COLD-WEATHER CELEBRATION OF THE BAY AREA’S OPEN SPACES

A brief history of how the Bay Area built a world-class system that can be enjoyed year-round

What is a park?

Most of us probably think first of a green space with trees, picnic tables, playgrounds or campgrounds. There could also be a creek, river or reservoir — and hiking trails, too, maybe leading to waterfalls or mountaintops.

But the Bay Area’s spectacular variety of parks is on another level, with open spaces, recreation areas, islands, historic sites, gardens, wetlands, urban “pocket parks,” neighborhood playgrounds and Pacific beaches, along with a national seashore, 350 miles of trail circumnavigating San Francisco Bay and several world-famous tourist destinations. It’s a system that compares to any major metropolitan area anywhere in the

world, parks experts say.

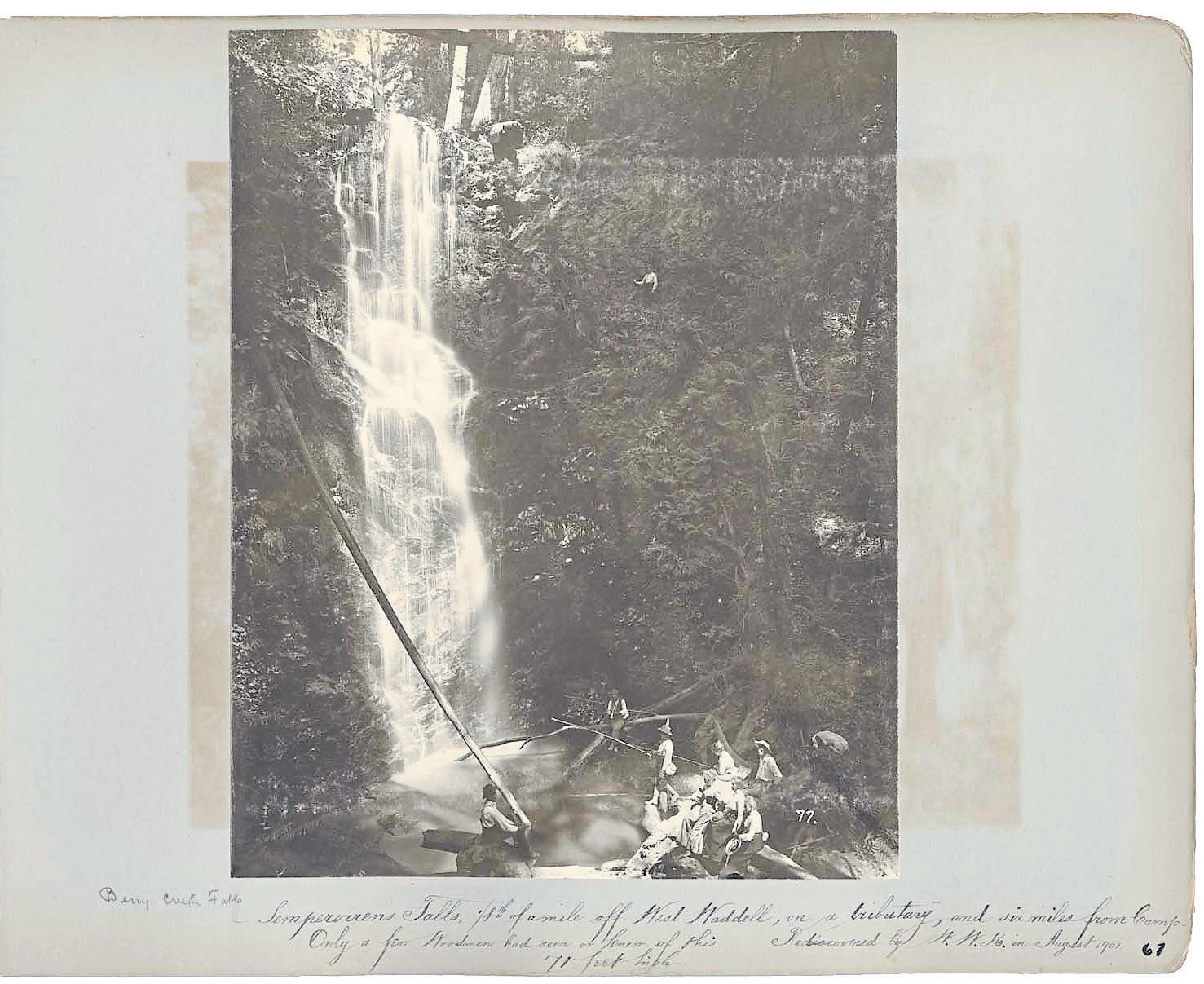

Managed by the state, special districts and the U.S. government as well as by counties, cities, nonprofits and other entities, these parks offer a seemingly infinite number of things to discover and to do, including in wilderness areas only minutes from busy cities and suburbs.

The best part is that with our mild Mediterranean climate, people can hike, bike, ride horses, rock climb, surf, hang glide, bird watch and study plants year-round — even in cold-weather months. Especially in cold-weather months, even, since, thanks to the ever-climbing summer heat, a November hike in the Bay Area can often be infinitely more enjoyable than one in late July.

Many of our Bay Area parks engage with history, culture and the people who’ve lived here, including Native Americans, Spanish missionaries, American settlers, Civil War soldiers, immigrants, Rosie the Riveters and famous writers, musicians, civil rights leaders and federal prisoners.

But it almost always starts with nature, whether it be a park that stretches across thousands of acres of redwood and oak forest or one that occupies a city block amid urban high-rises. Even parks created around historic homes, forts, ships, factories, mines or a Cold War missile site tend to be set in some of the

Bay Area’s most scenic locations. And our unique ecosystem is one reason there are so many different kinds of parks in the first place.

“I think that any story about parks in the Bay Area has to begin with biodiversity,” said Victoria Schlesinger, editor-inchief of Bay Nature Magazine.

“It’s that biodiversity that is born out of our really dynamic, diverse habitats in California and specifically in the Bay Area. Those habitats are the reason we all love parks here.”

Parks also wouldn’t exist here in such abundance if communities had not come together, in a very organic way, to protect favorite outdoor spaces for the benefit of the public, said Jessica Carter, director of parks and public engagement at Save the Redwoods League. “Parks and natural public spaces are a really integral part of the greater Bay

Area landscape and culture,” she said. “You don’t have to go far to find a park and people enjoying time outdoors in a wide variety of ways that are meaningful to them.”

The desire for public parks actually originated from the revolutionary ideals on which this nation was founded, said Breck Parkman, a retired senior archaeologist with the California State Parks. By the mid-1800s, “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and “all men are created equal” translated into a growing imperative here and nationally to protect the natural environment, both for its own sake and for people’s health and happiness. Over the past century, residents in the Bay Area have shown their willingness to devote public money and other resources to create and maintain parks for the common good.

“The populace here has

always been so much more aware and so consistently supportive of conservation efforts, voting over and over again to support these things, and the result of that is we just have some of the most spectacular public parks in the country,” said Sara Barth, executive director of the Sempervirens Fund. Given the history of Silicon Valley innovation, local parks enthusiasts also have been pretty inventive in devising ways to protect, fund and manage these resources, she added.

It’s hard to conceive of a time when public parks did not exist. From ancient Persia to Renaissance Europe, only royalty or the very rich had access to lush gardens and vast tracts of land for leisure and sport. Industrialization in the 1800s changed that, with the establishment of large urban parks in London, Paris, New York and San Francisco to offer a respite to overcrowded conditions.

Transcendentalist writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau rhapsodized over nature representing the divine spirit of God. Similarly, religious leaders on both coasts urged the growing middle class to travel to the countryside to hike, camp and experience a sense of spiritual renewal and improved physical health, according to Kevin Starr, the late historian and California state librarian.

In 1860, Rev. Thomas Starr King, the newly appointed minister of the First Unitarian Church in San Francisco, returned from a transformative

trip to Yosemite, writing and preaching about the need to protect it from encroaching civilization. He and others convinced Abraham Lincoln, amid the horrors of the Civil War, to sign legislation making Yosemite the first wilderness area in the United States set aside for preservation and public use. Initially ceded to California to be its official first state park, Yosemite reverted back to federal control in 1906.

