by Annie Powers

by Annie Powers

envisioning new futures with THE Centre Pompidou, PARIS

Reframing Narratives with THE National Portrait Gallery, LONDON

FOSTERING GLOBAL DIALOGUE with THE Leeum Museum of Art, SEOUL

Elevating Underrepresented Voices with THE Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Exploring Craft and Architecture with THE Power Station of Art, Shanghai

Left: Architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers.

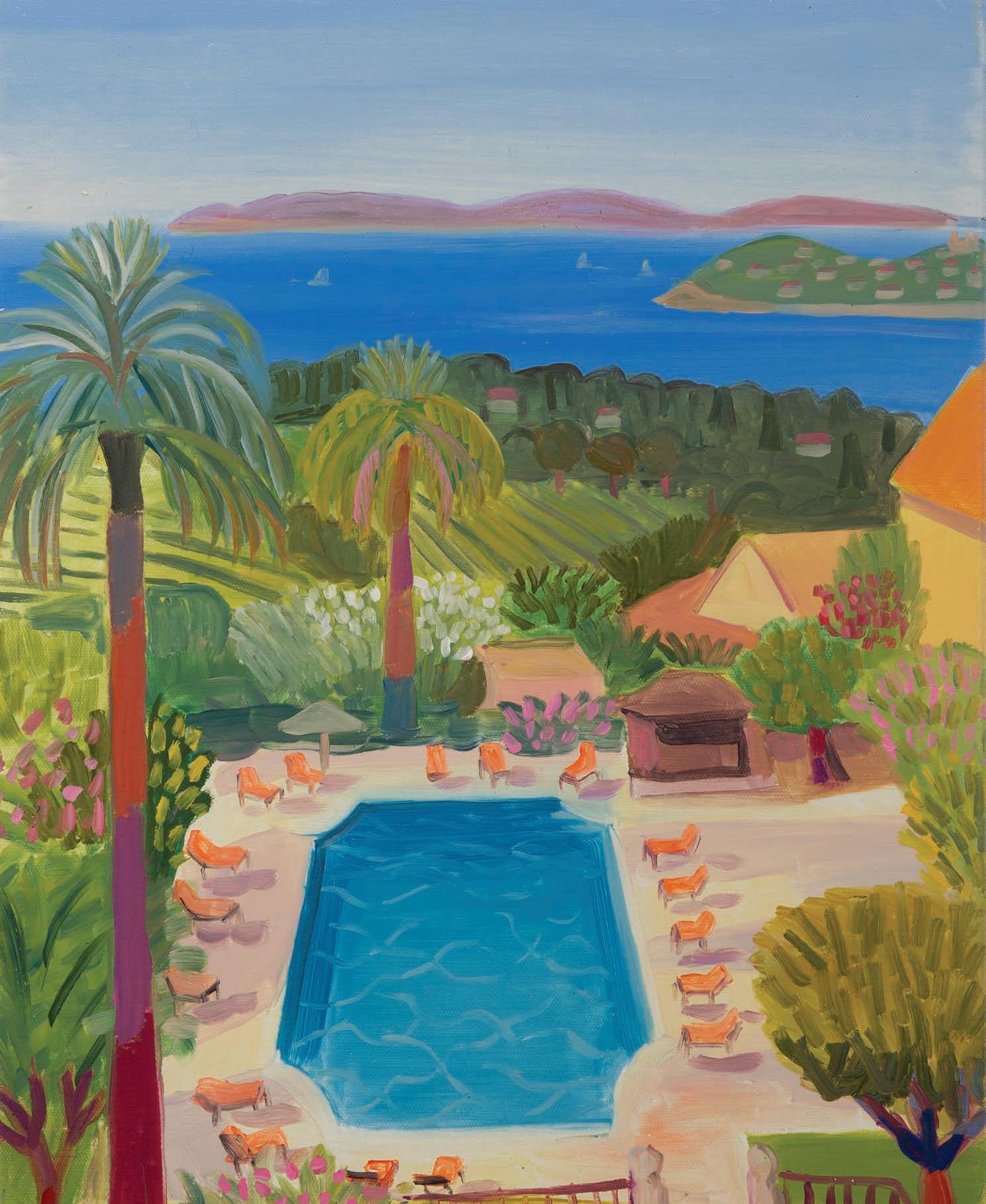

HALF GALLERY

NEW YORK

September 16–October 14

Steve Turner | 6830 Santa Monica Blvd | info@steveturner.la

Steve Turner | 6830 Santa Monica Blvd | info@steveturner.la

10 Lars Chittka Spirit Of The Beehive

14 Ponte

Photography by Jermaine Francis

22 Steve McQueen

Notes On Sunshine State

Text by Abbey Meaker

26 Julian Charrière

Interview by Oliver Kupper

50 John Waters & Gregg Araki

Another Homo Conversation

66 Devendra Banhart & Isabelle Albuquerque

In Conversation

Photography by Magnus Unnar

74 Power Images

Paul McCarthy & Judith Berstein In Conversation

92 Camille Bidault-Waddington Variations On A Theme

100 Alexandra Bachzetsis

Instinctive Gestures

Interview by Summer Bowie

110 Jan Gatewood

Attitude Becomes Form

Interview by Ikechukwu Casmir

Onyewuenyi

122 Emma Stern

Interview by Evan Moffitt

Photography by Jason Miller

132 Mike Kuchar

Interview by Oliver Kupper

Portraits by Pat Martin

142 Hajime Sorayama

Interview by Jeffrey Deitch

Photography by Flo Kohl

152 Harmony Korine

AggroDr1ft

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist

168 Jonny Negron

Edible Suffering

Interview by Oliver Misraje

178 The Animal Within Knows Better

Text by Angelo Flaccavento

180 Love Is A Primal Instinct

Balenciaga Winter

2023 Collection

Photography by Peter Ash Lee

Styling by Julie Ragolia

192 The Anatomy Lesson

All Clothing Hermès

Photography By Carlota Guerro

Styling by Julie Ragolia

208 The Archive Of Becoming

Photography by Jeremy Grier

Styling by Ronald Burton III

220 Now Why See

Will Always Be, New York

Photography By Annie Powers

Styling by Julie Ragolia

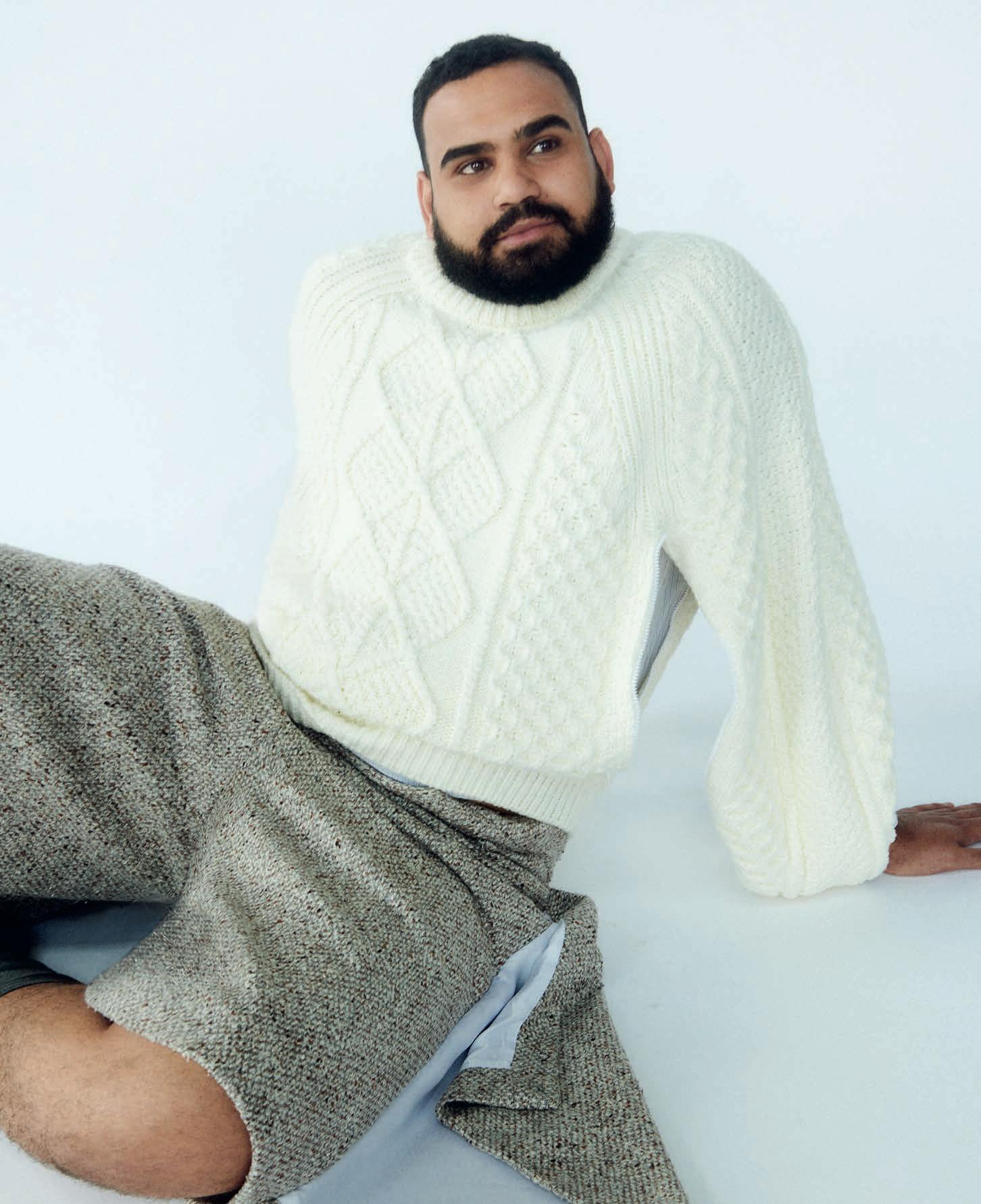

238 Metamorphosis

Photography by Parker Woods

Styling by Julie Ragolia

252 The Others

Photography by Fiona Torre

Styling by Julie Ragolia

270 Martine Syms

Text By Estelle Hoy

Photography by Kennedi Carter

282 International Defence Exhibition

Photographs By Roman Goebel & Jelka von Langen

Text by Oliver Misraje

300 Opioid Crisis Lookbook A Speculative Semiotics Special By Dasha Zaharova & Dustin Cauchi

Covers, from left to right

Harmony Korine by Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hermès by Carlota Guerrero

Samu by Parker Woods

Grace Valentine by Peter Ash Lee featuring Balenciaga Winter 2023 Collection

Now Why See by Annie Powers

Gregg Araki & John Waters

Martine Syms by Kennedi Carter

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Oliver Kupper

MANAGING EDITOR

Summer Bowie

FASHION DIRECTOR

Julie Ragolia

MARKET EDITOR

Cathleen Peters

ART DIRECTOR

Martin Major

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Alec Charlip

Camille Ange Pailler

Hakan Solak

Oliver Misraje

EDITORIAL ADVISER

Jeffrey Deitch

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Annie Powers

Bennet Perez

Carlota Guerro

David Brandon Geeting

Dustin Cauchi

Fiona Torre

Flo Kohl

Jason Miller

Jelka von Langen

Jeremy Grier

Jermaine Francis

Jesper D. Lund

Kennedi Carter

Levon Biss

Magnus Unnar

Nick Sethi

Parker Woods

Pat Martin

Peter Ash Lee

Rita Lino

Roman Goebel

CONTRIBUTORS

Abbey Meaker

Angelo Flaccavento

Camille Bidault-Waddington

Estelle Hoy

Evan Moffit

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi

Ronald Burton III

FASHION ASSISTANT

Sydney Sullivan

INTERNS

Barbara Norton

Chimera Mohammadi

Iris Stigell

Mia Milosevic

Rebecca Kremen

THANK YOU

Academy Museum

Ben Thornborough

Chateau Shatto

François Ghebaly

Gregory Gestner

Half Gallery

Hauser & Wirth

Hermes

Silke Lindner

Sprüth Magers

Strand Releasing

The Box Gallery

TYPEFACES

Dinamo

PRINTING

KOPA OFFSET PRINTING HOUSE

Industrijos g. 12, Kaunas, Lithuania

www.kopa.eu

OFFICE AUTRE LOS ANGELES

6711 Leland Way Los Angeles, CA 90028

GENERAL INQUIRIES, ADVERTISING & DISTRIBUTION

info@autre.love

FOLLOW AUTRE @autremagazine www.autre.love

ISSN 2767-7958

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Everything is instinctual. Buried deep in the hard drive of our genetic code, and in the cloud of our unconscious, we roam the earth guided by hidden, unlearned impulses. Although we are barely an evolutionary leap from our simian antecedents, our primitive instincts drive us in profound ways. Exploring our instinctual drives is important because it might answer unanswerable and eternal questions, like why do we make art? Although the answer is often a paradox, these epigenetic mechanisms are a complex biological blueprint for why we left palm prints on cave walls or why our bodies move to the beat or music or ornament our bodies.

Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung believed there are five essential instincts, or “psychic activities” outside of our control: creativity, reflection, activity, sexuality, and hunger. Jung also believed that fashion—ornamentation of our second skin—is part of these instinctual drives. He surmised that tapping into these drives would unleash us from the repressive shackles of the civilized world.

Understanding our unconscious mind and the symbols of our dreams can help us understand the “forgotten language of the instincts.” How can these intuitive motivations help us navigate our new scorched earth and imagine a better future? The instinct issue is an exploration of these animalistic and mammalian hidden hereditary desires pulsating just under the surface and the symbols we produce to deny our ancient animal selves.

