Steinmüller Africa

Power generation is a major driver of production, but mitigating emissions from the combustion process is vital. This is where Steinmüller Africa, under the directorship of Moso Bolofo, is delivering solutions.

Global Reach. Local Precision.

Leadership Assessment

Measuring Leadership with a Sustainability Lens

Executive Development

Optimising Organisational Performance

Employer Branding Strategies

With Global Industry-Specific Insights

Executive Search

Securing High-Impact Leaders for Long-term Success

22 IN FOCUS

How making sand from ore could solve a looming crisis

26 WOMEN

The Glass Cliff phenomenon: When leadership for women comes at the brink of collapse

32 POLICY

DMPR Budget Vote: Bold regulatory overhaul and targeted investments aim to transform mining and fuel a green-energy pivot

38 TRADE/ECONOMICS

Can zero tariffs drive real change? Inside China’s new trade policy and Africa’s energy-led future

42 REGULATORY

Building a legal framework for Namibia’s midstream infrastructure

48 FINANCE

Can the new Africa Energy Bank transform the continent’s refining and downstream future?

52 SUSTAINABILITY

Why green skills development is vital to drive sustainability in mining

A lot can change in 6 years our warranty promise won’t

6 years of change and our warranty protects your investment

A lot can change in 6 years. Our 6-year drivetrain warranty promise protects your investment against the test of time. Built to keep your business moving, supporting uptime, growth and daily operations, all the way. Ts and Cs apply.

HINO ALL THE WAY

56 ENVIRONMENT

Why the energy transition won’t be green until mine waste disasters are prevented

62 ENERGY

Why Africa’s leapfrogging from oil and gas is not the quick energy fix the world seems to think it will be

66 CRITICAL MINERALS

South Africa’s new Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy 2025 marks a new frontier for sustainable growth

74 OIL

The long-awaited initial public offerings of Nigeria’s NNPC and Angola’s Sonangol signal a seismic shift in Africa’s oil industry

78 GAS

Natural gas and Africa’s energy future: balancing growth and sustainability

82 TECHNOLOGY

How AI–powered enhanced oil recovery is breathing new life into southern Africa’s ageing oilfields

90 HEALTH & SAFETY

Controlling dust and managing road surfaces are vital for safe, efficient operations in mining

96 WATER

How artificial intelligence is transforming water treatment management in African mining

For decades, mining has been the backbone of southern Africa’s economies. But today, the industry stands at a critical crossroads. As global markets, investors and regulators place increasing pressure on environmental, social & governance (ESG) performance, the future of mining depends not just on what is extracted from the earth—but on how responsibly it is done.

Driving sustainability in mining is no longer optional. It is a business imperative.

This begins with managing environmental risks—particularly tailings and wastewater. Catastrophic tailings failures globally have shown the human and ecological cost of poor waste management. Forward-thinking mines are now investing in dry-stack tailings, water recycling and closed-loop systems that significantly reduce contamination and freshwater use. These technologies not only protect communities but also safeguard a mine’s social licence to operate.

But sustainability is also about people. As the industry pivots toward greener operations, workers must be equipped with the skills to match. From technicians maintaining solar arrays to operators using AI–driven monitoring systems, green skills are becoming core to modern mining roles. Investing in employee training is both a moral and strategic necessity.

Renewable energy is another powerful tool. Across the region, mines are deploying solar and wind solutions to reduce reliance on costly, unstable grids and diesel generators. These transitions cut emissions and operational costs—delivering both environmental and financial returns.

Lastly, AI technologies are transforming how sustainability goals are met. Real-time data can now track emissions, optimise energy use and detect environmental risks before they escalate—enabling smarter, faster decisions.

The path to a sustainable mining future lies in innovation, collaboration and bold leadership. Those who embrace change today will shape a stronger, greener and more resilient industry for generations to come.

mining news

PUBLISHER: Donovan Abrahams

MANAGING EDITOR: Tania Griffin

DESIGN: Erin Esau

EDITORIAL SOURCES: NJ Ayuk, Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, SA Oil and Gas Alliance, Dust-A-Side, Africa Energy Week, Gaby PatonThomas, TheConversation.com, BizCommunity.com

STAFF WRITER: Matthew van Schalkwyk

IMAGES: iStockPhoto, WIkimedia Commons

PROJECT MANAGER: Viwe Ncapai

ADVERTISING EXECUTIVES: Viwe Ncapai, Lunga Ziwele

ONLINE CO-ORDINATOR: Tharwuah Slemang

IT & SOCIAL MEDIA: Tharwuah Slemang

CLIENT LIAISON: Majdah Rogers

ACCOUNTS: Benita Abrahams, Bianca Alfos

HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGER: Colin Samuels

PRINTER: Novus Print

DISTRIBUTION: www.africanminingnews.co.za, www.issuu.com

DIRECTORS: Donovan Abrahams, Colin Samuels

PUBLISHED BY: Aveng Media

Boland Bank Building, 5th Floor 18 Lower Burg Street Cape Town, 8000

DISCLAIMER:

Tel: 021 418 3090

Fax: 021 418 3064

Email: reception@avengmedia.co.za

Website: www.avengmedia.co.za

© 2025 African Mining News magazine is published by Aveng Media (Pty) Ltd. The Publisher and Editor are not responsible for any unsolicited material. All information correct at time of print.

Rub shoulders and conduct business with the high-flyers in the African mining industry

Uganda International Oil & Gas Summit 2025

Kampala Serena Hotel, Uganda uiogs.com

Held under the patronage of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, UIOGS has cemented its role as East Africa’s must-attend gathering for oil and gas leaders. Every year, it brings together senior government officials, global operators, investors, service providers and policymakers. Under the theme, “The Refinery: An East African Affair”, this year’s summit will explore how downstream development and crossborder co-operation are shaping a new era of regional prosperity.

African Energy Week

29 September to 3 October

Cape Town International Convention Centre, South Africa aecweek.com

African Energy Week (AEW) is the African Energy Chamber’s annual event, uniting African energy leaders, global investors and executives from across the public and private sector for four days of intense dialogue on the future of the African energy industry. AEW promotes the role the continent plays in global energy matters, centred around African-led dialogue and decision-making.

African Mining Week 1 to 3 October

Cape Town International Convention Centre, South Africa african-miningweek.com

African Mining Week is the ultimate platform to explore the continent’s rich mining opportunities. With Africa home to the world’s largest reserves of key minerals like lithium, cobalt and copper, as well as gold, diamonds and iron ore, the event provides insights into untapped resources, new projects and emerging markets that are driving global innovation and industrial growth.

Joburg Indaba 8 & 9 October

Inanda Club, Sandton, Johannesburg, South Africa

www.joburgindaba.com

Critical and constructive conversations are one of the stand-out features of the Joburg Indaba, serving the industry with robust discussions that get to the crux of the key issues. The event will once again bring together an outstanding panel of speakers including CEOs and senior representatives from all major mining houses, local and international investors, government, parastatals, experts from legal and advisory firms, and representatives from communities and organised labour.

Sustainability & ESG Africa Conference & Expo

15 & 16 October

Sandton Convention Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa esgafricaconference.com

This highly anticipated event provides an unparalleled platform for industry pioneers and experts to come together and tackle the common challenges associated with embedding sustainability and ESG practices within organisations. The conference’s core theme, “Adapt. Innovate. Succeed— Driving Sustainability in Changing Times”, underscores the essential role that leaders play in ensuring their organisations align with ESG principles and integrate them into their overall strategy.

9th International PGM Conference

27 & 28 October

Sun City, Rustenburg, South Africa

www.saimm.co.za

The Platinum Conference Series continues to address the opportunities and challenges facing the global platinum group metals (PGM) industry. As the sector faces increasing demand—from

technological innovation and decarbonisation to cost management and market volatility—the 9th edition offers a critical platform for addressing these challenges head-on. Attendees can expect high-quality technical papers and presentations, robust networking opportunities and strategic insights that help shape the future of the industry.

2025 MineSafe Conference and Industry Awards

19 to 21 November

Emperors Palace, Johannesburg, South Africa

www.saimm.co.za

A key event dedicated to enhancing safety, health and environmental practices within the mining and metallurgical industry. This conference will serve as a vital platform for knowledge-sharing and idea exchange among key stakeholders including mining companies, the Department of Mineral & Petroleum Resources, the Minerals Council South Africa, labour unions, and health and safety practitioners at all levels in the minerals industry.

