AU

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

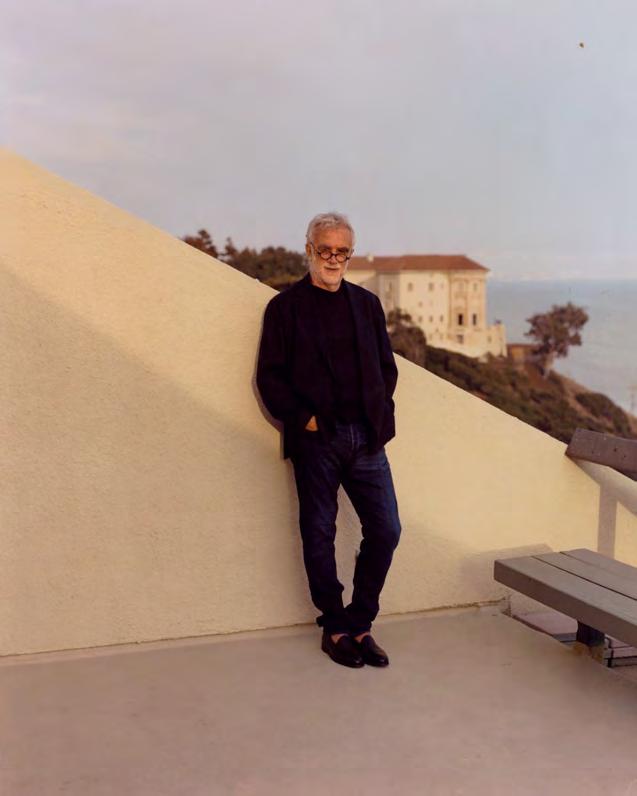

Oliver Kupper

MANAGING EDITOR

Summer Bowie

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

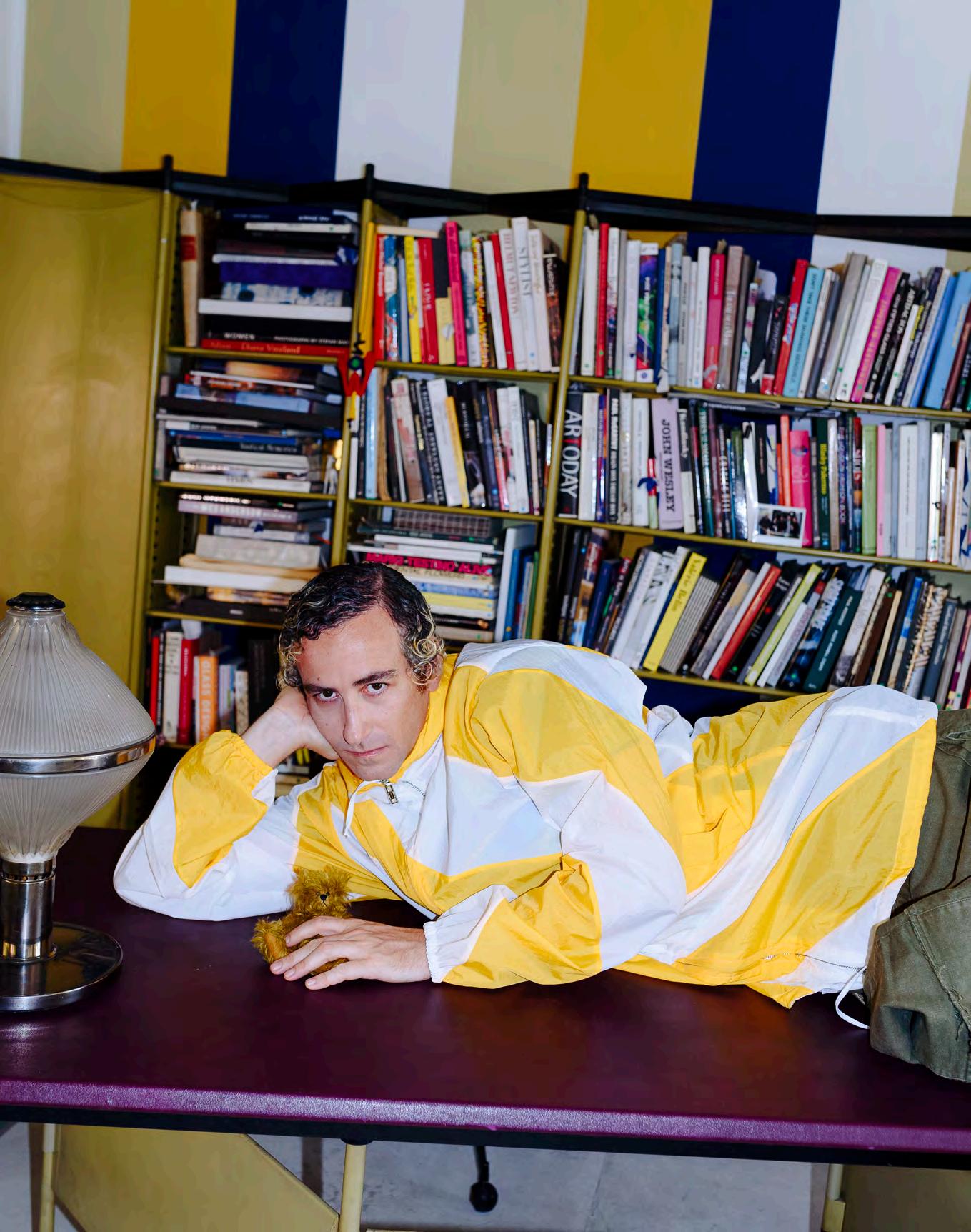

Toby Grimditch

FASHION EDITOR

Hakan Solak

JUNIOR FASHION EDITOR

Camille Pailler

NEW YORK EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Alec Charlip

ART DIRECTOR

True Love Industries

PRODUCTION

Laura Howes

INTERNS

Andrea Riano

Stella Peacock-Berardini

Anni Pullagura

Billy Lobos

Chloe & Chenelle

Defne Ayas

Edward James Lee

Hamish Wirgman

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Jeffrey Deitch

Jonny Woo Jordan Richman

Linn Phyllis Seeger

Marie Louise Von Haselberg

Max Jolivet

Michael Slenske

Naomi Miller Noemi Polo

Forensic Architecture

Gagosian

Grindr

IDEA Books

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Kunsthaus Bregenz Kurimanzutto

Marni

Michael Stipe

Praying REM Uncle Paulie's Deli

KOPA OFFSET PRINTING HOUSE

Industrijos g. 12, Kaunas, Lithuania www.kopa.eu

Oliver Misraje

Robert Longo

Sami Knight

Andy Jackson Clément Pascal

Coley Brown Damien Maloney David Brandon Geeting Denny Sachtelben Dustin Lynn Jason Nocito Javier Castán

Jermaine Francis Joseph Kadow Jules Moskovtchenko Liberto Fillo Magnus Unnar Matias Alfonso Max Farago

NTI

Nadia Lee Cohen Nick Sethi Pat Martin Patrcio Malagón Paulo Sutch Rob Kulisek Sina Östlund Suzi & Leo Victoria Pidust

Camera (ABC Dinamo)

Digestive (Jérémy Landes)

Tomato Grotesk (Andrea Biggio)

Whyte Inktrap (ABC Dinamo) ZIGZAG (Benoît Bodhuin)

Allison Berry Center For Spatial Technologies David Zwirner Dream Factory Studio Eva Chimento

AUTRE LOS ANGELES

6711 Leland Way Los Angeles, CA 90028

GENERAL INQUIRIES, ADVERTISING & DISTRIBUTION info@autre.love

FOLLOW AUTRE @autremagazine www.autre.love

ISSN 2767-7958

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

IMAGE Jeremy Shaw, Phase Shifting Index, 2020 seven-channel video installation, multi-channel sound, lights. Installation view Centre Pompidou 2020. Photo Timo Ohler.ALL RELIGIONS ARE CULTS, Letter From The Editors 25

MOBILIZATION, Victoria Pidust & Volo Bevza on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine 28—29

THE ARCHITECTURE OF VIOLENCE, A Conversation Between Eyal Weizman and Maksym Rokmaniko 30—35

