S/S23 Utopia

S/S23 Utopia

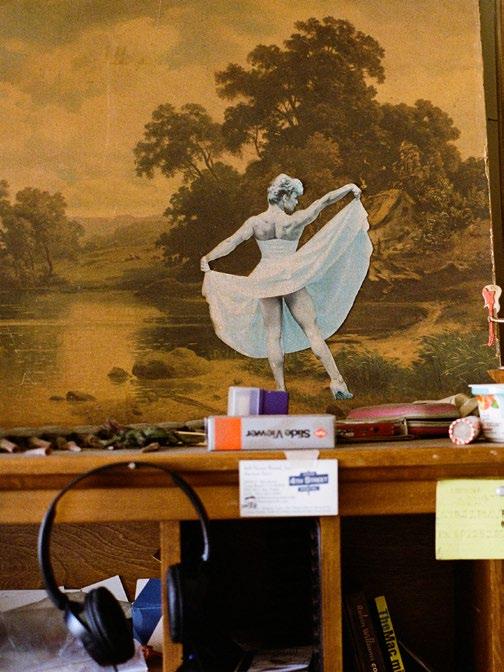

Marina Abramović by Justin French

Marina Abramović by Justin French

Marina Abramović by Justin French

Marina Abramović by Justin French

APRIL 26 — JULY 7, 2023

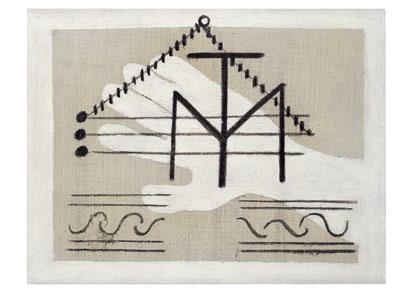

MARKUS LÜPERTZ

MARKUS THE PAINTER

OR THE RATIO OF THE IMPOSSIBLE

APRIL 21 - JUNE 11, 2023

VITO SCHNABEL GALLERY

OLD SANTA MONICA POST OFFICE

ARTISTS: KEITH BOADWEE | HEATHER DAY | HOWARD FONDA | BELLA FOSTER

ERIK FRYDENBORG | TAMARA GONZALES | KELLY LYNN JONES | CRAIG KUCIA

LIZ MARKUS | ANTHONY MILER | HEATHER RASMUSSEN | JENNIFER ROCHLIN

ADRIANNE RUBENSTEIN | RYAN SCHNEIDER | NORA SHIELDS | DEVIN TROY

STROTHER | JAMES ULMER | BENJAMIN WEISSMAN | MARYAM YOUSIF

WWW.THE-PIT.LA

IMAGE: JENNIFER ROCHLIN, RIDING WAVES & BIKES, 2022, GLAZED CERAMIC, 21 x 18 x 18 IN., 53.3 x 45.7 x 45.7 CM, JR0099

IMAGE: JENNIFER ROCHLIN, RIDING WAVES & BIKES, 2022, GLAZED CERAMIC, 21 x 18 x 18 IN., 53.3 x 45.7 x 45.7 CM, JR0099

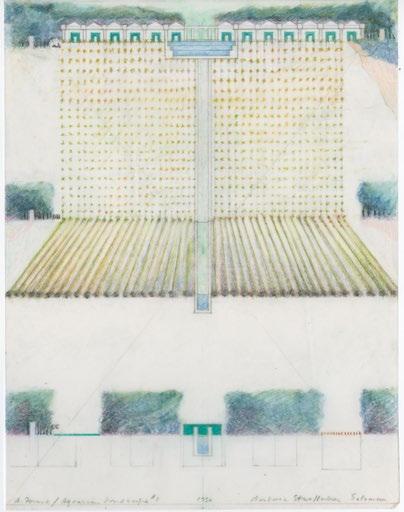

22 Agnes Denes

Survival Structures for Humanity

Text by Abbey Meaker

24 Diva Amon

Deep Sea Discoveries

Interview by Kaylee Gibson

28 Halcyon Days

Photography by Mat+Kat

Styling by Shana Arnold

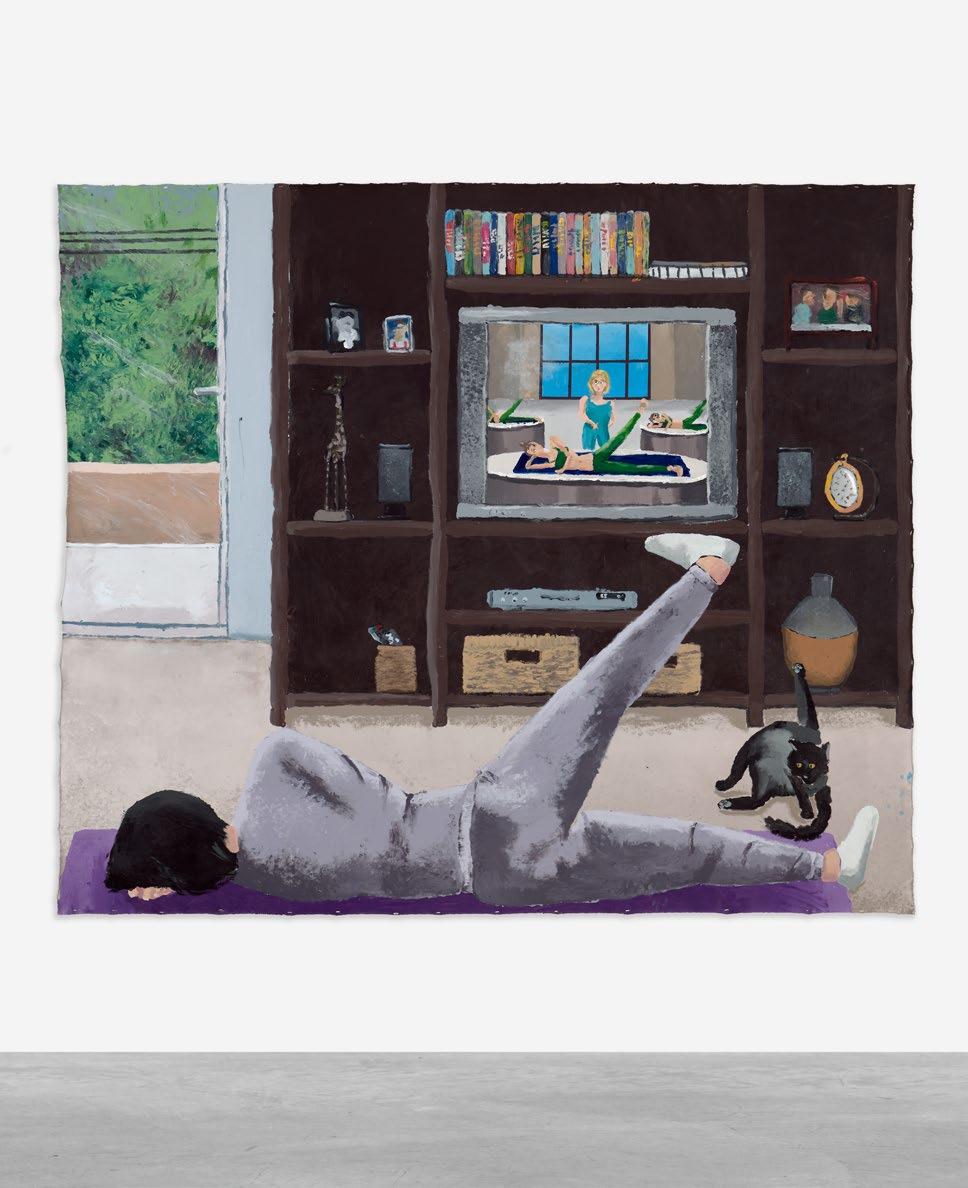

34 Nikki Maloof

Domestic Tableaux

Interview by Oliver Kupper

38 Extra, Extra

Photography by Jermaine Francis

Styling by Naomi Miller

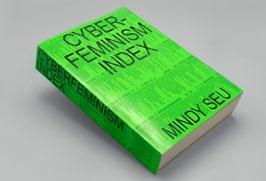

46 Mindy Seu

Cyberfeminism Index

Interview by Lara Schoorl

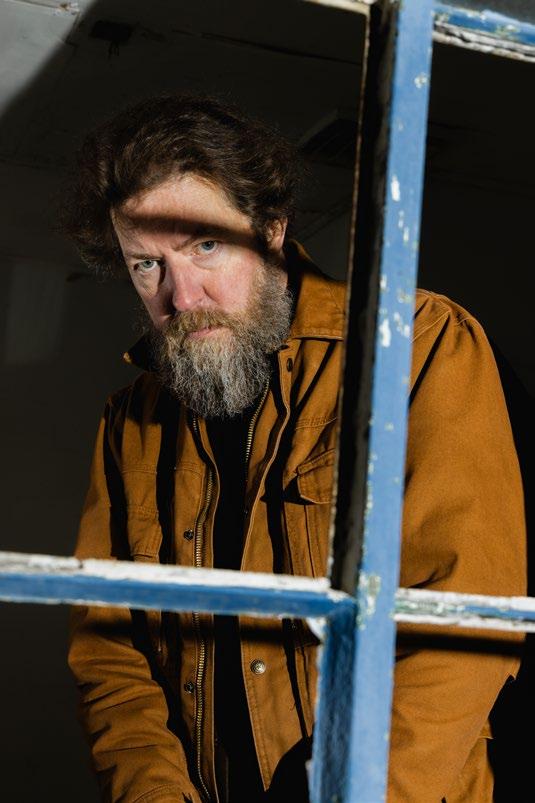

48 Ken Layne

Take Care, It’s a Desert Out There

Text by Oliver Misraje

52 The View From Future’s Past

