MSU’s infrastructure isn’t merely built on concrete and cement, but more importantly on its over fifty-decades legacy of academic excellence and its meaningful contributions to the Filipino nation-building, particularly in the regions of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan to which it was originally made for.

But like many other buildings, its walls remain vulnerable to vandalism. In the case of Mindanao State University – General Santos (MSU- Gensan), recent desecration of its high-fences (which to most seemed rather too difficult to climb over, a painful irony to accessible education it so often boasts) have struck a crisis of identity among MSUans—well, if it didn’t disturb others, they might want to check whether their moral compass still points to the right direction or not.

News went out in the open on May 14—for all to see, for everyone to feast upon: a certain “Mr. College President” of a student organization in MSU-Gensan, whom most people quickly assumed to be the person in question, was alleged to have sexually assaulted Robert James Diaz who recalled in his Facebook post the horrendous and traumatic details of the molestations of his assailant. He is an alumnus of the same college who went to celebrate with his juniors who had just passed their licensure examinations in an overnight party. Diaz found himself helplessly drunk and vulnerable in the presence of a junior he once thought of as bubbly and kind— descriptions that many took as indirect clues. He recounted in his now-privatized post that Mr. College President kissed him and touched him around his intimate body parts—all these as he was left alone with him in the room.

The principle of presumed innocence, until proof of guilt beyond reasonable doubt is arrived at in the court of law, leaves room for the accused to, by all means of legal formalities and reservations, remain innocent. Although he was unnamed in Diaz’s Facebook post, Mr. College President was identified and decided upon (almost as if unanimously) by the watchful people based on common sense and how the post

seemed to have obviously pointed itself towards him. Nevertheless, the principle set forth by our law maintains his innocence and the case now rests on their personal navigations of the situation. Still, the issue at hand leads us to a question: what has our Dakilang Pamantasan become? And yes, an inquiry on our identity as an institution is an inquiry on ourselves: what does it mean to be an iskolar ng bayan? Well, it surely doesn’t mean to be involved as perpetrators of the horrors of a scandal as gravely serious as a sexual assault, because regardless of Mr. College President’s innocence or guilt, much damage has been done against our Pamantansan’s almost all-holy and divine façade.

Concerningly, this isn’t solely the ghost that is currently haunting MSU-Gensan’s eerily silent academic community—what with their clamor and noise dying out as soon as the excitement over a hot and almost-seeming high school gossip fades into nothingness. Hold your brushes because the vandals just can’t be covered yet by a new stroke of paint—as if one incident isn’t enough, another adds to the list (and to think that this is only one among the few publicized cases) as an equally horrifying case of alleged rape committed by another MSUan, tagged as K.C.E., took center-stage on May 6 through a post published in the ever-sumbonganng-bayan Facebook page BUHAY MSUAN.

The post called out K.C.E. for what it claimed were his “unforgivable and disgusting acts” towards his victims, as one of them purportedly approached whoever messaged BUHAY MSUAN to tell her gut-wrenching experience from him. The narrative was almost no less different than the common scheming of sexual offenders—yet it was no less traumatic for the victim too. According to the public post in the said Facebook page, K.C.E. allegedly kissed the girl’s neck in a public library. Whether the post was pertaining to the University Library in MSU-Gensan or not remains unclear. Point is, the victim was being sexually harassed, was told that he owned her as he ‘squeezed’ her neck—and what’s more frightening is the fact that the shadow of danger lingered right directly at her back. K.C.E. reportedly knew where

is it?)

to find her, he knew her address—the post claimed he was stalking her.

While a complaint has already been filed in the SSC Straw Desk and legal advice has been sought (as updated by BUHAY MSUAN on May 14), the alarm has been raised: somewhere, someone out there can commit crimes like this and drag the feet of our Pamantasang Mindanao along the way—and it doesn’t even have to happen inside its walls. This isn’t MSU, yet, it appears as though it is being put on trial too. Years and years of a well-built reputation tainted.

True enough, one more publicized issue on BUHAY MSUAN made everyone sigh and grow wary. This time, it wore a different color but still painted the same problem: a group chat among MSUans who exchanged photos and videos containing sexual content. No, they weren’t simply sharing pornographic photos and videos taken from the nternet—they collected from their own experience. Then, they pigged out on these like delicacies in a banquet.

Naunsa naman ning MSU? It’s a question shared by many, pressed against the irony that these cases put MSU-Gensan in the center of a spectacle: how can these happen involving its students? The irony is painfully obvious, MSU-Gensan is a peace university. Yet, so far, these cases tell a different reality. But the moral weight of all these shouldn’t just be carried by our Dakilang Pamantasan. It’s a shared burden among all of us.

As to what it means to be worthy of the people’s taxes, we answer it not by words, but by actions—excelling in our academics, contributing to research in different fields, producing works of art to tell their stories, and extending our help to the communities beyond our high-walls. These taxes represent the collective hardwork and hope of Filipino workers, and so we ought to be good, to do good—that is the least we can do to honor their sacrifices. We answer it definitely not by committing criminal and immoral activities that risk our Pamantasang Mindanao to become a cradle of law-breakers, when it should

be home to scholars, nation-builders, and future leaders of our nation.

In the context of a public university—one built on the dreams of the nation and the sacrifices of the Filipino people—this is not just an issue built on leniency and liberation. It is a crisis of identity. As Iskolars ng Bayan, we are expected to not only bearers of academic excellence, but also to ethical leadership. The privilege of free and quality education comes with the unspoken vow to be socially conscious, morally upright, and brave enough to speak out against wrong— even if it means confronting uncomfortable truths that could tarnish the image of our own university.

What does it mean to be an Iskolar ng Bayan if we cannot uphold the dignity and safety

legal formalities and reservations, remain innocent. Although he was unnamed in Diaz’s Facebook post, Mr. College President was identified and decided upon (almost as if unanimously) by the watchful people based on common sense and how the post seemed to have obviously pointed itself towards him. Nevertheless, the principle set forth by our law maintains his innocence and the case now rests on their personal navigations of the situation. Still, the issue at hand leads us to a question: what has our Dakilang Pamantasan become? And yes, an inquiry on our identity as an institution is an inquiry on ourselves: what does it mean to be an iskolar ng bayan? Well, it surely doesn’t mean to be involved as perpetrators of the horrors of a scandal as gravely serious as a sexual assault, because regardless of Mr. College President’s innocence or guilt, much damage has been done against our Pamantansan’s almost all-holy and divine façade.

of those around us? How can we claim to serve the people when we ignore injustice in our own halls? The sexual assault cases reported on campus demands more than sympathy; it demands structural response. We call on the administration to urgently recalibrate its existing policies on sexual misconduct. It is about time for an accessible and transparent process that ensures preventive and punitive measures for similar cases. More than that, we call for a strengthened awareness about sexual assault through sustained education, clear protocols, and support systems that empower, not intimidate.

We are Iskolars ng Bayan not only in title, but in responsibility. These values are tested not in times of peace, but in moments like this—when the easy way out is to

stay away from controversies, to protect our esteemed reputation rather than the victims, and to prioritize facade over accountability.

This is not MSU-Gensan, many would insist—perhaps out of instinct, perhaps out of denial. But if we are to be honest, these might be only the stories that surfaced, a tip of the iceberg if we may tell. For every post that went viral, how many more remain untold—buried in fear, shame, or silence? If these events reveal anything, it’s that the MSU-Gensan we think we know may not be the same MSU-Gensan everyone has experienced. And so the question must be asked not to defame but confront this unsettling truth: This is not MSU-Gensan… or is it?