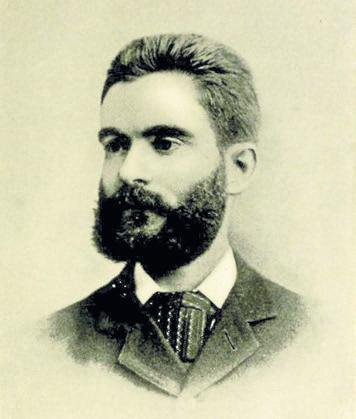

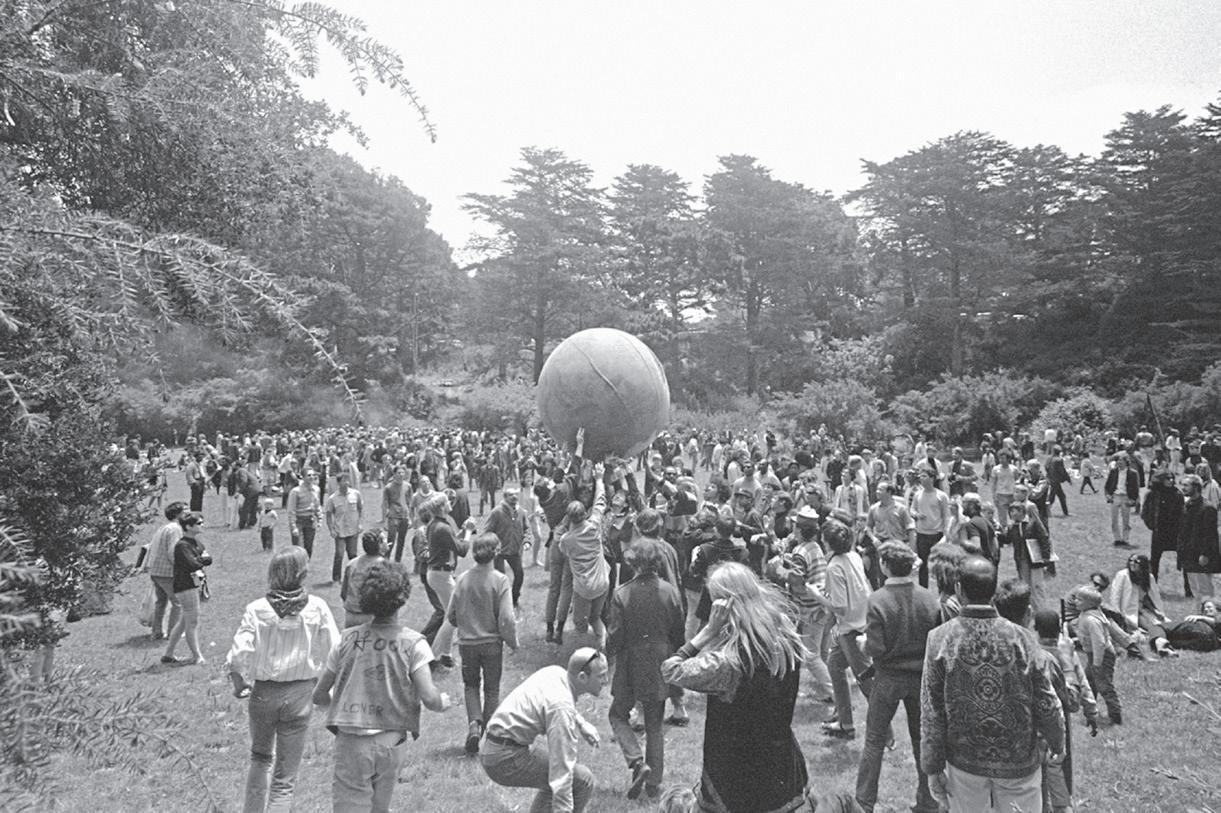

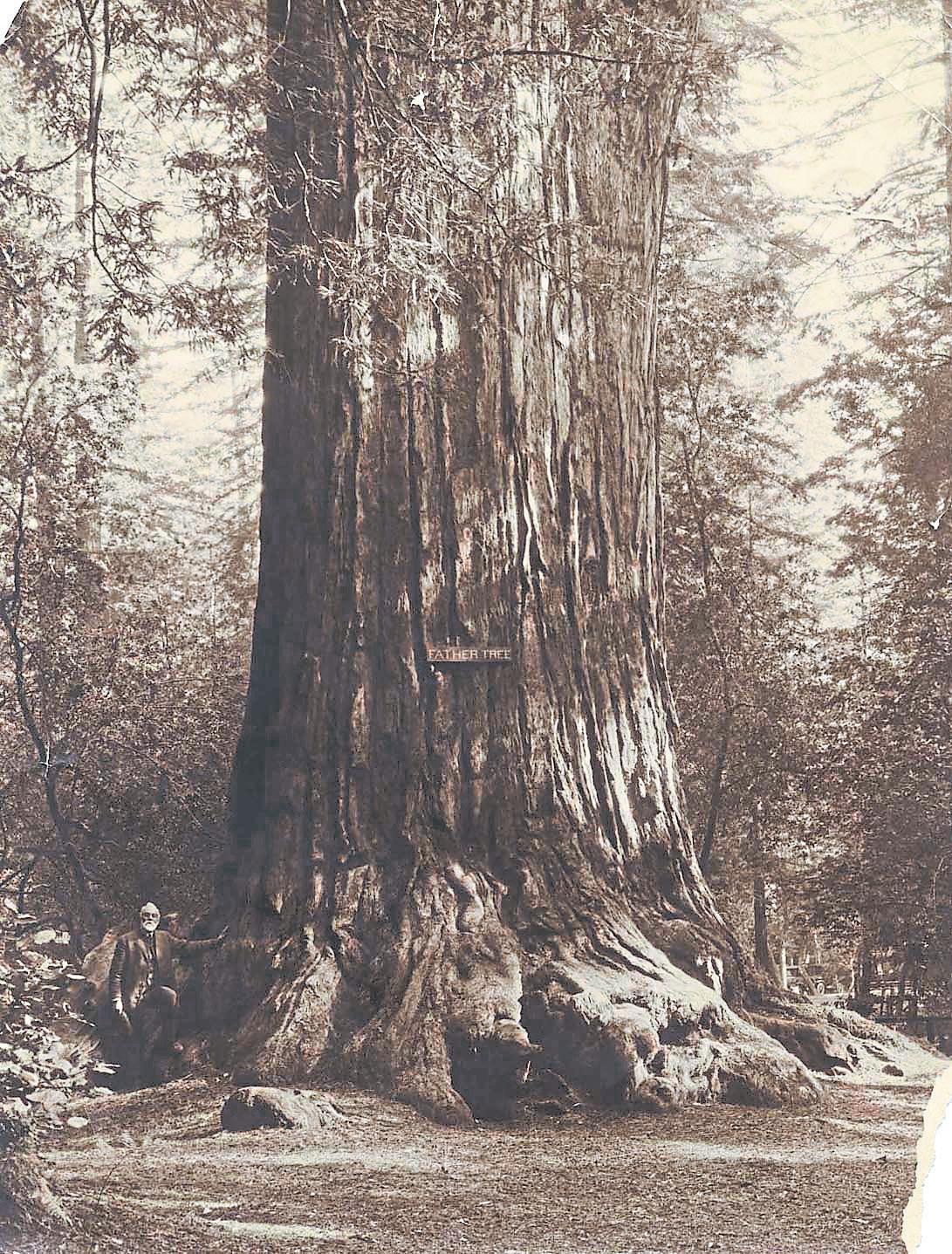

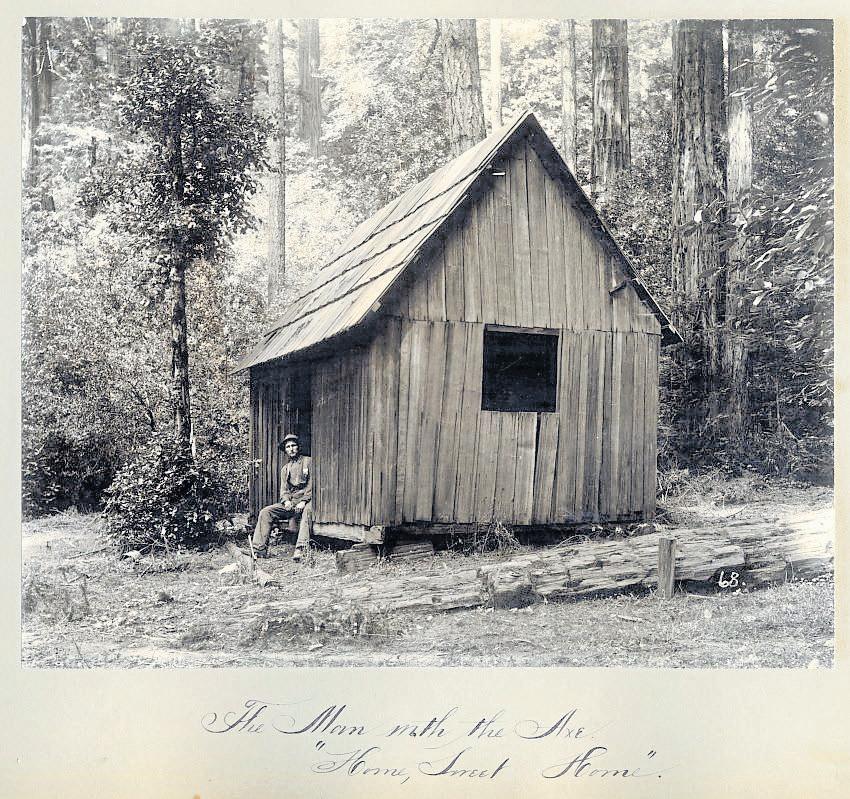

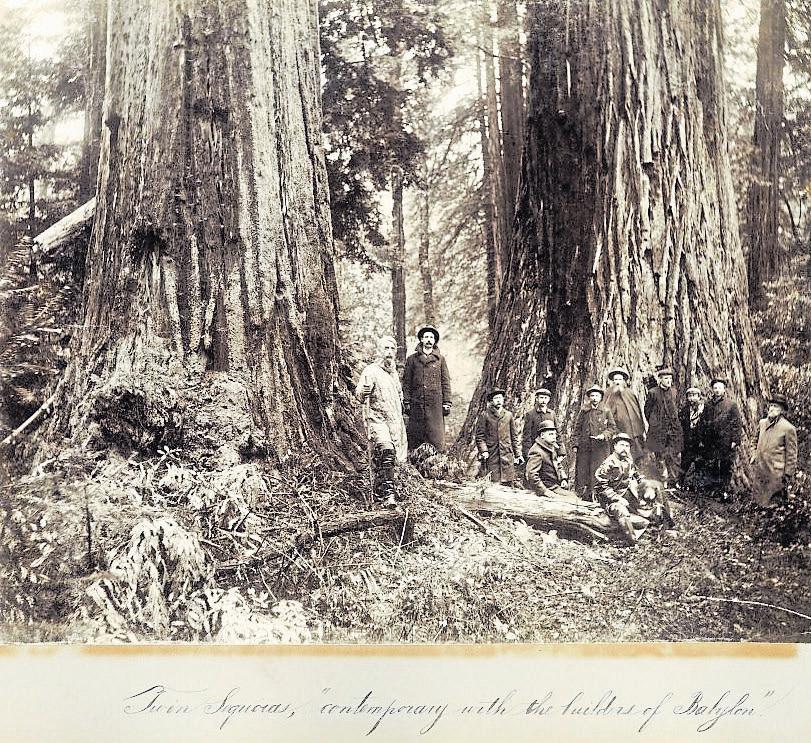

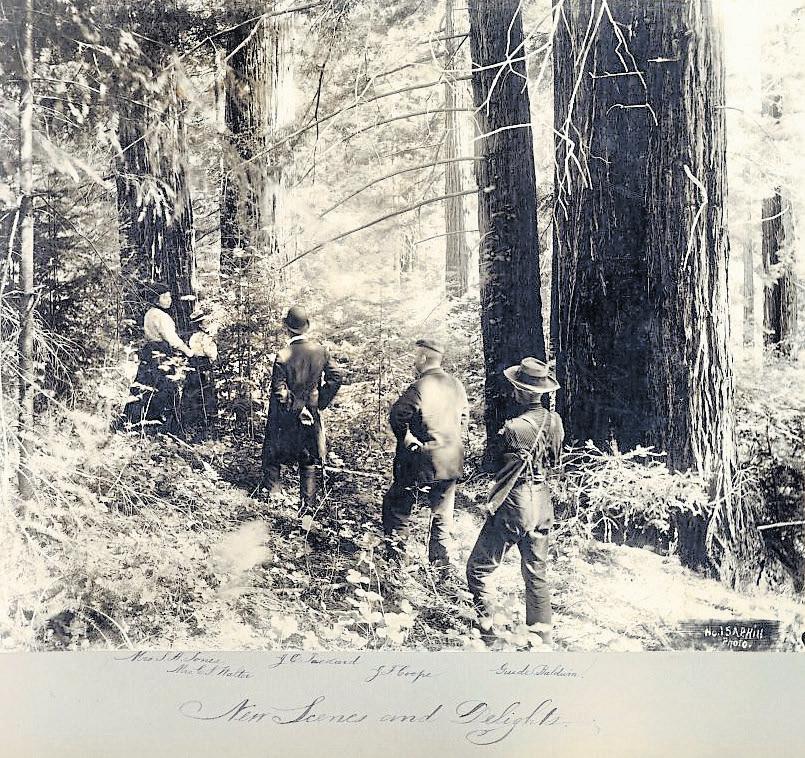

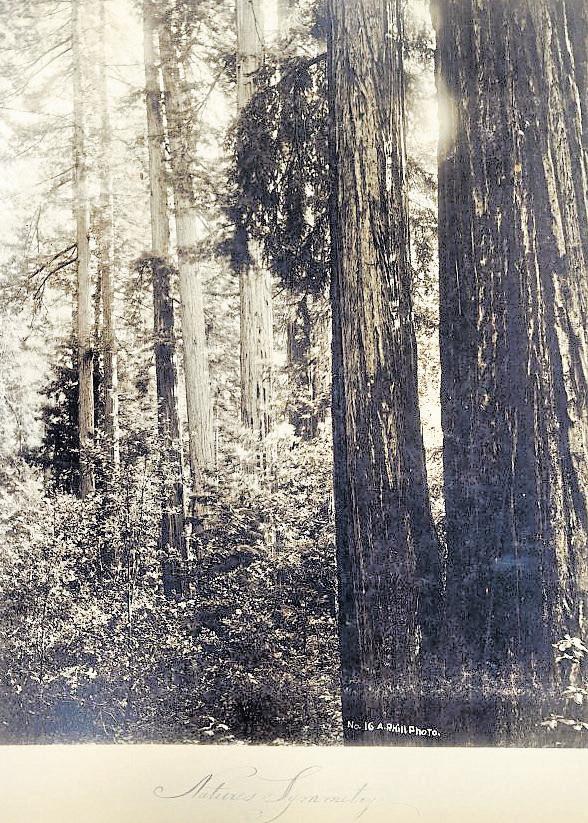

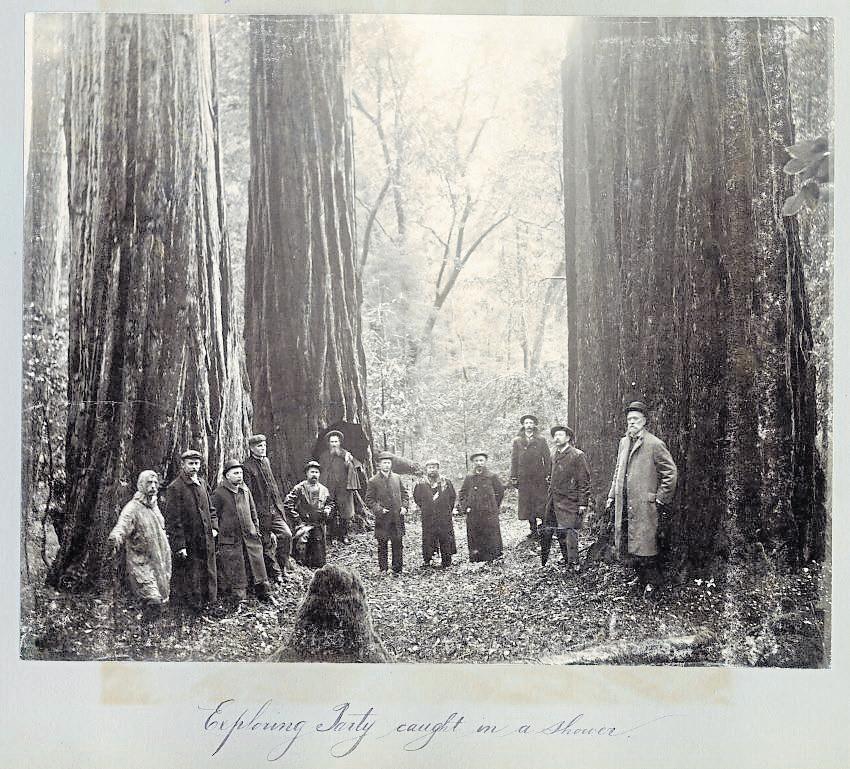

In the Bay Area, John Muir and other early naturalists soon turned their attention to another precious California resource: coastal redwoods. Indeed, concern about rampant logging in the Santa Cruz mountains, following the Gold Rush and the opening of the transcontinental railroad, ignited the region’s parks movement, according to Barth.

As people started to realize that this once “vast, unending

forest” could soon disappear, a “real shift in mindset” occurred, accompanied by a growing appreciation of the trees themselves “as a remarkable feat of nature to be in awe of and to celebrate,” Barth continued. With a focus on saving oldgrowth forests in Big Basin, San Jose photographer Andrew P. Hill and the newly formed Sempervirens Club lobbied the state to purchase 2,500 acres there to open a park in 1902.

Another Bay Area nonprofit, the Save the Redwoods League, took the battle for forest preserves statewide, leading

California to establish a statewide parks system in 1927.

The following year, the public overwhelmingly voted for a $6 million bond to acquire more land for state parks. This new system also would include historic and cultural sites around the Bay Area, such as the Bear Flag Monument and General Vallejo’s Petaluma adobe in Sonoma County.

“It’s like they tossed this rock into a pond, and the ripples were not just the protected acres at what is now Big Basin, but it spurred the creation of a state park system here in California,

which became a model for what other states have since emulated,” Barth said.

Meanwhile, Bay Area cities, towns and counties also got into the parks business, if only to create leafy town squares as civic gathering spots. San Jose had grander ambitions, turning more than 700 rugged acres in Alum Rock Canyon into one of the state’s first municipal parks just two years after San Francisco opened Golden Gate Park in 1870.

The Great Depression in the 1930s provided impetus for even greater parks expansion. Franklin Roosevelt initiated the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Work Progress Administration as part of the New Deal, putting destitute Americans to work by building roads, dams, bridges, libraries, schools — and parks.

Even during this national crisis, “Americans rolled up their sleeves, stood shoulder-to-shoulder, and worked to improve our nation,” Parkman said. The WPA upgraded municipal parks in San Francisco, while also building Berkeley’s aquatic park and rose gardens there and in San Jose and Oakland.