Text by Mike Davis

Photography by Zoe Chait

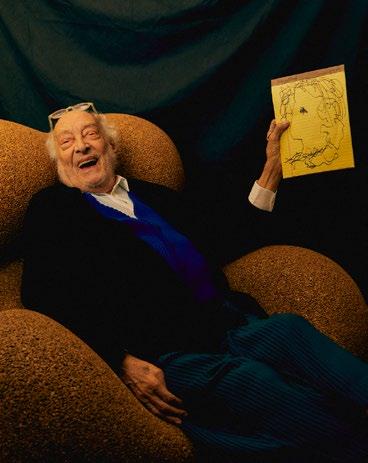

56 Norman Klein

Diamonds on Black Velvet

Interview by Benno Herz

Photography by Pat Martin

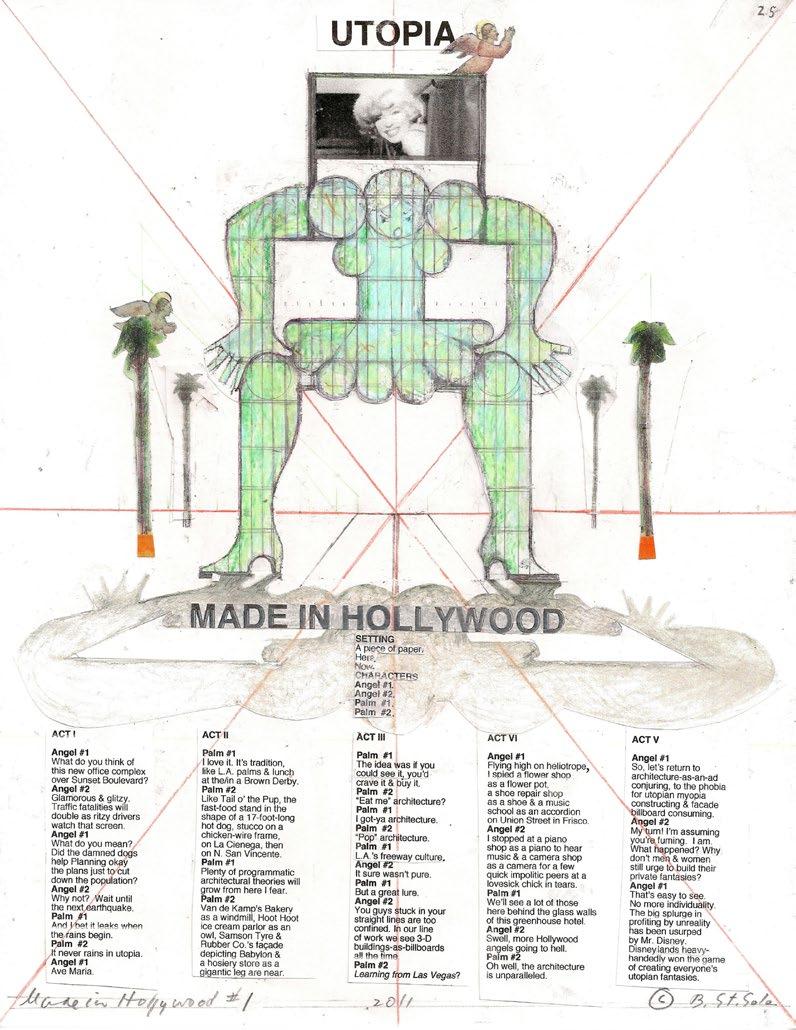

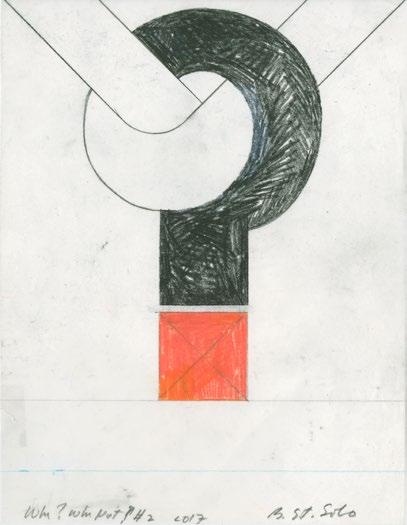

62 Barbara Stauffacher Solomon

Interview by Oliver Kupper

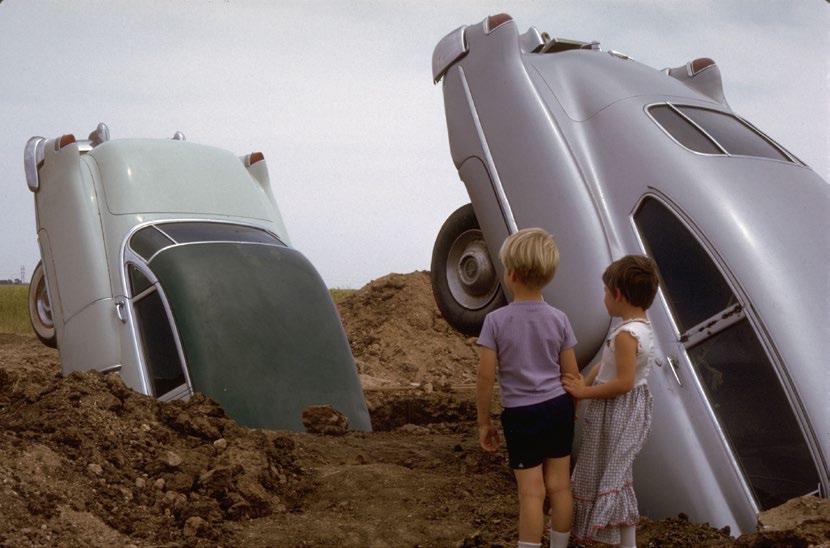

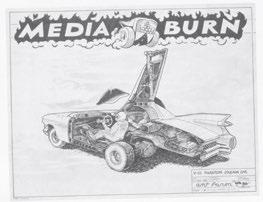

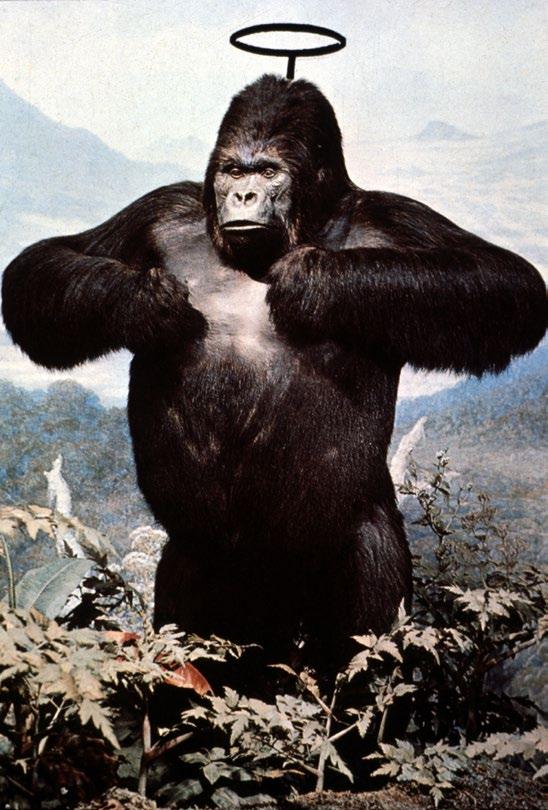

70 Ant Farm

An interview of Chip Lord

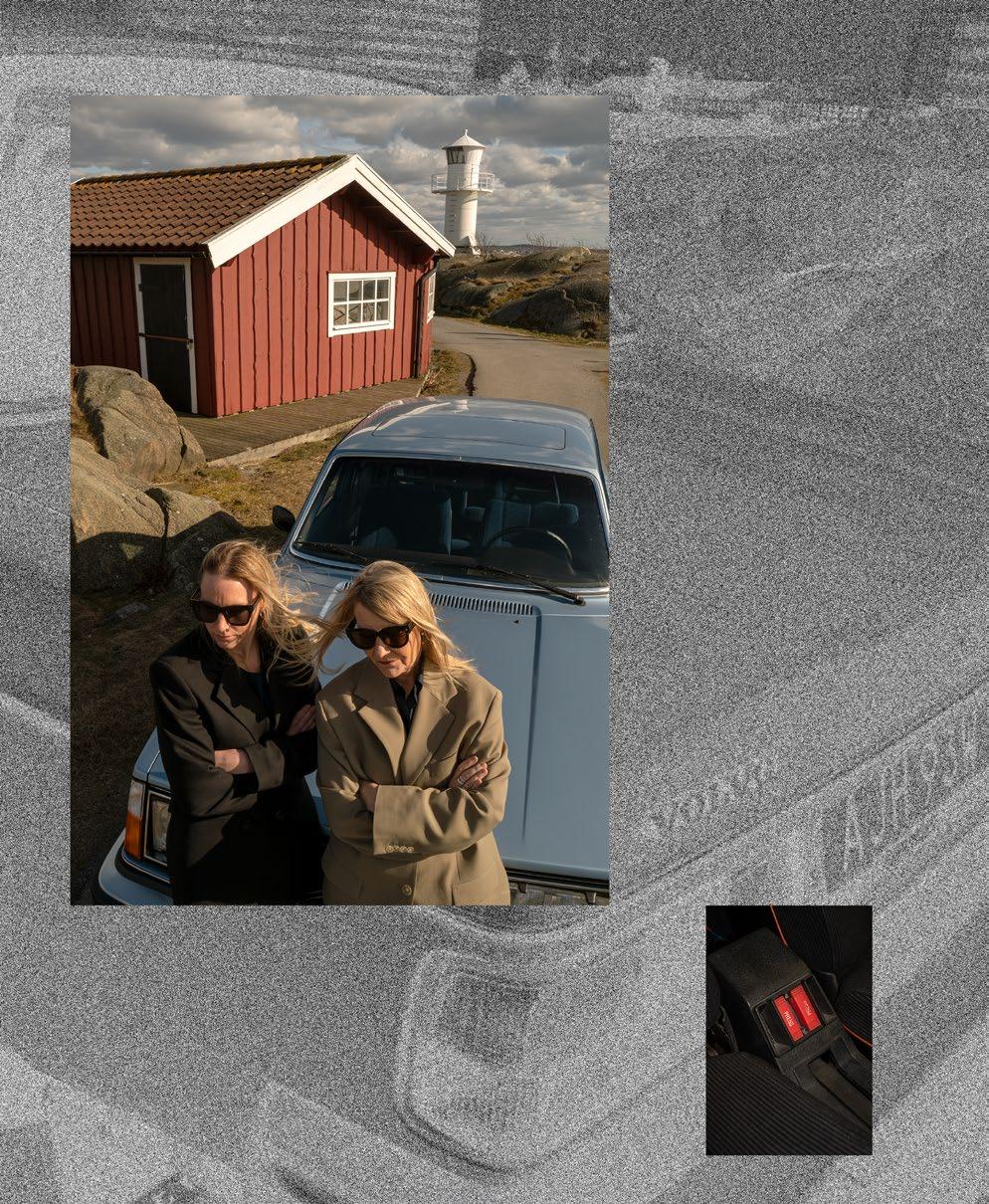

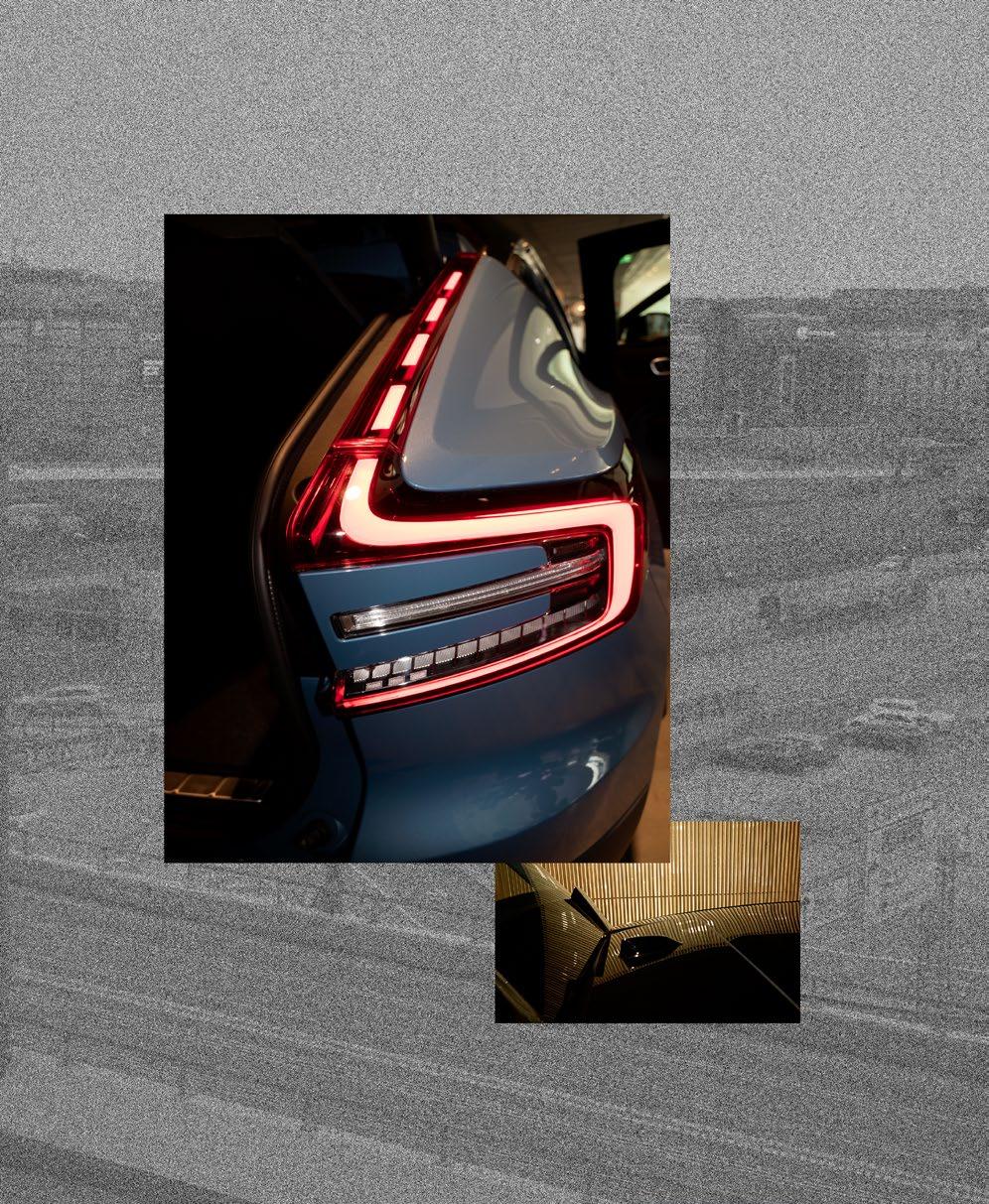

78 Volvo

Human Design

Interview by Oliver Kupper

Photography by Kuba Ryniewicz

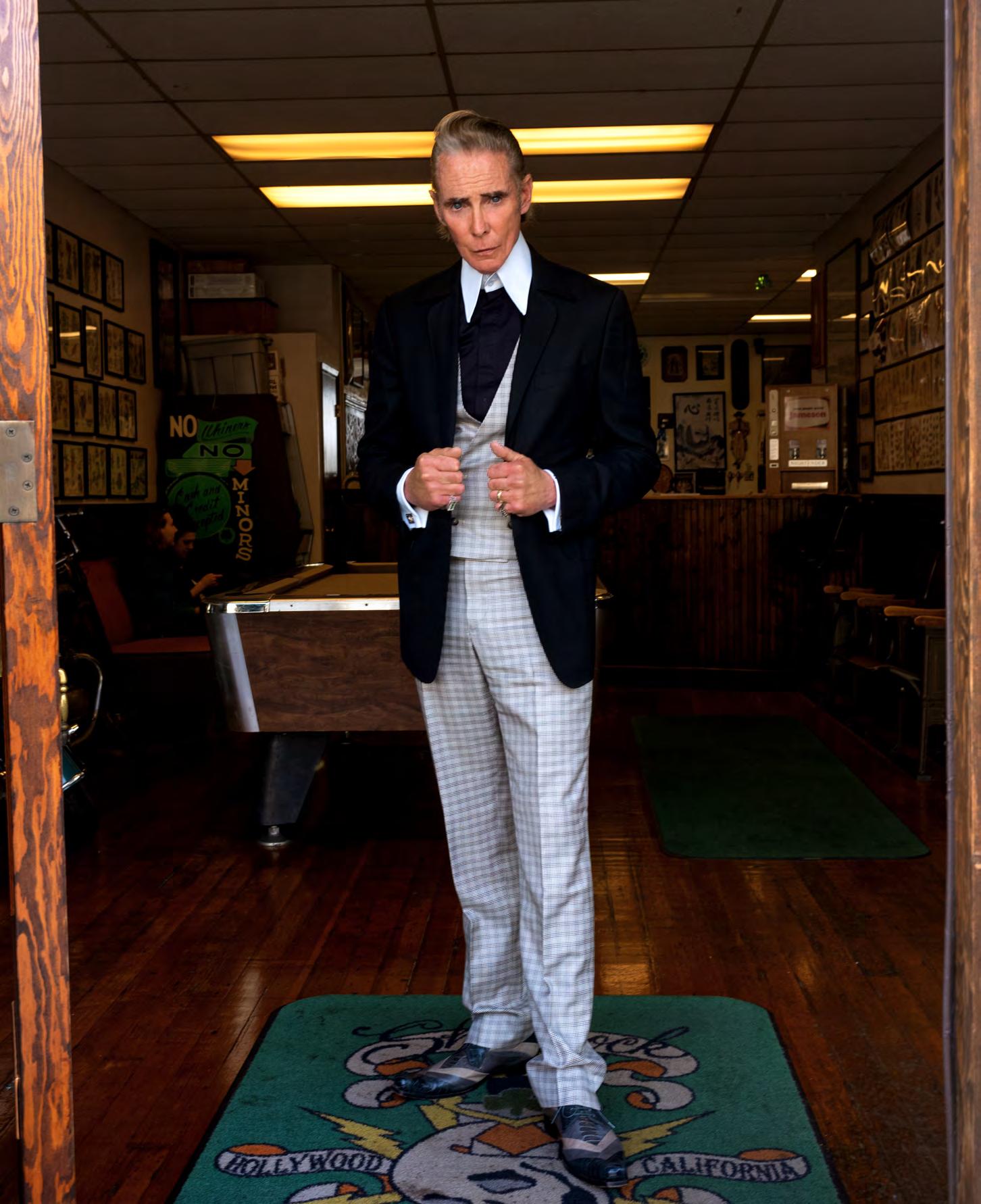

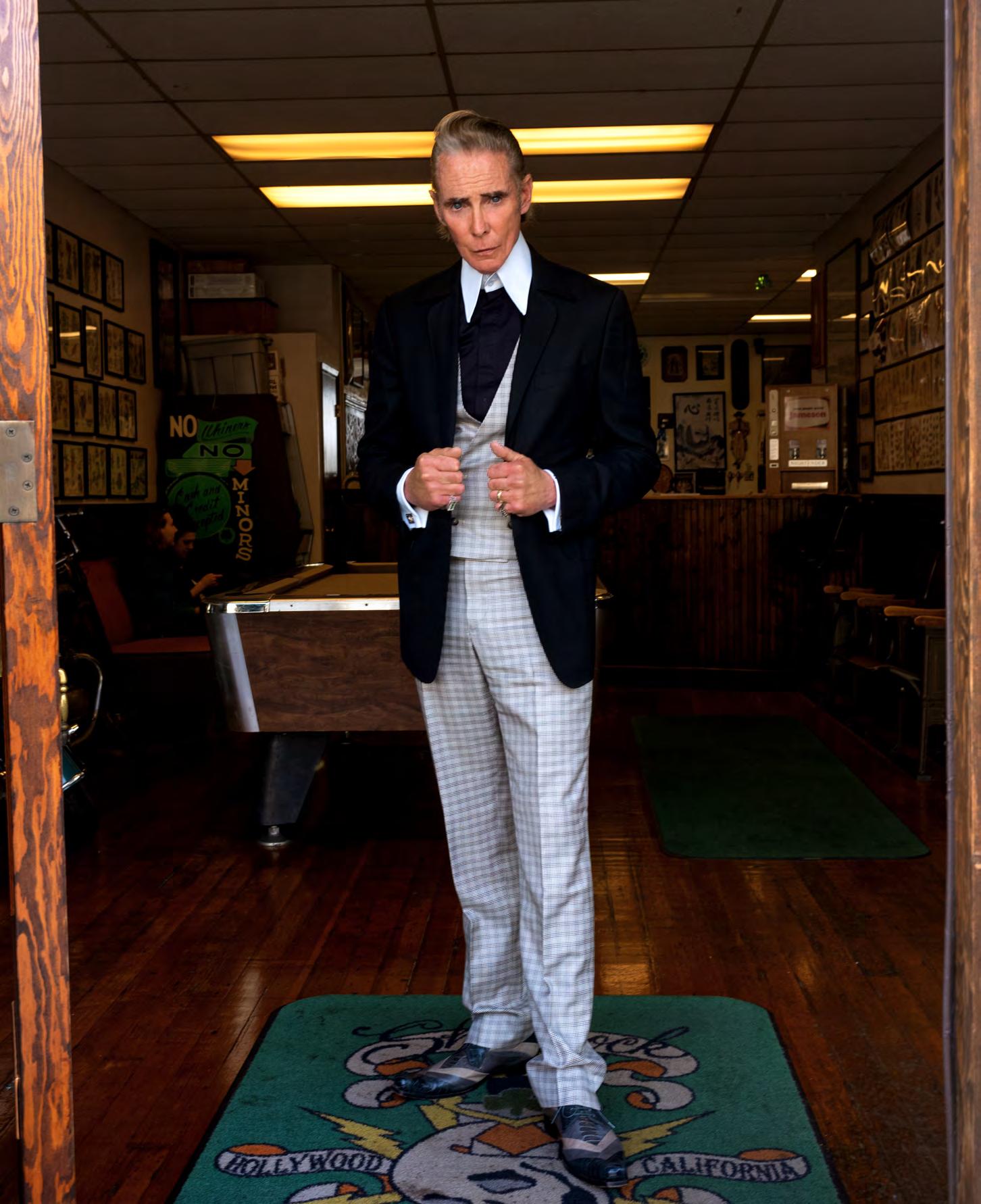

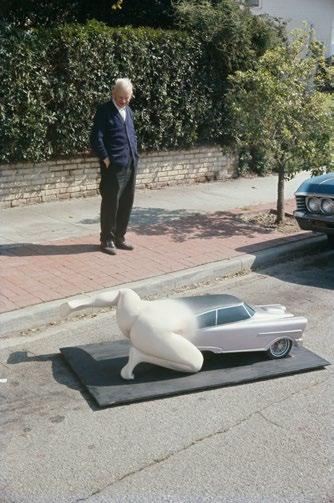

86 Pippa Garner

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist

Photography by Jesper D. Lund

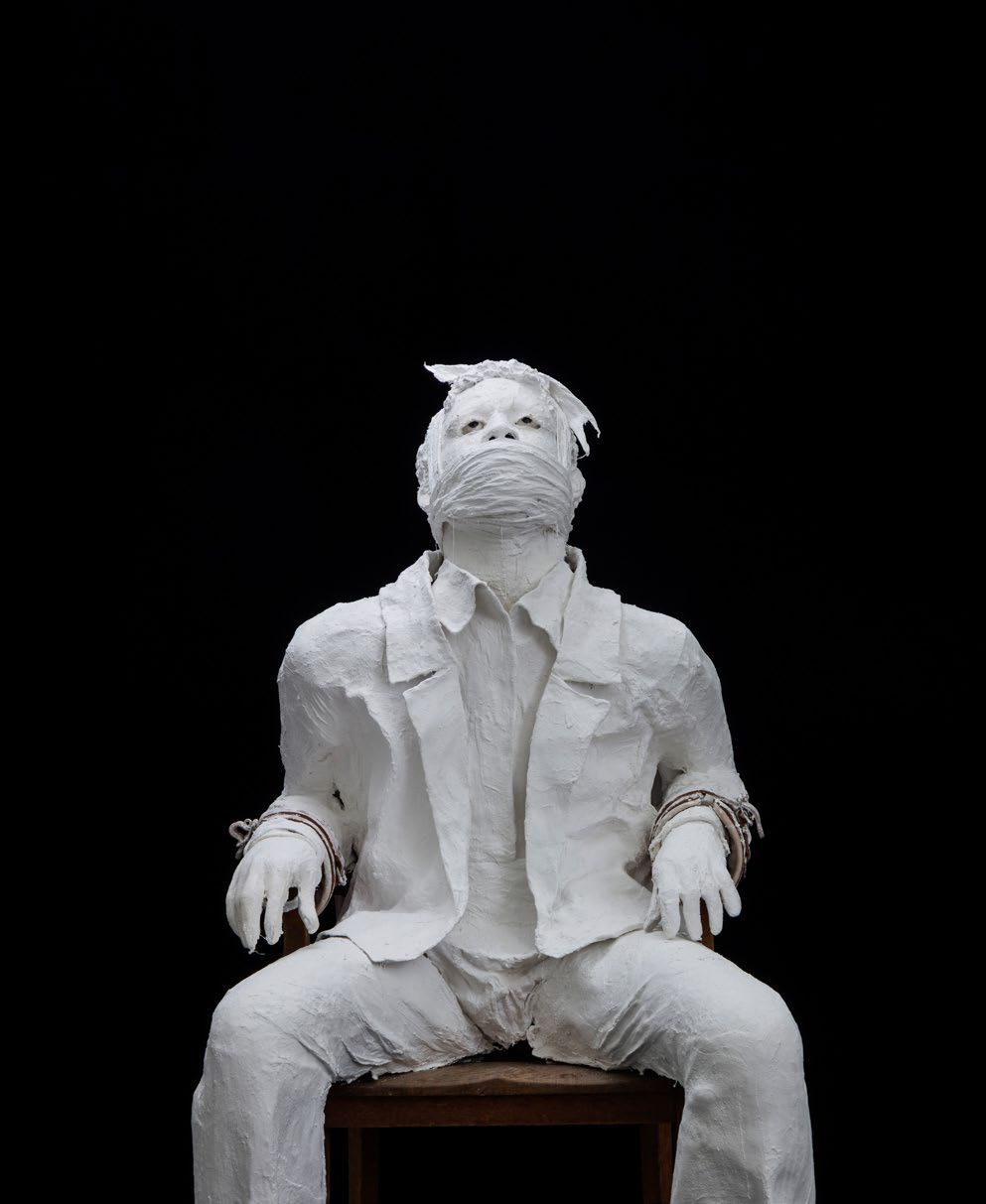

96 Adrián Villar Rojas

Rhizomatic Utopias

Interview by Oliver Kupper

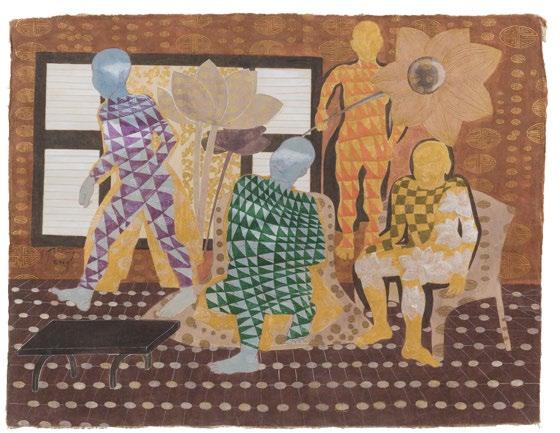

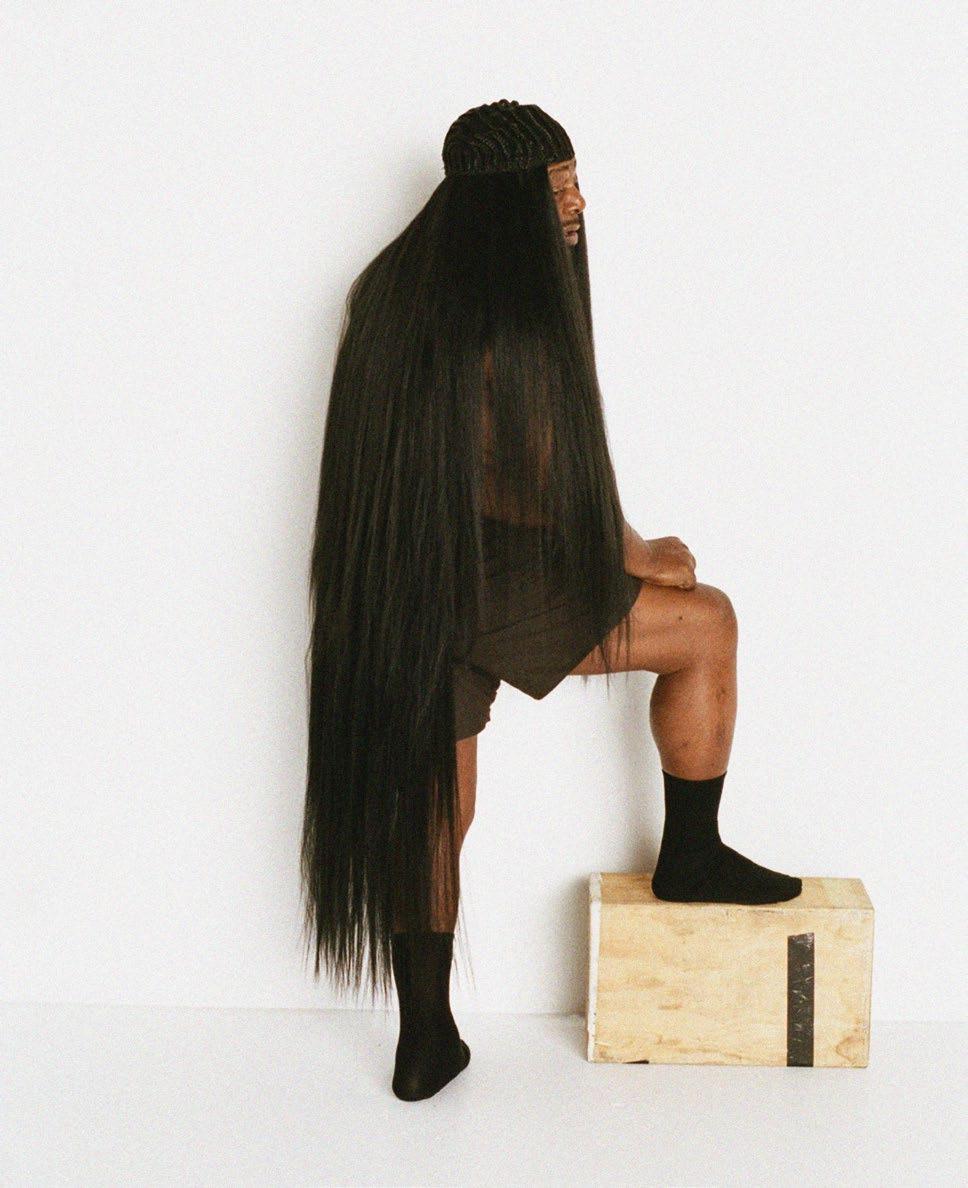

102 Korakrit Arunanondchai

Interview by Oliver Kupper

Portraits by Jason Nocito

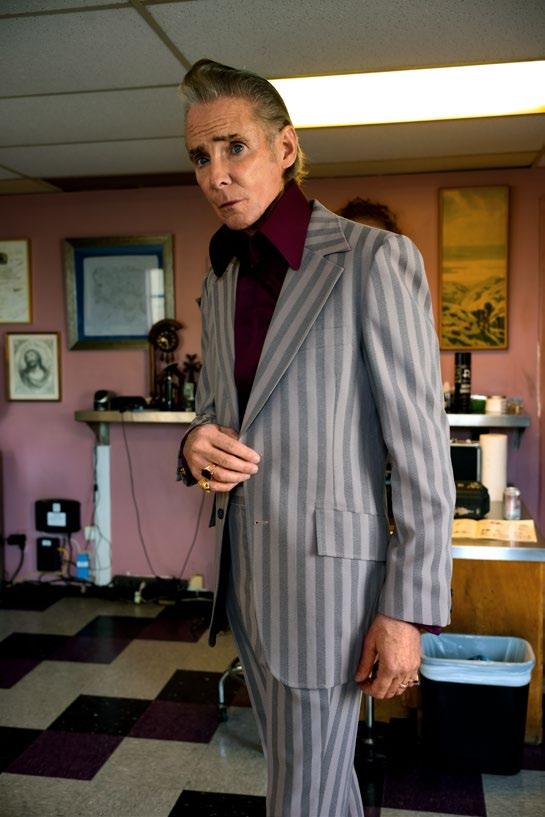

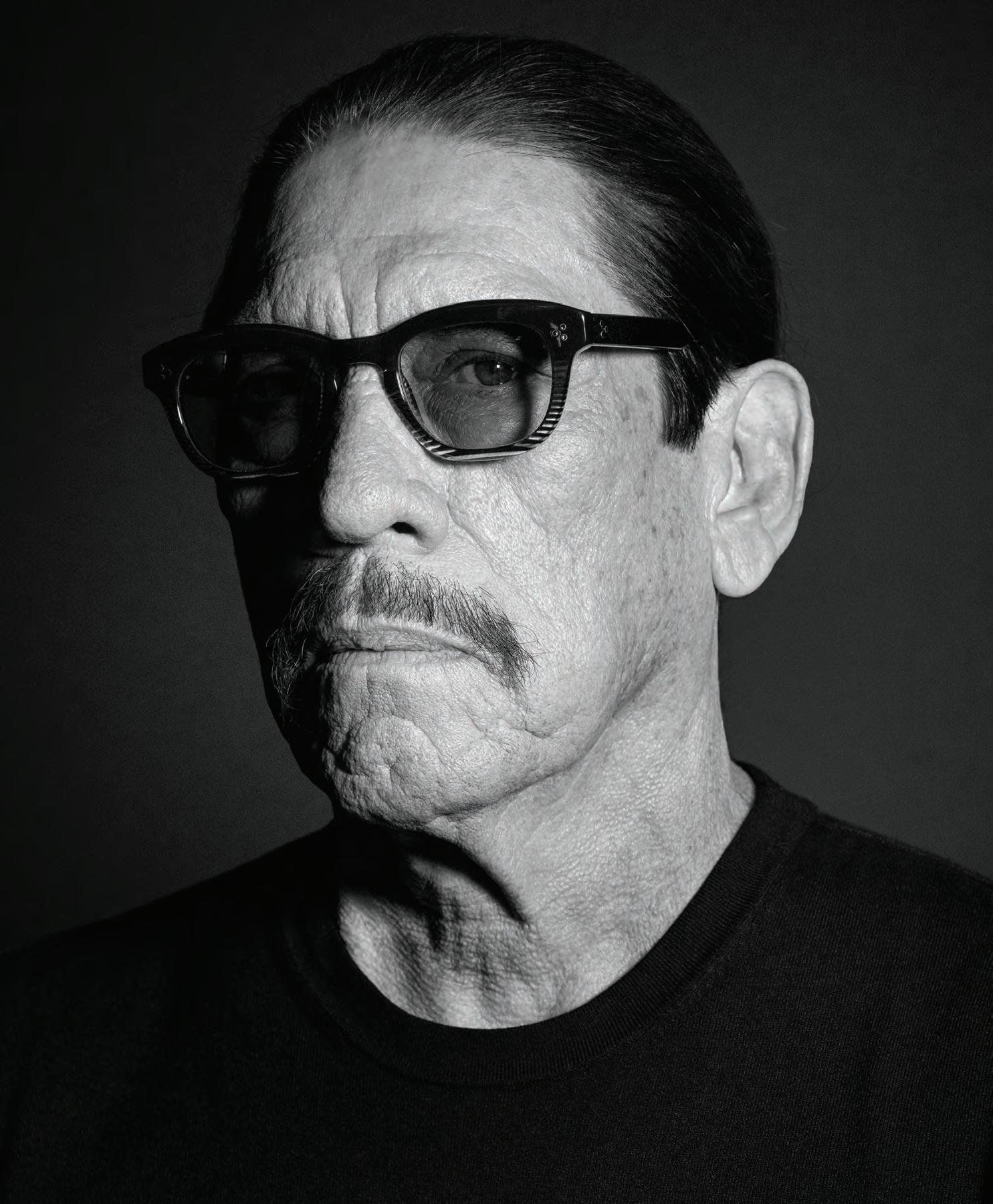

110 Mark Mahoney

Interview and

Portraits by Nan Goldin

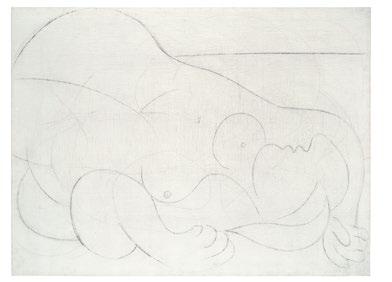

124 Scent Memory

Diana Widmaier Picasso, Manuel Solano, and Rodrigo Garcia in Conversation

Portrait by Vincent Wechselberger

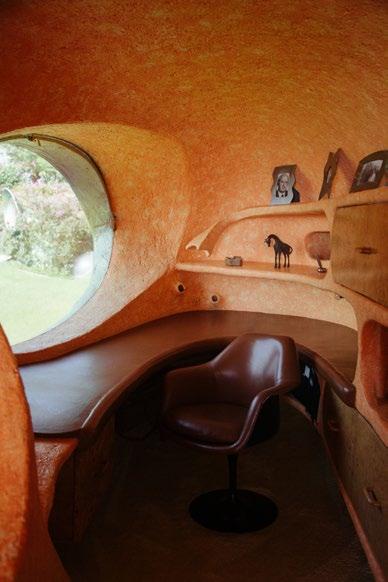

132 Javier Senosiain

Organic Architecture

Interview by Dakin Hart

Photographs by Olivia Lopez

140 Frank Gehry and Charles Arnoldi

What The Fuck Is A Glass Box?