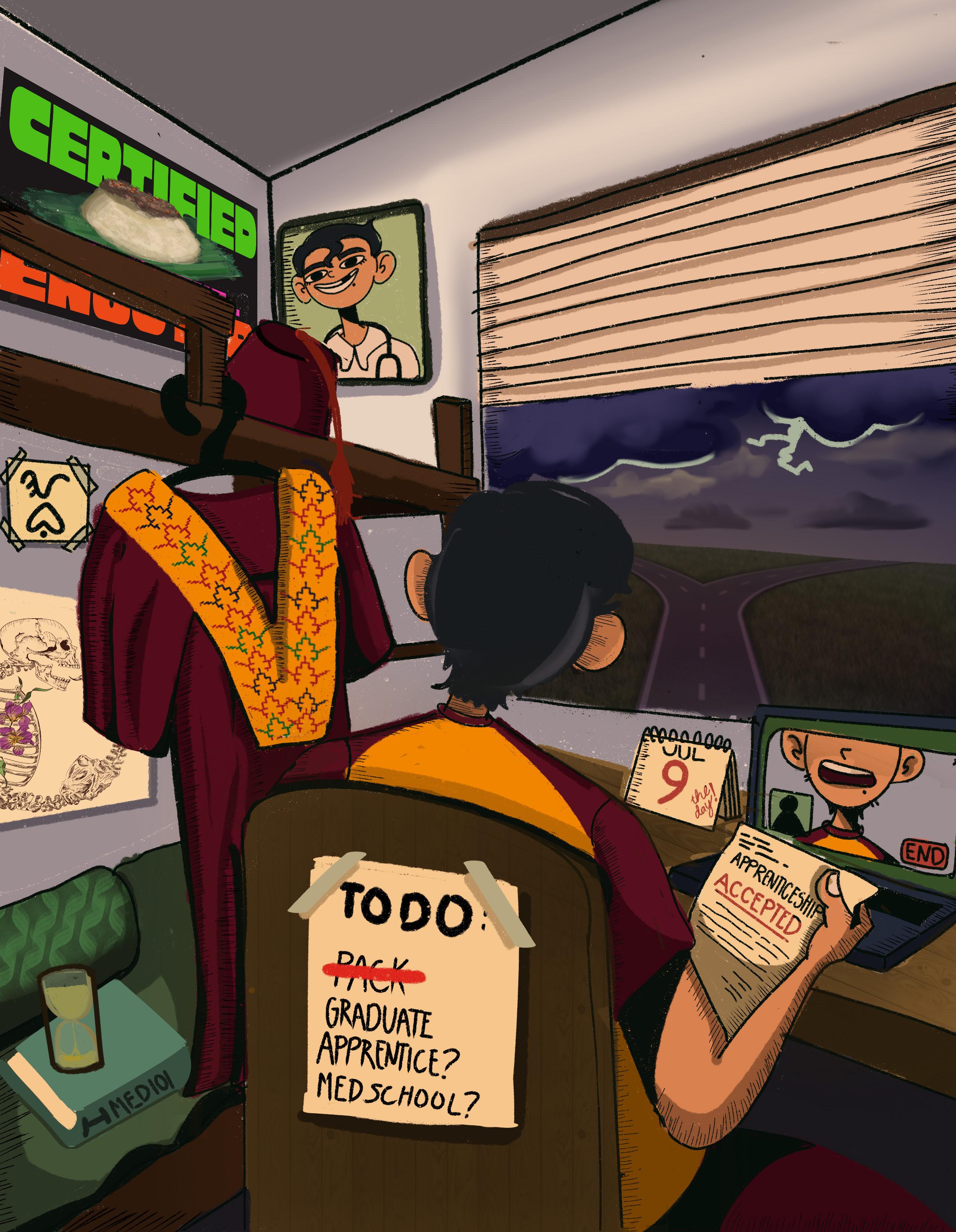

Cartoon by Mikee

Concerningly, this isn’t solely the ghost that is currently haunting MSU-Gensan’s eerily silent academic community—what with their clamor and noise dying out as soon as the excitement over a hot and almostseeming high school gossip fades into nothingness. Hold your brushes because the vandals just can’t be covered yet by a new stroke of paint—as if one incident isn’t enough, another adds to the list (and to think that this is only one among the few publicized cases) as an equally horrifying case of alleged rape committed by another MSUan, tagged as K.C.E., took centerstage on May 6 through a post published in the ever-sumbongan-ng-bayan Facebook

GENERAL SANTOS CITY, SOCCSKSARGEN — As the academic year draws to a close, graduating students from Mindanao State University – General Santos (MSU-GSC) are leaving behind more than just academic achievements; they’re helping build a literacy legacy across SOCCSKSARGEN.

The Tara, Basa! Tutoring Program (TBTP), a flagship social protection initiative, is a collaborative effort spearheaded by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in partnership with the Department of Education (DepEd) and other key agencies.

It addresses critical reading gaps among struggling elementary learners while offering temporary employment to financially challenged college students, who serve as either tutors or Youth Development Workers (YDWs).

For MSU-GSC’s fourth-year students Honelyn Phala, Christine Fae Layan, Almaira Magangcong, and Nickolai Villagas, the program is more than just a work opportunity; it’s a platform for meaningful change.

While financial support was a practical motivator, these students also emphasized their commitment to social impact.

Layan, for instance, initially highlighted the value of work experience, stating, “What initially motivated me to apply for TBTP is the work experience I can include in my CV.”

She further elaborated that “truthfully, the money incentives or cash-for-work that will be given to us is really a factor to apply in the program.”

Phala, however, was primarily driven by the desire to help children struggling with reading and parents who lacked the resources to guide them, saying she wanted “to make a real difference.”

Magangcong, inspired by her peers, joined the program later. She noted, “It was only when I reached fourth year and saw many of my friends joining that I got motivated too.”

Villegas also admitted his motivation extended beyond financial aid, which he noted would significantly help with thesis expenses and future enrollment, stating he also joined “to have an

experience in facilitating nanay-tatay student and to enhance my teaching skills.”

Each student contributed in unique and essential ways to the program’s goals.

As a tutor, Phala directly assisted children with reading. She recounted how one initially shy learner gradually became “more enthusiastic and confident” through consistent, engaging sessions, adding, “that moment made me feel proud and happy.”

Meanwhile, Layan, Magangcong, and Villagas focused on working with parents to foster long-term literacy development at home.

Layan expressed deep fulfillment in teaching parents effective strategies and reshaping their perspectives on education, believing that change must begin at home.

Meanwhile, Magangcong, who conducted sessions such as the emotionally resonant “I Love You More,” witnessed profound moments, like parents expressing affection to their children for the first time.

“These small but powerful exchanges reveal how literacy is not just about books,” Magangcong reflected. “It’s about relationships, confidence, and communication.”

Villagas also noted significant transformation in the parents he handled, observing, “I already noticed that even though the program was not finished yet, those parents transform into better people than before.”

He proudly added that many parents genuinely sought knowledge, not just the allowance.

When asked about the challenges they faced, the students recounted encountering issues ranging from parental unavailability to managing group dynamics.

Phala emphasized the importance of patience and persistence: she built rapport with families through consistent visits and simple, practical tips.

“Some parents are too busy or unsure how to help their children. I try to meet them halfway by giving simple tips and explaining things clearly,” she said.

Magangcong, fluent in multiple local languages, used her linguistic skills to bridge gaps and ensure no family felt left out.

“Some parents preferred speaking in their mother tongue, which I, fortunately, also speak. I took this as an opportunity to translate and clarify the messages during sharing sessions, helping everyone understand each other better and learn together,” she shared.

To make sessions enjoyable, Villagas employed casual conversations, jokingly referring to his approach as “chika minute adik,” and admitted that he would also chat with parents.

Despite the informal tone, Villagas said these sessions tackled real parenting issues and strategies, making them both fun and meaningful.

For these students, the idea of leaving a legacy is not abstract—it’s visible in every child who can now read with confidence and every parent who feels empowered to teach.

Layan shared that she envisioned a future where their work continues to bear fruit, where the “learning will stay in the hearts and minds of the parents.”

Moreover, Phala described her contributions as “planting seeds” for long-term growth, stating, “If a child becomes a better reader and a parent learns how to help, that impact can last a long time.”

Beyond the immediate social impact, the program also sharpened the students’ professional skills— teaching, communication, and leadership—all of which align with their aspirations in education, community development, or public service.

Villagas shared that he is optimistic that if the program continues, it can “address the educational crisis in the country while supporting students facing financial struggles.”

As they prepare to graduate, these seniors carry with them not just academic accomplishments, but the tangible fulfillment of having contributed to a vital cause.

‘Hindi

Admission Director aminadong inklusibo ang sistema matapos umani ng batikos sa social media

LYNXTER GYBRIEL LEAÑO, DAVE MODINA

Malaki ang naging panindigan ni Prof. Rhumer S. Lañojan, Director of Office Admission, MSU-GenSan, na hindi “anti-poor” ang bagong inilabas na admission policy ng pamantasan sa kabila ng mga bumabatikos sa social media na hindi umano patas sa lahat ang naturang sistema.

Ayon kay Prof. Lañojan, ang binagong paraan na makapasok sa unibersidad ay nagbibigay-prayoridad sa mga marginalized groups kabilang na ang mga Indigenous People at Moro.

“Well, I beg to disagree... hindi pa nila nakita ang beauty... I hope that sooner or later, they will see the wisdom... this policy, this admission policy is actually very pro-poor and, hindi siya anti-poor, very pro-poor and pro-IP at moro siya,” paglilinaw pa niya.

Dagdag pa ng direktor, sa tingin niya nagsimula ang pambabatikos dahil sa mga maling interpretasyon tungkol sa admission policy sa kadahilanang mahirap na rin ang proseso.

“Can you imagine that simple act of, parang pagkakamali ng interpretation, nag-escalate siya. But we appreciate those people na nagtanong, tumawag. I don’t know kung yung nag-post sa social media kung nagtanong ba siya ng tamang tao sa opisina,” giit niya.

Sistema ng bagong Admission Policy

Kung titingnan ang magiging bagong polisiya na siyang hinango sa pamamaraan ng MSU Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), hinati sa tatlong kategorya ang admission–merit-based admissions, regular admissions, at I.D.E.A admissions.

Sa ilalim ng merit-based admissions, bubuuin ito ng 20% na mga estudyanteng papasok sa pamantasan na kung saan pagbabasehan lamang ang kanilang naging iskor sa MSU-SASE.

Animnapung porsiyento naman ang mga mag-aaral ang kukunin sa regular admissions batay sa mga pamantayan tulad ng MSU-SASE score, Grade 12 general average grade, financial status, at program-specific requirements.

Habang sa kategoryang Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA) admission, 10% naman ang inalaan sa mga estudyanteng IP at Moro at 10% rin sa mga hindi IP at Moro kaakibat ang mga kriteryang dapat ikaw ay first generation college student, child of persons deprived of liberty, PWD, child of solo parent/solo parent, other protected characteristics, at employee dependent.

Dahil dito, mariing iginiit ni Prof. Lañojan na dadaan ang lahat sa butas ng karayom bago makapasok sa MSUGenSan dahil ayon kay Chancellor Shidik Zed T. Abantas, inaasahang 2,880 lamang ang kayang tanggapin ng unibersidad mula sa 5,925 na gustong pumasok sa pamantasan.

“There will be more or less 10,000 na hindi makakapasok. That is why this competition is not just about battle of sino ang pinakamahirap, sino ang pinakamatalino, sino ang pinakamagaling, but this is also a battle of sino ang pinakamarunong. Marunong sumunod sa proseso. Hindi ‘yung nagpapaawa ka d’yan na ikaw ang pinakamahirap na ‘di rin naman nag-follow ng instruction,” paalala niya.