This issue is a dark and seductive Jungian exploration of these buried, hereditary desires pulsating just under the surface. How do we break out of the hive mind and listen to our intuition?

— Oliver Kupper and Summer Bowie

Instinct is biologically hardwired into all organisms, but that doesn’t mean these ancient inclinations can’t be rewired and recoded to adapt to a changing world. For the past five decades, German zoologist Lars Chittka, a widely cited expert on insect sensory systems, behavior, communication, and cognition, has performed groundbreaking experiments with honeybees and bumblebees. Using flower reward models, he has discovered that these insects—once thought to be simple robotic droids of their primitive nature—have powerful emotions that rival humans. Chittka and his team have discovered that bees self-medicate, use tools, foresee the outcomes of their actions, and learn complex dances in the dark of their hives to share the location and distance of food sources. His book, Mind Of A Bee (2022), gathers his deep insights on bee intelligence and looks beyond the hive mind psychology. But what can bees teach us about ourselves?

Interview by OLIVER KUPPER Portrait by JESPER D. LUNDAn Interview of Ecologist and Zoologist Lars Chittka On The Emotional Intelligence of Bees

OLIVER KUPPER What is your definition of instinct?

LARS CHITTKA That's a very good question. As opposed to a behavior that's acquired through learning, it's one you are equipped with from birth, or you're pre-equipped to develop at some point in life. That doesn't mean that it's unalterable, but at least there's something there from the start. We humans often think that we're entirely free from instincts. And we are perhaps freer from instincts than most other animals, but we do have them. There are behavior routines that are common and pre-configured in all humans—so long as they don't have any disorders—such as language: the key ingredient of culture.

KUPPER In your book, The Mind Of A Bee (2022), you have a chapter dedicated to instinct. Can you talk about how instinct plays a role in insect intelligence and emotion?

CHITTKA There is a sense that insects are basically little robots that are entirely pre-configured with everything they need to do in their lives. It is true that there is an amazing repertoire in social insects when it comes to innate behaviors. In honeybees, the construction of a hexagonal honeycomb is at least partially innate. They fine-tune it by learning, but no other animal does it in this form, and to some extent, that is an instinct. Likewise, the ways larvae are provided with food are instinctual. So, there is a very high diversity of innate or instinctive behavioral routines in social insects. But on the other hand, they can learn a lot. And that is the part that's often forgotten. I think people see this as being one or the other: if there's lots of instinct, then these animals might not be able to learn much. Of course, we have discovered that they not only learn things that you might predict, like how to use flower colors or scents as predictors of the sugar rewards that bees find in flowers, or the location of their hive, but they can also learn things that they don't encounter in their daily lives. They can count, recognize images of human faces, use tools, and manipulate objects. They are pre-configured to be really good learners. There are also some good examples where instinct and flexibility come together. For example,

they obtain all of their nutrition from flowers, which means that they have to be really good at finding just the flowers that offer the best rewards. This means they have to then learn how these flowers look. Bees can learn to associate flower signals, patterns, and colors with rewards, but they don't know which particular signals these will actually be; they're flexible in that regard. Having flexibility is part of their configuration.

KUPPER When did you become interested in insects, particularly bees?

CHITTKA I've worked with bees since 1987. Even as a kid, I found them fascinating in terms of their weirdness. My mother reminded me recently of when I liked to use my fishing net to catch about a hundred hornets by putting the net over the nest, and then the net over a bucket. I had this whole bucket full of hornets and miraculously managed not

to get stung. My parents were completely freaked out by this. Also, I had this single by The Cure, “The Walk” (1983), which featured a big fly on the cover. I was probably about eighteen then. This was a while before I became interested in insects scientifically, which started later in the ’80s.

KUPPER In the beginning, you weren’t necessarily focused on insect intelligence or sentience.

CHITTKA For a long time, I was fascinated by the perceptual world of bees—the way that they see the world in completely different colors and through completely different sensory filters than we do, and to some extent, by their intelligence. For example, the numerosity study was quite early actually in my career. That was in the early ’90s. At that stage, and actually, for another ten to fifteen years, I didn't yet extrapolate from the work that we did on bee intelligence the question of, hey, if they're that smart, maybe they also can feel something? It was a very different world then. When I was a Ph.D. student in the ’90s, I remember discussions with established neuroscientists who claimed that there was nothing to worry about by doing invasive neuroscientific procedures on cats or monkeys, because they weren’t considered sentient. Of course, now there is much more scientific work on animal welfare. In the entire field, we're nudging each other to explore these very different minds from ours.