Portraits by Magnus Unnar

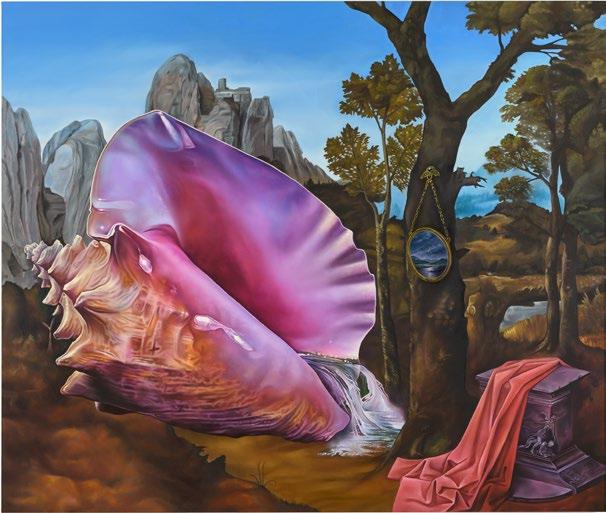

150 Ariana Papademetropoulos

Interview by Jeffrey Deitch

Portraits by Max Farago

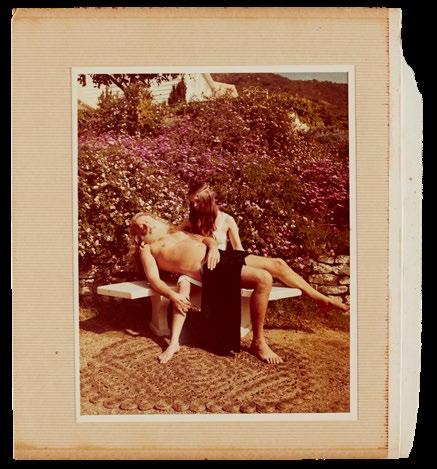

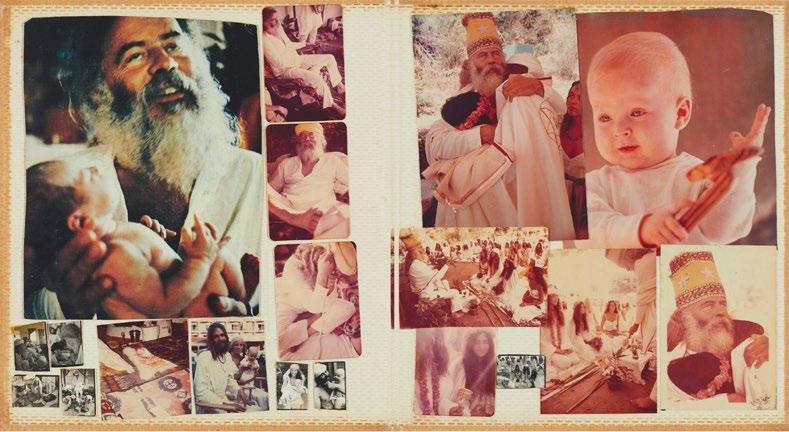

160 The Source Family

Isis Aquarian and Jodi Wille in Conversation

166 Sisters of the Valley

Interview by Summer Bowie

Photography by Damien Maloney

174 Robert D’Allesandro

Another Way Of Living

Interview by Julie Ragolia

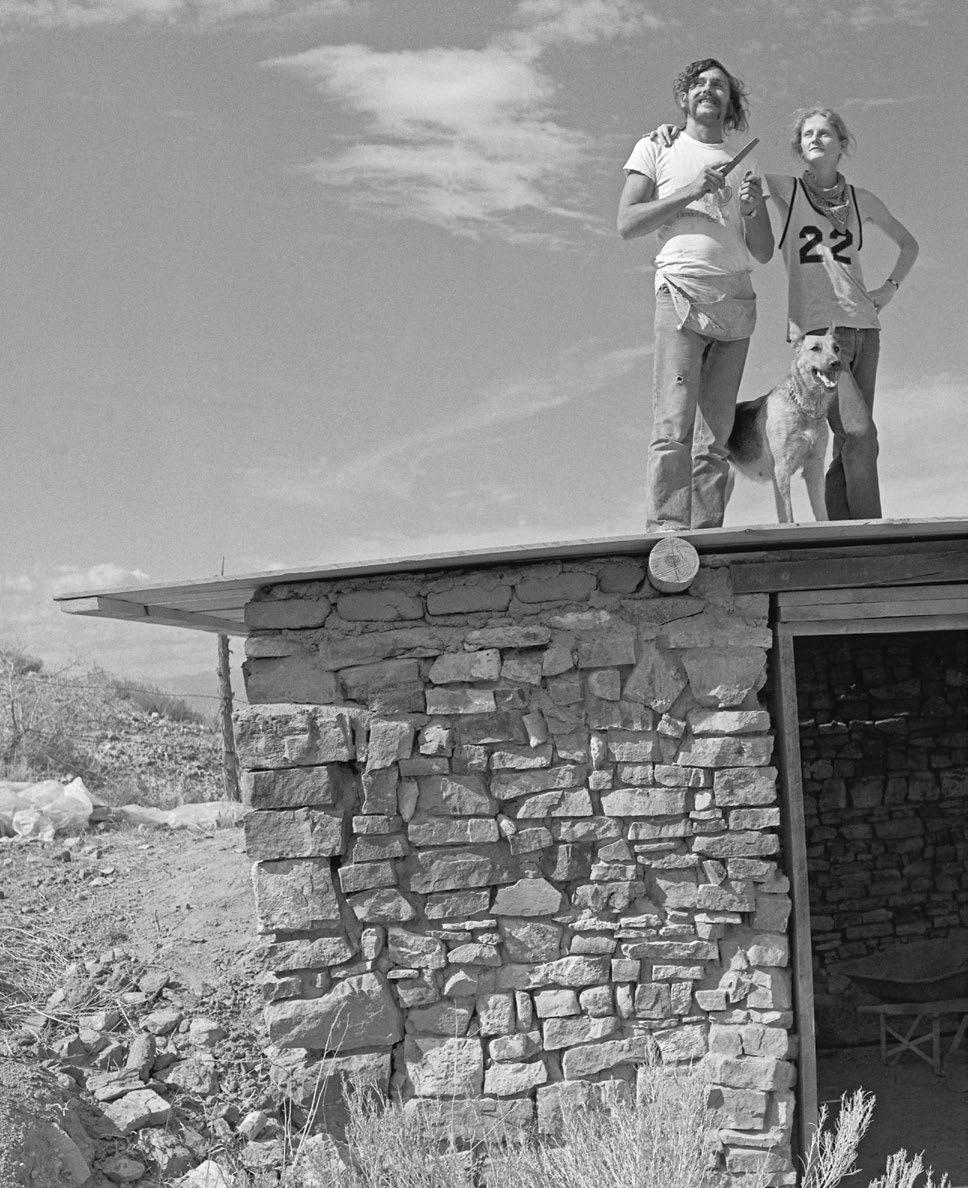

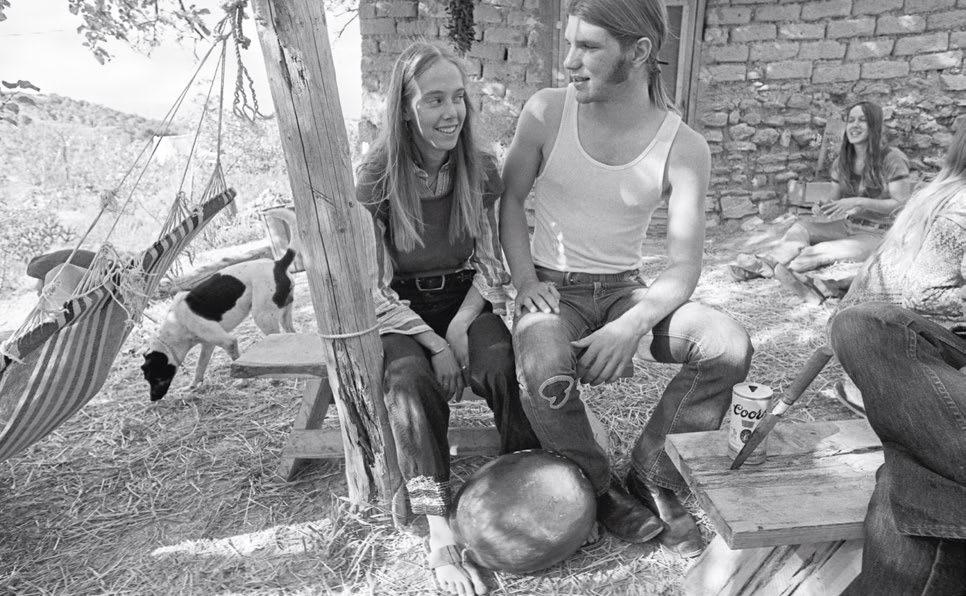

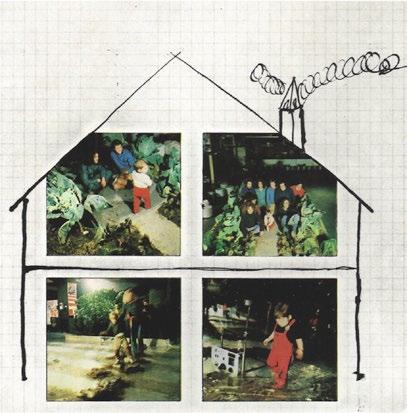

180 Salmon Creek Farm

Fritz Haeg

Interview by Jay Ezra Nayssan

Photography by Ethan DeLorenzo

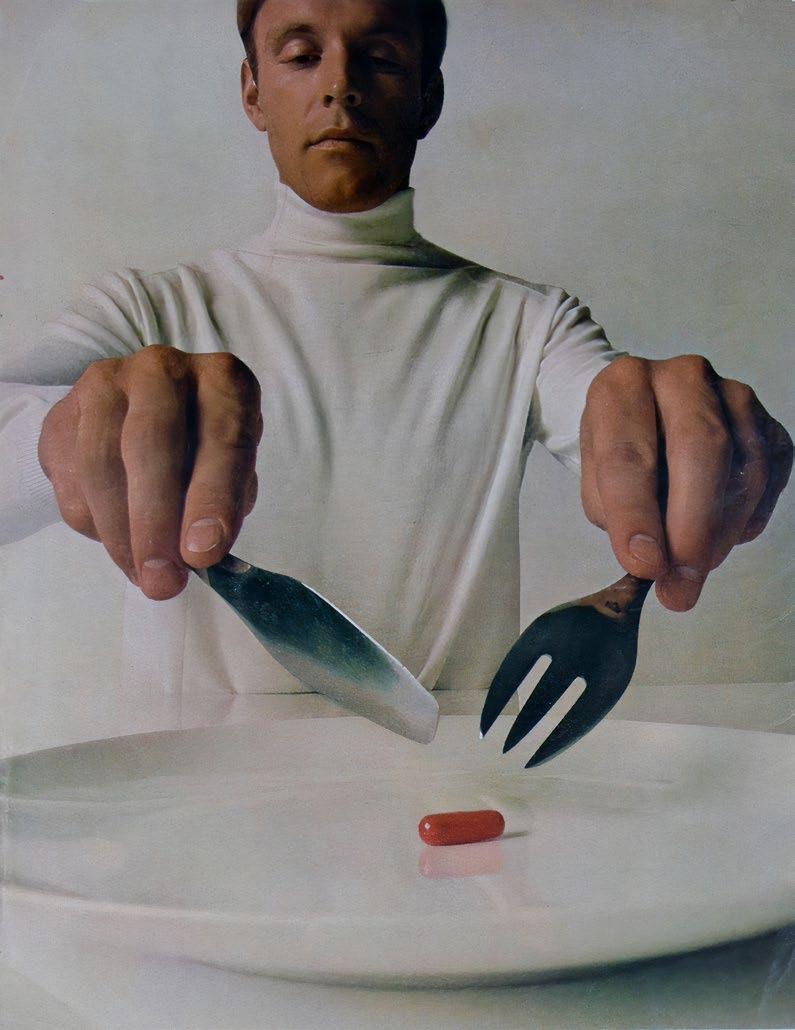

188 François Dallegret

Utopia Is A Pile Of Shit

Text by Justin Beal

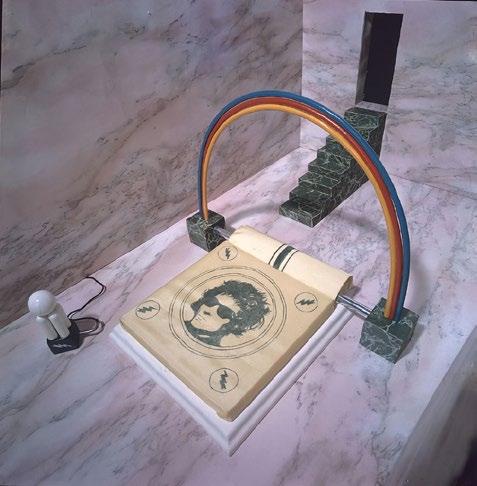

194 Haus-Rucker-Co

Günther Zamp Kelp

Interview by Charlotte Martens

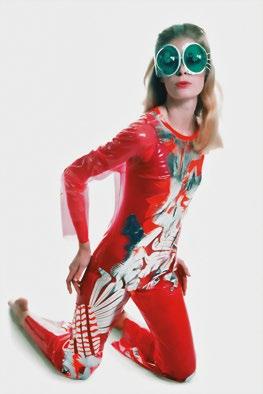

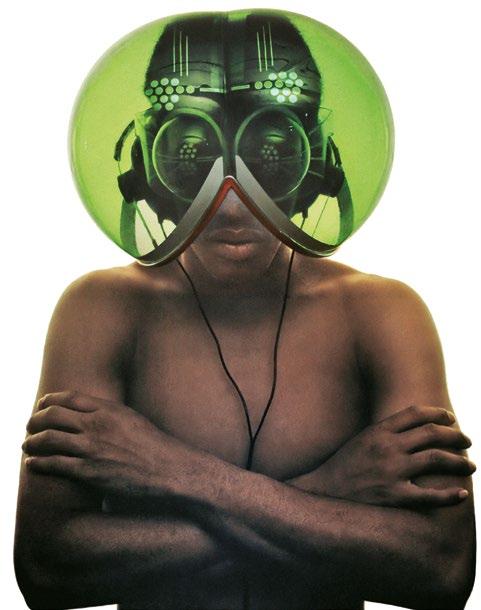

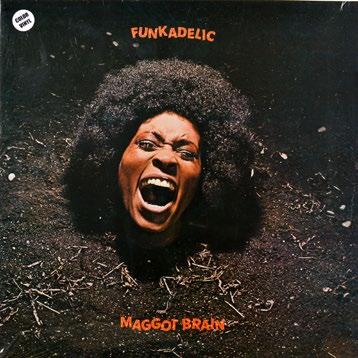

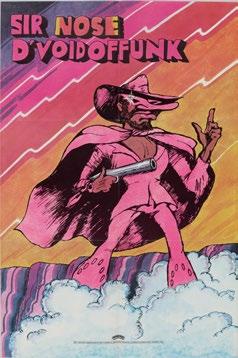

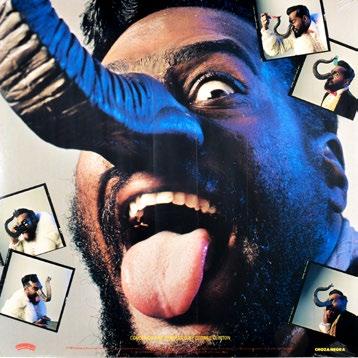

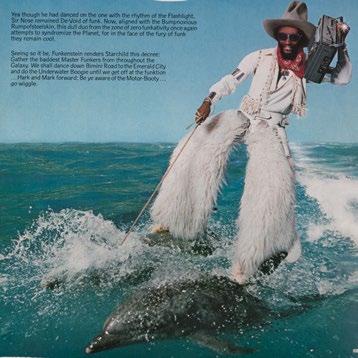

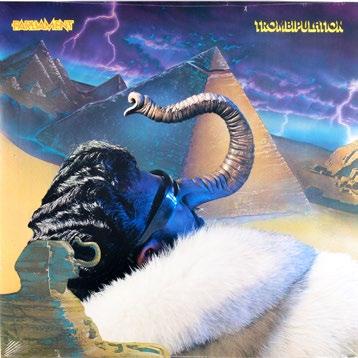

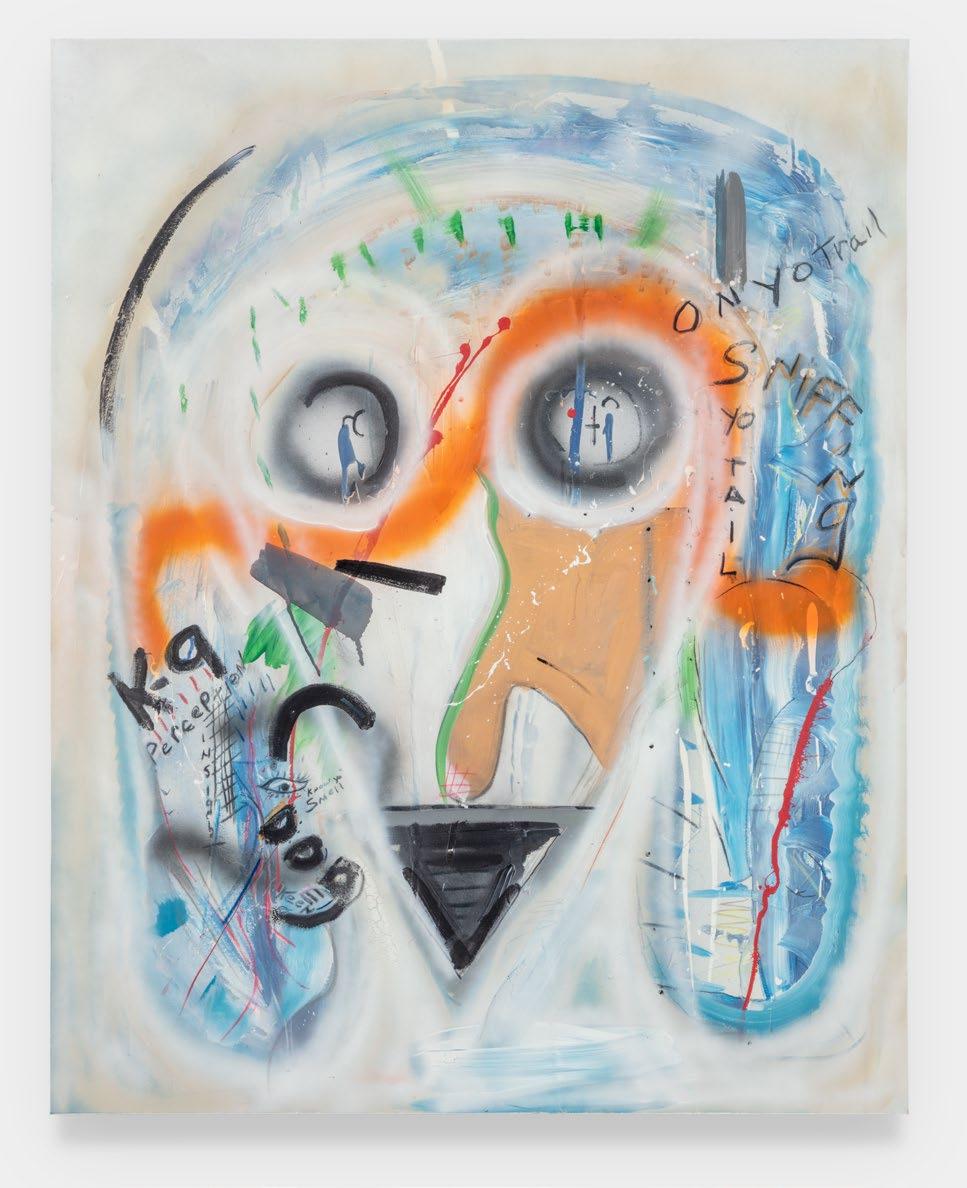

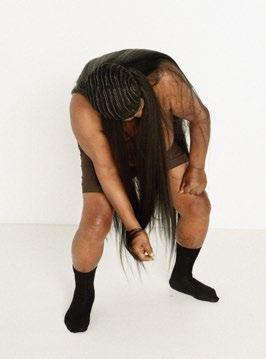

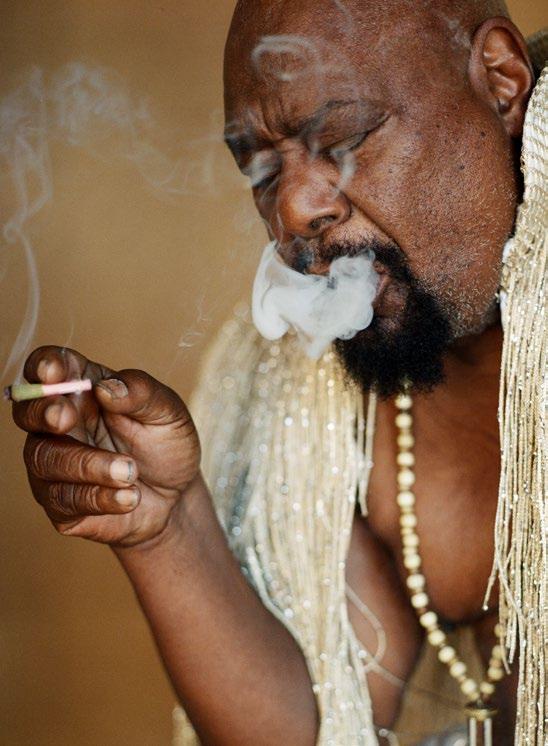

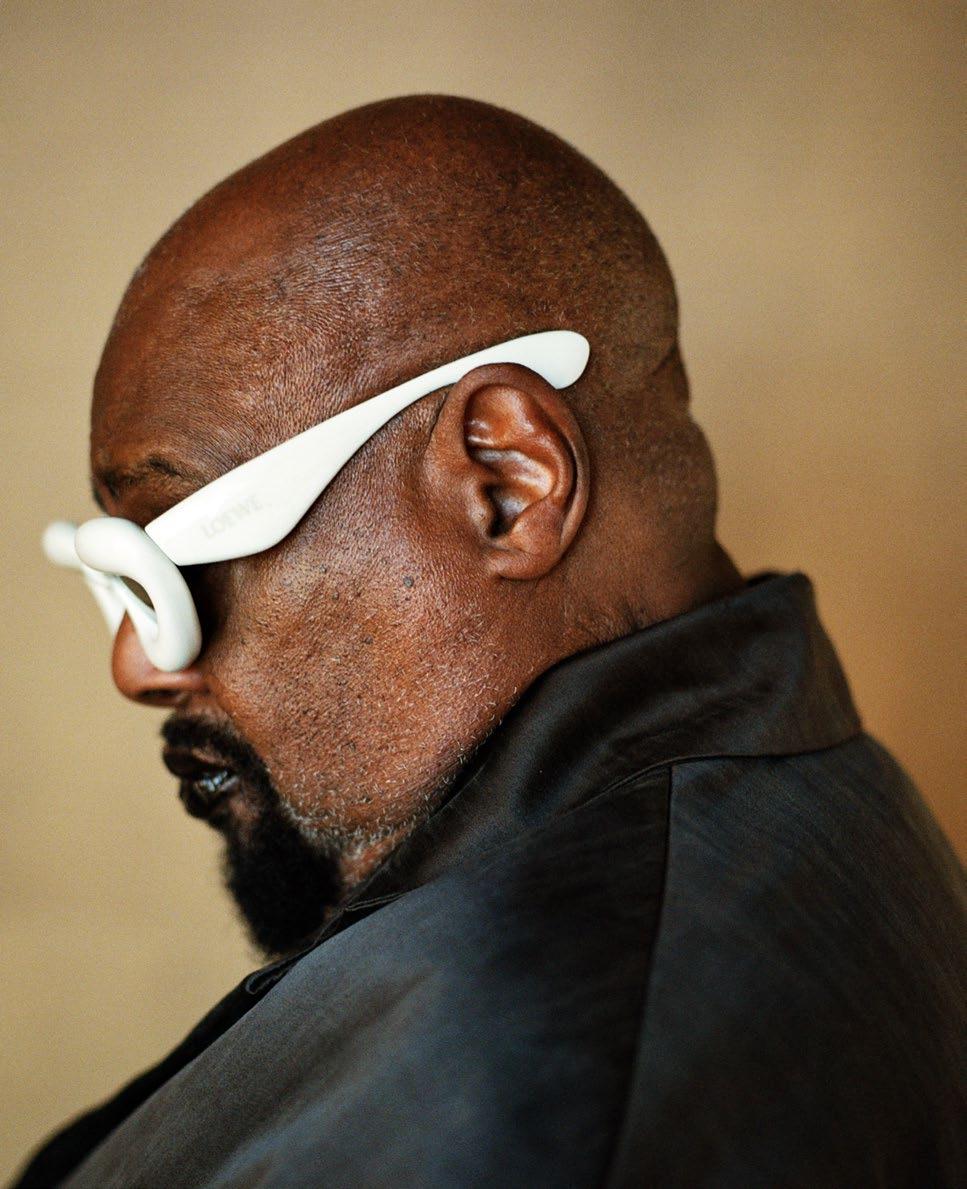

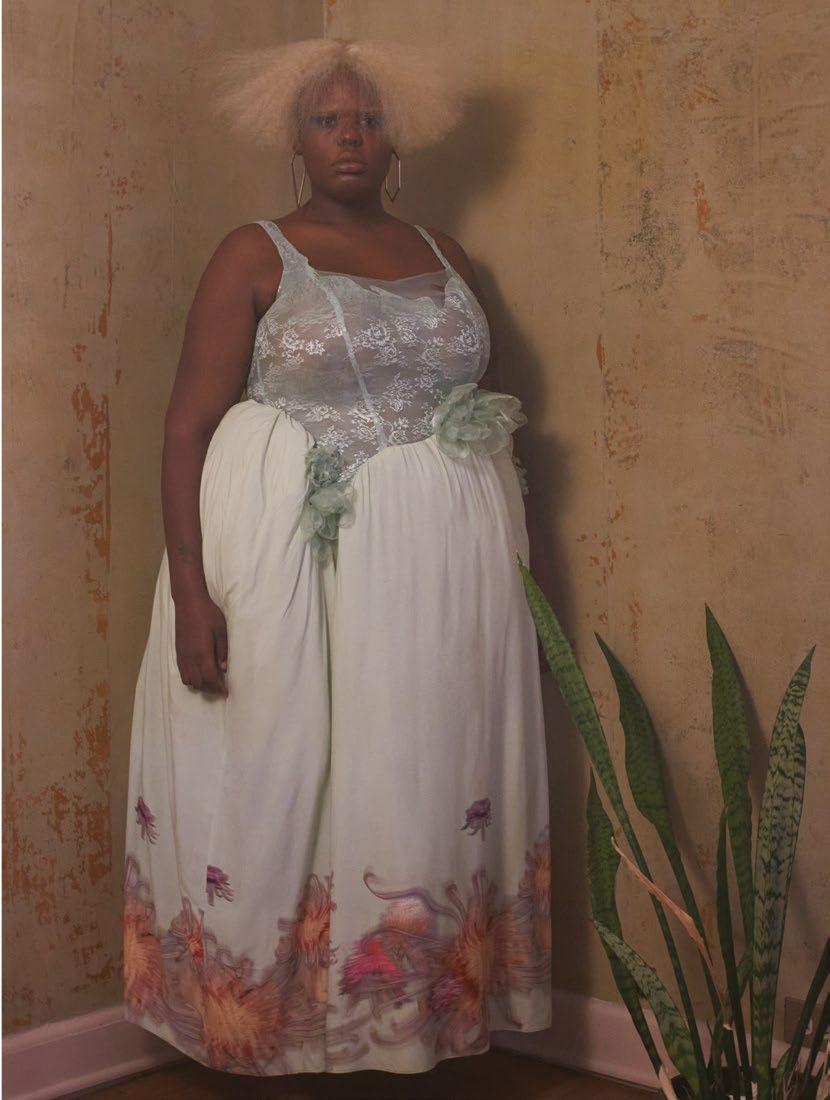

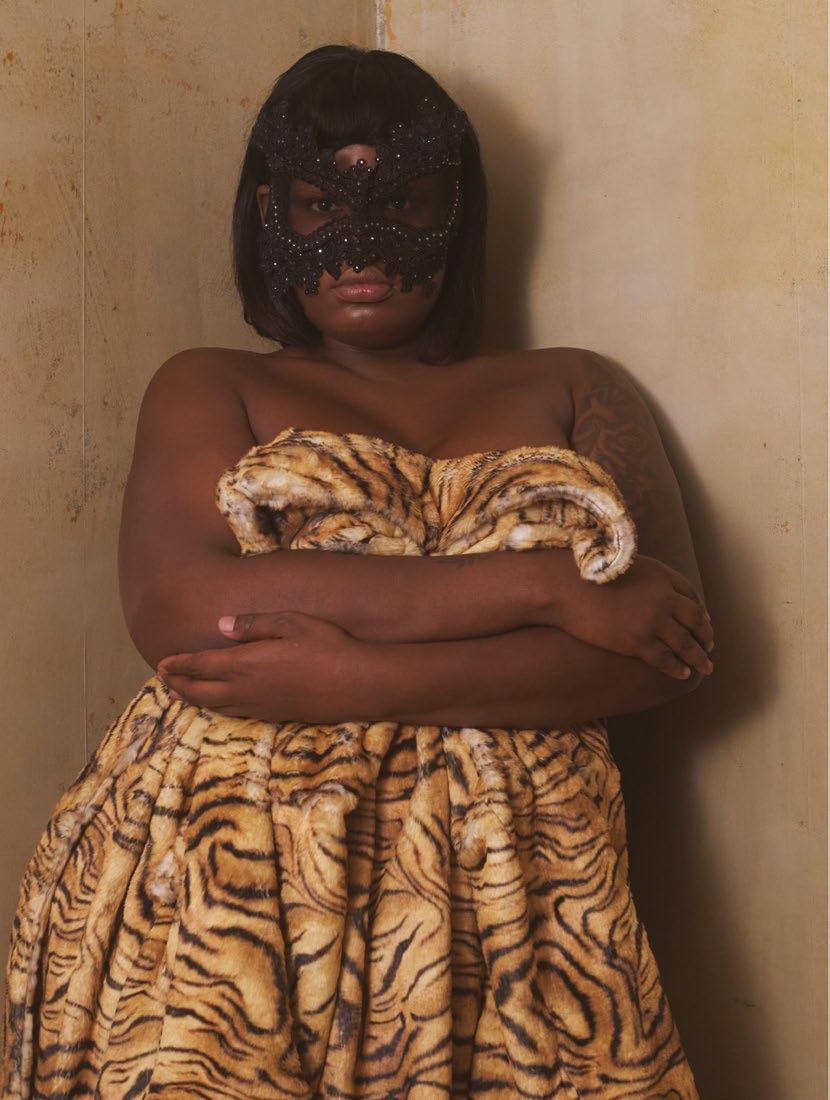

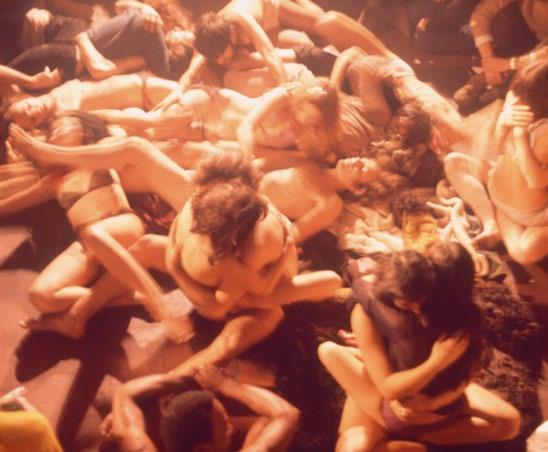

200 Funktopia

George Clinton Interviewed by Lauren Halsey, with Overton Loyd

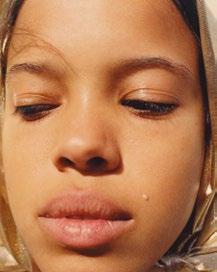

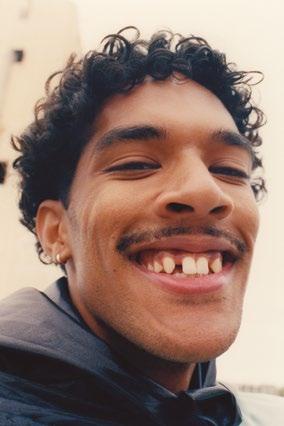

Portraits by Kennedi Carter

Styling by Julie Ragolia

220 It’s all in the process: A call for intellectual integrity in fashion

Text by Angelo Flaccavento

222 One, In A Sum Of Many

Photography by Parker Woods

Styling by Julie Ragolia

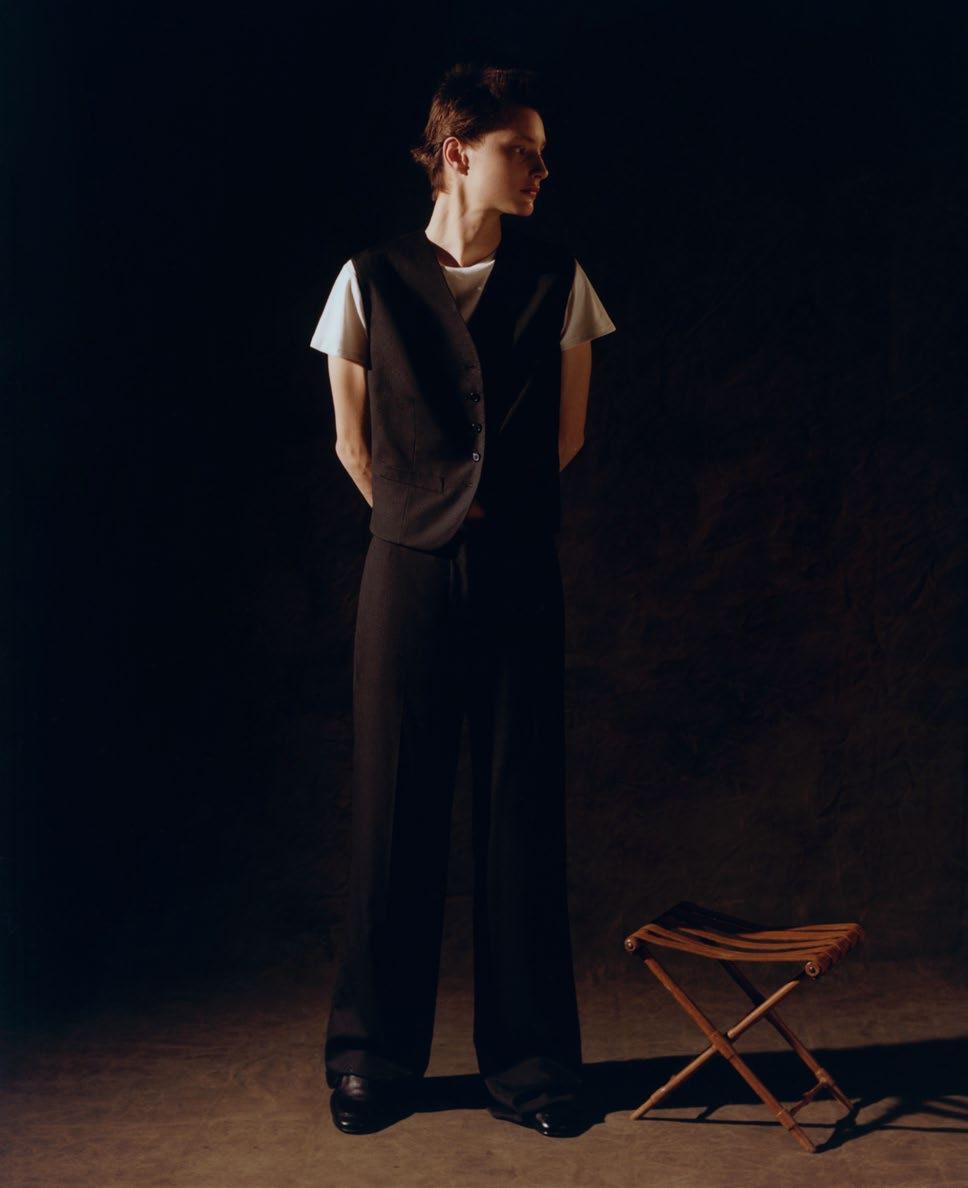

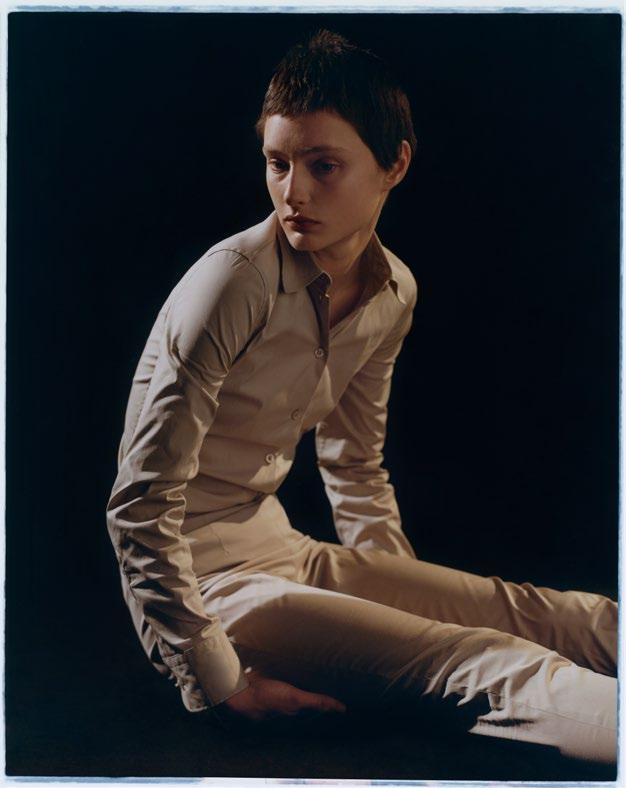

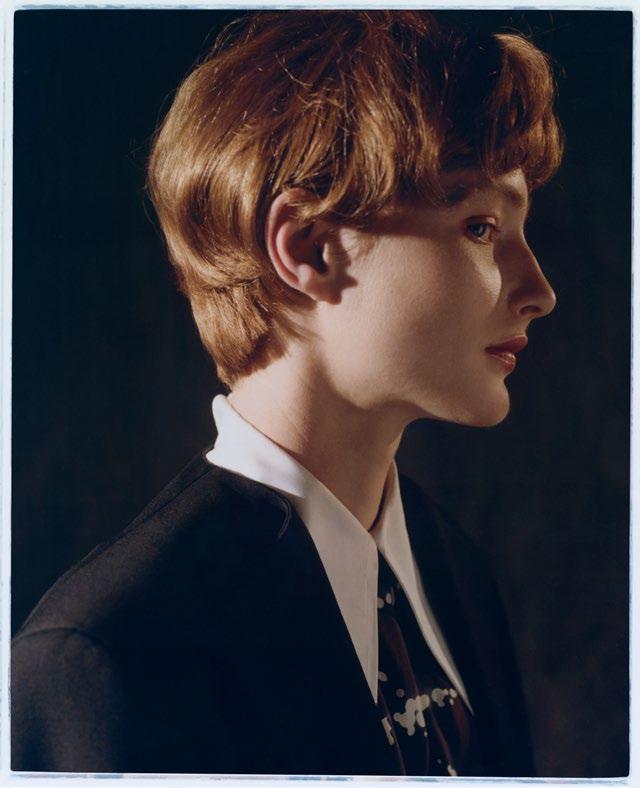

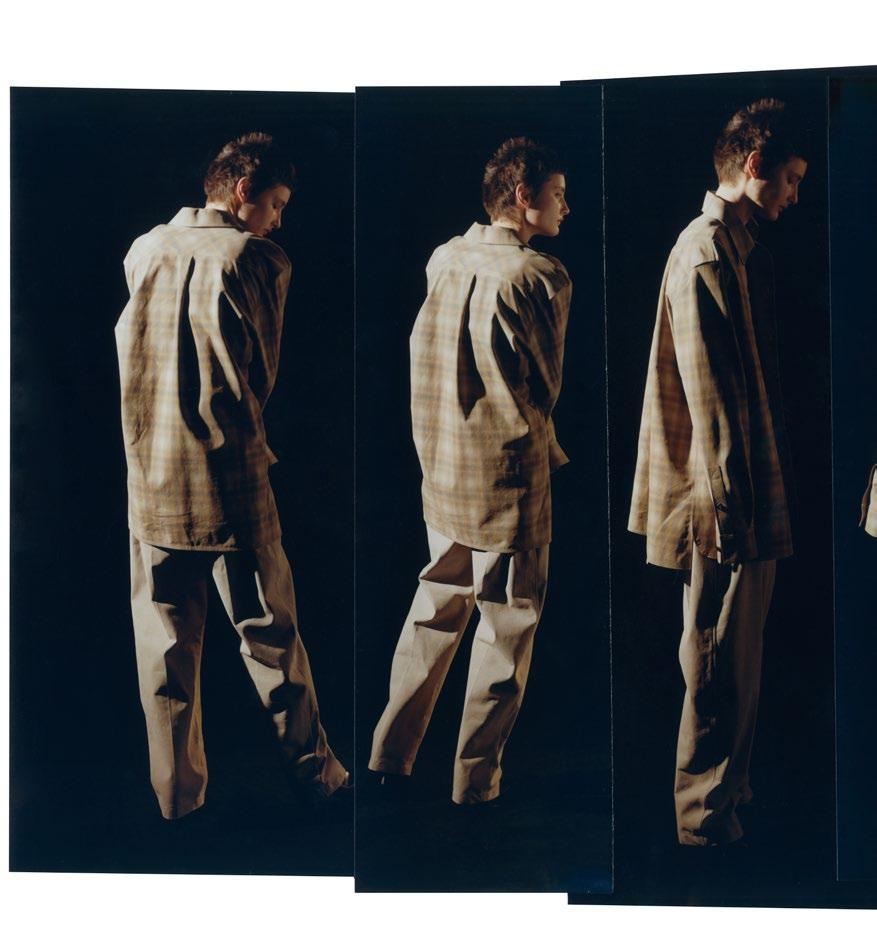

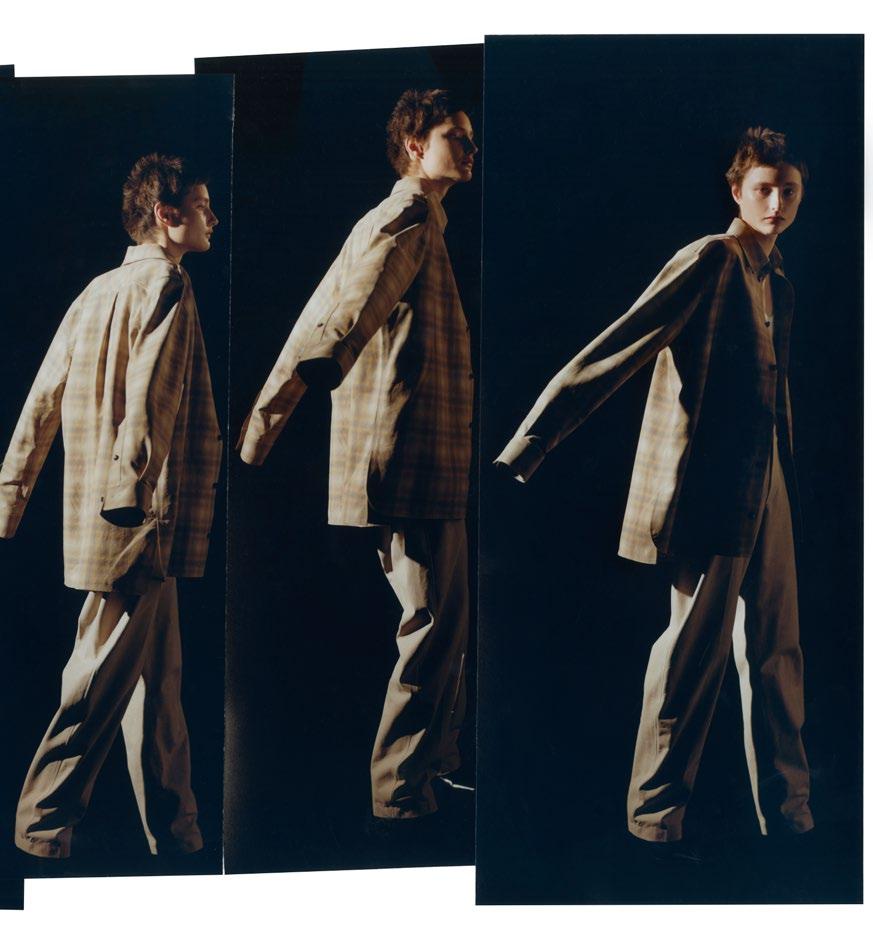

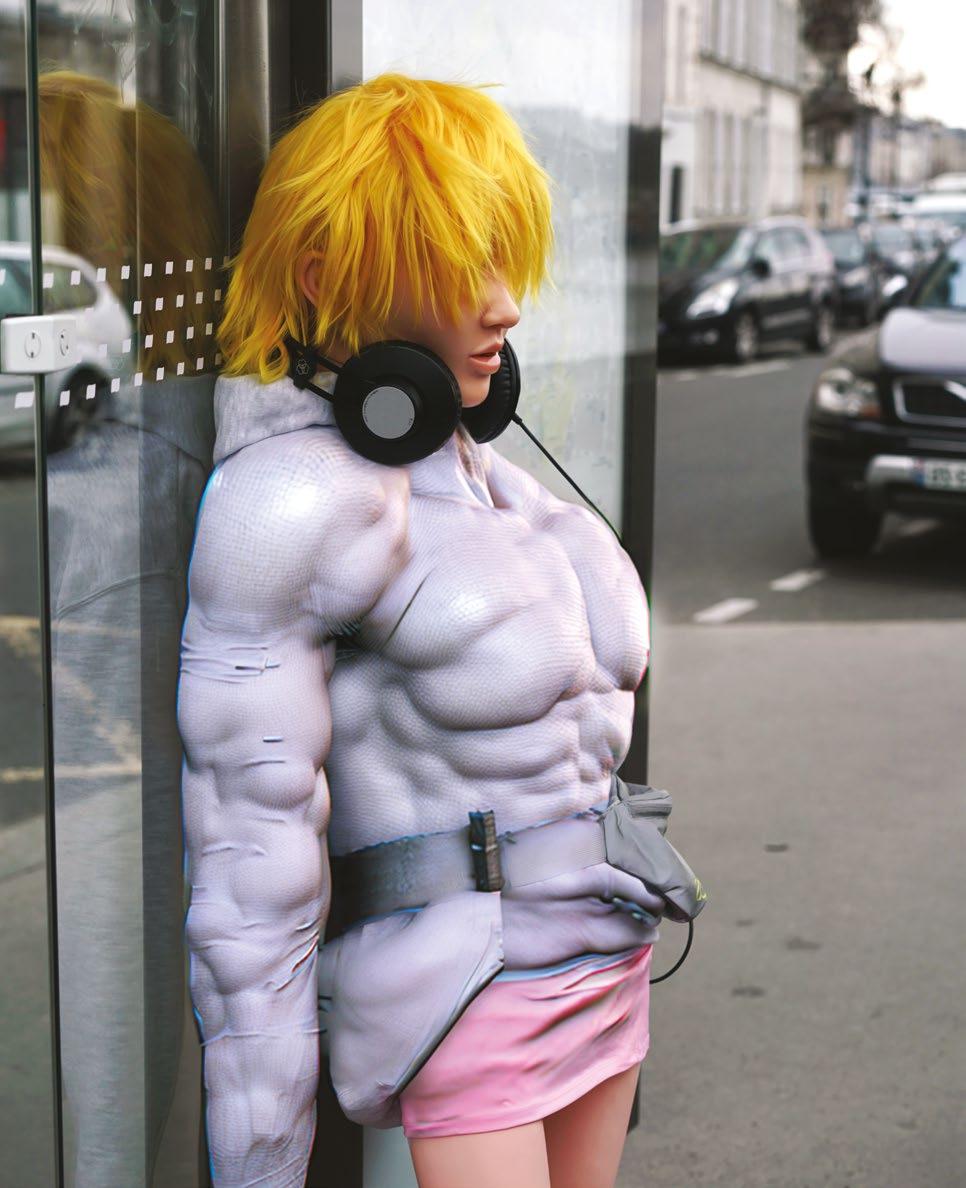

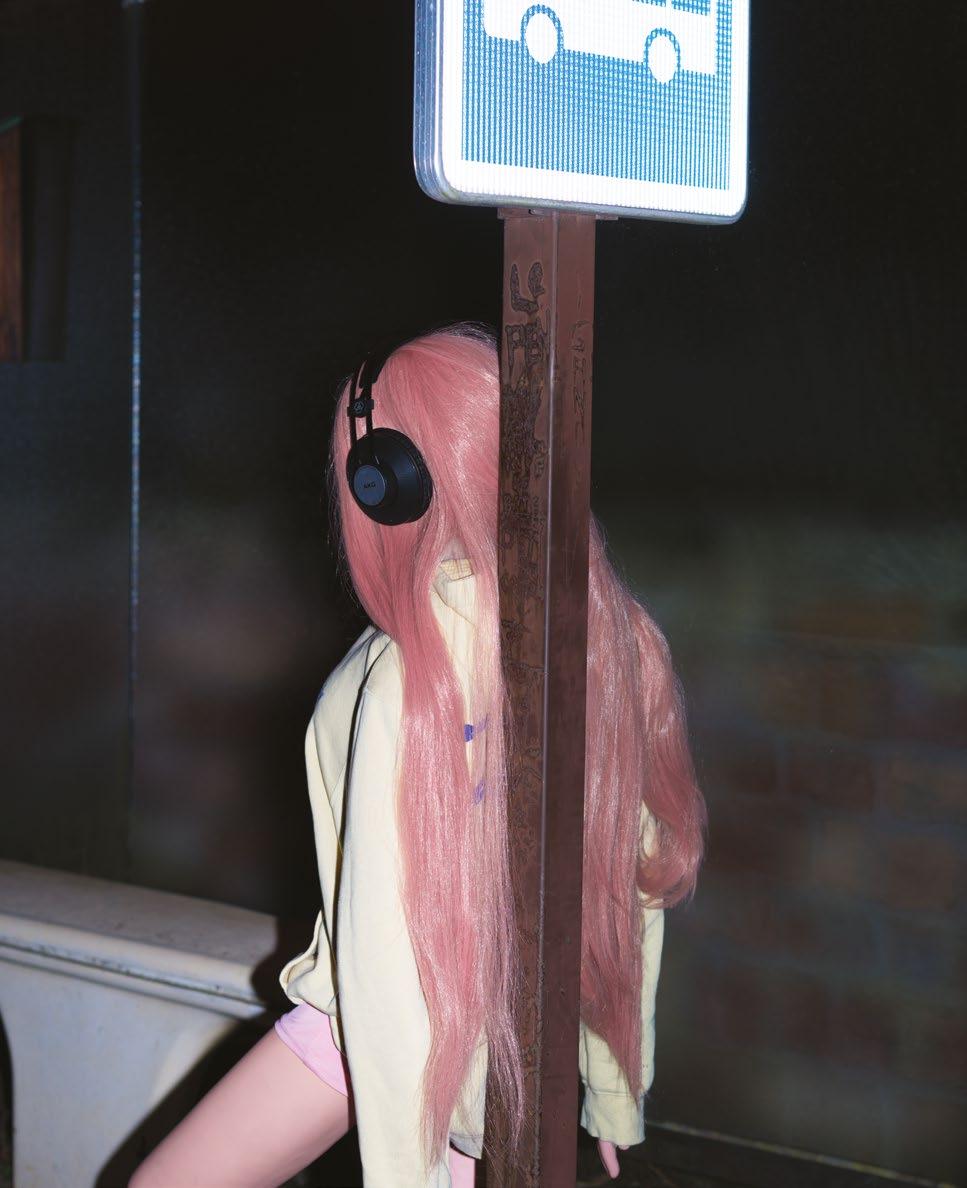

236 Dysfunctional Bauhaus

CELINE HOMME

Spring/Summer 2023

Photography by Davey Adésida

Styling by Julie Ragolia

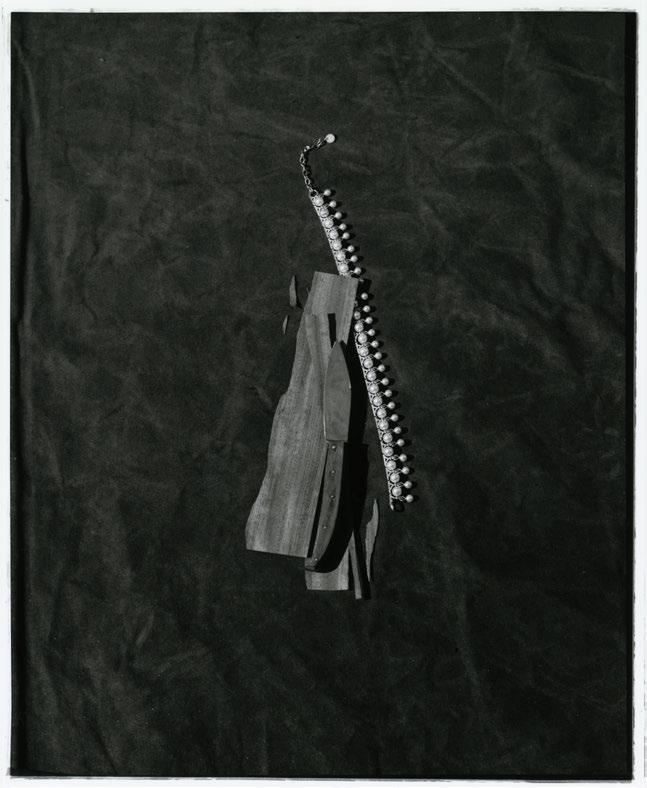

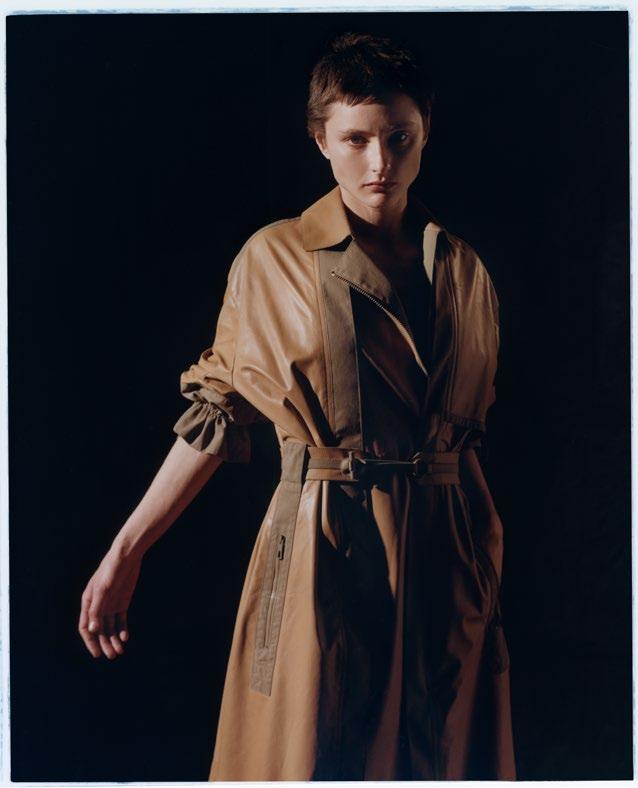

248 Excavation

Photography by Jaime Cabrera Huidobro

Styling by Julie Ragolia

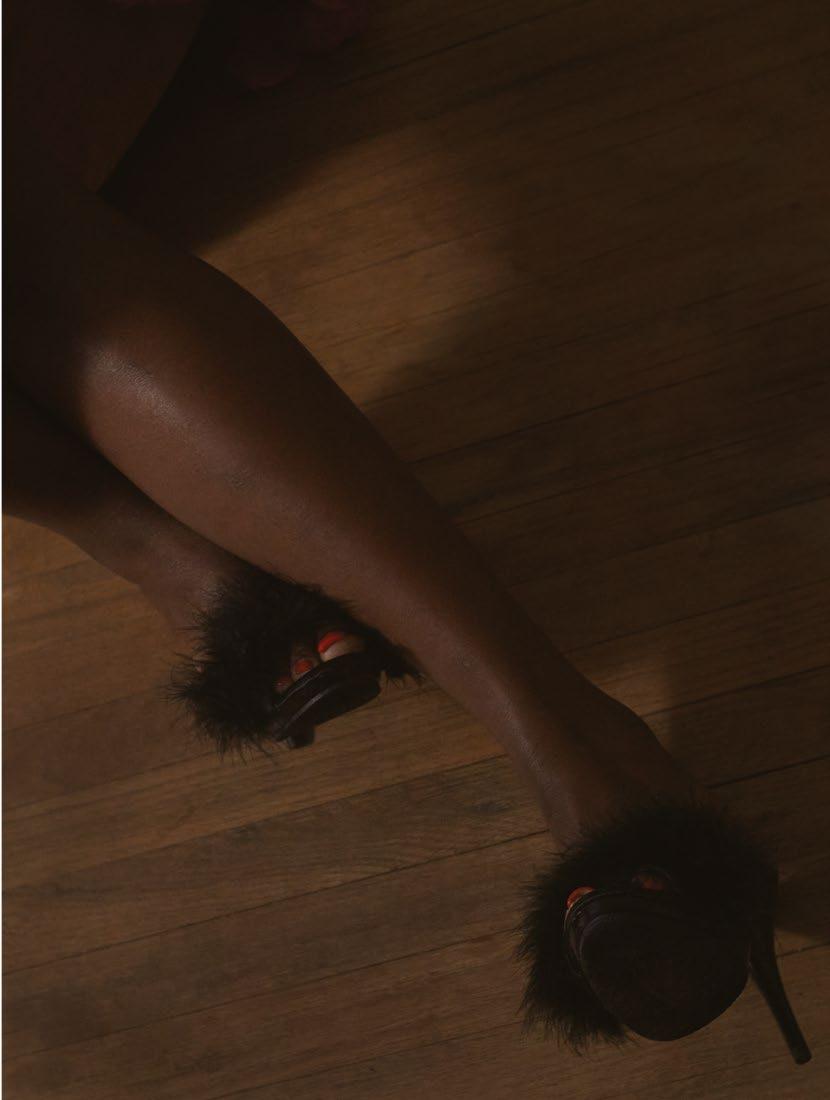

272 My Body, My Pleasure

Gia Love by Katsu Naito

Styling by Julie Ragolia

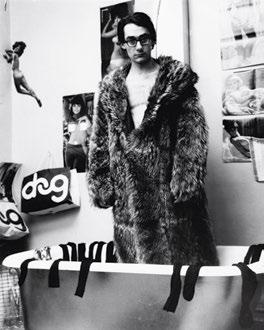

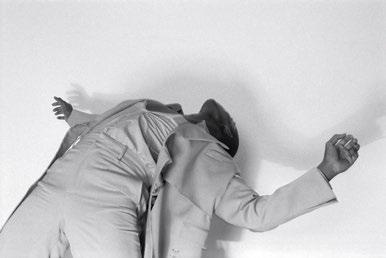

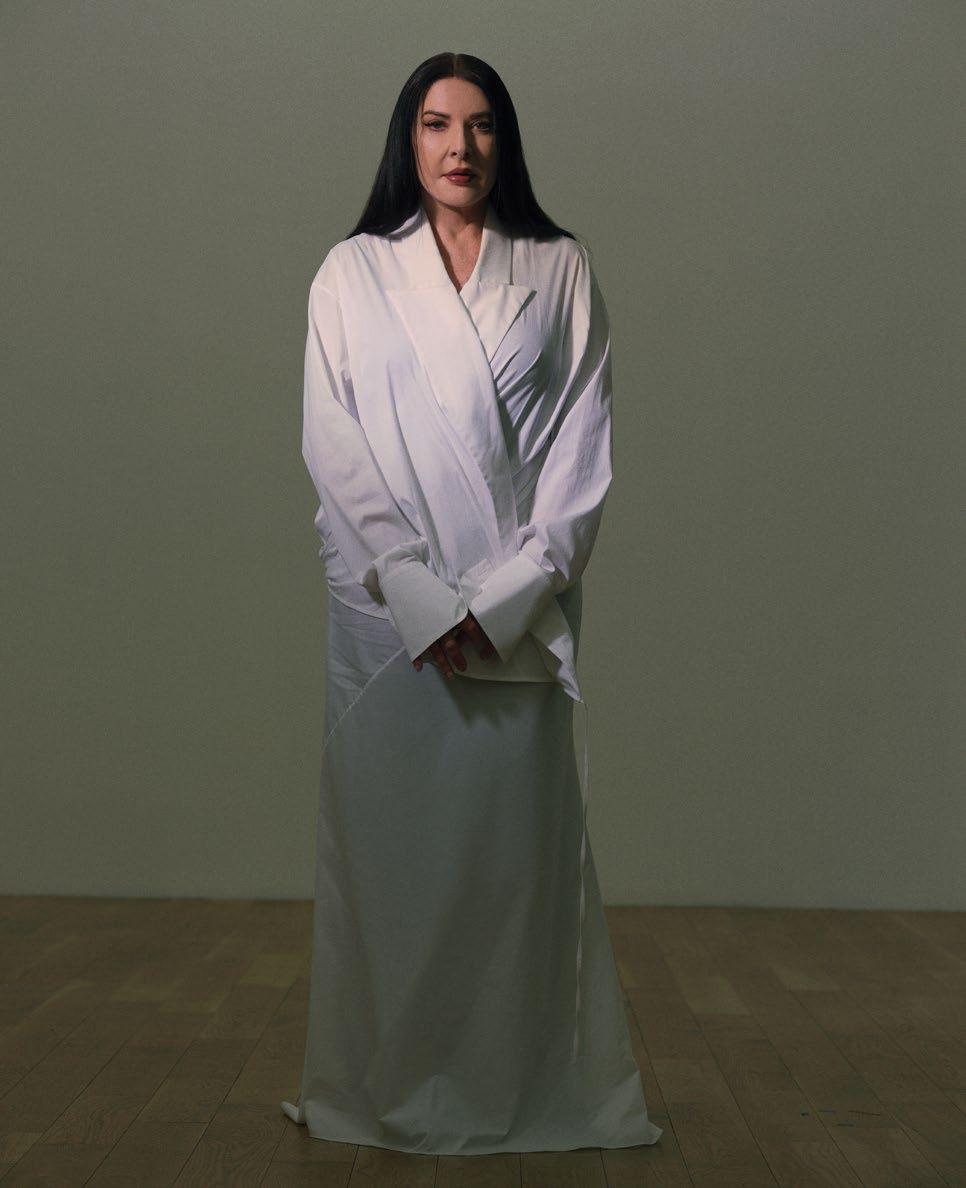

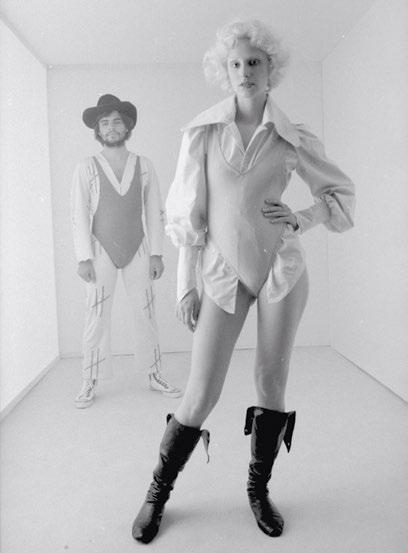

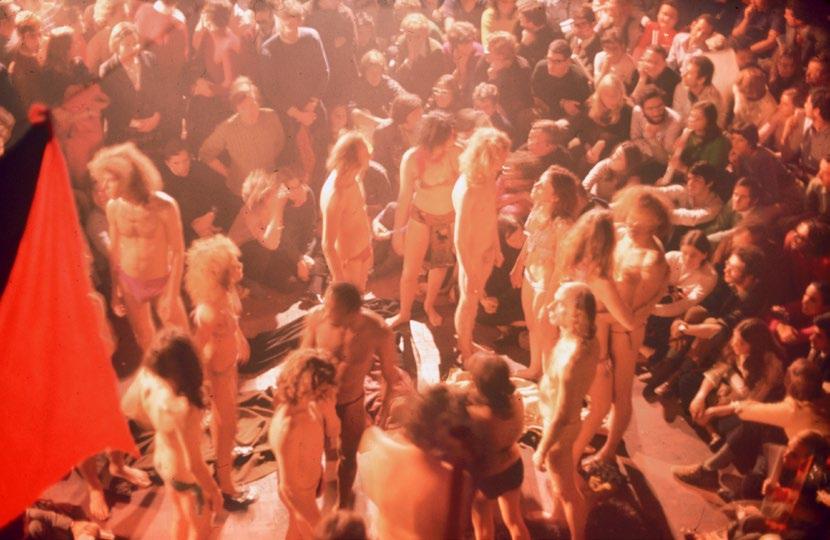

292 Marina Abramović

Interview by Miles Greenberg

Photography by Justin French

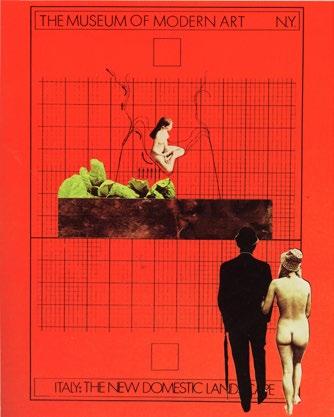

304 Italian Radical Design

Featuring Superstudio, Archizoom, UFO, Gruppo 9999, & Gaetano Pesce

338 In Every Dream A Heartache By Fee-Gloria Grönemeyer

Featuring Jawara Alleyne

352 Craig McDean In Antarctica

328 The Earthly Community

Reflections on the Last Utopia

Text by Achille Mbembe

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Oliver Kupper

MANAGING EDITOR

Summer Bowie

FASHION DIRECTOR

Julie Ragolia

MARKET EDITOR

Cathleen Peters

FASHION EDITOR

Hakan Solak

JUNIOR FASHION EDITOR

Camile Ange Pailler

NEW YORK EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Alec Charlip

ART DIRECTOR

Martin Major

TYPEFACES

Dinamo

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Craig McDean

Damien Maloney

Davey Adésida

Dustin Lynn

Ethan DeLorenzo

Fee-Gloria Grönemeyer

Jaime Cabrera Huidobro

Jason Nocito

Jermaine Francis

Jesper D. Lund

Justin French

Katsu Naito

Kennedi Carter

Kuba Ryniewicz

Lea Winkler

Magnus Unnar

Mat+Kat

Max Farago

Michael Tyrone Delaney

Nan Goldin

Noua Unu

Olivia Lopez

Parker Woods

Pat Martin

Robert D’Allesandro

Vincent Wechselberger

Zoe Chait

CONTRIBUTORS

Abbey Meaker

Achille Mbembe

Angelo Flaccavento

Benno Herz

Charlotte Martens

Dakin Hart

Francesca Balena Arista

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Isabelle Adams

Jay Ezra Nayssan

Jeffrey Deitch

Justin Beal

Kaylee Gibson

Lara Schoorl

Lauren Halsey

Mike Davis

Miles Greenberg

Naomi Miller

Oliver Misraje

Shayna Arnold

INTERNS

Chimera Mohammadi

Rebecca Kremen

SPECIAL THANKS

Bottega Veneta

Clearing Gallery

Dream Factory LA Studio

Future Perfect

Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

Lorraine Two Testro

Marian Goodman Gallery

Max Shackleton

Melahn Frierson

Michael Slenske

Nicodim Gallery

Nicole Mahoney

Nicoletta Morozzi

Perrotin

R & Company

Rena Bransten Gallery

Salmon Creek Farm

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Shamrock Social Club

Stars Gallery

The Noguchi Museum

Thomas Mann House

Uncle Paulie’s Deli

V2_

Verso

Vito Schnabel Gallery

Von Bartha Gallery

PRINTING

KOPA OFFSET PRINTING HOUSE

Industrijos g. 12, Kaunas, Lithuania

www.kopa.eu

OFFICE

AUTRE LOS ANGELES

6711 Leland Way

Los Angeles, CA 90028

GENERAL INQUIRIES, ADVERTISING & DISTRIBUTION

info@autre.love

FOLLOW AUTRE

@autremagazine

www.autre.love

ISSN 2767-7958

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

What is utopia and why does it seduce us? What we learned through the making of this issue is that utopia is antipodal, contagious, fragmented, and holographic. It is a mirror of our repressed desires like a conceptual camera obscura. It is also a work in progress—continually writing itself in and out of history. We have watched utopian movements rise and fall with fascination, but the utopian urge is still forever important, because what else is there? These contradictions are what make the search for paradise so inherently quixotic, elusive, and tantalizing. This issue is an exploration of these edenic visions—past, present, and future.