Kaya naman dismayado ang direktor sa mga agad humusga sa bagong polisiya dahil bukas ang kanilang

tanggapan sa anumang tanong tungkol dito. “All concerns kasi alam natin na medyo iba ‘yung pagkainterpret, pagka-absorb ng mga prospect natin na client. Mga iyon ang nagiging problema doon. I think may isa, dalawa doon na nag-post sa social media and then medyo mali ‘yung pagka-interpret. So anyway, kaya najudge yung policy as anti-poor, ano daw, nagtatago sa something like... parang nagbabalat kayo yung message niya,” saad ni Lañojan.

Salaysay ng mga umaasang mag-aaral Pumutok ang naturang pagbatikos sa admission policy nang kumalat noong Mayo 24 ang isang post ng isang hindi kilalang personalidad sa isang page na may kaugnayan sa unibersidad.

Ayon sa post, ang bagong paraan ng admission ay tila taliwas sa kakayahan ng pamantasan na isang pampublikong unibersidad.

Sumasang-ayon naman si Brent Breo Magbanua, isa sa mga nagbabakasakaling makapasok ng pamantasan at mula sa Holy Trinity College. Ayon sa kanya, sobrang hassle ng mga dapat sundin na mga requirements para sa mga estudyanteng walang access sa kahit na anong transportasyon.

“I remember someone who had to travel for hours just to get a BIR certificate, only to be told kulang pa raw ‘yung dala niya. He ended up going back three times — gastos, pagod, at sayang sa oras — just for one requirement. Parang sobrang layo sa idea ng “accessible” and “studentfriendly,” saad ni Magbanua.

Dagdag pa niya, may kakulangan din sa transparency ang nasabing polisiya at hiniling na sana ito ay klaro, inklusibo, at may konting konsiderasyon sa realidad ng maraming estudyante para sa mga susunod na taon.

“To the people behind the admission process, I appreciate the intention. Kita naman na gusto niyong paandarin ang mas modern at progressive na system. Pero sana po, huwag rin makalimutang pakinggan ‘yung mismong mga apektado — kami,” mensahe niya.

“The feedback, the struggles, the confusion — lahat ‘yon mahalaga. I hope you take them seriously and make adjustments where needed. Gusto rin naman naming mag-work ito. Sana this process grows into something truly inclusive and accessible for every student who dreams of studying at MSU,” dagdag ni Magbanua.

Magkatulad rin ang naging sentimyento ni Reinha Karyll Suloy mula Maasim, Sarangani Province na kung saan maituturing niyang pinakamahirap na bahagi ng enrolment process ay ang pagkuha ng BIR Certificate.

“Akala ko na diretso lang sa BIR, ‘yun pala need pa magpa-affidavit sa attorney ng Certificate of Low Income and also pangalawang beses akong bumalik kasi wala akong parent na kasama (which is my father is a part of

12,844

PWD). Halos apat na beses akong bumalik sa Gensan at dumating sa part na wala na akong pera but it’s okay lang,” pahayag niya.

Iminungkahi rin niya sa admission office ang pagbibigay ng mas maagang abiso tungkol sa mga kailangang ihanda upang maging maayos at mas mabilis ang pagproseso ng mga requirements.

Pagpapatupad ng bagong polisiya

Matatandaang matagal inilabas ng admission office ang mga requirements para sa enrolment process sapagkat dahil raw ito sa hinihintay nilang mandato mula sa Board of Regents (BOR) upang opisyal na ipatupad ang naturang admission policy.

Batay sa naging interbyu ng Bagwis kay Prof. Lañojan, sinimulan nila ang pagtatrabaho sa naturang bagong sistema noong Marso ngayong taon nang bisitahin nila ang mga unibersidad ng Mindanao kagaya ng MSUMarawi, MSU-IIT, University of Southern Minadanao, Xavier University upang e-benchmark ang kani-kanilang admission policies.

“Isa sa mga direction as the new admission director, I was tasked to benchmark also MSU- IIT’s admission process kasi matagal-tagal na nilang na-implement ‘yung proseso nila. And I think, ano na sila, parang seamless na ‘yung proseso nila. Hindi mo na sila halos mararamdaman na medyo may mga questions,” saad niya.

Agad namang hinango ng admission office ang naging admission policy ng MSU-IIT at inangkop sa MSUGenSan na kung saan dumaan sa matinding proseso bago maaprubahan ng BOR.

Giit pa niya na umabot sa punto na kinukulit na ang kanilang tanggapan dahil marami ng estudyante ang nagpapa-enroll sa mga ibang paaralan ngunit hindi pa nila naipapalabas ang requirements.

“May mga orders din kasi kami hinihintay. That is why nung sabi... O, sige, pwede na i-post yung requirements muna. Huwag muna yung criteria. Napansin n’yo ba yun? Requirements lan g muna. Medyo doon nagkakarequirements. Eventually, after two weeks yata ‘yun. May go-signal kasi approved na ‘yung time, or approved na siya, that was the time na pinost na namin yung criteria. So, in other words, meron kaming sinusunod na order, mandate. I mean, order from the top management,” diin ng direktor.

Kung kaya’t naiintindihan din niya ang iilan sa mga naging komento ukol sa admission policy ngunit sinisigurado rin ni Prof. Lañojan na ito ay pro-poor, pro-IP at Moro.

Sa kasalukuyan, tinitiyak na ng admission office ngayon ang pag-verify ng mahigit 12,000 na mga magaaral na gustong pumasok upang masigurado ang makatarungang sistema ng bagong ikinasang admission policy.

5,925

Number of students expressing their intent to enroll

2,880

Expected number of students that

Where should sexual harassment cases be reported in MSUGenSan?

The Committee on Decorum and Investigation (CODI) of Mindanao State University—General Santos (MSU-GenSan) is the committee tasked with receiving complaints and investigating Gender-Based Sexual Harassment (GBSH) cases among university constituents.

In an interview with Bagwis, Atty. Hanna-Tunisia F. Usman, the present chairperson of the CODI, affirmed that while the university’s CODI manual is still awaiting approval from the MSU Board of Regents (BOR), it is already effective and a copy of it will be distributed once it is approved by the BOR.

“The major task of CODI is to receive complaints and investigate Gender-Based Sexual Harassment cases. So, saklaw nito ‘yung offenses under Safe Spaces Act or RA 11313 and other [laws] related to gender-based offenses,” Atty. Usman told Bagwis.

GBSH in streets and public spaces, as defined in Section 5 of the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of RA 11313, is any unwanted and uninvited sexual behavior or remark directed at any person, regardless of intent.

This includes acts such as catcalling, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, and misogynistic slurs, persistent comments on appearance, repeated requests for personal details, sexual jokes or suggestions, lewd gestures or acts like flashing or groping, intrusive gazing, and stalking.

While the university also has the Student Disciplinary Board (SDB) which handles disciplinary cases involving students, Atty. Usman explained that the CODI exists specifically to handle all cases that can be categorized as GBSH.

1. Upon receiving the counter-affidavit:

- CODI holds an internal meeting to deliberate next steps

- CODI may:

> Request additional documents from the respondent

> Schedule a hearing or face-to-face interview

• Who: The complainant submits a complaint to CODI.

• Where:

- Planning Office, 2nd floor, Y Building

- SSC Straw Desk

- College orgs Straw Desks

- GAD focal system

Requirement: The complaint must file the complaint under oath, meaning the complainant swears to the truthfulness of the information reported.

• Content of the Complaint:

- Full name, address, and other identifying information of the complainant

- Description of the incident

- Evidence (must be under oath)

- Acceptable forms of evidence include screenshots, photos, and other supporting documents.

• Once all necessary information is provided:

- CODI notifies the respondent (person being complained of).

- The respondent is required to submit a counter-affidavit addressing all allegations.

- Deadline: The respondent has 3 days to submit this counter-affidavit.

- Supporting evidence may be attached.

- The respondent must also furnish a copy of the counter-affidavit to the complainant through the CODI

For student respondents: CODI will notify the following offices (not as a sanction, but for awareness):

- Office of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs (OVCAA)

- Office of the Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs (OVCSA)

- The Dean of the college where the student is enrolled in Especially during graduation season, off-sem, or when a student plans to take a leave of absence.

After gathering sufficient information:

- CODI conducts a final deliberation.

- Drafts recommendations and proposed sanctions based on:

> CHED guidelines

> Applicable laws and policies

- Possible sanctions (for both students, faculty, and staff)may include:

> Written warning

> Reprimand

> Suspension

> Dismissal

> Expulsion (for students)

> Termination of Contract (for faculty and staff)

> Permanent Ban (for thirdparty providers, e.g caterers, construction workers)

- CODI informs all involved parties of the recommendation.

Atty. Usman clarified that CODI’s process is only disciplinary and administrative, and therefore advises complainants whose cases are heavy to report the case to external authorities like the Philippine National Police (PNP).

“Kunware, rape or sexual assault, kung mag-file siya [the complainant] ug kaso sa gawas, lahi to siya. Lahi man ang liability didto kay criminal man to. Sa [CODI] dili man [criminal] ang nature sa pagkaso sa CODI,” Atty. Usman explained.

Additionally, she explained that if the CODI dismisses the case as it wasn’t proven upon the CODI’s level of investigation, the complainant can still file a case to the external authorities.

“Kasi the regular court has all the power and authority to investigate also na ang liability is criminal in nature. Sa CODI, dili man diba. Dili pod mga attorney ug dili pud judges ang galingkod sa committee,” she clarified.

Other steps taken by CODI

Atty. Usman also mentioned that there are other steps taken by them such as referring the complainants to the Office of Guidance and Counseling for assistance, or to the Medical Services Department for a health check up, especially if they assess that the complainant is “bothered”.