Meanwhile, the “CCC boys” installed stonework camp stoves and the Summit Museum at Mount Diablo State Park and built trails and the fire lookout on top of Mount Tamalpais. They also crafted the historic, wood-timber headquarters building at Big Basin State Park, which sadly was among buildings destroyed in the CZU

Lightning Complex wildfires of 2020.

The original CCC and WPA labor also were crucial to the establishment of the East Bay Regional Parks District. Launched in 1934, this special district became a national model for how to balance public access with protecting thousands of acres of watershed, experts say. For four of the original parks — including Tilden and the future Dr. Aurelia Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park — CCC and WPA

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

workers built trails, restrooms, bathhouses and even a botanical garden in the hills above downtown Oakland. More than 90 years later, the district has expanded to 73 parks in Contra Costa and Alameda counties, encompassing vast wilderness areas, major reservoirs, historic buildings and scenic shorelines.

The environmental movement of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s spurred the next wave of major conservation efforts. Santa Clara County formalized its parks

department in 1956 to eventually encompass 28 parks, including Almaden Quicksilver County Park, Guadalupe Reservoir and Joseph D. Grant County Park. The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space was founded in 1972 to create a future 70,000acre “greenbelt” of wetlands, grasslands and redwood forests stretching across San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.

That same year, a consortium of local residents, conservation groups and politicians suc-

cessfully lobbied for a federal bill, signed by Richard Nixon, to establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. The bill allowed the National Park Service to buy up some of the Bay Area’s most spectacular real estate from the U.S. Army, eventually opening public access to Alcatraz, the Marin Headlands and the Presidio. The GGNRA, which also includes Fort Point, Crissy Field and Muir Woods, is now one of the largest urban park areas in the world.

To be sure, parks here face challenges, including threats from wildfires, periodic budget cuts and, more recently, political intrigue in Washington, D.C. But they also continue to expand and evolve, with periodic news about a park acquiring new acres of open space or creatively reclaiming land in a former military base, industrial area or even under a freeway. These days, parks serve as hubs for public education and research on environmental sustainability and strive to make themselves as accessible as possible to the largest number of people. As Barth put it, parks don’t “just happen.” And even once a park is established, managers have to help people “experience it in different ways as recreational needs change,” she said, adding, “It’s an ongoing process.”

There’ll be glad glidings this holiday season at skating rinks around the Bay

BY JASON MASTRODONATO

While the Bay Area might not be known as a hotbed for sports played on ice, there’s a magical transformation that takes place each year around the holidays.

The number of ice skating rinks nearly triples, even though temperatures rarely drop below freezing. For at least two months a year, the outdoor pop-ups are hosting children learning to skate for the first time, lovers sharing a romantic date night and friends of all ages taking a spin while holiday tunes fill the air.

In San Ramon on Nov. 9, Olympic gold medalist Kristi Yamaguchi kicked off the ice skating season by opening her holiday ice rink at City Center Bishop Ranch for the fourth consecutive year.

Yamaguchi, who grew up in Fremont and graduated from Mission San Jose High School, became the first Asian American woman to win a gold medal in figure skating at the 1992 Olympics in France. (She met her future husband, ice hockey player Bret Hedican, at the Olympics, too.)

Last season, she hosted an ice skating clinic for kids and holiday events that benefited her Always Dream foundation dedicated to providing books to low-income families.

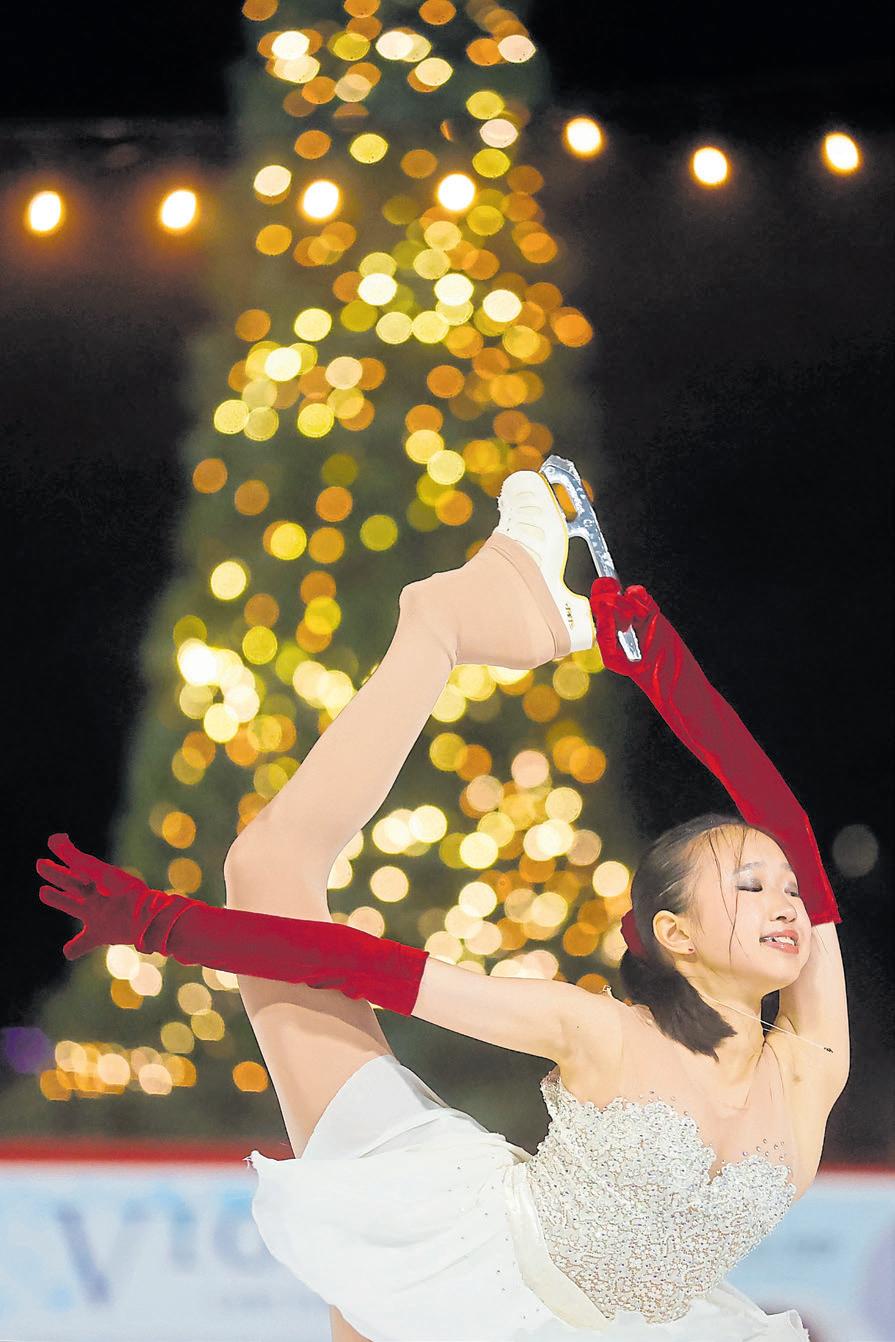

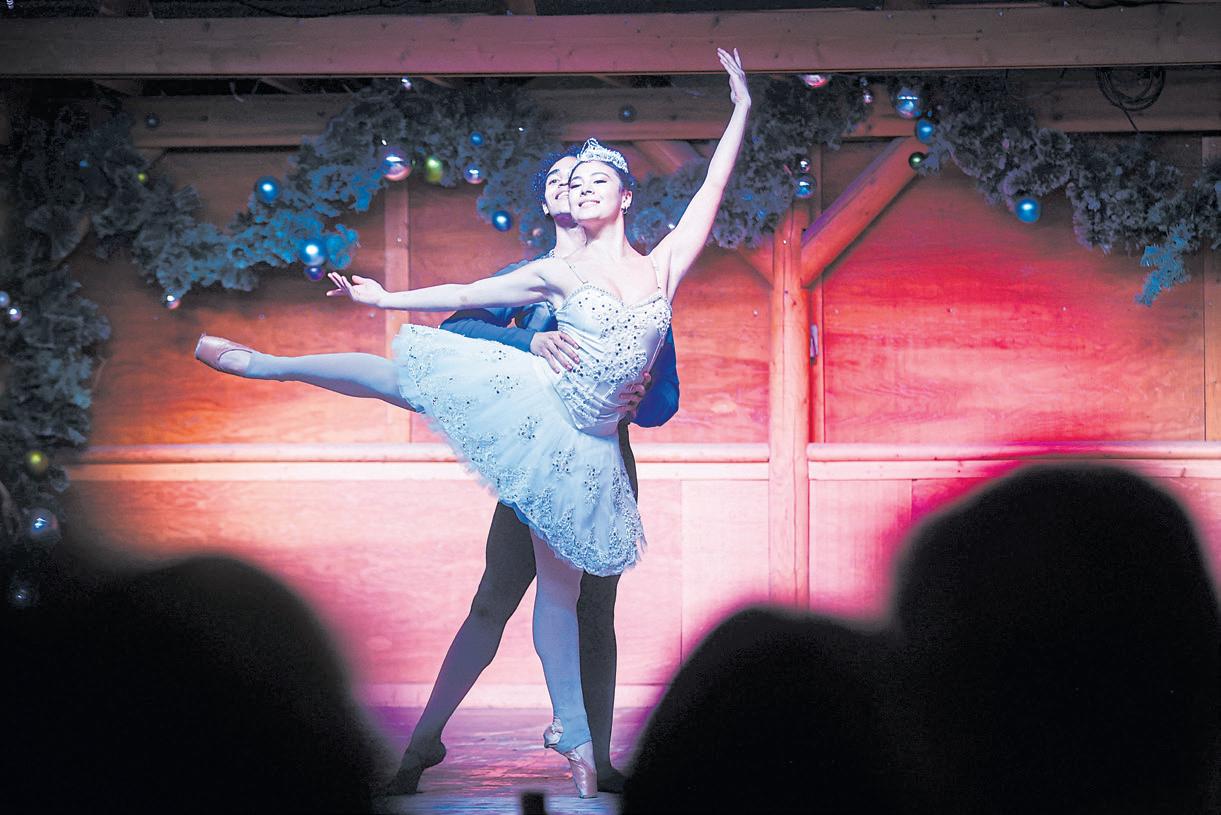

Above: Zoe Huynh skates for Silicon Valley Ice Skating Association’s Gala In the Stars at San Mateo Ice Rink.

SHAE HAMMOND/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Right: Olympic figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi helps a novice skater during Yamaguchi’s Always Dream Foundation event in 2018 in San Jose.

DAI SUGANO/STAFF ARCHIVES

Each year, Bishop Ranch’s restaurants and breweries up their seasonal game with holiday beers and cocktails, while coffee and hot chocolate can be found at the center’s cafes, including Philz.

Holiday pop-up stores are often erected while the ice skating rink hosts ugly sweater competitions, Disney-themed costume nights and Taylor Swift nights.

And don’t miss a visit with Santa, who can be found posing for photos and giving out gifts at the ice rink beginning on Black Friday. During the Christmas season, he appears every Saturday and Sunday as well as on select Fridays.

Details: Open Nov. 7 through Jan. 4 at 6000 Bollinger Canyon Road in San Ramon; citycenterbishopranch.com.

But Kristi Yamaguchi Holiday Ice Rink isn’t the only ice skating haven that disappears when the holiday magic has faded. A few of the ice rinks below are available to skate on throughout the year, but most of them are seasonal. So to get into the spirit while you can, hit one of these rinks this season:

Outdoor ice rinks abound during the holidays, but Palo Alto’s Winter Lodge — the Peninsula’s go-to ice skating destination since it opened in

1956 — is open from Oct. 18 all the way through April 12. Both public sessions and classes are available. Things get festive when the holiday tree goes up the week after Thanksgiving. (It’ll stay up through the first week of the new year).

Details: Open skate sessions are by reservation at 3009 Middlefield Road in Palo Alto; winterlodge.com.

The 18th annual holiday celebration at Union Square will once again feature a festive

ice rink to host events such as Drag Queens on Ice (Dec. 4), a silent skate party (Dec. 11) and ‘80s-themed Friday night celebrations (second Friday of each month). And don’t forget about the New Year’s Day Polar Bear Skate, which follows the Canadian tradition of wearing swimsuits or creative beach attire on the ice, with prizes awarded for the most innovative looks.

Details: Open 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. daily from Nov. 5 through Jan. 19 at 333 Post St. in San Francisco; unionsquareicerink.com.

It’ll be snowing in Napa once again this winter, as the Napa Valley compound creates its own flurries for folks skating in the largest outdoor ice skating rink in Wine Country. There are also igloo and fire-pit experiences, the “Santa’s Tavern” pop-up serving hot toddies and holiday cocktails and visits with Santa and some favorite princesses available for the kids. New this year are hands-on workshops that teach families to make gingerbread houses and wreaths as well as a cocktail mixing class for couples.

Details: Open 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily, Nov. 25 through Jan. 4, at 875 Bordeaux Way in Napa; napavalley.com.

Right in the middle of the Winter Lights festival, this fully synthetic ice rink requires no energy or water to maintain, while allowing a smooth surface perfect for beginners. It kicks off the day after Thanksgiving with a tree-lighting celebration on Courthouse Square, holiday treats and visits with Santa.

Details: Nov. 29 through Dec. 28 at Old Courthouse Square in Santa Rosa; downtownsantarosa.org.

This year will feature the 20th anniversary celebration of Walnut Creek’s seasonal outdoor rink, which offers cozy rinkside fire pits for rent during your

Malila Becton, from Oakland, skates with her children Yaxche, 6, and Avo, 4, at the Kristi Yamaguchi Holiday Ice Rink at City Center Bishop Ranch in San Ramon.