In the early 1500s, social philosopher Thomas More dreamed of an imaginary island society. Egalitarian in nature, this new world had no war or private property, there was freedom of religion, socialized medicine, and other echoes of communal living. He called this island Utopia; a combination of the Greek roots ‘ou’ (not) and ‘topos’ (place), which translates to nowhere. Even More knew a place like this could probably never exist—not truly, especially in a Europe just waking up from the Dark Ages. But More’s road to nowhere would inspire future societies in ways he would have never imagined. Even before the burgeoning Age Of Reason, these ideal cities, shangri-las, and arcadias have deeply informed the political structures of our contemporary industrialized society—through revolutions, architecture, art, philosophy, literature, design, sex, pleasure, desire, and even our domestic environments. What psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud and philosophers like Karl Marx— and later Herbert Marcuse—knew is that utopia is not really a place, it is a primordial desire, a stand-in for eros, forever trapped inside us as we try to navigate the modern world.

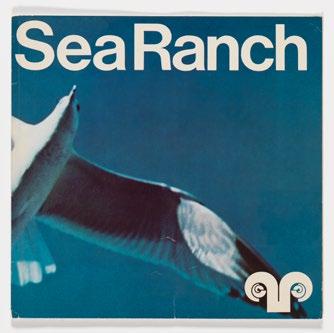

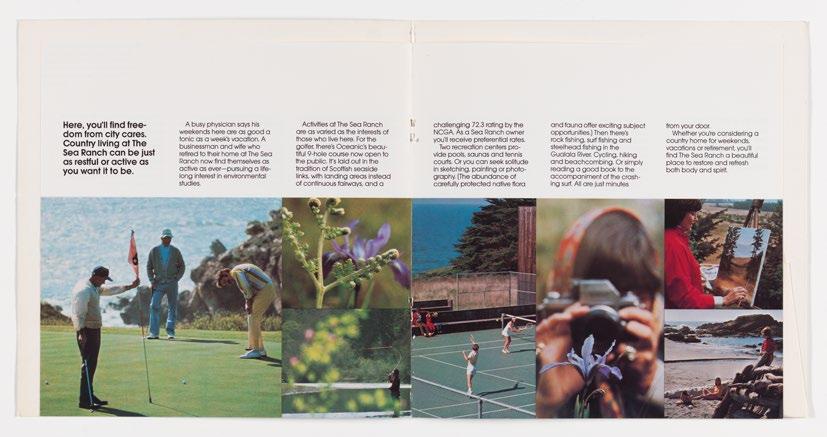

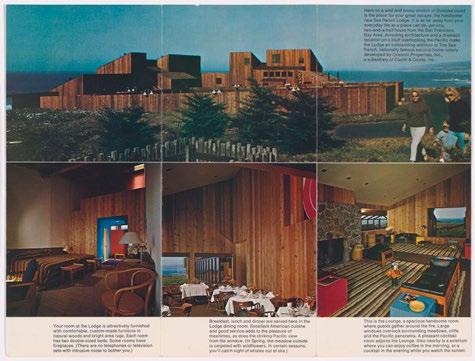

In the 1960s, a new wave of utopian thinking began to swell among young people around the world. The old systems were failing, as the rise of mass consumerism and the ideologies of capitalism were killing them. They experimented with communal living, started radical architectural collectives, and lit the fuse for a psychedelic and sexual revolution. We explore these movements closely. From the Radical Design movement in Italy where young designers waged a war on traditional architecture, to Haus-Rucker-Co in Vienna who attempted to mimic the hallucinogenic experience through mind altering environments, to the California acid modernism of Sea Ranch and the commune of Salmon Creek Farm, which has undergone a 21st-century, queer rewilding by artist Fritz Haeg. We also take a funkadelic journey with George Clinton through a dialogue with artist Lauren Halsey, digging into his Afrofuturist vision of a new, Black utopia.

As the world becomes darker, dreaming of utopia is more important than ever. Our survival depends on imagining a better future, a better world. We invest in our imagination of the ideal, not only because our current reality fails to satisfy, but because the status quo poses an existential threat to our entire species and many others. In an excerpt from Achille Mbembe’s The Last Utopia, we underscore his notion that a radical decolonization of the planet is not a geographically specific concern, but a generational one. In the end, our most pernicious enemy doesn’t belong to any particular party or ideology, it is the seduction of nihilism that afflicts each and every one of us.

— Oliver Kupper and Summer Bowie

The point is not of planning utopias; the point is about practicing them. And I think this is not a question of “should we do it or should we persist in the existing order? It’s a much more radical question, a matter of survival: the future will be utopian or there will be none. – Slavoj

ŽižekUtopia is not a place; it’s a shooting star: it appears suddenly, in the eye of the mind, bright and mesmerizing, mysterious. It demands our full attention before vanishing. Utopia is not a place; it’s a moment in time, a note in tune. Utopia is a transgression. It is a question, a confrontation. It can only exist outside of our imaginations in small gestures. We can’t go there; we can’t live there, and the moment we try, the dream collapses. Utopia is not perfection; it’s freedom. In the tide of our experience on Earth, moments of utopia find us in the awareness of our interconnectedness, of acknowledging our finitude without being silenced by it. For a moment, it liberates us, and with the wind it goes.

There have been periods throughout history when the notion of utopia becomes part of the cultural zeitgeist, contemplated by artists, philosophers, and writers in the realm of an imagined paradise. Marie-Hélène Brousse opened her 2017 lecture entitled “Identities as Politics, Identification as Process, and Identity as Symptom” by arguing the fact that the dominant conception of identity is an ideal identity, whole and stable, unified and intentional (utopia). Contrary to such a view, Lacanian psychoanalysis posits that life is something which goes “à la dérive” (adrift). In other words, the idea of a unified identity is a lie, as the structure of the unconscious goes against the possibility of such a unity. The real utopia—cultivation of identity to oneself and the world around them—is one of quotidian practices. It is not an existence free of antagonisms. Our murky origins and inner workings have depth. From this dusky bloom we come with questions, compelled by curiosity and a need for connection. We follow that drive to dark places, and there we find a lighthouse, the artist. Artists are stewards of meaning, and as I consider experiential notions of utopia, I continually return to the work of Agnes Denes.

Utopia is an offering made by the hands of an artist. It is an act of creation. It is planting a wheat field on two acres in lower Manhattan as the artist Agnes Denes did in 1982. Wheatfield — A Confrontation, was sited on a landfill created when the World Trade Center was constructed in the late 1960s-early 1970s. This artwork was intentionally and aptly placed in the shadow of the towers, a stone’s throw from Wall Street with the Statue of Liberty in view. It yielded over one thousand pounds of healthy amber wheat, and in the months the wheat was maintained—on this property worth billions, representing some of the world’s greatest wealth—a compelling paradox was unearthed, a profound statement on the implications of global commerce, wealth disparity, and misplaced priorities on the culture and condition of the earth itself. Forty years later, this prescient work echoes with overwhelming urgency.