MSGBC Oil, Gas & Power 2025 9 & 10 December

Centre International de Conférences Abdou Diouf, Dakar, Senegal msgbcoilgasandpower.com

A hot spot for global energy investment, the MSGBC region is home to promising upstream acreage, integrated infrastructure projects and future-oriented development plans. MSGBC Oil, Gas & Power has emerged as the leading platform for industry leaders, innovators and policymakers across the MSGBC basin. With momentum from previous successes, MSGBC 2025 promises to be the most transformative edition yet, providing unparalleled opportunities for investors, project developers, international operators and service providers.

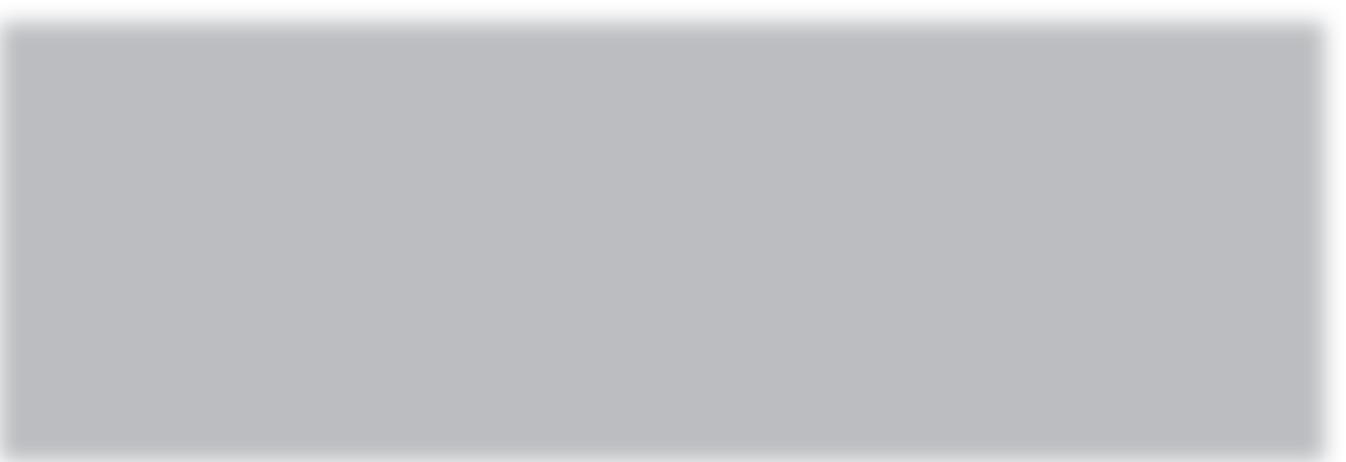

Power generation is a major driver of production, but mitigating emissions from the combustion process is vital. This is where Steinmüller Africa, under the directorship of Moso Bolofo, is delivering solutions

In the world of technological advancements—regarding mining and engineering excellence, and various power resources—Moso Bolofo, director of Steinmüller Africa, provides invaluable insight into these sectors and what they represent for him and his company as a major player in the industry.

Steinmüller Africa specialises in manufacturing, power generation and environmental technology in industrial plants, among others. Established in 1962, it has been a cornerstone of engineering excellence for decades. From designing cutting-edge industrial facilities to implementing advanced technologies, the company is dedicated to delivering solutions that exceed expectations.

Bolofo says engineers in various fields focus on power generation as a major driver of production, but mitigating emissions from the combustion process is vital. This is an ongoing dialogue and initiative in South Africa, he asserts.

The African Mining News team sat down with Bolofo at this year’s Enlit Africa Expo, hosted at the Cape Town International Convention Centre.

The company’s collaboration with several business partners at this year’s expo was critical. Steinmüller Africa’s core involvement and manufacturing in power, mining, pulp and paper, petrochemical and other industries spans the globe. It offers professional—and, most importantly—sustainable input and expertise with mechanical and innovative engineering designed for the future, while analysing ongoing rates of success of multiple projects.

This forms the framework for the business; one that Bolofo says is important to form opinions and drive issues forward intrinsically. In the

company’s effort to build successful business relationships through collaboration, Bolofo said: “We have to drive a co-ordinated effort in order to grow the industry, grow the economy … while mitigating negative environmental impacts.”

It is Steinmüller Africa’s well-rounded approach to these value chains that forms its long-term mission to be an effective multidisciplinary partner covering all the bases pertaining to the life cycles in the process industry.

Bolofo emphasised that major industrial plants localised in Africa and South Africa form part of a much bigger picture, generating skills development within Africa and supporting funding for students specialising in this field. Steinmüller Africa is a leading industrial services provider, one that Bolofo is proud to be part of, explaining that funding students in this field of work at Wits University, the University of Cape Town and other technikons “is at the core of what we try and do”.

Apart from fuelling Africa’s next generation of entrepreneurs and industry leaders, Steinmüller Africa builds bridges continuously. Each phase— from consulting to its tailored services and upholding the most impeccable values of safety, to the maintenance of plant expansion—forms part of the company’s mission to deliver the best in technological advancement and expertise.

We asked Bolofo about some of the main factors involved in furthering growth on the African continent, regarding environmental technology.

“We have had our engineers take part in conferences like Enlit Africa, looking at what impact we could have on power generation plants, the numerical analysis that models things like combustion and so

forth. Which then enables us to design plants by using the latest alloys, for instance, you can use higher temperatures. This allows you to use less coal for the same output; you use less water for the same output. We also have the ability to assist plants, about which we are quite excited, and the new strategies for mitigating emissions, such as carbon capture and the like, ” he explained.

“Our capability in the sector for manufacturing, installation and supporting clients will play quite a good role in ensuring that as we progress we continue to maintain the coal plants and mitigate emissions. That’s what we need overall.”

Bolofo expanded on this: “We have also been acting quite actively with CSP [concentrated solar power] plants, using steam to generate electricity. So we are looking at a whole variety of activities in the power generation industry.”

When asked about the mining sector in South Africa and Africa as an inseparable infrastructure of societal development and sustainability, Bolofo crucially indicated that the narrative of the past has changed dramatically. “What I am happy about is that throughout the continent, politicians as well as industries have come to accept that we need to grow and industrialise. With our mining resources, we have to find ways of optimising these, how we use them and what we do to negate some of the associated negatives.

“However, at the end of the day, the issue is that we must use those resources for the 600-odd million people who don’t have access to things like electricity and so on—it’s going to take our mining resources to get to that point.”

He continued , “If you look at the IRP [Integrated Resource Plan]

and the provision of electricity, going forward many of the mining houses are the ones will be generating their own resources [as independent power producers, IPPs] in order to increase their output—and possibly selling back some of that electricity and so on. But at least this is self-sufficient. All these issues are around there being no finance, but our miners already have that in place. These are the very first people you can be sure will play a big role in the IPP space.”

Bolofo stressed that the growth of the economy will depend heavily on the mining sector. “This is part of the backbone. And when you look at new technologies—whether it’s smartphones or electric vehicles or whatever else—these are manufactured using specialised [critical] minerals. These can be found right here on the African continent. People are saying we must beneficiate these minerals and manufacture our own products rather than buy finished goods [from other countries]. I can foresee that for our coming generation, that’s where the growth will be. Hence, it is important that we develop the skills to be able to do it for ourselves.”

How has Steinmüller Africa built sustainable and equitable solutions for the future? The director’s answer was well-informed, saying that minerals and mining technologies work hand in hand with the IRP. “These technologies are required together, to move industry forward. But at the same time, you cannot underplay the large number of artisanal skills needed so that we continue to grow. Which makes us quite independent as South Africa in dealing with the requirements for the future,” he commented.

We enquired how important it is to encourage African and local leaders to demonstrate skills development in the industry. “We are a level-one BBBEE accredited company, so there are various [requirements to be met]. And for us, it’s vitally important both in our manufacturing facilities and locally grown skills in terms of devising solutions for problems.

“With regard to locally developed skills, our business model is to support our clients right through the lifecycle of their plant: whether that’s a concept or design, manufacturing or installation of that plant. Or ongoing maintenance—life extension as well as dismantlement. As much as we were originally a company with roots in Germany, everything we’re doing now is locally grown. And that, for me, is a great thing.”