KUPPER There's nothing scientifically conclusive, but you're pretty close to confirming that bees can indeed feel things.

CHITTKA You're right. There's no universally accepted proof that anything is conscious or sentient. And we see this very prominently at the moment in the media when people are asking the question of when artificial intelligence systems could be sentient or conscious. It's not an easy question. We have to rely on probabilities and common sense. For anyone with a pet dog, if you know your animal well, it becomes quite obvious that there is something going on in their heads—they're not just reflex machines. But there are still people out there who claim that the human animal is the only one with consciousness. With bees, as you say, like with other non-human, non-speaking entities, we still have no certainty. But from the probabilities that we see across

a range of different experiments—not just psychological or behavioral studies, but also neurobiological and hormonal ones—it seems quite likely that there are some emotions.

KUPPER And it's impossible to know what those emotions are. However, it's still interesting to speculate.

CHITTKA As you suspect, it's very hard to answer that question. Even in humans—let's say we identify a piece of music that we both like, we might feel the same thing while we're listening to it, but it's very hard to compare such things. It’s even more difficult with an organism that can't verbally comment on what it's experiencing.

KUPPER But bees have some kind of language. Can you talk a little bit about the language of bees?

CHITTKA The communication system of bees, of course, is fantastically alien. They communicate through stereotypical movements or dance. They do this on a vertical surface in the complete darkness of the hive. They can't see each other, so they have to feel each other doing this dance. And the dance language informs other bees within the hive of the coordinates of a food source. They are dancing in a roughly figure-eight-shaped movement pattern again and again. Where the two lines cross over on the number eight, there is sort of a horizontal section where the bees run straight ahead before doing a semi-circle to one side, then a semi-circle to the other side. But this central straight run is the most informative bit. The angle of the run is relative to the angle of the food source relative to the sun and the hive. So, if that run goes straight up before doing the next half circle, that tells other bees to fly in the direction of the sun. So, up means fly to the sun. If it's straight down, that tells the other bees to fly opposite the direction of the sun. And let's say if it's 90 degrees to the right of gravity in the darkness of the hive, that tells other bees to fly 90 degrees to the right of the sun. The longer this run, the further away the food. So, there is a kind of symbolic indication of the direction and distance. And to come back to the overarching theme here, this is of course an instinct that is on display. No other species of animal does anything even closely similar. Back to the dichotomy between instinct and learning, just a

few months ago, there was a new study that came out showing that honeybees have to learn precision in their dance. If they don't get the opportunity to attend other bee dances while they're very young, they still display the dance language, but it’s quite a messy dance and not very accurate.

KUPPER Our relationship with bees is ancient, which makes them even more important to understand. Can you talk a little bit about our history with bees and human civilization?

CHITTKA Most people are now aware that bees are important because they pollinate our crops and our pretty garden flowers. That's a perspective only through utility, of course. But the other thing that they provide for us is sweetness by way of honey. For many millennia, before you could go down to the convenience store to buy a bag of sweets, the sweetest food was honey. And people have known this for a long time. There are many prehistoric cave paintings depicting humans raiding honeybee colonies. In prehistory, before people came up with the idea of putting bees in boxes, they were stealing from wild colonies because they knew it was such a precious commodity. Beekeeping became a trick to have constant access to honey. This happened in many cultures, not just in Europe. The Mayans had their own species of bees, Asian bees were also kept for many millennia, and then in Egypt as well. So, this practice of

keeping bees in boxes for honey production is also an ancient one. On top of that, in many cultures, bees, because of their perhaps complex societies, were revered as deities or something magical. For example, in the Mayan culture, there are beautiful depictions of the bee queen. And there are some people who think that the consumption of energy-rich honey in our distant evolution might have given us the kind of energy that we needed to grow our brains as big as they are. It's a beautiful speculation.

The interesting thing is that, indeed, all great apes also steal honey from bees and many use two sticks to reach into bee colonies to steal honey. Even some present-day hunter-gatherer societies still spend quite a bit of their time looking for honey in the wild. It’s a very precious commodity, and it's been with us for a long time.

KUPPER I've seen footage of people harvesting hallucinogenic honey.

CHITTKA This is in tropical Asia where some species of bees actually do not nest in boxes and can't be domesticated because they're actually very aggressive. They're also huge. They are hornet sized. They have just a single two-dimensional comb, but it's the size of a steam engine wheel. They're huge structures, usually attached to overhanging cliffs or sometimes tall trees. The honey from these colonies is not easy to obtain because you have

to climb up and down at great heights. Some varieties of this type of honey are hallucinogenic, but others are just revered for their sweetness. Harvesting the honey involves tying a really flimsy ladder to a tree at the top of a cliff, then climbing down this ladder with no protection. It's part of these professional honey hunters' pride that they don't wear a veil. They're also suspended several dozen meters in the air, under constant attack from these highly aggressive bees holding on with one hand to the ladder, they then cut pieces of comb from these colonies while someone else underneath stands there with a bucket trying to capture and catch the pieces of comb. So, you’re risking your life in multiple different ways at the same time.

KUPPER Industrial beekeeping causes an enormous amount of stress to the hives. Can you talk about almond milk harvesting in California and the damage done to bees that are used as pollinators?

CHITTKA The usage of bees in this sort of big business pollination industry is probably aligned with the outdated notion that they are reflex machines and there's nothing to worry about. Imagine during the peak of the Covid pandemic, moving the entire US population to Long Island, keeping them all there for three weeks, and then sending everyone back. There wouldn't have been a single person spared, presumably. But that's more or less exactly what happens with migratory beekeeping. A large fraction of North American honeybees are ferried into a very tiny portion of the country where they are exposed to monocultures of flowers, which are also heavily coated in pesticides. So, there's no diversity of floral food. And then, they're brought back to either their region of origin or another part of the country where a different crop is growing. All of this, of course, is extremely stressful. You have seen these reports of Colony Collapse Disorder in the media. In my opinion, this is just basically the result of very inconsiderate beekeeping practices. Your average backyard beekeeper who looks lovingly after a few colonies, typically doesn't have these same kinds of problems.

KUPPER Aside from dismantling monoculture industrialization, what are some of the solutions for protecting bees from these industries?

CHITTKA I think it's fair to say that any improvements in welfare will cost money. If you want to pollinate the California almonds while also taking into consideration the welfare of the bees, then you'd have to do it with fewer bees—with hives that are in the area anyway. It's possible that having a reduced number of bees, and largely local bees, would probably reduce the crop to some extent. Of course, you'd also have to provide more than a monoculture. And you would have to set aside some field margins to grow other wildflowers so that there's more diversity. But I'm guessing farmers won't necessarily like that because it will cut maybe 10% of the area that they're currently using for almond monoculture. The price of your almond milk might go up a bit, but I think that's probably what needs to be done.

KUPPER What's the greatest lesson you've learned from your work with bees?

CHITTKA Well, the big picture idea is that I have more respect for the strange minds of other animals. My journey began really with a fascination for the strange sensory world and the general strangeness of social insects. In the past, people have commented that bees are a bit like magic—the more you draw out of them, the more you discover. And on a discovery-by-discovery basis, it's been a bit like that. When we first found out that bees can count, everyone stood there in disbelief. And that continued when we trained them to recognize photos of humans. And when we first saw them rolling a ball to a destination, and so on. Five years earlier, we wouldn’t even have thought this was possible. There have been lots of really rewarding things that we've had the fortune to see.

In one experiment, bees chose to roll balls around rather than visiting feeding stations—a form of play. Courtesy of Levon BissHarry Pontefract is one of the most promising young clothing designers working today. After graduating from Central Saint Martins, he met Jonathan Anderson and worked for Spanish luxury fashion house Loewe. After six years, he started his own label. Ponte is a deeply intellectual treatise on the clothing as a second skin, a parable for identity in an age of blurred truths and climate disaster. Ponte is a beautiful farrago of deadstock fabrics, discarded objects, and unorthodox silhouettes—the results are textile sculptures that challenge traditional sartorial expectations.

Fashion by HARRY PONTEFRACT

Photography by JERMAINE FRANCIS

Denim jeans with studded elasticated waistband

Deadstock shearling hooded dress and vintage cap

Models: Ker @ Menace, Ryan Skelton

Hair: Masayoshi Fujita

Makeup: Maho Moriyama

Casting: Tytiah @ Unit C London

Lighting: Pro Lighting London

Retoucher: Jonathon Doe

Photographer Assistant: Ian Conspicuous

“Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments, only later do they make themselves known, from their scars.”

