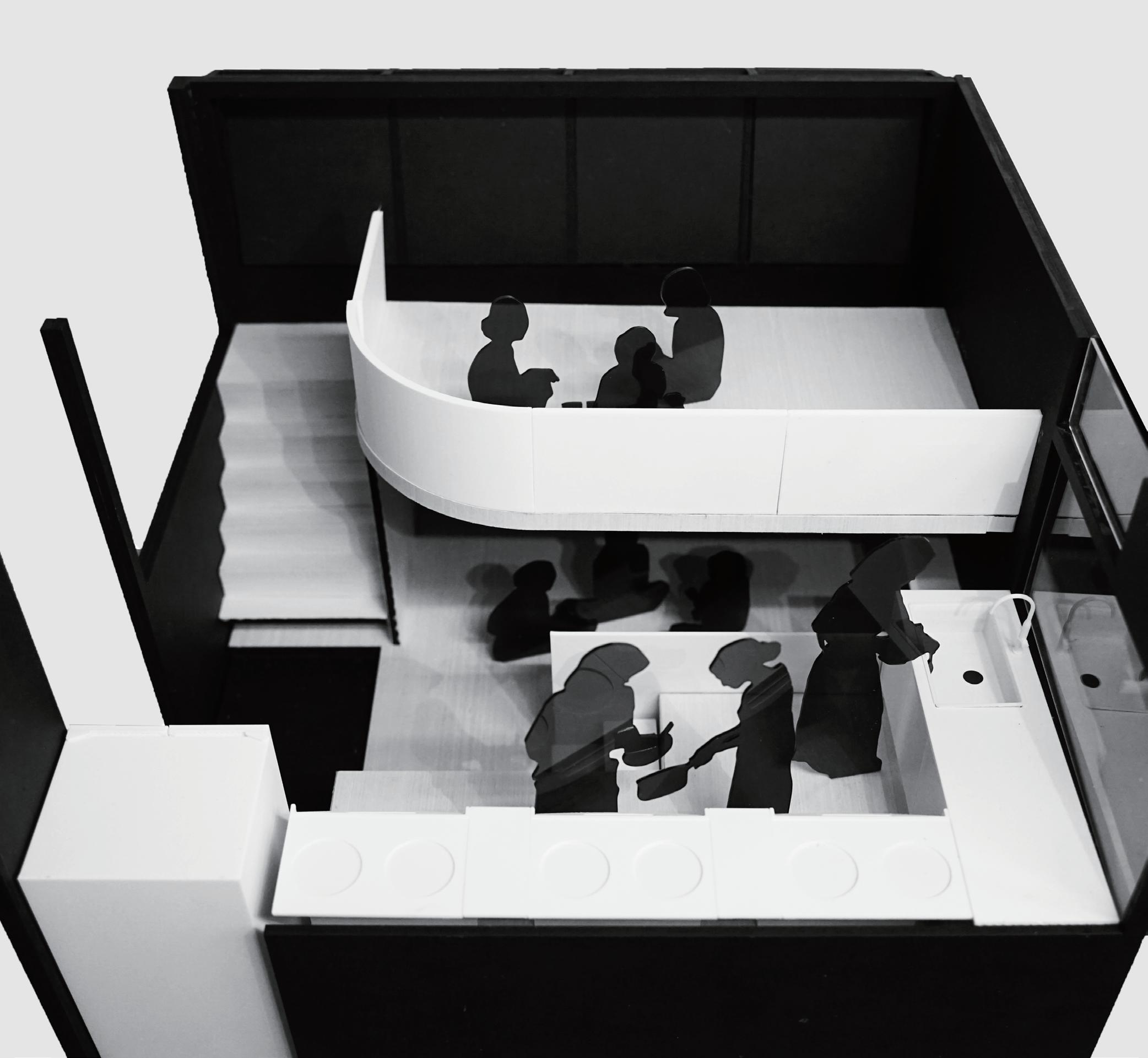

This project reimagines domestic helper living conditions by consolidating fragmented, substandard maid rooms into collective dormitory units within existing residential towers. The design transforms current 2.5m² single-occupancy rooms into shared living spaces that address fundamental needs for dignity, functionality, and cultural expression.