Bolofo’s execution of Steinmüller Africa’s vision and innovation in energy efficiency, concerning environmental and mineral engineering, is nothing short of brilliant. He has defined a novel narrative that spearheads sustainability, working hand in hand with the mining sector and many areas of energy production. Demystifying what once lay in the past to create a new lens for the future: one of generational change, of artisanal prowess and of a self-sustaining industry.

For more information, visit www.bilfinger.com/en/za.

Cost effective, locally pioneered proprietary solutions providing:

• Recovery and refining of base and precious metal values from complex solid and liquid wastes

• Development of hydro and pyro-metallurgical extraction solutions for the mining and petrochemical industry

• In house analytical laboratory services for the analyses of major, minor and trace ele ments

• Critical pre-analysis preparation of samples from drying, crushing and pulverising

Cost effective, locally pioneered proprietary solutions providing:

• Fire Assay facilities for the collection and determination of precious meta ls For a winning solution ... speak to us

• Recovery and refining of base and precious metal values from complex solid and liquid wastes.

• Development of hydro and pyro -metallurgical extraction solutions for the mining and petrochemical industry

• In house analytical laboratory services for the analyses of major, minor and trace ele ments.

• Critical pre-analysis preparation of samples from drying, crushing and pulverising • Fire Assay facilities for the collection and determination of precious meta ls. ution ... speak to us

yolanda@goldenpond67.co.za www. goldenpond 67. co. za

How a South African leader in hydro- and pyrometallurgy is redefining laboratory excellence and building the future of metals recovery

Yolanda Niharoo

Managing Director, Golden Pond Trading 67 (Pty) Ltd

MBA | National Diploma in Analytical Chemistry

In the heart of Roodepoort, Gauteng, a quiet but significant revolution in metallurgy is taking place. Golden Pond 67, a hydro- and pyrometallurgical enterprise founded in 2004, has grown into one of South Africa’s most respected names in the recovery of precious metals and the production of specialised metal chemicals.

What sets the company apart is not only its ability to extract value from waste and complex materials but also its world-class laboratory services and continuous investment in research and development (R&D).

Golden Pond 67 is more than just a metals recovery business: It is a company where scientific rigour, sustainability and innovation converge to unlock value for the mining sector and beyond.

Golden Pond 67 was founded more than two decades ago by Dr Gerhard Overbeek, Dr Sanjeev Debipersadh and Jacobus Petrus (Kobus) van den Bergh: three seasoned professionals with extensive backgrounds in metallurgy, chemical engineering and mineral processing. Their vision was clear: to bridge the widening gap in South Africa’s capacity for the recovery and refining of precious metals from waste streams, low-grade material and secondary resources.

Dr Overbeek, a technical visionary, laid down much of the scientific foundation that still guides the company today. His mentorship of Dr Debipersadh ensured that institutional knowledge was carried forward when he retired in 2019.

Today, under the leadership of managing director Yolanda Niharoo, Golden Pond 67 has flourished as a debt-free, black economically empowered privately owned company with a reputation for reliability and excellence.

Golden Pond’s leadership team combines deep technical expertise with strong business acumen:

Yolanda brings nearly three decades of experience in analytical chemistry and a strong portfolio of qualifications that extend into business administration that includes a Master of Business Administration (MBA), compliance and safety management. Her blend of technical and regulatory knowledge ensures the company’s operations meet the highest standards while positioning it for sustainable growth.

Dr Debipersadh, now technical director, embodies the company’s dual commitment to engineering excellence and sustainability. With a PhD in Environmental Management alongside qualifications in chemical engineering, taxation and a Master of Business Administration (MBA), he has been instrumental in shaping Golden Pond’s eco-friendly processes and expanding its production capacity.

Meanwhile, co-founder Van den Bergh contributes over 45 years of experience in metallurgical operations and strategy, anchoring the company’s work in both technical and commercial realities. His expertise is further strengthened by a Master of Business Administration (MBA).

Together, this leadership trio exemplifies Golden Pond’s

philosophy of balancing science, sustainability and business sense.

If Golden Pond 67 is an engine for value recovery, then its in-house laboratory is the beating heart that powers it. Accredited by the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) since 2010, the lab is internationally recognised for its technical competence and quality assurance.

The facility is equipped with two inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICPOES) instruments: state-of-the-art tools that provide high-precision elemental analysis across a vast range of materials. These instruments allow the lab to accurately determine the presence and concentration of precious metals, even in highly complex waste streams or low-grade material.

Supporting the ICP-OES instruments are fire assay facilities and a comprehensive sample preparation suite. Fire assay, a time-honoured method still regarded as the gold standard for precious metal analysis, complements the speed and precision of modern spectroscopic techniques. Together, these capabilities allow Golden Pond 67 to deliver rapid, reliable results to its clients—an invaluable service in industries where accuracy translates directly into profitability.

But the company does not stop there. Recognising the growing demand for its services, Golden Pond has already earmarked funds to expand its laboratory capacity with additional advanced equipment. This proactive investment strategy ensures the lab will continue to meet the sector’s rising analytical needs while maintaining short turnaround times and uncompromising quality.

“Our lab is not just a support function—it is a cornerstone of our refining operations,” says Yolanda. “It gives us the agility to analyse, adapt and refine processes in real time, ensuring maximum recovery and purity. Our analytical capabilities not only validate our processes but also open new doors for innovation and growth. The lab is where ideas are tested, refined and transformed into value for our clients.”

Precious metals recovery is rarely straightforward; feedstocks can range from low-grade effluents to highly variable industrial residues. Off-the-shelf methods seldom work. Instead, Golden Pond 67 thrives on innovation, leveraging its scientific depth to develop tailored hydro- and pyrometallurgical processes for each material profile.

Its in-house R&D division develops customised techniques to recover platinum group metals (PGMs), gold and base metals from materials that would otherwise be deemed uneconomical or too complex to process. This agility has helped the company carve out a niche. Whether buying material outright or refining on behalf of clients, Golden Pond 67 consistently delivers recoveries that maximise value.

The company’s portfolio includes processing spent low-grade catalysts, petrochemical low-grade residues and low-grade effluents. Each material stream is unique, and Golden Pond’s scientists and engineers take pride in designing bespoke recovery procedures. This capability not only maximises yields but also reduces waste, making the company a key partner for mining operations, refineries and industrial producers alike.

Such R&D efforts are not confined to process development alone. They extend into the optimisation of eco-friendly technologies, from reagent recovery to water reuse. For example, Golden Pond’s electro-winning plant not only extracts valuable metals but also recovers reagents from effluent waste, repurposing them in ongoing processes. This approach reduces costs, conserves resources and strengthens the company’s circular economy model.

Dr Debipersadh emphasises that research is not an optional extra: “In our sector, materials are increasingly complex. Without in-house R&D, you fall behind. We’ve made innovation a core business function, ensuring we can keep unlocking value from feedstocks others would consider waste.”

In an era where environmental, social & governance has become central to business reputation and investor confidence, Golden Pond 67 stands out for its proactive sustainability practices.

The company operates with reverse-osmosis systems to treat and recycle wastewater contaminated with heavy metals, sulphates and industrial effluents. Energy conservation measures, such as eliminating non-essential power use, further reduce its environmental footprint. Its waste recovery model minimises hazardous materials sent to landfills and ensures compliance with South Africa’s environmental legislation.

From its founding, Golden Pond 67 has operated with sustainability in mind; its emphasis on health and safety is as rigorous as its scientific methods. The company adheres to the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA 85 of 1993) and currently holds a prestigious five-star NOSA accreditation—a benchmark for excellence in operational risk management.

Equally important is the company’s dedication to people development. Through mentorship programmes, in-house training, internships and bursaries, Golden Pond 67 ensures knowledge transfer in hydro- and pyrometallurgy as well as analytical chemistry.

It invests heavily in internal training, workplace safety and professional development. Senior managers mentor younger staff in hydro- and pyrometallurgy as well as analytical chemistry—ensuring knowledge transfer between generations.

The internship and bursary programmes offer students practical experience in its labs and plants. These initiatives not only strengthen the pipeline of local talent but also reinforce Golden Pond 67’s commitment to employment equity—the latter of which remains central, with strong representation of women and historically disadvantaged groups in leadership positions.

Golden Pond 67’s sense of responsibility extends well beyond its gates. Its flagship corporate social responsibility programme is its long-term partnership with Strelitzia Secondary School. The company has funded and built fully equipped science and physics laboratories, established a computer science centre, and provides annual upkeep funding to ensure these facilities remain functional. Tutoring programmes for Grade 10–12 students further reflect Golden Pond’s belief that education is the foundation for lasting social and economic progress.