Agnes Denes, whose work has never been easy to categorize, is an artist who has continually engaged with the notion of utopia in tangible ways. Her practice, which investigates philosophy, science, linguistics, and history, is grounded in socio-political concepts and ecological concerns. Her work is motivated by a curiosity about the human mind, how we think, how we evolve, how time changes us, and how previous

generations inform current and future generations. Denes describes her entry into visual expression as an exit from the ivory tower of her studio into a world of concerns. For more than fifty years, Denes has used her work to call attention to and protest damaging systems of power, deteriorating values, and the ways in which our interests, choices, and problems interfere with and harm the whole of Earth’s ecosystems.

Her poetic eco-philosophical work Rice/Tree/Burial, first realized in 1968, began with a private ritual, a symbolic event and declaration of her commitment to the environment and human concerns, namely how one informs the other. Like chapters in a story, Denes began by planting rice. In the 1977 iteration of this work, the ritual was re-enacted and realized at full scale in Lewiston, New York. She planted a halfacre of rice in a field 150 feet above the Niagara Gorge. The site marked the birthplace of Niagara Falls between Canada and the US, twelve thousand years ago. Rice represented a universal substance, that which brings forth and sustains life.

She chained together a series of trees in a sacred Native American forest. The chains symbolized connection, linkage in time and material, and our interference with natural processes. Reorienting these trees created, in a sense, a new ecosystem. Introducing new elements and materials, like a dam in a river, sets a cascading change into motion. The echo of interconnectedness sound.

The final chapter included the burial of a time capsule to be opened in one thousand years. It contained only the filmed responses to a series of philosophical questions that had traveled around the world, and a long letter the artist addressed "Dear Homo Futurus." The contents of the time capsule sym-

“The threads of existence have become so tightly interwoven that one pull in any direction can distort the whole fabric, affecting millions of threads.”

bolized human intellect and evolution, clues as to the values of previous Earth generations.

Though conceptually rigorous, the acts involved in the rituals are everyday practices: hands in the soil, sowing seeds, burying the sacred, the symbolic, total absorption in the mundane. This work reminds us that ideas in the context of art can be more than flimsy imaginative notions, they can be used in the deconstructive remaking of the world. These gestures, the enactment of utopias, will bleed out, soaking our tightly interwoven fabric with new color and texture.

In my exchange with Agnes, she told me, and asked that I share with you, that we must turn around inside ourselves and look through a different window. To make sure we ask the right questions, questions that open the soul. The artist said she wanted to sit down with everyone reading this and start a conversation they would walk away from with a full heart, an open mind, and enough curiosity to kill a cat. I propose that we speak with Agnes, ourselves, each other, the past, the future, through a series of existential questions she buried in 1977:

1. What governs your actions? Do you think there is a force influencing what happens?

2. How do you feel about death?

3. What would you say the human purpose is?

4. What do you think will ultimately prove more important to humanity, science or love?

5. What is love?

6. What would perfect existence consist of?

Text by ABBEY MEAKERBack in 2021, I found myself at the Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by scholar Hashim Sarkis, which sought to answer the question: “How will we live together?” One of the most poignant exhibitions was held at the Danish pavilion, which was completely transformed by architecture studio Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter and curator

Marianne Krogh. In an exposed cyclical system of piping, rainwater was collected from outside and taken on a closed-loop journey through the space. Visitors become part of this system—a poetically visible merging of nature—by drinking a cup of tea brewed with leaves from herbal plants that absorbed the water. Sipping my tea, listening to the calming streams, traversing the city by water taxi through its

KAYLEE GIBSON: What roles do the deep oceans play in our planet’s ecosystem?

DIVA AMON: Our deep oceans are a reservoir of biodiversity, but it goes beyond that—it is a journey through time. Because of their huge size, they provide over 96% of the habitable space on Earth, they cover a vast percentage of our planet's surface, and that size is what really allows them to play such a significant role. They regulate the climate by absorbing heat and sequestering carbon. They provide food for billions with their provision of fisheries. And then, there’s nutrient cycling. Cycling nutrients on the planet is everything … it is life as we know it. It also plays a large role in detoxification. So, we have nutrient cycling, elemental cycling, and really big services like

Interview by KAYLEE GIBSONfamous canals that pour out into the Adriatic Sea, I pondered our planetary water system, and how it links us all. Deep sea marine biologist Diva Amon feels the same obligation and urgency to highlight this link. The deep sea, which is defined as a depth where light begins to fade, is the largest habitable ecosystem of our planet, yet it lies furthest from our reach. Not only does it regulate our planet’s climate at large—it also has the potential to solve some of humanity’s greatest challenges.