Chris Marker

What if instincts are actually descendants of memories? Memories are fragmented downloads of experiences–impressions, the essence of things seen, felt, endured. My father’s roses, the grass my mom planted over his garden–its smell, light through trees animated by the wind, the transporting song of a mourning dove. These interior recordings create invisible, connective chords, memory material. We come in with genetically encoded instincts; some may be translated memories of our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etcetera. They too were linked by invisible chords, to each other and beyond. This ‘memory material’ creates an ever-expanding web of desires and drives that evolve through our own becoming.

Some of these instincts may be innate, raw materials, while others are profoundly individual, organic. In one person, suffering will create a prison and in another, liberation. Perhaps it is the soul, the unknowable thing that pushes us through time with a deep sense of knowing: material folding and unfolding. I would argue that the function of cinema is to explore these sense impressions, the murk of our desires. Film is exploration, rehabilitation, salvation; it uncovers what is concealed, brings to life the unseen, those invisible chords by which we are connected to infinite worlds.

The visionary artist and filmmaker, Sir Steve McQueen, has mastered storytelling beyond the limitations of language. Like feeling your way through a dark room, the experience of watching a Steve McQueen film is completely and viscerally experiential. McQueen forces us to see with all of our senses. He directs and holds our gaze upon what seem like banal moments; however, it is in these scenes that we find the essence of not only the film but of that mysterious invisible thing that guides and connects us: a light flickering upon the intangible, the invisible web of us. The depth of experience in being human. Through this durational observation, a scene from a movie becomes pregnant with meaning, like a photograph in which you continue to find new information, greater depths. McQueen assigns a moment to our memory, keeps the camera rolling, elongating a moment for what feels like

too long. There is a thought process that unfolds: why am I still looking at this? When will the next scene begin? There is an instinct to look away, but we are forced to keep looking until we’ve had adequate time to contend with what we have seen and felt.

Many of McQueen’s films are historical, and always about the individual, conflicted figures—their depth, interiority, the dynamics of relationships: that of families, lovers, friends, a political prisoner and his priest. Within the larger context of these stories and their historical significance are intricate, raw depictions of people and relationships, and the richness and complexities of in-between moments. We are asked to actively consider horrific truths of both the past and the present, where we come from and where we are now, what connects us in our humanness, where we have and continue to falter. McQueen deals with specific historical events as well as universal themes, particularly concerning loss, self-reckoning, and lib-

eration: political prisoner Bobby Sands and the Hunger Strikes in 1980s Northern Ireland (Hunger, 2008); the story of Solomon Northup, a free black man from upstate New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South (12 Years a Slave, 2013); Frank Crichlow’s Mangrove restaurant in west London, and the trial of the Mangrove Nine in 1970 (Mangrove, 2020).

“Mangrove”, from the Small Axe series, is a historical drama about the Mangrove restaurant in west London, opened in 1968 by Frank Crichlow, a Trinidadian immigrant. The restaurant was a sanctuary, an integral meeting space for the Black community in the Notting Hill neighborhood, particularly for Black activists, artists, and intellectuals. In the restaurant, McQueen has created a warm, immersive environment; it vibrates with atmosphere and life. Music is always playing and patrons are engaged in lively conversation, floating in and out of the space, signaling a feeling of safety, community, and home

beyond the restaurant's physical borders. Crichlow is faced with relentless, violent, and baseless police raids led by sadistic officer Frank Pulley. The film jumps between the vibrant warmth of the Mangrove and the stark, cold monochrome of the police station: the life-giving glow of the sun, burning and suspended in vast, cold space. The police see the Mangrove as a transgression, a threat to the white British way. After a particularly violent sequence in the restaurant, a colander is knocked off its base. In a lingering shot, the camera traces the chaotic violence down to the kitchen floor where that colander aggressively rocks to its final rest. The plea to keep looking when the instinct is to look away from violence is challenging but comes with its rewards. The rocking colander lulls the viewer through conflicting emotions: the desire to get through the scene, to skip over what has happened, engenders a kind of

reckoning. We are forced to process what we’ve just seen before moving on.

The harassment of the police forced Crichlow into becoming an activist. In response, on August 9, 1970, the Black community organized a march in which 150 people protested police conduct. The police again provoked violence, and a number of the protesters were arrested and charged: Frank Crichlow, activist Barbara Beese, Trinidadian Black Panther leader Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Trinidadian activist Darcus Howe, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Carlisle Innis, Rothwell Kentish, Rupert Boyce, and Godfrey Millett. Their trial lasted fifty-five days, and though not all of the charges against the Mangrove Nine were acquitted, the trial became the first judicial acknowledgment of behavior motivated by racial hatred within the metropolitan police. It was a critical case in the British Civil Rights Movement. For many children, “Mangrove” has created a connec-

tion to a time their parents may not have talked much about but that likely influenced their relationships. The present is imbued with sense impressions–wounds–of the past.

Steve McQueen’s latest artwork, Sunshine State, is weighted, ripe with memory material. In the two-channel video installation, projected on both sides of two screens, one placed beside the other, McQueen weaves the deeply personal with the historical. The work opens with footage of a burning sun and unfolds into scenes from the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, a musical drama and first feature length film with synchronized dialogue, the first “talkie.” The film stars actor and singer Al Jolson, who is shown applying blackface makeup in preparation for a Broadway dress rehearsal. Against a black backdrop, the blackface is never actually shown. In McQueen’s version, only Jolson’s suit and white minstrel gloves can be seen. The rest disappears; he becomes invisible. Juxtaposed with the black and white images of The Jazz Singer are video fragments of the blazing orange sun, a burning, breathing neon orb. Over the video is McQueen’s voice recounting a devastating story his father shared with him just before his death. The story is told in full, then repeated until fragmented, distorted. It is a life transforming story, like a door to a dark room opening to the sun. His father was taken from the West Indies to work picking oranges in Florida, where a casual visit to a bar after work ended in traumatizing, fatal violence.

It’s impossible to know to what degree this unknown experience, its memory, its wound, has informed McQueen’s art practice, but he has largely uncovered and shed a light on stories and people who were unseen, ignored, erased. There is liberation in being witnessed, in being seen, and through observing and absorbing, the invisible chords that connect us are fortified. His father’s final words, “hold me tight,” are recited as a chant, a mantra to the sun-burning on in a vast dark space. In an interview, McQueen asks himself what he discovered looking back on the years-long process of creating “Sunshine State”: “I suppose I was carrying shit with me… heavy shit, and I didn’t know I was carrying it. I think that weight is what I discovered, of what you carry with you, and I don't know if I’m lighter, but I’m more appreciative.”

Traveling the world—from Greenland to Bikini Atoll—FrenchSwiss artist Julian Charrière captures the debris of human impact on Earth. Using myriad mediums, he exposes the layers of sedimentary scar tissue as a result of our unbridled ambition to conquer nature, and decodes the ecological algebra within its complex systems. Balancing anthropogenic and cosmic time scales, he fuses fine art and scientific practices to discover where we fit into this ancient equation. In

Buried Sunshine, which will debut this fall at Sean Kelly gallery in Los Angeles, he explores the fraught history of oil extraction in Los Angeles; the world’s largest urban petroleum field. Using heliography—one of the oldest photographic techniques using light-sensitive emulsion incorporating tar from La Brea, McKittrick, and Carpinteria Tar Pits—he creates an abstract aerial view of the wastelands. Charrière's oeuvre asks eternal questions: how did we get to now and will we survive tomorrow?

Interview by OLIVER KUPPER

Julian Charrière, And Beneath It All Flows Liquid Fire , 2019

Video still. Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Interview by OLIVER KUPPER

Julian Charrière, And Beneath It All Flows Liquid Fire , 2019

Video still. Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

OLIVER KUPPER You are currently in Greenland; can you talk a little bit about what you are doing there and why the country is so important in your practice?

JULIAN CHARRIÈRE There is something about the topography of Greenland, or perhaps the lack of topography, which I am drawn towards. Without trees and houses, the landscape itself is a blurred boundary between sky, and ice, and land. Even circadian rhythms come undone there, since the planetary tilt delivers entire seasons of white light, and then months of uninterrupted darkness. I am traveling there with a scientific expedition, joining the scientists on a journey around East Greenland. During this time, we live on an icebreaker and trace the coastline, allowing samples to be collected from otherwise difficult-to-reach locations. For me, it marks the first step of an upcoming project, for which I am trialing a new ROV

CHARRIÈRE I think instinct plays an integral role in my output, fused always with curiosity, though I would maybe describe it more as intuition. And honing that is part of what makes artists capable of approaching ambiguous, complex, and dense topics, which might otherwise seem daunting. Even when encountering something opaque, you can instinctively choose a thread to pull on or descend into a certain rabbit hole, guided by the voices that echo from within it. My intuition has, at times, unleashed an instinct leading me down some very strange paths. From polar ice sheets to the depths of palm oil plantations, these are locales that at first glance might seem remote or liminal, until you arrive and realize that these are places. They are as much homes to the human and non-human animals who live or lived there as your home is to you. Of course, it is exciting to dive in the Bikini Atoll and see the hulls of warships sunk

KUPPER When did you become interested in the natural world and when did the ecological enter your artistic lexicon?