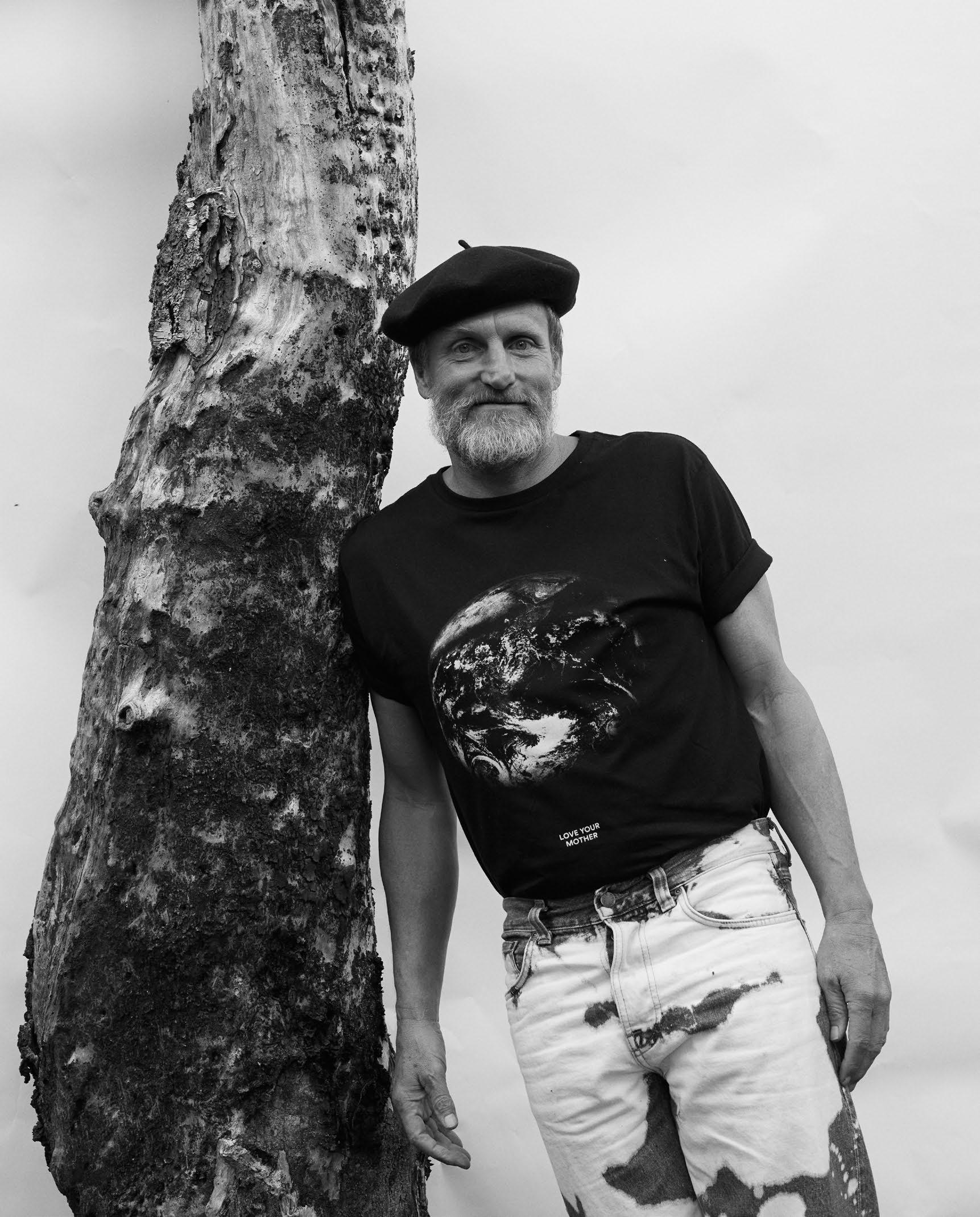

PIET HEIN EEK, Design In The Age Of Crisis 36—39

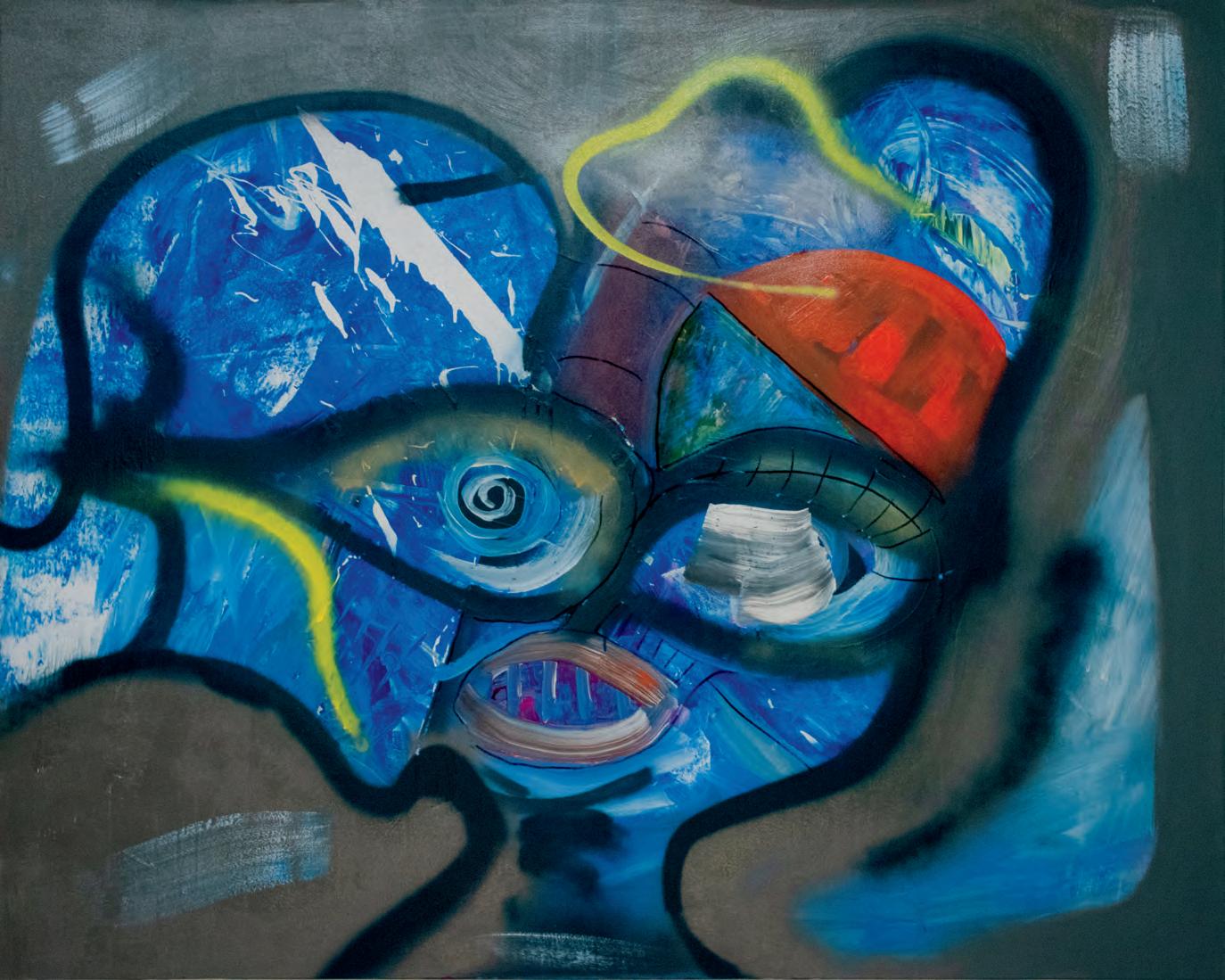

THE FRAGILITY OF MEMORY, Greg Ito Interviewed by Anni Pullagura 40—45

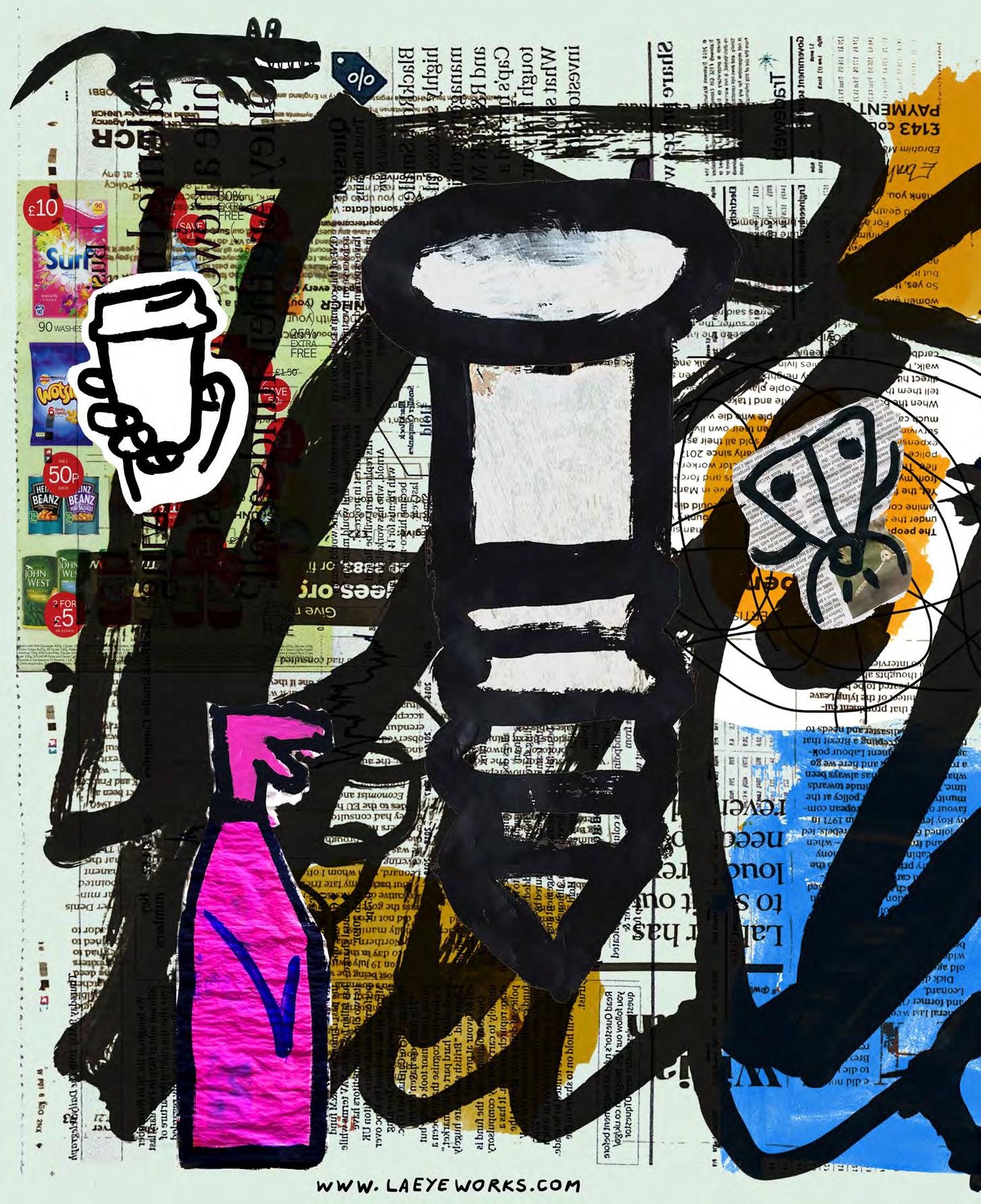

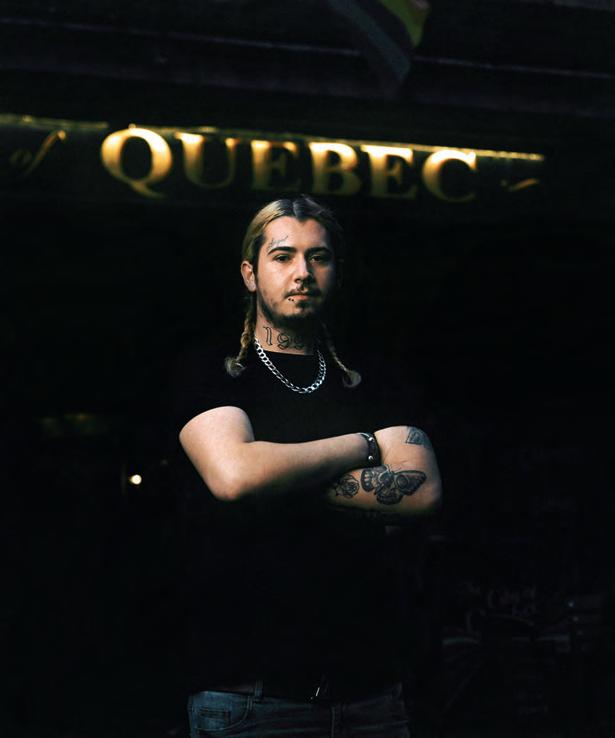

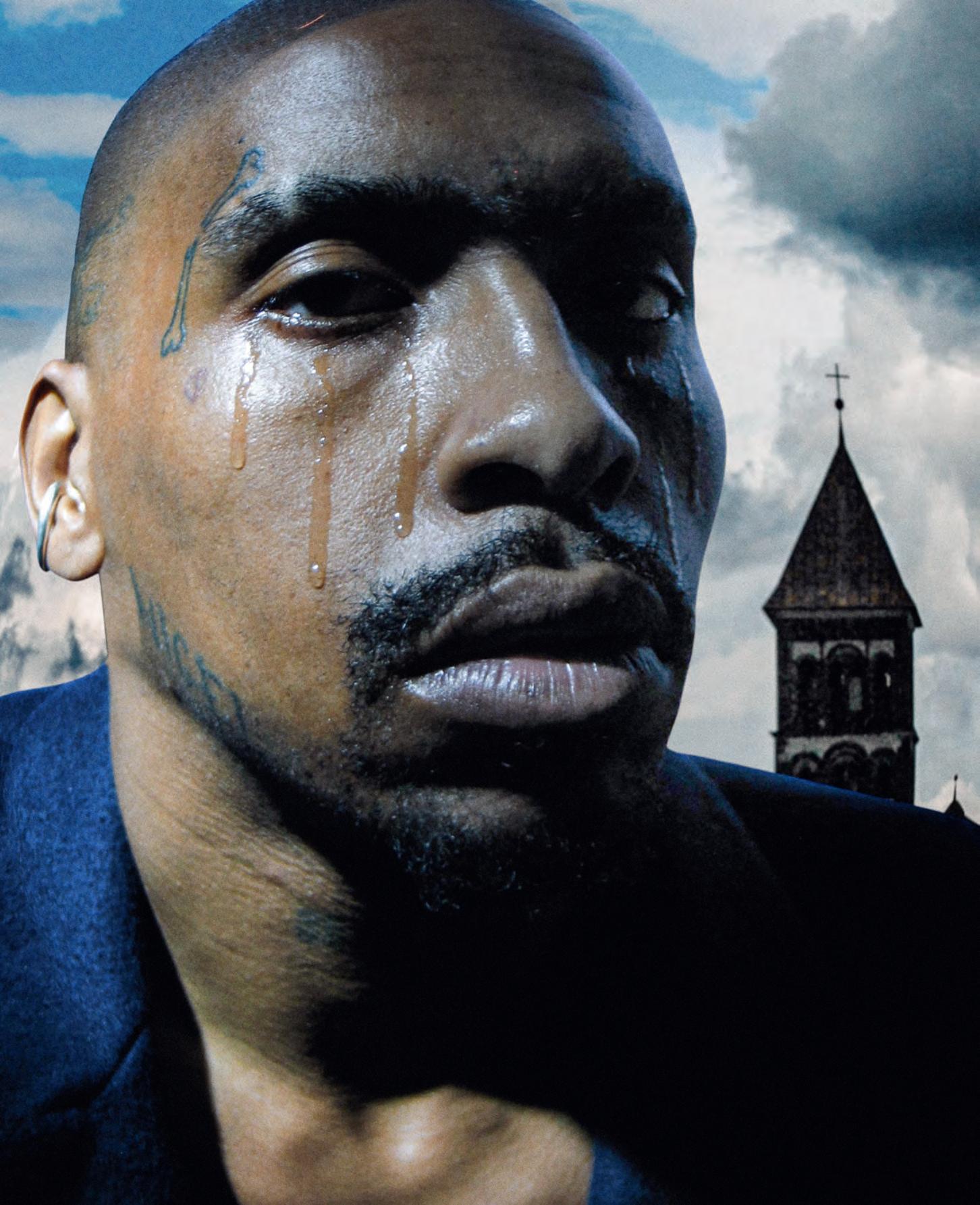

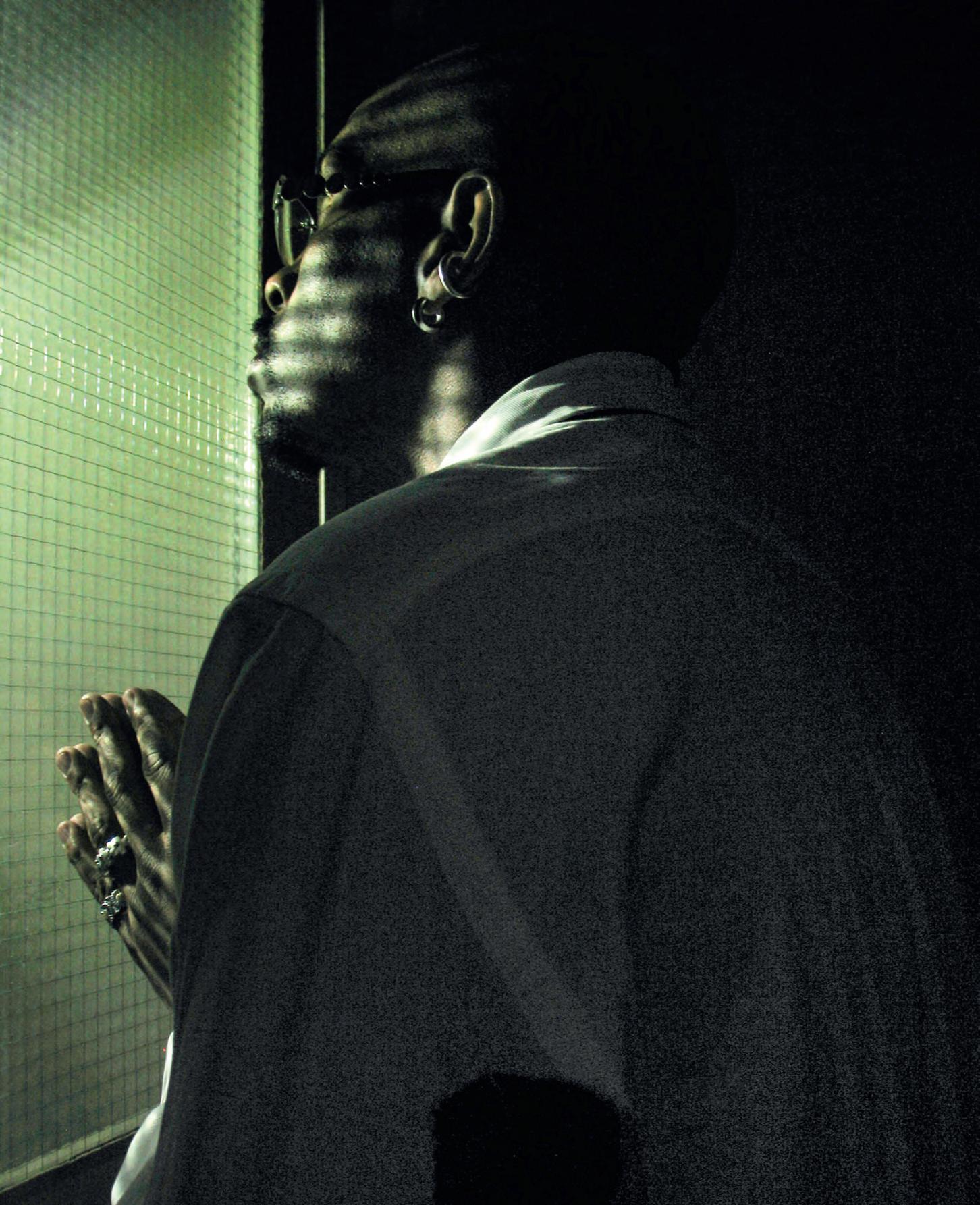

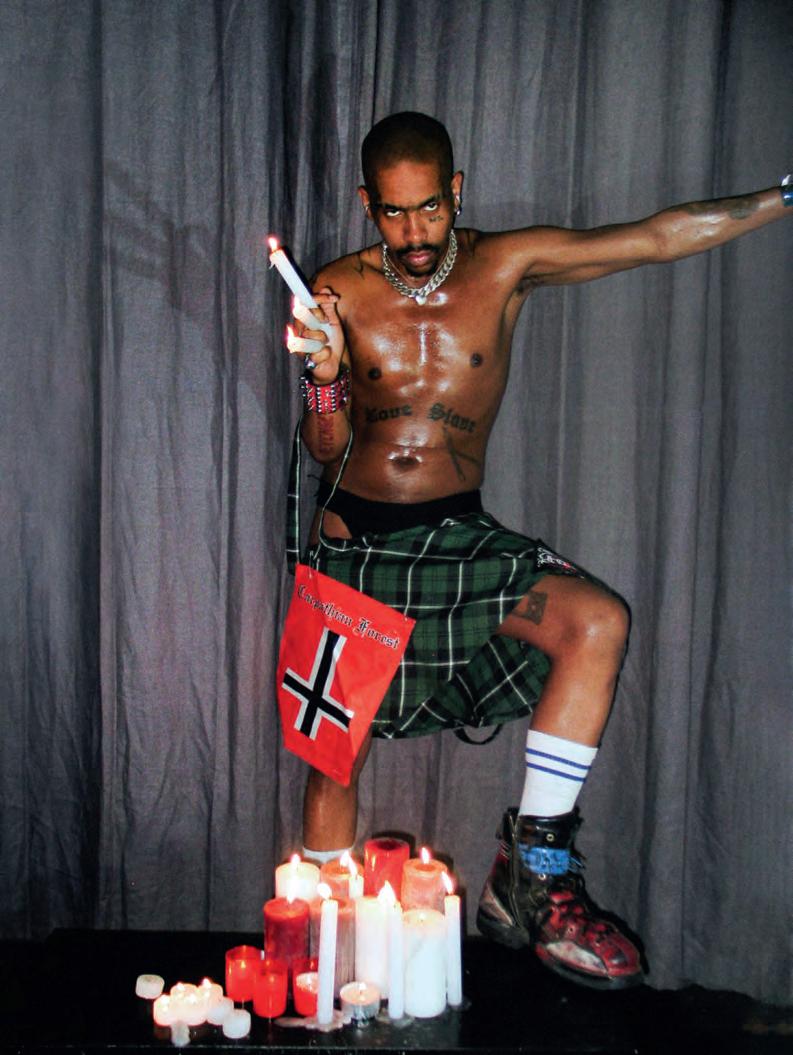

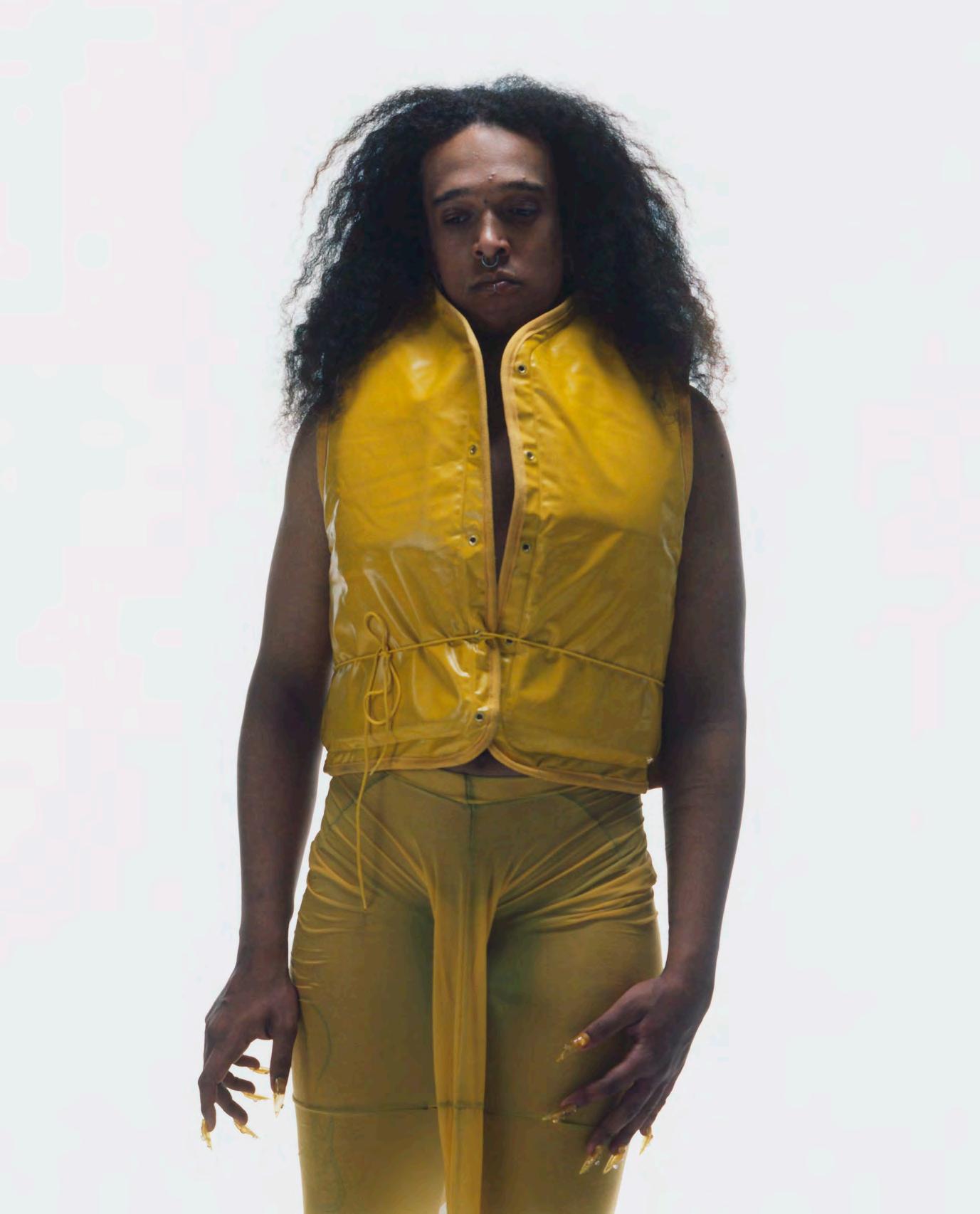

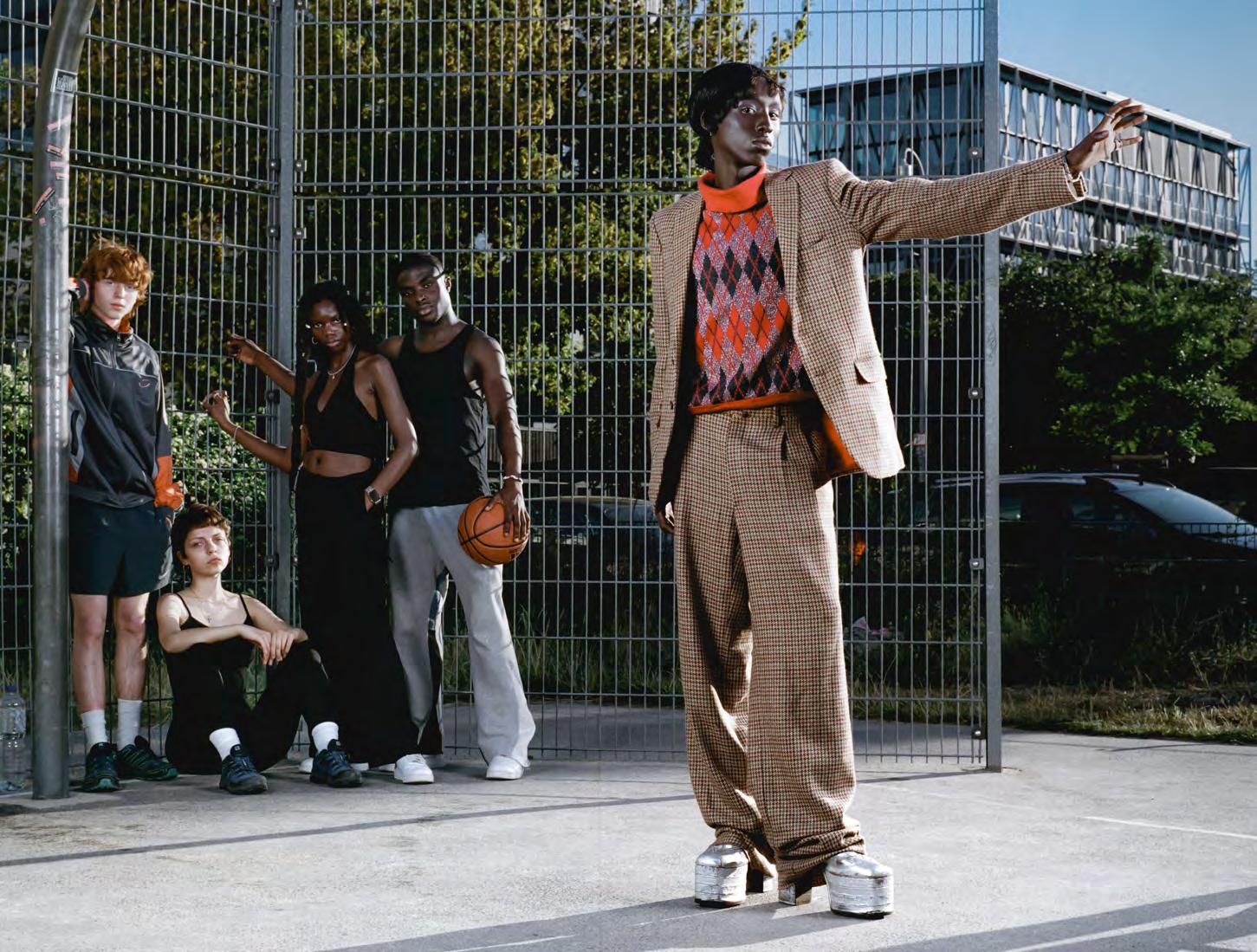

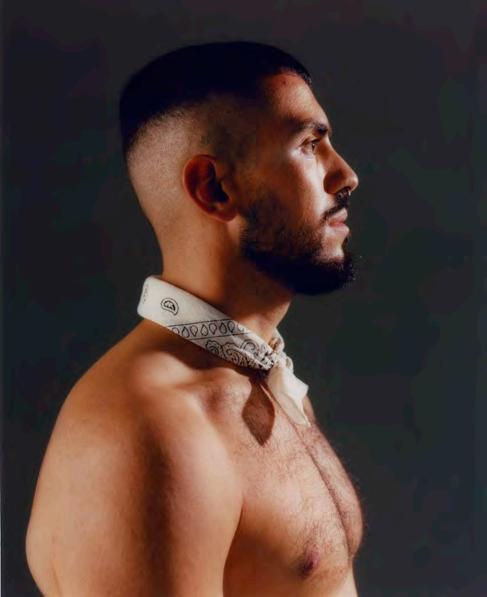

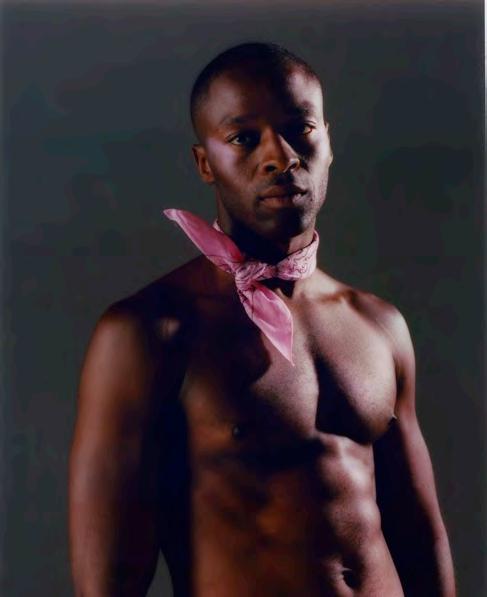

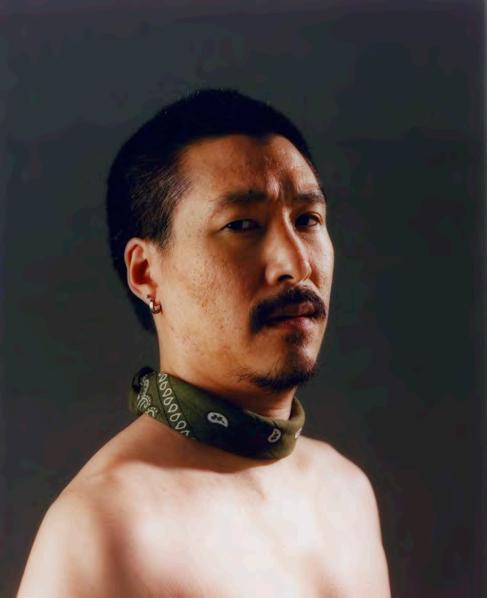

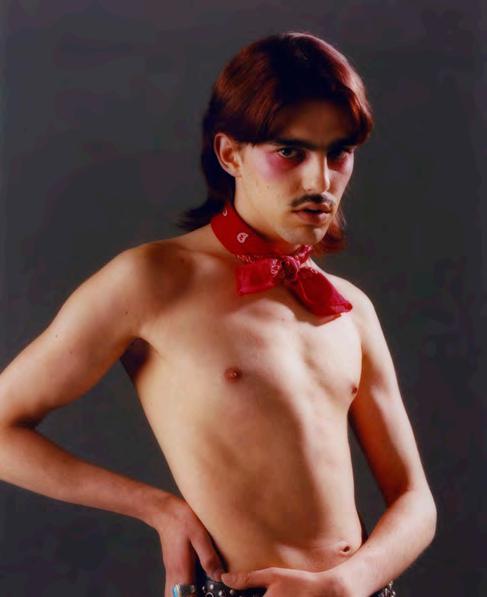

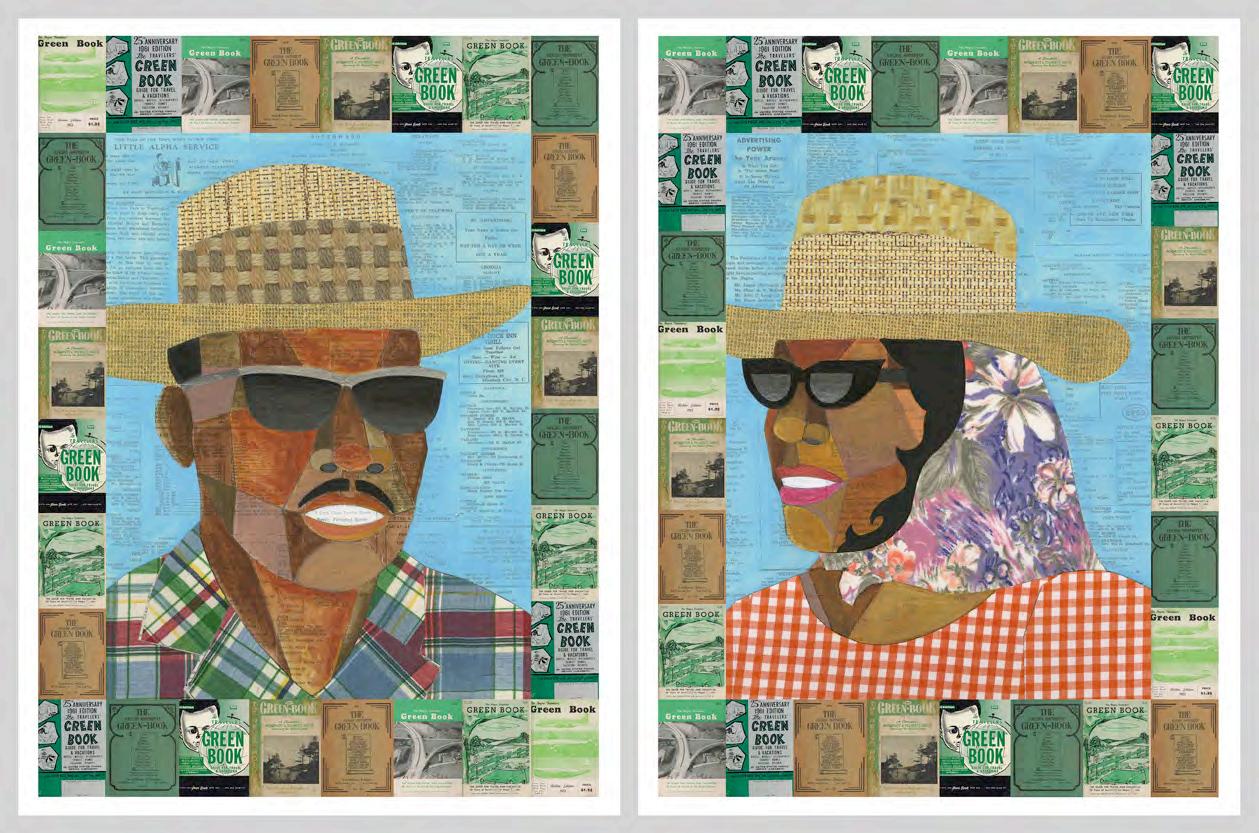

JERMAINE FRANCIS, No Fake News Here 46—59