primary production. They provide a home for so many animals. There are also so many potential pharmaceuticals that could come from the deep sea. Life in the deep ocean evolved in these extreme conditions: high pressure zones, close to freezing temperatures, darkness, so many of those animals have genetic material that could be quite interesting to us in the future—for pharmaceuticals, or biomaterials, or for industrial agents.

GIBSON: Biomaterials are so interesting. Can you give a few examples of these?

AMON: Sure, there’s a species called a glass sponge, it’s not actually made of glass, it’s made of silica. They look like fiberglass and have these beautiful, intricate structures. These creatures have been used as inspiration to make more efficient fiber optic cables. Another example of biomaterial comes from dead whales. When whales die, they usually end up down in the deep sea where they become food and shelter. Some bacteria break down the

fats in whale bones most effectively at deep sea temperatures, so 3-4 degrees Celsius. These enzymes have been utilized for more climate-friendly laundry detergents because they remove stains at lower temperatures.

GIBSON: These are very new findings and applications, but it seems like there’s still a lot to discover.

AMON: We’re just scratching the surface. There are only maybe thirty of these applications so far. We know probably 1/3 of the multicellular species. They think there are close to 1 million species that live in the deep sea, and about 2/3 of those still have not even been discovered, and that’s not even taking into account unicellular species. There’s so much to be discovered, so much that we could potentially use. All of that life is linked to the functions and the services that keep our planet ticking. There’s this untapped reservoir of potential use and benefit to us that could help with some of the most profound challenges of the future.

GIBSON: Can you predict the potential of those undiscovered species in any way?

AMON: In terms of microbial life, there will be things that are entirely unexpected. And there are single corals that can live for over 4,000 years. Think of how much has happened in human history in that time. There are sponges that live for over 10,000 years. Not only are we seeing new life, but we are also seeing it in new ways. There are these teams in California that have been doing amazing work on bioluminescence, a phenomenon where animals create their own light. In the past ten years, we’ve realized that it’s far more common than previously thought. The majority of the species in the deep sea create their own light, and because of the vastness of the deep sea, bioluminescence is possibly the most common form of communication on the planet. So, it’s really rewriting paradigms, which is what I think we’ll see more of in the coming years. We’re at a pivotal point in ocean exploration, and we’re conducting research in more effective ways, which is leading to discoveries that we never could have dreamed of.

GIBSON: That’s so fascinating.

So, much of our understanding of life on Earth has been linked to our reliance on both oxygen and sunlight, but our deep oceans func-

tion so much differently.

AMON: It wasn't very long ago that we realized there are entire ecosystems in the deep sea that can exist completely in the absence of sunlight or oxygen. A lot of life in the deep sea relies on food from the sea surface: dead animals like whales, plankton, and fish. But about fifty years ago, hydrothermal vents were discovered, and those are these incredible environments where life doesn’t actually use the photosynthesis-related food chain that 99.9% of life on Earth relies on for its existence. Instead of using sunlight as their ultimate source of energy, they use chemical energy. So, there’ll be methane seeping from the sea floor, or hydrogen sulfate, and life has evolved to use that as the starting block of their food chain. You get to those places in the deep sea and they are booming with life.

GIBSON: What do you think this

means for the future of society and how we think about our oceans?

AMON: A hundred years ago we thought of the ocean as this deep, dark place, like a vacuum with no life. Since then, our explorations and discoveries have shifted so many paradigms, allowing us to realize that life not only finds a way, but thrives in these places, changing everything we previously thought was possible. I think that lends itself to life on other planets. If life can exist in these extreme places on our own planet, what’s to say it doesn’t exist on other planets that exist under extreme conditions? It’s really about showing what’s possible and rewriting the laws of biology.

Apart from that, the slightly cynical answer is that while more people are engaging with the deep sea than ever, it’s still not enough. Many people still have this idea that there’s not much to conserve there, and as a result, I worry

Sea Slug.that it’s seen as this final frontier on Earth, which is a very challenging mentality. Economists have a term called the ‘blue economy.’ It’s a real push to harness all the resources the deep ocean has to offer. There’s nothing wrong with that as long as it’s done in a way that is not just sustainable, but also restorative. What we are seeing now with some of the industries that are pushing into the deep sea are attempts to exploit it. Fisheries have been operating for decades in the deep sea and there’s been purposeful dumping in the past, but now there’s an accidental sort of pollution. We’re seeing oil and gas going deeper and deeper, we’re seeing deep sea mining on the horizon, and a lot of those industries benefit from the notion that there’s not a lot of life down there. All of this knowledge is not as mainstream as it should be, so we risk losing species, losing habitats, losing those functions and services that we rely on.