CHARRIÈRE Even from an early age I was interested in immersing myself in my surroundings, and so I spent a lot of time in the natural landscape interacting with snakes, and frogs, and birds, and plants. It has always felt like an integral part of my being and how I evolved in the world. As a kid, it wasn’t so reflected, and this idea of immersion and encounter only began fully developing when I started studying art. It expanded into this idea of meeting a particular landscape, rendering it a tool for thinking about how we think about ‘nature’—how it is framed as a milieu, or a system, or whatever. In terms of environmental perspectives, this is almost always present, since when you investigate such topics you almost inevitably arrive at the ecological meltdown which looms ahead.

KUPPER The summer of 2023 was the hottest in recorded history. Your work deeply explores the impact that humans have on our natural world and landscapes. Why don’t you think our survival instinct kicks in with these dire warnings about the planet?

(remotely operated underwater vehicle) in the icy surrounding waters. Filming below the surface of the Greenland Sea, you quickly realize that global warming is not only causing glaciers and icebergs to disappear, but that with them entire oceanic ecosystems dissolve.

KUPPER The theme of this issue is instinct. I think a lot of artists unleash their instincts, or unlearned impulses, to drive their creativity. What does instinct mean to you and how does it drive your work, especially when it comes to your immense, adventurous spirit?

by the US during nuclear tests in the 1950s, but the adventure is secondary to the encounter with that history, and especially how we relate to it today. The first instinctual spark of curiosity is almost gravitationally connected to that physical encounter, tethered to it like those distance lines cave divers follow in the dark, leading them through the unknown. You feel there is something beneath or beyond—some long-forgotten history, or fate, or lively material shuffling around—and so you listen to your gut, and look beneath the rind, and see what you can maybe bring into the light.

CHARRIÈRE Complacency is a tricky thing. But I think it is critical to examine who is responsible for the situation we are in and what one can conceivably expect from individuals. It’s like how British Petroleum in the early 2000s popularized the expression ‘carbon footprint,’ devising a marketing campaign that bestowed upon us the idea that environmental pollution is the responsibility of private citizens, rather than the oil companies. More so than asking why our survival instinct hasn’t kicked in, maybe we can investigate the often-reciprocal relationships between political systems and corporations. How can we require scrutiny and transparency? How can we build platforms and communities or even start conversations about the industrial actions that, while conducted out of the public’s view, will have devastating consequences for our planet? One of the reasons why I think our response may appear so apathetic is because climate change is vastly abstract. Our human reaction time is incompatible with it, making global warming feel fast and slow at the same time. It only becomes somewhat tangible

when you encounter it firsthand: when your commute to work is flooded, or your house is engulfed in fire, or a garden that was once abuzz with life is dead quiet in midsummer. I think one strength of art is that it can be used to countermand this kind of apathy by exploring challenging topics and uncomfortable feelings; deconstructing the arbitrary and systemic, thus perhaps providing tools for dealing with the terrifying uncertainty that might otherwise shut us down emotionally.

KUPPER Do you feel there are too few artists leaving their studios to tackle these major issues of our time? Is a studio painting practice self-serving in the age of the climate crisis?

CHARRIÈRE No, I wouldn’t say I feel that way. A painter should paint, whereas another artist might need to travel to dream. It would be reductive to art as a vocation if there was pressure to conform to political themes, even if those themes are urgent ones. And really, how interested would we be if every artwork we experienced was didactically about climate change? In my work, there are often environmental themes present, but these are often enmeshed in other perspectives as well. With my latest film Controlled Burn, for instance, the meta-layer is very much about extractivism, visually foregrounding the buildings we construct and spaces we carve out for energy production. But while it features a power plant cooling tower, an abandoned open-pit coal mine, and a towering ocean oil rig, it also explores other things beyond environmental degradation. In the film, you soar through reversing pyrotechnics, mirroring the intense power released by our terraforming. But it is also about the past biomes that now constitute our coal, and petroleum, and natural gas: the Carboniferous woodlands that outgrew themselves and condensed in the earth to what we now repatriate as resources. It is not explicitly about tackling a major issue but acts as a cosmic meditation on energy transformation. Someone could argue that what we need are more explicitly environmental works, but art often operates in less obvious and more ambiguous ways, and that is a strength.

KUPPER Fire has been a central theme in your work, but also ice and glaciers. There seems to be a fascination with the primordial and the elemental. Where did this

fascination come from and what is the symbolism of fire and ice?

CHARRIÈRE

Our history with fire, but also the history fire has with our planet, was something I delved into recently for my exhibition, Controlled Burn, at the Langen Foundation. It foregrounded one of the reasons why I am interested in these kinds of biochemical processes: the fact that they have fates of their own, often long predating our hominid entry onto the planetary scene. The first fires emerged from the very properties of life. To paraphrase the fire ecologist Stephen J. Pyne, the story of fire is the story of oxygen and plants. Without either, the ignition of lightning would never flourish into flame. So, as life ascends from the seas and begins to grow on land, we also encounter the earliest flames, with the earliest record dating from charcoal in rocks some 420 million years ago. This was in part an inspiration for Panchronic Garden, which is a dark and crackling installation in the show. Set in a reflective and coal-based scenography, it figures ancestral plants to those who lived during the Carboniferous era. Entering this smoldering coal seam, the visitor can listen to a real-time soundscape produced by the ‘umwelt’ experienced by the vegetation in the space. Now and then, a fluorescent flash erupts in the space—perhaps the ignition of that first coming-together of the components that necessitate fire. But then, sweeping through that deep time, we arrive in the era of humankind. Fire integrates into our agriculture, and then to a degree manufactured in our combustion engines, not only burning the raw materials of the present but the lithic landscapes of the past. Oil, and coal, and natural gas are extracted and burned for fuel, warming the future. In my work, I am drawn to investigate these cycles and systems, with which our idea of reality is inextricably linked. Ice too holds histories, suspending within it registers of past atmospheres, yet for us living in the so-called Anthropocene era, the icebergs, and ice sheets, and glaciers also act as clocks, physically counting down toward an uncertain future. There is also the paradoxical situation where neither state is particularly compatible with human beings. Both ice and fire are entities with which our bodies cannot cope—thus we are confronted with agencies beyond our immediate control.

KUPPER One of your most symbolic works is And Beneath It All Flows Liquid Fire, which adds another layer of symbolic meaning. Can you talk about this iconic work and how the fountain is connected to civilization?

CHARRIÈRE Alongside the control of fire, the fountain represents one of the most fundamental achievements of human civilization, since the invention of wells shifted us from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary one—in turn giving rise to agriculture and thus sowing the seeds for future industrialization. As a symbol, it has this rich and poetic history, from the original spring fountain where it provided vital water, to the ornamental versions that publicly displayed not only the technical achievements of the jets, but the power and ‘overflowing’ wealth of those who could afford to install them. In this sense, And Beneath It All Flows Liquid Fire is a memorial of anthropogenic hubris; our belief that the natural world can be dominated and natural elements controlled. But it can be interpreted in many ways, with the presence of fire anachronistically engulfing it, pointing to the nether realms beyond our purvey. How beneath the political debates, philosophical reflection and symbolism, there lies the original and autonomous state of the planet, free from human interpretation. How deep beneath the Earth’s surface, between the outermost crust and the inner core, magma constantly churns. I was interested in juxtaposing this uncanny underworld, where liquid fire constantly flows inside of a recognizable structure like the fountain. And while I wanted to point to the ambiguity of fire, a power which, like us, is capable of both creation and destruction, it is maybe unavoidable in the current climate of erratic wildfires and rising temperatures for the work not to feel a little like an omen.

KUPPER Not only has this summer been blazing hot, but there has been a renewed concern with nuclear devastation—can you talk about your experimentations with atomic CHARRIÈREenergy?

In a way, our belief that we can control elements, as with water in the previous question, becomes truly unhinged when we begin developing nuclear weapons. As we are no longer trying to command simply an Earthly

element, but the atomic power housed by stars. I first began working with radioactive materials in my series Polygon.

I traveled to the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan where the USSR conducted its nuclear tests. In the production of the photo series, the negatives were exposed to local sand, which was still radioactive from the site. Though invisible to the human eye, the radioactivity seared bursts of white light onto the final photographs. I returned to this method in a more expansive project where I, together with curator and writer Nadim Samman, journeyed to the Marshall Islands; to the atolls where the U.S. detonated some of the world’s most powerful nuclear weapons in the 1950s. It especially focused on the Bikini Atoll—a now deserted but once-populated island whose citizens were displaced by the tests. It is easy to think of this tropical island as remote, situated on the very edge of the world, but it was very much home to the Bikinnians. Even after some half-hearted clean-up efforts by the Americans, it is completely unlivable with the ground still containing the radioactive substance cesium-139, effectively poisoning any locally-grown produce. The world quite quickly forgot about the people on these atolls whose legacy fell by the wayside of the spectacular images the US took of the detonations. A large part of this military project was about visually documenting the violent potential of the US military; a way to disseminate its power through media. In a sense, I too documented this action with my photo series First Light. It was not an encounter with the thermonuclear reactions, but rather a portrait of the white shadow eternally expanding from the events themselves. A meeting with a cosmic specter who still haunts the beaches: the radioactivity forever crackling on the atoll. It is strange, of course, to think how much and how little has changed since. Returning to political conditions similar to those of the Cold War, it is hard to not feel like we are reaping what we sowed during that first nuclear arms race.