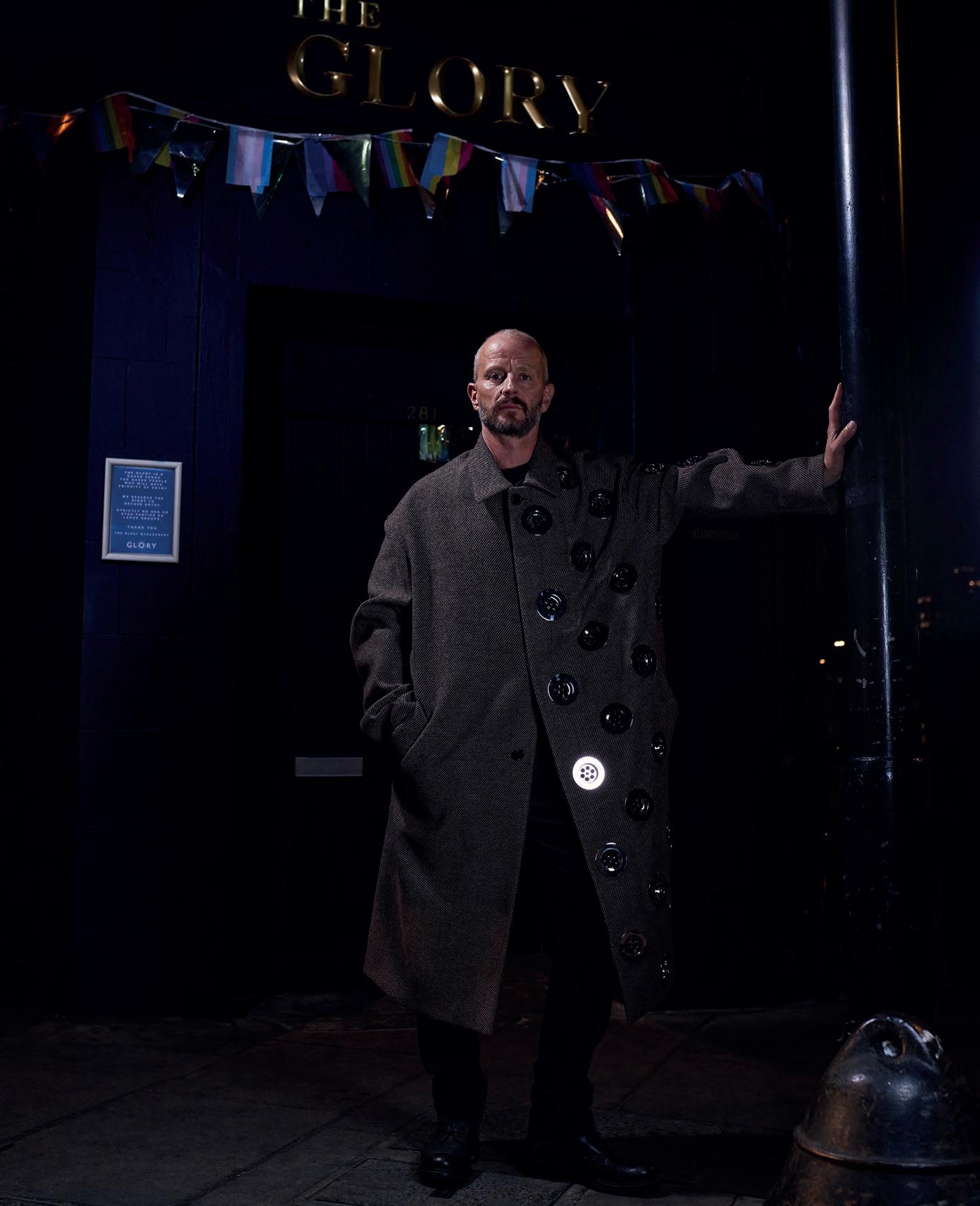

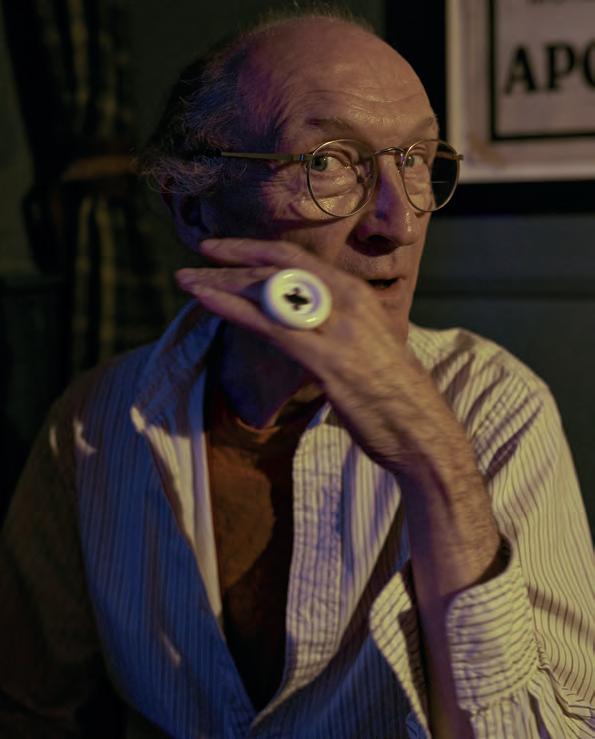

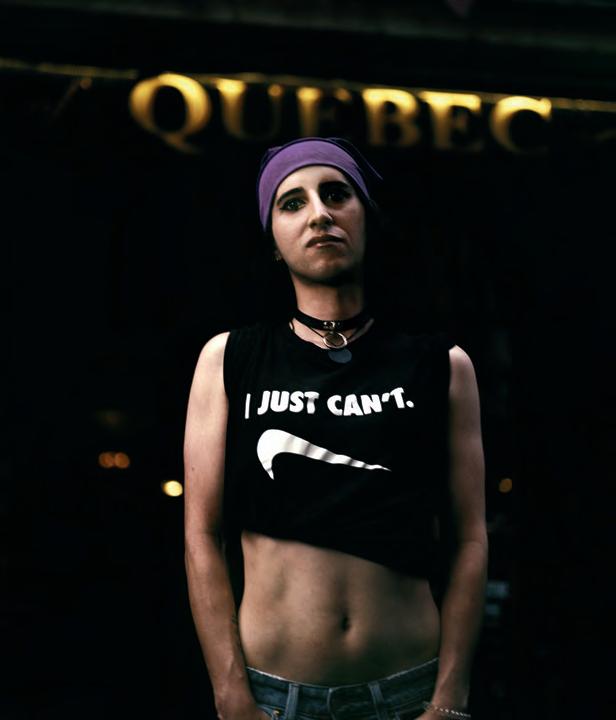

PUBLIC HOUSE, Exploring The Queer Pubs Of London 60—83

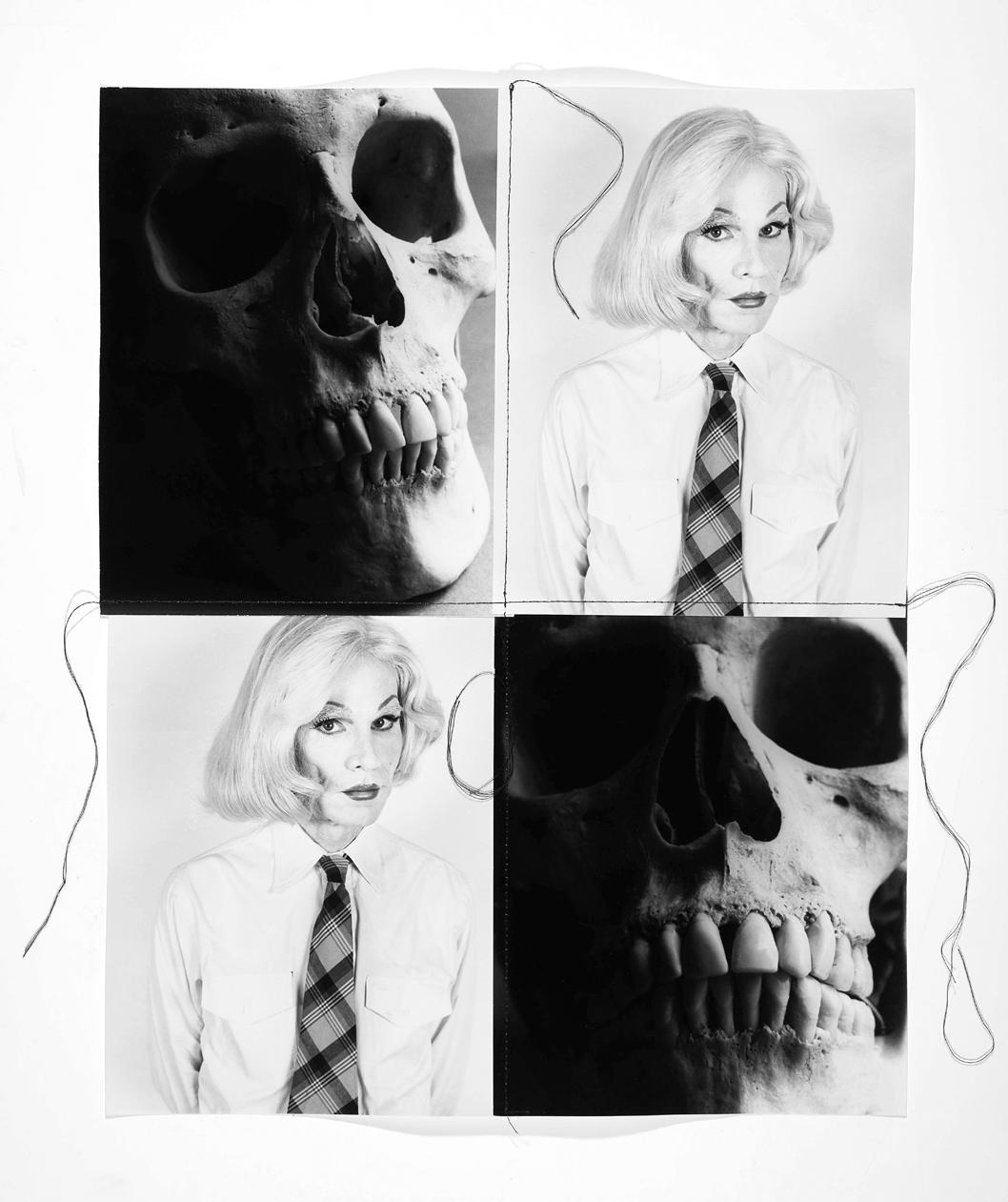

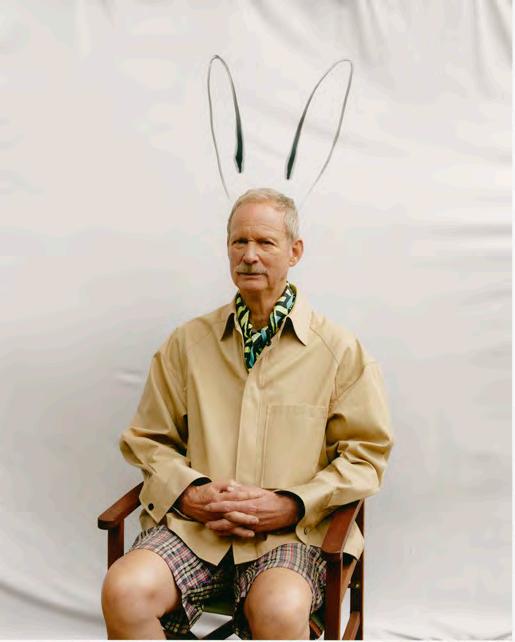

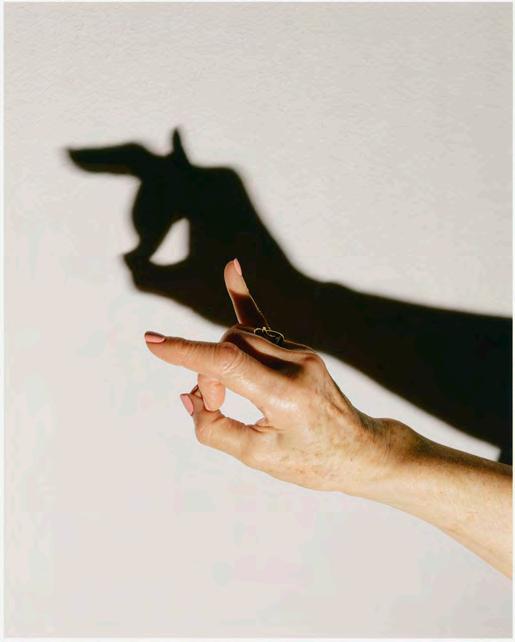

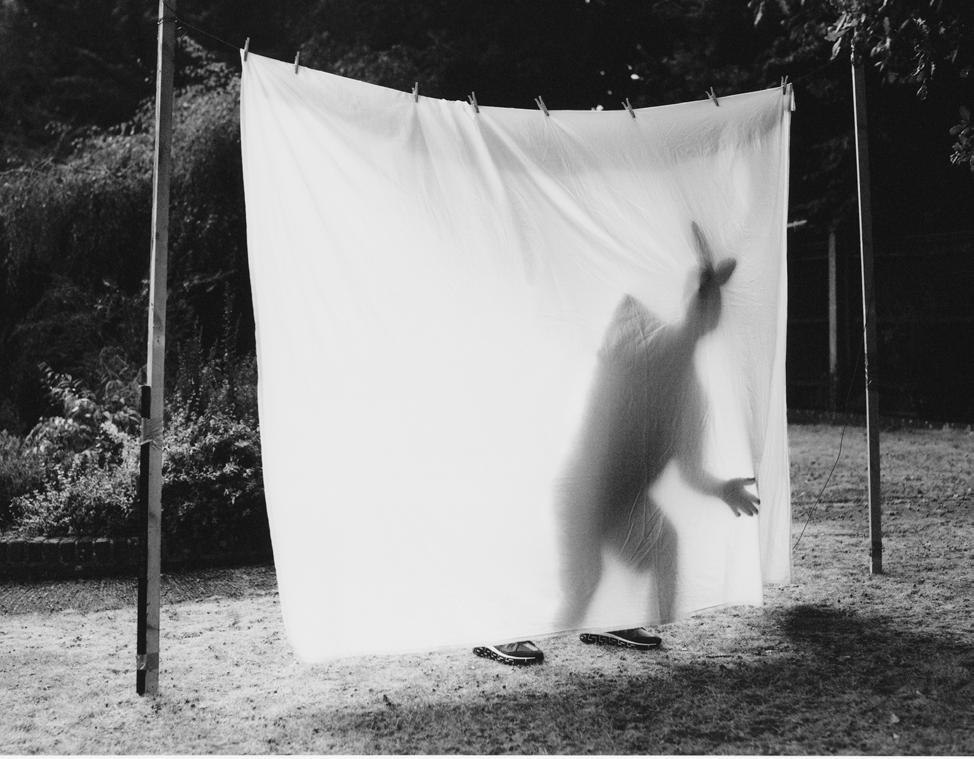

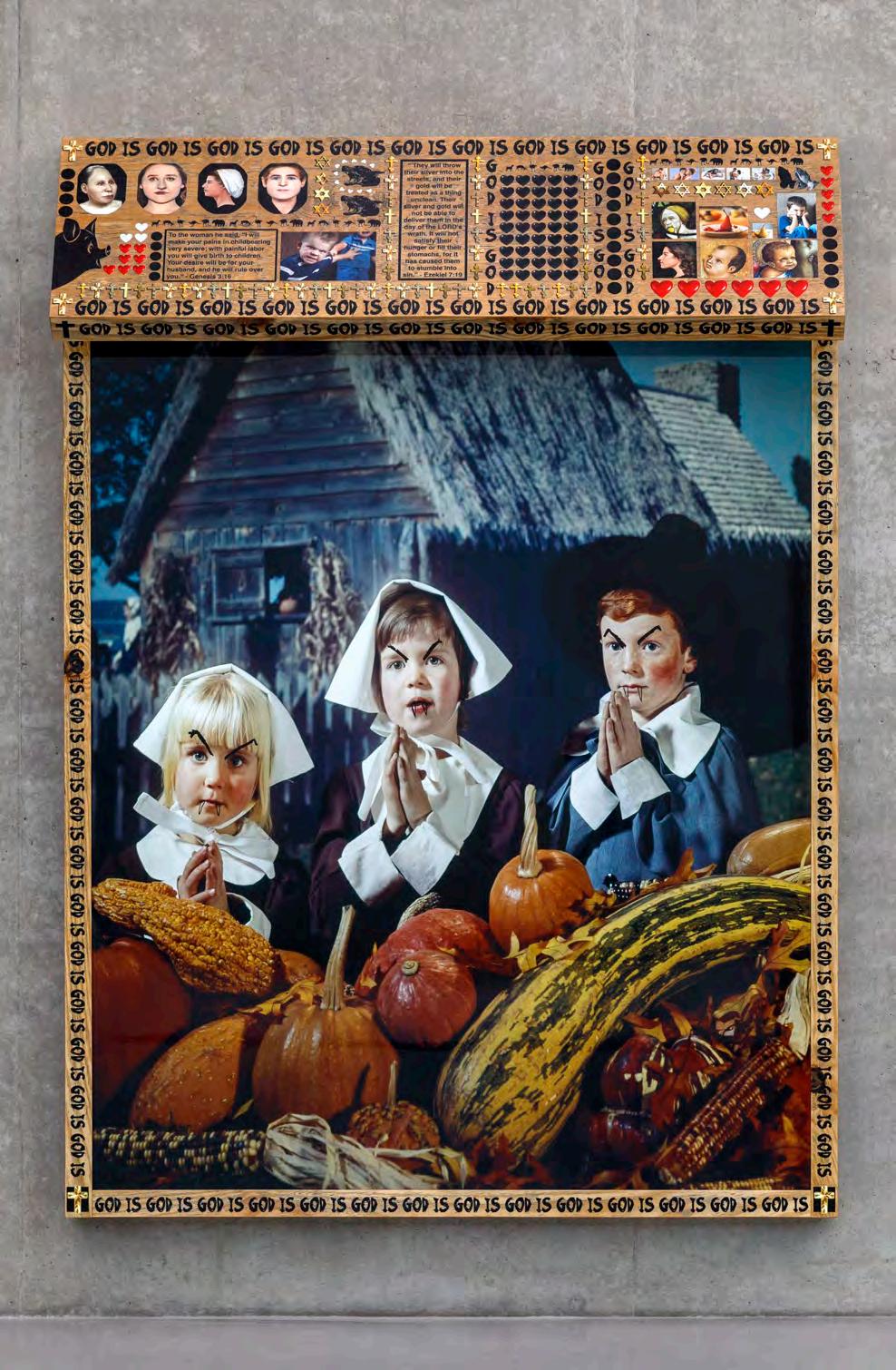

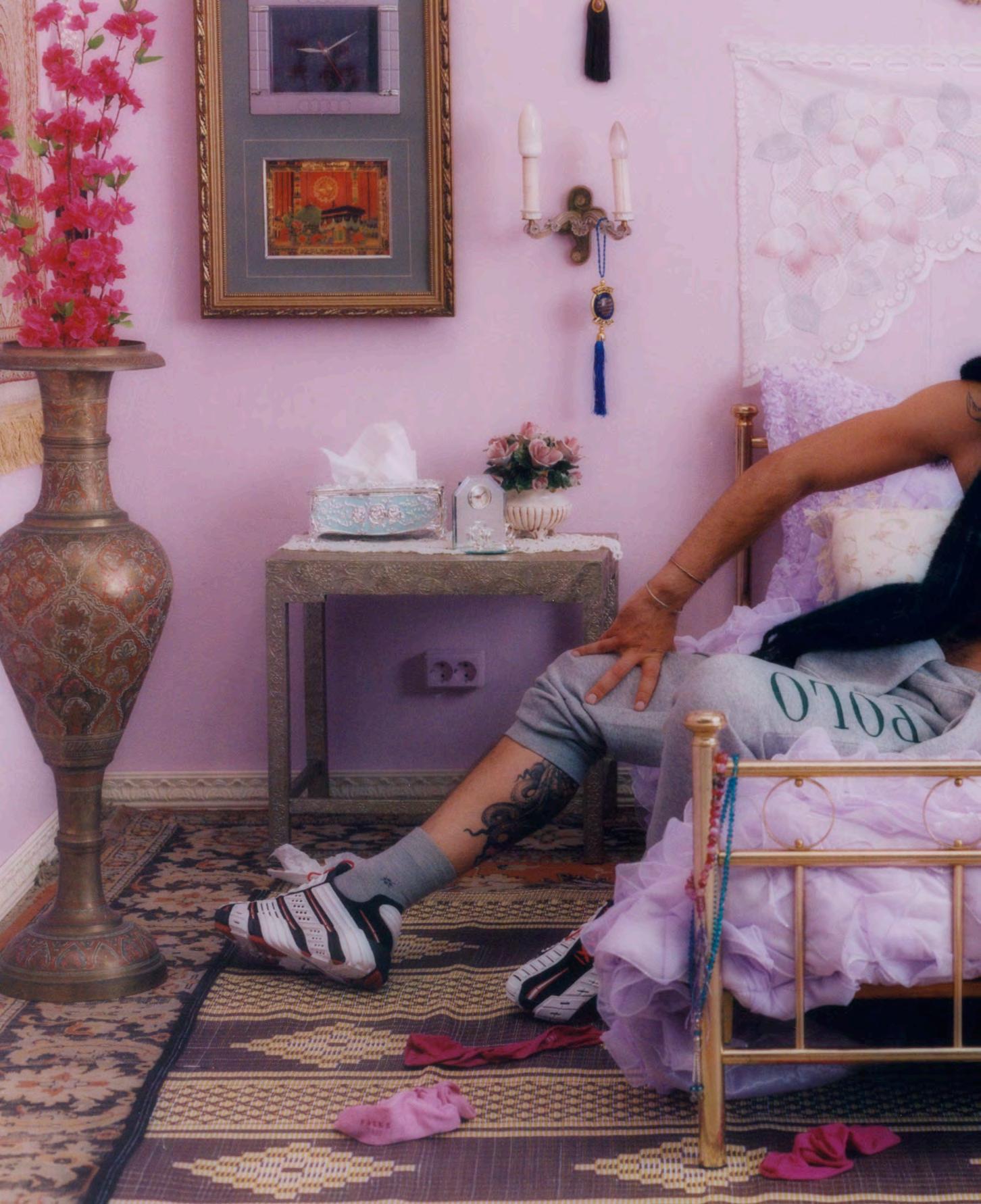

BREEDERS, by Daniel Roché and Marie-Louise von Haselberg 84—99

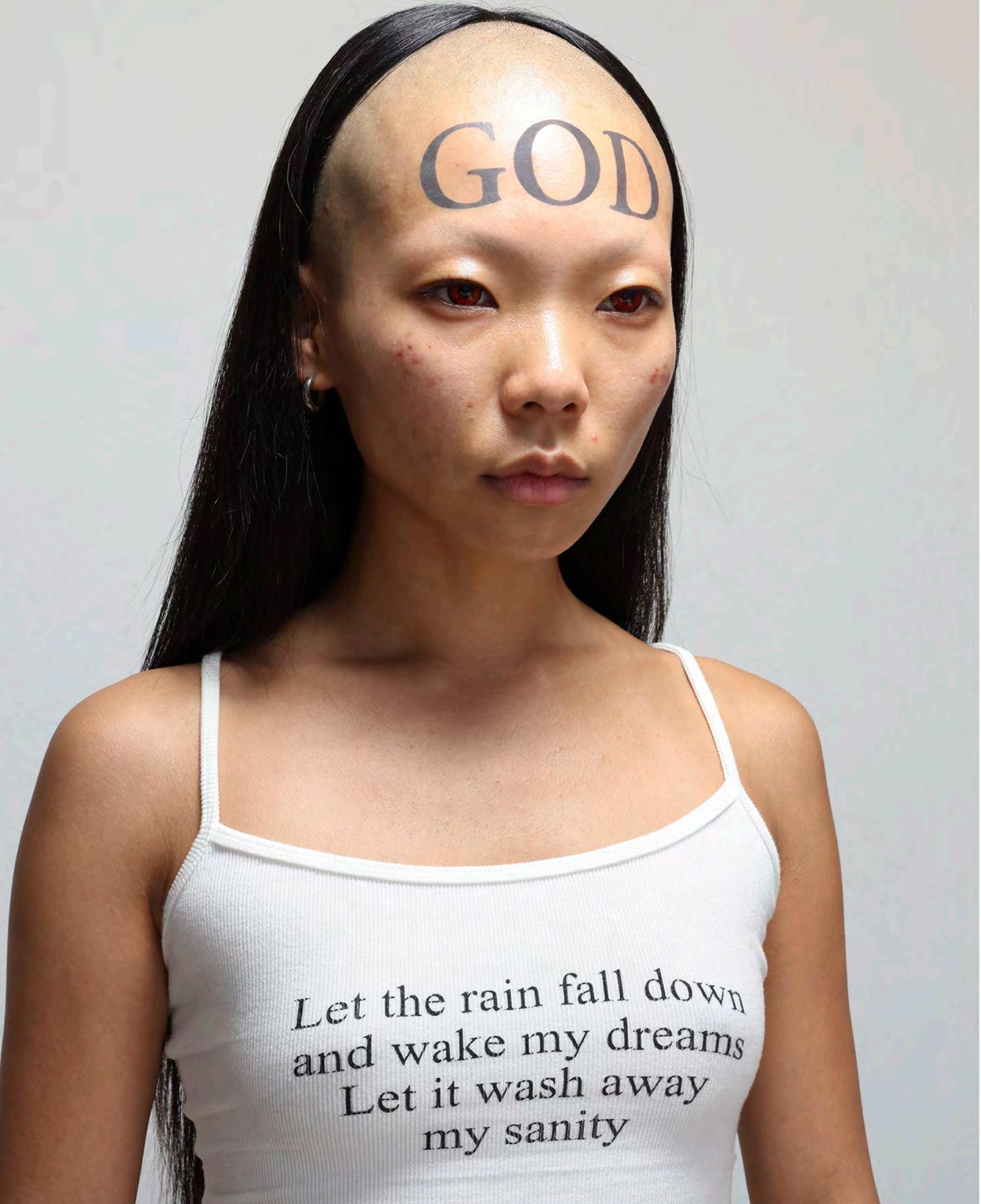

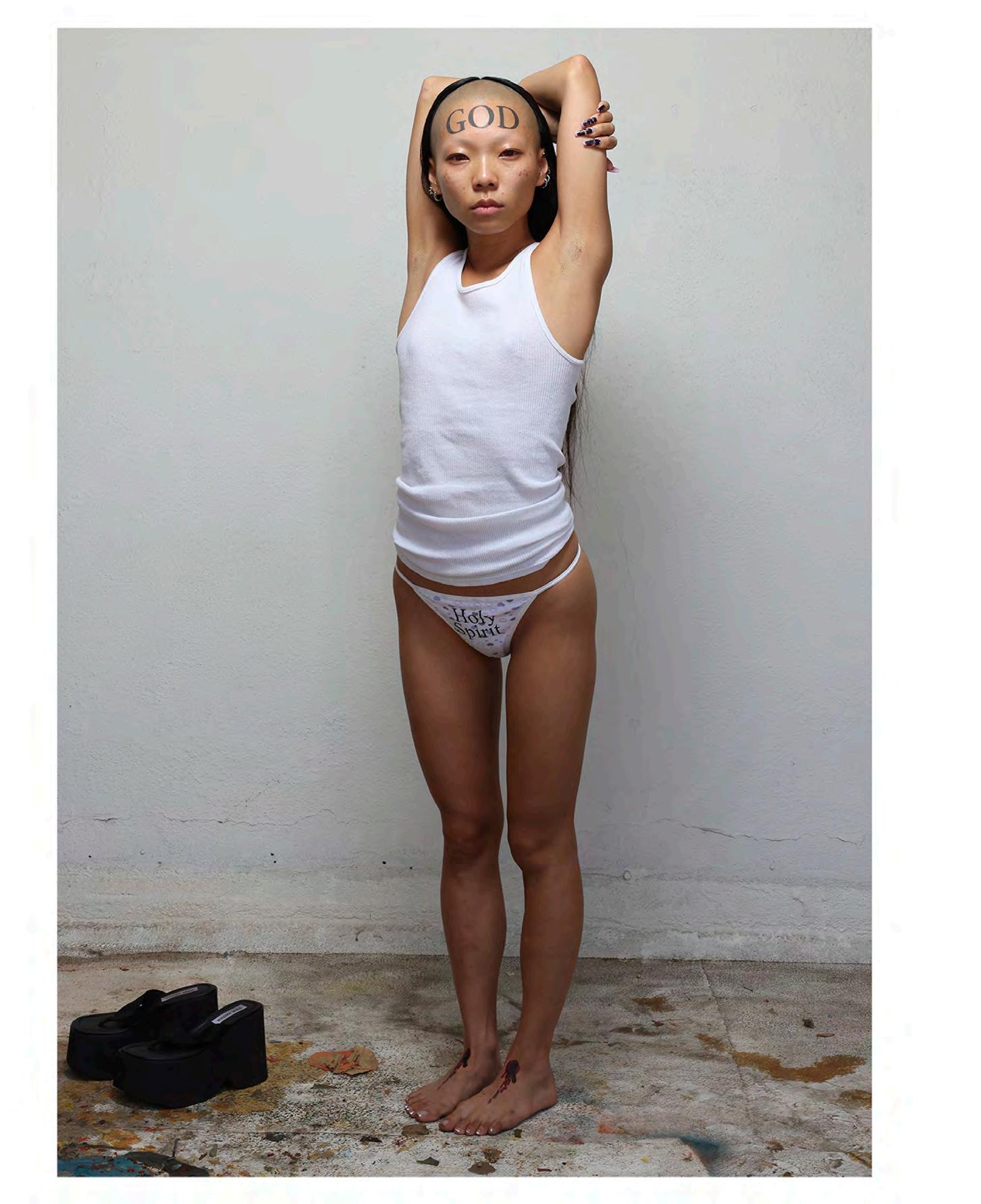

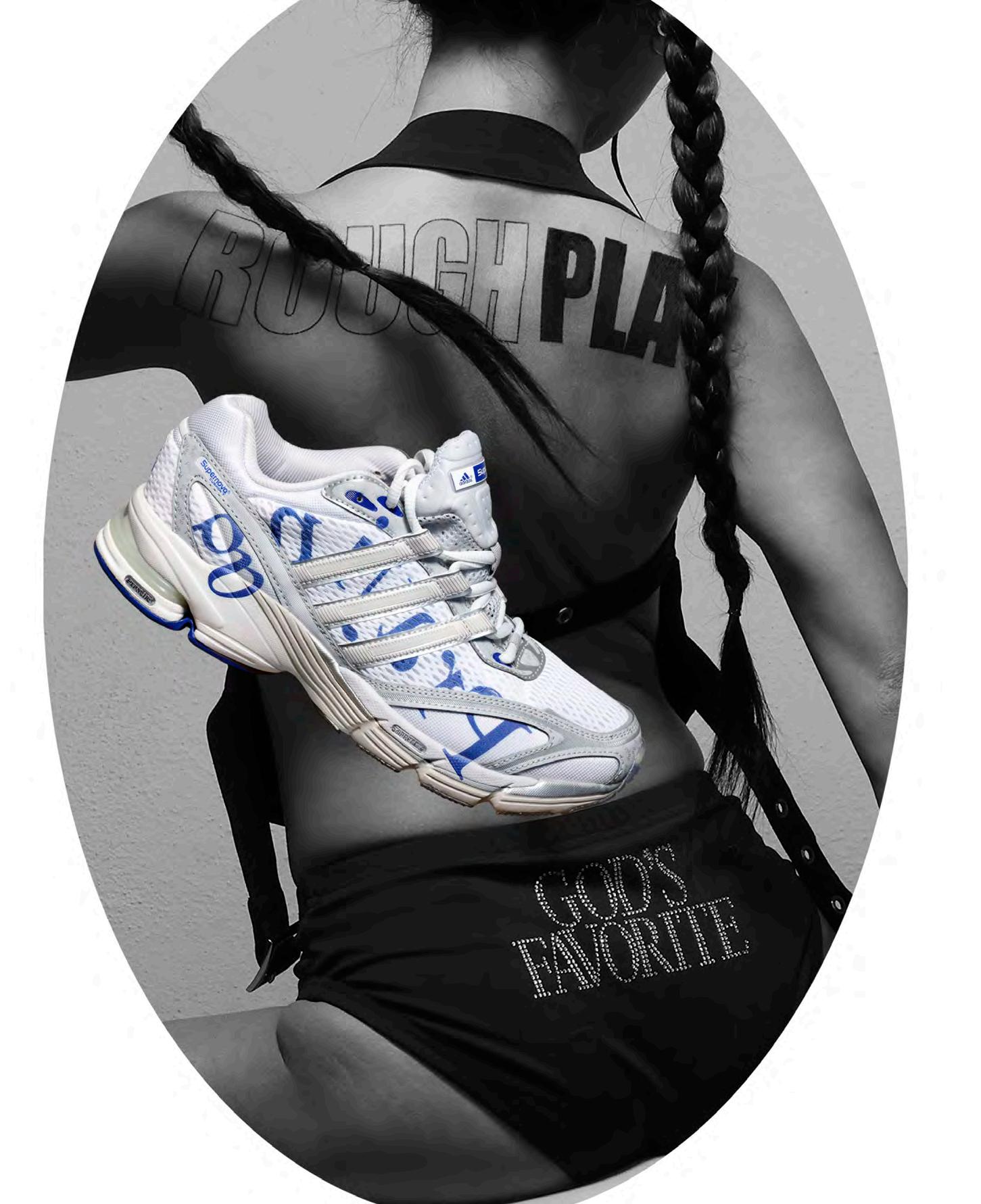

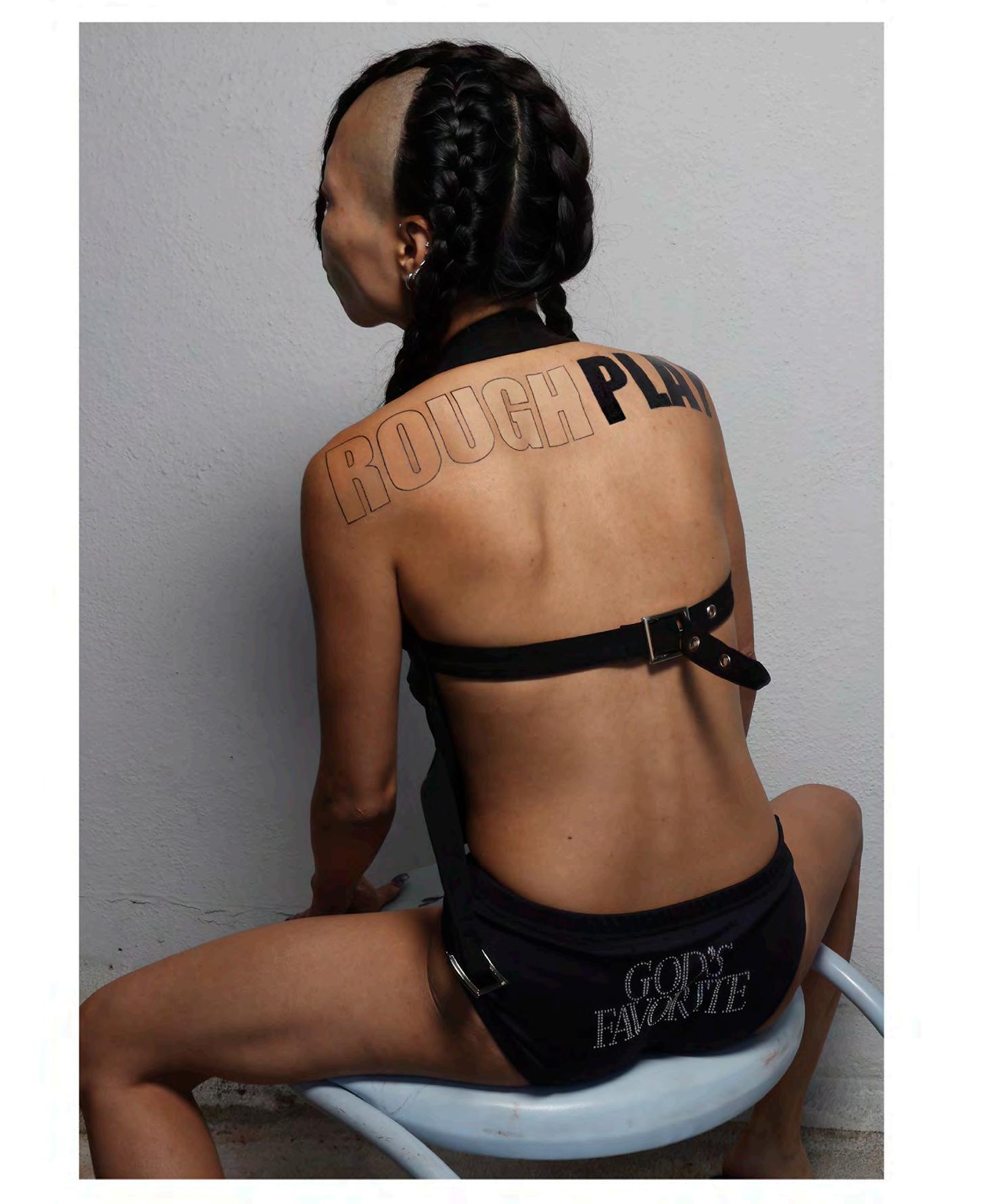

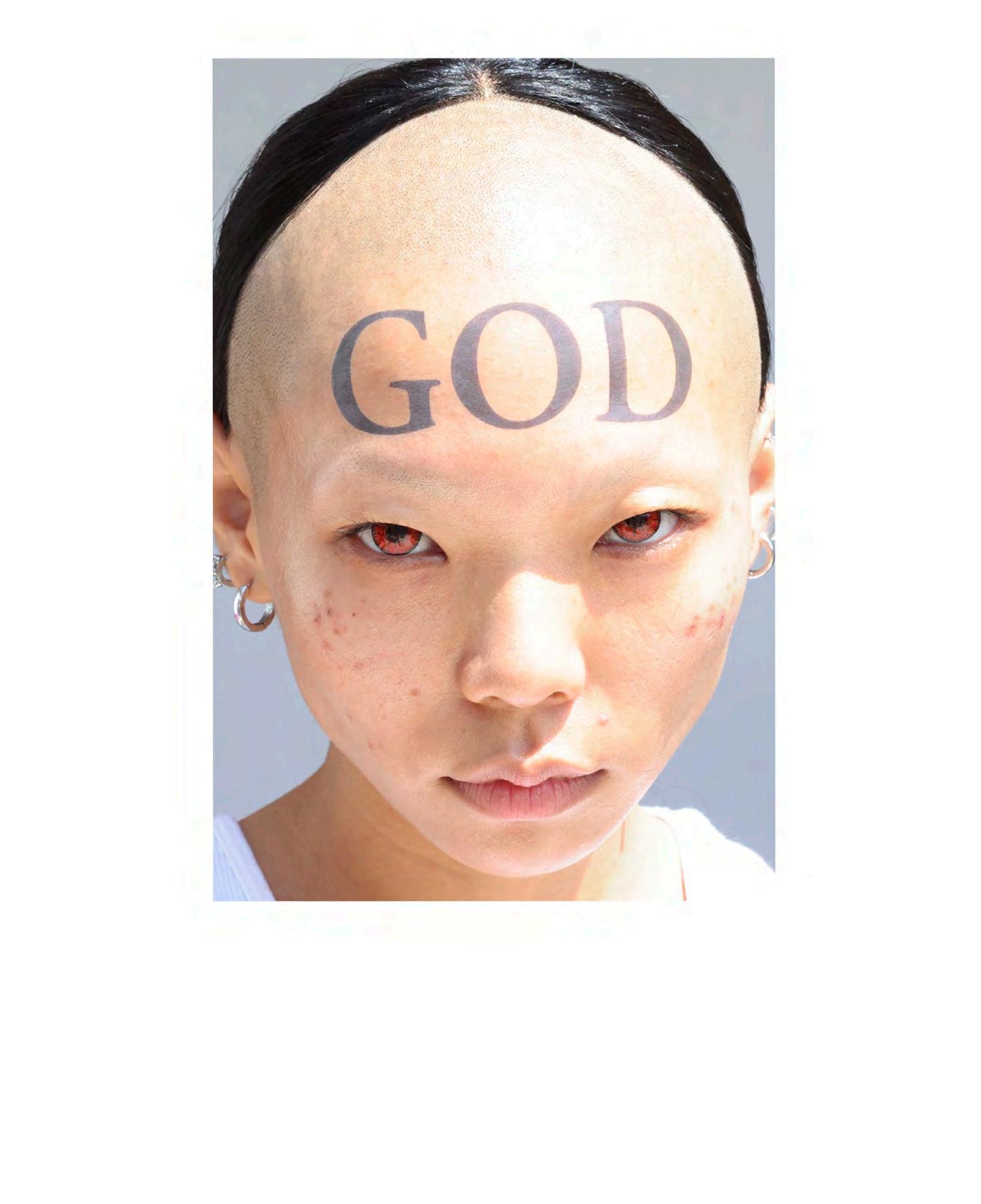

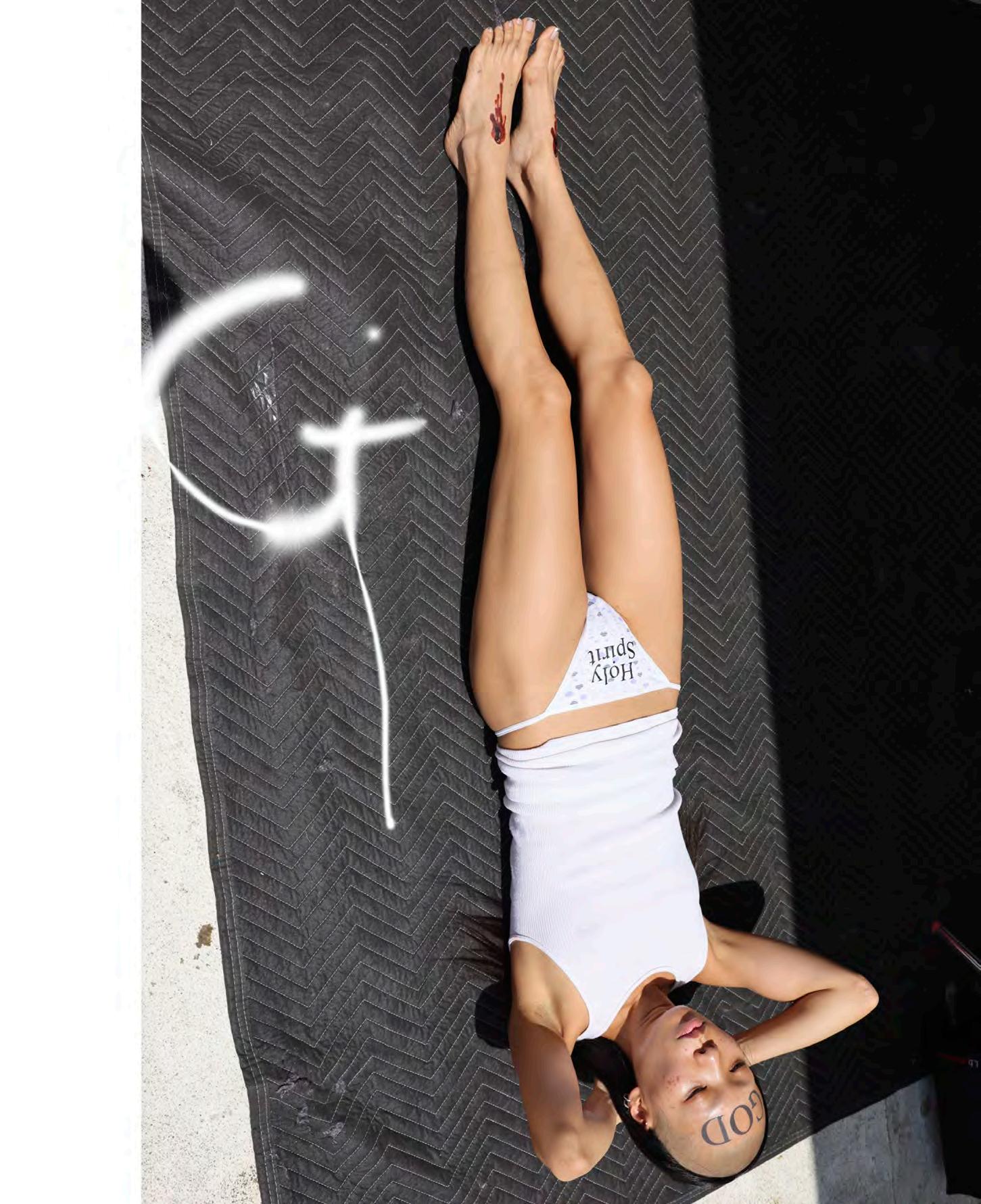