“Supporting education is supporting the future of South Africa. Education is where our impact multiplies,” says Yolanda. “By investing in science education, we are investing in the next genera-

tion of metallurgists, chemists and leaders.”

Golden Pond 67 contributes significantly to South Africa’s economy, both by recovering valuable metals and by enabling mines to monetise lowgrade or waste materials. In doing so, it alleviates pressure on primary resources, supports local employment, stimulates the recycling economy and generates exportable refined metals that boost foreign exchange earnings.

The company also plays a critical role for small- and mid-tier mining operations by making advanced refining services accessible and affordable. Its reputation for reliability and scientific rigour has made it a trusted partner across the value chain.

Golden Pond 67 is not resting on its achievements. Current projects include beneficiation of metals from increasingly complex materials such as low-grade effluents and spent catalysts and PGM residues. The company is also exploring expansions to its laboratory infrastructure to support higher volumes and more sophisticated analyses.

With the continued integration of advanced instrumentation and

eco-friendly processes, Golden Pond is positioning itself not only as a refiner but also as a research-driven hub of metallurgical innovation in southern Africa.

Golden Pond 67’s story is one of scientific excellence put into service of industry and environment alike. From its SANAS-accredited laboratory to its in-house R&D team, the company has cultivated a reputation for precision, innovation and sustainability. At a time when the mining sector faces mounting pressures—from volatile markets to environmental accountability—Golden Pond provides a model of how science and business can come together to create value while reducing impact.

As it expands its laboratory capabilities and continues to pioneer tailored recovery processes, it stands at the forefront of metallurgical innovation in South Africa. With global demand for PGMs and other metals remaining strong—driven by sectors from automotive catalysts to renewable energy technologies—the company’s role as a recovery and refining partner is more critical than ever.

As Yolanda reflects, the journey of Golden Pond 67 is far from complete.

“We’ve built a business on science and integrity. But what excites me most is how much more we can do: in the lab, in sustainability, in skills development. We are continuously growing, continuously improving. That’s what makes Golden Pond 67 unique.”

With its combination of world-class laboratory services, rigorous R&D and commitment to sustainability, the company will surely remain a key player in the southern African mining ecosystem for years to come.

For further information, contact Yolanda Niharoo at +27 (0) 71 604 9787, email yolanda@goldenpond67.co.za or visit www.goldenpond67.co.za.

Maisha Social Solutions was established in 2016, and over the last nine years has worked with several large-scale mining companies and renewable energy projects on topics critical to social performance, environmental management and governance.

Geralda Wildschutt is committed to leveraging her influential roles as CEO of Maisha Social Solutions and as independent board director of Caledonia Mining Corporation Plc and Northam Platinum Holdings, to support sustainability in the mining and renewable energy sectors across Africa. She has over 30 years of working experience across management, mining, banking and the social sector.

Wildschutt explains that executives and boards have to understand the criticality of building trusting relationships with the governments and communities that host mines and renewable energy plants i.e. the elusive social licence to operate (SLTO). With poor relationships and no SLTO in place, the end result is often conflict, and the ‘cost of conflict’ can be high— when communities block roads and operational stoppages occur.

She points out that it is critical for companies working in or considering entering Africa to be knowledgeable about the ‘social’ element of ESG. She explains that when crafting an ESG strategy, the high levels of poverty, unemployment and expectations on

companies from the local communities cannot be ignored.

Working with her team, Wildschutt works from the boardroom to the local community level, helping solve sustainability matters. She believes it is imperative for boards and executives to engage with the communities where their workers live and where their operations may have negative impacts on lives and livelihoods.

Under Wildschutt’s leadership, Maisha Social Solutions has won several accolades and recognition. The company’s gender and recruitment approach led to it winning the Standard Bank Top Gender Empowered Company 2022 award.

One of Maisha’s significant achievements is its numerous repeat and loyal clients. Wildschutt says she is proud to be associated with these clients.

Additionally, she is proud the Maisha team has worked in several countries in 2024 and 2025, including South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “The company has also made it

possible for several women to travel and work outside of South Africa,” she adds.

Maisha also invests in training for its employees, including the Social Impact Assessment course with the International Association for Impact Assessment, which Cybil Maneveldt and Nonkululeko Sikakane will complete in 2025.

Wildschutt herself has several personal achievements to her credit. She was the winner in the Mail & Guardian’s Top 50 Power Women 2021 (Mining Woman Category) and a winner in the World Women Leadership Congress Awards 2024.

Maisha Social Solutions is an advisory and consultancy business. Its mission is to “achieve sustainability of our planet, our business and the businesses of our clients.”

Wildschutt says the company believes in staying small and agile to provide tailor-made solutions to clients in all topics of ESG. For example, Maisha assists mining and renewable energy companies to deliver their ESG responsibilities and country-level requirements successfully. She highlights that mining is critical to extract the minerals people need for the green economy, but it is essential to do so responsibly to protect the environment and the people.

Maisha is known for effectively doing social research, stakeholder engagement planning, land use management, physical and economic displacement planning, corporate social responsibility strategies, public participation processes, human rights due diligence, socio-economic impact studies, and more.

Wildschutt finds it enormously satisfying to work with clients in a very hands-on way, discussing their challenges, doing social research in communities across southern Africa, and providing solutions to executives.

“Sustainability is our business,” Wildschutt says. Maisha Social Solutions assists companies in achieving

sustainability, with a focus on the planet and people. She points out that the business case has been made: Companies cannot be sustainable if they solely drive a profit agenda while ignoring their negative impacts on the environment and people.

“We advise and support companies to achieve their triple bottom-line goals,” Wildschutt says. “As a business, Maisha also invests in social projects, with a strong focus on gender-based violence and femicide (GBVF).

Maisha has funded the Feminist Clinic hosted by the Women’s Legal Centre in 2024 and 2025. The Women’s Legal Centre works toward the advancement of women’s right to bodily autonomy and to be free from violence. Its Feminist Clinic ensures female lawyers are equipped to render services in a society where GBVF is pervasive. The social investment projects that Maisha chooses are mostly in support of women.

Wildschutt firmly believes all companies must play a role in the protection of the planet. They must focus on crafting strategies for climate action, biodiversity, water management and land management. In addition to that, they have to understand the interconnectedness of the critical risks in each

jurisdiction where they want to do business, she says.

She shares that she attended workshops arranged by the Climate Governance Initiative and the World Economic Forum, in June 2024. These workshops brought a number of board directors together on the topic of “Mobilising Directors for Climate Action”. By attending, she learnt about the strategies of various companies.

Wildschutt asserts it is vital for all independent directors and executives on boards to continue to learn and stay in touch with a fast-changing world. Because the issues of artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, extreme weather conditions as well as social challenges of extreme poverty and food insecurity will require interventions from businesses.

For further information, email geralda@maishasocialsolutions.co.za or telephone +27 (0) 71 857 4147.

It is critical for companies working in or considering entering Africa to be knowledgeable about the ‘social’ element of ESG

How making sand from ore could solve a looming crisis

We must and will take a proactive role in mining ventures, from equity stakes to operational partnerships.

Every year, the world consumes around 50 billion tonnes of sand, gravel and crushed stone. The astonishing scale of this demand is hard to comprehend—12.5 million Olympic-sized swimming pools per year, making it the most-used solid material by humans.

Most of us do not see the sand and gravel all around us. It is hidden in concrete footpaths and buildings, the glass in our windows and in the microchips that drive our technology.

Demand is set to increase further: even as the extraction of sand and gravel from rivers, lakes, beaches and oceans is triggering an environmental crisis.

Sand does renew naturally, but in many regions, natural sand supplies are being depleted far faster than they can be replenished. Desert sand often has grains too round for use in con-

struction, and deserts are usually far from cities; while sand alternatives made by crushing rock are energyand emissions-intensive.

But there is a major opportunity here, as we outline in our new research (tinyurl.com/ccfbdu86). Every year, the mining industry crushes and discards billions of tonnes of the same minerals as waste during the process of mining metals. By volume, mining waste is the single largest source of waste we make.

There is nothing magical about sand. It is made up of particles of weathered rock. Gravel is larger particles. Our research has found companies mining metals can get more out of their ores, by processing the ore to produce sand as well.