KUPPER Can you talk about your upcoming show, Buried Sunshine, at Sean Kelly in Los Angeles?

CHARRIÈRE With Buried Sunshine, the aim is to bring together a miseen-abyme of the geological materials, especially those which we utilize as tools and resources. A large part of the

show is also about prying at the veneer of Los Angeles, which is the world’s largest urban oil field. It includes the aforementioned film, Controlled Burn, and a new series of heliographic works with which I wanted to unearth some of the fossilized sunshine upon which the mythos of the city is constructed. Because when you think about it, Los Angeles is a spatial anomaly, built both on top of and by hydrocarbons. Without the overwhelming abundance of oil, the film industry boom might never have exploded as it did. And to this day, one-third of residents live within a mile of a drilling site, yet those

perspective, it shows the immense Kern River Oil Field in the San Joaquin Valley, the Placerita, and Aliso Canyon Oil Fields in Santa Clarita, and the giant Inglewood Oil Field, which from this point of view becomes abstracted, like an oil spill through reality. Presented alongside these new works are the sculptures Thickens, pools, flows, rushes, and slows, which consist of large pieces of obsidian. The material is a type of volcanic glass produced from congealed magma during eruptions, and when you look into its seemingly depthless interior, you see why, historically, many cultures used it for divination.

derricks are whimsically hidden behind shopping malls and artificial buildings, forging a contradictory paradise, as much a nightmare as a dream.

The heliographs, named Buried Sunshines Burn, are made using one of photography’s oldest techniques, first developed by French inventor Nicéphore Niépce in 1822. It is a production method I first began experimenting with for my series A Sky Taste of Rock in 2016. To make heliographs, you use a light-sensitive emulsion, made in this case with regional tar collected from the La Brea, McKittrick, and Carpinteria Tar Pits in California, creating photographic imprints of local oil fields on highly polished, stainless steel plates. Shot from a bird’s eye

With the show, I sought to contrast the dark vitality of these materials, from obsidian to coal and petroleum, with the colossal nuclear fusion of the sun: the celestial ignition for our planetary machinery. I wanted to suspend the visitor like a speck of dust in this cosmic sunbeam, revealing how light is not as immaterial as we believe. But rather show it as a topography, reaching from the silver lining of our exosphere to the deep carbon orbiting Earth’s core. It not only shines but sediments, registering in the strata much like a camera captures an image on a light-sensitive surface. It too is a photograph, opening portals to other places and times far beyond the present.

Disdain for authority, wide open sexual fluidity and addiction, homicidal mania, bodily secretions, religious blasphemy, bestiality, incest, and pedophilia—John Waters and Gregg Araki’s pornographically electric gems of silver screen beauty have forever changed the cinematic medium. In the fall of 2023, John Waters will see his first comprehensive directorial retrospective at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Pope Of Trash will have costumes, props, handwritten scripts, correspondence, scrapbooks, photographs, film clips, and more. At the same museum, Araki will present the world premiere of his newly restored queer classic Nowhere (1997), alongside Totally F***ed Up (1993), and The Doom Generation (1995), which comprise what became known as his "Teenage Apocalypse" trilogy. In this historic, career-spanning conversation, Waters and Araki discuss their lifetime of celluloid perversions.

John Waters I'm against instinct. Do you know why? I resent that I have to take a shit every day. I resent that I didn't think up sex, but I have to do it. Anything that isn't my idea that I have to do, I hate. But it’s amazing that some people think they have invented things. Gregg Araki I feel like you did invent things. That's why, to me John, you're like the North Star. You're the OG one, right? I mean, there were obviously underground, experimental filmmakers before you, like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren, and all that stuff, but you brought it all together. I feel super fortunate. In the age that I was born, there was punk rock music, New Wave music, queer culture, Sundance, and indie cinema. Everything in my career, all the films I've made, have lined up with this timeline of the rise of indie cinema. I was just basically in the right place at the right time. But you're about ten years ahead of me.

JW I know, but still, I lived in Baltimore. You lived in LA where you could see these movies. I just read about them from Jonas Mekas’s column, or we'd go to New York and see them. But I saw Jean Genet movies, Kenneth Anger (like his first film Fireworks [1947]), the Kuchar Brothers, and Warhol. Certainly Warhol. At the same time, I was watching Russ Meyer and Herschell Gordon Lewis movies.

GA For my generation—filmmakers like Christine Vachon, Richard Linklater, Allison Anders, Gus Van Sant—it felt like a high school class. There were Sundance and independent distributors. There was a structure for indie cinema that existed in those days that was sort of growing as we were all making movies, and we were all growing as filmmakers. But you were kind of before all that, you know what I mean?

JW Underground cinema was really non-theatrical except for the main three cities. Where you went was the college market and it was huge. That's where people went to see my movies. We toured college markets everywhere.

GA I remember seeing them. They used to show them on 16mm.

JW …And I'd come out and Divine would throw dead fish in the audience and a fake cop would come on stage and bust us, and Divine would strangle him, and the movie would start. We had a vaudeville act.

GA So, American indie cinema didn't exist before?

JW The way it existed was The Film-Makers' Cooperative, which was founded by Jonas Mekas. But there were way less places to play.

GA And also way less populous. Do you know what I mean? I remember seeing Kenneth Anger in an experimental film class when I was an undergrad. It was very underground, but it didn't have that element of entertainment and comedy. It didn't have what you brought to it, you know, the vaudevillian. (laughs)

JW Really, I made exploitation films for art theaters. And there wasn't any such thing as that really.

GA As I said, you were the North Star. You were the one that paved the way for everybody.

JW Well, that's very sweet. I was a mudslide ahead of you. (laughs)

GA (laughs) I mean, it's real. Your significance in that world is never to be questioned. I was always in the right place at the right time, but you were even more in the right place.

JW No, I was in the wrong place at the wrong time! I still am. I still live in Baltimore. If I had ever moved to LA it would've been the worst thing for my career because they would've gotten used to me. And then when I’d go pitch a movie, they’d say, “Oh, we'll see him at a party next week.”

GA But you were there for everything. You went right to Studio 54, right? Like with Halston and all those people?

JW I hated Studio 54. No, we made fun of that. We were at the Mudd Club. We hated disco. No, I couldn't stand Halston, actually. And he had the worst boyfriend ever. He was too much of a pissy old queen. I was at the Mudd Club, I was at Area. We couldn’t get into Studio 54.

GA I remember you telling me that you were at the first Sex Pistols concert.

JW I saw the Sex Pistols in Manchester in London. Somebody took me before they even came to America—before I'd ever heard of punk. And when I saw them, I thought, oh my god. Divine saw the punk girl, Jordan—with her spikes and everything—and said he felt like Plain Jane for the first time ever.

GA As I said, you were literally always at the right place—the epicenter of everything.

JW And now here we are, Gregg. Who would have ever thought that we would be together talking about being in the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures?

GA It's fucking nuts, right? (laughs)

JW (laughs) It gives hope to everybody.

GA It's like when I got into Cannes for the first time—I was in The Directors' Fortnight with Smiley Face (2007) and then Cannes proper for Kaboom (2010). If you're around long enough, eventually they open the doors.

JW Cannes was always great to me too. Are you kidding? They always like nutcase American film directors. The only thing I could think of that's up there for me along with this Academy Museum show, was when I was on the jury at Cannes with Jeanne Moreau. Now how did that ever happen? That was pretty amazing.

GA Were you on the real jury?

JW Yeah. The competition jury.

GA Jesus. That’s crazy.

JW Yeah. It was exciting. Black tie every night. Being with Jeanne Moreau, who chain-smoked and had a hundred pairs of sunglasses, I said, “It’s so sad that [Michelangelo] Antonioni can't talk anymore.” And she said, “Why? He never said anything anyway.”

GA That's fucking hilarious. So, we should talk about your grand exhibition opening in the fall?

JW My directorial exhibition.

GA Wait, directorial?

JW It’s really everything about my movies. It has nothing to do with anything else. And they've been working on it for three years. Everything they got from film archives, and they went, and found every crew member, props, handwritten things, costumes, everything. It's really exciting though, and I get to see it before I'm dead. It's really good.

GA So, there’s nothing from your personal collection?