JEREMY SHAW, Accessing Altered States 100—109 PRAYING, by Paulo Sutch 110—121

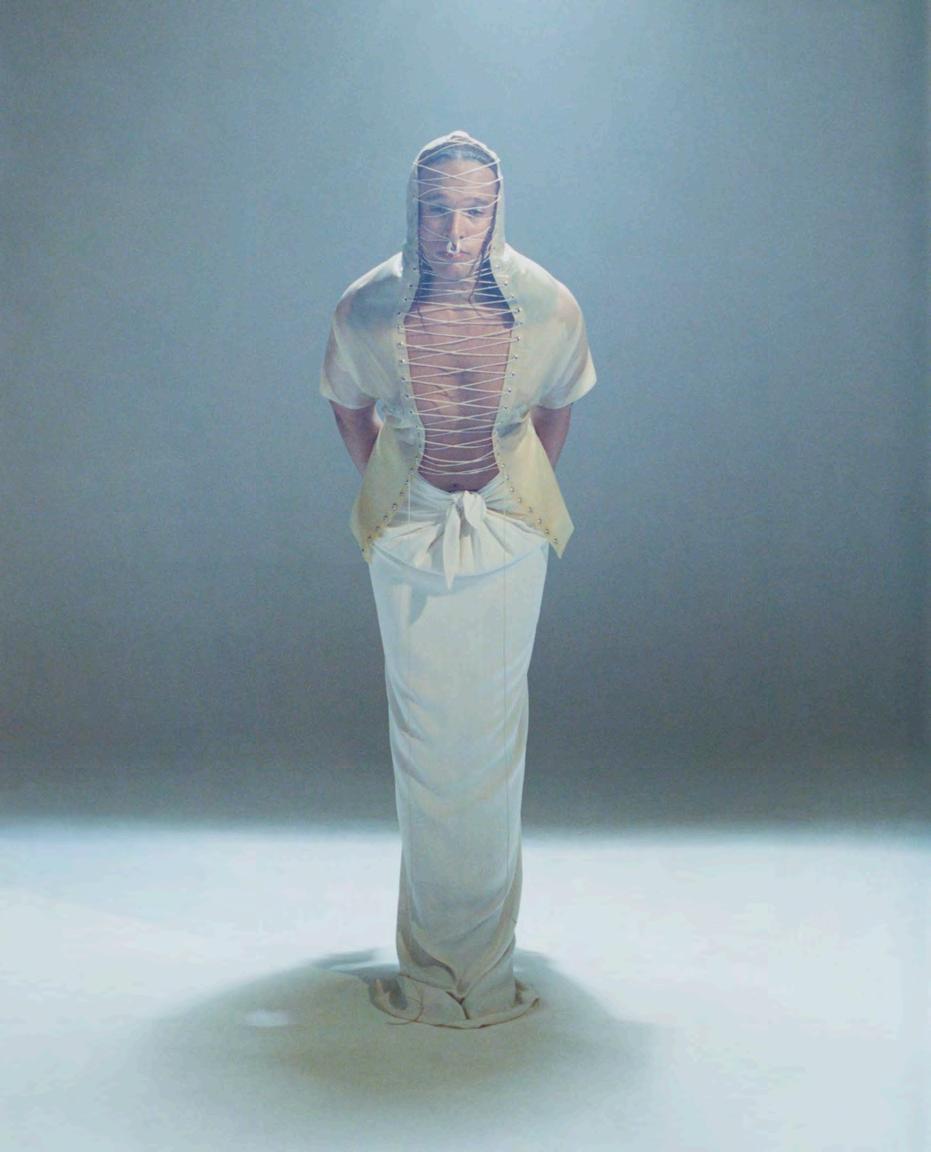

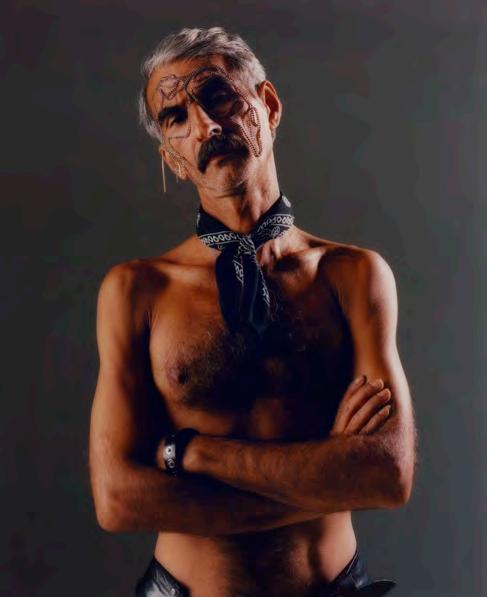

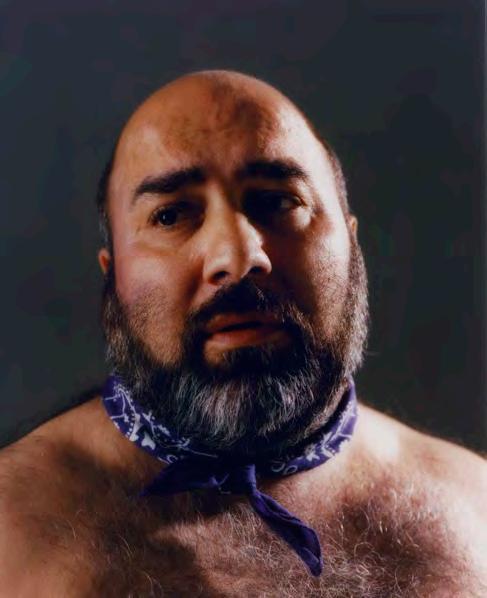

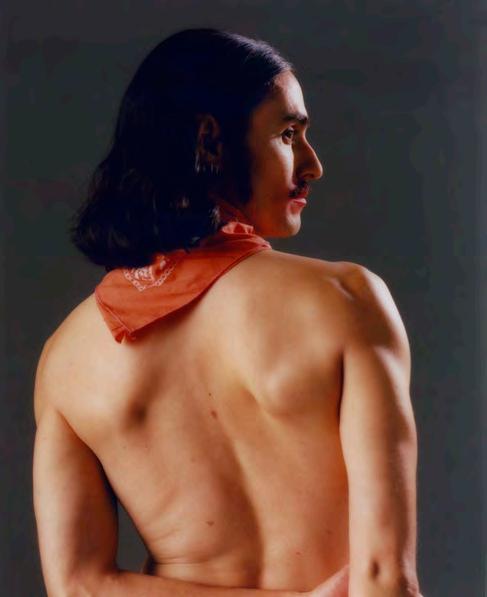

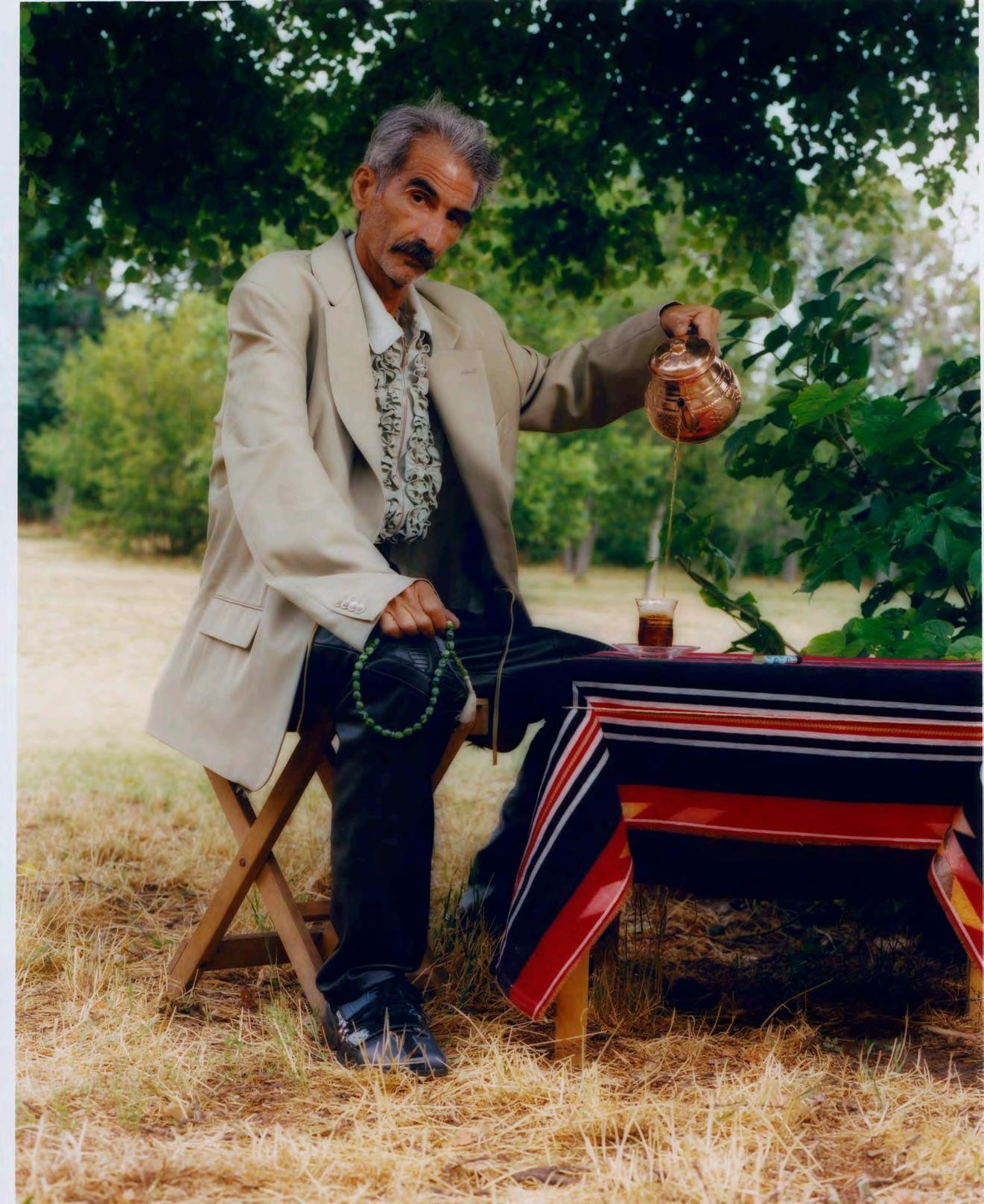

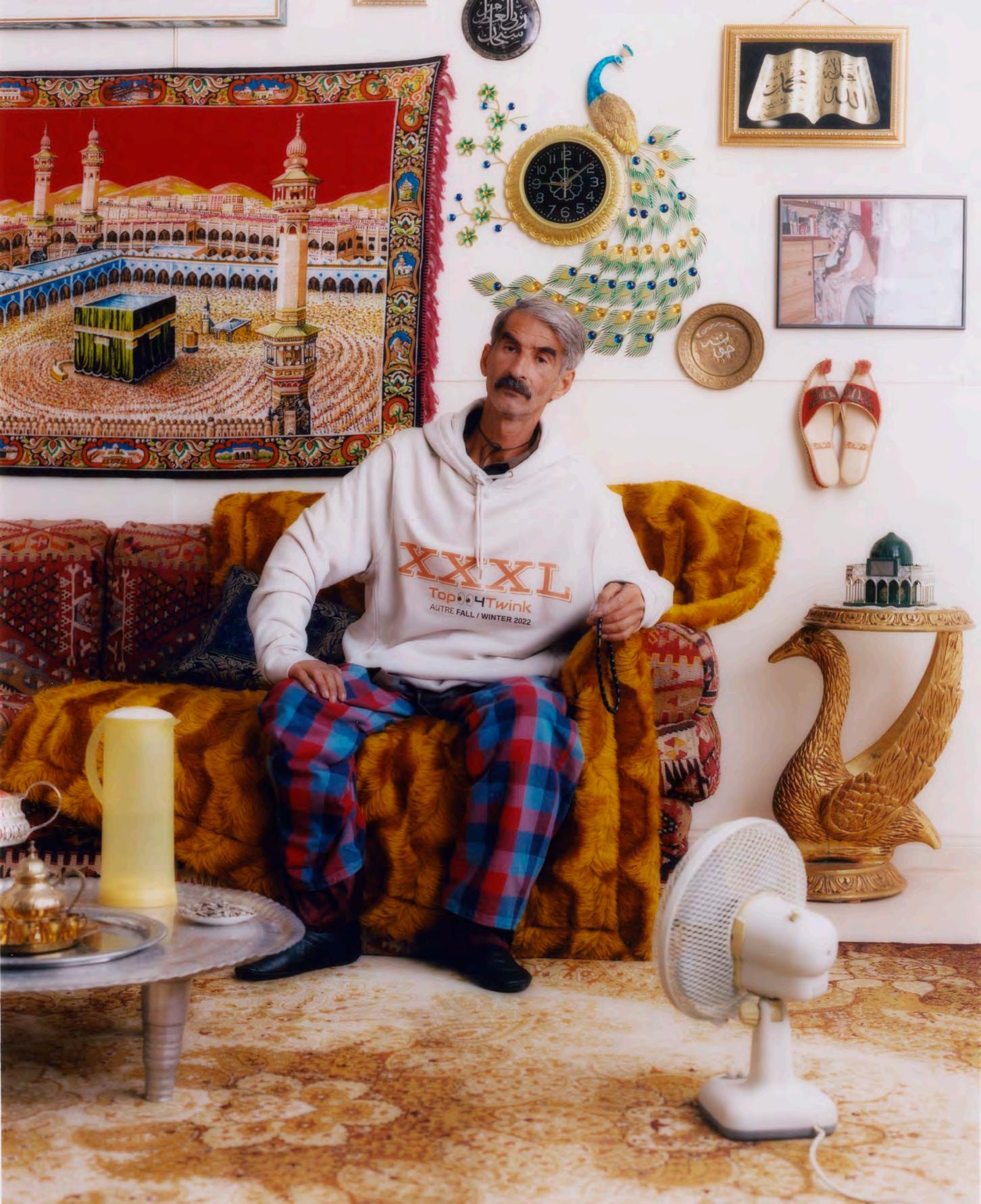

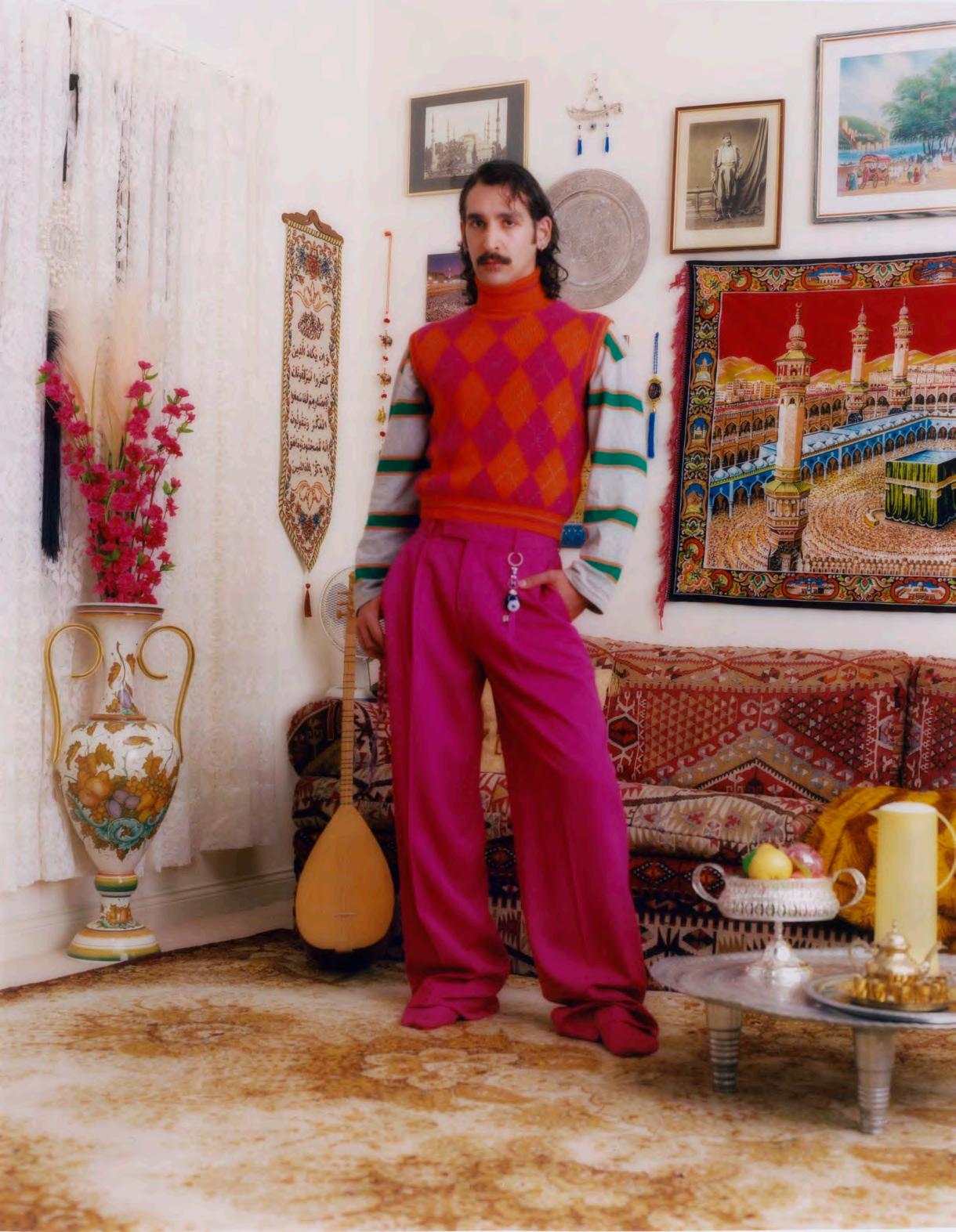

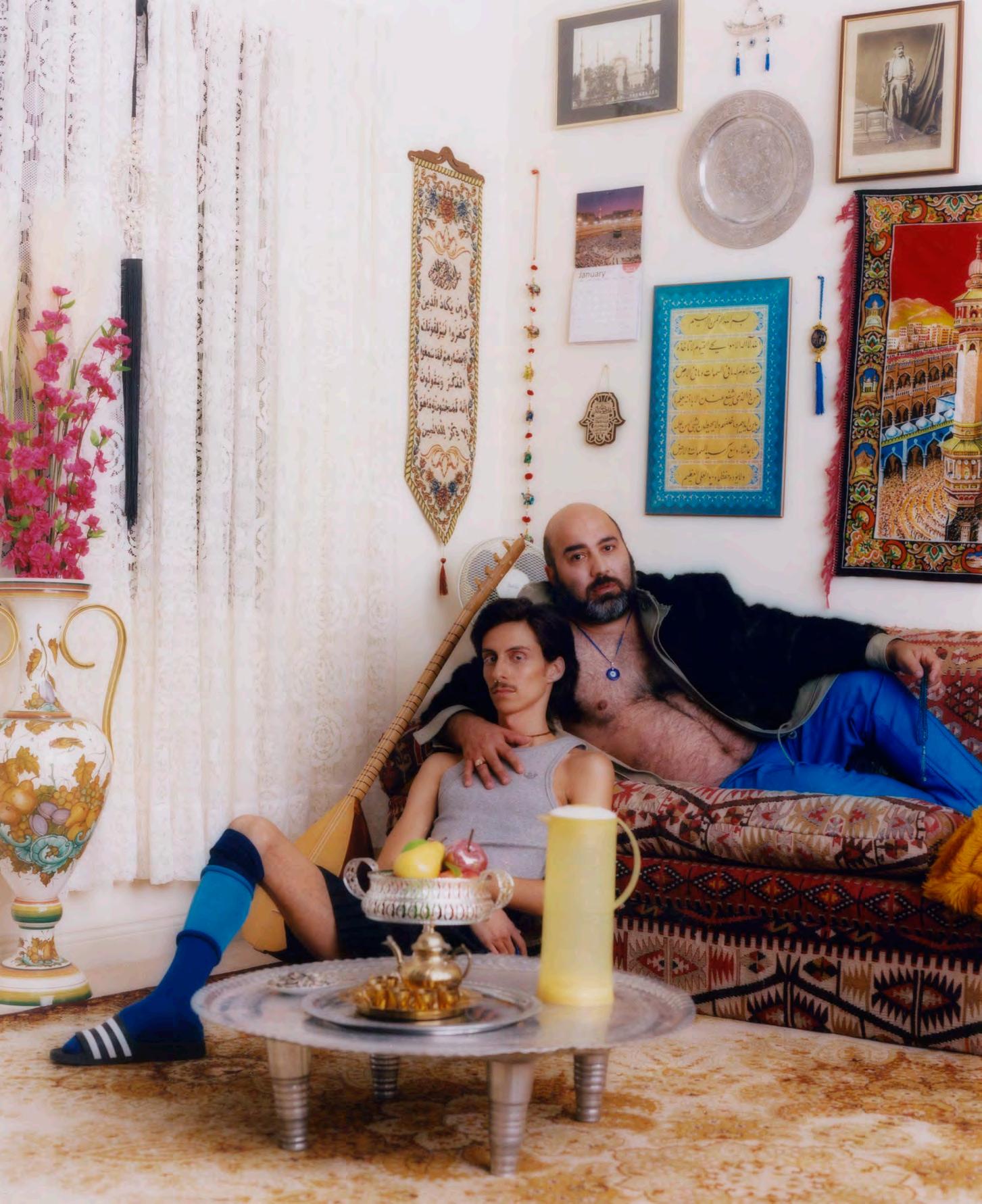

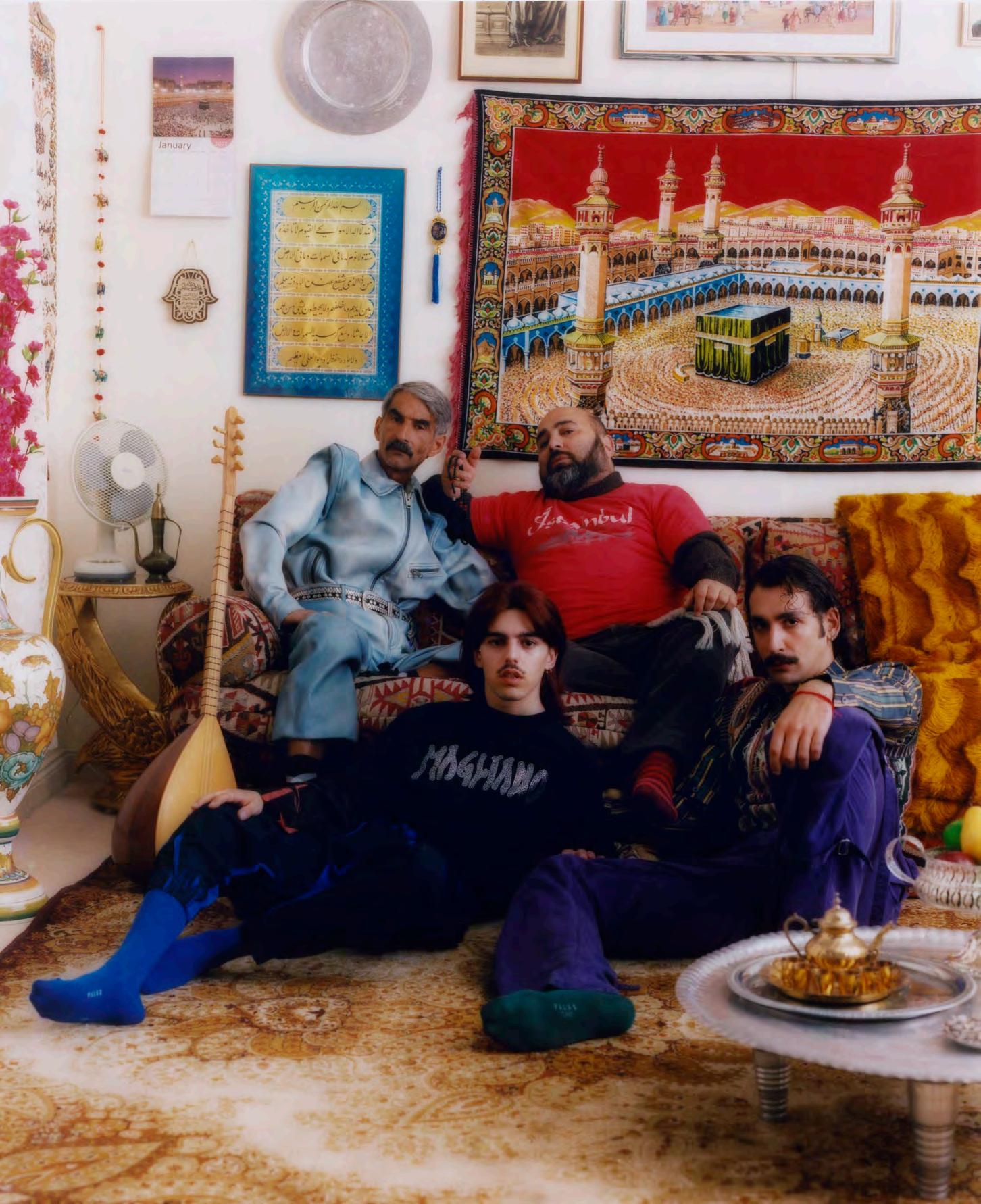

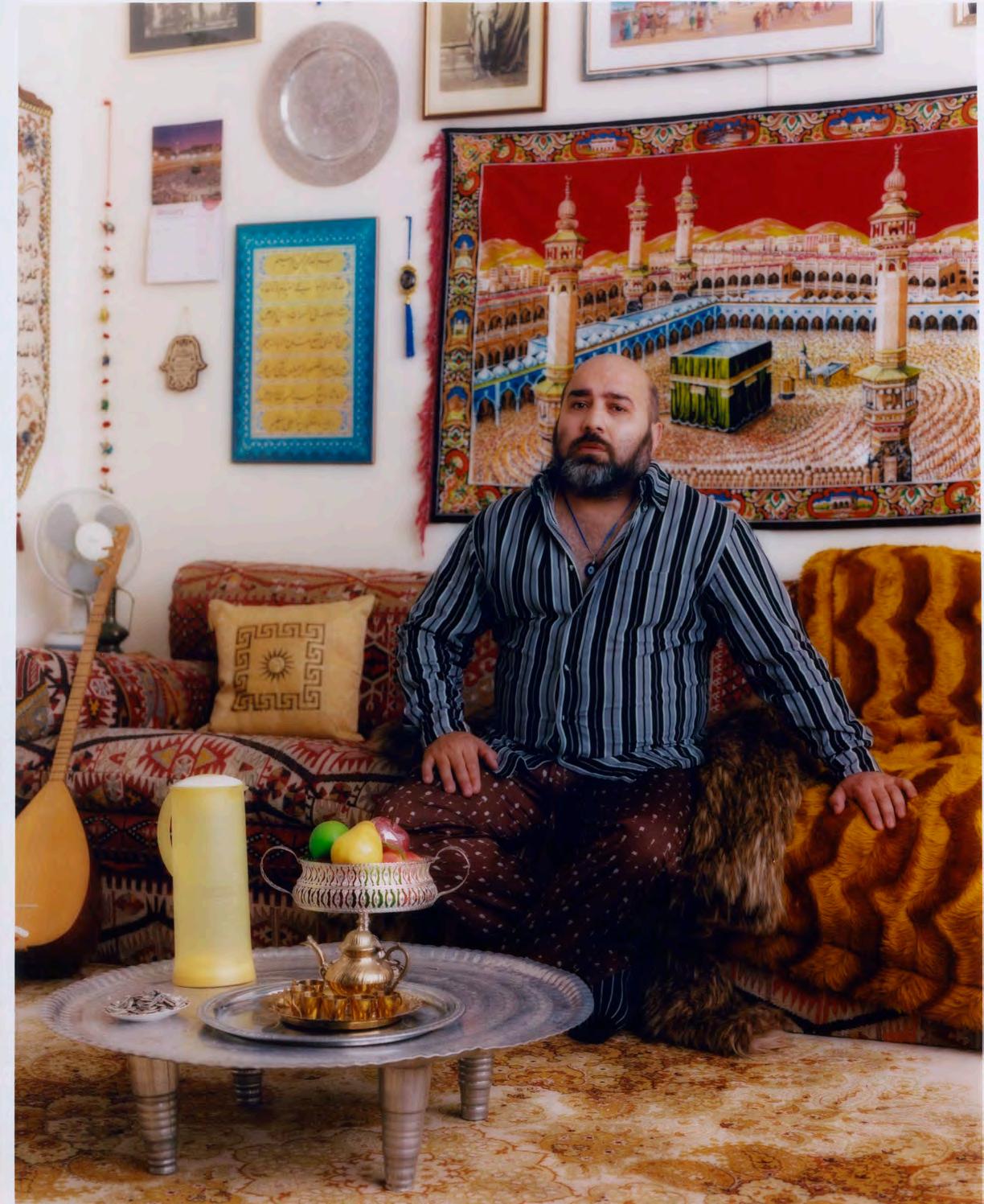

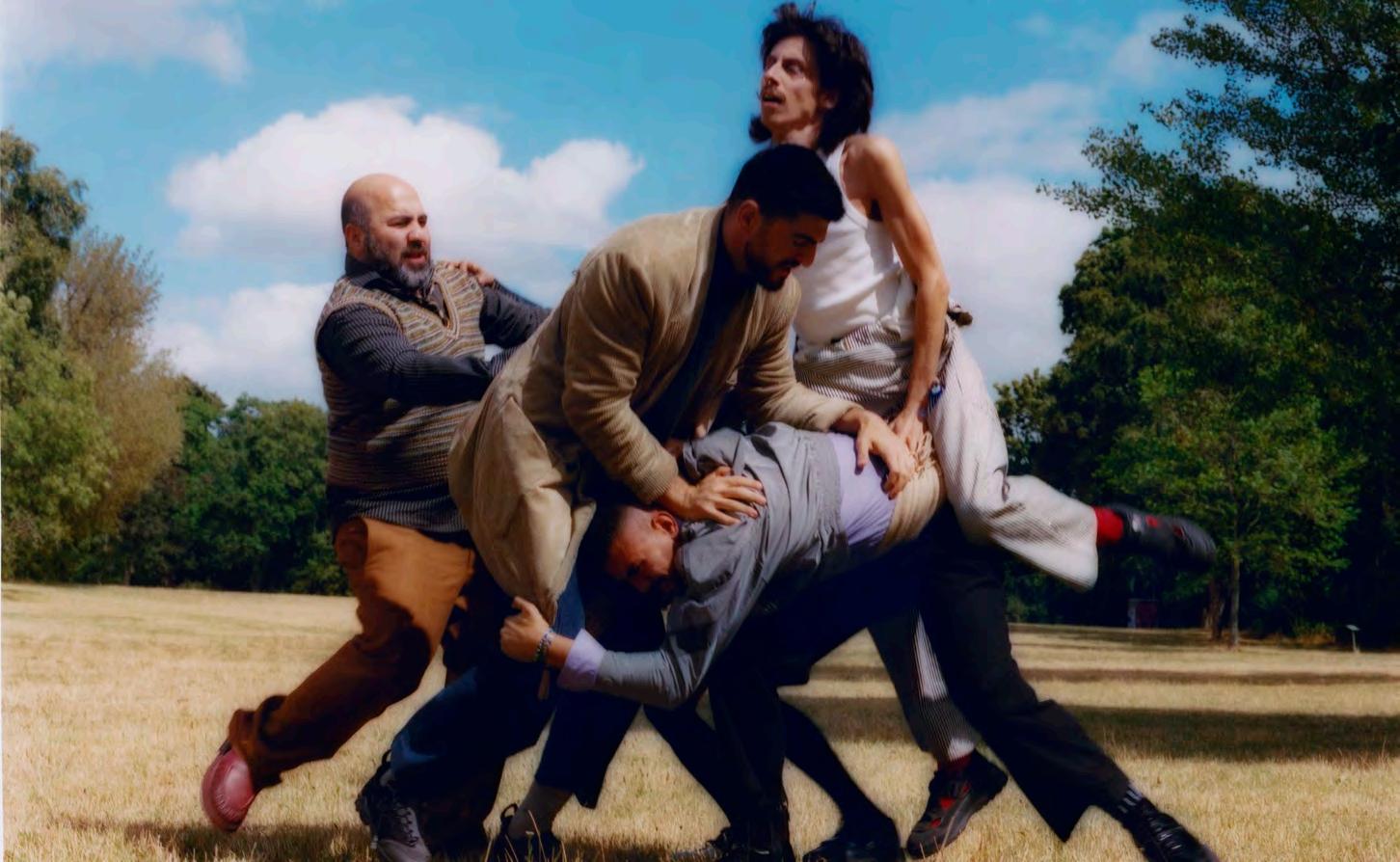

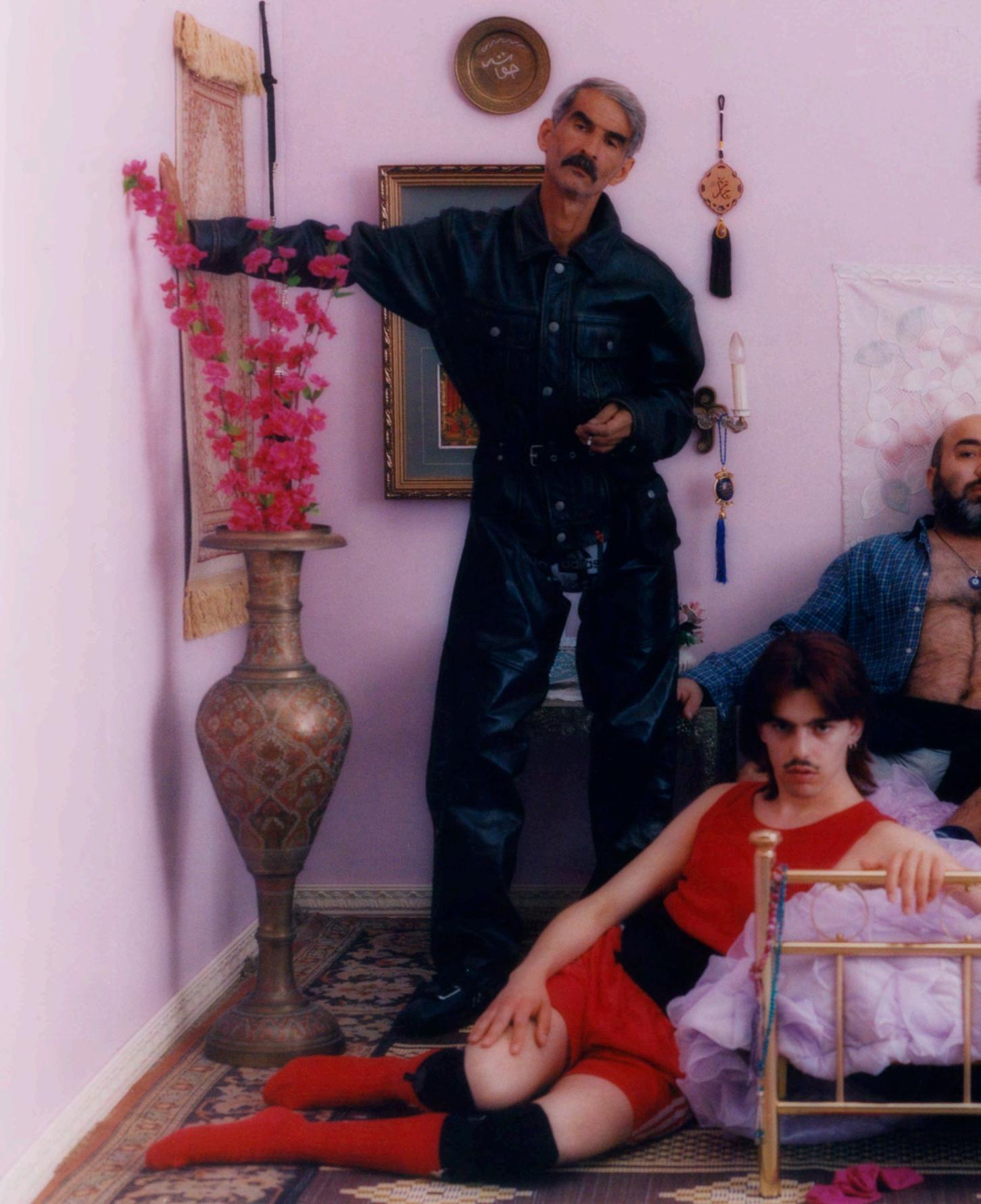

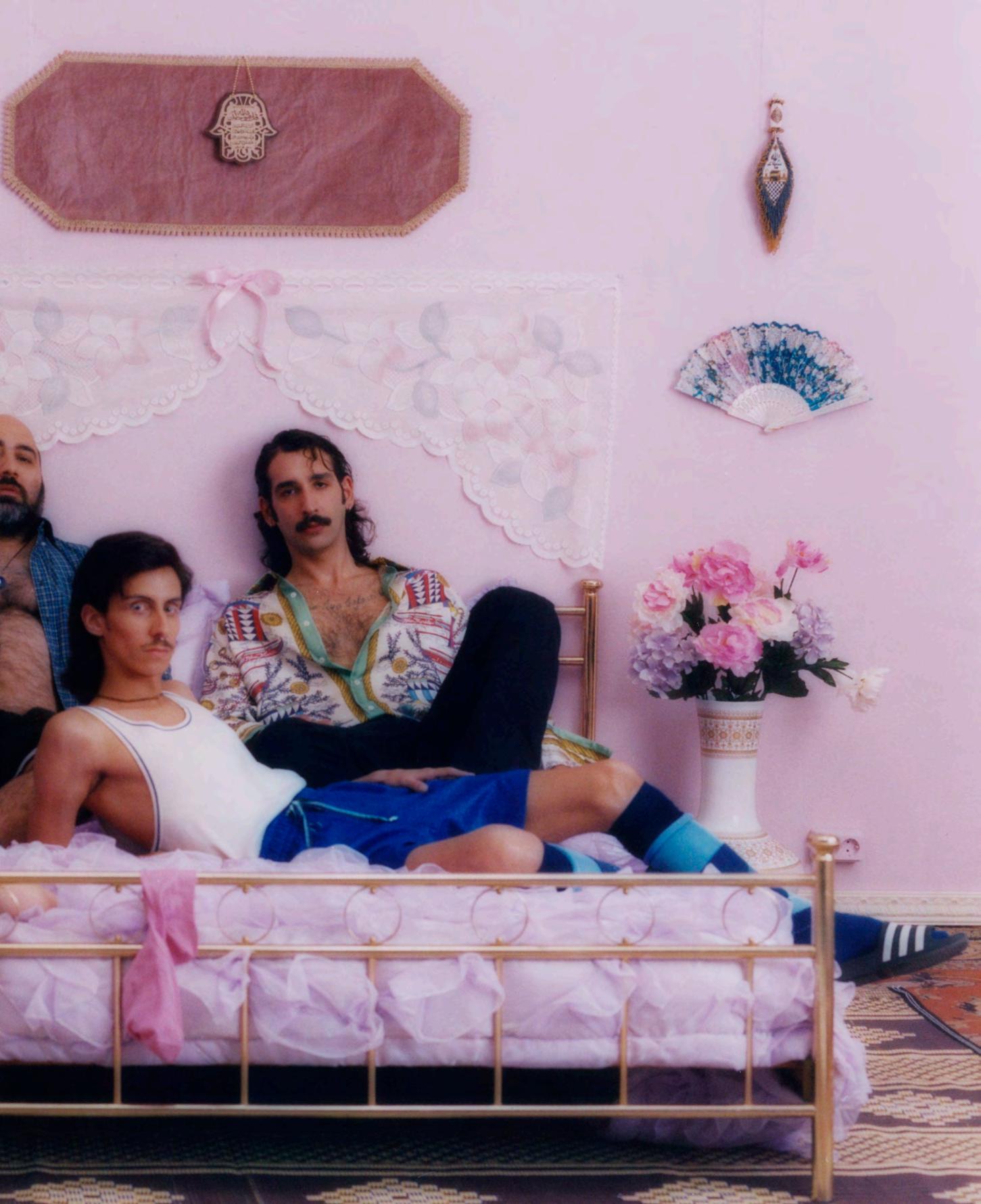

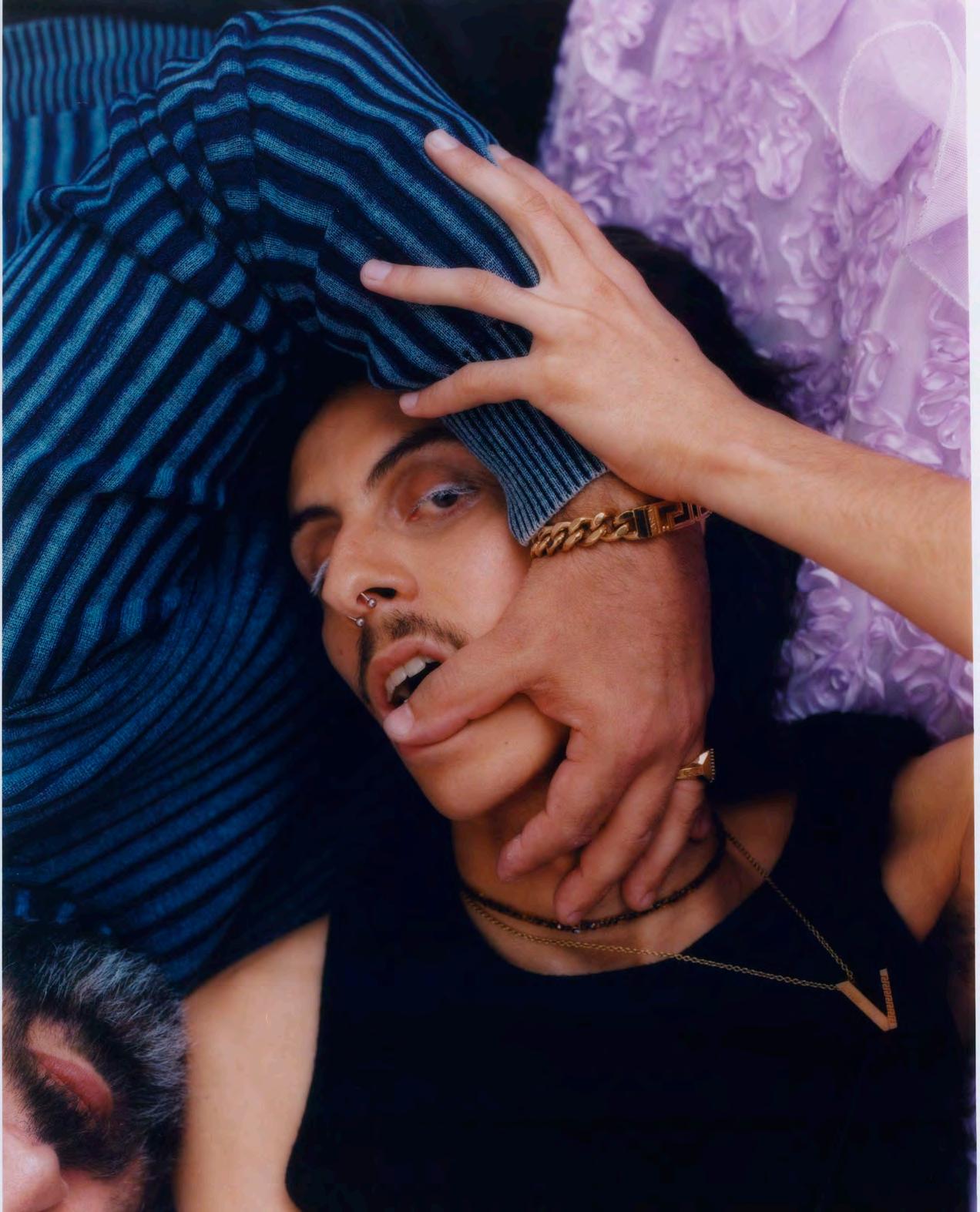

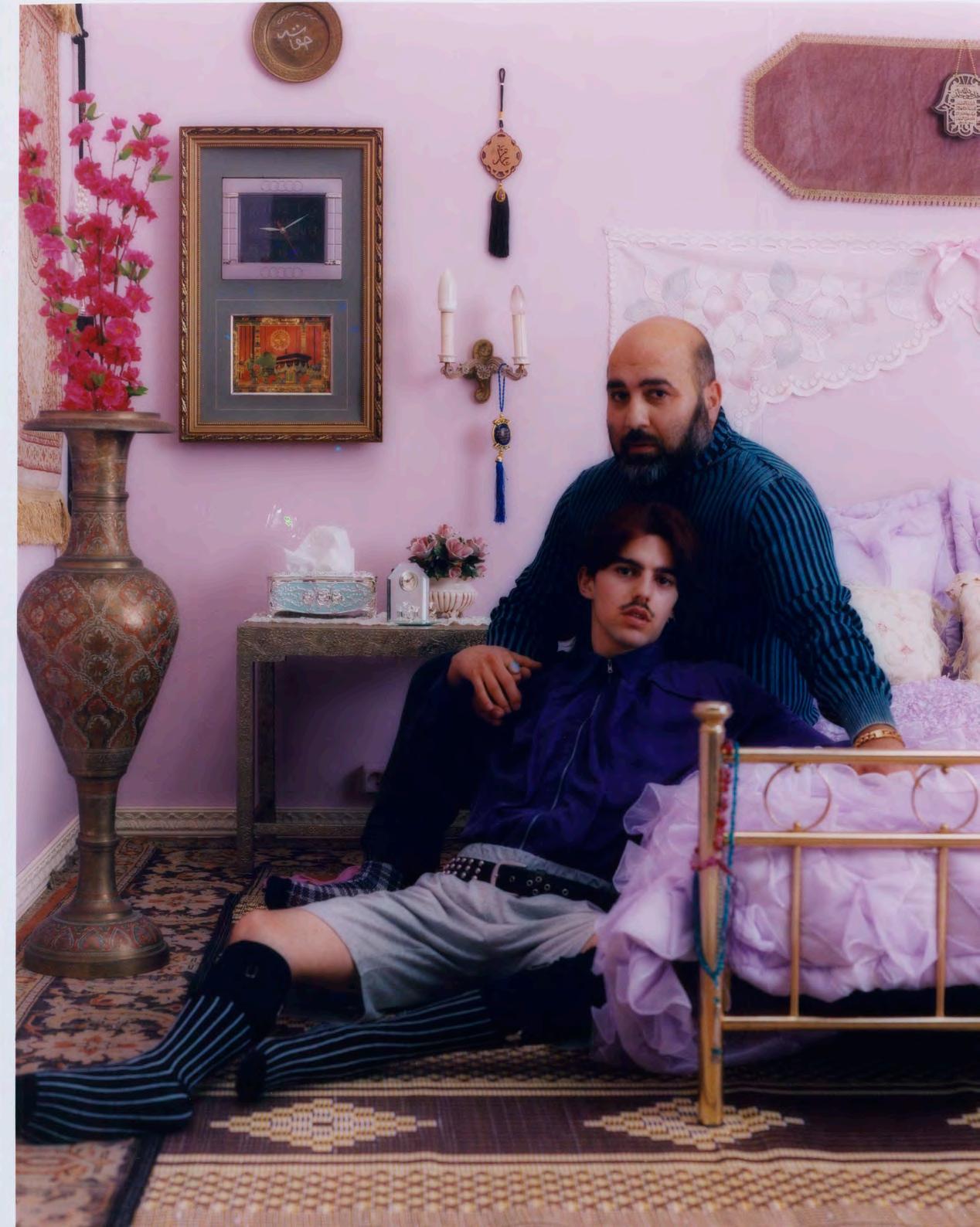

MACHO SENTIMENTAL, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane 122—129