This would solve two problems at once: how to avoid mining waste, and how to tackle the sand crisis. We dub this ‘nose-to-tail’ mining, following the trend in gastronomy to use every part of an animal.

The metal sulphides, oxides and carbonates that can be turned into iron, copper and other metals are only a small fraction of the huge volumes of ore which have to be processed. Every

year, the world produces about 13 billion tonnes of tailings—the groundup rock left over after valuable metals are extracted—and another 72 billion tonnes of waste rock, which has been blasted but not ground up.

For decades, scientists have dreamt of using tailings as a substitute for natural sand. Tailings are often rich in silicates, the principal component of sand.

But to date, the reality has been disappointing. More than 18 000 research papers have been published on the topic in the last 25 years. But only a handful of mines have found ways to repurpose and sell tailings.

Why? First, tailings rarely meet the strict specifications required for construction materials, such as the size of the particles, the mineral composition and the durability.

Second, they come with a stigma. Tailings often contain hazardous substances liberated during mining. This makes governments and consumers understandably cautious about using mining waste in homes and our built environment.

Neither of these problems is insurmountable. In our research, we propose a new solution: manufacture sand directly from ore.

Converting rock into metal is a complex, multi-step process that differs by type of metal and by type of ore. After crushing, the minerals in the ore are typically separated using flotation, where the metal-containing sulphide minerals attach to tiny bubbles that float up through the slurry of rock and water.

At this stage, leftover ore is normally separated out to be disposed of as waste. But if we continue to process the ore, such as by spinning it in a cyclone, impurities can be removed and the right particle size and shape can be achieved to meet the specifications for sand.

We have dubbed this ‘ore-sand’, to distinguish it from tailings. It is not made from waste tailings—it is a deliberate product of the ore.

This is not just theory. At the iron ore mine Brucutu in Brazil, the mining company Vale is already producing one million tonnes of ore-sand annually. The sand is used in road construction, brickmaking and concrete.

The move came from tragedy. In 2015 (Mariana Dam disaster) and 2019 (Brumadinho Dam disaster), the dams constructed to store tailings at two of Vale’s iron ore mines collapsed, triggering deadly mudflows. Hundreds of people died—many of them company employees—and the environmental consequences are ongoing.

In response, the company funded researchers (such as our group) to find ways to reduce reliance on tailings dams in favour of better alternatives (tinyurl.com/c3hssx75).

Following our work with Vale, we investigated the possibility of making ore-sand from other types of mineral ores such as copper and gold. We have run successful trials at Newmont’s Cadia copper-gold mine in Australia. Here, using innovative methods (tinyurl.com/3zhxxds9) we have produced a coarser ore-sand that does not require as much blending with other sand.

Ore-sand processing makes the most sense for mines located close to cities. This is for two reasons: to

avoid the risk of tailings dams to people living nearby, and to reduce the transport costs of moving sand long distances.

Our earlier research showed almost half the world’s sand consumption happens within 100 kilometres of a mine that could produce ore-sand as well as metals. Since metal mining already requires intensive crushing and grinding, we found ore-sand can be produced with lower energy consumption and carbon emissions than the extraction of conventional sands.

For any new idea or industry, the hardest part is to go from early trials to widespread adoption. It will not be easy to make ore-sand a reality.

Inertia is one reason. Mining companies have well-established processes. It takes time and work to intro-

duce new methods.

Industry buy-in and collaboration, supportive government policies and market acceptance will be needed. Major sand buyers such as the construction industry need to be able to test and trust the product.

The upside is real, though. Oresand offers us a rare chance to tackle two hard environmental problems at once: by slashing the staggering volume of mining waste and reducing the need for potentially dangerous tailings dams, and offering a better alternative to destructive sand extraction.

Daniel Franks Professor and Director Global Centre for Mineral Security The University of Queensland

Not every site needs a 6x6. So why run one when a Bell 4x4 ADT gets the job done smarter? By removing the middle axle, you eliminate tyre scuffing, reduce wear on tyres and road surfaces, and gain a tighter turning circle – perfect for confined spaces.

Enjoy all the performance and productivity you expect from our 6x6 - but at a lower overall cost.

When leadership for women comes at the brink of collapse

Leadership is often portrayed as the pinnacle of success— an acknowledgment of competence, confidence and charisma. But what happens when that opportunity arrives not at the peak of a company’s fortunes but at its most precarious edge?

Welcome to the ‘glass cliff’, a term that describes a subtle yet insidious form of gender bias: women being appointed to top leadership roles during times of crisis, when the risk of failure is at its highest.

The phenomenon does not just challenge notions of progress in gender equity; it calls into question the very conditions under which women are allowed to lead.

Coined by University of Exeter researchers Michelle Ryan and Alexander Haslam in 2005, the term builds on the metaphor of the ‘glass ceiling’—the invisible barrier preventing women from reaching top leadership roles. But while the ceiling implies exclusion, the cliff suggests danger. Their research found that women were more likely to be appointed to leadership positions during times of poor company performance or turbulence—periods where failure is not only more likely, but almost inevitable.

In these moments of crisis, organisations appear willing to gamble on someone ‘different’, often turning to women or people from marginalised backgrounds in the hope that a new face may signal change. But these appointments can be poison chalices.

If things go wrong, the blame lands squarely on the leader, and the woman at the helm becomes the scapegoat for longstanding, systemic problems.

Some of the most well-known business cases illustrate this phenomenon vividly. Take Marissa Mayer, appointed CEO of Yahoo! in 2012. Mayer, a former Google executive, was brought in to revive the ailing tech giant. Despite her efforts to rebrand and restructure, Yahoo!’s decline was already well underway. She resigned in 2017 following the company’s sale to Verizon. While some blamed her leadership, others pointed out the company was already entrenched in years of strategic failure long before Mayer’s tenure.

Similarly, Mary Barra became CEO of General Motors in 2014—the first woman to lead a major global automaker—just as the company was mired in a massive vehicle recall scandal. Her appointment was historic, but her leadership was tested immediately by damage control rather than innovation.

In the world of politics, Theresa May took the reins as United Kingdom Prime Minister after the Brexit vote—a chaotic period in British politics. Her tenure was defined by infighting, failed negotiations and an eventual resignation. Her critics were loud, but few acknowledged the impossible task she had inherited.

In Africa, examples are more nuanced, but equally significant. Phuthi Mahanyele-Dabengwa, appointed CEO of Naspers South Africa in 2019, became the first black woman to lead a major listed company in the country. Naspers was already navigating complicated terrain: reputational concerns, criticism over monopolistic behaviour and a shifting media landscape. While her leadership continues and has not resulted in ‘failure’, it underscores how women in Africa, particularly black women, are often brought into leadership roles at moments that demand enormous repair

work, not just operational but symbolic.

Another example is Mamphela Ramphele, who in 2013 launched a new political party, Agang SA, to contest South Africa’s troubled post-apartheid democracy. While not a corporate case, her appointment as a leader in a fractured political landscape—only to be quickly undermined by internal conflict and party disintegration—mirrors the same dynamics.

In Nigeria, Arunma Oteh, appointed director-general of the Securities and Exchange Commission during a time of financial scandal and public mistrust, faced enormous institutional resistance. Despite her credentials and reforms, she was consistently targeted and eventually forced out. Crit-

ics say she paid the price for trying to clean up a mess she did not create.

The glass cliff is underpinned by cultural stereotypes. Women are often seen as more empathetic, nurturing or collaborative—traits perceived as helpful in a crisis. In other words, when companies need to project an image of change or healing, they often reach for a woman. But once the crisis proves harder to solve than expected, these same traits are used against them: She was too emotional, not decisive enough, lacked strategic focus...

Moreover, the scarcity of leadership opportunities for women means they may feel compelled to accept high-risk roles. As South African businesswoman Irene Charnley once said, “You don’t get to choose the perfect time. You take the opportunity when it comes, and you make it work—even if the odds are stacked against you.”

Several women have spoken out about the challenges of leading from the cliff’s edge. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, current director-general of the World Trade Organization and former Nigerian finance minister, is no stranger to high-stakes roles. “Leadership as a

woman in crisis is not new. What’s new is that we’re now naming it. Women aren’t crisis managers by nature—we’ve just been handed the fire and told to put it out.”