“We’ve already been doing this for two years actually kasi may mga student na ayaw talaga nilang mag [file] ng complaint but they just want it to be recorded for data purposes or gusto lang nila ma-raise ‘yung awareness na nangyayari,”

- CODI submits its recommendations to the Office of the Chancellor (OC)

- The OC may:

> Forward the recommendations to the Board of Regents (BOR) for approval

> Request a review by the Legal Services Office, if doubtful of the procedure of the CODI, before submitting to the BOR

Note: Even while awaiting BOR approval, the CODI’s recommendations may already be implemented immediately if necessary (e.g. if the CODI recommends for a suspension, the person complained of will be effectively suspended)

Preventive Suspension: The CODI also has the power to recommend for preventive suspension of the person complained of if their continued presence poses a threat or risk (e.g. if the complainant and respondent are classmates or if the respondent is the complainant’s professor)

Atty. Usman said.

Because of this, they have also conducted a series of seminars introducing the CODI as well as the Safe Spaces Act, also known as the Bawal Bastos Law.

When asked if invitations from university organizations for talks or seminars on the Safe Spaces Act are subject for a fee, Atty. Usman affirmed that they do it for free.

“We do it for free. We love that. Sabi ko nga dati sa OSA nung wala pang Vice Chancellor [for Student Affairs] sabi ko na ‘yung mga student organizations dapat before accreditation dadaan muna sila ng seminars kahit 2-hour lecture lang, awareness lang, na this is our existing policy on safe space, this is what we do, this is what we can do,” Atty. Usman stated.

SSC, GAD, student orgs’ role

The Supreme Student Council (SSC), specifically to its Students Rights and Welfare (STRAW) Desk and GAD focal persons, also receives complaints which they refer to the CODI.

“Syempre kami, ‘yung mga committee members [ng CODI], if makikita mo, lahat ito, faculty and mga directors, so very busy. We cannot immediately answer to the call or whatever na needed. So very helpful sa amin ang STRAW desk, very helpful sa amin ang GAD representative, whoever sila and whoever sa GAD focal system natin kasi they’re well aware also of the existence of CODI. So pag alam nila na gender-based sexual harassment ito, isumbong na ‘yan sa CODI.”

Persons complained of:

- Students

- Professors or faculty and staff members

- Third-party suppliers

> Construction workers

> Drivers

> Caterers for events

> Other guests and visitors

Additionally, the CODI aims to develop a training program on psychosocial intervention for GBSH, where students will be equipped to support victims of sexual harassment.

This initiative is similar to the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) training of the Office of Guidance and Counseling last academic year, but specifically focused on GBSH-related cases.

Atty. Usman also shared that the members of the committee—composed of Ruhama Gomez, Director of the Gender and Development (GAD) Office and Center for Women Studies (CWS); Sheila Marie Esma-Magriaga, RN, from the Medical Services Department; Prof. Rhumer S. Lañojan, from the OVCSA; Usman M. Disalongan, JD, Director of the Human Resource Management Office (HRMO); Dennis Toroba, from the Civil Security Unit; Diane Mae Ulanday-Lozano; Jinny Chee Kee; Thucydides Salunga; Hania-Persia F. Usman, RPm, Director of the Office of Guidance and Counseling; representative from the Administrative Staff and Support Services Association (ASSSA); and the president of the SSC—are under a confidentiality rule.

“Dati kasi may mga narinig kami na cases, takot ‘yung mga bata na ‘yung issue nila, malaman. Under our CODI manual, we really commit there na ang committee members are under confidentiality rule. May nilagay kami doon na provision na we are bound to protect the information of the parties,” Atty. Usman mentioned.

JESSIE REY RUERAS

Noong 24 Mayo 2025, umani ng atensyon sa Facebook page na Buhay MSUan ang ilang hinaing ng mga aplikante, estudyante ultimo organisasyon hinggil sa bagong admission requirements ng MSU-General Santos, partikular ang obligasyon na magsumite ng Income Tax Return (ITR) ng parehong magulang. Kasunod din nito ay ang mga kabi-kabilaang mga sentimentong naibabahagi ng iba pang mga aplikante sa public group page na MemeSU. At sa kauna-unahang pagkakataon, ang patakarang ito ay ipinatupad nang may pagkabigla, komplikado at maaaring maging salat sa konsiderasyon. Bilang isang unibersidad na nilikha ng batas upang magsilbi sa mga nasa laylayan ng lipunan, nagiging salungat nga ba ito sa diwa ng Republic Acts No. 1387 at 1893 na siyang pundasyon ng MSU? Epektibo nga ba ang bagong sistema sa pagpili ng karapat-dapat na estudyante, at naihanda ba ang mga aplikante sa ganitong pagbabago?

Ayon sa Office of Admission ng MSUGensan, ang pangunahing layunin ng bagong admission policy ay tiyakin ang transparency at fairness sa pagtanggap ng mga estudyante. Ayon pa sa kanila, ang requirement ng ITR o katumbas na dokumento ay bahagi ng integrity check upang maiwasan ang fraud sa income declaration. Bagamat mahirap sa ilang aplikante, hindi ito bagong polisiya sa ibang pamantasan. Sa katunayan, ayon sa Admission Head na si Sir Rhumer Lañojan, ito ay bahagi ng benchmarking effort mula sa Mindanao State UniversityIlligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT) at iba pang unibersidad na matagumpay na nagpapatupad ng katulad na sistema. Ngunit nang inilapat sa bagong proseso ng admission sa nasabing pamantasan, tila hindi nakabalanse ang karanasan ng bawat estudyanteng nangangarap na makapasok sa unibersidad.

Ayon kay Lañojan, ang bagong sistema ay hindi basta-bastang ipinasa. Dumaan ito sa malalim na deliberasyon at mga konsultasyon sa iba’t ibang opisyal at kinatawan ng unibersidad, kabilang ang Chancellor, Vice Chancellors, mga Dean, at maging ang Supreme Student Council. Layunin nitong ihanda

ang MSU-Gensan upang maging mas competitive at maipantay sa iba pang campus tulad ng MSU-IIT. Bagamat ito ang unang implementasyon, natural lang na magkaroon ng mga hamon sa simula. Masasabing bigo sa ilang aspeto dahil sa kawalan ng malawak na konsiderasyon, ngunit ang paggulong ng bagong sistema sa kasalukuyan ay magbabago patungo sa hinaharap.

Hindi lingid sa ating kaalaman na ang sitwasyong ito ang naging dahilan ng pagkabigla ng karamihan sa mg estudyante at magulang na naging resulta ng emosyonal distress mapapersonal man o onlayn. Ayon kay Lañojan, maaaring may naging misinterpretasyon sa initial announcements. “We appreciate those who asked questions properly,” aniya. Ipinunto rin niyang may iilang aplikante na hindi nakikipag-ugnayan sa opisina at agad na naglabas ng opinyon online. Sa panahong hindi pa rin putol ang lubid ang lubid ng disimpormasyon at sa personal na bahagi ng ating buhay, ang pag-uusap ng masinsinan at pag-tuon sa mga tamang taong lalabasan ng iyong hinaing ay mahalaga sa pagbuo ng epektibong komunikasyon. Aminin man o sa hindi, lahat ng away ay siyang dahilan ng hindi pagkakaunawaan na dapat ay hindi pairalin sa mga seryosong kalagayan.

Ayon pa sa Office of Admissions, bukas sila sa mga concerns at nakahandang tumulong. Isa sa kanilang hakbang ay ang pag-extend ng deadline sa pagsumite ng requirements upang mabigyan ng sapat na oras ang mga aplikante. Malinaw pa sa bolang kristal na ang intensyon ay hindi upang hadlangan ang mahihirap, kundi upang maging patas sa lahat ng nagnanais pumasok sa unibersidad. Ayon sa kanila, higit na makikinabang ang tunay na mahihirap kung magiging maayos at tapat ang proseso ng income verification. Sa tala ng Mindanao Development Authority noong Enero 2025, bumagsak mula sa 18.1% noong 2021 sa 15.5% noong 2023 ang tinatayang poverty rate sa Mindanao na posibleng mas bababa pa sa susunod na taon. Sumasalamin ito na mas dudumugin pa ang mga pampublikong unibersidad sa hinaharap sa kadahilanang praktikalidad.

Giit ni Lañojan, hindi anti-poor ang patakaran. Sa katunayan, nakasaad sa Agenda 2 ng bagong Chancellor ang pagtutok sa poorest of the poor. May mekanismo rin para sa mga Moro at IP applicants, kung saan nakalaan ang 20% ng slots. Sa usapin ng inclusion, tiniyak ng opisina na may 10% quota para sa Moro applicants, 10% sa non-Moro IPs, at 20% para sa merit-based selection. Ayon sa kanya, “We want to give the public a chance to rise.” Kaya sa halip na isiping

nabibigyan lamang nito ang lamat sa akses, mas nararapat na tingnan ito bilang pagtatangkang isulong ang mas makatarungan at mas sistematikong admission. Sa mga naunang proseso, hindi maiiwasang may mga nakakapasok na mga hindi dapat

karapatdapat

at na

magkamayaw sa pag-abot ng kalidad at libreng edukasyon ngunit nabigo ng sistemang kulang sa pagiging bukas. “We understand na maraming nagulat, pero we also emphasized na lahat ay dumaan sa tamang proseso at maraming platforms na ibinigay para magtanong,” ani Lañojan. Aminado rin siyang dapat pag-ibayuhin pa ang pagpapaliwanag at information dissemination. Sa kabilang banda, inaasahan din ng opisina ang aktibong partisipasyon ng aplikante sa proseso. Nakakadismaya lang isipin na marami agad ang nagkaundagaga sa pagsunod sa mga kinakailangang asikasuhin upang mahabol ng itinakdang huling araw ngunit ito rin ang naging mitsa upang ilang ulit na dumadagdag ng pinal na araw ng pagsusumite ng mga rekwarments.

ityapwera ang mga nasa laylayang hindi

Bagamat may mga butas at pagkukulang sa implementasyon, sentro pa rin nito ang pagkakaroon ng sapat na batayan ang polisiya sa prinsipyo ng pagkakapantay-pantay at integridad. Masasabing tila isang pakpak ang implementasyong ito na pinakawalan sa isang hawla at nagiging bulag lang ang sistema nang mapuruhan ang pakpak nito at hindi makalipad ng perpekto sa sariling destinasyon. Gayunpaman, lumilitaw sa mga ulat at panayam na may kakulangan sa information dissemination at logistical support sa pagpapatupad ng bagong polisiya. Kung tutuusin, hindi ang layunin ang problema, kundi ang transisyon at kakulangan sa lokal na suporta para sa mga aplikante mula sa malalayong lugar. Masaklap man na katotohanan, ngunit marami pa rin ang mga bayang kay tagal umusad dala ng pang-aagrabiyado ng mga nasa matataas na posisyon na puro pagbabango sa mga pangalan ang ginagawa ngunit pagtutok sa problema sa edukasyon ay nababalewala.