JW No, it has nothing to do with my artwork at all. I don't have one thing in my house about my movies. There's nothing in my career hanging around. There are some things in my office, but most of it is at the Cinema Archives at Wesleyan, which started in the ’80s. So, it's the most glamorous storage ever. They also have Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese, and Ingrid Bergman’s archives. I met Clint Eastwood there and I said, “Just think, Divine's fake pubic hair will be next to Dirty Harry's badge.” And he was really great about it and laughed and everything.

GA So, who's curating it then?

JW Dara Jaffe and Jenny He have spent three years on this. There's a beautiful catalog. There’s lots of stuff going on with it. So, they've been everywhere. They've done an absolutely amazing job. They know more about me than I do.

GA I haven't seen you for a while. When was the last time I saw you?

JW I don't know, but I was looking through my research about you, and I love the fact that Roger Ebert was mean to you too. He used to do these horrible reviews, and then say to me, “Hi, John! Would you do my panel?” And I thought, “I’m a professional, but am I a masochist?” And I did it because he did one great thing, he wrote Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), which is one of the best satires that was ever known to man! And he wrote that because he likes big tits! But thinking of that “thumbs up” and “thumbs down,” how tired was that? I was nice to him always, and he was always so mean to me, and I was happy to see he was mean to you too (laughs).

GA Well, was he ever a fan of anything?

JW No! He wrote once about Pink Flamingos (1972), kind of like, it wasn't for him, but recognizing its power. But then, he wrote mean stuff about it over and over every other time. I don't remember if he ever gave us a good review, but especially in all my Hollywood movies, he was really mean. And then, I'd see him and he’d go, “Hi, John!” We were very nice to each other and everything, but that is being a pro.

GA It’s part of Hollywood.

JW I was never angry. I was treated fairly my whole life in Hollywood. I love that documentary—when Janis Joplin, after she became a star, went back to her high school reunion because they were so mean to her. They were still mean to her, even though she was famous. (laughs) So that’s the thing, don't go back to your high school reunion. I've never been to mine once.

GA But wait, were you in the book? Doom Generation was in his book, I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie (2000), which was his list of the worst movies ever made. Were you in that book too?

JW But at least we weren't on the most mediocre list. I love being the worst and the best. It's the middle I've always had trouble with my whole life.

GA Well, I told you he loved Mysterious Skin (2004). It was so crazy. His review was literally like I had never directed anything before. He didn't mention anything I'd ever done before.

JW Is that the only novel you adapted?

GA It's the only novel, Yeah.

JW So, do you think he liked it because it was based on a novel?

GA Mysterious Skin was a weird movie because a lot of people who hate me, love that movie (laughs). It was kind of like the movie that everybody loves because it was about such a serious subject matter. But it's funny, when I made it, I really thought it was going to be the end of my career. I really thought this movie was just so out there—I mean, I've always been so polarizing— but I thought people were going to run me out of town.

“People jerk off to Gregg’s movies, nobody jerks off to mine. And I think that’s important, Gregg. I honor you for that.” — John Waters

JW But then, didn't you always think all your films would be hits? I did. I was always amazed when they weren't (laughs). I always wanted them to be. I never thought: I'm making this arty little weird movie.

GA When we were touring with the revival of Doom Generation, I told the audience, it's just so meaningful to me and James [Duval] that the love for this movie exists twenty-eight years later, you know? We always loved this movie—this little queer fuckin’ underground crazy movie. But it's like the idea that other people love it and they keep the fire burning for it for decades.

JW And it’s not old hat to the next generation, which usually things are.

GA It's amazing. It’s definitely what keeps us going: the idea that we just march to our own drummer, and do our own thing. And you know, I think you have to be a little bit crazy to be a filmmaker.

JW I knew about you from the gay punk scene. That's how I first knew about you. And I feel the most comfortable in the punk world. Those are my people because there are ten good queers there that I like. And they're always on the down low in the punk world anyway. When I first saw your films, you were one of the first “gay is not enough” filmmakers who I really like.

GA I told you that's where the The Doom Generation came from. The producer, Jim Stark, came up to me and said, “If you can make me a heterosexual movie, I'll get you a million dollars in financing for it.” The Living End (1992) and Totally F***ed Up (1993) were made for twenty grand or whatever. So, he was like, “You make these gay movies that gay people hate (laughs). They're too punk for gay people. If you do a heterosexual movie, I'll get you a real budget for it.”

I remember The Living End, especially, was triggering for so many gay people. And I wrote Doom Generation in my sort of punky way of making it the queerest heterosexual movie ever with this really exaggerated queer subtext to it.

JW But now, it's so different. There’s that really cute DJ Diplo that said, “Well, I’m not not gay.” And because you had a girlfriend that you got a lot of shit about, you can say, “I'm not not straight.”

GA (laughs) Yeah. And when I was dating a woman in the mid-90s…

JW It was so hilarious that you got shit—I gave you so much shit. GA ...You said, “He just went in.” (laughs)

JW That was the most radical thing you can do. And I keep saying, “What stunt am I going to do for my 80th birthday?” I hitchhiked across the country in my sixties. I took acid in my seventies. Maybe I’ll turn straight in my eighties.

GA That was probably one of the most scandalous things ever because I had been known as this Queer New Wave filmmaker. And I remember being on the Sundance jury in 1996—I was there with Kathleen [Robertson], and we were stupid, and young, and in love, and were making out at every party. People’s jaws were literally dropping. It was crazy.

JW (laughs) I think it's great because people give you shit about it, which really makes me laugh that you can come out of the closet, but can you go in and out, in and out? Can't it be a revolving door? You're lucky. Everybody's cute. I wish I was bisexual. But I'm interested in what the young people are doing. As soon as you say, “Oh, we had more fun [than today’s youth] when we were young,” that means you're an old fart and don't matter anymore (laughs). Because they're having just as much fun right now.

GA Are they?

JW Yeah, they are. Oh yeah.

GA I hope so.

JW They're having just as much fun and they're scandalizing us with a new sexual revolution.

GA I hope you're right. I am actually concerned about the newer generation in the sense that they aren't having sex anymore. There’s too much social media and texting.

JW They don't have any parts anymore to have sex with! They can't figure out where it goes, which is real anarchy. Like, you go home with somebody now, they take off their clothes, and you have no idea what's going to be underneath there.

GA (Laughs) Yeah. I love that. It's really interesting—when we do these Doom Generation screenings, I just expect it to be a nostalgia trip, but at least half the audience, sometimes 85%, is all young people.

JW I know. Me too. That's great, Gregg, do you know how hard that is to get?

GA It's amazing to me.

JW No, it's the ultimate compliment.

GA Like, how do you even know about this movie? You weren't even born! Your parents weren’t born.

JW (Laughs) They weren't born when I made my last movie, much less the first one. I just did a tour in Paris for my book, and little 20-year-old French kids gave me poetry books they had written about me. It was amazing and incredibly exciting. If you're a director, you always have to go with your movies. You have to meet the ticket buyers. I always believe you have to be out there involved in the selling of it. I know you don't like to travel, but I have a fear of not flying.

GA Yeah, I know we've talked about that. I'm not a big traveler, but I do it. But you're afraid to not be touring everywhere.

JW I am. Because Elton John told me, and it's true, “Once you stop touring, it's over.” And you can't blink either, because somebody's ready to steal your place, Gregg! Remember that—somebody in LA is trying to steal your place.

GA But didn't Elton John just stop touring?

JW Yeah, but he didn't say he was never performing again. He just wasn’t going to do 150 shows a year. (laughs) Do you know who tours the most? My idol, the mentalist, The Amazing Kreskin. He plays 300 nightclub gigs a year, and he must be 85. I have him in my book under A. I just call him Amazing. What a great career.

GA Did you see the Joan Rivers documentary? That’s how she was too.

JW I think either one of us, wherever we had been born or lived, would do the same thing. We would kind of glorify what's going on in the city that some people are against. We would praise what others put down. LA is very much a character in your movies, but in a good way, in an exciting way. You're not going to meet the cheesy sitcom stars, or if you are, something bad happens to 'em. And

Previous page

the characters are always sexy. People jerk off to Gregg's movies, nobody jerks off to mine. And I think that's important, Gregg. I honor you for that.

GA (laughs) I remember when Now Apocalypse (2019), my Starz show premiered, somebody took a screencap of them watching the show on an iPad and jerking off at the same time. (laughs)

JW I had the guy with a singing asshole—who's a straight guy by the way—tell me it was a yoga exercise and he said, “Would you like me to audition?” I said, “I believe you. No, that's okay.”

GA (laughs) But yeah, it's very true that Los Angeles is a huge part of my movies and a huge inspiration for me. I remember when I was in film school somebody said to me, “Living in LA is like being inside a giant cartoon.” You know what I mean? And that's why I love it here: it's so surreal and you just see the craziest shit. One of the things I love about LA is people just don't care. You can walk around naked with a chicken head on and people won't blink twice because it's LA. Whereas in Santa Barbara, or Goleta where I was born, which is a suburb of Santa Barbara, if you have an earring or something and walk into a restaurant, people stare at you. You hate it here because it's the center of Hollywood.