South African executive and entrepreneur Basani Maluleke, the first black woman CEO of a South African bank (African Bank), resigned after less than three years, citing personal reasons. But insiders noted her tenure was marked by difficult restructuring decisions and cultural resistance. Reflecting on her journey, Maluleke told Business Day: “Sometimes, the window for change is opened only a crack—and you’re expected to perform a miracle through it.”

And in the corporate world, Indra Nooyi, former CEO of PepsiCo, noted: “As a woman, you’re constantly under the microscope. If you succeed, it’s questioned. If you fail, it’s definitive.”

To dismantle the glass cliff, we must confront the conditions that create it. First, leadership appointments must be paired with support systems: mentorship, governance reform and realistic expectations. Appointing a woman or person of colour in crisis must not be a public relations exercise but a sincere investment in transformation.

Secondly, boards and political organisations must be held accountable for creating inclusive pipelines—not just parachuting women into impossible positions. It is not leadership if the parachute opens just inches from the ground.

And finally, society must stop viewing failure through a gendered lens. Male CEOs often fail upward—leaving one post and landing in another without reputational damage. Women rarely get the same courtesy.

The glass cliff does not reflect a woman’s failure; it reflects systemic failure. Failure to support, failure to nurture diverse leadership earlier, and failure to recognise that placing someone at the helm of a ship already sinking is not empowerment—it’s abandonment.

Leadership should not come only in crisis. Until women are appointed in times of growth as often as they are in times of chaos, true equality will remain elusive.

As Michelle Ryan, co-originator of the term, puts it: “It’s not that women can’t lead in crisis—it’s that they should not only be called upon when all else has failed.”

It is time we stop celebrating the appointment of women to glass cliffs, and start demanding better ledges from which they can soar.

When Tshidi Dlungwane founded Stenda Trading in 2016, she was stepping into one of the toughest industries in South Africa while challenging entrenched perceptions about who belongs in mining.

Today, that pioneering business has grown into the Stenda Group, a diversified enterprise active in mining, technical services, finance and project development. It is a story of resilience, entrepreneurship and a belief in mining’s power to drive economic and social progress.

“The Stenda Group is a family of companies built to drive value across mining, finance and related services,” explains Tshidi, who serves as managing director. “Our portfolio includes Stenda Trading, Stenda Mining, Stenda Finance and Stenda Resources.”

The seed was planted with Stenda Trading, which Tshidi launched after leaving employment at the mines. She had identified a gap in the market: a lack of female-owned, technically focused service providers in the mining sector. “I believe in the power of women and the importance of representation,” she reflects.

Stenda Trading established itself as a reliable partner to South Africa’s leading operators, offering services ranging from ventilation and conveyor maintenance to contract mining. Its reputation for efficiency and safety opened the door for wider ambitions.

Through Stenda Mining, the group now holds equity in a vanadium and iron ore project approaching commissioning: a flagship initiative expected to bring large-scale employment and business development opportunities in its host communities. “We see it as a milestone that will allow us to contribute more directly to South Africa’s growth,” says Tshidi.

Stenda Resources focuses on longterm growth, moving brownfield to greenfield projects and integrating

How Stenda Group is building value and empowering communities in the South African mining industry

the group more deeply into the mining value chain. “We are looking at vertical integration to ensure we not only provide services but also take part in exploration, development and optimisation of mineral reserves,” she adds.

An unusual but impactful initiative is Stenda Finance, a micro-lending entity created to support the group’s workforce of more than 300 employees. “Stenda Finance was designed with our people in mind,” says Tshidi. “By giving them access to responsible financial assistance, we strengthen both our business and their personal resilience.”

Tshidi’s personal journey is as compelling as the group’s. With a degree in Metallurgical and Materials Engineering from the University of Pretoria and an MBA from GIBS, she entered the mining industry on a bursary from Anglo Coal (now Thunge-

“I believe in the power of women and the importance of representation.”

la) and began at the coal mines of Emalahleni. “I spent several years honing my technical skills and gaining a deep understanding of the mining value chain,” she recalls.

Ultimately, she decided to leverage her skills and leadership to build something of her own. “Entrepreneurship is vital to addressing many of our country’s greatest challenges. For an economy to grow and for innovation to thrive, fostering an entrepreneurial culture is essential.”

As a black woman entrepreneur in mining, she has faced many challenges. “Gender stereotyping often means my credibility is questioned,” she acknowledges. Access to market has also been a hurdle, with entrenched supplier relationships limiting opportunities for new entrants. “There is still considerable gatekeeping. And the shortage of mentors who can guide and advocate for

emerging women leaders makes the journey even harder.”

Despite these obstacles, Stenda Group has steadily expanded its footprint, underpinned by a strong embrace of environmental, social & governance (ESG) values. “At Stenda, we prioritise hiring from host communities, upskilling local youth, and sourcing goods and services from local businesses. We also work with our clients to reduce environmental impacts and promote sustainable mining practices,” Tshidi explains.

What does she say to those who call mining a ‘sunset industry’? Her response is pragmatic: “The global energy transition is real and necessary, but it’s not an overnight switch. Coal and other fossil fuels still play a critical role in ensuring energy security and supporting industrial development, especially in emerging economies like South Africa.”

At the same time, she stresses that mining is indispensable for the re-

newable energy future itself. “Mining underpins the very technologies needed for the transition: from copper and lithium for batteries to rare earths for wind turbines. The future of mining is about responsible extraction and innovation, not closing the door on essential resources.”

From its roots as a small, woman-led service company to its present role as an integrated mining group, Stenda has carved out a distinctive place in the South African mining landscape. With new projects coming online, a workforce-focused philosophy and a commitment to ESG values, the group is well-positioned to shape the sector’s next chapter.

“Ultimately, our vision is about building a resilient, integrated ecosystem that adapts to market dynamics and delivers measurable impact,” concludes Tshidi. “Mining is evolving, and so are we.”

For more information, visit stendagroup.com.

“Entrepreneurship is vital to addressing many of our country’s greatest challenges.”

DMPR Budget Vote: Bold regulatory overhaul and targeted investments aim to transform mining and fuel a green-energy pivot

In Minister of Mineral and Petroleum Resources Gwede Mantashe’s Budget Vote speech delivered in July 2025 set the tone for an era of structural reform in South Africa’s mineral and petroleum industries. Against the backdrop of global economic pressure, budgetary constraints and sluggish commodity prices, he presented a proactive strategy rooted in regulation, growth, inclusivity and sustainability.

Following a reconfiguration that separated mineral/petroleum responsibilities from energy, the department’s renewed mandate aims for sharply defined focus and efficiency.

Minister Mantashe opened with recognition of South Africa’s enduring structural economic challenges: persistent poverty, the high cost of living, and the need for inclusive growth. He emphasised the government’s intent to position mining and petroleum as engines of socio-economic transformation, aligned to the National Development Plan Vision 2030 and the Medium-Term Development Plan.

The strategic framework of the DMPR centres on five core pillars:

1. Investment promotion through legislative harmonisation and streamlined approval pathways.

2. Sector transformation, boosting participation by historically disadvantaged persons.

3. Environmental sustainability, including enforcement and rehabilitation of derelict/ownerless mines.

4. Regional integration, leveraging Africa-wide trade and co-operation platforms.

5. Institutional capacity, aimed at tech-driven agility and good governance.

Mantashe described this structure as not just aspirational but operational, backed by legislative reform and regulatory realignment designed to turn policy intentions into tangible outcomes.

FISCAL ALLOCATION: R2.86 BILLION FOCUSED FOR IMPACT

A key highlight for the mining community is the R2.86 billion allocation for 2025/26. This funding is calibrated to: underwrite policy and regulatory reviews, including the drafting of bills and gazetting of regulations; supervise environmental compliance and mine rehabilitation; enhance regional co-operation initiatives; and strengthen institutional structures, including audits and digital capacity.

Although fiscal constraints persist, Mantashe reassured members of Parliament that scarce public funds would be targeted to regulatory priorities, investment facilitation and sector transformation.

GLOBAL GEOPOLITICAL LANDSCAPE: RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES

The minister described a challenging global backdrop: economic fragility, trade tensions and geopolitical volatility. He highlighted specific threats like the recent 30% reciprocal tariffs by the United States, affecting South African diamonds and iron ore exports—minor in dollar terms relative to coal or platinum group metals, but potentially disruptive.