GIBSON: How can we engage the public more? What do you think that looks like?

AMON: That's really the challenging

question. Unfortunately, deep sea exploration and deep sea science is incredibly expensive. It's akin to space exploration. It’s very high tech and very high skill, which means it’s not accessible to the majority of humankind. And that has resulted in it being colonized by a small set of humanity. If we can begin to remove those barriers so that more of humankind can participate in those conversations, we can develop a better understanding of what’s there and how best to manage and protect it. Ultimately, there's a big geopolitical issue here. Scientists have had the privilege of researching these parts of the planet that no one else has seen. I do wish that more scientists would utilize that privilege to the benefit of the deep sea itself. Thankfully, we’re seeing a rise in scientific exploration being live streamed. We're also seeing more mainstream documentaries being made such as it being featured on The Blue Planet. There’s a lot in the works that will bring the deep sea to millions of people around the world. We need to take it to the policymakers who are

drafting regulations now that will be in place for decades, if not centuries, and will be pivotal for our ocean and its management. We ourselves have a big role to play.

GIBSON: It is so wild to me that the International Seabed Authority (an off-shoot agency of the UN) is essentially deciding the fate of the deep oceans. Are they playing an effective role in their protection?

AMON: There are so many issues happening around the ISA. Since 2018, I've been going to their meetings twice a year, and you see in the room that not every country is at the table. They all have a seat, but they're not necessarily present. That is often due to a lack of resources. It’s not considered a priority. Many countries can't afford to send delegates there for three weeks a year. As a result, the voices that tend to be the loudest are the ones that are ultimately going to benefit. Intergovernmental processes are not perfect, but it's particularly glaring at the ISA.

GIBSON: I had no idea until

Diva Amon diving with Manta Rays.recently that permits are being issued to mine the deep sea, nor that the ISA even existed. How likely is it that deep sea mining will happen?

AMON: Very likely, unfortunately. That devastates me. But I think there are so many brilliant organizations doing their best to at least delay it. As of now, the Republic of Nauru, Pacific Island triggered a two-year rule. That means by June 2023, they could be issued an exploitation license and that’s it. Not only is this entirely out of step with much of what humankind is talking about now, but what’s most distressing is the fact that biodiversity loss is the highest we’ve seen within human history, the climate crisis is spiraling out of control, and here is this UN-related body that is essentially trying to kick-start what is going to be an extremely disruptive industry in one of the most pristine parts of the planet. It’s completely at odds with what we should be doing. A lot of people are saying, “Well, we need the metals for the climate crisis.” But that's a band-aid. Let’s not mince words. We’re working our way through the planet's resources and ultimately just finding new things to use and destroy.

GIBSON: If deep sea mining were to happen in just a small area, would that have effects on very large areas?

AMON: We really don't know. A big part of the problem is that more than 99% of the deep sea floor has never actually been visualized with human eyes, nor with a camera. A lot of it is based on modeling. We're using the best

data we can to inform those models, but it's still mostly unverified. I used to work for the University of Hawaii and the contract I was working on was for one of these mining companies trying to understand which lifeforms exist in the Clarion Clipperton zone (between Hawaii and Mexico). We went out on a cruise in 2013, which was the first time anybody had seen that sea floor, and over 50% of the large animals we saw were entirely new species to science. And now, more scientific teams have been observing through CCTV that 70-90% of the species there are new to science. And that's just multicellular species. We're not even talking about microbes. So, we're operating in this real dearth of information, and not just about what's there, but how it might be impacted. If we don't know how the animals will be impacted, we don't really know how the functions and services that we rely on will be impacted. The parts of the planet that have been licensed off in these areas, and there are about eighteen licenses out there, each of them is about the size of Sri Lanka. These are not small places, and we know that all life in the path of the machine will be killed. There will be huge dust plumes kicked up off of the sea floor from the mining machinery, all of the minerals will be pumped up to the surface, they will be separated from the water, and that water will be pumped back into the ocean. That water will have metals, it will be a different temperature, it'll be a different chemistry, and it will essentially be a form of pollution. That's going to create another one of these plumes that has the potential to suffocate animals, or render them blind. The currents have the potential to take these plumes to further areas and the footprint will be much, much larger, and we're not even talking about noise, which travels huge distances in the deep. There’s so much to consider and it's been acknowledged that there will be species extinctions. Ultimately, when those things happen, there will be impacts to the fisheries that much of the world relies on. There’s grave concern about the impacts on the carbon sequestration capability of the deep ocean. There are so many unknowns that it's really worrying to think about an industry on this scale. We should be taking a very precautionary approach. And, if we do decide that we absolutely need these metals for our survival, then

we should start small—just license one entity to begin with, and then do lots of monitoring around it. But that's not what’s expected to happen. There have been thirty-two licenses granted globally, and most of those places don't have protected areas in place yet. Most of those places don't even know what lives there.

GIBSON: Is there anything we can do to keep this from happening?

AMON: That's the real challenge about the deep sea. It’s not like we can go out there and protest. So, the first thing we can do is talk about this, the more people who know about this, the better. Many well-known countries are participating in deep sea mining. France has a contract area, Germany has several contracts, and so does the UK. Apart from that, it's about consumption. The oil companies came up with ‘carbon footprints’ to try to put the onus on us, the individuals, for pollution, rather than themselves. But there is something to be said about living more consciously, and thinking about where everything we buy comes from. Each of us has a cellphone, and those use about sixty different types of metals. So, trying to consume less is important and also pushing for technology that can be recycled more easily, or technology that can be fixed. I think we are seeing those shifts in society. It's just not happening quickly enough. It's a tough one. People aren’t engaging firsthand with the environment of the deep sea, so it’s a hard one to get people on board, even though it’s absolutely essential to us being here.

GIBSON: I did read that Samsung, BMW, Google, and Volvo vowed to not use any metals mined from the deep oceans.

AMON: Yes. Steps are happening. These four major corporations have come forward and pledged to not source any of their production materials from the deep sea, at least until it is deemed to not be destructive. Seeing these big corporations willing to take a stand on this was probably the most hopeful thing that has happened. I hope it really is this pivotal event where after these four, we see more and more coming forward. Ultimately, many corporations know that they are rewarded for good behavior by their consumers, so their leadership in this area has been very refreshing.

Photography by MAT+KAT

Styling by SHAYNA ARNOLD

Photography by MAT+KAT

Styling by SHAYNA ARNOLD

Zamir

Rick

(left to right) Kathy wears Issey Miyake polyester dress, and Shayna Arnold metallic lamé earrings; Seffa wears Loewe steel mini dress.

(left to right) Kathy wears Issey Miyake polyester dress, and Shayna Arnold metallic lamé earrings; Seffa wears Loewe steel mini dress.

Kennedy wears CDLM cotton sateen jacket and washed satin dress, Shayna Arnold metallic lamé sleeves, and cotton spandex and metallic lamé tights.

(left to right) Amandine wears Pucci sequined nylon dress; Mikala wears Pucci lycra dress; Ayan wears Pucci lycra dress. All wear Shayna Arnold metallic lamé head scarf, belt, and leg bands, and Maryam Nassir Zadeh leather shoes.

Tytianna wears Giovanna Flores cotton dress and Maryam Nassir Zadeh stone bracelets.

Denzel wears Loewe nappa calfskin jacket and nappa leather shorts, Shayna Arnold metallic lamé cape, and Adidas sneakers.

Casting: Harper Slate

Models: Zamir Fair, Seffa Klein, Kathy Klein, Amandine Pouilly @ Heroes Model Management, Kennedy Vance, Mikaila O'Conner @ No Agency NY, Ayan View, Tytianna Harris, Denzel Simmons

Denzel wears Shayna Arnold metallic lamé cape.

Nikki Maloof, The Apple Tree, 2022. Oil on Linen. 70 x 54 inch.

Nikki Maloof, The Apple Tree, 2022. Oil on Linen. 70 x 54 inch.

Nikki Maloof’s domestic tableaux are startling and at the same time humorous reminders of our own existence. Bright, prismatic, and dreamlike, her paintings grapple with unexpectedness— freeze-frames before the tragicomedy unfolds. Fragments of a scream before a murder. A foot descending a staircase, a hawk’s talons moments from clutching a dove, a hand behind a curtain. The uncanniness is haunting and visceral. Maloof’s exhibition, Skunk Hour, which was on view at Perrotin gallery in New York, explored a new suite of paintings, many of which feature culinary activity in the home. The title is borrowed from a Robert Lowell poem of the same name. “I myself am hell;” he writes, “nobody’s here— / only skunks, that search / in the moonlight for a bite to eat.” Living and painting in South Hadley, Massachusetts, Maloof’s rural surroundings invite a poetic interiority that is rife with symbolism akin to Dutch still life—the bones of fish on a plate, a dog’s hungry eyes, the artist’s own reflection in a knife blade, her paintings invite us into another, stranger world.

OLIVER KUPPER: Where are you based these days?

NIKKI MALOOF: I live in Western Mass[achusetts]. My husband is from this area originally, and we would visit a lot when we were still living in the city. About six years ago, we decided to move. So, this is where we live.

KUPPER: I love that area. It has a weird, mystical quality.

MALOOF: Very hippie-dominated, kind of arty. But also, the colleges bring a lot of young people, so it's a cool place.

KUPPER: I want to start with your chosen medium, which is still life. I'm curious what first attracted you to the medium?

MALOOF: Well, I went to Indiana University, and it's a very traditional painting school. So, I really learned how to paint from painting still lifes. When you paint something from life, you turn off your brain and you're just doing it. It’s something I would pepper in with other things that I was doing in the past that had more to do with my imagination, and it's just always been there. But, when it came to this body of work, I retreated more into the home as a setting. I started wanting to treat the spaces in a home like a character and not necessarily paint the people that inhabit them. That lent itself to looking to the objects that we surround ourselves with for ways of conveying meaning. I'm very attracted to houses and the things that we compile. I'm always following a little trail of crumbs and one painting will lead to the next. It started with animals, but then it slowly became about our interaction with the domestic space.

KUPPER: I think of the Dutch still life painters and how portraiture completely started dropping out of those paintings in this very surreal way.

MALOOF: For a long time, that kind of painting would not have been the thing that I related to as a more developed painter. As a young painter, I would always walk past those paintings, and it's been an interesting challenge to try and make a still life catch your attention or convey emotion because they're sort of inert.

KUPPER: Even though those paintings are about objects, each object has this deeply spiritual quality.

MALOOF: When I started to look deeper at those works, I became aware

of a whole language that is lost at first when you just think, oh, like fruit, whatever. I find that really intriguing—that there are little messages all the time.

KUPPER: Seafood became part of those Dutch still lifes because of their connection to water. In your work, there are also some symbolic notions of seafood. Can you talk a little bit about the symbolism in your work and about some of the different objects that reoccur?

MALOOF: Painting things like seafood began years ago when I was painting a lot of domestic animals—trying to make stand-ins for us. I was thinking about the way that we interact with animals on an everyday basis. One of the biggest ways we interact with animals is by eating them. It's this relationship where we tend to look away really quickly because it can be a weird reckoning, especially when you look at the industry of it. So, I was thinking I should enter the kitchen because that's where we actually interact with animals. I thought it might be a challenge to make a fish seem emotive, and I wanted to borrow from the realm of the Dutch fish paintings, but make it my own by breathing some weird life into them. Fish are strange because we feel almost nothing for them, but then they look so alive compared to any other thing that we come in contact with. There's a dark humor there—something that’s kind of ridiculous about it all. Also, painting fish and food is extremely delightful, and I think if something seems weirdly fun, there’s usually some reason that you need to go there. If the desire is there, I usually follow it, and then see if it has any repercussions.

KUPPER: There's also this humorous, dark side to a lot of the work. During the pandemic, and also during the Plague, painting started to become very dark and strange, and people started dealing with their emotions in different ways.

MALOOF: Yeah, I'm really attracted to anything that is on the line. All art forms that are one foot in lightness, one foot in darkness are really intriguing. I feel like that's what it is to be alive. Ideally, you want to be on the light side, but that's an almost impossible place to remain. Being a human, there are too many factors to grapple with. So, that tone really makes sense to me.

KUPPER: The title of your new show, Skunk Hour, was inspired by a Robert Lowell poem. It’s interesting to hear about an artist’s inspirations outside of painting.

MALOOF: I've been really interested in poetry since grad school. I look to it for answers in a way that I can't with painting. A poem conveys meaning without telling you exactly what the answer is and I found it very freeing when I realized that you don't have to explain everything—that the artwork takes on a life of its own. I like that Robert Lowell poem because you're basically following him as he drives around his town and notices things. He's describing it and slowly coming to terms with his own mind. It goes from being somewhat light to this intense, dark place. And when you're in a space that's so familiar to you, like your home or your neighborhood, those things do occasionally hit you. That’s the whole point of the show: the realization that there are moments in our everyday lives that are so intense, and we notice them, but they’re always in the background, and then we have to move on. Skunk Hour is like nighttime when we're alone with our thoughts. It’s about the way that we deal with existential experiences in everyday life.

KUPPER: There's this interesting sensorial notion of being reminded of your own mortality.

MALOOF: Yeah! When I moved out here, I realized that when you're a little bit closer to nature, it hits you all the time. You could be walking, and then see a hawk dismembering something, and it makes you think of so many things, but then you just carry on with your day. I wanted to paint those experiences and feelings. As far as other inspirations, I like the more confessional poets, like Sylvia Plath. She is definitely a figure that looms large in my mind. Stylistically I get a lot from her work. She would often take instances from everyday life and electrify them into a kind of psychodrama or operatic grandeur full of darkness and pathos.

KUPPER: And you're sort of in Sylvia Plath territory now.

MALOOF: I am. She is a figure who created under intense pressure … pressure to be a good mother and the pressure of her intense ambition. I relate to those struggles a lot. Under all of that stress her work took shape almost like how a diamond is formed. The facts of her death aside, her art can be a

reminder that sometimes the difficult aspects of life can also be the fuel to a fire that’s within us. I guess that’s a utopian view of art making for sure.

KUPPER: I read about the epiphany you had with this exhibition: seeing a newborn deer in the morning and then a dead neighbor being wheeled out of their house.

MALOOF: That was the craziest day. It was this perfect spring day and so strangely bookended like that. I woke up, was having coffee, and then I saw these little ears poking out of an iris bed in my neighbor's yard. When I went over, it was a brand new, baby fawn. And then, at the end of the day, there was a neighbor of ours who had been ill for a while, and it was just so surreal to see the car drive up and take him away. But homes are where everything happens. They’re full of humdrum experiences— chopping onions, folding laundry—and then they’re peppered in with these very dramatic moments as well.

KUPPER: Would you say there's a sense of psychological self-portraiture, even in the still lifes?

MALOOF: That's really what the goal is—to convey what it's like to feel like laughing and crying on the same day; to exist in that. I grew up playing with dollhouses, and imagined worlds were a big part of my being a child. That has to inform some part of it.

KUPPER: There's also a societal aspect of it where the woman's place is in the home.

MALOOF: There's a residue of that, for sure. I'm from the Midwest and was raised by people who were very patriarchal. We went to school, but while it was clear that you were to get married, there wasn't such an emphasis on becoming a successful person.

KUPPER: The heteronormative American dream.

MALOOF: Yeah, there's tension there with having this type of career and having kids. I'm watching their experience of the world from a different vantage point. I garden a lot, which has made me acutely aware of how we’re not that different from that fawn or any of the creatures we come across. That's another thing that I think about in the work: how do we fit into it all?

KUPPER: Would you say that your work is utopic in any way?

MALOOF: I don’t think of my paintings as utopias, but I definitely think of the act of painting as the closest

thing to a utopia I can imagine. It’s not unlike the way I would arrange a dollhouse as a kid. It’s where I can have everything the way I want it and play with ideas freely.

KUPPER: In your work, it feels like the reality comes from the sense of paradise lost. The apple tree has a very Edenic quality to it. Can you talk about that painting specifically?

MALOOF: Well, I try to grow food all the time here, and I fail at it most of the time, but the orchard attracted me because of how it would work, paint-wise. In a tree, of course, there's birds and bird nests, and I immediately was like, oh, bird nest and then a hawk devouring a bird right next to it. I was thinking about the way that you move a person's eye around a painting, almost like the way that a child would draw a life cycle. This was also the first time I put myself in a painting in probably a decade. Mostly because I was thinking about the way that scale changes meaning in a painting. I made myself almost the same size as an apple to address the way we’re not as important as we think. I feel like that painting hit every note that I was trying for.

KUPPER: There's a strong sense of time in it. It's like a clock.

MALOOF: Time is definitely a thing I don't talk about enough in the work. When you have kids, you suddenly feel like everything is a clock. You're really aware of it ticking, and it's deaf-

ening sometimes. I did it in one other painting called Life Cycles. It's a dinner scene where you follow the fish from an egg to the bones.

KUPPER: There's a sense that you're watching a time bomb of our mortality.

MALOOF: It's something I think about all the time. Does it seem very morbid to you? (laughs)

KUPPER: No, you deal with the morbid aspect of it with a lot of humor.

MALOOF: Humor is definitely the thing that I use to offset all of these intense thoughts—to try and lessen the blow or something. That's where color and paint come in. The meaning comes from finding a way to manipulate this weird material that just is so deeply fun and pleasurable. I want you to experience that as much as all the darker things. There's a lot of levity with paint.

KUPPER: Art can be fun, and it should be fun. That's where the utopian idealism comes from.

MALOOF: Maybe they're utopias and I didn't know it. Do you think they're utopic?

KUPPER: I do. I think they're your own invented utopias.

MALOOF: Maybe they are a place where I can have everything I want, and arrange it just so, and live in it for a while. I never thought of it that way because I don't think our reality lends itself to utopia. Our everyday life is

far from it. It's not the first thing I think about, but I guess it is the place that I go to make sense of it all. So sure, it can be a utopic place.

KUPPER: I think that if you can invent your reality in a painting, and even if they're based in realism, there's still a utopic urge in that creation of a world. There's also this clash—psychologically and philosophically—between your Judeo-Christian upbringing with its heteronormative ideas about one’s place in society and the realization of our own mortality.

MALOOF: There's definitely a theatrical element to it all. The worlds that I create are far from my actual reality. The Judeo-Christian thing isn’t such a big part of it, but there’s always a residue in how you approach things that are based on your early conceptions from childhood.

KUPPER: Where do you think that humor you employ originated from?

MALOOF: I have four sisters, and I'm the middle, so I was probably the one who was trying to make people laugh most of my life. But I've always gravitated toward things that have humor embedded in some way. I think about musicians that do it and I’m always trying to strike a balance with each painting. You're balancing the color, the composition, and the tone so that the song works. Humor is one aspect of that orchestration. It’s putting together all these harmonies and trying to make them work.

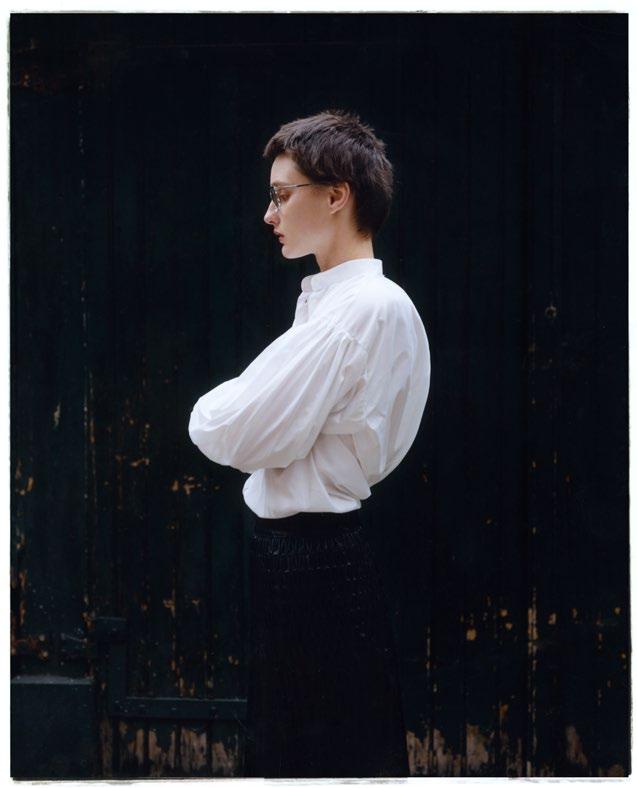

Alexander McQueen polyfaille dress, Hobo jeweled leather bag, Slash leather bag, and metal earrings

Rejina Pyo wool blend jacket; Margaret Howell heavy cotton poplin shirt, cotton linen trousers and tie, pebble leather Doctor’s bag and Rambler’s bag

Chloé Patchwork calfskin leather bag; CELINE by Hedi Slimane Triomphe leather bag; Gucci Jackie 1961 leather bag and Jackie 1961 canvas and leather bag

Lemaire polyamide, linen and cotton parka, cotton poplin shirt, silk and polyamide trousers, metal flask, leather flask, leather flask case, Mini Camera leather bag, Case leather bag, and Croissant coin purse

Acne Studios cotton sweatshirt; Uniqlo U denim jeans; Acne Studios

Musubi leather bags, and Micro

Distortion leather clutch

Model: Alicja @ Storm Management

Hair: Tosh

Makeup: Claire Urquhart

Casting: Tytiah @ Unit C

Fashion Assistant: Flo Thompson

Thanks To Studio Too Young Too Simple

LARA SCHOORL: Do you think it is possible to invent a new type of cyber-utopia outside of the surveillant, capitalist, algorithmic framework?

MINDY SEU: During the Cyberfeminism Index panel at the New Museum with E. Jane, Tega Brain, Prema Murthy, and McKenzie Wark, we tried to trace the evolution of what’s happened from the early ’90s until now. This idea of the utopic internet was very palpable in the ’90s because it was the first introduction to this new technology that promised global connectivity, the ability to be everywhere all the time with those that were not in close physical proximity. However, people quickly began to realize that, while the internet did afford these new potentials, it was also very much guided by the infrastructure that the internet was created on, which was born from the military industrial complex. This ultimately shapes the platforms we use now and the behaviors that these platforms perpetuate: things like surveillance, censorship, and data extraction. In my essay, “The Metaverse is a Contested Territory” for Pioneer Works, my good friend and Cyberfemi-

For over three years, designer and technologist Mindy Seu has been gathering online activism and net art from the 1990s onwards. Commissioned by Rhizome in 2020, the growing collection of text and imagery forms the always-in-progress web database Cyberfeminism Index. By way of a “submit” button, anyone can contribute to the project making both the creation and outcome accessible to everyone. In 2023, the Index was translated to print by Inventory Press and includes over 700 short entries with scholarly texts on the hacktivist utopias of the internet’s nascent years.