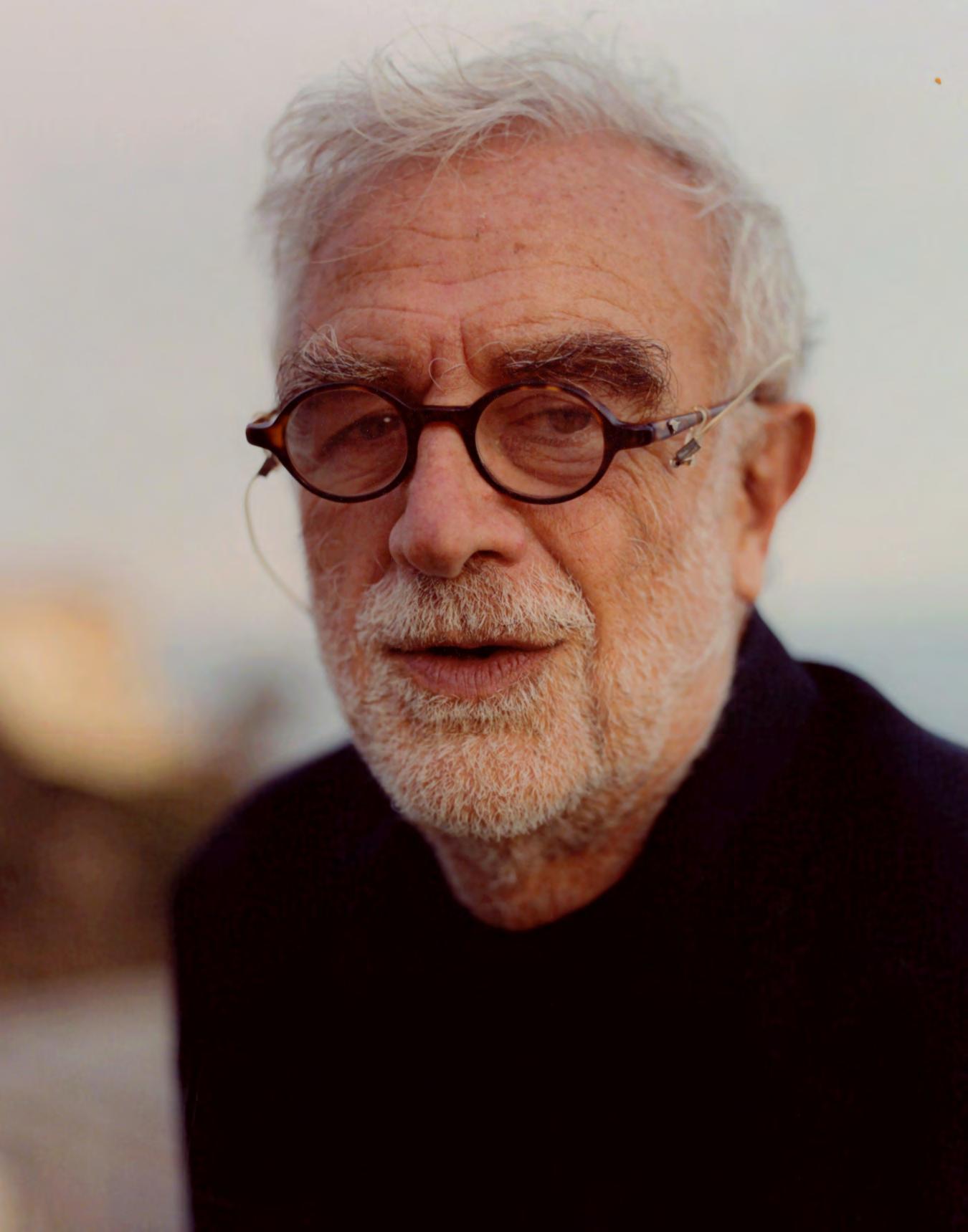

EATING THE RICH, An Interview of Ruben Östlund 130—145

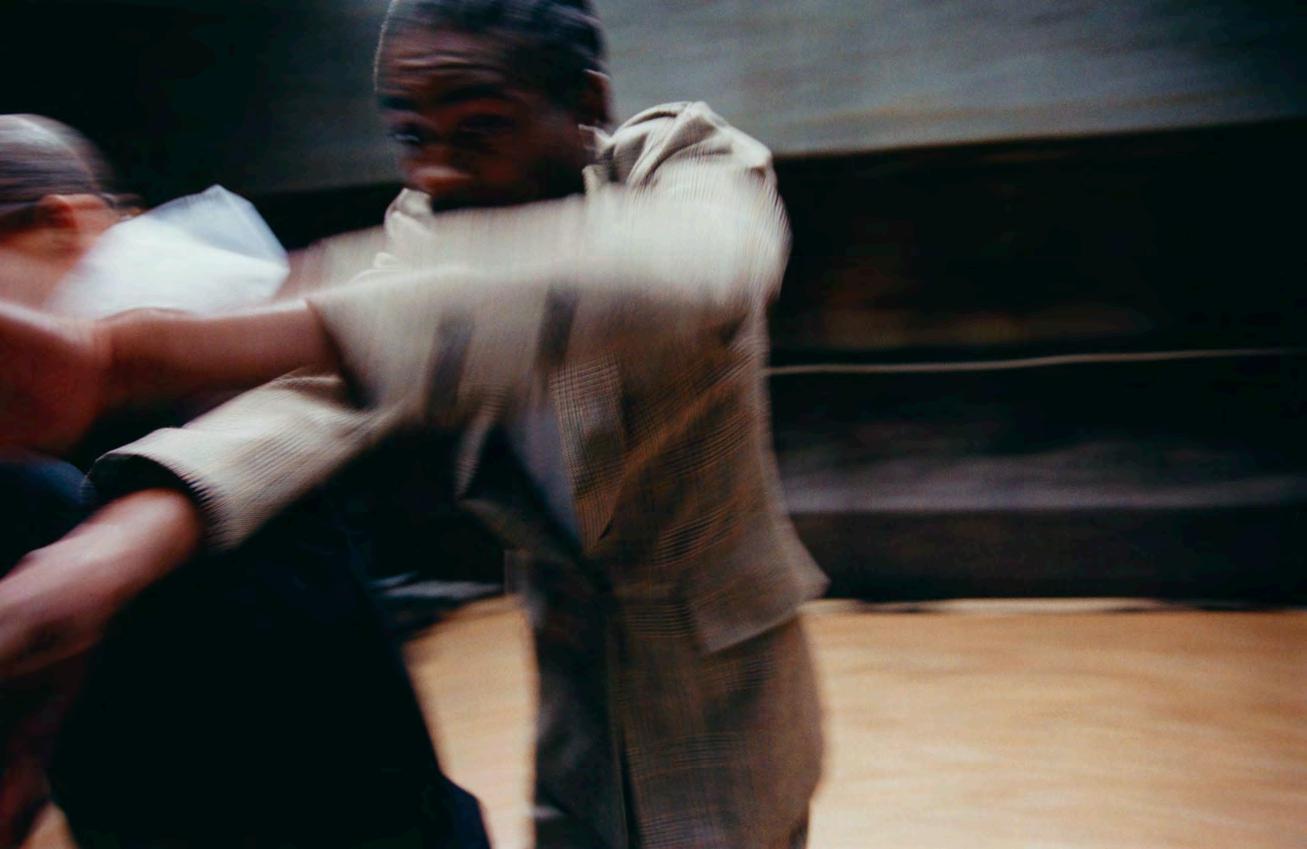

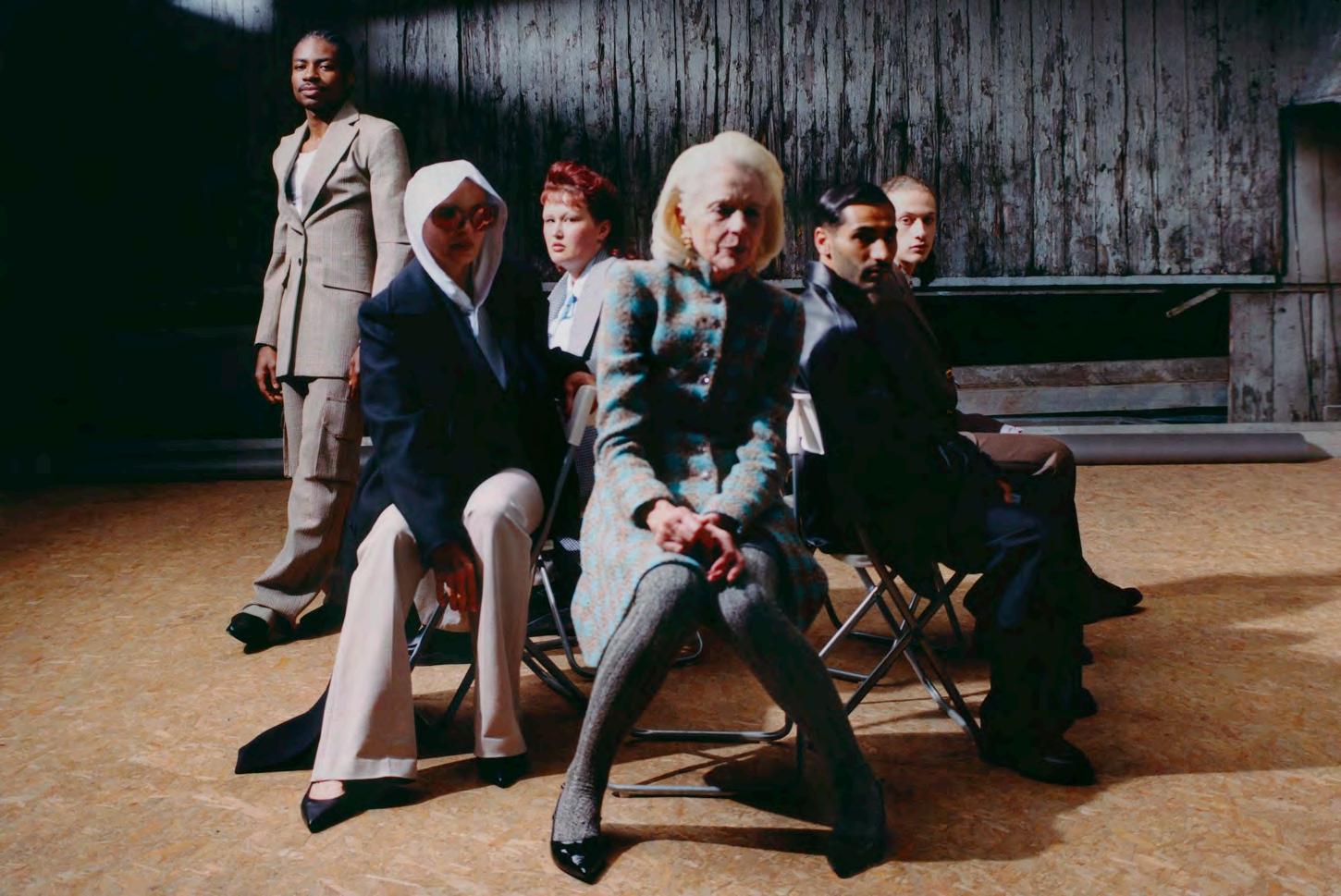

MUSICAL CHAIRS , A Story About False Scarcity by NTI 146—159

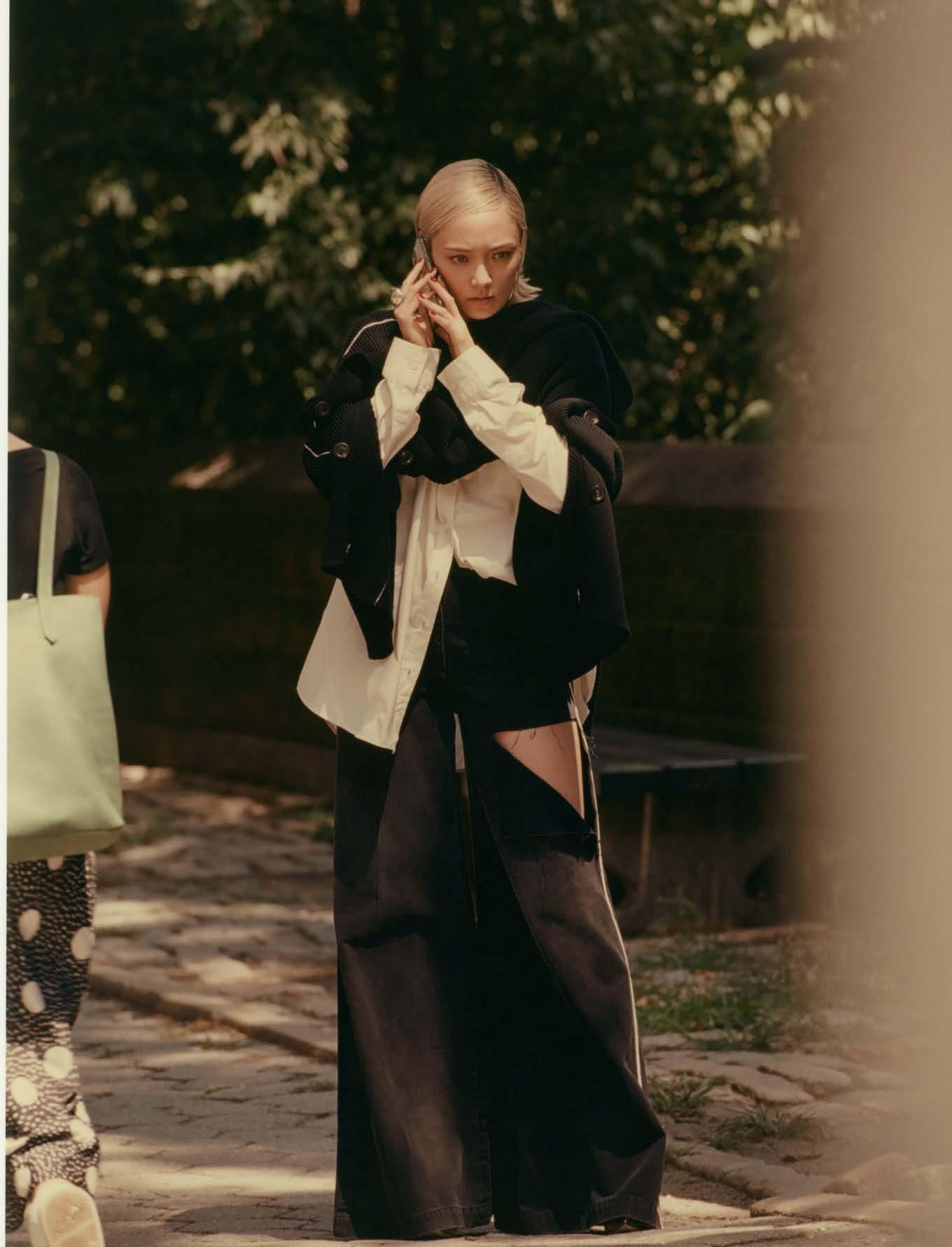

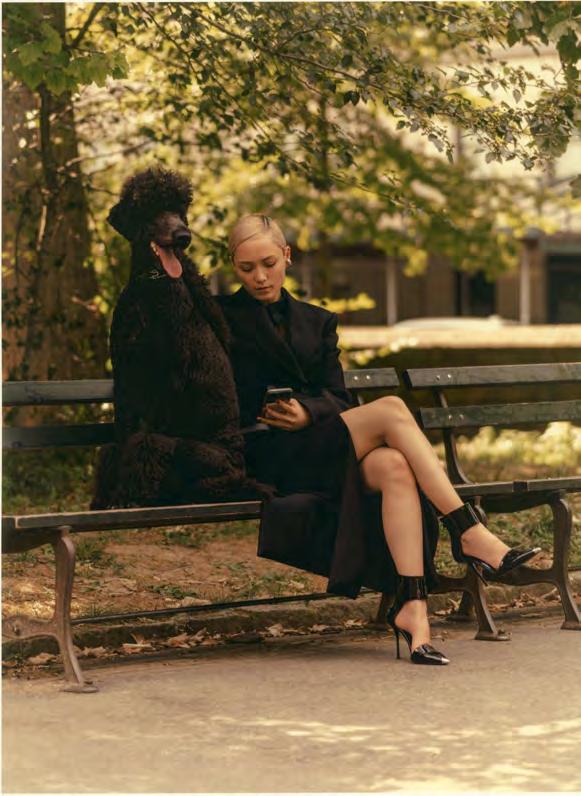

FAIR GAME , Featuring Pom Klementieff 160—171

CERISE CASTLE, Uncovering The Deputy Police Gangs Within The Los Angeles Sheriff's Department 172—175