NHAT V. MEYER/ STAFF ARCHIVES

skating session and ice slide tubing. Special events often include pickup hockey games, a cafe and more.

Details: Open Nov. 21 through Jan. 16 at Civic Park on 1365 Civic Drive in Walnut Creek; walnutcreekonice.com.

An outdoor pop-up rink offers free community skate days on select days through the season. Tent for parties available to rent.

Details: Open Nov. 14 through Jan. 11 at Central Park on 50 E. Fifth Ave. in San Mateo; onicerinks.com.

Smack in the middle of Circle of Palms Plaza, between the San Jose Museum of Art and Signia by Hilton Hotel, Downtown Ice is back for its 32nd holiday season.

Details: Open Nov. 21 through Jan. 15 at 120 S. Market St. in San Jose; sjdowntownice.com.

The annual Winter Wonderland invites guests to visit a garden transformed into a magical fantasyland for kids of all ages. At the outdoor skating rink, there’s snow, music, snacks and hot cocoa. This year, the center is celebrating its 80th anniversary. Keep an eye on the website for exact WinterFest dates when they’re announced.

Details: Dates to come at 30 Sir Francis Drake Blvd. in Ross; maringarden.org.

The indoor ice rink is open all year and provides public skating, lessons, drop-in hockey games, freestyle hours and other special events.

Details: See website for the full schedule at 519 18th St., Oakland; oaklandice. com/

Public skating, private lessons, adult hockey, broomball and other events are hosted at both TriValley Ice locations all year.

Details: TriValley Ice, 7212 San Ramon Road in Dublin and 6611 Preston Ave. in Livermore; dublinice.com.

Busting the myth that the Bay Area has no cold-season colors

BY JOHN METCALFE

If Vermont has leaf peepers, what does California have? Redwood watchers? Cactus contemplators?

It turns out you don’t need to fumble with semantics. California has leaf peepers, too, they’re just working on a more subtle level. And as with the later months of the year on the East Coast, you’ll find them out in force right now, basking in the vast changing of colors: from summer’s green to brilliant yellows, electric blues, deep purples and lipstick reds.

Folks who don’t notice the West’s seasonal color shift are “not looking very hard,” says Lara Kaylor of CaliforniaFallColor.com (motto: “Autumn Happens Here, Too”).

Kaylor is the website’s self-described “Leaf Peeper in Charge” who manages a network of 100-plus “color spotters” sending in tips from all over California. (Become one by emailing editor@ californiafallcolor.com.) From the gold of quaking aspens in the mountains to the blush of a mushroom poking through forest duff, she maintains an up-to-date log of fall displays in California, so hikers and photographers can plan leaf-peeping trips.

“It’s a very, very different type of fall color. It really is not an apples-to-apples comparison” to

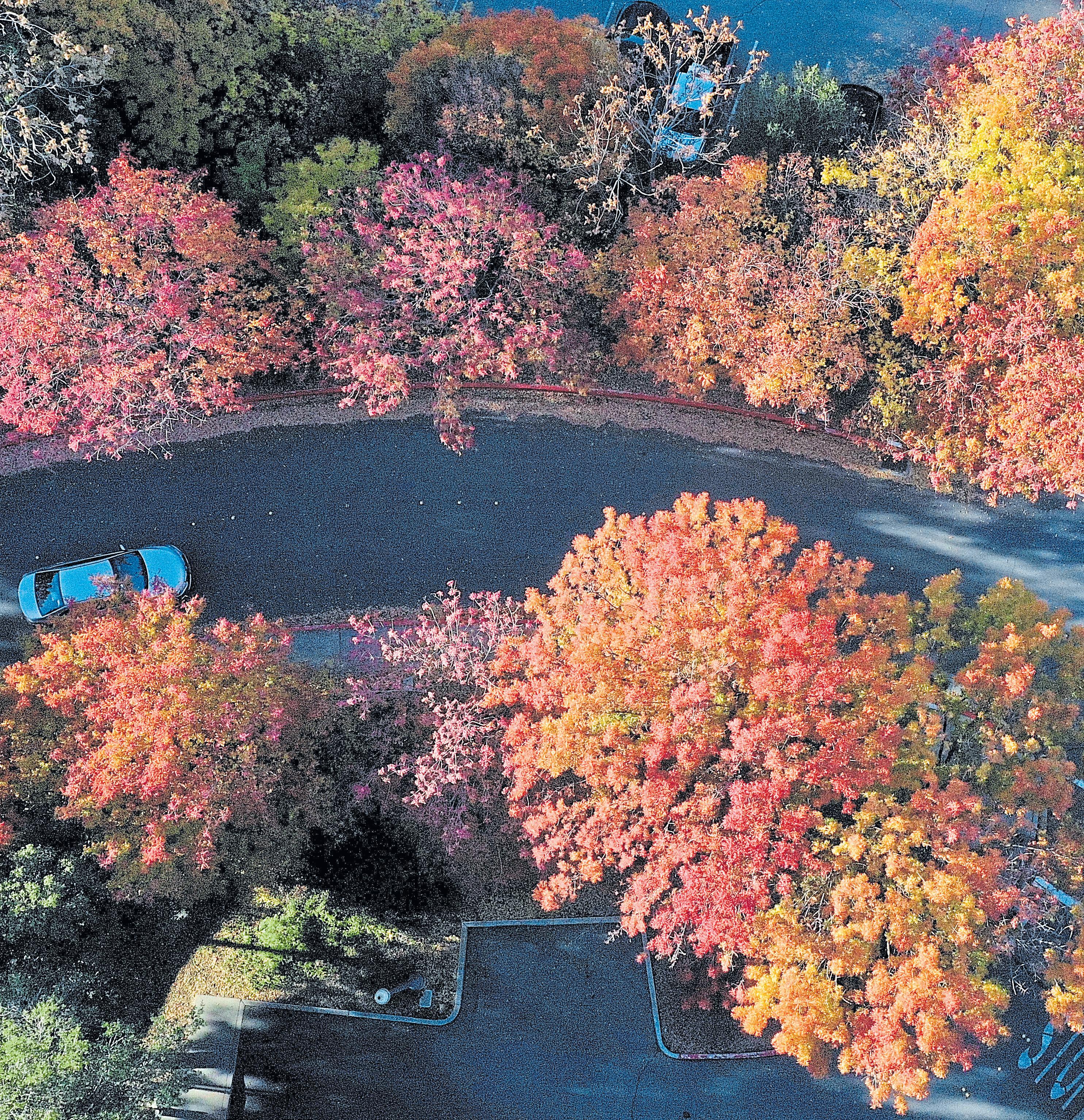

An aerial view above Clayton reveals a fall burst of color.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

other places in the U.S., says Kaylor. “On the East Coast, you’re driving down the highway, and it’s just swaths and swaths of trees. Fall color in California is more like sections of color. And a lot of times they’re set up against dramatic landscapes, like around a lake by a mountainous backdrop.”

Generally speaking, trees in Northern California begin changing color at the end of summer in the higher locations first. From the mountains the change trickles down to lower regions, descending at a rate of 500-1,000 feet a week. By November, fall color has spread to the flatlands and coast and also to vineyards, which are innumerable but often forgotten.

Timing depends on a few things, such as the temperature and precipitation from as far back as a year ago. “Our winter and spring was near-average to average for 2024 to ’25,” she says. “So we’re expecting things to be pretty much on track this year.”

Ready to get out and start peepin’? (Please don’t phrase it that way if you run into the police.) Here are a few tips that might prove helpful.

Just like zoos are concentrated displays of animal diversity, arboretums and botanical gardens are prime spots to see many types of plants undergo transformations.

“The University of California’s Botanical Garden in Berkeley is a great place to see fall color starting in October and

November, depending on the weather,” says Holly Forbes, a recently retired curator for the garden. “The Asian Collection is especially nice with maples and dogwoods, among many other plants with fall color. The Eastern North American and Mexican/Central American collections also offer fall color shows.”

In the South Bay, there’s plenty to observe during changing seasons. “If you just use all

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/ STAFF ARCHIVES

of your senses while you’re out in nature, there’s a lot to take in,” says Leigh Ann Gessner, public affairs specialist for the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District.

With 25 open-space preserves throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains area and 250 miles of trails, Midpen delivers a full-force fire hose of autumn’s glory. (It also offers fall-themed outings with volunteer naturalists to offer the public deeper

connections with nature; check the schedule at openspace.org).

“Birds migrate through our area or to our area to overwinter, and fall is a really great time to look and listen for them,” says Gessner. “You can even notice how the angle of the light shifts as the season is changing, and the sky seems a deeper blue. And just a different smell flutters around you — either on a warm fall afternoon or even after some of those first rains,

you’ll have some really rich smells.”

The Bay Area’s natural color palette: What to look for and where to go

RedSome of the loveliest fall displays are put on by pickleweed (Salicornia), a low-lying succulent that thrives in salt-marsh habitats. This plant turns bright red as the season shifts. It’s an

important food source for the Bay Area’s endangered (and cute) salt-marsh harvest mouse.

A showy plant is toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), which has red berries in December. They look like cinnamon Red Hot candies clustered on branches. A scenic place to admire them is on Summit Road leading to the top of Mt. Diablo.

Hollyleaf redberry (Rhamnus ilicifolia) fruits in September through November. They are little globules of bright red and are often found in higher-up locations.

California fuchsia (Epilobium canum) blooms can be found through December. They’re native to the California foothills and coastal areas and look like garish trumpets — thin

tubes expanding into vibrant red mouths. They’re also called Hummingbird Flowers, because the birds can’t get enough of them.

Grape leaves transition to orange, fiery red and even purple before the vines go dormant for winter. Napa and Sonoma and other wine-making regions are the obvious picks for peeping them. But the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District has its own remnant vines preserved as public attractions.

“One that comes to mind is Bear Creek Redwoods Preserve, which is in the South Bay near Los Gatos,” says Gessner. “Before it was a public open space, it was a place where people went to study to become Catholic priests. They made wine, so they grew grapes out there. And we have an arbor with some of the wine grapes on it from that time (in the 1930s-1950s).”

And crimson hues are found everywhere in the Bay Area, thanks to a plant you should admire from afar: poison oak. “Some of the most striking fall colors are displayed by poison oak, which turns pink and brilliant red in the fall — and makes the itchy plant much easier to pick out from its neighbors,” says Gessner.

“Despite its bad reputation, poison-oak berries are a great food source for native birds migrating south for winter, and the plant is very pretty to look at.”

One of the few native trees in the region that provides “classic” fall colors is the bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum). The leaves turn yellow and gold in the autumn, and some get as big as dinner plates. Bigleaf maples thrive in moist conditions like creek corridors and among redwoods.

Ginkgo trees, aside from

being a source of stinky nuts, undergo a seasonal yellowing that some refer to as “Golden Week.” They’re well-adapted to urban environments and often are planted as street trees. You’ll find clusters of them from Oakland to Mountain View to Alameda, where locals call the carpets of wind-blown leaves “Alameda snow.” (It’s the one time you’ll want to play in yellow snow.)

Ready for something completely different? Heermann’s Tarweed is only found in California and has yellow, fractal-like blooms that last into November. The plant is sticky to the touch and smells like pine resin and cocoa butter. Fun fact: It was named for naturalist Adolphus Lewis Heermann, who perished while hunting after stumbling and shooting himself with a rifle.

Many plants have quiet explosions of white blossoms in cold weather. Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) produces white to cream-colored flowers, and the seeds later puff up into furry masses to give the bush an animalistic appearance. You can find these all over but especially in the East Bay.

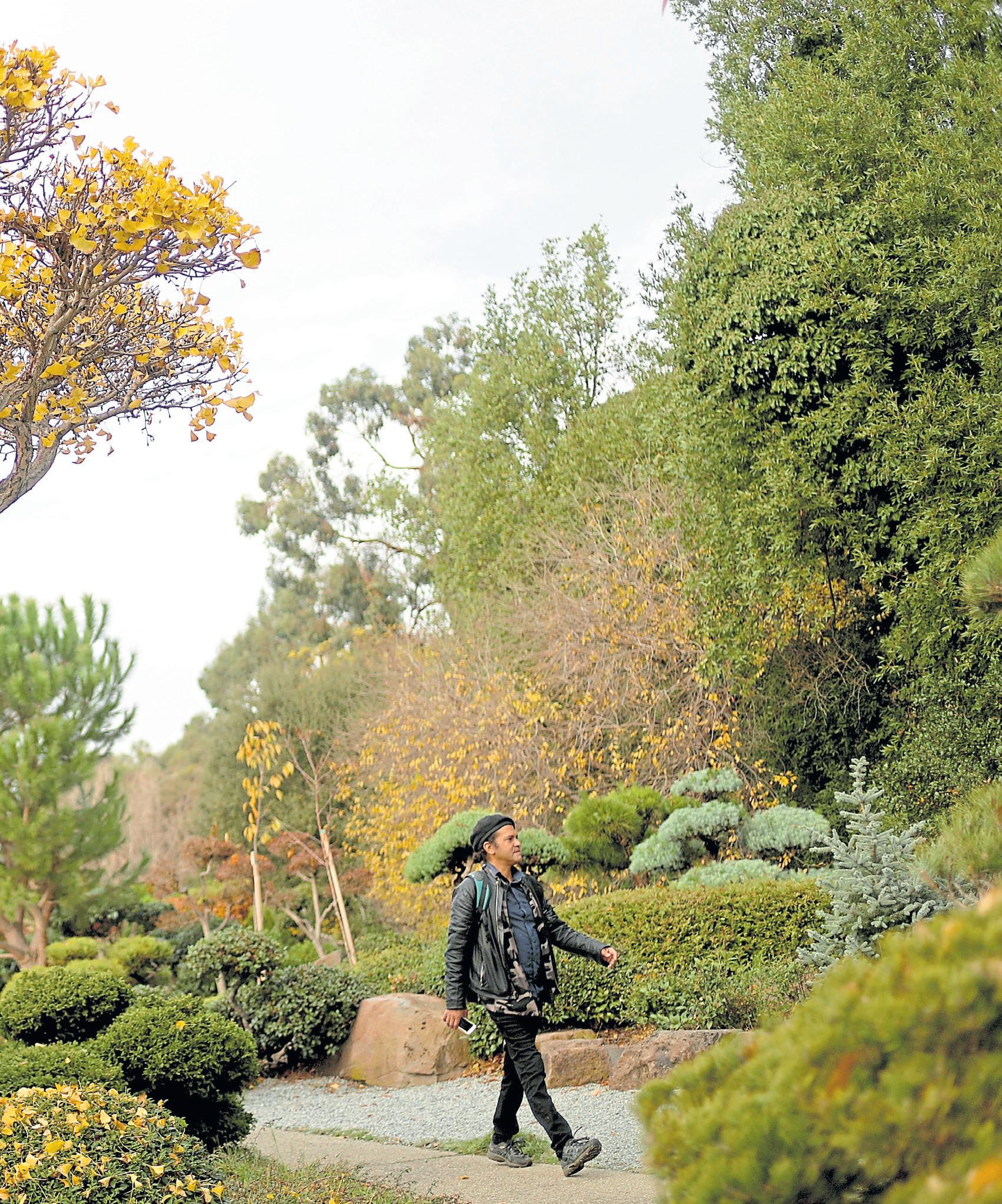

Colorful leaves surround a visitor in Hayward’s Japanese Garden.