The proposal establishes self-sufficient dwelling clusters by repurposing underutilized building areas such as refuge floors and service cores. Each unit combines private sleeping cubicles with communal amenities, including shared kitchens, sanitation facilities, laundry rooms, and multifunctional spaces accommodating both Indonesian Muslim and Filipino Christian cultural practices. This spatial reorganization achieves three primary objectives: improved living standards through shared resources, enhanced social connectivity through designated gathering areas, and preserved proximity to employer households while establishing clear physical boundaries to prevent excessive work demands.

Spatial justice is pursued through efficient area reallocation, converting previously marginal spaces into habitable environments with natural light and ventilation. Social wellbeing is supported through culturally specific design elements like prayer zones and cooking stations that enable traditional meal preparation. The strategic placement of dormitories within host buildings maintains necessary accessibility for caregiving duties while establishing crucial separation between work and rest spaces.

By redefining helper accommodations as dignified living environments rather than service zones, this project presents a replicable model for migrant labor housing in high-density cities. The design demonstrates how thoughtful spatial reorganization can elevate living standards within existing building constraints, offering a pragmatic yet transformative approach to equitable urban housing solutions.

1:20 Final model , rest cubicles, total of 8 rest cubicles and a clear-out for a 95 cm wide double loaded corridor space within one floor.

Multifunctional space for Muslim and Christian cultural practices (top left); shared kitchen for small catch up and food preparation on restday (bottom left); overview of stacked floor-to-floor arrangement for washroom, multifunction room and rest cubicles.

COLLECTIVE

Clothes

Valuables

Shoes

COLLECTIVE LIVING QUARTER FOR DOMESTIC HELPERS

Prayer room / multi-function room / 1:12

Breathing gap between preparation zone and main space

Corridor / drying zone

Cleansing area

Step to enter

Drain (wetzone)

Prayer Mat Organizer

Prayer Room / Function Room

Altar / Sidetable

Retractable table

Religious objects for swapping of altar space

Cushions

Steps to exit

Final design, 1:10 operable "dollhouse" model. Each occupant would share a 1.9m tall entryway, 1.4m tall sleeping zone and 90cm tall storage area. These 3 zones are stacked in a way to offset and share the headroom between two occupants at each of the spot of events.

Considered the space is small, I inserted a metal louvre that would serves as the constant air exchange within the room. Storage units are rotational, as a customization of internal exposure, also to let the user better access to it when standing up right at the entryway.

Though seemingly minor, the rotational shelf embodies the project's core philosophy. This compact unit consolidates personal essentials—clothes, valuables, and meaningful decor like photos or plants—while its rotating mechanism serves dual purposes. It provides ergonomic access from the private cabin while allowing controlled exposure to the communal corridor, creating a subtle threshold between personal and shared spaces. More than storage, it performs psychological work: enabling helpers to curate their visibility to others. In this modest intervention lies the thesis' central ambition—to address both physical needs and the deeper human desire for self-expression within constrained environments.

The decision regarding cabin privacy remained unresolved until the thesis's final stages. From a design perspective, merging two cabins to create shared living quarters—similar to university dormitories—presented compelling opportunities. This configuration could foster stronger social bonds among helpers, potentially alleviating the isolation inherent in their work. However, through direct engagement with domestic workers, I learned that many prioritize private space above communal benefits. Their preference likely stems from being constantly exposed to social demands during long working hours, making personal retreat essential rather than optional.

Some Indonesian has the habit of sitting on the ground with a kind of woven rug. While Filipino mostly sit on the table. This tiered arrangement creates natural sightlines between cooking and seating areas, encouraging conversation across groups during meal preparation. Shared meals become opportunities for cultural exchange and community building among migrant workers.

The shared cooking space was intentionally designed to facilitate cultural gathering practices observed among domestic helpers. For Indonesian workers in particular, food preparation and sharing form an integral part of social bonding, often seen during their Sunday gatherings in public spaces. The cooking corner was dedicated to them as to enable themselves getting socially connected.

The sleeping quarters reimagine capsule living next to a rotating shelf unit that transforms spatial functionality. Each shelve pivots to either: face a full-height changing space (maximizing storage access), or open up to a communal area to invite interaction (half-height bed space becomes a semi-public seat). Headroom is meticulously calibrated to accommodate natural body movements (sitting, stretching), while perforated metal panels serve dual purposes. Ensuring cross-ventilation when doors are closed. Also acted as occupancy signals—diffused light patterns indicate use without intrusive signage.

This design balances privacy and community, allowing helpers to control their exposure to shared living while maintaining airflow and visual connectivity.

The room serves Muslim prayer primarily but converts for Christian use through zoning via elevation change:

Lower "wet" zone: Tiled foot-washing area with grated flooring and floor drains.