Naglabas naman ng hinaing ang isang upcoming 1st Year mula Tupi National High School na si Zareina Marie Balaso, aniya, “Honestly, frustrating po talaga ang mag wait ng update from MSU-GSC since wala po talaga assurance na completely admitted kana sa University. Aside from

this, limited lang po kasi ang slot ng binigay ng school so mahirap po for us students if hindi makakuha ng slot sa gusto naming course.” Na sa kasalukuyan ay nasa validation at scoring process na ngunit ang usad ay pabagal nang pabagal lalo na’t in-extend muli ito sa ika-15 ng Hunyo gayong halos lahat ng mga unibersidad sa bansa ay bukas na para sa enrollment sa pagsisimula ng pasukan.

“The new admission process is actually nice, but I hope na-explain po ng maayos sa amin ang new process since ang nangyayari po is sadyang pumapasa lang kami ng requirements but di aware sa susunod na steps,” dagdag pa nito. Tila wala pa ring kasiguraduhan para sa mahigit labindalawang libong estudyante ang gustong makapasok sa pamantasan lalo na’t mahigit 2800 lamang ang makakapasok. Lubhang nakakapanghinayang ngunit tugon ng administrasyon ay para masiguro ang masusing pag-analisa sa sinumang dapat na makapasok na dadaan muna sa butas ng karayom.

Kung ang layunin ay maging inklusibo, kailangang tugunan ang mga praktikal na balakid para makamit ito.

Ang pagreporma sa sistema ay hindi dapat maging pabigla-bigla, ito’y dapat isinasagawa nang may sapat na konsultasyon, suporta, at transisyonal na plano. “

Sa ganitong paraan, maiiwasan ang hindi pagkakaunawaan, at higit sa lahat, maisusulong ang edukasyon bilang karapatan hindi pribilehiyong para lamang sa may kakayahang magkompleto ng hinihinging kinakailangan. Maging bukas sana tayo sa pag-unawa sa bawat isa dahil ang inaakala nating imposible ay hindi pa pinal kung sa unang sipat, ito’y naukitan na ng hindi pagtanggap at bahid ng lamat. Maging pantay sana ang sistema at kakayahan ng mga taong umunawa sa isa’t isa dahil ang misyong ito ay hindi layong tuluyang maging posible.

In a bold move to realign and expand its student services, MSU-GenSan overhauls its Office of Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs (OVCSA) into the Office of Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs and Services (OVCSAS), marking a structural overhaul to provide more holistic services for students in the university community.

Following the Board of Regents Resolutions No. 131 and 132, Series of 2025., through the vision of the chancellor Atty. Shidik Abantas and implemented under the leadership of Dr. Norman Ralph Isla, the reorganization sheds purely academic functions like admission and consolidates student life services under one umbrella.

The initiative also aligns with national directives such as CHED Memorandum Order No. 9, Series of 2013, which emphasizes the concept of “Student Development Services”.

Isla explained that the removal of the Admission and other offices from OVCSAS was part of the administration’s effort to revamp its structure.

“Yeah, it’s part of the calibration..we want to streamline the brothers and sisters of the offices, which the admission—of course, we love admission really….it’s more of academic,” the vice chancellor addressed.

He added that while Academic Affairs oversees a student’s journey from admission to graduation, OVCSAS will focus on student retention, co-curricular activities, and overall student life.

The OVCSAS head noted three key revamps and additions within the department, which makes the student approach scope bigger.

“There’s the Sports Development Office, which was previously in the Office of the Chancellor, it was given to us to be more focused in terms of students, for our student-athletes, Cultural Affairs Office for culture and arts skills that has a duty in terms of cultural arts education and sensitivity to students.” Isla added.

The biggest addition to them was the medical services, aimed to highlight the medical education, at the same time, the more adept services to the families, medical and health.

Two pilot offices are said to be in development, such as the Center for Learning and Academic Support Services (CLASS) that will support tutoring programs and offer equipment lending, and the Job Placement Office that will connect students to job vacancies, offer email notifications for fresh grads, and prepare students for employment.

“Because honestly, yung JPO na yan, inoffer yan sa atin. Kasi lagi tayo naging job fair, pero kunti lang nakahire... Kaya itong mga bagong office... they are future-thinking,” Isla stated.

The aforementioned job office is set to inaugurate on June 19.

In light of recent issues involving student protection, OVCSAS is also doubling down on legal education and gender sensitivity.

“Lagi natin pinapromote yun siya, yung ‘Bawal-Bastos’ Law. Marami talagang challenges na nangyayari… We partnered with Gender and Development, a program as Center for Women’s Studies,” the vice chancellor relayed.

OVCSAS is also integrating and implementing the RAPIDS program — which stands for Respect and Responsible, Amazing, Peace-Oriented, Inclusivity, DrugFree, and Sustainable, that promotes a safer and cleaner campus.

“We really want the students, not only to be good in academics, but they have a support system coming from us... whether it’s mental health, medical health, student projects and activities, sports, culture and arts, or even residences,” Isla emphasized.

Recent projects already reflect this studentfocused vision, with upcoming facilities include the infirmary and primary health care unit, as well as a Virtual Learning Studio which will serve as a space for workshops, thesis defenses, and multimedia learning.

The head acknowledged that while they are still facing budget challenges, improvements have been made through harmonization.

With a strengthened structure, it is positioning itself not just as a university office, but as a vital partner in every student’s academic journey in the university.

As the seniors' tassels are turned and diplomas received, a different story unfolds far from the stage: stories of grit, heartbreak, and determination among incoming freshmen trying to secure a slot at their dream university. Yet, even as MSU prepares to open a new chapter for its incoming freshmen, it is worth asking: at what cost does this dream truly come true? While graduates celebrate the finish line, the next generation of learners stands quietly in line, struggling not due to low scores, but because of a burdensome admission process that often demands too much from those who have too little.

For many students, what draws them to MSU goes beyond its academic reputation. The university offers diverse academic opportunities and crucial financial assistance programs, providing avenues for students who can't afford high tuition fees. However, the road to those pathways is not paved with ease. Applicants are asked to secure an array of documents, including both parents’ Income Tax Returns (ITRs) or Certifications of No Income, among others— a process that has been physically, financially, and emotionally tough for many, especially for those with parents who are physically absent and those who can’t afford transportation and other necessary fees.

MSU is more than a university— it's a lifeline

For an incoming freshman, MSU is more than just a school— it’s a lifeline, a shared dream. “MSU is my top choice because it's both mine and my mom's dream school, and it offers opportunities for students like me who can't afford high tuition fees,” shares an aspiring MSUan, who recently navigated the arduous admission process.

Like many applicants, she found the admission process to be a test of patience and endurance. She admits, “It’s indeed tiring but worth it. You have to be early to line up and get a number for the certification of no income from BIR. It’s a test of patience,” highlighting the often-overlooked practical hurdles. For her, each form submitted and document filed brought her one step closer to her dream, and that, she says, made it all worth it.

But not everyone can hold on to that hope.

She recounts how some of her equally determined friends found the process an insurmountable burden.

“

It is very inconvenient and complicated for them, especially those not living with their parents. They had to prepare more documents like authorization letters, and even then, the process was exhausting. Some of them did their very best but realized that privileged students will mostly get the favor.

This observation points to a deeper, systemic issue within the admission system, risking the exclusion of the very students MSU was originally established to serve.

Yet, amid the burden of requirements and the weight of uncertainty, a flicker of hope persists. “I’m excited. It’s a new adventure for me. I feel a little nervous, but when I think about MSU as mine and my mom’s dream school, that makes me feel brave,” she shares.

The ‘IDEA’l future of MSU: Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA) Admissions

The Office of Admission imperatively champions the principles of fairness, inclusion, and academic opportunity. With the introduction of the Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA) Admissions, a transformative framework has been established.

The IDEA Admissions uplifts those longmarginalized communities by offering them a higher chance at education. It is for the students who carry the burden from long lines of generations yet dream of breaking the cycle. IDEA represents a framework that no longer considers merit by privilege alone, but by talent, need, and potential. It justifies equity over equality—justice over judgment—breaking down barriers to education to make way for those who need it most.

In particular, the IDEA Admissions accounts for 20% of MSU-General Santos’ admission slots and is subdivided into two, allocating 10% for Moro and Indigenous Peoples (IP) students and 10% for non-Moro and

non-IP students who still belong to culturally vulnerable groups. Both subcategories mainly include specific selection criteria; beyond SASE scores and Senior High School grades, they also consider financial status, whether a student is a firstgeneration college attendee, and other protected characteristics, such as being a working student.