ANDA CHU/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Coast silk tassel (Garrya elliptica) blooms in January with white flowers hanging down in clusters that look like strings of garland. It’s quite pretty — like a living version of winter icicles. Look for these around Mt. Diablo and in the Berkeley hills.

Milkmaids (Cardamine californica) are another early bloomer starting in January and continuing into spring,

depending where they grow. They are small and white and look like lost stars. They grow all over, with many sightings in the North Bay around Mount Tam.

The hilly East Bay is prime habitat for colorful birds. “We have scrub jays with their blue feathers and acorn woodpeckers with a splash of red on their heads,” says Sharon Peterson, an interpreter at Mount Diablo State Park. “They have a redand-black patch on the back of their head and are very vocal and live in family communities. They have kind of funny faces.”

Monterey Bay sometimes sees orange-and-black monarch butterflies migrating at the end of the year. The city of Pacific Grove — nickname, “Butterfly Town, USA” — maintains a Monarch Grove Sanctuary to host these beautiful, endangered creatures. Monarch season there typically reaches a peak from November to January.

Bulging masses of insects might or might not be cute, but they are undeniably colorful. During the winter, groups of ladybugs (technically known as “lovelies”) can be found huddled for warmth and six-legged company in many regional parks. A famous one is Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park in Oakland, where the bugs like to convene (probably following last year’s pheromones) at the intersection of the Stream and Prince trails.

An uncommon color in nature — electric blue — is stirred up in local waters, thanks to bioluminescent plankton. Though it tends to appear with more force during warmer months, this Aurora Borealis of the ocean can be observed well into fall. Outfitters rent kayaks to observe the phenomenon from above, with fish and seals making trails of pale fire in the water. (To name a couple, there’s Blue Waters Kayaking near Tomales Bay and Kayak Connection near Monterey.)

Suffer six cold-weather hikes and reap the rewards

JOSIE LEPE/STAFF ARCHIVES; RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

BY JASON MASTRODONATO

Poison oak in shades of green and red guard the aromatic bay trees on one side of the paved pathway along Lake Chabot, while a steep drop off to the water looms on the other.

Beyond the trees to the right is another world entirely, a dense park full of side quests and wildlife. At one point, a handsome buck came within viewing distance of the trail before it sensed a camera lens and ran back into the brush.

On the lake to the left, four people lounged on a lazy pontoon boat. Fishermen huddled on a nearby pier. A man with rolled-up sleeves and dirt under his fingernails was winding his reel. Patches of green and brown land covered the rolling hills behind the water.

We took this hike on a sunny day in September, but it’s easy to see why it’s a top pick for a great place to go during winter months. Imagine fog settling over the lake and a cool breeze coming off the water. And with gravel pathways that should be just as reliable during wet seasons, this hike made the top of our list of great cool weather hikes in the Bay Area.

About a mile into our walk along the East Shore Trail, we heard a woman yelp. As we got closer, she pointed to the water.

“A wood duck!” she yelled. “I’ve never seen one here before.”

Gleefully sure of her finding, she bid us adieu and continued walking down the path until all was quiet again. The serenity of

Lake Chabot is built around this dichotomy: large periods of isolated quiet occasionally interrupted by pleasant social interaction.

Most of the hike is along a paved pathway, making it good for any weather.

Early morning hikers report fog and a cool breeze off the lake, with temperatures getting as low as the 30s in the early morning of winter months. Catch it in the early afternoon in the summer or fall, and you’re bound to get sweaty and perhaps even a little sunburned.

Without too much elevation, Lake Chabot is welcoming for folks of all ages and fitness levels. A walk completely around the lake’s perimeter is 10 miles, but it’s not necessary to go that far.

Start at the marina cafe and head northeast up the East Shore Trail for the easiest adventure, with almost immediate payoffs of amazing views of the water.

There are outhouses every half-mile or so and a few opportunities to veer off the path to go explore the shaded areas of the park.

Maybe a half-mile in, just before Catfish Landing, keep your eyes peeled on the hill to your right, and you’ll stumble into an isolated picnic table surrounded by old trees. It’s beckoning for a romantic lunch or a quiet meditation break.

Another half-mile in and you’ll reach a brief, tree-lined excursion that leads you around a short bend, then out the other side with a brand new view of the water. It’s called Raccoon Point.

There are benches on high land with perfect views and sunshine on a warm day. And a few more benches along the water below.

We stopped here to rest and have a snack. The

Hikers take in the view of the San Francisco Bay at sunset from Coyote Hills Regional Park

DAI SUGANO/STAFF

dogs appreciated the shade underneath a tree. On a cool morning, the mist over the lake could make for a particularly refreshing break.

There’s something about braving chilly weather and enduring the elements that makes a hike particularly rewarding. In fact, there’s science behind this.

Yale University psychologist Paul Bloom wrote a book about it. It’s called, “The Sweet Spot,”

and it explores the reasons why some folks love pushing themselves through pain.

Why do people like to watch movies that scare them? Or risk total heartbreak for love? Why do runners endure 26-mile marathons if their bodies fight against them for half the race? And why do people want to climb Mount Everest when at least a half dozen die trying every year?

“If you suffer for something

that gives delight, soon the suffering itself can give joy,” Bloom writes. He talks about Type 2 fun, how it might not feel fun while you’re doing it, but it shapes the narrative you’re able to tell yourself about who you are: the type of person who can endure challenges and come out the other side.

“Some degree of misery and suffering is essential to a rich and meaningful life,” he says. He shares other ideas of why

people like to push themselves, noting the importance of the respect and admiration we receive from others. Tell your partner you hiked 8 miles in the freezing cold, for example, and they might respect your grit and determination.

Or maybe they’ll call you crazy.

If you enjoy that kind of attention — positive or negative — and want to experience some chilly Type 2 fun outdoor hikes this winter, we’ve put together a list for you. Most of these trails are paved to help prevent you from slipping into the mud during the particularly wet times of year. And they all can be adjusted for your desired level of difficulty.

Hope you have fun. Unless you’re looking for misery, in which case, we hope you hate these:

Coyote Hills Regional Park Fremont

Here’s a nice and easy place to find paved loops around marshlands and low hills across nearly 1,000 acres. You can find plenty of bird life, too, particularly during migration season. Expect to see pelicans, hawks and egrets, among others swirling the preserved wetlands. And be ready for a strong breeze, as the park is quite flat and wide open.

Rocky Ridge Trail Las Trampas in San Ramon

It’s steep, with about 1,000feet of elevation gain in the first mile, but the trail is paved and much more manageable in cool weather. Careful of the steep sections, but you’ll be rewarded with beautiful views of Mount Diablo.

There are a lot of ways to explore this one, but the Mitchell Canyon trailhead at 96 Mitchell Canyon Road in Clayton can kick off the easiest option, a gentle journey that stops before the trail becomes steep after 2 miles. At the 2-mile mark, take an optional footpath down to the creek to have a picnic, then head back.

The Back Creek Loop or the Eagle Peak Loop can provide extended difficulty with steep elevation gains, for those looking for a difficult challenge.

Hike from the foothill staging area up the rolling hills for a 6-mile journey. It’s all gravel and makes for reportedly pleasant conditions, even after it’s rained. The views of the valley can be aided by the winter fog. Dress in layers and stay alert for wild pigs and turkeys!

There are plenty of options to choose from when considering a hike through Alum Rock Park, a historical park just a few miles from downtown San Jose. The 3-mile hike along the Penitencia Creek Trail offers minimal elevation on a mostly narrow path. Hikers report that it can be too hot during the summer, making it an ideal spot to check out in cooler months. There are 13 miles of trails in total, with many offering sensational views of the city along mostly paved or hard-dirt-packed pathways.

Los Gatos’ “Fantasy of Lights” is a family tradition that shines brighter every year

BY SAL PIZARRO

For 11 months of the year, Vasona Lake County Park is a perfectly beautiful spot in Los Gatos where you can enjoy a picnic, walk the creek trail or just chill out by the lake. But every December, it’s transformed into something so wildly different, it’s easy to forget you’re in the same park.

I’m talking about “Fantasy of Lights,” the annual light display that is equal parts sentiment and silliness. It’s truly spectacular for the very young, and then for many families — including mine — it’s something you keep doing because you’ve always done it. That’s the literal definition of tradition, and that’s why we love it.

Fantasy of Lights first took place in 1999, though it feels like there never was a time without it. My wife Amy and I remember visiting it for the first time in the mid-2000s and thinking it was kitschy fun but not something we needed to do every year.

Then we had kids — and it changed everything.

There’s really nothing better than watching your kids’ eyes light up as you drive through the colorful tunnel of flashing bulbs at the start or hearing them begging you to slow down so they can see Santa Claus shoot one more one-handed basket. They sing along to the radio soundtrack, somehow managing to learn the words to obscure

of

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF ARCHIVES

every year

Christmas songs like “Dominick the Donkey” and “Mi Burrito Sabanero.”

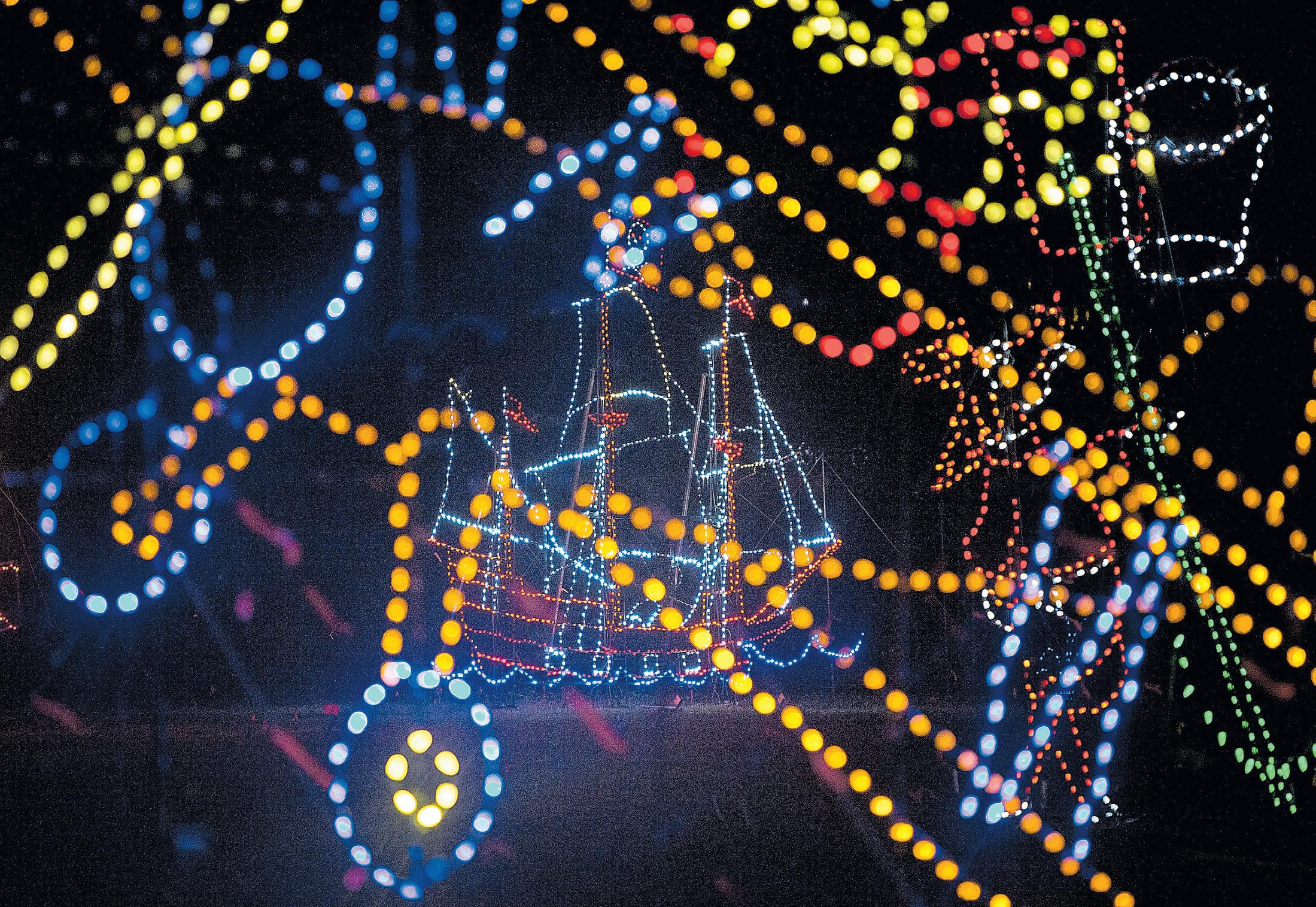

And then comes that magical moment when your kids notice the random holiday non sequiturs: Why are all these dinosaurs milling around? Why is there a volcano? Or the big pirate ship? And what’s the deal with that sea serpent?