Upper "dry" zone: Prayer/congregation space with side cabinet.

The cabinet would allow them to store ceremonial objects :

Cabinet A (Muslim): Rollable prayer mats, tasbih beads, and mukena robes.

Cabinet B (Christian): Folding stools, bilingual Bibles, and battery-operated LED candles.

Groups must reset the room post-use (e.g., stowing mats/chairs, wiping floors).

Eliminating fixed partitions maximizes usable area (9.5m²) while ensuring clear sightlines for safety.

purposes. Ensuring cross-ventilation when doors are closed. Also acted as occupancy signals—diffused light patterns indicate use without intrusive signage.

This design balances privacy and community, allowing helpers to control their exposure to shared living while maintaining airflow and visual connectivity.

The kitchen bridges cultural habits through a mid-level cooking space that mediates two dining decks: Storage is optimized for Sunday rituals: Collapsible tents, picnic mats under staircase. Luggages for restday travel were placed under the cooking platform

Upper deck (floor seating): For Indonesian helpers who traditionally eat on mats (lesehan).

Lower deck (tables/chairs): For Filipino-style group dining.

The tiered layout encourages incidental interaction during meal prep, while storage supports off-site gatherings. By elevating the cooking zone, the design naturally funnels social interchange.

Cabinet A (Muslim): Rollable prayer mats, tasbih beads, and mukena robes.

Cabinet B (Christian): Folding stools, bilingual Bibles, and battery-operated LED candles.

Groups must reset the room post-use (e.g., stowing mats/chairs, wiping floors).

Eliminating fixed partitions maximizes usable area (9.5m²) while ensuring clear sightlines for safety.

THE INTIMATE OUTSIDER

Six full-size shower-toilet cubicles (1.3m × 1.4m each) are arranged to optimize morning peak flow. Central sink island with 8 faucets spaced 40cm apart to prevent crowding. Originally the space could plan for 7 cubicles, but reduced to 6 to maintain clearance between cubicle doors and elbow room for drying/changing.

The bathroom intentionally adopts a residential-scale design—prioritizing familiarity over architectural innovation. Unlike other dormitory spaces requiring specialized solutions, bathrooms benefit most from replicating standard household layouts. Spatial dignity is achieved not through reinvention, but through normalization of the most basic domestic standard.

16 Reflection

This design outcome surely is not a generous space, but it represent the bare minimal that should be workable within nowadays Hong Kong. If there is a tiny bit more external dedication from the government or the general public, then the scheme ought to be a lot more attractive. Its value lies not in offering generous spaces, but in proving that measurable upgrades are possible with minimal external support from policymakers or developers.

Some critiques noted the project’s limited understanding of domestic helpers as a occupation. While deeper analysis of daily routines and work challenges could surely inform more tailored solutions, this study prioritizes breadth over depth. It focuses first on establishing spatial dignity as a fundamental right, deliberately avoiding designs that might imply helper's routine. The proposed physical separation between living and workspaces intentionally reframes the helper-host relationship, creating room for future discussions about fair labor boundaries.

The proposal acknowledges its limitations as a first-step intervention. I do not claim to resolve systemic issues tied to policy or cultural attitudes, but rather seeks to demonstrate that even within tight constraints, humane living standards are architecturally achievable. As Hong Kong’s reliance on domestic labor intensifies, this project underscores the professional responsibility of designers to establish measurable benchmarks—not as final solutions, but as catalysts for ongoing improvement. The scheme’s true success would be in shifting perceptions of what constitutes acceptable helper accommodations, creating momentum for further refinements that address both spatial and social dimensions of this complex issue.

Bibliography

Constable, Nicole. Maid to Order in Hong Kong: Stories of Migrant Workers. 2nd ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007.

GovHK. A Concise Guide to Employing Foreign Domestic Helpers. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://www.gov.hk/en/theme/ guidebook/employment/family/foreigndomestichelper.htm](https://www.gov.hk/en/theme/ guidebook/employment/family/foreigndomestichelper.htm).

Hong Kong Labour Department. Foreign Domestic Helpers – Rights and Obligations. Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://www.fdh.labour.gov.hk/tc/home.html](https://www.fdh.labour.gov.hk/tc/ home.html).

CNN. "Hong Kong’s Live-in Rule for Domestic Workers Faces Legal Challenge." July 9, 2020. [https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2020/07/09/asia/hong-kong-helper-live-in-rule-intl-hnk](https://amp. cnn.com/cnn/2020/07/09/asia/hong-kong-helper-live-in-rule-intl-hnk).