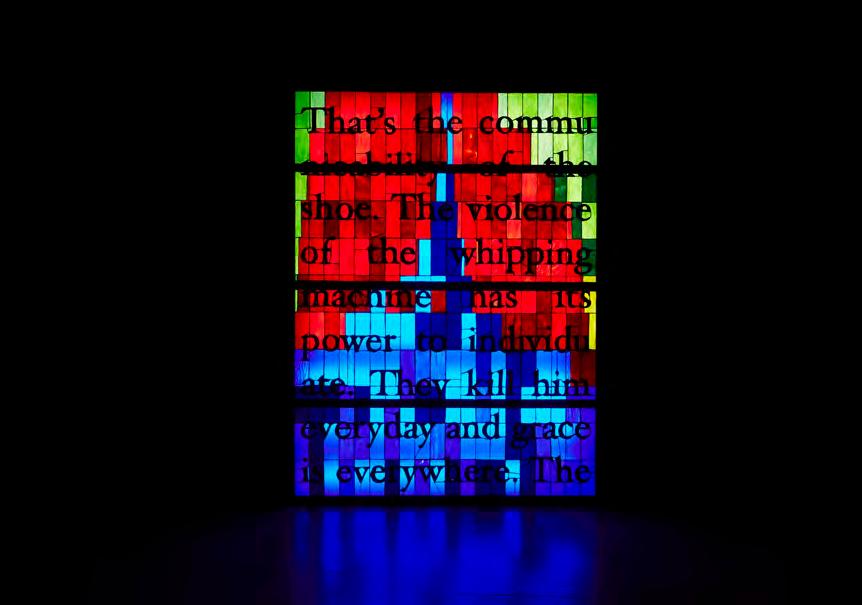

JORDAN WOLFSON, Interview By Jeffrey Deitch 176—191

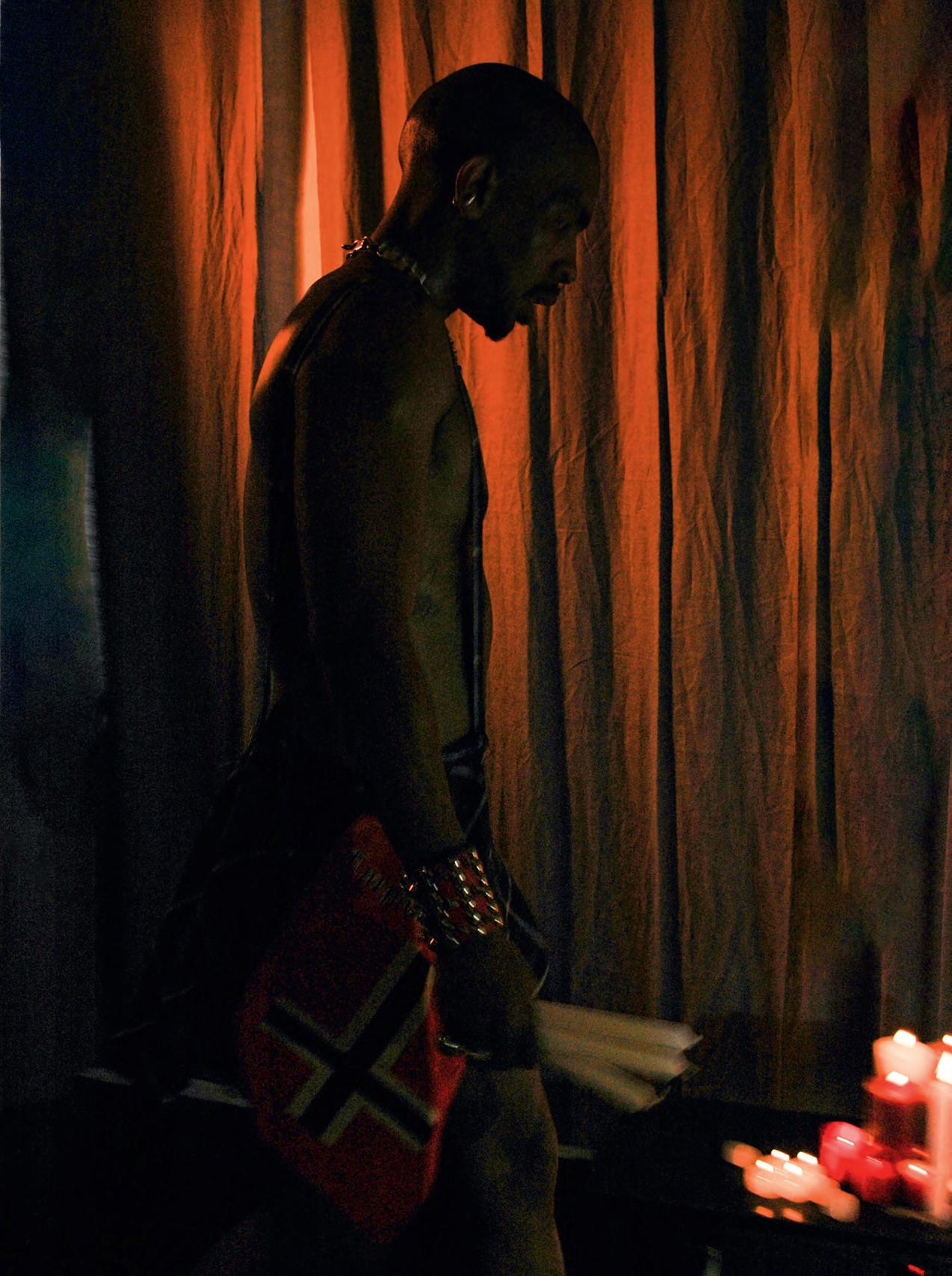

RITUAL, by Rob Kulisek & Billy lobos 192—203

THE PROSECUTOR, An Interview of Luis Moreno Ocampo 204—207

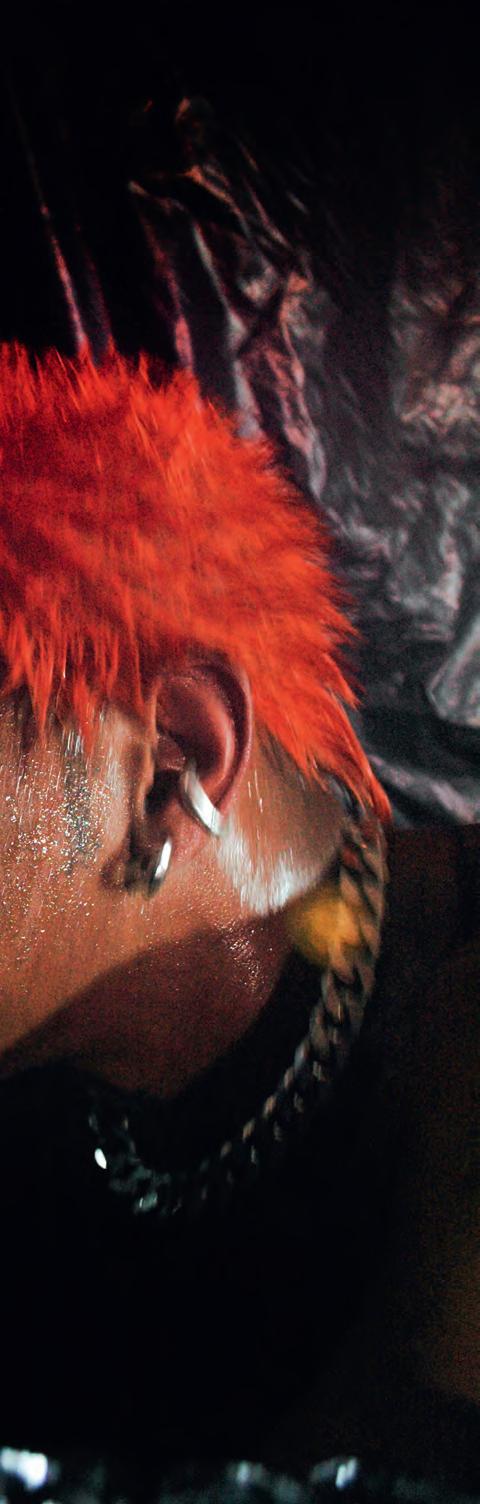

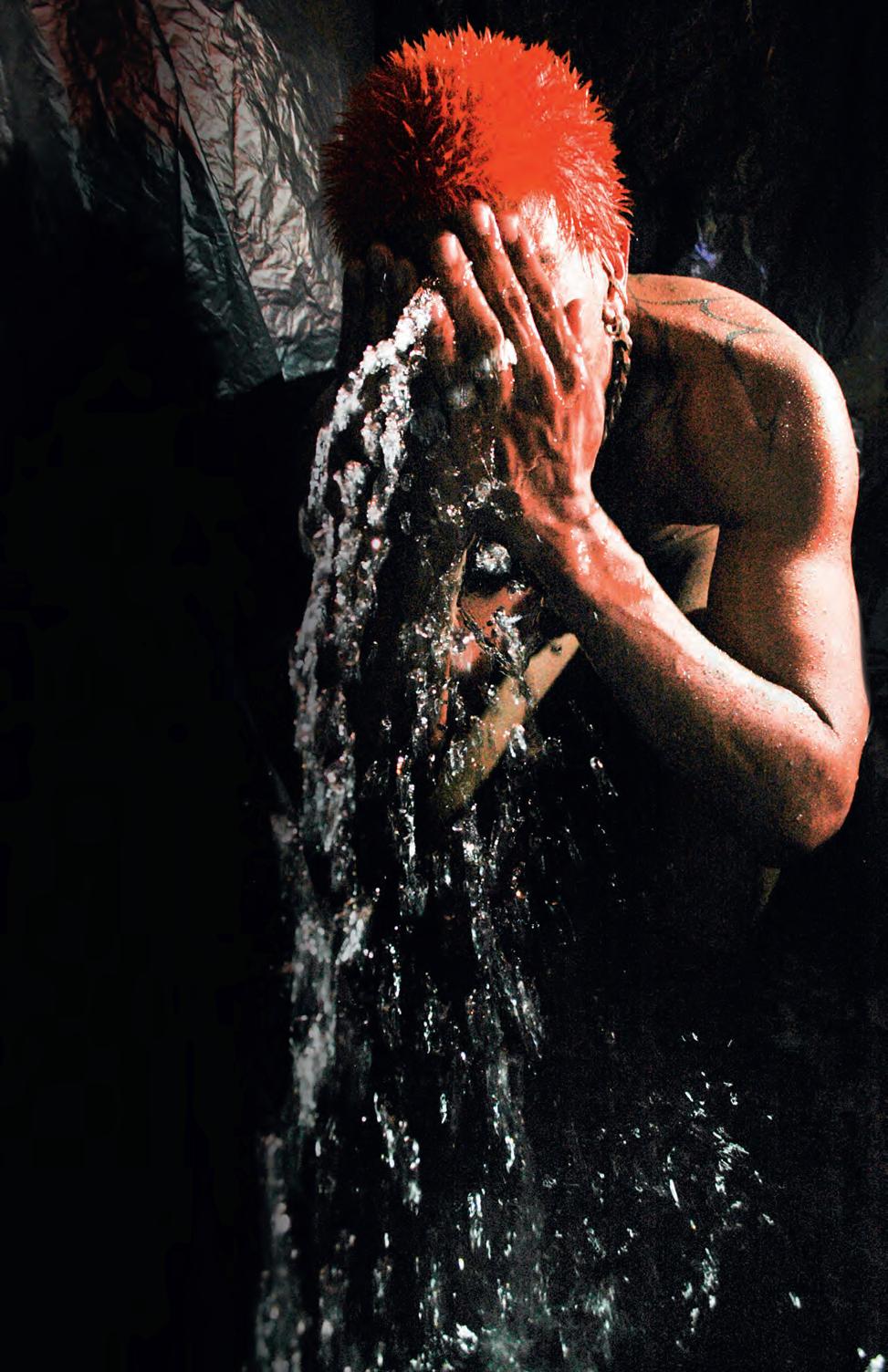

ICEBOY VIOLET, by Jules Moskovtchenko 208—217

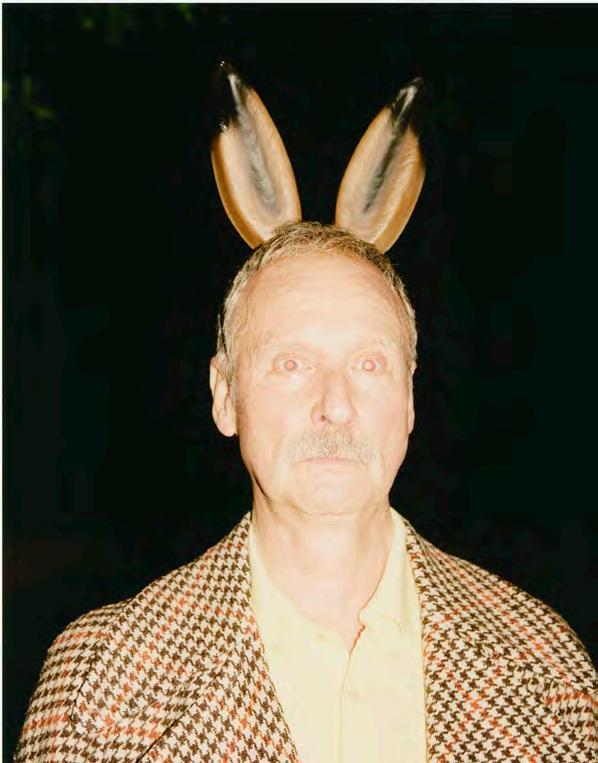

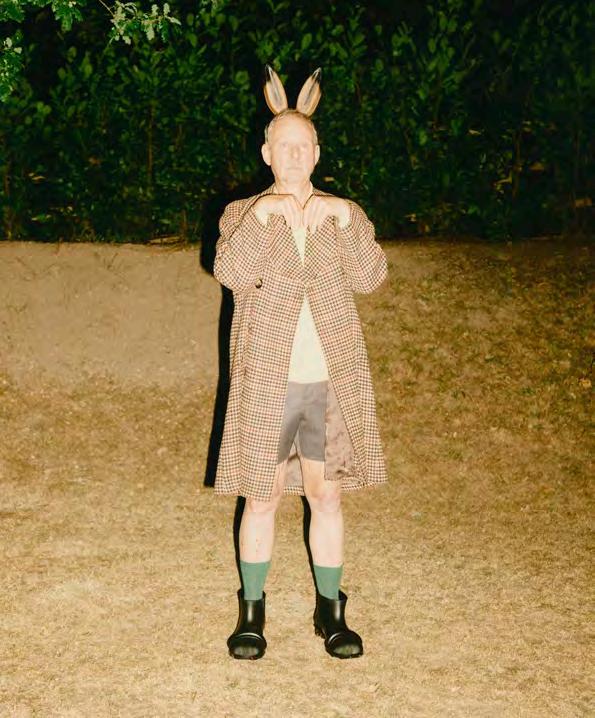

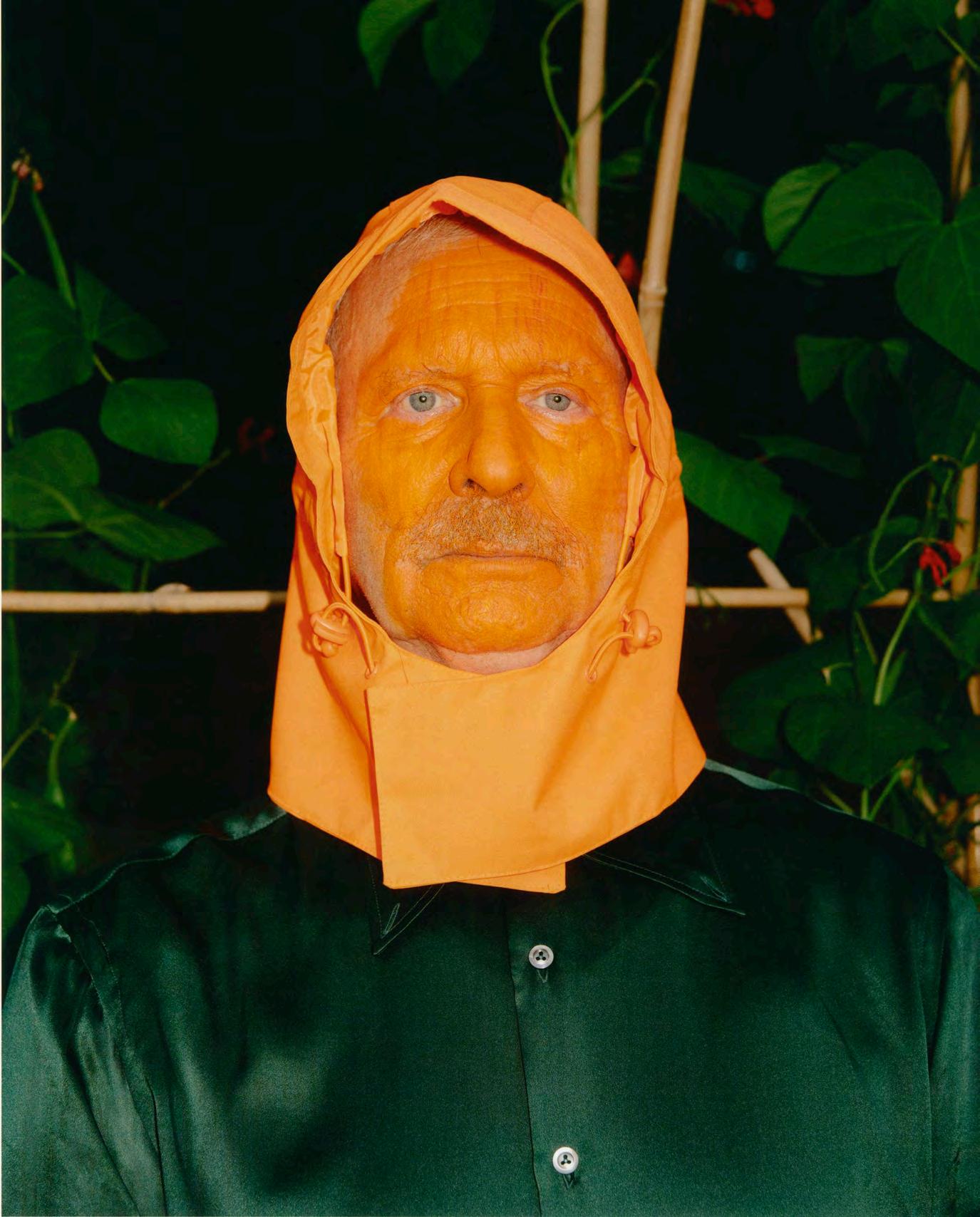

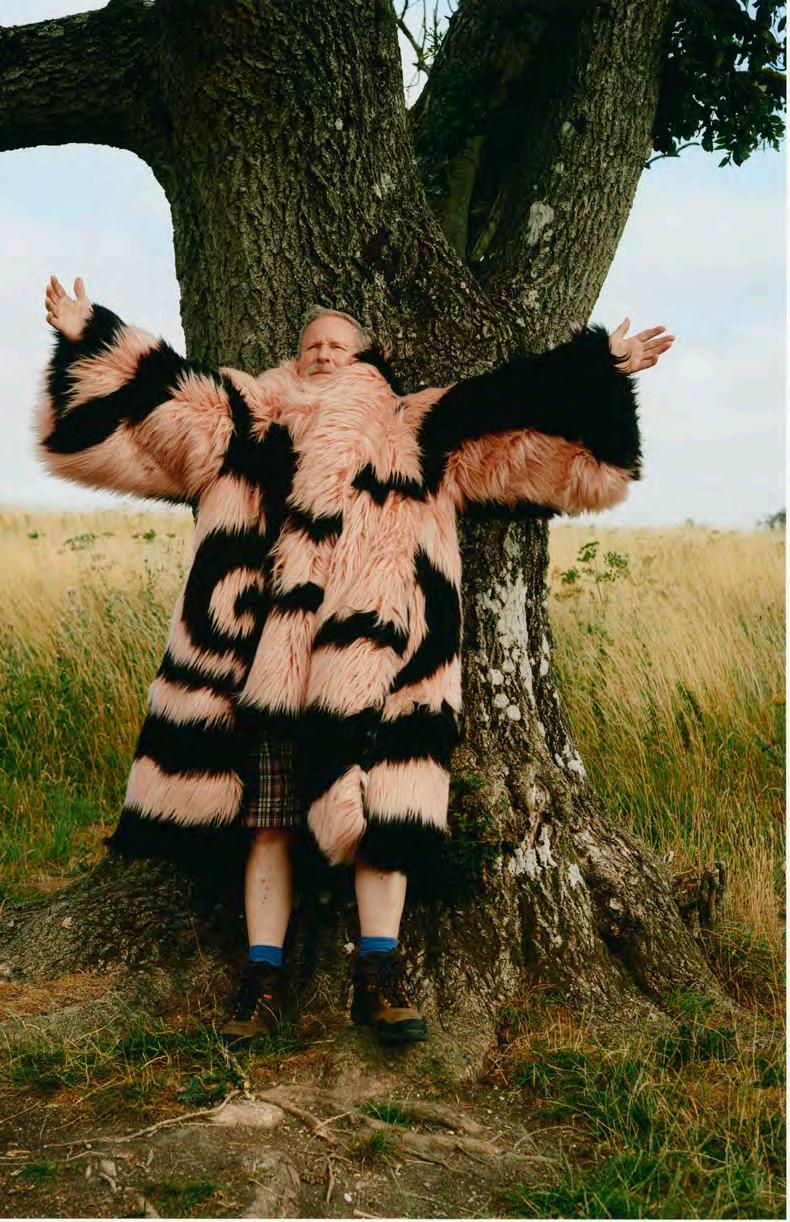

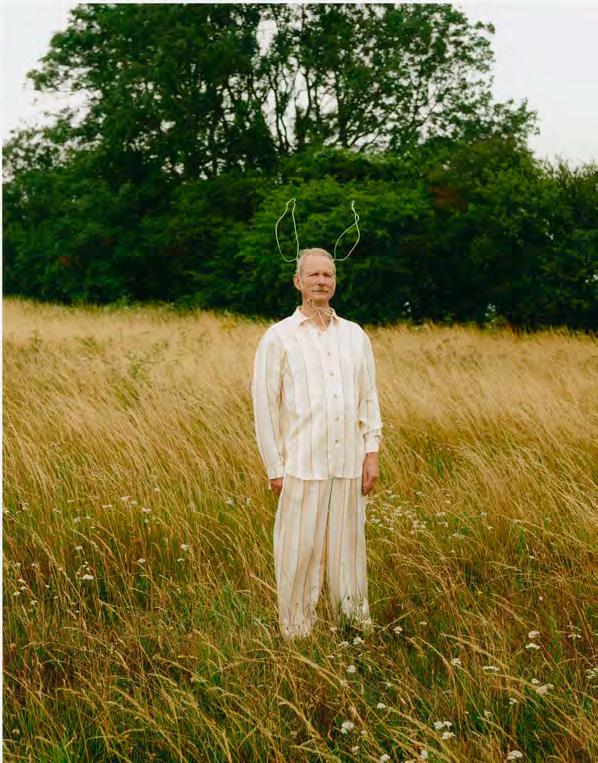

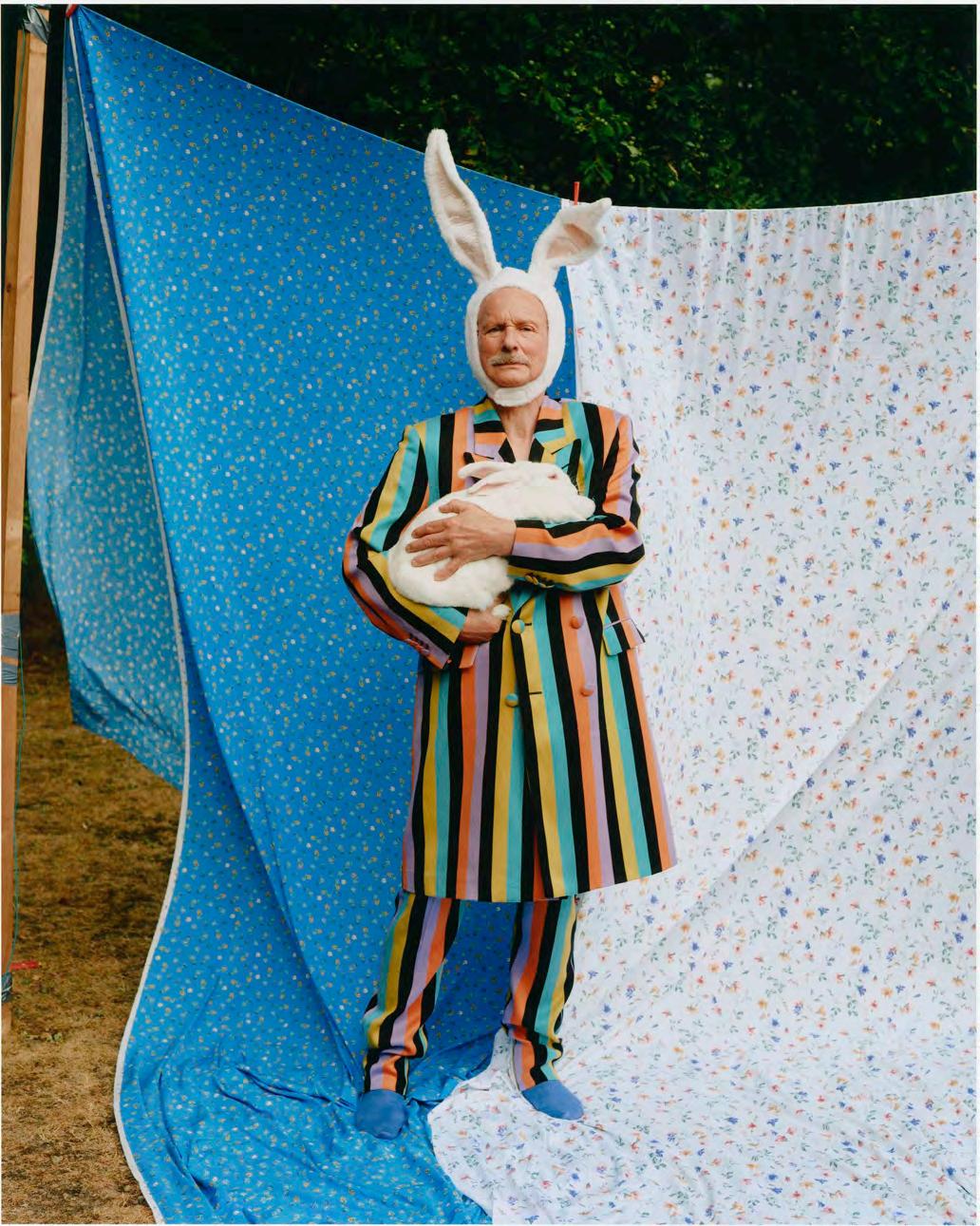

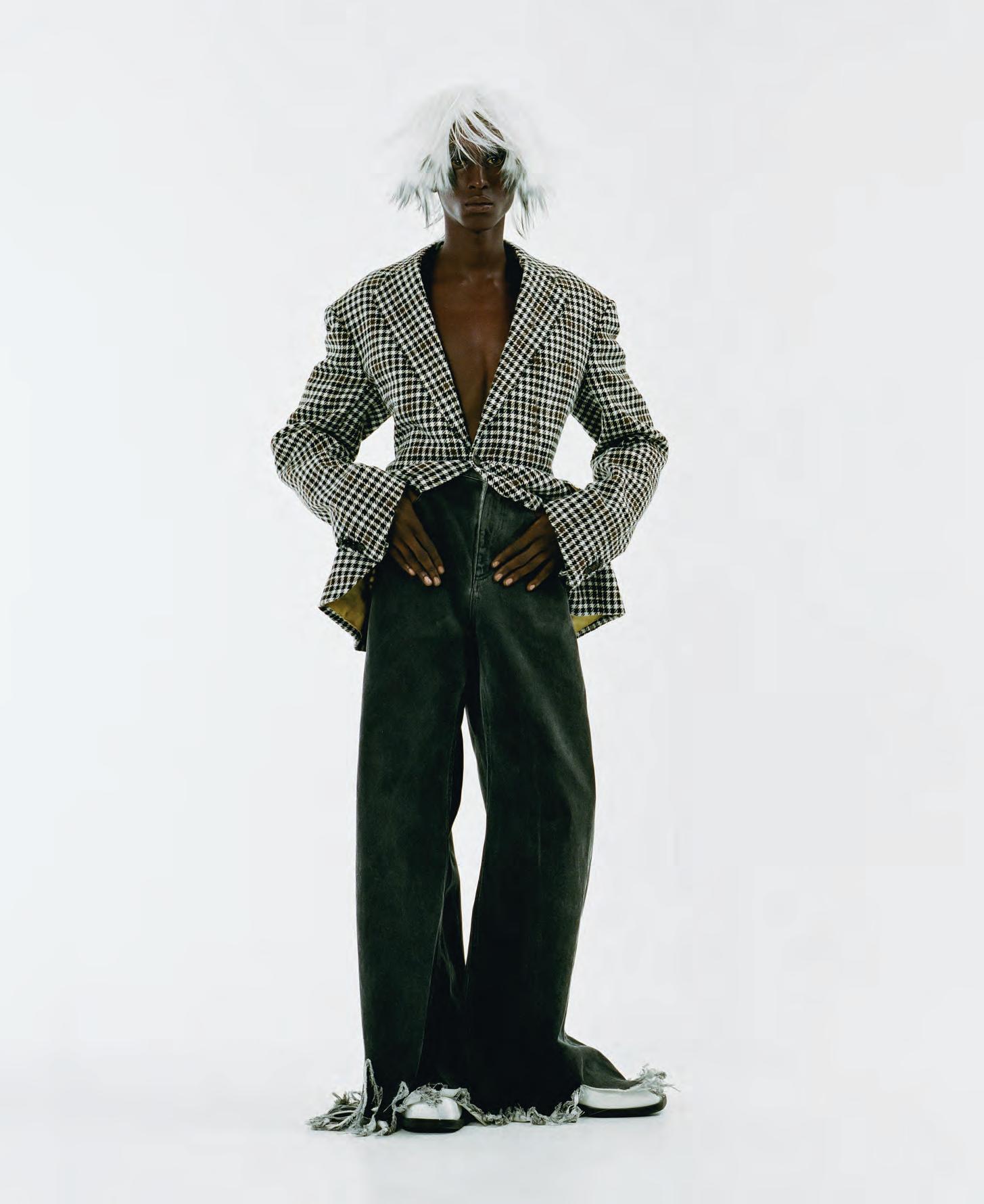

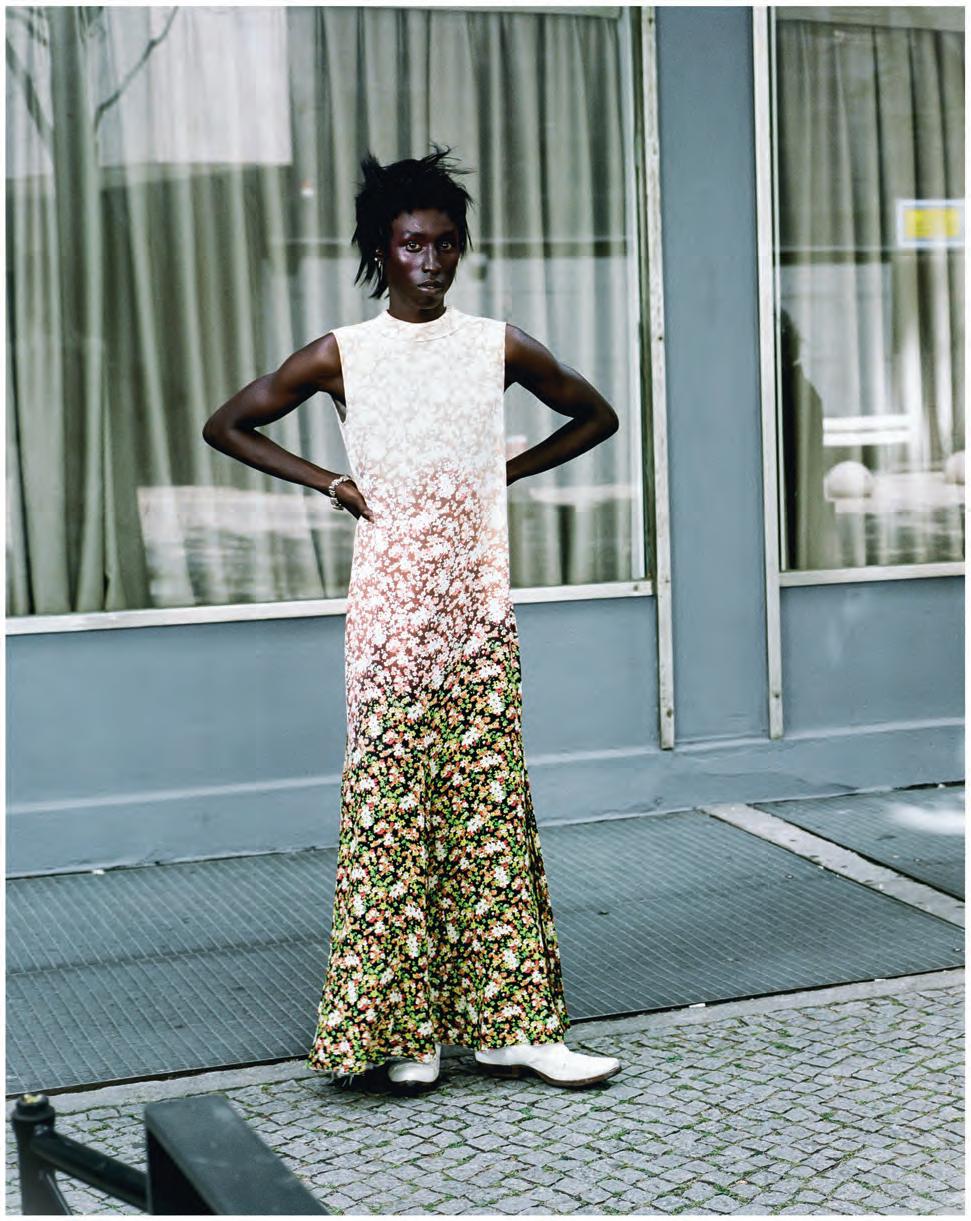

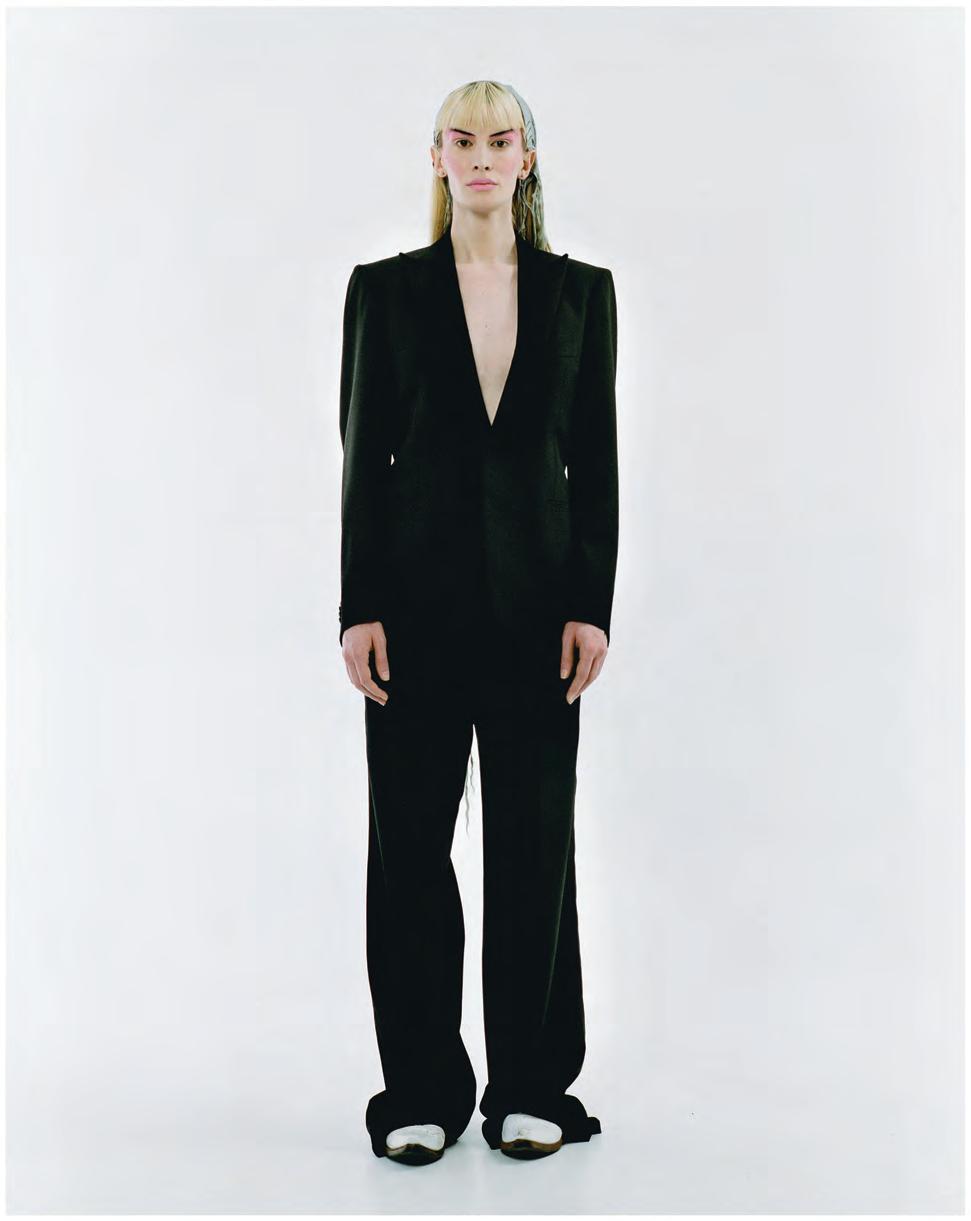

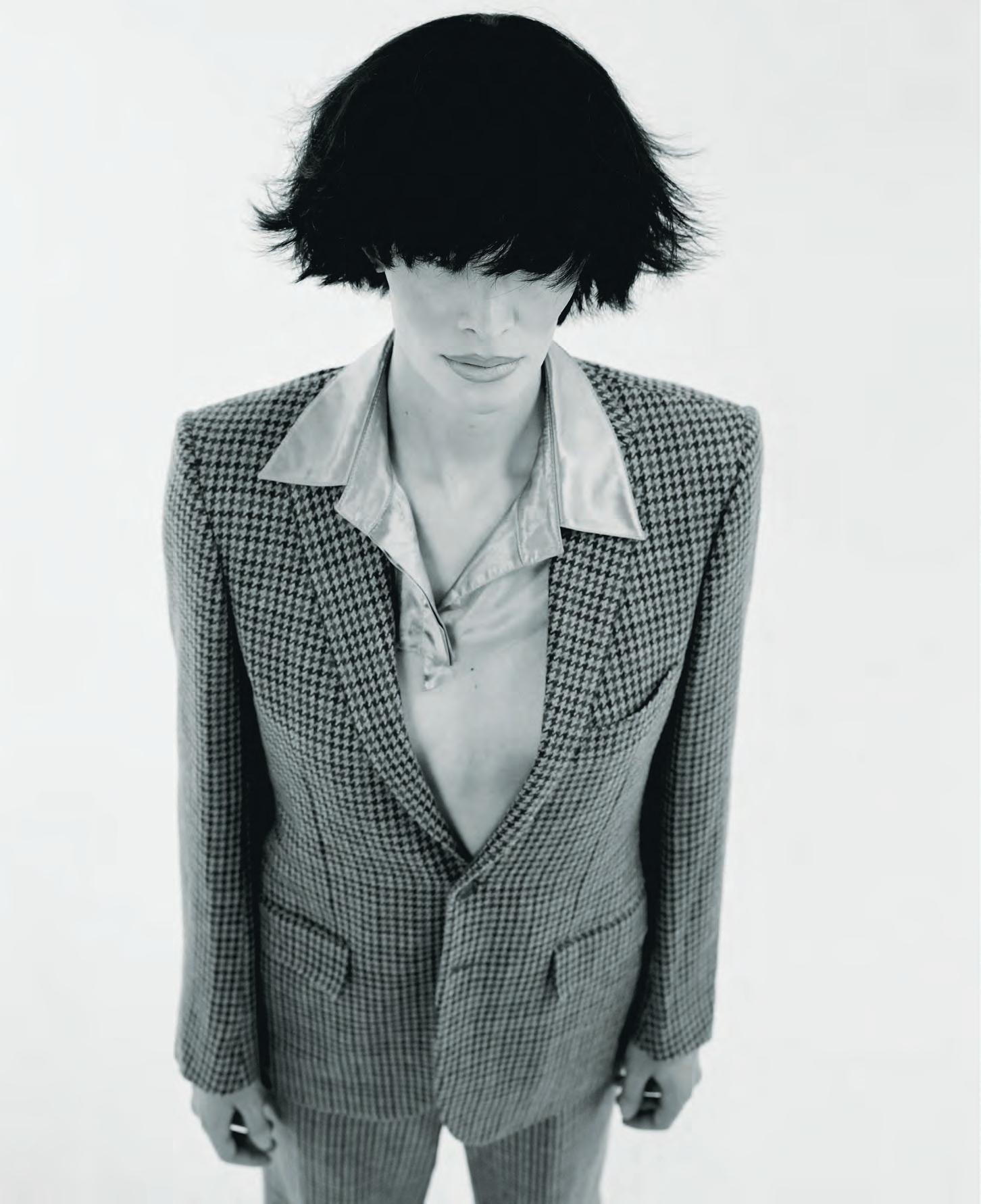

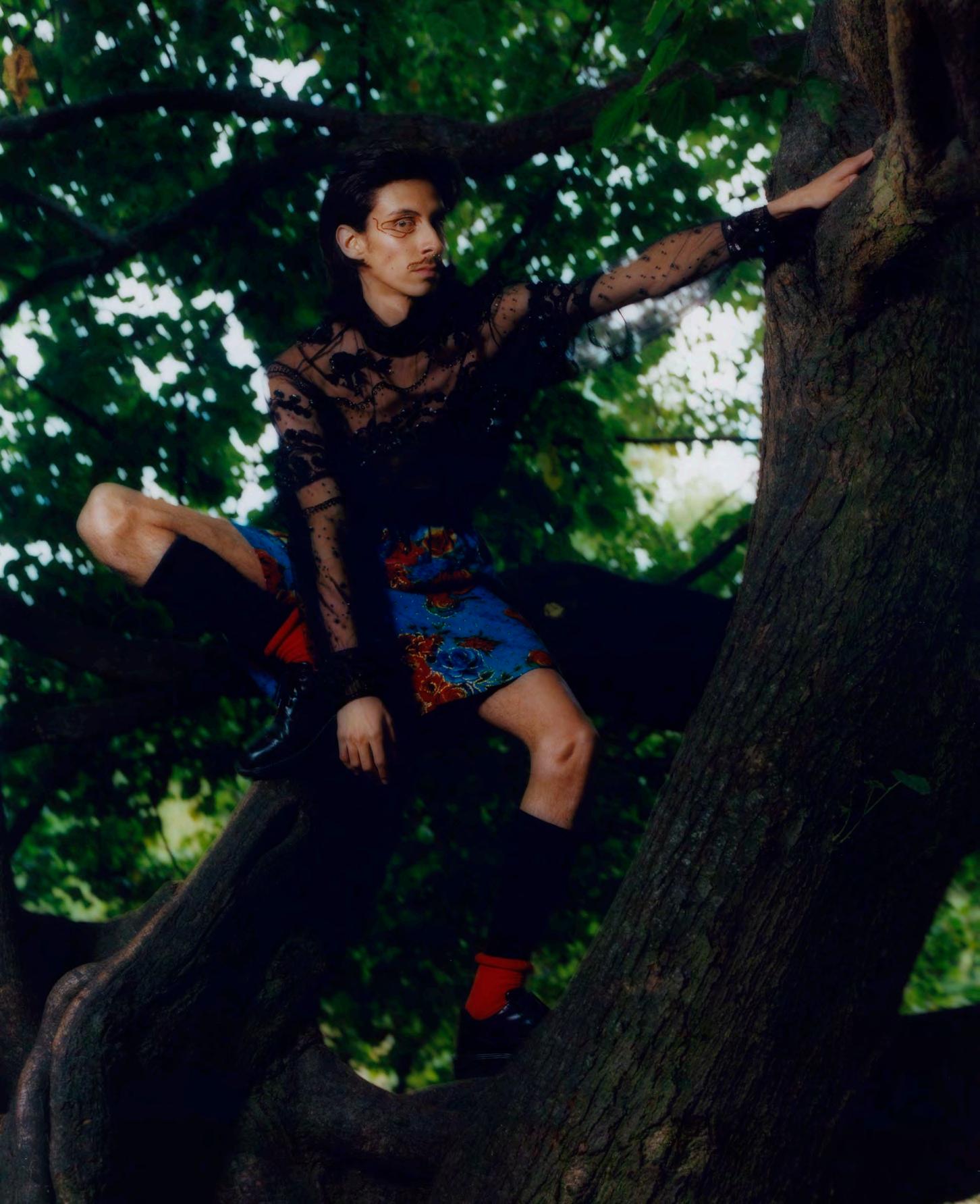

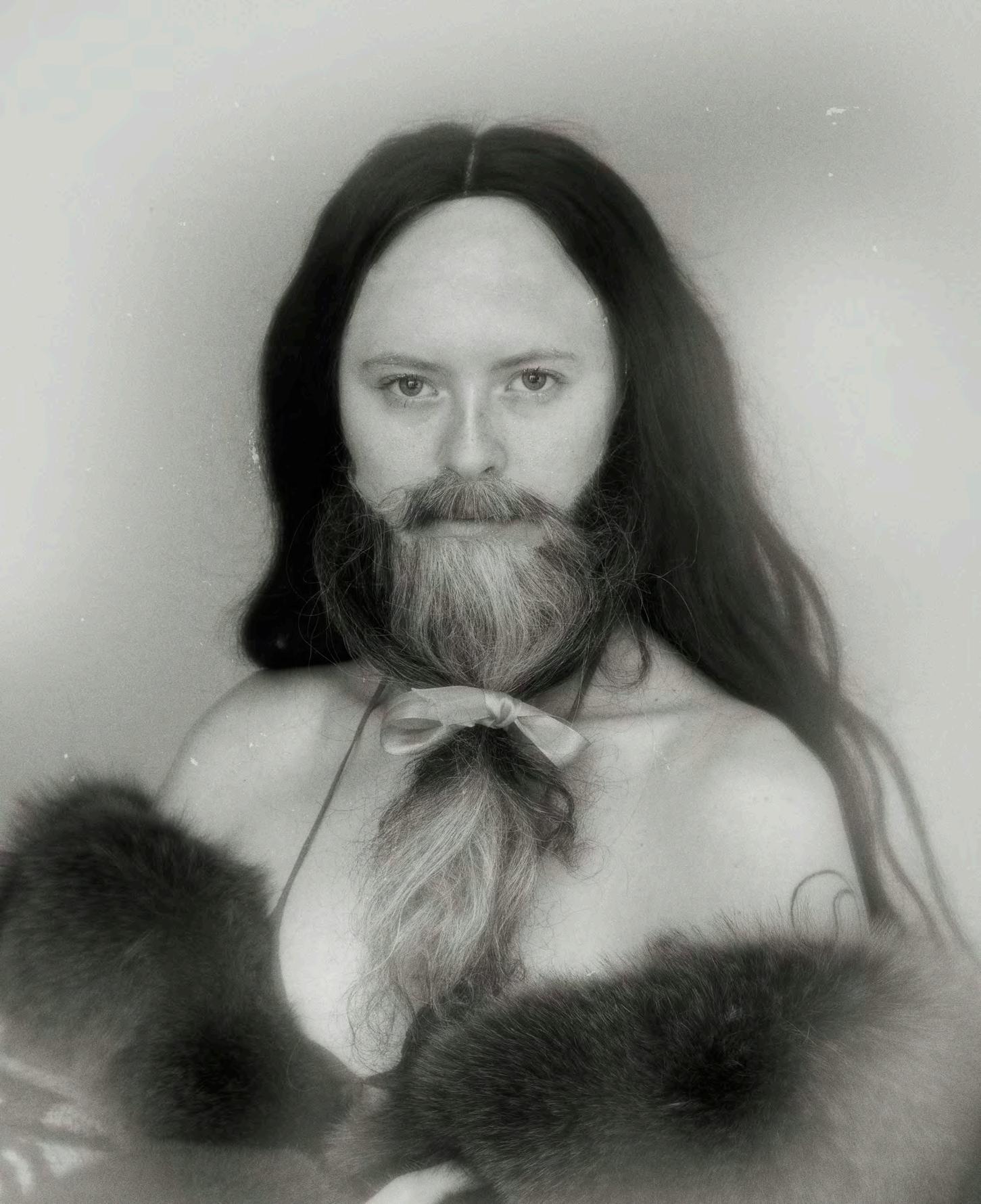

PAGAN FASHION, An Interview of Marni's Francesco Risso 218—239

A TALE OF LOST CHATS, A Special Collaboration with Grindr 240—261

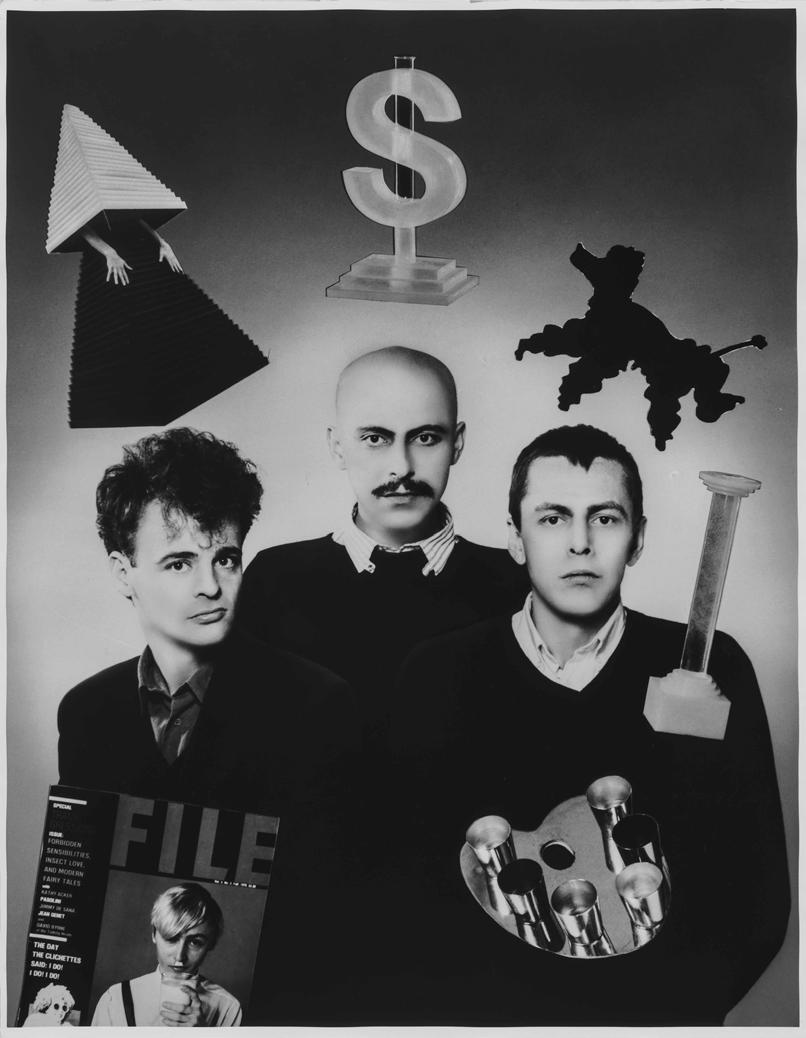

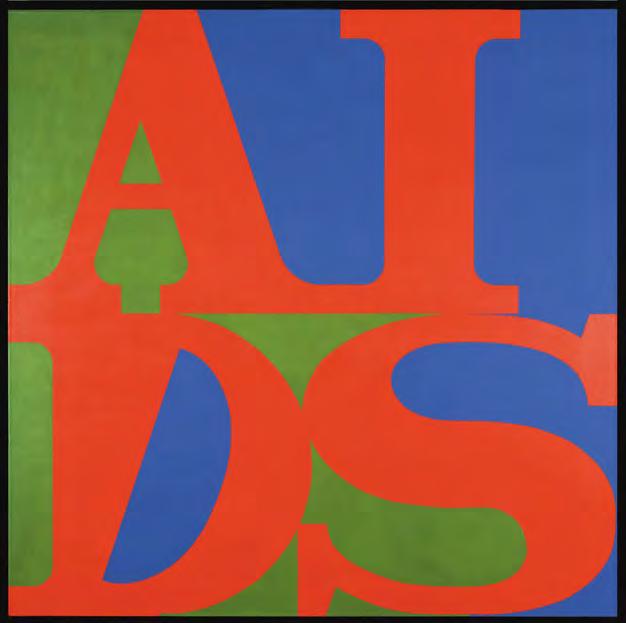

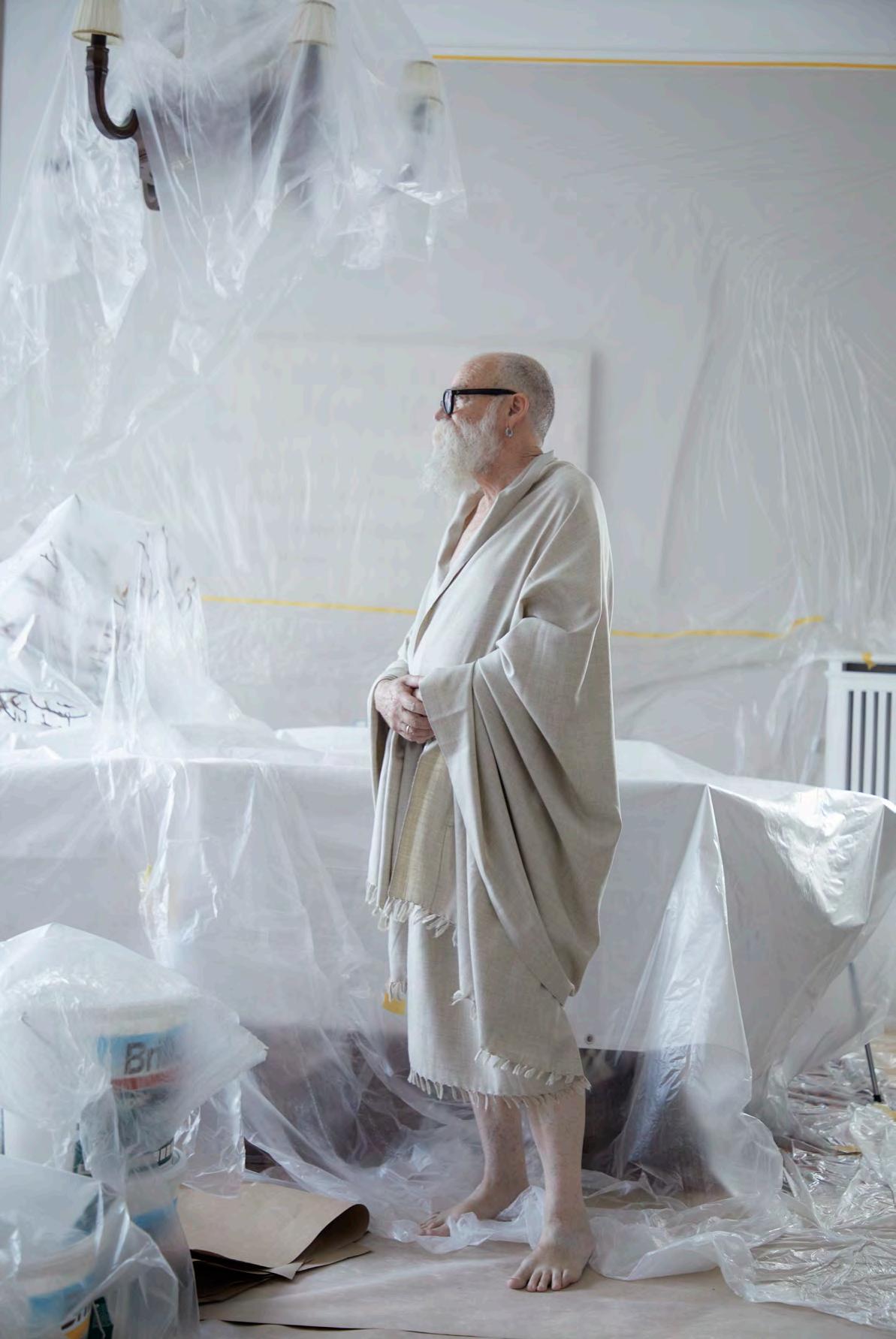

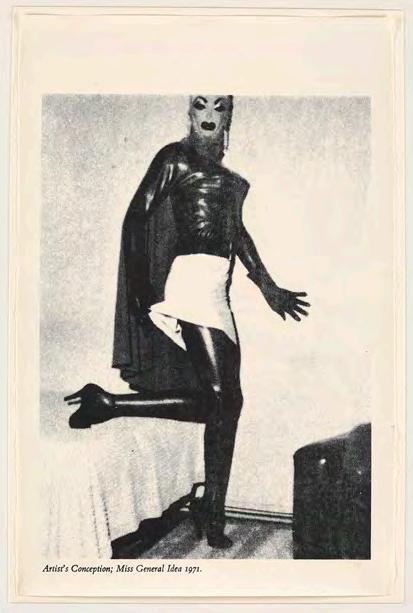

AA BRONSON, Interview by Defne Ayas 262—269

MY FATHER IS A GURU, by Suzie & Leo 270—287

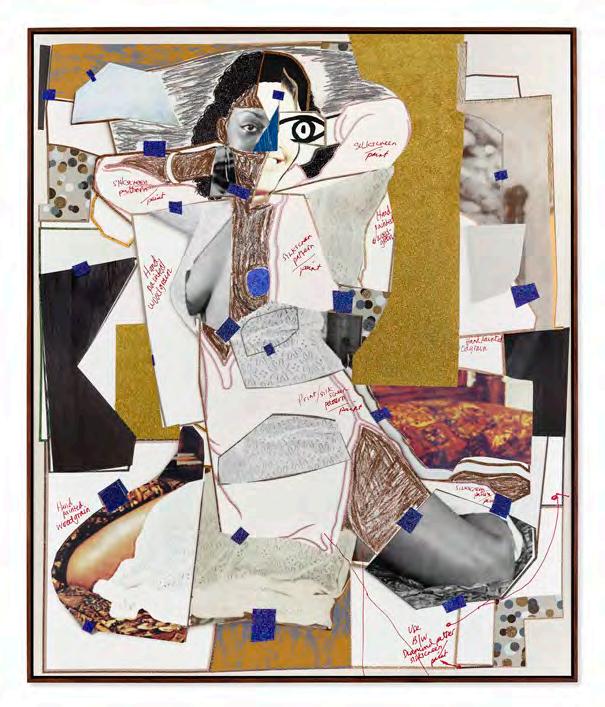

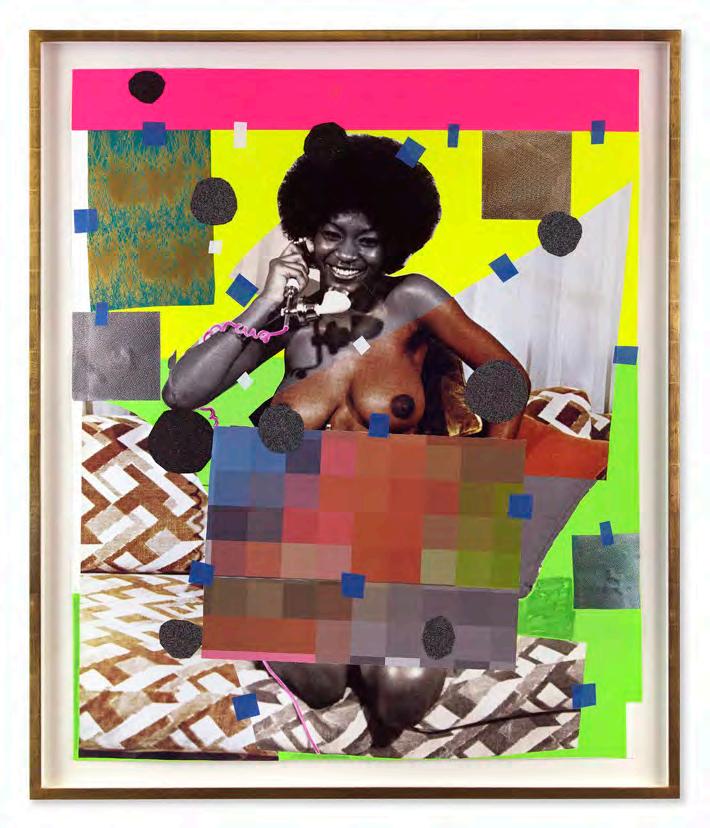

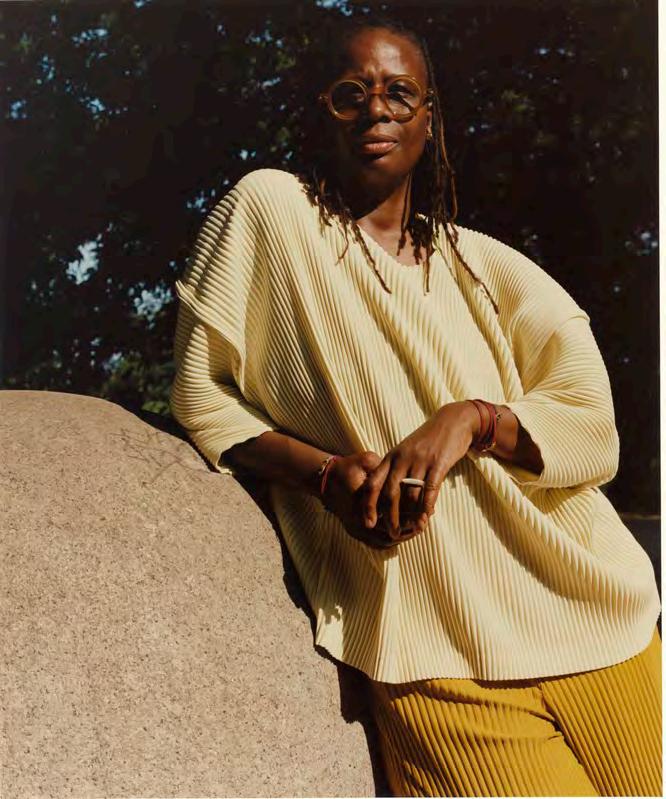

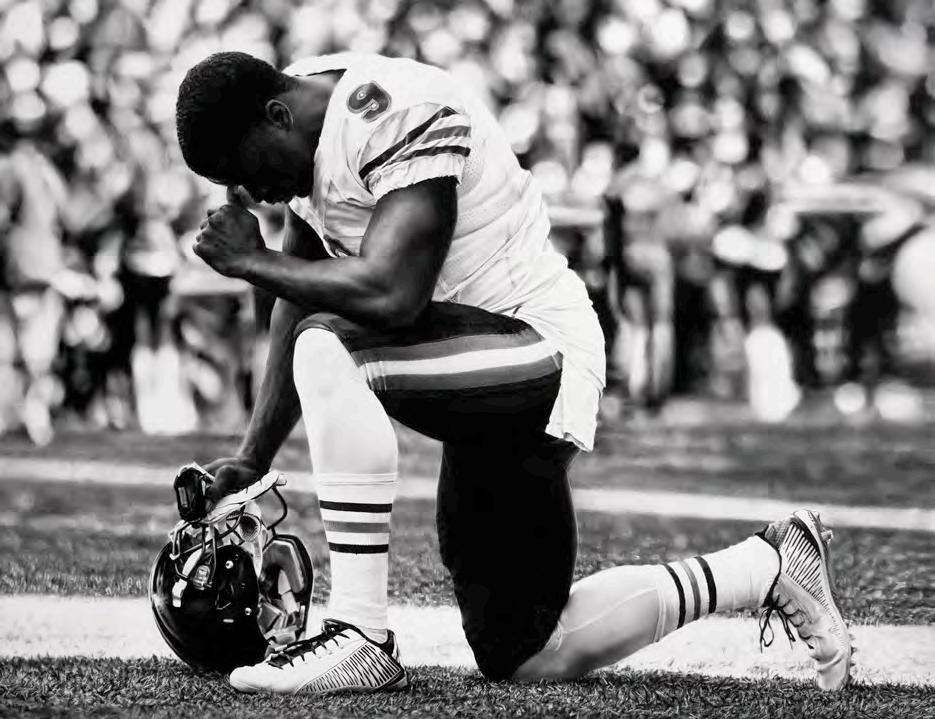

PEE-WEE & NADIA'S PLAYHOUSE, Pee-wee Herman by Nadia Lee Cohen 288—295 WU TSANG , Queer Spaces, Activism, and Cinema 296—301 BROOKLYN BOHÈME, Mickalene Thomas and Derrick Adams In Conversation 30—31 WILLIAM STROBECK: NO WAY TO LOSE, Photographs by Jason Nocito 308—323

ODILIA ROMERO, Reversing The Erasure Of Indigenous Voices, photographs by Max Farago 324—329

LUKE KEMP, On Existential Threats With A Portfolio of Artwork by Robert Longo 330—335

MICHAEL STIPE, An Interview By Hans Ulrich Obrist and Photographs by Nick Sethi 336—343 BECOMING TOMORROW, by Liberto Fillo 344—353

The ghosts of the past keeping visiting us. Is this déjà vu or something more sinister? In 1991, Rodney King was beaten nearly to death by officers of the Los Angeles Police Department in a case of excessive use of force that catalyzed a wave of uprisings in the streets of Los Angeles. That same year saw the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the official sovereignty of Ukraine. And in 1991, R.E.M.’s surprise hit single, “Losing My Religion”, echoed through the radio waves like a generational anthem. With its evocatively yearning and ambiguous lyrics, the song, written by Michael Stipe (who gives a candid interview to Hans Ulrich Obrist for this issue), is about the torment of love and newfound fame, but it could just as easily be a soundtrack for the time we are living in now. In an age when privacy is an illusion, the bells of sectarian bloodshed and an irreversible climate emergency are ringing louder than ever. We are all under the spotlight, collectively losing our religion. This issue is a startling exploration of changing belief systems in the age of information and disinformation, secularization, conspiracy theory and a testament to contemporary life in a burning hot post-truth world. It is an issue about the violence of borders, invisible enemies, and the hauntology of history.

Our current predicament is laid out perfectly in Guy Debord’s vital and prescient text, The Society of the Spectacle (1967)—our commodity fetishization and rabid consumerism have led to the flattening of culture and class alienation. We spend our days absorbed in the spectacle—awash in images of other people’s lives mediated by filters and celebrity deepfakes. We mimic the movements of others like social chameleons in a glass cage. History has no meaning, the present is a wasteland, and the future is unimaginable. We find spirituality in products, salvation in status, and holiness in interminable work. The logo has replaced the cross. The work hard, play hard, hustle culture ethos is nothing more than capitalist mythos forcing us into indentured labor so that we can meet the cost of living—a term of utter brutality normalized and neutralized by the white noise of necropolitics.

In 1972, MIT published a damning report predicting complete societal collapse by the mid-21st century due to rapid growth and the excessive mining of finite resources. While it was initially dismissed as being overly alarmist, a recent reevaluation of the study updated with fifty years of data strongly suggests that we are right on track for this collapse by roughly 2040, rather than the initial estimation of 2050.

In his latest book, Brutalisme (2020), Achille Mbembe proposes that the arrival of the 21st century has seen a spectacular return to animism. Only, unlike the 19th century model of worshiping objects that were believed to embody the spirits of ancestors, this newer version is characterized by the worship of self and of our numerous selves as objects. We talk to Wu Tsang about her new production of Pinocchio in which the sentience of the protagonist begins during his life as a tree, calling into question notions of ontology and their origins. We talk to Jeremy Shaw about the role of faith in our very survival, which explains why Mbembe underscores the ethical duty of Western institutions in the restitution of African art.

It seems only logical that a society, which subsists on the extraction of raw materials from a finite planet would be fated to such a spiritual ouroboros. In a conversation between Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture and Maksym Rokmaniko of Center for Spatial Technologies we learn about the art of counter forensics in holding nation-states accountable for the ravages of civil unrest. Luis Moreno Ocampo, the former chief prosecutor to the International Criminal Court tells us that “there is no chaos. Only complexity”, and Luke Kemp, a researcher at Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, tells us that societal collapse is often a boon to the masses.

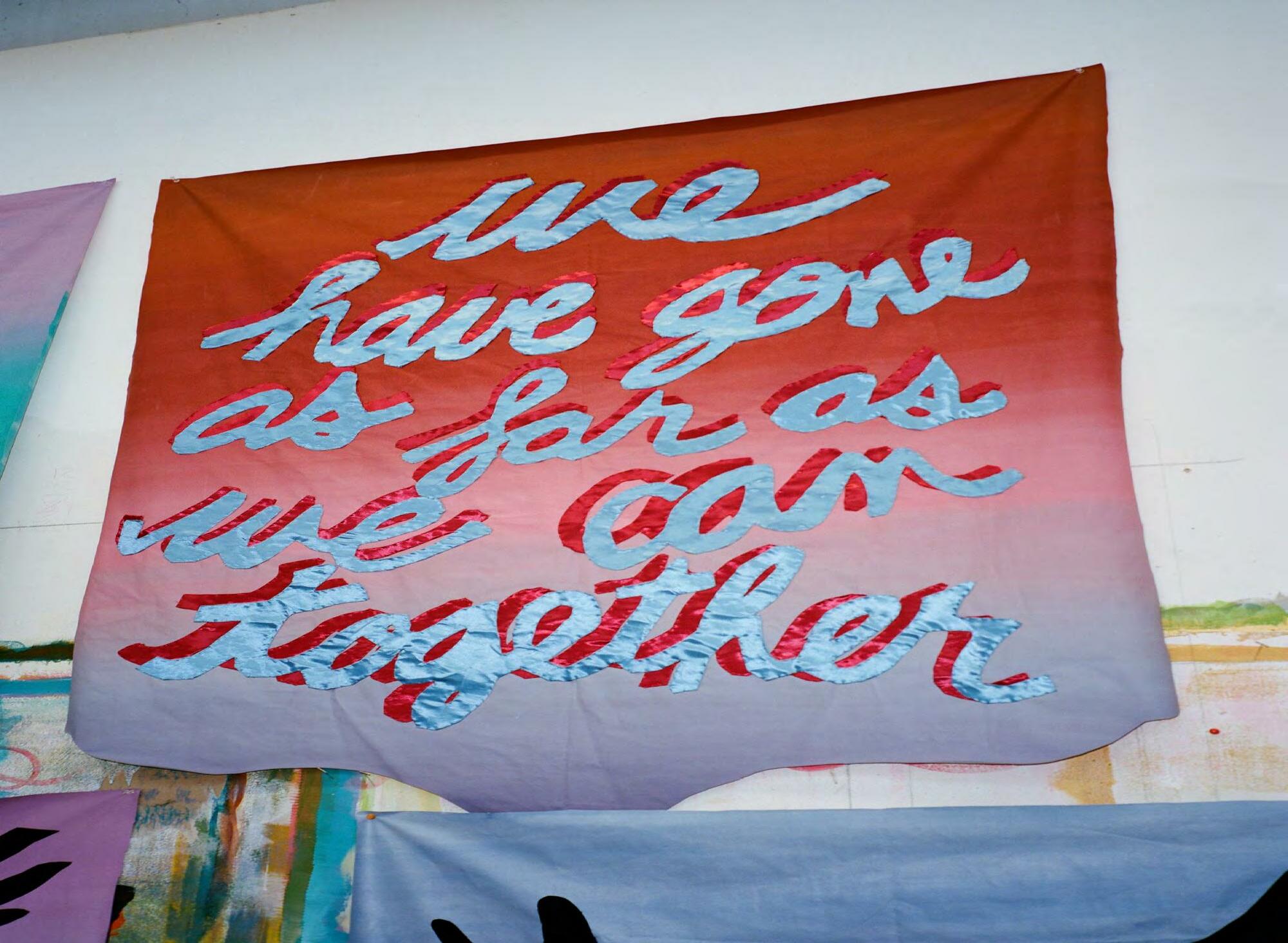

This issue is not about religion—it is about faith in all of its illusive forms. It is about the perils of isolation and nihilism. It is about the role of mutual support networks as we rebuild our faith in the society to which we wish to belong. It is a time to break from the age of individualism and welcome the other. Our survival is dependent on it.

— Oliver Kupper and Summer Bowie

When the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine began, the country responded with an unprecedented civilian defensive that stunned occupying forces. Four days before the war, photographer Victoria Pidust, and artist, Volo Bevza returned to their home country for Bevza's solo exhibition at WTFoundation. The opening happened to fall on the day of the invasion. With the exhibition canceled, Bevza decided to stay in Ukraine to help make antitank obstacles called 'hedgehogs.' Pidust photographed the process. They built hundreds of hedgehogs and beds for soldiers as the bombs fell all around them.

CAMILLE ANGE PAILLER First of all, can you give us some context for your trip to Ukraine?

VOLO BEVZA We traveled to Kyiv on February 20th, 2022 for the opening of my solo show Softimage at WTFoundation. The opening was scheduled to take place on the 24th, but that turned out to be the day that the Russians launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine. For six to eight weeks prior to the invasion, we were attending demonstrations in Berlin against the war and the accumulation of troops on the Ukrainian border. We already knew it could happen, but after speaking with friends in Berlin we decided to fly home and do a show to oppose Putin’s suppression of normal cultural life and work in Kyiv; to oppose the fear.

PAILLER Why did you stay and in which area? Were you with your family?

VICTORIA PIDUST We were in Kyiv when it started. My brother called us at five in the morning and woke us up, his windows were shaking from missile explosions. We

were going to stay with Volo’s parents in the suburbs, but just as we got in the taxi, his father called to say he had tested positive for coronavirus. So, we went to Volo’s brother in Vyshneve, in another suburb of Kyiv, and stayed there for one terrible night. We had to barricade the windows to protect ourselves from the explosions. We heard planes, helicopters, and missiles. The next day, we took an evacuation train with my brother and went to Lviv to stay at his friend’s parents’ place. Volo’s parents and brother came a few weeks later and part of my family came to Lviv as well. I stayed with the family for one month to see how the events would go. Then, I left for Germany with my grandmother, aunt, and cousin to bring them to a safe place, because my native town, Nikopol, is very close to the frontline.

PAILLER Victoria, where did you get the idea of photographing the hedgehogs that Volo was making?

PIDUST When we first came to Lviv, we stayed at artist, Roman Romanyshyn’s place.

Near their house there was a glass and metal workshop, which was considered the best in the country fifteen years ago. The guys were making antitank obstacles, or ‘hedgehogs’. So, we joined them; Volo helped to build them and I photographed. We couldn’t think about art the first week, as we were still too in shock. It was best to just do the work without any intellectual labor, just doing. When the metalwork was finished, we started with fundraising and giving interviews to the media. Several friends and others from Germany helped us out. With Gallery Judith Andreae, we managed to collect around 25,000 €. The guys built a few hundred Hedgehogs for the whole country, as well as several beds for soldiers and others who were displaced inside the country. We also spent money for territorial defenses and humanitarian needs.

PAILLER How would you compare your artistic vision in the treatment of war with that of the press?

PIDUST There are many brave and professional people from all over the world who are clarifying the reality of this terrible war. We are all thankful to them for the jobs they are doing. Some of them gave their lives. I need to set my sights on the photograph— to see and show the abstractness of reality through lens-based pictures. I do this with the help of algorithms to show a variety of human perceptions, how events can be perceived or manipulated based on certain facts through photography and other digital media on the internet in our time of post-truth.

PAILLER Do you think you will continue to document and use these photographs for future projects? If so, can you tell me more about it?

PIDUST Yes, I did some works for an iPhone series in Lviv and Kyiv, I also did some photographs for photogrammetric works. As for Volo, we were in Kyiv one more time again in April to document some destruction for our latest group exhibition POSTOST: Ukraine. And I will be back in Ukraine again soon.

PAILLER How do you feel after all this to be back in Berlin?

PIDUST We are feeling huge support from the people of Europe, our friends and colleagues, but not enough from the German government. They continue to buy Russian oil, thus financing the war and they still haven't delivered any heavy weapons, even though they promised them months ago. It’s disappointing because with the help of Europe, we can win this war together. It is an identity war. The Russians want to destroy the

Ukrainian identity: our country, our heritage, our people. There is a new definition for Russian terror, ‘Russism.’ They have been doing this for five hundred years. It must be finished soon. Ukraine is part of Europe. Ukrainians defend democracy. We are a free country with people who are ready to fight for European values, to protect Europe, and we will win very soon. We want to thank every nation and every single person that stands with Ukraine.

end

Shortly after 5pm on March 1st, 2022, Russia rained down two air-launched cruise missiles on the Kyiv TV tower. The first missile was a direct hit, exploding just below the control tower. The second missile seemingly missed the tower and landed close to a Soviet-era sports complex, virtually destroying the structure. The attack was not the deadliest or the most injurious (five people were killed and five people were wounded). Nor was it the most militarily effective—most TV channels were back up and running in about an hour after the strike. Nevertheless, the objective was deadly clear: to cut off information, demoralize, and control the narrative, a post-truth tactic all too common with Putin and the Russian armed forces. Over the course of a month, there would be a total of ten attacks on TV towers throughout the country. But the attack on the TV tower in Kyiv also had deeper, stranger, and darker historical ramifications. In Putin’s new ideological war, haunted by the ghosts of the former Soviet Union and the brutality of World War II, he offers the delusional promise to “denazify” Ukraine, the implications of which are equally ironic and irrational. The tower is located in a territory called Babyn Yar, a ravine in the center of the city where one of the largest massacres was committed by the Nazis. In 1941, over the course of two days, death squads killed over 33,000 Jews. Between 1941 and 1943, over 100,000 Jews, Ukrainian political prisoners, Romas, Soviet prisoners of war, and psychiatric patients would be murdered on the grounds of Babyn Yar. As Soviet forces were closing in on the Nazis, prisoners from the Syrets concentration camp were forced to dig up the bodies and incinerate them. After the war, at the directive of Stalin to erase the memory of the Holocaust, the ravine was filled in by liquid mud. History vanished. From February 2020 to February 2022, Maksym Rokmaniko and the research organization he founded, Center for Spatial Technologies—with a commission from the Holocaust Memorial Center—have been using a vast array of tools to investigate and digitally reconstruct the topography of Babyn Yar, discovering long buried secrets in the process. The TV tower itself, and multiple structures within the vicinity, were built on Jewish, Muslim and Orthodox Russian burial sites from the 19th century. The sports complex, Avangard Gym, destroyed by the second missile, was due to become the Museum of Holocaust in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. With these findings, Maksym reached out to Eyal Weizman, founder of groundbreaking multidisciplinary research group, Forensic Architecture—established in 2011 at Goldsmiths, University of London—to join him in drawing the parallels between Babyn Yar and the attack on the Kyiv TV tower. When the war broke out, Weizman used his network to help Rokmaniko escape Ukraine. From Forensic Architecture’s Berlin office, Weizman and Rokmaniko discuss Babyn Yar and the unique architecture of violence.