This offers a newer, more accessible, and holistic pathway for students of all backgrounds and abilities. Initiating opportunity for them sparks hope and societal advancement for all. It is not just a system of admission—it is a movement for transformation, a mission for representation, and a promise of a better, fairer future. Education, through IDEA, becomes not only a right but a real, attainable reality.

With the new admission system, opportunities are democratized, especially for the less privileged with economic constraints and limited access to quality education. This paradigm shift paves the way for inclusivity and equitable access to a higher form of learning. Stemmed from the recognition and addressing of economic disparities, this more inclusive and studentcentered approach shows the genuine essence of studying at a state university. For MSUans, the principles of equity and social consciousness place the value of education at the core of every effort and toward student empowerment. Students whose parents raised them alone, work tirelessly overseas as OFWs, or struggle to make ends meet with low income are finally given a fairer chance at university admission through this new system. Behind every application is a story to tell—a story of sacrifice, resilience, and hope. No matter where a student comes from, each one carries the same right: the right to a proper, meaningful education. In every life story, one truth should remain: education is not just a path to knowledge; it is a path to liberty and freedom.

For those who have long been overlooked, MSU, through IDEA, now offers a truly fair chance at education—a chance for things to finally go their way.

ALJIM KUDARAT, FAYROUZ OMAR

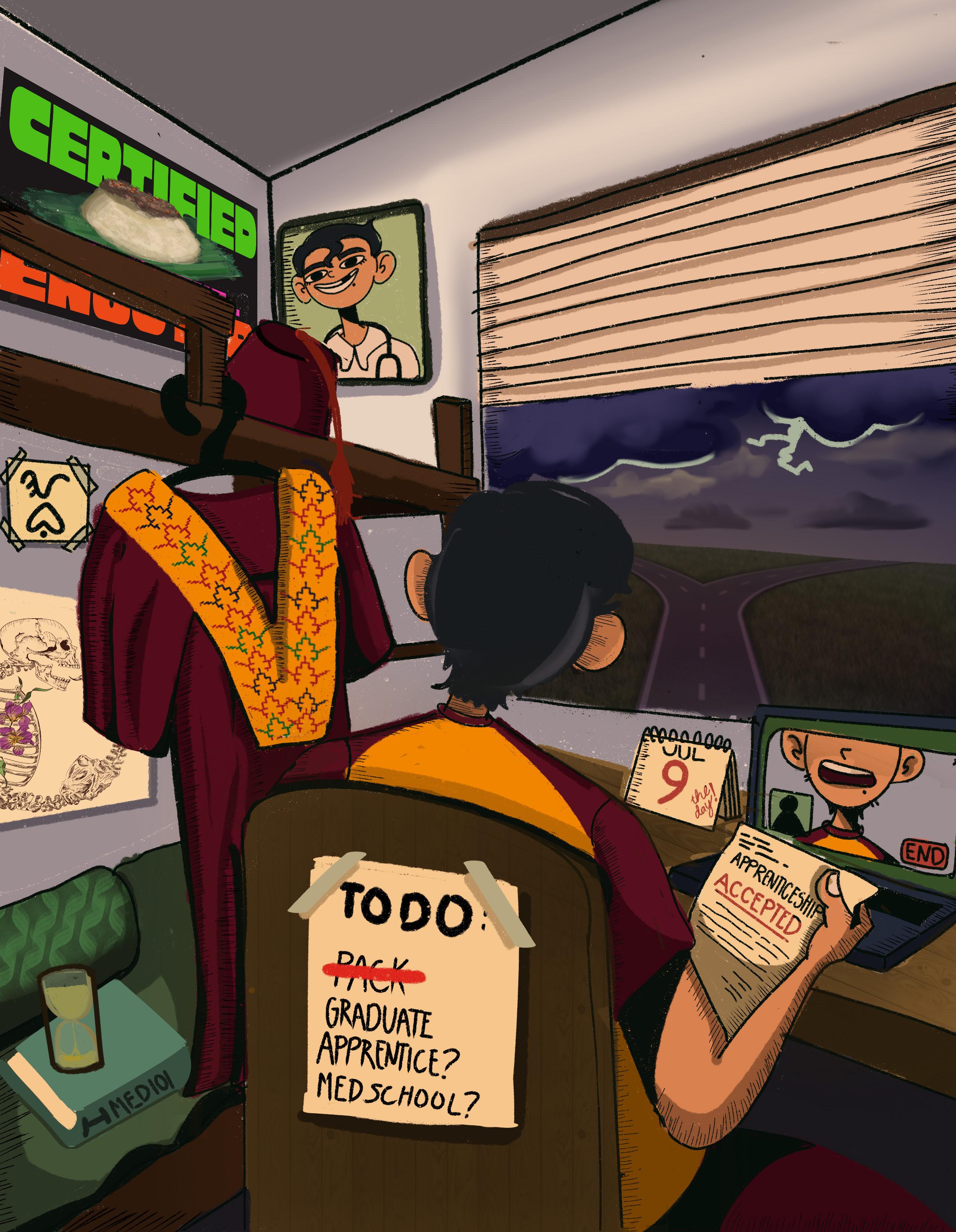

“Dzai, mu-graduate na jud sowk! Makatrabaho na ta ani, nya mudato and successful sa layff kay MSUan baya!”

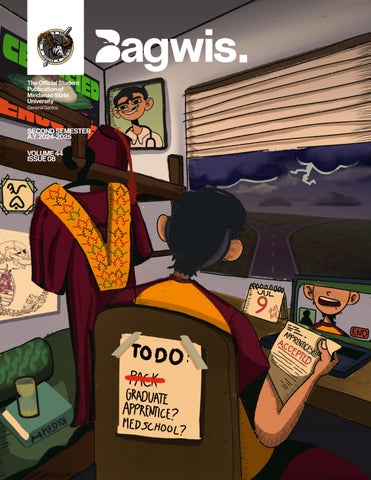

The long wait is over. Marching in dignified sotra togas, adorned with intricately woven langkit threaded with stories of resilience, setbacks, and small victories—the grueling academic journey finally reaches its ceremonial end. No more hell weeks, no more sleepless nights, no more frantic cramming, no more suffocating deadlines… or is it?

“Wa gihapon nay pulos mga gah kung wa moy backer! Hahaha!”

Well… what now?

As the world beyond the stage opens its gates, hopes burn brighter than the noonday sun. But reality? It whispers with a silence so deafening, it stuns. In a society that proudly declares we are all racing toward the same future, it forgets to say that only a few begin with cushioned running shoes, while most stand barefoot on the scorching starting line. Yet still, the gun has already fired.

The Great (Un)equalizer Graduates, hark! For a paradox so sharp it slices through your jam-packed résumés: “You need experience to get hired, but you need to get hired to gain experience.”

This is where the haunting begins. The post-grad job hunt in the Philippines is less a career ladder and more a rotating hamster wheel—painfully circular. Sadly, opportunity remains so turbid it drowns the dreams these graduates hold onto in a vast ocean of uncertainty.

According to the latest data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the country’s unemployment rate rose to 4.1% in April—marking the highest in the last three months. This equates to 2.06 million jobless Filipinos, a notable increase from 1.93 million in March. Behind those numbers are thousands of fresh graduates stuck in limbo, one of which is the cruel irony of employers demanding two years of experience for entry-level roles yet providing no pathway to gain that very experience.

Even more dire, moreover, in a nation where education is hailed as the great equalizer, it is alarming that those with college degrees make up the largest share of the unemployed. In the article published by The Philippine Daily Inquirer by columnist Cielito F. Habito, data shows that the number of jobless college graduates climbed from 26.9% in 2020 to 35.6%, with 44.1% having reached at least some level of tertiary education. Say they now get a job; that, however, often leads only to bare-

bones employment—stripped of choice, there has never been.

This labor market absurdity does not exist in a vacuum. It festers under the weight of poor labor protections, the infamous padrino system, and government agencies ill-equipped to support the workforce. Economic progress exists, yes—but it serves only a few. The majority suffer under the failures of those in power to address the economic inequalities facing the country. This all boils down to a system too rigid to recalibrate, one driven by self-serving policies aimed not at real progress but at political survival.

And yet, it is not the job system that bears the shame—but the jobless, still waiting at doors that refuse to open.

Face the Deadlines

“Walay deadline ang pagka-successful,” so goes the viral mantra echoed across social media, courtesy of influencer Bite King. But let us be real—that comfort is a luxury only the privileged can afford. For the working-class MSUan who once survived a week without remittance from their hardworking parents, skipped classes for night shifts, or nearly failed a subject because survival was the higher priority— success does not wait; it demands. And worse, it demands deadlines.

While the PSA reports a decline in the national poverty rate—from 18.1% in 2021 to 15.5% in 2023— this statistical progress remains difficult to reconcile with grassroots realities. On the ground, rising prices of basic commodities and persistent lack of job opportunities continue to widen the gap between data and daily survival.

Although some may dismiss MSUans as “highly privileged” for being able to study at a state-funded university, it is imperative to learn that this institution was founded as a response to the “Mindanao Problem,” envisioned to bring together Moro, Cultural Minorities, and Christian communities from the Southern Philippines. This vision reflects the deeply rooted socioeconomic backdrop its students come from—one underscored by the 2023 data identifying Indigenous Peoples (32.4%), fisherfolk (27.4%), and farmers (27.0%) as sectors with the highest poverty incidence. These statistics mirror the lived experiences of many MSUans, for whom education is not just a right but the last line of hope toward a better and more dignified future.

Yet at the end of the day, hard work alone is never enough. The game has always been biased in favor of those born closer to the finish line. “Work harder,” they say. But harder than whom? Than someone who already inherited the generational wealth? Studying

at a state university like MSU is an act of defiance, not privilege. It is where the barefoot meet the world in borrowed shoes. But if the finish line remains guarded by class, then maybe it is not the students who should run harder—but the system that must be slowed down and, therefore, halted.