But those have all become part of the fun, and we turn down the music and roll down our windows in the “Dinosaur Den” to listen to the jungle sounds as we creep along through a Vasona parking lot I literally would not be able to identify in the daylight.

It was during those years, when our kids were young enough to still be strapped into booster seats, that I was stunned — in the way that only new parents can be — by how many people let their kids pop up through their sunroofs to enjoy the lights. No seat belts! Too many cars with distracted drivers! What if there’s an accident? I wrote a column wagging my finger at the scofflaws and the way the county parks department basically looked the other way.

Not surprisingly, the overwhelming response from readers told me to stop being a killjoy. Nearly a decade later, I’ve softened my stance and tried my best to ignore my inner scold during the 25 minutes or so it takes to complete the mile-anda-half drive through the park. Our kids still haven’t gotten the chance to pop through the sunroof, as the roof rack on our Toyota makes such a maneuver impossible, or at least very uncomfortable. Darn.

For a holiday tradition that seems so reliably unchanging year after year, Fantasy of Lights has actually evolved quite a bit in its 26-year run. To begin with, it’s grown from fewer than 30 displays to more than 50. And nearly all of them are now illuminated by energy-saving, longer-lasting LED lights (though there are still a few

incandescents around for old time’s sake).

To celebrate Fantasy of Lights’ 15th annual edition in 2013, the Santa Clara County Parks Department added a one-night walk-through option. It was so popular that it has become its own tradition, stretching to two nights and selling out 19,000 tickets every year now. (This year’s walk-through nights are Dec. 6 and 7.) In recent years, visitors have also been given little cardboard glasses — like the old 3-D glasses at the movies — that add a snowflake or other holiday features to the viewing experience.

As the event’s popularity grew over the years, it created huge traffic jams along Blossom Hill Road, Lark Avenue and University Avenue, as families jockeyed to get in during both prime weekend evenings and on week-

When: Walk-through, Dec. 6-7; Drive-through, Dec. 9-30, 6-10 p.m.

Where: 333 Blossom Hill Road, Los Gatos

Admission: 2024 regular vehicle price, $30; 2024 walk-through price, $8-$17. Reservations required.

Website: parks.santaclaracounty. gov/FantasyofLights

week. Tickets go quickly, so it’s best to grab them when they go on sale on Nov. 1.

Above: Vasona’s holiday lights are known for their eclectic displays, including this ship firing its cannons. Left: A 90-foot twinkling tree at 2013’s Fantasy of Lights.

LIPO CHING/STAFF ARCHIVES

nights when you would think the crowds would be lighter (they rarely were). This created huge headaches for Los Gatos residents and business owners and honestly made it a lot less fun for families, who might wait an hour or more in line to get in.

So in 2016, Fantasy of Lights switched to a reservation-only system. Tickets had to be purchased in advance online for a specific day and time window — no more driving up the night you wanted to visit. There were still long lines, but they were more manageable, and it spread out the crowds throughout the

We generally aim for a Tuesday or Wednesday night around 7 p.m., leaving our house near downtown San Jose in plenty of time for another of our Fantasy of Lights traditions: grabbing dinner before to eat in the car from the Happy Hound on Los Gatos Boulevard. Nobody in the family remembers when or why we started that tradition, but it has stuck. Pro tips: Don’t try to eat a chili dog in the car, but the family size bag of fries is a must. Last year, the parks department decided to shake things up and changed the configuration in a major way for the first time, even moving the dinosaurs from their traditional spot. Feedback was good enough that they’re keeping it that way for this year, and within a few years, there’ll be a whole new generation of families visiting who won’t even remember the way things used to be.

As our kids get older — and closer to flying away from home altogether — we’ve already lost the annual photo with Santa, and they’re starting to grumble when I put on “Miracle on 34th Street.” But this may be one holiday tradition we hold on to for as long as we can — or at least until one of them can drive, and I can try to fit myself up through the sunroof.

Winter is the best time to discover what California’s elephant seals can teach us about life

BY JOHN METCALFE

What can an elephant seal — a 4,000 pound, bellowing monstrosity that looks like a melted Yankee Candle — teach us about the world?

Plenty, it turns out.

“The animals are amazing. I mean, everything they do is extreme,” says Daniel Costa, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. “They’re the deepest-diving pinniped and they dive for longer than any other seal or sea lion. They also fast for longer. Everything they do is just pushing the limits.”

In the Bay Area, one of the best places to observe elephant seals is Año Nuevo State Park in San Mateo County. The first stop is usually the visitor center, which used to be a creamery, and is filled with fun seal facts like “northern elephant seals spend up to 10 months of the year at sea” and that their favorite foods include “opalescent squid and Pacific hagfish.”

A trail leads for more than a mile over boardwalk and drifting sand, past a gray cliff jutting into the ocean like a slumped-over seal, before arriving at shoreline viewing

areas. Here, depending on the time of year, visitors will encounter a sleepy handful or a rowdy convention of elephant seals.

In the fall and early winter, there might be 20 creatures lounging there, occasionally galumphing or issuing a burp noise that echoes over the water. But during the breeding season — which this year runs from December 15-March 31 and requires reservations to attend — it’s a whole different story.

“February is my favorite time to visit. That’s when the big alphas are here,” one of the park’s red-clad docents recently told tourists. “You see births, you see fighting, you see harems — it’s crazy. On the path here, you might see an elephant seal charging toward you like it’s ‘National Geographic.’” (Not intentionally, she clarifies. It’s just that when they get so worked up, they buffalo around with little regard to smaller things in their way.)

Whatever the time of year, it’s quite the experience to meet an elephant seal.

“The males and females are called dimorphic, meaning they have incredibly different body sizes. Males can get up to 5,000 pounds, and females are 1,2001,500 pounds,” says Susan Blake, an interpreter at Año Nuevo State Park. “They look the same

It’s exciting to visit the elephant seals at Año Nuevo State Park in Pescadero — but these seals couldn’t care less.

until they’re about 3 years old, then the males start growing that big nose and start growing really big. They have a chest shield, a thickened layer of skin that helps them during fights and gets scarred. The big nose is thought to be a male-to-male signal of strength and age.”

Two male northern elephant seals fight along a beach at Año Nuevo State Park.

That these seals can live to healthy old age is remarkable. Humans once hunted them rapaciously for their sweet, sweet oil.

“The whaling ships would come over and hunt whales, and then they would also leave a group of people on the shore to kill the seals and render their blubber,” says Costa. “They sort of used that to top off their trip, and by (the late 1800s), elephant seals were thought to be extinct.”

In 1892, a research team stumbled across a tiny colony — literally just a dozen elephant seals — on Guadalupe Island off the coast of Mexico’s Baja California. “Back then, if you saw an animal you thought was extinct, you needed to put it in the museum,” Costa says. “So they shot all 12 of them. Then they lost several loading them onto the ship. A note from the expedition said something like: ‘It was sad for the elephant seal. But the thirst of science must be quenched.’”

A few must have survived, because the species made a comeback. Soon, Mexico laid down a ban on hunting them. In

the 1970s, they were sheltered in the United States by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Today, there are thought to be 250,000 northern elephant seals, with about 2,000 in Año Nuevo alone, and other breeding grounds in Point Reyes, Humboldt County and Vancouver Island.

They definitely make their presence known; the universe

has gifted these biological equivalents of Stonehenge blocks the ability to tremendously roar.

“Males have that big bellow. If you haven’t heard that threat call, it’s ‘buh-buh-buh-buhboom,’” says Blake. “Every male above a certain age has a unique call; it’s like their name. Sometimes, they slam their chest down, and that can actually

travel some ways and that will show their size. If need be, then a fight starts — sometimes, it just takes a bite or two toward the neck region (to end it).”

When physical romance happens, it’s not like a Hallmark movie.

“Males have an internal penis. You don’t want things floating around underwater, right?

Their penis is pretty large, so everything is streamlined,” says Blake. “They mount a female, and she sometimes makes sounds, sometimes not. It can be hard to tell if the mating was successful. Usually, how we know a birth happened is because hundreds of seagulls swoop down to pick at the afterbirth — and then you see

a little wriggling, black, slimy pup.”

The pups have the epicurean delight of suckling one of the highest fat-content milks in the animal kingdom. That is, if they can locate their mother’s “inverted nipples,” says Blake. “We’re sometimes out there saying, ‘Go left, go left! A little higher!’”

The young ones swell from 70 to 300 pounds almost a month later. Some have the good fortune to feed from two moms at once, granting them a massive growth spurt and the nickname “super weaners” or — and this is a real technical term — “double mother suckers.”

At some point, they undergo something called an “explo-

Above:

For details on 2025-2026’s seasonal elephant-seal experiences, including mandatory reservations, hiking details and black-out periods, visit Año Nuevo State Park’s website at parks. ca.gov/?page_id=523

sive molt.” “All their skin and hair comes off,” says Costa. “It looks like there’s something wrong with them.” Because elephant-seal facts always come in fun multiples, this molting results in a strange phenomenon where the shoreline becomes contaminated with mercury. That’s the result of the creatures’ deep-sea diet of heavy metal-eating tuna and swordfish.

An elephant seal’s life is a constant cycle of hunting, breeding and traveling. Electronic tracking shows that it’s not uncommon for females to swim to the International Date Line, then turn around and come back. While they’re often on the move, they themselves have to move quickly to avoid being eaten by orcas and sharks.

“Off of Año Nuevo, we have a white-shark hot spot. They come in, usually around November and December, when the huge male and pregnant female seals are coming in,” says Blake. Researchers at Stanford University maintain a buoy that pings when tagged sharks are in the area, and during feeding season it’s “just going off constantly.”

Seals have done much to advance marine science and oceanography. Costa is part of an international Elephant Seal Research program that’s existed in one form or another for six decades; he jokingly refers to the animals as research assistants. There are ongoing investigations into how seal defecation provides valuable nutrients to the lower layers of the ocean. And it’s thought that elephant-seal carcasses — a massive buffet

by anyone’s standards — might act like “whale falls,” in death, feeding creatures at the bottom of the abyss.

“The ocean is very sparsely sampled, because it’s expensive and difficult to do. It’s very inexpensive for us to put sensors on elephant seals,” says Costa.

“We have one that measures chlorophyll content. And if you remember the ‘warm blob’ that happened some years ago in the Pacific, we were able to define the structure of that blob because elephant seals were measuring the blob down to depth.”

One seal that was part of a

KARL MONDON/STAFF

Right: A northern elephant seal allows a photographer to capture a close-up of its whiskers.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF ARCHIVES

study even taught Costa a valuable lesson in bite force.

“I had a female that was slightly drugged and coming out of it, and she latched on to my arm,” he recalls. “Fortunately, I had a really thick wool jacket

on. But it was a little intimidating to have this female head on my arm, and it left a big contusion that took a month to heal.”

Love bites aside, Costa believes it’s good these seals are doing what they’re doing.

“I like to talk about elephant seals as a success story,” he says.

“There’s so much gloom and doom today, but these animals came from less than 25 individuals 120 years ago to expand in population and continue to move north ... We didn’t do any innovation other than just say, ‘Hands off, let’s just let them do their thing.’ I think in that, there’s a story.”

You’ll find a warming sip to suit your every chocolate taste at these specialty cafes

BY KATE BRADSHAW

While the Bay Area may be blessed with comparatively temperate weather year-round, there are still some days when the temperature drops, the sky turns gray or the rain clouds descend, bringing the winter blues with them. That’s when it’s time to make like Harry Potter and chase those dementors away with some chocolate — hot chocolate, to be exact.

Here are five stellar spots around the Bay Area for picking up a piping mug of cocoa that’s not just satisfying but also memorable.