OLIVER KUPPER Eyal, can you tell me about Forensic Architecture, how it started, its core missions, and where it’s going?

EYAL WEIZMAN Forensic Architecture emerged from an experimental program that was set up at Goldsmiths [University of London] back in 2005. It was a multidisciplinary group of practitioners, filmmakers, curators, writers, and architects. At some point, we were discontent with critique and we needed our analysis to play out in the most antagonistic and difficult forum, which is in a legal setting. It started almost as a strange proposition: let’s come up with a forensic agency. So, imagine a group of creatives thinking: we need to reclaim forensics, we need to take it back out of the jaw of the pit bull. How do we create a counter state practice? A practice that actually only targets states, which is what we call the inversion of the forensic gaze, or counter forensics. Then, we engaged with a number of investigations that immediately triggered an amount of attention that we were completely unready for. A UN Special Rapporteur heard our talk at an academic conference at Goldsmiths and gave us the most incredible commission, which was to monitor CIA targeted assassinations in Somalia, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Yemen, and Israeli strikes in Gaza. It was the time when targeted assassinations shifted to buildings, to cars on the road, to camps in the countryside. All of a sudden, a kind of an architectural reconstruction of those buildings that were targeted became the most important evidence. Then, we were flooded with commissions. Of course, it is all based on my architectural practice in Palestine—mapping the urban warfare of Israeli Occupation in the West Bank in Gaza, and trying to understand the Israeli Army’s use of critical theory, like [Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari, which was a ridiculous abuse of theory. Then slowly, Forensic Architecture evolved from that kind of proposition into an agency in 2011. But now, we are at the stage in Forensic Architecture where we decided to dematerialize. It hasn’t completely happened yet, but we want to become fifteen different organizations, each one with different names, operating in local dialects in relation to different conflicts worldwide.

KUPPER In this issue, we are looking at how the violence of various belief systems operate in the chaotic times we are living in. Maksym, can you tell me about The Center for Spatial Technologies and some of the projects you are working on?

MAKSYM ROKMANIKO The Center for Spatial Technologies was much more of an experimental design practice that hacked around using all these clever tools to understand and study complex systems and societal issues. A lot of the things we first researched were around the housing crisis. For instance, we looked at the High Line in New York and the rise in property value as a result of publicly funded infrastructure. We are currently working on a case investigating the bombing of the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theatre in Mariupol. But the TV tower case in Babyn Yar was an important stepping stone. We were working on it for two years before the war with support from the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, and that is how I met Eyal [Weizman]. We were using the tools and methods of Forensic Architecture, but studying war crimes wasn’t the plan. The Babyn Yar project was fairly long and complicated, because the Holocaust Memorial Center wanted to build a

series of museums on the site. I showed Eyal the work I was doing and the feedback was positive. For three and a half hours we went into a lot of niche historic stuff.

WEIZMAN Seeing the work that Maks and his colleagues had done at Babyn Yar in Kiev was one of the most original projects I had seen. They were starting from something like Forensic Architecture and diving into Second World War history, using historical documents and open social investigations, pulling videos from online, geolocating them, and building them into models. And they were doing it all from photographs that were taken in 1941. We were thinking, wow, we are seeing something that cracks history open. When Maks was showing it to me, it blew my mind. The key, in my view of reading their work, was to understand a topography that no longer exists. Because that place was unknown, you need to conceptualize it: Babyn Yar is a kind of ravine, and the entire use of that place was a site of mass murder. That massacre took place in a topographical depression in the middle of the city, a place that is both central and hidden. Every photograph included a bit of that topography that started to change over time. The ravine had sort of collapsed on the buried bodies—the Soviets flattened it with mud. So, the story of the ravine is a story about terraforming and continuous transformation. A group of young Ukrainian architects discovered something that the most serious Holocaust historians couldn’t manage to find in eighty years, and that got my attention.

ROKMANIKO When we discovered the burial site at Babyn Yar, it was a moment where we had to basically revisit Forensic Architecture’s work from A to Z, just to ensure we were not missing any tools we could be using. That is the first time I met Eyal and really dove into what could theoretically be a Forensic Architecture project, and we were still working on research for this project up until the war broke out in February of this year. Up until then, Spatial Technologies were mainly involved with the reconstruction of this important location in Kiev as a site of mass killing by the Nazis. We also looked at Babyn Yar as a site where the Germans set up labor camps with Jews and other prisoners who were forced to dig out the bodies and burn them to erase the evidence. So, we had a lot of work to do. When Eyal reached out to ask if I was okay, I replied and said we were already looking at some of the missile strikes. We were mapping things to understand what was hit and what types of missiles they were using. When the missile that targeted the Kiev TV tower missed and hit the area very close to Babyn Yar, we knew that this is the first case that we wanted to look at, and it was the first collaboration with Forensic Architecture.

KUPPER What was that moment like, when they started raining down missiles? How long was the period between going into hiding and meeting up with Eyal in Berlin?

ROKMANIKO I got a message from Eyal when I was with my parents, my girlfriend, and her kid, in a car leaving Kiev, on the 25th of February. I was very happy to hear from him, although I did not respond immediately because it was a massive ordeal. We evacuated from Kiev to western Ukraine. I spent a couple of months in the Carpathian Mountains. But all the work before the war, and all of that thinking about sustainability, materials, and equitable housing, everything completely stopped. We were obsessively looking at these strikes, and to be honest,

it isn’t an overstatement to say we could not do anything else. These things were happening and we were curious about what was going on. So, we started to work immediately with Eyal and Forensic Architecture, and it was important because they helped us leave Ukraine. I think we are one of those future organizations that Forensics will dissolve into. Their Berlin office is our new home, which is where we are speaking to you from. I remember saying to Eyal that there were too many obstacles in our way in Ukraine.

WEIZMAN We were thinking that Ukraine was going to fall any day. And we had the top worldwide expert in encryption and digital security basically making Maks disappear online and offline. It took six weeks to get him out, but now he is here. When people come from a war zone, you are so happy that they are safe, but then there is a whole other process that begins. And there was a whole office, not just Maks. And they became like Twitter junkies. Every time there was another missile strike in Kiev, the entire office was under the emotional shrapnel of that missile. So, I thought it would be interesting to ask Maks and the team if they were interested in working on other things. We received a strange invitation from the House Of World Culture (Haus der Kulturen der Welt—HKW), which is a major art and intellectual space in Berlin. The HKW were organizing an event in honor of David Graeber and David Wengrow for their new book The Dawn of Everything (2021), which is a super important book on archeology that just came out and is being discussed everywhere. It’s a book about political philosophy based on archeological evidence, and it’s perhaps the best counter forensic project I have ever seen. They are digging and looking at archaeological evidence from the Neolithic/Paleolithic threshold, and finding evidence that completely transforms the perceived history of cities. Cities don’t need to be apparatuses for control, surveillance, slavery and subjugation of women and others—they could be places of debate, equality, and creativity. The most insane thing was that one of the cities that made this paradigm shift was in Ukraine. In recent decades, archeologists discovered a city in the center of Ukraine, a city from 7,000 years ago—older than the cities in Mesopotamia—without temples, without elite burials, essentially without classes. So, the HKW asked Forensic Architecture to do what we are doing, but in the Neolithic era, and connect what Maks is doing in Ukraine with what was happening 7,000 years ago. The lecture is online, but I thought it was an important project to get their mind off the war.

KUPPER You both grew up very close to the echoes of war. Eyal, you grew up in Haifa, which still had remnants of Palestinian communities. And Maksym, you grew up with the ghost of the Holocaust and Russian entanglement. Can you talk a little about that and how that inspired your interest in architecture?

ROKMANIKO The one thing from your question that resonates is the Russian entanglement. For my family, it was quite specific. I grew up very curious about Russian culture, mainly because my family prohibited it. I remember my dad chasing me around for using Russian words. But all this dislike of Russian culture made me more interested, which annoyed my family. Now it seems like I have to almost align with how my family feels about Russia. It’s something I am dealing with now.

KUPPER When did architecture start to come into the fray? When did it take the form that it took, in terms of your mapping histories?

ROKMANIKO From the hacker culture in Ukraine. I grew up downloading software, torrents, and playing with it. Software that is meant to design plane engines or architectural software. Even in high school, I was making walls and doors. And I was always good at math. I won second place in Ukraine in the Olympics for Mathematics. And my dad is a painter, so it’s a sweet spot between those things.

KUPPER And Eyal, what about your background, growing up in Haifa, Israel—how did that inspire your architectural interests?

WEIZMAN I can’t distill it, because one’s decisions in life are very complex, but politically, like many people of my generation, we were existing between twin shadows. On the one hand, my family are Auschwitz survivors. I still have very strong living memories of my grandparents and their difficulty adjusting. But then, there was my own lived reality of the Israeli apartheid, in which I was part of the dominant group. All of that started to exist in strange spatial, architectural forms in Haifa. It was this Palestinian modernism that was between traditional stone construction and fine line, British-imported colonial modernism, which produced a dialect of modernism in Haifa and the whole topography, where Jewish neighborhoods exist on top of the remnants of scattered Palestinian

groups. But I was reading philosophy and trying to make peace with the fact that maybe one day I would study architecture, and that one day I was going to be able to write philosophy through stone and the built environment. My inclination was always a very theoretic, text-based, approach to architecture. The idea was architecture as optics, understanding political, social, and economic realities as they become form. And the form was really interesting to me. In my recent book, Investigative Aesthetics [Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth] (2021), we had this term hyper-aesthetics, which is a way of augmenting the capacity of a surface, of matter, of the built environment, to be read as a trace of something. If aesthetics is the way we perceive the world, then hyper-aesthetics is to augment it conceptually, technologically, by networking signals from different places, traces on the wall, with a video, a fragment of traumatized memory, you connect them together into what we call a hyper-aesthetic assemblage.

KUPPER Can you talk about your definitions of architecture through your own practices, but also how architecture and war tie into each other today?

WEIZMAN I think that forms of violence and domination are articulated as spatial transformations. To dominate people, you need to conceive of an environment that will facilitate that domination. When you fight in a city, you redesign the city for destruction. You open new boulevards,

remove strategic points, build walls, checkpoints, and lookout points, as you redesign the optics of an urban environment. We usually separate construction and deconstruction, but I believe that they belong to a meta category of spatial transformations. So, when you are thinking about the relation of war to architecture, construction and deconstruction become contiguous—it is transformational space. You destroy something, you move it, you build with it, you create with it—even a pile of rubble becomes strategic when it blocks a road. You asked for my definition of architecture: it is matter slowly changing form, but continuously, in an elastic medium— almost in an incessant mode of transformation.

KUPPER Earlier, you talked about the Israeli’s co-option of Situationist philosophy in their attacks. Can you talk a little about rhizomatic movement and the analogy you used of a worm eating its way through an apple?