JW I don't hate it because it's the center of Hollywood. I hate it because it's suburban. I don't hate LA. I have some of my greatest friends there. When things are going well, LA is so fabulous. When they aren't, it can be terrible for me. When things go bad in your career, it's kind of the worst place for me to be. In Baltimore, no one's in show business that much. I have trouble in LA ever meeting anybody who isn't in show business. But I've had some of the best times in my life in LA. My movies do well there. You can read my book, Mr. Know-It-All (2019): I'm not bitter about one thing. Hollywood treated me fairly from the beginning to the end. I climbed my way to the top and climbed right back down.

GA But the question is, did you treat Hollywood fairly? (laughs)

JW No! They'd say. Because the executives that greenlit my movies—they liked them twenty years later, but they didn't make money then, and they got fired. They don't care if people like it twenty years later; they get to greenlight three movies a year and they better be hits.

GA Did you self-finance your first movies or how did you make your first movie?

JW Well, I borrowed it. I raised the money all the way up to Polyester (1981). I raised the money and paid everybody back. So everybody that I ever knew personally got their money back from me and still gets their money. Even when they die, I give their kids money. The studios didn't always pay them back. Luckily, I own Pink Flamingos. I own all my movies up until Polyester. But who would ever imagine that Warner Brothers would be the distributor of Desperate Living (1970)? Who would have ever thought that Janus Films would distribute Multiple Maniacs (1970)? I used to see the Janus Films logo ahead of [Ingmar] Bergman and [François] Truffaut films.

GA That's where you belong, you know, in Criterion and Janus Films along with the Battleship Potemkin (1925).

JW When I was starting with Fine Line, which was the arty part of New Line, they made up Saliva Films, which I hated. That was to avoid police prosecution for Pink Flamingos.

GA As I said, you kind of have to be a little bit crazy to be a filmmaker or an interesting filmmaker. You really just have to believe in what your vision is.

JW I didn't have any idea what I was doing! You went to film school. The first movie I made was Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964). It's very Dogma 95 without realizing it. I didn't know there was editing. I just shot each scene of the movie in order and that was the movie.

GA (laughs) You have to believe in your own voice. I just have a very myopic view of what I do. I collaborate, I listen to people, and I listen to the DP or actors, if someone has an idea or something, but for the most part, I just have a vision. It’s almost like a mental illness; it’s like, yeah, this is what I'm gonna do.

JW Exactly. That's the only way anybody gets their first movie made. You don't even consider that you can't make this movie. People say later, “Did you have fun making that movie?.” Fun? Fun is when it's a hit and you're having a drink two years later. Fun? Being outside for those early movies—outside for twenty-hour days—you want something to eat? Go into the woods, find it, kill it, and cook it.

GA I have to say, in retrospect, I had fun. I have super fond memories.

JW I'm proud of it in retrospect, but not fun. Like, haha, lalala, isn't this fun?

GA In the moment, I'm not having fun. Because it's so stressful. It's so much work and you're just so focused, but in retrospect, I look back on it as a really warm memory. I mean, we're lucky, we've gotten to make a handful of movies. And each one, they're like my kids.

JW Yeah, and you can't pick your favorite. I always like the one that did the worst. You have to just stick up for the one that has a problem.

GA (laughs) You like the one that's neglected, you know what I mean? Like the real popular one, the one that's super successful, it's just like, oh yeah, that one. But then, there's the one that has the problems.

JW Yours are very different. To me, all my movies are sort of exactly the same. They have one moral: don't judge other people, make the people you don’t agree with laugh, and then they'll listen.

GA Is that the overriding theme? The overriding themes are not that different for my movies then, I would say.

JW No, I disagree. Your movies have the same joy in them. What you're saying is that people who don't rebel by the time they're twenty, usually have a very dull life. The prom queens and the football stars, it's downhill from the day they graduate. It really is. You see them later and you think, oh my god. I’m also against homeschooling. I think that's crazy too. You have to learn how to get through it. That's how you learn to do everything. And I always used humor. The people that would have beat me up didn't, because I could make them laugh at authority, which made me safe. You can't tell your children to just go make fun of the teachers and the kids won't beat you up. But it does work.

GA Well, neither of us has real kids. We just have celluloid kids. JW I like kids. And they come over to me now because I was in the Alvin and the Chipmunks movie. I look like a child molester, so it's awkward in airports. But if we had to make our movies today, I guess we’d have an intimacy expert telling Divine that it's okay to be fucked by a lobster. (laughs)

GA You'd have an intimacy coordinator telling the guy with the singing asshole that it’s okay.

JW Divine would drink her own urine rather than eat dog shit in a more Hindu, kind of politically correct, way.

GA I don't think my films would change really at all. The only issue is social media. When I made my TV show in 2018, one of the issues is so much of the fucking movie is texting, and on a device—so many inserts of texting.

JW That's a whole other third unit.

GA Story-wise, and script-wise, it's such a pain in the ass. I'm working on one thing now and I'm just setting it in the ’90s, so you don't have to deal with that device.

JW Even though I was a chain-smoker, I never had anybody smoke cigarettes in my movies because of continuity problems. If you ever wanted to cut to make a scene shorter, then their cigarette is half-smoked in one second. Or don’t have people yawn in a movie, because then the audience does, or look at their watch. If people are yawning or looking at their watch while they're watching your movie, that means it's boring.

GA Those are good rules. You should put those in a rule book.

JW Also, don't ever say the word “cult” in Hollywood when you’re trying to raise money. That means ten smart people liked it and you’ve lost the entire budget. My advice is to go see every movie. Watch it without the sound and you can really tell how it's made and see the ones that work and what didn't work. Read Variety every day—you have to learn the business and see everything. And two people have to like it besides the person you're fucking and your mother.

GA I'm taking that advice.

JW And if you ever think you should cut a scene, you should because all movies are too long.

GA I’m currently remastering Doom Generation, again, re-mastering Nowhere—both those movies are like 82, or 83 minutes.

JW That's perfect.

GA Remember, John, this isn't the first time we met. I remember winning the Filmmaker on the Edge Award at Provincetown for Mysterious Skin, in like 2004. And you presented the award. Backstage you were like, “Oh, you know, Mysterious Skin is great, but I really miss the old-school Gregg Araki movies.” Kaboom was one of the ideas I was working on at that time and that comment was just lodged in my brain. And Kaboom was very much inspired by what you said to me.

JW Oh, don’t pay attention to anything I say. Take it like a bad note from the studio.

GA Kaboom is all my themes and motifs—almost like my greatest hits, like every movie I've ever done—rolled up into one.

JW Are your parents alive?

GA Yes, both of them.

JW Have you sat with them and watched your movies?

GA I have not. Particularly with The Living End, I was like, do NOT see this movie.

JW Me too, but then they feel like they have to.

GA My family is super supportive and they've always supported me, and it’s amazing.

JW Mine too, but my father once said, “It was fun. I hope I never see it again.” And that was the best blurb.

GA One time my parents actually drove to Los Angeles and watched The Living End at The Regent Showcase on La Brea. It was a matinee screening. I told them specifically not to watch it. And the theater manager told my mom, “Ma'am, I think you're in the wrong theater.” (laughs) My mom told him, “No, no, I wanna see it.” Thinking about my parents watching my movies, I could never make my movies. You know what I mean?

JW The reason people like our movies is because they know their own parents would be horrified.

GA It's a parent-free zone, you know, and you could just express all the craziest shit you want.

JW I filmed Multiple Maniacs on my parent's front lawn. You know, “the cavalcade of perversion!” They were very accepting. They were horrified, but I think they figured, what else could I do? Really? What else could I do? Hag In A Black Leather Jacket. For that movie, my grandmother gave me the camera.

GA Was it a Bolex?

JW No, it was a little Brownie! A Bolex, are you kidding? This was a little Brownie—an 8mm camera. And I shot it on the roof of my parent's house. It's a Ku Klux Klan man marrying a white woman and a black man. I don't know what I was thinking about, but it was very influenced by the Theatre of the Ridiculous at the time. That's what I would say was the big influence. It was fifteen minutes long and it showed once in a beatnik coffee house.

GA Do kids have that now?

JW Well, it would be online, it would be on the phone. It's a whole different way. We don't care, you know, phones look better. You can't see the mistakes (laughs). Who wants to see Hag In A Black Leather Jacket in 70mm? You know? I guess that would be a new experience.

GA Or IMAX.

JW Yeah, exactly. I saw Jackass in IMAX, the last one, and I never saw someone's balls that big in pain on a screen. Well, it was great talking to you, Gregg. I'll see you at the Academy Museum this fall. I'll see you at dinner.

GA Thank you, John, for doing this. I know you're so busy.

JW All right. Toodle-oo.

“One time my parents actually drove to Los Angeles and watched The Living End at The Regent Showcase on La Brea. It was a matinee screening. I told them specifically not to watch it.”