TIMOTHY ADAMS CHOCOLATES

Palo Alto

Timothy Woods and Adams Holland, a Sausalito-based couple, opened their Palo Alto chocolaterie 12 years ago, drawing its title from a mashup of their first

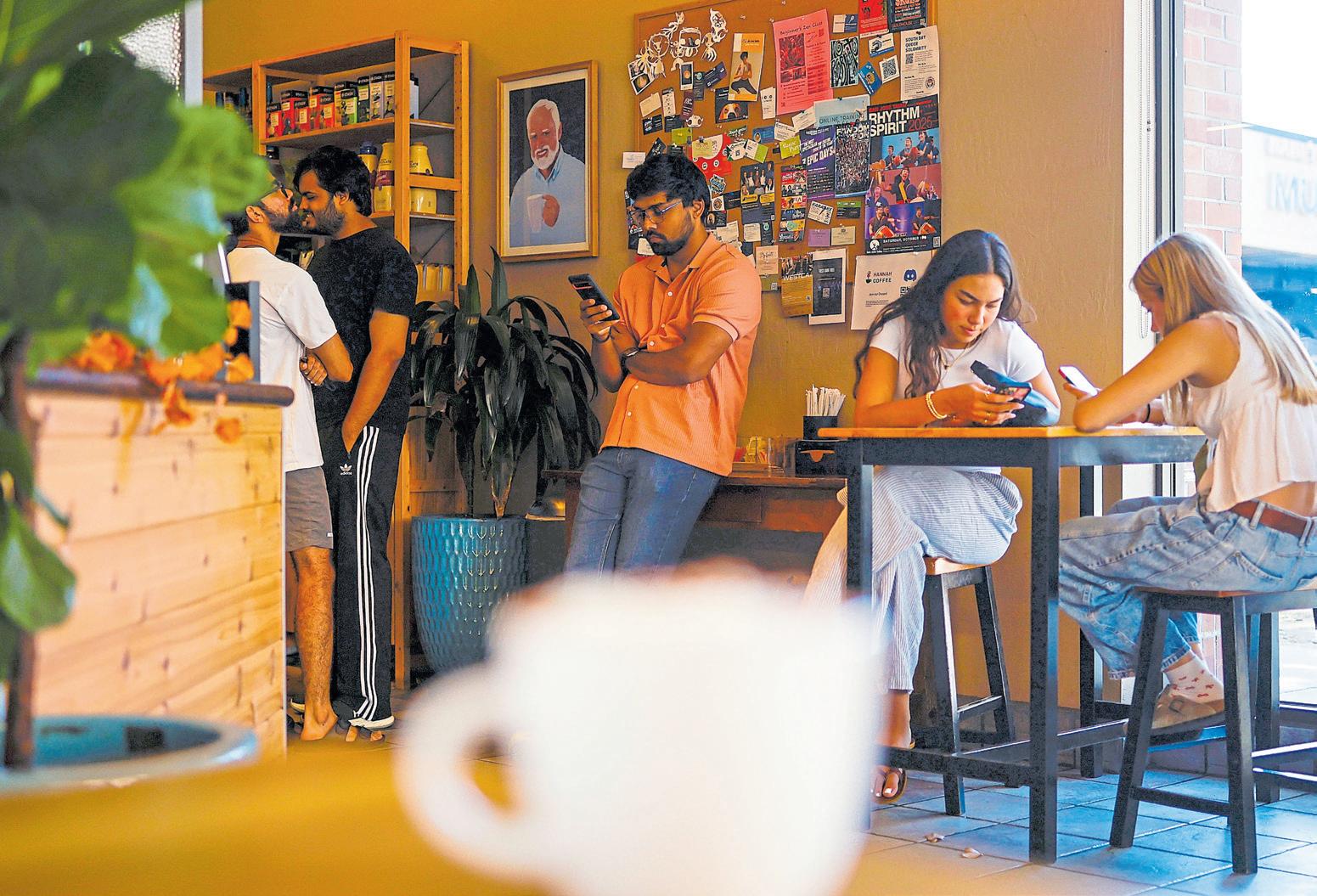

A cup of hot chocolate topped with whipped cream and cocoa powder awaits a customer at Hannah Coffee Co. in San Jose.

names. Woods initially trained as an architect, and then found his way into the world of food, working as a chef at a farm-totable restaurant in Fresno before becoming a chocolatier. “I love people, and I love doing things well,” Woods says.

Pink and purple flowers explode from planters outside the shop, complementing the pink rabbit that’s the shop’s logo as well as its interior color scheme. But all the bright colors pale in comparison to the colors inside the shop’s central counter, a display case gleaming with meticulously decorated artisan truffles. Visitors must tear their eyes away to study the drinking chocolate menu, which features 10 different gradations of chocolate for sipping, from white chocolate to dark Valrhona varieties, up to 100 percent bittersweet Republic del Cacao chocolate. The resulting beverage is half melted chocolate, half

the customer’s liquid of choice — but it tastes better to go with whole milk over the nondairy almond milk option, according to Woods. Then, it’s topped with a homemade marshmallow.

The 62 percent Valrhona Satilia dark chocolate option hits a careful balance of intensity and drinkability that blankets one’s mouth in a rich chocolate flavor without overwhelming it.

Details: Open noon-9 p.m. TuesdaysFridays and 12:30-9 p.m. Saturdays at 539 Bryant St., Palo Alto; timothyadamschocolates.com.

San Jose

At Hannah Coffee in San Jose, you know what’s in your drink — because the cafe team publishes each recipe on its website. Manager Andrew Harms says that the transparency helps not just their customers but other coffee shops looking to craft tasty beverages.

Their hot chocolate recipe uses 100 percent cocoa powder, which lets them customize the amount of sugar in each drink and allows for a sugar-free option, he says. It also contains white chocolate sauce, cane sugar syrup, steamed milk, whipped cream and a dusting of cocoa powder on top.

The team is constantly trying to improve their recipes and recently did a taste test of 20 different types of vanilla syrup, according to Ryan Bavetta, who helps to operate the coffee shop that his wife, Salome Bavetta, owns. After experimenting with different cocoa powders and syrups, they opted to stick with Hershey’s cocoa powder, which provides an equally rich –and more cost-effective — alternative to other brands, according to Ryan Bavetta. “We put a lot of research and taste testing in,” he says.

Details: Open 6 a.m.-5 p.m. daily at

Above: A hot chocolate with marshmallow, left, a hot chocolate with whipped cream, and a regular hot

are among the options available at Timothy Adams Chocolates in Palo Alto.

Left: This Ecuadorian dark chocolate ganache with orange blossom, floral notes and woody undertones with refined bitterness pair well with the hot chocolate at Timothy Adams Chocolates.

RAY CHAVEZ, JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF

754 The Alameda #80, San Jose; hannahcoffee.com.

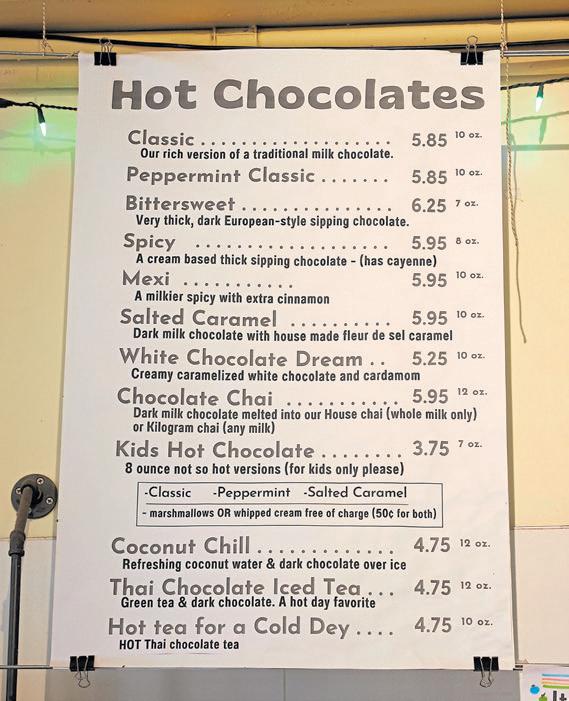

THE CHOCOLATE DRAGON BITTERSWEET CAFE AND BAKERY

Oakland

In a cozy storefront nestled in Oakland’s Rockridge neighborhood, The Chocolate Dragon Bittersweet Cafe & Bakery, owned by Lise Dale, a baker and barista from New Mexico, has a cocoa offering for every kind of hot chocolate fan, from the sweet salted caramel cocoa — featuring the shop’s house-made fleur de sel caramel sauce — all the way to the dairy-free bittersweet option, blending chocolate with hot water for a dense, indulgent sipping experience. And then there are the spiced options, like Mexican hot chocolate and

chocolate chai, plus a white chocolate version with notes of cardamom and caramel. Note: You may want to bring a buddy or a book rather than a laptop, since the cafe has a strict no laptops or wifi policy on weekends, including Fridays.

Details: Open 8:30 a.m.-8:30 p.m. Tuesdays-Thursdays, 8:30 a.m.-9:30 p.m. Fridays-Saturdays, and 9 a.m.-7 p.m. Sundays at 5427 College Ave., Oakland; chocolatedragoncafe.com.

Walnut Creek

Tifa Chocolate and Gelato opened its doors in Walnut Creek just a few months ago, in July, as the Bay Area’s first franchise of an Agoura Hillsbased brand. Owned by Naina

Balupari, this shop has hot chocolate that comes from couverture chocolate imported from Belgium. It’s then dissolved into half-and-half and steamed, and milk is added (nondairy milk options are also available) along with any additional flavors the customer might request. “Everything is really fresh,” she says. The drinking chocolate is endlessly customizable — from a dark, milk or white chocolate base to additional flavors, like cardamom, rose, chai spice, maple or honey, among others. And you can sip it in a cup or over gelato. The gelateria makes 24 flavors of gelato in-house, including pistachio lemon curd, strawberry rose sorbetto and, for the fall, brown butter pumpkin cheesecake.

Details: Open 10 a.m.-10 p.m. SundaysThursdays and 10 a.m.-11 p.m. FridaysSaturdays at 1545 Locust St., Walnut Creek; tifachocolateandgelato.com.

Made with San Francisco’s Ghirardelli chocolate, this cocoa is light, sweet, a tad frothy and a cozy accompaniment for keeping one’s hands warm at this cafe situated next to the Bay. That said, this particular location of Equator Coffees is just inside a new tech office campus, so if that gives you the ick when you’re in the mood to recreate, take your cocoa to go and head out for a stroll along the Bay Trail instead. You can see planes coming in to land at SFO and shorebirds aplenty as you walk along Coyote Point County Park, passing a beach and a hilly waterfront eucalyptus grove along the way. Stroll a tad farther, and you’ll arrive at CuriOdyssey, a family-friendly science playground and zoo.

Details: Open 7 a.m.-4 p.m. daily at 312 Airport Blvd., Burlingame; equatorcoffees.com.

BY MARTHA ROSS

On a sunny morning in late September, Breck Parkman sat at a picnic table in the historic Sonoma Plaza, across the street from the city’s 1823 mission, the barracks that once housed Mexican troops and the office where he was based during some of his 36 years as a senior California State Parks archaeologist.

In that job, the 73-year-old Parkman used artifacts found in old ruins or the chemistry of rocks and layers of soil to piece together possible narratives about life in the Bay Area — as far back as tens of thousands of years ago or as recently as the late 20th century. More than being a scientist or historian, Parkman has always seen himself as a storyteller with an innate curiosity about other worlds and a desire to imagine the people who lived in them.

True to that vision of himself, Parkman began to paint scenes and characters as he sat at the table, including how the plaza once didn’t have trees or grass and certainly wasn’t surrounded by upscale wine country boutiques and restaurants. The sounds would have been different, too, he said — no cars rumbling past or children laughing in a playground.

“There are layers of life that we don’t see, you know, and layers

upon layers. So for me, I’m looking at when Vallejo was here,” Parkman said, in a faint lilt of his native Georgia. General Mariano Vallejo was the Mexican commander who established the eight-acre plaza in 1835.

Parkman said he could imagine the plaza “as it if were just yesterday,” when Vallejo’s soldiers used it as a parade ground. “You can see San Francisco Bay from here,” he said. “And as I go back earlier, 15,000 years ago, you would see mammoths and sabertooths.”

One of Parkman’s favorite research interests has been the Ice Age Columbian mammoths that roamed the Bay Area for thousands of years, across coastal plains that he calls the “California Serengeti.” Although Parkman retired in 2017, he continues to write, lecture and post YouTube videos about a variety of topics inspired by his extensive fieldwork and personal experiences as a husband and father.

Parkman knows that when people hear about his job, they might think of an Indiana

Breck Parkman, a retired archaeologist for California State Parks, stands inside the chapel area of Mission San Francisco de Solano in Sonoma.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

Parkman found these buttons, above, and this Indian head penny, right, dated 1890 on site of the October 12, 2008, Angel

Jones type, swooping in to recover an idol from an ancient tomb Or a dust-covered scientist, digging through ruins to find artifacts to catalog for a museum. To Parkman, the job has always been so much more.

“You’re looking at the bigger picture,” he said. He’s been able to look at that bigger picture in places all over the world: the Canadian Plains, the Australian Outback, Central Siberia and the south coast of Peru, where he helped an archaeologist friend recover 2,000 year-old mummified human remains that had been unearthed by generations of looters.

But he’s been just as fascinated by what he’s discovered closer to home. Two years after he was hired to work for the state parks in 1981, he was assigned to Northern California, eventually becoming a senior archaeologist, managing cultural resources at more than 70 parks, from Del Norte County to Angel Island to Alturus in the far northeast.

For a scientist/storyteller, Bay Area parks have given him a lot to work with. He’s investigated early Paleo-Indian migration along the West Coast, Elizabethan California and the archaeological history of Fort Ross State Historic Park, when it was an outpost for Russian fur traders in the early 1800s.

Parkman has garnered media attention for his studies in contemporary archaeology, including the secret lives of soldiers who passed through Angel Island, Beat-era artists and his “55th raincoat” theory about the 1962 escape from Alcatraz.

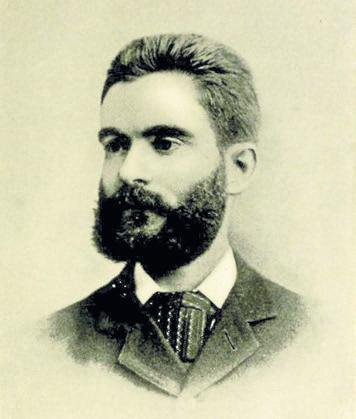

He may be best known for sifting through the charred ruins of the Burdell mansion at Olompali State Historic Park in Novato in 2009 to understand the lives of the people who participated in one of the Bay Area’s famous 1960s counterculture experiments: the Chosen Family commune. He explained how several families, loosely affiliated with the Grateful Dead, came together in 1967 to create “a new way of living” and of “getting along in the world.” Unfortunately, their idealism collapsed as outsiders who didn’t share their values moved in. The commune disbanded in 1969 after a

In January of 2009, Breck Parkman explored the burnedout Burdell mansion at Olompali State Park in Novato.

ROBERT TONG/STAFF ARCHIVES

fire destroyed the mansion.