The graduation toga barely dries from the laundry before the question comes knocking: “May trabaho ka na?” from relatives you barely know at family gatherings, to neighbors passing by the sari-sari store, to your own parents. It’s not meant to wound, but it cuts deeper than most questions can. Because beneath it lies the real question: “Kailan mo kami matutulungan?”

There is no buffer zone between tassel and toil. No time to breathe, to rest, to figure things out. For some, graduation means finally being able to chase their passion. For others, it means shelving it indefinitely. Because the family has bills, a sibling has tuition, the rent is due—and hope doesn’t put rice on the table.

For many Filipino graduates, especially Iskolars ng Bayan, the diploma isn’t just a piece of paper—it’s a receipt. Proof of years of sacrifice not just by the student, but by their community, and even the state. Proof of families pawning jewelry, taking out loans, or selling livestock just to keep one child in school. That proof carries hope. That hope becomes pressure, and that pressure becomes currency: you’re expected to pay it forward. Fast. The degree is meant to be a ticket to better days, but it also becomes a silent contract: Bayaran mo na ang utang na loob.

Then come the comparisons. Cousins working abroad. Batchmates with six-digit salaries. Children of family friends already paying for house repairs. The graduate isn’t just expected to succeed; they’re expected to do it first, fast, and flawlessly. They must prove the sacrifices were worth it, that they are not “sayang.” The gratitude that once inspired them now feels like a scoreboard. And if they stumble, even for a second, the whispers begin: “Anong nangyari sa kanya?”

The newly employed graduate isn’t just expected to build a future—they’re expected to fix a past, uplift a family, and prove that none of the sacrifices were in vain. Giving back should come from abundance, not burnout. The question is not whether they should help—it’s whether we’ve helped them enough to stand on solid ground before they’re asked to carry others. Are we truly empowering them or exhausting them?

After all the noise—the speeches, the ceremonies, the congratulatory posts— comes a silence no one prepares you for. It’s in this silence where the real work begins.

Not everyone leaps from graduation into their dream job. Some pause. Some stumble. Some take detours that don’t fit neatly into LinkedIn bios or family group chats. But that doesn’t mean they’re lost. It just means they’re becoming.

We often measure success in job offers, salaries, and titles—but for many young Filipinos, the first steps after graduation are filled with invisible work: grieving unmet expectations, rebuilding confidence after rejections, and navigating the pressure to be okay when they’re not.

There’s bravery in choosing rest over burnout. There’s quiet courage in taking the longer path, especially when society demands shortcuts. And there’s dignity in building a life not for applause, but for peace.

So when a graduate takes their time, don’t rush them. When they choose a different path, don’t shame them. Because the road less traveled might not be fast or loud, but it is full of intention.

It is where many begin to walk not just toward a career, but toward themselves.

And that, more than anything, deserves recognition.

Well… what now?

Throughout this journey, we’ve unmasked the truth behind that silence: that not all starting lines are equal; that the job market demands what it never equips; that Filipino culture can burden more than it uplifts; and that quiet, unseen struggles deserve the same recognition as loud achievements.

Let this be the truth we offer—not just to graduates, but to everyone watching them take their first uncertain steps into adulthood: they are not late; they are not behind. Success isn’t a race, and life doesn’t hand out medals for exhaustion.

This isn’t the finish line. But it is a line—one that they now have the right to draw themselves. Boldly, if they’re ready. Slowly, if they need to. Messily, if that’s what it takes.

And to all who expect them to soar before they’ve even had a chance to breathe— Let this not be a finish line we push people over—but a starting line we walk beside them on.

lies ahead after the

One thing’s for sure, it wouldn’t be so easy.

Nothing beats the joy of wearing that maroon toga, a dream long cherished, as you exit the university with your hard-earned diploma. You sit there waiting for your name to be called, heart brimming with the promise of a world ready for your exploration… until you aren’t.

Let’s face it: the hardships, the prayers, the dread of waiting for your thesis to be put into hardbound… Nothing in this world could ever repay the efforts of an MSUan except for the long-awaited graduation (and some money garlands to add). But despite counting days instead of sheep just to wait for that most-awaited day to come, there is another barrier that may keep you from having a wink at night: what comes next after graduation, really?

CATHYLENE BULADO, LLIANAH MORA “

that feeling might actually be you just feeling antsy, but who knows? After all, there is nothing more uncertain than landing a job or reaching the expected salary you once wished for while throwing a coin in a random fountain.

In a survey conducted by Bagwis, data revealed that the majority of the alumni believe that a degree or a license is not enough to land their ideal job. Well, that’s a bummer, isn’t it? Factors such as work experience, a sufficient skill set, and the backer system make it difficult to immediately land a bingo on the job vacancy you may have waited for, along with… a pool of people, honestly.

Well, if there’s only one thing to sum up everything, then it would be the fact that the world is certainly a vast plane.

Congratulations on graduating! So, what’s next?

You’re probably not into making the drastic choices or feeling that you are nearing your doomsday. Well, perhaps

In fact, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) recorded an increase in the unemployment rate, rising to 4.1% this April from the 3.9% joblessness ratio. This means that 2.06 million Filipinos are unemployed, whereas there were 1.3 million recorded in March.

This depicts how employment in the country remains to be a grappling concern over the years, and for graduates of MSU, this is also the

problem one must face in order to tread on the uncertain path one is to take. Be it a 5-year experience and a PhD in accountancy when applying to be a cashier, or an aunt who happens to work in the same company you desire to be in, there is no easy way to sink your teeth into the pool of employment.

According to a response from an alumnus, having a degree or a license is only the starting point to your grinding journey as you climb up the ladder of employment success.

“I believe my degree and future licensure are essential but not enough to land my ideal teaching job. Schools also look for teaching experience, communication skills, and a passion for education. To stand out, I need to show that I can apply what I’ve learned in real classrooms and continue growing as a professional,” she shared.

If there’s one thing out there, maybe it’s the job qualifications of your desired job being similar to that of Potato Corner’s high-profile hiring controversy.

Now here’s the undeniable truth: That institutional logo in your diploma won’t magically land you a job. It’s a tough pill to swallow, but really— being a graduate of MSU-Gensan doesn’t come with a golden ticket. When asked if being an MSU-Gensan graduate gives you an edge in job applications, 28 out of 45 said yes. But the remaining 17? They would rather say connections and political affiliations would back you up more.

And that says a lot in the current employment landscape in the Philippines.

Sure, some believe that MSUans are naturally madiskarte—hardened by the relentless storms of thesis defenses, the demanding side quests of special projects during final exams, and the extended school days—sacrificing a month’s rest before the yet again dreadful semester. Undeniably, there is a certain pride in being built from the chaotic system that raised a selfsufficient and enduring student body. But now take it from the lenses of a breadwinner MSUan, someone who

has to work three times harder just to stay afloat while juggling deadlines and part-time jobs, who smiles through fatigue and licks pleasantries just to keep vital connections warm.

For them, this isn’t merely about chasing dreams. It’s about surviving. And when survival is the baseline, the system feels even more rigged. Because oftentimes, sometimes it’s not about what you know and where you came from but who you know and how high they are on the ladder.

So, what now?

You leave the university gates with a diploma in hand (a few medals, perhaps) and a heart brimming with hope. Yet, disappointingly, you only get to meet a world that is not as romantic and magical as your graduation rites made it out to be. It’s a world where your hard-earned degree is merely one item on an extensive checklist, and the elusive ‘ideal job’ begins to feel like a mythical concept, accessible only to a fortunate few.

But don’t fret, for this is far from

doomsday. If anything, this is just the beginning of a new kind of hustle. One where your patience will be tested more than your thesis partner ever did. One where rejection becomes routine and the taste of “almost” becomes all too familiar.

Yet you move. You adjust. You try again.

Because as cliché as it sounds, being raised in this heat and dust has its perks—a resilient spirit. Though it may bend, bruise, and occasionally burn out, it simply refuses to break. It shows up better and braver, over and over again.

And should you wonder in the future where all the ‘flying colors’ of your youth went, know that they did not fade. They have blended seamlessly into the rich background of new responsibilities that inevitably accompany adulthood, quietly guiding your next steps— perhaps a bit quieter now, but undeniably just as bold.

Because this world? It’s a vast plane. And you? You’re still learning how to fly.

I arrived without the loud hellos, no group chat waiting, no seat saved with a smile. just me— and a campus that didn’t notice, but somehow let me stay.

My world was small— stitched between lectures and the quiet walk home. others had tambayans, I had corners, and the hush of a room that knew my name when no one else did.

Some afternoons, I took the long way back. soft steps beneath the setting sun, and in that golden hues, I’d wonder— will someone ever walk beside me? will there be a voice to break the silence, a seat saved just for me? a loud hello?

I asked questions I never said aloud— can I really make it? am I enough for the world that waits outside this room?

There were nights the weight of doubt— heavy enough to keep my eyes open. I counted failures like ceiling cracks, a thousand thoughts, tangled—a mess.

Held on to dreams that felt too heavy for one pair of hands, dreams that felt like a burden, a curse I cannot tame.

Yet in stillness, in shadows, in a four cornered room, I softened. I stretched. I bloomed— not loudly, but enough, just enough. I was not the loudest, not the most known. but I was here. present in my tranquility, shaped by silence, by scribbled pages, by the courage to keep moving when no one was watching.

And soon, this chapter will fold close. no grand farewell, no crowd. just me— carrying the strength I built in solitude, and the quiet truth that even without noise, without applause, I can make it,

Because I have learned— even silence has its own season. and some of us, rooted in solitude, do not just bloom— we blossom quietly, delicately, in places the world forgets to look,

Alone, in the rooms we chose to grow in.