Despite these risks, South Africa’s mining sector showed resilience: After a contraction in 2023, mining gross domestic product rebounded by 0.3% in 2024, contributing R451 billion and sustaining its 6% share of national GDP. However, commodities like platinum, man-

ganese, chrome and coal continue to face depressed prices, underscoring the importance of diversification and value-added processing downstream.

Mantashe reinforced the department’s commitment to:

• revising policies and reducing bureaucratic delays, to promote domestic beneficiation close to production sites.

• reviewing ownership, licensing and empowerment frameworks to secure meaningful economic participation by previously underrepresented groups.

• strengthening environmental enforcement and accelerating the rehabilitation of abandoned mines.

Deputy Minister Phumzile Mgcina disclosed that in 2024/25, R180 million supported Mintek in addressing four asbestos operations and closing 280 unsafe openings in Limpopo and the Northern Cape.

These measures align with President Cyril Ramaphosa’s call for a “capable, ethical and developmental state”: a theme echoed in Mgcina’s report of clean audits at all DMPR enti-

We build machines to answer the needs of societ y.

Machine engineering and technology that help extract materials essential to daily life are also helping preserve lives and reclaim land.

At customer sites around the world, Komatsu dozers merge decades of engineering expertise with cutting-edge technology to carry out their work with power, precision and efficiency. The results shape much of our modern life, providing core minerals that power our cellphones and new generations of electric vehicles.

Tel: +27 11 923 1000

ww w.komatsu.co. z a

www.komatsu.co.za

ties, including Alexkor, which recently transferred from Public Enterprises.

Environmental accountability is a central theme. Minister Mantashe pledged that every mine closure would include rehabilitation, regulatory compliance would be strictly enforced, and derelict mine sites would be remediated.

The past year’s results—tempered by slower global demand—were nevertheless marked by improved environmental performance driven in part by healthier departmental oversight and dedicated budget commitments.

These efforts reflect the government’s recognition of environmental oversight not only as a regulatory requirement but as a strategic necessity: mitigating public health risks, restoring ecological viability and attracting greenfield and brownfield investments in a world increasingly sensitive to environmental, social & governance (ESG) credentials.

The speech reinforced the importance of institutional modernisation within the DMPR. The 2025/26 budget supports: upgrading IT platforms for faster licensing and compliance processing; building human capital within inspectorates and regulatory divisions; and ensuring state-owned entities under its purview maintain clean financial audits—an important marker of credibility in the domestic and global capital markets.

For mining companies operating in South Africa and neighbouring states, these developments promise clearer rules, more predictable timelines and fewer compliance bottlenecks

Mantashe highlighted the department’s intent to engage more deeply with regional integration frameworks across the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union. He forecast increased use of bilateral mining agreements to

facilitate trade and joint exploration ventures, underlining South Africa’s strategic position as a gateway for capital and expertise in mineral-rich Africa.

Beyond the Budget Vote itself, Mantashe noted the recent Cabinet approval of a Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy (see article elsewhere in this edition), supported by the publication of a Mineral Resources Development Bill. This policy framework positions South Africa to capitalise on high-value commodities like platinum, manganese, iron ore, coal and chrome—selected through robust analysis of strategic importance, industrial applicability, employment and export potential.

A transformative pivot toward critical mineral beneficiation and global supply chain integration is underway.

1. Licensing and regulatory certainty

Ongoing policy reviews and co-ordination of legislation suggest streamlined processes—with shorter timelines for exploration permits, mining rights applications and environmental authorisations.

2. Investment in beneficiation

By zoning resources toward value-added processing near production sites, the government signals its intention to deepen the domestic metals ecosystem: from raw output to semi-finished and finished goods, potentially magnifying both export value and local employment.

Policymakers are increasingly attuned to ESG performance. With reinforced audits, environmental oversight and transparent governance, globally minded investors can anticipate improved risk profiles among compliant operators.

4. Transformation imperatives

Heightened focus on historically disadvantaged individuals—supported by budget, policy and monitoring—imposes a new standard of transformation. While larger companies may have existing initiatives, junior and

mid-tier miners must prepare to meet escalated benchmarks.

5. Regional strategy

Expect more strategic outreach through platforms such as the SADC and the African Continental Free Trade Area. Opportunities for regional exploration, cross-border licensing and fund attraction are rising, demanding preparedness from provincial and pan-African players.

Minister Mantashe projected 2025/26 as a year of strategic consolidation. With a departmental structure honed by separation from energy, a robust R2.86-billion budget and policy scaffolding aimed at transformation and ESG compliance, the DMPR appears poised to catalyse a mineral policy renaissance.

For mining businesses—not just in South Africa but across southern Africa—this moment heralds a shift: from commodity extraction to structured value chains, from accommodative fiscal regimes to vetted transformation and environmental stewardship, and from national regulation to continental competitiveness.

As the minister closed his address, he underlined unity across the government, the department’s leadership and stakeholders—making clear that mining, aligned with national priorities, can and must support inclusive growth, employment creation and sustainable development.

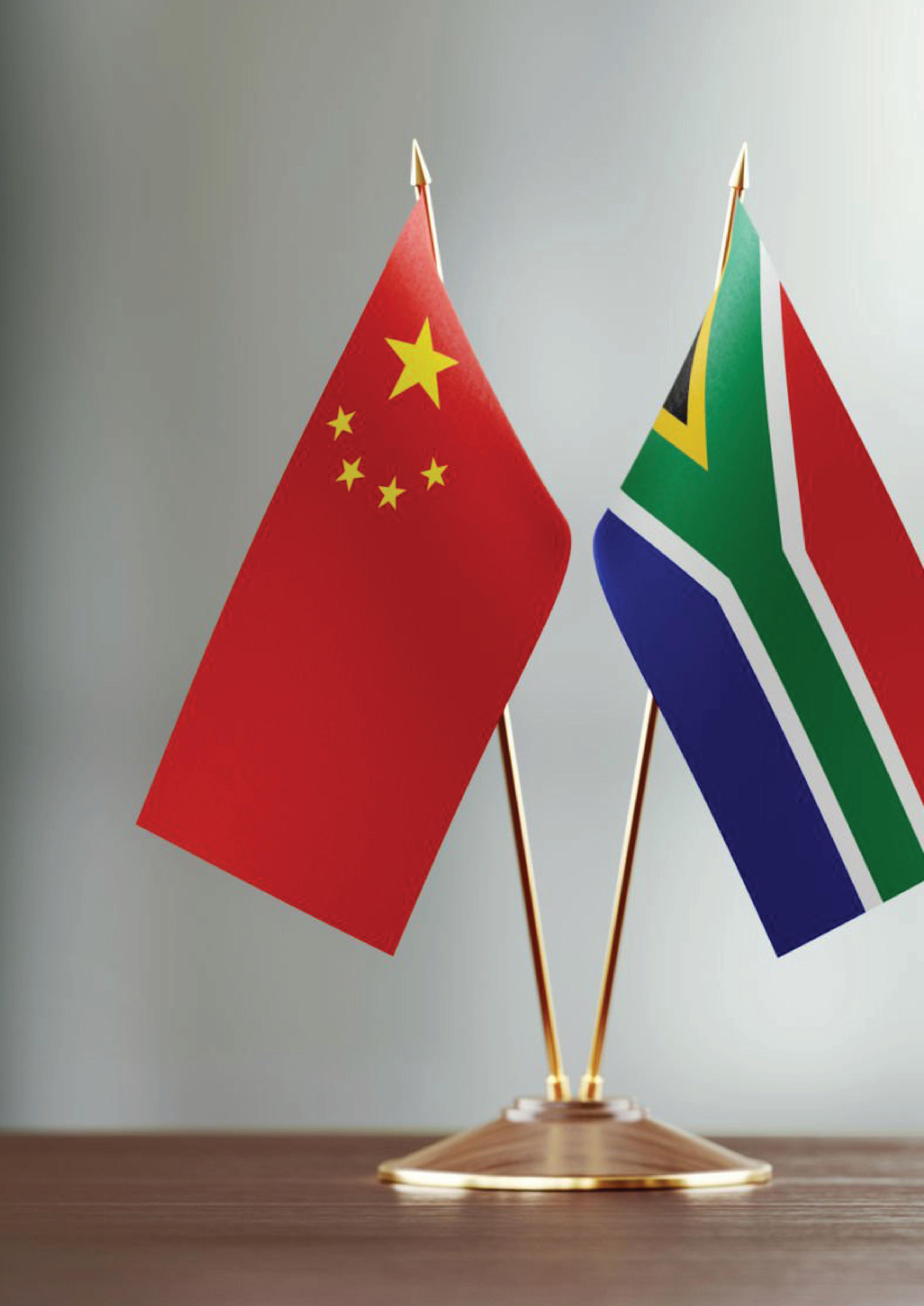

Can zero tariffs drive real change? Inside China’s new trade policy and Africa’s energy-led future

China’s expanded zero-tariff policy offers new export opportunities for Africa, but without parallel investment in energy and industrial infrastructure, the continent risks missing its chance to drive real economic transformation.