Among other things, Parkman studied the remnants of more than 90 vinyl records found in the ruins, concluding that the range of artists represented in the collection — from the Beatles and Bob Dylan to Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra — defied stereotypes about commune hippies, showing instead a surprising diversity in the ages and personal tastes of residents.

Parkman’s path to a 1960s commune began with his own experiences as a child in mid20th-century America. Growing up in southern Georgia, he had always been interested in archaeology, as he sometimes found Native American arrowheads and pottery shards in plowed fields near his home. The first book he ever remembers reading was about Native Americans.

But contemporary events also intrigued him — he grew up painfully aware of racial segregation while receiving an early introduction to the civil rights movement. When he was 5, his family’s Black babysitter took him and his little sister to a large gathering. He remembers sitting on his babysitter’s shoulders amid a crowd of Black onlookers who all were mesmerized by a speaker — Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I picked up on the energy, and it was, like, put your finger in the electrical socket,” he said.

An early encounter with another American icon planted the seed of his desire to become a civil servant. In third grade, he and his classmates lined

the streets to see presidential candidate John F. Kennedy drive by. “I was the first person at the end of the line. I waved, and he looked up, and he waved at me. I didn’t have a clue who he was, but when I found out who he was, he became my hero and I read everything he wrote.”

Parkman initially considered going to medical school but instead came to the Bay Area in 1971 to pursue his first love of archaeology. He got his bachelor’s and master’s degree at what

ARCHIVES

was then Cal State Hayward and remembers how the environmental movement awakened people to the need to protect and support parks.

His early assignments were in San Diego County before he came north as the first state archaeologist assigned to the field and honed his belief that studying cultures of the past explains where we have been and how to prepare for the future. He also developed his love of doing the scientific

detective work to uncover little-known narratives, though he came to appreciate that sometimes those discoveries come about by accident.

For example, one of his proudest accomplishments was finding rocks along the Sonoma Coast that he believes were a popular attraction for Columbian mammoths of the late Pleistocene, from about 11,500 years ago. On otherwise craggy seastacks near Goat Rock in Sonoma Coast State

Park, Parkman found atypically shiny patches about 10 to 14 feet above the ground. That’s where, he believes, these long-extinct megafauna rhythmically rubbed against the rocks in a form of self-grooming, similar to how African elephants rid their hides of itchy ectoparasites

Parkman said this discovery might not have been possible had he and a paleontologist colleague not decided to proceed with doing some fieldwork near those rocks on Sept. 12,

looks at the ancient rock stack on a lupine covered terrace on the Sonoma Coast in 2002. He believes the rock stack is Pleistocene Park, where rock edges and overhangs show high gloss rubbings were made 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, when the rocks were used as scratching posts by herds of migrating mastodons and mammoths.

DEMOCRAT ARCHIVES

and supervisor

2001, the day after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. As they hiked along the coast, they noticed no planes in the skies or ships on the ocean, save for a Coast Guard aircraft flying circles, and possibly several submarine periscopes popping up. Instead of a usual 10-minute lunch, they sat beneath those rocks for more than an hour to ponder whether the United States was at war, giving Parkman the time to notice those shiny patches.

“You know, finding that in a lot of ways changed my life, because I never thought much about the Ice Age,” he said. That fascination has led to more recent, post-retirement explorations into the role that the lowly dung and the lofty condor play in maintaining environmental health and balance.

Personal projects have kept Parkman busy, such as chronicling the life he shared with his photographer wife, Diane Askew, and 19-year-old son while living at Sugar Loaf Ridge State Park. He’s posted a moving YouTube tribute to Diane, who died in December 2021, as a contemplation on death and grief. He speaks of all the “falling stars” in the sky the night she died, “too many” to catch. Only recently, he said, has he been able to go outside at night and look up.

Stories about death, as part of that arc of life, came up in other ways as Parkman talked at the picnic table. He recalled organizing the installation of a set of plaques outside the mission, listing the names of Wappo, Patwin, Pomo and Coast Miwok people who labored and were buried there. He also related his vision of the plaza 15,000 years ago or in the 1830s to the collapse of time and memories he imagines could occur during our transition from life to death: “Maybe that second of time in that white room is actually eternity?”

The ever-evolving Christmas in the Park continues to flood downtown San Jose with festive holiday fun

BY SAL PIZARRO

About 800,000 people every year make a visit to Plaza de Cesar Chavez in downtown San Jose part of their holiday tradition.

Of course, it’s not to visit the “Plumed Serpent” statue or relax on a bench overlooking the Tech Interactive. No, for five weeks spanning Thanksgiving weekend to New Year’s Day, the two-acre park’s biggest draw for nearly 50 years has been Christmas in the Park — a kitschy and whimsical collection of animatronic displays, hundreds of decorated trees and a chance to visit with Santa himself. Ted Lopez, who took over in August 2025 as executive director of Christmas in the Park, said his own family has had a Christmas in the

Park tradition as long as he can remember. “We always have to take a photo under the big tree,” he said. “That’s just a staple of the holidays for us.”

Christmas in the Park and Plaza de Cesar Chavez seem made for each other, and it’s probably difficult for anyone under the age of 50 to imagine a holiday season at the park without it (though that sadly happened during the first COVID-19

winter of 2020, prompting the creation of the drive-through event that continues today at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds).

South Bay residents who go farther back than that can remember the years when the display was installed on the lawn in front of the old San Jose City Hall on North First Street for a few years in the 1970s. And some still have fond memories

of when everything was still on Willow Street, decorating the Lima Family mortuary every year from 1950 to 1969. They may have less fond memories

of the enormous traffic jams it caused, which was part of the reason Don Lima donated the whole thing to the city in 1970. City leaders did their best

Scrooge impression in 1978, insisting that recently passed tax measure Prop. 13 made installing a joyful but ultimately extraneous holiday display in the park a low priority, budget-wise. Volunteers offered to set everything up in 1979, but city unions decided that holiday gift wasn’t to their liking, and the parks department didn’t bother to order any artificial snow. Bah, humbug, indeed.

In March of 1980, then-City Council member Tom McEnery penned a piece in the Mercury News urging the city to start planning early to stage the event and to avail itself of private philanthropy to keep it going. It worked, and Christmas in the Park — as it became officially known in 1982 — became an institution.

of some and dismay of others — the Satanic Temple of Silicon Valley for several years.

For many, Christmas in the Park’s displays of elves rescuing a stuck Santa from a chimney, the one-room schoolhouse or the Nativity scene seem like they’ve all been there forever, unchanging in our memories. But the park — and the display — have undergone lots of changes over the years.

Very few of today’s displays predate the 1990s, with some being renovated over the years to either spruce them up or change their theme. The “Children All Over the World” display went from being a ripoff of “It’s a Small World” to having an environmental theme with a paint makeover and new recycling vests for the kids.

The Lima train was built in 1994 to honor Christmas in the Park’s founding family. The Willow Street display included a miniature train, and the “new” nonmoving train includes parts of some original artifacts from those days. Every year, there’s either a new display or a refurbished one to find.

And while the park itself hasn’t grown, Christmas in the Park’s footprint sure has. A vendor village was created at the south end of the park, joining the Kiwanis Club booth that has long been staked out next to Santa’s house. The San Jose Downtown Association brought its Downtown Ice skating rink to the adjacent Circle of Palms, and the Winter Wonderland carnival rides added to the fun along Park Avenue and Paseo de San Antonio.

When the Great Recession again forced the city to tighten its belt, volunteers formed a nonprofit organization to keep the event alive — and actually did a lot more than that. They grew the event through corporate partnerships and kept it feeling local by continuing to provide

a community stage for nightly entertainment.

The “Enchanted Forest” of about 600 trees continues to be decorated by Santa Clara County companies, schools, scouting units and other community organizations, including — to the amusement

Lopez, Christmas in the Park’s executive director, says his job is to keep that holiday tradition going and to give people a happy reason to come back every year. “To me, Christmas in the Park is an amusement park that’s open for 35 days,” he said.

BY JASON MASTRODONATO

There isn’t a nook or cranny in the Almaden Valley that Ali Henry hasn’t spent time in. She grew up here, camping, boating and fishing with her dad and her grandparents. Those long, sun-drenched days on the water often finished with fresh-caught trout sizzling over a campfire.

Today, Henry is devoting her life to preserving and celebrating some of her favorite childhood hangouts as Santa Clara County Parks’ first-ever woman chief park ranger.

But as much as she loves the outdoors, it wasn’t the places itself that motivated her to a life of service in the parks system. It was the people she explored those places with.

“Looking back,” she said, “it was the time spent with those family members outside. And now I want to give that to my kids.”

Henry’s childhood memories are shaping the ones she hopes to help others now form. Her goal? Get kids off their phones and get them outside, being social, experiencing nature and soaking up sunshine.

“I see a shift and change in my kids for the better when we’re able to spend time outside,” she said. Most of Henry’s childhood memories are outside. She attended Pioneer High School and was active

more than 55,000 acres of public park lands.

in athletics, competing in swimming, cheerleading and dance.

On the weekends, she was active and community-oriented. As the oldest of three children in her family, she felt like leadership was in her DNA.

“When the street lights would come on, we knew that was kind of the time to go home, but we would spend all day outside,” she remembered.

After high school, she was unsure what to do with her life. She just knew she wanted to stay involved in the community and stay outside.

In 2011, she took a part-time seasonal job as an extra-help park service attendant at Coyote Lake.

“She worked in the kiosk collecting fees,” remembered Brian Christensen, now a park ranger supervisor who has worked with Henry throughout her career.

“We saw her enthusiasm. If you always have a smile on your face, you know they’re fit for the park services.”

After finishing up her education, meeting the minimum requirements to be a ranger and completing the intensive 16-week academy training program and another 14 weeks of field training, Henry took a full-time job as a park ranger. Christensen soon noticed they shared the same passion: helping people.

“She has a passion for the

folks and people that work under her,” he said.

Henry worked her way up through various responsibilities in the parks system, gaining both fieldwork and leadership skills and spending most of her days outdoors.

She often noticed she was one of few women taking on leadership positions.

“There definitely have, in the past, been more dominant males who do this role, and that’s really traditional in public safety,” Henry said. “But you see a shift now in law enforcement and fire services.”

This July, she became the first-ever woman chief of parks in Santa Clara County, overseeing 28 parks.

“I’m very proud of that,” she said.

While she now spends more time inside at her computer and misses her time outdoors, she’s focused a lot of energy on recruiting new rangers and community outreach to teach people the importance of the local parks system.

Seeing little girls feel the enthusiasm for the outdoors has been particularly rewarding.

“It’s extremely important for kids to see themselves reflected in the folks that are doing the job every day,” Henry said. “For the next generation of folks looking into the public surface, it’s extremely important that we have a diverse workforce.”

In the spirit of sharing her lifelong passion for the local parks system, Henry made a list of her favorite places for people to visit.

For folks who are new to exploring the local parks, she

recommends:

Hellyer County Park, San Jose: Especially for families with young kids or those looking for an easy escape from the city, Hellyer’s flat, paved trails are great to walk or bike, while Coyote Creek Trail provides some great views and plenty of bird sounds, and the fishing is good on Cottonwood Lake.

Vasona Lake County Park, Los Gatos: A nice spot to have some gentle fun on the water,

Vasona Lake County Park in Los Gatos is one of the most popular parks in the South Bay.

NHAT V. MEYER/ STAFF

Vasona Lake offers pedal boat rentals and accessible trails near Oak Meadow Park.

Coyote Lake, Harvey Bear Ranch County Park, Gilroy: Perfect for people new to hiking and looking for less-crowded trails. Fishing enthusiasts will find black bass, bluegill, black crappie and Eurasian carp.

And for the veteran Santa Clara Parks adventurers, here are a few of Henry’s favorite spots that are off the beaten path:

Grant County Park, San Jose: With more than 10,000 acres and 50 miles of trails, this is the largest park in the county. It boasts some advanced hiking opportunities for folks looking for solitude or expansive vistas. And there are some particularly pretty sights during the wildflower season in the spring.

Calero County Park, San Jose: Henry grew up spending a ton of time in Calero and recommends spending an entire day there. It’s perfect to find a 10- or

15-mile hike with gorgeous views of Almaden Valley. The 4-mile climbs up the Serpentine Loop Trail or Los Cerritos Trail can present enjoyable challenges.

Parks and community services director, San Ramon

One day earlier this summer, Henry Perezalonso was standing on the grass at Serra Park in Sunnyvale, celebrating his 40th

reunion from Homestead High School, when he looked around and suddenly realized something: This is where he had his first job.

“We were literally gathering in the same place I once worked summer programs,” he said.

His first job was as a recreation leader for after-school and summer programs in Sunnyvale. He wanted to help kids get outside, use local parks space and connect with each other. He didn’t think it was a feasible job long-term, but he knew he loved doing it.

“I connected with the kids, I enjoyed the play, and it was a fun little thing that I never thought was going to be a career,” he said. “Now it’s been 39 summers. That’s how I count my career, in summers.”

After his first summer of working in recreation, he felt

Flanks of trees frame Henry Perezalonso, San Ramon’s director of parks and community services, at Central Park.

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

a little lost, so he joined the Marine Corps in 1988. He figured it would be a good start towards his goal of becoming a public safety officer. After boot camp, while he was on reserves, his life took another left turn: Some friends started a DJ and party planning company in Los Angeles and wanted him to join.

That was fun for a while, then led to a job as a tour guide, then a job testing game shows in L.A. (remember “Legends of the Hidden Temple?”), then a gig with the city of Beverly Hills, where he was planning adult sports and after-school programs in local parks, then a job as an assistant athletic director of a sports club.

“We were just trying to make money in our 20s, doing whatever came our way,” he said. “So many people feel lost, or they don’t understand that what

they’re doing might lead them somewhere.”