VINCENT IVAN ESQUIVEL

Their hands gripped every pistol across their head.

“Did I pass? ” a sign of warning?

“Am I on time to graduate? ” maybe involved in maroon hundreds?

Marching steps revolting like a haunting gaze around the hardest goal of trying with a doubting face The maroon toga was the goal.

One-Time Walk Like a Bestow

Get even and aim for uplift, not indirect circumstances. more often a result or a direct happenstance Quick, quick! joyness reflects a detailed rewinding.

Standing broad-shouldered even on a bitter ending brokenness or weariness to define the exact terms

But one thing you’ll know is that those tears of heartbreak were the tears that would burst for a wider zygomaticus humbly dancing in a shimmering fabric were wondrous were once doubt and handling it on your own isn’t just shouting

But a roar that was equal to success rose and not defeated, kid.

Roads do not end, and habits do not depend. Make “goal” a habit for a greater elevation beyond your reach...

You were far ahead and expanding every time you tried to take a step. absorbing every zygomaticus aound hundreds were stories were all different but tells one tale and that is to success

KIRUZA KIRUZA

She no longer flinches at silence— only the kind that precedes collapse.

There was a morning, where dawn didn’t rise—it ruptured. Hands trembling over a breath she wasn’t sure would come back. It did. But something else didn’t. Now, rest is rationed. Joy comes in cautious increments. She walks halls sunlit yet haunted, wears the maroon toga

like a shroud and a crown. They cheer her name. But only she knows what it cost to make it this far without disintegrating. And yet, she does not unravel— she endures like dusk before a storm: tender, and terrifying.

There is a famine in the soul of the ambitious poor— a gnawing that success must be swift, lest time expire, lest fate reclaim its debt. At twenty, the clock is a guillotine. We whisper CVs like rosaries, count missed opportunities as sins. Will brilliance suffice,

“Asa ta mamastil?”

“likod sa CAS, ila ante.”

The classroom witnessed how my palm sweated when my name was called, how my mouth dried and stuttered because of fear, my secret sighs, nervous foot taps, and my unspoken prayer before a quiz started. Yes, the chairs, the desk, the whiteboard,

and every corner of the classroom knew every rhythm of my academic struggles. And so is the pastil ni ante. The fifteen-peso rice, topped with either shredded chicken or tuna, wrapped in an aromatic banana leaf, knew not only every formula I murmured and the dumb mnemonics I created but also how I dozed off to take a break for the day. It is not just fifteen pesos. It is worth a lot more. Each bite is reassurance,

if you still sleep beside scarcity? Will dignity feed you, when the world demands returns before it grants rest? They told us we could make it. They never said how long we’d have to starve before we do. Still— we dare to hunger.

Like a lost cause,

I’m drifting through the waves of time, Or caught beneath the fault line’s silent crack A weeping soul on an infinite track

Will I ever get to feel

The wistful comfort of the maroon gown, Cloaking my weary, weathered skin, And the sweet burden of a tassel-tipped dream?

Slowly tiptoeing,

Towards and endless marathon of life

One heartbeat away from the endor the beginning of another mile to meet

I am hopeful that one day, I’ll be more than just a fading echoNo longer drifting like a lost cause And be swept away in the ocean of my quiet weeping

“kayanon nako ang quiz!” And I did. Not just the quizzes, but also every exam, every fall, every fear, and every uncertainty. I was held.I was comforted. By fifteen pesos. By a pastil. For every graduating MSUan student, “asa ta mamastil” is not a phrase for food. It was the pause between struggles, the soft spot in a tiring day.

For us it meant, “asa ta mupahuway?”

A. GILIW

We came here unsure, just kids with backpacks and big dreams. Found friends in strangers, found strength in small wins and sleepless nights.

We laughed in hallways, cried quietly over grades, stared at the sky wondering, “Kaya pa ba?” But somehow—we made it.

Now, it’s the season of goodbyes. Last walks.

Last tambay.

Last time seeing familiar faces before we all go chasing different suns.

It’s scary, di ba?

Not knowing what comes next. But there’s something beautiful in that, too. In starting again. In carrying these memories as proof that we once belonged.

MSU will always be a part of us— not just the place, but the people, the moments, the growth.

So here’s to the road ahead: messy, exciting, and wide open. Let’s go—with a little fear, a lot of hope, and everything we’ve become.

SALAMANGKERONG_UMIIYAK Para kay Mamang

Tapos na rin, sa wakas. Hawak ko ang huling papel, nanginginig ang kamay ko hindi sa pagod, kundi sa tuwa. Habang palabas ng silid-aklatan, dama ko ang bigat ng bawat hakbang, hindi dahil sa paglalakad, kundi dahil sa dami ng sakripisyong kailangang pagdaanan para makarating dito.

“Mamang, pauwi na ho ako,” halos pabulong kong sabi sa telepono, pinipigil ang luha.

“Mang. ga-graduate na ho ako sa makalawa. Gusto ko kayo ang magsabit ng medalya ko.”

Sandaling katahimikan.

“Anak... talaga ba? Ay Diyos ko, salamat! Maghahanda tayo. Tamang-tama, may naitabi pa akong kaunti mula sa paglalaba ko sa kapitbahay. Ano bang gusto mo?”

“Mang, ‘wag na ho kayong mag-abala. Ako na. Ako naman ang mag-aalaga sa inyo. Hindi niyo na kailangang maglaba. Hindi na kayo dapat mapagod. Salamat, Mang. sa lahat.”

Napahagulgol na ako. Hindi ko na kayang pigilan.

“Sus, anak... ikaw talaga. Sige na, magluluto ako ng pansit. paborito mo, ‘di ba? Ingat sa biyahe ha. I labyu nak.”

“I labyu too, Mang.”

Hindi ko alam kung ano ang nakalaan para sa aking kinabukasan, pero sigurado ako sa isang bagay. Lalaban ako, para sa kanya. Para kay Mamang. Para sa lahat ng paghihirap niyang pinalitan ng pagmamahal. I labyu mang.

ROJON KARL S. MACAPAS

Sa bawat araw ng ating huling taon, lihim kitang pinagmamasdan mula sa malayo. Sa bawat ngiti mo, unti-unting nahulog ang pusong matagal nang nanahimik.

Ako si Maxi, ang tahimik sa sulok, laging may dalang kwaderno. Doon ko isinulat ang mga damdaming hindi ko nasabi. Hindi dahil mahina ako, kundi dahil takot akong baka lumayo ka kapag nalaman mo.

Ngayong magpapaalam na tayo sa eskwela, isinulat ko ang lahat sa huling pahina ng aking kuwaderno. Iniwan ko ito sa paborito mong upuan. Baka sakaling mapansin mo. Baka sakaling basahin mo.

Kasabay ng mga yapak mo pauwi, ako’y tahimik na sumusunod. Umaasang kahit sa ating pagtatapos, may simula pa rin na sisibol para sa ating dalawa.

Baka may sinulid pa nang tadhana sa pagitan natin na hindi natin nakikita.

Baka sa hinaharap, magtagpo muli tayo—hindi na bilang kaklase, kundi bilang dalawang taong handang humarap sa katotohanan.

At kung hindi man, ayos lang. Ang mahalaga, minsan kitang minahal; tapat, tahimik, at buo.

Paalam. At salamat sa mga sandaling ikaw lang ang laman ng bawat pahina ng aking munting kwaderno.

ANGELIE MAE LAPATING

Can someone remind me—

When did I start fearing the sunrise? I didn’t grow fangs or crave for blood. I just became the kind of ‘vamfire’ MSU quietly creates.

The kind that feeds overflowing pastil to my running-dry wallet. From late-night reading modules to fighting centro bottles— not to celebrate, but to forget.

Symptoms started with my first removal exam. They called it second chance, but to me, it was the first sign I wasn’t the human I used to be.

And I wasn’t alone.

Pit, with red eyes from thesis tears. Jims, paling and failing from OJT. Payb, missing attendance. Hart, saving deadlines but herself. We weren’t alive at sunrise, but we weren’t dead at dawn either. We just learned how to survive in the dark.

Maybe, we will be haunted by our ghosts— But this isn’t a horror story. What we thought a stop was a step of MSU To nurture fangs who aren’t afraid of any “degrees”.

To be covered in maroon is not the end— but it’ll be our first morning in a long time that doesn’t feel scary anymore. In a campus of Vella’s, I will always cry—and feyt—for this class of ‘vamfires’.

They told me college would break me. They didn’t say it would almost bury me. With my knees on cold tile and my mother’s breath stuttering beneath my hands. She lived. Butsomething in me did not.

Since then, sleep feels reckless. I lie awake till dawn, heart braced for a sound—the thud, the gasp, the silence I cannot unhear. I watched the hours bleed past three, fearing that rest would cost me everything.

Yet still, I rose.

Dragged my feet across MSU-Gensan’s sunstruck pavements, sweat and dreams clinging likeshadows. Still chewed through scorching hot pastil behind H—tongue burning, deadlines blurring, grief folded beneath a laugh.

No one teaches you how to carry on when you’re scared all the time. But I did. I do. Now the maroon toga waits—that cloth of longing every MSUan dreams of. But it’s not the end they promised. It is but a door.

The world beyond does not care how weary you are. It only asks: Wilt thou endure?

And I shall. Not unscarred, but steadier. Forged not by lecture—but built by the nights I outlived

DONNEL PIERCE DEPARINE

I told myself I won’t miss this place— the heat, the dust, the crowd, the rooms with defective chairs.

who would miss the sleepless nights in confined dormitories?

or the anxiety of an oral exam or the financial ruin of an OJT?

who would miss riding the cramped jeeps? with bodies drenched in sweat with faces you barely recognize?