After World War 2, the United States and its Western allies created a set of international agreements and institutions to govern attitudes to mutual defence, economics and human rights. For decades, this created stable alliances and predictable economic plans.

But, unlike his predecessors, incumbent US president Donald Trump believes international organisations

While the world needs a stable environment to promote economic growth, Beijing needs this stability for reasons that go beyond economics.

Unlike liberal democracies that derive their legitimacy through elections, a large part of Beijing’s legitimacy comes from its ability to deliver sustained economic prosperity to the Chinese people. But with a battered economy that was first triggered by a real estate crisis in 2021, this task of maintaining legitimacy has become more difficult.

Exporting its way of out the economic slump may have been on Beijing’s books, as this was one of China’s traditional methods for promoting economic growth. But Trump’s trade war has made this an increasingly difficult prospect, especially to the US, which imports 14.8% of total Chinese exports.

As a result, fixing China’s economy has become a priority for the Chinese government.

China’s zero-tariff policy for African goods has expanded rapidly in recent years, with 53 of the continent’s countries now eligible to export their taxable goods to the Chinese market duty-free. Promoted as a vehicle

undermine US interests and sovereignty. He has withdrawn the US from the World Health Organization, and there is speculation he could reduce US commitment to the United Nations. US investment in NATO’s mutual +defence pact remains under discussion.

But while Washington is busy sounding the retreat from the very world order it had a hand in building, Beijing is looking to increase its international role. Chinese leadership in international agencies affiliated with the UN has increased over the years, and so has its financial commitment to international institutions.

That’s not all. China is also a prominent member of trade coalitions such as the 15-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, and

the 10-member BRICS group (led by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). These groups not only promote greater economic integration among its members but may reduce members’ reliance on the US economy and the US dollar. Amid an increasingly volatile US, China’s presence as the second largest economy in the world in these trade groups would be useful.

Now with the whole world negotiating new US trade deals, most nations see their relationship with the US as unstable. China sees this as a golden opportunity to position itself as a global counterbalance to the US. One of its policies is to “deliver greater security, prosperity and respect for developing countries”, and this is particularly relevant in African nations, where US aid is being reduced rapidly.

for deeper Sino-African co-operation and shared prosperity, the policy has gained attention for its potential to open access to one of the world’s largest consumer markets.

But as the continent looks to secure long-term development and industrial transformation, a central question arises: Will trade preferences like this serve as a catalyst for Africa’s economic evolution, or simply reinforce its role as a low-value commodity supplier?

Eswatini—one of the few African countries that maintains diplomatic ties with Taiwan—was excluded from the tariff breaks, underscoring that

access to China’s market remains conditional. The expanded duty-free and tax incentives also appear as a counter to the Trump-era tariffs, placing Africa in the throes of the China–US trade war.

The broader question for the continent is whether these expanding trade policies can deliver tangible, scalable benefits. Africa’s ability to meet its development and energy access goals will depend not only on increased trade but on how effectively such policies translate into investment in infrastructure, energy and industrial growth.

Tariff-free access does little to change that if non-tariff barriers, unreliable power supply or inadequate transport logistics continue to undermine competitiveness.

On paper, zero-tariff access is a welcome opportunity. For African countries seeking to diversify export destinations and boost agricultural, mineral and energy-based trade, the initiative offers a cost advantage that could help expand trade volumes. For oil and gas producers, there may be openings to increase exports of refined products, petrochemicals or fertilisers, if the necessary processing capacity exists.

But therein lies the challenge. Most African countries lack the industrial and energy infrastructure to capitalise on such preferences. Many exports continue to be raw or semi-processed materials with limited value retention on the continent. Tariff-free access does little to change that if non-tariff barriers, unreliable power supply or inadequate transport logistics continue to undermine competitiveness.

Energy sits at the core of that equation. Africa’s path to economic sovereignty depends on its ability to convert natural resources into industrial products: a process that begins with investment in upstream development and extends through midstream lo-

gistics and downstream transformation. Whether it is building pipelines and liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure, electrifying industrial corridors or developing fertiliser and plastics manufacturing hubs, Africa’s energy systems must evolve to support trade ambitions.

Several countries are already moving in that direction. Nigeria is pushing forward with its gas commercialisation strategy; Mozambique is scaling up LNG; Senegal and Mauritania are emerging as cross-border gas hubs. These projects not only generate export revenue but create the foundation for broader economic diversification: from petrochemical industries to power generation for local factories.

Meanwhile, the African Continental Free Trade Area provides the framework to harmonise standards, reduce internal tariffs and build common infrastructure such as pipelines, ports and refineries, thereby enabling economies of scale and intra-African trade. If combined with external access like China’s zero-tariff policy, this dual ap-

proach could allow African nations to integrate vertically and horizontally, moving from fragmented markets to unified production ecosystems.

Still, risks remain. Trade with China remains heavily skewed toward raw materials, with manufactured imports often undercutting local industries. Without targeted support for African manufacturing, technology transfer and local content, tariff preferences risk entrenching the continent’s supplier status rather than overturning it. African governments must therefore ensure policies (both trade- and energy-related) are designed to channel benefits inward, not just extract them outward.

“[Africa can] seize agency in its global partnerships. Energy security, industrialisation and trade access must be viewed not in silos but as interconnected levers for longterm prosperity,” notes NJ Ayuk, executive chairperson of the African Energy Chamber.

Sources: Africa Energy Week, Chee Meng Tan/TheConversation.com

Developments in Namibia’s mining law are underway, evolving in pursuit of a careful balance

The government is eager to modernise laws and ensure the country’s mineral wealth benefits its people

In Namibia, the mining sector is critical to the economy and mineral assets form a major source of national wealth. The country’s mining industry developed relatively early, based mostly on diamonds discovered in around 1986. The initial reserves were high quality gem diamonds. Other metals (mainly copper, zinc and lead) were exploited in the country.

Namibia’s mining sector is currently undergoing a quiet transformation, supported by a government eager to modernise laws and ensure the country’s mineral wealth benefits its people. Namibia has long held a reputation as a stable and attractive jurisdiction for global investors.

Now, a suite of legislative reforms and regulatory changes are reshaping the landscape, with significant consequences for both industry insiders and local stakeholders.

The latest push for reform centres on the Minerals (Prospecting and Mining) Act of 1992 (“the Act”), which has been the backbone of mining law since independence. Recognising that global standards and national ambitions have evolved, authorities are reviewing the Act to strengthen state oversight, align with international environmental and governance best practices, and promote transparency in licensing.

A draft amendment bill, currently under public consultation, seeks to introduce stricter requirements for work programmes, local content and corporate social responsibility, aiming to redress past inequities and position Namibia for sustainable growth.

Policy shifts are equally evident in efforts to increase local participation and value addition. The Ministry of Industrialisation, Mines and Ener-

gy has signalled that future mining ventures will need greater Namibian ownership, and that beneficiation— especially for diamonds and uranium—must increasingly happen within the country’s borders.

Joint ventures with local or stateowned entities may become standard: a move intended to maximise national benefit even as it raises concerns among international firms about regulatory burdens.

Reforms are not limited to ownership and licensing. Namibia’s fiscal regime for mining is also under review, with changes proposed to royalty rates for strategic minerals and the introduction of profit-based taxes to capture windfall gains. Tax incentives targeting exploration and regional development round out the economic package, as the government seeks a balance between attracting investment and securing a fair share of revenues.

Environmental stewardship is moving to the fore of legislative priorities. Stricter requirements for environmental impact assessments, robust baseline data and mandatory management plans are being introduced, along with greater emphasis on post-mining rehabilitation and financial assurances to cover environmental liabilities. These steps reflect Namibia’s obligations under interna-

tional conventions and its determination to balance economic development with ecological protection.

A separate review of the Mine, Health and Safety Regulations is also underway, with the intention of replacing the outdated 1968 ordinance.