Dimsum Daily. "Debate Ignites Over ‘Coffin-Sized’ Domestic Helper Space in Two-Bedroom Flats." Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://www.dimsumdaily.hk/debate-ignites-over-suspendedcoffin-sized-domestic-helpers-space-in-two-bedroom-flats-living-room/](https://www. dimsumdaily.hk/debate-ignites-over-suspended-coffin-sized-domestic-helpers-space-in-twobedroom-flats-living-room/).

Hong Kong Free Press "Hong Kong Domestic Workers Made to Live in Bathrooms, Closets, on Balconies and Roofs." , May 10, 2017. [https://hongkongfp.com/2017/05/10/hong-kong-domesticworkers-made-to-live-in-bathrooms-closets-on-balconies-and-roofs/](https://hongkongfp. com/2017/05/10/hong-kong-domestic-workers-made-to-live-in-bathrooms-closets-onbalconies-and-roofs/).

South China Morning Post (SCMP) "Hong Kong’s Domestic Helpers and Where They Sleep." , multimedia infographic. Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/ news/hong-kong/article/3290257/helpers-bedtime-stories/](https://multimedia.scmp.com/ infographics/news/hong-kong/article/3290257/helpers-bedtime-stories/).

HKET Topick. "Public Housing Residents Struggle with FDH Accommodation: Sleeping in Living Rooms Raises Legal Concerns." Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://topick.hket.com/ article/3397868/【公屋外傭】住 200 呎公屋安排工人姐姐瞓廳 %E3%80%80 僱主憂難請人:買個 床架再整塊簾 ]

House730. "Hong Kong’s Tiny Apartments: Is It Illegal for Foreign Domestic Helpers to Sleep in the Living Room?" Accessed June 11, 2025. [https://www.house730.com/news/28847/ 港人住屋 細 - 外傭瞓廳隨時犯法 /](https://www.house730.com/news/28847/ 港人住屋細 - 外傭瞓廳隨時犯 法 /).

House730. "Lohas Park Phase 8 – Sea To Sky Property Listing." Accessed June 11, 2025. [https:// www.house730.com/en-us/buy-property-8069646/Lohas-Park-Lohas-Park-Phase-8-Sea-ToSky/](https://www.house730.com/en-us/buy-property-8069646/Lohas-Park-Lohas-Park-Phase8-Sea-To-Sky/).

SquareFoot Hong Kong "Things to Consider for Domestic Helper Accommodation in Hong Kong.". [https://www.squarefoot.com.hk/en/news/what-to-consider-for-domestic-workeraccommodation-66989](https://www.squarefoot.com.hk/en/news/what-to-consider-fordomestic-worker-accommodation-66989).

Wong, Maggie Hiufu. “Hong Kong’s Sleep Pods Offer Tiny Respite for the City’s Exhausted Workers.” CNN Travel. June 10, 2025. Accessed [05Apr2025]. https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/travel/ article/hk-sleep-capsules.

Chang, Gary. "Nano Scale: Gary Chang Explores Compact Living and the Future of Dense Cities." ArchDaily, June 30, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/949150/nano-scale-gary-chang-explorescompact-living-and-the-future-of-dense-cities.

The Standard. "Sixteen New Elderly Homes Will Launch Next Year: Welfare Chief." November 17, 2022. https://www.thestandard.com.hk/breaking-news/article/189016/Sixteen-new-elderlyhomes-will-launch-next-year-welfare-chief.

Race, Space + Architecture "Carving Through Rigid Space: Filipina Domestic Workers at Statue Square, Hong Kong." , McGill University. Accessed [May 01, 2025]. https://www.mcgill.ca/racespace/article/arch-355/carving-through-rigid-space-filipina-domestic-workers-statue-squarehong-kong.

Fair Agency. "Do I Have to Provide a Separate Room for My Domestic Helper?" Accessed [May 01, 2025]. https://fairagency.org/answers/do-i-have-to-provide-separate-room-domestic-helper/.

ArchDaily. "School Dormitory for 100 Students / ASA Studio." Accessed [May 01, 2025]. https:// www.archdaily.com/910645/school-dormitory-for-100-students-asa-studio?ad_medium=gallery

Prematilleke, Madhura. "The Bill of Rights." Accessed [May 01, 2025]. https:// madhuraprematilleke.com/Bill-of-Rights.