WEIZMAN This is where construction and deconstruction becomes materially illustrated. So, the Israeli military was caught off guard, like many other militaries, when war got into the city. Then, they understood that they had to master a whole new philosophy of space from post-colonialism to architectural theory, to system analysis. So, they were developing schools of architecture and all this progressive stuff that we were reading, such as Liberation theory, was subverted into the military. They realized the safest, most surprising,

and effective way for them to move through the contiguous fabric between Palestinian cities is to move between walls, sometimes into the floor through 100-meter long tunnels that were eating into the city. This is a way of redesigning. We believe that the city dictates our movement, in war this changes, movement dictates space—the way you move is to break your way through, and that becomes the organizing principle of space. This is where [Jacques] Derrida, Deleuze and Guattari, and all the Situationist International philosophies started to be abused as a technique. I was very interested in that, and strangely, when I published that piece in a very radical, left wing journal in Israel, we got sued by Aviv Kokhavi, who is now the Lieutenant General of the Israeli Army. I was writing about him and what he was doing, and he got an AmericanIsraeli heavyweight legal team. They tried to get me to change my piece and I was not willing to change anything. This started an entire debate about how we write theory in a state of colonial struggle. There is a way in which you can speak immaterially about things, in general ideological terms, but then nobody cares. However, if you say that person did this, you are in the realm of investigative journalism, and that was my call. We need to combine investigative journalism with political theory, and that is the kind of machine that can deal with colonial situations.

ROKMANIKO There is a theorist that I started to read early named Keller Easterling, she always talks about a city being a product of this infrastructural logic that produced the city. In the architecture of cities, there is an object form, but also an active form. We engaged with this logic when we did all those hacking exercises. The TV tower in Kiev is infrastructure at its purist: media networks and communication systems that transmit all kinds of signals for radio and TV, and towers also have transmitters for military purposes. So, you can see how important TV towers are. This is still unpublished, but we started to look at all the towers that were targeted from the beginning of the war. We found a tower, which was newly financed by Ukraine’s presidential office in the town of Komyshivka, that the Donetsk People’s Militia were targeting in November 2021. It was a brand-new project that was meant to transmit Ukrainian voices into the territories that are contested and it immediately got targeted. In this way, you can see the practical meaning here, in how these electromagnetic waves come from both sides to fight for territory. In these contested places under Russian control, at some point people start believing the narratives they hear, especially elderly people who can’t navigate these post-truth scenarios.

Suddenly, you hear these missiles exploding all the time and you do not know what to believe. Then you turn to the radio and there is a Russian voice that announces “Ukrainians betrayed you. They started to shell your city.”

KUPPER Why was the attack on the TV tower so symbolic?

ROKMANIKO In Kiev, I could see the TV tower from my bedroom, so I lived super close to Babyn Yar. It is a massive landmark. It’s the tallest structure in Kiev, maybe Ukraine, so it’s impossible to not know about it. The attack on it carries a symbolic meaning simply because of its visibility. Then, there is the intention to take down the means of communication, so Russia can have a monopoly on communication. But we also looked at the more unintended aspects and symbols of this attack. For

example, one of the missiles missed the TV tower and landed in an area where civilians were killed, and we know exactly where their bodies are. There is footage of the area being extinguished by firemen. But then, of course, the building that caught fire is a building called Avangard Sports Complex, which was built on a Jewish cemetery and is meters away from the ravines of Babyn Yar, and was going to be turned into the Holocaust Museum. In fact, I was in the presentation with president Volodymyr Zelensky when we were explaining our goals for this memorial complex that they were planning. So, it is ironic that in Putin’s project of “denazification,” one of the first missile strikes is a major Holocaust burial site. With war crimes, it is important to know exactly what happened—where those missiles came from and what types of munitions were used. Then, you go through this metaphorical idea that pierces through the site, this land that we consider sacred to the Jewish population of Kiev and everywhere else. Suddenly, you have these corpses lying on that ground and you have this immediate invocation of the events that happened here before. We are, of course, the people who spatially know more about this area than anyone else.

KUPPER It is really interesting to use the technology of not only algorithms and spatial technology, but also cameras—the same technology that their missiles use—to see through these environments. Maybe you could tell me about some of the tools that you use to needle through these environments.

ROKMANIKO The site doesn’t look like other European Holocaust memorials, it is a Soviet spin on that. It doesn’t say anything specific about the Jews. We know that in 1948 there were competitions to memorialize Babyn Yar and there were attempts to find the best architects to build a memorial addressing the horrors that occurred there. But at the time, something had shifted with Stalin’s relationship to the Jews. And since we all knew about this site, we also knew how little people understood about where those mass shootings took place. There is a Nazi military photographer named Johannes Hählee, and he arrived in Kyiv to specifically take photographs for Nazi propaganda. He shot a roll of film that he never gave to his bosses. When he died in Normandy, the film wound up in the hands of his wife, who sold it to a German journalist, and it was later used at the Nuremberg Trials. Within these photographs, you can see how profoundly the topography has changed from then until today. We are trying to get all these materials together and structure them in a way that makes sense, so that we can cross reference them. Once we had a 3D model, we could look at the whole topographical map. One of our colleagues is a technical magician and he managed to build an algorithm that allows you to project into a photograph and look at a certain landscape. So, that was the work that we did at the very beginning. Then, we started discovering where the bodies were—over 33,000 bodies. On top of 3D modeling, we also had witness testimonies.

KUPPER Do you think that Putin's forces knew that there were plans for a memorial?

ROKMANIKO The second missile was clearly targeting the TV tower. But this is the reason why we wanted to go into this historic strata. You can see a similar logic by the Soviets when they built the TV center in the first place. First, they got rid of a Jewish cemetery to build the tower and another building

across the street. And this logic is coming from Moscow, a logic that is deeply colonial in its nature.

For example, the TV tower was originally planned for Moscow and it would have been the largest structure in the world, so they needed to shrink the one they built in Kiev to ensure it was smaller than the one in Moscow. Also, Kiev had to wait ten years for a TV tower until the one in Moscow was finished. So, this cultural erasure has many layers. Like in Mariupol with the theater that was bombed—it was built on the grounds where a church was destroyed by the Soviets in the 1930s when they exploded all these cultural heritage places for ideological reasons. So, these are the links that me and Eyal are looking at. How can we explain this war in a way that is not coming out of the blue. This has been going on for centuries. During the Bolshevik Revolution, the Soviets needed to consider the Ukrainian's autonomy, but by the ‘30s, when they gained this control, they went back and tried to control their territories. They killed the smartest people in Ukraine, destroyed churches. Everything that is happening today has a similar logic and a similar desire.

KUPPER Eyal, you mentioned that Forensic Architecture will start to decentralize into fifteen different groups. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

EYAL We have done a lot of work with the Colombian Truth Commission, so we opened an office in Bogotá. In Mexico, we looked at the disappearance of forty-four students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College, so now we are opening an office in Mexico. We have an office in Palestine with a hacker human rights organization, which unfortunately Israel has banned claiming it’s a terrorist group.

KUPPER And Maksym, what are some of the projects you are working on now?

ROKMANIKO We are currently looking at grain, and how the Ukrainian food supply chain has been broken. How Russians have taken over farms, and grain storage facilities. We’re also looking at the historic references of Stalin’s Holodomor [Terror-Famine] in the 1930s, which aimed to get rid of Ukrainian speaking populations in Central Ukraine. Four to seven million people starved to death. The project with grain is infrastructural, so we are mapping territory and trying to understand how the grain is being produced. A big part of that is sunflower seeds. All of this food supply and grain is distributed across Ukraine in a certain way, and there is infrastructure to support this process. But it is cut off by Russian territories. They just opened the Odessa port, but we want to know how much of it is opened and controlled. In Mykolaiv, we researched a case about the bombing of an administrative building that is a major agricultural terminal. So, we are looking at the weaponization of food and trying to study these things in a historical context, which is critical to understanding the war.

In 1992, Piet Hein Eek created a cupboard made from reclaimed wood as his final project before graduating from the Academy for Industrial Design in Eindhoven, Netherlands. Eek’s “Scrap Wood Cupboards” became an instant success and made him one of Holland’s most important designers. He used the money from those first sales to start his own design studio in 1992. Today, the studio includes a 10,000 square meter multi-purpose space in Eindhoven, which includes a restaurant, a shop, a gallery, a showroom, and now a hotel. A master craftsman with a DIY ethos and a devilish sense of humor, he has turned discarded timber into an empire of sustainably-designed furniture that is the absolute antithesis of the industry’s ethos of cheap materiality and mass production. In an age of crisis and supply chain chaos, Eek has the last laugh.

OLIVER KUPPER Your design process seems to be very self-sustaining in a time of global crisis and supply chain issues. What has this time been like for you as a designer and an artist?

PIET HEIN EEK It's not the first time that there has been chaos. Around the disaster of the Twin Towers, there was chaos. And then, we had the bank crisis after that. And now, we have the COVID crisis, which is actually the least of everything. In general, a crisis is something that comes and goes. So for me, it doesn't feel that special. I think the latest one got fueled by many other things happening at the same time. It's the most psychological crisis. Normally, when there is a real crisis we are doing okay, and when the whole world is enjoying life, we are doing shit (laughs). I don't know why, but our company always performs the opposite way. During the coronavirus crisis, we rebooted a lot of things. And after a few months, we have been doing better than ever before.

KUPPER What are some of the crises that exist within the studio?

EEK It's always something. When I was younger, I thought any crisis would be the end of the world. When you read about The Great Depression, you get the impression that the whole world stopped functioning. Of course, there were a lot of poor people, but a huge amount of people still worked and made money. So, the economy goes on, even during the worst crisis. I didn't know this when I started. And now, I know that a crisis

can pass without even hurting your company, or sometimes it can even help your company. The biggest general crisis we had was actually because of ourselves. We are a production company, and if you don't cherish a production company or maintain it, that's not the best thing. At a certain moment, we were performing so badly that the outcome was negative. Even if we sold more tables, we had bigger problems, because we lost money on every product. Due to the pandemic, we had to change. I tried several times to change, but people were not so convinced. And because of the coronavirus, everybody was aware that the world might fall apart. So, they took themselves into consideration. If you are not productive, the production has to change their way of working, and there was a huge difference before and after.

KUPPER You seem to embrace crises in an interesting way. You like to solve problems. There's your famous Crisis Chair. Can you talk about the Crisis Chair in terms of it being a symbolic design object of our times?

EEK That chair was actually designed during the Twin Towers attack. I was annoyed during that time, because everybody in Holland was complaining about the crisis and about the lack of money, and so on. But no one was actually hurt by anything—everybody was equally rich, but still complaining. So I thought, if you are complaining so much, I'll just give you an inexpensive chair

that you can put together yourself. It was like a cynical joke. Here's a chair for your little thoughts. It became our most successful series, and also the most affordable.

KUPPER There's a lot of conceptual ideas and philosophies behind your designs. And some of them are funny. Where does that humor come from?

EEK I think it's because I look around and I always think the opposite thing. If you reverse almost everything, it is often funny. And if you turn things around, it also opens up your eyes and it's more fun. When it's successful, it becomes an even better story. We have a lot of products that come from being annoyed about things and just doing it the way you want, which is not often economical. There are so many things we do that you don't do if you want to be successful. And sometimes it works.

KUPPER Most people choose the path of least resistance. You've chosen the path of almost all resistance.

EEK It feels like that, but I don't feel it myself. It's an attitude. I always try to stay close to my own way of thinking and what I think is important. If It goes wrong it goes wrong, and something will come from that.

KUPPER Going back a little bit, I read that you used to make furniture out of matchbooks. Was that your first experiment in designing objects?

EEK I made complete houses from matchbooks, and I built the furniture for these houses too. As a child, I was always making things. My mother used these matchbooks to make fire on the gas stove, so there was always material. It is actually quite similar to what I do now. Now I have bigger machines. The room where I was sleeping and working when I was a kid was very small, so no machines, no possibilities, except for the matches, the glue, and the knife. And now, I have a factory with machines, carpenters, and welders. But that was the starting point for the creativity and for the production.

KUPPER What did your parents do? Were they supportive of your creative pursuits?

If you reuse material, it doesn't always mean it's good for the environment, because oftentimes it takes more energy to reuse than to use something that is new. It took me twenty years to find a better description, which was inspired by the holiday homes we made in the Dordogne region of France. I found out that the houses that were built there, around 150 to 200 years ago, were built alongside a small river, because it's a water mill. Also, they were made there because of the stones uphill, which were for the stone yard, and there was plenty of wood and timber around. The first time I slept at the mill, I found out that in winter time, the sun sets right on the mill. So, they knew exactly what nature gave them, and the possibilities they were

it because it was twenty times more expensive than our most expensive table, and we sold it. Easy. It was a total surprise.

KUPPER I've seen those tables. It almost has a trompe-l'oeil quality—it goes beyond reclaimed wood and starts to look like ceramics.

EEK Everybody in the world tries to do things efficiently, and the whole idea about this is, let'stry todoitinefficientlyandseewhatcomesout. The contrast with the world and the way we normally behave is so big that I think this is one of the reasons why people like it. It's a coincidence that it works. It's a joke actually. (laughs)

KUPPER Most of your work is one of one. But when you collaborated with Ikea, that seemed like a big leap in terms of mass producing products. How did that project come about?

EEK They were both teachers and they supported me enormously when I was young, but not specifically in what I did. It was always seen as stupid that I was only working with my hands. I didn't like school and so they said, “Okay, he's going to be a carpenter,” which is one of the oldest practices in the world. My father loved that. You hear often from people who are educated that they want their children to also be educated. I also had a lot of energy, high energy—I still have high energy, but at that time it was extreme. I got in fights almost every day at school, and everywhere. I was not the easiest child, but they supported me as a person. Everybody, the neighbors, thought that I would be a criminal or something.

KUPPER So, you put your anger into design.

EEK I was playing football at that time, because I had to get rid of my energy. That was one of the major themes when I was young. After graduation, I started working so hard that there was no energy left.

KUPPER In the beginning, was it the material or was it the objects that attracted you?

EEK I never start with an object. For me, designing is a process that comes to me in a split second. I have in mind what it should be, and then there's an image. I don't know how to describe it. It's not like the product, but I have an idea that is sort of the archetype of what will be made. I won't make it if I can't keep this archetype.

KUPPER I want to talk a little bit about the Calvinist influence within Dutch design, especially in terms of efficiency and the lack of waste. How has that influenced your practice?

EEK If you ask me specifically about the words Calvinistic and efficient, I think about Holland. So, I think within the field of designers in Holland, I'm one of the best or worst examples of this Dutch mentality. I don't throw things away and I want to be efficient. All my work has a pragmatic approach. And I always felt very annoyed about the recycling and eco-friendly stigma that was created around me, because there is so much more to it.

given by nature. They didn't have a choice. This was the very start of industrialization. Since then, of course, we created the sort of endless amount of freedom to choose what you want. It’s the adage of our times. So, if you want to have marble in your home, it doesn't matter because it will be taken from Egypt, put on a boat, and you’ll have it in your bathroom. This freedom is actually a false freedom. I think you ruin the world by thinking that everything is possible instead of thinking that you use what's available around you. For me personally, it's my way of working.

KUPPER There's almost a transcendental aspect of your practice, especially in terms of the extreme labor involved. There are multiple layers of sanding and lacquering. Can you talk about that part of your design practice?

EEK As a child, I made the smallest things, but spent an enormous number of hours on them. Adding hours to something is sort of fun. Maybe it's masochistic, but it's the opposite of what everybody does. I realized very early in my practice that I was fascinated with labor. And why should I limit hours because it's affordable? They are my hours, you know? I also realized that we throw away scrap wood because to keep it on the shelf is too expensive. So, I thought it was totally idiotic that you throw away this material. Why not turn it around and act as if labor costs nothing, and at the same time treat material like it's worth a fortune? Why not design as if the world is like that? And then, we started piling up and puzzling with reclaimed wood from containers. And at a certain moment we made a table, but it was extremely rough. So I said, “Why not lacquer it ten times. As long as it's a lot of work, just do it.” So, we spent as many hours as possible sanding and lacquering. This process was inspired by a found motorboat we renovated years before, which was also like meditation. I wanted the table to be smooth and shiny like the motorboat. But instead of smooth and shiny, it looked like ceramic tiles because the lacquer became attracted to the colors in the reclaimed wood. We thought we would never sell

EEK We got that commission because I met Karin Gustavsson, who has worked at Ikea as a lead designer for a long time. We were becoming friends and each time we saw each other, we talked, and we laughed, and wanted to do something together. Finally, she said, “Okay, we're just going to do it. Next week, I'll call you and we're starting this project.” So, it was very personal. It was not a company thing. It's a nice way to collaborate because it's more about your intuition. In the end, we looked at what resources were available and what we could do with them. They wanted some products for the ceramic industry in Vietnam, and some wooden pieces for the Polish factories, because nobody liked the shiny pine furniture anymore. So, we made a very rough version. She gave me the problems they had and we tried to solve them by designing in a different way than they were used to, which was also extremely funny once in a while. Their factories are used to working in a certain way, so if you try to do something different, you'll get a really funny response. In the end, Ikea has had the biggest influence on the democratization of global design. But I thought it could and should be better. If you make a couch, why don't you put the legs in the right place?

KUPPER I want to talk a little bit about building community in a time of crisis. A central part of your factory is the restaurant. Can you talk about how the restaurant adds to the communal aspect of what you're building?

EEK When we started in this building, instead of hiding away, we decided to open up. More people knew us by then, the collection was bigger, and people were willing to buy our products. So, it was a good moment to change the building and our attitude from being hidden on the street to welcoming. We had a lot of clients coming from far away, so I figured we should offer them something to eat. We had a lunch room, which eventually became a restaurant, and it also becomes like a showroom, a gallery, and a shop, with different products. We wanted to create a complete world, and this became more and more the theme in the building. Last year, we added a hotel, which also has a restaurant.

KUPPER I want to talk about your use of military fabric from tents, which is one of my favorite series that you've made. How did those pieces come about and where did you source these military tents?

"I think you ruin the world by thinking that everything is possible instead of thinking of using what's available around you. "

EEK We always buy a lot of materials and machines at auctions. Right from the beginning, we bought half of our machinery at auction. When there's a crisis, we buy a lot faster. It's good for us sometimes. When the US Army was retreating from Europe and demilitarizing, there was a huge amount of material left behind. So, there are two auction houses that are both Dutch who sell these materials, and one of the things they sell is army tents. I liked the fabric. It's a beautiful material. The quality is, of course, amazing. And the funny thing is that we sell most of those items to America. So, people buy the Dutch made, highlabor-cost products, relatively expensively with American fabric. And it goes back to New York and LA. There’s another funny joke.

KUPPER What is your advice to young designers in terms of solving solutions for this new world that we're in?

EEK That's a difficult one, because it seems hard for young people to find the proper way. For more than a hundred years, you negotiated your hours so that you work as little as possible for the most money possible in order to be able to enjoy your free time. This is nice, but it neglects the quality of work. If you work three hours a week and it's lousy work, then you will never be happy. And now, they don't want to work because if it's only for money, there’s no real value in that. The whole idea is that you have to find a balance between work and freedom, but you also have to find the quality of work that you are satisfied with. I think now is the perfect time to experiment with this idea. Designers have a beautiful profession that can be fulfilling. To create is the most wonderful thing in the world. For me, the way I approach work is to first create the environment. With nice people and a nice place, chances are that you'll be happy.

Greg Ito describes himself as a storyteller. Known primarily for his paintings—bearing a distinctive, illustrative style that omits the gestural painted mark, masking the presence of his hand almost entirely— the Los Angeles-based artist’s recent experiments in installation and performance are perhaps his most personal work, laden with family stories and heavy with questions of responsibility to those experiences. We met virtually for this conversation, where I asked Ito about this choice to engage more intentionally with his own history and beliefs in his art practice.

ANNI PULLAGURA I’ve been thinking about empathy in contemporary art, how some artists are tasked with helping people deal with their feelings about really large systemic or personal traumas. And then, thinking about how artists choose to engage with the burden of having to account for these histories through artwork.

As much as I believe that art is a way to ask really difficult questions, I’m also cognizant of who gets tasked to do that work and who doesn’t have to necessarily address those kinds of questions.

GREG ITO I have been coincidentally thinking about a lot of the same ideas. I’m an artist, and enjoy curating, and I contribute to our family-run space Sow & Tailor in LA. I just love art. I grew up around art and I’m fortunate to see and experience a lot of it.

I’m a fourth-generation Japanese American, but growing up I didn’t feel the burden or pressure of being overly Japanese. I still hold my Japanese ancestry very closely and the memories I had growing up at my local Japanese Community Center in Venice, but I had to distance myself [because I felt that] my art was not focused on being Japanese American, and needed to develop in a broader cultural spectrum. It was really just about emotions. The first body of work that I really felt like, this is me, are these vignette paintings inspired by Rothko that I started painting in 2014. They have these segmented registries on the painting where I placed symbols and scenes—painted flat and crisp so you don’t see the artistic hand. I wanted to remove myself from the surface, [so that the painting exists] like how a sign lives on the street.

It’s there to communicate with an audience, but it’s not supposed to show the gesture of the artist. I wanted these paintings to present openended stories where they are inspired by my personal life and things that I was going through, but offered a visual space for others to reflect on their own personal histories and experiences.

Over time, I started seeing these segmented areas in the paintings begin to overlap and open up. They started to become portals like a window, doorway, or a keyhole. It was becoming more of a world that I was creating. That’s how my experiences became an entry point for me as an artist and the growth of my practice.

I think right now, a lot of people are using identity to give structure to their work, and they’re retelling stories that are important to them. Every artist should tell their story, but I’ve been wondering what happens after these histories are unearthed. Recently for the first time in my last exhibition at ICA San Diego, I told my family’s story in depth. I’ve never done this before. I could only share the little I knew, which was hard to talk about, even for my grandparents when they were still with us. Growing up, they didn’t want to talk about their experiences in the camp. They were young when they were interned. After the war, they just wanted to acclimate to normal life, to let go, to live on, and start a family. As a person from the younger generation, you hope to preserve those things that can be lost. If these histories aren’t recorded, they’re gone forever. And I used to beat myself up over it because I really have trouble remembering all that information. I don't have the time to archive everything. It's a whole lifetime's

worth of work. And for me it's like, what do I hold onto? Do I hold onto all the little grains of sand and as much of the information that I can, or do I just hold a polished stone? The transformation from a deep, expansive past experience to a more simplified family legend or folklore.

These are the things I think about—the fragility of memories and the pressure that younger generations have to preserve those memories.

PULLAGURA I’m interested in how you describe the segmented sections in your paintings as a breakthrough—that you'd found a form that was interesting for you intellectually, but also formally. Treating the canvas in these disparate kinds of sections provides many entryways into the artwork. The window or the keyhole is as much about the viewer coming in from their own perspective as it is about you pouring yourself into these separate sections on the canvas. That’s an interesting way empathy can be performed unexpectedly in the art encounter, leaving the experience open for people and even yourself to come and go.

ITO I like to frame my work as if you were to look in a dirty mirror. It's not clear but it’s still a reflection of yourself.

First and foremost, access is one of the most important things in my practice. You don't need to know my history or read a thick text to understand it, to enjoy the work, or even to be critical of it. But specifically for my show [All You Can Carry] at ICA San Diego [North], I really just wanted to share our story so that people knew more about me as an artist; where I'm coming from, and my inspirations for living. It felt safe to unpack

this history at a museum versus a commercial gallery. Painting, sculpture, installation, and family ephemera coalesced into an exhibition. It came together with a final performance of me carrying buckets of water up this hillside [where an installation of a charred house foundation acts as a flower bed]. At first, they were going to be large, five-gallon buckets filled to the brim with water, and I wanted it to be this strenuous struggle.

In my head it sounded so beautiful, because my grandfather walked up a hill to keep watch at the [Gila River Internment Camp, Arizona] camp’s water tower every day—that was his job there. I thought I wanted to replay those feelings where I'm carrying this water and the trauma of their experience. But the performance ended up so intimate and so quiet and peaceful, and it made me realize I didn't need it to be a strenuous, sad, backbreaking experience. I don’t even know for sure what his feelings were walking up that hill every day. Instead, I needed my performance to be nourishing and accommodating for whomever showed up. It gave me space to ask myself, how do I really want this performance to operate, and why am I sharing our story? Did I want people to just see me struggling, so they feel bad for me and for my grandparents' experience—one that I’m still learning about myself? So, I was like, okay, it's not about exploiting this struggle. I selected smaller buckets for the performance, and at first it was just gonna be me sprinkling the water on my outdoor installation at the top of the hill where seeds were planted by visitors, but at the last minute I asked [my wife] Karen and [my daughter] Spring to water the sculpture with me. And then, I asked the audience to water the seeds and just think about whatever connects with them. In the end, it had to be inclusive and a transformational moment for everyone, not just me.

PULLAGURA It’s an important question: why do we expect suffering to be instructive? I’ve heard you speak before about how sometimes a loss of that past can be instructive, too. What does it mean, and how is it possible to let go of the pressure we put on ourselves to account for our incomplete stories? That sense of incompleteness reminds me of how you remove your hand from your painting, that gesture of markmaking. Perhaps accepting the incompleteness is a refusal to perform certain expectations about how to tell your story. There’s also a sense of protection in that absence of the artist’s hand, or the covered faces in the family photographs you exhibited, not just your family’s personal stories, but also protection for yourself as an artist.

ITO And the protection of my daughter. I don't want her to have to feel that pressure to carry these stories if she doesn’t want to. My brother is a research-based artist. He really respects the way that things should be done, and how information should be accessed, and cataloged and shown, and he has taught me a lot about that. We were talking one day and he's like, “You know, we're gonna be the ones that carry the family legacy, out of all our cousins.” In my head, I was just like, I don't want that responsibility. Thinking about it made me shake, because it really is hard to carry those expectations on your shoulders. Obviously, I want

to preserve as much information as possible about my family, but the way that he said it struck a chord and made me think. If I’m always cataloging and archiving the past, I feel like I'm missing out on what's happening in front of me, you know?

PULLAGURA There are different ways that responsibility to the past can be carried forward. There's the cataloging, the archiving, and preserving for whatever future purpose. Storytelling is another way, too. There are things that are held in stories that will always exceed the catalog and the archive.

That makes me think of your comments about the liberation of loss and what that means: to acknowledge the fear of loss and giving that fear its place. Just like the seeds you had visitors plant in your ICA San Diego exhibition, and then watered months later, or the butterflies that left

exists and you need to have a splash of chaos in your practice. Most artists are very chaotic, but having some chaos integrated into the actual work is great.

I like a lot of the California conceptualists’ work, like Chris Burden, Paul Kos, postwar Japanese performance, like the Gutai movement. And then Ed Ruscha and John Baldessari. And I loved looking at Takashi Murakami when I was growing up. I feel like all of those artists embrace chaos in their own special ways. You can see how their work synthesized into my practice. And then Urs Fischer, who’s an artist that’s like, I'm gonna do whatever the hell I want and I'm gonna stick it in the same room and you're gonna like it. When I saw his show at MOCA in LA, it blew my mind—specifically the participatory elements. The clay installation

and reproduced somewhere else at your solo exhibition with Anat Ebgi Gallery in Los Angeles. At a certain point, we have to let go of that control, or that need to be responsible for the future in a direct way. It’s so much larger than each of us.

ITO I'm just trying to allow myself to not be in control of everything. I'm very much detailoriented and feel a need to keep agency and control—you can tell by looking at my paintings and installations, perfectly tailored. But having to hold onto something for so long, it gets tiring. I can give myself a little bit more breathing room by allowing myself to be who I am and not feel so heavily tied to ancestry. I would rather be empathetic to the communities that share the same kind of stories. How are we all connected? That's the big question. Because I was talking about it with my studio manager and she said, “We're going through a global extinction event. Now it’s official.” And I'm like, wow,allthis preservation,allthishardwork,allthisfrustration and hardship is just going to fade away, just like all the other civilizations that lived before us. The only thing that is going to be remembered is what gets dug up out of the ground. I know that sounds really dark.

PULLAGURA No, I really don't think it is.

ITO It’s dark, but it's also beautiful, too. You know, being able to live your life knowing it will end one day. Like with my daughter, Spring— she has been the inspiration for everything since she entered my life. She was the inspiration for my last solo show, the big installation with the butterflies. She was the inspiration for my ICA San Diego show, my first museum show—I want her to know her dad wants to share our history and for her to be a part of it with the performance. I really wanted her to be there, because there was a chance she couldn’t make it and that broke my heart. I'm kind of realizing it right now, talking to you, that I needed to have elements in the work that I couldn't control. There’s a chaos in life that

at the Geffen Contemporary, he just had tens of thousands of pounds of clay dropped off at the museum and invited normal people to come in and sculpt whatever they wanted. The whole square footage of the museum’s industrial location in Little Tokyo was full of everybody's little, handmade objects. It was beautiful. It was a show shaped by the people.

PULLAGURA So, do you think you'll do performance again?

ITO I want to do more performance, for sure. I learned a little bit from doing it this first time, just scratching the surface, but I was so vulnerable. I was like, Idon'tknowwhatI'mdoing. I don't know how people are going to react. Will people think this performance is stupid? There were a lot of inner child moments I had to face. But I’m happy I did it and I’m happy my family was there to support me. It will have shaped my practice forever.

PULLAGURA The vulnerability of art making is something that I'm continuously impressed by of artists.

ITO It's intense, you know? During the months leading up to the ICA San Diego show, it was just so taxing on me, an emotional whirlwind. It even caused some friction with some of my family members too. My brother was tapping me on the shoulder being like, “Hey, you know, I'm not telling you how to do things, but….” It really informed me of how working with this material is important and needs the time, space, and energy to talk about correctly. And then, you see other artists who aren't taking those kinds of considerations and it just seems a little exploitative when done cheaply. Having down time between my exhibition and the performance was super important, because it allowed me to heal and re-center myself. And then, when I did the performance, I was like, this isn't about me suffering for my grandparents’ experience. It's just about being with my family and people, focusing on watering these seeds

together and helping them grow from the ashes. And yes, the performance was inspired by where I came from, but it changed to be about this new journey I’m embarking on, together with our group procession carrying life’s nectar, water, to this high vantage point on the hill with the cool breeze on our faces, the sun setting and for everyone to just share a nice moment with strangers, feel safe, held, and listened to. In the end, it wasn’t about me. It's about us.

PULLAGURA I wanted to make sure to talk about the environments that you create to present your paintings. You described them as staged treatments. How did you arrive at that?

ITO When I was in school, there was a big relational aesthetics conversation happening as well as the agency of the image versus object, and how things are staged and placed around one another shaping the viewer's experience. How does one object give context to an image and vice versa? And then, how does the work create social circumstance? It was very much about exhibition design to me, tailoring an experience for viewers, and also being able to access different ideas with different mediums. I grew up painting, but also hated painting at times. I received a BFA in painting from SFAI and I was in the studio every day, but there was a New Genres department too. So, I did a lot of New Genres courses to mix things up. George Kuchar was teaching there at the time, and my painting professor Carlos Villa, an amazing Filipino painter really pushed what a painting can be. Also, Paul Kos would come by the campus once in a while too. That school had such a rich history. As I was focusing on painting in school, all these new conversations were happening and was just like, what am I doing? So, I started making sculptures and diving aesthetically into this kind of cleaner style of exhibiting work, which was very clinical, clean, minimal. You know, enjoy the beauty of this empty floor kind of work. It's delicate. It's very sensitive. But then, all my friends who weren’t in art school were like, what is this? They told me, “I miss the paintings.” And I was like, this is not the kind of art I wanna make. Why am I making art that only the art community can connect with? This is not how I want art to operate in general, to be exclusive and inaccessible to others that don’t have the same training as me. When I moved back to LA from San Francisco, I started seeing how these new paintings I was making operated on a whole new level, where I'm connecting with people. I'm telling my story; they're telling their stories. There's this very intimate exchange, and I wanted the space to conduct that without me being there.

So, I needed to start fabricating space as an open hand to hold and guide the viewer, using that exhibition’s design to build a transformative experience when visiting the show. They look at the paintings, they turn around, and they see a sculpture with an object from that painting. They turn around again, going back to reinvestigate the painting, the way it flows and carries into the next work and the next. When I moved back home from my time in San Francisco, I was basically starting from scratch. So, I started working on movie sets in the art department and working on scenic

and props mainly for commercials. I took this use of “treatments” like lighting design, painted walls, and floor coverings and injected it into my art practice to see how I can build experience, because experience is what shapes people, and experience is what we hold onto, and experience is transformational.

PULLAGURA I learned from another curator the principle that an exhibition is an argument made in space. It’s about the environment and the movement and relationship between objects and people. I think about the haptic experience when organizing an exhibition: how will this feel in space, in these relations?

ITO At the Anat Ebgi exhibition I did a sound installation, something I’ve never done before. It was the sound of waves sourced from a sound machine which we actually had in our room throughout my wife’s pregnancy during the peak of COVID in Los Angeles. It was a difficult pregnancy, and it was a time of high stress and anxiety for us, but it rested on her shoulders more heavily. The sound machine played 24 hours a day, and really helped her drift away and have a little bit of peace during these difficult times. So, for the show, I built a house in the gallery, one large enough that you could walk inside of it. The front of the house looks like a cute little homestead, a symbol of a home that I was painting a lot in my work. At first it looks inviting, but when you step into the house, the whole back side was burned down. It was just covered in black and it smelled like burned wood. And the inside of the house was painted super bright red, which just evoked this heightened sense of anxiety, but with the sound of waves lapping over the sand playing over and over and over again brought a contrasting sensation to the room. And it is this contrast that I feel we all have within us. When someone asks us how we’re doing, we normally say “I’m good” or “I’m okay,” but in the back of our minds we all have this fire that is burning. It could be the loss of a loved one, someone who is sick, maybe even a parking ticket that pushed us over the edge that day. Life is like a rollercoaster. It goes up, it goes down, it goes side to side, and flips, and turns onto itself. It’s scary, but it’s also joyful and exciting, and sometimes it’s just best to let go of the safety bar, put your hand up, and enjoy the ride.

How is one? One is buoyantly dysphoric. I dreamed about the nuclear war and Putin kept dropping bombs whilst I was cutting down a Christmas tree in the woods. The truth is, the horror of Christmas is far more a reality for me than the war. It’s all happening at the same time. I mean, I’ve been up since 3:30 am; watched Queer Eye all night. Had three coffees before dawn at the hotel bar. Great time to be doing a solo show. I’m so in despair with Europe, it’s terrifying. The lines between left and right are very thin. They don’t real ize it but they are merging. In the end we all were Thatcher’s children. I don’t know what’s going on but half of the park is closed. Is it mercury retrograde? Anyways, I’m navigating around it. Have I mentioned how much I hate people? It didn’t really sink in until Monday when I woke up. That stuff creeps up on you.

I am so bored of the art world not being able to be comfortable with looking at the work in the context of its space. Let’s face it, Du champ put a urinal in a gallery—no need for explanation. Did I tell you I dreamed about Darth Vader the other day? Dreams and con sumerism are both really interesting. There is a brilliant quote about how artists are the ‘stormtroopers of gentrification’. Makes me wanna go to Mayfair again. Instead I’m sitting at Elephant Park with my feet in the fountain reading Specters of Marx and filming dogs.