Interview by LARA SCHOORL Portrait by LEA WINKLER

Interview by LARA SCHOORL Portrait by LEA WINKLER

nism Index collaborator Melanie Hoff describes what pushes people to imagine is the need to imagine: a survival mechanism to find release from the pressures of your current reality. Some examples of this were given throughout the panel.

E. Jane talked about the liberatory potentials of bespoke and local experimental music communities. Tega Brain talked about projects that consider the materiality of the internet and the physical implications of these seemingly ephemeral networks that we use. There are definitely potentials for how we can begin to think of not necessarily a utopia, but broader views of how the internet might be able to serve more people rather than the smaller minority.

SCHOORL: It seems as though the internet is almost showing us that this need to imagine is universal. Even if the status quo might work for some—arguably it does not work perfectly for any person— the internet has made visible the failures, corruptions, shortcomings, and discriminations of and within all kinds of systems. Perhaps free imagination is not fully possible on the internet itself

now, or not as was anticipated, but it has made visible the need for imagination and change across the globe and all demographic groups.

SEU: Absolutely. And as you are saying, in some ways the internet did allow more people to publish these kinds of narratives online without the gatekeeping of more “legitimate” institutions.

SCHOORL: Typically, things are now translated from print to online, but you did the inverse. What are your thoughts behind turning the online archive into a book?

Something that continues to morph organically through submissions into a more or less fixed, prescribed format?

SEU: Because my background is in graphic design, I have always believed that print and web are very complementary. In Richard Bolt, Muriel Cooper, and Nicholas Negroponte’s “Books with Pages” 1978 proposal to the National Science Foundation, they describe how soft copies are seen as ephemeral and dynamic whereas hard copies are seen as immutable, permanent, or more reputable because of how academia valorizes printed volumes. But, with my

website collaborator Angeline Meitzler, we tried to flip this hierarchy. The book, while it did come after the website, acts like a snapshot or a document of the website’s mutation, whereas the website acts an ever-growing, collective, living index, to grow in perpetuity. Even since we (my book collaborators Laura Coombs and Lily Healey) froze the website’s contents to create the manuscript for the book, the online database has already received 300 more submissions. The book functions as a call to action for the website to continue gathering ideas of cyberfeminism’s mutation moving forward. That said, with my publisher Inventory Press, we made sure the book was included in the Library of Congress. When creating these revisionist histories, grassroots information activism must contend with the perceived legitimacy of “forever institutions” by penetrating it, hacking it.

SCHOORL: Thinking about physical versus online spaces, where do you think safety and accessibility of both people, information and/ or archives, like the Cyberfeminism Index, are better achieved, online or in print? Or does a hybrid environment foster these more widely?

SEU: Generally, especially with people who resonate with cyberfeminism, there is an appreciation for complexity. It is never the binary of this is better than that, but rather seeing the pros and cons of both media and how elements of both can be used to achieve the community’s goals. For example, with print, you do have these connotations of legitimacy, but we also see the rise of sneakernets, which are physical transfers of digital media rather than using online networks as a way to avoid different methods of surveillance. With the web, there is the ability to have a dynamically changing environment that updates over time. The co-existence of print and web allows both to grow.

SCHOORL: I keep returning to the word “hybrid” when thinking about the future. I recognize it in so many of the entries in the Index: William Gibson’s cyberspace, Donna Haraway’s cyborg, E. Jane’s anecdote about us needing air to breathe, Ada Lovelace and Jacquard’s loom, and more. How do you consider a hybrid online-physical point of view?

SEU: It makes sense why people think the internet is ephemeral and accessible; we have these computers in our pockets that have become extensions of our bodies. It is harder to see the physical infrastructures that make this thing possible: fiber optic cables running along the ocean floor, or the rare earth minerals that make up our phones, typically mined in Latin America in places that have very few or non-existent labor laws. Even after our devices die, they are very hard to recycle so they end up in e-waste graveyards in Guiyu, China where people break apart the phones to sell different parts, and the remainder is burned, leading to a very cancerous environment for those who live there. I expand on these ideas in a forthcoming essay called “The Internet Exists on Planet Earth,” commissioned by Geoff Han for Source Type and Tai Kwun Contemporary that attempts to unpack the materialism of the internet. For one of the people who coined cyberfeminism, Sadie Plant, materialism is a huge component of her seminal book Zeroes and Ones (1997). In it, she gives a retelling of techno-history, redefines what technology actually includes, and details the ecosystem in which technology lives.

SCHOORL: Do you think it is possible to be completely inclusive, even if attempted? Is it more conceivable for utopia to be actually plural: utopias? Or, are they indeed meant to literally exist “nowhere?”

SEU: Generally, universalisms cannot exist. The utopias that are evangelized do not account for the many different perspectives and demographics that true equity requires. Rather than thinking of utopia as a space, we can think of utopia as principles. There are principles that could be embedded in our current landscape to benefit the masses, such as file sharing, basic income, open borders. Lately, I

have been thinking about scalability. A couple of years ago, I co-organized an exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery with Roxana Fabius and Patricia Hernandez called the Scalability Project, whose title was borrowed from Anna L. Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World [2015]. Scalability was also a tenant of this year’s Transmediale in Germany. Scalability implies a smooth, seamless, hyper-efficient growth pattern, but the breaking points it reveals inevitably create conditions for change. Legacy Russell writes that “the glitch is the correction to the machine.” Instead of the glitch as an error, it is an amendment, a reexamination of the problem. Another activist and scholar, adrienne maree brown, and her collaborator Walidah Imarisha, introduce the concept of fractalism, the creation of principles for a small local community that can grow as a spiral, with clear mutations at different levels in order to bring in more and more people. It is this idea of constant evolution rather than seamless scalability. We’re embracing glitchiness, bumpiness, and the errant. SCHOORL: I know the project does not aim to define cyberfeminism, but do you have a particular understanding of the word “cyber”? SEU: I think about “cyber” in the context of how it has been used in history and through its etymology. The prefix “cyber” first emerged in Norbert Weiner’s cybernetics in the ’40s. In simplistic terms, it proposed the idea that you are impacting the system just as it is impacting you. It’s all about feedback. Then, cyber appeared in cyberspace in William Gibson’s Neuromancer [1984]. This sci-fi novel was important because it predicted the sensory networked online landscapes that we are very much talking about today. But Gibson’s Neuromancer was also shaped by the white male gaze, with fembots and cyberbabes and depictions of women with assistant or robotic-like roles. He also created a very oriental landscape that is devoid of actual Asian figures. When “cyber” was then fixed to “feminism” to create “cyberfeminism” by VNS Matrix and Sadie Plant in the 1990s, it felt like a provocation for feminists, marginalized communities, or women to reshape what cyberspace could be.

It’s 10:30 PM and we’re much deeper into the Mojave than where we met Ken Layne at the Joshua Tree visitor center. It’s full dark. No stars—yet. Clouds drifted in an hour ago, making for bad UFO-hunting weather, but if we drive far enough east, we might beat the overcast. Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 is playing from the speaker system in his Subaru. “What’s that?” Ken Layne interjects suddenly in his characteristic sandpaper drawl, “It’s very low, it just went out.”

“I saw it,” says Isabelle Adams from the backseat. She’s an LA-based painter and inaugural member of our off-brand Scooby gang. “If you look in the corner near the base of the mountain … oh wait it’s gone.” Michael Tyrone, the photographer, and I strain our eyes to no avail.

“Was it blinking?” He asks, "If it blinks, it’s probably just a navigation light for aircraft.” He tells us that most sightings of unidentified flying objects are easily explained; extraordinary things rarely happen when you’re looking for them. Twinkling lights are usually just planets. Stationary orbs that blink out after ten minutes are probably military flares (the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center carries out frequent training drills nearby). Then, there's an aerial phenomenon that isn’t as easily explained, “now and then you see something that simply doesn’t make any sense,” he says,

“It’s just silly. It’s not dramatic.” The third kind of sighting (not to be confused with the Hyneck’s scale commonly used by ufologists) are experiences so awesome—in the biblical sense of the word—that you brush up against something ephemeral and undeniably original. Ken has only experienced this once in his life. In 2001, he was driving down Highway 395 with his then-wife in the passenger’s seat when they noticed a light to the north. It seemed innocuous enough, though something felt off. It moved erratically as though untethered from the horizon. The pair debated what it might be for a few moments, when suddenly and without warning, it was gone, and in its place was a large, black triangle, about 200 feet in diameter. Its corners glowed and a spotlight emanated from its center, illuminating the desert floor below with a brilliant intensity, like a “great, unblinking eye” as Ken described it. He hit the gas. The car got nearer. But when he pulled to the curb and rushed out, the mysterious triangle was gone, vanished without a trace or residue to affirm its presence.

Life above a fault line can be a perilous thing—the threat of the San Andreas fault swallowing the county notwithstanding, the constant tremors seem to inform the psyche of those living above it. Ken is something of an antenna himself for the murmurs and reverberations of California’s inland desert, picking up and broadcasting

tales of the uncanny to all the lot lizards, and hippies, and hipsters, and occultists who color the landscape. On his radio show and newsletter, The Desert Oracle, for which he has attracted a cult following since its genesis in 2015, Ken adopts the cadence of an old time-y creep show host, but with a folklorist’s edge. His stories—whether they be about haunted petroglyphs, the Yucca Man, or missing tourists—are about the cryptids as much as they are about the people who encountered them. It’s the vestiges of his past career as a journalist, including a stint as a crime writer in Oceanside, that appeals to his more skeptical readers.

Ken grew up in New Orleans but moved to Phoenix when he was in middle school. His formative years in the Sonoran Desert are visible in the structures of his narratives. They unravel like a meandering stroll in the desert—winding, and seemingly aimless, until you reach the open expanse of a question mark where you were expecting a period. It’s that big, looming uncertainty that is so tantalizing; the suggestion that maybe, there really is something out there lurking in the dark. “Storytelling, which is the oldest form of human entertainment, probably after sex and mushrooms, has to involve set and setting,” Ken says to us after pointing out the rusted exoskeleton of an incinerated car next to a sign welcoming us to Wonder Valley, “To tell a story by

a fire is one of the most primal things, a perfect setting. There’s not a lot of hyperbole in a good campfire story, you should just tell the narrative and the place, and everybody’s personal experiences all conspire together to make something greater than the parts.”

We reach a roadblock. Michael suggests we utilize the dim glow of the traffic cone to take some portraits. “We are now officially in the wilderness,” Ken says, stepping out to the dazzling, unobstructed spine of the Milky Way. Izzy and I take turns holding flashlights pointed toward Ken, casting ominous shadows on his face. He’s a natural model. No longer Ken Layne, this is the Desert Oracle in action. His gaze twinkles with a discreet intrigue that softens his otherwise shrouded face. The alter-ego has itself become an integral part of the mythos of Joshua Tree; an archetypical wandering stage that retains fragments of his heroes, like Edward Abbey of The Desert Solitaire and Art Bell. Between camera flashes, Ken tells us about his closest companion, a German Shorthair Pointer dog. It’s a breed of hunting dog that are usually cast away for their aggression, but Ken is drawn to outcasts.

As we get back into his car, I ask Ken about that aforementioned journalistic scrutiny. He pauses a beat, then says, “A story, warts and all, is much more interesting than the kind the UFO fanatics tell, which is something like ‘Oh, a person of the most unimpeachable character, never touched liquor, blah blah blah.’ Like, c’mon. He’s already sounding really weird. When stories gauge the reality of the human condition, they’re naturally more real. They resonate. No one’s trying to sell you anything along the way. No one’s trying to convince you the government is cov-

ering up aliens eating strawberry ice cream in an underground base somewhere.”

“Weren’t you on Ancient Aliens?” Michael asks from the backseat. Ken laughs. “Touché. I’ve repented down in the river for that.” And in his defense, he was only in two episodes. One was a history lesson on the Integratron out in Landers, a cupola structure built by aviation engineer and ufologist George Van Tassel, allegedly capable of generating enough electrostatic energy to suspend gravity, extend our life spans, and facilitate time travel. The other segment was a cultural debriefing on the viral meme about storming area 51 to see dem aliens.

Fans of The Desert Oracle often occupy a more cosmopolitan demographic, which some journalists have attributed to the “escapism” of his stories. Escapism is a misnomer. The appeal lies in the return to meaning and a resistance to the sinking feeling of post-modernity that we are losing our archetypes— the haunted house at the end of the street, knowing how to differentiate between good and bad winds, which roads a ghostly woman in white frequents. I grew up in Sun City, a small town in the desert not terribly far from Ken’s haunts. Like him, my dispositions were shaped by the landscape. I discovered The Desert Oracle in my senior year of college while working on my thesis, a hauntological study of our local monster, Taquitch—a shape-shifting, child-eating, “meteor spirit” that prowls the San Jacinto Mountains. Taquitch originally appeared in the mythology of the Payómkawichum tribes who still occupy the area, but legends persist today. I was interested in the ways these paranormal stories were a metaphorical vehicle for sociological phenomena. The Inland Empire is riddled with poverty, addiction and despair, and as a result, experiences higher rates of domestic violence and lower child expectancies. It is haunted either way you look at it. Ken talked about Taquitch on the twenty-first episode of his radio show. On our way back to Joshua Tree, we make a stop at Roy’s Motel and Cafe, a defunct relic of Googie architecture. While poking around abandoned motel rooms, we discuss the merits of the hauntological approach. Ken ultimately disagrees with the notion of trauma as a prerequisite for a haunting; some things are older than us and more original to this world than we can comprehend. Even so, he is

well aware of the ‘cultural dressings,’ as he puts it, often applied to paranormal phenomena. Take UFO sightings— while observed across cultures since time immemorial, explanations of such often reflect the dispositions of the times. He tells us that there’s nothing actually connecting UFOs to extraterrestrials. The theory appeared in conjunction with the Cold War and the space race. During the Industrial Age, many explained them as the inventions of eccentric, steampunk robber barons. In Medieval times, they were thought to be witches with lanterns hanging from their broomsticks.

The fault line that the Inland Empire (which includes Joshua Tree) sits upon, demarcates it geographically, as well as symbolically. To the Western imagination, it is the ultimate nowhere; a psychic space to project its dreams,

ideals, anxieties, and nightmares. The idea of the desert as barren is a colonial project, one that has historically been used to justify its desecration since the frontier period. We’re driving through Amboy when Ken tells me, “One of the biggest misconceptions about the desert is that it’s barren. Desert means wilderness. It’s Greek, borrowed from the Latin deserto. Not arid, not barren, but untamed, uncultivated wilderness. It’s where Pan ran around in the primal wilderness. Ancient Greece was the desert. Civilization is born in the desert.” The Desert Oracle repopulates the landscape. While his documentation of hibernating birds native to the Southwest might seem mundane in comparison to shape-shifting monsters, it's where his Transcendentalist musings are most poignant, revealing a gentle, more meditative side to Ken.

Cultivating a sense of awe for the desert is an important part of its conservation. Advocates for environmental personhood also seek to reimbue the landscape with soulfulness. In 2020, tractors in Arizona leveled the earth for the construction of the US-Mexico border wall, unceremoniously demolishing 200-year-old Saguaro cacti in the process. The Saguaro are sacred to the Hia-Ced O’odham tribe, whose ancestral grounds lay 200 yards away from the site. After fiercely resisting the construction, the tribe successfully passed a resolution affirming the legal personhood of the Saguaro. In an op-ed piece for Emergence Magazine, tribal member and activist Lorraine Eiler wrote, “When something is acknowledged as a person with rights, it is much more difficult to overlook the infliction of harm. This resolution has brought us one step closer to bridging our spiritual understanding of how to sustain life with the practices of the dominating culture.”

We’re driving down Amboy Road when Ken stops the car. He pulls the keys out of the ignition. The road is empty beyond the receding taillights of a distant car far behind us. “I had us meet up on a weekday because I wanted to avoid the traffic going into Death Valley. You lose the mystery when it’s filled with Audis.” He tells us to watch the taillights until they disappear beyond the bend. We oblige. After several minutes, the lights blink out.

“It’s a long way, right? About ten or eleven miles. One night, I was coming back from Death Valley and I was the only car on the road. Moonless night just like tonight. I’m doing 65 or something. It’s a 55 limit so you’re always watching for that occasional CHP dispatch. Suddenly, I see what seems to be a car’s lights appear, and what I notice in my rearview, is that it is racing, like Roadrunner, Coyote cartoon speed. I'm driving, and my first thought, of course, is it’s a cop, so I slow down, and it keeps on coming up-up-up-up,” Ken says, stressing the word up like a rapid-fire machine gun. “It’s like the brightest high beams, and it comes right up to my ass. So now, I’m thinking it’s just some jackasses coming back from Vegas. I start slowing down to let the car pass me. I’ve come to a complete stop. And it’s still there, just blinding me. I turn around to look out, and this is the first time it occurs to me: the

lights aren’t attached to anything, they're just floating there, and I have just a moment to try and rationalize it, when the lights retreat at the same speed they came up ZUUUUUUUUERRR. It doesn’t turn around. No sound. No nothing. All the way down, until it blinks out in the end.” Ken lets the story dangle in the air for a moment. Beethoven’s Symphony no. 13 opus. 135 plays quietly from his sound system, lending itself to the eerie atmosphere. We stop at Out There Bar in 29 Palms for a nightcap. It’s neon-lit inside and the walls are painted with murals of varying cowboy iconography. The bartender and several straggling patrons look at Ken with a glimmer of recognition. I forgot my ID card at home but the bartender winks at us and says she’ll make an exception just this once. While Izzy and Michael go head to head in shuffleboard, Ken and I drink tequila at a table and talk about the Puritan origins of the environmental movement; how theologians like Emerson and Thoreau saw corruption in all things made by man, so they glorified nature as the true expression of god. When I mention that my father was a pastor, he tells me, “There’s nothing better in the world for maneuvering through life than a semi-educated, literate redneck.” Afterward, the four of us take pictures in a photo booth (Michael sits on Ken’s lap) then Ken drives us to the Joshua Tree Visitor Center where we left our car. On the way, we share stories of our respective encounters with the otherworldly. Michael tells us about a night in Griffith Park when he saw a coyote stand upright on its hind legs and run off into the chaparral. A few weeks later, the tale of the Coyote Man appears in The Desert Oracle.

As Izzy drives us home to our remote outpost in Landers, the absence of Ken is palpable. Peggy Lee croons on the radio and the shadows cast by the Joshua trees look a bit more animated; the world a bit more occupied.

The best place to view Los Angeles of the next millennium is from the ruins of its alternative future. Standing on the sturdy cobblestone foundations of the General Assembly Hall of the Socialist city of Llano del Rio - Open Shop Los Angeles's utopian antipode - you can sometimes watch the Space Shuttle in its elegant final descent towards Rogers Dry Lake. Dimly on the horizon are the giant sheds of Air Force Plant 42 where Stealth Bombers (each costing the equivalent of 10,000 public housing units) and other, still top secret, hot rods of the apocalypse are assembled. Closer at hand, across a few miles of creosote and burro bush, and the occasional grove of that astonishing yucca, the Joshua tree, is the advance guard of approaching suburbia, tract homes on point.

The desert around Llano has been prepared like a virgin bride for its eventual union with the Metropolis: hundreds of square miles of vacant space engridded to accept the future millions, with strange, prophetic street signs marking phantom intersections like ‘250th Street and Avenue K’. Even the eerie trough of the San Andreas Fault, just south of Llano over a foreboding escarpment, is being gingerly surveyed for designer home sites. Nuptial music is provided by the daily commotion of 10,000 vehicles hurtling past Llano on ‘Pearblossom Highway’ —the deadliest stretch of two-lane blacktop in California.

When Llano’s original colonists, eight youngsters from the Young Peoples’ Socialist League (YPSL), first arrived at the ‘Plymouth Rock of the Cooperative Commonwealth’ in 1914, this part of the high Mojave Desert, misnamed the Antelope Valley, had a population of a few thousand ranchers, borax miners and railroad workers as well as some armed guards to protect the newly-built aqueduct from sabotage. Los Angeles was then a city of 300,000 (the population of the Antelope Valley today), and its urban edge, now visible from Llano, was in the new suburb of Hollywood, where D. W. Griffith and his cast of thousands were just finishing an epic romance of the Ku Klux Klan, Birth of a Nation. In their day-long drive from the Labor Temple in Downtown Los Angeles to Llano over ninety miles of rutted wagon road, the YPSLs in their red Model-T trucks passed by scores of billboards, planted amid beet fields and walnut orchards, advertising the impending subdi-

vision of the San Fernando Valley (owned by the city’s richest men and annexed the following year as the culmination of the famous ‘water conspiracy’ fictionally celebrated in Polanski’s Chinatown).

Three-quarters of a century later, 40,000 Antelope Valley commuters slither bumper-to-bumper each morning through Soledad Pass on their way to long-distance jobs in the smog-shrouded and overdeveloped San Fernando Valley. Briefly a Red Desert in the heyday of Llano (1914-18), the high Mojave for the last fifty years has been preeminently the Pentagon’s playground. Patton’s army trained here to meet Rommel (the ancient tank tracks are still visible), while Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier over the Antelope Valley in his Bell X-1 rocket plane. Under the 18,000 square— mile, ineffable blue dome of R-2508—‘the most important military airspace in the world’ - ninety thousand military training sorties are still flown every year.

But as developable land has disappeared throughout the coastal plains and inland basins, and soaring land inflation has reduced access to new housing to less than 15% of the population, the militarized desert has suddenly become the last frontier of the Southern California Dream. The pattern of urbanization here is what design critic Peter Plagens once called the ‘ecology of evil.’ Developers don’t grow homes in the desert—this isn’t Marrakesh or even Tucson—they just clear, grade and pave, hook up some pipes to the local artificial river (the federally subsidized California Aqueduct), build a security wall and plug in the